Bolivia is still one of the poorest countries in South America and in the 1930s it was a developing country that was definitely not the desired destination of refugees from Vienna like the United States, Brazil, Argentina or Chile, where the living conditions were similar to Central Europe. But Bolivia ended up as a refuge for many who did not have any other choice and who were desperate to grab any visa available to be able to flee the Nazi terror. You sometimes had to bribe the diplomatic personnel at the embassies to get visas that later turned out to be faked, but even after a stop to immigration, Bolivia handled the issue flexibly and all those with visas, genuine or faked, were allowed into the country, most of them on agricultural visas, although they had no idea of farming. Fortunately for the refugees did Bolivia not annul faked visas, in contrast to other Latin American countries. The country that offered the refugees from Nazi terror rescue was riddled with economic crises, unrests and military coups and had lost a large part of its territory in the “Chaco War” against Paraguay. The German community that had settled in Bolivia before 1938 was under the influence of the NSDAP, led by the German ambassador. Therefore the possibilities for making a living were very limited for the Austrian and German Jewish immigrants; they were restricted by the German community, the Bolivian administration and the Bolivian professional associations. Only few joined agricultural projects, like those of the mining entrepreneur Mauricio Hochschild, most resorted to small retail trade and craftsmanship, where they competed with the local population and thereby triggered some resentment. Within three years the approximately 7,000 to 8,000 refugees to Bolivia formed the largest foreign community there, but most of them moved on to other countries, such as the United States, Chile, Argentine and Uruguay as soon as it was possible. In 1945 around 4,800 Jewish immigrants still lived in Bolivia. The tropical and sub-tropical climate and the extreme altitude were a huge challenge to the immigrants, but the country saved the lives of many refugees from persecution of the “Third Reich” – it accepted the largest numbers of Jewish refugees from Europe of all Latin American countries relative to its inhabitants and my relatives always preserved a loving memory of the beauty of the country and its colourful population mix.

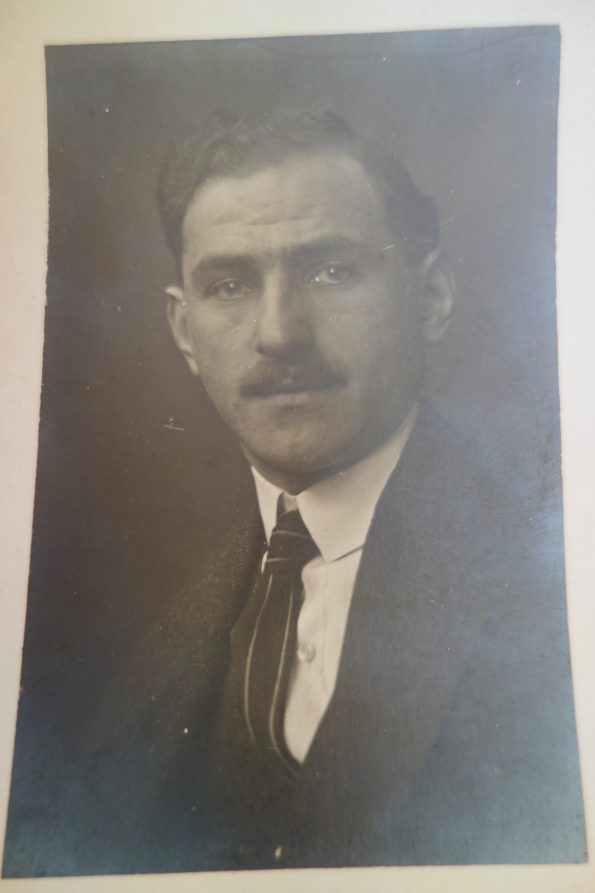

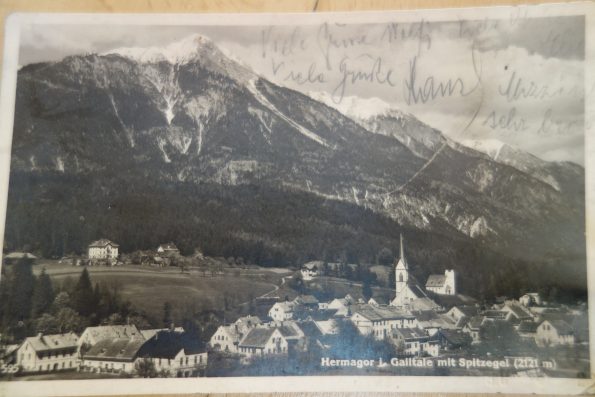

My great-uncle Karl Elzholz, a mechanic at the Vienna tramways, was married to the youngest sister of my grandmother, Marianne (Mitzi), who was several years younger than him. She was his much loved second wife, after his first wife had died young from a lung disease. They had no children and decided rather late that they had to flee Vienna when Hitler invaded Austria in March 1938. Karl was an enthusiastic socialist and a dedicated patriot of the young Austrian republic. As most of the possible destinations had already closed their borders, he managed to procure a visa for Bolivia as an agricultural worker. Karl was a skilled mountain hiker and they fled Austria across the Alps in the winter 1938/39. The last message that my great-grandparents and my grandparents in Vienna received from them was a postcard from Hermagor in Carinthia with the following message:

Dearest parents, Don’t worry and don’t get excited. We are very well. We eat, drink and wait. We have passed the border without problems. There is a lot of room in the train, so we will sleep well. It is half past six and we are already at the border. Many, many kisses, yours Mitzi. Greetings Karl

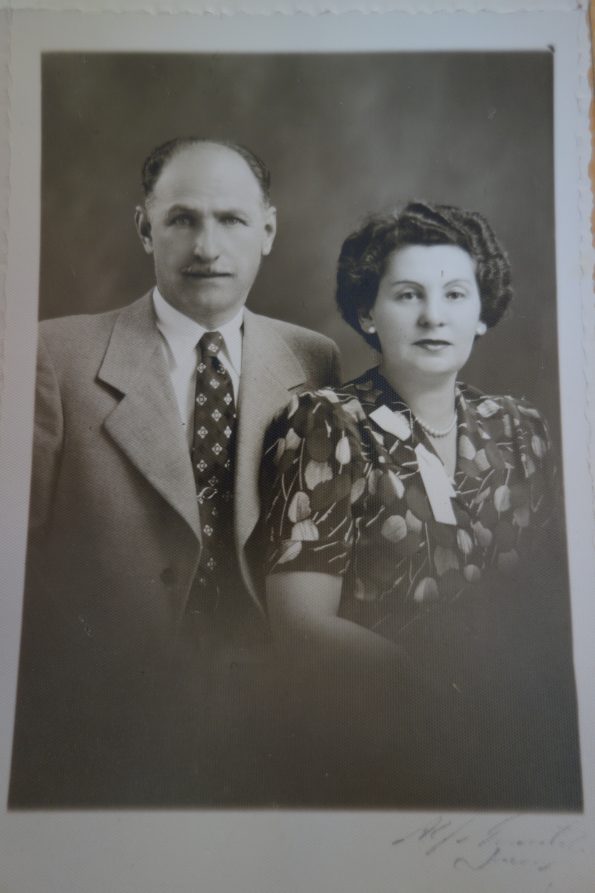

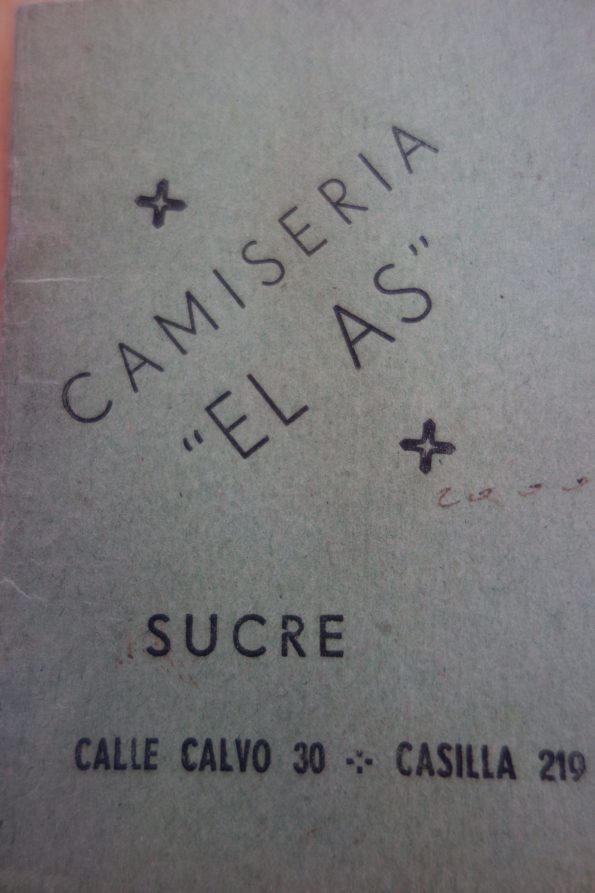

They boarded a ship in the Italian port of Genova for Bolivia. Only after the war my grandmother heard from them again and to the surprise of the whole family Karl was now married to Käthe, the eldest sister of my grandmother, who had fled to England; and Mitzi had married a German refugee, Bill Stern. All four of them lived in Sucre and ran a business together producing and selling shirts. The family in Vienna was most astonished and amused and only found out about the circumstances of their exile in Sucre, Bolivia, after the return of Karl and Käthe to Vienna in 1948. Mitzi and Bill migrated from Bolivia to the United States after the war and returned to Vienna after retirement.

After the civil war of February 1934, the establishment of an Austro-fascist regime and the ban of socialist and communist parties, a new constitution was decreed in Austria in May 1934 that stressed the “Christian-German” character of the state. Still the constitution guaranteed equal rights to all Austrian citizens of all beliefs. Yet this same constitution paved the way for the discrimination of the Jewish citizens by introducing quotas for Jews in schools, hospitals, banks, the public administration and the economy. Anti-Semitic propaganda and agitation was not reigned in, on the contrary, anti-Semitism spread among the disillusioned lower and middle classes and the NSDAP’s membership grew. After the takeover of the Nazis in March 1938 more and more Austrian Jews had to consider emigration. The Austrian writer Hans Maier, later known as Jean Améry, expressed the state of mind of people, just like Karl who was an agnostic, socialist and supporter of the Austrian Republic, born in Vienna in 1890: He was already 48 years old and did not want to leave, on the one hand because he did not want to spend money for the long journey abroad, on the other hand because he just did not intend to leave Austria, his homeland. He was sure that he belonged here and that was the place where he wanted to live. No one would be able to chase him out of this country; he was determined to remain, according to the motto of an old Viennese song “Erst wenn’s aus wird sein, mit aner Musi und an Wein…..” (Only when it is over, when there is no more music and wine…) – until it was nearly too late.

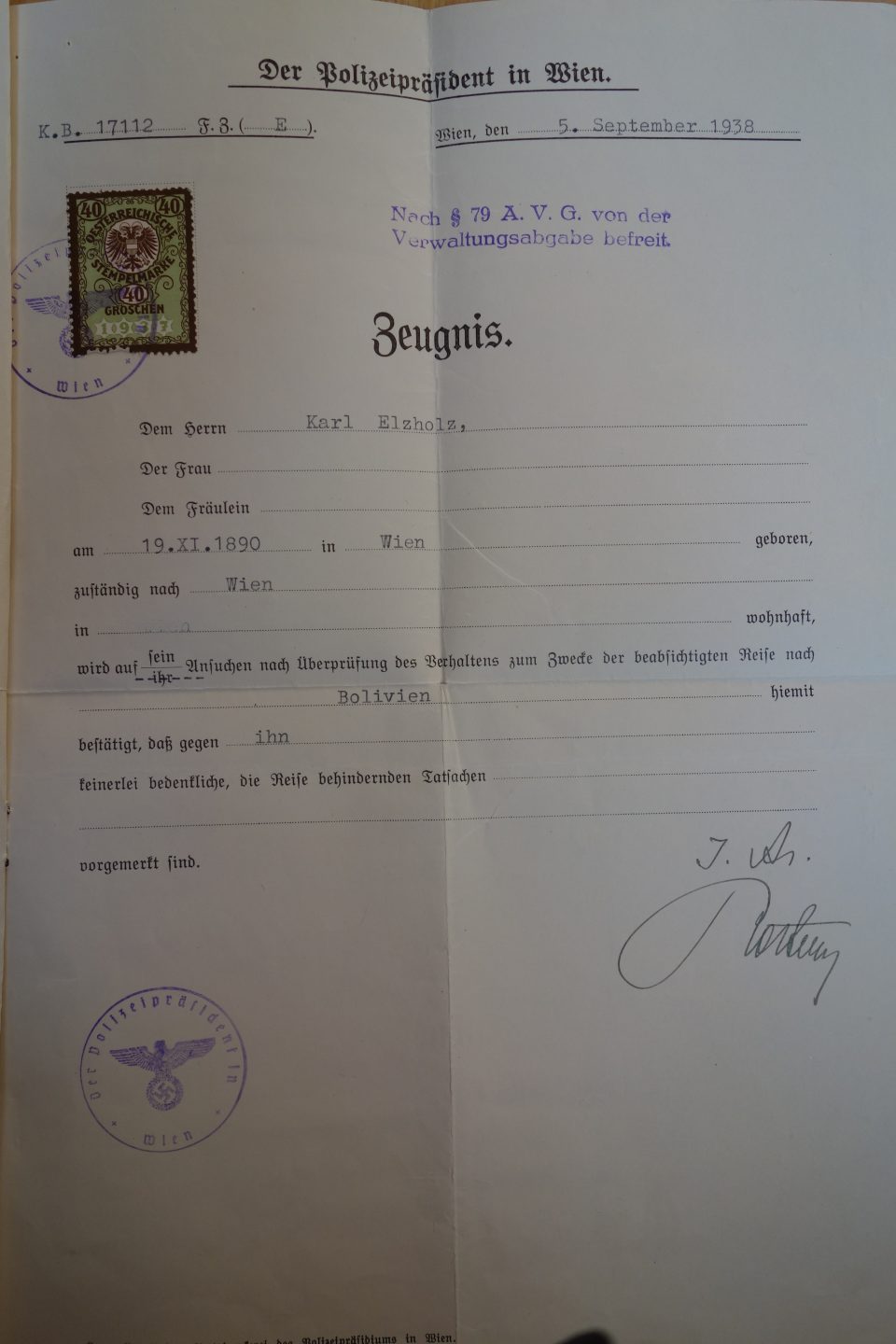

The markets in Europe and the rest of the world only recovered slowly from the Great Depression of 1929 and that restricted the possibilities of migration abroad considerably. Some countries accepted farmers and industrial workers, but for skilled workers and business people nearly no countries offered a safe haven because they would compete with the local population. After the annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany, Adolf Eichmann declared his strong will to “solve the Jewish problem” and speeded up the forced emigration of Jews from Austria. The three pillars of his programme were that first, emigration was not an option for Jews, but a duty; second, Jewish agencies and organisations were responsible for the execution of this order and third, Jews were not allowed to take any of their possessions with them except the small amount of money they needed to enter the country of destination – everything else was confiscated by the state. Eichmann’s central organisation for the emigration of Jews was located in a former Rothschild villa in Vienna. Here all who had to emigrate had to queue up for their emigration documents. Within two weeks after the issuing of the passport stamped with a “J” (for Jewish) the person had to leave the country otherwise he or she would be deported to a concentration camp. Eichmann’s systematic and bureaucratic Viennese model of forced emigration of Jews was much admired by the Nazis and copied in the rest of the “Third Reich”.

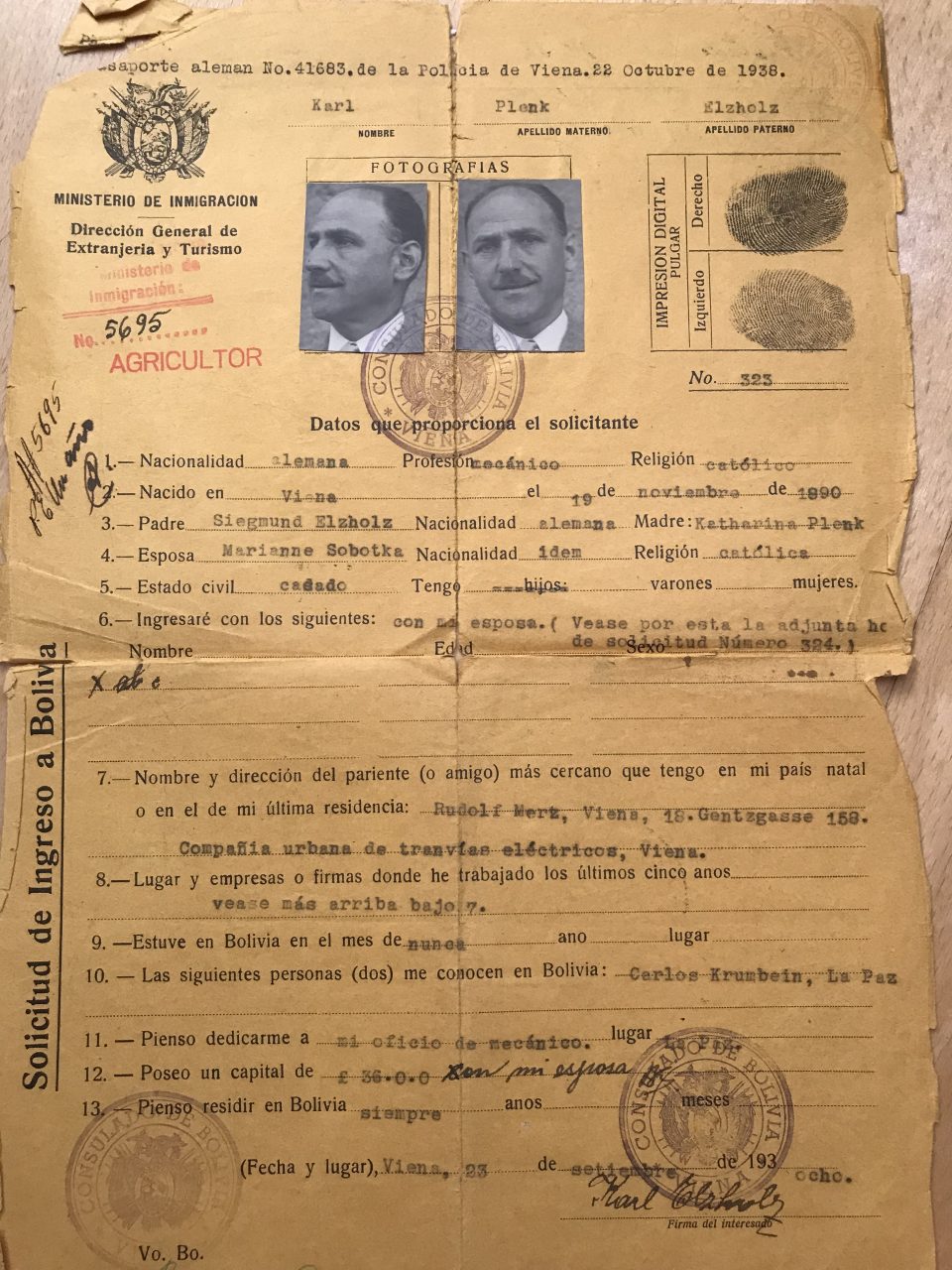

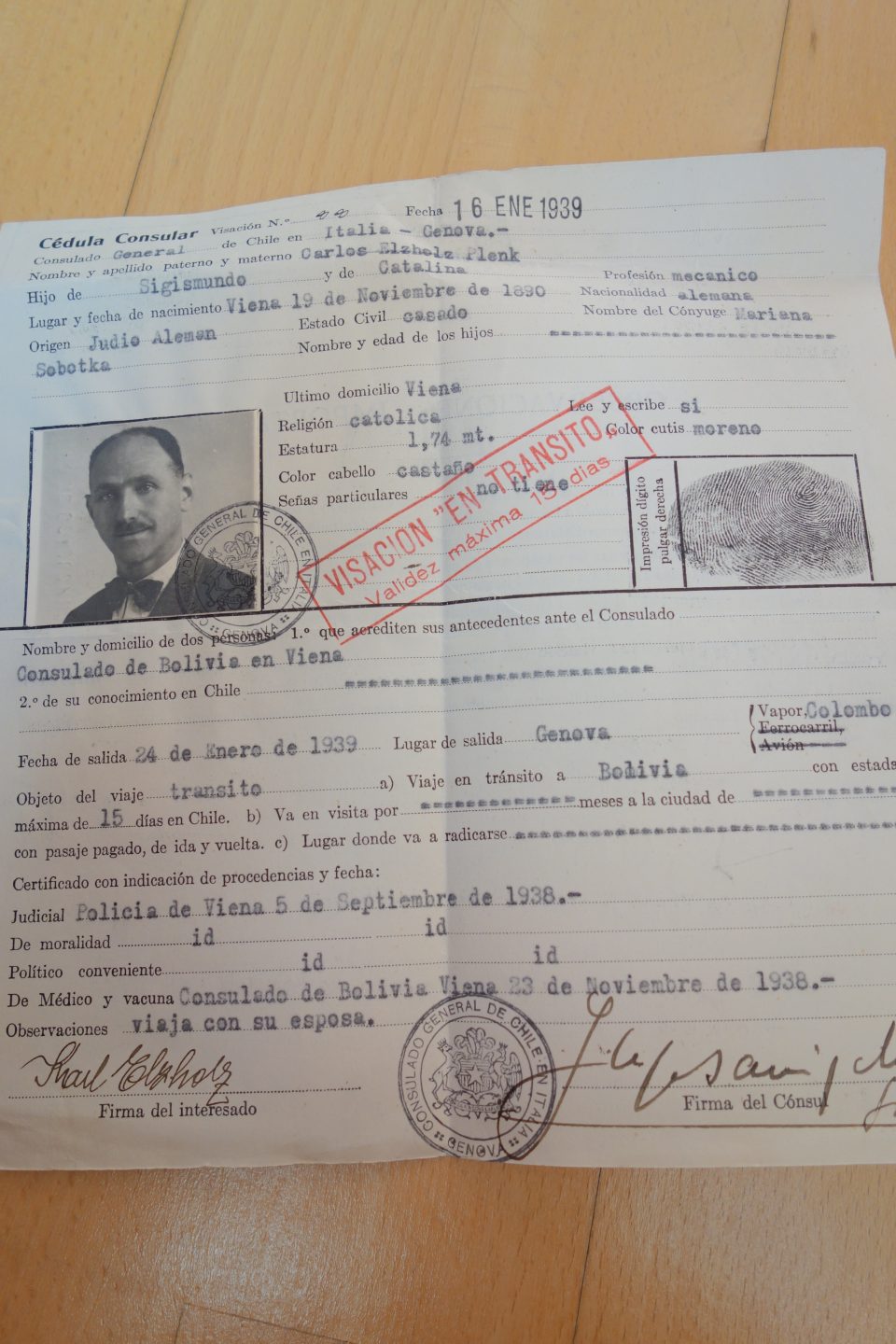

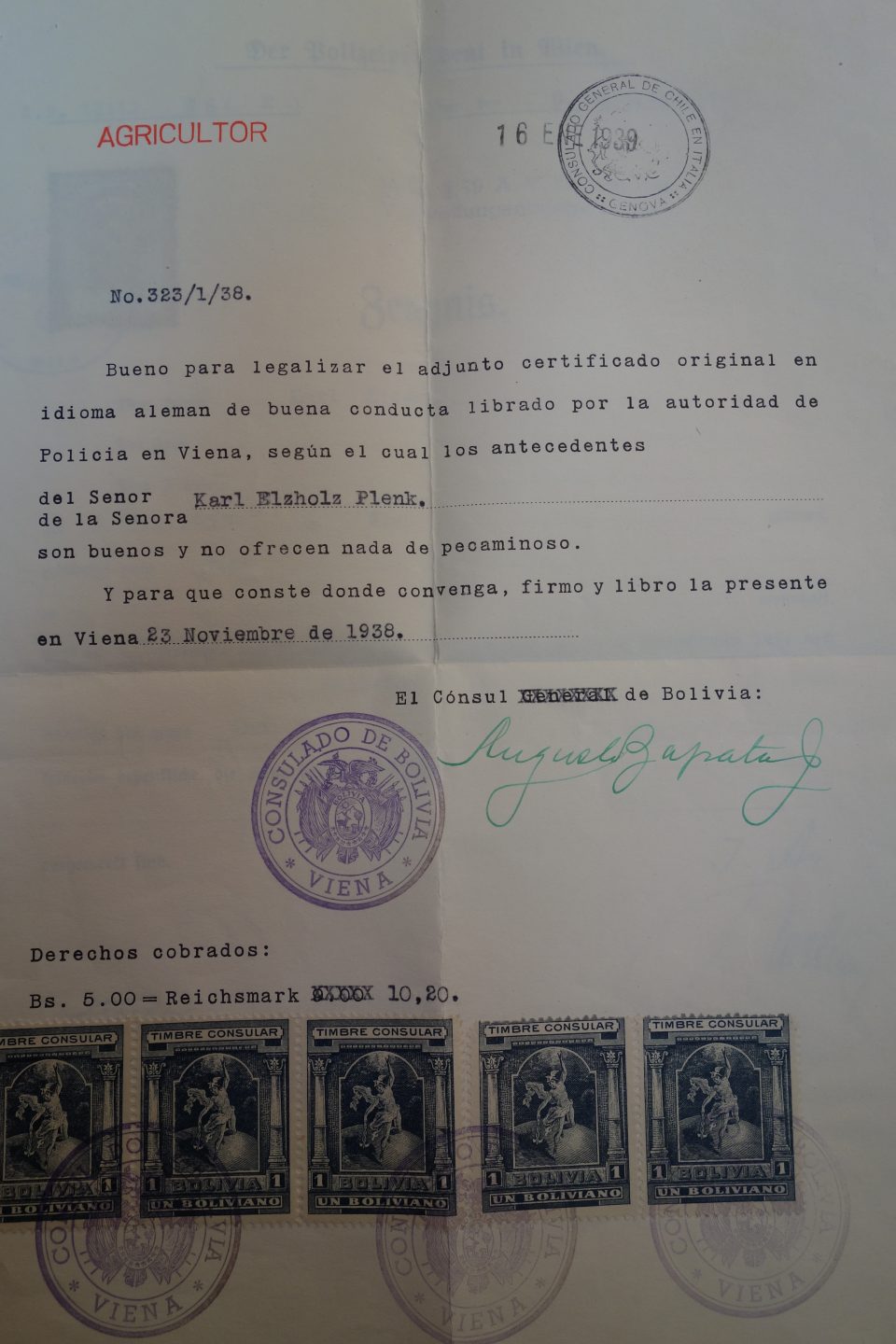

Daily thousands of people queued up before daybreak in front of police stations, central emigration offices, consulates and embassies in order to receive the necessary documents for emigration and may be also financial assistance of Jewish aid organisations for the journey. The bureaucratic processes required from every applicant to produce a number of official documents within a certain period of time and in the right sequence. So if the applicant received document number two, for example, after the deadline noted in document one, he had to start the whole procedure again. These long queues were often targets of Nazi attacks and who could afford it, asked other Jews to wait in the queues for them in exchange for payment. Some of the documents that Karl had to procure and that have survived the flight can be seen below, like the health and vaccination certificate, the police certificate of good conduct and the application for entry in Bolivia with his wife Marianne and a deposit of 36 pounds. He named Carlos Krumbein in La Paz as the person he knew and who could vouch for him in Bolivia.

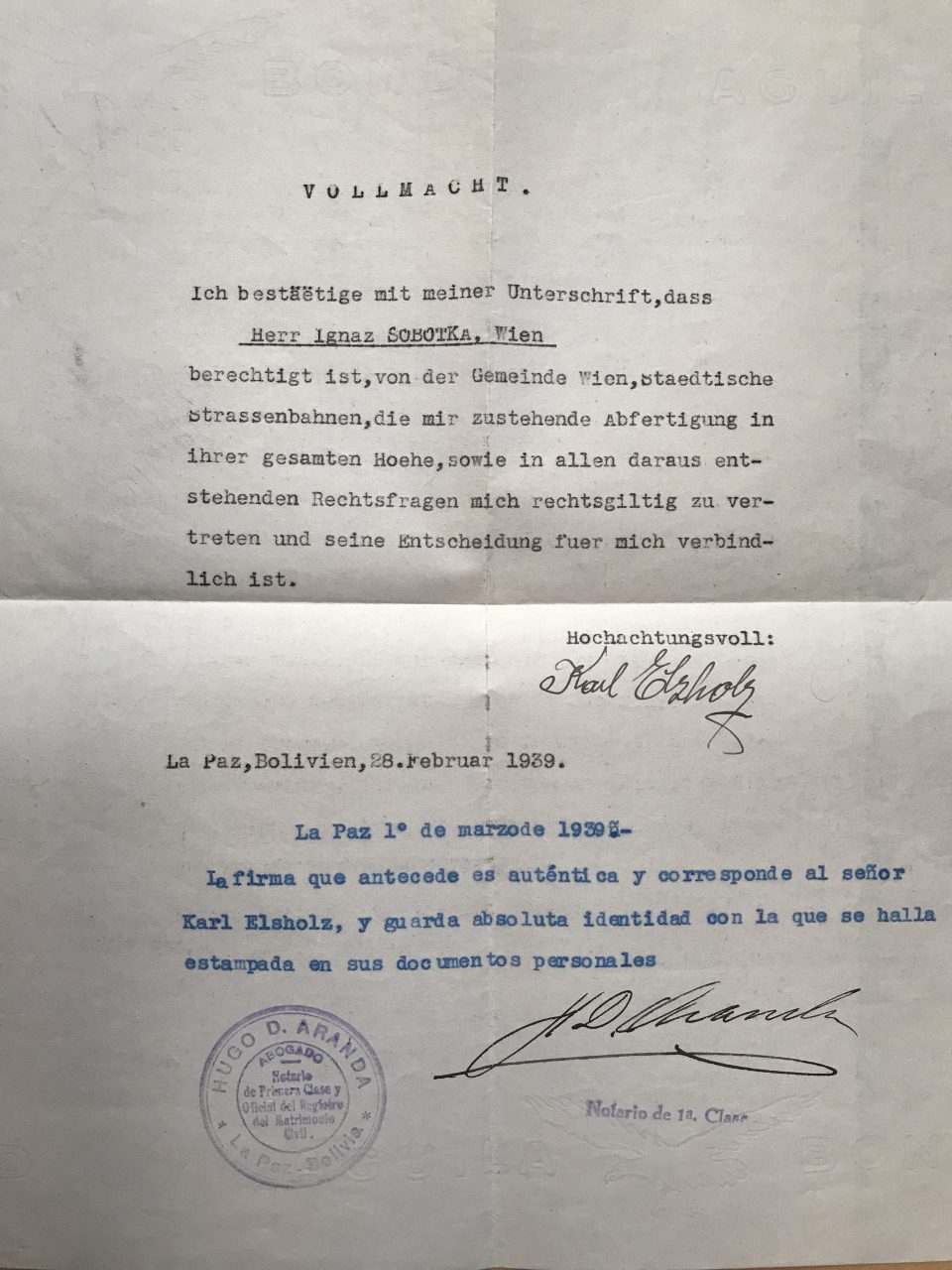

Most Latin American states demanded a deposit of a certain sum of money (in Bolivia a deposit of 2,500 US dollars at the Bolivian Central Bank from 1939 on) and / or a relative in the country who would guarantee the support of the immigrant. The absurdity of the situation is illustrated by the fact that all those who were forced to emigrate had to pay a so-called “Reichsfluchtsteuer” (a tax on fleeing the Third Reich) before all their possessions were confiscated. An interesting document is preserved wherein Karl handed over the authority to collect the redundancy payment he was entitled to after being made redundant by the Viennese tramways, where he had worked as a mechanic, to his father-in-law, my great-grandfather Ignaz Sobotka. The document was sent to Vienna from La Paz in Bolivia on 28 February 1939. At that time Ignaz was already interned in a so-called “Sammelwohnung” (a flat where Jews were “collected” before deportation) in the 2nd district of Vienna and all his possessions had been confiscated. It is touching to see that Karl still believed in the smooth working of the Austrian bureaucracy at a time when Jews were already deprived of all civil rights and all their fortune. Of course, Ignaz never received that money to keep it safe for Karl.

Valid immigration visa became an obsession for Viennese Jews as one country after the other closed its borders to refugees. Emigration visas, transit visas for the countries that had to be traversed on the journey to the final destination were all linked to a valid immigration visa. As nearly all borders in continental Europe were already closed for emigrants by the end of 1938, the people had no choice but to apply for immigration to any country that would allow them entrance. Corruption and fraud were widespread and lots of desperate people ended up with invalid documents. Even consulates and embassies, for example those of Uruguay, Bolivia, Cuba and Brasilia sold illegal immigration documents. After the outbreak of the Second World War passenger transport across the Atlantic virtually came to a halt and the only chance to escape from the “Third Reich” was to traverse Siberia and East Asia to get to Latin America, which only a few hundred succeeded in. But thousands were rescued by settling in Shanghai– among them also relatives of my grandmother. At that time Shanghai was an international Chinese territory and the only place in the world that did not require immigration documents.

After reaching the Italian border the Viennese refugees headed for Genova where Italian companies transported passengers to Latin America; many of them Austrian and German emigrants to South America. The “Virgilio”, “Orazio”, and the “Augustus” were three of those ships of the “Italia Line” that serviced this route. The journey took one month with stops in Marseille, Barcelona, Las Palmas, Trinidad, La Guaira, then after passing the Panama Canal, Baranquilla, Callao, Arica and Antofogasta. The final destination for those going to Bolivia was Arica, the most northern harbour in Chile. From there the refugees took the train to Bolivia. The “Vigilio”, built in 1927, transported 110 passengers in the first class, 200 in the second and 400 in the third class with 240 crew members. It was slightly bigger than the “Orazio”, but much smaller than the three times bigger flagship “Augustus”. All passenger ships of the “Italia Line” on course to Latin America from Genova to Valparaiso in Chile and back to Genova made the trip within 10 weeks. The Italian “Lloyd Triestino” ran passenger ships to the western coast of Latin America and to Arica, too, starting the journey in Trieste. Arica was the harbour of arrival for all migrants to Bolivia. It was chosen because of its isolated position in a desert area on the foot of the promontory of Morro. Neither Santiago nor other more attractive destinations could be reached from there. From Arica the only travel destination by land was La Paz, which could be accessed solely by train, which ran only twice a week and climbed thousands of meters of altitude across the plateau of the Andean mountains.

In 1939 the Italian harbours remained partly open for emigrants and ships leaving from Genova still transported thousands of Jewish and non-Jewish passengers to South America, but when the fascist Italian state gave up its neutrality and joined Hitler in the war in 1940, these transports stopped. During the time of the Second World War it was practically impossible to reach Latin America from continental Europe. So Käthe was lucky that she had found refuge in England because from there she could join Karl in Bolivia on an Allied escort vessel during the war.

In January 1940 a catastrophe hit the ship “Orazio” on the way to Valparaiso. The Italian ship had already transported thousands of refugees to South America, yet this would be her last journey. Due to the outbreak of the war in September 1939 and the strict immigration rules in all American states there were only 442 passengers on board with the destination Bolivia. One day after its departure, on the 20th of January the “Orazio” was stopped near the French coast and panic among the emigrants broke out on the ship, but as in all their passports the red stamp “J” of the Nazi authorities was visible they were not considered a threat and the ship was allowed to continue its course. But in the early morning hours of the 21 January near the coast of Toulon there was an explosion in the machine room. Five Italian seamen died instantly and a fire broke out on board. Only nine to ten hours after the mayday signals were launched a French water airplane arrived and surveyed the situation. Further two hours later a French war vessel reached the burning “Orazio”, the same ship that had stopped the “Orazio” the day before. It is assumed that the ship was either hit by a mine or a torpedo and that’s why it took so long until the civil passengers were rescued, although the incident had occurred only 38 miles south of Toulon. 114 people died in that accident and the remaining passengers had lost all their documents, which made it impossible for them to travel on to Bolivia as planned. Newly founded refugee clubs and Jewish refuge organisations tried to assist the ones that were stranded in hospitals in southern France and Italy. They jointly managed to get all survivors onto the ship “Augustus” in Genova, so that they arrived in La Paz on the 19th of March 1940. The arrival was celebrated there by the Jewish refugees. The German-language weekly magazine “Rundschau von Illimani” in Bolivia reported the drama of the “Orazio”.

On board the ships a collective identity of the emigrants developed, an identity of expulsion, dispossession and the first idea of what it meant to be a refugee. At the starting point of this journey lay the home country, from which they were driven against their will, the cultural and social environment, the friends and relatives that were left behind and at the point of destination lay the country of asylum, foreign, unknown, which was awaited with gratitude and relief. Expectations, new challenges and hope for a better future were mingled with unease and uncertainty. The emigrants on board swayed between hope, optimism, fear and grief, the typical characteristics of a “refugee identity”. For all the refugees from Central Europe Bolivia had just been a white spot on the map of South America. They knew nearly nothing of the geographic and climatic conditions there and even less of the history, political and economic situation. Most had an unclear picture of the enormous cultural diversity and the social divisions in their country of refuge. What they knew was based on stereotypes, such as Catholic, Spanish-speaking and Indians. Those that tried to inform themselves about Bolivia, as soon as they had received the immigration documents, had to rely on travel literature of the 1920s and the novels of the German writer Karl May, ironically the favourite author of Hitler. Karl May had written two novels about Bolivia without ever having set foot in Latin America: “The Legacy of the Incas” and “Across the Cordilleras”.

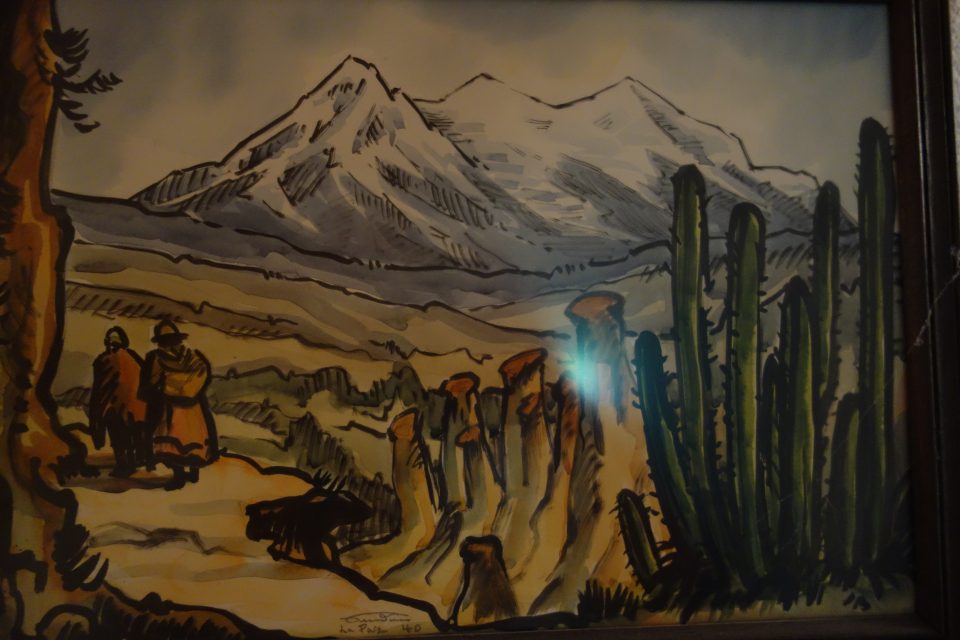

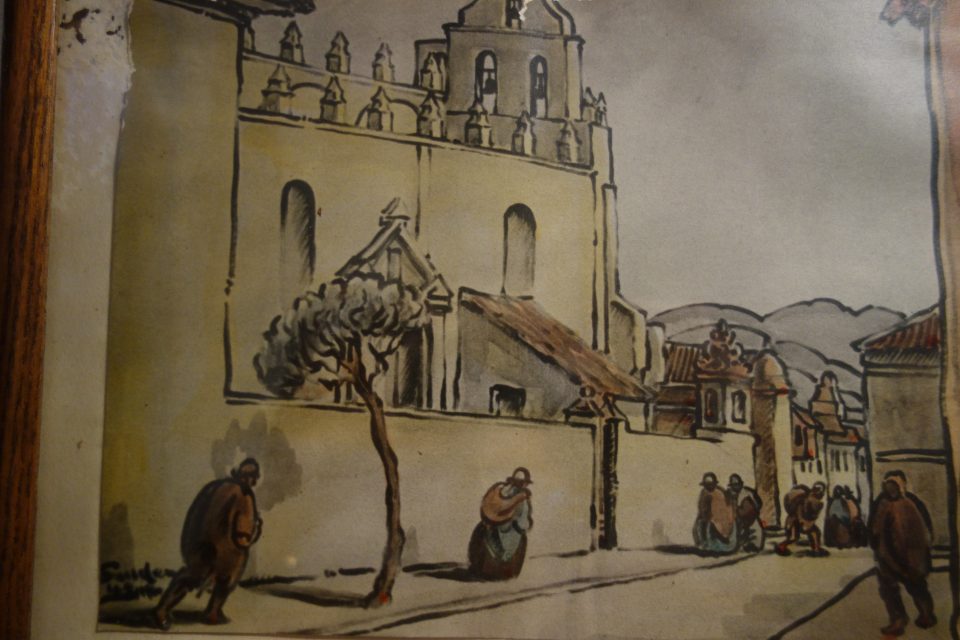

In Arica Jewish refugee committees organised accommodation for the refugees until the train to Bolivia arrived. These trains were often delayed due to natural catastrophes such as landslides and when they finally arrived they were hopelessly overcrowded. Two engines had to pull the train up the mountains from the coast. On the two-day train journey from Arica in northern Chile into Bolivia across the Cordillera Occidental at more than 4,000 meters of altitude they encountered a landscape and settlements that had nothing in common with what they knew from Europe. In Charana, the frontier town between Chile and Bolivia, the train halted overnight. The following morning it departed in the direction of La Paz and most of the European passengers suffered severely from high altitude illness called “soroche”. After a stopover in Viacha the train crossed the Altopiano before it arrived in La Paz with the view of the Illimani (6,439m) in the distance. This panorama must have mightily impressed Karl who was a skilled mountain climber and enthusiastic alpinist. Karl and his later wife Käthe often talked about the wonderful nature, the mountains, the colourfully dressed indigenous population and their skills in crafts as silver-and goldsmiths, carpet weavers and so on. They were not just thankful but enticed by the country’s beauty. For many the tropical and semi-tropical climate and the extreme altitude were unbearable, but not so for Karl and Käthe. They both had learned some Spanish, yet the indigenous population often did not speak Spanish, just their Indian languages. The encounters with the local population were fascinating for the newly arrived immigrants. They were attracted by the exotic appearance of the Indians, by novelty, adventure and the aesthetics of the unknown. The paintings that Karl and Käthe brought back to Vienna tell the story of their fascination.

The marriage of Karl and Mitzi, who was nearly 20 years his junior did not survive the stress of the flight and they divorced, but they seemed not to have fallen out and established a new existence together in Sucre. From the beginning of 1942 pictures have survived which Karl sent to Käthe in England describing his life in Bolivia and waiting for her arrival. He had of course known her well from the time in Vienna as the elder sister of his wife.

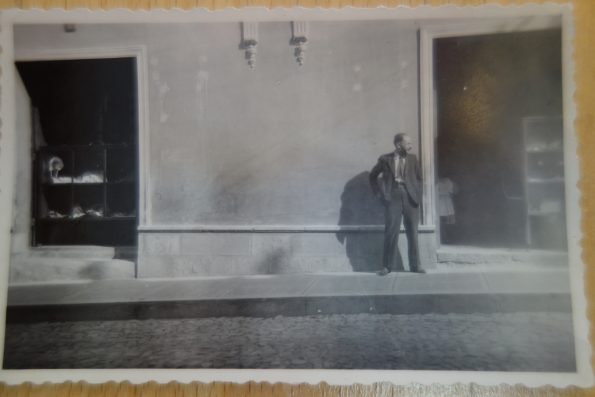

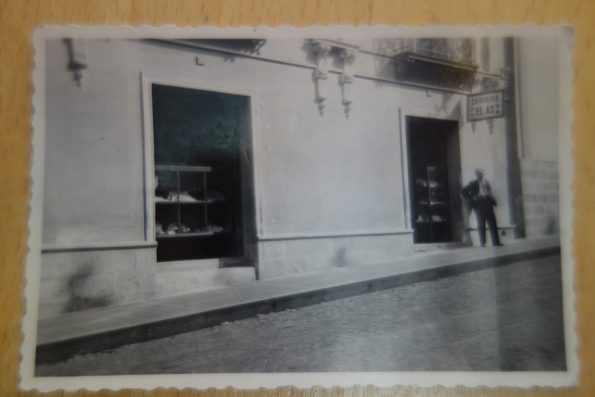

March 1942: “In this house with the two signs, “El-As”, there is our shirt factory and shop. In the first shop window with the bald head that’s me and in the second window that’s Marianne with her partner. We own and run the shop together. And I live in the back of this house.”

“The shop with the two shop windows and your Karl. I hope I can see you soon in the shop; you cannot expand the business very much because there is a lack of material here. But we are satisfied and I hope you will like it, too.”

“Our second car with which we moved our possessions. It brought us safely to Sucre. On top we two sat and the women in the driver’s cabin. In this way we drove for three days. In the car there is everything that we own.”

“Placa Sucre March 1942: In the centre of the town the church and on the right a most beautiful park. I would love to go walking with you here. The square is at 2,800 meters altitude!”

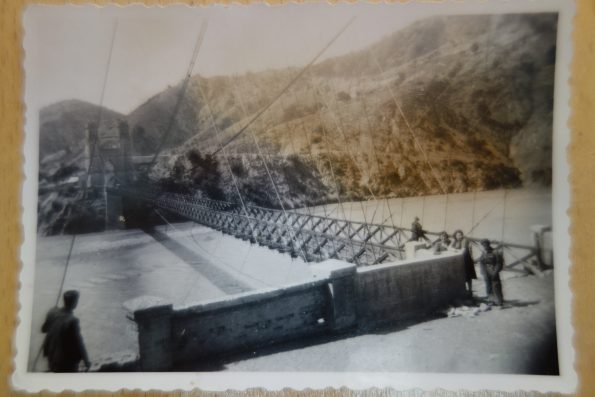

“March 1942: The river Bilcomayer: here we crossed over a modern suspension bridge. In the rainy season this is a mighty river. Your sister in the middle. I’m always the one who has to take the photos and that’s why I’m seldom in the pictures.”

December 1942: “The shop of Marianne and myself. I just received letter number 27, but I can’t answer now because the post has already been collected. Yours Karl”

Sucre, 24 December 1942: “My dear Käthe! Today is Christmas Eve. They don’t celebrate Christmas here as in Europe, but gradually the festivities are introduced here as well. The weather is warm – naturally – as it is summer here. The photo shows the shop where the shirts are made. With the next letter I’ll send you more photos. Hopefully, we’ll be together soon. Greetings and kisses yours Karl”

On the 8th of July 1943 Karl officially announced the intention to marry Käthe, living in London, witnessed by three Bolivian notaries in Sucre. Their “long-distance wedding” finally took place more than a year later in the Bolivian consulate in London on the 11th of August 1943, where Karl was represented by Norbert Katz, Käthe’s brother-in-law and Karl’s former brother-in-law, who was married to Agi, another of the four “Sobotka sisters”. Käthe finally arrived in Bolivia on board Allied escort vessels from England in 1944 and was united with her new husband.

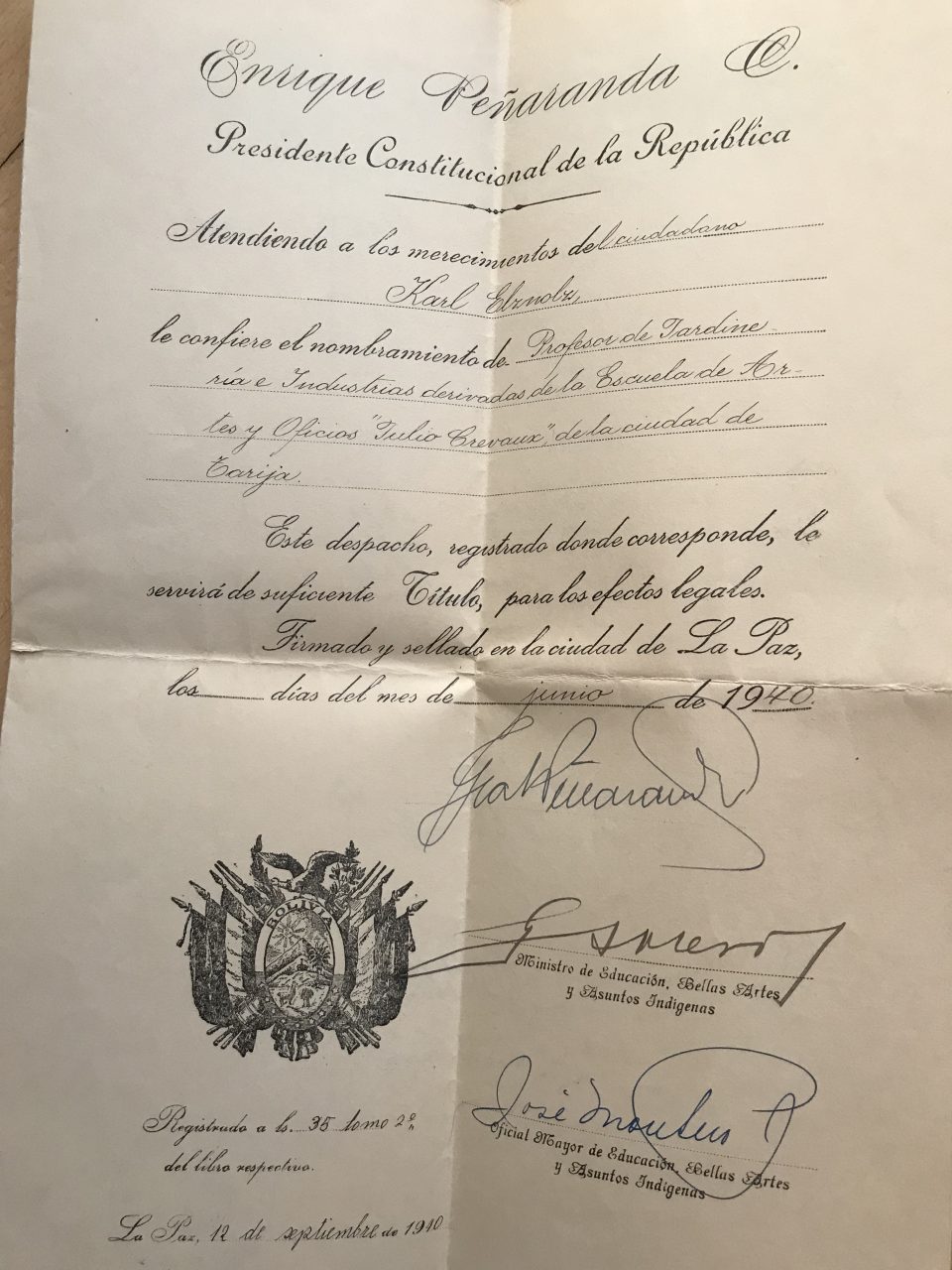

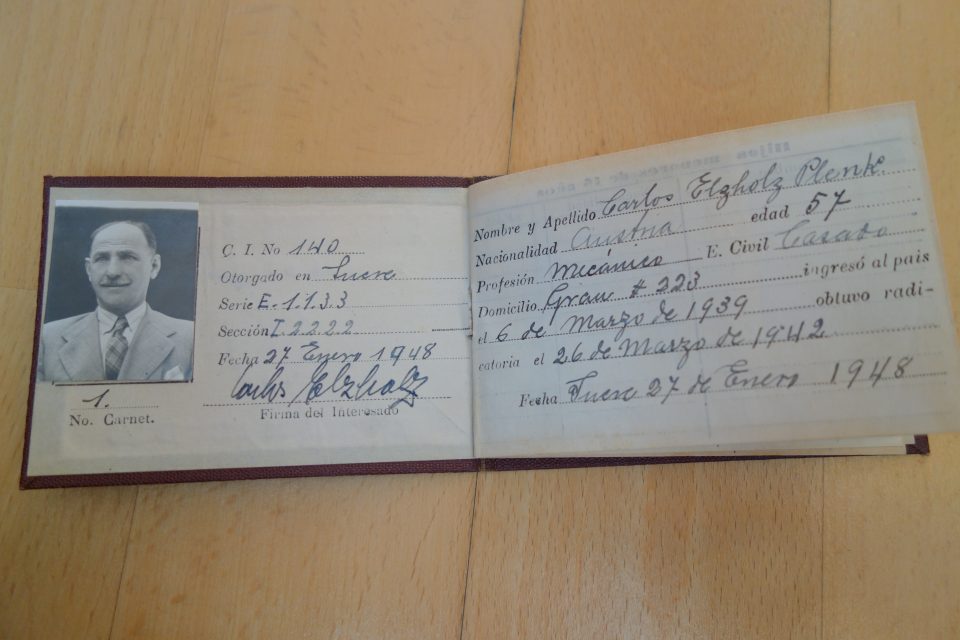

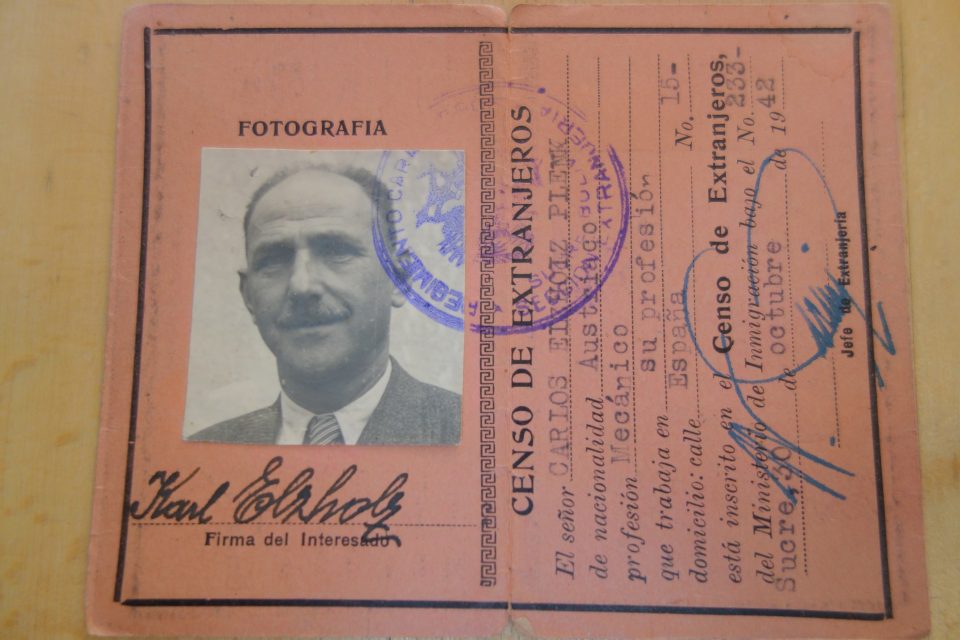

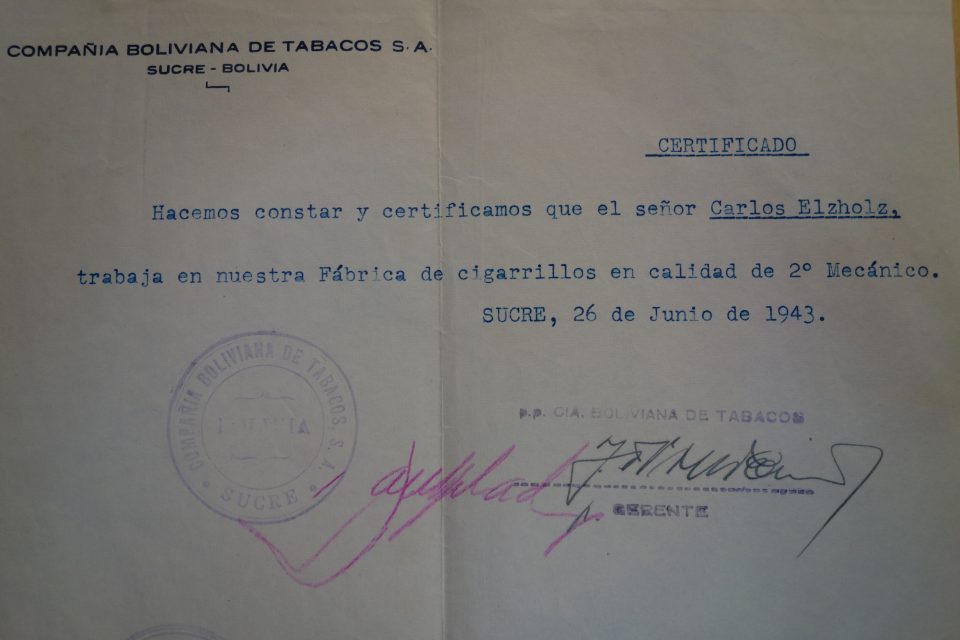

Karl was granted a visa for immigration to Bolivia as a farmer. The Bolivian documents issued by the Bolivian consulate in Vienna on the 23 of September 1938 for Karl Elzholz and his wife Marianne are stamped “AGRICULTOR”. It is mentioned that he would like to work in his profession as “mecánico” and the person he knows in Bolivia is “Carlos Krumbein, La Paz”. Another document was drawn up by the Bolivian consulate in Vienna on 23 November 1938 and completed by the Chilean consulate in Genova mentioning the destination Arica on 16 January 1939 and it is stamped “AGRICULTOR” as well. After his arrival he participated in trainings as a mechanic and metal worker in Tarija in the “Escuela de Artes y Oficios” from March 1939 until February 1942 to get his professional status accredited. He found a job in the “Compania Boliviana de Tabacos” in Sucre where he worked as a mechanic repairing and installing machines for the production of cigars, but later on he left the job to set up his own business together with Marianne and Bill. He and Marianne never worked as farmers in Bolivia. They had no experience and probably also no intention to do so as Marianne was a trained seamstress and Karl a mechanic. So why did they migrate to Bolivia on an agricultural visa? Because that was one of the last possibilities to escape from Nazi terror.

The Bolivian Colonizing Corporation or “Sociedad Colonizadora de Bolovia” SOCOBO, founded by the German-Jewish mining entrepreneur Mauricio Hochschild, was set up in 1939 in cooperation with the “Joint” or JDC (American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee in New York) in order to settle Jewish refugees in the deserted northern Yungas area to cultivate the land. This was just one of several attempts at establishing agricultural colonies in depopulated areas of Bolivia. Already in the 1930s before the wave of Jewish refugees reached Latin America, the Bolivian government had started similar projects of settling farmers on deserted areas of the country. After the end of the very costly war with Paraguay for the Chaco area from 1932 to 1935, the government tried to reorganise and modernise the Bolivian state. The loss of the resource-rich region of Chaco had serious consequences for the Bolivian population. 650.000 soldiers, a quarter of the army, were dead or prisoners of war, mostly Indians, which constituted a large percentage in a population of 3.25 million. In a military coup Colonel David Toro and Colonel Germán Busch took power in 1936 and carried out radical socio-political reforms. Busch was the son of a German doctor and a Bolivian woman and had the idea of attracting European immigrants as agricultural settlers to Bolivia. They were supposed to develop the subtropical and tropical regions agriculturally. Consequently the Bolivian consulates in Europe were advised to offer to prospective immigrants the incentive of a piece of land and free transit inside Bolivia as well as financial help in the form of grants for one year after arrival. Around 200 persons arrived from Central Europe and settled in 1936 in two colonies in the province of Santa Cruz and Cochabamba. Both projects failed within a short time because the immigrants suffered from malaria and were unable to establish settlements in a region without any infrastructure. Despite this failure Germán Busch stuck to his idea and it seems that he was behind the peddling of illegally issued overpriced agricultural visas to Bolivia. In the course of the year 1938 and especially after the pogroms of November 1938, the “Reichskristallnacht”, many Jewish refugees reached Bolivia with agricultural visas, such as Karl and his wife. Between 1938 and 1940 Jewish entrepreneurs in Bolivia and Jewish refugee organisations tried to convince leading politicians in Bolivia to even increase the number of Jewish immigrants allowed into the country. Mauricio Hochschild was the driving force behind this strategy. Together with Simon Patino and the family Aramayo he was one of the three big mining operators in Bolivia and a Bolivian citizen. These companies mined, processed and sold tin, lead, silver and other metals. Hochschild had acquired experience in the mining industry in the Austro-Hungarian Empire and Australia before he settled in South America after World War I. He orchestrated the merger of several small mining companies in the famous Cerro de Potosí, which had been the fabulously rich silver mine of the Spanish Empire, to form the “Compania Unificada del Cerro de Potosí”. With a newly developed German method he was capable of extracting tin from old and deserted mines and depots and by the end of the 1920s he controlled a third of the whole Bolivian mining industry. He was an agnostic, like Karl, and had close contacts to political and military leaders of the country. He spoke Spanish, English, French and German fluently and took over the role of principal adviser in all refugee matters in the 1930s and 1940s. In January 1939 he founded the aid organisation SOPRO (Sociedad de Protección a los Imigrantes Isrealitas) in La Paz with branches in Cochabamba, Oruro, Potosí, Sucre and Tarija. This aid organisation supported newly arrived immigrants with accommodation and loans for the setting up of small businesses. It also ran a hospital and sanatorium, a children’s home, a kindergarten in La Paz and a home for the elderly in Cochabamba. Despite the success of SOPRO, Hochschild saw the risk the influx of more and more refugees posed for the image and the acceptance of the Jewish immigrants in Bolivia. Bolivia suffered under a serious economic crisis after the Chaco war in 1938 and 1939. The key question was how the immigrants could be integrated in the Bolivian economy without harming the local population. Where could they settle without constituting a threat to Bolivian entrepreneurs and workers? Nearly all those who arrived with an agricultural visa came from urban areas with no agricultural experience. Some Jewish aid organisations had offered retraining courses before their departure, but most immigrants tried to settle in La Paz or Cochabamba after their arrival and work in their professional fields. Lawyers and artists had no possibilities to find jobs and employment in trade was rare due to the economic crisis. German companies established in Bolivia were mostly run by Nazi sympathisers and did not employ Jews. The immigrants could not find employment as unskilled workers because these jobs were reserved for Indians, who were massively exploited – they were called “peones”. Yet plumbers, electricians, carpenters and mechanics were in high demand, which was an asset for Karl. Dressmakers, hatters, watchmakers set up businesses or traded used goods, just as Karl, Mitzi and Bill who founded a small shirt-making factory and shop in Sucre. Others opened small restaurants, coffeehouses, bakeries or libraries. Those were market niches in the Bolivian economy, where the immigrants did not compete with the local population.

There was the danger that the flood of immigrants could get out of control and contribute to a rise of anti-Semitic sentiment in the country. That’s why Hochschild attempted to transfer the immigrants from the urban centres to agricultural colonies. He opened agricultural training centres to prepare the immigrants for their tasks in the depopulated areas of the country that lacked any infrastructure. The government supported this strategy because Bolivia was severely dependent on imports of primary products, such as wheat from Canada and Argentina, rice from India, sugar from Java and coffee from Brasile and Colombia. These agricultural colonies should make Bolivia less dependent on agricultural imports and the volatile prices of primary products. The “Joint” and American financiers promised to finance the projects and assist Bolivia financially if Bolivia consented to accept more refugees. These agricultural colonies were to be established in the Chaparé zone. In 1940 the organisation SOCOBO was founded to organise this settlement project. After the outbreak of the war in Europe it was virtually impossible to flee from the continent, so the aid organisations concentrated on the effort to rescue those Jews that were stranded somewhere in western Europe on their way to escape from the Nazi regime. In 1939 President Busch, who had supported the idea of settling refuges in deserted areas, died under mysterious circumstances. The settlers in the Chaparé zone were faced with endemic diseases, a lack of infrastructure and wrong agricultural policies. Felipe Bonoli, an Argentine agronomist of Italian descent, selected a territory in the Yungas which was named “Buena Tierra”, but was not arable at all. Although it was only 90 kilometres from La Paz, it took the settlers approximately six hours to get to the capital city, whereby part of the way could only be managed on a donkey or on foot. Therefore a priority was the construction of a road connection to La Paz. The settlers were completely isolated in their new home and had to face the challenges of extreme altitude and unknown diseases. Their relationship to the indigenous Indian population, who were hired as workers on the plantation, was amicable, but the lack of knowledge of the Indian languages often led to misunderstandings. Yet the social hierarchies in Bolivia posed an advantage for the Jewish immigrants, because the Indians were on the lowest rung of the social ladder and were mercilessly exploited by the white Bolivian middle class, so the landless refugees were not the least respected members of Bolivian society. The project organisers had presumed that the farmers would be self-sufficient after a year. Bonoli had planned the plantation of bananas, tangerines, pineapples and coffee to be sold in Bolivian cities and abroad. Furthermore the planting of fruit, vegetables, cocoa and coca, as well as the breeding of sheep, goats, cows and fowl was projected. The plan was badly calculated and overoptimistic. The topography was not suitable for the growing of these products, so the project failed. A new project leader, Otto Braun, suggested splitting up the huge plantation into small plots that were planted by the individual settler families. This second attempt at establishing a prosperous agricultural colony in the Yungas failed as well. At the end of 1943 the Bolivian president Enrique Penraranda, who had supported the settlement of Jewish immigrants in the country, was overthrown by a military junta with fascist tendencies. Yet in the middle of 1944 when it became obvious that the Allied forces would win the war, the Bolivian junta approached the United States again, but meanwhile most settlers had already left “Buena Tierra”. The last agricultural settlement projects in Bolivia had finally failed.

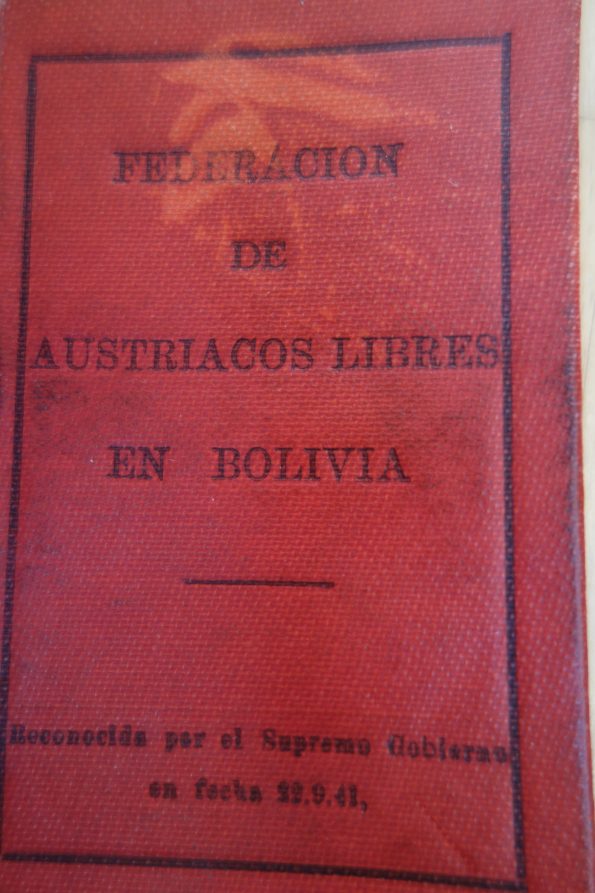

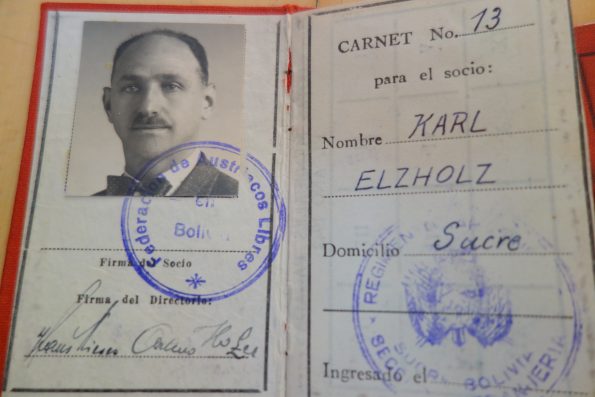

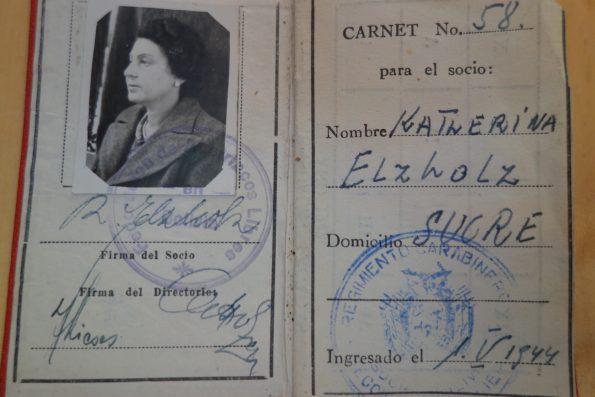

The Austrian refugees founded Austrian clubs in the cities of Bolivia. In Sucre Karl and Käthe were members of the “Federacion de Austriacos libres en Bolivia” (“Federation of Free Austrians in Bolivia”), founded in 1941. Karl’s membership booklet that has survived starts with monthly payments in 1942. It carries the number 13, which means that he was among the first members in Sucre. Käthe joined the club in May 1944 and her membership number is 58. The club’s goal is evidenced in the membership booklet: “The FEDERACION DE AUSTRIACOS LIBRES EN BOLIVIA fights for the liberation of Austria from National-Socialist dictatorship together with all other organisations worldwide with the same aim and together with all democratic institutions that fight the Third Reich. The federation does not allow any party or racial policy in its ranks. It does not interfere with the domestic or foreign policy of Bolivia, but is prepared to support the country in fighting any type of totalitarianism at any time. The federation accepts the membership of all people who can provide documents that prove their connection to the Austrian nation and who pledge themselves unconditionally to democratic principles.” The membership in this club has to be seen as an expression of devotion to the mother country from which its members were expelled and an unconditional commitment to the democratic republic of Austria to whose reconstruction the members wanted to contribute. It further demonstrates their firm conviction that they would return to Austria after the defeat of the Nazi dictatorship. The daily lives of the refugees from Nazi terror in Bolivia were pervaded by yearning for the home country, nostalgia for its lifestyle and culture and a feeling of bitterness due to the rejection and expulsion they had experienced in Austria. “The Federation of Free Austrians in Bolivia” stressed with its clear anti-fascist attitude the necessity of the establishment of a free and democratic Austria and the annulment of the “Anschluß” of 1938. Additionally more exile clubs were set up in Bolivia, many of them social democratic, such as the “Club Amistad”. These clubs organised musical and theatrical events, outings, Christmas celebrations and helped the new arrivals, too. Many of these social democrats returned to Austria soon after the war, as did Karl and Käthe, to help rebuild the country.

This nostalgia for Austria, the “World of Yesterday” and the concentration on positive memories might have helped Karl and the other refugees to overcome the difficulties of exile and offered an impetus for coping with the daily life in Bolivia and for coming up with creative solutions to make a living there, such as establishing a shirt factory which none of them would have even considered at home. The club meetings, the companionship, the meeting with compatriots might have alleviated the sentiment of cultural uprooting and isolation. A collective identity was created which was a reflection of the former cultural reality in Vienna. “Little Vienna” developed gradually in the Andean mountains in cities like La Paz, Cochabamba, Oruro and Sucre. The local German language paper “Rundschau vom Illimani” of 1939 and 1940 illustrates that the newly arrived immigrants had managed to establish themselves in the Bolivian society very quickly. The businesses that advertised in the paper were for example the “Café Viena”, the “Club Metropol”, the “Café-Restaurant Weiner” and so on. The shops offered Central European delicacies and also fashion, as for instance the “Casa Paris-Viena” or the “Peleteria Viena”. There was a bookshop “La Amerika” that sold German editions of Franz Werfel and other Central European writers. A German library was established as well and the refugees organised cultural events like cabaret performances in Viennese dialect and readings of Hofmannsthal and Schnitzler. The immigrants founded the “Collegium Musicum” that played concerts of Mozart, Beethoven and Schubert. The “Rundschau vom Illimani” reported on these events and the Bolivian national radio station “Radio Nacional” broadcast every week a one-hour German radio programme, presented by exiled artists and actors. The club “Federation of Free Austrians in Bolivia” organised family dinners with Austrian food such as “Gulasch” and “Apfelstrudel” and music, theatre and cabaret evenings. The isolated position of the country and the large number of German-speaking immigrants facilitated the development of a vibrant cultural scene in exile. The first German language stage developed from a one-hour radio broadcast in German on “Radio Nacional”, created by the Austrian Victor Parlaghi, the actresses Lili Fröhlich and Erna Terrel and the writer Georg Terramare. The Viennese Terramare and his wife Erna Terrel became important personalities in the German-speaking cultural circles in Bolivia. Both had been working for the German Theatre in Prague. They managed to organise a permanent actors’ group made up of professionals and volunteers, most from the “Federation of Free Austrians”, and performed several theatrical pieces. In 1943 they put on stage the world premiere of Terramare’s drama “Hofopernballett” (“The Ballet of the Court Opera”). The journalist Frith Kalmar was president of the organisation and reported that most Austrians in Bolivia were members of this club. In 1944 they opened their own club house with a theatre stage in La Paz, where they played until the late 1940s. Lectures, films and a club paper formed part of the cultural programme. After the death of Georg Terramare, Erna Terrel and Fritz Kalmar went with their group of actors to Montevideo. In Cochabamba the couple Lotte Hassel and Georg Braun, both actors, organised a theatre group “Neue Bühne Cochabamba” which existed until 1947 and consisted of volunteers only. In Sucre the “Federation of Free Austrians” had 50 members and they organised Viennese programmes on several broadcasting stations, the “Horas Austriacas” with music and speeches for a free Austria.

There were also attempts at strengthening a German-Jewish identity in Bolivia by founding the “Comunidad Israelita” in La Paz in 1939, but Karl and Käthe both were agnostics and not in any way attached to Jewish religion. Before the arrival of thousands of Central European Jews in Bolivia, the number of Jews there was insignificant. Baptised Sephardic Jews were among the Spanish colonisers in the region that became the Republic of Bolivia in 1825. A large part of them settled in Santa Cruz and completely ignored their Jewish origin. In the following century only very few Jews migrated to Bolivia; a census of 1917 records 20-25 Jews. The number slightly increased in the wake of the First World War and the Russian Revolution, racism and anti-Semitism in Central and Eastern Europe. Yet contemporary data suggest that only a few hundred Jews lived in Bolivia in the middle of 1938. Of the 7,000 racially persecuted Austrians that had found refuge in Latin America, it is estimated that around 1,000 settled in Bolivia. Overall, it is estimated that only 150 immigrants lived in Sucre, where Karl, Käthe, Mitzi and Bill ran their shirt business, whereas most had settled in La Paz (2,600), Cochabamba (1,000) and Oruro (200). The largest percentage of Jewish immigrants was between 35 and 50 years old (35%), 20% up to the age of 20, and 20% between 20 and 25 years of age. The large majority were traders (85%), 5 % free-lancers and only 5% farmers. Without doubt did the Jewish immigrants contribute to the economy of the country with their human capital and expertise more than with the financial capital they were able to transfer to the country, which was rigorously restricted by the Nazi emigration laws.

Finding accommodation for the thousands that arrived was difficult, so the aid organisation SOPRO rented big houses in La Paz and Cochabamba and organised the administration of these boarding houses. But the aid organisations were not prepared to support able workers for a longer period of time, which meant that the people had to take on any jobs they could find as soon as possible. Yet there is no indication that anyone had to live in destitution. For Jews with an academic education it was much more difficult to find occupation in their lines of business because they had to have their degrees accredited, which was very complicated. Skilled workers, like Karl, were in a much better position to find a job immediately. In effect all immigrants reached at least middle-class status in less than a decade in Bolivia. The Bolivian state could not promote the economic integration of the immigrants at all; the integration depended solely on the initiative of the individual and on the support of Jewish aid organisations like SOPRO. The organisation granted loans to prospective small entrepreneurs. Until August 1943 SOPRO had offered 210 loans for the foundation of small enterprises and 15 loans for the establishment of workshops of artisans. The aid organisations also subsidised or financed re-trainings or courses for accreditation. It can be assumed that they helped finance the courses Karl took to get his mechanic training acknowledged in Bolivia and that they granted a loan for the setting up of the shirt factory in Sucre. Between January 1939 and December 1942 the aid organisation invested 160,000 US dollars and recorded all loans in its books meticulously. If the loans were not paid back punctually, sanctions were imposed. A pronounced work ethic and the permanent striving for better living conditions characterised the integration process of these immigrants. They accepted any kind of job to make a living and were very flexible. They profited from an expansion of the economy as a result of the higher demand due to the armament projects of the Second World War and after the end of the war the reconstruction programmes in Western Europe and Japan. This led to a dramatic increase in the demand for raw materials, especially tin and other metals. At the same time the domestic demand for household and convenience goods could not be supplied locally, which offered a market niche for the immigrants, who opened all types of workshops like the shirt factory of Karl. These economic activities of the refugees boosted the Bolivian economy further. Another factor that contributed to the quick integration of the Jewish refugees in the Bolivian economy was the social structure in Bolivia. In the 1940s Bolivia had around three million inhabitants, 70 per cent of which were indigenous Indian farmers who were practically excluded from the domestic market because they produced for their own requirements on the country estates or in the village communities. So the arrival of the refugees had a decisive impact on the Bolivian domestic market. By their increased consumption and the support they offered to each other they created an endogenous market in Bolivia. The Eastern European Jews who had arrived before 1938 and were in the textile trade allowed the new arrivals to sell their wares in the streets, houses and offices for a commission, for example. Maurizio Hochschild offered jobs to the refugees as well as the organisation SOPRO, which needed administrative personnel and all sorts of staff for their boarding houses, children’s homes and old people’s homes. At the same time lots of restaurants, sweet shops, coffee houses, bakeries, groceries, repair shops and recreational facilities opened. The Austrian couple Paschkus, for instance offered first-class Viennese delicacies, accompanied by piano music played by Mr. Paschkus in the “Vindobona”, which was always crowded.

As many of the immigrants were merchants or traders, 85 per cent were in trade, 12 per cent in textile production and only 5 per cent in agriculture according to a survey carried out at the end of 1942. Why so few immigrants took up farming, despite the government’s intention to settle the refugees as farmers in deserted areas, can be ascribed to several reasons. It was not just the lack of agricultural knowledge of the immigrants, but even more so the ownership structure of the farmland, topographical factors, the quality of the soil, the inferior state of the infrastructure and the lack of public support. In 1940 86 per cent of the population lived in the western part of the country, on the high plateau and the Andean valleys. The fertile areas were owned by few large landowners, while the arid infertile land was in the hands of centuries-old Indian village communities. The remaining percentage of the population lived in the tropical and subtropical areas in the east, which took up 70 per cent of the territory and these people were concentrated around the few cities. Due to the lack of infrastructure this area was totally isolated from the rest of the country. What’s more, after the lost war against Chile the country had no access to the sea. Most of the Jews who migrated to these remote rural areas worked as administrators, white collar workers or tenant farmers. In order to counter the rising anti-Semitism, the Bolivian state and SOPRO tried to transfer as many of the Jews as possible from La Paz and Cochabamba to the countryside in 1939 and 1940. This project had to fail because it was naïve to assume that the Jews would succeed in colonising this area, where the indigenous population had failed due to the unfavourable climate and the lack of infrastructure. Agricultural projects supported by state subsidies failed just as did those initiated by the immigrants themselves. Overall, the successful economic integration of the refugees within a few years originated from an ideal mixture of spotting market niches, imagination and craft skills. The access to the labour market was facilitated also for women – which was are in Bolivian middle-class society – who spoke English and/ or German as they found jobs as secretaries or translators. Financial support of the Jewish aid organisations, mutual assistance and survival instinct explain why most of the immigrants managed to get out of a very precarious economic condition and rise to members of the Bolivian middle class within just a few years.

In the 1930s and 1940s Bolivia was characterised by pronounced social differences and ethnic tensions. Of the 70 per cent Indians, mostly Aymara and Quechua Indians, the majority lived in the western areas under semi-feudal conditions and were dependent on rural landowners. They spoke indigenous languages only and were excluded from the economy of the country. It is estimated that only 15 per cent of the Bolivian population had civil rights. Among these “citoyens” large landowners, mine owners and free lancers formed an oligarchy and the remaining part of the 15 per cent formed the urban middle class which had developed thanks to the mining and processing of tin. The refugees, who had been part of the European middle class, moved between the oligarchy and the Bolivian bourgeoisie immediately from the start, which caused tensions with this privileged Bolivian social group. The reasons for these problems were more of a socio-cultural nature than of an economic one. The immigrants themselves were a very heterogeneous group, from monarchists to communists, from atheists to believers, from workers and traders to doctors and musicians. But the majority of the Jewish immigrants had no longer any connection to Jewish religion and tradition; they were Austrians or Germans and many of them baptised or agnostics, just as Karl, Käthe and Mitzi. What had made them into “Jews” was the racism of the “Third Reich”, by which they were transferred back to the time before assimilation. But now they were all in the same boat – they were without a mother country. The religious element played nearly no role at all, but what was important was the fact that they were all victims of Nazi terror. Yet there were also tension among the Jewish refugees, namely between the German-speakers and the Yiddish-speakers from Eastern Europe who were seen by the immigrants from Austria and Germany as unwilling to integrate, to learn Spanish and by that to promote anti-Semitism in the host country. Most of the immigrants who had children, sent them to Bolivian state schools in La Paz, Cochabamba or Sucre or to Catholic private schools or the “Colegio Americano” where the children were taught on the basis of north American curricula and where English was the second language. In La Paz there was the “Escuela Boliviana-Israelita”, where a focus was laid on the teaching of the Spanish language. The “educación cívica” taught local geography and history, but other than that the curriculum was similar to Austrian or German schools. The pupils could refrain from attending Jewish religion and history lessons. Apart from some Bolivians, many teachers were refugees from Central Europe.

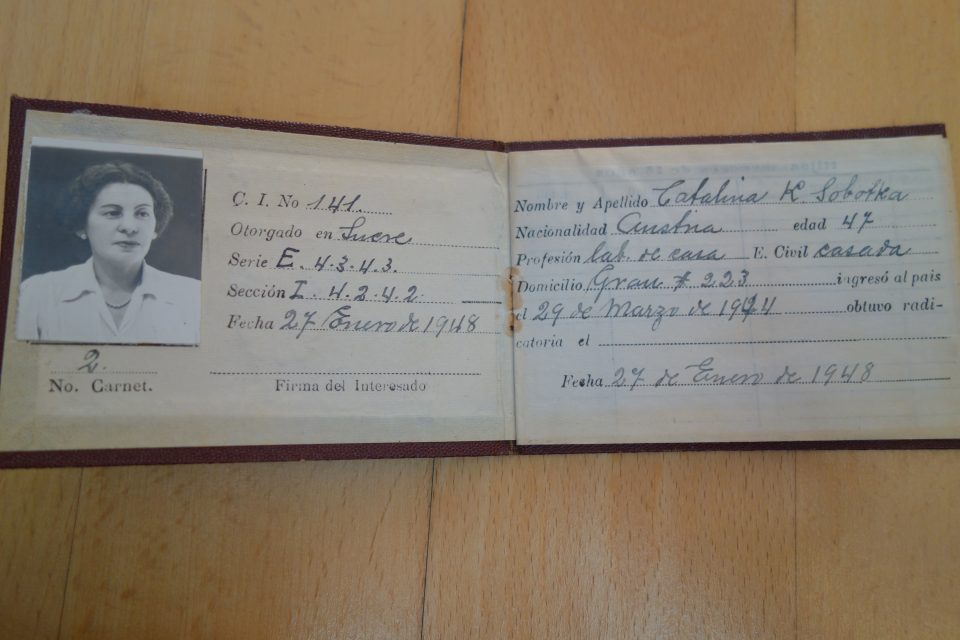

After the suicide of President Busch, the government of General Penaranda tried to ease the tensions and fight the rising anti-Semitism in La Paz and Cochabamba. In his New Year address to the population in 1941 Penaranda demanded from the refugees an attitude based on three principles: 1. Unconditional respect of the law and the traditions of Bolivia; 2. A commitment to an efficient economic and social integration in the Bolivian society; 3. Productive work that contributes to the country’s economic development. It is believed that this message helped ease the tensions between the immigrants and the Bolivian middle class. Anyway, in Sucre, were Karl, Mitzi and Käthe lived, the atmosphere was very amicable and the refugees were not just accepted, but welcomed. One reason might have been the relatively small number of immigrants that had settled there and the fact that most of them were skilled. Even in the tightly-knit Bolivian middle class community of Sucre they were respected and social relationships developed. It seems that they all had closer contact to one or the other Bolivian. This Bolivian educated class had travelled a lot to Europe before the war; they spoke French and /or English and were open-minded. The newly arrived produced and offered goods that were in high demand, like fashionable clothes, they offered jobs and training to local people, which benefitted the Bolivian society. So the situation constituted an asset for both sides. What all the refugees from Austria had in common was the intention to fight National-Socialism. They wanted to stress the separate Austrian identity as distinct from the German identity and to re-establish a free and independent Austrian Republic. Their tireless efforts were successful when in 1942 the Bolivian government recognised the Austrian nationality and in the Bolivian “Censo de extranjeros” Karl is registered as “nacionalidad Austriaco” despite the fact that at that time Austria did not exist as a state. The document was issued in Sucre on the 30th of October 1942. So in November 1942 the Austrian Catholic refugee Georg Terramare, a writer and actor wrote the lyrics to the last movement of Beethoven’s “Eroica” symphony as an “Austrian Exile Anthem”, in contrast to the old anthem that was based on a Haydn melody and had been adopted by the Germans.

Unfortunately, the newly arrived immigrants encountered anti-Semitic tendencies among the Bolivian middle-class, a situation that they had tried to escape from. Many of the anti-Semitic stereotypes prevalent in Bolivia dated back to Spanish-Catholic tradition which blamed the Jews for the death of Jesus Christ. But the newly erupting anti-Semitic reactions in Bolivia were definitely triggered by Nazi propaganda and by activities of German diplomats and German Nazis in Bolivia as well as fascist tendencies, the Spanish Falange, among the military and civilian Bolivian élite. Several Nazis and Nazi sympathisers in the German community campaigned against the immigrants and tried to achieve their expulsion from Bolivia. Many of these worked with and for the Nazi regime in Germany. The Germans that sympathised with the Nazis celebrated every victory of the German “Wehrmacht” in the Café “Dona Margarita Zyball” in Sucre. In 1941 a conspiracy of Nazi-friendly plotters against President Enrique Penaranda was uncovered which led to the expulsion of the German ambassador and a clampdown against fascist and leftist opponents of the regime. But in 1942 anti-Jewish sentiments flared up again when the Nazis continued to stir anti-Semitism in Bolivia in an attempt to rouse the population against the refugees and to steer the Bolivian government towards supporting Nazi Germany and away from a US- and UK-friendly policy. The German embassy, above all, financed the most aggressive anti-Semitic newspapers, such as “La Razón”, “La Calle”, “El Imparcial”. “El País” and “La Prensa”. Before the outbreak of the war German companies had thrived in Bolivia; they had supplied remote areas with the newest German technology and had offered loans to local businesses. Many of these German businessmen were dedicated followers of Hitler. They also supplied and trained the Bolivian army and after 1939 the Hitler regime stepped up its efforts to interfere diplomatically and economically in Bolivian domestic affairs. The German school in La Paz “El Colegio Alemán” was turned into a centre for spreading Nazi ideology in Bolivia. At the beginning of the Second World War the Allied forces even feared that the Nazis planned an indirect take-over of the Bolivian government because Hitler wanted access to the resource-rich region. At the time of the peak of the refugee influx, the “Third Reich” and the Allied Forces each tried to shift the power balance in Bolivia in their favour with the help of aggressive propaganda campaigns. It was in the interest of the American government to know Bolivia on its side. That’s why the US granted considerable low interest rate loans to Bolivia. The refugee community was much relieved when in January 1942 Bolivia officially supported the Allied war effort and broke off all diplomatic relations to Germany and Japan. When at the end of 1943 a military junta replaced President Penaranda, it took some time until the junta took serious measures against Germany. But in the end the economic dependency from the United States made it necessary for the junta to take action against the Germans in Bolivia who supported Hitler and when it became obvious that Nazi Germany would lose the war, the junta arrested the Hitler supporters in Bolivia that were named in the black list issued by the Allied Forces, the so-called “Fifth Column”, among them German entrepreneurs and teachers at the German schools. They were transferred to US camps, but most of them returned to Bolivia, not even a year after the end of the war. Nevertheless, the role that Bolivia played in rescuing thousands of refugees should not be underestimated, just because after the end of the war Nazi war criminals hid there. Some of them were picked up later, most of all due to the trial of Klaus Barbie in France. Bolivian military dictators had protected the likes of Klaus Barbie for years and in the 1940s and 1950s many Jewish refugees feared they would come across a Nazi war criminal in the streets of La Paz or another Bolivian city.

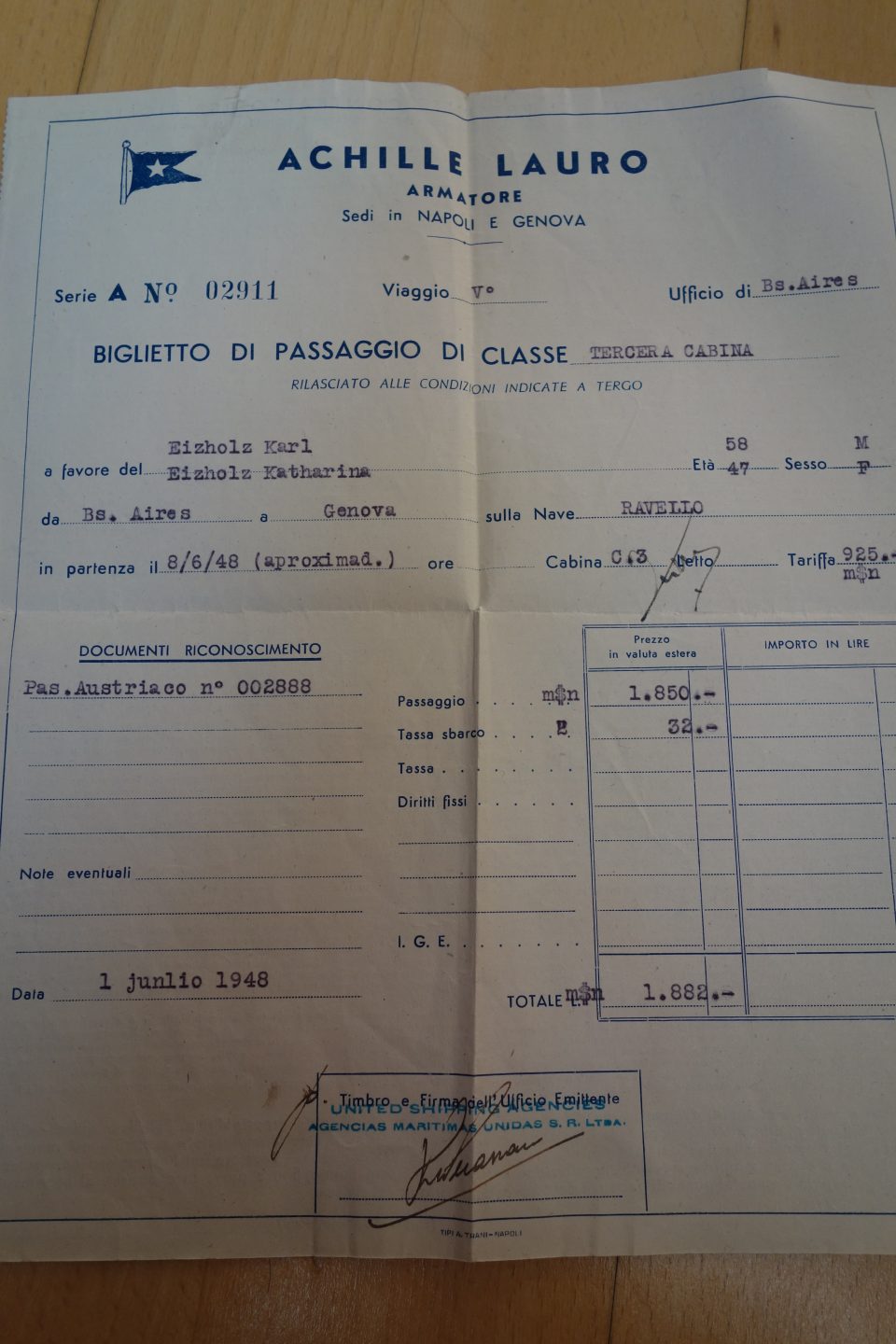

Anyway, most of the refugees returned to their home countries after the war or moved on to another South American country or to the United States, like Mitzi and Bill Stern. Those who remained were just given “resident alien” status. Acquiring the Bolivian citizenship was a very long-winded procedure hampered by red tape and years of waiting. Karl and Käthe did not seriously consider staying in Bolivia after the war, although they were immensely grateful for the country to have offered them refuge and they liked living there. They were patriotic Austrians and took the chance to return to Vienna as soon as it seemed safe. On the 8th of July 1948 they boarded the ship “Ravello” of the Italian shipping company “Archille Lauro” in Bueonos Aires to Genova.

On a photo with the ship “Ravello” in Buenos Aires they wrote home to their family: “My dears! I’m writing to you just before departure. Your warning letter came too late, but hopefully everything will end well. Karl thinks you should not be silly and go; one cannot continuously consider this way or that way, but one has to set oneself a goal. Stay healthy and many, many kisses Yours Käthe. I would like it better here than in Vienna, but now we are leaving. Yours Karl”

The warning in the letter, mentioned above, must have pointed to the critical economic situation in Austria after 1945, the harsh winter of 1947 together with the failure of the harvest which led to a shortage of food and practically everything else. Those refugees that returned to Austria not only had to face dire conditions, but a still prevalent anti-Semitism; no effective persecution of Nazi party members and war criminals had taken place by the Austrians and no proper restitution of stolen property was carried out. It is estimated that of 130,000 refugees only 8,000 returned to Austria until 1959. Political refugees felt they had to return as soon as possible to help build up a new democratic Austria and that is how Karl and Käthe, as social-democrats, felt. Many of the political refugees were active in exile clubs and they tried to convince their compatriots to return to the home country as soon as possible. In September 1944 the Free Austrian Movement organised a conference in London to clarify the conditions of return to Austria for those who had found refuge in the UK and elsewhere. But no post-war Austrian government ever invited the exiled refugees back to Austria. The conservative and the socialist parties were reluctant to welcome the Jewish exiles back home; some political representatives even rejected their return outright. This changed only after Bruno Kreisky became chancellor of Austria in the 1970s, himself a refugee who had escaped to Sweden.

The emigration from Bolivia can be divided into three phases: The first, between 1940 and 1944 was mostly illegal emigration to one of the neighbouring countries, such as Chile and Argentina and to the United States; the second between 1945 and 1951 was the period in which Käthe and Karl left Bolivia for Austria; the third phase started after the revolution in Bolivia in 1952 and was the phase with the largest number of emigrants. Between 1945 and 1951 many social democrats and communists returned to their mother countries because they saw it as their duty to help rebuild their home countries. The social democratic refugees were ten times more than the communist refugees in Bolivia and most of them returned to Austria. Among the Austrian communists was Julius Deutsch, who returned in 1946 and worked for a publisher; among the socialists there was Heinz Markstein, who returned to Austria in 1951 and worked as a journalist and writer of children’s books, and Axel Deutsch, who wanted to contribute politically to the establishment of a new social-democratic Austria. The biggest obstacle for the emigrants, namely acquiring a ticket on a passenger ship to Europe, was now removed. What remained was procuring the money to pay for the fare. Why many families only left in the 1950s and 1960s was due to the fact that they lacked the means to pay for the transit. In the early 1950s still 4,300 refugees lived in Bolivia; 3,000 of them in Pa Paz. Most of them left between 1952 and 1985. A three-day bloody revolution in April 1952 resulted in the takeover of the power by the “Movimiento Nacionalista Revolucionario” which resulted in terminating the power of the oligarchy that had ruled Bolivia since the 19th century.

What were the reasons why the refugees returned to Austria? 1. They wanted to rebuild their home country; 2. The possibilities to work in their professions were limited in Bolivia; 3. They were homesick; 4. The lack of economic development in their host country. What the refugees had offered to Bolivia was an economic growth dynamic, innovation, creation of jobs and a modernisation of cities like La Paz. Their work ethic and morale as well as their thriftiness were appreciated by the local population. Karl and Käthe loved their time in Bolivia – it was an interesting and challenging period of their lives despite the circumstances and they often talked about the loving memories they had of Sucre, the wonderful nature and the kind people. They missed Bolivia a little bit and they were most thankful for the refuge they had been offered. They sometimes spoke a few words of Spanish to recreate the atmosphere of a country they loved. I remember Karl’s “vamanos” whenever we were supposed to go. He had probably worked hard on learning Spanish because he was not so gifted at languages as Käthe.

Literature:

León E. Bieber, Jüdisches Leben in Bolivien. Die Einwanderungswelle 1938-1940, 2012

Edith Blaschitz, Wie weit ist Wien. Lateinamerika als Exil für österreichische Schriftsteller und Künstler, Picus Wien 1995

Lia Levi, Questa sera è già domani, 2018

Fritz Kalmar, Das Herz europaschwer. Heimwehgeschichten aus Südamerika, 1998

Wolfgang Neugebauer, Siegwald Ganglmair, Remigration, Dokumentationsarchiv des österreichischen Widerstandes, JB 2003, Wien 2003

Thomas Schmidinger, Fluchtpunkt Lateinamerika – Österreichische Emigration in Lateinamerika, Politix Nr. 24, Wien 2007

Leo Spitzer, Hotel Bolivia. Auf den Spuren der Erinnerung an eine Zuflucht vor dem Nationalsozialismus, 1998