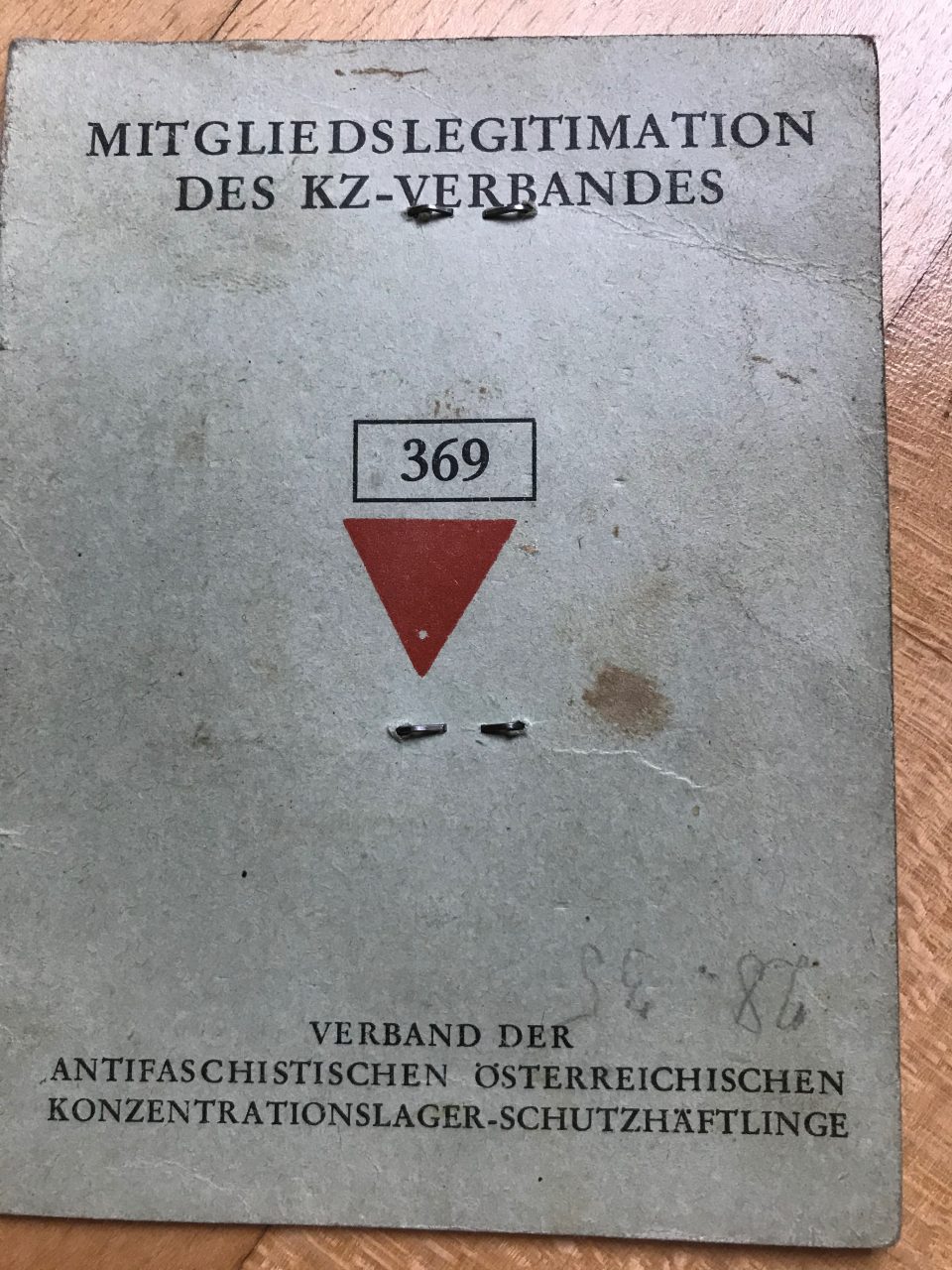

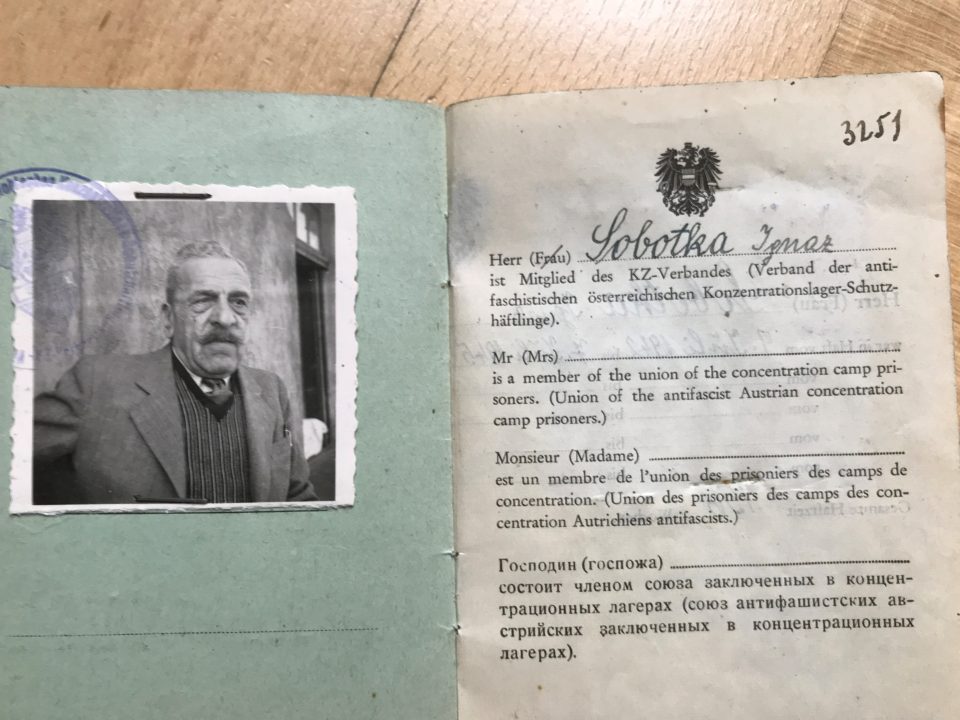

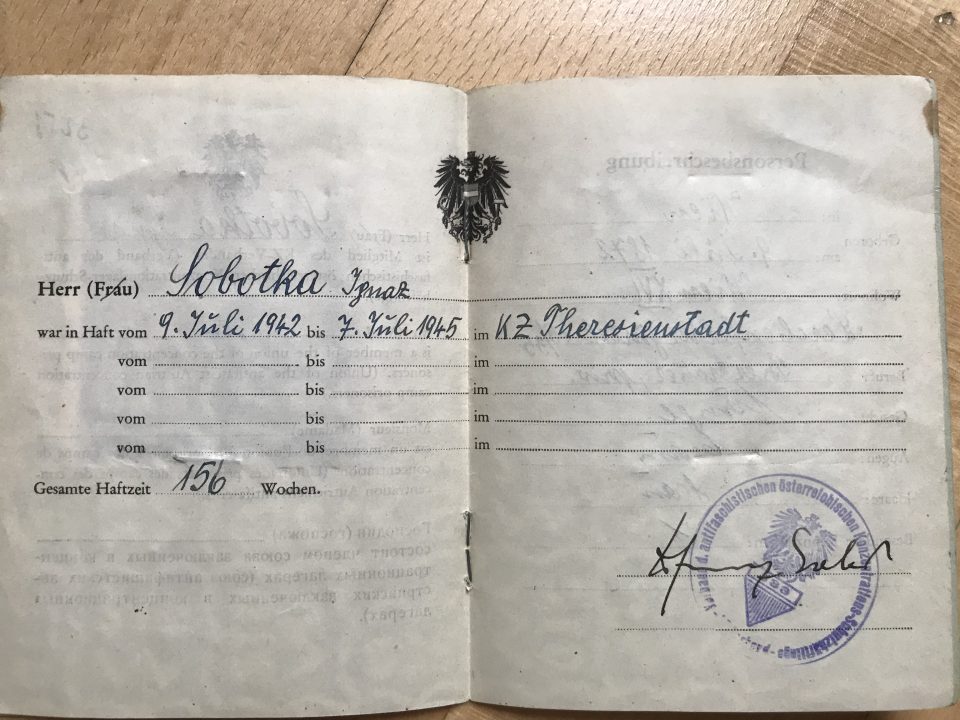

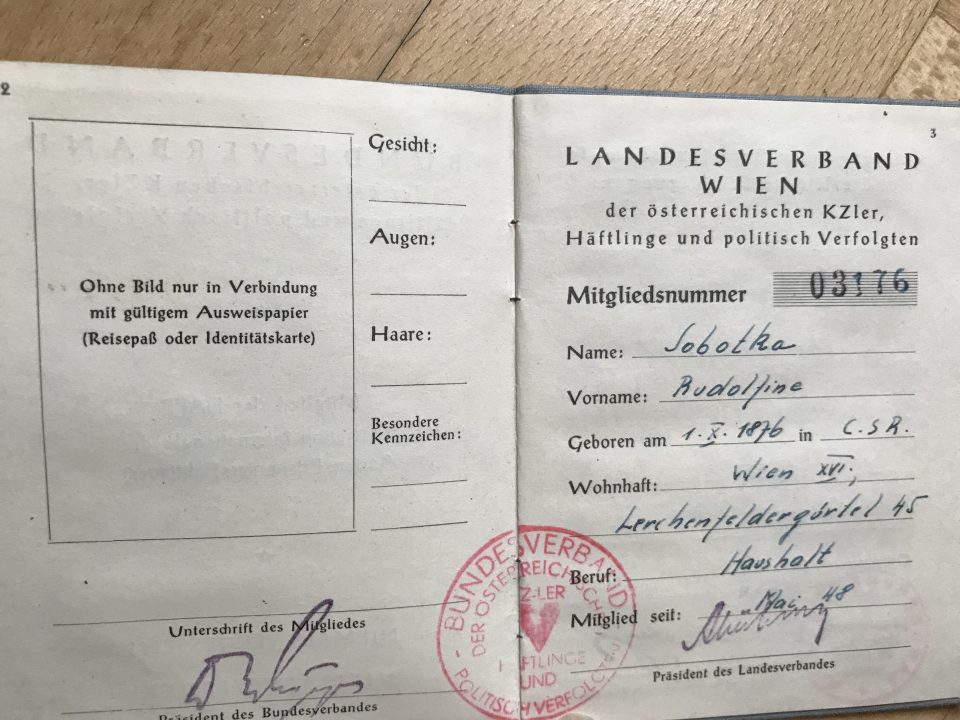

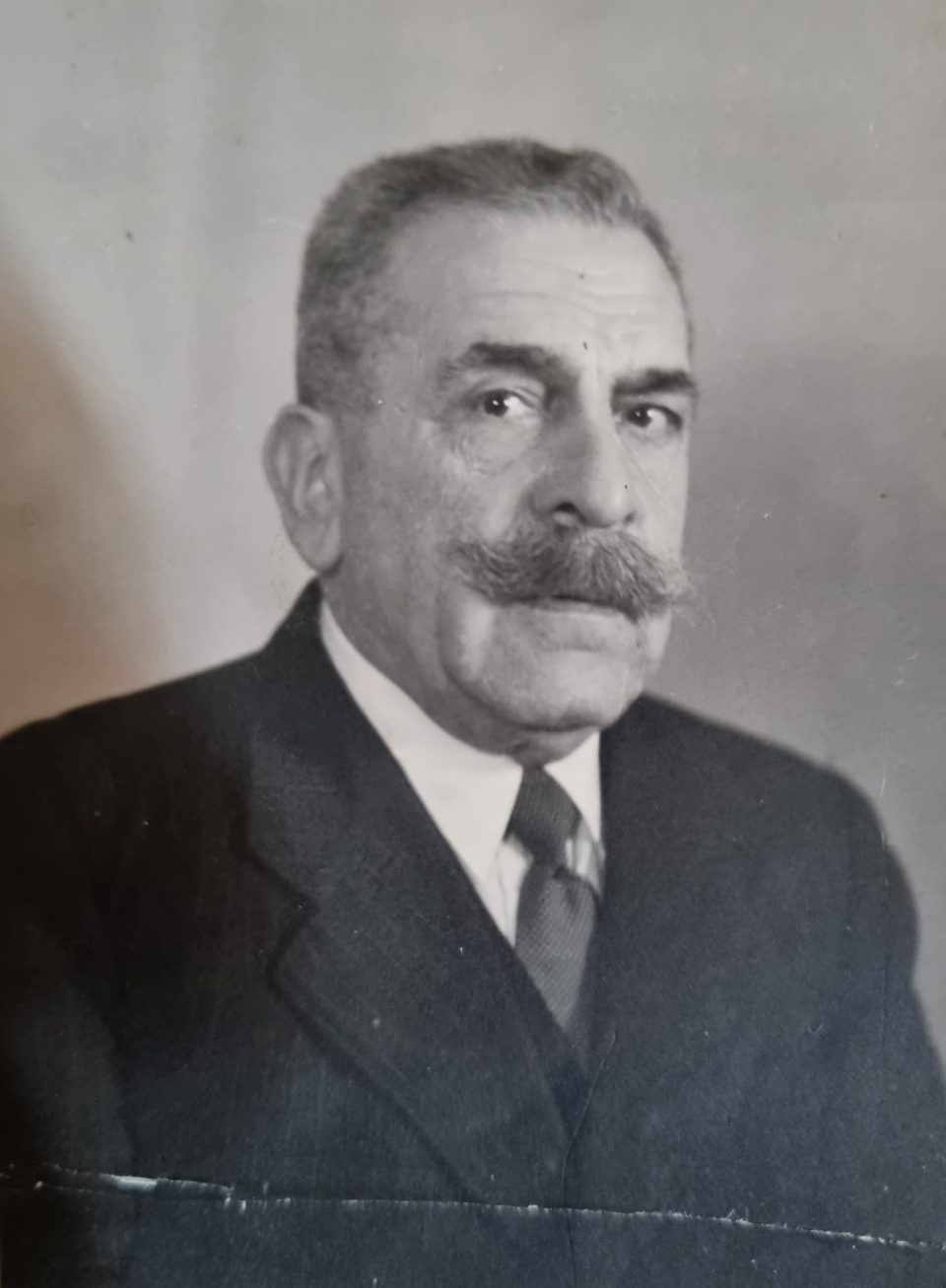

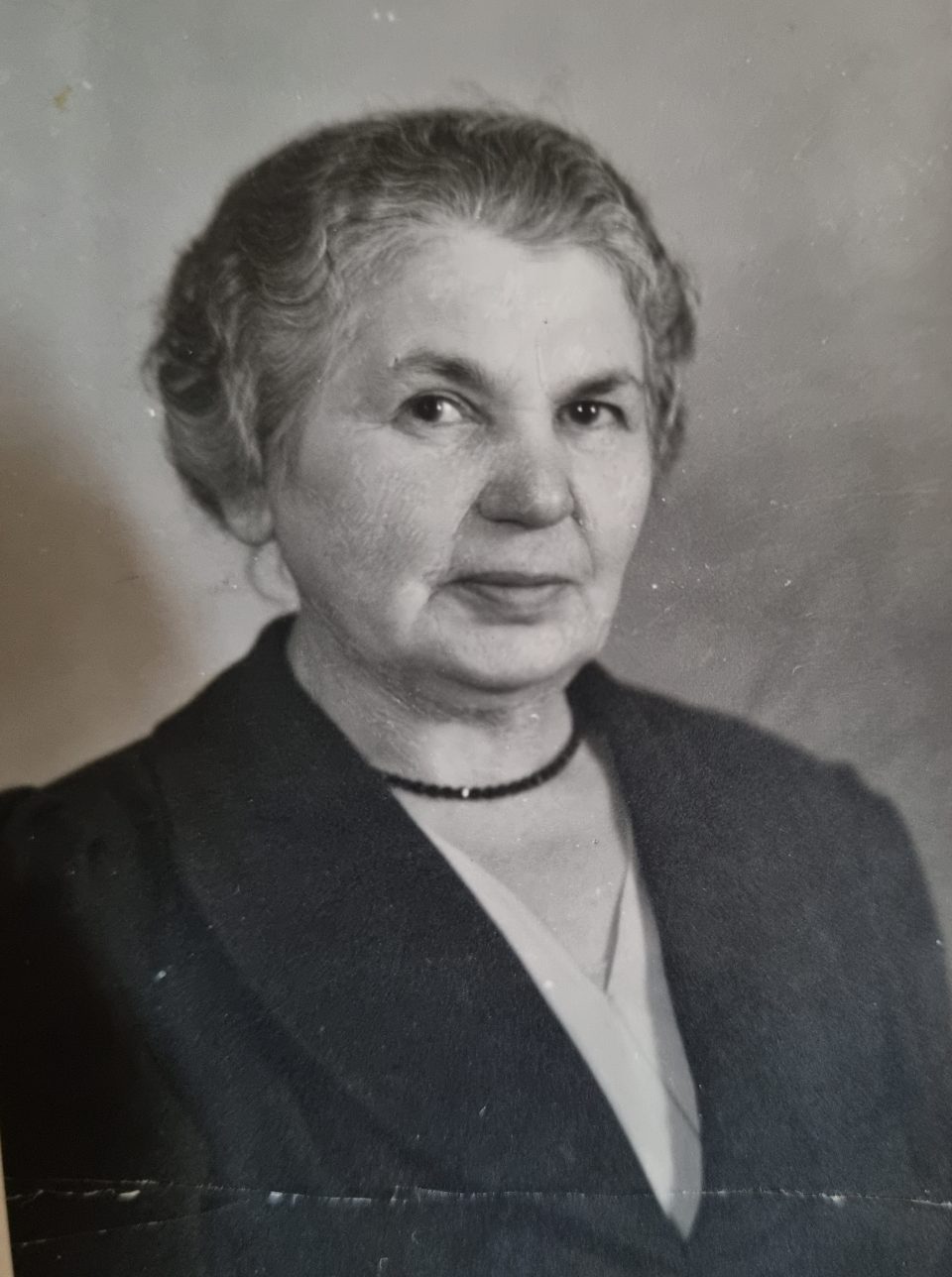

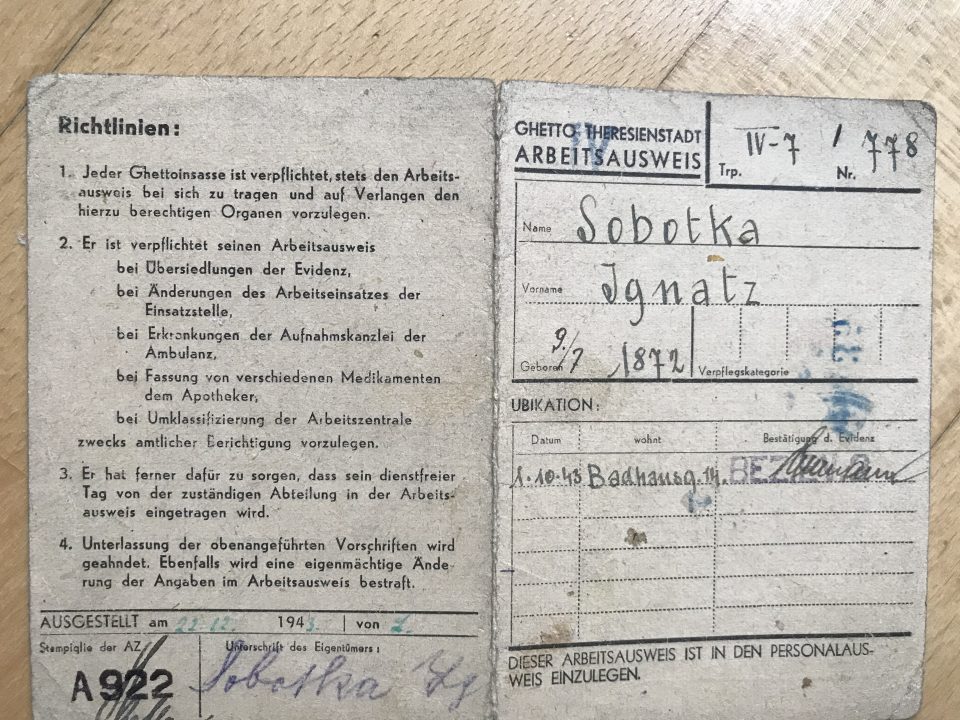

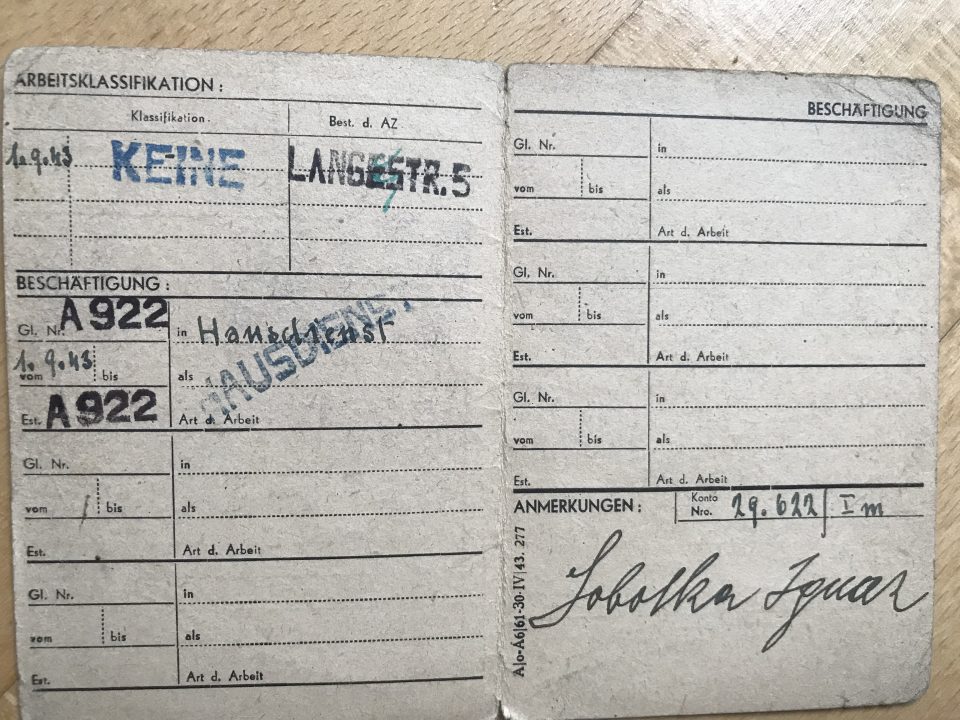

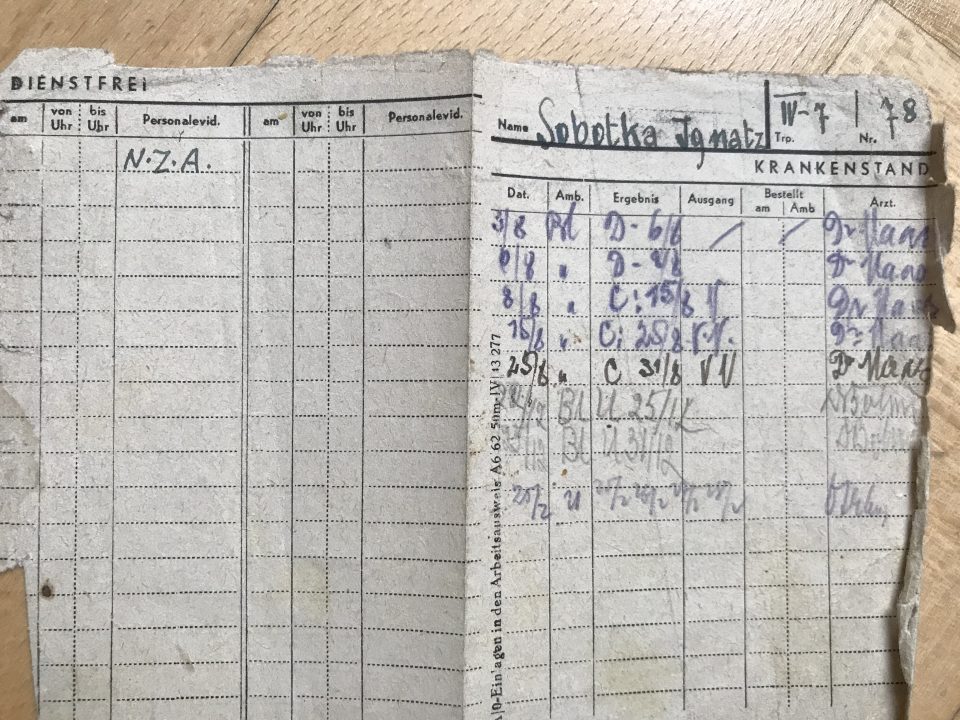

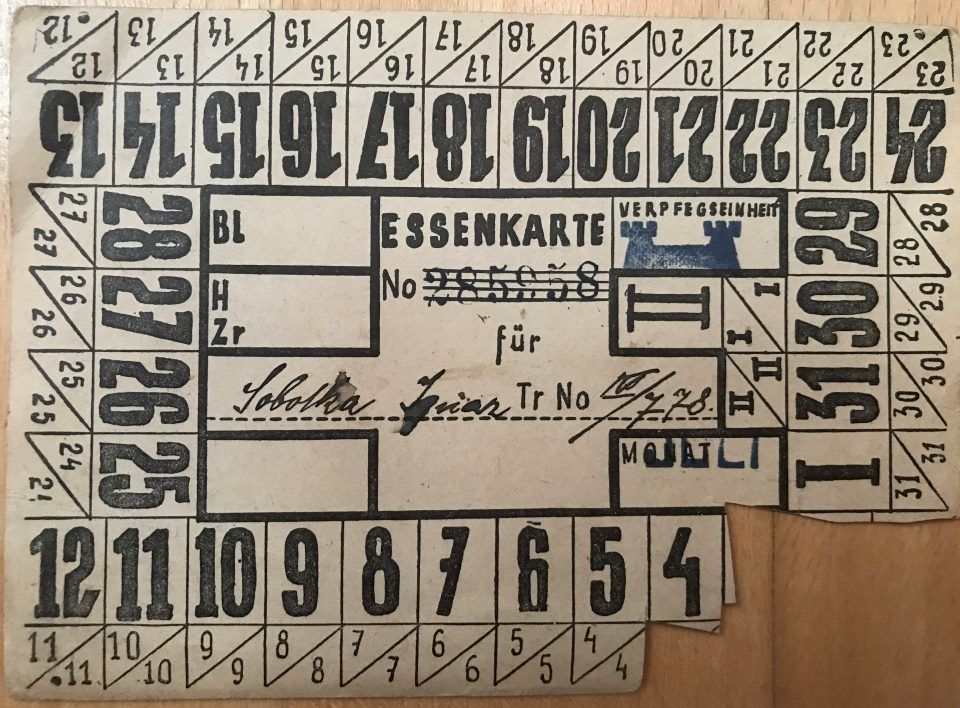

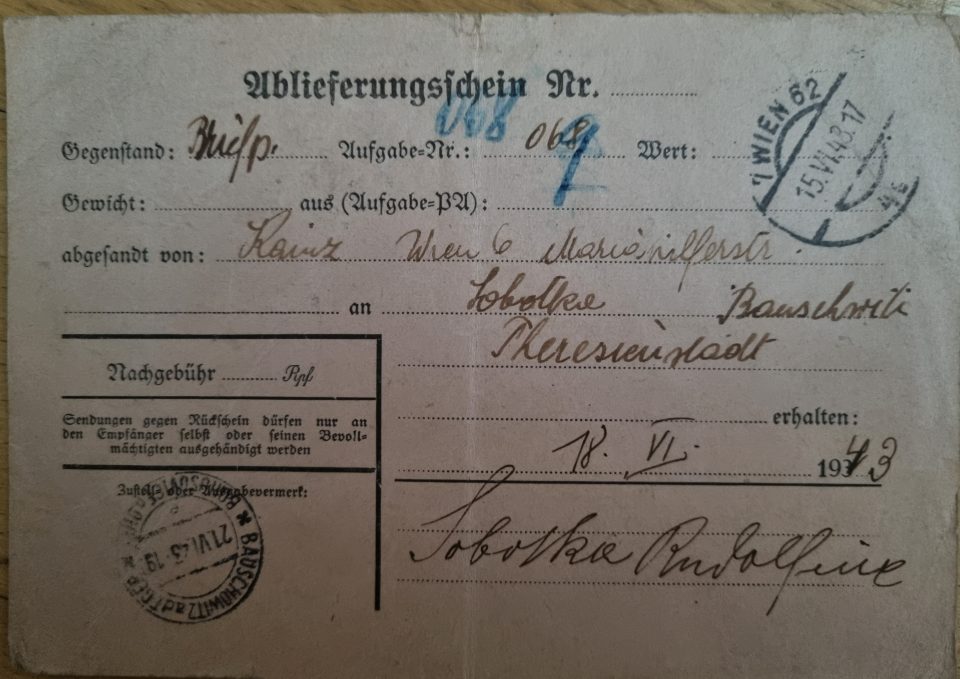

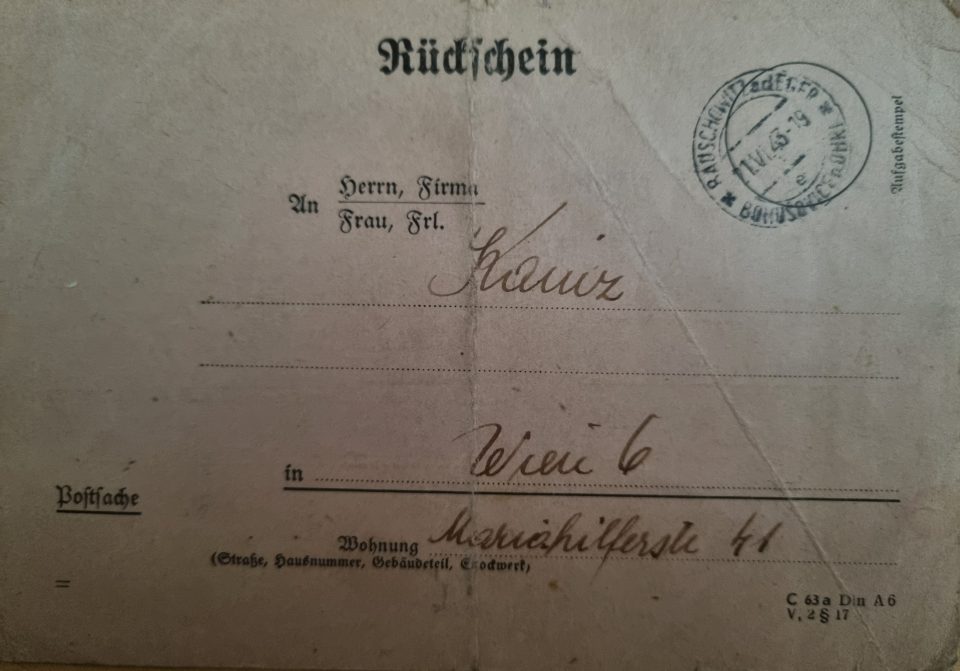

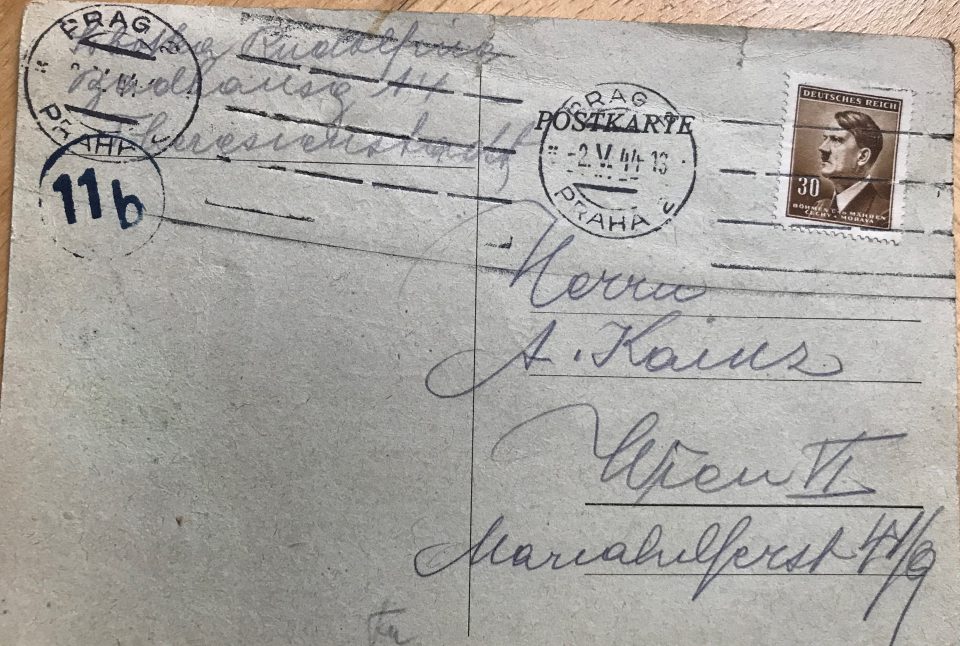

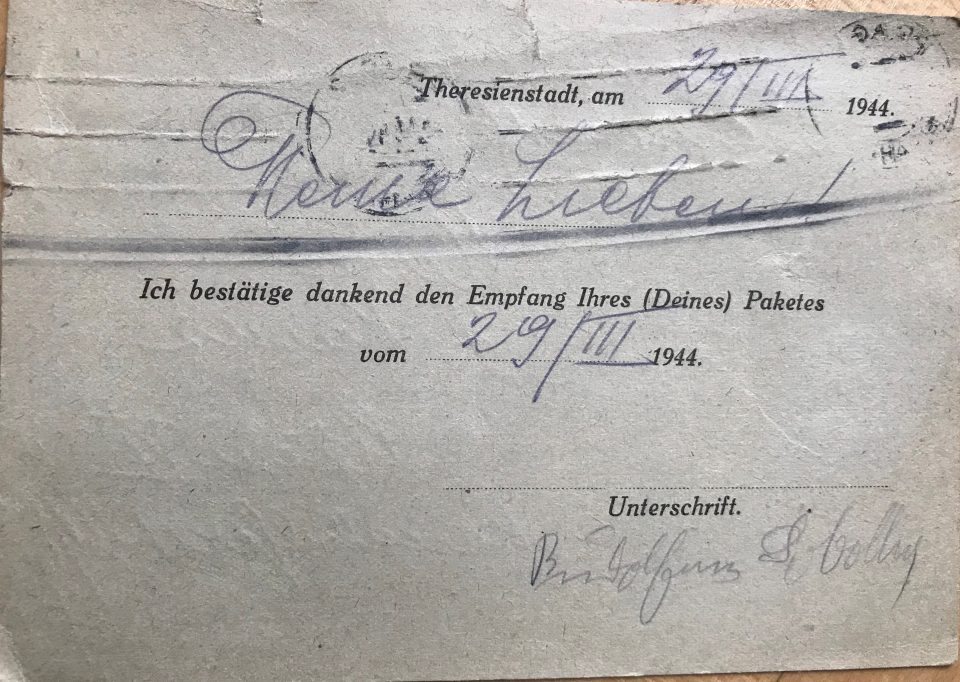

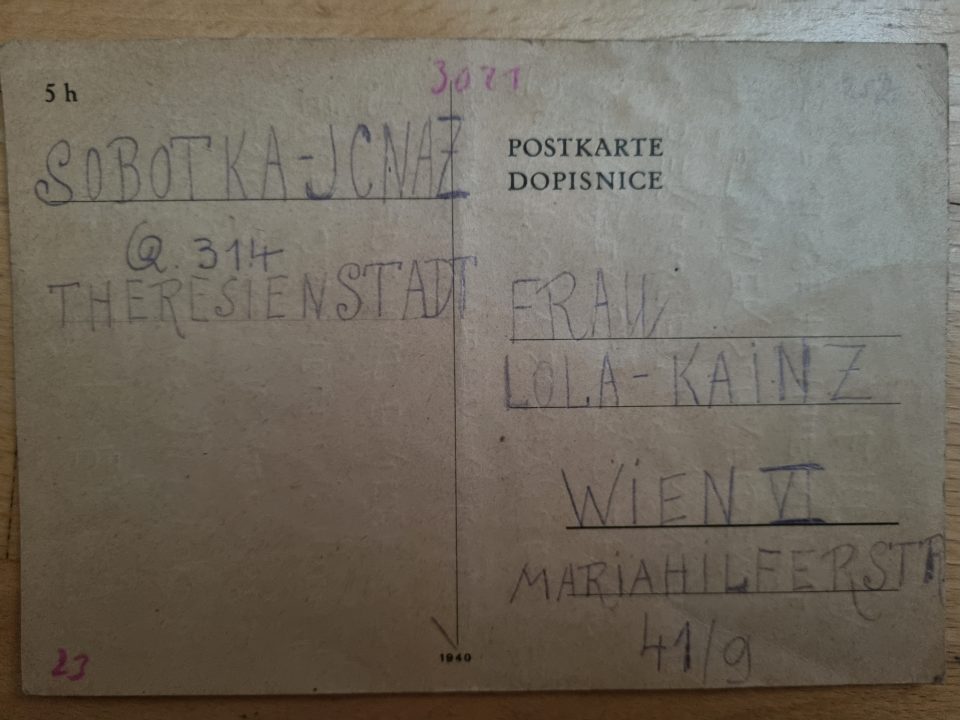

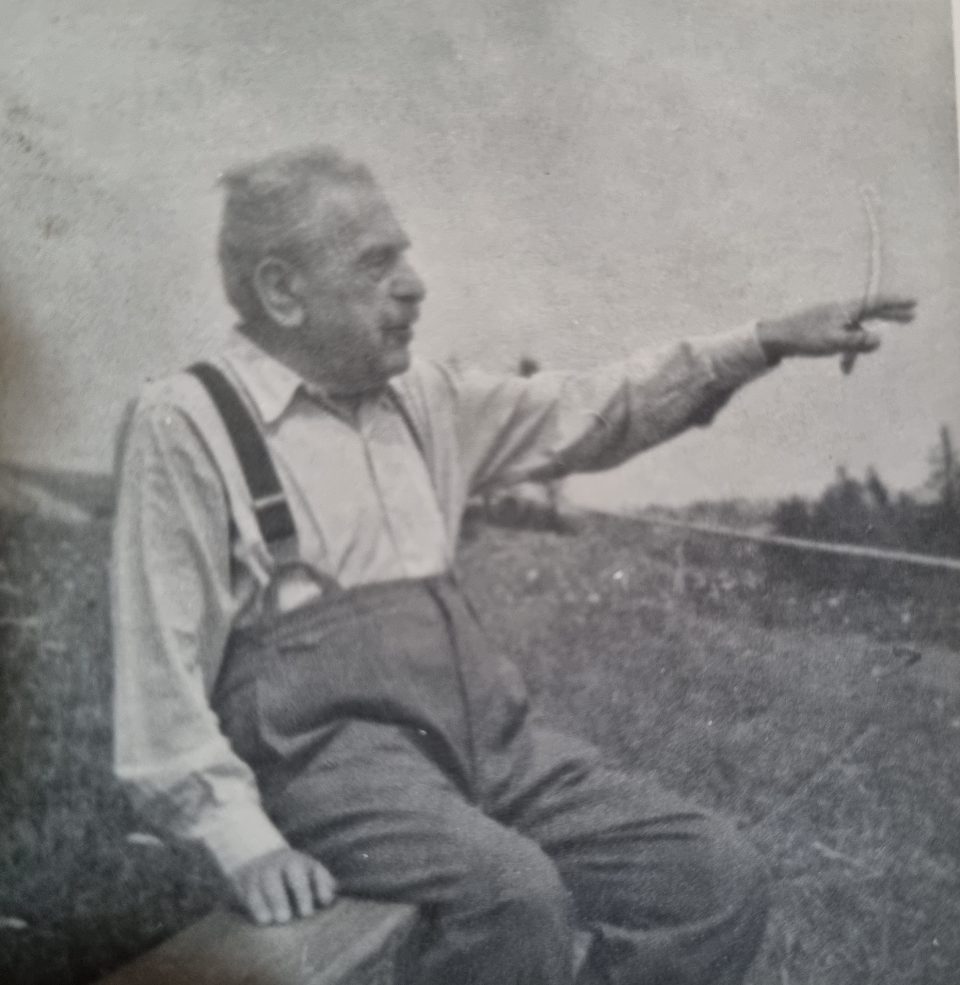

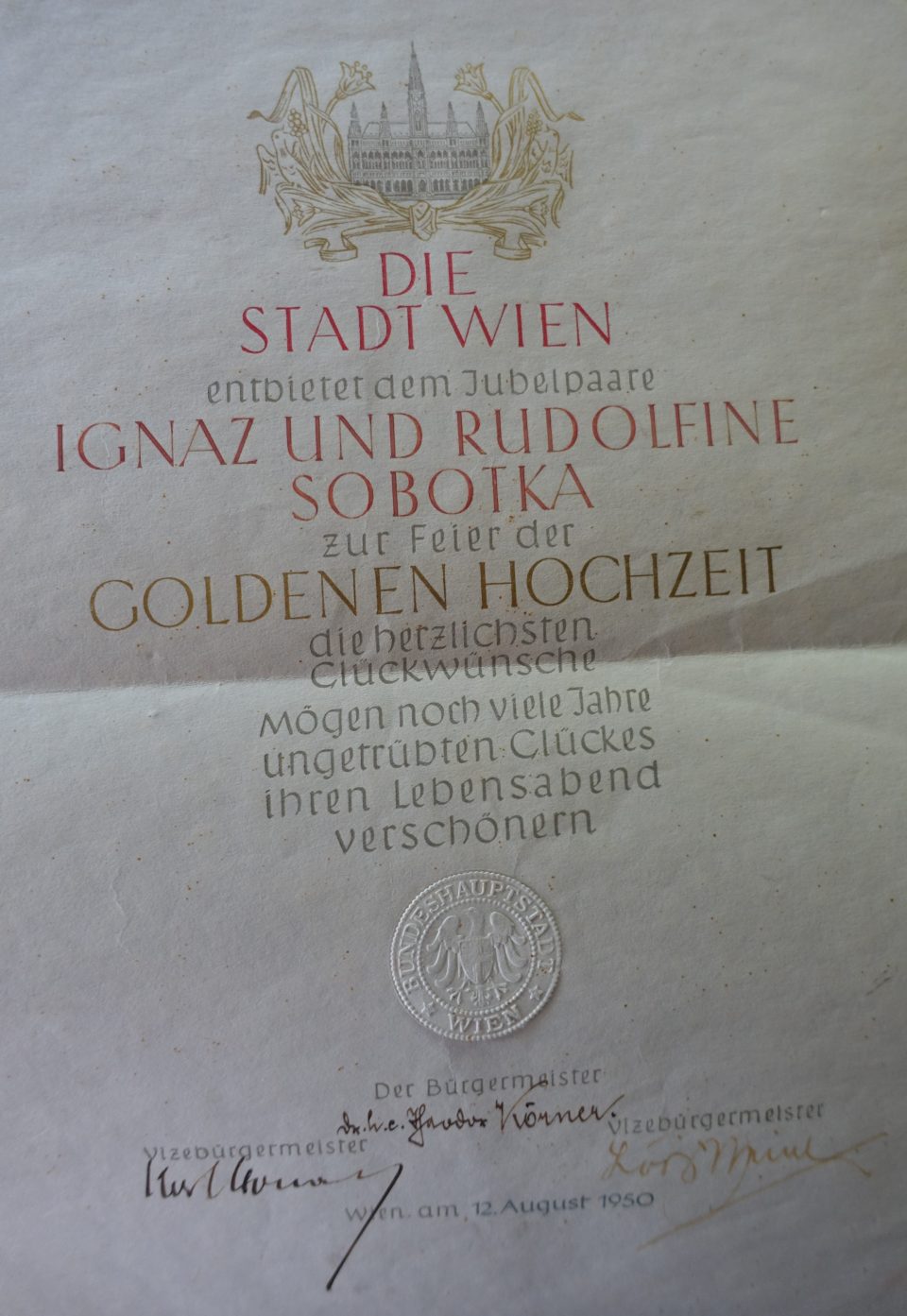

This article deals with the desperate attempts of the prisoners of the KZ (concentration camp) Theresienstadt at keeping up appearances of a fragile normality and at maintaining scraps of human dignity under the inhuman conditions of the NS (National Socialist) concentration camp. Furthermore, this research would like to destroy once and for all the myth the Nazi propaganda had created for the international public of the KZ Theresienstadt as a “Jewish ghetto for the privileged and the old”, where music, art and theatre thrived. This vicious piece of NS propaganda has been so long-lived and tenacious that it sometimes pervades documentaries about the KZ Theresienstadt even today and often involuntarily creates a romanticised picture of life in this atrocious collection and transit camp. My great-grandparents Ignaz and Rudolfine Sobotka were imprisoned there from 9 July 1942 until liberation by the Allied armies on 9 May 1945. They miraculously survived the hardships and the terror and returned to Vienna and the family of their daughter Lola, my grandmother. They formed part of the group of elderly prisoners who were crowded into this former Austro-Hungarian fortress city. Ignaz was born on 9 July 1872 and Rudolfine, called Ritschi, on 1 October 1876. So, Ignaz was imprisoned on his 70th birthday and Ritschi was turning 66 in October when she arrived at the concentration camp in July 1942. At the end of the Habsburg Empire they were quite well-to-do middle class Viennese citizens. Ignaz was born in Vienna and after training as a beer brewer he ran the brewery in Kaiser-Ebersdorf near Vienna as a manager. He got to know Ritschi in Eywanowitz in Moravia, when he was working at the brewery there. She was the daughter of the local family doctor and moved with Ignaz to Vienna after the birth of the second of their four daughters. (see article: “The Career as a Beer Brewer in Vienna”). Here are some documents that have been preserved from their stay in the KZ Theresienstadt (KL Terezin in Czech):

In Vienna Ignaz and Ritschi’s situation worsened when the Austro-Fascists took power in February 1934 and Ignaz lost his job as the brewery’s manager.

Left: Ignaz and Ritschi with their daughter Lola and her husband Toni and Herta, my mother, on Ritschi’s lap in 1934

Right: They lived on Margaretengürtel in Vienna, where heavy civil-war fighting took place in February 1934, when the Austro-Fascists put an end to democracy in Austria. One of their sons-in-law, Karl Elzholz, lived there, too, and took a photo of the damaged public housing building and “Konsum market” (co-operative market), where army and police had shot at the Socialists in the building

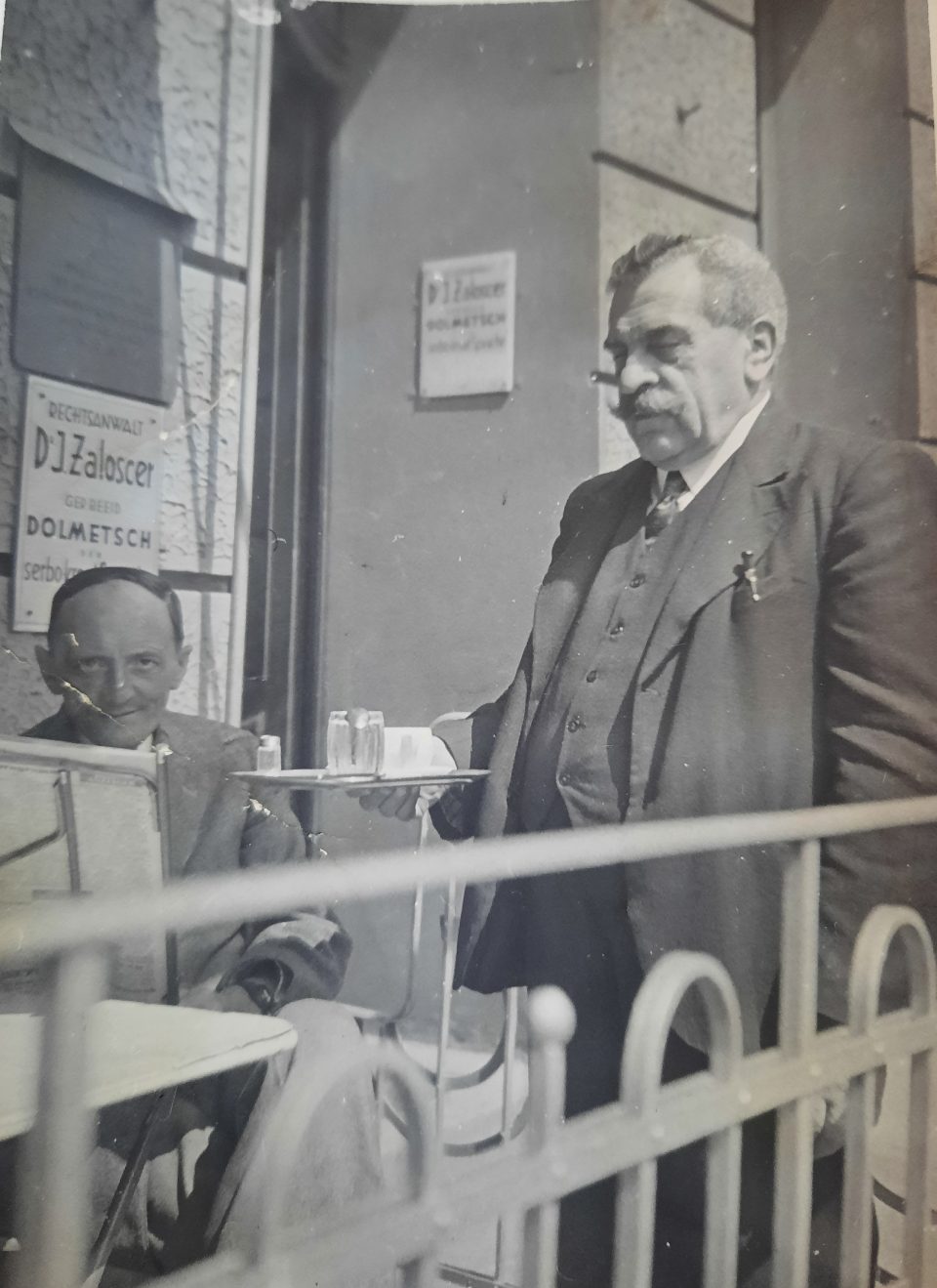

Ignaz and Ritschi both helped Lola and Toni run a coffee house at Hamerlingplatz (see article: “Viennese Suburban Coffee Houses”) in the 8th district of Vienna

When they lost their flat due to the NS race laws, directed against the Jewish population in Vienna, they moved in with Lola, Toni and Herta. Ignaz had to do forced labour for the road construction firm Teerag until they were ordered to move into a “Sammelwohnung” (collective flat) in the 2nd district of Vienna (see article “Nazi Collective Camps in Vienna…”) before their deportation to the KZ Theresienstadt. Their three daughters and their husbands who had managed to flee from Vienna in 1938 / 1939 had tried to get their parents out of Nazi-ruled Vienna, but for the elderly without money it had become impossible to leave because no country wanted to grant them a work or residence permit. Unfortunately, their daughters Käthe and Agi failed to get them visas to join them in England, and Mitzi and Karl were unsuccessful in obtaining permits for entry in Bolivia, where they had fled to. So, they had to remain in Vienna with their daughter Lola and her non-Jewish “Aryan” husband Toni, who in the end was unable to protect them.

From March 1938 on the mass emigration of Jews from Austria was speeded up and any country that was prepared to grant them a work permit and a visa became a potential destination. Despite all difficulties and despite having been robbed of their savings and their movable possessions many Austrian Jews managed to leave the country in time. At the beginning of 1938 185,246 Jews lived in Austria and before the deportation to concentration camps started in 1941 128,500 had succeeded in fleeing the area. Yet it should not be forgotten that many of them were soon afterwards caught up in the Nazi terror and persecution because they had sought refuge in countries which were later occupied by the German “Third Reich” during the 2nd World War. Those who had been left behind, became victims of the Nazi “Endlösung der Judenfrage Europas” (Final solution to Europe’s Jewish question). After the outbreak of World War II in September 1939 58,000 elderly and sick Jewish citizens had remained in Austria, most of them in Vienna, with practically no chance to flee; of these only 2,000 managed to leave until 23 October 1941. After this date any emigration of Jews was categorically prohibited. In Vienna Jews were harassed, abused, used as forced labour and then hoarded into so-called “Sammelwohnungen” (collective flats) in the 2nd district before their deportation to concentration camps.

The term “KZ Theresienstadt” is applied here because it was the term used by the survivors, which is documented in the book of commemoration “Theresienstadt” (see: literature list), where former prisoners of Theresienstadt used the term “KZ Theresienstadt” exclusively, and Ignaz and Ritschi called it a KZ, too. That is why the term is being used here; in deference to the victims, whose memories should not to be questioned. There are discussions among historians about the technicalities of the organisation of Theresienstadt in the NS bureaucracy, which can be considered irrelevant in an analysis of the living conditions there. According to these historians’ findings Theresienstadt was neither a ghetto nor a concentration camp, but in fact a kind of collection and transit camp. No matter which term is used for the terror regime there, the truth remains that thousands of prisoners died of famine, disease and maltreatment and were transported to the death camps from there. In the small fortress of Theresienstadt many prisoners were murdered on site and the death rates in the KZ Theresienstadt were so high that a crematorium had to built to deal with the large amount of dead bodies.

The Austro-Hungarian emperor Joseph II had this fortified city, Theresienstadt, built in the Czech lands at the end of the 18th century and named it after his just deceased mother, Empress Maria Theresia. It was strategically important in the confrontation with Prussia, but was never involved in any acts of warfare and remained a garrison town. The small fortress was used as a prison for military and political prisoners in the 19th century. Already in 1940, the Nazis established a GESTAPO prison there, while at the end of 1941 the grand fortress, the fortified city, was used as a collection and transit camp, called “Ghetto Theresienstadt”, for Jews from Bohemia and Moravia initially, then from Austria and Germany and finally from other Nazi-occupied parts of Europe, too. Before the Nazi occupation the city housed 7,000 people including soldiers, while the Nazis planned to cram 50,000 to 60,000 Jews into the city. The original inhabitants of Theresienstadt were forced to leave. On 18 September 1942 the highest number of people imprisoned there was registered as 58,497, but due to the mass transports from KZ Theresienstadt to extermination camps, such as Auschwitz, the fluctuation of numbers was huge. All in all, from the so-called “Protektorat” (the Nazi-occupied parts of Bohemia and Moravia) 74,000 Jews were deported to the KZ Theresienstadt, 43,000 from Germany, more than 15,000 from Austria, 5,000 from the Netherlands, 466 from Denmark, 1,500 from Slovakia and around 1,000 from Hungary. Towards the end of the war 15,000 prisoners from liquidated concentration camps in the east were transported to Theresienstadt, as well. Overall, 150,000 were imprisoned in the KZ Theresienstadt.

The KZ Theresienstadt is characterised by shameless cynicism, diabolic deception, and hypocrisy of the Nazi perpetrators even more than any other Nazi centres of internment and extermination. The world public was systematically and cunningly deceived about the true purpose of this “Ghetto Theresienstadt” and consequently did not see through the genocidal intentions of the NS race policies. On top of that, the victims of NS terror were forced to participate in the charade, as for example the “beautification programme” which was staged in preparation for the visit of an international Red Cross delegation and the production of a propaganda film. The prisoners were furthermore coerced to serve the Nazis by organising the administration of the KZ themselves on orders from the SS commanders. The NS cheat and deceptive manoeuvre has unfortunately been successful until today. Even in serious research literature it is still mentioned that the living conditions in Theresienstadt were supposedly much better than in other concentration camps, that children and young people were offered formal education and nowhere hints to the “rich cultural life in the ghetto” are missing. The fascination with the artistic, literary, and intellectual productivity there must be uncoupled from the abysmal conditions under which the activities took place. Otherwise, such analyses present a distorted and unrealistic image of life in the KZ Theresienstadt. It is a shame that more than 70 years after its liberation the NS propaganda still nourishes this illusion of Theresienstadt as “the better KZ”. Nowadays it is very difficult to say how much the world knew about the conditions there and in how far the global public closed their eyes and did not want to see the genocide. It is still impossible to imagine what life was like in the KZ Theresienstadt; a life between hope and terror, between deception and extinction.

KZ Theresienstadt “Little Fortress”

Prison cells in the “Little Fortress” and “water boarding” torture of prisoners

“Jewish self-administration”

The cultural activity is a sign that especially the younger generations did not want to give up the fight for a decent life and they strived to guarantee a better future for the youngest prisoners. This is proven by the fact that thousands of children were provided with some sort of instruction despite strict prohibition and that some even fragile connection to the outside world was maintained under mortal danger. News about a defeat of the Nazi terror regime and the belief in salvation were kept alive despite the hopeless and desperate situation the prisoners found themselves in. The inhabitants of this “false ghetto” clung to human dignity despite the inhuman conditions that prevailed in the KZ Theresienstadt. From today’s point of view, it is incomprehensible why the Jewish administration, which was acting on order from the Nazis, did not comprehend the futility of their attempts at cooperating with the Nazis in order to improve the living conditions of the prisoners. Even at the very end they did not inform the prisoners about what they knew – or at least suspected – was happening at those “Osttransporte” (transports east: deportations to extermination camps in the east); probably in order not to dash the last slivers of hope and maybe also to prevent a riot which they feared would end in mass slaughter. Did the Council of Elders, appointed by the Nazis to administer the KZ Theresienstadt under their orders, never see through the deception of the NS authorities, although the first two of the three successive “Judenältesten” (Jewish Elders, the chairmen of the Council of Elders) were deported and murdered?

H.G. Adler, a Jewish intellectual from Prague and prisoner in Theresienstadt and Auschwitz, published the first comprehensive historical, sociological, and psychological study of life in the KZ Theresienstadt, in which he harshly criticised the “Jewish self-administration” which he considered too obsequious and naïve in their dealings with the SS commanders. It is known that many of the prisoners shared Adler’s assessment. The representatives of the so-called “Jewish self-administration” were much hated, although they tried to organise life in the city in a way that was as efficient as possible under the restricted circumstances. The three Jewish Elders, who were appointed by the Nazis, were selected because they were considered soft bourgeois intellectuals who could be easily manipulated and deceived. The Council of Elders believed that it would be possible to improve the living conditions in Theresienstadt for the imprisoned Jews by cooperating with the Nazis and by gaining the favour of the SS. After the murder of the first two Jewish Elders, Jakob Edelstein and Paul Eppstein, Benjamin Murmelstein, the third one, took over and he was the only one who survived the holocaust. In fact, the possibilities for action of the Council of Elders were very limited, which can be seen in the murder of Eppstein, who was killed in the small fortress because he had protested against mass deportations from Theresienstadt to the east. The Jewish administration first tried to protect the elderly from deportation since they were seen as trustees of their emigrated children and grandchildren. In hindsight an official appeal to resistance and the hiding of prisoners might have saved more lives. Yet it must be considered that at that stage the Jewish community had already been robbed of their most active members by emigration and deportation to death camps. The most active and defiant group were the young Jewish-Czech prisoners, who were also the first to be deported to the east. Order and rule-abiding were the most important virtues propagated by the Jewish Elders, which distanced them even more from the prisoners and the last one, Murmelstein, was even hated more than his predecessors. After the war Gershom Scholem and Hannah Arendt pronounced him guilty as a willing Nazi collaborator. Murmelstein was imprisoned for 18 months after liberation on 9 May 1945 before he was acquitted again. He insisted that he had been acting in the Jewish Community’s best interest, but he – a well-nourished choleric person – was despised by his emaciated co-prisoners, who blamed him for enjoying the limited power he was granted by the SS and for shouting and ordering people around. He knew what terrible destiny was awaiting those who were deported east, but chose not to make this knowledge public. Until his death in Rome in 1989 he remained a pariah in the Jewish community and the senior rabbi of Rome even denied him the death prayer in the synagogue.

One Jewish Kapo (a KZ prisoner who was ordered to supervise his co-prisoners), Paul Raphaelsohn, who had been deported to Theresienstadt from his home in Mönchengladbach in July 1942, was a notorious sadist. He tortured his co-prisoners under the command of SS-Obersturmführer Franz Stuschka even at a time when it was already obvious that the NS regime was about to collapse. When the KZ Theresienstadt was liberated, the prisoners arrested Raphaelsohn, but he managed to escape to his hometown. There a former prisoner recognised him and he was arrested by the British Commanders in April 1947 and handed over to the Czechoslovakian state, where he was sentenced to death and executed in May 1947. He was the only Jew among 7,000 war criminals who were sentenced to death in Czechoslovakia. In comparison, Franz Stuschka, an SS commander, was sentenced to seven years imprisonment in Vienna, which tells a lot about the lenient judicial treatment of Nazis in post-war Austria. By the way, all three SS commanders of the “KZ Theresienstadt” were born Austrians: SS-Hauptsturmführer Siegfried Seidl, SS-Obersturmführer Anton Burger and SS-Obersturmführer Karl Rahm. Seidl and Rahm were arrested by the Allied Forces, Seidl by the Soviets, and Rahm by the Americans. Seidl was executed in Vienna in February 1947 and Rahm, who had fled to Steyr, was imprisoned in the US camp Glasenbach and executed in 1947, too. But the destiny of Burger again illustrates the unwillingness of the Austrian judicial system to prosecute war criminals with the knowledge and cooperation of the local population, as soon as the Allied Forces had left Austria in 1955. Anton Burger returned to Altaussee in the Austrian Salzkammergut in 1945 and started a bourgeois life, which lasted 46 years. He lived there under a false name without ever being accused or prosecuted, although an arrest warrant had been issued in 1947. He even applied for Austrian citizenship under his real name in 1959 (as an illegal Nazi he had accepted the German citizenship in 1935). Burger was without remorse and had probably forgotten the 1,196 children from Bialystok, he had had deported from Theresienstadt to Auschwitz on 5 October 1943 and who were all murdered immediately after their arrival.

One could ask: why did the prisoners in the KZ Theresienstadt resort to cultural activities, participate in and attend literary, musical, theatrical performances, and scientific talks and discussions under these circumstances? Well, many of them were from the bourgeoise middle class; they were artists, intellectuals, business people and they tried to maintain some sort of human dignity and some – even if irrational- normality in the face of terror. How could anyone assume that the KZ Theresienstadt was, as the Nazis pretended “Theresienbad”, namely a spa, just because the level of cultural activity was high? When Auschwitz was hell, Theresienstadt was the antechamber to hell. There cultural activities were still possible and for many this attachment to a hypertrophic cultural life signified a fanatic clinging to a last certainty: we are human beings despite everything and if we perish, this sacrifice should not have been in vain; we want to give it meaning.

Living conditions in the KZ Theresienstadt

The age structure, ethnic makeup and the living conditions of the prisoners

Over the year 1942 32,721 Jews were deported from Vienna, two thirds of them women and children. Initially Theresienstadt was to be the destination for the elderly and those who had been wounded in the 1st World War or had received honours. In the second half of 1942 13,926 Austrian Jews were deported to Theresienstadt, mostly the elderly. In Austria only 7,000 Jews remained, the majority of which lived in so-called “mixed marriages” with one non-Jewish “Aryan” partner, like my grandmother Lola, who was married to Toni (see article: “Mixed marriages and mixed-race children in Vienna”). The “Central Office for Jewish Emigration” in Vienna was responsible for drawing up lists of those members of the Jewish Community who were to be deported and they had to set up special Jewish police, which had to force those who had received a deportation order to cooperate. This “JUPO” (“Judenpolizei”) was detested by the Jewish population and when JUPO members were transported to the KZ Theresienstadt, they were beaten up by the prisoners there and were immediately sent to the KZ Auschwitz. In October 1942 the deportation from Vienna was completed and the Jewish Community was officially dissolved. Its remaining assets were transferred to the “Emigration Fund of Bohemia and Moravia”. The Nazis pretended that the money was used to pay for the “board and lodging of the Viennese Jews in Theresienstadt”. This was part of the infamous and vile Nazi method of using the victims and their assets as tools for their own destruction and to play the persecuted off against each other; JUPOs against Jewish citizens, Jewish administration and Kapos against co-prisoners, Czech Jews against German-speaking Jews etc. The supposedly autonomous “self-administration” of the so-called “Ghetto Theresienstadt” was one of many malicious Nazi hoaxes. In reality, Theresienstadt was a collection and transit camp on the way to the final extermination of European Jews and not a “ghetto for the privileged and the old”.

While only 27 per cent of the Jews from Bohemia and Moravia were over 60 years old, the majority of Jews who arrived in 1942 from Germany and Austria were elderly. The Council of Elders decided to give preference to the young and those who were able to work in so far as they received the larger food rations, which meant that the food rations for the elderly had to be cut continuously. The elderly suffered the most from famine and often died of undernourishment. Again the Nazis managed to put the responsibility and the blame for the abysmal conditions in the KZ Theresienstadt on the Jews themselves because the distribution of the meagre food supplies was handed over to the Jewish administration. In the end, the Council of Elders had to make the hard choices who to feed and who to starve. The overcrowding and the lack of sanitary facilities led to the spread of famine-related diseases and epidemics, parasites, pests, and diarrhoea. The conditions under which the prisoners had to live were shocking and disgusting, although the prisoners tried to maintain at least a minimum of human dignity. A group of young detainees from Bohemia and Moravia organised an aid service for the feeble, helpless, and needy old prisoners and attempted to care for them in their scarce leisure time, after the many hours of hard labour. On orders from the SS the Council of the Elders had to draw up lists of prisoners to be deported from the KZ Theresienstadt to the east. Here, too, the blame was put on the Jewish administration by the Nazis, although they decreed the deportations. The Nazis further demanded that first the Jews from Bohemia and Moravia, who had built up the “ghetto”, were to be deported first and for the time being the elderly from the “Third Reich” were to be spared. This, as intended by the Nazis, led to serious tension between German- and Czech-speaking detainees. As most German-speaking Jews did not understand Czech, misunderstandings and hostilities occurred. Yet the responsibility for drawing up the lists was with the Council of Elders and the Kapos, who additionally had to keep several hundred deportees in reserve – usually 500 – , if someone on the list for the next transport died or was for the time being exempt from deportation.

Ignaz and Ritschi never spoke about their time in the KZ Theresienstadt; they usually covered their lower arms when in public, so that the tattooed KZ number would not show. It seems they wanted to blot out this atrocious experience. They both returned to Vienna in 1945 seriously ill. In the family there was the rumour that with them a nephew of Ignaz was imprisoned in the KZ Theresienstadt who was made KAPO and they only survived because he managed to strike their names off the deportation lists. Whether that was true or not, cannot be proved to day, but it is probable, especially for the time when the elderly from the “Third Reich” were no longer exempt from deportation east. Ignaz seemed to have been able to hold on to a job despite his age, namely in domestic service, which could have protected them as well. Nevertheless, a job was never a guarantee against deportation to an extermination camp, as the destiny of thousands of NS victims shows.

The protection of the elderly ended in September 1942, when the concentration camp was most overcrowded, the destitution and hardships were worst, and 58,491 persons were squeezed into the fortressed city. At that time only 57 per cent were over 65 years old. As chaos reigned and the living conditions were unbearable, the simple solution of the Nazis was to deport large numbers of prisoners east and to lift the ban on deporting old prisoners. From 19 until the 29 September 1942 11,004 Jews over 65 from Austria and Germany were deported to the extermination camps of Treblinka and Maly Trostinez. Only one man of this group survived. In October 1942 6,866 prisoners over 60 from Bohemia and Moravia were deported to Treblinka; of those only two young carers survived. The deportations again escalated in October 1944 when around 18,000 were deported to Auschwitz, among them more than 4,000 elderly who had been protected from deportation until then. As soon as the prisoners had managed to improve their living conditions in Theresienstadt again, the reaction of the Nazis was to transport another 8,613 prisoners to the city from the end of December 1944 until April 1945, most of them under 40 years of age.

All in all, more than 65,000 Austrian Jews were murdered in Nazi concentration camps; only 1,747 survived and returned to Austria after the war. Of 15,534 Jews who were deported from Vienna to Theresienstadt 13,822 died of famine and diseases or were killed in extermination camps. 1,311 lived to see the day of liberation.

Elderly prisoners

Studies, research, and documentation have concentrated on the so-called “Jewish self-administration”, forced labour, children and intellectual and artistic life in the KZ Theresienstadt, but very little is known about the everyday life of the many elderlies. One valuable document is the diary of the Viennese lady Camilla Hirsch, who arrived in Theresienstadt at the age of 73. Her diary was discovered by the sisters Miriam and Ruth née Wolf in Israel and handed over to “Breit Theresienstadt” in 2009. Camilla Hirsch was the sister of their grandfather and they had no idea how this diary had ended up in their attic. Camilla wrote the diary for her children, who she hoped to see again after liberation. She did not return to Vienna because of the terrible memories of persecution and died in poverty in Switzerland.

The imprisoned artists, the “Theresienstadt painters”, secretly documented the life of the elderly in their works of art. The elderly seemed to have been a fascinating subject matter for them, more than in any other concentration camp, where the focus was usually on children. They portrayed the old prisoners in all their distress, famine, and suffering. The paintings show the tragic decay and the unbearable living conditions the elderly had to endure. The conditions in Theresienstadt were terrible for all the detainees, but most of all for the old. Their faces express the deep sadness, isolation, desperation, and loneliness they felt and the hunger and sickness they had to deal with. The children and youth magazines, such as “Vedem”, “Kamerad” or “Rim Rim Rim”, which were circulated in Theresienstadt, tell a little more about the everyday life of the old as well as the essays of Karl Fleischmann, an imprisoned painter and poet. It was shocking for the young to see how the old gradually lost their dignity and ended up helpless, sordid, and hopeless. Actually, the young were disgusted by the sight of these undignified human creatures. Every moment in Theresienstadt was characterised by fear; fear of deportation east, fear of hunger, of sickness, exacerbated by overcrowding, the lack of privacy and hygiene. Consequently, the suicide rate among the elderly was extremely high. Especially those who had no friends or relatives in Theresienstadt suffered tremendously from loneliness, which was only relieved when they were allowed to attend a performance or when young people came to celebrate their birthday. Furthermore, the old prisoners were afflicted most by the tensions between the Czech- and the German-speaking prisoners, whereby the Czechs blamed the German-speakers for speaking the language of the oppressors. What is more, it must be noted that the young were generally preferred by the Jewish administration because they represented the future and so tensions arose between the young and the old, too. Any increase in food rations for the young was to the disadvantage of the old. Even those of the elderly who arrived in Theresienstadt in good health, such as Camilla, Ignaz and Ritschi, soon became weaker and susceptible to all kinds of diseases because the food was not only insufficient, but also not nourishing; it consisted of potatoes, watery soup, or coffee substitute, never any vegetables, fruit or meat. The unheated and unlighted barracks were so crowded that they reminded the prisoners of graves. At night they had to lie down one after the other in order to be able to squeeze themselves into the narrow available space of around 75 cm. The old prisoners had to rely on the concentration camp’s self-organised haphazard health care system, which lacked everything from medication to medical equipment. The threat of transports to the east loomed over everything. So, the fear of finding your name on the list for the next transport or on the reserve list continuously weighed on the minds of the detainees. On top of that, random censuses of prisoners were ordered by the SS, the worst of which was the census on 11 November 1943, where the prisoners were exposed to freezing temperatures for many hours, standing in the open fields without any possibilities to sit, rest or warm up. Around 300 people, mostly elderly, died because of this useless census, as once more the exact number of prisoners could not be stablished anyway.

Most important for the elderly in coping with their loneliness was the establishment and upkeep of personal contacts, the participation in rare common activities and events. Even if they did not have to work, several older people tried to get a job, such as Camilla and Ignaz; some kind office work or house duty, because privileges might then be granted, such as the permission to leave your house to visit friends and relatives in other buildings or in the hospital. Initially, all other prisoners could only leave their house for work or with consent of the House Elder (a prisoner responsible for a barrack or house). One of the worst experiences was constant hunger: on average the elderly lost half their body weight during their stay in Theresienstadt, as Camilla Hirsch wrote in her diary. Eventually the SS permission to receive parcels from outside the concentration camp brought some relief for few prisoners. Unfortunately for most it was nearly impossible to make contact to someone outside the camp who would be prepared to send them food because most of their friends and relatives had emigrated or were imprisoned themselves or dead. Ignaz and Ritschi were lucky, because they could receive parcels from my grandmother Lola, who was married to an “Aryan”. Others tried to contact international aid organisations in neutral countries, such as Switzerland and Sweden. The content of the parcels was then shared among relatives or friends or bartered. Often the receipt of parcels was prohibited or the content was confiscated by the SS. Sometimes for months, no parcels arrived and even more people succumbed to famine-related diseases such as diarrhoea, stomach pains, the flu, lung and heart diseases and cystitis and especially the old died of these illnesses. The night was the worst period, if for example you had to use the bathroom in the complete darkness – there was no lighting in the whole city after nightfall – , where many stumbled and fell. If they managed to arrive at the common toilets, they had to queue because there were only very few. At night the sleepers had to fight against all kinds of vermin, such as flees, lice and bedbugs, and had to endure the cold and wet weather conditions without any heating.

Improvised health services

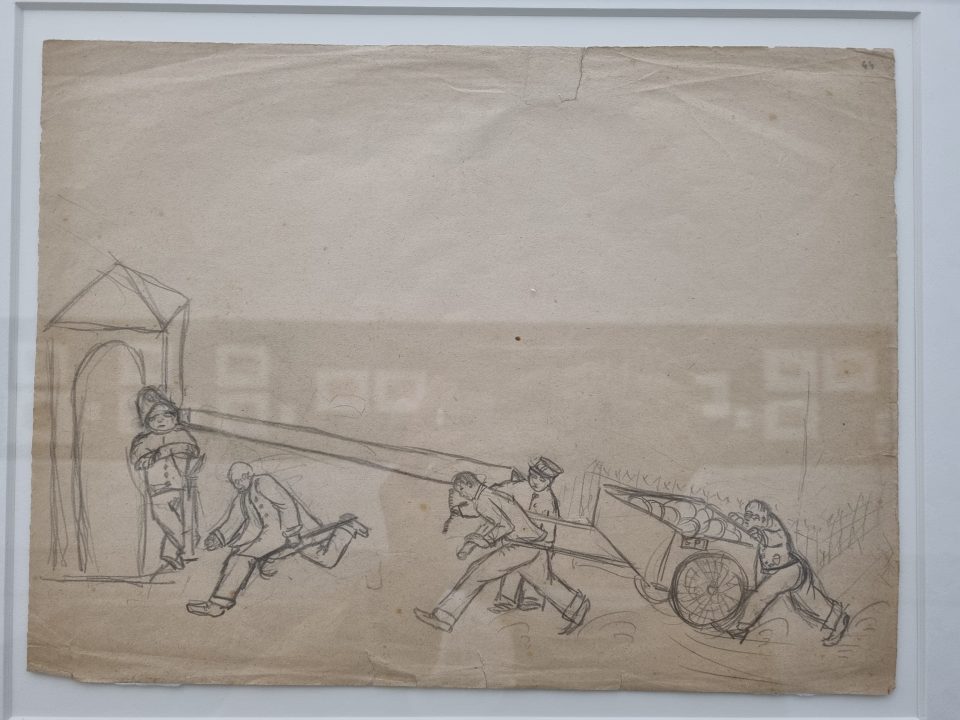

It was the aim of the GESTAPO to speed up the deterioration of the health status of the prisoners at all costs and only the unfailing care of the imprisoned nurses and doctors prevented a successful completion of the GESTAPO’s deadly scheme, as Dr. Erich Springer, a medical doctor from Prague, who was deported to Theresienstadt in 1941 and headed the surgical department there, reported later. After the installation of the KZ Theresienstadt Dr. Erich Klapp asked to have a patient with acute appendicitis transferred to a hospital outside the KZ at the end of 1941 because they lacked medication, surgical instruments, and sterilisation there. He was told by the SS that he should never again make such demands, otherwise he would have to face severe punishment. So, the Jewish administration had to improvise: when they found in one of the attics an old bath stove, they installed it in a deserted bathroom, and turned the room into an improvised operating theatre, where they could heat water. They collected linen from the prisoners and equipped some sick rooms and a haphazard outpatient service. If possible, the imprisoned doctors and nurses attended to the patients in the barracks where they lay on straw, up to several hundred in one room. When a scarlet fever epidemic broke out in December 1941 it was very difficult to isolate the sick. Several of those who tended the sick eventually died of infectious diseases. Operations had to be avoided if possible because the lack of hygiene and the absence of any instruments for sterilisation increased the risk of sepsis enormously. For necessary amputations they had to use a carpenter’s saw they had found in one f the houses. From 1942 on, everything the newly arrived prisoners carried with them in their luggage was taken from them by the SS. Nearly all of the prisoners had packed some sort of medication, which was of no interest for the SS. So, this was then collected and sorted and delivered to the central pharmacy. Although it was forbidden under penalty of death to smuggle letters with an appeal for medication outside the KZ, the prisoners managed to leak some information about the conditions in the KZ Theresienstadt. As a consequence, new arrivals brought some medicine with them, which could then be used by the improvised health services. Springer stressed that there were several famous specialists imprisoned in Theresienstadt who looked after the sick. Unfortunately, a large number of them did not survive the holocaust, such as Professor Pick, Professor Strauss, Professor Werner and Professor Hirschfeld. He further noted that the mortality rate increased tremendously from August 1942 until March 1943 with a peak in September with 130 daily deaths on average. During this period elderly sick people were transported to the KZ Theresienstadt who had been bed-ridden before their deportation. They therefore did not survive the transport or the first days in the KZ. That is why a crematorium with eight furnaces had to be built for the KZ Theresienstadt. It was clear that the Nazis had already made meticulous plans for the extermination of all European Jews, also in Theresienstadt. Additionally, the health services had to organise a special group of men who carried the sick and the dead on stretchers and funeral carts. The prisoners had to run many kilometres daily, but finally all these carriers were deported to death camps and only very few survived. Initially the medical personnel could declare some fatally sick patients “non-transportable,” so they would not be deported east. But from autumn of 1944 on even the “non-transportable” prisoners were no longer exempt from deportations, unless it was clear that the patient would not survive the transport from the barracks to the train carriage. Springer further stressed that it was strictly forbidden to allow pregnancies in the KZ Theresienstadt; the doctors were forced to abort all foetuses. Any contact between partners was severely punished and only in very special cases it was permitted to give birth to a baby in the KZ Theresienstadt. Sometimes when women arrived pregnant, they were allowed to give birth and were immediately afterwards deported to death camps together with their new-borns. Springer knew of only one child who was born in Theresienstadt and survived. The simple fact that no more deportations took place after the child was born saved it. To his great regret doctor Springer noted that even after the day of liberation many people died due to the outbreak of a terrible typhus epidemic, among them 44 doctor and nurses.

Communication to the world outside

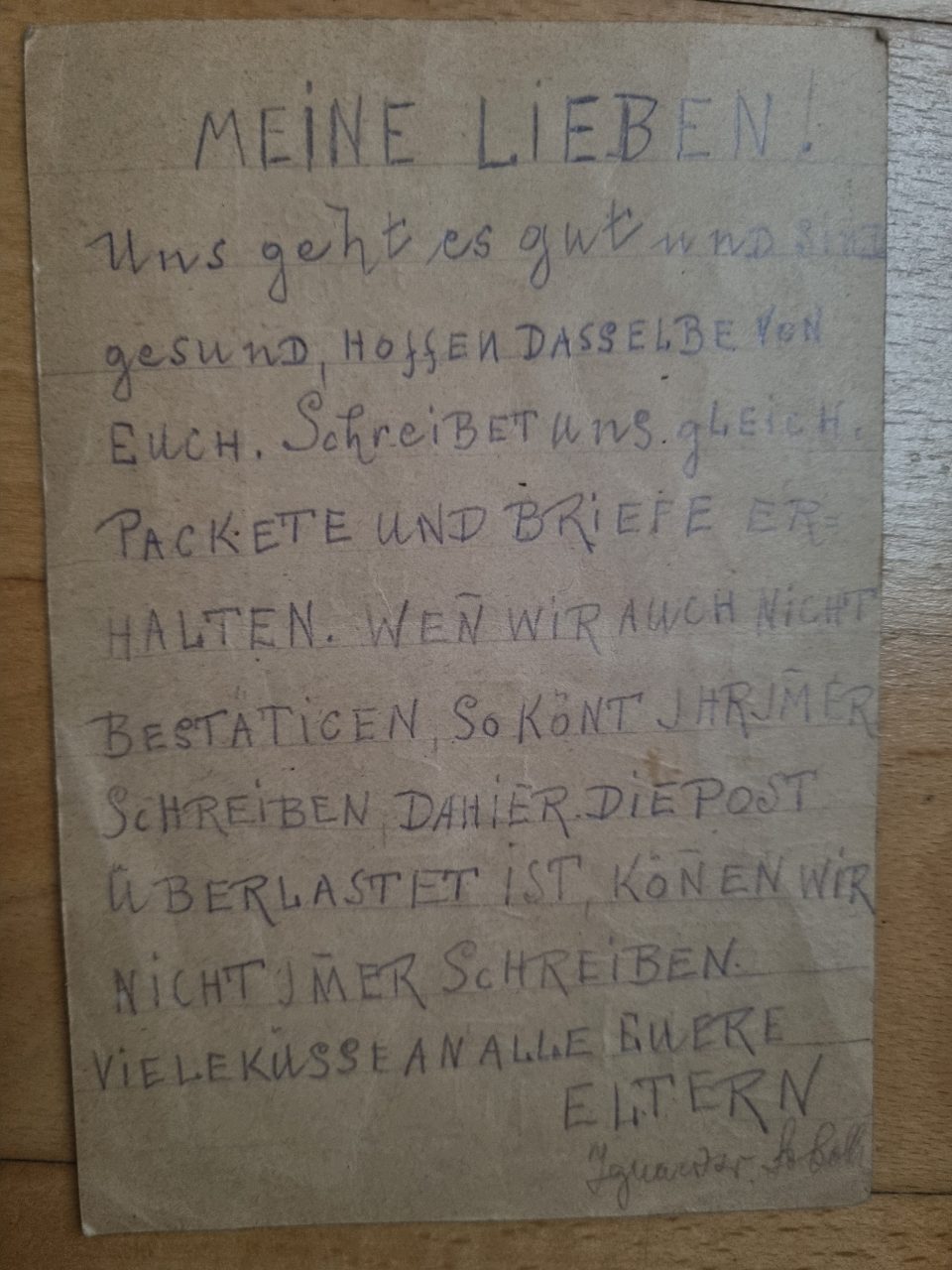

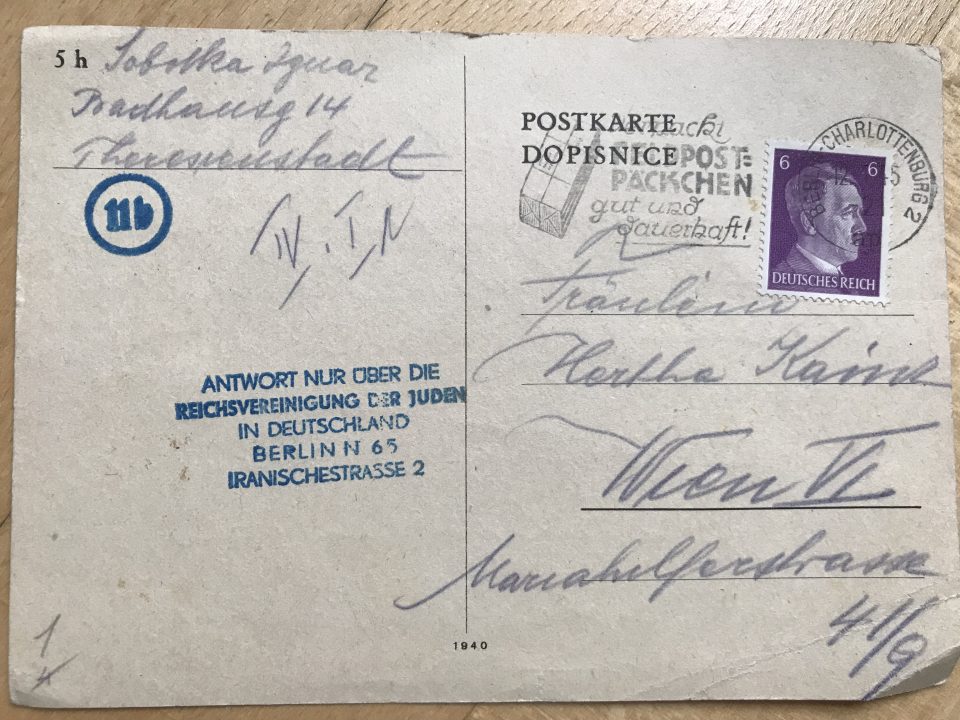

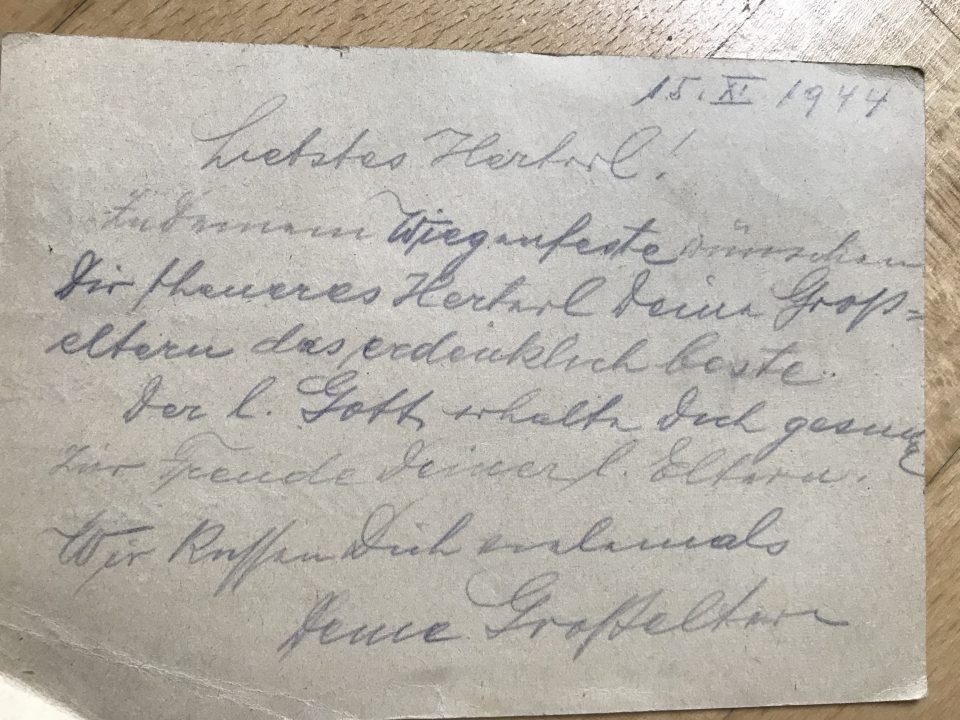

Most of all, the old prisoners constantly worried about their families, children and grandchildren; whether they had been able to escape, where they were, if they would see them again, since news from outside Theresienstadt were rare. The prisoners were sometimes permitted to send prefabricated postcards to thank their relatives or friends for a parcel and occasionally, they were even allowed to write a post card themselves or have it written by a young person. Initially this was only possible if the post card was written in block lettering. Of course, every communication was checked by the SS, yet occasionally giving the permission to write helped the Nazis to keep up the appearance that everything was “fine” in this “ghetto for the privileged and the old”.

All in all, 15 such postcards of Ignaz and Ritschi have been preserved

Secret compilation of cookbooks and dealing with famine

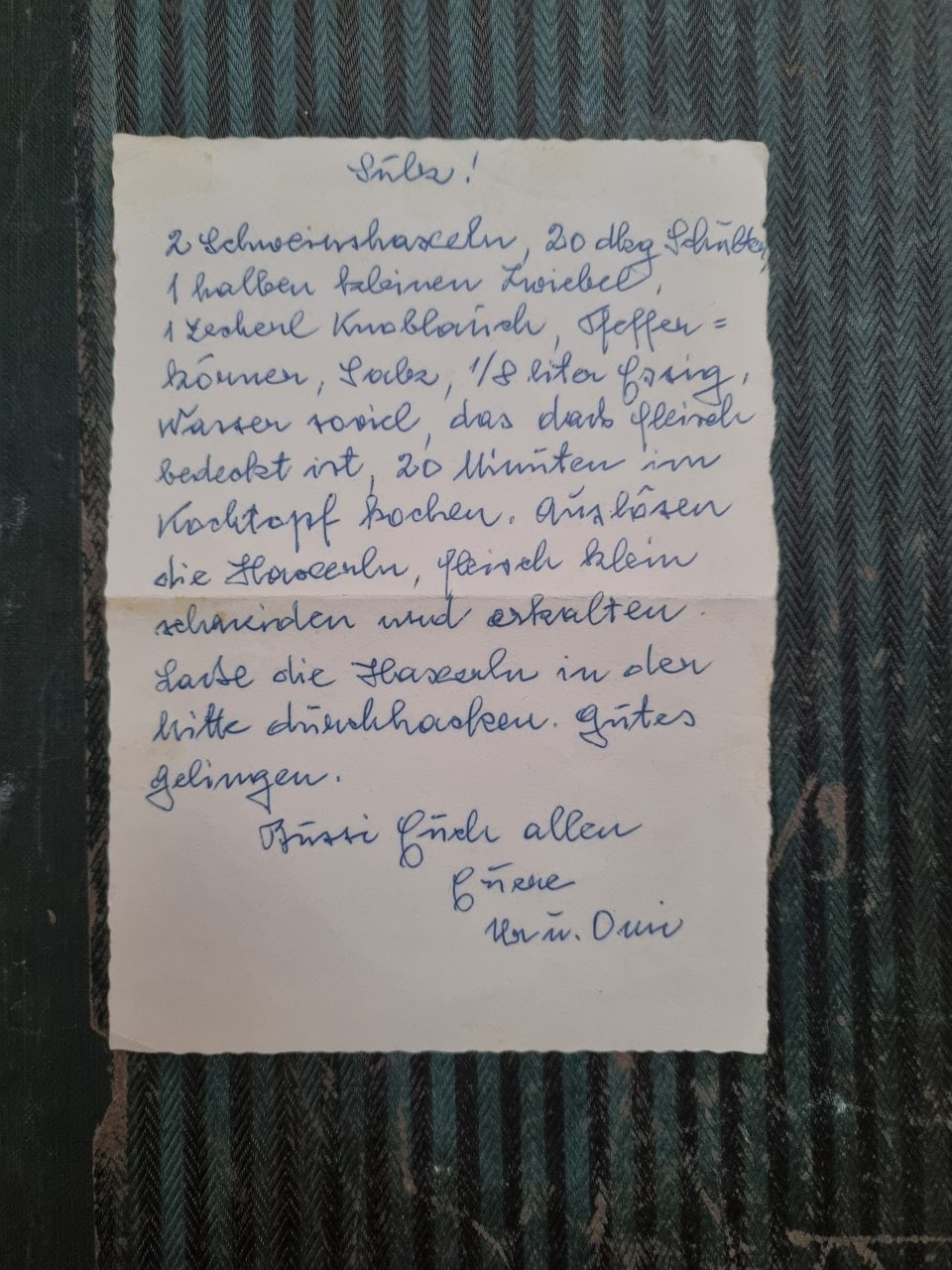

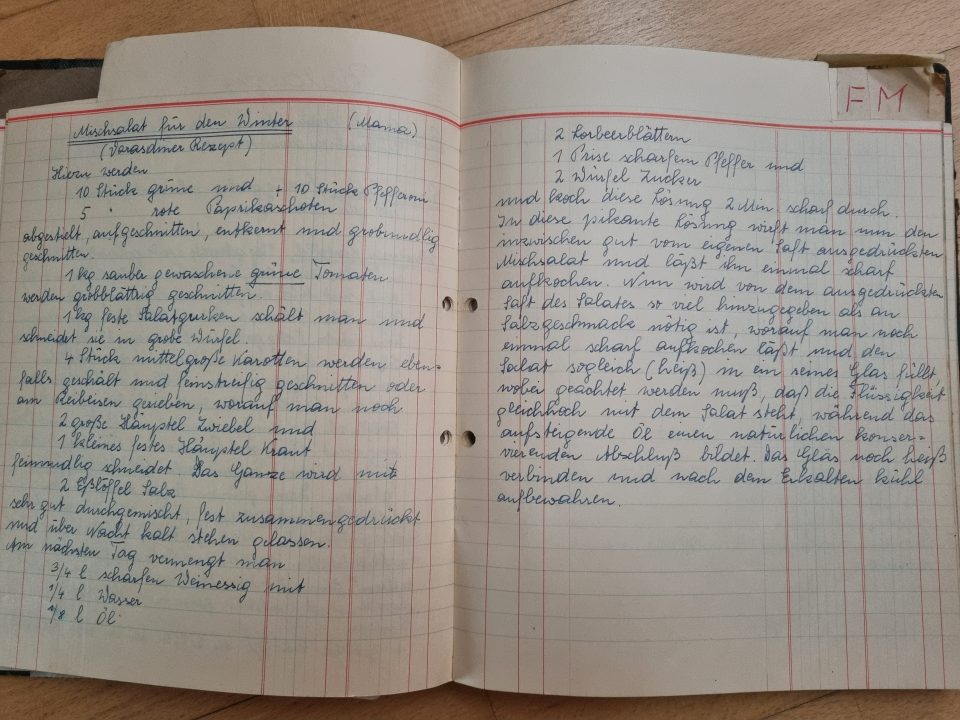

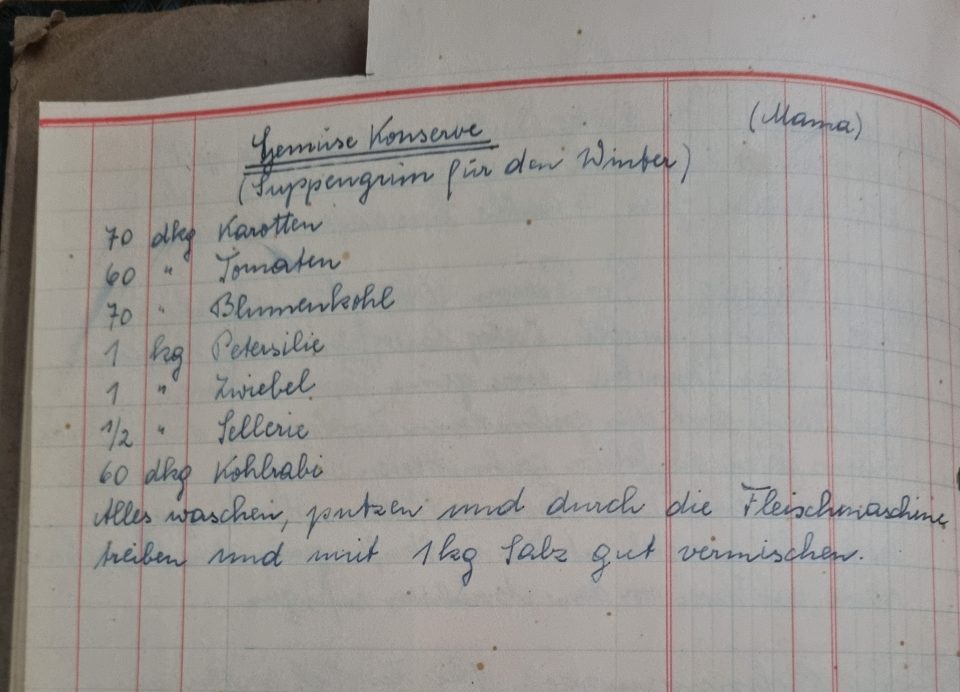

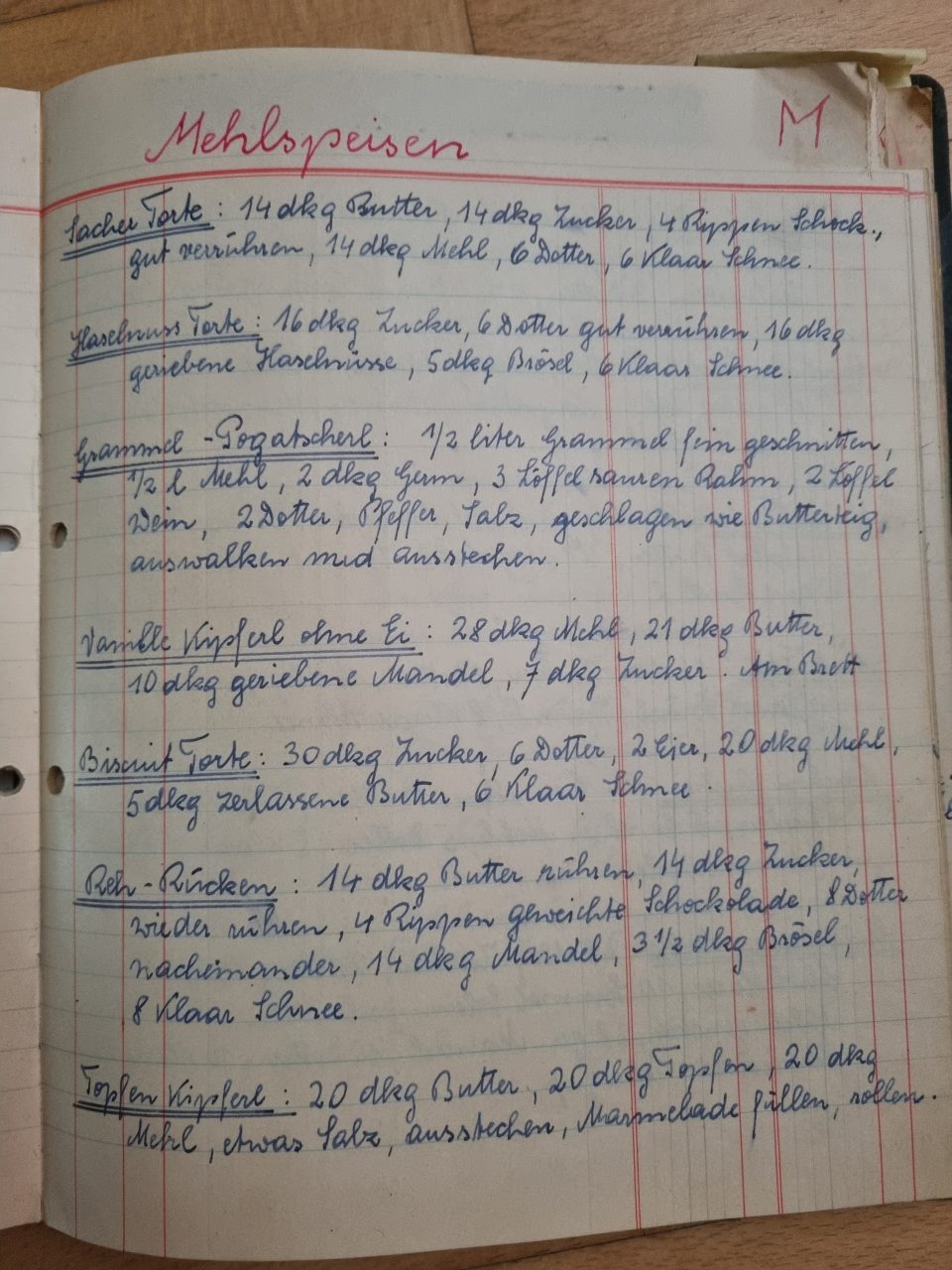

Many of the old people just gave up, were listless and depressed, and did not see any sense in going on living, especially when every other day someone they knew was either deported or died – between 106 and 156 persons died in the KZ Theresienstadt every day -and no one had the strength to mourn the dead any more, because they were all so exhausted and apathetic, Camilla Hirsch wrote in her diary. Whenever a dysentery epidemic broke out, the old were especially affected. Thousands were so weak that they could not get up and literally died in their own excrement. Some of the elderly persevered because they hoped to see their children, relatives and friends after liberation and their survival tools were optimism, humour, and initiative in finding creative solutions to the perpetually arising problems. One way of coping with terror, squalor and famine was recalling the memory of better times, which several women in Theresienstadt did by secretly collecting recipes and compiling cookery books. It can be assumed that Ritschi, who was a good cook and had run the kitchen in Lola and Toni’s coffeehouse, contributed some of her recipes. The cookbooks that were compiled by women in Theresienstadt must be considered a manifestation of defiance, of a mental revolt against famine and the harshness of living conditions in general. They imagined a time when food was still available, when they had homes and kitchens and could cook for their families and celebrate feasts. Recalling the recipes constituted an act of discipline and required the suppressing of the rampant feeling of hunger, recreating an ordinary world, and dreaming of liberation and the time after imprisonment. The cookery books are a document to the extraordinary capacity of the human mind to transcend its harsh surroundings and defy dehumanisation.

Paper was rare and its possession was illegal and if discovered harshly punished. This can be seen in the document above, where the acquisition of a small amount of writing paper required special permission and was minutely documented. So, every scrap of paper available was used to note down the recipes; across a photograph of Hitler or on multiple copies of propaganda leaflets of the Third Reich. But the writing down of well-loved recipes might have brought comfort amid chaos and brutality. The collection of Mina Pächter was discovered in an apartment on Manhattan’s East Side quarter of a century after the liberation of the KZ Theresienstadt. Before Mina died in Theresienstadt she entrusted the small package to a friend and asked him to get it to her daughter in Palestine, but he had no address and could not find her daughter, who meanwhile had moved to the United States. No one knows exactly how the package then found its way to Manhattan, but finally Mina’s deathbed gift to her daughter, the “Kochbuch” (cookbook), was delivered.

In order to survive the prisoners had to imagine things, such as roaming on a summer meadow, and above all, they constantly thought and spoke about food. Talking about it seemed to have helped to keep up their spirits. Women shared recipes in their crowded unlit dormitories at night; they even had discussions and arguments about the correct way of preparing certain dishes. They called it “cooking with their mouths”. Mina Pächter’s collection is not the only one which has survived. Two smaller manuscripts, one entirely written in Theresienstadt and one partially written there, are preserved in Israel’s “Beit Theresienstadt” cultural centre and there are more than three recipe collections at Israel’s “Yad Vashem” memorial institution. It can be assumed that several more cookbooks were written in Theresienstadt and elsewhere. One very interesting one is a four-part manuscript written by Malka Zimmet in the Lenzing forced labour camp, a subcamp of the KZ Mauthausen in Austria, which is preserved in “Yad Vashem”, too. In “Beit Theresienstadt” the manuscripts of Arnostka Klein and Jaroslav Budlovsky are stored. Budlovsky included in his collection of recipes a record of events at Theresienstadt and the working and living conditions of himself and his fellow prisoners. The collections of recipes were written in German and Czech and reflected the cultural background of the prisoners, where cooking and baking was central to the families and societies of Central Europe. Most of the recipes illustrate the cooking tradition of the former Habsburg Empire, a mixture of Bohemian, Moravian, Slovak, Hungarian, Slovenian, Polish, Austrian, Balkan, and other traditions. Handwritten cookbooks, which are handed down in families from mothers to daughters, from aunts to nieces, from grandmothers to grandchildren, have a long tradition in Central Europe. Perhaps Mina Pächter and others tried to preserve this custom, even under KZ circumstances. The Central European middle class placed great emphasis on the pleasures of the table, which can be seen in the collections of recipes. The cooking tradition of the Austro-Hungarian Empire was well-known for its soups, roast birds, smoked meats, savoury sausages, wild mushrooms, the use of poppy seeds and beer, goulash, Wiener Schnitzel, a large variety of dumplings, served from soup to dessert, cheeses, and an enormous variety of sweet dishes from yeasted pastries to “palachinky” (sweet thin pancakes). Ritschi came from this tradition, too; she was born and raised in Moravia and had moved to Vienna as a married woman. She passed down recipes in the family, to her daughters and to her granddaughter Herta who kept a hand-written cookbook, too.

The writing down of anything, be it recipes, musical notes or diaries was strictly forbidden by the SS, but went largely unnoticed as it was done secretly and if a recipe came up, it was probably not considered important or significant. The writers were very creative in contriving ways to continue their writing after long hours of forced labour in the crowded and unlit quarters especially of the old. The SS might even have turned a blind eye to such endeavours or used it for their propaganda. The reality in the KZ Theresienstadt was that people had to queue for hours in all kinds of weather for their daily ration of soup and for the elderly very often nothing was left, when it was their turn and they had to go without any food. They then resorted to picking raw potato peels or scraps of rotten food from garbage heaps, which further damaged their health. The “soups” were described as tasteless or disgusting. A small loaf of bread for the young had to last three days and if they were fortunate, there was some margarine, barley or turnips and now and then a tiny bit of meat in the soup, too. But that was never the case for the old, who starved the most. There was never any fruit or vegetables and Norbert Troller, an artist imprisoned in Theresienstadt, spoke of salads they tried to make of weeds. For birthday celebrations the prisoners improvised, for example a palm-sized cake made of mashed potatoes with a little sugar on top. Troller described the “Ghetto Torte” of Ms. Windholz, which “tasted almost exactly like a the famous Sachertorte”, the recipe of which was secret, but contained bread, coffee substitute, saccharine, a trace of margarine and lots of good wishes; “very impressive and irresistible”. Troller reported, “Like everyone else, I suffered greatly from hunger, so that I was plagued all through the day with thoughts of the kind of food I had been used to, as compared to the food we received… hunger weakened and absorbed every thought”. The Council of Elders realised early on that the limited supplies could not be distributed evenly. So, they decided that the fewest calories and the worst accommodations would have to go to those least likely to survive the ordeal of the KZ Theresienstadt. These people were sacrificed, so the younger ones might live. How one fared depended to some extent on how well one could negotiate the system; if you had something you could trade for extra food, for instance a portrait, a sketch or something from a parcel; or they tried to get jobs which permitted them better access to additional provisions. The parcels Toni and Lola sent to their parents from Vienna might have been the decisive contribution to Ignaz and Ritschi’s survival, apart from Ignaz’ job in “domestic services”. Most of the other old people had nothing to barter and no access to any extra food. Starving elderly men and women begged for some watery soup made from synthetic lentil or pea powder, and dug for food in garbage heaps rotting in the courtyards of the barracks. In the morning, at noon, and in the evening, they patiently queued up for food, clutching saucepans, mugs or tins, and were glad to eventually get a few gulps of coffee substitute, as can be seen in sketches made by the “artists of Theresienstadt”. The decision to drastically reduce the rations of the elderly transformed many of them into scavengers and beggars. As a result of eating raw peelings, many developed severe enteritis and diarrhoea, a chronic condition especially among the old in the KZ Theresienstadt. Many ended up with a hunger oedema and could not take care of themselves anymore and eventually died in the “ghetto hospital” like Mina Pächter in 1944. The distress of the prisoners can also be discerned from the collection of recipes; some are muddled or incomplete, some ingredients are left out or the process of cooking is omitted, probably due to illness, transport east or death of the contributor. The recipes sometimes reflect wartime cooking practices, for example a recipe for “Kriegsmehlspeise” (war dessert) or recipes for famous Austro-Hungarian cakes such as “Tobosch Torte” and others include imitation honey, coffee substitute or margarine instead of butter. Eggs often appear in parentheses because they were rationed in wartime, which meant they were supposed to be used, but their use was optional. Most of the recipes in Mina’s collection were written in German, only a few in Czech. As the Bohemian and Moravian Jews were in general among the most assimilated in Europe, they mostly knew German, even if it was their second language. Mina wrote in her recipe for stuffed eggs (“Gefüllte Eier”), “Lasse der Fantasie freien Lauf“ (Let fantasy run free), which tells a lot about the survival function of the recipe collections.

Many dishes were traditional ones, others pay tribute to war conditions. Here are some interesting examples of Mina’a collection: “Bohnen Torte” (bean cake), “Kirsch-Zwetschken Knödel” (cherry-plum dumplings), “Ausgiebige Schokolade Torte” (rich chocolate cake), “Apfel Knödel” (apple dumpling), “Zwiebel Kuchen” (onion cake), “Billige Hagebutt Pusserln” (cheap rose-hip kisses), “Schüsselpastete” (paté in a bowl), “Hagebutten Mehlspeise” (rose-hip dessert), “Schokoladen Strudel oder Kapuziner Strudel” (chocolate strudel or Kapuziner strudel), “Kapuziner Nockerl (Suppe)” (Kapuziner dumplings for soup), “Heu und Stroh” (hay and straw), “Badener Caramell Bonbons” (caramels from Baden) or “Korn Schnaps” (rye schnaps).

Here just a few extraordinary recipes, written in German, in an English translation:

“Caramels from Baden”

Caramelize 30 decagrams of sugar without water, add 1/3 litre of very strong coffee, 1/8 litre cream and bring to the boil. Add 8 decagrams best quality butter and cook until the mixture thickens. Pour into a buttered candy pan. With the back of a knife divide it before it completely cools. Then break it into cubes and wrap in parchment and then in pink paper.

“Rye Schnaps”

1/2kg grains of rye, 2 decagrams yeast, crumbled. Bring 60 decagrams sugar with a little water to a boil. Pour the cool liquid into a jar and fill with water. Cover it tightly with paper and perforate it. Let it stand for 10 days in a warm place and then filter the liquid through a piece of linen and pour into bottles.

“Hay and Straw”

Make a noodle dough from 1/2kg flour, 2 eggs, 2-3 tablespoons white wine, 2-3 tablespoons thick sour cream. Roll out the dough medium thick. Cut short noodles and fry them in hot fat. Remove them and put them into a soufflé dish. Sprinkle them with sugar, cinnamon, and many raisins. Now make a delicate vanilla cream, add a little raw cream, and pour over the fried noodles. Put the dish into a hot oven and bake it a little and serve it in the soufflé dish.

“Rose-Hip Dessert”

Blend vigorously 12 decagrams butter with 4 egg yolks and 20 decagrams sugar, lemon rind, 15 decagrams hazelnuts, and add half a jar of rose-hip jam. Add 20 decagrams breadcrumbs and “snow” of stiffly beaten egg whites. Bake it slowly.

“Cheap Rose-Hip Kisses”

4-5 egg whites stiffly beaten to “snow”, add 20 decagrams sugar and 15 decagrams hazelnuts. Beat in a water bath until thick and warm. Add 4-5 spoons rose-hip jam and 3-4 spoons maize starch or potato starch. With a small spoon make “kisses” on “oblaten” (small round wafers) and bake at low temperature.

“Onion Cake”

Make a flaky dough or puff pastry. Put it very thinly on a greased baking paper. Now stew about ten sliced onions in 15 decagrams of fat without browning them. Add 1 spoon of caraway seeds, a pinch of salt, 2-3 sugar cubes and 3 spoons of flour, set it aside. When cool, add 3 egg yolks, 1 glass thick sour cream and “snow” of three egg whites. Spread this on the dough layer and bake it at medium temperature in the oven and then cut into small squares.

Children, their paintings and their contact to the elderly

Although the aim of the Council of Elders was to prefer the young to the old and offer them chances of survival, unfortunately the vast majority of children who passed through Theresienstadt were murdered by the Nazis: of a total of around 15,000 children under the age of 15 only around 100 survived. In fact, from the start the Nazis had no intention of letting any of the Jews of the KZ Theresienstadt survive the war, yet they seemed concerned about the “ghetto’s” appearance in the eyes of the outside world. Bewildering ambiguities took place. Most of the inhabitants were aware of the shocking air of deception in which they lived. Some were more aware than others. The Council of Elders, their staff and the Kapos, who were forced to draw up the lists of deportation orders, probably knew they were sending those people to near certain death, at least in 1944. It is said that Rabbi Leo Baeck had learned about the full horror of Auschwitz already in 1943, but he opted for not telling the truth to the other prisoners because he feared panic, despair, and mass suicide in Theresienstadt. In July 1943 a transport arrived with around 1,200 Jewish children from Bialystok in Poland, famished, caked with dirt, and crawling with lice. They were placed in an off-limits area. No one was allowed to contact them. When they were taken to the shower room, they resisted with all their might to be dragged there, because they must have seen what had happened to their parents who had been killed in gas chambers. 53 doctors and nurses were selected from the prisoners to look after them and no one else was allowed near them, not even the Council of Elders. It was discovered that they were the survivors of the Bialystok ghetto, which had risen against the Nazis and had been burned to ground. At least at that point in time the Council of Elders must have known what was happening to those who were deported east. Six weeks later the children together with the doctors and nurses were transported to Auschwitz and murdered there.

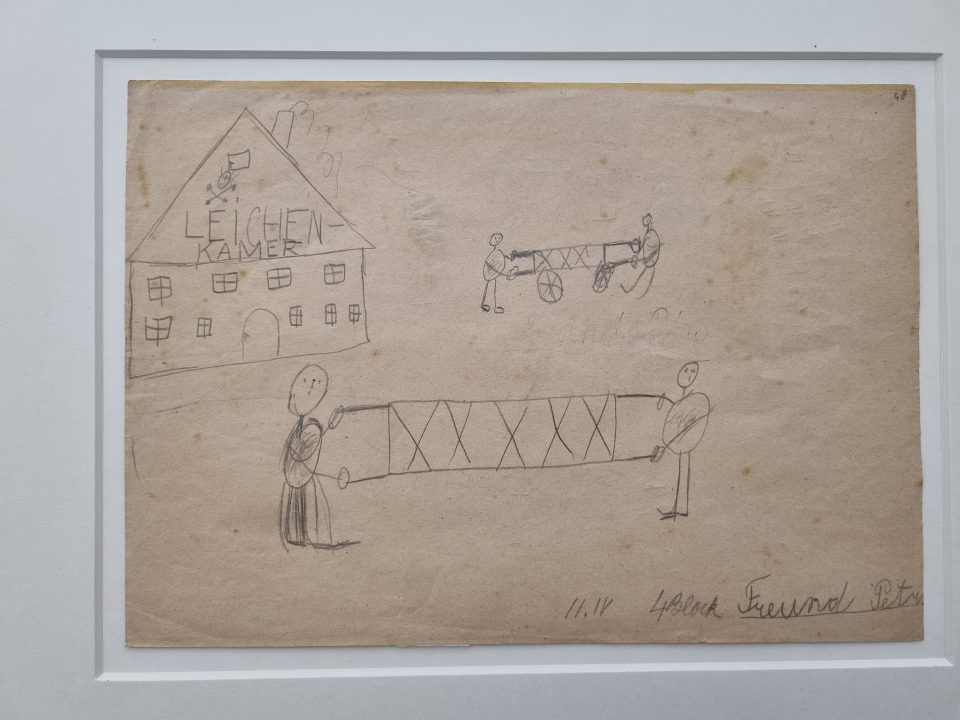

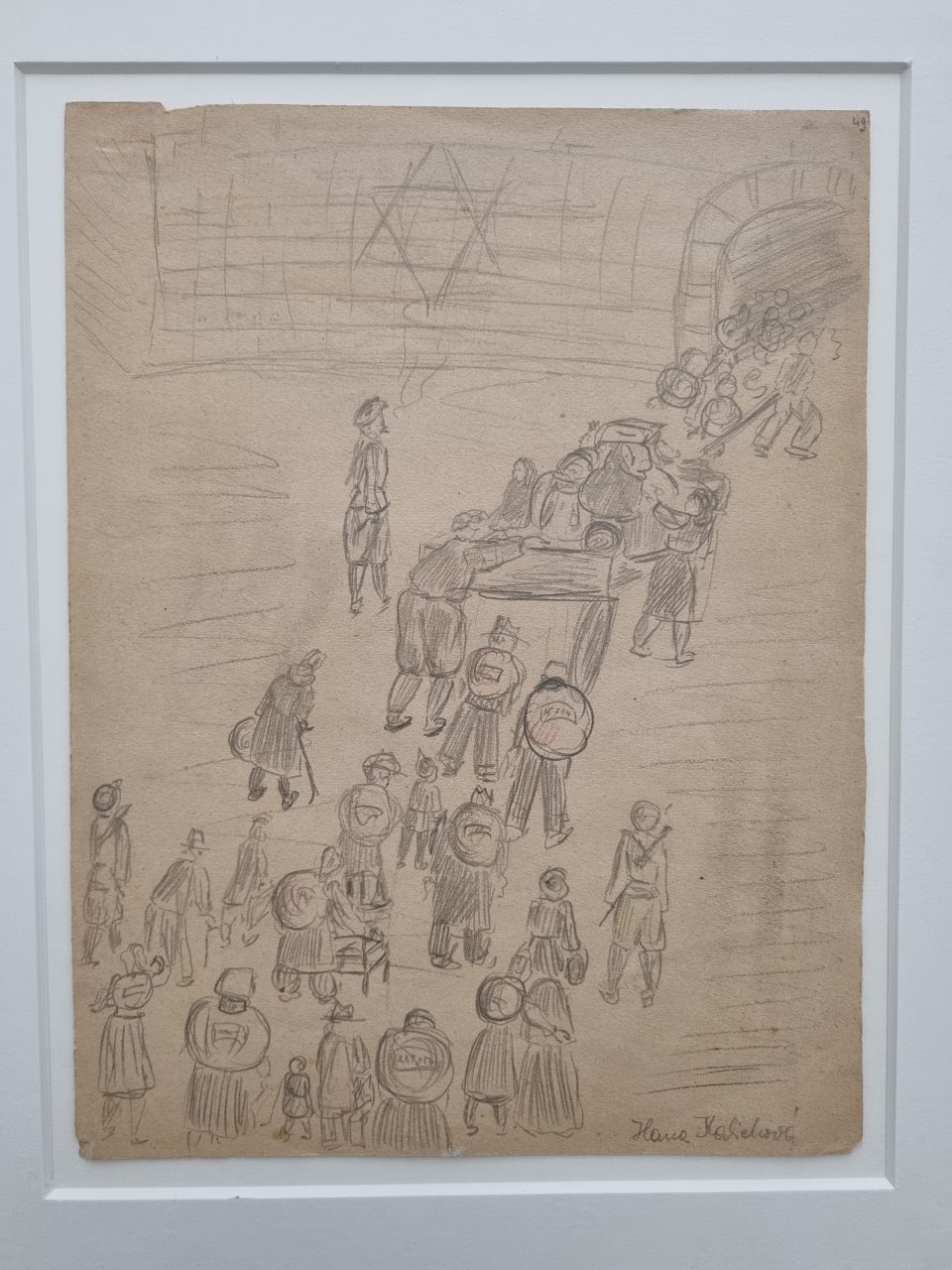

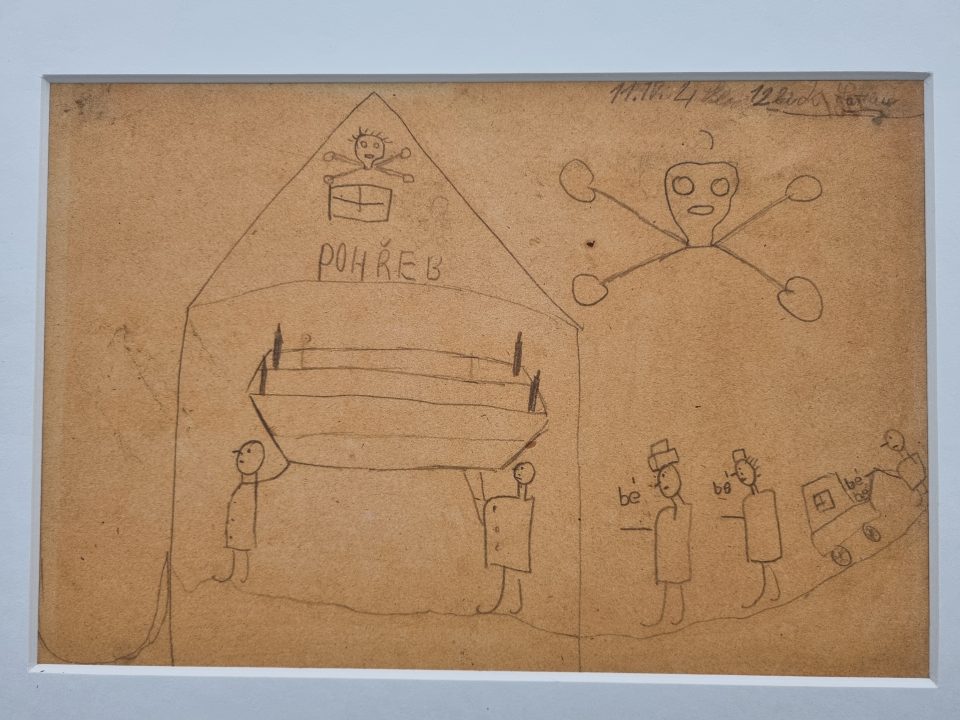

Yet how much did the children know? Did they know that death lay awaiting for them? Many of them most likely did, as can be gleaned from the messages in their pictures and their poems. 4,000 children’s drawings from Theresienstadt are stored in the archives of the Jewish Museum in Prague. They were preserved in envelopes bearing the numbers of the different children’s homes, where they were housed and received sporadic secret lessons, because any type of proper schooling was strictly forbidden. The great majority of drawings date from the first half of 1944. Fewer are found from the autumn of 1944, when continuous transports to Auschwitz reduced the number of children until very few remained in Theresienstadt. The children lived, locked within walls and courtyards, crowded into children’s homes that lacked even the most basic necessities, such as toilets. The children played in the barracks yard and the courtyards of their children’s homes. Sometimes they were permitted to breathe a little fresh air on the ramparts. From the age of 14 they had to work and live the life of an adult. The smaller ones acted out plays and even staged a children’s opera, “Brundibar” in a Nazi effort to deceitfully impress the International Red Cross commission. Secretly the children were guided to draw and paint their world and their dreams. They saw everything that the adults saw, too; the endless lines queuing for food, the funeral carts drawn by humans, which were used to carry bread as well as corpses, the primitive hospital, the piling up of coffins, the SS at roll calls, and the executions. But they also saw a dream world of butterflies, flowers, meadows, their homes before imprisonment and their pets, fairies, princesses, and witches. Their poems and drawings are signed with their names and often their “home numbers”. That is how their destiny could later be traced; most of them died in Auschwitz in 1944.

One of the well-known artists in Auschwitz was Vienna-born and Bauhaus-trained Friedl Dicker-Brandeis, who dedicated her life in Theresienstadt to the secret teaching of children in art classes. She arrived in Theresienstadt in December 1942. Others who taught received compensation in bread, but she would accept no payment for her teaching. Although she had no pedagogical training and did not speak Czech, she had a natural talent for capturing the attention of the children and arousing enthusiasm for drawing in them. She herself drew very little and saved the paper, pencils, and paint for the clandestine lessons with the children. In that way she helped restore an inner balance in the terrified children, at least for a brief period. Friedl Dicker- Brandeis did exercises in breathing and rhythm with the children, had them study reproduction, texture, and colour. She told them stories or required them to draw objects she had mentioned twice in a story, and she guided them to paint their concealed inner worlds and their tortured emotions. Willy Groag, who was the last principal of the girls’ home L-410 in the KZ Theresienstadt, was entrusted with two suitcases of children’s drawings in August 1945 by Raja Engländerova, a former student of Friedl Dicker- Brandeis. He brought the suitcases to the Prague Jewish Community, where for ten years they were collecting dust before they were rediscovered and exhibited.

Friedl Dicker -Brandeis carefully chose the topics of her drawing lessons to provoke reactions in the children, to be able to draw on the children’s wealth of experience in their own personal ways. She asked the children to put their names or monograms on their drawings. The constant repetition of their names gave the children a renewed sense of identity and strengthened their shattered self-esteem. Their everyday lives were characterised by numbers, but the drawings should bear their names, not their KZ numbers tattooed into their arms or their children’s home numbers. Dicker-Brandeis drew up a text based on her experiences with the drawing lessons: “Kinderzeichnen” (Children`s Drawing) and she presented it to teachers and supervisors in July 1943, at the first anniversary of the children’s homes in the KZ Theresienstadt. In this lecture she analysed the importance of children’s art work as an expression of freedom and talked about the characteristics of child psychology and the importance of group work and how the creativity of children could be promoted. On 17 July 1943 an exhibition of the children’s drawings could be seen in the basement of the children’s home L-410.

On 28 September 1944 her husband, Pavel Brandeis, received a deportation order along with 4,000 other men and was transported to Auschwitz. Friedl joined many other women and children in volunteering for the next transport in the hope of being reunited with their husbands at their final destination. “Transport Eo” with 1,550 prisoners, mostly women and children, left Theresienstadt on 6 October 1944. On their arrival in Auschwitz-Birkenau SS doctor Josef Mengele selected 190 girls from the first and second waggon of the train for medical experiments and on 9 October most of the prisoners were gassed, among them Friedl. Her husband survived the holocaust.

There was quite some interaction between the old prisoners and the children, although they were housed separately. Some of the elderly, who were no longer able to work but not too ill, gave secret lessons to the children, told them stories and some of the children who were crowded into homes, such as L-414, visited the old, who could no longer move and had no relatives, in their houses or the barracks hospital and read to them or brought them some scraps of food. Ruth Klüger, a Viennese girl, was deported to Theresienstadt with her mother and grandmother and was moved into the children’s home L-414. Her mother fell seriously ill with hepatitis and her grandmother died during one of the recurring epidemics in the KZ. Ruth survived and wrote about her experiences in her book “weiter leben. Eine Jugend” (Going on Living. A Youth). She reported that proper schooling was strictly prohibited by the SS and she wondered why the Nazis saw a threat in the Jewish intellect, which they pretended to despise. For the children the “learning ban” had a special attraction. Theresienstadt was full of young and old Jewish intellectuals, university professors, scientists, teachers, artists, and writers. Some of these adults secretly gathered small groups of children and told them interesting things about European culture; those who were forced to work, in the evenings and the old during the day. As soon as a German patrol was sighted, whatever piece of paper was used in these informal lessons disappeared and the children dispersed. Although the Council of Elders with the permission of the SS established a lending library there were few books available for lessons. These were handled with care; for instance, an art history book with reproductions of famous pieces of art, which an art historian explained to the children. Ruth remembered a professor of literature who gave lessons on literary history in a tiny storeroom some evenings. An old lady tried to teach Ruth how to properly recite poetry in the hopelessly overcrowded room she had to live in. Rabbi Leo Baeck from Berlin talked to children in an attic about the creation of the world. In the summer of 1943, they celebrated the 60th birthday of the writer Franz Kafka from Prague, who was not world-famous then, but the cultured inmates of the KZ Theresienstadt already knew about his importance for European culture. His favourite sister Ottla was one of the nurses and doctors who was ordered to accompany the children of Bialystok on their transport to Auschwitz and was murdered there. They had all believed they would be transported abroad and rescued, Ruth Klüger reported. Ruth remembered attending informal performances of musicians, cabaret artists and actors who recited carefully selected classical texts to protest against their imprisonment and the listeners all understood, what they were aiming at. In this way the artists and the audience with their enthusiastic applause made a stand, and put up silent resistance. One mother was sometimes allowed to visit her daughter in the children’s home where Ruth was housed and told her daughter about Greek history; Ruth was enthralled because her mother was unable to do that. It was surprising how creative people were, when they only had conversation as a tool of distraction from distress and terror. The 20 months in Theresienstadt turned Ruth, a very shy and withdrawn girl, into a “social human being”, she said, and she admired her co-prisoners who showed enormous assertiveness by applying their intellect, their gift for dialogue, their love of art, theatre, and humour. Ruth said that she had hated Theresienstadt, the dirt, the overcrowding, the lack of privacy – not even on the toilet they were alone – , the fear, and the terror of the guards. They were all treated like the ”scum of the earth” and they felt like that. But she had encountered many wonderful people among the adult prisoners who she admired and to whom she felt grateful.

Helga Pollak-Kinsky was another of the few lucky children who survived the KZ Theresienstadt. She lived in room 28 of a children’s home and wrote a diary there during the years 1943/44. She formed part of the group of children who received drawing lessons from Friedl Dicker-Brandeis, who often came to room 28. Those were moments of light-heartedness and carefreeness for her. Helga stressed that Friedl was an excellent pedagogue and the girls enjoyed the lessons with her. She never put pressure on the girls, but managed to awake their creative spirit and encouraged them to paint what they wished for, what they enjoyed. She could evoke a positive feeling in the children und Helga was certain that Friedl was an important initiator of art therapy. She further stressed that so many adults with amazing pedagogical qualities cared for the children in the children’s homes and she dismissed H.G. Adler’s judgment that the youth welfare efforts of the Jewish administration had failed. It was not just Friedl Dicker-Brandeis, but also Mrs. Brumlik who taught them geography and history, but also their carers Ella Pollak, Eva Weiss, Eva Eckstein, Rita Böhm and the social worker Margit Mühlstein, who did an excellent job in trying to make the girls’ lives somehow bearable, to shield them from the harsh reality of the KZ and to soothe their fears. It was very difficult for them to care for 30 girls locked in a room of 30 m² day and night. They sang a lot with Ella Pollak, who was an excellent vocal pedagogue; they learned German, Czech, Hebrew and even a Dutch song and of course the songs of the children’s opera “Brundibar”, written and performed in Theresienstadt, which was “their anthem”.

“Beautification” of the KZ and the NS deceit: Red Cross visits & NS propaganda films

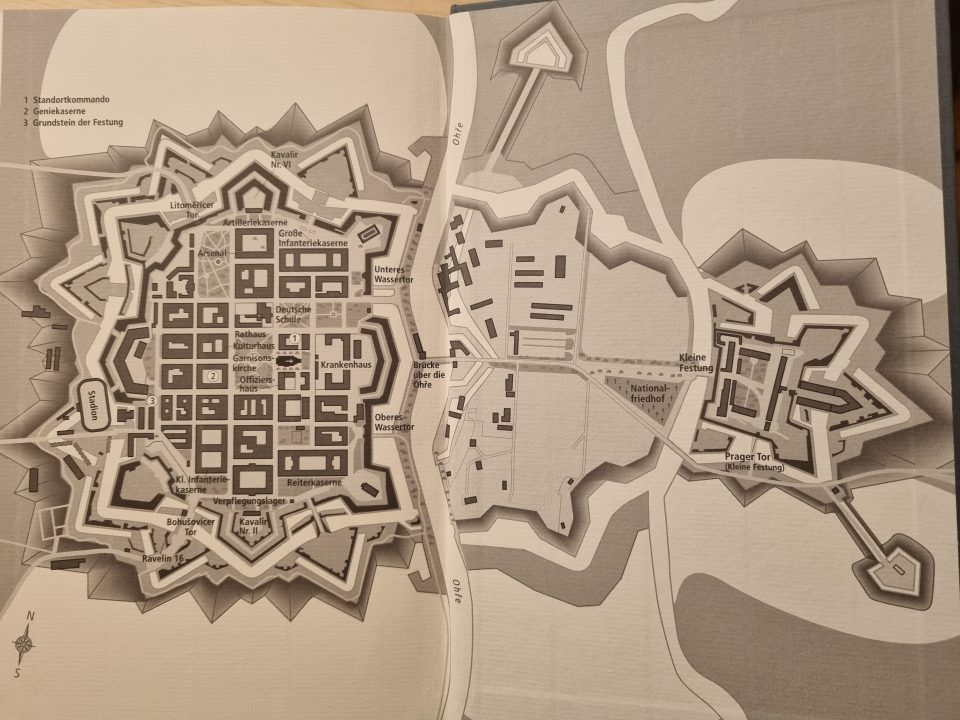

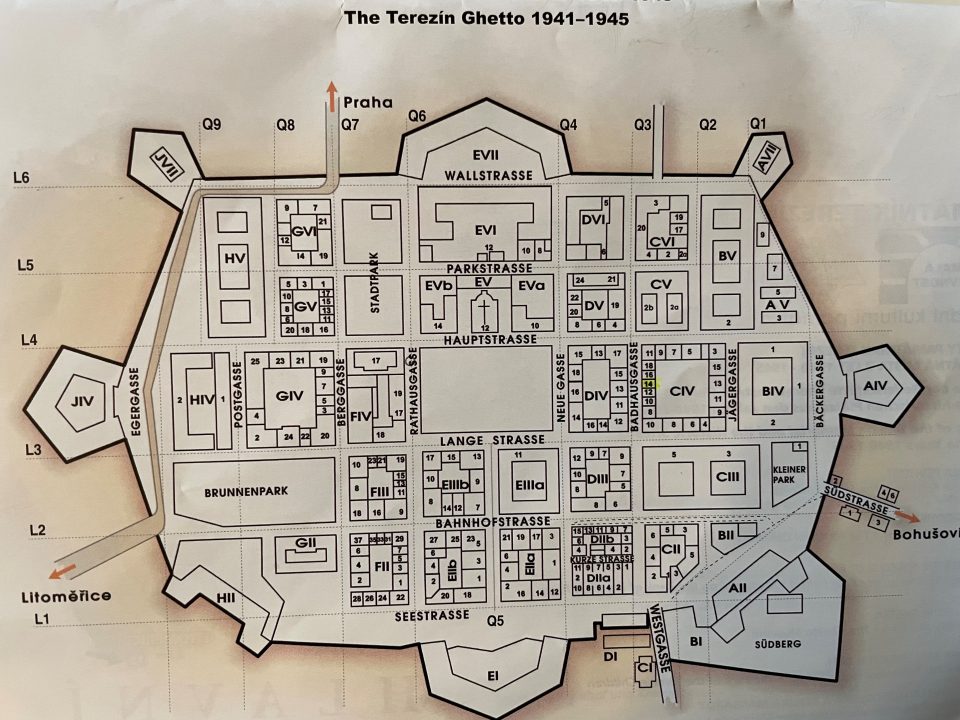

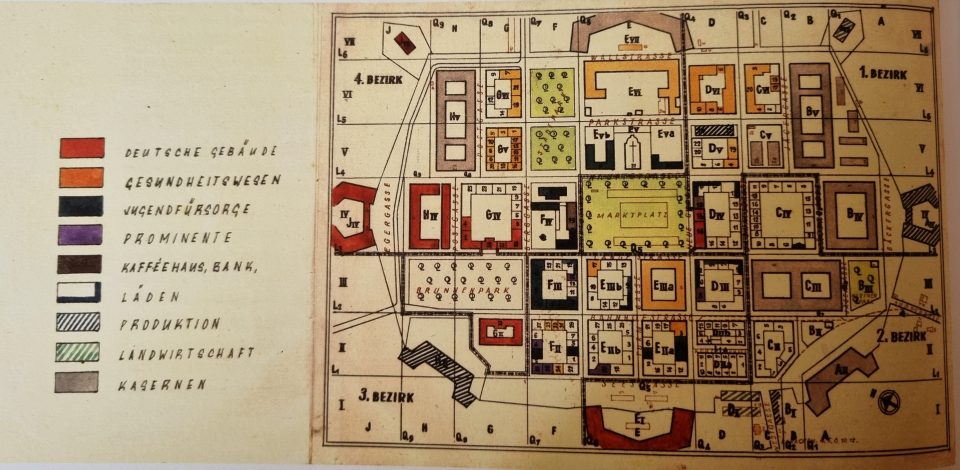

Map of the KZ Theresienstadt of 1943. Ignaz and Ritschi Sobotka were housed at Badhausgasse 14 (yellow). The names which were given to the streets were chosen to mislead the international public about the true intention of the KZ and to create the illusion of a “resort for elderly and privileged Jews”.

House and street where Ignaz and Ritschi were detained in today’s Terecin

Almost all Austrian Jews who were sent to Theresienstadt were deported from Vienna during a four-month period from 21 June until 10 October 1942. Thirteen transports brought about 14,000 prisoners with an average age of 69 years. Most of all, the German prisoners had been told that Theresienstadt was a spa town where they could live out their days in comfort, if they signed over their property to the Third Reich, so they sometimes arrived in elegant clothes. The Austrian Jews had no illusions any more because they had already been radically and efficiently dispossessed and humiliated before their departure.

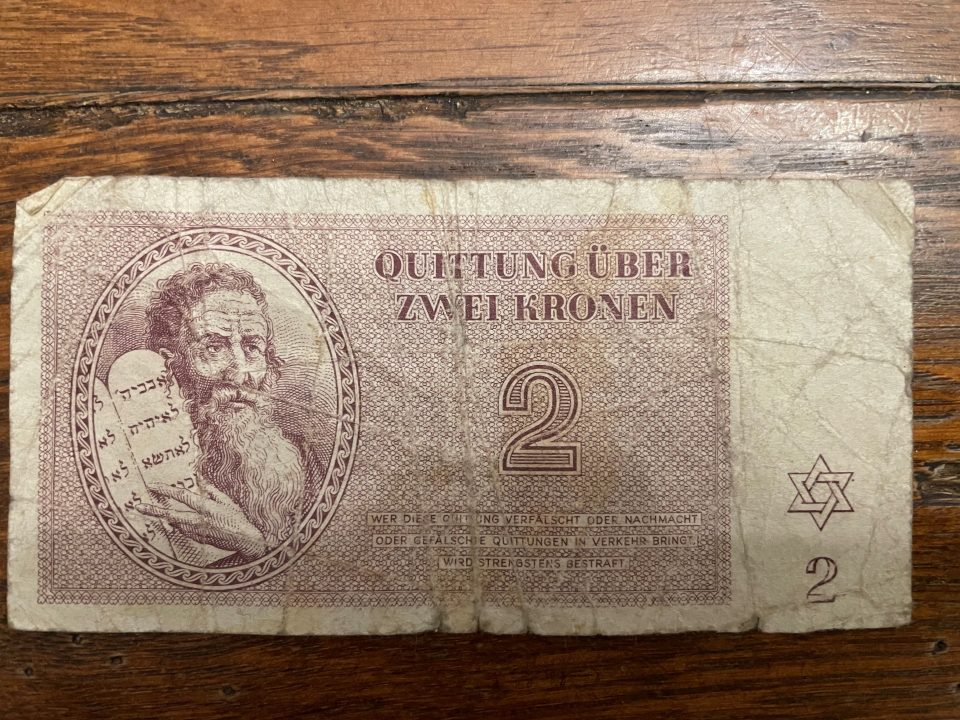

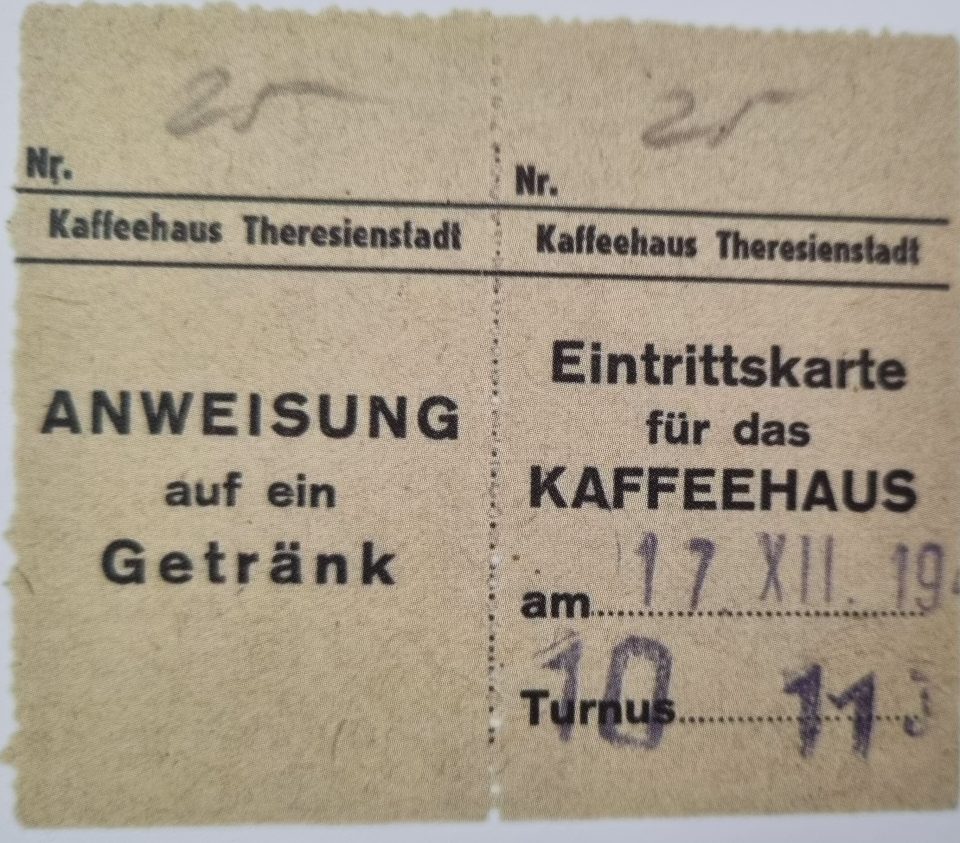

Ludwig Hift, a Viennese banker, was deported to Theresienstadt in October 1942 and described that he was ordered to draw up plans for setting up a “Bank of the Jewish Self-Administration”, which was supposed to issue special “Lagergeld” (camp currency) and confiscate any money prisoners brought with them or received. The NS deceit was meticulously planned: all prisoners received monthly amounts of camp currency according to their status from the Council of Elders to the non-working old, but this camp money was deposited in a frozen “savings account”, to which the prisoners had no access. In March 1943 the first current account and savings account cards were delivered from nearby Bauschwitz and the first banknotes from the national bank in Prague. Desider Friedmann from the Viennese Jewish Community was appointed head of this bank to give some semblance of respectability to this bogus institution in the eyes of the international public. If relatives or friends from outside transferred money to prisoners, the amount was immediately credited to their phoney accounts and not even paid out in camp currency. Although the money went directly to the SS camp authorities in the form of this mock bank, the recipient had to sign that he or she had received the money. None of the prisoners took this bank seriously, as they saw through this Nazi scam. But the bank figured prominently in the visit of the International Red Cross and the NS propaganda film. In the summer of 1945, the bank was dissolved by the Soviet army and the blocked money amounted to 20,000 Czechoslovakian crowns, which could now be paid out to owners. But apart from the approximately 1,000 persons still remaining in Theresienstadt, only a few hundred survivors applied for the 1,000 to 5,000 Czechoslovakian crowns they were entitled to.

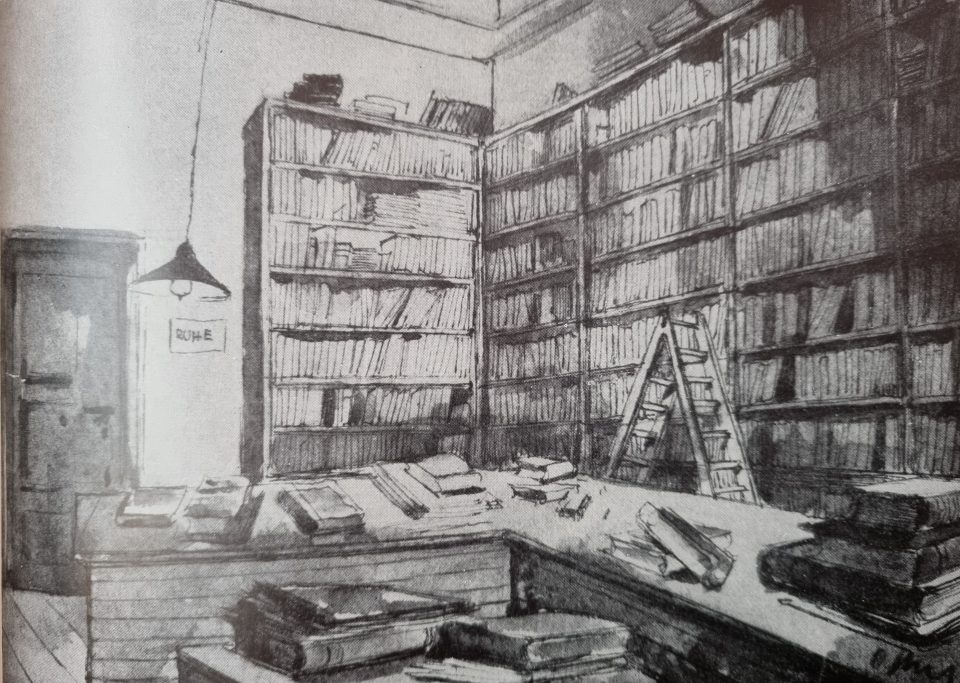

On 17 November 1942 a library was set up in front of the “Hamburger barracks”, which was headed by Emil Utitz, a university professor from Prague. The conditions under which the library had to offer its services were very difficult. Continuous epidemics, no disinfectants, the prevalent dirt, and grime caused many illnesses among those who worked in the library. Usually only half the staff was able to work. Parcels of books were delivered to the different barracks and houses and the House Elders were to distribute the books to those interested. The lending library did not function very well, since often books were not returned because the last reader died or was deported and no one knew where the book had ended up and no one had the strength, energy, or motivation to look for it. The majority of books came from the luggage of the new arrivals, which was confiscated and after checking the books, the ones which were of no use for the SS and not considered “dangerous or subversive” were passed on to the library, as well as books which were confiscated in Jewish institutions, which were closed down by the Nazis. Unfortunately, the tastes of the readers could not be met, as there were many religious books, scientific books and nearly no novels, light-hearted romances, children’s books, and practically no Czech books.

Since 1943 it was possible to spend some time in the reading room of the library and the prisoners had to pay 50 crowns camp currency to use the library, which was no problem for the interested detainees. They could not do anything else with this useless camp currency anyway, apart from purchasing a cup of coffee substitute in the “coffee house”, which had been set up for the visit of the International Red Cross, if the prisoner got the permission to sit there. Suddenly in May 1944 the library had to be moved to a former inn (L 514) within three days and nights in preparation for the Red Cross inspection. The elderly and sick who had been housed there before had to be evacuated overnight. Many of those who helped with the transport of the elderly and sick and who carried the books were immediately after completion of these tasks deported east before the international visitors arrived.

In November 1942 the International Red Cross, prompted by the World Jewish Congress, asked for permission to inspect concentration camps. After 466 Danish Jews had been deported to Theresienstadt in October 1943, also Danish officials requested to see the “Ghetto Theresienstadt”. The Nazis then realised that a carefully orchestrated visit of Theresienstadt could help them refute reports about the true conditions in concentration camps in general. So, the KZ Theresienstadt was thoroughly prepared for its role as a “Jewish settlement area”. A few so-called “shops” were opened with an extremely limited selection of mostly used goods, which were supposed to make Theresienstadt look less prison-like. A “coffeehouse” was opened where prisoners according to a ticket system could sit for some time with a cup of coffee substitute and listen to an orchestra made up of their fellow prisoners. Some public spaces were established, as can be seen on the maps above, and prisoners were no longer confined to their barracks. So, they could attend cultural performances, which were now allowed to function because they supported the Nazi propaganda plans. The city beautification in preparation for the Red Cross visit was officially ordered to begin in December 1943 and throughout the spring of 1944 the prisoners had to participate in the charade of renovating the city in places where the delegation was to have their guided tour. First the number of prisoners had to be reduced to deal with the problem of overcrowding. Most of all, orphans and those suffering of tuberculosis had to disappear. 7,500 were deported east and when the list for the third transport was ready, the SS-commander Rahm interfered and picked out some young people and nice-looking girls, who were to remain in Theresienstadt to be presented to the Red Cross delegation. The tragic spectacle of striking prisoners off the list of the third transport and adding others to it to fulfil the required quota lasted the whole night – Rahm himself decided about life and death of the prisoners. Loading the prisoners onto the railway waggons then took the whole day because some prisoners tried to escape and hid in the city. So, those from the “reserve list” were loaded onto the waggons to replace the missing prisoners. The visit took place on 23 June 1944 and all SS-men appeared in civilian clothes except SS-commander Rahm. Early in the morning women had to scrub the pavements. Then SS-men led the guided tour “accidentally” past a group of nice girls walking towards fields with agricultural tools, past bakers who unloaded bread wearing white gloves. In the “community hall” an orchestra was playing and when the commission reached the sports ground, the players scored a goal in front of the imprisoned spectators, who were forced to attend the spectacle. “Accidentally” just at the moment when the commission passed the “greengrocer” fresh vegetables were delivered and in the spick-and-span dining hall neat waitresses served excellent lunches. Children were riding on a merry-go-round and the director of the “bank” was smoking a cigar. The commission did not know that the same man had just spent three months in the prison of the small fortress for smoking a cigarette, which was strictly forbidden. Eppstein, heading the Council of Elders, was dressed in a black suit, and was driven in a car by one of the cruellest SS-men of the KZ, who ironically bowed submissively when opening the car door for Eppstein in front of the commission. In the main square the “city orchestra” played a military march. Old, sick, or blind prisoners were not allowed to leave their barracks that day and even the Czech policemen, who had to patrol the KZ normally, were not to be seen. The Red Cross officials looked around, asked polite questions, and seemed impressed. It cannot be verified nowadays, whether they were actually deceived by the Nazis or whether they reported positively because they did not care or did not know what else they could do, although the war was already going poorly for the Germans. As soon as the visitors had left, the perfidious deceit continued, the drama of lies was not over yet, when a film crew arrived.

In August and September 1944, a Nazi propaganda film was shot. Outside the walls of the fortified city a stage was erected on a meadow and an entertainment programme for thousands of prisoners was presented there. At the banks of the river Eger a bath was built and specially selected prisoners had to perform high diving stunts. Immediately after the end of the filming the bath disappeared. In the “coffee house” a group of former well-known ministers, officers, professors, and scientists – now prisoners – were filmed, dressed in respectable clothes. A proper “children’s home” was presented as well as a post office that delivered parcels. Groups of people were shown at the mock “bank” who deposited money and withdrew money from their bank accounts. Hans Hofer, a comedian from Prague, who was deported to Theresienstadt in 1942 and then in 1944 to Auschwitz and Kaufering-Allach, survived the holocaust and talked about the production of NS propaganda films in Theresienstadt after the war: At the end of 1942 Goebbels and the propaganda ministry of the Third Reich undertook a first attempt at making a propaganda film about Theresienstadt. They were the producers of this film that featured tens of thousands of unpaid stage extras, the prisoners. The NS intention was to counter the bad press they had abroad, the “atrocity propaganda” of the Allied Forces. The first part of the film had already been filmed in Prague and the second part in Theresienstadt. It told the story of “Mr. Holländer” and his transport from Prague to Theresienstadt and his life there. The involuntary actor and his wife were soon after their brief career as “actors” murdered in the gas chambers of Auschwitz. The film was once shown in Prague and then disappeared because it showed the dirt and dreariness of life in the “ghetto for the privileged” and so was useless for propaganda purposes. Then the second time round a professional film team was hired and the “beautified “ KZ Theresienstadt was now the perfect stage for this NS deceit, titled “Der Führer schenkt den Juden eine Stadt” (The Führer Presents the Jews with a City). Kurt Gerron, a famous director and actor in many UFA-films, had arrived with a transport from Holland in Theresienstadt. He started the filming at the bank, then the post office, the SS swimming pool, and then the high diving at the Eger river. While most of the prisoners reacted with passive resistance, there were some who were keen on appearing in the film. On the other hand, most prisoners immediately disappeared as soon as they saw a person with a white arm band with the word “Film” on it. The SS contracting authority wanted to see only stage extras in the film who looked like the Jews of the NS race theory. Yet, Hans Hofer wrote that it was extremely difficult to find those people among the prisoners in Theresienstadt, because he had never seen more blond and Nordic-looking people in any other place. But whoever was blond was not chosen as a stage extra. Consequently, the female high diving champion was not to perform in the film because she was blond. Firemen in new uniforms extinguished a mock fire. The opera “Hoffmanns Erzählungen” (The Tales of Hoffmann) was performed, for which the prisoners had to make the stage props and costumes and the “orchestra of Theresienstadt” played, conducted by Karel Ancerl from Prague. The musicians had been issued dark suits for the occasion, but there were no matching shoes, so flower boxes had to be arranged around the stage, which hid the wooden shoes of the prisoners playing the instruments and of the conductor. Even a bogus operation in the hospital and small children in a crèche were filmed. Kurt Gerron never saw the scenes he had filmed. It is unknown what happened to this propaganda production after it was developed and copied in Prague and sent to Berlin. Some fragments of the film were discovered in 1965 near Melnik in Czechoslovakia. It was a typically outrageous piece of pure antisemitic Nazi propaganda. Kurt Gerron, was sent off to Auschwitz together with hundreds of others who had been forced to take part in that ruse and died in the gas chambers there.

The Czech conductor Karel Ancerl remembered that the many excellent scientists, actors, comedians, and musicians, who were imprisoned in the KZ Theresienstadt, were to be thanked for the efforts they made under these abysmal circumstances to offer a few hours of joy to the prisoners by organising improvised lectures and performances in attics and cellars after their hard work, often at night and often secretly under threat of punishment. Ancerl reported that even at a time when the Nazis allowed the formation of an orchestra due to the upcoming international visit and the filming, it was difficult to get the musicians together because of the high fluctuation of arriving and departing transports and the lack of instruments. Usually, they had more musicians than instruments. Furthermore, they lacked scores, they lacked paper and ink to copy the few existing scores. Any copying and any rehearsals had to take place after long hours of exhausting forced labour. But the enthusiasm of the musicians was so catching that nearly no one missed a rehearsal. Ancerl stressed that he would be for ever grateful to all those doctors, House Elders, professors, agricultural workers, and carriers of Theresienstadt, who helped to set up this orchestra, which existed for less than a year. In a wonderful way it showed the “power of music” which helped the prisoners to overcome the worst hardships. They performed Antonin Dvorak’s “Serenade for Strings” and Josef Suk’s “Meditation über den Choral des heiligen Wenzel” (Meditation over the choral of Saint Wenzel) and several other pieces of classical music. Ancerl pointed out that a composition of the imprisoned composer Paul Haas, “Phantasie für Streichinstrumente” (A fantasy for Strings), which Haas had written in Theresienstadt, was premiered by the “orchestra of Theresienstadt”. This performance featured in the propaganda film as well. Ancerl further noted that unfortunately apart from himself only three more colleagues of this “orchestra of Theresienstadt” survived the holocaust.