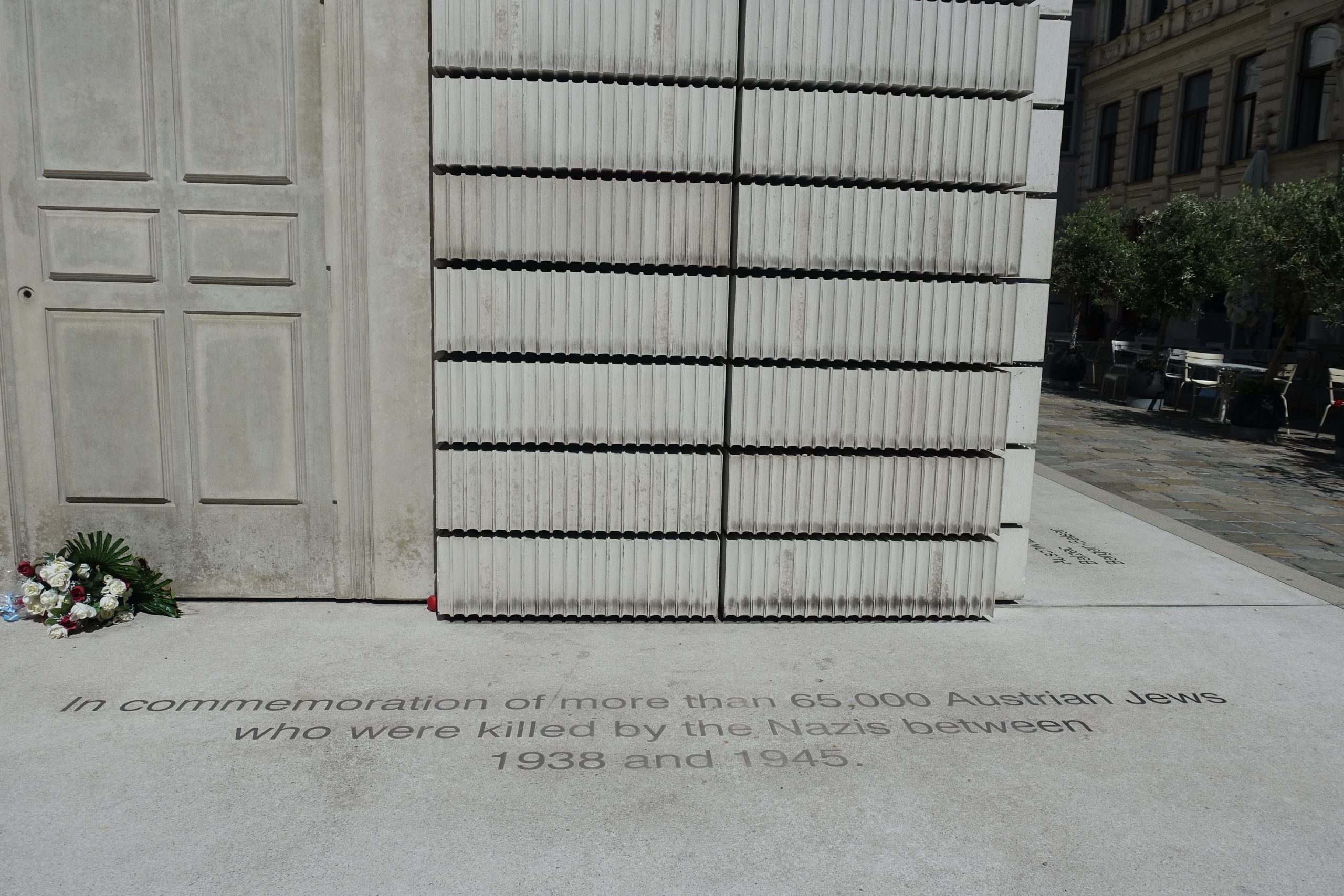

Memorial for the victims of deportation 1941/1942 at the location of the former train station “Aspangbahnhof” in the 3rd district of Vienna

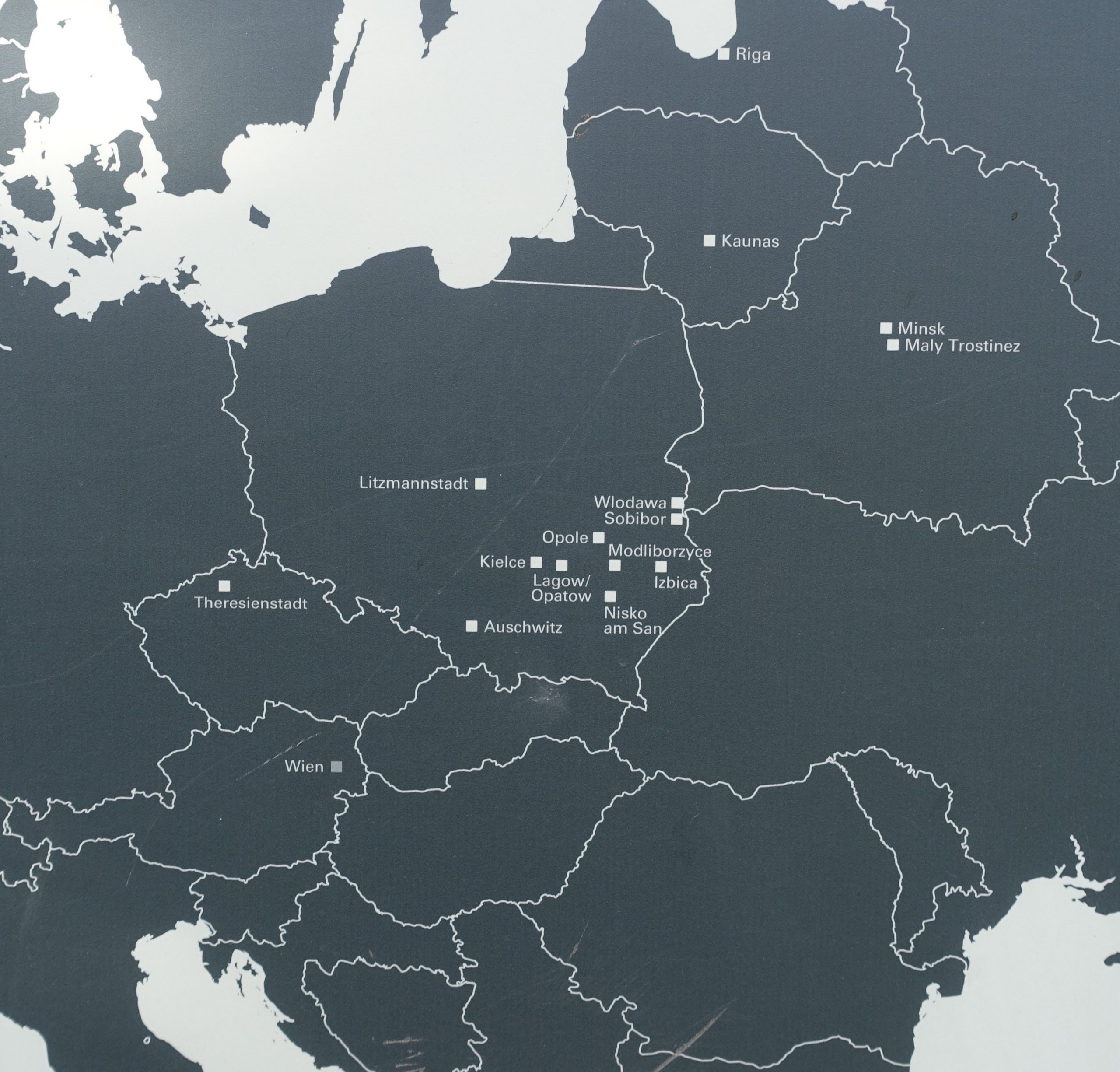

This map shows the ghettos and concentration camps the Nazis deported the Jewish population to from the collection camps in Vienna via the “Aspang” train station

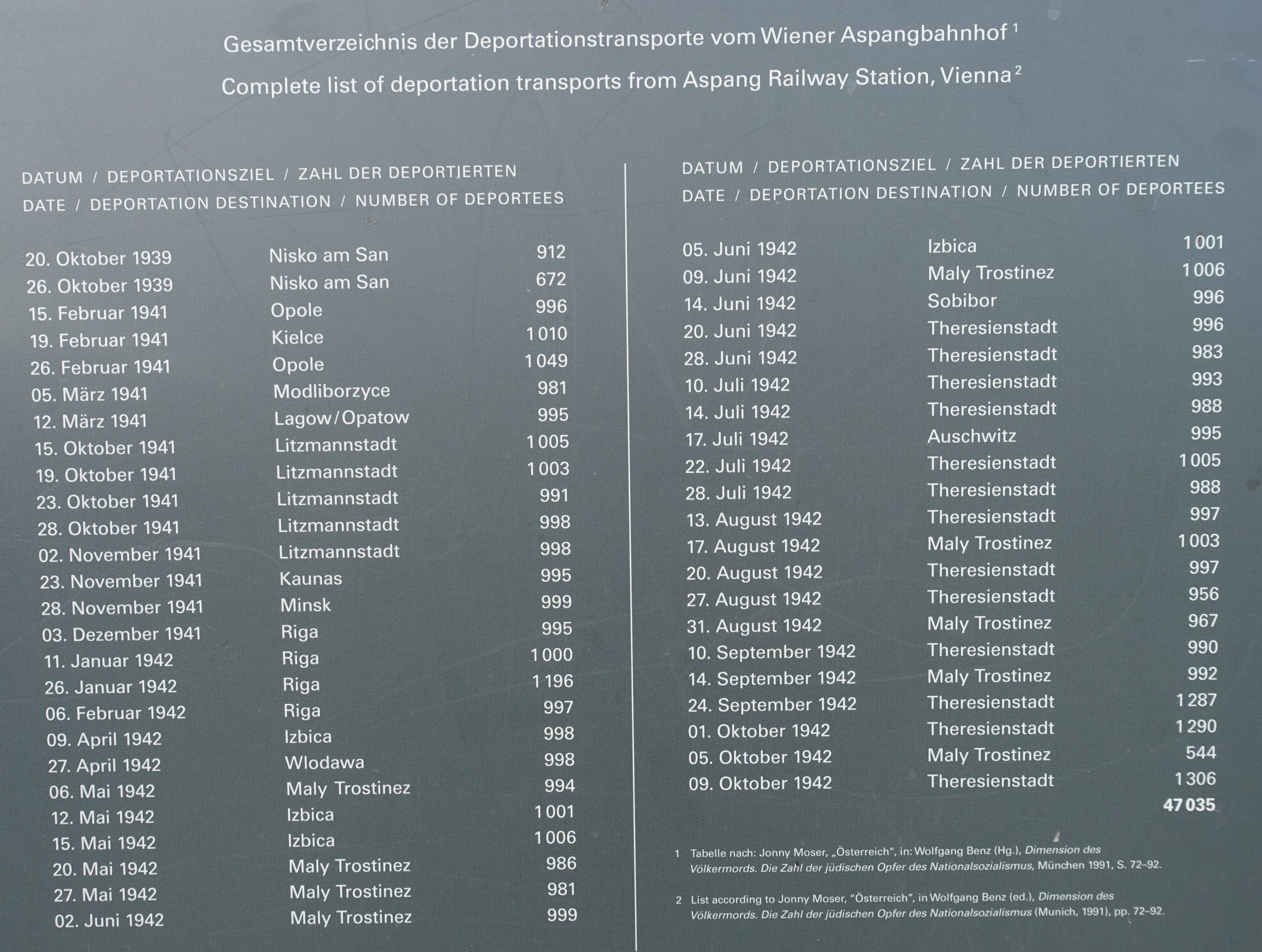

The list with the dates and destinations of the 47 transports from the Aspang train station to ghettos and concentration camps 1939, 1941/1942. My great-grandparents Ignaz and Rudolfine Sobotka were to be deported on the 28 July 1942 to Theresienstadt, but then their transport was postponed to 13 August1942

The famous Viennese artist, the painter Arik Brauer, reported in an interview that a school mate and friend of his had come running to his flat in the 16th district of Vienna, Ottakring, when they were both around 13 years old, telling Arik that the next day he and his family had to report to the Nazi authorities in a collection camp in the 2nd district. He wanted his friend to have his collection of books by Karl May, a very popular adventure book writer of the time, because he was not allowed to take the books with him and he wanted to say good bye to Arik, too. Arik asked him why he did not run away and his friend answered, “Where shall I run to?” At that time no one believed that this transfer to the collective camps (“Sammellager”) in Vienna, also euphemistically called “collective flats” (“Sammelwohnungen”), led straight to the extermination camps of the Nazis. The former chief rabbi of Vienna, Chaim Eisenberg, told the story of his father who had survived in hiding as a “U-Boot”: he had never laughed so much in his life as during these terribly trying times. Jewish humour kept them alive and helped them not to give up hope. But many could not bear the humiliation and terror and committed suicide. More than 130,000 people could flee before the complete ban of emigration of Jews in October 1941. Yet around 17,000 of those were caught up by the Nazi terror machine in their countries of refuge, such as France, the Netherlands and Belgium. In the years 1941/1942 45,527 persons were hauled from the Viennese collective camps via the “Aspang” train station in 47 transports to ghettos and concentration camps in the “East” (as the Nazis called the occupied territories in Central and Eastern Europe), among them my great-grandparents, Ignaz and Rudolfine Sobotka. They were interned in a collective camp in Krumbaumgasse 6/14 in the 2nd district of Vienna on 9 July 1942 before they were deported to the ghetto Theresienstadt (today Terezin) on 13 August 1942. They were liberated after three years of imprisonment by the Allied Forces on 7 July 1945. Of the 1,634 people who are recorded as “U-Boote” in Vienna 1,000 survived more than one year in hiding, more than 400 attempted to survive in hiding, but were discovered before disappearing successfully and were deported. All in all 66,000 Austrian Jews were murdered in the Shoah and Vienna became a model for the organisation of Nazi terror and the extermination of the Jewish population, which was later copied in the rest of the German “Third Reich”.

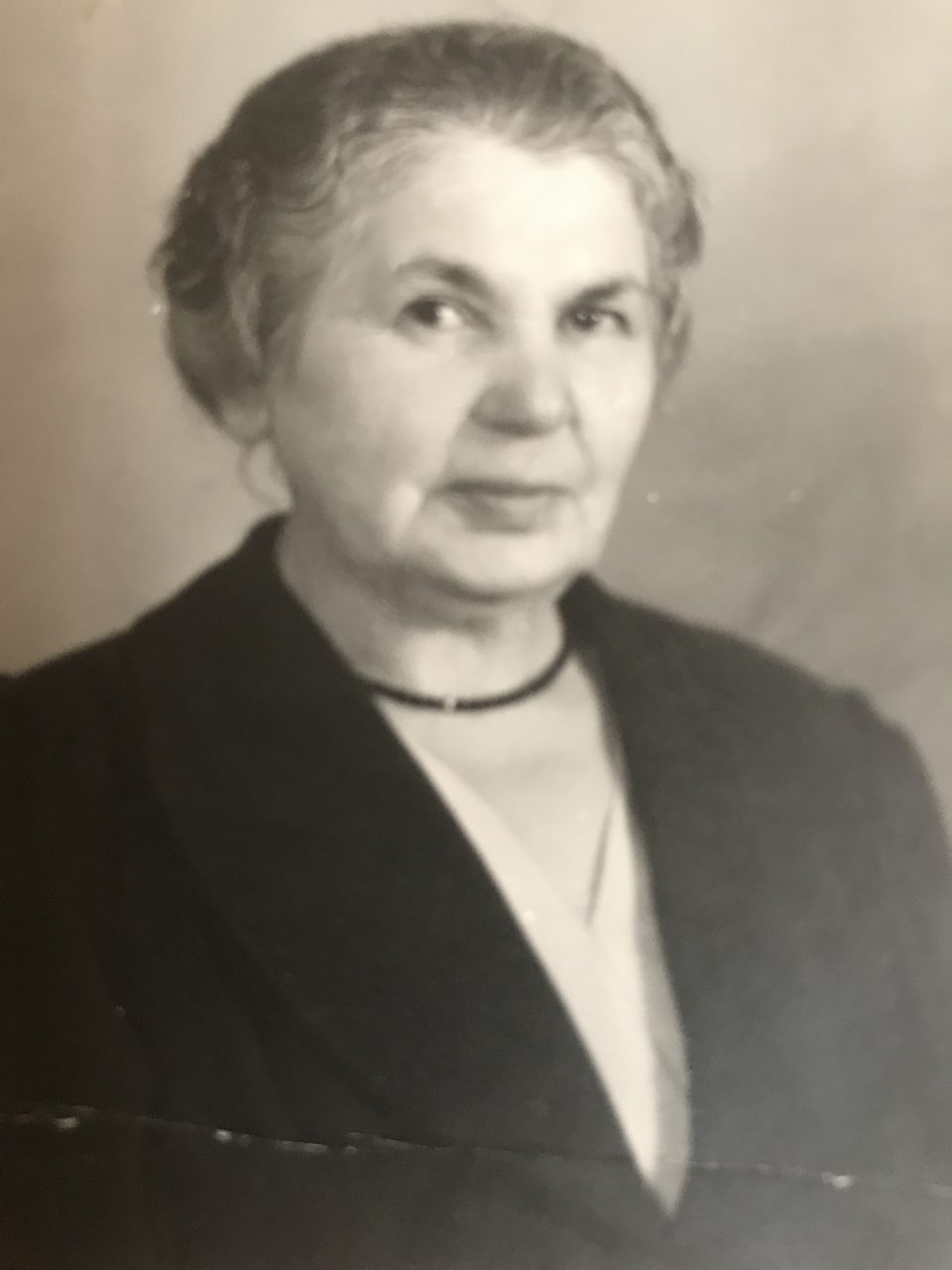

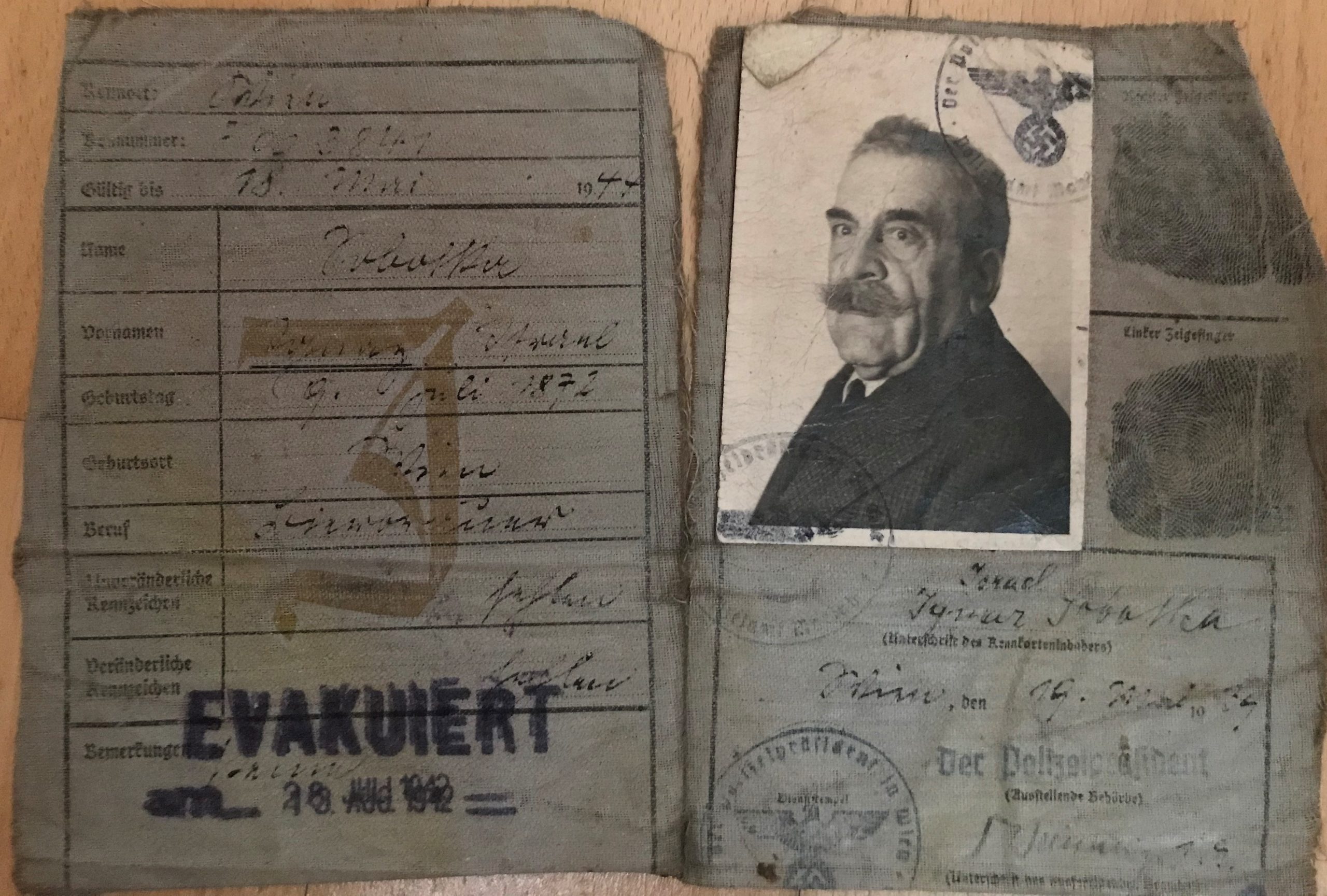

Rudolfine (born on 1 October 1876) and Ignaz Sobotka (born on 9 July 1872). They were forced into a collective camp and then deported at the ages of 66 and 70

The collective camp in Krumbaumgasse 6/14 in the 2nd district of Vienna, where Rudolfine (Ritschi) and Ignaz Sobotka were held prisoners until their deportation to Theresienstadt

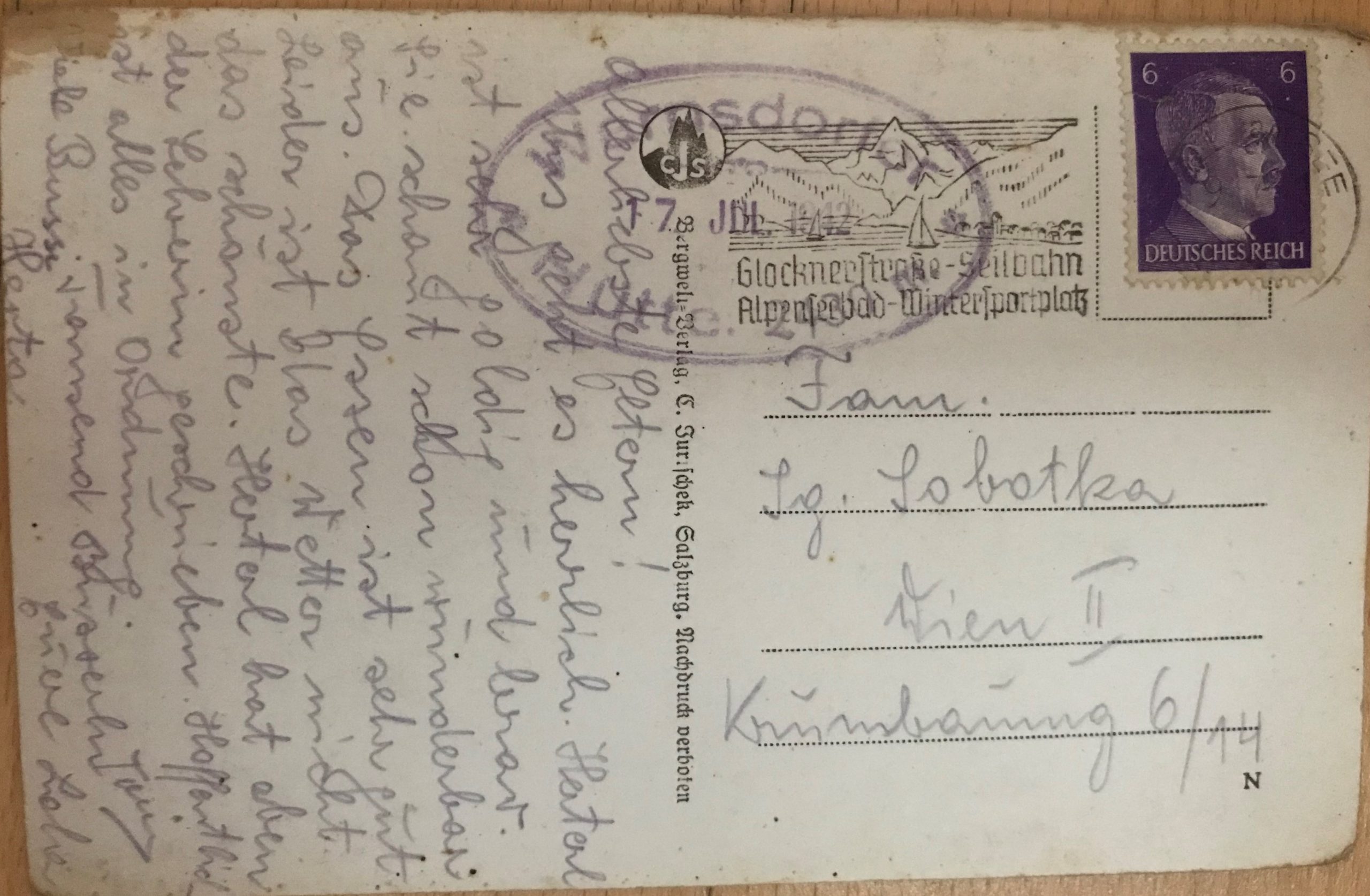

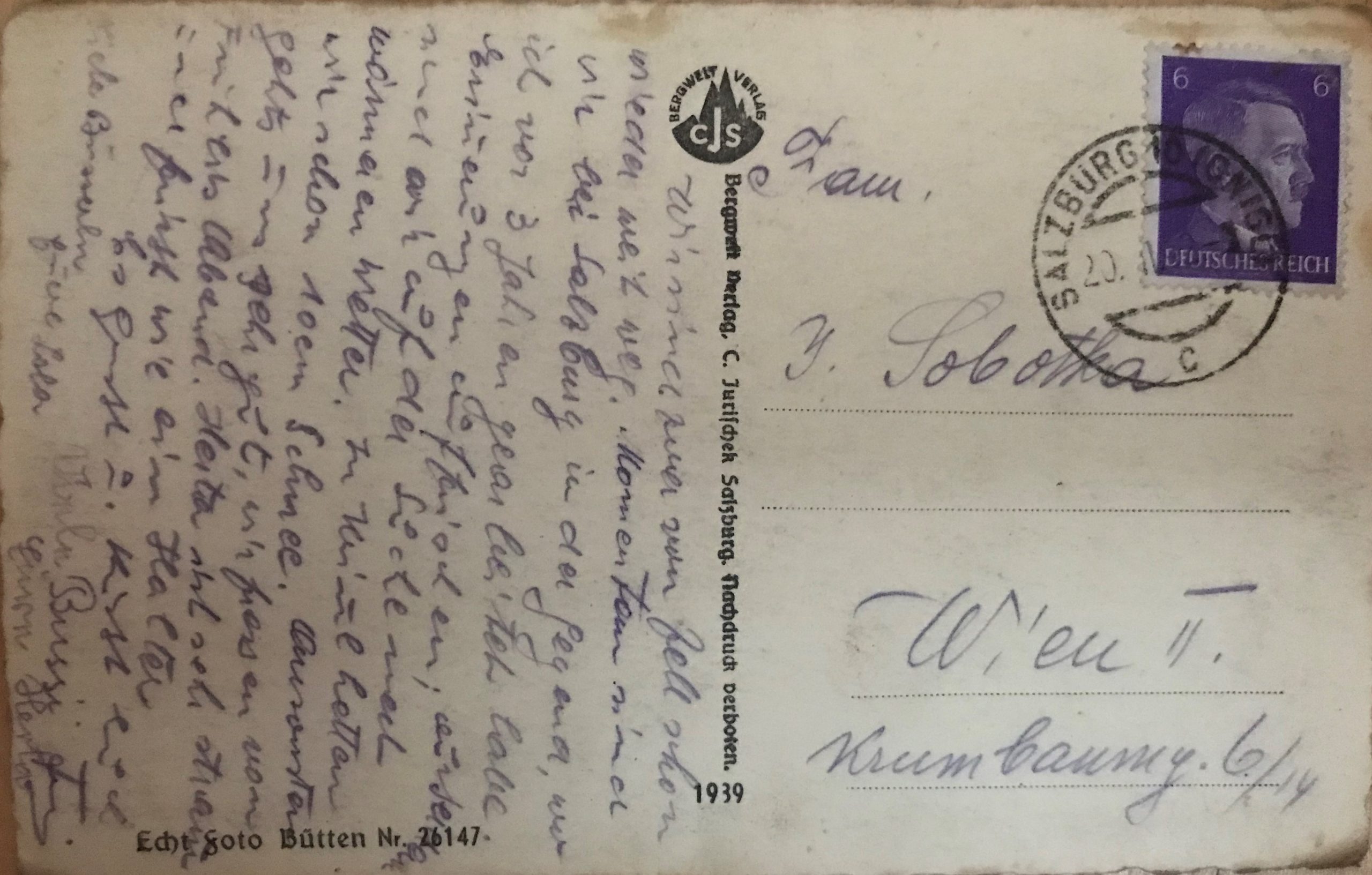

The postcard my grandmother Lola Kainz sent to her parents in the collective camp from their mountaineering holidays in the Großglockner region in Salzburg

“Dearest parents, We are great. Herterl (my mother) is a sweet and good girl and looks great. The food is wonderful here. Unfortunately the weather is not too good. Herterl has just written to her teacher. Hopefully everything is ok. Many kisses Herta. Thousand kisses Lola and Toni”

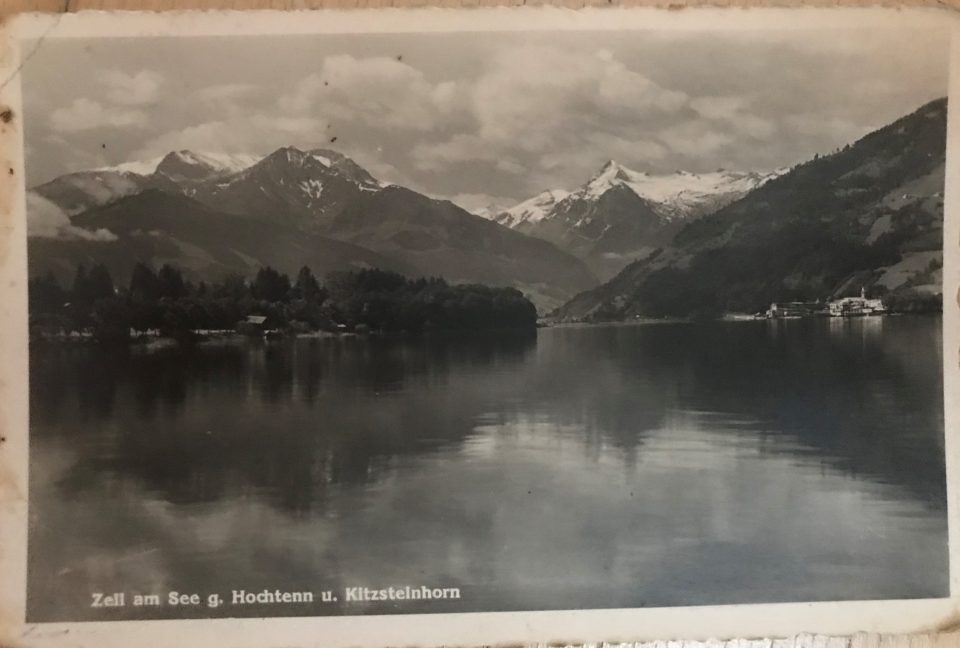

The postcard my grandfather Toni sent them from the same holiday from Zell am See

“We are already far away from Zell am See. At the moment we are in Salzburg in the region where I worked three years ago; refreshing memories; most of all we are looking for warmer weather. In Krimml we already had 10 cm of snow. Otherwise we are doing fine; we are shovelling food from morning till evening. Herta has put on weight and eats a lot. Greetings and kisses Toni. Many kisses, yours Lola. Many kisses, yours, Herta.”

The content of the two postcards, which were sent to Ignaz and Ritschi in the collective camp by their daughter Lola and their son-in-law Toni, support the statement of Arik Brauer that the families were not aware of the deadly seriousness of the GESTAPO orders to report at the collective camps and that the stay there was just a transition to the deportation to ghettos and concentration camps. But the banality of the reports about holiday experiences, food and weather in Salzburg might also have been intended to boost the morale of the parents and to sound positive, optimistic and hopeful. Ignaz and Ritschi never talked about their experiences during the time of imprisonment from 9 July 19242 until 7 July 1945. That’s why it is so important to research this dark period of Viennese history now in times of rising anti-Semitism in an attempt to prevent similar disasters in future, because as the writer William Faulkner once said, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

“Better times” before 1938 in Vienna:

Ignaz and Ritschi as a young couple:

Ignaz and Ritschi in the inn of their son-in-law, Toni Kainz, my grandfather, before the takeover of the Nazis in March 1938 (see article “Viennese inns”)

Ignaz with two of his four daughters, Mitzi and Käthe before their flight from Vienna

In Vienna the transport to the Nazi death camps started in the centre of the city under the eyes of the local population. Collective camps were organised by the Nazis, mostly in the districts 2, 9 and 20 of Vienna, where the Jewish population was “summoned” to and where they had to remain under abysmally crammed and unhygienic conditions until they received the “evacuation order”, which meant that they were transported on open trucks to the Aspang train station in the 3rd district, in the centre of Vienna as well, from where they were hauled to the ghettos and concentration camps of Auschwitz, Nisko am San, Opole, Litzmannstadt (Lodz), Sobibor, Izbica, Riga, Minsk, Maly Trostinec, Theresienstadt and others, in the “East”, as the Nazis called it. The largest part of the 66,000 Austrian Shoah victims was sent to their death via these collective camps, many of them from the flats in the 2nd district in Kleine Sperlgasse, Castellezgasse and Malzgasse. Historically the importance of the collective camps in Vienna reaches far beyond Vienna and Austria because Vienna was the Nazi field for experimentation with respect to systematisation and radicalisation of anti-Jewish measures and for the organisation and execution of deportations since 1941. The Viennese model of forcing the official representatives of the Jewish religious community (“Israelitische Kultusgemeinde” IKG) to become agents of their own destruction and tools of the Nazi terror regime was later copied in Berlin, Prague, Brno and other cities of the “Third Reich” and so-called “deportation experts” were sent from Vienna to many regions of Europe which were occupied by the Nazis.

The large deportations started in Vienna in February 1941. At the beginning of that year still 61,000 people who were defined as “Jews” by the Nazis on the basis of the Nuremberg race laws lived in the city. Before the “Anschluss” (the takeover of the Nazis) in Austria 181,882 people were registered at the Jewish religious community (IKG) and 167,249 of them lived in Vienna. It is important to mention that several Austrians who were considered “Jews” by the Nazis were agnostics or had converted to Christian religions and these were not registered at the IKG. When the Nazi Nuremberg race laws took effect in Austria on 20 May 1938 around 201,000 people were defined as “Jewish” and around 180,000 of them lived in Vienna. This meant that Vienna was the city with the largest proportion of Jewish inhabitants in the whole German “Third Reich” in May 1939, when the census was taken.

Even before German soldiers crossed the border to Austria on 12 March 1938, the country was inundated by national-socialist ideology. Overnight Austrian Jews were defenceless and without rights and had to face pogrom-like violence, whereby the police did not interfere. Members of the SA (“Sturmabteilung”) and HJ (“Hitler Jugend”) robbed and looted Jewish shops and property and forced their Jewish fellow citizens to clean the streets on their knees, wiping away pro-Austrian slogans. The extent to which Austrian Jews were subjected to anti-Semitic violence was unprecedented in the whole of the Nazi-ruled territory at that time. In Germany similar atrocities took place later during the November pogroms 1938. Jews lost their jobs, children were excluded from higher education; Jews were expropriated and driven to emigration. In August 1938 Adolf Eichmann headed the “Zentralstelle für jüdische Auswanderung” (“Central Office for Jewish Emigration”), which together with the GESTAPO (“Geheime Staatspolizei” – secret police) coordinated and executed the systematic robbing and expropriation of the Jewish population, forcing the penniless into emigration. The head quarter of this organisation was the expropriated former “Rothschild Palais” in Prinz-Eugenstrasse 20-22 (today the location of the Viennese Chamber of Labour) In 1950 the building was restituted to Louis Rothschild, who sold it to the Viennese Chamber of Labour in 1954. Despite the protests of the Austrian Monuments Preservation Office, the Chamber auctioned off the whole valuable interior and furnishing and pulled down the only slightly damaged Rothschild Palais. Surprisingly, in the ballroom of a dancing school in the 17th district in Kalvarienberggasse 28 the only known remnants of the lavish furnishings of 1728 of the Rothschild Palais are preserved.

The official representation of the Jewish religious community the IKG (“Israelitische Kultusgemeinde”) was reorganised and forced to concentrate its activities solely on emigration and welfare of Jews. In Vienna attacks at synagogues and Jewish institutions preceded the nation-wide November pogroms of 9/10 November 1938. All of the 96 synagogues and prayer houses of Vienna were devastated and 42 completely destroyed by fire. Already in early summer of 1938 Jews were evicted from council houses and in spring 1939 the housing department of the city of Vienna ordered all Viennese landlords to evict Jewish tenants. All of those homeless people were then crammed into houses that were still owned by Jews. That’s how so called “collective flats” were created in “Jewish houses” in the 1st, 2nd,9th and 20th districts of Vienna. Many of these homeless families were resettled several times as the Jewish house owners were successively expropriated. When the Jews were expelled from the federal states of Austria, which was now called the “Ostmark” of the “Third Reich”, all these Jews ended up in Vienna and the IKG had to care for them. Consequently the IKG organised 16 soup kitchens which fed 36,000 people in August 1939. As more and more younger people fled abroad, the IKG had to take care of the remaining elderly who had no chance of emigration because no country in the world was prepared to accept elderly refugees. Until 1941 the IKG had to establish eight more homes for the elderly, additionally to the one existing in Seegasse in the 9th district since 1890. From the summer of 1942 on all of the inmates were deported to the KZ Theresienstadt, the “ghetto for the elderly”. Also in my family only the grandparents, Ignaz and Ritschi, remained in Vienna, while three of their four daughters emigrated with their families. Only one daughter, my grandmother Lola, remained in Vienna because she was married to an “Aryan” husband, Toni, and felt safe (see the article on “Mixed marriages”). So Ignaz and Ritschi were seemingly lucky because they had a daughter and a son-in-law who could care for them. No one assumed at that time that this elderly penniless couple would be deported to a concentration camp. Ignaz was the prototype of what would be called a “typical Viennese”: born in Vienna, speaking Viennese dialect, beer brewer and former manager of a brewery (see article on “Brewers in Vienna”), a regular customer of typical Viennese inns and a fan of Viennese folk songs (his favourite was “Das silberne Kanderl” – “The small silver pitcher”), which he listened to at the “Heurigen” (inns where the new wine is sold, mostly on the outskirts of Vienna). Every evening he trimmed his large elegant moustache, which reminded of the times of the Habsburg Empire, and formed it over night with a moustache trainer. He did not in the least believe that he would be affected by anti-Jewish Nazi race laws.

Former Rothschild hospital at Währinger Gürtel, today WIFI Wien, a training facility and University of Applied Sciences of the Vienna Chamber of Commerce

After the application of the Nuremberg race laws in Austria the only hospital in Vienna that was allowed to accept Jewish patients was the “Rothschild hospital” at Währinger Gürtel. The hospital had been founded in 1873 by the Rothschild family and had welcomed patients of all religions. Famous doctors such as Zuckerkandl and Frankl worked there. In September and October 1942 the last patients, doctors and nurses were deported from the hospital to the death camps. The surgeon Max Jerusalem and his wife committed suicide just before their deportation to Theresienstadt in September 1942. Most of the employees of the Rothschild hospital, who were deported to Theresienstadt, among them the famous doctor Victor Frankl and his family, were later hauled to Auschwitz in autumn 1944 and murdered there in the gas chambers. The Nazis closed the hospital in late 1942; briefly it acted as a collective camp and was then used as a military hospital. The huge building was partly damaged by bombs at the end of the war, but still housed around 250,000 displaced persons, mostly Jewish refugees who had been freed from concentration camps, between 1945 and 1952. In the year 1956 Hungarian refugees, who had fled from the Soviet military repression of the Hungarian Revolution, found shelter in the Rothschild hospital. In 1949 it was restituted to the IKG, but a reconstruction of the building could not be financed, so it was sold to the Vienna Chamber of Trade (today Chamber of Commerce), which demolished the Rothschild hospital and erected a new building in 1960 to house the WIFI training centre. After years of negotiations, the Vienna Chamber of Commerce finally in 2010 allowed a small commemorative plaque to be fixed in the entrance hall of the WIFI building, but the victims of the holocaust are not mentioned with one word there.

After the closure of the Rothschild hospital for Jewish patients in November 1942 a small hospital facility was maintained in Malzgasse in the 2nd district for Jewish partners in so-called “mixed marriages”, like Lola, because they were not to be treated anywhere else. The situation of Jewish children and young people in Vienna was equally disastrous. Of the nine Jewish children’s homes and day care centres that had existed in 1938, all were closed by the end of 1939. The IKG tried to get as many children as possible out of the country and the few children that remained until the end of the war in the only existing home in Mohapelgasse 3 (today Tempelgasse 3) were children who were “protected” by an “Aryan” parent.

In the years 1941/1942 the Nazi authorities passed an abundance of further race laws that restricted the lives of the Jewish fellow citizens (see article on “Mixed marriages”), but the most humiliating and most stigmatising was the obligation to visibly wear a yellow Star of David in public and the integration of Jews in the forced labour system. From October 1941 on it was no longer possible for Jews to escape from the Nazi territory. With the end of the large deportations in October 1942, the IKG was dissolved and on 1 November 1942 the “Ältestenrat der Juden in Wien” (“Council of Elders”) was established, which was now responsible for all persons considered as Jews according to the Nuremberg race laws and not just the ones registered in the Jewish religious community. Of the 5,500 persons who remained in Vienna, more or less only those who were protected by an “Aryan” partner or parent survived until the end of the war together with 200 persons from the “Ältestenrat”.

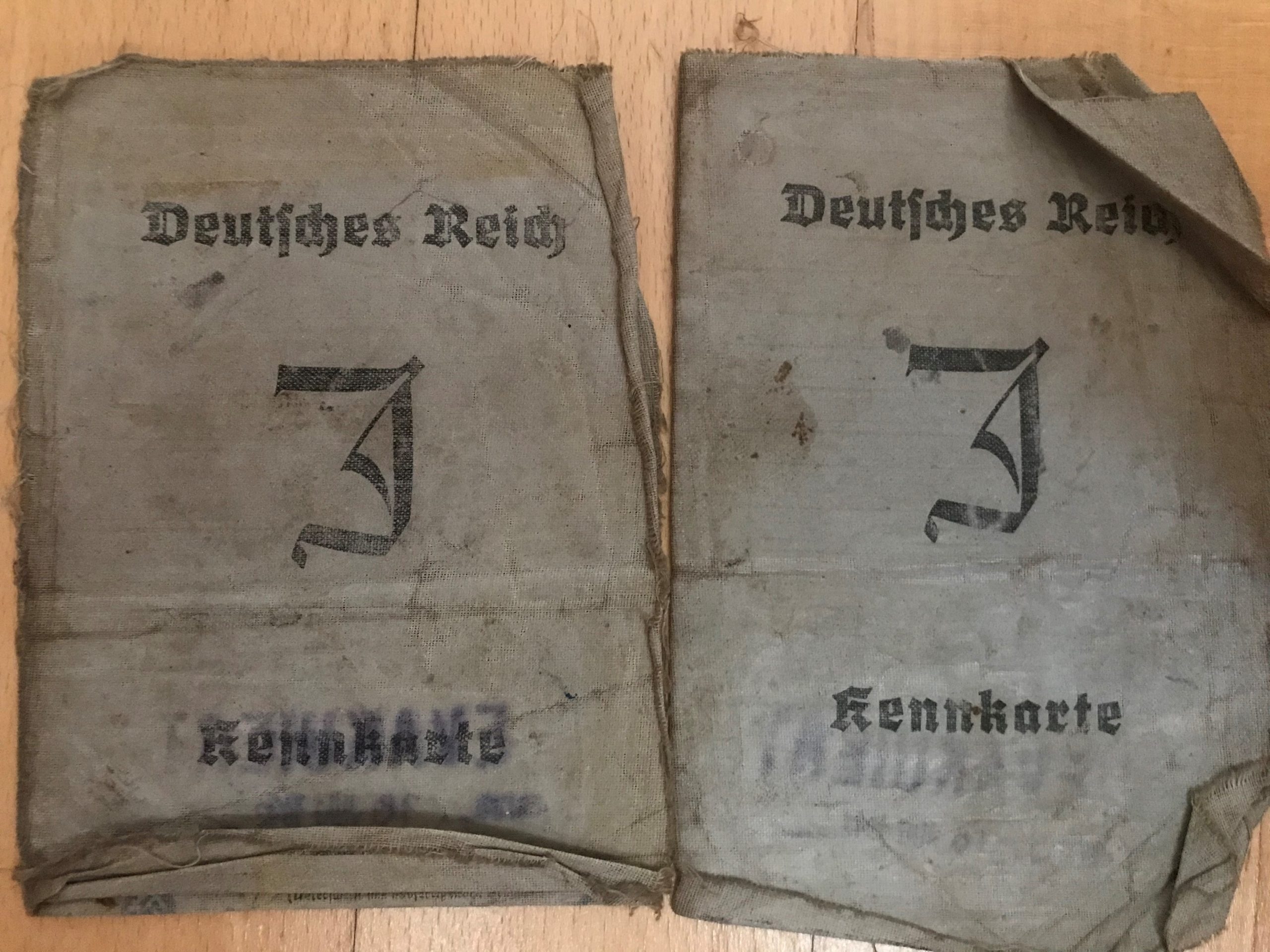

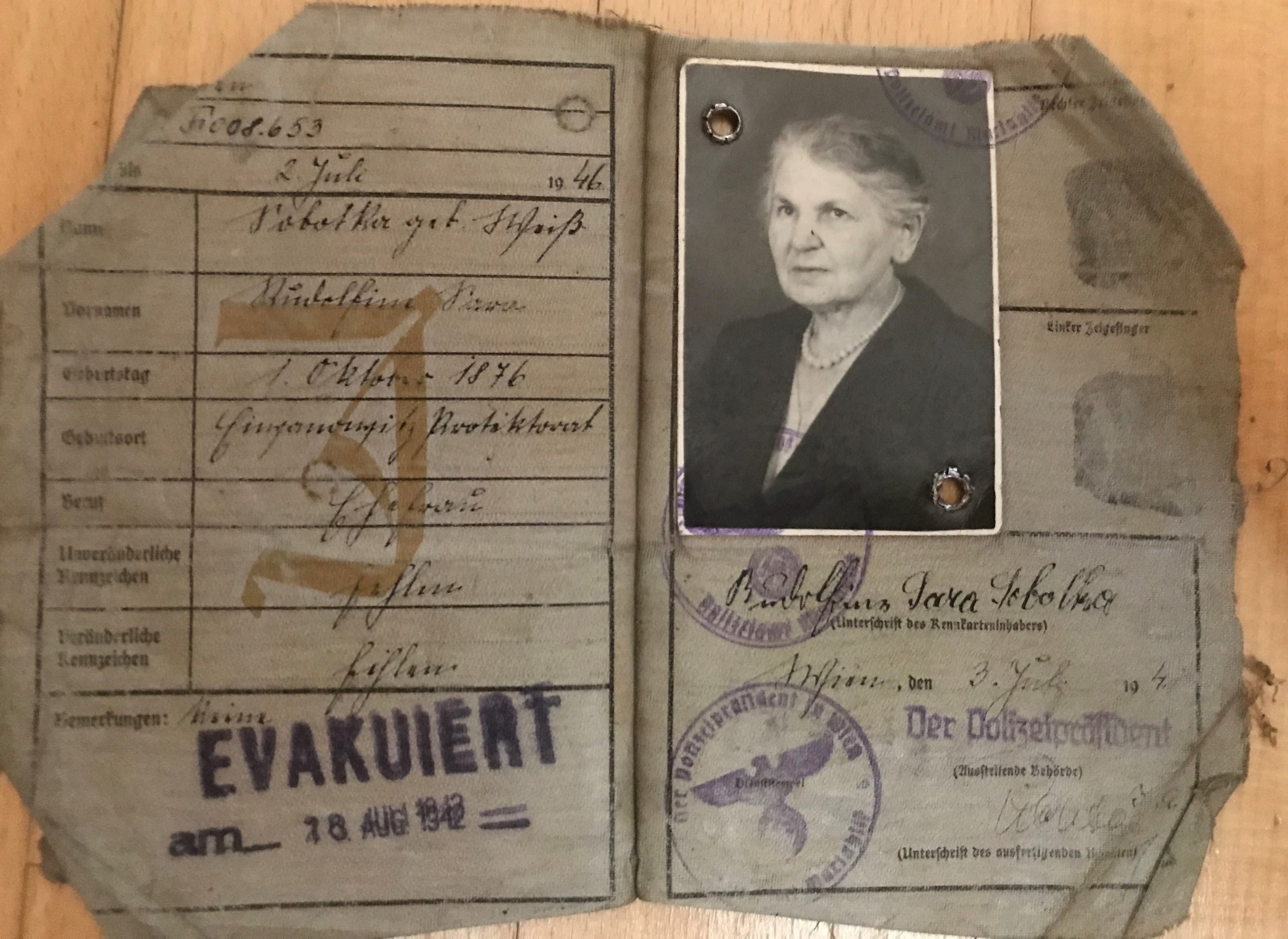

“Kennkarten”: IDs marked with a “J” for Jew issued to the Jewish population by the Nazis

“Kennkarte” of Ignaz Sobotka. As the stamp “EVAKUIERT” shows Ignaz and Rudolfine Sobotka were to be deported on the 28 July 1942 from the Aspang train station to Theresienstadt, but then their transport was postponed to 13 August 1942

“Kennkarte” of Rudolfine Sobotka

The Nazis had thought about a deportation of Jews already before the outbreak of World War II, but with the occupation of large parts of Poland after 1 September 1939 such plans were further developed. On 10 October 1939 the Viennese head of the IKG, Josef Löwenherz, was told that soon Viennese Jews would be “resettled” in Poland. The IKG was ordered to select 1,000 to 1,200 able men who were prepared to emigrate and who were skilled artisans. Löwenherz refused to draw up a deportation list and asked those who were interested in a “resettlement” in Poland to voluntarily register. As very few men volunteered, the IKG was forced to add further names of the Jewish religious community to the list. All of them had to appear at the Aspang train station and queue alphabetically. On 20 and 26 October 1939 two transports left from the Aspang train station to Nisko. Already few days earlier 901 Jewish men had been transported to Nisko from Ostrava (Czech Republic) and 875 from Katowice (Poland). The project of establishing a “Jewish reservation” in Nisko was doomed to failure because the swampy area at the border to the Soviet Union was devastated by war. The majority of the deported men were driven on foot across the new German-Soviet border without their luggage. Many died, ended up in Soviet prison camps or were killed by the SS (NS “Schutzstaffel”). A third transport from Vienna to Nisko, this time including women and children at the beginning of November 1939 was redirected back to collection camps in Vienna, where these people were interned until February 1940, when the Nisko project was finally cancelled. On 24 March 1940 Hermann Goering, responsible for the Nazi Four-Year Plan, prohibited any more transports to Nisko because the project of “Jewish resettlement” was inefficient. Some of the deported managed to return to Vienna, but most of them ended up in later transports to concentration camps. Nevertheless the experiences of the failed Nisko project offered the Nazis valuable information for how a practical involvement of the IKG could work.

In October 1940 the new Nazi governor in Vienna, Baldur von Schirach, urged Hitler to allow the deportation of the Viennese Jews and on 3 December 1940 he received Hitler’s permission. At that time the number of Jews (according to the definition of the Nuremberg race laws) in Vienna, including many from the former Austrian federal states who were nearly all hauled to Vienna, was still 61,135. In February and March 1941 5,000 of those were deported to the small Polish cities Opole, Kielce, Modliborzyce and Opatow. At that time only Jews in “mixed marriages” and foreign citizens were exempt from deportations and since February 1941 Jews were not allowed to leave the area of Vienna. This restriction of free movement was put into place in the rest of Germany half a year later in September 1941. The organisation of these deportations already followed the guidelines of the later large deportations from Vienna. At the same time a number of collective camps were established in flats in the 2nd, 9th and 20th district mostly. The majority of those who were deported from the collective camps in the spring of 1941 were murdered approximately a year later in the concentration camps Belzec, Sobibor and Treblinka. Adolf Eichmann’s successor as head of the “Zentralstelle für jüdische Auswanderung” (“Central Office for Jewish Emigration”), Alois Brunner, ordered a “resettlement” of all Jews in Vienna to these collective camps. Also Sigmund Freud’s flat and surgery in Berggasse 19 in the 9th district was turned into a collective camp. Today the names of these unfortunate inmates are listed in the Sigmund Freud Museum. Brunner forced the IKG to announce this fact in its paper, the “Jüdisches Nachrichtenblatt”: the Jews had to squeeze together in the assigned flats and leave behind all their furniture – the alternative was more deportations. But with the Nazi attack on the Soviet Union in June 1941 the Nazi policy with respect to Jews changed from forced migration to extinction. In autumn 1941 the systematic deportations to ghettos and concentration camps in the “East” started. On 30 September 1941, the eve before Yom Kippur, the highest Jewish holiday, Brunner ordered Löwenherz to appear in his office and told him that a part of the Viennese Jews would be “resettled” to Litzmannstadt (Lodz). There they were supposed to work in the armaments industry. The first large nation-wide deportation took place on 15 October 1941 from the Aspang train station. All in all, in Vienna more than 40,000 people were hauled from the Aspang train station in transports of 1,000 persons each to the “East” within one year. In order to collect and house the large numbers of deported in Vienna, more flats were turned into collective camps. The Nazis meticulously documented every transport: the IKG had to draw up lists of persons in every transport including names, birth dates and last addresses and to duplicate those lists.

The first step on the way to the death camps was the “summoning”. The “Zentralstelle” drew up the lists of the persons who were to be deported and forced the IKG to cooperate, initially allowing the IKG to strike persons off the list who they considered important for the running of the organisation and to replace them by other people. The IKG then had to send postcards to the people who were to be deported summoning them to the collective camps. Those who did not appear were traced and arrested by the GESTAPO. The IKG further had to instruct the persons about to be deported how to comply with the official rules and regulations, namely that they had to register all their remaining assets, that they had to hand in the remaining food stamps of the whole family and the keys to their flats with addresses and names of the landlords. Everyone was allowed to carry two suitcases of not more than 50 kilos, the content of which was restricted to linen, clothing and hygiene articles. The suitcases were to be marked with name and address of the owner in white oil paint. Those who received the postcard with the “summoning order” often tried to leave mementos or photos with friends and relatives or wrote fare well notes. The only memento my great-grandparents, Ignaz and Ritschi, managed to give to their daughter Lola, was Ignaz’ pocket watch, which she was able to keep safe for him until the end of the war:

Ignaz Sobotka’s pocket watch with his initials “IS”

A further serious deterioration of the living conditions of the Jews in Vienna constituted the introduction of the stigmatisation by the obligation to wear a highly visible yellow Star of David in public on the left side of the outer garments from 19 September 1941 on. Only Jews in “mixed marriages” with “Aryan” husbands or with children who were “mixed race of the first degree”, like my grandmother Lola and my mother Herta, were exempt. The standardised yellow Stars of David were issued by the IKG at the price of 10 Pfennige from institutions of the IKG and at the “Zentralfriedhof” (Central Cemetery). Those who were no members of the Jewish religious community had to collect the Stars of David from the special organisation AHO (“Auswanderungs-Hilfsorganisation für nichtmosaische Juden in der Ostmark”). Additionally the IKG had to draw up a list of all issued Stars of David per district of Vienna. From these lists it can be seen that despite a concentration of the Jewish population in the districts 1, 2, 9 and 20, still a sizable amount of Jews lived in other districts at that point in time. When issuing the yellow Stars of David the IKG was coerced to list all Viennese Jews with name, birth date, address and their “Kennkartennummer” =ID number (see above: Kennkarten of Ignaz and Rudolfine Sobotka). All these data had to be handed over to the “Zentralstelle”, which used them to draw up the lists of deportations. This stigmatisation led to a sharp increase in harassments, attacks and abuse of Jews in public, so that many Viennese Jews did not dare to go out any more. Jews were spat on in the streets, pushed from the pavement and Jewish children were slapped and insulted. Young Jews sometimes covered up the yellow star to go to the cinema, for example, which was strictly prohibited. But there were also people who showed pity, especially to children, and secretly gave them fruit or sweets, which they were not allowed to have. Since April 1942 all flats with Jewish tenants were marked with a white Star of David on the door and Jews had to wear the yellow star also indoors, at work for example. There was basically no place for Jews to move in public unstigmatised. The building of the IKG together with the terrace of the nearby “Kornhäuslturm” in the 1st district and the Jewish part of the Central Cemetery (“Zentralfriedhof 4.Tor”), where fruit and vegetables were grown on free plots, became the only “safe” places in Vienna for Jews.

After the “summoning”, the next step was the “collecting”. Soon the “Zentralstelle” did no longer rely on the postcard system for summoning the persons to the collective camps, but they resorted to a system of “collecting” the persons from their flats. The SS carried out raids in the districts where many Jews lived together with employees of the IKG, who were forced to act as “collectors” or “marshals”. Formerly, the postcards sent by the IKG to the people who were to be deported, allowed some of them to escape the summoning of the Nazis and that’s why Alois Brunner introduced this new system. The brutality with which the SS executed his orders induced Josef Löwenherz to cooperate and send the IKG employees to accompany the SS. The Jewish “collectors”, around 400 to 500 men, were equipped with an identification disc by the “Zentralstelle” and they had to wear coloured armbands with their identification number: yellow for “collectors”, blue for “collective camp supervisors” and green for “luggage handlers”. The “Zentralstelle” used the tenant lists of the housing office of the IKG because due to multiple evictions people were moved from one address to the next and were therefore difficult to find. There were rigid orders how such raids were to be executed: First the house or the whole street was cordoned off, then two “collectors” were positioned in front of the door to the flat. Next the SS together with a Jewish marshal entered the flat, asked the tenants to fill in the forms listing the inhabitants’ property and the whereabouts of missing family members. The Jewish “collectors” had to help with the packing and prevent any escape attempts. Two hours later the inhabitants were transported on waiting trucks with their hand luggage to the collective camps in broad daylight under the eyes of their fellow citizens. So no one could later say that they had not known anything about what had happened to their Jewish fellow citizens. The “collectors” later delivered the suitcases at the respective collective camps. If someone was not found at home, it was the task of the “collectors” to wait for the person and drag him or her to the collective camp. The question is why did the IKG cooperate? The “Zentralstelle” threatened that every collector who did not succeed in bringing in all family members to the collective camp would immediately be deported to the “East” together with his family. The SS man responsible for a collective camp then checked the arrivals against the list of the “Zentralstelle” and if there were discrepancies, the IKG officials were immediately deported with their families. The IKG officials were under immense pressure and often acted brutally against the persons who were to be “collected”. In any case they were hated and despised by the Jewish population. But some showed mercy and tried to assist the deported. Anyway, in the end they were not protected: at the end of the large deportations in autumn 1942 the majority of all “collectors” and “marshals” and other employees of the IKG were deported and murdered as well. Additionally there was a group of six Jewish men who were unofficially called the “Jewish Police” (JUPO) and reported directly to the NS authorities. They were to supervise the “collectors” and see to it that all valuables of the deported were delivered to the GESTAPO and they had to search for those who had escaped and were living underground as “U-Boote”. Finally, the members of the JUPO were deported in 1943, too. There were few Jewish GESTAPO informers, such as Rudolf Klinger, who abused the trust of the interned and betrayed “U-Boote” and resistance groups. But also Jewish informers were only temporarily protected from deportation because they knew too much and could be dangerous for the NS authorities. Rudolf Klinger was deported to Auschwitz and murdered in October 1943.

Every collective camp had to run a precise documentation with daily entries, where for example several times a day the number of inmates was counted, special events were recorded and the report was signed by the SS at the end of the day. Some of these books have been preserved and they offer an insight into the last days of the interned persons in Vienna before their deportation to the “East”. Rare discharges from the collective camps were recorded as well, usually when a mistake had occurred and a partner in a mixed marriage had been interned. To keep up the myth of “resettlements” initially the younger family members were first deported and elderly family members were kept in the collective camps until the deportations to the “ghetto of the elders” in Theresienstadt started in June 1942. Fragile elderly persons were until then transferred to homes for the elderly and the Rothschild hospital. All these transfers and deaths, many of them suicides, were recorded in the daily documentations.

One of the many “memory stones”, also called “stumbling stones”, which commemorate those who lived in Vienna and were murdered in the holocaust. Some feel that the stones, which are mostly cemented into the pavements in front of the entrances of the houses where the victims lived, should be placed in the walls so that they are not trampled on by passers-by. On the other hand others feel that if you “stumble” over a memory stone you are reminded of Vienna’s tragic past. Actually, many property owners refuse to have those plaques placed on their facades. Unfortunately removals of plaques by property owners still happen: recently in the 8th district, Schmidgasse 14, a former US embassy building, which was restituted and turned into a luxury apartment building in prime location behind “Rathaus”. First the memory stones for the Jewish family Fürth, who ran a hospital there until 1938, were moved to a side entrance and now they have completely disappeared (see article “Vienna 1945”). The plaque above tells about 55 Jewish adults and 6 children who had been crammed into a “Sammellager” in the 2nd district of Vienna near the one of Ignaz and Ritschi before they were deported, whereof only four survived the holocaust. Volunteers regularly clean those memory stones on Viennese pavements and they report that the tenants in most houses look after these brass plaques and try to prevent any soiling or defacing of them because they want to safeguard the memory of these people.

Little is known about life in the collective camps, because contact to the outside world was prohibited and only few of the interned survived and those who did, rarely talked about their experiences. Only few messages or letters could be smuggled out of the collective camps and they described a disastrous situation. All furniture was removed from the flats or school rooms and many people were crammed into these spaces on mattresses or straw sacks or on the bare floor. The rooms were not heated and there were no covers. Everyone was limited to the space of his or her mattress or straw sack. There were only very few toilets and wash basins, vermin was rampant; there was little medical support and the food rations were meagre because the IKG had to pay for medical and food supply from its scarce resources. Furthermore the violence and aggression of the SS personnel was unsupportable. Some of the interned who were ordered to work outside the collective camps could smuggle letters or money into the camp. The youth welfare worker Franzi Löw, who worked for the IKG, managed to assist some of the people in the collective camps and prevented the deportation of some children in Jewish children’s homes, because she worked together with the Jesuit Pater Born of the “Agency for non-Aryan Catholics” and procured names of “Aryan” fathers for these children. Usually the people only remained a few days in the collective camps, but sometimes, due to the need for certain administrative clarifications, a stay could take a few weeks or months, as was the case with Ignaz and Ritschi Sobotka (from the beginning of July until the middle of August 1942). The people feared the internment in the collective camps and tried to escape, but it was extremely difficult to survive underground in Vienna because very few “Aryan” Viennese were prepared to help Jews and hide them: first, because the punishments for such actions were very harsh and second, because there was the permanent threat that the helpers were betrayed by informers. Because of immense pressures on the “U-Boot”” and the helpers, many gave up and reported at the collective camps or tried to commit suicide. In GESTAPO reports in the first three weeks of the large deportations 84 suicides and 87 suicide attempts of Jews were recorded. All in all, until October 1942 390 Jewish suicides and 277 suicide attempts were registered by the GESTAPO. The documentation of the SS in charge of the collective camps mentioned in the daily entries of the Jewish health care personnel suicide attempts by poisoning, taking sleeping pills, jumping out of the window etc.

Locations of collective camps in the 2nd district near Karmelitermarkt

The living conditions in the collective camps as locations of transit were disastrous, but they were incomparable to the circumstances that awaited the deported in the concentration camps. The IKG was to nourish around 1,100 people at a time, which was extremely difficult because they lacked means and ingredients, so the food ration was mostly soup and a tiny piece of butter. The inmates were involved in dispensing the food and the cleaning. Interned persons also had to clean the carriages at the Aspang train station. Now and then the imprisoned could secretly receive parcels, letters or money in the collective camp with the help of IKG personnel. Ignaz and Ritschi must have received the two postcards from their daughter Lola and family via this channel. Money was necessary to procure necessary goods via the booming black market. An important survival strategy in the collective camp was to be assigned work, either inside the collective camp in the kitchen or cleaning tasks or outside at the Aspang train station. Unfortunately the inmates were confronted with insults and attacks from the Viennese population there. Sexual violence by the SS and forced prostitution of young Jewish girls and women is documented in the collective camps, too.

Area of the Karmelitermarkt in the 2nd district

The “commissioning” was the much feared last act before the deportation and decided about dischargement, postponement or instant deportation. Anton Brunner (later called Brunner II) was responsible at the “Zentralstelle” for “commissioning” and during the interrogations after the war he admitted to the “commissioning” of 48,000 people, nearly all of which were deported to concentration camps. The aim of “commissioning” was to have at least 1,000 persons “ready” for the next transport to the “East”. The SS, GESTAPO, a Jewish doctor and IKG personnel were present at the “commissioning”. The interned had to present their documents on tables in front of them and their passports and other documents were torn up and their Jewish ID “Kennkarte” was stamped with “evacuated” and the date (see “Kennkarte of Ignaz and Rudolfine above). Furthermore the “evacuated” had to sign a waiver of all property and had to hand over all their valuables and nearly all cash. The Jewish doctors could ask for a postponement of deportation due to medical reasons, but this was not necessarily accepted. Paul Klaar was the senior physician responsible for all collective camps and had to be present at the loading of the people at the Aspang train station, too. The “Viennese Model” of systematic “collecting” and collective camps was so “successful” for the Nazis that Alois Brunner was sent to Berlin in November 1942 to apply the “Viennese Model” in the rest of the “Third Reich”.

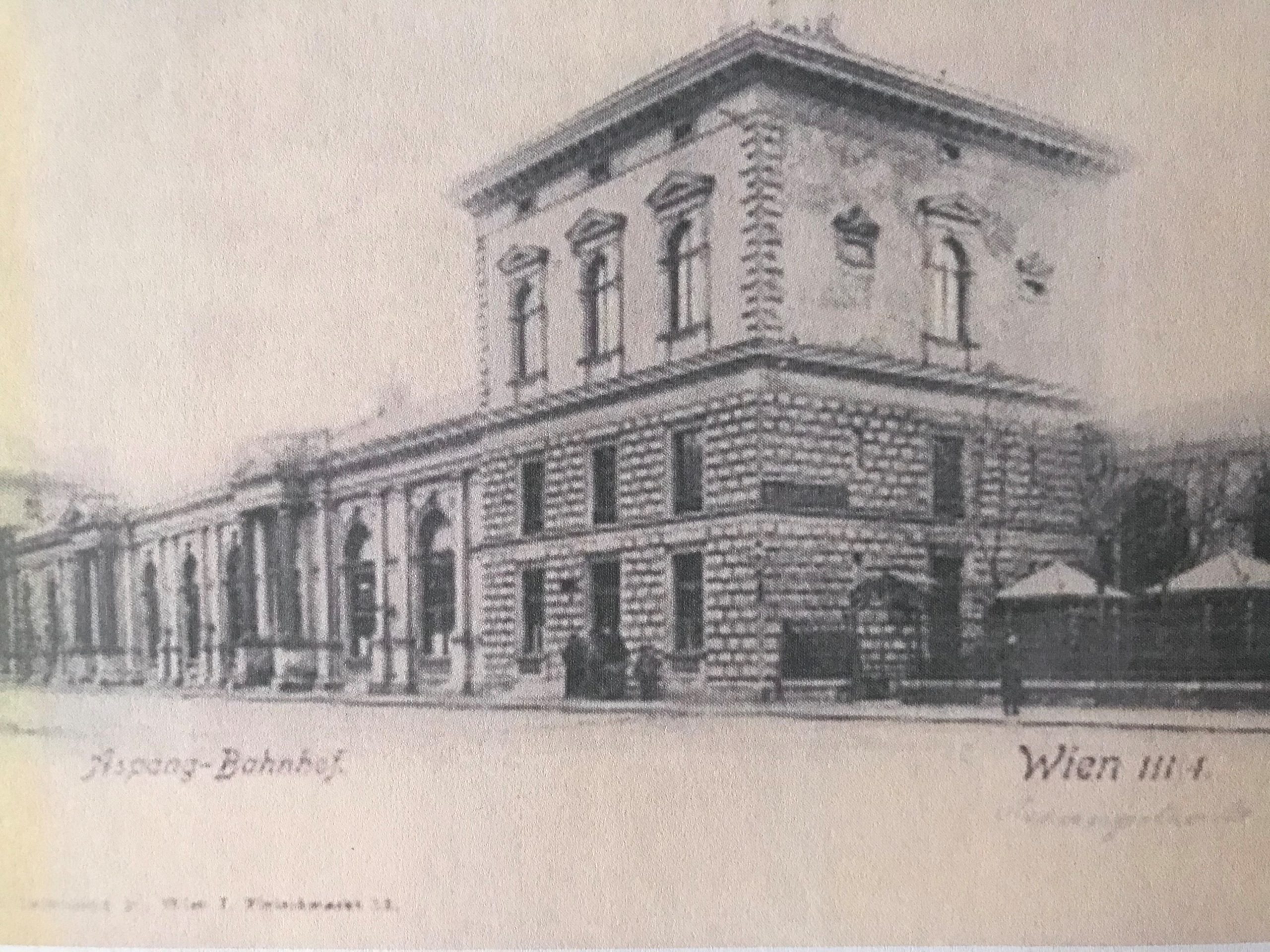

Postcard of the Aspang train station

Contrary to Germany, where the Jewish population was deported from several cities, the central location for deportation in the “Ostmark” (Austria under the Nazis) was the Aspang train station in the 3rd district of Vienna, which was less busy than the other train stations in Vienna, but it was in the centre of town, so that the weekly transports of 1,000 Jews to the “East” could be watched by the Viennese population. This train station was opened in 1881 and the private train line ran south of Vienna via Wiener Neustadt to Aspang. The original idea was to erect a trans-European train connection from Vienna via Zagreb to Saloniki in Greece. The project failed and in 1899 the Belgian consortium sold the train line to a private Austrian rail company, which held the “Wien-Aspang” train line until it was incorporated in the state-owned Austrian Railway Company in 1937. On the day of the deportation the Jewish population was hauled into open trucks and transported to the Aspang train station. This was the last possible moment to try to commit suicide by jumping off the running truck. Originally the people were crammed into rail carriages for persons and later, especially for the transports to Maly Trostinec, into rail carriages for livestock. The conditions of these train transports of two days to one week were abysmal. The carriages were not heated, they were overcrowded; there was not enough food or water for the deported. The last of the large deportations took place on 9 October 1942 to Theresienstadt, which meant that two thirds of the Jews living in Vienna in 1941 had been deported. Now was the time to close down all the institutions of the IKG and to deport the IKG personnel. All the remaining elderly were deported to Theresienstadt, when the homes for the elderly were closed. From then on most transports left from the North Station. It is estimated that between 1943 and 1945 around 3,250 Jews were deported to mostly Auschwitz and Theresienstadt from there. In March 1945, just before the end of the war, 1,073 Hungarian Jews were deported to Theresienstadt from the North Station.

Holocaust memorial at the Judenplatz in the 1st district

Eight men were identified as the main perpetrators in the Nazi collective camps, which were organised by the “Zentralstelle”, in the trials after 1945 by the Soviets: Alois Brunner (Brunner I), Anton Brunner (Brunner II), Ernst Brückler, Herbert Gerbing, Ernst Girzick, Alfred Slawik, Josef Weiszl and Anton Zita. All the perpetrators had several things in common: every one of them was around 30 years old, except Anton Brunner, who was already over 40. Nearly all of them had achieved very little before their career in the NS administration. They had completed apprenticeships, but had experienced long periods of unemployment and many of them had already been illegal Nazis in Austria before 1938. They all applied physical and psychological violence with relish and abused, beat up and humiliated Jews, be it workers like themselves or middle-class professionals or intellectuals. They robbed and extorted their victims and indulged in their defencelessness. After the end of the large deportations in Vienna, they acted in other European cities under Nazi domination as “Viennese deportation experts” and by that initiated a new stage of accelerated violence there. They were all offenders by conviction, i.e. they were convinced of the importance and validity of their deeds and they and their wives were in close friendly contact. They more than fulfilled their orders; for example they even arrested people in their leisure time and humiliated victims in the street when strolling with their families. After 1945 they either escaped or only received very short prison sentences from which they were released early. The only exception is Anton Brunner, who was sentenced to death by a Soviet people’s court in Vienna and executed in May 1946. All others were either in freedom again ten years after the war or had escaped abroad like Alois Brunner, who lived undisturbed until 1954 in Essen, Germany, and then in Syria until his death.

Memory stones for those who tried to survive in hiding as a “U-Boot” in the 2nd district

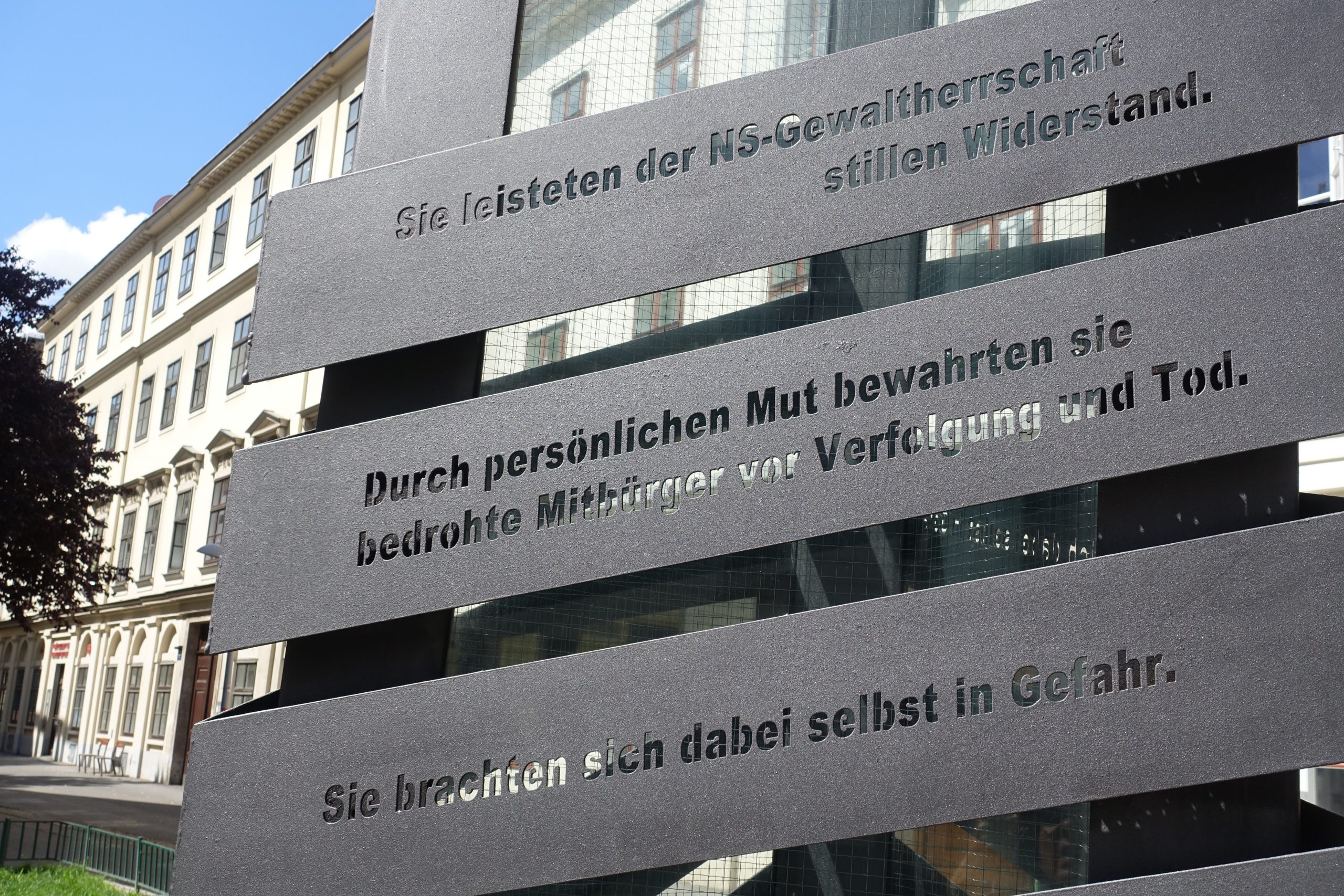

Memorial to the helpers who resisted Nazi terror by helping Jews in hiding

There were few possibilities for Jews to escape the Nazi persecution in Vienna. They first tried to disappear and go into hiding with non-Jewish friends or relatives immediately after the “Anschluss” in March or after the November Pogrom 1938, usually only for a few days or weeks to organise their escape abroad. Who did not succeed in finding exile abroad was defencelessly exposed to Nazi terror because from September 1939 on flight was nearly impossible. So to escape from a “summoning” to a collective camp and the deportation to the “East”, several persons decided spontaneously to go into hiding because they already suspected that the word “resettlement” was a euphemism for something much worse. Soldiers on home leave, escaped concentration camp prisoners and reports from foreign radio station, which the people listened to despite the threat of severe punishment, told about indescribable crimes in the “East”. The Jews in hiding soon called themselves “U-Boote”. What did they have in common? They were illegally living “underground” at one or more places, took on a new identity, used false or manipulated papers and as they were registered nowhere, they had to rely on help from others because they had no food stamps or clothing or shoe stamps and nothing could be bought without those except on the black market, where prices skyrocketed. The persecuted Jews might be able to buy certificates of baptism or other documents or they changed the date, when they had left the Jewish religious community to before September 1935, so that the Nuremberg race laws did not apply. Even civil servants of NS authorities made money by selling wrong “Aryan certificates”. 340 people are documented who went into hiding with a false identity. Another possibility was to fake a suicide. This had to be well prepared, which shows the example of Walter Baumgartner, who with the help of the secretary of the Protestant community, Eva Benes, left his clothes and a farewell letter at the Danube and disappeared. He hid in the Protestant community and married his helper Eva after the war in June 1945. Unfortunately he was physically and psychologically so exhausted that he actually committed suicide at the beginning of September 1945. Sources which allow an estimate of the number of people in hiding in Vienna are the GESTAPO reports about failed attempts at disappearing, oral reports of “U-Boote” and applications for compensation after the end of the war. According to these sources 1,634 persons of Jewish descent were in hiding in Vienna between March 1938 and April 1945; one third of them was killed. Yet it can be assumed that many more persons tried to disappear, but were murdered in the holocaust, so no documentation is available.

Approximately 1,000 people survived longer than one year in hiding; 52 per cent of them women, who had better survival chances than men, firstly because during the war able men, not in uniform, walking the streets of Vienna were automatically suspect and secondly, if they were arrested, they could easily be identified as Jews due to circumcision. Nearly 60 children lived as “U-Boote” and 20 of them were born after March 1938. Children normally lived with one parent in hiding, whereas adolescents usually had to look after themselves from 15 years of age on. Every “U-Boot” needed two or more helpers to survive. But the more persons knew about a “U-Boot” the more precarious the situation became. The majority of Jews in hiding were lower or middle class, while their helpers were mostly workers or lower middle class. 60 per cent of all helpers were women and often their husbands, who were fighting in the war, were not informed. So when the husbands returned on home leave a new hiding place had to be found during this time. In most cases only one person was hidden and nearly always for free, out of mercy and for purely humanitarian reasons. 53 per cent of the “U-Boote” lived for a longer period at one address, which means that the chances of survival were higher if not too many changes of residence were necessary. 19 per cent had two residences in hiding and 15 per cent three or four. 13 per cent had to look for a new hiding place more than four times. The first addresses of many “U-Boote” were in the districts 1, 2 and 9, where already before 1938 many Jewish citizens lived. The people in hiding tried to take on any jobs available which were to be had without documentation in order to make money. Many women worked in households, did cleaning and sewing jobs, instructed children and men worked in gardening or construction whenever possible. It was essential not to stand out in public, which meant to speak Viennese dialect, not to look grubby and most importantly to fit in with respect to clothing and behaviour. Blond hair and blue eyes were an asset, as well as wearing traditional clothing or HJ uniforms for boys and BdM (Nazi youth association for girls “Bund deutscher Mädchen”) uniforms for girls. Children had to be trained not to speak out and give anything away and if they were in their shelter not to make the slightest sound.

Sometimes it was a spontaneous decision to provide shelter for a persecuted friend, as for example the famous actress Dorothea Neff, who decided to hide the young costume designer Lilly Wolff in her flat when she received the “summoning” to appear in a collective camp. Others prepared for a life in hiding, usually for their children with “foster parents”. But most of the persecuted Jews had no plan at all and roamed the city, took trams from one end station to the next and spent the nights on cemeteries and in garden centres near graveyards on the outskirts of the city. In winter the tracks in the snow might have betrayed them, so they had to find other hiding places. Apart from trying to find lodgings the provision of food was the most urgent matter. As the food stamps were not generous at all, it was virtually impossible to feed a second person on the issued food stamps. So the helpers and “U-Boote” tried to manipulate or forge food stamps, usually with little success. Practically everything was rationed, which left only the black market, where essential goods could be bought in exchange for money, jewellery or other valuables. This was extremely risky for helpers and “U-Boote”, because trading on the black market was threatened with harsh punishments, and most of all, you could be detected and uncovered there. Some tried to establish contacts to farmers, who were strictly supervised as well, but they often had some hidden reserves to sell. Some inns offered so-called “Stammgerichte”, meatless and fatless cooked vegetables and potatoes, which could be bought without food stamps. Even if it was risky to eat at an inn, many “U-Boote” took the chance to get a decent meal there now and then. Hygiene posed another serious problem, because most of the flats of the working and lower middle class in Vienna had running water and toilets only outside in the staircase or corridor, where all tenants had access. So the chance to encounter an informer was very high. The biggest threat for “U-Boote” as well as helpers was an illness or tooth ache, as it was virtually impossible to get medical help as a “U-Boot”. The worst case scenario was the death of a person in hiding because the helpers had to somehow get rid of the body without arousing attention. One helper had to bury a couple on the grounds of a garden centre in the 17th district near the cemetery for example.

The fear of being discovered or betrayed by one of the many informers was omnipresent. How did the people cope with this permanent stress? One strategy was thinking and planning just from one day to the next and the other one was humour. Viktor Frankl stated that humour was a weapon of the soul in the fight for survival and that humour was an important tool to create distance and to put oneself above a situation. Here are some of the Jewish jokes that were told at the time to amuse and entertain the distraught persons:

Two chess players in the Café Sperlhof: Grün asks, “Lilienthal, what are we playing for?” “I would say for honour.” “And what do I do with your honour if I win?”

Lilienthal meets his friend Grün in the Café Museum: “Aaron, let’s play a game of chess!” “No, I’ve just lost my wife. I don’t feel like amusing myself.” “Well, then choose the black chessmen.”

When Hitler takes power in Germany, Kenigsberg goes to Berlin. When he comes back, he tells Gebirtig, “I’ve seen Goebbels. He looks like Apoll…” “Are you mad? This tiny cripple!” “Let me finish my sentence! He looks like a Polish Jew.”

Just after the takeover of the Nazis in Vienna Kenigsberg and Gebirtig are in their favourite café. Suddenly Kenigsberg says mournfully, “Moses was definitely a stupid ass!” “For heaven’s sake! What do you say about our great prophet? He led us out of Egypt!” “Just because of that! Had he not led us out, I would have an English passport now!”

1937, discussion about the danger of the “Anschluss”: Poznan is optimistic, “Hitler will never march into Austria or else there would be war. Look at the globe: there is the small Germany in the middle – and this all belongs to England, that to France and that to huge Russia, not to speak of America…” “Yes, I know, but does Hitler know it?”

The Nazis are in Vienna. At night in a lonely lane a tall drunken Goi (non-Jew) encounters the timid Poznan and shouts, “You are a Jew!” Poznan, frightened, answers, “And you? You are completely drunk.” “Yes, but that is over by tomorrow morning.”

Asher Landau from Switzerland visits his friend Kenigsberg in Vienna, “How are you under the Nazi regime?” “Like a tapeworm: I wriggle through the brown masses and wait until I’m purged (deported).”

Vienna after the “Anschluss”: In a crowd a uniformed SA-man (NS “Sturmabteilung”) steps on a passer-by’s foot who reacts with a punch. Zalman Zelig then slaps the SA-man, too. A policeman arrives and asks the passer-by, “How dare you slap an SA-man?” “I’m so sorry, I beg your pardon, but the pain was too much; it was an involuntary reaction.” To Zelig, “Ok, yes, but how dare you as an uninvolved Jew slap a SA-man?” “Well, I saw that they slapped the Nazis and I thought it was allowed again.”

Passport office, Vienna 1938: Kenigsberg wants a passport. “Where do you want to go”, asks the official. “I don’t know.” “You have to name a destination.” Kenigsberg shrugs, but the official is good-natured and points to a globe, “Choose a destination and fill it in your application.” Kenigsberg slowly swivels the globe several times and then asks, “Can’t you offer me anything better?”

Kenigsberg and Gebirtig have fled from Vienna and are waiting in Marseille for their boat. They talk about what will happen in ten years’ time: Gebirtig says, “I will be back in Vienna. I will stroll in the Prater with my Rebecca. An old man in rags will come and I will proudly pass by him and say to Rebecca: Look, there he goes, this Hitler.” Kenigsberg answers, “I knew you were a coward! I will also be in Vienna again and I will sit in the Café Herrenhof and read the “Presse”. I will have read the paper and will put it aside. Then I will read the “Wiener Zeitung”. A man will come and ask politely: Excuse me, Sir, is the “Presse” available? And I will hardly look up and just say: Not for you, Mr. Hitler!”

More than 400 cases were recorded by the GESTAPO where the attempt at disappearing failed. Mostly the “U-Boote” were uncovered by informers who the GESTAPO especially employed to discover hidden Jews and by neighbours and acquaintances who reported “U-Boote” to the NS authorities. If the helpers could be disclosed too, they were accused of a “friendly attitude towards Jews” and were arrested. At least 30 known helpers did not survive their imprisonment and internment in a concentration camp. The Allied bombardments further endangered the “U-Boote” because they could not find refuge in bomb shelters or cellars, but on the other hand for them the bombardments were a sign of the imminent liberation. Unfortunately several Jews and their helpers died in the bombardments. Even during the last days of the “Third Reich” the GESTAPO and the ubiquitous informers searched for hidden Jews in Vienna. Especially in the chaos of the last days of the war some fanatical Nazis hunted hidden Jews in cellars and garden huts in the outskirts of Vienna. On 11 April 1945 the SS dragged hidden Jews out of cellars in Förstergasse in the 2nd district and shot nine of them.

With the end of the war came relief and the surfacing of the “U-Boote”. Above all, they could now protect their helpers in the chaos of the last days of fighting and the arrival of the Soviet troops. The yellow Star of David was now no longer a stigma, but could be life-saving. They made clear to the Soviet soldiers that their helpers were not hidden Nazis, but on the contrary, had protected them from Nazi terror. But only very few of the former “U-Boote” could take up their former lives again and especially children and young people had to learn social behaviour and make up for years without schooling or education of any kind. When the atrocities of the death camps became public, the mourning for the dead eclipsed the joy of survival and many posed the question, “Why was it me who survived?” Traumata and fear pervaded the following years of the former “U-Boote” in the same way as the survivors of collective camps and concentration camps, like Ignaz and Ritschi. After 1945 the Republic of Austria did not acknowledge the demands for compensation of “U-Boote” until the legal reforms of the 1970s and also the helpers who were imprisoned in concentration camps were not compensated. In the case of Ella Lingens, who had spent two years in Auschwitz for hiding a “U-Boot”, an administrative notice of 1948 refused her claims for compensation on the basis that “hiding Jews was a private matter and not resistance”.

LITERATURE:

- Adunka, Evelyn, Anderl, Gabriele, Jüdisches Ottakring und Hernals, Mandelbaum Verlag 2020

- Habres, Christof, Moische, wohin fährst du? Wien und der jüdische Witz, Metroverlag Wien 2010

- Hecht, Dieter; Raggam-Blesch, Michaela; Uhl, Heidemarie (ed.), Letzte Orte. Die Wiener Sammellager und die Deportationen 1941/42, Mandelbaum Verlag Wien 2019

- Hofmann, Thomas & Beyerl, Beppo, Die Stadt von gestern. Entdeckungsreise durch das verschwundene Wien, Styria Verlag 2018

- Ungar-Klein, Brigitte, Schattenexistenz. Jüdische U-Boote in Wien 1938-1945, Picus Verlag Wien 2019