THE OTHER SIDE OF THE COIN OF FIN-DE-SIÈCLE VIENNA: LIVING CONDITIONS OF WORKERS IN THE VIENNESE OUTER DISTRICTS FAVORITEN, OTTAKRING AND HERNALS & SOCIAL ADVANCEMENT VIA APPRENTICESHIP AND VOCATIONAL TRAINING

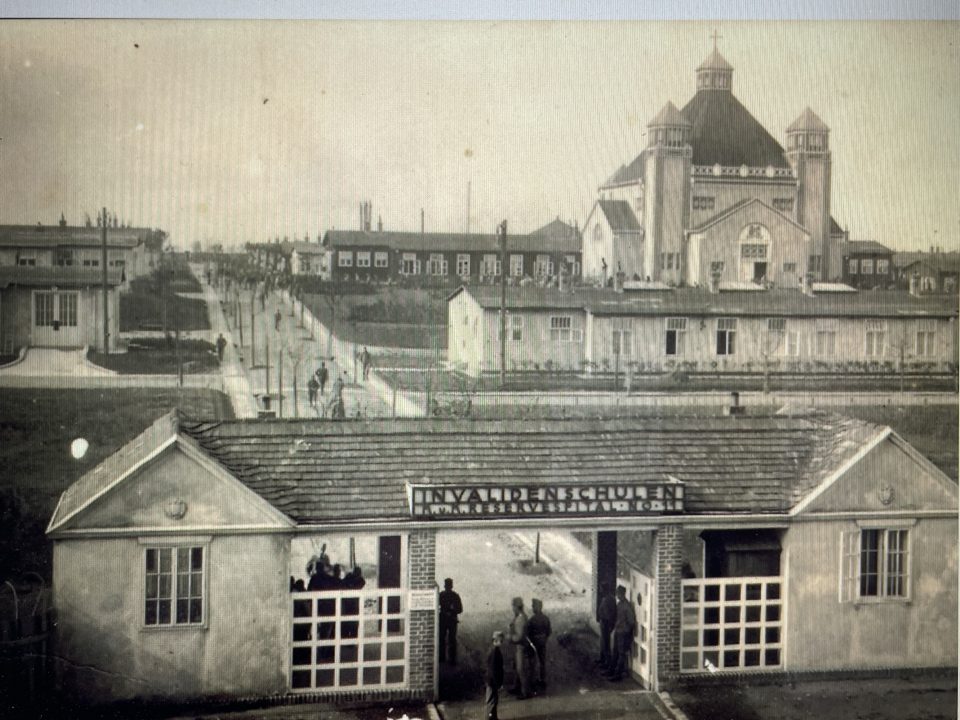

Area of the “Schleierbaracken” in the Viennese working-class district of Favoriten, Schleiergasse 17, at the beginning of the 20th century. Left: the rehabilitation and re-training centre for invalid soldiers of World War I. Right: after the end of World War I, the wooden barracks were rented to small suburban businesses as workshops and used until the 1970s

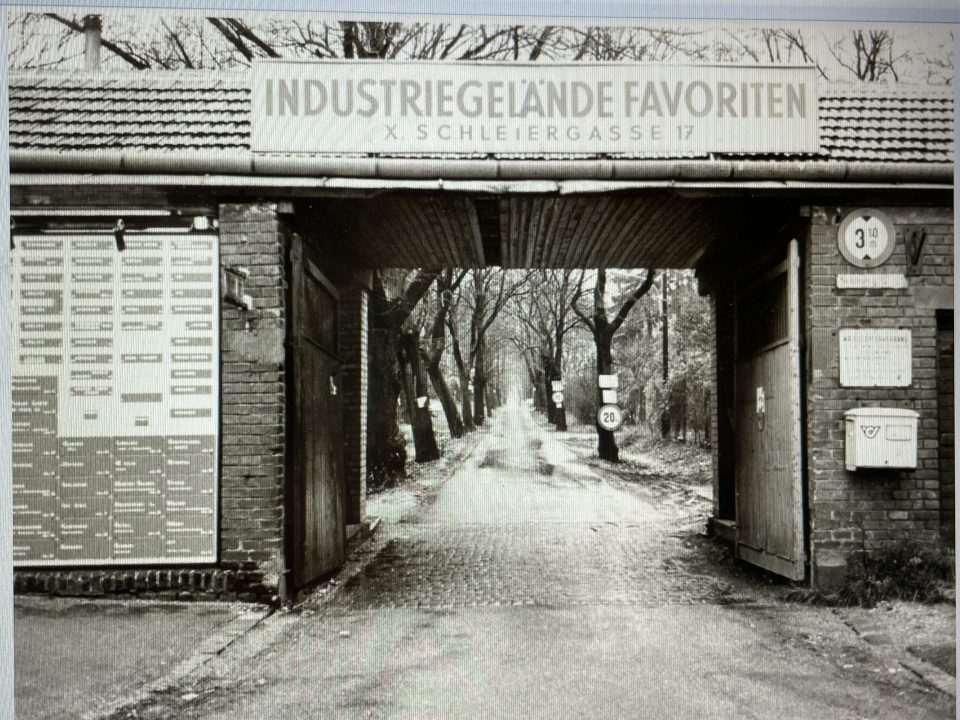

Today only few of the wooden barracks, which were used as workshops have remained; a part of the area was turned into a small park. The street signs with the address Schleiergasse 17, 10th district Favoriten, are still there:

My mother, Herta Tautz, was a master dressmaker and I remember the trips with her to the outskirts of Vienna, to the “Schleierbaracken”, to buy fabrics. There was an abundance of different fabrics on offer in the factory outlets at very low prices, which were affordable for the less well-off like us. The sales outlets for textiles were always crowded, because professional tailors as well as amateur seamstresses bought everything they needed for making clothes there. I always enjoyed the outings to the wooden barracks in the outskirts, which usually took half a day, because that meant my mother would sew some new dress for me.

Herta, the seamstress (left), me and Herta, my mother, both of us dressed in her creations in 1963

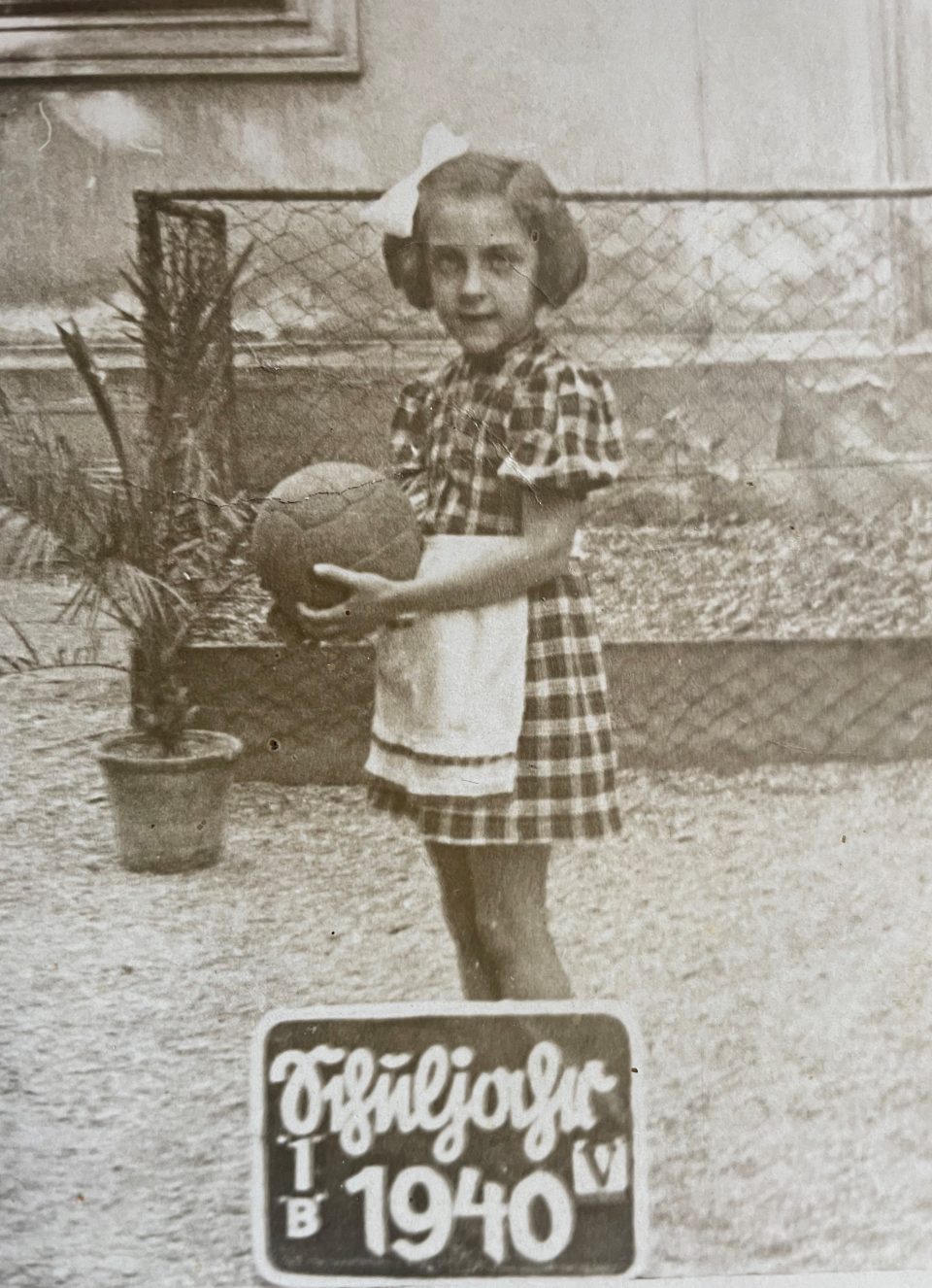

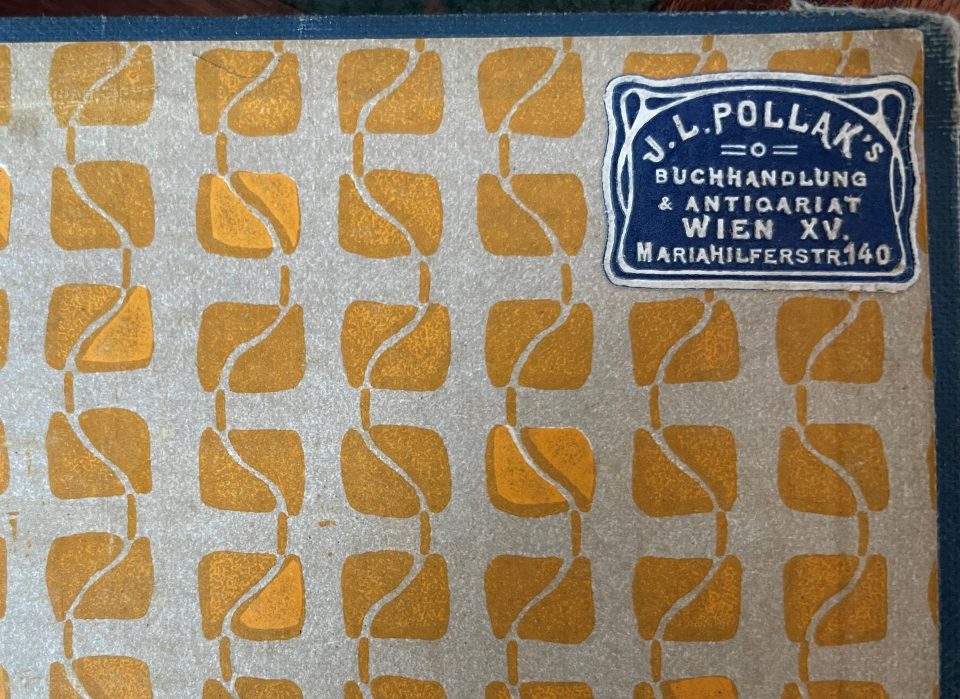

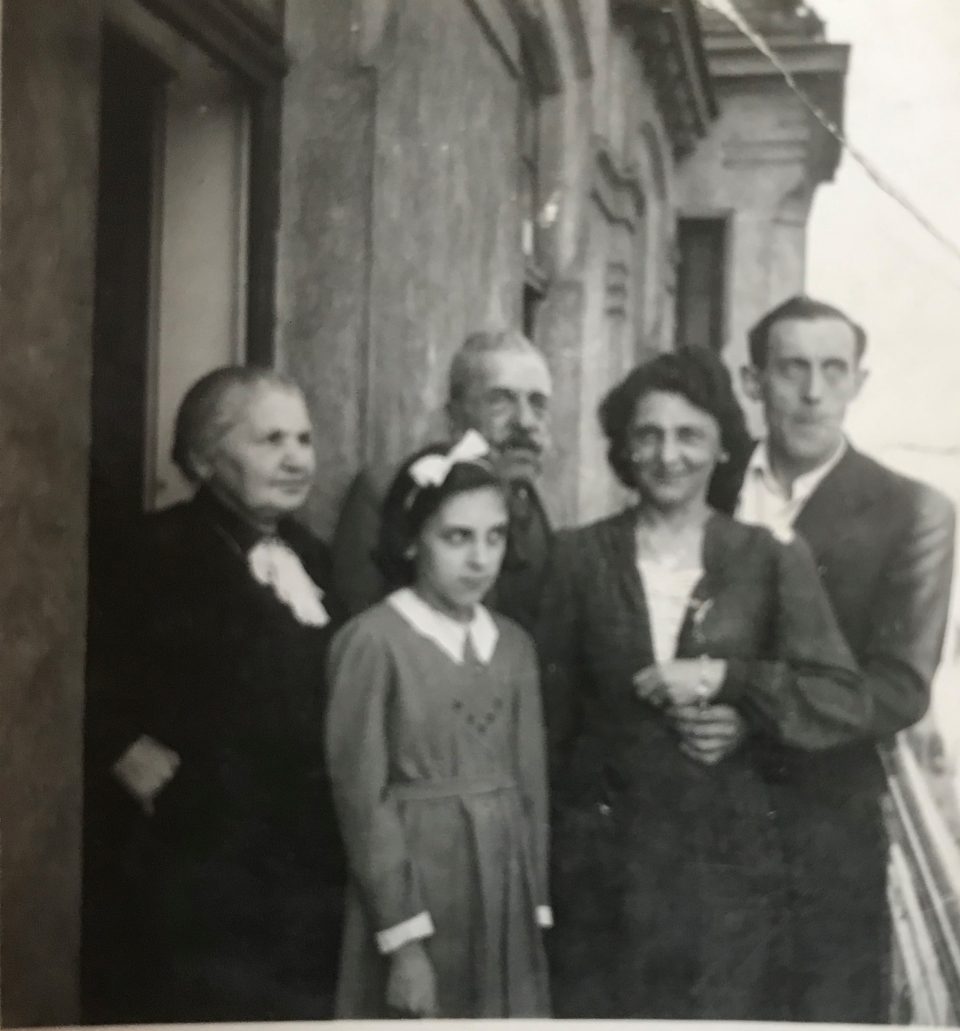

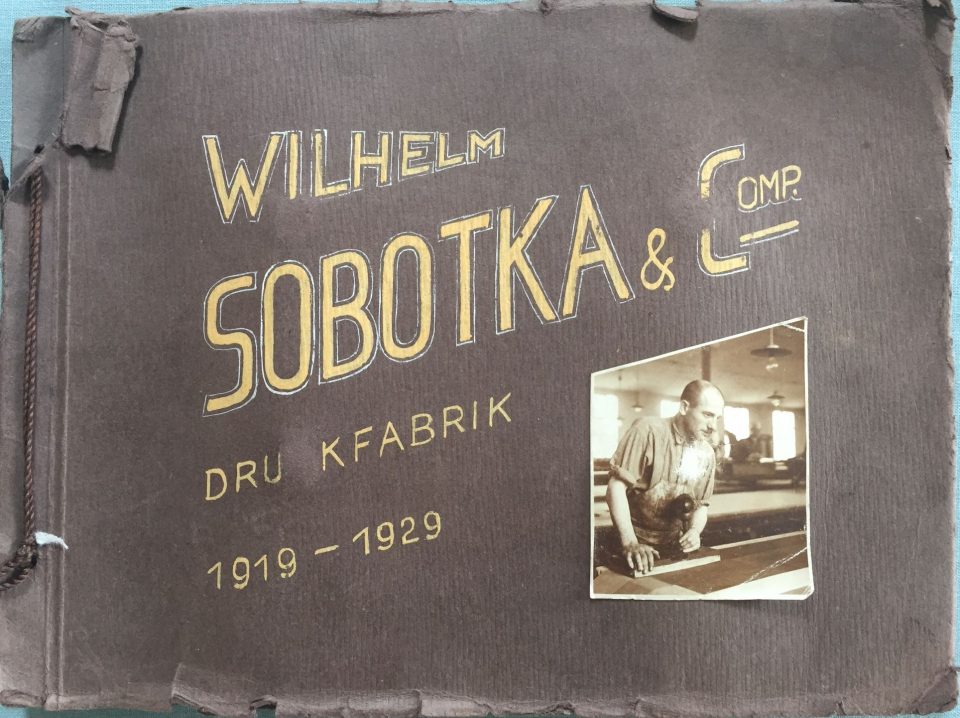

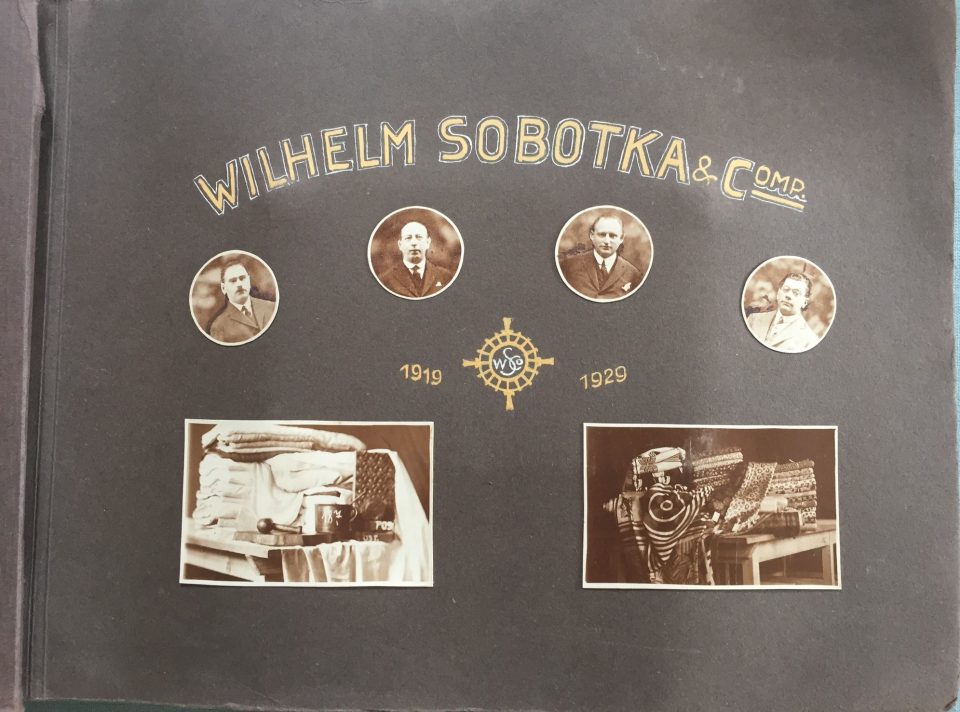

Another much more interesting personal connection to the “Schleierbaracken” were the workshops which the youngest brother of my great-grandfather, Ignaz Sobotka, Wilhelm Sobotka, had rented there in 1919 and where he printed textiles until the Nazis disowned him because of his Jewish origin and seized his business and all his possessions in 1938. He managed to flee Vienna with his wife Marta and his younger son Walter to Belgium, but was caught up by the Nazis there. They were deported to France, Camp des Milles in Drancy and from there Wilhelm and Marta were dragged to Auschwitz, where the couple was murdered on 19 August 1942 in the Nazi KZ (concentration camp). Their two sons, Hans and Walter Sobotka, survived and miraculously the photo album that celebrated the 10th anniversary of the foundation of the textile printing company was rescued, too. Hans, born in 1920 in Vienna, fled to England with the album and joined the British Army to fight the Nazis. After the end of World War II, he moved to Australia, but the landlady, where he had stayed in England had kept his photo album safe all those years and when he came to England to visit her, she handed over this album. It contains photos of the workshops in the “Schleierbaracken”, the workers, the office, and the shop in the 1st district of Vienna, Tiefer Graben. The photos of Wilhelm’s album are © Valérie Sobotka & John Stenford.

“Wilhelm Sobotka & Partners, Printing Factory 1919-1929” with a photo of a worker (left) and all four partners, Wilhelm on the right, with samples of the printed fabrics they produced in the “Schleierbaracken” (right)

One of the company’s workshops in the “Schleierbaracken” (left) and inside a workshop a worker printing a cloth (right)

Another much more important hub of industrial history in Favoriten was the “Wienerberger” brick factory on the Wienerberg, where Josef Sobotka, the father of Ignaz and Wilhelm worked as a foreman. How did this come about? Josef Sobotka was born in Chysky in today’s Chechia, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, with a sizable Jewish minority. He married Rosalia Fried, called Sali, from Brno. The new Imperial State Treaty of 1867 allowed the Jewish minority to move freely inside the Habsburg Empire and to train for and exercise all trades, offering freedom of movement and freedom of trade to all citizens of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Josef and Sali took the chance to leave the impoverished place of Chysky with their first three children, Hermann, Julius and Amalie, called Mali, and moved to the capital city of the Empire, Vienna around 1869. Josef found work in the huge brick factory “Wienerberger”, south of Vienna in Oberlaa as a foreman. In Oberlaa their last three children Ignaz, my great-grandfather, who later ran a brewery in Kaiser Ebersdorf near Vienna, and Wilhelm, who became an entrepreneur in textile printing, and Leni, were born.

The huge brickyard was basically run by thousands of poor, often illiterate Czech menial workers who had migrated from Moravia and Bohemia to Vienna to find work. It can be assumed that Josef Sobotka, who was literate, spoke German and seemed to have had some basic education, as most male Jews living in Bohemia and Moravia, was hired in a more elevated position, namely as a foreman or crew leader at “Wienerberger’s”. This meant that he and his family enjoyed better living and working conditions than the vast majority of unskilled workers, called deprecatorily “Ziegelböhm” (Brick Bohemians) by the Viennese. They lived on site of the factory, renting one of the worker’s dwellings for families of artisans and crew leaders, “Ober Laa 153” (see birth certificate of Ignaz below), consisting of two rooms and a kitchen. It is possible that Josef had already worked for a Czech landowner in Chysky, as these landowners sometimes employed members of the Jewish minority to run small brick yards or furnaces in the countryside on the basis of their rudimentary education in reading, writing, and arithmetic.

Ignaz was born in 1872 and Wilhelm, called Willi, in 1889 in Oberlaa and the family formed part of the Viennese proletariat. They renounced all connections to Jewish traditions and lived a secular life, completely merging into the indigenous Viennese milieu. Josef wanted his offsprings to fit into the Viennese society and climb the social ladder. Josef had a jolly character; he loved drinking and gambling, but he also saw to it that all his four sons learned a trade, which enabled them to become part of the Viennese middle class and escape the poverty of the proletariat. In 1890 Josef Sobotka had already been promoted to brick yard manager in the factory in Breitensee, then in the 16th district of Vienna, Ottakring, today in the 14th district (see document “Lehrzeugnis” below).

…