VIENNESE SUBURBAN COFFEE HOUSES UNTIL WORLD WAR II

Café Hummel, Josefstädterstrasse (next to Hamerlingpark) in the suburb of Josefstadt. The house was built in 1805 and in 1856 an inn opened there which was later turned into a coffee house. In 1896 a vaudevillian singer, Carola Biedermann, wife of the Viennese folk singer Julius Biedermann took over the coffee house and named it “Café Carola”. This coffee house offered separate reading and gaming rooms, a smoking room and a ladies’ room, as well as a conservatory with palm trees. The couple had to flee from its creditors to New York and the new owner staged daily concerts and kept the coffee house open the whole night. Among the many owners that followed was Joseph Carlo Popper, who had worked as a lion tamer and circus employee in South Africa in his youth and had earned his living as a gold digger. In memory of his youth he called the coffee house “Café Pretoria”. The coffee house changed its name often until 1937, when the family Hummel finally bought it.

In the vicinity, just outside the “Linienwall” (today’s Gürtel) in the suburb Neulerchenfeld, a coffee house with a conservatory, palm trees and parrots continued this tradition until the 1960s, the “Café Wintergarten”, where I went with my grandmother, Lola, as a child. Today it’s a musical event location, the “Café Concerto”.

In 1934 my grandparents, Toni and Lola Kainz, took over the running of a coffee house on Hamerlingplatz in the suburb of Josefstadt. My grandmother loved the contact to the guests and my great-grandmother Ritschi (Rudolphine Sobotka) helped with the cooking. Her specialities were “Krautfleckerl” (small pasta with cabbage), a Jewish speciality that is much praised in Friedrich Torberg’s book “Die Tante Jolesch” (Aunt Jolesch), “Sulz” (brawn) and sweet dishes, such as “Buchteln”, chocolate cake and “Apfelstrudel”. The recipes of these coffee house classics have been passed on in the family.

Here are some simple and tasty recipes of Ritschi and Lola, which are typical Viennese coffee house specialities. There are not always precise indications of quantity as the recipes were communicated orally:

Simple chocolate cake

Ingredients: 40g butter, 100g sugar, 1 egg, 40g cocoa, some milk, 1/2 package of baking powder, 150g flour

Mix everything and beat for some time, then bake in the oven in a square baking dish until no longer liquid inside. Fill with the following cream:

100g butter, 3 soup spoons of cocoa, 2 soup spoons of black coffee, 3 soup spoons of sugar and whip everything until it is creamy

“Buchteln”

Mix 500g flour with active dry yeast, 250g butter, 3 eggs, 70g sugar and ¼ l of milk and beat for at least 10 minutes. Then put the dough in a warm place to rest for an hour. As soon as it has doubled its volume, cut it in small dumplings, fill them with a special plum jam (Zwetschkenröster) or sweetened cottage cheese, then dip the dumpling in melted butter and fill a square baking tray with the dumplings. Let the dish rest in a warm place for half an hour before baking in the oven until the dumplings are golden. Serve them still warm.

“Krautfleckerl”

Cook 250g small square noodle pasta “al dente”. Meanwhile slice half a white cabbage thinly. Heat a little lard, add a little sugar and cumin. Then fry the white cabbage until it is brown, add pepper and salt and in the end mix it with the small pasta noodles.

“Sulz”

Fill a pressure cooker with: 4 pig’s feet, and a pig’s tail, 400g tender pork meat, an onion, two garlic cloves, salt, pepper, 1/8 l of vinegar, a carrot, some celery, some parsley and fill the pot with water until everything is totally covered. Cook in the pressure cooker for an hour. Then pour the liquid into a porcelain bowl through a sieve and cut up the meat in small slices together with some of the jellied skin of the pig and stir it into the liquid. Put it into the fridge overnight. When solid, cut it up in slices and serve with thinly sliced onions and a little bit of vinegar and sunflower oil.

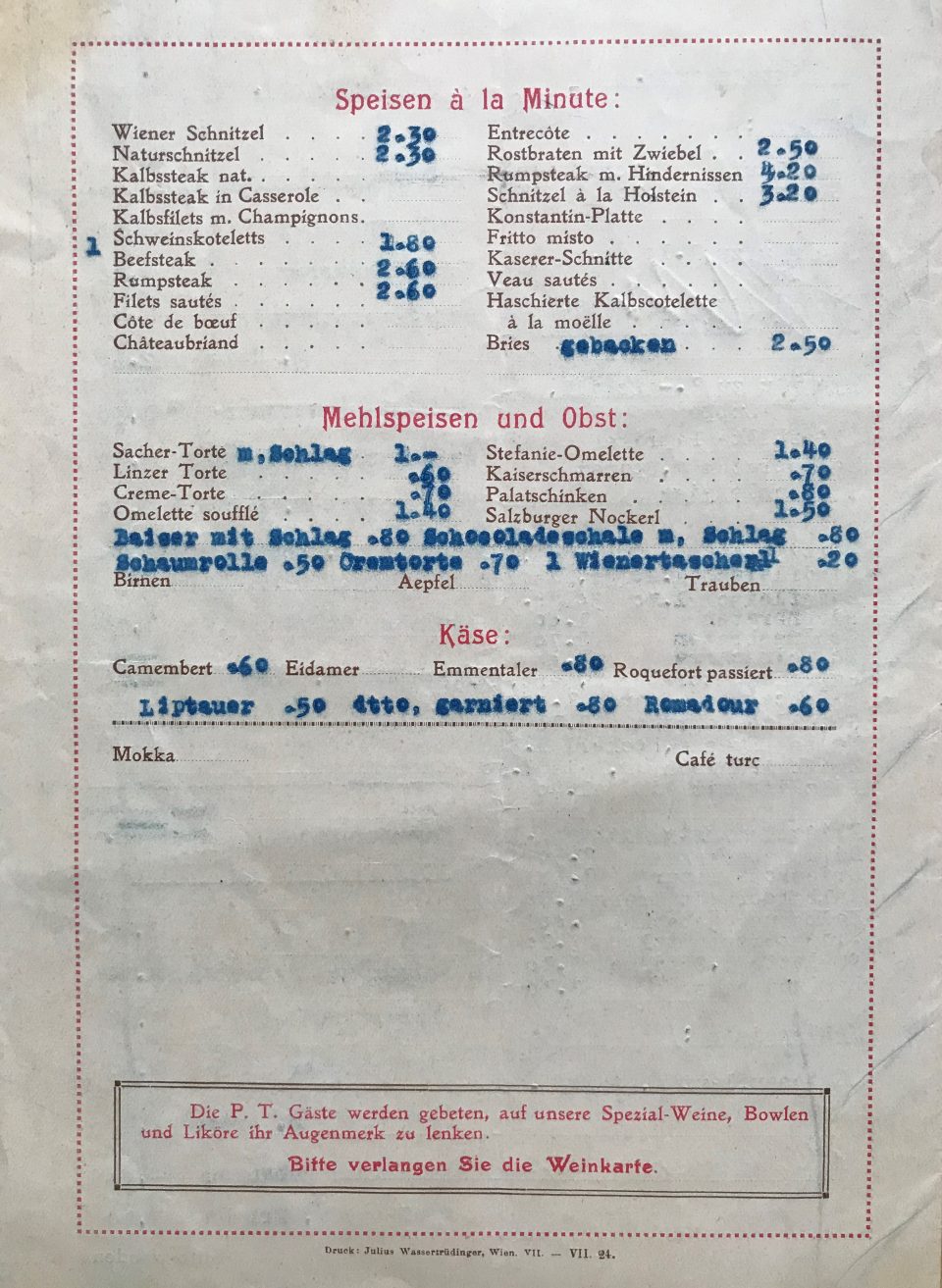

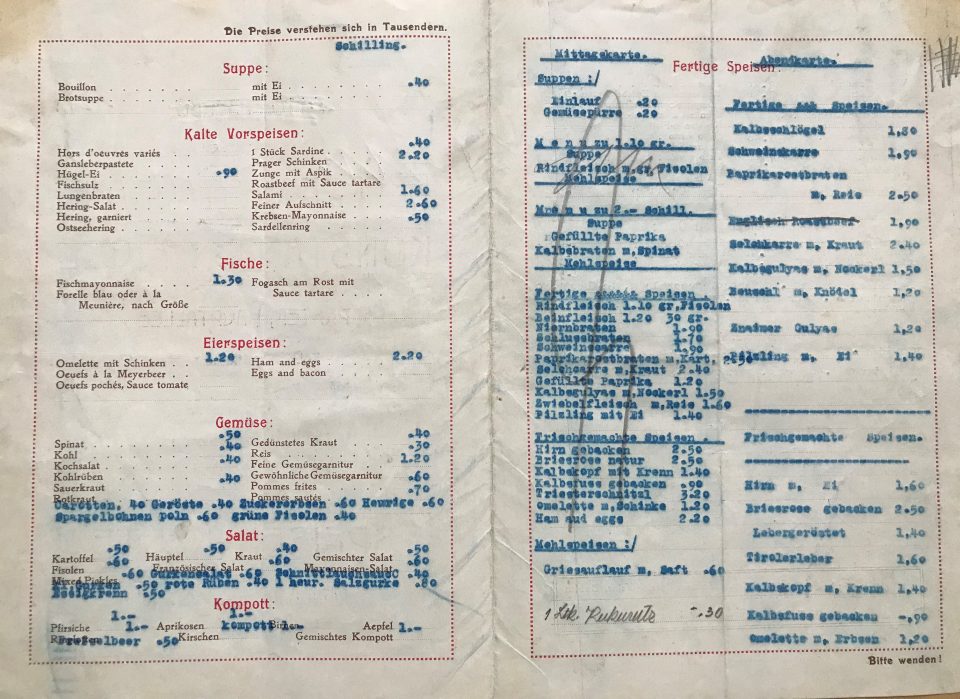

Menu card of the coffee house and restaurant in the suburb Leopoldstadt, Prater “Konstantinhügel” , 1927

In some Viennese coffee house coffee was formerly made in the traditional porcelain “Karlsbader” coffee makers – widespread in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Two of my grandmother’s “Karlsbaders” have survived. When preparing the coffee, she added a pinch of salt and a spoonful of cacao to the ground coffee beans in the porcelain sieve before slowly pouring the boiling water over it.

“Karlsbader” coffee makers