INNOVATIVE VIENNESE HOUSING CONCEPTS FOR THE WEALTHY AND THE WORKING CLASS (1872-1933) AND THE CONTRIBUTION OF VIENNESE JEWS AS ARCHITECTS, ENTREPRENEURS AND TENANTS

“Cottage Quarter “ Vienna, Währing

On 14 March 1872 the “Wiener Cottage Verein” (Viennese Cottage Association) was founded, initiated by the famous “Ringstrassen” architect Heinrich von Ferstl, whose aim was to counter the pressing need for housing in the overcrowded city of Vienna and to plan a “garden city” following the English model. In the houses and villas which were erected there several writers, artists, actors, scientists, entrepreneurs, many of them of Jewish descent, lived in this “garden city” at least for some time. The first tenants had to walk there from the city, but from 1889 a horse-drawn tramway ran to the “Cottage Quarter” and from 1907 the tram number 40 left the city at the stop “Stock Exchange” and ran to Sternwartestrasse and Gymnasiumstrasse and along “Währinger Park”, which had been the cemetery of the suburb Währing until 1923, where the writers Franz Grillparzer and Johann Nestroy were buried. From there the tram 40 reached the “Türkenschanzpark”. The name is derived from the place where the Turkish army, which besieged Vienna in 1683, had entrenched itself. In 1872 Edmund Kral and Heinrich von Ferstl founded the “Cottage Association”, which bought the gravel and sand pits below the former trenches and initiated a housing project which was supposed to realise their idea of modern and healthy living in one- and two-family houses. Ferstl’s dream of a different form of housing was modelled on the concept of “idyllic English garden cities”. Between 1873 and 1930 houses and villas were built imitating historical styles, others were modern houses designed by innovative architects like Josef Hoffmann. All of them were free standing town houses with a front and a back garden in an idyllic green oasis for the well-to-do.

A “Cottage Quarter” similar to the one in the suburbs of Währing and Döbling was established in the suburb Hietzing between the imperial castle Schönbrunn and the imperial hunting ground, the Lainzer Tiergarten, the “Hietzinger Cottage”. There a start was made in 1883, when the entertainment park of Carl Schwender called “Neue Welt” (“New World”), went bankrupt. This ground was divided up into plots of land for the construction of another “garden city”, which was called “Neue Welt”, too. Many of the proprietors and tenants of the “Viennese Cottage Quarters” were forced into exile after the takeover of the Nazis, the “Anschluß”, in March 1938 and several did not only lose their fortunes, but also their lives in the Nazi terror.

Nearly 50 years after the foundation of the first “Cottage Association” the dream of modern and healthy living in Vienna was to be realised for the working class as well. When in 1919 the Social Democratic Party took over the running of the city of Vienna, the party devised an ambitious plan of creating at the start terraced houses in settlements and then blocks of flats with modern amenities to alleviate the drastic housing shortage. Between 1923 and 1933 63,934 affordable, light and healthy flats were built for workers and their families in a world-wide unique social housing project of the time. In the housing concept of “Red Vienna” several modern architects, like Josef Frank, intellectuals, health experts, pedagogues, like Friedl Dicker and Franz Singer, and sociologists like Otto Glöckel, Siegfried Bernfeld or Max Adler were involved; many of them with Jewish backgrounds. Unfortunately all the Jewish tenants could enjoy the benefits of the new flats only briefly because they were the first to be evicted from the social housing projects after the “Anschluß” (the takeover of the Nazis) in March 1938, among them my great-uncle Karl Elzholz and his wife Mitzi, who were chased out of their flat in the “Reumannhof” at Margaretengürtel 102/15/17. They both managed to flee to Bolivia. After the war Karl returned to Vienna and moved into a newly built social housing complex nearby.

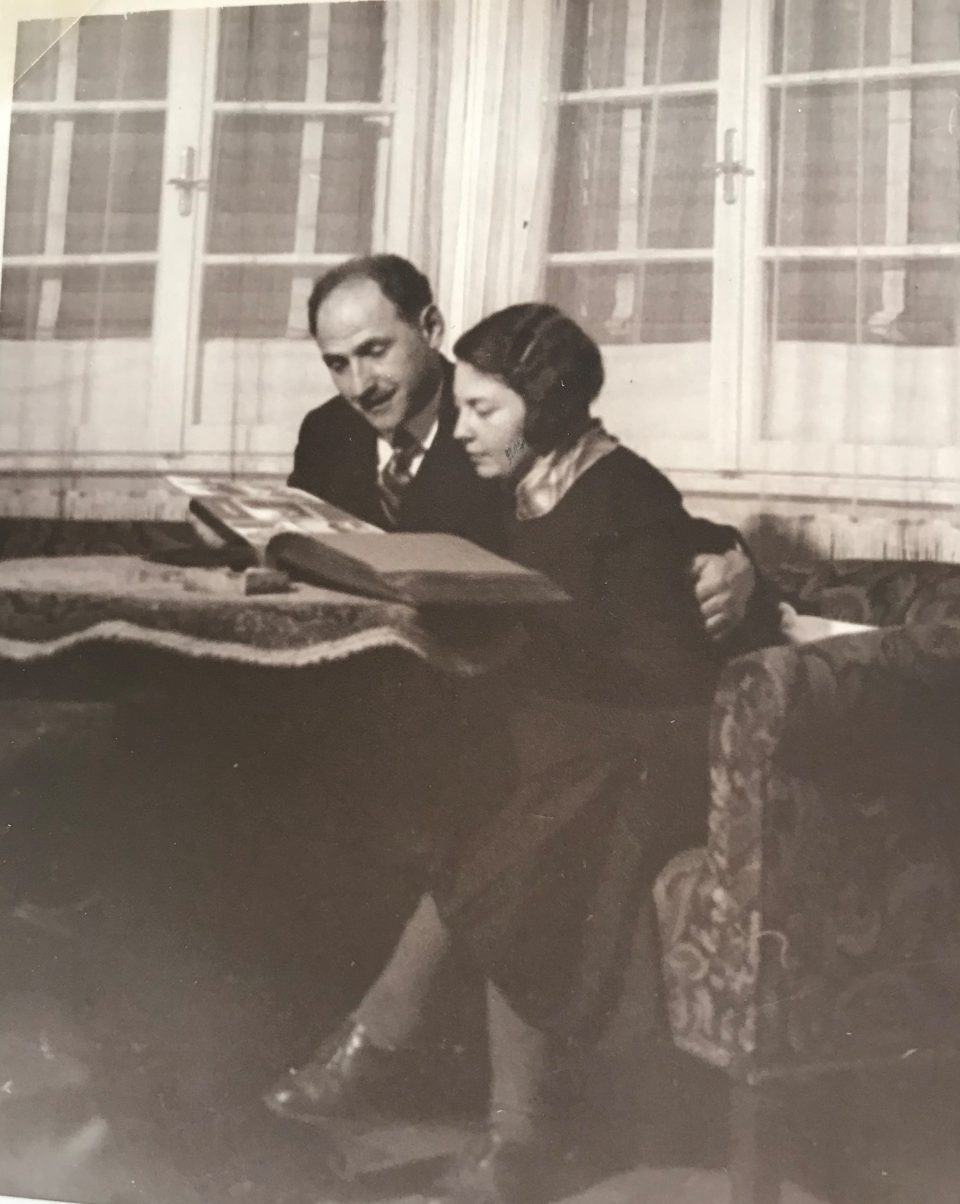

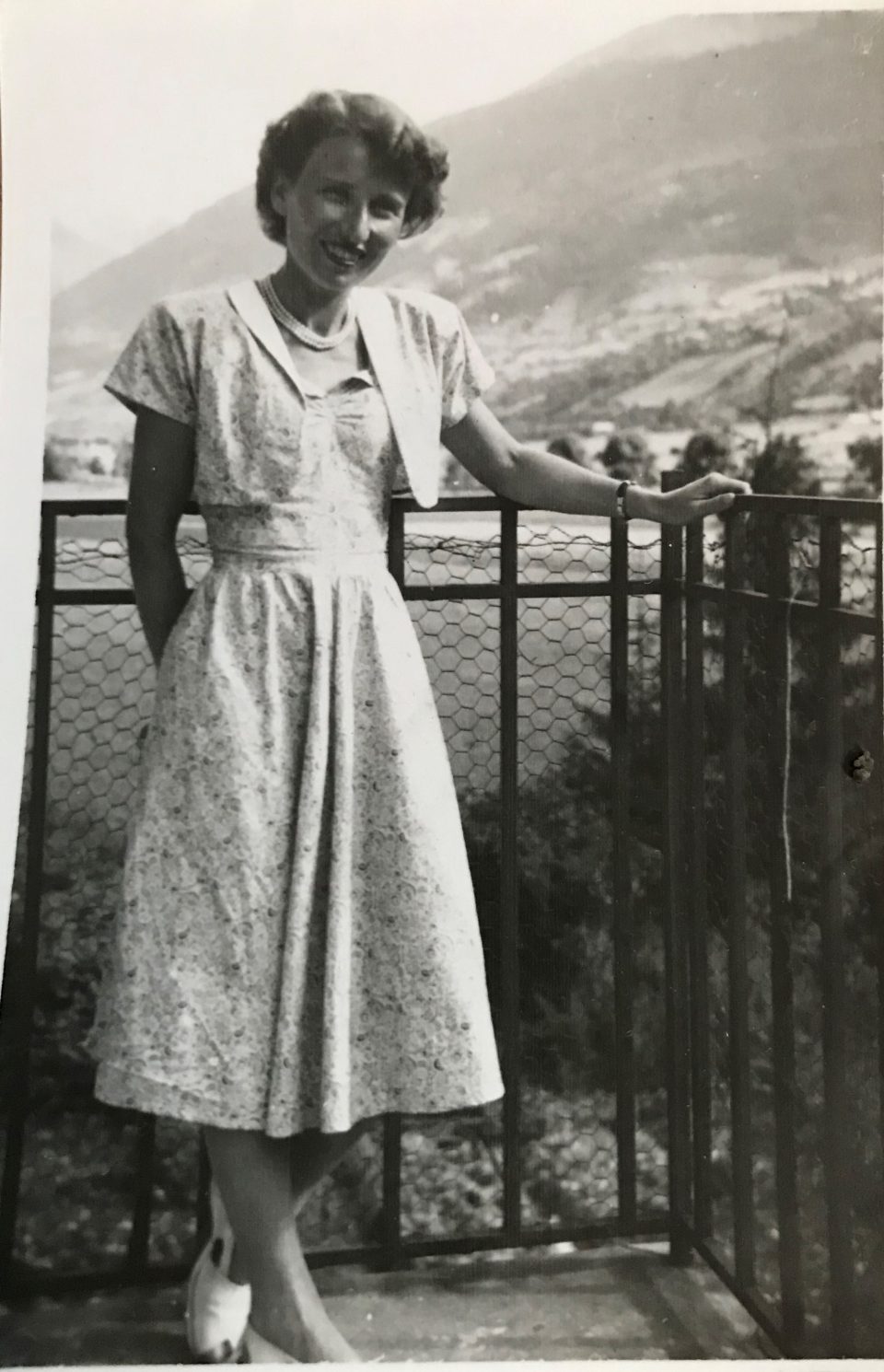

My great-aunt Mitzi in front of the “Reumannhof”, a social housing project of Red Vienna, where she lived with my great-uncle Karl Elzholz until their eviction in 1938 – both together in their flat

The only member of my large family who was well-off enough to move intone of the high-end housing projects of the “Hietzinger Cottage” was Henny Singer, who was a niece of my other great-uncle Norbert Katz. She had survived the holocaust in Israel and returned to Vienna after the war with her wealthy husband Josef Singer, who was a textile trader in the “Viennese Textile Quarter”. They moved into a villa in Hietzing in Alban-Berg-Weg 2/24.

Henny Singer, my aunt, after the war -and together with her young cousins, Susie and Josie Katz

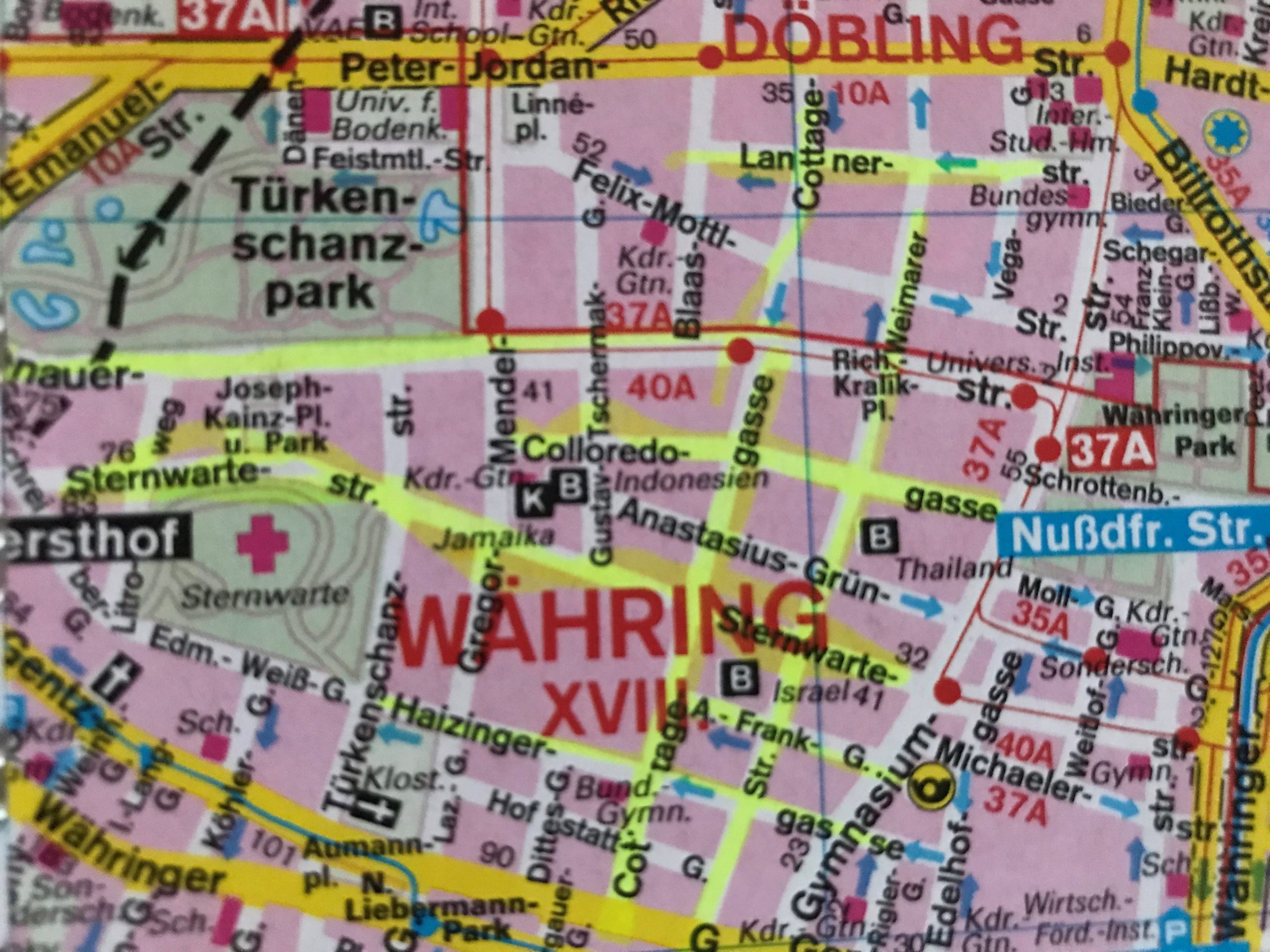

“Cottage Quarter” in Währing & Döbling (most interesting villas in the roads marked in yellow)

The first “Cottage Quarter” was planned in the suburbs of Währing and Döbling in the west of Vienna between Gymnasiumstrasse, Haizingergasse, Sternwartestrasse and Cottagegasse. On 9 April 1873 the “Viennese Cottage Association” was turned into a cooperative with unlimited liability. The members signed a commitment that forbid the building of houses which would in any way block the view of the other members, or restrict their access to light and fresh air. Additionally no trade was to be run on these premises which would disturb the other proprietors by polluting the air or producing noise or causing the danger of fires. Further regulations stipulated that every house was to have two floors only and a minimum distance to the next house was to be kept. All houses of one block had to form a square block with the gardens in the middle so that a garden complex was to be formed at the centre of a block. The building contractor was free to choose the architectural style, but the house had to fit into the character of the “Cottage Quarter” and by that help form a harmonious unity. This voluntary commitment of the members of the association was known as the “Cottage Servitut” and this was cited in the land register. It is still valid today and has helped to create a leafy suburban residential neighbourhood with interesting villas in historical and art nouveau styles. The architect and founder Ferstl was the first chairman of the “Cottage Association”, Archduke Karl Ludwig took over the “Protectorate” and the architect Carl von Borowski was in charge of the site management. He also developed the basic architectural concept of the first villas. The terrain was an open space at 388m altitude with rich water reserves and a fertile ground for gardening. The price at the time of the foundation of the association was affordable at 14.50-18.50 crowns per square fathom. The first 50 lots found many buyers and the architectural concept for the houses was modelled on English one- family houses, which meant, just one floor, which was cheaper and a floor plan then common in England: namely a basement with kitchen and store rooms; a ground floor with dining room, smoking room and lounge and finally on the first floor living room and bed rooms. Many of the clients opposed this architectural concept because they were used to the Viennese housing design of having all the rooms on one floor. The association had to convince the clients of the benefits of the new floor plans because otherwise they would violate their ideal of a garden city. To make the houses affordable a flat to rent was included in the attic, so that in the end four floors were erected on a rather small building plot and enough space for the garden was saved. Every house had to have a small front garden and the larger back garden of a block had to be directed towards the other back gardens to form a large green space in the middle, which was considered essential because it created a bigger “air reservoir”. This type of urban housing was until that point of time completely unknown in Vienna and the leading architect was Carl von Bokowski together with Anton Zöchmann and Julius Deininger.

After the first building phase approximately ten new houses were built per year according to the guidelines of the association under the leadership of the architect Karl Haas, a student of Ferstl. At that time a plot of 220 square fathoms cost 3,200 crowns and the cheapest house with four rooms plus ancillary rooms cost 10,000-12,000 crowns including the price of the building plot. The first houses were simple and cost-efficient with two to maximum four rooms, the staircases were steep and narrow, toilet and bathroom positioned in inconvenient corners of the house. When all the ground the association had bought in 1973 was used up, more land was acquired in the adjoining suburb of Döbling by the association in 1884. In this second building phase new types of family houses were planned and constructed with a greater variety of floor plans and richer decorations imitating Renaissance and Baroque styles. The rising property prices attracted a richer clientele, which had an effect on the architectural planning. The rooms were now larger, the staircases grander, the antechambers more representative and the furnishings much more luxurious. By 1906 a model house had been designed by Gustav Tschermak which tried to incorporate all the experiences of the “Cottage Association” of the last thirty years. It has to be noted that by this time the largest part of the first 260 family houses had been planned and built by the site management of the “Cottage Association” according to designs of different architects. Furthermore the association planted 1,900 trees in all streets of the “Cottage Quarter” and the adjoining “Türkenschanzpark” was opened to the public in 1888. In 1905 the quarter comprised 640,000 square metres with 387 family houses in 16 alleys. The area boasted primary and higher schools, an ice rink, tennis courts, a casino association, a police station and a post office, but no shops or restaurants and cafés.

This innovative urban planning model was so successful that it was copied elsewhere and in 1910 the City of Vienna took up this concept and incorporated it in its building regulations and area zoning plan. Today the voluntary commitment of the “Viennese Cottage Association” represents public law and the aim of the association is to conserve the special character of this neighbourhood.

One of the targets of the founders was to convince the Viennese bourgeoisie of the advantages of a family town house with garden and to compensate the lack of green space in the inner city areas. In a way it was the counter-concept to the expensive inner city blocks of flats. The architect Heinrich von Ferstel and the art historian Rudolf Eitelberger opposed the building speculation in those huge blocks of flats and wanted to improve the quality of housing in Vienna by constructing smaller units. Their ideal was the “English philosophy of housing”. The first fifty family houses were planned in detached and semi-detached form by Carl Ritter von Bokowski and the plots were rather small. Later on some rich owners wanted to show off their wealth, so their houses were built in more opulent styles and the plots were larger. Originally the villas were built in the “English style”, but when Hermann Müller took over the site management of the “Cottage Association”, French- and Italian-style villas were erected as well. In 1961 the “Cottage Quarter” in Währing and Döbling comprised 84.27 ha net building land and 6,644 inhabitants. In the wake of the “Viennese Cottage Association” in other suburbs of Vienna similar “Cottage Quarters” for the well-to-do were established, for example in Hietzing, in Gersthof, Hütteldorf, the Prater and Lainz.

“Cottage Quarter” in Hietzing (most interesting villas in the roads marked in yellow)