German World War II defensive constructions at the French Channel coast

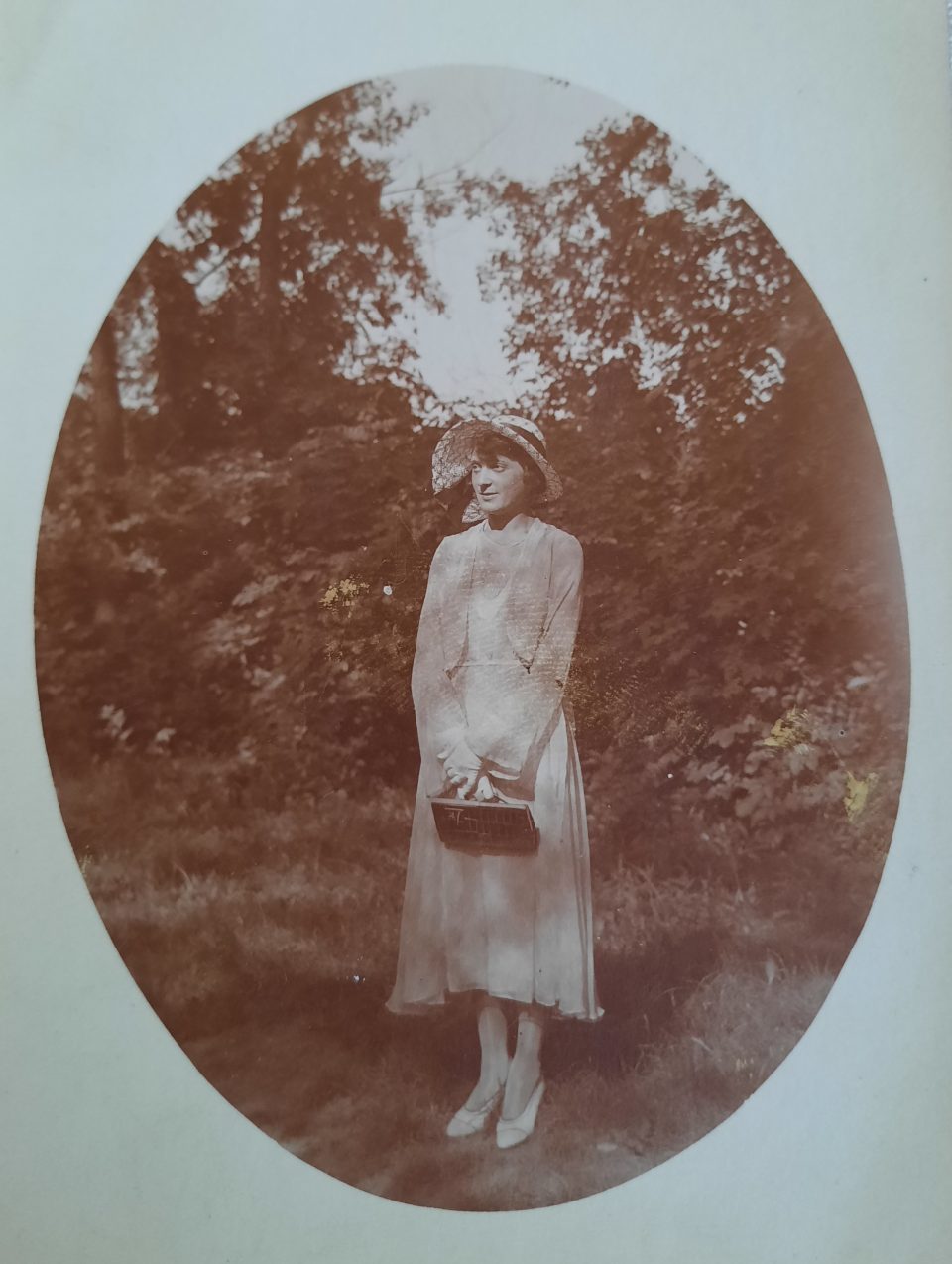

Lola, the sapper Toni’s beloved wife, before their marriage on the left and on the right Toni with Lola standing and Lola’s parents, Ritschi and Ignaz, with their little granddaughter Herta before the war

Anton Kainz (Toni), my grandfather, was drafted to the German “Wehrmacht” in March 1939 a year after Hitler had incorporated Austria into the German “Reich”. When the 2nd World War had broken out in Septmeber1939 Toni was assigned to the “3rd Sappers’ Battalion XVII 79/B” of the German “Wehrmacht” as sapper (“Bausoldat”) in February 1940 and had to complete ten weeks of training. He was sent to France in June 1940 and remained there until September 1940. From September 1940 until June 1941 he was with the “2nd Sappers’ Battalion 153 /288” in Poland (the then so-called “Generalgouvernement”) until he was dismissed from the German “Wehrmacht” and declared “not to be used” (“nicht zu verwenden: nzv”) because he refused to divorce his Jewish wife, Lola, my grandmother. In this one year as a soldier he wrote 246 long letters and a few postcards to his beloved wife and daughter with detailed descriptions of the life of a common soldier, his tasks and activities, his feelings and emotions and his attempts at handling the precarious situation of his wife and daughter in Vienna from a distance. He was 34 years old when he was drafted and had been trained as cook and waiter in his father’s inn in Vienna in the 18th district Währing. He had travelled to Switzerland and France during his years of professional formation and after quitting the “Anton Kainz Inn” he ran a coffee house in Vienna in the 8th district Josefstadt from 1935 until 1937 together with Lola (see article on “Viennese suburban coffee houses”).

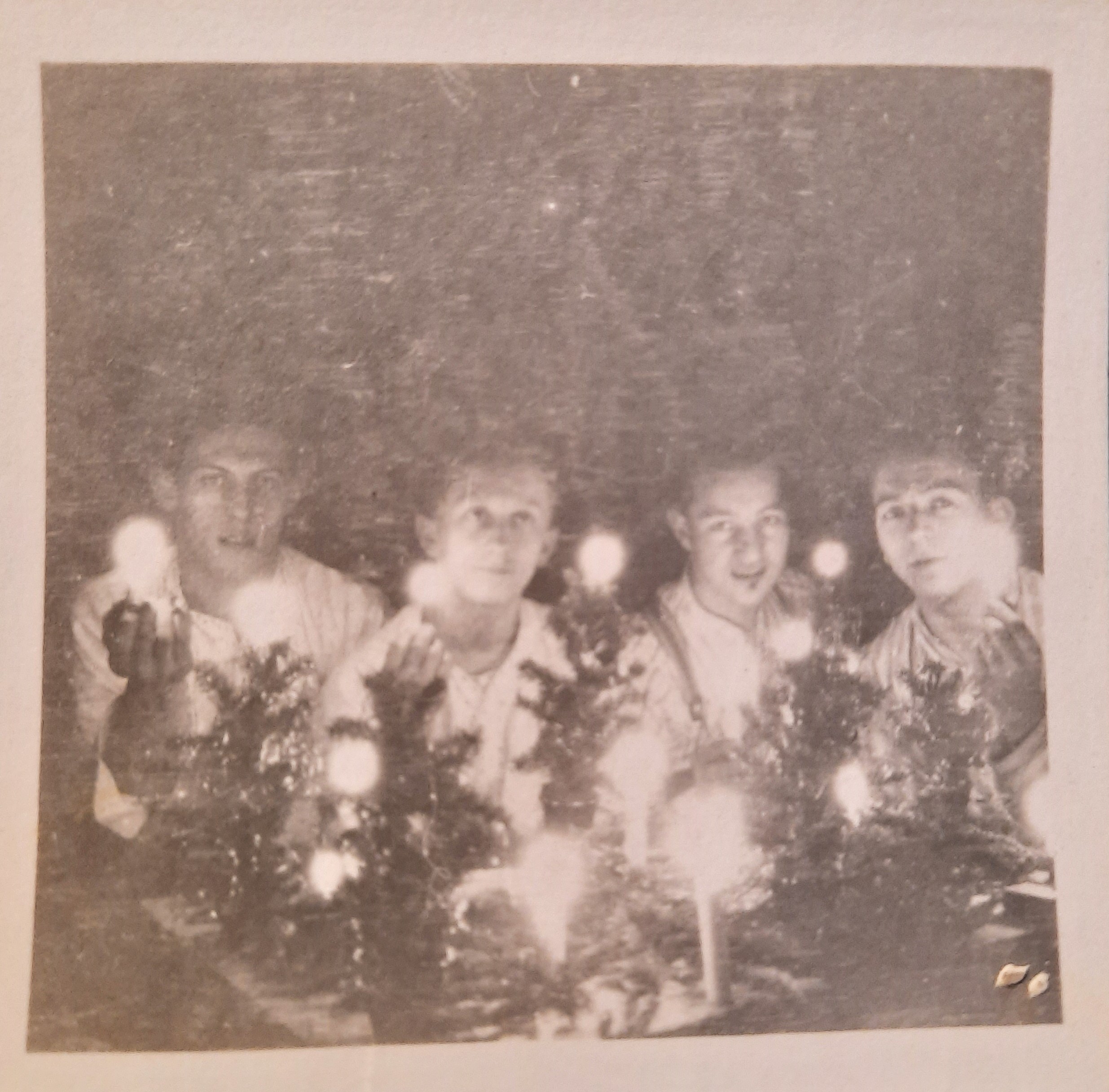

Toni (on the left) in St. Moritz, Switzerland, New Year’s Eve 1925/26 with three young colleagues working there, too.

From May 1939 on he worked in the restaurant service of “Mitropa”, the “Central European Restaurant and Sleeping Car Company” with destinations in many European cities and later at a fish monger’s in the 1st district of Vienna “Hofbauer & Hammerschmidt”.

A postcard Toni wrote, picturing a “Mitropa” railway company’s dining car, on 22 July 1939 on the track Vienna- Villach

Toni spoke a little French and loved the French way of life, art and culture and the cuisine. He himself was an amateur painter, photographer and enjoyed playing the piano, especially four-handed together with his wife Lola. Toni was a keen sportsman, too; he loved tennis, football, skiing, hiking, climbing and sailing. To his great regret he came back to France as a member of a conquering army and he reported how ashamed he was of the behaviour of some of his comrades, in France as well as later in Poland. A detailed analysis of his documented experiences forms the core of this article.

Toni in the “Wehrmacht” uniform

The integration of Austrian soldiers in the German “Wehrmacht” revealed prejudices on both sides from the beginning of the war on. Some reports characterise the relationship between Austrian and German soldiers as friendly, but most contemporary witnesses stress the condescending and contemptuous attitude of the Germans towards the Austrian soldiers, which might have been rooted in the Prussian disdain for the former Austro-Hungarian army. The Austrians called all men with origins north of Bavaria “Prussians”, disparagingly “Marmeladinger” or “Piefkes”, whereas the Austrians were called “Ostmärker” (The NS name for people from former Austria), pejoratively “Kamerad Schnürschuh” (Comrade Lace-up), by the Germans, signifying the supposed lack of soldierly qualities. Consequently the Austrian soldiers had to succumb to degrading treatment by German military instructors. This derogatory attitude of German sergeants was often copied by ordinary German soldiers. The classical prejudice persisted, namely that Austrian soldiers were “inferior material”. In the melting pot of the German “Wehrmacht” the Austrians as “Ostmärker” (after the annexation of Austria by the German Nazis) were classified together with the soldiers from the German “Altreich” as “Volksgruppe 1” (“Ethnic Group 1”), the German ethnic soldiers from Silesia and Czechoslovakia “Ethnic Group 2 or 3” and those from Poland “Ethnic Group 4”. Despite being in group 1 the Austrians were treated with arrogance and condescension, just as the other German-speakers from Central, Eastern and South-Eastern Europe. Sometimes even Bavarians had to succumb to degrading treatment. Some German officers resorted to fierce threats, especially towards the end of the war, stating that Austrians were unreliable, cowardly and only to be used as cannon fodder. Austrian privates also tended to be assigned the worst accommodations. Yet some Austrian soldiers reported that a friendly and comradely relationship with German soldiers was possible, but that they were usually careful, most of all when discussing political issues, because an imprudent or rash comment could have very serious consequences.

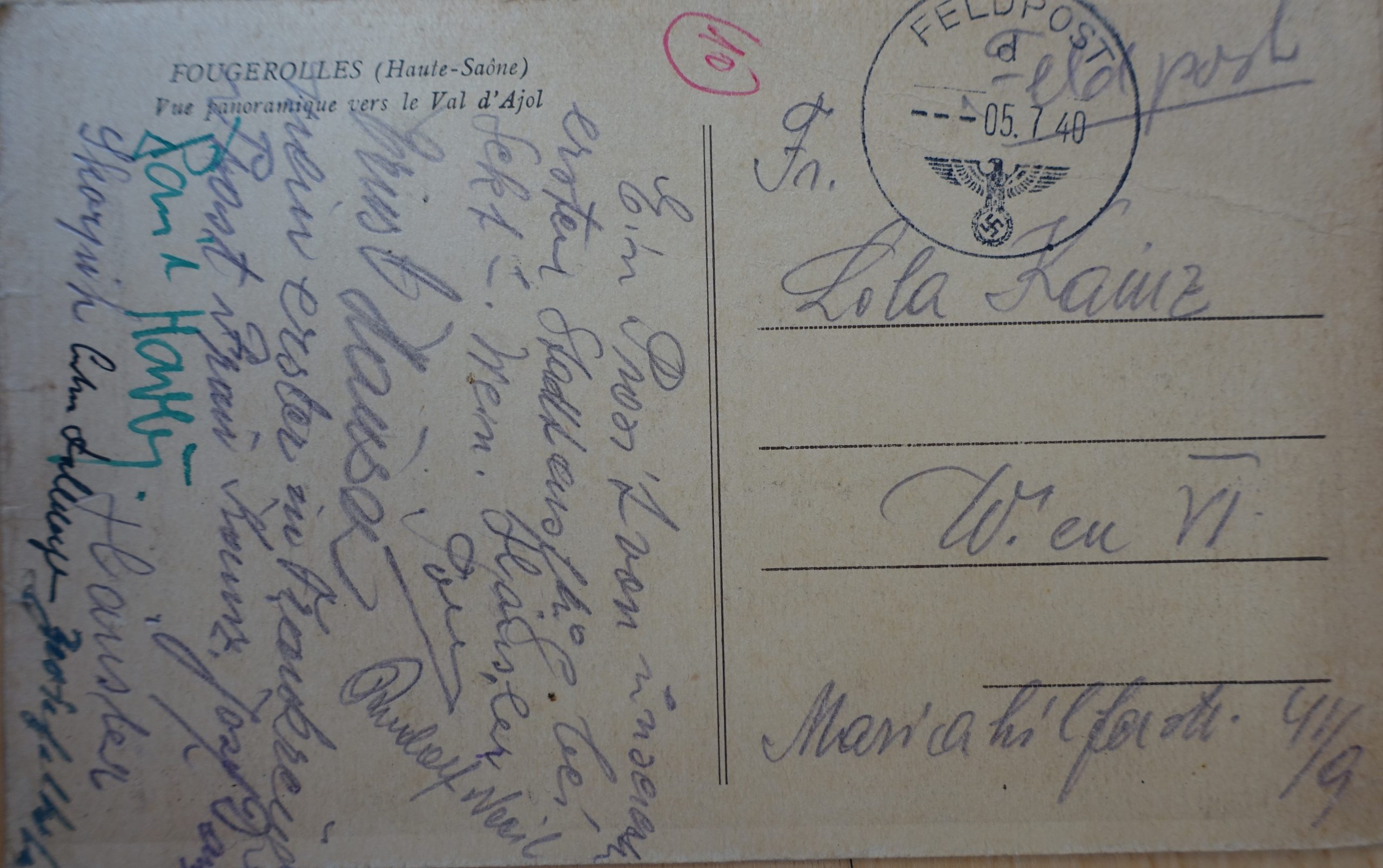

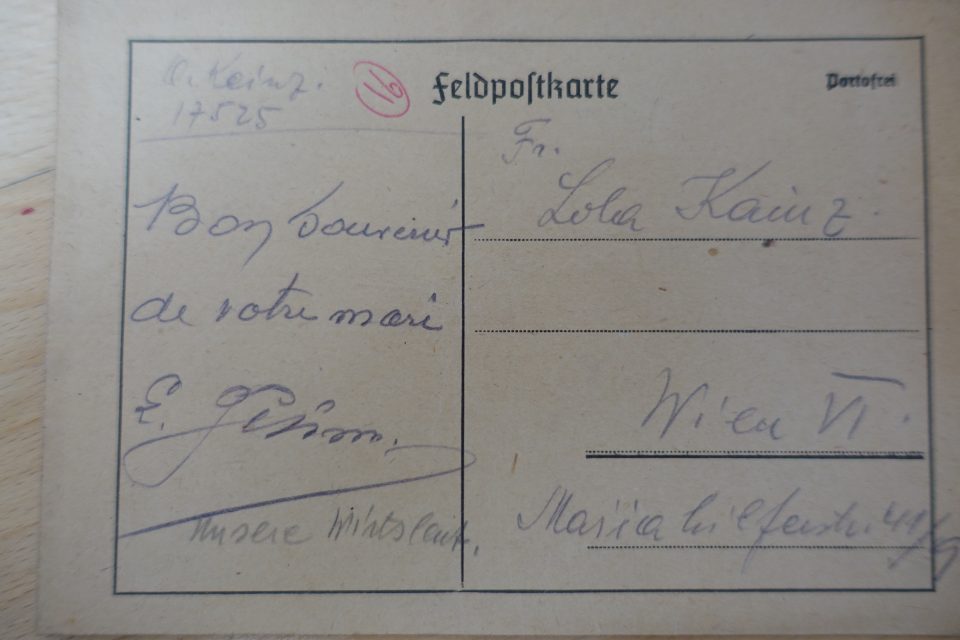

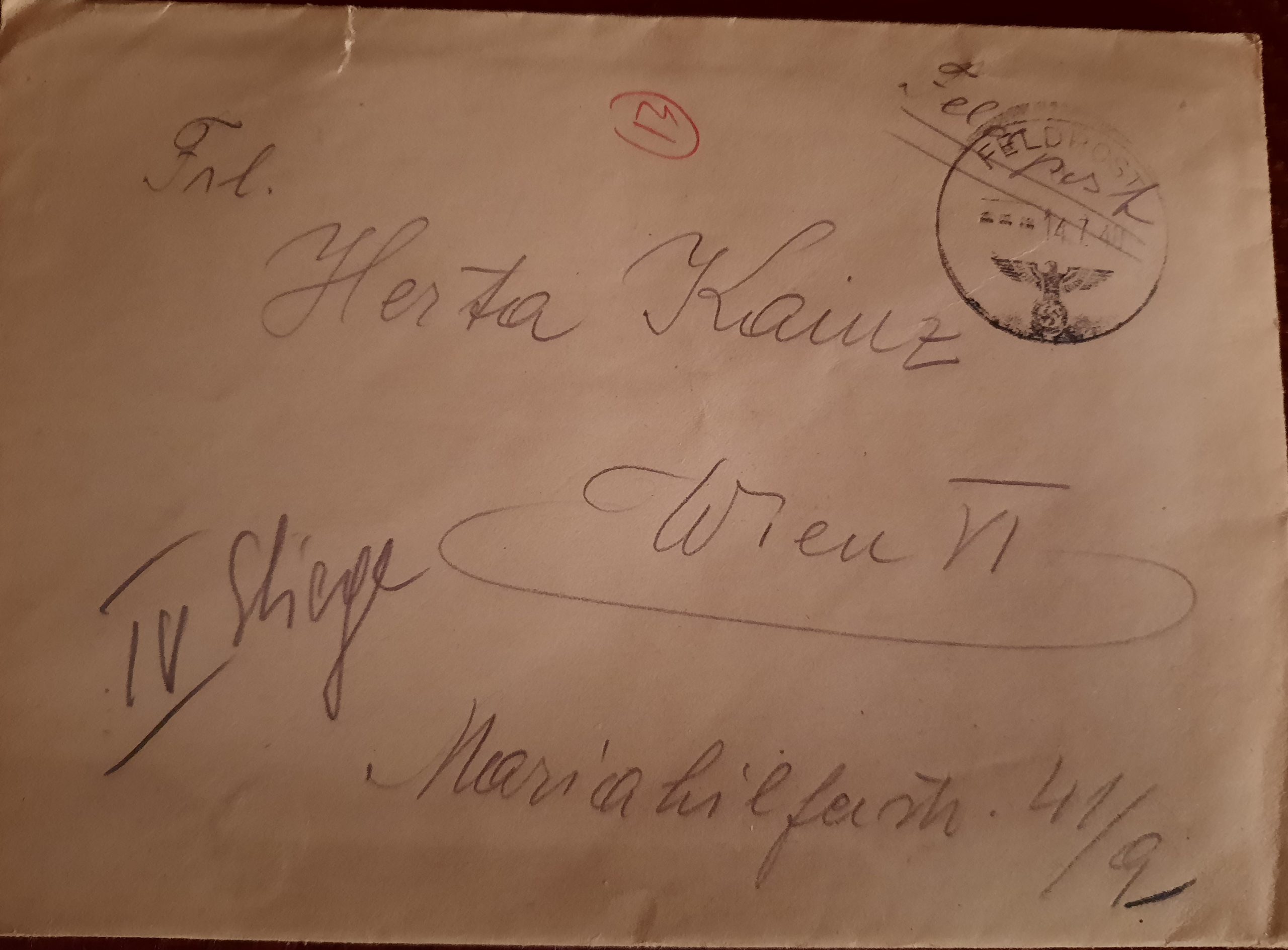

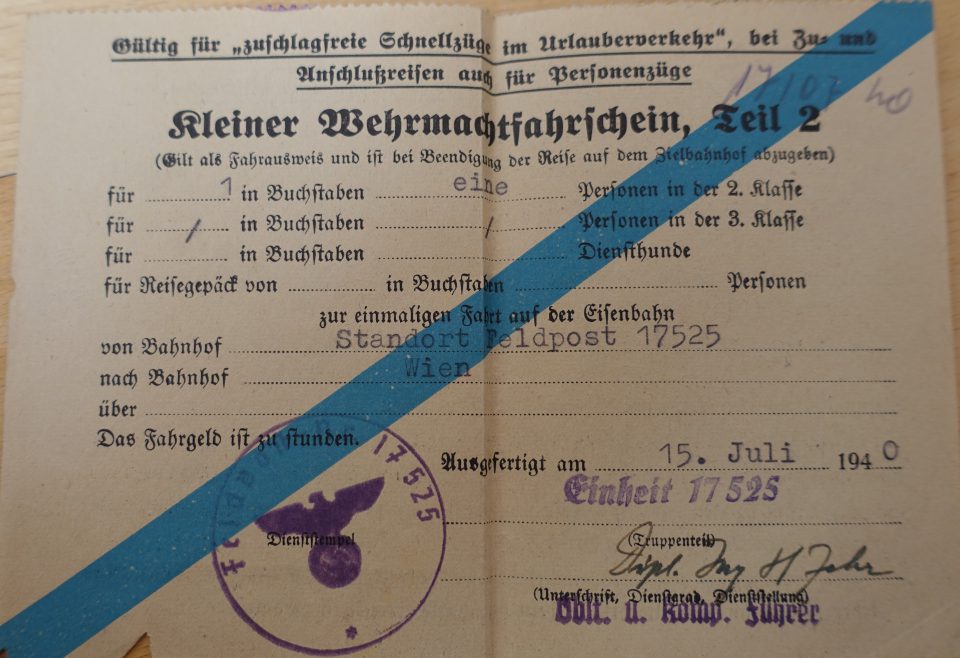

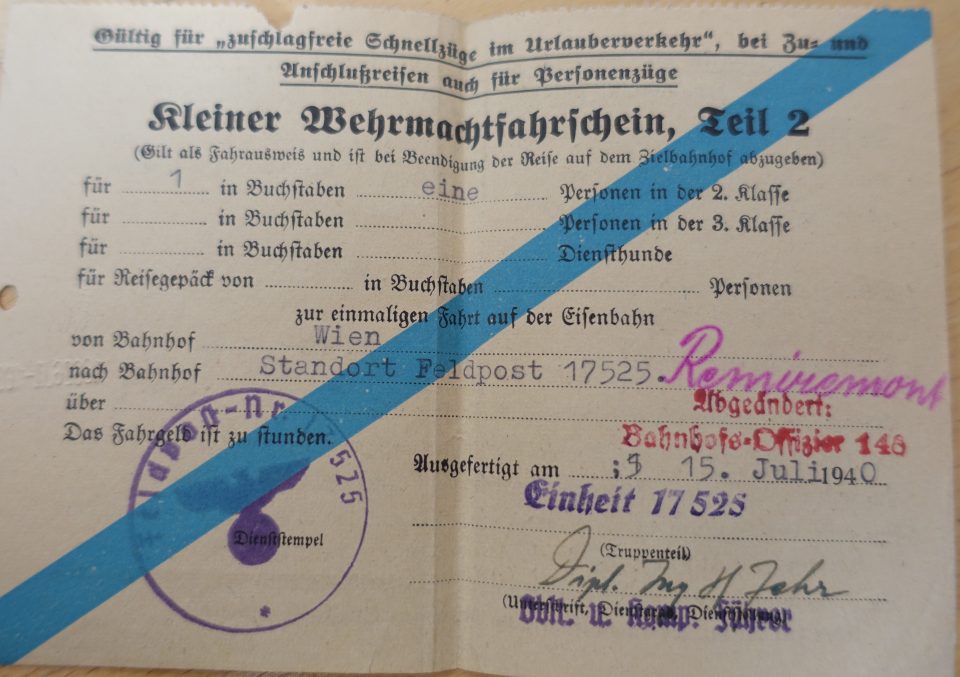

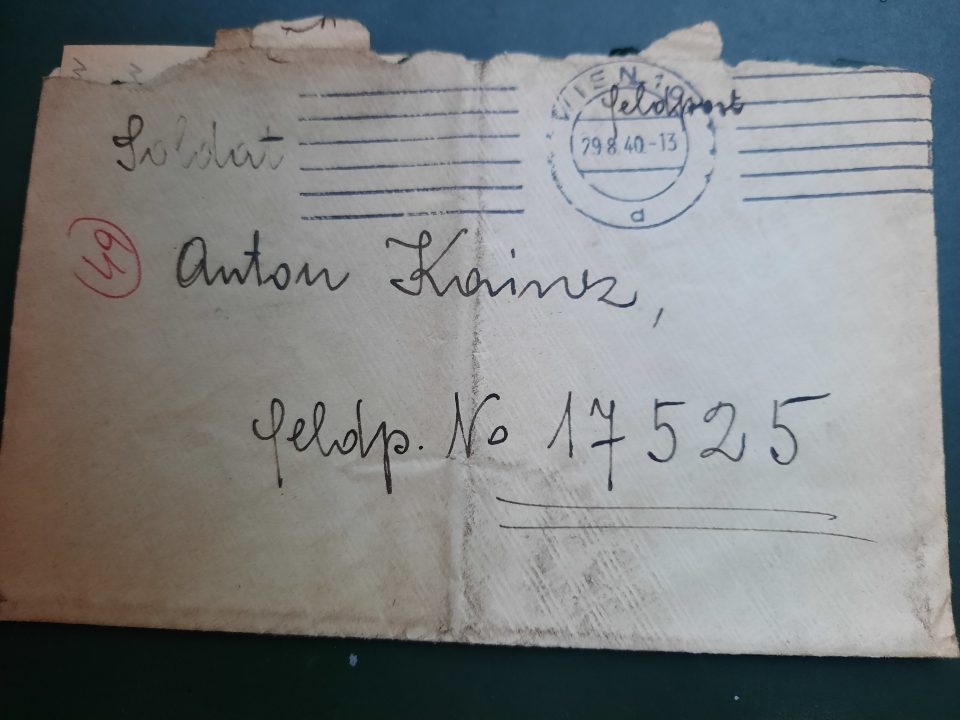

The important connection to the home country was guaranteed by the forces’ postal service of the “Wehrmacht”, which was astonishingly efficient. The ordinary soldier was forbidden to keep a diary. Several soldiers circumvented this ban, but these diaries usually only survived if the soldiers managed to hide them at home in the form of loose sheets. Taking photos, nevertheless, was permitted as long as the soldiers did not take photos of military installations or actions. Photography had become a popular hobby since the early 1930s and the soldiers photographed more or less everything without facing any sanctions. Most soldiers sent the photos home in letters and this is the way how just a few of Toni’s photos survived. Another important channel of information was the exchange of letters. The daily mail call was one of the most important distractions from military routine and a very important moral support for the soldiers. This was the reason why the High Command put emphasis on the smooth functioning of the army’s postal service. Several thousand people were responsible for a frictionless postal connection between the home territories and the military front-line. The service was hierarchically organised, just like the army. Due to secrecy reasons neither the military unit nor the geographical position of the soldier were to be mentioned in the address, but only the name, rank and the forces’ five-digit postal service number. Parcels up to 250g could be sent free of charge and up to 1kg 0.20 RM (Reichsmark) had to be paid (the daily pay of a private was 1 RM). The soldiers “lived” from one mail call to the next – so important was the connection to their families. Usually the service was regular and took two to three weeks from home to the front-line or vice versa. Except for special cases, the letters were not censured because that would have delayed delivery endlessly considering the amount of letters dispatched every day. But if the army command had letters censured they tried to make it look as if the writer himself had crossed out some words. Yet the army made the soldiers believe that their mail was checked regularly, so that no military information or bad news was disclosed. Most soldiers did not report negative or disastrous news home anyway because they did not want to upset their families. Some sent coded messages to and fro, one of which is also mentioned in the letters below. The postal service was only interrupted during a transfer of troops and before and during an attack.

The other important distraction the soldiers were looking forward to was furlough or home leave. It was stipulated that “Wehrmacht” soldiers were entitled to two weeks’ home leave in their second year of service, three from their third year on and four from their ninth year on. Additionally special furlough could be granted in case of serious family matters, as in the case of Toni, the death of his mother, or for health reasons or university studies. Before or during a campaign all furloughs were cancelled and those on home leave had to return to the front-line. In the course of the war some soldiers could not go home for two or more years, which had disastrous effects on their psyche. Some even committed suicide, although there are no official records of these suicides, only reports of contemporary witnesses. For the journey home and back the army paid for the train tickets and the soldiers could travel on any train available, but it usually took them a long time to get home and many changes of trains, which is documented in Toni’s letters. Yet the days of the journey were not included in the duration of their furlough. If the soldier wanted to travel somewhere during his home leave he had to apply for a permit and the train tickets, otherwise he had to face serious sanctions. He had to wear his uniform and only with a special permission was he allowed to put on civilian clothes. If a soldier did not return to his division after his home leave or tried to hide or disappear, this meant certain death. It was known that the chances of survival were higher as a front-line soldier than as a deserter. The army bureaucracy at home and its “substitute army” worked as smoothly as the front-line army with an intricate web of supervision and control. The military police was everywhere, in the cities, in the country, in bars and restaurants, on trains and buses, at traffic junctions and they were manned by fanatical NSDAP party members. Without his marching orders, a soldier was lost. But with his marching orders he just had to report to the military authorities in every town he passed through. In larger cities the authorities sometimes even organised accommodation and sightseeing. Toni wrote to Lola how much he enjoyed those journeys because there was so much to see. He would have been a globetrotter, he only lacked money, time and opportunity. Some soldiers were granted extra furlough for special bravery or “to sort out unpleasant occurrences at home”, such as “unfaithfulness of the wife”, “foreigners who were accommodated in their homes” or homes which were destroyed by bombs. A furlough ban was the worst punishment for any soldier.

Receiving unbiased and objective information was a challenging task for ordinary soldiers as all media were under the NS party control in the “Third Reich”. At the front-line newspapers arrived by mail weeks later and not all barracks provided radios. The army command had set up an army radio station which briefly reported the latest news daily, but as soon as the “Wehrmacht” was no longer winning battles, but losing them, the news reports were increasingly distorted and used for propaganda purposes. Privates had nearly no knowledge of what was going on, as can be seen from Toni’s letters. When they were transferred they were not told where to, even when they were already on the trains or trucks. They had to rely on rumours. Every piece of information was checked and censured by the army and the party.

Hygiene in the army was of the highest priority, especially when with the outbreak of the war the infection rates of venereal diseases rose dramatically. Taking a bath or doing the laundry at the front-line was often a real problem for ordinary soldiers, and what’s more the ubiquitous plague of lice. So soldiers took to swimming in rivers and lakes whenever possible. Furthermore the soldiers were regularly vaccinated – Toni mentioned the inoculations against typhoid fever. When Toni was working in the kitchen urine and stool samples of all cooks were tested for hygienic reasons, as is known from his letters.

War memorial in Normandy

Hitler’s next target after attacking Poland in September 1939 was France and this was the sequence of events of the invasion of France by Nazi Germany: Since September 1939 France and Britain had been at war with Nazi Germany, but in the first months there had been nearly no fighting. The Allies wanted to strangle the Nazi war economy by imposing a blockade while at the same time building up their own military potential. Their plan was to mount an offensive in 1941 or even 1942 as soon as their armies were fully prepared. They hoped to hold the Germans off, if they attacked in the meantime. The old fortifications of the “Maginot Line” protected the French-German border, but the frontier with Belgium and Luxemburg was unprotected. To the Allies’ surprise the Germans launched an offensive on 10 May 1940 invading Holland, Belgium and France. Already three days later the Germans crossed the river Meuse and moved towards the British Channel. This military move threatened to cut off the British, French and Belgian armies in Belgium. After the capitulation of Holland and Belgium a large part of the British forces was evacuated across the Channel between 26 May and 4 June from the port of Dunkirk. At that point in time there was almost no more British military presence on Continental Europe. That was the chance for the German Nazis to turn south towards the centre of France. The French government decided to evacuate Paris on 10 June 1940 and the Germans arrived there four days later. On 22 June the French government had to sign an armistice with Germany, which meant that in only six weeks the French had been defeated by the German Nazis. A huge wave of people was moving south from Paris fleeing the German troops. The immediate consequences of the defeat were disastrous for France. Half of the country was occupied by German troops and in an unoccupied area in the south an authoritarian regime with its capital at Vichy was installed by the grace of Hitler under Marshall Pétain. As a consequence that was the end of democracy in the whole of France until the liberation by British and American armies in 1944. Yet the trauma of the defeat of 1940 and the following Nazi occupation continued to mark the French people for many years to come. The “Fall of France” was an event that resonated throughout the world as the disaster of the destruction of a most civilised and cultured nation. In fact, the defeat of France in 1940 led to a massive escalation of World War II and turned a so far European conflict into a worldwide war. The totality and speed of the French collapse surprised everyone. The Fall of France was not just a military defeat, but also signified the collapse of a political system, the break-down of the alliance with Great Britain and in the end almost a disintegration of the French society.

In the interwar years France had been a pacifist nation. The memories of the 1st World War weighed heavily with 1.3 million Frenchmen dead, 1 million war invalids, 600,000 widows and 750,000 orphans. Unlike Britain and Germany, France had suffered severely because the war had been largely fought on its territory. By the end of the 1st World War many towns in the north-east had been destroyed as well as a large part of the fertile agricultural land. The rebuilding of this devastated area took ten years. As a consequence of these experiences the French were profoundly pacifist. Some of this pacifism was rooted in exhaustion and a deep pessimism, whether the country could survive another war. The pacifist mood changed after the Munich Agreement of September 1938 with Hitler when it was proven that Hitler could not be trusted. In July 1939 a poll showed that 70% of French now were prepared to resist another aggressive German move. When eventually war was declared in September 1939 it seemed that the pacifist atmosphere had subsided. The French did not show great enthusiasm for war, but they accepted the necessity to resist Hitler. Even after the declaration of war many people still hoped for peace. In the months of waiting that followed the war declaration, morale both in the French army and among civilians deteriorated. The patriotic rhetoric of 1914 did no longer work in 1940. The question was what Britain and France were fighting for after the fall of Poland. At that point in time the war was not yet seen as a fight against Fascism in France.

It is further clear that in 1940 France was a country in economic and demographic decline and was being outstripped by Germany. The confidence of France that they could win a confrontation with Germany rested on the trust in the alliance with Britain. When de Gaulle went to London in 1940, he declared that the defeat of France was only the first round in a world war. There are many myths about Germany in 1940, especially the elusive notion of “Blitzkrieg” (“lightening war”), which was supposed to have been a specially conceived strategy. In reality the “Blitzkrieg” emerged in a haphazard way from the experience of the French campaign, whose success surprised the Germans as much as the Allies. Germany’s victory in France only led to the adoption of the “Blitzkrieg” concept afterwards with the invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941. Nonetheless, the German plan for the attack on France could just as well have gone wrong. It is well known that the Nazi administration was chaotic and inefficient, especially with respect to rearmament, although they had a head start over the British and the French. The German army in 1940 for example was more dependent on horse-drawn transport than the French. Furthermore the morale among German soldiers was rather low, too. Even the German security police reported in 1939 that the Germans were full of resignation, fear of war and longing for peace. At a governmental press conference on 1 September 1939 journalists in Germany were instructed not to use the word “war” in headlines to avoid a mass panic. Even the German High Command was worried about the “lack of fighting spirit” among the German soldiers during the Polish campaign. That’s why the German military leaders viewed the Fall of France in 1940 as a “miracle”. The greatest German weapon in the French campaign was the element of surprise.

The defeat’s immediate consequences were the collapse of the Third French Republic and the ideological crusade of the “Vichy regime” to remake France. Pétain signed the armistice with Germany on 22 June 1940 and according to its terms France was split up into an “Occupied Zone” in the North and along the Atlantic coast and an “Unoccupied Zone” in the South. The new regime in the “Unoccupied Zone” was to be authoritarian and anti-democratic, although the armistice as such did not foresee any political arrangements there. The opponents of the French Republic took over in Vichy. Yet Vichy rested on more than just political reaction and revenge. Marshal Pétain was really popular among the population, not just as war hero of the 1st World War. His speeches about authority, family and security appealed to the French and the defeat provided Vichy with its moral authority and formed the foundation of the Vichy regime. Since the defeat of France seemed to ensure a German hegemony over Europe, the Vichy regime collaborated with the German conqueror. This pro-German stance was partly driven by ideological affinity; the regime was even close to re-entering the war on the side of Germany. By the end of 1941 a European war had become a global one and the military powers of the United States and the Soviet Union dwarfed the European ones and eventually led to the bipolar world of the Cold War after 1945.

The Belgian coast

To France, which had to sign an armistice agreement on 22 June 1940, the Germans had a special relationship; they respected the French as a “cultured nation”, as opposed to their attitude towards the Russians and other Slav peoples who the German Nazis considered inferior. Not all French were hostile to “Wehrmacht” soldiers, too, as can be deducted from Toni’s reports, which came from the region of Alsace-Lorraine. They were astonished about the quick defeat and 12,000 Frenchmen joined the German “Wehrmacht” later to fight against the Soviet Union. 8,000 Frenchmen even enlisted as volunteers in the “Waffen-SS” in the SS-Division “Charlemagne”. Many of those young French volunteers wanted to fight against Communism and for a “Nouvelle Europe”. Only very few of them survived World War II. On the other hand, several Frenchmen and women fiercely fought against the German invaders in the “Résistance” and many of them lost their lives in the fight against the occupiers, too.

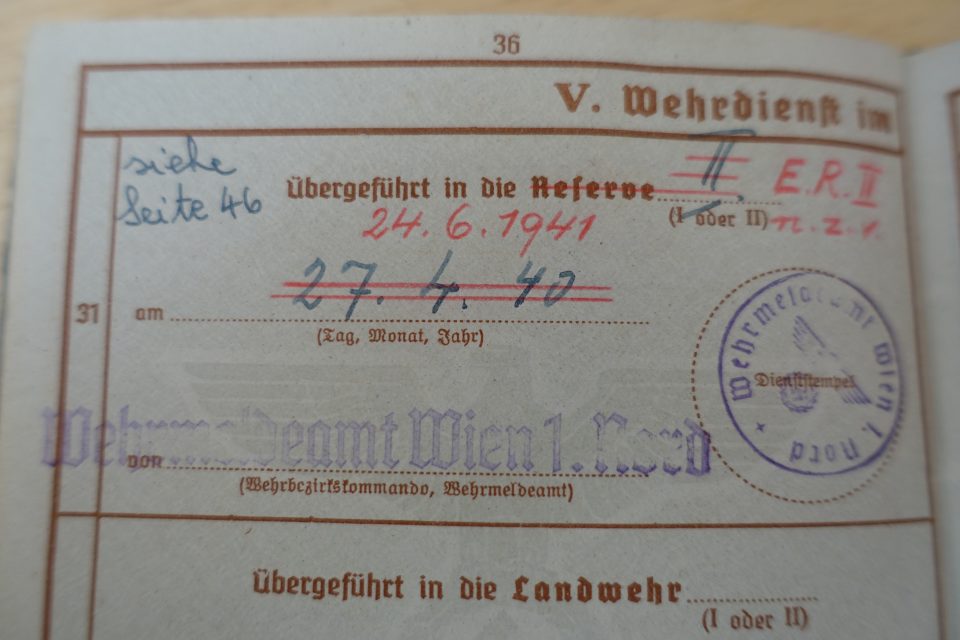

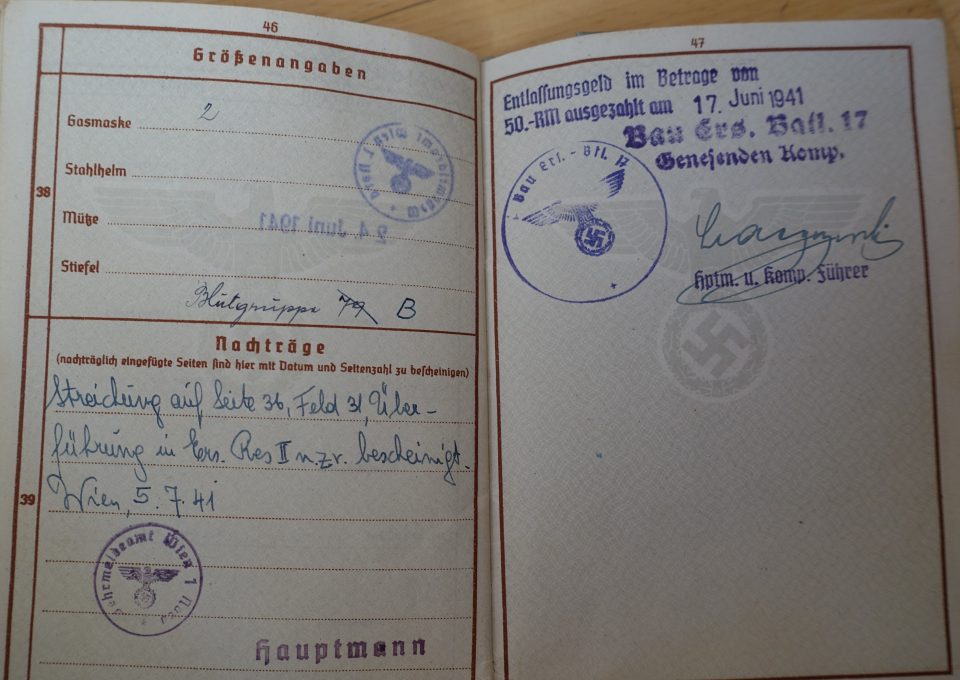

Anton Kainz was drafted to the German Wehrmacht on 1 February 1940 and went with the 2nd Sappers’ Battalion 153 to France on 21 June 1940 and later to Poland, which period will be discussed in part 2 of this article. He was dismissed from the army on 17 June 1941 and was transferred to the home front “Vienna 1 North” on the basis that he was declared “n.z.v.” (not to be used) because he strictly refused to divorce his Jewish wife Lola, as already mentioned above.

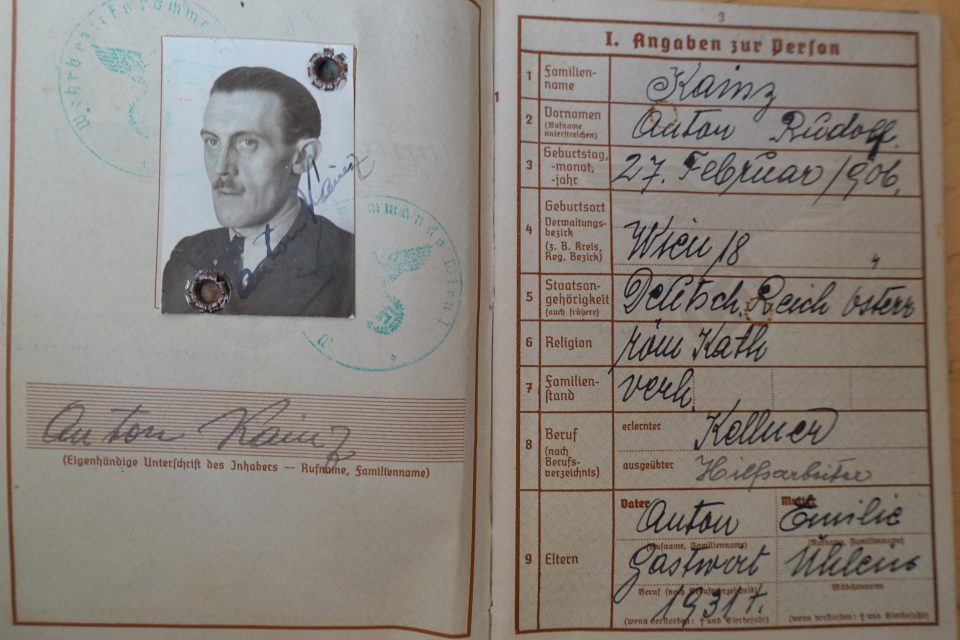

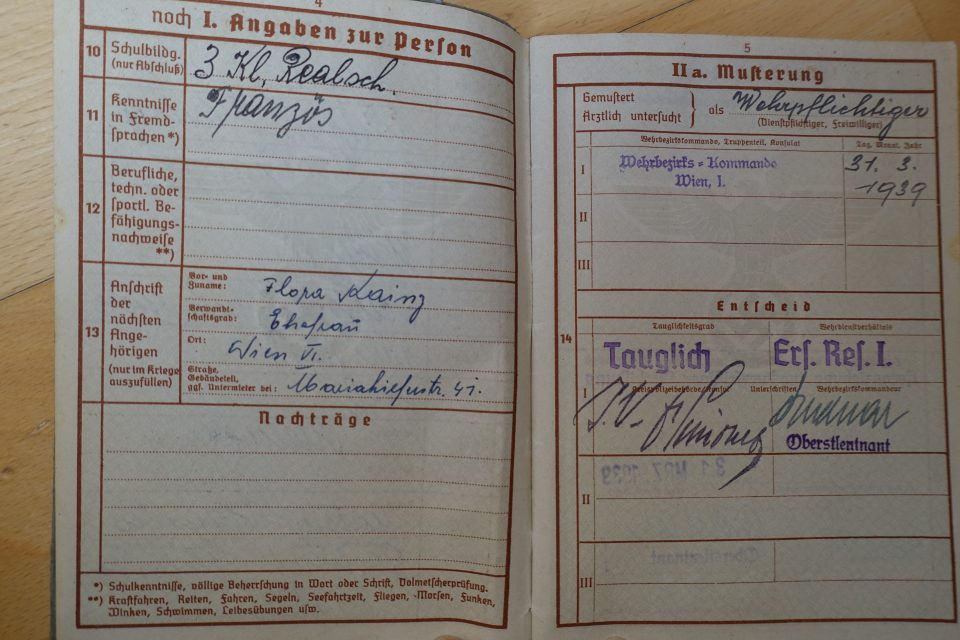

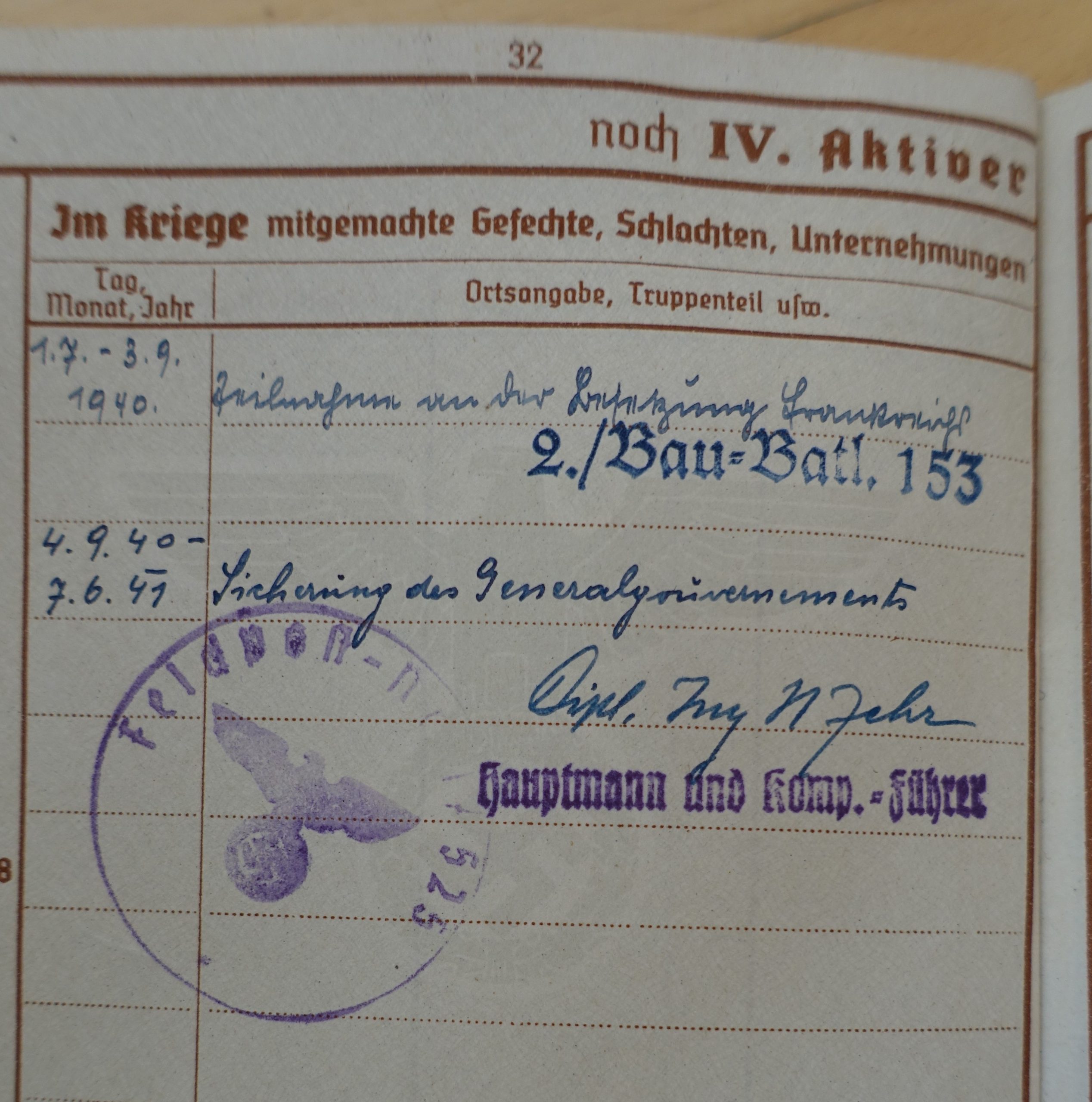

Toni’s military service book:

Toni was stationed in France from 1 July until 3 September 1940 and from 4 September 1940 until 7 June 1941 in Poland

“n.z.v.” is entered into his military service book in red and once more below:

The historical analysis of the 246 letters which Toni wrote to his wife in this period is divided into three categories: first, information about the military campaign, where he was stationed, the military tasks and operations, and the conditions of the military service; second, in which way he tried to support his family in Vienna and how he organised important tasks at home from a distance and third, his emotional conditions on the military front-line.

Only one letter of his wife Lola has been preserved because she destroyed all her own letters before her death, but seemed to have missed this one, which had slipped between Toni’s letters. When she moved into a seniors’ residence she wanted to throw away all letters, but she could not bring herself to get rid of Toni’s letters and fortunately passed them on to my mother and me. She confessed that she had not realised before, how much her husband had loved her. Furthermore she preserved a letter from Toni’s sister Milly to him by chance and the letter of a comrade of his. In her only preserved letter Lola mostly reported about her bickering with neighbours, fights for food rations and asked for goods he could procure in France, which were unavailable in Vienna. She seems not to have written as much as her husband because Toni often complained in his letters that again no letter of her had been handed over to him at the daily mail call, although she had promised to write regularly.

THE MILITARY CAMPAIGN:

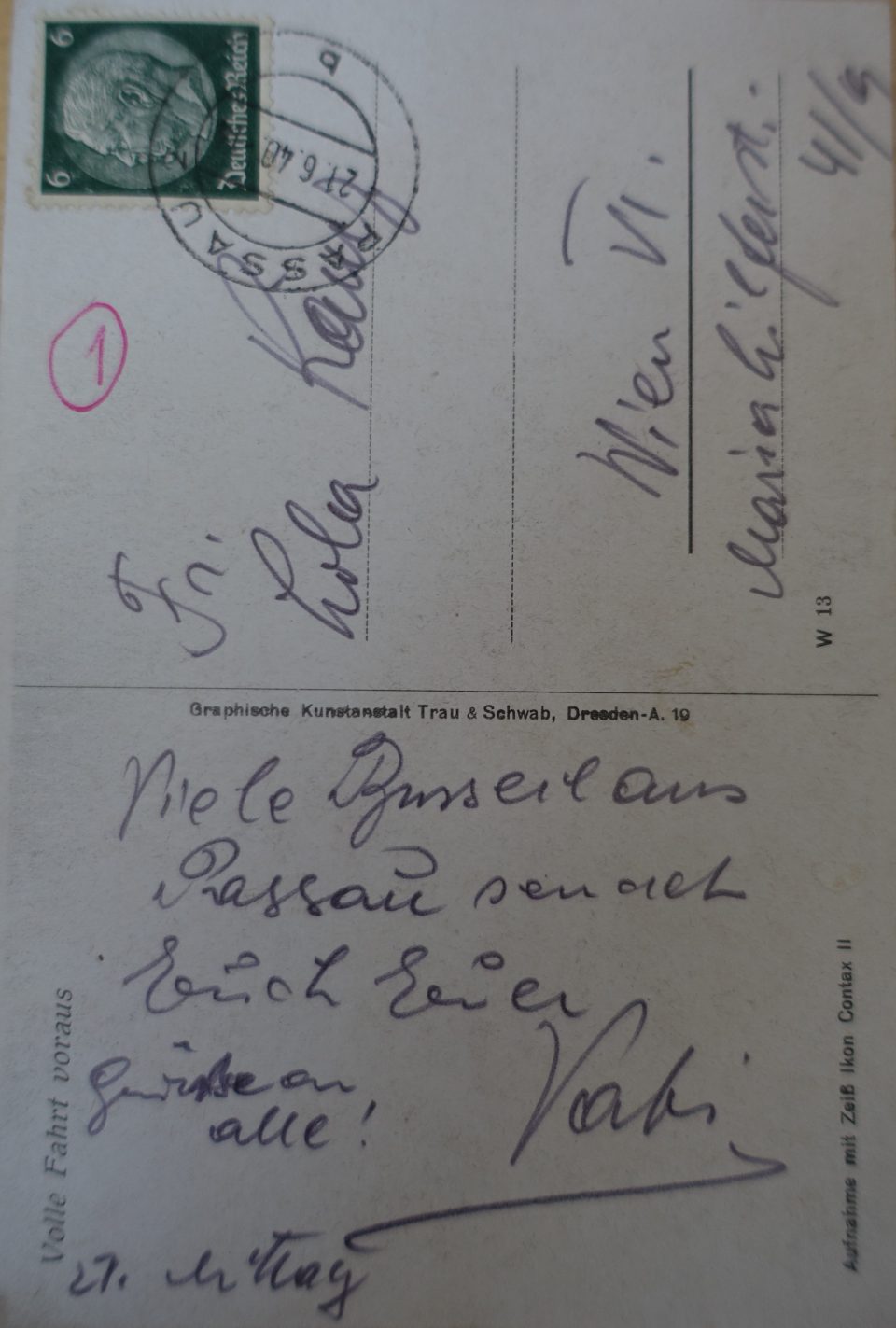

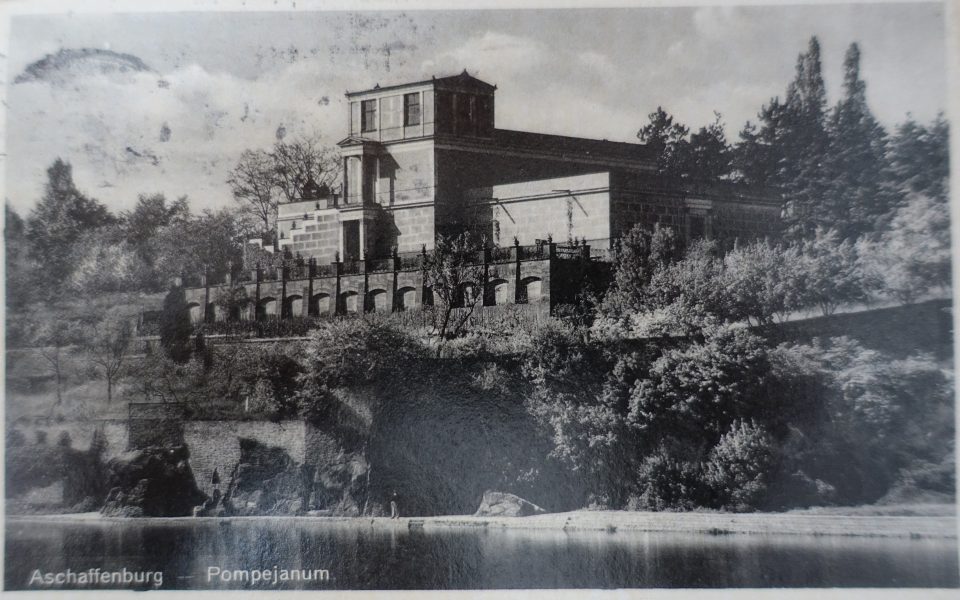

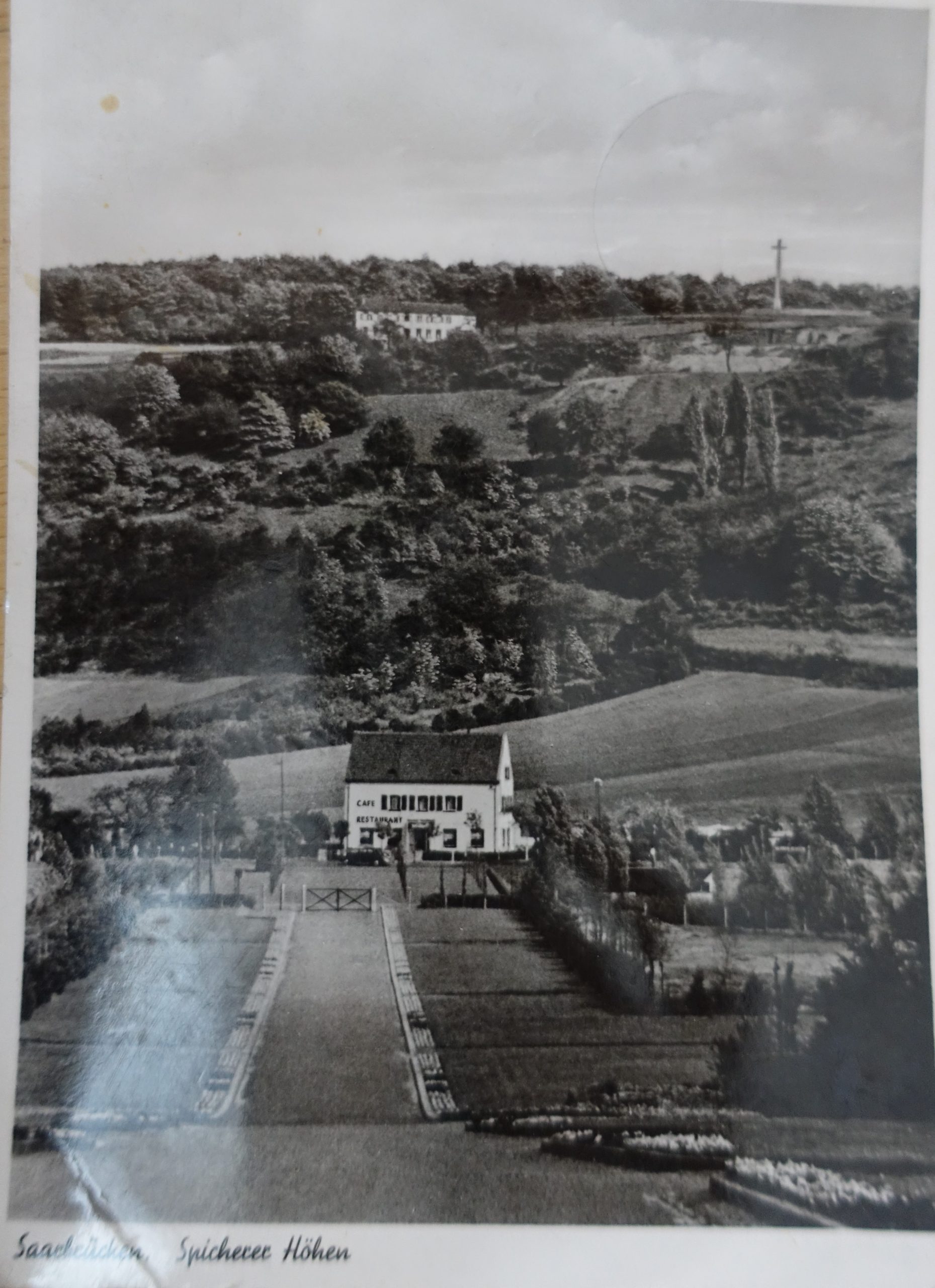

The first two postcards which Toni sent to Lola and his daughter, Herta, were from Passau on 21 June and Aschaffenburg in Germany on 22 June 1940 on the way to France. He mentioned that so far everything was quiet and they were quickly moving on.

On the evening of 22 June he wrote one more postcard from St. Ingbert train station:

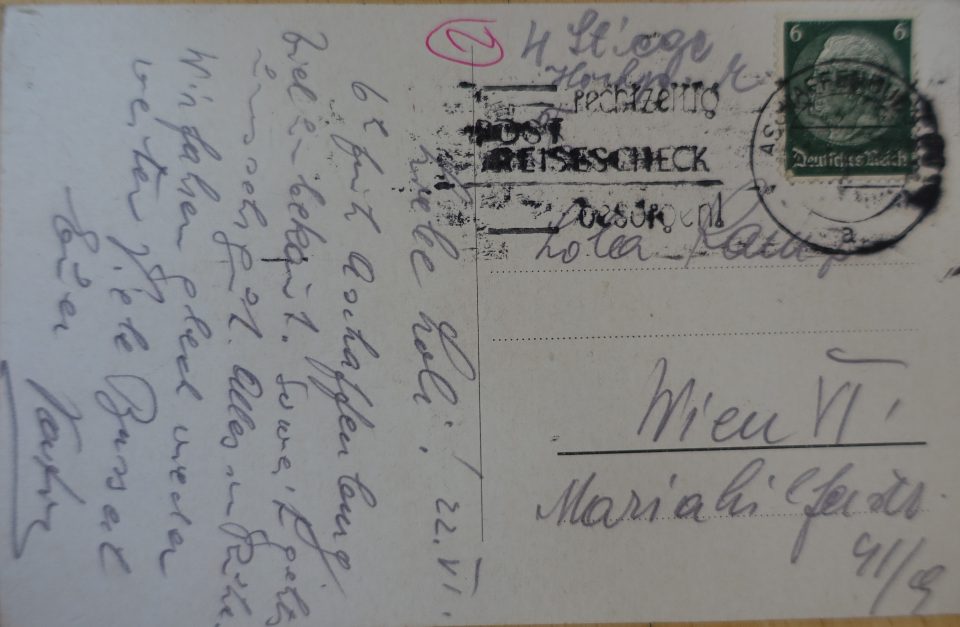

On 23 June Toni sent the next postcard from Karlsruhe on the Rhine writing that they had been travelling around senselessly and they were dispatched back to Homburg, “but some time we will land in the right place”. They were supposedly travelling in the direction of Strasbourg, but had no reliable information.

In his letter from 24 June he told his “dear Loli” that they were still stuck in Kehl am Rhein opposite Strasbourg. Kehl was wonderful and the houses showed little damage. It was much less serious than the people said if you took into account that the city was 200 m from the French border. If you did not look too closely, you would not imagine that there had been shootings. “On the other side of the Rhine it naturally looks very different. This morning we looked at the fortifications at the Rhine and one can understand that no Frenchman could penetrate them. There is bunker next to bunker and so solid you won’t believe it. Tomorrow morning we will move on and we don’t know yet whether by car or on foot, app. 100 km – this will be quite funny. Just imagine I was nominated “Nährvater der Kompanie” (nurturer of the company) because we cook for ourselves. There is more than enough food. The people are delighted with my cooking skills. I’m busy the whole day with cooking, for example in the morning coffee (from beans!), bread and butter, at lunch time pork with rice and potatoes and in the evening two wedges of soft cheese, butter and tea. Not bad! Tomorrow morning I will probably start cooking coffee and tea at 3 am, so that “my greedy-guts” get their fill. I can tell you I really like this job. Today the first inhabitants have returned and finally some life returns to the city… In future I might not be able to write so much because I will have to write via FP (“Feldpost” – forces’ postal service).” He sent greetings to his “Puppi”, his daughter, and the “old ones”, his Jewish parents-in-law, Ignaz and Rudolfine (Ritschi) Sobotka, who stayed with Lola most of the time after being evicted from their flat until they were deported (see article on “Collective Camps in Vienna”) and all relations.

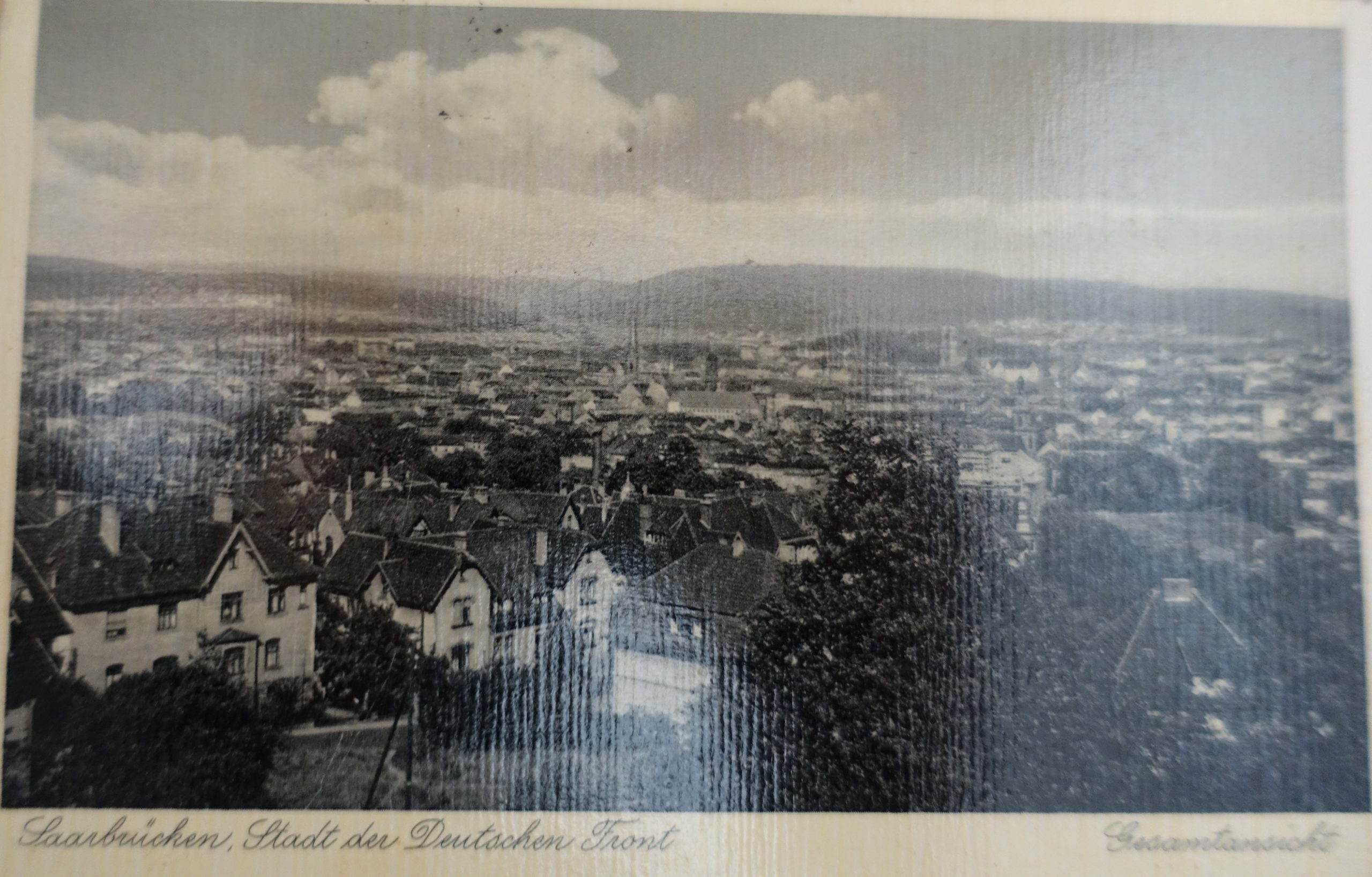

On 26 June Toni wrote, “For a change we are now in Saarbrücken. I have lots of work in the kitchen, but everything is working out fine and I’m happy about that. Today we received provisioning for two days: half a pig, 20 kg sausages, 1.5 kg coffee, 400 g tea, 8 kg margarine, 200(?) potatoes, 8 crates of young carrots, cigarettes and cigars (6 per day each), 8 kg cheese and so one. So we won’t starve. Saarbrücken is a beautiful big city and there is no damage to be seen…”

On 28 June Toni reported that they were still in Saarbrücken, but the next day at 9 o’clock they were said to be leaving. They were still doing great, but he was looking forward to coming to a cheaper region because half a litre of beer cost 5 Pf. (pfennings) and Toni loved his beer and his cigarettes. He was in charge of provisioning and the kitchen and had just received the provisions for three days (a whole pig etc.) and he reported that they would have to take all that with them to the next place; where that would be was unknown.

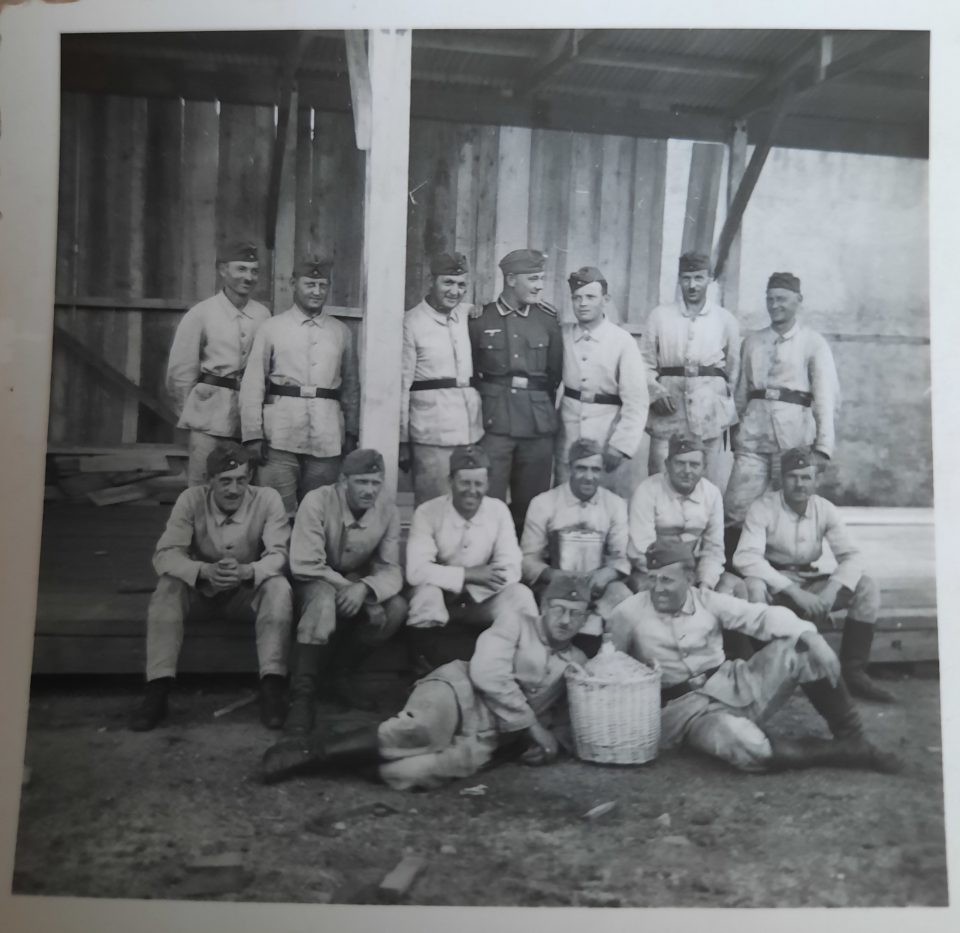

On 30 June Toni wrote to his “Liebes Frauerl”(Dear little wife) that they had finally reached their destination and that their group would be divided up in the morning: “The area is very beautiful and there is way enough food. What we are doing here is unknown. I feel fine and I’m healthy. Sergeant Wlk has returned home to Vienna this morning and he will come to you with a parcel and I hope you will be at home…. The streets here are full of discarded weapons and uniform rags, and masses of cars which are shot to pieces. In the ditches there are abandoned heavy artillery pieces. In the streets there are construction troops everywhere building bridges and repairing roads. Within a short time nothing will be visible of the war.” Life could be wonderful here, he noted, ”… half a litre of beer 5 Pf.(“Pfennige”), a bottle of excellent red wine 25 Pf., 500 g “Emmentaler” cheese 50 Pf., 500 g “Krakauer” sausage 45 Pf., a bottle of champagne 1.50 RM (Reichsmark) etc., but unfortunately everything is sold out in the village…..Today I picked the first cherries. There is lots of fruit here. We three could live here wonderfully on my pay. At the moment I have no money because until now life was really expensive. Now you should see us all lying in the meadows writing letters (at the moment we are all together still).” Toni probably meant that all the Viennese and Austrian sappers were still together. The sappers were the least prestigious and least respected units in the German “Wehrmacht”.

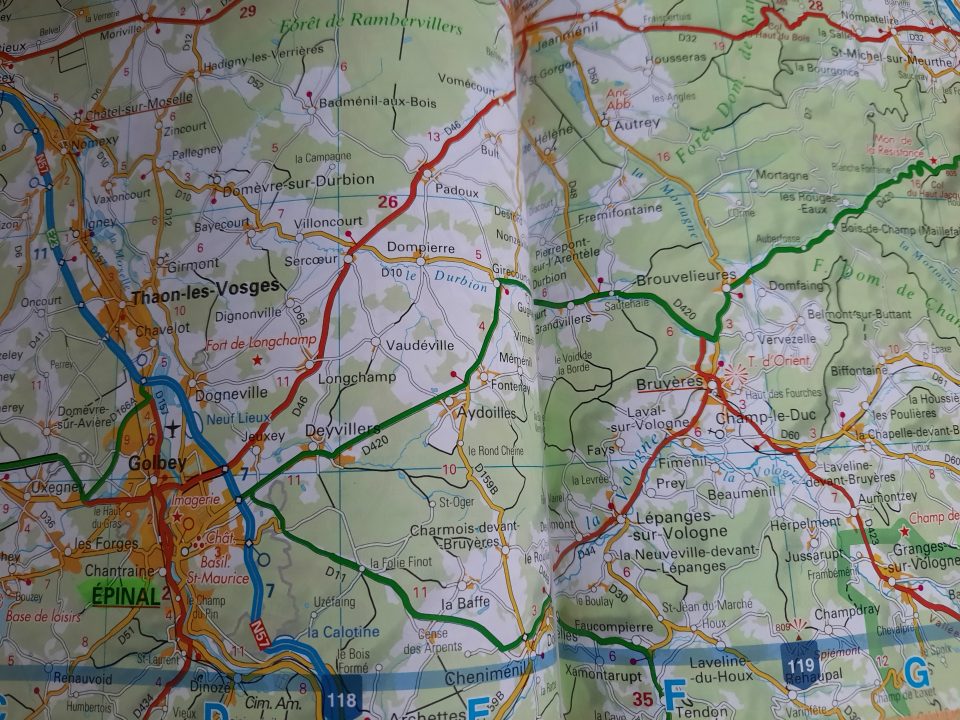

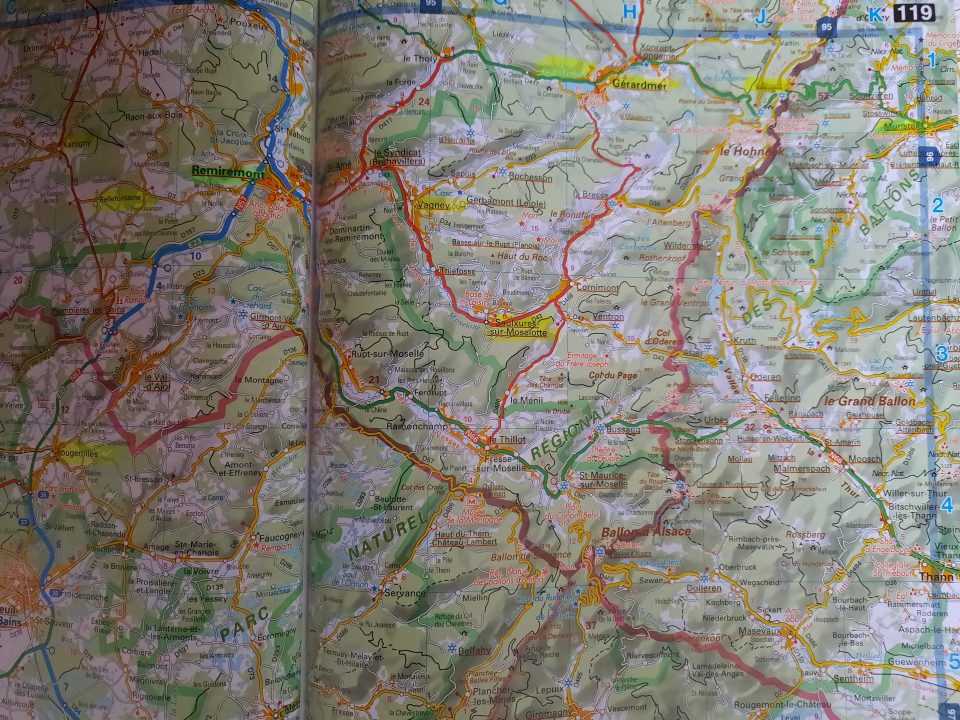

On 1 July Toni described in detail his journey from Vienna to France in a letter to Lola and advised her to look it up on a map (which I am quite sure she did not do because she was too busy with other matters and did not really care – she was no intellectual. For her it was most important that Toni was well): On 20 June he left Vienna at 19.45 from the North Station, from where they went via Penzing – Hütteldorf – Linz – Wels to Passau. In Linz the train was stuck for nearly the whole night due to air raid alarm. Anyway, they did not move during the night usually. They went on via Plattling, where they received good coffee with milk, Regensburg, Neumarkt, Nürnberg (where tea was distributed), Würzburg and Aschaffenburg, where they remained for the night. Then they were transported to Damstadt, Biebesheim am Rhein, Worms, Ludwigshafen, where they ate black pudding, salad, potatoes and soup for lunch and visited the town, then Landau, Pirmasens Nord, Homburg, St.Ingbert, where they were supposed to meet up with their battalion, but it was not there, so they ate soup and moved late at night back to Homburg again. In the morning they arrived in Mühlacker and went on via Pforzheim, Karlsruhe, Rastatt, Baden Oos, Appenweier, where they rested for five hours and finally reached Kehl near Strasbourg on the evening of the 23rd. Kehl is situated on the Rhine river and they saw the French fortifications on the other bank of the river and “crawled around in the bunkers” on their side. The city was still evacuated and empty. There was little destruction, just around four to five shell craters. On the next day the first inhabitants returned. On the 25th they left Kehl at 6 o’clock in the morning back to Appenweier and Karlsruhe, where Toni had time to go sightseeing with a comrade. In the evening they crossed the Rhine in Karlsruhe and went to Landau – Neustadt an der Weinstrasse – Kaiserslautern –Homburg – Neunkirchen and Saarbrücken. Also this big city had been evacuated, but Toni could not see any damage. He took a tram for 25 minutes to Dudweiler, where everything seemed normal and the crowds of people made him dizzy. On the 28th they were finally informed about the location of their battalion and left on the 29th at 9 am in five buses. As Toni had received provisions the day before, they took everything with them: 1 pig, 15kg butter, 3 bags of potatoes, coffee, tea, sugar, sausages etc. They travelled across the Vosges mountains, which Toni enjoyed tremendously: Saarbrücken – Saargemünd – Rauwiller – Sarrebourg – Blamont – Baccarat – Rambervillas – Epinal – Remiremont – Plombières les bains – Fougeroles – Pretourup, where they arrived at 23.30.

They were stationed in this little farming village and slept well in a garage on straw. In the morning they exercised, “but very leisurely”, as Toni mentioned. He received his pay of 17 RM or 360 francs, which seemed a lot of money, but useless as there was nothing to purchase. They were staying in a distillery, but the schnapps was so strong that you could not drink it, Toni said. Otherwise it was ok there, but very boring, so they did the laundry in the afternoon: “You should have seen us!” He asked Lola to send him two short briefs and to ask Häusler’s wife to send him two shirts with short sleeves. They were having their dinner in the garden of the distillery: liver pâté, butter and coffee. Their superiors seemed to be ok, but he would rather be at home and was impatiently waiting for the first letter from Lola. He would love to have Lola and Herta with him, where there was so much fruit, cherries everywhere, black and white ones, very, very sweet. So he had climbed the trees for their dessert.

Toni’s first postcard from France and his first visit of the city (5 July 1940): Fougerolles (Haute Saone) with the signatures of some comrades toasting with champagne:

Fougerolles today: left: production of “Kirsch” schnapps, right: memorial for the murdered Résistance fighters

On 4 July 1940 Toni wrote home that there were many broken bicycles in the area where they were stationed, so he and Häusler started to repair some. On their day off they left at 6.30 in the morning and went 25 minutes on foot to Fougeroles. The place was deserted and there was nothing to buy, but thanks to his little knowledge of French he procured half a loaf of bread for 50 cents and two chocolate bars for 20 francs. Finally they took some drinks in an inn. One glass of beer was 3 francs and then Hauser offered a bottle of champagne while Toni bought a bottle of wine. The whole excursion cost him 2.50 RM, but it was more than he could drink and they were back at the distillery at half past 9. They had prepared a football ground and they organised matches there, but he missed work and hated that there was nothing to do but the daily drills. Toni also described the typical daily menu to Lola: consommé, beef and beans for lunch, salami, pickles, Emmentaler cheese and butter for dinner and in between tea with strong schnapps.

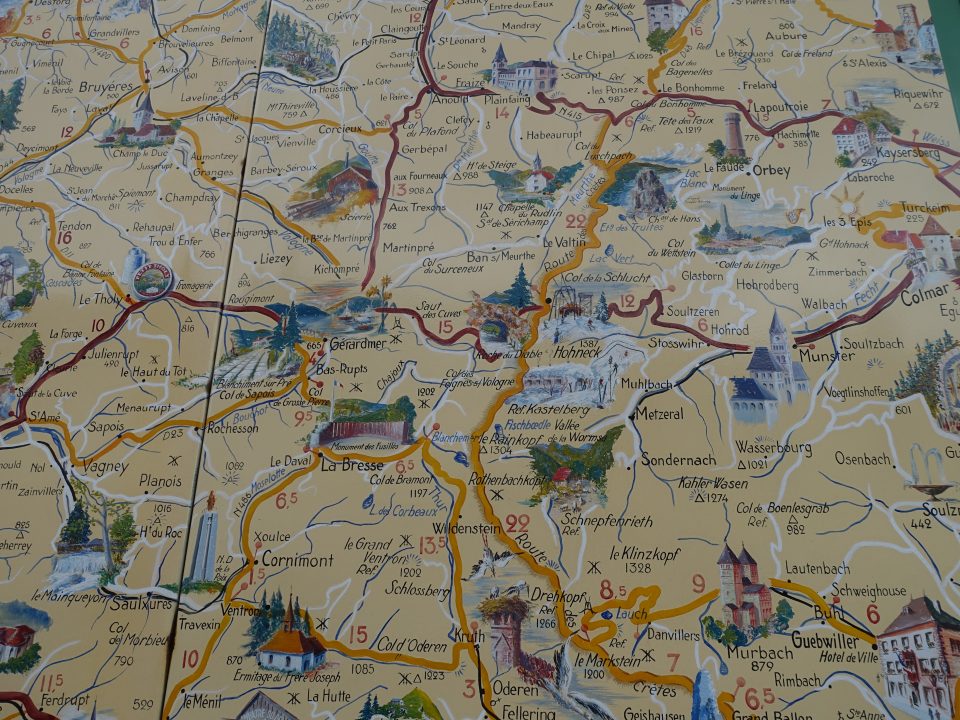

Maps of the north-eastern region of France in which Toni was stationed

Épinal today

On 8 July they had reached Bellefontaine after a twenty-kilometre march in pouring rain, which is near Xertigny and Epinal, which meant that they were turning back again towards the German border. There they were billeted in a school, which was quite nice apart from the constant rain. They were marching around in the area and on his afternoon off, when the weather was fine, he went swimming in a pond full of water lilies and picked blueberries. Their platoon searched a forest for spoils and they found two cannons, a lot of ammunition, a motorcycle, a bus, machine guns and other stuff. He now had another 24-hour sentry duty and he commented in his letter of 12 July, “So the days go by, completely useless. Why we are here, we don’t know. What we are doing is nonsense, only wasting our time”. They did not get any more the war bonus, only 1 RM per day, which was enough for him, but he could not save anything and he was looking forward to the cigarettes she had sent him and which would hopefully arrive soon because he did not have anything proper to smoke any more. The next day Toni lamented that the cigarettes still had not arrived and that he had been living for days on cigarettes begged from his comrades, but fortunately he had really nice and generous friends in his platoon. He stressed that they could not get enough letters – and enough cigarettes! All their friends and relatives at home should think of him and send some cigarettes as well, not expensive ones, “Drama” would do. They had enough food, sometimes it was more than he could eat, but there was very little change and it consisted mostly of tinned food, legumes, tea and coffee. He listed for Lola the menu of the last days: for lunch tinned beans or lentils, tinned stew of peas and pork, pea soup, potato soup, pork with noodles, beans with pork, lentils with pork – all tinned, and for dinner butter, tinned liver pâté, tinned cheese and lard. What he really missed was a nice sweet dish (in the Viennese tradition). Unfortunately, the following day he wrote that he had been terribly sick during the night because the tinned cheese had been rotten and he felt frightfully weak.

When his sentry duty was over, Toni was unable to get to sleep, so he sat down to write another letter at the desk of the mayor of Bellefontaine at 11 at night, because he had duty at the local command post in the “Mairie” (townhall). In the evening Toni and his friends (Häusler, Hauser, Havlu, Dann,…) sometimes went to their favourite café in town and he was the interpreter for this group, “…me, the old Autrichien, Viennois”. The indigenous population appreciated that and consequently a local female innkeeper always reserved 12 bottles of beer for them daily, although beer was practically nowhere to be found in Bellefontaine, “You can imagine the envy of the other soldiers! Sunday is our day off and I have already arranged something for that day which I will tell you later.” He closed the letter with many, many kisses to his two little ones who would still be fast asleep.

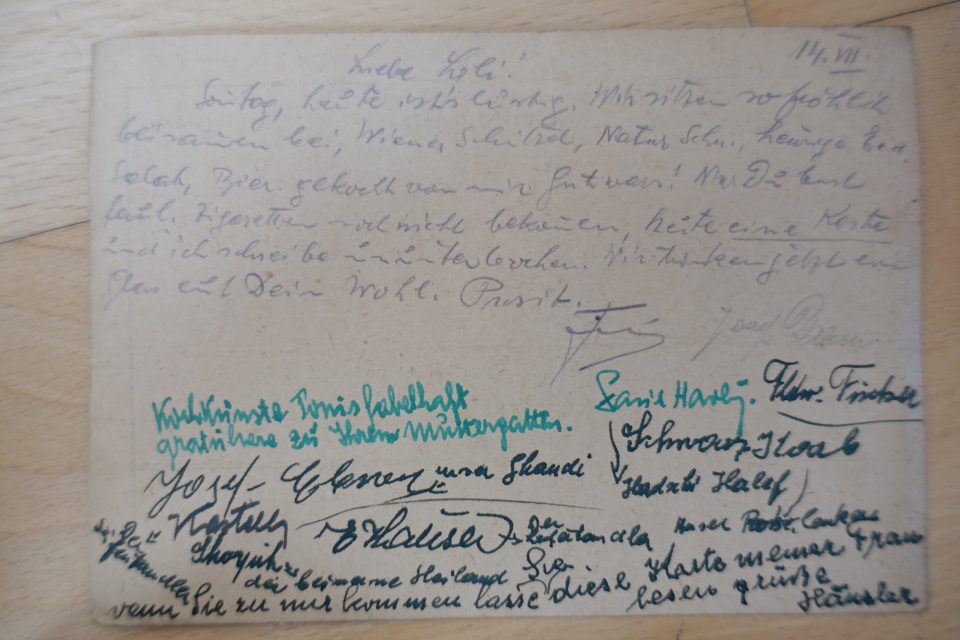

The Sunday surprise was that Toni had arranged with the local innkeepers in Bellefontaine that he would cook there for them and his friends. He described the day in the postcard of 14 July 1940, “Dear Loli! Today, Sunday, we are having a lot of fun, sitting here jollily eating Wiener Schnitzel, Naturschnitzel, new potatoes, salad and beer, all cooked by myself. It was excellent!…. Now we are toasting you with a glass of wine. Cheers, Toni”. Apart from all of Toni’s friends, the French innkeepers also sent their regards, “Bon souvenir de votre mari”:

This shows the friendly relationship Toni could establish to the local population despite the atrocious circumstances of the German occupation of France. His appreciative and respectful attitude towards the French becomes apparent and Toni seemed to have stressed his being an Austrian and Viennese, not a German, which might have helped. The French innkeepers were so generous as to offer Toni the use of their kitchen to show his cooking skills.

Toni on the right and two of his friends

Toni in the second row on the left (sitting)

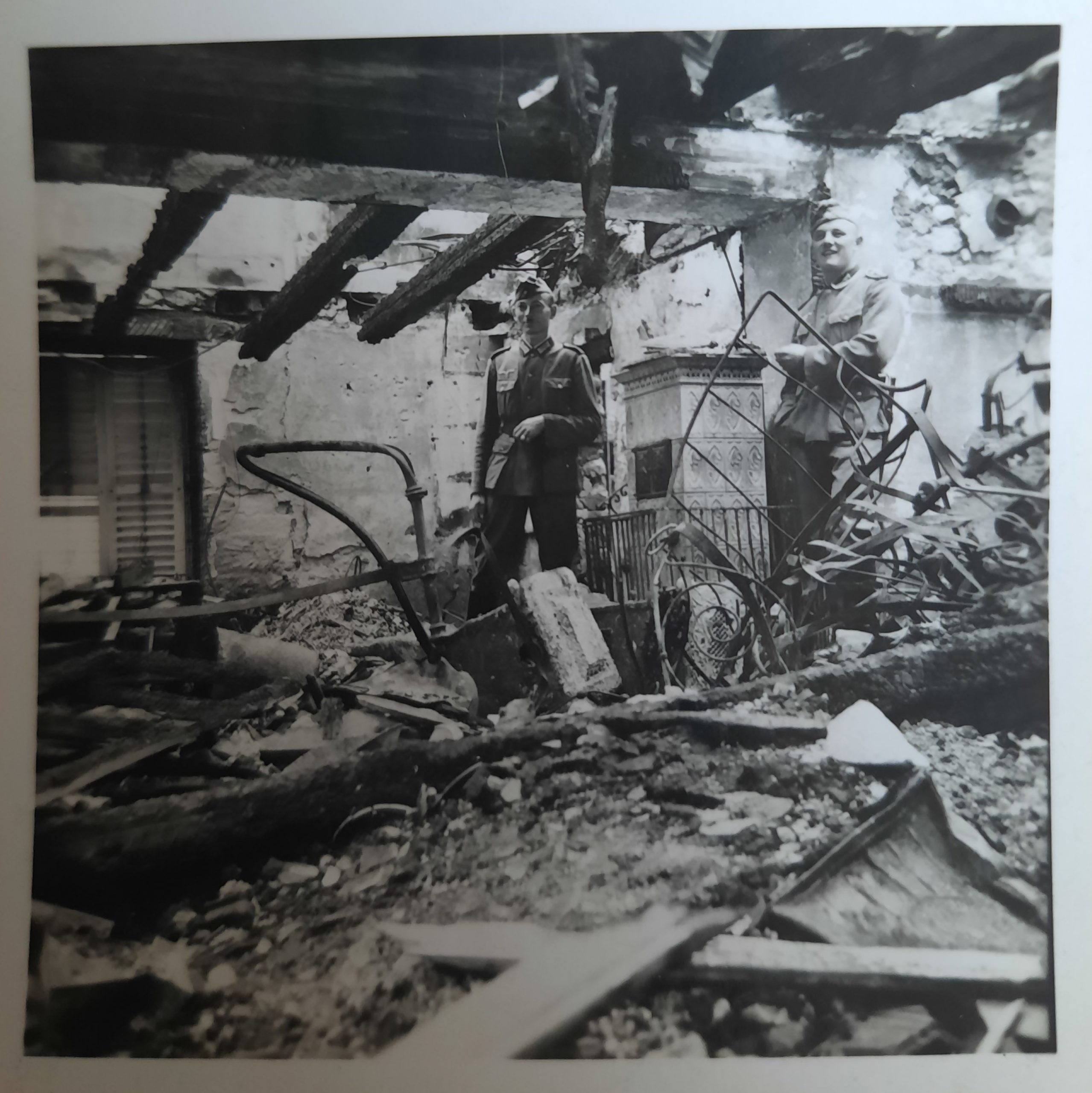

On 28 July Toni returned from his short home leave due to his mother’s death to the front-line. He described the journey back to France to Lola in detail (reminding her again that she should check the route on a map): by express train from Vienna – Linz – Salzburg – Munich – Augsburg – Ulm – Stuttgart – Bietigheim – Vailingen – Pforzheim – Karlsruhe – Rastatt – Offenburg – Freiburg – Breisach – Colmar. There he slept well on straw in a school and then continued on foot with two other soldiers who were heading in the same direction “like travelling artisans”. They were picked up by military vehicles and trucks till they reached Münster, which was in a disastrous state. There Toni stopped a private car and the small group hitch-hiked with the priest of Münster who offered them cigarettes and took them to La Schlucht at 1100 altitude. Toni enjoyed the ride, the landscape and the spectacular view, which reminded him of the Semmering (mountain area south of Vienna). There was a German occupation post in La Schlucht, where they were fed coffee, bread and butter. A private car then took them to Gérardmer – Vagney – Saulxures and in another car back to Vagney and Remiremont. In Remiremont Toni met up with two comrades, visited the fort and enjoyed coffee and a game of billiard and quite some wine and beer. He assumed that they would already have been waiting for them in the barracks.

A burnt down house in Remiremont

Remiremont today

Map of the region

A day later he wrote that he had already spent all his money on the goods he was supposed to purchase in France: for Lola cosmetic powder, soap, tissue for two ladies’ suits, a pair of shoes, some elastic bands and some pepper. He could not get any paprika, but he had ordered some and hoped he would receive it soon. Furthermore he had made a deposit on a nice winter dress for “Pupperl” (Herta) and he would collect it as soon as he got his pay on Thursday. It was 185 francs and he hoped it would fit her. “It’s all about money… I looked at some finest French perfume and if I have saved enough money, I’ll get you some for 100 francs. Tonight I dined excellently in private: wonderful soup, rabbit in wine sauce and dumplings. Tomorrow I will wrap up the parcels. I hope you will receive everything. I can’t get any nice silk, except in black. Today I saw a beautiful ready-made dress for you and if I have enough money I will buy it for you, you just have to make some changes, but it’s worth it. It costs 14 RM and weighs 650g”. He had voluntarily helped with construction works at the train station in order to get half a day off for shopping. On 1 August he had to inform Lola that he could not purchase the dress because he had only 2 RM left for a whole week, but if she could manage to send him some RMs she should tell him what else she would like to have. He was sending the third parcel and also some wool for his sister Milly.

Toni told Lola that he had put a bag of pepper into the shoes he had sent her and that now they were allowed to send a parcel of 500 g once a week. But Toni found ways to dispatch more parcels in the names of comrades who did not send parcels home, for example one to his sister Milly in the name of Viktor Maderthaner, his lance corporal, and he told Lola to inform Milly about the parcel and that they should share the soap and powder in it. He further explained to her that if she sent him money she now had to first exchange it into “army currency” (“Frontgeld”) at a bank because they could not exchange money any more at the front-line and they were no longer allowed to spend German currency. This means that the Nazi government practically stopped the outflow of domestic currency and by that made the use of RM abroad virtually impossible. Toni told his wife that there was still so much to buy in France and he hoped she liked the shoes because they were the only ones he could get, but he had found none for Milly. He was looking forward to “Puppi” getting her dress, which he thought they would love. Next he would like to purchase a clock for 150-180 francs (7.5-9 RM). As soon as he would get his pay he would purchase the dress for Herta and send it to their friend Turl in the name of a comrade who did not send anything home but whom he still had to find. So during his stay in the army, Toni was constantly thinking of his wife and daughter and trying to procure presents that they would appreciate and love, but unfortunately the pay of a private soldier in the German army was very low, so it was necessary that Lola sent money from Vienna, too, in order for Toni to make all those purchases.

Toni had asked his superiors and there was a chance that he would be transferred to the kitchen and what was more good news, he might get home leave in September. On 2 August Toni described the situation in the camp. Sentry duty was bearable for him who was very fit, “one hour strolling around with a steel helmet and a gun and then four hours off duty”. At one o’clock food that was left over from lunch was distributed to the poor of the town. At that time already 40-50 women, men and children were waiting at the gate and as soon as a soldier came with the pot, they all made a dash for him. The people were grateful for anything to eat and the cook saw to it that the portions were shared out equally; after dinner, the same “spectacle”! The day before Toni had gone shopping again because a factory was selling off their stocks and he had seen beautiful things such as 4 m of silky linen with crests in light blue (2.30 RM), very fine material for underwear in light blue, light green, pink, salmon, white (0.80 RM), linen for dresses, plain and patterned, and very nice material for pyjamas and dressing gowns. There was another factory for men’s and ladies’ suits and a comrade had bought a ladies’ suit for 5 RM a few days ago there, “nothing special, but ok”. He had already sent parcels home with tea and coffee, which they received at the army, for Lola, Milly and Turl and he was due to get more in packets of 50g. He had heard rumours that their platoon would be transferred from Remiremont back to Bellefontaine, which he did not appreciate because “there was nothing to be bought there”. Toni was writing in between sentry duties and he mentioned on 2 August that at the moment he was having ”bunker duty”, which meant prison duty. He had to guard five soldiers, among them two officers, not from their corps. His only task was to accompany them to the toilet. The weather was great, yet it was getting boring, because he knew all the shops and had no money to buy anything, so what should he do? The day before he still had 3 RM, which was enough to go shopping there (“2.30 RM for cloth, 0.30 for tea and still 0.40 left for 5 glasses of beer!”). It was not like in Vienna, where you could not go out unless you had 10 RM. Here Lola could get a whole outfit for 50 RM and Toni still wanted to send her material for a lady’s suit, which she needed urgently. She could purchase the sewing pattern and sew it herself. Did she need any sewing silk?

When reading these letters I was wondering what Lola would have done with all that cloth, Toni bought for her because as far as I know she had never sewn a dress or suit. She probably had someone sew something for her or she bartered the material for something else. Toni was extremely generous all his life and spent money on presents and beautiful gadgets as soon as he had some. I remember the gorgeous huge Christmas tree that he decorated every year with the most elaborate glass ornaments and the many presents he brought home for us from his travels with Lola in the early 1960s, which he then laid out decoratively on a table for us to admire and take home. He just could not handle money, but always spent it to make his family happy. He could only indulge in his great passion for travel with Lola from late 1959 on until December 1964, when he suddenly died of a heart attack because after 1945 Toni and Lola cared for Lola’s parents Ignaz and Ritschi, who had returned from the concentration camp in Theresienstadt, in their common flat until Ritschi died in January 1958 and Ignaz a year later in August 1959.

On 4 August 1940 Toni mentioned a beautiful Sunday outing after lunch (beef broth, beef with mashed potatoes and gherkins): they left at 1pm, Toni, Pauli, Karl, Peppi and Hans and walked up to St.Mont in one and a half hours, where they had a wonderful view and were basking in the sun in their bathing trunks. At 5pm they descended and took dinner in an inn and had “five beers and 2 wine” (each?). When they were about to leave, some officers arrived and they had to stay and drink Sherry with them. It was a lot of fun; they sang “all known Viennese folk songs” and started back to the barracks all together at half past 9. Toni was glad that it had been such a nice Sunday because he dreaded time off with nothing to do as it induced him to think of Lola and Herta constantly.

Les Voges today: Schirmeck

Senones today

Senones: memorials of the killed and murdered during World War II

Left: Bellefontaine, right: Gérardmer today

On 6 August Toni described his work as a carpenter in the army. He enjoyed working outdoors although there was more to do, but he liked this type of work very much. And above all, they could fetch a nice breakfast with sausage, cheese and butter from the provisioning facilities for themselves; now and then they got some very nice Bordeaux wine and then ended up quite tipsy. Every day he liked the area around Remiremont better and he would have been completely satisfied and happy if Lola and Herta could be there with him. He had gone on a walk along the river Mosel and he assumed that Lola would love it. He bought half a kilo of fresh tomatoes and ate them together with some sausage and beer in an inn. It would be paradise, if they could be with him. So meanwhile he was looking for a nice umbrella for Lola. The problem was only the weight of the parcel which must not be exceeded. A day later Toni wrote that these had been two days with lots of alcohol for them as carpenters because they had been celebrating the topping-out of the building they were constructing. For the time being, he said, he was a roofer in the army. The hall they were building was 73 m in length and 6 m in width. In the topping-out ceremony the day before they had consumed 20 l of wine, 72 glasses of beer, which a comrade who was going on furlough had offered. Again they had sung a lot of Viennese songs and the next day they had started to tile the roof. The provisioning station offered them 1 liver sausage, 3 pickles, butter and 1 litre of wine each for their work and Toni wrote that he by now had had enough of wine because they were “drowning” in it.

Toni had made friends with a family of workers who lived opposite the barracks and he visited them frequently for a chat with the “old one” (the grandfather?). He could order food there and get beer and good coffee. Once he wrote that he was looking forward to a meal of five scrambled eggs in butter with onions, a salad and beer he had ordered at the house of the family. He raved about the beauty of the landscape and the sunsets with the mountains in the background. He also appreciated the food in summer because the canteen offered lots of fresh vegetables and salads, green beans, carrots and cucumber salad and he hoped that also Loli would put on a little weight because he did not want to see her still so skinny when he came home again. The barracks were continually swarming with rumours, once they were said to return to Vienna within six weeks, then they were said to be transferred to the coast. Later it was whispered that they would have to go on foot to Metz, but you were not supposed to believe any of the grapevine.

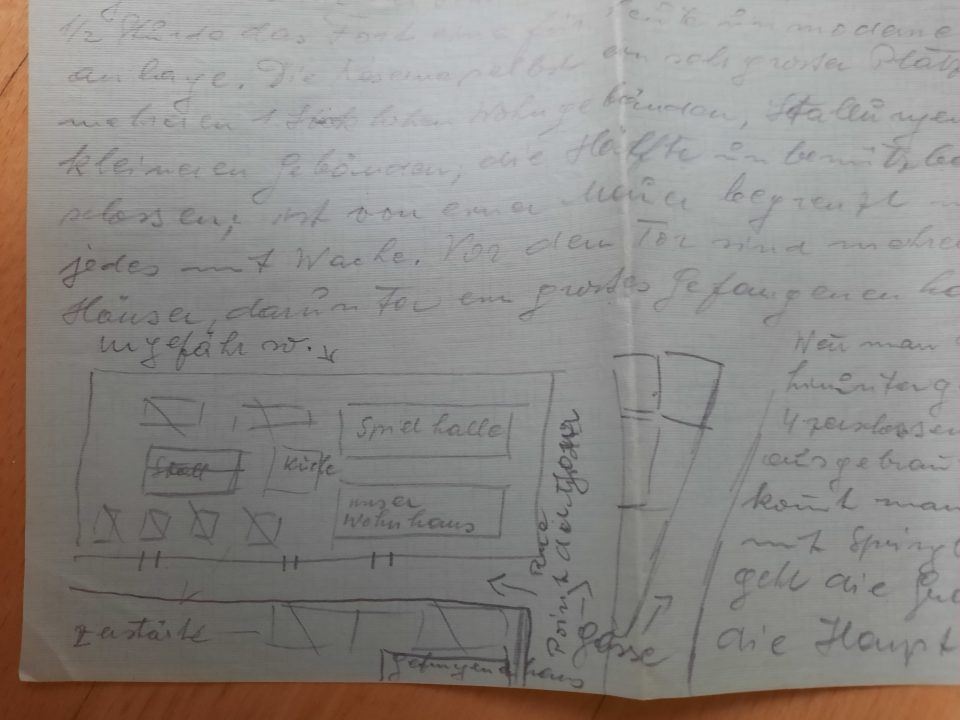

On 11 August Toni included in his letter a drawing of the buildings they were constructing

On his free Sunday he wanted to go on an excursion with his friends by bike, but after 2 km his bike broke down and he had to push it home. Toni hated it when there was nothing to do; there was nothing going on in town, “and you can’t get drunk all the time”, so he described the environment and his work to Lola in a letter. He was still constructing the hall, so he had no sentry duty like the others, who had lots to do because several comrades were on holiday and they had to guard many buildings, not just the barracks, but also the fort on the mountain and the collection point for all the booty. The barracks were outside the town on a hill and behind it the fort on the mountain: half an hour on foot and for the taste of the time an old-fashioned fortification. The barracks consisted of a large square with several buildings of one floor, living quarters and stables (as can be seen in the drawing). Half of the buildings were unusable because they were destroyed and the whole area was surrounded by a wall with three gates, which were all guarded. Outside the gates there was a huge prison and several devastated houses. If you walked down the road there were four burnt out houses on the right and further down there was a square with a fountain and then the Grand Rue started, which was the main shopping street. The Grand Rue was a nice arcaded street, “like the Maria Theresienstrasse in Innsbruck”, with narrow two-storey houses, coffee houses and inns. After around ten minutes you reached the train station and that was more or less it. The town is situated in a valley at 600-700m altitude, surrounded by mountains and intersected by the river Mosel. In the whole of the town you could find 26 coffee houses and inns.

When he received his pay on 10 August only 3RM were left after he had paid back his debts. He told Lola that he needed nothing: he had knives and a dictionary, just cigarettes and money if she could spare some, so that he could send her more parcels. He had already prepared two parcels for the following week and if he could get some money he could send one more with a comrade who was going home to Vienna. It was extremely hot, especially when he was working on the roof and he was already suntanned “like a negro”. For health reasons they had again been vaccinated against typhoid fever.

The French ”neighbours” of Toni, opposite the barracks, were a haven for him. He went there to chat, eat and drink, purchase good coffee which was not freely available and he even cooked there for all of them with provisions he had from the barracks kitchen. He stated that in fact he was lucky “as usual”, because he still could remain in Remiremont with his division whereas others had already left for Poland and another division was being transferred to some place 100 km from there.

When Toni was hoping that within approximately four weeks he would be due for furlough, he wanted to buy as many presents as possible because he was allowed to carry luggage of 10 kg with him on home leave. He had meanwhile found a way to exchange RM, so whatever money Lola could spare she should send him, not for himself because he needed little, but for the many beautiful things he had seen in France for Lola and Herta. Since his arrival in France he had already sent seven parcels to Lola and one to Milly and he advised her not to share the contents with anyone, everything was just for her, Herta and the in-laws. Toni knew how generous Lola was! Before his furlough he wanted to buy some aluminium pots and an electric iron, too, which were much cheaper in France.

In his spare time Toni once went fishing with an officer, but they did not catch anything. Nevertheless, he enjoyed the outdoors experience tremendously and then bought three marvellous crème puffs in town as a dessert. He missed the cakes and sweet dishes from home, so he loved going to the cafés and playing billiard with his friends, Hauser and Häusler and others, drinking coffee with cake, beer and wine. Sometimes he ate in a restaurant in the evening because he loved the French cuisine. He wrote that on 15 August he had dined for 1RM: excellent beef broth, roast chicken with “pommes frites” and green peas, schnapps and then espresso with home-made cookies. But he would have enjoyed it much more if Lola had dined with him. Toni was a true gourmet, which is not surprising as he was the son of an innkeeper and a trained cook and waiter.

Meanwhile his division had been reduced from 200 to 100 soldiers and in the following days they would make an excursion on carts decorated with garlands made of brushwood. On 18 August Toni sent photos he had made on his trip to France to Lola and in a letter he described the river Neckar and the fortifications between Breisach and Colmar, which had not been attacked because they were already outdated and crumbling, the view from la Schlucht and the group of children in Saulxures-sur-Moselotte who offered him garlands of flowers and the view from the fort towards Remiremont. Unfortunately these photos are lost. He wrote that it was now possible to have films developed and printed, so he could show Lola what it was like in the area and what they had built. He included the photos in his letters to Lola and Milly and asked Lola to keep them safe for his return.

La Schlucht today

On 19 August Toni described a wonderful hiking tour he had done the afternoon before with three comrades up the mountain behind the barracks. The weather was still beautiful, but in the evening it was already getting cold because the mountain ranges were close. On the way they found loads of huge (“thumb-thick”) brambles and he mused that Lola would have picked ten kilos. Up the mountain after approximately six and a half kilometres they ate at an inn and on the way back he was still hungry, so he visited his friends opposite the barracks and had potatoes with butter and coffee there. He said that he had certainly put on weight – he was an extremely lank and tall man – and he hoped that Lola would put on a little weight, too, which was illusory considering the stress she had to endure as a Jewess in Vienna. On 19 August his division had the announced parade. They left at seven in the morning with four decorated carts and drove five hours to Gérardmer to a beautiful lake, Lac de Gérardmer, in bad weather. There they had three hours to discover the beautiful city (“à la Gmunden”- in the Austrian Salzkammergut) and have lunch. Toni reported that the church was totally destroyed and the church bell had crashed from the belfry to the ground due to the fire (“How terrible, otherwise no significant damage!”). In Gérardmer Toni bought a nice clock for 5RM – from the pay he would receive the next day-, but he would have to take it home on furlough because it was too heavy to be sent in a parcel and he thought that Lola would like it. Furthermore he bought two tins of finest French liver pâté, which he would send her in a parcel. On the way back it started to rain and they were drenched when they arrived in the barracks at 8pm. Once a day food was distributed to the local population from what was left over in the barracks kitchen and Toni wrote that whenever it was his turn to distribute food, the children already knew him and shouted, “Antoine, du pain!” and there was a big confusion and never enough bread. In the end he unfortunately had to send them all home when nothing was left. His French friends from opposite the barracks organised for him rare goods to buy such as tea, coffee and the woman came to the barracks to let him know whenever she had managed to procure something for him. Spices were easily available except for paprika and cocoa and chocolate, which were rare. Toni sent shampoo, soap and powder home as well because these seemed to be much better in France.

Lac Gérardmer today

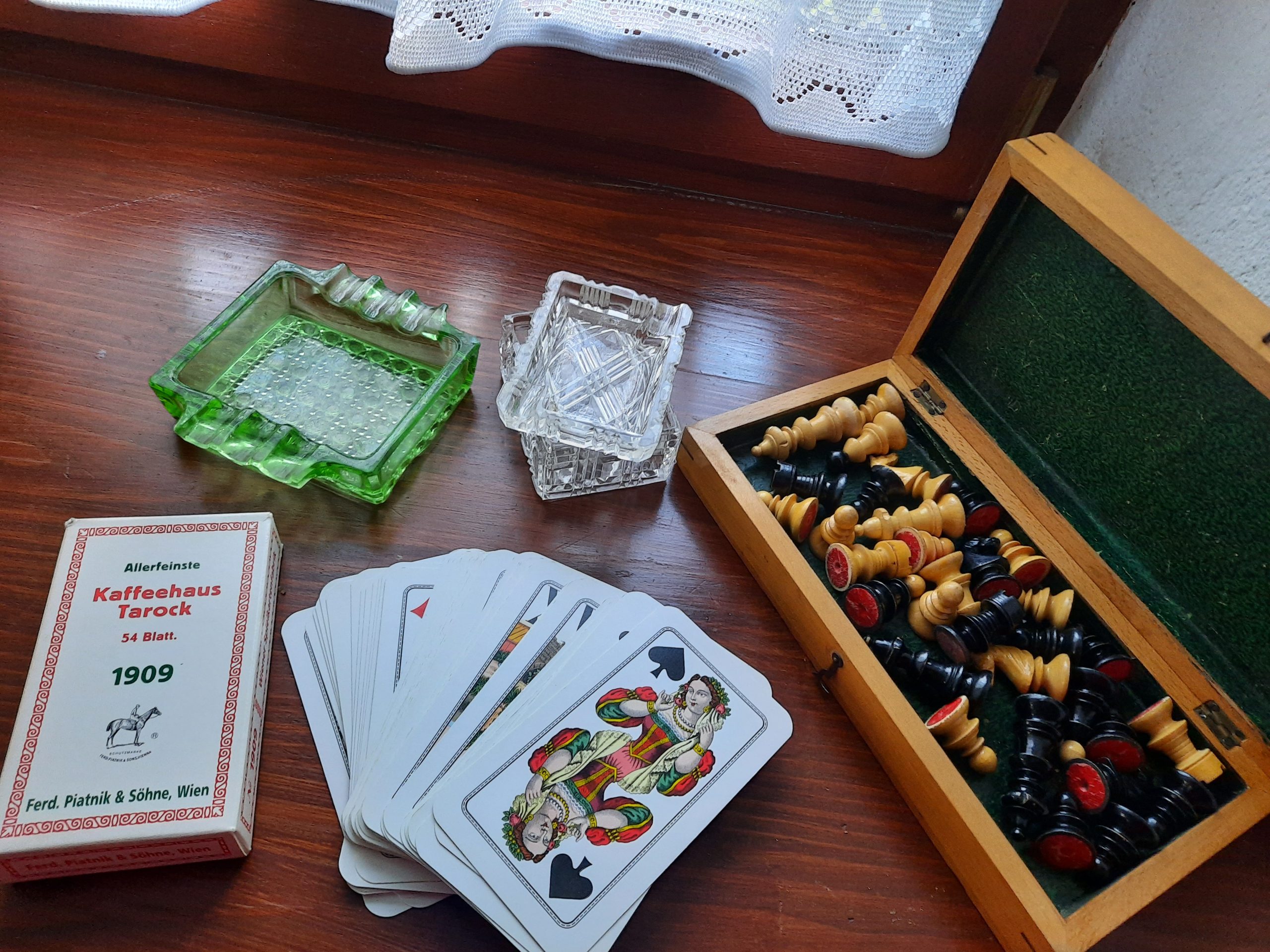

Lola was worried that Toni might have exhausting duties in the army and he responded in an amused way that he was not “a member of this club” and he knew how to come to terms with this system because “above all, a good soldier has to camouflage at the right moment”. He would be able to sort out everything: from the next day on he was to be transferred to the kitchen. Next Toni wrote that he had had his début in the kitchen and “nobody died, on the contrary I even received some praise.” He had cooked beef broth with noodles, beef and roast potatoes. The problem with the potatoes was that he lacked pickled gherkins, marjoram and common thyme, but he made do with a little vinegar and laurel. The next day he would do beef and a purée of peas. It was getting cold and rain showers were frequent, so they had already started to heat the dining room. His duty in the kitchen was from 7 am to 6 pm. By then he was usually exhausted and had to go for a walk to town because there was quite a lot of work in the kitchen. At 7am he had to prepare the meat that had been delivered, for example cut the shoulder of a beef. Then he had to cook the beef broth, prepare the vegetables for the side dish, for example chop the onions and cook the sauce. All of this took quite long because he had to prepare the food for so many soldiers and he only had a small stove because the big cooking vessels were still outdoors. But he had had a big wood stove installed in his kitchen with a huge stove plate that day, so it would no longer take him two and a half hours to roast the huge amount of onions for lunch. He was happy to report that “until then his comrades were satisfied with his cooking skills”. After work he went to the “gaming hall” in the barracks for bowling with “tin balls”. There were three billiard tables and five table football machines with eleven football players and a rubber ball, which was unknown in Vienna at that time and which Toni found really funny. Furthermore there were six to eight tables for card games and as the weather was getting worse, the gaming hall was always crowded.

His friend Pauli was going home on 1 September because his wife had applied for his furlough as she was expected to give birth by then and Pauli would pack one to one and a half kg in his luggage for Toni to take to Lola. He hoped that he could go on home leave in September as well and then he would like to bring Lola an umbrella, which she needed urgently as they were really cheap in France. When Toni heard that Lola could not get any vegetables and fruit in Vienna, he was really devastated because they had so much of it in France, for example three big pears for dinner each.

Toni reported that he had observed a very old tradition in town, namely an official with a drum who walked across town every four to five days announcing the latest news, for example that the following week the new bread coupons for September would be distributed and from 1 September on the coal coupons. After work Toni often spend the evenings in the house or garden of his French neighbours and paid them for some beer, wine or for some food. He liked talking to the old man who only spoke French, but nevertheless “we talk for hours”. Once Toni brought him the empty body of a French projectile and the old man would make a lighter for Toni as a souvenir. He was glad that the comrades liked his cooking and he put a lot of effort into it, so he was also asked to cook special meals for the officers and the administration. There were another 19 soldiers, who worked outside and received their lunch in the evening and Toni said, ”They are storming in hungry like wolves and I’m so happy when they devour everything with gusto”.

Toni’s sister Milly sent him in her letter of 26 August a mysterious message, namely that Hans and Turl, his friends, had had the ingenious idea to send him the “wrapping tissue of the wine bottle in an envelope” and she was afraid that the envelope might have been confiscated because it must have looked suspicious, yet Toni would know what it meant and he should let her know whether he had received it. Was it a joke among buddies or a serious message? We will never know now as Toni’s letters to Milly are lost.

On the afternoon of 25 August Toni and some comrades went together with the Alsatian family, who he knew and where he sometimes went for dinner, to an inn on the mountain. There they invited the family and had lots of beer and wine. He had been shopping again in town after he had finished in the kitchen: a leather pouch for tobacco for Ignaz, some surprises for Lola, and he wanted to bring a doll for Herta. He was very proud that he was able to convince his sergeant that he could serve more than cooked beef to the soldiers. So that day he had been shopping for the new menu and the next day he would cook cauliflower soup, roast beef with salty potatoes and lettuce. It was a tough job because those employed in the kitchen were afraid that they would have more work. In the morning the sergeant had specially called him and asked him to do the roast beef himself. “You know, if you introduce new things you immediately have lots of enemies and envy crops up immediately. So I have to act wisely- politically. But one cook is going on furlough soon, so I’ll have more room for manoeuvre.”

Toni wrote on 30 August that he weighed already 78 kg; he would become a fattening pig and he was worried because Lola still had not put on weight. He further reported that all cooks had to send in urine and stool samples for health checks “and soon they will ask for brain samples, but then some will be in deep trouble!” He described to Lola the organisation in the kitchen where the chef had no idea of professional cooking, but fortunately he did not interfere with Toni and allowed him to do as he liked: he always said, “If you think so?!” Toni told her that even she understood more of cooking than any of those “chefs” and he could easily compete with them. When they were doing steamed cabbage, the chef asked Toni what for he was chopping and roasting onions and when he added a little sugar “the chef could not stop shaking his head”. He thought they would definitely keep him in the kitchen because the soldiers appreciated his meals and he had planned this transfer in case he was sent to Poland as several comrades of his division before. There he would rather work as a cook than be in the field and do the “dirty work”.

Suddenly the news came that his division would have to leave within a few days. Toni was very worried and stressed, but he said that so far he had been lucky and he hoped that his luck would not desert him. There was the slight hope that their decampment would be postponed again. Rumours said that they would be transferred to Poland, “which would be terrible”. Meanwhile he tried to get hold on some money to buy in France as much as possible and send to Lola the last parcels from France, if possible with Pauli who might be able to have his furlough before the decampment. She definitely needed a winter coat which he had seen for 25-30 RM. He had already bought a table cloth and six napkins which he hoped she would like and he had seen very nice soft towels. Toni would have to wait a little longer before he could go home and until they were at their point of destination she would not receive any mail from him and vice versa.

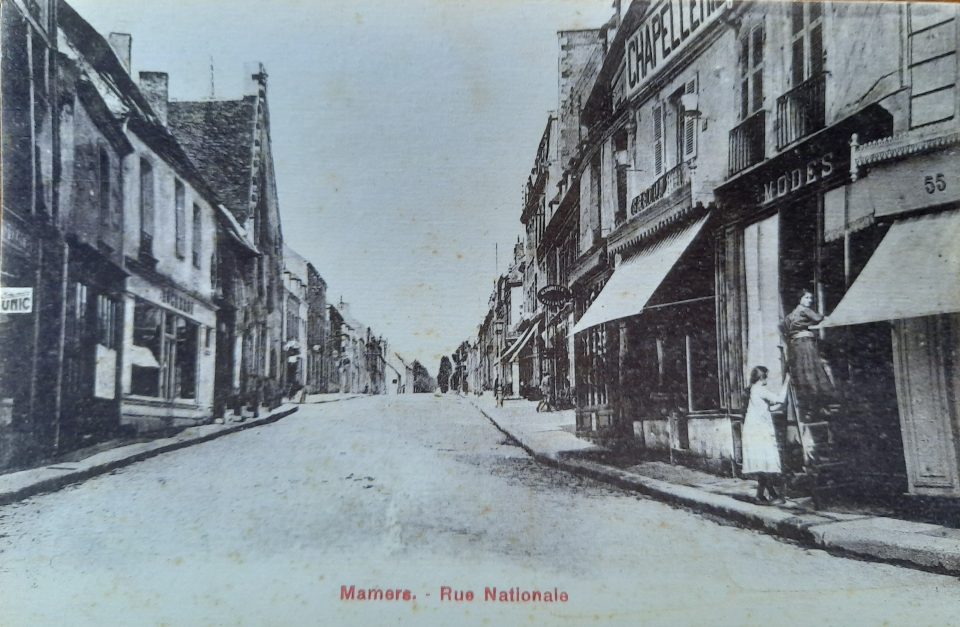

Toni bought this postcard of Mamers in France, a place he could not see any more before being transferred to Poland

On 2 September Toni wrote from the train: they were still in Remiremont, but for 24 hours the train had not moved. The day before at 8 am they had started with the decampment and the loading and the train should have left at 10 am the day before. He was with the kitchen in an open carriage and they were cooking the whole day. During the night he slept under an improvised tent in the open carriage. But what he really wanted to know was their destination. It would be Poland, but where? If the weather continued to be nice, he would have a nice journey with a good view in the open carriage. Pauli would hopefully have delivered his two parcels to Lola, but what they all desired was to go home! They had written on the train carriages; “Jetzt geht’s heim to Mutti” (Now we are going home to Mummy) and “Mutti, Mutti, Vati kommt” (Mummy, mummy, daddy is coming). He had been really angry when they had received their pay: 9 RM, which did not suffice for purchasing the many things he wanted Lola to have. He would not have the chance to make any more purchases because he had heard that there was little to buy in Poland and what was available, was extremely expensive. “I tell you I want to quit this club! There were a lot of emotions when we left. When I said good bye to the family opposite the barracks, the old man cried like a child and said that so nice and decent people would not come again soon. I had to drink some wine with him and he gave me some cigars and the lighter he had made for me. So really nice! The Alsatian family was so kind to me, too, but I didn’t have much time to say good bye because I had to pack the kitchen.”

On 5 September the train stopped in Tarnow, the weather was good and the journey wonderful. On 6 September 1940 Toni arrived at the destination of his division in Sanok in Poland. His experiences there will be described in the second part of this article:

THE HOME FRONT:

As soon as Toni had to leave Vienna he sent a letter or postcard daily to his wife Lola, sometimes even two, and a few to his daughter, Herta, who had just learned to write. As an avid letter writer he wrote letters to his sister Milly and to his friends, especially Turl and Hans, too. In Toni’s letter of 30 June 1940 he told Lola that now she could finally write to him: “B.S. Anton Kainz Feldpost Nr. 17525” and he hoped that she would write often and very detailed. He further asked her whether she had eventually put on a little weight (Lola was extremely thin, especially since she had to face many hardships related to the dictatorship of the Nazis in Austria) and whether Herta was a good girl (which she always was as at the time she was just six years of age). Toni was yearning for a message from them. He told Lola that she did not need to send him anything except cigarettes of the brand “Drama” because despite the fact that cigarettes were very cheap in France (a package of 20 4.5 franc = 22 Pf.) they were of very bad quality and soldiers never got enough (Toni was a heavy smoker; he smoked two to three packages a day). Toni wanted to know how Ignaz and Ritschi (his parents-in-law) were, whether they were well and whether Ignaz had a job. He asked about their friends Turl and Hans and if they often visited Lola and how his sister Milly and his mother were. He promised to send her a parcel as soon as he would come to the village. His sergeant Wlk would bring the presents Toni had bought for her to Vienna. There would be no more cake because from now on the army would supply them. Toni was impatient to hear whether she had met the two comrades on home leave who had parcels for her.

On 4 July Toni sent two parcels with a pair of shoes for Lola, which he had managed to buy in France. He had to send them separately because a parcel was not supposed to weigh more than 250g. He was trying to send them some cocoa for Herta, but had not been able to purchase any so far. He had added a few cigars for Ignaz in the parcel and hoped he would enjoy them. Toni was worried if Lola punctually received her money and whether the company (the fish monger where Toni had worked) had already paid her what they owed to Toni. He later angrily reported that the two parcels with the shoes had been returned to him by the forces’ postal service without any explanation.

On 8 July Toni confirmed that the telegram informing him about the death of his mother, Emilie Kainz, had arrived and he was told the content by his sergeant, but he himself did not receive it. He would be granted home leave, but it was uncertain when. Transport to the border to Germany was rare and one comrade had already been waiting for five days after his father had died. So Toni assumed they might be going home together and he was very much looking forward to seeing Lola and Herta. Toni was wondering why his mother had died so suddenly.

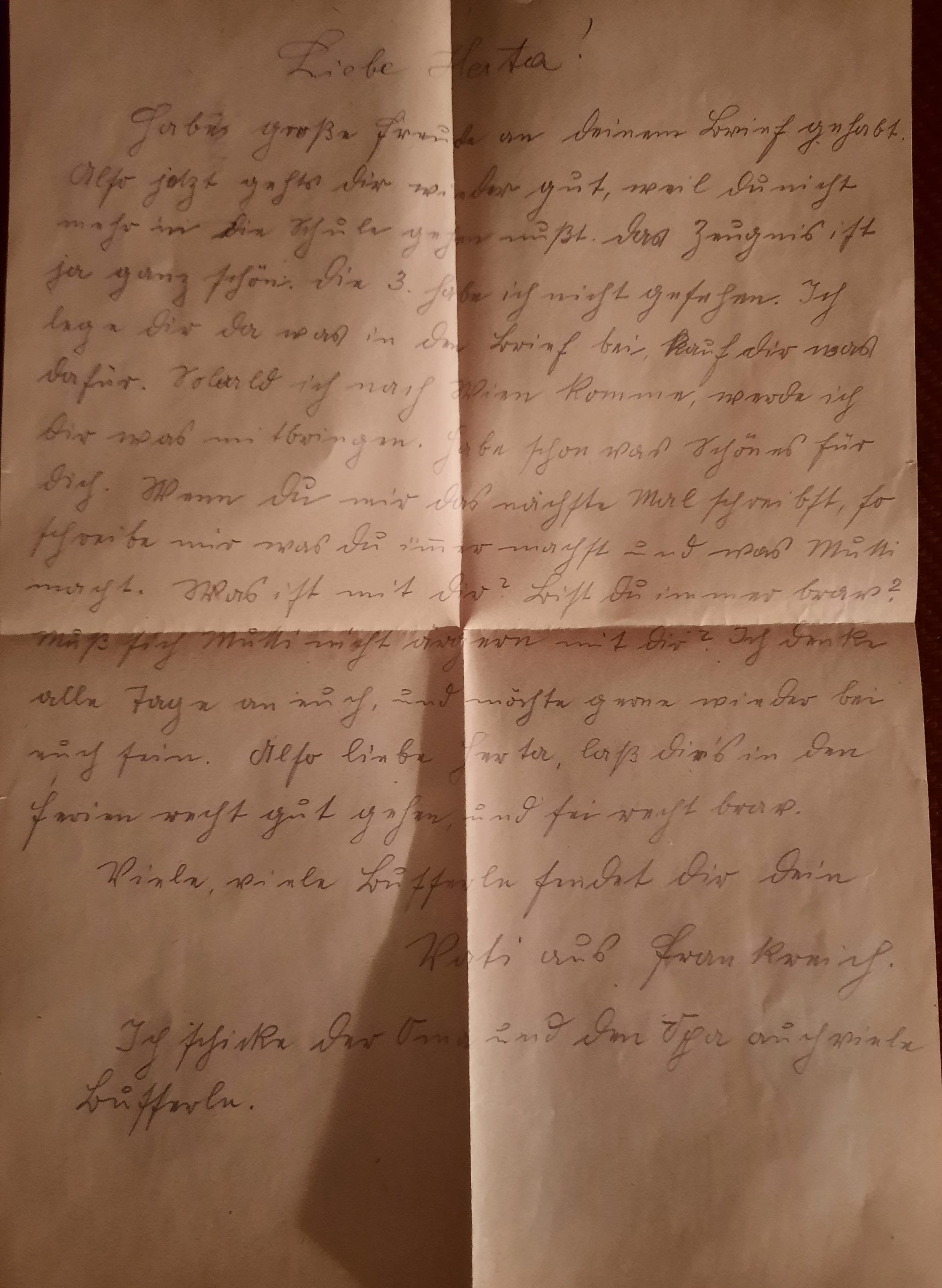

At the beginning of the school holidays Toni wrote a letter to his daughter Herta using the old German cursive handwriting, which was taught at school during the Nazi period, and which she had to learn. He never used it otherwise and one can see that he tried hard to write clearly and legibly. He hoped that she was well again after her illness and congratulated his daughter on her performance at school, telling her to buy herself something nice with the money he had put into the letter. He furthermore told her that he had already bought a present for her, which he would bring along on his special home leave.

Toni’s letter to his daughter Herta of 14 July 1940 (she was 6 years old then) in old German cursive handwriting. Herta had a very close relationship to her father all her life; she adored and loved him deeply.

During Herta’s illness Lola seemed to have had problems to get treatment for her. She was told that Toni had not paid the health insurance, but in reality this was most probably due to the fact that Lola was Jewish and Herta a “mixed-race” child (see article and “Mixed marriages”). Toni was angry and worried, and advised her to contact Dr. Steiner, who was responsible for wages and salaries at the fish monger’s (“Fischhandelsgesellschaft Hofbauer & Hammerschmidt, 1st district of Vienna, Zentralfischmarkt”). He remarked that he might owe the social insurance a maximum of 1-2 RM and Lola should send his best greetings to all employees at the fish monger’s.

On 12 July Toni told Lola that he still did not know when he would be able to get furlough for his mother’s death as no one showed respect for an ordinary soldier. So Lola and his sister, Milly, would both have to deal with the inheritance matters and he was glad that Lola was on such good terms with Milly. He hoped they would sort out the legal matters together. He had given tea, coffee and sausages to his sergeant Wlk, who was on home leave and had promised to hand over half of all the provisions to Lola. Yet Toni was very worried that Wlk seemed not to have visited Lola in Vienna so far. Toni was happy that the “old one” (Ignaz) had found a job, so he would not be “bored” and he told Lola that it was ok and that she was brave staying all alone with Herta in the flat, “it would be a shame if you were afraid”. Of course, Lola was in fear of the Nazis and felt unprotected, but Toni tried to soothe her and boost her morale. Their friends, like Turl or Hans, who had remained in Vienna, were very important for Lola because she felt they might protect her as long as Toni was in the army. As a Jew she was extremely vulnerable and at risk. She was not even allowed to enter Herta’s school building and talk to the teacher or to accompany her to the doctor’s or to a hospital, neither were Herta’s grandparents, Ignaz and Ritchi. She was completely reliant on Toni, but he was in the army and Toni’s parents had already died. So their friends and Milly were of great support for her.

The two train tickets the army issued on 15 July 1940 for Toni when he was granted special furlough due to his mother’s death to Vienna and back to Remiremont in France

Soon after his return from his special home leave on 1 August Toni told his wife that she should pass on the message to their friend Turl that he should not do any stupidity. It can be assumed that he warned him to abstain from dangerous actions against the regime. On 2 August he wrote that he had received Lola’s first letter since he had left Vienna a week ago and time felt endless! He explained to her that she did not understand the calculations related to his mother’s heritage, namely the house in Währingerstrasse where the “Anton Kainz” inn had been (see article on Suburban Inns): “If we assume the value of the house at 30,000 RM, minus the mortgage of 5,000 RM and the interest of 1,000 RM and 1,000 RM for Paumgarten, which makes 7,000 RM. Therefore 23,000 RM remain, so a quarter is 5,750 RM. If you read the contract diligently you will understand it!” One can assume that Lola felt they had been cheated, when the heritage of Emilie Kainz, Toni’s mother, was distributed and Toni tried to assuage her. In his letter of 22 August he assured Lola that he thought it had been the right thing to accept the share of the heritage of his mother’s house because everything else would have cost them a lot of money in lawyer’s fees and taxes. He wouldn’t have known of a better investment and it spared them a lot of hassle.

He was astonished and pleased, how kind his sister Milly was and how often she wrote long letters to him and sent him money and cigarettes. She also spoke nicely about Lola and Herta and he thought she was a bit jealous because they had all the love they could think of, and she had none. Milly had inherited nearly everything after their mother’s death, but was alone and now in love with Hans Schäfer, who was a very nice friend of Lola and Toni’s, but a womanizer. Maybe Milly was aware that their mother had been unfair to deprive Toni of his heritage because of Lola being of Jewish origin and that’s why she gave Lola some money every month. One of Milly’s letters (of 26 August 1940) has been preserved, where it can be seen that she wrote very kind and loving letters to her brother and was kind to Lola and Herta. She also urged Toni to send Lola clothes and tissue because she needed it and because she was so proud of Toni, who wrote her so many letters and sent her so many parcels. She would just like to have some silk in dark blue, too, which he had sent to Lola and she specially praised Toni’s excellent taste. He did not need to send her any more spices because they were now again available in Vienna. She mentioned that she was a bit jealous that she had to pass on the photos Toni had sent her in his letter to Lola, but she hoped she would see him soon on his next furlough. She further told him about a very nice walking tour on Sunday she and Hans had done together with Lola and Herta and Turl, his wife Elsa and son Fritzi (who was about Herta’s age) and mother Turek from Mauer to the Walpergerhütte and back to Hütteldorf and how astonished she was that the two children were already very able hikers.

On 6 August Toni worried in his letter, whether Lola would receive the money from his employer, the fish monger, so that she could pay the health insurance. He further asked her to go to the company and send his best regards and in doing so tell his colleagues in a roundabout way that cigarettes were much appreciated by him. Additionally Toni wanted to know how Ignaz was doing at work and he promised him some French tobacco. Furthermore he reminded Lola to tell Turl that he should start repairing the stove for her.

On 13 August Toni was sitting in the most elegant café of Remiremont, “just like our Hamerlinghof” (this was an elegant café and restaurant in the same square where Lola and Toni had had their coffee house) with Häusler and after some games of billiard and an excellent blueberry cake with espresso he was writing a four-page letter to Lola. He told her not to accept any “orders” for parcels from other people; the parcels were only for her and Herta or Milly. All parcels were now limited to 500 g and he did not purchase anything for himself, everything was just for them. Those were real bargains because the quality in France was superior and in Vienna everything was much more expensive. Furthermore he stressed that Lola was entitled to represent him in Vienna while he was in the army and she should try to hold her ground because it was her right to receive the 21 RM the company owed Toni for the two weeks he had worked overtime in Ottakring and he urged her to go back to the company and claim the money. If it was necessary she should go to the boss, Hofbauer, himself and explain the matter to him. As Lola could not get any “Frontgeld” (army currency), she should send him Reichsmark and he would find a way to exchange the money.

He had laughed a lot about the letter Herta had written to him thanking him for the dress. She should always write the letters on her own, Toni said, so she would learn to write properly. He was lucky to have procured proper coffee again and had already made two parcels for her, one of which he will probably send to Hans (because he was not allowed to send so many parcels to his wife), so that she could drink some really good coffee again. She should of course cook it for the “old ones”, too, but she should not waste it on “the old drinking buddies”. Toni wanted to buy so much for her, but first it was difficult to decide what to buy and second and most importantly, he needed money for the purchases which he did not have.

In the letter which Lola had written to Toni on 28 August and which she had overlooked and not destroyed Lola told her husband how much she missed him and that she was very happy about all the parcels, but what she really wanted, was only him! She was glad to receive his photos and had looked at him through a magnifying glass. She thought that he looked ill and she worried that in the kitchen he had much more work than before as a construction worker. She further mentioned that now some people were suddenly very friendly to her because they had heard what Toni could procure in France, “…wie ihnen allen auf einmal die Liab einschiesst!” (…they all suddenly discover their love for us). But the Tureks (Turl and his family) had always been so kind to Lola and Herta; they regularly brought fruit and sweets for Herta, who was not well and had to be taken to the doctor’s.

Lola’s letter to Toni

Toni answered his wife how much he pitied his sister, Milly, because of her difficult relationship to Hans. Hans had sent a postcard to Toni from a “Heurigen” in Vienna (a place where the new wine is sold, usually with a garden and music) with several women sending him hottest kisses (Maly, Mizzi, Melly), but she should not say a word to Milly. He urged Lola to collect all the photos he sent to Vienna because he wanted to make an album after the war. Unfortunately this album, if he ever made it, is lost.

THE EMOTIONAL STATUS: