“Cottage Quarter “ Vienna, Währing

On 14 March 1872 the “Wiener Cottage Verein” (Viennese Cottage Association) was founded, initiated by the famous “Ringstrassen” architect Heinrich von Ferstl, whose aim was to counter the pressing need for housing in the overcrowded city of Vienna and to plan a “garden city” following the English model. In the houses and villas which were erected there several writers, artists, actors, scientists, entrepreneurs, many of them of Jewish descent, lived in this “garden city” at least for some time. The first tenants had to walk there from the city, but from 1889 a horse-drawn tramway ran to the “Cottage Quarter” and from 1907 the tram number 40 left the city at the stop “Stock Exchange” and ran to Sternwartestrasse and Gymnasiumstrasse and along “Währinger Park”, which had been the cemetery of the suburb Währing until 1923, where the writers Franz Grillparzer and Johann Nestroy were buried. From there the tram 40 reached the “Türkenschanzpark”. The name is derived from the place where the Turkish army, which besieged Vienna in 1683, had entrenched itself. In 1872 Edmund Kral and Heinrich von Ferstl founded the “Cottage Association”, which bought the gravel and sand pits below the former trenches and initiated a housing project which was supposed to realise their idea of modern and healthy living in one- and two-family houses. Ferstl’s dream of a different form of housing was modelled on the concept of “idyllic English garden cities”. Between 1873 and 1930 houses and villas were built imitating historical styles, others were modern houses designed by innovative architects like Josef Hoffmann. All of them were free standing town houses with a front and a back garden in an idyllic green oasis for the well-to-do.

A “Cottage Quarter” similar to the one in the suburbs of Währing and Döbling was established in the suburb Hietzing between the imperial castle Schönbrunn and the imperial hunting ground, the Lainzer Tiergarten, the “Hietzinger Cottage”. There a start was made in 1883, when the entertainment park of Carl Schwender called “Neue Welt” (“New World”), went bankrupt. This ground was divided up into plots of land for the construction of another “garden city”, which was called “Neue Welt”, too. Many of the proprietors and tenants of the “Viennese Cottage Quarters” were forced into exile after the takeover of the Nazis, the “Anschluß”, in March 1938 and several did not only lose their fortunes, but also their lives in the Nazi terror.

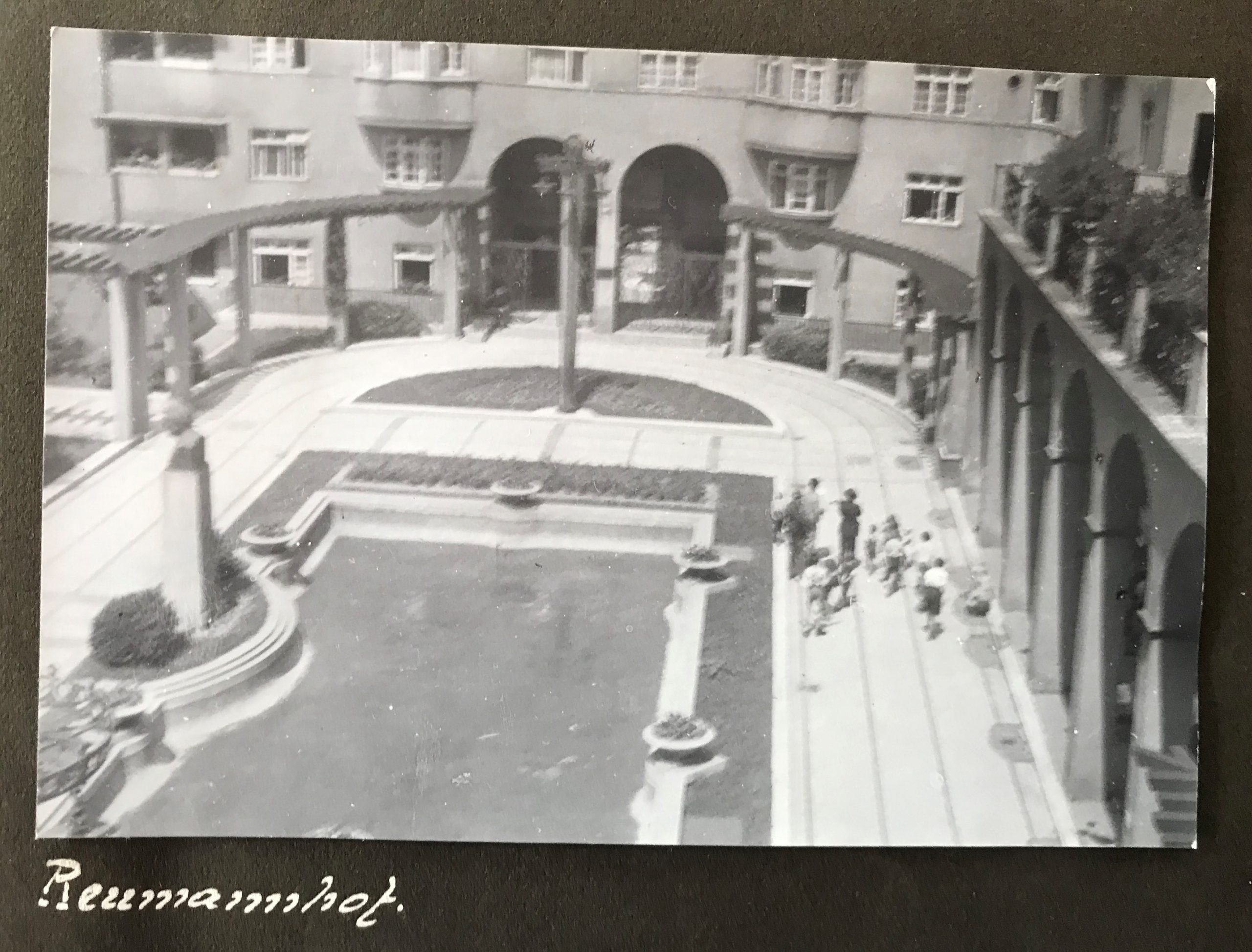

Nearly 50 years after the foundation of the first “Cottage Association” the dream of modern and healthy living in Vienna was to be realised for the working class as well. When in 1919 the Social Democratic Party took over the running of the city of Vienna, the party devised an ambitious plan of creating at the start terraced houses in settlements and then blocks of flats with modern amenities to alleviate the drastic housing shortage. Between 1923 and 1933 63,934 affordable, light and healthy flats were built for workers and their families in a world-wide unique social housing project of the time. In the housing concept of “Red Vienna” several modern architects, like Josef Frank, intellectuals, health experts, pedagogues, like Friedl Dicker and Franz Singer, and sociologists like Otto Glöckel, Siegfried Bernfeld or Max Adler were involved; many of them with Jewish backgrounds. Unfortunately all the Jewish tenants could enjoy the benefits of the new flats only briefly because they were the first to be evicted from the social housing projects after the “Anschluß” (the takeover of the Nazis) in March 1938, among them my great-uncle Karl Elzholz and his wife Mitzi, who were chased out of their flat in the “Reumannhof” at Margaretengürtel 102/15/17. They both managed to flee to Bolivia. After the war Karl returned to Vienna and moved into a newly built social housing complex nearby.

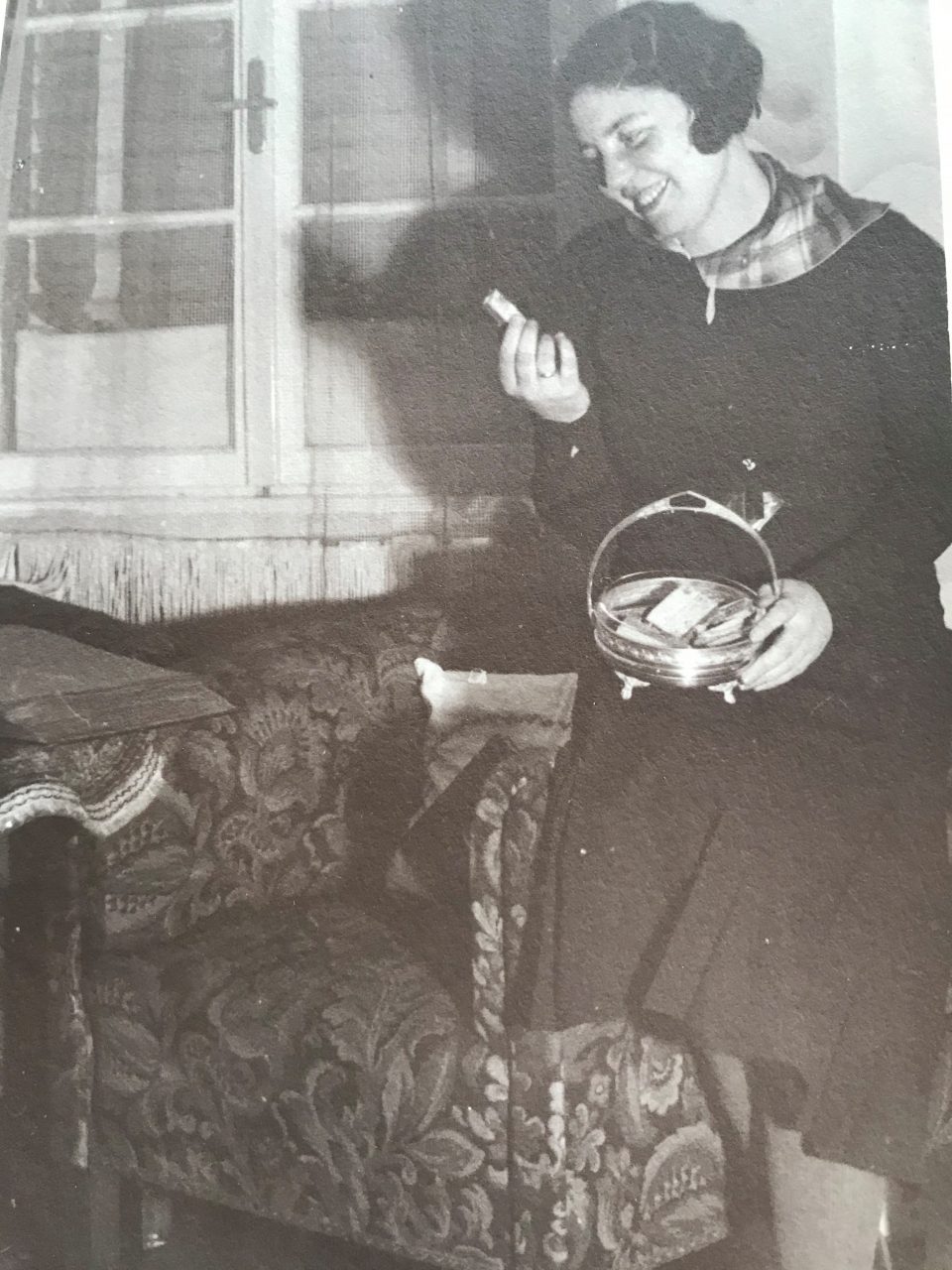

My great-aunt Mitzi in front of the “Reumannhof”, a social housing project of Red Vienna, where she lived with my great-uncle Karl Elzholz until their eviction in 1938 – both together in their flat

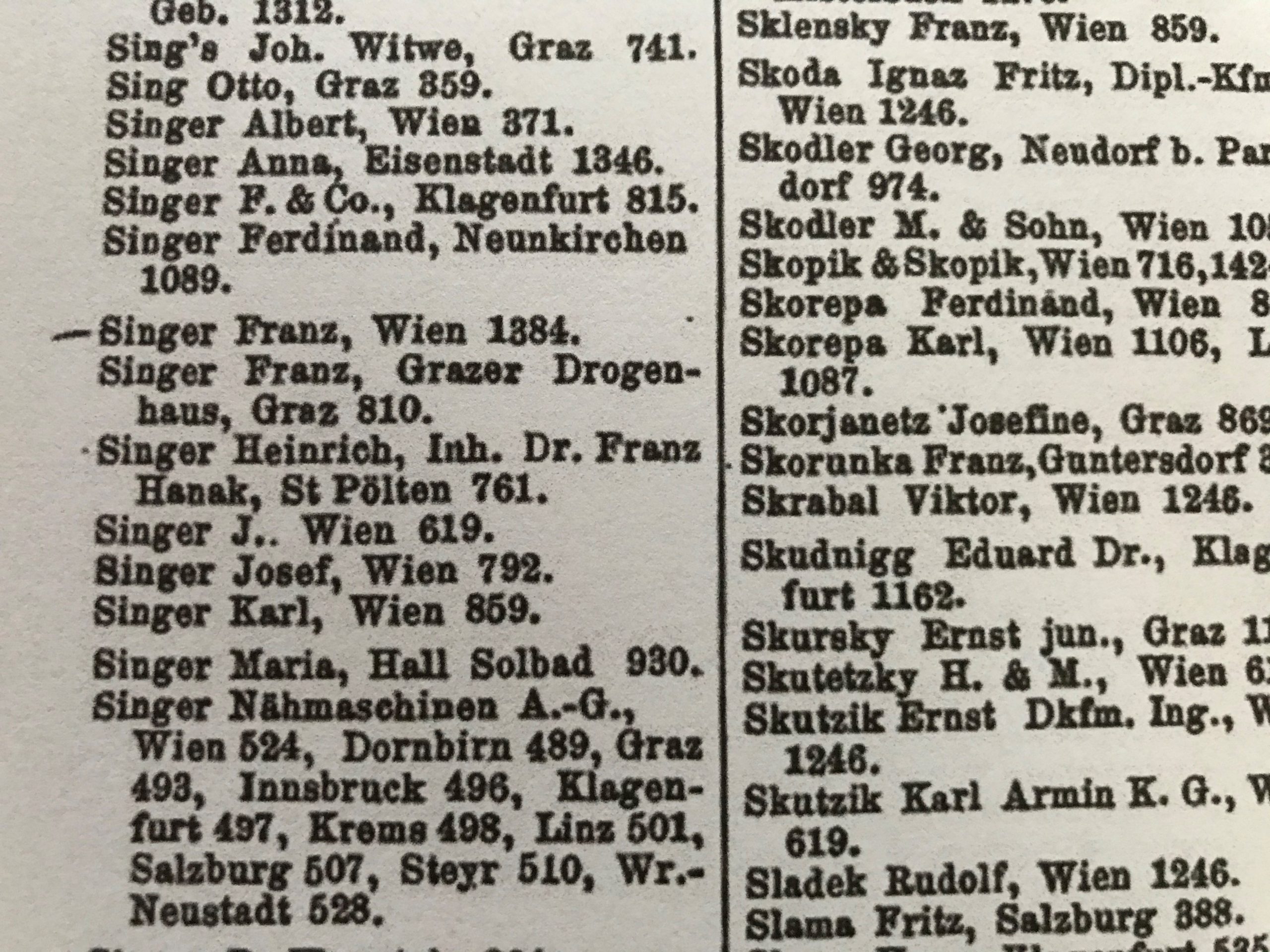

The only member of my large family who was well-off enough to move intone of the high-end housing projects of the “Hietzinger Cottage” was Henny Singer, who was a niece of my other great-uncle Norbert Katz. She had survived the holocaust in Israel and returned to Vienna after the war with her wealthy husband Josef Singer, who was a textile trader in the “Viennese Textile Quarter”. They moved into a villa in Hietzing in Alban-Berg-Weg 2/24.

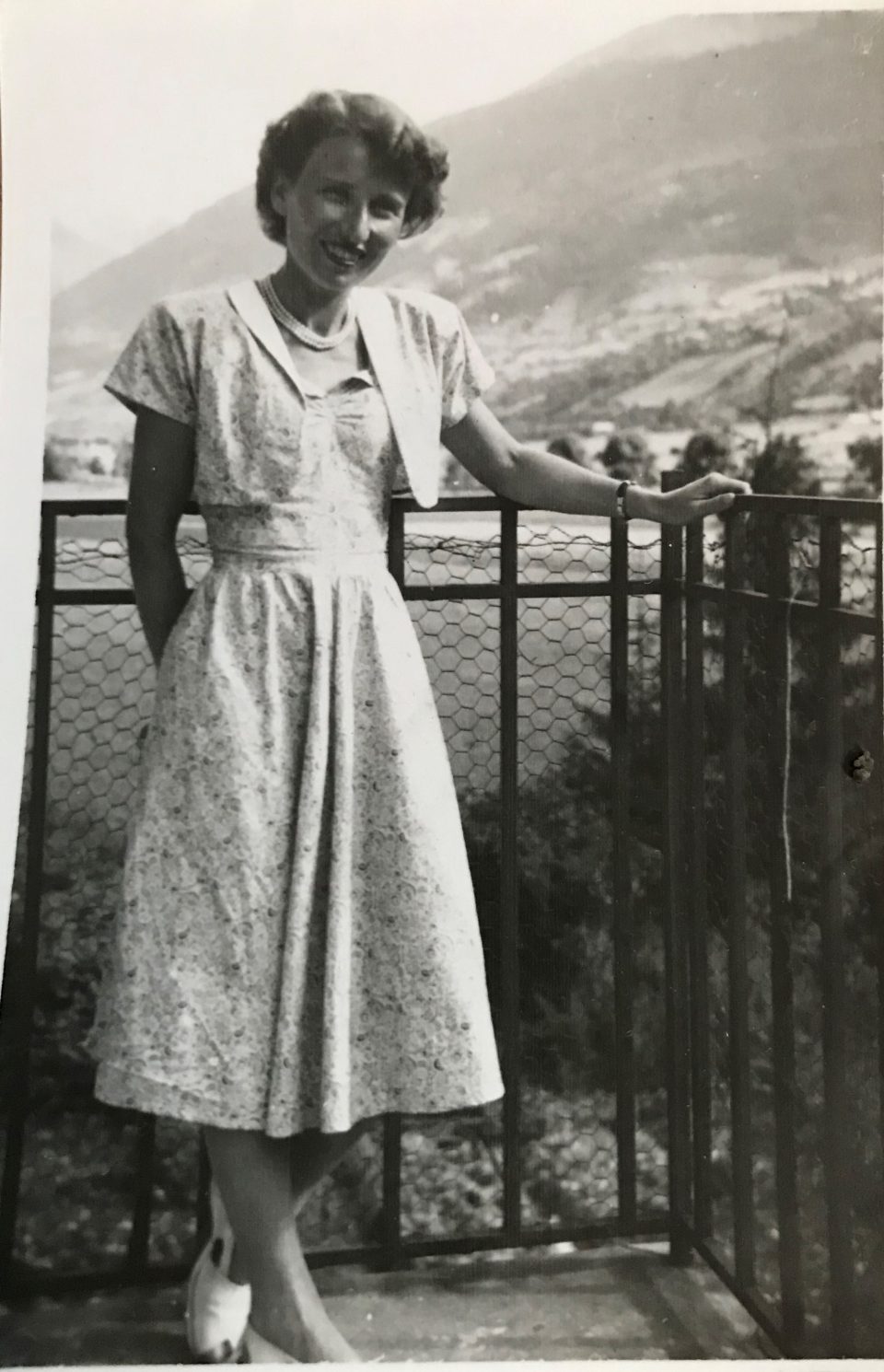

Henny Singer, my aunt, after the war -and together with her young cousins, Susie and Josie Katz

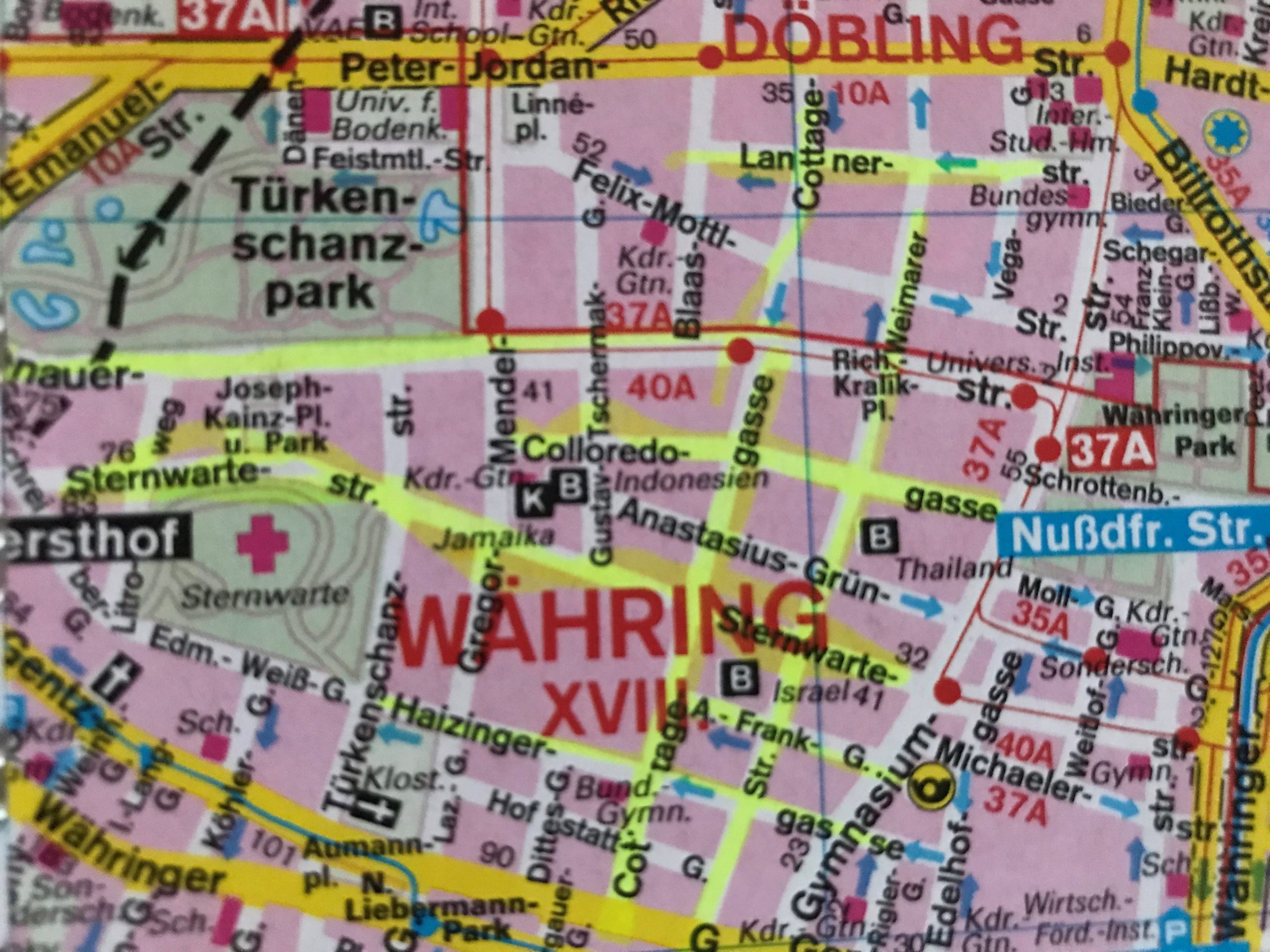

“Cottage Quarter” in Währing & Döbling (most interesting villas in the roads marked in yellow)

The first “Cottage Quarter” was planned in the suburbs of Währing and Döbling in the west of Vienna between Gymnasiumstrasse, Haizingergasse, Sternwartestrasse and Cottagegasse. On 9 April 1873 the “Viennese Cottage Association” was turned into a cooperative with unlimited liability. The members signed a commitment that forbid the building of houses which would in any way block the view of the other members, or restrict their access to light and fresh air. Additionally no trade was to be run on these premises which would disturb the other proprietors by polluting the air or producing noise or causing the danger of fires. Further regulations stipulated that every house was to have two floors only and a minimum distance to the next house was to be kept. All houses of one block had to form a square block with the gardens in the middle so that a garden complex was to be formed at the centre of a block. The building contractor was free to choose the architectural style, but the house had to fit into the character of the “Cottage Quarter” and by that help form a harmonious unity. This voluntary commitment of the members of the association was known as the “Cottage Servitut” and this was cited in the land register. It is still valid today and has helped to create a leafy suburban residential neighbourhood with interesting villas in historical and art nouveau styles. The architect and founder Ferstl was the first chairman of the “Cottage Association”, Archduke Karl Ludwig took over the “Protectorate” and the architect Carl von Borowski was in charge of the site management. He also developed the basic architectural concept of the first villas. The terrain was an open space at 388m altitude with rich water reserves and a fertile ground for gardening. The price at the time of the foundation of the association was affordable at 14.50-18.50 crowns per square fathom. The first 50 lots found many buyers and the architectural concept for the houses was modelled on English one- family houses, which meant, just one floor, which was cheaper and a floor plan then common in England: namely a basement with kitchen and store rooms; a ground floor with dining room, smoking room and lounge and finally on the first floor living room and bed rooms. Many of the clients opposed this architectural concept because they were used to the Viennese housing design of having all the rooms on one floor. The association had to convince the clients of the benefits of the new floor plans because otherwise they would violate their ideal of a garden city. To make the houses affordable a flat to rent was included in the attic, so that in the end four floors were erected on a rather small building plot and enough space for the garden was saved. Every house had to have a small front garden and the larger back garden of a block had to be directed towards the other back gardens to form a large green space in the middle, which was considered essential because it created a bigger “air reservoir”. This type of urban housing was until that point of time completely unknown in Vienna and the leading architect was Carl von Bokowski together with Anton Zöchmann and Julius Deininger.

After the first building phase approximately ten new houses were built per year according to the guidelines of the association under the leadership of the architect Karl Haas, a student of Ferstl. At that time a plot of 220 square fathoms cost 3,200 crowns and the cheapest house with four rooms plus ancillary rooms cost 10,000-12,000 crowns including the price of the building plot. The first houses were simple and cost-efficient with two to maximum four rooms, the staircases were steep and narrow, toilet and bathroom positioned in inconvenient corners of the house. When all the ground the association had bought in 1973 was used up, more land was acquired in the adjoining suburb of Döbling by the association in 1884. In this second building phase new types of family houses were planned and constructed with a greater variety of floor plans and richer decorations imitating Renaissance and Baroque styles. The rising property prices attracted a richer clientele, which had an effect on the architectural planning. The rooms were now larger, the staircases grander, the antechambers more representative and the furnishings much more luxurious. By 1906 a model house had been designed by Gustav Tschermak which tried to incorporate all the experiences of the “Cottage Association” of the last thirty years. It has to be noted that by this time the largest part of the first 260 family houses had been planned and built by the site management of the “Cottage Association” according to designs of different architects. Furthermore the association planted 1,900 trees in all streets of the “Cottage Quarter” and the adjoining “Türkenschanzpark” was opened to the public in 1888. In 1905 the quarter comprised 640,000 square metres with 387 family houses in 16 alleys. The area boasted primary and higher schools, an ice rink, tennis courts, a casino association, a police station and a post office, but no shops or restaurants and cafés.

This innovative urban planning model was so successful that it was copied elsewhere and in 1910 the City of Vienna took up this concept and incorporated it in its building regulations and area zoning plan. Today the voluntary commitment of the “Viennese Cottage Association” represents public law and the aim of the association is to conserve the special character of this neighbourhood.

One of the targets of the founders was to convince the Viennese bourgeoisie of the advantages of a family town house with garden and to compensate the lack of green space in the inner city areas. In a way it was the counter-concept to the expensive inner city blocks of flats. The architect Heinrich von Ferstel and the art historian Rudolf Eitelberger opposed the building speculation in those huge blocks of flats and wanted to improve the quality of housing in Vienna by constructing smaller units. Their ideal was the “English philosophy of housing”. The first fifty family houses were planned in detached and semi-detached form by Carl Ritter von Bokowski and the plots were rather small. Later on some rich owners wanted to show off their wealth, so their houses were built in more opulent styles and the plots were larger. Originally the villas were built in the “English style”, but when Hermann Müller took over the site management of the “Cottage Association”, French- and Italian-style villas were erected as well. In 1961 the “Cottage Quarter” in Währing and Döbling comprised 84.27 ha net building land and 6,644 inhabitants. In the wake of the “Viennese Cottage Association” in other suburbs of Vienna similar “Cottage Quarters” for the well-to-do were established, for example in Hietzing, in Gersthof, Hütteldorf, the Prater and Lainz.

“Cottage Quarter” in Hietzing (most interesting villas in the roads marked in yellow)

So what was the Jewish influence and who were the people who lived in these” Cottage Quarters”? By starting with the one in Währing and Döbling it is essential to mention one of the most important contemporary Austrian painters, the “Fantastic Realist” Arik Brauer. He was born in the poor Viennese suburb of Ottakring as the son of a Jewish shoemaker from Lithuania. His father was murdered in a Nazi concentration camp and Arik survived in hiding in Vienna together with his mother and sister as a so-called “U-Boot”. In the impoverished neighbourhood where they lived before the deportation of the father, he was confronted with racist anti-Semitism daily and he said that anti-Semitism turned him into a Jew; he wouldn’t have been a Jew without the Nazis. After the end of the war he started to study at the Academy of Arts in Vienna at the age of 16 and became one of the circle of the five representatives of the “Viennese School of Fantastic Realism” together with Ernst Fuchs, Anton Lehmden , Rudolf Hausner and Wolfgang Hutter. He emigrated to Israel, where he married and built a house. But he continued to live in Vienna as well and found a historical villa in the “Cottage Quarter” in the 1970s, which he turned into a private museum. His painter colleague Ernst Fuchs did the same and his villa in the “Cottage Quarter” of Hütteldorf, built by Otto Wagner, is a private museum, too. Anton Lehmden, another of the “band of five” once said that they had not inherited their villas, they had earned them by painting. Arik Brauer quipped that like all Jews he wanted to die in Israel, but he preferred to live in Vienna.

The writer Richard Beer-Hofmann was a graduated jurist and an eminent member of the literary circle of “Jung Wien” (“Young Vienna”) around Arthur Schnitzler. He is portrayed in Schnitzler’s drama “Der Reigen” (“La Ronde”) as „Robert“. He moved into a villa in Hasnerstrasse, designed by Josef Hoffmann. After the “Anschluß” of the Nazis in 1938 he had to sell all his possessions to pay for the “Reichsfluchtsteuer” (a Nazi tax levied on those who were forced to emigrate) for himself and his wife. His wife died of a heart attack during their flight in Zurich and Beer-Hofmann himself died in 1945 in his American exile. He was buried together with his wife in the Jewish cemetery in Zurich, Switzerland. In the same cemetery his fellow Viennese writer Felix Salten, the creator of “Bambi”, was buried, another inhabitant of the “Cottage Quarter”. In 1909 he moved with his family into a villa in Cottagegasse, where Arthur Schnitzler and other artists had bought or rented houses. Salten’s villa became a meeting place for these artists, among them Hermann Bahr, who had a villa built for himself in the “Cottage Quarter” in Hietzing by the famous architect Joseph Maria Olbrich. Felix Salten was a brilliant writer of novels, drama, essays and feuilletons in which he painted an ironic picture of the Viennese, supported the literary and artistic innovations of Max Reinhardt and the Viennese cabaret and shared the ideas of Theodor Herzl for the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine. Yet his best-selling novel was “Bambi. Eine Lebensgeschichte aus dem Walde” (“Bambi. A Life Story from the Woods”) which was translated by John Galsworthy into English in 1928. It became world famous, when Walt Disney turned the plot into an animated cartoon film in 1942. In reality this book is much more than a children’s story, it is a philosophical treatise of mankind in the setting of the forest. It deals with the relationship between the weak and the strong, the wealthy and the poor; it is about conflict, loneliness and dying. He experienced anti-Semitic aggression already in 1918, when the Habsburg Empire broke down and he had to move out of his villa temporarily. In 1935 the German Nazis forbid his books because he was of Jewish-Hungarian descent – his real name was Siegmund Salzmann. But Salten remained calm and never believed that he could be forced to leave his home town Vienna. His friend and fellow writer Stefan Zweig was very concerned about the political climate in Austria and in April 1938 offered him refuge abroad, but Salten did not want to emigrate. Just a few weeks later his house, his possessions and his archive were requisitioned by the Nazis. The Saltens’ daughter, who lived in Switzerland, managed to get her parents out of Vienna, but Salten was not allowed to work in Switzerland and experienced serious financial troubles, especially because he had sold all his rights to “Bambi” to Walt Disney for 5,000 US dollars. His other best-selling novel, “Josefine Mutzenbacher”, had been published anonymously in 1906 by the small editor “Erotica” and painted an erotic picture of fin-de-siècle Vienna and its common people, the servants, the prostitutes, the innkeepers and the tenants. Salten was unable to prove his authorship, when he needed the money most. He had published over 50 books, which were translated into 33 languages and in the end he died impoverished in Switzerland in 1945.

When Arthur Schnitzler, the doctor and famous writer of erotic and psychoanalytical drama and satirist of the Viennese bourgeois lifestyle he knew so well, moved into the “Cottage Quarter” of Währing in 1910, his friends were already there: Felix Salten, Richard Beer-Hofmann. His wife, Olga Schnitzler, had had acting lessons with the famous actor of the Burgtheater Alexander Römpler and when he died, his wife, the actress Hedwig Bleibtreu, did not want to stay on in the villa in Sternwartestrasse. Schnitzler bought the house for 95,000 crowns, although he had no money. He borrowed half of the sum from his brother and for the remaining amount he took out a mortgage loan. The new environment did not improve the atmosphere in the family and due to the permanent crisis the marriage was heading towards divorce. Nature seemed to be the only place where Schnitzler was calm and relaxed and he enjoyed the walks in the Vienna Woods nearby. His neighbour, the painter and graphic designer Ferdinand Schmutzer, had a house constructed for his family by the architect Robert Oerley in 1911 and this led to a productive artistic cooperation. Schmutzer illustrated Schnitzler’s novellas. When his beloved daughter Lili committed suicide in 1928 Schnitzler was devastated. He died in 1931 and was spared the disaster of the anti-Semitic excesses of the Nazis. Nevertheless, despite his success he had experienced anti-Semitism in Vienna, which he expressed in his brilliant drama “Professor Bernhardi”. Arthur Schnitzler and Sigmund Freud were kindred spirits, yet they only met in 1922 for the first time and their correspondence remained sporadic. In 1926 Schnitzler visited Freud, when he is treated at the “Cottage Sanatorium” for cancer. Schnitzler’s grandson Michael Schnitzler, the son of Heinrich Schnitzler, was an excellent musician – at the age of twenty he was first concert master of the “Wiener Symphoniker” – and explorer and preserver of the jungle in Costa Rica. When he stayed in Vienna he lived in a house near his grandfather’s in Sternwartestrasse. He was born in exile in California, where his father, Heinrich Schnitzler, had emigrated to. Heinrich Schnitzler wanted to return after the war to Vienna to work again as stage director on the most famous Viennese stages and the adolescent Michael was happy to get to know the country that had chased away his family.

Georg Stefan Troller was born in 1921 in Vienna and had to flee in 1938. His autobiography “Wohin und zurück – Welcome in Vienna” (“Whereto and back- Welcome to Vienna”) was successfully filmed by the director Axel Corti. He later said that like many Viennese he had loved and hated the city at the same time, yet the city had never left him indifferent. Troller was sixteen at the time of the “Anschluß” and that was the moment his childhood ended. A sense of uprooting, disjointedness and the pointlessness of permanent flight pervades his autobiography. He fled via Brno in Czechoslovakia, where his small suitcase with his only book: Karl Kraus “Die letzten Tage der Menschheit” (“The Last Days of Mankind”) was stolen, to France with the help of a faked visa to Uruguay. From an internment camp in France he managed to flee to the United States. As a soldier in the US Army he returned to Europe as an interpreter. When he was not accepted as a student in Vienna, he went to Paris to study at the Sorbonne and consequently Paris became his new home. His father had come to Vienna from Brno as a fur trader and Georg Troller was raised in the “Vienna Textile Quarter” around Rudolfsplatz near Neutorgasse, where his father’s shop was located. In 1930 the family moved into the “Cottage Quarter” in Vegagasse into a villa, which the architect Robert Oerley had planned. The rent that the three tenant families in the house were supposed to pay had to cover the costs, but as they failed to pay, the Trollers had to sell the house and rent a smaller one in Peter Jordan Straße. Troller’s attitude to Austria remained very critical, but he always loved his home town Vienna – the most beautiful city in the world for him, to which he dedicated his book “My Vienna 1918-1938”, an expression of his yearning for “Heimat” and his lost childhood.

Hertha Pauli was born 1906 in Anton-Frank-Gasse in the “Cottage Quarter” and became an actress and writer. Her biography of the pacifist Bertha von Suttner was banned in Nazi Germany and when she read from her book in the Austrian national radio station, Nazi supporters threw stink bombs into the studio. She lived in a small apartment in the attic of a house in Weimarerstraße where she ran a literary agency with Karl Frucht. They edited texts by Joseph Roth, Ödon von Horvath, Alfred Polgar, Egon Fridell and Theodor Csokor. Three days after the “Anschluß” young Nazis stormed the flat of her friend Egon Fridell in Gentzgasse and ordered him to “scrub the streets”, which he refused and jumped from the window of his study to his death. By that time Hertha had already fled together with Karl Frucht via Switzerland to Paris. Both published their memoirs of the flight. In Paris they met the writer Ödon von Horvath, who was killed in 1938 during a thunderstorm by a falling tree on the Champs–Elysées. Hertha only narrowly escaped deportation in 1940 and could flee to southern France, where she met Alma and Franz Werfel, the famous author, and via the Pyrenees she reached Lisboa. There the “Emergency Rescue Committee” of Varian Fry organised a ship passage for her to the United States. Varian Fry was also called the “Angel of Marseille” because his “Emergency Rescue Committee” helped 4,000 people who were trapped in southern “Vichy” France to flee from Nazi persecution on foot across the Pyrenees and by boat or plane via Lisboa to the USA in 1940/1941. Fry, a Harvard graduate, organised visas, affidavits, money and tickets for ships and planes with the support of Eleonore Roosevelt, the wife of the US President. Bil Spira, an illustrator and friend of the poet Jury Soyfer, who was killed in the holocaust, had fled to France, too, and forged documents for Fry’s organisation. He was betrayed but in the end survived a succession of concentration camps.

Gustav Mahler, the composer and director of the Vienna State Opera, and Guido Adler, one of the founding fathers of modern musicology, both came from Iglau in Moravia to Vienna and were students of Anton Bruckner. They remained close friends in Vienna. Mahler dedicated the sheet music to his composition “Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen” (I’m Lost to the World”) to his friend Guido Adler for his 50th birthday. The original copy formed part of the precious library and archive which the professor of musicology at the University of Vienna kept at his house in Lannerstrasse in the “Cottage Quarter”. When he died in 1941 the whole library including autographs by Arthur Schnitzler, Adler’s correspondence with Bruckner, Brahms, Richard Strauss and Alma and Gustav Mahler and an original death mask of Beethoven, was “Aryanised” by the Nazis. Adler’s daughter Melanie Adler was unable to rescue the library, because Adler’s successor at the university, Erich Schrenk, contacted the GESTAPO and managed to have the whole library transported to his institute in May 1942. At the same time Melanie was deported to Minsk and later murdered in the KZ Maly Trostinez. Adler’s son Hubert Joachim Adler had meanwhile fled to the United States in August 1938. He managed to get his father’s library back after the war and to sell it to the University of Georgia before he committed suicide. But the Mahler autograph was still missing. It tuned out that the Viennese lawyer Richard Heiserer, who had “represented” Melanie Adler when her father’s library was requisitioned by the Nazis, had kept the Mahler autograph for himself. His role in the GESTAPO raid and robbery of the precious library, as well as the role of Erich Schrenk, who remained at the Vienna university after 1945 as a much esteemed professor of musicology, was never investigated. The autograph was restored to the family in 2004 and sold at Sotheby’s in London for 420,000 British pounds to the Morgan Library New York.

The musical genius Erich Wolfgang Korngold bought a house in Sternwartestrasse in the “Cottage Quarter” in 1930 to live there with his wife and two sons, away from his dominant father Julius Korngold, a much feared musical critic of the newspaper “Die Neue Freie Presse”, who managed his child prodigy Erich with severity. Early on Gustav Mahler recognised the genius in Korngold and at the age of 23 Korngold experienced his first Europe-wide success with the opera “Die tote Stadt” (“The Dead City”) in 1920; in the same year he had his debut as conductor. Next to Richard Strauss he was the most played opera composer of the time. Additionally he contributed a lot to the revival of the operetta and worked together with Max Reinhardt, the innovative stage director and founder of the Salzburg Festival and director of the “”Theater in der Josefstadt”. Korngold went to the United States to compose for the new medium film with great success. Despite many new offers from Hollywood the family returned to Vienna in 1935, but the racist atmosphere in the Austro-fascist country convinced the Korngolds to return to the USA only three months after their arrival. Korngold, together with Max Steiner and Bernard Herrmann, became the most important composer of film music in the classical era of Hollywood. He modernised the genre of film music by working for Warner Brothers Studios as a composer. He looked at a film as if it were the libretto of an opera and composed the music for the whole film in that way. Until 1938 he commuted between Vienna and California, but after the “Anschluß” his villa in Vienna was “Aryanised” and the furniture, paintings, the library and all sheet music was robbed. When he returned to Austria in 1949, he was not well received; his house was restored to him, but empty. His library and archive of sheet music was never restituted, so the family went back to the United States. Korngold was completely forgotten in Austrria for many decades, just as his colleague at Hollywood, Max Steiner, a Viennese from Leopoldstadt, who was nominated for 24 Oscars for his film music and composed the music for famous Hollywood films like “Gone with the Wind” and “Casablanca”. Both were students of Gustav Mahler and Richard Strauss and outstanding musicians from Vienna.

Like many famous Viennese, such as Franz Lehár, Max Reinhard, Franz Molnar, Felix Salten, Karl Farkas and Theodor Herzl, Emmerich Kálmán was a born Hungarian. He came to Vienna as a young man to work in the operetta business and became one of its most eminent composers with operettas such as “Die Csárdásfürstin” (“The Csárdás Princess”), “Gräfin Mariza”(“Duchess Mariza”) and “Die Zirkusprinzessin” (“The Circus Princess”). With his wife Vera, an extravagant society girl, he moved into a villa near Korngold in 1935. His wife had the house, which was built in 1909, restructured by the architect Heinz Rollig, but they only lived there for four years. After the “Anschluß” the Kálmáns had to flee from Vienna. They first migrated to Paris and then via Genova to the United States. But in Los Angeles no one was interested in operettas and in his fifties Kálmán had to adapt his compositions to the American taste with little success. In exile his wife left him and their three children to marry a dashing gentleman who died in a plane crash and tender-hearted Kálmán married her a second time. He died, a broken man, in Paris in 1953.

Theodor Herzl was a tenant in Weimarer Straße in the “Cottage Quarter”, but there is no commemorative plaque at the façade, which houses the embassy of Thailand today. He is seen as the founder of the idea of a “State for the Jews” by publishing “Der Judenstaat” (“The Jewish State”). In 1897 he opened the “First Zionist World Congress” in Basel in Switzerland. First he lived near Sigmund Freud in Berggasse, but then moved to the “Cottage Quarter”. He was only 44 when he died in 1904 and in his last will he stipulated that he wanted a pauper’s burial without flowers or eulogies. Nevertheless 10,000 people attended his funeral procession at the Döbling cemetery. When finally the state of Israel was founded in 1948, his remains were buried in Jerusalem.

Also in the “Hietzinger Cottage” several interesting personalities with Jewish background rented or bought houses. One of them was Leo Fall, who was a representative of the second important era of the Viennese operetta, the “Silver Era”, together with Franz Lehár and Emmerich Kálmán. He was born in Olmütz of Jewish parents, studied in Vienna and became musical director and solo violinist. In 1909 he bought the “Villa Dollarprinzessin” in Lainzer Straße with the money he earned for the operetta of the same name “Die Dollarprinzessin” (“The Dollar Princess”), which was a huge international success, as was “Die Rose von Stambul” (“The Rose of Stambul”). The Viennese architect Ludwig Ramler restructured the villa for the composer of the most frivolous operettas of the 1910s and 1920s. He and his wife spent the money as he earned it until Fall was finally bankrupt. After his death in 1925 his wife had to sell the villa, which was heavily mortgaged together with the rest of their possessions. When the Nazis took over, performances of Fall’s operettas were forbidden and both his brothers who were composers, too, died in Nazi concentration camps. In Hietzinger Hauptstrasse the silk producer Franz Zweig, a relative of the famous author of “Die Welt von gestern” (“The World of Yesterday”), Stefan Zweig, had the architect Josef Hudetz, a student of one of the architects of the Vienna State Opera, Eduard van der Nüll, build a villa for him with turrets, oriels and gables in 1902/03, which today houses the embassy of Poland. But also Zweig had to sell his villa because he had accumulated enormous debts.

Five out of the 60 villas the architect Adolf Loos built were erected in the “Hietzinger Cottage” and his designs were characterised by aesthetic simplicity, in contrast to Hudetz. Loos’ concepts were so innovative and rvolutionary that authorities and neighbours complained about the bareness of the facades and asked that they were to be a overgrown by plants, at least. Loos’ architectural idea was that richness of design was supposed to be located inside and not to be seen from outside. One of the most radical concepts he realised in the “Cottage Quarter” was the house for the textile factory owner and producer of artificial flowers and feather arrangements Hugo Steiner and his wife Lilly in St.Veit-Gasse in 1910, which formed a drastic contrast to the surrounding art nouveau buildings. Lilly Steiner was a graphic designer, who had attended the art school for women in Vienna, which had been founded by Tina Blau and Rosa Mayreder. In the following years the “Villa Steiner” became a meeting place for the intellectuals and artists of the time in Vienna, among them Egon Schiele who portrayed Lilly. The family Steiner was one of the most important principals for Loos. Steiner’s sister Gisela Wolff was married to the owner of the luxury tailor at the Graben in the city of Vienna, Knize, for whom Loos designed the famous shop in 1910, which still exists today. From Vienna the Steiners moved to Paris, where finally Lilly was recognised as an influential artist and in 1932 their villa in the “Cottage Quarter” was bought by the architect Arnold Karplus, who worked on housing projects for “Red Vienna”, for instance the “Friedrich-Dittes-Hof” and was influenced by Adolf Loos and Josef Frank. His daughter Ruth Karplus was an important fashion designer, who migrated to the United States after the “Anschluß”. After the war she was finally able to marry the love of her youth, Hans Altmann, who had grown up nearby, in Hietzinger Hauptstraße. Also his family of textile producers was chased out of Vienna. Their possessions and their “Villa Hohenfels” were requisitioned by the Nazis in 1938 and sold for a mere song, whereby their precious “Lobmeyr” glass wares later surfaced in the household of the leading German Nazi, Hermann Göring.

In Wenzgasse Josef Frank built the innovative “Villa Beer”, one of the most beautiful examples of Viennese modern architecture. Tenants were the famous tenors Richard Tauber in 1932 and Jan Kiepura in 1937 (see the article “The Viennese and Classical Music”). Frank wanted to free the people from bourgeois prejudices and offer them a bohemian–like environment with different types of spatial experiences, such as cosy corners, open stair cases, different heights and surprising views. In 1930 he realised this ambitious concept for the director of a rubber factory, Julius Beer. Frank designed the whole interior, too. Frank had to flee to Sweden and significantly influenced Swedish design there. In 1927 he said that “modern” was only what offered complete freedom. He advocated a harmony of house and garden, nature and social life, lifestyle and wellness. He stood for variety instead of uniformity, disorder instead of standardisation, coincidence instead of planning. He was in opposition to Adolf Loos with these ideas of his. Furthermore in 1932 Frank initiated the famous “Werkbund-Gartensiedlung” in Hietzing with 64 model houses and planned several public housing complexes of “Red Vienna”, e.g. the ”Leopoldine-Glöckel-Hof”. His architectural philosophy can be summed up with a quote: “Beauty for All”.

Siegfried Trebitsch was born into a Jewish family of silk producers in Vienna, but he wanted to become a writer. He befriended Theodor Herzl, Hermann Bahr and Felix Salten, but he had real talent as a translator, first of French authors and then of George Bernard Shaw, whom he made famous in the German-speaking area. He married a widowed Hungarian princess, whose money they spent on having a house built in Maxingstraße near the imperial castle Schönbrunn in 1907/08 by Ernst Gotthilf, a student of Fellner & Helmer, the architects who planned many of the monarchy’s theatres and opera houses. At the outbreak of the First World War, Shaw wrote to Trebitsch how terrible that situation was “…you and I at war – it couldn’t be more absurd!” After the “Anschluß” the Trebitsch villa was seized by the Nazis and their property sold to pay for the “Reichsfluchtsteuer”. At nearly 70 years of age Trebitsch and his wife had to flee Austria in 1938, first to Paris, where in the summer of 1939 they received the French citizenship. But when the German troops invaded Paris, they had to continue their flight to Switzerland, where he had no possibility to earn money. G.B.Shaw tried to support him financially from England because Trebitsch could not get a passage to the USA. The couple considered suicide, yet after the news of the suicide of Stefan Zweig and his wife in their exile in Brasil, they desisted from this plan. In 1951 Trebitsch wrote his memoirs “Chronik eines Lebens” (“Chronicle of a Life”), dedicated to his friend Stefan Zweig.

Carry Hauser lived in the “Hietzinger Cottage” in Maxingstraße with his family, too. He worked as a graphic designer and stage designer for the Vienna “Burgtheater” and the Salzburg Festival. As soon as the Nazis took over he was banned from working in Austria, but he could not get to Australia any more, where he had been offered a job at the art college. His five-year old son was sent to England via a “Kindertransport” (see the article on “Kindertransports”). His wife managed to flee to the Netherlands, where the boy joined her later. Yet when the Nazis invaded the Netherlands, Hauser’s wife and son had to go “underground” in a retirement home. Carry Hauser himself had meanwhile reached Switzerland, where relatives of his wife supported him. Their children were Maximilian and Maria Schell, who after the war became famous actors. The whole family Hauser was reunited in Switzerland after the war before they returned to Vienna. Hauser designed many mosaics, sgraffitos and frescoes for Viennese public housing projects after the war.

Heinrich Eisenbach, a well-known, now forgotten Viennese Jewish comedian, lived in Trauttmannsdorfgasse. At the beginning of the 20th century he was the most celebrated of cabaret performers in concert cafés and on cabaret stages. He became a member of the famous cabaret group “Budapester Orpheumgesellschaft” in Vienna. He influenced and supported young cabaret stars and comedians, for example Karl Farkas, Fritz Grünbaum and Hans Moser. When he died in 1923, five years after his Friend Alexander Girardi, his whole library and collection of Chinese and Japanese art, of which he was an expert, were auctioned off. Nearby in Auhofstraße another comedian, Hans Moser, bought a house in 1931, which was built in 1900. But he mostly lived in the small concierge flat because he wanted to save money on heating and electricity – he was famous for his stinginess. After the “Anschluß” this extremely popular film comedian lived in constant fear that his Jewish wife Blanca would be deported. He refused to divorce her and consequently tried to get some special concessions for his wife from the Nazis. He even appealed in a letter to Hitler, but in vain. So he sent her to a secure place in Budapest, where he visited her every weekend. His daughter had managed to flee to Paris and then on to Buenos Aires.

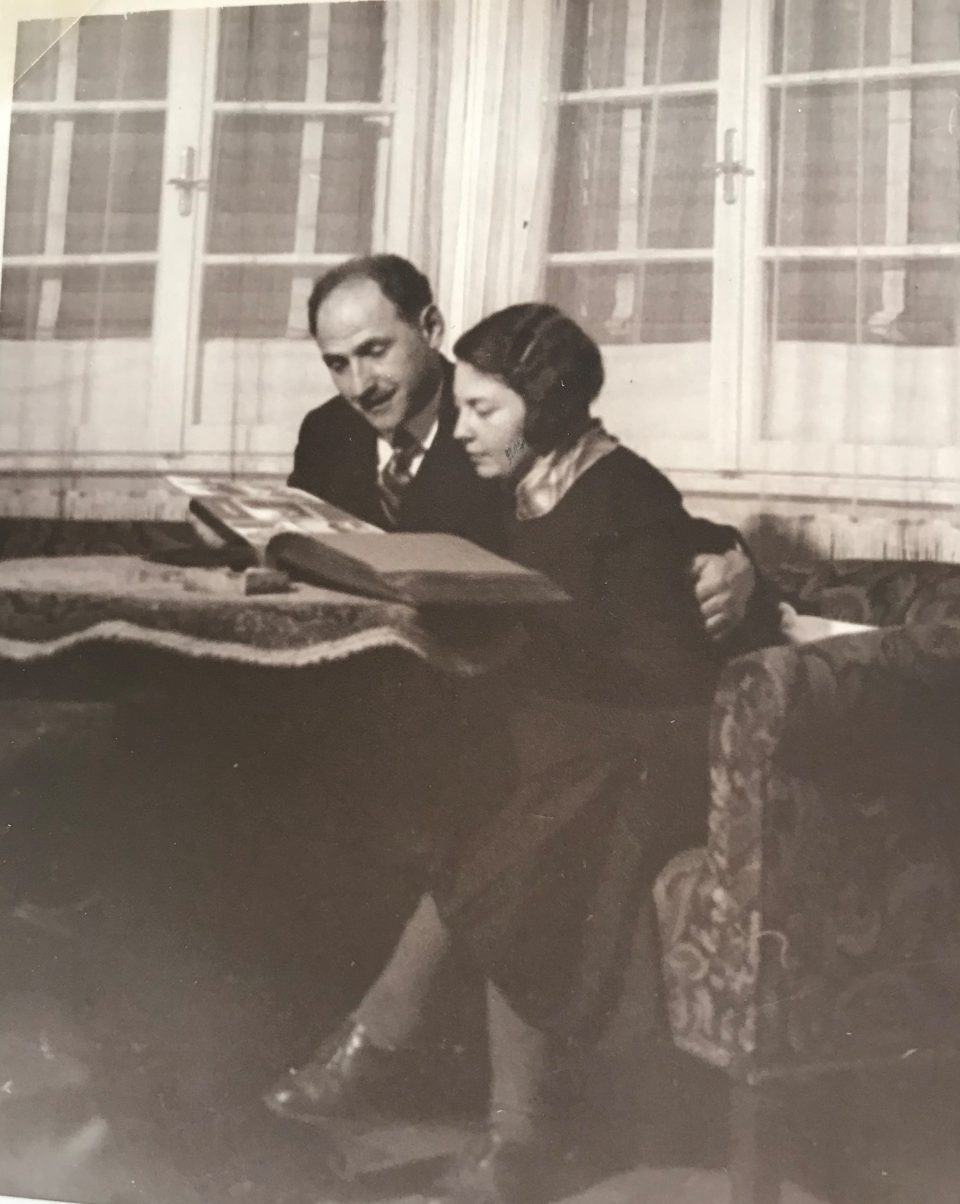

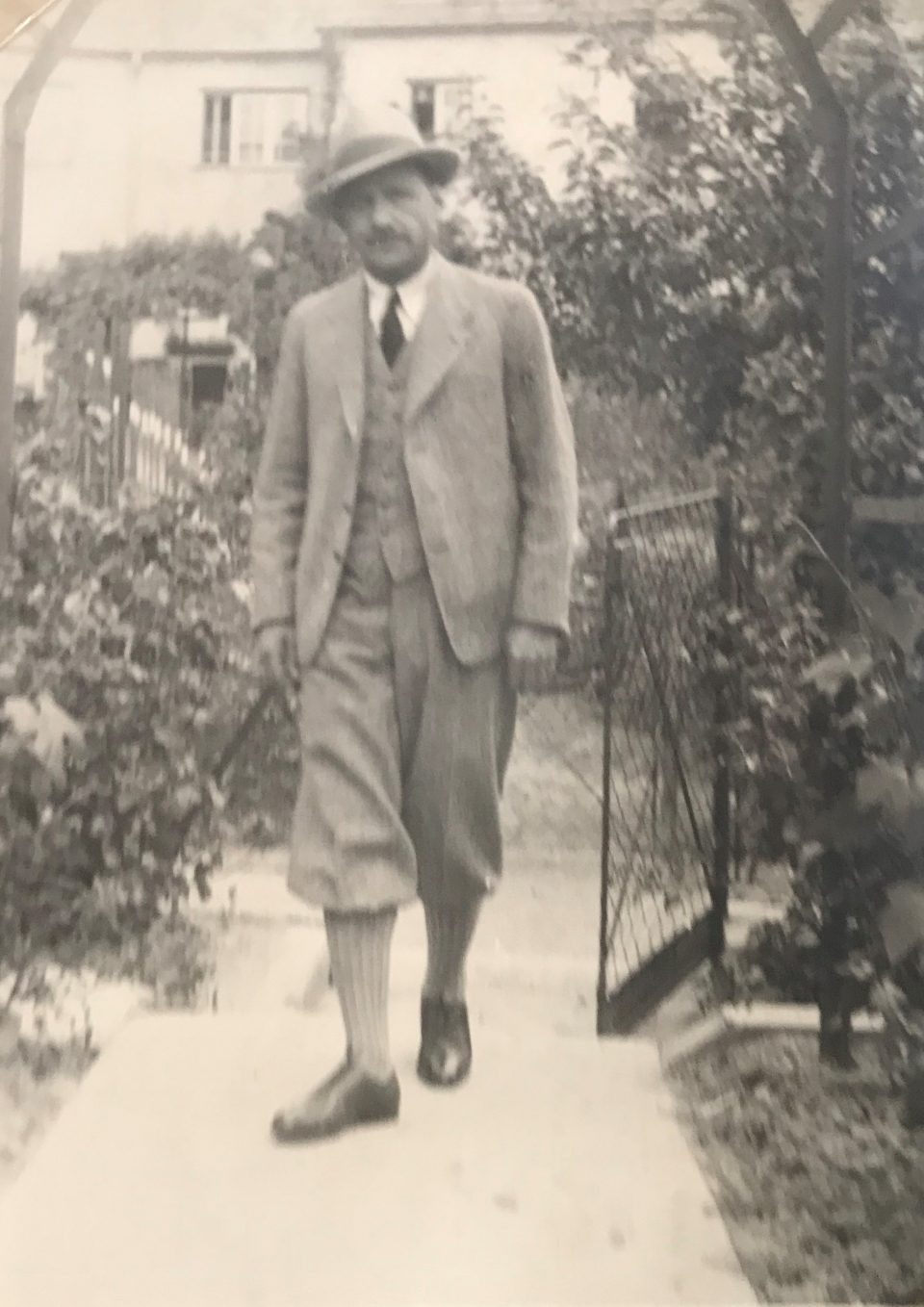

Henny Singer with her husband Josef (Peperl) Singer (left) and her uncle Norbert Katz (right) together with her aunt Agi Katz (left) and her cousin Josie Katz (left)

After their return from exile in Israel, Josef Singer set up a flourishing textile business in the “Vienna Textile Quarter”. In the Austrian business register of 1953 (“Handels Compass” p.165) he is listed above. After his early death Henny took over the running of the business. The proceeds of this enterprise allowed them to buy a bungalow in Alban-Berg-Weg 2 in the Hietzinger “Cottage Quarter”.

Henny Singer (on the right) on the veranda with her aunt Käthe Elzholz, my great-aunt

The architects who influenced the architectural appearance of the “Cottage Quarter” in Währing and Döbling were next to Heinrich von Ferstel, Carl von Bokowski, Josef Hoffmann, Franz von Neumann, Fellner and Helmer, Adolf Loos, Robert Oerley and Oskar Marmorek. In 1892 the suburb of Währing became a district of Vienna and the subsequent change in the social structure in the “Cottage Quarter” had led to a move from an economical and simple style to a more elaborate and luxurious style for a wealthier clientele. Between 1890 and 1914 not only one and two-family houses were constructed, but also tenant-occupied villas. The “simple Cottage Quarter” had turned into a luxury neighbourhood. The influence of Hoffmann, Loos and Oerley modernised the appearance of the new houses. Loos and Hoffmann represented juxtapositions of “Viennese Modernism” in architecture. In the “Cottage Quarter” of Hietzing Loos realised for the first time the new type of a terraced house in 1912, the “Villa Scheu”, without decorative elements, plain walls on three levels with a flat roof. His philosophy and artistic concept comprised all aspects of life from clothing to furniture, from food to shops and houses. His aim was to “turn workers into aristocrats instead of all people into proletarians”. The other “modernist”, Robert Oerley was a trained carpenter and master builder, but a self-made architect. He is still known as the creator of the flower pots in front of the Viennese “Secession”. His simple unadorned style can be seen in the twenty villas and the two-tenant-occupied houses he designed in the “Cottage Quarter”, his own villa in Lannerstrasse and the one of Ferdinand Schmutzer in Sternwartestraße.

Hubert Gessner, a student of Otto Wagner, was one of the most important architects of “Red Vienna” and the working class movement – and a “moderate modernist”. He planned and built icons of “Red Vienna”, such as the “Reumannhof” (1924/25), where my great-uncle Karl and Mitzi lived, the “Lassallehof” (1925), the garden city “Jedlesee” (1924-1932), the “Favoritner Arbeiterheim” (1902), the “Vorwärts” building (1907), the headquarter of the Social Democratic Party and its publishing and printing house. Gessner built several factories, administrative buildings and big public housing projects, but also one-family houses like his own villa in Sternwartestraße, the “Gessner Villa”, which he sold to a friend. When the villa was “Aryanised” by the Nazis, the conductor Karl Böhm moved in. Gessner himself lived in a flat of one of the tenant-occupied houses he had built in the area. After the Austro-fascist coup d’état in Austria in 1934, Gessner did not get any more big commissions and died in 1943. Another of the important architects, Oskar Marmorek, had a tragic fate; he suffered severe attacks of depression and committed suicide in 1909 in front of his father’s grave at the Viennese “Zentralfriedhof” at the age of 46. He was not only an appreciated architect, but also a Zionist and pioneer of a state for the Jews and an urban planner for the city of Vienna. The world-wide first entertainment parks in the “Prater” in 1895 were designed by Marmorek, the “English Garden” and “Venice in Vienna”. He built the first big tenant-occupied art nouveau houses in Vienna, for example the “Nestroyhof” in 1898 and the “Rüdigerhof” with its famous coffeehouse and several of the one-family villas in the “Cottage Quarter”. Marmorek was a close collaborator of Theordor Herzl and planned buildings for the future state of Palestine, which were never realised, but his memorial for Theodor Herzl at the Döblinger cemetery was.

Karl Elzholz’ photo of the view from their flat in the newly erected “Reumannhof”, one of the prestigious housing projects of “Red Vienna”

Karl, a Social Democrat, took photos of the furnishings of their new flat in “Reumanhof”, which appear quite bourgeois:

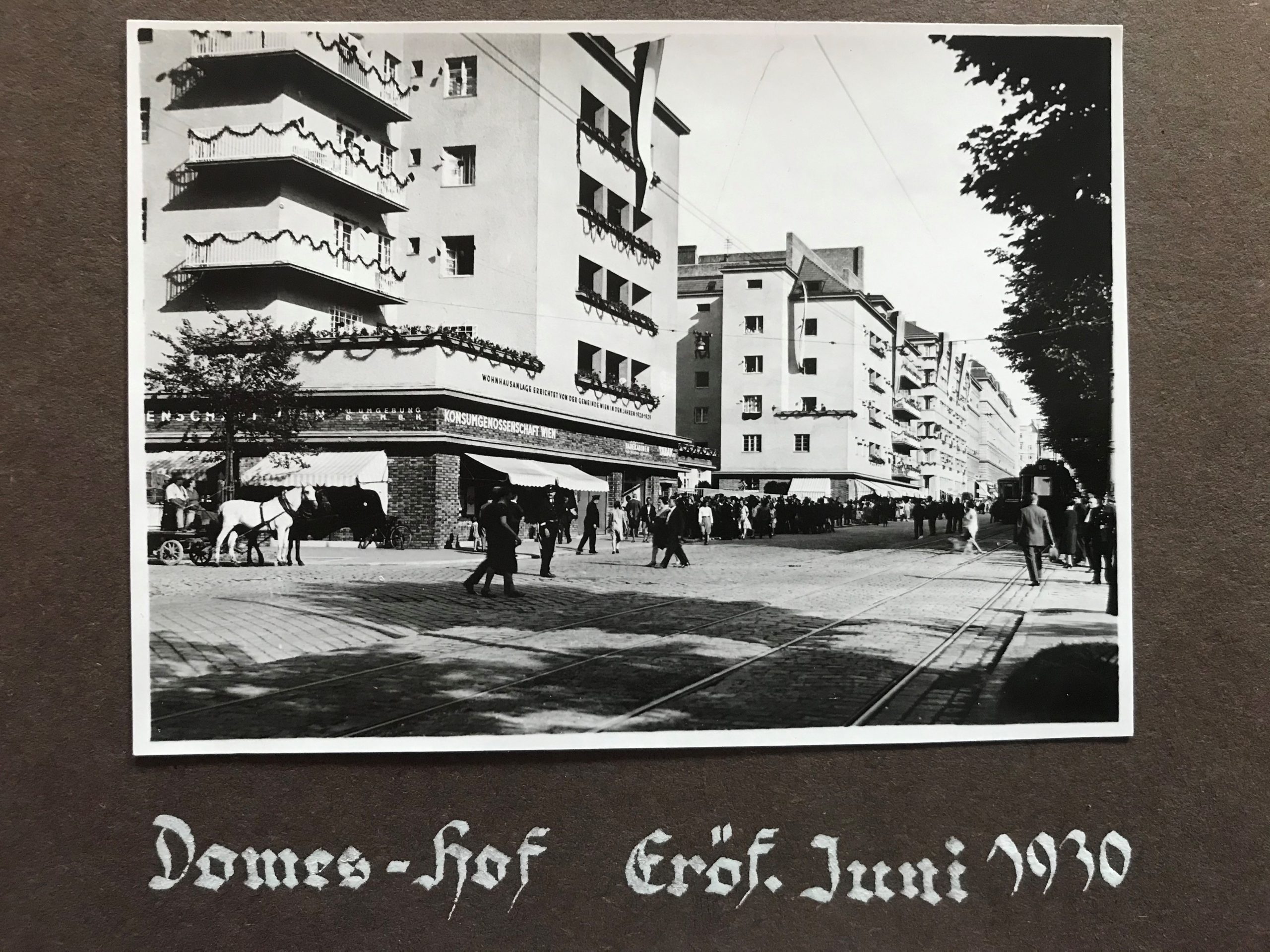

The “Reumannhof” was a public housing project of “Red Vienna” with 483 flats which was erected between 1924 and 1926 by the architect Hubert Johann Gessner on the area of the so-called “Drasche Gürtel”. This was a property of around 800,000 square metres which the family of entrepreneurs, Drasche, who ran the huge brickworks south of Vienna (today’s “Wienerberger”), had acquired before World War I with the plan to erect private tenant-occupied blocks of flats. Yet after World War I the private housing market collapsed and the high taxation that the newly elected city administration of Vienna levied on empty building ground prompted the Drasche family to sell the whole property to the city of Vienna, which built six large public housing projects on this ground, among them the “Reumannhof”, the “Metzleinstaler Hof” and the “Franz-Domes-Hof”. On 12 February 1934 police and army units of the Austrian government attacked the Reumannhof just after the outbreak of the civil war, the “Februarkämpfe” between the Austro-fascist “Vaterländische Front” and the Social Democrats. The resistance of the military arm of the Social Democrats, the “Republikanischer Schutzbund”, was broken by the Austro-fascists within a very short time. Four years later the Nazis took over and among the 26 families that were evicted from the “Reumannhof”, immediately after the “Anschluß” in March 1938, were my great –uncle and great-aunt Karl and Mitzi Elzholz.

With his camera Karl documented the opening ceremony of the public housing project “Franz-Domes-Hof” on Margaretengürtel in 1930

After the end of World War I and with the establishment of the 1st Austrian Republic the Social Democrats had the majority in the city council of Vienna. When in 1922 Vienna became an independent federal state, the reform project of “Red Vienna” could be realised by the city council. It is surprising and tragic at the same time that among the first Jewish tenants to be evicted in Vienna in March 1938 were the ones living in the public housing projects of “Red Vienna” and it was often the neighbours who were keen on their flats who reported tenants with a supposedly Jewish background to the Nazi authorities. Of the around 63,000 flats which were erected in the approximately ten years of “Red Vienna”, many were built in Margareten, the fifth district of Vienna. Most of the buildings are now listed as a national heritage and several of the architects were of Jewish background, such as Egon Riess, Fritz Judtmann, Adolf Jelletz or Julius Lichtblau, who managed to flee to the United States and taught at the Rhode Island School of Design and was d designer for Macy’s department store in New York. The before mentioned Jewish architect Oskar Marmorek, born in 1863 in Austrian Galicia, today the Western Ukraine, planned a lot of spectacular buildings in Vienna.

“Türkenritthof”(1927-1929) with the commemorative plaque for one of the Social Democrats killed by the Austro-fascists during the civil war in February 1934

After World War I the city of Vienna had to deal with famine, unemployment, extreme destitution and a disastrous housing situation. Of the 554,545 existing flats 405,991 were tiny apartments, where five to six people lived, often renting beds for several hours to pay for the rent that took up more than half of their income. Soldiers returning from prisoner-of-war camps, people stranded in Vienna arriving from different parts of the former Austro-Hungarian Empire created a substantial anarchic element in the city. They started to cut down the Vienna Woods for fire wood and established illegal “wild settlements” wherever possible. The city council tried to counter this trend by initiating a huge publicly funded housing project. Two opposing factions characterised this first planning phase: the “realists” who wanted to use building ground acquired by the city for quick urban development including roads, gas, electricity, water and canal installations. The “avant-garde” faction preferred to use the potential of the “settlers” with self-help, self-built projects and the cooperative model. Furthermore they wanted to adapt the “garden city concept” of the 1870s, described above, to working class needs. The “realists” promoted the establishment of city-owned enterprises, such as brickworks, carpentries, stone masonries to provide work and to supply the building material for the housing projects at affordable prices. As an urgent solution to the disastrous housing situation was necessary, simple and cheap floor plans were initially preferred, which meant for instance an abandonment of private bathrooms in the first projects. The focus was on the complexity of public space which included the equipment of housing projects with public baths, laundries, libraries, kindergartens, shops, surgeries and meeting rooms for all types of socialist associations. All the housing projects were characterised by large leafy courtyards, which on the one hand were to create a cosy natural atmosphere and on the other hand had the function of protection and supervision of the public space within the housing project.

“Davidhof” (1926/27)

“Eiflerhof” (1929-1931), named after Alexander Eifler, who was a leader of the “Republikanischer Schutzbund” and was murdered in the KZ Dachau

The architecture of “Red Vienna” sent a propaganda message and assisted the identification process of the working class, but it was at the same time very conventional. Probably due to the radical concept of financing the buildings by taxes levied on the well-to-do, the “Breitnersteuern” (a house building tax), the public housing projects were planned to fit into the historical structure and appearance of the city; they had to blend in and not to shock with radical avant-garde styles. The architecture of “Red Vienna” in a way imitated bourgeois models and resorted to representative public statements by image cultivation similar to the aristocracy of the 19th century. After World War I “Red Vienna” employed many of the jobless architects from very different architectural schools, many of them students of Otto Wagner, who continued their imperial traditions in a modified way. It is interesting to see that many of the architects who worked for “Red Vienna” had before planned and designed the villas in the Viennese “Cottage Quarters”. A typical example is the before mentioned leftist Jewish intellectual Josef Frank, who fought against the Viennese architectural traditions on the one hand and the international avant-garde, such as the “Bauhaus”, on the other hand. He propagated an aesthetic pluralism as an expression of a democratic cultural model. As chairman of the famous Viennese “Werkbund” he drove his colleagues from the German “Werkbundsiedlung” crazy, when he put a Persian rug into his modern house in Stuttgart in 1927. With respect to the Viennese public housing projects he rejected the term “Volkswohnpalast” (“Palace of the people”) because he thought that an imitation of aristocratic living did not serve the purposes of the workers, they had deserved something better, something more authentic. The Social Democrats should not try to copy the “Ringstraßen” architecture. Frank spoke out against the economical floor plan of council house flats: hall – living room – kitchen, which imitated the bourgeois household on a tiny scale. On the contrary, he preferred the kitchen-diner, which served the lifestyle of the working class better. In the end, he still believed in the settlement movement of terraced houses and the ideal of the garden city for the workers. Frank was an advocate of the private sphere, the freedom of mixing styles and tastes to create a cosy and comfortable atmosphere. He stubbornly resisted any form of supervision in public space. After the Austro-fascist takeover in Austria in 1934 he was driven into exile and as an intellectual and architect he finally gave up hope and resigned.

“Wiedenhofer-Hof” (1924/25) planned by Josef Frank

Otto Neurath, on the contrary, advocated an innovative urban planning model for the new Viennese housing concepts with an array of built-in common public facilities to create a harmonious and closed entity. This ideal of a public housing concept stood in stark contrast to the middle-class model of a small house with garden that is separated from the neighbouring ones and adorned with lots of bric-a-brac. In 1924 Neurath pleaded for an urban plan that in a uniform way integrated huge blocks via roads, courtyards and open passages. To his mind a confident worker should not imitate bourgeois lifestyles, but create a new form that expressed community spirit outdoors and indoors.

A common laundry in the “Schuhmeierhof” (1923/24)

“Friedrich-Becke-Hof” (1926)

Well, my great-uncle Karl, a convinced Social Democrat, and my great-aunt Mitzi still expressed a very middle-class taste in the furnishing of their flat as can be seen in Karl’s photos of their flat. They were supporters of the settlement movement as well, although they did not live in such a house, but friends and relatives did. Karl’s photos below document life in such settlements in Vienna in the 1920s and 1930s.

Settlement in Stadlau, Neustraßäckersiedlung:

Karl’s sister, Gusti Spitzer, on the right

Self-building of a house in the settlement by the settlers

Ignaz and Ritschi Sobotka, my great-grandparents at the window

The Social Democratic city administration, which was principally favouring the settlements, managed to channel the illegal settlement movement from 1919 on. They granted the settlers cheap credit and turned most of the land the “wild settlers” had occupied into legal building ground by creating a zone for settlements and allotment gardens. From 1921 on organised settlements on a cooperative basis were supported by the city financially and with building material. The famous “Wiener Siedlerbewegung” (“Viennese Settlement Movement”) was further characterised by the incorporation of self-building, namely the hours of manual labour that the settlers invested in constructing the settlement. The new city office for settlements accompanied the building of the settlements organisationally and architecturally. In this way approximately 50 settlements were created, for example the “Mustersiedlung Heuberg” by the famous architect Adolf Loos. One of the few female architects, Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky, was involved in the planning of several settlements between 1920 and 1925. In this way these grassroots settlements, which were self-founded and self-administered by the settlers, created the first big flat-roofed settlements in Vienna. Yet this commitment of the city administration to the “garden city concept” of the first settlements was superseded in the years 1924 to 1930 by a switch to big blocks of flats in order to be able to house more of the destitute workers. Furthermore did the new great public housing projects reflect better the new self-confidence of the working class than small one-family houses. Although the city of Vienna acquired lots of building ground for its housing projects, Social Democrats like Otto Neurath thought that the trend to bourgeois housing concepts might “corrupt” the working class. In his eyes settlers’ cooperatives could lead to the small-mindedness of bourgeois associations. He pleaded for industrial large sizes and structured planning in the city’s housing philosophy. It can be assumed that from 1918 until 1938 one quarter of the Viennese settlements of all kinds developed from bottom-up initiatives. In 1936 the number of inhabitants of originally informal settlements, so-called “Bretteldörfer”, was estimated at 5,000 and although the holding of animals was officially restricted, 70 cows, 105 goats, 493 pigs and 2,787 chickens and geese, 812 rabbits and 30 horses were counted there in the same year. The Social Democratic city administration vacillated between accepting and promoting working class initiative and eradicating any anarchical element by imposing rules and regulation for safety, sanitation etc.

“Adelheid-Popp-Hof” (1932/33), named after one of the first female members of Parliament

The innovative reform settlement “Eden” had received land from the city of Vienna in the west. It was a socially and financially difficult project, but it survived Austro-fascism and National Socialism and is now known for the model houses and the children’s home which were planned by Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky. The 300 members of “Eden” worked themselves 30,000 hours on the building sites. The “Freihofsiedlung” in Vienna Donaustadt is another example of the settlement movement. In 1923 the first 99 houses for the tramway workers and the workers of the electricity and gas works of the city were built. From 1924 on the settlement was enlarged by establishing two housing cooperatives, which resulted in the largest terraced housing complex in Vienna until today with 1,014 houses. In order to move into such a house, the settler had to help with the infrastructure provision and the construction of the terraced houses. The city of Vienna took over 85 per cent of the costs and the remaining 15 per cent had to come from the settlers. If the settler did not have the capital, he could work 1,600-3,000 hours – depending on the type of project. In the end 80 per cent of building work was taken on by the settlers themselves. This replaced any lack of capital and lowered the threshold for settlers to move into such a house. Many of the settlers had to rely on self-building and self-supply due to the high unemployment rate, so they identified with the cooperative idea of the settlement movement. As a consequence, workshops were set up for the production of building materials, tools, machinery, furniture and kitchen wares, and additionally garden associations, which provided cheap seeds and plants, were founded. The settlers organised insurances and veterinary services at low prices. By that they tried to achieve a high degree of self-sufficiency and divest certain production areas of the free market mechanism. The cooperatives were the owners of the houses in order to prevent any future claims to ownership of the houses by the tenants. But the settlers were offered a “hereditary tenancy”, which meant that the children of the settlers had the right to move into the houses. This led to the fact that even today many descendants of original settlers still live in these houses, often in the fourth generation.

Design details in the “Eifflerhof” and the “Friedrich-Becke-Hof”

The architects who got involved in the settlement movement were, apart from the above mentioned, Josef Frank, Hugo Mayer, Franz Schacherl, Karl Schartelmüller, Franz Schuster, Heinrich Tessenow among others. But in the long run the settlements were more costly than blocks of flats. Despite the criticism of the International Congress of Housing and Urban Planning in Vienna in 1926, the city of Vienna turned to large housing projects in the following years. Nevertheless, the concept of the “garden city” was now incorporated in the large projects by reducing the number of floors and opening up ample leafy courtyards within the housing estates. The last big project of the settlement movement was the “Wiener Werkbundsiedlung” of 1932, whose 70 model houses were considered the ideal of innovative, healthy and happy “proletarian living”. The large blocks of flats of “Red Vienna” were grouped around courtyards and were designed to contrast the Viennese tenant-occupied private houses, the “Zinshäuser”, which were richly decorated on the facades, but provided abysmal, crammed and dreary housing at enormously high rents inside. The “Rabenhof” and the “Karl-Marx-Hof” are famous examples of these new large housing projects of “Red Vienna”. Their architecture is meanwhile considered “iconic”.

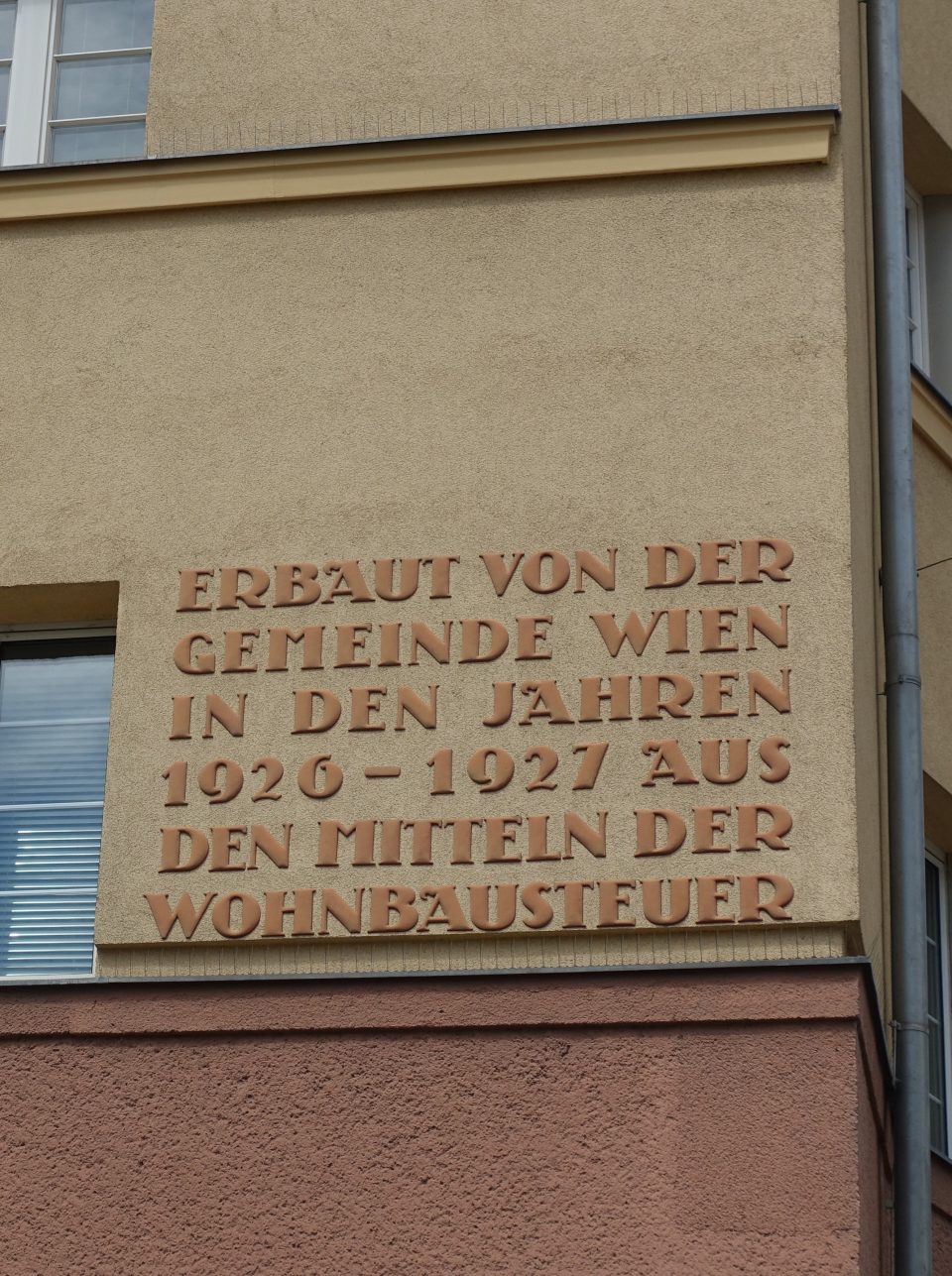

Several of the architects involved were students of Otto Wagner, but they were skilled at adapting the architectural plans to the demands of economical, functional and sober floor plans and design. The city authorities standardised only the sizes of the flats, the amount of air and light that had to penetrate the flats, but left the rest to the imagination of the architects. The city did not resort to prefab construction, but insisted on conventional building techniques in order to create as many jobs as possible and keep the quality high. The housing projects were characterised by high quality design of windows, staircases, lighting and opulent garden architecture in the court yards. The rare sculptures and mosaics on the facades were designed to trigger identification with “Red Vienna”, as did the labelling of the housing projects and the inscriptions on the facades which mentioned that the project was financed by the special house building tax. The Viennese poet of Jewish descent Jura Soyfer illustrated the hate of the Austro-fascists against these housing projects of “Red Vienna”: They were enraged when they read the names of the housing projects, such as Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels or Lassalle – internationally well-known socialists. These Austro-Fascists saw “civil war fortresses” in the housing projects, “tanks” in the city’s garbage collection vans, “arsenals of weapons” in the city’s kindergartens and “parade grounds” in the playgrounds of the city. The quick suppression of the Social Democrats’ upheaval in February 1934 by the Austro-fascist government proved wrong the rumour that the public housing complexes of “Red Vienna” were “fortresses of Social Democracy”. The Karl-Marx-Hof, the Reumannhof and the Goethehof among others were heavily bombarded by the artillery of the police and the army and many flats and communal facilities were damaged. This caused a severe rift in the Viennese society that lasted for decades. Until the 1970s the machinegun shots could be seen in the walls of the Goethehof and on the 12th of February commemorative wreath-laying ceremonies were held in some public housing estates for victims of the civil war of 1934.

The “Friedrich-Becke-Hof” (1926)

Inscription on the “Davidhof” on the left mentioning the financing by the special house building tax. On the right, the term “Volkswohnhaus” (People’s housing estate”) can be seen in an early project of “Red Vienna” of 1923

Literature:

Anderl, Gabriele, Jüdisches Leben in Wien-Margareten, Mandelbaum Verlag 2019

Das Wiener Cottage, seine Entstehung und Entwicklung, in: Zeitschrift des österreichischen Ingenieur-und Architekturvereines Nr.5, 58.Jg, 02.02.1906

Gruber, Helmut, Red Vienna. Experiment in Working-Class Culture 1919-1934, Oxford University Press 1991

Riedl, Joachim (Hrg), Wien, Stadt der Juden. Die Welt der Tante Jolesch, Zsolnay 2004

Rosenberger, Werner, Hietzing. Von Künstlervillen & Künstlerleben, Amalthea Verlag 2018

Rosenberger, Werner, Im Cottage. Wiens erste Adressen und ihre berühmten Bewohner, Metroverlag 2014

Schwarz, Werner ua (Hrg), Das Rote Wien 1919-1934, Wien Museum 2019

Wiener Cottage Verein, Folder 2019