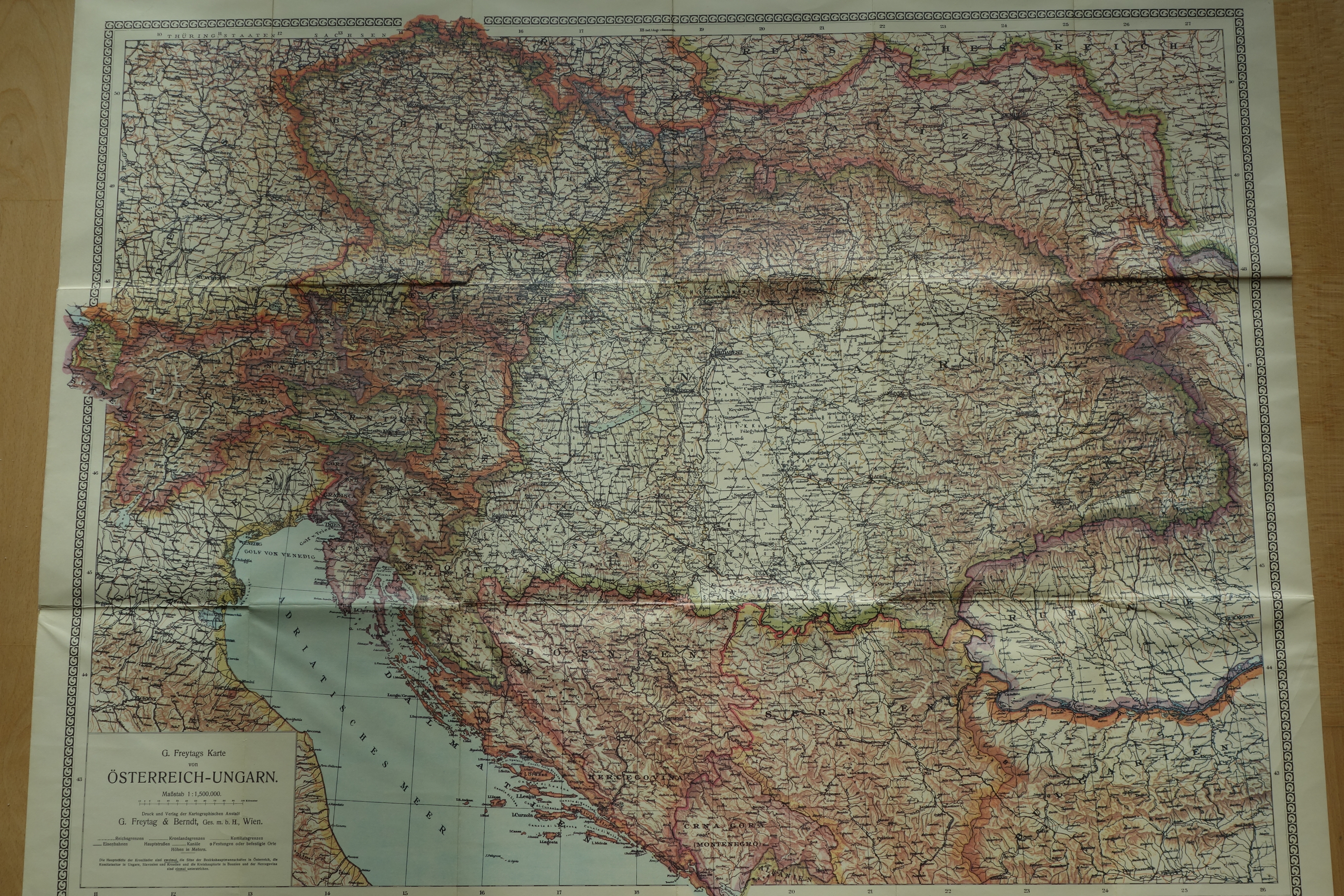

CENTRAL EUROPE AND THE AUSTRO-HUNGARIAN EMPIRE: ATTEMPTS AT CREATING A UNIFYING IDENTITY DESPITE RISING NATIONALISM

Brno, Czech Republic

In the last years researchers of Central and Eastern Europe have revised the widespread assumptions of the Austro-Hungarian Empire that comprised a large part of this area and ended in 1918. They no longer see it as an economically inefficient multi-national anachronism to the late 19th century nation states of Europe. New studies focus on the vibrant political cultures and the interesting attempts at interpreting local and regional phenomena in this multi-ethnic and multi-religious empire. General studies of Europe and modern history tend to treat the region of Central Europe as an exceptional corner of Europe due to the presence of several ethnic and religious groups in its societies, but also because of its economic development, often – unjustly – characterised as “backward”. Historians of self-styled nation states might have to think more creatively about cultural differences that may lurk just below the surface of assertions of national homogeneity. This is especially necessary at the time when the European Union is again facing new outbreaks of nationalism and even regions in the established nation states of Western Europe show serious tendencies of separation, e.g. Catalonia or Scotland.

Even some books written recently on the topic of World War I continued the tradition of portraying the Habsburg Empire as a state on the verge of collapse even before the outbreak of the war due to nationalist conflicts. Since the collapse of the empire narratives of nationhood have dominated its history. This interpretation ignores the fact that the Austro-Hungarian Empire was very similar to the other European states of the time, but at the same time pioneered new ideas of nationhood and new practices of governance thanks to its multi-ethnic population of 50 million. Some of the character, the developments and the enduring legacies of this Habsburg Empire are still visible in Central Europe. Therefore it is essential for once to abandon traditional presumptions about the primacy of nationhood in the region and to focus on the Austro-Hungarian institutions such as schools, the judicial system or the Austrian census that managed practical issues surrounding linguistic and ethnic diversity. This research undermines the notion that the existence of language differences dominated social relationships and institutional developments in Central Europe. On the contrary, imperial institutions and administrative practices helped shape nationalist efforts. Furthermore the surviving presumptions of economic backwardness or unbridgeable difference that allegedly made Central Europe different from the rest of Europe were revised in recent decades and historians have pointed out the remarkable creativity and innovation of the empire’s institutions in tackling diversity. Looking at the last decades of the Habsburg Empire might offer different views at subjects like nationhood, multilingualism and indifference to nationhood, especially at times of crisis of solidarity in the European Union.

…