AN ANALYSIS OF CHILDREN’S & YOUTH LITERATURE IN VIENNA DURING THE AUSTRO-FASCIST, THE NATIONAL SOCIALIST PERIOD AND THE POST-WORLD WAR II YEARS: SURPRISING CONTINUITY & DEALING WITH PAINFUL HISTORY

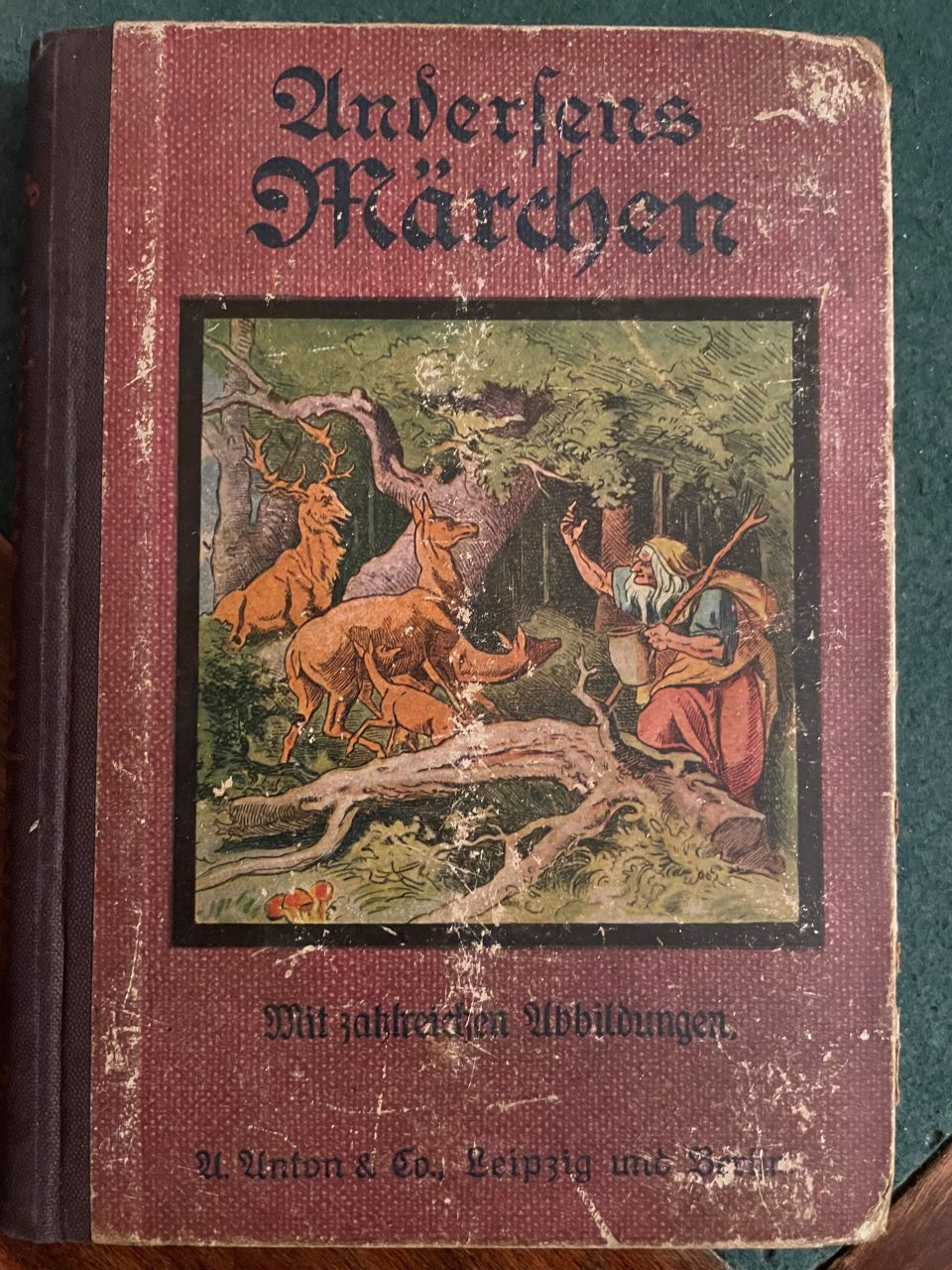

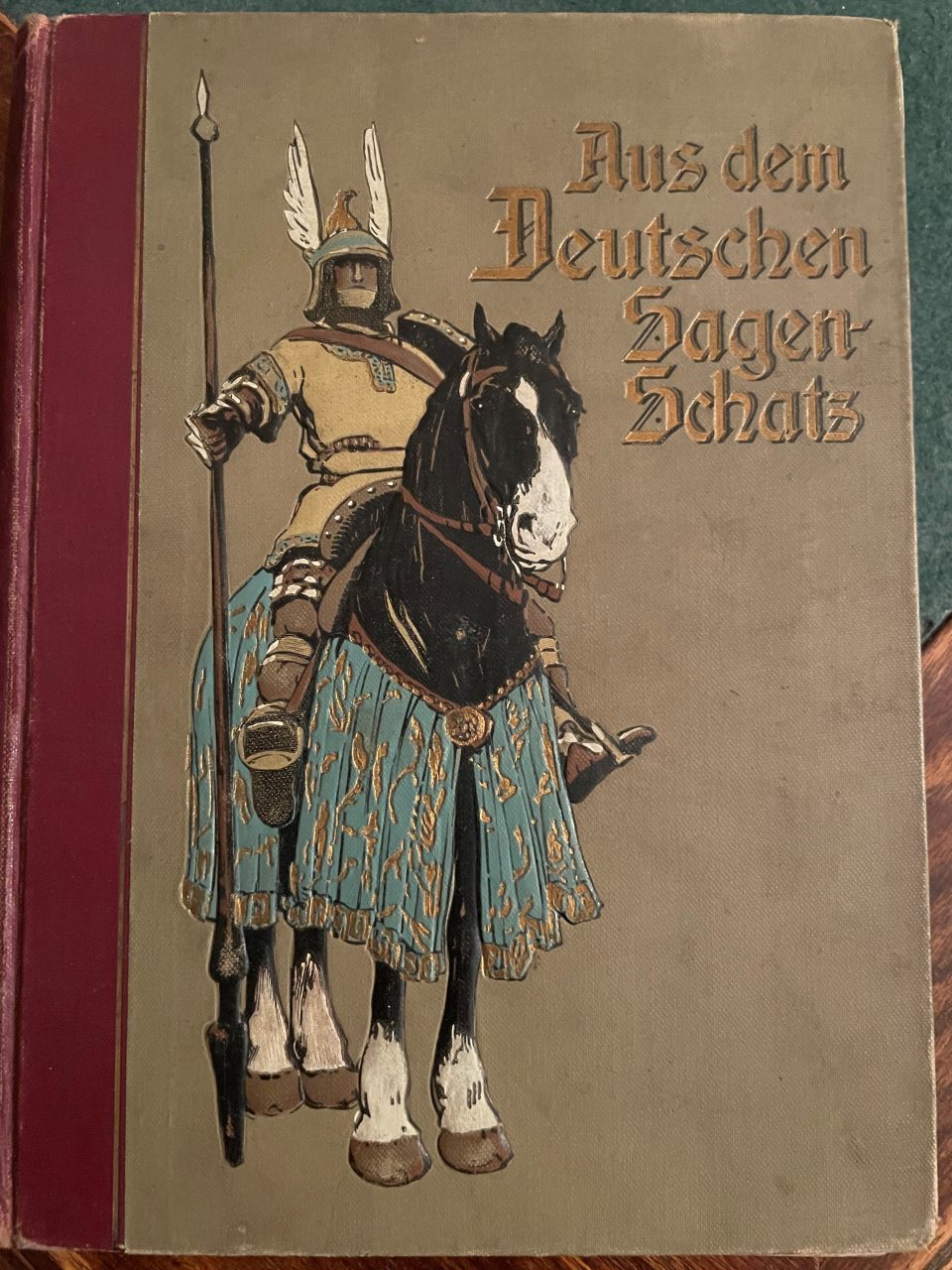

Fairy tales were much promoted before, during and after the National Socialist period in Vienna and in the whole of Austria and Germany

Children’s and youth literature was regarded as an important tool for influencing young people and inoculating them with the National Socialist ideology by the NS leaders, but they were not the first ones. The Austro-Fascists, who took power in Austria in 1933 by ousting the democratically elected Austrian parliament of the First Republic, cleansed the libraries and schools of “unwanted” children’s and youth literature and promoted a limited selection of pedagogically backward books to entice the young for their nationalistic, fundamentalist Roman Catholic view of the world. Fairy tales and legends, especially Germanic and Nordic myths, were considered appropriate topics for young people by Austro-Fascists as well as by National Socialists in Vienna. Yet the Austro-Fascists were not well-organised enough to come up with a coherent pedagogical concept of creating Austro-Fascist children’s and youth literature. Despite their tightly-knit party structure the National Socialists, who represented a strong underground power in Austria during their time of illegality in the Austro-Fascist period between 1933 and 1938, had no clear-cut view of what a National Socialist children’s and youth literature had to look like as well, when they took power in Austria in March 1938. The only consensual aim was to serve the NS ideology, but the NS representatives of various institutions and authorities followed different strategies to reach this common goal. It is surprising that too blunt propaganda of NS ideology in children’s books, which was for instance offered by fervent former illegal Austrian National Socialist writers, was rejected by the “Reichsschrifttumskammer” (NS Chamber of Writers). Their aim was to influence the young subconsciously via sentiment and emotions without making the intended manipulations too visible. So, in a nutshell, children’s books were to be sophisticated indoctrination tools.

In fact, most skilled and well-known authors of German-language children’s books had fled Austria, were persecuted, or were not prepared to be abused by the regime for its ideological purposes. Consequently, the NS regime lacked gifted writers of children’s literature. The majority of the material produced for the young in this period constituted of easy poems, rhymes and lyrics for patriotic songs and marches, which could be publicly recited and sung individually or in groups at youth camps, party celebrations and in schools. Another important category were handbooks for organising group events, camps, and meetings of the HJ (obligatory membership of all boys in the NS “Hitlerjugend”) or BdM (obligatory membership of all girls in the NS “Bund deutscher Mädchen”), filled with appropriate National Socialist games, poems, songs, sports events, and activities in preparation for war. An important requirement for children’s and youth literature was its facility to be read in public and not alone. Reading material was supposed to promote NS group activities; stories and rhymes were supposed to be read out loud by mothers, teachers, youth leaders to enthuse the young for the ideas of National Socialism. Book worms were not appreciated, on the contrary, reading alone in your room was seen as dangerous subversive treason. Jews, who the Nazis staged in their xenophobic propaganda as the worst enemies of Hitler’s “Third Reich”, were characterised as bookish, learned, reading alone in their study rooms; all negative characteristics for the Nazis, who promoted a fit, sporty and outdoors group spirit of the “young German”.

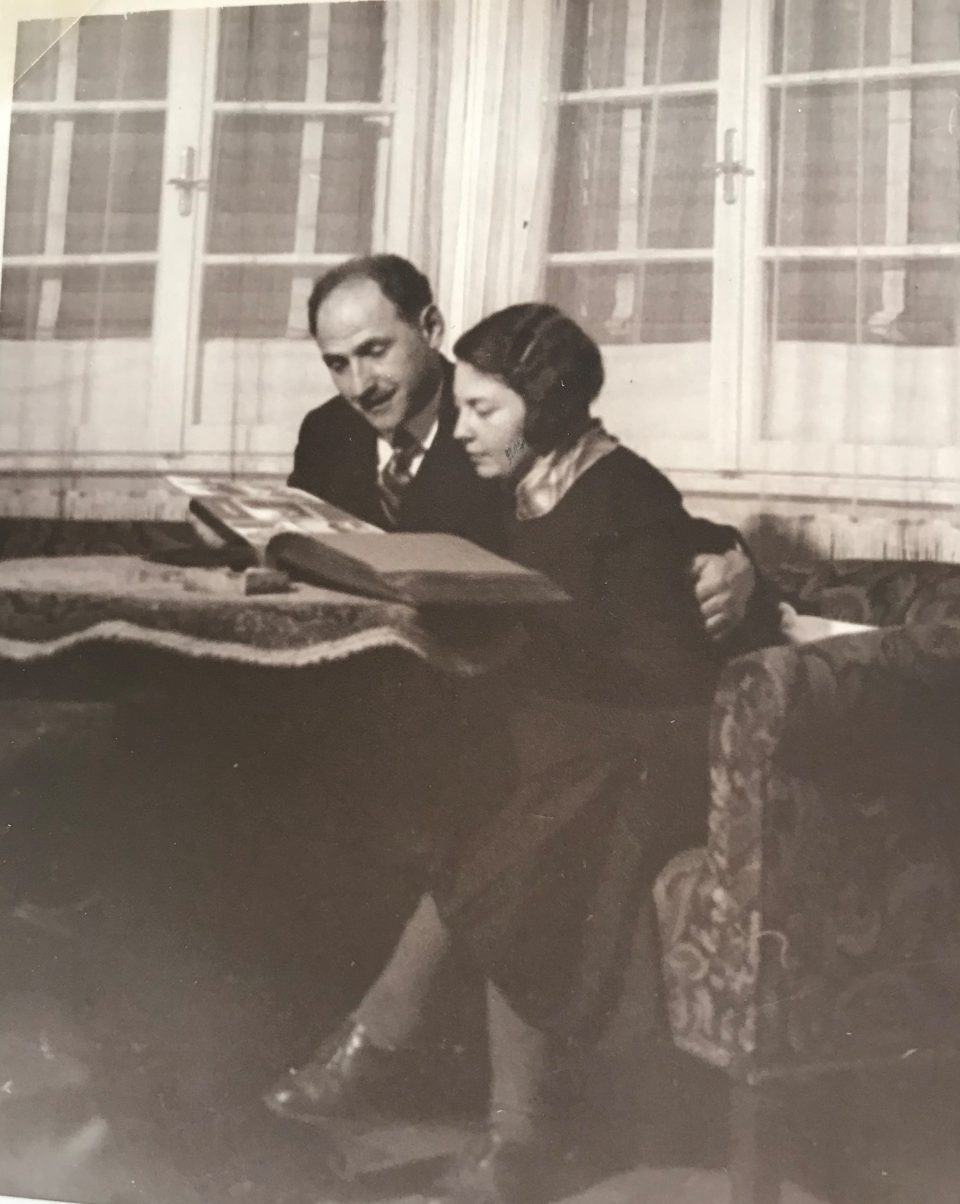

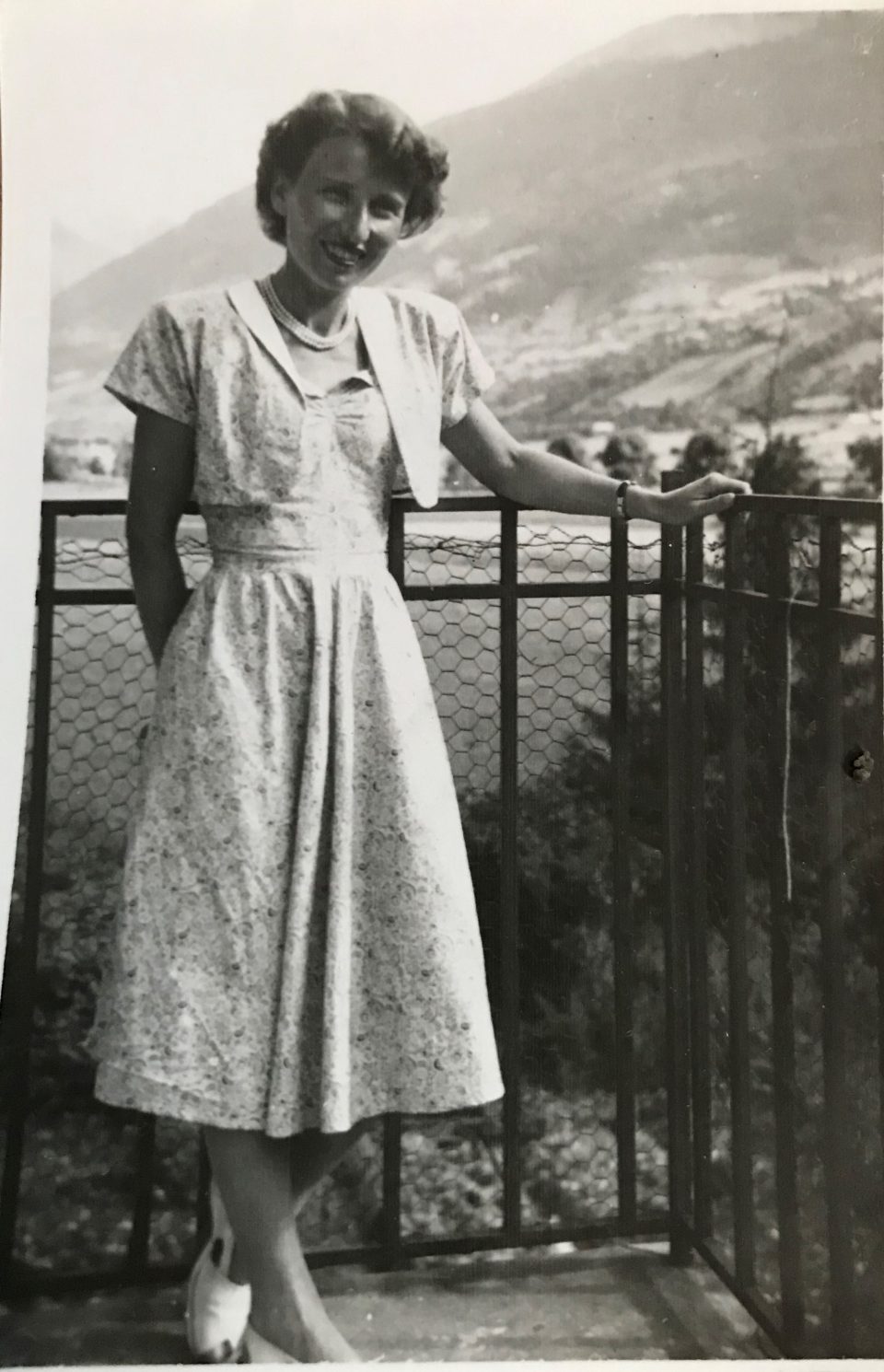

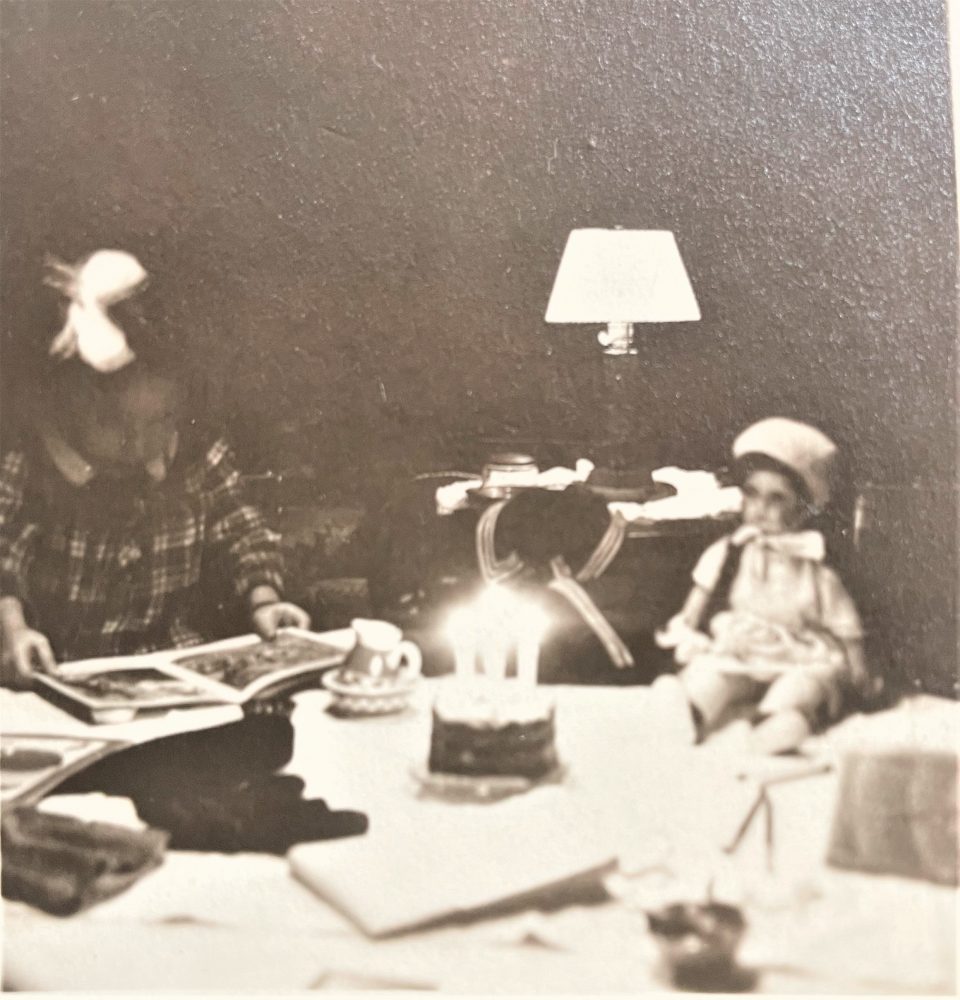

Herta on her third birthday on 24 November 1936 – she was an avid reader of picture books already then (left), and hiking in the Vienna Wood with her mother, Lola (right)

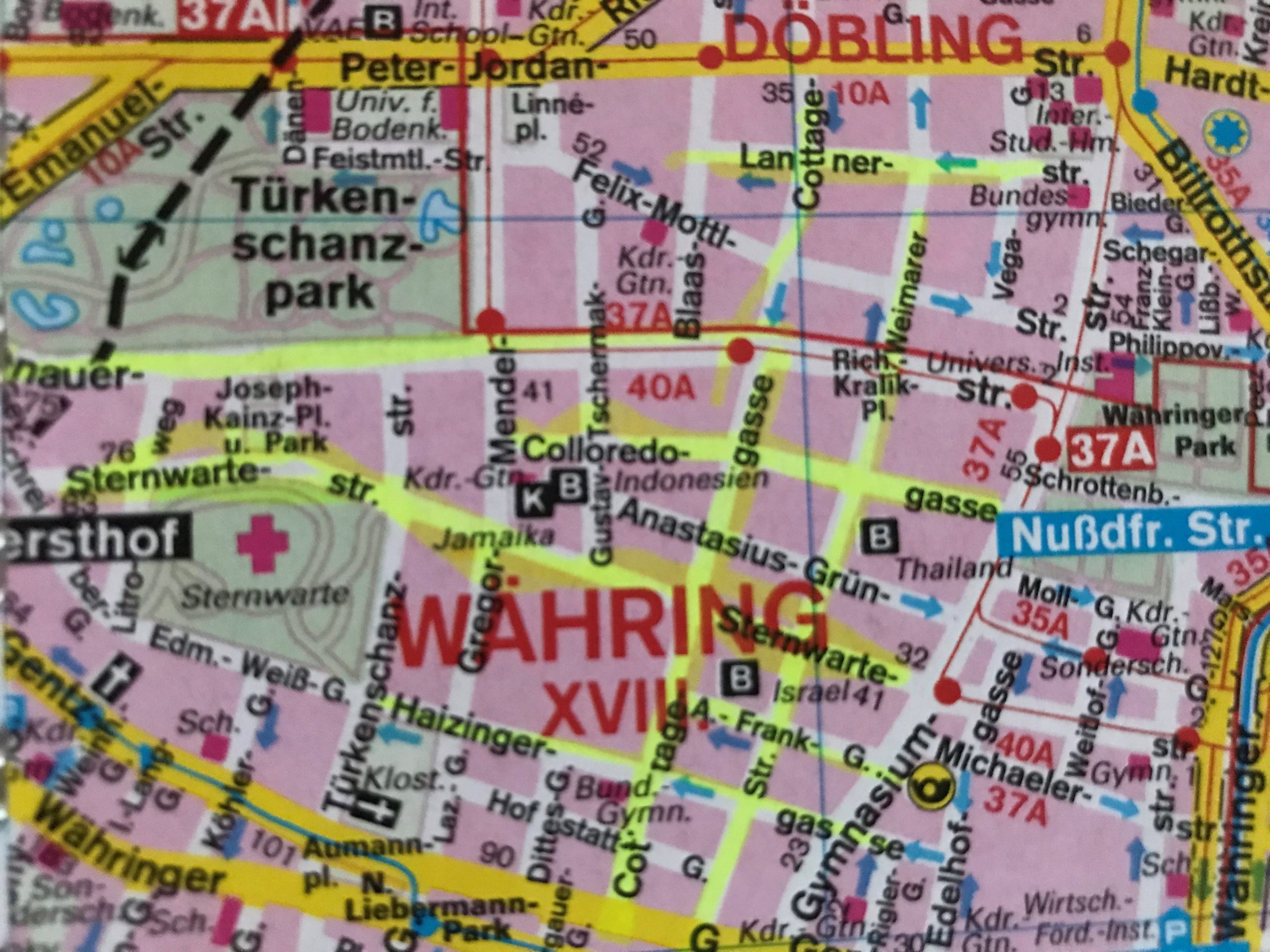

Herta Kainz, my mother, was exactly such a bookworm; a shy withdrawn little girl who was born in Vienna on 24 November 1933 and started school in September 1940 in the midst of NS terror in Vienna. Her mother, Lola Kainz, was a born Jew who had converted to Roman Catholicism when she married Herta’s father, Toni Kainz. Herta was an only child who was much loved and cared for by her parents and her family, but she had to live under very precarious conditions because of the Jewish origin of her mother and her mother’s family. Herta was brandished a “Mischling 1. Grades” (a first degree mixed-race child) and excluded from all activities “Aryan” children were supposed to participate in. Her father Toni, who stood by his wife and daughter during these trying times, had been dispossessed by his family, innkeepers in the bourgeois Viennese district of Währing, and was working as a fishmonger. He was drafted by the Nazis and participated as a sapper in the German military campaigns Of World War II in France and Poland before he was considered “unreliable” by the Nazis, because he refused to divorce his Jewish wife and was transferred to the home front working as a fishmonger in war food supply.

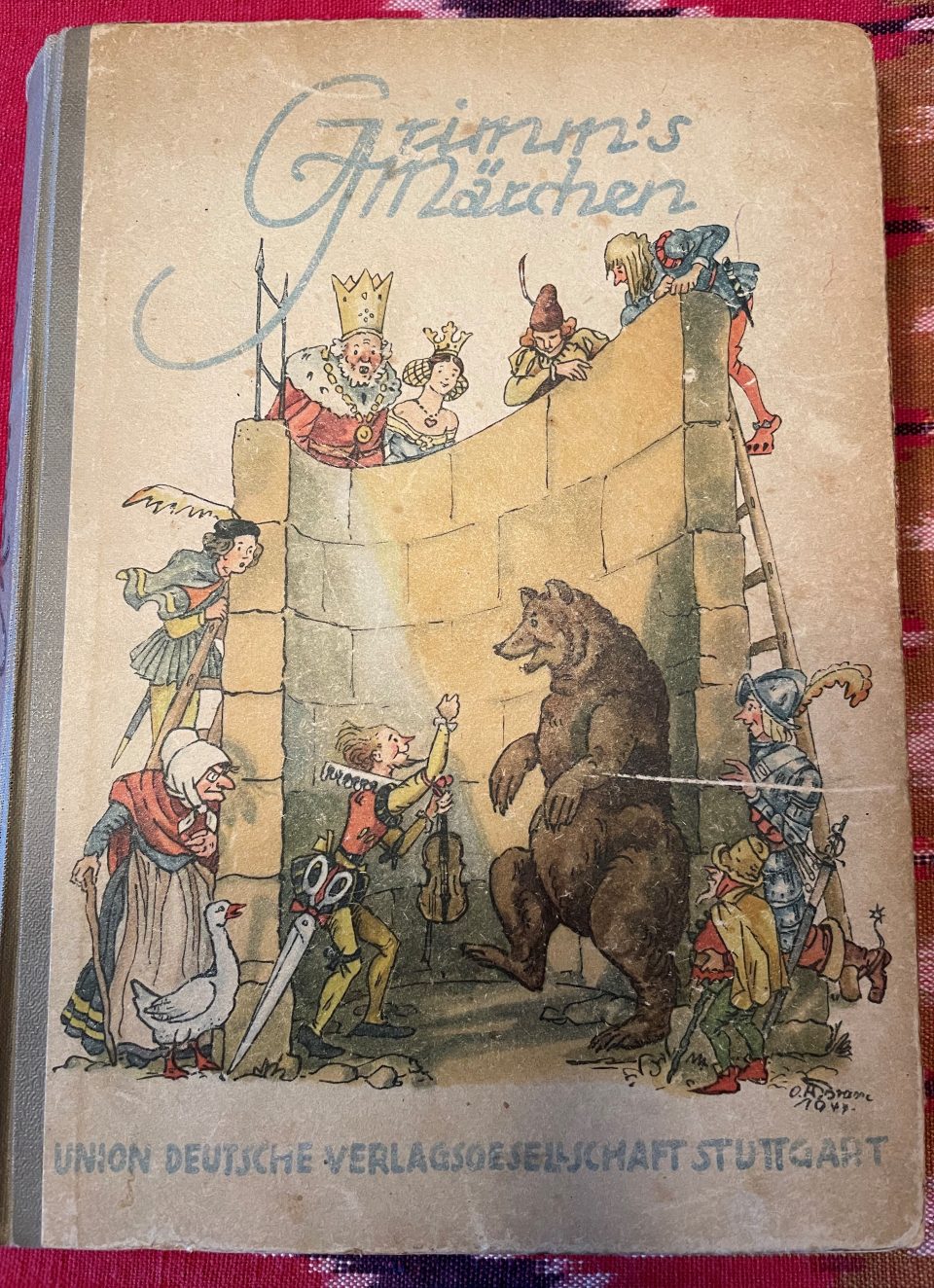

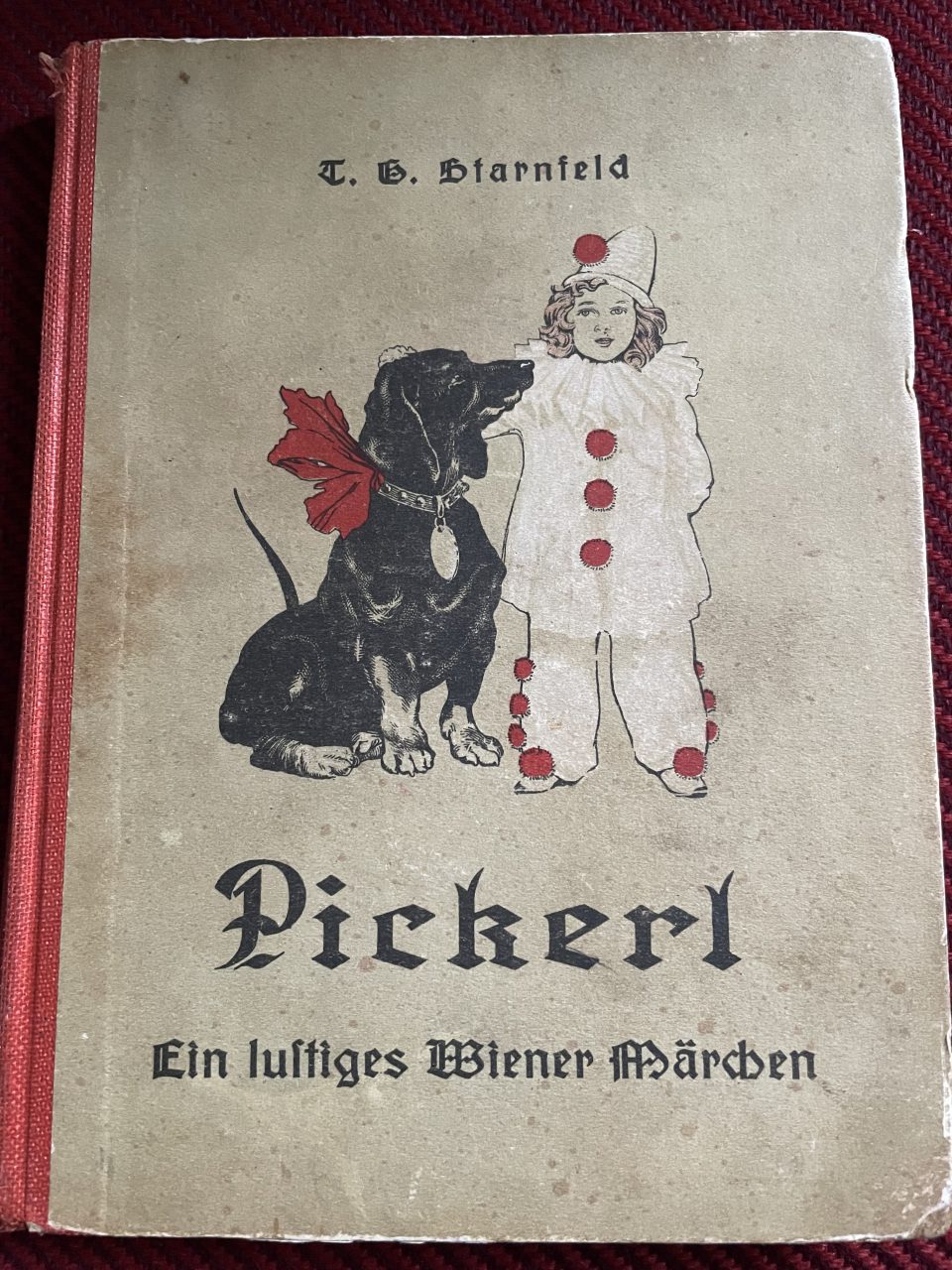

Herta’s mother, Lola, was constricted to do forced labour in the war industry. Herta as a small child had to watch the deportation of her beloved grandparents, Ignaz and Josefine Sobotka, and the exclusion, stigmatisation, and discrimination of her mother. Lola was for instance not allowed to go to a doctor or hospital or to enter the school building, where Herta started primary school. Herta was supposed to sit separately in the last row to mark her out as an “inferior mixed-race child”, who was not allowed to participate in any school festivities. Only thanks to the altruistic commitment of her young teacher, Helene Pfleger, who ignored the NS regulations risking her own career and life, the needs of the children, including Herta’s, were put first in Ms Pfleger’s classroom and not NS ideology. Herta and her teacher stayed in contact all their lives and Herta was for ever thankful to Ms. Pfleger for the love and care she had given to her. At home Herta was in constant fear of a knock at the door of their small two-room flat in Mariahilferstrasse, because that could mean that SS men were coming for her mother. Already as a small girl she knew she had to run for help to her father’s fish shop as soon as her mother was deported by the Nazis. This threat and this fear remained deep in her psyche for a long time. As a result, stories and books became her rescue haven; a dream world she could withdraw to from the terror of the real world around her. Her books and the diary she started to write after the war are the primary sources of this analysis of children’s and youth literature during the Austro-Fascist, National Socialist and post-war years in Vienna. As her family was poor, she owned very few books and those were second-hand books. What is more, buying at an antiquarian’s was the only chance to acquire books which were not on the NS lists of recommended books.

The main source of reading material for poorer children were public libraries, where the lending of books was usually free of charge for pupils. In 1878 the first two public libraries were opened in Vienna, followed by several workers’ libraries before and after World War I, which were founded by workers’ associations that wanted to promote the education of the Viennese working class. The Austro-Fascists closed the workers’ libraries in 1934 and after eliminating “unwanted” books from these libraries, reopened them. In 1938 the Nazis cleansed the libraries of all Jewish and politically ostracised authors, who had not already been eliminated by the Austro-Fascists, and renamed them “City Libraries”. Immediately after World War II the Viennese public libraries were opened again in 1945 and stocked with books, some of which provided by the Allied liberators, mostly by the Americans. But many of the old books remained on stock or were re-edited with slight alterations omitting crass racist passages and blunt Nazi ideology.

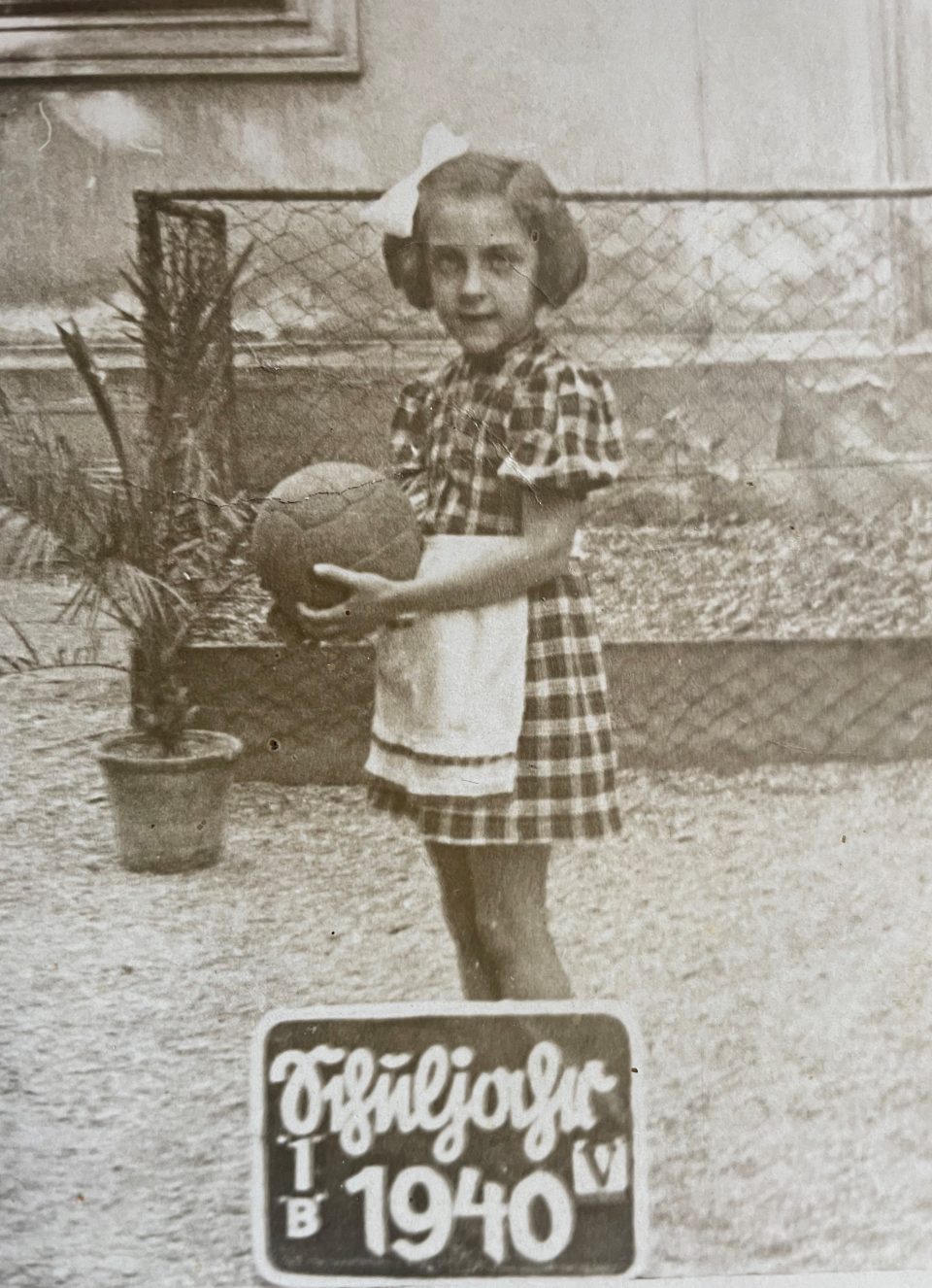

Herta during her first school year 1940 and after the war on the balcony of the family’s new flat on Lerchenfeldergürtel in the workers’ district of Ottakring

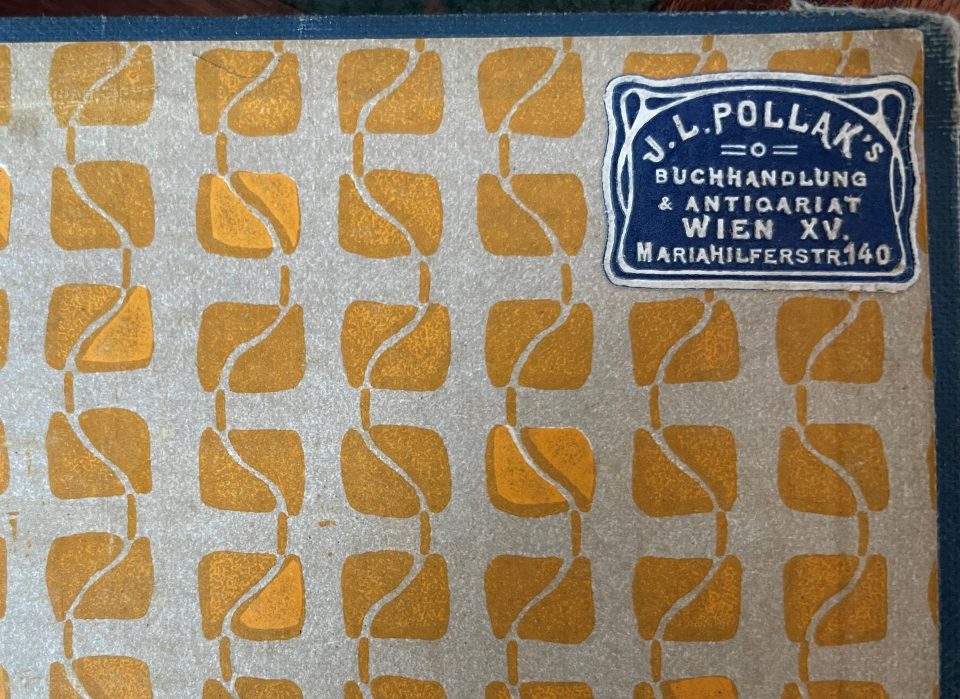

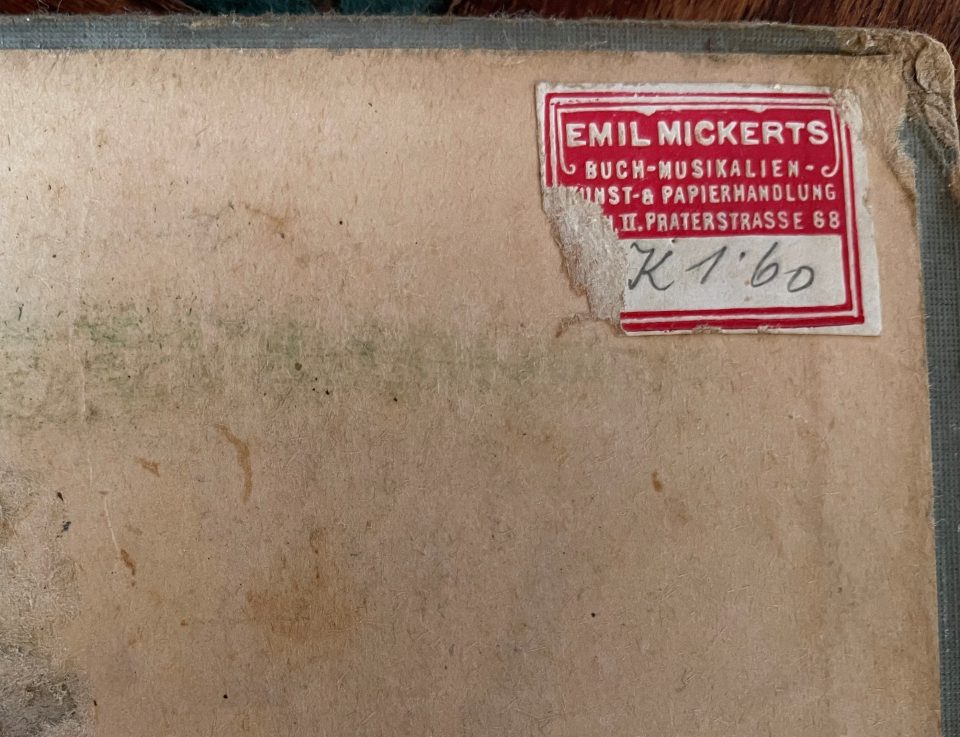

Second-hand bookstores, where Herta’s parents bought the few books for her they could afford during and after World War II

…