POST WORLD-WAR II REVIVAL OF JEWISH TEXTILE TRADING IN VIENNA ACCOMPANIED BY PERSISTENT ANTISEMITISM

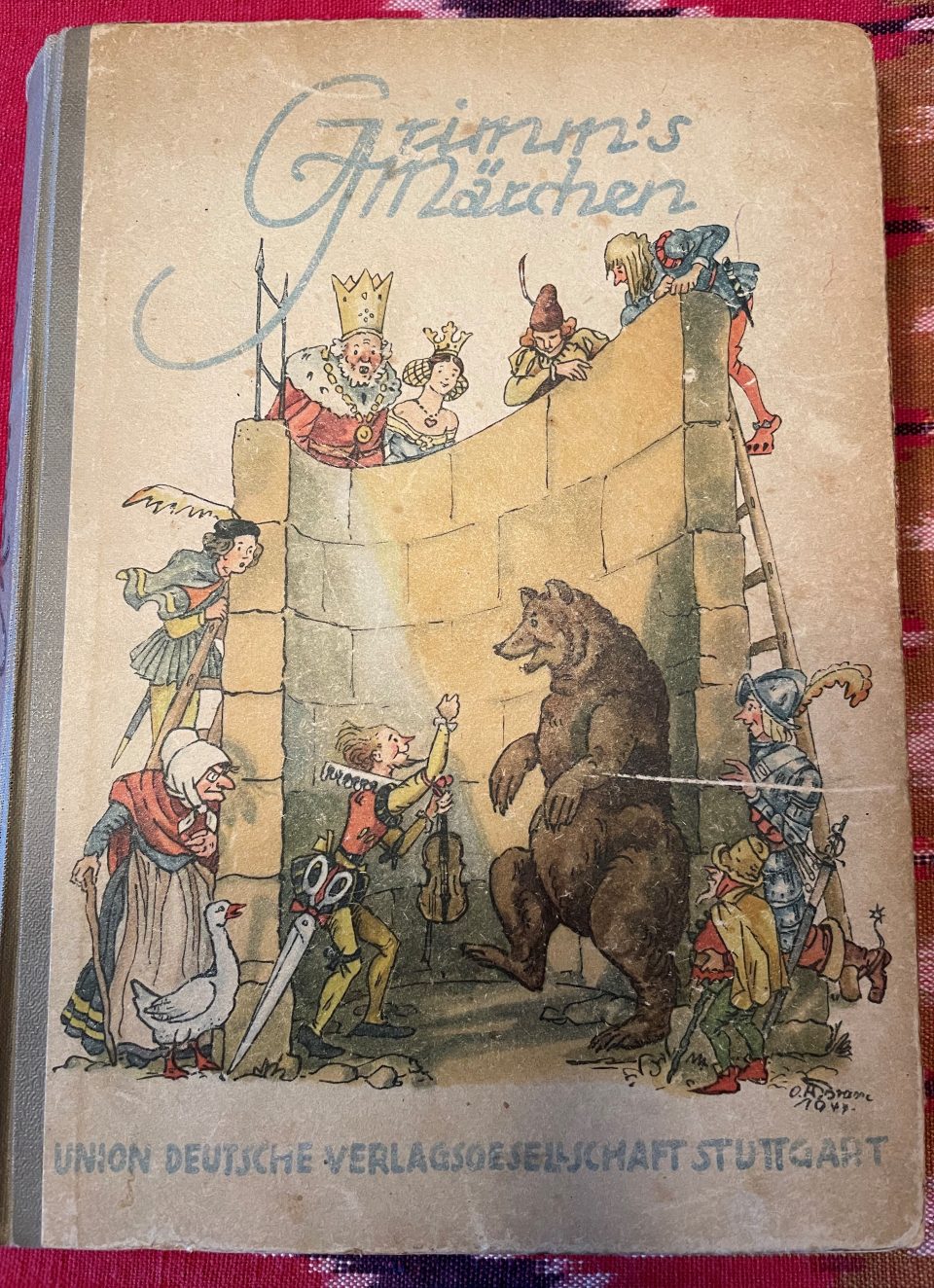

“Textile Quarter” in the 1st district of Vienna near the Danube Canal

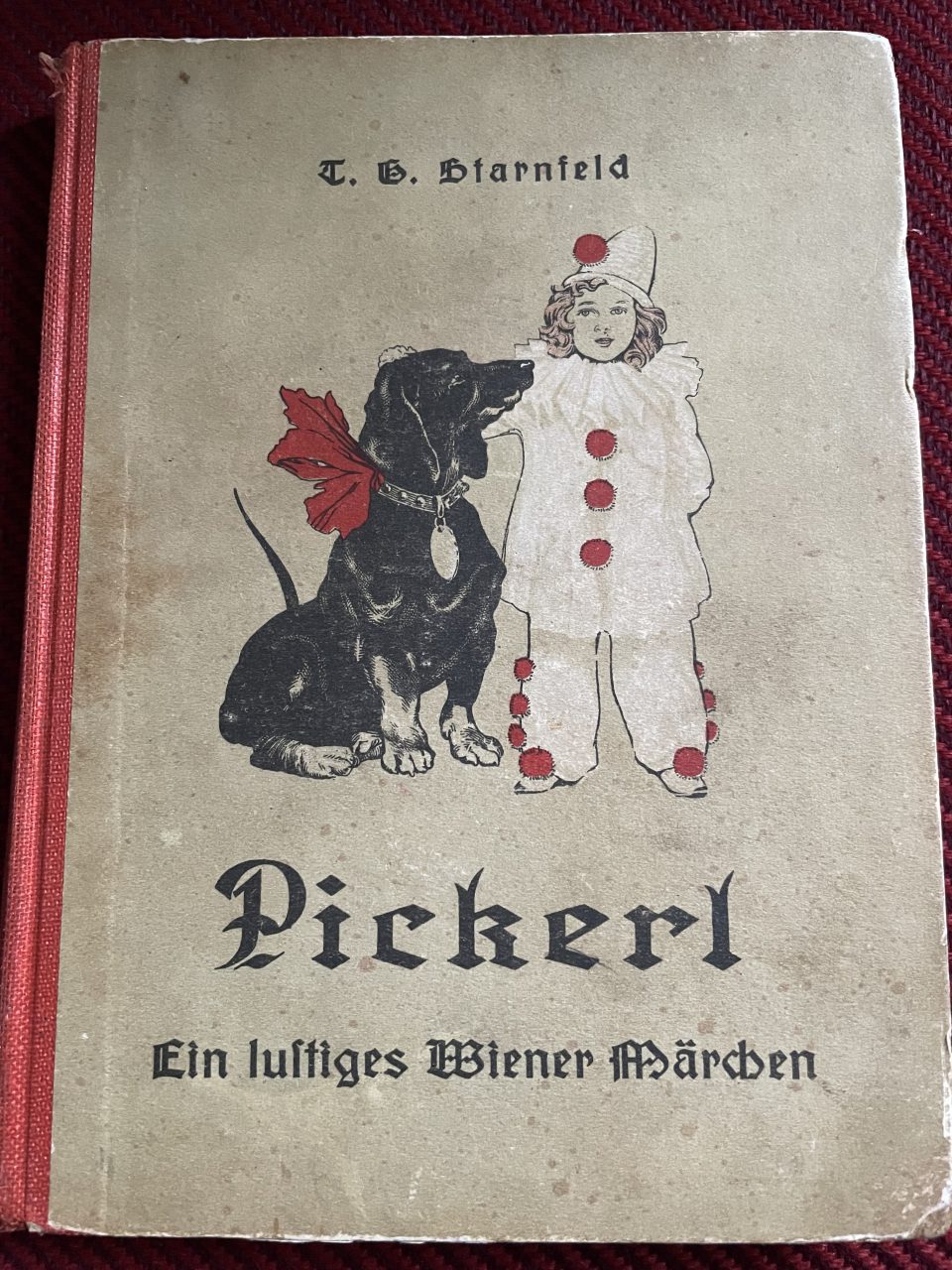

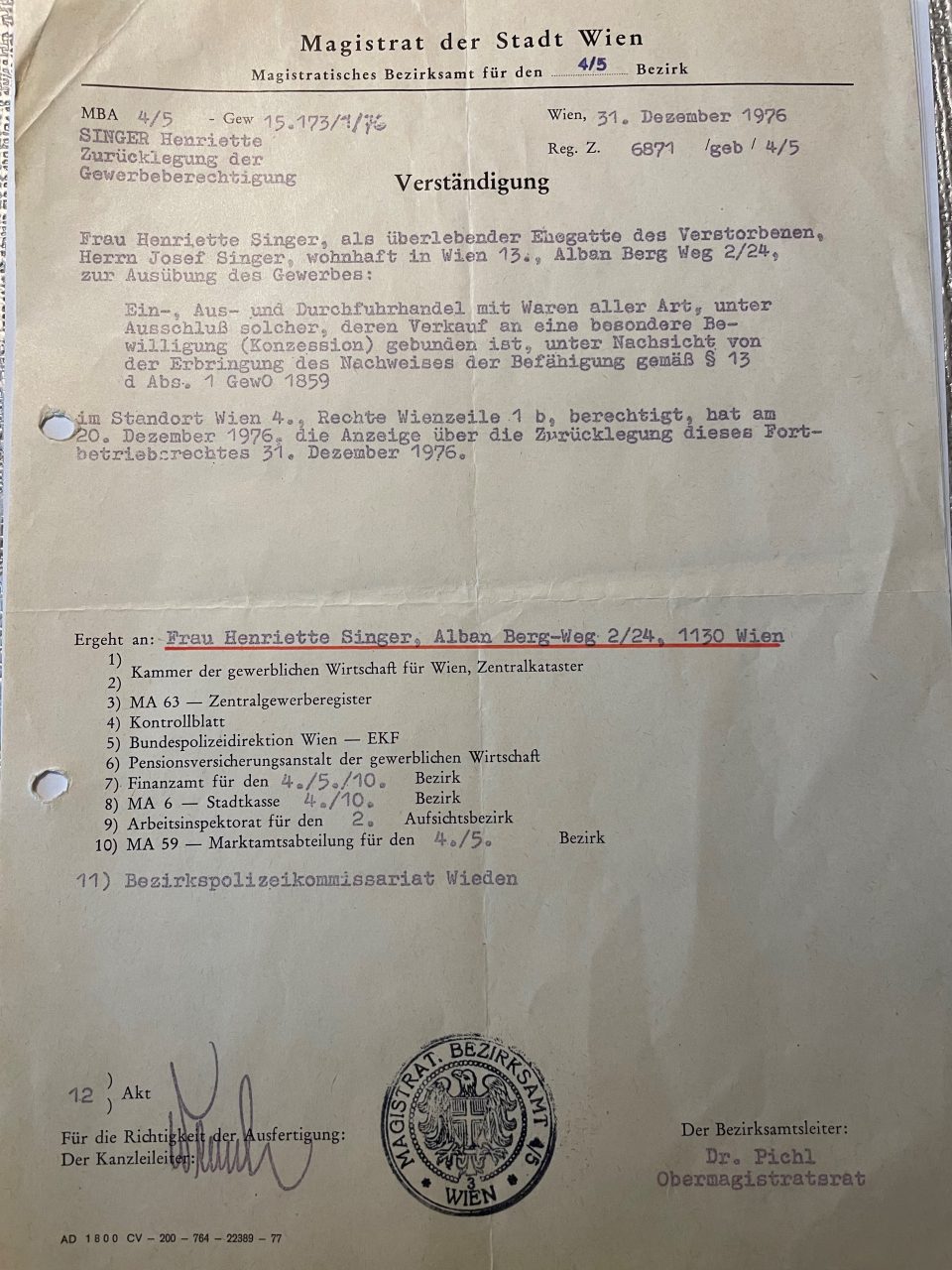

Textile trading on “Naschmarkt”. Left: former textile wholesale and retail trading of Josef and Henriette Singer & partner at Rechte Wienzeile 1b (Bärenmühlendurchgang) in the 4th district of Vienna, Naschmarkt

Textile wholesale and retail business “Singer & Partner”

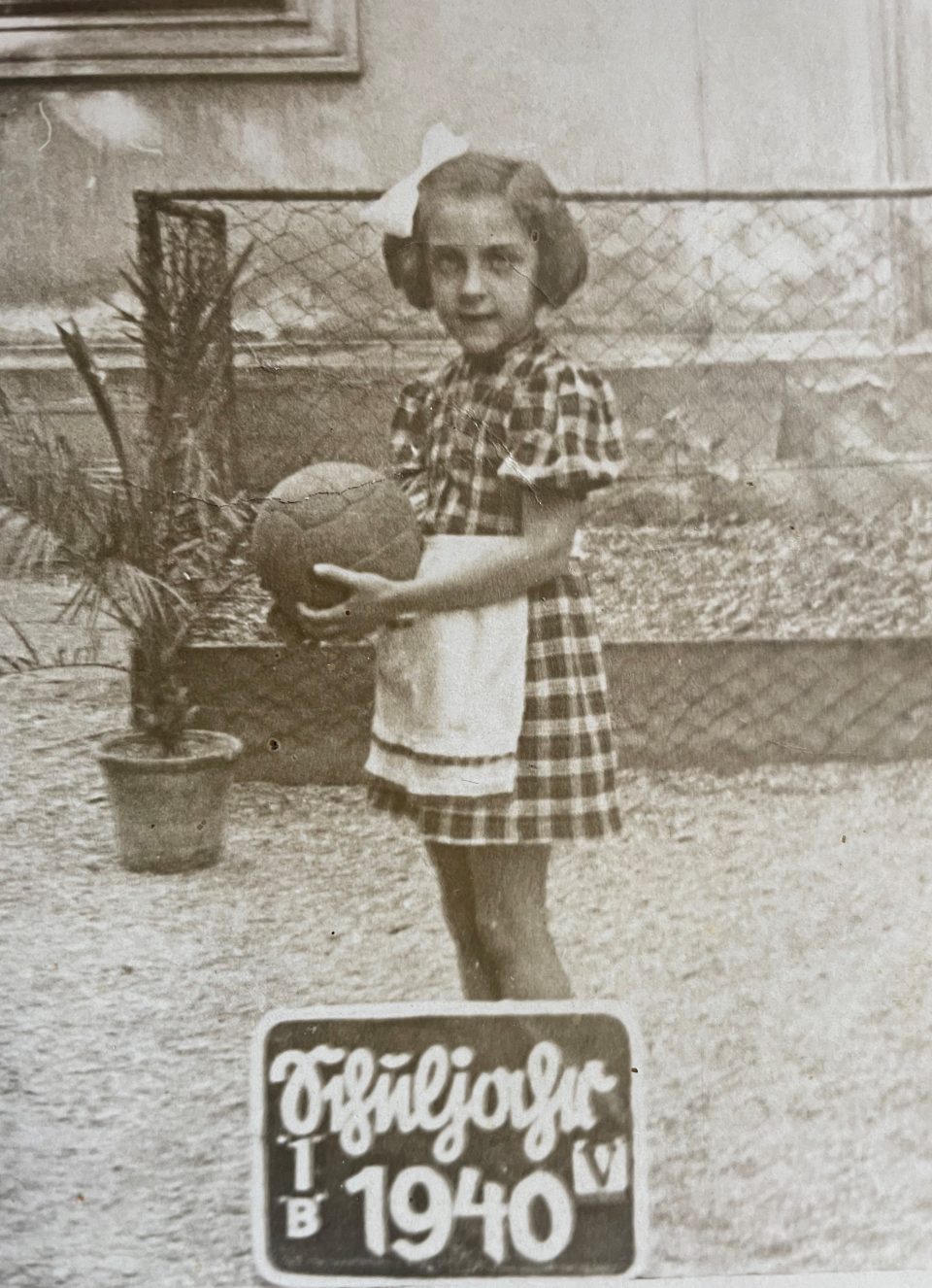

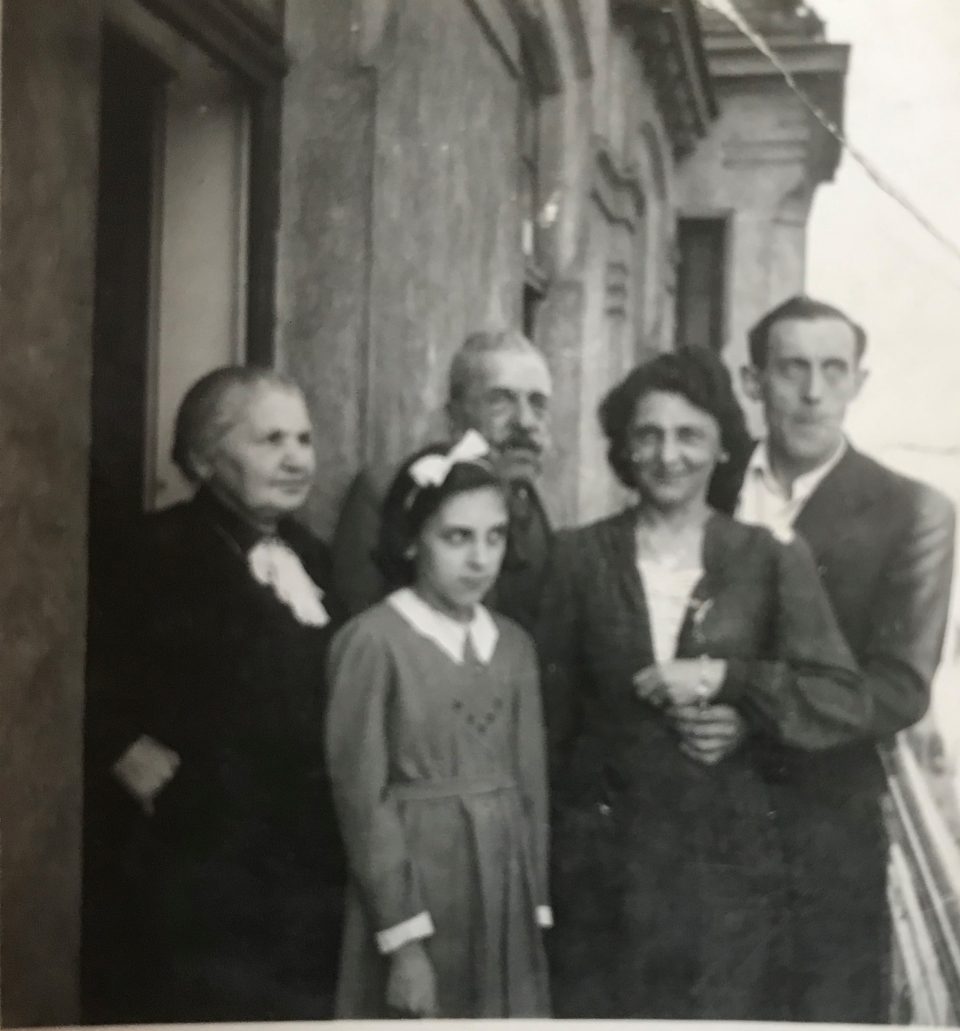

A typical example of a small enterprise in textile trading of Jewish-born Viennese after World War II is the partnership of Josef and Henny Singer at Rechte Wienzeile 1b (Bärenmühlendurchgang) at the “Naschmarkt”. Henriette (Henny) Singer, née Katz, born in 1923, was my aunt. She had survived the Holocaust in Palestine,

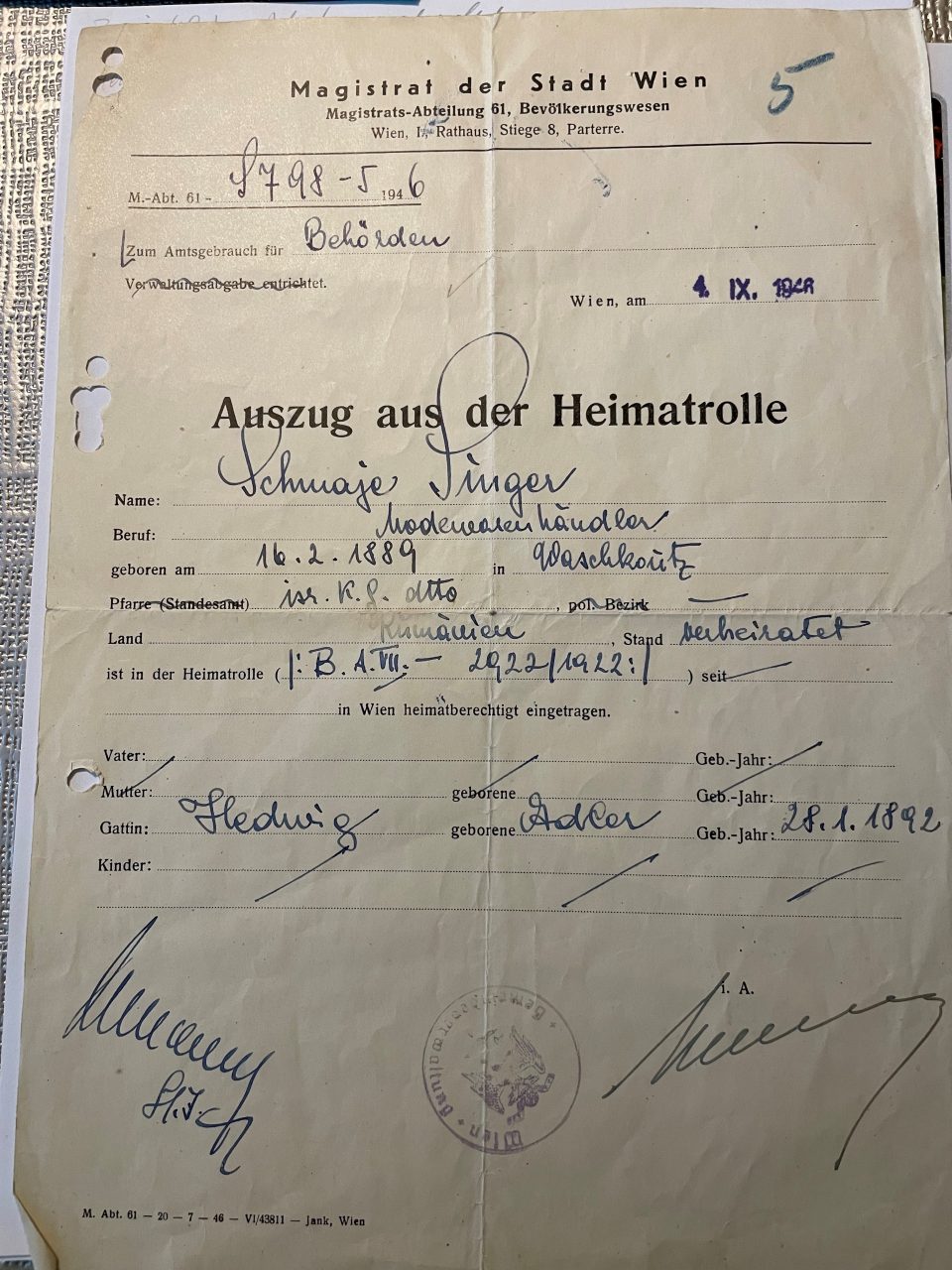

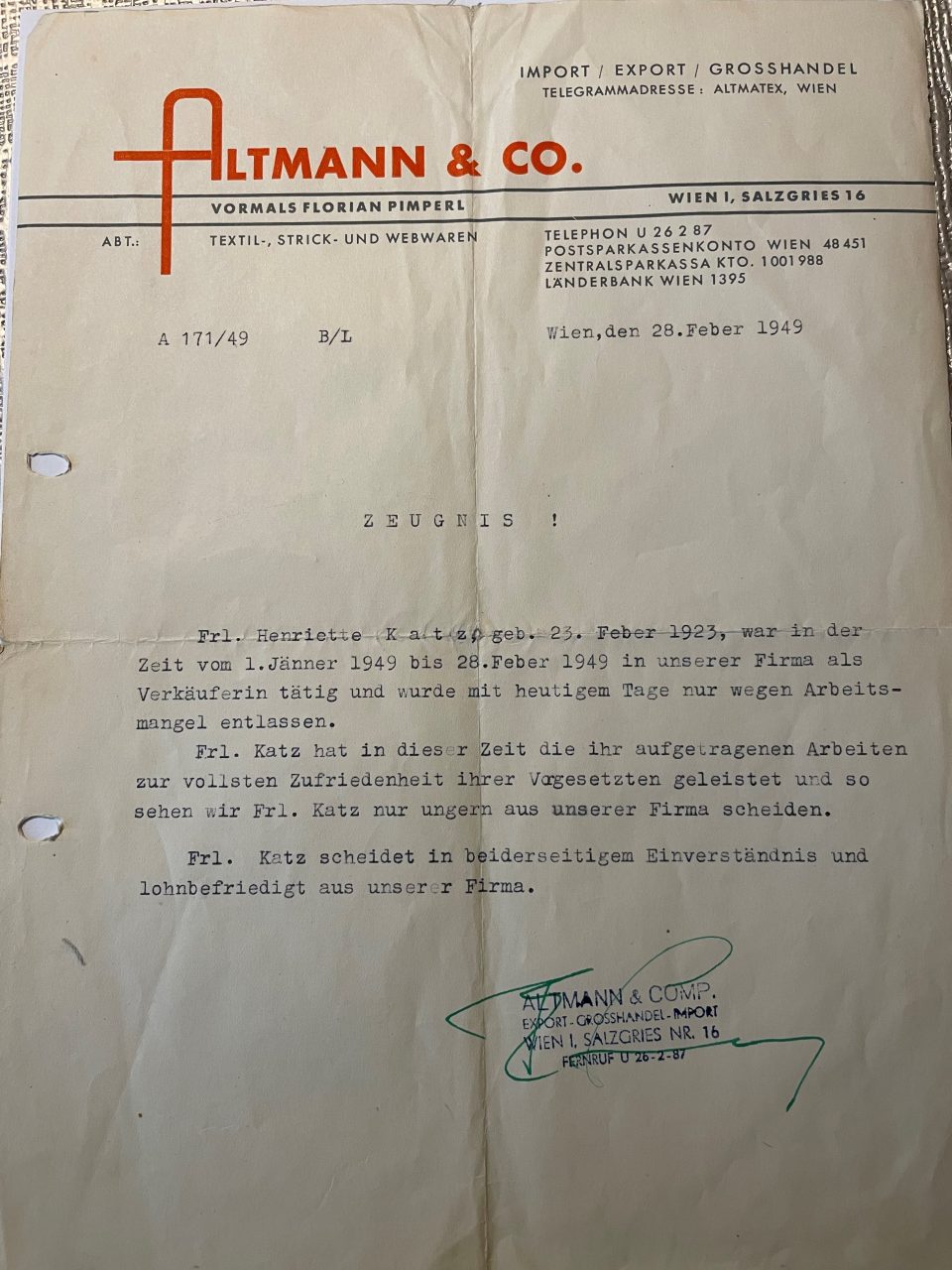

where she met her future husband, Josef (Pepi) Singer, born in 1921, another Austrian refugee. Both were born in Vienna and had to flee the deadly persecution of the Nazis as youngsters; they were both Jewish-born, but from assimilated families, agnostics and committed Austrians. Soon after the end of World War II they returned to Austria, where Pepi worked as a cutter at a tailor’s shop. Henny had trained as a dressmaker in Tel Aviv and soon after her return and before her marriage she worked in the “Textile Quarter” in Vienna at the company “Altmann & Co” on Salzgries 16 in the 1st district of Vienna as a salesgirl. Pepi later continued the family tradition of textile trading by founding his own small wholesale and retail business with a partner. His father, Schmaje (Sami) Singer had been born in Waschkoutz in the Austro-Hungarian region of Bukovina (in 1918 Waschkiwzi became part of Romania after the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, then was incorporated into the Soviet Union and since 1991 it has been a town in Ukraine). Sami moved to Vienna, where he married Hedwig Adler, born in Pohrlitz / Pohorelice in southern Moravia, also in the Austro-Hungarian Empire (after World War I it became a region in Czechoslovakia, today Czechia). In Vienna he worked as a “Modewarenhändler” (a “trader of fashion”) before the Nazi takeover in 1938. Sami Singer died in exile in Jerusalem and Pepi returned to Vienna with his mother Hedwig. They all three, Pepi, Henny and Hedwig, lived together with others who had just returned from exile in a big flat in Favoritenstrasse 40 in the 4th district of Vienna. Henny and Pepi married in June 1949 in Vienna and started a textile trading business with a partner.

Left: Sami Singer’s certificate of citizenship stating his profession as “fashion trader” in Vienna.

Right: Henny’s employment in the Viennese “Textile Quarter” at “Altmann & Co” in 1949

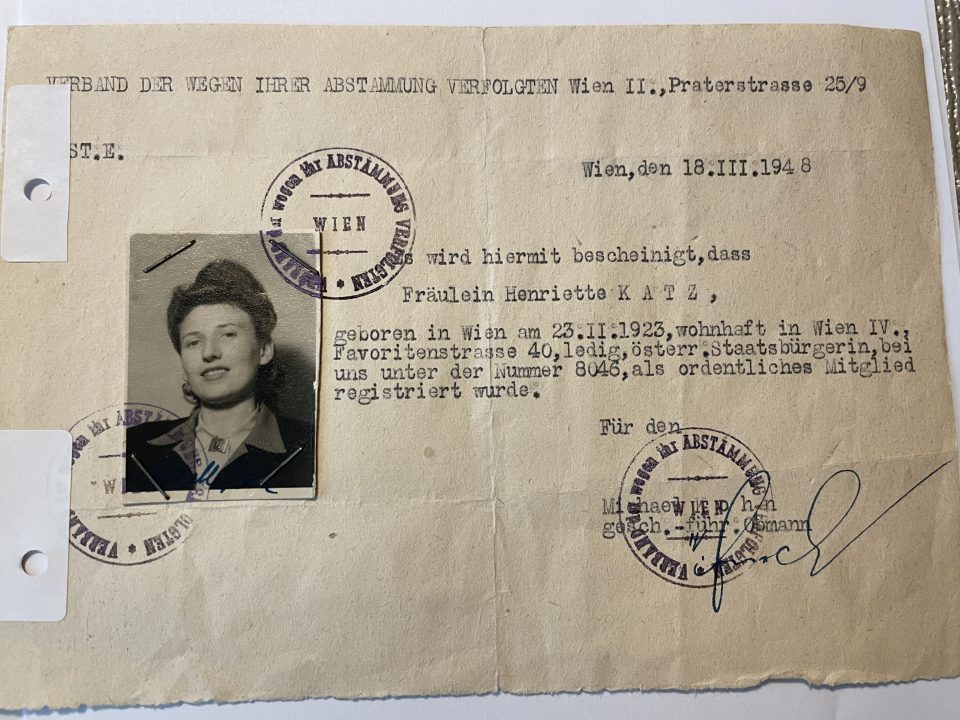

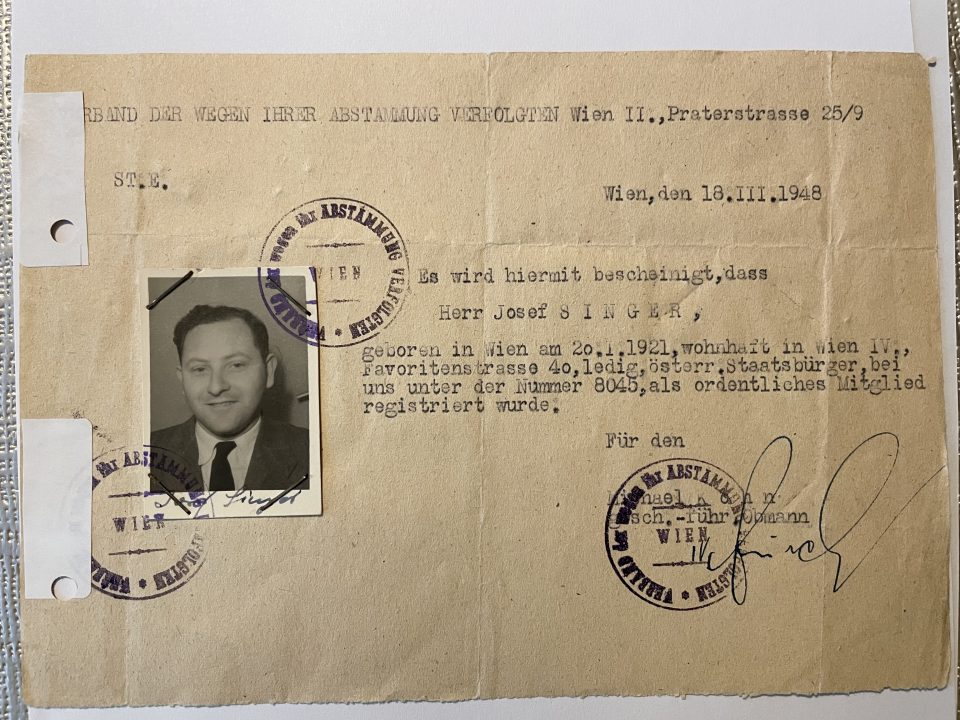

Back in Vienna, both Henny and Pepi became members of the” Association of those Persecuted due to their Origin” in 18 March 1948, see the two documents below:

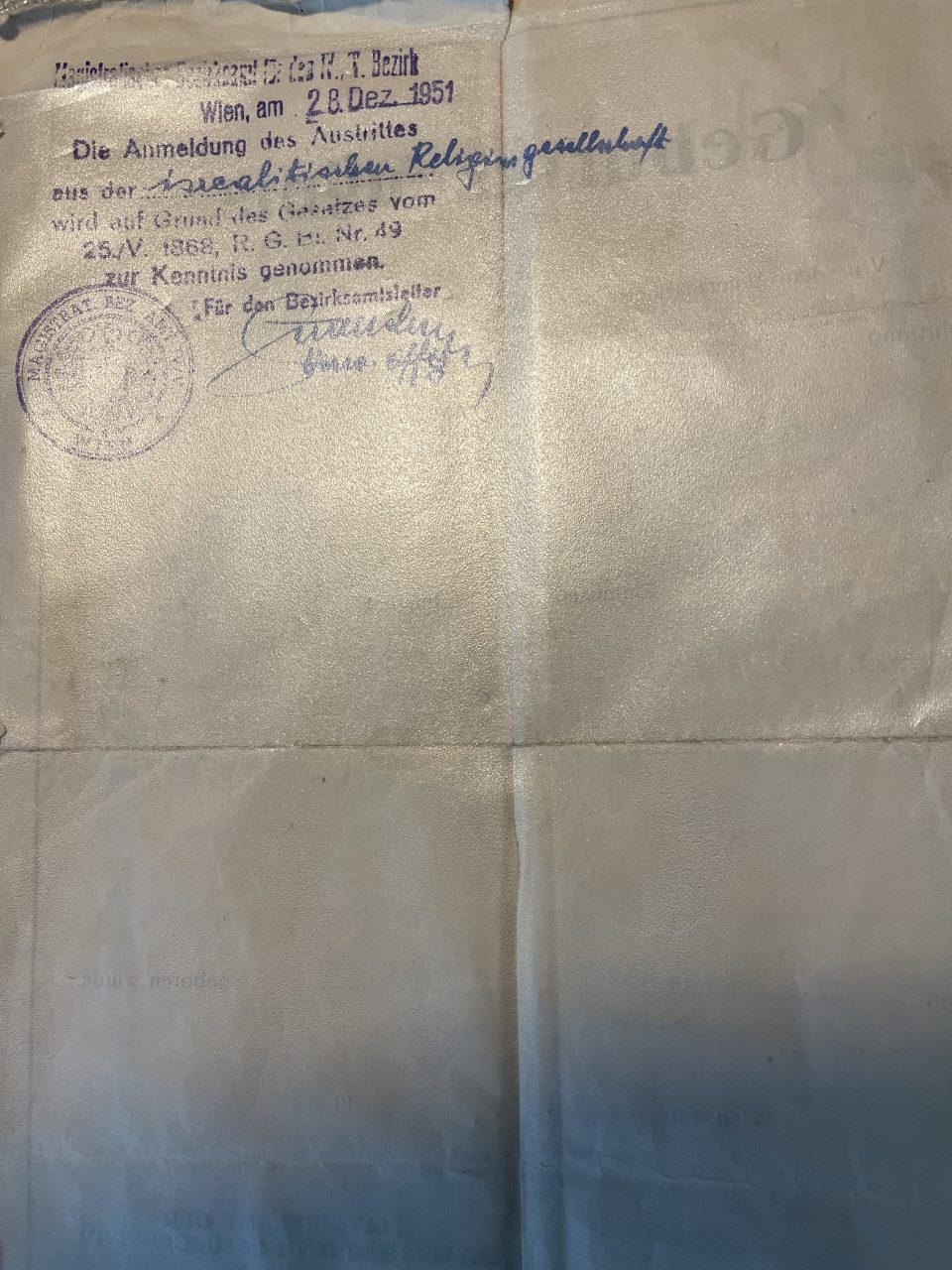

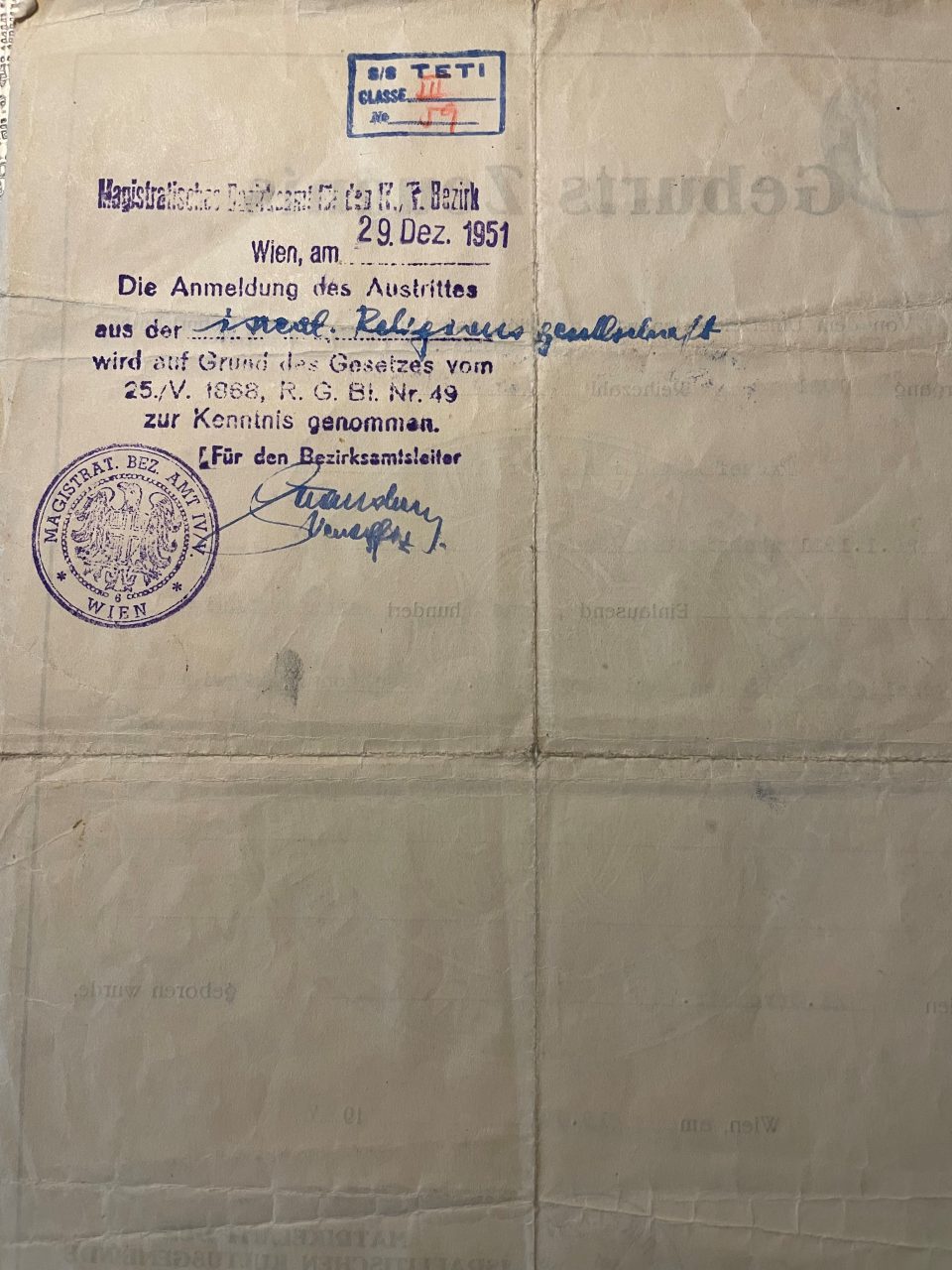

As agnostics they both officially left the Jewish Community (“Israelitische Religionsgemeinschaft – Cultus Gemeinde”) in December 1951:

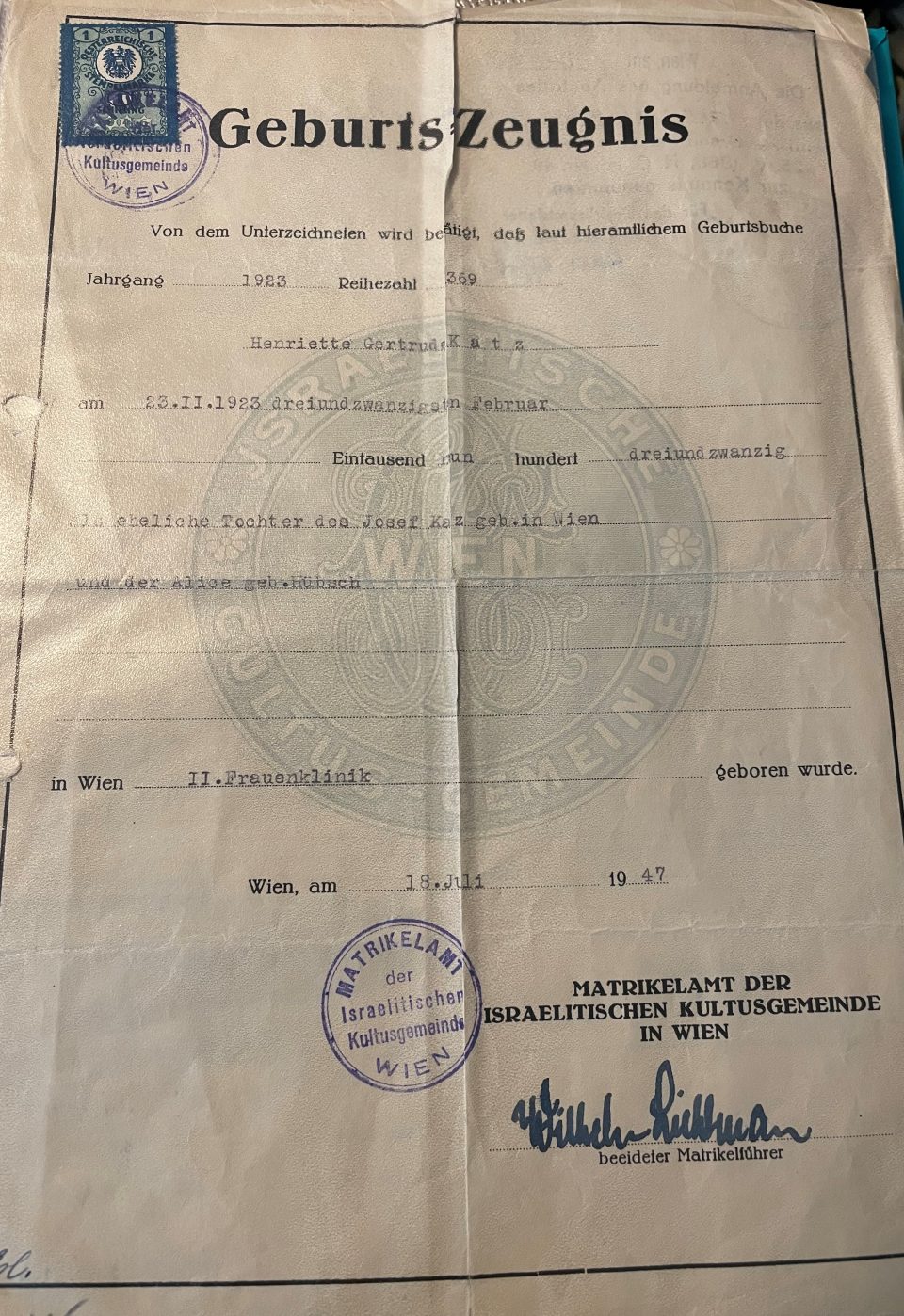

Henny’s birth certificate with the respective remark on the back about quitting the Jewish Religious Community

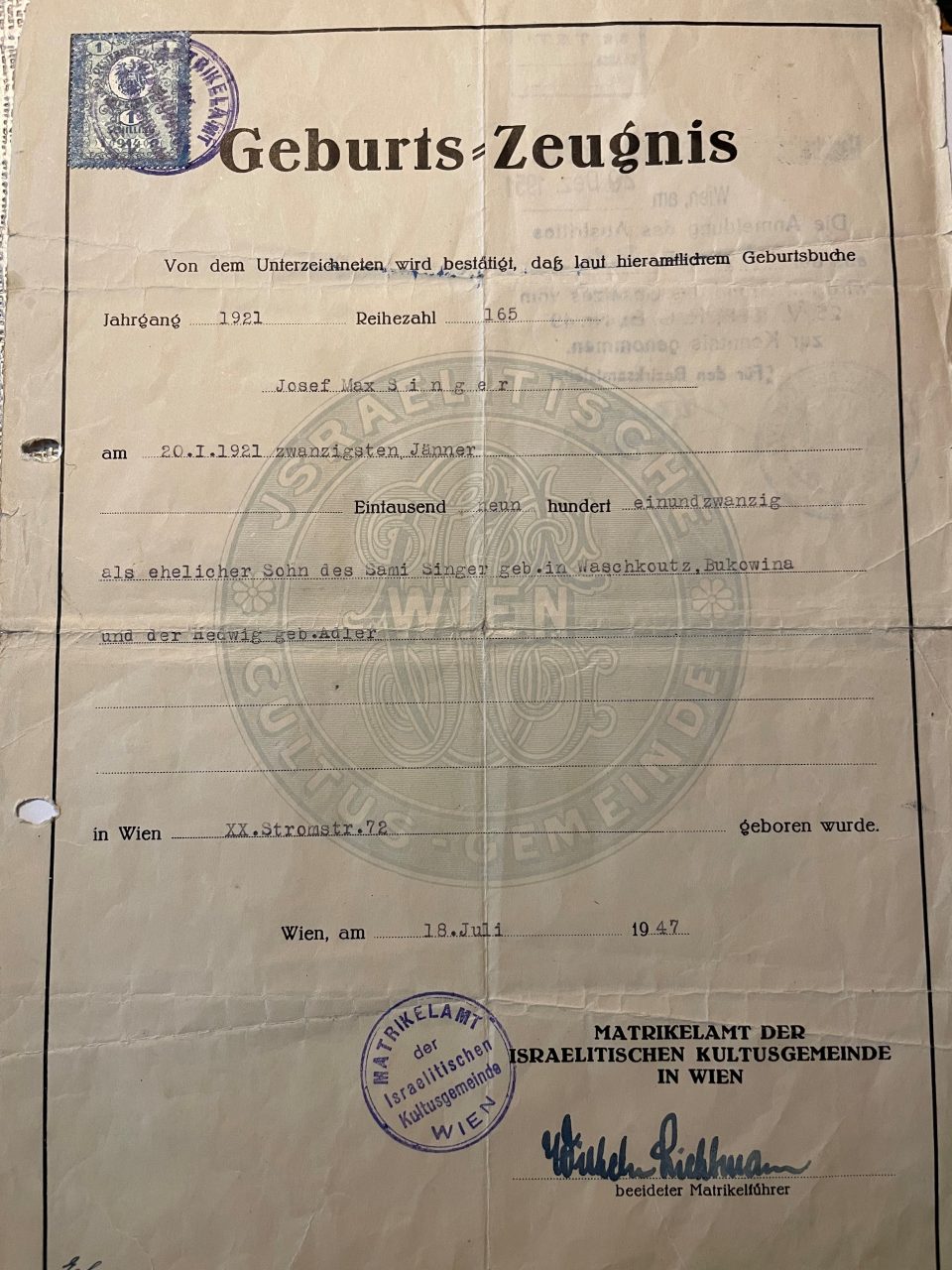

Pepi’s birth certificate with the respective remark on the back about quitting the Jewish Religious Community

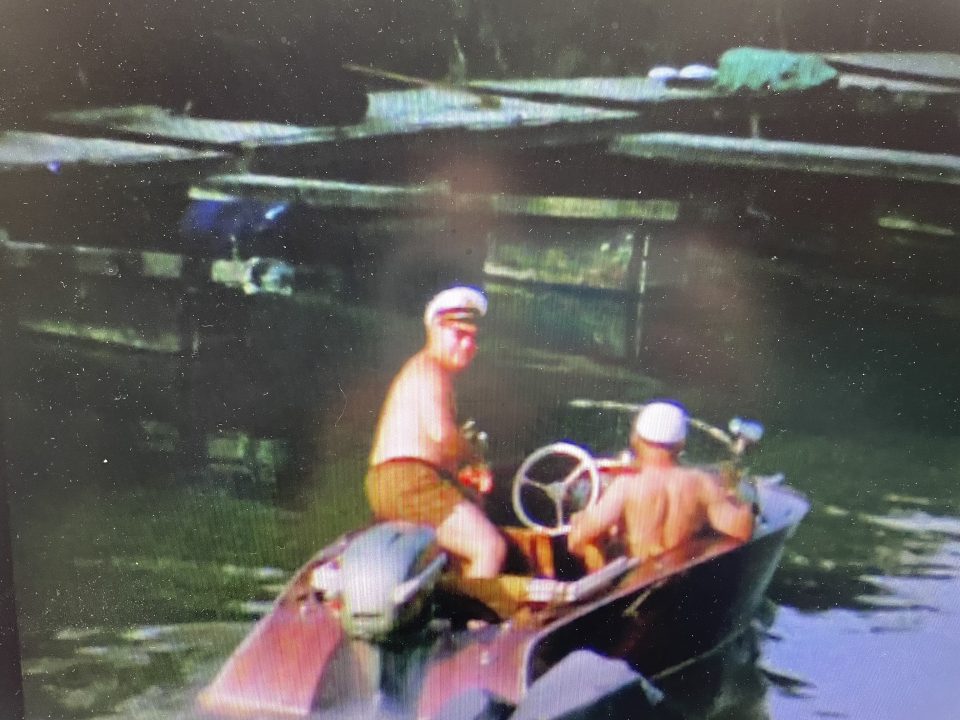

Together with another couple Pepi and Henny rented a wooden cottage on stilts in Greifenstein at the Danube, near Vienna, and spent their weekends and summer holidays there. Pepi loved his small motorboat and took family and friends on short cruises on the Danube in the 1950s and 1960s:

Left: Pepi at the steering wheel, Norbert Katz, Henny’s favourite uncle and a former Viennese footballer on visit from England, on the left and her uncle Karl Elzholz a mechanic at the Vienna Tramways in the middle – both of them my great-uncles

Right: from left to right: my grandmother Lola, Pepi, Norbert and Karl

Pepi and Henny loved to entertain family and friends

On two different visits of the Katz family from England to Vienna. Left: Pepi with Norbert and his wife, my great-aunt Agi; right: Pepi and Henny in the middle, Norbert and Agi on the right

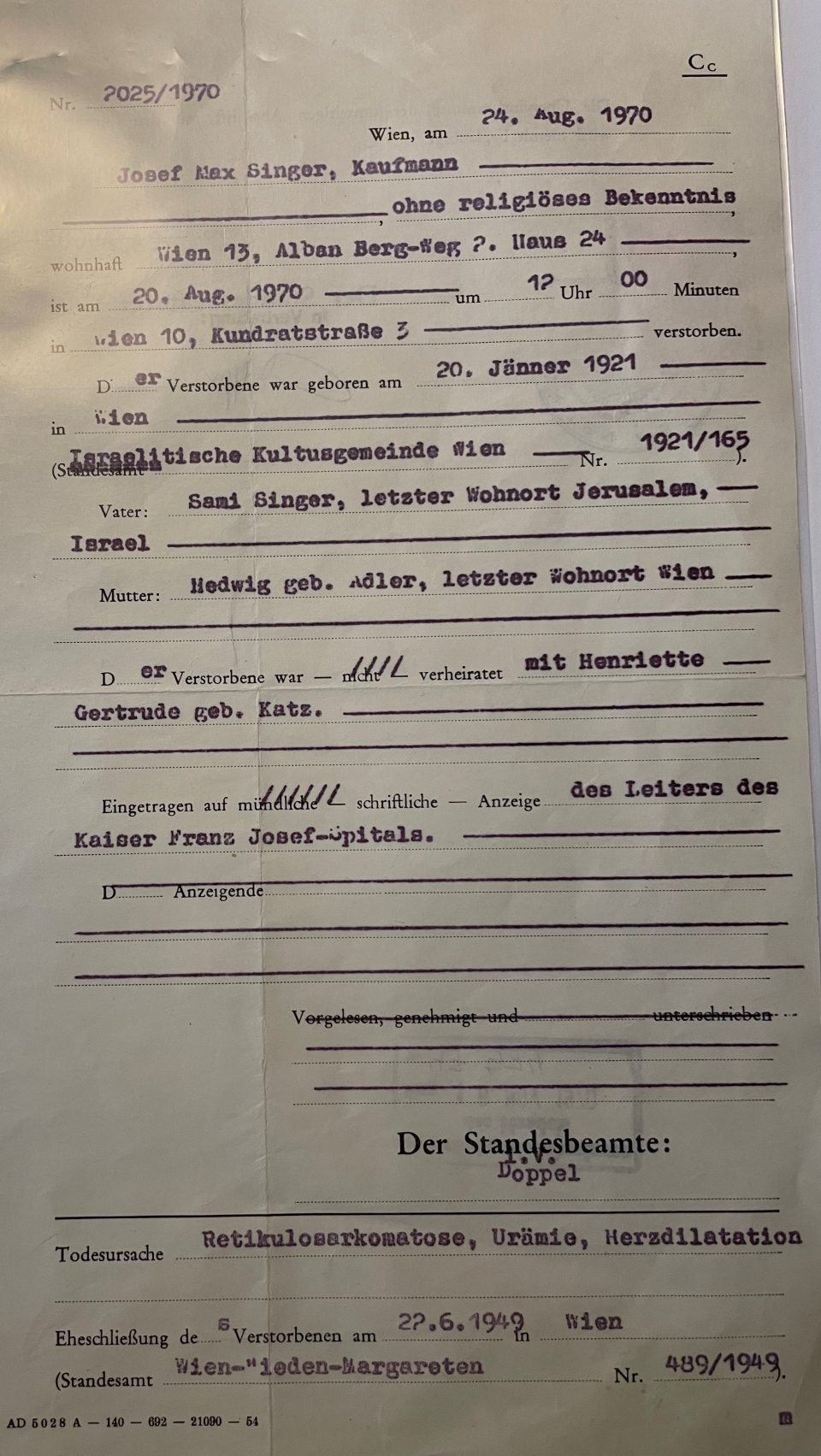

Pepi died of cancer in 1970 and Henny continued the textile trading business until 1976, when she handed back the business license for trading in textiles and took on various secretarial jobs as an employee until her retirement:

Left: death certificate of Josef Singer, right: Henriette Singer returning her business license

The entrance to the Singer’s textile wholesale and retail shop, Rechte Wienzeile, today

Henny with my great-aunt Käthe Elzholz, the wife of Karl, on the left and with my grandmother Lola on the right

Left: Henny with Käthe and with Henny’s new partner Richard Brauneis, a tailor. Right: Henny with Käthe

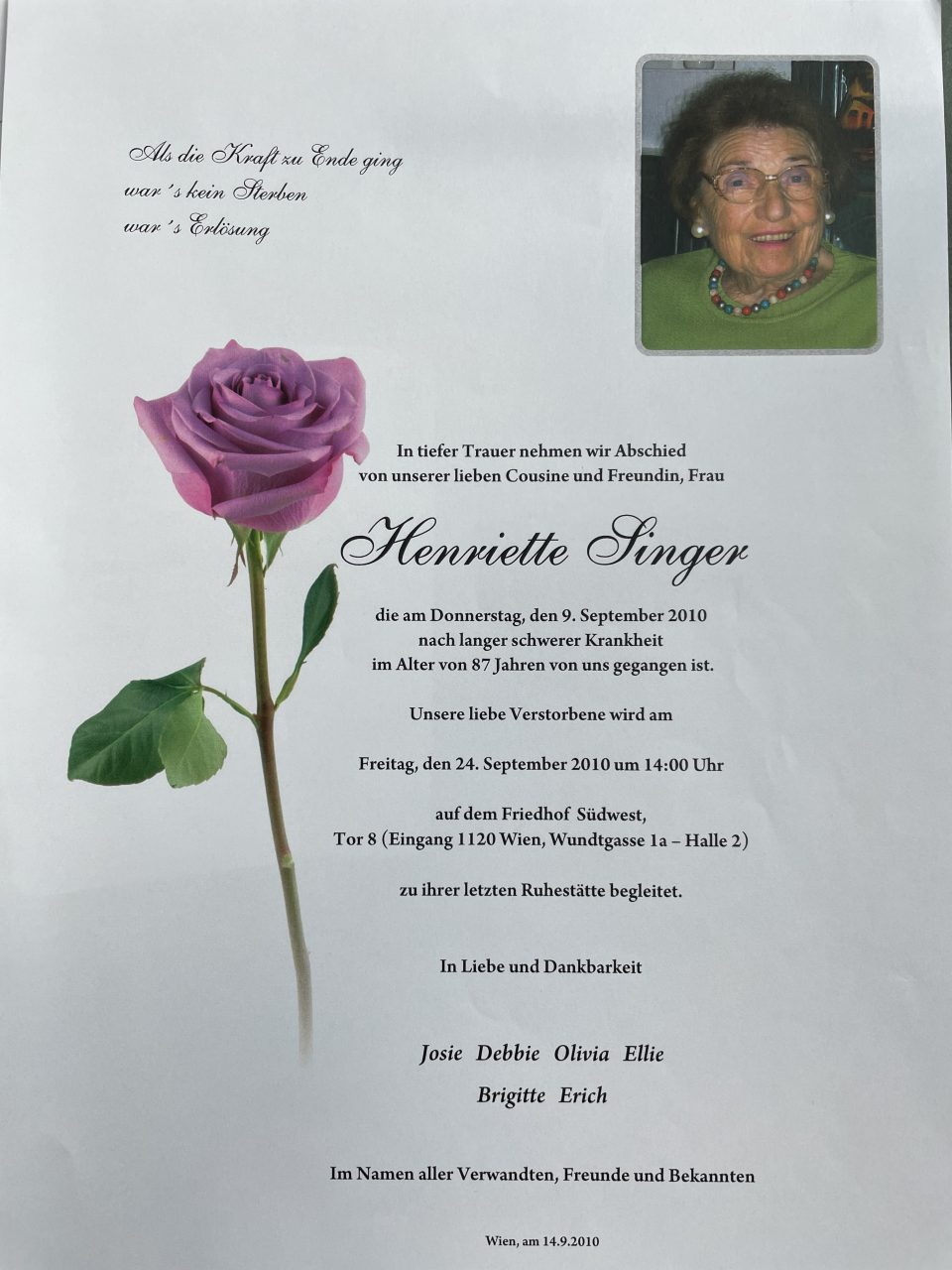

Henny died in 2010 and is buried at the “Südwest Friedhof” together with “her two men”, Pepi and Richard

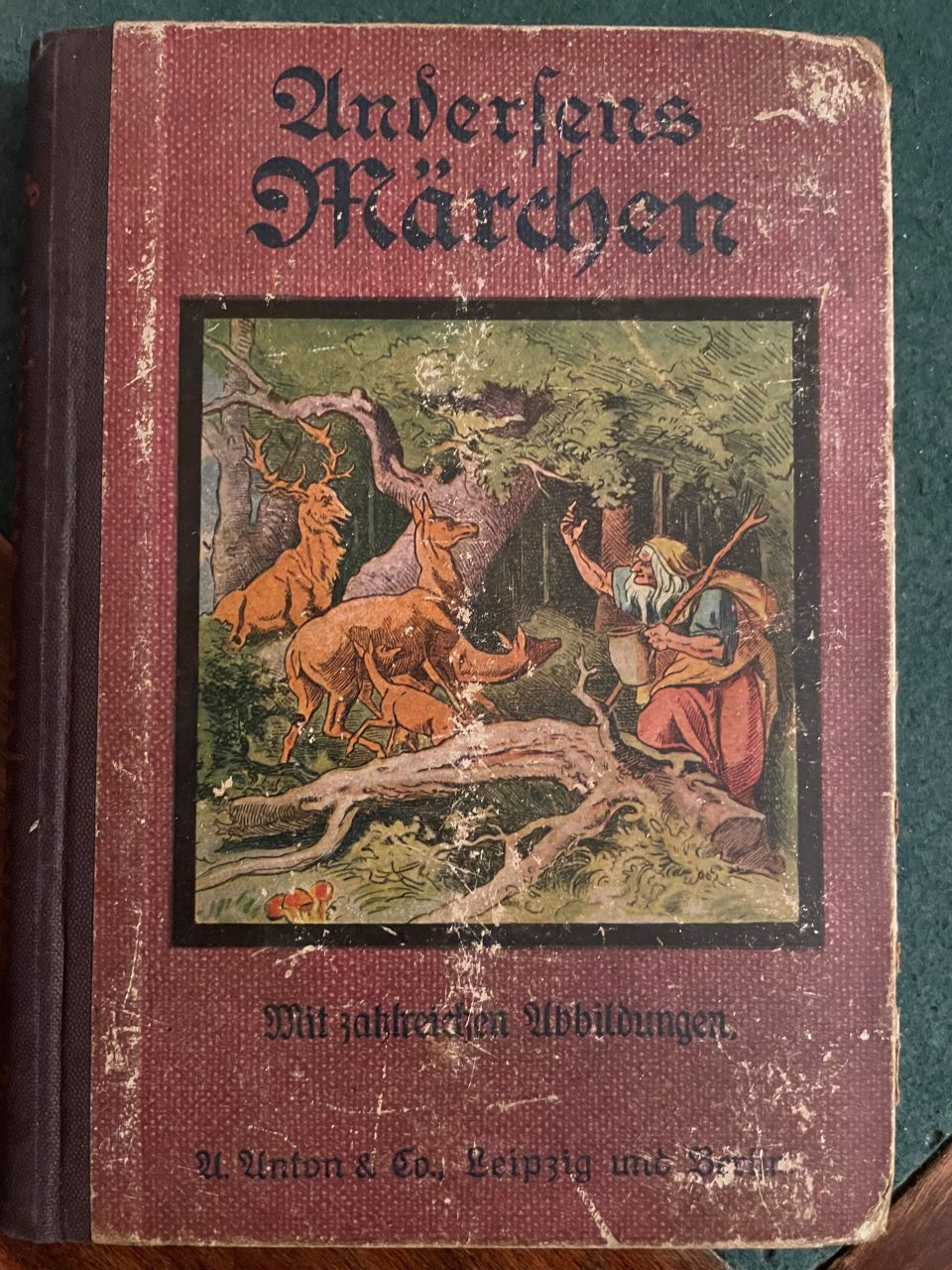

Post-World War II trading at the “Textile Quarter”

After the Second World War Vienna was totally destroyed and the economy was on its knees. Antisemitic persecution and the Holocaust had wiped out the Jewish minority and the few who had survived the murderous Nazi regime of Adolf Hitler in exile were not welcome in their native country. Austria quickly styled itself as the first victim of Hitler and restitution and restoration were hindered by the 2nd Austrian Republic’s administration and judicial system, where ever possible. Applications for restitution were complicated and long-winded and involved great financial losses and concessions on the side of the victims of illegal NS expropriation. What’s more, the largest part of the Viennese Jewish population had not been well-to-do before the war. They had been workers, traders, or employees in different sectors of the economy and therefore had no rights to claim compensation at that time. Only few returned, such as Henny and Pepi, and tried to make a living again in Vienna, the city that had robbed them of their youth, family and belongings; had chased them away and murdered their friends and relatives. Immediately after the war a few of those survivors set up business again in the “traditional Jewish” wholesale and retail textile trade, many of them in the former “Textile Quarter” (Textilviertel) near the Danube Canal (Franz-Josefs-Kai) around “Rudolfsplatz”, others in the vicinity of “Mariahilferstrasse” and “Naschmarkt”, traditional trading quarters, too. The old “Textile Quarter” experienced a true revival in the 1950s, when released NS concentration camp (KZ) survivors from Poland, Hungary, Romania, and Czechoslovakia ended up in Vienna after the expulsion from their former home countries, now under Soviet rule. The “Textile Quarter” was turned into their economic, social, and cultural home and acted as place of revival of the tiny Jewish community. For the Viennese the “Textile Quarter” represented the opportunity to pick up a bargain, when looking for any type of textiles from bedlinen to towels, shirts, coats, workwear and even shoes and accessories. What they could not find in one little shop, they chased down in the neighbouring one.

While the elegant department stores in the city centre, most of them founded by Jewish entrepreneurs at the end of the 19th century, did not survive the Nazi period of persecution and expropriation, the “Textile Quarter” experienced a revival in the 1950s. But the area and the shops were anything but glamorous. They were tiny, crowded and crammed with cheap textile wares. The window displays were not designed in any way, but tried to show everything that was on offer. Yet the shops were social meeting points and the customers appreciated the chats with the proprietors and the children loved the sweets they received from the shop owners. There was the shop of “Mr. Doft” or the “Zalcotex” business, which had been set up by the partners Schmidt and Zahler, both originally from Stanislav in the Austro-Hungarian region of Galicia, and was well-known for its wholesale and retail trading in shirts made of nylon and its dressing gowns and pyjamas. Another famous shop in the quarter was “Wachtel & Co”. Mr. Wachtel came from Lemberg (Lviv) in Galicia, too, and had survived several NS concentration camps. After his liberation he was looking for work in Vienna, like many other former Jewish concentration camp prisoners.

The textile business “Wachtel & Co” near Rudolfsplatz in the 1st district of Vienna

Rudolfsplatz today and the official representation of the textile industry in Austria

The Austrian government did not welcome the founders of these small businesses, on the contrary. The antisemitism that was already prevalent in Vienna before the Nazi period was as widespread and persistent as ever. The only difference was that it simmered under the surface and was not openly expressed for fear of repressions from the Allied armies, the Soviets, the Americans, the British and the French, which administered Vienna and Austria until 1955. That’s why non-Jewish Viennese often “lent” their business licenses to the Jewish owners and rented the business locations in their names for the Jewish traders for a fee. Due to the success of these small enterprises the businesses soon expanded and rented neighbouring premises. Mr. Wachtel started with workwear and later added shirts, socks, pyjamas, children’s wear, underwear, and towels. He was well-liked as a competent retailer in his shop and he furthermore acted as a wholesaler and delivered his textiles to small shops in the country. 60 per cent of his customers were regulars, who also came for a chat. Before Christmas the customers were queuing up in front of the door of his small shop and consequently, Mr. Wachtel was fined by the police for obstructing the pavement in front of his shop.

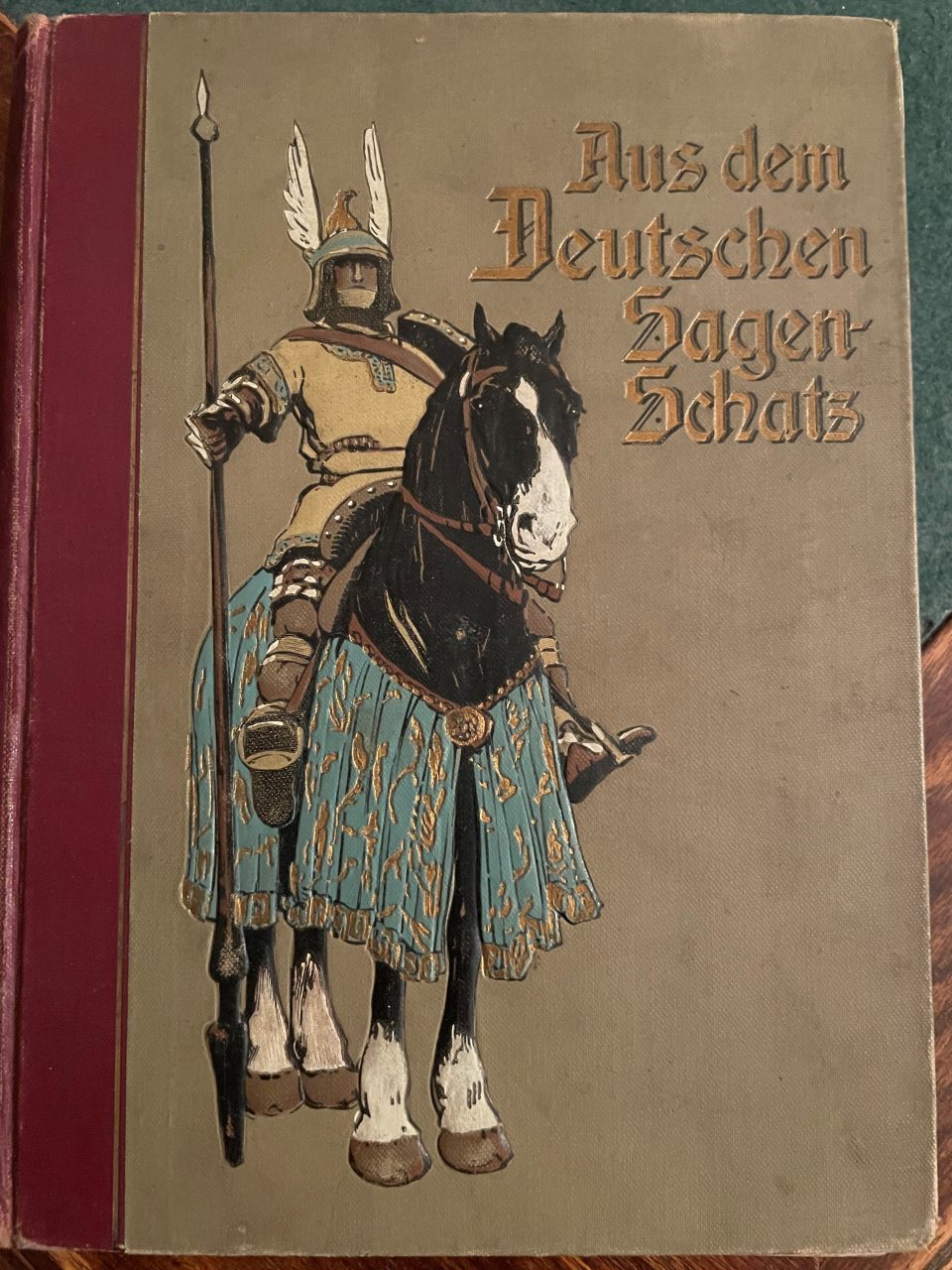

The founders of “Haritex”, Mr. and Ms. Edelman, came from Romania and they specialised in shawls, which they imported from Italy and Japan, and fashionable bleached jeans from Padova. As wholesalers they delivered their wares to market stalls all over Austria. Another famous shop in Vorlaufstrasse was “Silesia”, the only business that had already existed before the war in the “Textile Quarter”. One of the brothers Geiringer was murdered in Dachau and one could find refuge in England. When Leo Geiringer returned to Vienna, his former shop was in ruins, commercially and physically, and the reconstruction turned out to be very difficult under the conditions of post-war Austria. His customers were mostly dressmakers and tailors, who bought fabric and sewing accessories. In the first difficult years after the war “Silesia” entered into barter agreements with the tailors and dressmakers: they brought wool from farmers to the shop in exchange for fabrics and sewing accessories. Apart from professional tailors, who were under pressure because the customers moved from made-to-measure clothing towards off-the-peg clothing, “Silesia” increasingly targeted private amateur dressmakers. Twice a year the tailors were supplied with so-called “collections” or “bundles” of samples of what was on offer in that season. Every season 6,000 to 7,000 such sample booklets were glued together by women on the upper floor of the shop. When in the 1970s Jews facing repression emigrated from the Soviet Union to Israel via Vienna, several of them remained in the city and as the women had no qualifications and did not know German, Mr. Wachtel offered them these jobs to make a living.

“Haritex” and “Landhaus” shops in the “Textile Quarter” today

“Heinrich Klos” sewing accessories

Since the 1980s and 1990s more and more of these enterprises closed, when the proprietors retired and their children, who had studied, took on other jobs. Another trigger for the economic downturn of the “Textile Quarter” after three decades of economic boom was the foundation of a fashion centre in the 11th district of Vienna, in St. Marx, in 1977/78 by Leopold Böhm, the owner of the textile business “Schöps”. He had been able to flee Vienna in time and served in the British army. After his return he built up a successful Austrian fashion chain store together with his uncle Richard Schöps, offering affordable textiles. The fashion centre in St. Marx offered more space and parking facilities, which attracted customers not just from Vienna, but from the rural regions in the vicinity, too. Some of the wholesalers of the “Textile Quarter” moved there, but did not survive the transfer for long, because they suffered from the location on the periphery and they lacked the retail business revenue of the “Textile Quarter”. “ADA STEIN Textilimport”, on the contrary, profited from the transfer. Erich Stein had fled from the Nazis with his family to Italy and had survived in hiding in Naples. He married Ada Bardi, an Italian, and in the 1960s he started importing textiles from Italy to Austria in his private car. He then opened a bigger shop in Marc-Aurelstrasse in the “Textile Quarter” and launched the brand “MarcAurel l4”. His Viennese business bought fabrics near Lake Como and had them sewn in Toscana, near Florence. His slogan was “Vienna-Florence-Paris”: Vienna – the headquarter, Florence – the production site, Paris – the inspiration for the designs (where the designs were spied). A successful line of children’s clothes, which he named after his wife “Bardi”, was launched as well. Every Monday the new clothes were delivered in trucks to Marc- Aurelstrasse, where the customers were already waiting, sorting through the card board boxes, filled with the “latest fashion from Florence and Paris”. Erich Stein moved to the fashion centre in St. Marx and together with his wife organised fashion shows there, offering free of charge drinks and snacks to their customers. As his business, now called “ADA STEIN Textilimport”, was located directly next to the entrance, it soon became a popular meeting point. When in 1995 Austria joined the European Union, imports from Italy were no longer profitable and the business shut down a year later.

…