Fairy tales were much promoted before, during and after the National Socialist period in Vienna and in the whole of Austria and Germany

Children’s and youth literature was regarded as an important tool for influencing young people and inoculating them with the National Socialist ideology by the NS leaders, but they were not the first ones. The Austro-Fascists, who took power in Austria in 1933 by ousting the democratically elected Austrian parliament of the First Republic, cleansed the libraries and schools of “unwanted” children’s and youth literature and promoted a limited selection of pedagogically backward books to entice the young for their nationalistic, fundamentalist Roman Catholic view of the world. Fairy tales and legends, especially Germanic and Nordic myths, were considered appropriate topics for young people by Austro-Fascists as well as by National Socialists in Vienna. Yet the Austro-Fascists were not well-organised enough to come up with a coherent pedagogical concept of creating Austro-Fascist children’s and youth literature. Despite their tightly-knit party structure the National Socialists, who represented a strong underground power in Austria during their time of illegality in the Austro-Fascist period between 1933 and 1938, had no clear-cut view of what a National Socialist children’s and youth literature had to look like as well, when they took power in Austria in March 1938. The only consensual aim was to serve the NS ideology, but the NS representatives of various institutions and authorities followed different strategies to reach this common goal. It is surprising that too blunt propaganda of NS ideology in children’s books, which was for instance offered by fervent former illegal Austrian National Socialist writers, was rejected by the “Reichsschrifttumskammer” (NS Chamber of Writers). Their aim was to influence the young subconsciously via sentiment and emotions without making the intended manipulations too visible. So, in a nutshell, children’s books were to be sophisticated indoctrination tools.

In fact, most skilled and well-known authors of German-language children’s books had fled Austria, were persecuted, or were not prepared to be abused by the regime for its ideological purposes. Consequently, the NS regime lacked gifted writers of children’s literature. The majority of the material produced for the young in this period constituted of easy poems, rhymes and lyrics for patriotic songs and marches, which could be publicly recited and sung individually or in groups at youth camps, party celebrations and in schools. Another important category were handbooks for organising group events, camps, and meetings of the HJ (obligatory membership of all boys in the NS “Hitlerjugend”) or BdM (obligatory membership of all girls in the NS “Bund deutscher Mädchen”), filled with appropriate National Socialist games, poems, songs, sports events, and activities in preparation for war. An important requirement for children’s and youth literature was its facility to be read in public and not alone. Reading material was supposed to promote NS group activities; stories and rhymes were supposed to be read out loud by mothers, teachers, youth leaders to enthuse the young for the ideas of National Socialism. Book worms were not appreciated, on the contrary, reading alone in your room was seen as dangerous subversive treason. Jews, who the Nazis staged in their xenophobic propaganda as the worst enemies of Hitler’s “Third Reich”, were characterised as bookish, learned, reading alone in their study rooms; all negative characteristics for the Nazis, who promoted a fit, sporty and outdoors group spirit of the “young German”.

Herta on her third birthday on 24 November 1936 – she was an avid reader of picture books already then (left), and hiking in the Vienna Wood with her mother, Lola (right)

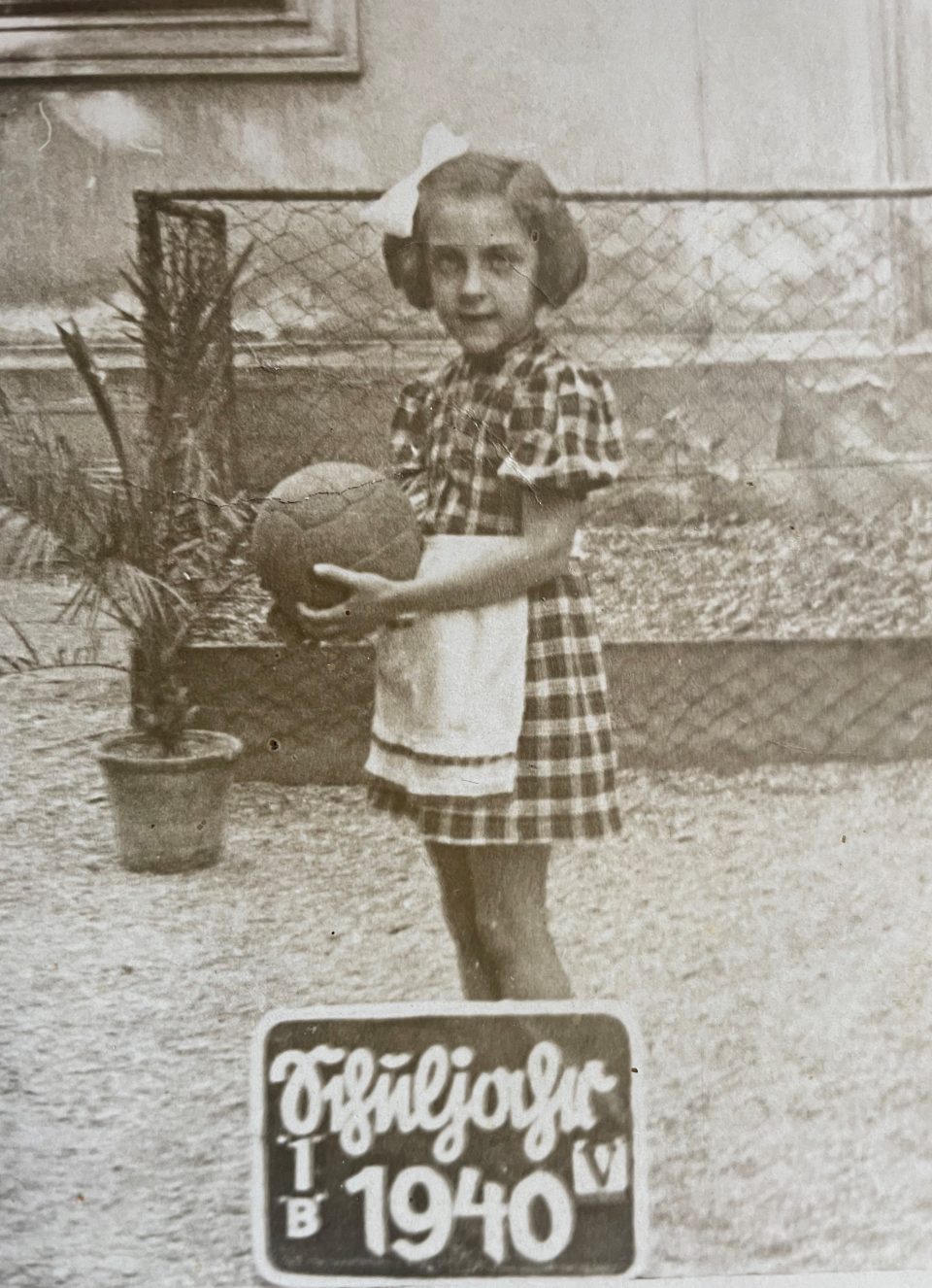

Herta Kainz, my mother, was exactly such a bookworm; a shy withdrawn little girl who was born in Vienna on 24 November 1933 and started school in September 1940 in the midst of NS terror in Vienna. Her mother, Lola Kainz, was a born Jew who had converted to Roman Catholicism when she married Herta’s father, Toni Kainz. Herta was an only child who was much loved and cared for by her parents and her family, but she had to live under very precarious conditions because of the Jewish origin of her mother and her mother’s family. Herta was brandished a “Mischling 1. Grades” (a first degree mixed-race child) and excluded from all activities “Aryan” children were supposed to participate in. Her father Toni, who stood by his wife and daughter during these trying times, had been dispossessed by his family, innkeepers in the bourgeois Viennese district of Währing, and was working as a fishmonger. He was drafted by the Nazis and participated as a sapper in the German military campaigns Of World War II in France and Poland before he was considered “unreliable” by the Nazis, because he refused to divorce his Jewish wife and was transferred to the home front working as a fishmonger in war food supply.

Herta’s mother, Lola, was constricted to do forced labour in the war industry. Herta as a small child had to watch the deportation of her beloved grandparents, Ignaz and Josefine Sobotka, and the exclusion, stigmatisation, and discrimination of her mother. Lola was for instance not allowed to go to a doctor or hospital or to enter the school building, where Herta started primary school. Herta was supposed to sit separately in the last row to mark her out as an “inferior mixed-race child”, who was not allowed to participate in any school festivities. Only thanks to the altruistic commitment of her young teacher, Helene Pfleger, who ignored the NS regulations risking her own career and life, the needs of the children, including Herta’s, were put first in Ms Pfleger’s classroom and not NS ideology. Herta and her teacher stayed in contact all their lives and Herta was for ever thankful to Ms. Pfleger for the love and care she had given to her. At home Herta was in constant fear of a knock at the door of their small two-room flat in Mariahilferstrasse, because that could mean that SS men were coming for her mother. Already as a small girl she knew she had to run for help to her father’s fish shop as soon as her mother was deported by the Nazis. This threat and this fear remained deep in her psyche for a long time. As a result, stories and books became her rescue haven; a dream world she could withdraw to from the terror of the real world around her. Her books and the diary she started to write after the war are the primary sources of this analysis of children’s and youth literature during the Austro-Fascist, National Socialist and post-war years in Vienna. As her family was poor, she owned very few books and those were second-hand books. What is more, buying at an antiquarian’s was the only chance to acquire books which were not on the NS lists of recommended books.

The main source of reading material for poorer children were public libraries, where the lending of books was usually free of charge for pupils. In 1878 the first two public libraries were opened in Vienna, followed by several workers’ libraries before and after World War I, which were founded by workers’ associations that wanted to promote the education of the Viennese working class. The Austro-Fascists closed the workers’ libraries in 1934 and after eliminating “unwanted” books from these libraries, reopened them. In 1938 the Nazis cleansed the libraries of all Jewish and politically ostracised authors, who had not already been eliminated by the Austro-Fascists, and renamed them “City Libraries”. Immediately after World War II the Viennese public libraries were opened again in 1945 and stocked with books, some of which provided by the Allied liberators, mostly by the Americans. But many of the old books remained on stock or were re-edited with slight alterations omitting crass racist passages and blunt Nazi ideology.

Herta during her first school year 1940 and after the war on the balcony of the family’s new flat on Lerchenfeldergürtel in the workers’ district of Ottakring

Second-hand bookstores, where Herta’s parents bought the few books for her they could afford during and after World War II

Austro-Fascist period 1933-1938

When the Austro-Fascist regime took over in Austria in 1933, the educational system was immediately restructured along the lines of Austro-Fascist ideology, which meant that the Roman Catholic Church was granted extensive influence on the education of the young, as opposed to the secular education system during the Austrian First Republic. Between 1920 and 1933 the Social Democratic city government had modernised the part of the educational system that was in the hands of the federal Austrian states, excluding higher education which was regulated by the conservative Christian Socialist Austrian government. They restructured kindergartens, primary and comprehensive schools in Vienna along the lines of Maria Montessori and Otto Glöckl, the innovative city counsellor for education. In contrast, the new Austro-Fascist laws stipulated that all pupils had to attend religious instruction if they wanted to pass their A-level exams. The access to higher education was restricted for girls, who were destined to be future housewives and mothers, as the Austro-Fascist regime propagated an outdated conservative model of femininity. The official cultural policy focused on pre-revolutionary ideals, meaning before the French Revolution of 1789, such as the Austrian Baroque and the period of fighting against Turkish invaders in 1529 (1st Turkish siege of Vienna) and 1683 (2nd Turkish siege of Vienna). The main aim was the suppression of the so-called “cultural Bolshevism”, as the Austro-Fascist Ernst Krenek labelled Social Democratic ideas. This cultural policy demonized all modern art disciplines and condemned them as “Communist”. In 1934 this retrogressivity is characterised by the Austrian writer Robert Musil, who said that it was not the evil spirit, but the evil spiritlessness that pervaded the Austrian cultural policy at that time. In this reactionary atmosphere more than 100,000 children’s books were eliminated from the libraries of the Social Democratic youth organisation “Kinderfreunde”, which were closed down in 1934. The discrimination of Jews became pervasive in this era, along the lines of Karl von Vogelsang, one of the ideological fathers of the Christian Socialist party, and Othmar Spann, who promoted the racist policy of excluding Jews from all spheres of public life. Such politicians prepared the ground for the open violence with which Jews were confronted in Vienna after the take-over of the Nazis in March 1938.

National Socialist period 1938-1945

Immediately after taking power the National Socialists ostracised all Jewish writers and removed their works from all public and school libraries. From 1938 until 1945 the Austrian educational system ceased to exist and the school system and educational policy was directed by the Ministry of Education in Berlin, which had an enormous impact on the children’s and youth literature read in Austria and on the many Austrian writers who wrote for young people and often worked as teachers as well. From 1930 until 1945 most of the literature for the young was imported from Germany. The only exception was the series “Wiener Klassenlektüre” (Viennese class literature), which had been published between 1920 and 1930 and offered around 10 booklets of works of famous writers for every school grade and could still be used in class in Vienna under NS rule.

The main goal of the National Socialists was the education of the young to produce obedient and convinced supporters of Adolf Hitler and the National Socialist regime. Already before the outbreak of World War II the indoctrination of the young was initiated on all levels possible, starting with the family, followed by compulsory National Socialist youth organisations and schools and last but not least children’s and youth literature. Intellectual skills and knowledge were definitely not in the focus of National Socialist educational policy, but sports and fitness in preparation for war and unconditional obedience to the party and the rulers. The Nazis tried to arouse the emotions of children and young people by continually staging grand party events and ceremonies, hero worship, memorial days, torchlight parades, seas of flags and flag salutes. All such ceremonies were ubiquitous in the whole “Third Reich” down to the smallest hamlet; in schools, in youth organisations, in the media, and in families. Unnoticed by the young, they were continuously indoctrinated by the National Socialist party in a comradely and friendly way; they were offered competitions, entertainment, and distraction. The NS policy tried to offer the “German youth“ everything they might be looking for: role models, community spirit, pleasure-oriented sensual activity, self-esteem, elite consciousness, national pride and racist superiority. All this was only for the “Aryan youth” and excluded all other young people; those of Jewish origin and other minorities, foreigners, or children of political adversaries. Symbols such as flags, fire, flourish of trumpets, blood and pathos were key to the Nazi ideology for the young. It was important for the Nazis to reach out to the young as soon as possible and confront them with and captivate them with central NS topics such as “Aryanism”, German nationalism, racism, allegiance, elitism, fighting spirit, ancestor and hero worship, veneration of motherhood and peasantry and the German claim for new settlement areas in the “East” – the earlier the better. That is why from the start the Nazis planned the designing of picture books for the very young, which conveyed these NS ideals. In a playful way children were supposed to learn what makes a good National Socialist. These authors did not refrain from the most atrocious racist clichés in picture books, fairy tales, legends, and school books in order to make the “young Germans” feel as members of the “Herrenrasse” (master race) and to incite hate against Jews and other minorities. In achieving this aim the Nazis strictly separated the sexes: girls were to be good housewives and mothers who gave birth to as many children as possible for the “Führer” Adolf Hitler and the boys were trained to be fighters in “his war”. The Nazis exploited the fact that children were most easily influenced and consequently children and adolescents were most affected by the NS propaganda machine and their lives were most radically changed by this criminal regime. Adults had had a life before the NS take-over, they had a job not necessarily linked to party organisations, but children were born into the NS regime, they attended NS schools, NS youth organisations, they watched NS films and as a result their whole lives were permeated by NS ideology.

It can hardly be imagined how difficult the lives of Viennese children were, who did not fit into the NS category of “Aryan” children. The persecution of Jews in Vienna was especially brutal, violent, and merciless and those who could not flee, ended up in concentration camps (KZ). But there were also those like Herta and her parents, who remained in the city because they felt no need to emigrate as they falsely believed the “Aryan status” of one family member protected the whole family.

After the deportation to the KZ Theresienstadt of her Jewish grandparents, who had lived with Toni, Lola and Herta in the tiny flat after being chased from their own flat for being Jewish, Herta was in continuous fear of her mother being deported, too. She was not allowed to tell anyone what was being talked about in the family and how they tried to survive under these terrible conditions. Their contempt of the NS regime was not to penetrate the four walls of their home. At school no one was supposed to know that they were sending parcels to their grandparents in the KZ Theresienstadt, no one must know where her aunts and uncles had emigrated to, no one must know that they were yearning for liberation by the Allied forces and no one must know that they were listening to Allied radio broadcasts, a “crime” which was punished by death. The Viennese Nazis especially targeted the assimilated Jews, such as Lola’s family. The reasons for this excessive violence probably lay in the fact that the Viennese assimilated Jews had formed an important part of the Viennese society and had completely merged with the rest of the population. As a consequence, finding a justification for this disproportionate hatred was more difficult for the Viennese Nazis and most of all, there was more to gain from integrated middle-class citizens via “Aryanisation”, i.e. expropriation of Jewish citizens by the Nazis. So, it is no wonder that Herta was a very shy, silent and withdrawn girl. But she was not lonely because she had her loving father and mother and she had one friend, called Herta Schörg, who was a wild, brave, and unruly adopted child – the contrary of Herta, but an outcast, too. She stood by Herta during all this time and spent a lot of free time with her. They were neighbouring children and were very close until adulthood. She would never have betrayed her friend Herta because she was “mixed-race”. Her adoptive parents were a nice couple, who loved their adopted girl, but were sometimes unable to cope with this wild creature. Herta Schörg had toys which Toni and Lola could not afford and my mother was only too happy to stay at her friend’s flat and play with her. At the time of fierce anti-Semitism in Vienna it was unusual for a couple like the Schörgs to be happy for their daughter to play with a “mixed-race” child and to welcome her warmly. My grandmother Lola was not too glad about this friendship of her daughter because she feared the unruly girl would get shy Herta into trouble, yet this never happened. My mother Herta was the silent bookworm and at home Herta spent most of her leisure time reading as soon as she had learned to read, while Herta Schörg, on the contrary, was an outdoors girl, who was rather interested in roaming the urban wasteland of the neighbourhood.

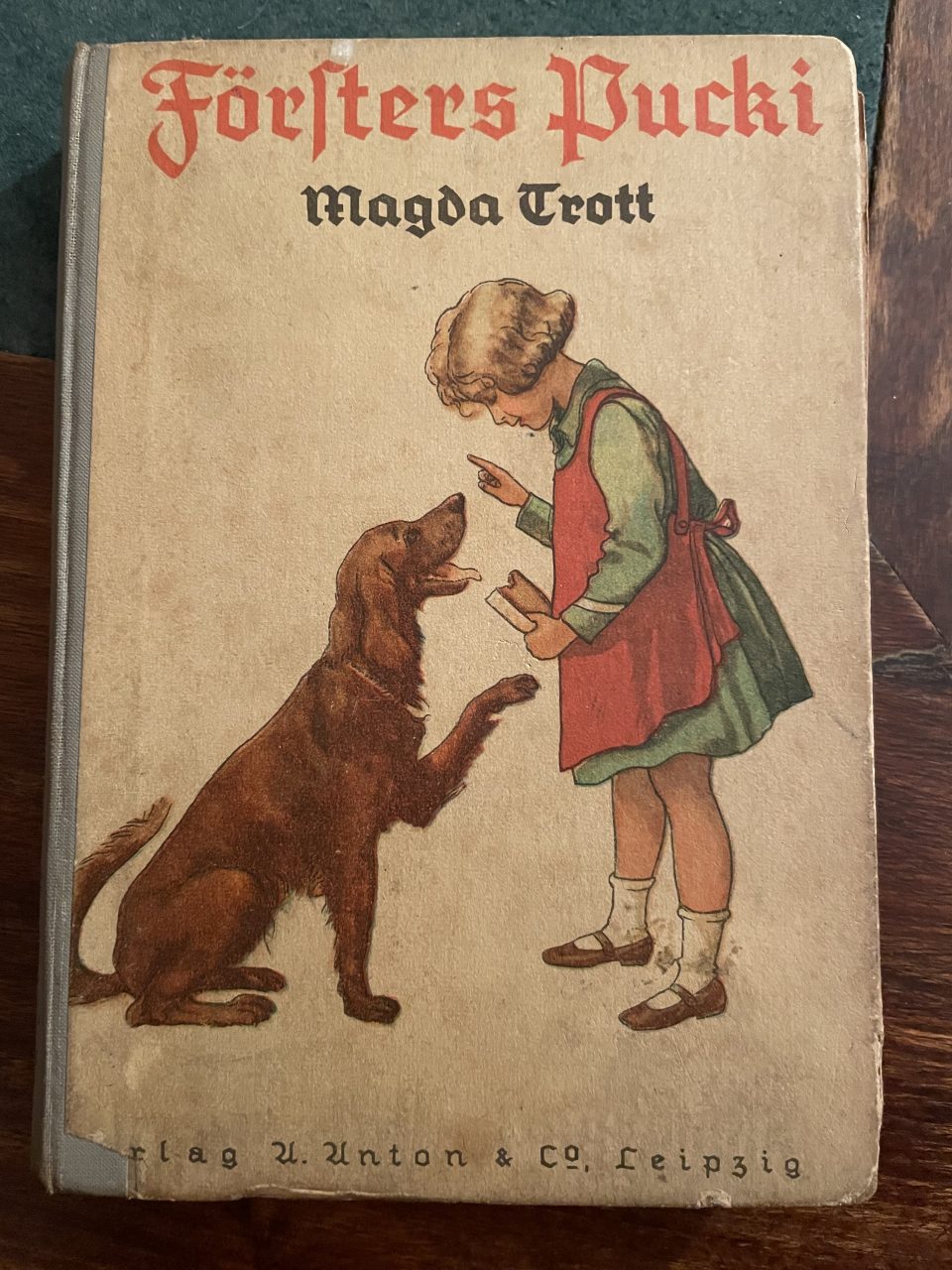

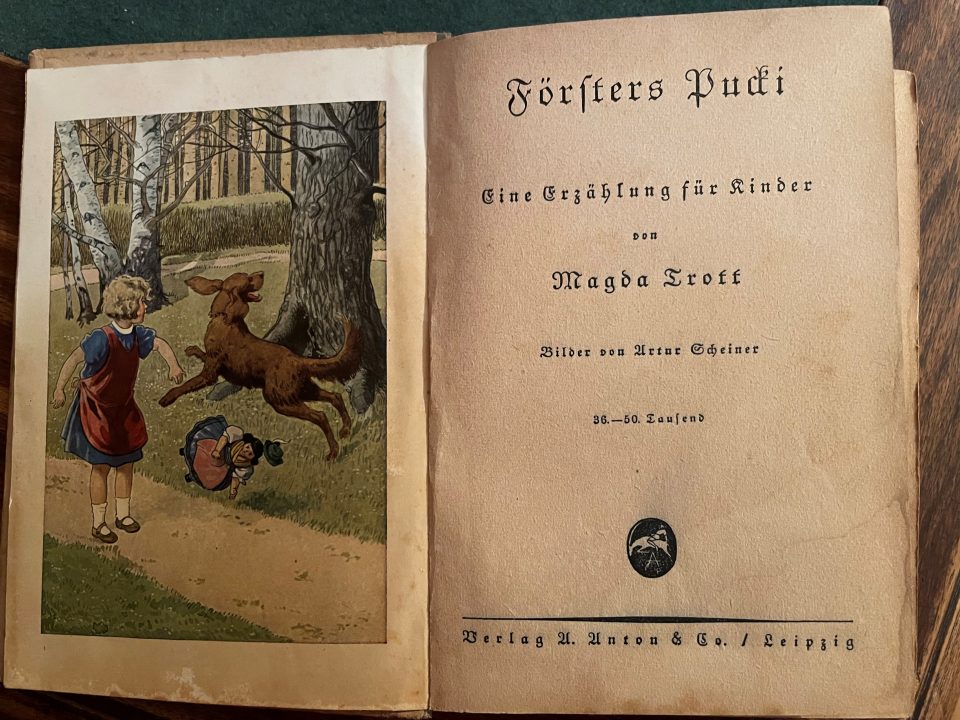

“Försters Pucki” by Magda Trott was one of Herta’s favourites. Magda Trott was a popular and prolific German authoress of trivial children’s and youth books, born in 1880. Some of her books were put on the list of “unwanted” literature by the Nazis in 1933

Several NS authorities and institutions in Germany and Austria tried to streamline the available children’s and youth literature by censoring books, drawing up lists of books, which had to be eliminated or even burned in hideous public book burning ceremonies. They listed recommended literature and awarded book prizes for NS appropriate young people’s literature. Yet there was no proper coordination between the different NS institutions, the Ministry of Propaganda, the Ministry of Education, the Youth Leadership, the public libraries and various party organisations, and therefore no consensus could be reached. NS censorship was characterised by stark arbitrariness. Overall there was just one certainty, namely which books and authors had to be definitely obliterated and scrapped from all libraries: works of so-called “traitors and foreign peoples” , “Marxist and Communist” literature, “pacifist” books, for example Erich Remarque, books that propagated an independent Austrian state, “Free Mason” literature, works that praised “entartete Kunst” (modern art in Nazi-speak), works which dealt with sexual pedagogy and sex education, so-called “Zivilisationsliteratur” (literature of civilisation), such as Erich Kästner, Heinrich Mann, Bertolt Brecht and all Jewish authors, for example Stefan Zweig, Arthur Schnitzler etc.

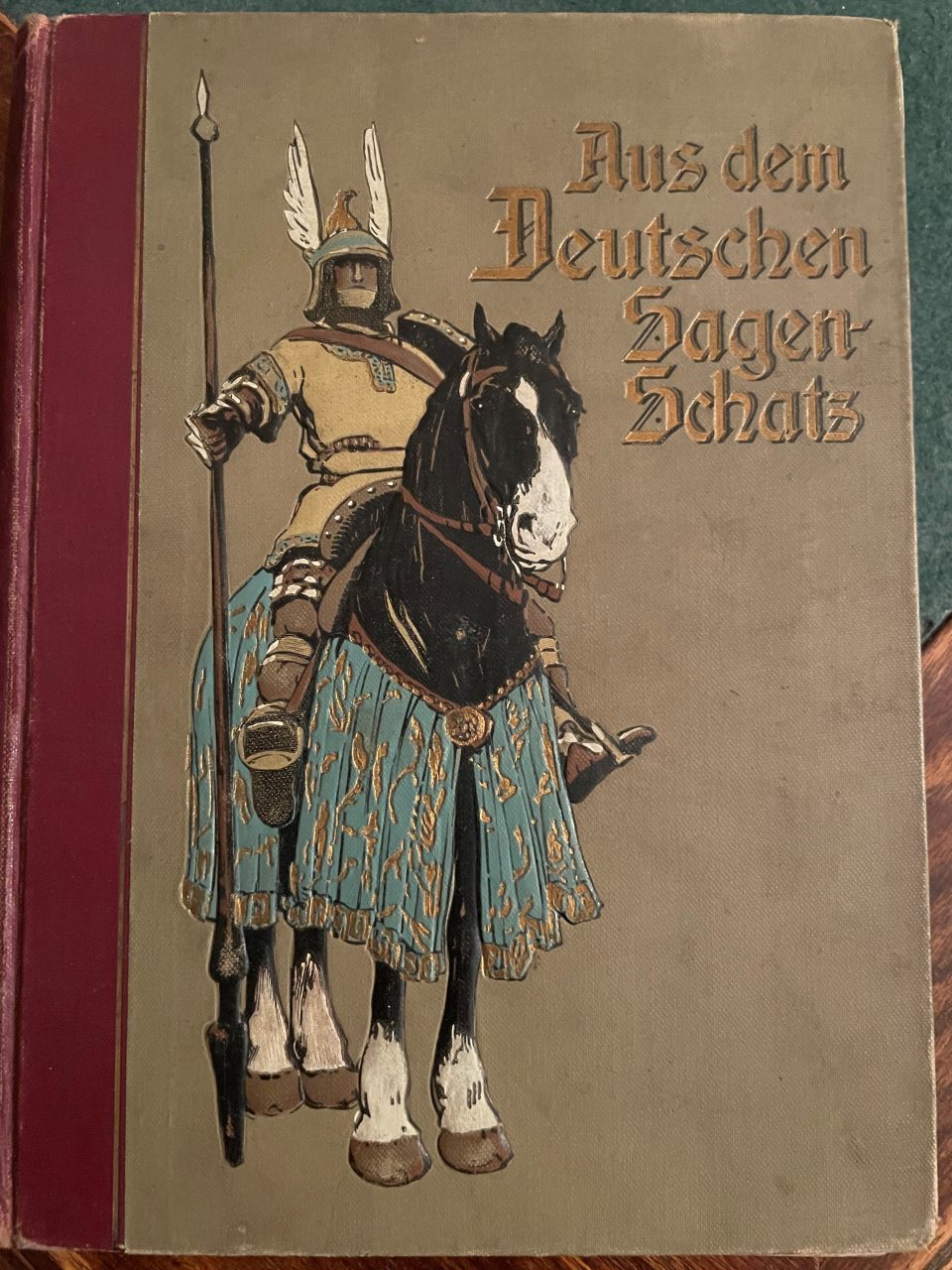

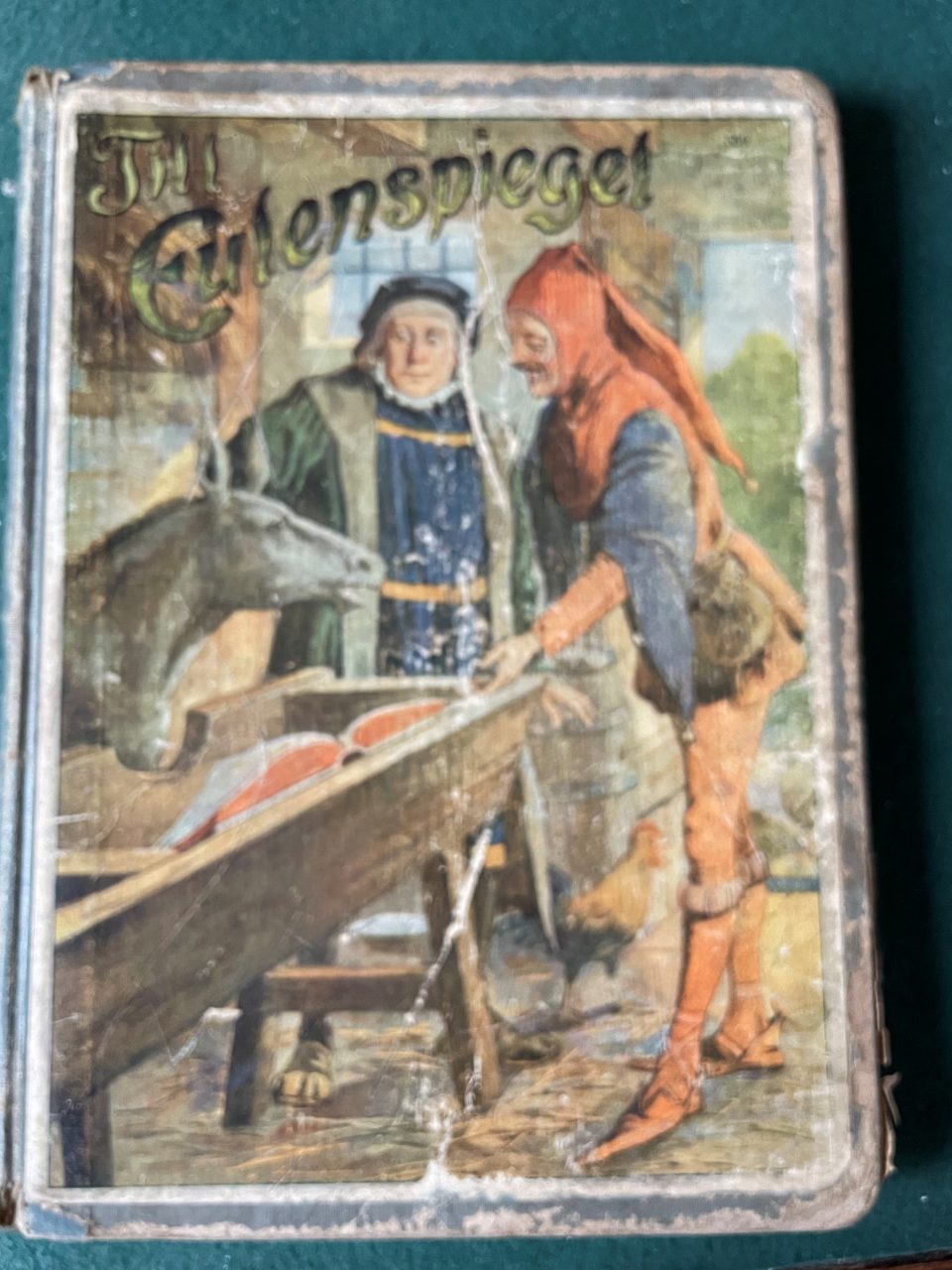

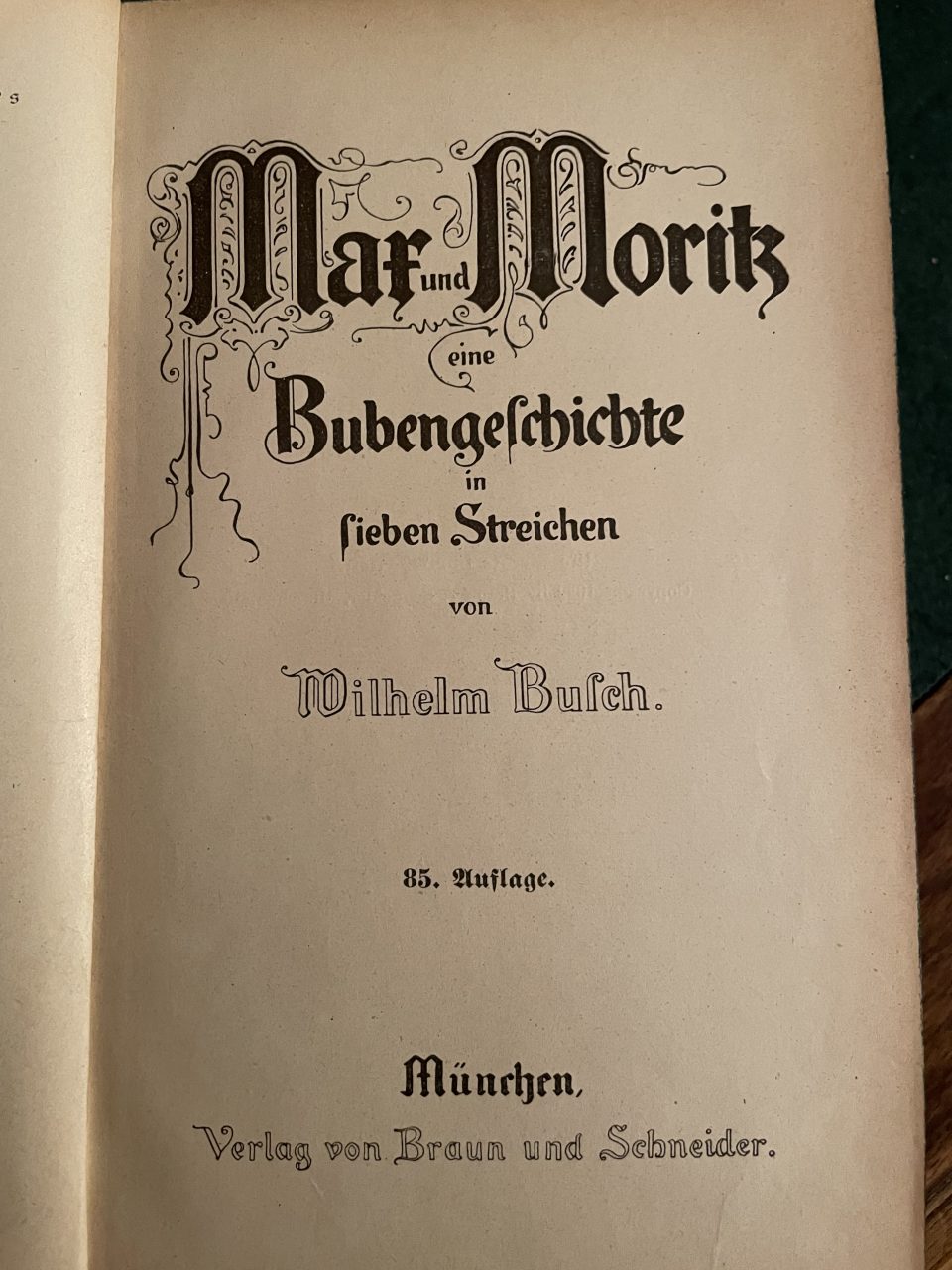

In several cases NS enthusiasts executed censorship way beyond the official regulations and applied assumed NS censorship rules for children’s and youth literature excessively; quite often these were Austrians, who were fervent NS supporters and often felt they had to compensate the “deficiency” that they were not born in the “Altreich” (“Germany proper”). They not only cleansed the libraries radically and at high speed of all “unwanted” literature, but also produced some embarrassing children’s and youth books that advertised NS ideology in a crass way. On the other hand, there were not only those teachers who were responsible for excessive NS censorship at school libraries, who outperformed NS politicians, but also those teachers who ignored NS regulations as best they could and kept some of the books which were on NS black lists in school libraries. All Catholic and worker’s libraries were closed by the Nazis and most of the books destroyed, only the NS conform books were transferred to school and public libraries. Despite various discrepancies the NS guidelines for recommended children’s and youth literature to which all Nazi authorities could agree, were the following: handbooks for organising games and sports events of NS youth organisations, books that aroused enthusiasm for German legends and German heroes, German landscape and peasantry, for adventures in faraway countries and stressed the yearning of all Germans worldwide to be integrated in the “Third Reich”; furthermore literature that dealt with plants, animals and the love of nature and the innovations of technology, old German or Nordic fairy tales, legends, and popular books, such as the picaresque novels of “Till Eulenspiegel” or “Max & Moritz” by Wilhelm Busch.

Picaresque novels “Till Eulenspiegel” & “Max und Moritz”, appreciated by the Nazis

Literary and aesthetic criteria were of no importance for the NS selection process of appropriate literature for young people. What was essential, was a focus on the representation of children as part of the German ethnic community, a preference of the countryside to the city, which was considered a place of dangerous libertarianism, a guide to self-reliance of children, because they were not to be spoilt at all costs, and finally a willingness to take responsibility and to act for the National Socialist cause. Eduard Rothemund, responsible for children’s and youth literature in the National Socialist Teachers’ Association (“NS Lehrerbund”) stressed that books on Adolf Hitler, Hermann Göring and Horst Wessel, National Socialist heroes, were to be promoted, as well as books on German history, the Prussian king Friedrich the Great, the First World War, German battles, German colonies, Nordic legends, German peasantry, and German natural landscapes. Of course, history was only presented from the point of view of NS historians. At the centre of the literature for the young there had to be the concepts of “Rasse, Blut und Boden” (race, blood, and land; meaning a racist view on history, ancestry, bloodline, and the aggressive claim of the Nazis for new settlement areas). All this, including war literature, was designed to prepare the boys and girls for war and their roles in it. That is why the market for historical children’s and youth literature was large, but it was still a market ruled by demand and supply and there are no numbers available how many of these pronounced National Socialist children’s books were really bought by private persons and not just distributed by the NS authorities to public and school libraries. Furthermore, as soon as the war started, an enormous lack of paper hindered the printing of books recommended by the Nazis. So, families had to buy books for their children in second-hand bookstores, where it was difficult for the Nazis to execute censorship effectively.

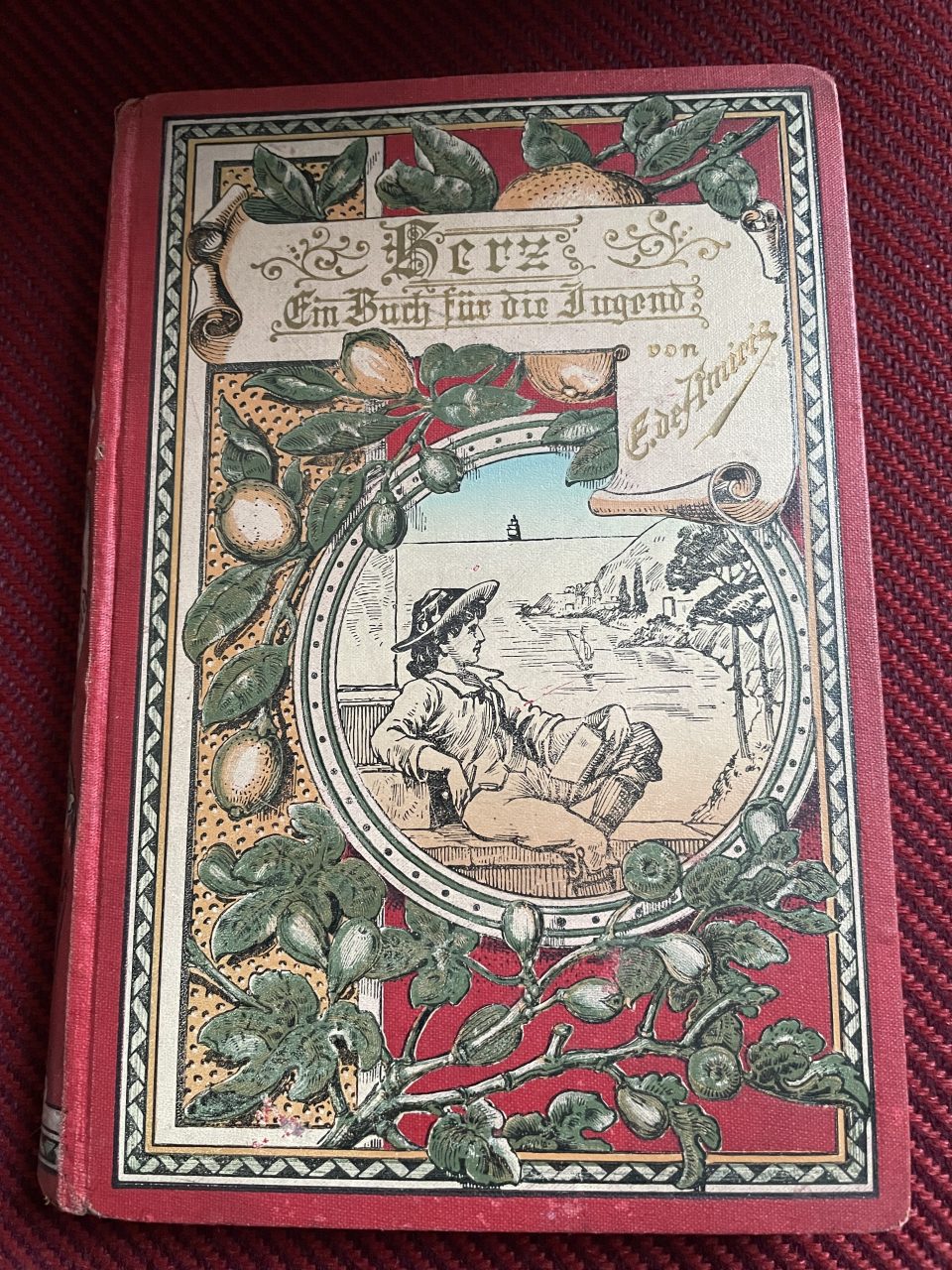

Left: “Herz. Ein Buch für die Jugend”, a book for adolescents decorated with acorns and oak leaves, a symbol of the Nazis

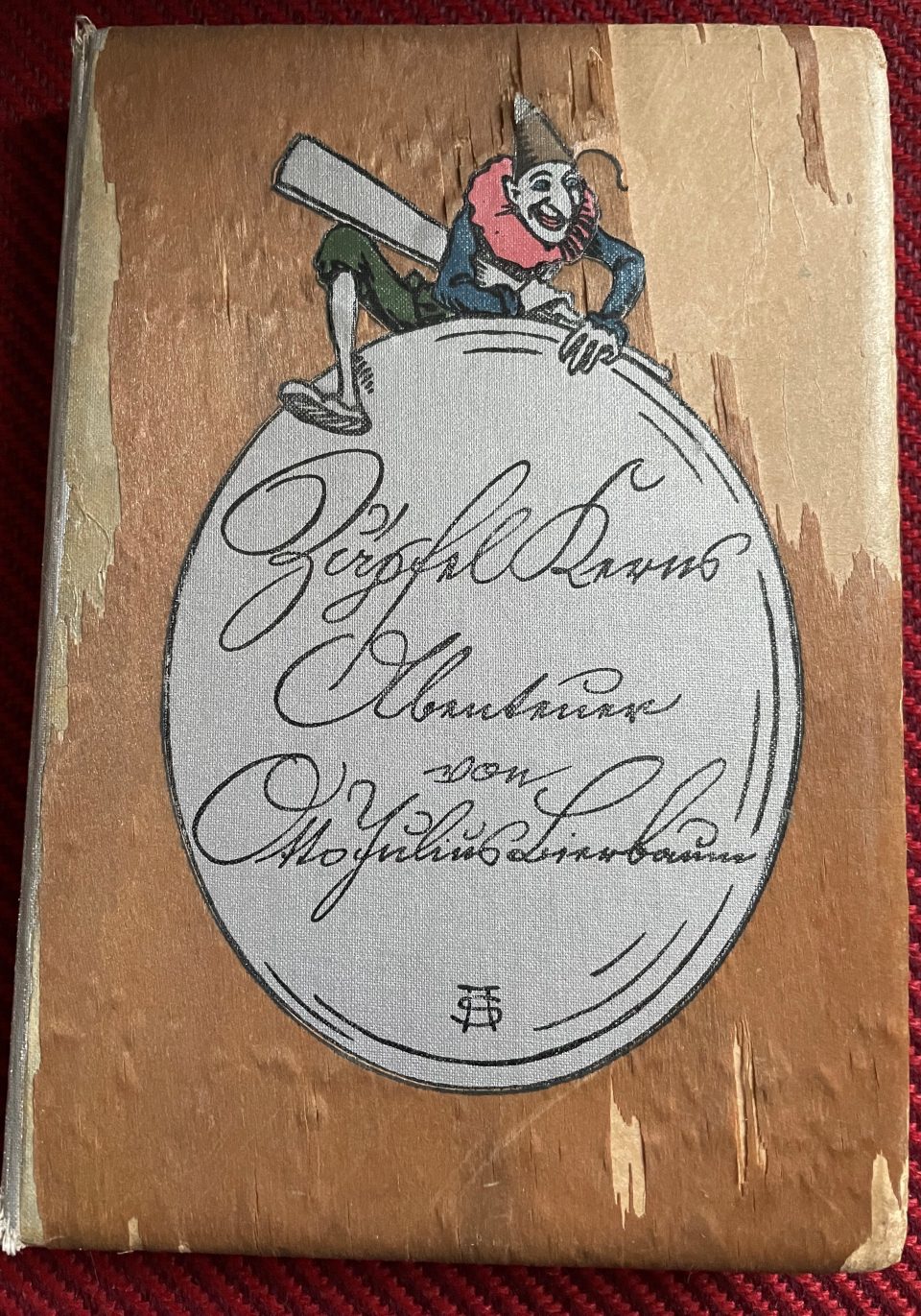

Right: A book printed in Gothic font, promoted by the Nazis, with adventures of “Kasperl” (Punch), a favourite NS character, here called “Zipfelkraus. Abenteuer von Otto Julius Leierbaum”

Initially the Nazis despised the very popular cheap “Groschenhefte” (“penny dreadful”), superficial and light entertainment cheaply printed, and prohibited their use for the education of children and young people. But in the course of World War II they changed their mind on the initiative of Goebbels’ Ministry of Propaganda and even started to publish a series of “Groschenhefte” for girls to enthuse them for the war, the “Mädelbücherei”. The Nazis had to make further concessions as in times of war the population was yearning for harmless entertainment, while due to NS cultural policy light entertainment literature was scarce or even unavailable. So, this gap had to be filled to keep up the spirits of the population, and ironically, German translations of English language literature were suddenly printed, which catered for the taste of the German public and met their need for apolitical romantic or thrilling entertainment, contrary to Nazi propaganda against the Allied forces, the USA and Great Britain. These books for young people were bought by many parents for their children, and they remained popular in Vienna long after the end of the war.

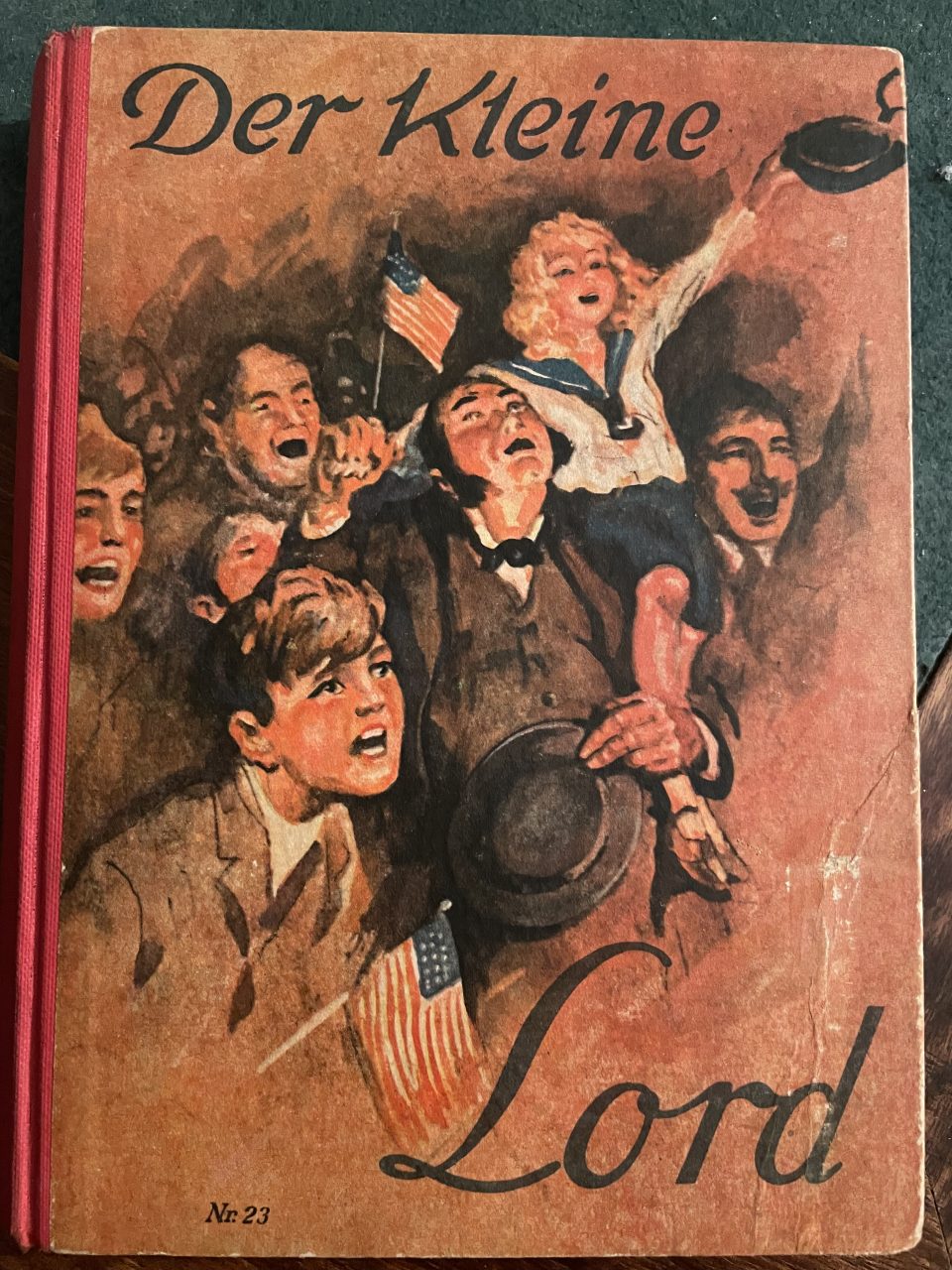

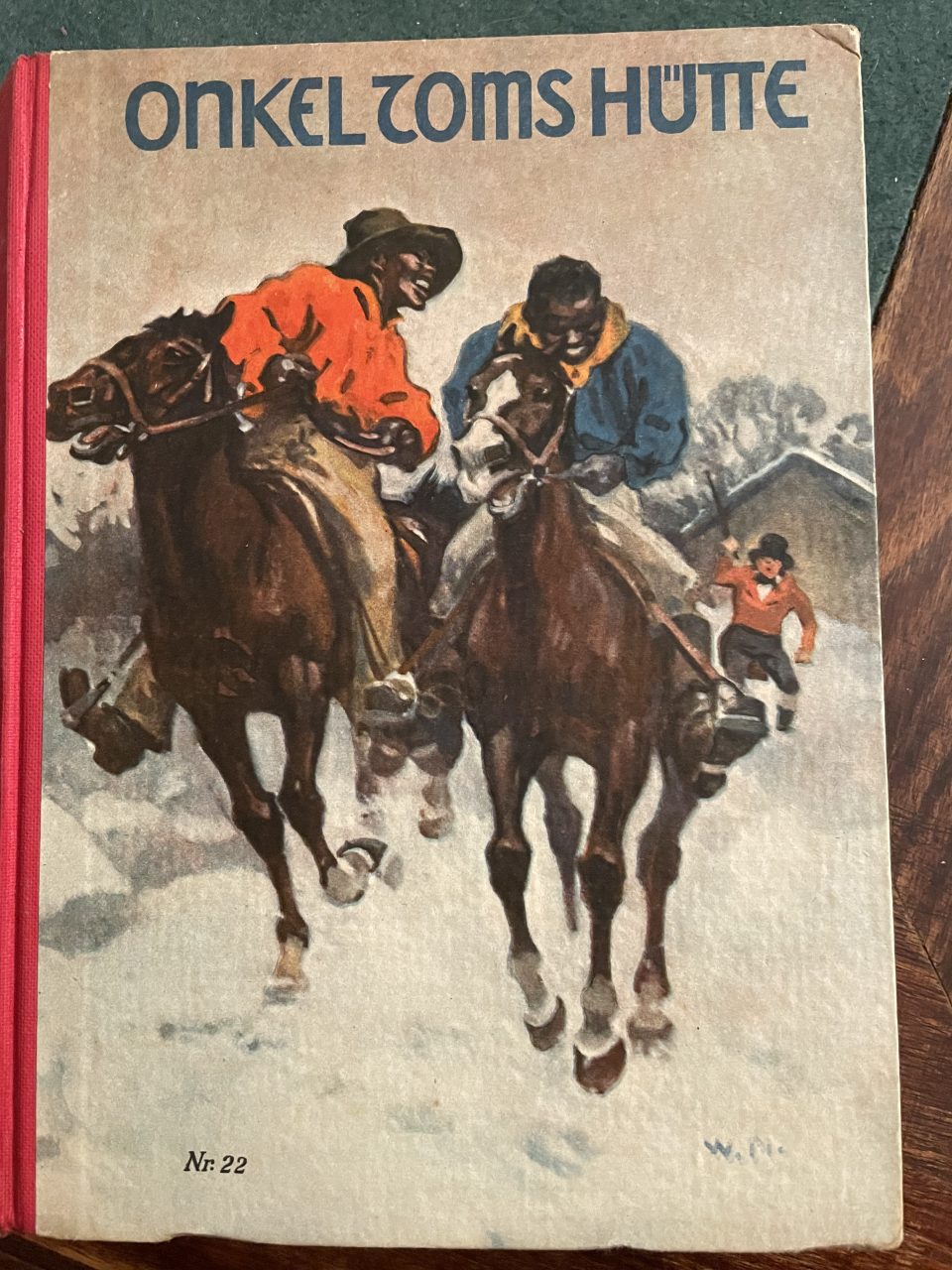

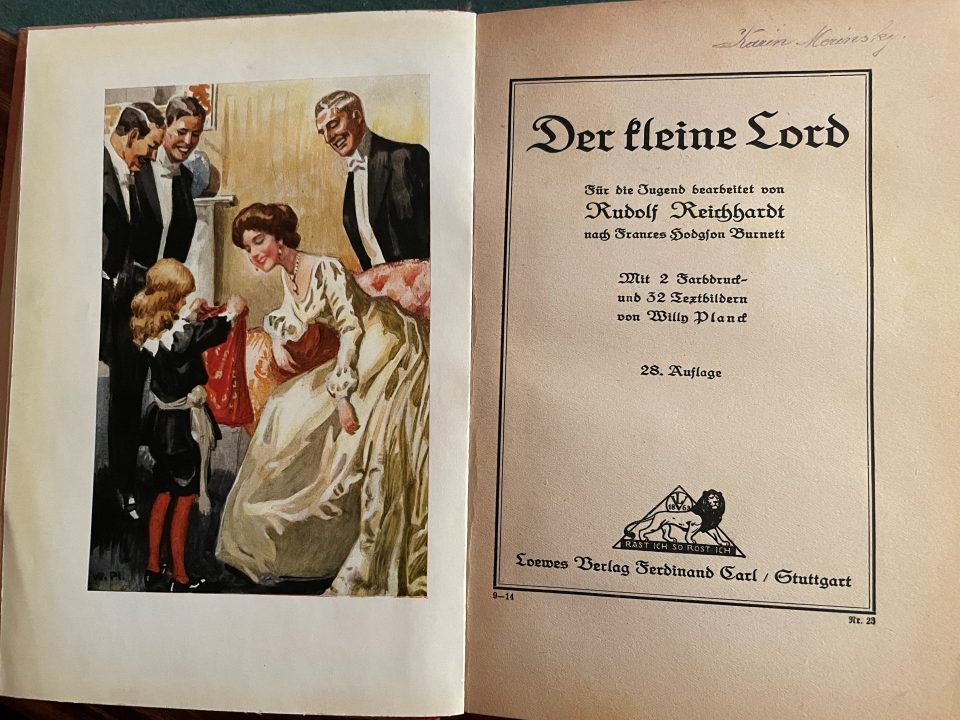

German translations of “Little Lord Fauntleroy” by Frances H. Burnett and of of Harriet Beecher- Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin”

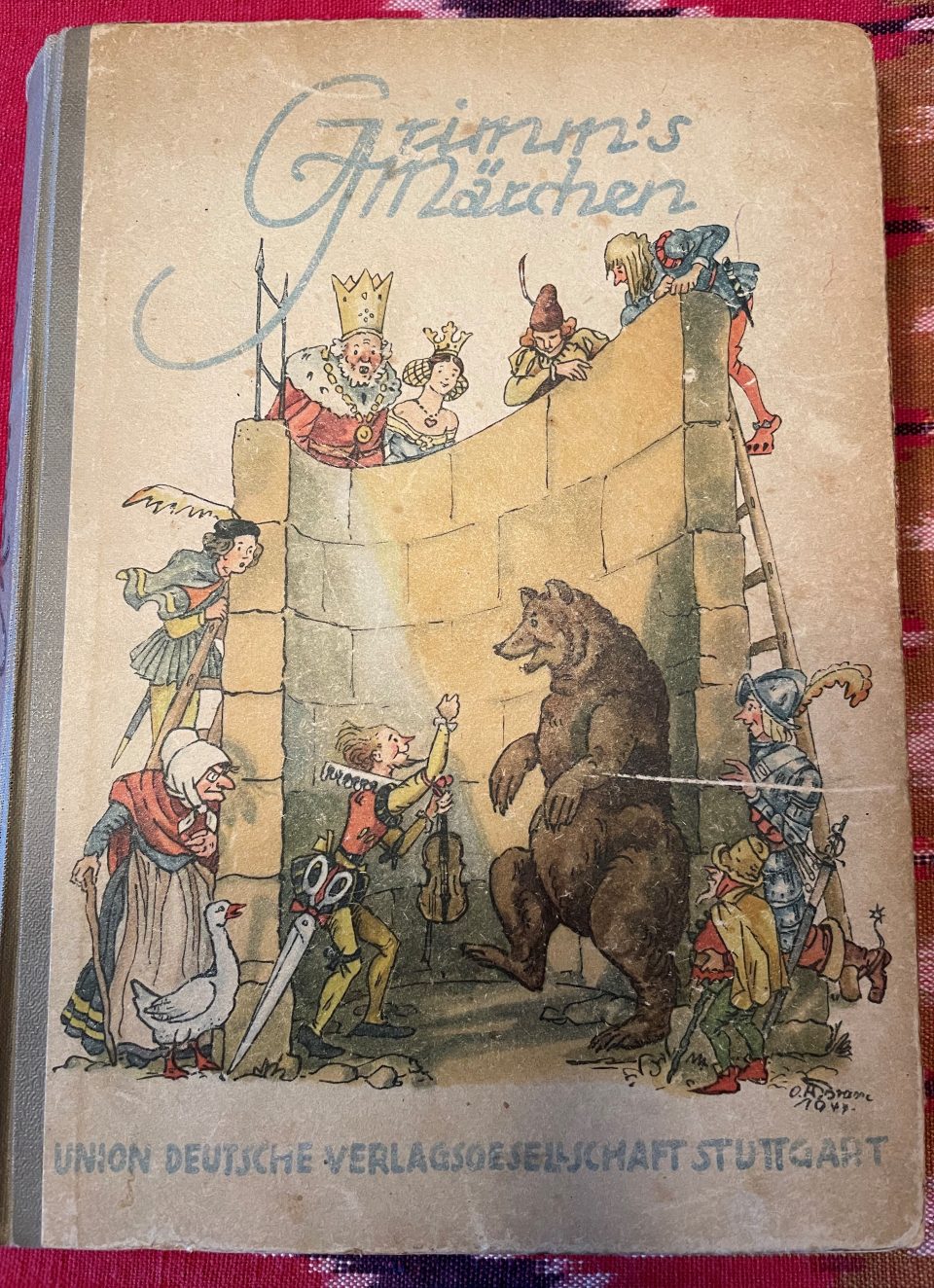

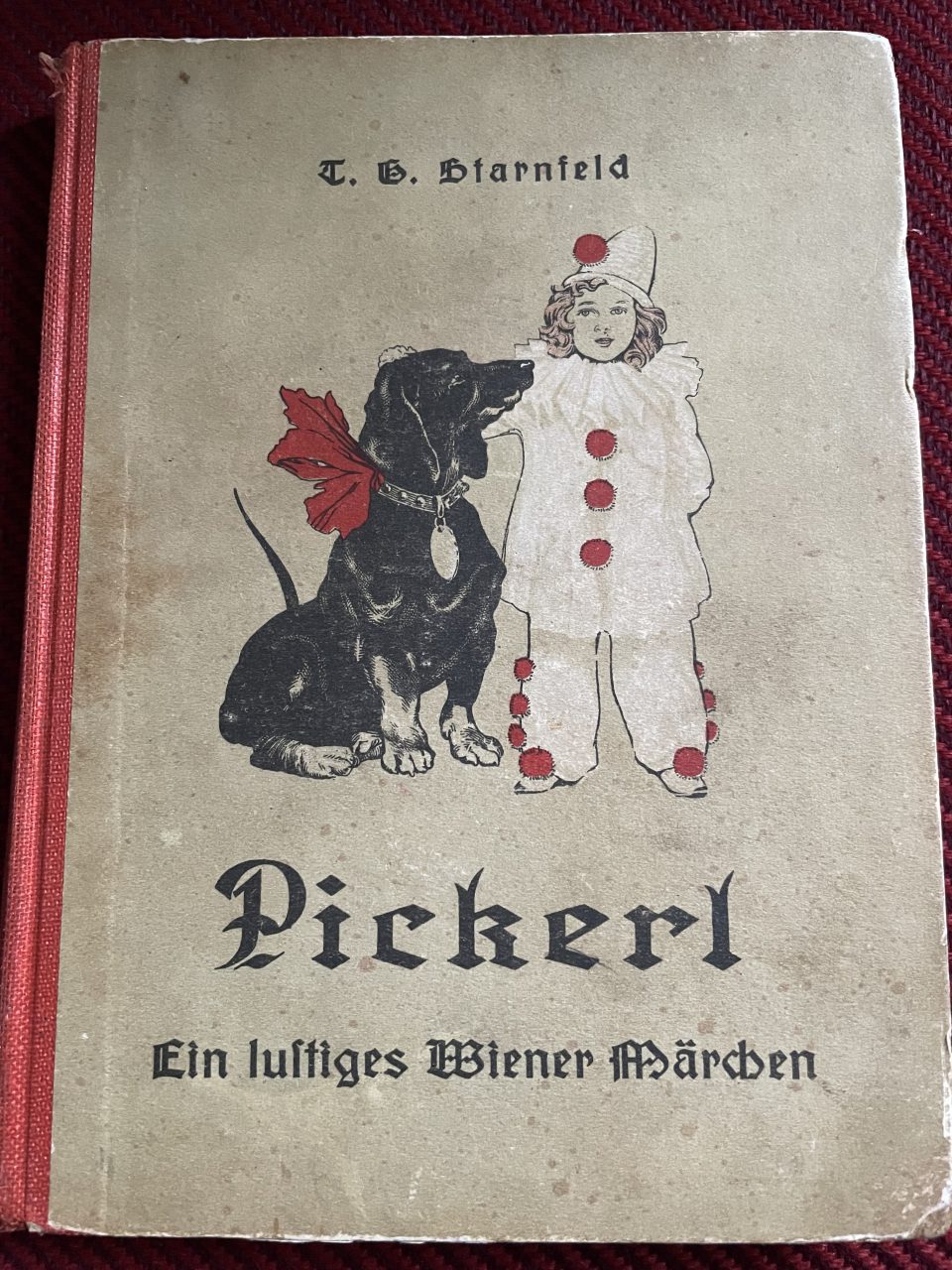

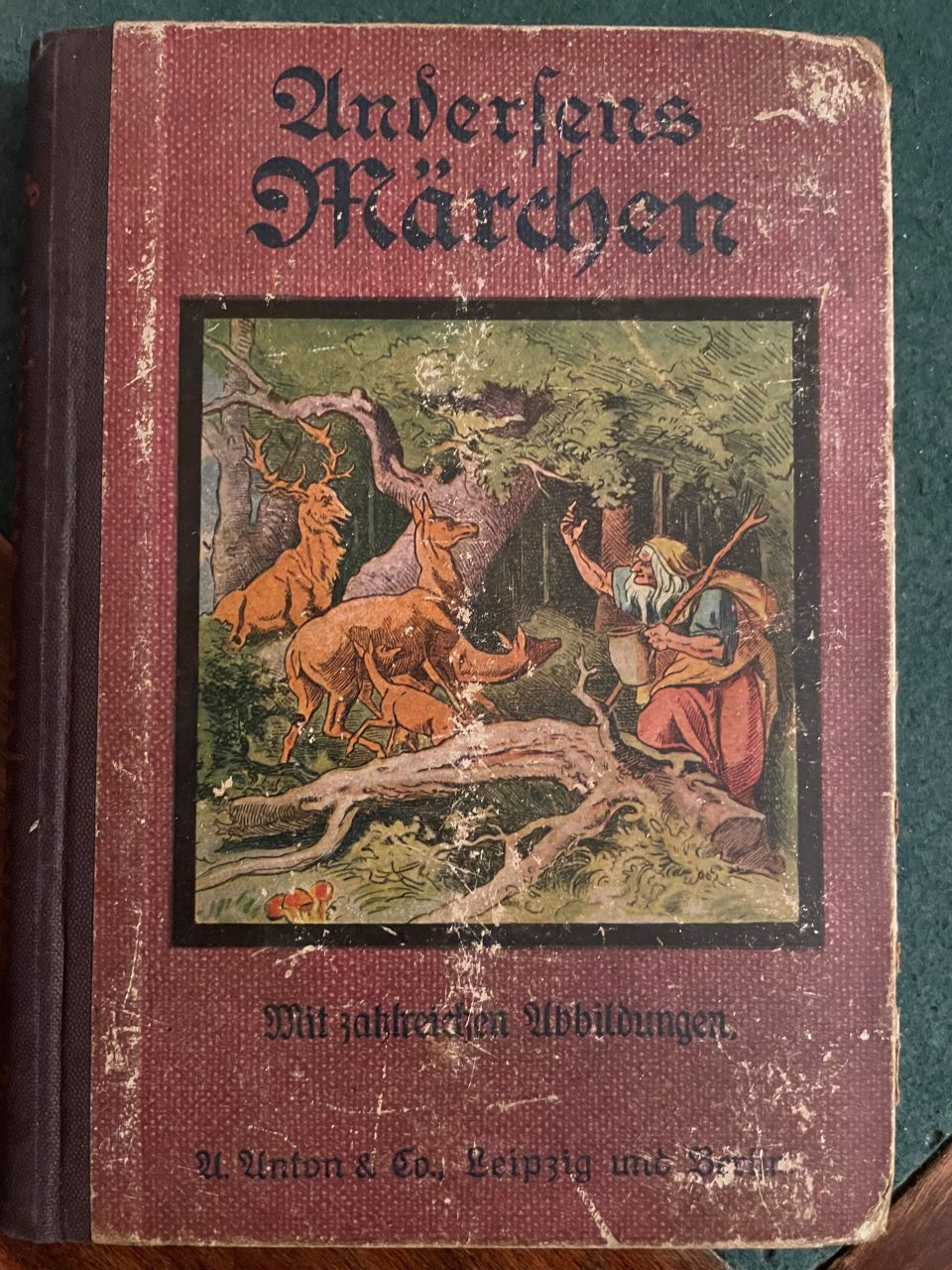

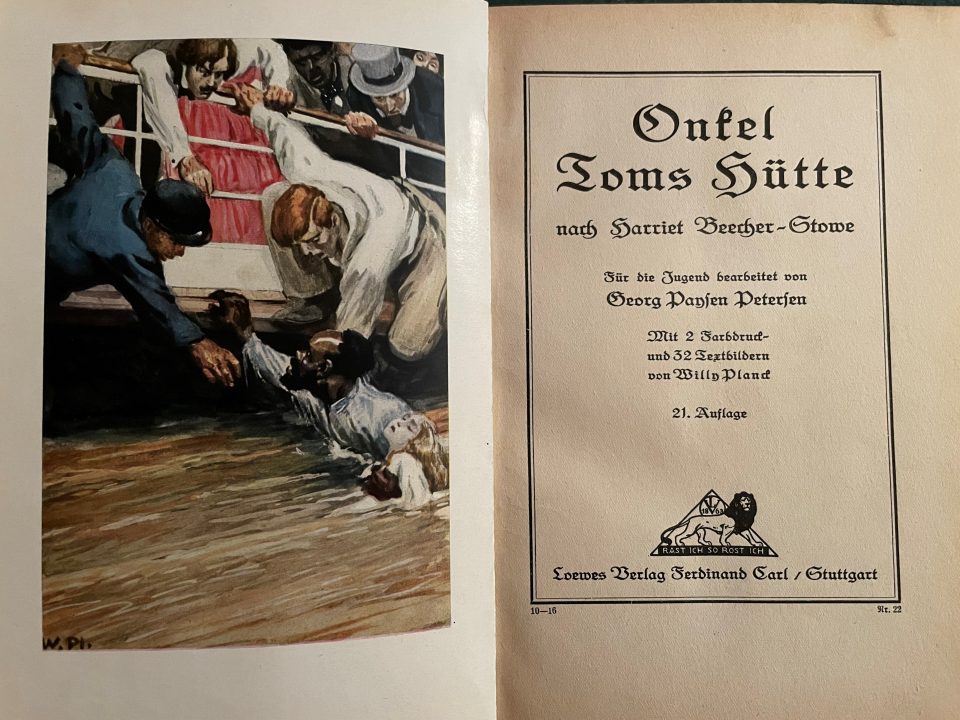

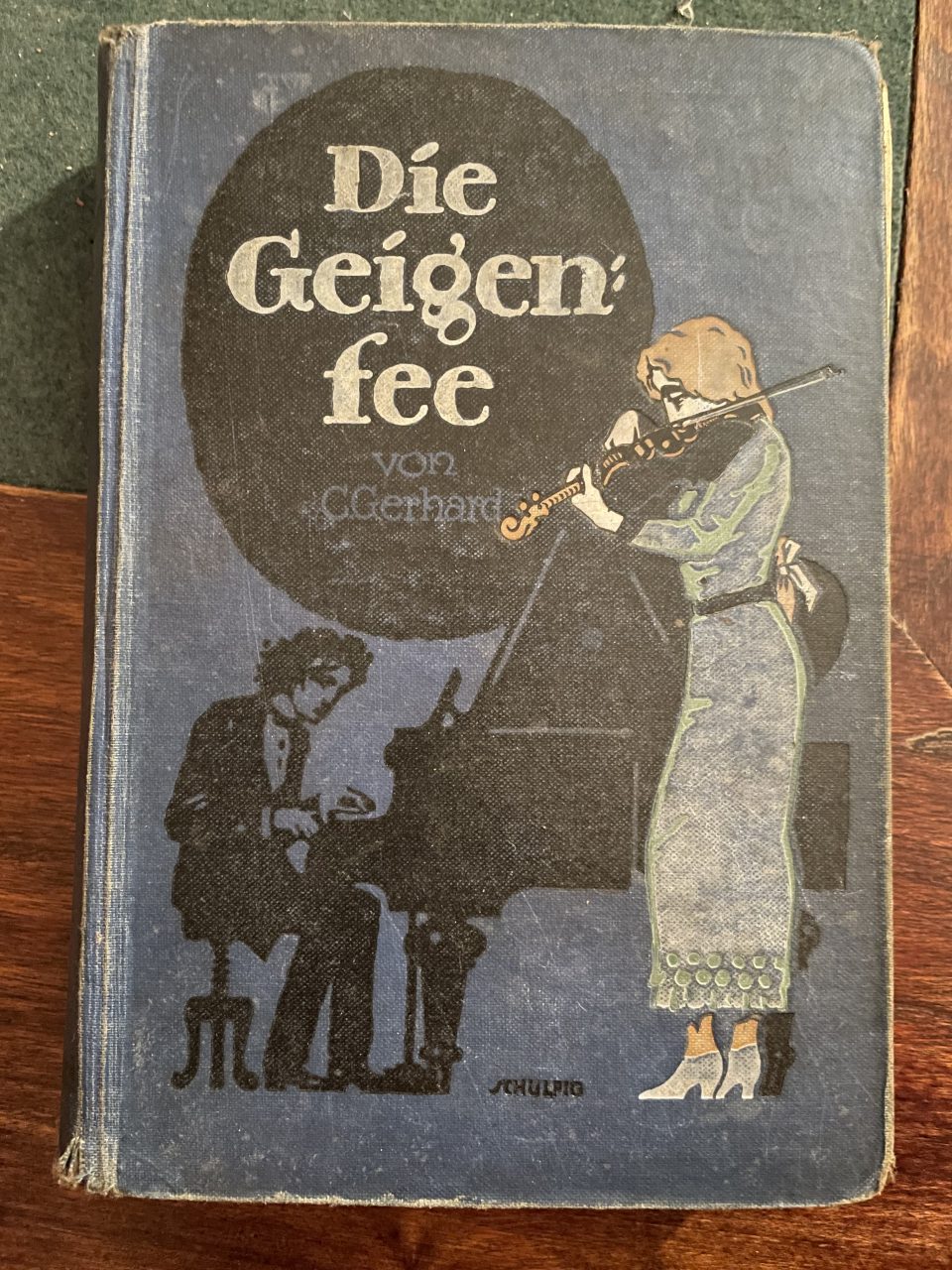

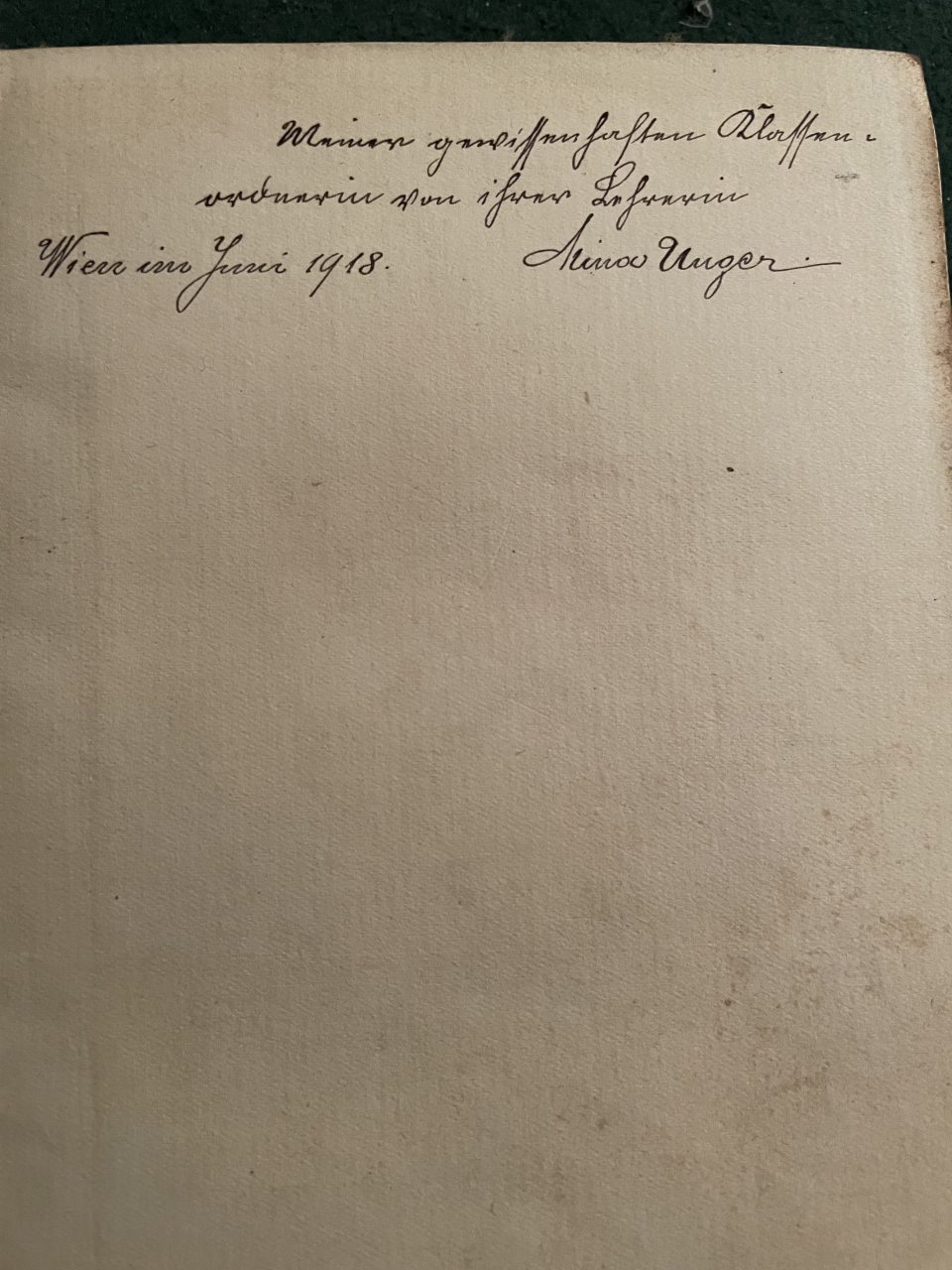

Children’s books were precious at the times of great need and they were therefore passed on from hand to hand, sold and bought in second-hand book stores in Vienna, which some samples from Herta’s personal library show:

“Die Geigenfee”(The Violin Fairy) by Clara Gerhard: The dedication of Vienna, June 1918 says, “Meiner gewissenhaften Klassenordnerin von ihrer Lehrerin Alina Unger“(For my conscientious prefect from your teacher)

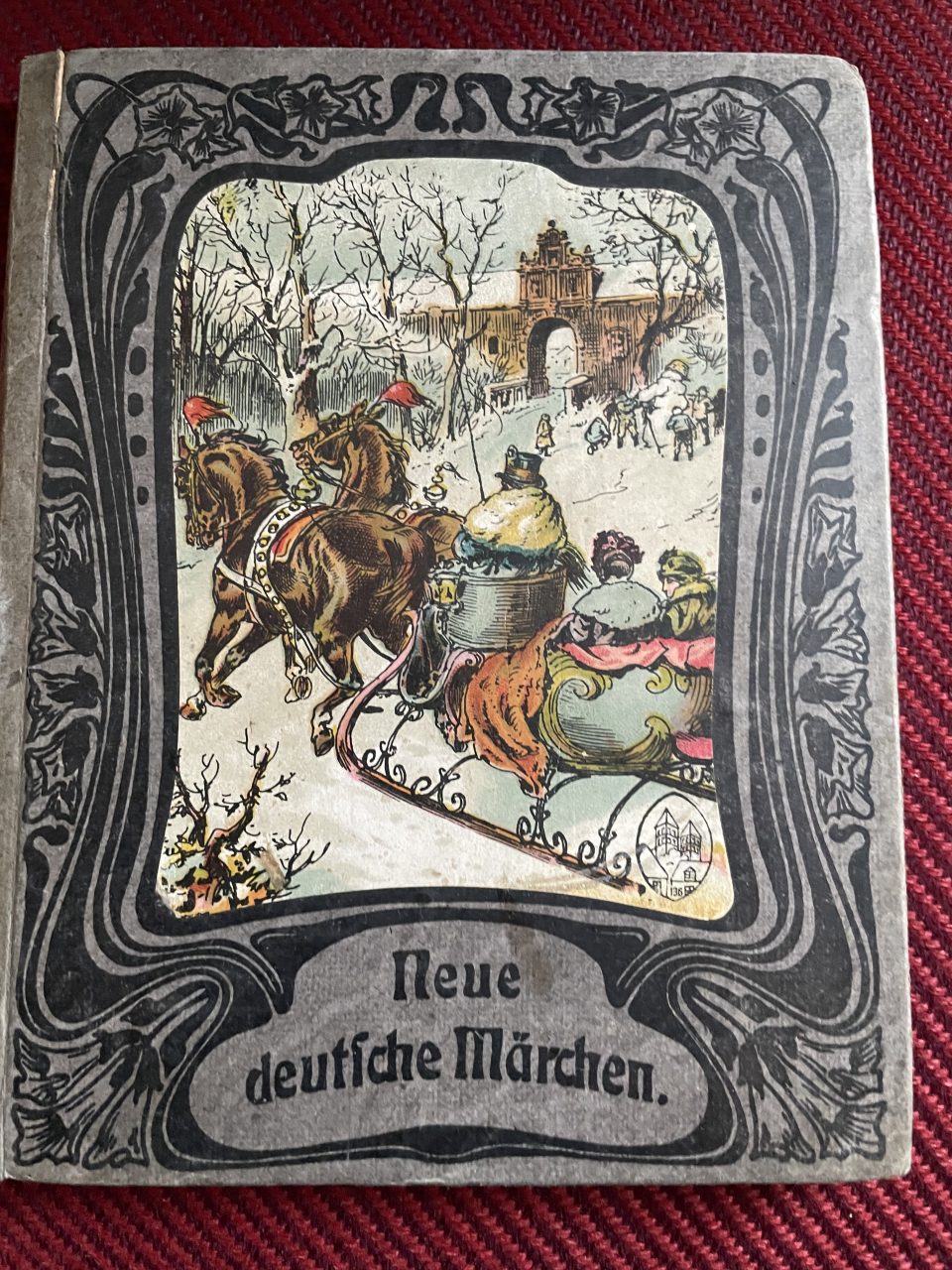

An edition of “New German Fairy Tales” with Herta’s stamp and a dedication of 14 January 1924: To Gerti Repp from her grandpa

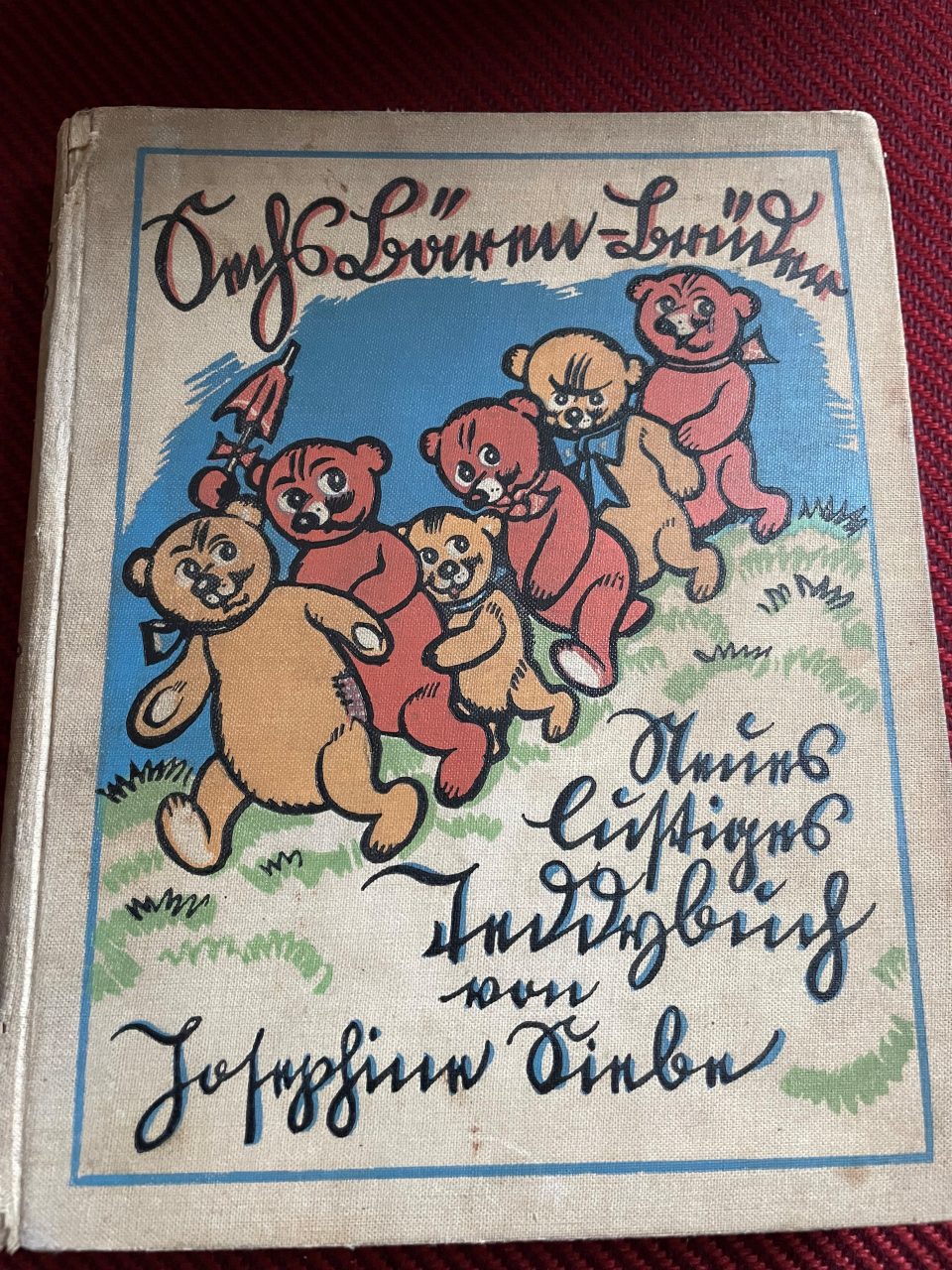

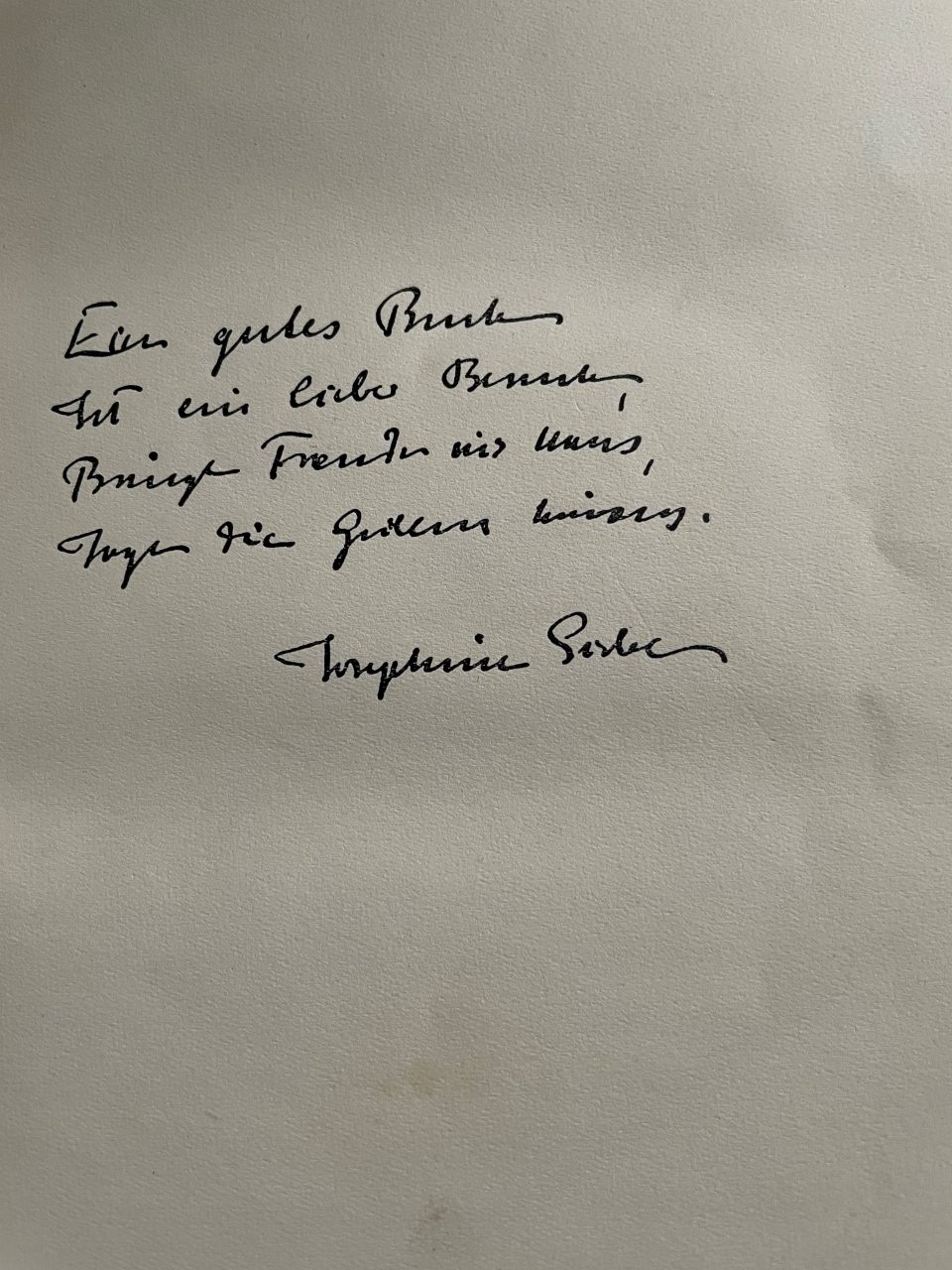

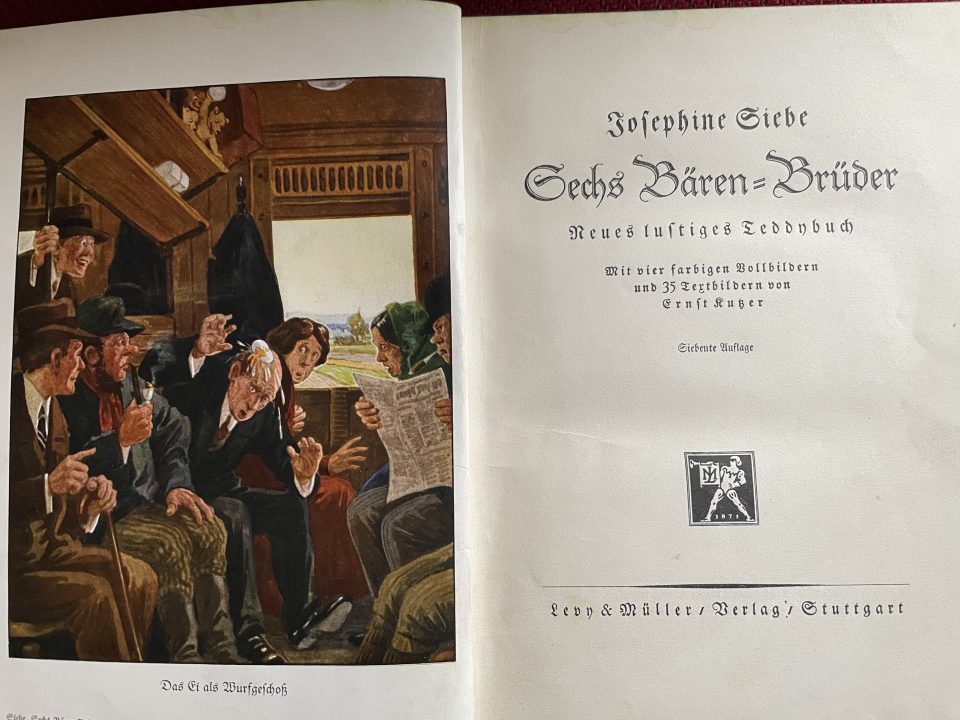

“Sechs Bären Brüder” (Six Bear Brothers) by Josephine Siebe (1927) as a present for a child with a poem praising the joys of possessing a good book. Josephine Siebe was a German children’s book authoress who focussed on stories set in the country, animal and “Kasperle” (Punch) stories and books for girls. She was born in 1870, yet her naïve books seemed to have satisfied NS criteria

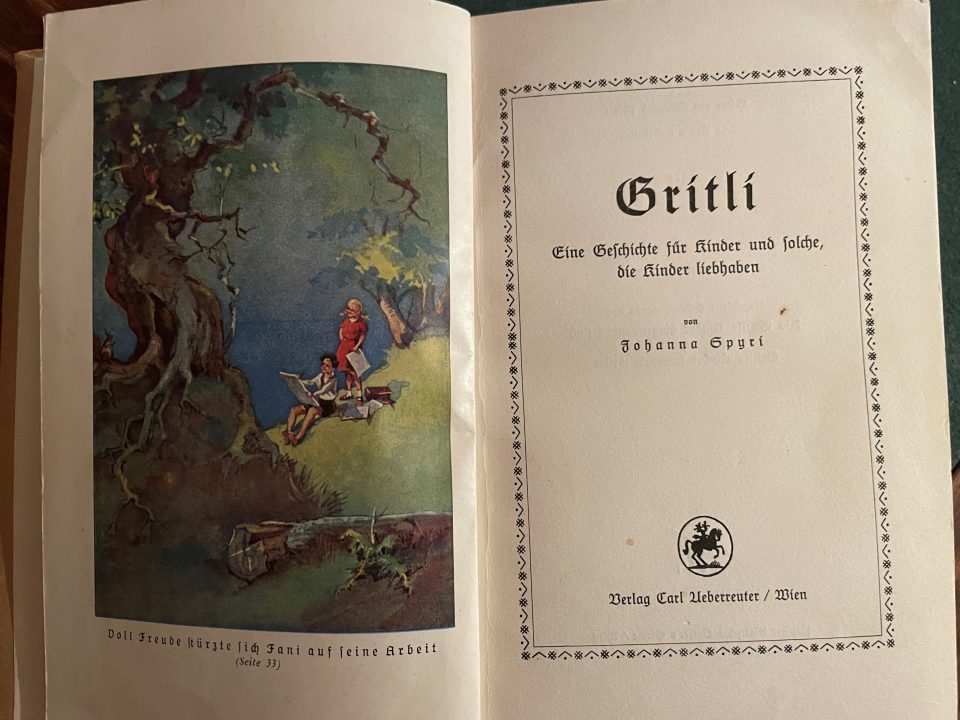

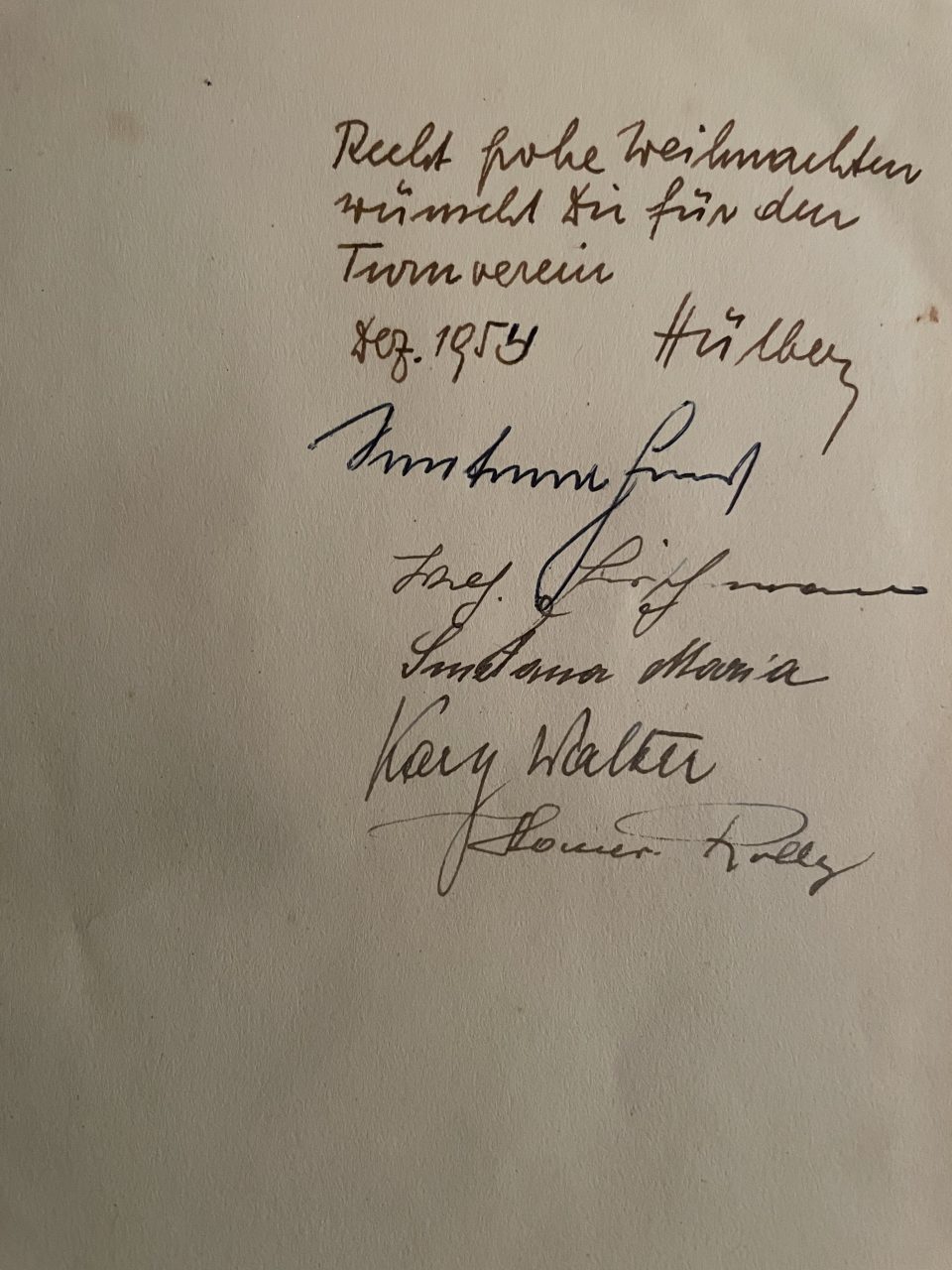

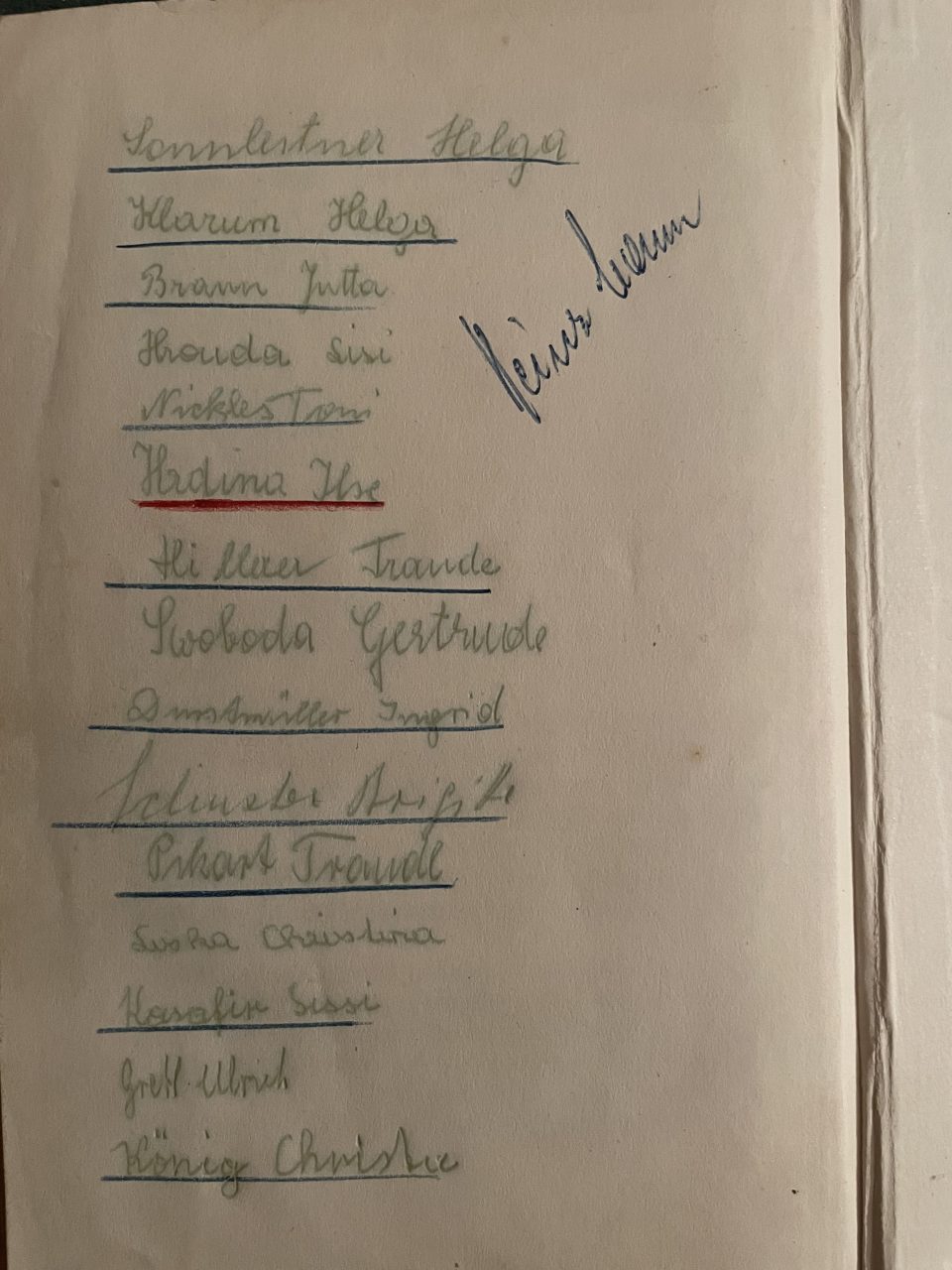

Johanna Spiri “Gritli” with the following dedication: Your gymnastics club wishes you a merry Christmas, December 1954. This book was passed on from one child to the next in the gymnastics club, until it was given to Herta

The NS Minister of Propaganda initiated the publishing of books for girls which were supposed to enhance their enthusiasm for “the adventure of war” to complement the books for boys which glorified World War I. One example was “Ingeborg. Ein deutsches Mädchen im großen Kriege“ (Ingeborg. A German Girl during the Great War) by Heinrich Maria Tiede, which was put on the list of recommended books by the Nazis. Fairy tales, especially those by the brothers Grimm, were promoted, too. Nevertheless, the lists of recommended children’s and youth literature were continuously revised, changed and amended because the various NS institutions were not in agreement about the ultimate methods of how to ideologically influence the young most efficiently. Discarded books were not to remain in the schools, but had to be handed over to waste paper collection centres, as soon as the paper shortage hit the economy. Everything that contradicted the “Nordic-Germanic” NS ideology had to be scrapped, together with anything that referred positively to Jews, monasteries and the Church or was not focussing enough on combat, adventure, and race.

Ideological influencing of the young was not supposed to start when they went to school, picture books with appropriate illustrations and texts were to preach National Socialism early on. The NS expert for education, Eduard Rothemund, stated the criteria for appropriate NS picture books in 1939. The books had to focus on the rural and ignore the urban aspects of life, portray children as members of the German racial community and stress self-reliance of children in contrast to spoilt bourgeois children, and finally promote NS “strict discipline and order” (Zucht und Ordnung). Ideologically harmless children’s books of the time before the Nazi takeover were re-edited by inserting NS ideological content more or less clumsily, for example “Hannerl in der Pilzstadt” (Hannerl in the Mushroom Town) by Annelies Umlauf-Lamatsch. Furthermore, so-called “Agitationsliteratur” (agitation literature) was very popular, which was designed to instruct children about how to think in an “ideologically correct” way. Girls were to be made aware of “their responsibility for the German race”. In this line Hertha Weber-Stummvoll‘s “Das Ostmarkmädel. Ein Erlebnisbuch aus den Anfangsjahren und der illegalen Kampfzeit des BdM in der Ostmark“ (The Girl from the ”Ostmark“ – former Austria – ; an Adventure Book about the Early Years and the Illegal Years of Fighting of the Union of German Girls in the “Ostmark”) was published in 1939. Ilse Ringler-Keller, NSDAP party member since May 1937, the time of illegality in Austria, and daughter of a convinced National Socialist, who held illegal meetings of the “Union of German Girls” (BdM) in her own flat, published in 1938 “Birkhild. Aus der Kampfzeit eines österreichischen BdM Mädels” (Birkhild. From the Time of Fighting of an Austrian BdM Girl). Marianne Nagl-Exner, who had herself been a BdM leader in Austria, dealt with the same topic in her book “Marthel war auch dabei” (Marthel Was with Them, too). Furthermore, Edith Helen Müller, of an Austrian National Socialist family as well, had her book “Ursel und ihre Mädel” (Ursel and Her Girls) printed in 1941, where she described the routines of girls in the BdM (Union of German Girls) wrapped up in a children’s story. In 1930 the Austrian authoress Annelies Umlauf-Lamatsch, who called herself “Märchenmutti” (fairy tale mother) and continued to be popular in Austria after 1945, wrote a children’s festival play for the birthday festivities of Adolf Hitler and a fairy tale for the May festivities, where the children decorated a photo of Hitler with flowers while reciting Umlauf-Lamatsch’s ideological children’s rhymes. The rhymes were easy to learn and the children probably enjoyed reciting them. Umlauf-Lamatsch also modified her “Mein erstes Geschichtenbuch” (My First Story Book) by inserting appropriate National Socialist passages in 1941. It started with the following words, “I know a house where happy people live. The mother is singing while cleaning. The father is whistling a happy tune while working. Since our Leader has arrived, the father has a job again. What luck… Above the sofa there is a picture of the Leader.” In another of the stories in this collection two girls play “shopping” and one asks, “I would like 100 g Chinese tea!” and the shop girl answers, “Chinese tea? I don’t want to hear of that! Why, don’t we have good German tea? Why should we import foreign tea, as we have our own wonderful tea? Sending our good money abroad? No, thanks! I won’t have any foreign tea in my shop and that’s it!”

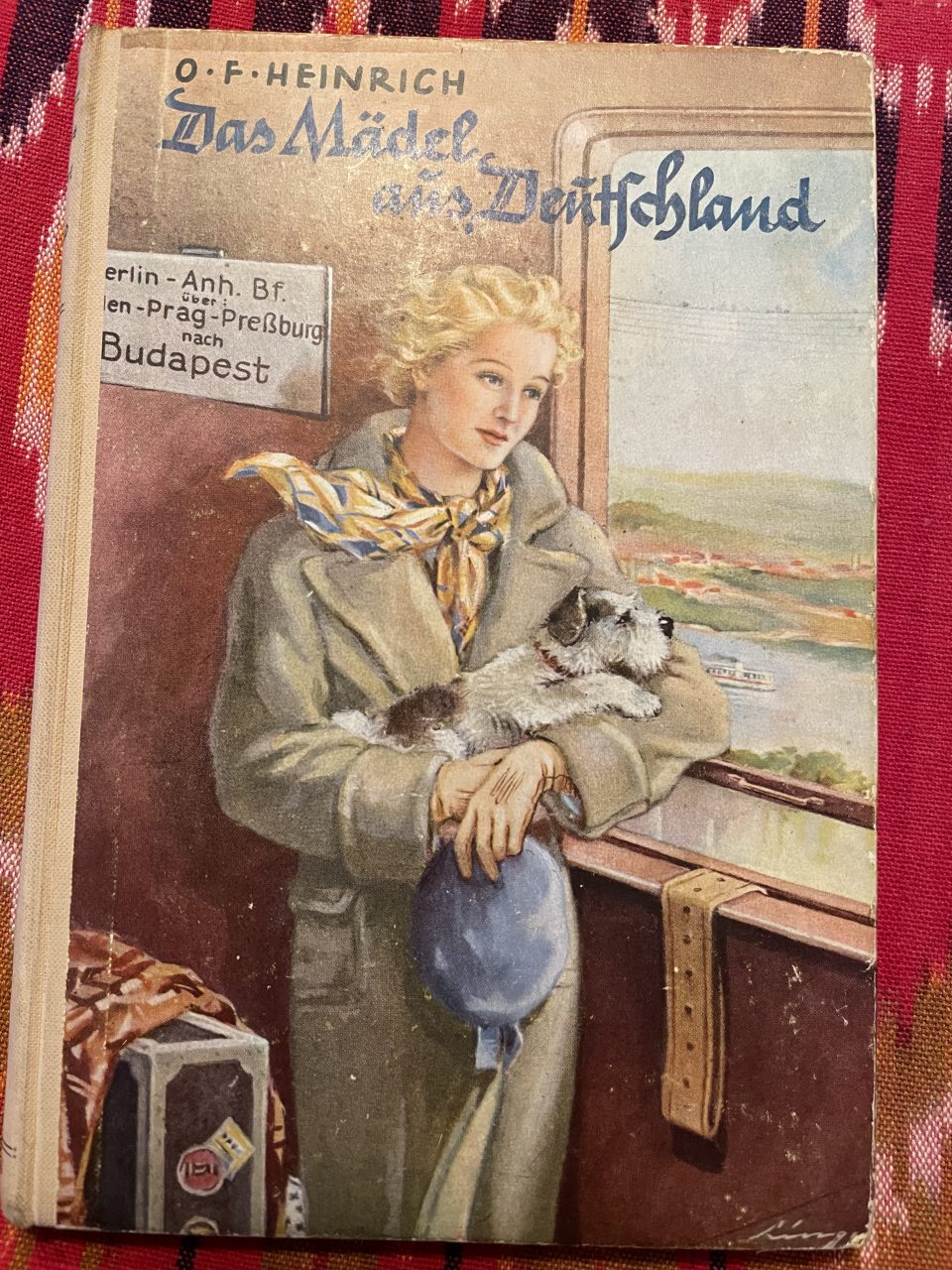

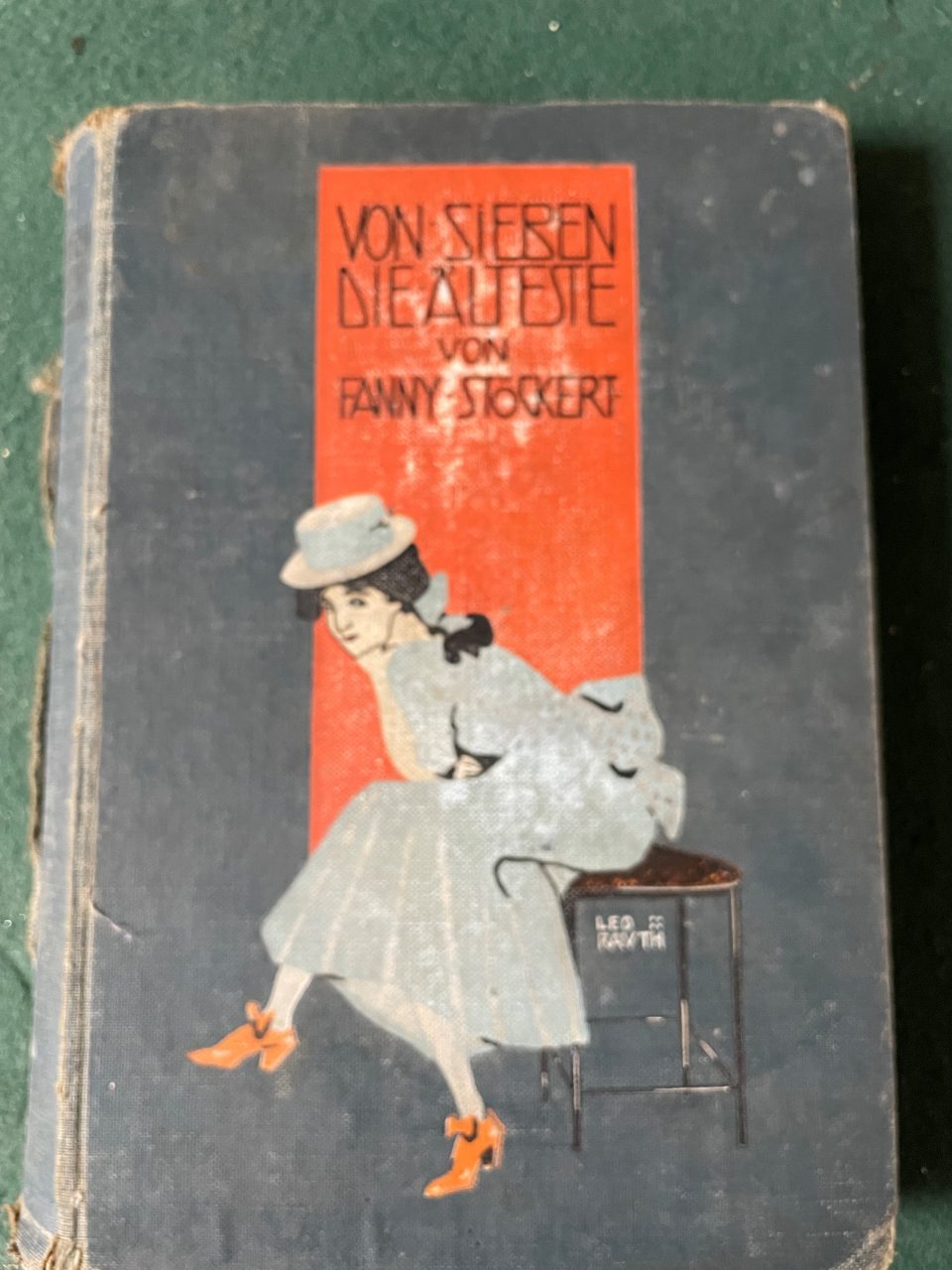

Left: O.F.Heinrich “Das Mädel aus Deutschland” (The Girl from Germany), 1939, is a typical NS publication for young females Right: The German writer Fanny Stöckert (1844-1908) published “Von sieben die Älteste“ (The Oldest out of Seven) in 1906 and although she was from a pastor’s family, her conservative book for adolescent girls was circulated during the NS period

In children’s and youth books published by the Nazis they always pursued an ideological purpose and a well-defined aim. This can be seen in Umlauf-Lamatsch’s children’s book “Hannerl in der Pilzstadt” (Hannerl in the Mushroom Town, 1941), which at first glance looks like a simple children’s story, where the girl Hannerl is prevented from picking a poisonous mushroom by a little imp who then takes her with him to the imp’s mushroom town, which is a replica of a German town in miniature. They hunt down all the poisonous mushrooms and eradicate them. The book’s publication was obviously commanded by an NS institution which promoted “the nourishment of the forest” in times of need during the war. The children’s book called on the young to actively participate in the search for food in the forest. This book was published in 1946 again without almost any changes; only “Volksgenossen” (national comrades) were replaced by “Mitmenschen” (fellow human beings). In a similar way her book “Pampf der Kartoffelkäfer” (Pampf, the Potato Beetle), published in 1943, contained bellicose terms, such as the “enemy beetle, the American arrived from Colorado and has to be extinguished”. This potato beetle is a “parasite, a freeloader, vermin, and a pack”. The potato beetles are distinctly marked with a “V” for “Verräter” (traitor), which could easily be associated by the children with the “J” sign that distinguished the Jewish population. Finally, the total extermination of the potato beetles is achieved by poisonous gas, which “does not harm the good beetles”.

The NS institutions promoted adventure books which glorified camp life, consecrations of flags, Germanic legends, and adventures of Germans in their colonies, too. Karl Springenschmid, NSDAP party member and responsible for book burnings in Salzburg in April 1938, had already published a picture book about Hitler in 1936, “Eine wahre Geschichte. Worte und Bilder von zwei Deutschen aus dem Auslande” (A True Story. Words and Pictures of 2 Germans from Abroad). Despite its open glorification of Adolf Hitler, “the small boy from Austria”, the picture book’s propaganda style seemed to have been too crude, even for the Nazis. Consequently, it only appeared on one recommendation list of 1938/39. The Nazis rather supported the Viennese authoress and illustrator Ida Bohatta-Morpurgo, who was admitted to the NS chamber of writers (“Reichsschrifttumskammer”) as early as July 1938 and who wrote stories of an idyllic world of animated plants and animals. Her popularity survived the NS regime. A more crudely propagandistic and anti-Semitic picture book of the Viennese Elvira Bauer was published in honour of the NS party congress in Nuremberg “Trau keinem Fuchs auf grüner Heid und keinem Jud bei seinem Eid” (Don’t Trust a Fox on the Green Heath and no Jew with his Oath) in 1936 at a time when the NSDAP was still forbidden in Austria.

What should not be underestimated is the enormous degree of influence the NS indoctrination had on young people who grew up in this time and were openly as well as subconsciously turned into enthusiastic supporters of the NS ideology from an early age on. Only those children who lived in a family that opposed the Nazis and where family members were brave enough to discuss the threats the NS regime posed – which was extremely dangerous -, were offered an alternative view of life. Quite often children and young adults were so indoctrinated by their teachers and NS youth group leaders and so fascinated by the glamour of the parades that they even turned against their families and sometimes even denounced them. When the “Third Reich” collapsed in April 1945 in Vienna, these children and young adults were shattered, their world had collapsed. Their disappointment was dramatic and they coped with it by deleting the memory of the NS period and their part in it. No young person in Austria who had lived some or all of his or her childhood and or adolescence during the NS period could escape this toxic influence except those children who were persecuted and somehow miraculously survived the terror in Austria, either in hiding or under special protection. From 1938 until 1945 everyday life was inundated with Nazi ideology; already small children were confronted with crass anti-Semitic prejudices, absurd race theories and war enthusiasm. This got worse as soon as the children had to join the HJ or the BdM and went to school.

In 1918 the eminent Viennese psychologist Charlotte Bühler had stressed the importance of fairy tales for fostering creativity and fantasy in children and coined the term “fairy tale age”. When she had to flee Vienna due to her Jewish origin, her theories were discredited. Instead, the fairy tale was turned into a manipulative tool for indoctrinating the young. The National Socialist world view was enforced by showing merciless brutality, a rigid system of so-called “justice”, actions of heroes, who were steered by superior orders, in fairy tales. That was the world of fairy tales and sagas that appealed to the NS authorities. An especially atrocious example is the fairy tale “Der Jude im Dorn” (The Jew in the Thorn), which was included in the first edition of the second volume of “Kinder-und Hausmärchen” (Fairy tales) of the brothers Grimm in 1815. It is a cruel anti-Semitic tale, where the supposed Jewish greed for money is punished by death. In 1894 the book was recommended as a Christmas present for children, which shows that an anti-Semitic consensus had already existed in large parts of the society before the Nazi take-over. National Socialists then turned this hatred against Jews, illustrated in the fairy tale, into a carte blanche to do with Jews whatever they wanted – a license to kill – because “they were criminals anyway” in the eyes of the Nazis. Another disgusting example is Johanna Harrer’s “Mutter, erzähl von Adolf Hitler! Ein Buch zum Vorlesen, Nacherzählen und Selbstlesen für kleinere und größere Kinder“ (Mother, Please Tell Us of Adolf Hitler! A Book to Read and Retell to Small Children and to Read for Older Children), 1940. In 16 chapters Harrer, a doctor and authoress, tells how happy the family is that they have a leader like Adolf Hitler and paints the idyllic picture of the mother who is mending socks and telling fairy tales of the ugly, nasty, and wicked Jews and how the eery “Trödeljakob” (Jacob the Jew) is doubting the victory of Hitler, which proves that the Jews have never been true members of the German community and must be done away with. Finally, the mother tells the children that they must help Hitler to win the war by being active in HJ and BdM and later as soldiers and as mothers bearing children for the “Führer”. These examples show the ruthless usurpation of children of all ages by the regime. Most of all, the children’s indoctrination must be unbroken. They were not permitted to get to know any other world outside the “Third Reich”. Adults could still make comparisons with the past, but children only knew life under the Nazi doctrine. So, the distorted cliches and stereotypes of the dirty, ugly, criminal Jew had to be repeated endlessly in books, magazines, on the radio, in films and discussions to imprint themselves in the minds of the children. For the smallest children these racist images were clothed in rhymes and accompanying pictures.

To sum up, the famous German writer Thomas Mann stated in 1945 that to his mind all German books printed between 1933 and 1945 were less than worthless and should not be touched at all. They should all be destroyed because blood and shame were attached to them. Nevertheless, several of these books were to a certain degree re-used or re-edited in Austria after 1945, even if slightly modified.

Viennese authors in exile

Representative of the many Viennese writers who did not manage to flee the terror and perished in Nazi death camps, the now forgotten German-speaking authoress Ilse Weber must be mentioned here. She was born in Vitkovice in Austro-Hungary in 1903 and wrote Jewish and other fairy tales, poems and plays for children, which she set to music and published in magazines and newspapers and on the radio. She and her family moved to Prague in 1939 when the repressions against Jews became unsupportable. In 1942 she was deported to the KZ Theresienstadt, where she looked after sick children in the ward there.

In the KZ Theresienstadt she continued to write poems and songs for children, two of which were very popular, namely the lullaby “Wiegala” and the song “Ich wander durch Theresienstadt” (I’m roaming across Theresienstadt), which she wrote for her elder son Hanus, who she had managed to put on a “Kindertransport” to England before the rest of the family was deported. Finally, when the children’s sick ward was to be transferred to the KZ Auschwitz, Ilse Weber volunteered to accompany the children there. They were all murdered in the gas chambers on 6 October 1944 immediately after their arrival; Ilse Weber together with her younger son Tommy and all the children from the sick ward in the KZ Theresienstadt. Her husband survived a NS labour camp and her elder son had been moved from England to Sweden and survived the holocaust there. Most of Ilse Weber’s work was published post-houmously.

All authors who wanted to publish during the “Third Reich” had to be accepted members of the “Reichsschrifttumskammer” (The NS Association of Writers) or they had to apply for special authorisation, as did Annelies Umlauf-Lamatsch, who supposedly did not manage to become a NS party member. So, what happened to those writers of children’s books who were no enthusiastic Nazis? There were those who were murdered like Ilse Weber, those who had emigrated, those who became part of the resistance and those who withdrew into “inner emigration”. All not NS conform children’s and youth literature could only be published abroad or after liberation in 1945. There was for instance Alex Wedding’s “Das Eismeer ruft. Die Abenteuer einer großen und einer kleinen Mannschaft”(The Arctic Ocean Calls. The Adventures of a Big and a Small Crew), published in London in 1936, or Anna Maria Jokl‘s “Die Perlmutterfarbe. Ein Kinderroman für fast alle Leute” (The Colour of Nacre. A children’s Novel for Nearly All People), which came out abroad in 1948 or Auguste Lazar’s “Jan auf der Zille” (Jan on the Barge) in 1950.

What kind of Viennese children’s literature appeared in exile? It must be noted that the Viennese adults who had to flee the Nazi regime usually stuck to their mother tongue regarding their reading habits, but their children went to schools in their host country, played with children in the foreign language and often quickly forgot German. That is why it was extremely difficult for German-writing authors of children’s and youth literature to publish abroad. Some braved a new start and began writing in a foreign tongue, such as Maria Gleit, Hertha Pauli and Oskar Seidlin. Hertha Pauli was urged by her publisher to turn to writing books for children to make a living. But many of the authors completely stopped writing in exile; the battle for survival superseded the urge to express themselves in writing. Yet others felt they could only overcome their trauma by writing and turned to children’s literature in a foreign language because that was linguistically less demanding und it was easier to find a publisher in exile.

Heinz Markstein was one Viennese author who published children’s books after his return from exile, integrating his experiences as a refugee. He was born in Vienna in 1924 in a family of assimilated Jews. His father, Rudolf Markstein, was the son of Mali Markstein, the sister of my great-grandfather, Ignaz Sobotka. His father and his uncle were imprisoned in the KZ Buchenwald immediately after the Nazi takeover in Austria because they were Socialists. Fortunately, they were released and managed to flee with the whole family, including young Heinzi and his sister Lisl, to Bolivia in March 1939. In La Paz the Marksteins were leading members of the “Association of Free Austria”, of which my great-uncle and great-aunt, Karl and Käthe Elzholz, were also members in Sucre, Bolivia.

See article: http://centraleuropeaneconomicandsocialhistory.com/viennese-in-exile-in-bolivia-1938-1948

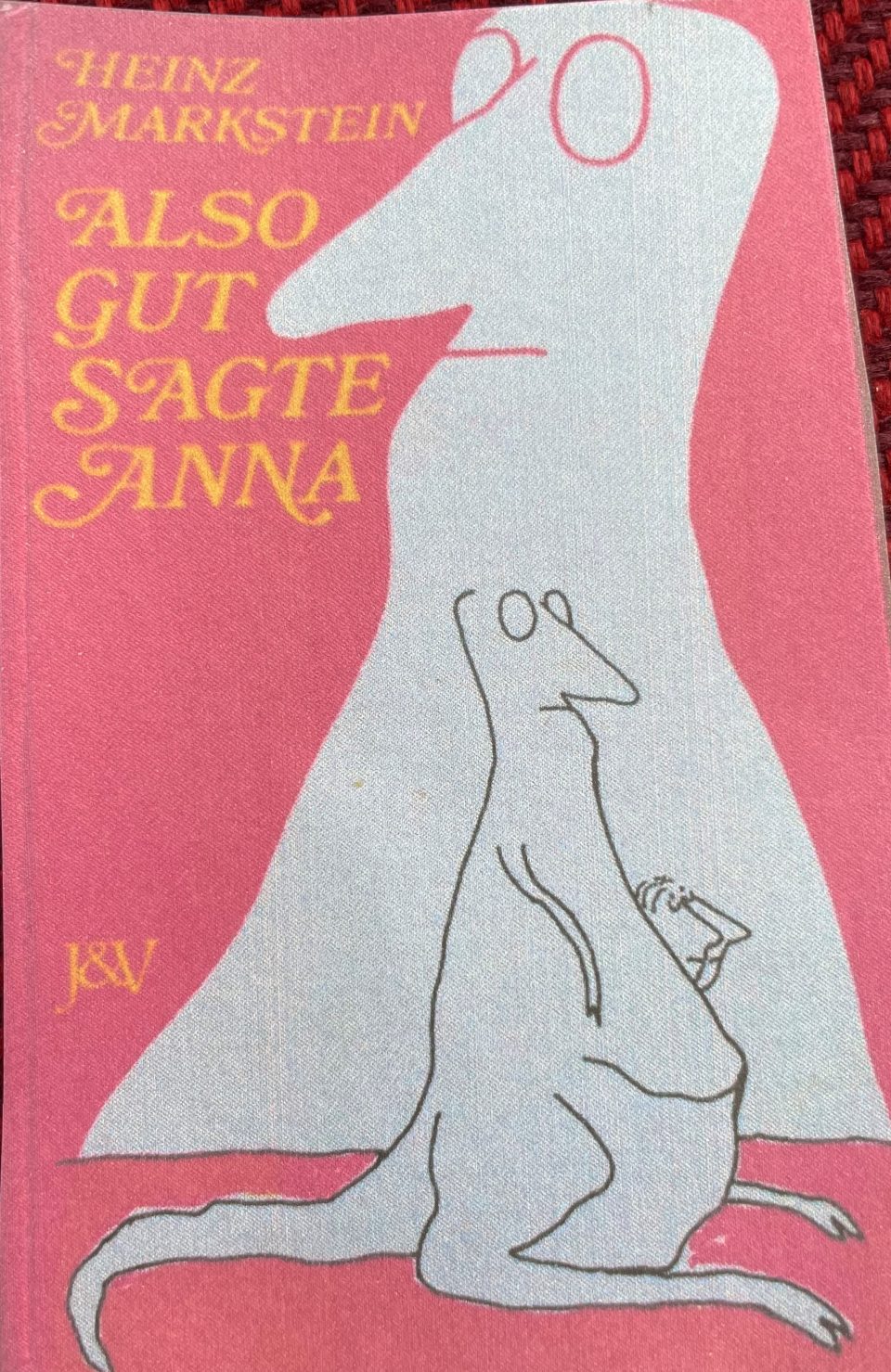

The whole Markstein family moved to Argentina in 1945 and Heinz Markstein was the only member of his family who returned to Vienna in 1951, where he worked as a free journalist for the radio and newspapers. For children he wrote radio and TV plays and two children’s and youth books, namely “Also gut, sagte Anna”, (Ok, Said Anna) published in Vienna in 1973 and “Salud, Pampa mia”, in Vienna in 1978. The first contains twelve funny stories for children, where Anna and Michael divide the week into 10 days: week days, wish days and in-between days. The second book is a youth book which tells the story of Peter, who tramps to Argentina with his backpack and his guitar to conquer the Pampa, yet he gets involved in a dangerous uprising of a village population there. As a leftist journalist Heinz Markstein was harshly criticised in Vienna after the withdrawal of the Allied Forced in 1955.

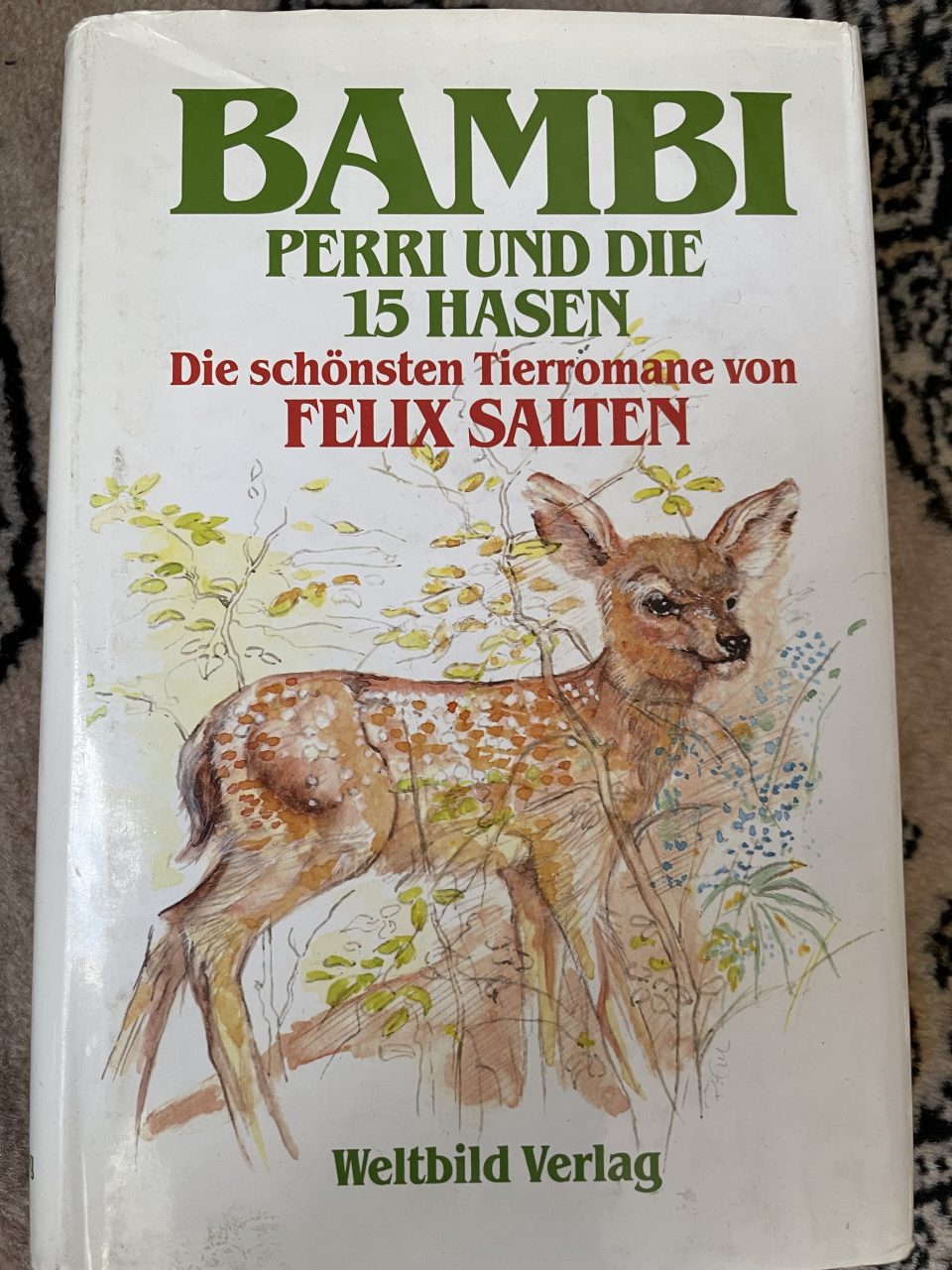

Heinz Markstein wrote “Also gut, sagte Anna“(Ok, Said Anna) after his return from exile, while Felix Salten wrote animal stories about deer, squirrels and rabbits before and during his exile

In 1938 the famous Viennese author, Felix Salten, had to flee to Switzerland at the age of 69 to escape the Nazi terror and continued to write animal stories there to make ends meet, as he lived very precariously in Zürich. The success of his world-famous book “Bambi” did not improve his economic situation at all, because he had been cheated by Walt Disney, who had cheaply bought the rights for the story without even mentioning Salten’s name. Above all, Salten’s multi-faceted coming-of-age story was turned into a superficial tacky animal story by the film company. Salten was deeply frustrated about being chased out of his beloved home-town Vienna and about being driven into exile. He loved the city dearly and felt rooted there, where he had earned the highest honours for his literary and journalistic work. He died in October 1945 in Zürich, half a year after the liberation of Vienna.

Auguste Lazar was born in Vienna in 1887 into a large Jewish family. She studied German literature in Vienna and graduated with a PhD in 1916. Her youngest sister, Maria Lazar, was a very gifted authoress, too. Auguste mostly wrote children’s books and was closely linked to the movement of reform pedagogy, teaching at several innovative schools in Vienna, the reform school of Eugenie Schwarzwald for example, before she moved with her husband to Dresden. She dealt with political questions in her children’s and youth literature. Her most famous children’s book is “Sally Bleistift in America” (Sally Pencil in America), which was published in 1935 in Moscow under her pseudonym Mary Macmillan. Sally Bleistift is an old Russian lady who earns her living in America by selling old clothes. She is in constant conflict with the police, but has a warm heart and welcomes outsiders in her home, where she lives with her granddaughter, Betti, a 15-year-old Indian boy, Redjacket, and the little black boy, John Brown, who was deposited on her doorstep one stormy night. He finds an old suitcase with Sally’s memorabilia from Russia and in that way opens a box of Pandora of memories of Sally’s house and shop in Russia, the anti-Semitism and persecution there. Lazar wrote another youth book, “Jan auf der Zille”(Jan on the Barge), in 1934, but it was not available in book stores until 1950, when it was printed in Dresden in East Germany, then a Soviet satellite state. There she was a representative of Socialist children’s literature and a model for other authors. Some of her books were filmed in Eastern Germany, too. Auguste Lazar mentioned that she wrote “Sally Bleistift” in protest against her own past and against the political and ideological attitudes of the society she had been born into.

Doris Orgel put the focus of her youth literature on political events as well. In her book “The Devil in Vienna” she integrated her personal experiences and told the events of the “Anschluss”, the Nazi takeover in Austria in March 1938, from the point of view of a Jewish girl in Vienna in the form of a diary. The girl Inge observes and judges the actions of the people around her and offers an insight into the inner world of a girl who is persecuted and has to emigrate. Doris Orgel, née Adelberg, was nine years old when her family had to flee Vienna. They first sought refuge in Zagreb, Yugoslavia, then continued their flight to England in 1939 and finally reached New York in 1940, where she took up her education again and became a well-known author of children’s literature. Her first two books, “Grandma’s Holidays” and “Sarah’s Room”, were both published in 1963 in English. “The Devil in Vienna” came out in 1978 and was translated into German two years later under a much more uncompromising title: “Ein blauer und ein grüner Luftballon” (A Blue and a Green Balloon), which shows the prevalent trend to minimalize the participation of Austrians in the NS regime and the unwillingness of confronting children with this “better-forgotten” past. In 1988 Walt Disney turned the book into the film “A Friendship in Vienna”.

Anna Gmeyner, born in Vienna in 1902, was very aware of the threat the political situation in Austria was posing to democracy, which she illustrated in her plays “Heer ohne Helden” (Army without Heroes) in 1929 and “Automatenbuffet” (Automatic Buffet) in 1932. In 1933 she emigrated to England and managed to publish her children’s book “Manja. Ein Roman um fünf Kinder” (Manja. A Novel about 5 Children) in 1938 in the Netherlands under her birth name Anna Reiner. She tells the story of five children of very different backgrounds during the time of rising National Socialism in Vienna: one jobless father blames the Jews for his misery and volunteers for the SS, while the Socialist worker who lives in the same house is deported to a concentration camp. Another neighbour is the Jewish family of Manja, who lives with her mother and two siblings in the same house. Furthermore, a liberal and very committed doctor and a bourgeois Jewish entrepreneur who denies his origins help to paint the picture of the dreary reality of Vienna in those years, all seen through the eyes of the Jewish girl Manja.

Anna Gmeyner’s daughter, Eva Ibbotson, born in Vienna in 1925, wrote in English only, as she had spent the years 1926 to 1930 in Scotland and after a brief return to Vienna in 1933, she returned to Edinburgh again. After her studies in London, she worked as a writer from 1953 on and described her childhood in Vienna and her experiences as an exiled child. She stressed that she wanted to entertain and she needed a happy ending and that is why she focused on an idyllic and totally unrealistic representation of Austria before World War I, as in her book “The Star of Kazan” of 2004, in total contrast to her mother’s very critical and realistic portrayal of the conditions in Austria. Eva Ibbotsen holds a unique position in Viennese literature for the young, as she clings to a positive image of Austria before the wars. The reason might be that she had to flee Austria as a young child and started to write children’s books much later in exile in English.

Children’s and youth literature in Austria after 1945

Seven years of National Socialism left behind a “waste land” with respect to children’s and youth literature in Austria. After 1945 Austria had to try to revive its tradition of Austrian art and culture and make up for the lost years by getting in contact with other European cultures and the rest of the world, from which Austria had been cut off during the Nazi period. Politically, socially and culturally Austria wanted to clear away the ruins and the rubble and together with it the memory of the war, the persecution, the death camps and Austria’s complicity and share of the guilt. Unfortunately, the new start after the end of the Second World War was in fact not a “Stunde Null” (a zero hour), which some wished for. That was also true for children’s literature. In its zeal to clear all children’s books from “filth and trash”, the authorities propagated a return to the 1930s and the Austro-Fascist period. Unfortunately, black lists appeared again and until 1954 books, which were considered filthy, lewd, sensational, or superficial, were burnt once more. Only few intellectuals opposed these measures, among them Erich Kästner, the German author of famous children’s books such as “Emil und die Detektive” (Emil and the Detectives) and “Das fliegende Klassenzimmer” (The Flying Classroom) – books, which were burnt under the Nazis. Kurt Kläber, who lived in exile in Switzerland during the war and wrote the youth book “Die rote Zora und ihre Bande” (The Red Zora and her Gang) under the pseudonym Kurt Held, which was published in 1941, spoke out against book cleansings as well. In the “Red Zora” he talks about his experiences with young people in Yugoslavia during the war. In Austria Richard Bamberger still promoted the theory of the “good youth book”, which represented an image of the young prevalent in the late Romantic and the “Biedermeier” period of the early 19th century. On the other hand, with the help of the liberating Allied Forces, child-oriented literature was promoted, too, influenced by “reform pedagogy”, where Vienna had been an important centre of research and practice before the Fascist take-over. Earlier than in Germany, the conveyance of human values in a form suitable for children, from the point of view of content and form, was seen as a prime goal in post-war pedagogy in Vienna.

Due to the lack of funds and the conservative atmosphere in Austria immediately after the war, a focus was put on the revival of “classical” youth literature and harmless books on animals and nature. Probably the shock of Nazi propaganda youth literature impeded the creation of a new indigenous Austrian youth literature in the first years after the war. What is more, there was practically no scientific interest in children’s and youth literature in Austria until the late 1950s. So, a significant new start was nowhere visible until the 1960s. That is also why the books by the NS “Märchenmutti” Annelies Umlauf-Lamatsch, illustrated by E.Kutzer, such as “Hannerl in der Pilzstadt (Hannerl in the Mushroom Town) and “Die Schneemänner” (The Snowmen) were still popular and re-edited in the after-war years.

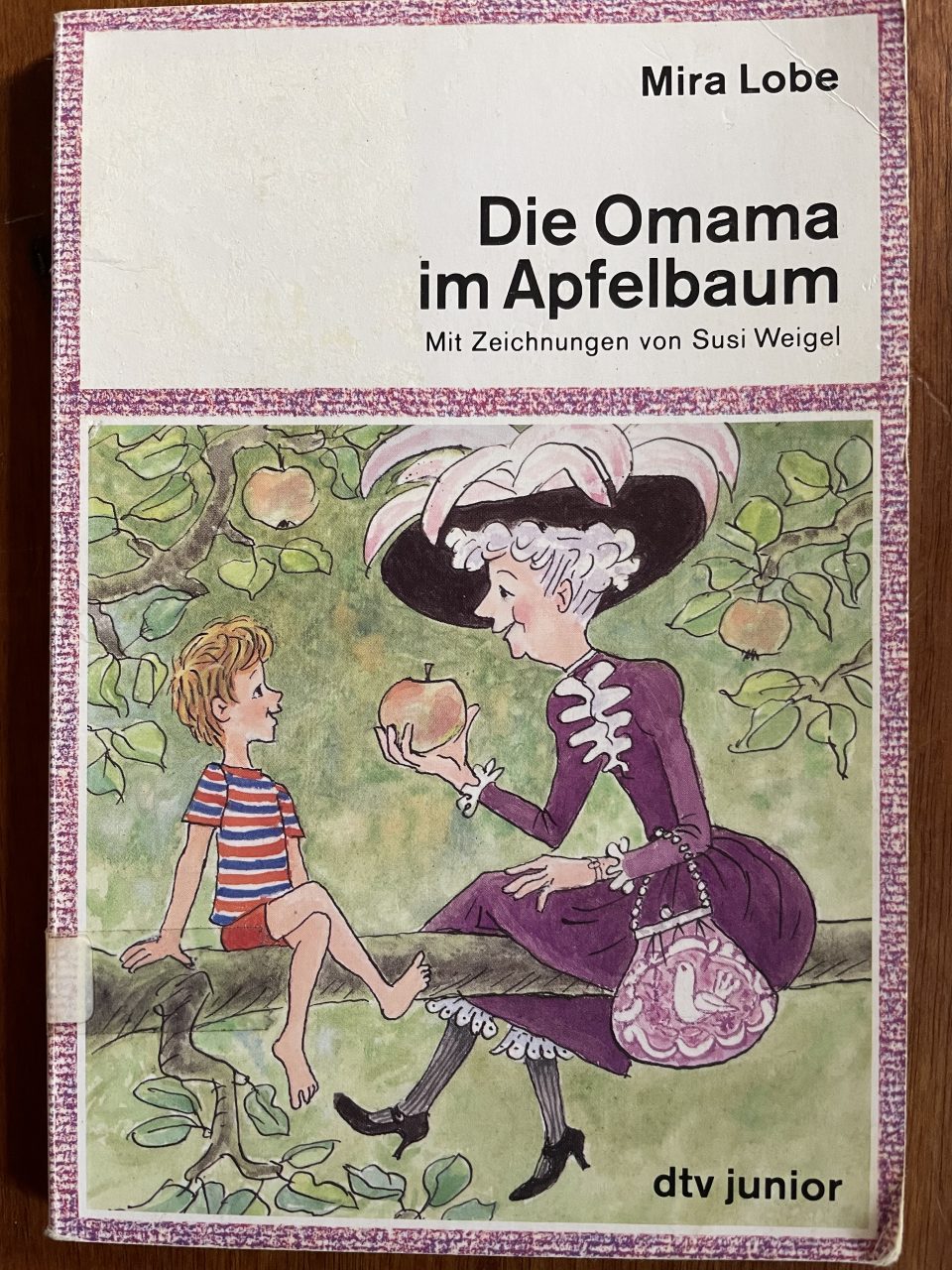

But fortunately, there were some new children’s books published in post-war Vienna as well. “Prinz Pips. Eine Spatzengeschichte aus Schönbrunn” (Prince Pips. The Story of a Sparrow from Schönbrunn) was a new book by Emmy Wohanka, which came out in 1945 and talked about a little sparrow in the park of Vienna’s Schönbrunn castle. Emmy Wohanka was a Viennese teacher and author of texts for children, who worked at the Vienna School Council after the war. Another new author was Vera Ferra-Mikura, who published “Der Märchenwebstuhl” (The Fairy Tale Weaving Loom) in 1946. She was born in Vienna in 1923 and started to work in the bird shop of her parents after completing comprehensive school. In 1948 she started writing children’s books. Her books are characterised by a kind of magic realism, but they also include social criticism. Yet she avoided negative or unclear endings because to her mind such endings left children despondent. She believed that children and adults could not live without illusions. Her stories about the “Stanisläuse” were very popular in Austria, where Vera Ferra-Mikura paved the way for magic realism in children‘s books. Mira Lobe was another of the new authoresses, who had published her book “Insu-Pu” – Die Insel der verlorenen Kinder” (The Island of the Lost Children) in 1948 in exile in Hebrew and then in 1951 in German. In this story children manage to establish a well-functioning peaceful state on an island where they are stranded after their ship was sunk during war. The book talks about the difficulties of living together in harmony and the personal responsibility of everyone for peaceful cooperation. Mira Lobe was born in Görlitz, Silesia, of Jewish parents, had to flee Germany during the NS period and found refuge in Palestine. In the early 1940s she started to write and illustrate children’s books in exile. In 1951 she came to Vienna with her family because her husband, Friedrich Lobe, worked at the “Theater Scala” in Vienna, which was subsidised by the Soviets. After a brief stay in Communist Eastern Germany, the family returned to Vienna, where her husband worked at the “Theater in der Josefstadt” as actor and stage director. Her greatest successes were the books “Die Omama im Apfelbaum” (Grandma in the Apple Tree) and “Das kleine ich-bin-ich“ (The Little I-am-I). Lobe supported the Viennese Social Democratic movement and closely worked together with the illustrator Susi Weigl.

In “Grandma in the Apple Tree” Mira Lobe tells the story of a boy who has no grandma and is yearning for one. Suddenly he encounters a very weird and funny old lady in the apple tree of his garden and experiences unconventional adventures with her.

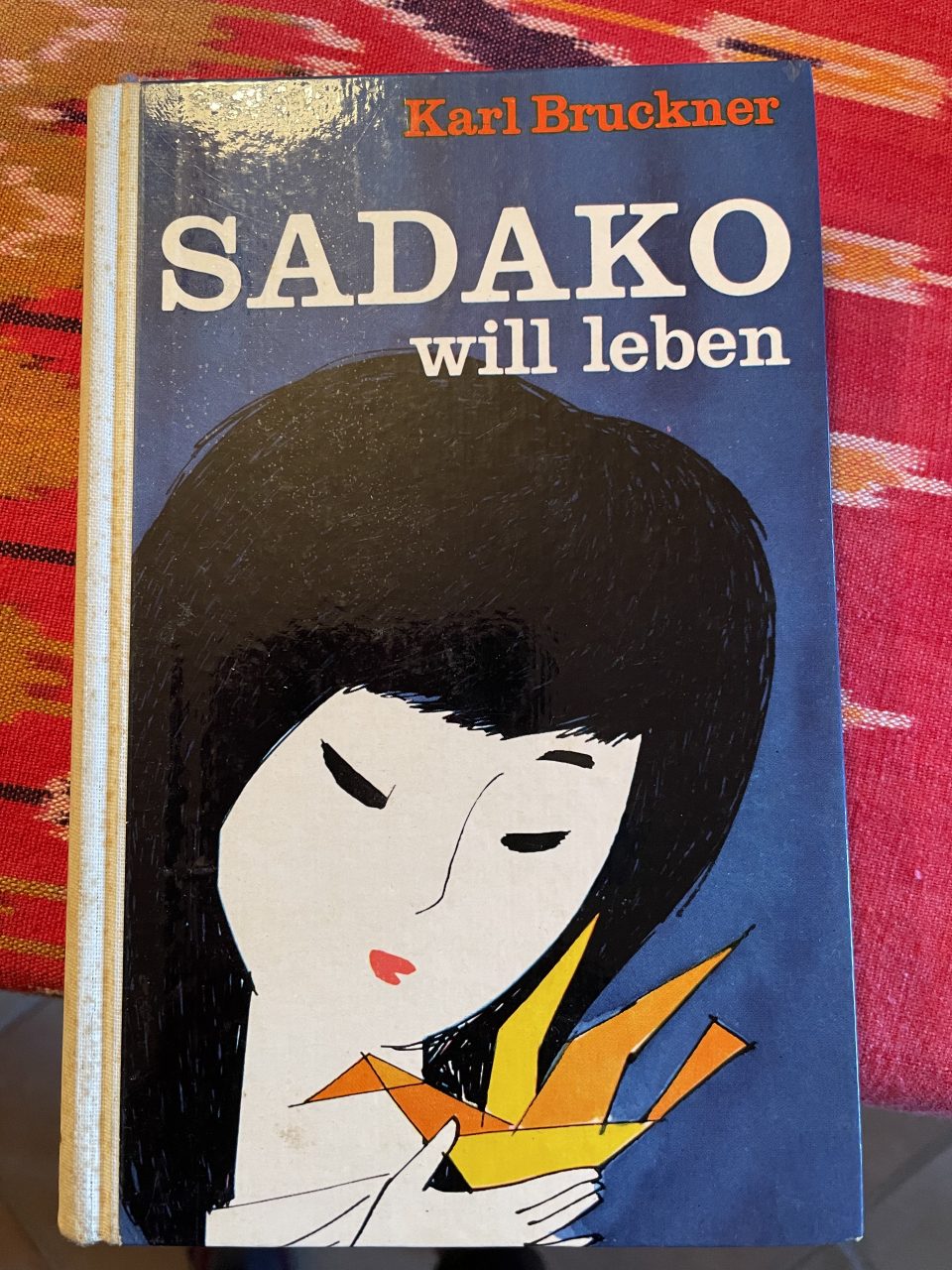

Karl Bruckner was from humble background in Vienna, born in the working-class district Ottaking in 1906 in a family of coachmen, called “Fiaker” in Vienna. He was trained in a similar line of business as a car mechanic and was a football enthusiast, spending his spare time on the rough wasteland of the “Schmelz” near a military parade ground on the outskirts of Vienna. In 1949 Karl Bruckner wrote “Die Spatzenelf” (The Sparrow–Eleven) about the progress of a group of poor boys, mad about football, on the way to becoming a team and to victory against the youth team of a famous football club. Slowly also political and social problems were dealt with in youth books of the post-war period and Bruckner was one of the most famous post-war writers of youth literature in Austria, who followed the path of a socially and politically critical approach, as opposed to the romanticised “Karl May” adventure literature. In 1953 his book “Giovanna im Sumpf” (Giovanna in the Bog) came on the market, which dealt with the demand for equality of opportunity, while in “Sadako will leben” (Sadako Wants to Live) of 1961 his topic was the World War II disaster of the atomic bombs, which exploded in Japan in 1945. There he tells the story of Sadako, who survives the bomb attack but later dies of leukaemia.

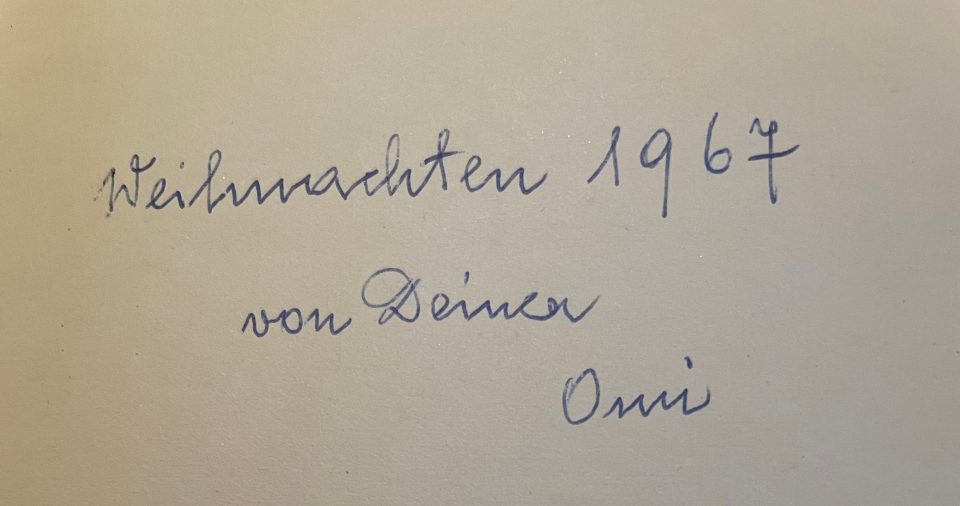

“Sadako will leben” (Sadako Wants to Live ) was given to me by my grandmother Lola in 1967 (see dedication). Karl Bruckner published it with a quote of Gotthold Ephraim Lessing saying that who does not lose his reason over certain things has no reason to lose.

Othmar Franz Lang was born in Vienna, too, in 1921 and was another Viennese socially critical youth book author. He wrote more than 60 books, several of which were translated into many languages, just as Karl Bruckner’s. In the youth book of 1955 “Die Männer von Kaprun” (The Men of Kaprun) Lang’s topic is the construction of the hydro-electric power plant Kaprun in the Austrian Alps, where my father, Werner Tautz, worked as a young man.

Lang describes the daily routine and the adventures of two students who finance their university studies by working on the construction site during several consecutive summers. The book only covers the post-war period until the completion of the power plant, not the NS period.

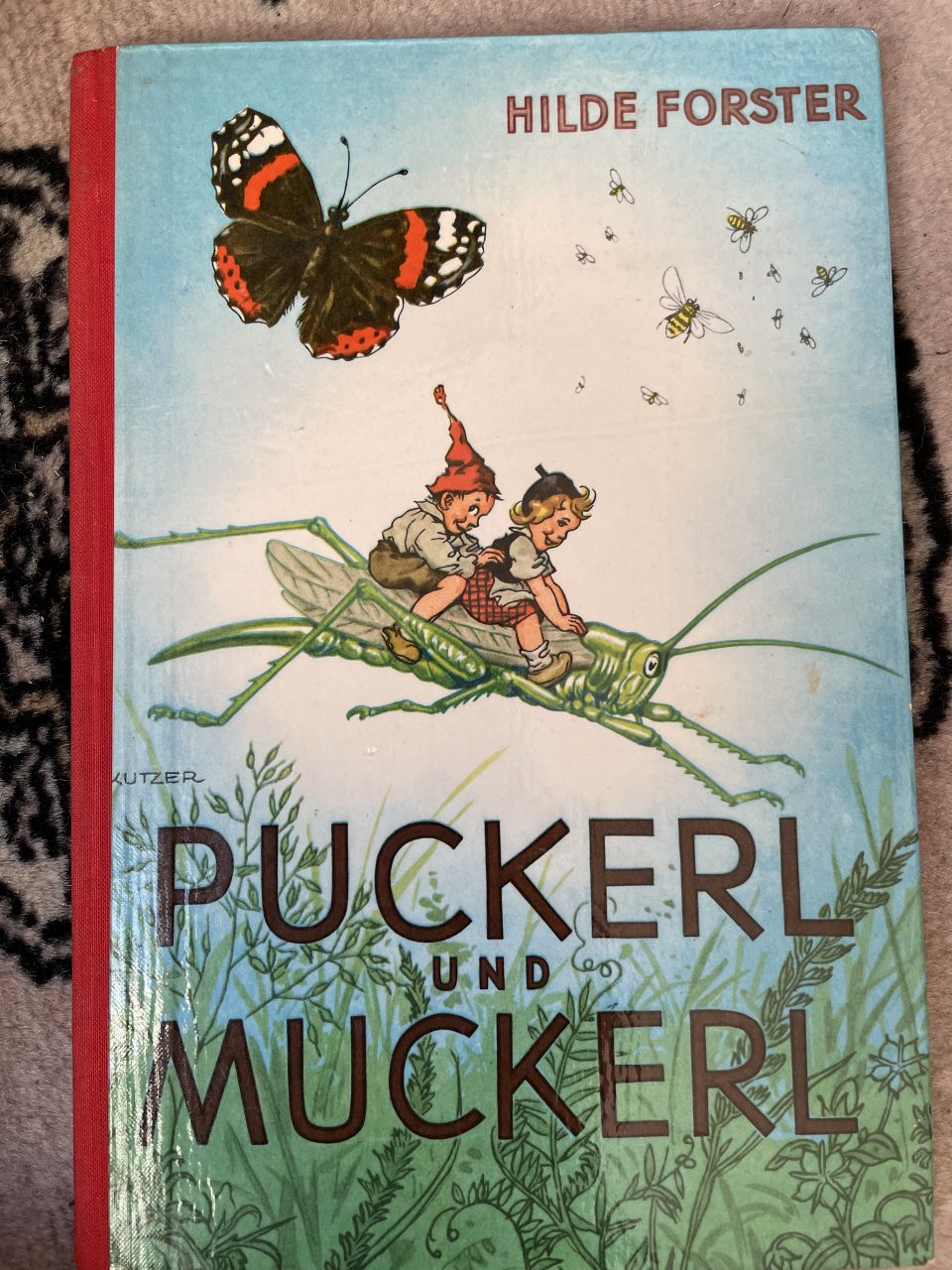

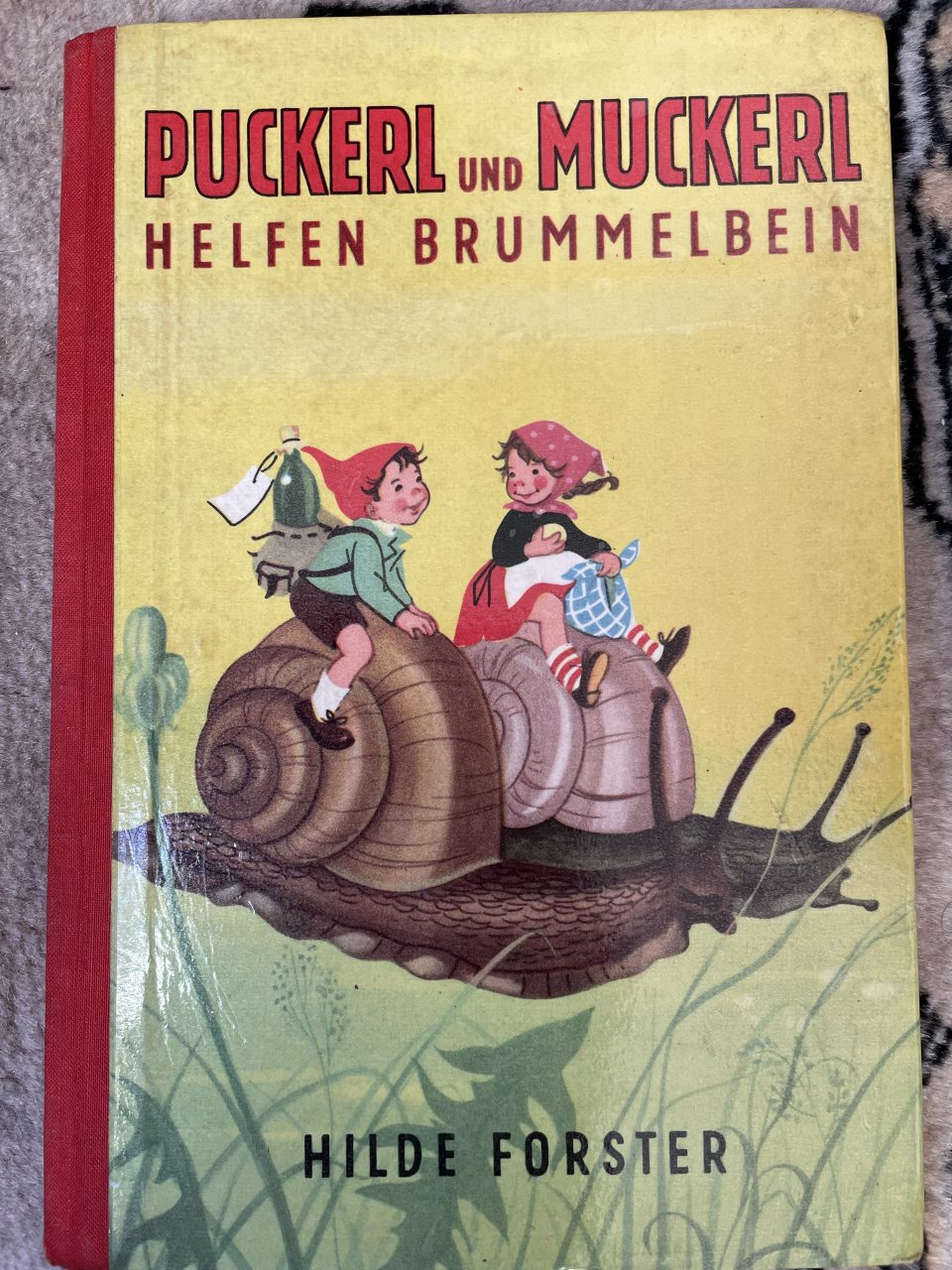

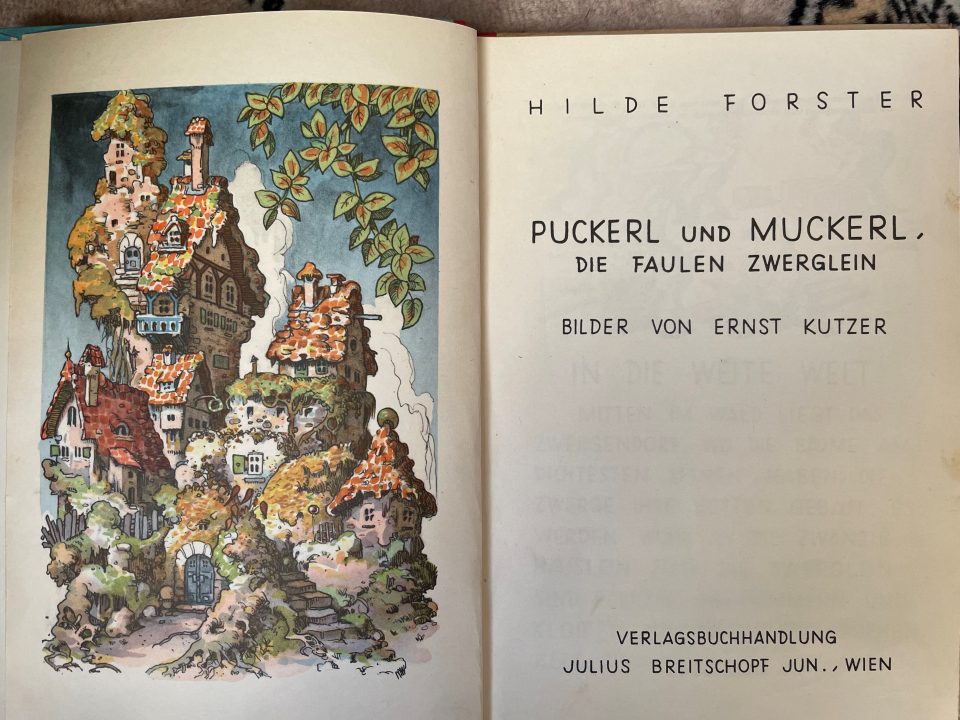

The Viennese writer of children’s and youth books, Hilde Forster, a primary school teacher born in Vienna in 1924, who started to write books and radio plays after the war, published “Puckerl und Muckerl, die faulen Zwerglein” (Pucker and Muckerl, the Lazy Little Dwarfs) in 1951. This book, as much of her other work, clearly shows the intended educational impact of never being idle, of helping others and working hard, set in idyllic natural surroundings.

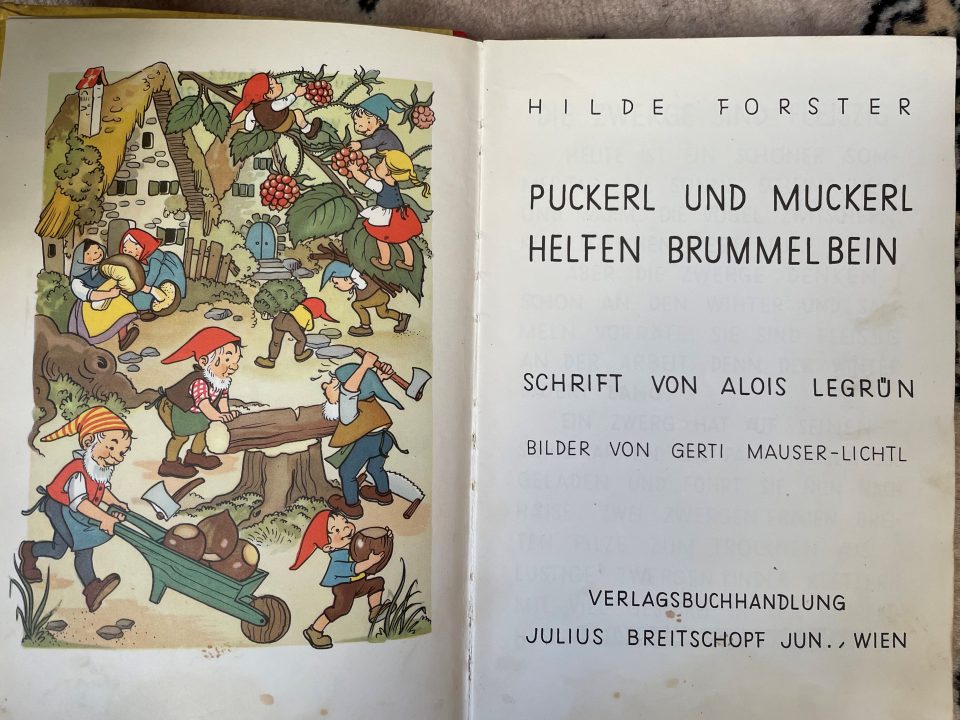

The two “Puckerl & Muckerl” books by Hilde Forster

The first volume was illustrated by Ernst Kutzer

The second second volume was illustrated by Gerti Mauser-Lichtl

Unfortunately, some of the authors of children’s and youth literature who were much appreciated by the Nazis managed to get their books published after the war again, as the example of Annelies Umlauf-Lamatsch shows. But she was not the only one. Franz Karl Ginzkey was an officer in the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy and in 1934 a prominent supporter of the Austro-Fascist regime. As he was a free mason, the National Socialists initially mistrusted him, but Hitler finally accepted him as NSDAP party member in January 1942, which Ginzkey thanked him with a couple of NS propaganda poems. Franz Karl Ginzkey’s “Hatschi Bratschis Luftballon” (The Balloon of Hatschi Bratschi) of 1903 was sold in Austrian bookshops in a new edition of 1960 with only slight changes. The black Africans Hatschi Bratschi meets on his travels in the hot-air balloon were originally portrayed as men-eaters, while in the 1960 version they are apes and new illustrations were provided by Wilfried Zeller-Zellenberg. Nevertheless, the whole book was still full of racist clichés, but sold well in Austria in the post-war years.

Children’s and youth books read in post-war Vienna

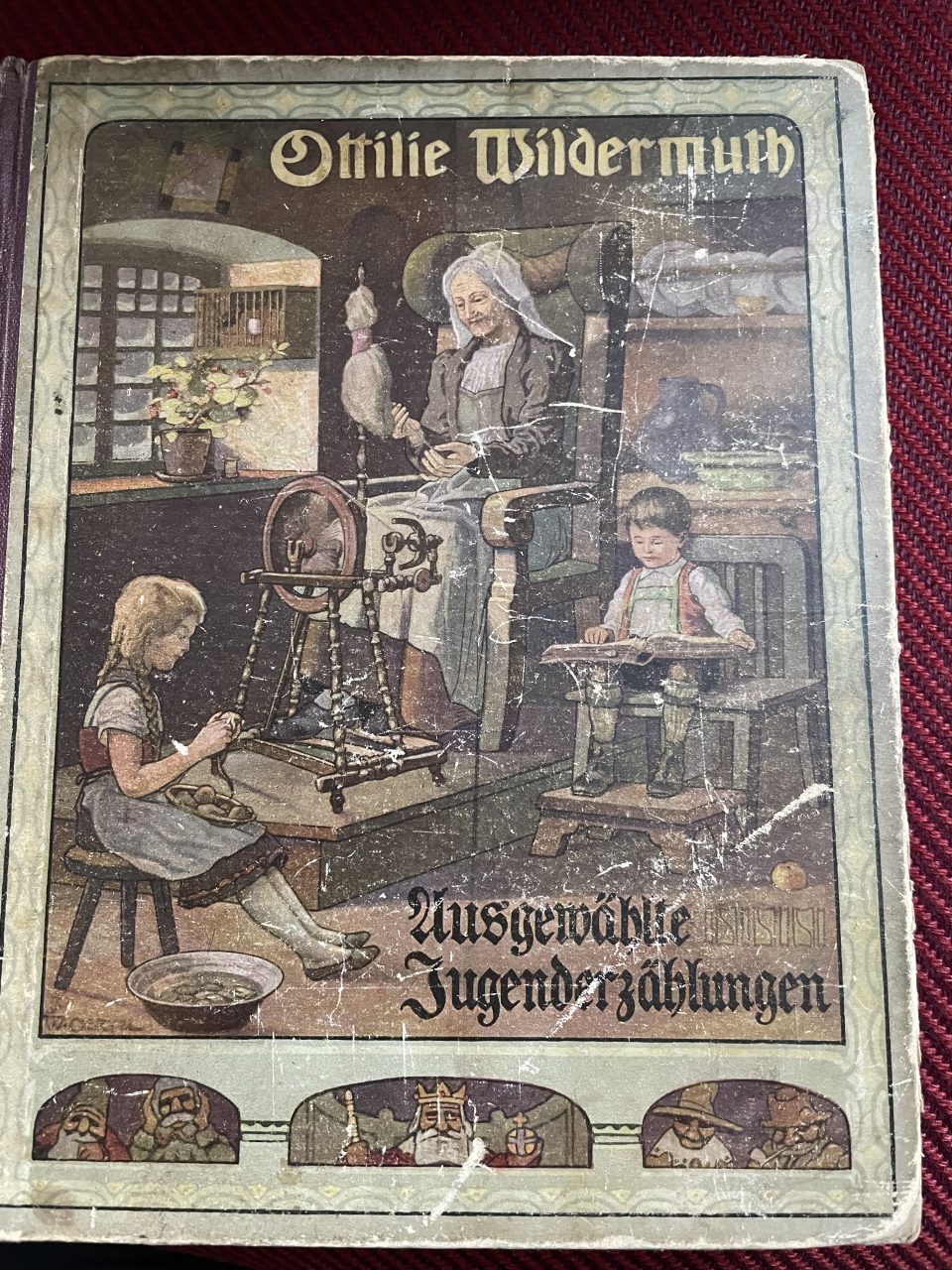

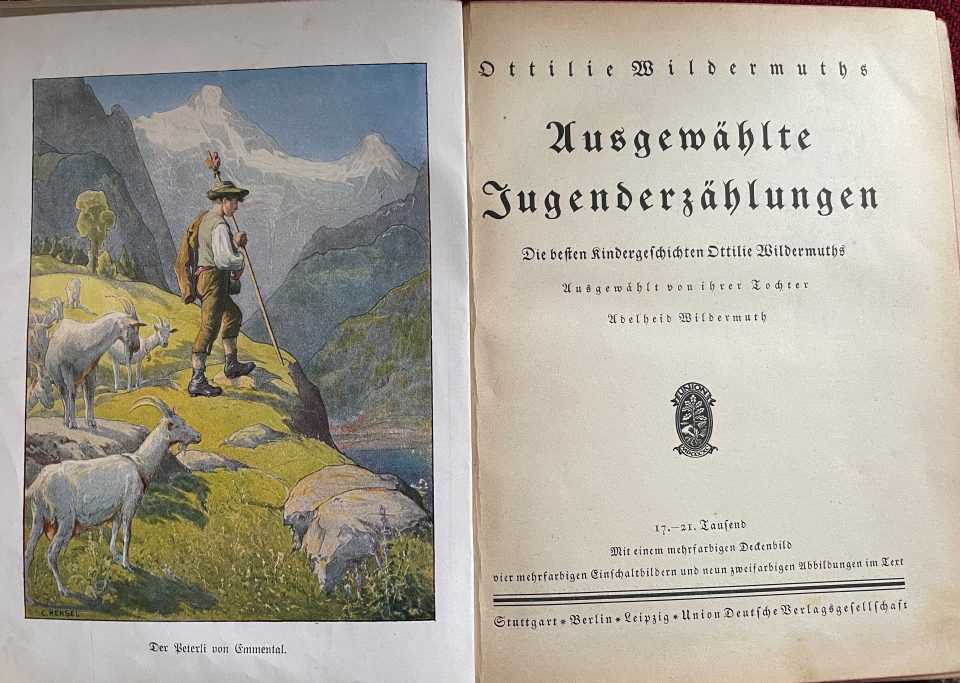

Of the youth books which Herta possessed in the dire years after liberation these were mostly stories which had been written many decades before, so had no direct connection to the NS period, which Austrians wanted to forget and ignore. First, there was Ottilie Wildermuth “Ausgewählte Jugenderzählungen” (Selected Tales for Youth), re-edited in 1916. Ottilie Wildermuth was born in 1817 In Germany and despite her eagerness to learn, which is proven by her starting to write stories and poems as a child, she received only a very rudimentary education. She acquired all her knowledge of literature and languages via self-studies and then married Professor Wildermuth, a professor of modern languages. She was a prolific writer of children’s and youth literature and a typical representative of this genre in the 19th century: romantic and idealised stories with the didactic aim of training young people to become reliable and devoted supporters of the state and Protestant church. Her popularity seemed to have extended in German-speaking areas way into the middle of the 20th century. This book was bought at an antiquarian’s for Herta.

Ottilie Wildermuth “Ausgewählte Jugenderzählungen” 1916

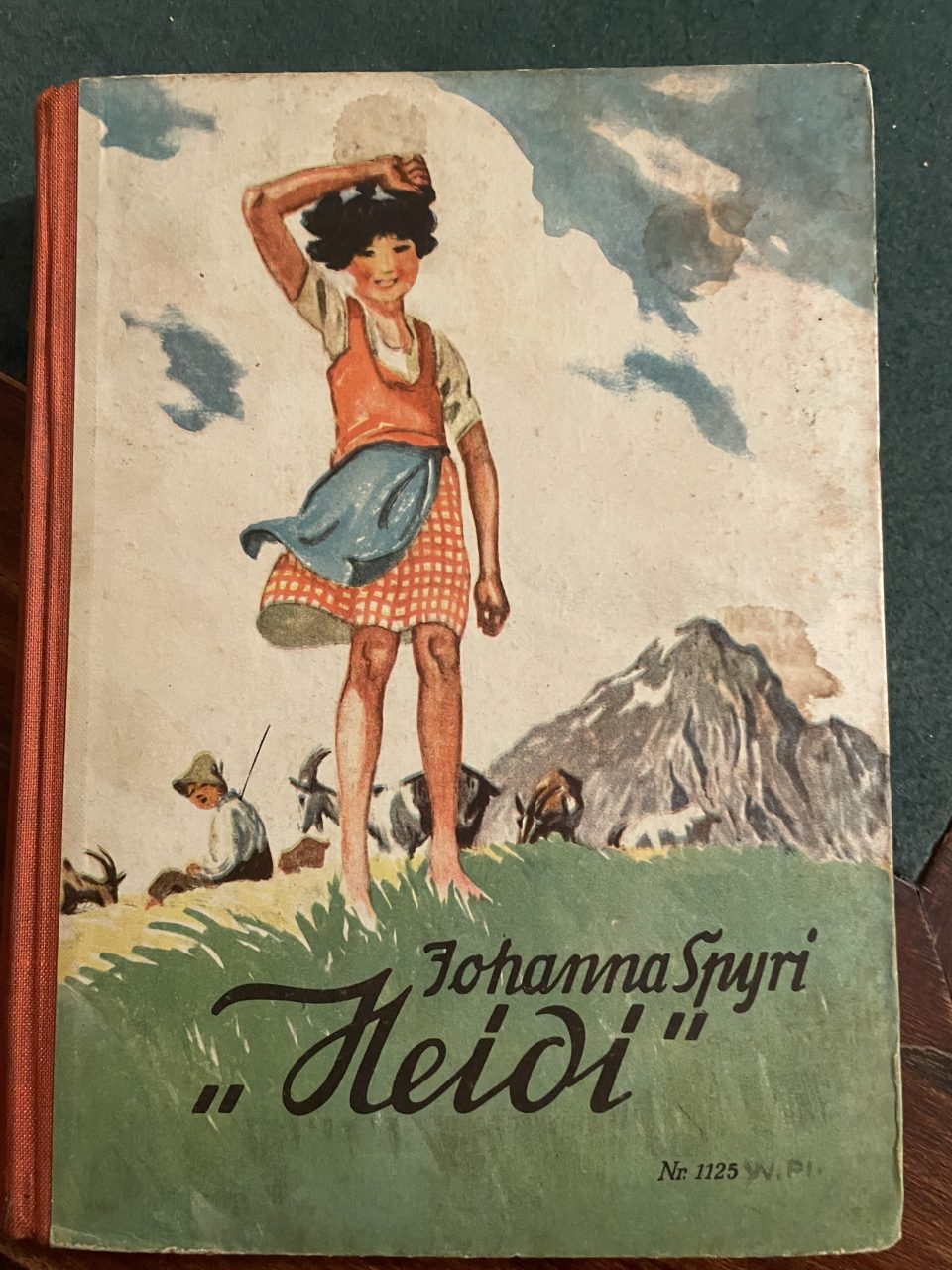

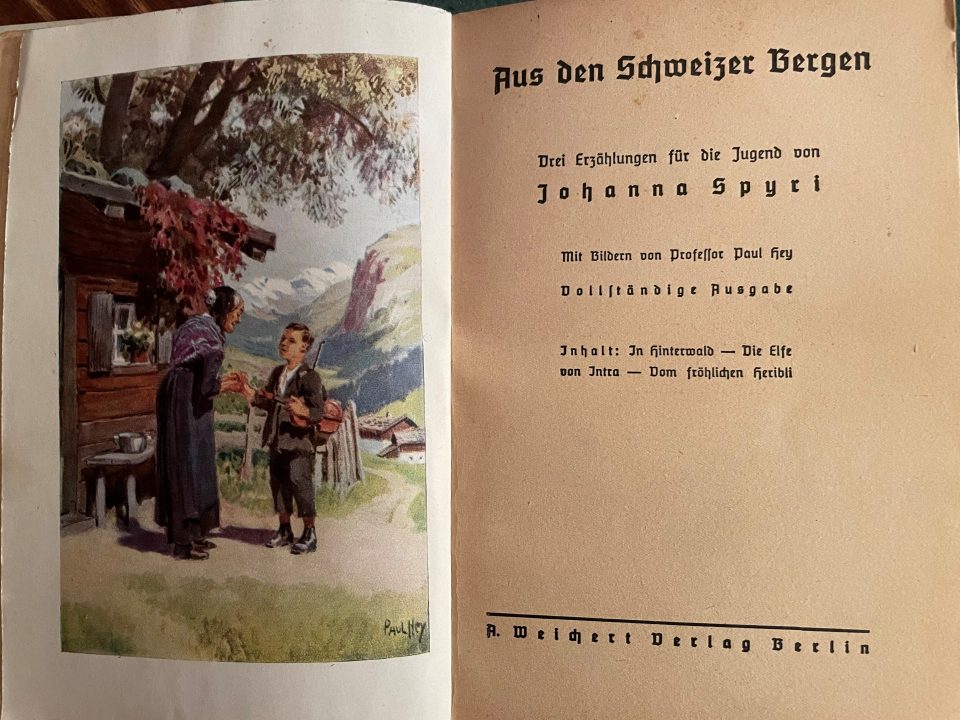

Second, Johanna Spyri was widely read in Vienna after 1945, too. As Wildermuth she was born at the beginning of the 19th century, in Switzerland in 1827. Despite her unhappy marriage and spouts of deep depression, she became the most well-known Swiss writer of children’s and youth books, especially driven be the success of the publication of “Heidi”, which was later filmed numerous times. Her descriptions of idyllic life in the Alps seemed to have especially appealed to Herta and her father Toni, who both loved mountaineering in the Austrian Alps, while Herta’s mother Lola was rather reluctantly accompanying them on their mountain tours. Lola was the one to more enjoy the jolly times in the mountain huts after the hikes.

See article: http://centraleuropeaneconomicandsocialhistory.com/the-alps-past-time-of-the-young-viennese-in-the-1920s-1930s

Johanna Spyri “Heidi” (published by the German Loewe Verlag for youth literature, 1880,) and “Aus den Schweizer Bergen“, 1888

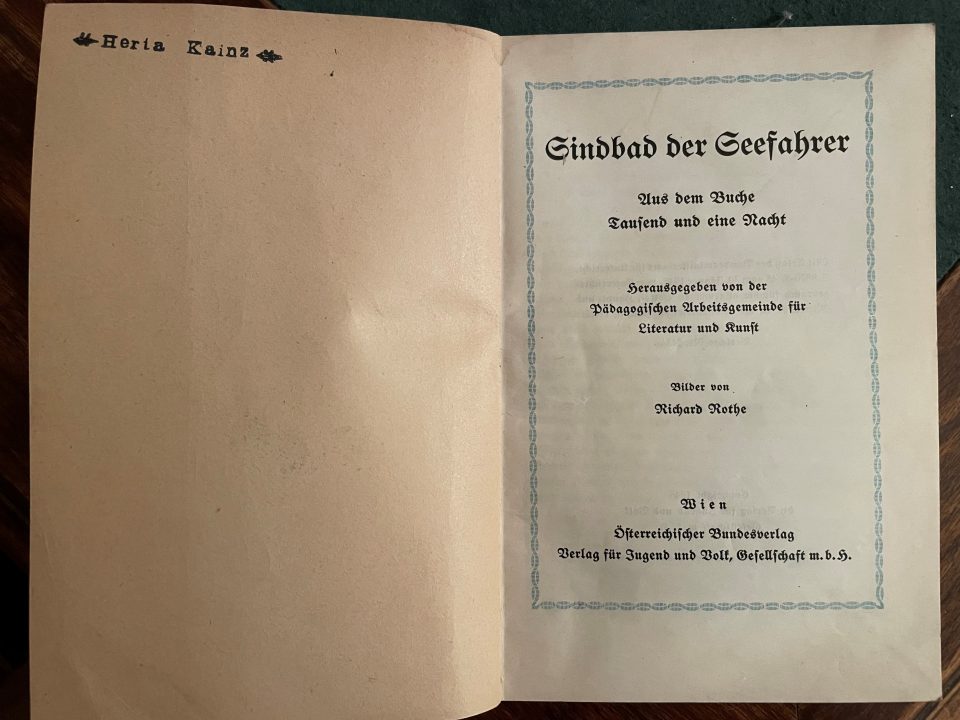

Third, adaptations of oriental tales of the far-away past were of great appeal, too, as they did not have the slightest connection to the youth literature canon of the Nazis, such as “The Tales of 1001 Nights”, which were published after the war by the Österreichischen Bundesverlag in cheap and affordable editions, such as this slender volume of “Sindbad, the Seafarer”.

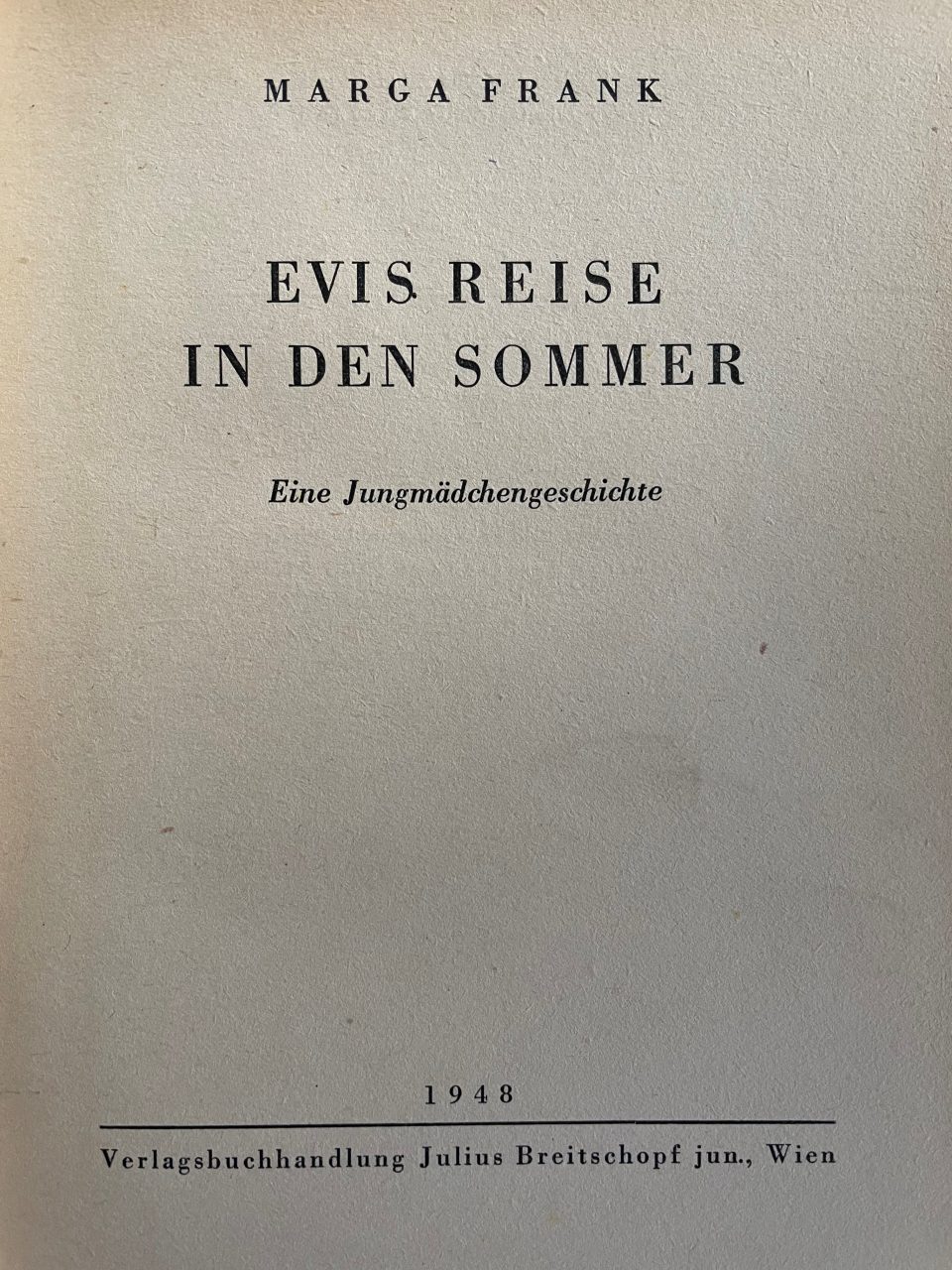

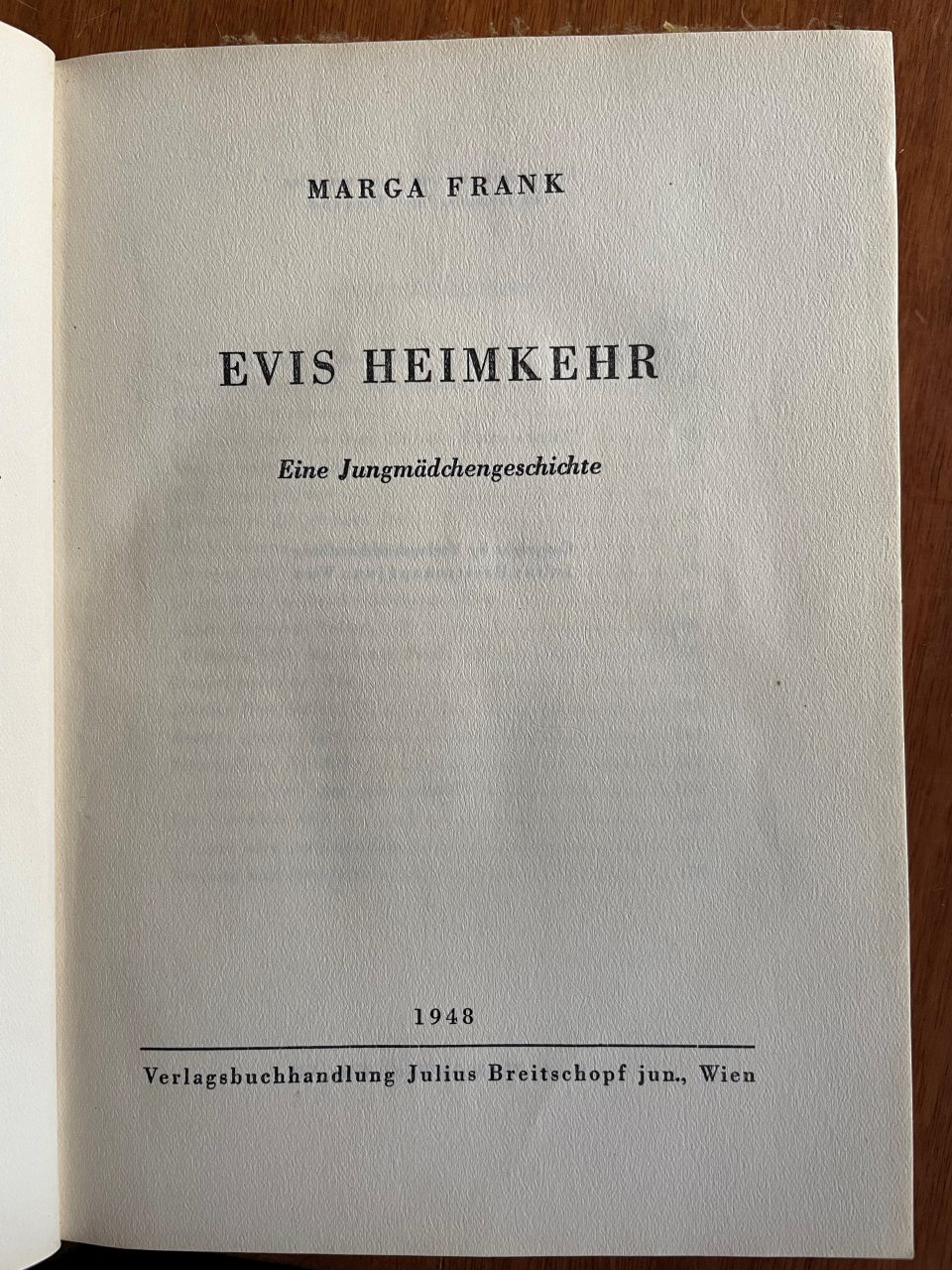

And finally, Marga Frank’s books for young girls “Evis Reise in den Sommer “(Evi’s Journey in the Summer), 1948 and “Evis Heimkehr” (Evi’s Homecoming), 1948, published by Verlag Julius Breitschopf jun. Wien. Marga Frank was born in 1922 in Vienna and worked for the radio after the war. In order to support her family she started to work for the RAVAG (the forerunner of the ORF) from October 1945 on. There she was responsible for children’s broadcasting from the beginning of the the foundation of the ORF (Austrian Broadcasting Corporation) in 1955 and designed the broadcast “Das Traummännlein kommt”, which was the most popular broadcast for children at the time. Frank wrote radio plays for children and books for children, young girls and fairy tales. She started her writing career because she believed that there were no appealing modern books for young readers on the market in Austria, whereby she had to write at night because of her full-time job as a journalist. From 1946 on she worked for the children’s programme of “Radio Wien”and wrote for the “Kinderpost”, a children’s magazine, too. Her series of books about “Evi” became a bestseller in Austria and she continued to write until the early 1980s. Nevertheless, Marga Frank is now virtually unknown. She was the only contemporary youth authoress, of which Herta possessed books. One reason might have been that they were circulated in cheap and affordable editions.

An important turning point was the year 1950, when the US army started to promote the translation of English language authors in Austria, US films were shown in German, and English language plays were staged in German in Vienna, which deeply impressed my mother, who wrote about these experiences in her diary.

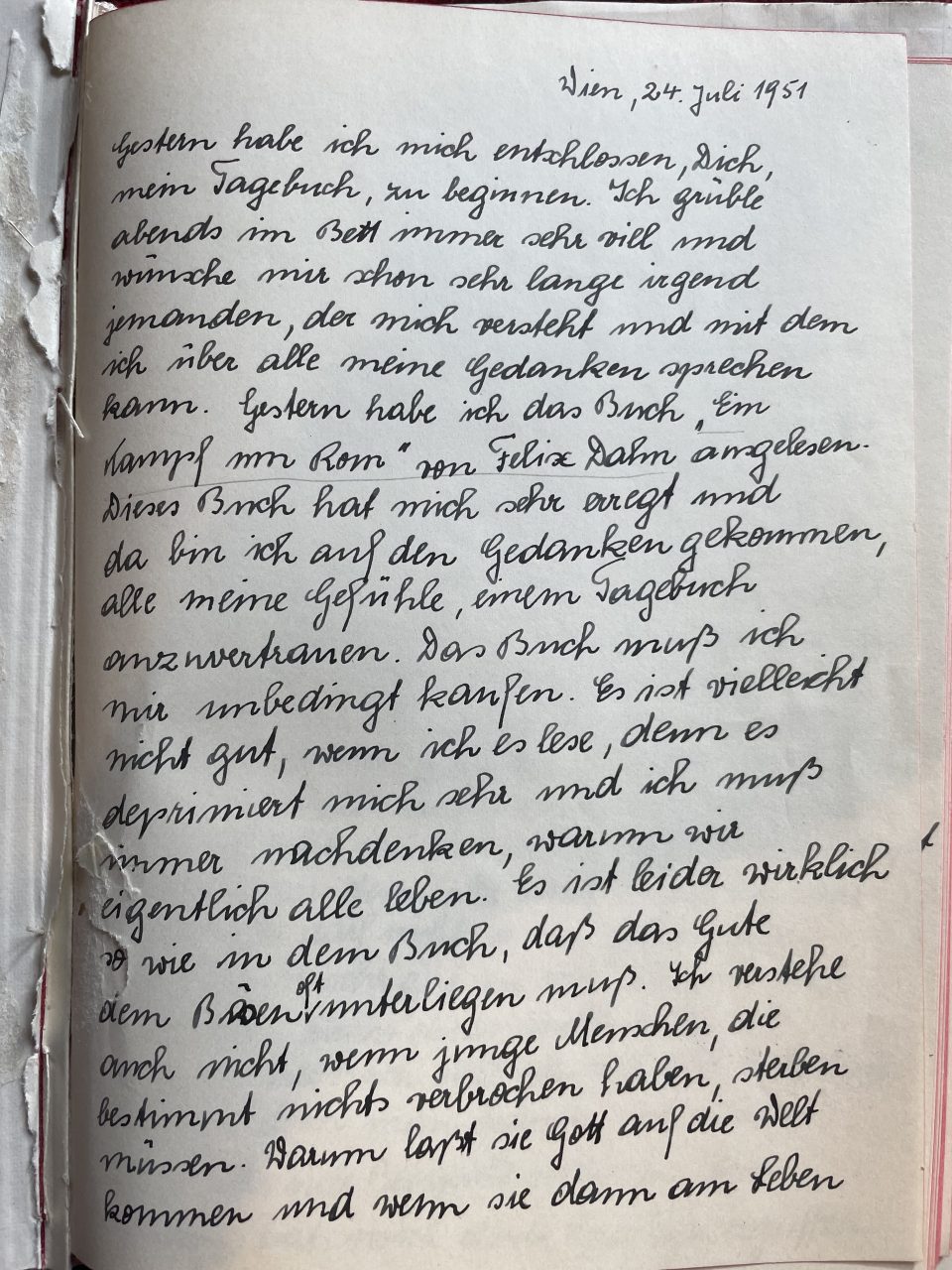

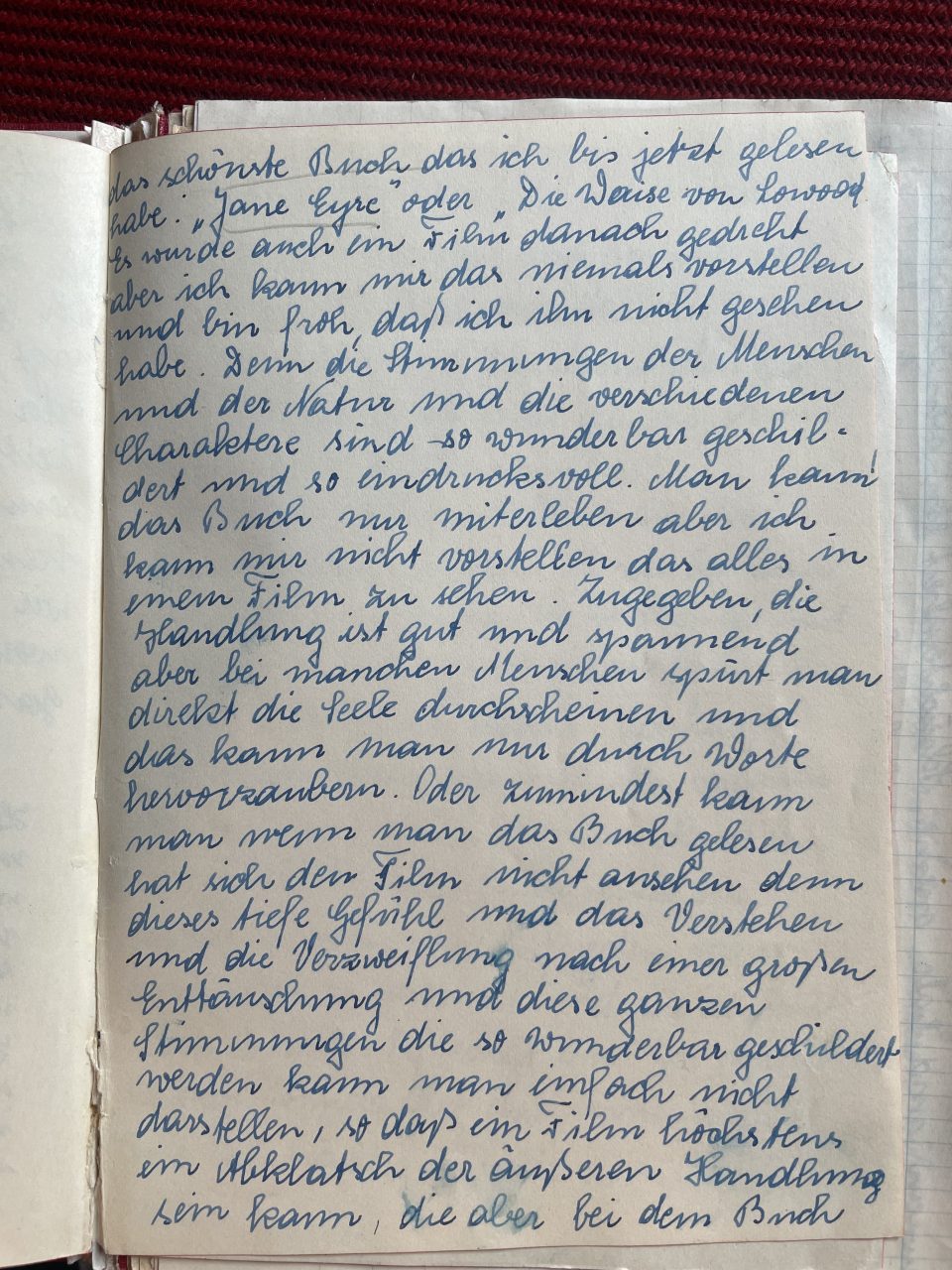

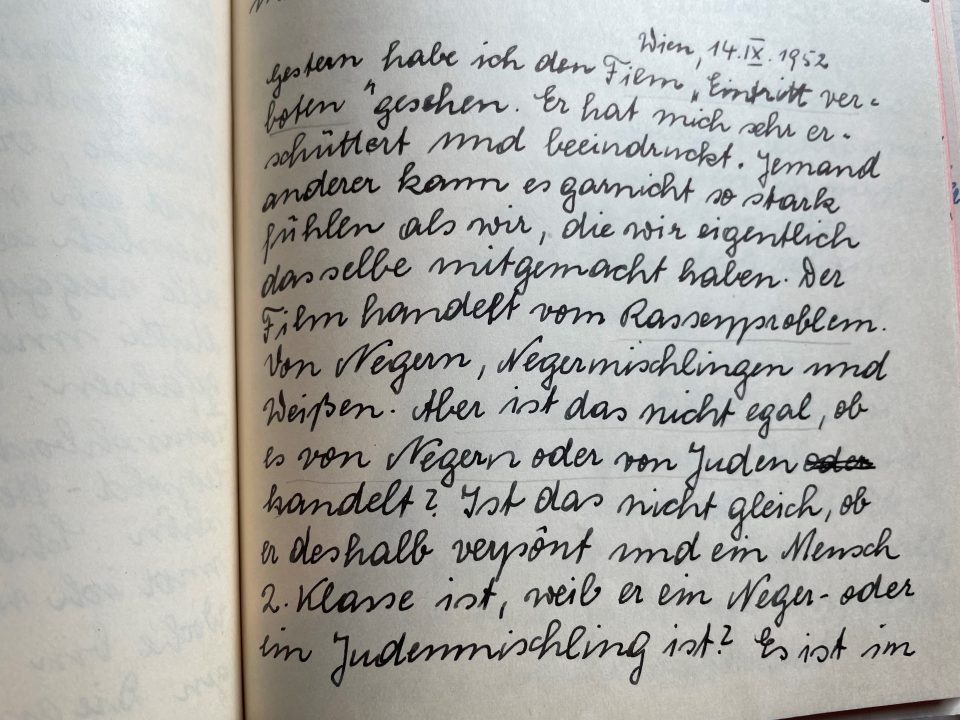

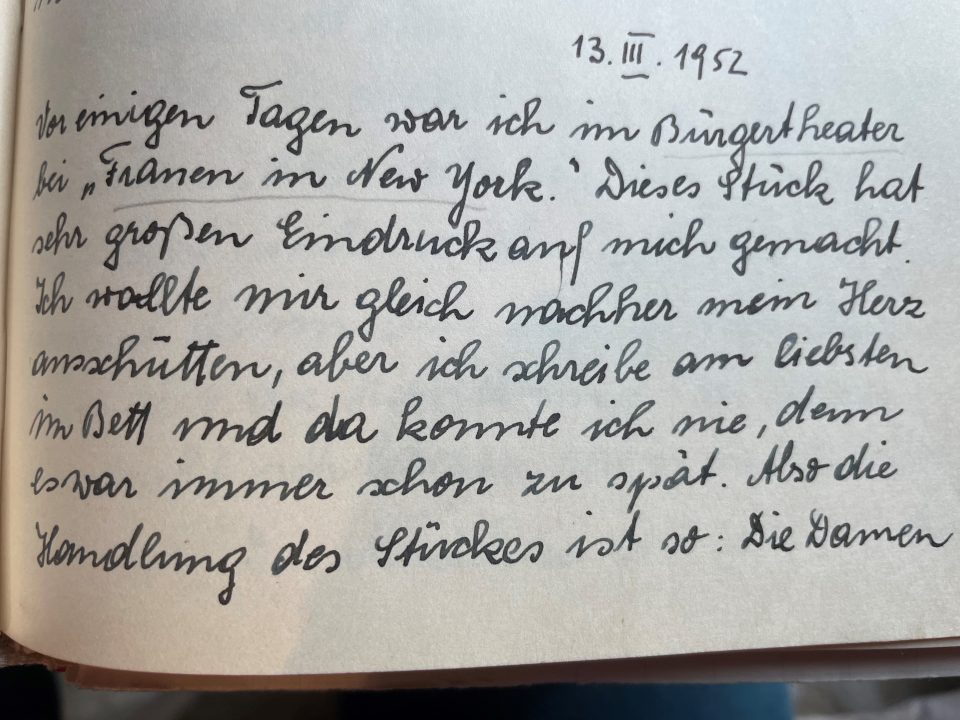

Herta’s diary entries about Felix Dahn “Ein Kampf um Rom“ and about “Jane Eyre” by Charlotte Bronte (1847), the US film “Off Limits” (Eintritt verboten) of 1952 and the play “The Women” (Frauen in New York) of 1936

Herta as a teenager after the war, reading – her favourite hobby

Herta wrote in her diary that Dahn’s book had so excited her that she decided to start a diary to write about her feelings. She had borrowed the book from the library, but planned to buy it for herself, although she was not sure whether that would be a good idea as it depressed her and led her to ponder “why we are really here and why the good is always defeated by the bad and why young people have to die despite the fact that they have done nothing wrong. Why did God allow them to be born and when they then enjoy life, they have to die”. Herta mentions that in the book King Totila believes in all good and beautiful and is convinced that God will help his good cause and he will win, but in the end, he loses the battle. Herta asks, why he had to die although he was righteous. “I don’t know, I can no longer firmly believe. Maybe because I don’t understand. But I think it is said that those are blessed who don’t understand and still believe. I don’t want to say that I don’t believe in God, but I don’t understand why he puts up with all this suffering and tolerates wars, where so many people who are innocent, have to die….. Most of all, I was impressed by Duke Teja, who lost everything that was dear to him and still remains a good person and saves his people in the end. One must not despair if one loses everything, but has to set oneself a beautiful and noble goal and try to attain it.”

In her diary entry of 13 March 1952 Herta writes about a visit to the “Bürgertheater” to see the play “Frauen in New York”. This was a production of the American play “The Women” of 1936 by Clare Boothe Luce, which greatly impressed her. Herta retells the contents of the play; the ladies of New York’s “better society, but in reality, they are not better”, who fill their days with gossip, men, children and betrayal. Herta feels with the little girl who discovers that her parents want to divorce. “I understand how I would feel. I thought if my parents divorced, I would also not show my feelings, but I would despair. I often felt I heard my own thoughts in the play and saw myself on stage.” But what most touched Herta was the performance of Vilma Degischer as Mary. “If I hadn’t been ashamed in front of my parents and grandparents, I would have cried bitterly with Mary. It might sound kitschy, but it wasn’t like that. She (Vilma Degischer) must have suffered a lot to be able to act like that… I will never forget that.”

On 13 September 1952 Herta saw the German version of the US film “Eintritt verboten” (Off Limits) of the same year and she was truly shattered by the race problems in the USA. She writes, “No one can feel this as much as we do, who have suffered similar discrimination. The film talks about blacks, whites, and mixed-race people. Isn’t it the same whether it’s Jews or blacks? Isn’t it the same if someone is discriminated against whether he or she is Jewish or black or mixed-race? It is the same and that’s why the film touched me so much. I know what it means to persecute and torture someone who is innocent of how he was born. I can imagine what it meant for children to discover at the age of 20 that they were mixed-race and are therefore disadvantaged. I’m lucky that I have always known that I’m mixed-race because now I don’t care, but if I had been informed only now that would have been terrible. Now I think, if someone does not want to be in contact with me because of that, I need not be sad because this person is worthless, anyway. I will never be ashamed of who I am. I wish many would learn from the film that one must not distinguish between human being and human being. The most important thing is neither race nor religion, but a pure heart and a pure soul… I mean, a good person.”

On 9 April 1953 Herta noted in her diary that “Jane Eyre” by Charlotte Bronte was the most beautiful book she had read so far. She mentioned that there was a film as well, but she was glad she did not see it because she could not imagine that a film could adequately reflect the moods, the nature, and the characters of this wonderfully written novel. “The plot is good and thrilling, but you can directly see into the souls of the characters and that can only be achieved by words. Or at least, you cannot watch the film after having read the book because these deep emotions, the despair, and the great disappointment, which are so wonderfully described, cannot be shown in a film. A film can only be a cheap copy of the plot and cannot convey these deep emotions described in the novel.”

The time of the 1950s and 1960s in Vienna

In the 1950s some renown Austrian writers started to publish books for children and young adults, too. For example Johannes Mario Simmel, who was born in Vienna in 1924, wrote “Ein Autobus groß wie die Welt” (A Bus as Big as the World) in 1951 and “Meine Mutter darf es nie erfahren“ (My Mother Must never Hear about That) in 1952. Simmel’s Jewish father managed to flee to England, while most of his relatives were murdered in the holocaust. Johannes Mario Simmel grew up in Austria and England and after the war he worked as a journalist and translator and interpreter for the US Army, wrote novels and film scripts. At that time around twenty publishing houses edited children’s and youth literature in Austria, foremost “Österreichischer Bundesverlag”, “Verlag Jugend und Volk”, “Verlag Jungbrunnen”and “Verlag der Kinderfreunde”. A widespread phenomenon were book clubs, such as “Donauland”, which helped to propagate children’s and youth books, as book club members quarterly received recommended books. Fascinating topics, such as modern technology and exotic landscapes, which appealed to young adults, were covered in new books for adolescents, for instance the above mentioned book by Othmar Franz Lang about the construction of the hydroelectric power plant Kaprun, or books by famous adventurers, such as the diver Hans Hass “Unter Korallen und Haien” (Among Corals and Sharks) in 1950 , the climber Herbert Tichy “Cho-oyu” (Mount Cho Oyu) in 1955 or the mountaineer Heinrich Harrer “Sieben Jahre Tibet” (Seven Years in Tibet) in 1952.

Gertrud Schmirger, born in Carinthia in 1900, adapted the historical novel for children, but focussed on the far-away past. Her book “Die Katze der Herzogin. Erzählung aus der Babenbergerzeit” (The Cat of the Duchess. A Tale from the Times of the Babenberger) was put on the market in 1964 and was re-published several times, as were some of her other historical novels for a young reading public. Historical novels for young adults were very popular in the 1960s as well, for example Fritz Habeck’s “Der Kampf der Barbekane” (The Fight of the Barbicans) of 1960 or “Der Aufstand der Salzknechte” (The Riot of the Salt Labourers), 1966. Habeck was born in Neulengbach near Vienna in 1916, but later moved to Vienna. He worked as a journalist, author of historical novels for adolescents and adults, of film scripts and plays. Kurt Benesch was born in Vienna in 1926 and wrote a number of novels, non-fiction and youth literature, the most famous of which was “Nie zurück” (Never Back) of 1967, talking about the discovery of the “Franz-Josephs Land” by an Austro-Hungarian expedition. Often events from Austrian medieval history or the times of the Habsburg Empire were chosen, yet more recent Austrian history, especially the Austro-Fascist and the NS period, was avoided at all costs and no confrontation with the involvement of Austrians in the Nazi regime took place.

Nevertheless, there were few courageous authors who dared to break this unspoken taboo. One of them was Winfried Bruckner, who mentioned the holocaust in his book “Die toten Engel” (Dead Angels) in 1963, which deals with the uprising in the Warsaw ghetto of 1943. He was born in 1936 in Krems in Lower Austria and worked for the Austrian Trade Union Congress, while at the same time writing children’s and youth books, several of which were put on stage or filmed. Käthe Recheis was born in Upper Austria in 1928 and became a popular authoress of children’s books, living in Vienna and Hörsching near Linz. Her auto-biographical youth novel ”Schattennetz” (Net of Shadows) came out in 1964 and there she talks about the events related to the liberation of an Austrian NS concentration camp. Käthe Recheis was blamed for taking up such a monumental historic topic too early, when she wrote about her experiences as a 17-year-old girl, helping her father, the doctor Hans Recheis, in trying to save the lives of former KZ prisoners immediately after liberation; a futile battle against typhus, to which her father eventually succumbed, too. The above-mentioned Karl Bruckner published “Mann ohne Waffen” (Man without Weapons) in 1967, where he described life in Vienna from 1938 until 1945 and especially the day of liberation, the 13th of April 1945. Furthermore in the 1960s more books started integrating the latest findings in developmental psychology of children.

Rusia Lampl published, among others, two youth books about emigration and the life of girls in Israel, whose families had experienced persecution in Vienna and found refuge in Palestine. These two books “Der Sommer mit Ora” (The Summer with Ora), 1964 and “Eleanor”, 1966 impressed me a lot as a child and furthered my interest in the history of my family. Rosia Schlamm was born in Kroscienko, Austro-Hungarian Galicia, in 1901 and moved with her family to Vienna in 1909, where she studied art history and got interested in the Zionist movement. She married the music scientist Max Lampl and emigrated with him to Palestine in 1934. There she wrote radio plays and youth literature in German, treating Israeli subjects, but writing for a German-speaking public.

Rusia Lampel „Der Sommer mit Ora“ (1964) with a quote of Martin Buber at the Youth Day in Vienna 1918, “Youth is the eternal lucky chance of mankind”

Rusia Lampel‘s sequel „Eleanor. Wiedersehen mit Ora” 1966

The books portray the Israeli youth of the 1960s and Lampel describes in detail the lives of Israeli children and young adults and their families who had immigrated from Europe fleeing the Nazis. She mentions the difficulties of learning a new language, the problems they had with the climate and the different ways of life. The first book is written in the form of a diary by the 15-year-old Ora, whose parents came from Austria, and who encounters the 13-year-old spoilt American girl Eleanor during the summer months of 1961. Ora’s and Eleanor’s parents had spent time together in a so-called “Sammelwohnung” in Vienna, where they had been imprisoned by the Nazis.

Both families managed to escape to Palestine, but while Ora’s parents adapted to the life there, Eleanor’s parents took the first chance to emigrate further to the USA. They left without saying goodbye, fearing they would be despised and in fact, Ora’s parents were unwilling to forgive the Kobelmanns this betrayal. An interesting aspect of immigrant societies is highlighted, namely that the children who were already born in exile could not understand their parents’ wish to return to Austria, a country they had to flee from because of NS persecution. The born Israelis despise those immigrants from Austria or Germany who still try to be Austrians or Germans. The second book is written in the form of Eleanor’s diary, who returns after two years in the US to Israel; this time with her parents, both originally from Vienna. Her grandparents were murdered in the holocaust, which is something that Eleanor cannot overcome. In this book the harsh living conditions of the immigrants in Israel are described, but also the prevalent anti-Semitism in Austria before the war. Another topic is the guilt of children and grandchildren of NS offenders in the person of a girl whose grandfather was an active NSDAP party member in Germany and his granddaughter Franziska now wants to work hard in a Kibbuz to compensate this family guilt. Yet the focus of both books is on the views of young Israeli girls and their relationship to their Austrian or German family roots.

Reuven Kritz was born in Vienna in 1928 and came to Palestine at the age of ten, where he grew up in a Kibbuz. He later studied English and Hebrew literature and taught at the university of Tel Aviv. He wrote several books for young people and in his first one, “Morgenwind” (later “Morgenluft”), which came out in German in 1994 in Tel Aviv, he integrated his childhood memories of Vienna and his growing up in a Kibbuz in Palestine in the plot. The young Viennese protagonist Rafi is shocked by the fact that his parents want to divorce and his beloved father, a doctor, is leaving the family. Kritz describes the political situation in Vienna, when Rafi, who knows nothing about politics, suddenly notices lots of white swastika symbols on house walls and he befriends one of the boys who distribute such swastikas and asks him whether he could not become a Nazi, too, whereupon Kurt says to Rafi, „No way, your father is a Jew!” A second time, Rafi’s world collapses. When he emigrates to Palestine together with his father, he has to learn a new language and get to know a new way of life. This book is very autobiographical and shows the delicate humour of Kritz’s style of writing. Kritz is well-known in Israel, but totally ignored in Austria.