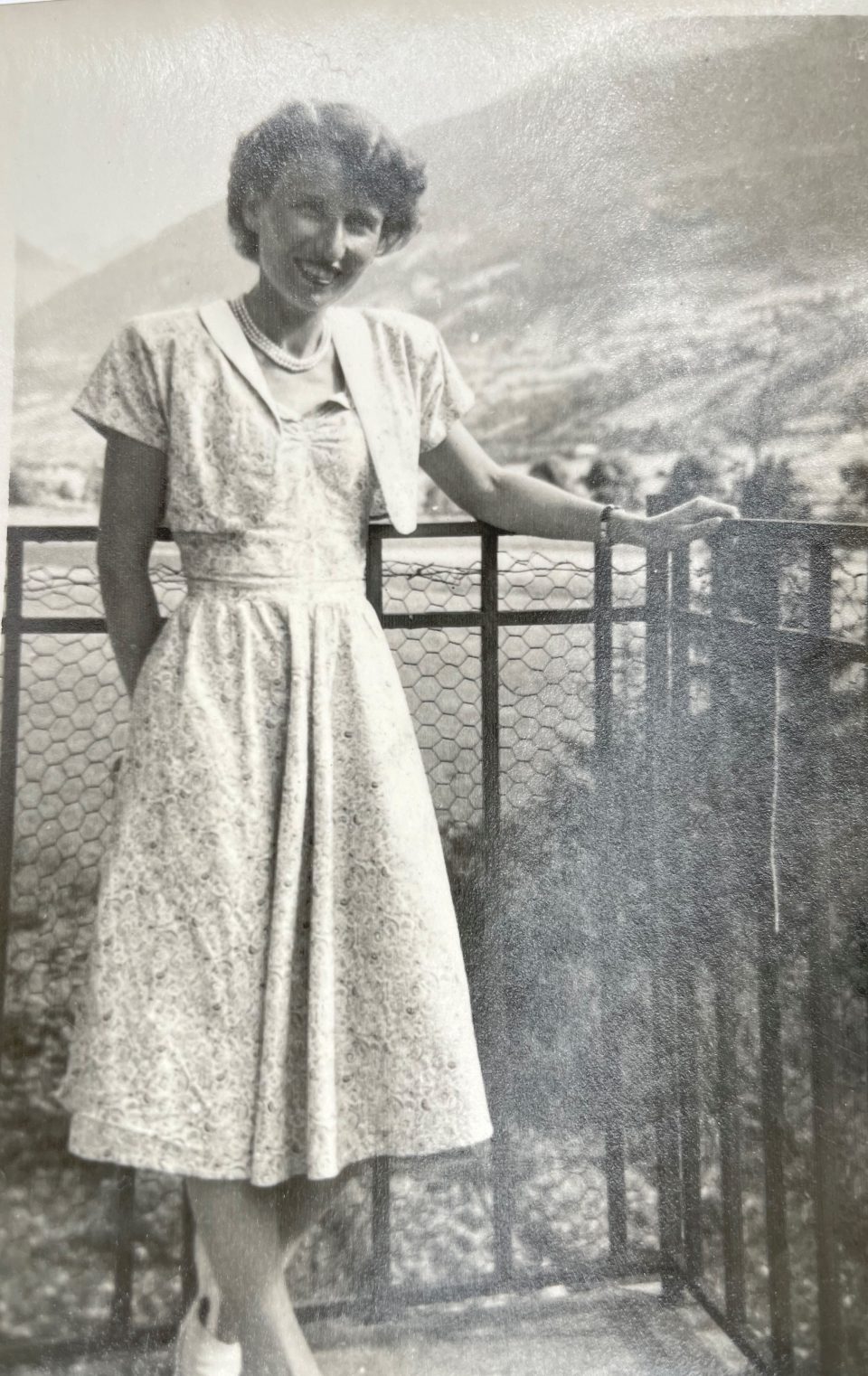

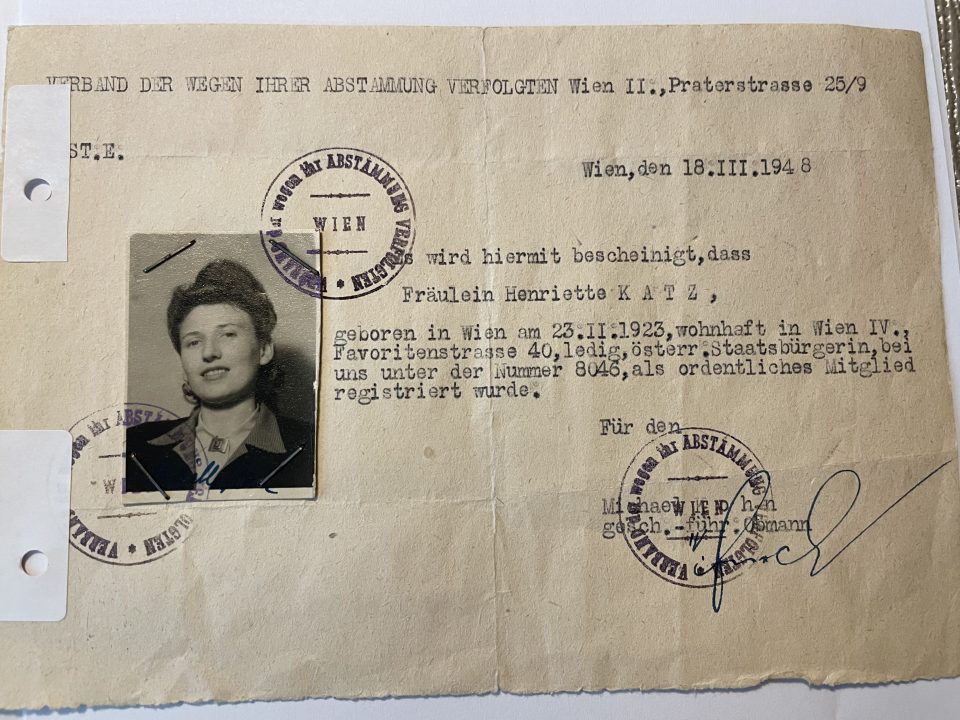

Henny Singer, née Katz, after her return to Vienna in 1948. All photos of her before the war were destroyed when her mother, Alice Katz, and her younger brother, Gerhard Katz, were deported to Opole and murdered

Henriette (Henny) Singer, née Katz, my mother’s cousin, was one of these adolescents who managed to flee from Vienna on an illegal transport to Palestine via the Danube, when the Second World War had already started, and to escape the holocaust. Her mother and her younger brother were not so fortunate and were murdered by the NS terror regime, probably in Opole, Poland. My mother, Herta Tautz, née Kainz, born on 24 November 1933, was 10 years younger than her cousin Henny, born on 23 February 1923. Henny was the niece of Herta’s uncle Norbert Katz, a famous Viennese footballer. See article:

Norbert Katz, Austrian national football team player

Before the outbreak of the Second World War the two girls did not see much of each other because of the age difference, but after the war and Henny’s return to Vienna they kept in contact until Herta’s worsening dementia made communication impossible. Henny died on 9 November 2010, five and a half years before Herta.

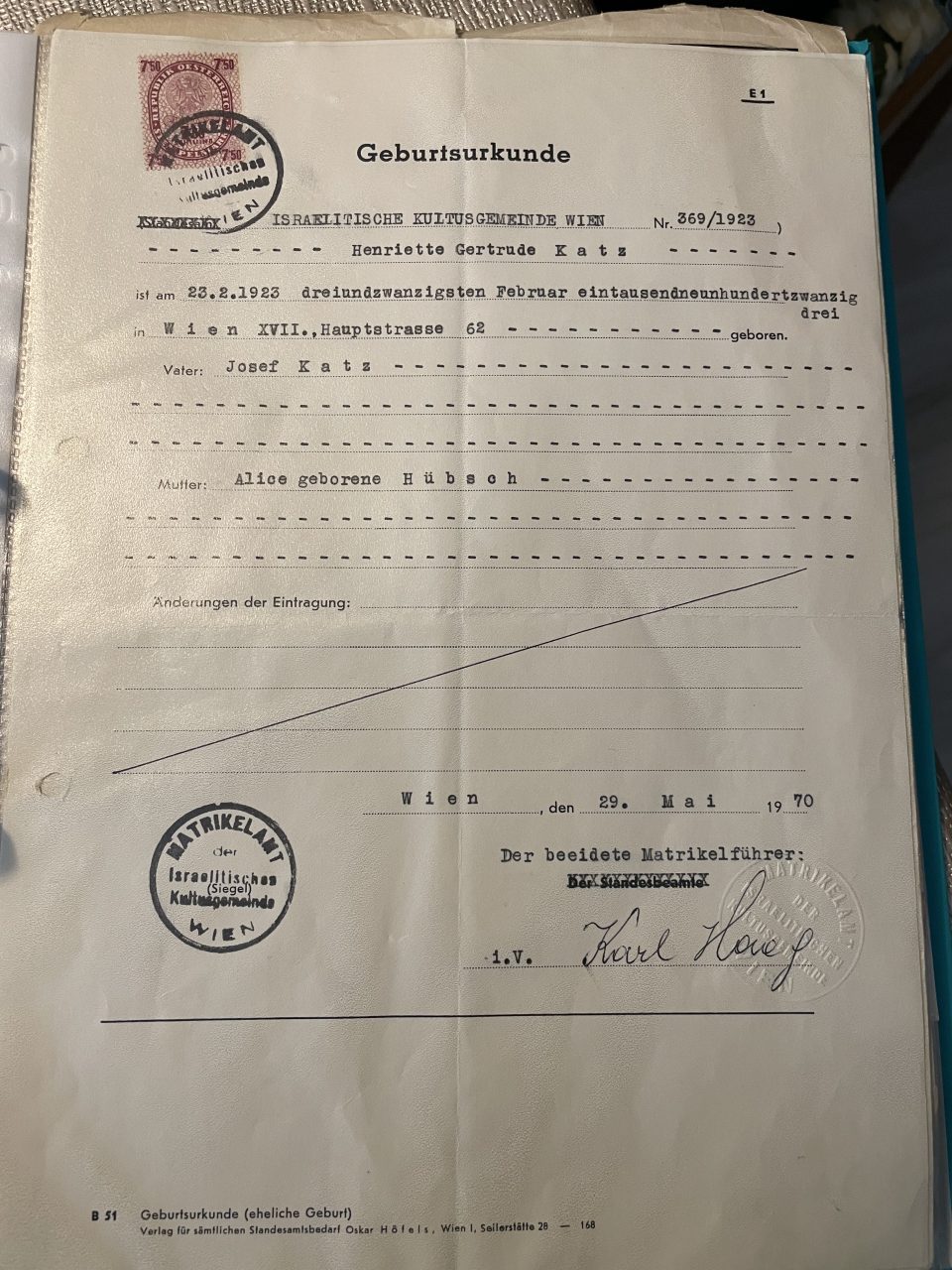

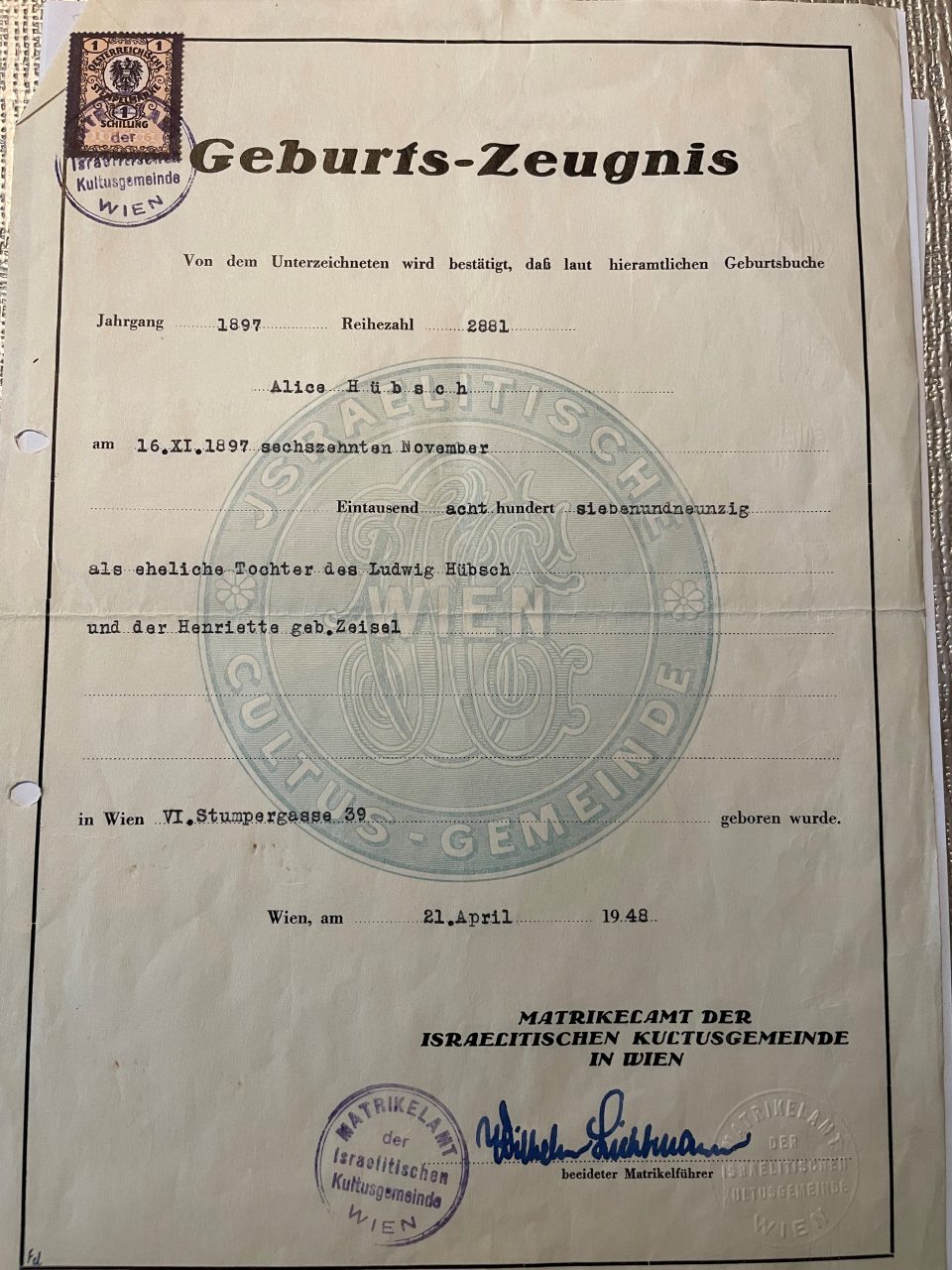

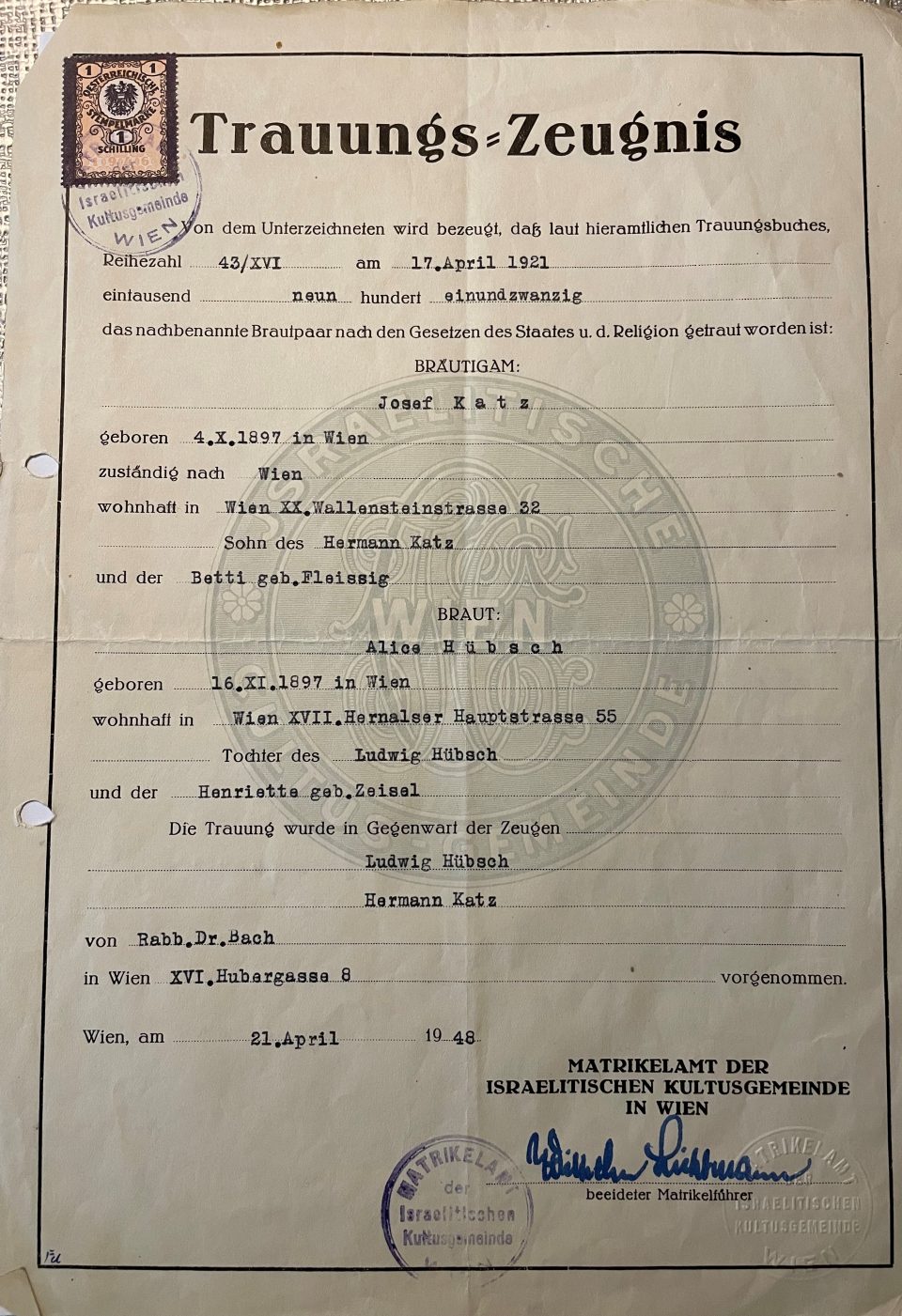

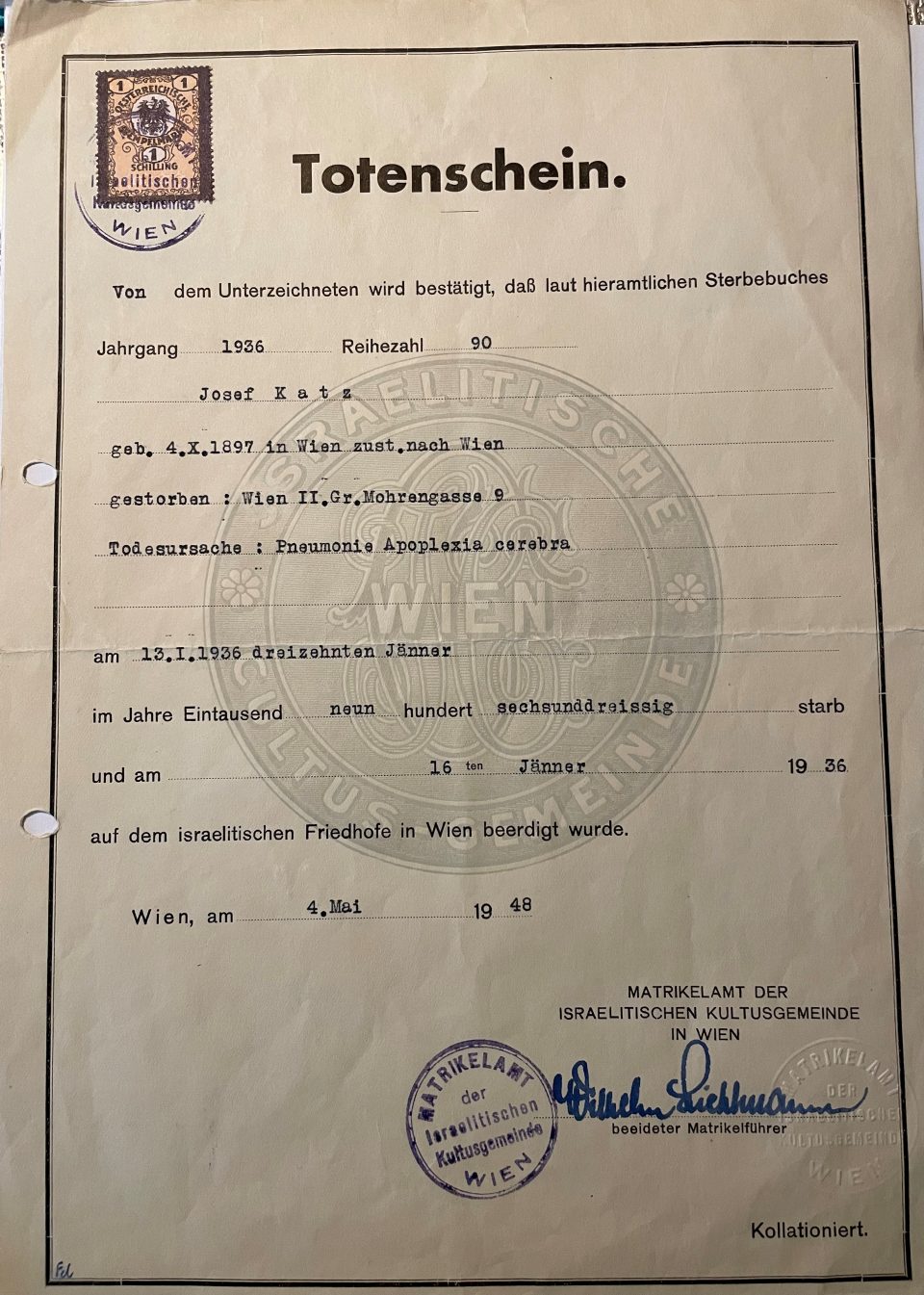

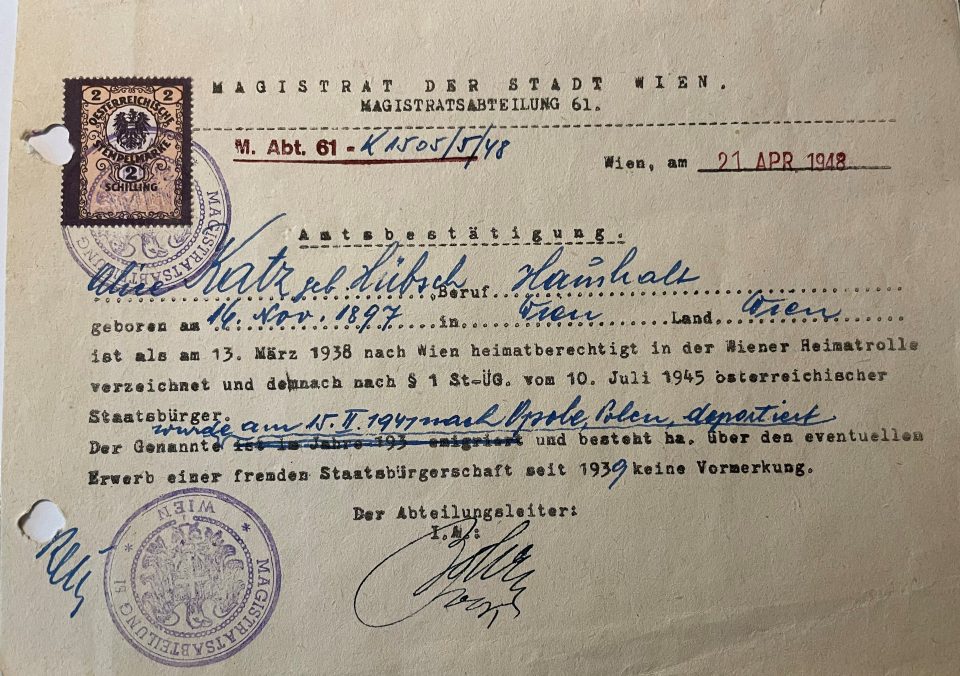

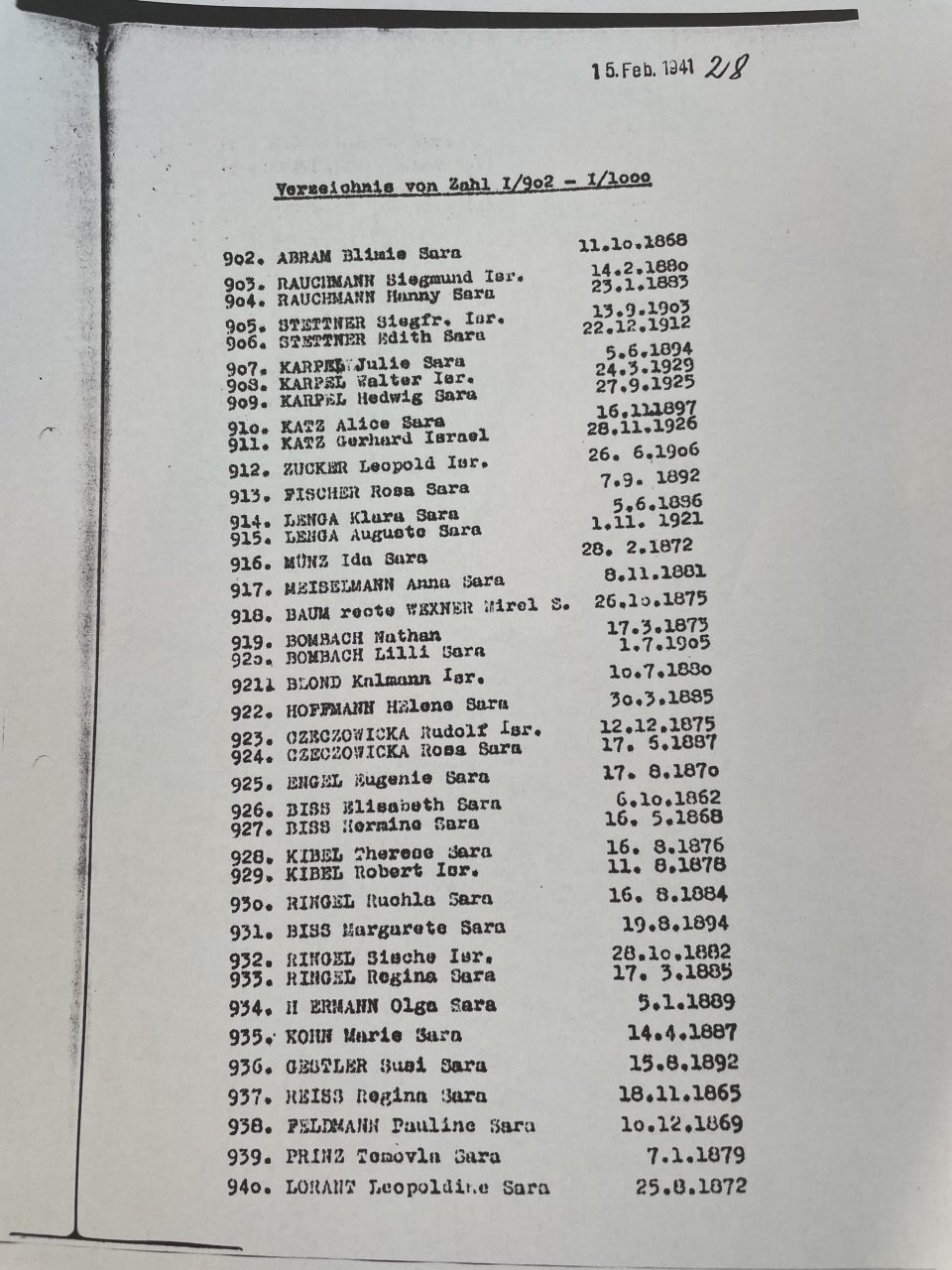

Henny had her birth certificate and her certificate of residence re-issued after the war because all her documents were lost in Vienna after the deportation of her mother and brother to the “Generalgouvernement” (the German- occupied territory of Poland) on the 15 February 1941

Henny was born Henriette Gertrude Katz in the 17th district of Vienna, Hernalser Hauptstrasse 62, as the first child of Josef Katz, the elder brother of Norbert Katz, the Viennese football star, who was her favourite uncle, and Alice Katz, née Hübsch.

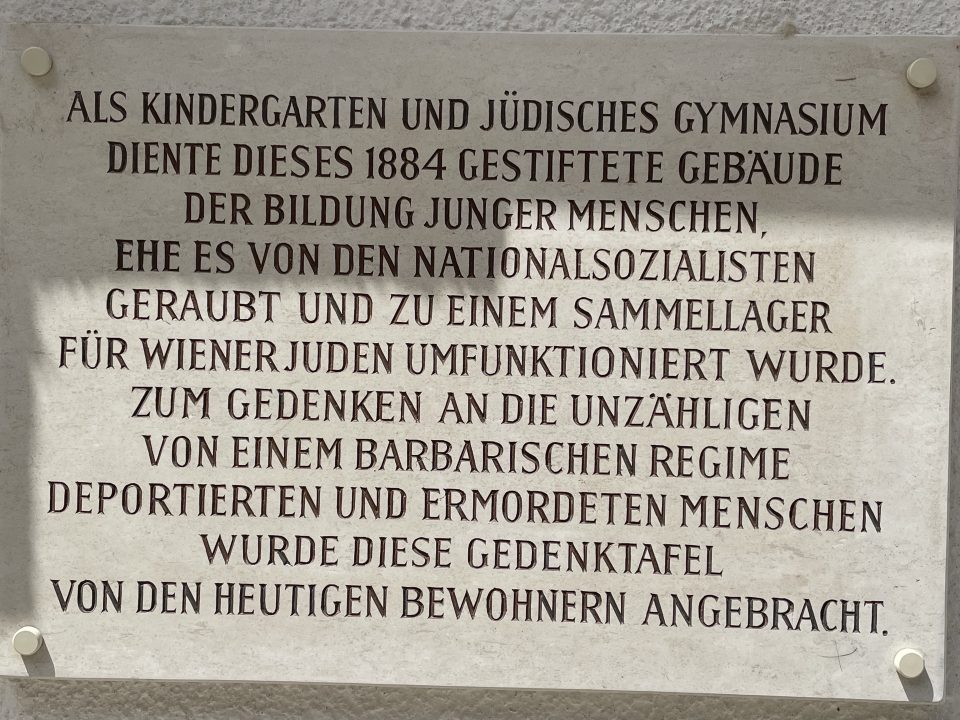

Both parents were assimilated Jews, born in Vienna. Her father Josef Katz, born on 4 October 1897, worked as a bank clerk at the Viennese Mercurbank in its branch office at Taborstrasse in the 2nd district of Vienna. He was only 38 years old, when he died in January 1936 of pneumonia and left Alice to care for herself, Henny, and her younger brother Gerhard, born on 28 November 1926. At the time of his death Henny was not quite thirteen years of age and her brother not yet ten. Alice was a housewife and received a pension for herself and her children from the Mercurbank. In the course of the Nazi takeover in Austria and the expropriation and disenfranchisement of all Viennese Jews, which entailed the total deprivation of all civil rights, the Mercurbank ceased its pension payments to Alice. In 1930 the family had moved to a flat in the same district, in Jörgerstrasse 49/2, where they were evicted soon after the “Anschluss” (the Nazi takeover in Austria in March 1938), because they were Jewish citizens. They were then transferred with few of their possessions to a so-called “Sammelwohnung” (collective camp) in Neuwaldeggerstrasse 41, where they lived in overcrowded circumstances with many other disenfranchised Viennese Jews, who had been evicted, too. See article:

The birth certificate of Alice Katz and the marriage certificate of Alice and Josef Katz of 1921

Henny managed to get a secretarial job at the “Israelitische Kultusgemeinde” IKG (the official Jewish representation) in Vienna in 1938, to help support the family. The IKG offices had been closed by the Nazis after the “Anschluss”, but were later reopened in order to organise the quick emigration of Jews from Vienna under NS orders of Adolf Eichmann. In the first years of the NS terror regime the Nazis aimed at “cleansing” the “Third Reich” of all Jews by expropriation and forced emigration before they switched to the policy of extermination of all Jews on the territory of Germany and all occupied countries. In this repressive atmosphere Henny, who came from an assimilated Jewish Viennese family, got in contact with Zionist youth organisations and the Youth Aliyah, founded by Recha Freier in Berlin, which organised transports of 15-to 17-year-old Jews to Palestine, which was under British mandate at the time. Henny participated in the preparation courses of the Youth Alijah to get ready for a life in Palestine, which included Hebrew language classes, information on history and culture in Palestine and practical training for a life in an agricultural kibbutz. It was clear that Henny would rather take over tasks such as sewing or jobs in the household than strenuous agricultural work because she suffered from a hip problem since her birth, congenital hip dysplasia. Her friends in the IKG urged her to leave Vienna, when the repressions and persecutions of Jews in Vienna worsened dramatically, but she did not want to leave her mother and younger brother behind. Her mother was completely exhausted and depressed by then and expressed the opinion that she and her family had never done any wrong, so what could happen to her and her son? Unfortunately, she misjudged the dramatic threat to the lives of Jews in Vienna because she saw herself as an “ordinary Viennese citizen”. She counted on her clean conscience as a model citizen, yet Jews had no citizen rights any more at that time.

Henny had planned to join her uncle, Norbert Katz and her aunt, Agi Katz, who had fled with their two-year-old twins, Susi and Josi, to England, but with the start of World War II in September 1939 the UK borders were closed to refugees from the “Third Reich”. See articles:

So finally, Henny decided to leave for Palestine on her own on a Youth Aliyah transport on 4 December 1939. In Bratislava she boarded the DDSG (“Donau Dampfschifffahrtsgesellschaft”, the former Austrian, now German state shipping company) ship “Grein” and travelled on to the Black Sea harbour Salina in Romania, from where she was transferred onto an ocean-going vessel that took her through the Dardanelles and across the Mediterranean to Haifa in Palestine. She was sixteen years of age and would turn seventeen in February 1940. A friend of Henny’s, Bernhard, who worked with her at the IKG and who also lived in the same collective camp in the 17th district of Vienna, Neuwaldeggerstrasse 41, had assisted Henny. He had put her name on the list of illegal youth transports to Palestine and had procured the visa for Bolivia. Henny was never supposed to go to Bolivia, but as the British authorities did no longer allow any Jewish migration to Palestine, the passengers on the ships down the Danube and across the Mediterranean needed “final visas” for other countries to receive transit visas for the countries they were crossing, and only few embassies of Latin American countries in Vienna still issued them.

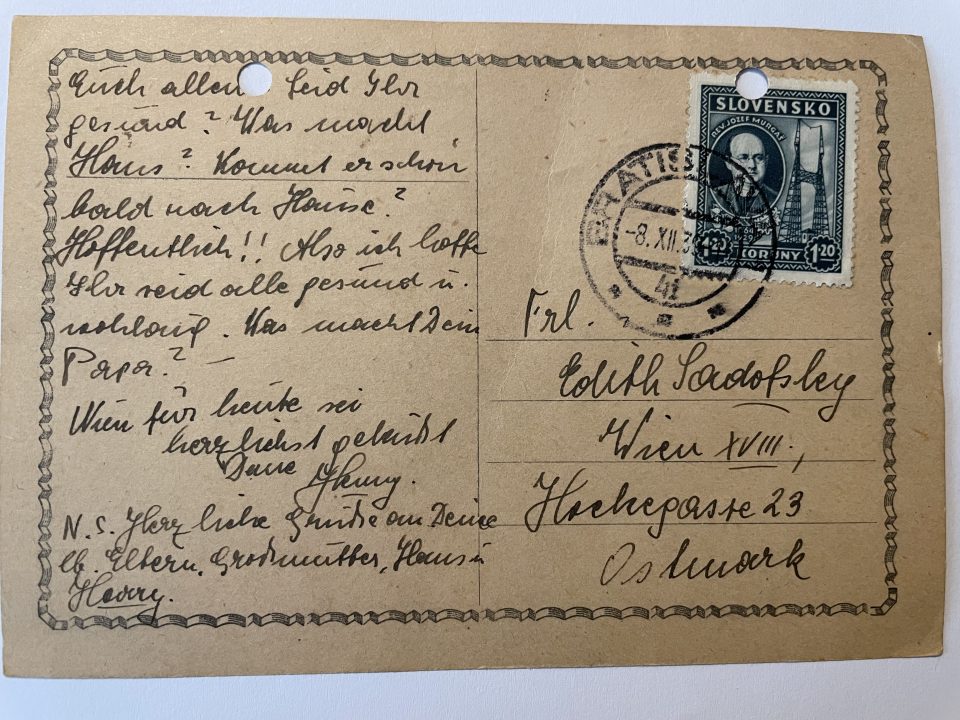

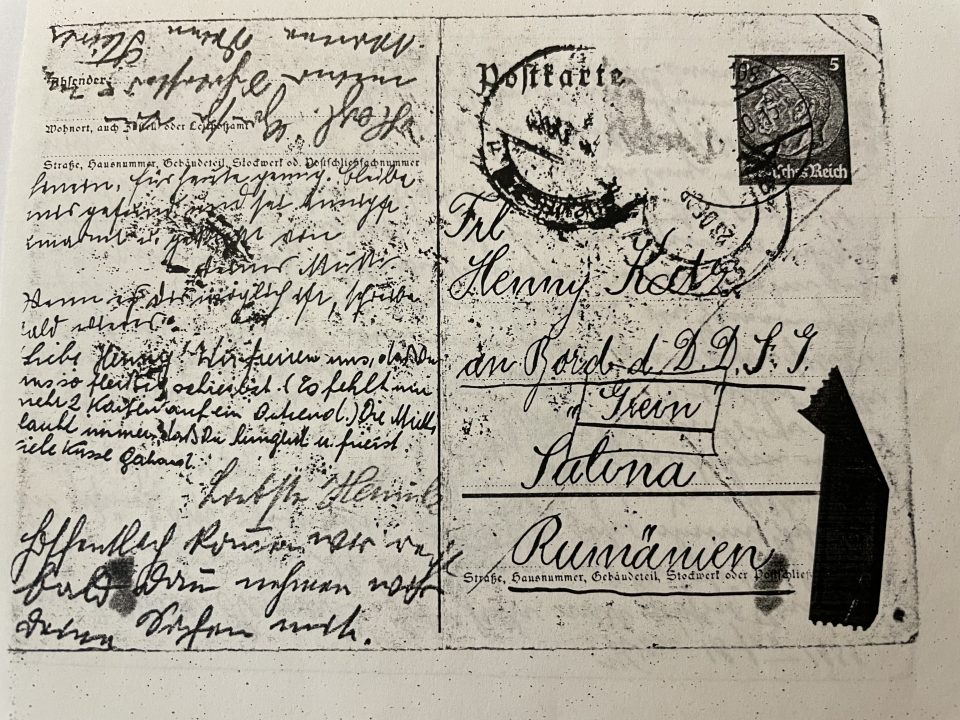

All documents and letters of Henny to her mother and brother in Vienna were lost due to their deportation to Opole, but a very interesting postcard, which Henny wrote to her friend Edith Sadofsky in Vienna on 7 December 1939, has been preserved. Henny was already on the ship “Grein” on the Danube in Bratislava and she told her friend that she was sorry that she could not phone her before her departure on Friday morning. Friday evening Henny arrived in Bratislava and stayed there in a hostel until Sunday morning, when they boarded “the beautiful German ship Grein. The ship is not very big, but offers enough comfort. They treat us well here and the food is very good. I’m at my ease here. We don’t know when we will depart. If I get the chance, I will write to you again soon.” Further Henny asked whether Edith could go to Neuwaldeggerstrasse and visit her mother and she asked after Edith’s family and Hans, probably her brother, who seemed to have been drafted to the “Wehrmacht” because Henny hoped that he would be home soon, and she sent greetings to the whole family of Edith.

Postcard written by Henny to her friend Edith Sadofsky on 7 December 1939 on board the ship “Grein” on the Danube in Bratislava, Slovakia

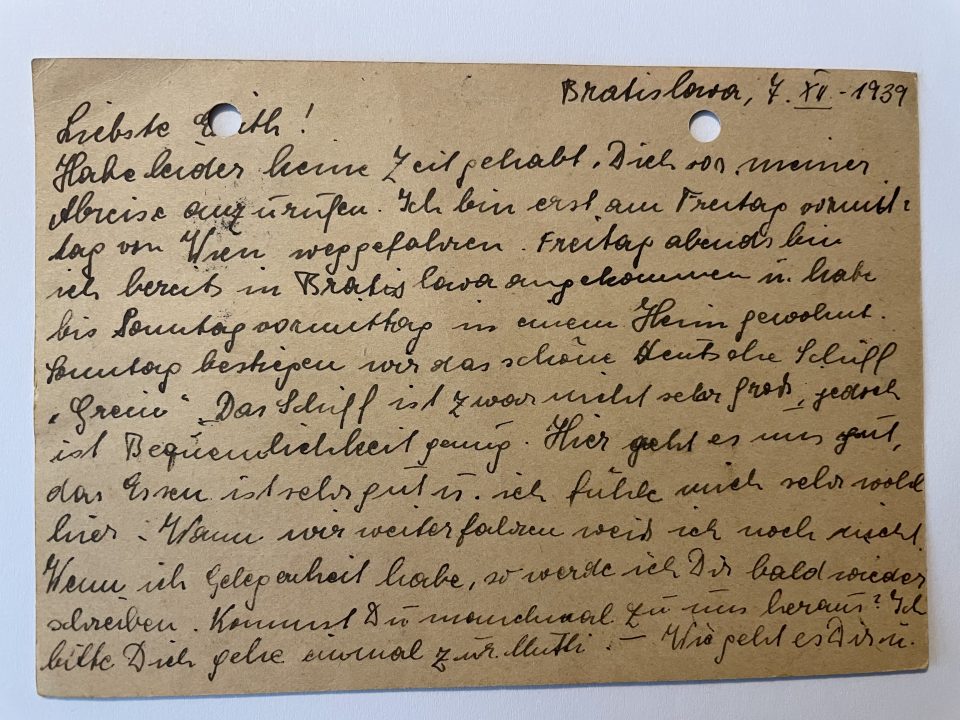

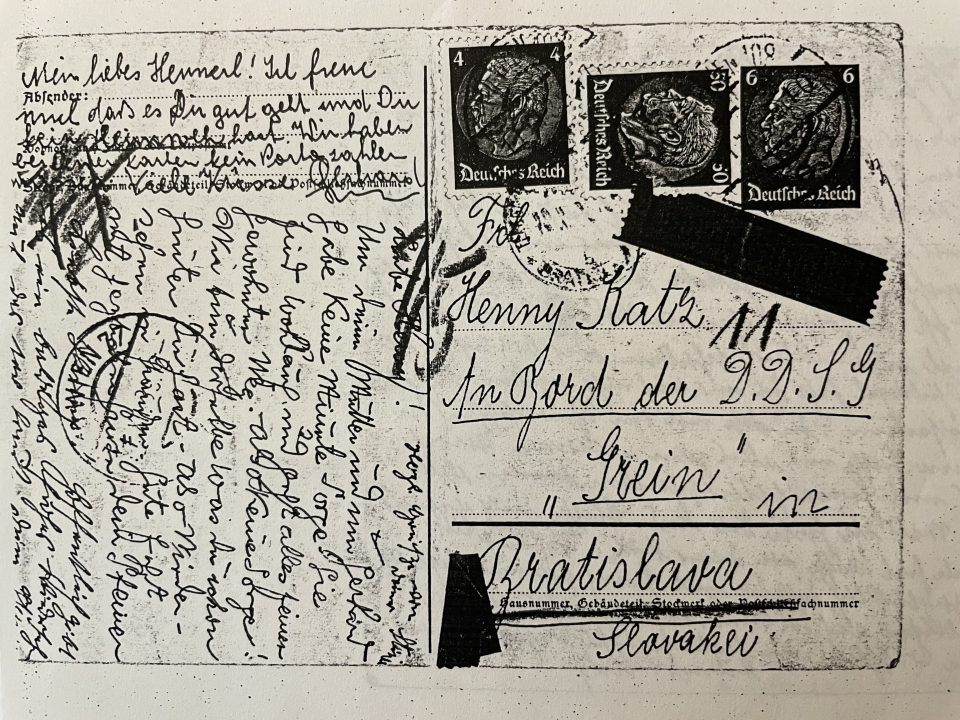

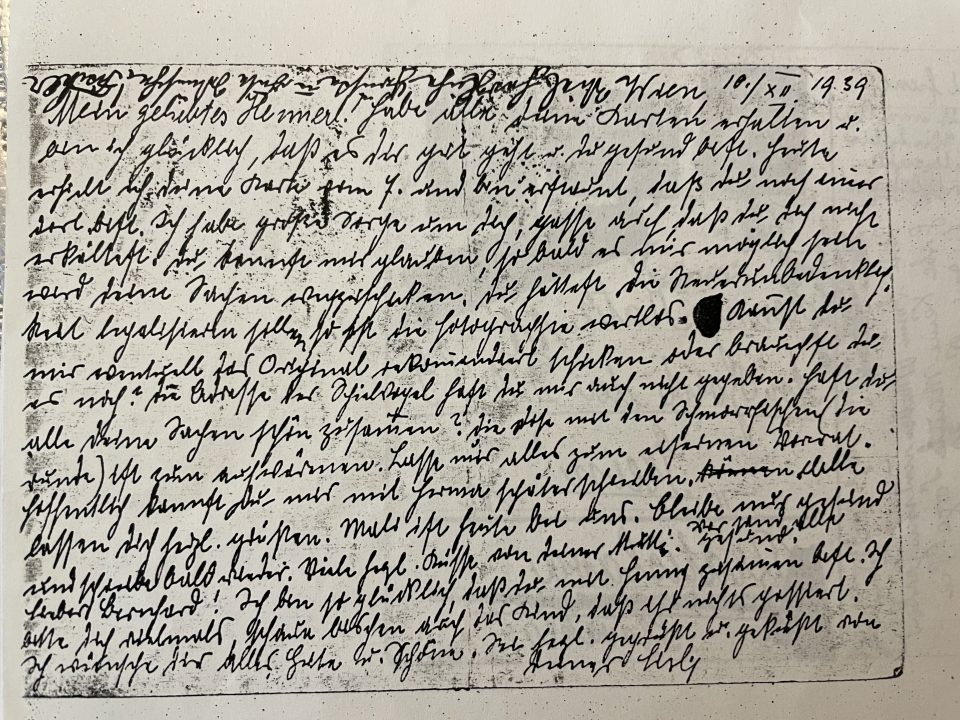

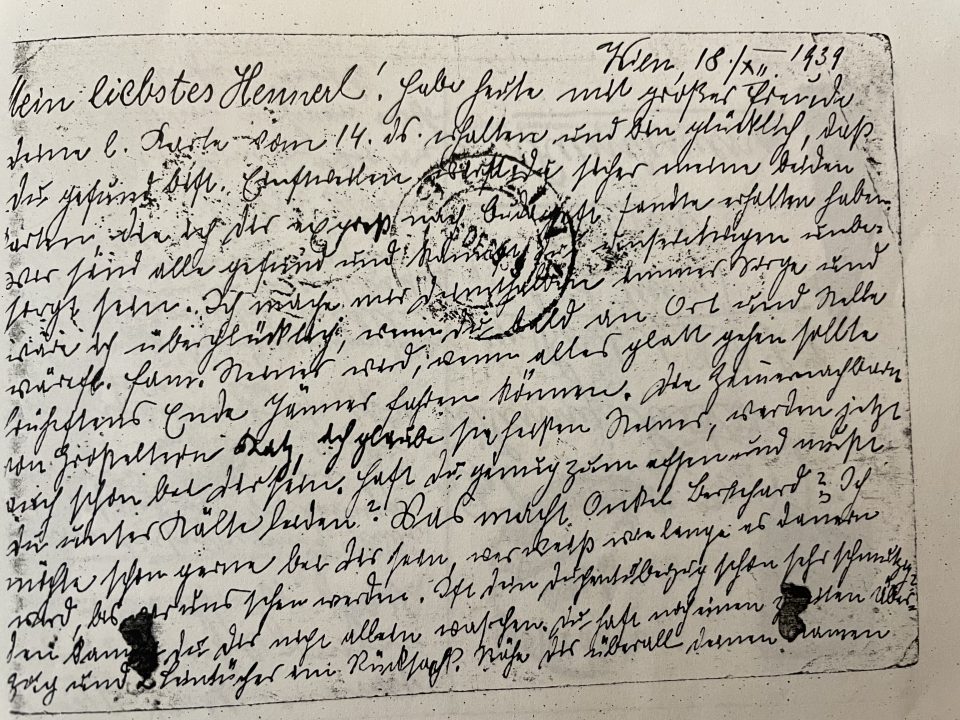

After her departure from Vienna, Henny received two postcards from her mother, which she was able to send from the collective camp in Neuwaldeggerstrasse. The first was sent to Bratislava and written on 10 December 1939 and started with “Mein geliebtes Hennerl” (My beloved Hennerl). She hoped that she was fine and in good health and she was so glad that she had received a postcard from Henny of 7 December – so Henny had written to her mother on the same day as she had sent the message to Edith. Alice was worried that her daughter was still in Bratislava and she was in great fear for her health and safety (It was already very cold in December1939 and the Danube would soon be frozen). She was worried that Henny might catch a cold and asked her whether she still had all her luggage. She hoped that she would remain healthy and would be able to write again soon. Alice sent Henny many greetings from friends in Vienna. Furthermore, Alice included a message to Bernhard and told him, how glad she was that he was travelling together with Henny and she wished him all the best for the voyage, too. Her brother, Gerhard, added a few lines, too, writing “Mein liebes Hennerl! (My dearest Hennerl! I’m so glad that you are well and are not homesick. We did not have to pay any postal charges for your card. Many kisses Gerhard”. Mr. Steiner (probably a co-resident in the collective camp) added that Henny should not worry about her mother and Gerhard, that they were fine and “everything is going the usual way. We are doing the same that you already know.” (There was strict censorship by the Nazis, so clandestine messages had to be included in mundane phrases) He wished her a good journey and another friend added that he hoped they would see each other soon.

Postcard of Alice Katz to her daughter Henny on the ship “Grein” in Bratislava, Slovakia, on 10 December 1939

Henny received the last postcard from her mother, written on 18 December 1939, in Salina, Romania, still on the ship “Grein”, supposedly waiting for the transfer onto an ocean-going vessel across the Mediterranean. Alice had just received Henny’s card of 14 December 1939 and was so happy to know that Henny was in good health and she was hoping that Henny would soon be “an Ort und Stelle” (at her destination – Alice was not supposed to mention where Henny was going to). Furthermore, Alice told her that a befriended family was hopefully leaving in January. Acquaintances of the grandparents Katz should already be “there”. Alice was worried that Henny would be suffering from the cold and that her clothes would already be very dirty and wondered if she was able to wash them. There was again a short message from Mr. Steiner and from Gerhard, too, who wrote that they were glad that she was writing so often – “there are just two cards missing to complete a dozen. Mother always thinks that you are hungry and freezing. Many kisses Gerhard ”.

After her return to Vienna Henny told us that there had been several “prostitutes” (It is unclear whether Henny at the age of 16 had really been aware of who these women were and maybe only reproduced what malicious passengers gossiped about these young women) on the ship with her and that they had been very kind and had looked after her and protected her from any inconveniences, which made her journey much more pleasurable and relaxed.

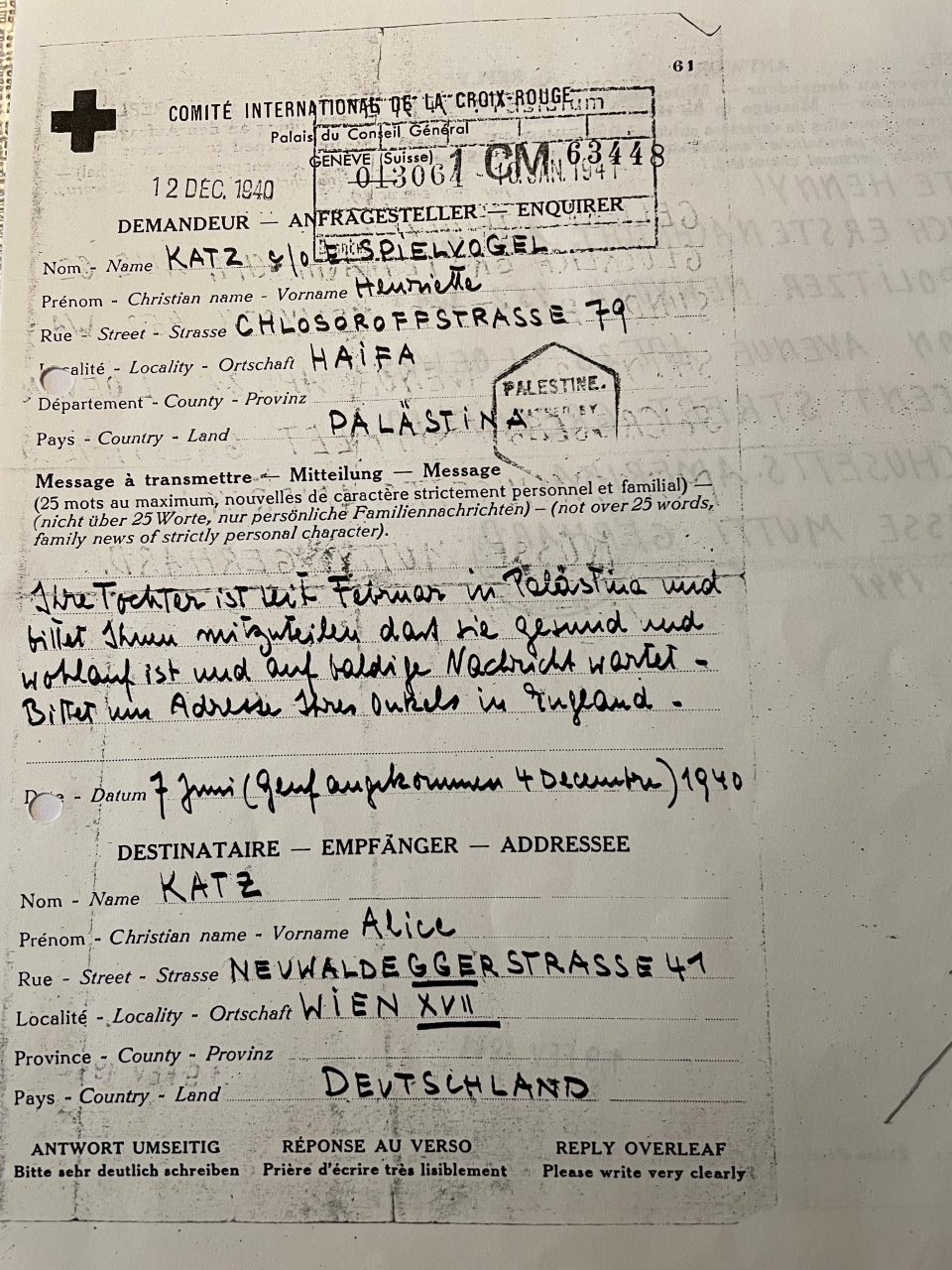

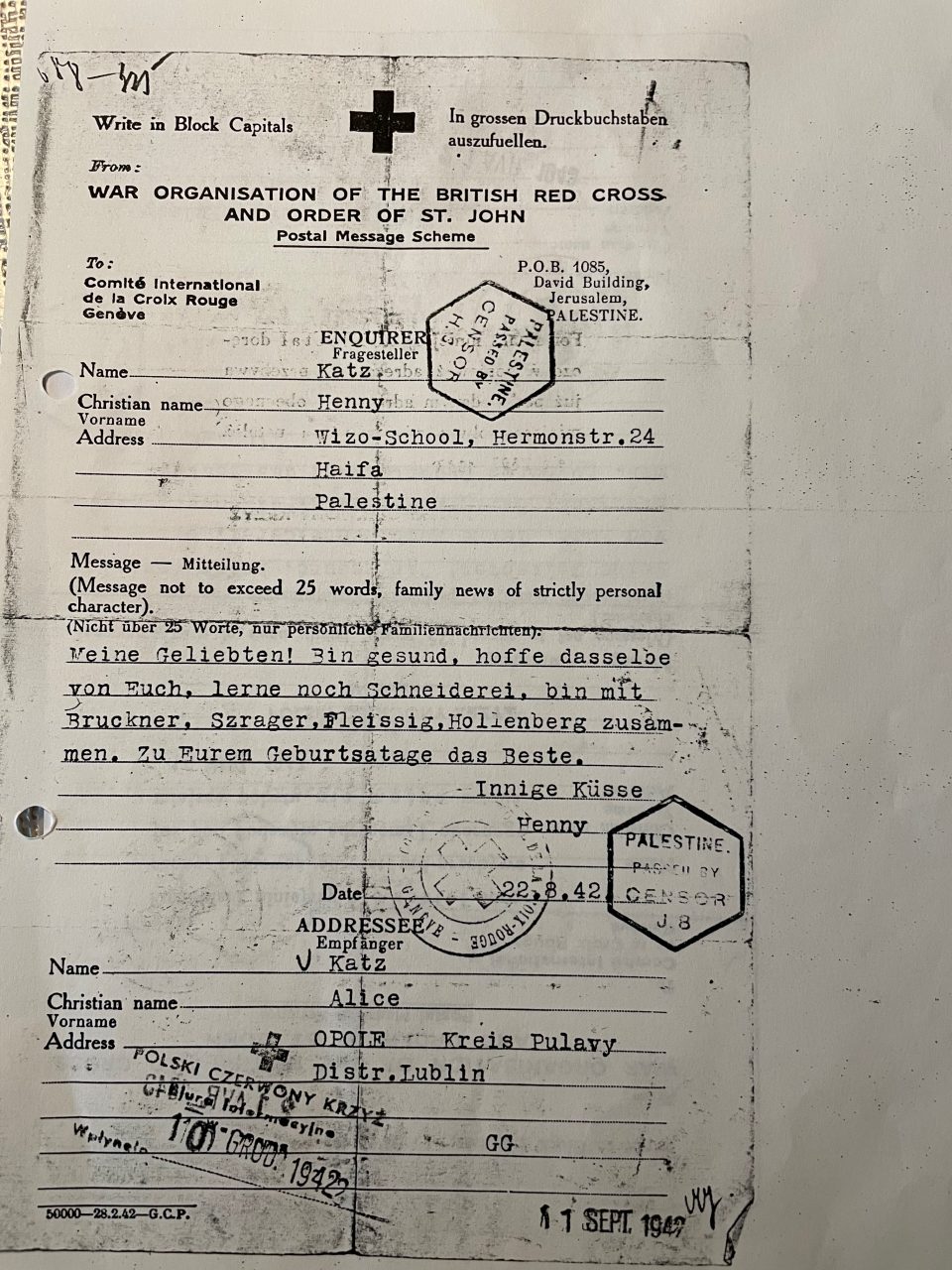

The first preserved communication between Henny in Palestine and her mother still in Vienna was one facilitated by the International Red Cross in Geneva, Switzerland. The communication was standardised, limited to 25 words, and took months to be delivered, but it enabled Henny and her mother to exchange a short message and by that receive a sign of life. It was the greatest worry of Henny and of all children and young people who had made it to a safe haven on their own, what had happened to their families who were still in the clutches of the Nazis; had they been able to flee, were they still in collective camps in Vienna or had they already been deported to the East or to a concentration camp? In the same way the relatives, who were still in Vienna, were in great fear, whether the youngsters had survived the dangerous trip and had reached Palestine safely. As Palestine was a British mandate territory and by that an enemy to Hitler’s “Third Reich” no other communication was possible except one organised by the International Red Cross in Geneva.

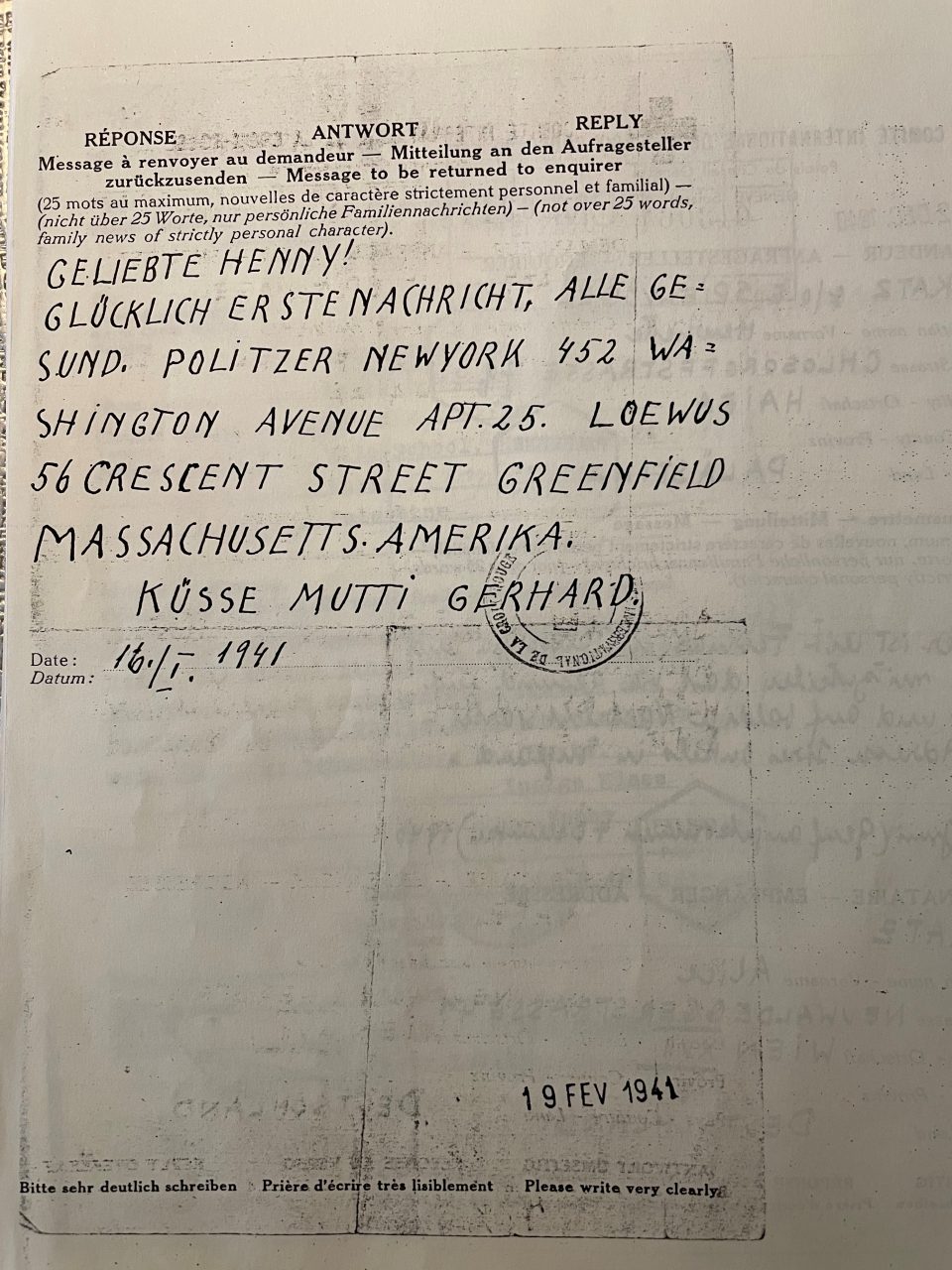

On 7 June 1940 Henny, who was then staying with a family called Spielvogel in Haifa, Chlosoroffstrasse 79 in Palestine, asked the Red Cross to forward the following message to her mother, Alice Katz in Vienna, 17th district, Neuwaldeggerstrasse 41, Germany: ”Your daughter has been in Palestine since February ands asks to let you know that she is well and healthy and is waiting for a message from you urgently. She asks for the address of her uncle in England.” This message reached Geneva on 4 December 1940 and was processed on 12 December 1940. Her mother’s response is dated 16 January 1941 and reached the Red Cross on 19 February 1941, when her mother had already been deported together with her brother to Opole from the Aspangbahnhof in Vienna on 15 February 1941. Her mother wrote in capital letters, which was an obligatory rule imposed by the Nazis, and the message could only contain 25 words of strictly personal character: “Beloved Henny! Happy first news, all well, Politzer NewYork 452 Washington Avenue Apt.25 Loewus 56 Crescent Street Greenfield Massachusetts America. Kisses Mummy Gerhard”. Apparently, her mother tried to get Henny in contact with relatives who had made it to the United States.

Red Cross communication between Henny and her mother, Alice Katz, sent from Palestine on 12 December 1940 and answered by her mother on 16 January 1941, just before her deportation to Opole on 15 February 1941

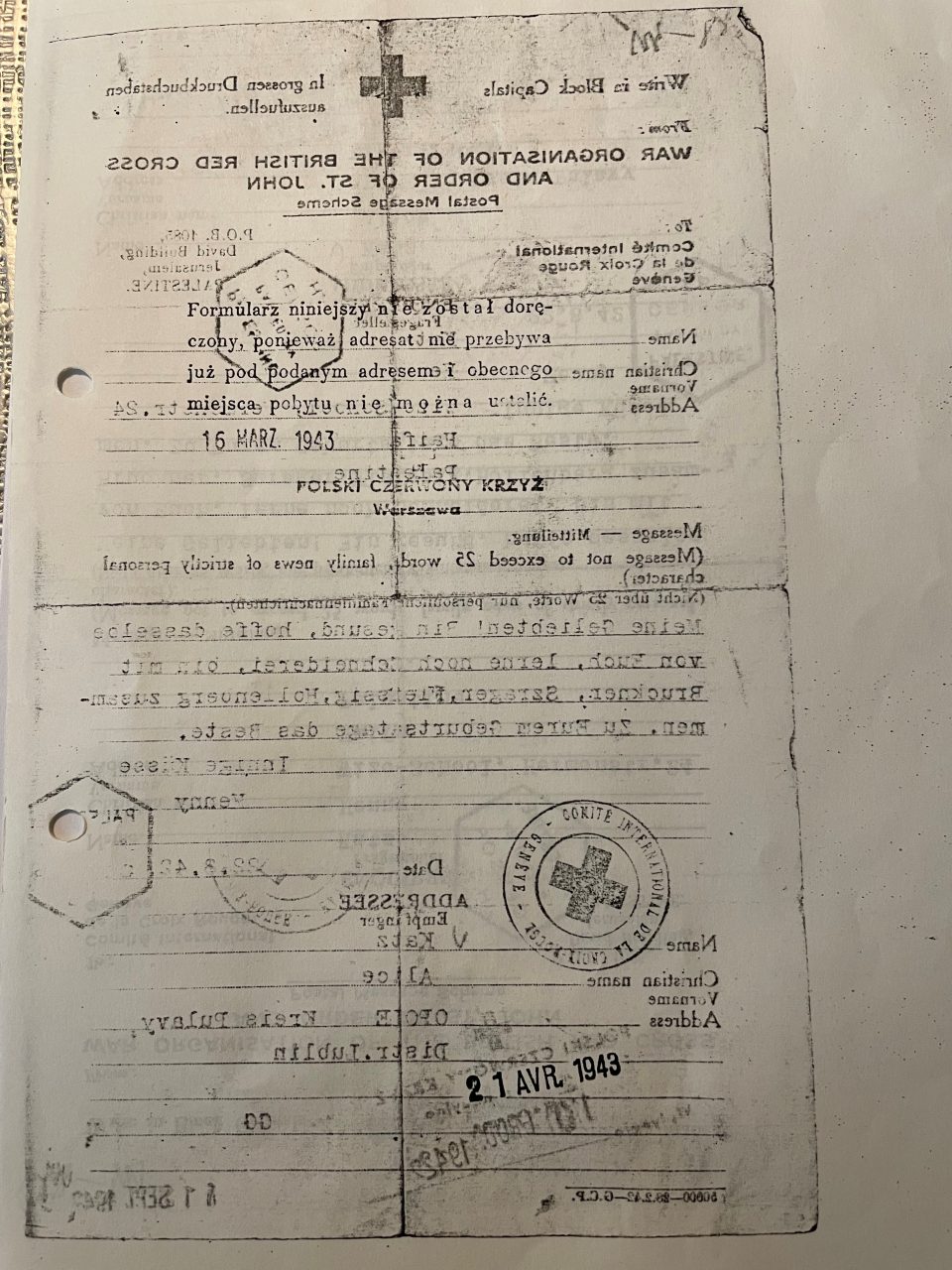

On 22 August 1942 Henny’s second and last attempt at getting in contact with her mother via the Red Cross was written from the WIZO (Women’s Zionist Organisation) – School in Hermonstrasse 24 in Haifa, Palestine, to Alice Katz in Opole, Pulavy, Lublin and was processed on 11 September 1942. Henny wrote, “My beloveds! Am healthy, hope the same of you, training dressmaking, am together with Bruckner, Szrager, Fleissig, Hollenberg. All the best for your birthdays. Heartfelt kisses Henny”. In this message Henny tried to let her mother and brother know who else had made it safely to Palestine together with her. Her mother’s birthday was the 16th of November and Gerhard’s the 28th of November, which they both most probably did not live to celebrate because they had already been murdered by the Nazis soon after their deportation to Poland; the exact places and dates of their deaths are unknown. On the back of the Red Cross message the answer of the Polish Red Cross in Warsaw on 16 March 1943 stated that the address of Alice Katz in Poland was unknown. This fatal news was communicated to the Red Cross in Geneva on 21 April 1943.

The second and last Red Cross communication of Henny of 22 August 1942 with no answer from Opole because her mother and brother had already been murdered

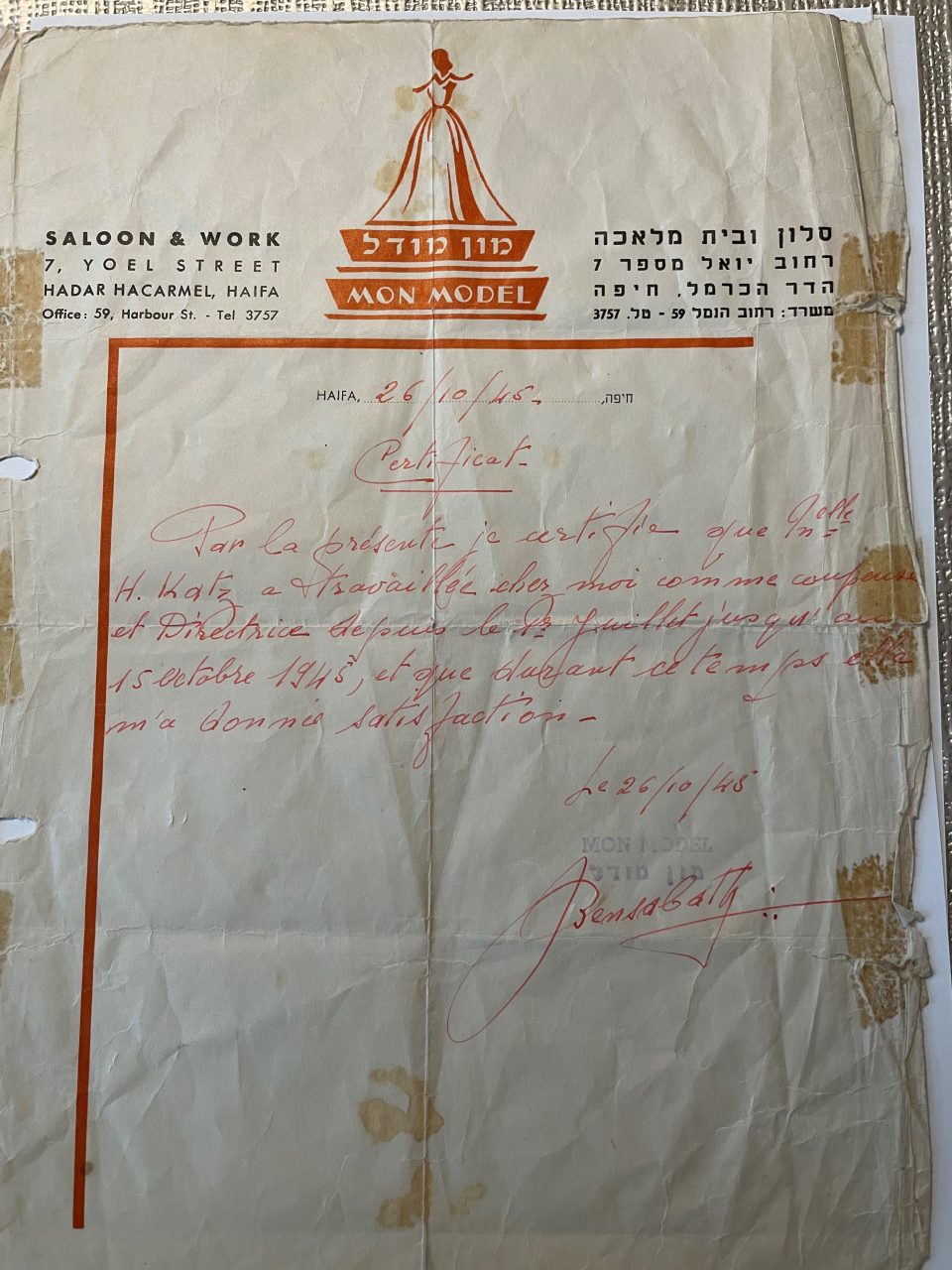

During her whole stay in Palestine Henny lived in Haifa, first with the Spielvogels, then at the dressmaker’s WIZO- school in Hermonstrasse 24 and later in Joshuastrasse 11. After her training, apart from other odd jobs, she worked for the enterprise “Mon Model” in Haifa as dressmaker and shop manager until 15 October 1945:

A sewing machine of the time

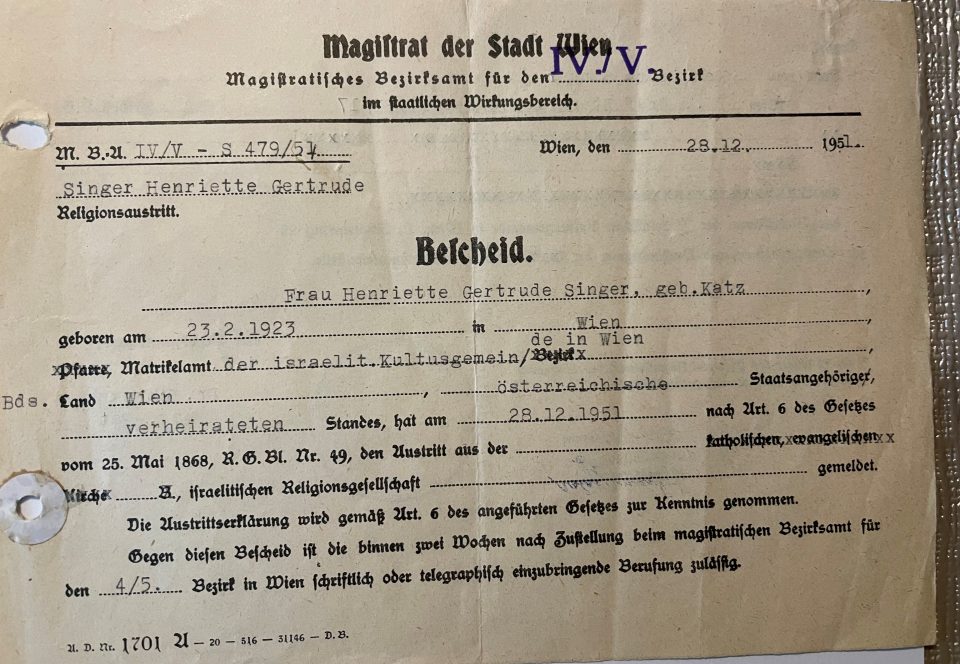

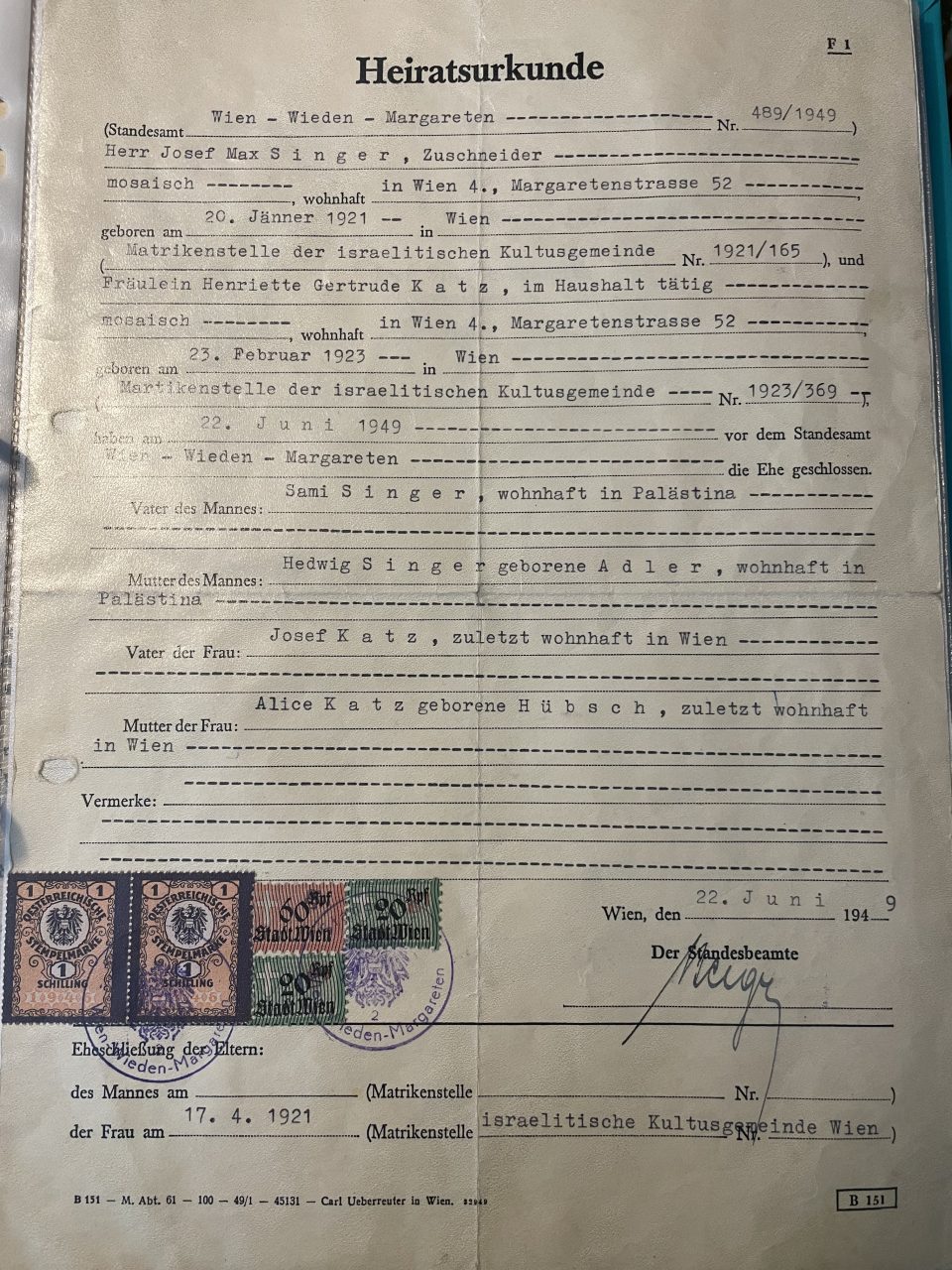

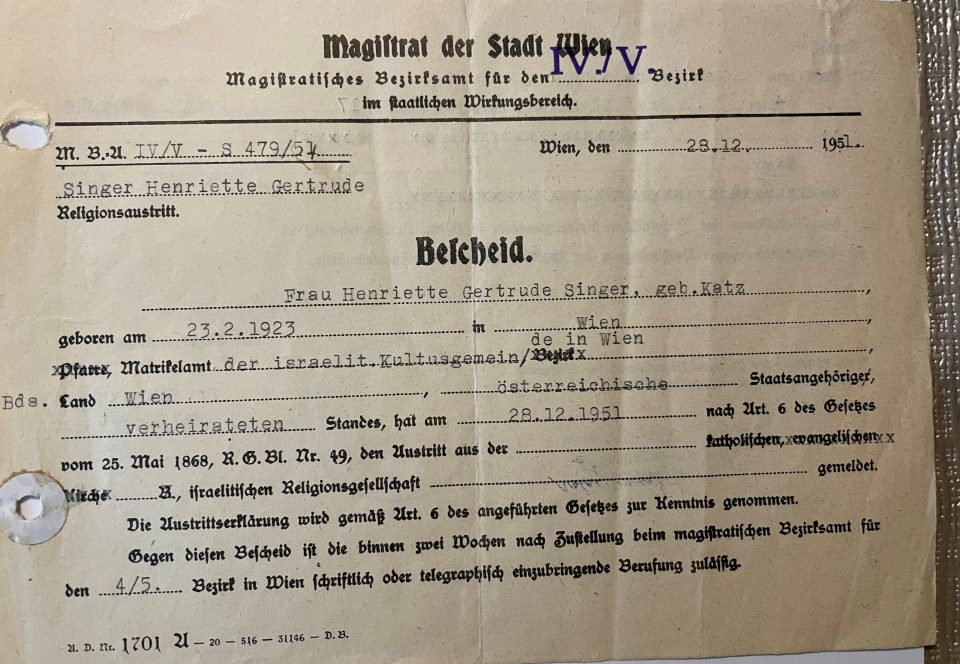

In Palestine Henny fell in love with a young Arab, who was the love of her life, but his family did not agree to their marriage. So, before she left Palestine for Vienna in 1948, she had met Josef (Pepi) Singer from Vienna, who had fled to Palestine, too, and was two years her senior. They decided to return to Vienna together and move in with other acquaintances in a big flat in the 4th district, Favoritenstrasse 40. They married in June 1949 in the 5th district of Vienna, Margareten, and in December 1951 they both quitted the Jewish religious community for good.

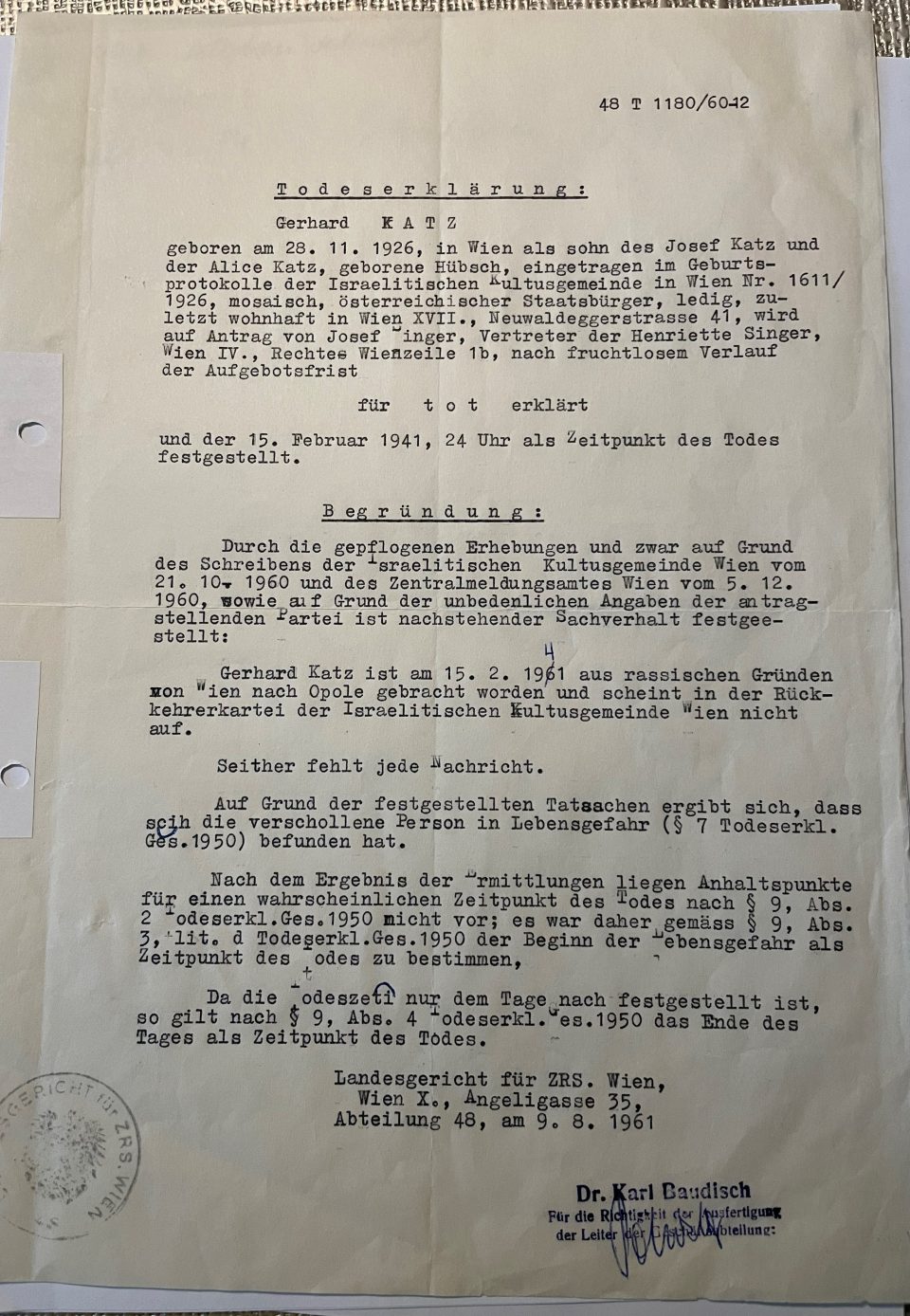

When Henny returned to Vienna after the end of the war in 1948, she tried to find out what had happened to her mother, Alice Katz, and her younger brother Gerhard and initiated official research, which resulted in the fact that both had been murdered after their deportation to Opole, a so-called NS ghetto in Poland, former Silesia. They were both declared dead, Alice on 8 May 1945 (end of World War II) and Gerhard on 15 February 1941 24.00 (day of the deportation) because no trace could be found, exactly where and when they had been murdered.

Official declarations of death of Alice Katz and her son Gerhard Katz

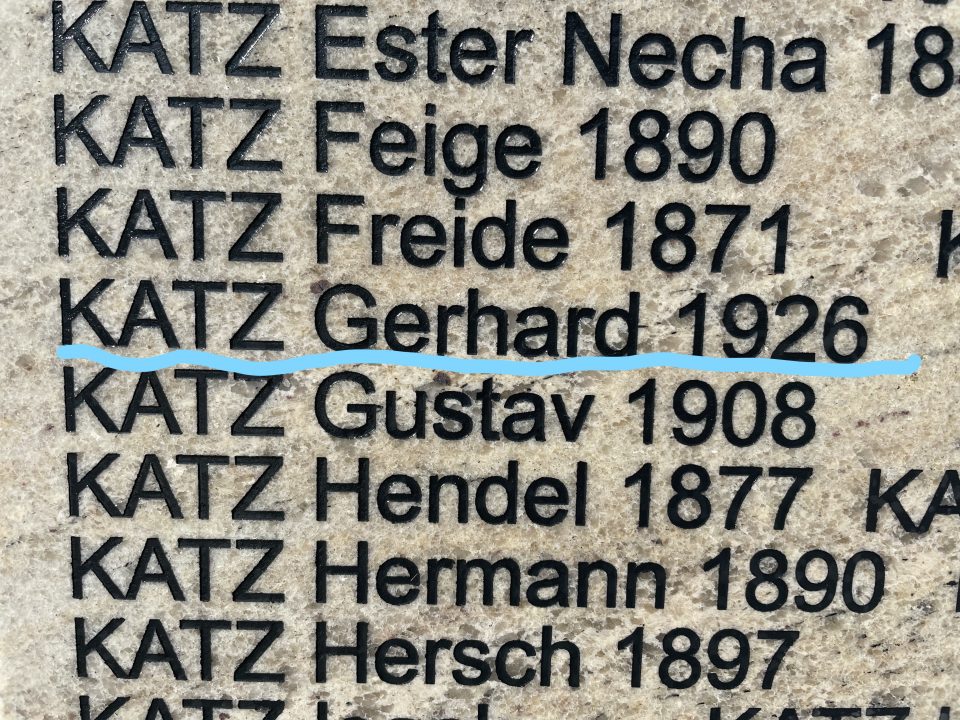

Their names can be found at the memorial for Austrian Jewish holocaust victims in front of the Austrian National Bank:

Evictions of Jewish Viennnese citizens from their flats and houses after the “Anschluss” in 1938

On 29 October 1938 the widow Alice and her two children Henny and Gerhard, were chased out of their flat in Jörgerstrasse 49/2 and transferred to a collective camp in Neuwaldeggerstrasse 41, where several Jewish families were crammed into a small space with only few possessions, which they were allowed to take with them. The family lived there under very straightened circumstances until February 1941, when Alice and Gerhard were transferred to the 2nd district of Vienna, Alice to Castellezgasse 35 and her son to Herminengasse 6/26, just before their transport to Aspangbahnhof and their deportation to Opole on 15 February 1941. Alice had refused to leave Vienna because she could not believe that poor and innocent people like them could be persecuted arbitrarily without cause. By then Henny had already left for Palestine in December 1939.

The house in the 17th district of Vienna, Jörgerstrasse 49/2 where the family lived before the NS persecution

Alice was interned in the same district as her young son before her deportation and subsequent murder, but in Castellezgasse 35, another collective camp.

Immediately after the “Anschluss”, denunciations of co-residents in Viennese apartment houses were common. Fellow tenants in an apartment house reported Jewish or supposedly Jewish residents to the GESTAPO in the hope of renting their flats after their eviction and of acquiring their furniture and possessions, which they were not allowed to take with them, at a bargain or even free of charge. Every evicted Jew was allowed only 50 kg of luggage, which had to include a second pair of shoes and two blankets. An avalanche of letters of denunciation arrived at the municipal housing department of Vienna, which proves that the share of responsibility of the non-Jewish Viennese population for eviction and expropriation of their Jewish fellow citizens was considerable. Not only official NSDAP organisations provided flats for their party members in this way, but also the general population, the ordinary Viennese, participated in this infamous wealth grab. The Jewish inhabitants had to watch helplessly as uniformed NS officials and civilians entered their homes, dragged away their furniture and possessions and effectively cleared their flats within days or few weeks. This happened under the eyes of the Viennese population and with their active collaboration. In March 1938 around 190,300 Jews lived in approximately 63,000 flats: 60,000 of them rental flats. Immediately in March 1938 so-called “wild aryanisations” took place; totally uncontrolled seizures of flats, where Jewish tenants lived. These actions lacked any legal legitimisation. In this way 44,000 flats were “aryanised” in Vienna until May 1939. In May 1939 the eviction of Jewish tenants by “aryan” landlords and land ladies was legalised in the “Ostmark”, former Austria, but the new law of tenancy did not yet force landlords to evict Jewish tenants. Nevertheless, 59,000 out of 60,000 flats were “aryanised” in Vienna until April 1945, whereby Jewish tenants had lost all tenant protection with the new law because they were excluded from the law of tenancy. This injustice was rarely rectified in Vienna after World War II.

In Hernals, the 17th district, where Alice Katz lived with her family, as in other districts, the local National Socialist SD-(Sicherheitsdienst) and SS-(Schutztruppe) men issued an internal ordinance on 5 October 1938 saying that as many Jews as possible were to be forced out of their flats and into emigration until 10 October 1938, but this NS terror action should be masked as “initiatives of ordinary citizens, not NS party raids, the use of violence against Jews was desirable”. Josef Löwenherz, the head of the IKG appointed by the Nazis, reported to the GESTAPO on 9 October 1938 that in the night of 5 October – the Jewish festive day of Jom Kippur was chosen on purpose – Jewish tenants in the 16th, 17th , 18th and 19th district were ordered to hand over the keys to their flats immediately, some were given 12 to 24 hours to leave their flats and sent to train stations, from where trains would take them out of the “Third Reich” without train tickets and even without passports. These actions contradicted the arrangement the Nazis had made with the IKG for an orderly emigration of Jews and showed the complicity of the local population with the Nazis. A month later in the pogrom of 9 and 10 November 1938 the irrational violence and terror unleashed among the Viennese population against their Jewish fellow citizens culminated in the burning of synagogues, the plundering of shops and flats and a wave of arrests of Jewish citizens. Together with many shops and flats in the 17th district, the synagogue in Hubergasse was burnt down and the fire brigade was not allowed to extinguish the fire, only to protect a neighbouring apartment house on Yppenplatz.

Deportations of Jews from Vienna to the NS “Ghetto” Opole, Poland

The large deportations of Jews from Vienna, starting on 15 February 1941, were the first ones and preceded those in the whole of the “Third Reich”, which began in October 1941. Already on 2 October 1940 Baldur von Schirach, the newly appointed governor of Vienna, had urged Adolf Hitler to decree a complete expulsion of all Viennese Jews to Poland, justifying the action with the “housing shortage” in Vienna. On 2 December 1940 Schirach was granted the permission for extensive deportations of Viennese Jews to the “Generalgouvernment”, the German- occupied Poland. On 23 January 1941 the head of the Viennese IKG, Josef Löwenherz, was ordered to Berlin to report to Adolf Eichmann the state of the Jewish emigration from Vienna, but did not meet Eichmann there. Instead, Eichmann’s substitute, Rolf Günther, told Löwenherz that rumours about pending large deportations of Viennese Jews to Poland were unfounded, although in fact the decision had already been made. Eichmann had established the “Zentralstelle für jüdische Auswanderung” (Central Organisation for the Emigration of Jews) in Vienna in 1938 and this organisation was now key for the selection of Viennese Jews for deportation by the SS. The destinations of the Viennese deportations to the East starting in February 1941 were the small Polish towns of Opole, Kielice, Modliborzyce, Lagow and Opatow, which were completely unprepared for the arrival of such large numbers of people. There is the testimony of Jakob Engel, who was on the first transport from Vienna, Aspangbahnhof, to Opole on 15 February 1941 together with Alice and Gerhard Katz. He reported that after a three-day train journey in cattle trucks they arrived in Opole. The villages were destitute, the population extremely poor and the living conditions of the indigenous population abysmal, everything mired in mud. The arriving Viennese were shocked and desperate and could not imagine how to survive under these conditions, especially as the money they were allowed to take with them would only last a week and then they would be facing starvation. Jakob Engel wrote that the refugees regretted the fact that their lives had not already been ended in Vienna. The local Jewish communities were responsible for board and lodging of the Viennese Jews, but they were too impoverished to offer sufficient help. The Jewish Social Self-Help organised soup kitchens, but soon there was famine everywhere and the outbreak of epidemics followed. Few deportees managed to flee and to return to Vienna, yet by escaping they were guilty of “a not permitted return from the East” and most of them were caught and deported again with the next transports. The largest part of those who were deported in early 1941 from Vienna to the “Generalgouvernement” and had survived the conditions there, which was most probably not the case for Gerhard, were subjected to the “Aktion Reinhard”, run by the Austrian Odilo Globocnik, and were murdered in the Nazi extermination camps Belzec, Sobibor and Treblinka together with Polish Jews. Of 2003 Viennese Jews, deported from Opole in the course of the “Aktion Reinhard” to death camps only 28 survived.

All in all, around 5,000 Viennese Jews were deported in February and March 1941. The last transport from Vienna in spring 1941 dragged 997 persons from Aspangbahnhof to Lagow and Opatow and immediately afterwards the already planned transports of 10,000 Viennese Jews were suspended due to the Balkans offensive of the German “Wehrmacht” and the preparations for the attack on the Soviet Union. Those Viennese Jews registered for the 6th transport, who had already been squeezed into the collective camps before departure of the train, were transferred. Löwenherz from the IKG in the name of Alois Brunner, the head of the “Zentralstelle für Jüdische Auswanderung”, then announced a resettlement of all Viennese Jews to collective camps in the 2nd, 9th and 20th district. Brunner, who had informed Löwenherz on 1 February 1941 about the transfer of a part of the Viennese Jews to Poland, now told him that the “Judenumsiedlung” (Jewish Resettlement) inside Vienna was the alternative to the deportation to the East – another Nazi lie.

In contrast to the deportations of October 1941 in the whole “Third Reich”, the early deportations from Vienna transported the Jews to “open ghettos” in Poland, where they could move freely inside the boundaries of the ghetto, but were not permitted to leave the ghetto. During these early deportation desperate efforts of the IKG continued to find possibilities of emigration for the Viennese Jews. After Hitler’s attack on the Soviet Union in June 1941 and the mass shootings that followed, the NS policy towards the Jewish population turned from expulsion to extermination, which was followed by the legal ban of emigration for Jews on 23 October 1941, which meant that the remaining Viennese Jews were trapped. Only very few managed to flee or hide as a “U-Boot” (submarines) in the city. See article:

Contrary to Brunner’s assurance, in the autumn of 1941 the systematic deportations to ghettos, concentration camps and extermination camps in the East were taken up again. For the organisation of this NS plan the “Viennese model” served as the blueprint for the systematic persecution and murder of the Jewish population in the whole “Third Reich”.

The two first wo transports were organised from Vienna to Opole, on 15 February (996 persons) and on 26 February 1941 (1.049 persons), all in all 2,045 people, who had to live in Opole under unimaginable conditions in mass quarters, suffering from hunger, the cold, and diseases, which meant that especially the old and the ill inhabitants of the ghetto died soon after their arrival. Of these 2,045 Viennese Jews only 28 survived the end of World War II. Within three months, from November 1941 until January 1942 21.4 per cent of the Viennese Jews died, as recorded by the Jewish Social Self-Help Organisation in February 1942. In May 1941 800 Viennese male Jews were sent to the slave labour camp Deblin.

Opole, in German Oppeln in Silesia, was a small town south of Lublin that housed a Jewish community with a rich tradition. At the start of World War II more than 4,000 Jews lived there, which accounted for 70 per cent of the inhabitants. After the start of the war many Jews from other parts of occupied Poland were transferred to Opole. Until March 1941 further 8,000 Jews were forced into its ghetto. They were housed in improvised mass accommodations under totally inadequate sanitary conditions. The ghetto was guarded by the Nazi SS (Schutzstaffel) and SD (Sicherheitsdienst) and by “Wehrmacht” soldiers. The inhabitants of the Opole ghetto were not allowed to work, so the only possibility to purchase food was the selling of their last possessions, if they could not get help from family and friends outside. Only one non-Jewish aid organisation tried to offer some help to the endangered Jews, the “Erzbischöfliche Hilfsstelle für nichtarische Katholiken” (Archbishopric Aid Organisation for Non-Aryan Catholics). Alice and Gerhard were among the 996 first arrivals from Vienna, who had been transported first to Pulawy in Poland and then to Opole, whereby the Viennese IKG had to organise the provisioning for their journey. When they arrived in the overcrowded ghetto, 7,000 Jews had already been crammed into the small town; in September 1939 after the German attack on Poland, the 2,500 inhabitants of Pulawy were chased from their hometown by the Nazis and had to be absorbed in the community of Opole. In 1940 the historical centre of Opole had been turned into a ghetto be the Nazis and the people had to be accommodated in the Synagogue, in the houses of the local population and in improvised shelters. After the more than 2,000 Viennese Jews, persecuted Jewish families from the “Generalgouvernement” arrived in Opole, too, so that more than 8,000 people were squeezed into the ghetto in the historical centre of Opole. In the spring of 1942, the Nazis started the liquidation of the ghetto Opole. While on 31 March 1942 1,950 persons were shipped to the death camp Belzec, more displaced Jews from Slovakia arrived in Opole. In the autumn of 1942 around 2,000 Jews were deported to the extermination camp Sobibor. When in October 1942 the ghetto was cleared, 500 Jews were shot on site and the remaining 8,000 who were able to work, were deported to a slave labour camp in Poniatowa, where they either died due to hard labour and those who survived were shot by the SS, when the camp was cleared in 1943. The head of the SS and police in the district Lublin was an Austrian, Odilo Globocnik, who organised the “Aktion Reinhard”, whereby nearly two million Jews were murdered in the “Generalgouvernement”. He and his Austrian subordinate, Hermann Höfle, trained “Wehrmacht” soldiers and Ukrainian volunteers, Trawniki, for the murder of the Jews in this region. The terrible ordeals of Alice and Gerhard must have found their fatal end either in the ghetto Opole or in one of these death camps.

The Youth Aliyah and Zionist youth organisations in Vienna

When Henny decided to flee to Palestine, she had no idea what ordeal her mother and her younger brother would have to go through. The situation for Jews in Vienna became increasingly unbearable. At first, the Nazis planned to dispossess the Jews and force them into emigration. In order to step up their flight, the SS threatened the Viennese Jews with newly enforced deportations, but the western countries of the “Free World” increasingly restricted immigration and especially after the outbreak of World War II in September 1939, Jews could only flee to a few selected countries overseas or join “illegal transports” to Palestine. These transports turned into a salvation programme, most of all for the young and it is a pity that Gerhard could not join his sister because he was only 13 and therefore too young. Alice only reluctantly gave her permission to Henny’s flight via the Youth Aliyah to Palestine and the preserved letters prove her maternal fears. The British authorities had a mandate over Palestine and had already restricted the influx of Jews to Palestine in response to Arab upheavals, as the local Arabs resented the rising number of Jewish settlers. As soon as the numerical contingent of Jewish immigrants to Palestine was exhausted, the only possibility for the destitute Jews, persecuted in the “Third Reich”, was illegal emigration to Palestine. When in May 1930 the British government froze legal immigration to Palestine by way of a White Paper proclamation, the smuggling of refugees in clandestine transports became all the more important. The British considered Jews born in the “Third Reich” – Austria was part of it since March 1938 under the new name “Ostmark” – to be “enemy aliens”, so they were not entitled to receive any of the much-craved immigration certificates. Only those who were lucky enough to have reached a neutral country on their flight before the proclamation could obtain such an immigration certificate under certain conditions. The Nazis did not officially prohibit the emigration of Jews after having robbed them of all their possessions and rights until the autumn of 1941, but from then on, the complete extinction of the Jewish population in all territories occupied by Hitler, was the new goal of the NS anti-Semitic policy and by that leaving the “Third Reich” and the NS-occupied countries was virtually impossible.

Mossad, a branch organisation of the Zionist Workers’ Party, was one of the groups which organised illegal transports to Palestine and the Youth Aliyah worked together with it. The Zionist Workers’ Party was closely linked to the umbrella organisation He-Haluts, which prepared young Jews for life in agricultural kibbutz in Palestine. They ran agricultural educational facilities, called Hachshara camps. As the anti-Semitic repression worsened in Vienna and the fear of new SS deportations to the East rose dramatically, the secretary general of He-Haluts and representative of the Mossad in Vienna, Georg Überall (later Ehud Avriel), decided in late 1939 that all remaining He-Haluts members had to leave immediately via the Danube, although no deep-sea vessels had been chartered yet to take the refugees from the Danube delta to Palestine. At first 120 Youth Aliyah members were put on this illegal transport from Vienna to Bratislava and further down the Danube. The Viennese refugees assembled on 25 November 1939 at the “Palästina-Amt” (Palestine Office) in Marc-Aurelstrasse 5 in the 1st district of Vienna, which organised Jewish emigration to Palestine, and were brought in buses to the train station and by train to Bratislava. For around 10 days they were interned in factories and hostels by the Fascist Slovakian pro-German puppet regime until the 822 refugees from Vienna together with around 280 Jewish refugees from Germany and occupied territories boarded the DDSG ship “Uranus”. Henny was extremely lucky that she was not on this transport, but boarded the vessel “Grein” later, in early December in Bratislava, because this group experienced the disaster of the “Kladovo Transport” (see below).

The Zionist organisation Youth Aliyah was founded by Recha Freier in Germany in 1932 and started operating in Vienna in 1938. From then on it focussed on the preparation and organisation of emigration of 15- to 17-year-old Jews to settlements and kibbutz in Palestine. So, Gerhard Katz would have been considered too young to accompany his sister Henny; nevertheless, some adolescents travelled together with their younger siblings. The IKG was forced to work together with the “Zentralstelle für jüdische Auswanderung” (Centre for Jewish Emigration) in Vienna and organise the emigration of Jews to all parts of the world except Palestine; for emigration to Palestine the “Palästina-Amt” was responsible. Due to the massive pressure on swift emigration of Jews there was urgent need for more personnel, and jobs in these organisations were in high demand because Jews were successively excluded from all types of employment. Henny was fortunate to be employed by the IKG, which had hired 27 new employees solely for the “Beratungsstelle der Jugend-Alijah” (Advisory Centre of the Youth Aliyah). It is interesting that the Nazis initially targeted especially the assimilated Jews, such as Henny’s family, who were representative of the large majority of Viennese Jews. Probably the assimilated Jews posed the greatest threat to the absurdly twisted NS racial theory and “Aryan” ideology, because the assimilated Viennese Jews were indistinguishable from the rest of the population. At a time when the possibilities for fleeing Vienna were already very much restricted, Palestine became the destination of last resort. Yet the number of immigration certificates did by far not meet the demand, even before the stop of immigration to Palestine by the British government. So, the rescue of Jewish children and adolescents had highest priority, in Austria and even with the British authorities. Few of the Viennese youngsters who were prepared for their departure to Palestine had had any connection to the Zionist movement before and in retrospective they remembered this time of community spirit as one of the most significant periods of their youth. The Youth Aliyah tried to offer Jewish young people professional perspectives in Palestine at a time when in Germany and Austria their possibilities for education and job opportunities had been more and more restricted. On the other hand, this initiative offered the chance to Palestine to be provided with well-trained young workers to build up the economy. Originally, a one-year training in a Hachshara camp was planned with a focus on agriculture and then a two-year stay at a kibbutz, Moshav or WIZO-camp in Palestine – Henny received her training as a dressmaker in a WIZO- camp (see above).

Despite the success of the Youth Aliyah programme, there was criticism from the start, especially because the target group were 15- to 17-year-old young people only. Some children found refuge in Palestine via so-called “Kinderanforderungsaktionen” (special requests for child immigration). The British authorities sometimes permitted the immigration of children, if already in Palestine living relatives “requested” them. In this way 116 such certificates were sent to Vienna, but they by far did not meet the demand. Similarly, pupil and student certificates were issued by the British, but unfortunately much too few, too. With the closure of the Hachshara camps in Austria, the Youth Aliyah tried to find places for such Hachshara traineeships abroad, for example in 1939 335 young Austrian Jews worked for farmers in England, Denmark, and Sweden. This was one possibility to get a few young people out of the “Third Reich” to safety. In the summer of 1940 still 320 boys and girls attended Youth Aliyah courses in Vienna and 590 youths and 300 children attended the Youth Aliyah (JUAL) school. After the start of the war the Youth Aliyah further tried to organise the transfer of children into “transit countries”, such as Yugoslavia (the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes or “First Yugoslav State”), Bulgaria and Romania. Despite great logistic difficulties – for example acquisition of transit visas, lack of means of transport for hire due to the war, terrible state of the hired buses and vessels, no accommodation available for the children – 400 children could flee from Austria between September 1939 and October 1940, thanks to the untiring efforts of the Youth Aliyah leader Aron Menczer. He postponed his own emigration to Palestine several times to help the children until he himself was deported to the KZ Theresienstadt and then transferred together with several hundred children, who he had been looking after, to the KZ Auschwitz, where he was murdered in 1943. In May 1941 the Youth Aliyah was officially dissolved by the Nazis and continued to operate illegally until September 1942. According to the IKG the Youth Aliyah had rescued a large part of the 13,598 10-to 18-year-old Jewish Austrians via illegal transports until the end of July 1940.

Illegal transports from Vienna to Palestine: organisation and financing

The financing of the whole project was very difficult because originally the costs for preparation and training of the young, administration of the training camps and organisation of the emigration to Palestine had to be borne by the local Jewish institutions and the families of the young emigrants. Yet the Viennese Jewish population had become completely impoverished by the NS spoliation, so that in 1939 only 10 per cent of the parents could contribute anything to the Youth Aliyah and the Jewish aid organisations had to rely on donations from abroad. To the British White Paper that practically ended the legal immigration to Palestine, the Zionists reacted with self-organised rescue operations to save Jews from the Nazi anti-Semitic policy, especially after the start of World War II. The British viewed this immigration as illegal, but the Zionists called it “free” or “independent” immigration; “Aliyah A”. legal immigration and “Aliyah Bet”, B in modern Hebrew – free (illegal) immigration. In their allegiance the Zionists were split; on the one hand they supported Great Britain in the war against Nazi Germany, on the other hand, the British were their enemy in Palestine because they forbid Jewish immigration and by that prevented the salvation of Jews from Nazi gas chambers. Certain radical Zionist groups resorted to political activism to voice their protest against British immigration policy in Palestine. The centre of the Aliyah Bet activities in Vienna was the law office of Willy Perl, which turned into the most important hub for rescue operations of European Jews in Fascist-occupied Europe. They convinced the Nazis to tacitly allow the “visa-free” emigration of Jews from the “Third Reich” to Palestine in order to “speed up Jewish emigration and to cause trouble for Great Britain”. The first “Aliyah Bet” transport left the Viennese South Station on 9 June 1939 under the watchful eyes of the GESTAPO with 380 members of Zionist associations for Yugoslavia, via Greece by train and then by boat to Palestine. The refugees were robbed of all their possessions, travelled in locked waggons across the Balkans and then were shipped in wretched fishing boats across the Mediterranean, under crowded unsanitary conditions with nearly no food and water. The hired crews earned their living with smuggling people and weapons. In the dark they landed in Palestine with the help of life boats, launched clandestinely from the Palestinian coast by the Zionist organisation which had been alerted via light signals. This first “Aliyah Bet” rescue operation was financed by international Jewish organisations, private persons, and the Viennese IKG. When news of this successful illegal landing in Palestine reached Vienna, the applications for “Aliyah Bet” transports soared and due to the lack of sea-going vessels that could be hired in times of war, whatever miserable state they were in and whatever dubious crew they employed, very strict criteria for selection of possible participants in the transports had to be applied, especially with respect to their mental and physical health status. Many long-term members and functionaries of Zionist associations were angry and despaired because they did not get a place on such a transport due to their failing health or their age.

Routes from Vienna to Palestine: along the Danube and across the Balkans

In January 1939 Perl’s law office on Stubenring in Vienna was officially closed by the Nazis and the NS “Ausschuss für jüdische Überseetransporte” (Committee for Jewish Overseas Transports), run by the Viennese Jew Berthold Storfer, took over the co-ordination of transports to Palestine. Perl and his assistants helped around 3,700 persons to flee the “Third Reich”, despite the fact that a large number of refugee boats were stopped by the British. One of Perl’s successes was the transport on the ship “Sakarya”, the largest refugee boat of European Jews. It transported more than 2,100 refugees from Vienna, Prague, and Budapest in February 1940 via Romania to Palestine. In Palestine the refugees were imprisoned in a refugee camp, but released after some time.

The refugees from Austria left Vienna penniless, just a backpack of not more than 8 kg was allowed, which contained the barest necessities; money and valuables were not permitted except 10 German “Reichsmarks”, which had to be handed over to the persons organising the transport. If a passenger carried valuables or money, they were confiscated at the border to Slovakia in Marchegg. The atmosphere in the transit camps in Bratislava, which were run by the Fascist regime of Jozef Tiso, was tense because there was never any information available, when a ship would depart and who would be able to board the vessel. Most of all, the transports in the winter of 1939 /1940 had to reckon with the freezing of the Danube and a halt of all shipping activities, which could mean that the refugees would be sent back across the border of the “Third Reich” to Vienna and deported to concentration camps from there.

The office of Storfer in Vienna’s 1st district, Rotgasse 8/7 was responsible for so-called “special transports” to Palestine as well as Shanghai, but meanwhile the possibilities for “Aliyah Bet” activities were much reduced. Storfer could only act on authority of the NS rulers and had to execute their orders; for example, they decreed that well-to-do Jews had to be preferred and that they had to pay for their own journey as well as for the journey of poorer Jews. As all of the Viennese Jews had already been robbed of their possessions, this meant that some would have managed to get money for their flight from relatives abroad, which would then help fill the NS war chest. What’s more, the participants of the transports had to procure an array of documents, stick to strict rules with respect to the allowed luggage, and sign rules of conduct for the voyage. They were strictly forbidden to take with them cameras, letters, written notes, addresses of persons who lived in non-neutral countries or any documents in a foreign language (not German). Participants were appointed who were responsible for the smooth running of the transport and the sharing of the necessary tasks on board of trains and boats. At the end of the year 1940 3,500 Jews from the “Third Reich” could flee to Palestine. All in all, Storfer’s office organised the flight of more than 7,000 Jews and financed the flight of 2,043 Austrian Jews. Yet he was a very much criticized personality, because he had to work together with the Nazis. This did not protect him in the end, when he was deported to the KZ Auschwitz in the summer of 1943 and murdered there.

In May 1940 the Danube ship “Pencho” left Bratislava, which was one of the worst “Aliya Bet” journeys. It was an old unseaworthy paddle-steamer, into which 513 people were squeezed and which was at sea for several months: it went down the Danube, across the Black Sea, the Marmara Sea and into the Aegean Sea, where it stranded on an uninhabited island. The Italian Navy rescued the refugees and interned them in a camp on the island of Rhodes. In the spring of 1941, they were transferred to Bari and then to the internment camp Ferramonti-Tarsia in Calabria. In the end, the passengers of the “Pencho” were lucky because they were liberated by the Allied Forces just before the GESTAPO and the SS reached them after the Germans had occupied Italy.

In September 1940 refugee groups from Austria, Germany, Bohemia and Moravia left from Vienna on four DDSG ships for Bratislava, then down the Danube to Tulcea, where they were transferred onto three ocean-going ships, the “Atlantic”; the “Pacific” and the “Milos” with the destination Palestine. Due to technical problems, the “Atlantic” was disabled and adrift and the British captured the boat and decided to deport the passengers to the island of Mauritius as a warning. They were in the course of trans-shipping the refugees from the “Atlantic” onto the “Patria” for transport to Mauritius, when the ship exploded and sank. The radical Zionist group “Haganah” had intended to stage a protest and force the British to allow the passengers to land in Palestine, but the explosion went awry and 260 people died. The survivors were allowed to land in Palestine and were interned in a refugee camp, but the 1,500 passengers who had not yet been transferred onto a vessel to Mauritius were deported nevertheless and had to remain on the island until the end of the war; 124 died there.

The conditions on the Danube ships as well as on the ocean-going vessels were disastrous; they were all in a terrible state of repair, the vessels were severely overcrowded, it was extremely cold in winter and the sanitary conditions were abysmal. There were much too few toilets for the hundreds of people, very few possibilities to wash, if any, and the provision of food was insufficient and of dubious quality. As a result, outbreaks of diarrhoea and other intestinal troubles were common and soon epidemics started to spread. People had to sleep on the planks or sitting up because there was so little space and they were exposed to the icy winds on board.

The Yugoslav Jewish community did its best to assist the passengers, especially when they were stranded in one of their Danube harbours, and the non-Jewish population was very welcoming to refugees, too. They treated them as guests in need of assistance. Several private aid organisations provided board and lodging, sanitary articles, clothes, and money for Jewish refugees and helped with the organisation of transport to a harbour in the Black Sea or the Mediterranean. Although the Yugoslav State was overwhelmed by the influx of Jewish refugees from Central Europe and consequently intensified the border controls, only very few refugees were actually sent back to the “Third Reich”. Especially the Serbs showed a lot of respect towards the plight of the Jewish refugees and treated them humanely, even under pressure from the Nazis, when they occupied Serbia after the German attack on Yugoslavia and Greece in April 1941. In contrast, the Croats were to a large degree attracted to Fascist ideas and when the Croatian Fascist Ustasha regime, a German puppet state, was established, the Croatian Fascists brutally persecuted not only the Jews and Roma, but also Serbs, who they considered to be Communists.

Willy Perl once mentioned that the “Aliyah Bet” fought a “four-front-war”: first and foremost, against the Nazis, second, against the British, who wanted to prevent Jewish immigration, third, against the Jewish settlers in Palestine, who considered the refugees as inadequate, and fourth, against the elements, such as storms, rough seas, hunger, cold, epidemics. The organisation ran enormous risks in setting up the operation; it had to overcome numerous obstacles as the British did not shy away from drastic measures in order to stop Jewish immigration in Palestine. They had detailed secret service information about the financing of the transports and the routes the ships took in the Mediterranean. They knew about the surge in illegal refugee numbers. In August 1939 alone seven vessels with 5,000 Austrian, German, and Czech refugees had left for Palestine. Therefore the British set up the “Danube Commission”, which was supposed to negotiate contracts with the transit countries Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, Romania, Greece and Hungary to block illegal transmigration of Jews from the “Third Reich” by land and water, and asked not to issue any transit visas unless a final destination visa was procured and to dissolve local “Aliyah Bet” organisations. The formal requirement of a “valid visa of final destination” was to be fulfilled and Willy Perl managed to procure Paraguayan visas for the participants, for example. As can be seen in the documents above, Henny had a Bolivian “final visa”. Of course, the British protested; first of all, both were landlocked countries and you would have needed another South American transit visa to reach these countries and second, who would travel to Paraguay or Bolivia via the Danube and the Black Sea? But the formal requirement of a “final visa” was fulfilled.

Before 1939 most transports from Vienna, the hub for all Central European escape routes, took the refugees by train across the Balkans to Greece, but that was no longer possible due to geographical and political reasons. That’s why, from 1939 on most transports were run down the Danube to Romanian harbours. The advantage for the organisers was the fact that they needed no transit visas for the Balkan states and that Romania was still very tolerant with respect to Jewish refugees. Transports then went via Vienna or Prague down the Danube to Constanta or Sulina, where Henny was transferred onto an ocean-going ship. In international waters the passengers were trans-shipped onto small fishing vessels in the dark in view of the Palestinian coast. For the British coast guards, it was difficult to seize the crews in international waters before the passengers were trans-shipped. On top of that, the British did not have the capacities to intern such large numbers of refugees in camps in Palestine, which would anyway have ignited protests among the local Jewish population, and above all, the refugees could not be detained forever. A terrible consequence of the strict approach of the British was the fact that private organisations, ship owners and crews demanded much higher compensations for illegal refugee transports. Estimates suggest that 6,000 to 7,000 Austrian Jews illegally emigrated to Palestine between 1938 and 1940.

Karl Pfeifer had moved from Austria to Hungary with his family because they had hoped for less anti-Semitic harassment and persecution in the country, where several family members had originally come from. Karl had a brother, who was 15 years his senior, and who had been inspired by the Zionist movement and had already emigrated to Palestine. Life for young Karl was difficult in Hungary, too, and when his mother died, he was left alone with his father, who desperately tried to make a living under very constricted circumstances. With a false identity Karl finally managed to leave Hungary for Palestine on 5 January 1943 in the hope of joining his elder brother Erwin. Hungary had been turned into a Fascist dictatorship, too, but only after the German occupation in 1944 Jews were obliged to wear the yellow star of David in public and were deported. He was 14 and the group of 52 children and adolescents also included two ten-year-old boys. Karl Pfeifer wrote in his memoirs that it was the responsibility of the older ones to instruct and supervise the younger ones, especially when they encountered check points, as the smaller children had to learn their new identities by heart first. The group left from the East Station in Budapest by train and crossed the border to Romania in Curtici. In Arad and Bukarest they were welcomed and fed and watered by the local Jewish communities. At the border to Bulgaria in Rustschuk they had to remain locked on the train at more than minus 20 degrees Celsius without heating and just a few blankets. Yet the Romanians as well as the Bulgarians were warm-hearted people and the train personnel distributed food and drinks to the children on the train. When GESTAPO men searched the train and tried to block the on-transport of the children to Istanbul, one of the youth leaders, who accompanied them, had the contact address of a Bulgarian minister and when the Bulgarian soldiers saw it, they allowed the train to pass. The group was extremely relieved, when they had left the German influence sphere. Their train arrived at the train station Sirkeci in Istanbul, from where the children were brought to a hostel in Galata. Here the atmosphere was tense; Jews had no protection and the memory of a recent refugee catastrophe was still vivid. At Christmas Day 1941 the ship “Struma” with a sign saying “Please save us” had been chased out to sea and sank drowning around 770 Jewish refugees.

After four days of rest the children were transported on a train from the Haider Pascha Station across Anatolia to Beirut. The children continually suffered from intestinal troubles due to the food they were not accustomed to. When they reached Syria, they entered Allied territory and French and British soldiers boarded the train that went to Aleppo, where representatives of the organisations Mossad and Aliyah Bet accompanied them. On 18 January 1943 they could finally leave the train in Beirut. On the next day the children were brought to the Palestine border at Rosch Hanikra in buses. They were welcomed by a German-speaking crowd in the city of Naharia and so had finally reached their destination and a safe haven in Haifa after a journey of two weeks.

As a place of last resort, several Austrian Jews tried to reach Palestine via the Balkans alone or in small groups. At the start of the war, the German border controls still tolerated illegal border crossings as they wanted to boost Jewish emigration. At the border the Germans checked the “exit stamp” in the passports stamped with a J for Jewish and seized any money except the allowed 10 Reichsmark and all valuables of the refugees, who had to sign that they would never ever return to the “Third Reich”. But then the refugees had to avoid being picked up by the Yugoslav border police, who were ordered to send back any persons illegally crossing the frontier after the government had tightened the restrictions on immigration due to the German policy of promoting illegal border crossings which was intended to destabilise the Yugoslav State. The refugees needed local guides to cross the border clandestinely and consequently, a network of escape agents who cooperated with smugglers was established. In Maribor, Marko Rosner, a Jewish shop owner, organised illegal border crossings. Already before their departure from Vienna, a secret meeting point with a guide was fixed and Rosner was in friendly contact with the Yugoslav border control, which in most cases acted in a very humane way. Rosner covered all the costs of transport and necessary bribery from his own funds. On the Austrian side of the border Josef Schleich, an electrician from Graz, organised illegal border crossings from October 1939 on with the tacit knowledge of the GESTAPO. The smuggling activity reached its hight from autumn 1940 until March 1941, when Jews were no longer allowed to leave Vienna. Schleich received small groups of four to five people, who had departed in Vienna, in his flat in Graz and then hid them on a chicken farm in Liebenau, where GESTAPO men regularly checked the names of the refugees. Schleich worked together with the Jewish community in Zagreb and smugglers in Maribor and seemed to have received generous compensation for his services. On some days up to a hundred illegal refugees tried to cross the border from Austria to Slovenia clandestinely, but in winter the mountain paths were barely passable. There are reports of young Jewish refugees who needed three or more attempts at illegal border crossings until they finally arrived on Yugoslav territory.

Selection of the young for the transports: preparation and adult attendants

As soon as Überall in Vienna had decided to organise illegal transports to Palestine, he first had to get Slovakian transit visas for the passengers, which he managed with the help of a frustrated Nazi, Ferdinand Ceipek, who supported the Jewish rescue transports and contacted the Slovakian consul, who procured the first transit visas at a low price. All young passengers had to provide a written permission of their parents or guardians. While the Mossad was searching for adequate sea-going vessels in Italy, Greece, Romania and Bulgaria, the persons responsible for the illegal transports in Vienna divided the selected passengers into groups of twenty people and appointed a group commander for every group.

Hundreds of young Austrian people were trained in Hachshara camps in the vicinity of Vienna and in Lower Austria, where they learned agricultural skills, which were not traditional Jewish professions in Austria, but urgently needed in Palestine. Furthermore, they learned about Jewish history, the geography and nature of Palestine, and were taught the basics of “modern Hebrew”, the common language used by Jews in Palestine, and first aid. The camps were led by “madrichim”, youth leaders and by teachers. In Vienna they started with improvised courses and later in the Youth Aliyah School (JUAL-Schule), where in half-day sessions the young received practical training as tailors, electricians, nurses, metal workers or tinsmiths, too. As soon as Jewish pupils were excluded from the public school system, the JUAL schools took over the function of proper schools for those Viennese children. They were housed in the “Dr.Krüger Heim”, the “Palästina-Amt” and the former “Chajes” grammar school in Vienna. After a three-month training the young people could move to a “preparation camp”. The Youth Aliyah had leased some land in the vicinity of Vienna, where the young people had to work for the farmers. One of these “preparation camps” was in Moosbrunn in Gramat-Neusiedl near Vienna, where 135 could work, another in Otterthal in the Wechsel region, where 90 youth were trained. After completion of this traineeship, they had to undergo a medical check which tested their physical and mental capabilities. The commission found that the physical and mental health of the young Jews had already seriously deteriorated. Nevertheless, only few did not pass the medical check-up: in 1939 1,276 young people were decreed fit to emigrate, 86 did not pass the check-up and 49 were suspended temporarily. Strict criteria of selection were applied during the preparation period in order to ensure that the young people would be able to cope with the drastic changes in their lives; the separation from their families, the different lifestyle in a kibbutz, the cultural and climatic changes.

Arrival in Palestine and life in a kibbutz

Despite these precautions, several of the adolescents who arrived in Palestine could not adapt to the novel conditions and complaints from the Jewish authorities in Palestine reached the IKG in Vienna. Especially young people from Austria were undernourished and in a precarious mental state and therefore unable to cope. This proves that the conditions under which young Jews had lived in Austria, most of them in Vienna, were especially harsh; they were confronted with continuous harassment, persecution, and deprivation. So, seriously traumatised children arrived alone in Palestine, tormented by homesickness and the experience of loss. The medical doctors in Vienna often passed off children as healthy, just because their lives were in danger if they remained in Vienna and not because they were fit to emigrate. Austrian youngsters ran away from their kibbutz in Palestine more frequently than others, probably because they disproportionally suffered from loneliness. The Jewish institutions in Palestine were worried about such instances of disobedience because the young were strictly forbidden to leave their camps unattended. What’s more, the Jewish institutions had to prove to the British authorities that their immigration model worked, so as not to endanger future Youth Aliyah rescue operations. Furthermore, it was the aim of the youth leaders in a kibbutz to educate the young along the lines of Zionist ideals and most of the youths from Austria came from an assimilated background without a Zionist upbringing, which might have made the transition for them more difficult. On the other hand, religious Jews who were used to an orthodox lifestyle, often hid this fact when applying for a Youth Aliyah transport in order to be able to get a place. Yet after their arrival in Palestine they found out that very few orthodox settlements were available and that they could not practise their orthodox religious lifestyle in a laicist kibbutz.

Most of all, the new daily routine, the hot climate, and the strange food caused problems for the young immigrants. Yet the tight schedule of the Youth Aliyah in Palestine, the programme of school, work, group activities, left little room for pondering and this could have alleviated the emotional stress of separation from the family and of uprootedness. There was very little space for personal development or indulging in personal interests, because the atmosphere in a kibbutz offered nearly no privacy and demanded a strict code of conduct. This might have been the reason why especially Austrian youths, who had been raised in a more relaxed and spoilt atmosphere in their families, could not adapt easily to this new way of life. After the end of the war many left Palestine (later Israel) for the United States for example, but a few also returned to Austria, like Henny, although they had no family there anymore because their relatives had been murdered in the holocaust.

When the Austrian Jews arrived in Palestine, the job market was already saturated after the arrival of earlier Jewish immigration waves. Due to the aggressive anti-Semitic expropriation policy in Austria, the Austrian Jewish refugees came to Palestine penniless. In Austria most of them had been in small-or medium-sized trade or in liberal professions. In Palestine, on the contrary, agricultural workers and skilled craftsmen, physical power and technical knowledge were in high demand. The new arrivals had to be retrained or trained first and therefore had to rely on financial support or do any odd jobs available. Only the young decided for a life in a kibbutz, because these adolescents who had arrived via the Youth Aliyah were integrated in a kibbutz or settlement, the adult refugees mostly moved to the cities.

Karl Pfeifer wrote in his memoirs how disillusioned he was, when he arrived in the kibbutz Maabarot, situated between Haifa and Tel Aviv, at the age of 14 in 1943. He was in a group of young people who were among the very few who had managed to flee to Palestine as late as January 1943. As they had been well-prepared in Budapest for a stay in a kibbutz and had undergone an extensive Zionist training, they were enthusiastic initially and hoped to experience the world of grass-roots democracy live. Kibbutz settlements were either agricultural or industrial enterprises with common ownership. All members received pocket money instead of a salary for the work they did. At the start, the adults often had to live in tents, the children were housed in children’s homes. There was a common kitchen and common dining room and weekly general meetings decided about all the activities in the kibbutz. Yet it must be taken into account that despite its ideological importance never more than five per cent of the Jewish population in Palestine lived in a kibbutz. There the refugee children experienced a radical rift with the lifestyle they had been used to in Central Europe. Soon they fell into a deep depression; they were homesick, they missed their families, they had to do hard agricultural labour, even at the age of 14, and they had no one to talk to. They withdrew into their inner selves and tried to cope with these huge problems alone, because they were ashamed. They were supposed to be strong and courageous, but in reality, they were not. Especially intellectually gifted and physically weak children like Karl, who was not used to hard labour, could not meet their daily targets of picking oranges, for example. For the first time Karl, who had been an excellent student, had to deal with complete personal failure. The young people started work at 5 o’clock in the morning during harvest seasons and in the afternoon, they attended lessons and learned modern Hebrew, which was difficult for children of assimilated Jewish families, who had never had any contact with Hebrew. But the children learned the language quickly, because at his arrival Karl could only talk to those children who understood German or Hungarian. So, if the children wanted to communicate with those from another ethnic backgrounds, they had to practise Hebrew. As the kibbutz Maabarot was not a religious one, the important religious feasts were celebrated with a national and historical rather than a religious touch. The children were urged to choose a Hebrew name and for bookworms like Karl a reading room provided a selection of books and newspapers, not just in Hebrew, but also in German. Their daily routine was rigorously planned: If there was no harvesting season, they had gymnastics from 6.00 to 6.15, then the children had to wash, put their things in order and had breakfast. They worked from 7.00-11.00, followed by a lunch break from 11.00 until 12.30, then they had lessons and after dinner at 18.00 they had to do their homework. Every day at 19.30 there was a group meeting, where the children received political training and current issues of life in the kibbutz were discussed. They had to go to bed early, except on festive days. The only day off was Saturday, when they made excursions to the sea or watched a play in Hebrew, where they did not understand a word at the beginning, or they went to the cinema. The educational aim of the Zionists was to turn the young into secular Jews, proud of their country Israel and Jewish history, and capable of speaking modern Hebrew. Often the children were too tired in the afternoon to attentively listen to lectures on history, geography, mathematics, or Jewish subjects. The Zionists wanted the young to become modern Jews, who did not rely on traditional religious rules and regulations and whose focus was on civil laws that regulated the living together of different peoples, inspired by Socialist ideas, and on the in-born right of Jews to live in Palestine. Karl stressed that anti-Semitism in his home country had driven him to Zionism. It took a long time until Karl was able to see his brother because Erwin was serving in the British Army. Since the start of the war Karl had only been able to communicate with his brother via the International Red Cross. The children had not been allowed to take any written notes or documents with them, when they escaped. So, they had to learn all the addresses of relatives and friends by heart. When finally, his brother Erwin was able to visit Karl in the kibbutz in April 1943, it was a very moving reunion. Erwin had not seen their mother before her death and both brothers would never see their father again.

Most Austrian Jews settled in the big cities, Haifa, Tel Aviv and Jerusalem. The young adapted more quickly because they learned the new language more easily as they were subject to intense social pressure from the institutions which had accommodated them; the kibbutz, the educational facilities, and youth hostels. The difficulties many Austrians had with their integration into the Palestine society are illustrated by the remigration numbers: most Austrian Jews returned from their exiles in Palestine and Shanghai. Nevertheless, only 4.5 per cent of all Austrian emigrants to Palestine returned to Austria after the war, and most of them did not remain in Austria, but moved on to the USA or Canada later.

Two dramatic escapes of young Jews to Palestine: the Kladovo transport and the children of the Villa Emma

THE KLADOVO TRANSPORT 1939-1942:

On 25 November 1939 a group of 1,002 people left Vienna for Bratislava, 822 of them Viennese Jews, on an illegal transport to Palestine, organised by Georg Überall. One third of the passengers were young He-Haluts members between 18 and 25 years of age, one third were children and adolescents under 17 years of age; some were accompanied by their parents, others under the guardianship of Zionist organisations. The final third were couples and older people who had managed to pay for their transport. Even though the Danube was going to freeze in December, the group departed because they feared a deportation by the Nazis. After ten days in Bratislava, where 100 passengers from Prague and Bratislava joined them, they boarded the DDSG ship “Uranus”, an excursion boat, but when they reached the Hungarian border, they were suddenly stopped and had to return to Bratislava, where they had to wait until 13 December, when they started their voyage once more. A few days later the refugees were trans-shipped mid-river onto three Yugoslav excursion boats, the “Car Nikola”, the “Car Dusan” and the “Kraljica Marija”, which Sime Spitzer, a representative of the Yugoslav Jewish community had chartered because the DDSG had refused to continue the trip on the “Uranus”. The DDSG argued that a re-shipment at the mouth of the Danube was uncertain, as no sea-going vessel was waiting in a Black Sea harbour. Again, the transport was stopped abruptly in the area where the states Yugoslavia, Romania and Bulgaria bordered the Danube, because the Romanian authorities did not permit the passage for the same reason. So, by 30 December 1939 the Danube had frozen and the three ships were led into the Yugoslav winter harbour of Kladovo near the Iron Gate. In winter the small town was virtually cut off from civilisations, 54 km from the nearest train station. Spitzer had to guarantee the provisioning of the group at a time when Yugoslavia was already flooded with thousands of Jewish refugees from the “Third Reich”, who were cared for in several refugee camps. Due to the cramped conditions, the icy temperatures and the unbearable sanitary conditions, the passengers were moved on land in barracks, tents, and private homes in Kladovo. Finally in May the Greek ship “Penelope” arrived, which was supposed to take the refugees to the Black Sea harbour Sulina, as soon as a deep-sea vessel had been procured. When a malaria epidemic broke out due to the nearby swamps and the hunger, dirt, and swarms of insects, which made life unbearable for the group, the refugees desperately tried to contact relatives and friends in Palestine and North America to send them immigration certificates and help them to flee to a safe place, but they overestimated the possibilities of their relatives abroad. More refugees who had crossed the border to Yugoslavia illegally joined the group in the hope of reaching Palestine. Consequently, the atmosphere was extremely tense, because again and again planned departure dates were cancelled at the last moment. In September 1940 they were able to move on, but they were driven upriver again to the Serbian town Sabac on the river Sava. The Mossad representatives desperately tried to raise funds for the on-journey of the Kladovo transport and managed to buy the vessel “Darien II” in Athens, but it could not rescue the Kladovo refugees, because before it reached them, it was redirected to another destination due to war events. Meanwhile the living conditions of the refugees in Sabac had improved a little; the young were housed in a grain mill, while the elderly were put up in private homes. Several passengers could earn some pocket money in the vicinity, but their hopes for a transport to the Black Sea were again dashed several times in the last minute. In late autumn the Mossad managed to organise a small transport of 160 refugees to Constanta and Istanbul, who had received British immigration certificates for Palestine. When the “Darien II” finally reached the Black Sea harbour Sulina, the remaining refugees were to board Yugoslav ships in Sabac to take them to Sulina on 2 December 1940, but the trip was cancelled again due to the freezing of the Danube. Unfortunately, Spitzer’s plan to take the group by special train to the border of Yugoslavia and Romania and then reach Sulina on tugboats hired by the Mossad failed as well. Just before the German attack on Yugoslavia a small group managed to escape to Palestine with immigration certificates on 16 March 1941. They went by train via Greece, Istanbul, and Aleppo to Beirut. In Palestine they were detained in the British detention camp Atlit and then transferred to kibbutz and settlements. Estimates of those who managed to survive in this way vary between 200 and 280 people, most of them Youth Aliyah members aged between 15 and 17 years of age, a few attendants, and some older girls with WIZO- certificates.

When the Germans attacked Yugoslavia and Greece and dissolved the Yugoslav State in April 1941, still 1,100 Jewish Kladovo refugees had remained in Sabac. The fierce persecution of Jews started immediately, yet the group had no chance to flee from German-occupied Serbia. After the German attack on the Soviet Union in June 1941, the Nazis started the systematic extermination of Jews and only a handful of the Kladovo refugees still in Sabac survived the war. In July they were all interned in military barracks and as the combat strength of the Yugoslav partisan groups, who fought against the German occupiers, increased, Hitler appointed the Austrian Franz Böhme highest NS commander in Serbia with the task of breaking partisan resistance. Two “Wehrmacht” divisions with mainly Austrian soldiers were stationed in Sabac under the command of the Austrian Walter Hinghofer. After a partisan attack 805 male Jews and Roma of the Sabac camp were executed in Zasavica by an execution commando of Hinghofer’s division. All men of the Kladovo transport fell victim to this reprisal in the autumn of 1941, while the women and children remained in the camp in Sabac with no knowledge of the destiny of the men. In January 1942 the women and children were deported to the Sajmiste concentration camp near Belgrade, where many froze or starved to death. All those still alive by March 1942 were told by the Austrian concentration camp commander, Herbert Andorfer, that they would be transferred to a better camp and with this malignant deceit he got the victims to mount willingly the trucks that had been prepared as mobile gas chambers. From March until June 1942 the refugees were driven in two trucks with 50 to 80 people each to the outer limits of Belgrade, where the trucks were stopped, the two drivers got off, switched a lever which directed exhaust fumes from the trucks into the interior and while riding through Belgrade the women and children in the trucks were gassed. In Avala, 15 km from Belgrade, pits had already been dug and the dead bodies of the women and children were dumped into the pits and quickly buried by slave labourers. By May 1942 all Jewish Sajmiste concentration camp inmates, among them all remaining women and children of the Kladovo transport, had been murdered. All in all, more than 1,000 participants of the Kladovo transport had died. The names of 190 out of estimated 200 survivors are known.

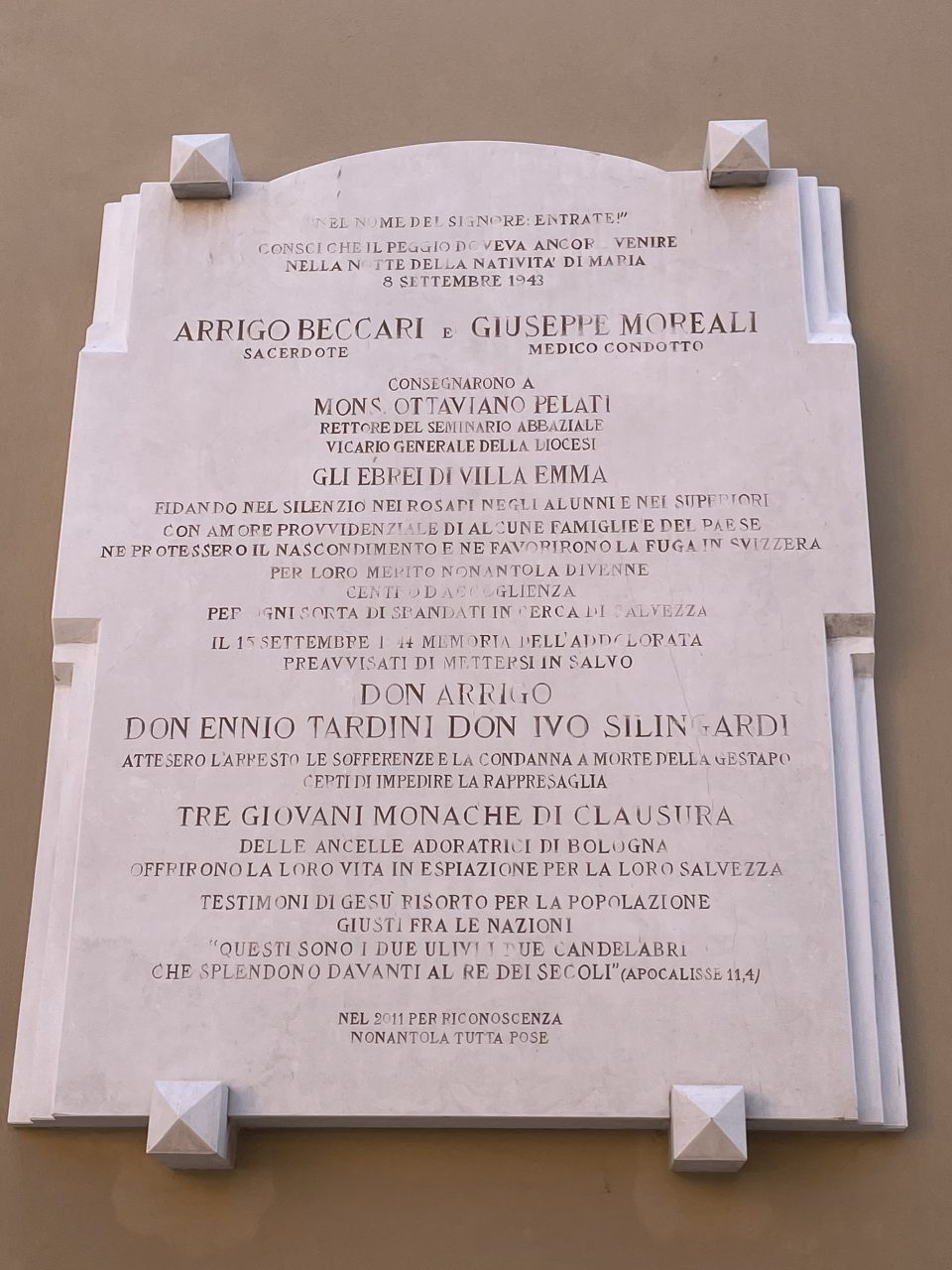

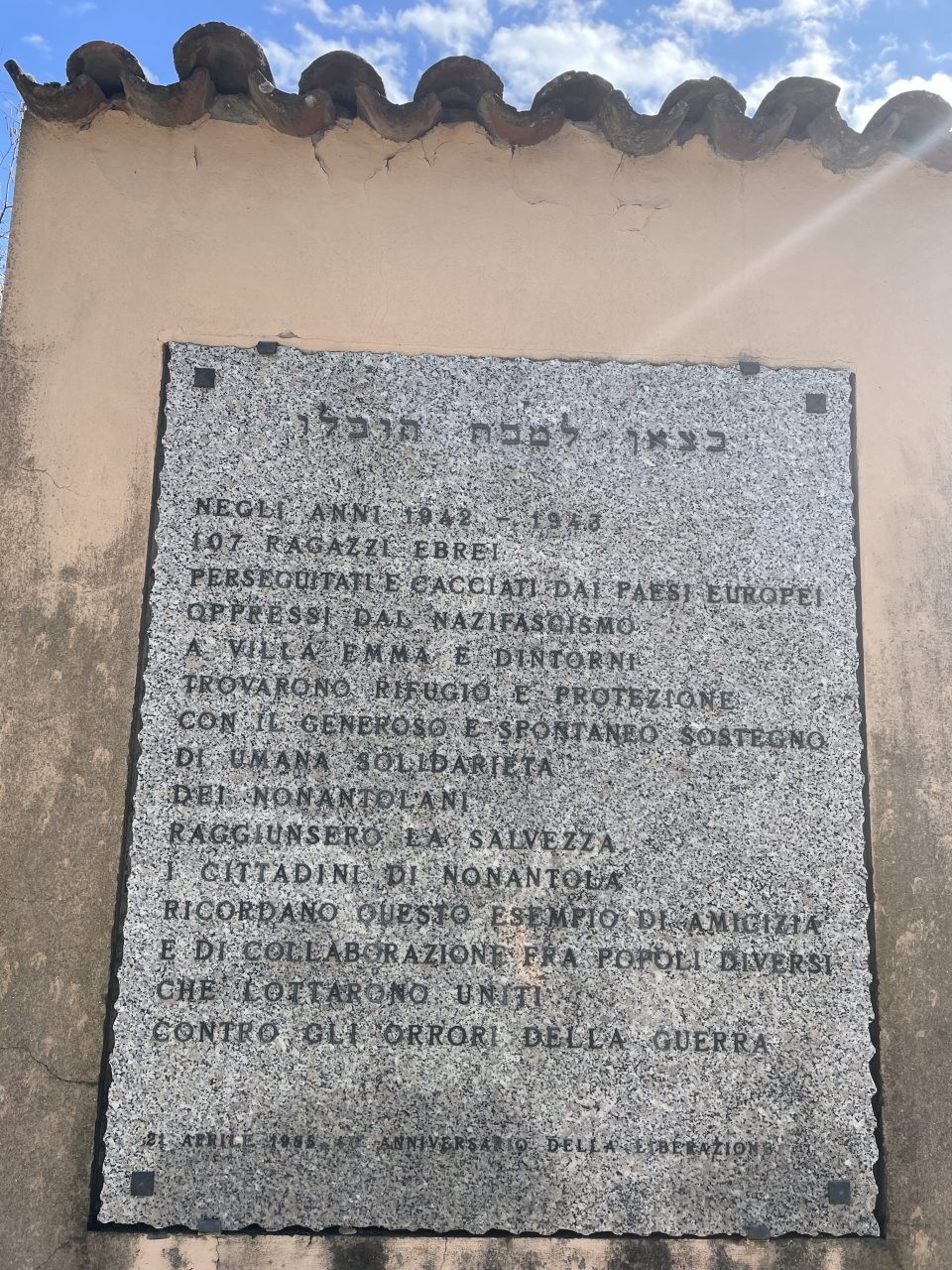

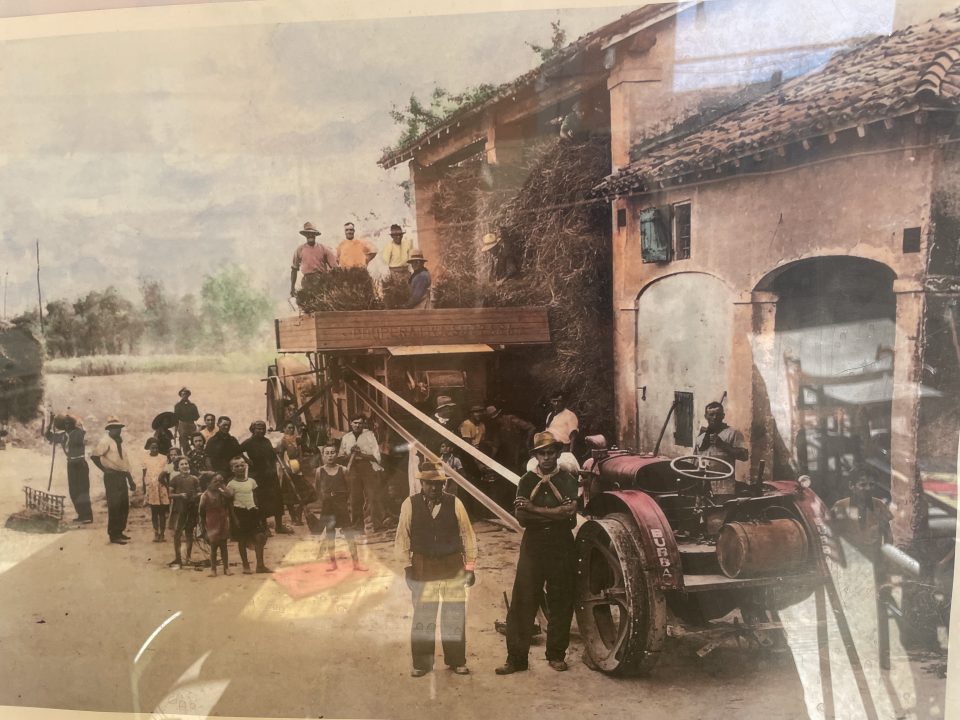

THE CHILDREN OF THE VILLA EMMA 1940-1945