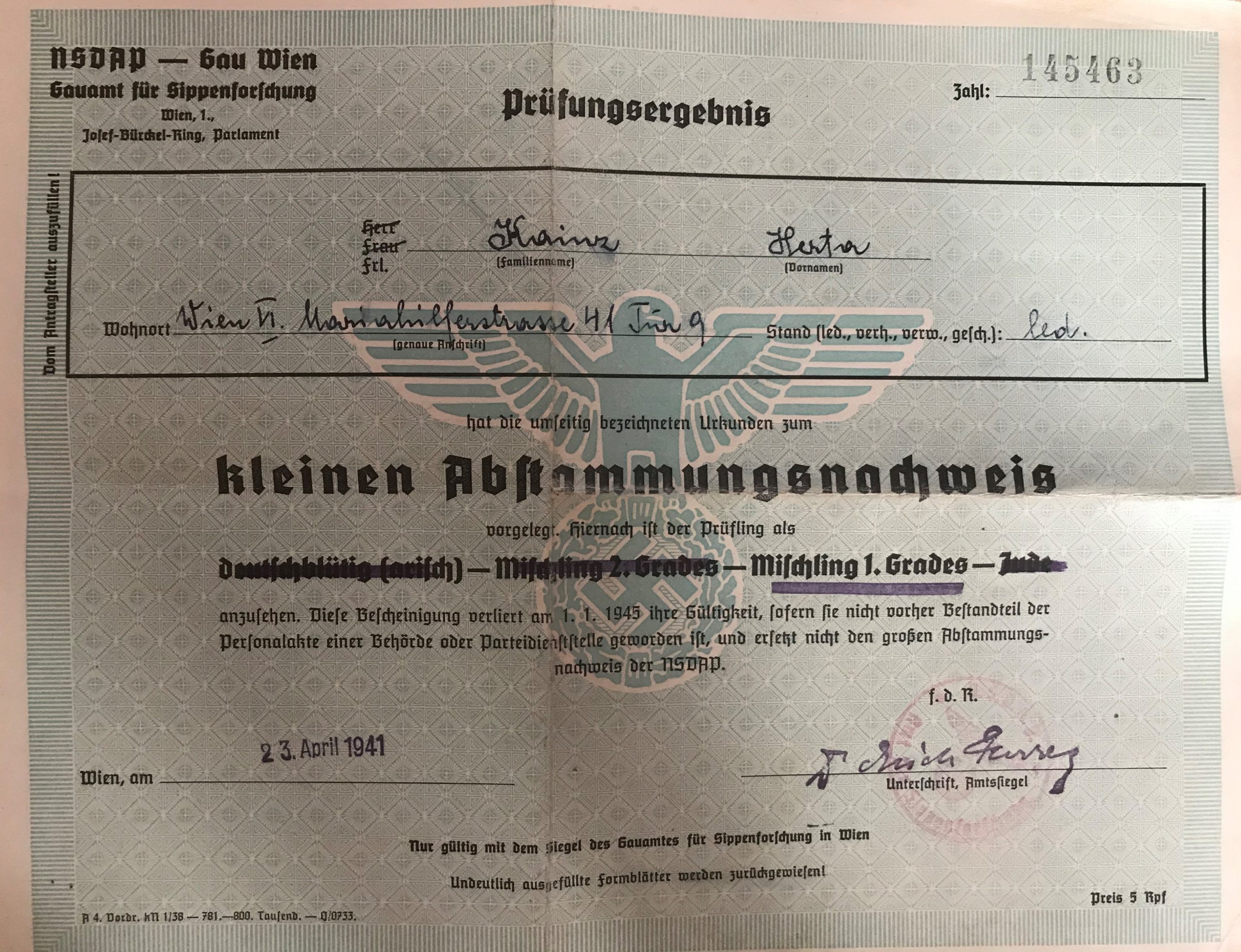

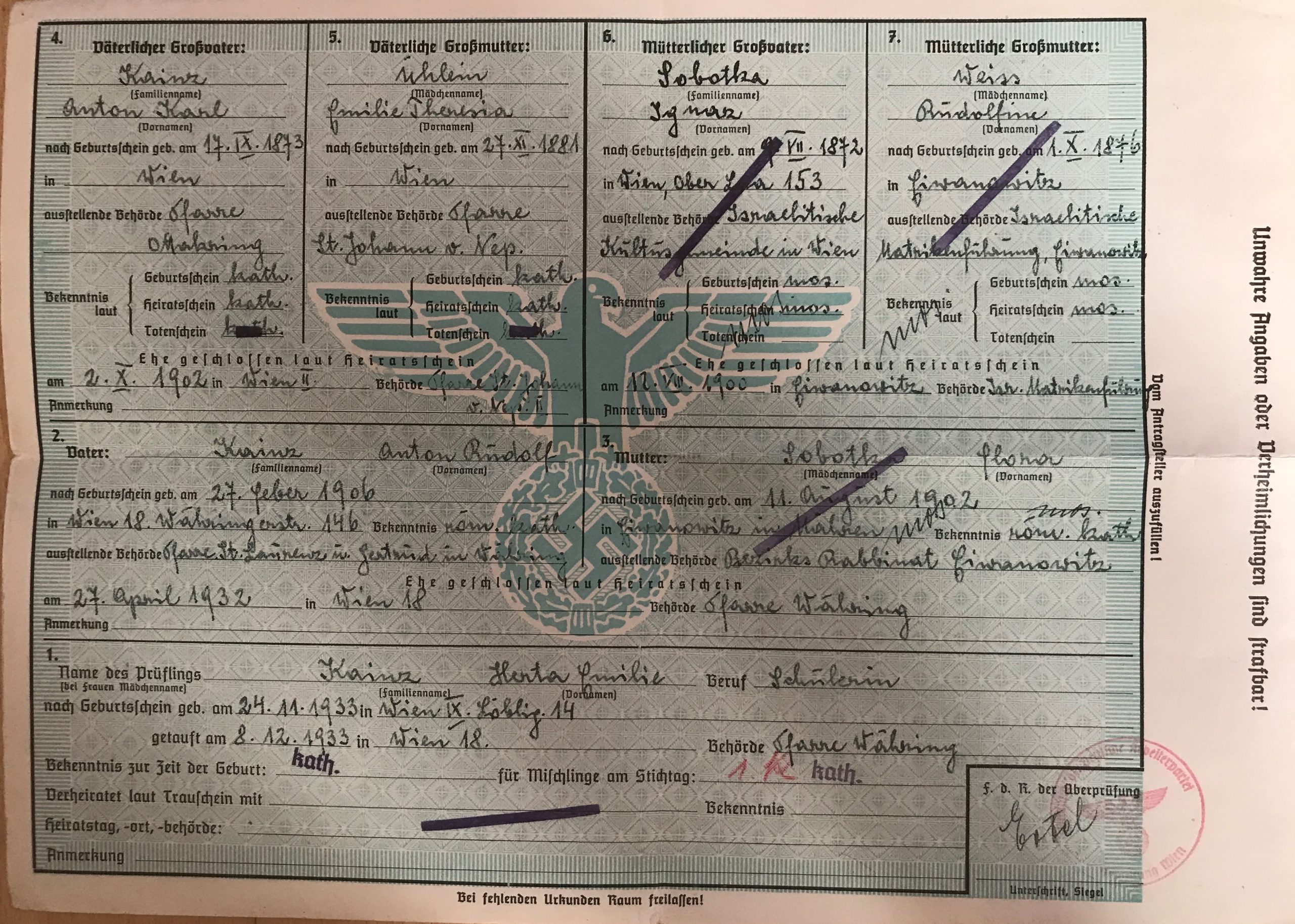

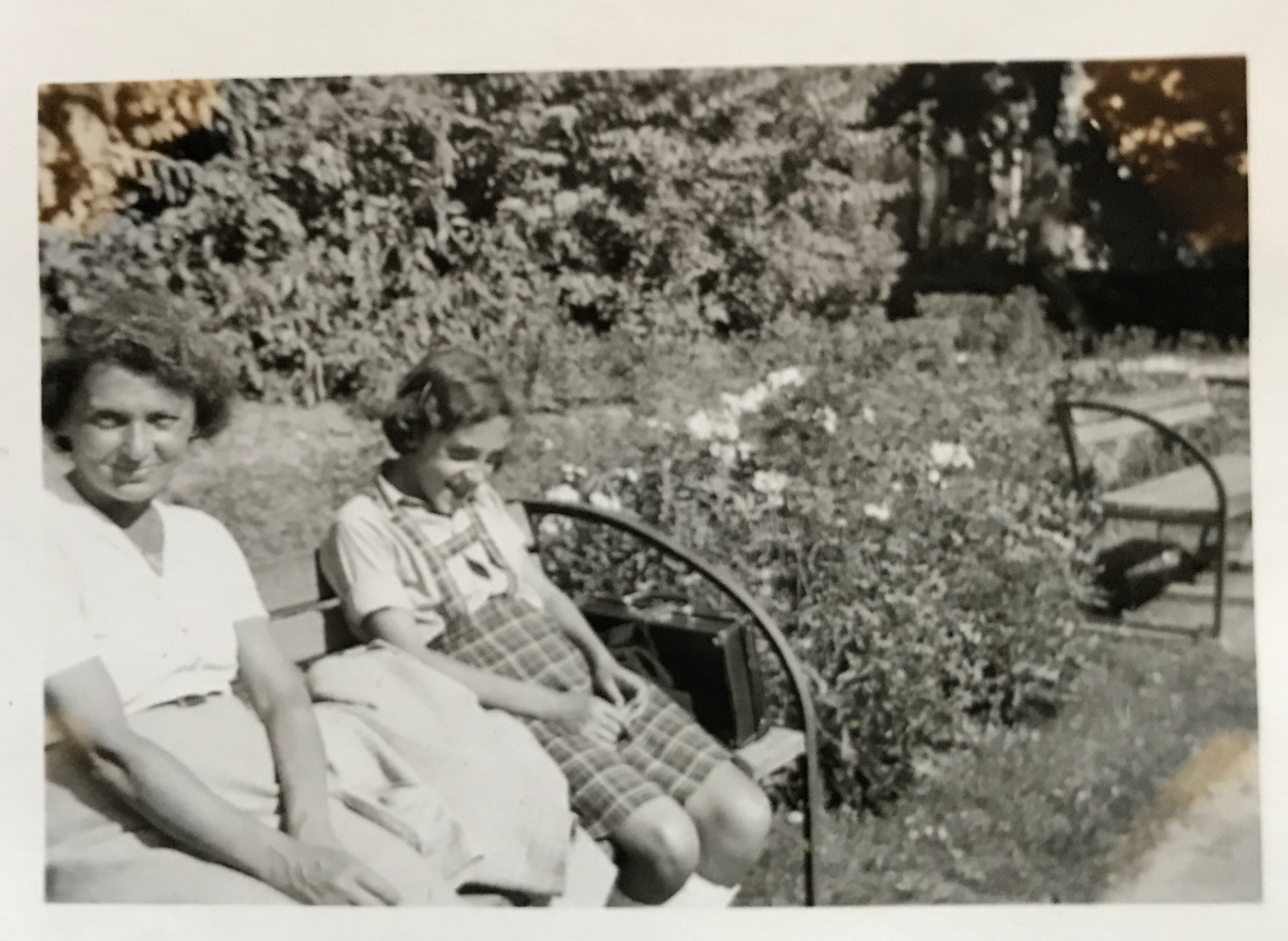

After the “Anschluß”, the takeover of the Nazis in Austria on 12 March 1938, the racial background of every citizen was documented according to the Nazi Nuremberg race laws and my mother, Herta, was classified as a “Mischling 1.Grades” (a “mixed race child of the 1st degree”) – as can be seen in the documents above. Her mother, my grandmother Lola (Flora Kainz), was a Catholic of Jewish descent with Jewish parents, my great-grand parents Ignaz and Rudolfine Sobotka, which meant that all of them had to bear the full brunt of racial discrimination of the Nazi dictatorship. But as long as my grandfather, Anton Kainz, the father of Herta, stood by his family and did not divorce my grandmother Lola, at least Lola and Herta were somehow “protected” because he was a certified “Aryan”. But this “protection” was constantly on the brink of being withdrawn, despite the fact that Toni loved his wife dearly and adored his daughter and would never have thought of giving in to Nazi pressure. This constant insecurity and permanent racial discrimination left deep scars especially in the psyche of Herta, who was four and a half years old at the time of the “Anschluß”. She first lost her aunts and uncles who had to flee Austria, then her grandparents, who were deported to the KZ Theresienstadt and then was in constant fear that her mother would be arrested and deported, too. At the end of the war she was eleven and a half and was not only terribly afraid of the Allied bomb attacks on Vienna, but even more of the knocking on the door and a surprise visit of the GESTAPO which would take away her mother. It was impressed on her by her father that she had to run to the fish shop where he was the branch manager and inform him immediately if anything happened to Lola. Herta remembered that her parents had lots of friends and kept in contact with them during the Nazi occupation. One of them was a high-ranking NSDAP party member and he proposed that Lola should hide in his flat in case of emergency, because no one would suspect him of secretly protecting a Jewess, so she would be safe at his place. But fortunately this was not necessary. Till the end of her life this fear accompanied Herta. Despite the tragic political circumstances and the discrimination she faced as a child, she stressed what a happy childhood she had had because her parents doted on her and this love carried her through those hard times – and the close friendship to a girl who lived in the same house in Mariahilferstrasse 41 and was an outcast just like her. Her name was Herta, too, and she was a very unruly foster child. This unlikely couple, the extremely timid and withdrawn Herta, my mother, and her daring wild playmate remained friends until old age despite the fact that their lives took very diverging paths: My mother became a master dressmaker and “the other” Herta a bar singer. Maybe the discrimination they faced as children created a lasting bond.

The fate of Jewish partners in “mixed marriages” and of “Mischlingskinder” (“mixed race children”) in Vienna was a doubly tragic one because after the war their sufferings were not recognised, neither by the 2nd Austrian Republic nor by the Jewish or Catholic community with the argument “nothing had happened to them – they had survived”. Yet the fast succumbing to a very severe form of dementia at a rather early age can be contributed to the trauma Herta had experienced during the Nazi occupation and that had never been diagnosed or treated. It seems that children carried these traumas with them all their lives and despite apparently functioning very well as adults, the harm that was done to their souls came up again much later in life once more.

Herta with her mother, Lola, and at the age of three, a very shy little girl

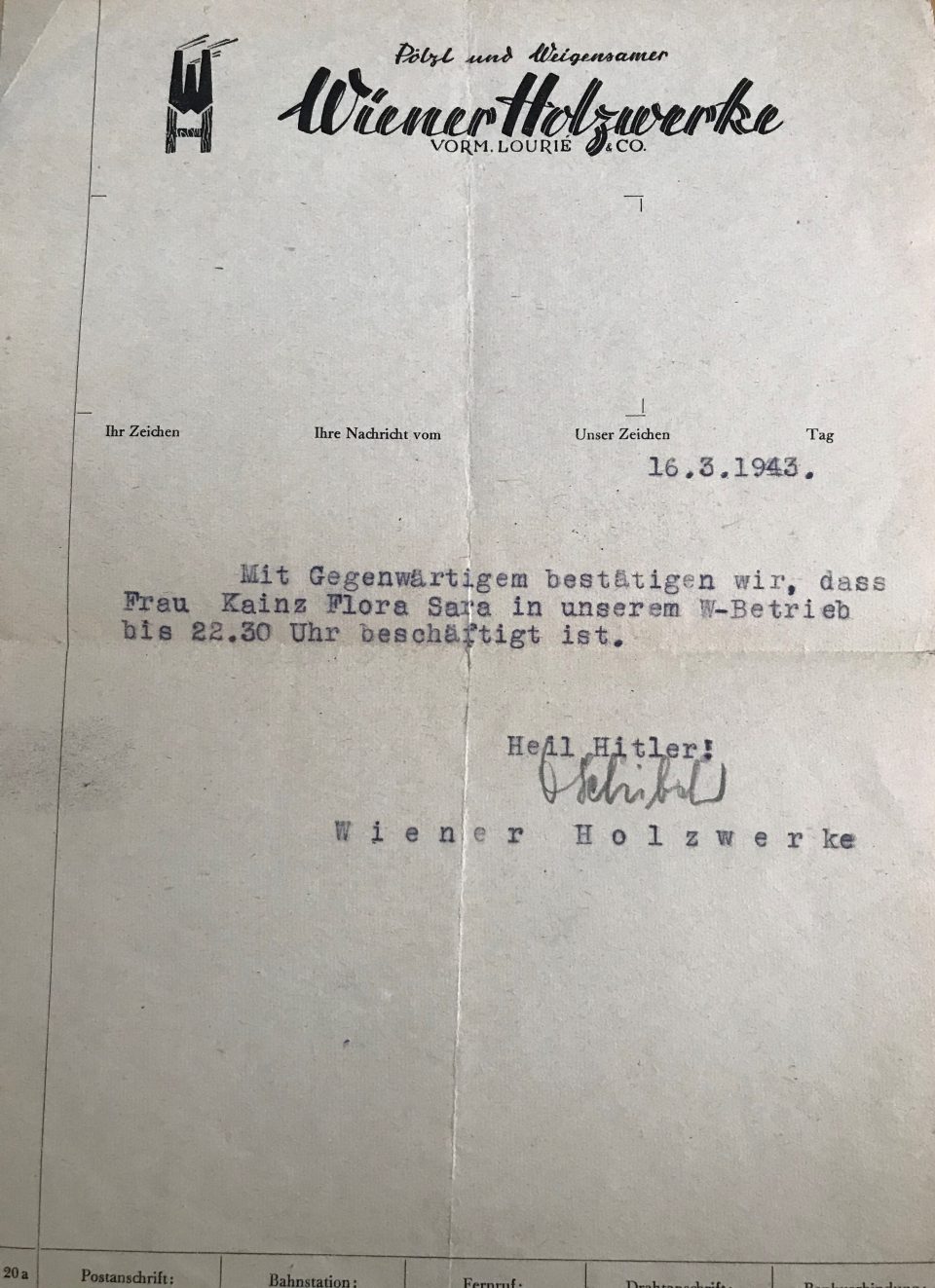

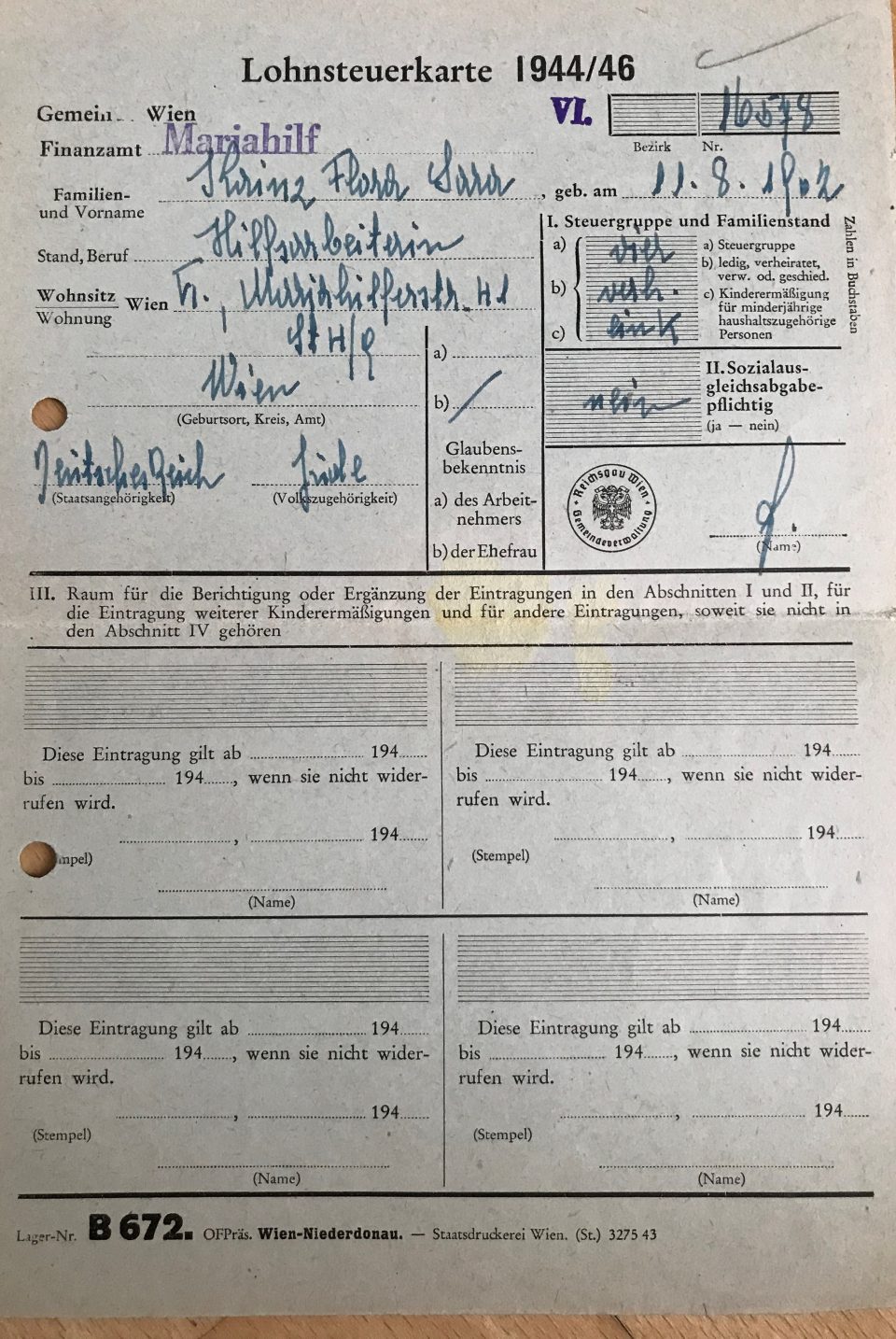

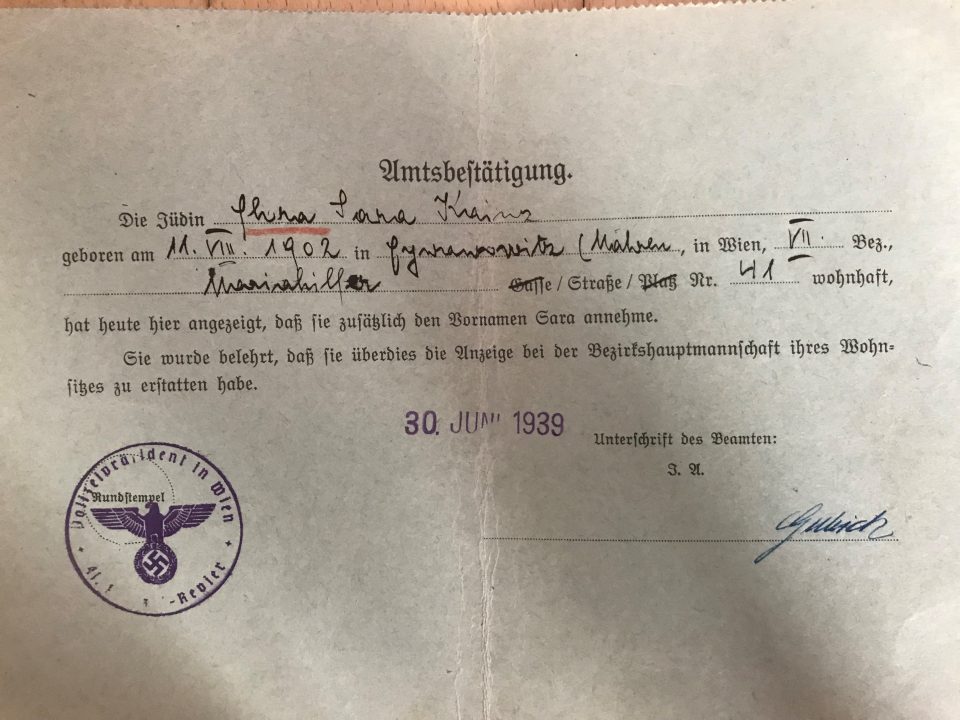

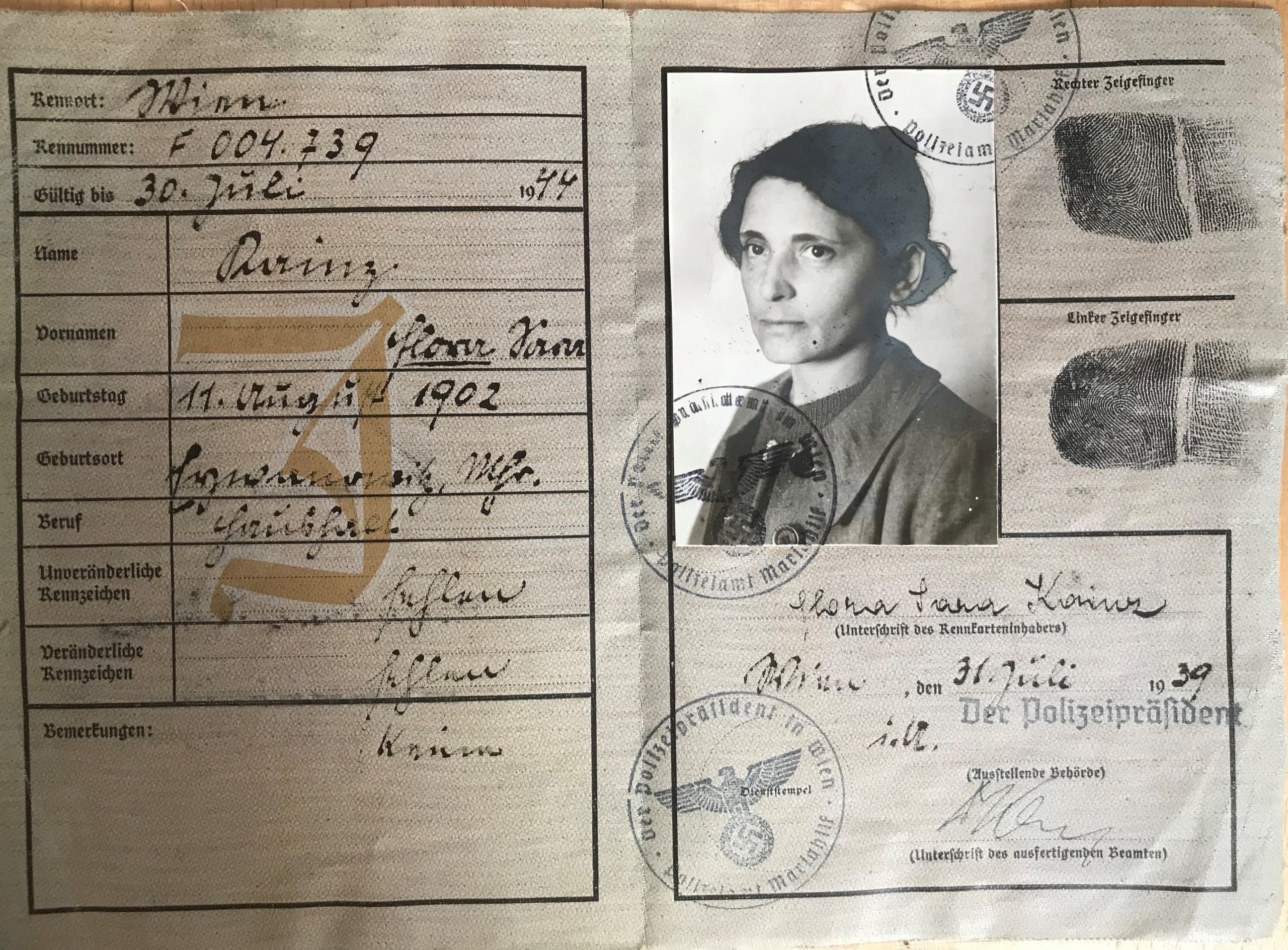

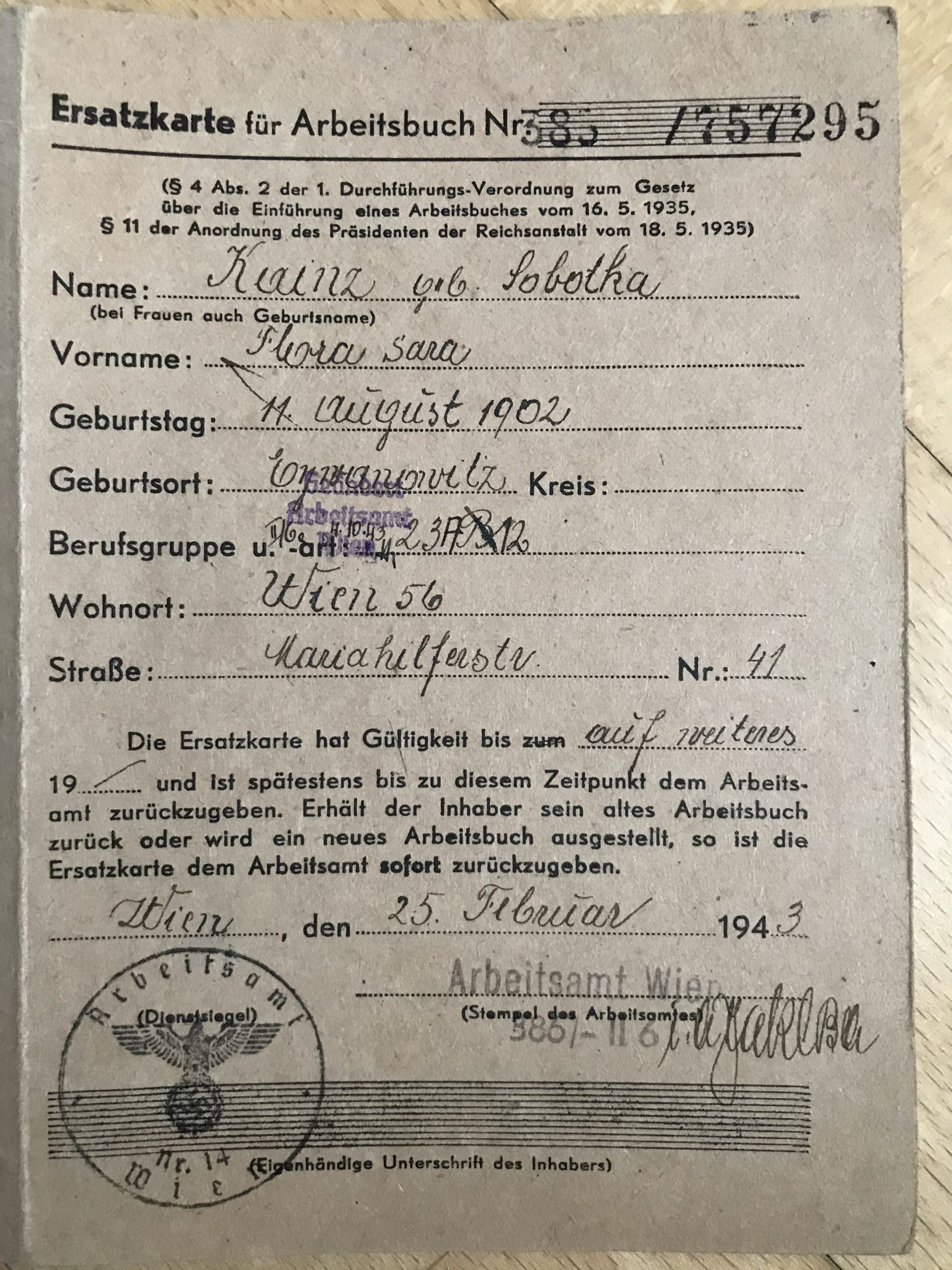

All Jewish women were forced by the Nazis to take on the name “Sara”, as can be seen in this document of the 30 June 1939 of my grandmother Flora Kainz, called Lola. Jewish men had to include “Israel” in their names.

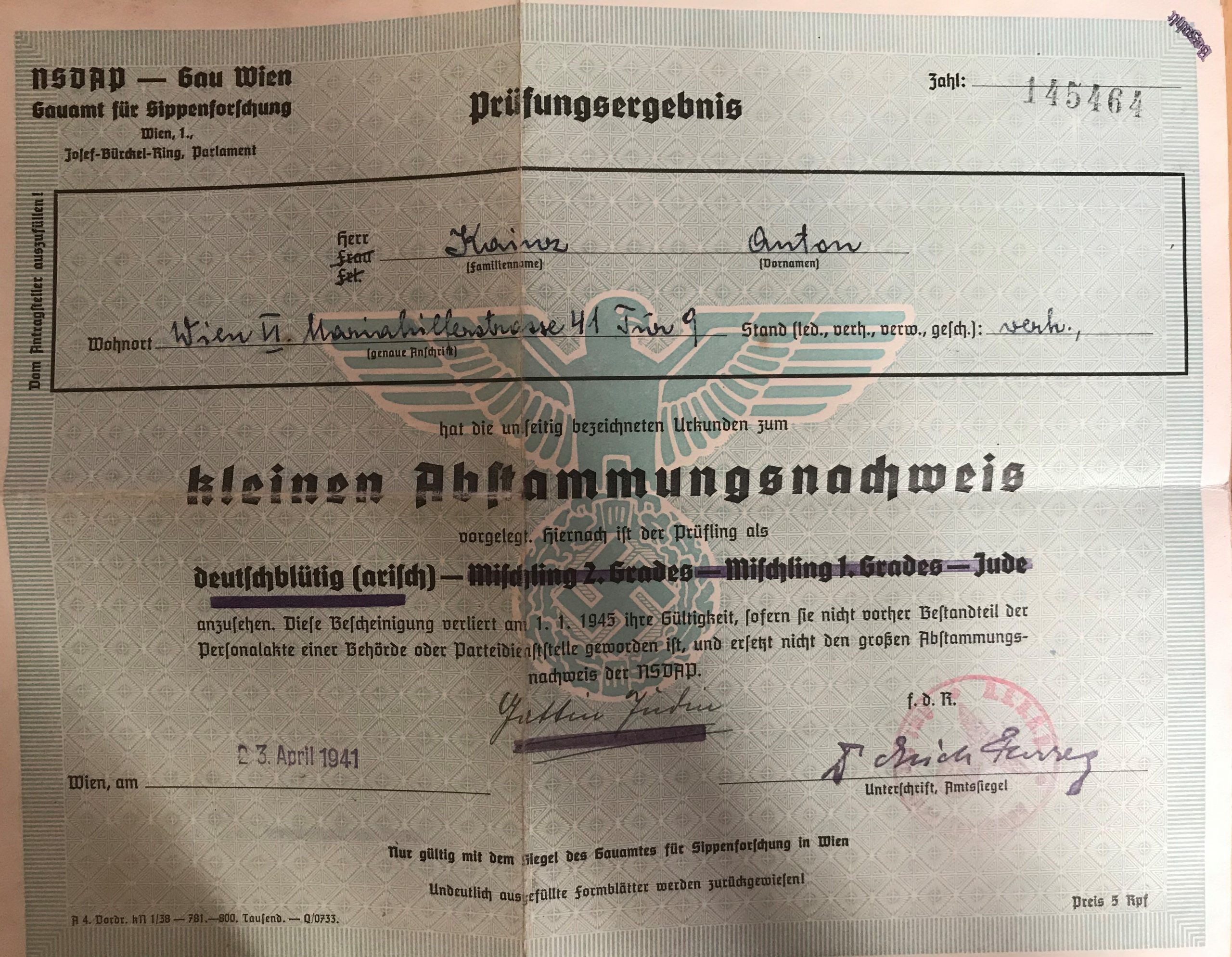

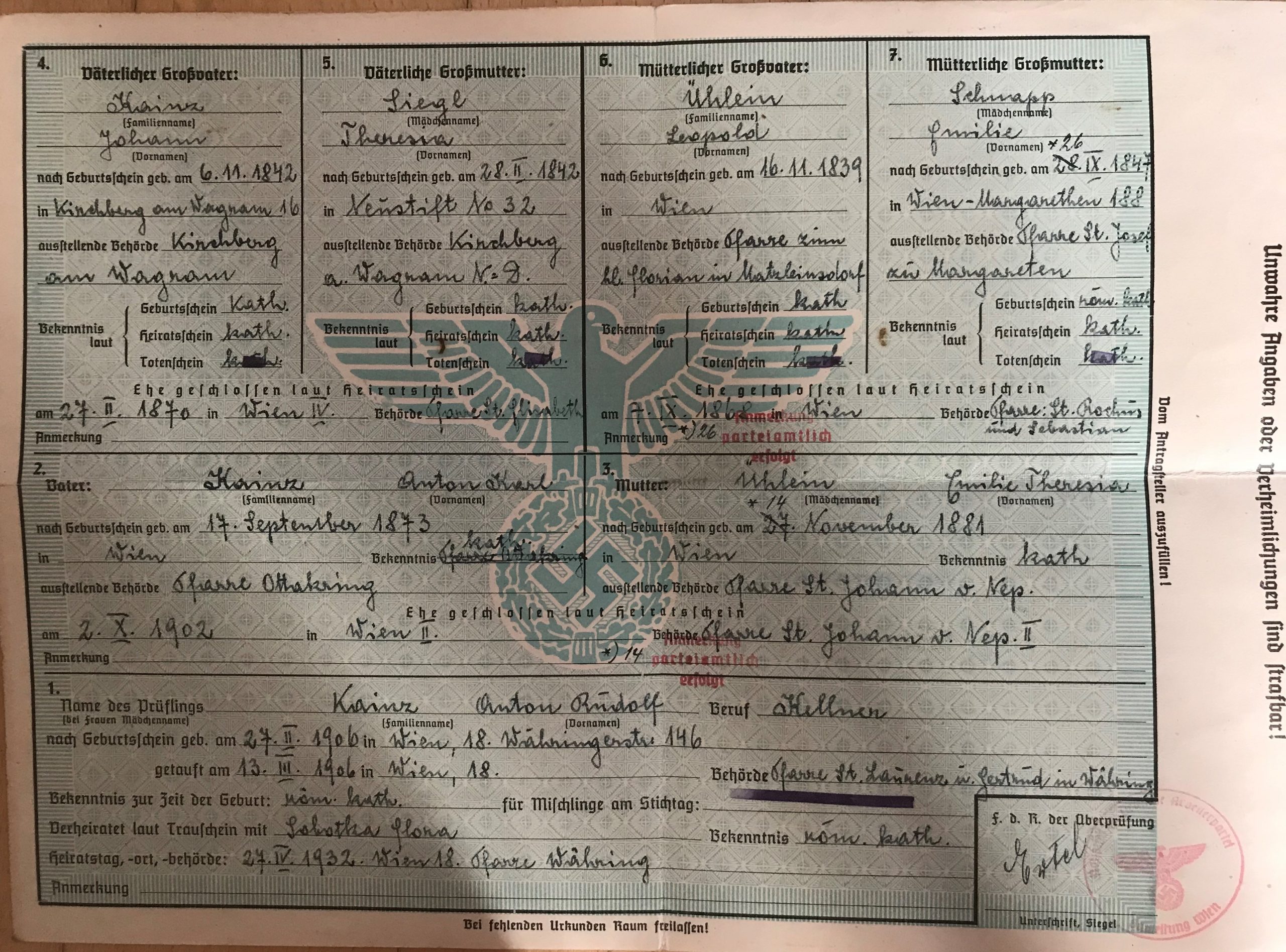

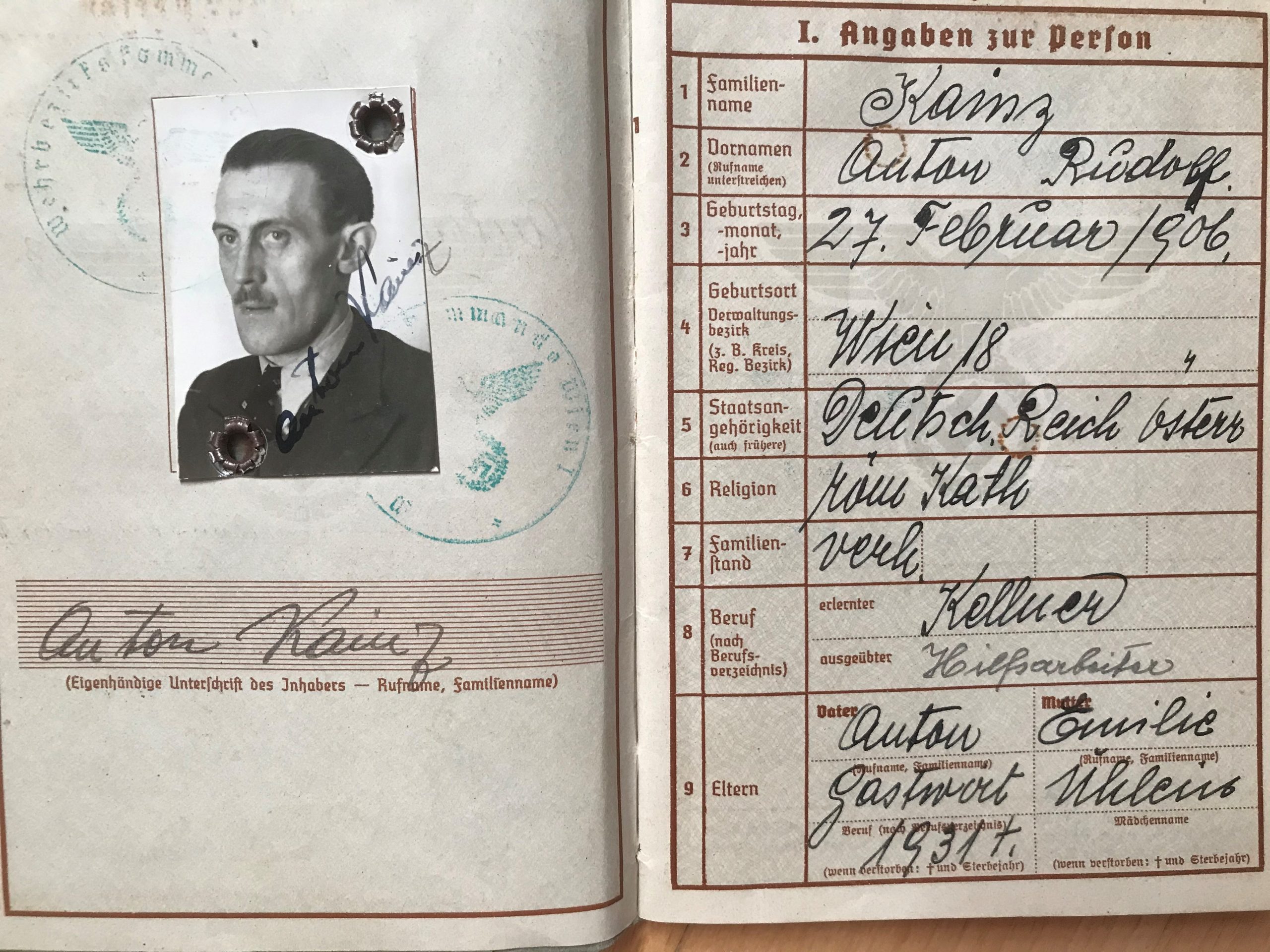

“Ariernachweis” (“Aryan Certificate) of Anton Kainz, Herta’s father. This document proved the “Aryan” status of Toni, which provided some fragile protection for Lola and Herta. The handwritten addition stated that Toni was married to a Jewess.

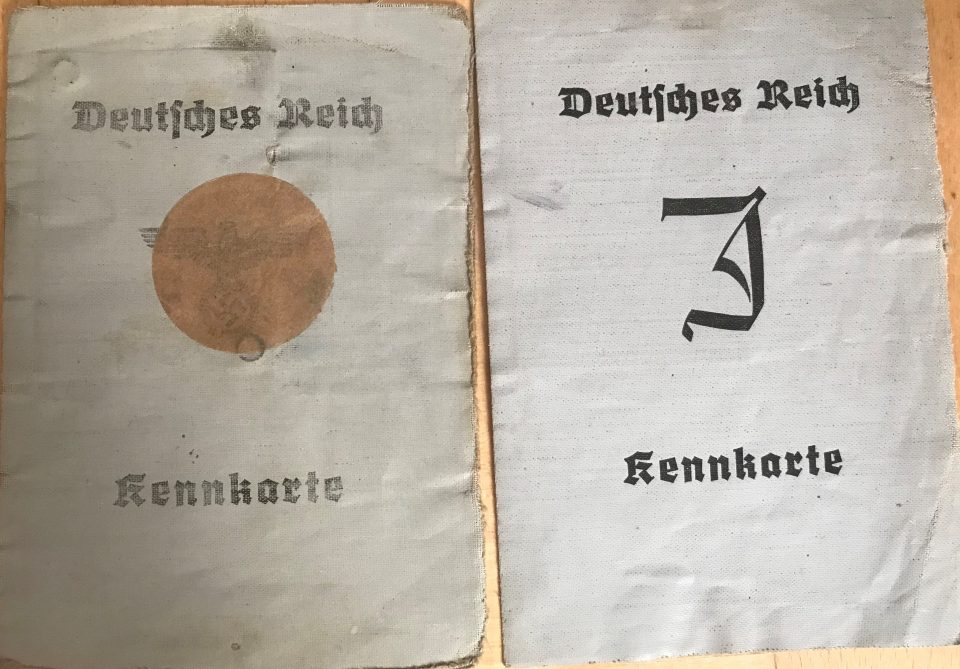

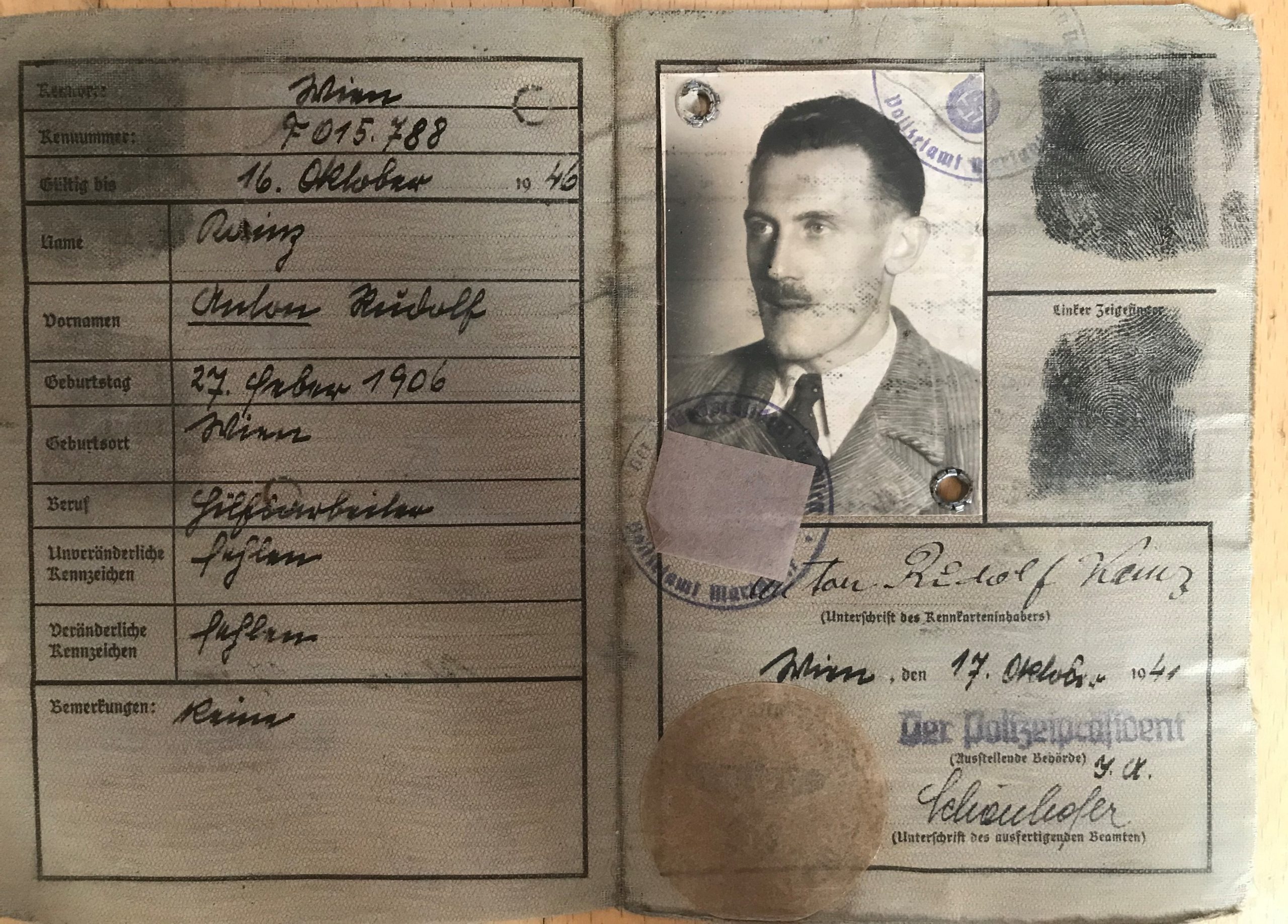

The Nazi IDs of Toni (left – the Nazi eagle was covered, probably because the ID was still in use after the liberation by the Allied Armies) and of Lola (right – marked with a “J” for Jewish)

If this photo of Lola of 1939 is compared to the photos of her before 1938 in the articles on classical music, suburban inns and suburban cafés on this research website, one can see that the happy-go-lucky beautiful young woman of those days had turned into a terrified, emaciated and desperate one within a year.

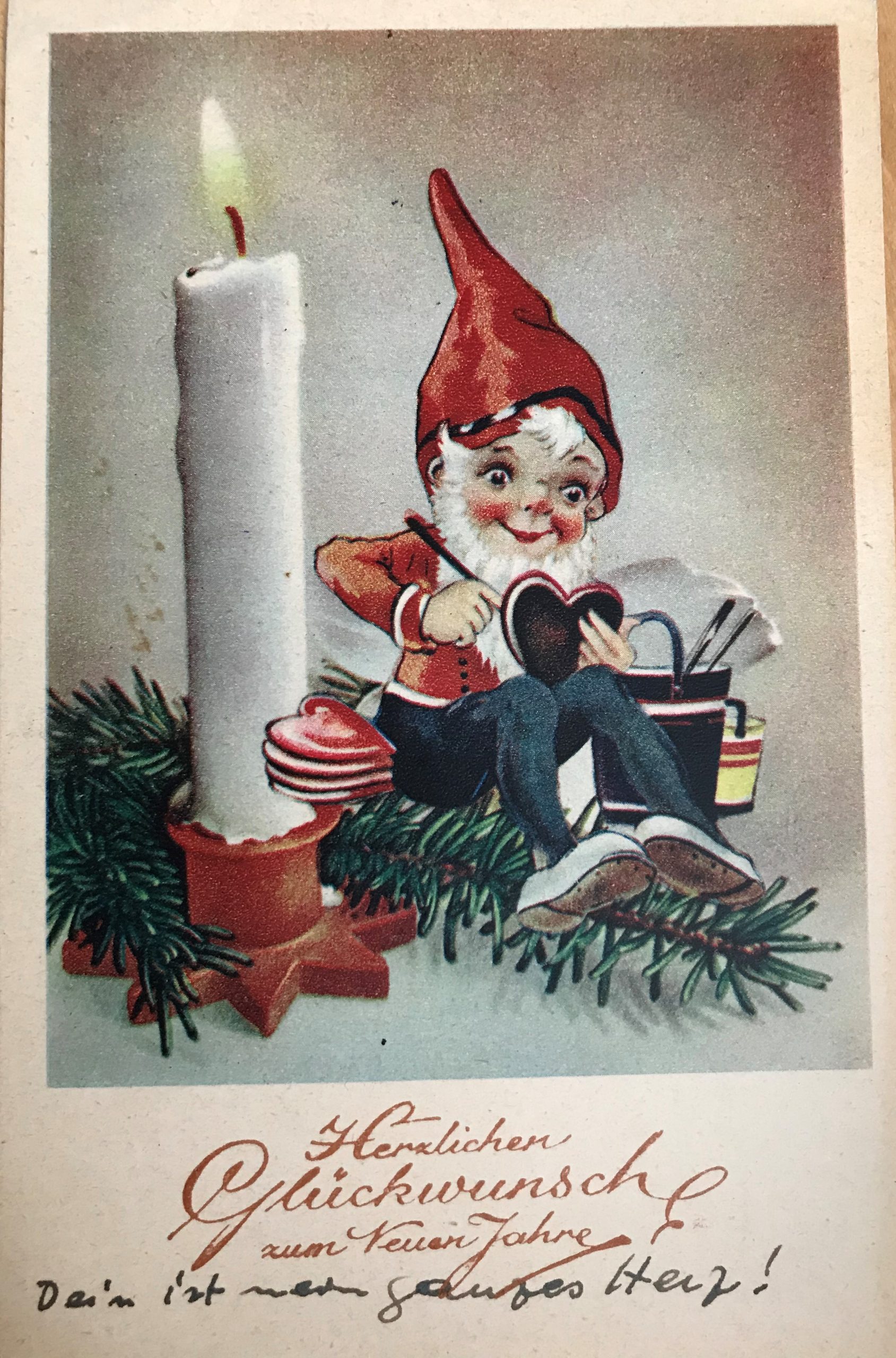

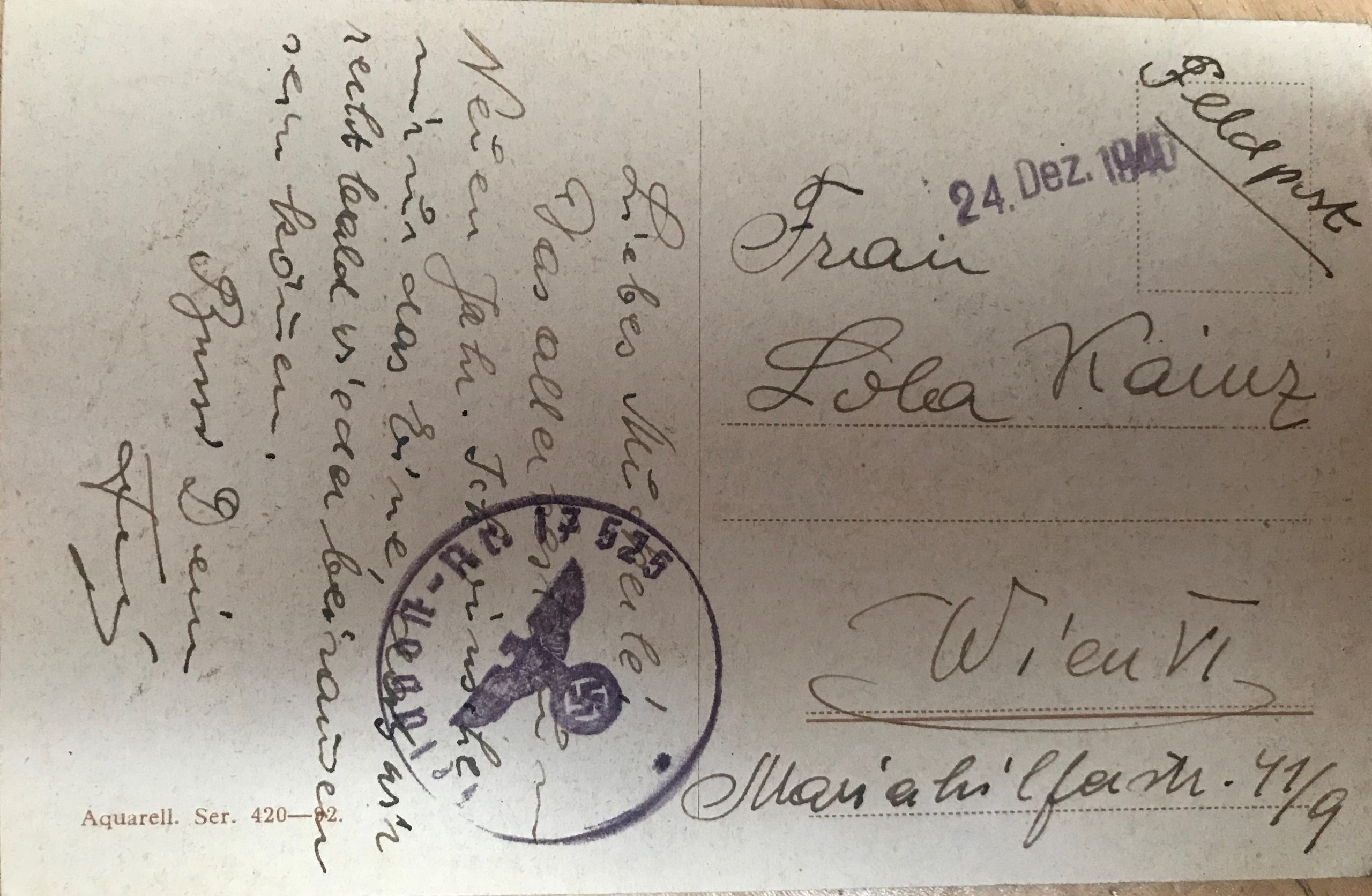

When Toni was drafted by the “Wehrmacht” for the campaign against France, he wrote this Christmas card to Lola from the front on the 24th December 1940 declaring his never ending love for her despite Nazi pressure to divorce her. He quoted the famous lines of the operetta aria “Das Land des Lächelns” by Franz Lehár: “Yours is my whole heart” on the front of the card.

The text Toni wrote, which was censured by the Army High Command, says: “Dearest Muckerle! All the best for the New Year. I only wish for one thing which is being together again very soon. Kisses, yours Toni”

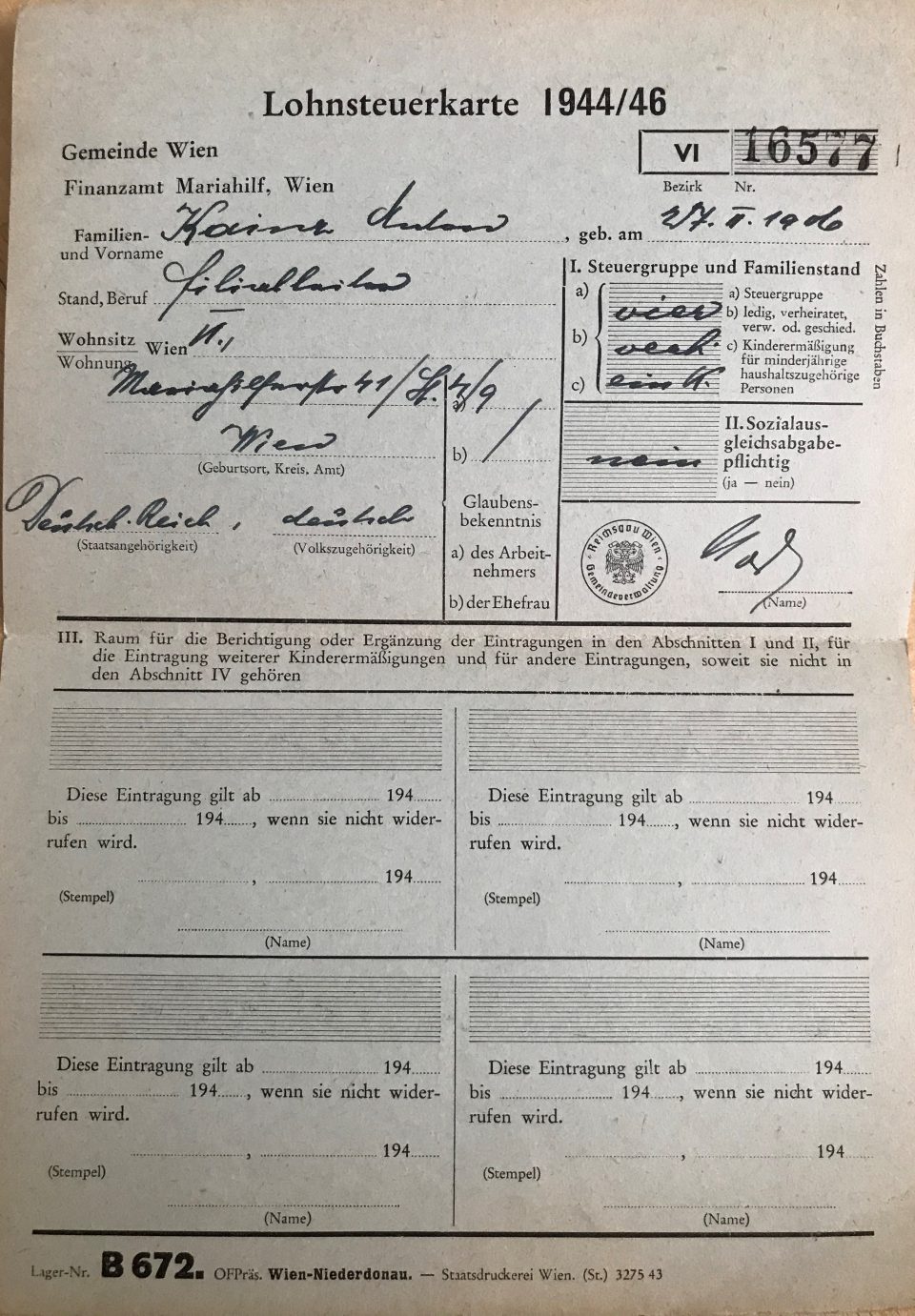

Toni,2nd on the right in front of the fish shop in Vienna, and his income tax card of 1944. He was made branch manager of a fishmonger’s after being dismissed from the army as “n.z.v.” (meaning “not to be used” ) because he had refused to divorce his Jewish-born wife, Lola. This is evidenced in his military service book in red:

The queues that formed in front of Toni’s fish shop during war time rationing

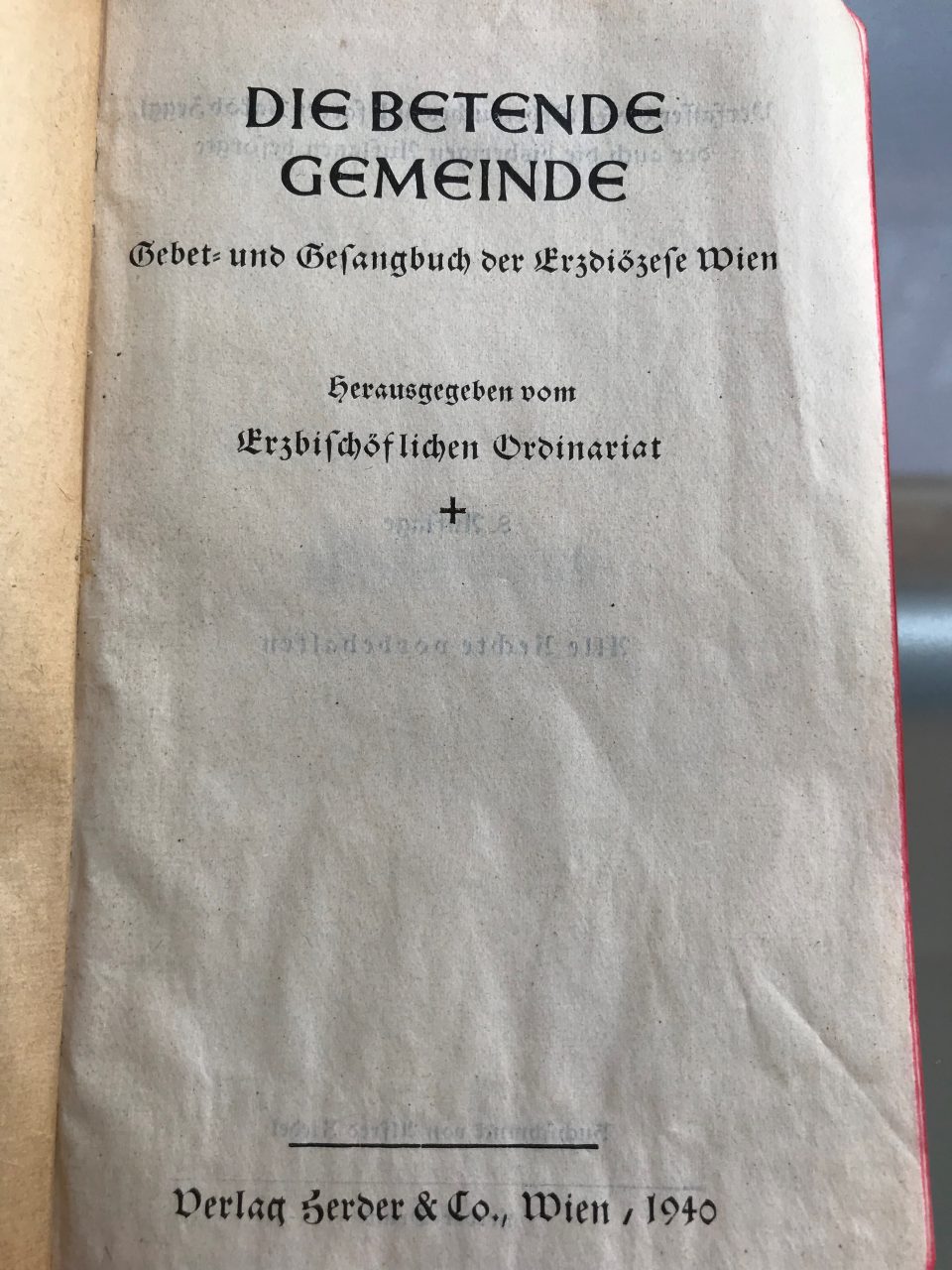

Only very few Jews survived the Nazi occupation in Vienna and most of them living either in “mixed marriages” or underground as so-called “U-Boote”. Yet they were permanently threatened by deportation. Many of the Jews in “mixed marriages” had converted to Christianity or were atheists and had very little or no connection to the Jewish community, just like my grandmother Lola, who had converted to Catholicism before marrying Toni and had been born into an assimilated Viennese Jewish family. Also my mother, Herta, was baptised and was a true believer all her life.

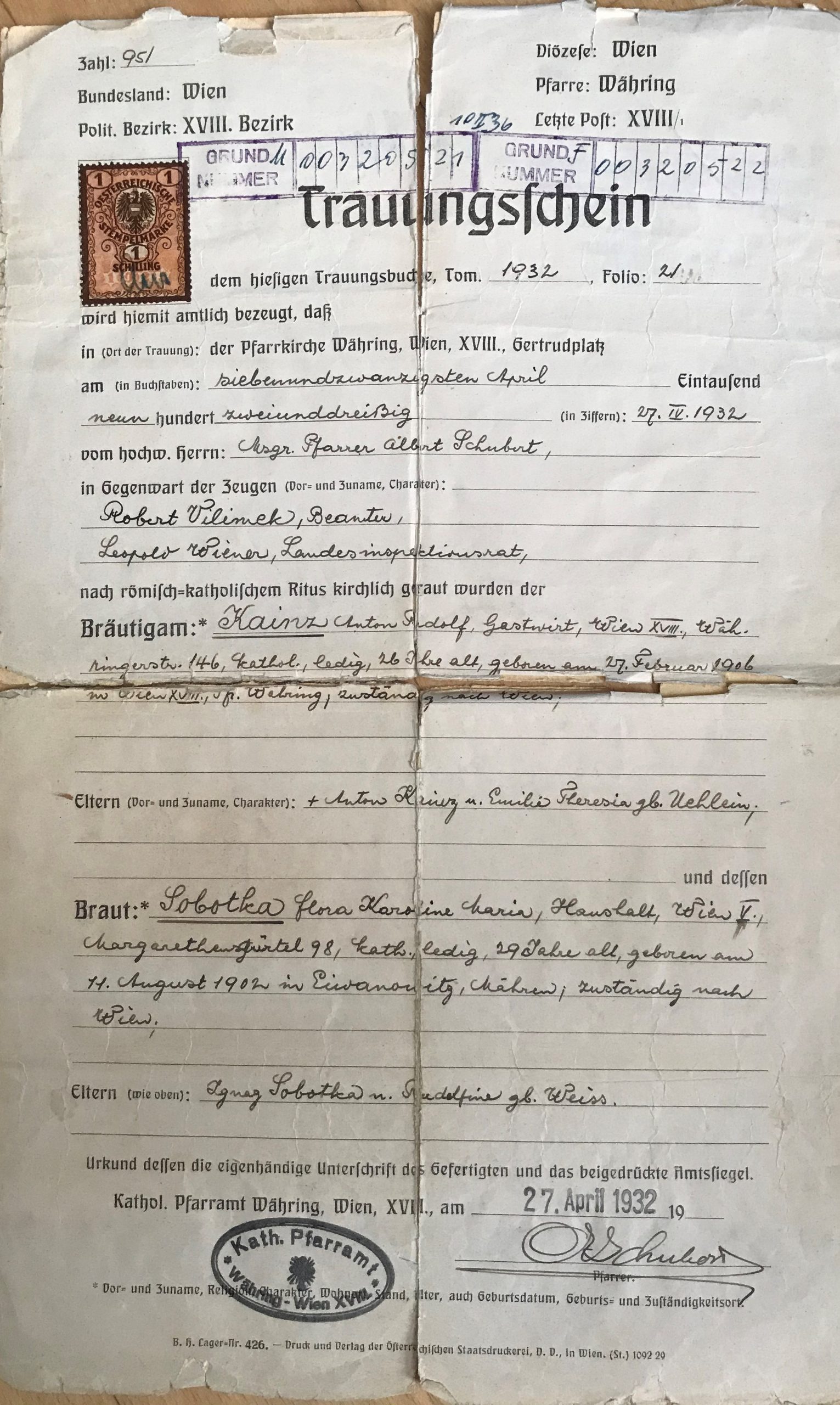

The Catholic marriage certificate of Lola and Toni, 27 April 1932 in the parish of Währing, Vienna

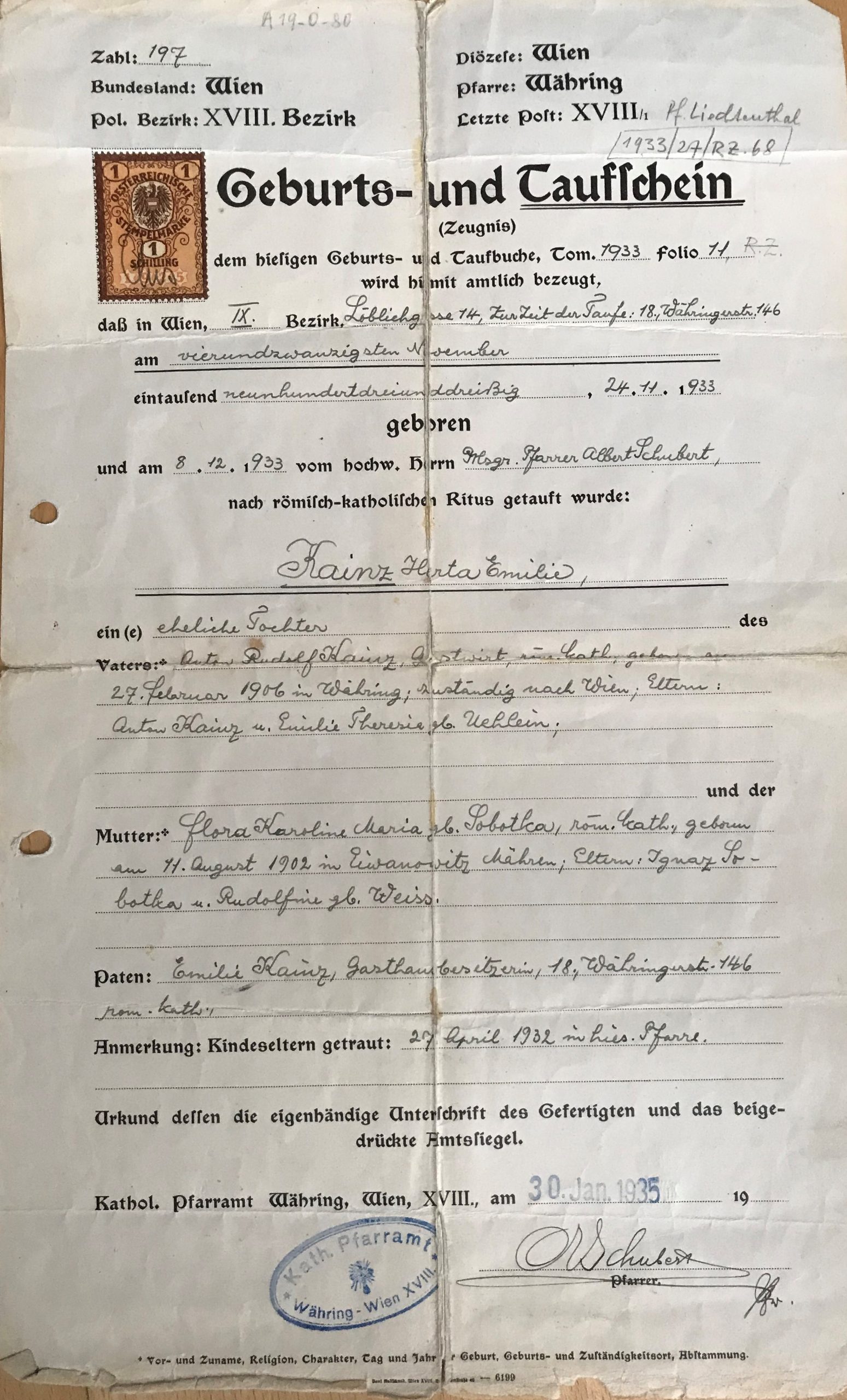

Herta was baptised on 8 December 1933 in the parish of Währing, Vienna

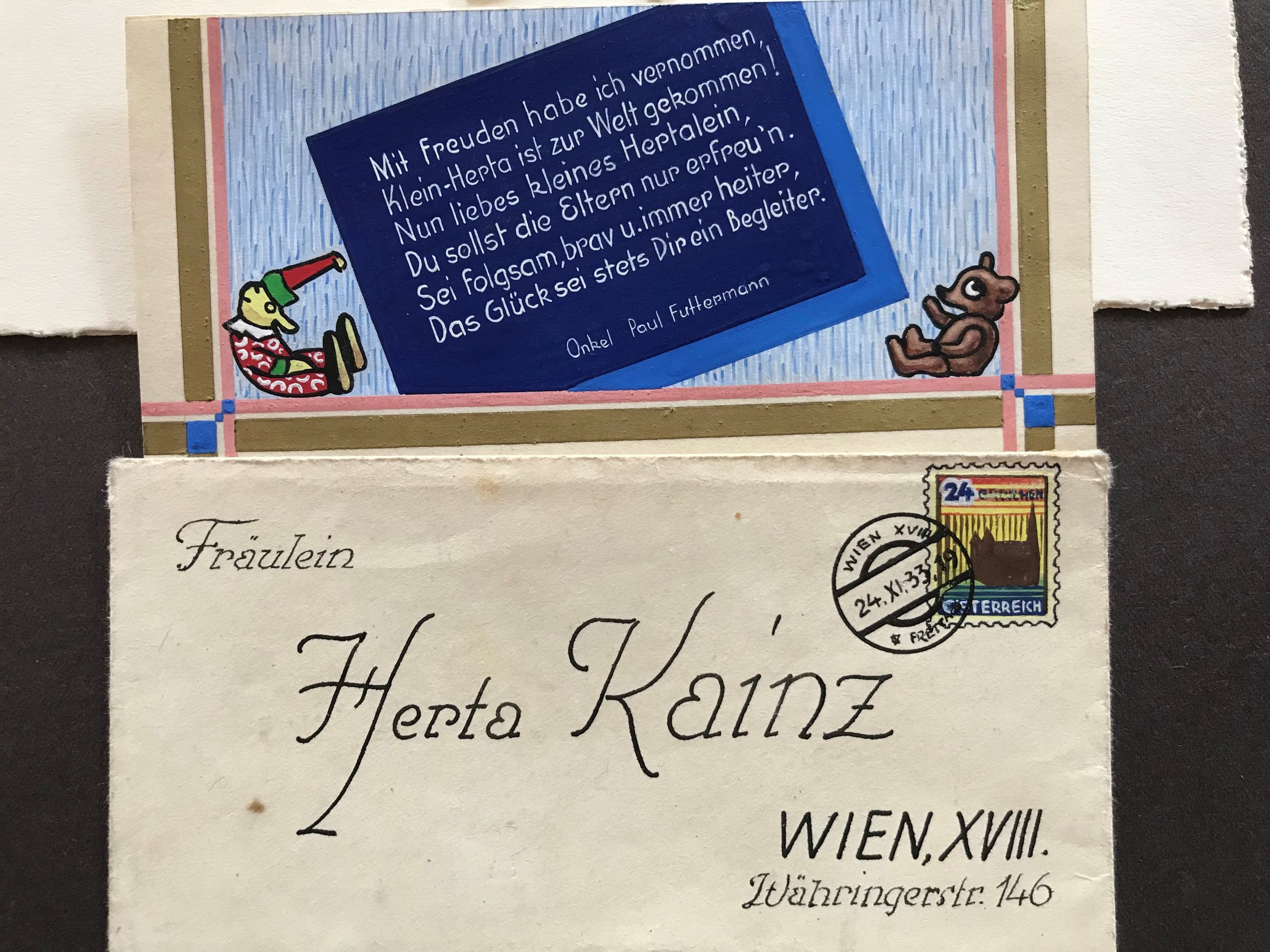

A hand-crafted birthday card was given to new-born Herta by her uncle Paul Futtermann

Herta at her First Communion (in the first row standing on the left)

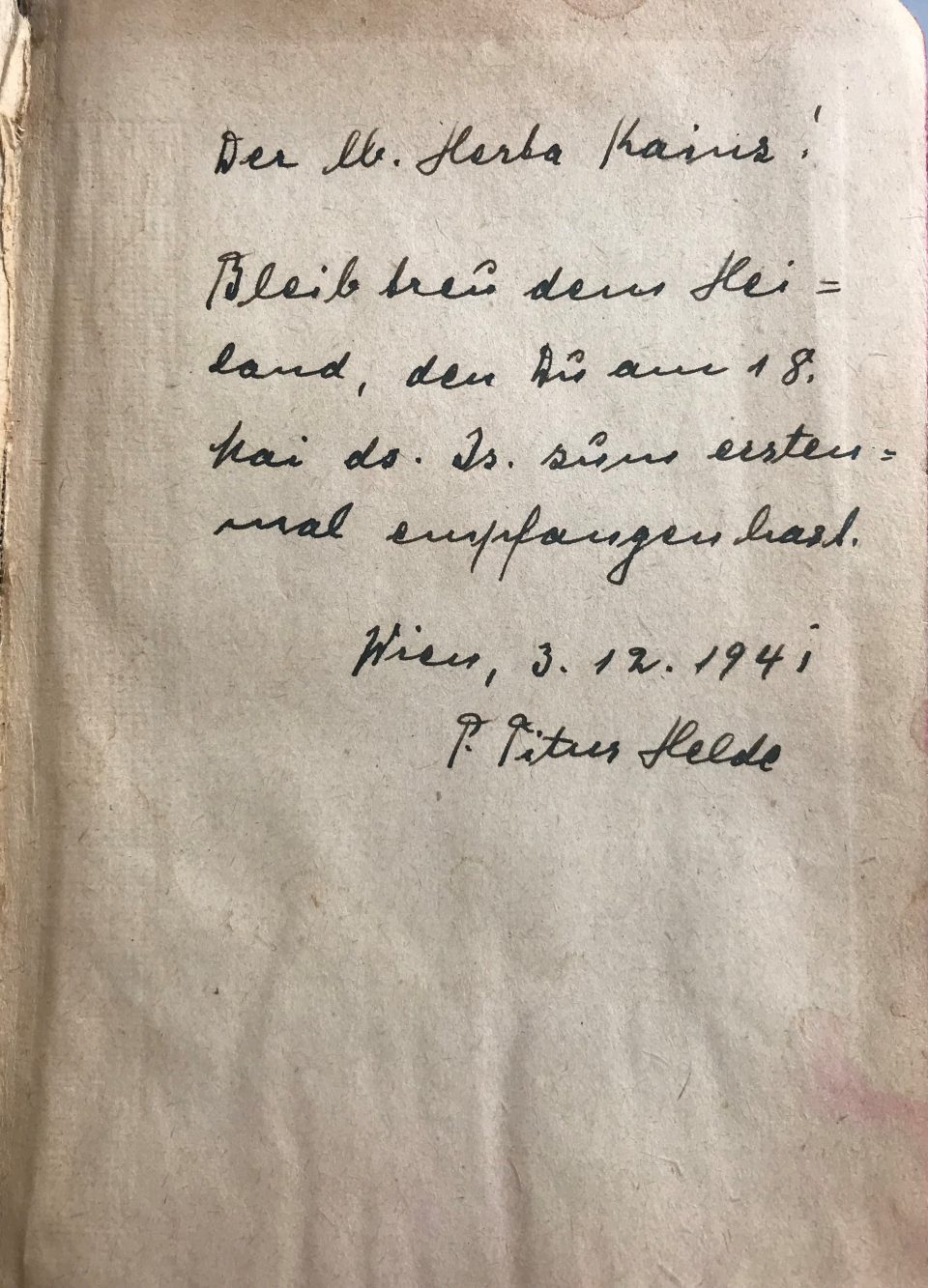

Below the dedication of her priest in her prayer book for her First Communion in 1941:

During the Habsburg Empire, which strictly regulated religious life, marriages between Jews and non-Jews were forbidden and these legal restrictions were maintained during the 1st Austrian Republic. So in case of marriage one partner had to convert to the other’s religion. An exception was the “Notzivilehe” (“emergency civil marriage”), which had to be applied for and one partner had to be unaffiliated with any religion. But anti-Semitic tendencies were already rife in Vienna since the end of the Habsburg Empire. After the “Anschluß” in March 1938 not only members of the Jewish community, but all persons of Jewish origin or family background were subjected to anti-Semitic discrimination on the basis of the Nazi Nuremberg Race Laws of the 14th of November 1935. Immediately these laws were implemented retroactively in Austria (with religious affiliation effective on 15 September 1935). These laws stipulated that persons with one Jewish and one non-Jewish parent were considered “Mischlinge” (“mixed-race”). They were either “Mischlinge 1.Grades”, like Herta, or “Geltungsjuden”. “Mischlinge 1.Grades” (“mixed race 1st degree”) were those who were baptised or atheist and they were considered neither Jewish nor “Aryan”. Those “mixed-race” people who were members of the Jewish community were so-called “Geltungsjuden” and were subject to the same degree of discrimination as the Jewish population. The fact that the Nazis had to resort to religious categories to underpin their racist policies underlines the absurdity of their ideology. “Aryan” partners in “mixed marriages” were continuously harassed because they were seen as a threat to the Nazi racist principles. According to the Nuremberg Race Laws “mixed marriages” were forbidden from 15 September 1935 onwards. In the end the existing “mixed marriages” were not dissolved, but there were permanent attempts at forcing the “Aryan” partners to divorce their Jewish spouses. As the majority of the “mixed couples” derived from a social background where religion did not play an important role, often their “mixed-race children” were confronted with the fact that one parent was of Jewish origin only after the “Anschluß”. But in several families in Vienna anti-Semitic prejudices against the Jewish partner were already present before the Nazi takeover; for example Toni’s mother was strictly against his marriage to Lola and pestered the young couple until they moved out of the house and inn they were running together.

Herta with her grandmother, Emilie Kainz, and her mother Lola. In honour of her grandmother she was baptised “Herta Emilie”.

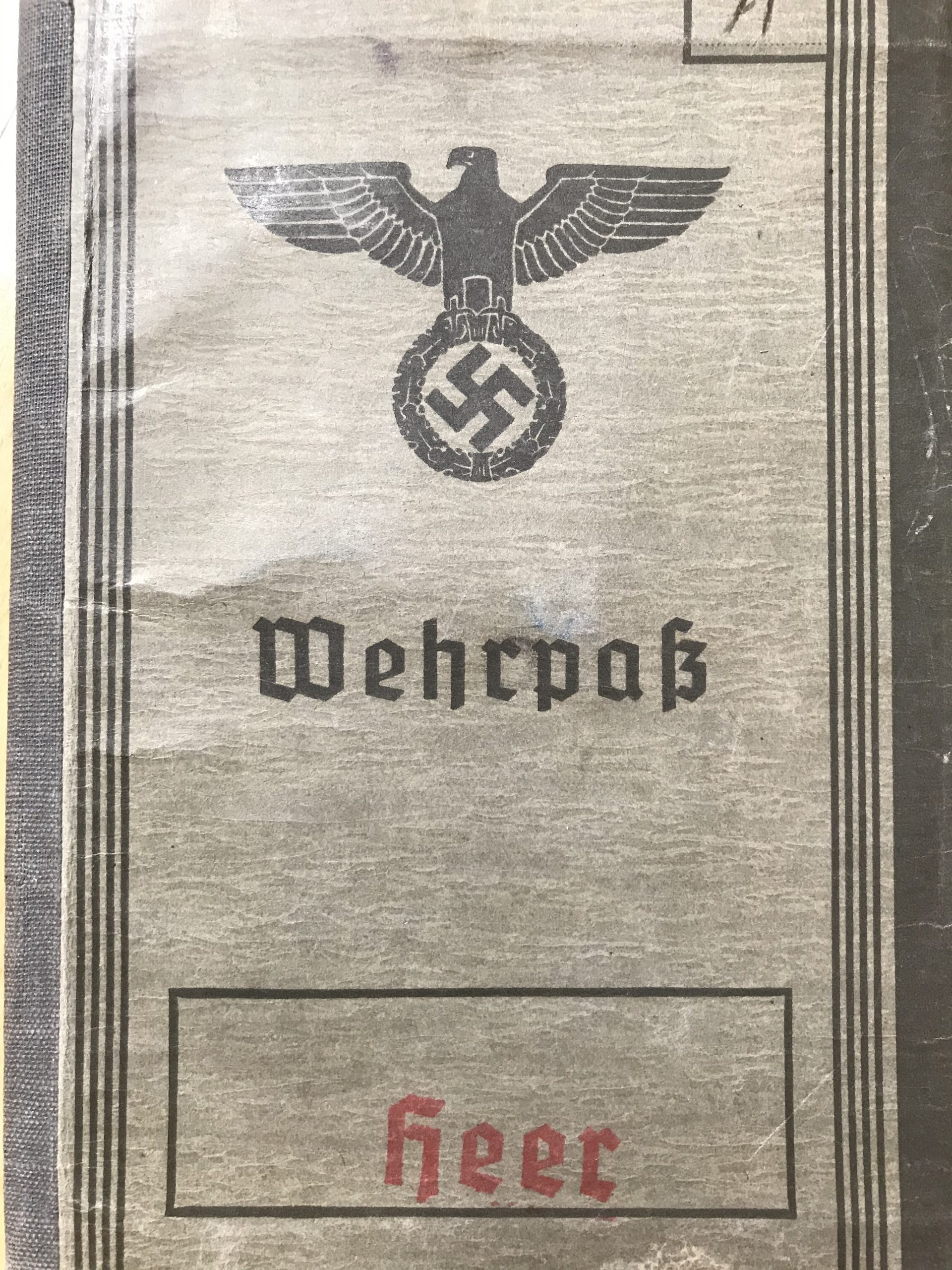

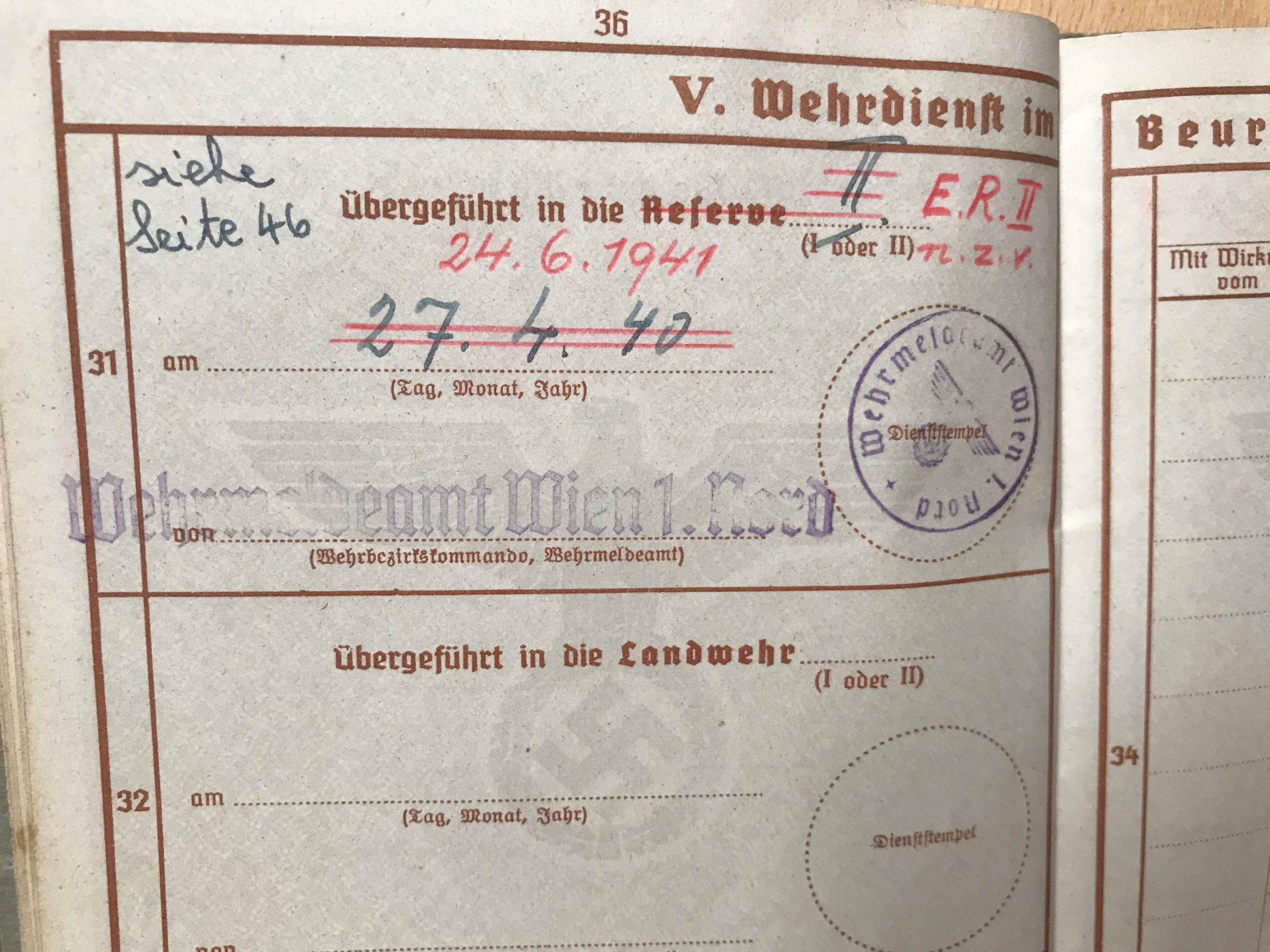

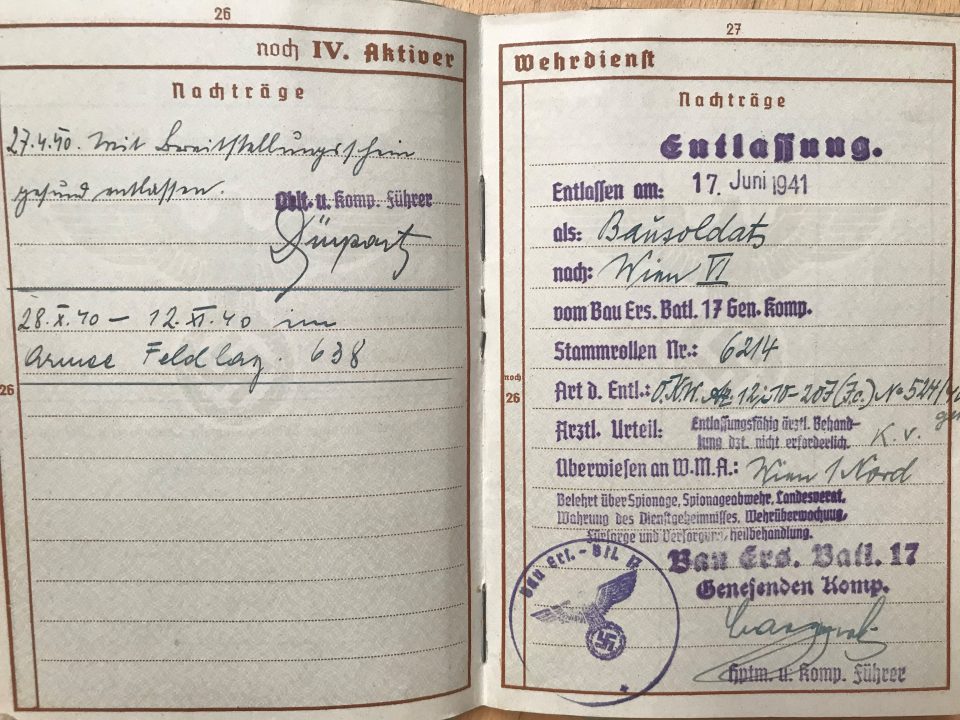

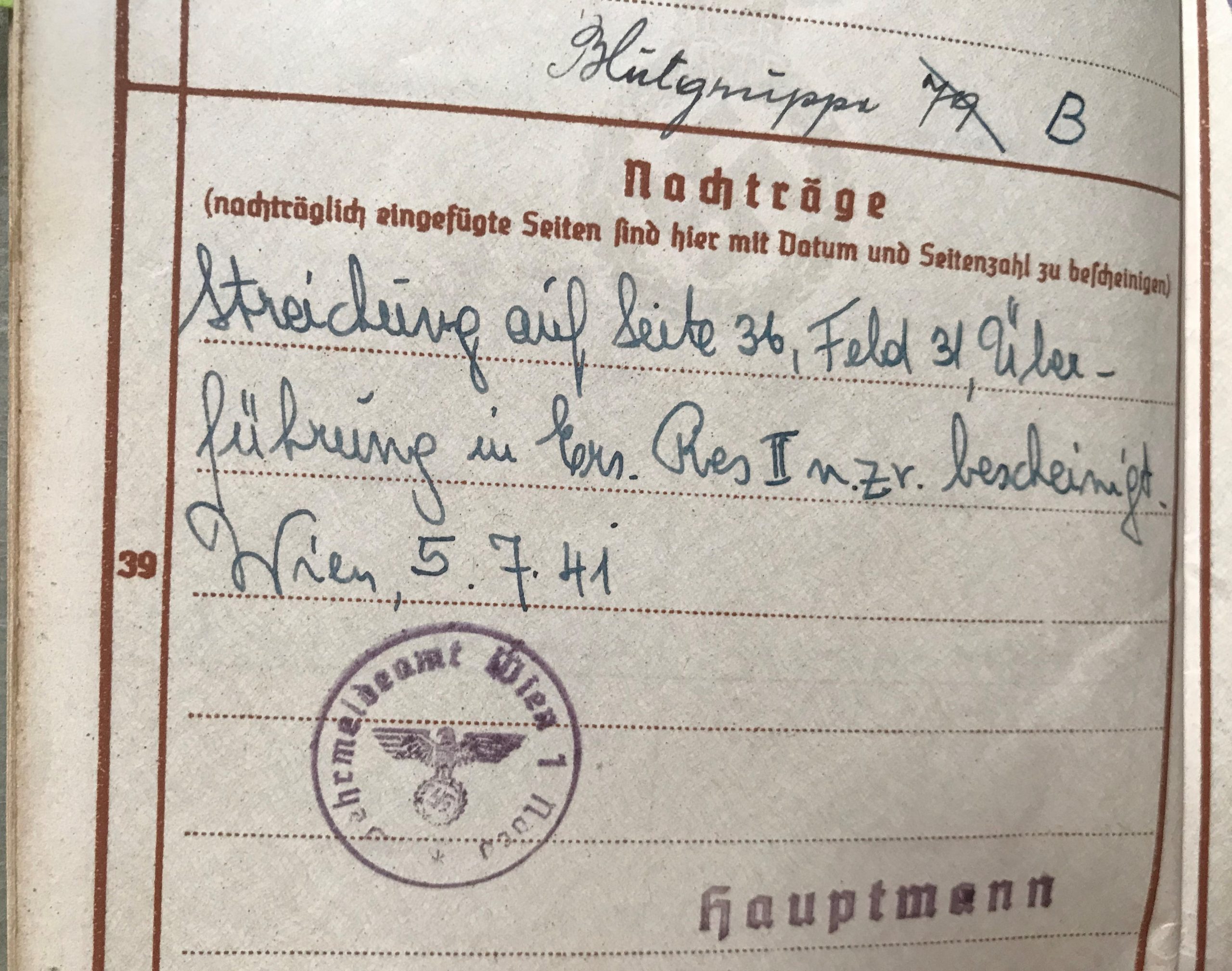

In May 1939 a census was carried out in the whole of the German “Reich” applying the criteria of the Nuremberg Race Laws. According to estimates 201,000 people who were categorised as Jews by the Nazis lived in Austria in 1938, most of them in Vienna. After the first wave of emigrations there remained 94,530 such persons in Austria in May 1939, 91.530 of them in Vienna. Consequently, Vienna had the highest proportion of Jewish population in the whole “Reich”. In this census 16.938 so-called “half-Jews” were registered in Austria, now called the “Ostmark”, 14.858 of them in Vienna. The majority of those were so-called “mixed-race persons 1st degree”. Immediately after the “Anschluß” some of those “mixed-race” children were obliged to participate in the Nazi Youth organisations, such as the “Hitlerjugend” for boys and the “Bund deutscher Mädchen” for girls, but half a year later they were considered “not worthy” and expelled. Herta reported that she was one of few girls in her primary school who was not allowed to participate, which underlined her status of pariah. Male “mixed-race” persons were drafted and had to serve in the army until the “Reich’s” High Command decided on 8 April 1940 via “Ausschlusserlass” (“exclusion decree”) that they were “unworthy” to serve in the army of the “Third Reich”. The abbreviation “n.z.v.” (“not to be used”) was then entered into their military service books. But also “Aryans” like Toni, who refused to divorce their Jewish spouse were “punished” by this “Ausschlusserlass” and Toni was sent back to Vienna from the military campaign against France to work in food supply as a manager of a fish shop, which was considered a sector essential to the war effort. Totally against the intentions of the Nazis, this was the rescue for Lola and Herta, because Toni remained in Vienna for the rest of the war and was able to protect his wife and daughter. This is another proof how absurd the Nazi ideology was as they could not have offered a better gift to Toni than dismissing him from the army and considering him “unworthy”.

Toni’s military service book

On 31 March 1939 Toni was declared an able-bodied (A1) soldier

On the 17 June 1941 he was dismissed from the army as “construction soldier” and transferred to “Vienna 1 North”

The second entry in Toni’s military service book which declared him “n.z.v.” (“not to be used”)

Toni’s “Ariernachweis” (proof of “Aryan” status”) was the precarious lifeline for his wife and daughter (see photos at the beginning of the article). In order not to provoke protests among “Aryans” the NS authorities decided after the November pogroms of the 9th and 10th November 1938 to allow some “mixed marriages” a privileged status, namely those where the husband was “Aryan” and the wife Jewish. They were allowed the same food rations as the non-Jewish population and could mostly remain in their flats, which was the case with Toni, Lola and Herta. If the husband was Jewish, the family was only privileged if there were children who were not members of the Jewish community. Yet families where the husband was “Aryan”, but the children were educated in a Jewish environment were not granted a privileged status. The consequence was that Jews of “non-privileged mixed marriages” and so-called “Geltungsjuden” had to wear a widely visible yellow Star of David on their clothing. At the “Wannsee Conference” of 20 January 1942 the leading Nazis decided on the precise mechanisms of how to exterminate the Jews in the whole “Third Reich” and the “mixed-marriages” were considered an “unsolved problem” and an “embarrassing blemish”. Several high-ranking party representatives pleaded for an integration of the Jews in “mixed marriages” and the “mixed-race children” in the deportation and extermination programme, so that these “embarrassing” groups of persons would finally “disappear”. Wilhelm Stuckart and Bernhard Lösener urged the start of a sterilisation campaign among these persons, but in the end this programme was not feasible. So the party leadership decided that “for now” these persons were not subjected to the extermination policy because the “psychological and political consequences on the home front on the part of the Aryan family members were incalculable”. Nevertheless, during the last years of the war the terror exercised against these “mixed families” was intensified. Especially “Geltungsjuden” and Jews in “not privileged mixed marriages” were permanently attacked in public because they had to wear the yellow Star of David and they suffered from frequent denunciation of fellow citizens. After the completion of the deportation of the majority of Jewish citizens to concentration camps in October 1942 the remaining members of “mixed families” were in the focus of attention of anti-Semites.

Already since October 1941 “friendly encounters” between Jews and “Aryans” were forbidden. The anti-Jewish legislation covered large parts of daily life and minor infringements led to arrest and deportation to concentration camps, such as covering up the Star of David on a coat or buying cakes for a Jewish family member or being caught purchasing eggs or milk. The absurd anti-Jewish laws prohibited school attendance, the keeping of pets, the buying of cakes, the use of public transports, setting foot in public parks or the Vienna Woods, the purchase of eggs, milk, meat and wheat products, going to cafés, restaurants or cinemas. Jews did not receive ration cards for clothes and shoes and much smaller food rations. All Jewish partners of foreign non-Jewish citizens and their “mixed-race children” were deported because they were not protected by their non-Jewish family members. Neighbours even informed against members of “privileged mixed marriages”, for instance for wearing traditional Austrian costumes or for listening to foreign radio stations or for going by bike to farmers to barter their clothes for food, which was strictly forbidden as well. Toni and Lola breached the rules as did many others. Lola was extremely good at bartering and when the family went to the countryside, it was Lola who talked to the farmers and she never returned without food. Most of all, it was common in the household of Toni and Lola to listen illegally to the Allied radio stations to know how near liberation was and Herta was trained not to tell anybody about it, which was not a problem as she was an extremely shy and obedient child. Divorce or the death of the “Aryan” partner meant instant deportation of the rest of the family to concentration camps. Notorious informers were concierges and neighbours in Vienna who wanted to move into the flats of the evicted families.

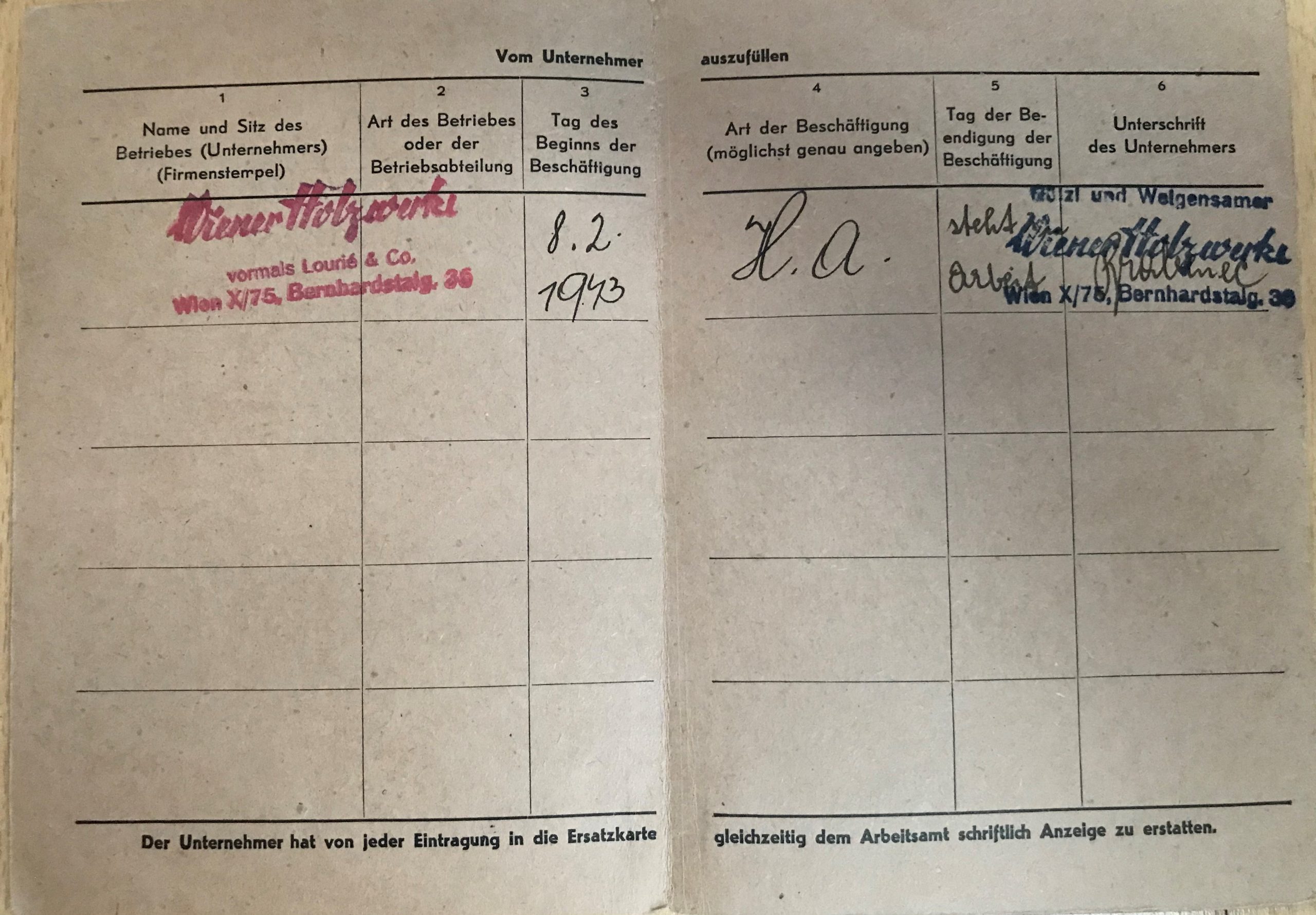

All remaining Jews were coerced to forced labour from 14 years of age on since October 1941 and in September 1944 the conditions of forced labour were further exacerbated: they had to work 60 hours per week, seven days a week; they had only Saturday and Sunday afternoon off.

Lola worked in “Wiener Holzwerke”, which a certificate of 16 March 1943 proves, where it is noted that she has to work until 22.30 at night. She is categorised as a Jewish manual worker on her income tax card of 1944

Lola’s “Work Book” shows that she was hired as forced labourer for the “Wiener Holzwerke” in 1943

The women who were forced labourers during the war and worked together in the same enterprise often formed a long-lasting bond of friendship. Lola met the “Mäderl” (“girls”) from their common time of forced labour until her death in 1991 in the “Extrazimmer” (separate room) of the Cafè Windhaag near Stubenbastei in the 1st district of Vienna, which is now Cafè Engländer, every Sunday afternoon. During the summer months they met at the “Meierei” (“dairy”) in Stadtpark (before it was the fashionable restaurant it is now). Lola told very little about this time of her life and she never complained or lamented her destiny. On the contrary, she always stressed the “sunny side of life” and narrated the funny and amusing stories she had experienced in those dark times.

Left: Lola in the middle in the brown lace dress among the ”Mäderl” ( “girls”) of the “Wiener Holzwerke”. Right: Lola’s “Mäderl” (“girls”) club with herself third on the right at the Café Windhaag

Immediately after the “Anschluß” Jews were forced out of the Viennese labour market and between 1938 and 1941 Viennese and German authorities independently drew up various regulations for forced labour of Jews in Vienna. On 3 October 1941, just before the start of the large-scale deportations, the Nazis created a universal rule book stating that the employment of Jews was not subject to the Employment Act, which meant that they had no employee rights and benefits. But in Austria and Vienna these strict rules had already been implemented before. Forced labour in Vienna was used for private as well as for public enterprises, but it was difficult to find employers because most forbid the employment of Jews on the basis of anti-Semitic race laws. A plan to build a barracks camp for 30,000 forced labourers near Vienna to be employed for road works and forestry was started in October 1938, but collapsed due to mismanagement. At the beginning the expulsion of Jews from the Austrian economy was devised with the aim to push as many as possible into emigration and to requisition their assets. But the SS wanted to exploit Jewish slave labour from the start and urged for so-called “retraining camps”.

In Vienna many forced labourers had to work for the army in enterprises such as the collection point for empty packaging in Leopoldstadt, the potato store houses in Liesing, the army horse stables in Kledering or a private leather textile firm in Mariahilf, which produced leather jackets for the army or in the factory of Schrack-Ericsson, where Jewish forced labour and “Aryan” workers were strictly separated. The worst place to end up was the huge garbage collection of Vienna, where today the United Nations building is situated. Since February 1941 an increasing number of adolescents were used as forced labourers for road construction, in gravel pits and for the building of the hydroelectric power plant in Kaprun, Salzburg. Most women were forced into working for enterprises that equipped the army, such as the “Wiener Holzwerke”, where Lola worked. In October 1943 Herman Göring ordered that even more “mixed-marriage” Jewish and “Aryan” partners and “mixed-race” persons had to be recruited for the “Organisation Todt”, whose main aim was to build defence structures and trenches in France and east of Vienna to protect the Nazis from the approaching Allied forces in the west and in the east. As soon as the “Aryan” male partners were drafted away from Vienna, the remaining wives and children were without protection and could be deported. The GESTAPO did not only procure forced labour, they also used it in their own enterprises, for instance the “Vugesta” which dealt in the possessions of the Jews evicted from their flats and houses.

In January 1945 the “Reichssicherheitshauptamt” ordered the deportation of all Jewish “mixed marriage” partners and “Geltungsjuden” to the KZ Theresienstadt. Around 1,600 so far protected persons were deported from several German cities. Fortunately the transport which was planned from Vienna to Theresienstadt at the end of February was cancelled at the last moment by the local Nazis, officially due to the fast approach of the Red Army. On 13 April 1945 Vienna was liberated by the Red Army and at that point of time 5,512 persons who were classified as “Jews” by the Nazis had survived in Vienna and additionally 1,000 persons who had been hidden by friends as so-called “U-Boote”.

Herta in the first form of primary school (first in the second row on the left with the white bow in her black hair) in the school year 1939/40

Herta in primary school (first row, second from the left)

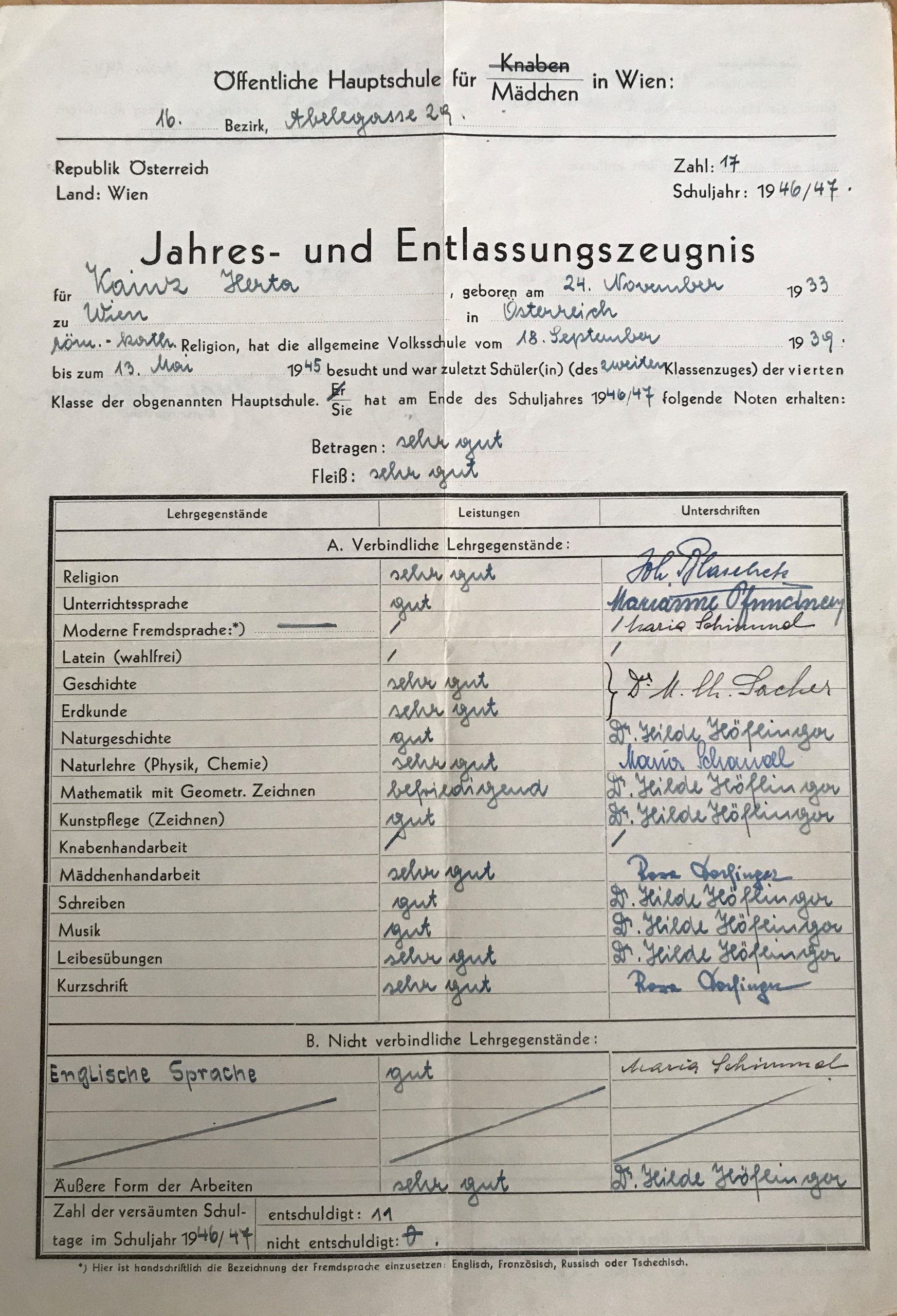

Racial discrimination, exclusion and repression affected the educational institutions as well. Immediately after the “Anschluss” in March 1938 the so-called “Geltungsjuden” were subjected to the same discriminatory restrictions as the Jews, which meant they were to be isolated from the rest of the population in Austria. Already on 27 April 1938 Jews and “Geltungsjuden” (approximately 1,400 in Austria) were expelled from grammar schools and on 16 May 1938 from primary and comprehensive schools, too. This is another proof that the Austrian Nazis acted earlier and much more aggressively than their German counterparts because in Germany the school expulsions took place after the November pogroms, namely half a year later. At the beginning of the Nazi rule “mixed-race” children were officially allowed to attend grammar schools, but with the edict of 2 July 1942 they were excluded from higher schools, which resulted in the fact that they could only attend primary schools. Herta was forced to stay on in primary school until the end of the war, when she was transferred to a comprehensive school, where she had to catch up a lot on several subjects. She remembered especially the English lessons, where she was too shy to mention that she did not understand a word because in primary school they were not taught any foreign languages. But she managed in the end, as the report card below shows. These children had lost out on their schooling and had to make up for those lost years of education after the war. The few Jewish children who had remained in Vienna after the large-scale deportations faced a complete ban on schooling from 20 June 1942 on. Yet several of them were educated secretly and consequently faced huge risks because the children and teachers were instantly deported in case of discovery.

From 18 September 1939 until 18 May 1945 she had to attend primary school, which means six years instead of four, and was transferred immediately after the liberation to a comprehensive school, where she performed very well, even in English.

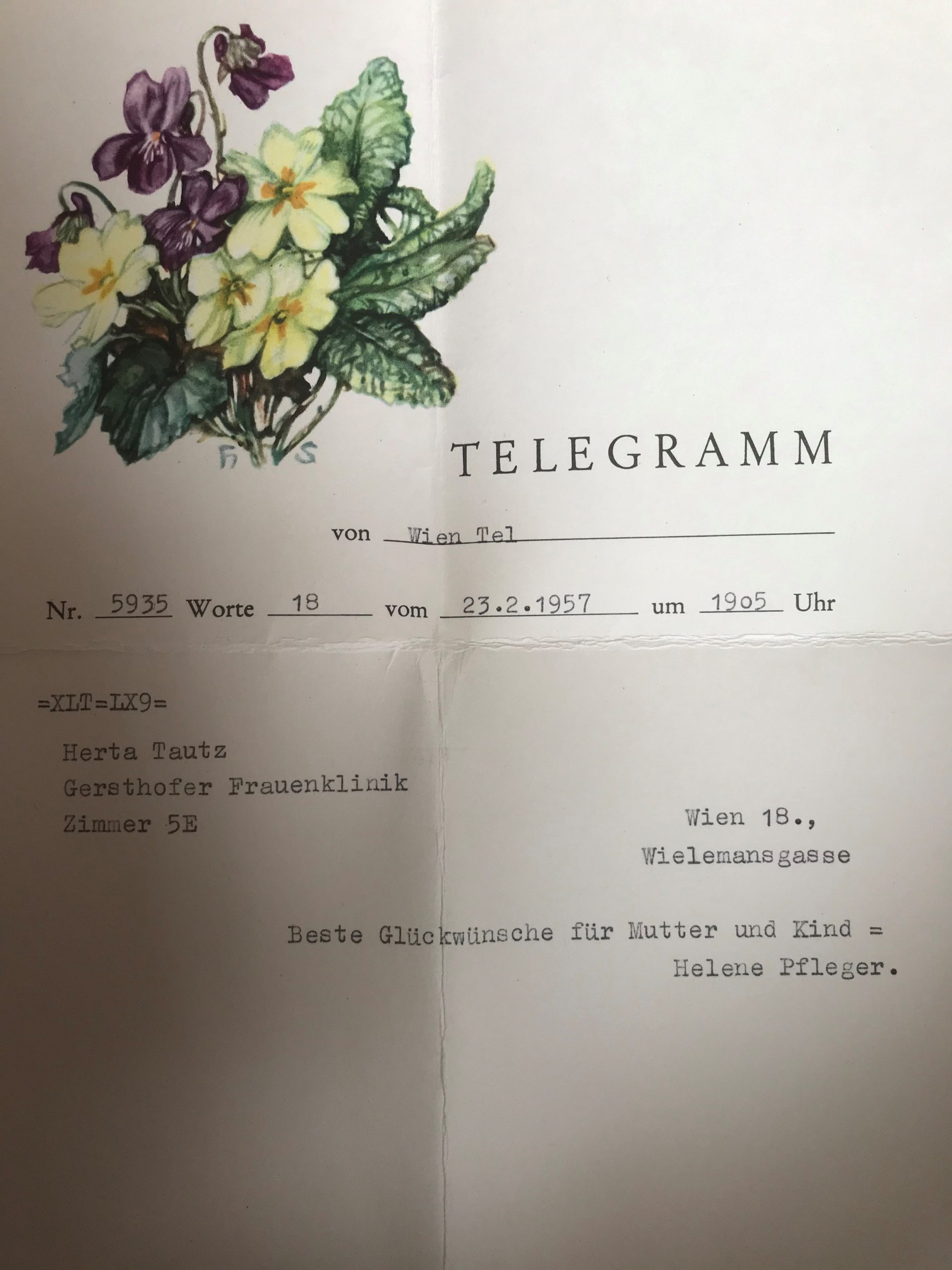

In July 2003 Matthias Wurm interviewed his grandmother, Herta, and Friederike Kren, another Viennese “mixed-race child” and Herta’s primary school teacher, Helene Pfleger, on their experiences at school during these years.

Matthias Wurm on the left, Herta on the right with Friederike Kren in the middle

Herta, born in 1933, adored her primary school teacher, Helene Pfleger, born in 1919, and kept in contact with her as long as she was able to. They had long telephone calls on their birthdays and again met up for this interview. Herta tremendously appreciated the loving care that this young teacher showed for her. Helene Pfleger risked a lot, because she did not comply with the racist rules and allowed Herta to sit in the first row instead of the last row in class, for example. Herta reported that she was a silent and extremely timid child and Mrs. Pfleger kept her close to her to be able to protect her. When the other pupils were loud and unruly, she smashed her ruler on the teacher’s desk, which scared Herta. Mrs. Pfleger then always stroked Herta to calm her. Mrs Pfleger created a climate of cooperation und mutual acceptance in class so that Herta never had the impression that she was rejected by the other pupils. With the permission of her parents she was allowed to attend Catholic religious instruction lessons and receive the First Communion. She remembered the great impression the visit of Cardinal Innitzer in the parish of Mariahilf made on her, when all the girls formed a guard of honour, clothed in white dresses. Herta remembered that she played with the children in the courtyard of the house where she lived in Mariahilferstrasse 41 and also visited them in their homes and vice versa. Herta further reported that nothing was hidden from her by her parents; she knew about the dangers her mother was facing and was involved in the contingency planning. She was informed about the eviction of her grandparents and their transfer to a “Sammelwohnung” (collective apartment) in the 2nd district of Vienna before their deportation to the KZ Theresienstadt and the food parcels they sent them to help them survive.

Friederike Kern, born in 1929, reported that she only realised in 1939 that she was a so-called ”mixed-race child” and that her father was a Jew, when these facts were revealed to her in the Catholic school she attended. She was not the only “mixed-race child” in this convent school and she was allowed to participate in all religious activities. She further mentioned that her grandmother on her father’s side had opposed the marriage of her parents and had insisted that she attended a Jewish school, which her parents refused and in the end this probably saved her life. Her best friend was an “Aryan” girl whose father was a convinced Nazi who prohibited his daughter to meet Friederike, but the girls continued to see each other secretly. They often visited a tailor named Rosenbaum in their house who had a shop on the ground floor and who gave them pieces of cloth and other haberdashery wares to play with. One day the girls noticed that the SS had dragged Mr Rosenbaum from his flat and pushed him down the stairs. The two girls tried to help him, but the Nazi father of Friederike’s friend was so furious that he kicked Friederike in the stomach. She had to be rushed off to hospital and had to be operated on. After the war he came to her to make excuses, which she did not accept. Her mother wanted to prevent her children from having to wear the yellow Star of David in public and so divorced Friederike’s father, who was able to flee to Switzerland, but Friederike’s Jewish grandparents were murdered by the Nazis. When the convent schools in Austria were closed, no other school wanted to accept her. So her mother, who was Czech, decided to return to occupied Czechoslovakia to live there with her sister. So Friederike had to attend a Czech primary school where she did not understand a word because she did not know Czech. Therefore she returned to Vienna before the end of the war at the age of 15. After arrival she was constrained to forced labour in the fields and in an ammunitions factory. She was terrified that the detonators she had to handle would explode in her hands and was therefore arrested for obstruction and imprisoned together with French prisoners-of-war and prostitutes behind the “Westbahnhof” (West Station) for eight days.

Herta (first row, second from the left) in primary school with her beloved teacher, Helene Pfleger

Helene Pfleger, Herta’s primary school teacher from the second to the fourth form, remembered that this was her first employment and the two “mixed-race” children in her class were the most docile and committed. Nevertheless she had to enter into their report card the worst grade for their behaviour in class, which was a three. A refusal of complying with this rule would have been sanctioned by instant dismissal. At her primary school she could treat the pupils equally in any other respect. She was informed by the school administration that Herta’s mother, Lola, was not permitted to set foot in the school’s premises because she was a Jew and Mrs. Pfleger remembered how fragile Lola was and how exhausted because she had to do forced labour and carry heavy boxes. So Toni, Herta’s father, was the one to come to school. When Herta contracted scarlet fever and had to be treated in hospital, her mother Lola was not allowed to enter the hospital because she was Jewish. So she had to stand in the street under the window of Herta’s sick room and they communicated via finger alphabet. During the time of Nazi rule Jews were not permitted to receive any medical treatment.

What really shocked Helene Pfleger was that after completion of the fourth form of primary school, the two “mixed-race” children were not allowed to move on to grammar school or comprehensive school, but had to stay on in primary school until the age of 14. So Helene Pfleger met up with Herta privately and instructed her on subject areas she would have learned in grammar school or comprehensive school, but that was not easily organised. The head master of a primary school had to be a member of the NS “Lehrerbund” (teacher association), but the director of this primary school in Mariahilf tried not to let party politics influence the teaching at his school and seemed to have protected his teachers and pupils from Nazi excesses, which finally resulted in his dismissal. He was transferred to Salzburg, where he had to transport milk and was later killed in an accident. Under his tenure the school day was not started with the “Hitler salute”, as in other schools, but instead of a cross there had to be a photo of Hitler in class. After four years of teaching Helene Pfleger had to pass an exam to receive her teaching certificate, which was to cover all relevant material, but in fact concentrated on Nazi ideology only. So the exam was a farce and was designed to humiliate her because she was not a party member and was pregnant out of wedlock. In the end the NS commission allowed her to pass with a three, her worst grade ever, and the chairman of the commission told her, she was granted the teaching permission although she was not an NS party member only because “she was offering Hitler a child”, which enraged her tremendously. Afterwards her head master told her that this exam had been deliberate torture and not a test of her competences. After the war Helene Pfleger was for many decades a dedicated primary school teacher and an esteemed head mistress.

Already on the 19th of March 1938 183 teachers were dismissed in Vienna on the basis of the Nuremberg Race Laws, seven days after the “Anschluss” on the 12th of March. The Viennese School Administration, located in the Palais Epstein on the “Ringstrasse”, issued decrees ordering the expulsion of Jewish pupils at the same time. The aim of this policy was the separation of Jewish and “Aryan” pupils. In schools with a high percentage of Jewish pupils initially “Jewish classes” were introduced or the pupils were sent to so-called “Jewish schools”, where teaching was very restricted under abysmal conditions. Often parents did not dare to send their children to these schools because they were attacked on their way to school. So the numbers of Jewish pupils decreased dramatically within a few months in Vienna. In the school year 1939/40 there were seven Jewish schools with 2,336 pupils and 72 teachers and in September 1940 only three schools remained. On 30 June 1942 all schools for Jewish children were closed and the teaching of Jewish children was prohibited, even private tutorials and kindergartens.

Immediately after the “Anschluß” not only all Jewish teachers were dismissed from Austrian schools, but also those teachers who were married to Jews. That’s why several teachers divorced their Jewish partners in order to keep their jobs, often not knowing that they signed their partner’s death sentence by this legal act. Those who stood by their Jewish partners were driven into social isolation and had to try and make a meagre living by offering private tutorials or taking on menial jobs. Despite this immense pressure on “Aryan” partners the divorce rate in Austria among “mixed marriages” was only around five per cent. When the Nazis introduced the civil marriage in Austria and simplified divorce procedures, many couples divorced who had been living in dysfunctional partnerships for many years. Some “mixed marriage” partners divorced their Jewish partners to improve the status of their “mixed-race” children, as in the case of Friederike Kern, or in order to be able to keep their flats. In March 1938 it was not yet clear what tragic consequences such a step could have for the Jewish partner. “Aryan” wives were usually exposed to even more pressure from NS authorities to divorce their Jewish husbands and many divorces took place after the arrest and deportation of their Jewish husbands and the failure to free them. In “non-privileged mixed marriages” the women had to care for the families alone after the Jewish partners had lost their jobs and they had to make ends meet on the meagre food rations because the Jewish partners received none or very little. They were often evicted from their flats together with their husbands and from 1942 on had to move with them to the so-called “Sammelwohnungen” (collective apartments), mostly in the 2nd district of Vienna, where many families were crammed into small spaces. Often non-Jewish neighbours suddenly turned out to be enthusiastic Nazis and denounced “mixed families” in order to get their hands on these flats.

The Nazi law “For the protection of German blood and German honour” of 1935 restricted the choice of partners for “mixed-race” persons. They were only permitted to marry other “mixed-race” persons. Any union with non-Jewish partners required a special permission which was practically never granted. Any such relationships out of wedlock were in constant danger of denunciation of neighbours or colleagues. A famous case was the one of Field Marshall Lieutenant Johann Friedländer (1882-1945), a high-ranking officer of the Austrian Army, who was “mixed race” and refused to divorce his Jewish wife Leona and was consequently classified as a Jew. In 1942 they had to move to a “Sammelwohnung” and in September 1943 they were deported to the KZ Theresienstadt. Leona died in 1944 and Johann was shot in 1945. “Geltungsjuden” could only marry other “Geltungsjuden” or Jews. Nevertheless many people did not comply with these humiliating regulations and continued their “illegal” relationships despite the constant threat of denunciation and deportation, as several documents prove. If they were discovered, their crime was “Rassenschande” (“shame to the race”) and they ended up in concentration camps.

Herta with her mother Lola after liberation by the Allied Forces on a park bench in Vienna. During the Nazi era Lola was forbidden to sit on park benches in Vienna

Here it is important to mention that in Austria the ground for anti-Semitic and racist policy was well prepared already before the takeover of the Nazis. The Austro-fascist dictatorship that toppled the 1st Republic in February 1934 immediately introduced obligatory Catholic religious instruction in schools with the aim of a “re-Catholization” of the Austrian society, which was much acclaimed by the Catholic authorities. Austro-fascism interfered aggressively in the organisation and running of the Austrian school system with the aim of increased selection and the boosting of elitism. Boys and girls were separated, school fees and entrance exams were introduced for grammar schools, private Catholic institutions were promoted and special schools for young women where they learned cooking, needlework etc. were established to prepare them for their future roles of mothers and wives. Already in this period separate Jewish classes were set up in public schools. The focus of the new curricula was on an education that was to be “religious, patriotic, moral and faithful to the nation”. Yet the desired adaptation of all the school books failed due to a lack of funds, so the teachers were ordered to include the patriotic and religious aspects of Austro-fascism in their teaching. Physical education for boys was a military preparation for the army and the schools were involved in the numerous celebrations and marches of the Austro-fascist party. Teachers were forced to become members of the party organisation “Vaterländische Front”, otherwise they would be dismissed. Friends of my great-aunt Käthe was the couple Neubauer. Dr.Johann Neubauer was a professor for natural sciences at the “Rainergymnasium” in the 5th district of Vienna. He acted as provisional headmaster there from 1925-1928 and was appointed headmaster in 1928. In 1934 after the Austro-fascist coup d’état he was dismissed, not just because he was a Social democrat, but because he was married to a Jewish wife.

Wide-spread anti-Semitism was an important characteristic of Austro-fascist policies and was linked to Catholic tradition as well as to German nationalistic tradition. Agitation against Jews was boosted by the party, although officially the party tried to differentiate itself from the German Nazis. In reality there was no difference, but the Austro-fascist party hoped to create a more positive image abroad to get their hands on international funds to revive the ailing economy. They tried to portray themselves in the eyes of the rest of the world as the “better Fascists”. In fact, religious, economic and racist anti-Semitism had already been at the heart of the party since the turn of the century. Bichlmayer, the leader of the Catholic “Paulus-Werk” and a prominent party member demanded that also newly baptised Jews should be subjected to discriminatory treatment. Leopold Kunschak, a member of the Austro-fascist elite, demanded already in 1919, in the first year of the 1st Republic, the passing of a law that systematically discriminated against Jews in Austria. He failed and tried again in 1936. But officially the party did not discriminate against Jews, which had economic reasons. First, tourism was one of the most important sectors of the weak Austrian economy and excluding Jews would have meant a drastic fall in revenues. The tourist location Zell am See, Salzburg, had advertised in its tourist brochure “Aryans preferred”, which was officially rejected by the party. Second, the party relied on financial support of the Jewish religious community and Jewish entrepreneurs and bankers. Officially Jews could become members of the “Vaterländische Front”, but only two of the 213 members of parliament were Jews. Unofficially inner-party anti-Semitism was wide-spread. The “Vaterländische Front” not only tolerated, but promoted these tendencies among their members. In the forefront there were the Tyrolian members, who demanded a much more pronounced anti-Jewish propaganda. Several attempts were made, for example by the party youth organisation “Österreichisches Jungvolk” to introduce a so-called “Aryan clause” that would prohibit the employment of Jews and by that gain support among the population. The discrimination of Jews was visible in many areas, for example the campaign “Christians buy from Christians” or a new edict that prohibited visiting customers in their homes or offering hire-purchase conditions, which targeted Jewish traders. Already in 1935 an agreement with Hitler’s Germany stipulated that anyone who wanted employment in the important Austrian film industry needed an “Aryan Certificate”. Young Jewish doctors were denied specialisation and a university career was virtually impossible for Jewish academics during the time of Austro-Fascism (1934-1938). The Tyrolian “Vaterländische Front” demanded in 1937 that Jewish intellectuals, lawyers, doctors, university professors, traders and engineers were to be reduced “to a number that represented their percentage in the population”. Furthermore they pleaded for a “cleansing” of the media, especially the state-owned radio stations, the magazines and newspapers from “Jewish journalists” and for a limit to the transfer of Jewish capital. Prejudices against Jews in the general public were reinforced and the image of Austria as a Catholic nation was boosted. A song of the party youth organisation “Österreichisches Jungvolk” ran lines like: “Wenn der Heimwehrmann ins Feld zieht, ja da hat er frohen Mut, und wenn das Judenblut vom Messer spritzt, geht es noch einmal so gut“ (When the „Heimwehrmann“ – member of the military arm of the party – goes to war, he is happy and when Jewish blood splashes from his knife, he is even happier). So one can see that the ground was already prepared for the later tragic development and this partially explains why the Austrian population to a large degree supported the Nazi policies and even acted more swiftly and mercilessly against their Jewish compatriots than the Germans.

Literature:

Anderl, Gabriele, Jüdisches Leben in Wien-Margareten, Mandelbaum Verlag 2019

Botz, Gerhard ua (Hg), Eine zerstörte Kultur. Jüdisches Leben und Antisemitismus in Wien seit dem 19.Jahrhundert, Czernin Verlag 2002

Dohmen, Herbert & Scholz, Nina, Denunziert. Jeder tut mit. Jeder denkt nach. Jeder meldet, Czernin Verlag 2003

Doubek, Günther, „Du wirst das später verstehen…“ Eine Vorstadtkindheit im Wien der dreißiger Jahre, Böhlau 2003

Fried, Erich, Mitunter sogar lachen. Erinnerungen, Wagenbach 2002

Fried, Erich, Kindheit in Wien. In: Vor der Flucht, hrg. vom BRG9 Erich Fried Gymnasium 2002

Hecht, Dieter ua, Topographie der Shoah. Gedächtnisorte des zerstörten jüdischen Wien, Mandelbaum Verlag 2017

Moritz, Stefan, Grüß Gott und Heil Hitler. Katholische Kirche und Nationalsozialismus in Österreich, Picus Verlag 2002

Meyer, Beate, „Jüdische Mischlinge“. Rassenpolitik und Verfolgungserfahrung 1933-1945, Dölling und Galitz Verlag 2002

Raggam-Blesch, Michaela, „Privileged“ under Nazi-rule: The Fate of Three Intermarried Families in Vienna, Journal of Genocide Research 2019

Tálos, Emmerich, Dass Austrofaschistische Österreich 1933-1938, LIT Verlag 2017

Winiewicz, Lida, Späte Gegend. Bühnenfassung, Zsolnay 1995

Winiewicz, Lida, Der verlorene Ton, Braumüller, 2016

Wurm, Matthias, Katholische “Mischlingskinder” in Wien zur Zeit der Nationalsozialisten, Fachbereichsarbeit 2004