“Textile Quarter” in the 1st district of Vienna near the Danube Canal

Textile trading on “Naschmarkt”. Left: former textile wholesale and retail trading of Josef and Henriette Singer & partner at Rechte Wienzeile 1b (Bärenmühlendurchgang) in the 4th district of Vienna, Naschmarkt

Textile wholesale and retail business “Singer & Partner”

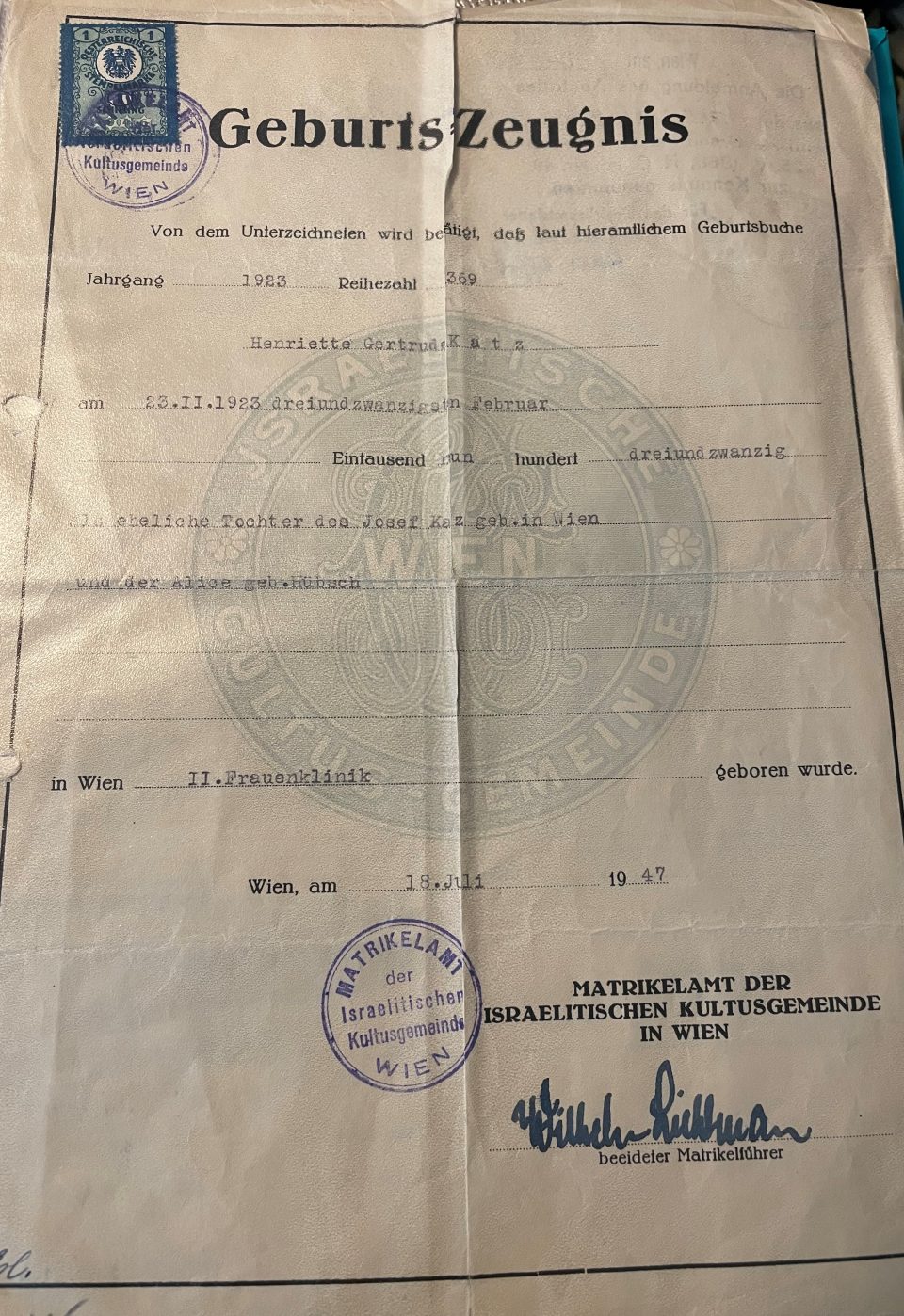

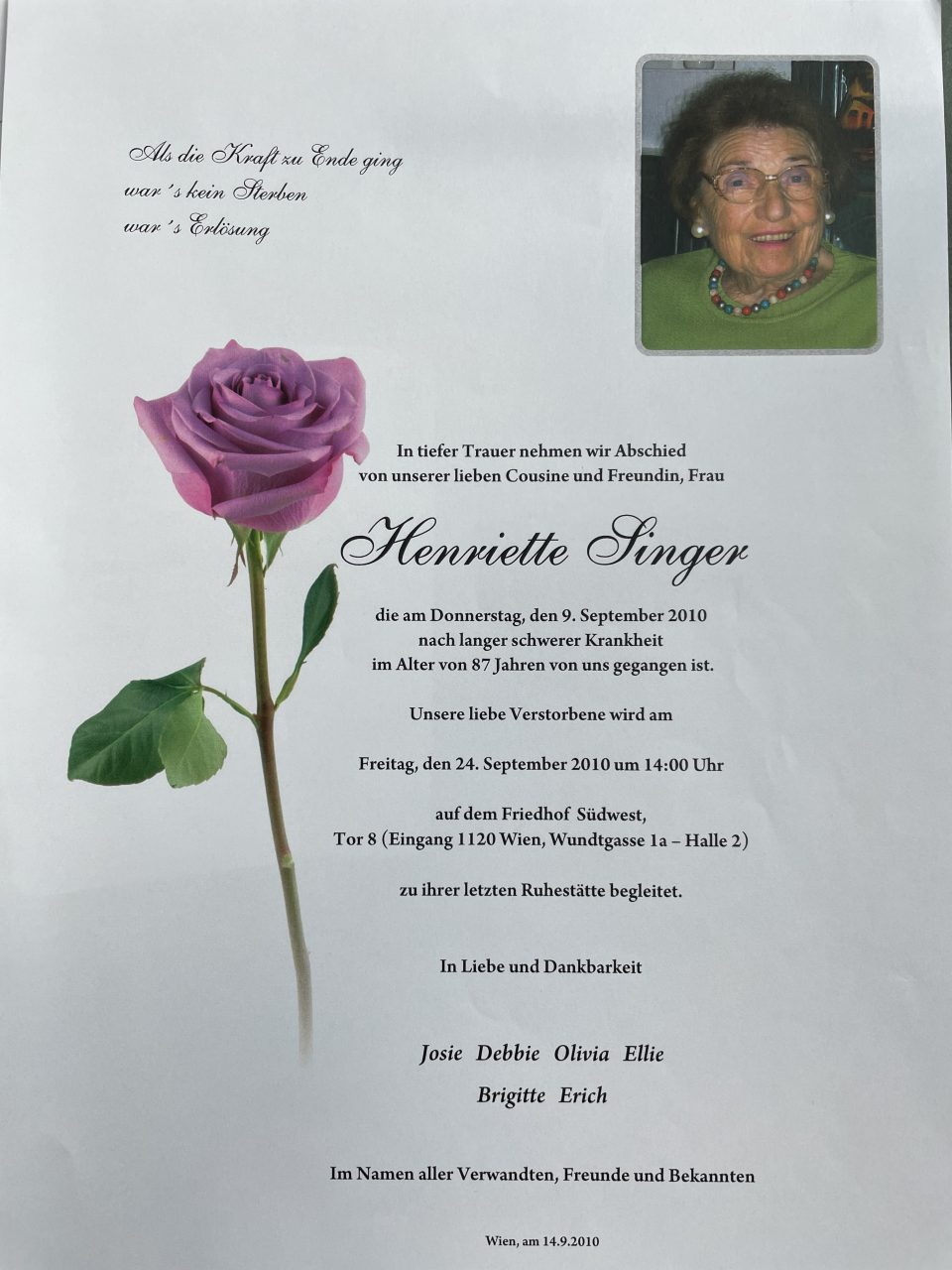

A typical example of a small enterprise in textile trading of Jewish-born Viennese after World War II is the partnership of Josef and Henny Singer at Rechte Wienzeile 1b (Bärenmühlendurchgang) at the “Naschmarkt”. Henriette (Henny) Singer, née Katz, born in 1923, was my aunt. She had survived the Holocaust in Palestine,

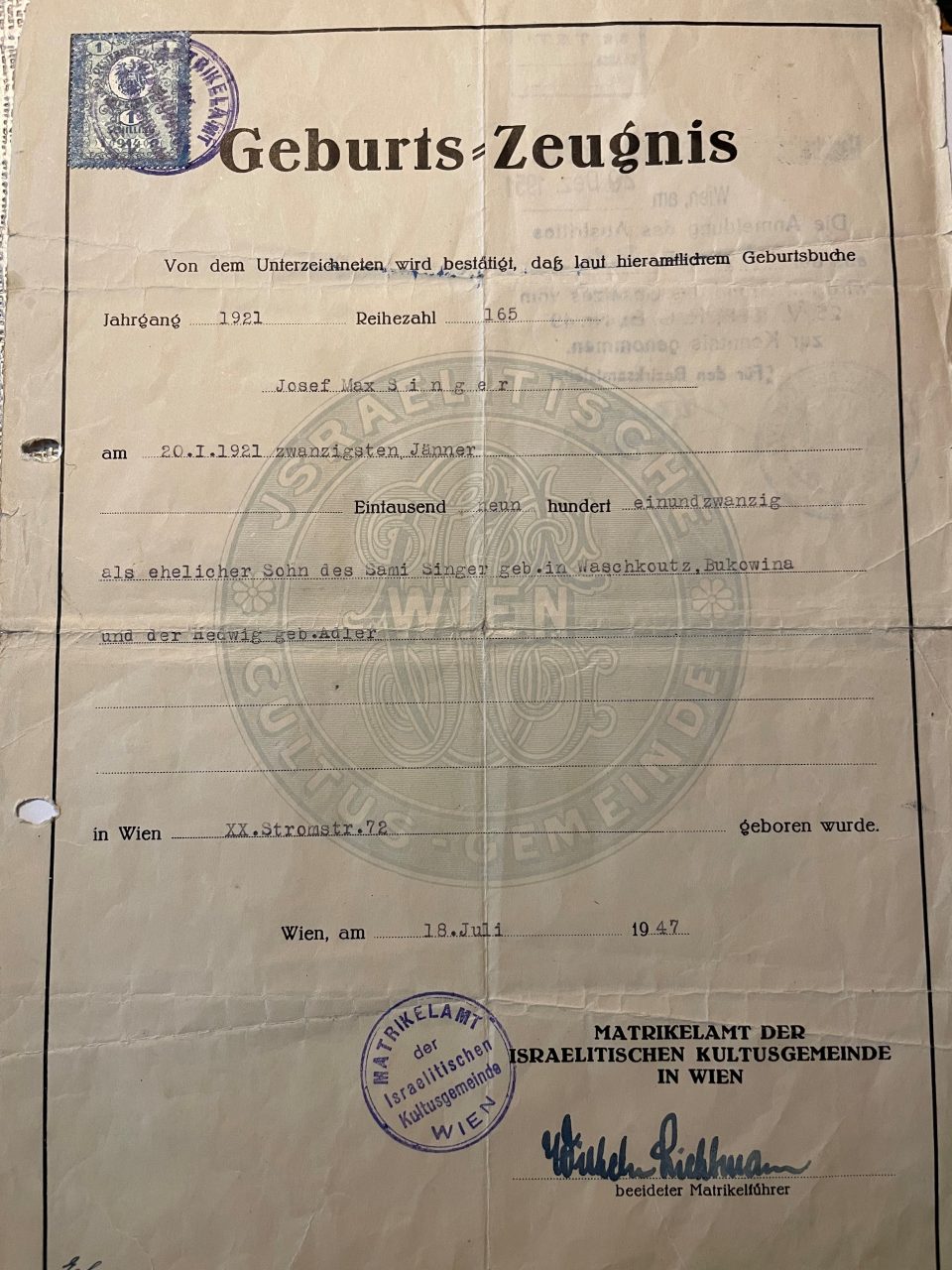

where she met her future husband, Josef (Pepi) Singer, born in 1921, another Austrian refugee. Both were born in Vienna and had to flee the deadly persecution of the Nazis as youngsters; they were both Jewish-born, but from assimilated families, agnostics and committed Austrians. Soon after the end of World War II they returned to Austria, where Pepi worked as a cutter at a tailor’s shop. Henny had trained as a dressmaker in Tel Aviv and soon after her return and before her marriage she worked in the “Textile Quarter” in Vienna at the company “Altmann & Co” on Salzgries 16 in the 1st district of Vienna as a salesgirl. Pepi later continued the family tradition of textile trading by founding his own small wholesale and retail business with a partner. His father, Schmaje (Sami) Singer had been born in Waschkoutz in the Austro-Hungarian region of Bukovina (in 1918 Waschkiwzi became part of Romania after the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, then was incorporated into the Soviet Union and since 1991 it has been a town in Ukraine). Sami moved to Vienna, where he married Hedwig Adler, born in Pohrlitz / Pohorelice in southern Moravia, also in the Austro-Hungarian Empire (after World War I it became a region in Czechoslovakia, today Czechia). In Vienna he worked as a “Modewarenhändler” (a “trader of fashion”) before the Nazi takeover in 1938. Sami Singer died in exile in Jerusalem and Pepi returned to Vienna with his mother Hedwig. They all three, Pepi, Henny and Hedwig, lived together with others who had just returned from exile in a big flat in Favoritenstrasse 40 in the 4th district of Vienna. Henny and Pepi married in June 1949 in Vienna and started a textile trading business with a partner.

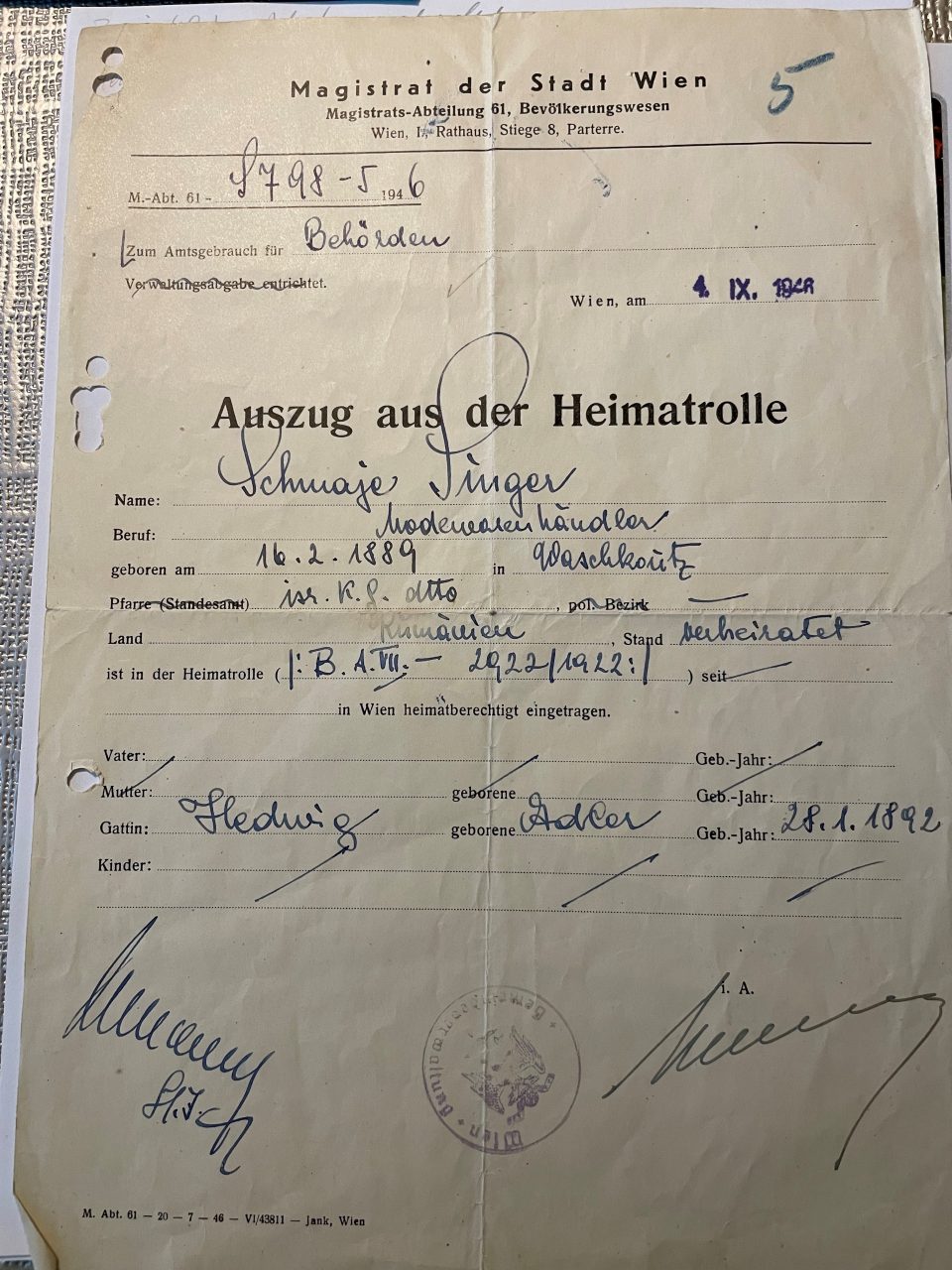

Left: Sami Singer’s certificate of citizenship stating his profession as “fashion trader” in Vienna.

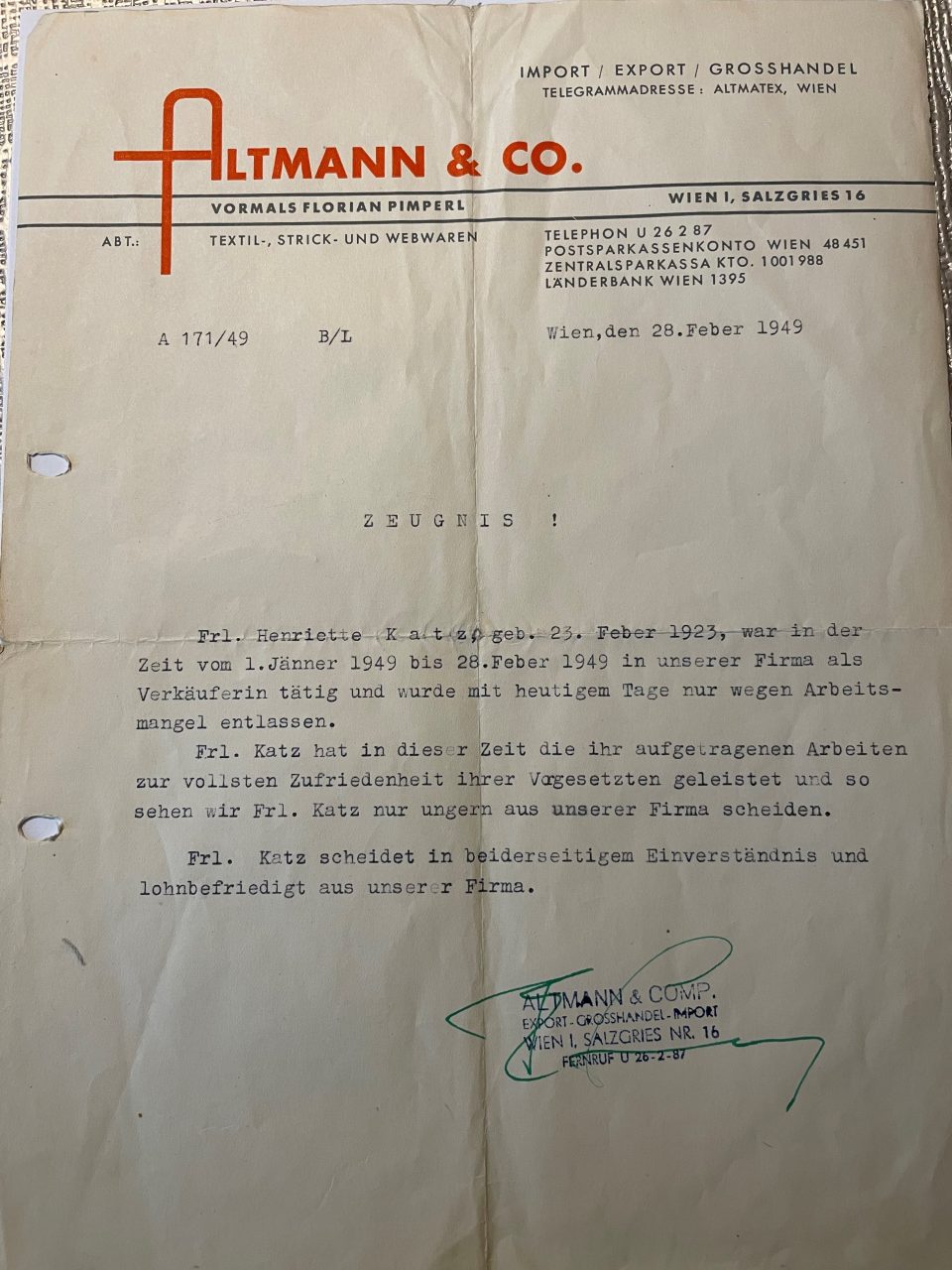

Right: Henny’s employment in the Viennese “Textile Quarter” at “Altmann & Co” in 1949

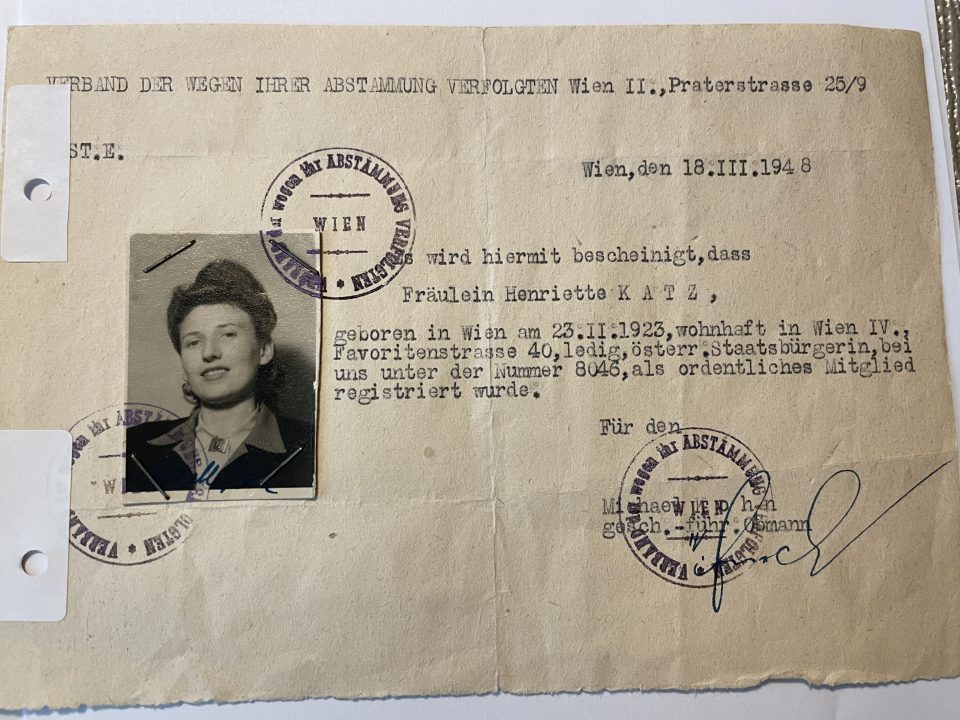

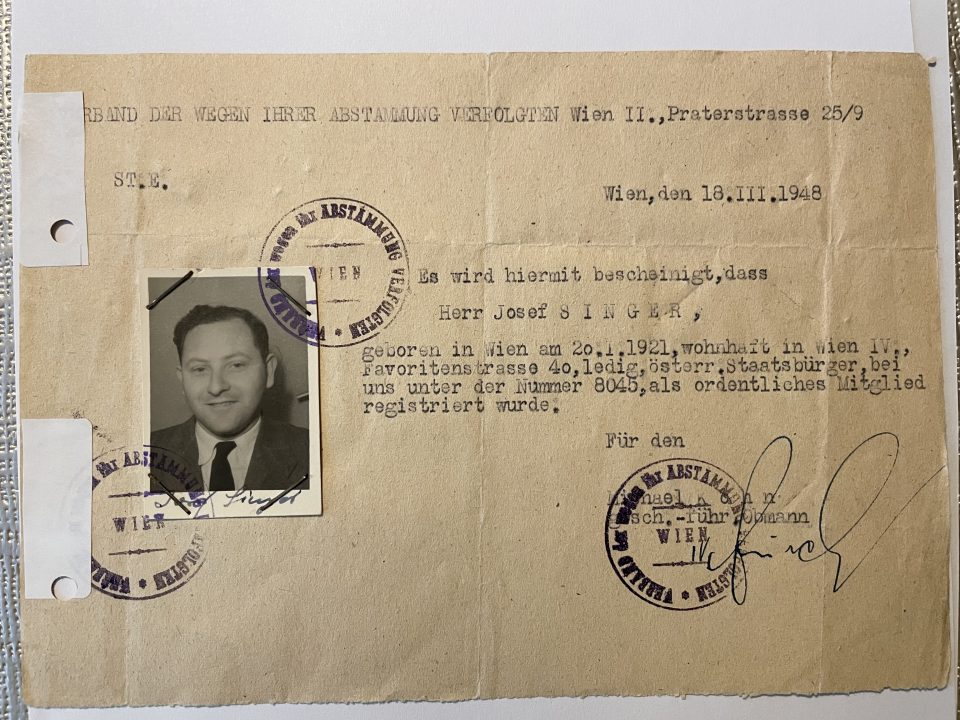

Back in Vienna, both Henny and Pepi became members of the” Association of those Persecuted due to their Origin” in 18 March 1948, see the two documents below:

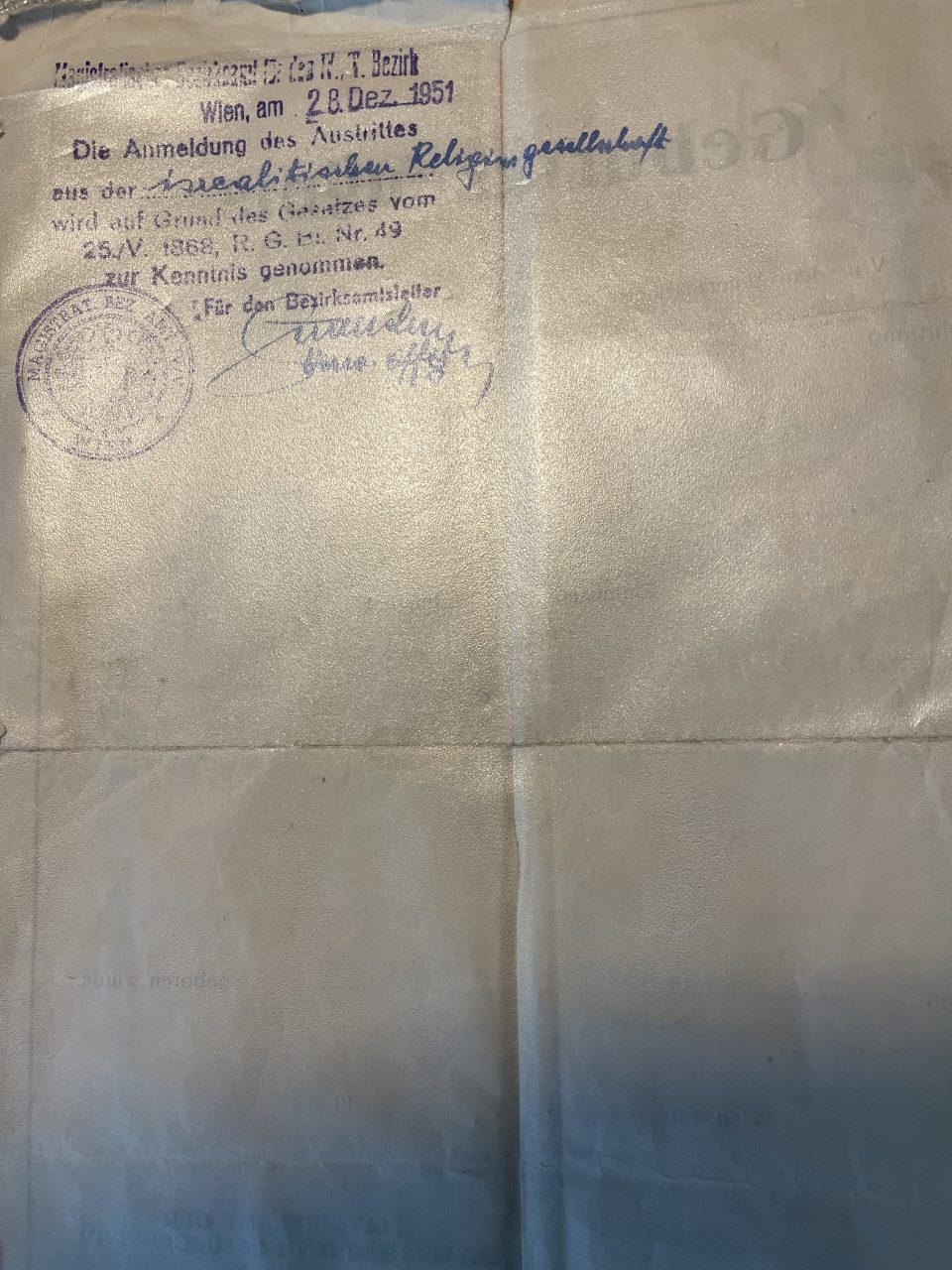

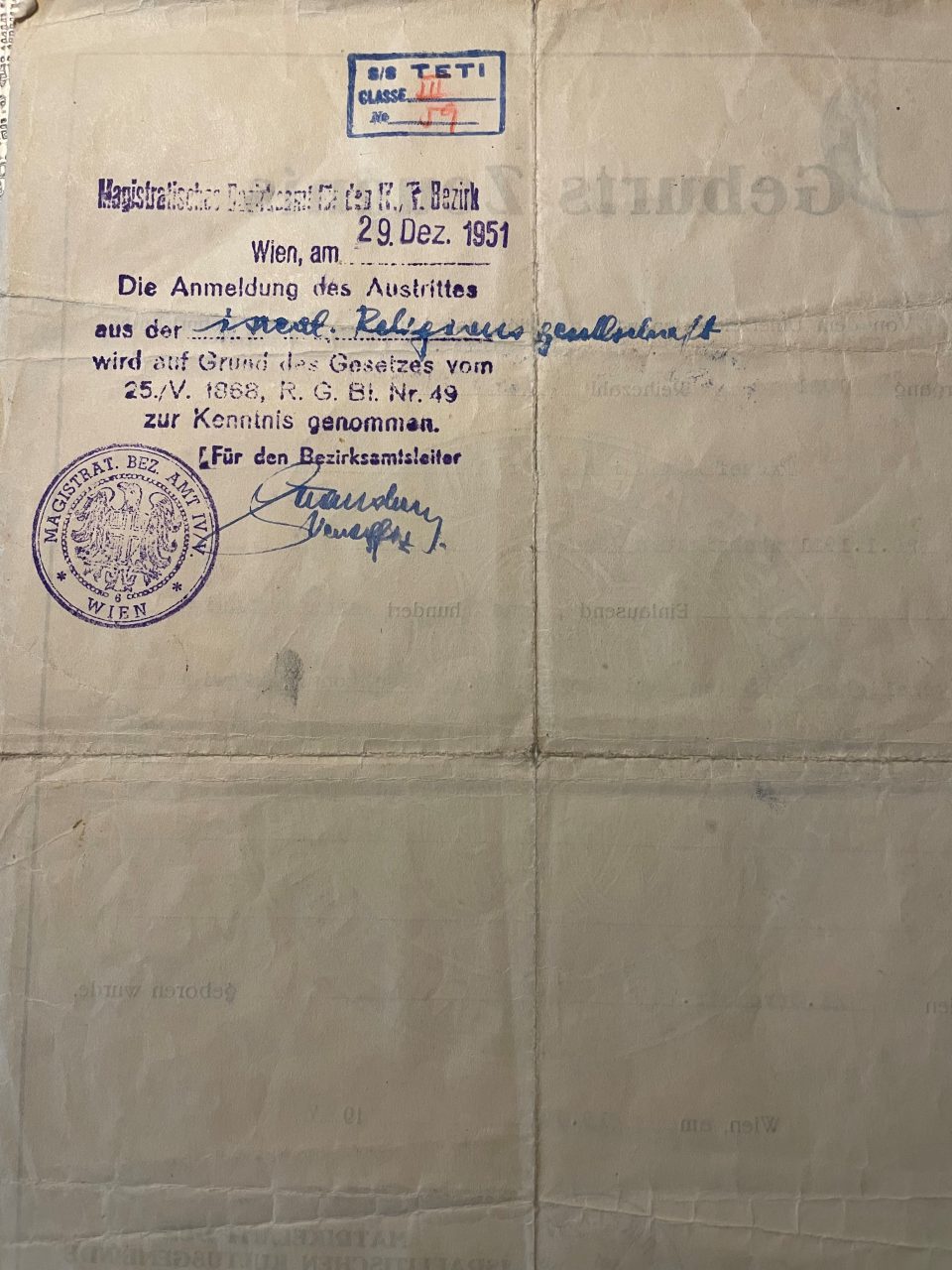

As agnostics they both officially left the Jewish Community (“Israelitische Religionsgemeinschaft – Cultus Gemeinde”) in December 1951:

Henny’s birth certificate with the respective remark on the back about quitting the Jewish Religious Community

Pepi’s birth certificate with the respective remark on the back about quitting the Jewish Religious Community

Together with another couple Pepi and Henny rented a wooden cottage on stilts in Greifenstein at the Danube, near Vienna, and spent their weekends and summer holidays there. Pepi loved his small motorboat and took family and friends on short cruises on the Danube in the 1950s and 1960s:

Left: Pepi at the steering wheel, Norbert Katz, Henny’s favourite uncle and a former Viennese footballer on visit from England, on the left and her uncle Karl Elzholz a mechanic at the Vienna Tramways in the middle – both of them my great-uncles

Right: from left to right: my grandmother Lola, Pepi, Norbert and Karl

Pepi and Henny loved to entertain family and friends

On two different visits of the Katz family from England to Vienna. Left: Pepi with Norbert and his wife, my great-aunt Agi; right: Pepi and Henny in the middle, Norbert and Agi on the right

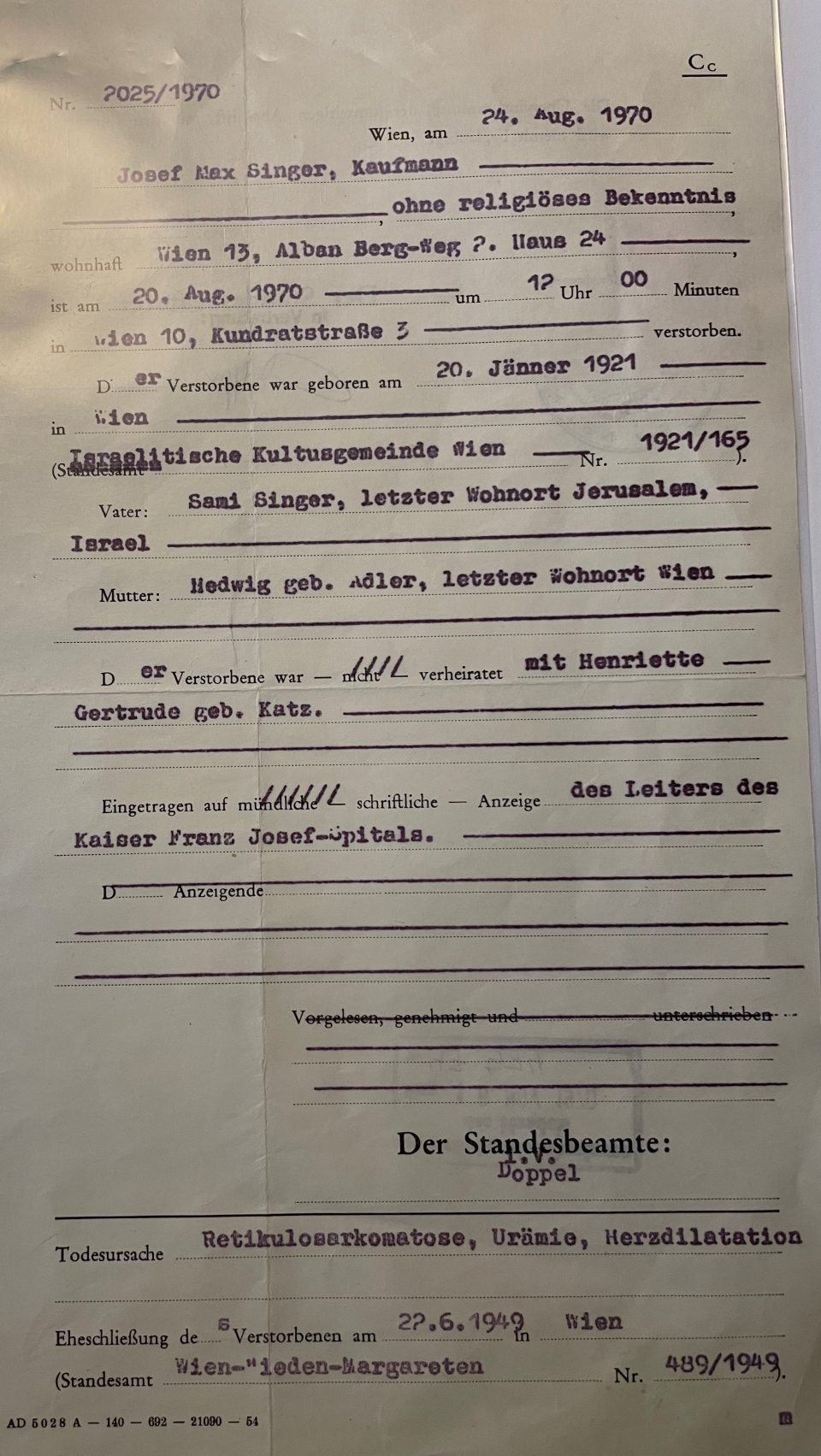

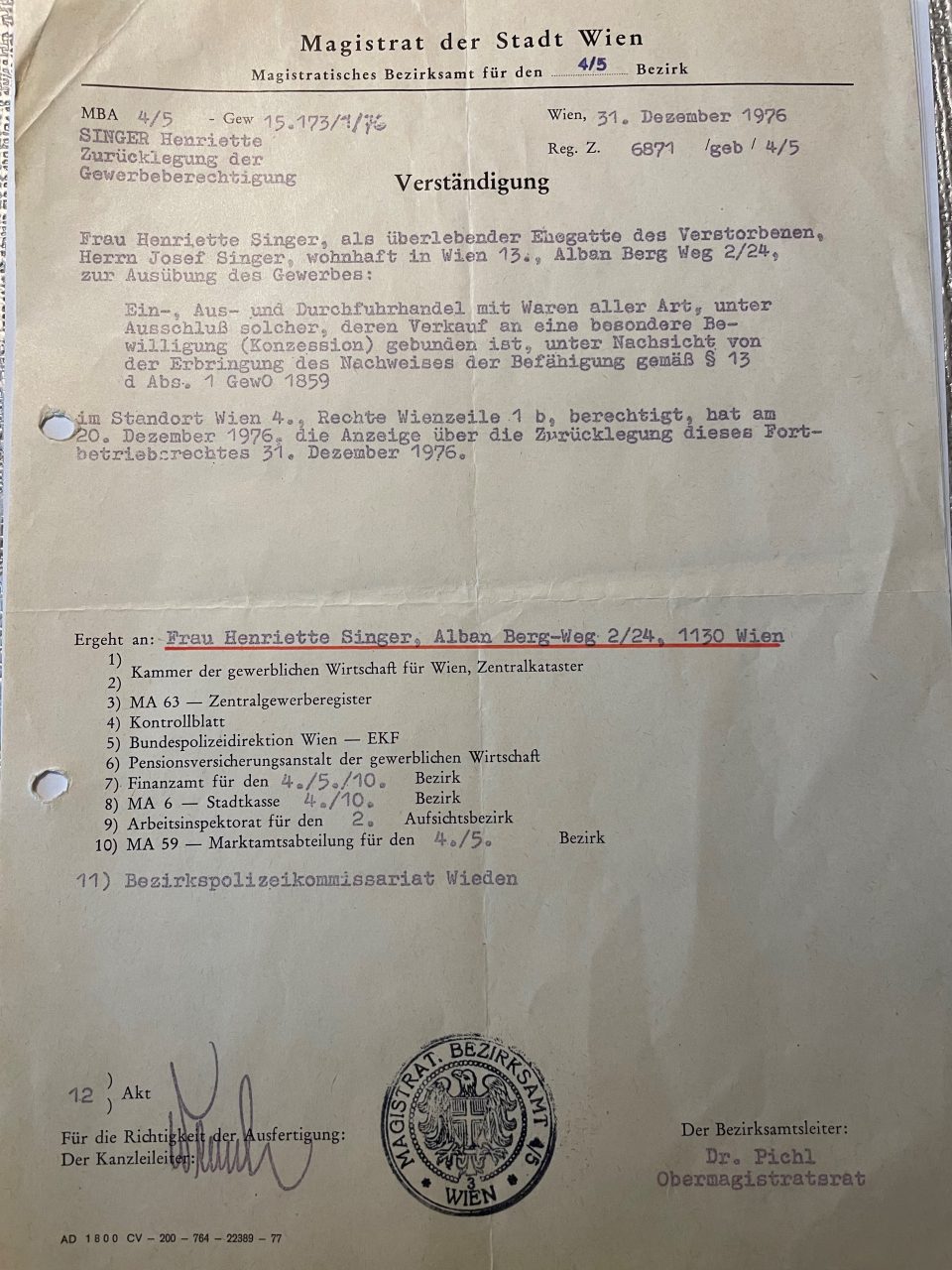

Pepi died of cancer in 1970 and Henny continued the textile trading business until 1976, when she handed back the business license for trading in textiles and took on various secretarial jobs as an employee until her retirement:

Left: death certificate of Josef Singer, right: Henriette Singer returning her business license

The entrance to the Singer’s textile wholesale and retail shop, Rechte Wienzeile, today

Henny with my great-aunt Käthe Elzholz, the wife of Karl, on the left and with my grandmother Lola on the right

Left: Henny with Käthe and with Henny’s new partner Richard Brauneis, a tailor. Right: Henny with Käthe

Henny died in 2010 and is buried at the “Südwest Friedhof” together with “her two men”, Pepi and Richard

Post-World War II trading at the “Textile Quarter”

After the Second World War Vienna was totally destroyed and the economy was on its knees. Antisemitic persecution and the Holocaust had wiped out the Jewish minority and the few who had survived the murderous Nazi regime of Adolf Hitler in exile were not welcome in their native country. Austria quickly styled itself as the first victim of Hitler and restitution and restoration were hindered by the 2nd Austrian Republic’s administration and judicial system, where ever possible. Applications for restitution were complicated and long-winded and involved great financial losses and concessions on the side of the victims of illegal NS expropriation. What’s more, the largest part of the Viennese Jewish population had not been well-to-do before the war. They had been workers, traders, or employees in different sectors of the economy and therefore had no rights to claim compensation at that time. Only few returned, such as Henny and Pepi, and tried to make a living again in Vienna, the city that had robbed them of their youth, family and belongings; had chased them away and murdered their friends and relatives. Immediately after the war a few of those survivors set up business again in the “traditional Jewish” wholesale and retail textile trade, many of them in the former “Textile Quarter” (Textilviertel) near the Danube Canal (Franz-Josefs-Kai) around “Rudolfsplatz”, others in the vicinity of “Mariahilferstrasse” and “Naschmarkt”, traditional trading quarters, too. The old “Textile Quarter” experienced a true revival in the 1950s, when released NS concentration camp (KZ) survivors from Poland, Hungary, Romania, and Czechoslovakia ended up in Vienna after the expulsion from their former home countries, now under Soviet rule. The “Textile Quarter” was turned into their economic, social, and cultural home and acted as place of revival of the tiny Jewish community. For the Viennese the “Textile Quarter” represented the opportunity to pick up a bargain, when looking for any type of textiles from bedlinen to towels, shirts, coats, workwear and even shoes and accessories. What they could not find in one little shop, they chased down in the neighbouring one.

While the elegant department stores in the city centre, most of them founded by Jewish entrepreneurs at the end of the 19th century, did not survive the Nazi period of persecution and expropriation, the “Textile Quarter” experienced a revival in the 1950s. But the area and the shops were anything but glamorous. They were tiny, crowded and crammed with cheap textile wares. The window displays were not designed in any way, but tried to show everything that was on offer. Yet the shops were social meeting points and the customers appreciated the chats with the proprietors and the children loved the sweets they received from the shop owners. There was the shop of “Mr. Doft” or the “Zalcotex” business, which had been set up by the partners Schmidt and Zahler, both originally from Stanislav in the Austro-Hungarian region of Galicia, and was well-known for its wholesale and retail trading in shirts made of nylon and its dressing gowns and pyjamas. Another famous shop in the quarter was “Wachtel & Co”. Mr. Wachtel came from Lemberg (Lviv) in Galicia, too, and had survived several NS concentration camps. After his liberation he was looking for work in Vienna, like many other former Jewish concentration camp prisoners.

The textile business “Wachtel & Co” near Rudolfsplatz in the 1st district of Vienna

Rudolfsplatz today and the official representation of the textile industry in Austria

The Austrian government did not welcome the founders of these small businesses, on the contrary. The antisemitism that was already prevalent in Vienna before the Nazi period was as widespread and persistent as ever. The only difference was that it simmered under the surface and was not openly expressed for fear of repressions from the Allied armies, the Soviets, the Americans, the British and the French, which administered Vienna and Austria until 1955. That’s why non-Jewish Viennese often “lent” their business licenses to the Jewish owners and rented the business locations in their names for the Jewish traders for a fee. Due to the success of these small enterprises the businesses soon expanded and rented neighbouring premises. Mr. Wachtel started with workwear and later added shirts, socks, pyjamas, children’s wear, underwear, and towels. He was well-liked as a competent retailer in his shop and he furthermore acted as a wholesaler and delivered his textiles to small shops in the country. 60 per cent of his customers were regulars, who also came for a chat. Before Christmas the customers were queuing up in front of the door of his small shop and consequently, Mr. Wachtel was fined by the police for obstructing the pavement in front of his shop.

The founders of “Haritex”, Mr. and Ms. Edelman, came from Romania and they specialised in shawls, which they imported from Italy and Japan, and fashionable bleached jeans from Padova. As wholesalers they delivered their wares to market stalls all over Austria. Another famous shop in Vorlaufstrasse was “Silesia”, the only business that had already existed before the war in the “Textile Quarter”. One of the brothers Geiringer was murdered in Dachau and one could find refuge in England. When Leo Geiringer returned to Vienna, his former shop was in ruins, commercially and physically, and the reconstruction turned out to be very difficult under the conditions of post-war Austria. His customers were mostly dressmakers and tailors, who bought fabric and sewing accessories. In the first difficult years after the war “Silesia” entered into barter agreements with the tailors and dressmakers: they brought wool from farmers to the shop in exchange for fabrics and sewing accessories. Apart from professional tailors, who were under pressure because the customers moved from made-to-measure clothing towards off-the-peg clothing, “Silesia” increasingly targeted private amateur dressmakers. Twice a year the tailors were supplied with so-called “collections” or “bundles” of samples of what was on offer in that season. Every season 6,000 to 7,000 such sample booklets were glued together by women on the upper floor of the shop. When in the 1970s Jews facing repression emigrated from the Soviet Union to Israel via Vienna, several of them remained in the city and as the women had no qualifications and did not know German, Mr. Wachtel offered them these jobs to make a living.

“Haritex” and “Landhaus” shops in the “Textile Quarter” today

“Heinrich Klos” sewing accessories

Since the 1980s and 1990s more and more of these enterprises closed, when the proprietors retired and their children, who had studied, took on other jobs. Another trigger for the economic downturn of the “Textile Quarter” after three decades of economic boom was the foundation of a fashion centre in the 11th district of Vienna, in St. Marx, in 1977/78 by Leopold Böhm, the owner of the textile business “Schöps”. He had been able to flee Vienna in time and served in the British army. After his return he built up a successful Austrian fashion chain store together with his uncle Richard Schöps, offering affordable textiles. The fashion centre in St. Marx offered more space and parking facilities, which attracted customers not just from Vienna, but from the rural regions in the vicinity, too. Some of the wholesalers of the “Textile Quarter” moved there, but did not survive the transfer for long, because they suffered from the location on the periphery and they lacked the retail business revenue of the “Textile Quarter”. “ADA STEIN Textilimport”, on the contrary, profited from the transfer. Erich Stein had fled from the Nazis with his family to Italy and had survived in hiding in Naples. He married Ada Bardi, an Italian, and in the 1960s he started importing textiles from Italy to Austria in his private car. He then opened a bigger shop in Marc-Aurelstrasse in the “Textile Quarter” and launched the brand “MarcAurel l4”. His Viennese business bought fabrics near Lake Como and had them sewn in Toscana, near Florence. His slogan was “Vienna-Florence-Paris”: Vienna – the headquarter, Florence – the production site, Paris – the inspiration for the designs (where the designs were spied). A successful line of children’s clothes, which he named after his wife “Bardi”, was launched as well. Every Monday the new clothes were delivered in trucks to Marc- Aurelstrasse, where the customers were already waiting, sorting through the card board boxes, filled with the “latest fashion from Florence and Paris”. Erich Stein moved to the fashion centre in St. Marx and together with his wife organised fashion shows there, offering free of charge drinks and snacks to their customers. As his business, now called “ADA STEIN Textilimport”, was located directly next to the entrance, it soon became a popular meeting point. When in 1995 Austria joined the European Union, imports from Italy were no longer profitable and the business shut down a year later.

Ben Segenreich, a Viennese journalist, was raised in the “Textile Quarter”, after his parents had fled from persecution in Communist Romania in 1947. His father Leon Segenreich started out producing rubber soles for the Austrian shoe production, “Segenreich Gummiwaren”, together with his father-in-law. When only Italian shoes were in high demand, he had to look for another source of income and as he was already elderly, he decided to take over a small textile wholesaler at Rudolfsplatz in the “Textile Quarter”. At that time the area between Wipplingerstrasse – Schottenring – Franz-Josefs-Kai – Rotenturmstrasse was called “Salzgries” or “Schmattesviertel” (from Polis szmata = rags) and not yet “Textile Quarter”. Most of Ben’s childhood friends and playmates were children of Jewish textile traders there. The advantage of this small community was that the Segenreichs, who had no knowledge of textile trading, could get advice from their neighbours and friends in the quarter. These traders had arrived in Vienna from Romania, Poland, Hungary, or Czechoslovakia 20 or 25 years before with no expertise, but had meanwhile acquired the necessary skills. This generation’s educational career had been interrupted or prevented by persecution and war, but they quickly identified a business opportunity or a market niche and took it up: in this case the demand for simple, good-quality, and affordable clothing in the post-war years. These people had to make a living from scratch without any assets and they spotted the chance. Rumour has it that Guido Sternberg from Czernowitz was the first one to restart business in this quarter of the bomb-shelled city. He had no money at all, but improvised an open-air market stall by putting a wooden plank across to bricks selling rags he found in the rubble. This was said to be the nucleus of the revived Jewish textile trade near the Danube Canal. Mr. Sternberg soon rented a shop in the vicinity as the demand for clothing was high.

The main problem for all traders after 1945 was the procurement of sellable textile wares in Vienna. One textile trader for example, Paul Schächter, had to satisfy a great demand for male socks, but the Lower-Austrian producer of socks and tights, “Ergee”, lacked rubber bands and could not produce. Flexible and creative as he was, Mr. Schächter procured the rubber bands in Czechoslovakia himself via an ingenious tri-lateral barter trade between Austria, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia, where rubber bands, shoe laces and goose fat were bartered. He was the first to import from Hongkong and South Korea, too. Mr. Horsky already had long-distance business connections and bought “shag coats”, called “Zottelmäntel”, in Afghanistan in the post-war years. Some of the traders set up production sites in the quarter with up to 30 employees. Special textile products were much sought after in certain years and they were surely to be had at an affordable price at the Jewish textile traders’, such as “shag coats” or “Nato jackets”. The standard product range was socks, underwear, pyjamas, dressing gowns, bed linen, blankets, towels, and handkerchiefs. Soon terry-cloth dressing gowns and tracksuits were the latest fashion and in high demand, but colourful flannel bed linen, warm long grey flannel underpants for men or work clothes, such as blue stiff overalls, were continuous bestsellers. Some business women tried their best with shop window display, but generally the shop windows showed as much as possible and the customers sorted through just arrived boxes of textile wares in the crammed shops to find what they were looking for. As most of the shops were retailers and wholesalers at the same time, the prices were flexibly “adapted” to the individual customer. An old Jewish joke illustrates this business practice: “Good day, Mr. Levi, how much are your salt herrings?”, “10 zloty a kilo”, “That’s a shame! At Kohn’s nearby they are 7 zloty!”, “Then buy them at Kohn’s!”, “At Kohn’s the salt herrings are sold out!”, “When they are sold out in my shop, they will only cost 7 zloty, too!” Yet the prices were always moderate in the “Textile Quarter”, even if the business practices were less than transparent. It was heard through the grapevine that once, when a tax inspector arrived at one of the shops and asked to see the account books, he was told that there were none. The shop owner provided a simple explanation for the absence of account books: “They are generally overvalued as they did not stand the test”.

In fact, the retailers who bought from Jewish textile wholesalers, were mostly small businesses, too, for example, general stores in the country, market traders or door-to-door sellers, mostly in rural areas. These traders, wholesalers as well as retailers, depended on each other, for example if the retailers wanted to offer their customers the prestigious brand “Huber”, which was produced in Vorarlberg, they could acquire the wares more cheaply at the “Textile Quarter” than at the production site, the factory “Huber”, because the wholesalers were on good terms with the producers in Vorarlberg. Roma and Sinti market traders regularly bought from the Jewish wholesalers and many of them were regular customers, who were treated with a lot of respect. Around Christmas business was so brisk that the shop owners and employees nearly broke down under the burden of Christmas season shoppers. Many Viennese bought practical and cheap Christmas presents for the whole family there, where they were also nicely wrapped by the personnel. At important Jewish holidays the area was more or less deserted, but regular customers knew, when Jewish religious holidays were on the calendar and they covered their demand before. All the traders in the quarter were competitors as well as colleagues and friends. They helped each other out with money and wares, whereby most business transactions were sealed by handshake. Towards the end of a working day some of the shops turned into discussion forums and chat rooms of regulars, passers-by, and other shops keepers. Business was becoming slack in the late 1960s and in the 1970s; customers could afford more expensive clothing; their tastes had changed and the sons and daughters of the post-war traders moved to academic professions. That’s why most of the businesses closed and today only some mementos of the post-war boom-time are visible.

Trading around “Naschmarkt”

Little known are the small Jewish textile retailers and wholesalers today, which cropped up around some of the Viennese markets, such as “Naschmarkt” and “Brunnenmarkt”, after World War II, several of which have now been replaced by small Muslim entrepreneurs from Turkey or Syria for example. Pepi and Henny Singer’s business was on “Naschmarkt”, where even today some such shops have survived:

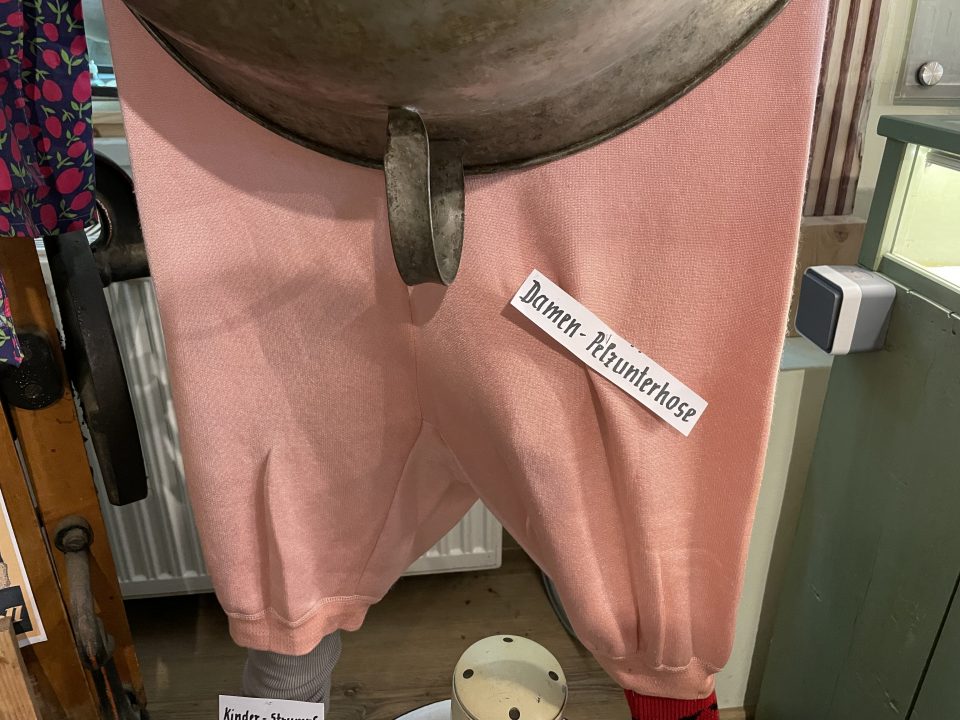

Pepi Singer had an acute business mind, too. Once he bought a huge consignment of warm long female knickers in pink at a bargain and Henny protested vehemently, because she could not see who they should sell this ugly underwear to. But alas, a very harsh winter followed and Pepi was able to get rid of all these warm female knickers within a very short time, selling them to the freezing females working at the market stalls at “Naschmarkt”.

The “famous” warm pink female knickers, called “Pelzunterhose” (fur knickers), a one-time success story of “Singer & partner”

The area, the “Wienzeile, Left and Right”, had long been an important route to the south from the city centre of Vienna. The name “Naschmarkt” is derived from the old name “Aschenmarkt”, probably due to a nearby ash and garbage deposit or an old name for a wooden milk bucket, “Asch”. Later the name was transformed into “Naschmarkt” because lots of sweet delicacies were offered on this market, where people could “naschen” (nibble sweets). The new market, which still exists today and is very popular, was built after the river Wien had been vaulted. From 1902 on three rows of market pavilions were erected and the building of the market office formed the end of this market boulevard, which was partly covered. The “Bärenmühle” (bear mill) was situated near the other end of the market, close to the city centre, but no milling activities had taken place there even before the vaulting of the river Wien. Nevertheless, the old name was transferred to a building of 1937/38, where Pepi Singer had his small textile depot on the ground floor. In the 18th century a bear from the Vienna woods had supposedly made its way into the city to this mill, but at that time a bear is only documented in the western quarter of Vienna, Hütteldorf. Yet Viennese urban legend moved the story of the bear and rescue of the miller by his menial to 1683, the second siege of Vienna by the Osman Turks and to the “Naschmarkt”.

Trading around “Brunnenmarkt”

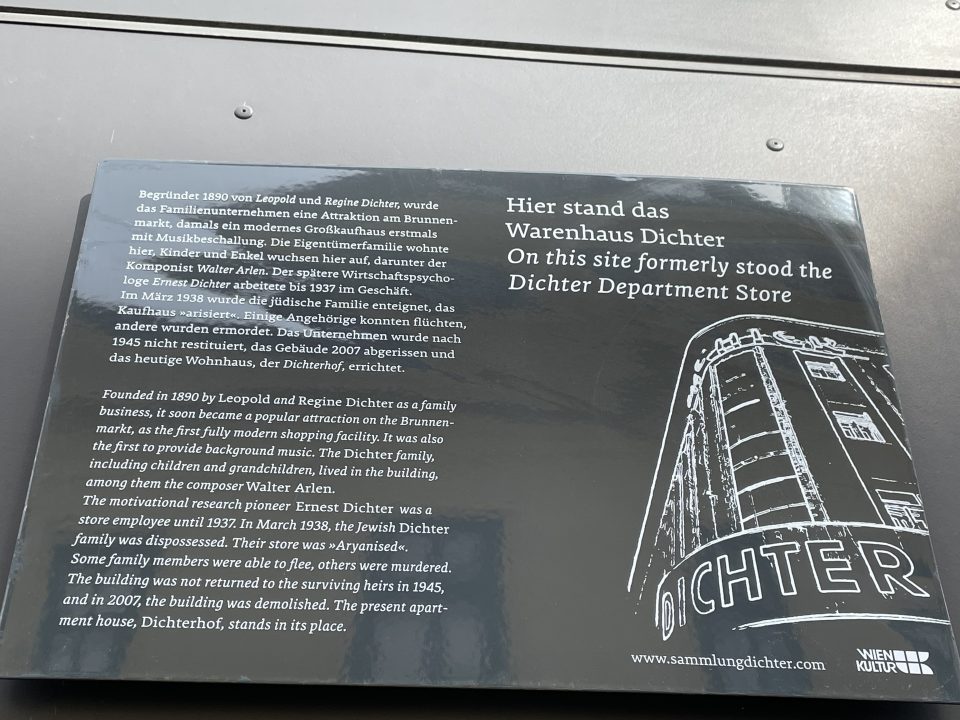

Around “Brunnenmarkt” there are still some small textile traders and tailors, now Muslim business men. Yet before World war II a well-known Jewish department store for the “little people” was situated there, in Brunnengasse 40, the “Kaufhaus Dichter”, now a block of flats. This suburban department store had been founded in 1890 by Leopold Dichter in Brunnengasse in close vicinity of the popular market. It offered a wide range of goods for daily needs and profited from regular customers and the passers-by of the market. The innovative marketing methods of Leopold Dichter attracted its clientele with popular “Schlager music” via loudspeakers and attractive window displays and a shopping passage. Immediately after the “Anschluss” in March 1938 (when Austria became part of Hitler’s “Third Reich”), the Dichter family was dispossessed and the “Aryaniser” Edmund Topolansky, a banker who had already served the Austro-Fascist regime and now served the Nazis, took over the department store. Most of the staff immediately turned against the Jewish owners and a part of the family Dichter could flee to England and New York, the other part was murdered in NS concentration camps. Although the family asked for restitution, the department store was not returned to them after the war, but sold to another “Aryaniser”, Oskar Seidenglanz who had taken over another department store in the periphery of Vienna, in Brigittenau, after the expropriation of Osias Schaja Sass. When Oskar Seidenglanz bought the former “Dichter Warenhaus”, he called it “Osei” after the one in Brigittenau, which had been restituted to its former owners.

Former “Kaufhaus Dichter”, Brunnengasse 40

Muslim textile and shoe traders and tailors at “Brunnenmarkt” today

Trading on “Mariahilferstrasse”

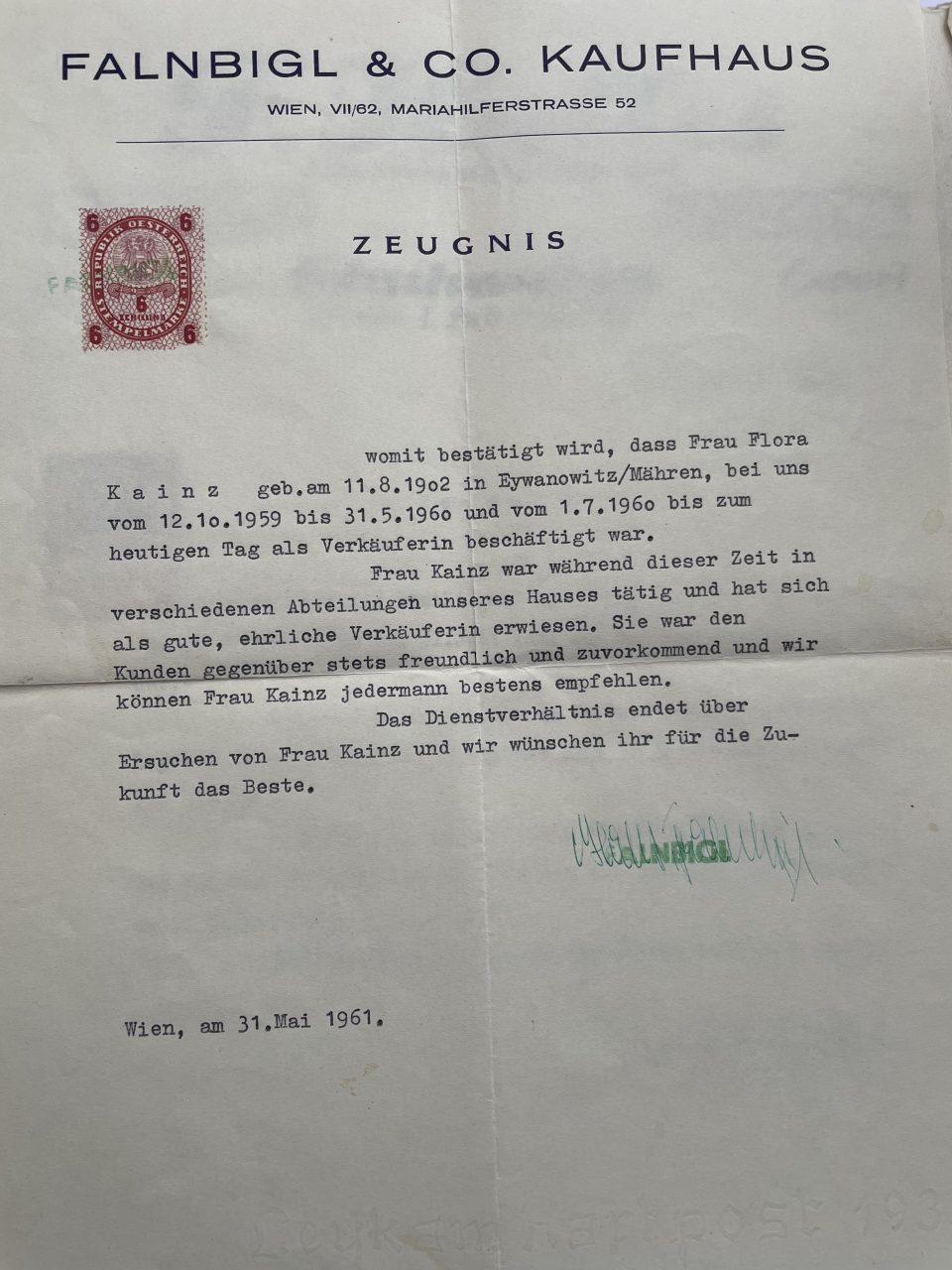

A far cry from the elegance of the period before 1938 were the resurrected department stores in Mariahilferstrasse after World War II, such as Gerngross and Herzmansky. My grandmother Lola, the aunt of Henny, worked there at the department store “Falnbigl” as a sales assistant.

Remnants of former glamour of the department store “Herzmansky”

Lola’s appraisal from the department store “Falnbigl & Co”, Mariahilferstrasse 52

Lola’s farewell dinner with her colleagues (Lola on the right), when she retired

Lola always liked a laugh: left: with her husband, my grandfather Toni and my great-uncle Karl at a “Heurigen” and right: with two friends

For centuries the road connecting the imperial castle “Hofburg” in the city centre with the Habsburg summer residence, the “Castle Schönbrunn” had been an important transit route and the Mariahilferstrasse even gained in importance with the production of silk, a luxury product much in demand in the imperial capital, which took place in the area called “Diamantengrund”, (diamond area) known for its wealth. So, step by step the Mariahilferstrasse and its vicinity developed into a shopping street in the 19th century. In 1869 a horse-drawn tram traversed the street, later the tram and the lighting were electrified and many new and elegant houses were erected along the street and in its side streets. Mariahilferstrasse turned into a hub for female clothing and ladies’ fashion. After 1918 and the end of the Habsburg Empire, shopping in Mariahilferstrasse, even if it was just window shopping, was still so popular that in 1934 the Austro-Fascist Trade Association issued a brochure in black and red “Kenn dich aus … beim Einkauf in der Mariahilferstrassse” (Know how to shop in Mariahilferstrasse), where Christian shops were printed in black and shops owned by Jews were printed in red and mixed proprietorship was marked with a red dot. The aim of this antisemitic brochure was to divert business away from Jewish shop owners towards Christian proprietors and openly denounce and vilify Jews even before the Nazis wiped out the long Jewish textile trade tradition in Mariahilferstrasse, the “Textile Quarter” and everywhere else in Vienna and Austria by expropriation and persecution. After the coming down of the Iron Curtain in 1989, the Mariahilferstrasse experienced a revival, when the neighbouring Hungarians, Czechs and Slovaks could finally freely travel to the West after the fall of Communism. They “invaded” Mariahilferstrasse, because they wanted to see what the West had to offer, but they could only purchase very little at the start because they lacked Western currencies.

History of textile trading in Vienna

In the course of a slight opening up of markets and a gradual watering down of guild rules in the 18th century some Greeks and Jews were allowed wholesale trading with the Osman Empire in Vienna. Since 1774 foreign traders had to submit proof of practical business knowledge and submit 30,000 guilders if they wanted to trade in the Habsburg Empire. They could then open a shop in Vienna or set up a factory, both of which caused enormous conflicts with local business owners. The revolution of 1848, the new liberal Trade Regulation Act of 1859, and the State Law of 1867, offering equal citizen rights to all people living in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, opened up new opportunities for the Jewish population, whose rights had been extremely restricted before. First of all, they could migrate to cities in the Empire, which were closed to them before or where settlement was precarious and linked to the payment of very high special taxes. Now Jews from the eastern impoverished parts of the Empire moved west, mostly to Vienna and Budapest. In Vienna new waves of migrants at the end of the 19th century, driven by terrible pogroms in Tsarist Russia, which in turn had put pressure on Austrian Galicia, threatened the status of the assimilated Viennese Jews, who had worked hard to gain the recognition of the Christian population. Most of the new Jewish migrants to Vienna came from very poor areas in the northeast of the Empire and were peddlers and traders who transferred their business to Vienna. Most of them were orthodox Jews who preferred Vienna to New York because they considered America as “not kosher”. That’s why mostly impoverished artisans who were not orthodox Jews and were prepared to take on more risk emigrated from the south-eastern parts of the Empire to New York. The assimilated Viennese Jews were embarrassed by the arrival of these destitute orthodox people in their traditional clothing, who spoke “Yiddish”, a language they did not appreciate because they considered it vulgar. So, they strictly differentiated between “Western and Eastern Jews” in Vienna.

When in the second half of the 19th century the Viennese textile industry moved north to the “Sudetenland” and the textile companies just had their headquarters in Vienna, the “Textile Quarter” near the Danube Canal developed. Since the 1860s more and more textile traders had clothes, linen, and shoes produced for their shops in Vienna or for export, too. In this way the first Jewish department stores were set up in the city centre: Philipp Haas, who started with carpets, Jacob Rothberger and Ludwig Zwieback, who were specialised in all sorts of clothing, all in the first district of Vienna and August Herzmansky and Paul Gerngross, who were textile traders, too, and set up the first department stores in Mariahilferstrasse. By the end of the 19th century the Mariahilferstrasse had become an important shopping street that matched the city centre with respect to variety and elegance of the wares on offer. Unfortunately, the Viennese middle class, which was hostile to the new liberal economic trends, found a spokesperson in the later Viennese mayor Karl Lueger, a populist and antisemite. They aggressively targeted not only the successful Jewish entrepreneurs, but also the small Jewish traders and peddlers. The trade regulations were again tightened in to restrict the trading of Jews and cheap antisemitic smear campaigns aimed at the new marketing methods, which had been introduced in the trade sector, such as advertising, special offers or seasonal sales. The new trade regulation act of 1907 tried to revert to pre-liberal times of guild dominance and asked for certificates of competence for every trade in order to harm the Jewish traders and to take away business from department stores. Consequently, at the age of department stores in Europe and the USA around 1900, Vienna was the capital with the fewest department stores due to Lueger’s policy. In 1902 there were only 17 department stores in Vienna with more than 100 employees and nearly all of them were situated in the city centre or Mariahilferstrasse, and all of them had started out as shopping outlets for household textiles and clothing. Vienna was lagging far behind, not only with respect to the number of department stores, but with respect to social plurality and the fluidity of the class structure. Urban department stores made it possible for women to go shopping on their own without a male chaperon and in the stores all classes mixed, those who just looked at the wares and those who could afford them. And there was much more on offer: fashion shows, restaurants, coffee houses, art and photo galleries, live music, and club rooms. Department stores promoted an independent lifestyle of urban women. Furthermore, they introduced modern business practices, such as fixed prices on price tags, payment in cash, seasonal sales, and the possibility to easily compare prices and quality. All this ran against the conservative and reactionary philosophy of life, which Lueger’s Christian Socialist Party and its supporters in the Viennese middle class of small and medium-sized artisans and traders stood for. In an attempt to fight back against department stores, members of Parliament shouted antisemitic slogans during the debates and lumped together department stores, modernism and Jews and propagated another expulsion of Jews from Vienna, the “18th Geserah”. In reaction to rising repressions more and more cooperatives in trade were founded in Vienna, most of all the first “Arbeiter-Konsumvereine” (Workers’ Cooperatives in Trade). Even a department store on Mariahilferstrasse was set up as a cooperative of around 100 traders, the “Mariahilfer Zentralpalast”, later “Stafa”. In the course of the 1st World War the building was taken over by the “Staatsangestellten-Fürsorge” (state employees’ relief), and despite changes of proprietorship in the years to come the abbreviation “Stafa” remained.

The situation for Jewish traders worsened after the break-down of the Habsburg Empire in 1918 and during the time of Austro-Fascism 1933 to 1938, when advertising and seasonal sales were restricted to help the indigenous small shop owners in Vienna. In fact, the number of small traders exploded in the inter-war years: around 85,000 in 1925, which was double the number of 1913. At the same time the Workers’ Cooperatives in Trade, “Konsum”, grew significantly in Vienna during the time of “Red Vienna”, when Vienna was governed by a Social Democratic majority. Many branches of “Konsum” were opened and constituted a competition for the small grocers. The Workers’ Cooperatives in Trade furthermore opened five GÖC (Großeinkaufsgesellschaft österreichischer Konsumvereine) department stores in the outer districts of Vienna, namely the 3rd, 7th, 8th, 16th, 20, and 21st, with a maximum of 40 employees for the daily needs of working-class families. The GÖC department stores were in no way as glamorous as the inner-city ones, but on a smaller scale they tried to offer a modern shopping experience with music from loud speakers, innovative advertising methods, the showing of films, the organisation of music and dance shows and afternoon coffee parties. All that stood in contrast with the meagre purchases the people could afford. In general, due to the extremely difficult economic situation in Austria after World War I and the Great Depression of 1929, trade experienced a drastic backlash in Vienna and old forms of trading such as peddling, trade in rags, and hire-purchase returned. In department stores 25 to 30 per cent of purchases were hire purchase, contrary to payment in cash only before the war. Nevertheless, consumer credit was discredited and seen as morally deprived by the ruling Conservatives. Banks usually offered consumer loans not in cash, but only in exchange for coupons of stores, which were in the hands of the respective banks. Hire-purchase increased the dependence of consumers towards small shop owners, who had allowed them credit, namely the registering of the daily purchases in a book (“Anschreiben”) and payment, as soon as salaries were paid out; a common rural practice which had returned to the city in dire times. Bigger shops dealt with hire-purchase customers in a back office or on upper floors only, because this form of payment was considered shameful.

Antisemitism in Vienna

During the NS Period 1938 until 1945 all Jewish businesses, big or small, were expropriated and the owners persecuted and murdered, if they were not able to flee the “Third Reich” in time. It should therefore be investigated whether the foundation for Hitler’s atrocious and murderous antisemitism was laid in Vienna at the beginning of the 20th century. The first Jews settling in Vienna are documented in 1150. Successive phases of expulsions, fired by religious Christian rage of the Viennese population, the murdering and burning of Jews and subsequent resettlements characterised the antisemitic landscape of Vienna over centuries. At the end of the 19th century the rise of the Christian Socialist Party under Karl Lueger then compared the defence of the Viennese against the threat of the Osman Turks in the two sieges of 1529 and 1683 with the “current defensive battle against Jews”. This was the start of a “modern form of antisemitism”, which hit the Viennese Jews in the happiest time of their existence in Vienna. The liberal government policies in the second half of the 19th century triggered an immigration wave of Jews in Vienna. In 1860 Jews constituted 2.2 per cent of the population, in 1890 8.7 per cent. These numbers only comprised those Jews registered with the Jewish religious community, the “Kultusgemeinde”, and not those who had assimilated, converted to Christianity or were agnostics. This trend of assimilation was very strong in Vienna and a distinction between assimilated and religious Jews became common only with the rise of aggressive modern antisemitism. Therefore, the estimated numbers of assimilated and religious Jews together were much higher. The largest majority of assimilated Viennese Jews were German speakers. Within the Habsburg Monarchy Vienna was not the city with the highest share of Jewish population: in Krakow the percentage of Jewish citizens was 50 per cent, in Lemberg (Lviv) and Budapest it was 25 per cent and in Prague 10 per cent. The finally attained emancipation and the craving for education spurred the Viennese Jews to great achievements and when their share in Viennese grammar schools and universities sored and when several of them entered the free professions of doctors and lawyers and promoted modern industrialisation, they evoked envy among the indigenous less successful Viennese.

It seemed that even assimilated and baptised Jews felt a “Jewish compulsion to deliver”; for example, the composer Gustav Mahler never hid his Jewish origin, but he was not happy with it and it urged him to work harder and perform better than his competitors. These Viennese Jews felt that after centuries of exclusion and persecution they could finally became part of the majority population via assimilation, conversion, and mixed marriages. The Emperor Franz Josef I, despite being a fervent Catholic, was welcoming towards Jews, promoted them and awarded them aristocratic titles, because they were responsible for a boom in the Empire’s economy and trade. Politically, the Jews repaid him by being strong supporters of the Habsburg Monarchy; politically most of them were Liberals or Social Democrats. After the stock market crash of 1873, this new form of antisemitism erupted first at the universities, where the renown professor of medicine, Theodor Billroth, protested against the large share of Jewish medical students in 1876. The important “German Student Fraternities” (“Burschenschaften”) immediately introduced an “Arierparagraphen” (statutes only allowing membership to “Aryans”), excluding Jewish students.

In 1881 Czar Alexander I was assassinated, which triggered atrocious massacres of Jews and successive pogroms. In fear of their lives, thousands of impoverished Jews fled the Russian Empire for the Habsburg Empire, especially Galicia. Around 200,000 roaming beggars appeared in the already poor region of Galicia. The more adventurous tried to cross the ocean to America, the more religious ones fled to the Empire’s big cities. Already a year later, in 1882, the “First International Jewish Congress” in Dresden, Germany, demanded a stop to the immigration of Russian Jews and a strict military border control. They further demanded that all citizen rights for Jews should be revoked and all Jews be put under “alien status”, because they only “pretended to assimilate and were a threat to Christianity”. In the Habsburg lands the Jews still felt secure because the state protected them, but around 1900 antisemitic politicians gained more and more support. In schools, theatres, factories and in Parliament antisemitic statistics were circulated that were supposed to prove the “Verjudung” (Jewish infiltration of Viennese society) of Vienna. They described a horror scenario of doomsday of the Christian civilisation und used the stereotype of the Eastern Jew as a bogeyman. The German Nationalist Party and the Christian Socialist Party organised demonstrations against Jewish peddlers in Vienna and launched aggressive campaigns against department stores and Jewish shops with slogans such as “Don’t buy from Jews” (“Kauft nicht bei Juden”). Attempts were even made at separating Jewish and Christian market stalls and in 1904 the magazine “Jahrbuch für deutsche Frauen und Mädchen” warned women not to buy Christmas presents in Jewish shops because that would “dishonour them and shame the German people”.

It became evident that despite all efforts of Viennese assimilated Jews to became part of the mainstream, they now shared the destiny of the Yiddish-speaking Eastern Jews. The assimilated German-speaking Jews were confronted with a paradoxical situation; they despised their origin, they loved German culture and language, but were not considered part of it. Consequently, assimilated Jews rediscovered their Jewishness and tried to fight antisemitism, such as the writer Arthur Schnitzler with his drama “Professor Bernhardi” or Theodor Herzl. Herzl had assimilated and had even been a member of a German student fraternity, yet now he saw the only solution for Jews in the setting up of a Jewish state in Palestine, the original home of the Jews, to create a refuge for the fleeing Eastern Jews. Zionism, the Jewish national movement, was born out of self-defence. Not many Viennese Jews supported this idea, because they felt as Austrians, such as the famous writer Karl Kraus, who stated that he would not donate “one crown for Zion”. A further Russian pogrom in Kishinev resulted in unspeakable cruelty and a Jewish massacre, which triggered another wave of refugees moving west. When charities tried to assist the fleeing Jews in Galicia, they were attacked by antisemites. Systematically the fear of new waves of Russian Jews fleeing to the West was propagated in the West. In 1905 the antisemites blamed the Jews for the Russian Revolution and spread rumours that the Jews wanted to provoke such a revolution in all Western countries and aimed for the “Jewish world supremacy”. When the Social Democrats demonstrated in Vienna for equal voting rights in 1905, the Christian Socialists under Lueger countered with the slogan “Down with the terror of Jews”. Lueger further stated in mass demonstrations of his voters that “if the Jews threaten our mother country, we will show no mercy” and he denounced all Social Democratic leaders as “Jews”. In Parliament Lueger’s party once again submitted a bill for a stop of Jewish immigration in 1906. This was the atmosphere that Adolf Hitler experienced, when he arrived in Vienna in 1907: it was the “Russians Jews’ own fault that they were massacred and persecuted because this was an act of Christian self-defence” (Rudolf Vrba, “Die Revolution in Russland”). Many newspapers and magazines, for example the “Deutsche Volksblatt”, which Hitler read, spread these horrific and absurd theories. They stirred up hatred against the “Jewish press”, the “money Jews”, and the “Jewish world supremacy”. Most of the brochures, newspapers, and magazines that Hitler read in Vienna were antisemitic and formed his concept of the Jew as the scapegoat and bogeyman. Nevertheless, Hitler had never had any negative experiences with Jews in Austria: The Jewish family doctor in Linz was much appreciated and cared for Hitler’s mother until her death. Hitler admired Gustav Mahler as an interpreter of Richard Wagner. At the age of 19 he was invited to musical evenings in the house of the Jewish family Jahoda. When he was homeless in Vienna in 1909, he received help and assistance of Jewish welfare organisations; he profited from Jewish donations for the homeless shelter in Meidling and the single men’s shelter in Brigittenau, where he stayed and had several Jewish friends. One of them, Neumann, gave him a coat, when Hitler had nothing to wear, and lent him some money, too, when Hitler was penniless. Several other Jewish inmates of the single men’s shelter assisted the young Hitler, such as Siegfried Löffler and Simon Robinson. Only Jewish art dealers bought Hitler’s pictures: Morgenstern, Landsberger and Altenberg. Samuel Morgenstern promoted Hitler and even recommended him to the Jewish lawyer Josef Feingold, who for his part supported Hitler. When Hitler stylised himself as the “saviour of the German race”, his antisemitism culminated and the hate against Jews became the motor and centre point of his policy. Until his suicide on 29 April 1945 his whole thinking circled around the total destruction of the Jewish race. This mania cannot be explained by his youth spent in Linz and Vienna only, the turning point of his obsession with Jews must have happened before he appeared in Munich as a politician in 1919, namely during world War I.

Habsburg Empire before the outbreak of World War I was characterised by multiple political crises despite the economic and cultural boom. First the destruction of the universalism of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy by the excessive raging of “identity policy” of the various ethnic groups. The more concessions the Austrian government made to the nationalities in its half of the Empire, the more cultural independence it granted, the more disadvantaged and discriminated against these ethnic and linguistic groups felt. To a large degree they just had a vague sensation of being disadvantaged, which, in reality, they were not, especially if compared to the situation of minorities in neighbouring countries. The feeling of missing out, of being neglected led to ever more heated dissociation and radical and immoderate demands for “nationalist identity”, to the detriment of the whole Austrian society. That led to the singular phenomenon that voters, who for the first time had been given equal voting rights for men, did no longer feel represented in Parliament by the traditional parties. Consequently, a new type of politician filled the gap, the populist “tribune of the people” modelled on Karl Lueger, who relentlessly abused the media for his own representation, shamelessly served his own clientele and unscrupulously used biased propaganda for himself. Hitler, just like his model Lueger, went so far as not to marry in order not to lose the support of his fanatic female supporters, who venerated him as the “New Messiah” – in the case of Lueger, these female fanatics were not even allowed to vote at that time. This new type of politicians presented the press and the media as their enemy, as long as they were not able to manipulate them. Lueger shouted “Jewish press”, targeting the liberal newspapers of the upper middle class, yet his perpetual attacks on Jewish journalists and feature writers were totally unfounded and irrational. Absurdly, the democratisation of the Parliament of the Austrian half of the Habsburg Empire and the inclusion of ever more groups in its representation destroyed the reputation of this democratic instrument. The various representatives of radical nationalist political parties obstructed the workings of the Parliament by blocking votes with day-long speeches in various languages, clowneries, and the refusal of any compromises. Another important phenomenon that destabilised the political structure of the Empire were the waves of migrants who represented an easy target for radical nationalistic and populist politicians. The large supranational region that had united Germans, Czechs, Italians, Croats, Slovenes, Slovaks, Poles, Ruthenes, Bosnians and several more ethnic groups, was being undermined by separatist demands for “nationalist identity policy”. These groups delegitimised a state that had guaranteed peace and prosperity for decades in this ethnically, linguistically, and religiously mixed region of Central Europe and, interestingly enough, the first ethnic group to aggressively enforce their uncompromising nationalistic claims to power were the Hungarians, to the detriment of all minorities living on the territory of the Hungarian half of the Empire. That is why several experts see parallels between the state of the European Union today and the Habsburg Empire before World War I.

Due to strict regulation and segregation by the Viennese guilds, Jews had been excluded from all guild-regulated professions and were not allowed to own property or till the land. They had been restricted to peddling, trading, and the credit business until the middle of the 19th century. Consequently, the Christian population of Vienna considered trade and finance as dirty businesses, although without those two, an economy could not function. After acquiring equal rights status, the Viennese Jews had sent their sons to universities and to a lesser degree their daughter to higher schools and so moved into the liberal professions, law and medicine. They took up the opportunities offered by industrialisation and set up factories, opened mines, built railways etc. At the same time Jewish associations tried to interest the young Jews for craftsmanship and agriculture, but with little success, because the generations-long restrictions were still engrained in the minds of the people. So, statistics of the empire of 1910 still showed a concentration of Jewish workers in trade and transport and Christian workers in agriculture and forestry. Especially in the deprived eastern part of the Empire many worked in sectors that were vanishing in the industrial age. The Jews who came from there to Vienna were called “Luftmenschen” (air people) because one did not know how they could make a living by peddling rags and rubbish – they were so poor, they were” living on air”. Some of them were doing better than others because they were lucky or had business acumen. Helene Maimann, the Viennese historian and authoress, reported that her grandfather had been able to build up a booming trade in pieces of cloth and sewing accessories in the 1920s. Yet he left the family and his fifteen-year-old son took over what was left of the business. With a horse-drawn carriage he picked up cloth scraps from large dressmakers in big bags and sold them on to small tailors. This type of rag business was extremely important for “little people” in Vienna, when they were in need of a coat, a suit or a dress, especially during the time of the Great Depression 1929 and the following years. Nevertheless, all those Jewish traders were faced with harsh antisemitism in Vienna and most lived under abysmal conditions in the Leopoldstadt, the 2nd district of Vienna.

The Danube Canal with a view towards “Leopoldstadt”

After the break-down of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the economically difficult times of the small Austrian Republic, the Nazi take-over in 1938, persecution and extermination in the Holocaust, only few of the Viennese Jews returned to Vienna after 1945. Many of them had already quitted the Jewish religious community (“Kultusgemeinde”) during the First Austrian Republic and had either converted to Christianity or were agnostics, but were declared “Jews” by Hitler’s antisemitic race laws – the Viennese artist Arik Brauer said, “It was Hitler who made me a Jew” – so they were not registered as Jews in any post-1945 statistics in Vienna. But those who were still members of the Viennese Jewish community settled again in the 2nd district of Vienna, Leopoldstadt, and lived very withdrawn and inconspicuous private lives; they did not want to draw attention to themselves. They were completely devasted by the experiences of concentration camps, flight, and exile. The concentration of religious Jews in this district of Vienna was at the end of the 20th century higher than during the First Republic: 40.5 per cent of the small number of Viennese Jews lived there in 2001 versus 28.9 per cent during the First Republic. Those who had returned to Vienna from exile and those few who had survived NS concentration camps and had settled again in Vienna, tried to link up to the “good times” of the community during the last decades of the Habsburg Empire and the era of cultural bloom of the Viennese fin-de-siècle.

Even after 1945 artists with Jewish roots significantly influenced the Viennese art scene, such as André Heller, Arik Brauer, Ernst Fuchs, Friedensreich Hundertwasser, and the literary scene, for example, Elfriede Gerstl, Elfriede Jelinek, Ilse Aichinger, Erica Fischer, Mira Lobe, or Hilde Spiel and in exile, Frederic Morton, or Ruth Klüger. In the second half of the 20th century a labelling of citizens as Austrian or Jewish was obsolete. Those who returned saw themselves as Austrians, otherwise they would not have returned or would not have remained here, because they were not at all made to feel at home. People like my grandmother Lola, or my aunt Henny and her husband Pepi saw themselves as Austrians and did not in any way openly demonstrate their Jewish origins, on they contrary, they rather denied them. Lola was a Catholic and wished for a Catholic burial, to be placed next to her Catholic husband Toni, while Henny and Pepi were agnostics. But sometimes a little memento of past Jewish customs cropped up. Lola for example made a soup of “Matzah dumplings” every year at “Pessover” season, when “Matzah” was available in the shops. Some of the “exile writers”, such as Jean Améry, dealt with questions of racism, migration, persecution and identity in Austria and Germany after World War II, but they were faced with a lot of public aggression and disdain. Helen Maimann remembered that her parents had returned to Vienna from England soon after the war. They were Communists and her father was a British soldier. Therefore, they were given a nice accommodation in a beautiful public housing complex in Hietzing, the 13th district of Vienna, “Lockerwiese”, an estate with small semi-detached houses within an ample park. NS party members had evicted the Jewish tenants in 1938 and had moved in. The Allied liberating forces moved those Nazis out of the houses, which were and still are owned by the City of Vienna and assigned them to those who were returning from exile. The former Nazi tenant of the Maimann’s house, Mr. Moriz, had emigrated to South Africa to avoid being held accountable for expropriating the former Jewish tenants and taking over the house. He appealed against the decision of expulsion and the Austrian courts reversed the Allied Forces’ decision and ordered the Maimanns to move out and make room for the former Nazi tenant. This was possible after the withdrawal of the Allied Forces from Austria in 1955, when the Austrian government tried to purge all former Nazis of guilt. Mr. Maimann was no longer a member of the British Army and he was a Communist. The Maimann family of four was moved to the outskirts of Vienna, to Altmannsdorf in the 12th district, Meidling, into a flat of 56 square metres in a new council house complex of three blocks around two courtyards. The small house in Löckerwiese had been home to them, because parents and children had made many friends and had been together with other Austrians, who had been in exile in England, too. Helene Maimann’s mother felt that being evicted from there was her “second exile”.

Such was the post-war atmosphere in Vienna with respect to Jews, assimilated or not, who had returned to Austria, lived inconspicuous lives, just trying to blend in the Austrian mainstream and just wanting to pick up the threads of their pre-1938 lives here.

Public housing estate “Lockerwiese”, Hietzing

Yet the children of the survivors, the “younger generation” of Austrian Jewish writers was and is much more outspoken than most of their already dead elders, such as Doron Rabinovic, Robert Schindel, Eva Menasse, Robet Menasse, Helene Maimann, to name just a few.

After 1945 Jean Améry was one of the first to warn against the new antisemitism of the Left and to point out that hate against Jews had not been extinguished by the Holocaust. The writer Hans Mayer, who took on the French name Jean Améry (an acronym of his German name) in protest against the Nazi regime after the war, was born in Vienna in 1912. He fled Austria, fought for the Résistance, got caught, was interned in concentration camps, and survived miraculously. He had sworn never to return to Austria and Germany after liberation. Yet the political situation in Western Europe, the antisemitism of the Left, of which he had felt to be a part of before, and the persistent persecution and expulsion of Jews in Soviet-dominated Eastern Europe, led him to return to Germany and become a much-praised feature writer there, who vehemently spoke out against any form of antisemitism. Améry had had a Christian upbringing in Vienna, but he chose to be a Jew after the experience of the Holocaust. After the forced heteronomy of the Nazis, it was his own choice to be called a Jew. Nevertheless, his relationship to Israel was difficult and ambiguous. As much as he criticised the policy of successive governments there, he was convinced that the existence of the state of Israel was essential, as it was a haven for all persecuted Jews and it had taught Israelis to keep their head high and to be never again abused and massacred defencelessly. He vehemently criticised the political Left in Western Europe, which practised blunt antisemitism under cover of so-called “anti-Zionism”. Améry was shocked and disgusted by the fact that he had to argue against his former allies, who had reverted to the same “old miserable antisemitism” by supporting the claims of Arab terrorists. In many excellent feature stories, he described “his Auschwitz” and hoped to arouse the public and raise awareness for the antisemitism that was persistently simmering under a morally clean surface. The xenophobic cliché of the “Jew with the big nose and the bowed legs who is running away from everything in fear” was still in the minds of the people in Austria, Germany, and Western Europe as such. But that image did not go well with the Leftist view of the “Israeli oppressor, who was torturing innocent Palestinians”. So, the political Left in the West and in the Soviet-dominated East had to create the “Anti-Israelism” or “Anti-Zionism”, which was easy in the East on the basis of an inherent old antisemitism there. And what’s worse, the Leftist intellectuals unquestioningly took over this political stance. Améry said that he had no personal connections to Israel, did not agree with the government policy, did not speak the language,e and the culture and religion were not his, but nevertheless, the existence of the state of Israel was of utmost importance for him because it was a pioneer state and in this state Jews were soldiers, farmers, engineer and “not just peddlers, traders and bankers”. No one could ever guarantee that in some corner of the world an autocratic regime would again turn against the Jews and persecute and murder them: “You can leave a party, but you can never quit being a Jew”. In that case Jews would not find refuge anywhere except in Israel. During the Cold War the Soviet Union decided that the Arab States were more important due to their oils resources than Israel and the Soviets supported them knowing that they were not at all progressive Communist countries. But the Soviet Union staged Israel as a bullwork of Capitalism, which it had never been since the beginning, when Jewish farmers dug up the earth of Palestine. “There is no honourable antisemitism; what the antisemite wishes and prepares for is the death of Jews”, said Jean Améry. He argued that Western Leftist parties used the term “Zionism”, for what the Nazis named “Jewish world supremacy”, and they described Israel as the “aggressor and oppressor of peaceful Palestinians, a militarist and fascist rogue state”. If one wanted to comprehend the phenomenon of Israel, one had to fully understand the catastrophe of the holocaust for Jews, he said.

Jews today are all the grandchildren and great-grandchildren of six million murdered victims. The state of Israel was founded on the basis of general international law, just as most other states in the world and the world cannot give up the support of Israel and hand over 8 million Israelis to the mercy of neighbouring Arab states, in whose schools generations of children have been taught “the holy hate against Jews”. Israelis will fight with everything they have against the dissolution of their home country because they will always have the tragic powerlessness of the Holocaust at the back of their minds. Hate against Jews today, just as all those centuries ago, does not just target Jews, but human beings in general and jeopardises human rights. Antisemitism signifies hate against Jews in general and today aims at the extinction of the democratic state of Israel, home to eight million Israelis. No other state in the world has been threatened with extinction so many times since its foundation. After 1945 and the indescribable tragedy of the Holocaust, two antisemitic political tendencies can be identified worldwide; the old radical nationalistic Right and the radical Left, which has associated with radical Palestinians and has called for the extinction of Israel. This must not be confused with criticism of the Israeli democratic government. It is the only democracy in the region and continuously tens of thousands of Israelis demonstrate against the policy of their government; they show a lot of empathy and they pity the plight of the disadvantaged Palestinians. Whenever and where-ever in the world local politicians need a scapegoat, a bogeyman, whenever strangers are to be exposed and blamed, the Jews are a ready victim, because since Roman times they have been persecuted and massacred, yet they are still here. Autocratic regimes might start with the Jews, but they will not stop there. They will then direct their hate against other groups in the society, as in Hitler’s “Third Reich”, against Poles, Czechs, Russians, Roma and Sinti, homosexuals, disabled persons – and not to forget, intellectuals.

LITERATURE

- Améry, Jean, Der neue Antisemitismus, Cotta 2024

- Améry, Jean, Essays on Antisemitism, Anti-Zionism, and the Left, Indiana University Press, Klett-Cotta 2021

- Brugger, Eveline u.a., Geschichte der Juden in Österreich, Ueberreuter 2006

- Hamann, Brigitte, Hitlers Wien. Lehrjahre eines Diktators, Piper 2021

- Jüdisches Museum Wien, Kauft bei Juden. Geschichte einer Wiener Geschäftskultur, Amalthea 2017

- Maimann, Helene, Der leuchtende Stern. Wir Kinder der Überlebenden, Zsolnay 2023

- Mattl, Siegfried, Geschichte Wiens. Das 20. Jahrhundert, Pichler 2000