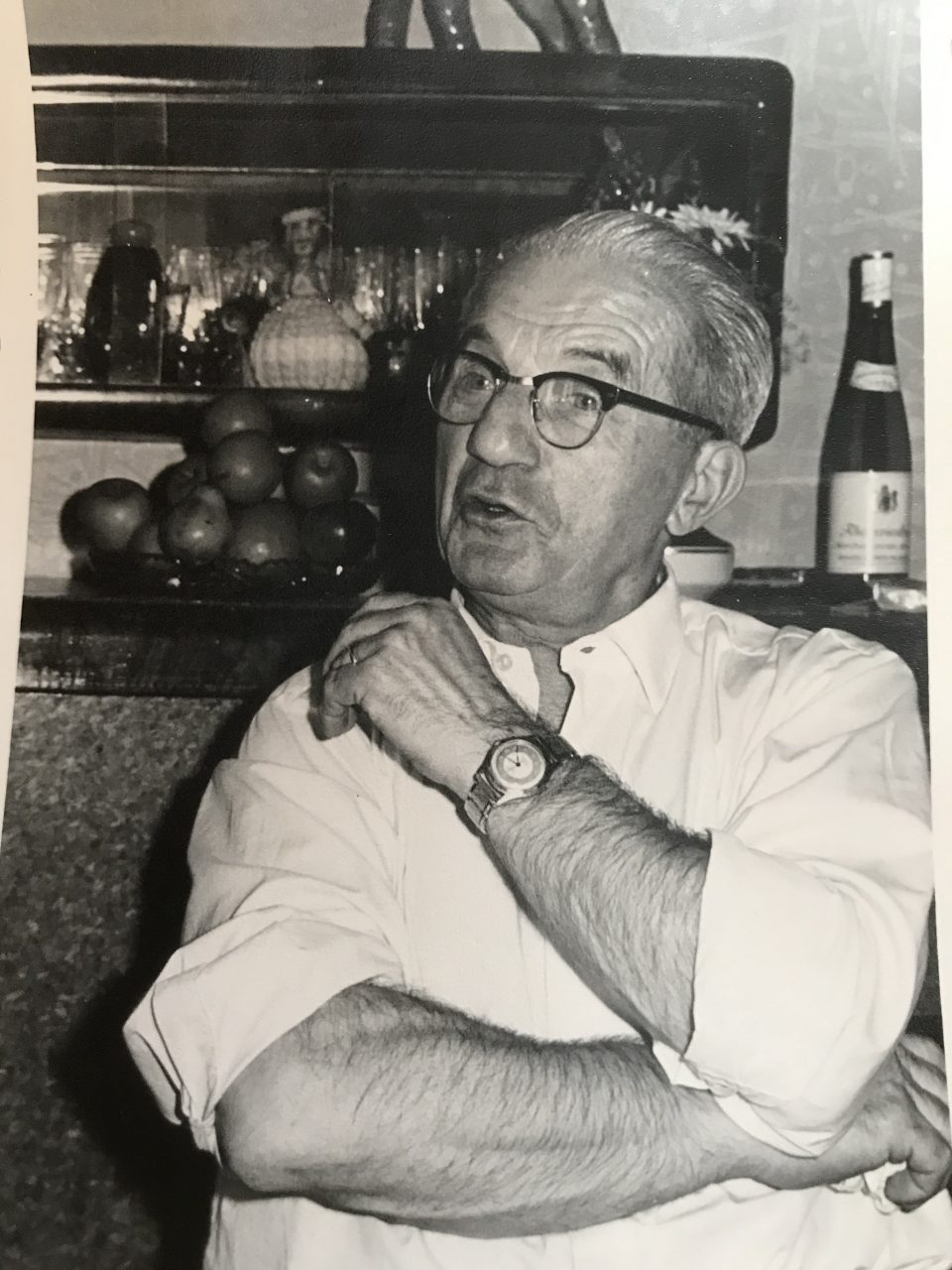

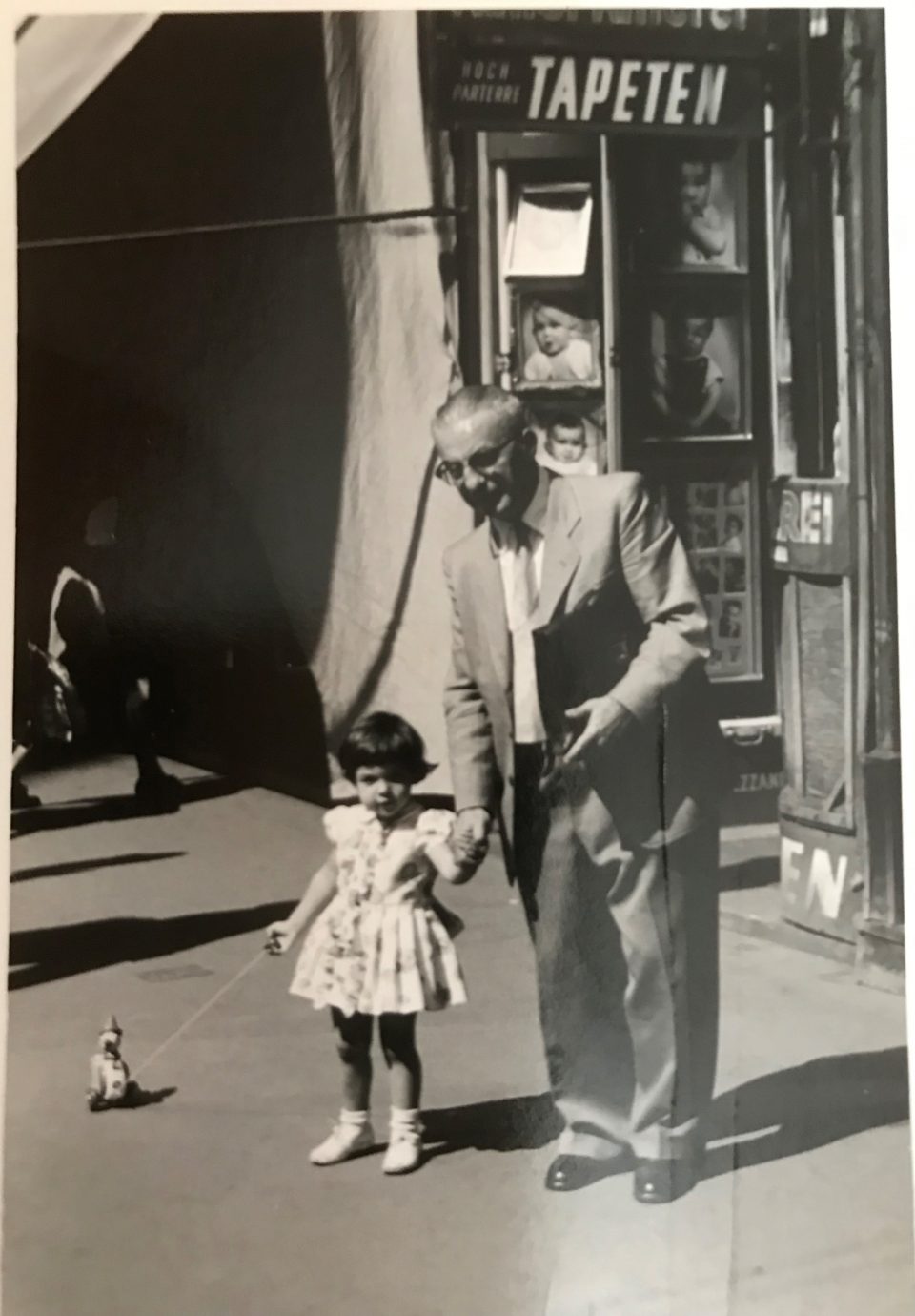

Norbert Katz, the husband of my great-aunt Agi, was a very talented and successful professional footballer in Vienna until he had to emigrate in 1938. As a very young player he became champion of the Austrian second league in 1919/20 with his team Hakoah Vienna and was Austrian Champion in the season 1924/25 with Hakoah Vienna. Later in England he was employed as a bank clerk, but continued to work as sports trainer and football functionary. This fact offers the chance to investigate the significance of football for the city of Vienna as a vehicle of identification with the young Austrian state. May great-aunt, Agi, was a free water Danube swimmer for the sports club Hakoah, one of the “Danube Maidens”, before she married Norbert. Swimming, just as football, was a very popular and internationally successful sport in Vienna in the 1920s and 1930s.

At the end of the 19th century the English sport football was introduced in Graz, Prague and Vienna, but Vienna soon took the lead because football was directly introduced by Englishmen in Vienna, whereas the clubs in Graz and Prague were subsidiaries of Frankfurt clubs. At that time many English people worked and lived in the Habsburg Empire’s capital city. They introduced the ethics of sport and its benefits for health and mind in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The gasworks in Simmering, for example, were an English subsidiary and the British company brought many English engineers, skilled workers and white collar staff to Vienna and they started to play football at the “Jesuitenwiese” in the Vienna Prater. Other important British companies that had established businesses in Vienna were Clayton & Shuttleworth, which produced agricultural machines and typewriters, Thomas Cook & Son, the travel agent, and several British sanitary firms. Gandon of the gas works, Gramlick, the owner of a British sanitary firm, Shires, a salesman of the “Underwood” typewriter, Blackey, the director of Clayton & Shuttleworth, Reverend Hechler of the Anglican Church in Vienna, Blyth of Stone & Blyth and Loew, director of the Viennese hat factory Böhm, these were the men who introduced football to Vienna. In 1892 they founded the “Vienna Cricket Club”, but cricket could not find enough players and spectators in Vienna, so the club decided to introduce football in Vienna, too, and in 1894 they changed the club’s name to “Vienna Cricket and Football club” (later “Austria Wien”). Just a few days earlier another group of Englishmen had registered the “First Vienna Football Club” with the imperial administration in 1984, which means the “Vienna” was the first Viennese football club in the city. The two clubs “First Vienna Football Club”, called “Vienna” and the “Vienna Cricket and Football Club”, called “Cricketer” (later FK Austria Wien) were based in Döbling and Heiligenstadt and their first players were the gardeners who Baron Nathaniel Rothschild had brought to Vienna to tend his gardens at the “Hohe Warte”. “Vienna” was the first Viennese football club that also accepted Austro-Hungarian players and was not exclusively managed by Englishmen. Franz Joli, son of the inspector of the Rothschild gardens was enthusiastic about football after his stay in England and he and his brother Max Joli boosted the enthusiasm for the new game among the local population. They started to play with the English gardeners in the Rothschild gardens. So, father Joli had to look for an appropriate football ground outside the gardens in order not to have the lovingly tended meadows of the Rothschild gardens devastated. The first football ground of the “Vienna” was an unused plot at the Heiligenstädterstraße, later the “Kuglerwiese”. The founding assembly took place at the inn “Zur schönen Aussicht” at the “Hohe Warte” on 22 August 1894 and the colours chosen for the club were blue and yellow, the colours of the Rothschild horses competing at the race course in Freudenau. The club was founded under the patronage of the director of the Rothschild bank in Vienna and Baron Rothschild paid for the rent of the football ground and subsidised the club. The first club pub was “Bittners Restaurant” at the Heiligenstädter Pfarrplatz. On the 15 November 1894 the first football match between the two rivalling clubs took place at the Kuglerwiese and the “Cricketer” won 4:0. This was the birth of the Viennese football sport.

The first English players who taught the Viennese the rules of the game were not professional footballers, many of them not even gifted sportsmen. Consequently the first matches were rather primitive and rustic, just as the equipment. The first match between the two newly founded clubs “Erster Arbeiter Fußball Klub” and the “Meidlinger FCI” in 1898 ended 1:1, whereby both clubs only managed to come up with nine instead of eleven players. In 1900 Nicholson was the president of the “Austrian Football Union” and he used the letter head of his company, Thomas Cook and Son, to write to the representatives of the clubs that they have to see to it that the matches start punctually on Sunday and that the rules, such as the duration of the match (two times 45 minutes) and a break, have to be observed. The first and only “match clock” in Vienna was the clock on the church tower of the Rudolfsheimer Church at the Kardinal Rauscherplatz in the vicinity of the football ground of the club “Rapid”, which told the players, the referee and the spectators the time and signalled the end of the game at all matches of the club “Rapid”. But that was the time not only of amateurism, but also of pure idealism for the sport. The club membership fees of the players made up the largest amount of the income of the clubs. Additional funds were raised through the sale of the programme leaflets at each match. Every player had to pay for his own equipment, which was extremely expensive at that time. They usually had to walk to the matches that took place in different parts of Vienna, which could take up to two hours or more one way, so many of them were already exhausted at the start of the game and dragged themselves home after a tough match.

In the season 1923/24 the club Hakoah Vienna won in London 5:0 against Westham United. That was the first time an Austrian club beat an English club on British territory. They were also the first Viennese football club that went on a tournament to another continent, namely Egypt and Palestine, where they won all their matches easily. Rapid Vienna travelled at the same time to Spain, Portugal and Belgium. In the following season, 1924/25 the first official professional football league in Austria was opened. The first and second league declared their commitment to professional football. The first league comprised 11 teams and the second 12 teams. The first and second team of the second league moved up to the first league in the next season. The rules and regulations for the professional league were drawn up with the help of Hugo Meisl. At the beginning of September the new professional footballers signed their contracts, but only few players changed teams. The officially recorded pay of the players does not reflect an accurate picture today because that was the time of spiralling inflation. The average salary the clubs paid their players amounted to one to four million crowns. The “Vienna Amateure” and “Hakoah” had the most expensive teams and offered their stars Spezi Schaffer (Vienna Amateure) and Bela Guttmann (Hakoah) 10 million crowns each. Rapid had an expensive team as well, but they decided to pay each player the same salary to boost the team spirit. The first professional season 1924/25 ended with a victory of Hakoah, which had an excellent and expensive team with six Hungarians and the “Vienna Amateure” in second place. Austria had introduced professionalism in football to put an end to the secret payments to players, which was widespread in many countries. But despite the fact that other countries did not follow the Austrian example, the Austrian Football Union decided to continue with the professionalization of football. The classical English amateurs then separated from the professional footballers who earned money in the “Cricketer”. The professionals became as “Amateure” and later “FK Austria Wien”, one of the best clubs in Austria.

In the course of the interwar years football became a “substitute home” for some people. In 1923, for example, thousands came to the match of the Austrian national team against Italy in the natural football arena of the “Hohe Warte”. The Austrian national team consisted only of players from Viennese clubs, nevertheless it represented Austria, the new republic which was only established in 1919. Hugo Meisl was a Jew and the head coach of the team; he was one of the most influential football experts and functionaries on the continent. The Austrian national football team assisted in creating an Austrian identity in economically and politically difficult times and the “Wonder Team” that won twelve international matches was the pride of the whole nation. The Austrians loved the team and identified with the footballers in an emotional way. When in 1931 the team beat Scotland 5:0 the admiration of the Austrians was limitless. “The Wonder Team” was the best national team of the continent for two years. Austria, Hungary and Czechoslovakia founded the forerunner of today’s Champions League in order to raise funds for their football clubs. It was the first transnational competition of football clubs. These three countries also stood for the so-called “Danube Football”, a special style of playing football that differentiated it from the English or French style. In Vienna experts even spoke of a special “Viennese Waltz” style. In 1932 Hugo Meisl travelled with the national team to England. Austria lost 3:4, but the enthusiasm of the Austrians was not dampened; they received the homecoming team in triumph. The Austrians’ fascination with football helped create a national identity via this team sport and the majority of Austrians started to believe in a country, that nobody had considered viable in Europe in 1919. The Austrians loved especially the “Viennese Waltz” style and the player who embodied that style was Matthias Sindelar, the “Paper Man”. He was asked to play for “Arsenal London” but preferred to stay in Vienna. Matthias Sindelar was the role model for Norbert Lopper from the Hakoah, who survived the Nazi concentration camps and led the club “Austria Wien” as secretary after the war. Three weeks after the “Anschluß” in 1938, when Austria was incorporated into Nazi Germany, a football match between Austria (which no longer existed) and Germany was staged by the Nazis and Matthias Sindelar was the captain of the Austrian team for the last time and among the four players from Rapid was also its star, Franz “Bimbo” Binder. Rumours had it that Germany had desired a draw, but the Austrian national team won its last match. All Jewish players and functionaries of “Austria Wien” had to flee or were deported and the Nazis used the remaining much loved football stars to promote the unification of Austria with Germany in the staged plebiscite and to speak for a “Yes” vote. Sindelar took over the leadership of the club “Austria Wien” after the Nazi takeover and was given a Café that had been requisitioned by the Nazis from its Jewish owner, the “Café Annahof” in Favoriten. Yet in 1939 he died under mysterious circumstances. The absurdity of today is the fact that a former largely Jewish sports club like “Austria Wien” nowadays faces the serious problem of Neo-nazi fan groups, just like the Viennese club “Rapid”.

The Viennese football culture was fed from two very different sources, the bourgeois coffee house culture and the workers’ suburbs. It was a phenomenon of the masses and Vienna had become a metropolis of this sport in Europe. “Rapid” was the first Viennese workers’ football club, founded in 1897. But the bourgeois clubs, such as “First Vienna Football Club” and “Cricketer” did not want to play against a workers’ club, so Rapid had no teams against which to play at the start. The first championships in the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy took place in 1911 and to the surprise of everyone the workers’ club Rapid won. The imperial army had promoted football as some kind of pre-military training and as a recreational activity for the soldiers. The fascination with football in Vienna and the arousal of the masses that is linked to this unspecified enthusiasm led Elias Canetti to write his book “Masses and Power” (Masse und Macht”). He had experienced the hysterical shouts of the Rapid fans at their football ground at the “Pfarrwiese”, when the Viennese Justice Palace was burnt down. The densly populated workers’ suburbs of Favoriten and Floridsdorf constituted a huge reservoir of young talented players. Football was a chance for the young workers to earn money and climb the social ladder. In the 1920s “Rapid” was one of the best teams in Europe and the strong support of the workers convinced Julius Tandler, one of the most important representatives of “Red Vienna”, that a football stadium had to be built for the workers as a beacon of the achievements of “Red Vienna”. The “Prater Stadium” was the most modern of its time and illustrates the commitment of the Austrian workers to the Austrian football team as a symbol of national identification. The second Workers’ Olympic Games took place in this stadium. It’s a great Austrian tragedy that also the famous workers’ football club “Rapid” willingly cooperated with Hitler, expelled all Jewish players and functionaries after 1938, the fans greeted the players with the “Hitler salute” and they even sacrificed their trophies to be melted for arms production. Both “Rapid” and “Austria” participated in the German football league during the Nazi regime. There was no resistance against the Nazis in the Austrian football scene after the Jewish football players and experts had been driven out of the country or murdered in the Holocaust except may be in the small club “Olympia 33”, a club of the Communist party which was founded in 1933.

How did the Jewish Viennese football club “Hakoah” rise to become the Austrian champion in 1924/25 in this anti-Semitic atmosphere? Already in 1895 a group of German and Austrian Jews founded a gymnastics club in Constantinople, today’s Istanbul, because as members of a German “Turnverein” they were confronted with anti-Semitic attacks. Soon a second club was set up in Philippopel, today’s Plovdiv in Bulgaria, and in 1897 one in Vienna, but all of them were only of local importance and were only known to insiders. The Second International Zionist Congress in 1898 propagated a new Jewish ideal of fitness, sports and a well-trained body. As a consequence a group of Jewish academics founded the Jewish gymnastics club „Bar Kochba“ in Berlin and eleven years later Jewish university graduates in Vienna set up “Hakoah”. This foundation was triggered by a football match in Vienna that took place a little earlier in 1909 between the Jewish Hungarian club “Vivo es Athletikai Club Budapest” against the reserve team of the “Vienna Cricket and Football Club”. The first club meeting took place in the reading room and oratory of the Jewish students in Vienna and Dr. Fritz Löhner was elected president. The name Hakoah was chosen because it signifies strength in Hebrew. The names of the newly established Jewish sports clubs stressed the ideological concept behind these foundations. Most of them had Hebrew names, such as “Bar Kochba”, referring to the leader of the Jewish revolt against the Romans 123-135 AD, or “Makkabi”, referring to Judas Makabi who defeated the Seleukides 165 BC, or “Hagibor” signifying fighter. These Jewish sports clubs were in many ways very similar to the German nationalist sports movement, the “Turnvereine”. Their agenda was not just about sports, but also about national identification. They opened the meetings with songs and dreamed of a national resurrection. But it would be too simplistic to reduce these sports clubs to their national ideology. Like the workers’ clubs or the Catholic sports clubs, they used sport to create a common identity and form a communal spirit that comprised all areas of daily life. It was a reaction to the anti-Semitic atmosphere in established sports clubs and strengthened their minority position. Zionist and assimilated Jews now had their own sports clubs. Zionist goals were not expressively mentioned in the statutes because that would have estranged the many assimilated Jews because only few Austrian Jews were Zionists. Hakoah never saw itself as a religious club, but it was a Jewish club. A compromise had to be found about observing the “Sabbath rules”, namely that it was up to the individual sports person whether he or she would take part in competitions on a Saturday. This was important as most of the competitions or matches took place on weekends. An episode of 1928 illustrates the dilemma for devout Jews: The football club “Hakoah Vienna” was invited to play in Philadelphia on a Saturday and the hotel of the players was 20 kilometres from the stadium. As the striker Lajos Hess, a devout Jew, would not use a means of transport on a Saturday, he had to walk to the stadium. He arrived in such an exhausted state that the coach and head of the football club, Arthur Baar, asked a substitute to take his place in the team.

Of the 17 Hakoah players of the Austrian championship team of 1924/25, the first professional Austrian football title, probably only one name might still be known: Bela Guttmann, the star of the team, who after the Second World War won the European Cup with Benfica Lissabon in 1961 and 1962 and was Austrian national team coach and the coach of “Austria Wien”; maybe also functionaries such as Ignaz Hermann Körner and Arthur Baar, who were Austrian football pioneers, or the goal keeper Karl Duldig, who became a well-known sculptor in Australia, but nobody remembers the Austrian national team players of Hakoah, the midfield players Richard Fried and Egon “Gitschi” Pollak, the strikers Moritz Häusler, Norbert Katz (my great-uncle) and Alexander Neufeld-Nemes and the defence player Max Scheuer. Yet in the 1920s and 1930s the Hakoah football players were the flagships of the Jewish sports club. They won the championship title at a time of rising anti-Semitism in Austria, especially on football grounds. Their second-place rival of the season was the “Wiener Amateure” (since 1926 FK Austria Wien), formerly the “Vienna Cricket and Football Club”. This club, too, was characterised by a strong Jewish element, in contrast to the majority of the other Austrian football clubs, but the “Amateure” represented an assimilated liberal bourgeois and intellectual group of sports enthusiasts from the start. Both clubs, “Hakoah” and the later “FK Austria Wien” were so-called “coffee house or city clubs” and were verbally abused as “Jews’ clubs”. Arthur Baar mentioned several cafés where Hakoah meetings were held in Vienna, among them the Café Jägerhof in the Porzellangasse, the Café in Augartenstraße, the Café Fetzer in Praterstraße, the Café Liechtenstein in the 9th district and the Café City in Werdertorgasse.

What both clubs further had in common was that they recruited excellent Hungarian players; Hakoah could even boast six Hungarian stars in its team, namely Guttmann, Fabian, Wegner, Neufeld-Nemes, Schwarcz and Eisenhoffer. The two clubs were criticised by the competition and the press, always with an anti-Semitic undercurrent, for their recruitment of foreign players. Yet in the 1930s the trans-nationality of the Central European football, the so-called “Danube Football” was the key to success, just as today. Without the international networks and exchanges between Budapest – Prague – Vienna the famous “Wonder Team” would not have achieved its fabulous successes and the Viennese clubs would not have performed as successfully as they had in the “Mitropacup”, the Champions League of the time. The mobility of the football professionals was driven by career prospects but also by financial interests at times of serious economic troubles. Also the football tournaments abroad were used to fill the coffers of the clubs, for example Hakoah’s trips to England, Poland, Egypt, Palestine and the United States. The two important guest appearances in the USA 1926 and 1927 raised the public awareness for the club and were a huge success abroad, but had drastic consequences. Eight team players left Hakoah and joined the financially much more attractive American soccer teams, among them also Guttmann. Some of the players returned later, when the US soccer teams got into financial troubles, but the Hakoah team never again had the quality of the early years and was finally relegated in 1936/37. Within only four days of the “Anschluß” (Austria becoming part of Nazi Germany) in March 1938, the Austrian football sport was made “Jew-free”, which means all Jewish players and functionaries were dismissed and Hakoah was dissolved. All matches with the club were cancelled, all points and all results annulled and the club’s financial assets were confiscated. At that time seven of the seventeen players of the championship team of 1924/25 were already abroad and for the remaining ones the trans-nationality of the “Danube Football” proved very useful because it helped most players and functionaries to get out of Austria in time. Their skills and knowledge about football assisted them to get employment abroad, as the Hakoah Youth player, Norbert Lopper, secretary of “Austria Wien” after the war, confirmed, who fled to Belgium in 1938 and played for the workers’ football club “Etoile” there and later changed to “Maccabi Bruxelles”, a club that was mostly made up of refugees. The defence player Josef Grünwald spent two years in the KZ Buchenwald before he could be bought out and brought to New York, where as a broken man he ran the bar “Joshy Gruenfeld’s Restaurant”, which became a meeting place for exiled Hakoah members. Bela Guttmann, like many of his Hungarian colleagues, returned to Hungary and Norbert Katz fled to Great Britain, following his wife, my great-aunt Agi, and his children. The defence player Max Scheuer was killed in the Holocaust; for him like for many older Hakoah players it was much more difficult to flee the Nazi regime because the young players were more in demand abroad than the older ones and the younger players were more mobile; they often did not have a wife and children to provide for. The probably most famous Holocaust victim of Hakoah was its first president, Fritz “Beda” Löhner, he was a well-known writer of song texts, librettist for among others the composer Franz Lehar, an essayist and journalist for the “Neues Wiener Abendblatt”. He was probably the best football journalist of the time and the so-called “Beda Evenings” that he organised were famous cultural events in Vienna and contributed to the budget of the club. He was already deported on the 1st of April 1938 to Dachau in the “Transport of Celebrities” and was later transferred to KZ Buchenwald, where he composed together with Hermann Leopoldi the famous “Buchenwald Song”. In 1942 he was transported to Auschwitz, where he was murdered on the 4th of December of the same year.

Sports events were often accompanied by cultural events and victory celebrations took on a musical touch with Hakoah. Fritz “Beda” Löhner organised so-called “Beda Evenings” every winter, where the famous stars of the Viennese cabaret performed for free to sponsor the Hakoah sports club. When in 1913/14 all the smaller ceremonial halls were already booked, Löhner had to rent the huge “Sofiensäle” in Vienna and he was afraid that they would remain half empty. On the contrary, the police had to block the entrances because so many people wanted to see the famous cabaret stars Fritz Grünbaum and Mela Mars. In the interwar years Viennese and international celebrities like Armin Berg, Karl Farkas, Max Hansen, Zarah Leander, Hermann Leopoldi and Fritz Wiesenthal performed for free in the Ronacher, Theater an der Wien and Kabarett Simpl to raise funds for Hakoah. A special combination of sport and culture proved the versatility of the Hakoah members, sportsmen and women: In 1920 they participated at a summer sports event in Leipzig, Germany, and it is reported that the footballers not only played an excellent match, they organised a cultural evening as well, where Koby Neumann acted as conférencier, Norbert Katz, my great-uncle, played the piano, Felix Slutzky the cello, Kurt John recited poetry and Egon Pollak sang the prologue of the opera “Pagliacci” by Leoncavallo. The Hakoah orchestra played at the festivities to celebrate the football champions of 1924/25, for example, where the orchestra performed Beethoven’s first symphony and Mozart’s overture to the opera “The Abduction from the Seraglio”. The festive dinner menus listed typical Austrian specialities, no hint of a “kosher” diet at that time.

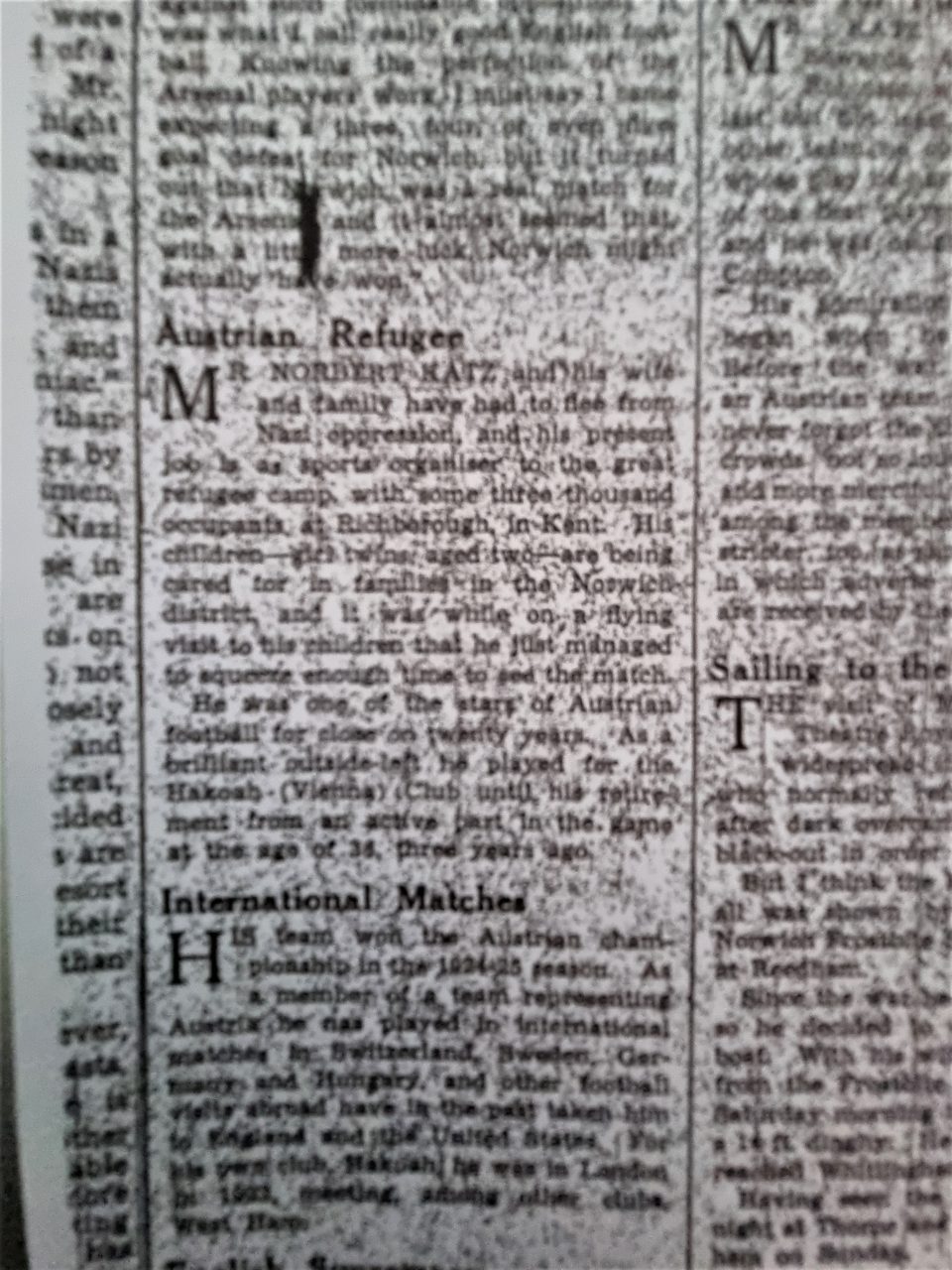

When Norbert Katz arrived in England after his flight from the persecution of the Nazis in Vienna, he was placed in a transit camp in Riseborough in Kent, where he coached the football team. His two-year-old twin daughters, Susi and Josi, were placed with two Quaker families in Norwich, one of which was the family of Bernard Canter (see article on “Kindertransports”), a journalist on both Norwich papers, the Eastern Daily Press and the Eastern Evening News. At the that time Bernard Canter wrote regular feature articles under the pen name “Whiffer”, an old Norwich name. In the Eastern Evening News issue of 13 November 1939 Canter wrote an article about a football match he visited together with Norbert Katz. He, who had probably never been to a football match before, was impressed by Norbert’s expert commentary. Norbert was on a visit of his daughters and Mr. Canter organised tickets to take Norbert to see Norwich City play. His article included Norbert’s comments on British football and the Norwich team from the point of view of his career with the Hakoah club as an international player. Further the article touched lightly on the Katz family’s terrible experiences as refugees and Norbert’s being in Norwich to visit his family: “Austrian Refugee. Mr. Norbert Katz and his wife and family have had to flee from Nazi oppression and his present job is a sports organiser to the great refugee camp, with some three thousand occupants, at Richborough, in Kent. His children – girl twins aged two – are being cared for in families in the Norwich district, and it was while on a flying visit to his children that he just managed to squeeze enough time to see the match (Norwich City vs. Arsenal). He was one of the stars of Austrian football for close on twenty years. As a brilliant outside-left he played for the Hakoah (Vienna) Club until his retirement from an active part in the game at the age of 36, three years ago. International Matches. His team won the Austrian championship in the 1924-25 season. As a member of a team representing Austria, he has played in international matches in Switzerland, Sweden, Germany and Hungary and other football visits abroad have in the past taken him to England and the United States. For his own club, Hakoah, he was in London in 1923, meeting, among other clubs, West Ham. English Supremacy. “When I see a game like this”, Mr. Katz told me, “I realise why English football has retained its supremacy. The mere winning of an isolated game here and there by a Continental team over an English one proves nothing. You have only to see a good English game to realise how much we on the Continent had to learn. I am always impressed with the first-class condition of English players, with their speed and with the forward ability to shoot equally accurately from any angle. Centre-half Play. “Another thing that always intrigues me about English play is the use of the centre-half as a sort of third back,” Mr. Katz added, “To the Continental player this seems the distinctive mark of the English team. On the Continent, on the other hand, the tradition has always been to make the centre-half a sixth forward. I believe the different English system arises from the greater strength of the English forward line. The forwards don’t need reinforcing, it’s the defence that needs strength to withstand the other people’s forwards.”….. His admiration for British football began when he was quite a boy. Before the war he saw Celtic beat an Austrian team by 9 goals to 2, and he never forgot the thrill. He finds English crowds not so loud as Viennese crowds and more merciful to referees! Discipline among the members of English teams is stricter, too, as shown by the ready way in which adverse rulings of the referee are received by the players.”

In the 1940s Norbert Katz coached Ealing and other English clubs and occasionally played matches, too. He and his family became British citizens and lived in London for the rest of his life.

Viennese dancing balls were and are famous world-wide and the” Viennese ball tradition” originated in the festivities linked to the Vienna Congress of 1814/15. At the end of the 19th century it became common that the various professions organised their own balls in Vienna, and later associations and clubs, too. The annual “Hakoah Redoute” was one of the most celebrated balls of Vienna. In 1935 4,000 visitors flocked to the “Sofiensäle”, where at midnight the famous tenor Joseph Schmidt sang for the ball guests. Only few days before the “Anschluss” on the 5th of March 1938 the last “Hakoah Redoute” took place in the “Sofiensäle”, where the Hakoah Vienna girls’ swim team, the famous “Danube Maidens”, together with the male swimmers performed a revue and presented the newly texted song “A Handballer’s Dream” sung to the melody of Fritz Spielmann and Stephan Weiss’s song “Schinkenfleckerln” (a famous Viennese dish). Additionally, the Hakoah organised summer balls and carnival balls where everyone had to appear in disguise. In 1932 the “Dianabad” (an elegant indoor swimming pool) was rented and completely transformed for the carnival festivities. The swimming pool was open the whole night and five jazz bands played there. They acted out a comical “sea battle of the 20th century” and there was a boxing fight. Visitors had to appear in evening dress, costume, pyjamas or beach attire. The fact that Hakoah had its own orchestra shows the importance of music for this sports club. The orchestra was known as the best amateur orchestra in Vienna. It was founded in 1919 and the first conductor manager was the composer Salomon Braslavsky. Rehearsals took place in the Wiener Konzerthaus and the orchestra played mostly, Mendelssohn-Bartholdy, Max Bruch, Joseph Haydn, Felix Salten, Josef Joachim, Anton Rubinstein, Maurice Ravel, Nikolai Rimski-Korsakow and, of course, the famous classics. Some of its members later worked as professional musicians. There was also a Hakoah chamber orchestra and a Hakoah mandolin orchestra.

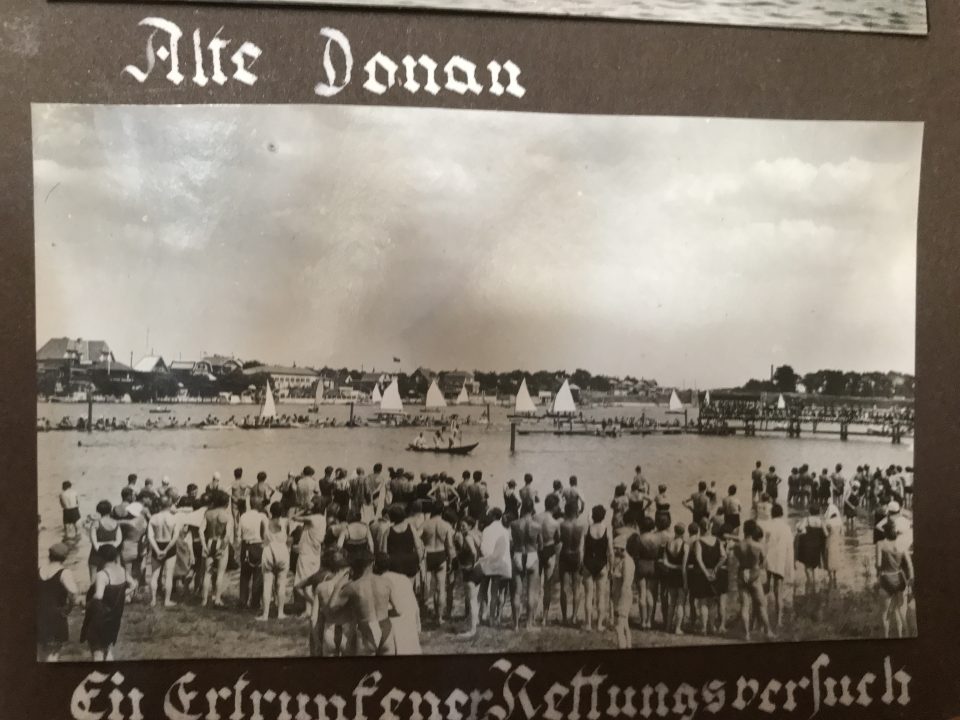

Swimming and rowing on the Danube, Vienna 1932 (Karl Elzholz on the right). From Karl’s photo album, the Old Danube 1931:

Apart from the Viennese footballers, the Vienna girls’ open water swim team was another sports success story of the 1920s and 1930s, many of them Hakoah sports women. They were called the “Danube Maidens” because of their nymph-like natures. Their legendary fame started in 1924, when the fifteen-year-old Hedy Bienenfeld, one of the Hakoah swimmers, dove from the Nußdorf canal gate. Half a million spectators crowded the banks of the Danube for the annual swimming competition “Across Vienna”. Men and women in formal dress lounged on the grass and children played along the river – swimming had become fashionable in Vienna. Next to football it was Vienna’s and Austria’s favourite sport. Vienna boasted a large number of open air swimming pools in the city and up and down the Danube and for the cold season there were numerous indoor swimming pools. The race “Across Vienna” was 7.5 kilometres long and the rivers was cold. The swimmers wore rubber caps and wool suits that hung heavy with water. Small boats patrolled the water and the coaches leaned over the sides to call out encouragement to their swimmers. Swimming into the wind, some swimmers tired and had to give up. At four o’clock in the afternoon Hedy Bienenfeld was the first to cross the finish line with her steady and relaxed breast stroke at the Rotunden bridge. The Hakoah swimmer Fritzy Löwy won the race the next year, 1925, as a freestyler. Hedy, whose stroke was the slower breaststroke, came in second. And Alfred Guth from the Hakoah team won the men’s open water swimming competition. About 400 swimmers participated in the river competition, among them Agi.

Since the end of the 19th century swimming had become a popular sport for a growing part of the population in Vienna. In 1887 the “First Vienna Amateur Swimming Club” was founded, followed by the “Workers’ Swimming Union Vienna” in 1909. Soon many female swimmers joined the clubs and participated in competitions, the most famous of which was the “River Championship” on the Danube with a race of 5 kilometres. Because of the popularity of the competition it was transferred nearer to the city to attract even more spectators. The “Danube Canal” had just been restructured and integrated into the cityscape and therefore offered the ideal venue. In 1912 the first race “Across Vienna” was staged there. The competition started in Nußdorf and ended at today’s Stadion bridge, a length of not quite 10 kilometres. It was organised by Leopold Mayer, one of the best swimmers of Austro-Hungary at the time and five-time champion of the “River Championships” on the Danube. It was cold and the temperature of the water was 11 degrees Celsius, so only 18 participants competed in the race, but 100,000 spectators spurned them on. Franz Schuh won the men’s competition and Else Straßhofer the women’s competition. That was the start of a very successful annual competition on the Danube Canal, which became the centre of Viennese water sports. The last competition during the Austro-Hungarian Empire took place in 1914, when Simon Orlik and Berta Zahourek won. After the war in 1919 the competition was taken up again, but on a shortened track of 7.5 kilometres from Nußdorf to the Rotunden bridge. Now all participants were required to pass a swimming test in advance to avoid the dramatic rescue operations of the past. The race “Across Vienna” had turned into a grand festivity for the Viennese; on average 250,000 people watched the competition on the banks of the Danube Canal. As the temperature of the water was a maximum of 14 degrees Celsius, the swimmers rubbed their bodies in fat to protect themselves against the cold. The champion of 1919 was Fritz Kohn with 47 minutes and 40 seconds. The female champion, Berta Zahourek, crossed the finish line with 49 minutes and 50 seconds. She won the race four times and was the first Austrian sports woman to win an Olympic medal. Fritzy Löwy and Heinrich Goldemund won three times each. Swimming was one of the few social areas in Vienna, where women were treated equally to men. In 1920 the organisation of “Across Vienna” was extended to three different types of sports; rowing and diving were incorporated as additional attractions to swimming. This time already 293 men and 73 women participated in the swimming competition. These were huge events that were reported in the press extensively. Yet from the mid-1920s on more and more spectators moved to the football grounds. In 1927 the race “Across Vienna” saw only 25,000 spectators and in 1931 the number fell to 6,000. This was also due to an increasing anti-Semitic mood in the population and anti-Semitic hostilities against the Jewish swimmers. The nationalist press agitated against Hakoah and the Jewish “Danube Maidens”, Fritzy Löw and Hedy Bienenfeld. The circumstances of the race with nasty political agitation and anti-Semitic attacks against the Jewish swimmers turned so catastrophic that in 1932 the competition was transferred to Lower Austria and the Danube between Dürnstein and Krems. The champions of this race from the sports club Hakoah were unjustly disqualified and some spectators threw stones at the Jewish swimmers. The organisers saw no possibility to continue the competition after this ugly incident. The champion Fritzy Löwy stated later that unfortunately anti-Semitism had influenced sports in Austria long before Hitler’s arrival. The race “Across Vienna”, once an annual sports highlight of Vienna had been turned into a political rally. The nationalistic press rallied that at the time nine out of ten participants at open water swimming competitions in Vienna were of Jewish descent, which exposed them to even more anti-Semitic polemics.

The coach who formed the star team of girl swimmers was Zsigo Wertheimer, who instilled discipline and the desire to excel in the young girls. In 1930 the young and charming model and swimmer, Hedy Bienenfeld, married her coach Zsigo Wertheimer, ten years her senior – a media scoop. Hedy also inspired the writer Friedrich Torberg. She was his inspiration for the character “Lisa” in his famous novel “The Pupil Gerber”. Valentin Rosenfeld ran the Hakoah swimming club from a series of small rooms below a café in Wiesingerstraße 11 in the first district of Vienna. By 1935 a second wave of swimmers had come of age. These included Judith and Hannie Deutsch, Lucie Goldner, Trude Hirschler, Ruth Langer and many more. Wertheimer’s and Rosenfeld’s years of grooming a champion girls’ swim team for Hakoah had paid off. Nineteen swimmers with an average age of 16 sailed form Trieste to Palestine for the second Maccabiah Games in 1935 (a kind of Olympic Games for Jews). The first games had been held in 1932, where the Austrian team – the smallest in the competition – had secured first place in the swimming events. Also in the second Maccabiah Games the Vienna swimmers Fritzy Löwy and Hedy Bienenfeld won a race each and together with two other girls the 400-meter relay. In Austria they excelled at all national competitions and held most Austrian records. Judith Deutsch, Lucie Goldner and Ruth Langer were invited to compete at the Olympic Games in Berlin in 1936. World-wide many called for a boycott to protest against the German Nazi regime and its treatment of “non-Aryans”. Seventeen-year old Judith Deutsch decided to boycott the games and Lucie Goldner and Ruth Langer followed her example. The Austrian sports authorities refused to accept their decision and erased all the three swimmers’ records and issued a lifetime disqualification from swimming competitions in Austria. After outrage in the European sports press, the ban was shortened to two years. For the competitors their boycott was a gift. No one thanked the girls for their personal act of passive resistance, which essentially cut short their swimming careers in 1936. Austria did not bring home any swimming medals from Berlin and for the rest of their lives Langer and Goldner felt sad watching the Olympic Games. In 1995 Otmar Bricks, the president of the Austrian Swimming League, apologised and invited Judith Deutsch to Austria to restore her titles and re-enter her name in the official record book, but Judith Deutsch refused to return to Austria telling them that they would have to come to Israel if they wanted to give her back her titles. The Austrian Ambassador to Israel therefore held a ceremony in Israel and restored all Deutsch’s titles and medals. Ruth Langer received the same invitation in London, but did not want to meet anyone from Austria, so she received the apology by mail. Fritzy Löwy and Hedy Bienenfeld returned to Vienna after the war, but most of the other swimmers settled elsewhere.

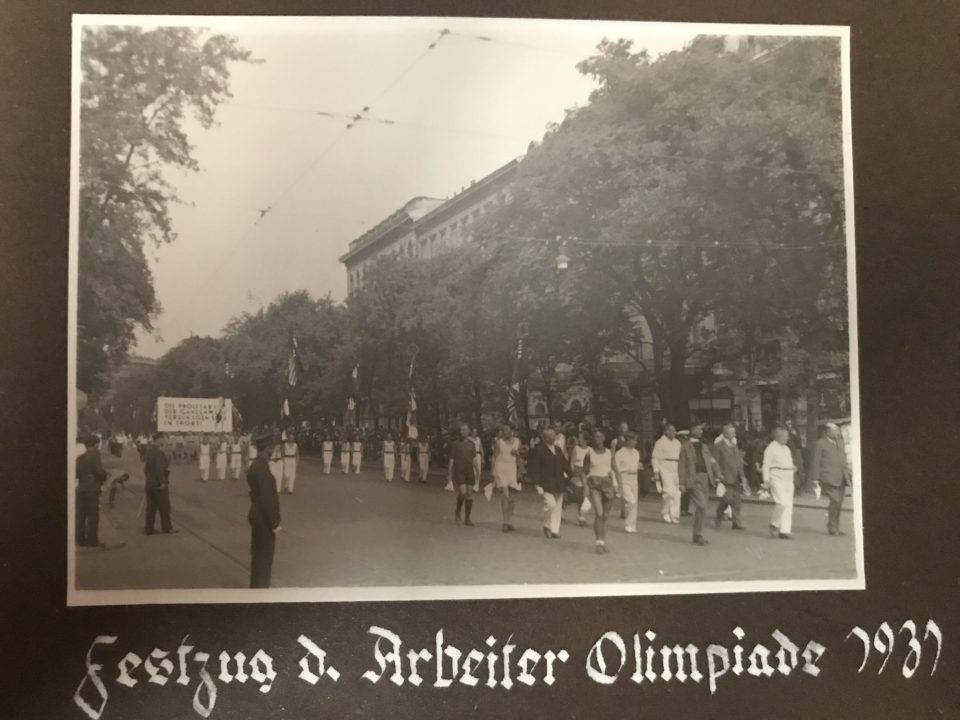

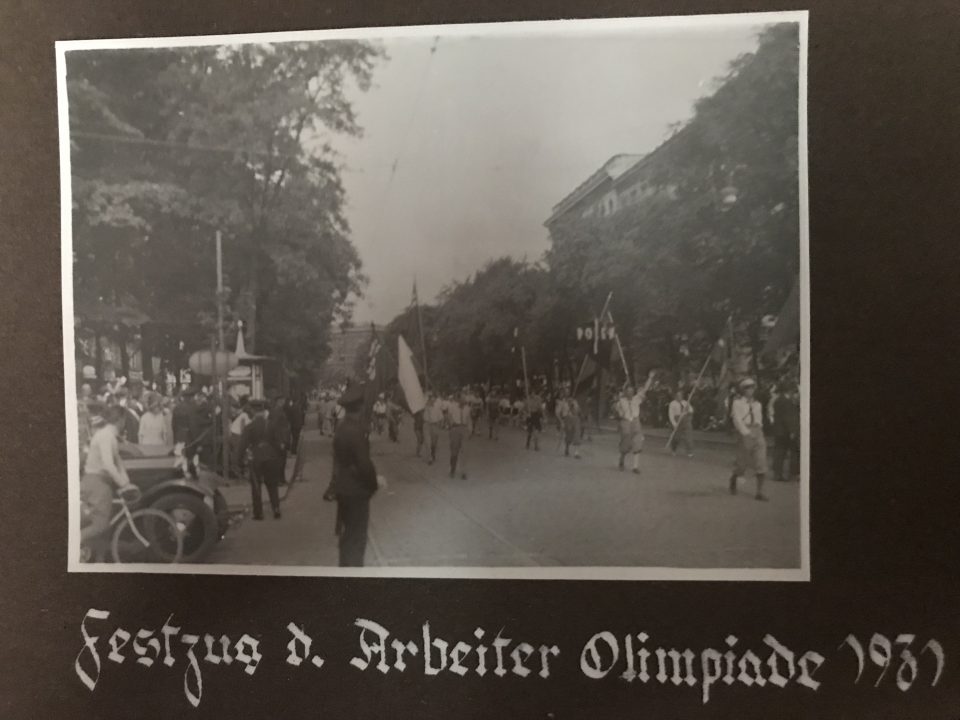

In the summer of 1931 one of the biggest sport events, the Workers’ Olympic Games, took place in Vienna and my great-uncle, Karl Elzholz, took some photos at the opening ceremony on the “Ringstrasse”:

Literature:

Susanne Helene Betz/ Monika Löscher /Pia Schölnberger (ed.), “…mehr als ein Sportverein” 100 Jahre Hakoah Wien 1909-2009, 2009

Österreichischer Fußbalbund (ed.), Geschichte des Fußballsportes in Österreich, 1951

F.R.Billisich, 80 violette Jahre. Die Wiener Austria im Spiegel der Zeit, 1991

Superjuden. Jüdische Identität im Fußballstadion, Jüdisches Museum Wien, 2023