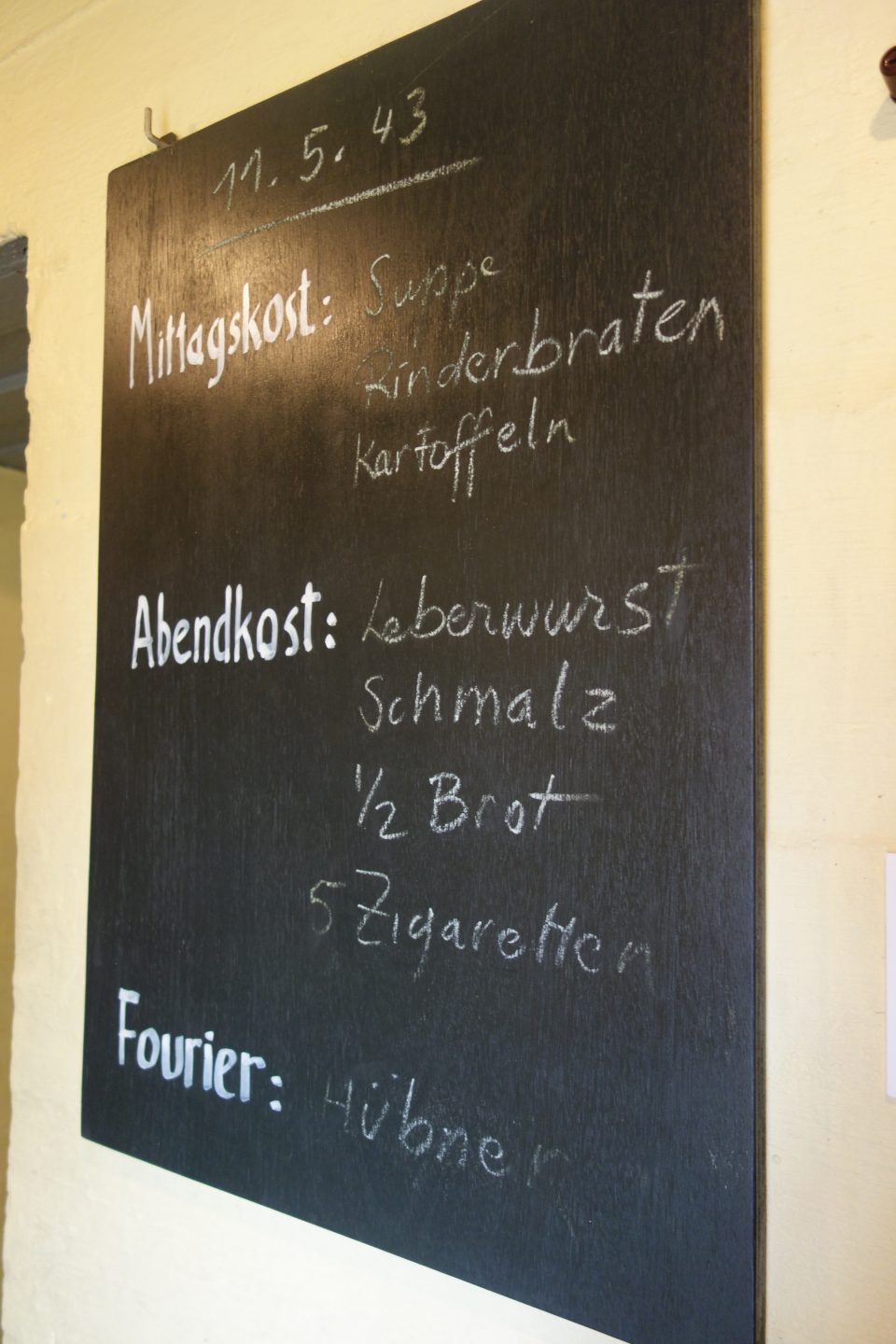

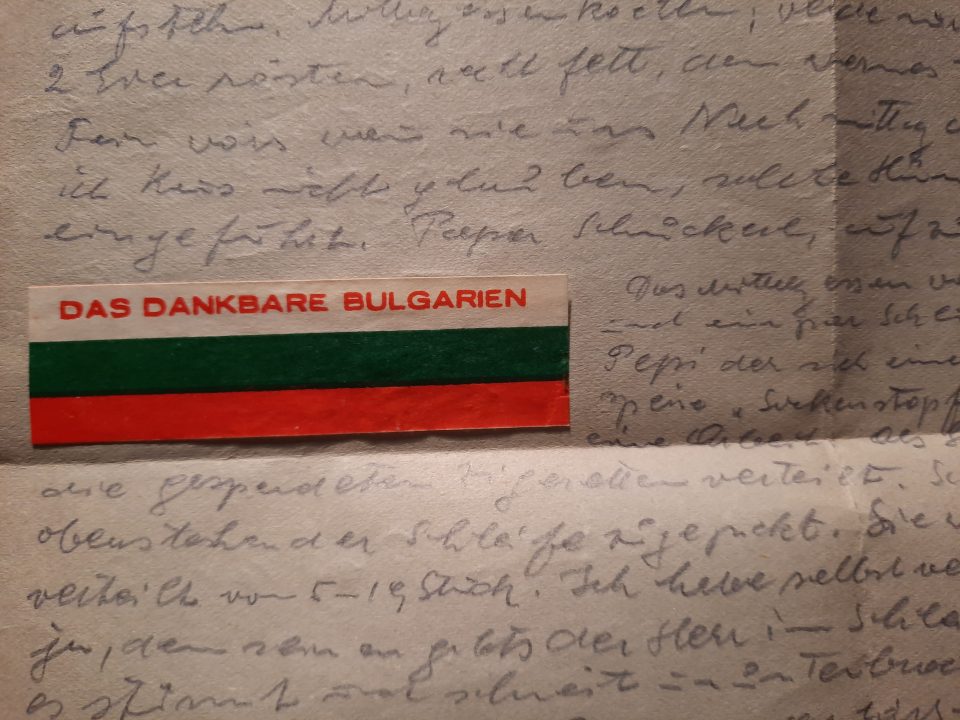

Left: Sample of a Wehrmacht menu (lunch: soup, beef and potatoes, dinner: liver pâté, lard, bread, 5 cigarettes) Right: A telephone with the warning: the enemy is listening in!

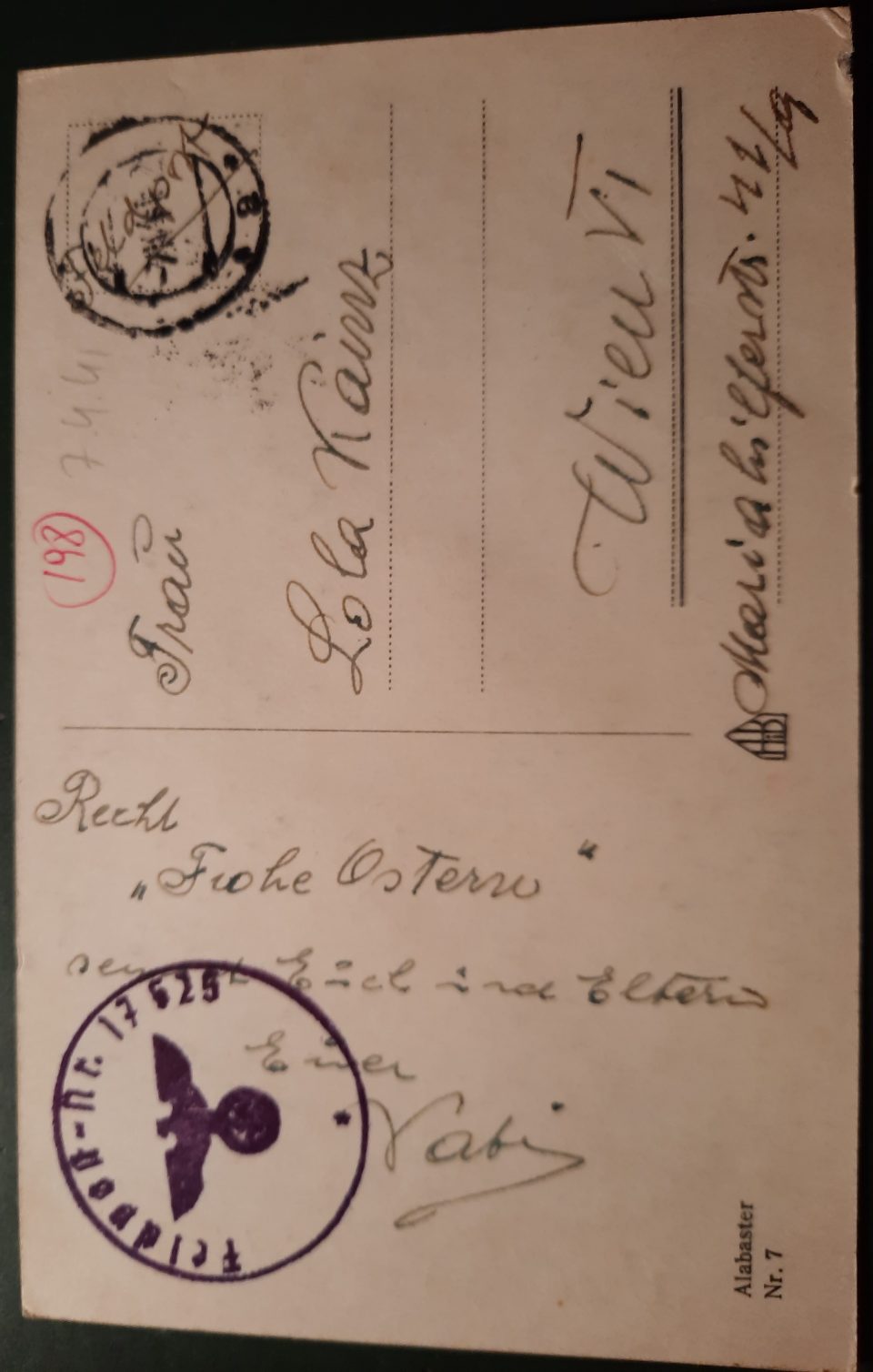

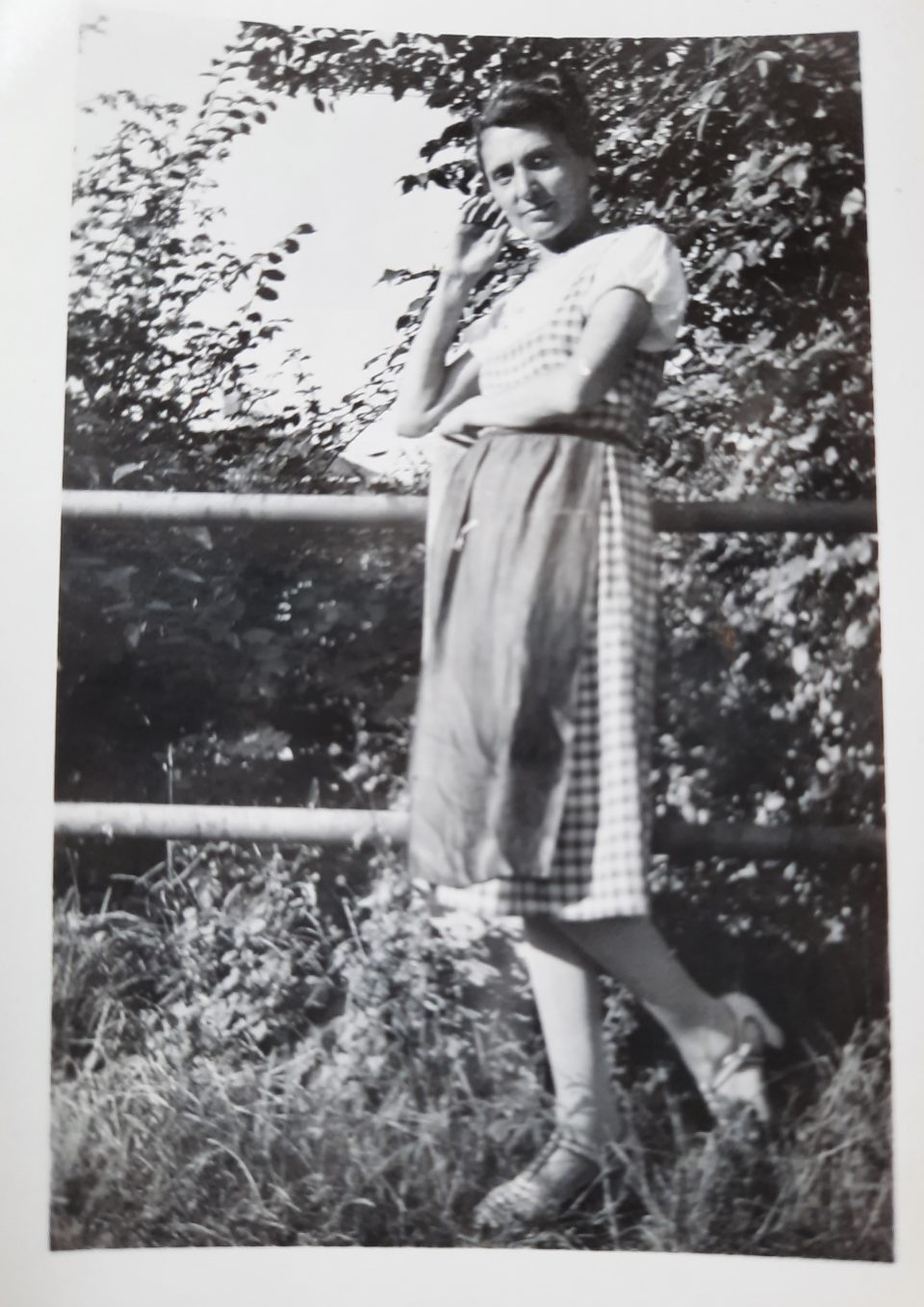

Toni and Lola as a newly-wed couple in Preßbaum near Vienna before the war

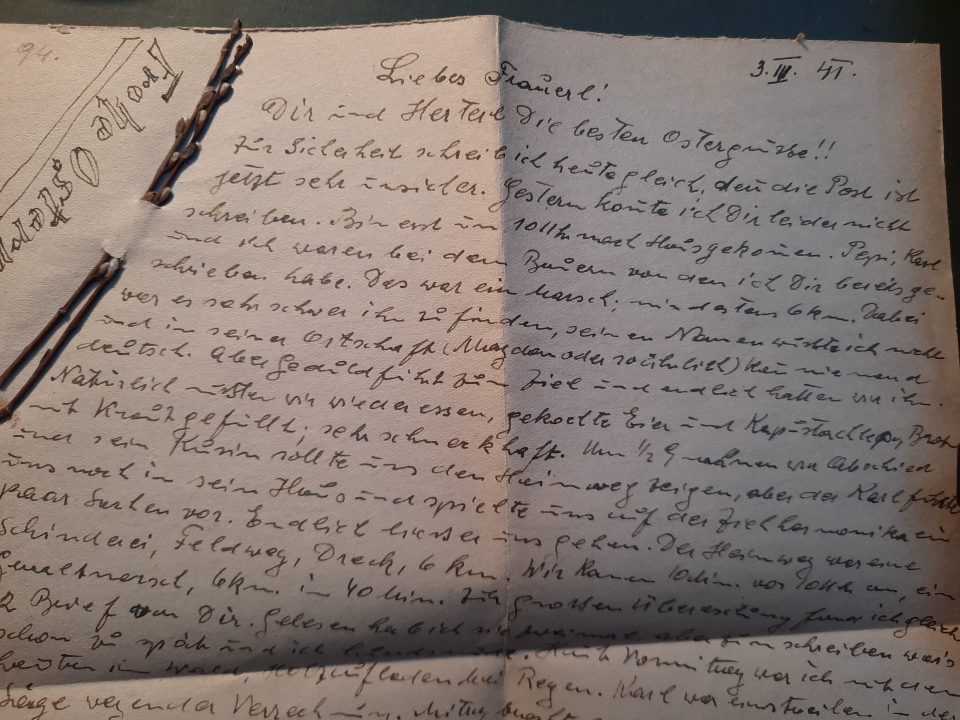

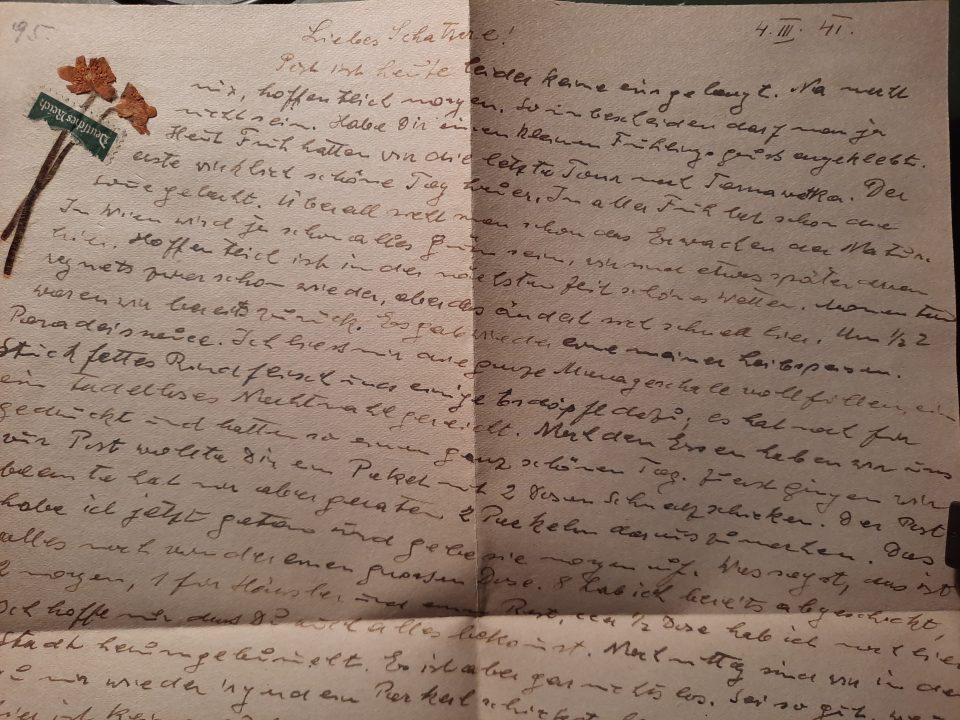

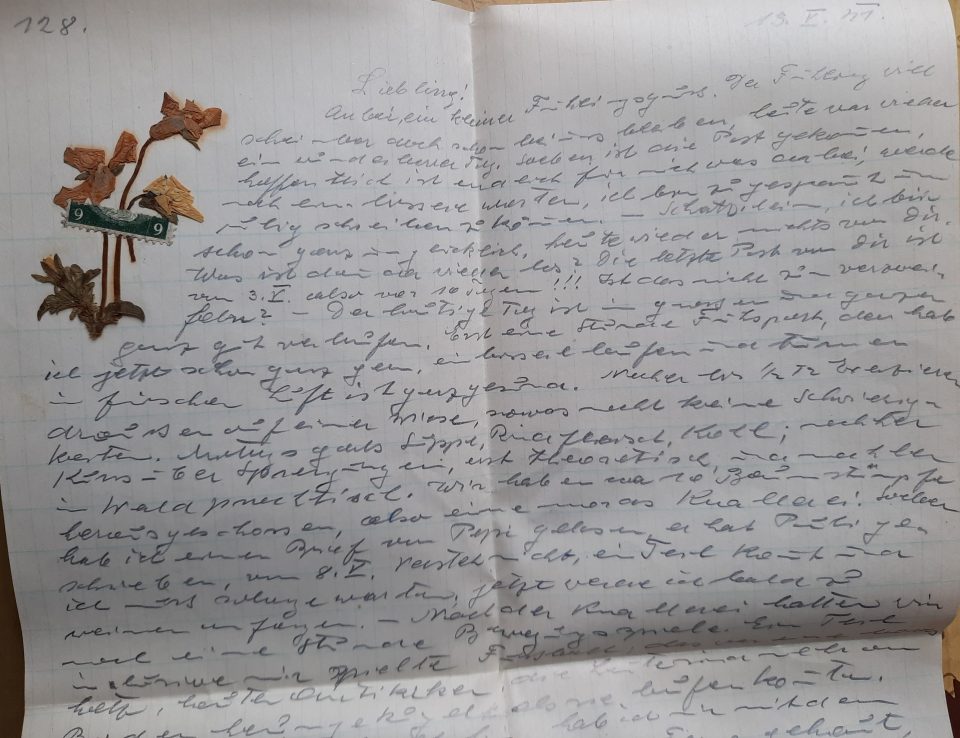

Anton Kainz (Toni), my grandfather, was drafted to the German Wehrmacht in March 1939, a year after Hitler had incorporated Austria into the German “Third Reich”. When the 2nd World War broke out in September 1939 Toni was assigned to the “3rd Sappers’ Battalion XVII 79/B” of the German Wehrmacht as a sapper (“Bausoldat”) in February 1940 and had to complete ten weeks of training in the Vienna Arsenal. He was sent to France in June 1940 and remained there until September 1940. From September 1940 until June 1941 he was with the “2nd Sappers’ Battalion 153 /288” in Poland (the then so-called “Generalgouvernement”) until he was dismissed from the German Wehrmacht and declared “n.z.v. (“nicht zu verwenden” – not to be used) because he refused to divorce his Jewish wife, Lola, my grandmother. In this one year as a soldier he wrote 246 long letters and a few postcards to his beloved wife and daughter with detailed descriptions of the life of a common soldier, his tasks and activities, his feelings and emotions and his attempts at handling the precarious situation of his wife and daughter in Vienna from a distance. A detailed analysis of his documented experiences forms the core of this article. The historical analysis of the 246 letters which Toni wrote to his wife in this period is divided into three categories: first, information about the military campaign, where he was stationed, the military tasks and operations, and the conditions of the military service; second, in which way he tried to support his family in Vienna and how he organised important tasks at home from a distance and third, his emotional conditions on the military front line.

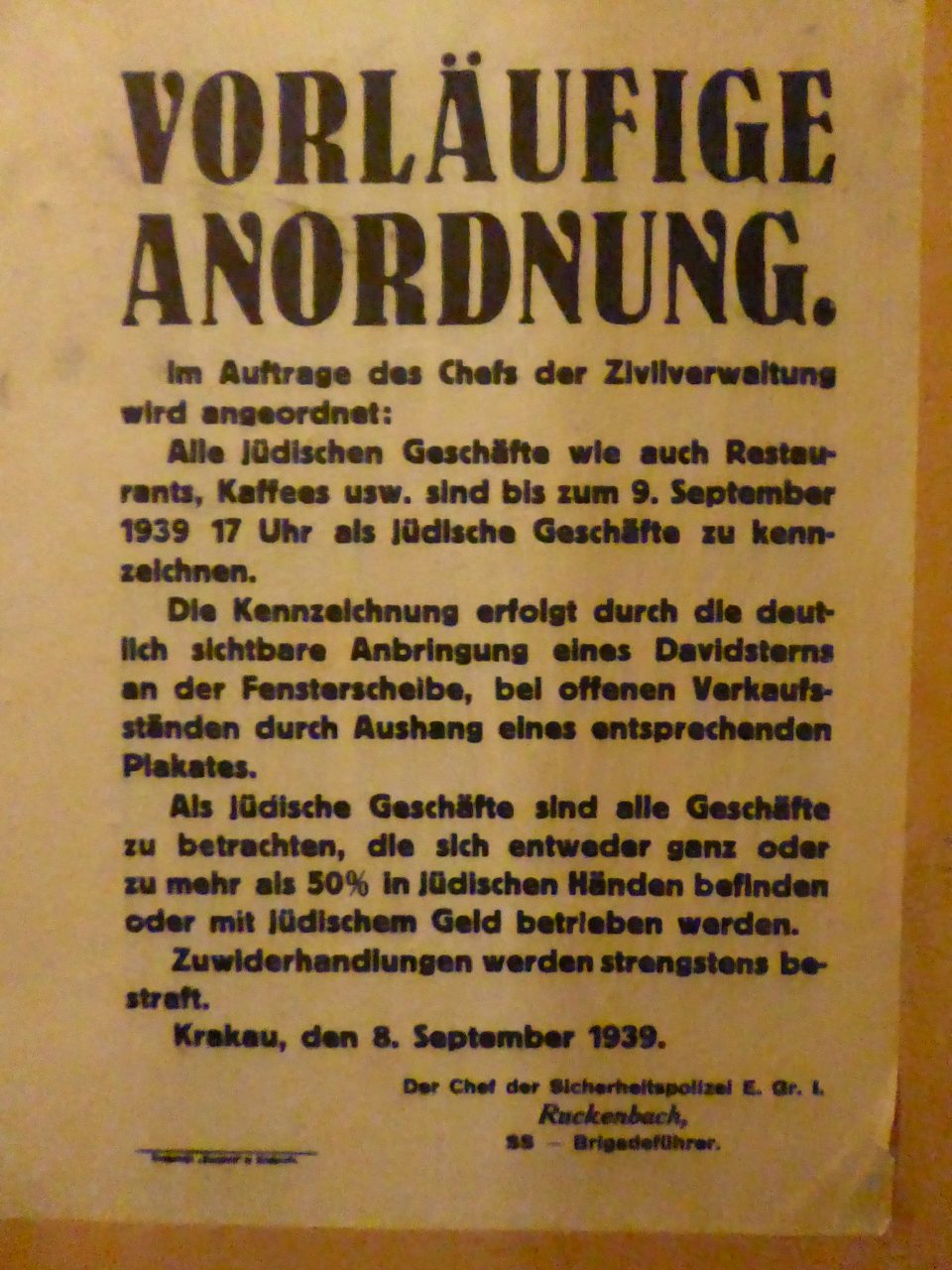

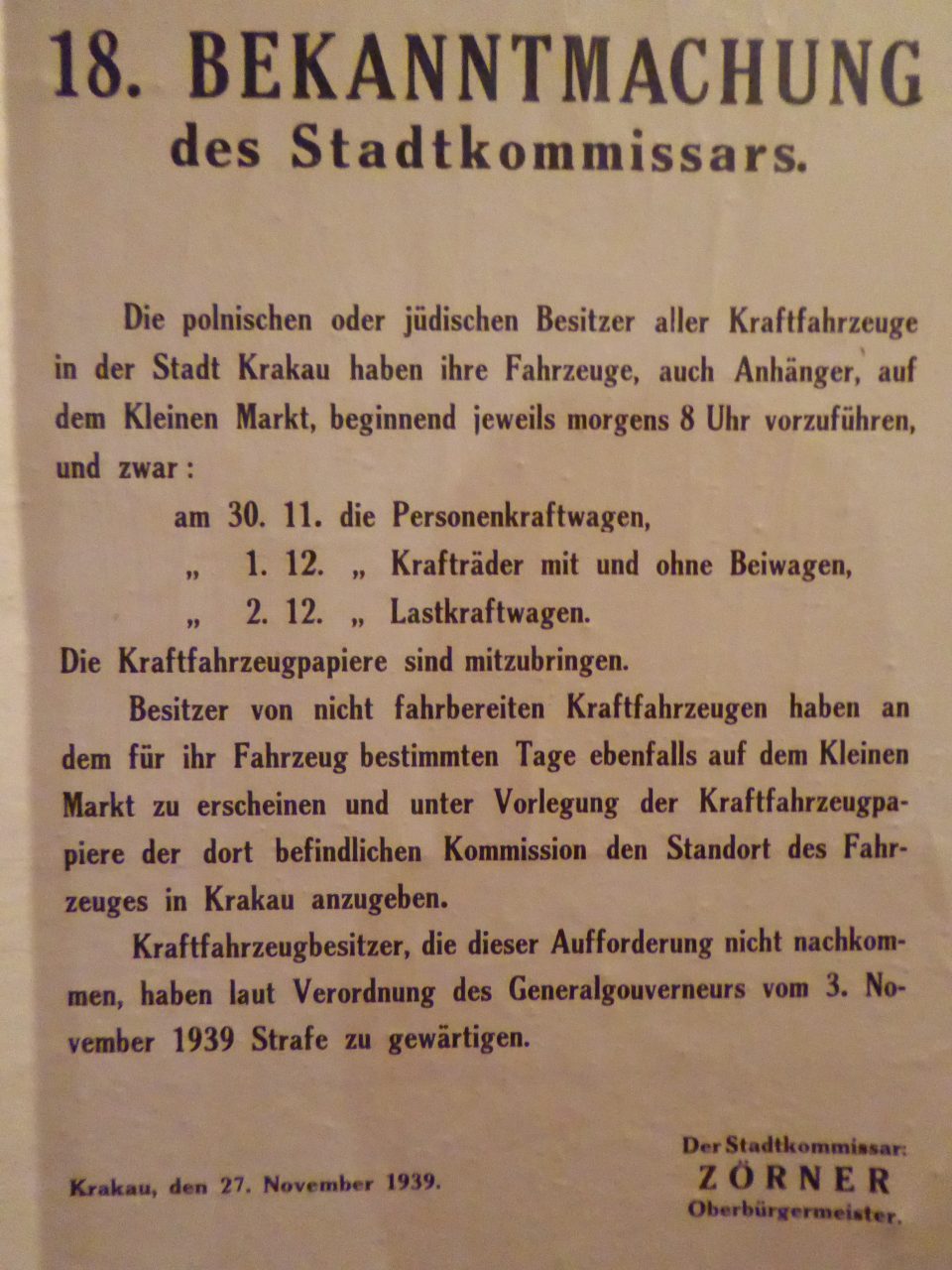

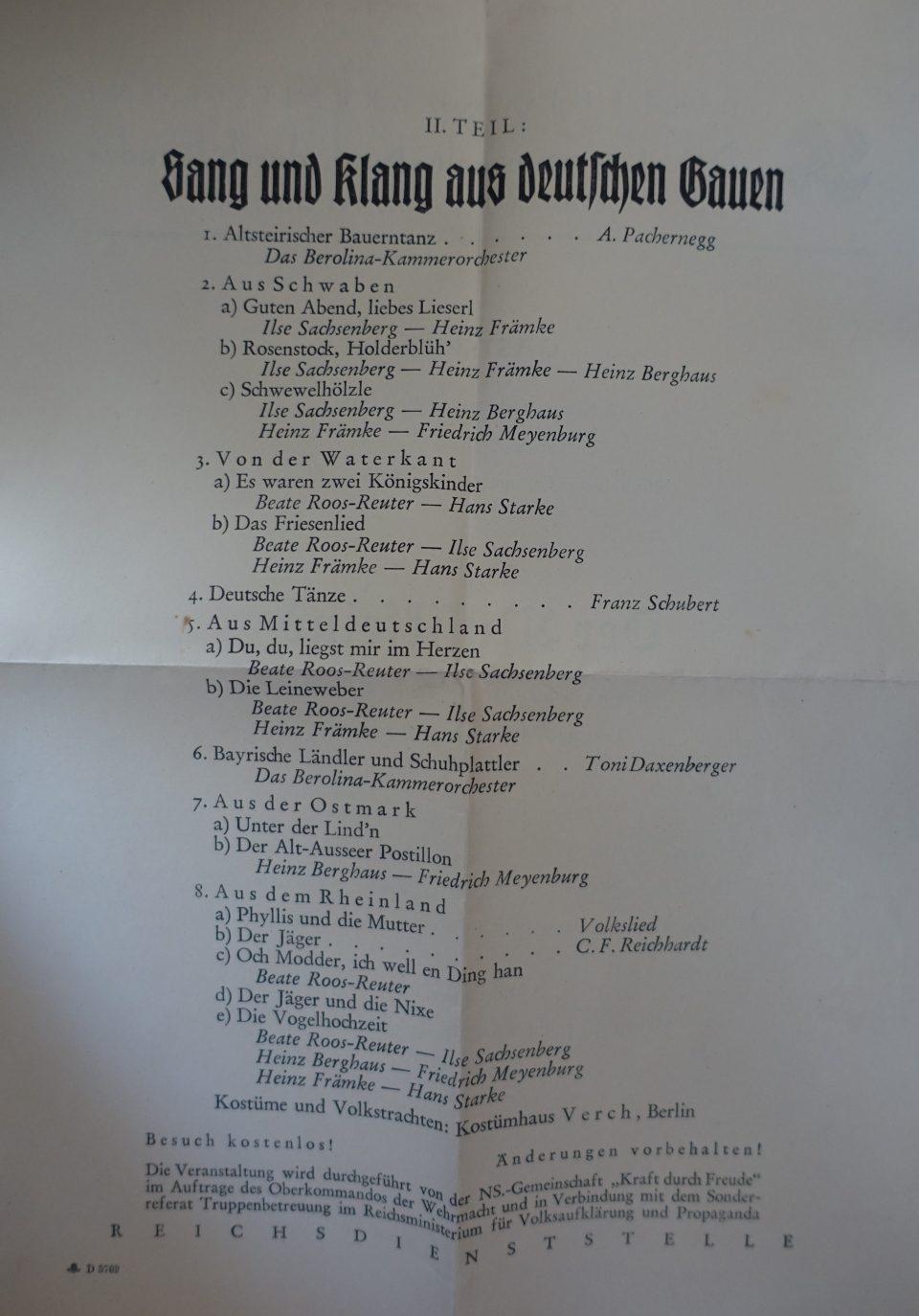

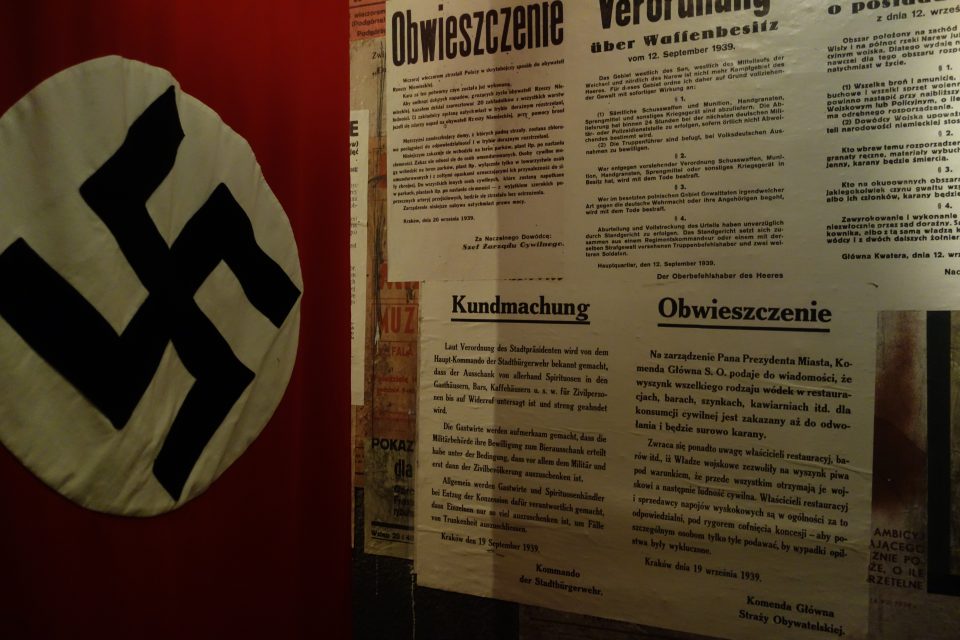

Public announcements by the German occupiers in Krakow on 8 September 1939 about the marking of all Jewish shops with a Star of David and on 27 November 1939 about the requisitioning of all Polish and Jewish private motorised vehicles

A public announcement in Krakow on 19 September 1939: Alcohol can only be offered in inns, cafés and bars to Wehrmacht soldiers and no longer to Polish civilians

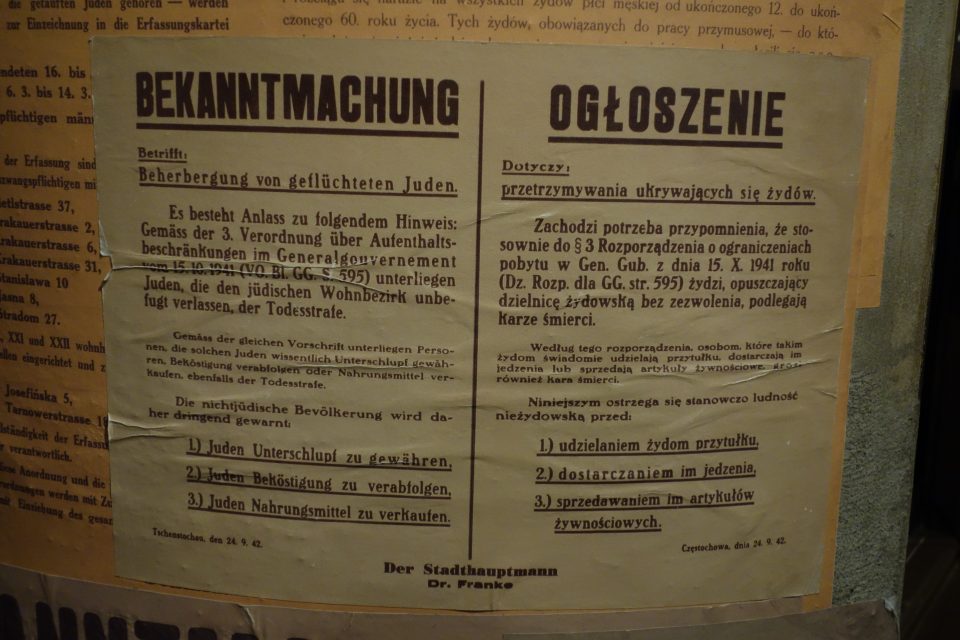

A public announcement in Krakow on 24 September 1942 informing Polish civilians about the drastic punishment they have to face if they assist Jews

On 1 September 1939 the German armed forces under Adolf Hitler attacked Poland, which was the start of World War II. Germany’s invasion of Poland was characterised by the so-called “blitzkrieg” strategy; a surprise attack of extensive bombing to destroy the enemy’s air capacity, infrastructure and communication lines, followed by a massive land invasion with large numbers of troops, tanks and artillery. As soon as the Germans had set up bases of operation in Poland, they started to annihilate any opposition to their Nazi regime. Although the Polish army counted 1 million soldiers, it was badly equipped and severe strategic miscalculations contributed to the fact that the Polish forces could not be a match for the technologically much more advanced German forces. The Poles had hoped for a Soviet intervention, but Stalin had signed with Hitler the Ribbentrop-Molotov Non-Aggression Pact already in August 1939, which secretly stated that Poland would be divided up between Hitler and Stalin. Great Britain and France declared war on Germany and Great Britain responded by bombing German territory three days later. Earlier on Britain and France had acquiesced to German rearmament and the annexation of Austria, the “Anschluss” in March 1938, because they were not prepared to fight another war against Germany so soon after the end of World War I. In September 1938 they even pressured Czechoslovakia to yield to Hitler’s demand for the incorporation of the Czech border region to Germany known as the “Sudetenland” with its large German-speaking population. Although Britain and France had guaranteed the integrity of the remaining Czechoslovakia, Hitler incorporated the Czechoslovak territory in March 1939, by that violating the Munich Agreement of September 1938.

In order to justify their attack on Poland the German military together with the SS staged a phony Polish attack on a German radio station and used this action to resort to “retaliation” against Poland. German troops reached Warsaw eight days later and started a siege of the city, which suffered severe damage and had to surrender on 28 September. The Polish forces were heavily outnumbered and despite tough resistance they were defeated within a few weeks. The Soviet Union invaded Eastern Poland on 17 September 1939 and Poland was divided along the Bug River into a German- and a Soviet-occupied territory. Some Polish soldiers managed to flee across the border to Romania and the West to join the Free Polish Forces. Several of them joined the British Royal Air Force and took part in the “Battle of Britain”. On October 1939 Hitler annexed the Polish territories along the Eastern German border, such as Western Prussia, Upper Silesia and the city of Danzig (Gdansk). The rest of the German-occupied Polish territory was subjugated under a Governor General, the Nazi Hans Frank, as the “Generalgouvernement” (General Government). Toni was stationed there as a Wehrmacht soldier from September 1940 until June 1941 after having served in France (see article part 1).

The British and French commanders were still stuck in World War I strategies and were totally unprepared for the “blitzkrieg” in Poland. War was only declared three days after the invasion on 3 September 1939 because the Western Allies had hoped that Hitler would respond to their demands and end the invasion. The hoped-for French and British offensive in the west did not take place. On the contrary, on 13 September French troops were ordered to fall back behind the defensive “Maginot Line”. Germany had gained a swift victory but that was only the start of World War II because Britain and France refused Germany’s offer for peace and so Hitler’s gamble had failed. He had been confident that the invasion of Poland would be brief and victorious because the Polish army was unprepared and that Neville Chamberlain, the British Prime minister, and Edouard Daladier, the French President, would rather opt for a peace settlement than wage another war. Hitler had won a substantial revision of the Peace Treaty of Versailles of 1919, ending World War I, which was by than widely regarded as an unfair penal peace even in the West, not just in Germany. Unfortunately many believed that communism posed the greater threat to Western democracies than fascism and welcomed a strong Germany as a bulwark against the Soviet Union. That is why Hitler had enjoyed astonishingly positive press coverage in Western democracies until 1938. Germany had even been allowed to host the Olympic Games of 1936, which were turned into a propaganda event for the Nazis. The positive climate ended after the “Munich Agreement” in March 1939, but Hitler was emboldened by his earlier successes and dismissed the concerns of his generals, but demanded total loyalty instead.

The German tanks quickly devastated the Polish defence, encircled the Polish troops and annihilated them as the German attackers far outnumbered the Polish army in manpower and equipment: 3,234 German fighter planes attacked 842 Polish ones. In this attack on Poland the German Wehrmacht lost 3,234 soldiers and 30,222 were wounded, whereas 123,000 Polish soldiers died and 133,700 were wounded and 694,000 were taken prisoner by the Germans. Now the terrible walk through hell started for Poland: the nearly complete extinction of the Polish Jews, the terrible suppression of the Polish people by the NS regime and the mass internment of Poles in slave labour camps. The Polish soldiers who had fought bravely to defend their country had had no chance in this unequal battle and many ended up in German and Soviet labour camps. Hate begot hate, which resulted in aggression against the German-speaking minority in Poland and in excessive anti-Semitic attacks against Jews by Poles. The Jews had to flee the German Nazis and their Polish compatriots. Nevertheless, those Poles who helped the Jewish population despite death threats by the Nazis should never be forgotten.

In August 1939 a secret additional protocol to the so-called “Hitler-Stalin-Pact” already stipulated the separation of north-eastern and south-eastern Europe into “spheres of interest” of Germany and the Soviet Union and by that the partition of Poland along the rivers Narew, Weichsel and San. From the 17 September on Soviet troops occupied the eastern part of Poland. But Hitler’s plan had just been to incorporate Poland without any disturbance of the Soviets and to gain an ideal starting position for his already planned attack on the Soviet Union. The rest of the world assumed that this pact would secure peace in Europe because they were unaware of the secret supplementary protocol. When Hitler invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941 he incorporated the Soviet-occupied Polish territories, too. The NS propaganda machine indoctrinated the German soldiers and the German public creating the image of “slawischer Untermensch” (Slavic subhuman being) and many of the German soldiers succumbed to this prejudice and believed they dealt with a “primitive people” when they were on Polish territory in the so-called “Generalgouvernement”. Yet most German soldiers acknowledged the bravery of the Polish soldiers, but had virtually no contact to the Polish population. What can be seen from the original documents is that Toni and his friends were different; they did build up friendly relationships with the local population.

The command of field marshal von Reichenau, commander of the 6th German Army, on 6 October 1941 constituted a defiance of the international law of war and put the Wehrmacht per definitionem at the same level as the SS, which was then responsible for genocide behind the front lines just as the SS and other NS organisations z.b.V. (“zur besonderen Verwendung”= for special use). Unfortunately, anti-Semitism was deeply rooted in the Polish population, too, and attacks against Jews were largely supported by the local population. In war diaries of German officers one can find many hints to their aggressive anti-Semitism, for example they wrote about “ugly and dirty Jews” and that “no one wants to be stationed in a city like Tarnow, which is a virtual Jew city”. But one can also find comments of ordinary privates who showed mercy and compassion towards the Polish Jews. The Viennese private Alfred Pietsch was shocked about the destitution of the inhabitants of the Warsaw ghetto and the squalor there when he had to deliver some furniture to the ghetto in 1942. The German soldiers knew about concentration camps, but the privates had no idea what was really going on there. All knew about the abuse and the mistreatment of the Jewish population, but it was virtually impossible to act against military orders. Nevertheless there was a small number of “silent heroes” who defied the holocaust and tried to rescue Jews. Helping Jews was more dangerous than allowing partisans to escape because it was always punished by immediate execution. In the memorial of Yad Vashem in Israel 83 Austrians are listed among the “Righteous among the Nations“, 45 of them were members of the German Wehrmacht.

How was the Austrian army integrated into the German Wehrmacht after the “Anschluss” in March 1938? During the First Republic the Austrian army was underfunded and little appreciated by the population. Contrary to the former k.&k. Habsburg Army, it was now a “politicised” army: from 1921 on the Austrian soldiers more or less had to be members of the Christian-Socialist “Wehrbund” and the army had to act as an obedient tool of the Christian-Socialist government, which became visible in the role the army took in the suppression of the Socialist protests in February 1934. After the ban of the Social Democratic Party, the Austro-Fascist regime relied in its defence on Mussolini’s Fascist Italy. Only when it became clear that Mussolini and Hitler were forging a pact, did the Austrian government decide to re-arm the Austrian Army. By introducing compulsory military service and re-introducing a general staff they violated the St. Germain peace treaty of 1919. Field marshal Alfred Jansa developed a defence plan in case of a German aggression, which was expected for the year 1939, but this “Jansa Plan” was so secret that even many divisional commanders were not informed. The Austrian High Command was anyway convinced that resistance was futile because the Austrian army was clearly inferior. Under the Austro-Fascist regime all soldiers and officers were supposed to be members of the Austro-Fascist “Vaterländische Front”, but the illegal National Socialist “NS-Soldatenring” was highly active inside the Austrian army and the climate therefore was characterised by mistrust and anonymous denunciation. On 11 March 1938 the partial mobilisation was announced and a marching order was issued to protect the border to Germany. Yet the officers were not informed by the government and the abdication speech of the Austrian Chancellor Schuschnigg caught them by surprise while they were having dinner. In the morning of 12 March they learned about the invasion of the German Wehrmacht and received the order to retreat into the barracks at 9.30. The enthusiasm of the Austrian population which welcomed Hitler and had already decorated official buildings, barracks and public transport with swastika flags surprised even many soldiers and overwhelmed them. Yet some officers were annoyed about the government’s decision not to show any resistance. Already on 14 March all Austrian officers and soldiers were sworn in to Adolf Hitler; only few dodged the ceremony which was not noticed in the existing turmoil, but those who officially refused to take the oath, were immediately dismissed and persecuted. Around 30 Austrian officers were imprisoned or deported into concentration camps, six of which died there. Furthermore, 123 “non-Aryans” (officers of Jewish descent) were dismissed from the army on the spot. The orders of the German High Command (von Bock and von Brauchitsch) of 14 March 1938 already marked the end of the Austrian army and the complete absorption into the German Wehrmacht, although the Austrian soldiers and officers were not aware of this fact at that point in time. The pompous military parade along the Viennese Ringstrasse on 15 March covered up the tragic side of the end of the Austrian army: 67 Austrian officers were dismissed and 50 officers who had had to leave the Austrian army before because of illegal membership in the NSDAP were reinstated. Just to mention two of the tragic destinies: the student at the military academy and son of the Austrian vice-chancellor, Herbert Fey, committed suicide after learning that his parents had taken their lives and the field marshal Johann Friedländer was dismissed as a Jew, lost his flat and was deported to the KZs Theresienstadt and Auschwitz, where he was murdered in 1945.

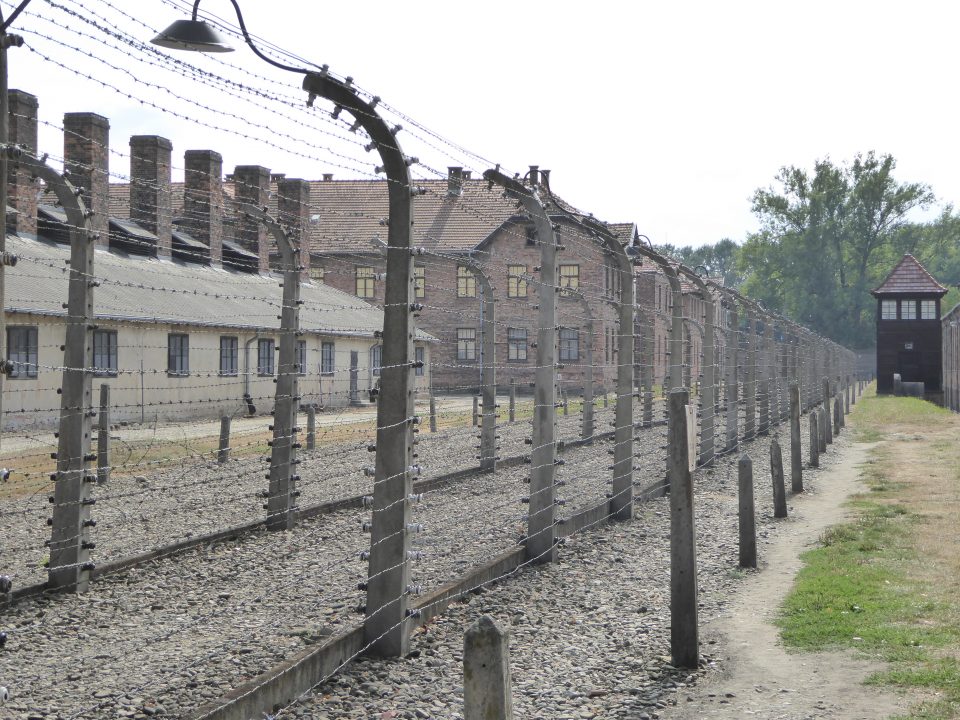

KZ Auschwitz Birkenau near Krakow

Most Austrian officers and soldiers were originally no National Socialists, but many were attracted by the prospect of a career in the Wehrmacht and the National Socialists in the Austrian army even dreamed of an Austrian independence within the German “Third Reich”. Yet Hitler did not accept any special status of the Austrians and was only interested in an increase in the number of soldiers for the Wehrmacht. Immediately compulsory military service was extended from one to two years and the Austrian soldiers were completely integrated in the German Wehrmacht. In a second wave of “cleansing” further 440 officers were dismissed, mostly on the basis of political attitude or because they had Jewish wives, like my grandfather Toni. The hopes for rewards and promotions of members of the formerly illegal “NS Soldatenring” were quickly dashed because the German Wehrmacht was basically apolitical and not too many close ties existed at that time between the NSDAP and the Wehrmacht.

On the other side of the front line around 10,000 Austrians fought together with the Allied Forces against Hitler. They were emigrants, persecuted Jews, Habsburg monarchists, Communists or Socialists who volunteered to fight in the alliance against Fascism; others deserted from the Wehrmacht and joined foreign armies. A family relative who was renamed John Collins in the UK, had fled from Vienna to Great Britain and joined the British Forces against Hitler. I got to know him as a child when visiting my great-aunt and great-uncle, Agi and Norbert Katz, in London and he was presented to me as a war hero – behind his back, of course. These Austrian soldiers were not always warmly welcomed, but treated with utmost mistrust. The President of the United States Roosevelt was in favour of establishing an “Austrian battalion” because that would support the idea of a future independent state of Austria. Yet many of the Austrian volunteers rejected the attempt of Otto von Habsburg, son of the last Habsburg emperor, of leading the Austrian battalion. In 1943 the “Infantry battalion 101” was dissolved without ever having reached the required manpower. Nevertheless thousands of Austrian and German volunteers were integrated in the US Army with the prospect of receiving US citizenship. Famous Austrians in the US Army who after the war played an important role in the cultural reconstruction of Austria were Ernst Haeussermann, director of the Vienna Burgtheater, Marcel Prawy, opera expert, Georg Kreisler, cabaret artist and Hans Habe, journalist. The Austrians and Germans were trained in the camps Ritchie and Sharp since the summer of 1942. Around 20,000 soldiers were trained in map reading, interrogation techniques, creating flyers and radio reports and most of all, in the set-up and working of the German Wehrmacht. Later in Europe they were called the “Ritchi and Sharp boys”. Approximately 10 per cent of the 7,000 Austrians who fought in the US army were trained there. They were used to procure secret information from the enemy, help interrogate German prisoners-of-war and destroy German morale by distributing millions of flyers over enemy territory and creating radio reports in Allied radio stations. In this way they tried to induce the civilian population and soldiers in Germany to surrender. After the war they assisted the Allies in identifying Nazis in occupied Austria, published the first newspapers and acted as cultural messengers. They were also among the first to set foot in the liberated Nazi concentration camps, they talked to the survivors and documented the holocaust.

1,500 Austrians served in the French “Légion étrangère”. After the “Fall of France” 1940 most of them fled abroad and some joined the British troops in North Africa. In this way five British sappers’ companies were formed consisting of Austrian and German emigrants. In 1944 an Austrian battalion of more than 500 men was established under French command and was sent in September 1945 to assist the French troops in the occupation of Austria. All in all approximately 4,000 Austrians served in the French army.

The only army where Austrians set up a separate fighting unit was in the Yugoslav army. In 1944 Austrians, mostly former fighters in the Spanish civil war, Communist emigrants and prisoners-of-war who wanted to escape interment in Soviet POW camps formed five Austrian battalions which were trained by the Soviets. All of them arrived in Vienna in the spring of 1945 and took over defence and security tasks in the eastern part of Austria.

Last but not least, 3,000 to 5,000 Austrians served in the British Army during World War II. At the beginning of the war they were integrated in the “Auxiliary Military Pioneer Corps” (AMPC), which was not armed. Until March 1940 five divisions were formed, which consisted exclusively of Austrian and German Jews; the Austrians constituted 26 per cent (628 soldiers). These volunteers were not automatically awarded British citizenship and were usually not armed, but used for construction works and the clearing of bomb debris. In 1940 four corps were despatched to France. All of them were evacuated from France across the British Channel. Between October 1940 and January 1941 ten more sappers’ corps were formed with 458 Austrian volunteers from British internment camps. So, all in all around 4,500 Austrian and German soldiers were active in 15 sappers’ divisions on the side of the British. In 1942 emigrants had access to officers’ training courses for the first time and in the spring of 1943 they were allowed to volunteer in all military services of the British forces. Many sappers now left these least appreciated corps and entered other British military services. This meant that additionally to the 1,400 Austrian sappers, further 1,600 Austrian soldiers actively fought in the British forces at nearly all front-lines. For their personal security in case of imprisonment by the German Wehrmacht they were given new names and a new identity. Few underwent special training and then acted as agents behind the enemy front lines. 60 of these Austrian agents in the service of the British were uncovered and executed. Several Austrians in British uniform were stationed in Austria after 1945 and helped with administering the occupied territories and acted as interpreters. A special Austrian battalion was never set up in the British forces, as its establishment had failed in the USA, although this was mentioned in the Moscow Declaration of 1943 as a condition and symbolic contribution to the liberation of Austria as an independent state. All attempts were unsuccessful due to the discord among the organisations of Austrians in exile. What was the destiny of German and Austrian Jews who ended up as prisoners-of-war of the German Wehrmacht? The German army soon found out who they were, especially if they were caught in an all emigrants sappers’ corps, but they constituted a problem for the Wehrmacht, which would not treat them as they handled all other Jews. So mostly they ended up in prisoner-of-war camps and were condemned to hard labour.

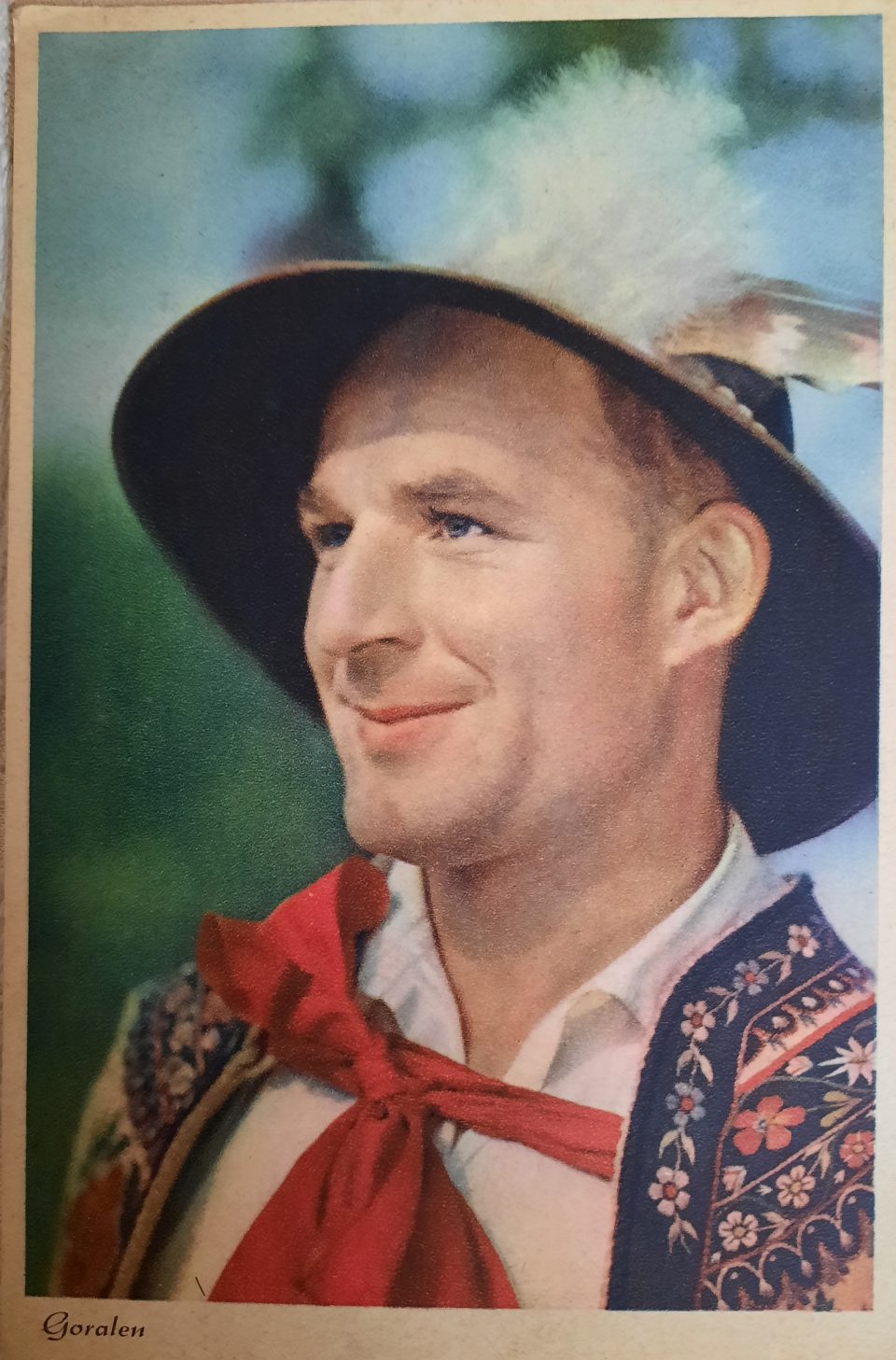

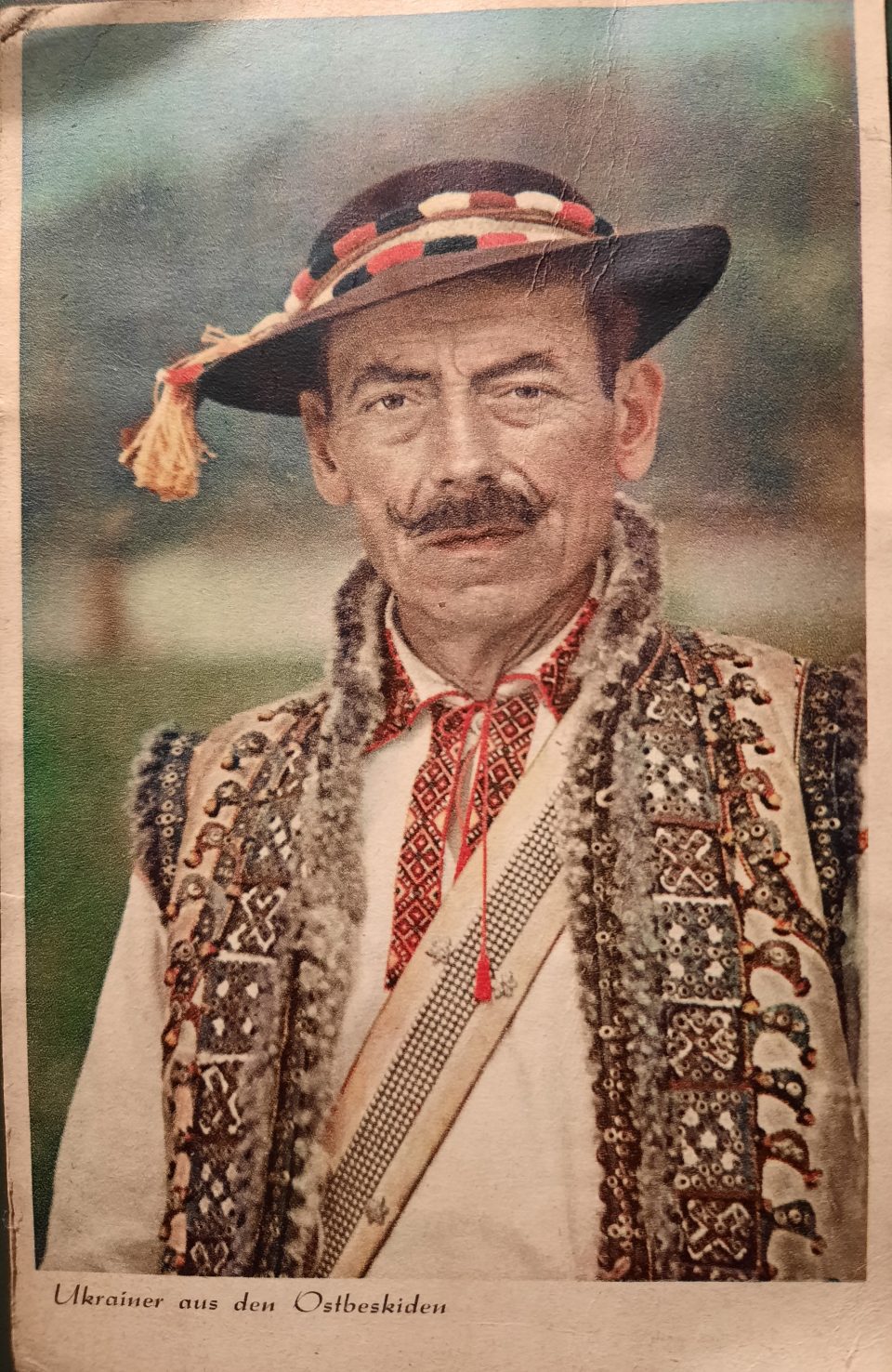

A post card from Poland which Toni kept

On 5 September the train transporting Toni and the other Wehrmacht soldiers of the “2nd Sappers’ Battalion” from France to Poland stopped in Tarnow, the weather was good and the journey wonderful, Toni wrote. On 6 September 1940 Toni arrived at Sanok, the first destination of his battalion in Poland.

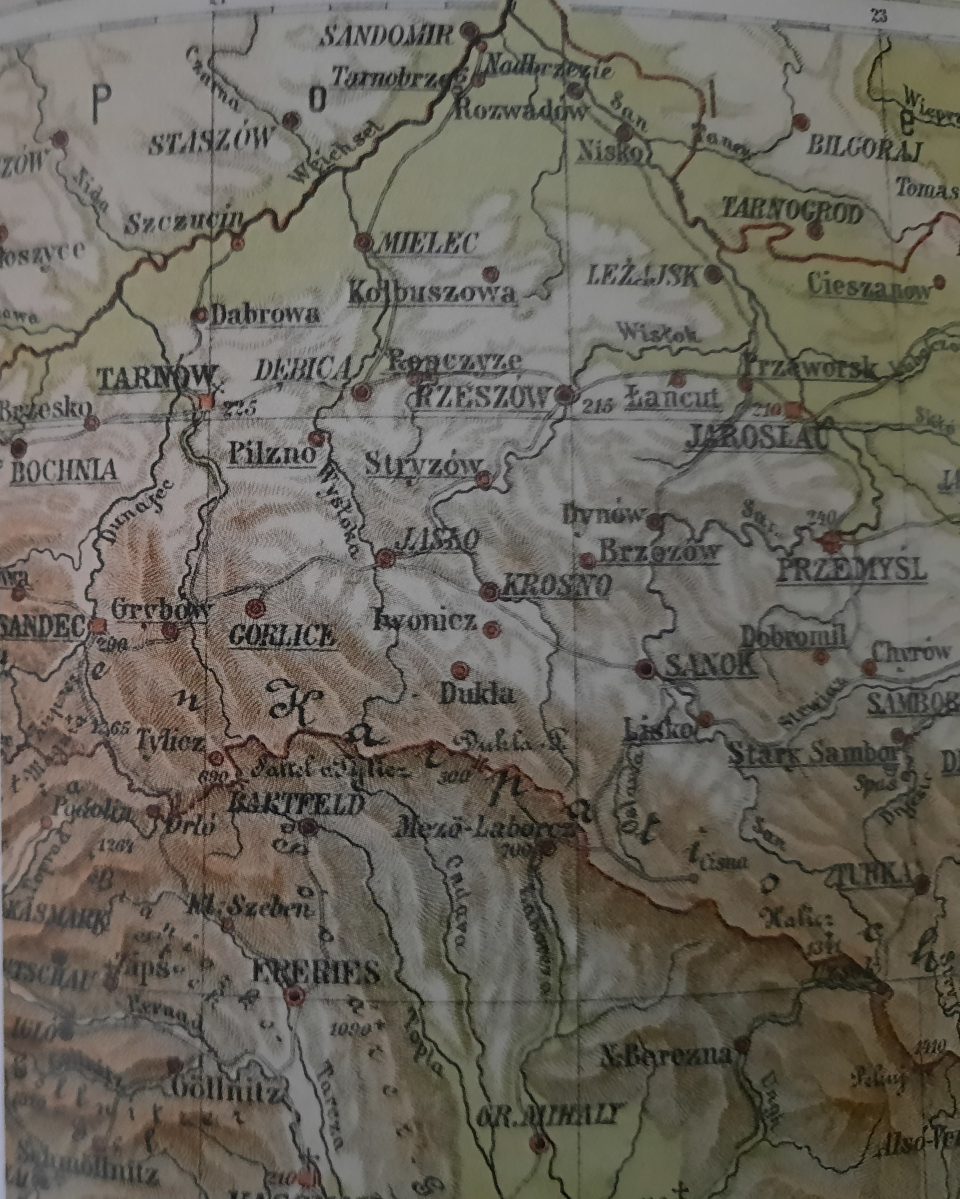

Map of the region as part of the Habsburg Empire’s crown land Galicia, showing Tarnow and Sanok

The Polish cities Sanok and Tarnow had been part of the Habsburg Empire’s province of Galicia after the first partition of Poland in 1772 until the end of World War I. In the course of the German assault on Poland Sanok was occupied by the Germans and was integrated into the so-called “Generalgouvernement”, just as Tarnow. Sanok was a frontier town between the German-occupied and the Soviet-occupied parts of Poland until the German attack on the Soviet Union and in 1940 the Polish underground movement established itself there. The population structure of the whole region was characterised be a large number of different minorities, such as Jews, Ukrainians, Lemkins, Boykins and Germans, several of which were forced to collaborate with the Nazis or did so voluntarily in the “Waffen-SS-Division Galicia”.

Tarnow had been one of the most important merchant towns in the Habsburg Empire. When the German Wehrmacht occupied Tarnow on 8 September 1939, many of the 25,000 Jewish inhabitants tried to flee eastwards, but on the other hand many Jewish refugees ended up in Tarnow who had been trying to escape the Nazis from occupied territories further west. It can be assumed that in 1942 30,000 Jews lived in Tarnow. But the German occupiers also harassed the Christian Poles. In June 1940 the first transport of Christian Polish prisoners to the KZ Auschwitz was organised by the GESTAPO; of these 728 prisoners only 200 survived. For the Jews the Nazis established a ghetto in Tarnow where they interned between 20,000 and 40,000 Polish Jews, who were exploited as slave labourers, most of which were finally deported to the extermination camps Belzec or Auschwitz –Birkenau and murdered there. The establishment of the Tarnow Ghetto was formally announced in March 1941. The final liquidation by the Nazis took place in August and September 1943 and in January 1945 the Soviets ended the Nazi occupation of Tarnow.

A photo Toni took of a sunset in Zamosc, Poland, in February 1941. In this town more than 10,000 Jews lived and the German occupiers set up a ghetto there as well and started deporting the Jews to Belzek in April 1942 until the final liquidation of the ghetto in October 1942

THE MILITARY CAMPAIGN

Toni took a photo of a German PAK (Panzerabwehrkanone)

Sanok

On 6 September 1940 Toni wrote to his beloved wife Lola that they were stuck in Sanok and waiting for the next transport. They were supposed to end up somewhere 40 km from Sanok in a godforsaken village. He was really desperate because this was a totally deserted area. They had just been on the banks of the river San and had looked towards Russia, which was approximately 300 km away. He thought it would be possible to purchase some things in Sanok, but everything was five to ten times more expensive than in France: 0.5 l of beer or 100 g sausage 50 Pf (Pfenninge) and a small piece of cake 30-40 Pf. Then Toni described in his letter the journey from France to Sanok, which he had enjoyed very much as there was good weather all the time: On 2 September they left Remiremont at 10.30 am and went via Luneville to Saarburg and Saargemünd, where they stayed overnight. There was an air raid at night and they could hear and see the attacks of the enemy airplanes and the responding German defence, but he had slept well in the hay on the open train carriage nevertheless. Then they were transported to Homburg – Ludwigshafen – Worms – Frankfurt – Hanau – Fulda – Hersfeld – Ronshausen – Eisenach, where he admired the many flowers, – Gotha – Erfurt – Leipzig, where they arrived on 3 September at 9 am, then to Dahlen – Riesa – Dresden – Bautzen – Greiffenberg – Hirschberg, where they crossed the “Riesengebirge”, a wonderful mountain landscape, – Gottesberg – Dittersbach, where ten furnaces were working at full capacity which turned the sky red from the glowing coal. The train then carried them to Königszelt – Breslau – Oppeln – Ratibor – Oderberg – Chybie – Auschwitz – Skawina- Krakau – Bochnia – Tarnow – Stroze Biecz – Jaslo – Sanok, where they arrived on 5 September at midnight. “You can see it was a journey across half of Europe. I would rather do without it and go home. Our kitchen was on an open carriage. So we had a good view, but also lots of wind, dirt and sun. We are dark as Negroes and dirty as pigs. Just imagine five days in the uniform without the possibility to wash properly or change clothes and very little sleep. We look like gipsies ….Today I don’t care at all: no money, nothing to smoke, nothing to drink, in one word a complete f….. I don’t need anything, just please send me writing paper, a pencil and razor blades.” The only certainty for Toni at that moment was that he would stay in the kitchen, which for him was the best option for the time being.

Sanok

On 8 September Toni reported that the place in which they had finally ended up was by far not as bad as he had expected. At the first village where they should have settled down, their sergeant could not find any place to stay. So they had to turn round with their kitchen after 10 km and they had to sleep in the train station. The next day they travelled 43 km north and then further 8 km before they reached Dynow on the river San. There they lodged in a small village called Notrocza, which was not to be found on any map. The kitchen staff had a nice room for six and opposite there was a nice castle which would be used as the head quarter of the corps. The castle was very derelict, so they had to put in a floor first. The baroness was from Graz (in Austria) and very nice, but the people were extremely poor because all their possessions were located across the river San and this territory was at that time occupied by the Soviet Union. “The people here are really friendly – totally different from what we were told – very hardworking and poor. Unfortunately there are just fields and fields and fields, even when the ground is steep, and nothing else. There is just one inn! One can buy beer here, but I haven’t tasted it yet. Tonight Hauser, Häusler, Kastel, Daun and me had dinner. First we bought eggs from different farmers until we had 24, then we bought 200 g butter, bread and 2 l of milk. At one of the farmer’s I made scrambled eggs for all, which was quite ok, but it cost us 3.50 RM (Reichsmark) or 7 zloty – in France we wouldn’t even have paid 1 RM. Also cigarettes are extremely expensive; the cheapest are 3 Pf and are finished after four to five puffs…. There is nothing to buy here, on the contrary, when the people hear that we were coming from France, they want to purchase our stuff at all costs: a comrade bought two suits for 26 RM in France and I saw that someone offered him 600 zloty for them.”

The forces’ postal service was not working yet in the region, but Toni hoped that he would receive a letter from Lola the next day, which would be the first after a week without mail. He had heard it through the grapevine that they might be able to go on furlough within two weeks and he told Lola that she could not image how much he was looking forward to coming home and being with her. But he could not tell her exactly when he would come because only on the evening before their departure those soldiers were named who were entitled to go on home leave. Anyway, he would try to get some food for her, such as eggs or a chicken. It was difficult to communicate with the people because they knew very little German and Toni said that now it would be an asset if he could speak at least a little Czech (His mother-in-law, Ritschi, was a German-speaker from Moravia, who knew Czech and Lola could communicate a little, but the family had moved to Kaiser Ebersdorf near Vienna when she was two). He numbered his letters and the pages, so that Lola could check whether she received all his mail because he had heard that in Poland the mail was unreliable and censured.

German military hospital unit

On 12 September he wrote that he had been transferred to the military hospital in Dynow against his will because of angina. Lola should not worry as he often suffered from this illness and he seemed to have caught a cold on the journey in the open carriage. When you really needed the doctors, they did not care and when you did not want to be treated, they dispatched you to the hospital, he complained. The doctor had applied some tincture against tonsillitis and the next day he would bring some sage to gargle with. He hoped he would be back in his kitchen soon, but at the moment he was just smoking and reading the papers, but no post had arrived yet. The other three soldiers in the hospital room were nice guys; one of them had received a parcel and had given each of them a packet of cigarettes. He would not stay longer than 2-3 days, he vowed. Toni was especially disappointed because there was a border check point where they were quartered and he had been given a partridge and the leg of a rabbit by one of the border patrol which he would have liked to cook for dinner. The day before, they had bought a barrel of beer and he had broached it. But as they did not have the appropriate equipment, they were all drenched. The weather was dreary and damp and it was getting cold, too. They had had to move the kitchen, otherwise they would have drowned in the mud. The day before they had received their pay, which was 20 zloty Polish currency (“Frontgeld”, army currency, was not valid in Poland).

On 10 September Toni wrote that for 10 days he had not had any letter from Lola and he desperately hoped for many letters soon. He was sitting in the kitchen, which actually was the garden in front of the horse and cattle stable, where they had set up the kitchen equipment. Until 5 pm when coffee would be served he had time to write, “There are no news, but what news could there be in this country. I always say we are visiting the devil’s mother-in-law here.” The food was ok; smoked meat the day before and tonight sardines in oil, but Toni would save them for Lola and eat some scrambled eggs instead. You could get as many eggs as you wanted from the farmers there, if you exchanged them for tobacco. Toni told Lola that he was already heavily indebted to one of his officers, sergeant Sündermann – “a really nice guy” –, and his pay had not arrived yet, just as the mail, but “debts don’t hurt!” The day before, Toni had had “a nice job”: one of the sergeants, who would take one of his letters to Vienna, had bought a goose for himself, but it was delivered alive and Toni helped him in extremis. He slaughtered and plucked it and the sergeant took a photo of him in action. At the moment the whole corps was discussing how to build a kitchen because as soon as the rains set in, they would be in deep trouble. But fortunately they still had sunshine, because as soon as it rained there would be mud everywhere. “You know, my dearest, with you I would even endure this place, but with you alone!” Working in the kitchen had the advantage that you did not have to abide with “all the nonsense” (drills and roll calls). All the others had to go through the drills every morning because there was nothing else to do. But on the other hand you had something to do the whole day when you were on the kitchen staff. He was yearning for Lola and Herta and he had heard through the grapevine that by the end of October, at the latest, they would be transferred back to Vienna, but you could never believe the rumours. “At some time this whole nonsense must be over! If only the war with England would be over, then the end might be nearer!” (Unfortunately Toni could not know that that was just the beginning.)

While Toni was being treated in the military hospital for angina, they brought in a soldier from the 4th division with a smashed in head, “one from each of the five divisions”. The food was now served from the 3rd division, which was “complete rubbish – I am not used to that in the 2nd division! I will be leaving soon from here!” They had been served “Wehrmacht soup” (“brrr!!”), rotten rice with compote and potato mash with tins and tea with nothing, but “fortunately we still have schnapps from France!” The next day he wrote that he had been sick from the food and that the doctor had promised to release him from duty for the time being. “If we don’t leave this damned Poland soon, we’ll all be sick”. On 15 September he was back with his 2nd division. He said he had fled the hospital and was glad that so much mail had been waiting for him from Lola, his sister Milly, his cousin Luisi and his friend Turl, who was such a good friend because he would repair the stove for Lola, and a parcel with cigarettes. In the afternoon at 4 pm they had had a “grand theatre performance”: rather primitive, but with respect to the circumstances quite nice: a magician, a small boy who performed as a contortionist and a hypnotising act; so the one and a half hours passed quickly. The weather was bad and he was sitting in the castle and waiting for the radio report. The castle was quite nice compared to the rest of the region: parquet floors everywhere, electric lights and three-metre high tiled stoves. Lola did not need to worry, the situation was not insecure here and the people were nice. There was no need to send him money, just cigarettes! There was nothing to buy and he did not want to go drinking, so he needed no money. On the contrary, the local population wanted to buy things from them! Lola should not send him any sweets any more, but give them to Herta, because here they could get some sweets every second day.

On 16 September Toni wrote from Nozdrzec that he hoped he would be able to go home for eight days soon. He was worried that he still had not received all letters and parcels which had been sent to him to France and he was not sure whether Lola had not sent him some money to France, too. He was hoping to bring her a goose, which he had already ordered, and some eggs to be pickled. He wanted to buy so much for them, but this was not easy because he was stationed at a customs frontier. Wednesday they had received a bar of chocolate which he had kept for Herta, and sardines for Lola. He would like to have at least some presents for them when he came home. Unfortunately he did not know when he would arrive in Vienna; he would just surprise them in the morning. In a letter Toni’s comrade from France, Peter Fiktorovits, wrote on 22 September that he was not allowed furlough and that also he had had to leave Lorraine and had been transferred to the “Reich” into a very dreary area. He was now serving in the High Command.

Krakow: historical Jewish quarter

Krakow: old Jewish cemetery

On 12 October Toni wrote the first letter to Lola after his return from furlough in Vienna, “Now I’m back in the Promised Land”. The journey had been ok and they had arrived in Krakow at 8.30. He had slept quite well in the corridor, not in the compartment on two newspaper pages and from Krakow they left half an hour later and managed to get a comfortable seat. They spent the time eating and sleeping. They arrived in Przeworsk at 14.05 and had to wait until 19.00 for the next train. They went to an inn and he had half a litre of beer and some brawn with onions for 1 RM. At 20.30 they arrived in Dynow and walked 6 km on foot in one hour to their barracks. At night he froze because it was already extremely cold and his luggage only arrived the next day at lunchtime. Toni reported that now a new chef was working in the kitchen, an arrogant fanatic, “nothing for me!” So he told his sergeant that he wanted to return to his corps and he was immediately transferred. They were lucky because they had just received proper beds and he furthermore asked Lola if she could procure a very small Polish-German dictionary for him because he wanted to be able to communicate a little with the local people. He wanted to sell the shoes he had brought from home and hoped he would get around 20 RM for them. He would then send the money to Lola so that she could purchase the hair trimmer he had seen in Vienna and send it to him. He had enjoyed the “Wiener Schnitzel” (Viennese speciality) she had packed for him and now he still had her “Grammeln” (greaves). He was thinking of her a lot and even kept talking to her in his letters. Had she got used to sleeping alone again? He was numbering all pages of his letters to Lola now and she should do the same, so that they could check whether all letters arrived complete. (It seems Toni suspected that the letters were censured and pages “disappeared”)

On Sunday Toni and his friend Pauli had been bartering the clothing and shoes they had brought from Vienna in the village and he asked Lola to send some more, for example his old grey jacket because he could get lard for it. Furthermore he could do with some old shaving razors if Ignaz (his father–in-law) had some. If Lola had some woollen jumpers or vests or a winter dress she did not wear any longer – but nothing shabby, she should wrap all that up because in Poland he could barter or sell them; also his shirts. She should give the parcel to his comrade Kastel who would leave Vienna on Saturday and take the clothes to Toni. Then Toni described such a bartering scene: they had gone to a farmer with all the stuff and within quarter of an hour the whole sitting room was full of people. All neighbours were present and then the fitting and the haggling started. Pauli had a suit of his grandfather with him, totally old-fashioned with very short and wide trouser legs. “We did not understand them and they did not understand us, but all were talking at the same time. For the summer suit I got 35 zloty, for the trousers 15 zloty, not bad?! For the Knickerbocker suit they wanted to give me 32 zloty, but I insisted on 34. Maybe tomorrow I can sell it for 40 zloty. The greatest show came next: Pauli had a torn black dress, a blue skirt with holes and a very wide black skirt in the folk style of the times of our great-grandmothers. The people were so enthusiastic and he got 65 zloty for all that! What do you say? Afterwards the people served bread, butter and vodka. As soon as I have received all our stuff, you can also send me the underskirts of my mother, which are worthless, but I could sell them here.” He said he would keep the money until someone of his comrades came to Vienna and he would then bring her the money, so that she could have a winter coat made for her and he could buy new trousers in Vienna. As soon as he had sold everything she could send him his grey trousers as well. Someone even wanted to buy his blanket, but that had to wait.

Toni reported that his and Paul’s duty was to roll out barbed wire and in the afternoon Karl Häusler helped them. For dinner they had a tin of herring which he would keep for Lola and Herta. Afterwards they went to the farmers again to sell clothes and then they both went to the farmer they had befriended and Toni made some scrambled eggs for them there. The farmer again urged Toni to give him his blanket, so Toni fetched it from the barracks. He liked it very much and wanted to give Toni 40 zloty, but Toni would not sell it under 50 zloty. He left the blanket with the farmer and wrote that the farmer would now ponder the whole night, but the next day he would surely get his 50 zloty. The people urged him to bring walking boots and shirts, so Toni asked Lola to send what she could find as soon as possible, but things in good condition, Toni stressed. The next day they would have the afternoon off because in the evening they were going to the theatre in Dynow and Toni was very curious what kind of childish show they would be presented with this time. The next day he wrote that the show had been cancelled, but he and Pauli had walked the 7 km to Dynow nevertheless and went to an inn, where they spent quite a lot of money on 150 g sausage and 2 pints of beer each and 9 schnapps in the next inn. He wrote he was a bit tipsy, but not drunk, “What else can you do here; you just get stupefied!” For dinner they had cheese in tins and jam, which he would not eat, so he and Pauli ate the remaining of “Grammeln” Lola had made. Afterwards they returned to the farmer who tricked him into selling him the blanket for 45 zloty and half a litre of Polish vodka, which they called “Wutky”. But Toni was satisfied because he had got all in all 200 zloty for the clothes and shoes, which was around 100 RM. That day the army had finally banned the selling of stuff to the local population, but Toni wrote to Lola, “Just send me the clothes and shoes. In the evening it is dark, so nobody sees anything. You just shouldn’t talk about it.” They had electric light in the barracks, but it was interrupted often and not very bright, so it was difficult to write litters, above all because there was so much noise with all the comrades playing card games. That’s why he needed a torch, the batteries for which he had already acquired. The forces’ postal service in Poland was abysmal and the parcels did not arrive at all or very late. So Toni urged his wife to complain in Vienna about the service and kick up a fuss in his name. He hoped that if she not only wrote his name and forces’ postal service number 17525, but added “via Krakow II Dynow”, the mail would finally arrive. Toni did not only write to his wife daily, but also to his sister and friends. Some evenings he wrote up to six letters and he already lacked writing paper and envelops, which Lola should send him. He was extremely worried and desperate when he did not receive a letter from Lola for a week or more because of the precarious situation Lola and Herta were in at home. He always sent his regards to his parents-in-law (“the oldies”, Ignaz and Ritschi). Whenever possible, he gave his letters to those comrades who were going home to Vienna. He also filed a complaint via his superior about the unacceptable handling of the mail in their region.

In October it was already very cold and in the morning everything was white, covered in frost, but during the day it got sunny when they were rolling out the barbed wire. Toni was worried that they might have to spend the winter in this godforsaken place. But there were new rumours that they would be transferred to the riflemen division, so that they could return to Austria. He wished for a stationing in the vicinity of Vienna in order to be able to visit Lola every one or two weeks. On 17 October Toni told Lola that he was not missing the kitchen duty. He was happy “walking around in the fresh air”, except that it was already very cold and a strong north wind was blowing. He had found a way to communicate with the local farmers, as the brother of one spoke quite good French. He was already on good terms with the indigenous population, just as in France. He had bought eggs and fresh milk from one of the farmers and had cooked for himself and Pauli a nice dinner. For Sunday he was planning to do “Backhendl” (a Viennese speciality: pieces of chicken rolled in flour, egg and bread crumbs and fried) for the two of them. His friend Pauli had become father and they had been celebrating in Dynow the new baby with Polish vodka, so they were already quite drunk, Toni wrote on 20 October. Pauli would be going to Vienna the next day and he would bring Lola 30 eggs, half a kilo of lard and the tins of fish and cheese Toni had saved for her. He hoped that this would help Lola put some food on the table. He urged her to send more clothes, shirts, suspenders, everything she could find, but she should not mention it to anyone. He could sell all this stuff in Poland and by that assist her in raising some money. In the morning he had been at the farmer’s with Pauli and they were invited for lunch. They were served “Pirogy”, a special national dish, which Toni adored. He immediately sent Lola the recipe, “You cut and roast fresh cabbage and onions, mix it with curd cheese, salt and pepper and prepare a dough for strudel, form little turnovers and fill them, cook them in salty water and serve them with brown butter.” Toni decided that the excessive drinking had to end because it was too expensive and also had a bad effect on his health. He had received his pay and complained that a “voluntary” donation of 2 zloty was automatically deducted. They now had to carry wood up the mountain nearby to build a wooden shelter there. It was already very cold in the morning and all the meadows were white with frost.

On 27 October winter had set in in the region; everything was white outside and it snowed thick flakes. They day before they had opened the “Soldateneheim” (soldiers’ home) in Dynow and Toni had a personal invitation from his sergeant, but he did not go there because he preferred to read Lola’s letter which had just arrived. The others reported that the performances were funny and the food good. He was sending her some photos, which she should keep for him because he planned to make an album when he came home. For the next day they had ordered “Backhendl” at a farmer’s and they were looking forward to this festive meal. He had had already some beers, when he was writing the letter, but he stressed that some alcohol was necessary to be able to stand this “charade”.

Toni had to be operated on his foot and before his operation Toni reported that Fritz Lang had again accompanied him to Rzeszow to a collection point for the sick because the military hospitals were too crowded. They had had a nice dinner at a farmer’s: Chicken simmered in butter with potatoes and a sort of horse radish sauce. It was excellent and he had eaten half the chicken! Fritz and he had rambled through the streets of Rzeszow, which ”… is very dirty. The shops are mostly grubby. It is interesting that the population consists of two thirds Jews, which can be seen on the armbands and at the shop fronts. Here you can see the true Kaftan Jews, extremely dirty. They have to clean the streets and that’s what they look like. I prefer the little village we are in because the people are much nicer there.”(Approximately a year later in December 1941 the Nazis established a ghetto in Rzeszow, from which around 22,000 Jews were deported to the KZ Belzec and mass executions of Jews took place in a forest near Rzeszow.) They had diagnosed his problem on the ankle a “ganglion”. After his operation in the military hospital Toni wrote on 28 October that there had been many operations on that day and he had to wait a long time on the operating table and watch another soldier being plastered “from the belly to the tips of his hair – like an iron virgin”. Then the surgeon cut a piece of his foot and closed the wound with 10 stitches and applied a loose plaster. He would have to remain in the collection point for ten days. He asked Lola to send his greetings to everyone because it was rather difficult for him to write more letters in bed.

On 30 October Toni was already much better. He described that he was lying in the gymnasium of a former Jewish school in Rzeszow, where the army had put up 23 beds and people were coming and going like in a beehive. The building was very grand, like a theatre with fabulous lighting, although only a third of the lamps were on. The only nasty thing was that he could not walk, only hop on one leg like a stork. He would have liked to have crutches, but they could not be procured; later on his friends presented him with a walking stick. So a comrade had to bring him the meals otherwise he would have to starve. Some parts of the building were well heated except the dormitory which was important because outside it was already winter. “Luckily in the bed next to mine there is a Viennese who is very nice. I have always said that you should not be sick in the army!… Some say that after a hospital stay you can be transferred back to the “Ersatztruppe” (reserve troops). It would be ok if the corps was ok, but if they were all veterans, I would not like that… Here time does not pass by – I still have to wait five more days until I receive post from you.” On 31 October he wrote that Lola was such a good nurse because his sister Milly had written to him how wonderfully Lola had cared for her during her sickness, “Why can’t you be with me. I would be running around within a few days! I tell you, you should taste the food here. Yesterday we were again offered an undefinable stew of lentils, carrots, potatoes and tinned meat without fat or spices and today very little cooked bacon and spinach?? – boiled leaves, chewy as straw and potatoes -everything without fat or spices. It is supposed to be a favourite dish of Hamburgers. I think at home not even the pigs would eat that… If I could just walk again because then I could buy something in an inn! There is still snow everywhere and it is extremely cold.” Toni was hoping to be allowed special leave after his stay in hospital, “If only the f…. war was over, then I could be with you again all the time!” 1 November was a holiday which meant there was no early wake-up call and the food was acceptable; a kind of undefinable onion-meat stew with little meat, but edible. On 2 November he was already much better and could walk around. He had helped in the kitchen with peeling potatoes, but he was looking forward to his first “outing” to the nearby inn to buy himself some beer and some tasty dinner. There was a cinema in Rzeszow; so maybe he would go there if he could still get tickets. Finally they had put a stove in the dormitory, “These are my news; you really become humble in this club!” In the cinema he saw “Erin Robinson”, which was not much, a typical political propaganda film “pour la mérite of the marines”. The only beautiful aspect was the nature scenes. In town he was able to purchase some cheap novels for 25 Pf., because he had nothing to read any more. The weather was very bad, cold and rainy and there was nothing to do, it was so dreary in this place. So he read from 8 am to 9 pm., which was getting boring, too. Otherwise they were just waiting for ”the feeding like zoo animals”. He had already saved four tins of fish for Lola and he was worried whether they had enough to eat in Vienna and whether they were not freezing in the flat. In his daily letters to Lola he would like to write more and he would also like to write to his friends and relatives “but in this deserted place there is nothing to write about”. On 3 November they had for once a nice lunch of roast veal with potatoes and vanilla pudding with chocolate sauce and in the evening he went for a beer to the “Restaurant Lemberg”, where they had music. Otherwise there was nothing enjoyable because for more than a week he had not received his mail. In fact he went out rarely, first of all because it cost too much money and secondly because there was so much mud everywhere.

Toni assumed that he would not be entitled to get some rehab furlough soon, maybe within two or three weeks, because his stay in the military hospital had been rather short. So he asked Lola to contact his boss Hofbauer and urge him to ask for Toni to be transferred to Vienna to work in the fish shop because for the fish monger this was the high season. He was sure that Hofbauer could get the permission so that he could finally go home or stay in Vienna for some time at least. There were others in Vienna, like Leitinger, who was drafted later than Toni and was already back home. The food was getting better, but it was mostly potatoes, “seems to be the staple food of the Piefkes (Germans)”. Toni was sure that some of her letters were missing and when he was back at the division he would look into this matter and complain.

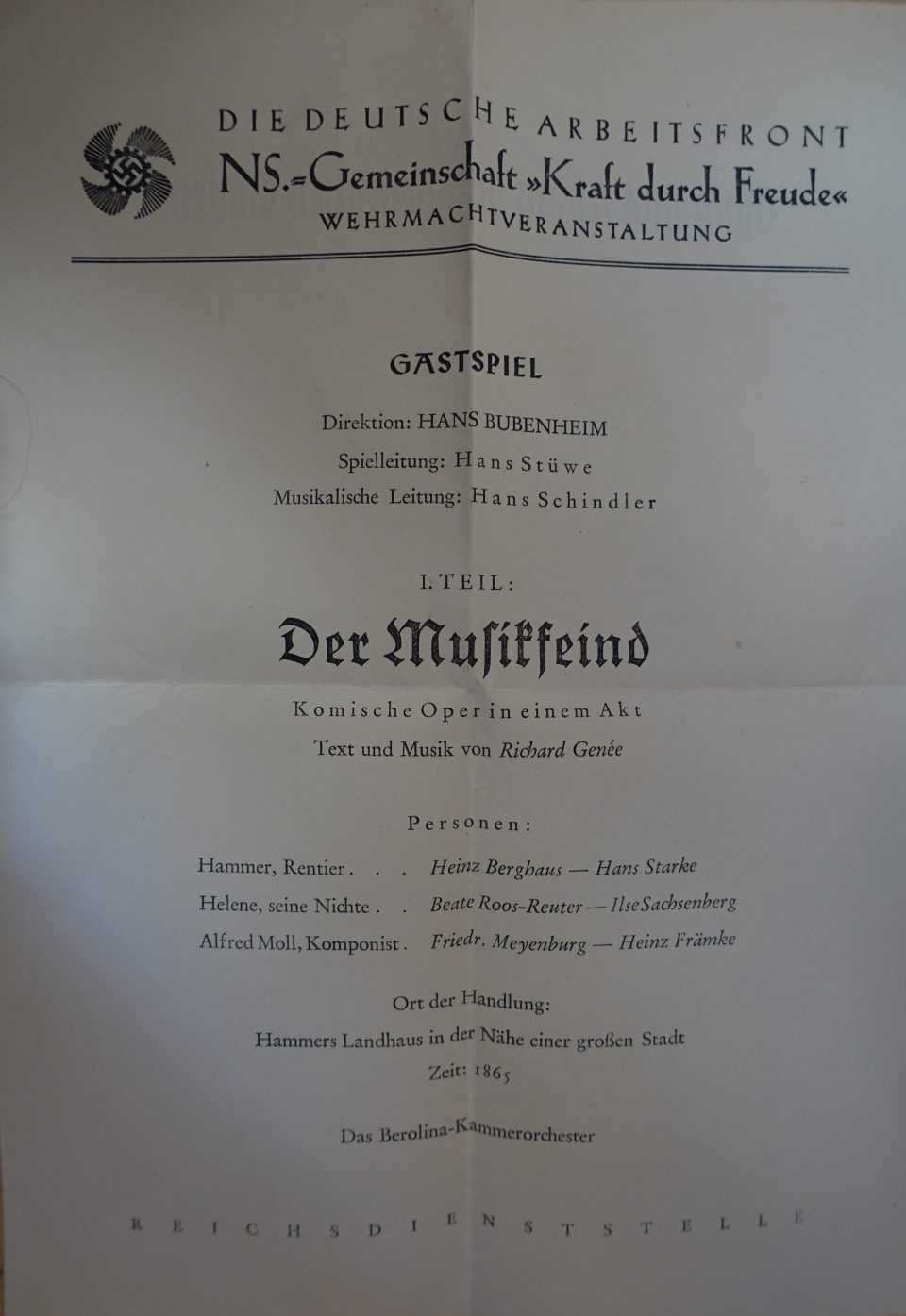

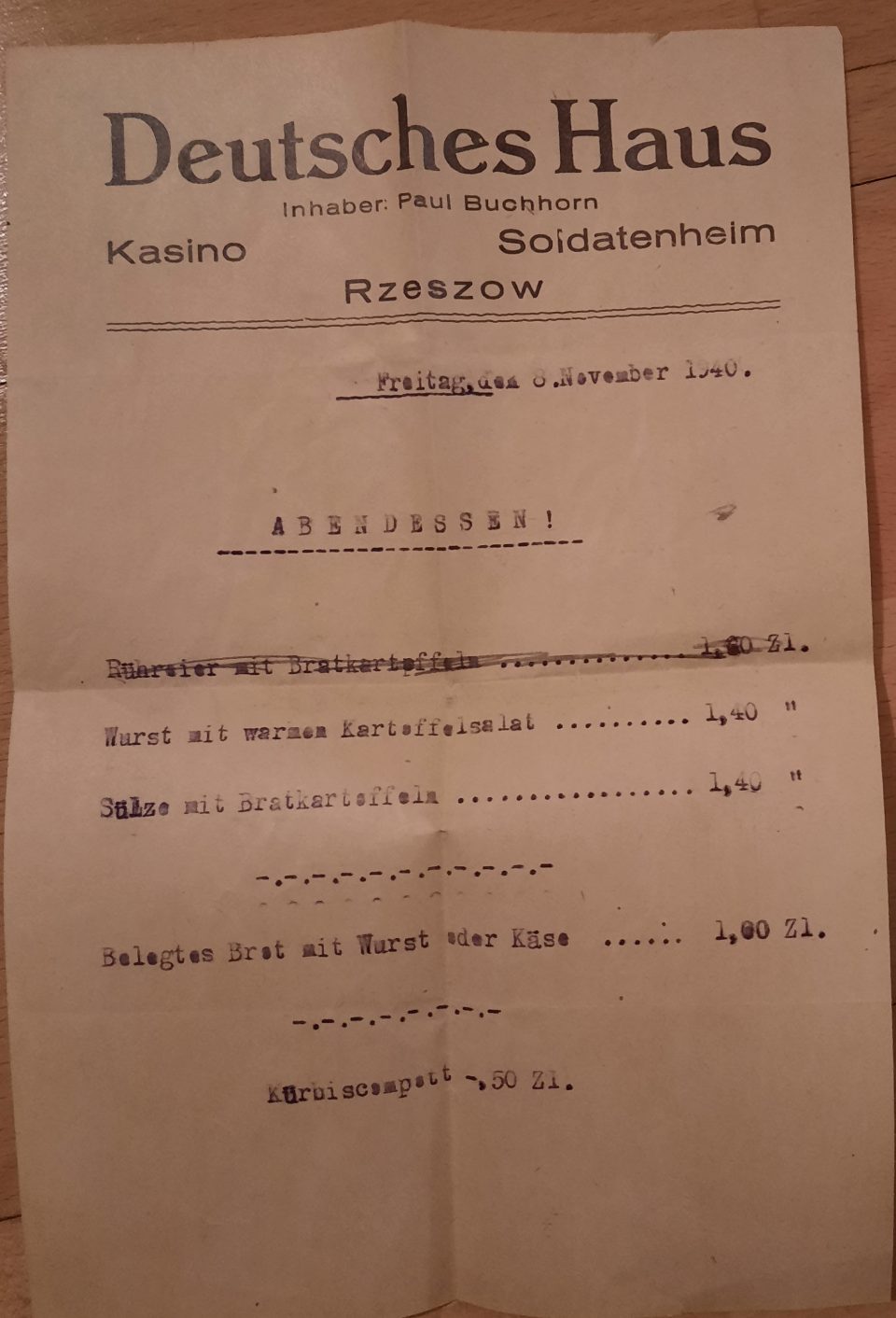

On 10 November Toni described his “first nice evening in Poland” to Lola: He was still in Rzeszow in the sickness ward, yet was already assisting in the canteen preparing spinach. The whole effort resulted in one of the terrible German stews called “Hamburger Allerlei” consisting of small pieces of pork, lentils, beans, carrots, potatoes, cauliflower and several unidentifiable ingredients, “You can imagine the taste!” But in the afternoon he went to town with the Viennese comrade, Kosmak, from the district Währing, like Toni himself, and they saw an advertisement in an inn “Concert tonight”, which would have been a nice distraction after all that “Hamburger Allerlei”. So after dinner (lard and a tin of sardines, which he kept for Lola) they went to town, full of distrust. Yet the first nice surprise was that the tickets were rather cheap and the venue really luxurious with boxes on the sides which were reserved for soldiers of the Wehrmacht. They rather self-consciously took seats in one of the boxes, when an expert waiter asked them in German what he could bring them. They ordered beer and goulash, which was excellent. Then the concert started: a piano, a cello, an accordion and a violin. “The musicians seemed a bit shy, like us. May be it was their first performance. But it was really nice; they played Viennese songs, waltzes of Strauss and modern music in between. Sometimes it was not harmonious, but after about ten bars you could hear what they wanted to play. Sometimes we had to laugh because especially the female accordionist and the pianist got into conflict. But meanwhile we are very humble with respect to our tastes and so it was a really nice evening. We had to leave at a quarter past eight because we had to be at the ward at nine. It wasn’t too expensive as well (beer 1 zloty, goulash 2 zloty), so we’ll return tomorrow and the Viennese comrade is really nice company. Unfortunately for half an hour we had to endure a disgusting spectacle. Three Piefkes, obviously Berliners, felt they had to perform, too. They played the piano, approximately like Herta, and their singing was abysmal. But the three guys enjoyed their performance so much that they did not want to stop, especially the song “Wannsee” was continuously repeated. I could not contain myself and said loudly that it would be best if they stopped now. I cannot hang back; I’m so ashamed of such idiots, especially in uniform.” Toni did not enjoy the concert the next evening because there was such a lot of turmoil, which he could not support. When Kaltenberger and Ebner visited him, they went for some beers and to the cinema in Rzeszow, which “was only 25 Pf, but it wasn’t worth more, “Scandal about a Cock”. A totally stupid comedy, but sometimes you could at least laugh.” Then they went to the new “Soldatenheim” (soldiers’ home), where beer and food (sausage with potato salad) was a little cheaper. Toni sent Lola the menu of this soldiers’ home so that she could see what the “Piefkes” ate.

The menu of the soldiers’ home in Rzeszow: scrambled eggs with roast potatoes, sausage with potato salad, brawn with roast potatoes, sandwich with sausage and cheese and pumpkin compote

While strolling through Rzeszow Toni did some window shopping and was shocked about the prices: a tin of sardines 8 sloty (= 4 RM), a tin of herrings 6 zloty, slippers for Lola 30 zloty, leather boots for Lola 300 zloty. “I cannot imagine how the people here can afford anything! A cleaner works here for 10 hours and then earns 5 zloty a day, from which the health insurance is deducted, so approximately 2 RM remain.”

Toni was passing the time in Rzeszow with reading – he bought books at the train station -, riddles and walking around in town, but that was boring because you could only always stroll along the same streets as there was too much mud. The weather was better now, but there was always frost at night. Furthermore he now had the chance to have his health checked, especially his heart and lungs, in the military hospital. “If they find something, it’s good to know.” They had him X-rayed at the hospital and found some calcification at the heart, but everything else was ok, so Toni was dismissed on 13 November and returned to his division on indoor duty. Toni was happy to be back with his comrades and most of all, he now received the letters from Lola, Herta and his friends and relatives as soon as they arrived and especially the parcels with his favourite cigarettes “Drama”. For Toni it was a tragedy that it was so very difficult to get cigarettes in Poland and the ones he was being sent from Vienna always arrived late.

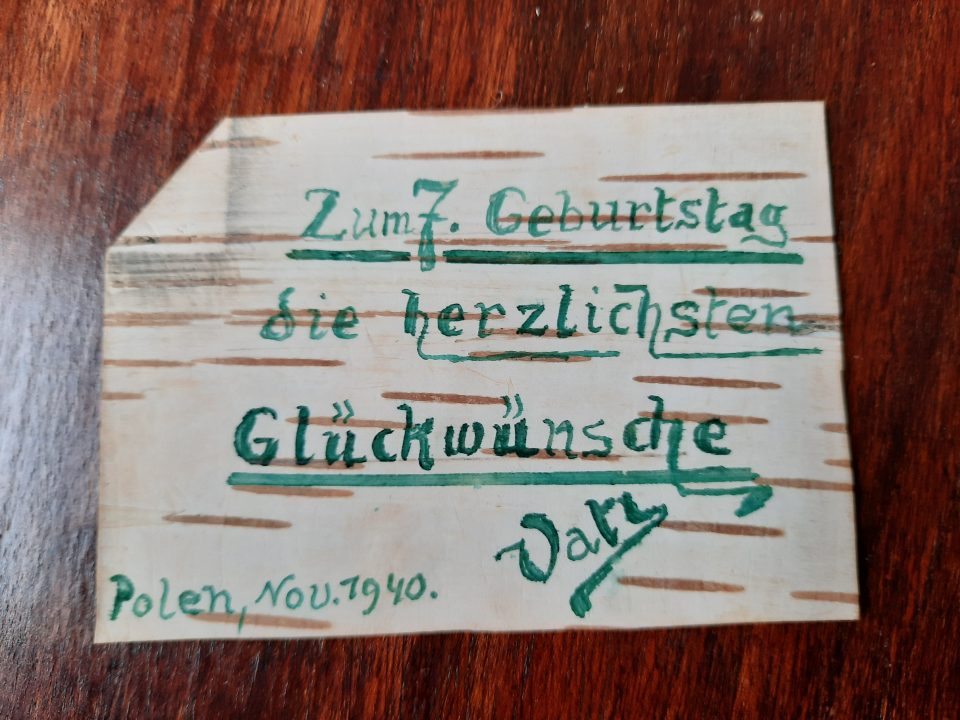

His tasks in the division were now easy jobs such as stapling firewood because he still could not wear his boots. Sometimes he went round in the village with his friend, the paramedic Fritz, who attended to the famers and there Toni saw under which deprived conditions those people had to live. They were all very friendly and paid Fritz with vodka. The soldiers were once in a while transported by car from Nozdrec to the bath in Dynow, which was the only chance to get a proper wash. Another distraction was football. On 17 November their division beat the 5th division of “Marmeladinger” (Germans) 5:2. The fanatic Baumgartner was there as a spectator, but was ignored by everybody, Toni wrote. On 18 November Toni received a parcel: Lola had sent him “Buchteln”, a Viennese sweet dish which was her speciality (see the article on “Viennese Sub-urban Coffee Houses”), which he loved, but most importantly cigarettes, which were so scarce! Lola soon afterwards sent him a cake, which he wrote was excellent. He sent his best birthday greetings to Herta (see below) and told her to think about a present she would like to have and which he would buy her as soon as he was home. It was such a pity, that he could not celebrate Herta’s 7th birthday with them, but he would be with them in his thoughts.

The birthday card for Herta’s 7th birthday on 24 November 1940, which Toni created for her.

As Toni’s ankle got inflamed and the scar festered, he was transferred back to the sickness ward and he hoped that the doctor, who was “a really nice guy who you can talk to” would recommend home leave for him. In Rzeszow they had found out that they could get food delivered from an inn and Toni wrote enthusiastically that they had had “Fleischlaberl” (meat balls) “the size of a hand” with potato salad and cabbage salad the day before at a reasonable price and for the next day they had ordered seven “Wiener Schnitzel”, which would be a feast! In fact, the “Wiener Schnitzel” with salad and potatoes were excellent and cost only 1.10 RM each!

On 24 November Toni was finally back at the barracks and at night in complete darkness he and his friend Pauli trudged through the deep mud to the farmers to sell clothes and purchase food for their families at home. Toni bought 1.5 kg poppy seeds, 1 kg fresh butter and 1 kg curd cheese and several kilos of lard. Toni said he would need a “furniture hauling truck” when he went home. For dinner they were invited by their friend Toczek, who served them two large helpings of Pirogy and milk, and afterwards, to his surprise, Toni was informed that two days later he would be on furlough in Vienna.

Back in Nozdrec he immediately sent Lola and Herta a parcel of food for the Christmas holidays on 20 December with a comrade who went to Vienna. He recounted his journey from Vienna to Poland, which had been full of obstacles. One hour after departure the windows and the walls of the train compartment were already covered in ice, so they could not sleep at night. In Debica they arrived two hours late and then ate a roast of veal with potatoes and salad and drank a couple of beers. The next train finally left at 6 pm, again two hours late, and they continued their journey for three hours in a freezing cold compartment in darkness, without light or heating. With a small, but heated and illuminated train they later left Przeworsk, but 15 km before they arrived at their destination, the train stopped due to an engine defect and they had to wait for another engine for hours. They finally arrived in Dynow at 3 am. There they were provided with a sledge at 5.30 am and returned with it to their barracks.

The officers were now pushing the soldiers to reach higher productivity and at the same time reducing the food rations, although they had to work under very harsh conditions: 30 cm of snow, minus 20-26 degrees Celsius, but fortunately no mud. “I think our officers want to earn themselves a few stars (decorations)!” Toni was really angry when he learned that only privileged soldiers (probably NSDAP party members) were allowed to celebrate Christmas and New Year at home. The only advantage was that they were rid of these officers over the holidays. Toni was back in the kitchen and wrote that they had visited with Pepi his befriended farmer, who welcomed them warmly and was enthusiastic about the harmonica they had brought with them. While Toni was on furlough he had slaughtered a pig and had kept two excellent smoked pieces for Toni and they had to taste the fresh black pudding with butter. Unfortunately they could not drink any vodka because they had had too much the day before, but the next day they would visit the farmer again and then they would be able to have some vodka again. Lola should see whether she could get more old clothes or shoes, especially children’s shoes this time. He could sell all that to the farmers. She should ask Milly, Hans, Turl or the “oldies”. She could give some of the stuff to Häusler or Ruthner, who were both in Vienna, and would take the stuff with them back to Poland. They could really make do with the money he got for the clothes and shoes. He would send her the money as soon as a comrade he could trust went to Vienna.

Alcohol seemed to play an enormous role among the soldiers in Poland, even more than in France, and especially around Christmas and New Year. Toni was back in the kitchen, which was advantageous for his wounded foot, but he had much more work to do from morning till evening. On 22 December he described to Lola how they had spent the evening before saying fare-well to Hauser, who could go home over Christmas: they were ten and had 1 barrel of beer, 3-4 l of schnapps, so they were all very drunk, “but without consequences. Only my memory is quite dim and Pepi was so drunk and sang continuously, so that I had to drag him home.” Toni was indignant when their sergeant bid fare-well to them in the morning and told the soldiers how sad he was that he could not celebrate Christmas with them. Toni despised this hypocrisy of the élites who had the privilege to go home for the holidays. Toni and some comrades would be going to his Polish friend Kaczi in the evening and bring him the harmonica again.

On 23 December Toni burnt his arm at the hot water cauldron, but the paramedic treated the burn with an ointment and it would be ok. There was uproar in his troop because for Christmas the army had allocated only 2 l schnapps, 2 bottles of sparkling wine and 4 l of wine for 20 men – and they had to pay for it! “…there will be a thimble full for everyone!” Toni begged Lola to send him some sugar for the farmer’s wife because the local population did not get any sugar at all. When selling their and Turl’s clothes and shoes, for which he received 108 zloty, he was invited by the farmer for dinner: 250 g sausage, mustard and two cups of fresh milk!

Christmas 1940 in Poland (Toni standing in the middle with the cut off face in the background), 24th December 1940

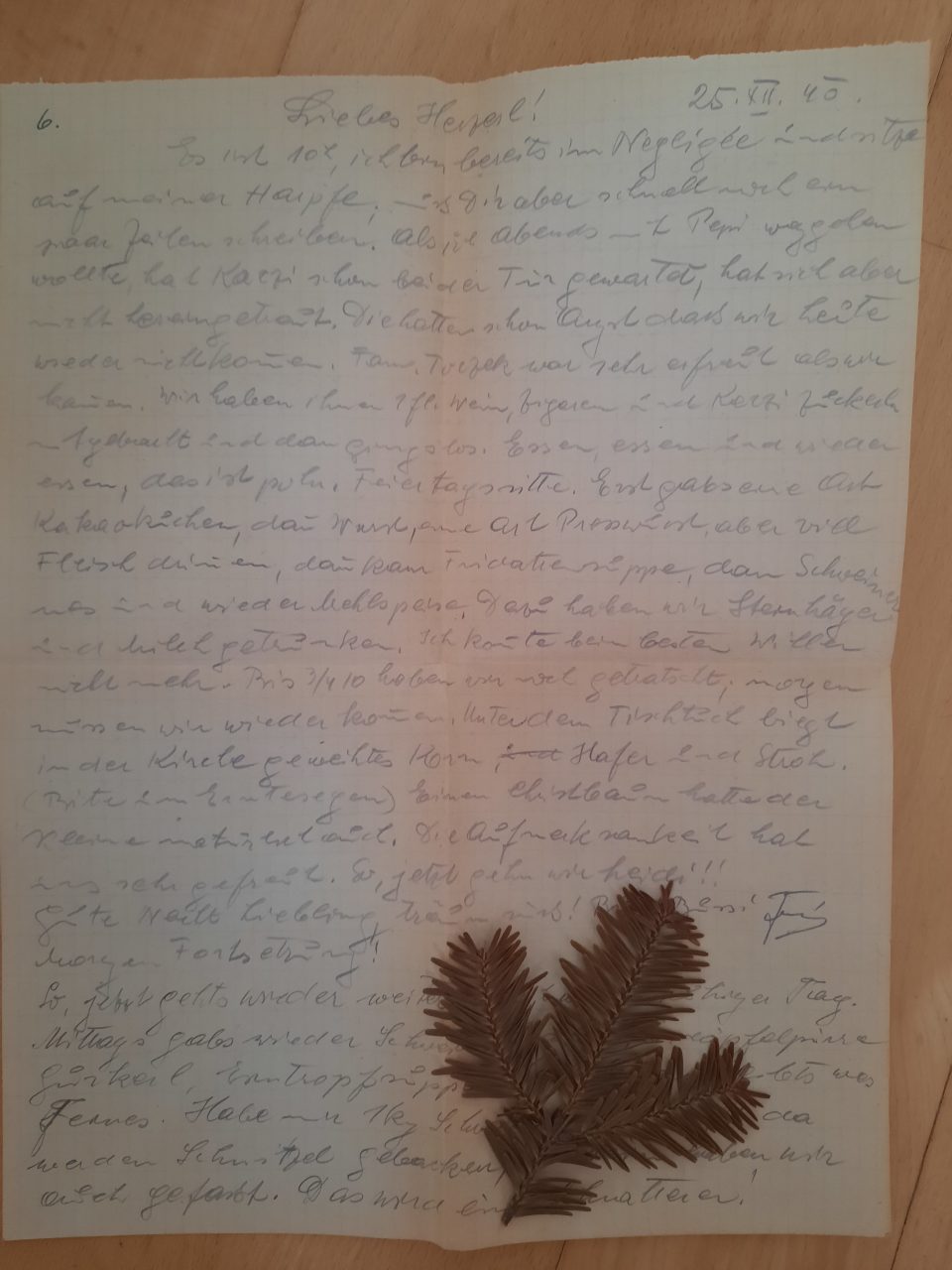

On 25 December Toni described to Lola how he had spent Christmas Eve in Nozdrec. On the 24th he had stayed in the kitchen until 7 pm making different types of sausages (“Bratwürste and Presswürste”). Sunday was always the day when they made sausages in the barracks kitchen; black pudding, brawn, roast sausages etc. When he was finished he was dead tired, but the extra ration for Christmas was ok: 250 g chocolate, half a bottle of sparkling wine, 1 packet of cookies, 1 bag of sweets, 250 g apples and half a litre of wine for each of them. Toni had kept one bottle of sparkling wine and two bars of chocolate for Lola and Herta. He did not enjoy the celebration on Christmas Eve; first because he was so tired and second, because he had to think of his family all the time. They had a nice little Christmas tree and sang a few Christmas songs, but then the binge drinking started. This time he only drank a few glasses of sparkling and some wine, but he was not in the mood for drinking, so he played cards with Pepi and Kaltenberger. Then Maxl, who was completely drunk, started together with others a huge brawl. They were lucky that the next day there were just a few black eyes and no one was seriously hurt. Toni went to bed at 10 pm because on the 25th he had to start in the kitchen at 5 am, but the others rioted until 3 am. Toni already worried what New Year’s Eve would be like. He made for himself scrambled eggs with greaves for Christmas morning. Then they prepared an excellent pork roast with a bean salad for lunch. In the evening Toni and Pepi had planned to visit their farmer – friend Toczek, who had invited them for Christmas, but their sergeant had forbidden everyone to leave the barracks. Yet the Polish family was so nice and the farmer came to the barracks and asked why Toni and Pepi did not come to them to celebrate and they had to promise him to visit the next day.

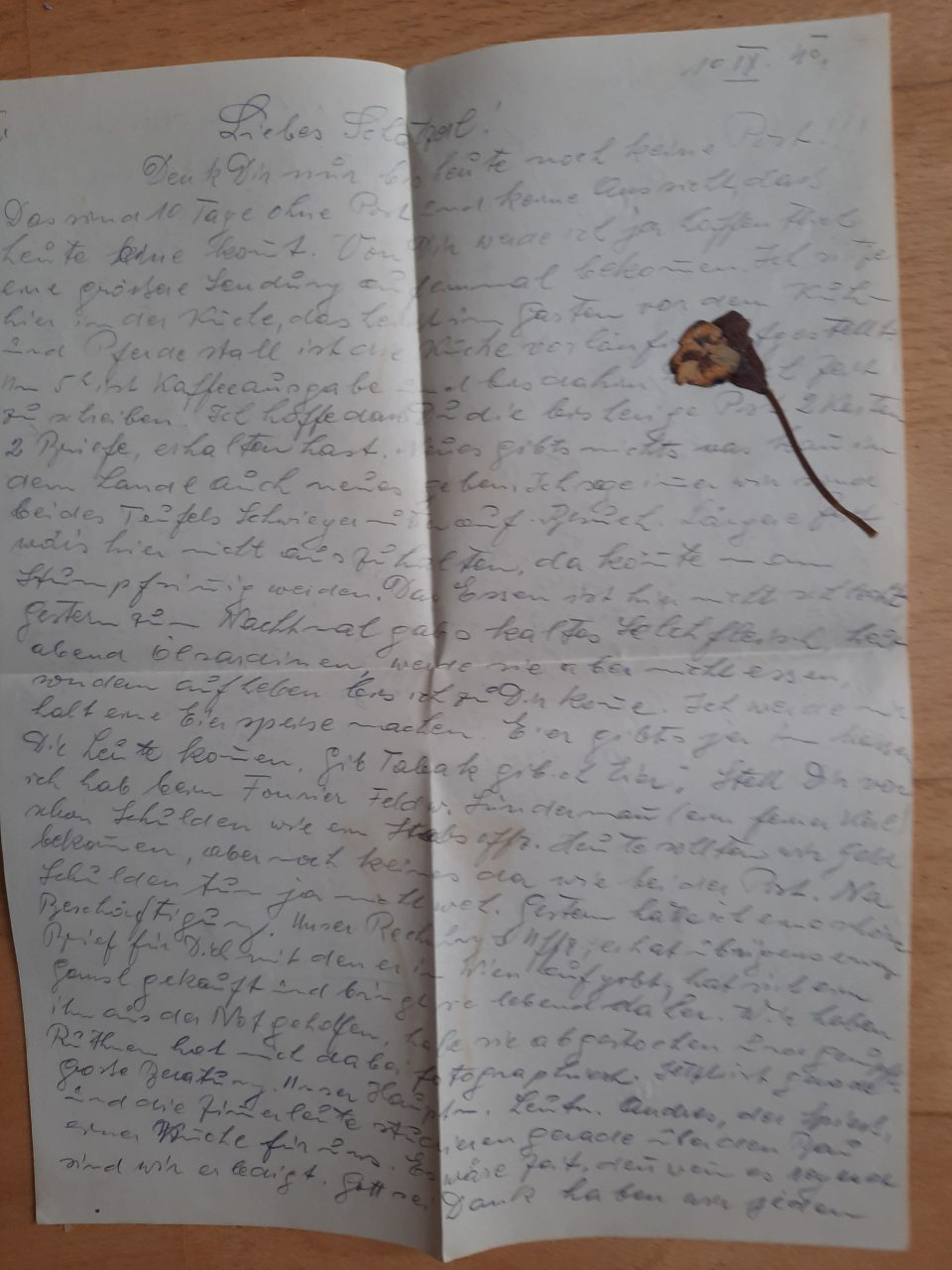

One of the two letters Toni wrote to Lola on 25 December with a dried pine twig from their Christmas tree

Toni then reported on the lovely evening they had spent with their farmer friends on 25 December: Kaczi had already been waiting for them at the gate of the barracks, afraid that they would again be prevented from going out. The family Turczek was so glad to see them. They had brought wine and cigarettes for them and sweets for Kaczi. Then the festivity started, “eating, eating, eating – this is a Polish Christmas custom. First they served a kind of cocoa cake, then different types of sausages, then beef broth with finely sliced pancakes, then pork roast, and finally again cakes. We drank milk and herb liquor. I couldn’t eat anything more! Then we chatted until quarter to 10 and they told us that we would have to come again the next day. Under the table cloth they had oat and straw consecrated in church (begging for a good harvest). Naturally they also had a Christmas tree. We were so touched by their hospitality.”

For the 26 December they cooked soup and pork roast with pickles and mashed potatoes for lunch and Toni had bought some pork, which would be turned into “Wiener Schnitzel” for dinner and served together with half a litre of wine for everyone. What a feast! His chef would purchase 8 kg ham for him, which he would like to bring home to Lola together with a bottle of sparkling wine for New Year’s Eve, but unfortunately no Viennese soldier was going home in the near future. Lola had sent Toni a parcel with a small Christmas tree and Christmas cookies and he was glad that she had received the money he had sent her with Pauli, so she would not have money worries over the Christmas holidays. When the next day another parcel arrived with sweets from Lola, Toni was so touched and asked whether she wanted to fatten him. He further told her she did not have to fear that he would become an alcoholic in Poland. He now did not feel like drinking any more, only very rarely. For New Year’s Eve they had received an invitation again from the Polish family Toczek, where it was certainly going to be much nicer than at the barracks. It was now extremely cold in Nozdrec, minus 20 degrees Celsius during the day, and in the morning they were freezing in the kitchen; they had to endure an icy wind and drifting snow. They had 50-60 cm of snow already. He reported that his comrades had loved his “Wiener Schnitzel”, which they did not know and for this evening they had cooked a sweet dish: milky rice with compote. He asked Lola again to look for more clothes to sell. If she rolled them up tightly she could pack more into one parcel and Pauli would drag the bundle to Poland when he went back to the barracks.

On 2 January Toni wrote that it seemed they would have to leave Nozdrec soon. They had not received their pay yet and no information at all where they would go to. What they all wanted was to go home, but one sergeant said they might be going to Norway, lieutenant-colonel Treitler believed they would be stationed in Romania or Greece, but Toni did not believe any of that. On 3 January Toni reported that the first group of the 2nd Division had already left and they would probably move the next day to Zamosc into the citadel. He was glad that Lola had received his first smoked ham, which was a bit grey in the middle. Toni assumed that it had not been salted properly, but the second one, which she was about to receive, should be better, because he himself had salted it. Now he had already packed his luggage and was waiting for transport the next day. He had said fare well to his Polish friends and it was difficult to get away because as soon as you arrived the vodka bottle was on the table and you had to drink, but he would have to be up at 2.30 am the next day preparing coffee and breakfast before departure. He had only had 6 small glasses of vodka, but he drank milk in between and also ate something, so he was not drunk. The farmers were really sad that they were leaving and Toni was sorry, too, because the local population was so nice and hospitable. They would probably not find such amiable friends in Zanosc, “ …but it might be a good turn of fate, otherwise we would have turned into alcoholics there.”

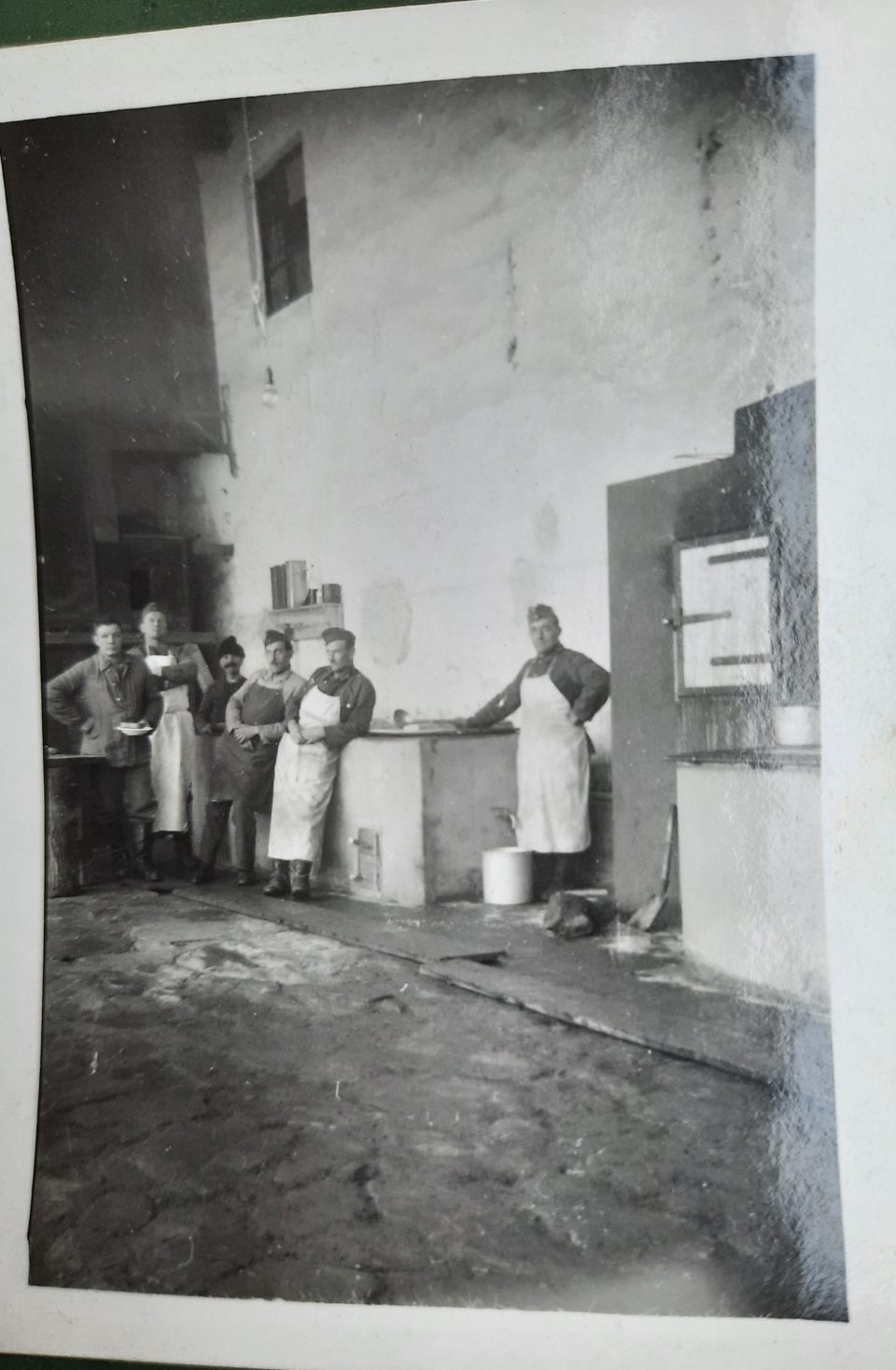

January 1941, NOZDREC, in the kitchen: Toni second on the right

Left: Toni in the kitchen in the middle, third from the right. The door on the right is the one to the smoking room. Right: Toni took a photo of lieutenant-colonel Treitler (in the middle) in the kitchen

Slaughtering of a pig: Toni standing on the right

Suddenly Toni’s corps was cut off from the outside world by a snow storm in Nozdrec. Richard, who had a parcel for Lola, was stuck in Dynow for three days. He wanted to hire a sledge for 100 zloty to get to Przeworsk, but there was no getting through, so they all returned to Nozdrec. The snow they had in Vienna was incomparable to what they experienced in Poland. They had to clear the paths twice a day from snow so that they could at least pass on foot. One morning when Toni had to go to the kitchen for his early morning duty, he sank into the snow up to his belly, “… now the snow is falling so densely, like a white curtain!” He had put up a trap and hoped he would catch a marten because he could sell the fur for 12 zloty. The road to Dynow and the rail tracks were impassable. The only working means of transport were sledges. The postal service was interrupted, too, but once in a while some mail arrived. In the evenings they visited the Toczek family, “We had to drink some very light coffee (with lots of milk), brr, brr!!! Tomorrow morning I’ll make some good coffee in the kitchen!”, or wrote letters or read, but the electricity was unreliable and the light very bad. Most of the comrades were playing cards in the evening and Toni sometimes joined in, but not too long because he hated the commotion and the noise of the players. He was trying to serve good meals to his comrades, but it was really difficult because they lacked ingredients, especially fat and meat. Today they had goulash and tomorrow they would cook beef in sauce with noodles. As he had not received any letters from Lola recently, he hoped that Pauli would bring some post from her, when he came back the following week.

On 7 January Toni informed Lola about the change in the army’s plans; his corps would not leave the barracks for the moment. He hoped that they would stay in Nozdrec for some time now and it might be his turn for another furlough within the next 4-5 weeks. They had now installed a permanent kitchen there with two cauldrons of 280 l each, two cauldrons of 100 l each, two large cooking plates and an oven in which you could roast half a pig. Furthermore they had a smoking room where they could smoke two pigs at the same time. Everything was now ready for cooking on a large scale and there was a lot to do. His friend Pepi was employed in the kitchen, too, and he quite liked it. He had to help with peeling potatoes and cutting cabbage, but it was much warmer in the kitchen and there was always some extra food. On the 9th January Toni was very satisfied with the working of the new kitchen equipment; they were even able to serve hot dinner, not just hot lunch. In the evening he would sell the clothes Lola had sent at the Toczek family’s because they were supposed to leave the barracks within the next few days, yet nobody knew where to. He would send her the money as soon as possible. He asked Lola to write to him daily because he only received every second or third letter from her and he tried to calm her, “Look, Pipilein, it’s no use being afraid, we can’t change anything and I certainly won’t act the hero!”

Toni had bought 27 kg of bacon and had cooked it and made lard and greaves in the kitchen the whole afternoon, when the sergeant and the lieutenant had come by and asked what he was doing. He explained to them that he was taking the lard home, so they were satisfied because “they were happy if you dragged as much home as possible.” (This was to compensate for the food shortages at the home front) In order to win them over Toni sent them fresh greaves for dinner. On 13 January Toni reported that they had been snowed in again with all roads and trains blocked for days. Within one hour the whole place was sunk in snow drifts. But that day there was marvellous weather with sunshine in a deep blue sky and all the mountains and meadows covered in snow. One could believe that they were staying in a wonderful country. Yet the temperature was extremely low, minus 27 degrees Celsius in the morning! When he entered the kitchen in the morning his coat collar, his eyebrows and eyelashes were covered in frost and the door of the kitchen was white with snow on the inside; “…but, anyway, better than the storm of the days before! What is really nasty is fetching water from the pump outside because my hand immediately gets frozen on to the handle of the pump.” They had already received their marching orders, but the snow storm had again delayed their departure. Their next destination was supposed to be Zamosc, 200 km to the north, “It won’t get better because that is genuine Poland, whereas here we are still in former Galicia. The people are certainly not as nice there as here.” Toni had discovered another farmer, where he had bought 5.5 kg of ham, “Very nice people! They immediately served us tea, sausage and butter. You don’t know how you can compensate them. Tomorrow I will fetch 1 kg poppy seeds.” The weather was still very bad and so they could not leave. Anyway, the kitchen was the last part of the division that left the barracks. Toni had already put on weight: 83 kg; he would soon be near the weight of the chef who weighed 136 kg! The photos of them in the kitchen were taken by Pepi (see above). He was sitting in the kitchen and writing letters there because it was the warmest place. Toni raved about the nights with full moon, when this place looked like a dream landscape: in the early morning you could see in the east the rising sun and in the west the descending moon and half an hour later the mountains were drenched in glowing red, “That is the most beautiful aspect of Poland!” There were lots of foxes, but they were difficult to shoot because they sensed the humans. Toni would rather stay there than move on because nobody knew what it would be like elsewhere. They would not have such a kitchen as this one. He was now smoking some sausages for Pauli; they would not get to a place as ideal as this one.

On 20 January 1941 Toni sent the left postcard to Lola with the comment, “Beware, don’t fall in love with this guy!” They had slaughtered a pig of 180kg and had celebrated this event with a “Sautanz”. They made sausages, salted the meat and smoked it and sold the smoked pieces to those going on home leave.