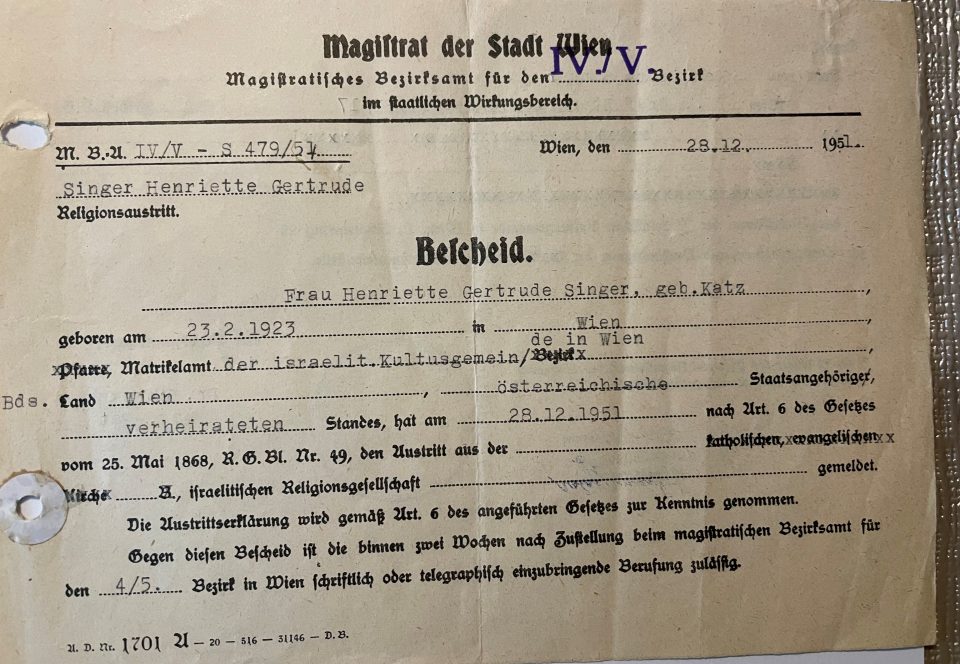

ILLEGAL RESCUE TRANSPORTS OF JEWISH CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS FROM VIENNA TO PALESTINE 1939-1945

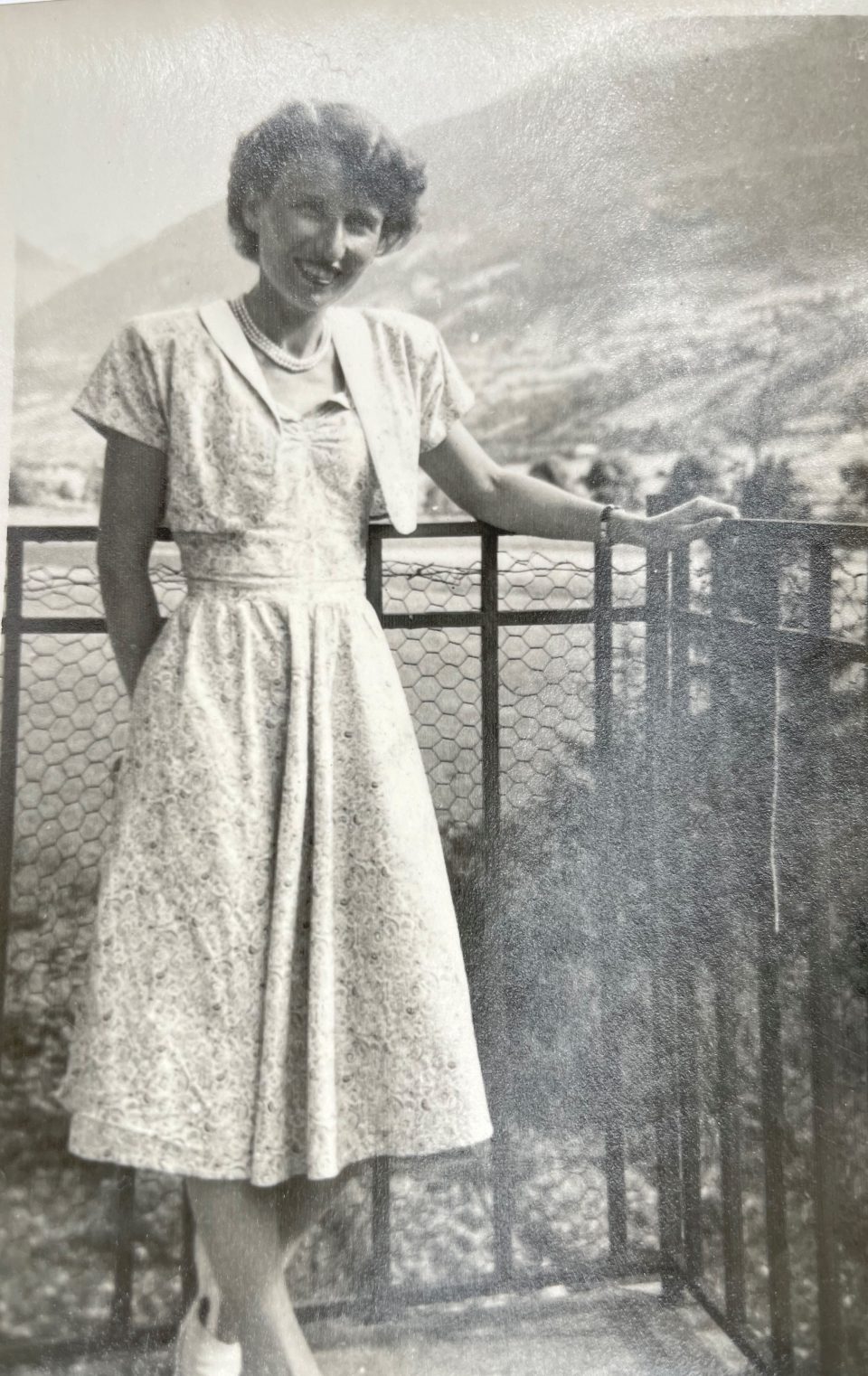

Henny Singer, née Katz, after her return to Vienna in 1948. All photos of her before the war were destroyed when her mother, Alice Katz, and her younger brother, Gerhard Katz, were deported to Opole and murdered

Henriette (Henny) Singer, née Katz, my mother’s cousin, was one of these adolescents who managed to flee from Vienna on an illegal transport to Palestine via the Danube, when the Second World War had already started, and to escape the holocaust. Her mother and her younger brother were not so fortunate and were murdered by the NS terror regime, probably in Opole, Poland. My mother, Herta Tautz, née Kainz, born on 24 November 1933, was 10 years younger than her cousin Henny, born on 23 February 1923. Henny was the niece of Herta’s uncle Norbert Katz, a famous Viennese footballer. See article:

Norbert Katz, Austrian national football team player

Before the outbreak of the Second World War the two girls did not see much of each other because of the age difference, but after the war and Henny’s return to Vienna they kept in contact until Herta’s worsening dementia made communication impossible. Henny died on 9 November 2010, five and a half years before Herta.

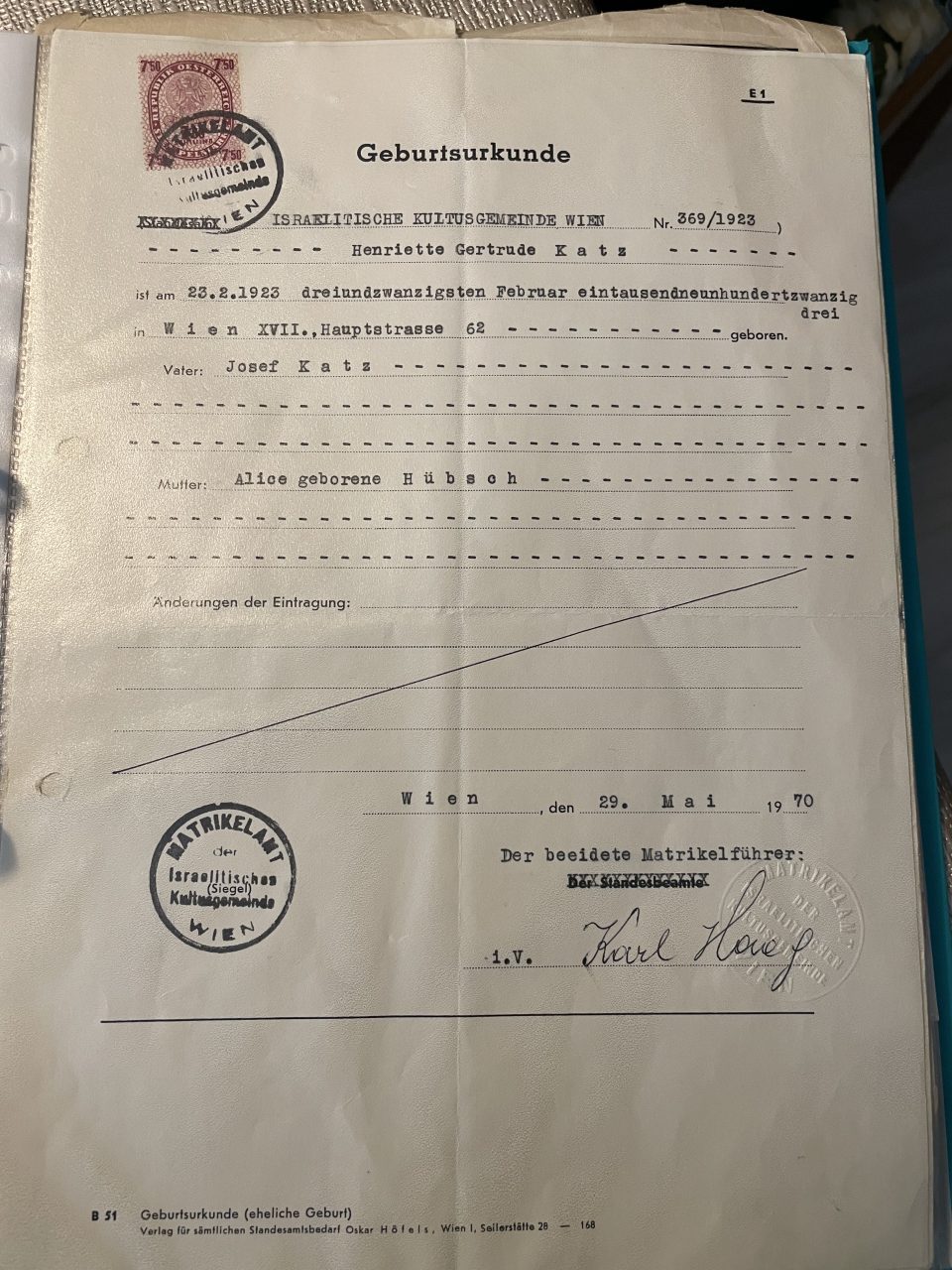

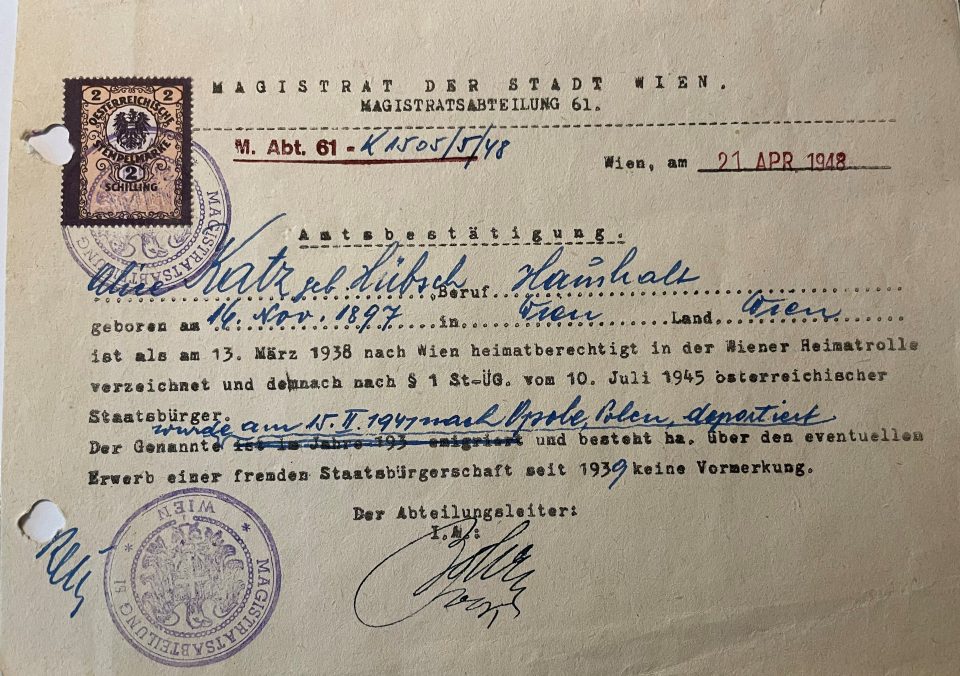

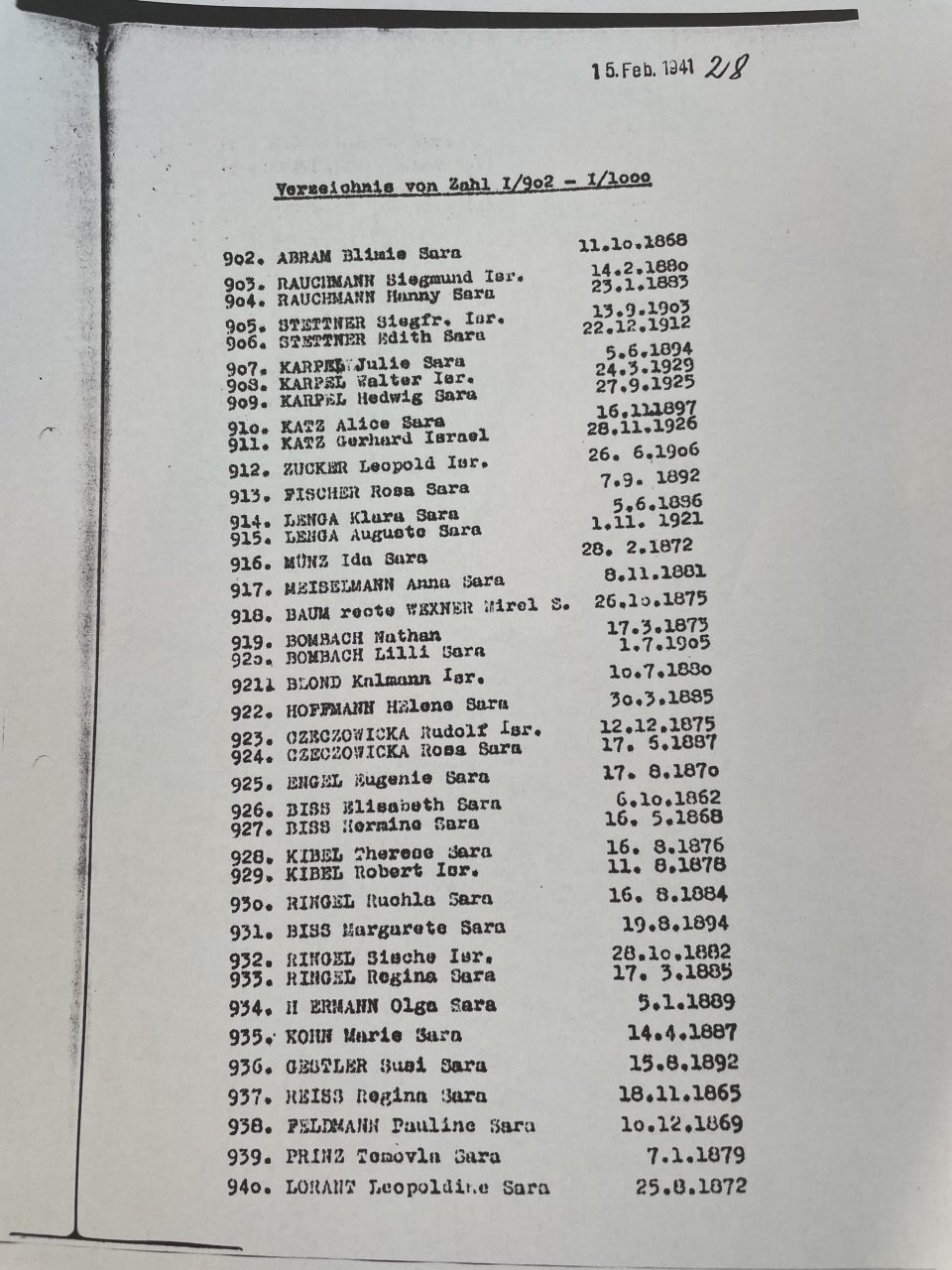

Henny had her birth certificate and her certificate of residence re-issued after the war because all her documents were lost in Vienna after the deportation of her mother and brother to the “Generalgouvernement” (the German- occupied territory of Poland) on the 15 February 1941

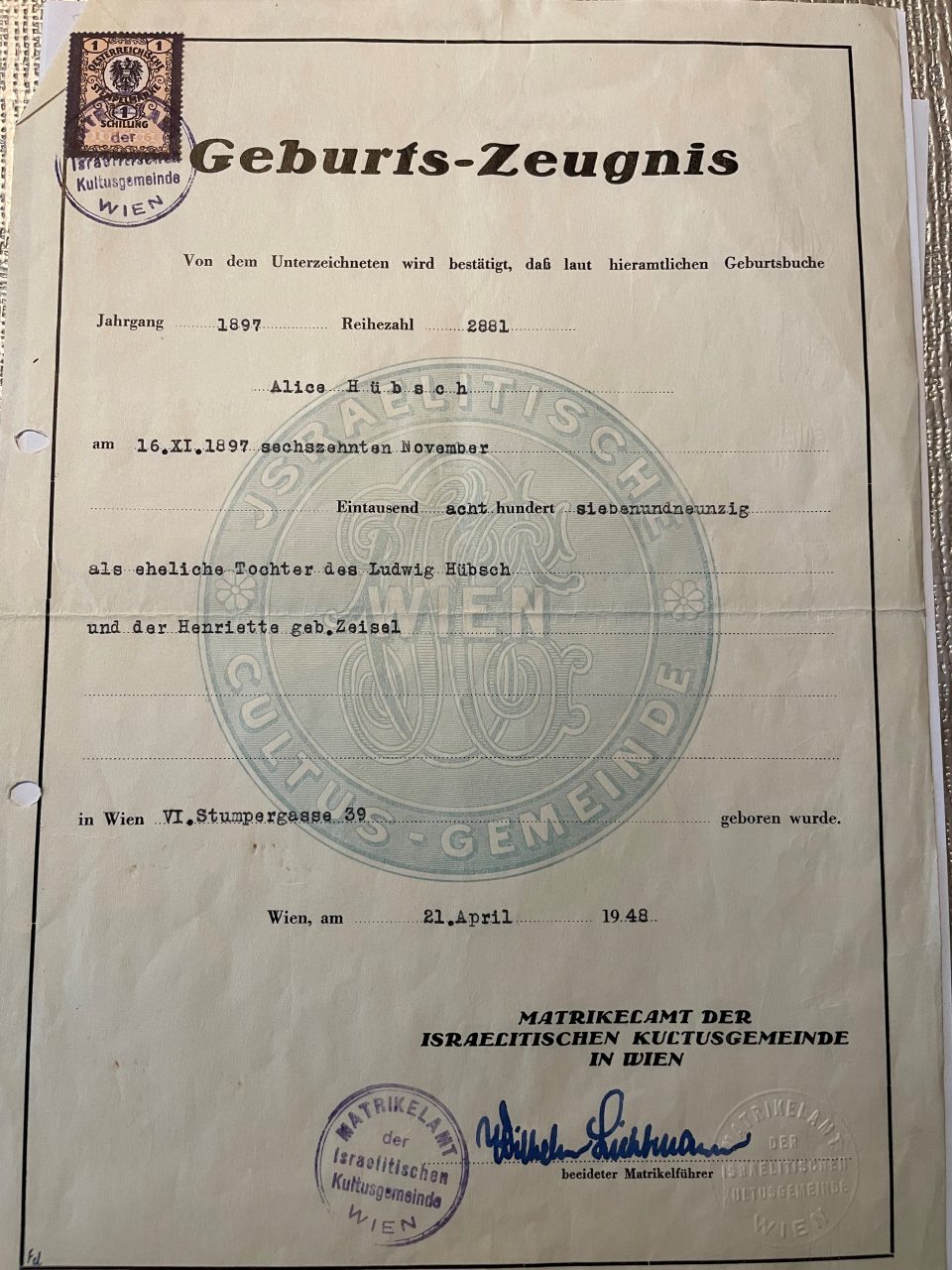

Henny was born Henriette Gertrude Katz in the 17th district of Vienna, Hernalser Hauptstrasse 62, as the first child of Josef Katz, the elder brother of Norbert Katz, the Viennese football star, who was her favourite uncle, and Alice Katz, née Hübsch.

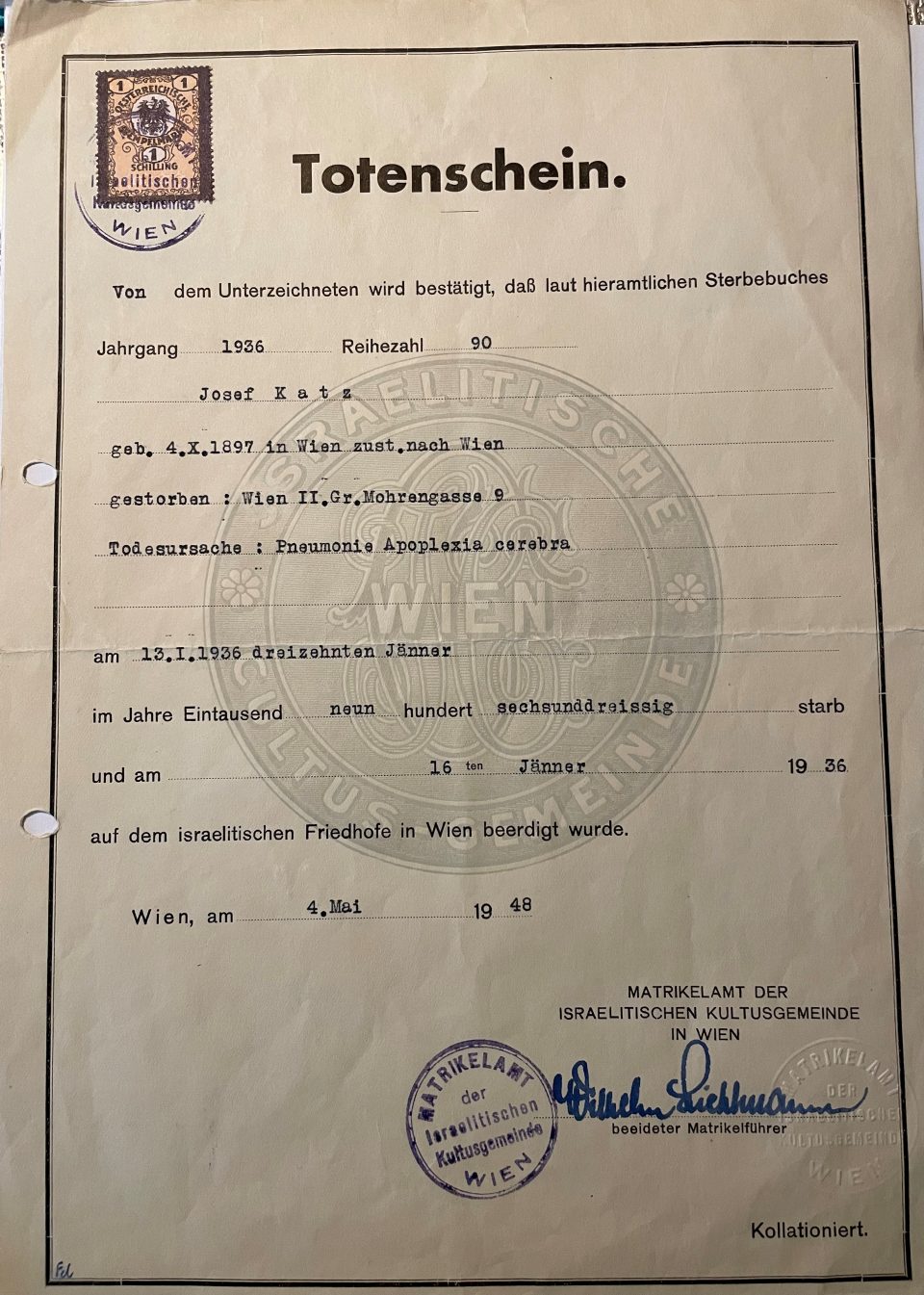

Both parents were assimilated Jews, born in Vienna. Her father Josef Katz, born on 4 October 1897, worked as a bank clerk at the Viennese Mercurbank in its branch office at Taborstrasse in the 2nd district of Vienna. He was only 38 years old, when he died in January 1936 of pneumonia and left Alice to care for herself, Henny, and her younger brother Gerhard, born on 28 November 1926. At the time of his death Henny was not quite thirteen years of age and her brother not yet ten. Alice was a housewife and received a pension for herself and her children from the Mercurbank. In the course of the Nazi takeover in Austria and the expropriation and disenfranchisement of all Viennese Jews, which entailed the total deprivation of all civil rights, the Mercurbank ceased its pension payments to Alice. In 1930 the family had moved to a flat in the same district, in Jörgerstrasse 49/2, where they were evicted soon after the “Anschluss” (the Nazi takeover in Austria in March 1938), because they were Jewish citizens. They were then transferred with few of their possessions to a so-called “Sammelwohnung” (collective camp) in Neuwaldeggerstrasse 41, where they lived in overcrowded circumstances with many other disenfranchised Viennese Jews, who had been evicted, too. See article:

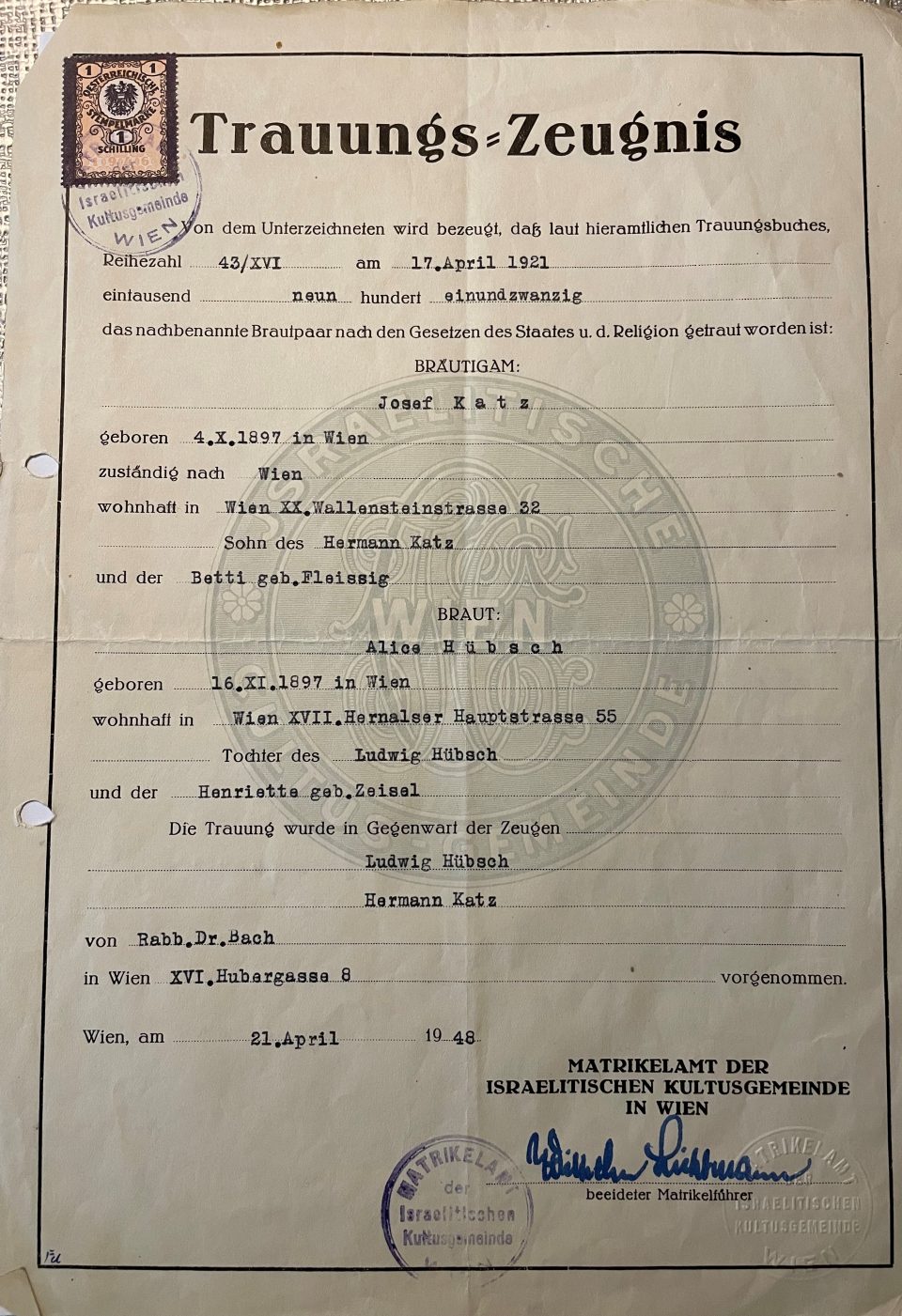

The birth certificate of Alice Katz and the marriage certificate of Alice and Josef Katz of 1921

Henny managed to get a secretarial job at the “Israelitische Kultusgemeinde” IKG (the official Jewish representation) in Vienna in 1938, to help support the family. The IKG offices had been closed by the Nazis after the “Anschluss”, but were later reopened in order to organise the quick emigration of Jews from Vienna under NS orders of Adolf Eichmann. In the first years of the NS terror regime the Nazis aimed at “cleansing” the “Third Reich” of all Jews by expropriation and forced emigration before they switched to the policy of extermination of all Jews on the territory of Germany and all occupied countries. In this repressive atmosphere Henny, who came from an assimilated Jewish Viennese family, got in contact with Zionist youth organisations and the Youth Aliyah, founded by Recha Freier in Berlin, which organised transports of 15-to 17-year-old Jews to Palestine, which was under British mandate at the time. Henny participated in the preparation courses of the Youth Alijah to get ready for a life in Palestine, which included Hebrew language classes, information on history and culture in Palestine and practical training for a life in an agricultural kibbutz. It was clear that Henny would rather take over tasks such as sewing or jobs in the household than strenuous agricultural work because she suffered from a hip problem since her birth, congenital hip dysplasia. Her friends in the IKG urged her to leave Vienna, when the repressions and persecutions of Jews in Vienna worsened dramatically, but she did not want to leave her mother and younger brother behind. Her mother was completely exhausted and depressed by then and expressed the opinion that she and her family had never done any wrong, so what could happen to her and her son? Unfortunately, she misjudged the dramatic threat to the lives of Jews in Vienna because she saw herself as an “ordinary Viennese citizen”. She counted on her clean conscience as a model citizen, yet Jews had no citizen rights any more at that time.

Henny had planned to join her uncle, Norbert Katz and her aunt, Agi Katz, who had fled with their two-year-old twins, Susi and Josi, to England, but with the start of World War II in September 1939 the UK borders were closed to refugees from the “Third Reich”. See articles:

So finally, Henny decided to leave for Palestine on her own on a Youth Aliyah transport on 4 December 1939. In Bratislava she boarded the DDSG (“Donau Dampfschifffahrtsgesellschaft”, the former Austrian, now German state shipping company) ship “Grein” and travelled on to the Black Sea harbour Salina in Romania, from where she was transferred onto an ocean-going vessel that took her through the Dardanelles and across the Mediterranean to Haifa in Palestine. She was sixteen years of age and would turn seventeen in February 1940. A friend of Henny’s, Bernhard, who worked with her at the IKG and who also lived in the same collective camp in the 17th district of Vienna, Neuwaldeggerstrasse 41, had assisted Henny. He had put her name on the list of illegal youth transports to Palestine and had procured the visa for Bolivia. Henny was never supposed to go to Bolivia, but as the British authorities did no longer allow any Jewish migration to Palestine, the passengers on the ships down the Danube and across the Mediterranean needed “final visas” for other countries to receive transit visas for the countries they were crossing, and only few embassies of Latin American countries in Vienna still issued them.