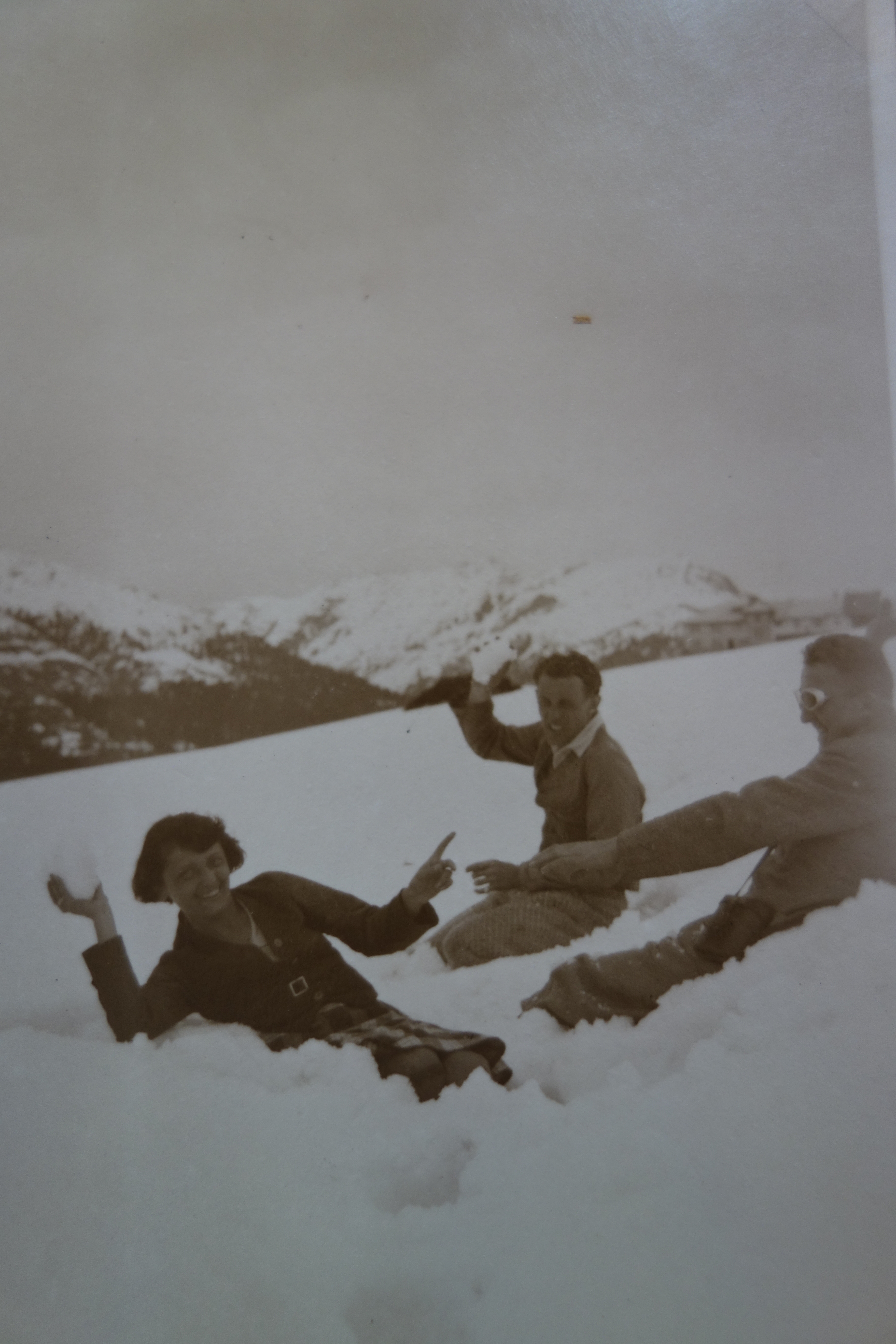

My grandmother Lola, Semmering 1931

My grandparents’, my great-uncles and great-aunts’ favourite leisure time activities on weekends and during holidays was hiking in the Vienna Woods, the last part of the Alps in the east, and the mountains south of Vienna, such as, Rax, Schneeberg, Gippel, Göller und Semmering and for longer vacations the whole area of the Austrian Alps, Southern Tyrol, Bavaria and Switzerland. How did that overwhelming passion for mountaineering and skiing among the younger Viennese generation in the 1920s and 1930s develop? Alpinism had evolved from an elitist sport of wealthy British tourists to the bourgeois leisure activity of “Sommerfrische” (summer holidays in the Alps) and a sport of intellectual and artistic circles in the 19th century to a widespread working class past time, too, in the 1st Austrian Republic (1919-1934/38).

Many of the beautiful black and white photos of hiking tours in the Austrian Alps were taken by my great-uncle, Karl Elzholz, a mechanic at the Viennese tramways, an atheist, a committed socialist and a member of the Alpine club “Naturfreunde”. He was married to my great-aunt, Mizzi, and later to her sister, my great-aunt, Käthe, and both of them were dedicated hikers as well and formed part of the groups of friends who went hiking in the vicinity of Vienna or on longer mountaineering tours to the Alps. They were experienced hikers and planned the tours themselves.

In the 19th century workers organised educational clubs because that was sometimes the only way to legally form workers’ associations. Later workers’ gymnastic clubs were established along the lines of German nationalist gymnasts’ associations, the “Turnerbewegung”. The aim of these clubs was to improve the health and fitness of the workers with the help sports activities and especially the exposure to “air, light and sun” was seen as beneficial. As a consequence those clubs soon moved out of the stuffy rooms of gyms into nature. That’s when walking and hiking became a popular leisure time activity of the working classes, too. In 1895 the Alpine club “Naturfreunde” (Nature’s Friends) was founded. Soon afterwards also skiing was made popular among the working class. Emmerich Wenger brought skis from a trip to Norway to Vienna and they tried them out at the “Bierhäuslberg” to the amusement of all present. After the First World War all workers’ sports clubs united under the umbrella organisation ASKÖ (“Arbeiterbund für Sport und Körperkultur in Österreich”). In 1931 the 2nd Workers’ Olympic Games took place in Austria, initiated by the ASKÖ: in February in the Semmering area and in July in Vienna in the newly erected stadium in Prater. In 1934 with the takeover of the Austro-fascist regime all workers’ clubs were declared illegal and only after the end of World War II the socialist sports organisation ASKÖ could be reactivated.

Karl in front of the new “Naturfreundehaus” Sonnblick 1932

The founding members of the Alpine club “Naturfreunde” did not want to publicise the event of its inception in 1895 because they feared for the jobs. The young Karl Renner, later a prominent socialist, drew up the statutes of the club. On Easter Sunday 1895 the first hiking tour was organised from the Vienna South Station to Mödling – Anninger – Hinterbrühl. 62 men and women participated, among them teachers, civil servants, students (e.g. Karl Renner) and many workers. This already illustrates the first opening up of this sport to all classes of the Viennese society, male and female. In September of the same year the official foundation took place in an inn in the Viennese suburb of Neulerchenfeld. The first headquarter of the club was in the founding member Alois Rohrauer’s flat. Originally hiking tours could only be organised in the vicinity of Vienna because the workers had to work on Saturdays. Karl Renner reported later that the leaders of the Socialist Party had opposed the foundation of an Alpine club because they felt the workers should take to the streets to protest against the government and fight for workers’ rights and not to go hiking in the mountains and enjoy nature instead. The “Nature’s Friends” justified their position by telling the party leaders that they were anyway active in the country promoting the ideas of socialism by distributing the Socialist paper “Arbeiterzeitung” in the mountain villages. In 1905 the international organisation of the “Nature’s Friends” was founded here. In 1933 the “Nature’s Friends” had 200,000 members in 22 countries, but in 1934 the organisation was forbidden in Austria and by that also the international headquarter had to be closed and moved to Zürich. Finally in 1988 it returned to Vienna. The main activities of the “Naturfreunde” (“Nature’s Friends”) were and are the building and running of mountain huts and refuges, the maintenance and signalling of mountain paths and climbing routes and the organisation of expeditions, just as the other Alpine clubs.

Mizzi on the Piz Buin 1934

The most famous and widespread Austrian Alpine clubs were all founded earlier in the 19th century as liberal bourgeois leisure clubs, such as the Austrian “Alpenverein”, “Touristenclub”, “Gebirgsverein” and “Alpenklub”. Workers’ clubs, Catholic and liberal sports clubs all catered for their clientele and tried to form their members ideologically along political, religious or national lines. Sport constituted an integral part of these organisations, but the primary aim of such clubs was to influence and pervade the whole life of the members. The “Alpenverein”, the biggest Alpine club, was founded in 1862 in the “Austrian Academy of Sciences” in Vienna, one of the most famous scientific institutions of the empire. It developed into the biggest Alpine club in Europe. The German “Alpenverein” was founded 7 years later and both Alpine clubs merged in 1873 to the “German-Austrian Alpine Club”.

My grandfather, Anton Kainz, was an enthusiastic sportsman himself, a dedicated tennis player, hiker and skier from the bourgeois middle class. As the son of an innkeeper in the fashionable district of “Währing” he could afford more expensive sports equipment. Thanks to his interest as a photographer, many interesting photos of his hiking and skiing tours have come to me. Politically, he was a liberal conservative all his life and he and my grandmother, Lola, were members of the Austrian “Alpenverein”, even during the Second World War. The childhood holidays of my mother, Herta, were always spent on mountain huts and she greatly enjoyed it. My grandmother was much less enthusiastic, although she had participated in all sorts of sports activities since her youth, such as hiking, skiing, tennis and so on. Her motivation was entertainment and having lots of fun in groups of young people rather than ambition. When she, my grandfather and my mother were on long hiking tours on their own she was unnerved, afraid of weather changes and “talked, or rather complained, her way up the mountain”. For her the real appeal of mountaineering started with the singing and joking in the mountain huts. Her membership in the “Alpenverein” must have turned into a problematic affair with the increasing anti-Semitism that pervaded this Alpine club since the rise of political anti-Semitism in Austria. When marrying my grandfather she converted to Roman Catholicism and was a committed Catholic all her life, but she was Jewish-born and in Nazi terminology my mother was a so called “mixed-race” child. Fortunately, my grandfather was a courageous, strong and steadfast personality who stood by his family all through those difficult times of Fascism and National Socialism and ignored whenever possible all racist restrictions for his wife and daughter. Even during the war he went hiking with them in the Alps and the happy-go-lucky, open and charming character of my grandmother seemed to have contributed to the fact that they were never found out. She was also the one who went to the farmers in times of need and got them with her charm to agree to barter some of their few possessions for urgently needed food.

“Alpenverein” membership cards of Lola and Toni

How had this Alpine sports club, the “Alpenverein”, turned into a haven for Nazis? Many student clubs and gymnasts’ clubs had started already in the 1880s and 1890s with the first wave of modern political anti-Semitism in Austria to include so-called “Arian clauses” in their statutes that excluded Jews from membership. When the “Alpenverein” was founded, it was an open and liberal club and this attitude was stressed by the founders and was upheld for the next three decades. This led to a political struggle within the organisation between the liberal cosmopolitan and the nationalist anti-Semitic faction. This conflict culminated in 1921 after the Austrian “Touristenclub” had accepted a so-called “Arian clause”. Then the Viennese section of the “Alpenverein”, “Austria” with approximately 2000 Jewish members (one third of the whole “Austria” section) and untold numbers of converted or agnostic “Jews” excluded all Jewish members as well. A large number of liberals and Jews had already left the organisation “Austria” and founded their own Alpine club section “Donauland”, but also this section was excluded from the umbrella organisation “Alpenverein” in 1924. At that point in time 96 out of 100 sections of the “Alpenverein” had already incorporated the “Arian clause” in their statutes. This exclusion of Jews from one of the biggest social organisations in the country took place long before the takeover of the Nazis in 1938 and was strongly supported by the mass media. The Alpine clubs, just as other sports clubs and students’ clubs, were already pervaded by Nazi ideology and the “swastika” in rudimentary form already figured prominently on badges and even on mountain huts. It took a long time until the Austrian “Alpenverein” was ready to confront the role it played in the Nazi regime. In the “Friesenberghaus” in the Zillertal Alps a commemorative plaque and an exhibition reminds of the racial fanaticism of the “Alpenverein” and the destiny of its Jewish members. This mountain refuge belonged to the Berlin section of the “Alpenverein”, which protested against the open anti-Semitism in the “Alpenverein” by quitting and transferring the hut to the liberal section “Donauland”. Similarly, the Austrian skiing association has to deal with its past, as it expelled all Jewish members from its club in the 1920s, too, even its former chairperson Rudolf Gomperz, who together with Hannes Schneider had founded and developed the modern skiing sport and skiing tourism at the Arlberg.

My Jewish-born relatives, my grandmother, my great-aunts Käthe and Mizzi and great-uncle Karl were convinced and dedicated democratic Austrians, had long renounced Judaism and had assimilated completely, yet the example of the “Alpenverein” shows that the ground was already paved in the 1920s for what followed in the 1938, the persecution of all Jewish-born Austrians despite the fact that many had completely identified with the Austrian state and had no connection to Judaism. This is the reason why so many did not heed the warning signals and remained in Austria until it was too late. When looking at the photos of hiking tours one can see the young hikers in traditional costume, “Dirndl” and leather trousers, in the mountains. This was considered the appropriate attire for hiking by city dwellers. Yet another absurd law was passed in March 1938 by the Austrian federal state of Salzburg which prohibited Jews the wearing of traditional Austrian costumes in Salzburg.

Children in Kals, 1932

Originally the nobility that followed Emperor Franz Joseph in the summer to Bad Ischl and other summer resorts started to wear traditional costumes when staying in the mountains, imitating the imperial family. The bourgeoisie that followed the nobility and flockked to traditional summer resorts, too, put on traditional attire in imitation of the emperor and the nobility in leather trousers and “Dirndl”, among them well-to-do Jewish families. In old photos Viennese artists, intellectuals, writers and scientists of the fin-de-siècle can all be seen dressed in traditional costume when staying in the mountains for “Sommerfrische”. Of course this play with fashion, dressing-up, nostalgia for simple country life and local flair expressed a bourgeois illusion of romantic peasant life. The German nationalists and anti-Semites spoke out against the wearing of traditional costume by Jews already at the end of the 19th century and mocked that the “Dirndl” was distorted into a “Jewish national costume” because so many Jewish women put it on in the summer holiday resorts of the Alps. Ironically, it had been the Viennese industrialist and collector Konrad Mautner and Jewish textile producers like the family Wallach in Munich who had made the “Dirndl” and the leather trousers decorated with edelweiss fashionable. The Viennese Eugenie Goldstein researched about the aesthetics of Alpine every-day life and left her considerable collection of Alpine folk art to the Vienna Folk Art Museum (“Volkskundemuseum”). Lilli Baitz had established a successful production of folk dress dolls (“Trachtenpuppen”) in Salzburg, Aussee and Berlin. Now they were all blamed for their enthusiasm for Alpine tradition and dress. Unfortunately this racist attitude finds imitators even today. Miguel Herz-Kestranek, the Austrian writer and actor, who received the Konrad-Mautner-Award for promoting traditional Alpine costume in 2008, was confronted with anti-Semitic attacks for wearing traditional Alpine costume; for example he received an anonymous letter with copies out of an old SS newspaper depicting anti-Semitic caricatures of Jews in traditional Alpine costume.

Lola and her daughter, Herta, in traditional costume 1943

In the 19th century the term “traditional costume” defined the attire of a certain (professional) group of people in a feudal hierarchical society. Today it is seen as a timeless regional dress of the different regions in Austria. Traditional costume and identity went hand in hand and formed group identities. In the early 20th century the traditional costume was abused as an instrument of a power struggle in the formation of national identities and an instrument of exclusion. The various traditional costume clubs that were founded in Austria around 1900 were turned into a mouthpiece of Austro-fascism after 1934. This tendency culminated in open racism and a yearning for an annexation of Austria into Nazi Germany among some of the groups. Alpine traditional costume was transformed into a characteristic of “Arian heritage” and by that sacrosanct. Traditional costume festivities in 1937 were propaganda events organised by illegal Nazis to promote the annexation. Absurdly enough many of the fashion houses that produced and sold traditional Alpine costumes, for example in Salzburg, were run be Jewish entrepreneurs. They were all of them immediately dispossessed after the annexation of Austria in March 1938.

For decades after the end of the Nazi regime the wearing of traditional costume was somehow polluted by this historical political abuse of a long-standing Alpine tradition. Fortunately in the 21st century the increasing attractiveness of wearing the traditional Alpine costume has shed this political burden and has become an important element of local identity in a unified, tolerant and open Europe. Those who know their roots can confront a globalised world in a positive and confident way. For the city dwellers the traditional costume is again an expression of the atmosphere of the “Sommerfrische”, “the lightness of being”, the “savoir vivre” of the 1920s and sometimes exhibits a bit of nostalgia for the long gone multi-cultural Habsburg Empire.

Honeymoon Lola and Toni, Krimml 1932

What drove young people into the mountains in the beginning of the 20th century, the middle class as well as the working class, was sport, entertainment, but above all their love of nature. Alpinism, “Sommerfrische” and modern skiing were expressions of this yearning for the beauty, roughness and energy of the Alps. A Jewish philosopher Samson Raphael Hirsch is quoted to have said, “When I will be standing in front of God, the Almighty will ask me: Did you see my Alps?” This love of the mountains manifests itself in the fact that both, my grandparents, Lola and Toni, and my great-uncle and great-aunt, Mizzi and Karl, spent their honeymoons in the Alps in the early 1930s. The Austrian poet Robert Schindel reports that after the Austro-fascist coup d’état in February 1934 some young socialists, “Nature’s Friends” hid on the Rax, a mountain south of Vienna, during the summer and whenever the police came up the mountain they hid in one of the many small huts, while the policemen drank their beers in the big mountain cottage “Karl-Ludwig-Haus” and since then “…. Schurli had a craving for the mountains. He said, ”The Rax always helps.”” Schindel believes that the Jewish love of the Alps was linked to the feeling that the mountains were egalitarian. The Alps did not differentiate between Jews, Christians and “Arians”, they cast off who they wanted and that’s why the Alpine clubs felt they had to make that difference.

“Sommerfrische”, Mizzi on the right, Gastein 1932

The Semmering, south of Vienna, had a special attraction for the Viennese intellectuals of the fin-de-siècle. They could meet there in the summer resort, the “Sommerfrische”, just as in the Viennese coffee house and continue their intellectual disputes and at the same time enjoy the relaxed atmosphere of the Alpine panorama. Egon Friedell, Peter Altenberg, Felix Salten, Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Arthur Schnitzler, Gustav Mahler, Arnold Schönberg and Sigmund Freud were inspired by the Semmering. But the ordinary Viennese enjoyed hiking in nature just as much, especially on longer holidays such as Easter, Whitsun or St. Peter & Paul, when they could go farther than the Vienna Woods to the mountains south of Vienna. The many beautiful black and white photos of Karl and Toni are a testimony of this love of nature. The places where the Viennese went for “Sommerfrische” were small provincial villages that were first discovered by the nobility, then the bourgeoisie and finally by the common people. These were places like Reichenau an der Rax, Semmering, Bad Aussee, Bad Ischl and so on. The intellectuals and artists as a consequence created the myth of the Alps and “Sommerfrische”. One of the best testimonies is Arthur Schnitzler’s drama “Das weite Land” (“The Wide Country”) which takes place in such a summer resort and describes the emotions a hiking tour can evoke, “…. the moment at the mountain top, the handshake, the delusion of belonging together, the feeling of immense joy, it was a sort of drunkenness, a mountain intoxication… it seems to be linked to 3,000 metres altitude, the thin air, and the danger.”

Lola “enjoying the Alpine atmosphere” on a skiing tour, Obertauern 1935

Anti-Semites ridiculed this Jewish love of the Alps and the summer resorts and deplored the “Jewification” of the Alpine villages. In Austria Fascist and National Socialist racist tendencies were widespread already after World War I and the authorities of the Austrian First Republic did not intervene and protect the attacked minorities. The mountains, the summer resorts and the Alpine clubs turned into a playground for later Nazis. From the point of view of the population of the rural countryside the Viennese city dwellers were anyway “dressed-up aliens” and the Jews were even “more alien”. In Austria the attacks on Jewish citizens who identified with the local culture and tradition of the summer resorts, the “Sommerfrische”, started already before the takeover of the Nazis. This phenomenon is called “Sommerfrischen anti-Semitism”. Karl Kraus sarcastically commented on this unconditional love of the mountains and the palpable tensions and threats in “The outing to the mountains”: “The throats become free in the mountains. What a wonder we don’t sing!” Friedrich Torberg expressed his love for the Alps in the poem “Yearning for Altaussee”, written in exile in California in 1942.

My great-uncle Karl with his third wife, my great-aunt Käthe, returned from exile in Bolivia soon after World War II and they, too, had never given up their yearning for the Alps and they went back to the mountains they had loved so much before 1938. They took me to the Vienna Woods and Karl carried me on his shoulders when I did not want to walk anymore and he hid the coloured Easter eggs of the “Easter bunny” for me in the Vienna Woods. I still cannot imagine how he had done that without me noticing. My grandfather Toni went on summer holidays to Schladming and other places in the Austrian Alps with us and carried me on his shoulders, too, smoking heavily to chase away the nasty mosquitos. The love for the Alps they had developed as young people, whether Christians, Jews or atheists in the 1920s and 1930s they preserved for the rest of their lives.

Literature:

Gruber, Helmut, Red Vienna. Experiment in Working-Class Culture 1919-1934, OUP 1991

Mit uns zieht die neue Zeit. Arbeiterkultur in Österreich 1918-1938, Vlg. Habarta & Habarta 1981

Hast du meine Alpen gesehen? Eine jüdische Beziehungsgeschichte, Bucher 2009

Brugger, Eveline u.a., Geschichte der Juden in Österreich, Überreuter 2006

Das rote Wien – Waschsalon, Lexikon, www.dasrotewien.at