The Viennese public transport system is one of Europe’s most efficient and affordable public transport systems. It all started with the first horse-drawn tramway in 1865 that connected the former gate in the city wall “Schottentor” with the suburb of “Hernals” which was famous for its many entertainment venues where famous musicians, like the family Strauss, Josef Lanner, the “Schrammeln” and many others performed. So this tramway was built to offer the Viennese a quick and more comfortable possibility to get to their leisure activities. The fast developing network of tramways – first horse-drawn, then steam-powered, too, and finally electric – employed an increasing number of tramway workers who were an ever-present appearance in the Viennese city scape at the end of the 19th and the 20th century. Their protest against the excessive exploitation by the private tramway owners in 1889 resulted in the first wide-spread strike in Vienna and gave a boost to the newly founded socialist movement of Victor Adler. The workers of the tramways also later remained a pocket of resistance, most of all in the Austro-Fascist era 1934-1938 and then during the time of Nazi occupation 1938-1945. A monument in Vienna lists the names of 42 Fascist and Nazi victims of the Vienna transport system workers 1934-1945 (3rd district of Vienna, Kappgasse1). The tramway workers who were active Socialist party members were either dismissed in 1934 when the Austro-Fascist regime of Engelbert Dollfuß put an end to the democratic system of the 1st Austrian Republic or after March 1938 when Hitler made Austria a part of the “Third Reich”. Then all workers of the Viennese tramways who were Jews or had Jewish ancestors were not only sacked but had to flee the country, such as my great-uncle Karl Elzholz, who managed a last-minute escape to Bolivia with his wife, my great-aunt, Marianne (Mitzi), the sister of my grandmother. Those who were unable to find refuge abroad were sent to Nazi concentration camps where many of them were murdered.

After the Second World War Karl, together with his new wife, Käthe, another of my great-aunts, (see article: “Viennese in Exile in Bolivia”) returned to Vienna in 1948 taking up his position as mechanic at the Viennese Tramways again. Karl was not only a very gifted mechanic, a skill which helped him to make a living in exile in Bolivia, back in Vienna he continued building gadgets from scraps of the tramway workshops and depots for his wife. Some of these beautiful items are still in use today:

A sewing box

A mechanical clock

A serving trolley

A historical survey of the Viennese tramways and their importance for the city, its inhabitants and the social and political developments has to start with an analysis of the infrastructural situation of the city in the 19th century. In the course of the 19th century Vienna, the capital city of the vast Habsburg Empire, was growing fast and was becoming extremely crowded within the city walls and the outer ring of fortification, the “Linienwall”. Instead of developing a proactive concept for the expanding city, the policy the city administration resorted to was the restriction of immigration. In 1829 customs offices opened along this outer ring, called “Linienämter”, where customs officers levied a hefty tax on all foodstuffs being delivered to the city, which made life extremely expensive inside the outer city wall. This meant that the poorer population moved to the suburbs outside the “Lininewall”. Consequently the demand for public transport from and to the suburbs was increasing fast, further boosted by the Industrial Revolution. More roads were built between the gates of the inner and the outer ring of fortification for horse-drawn carriages. In the course of just two decades the suburbs became densely populated as well and it was impossible to find space in the packed city to build railway stations for the newly established private railway lines. That’s why all in all seven railway stations were built in Vienna between 1838 and 1881, which were all terminal stations of railway lines of private entrepreneurs and located outside the inner city. Furthermore, these seven terminal stations were not interconnected, which meant that in many cases a journey on one of the railway lines took up less time than the travel in Vienna from one station to the other. In 1857 it was decreed that the inner as well as the outer fortifications were to be demolished to create more space in the overcrowded city. This led to the creation of the world-famous “Ringstrasse” and another less famous outer ring road, the “Gürtel”. Here, instead of abolishing the tax levied on food products, even more customs offices were installed which were closed only in 1918 when the Habsburg Monarchy ended. The Danube was regulated, too, to create more construction space and the suburbs were gradually incorporated into the city administration. As a result the number of inhabitants reached 2.3 million in 1918. Vienna was at that time one of the biggest cities in Europe and the world.

In 1865 the Swiss company “C.Schaek-Jaquet & Comp.” received the permission for the construction of the first horse-drawn tramway in Vienna from Schottentor to Hernals as a trial run. The four-kilometre long tramline was officially opened the same year and it was a big success because it was an economical and quick way to transport the Viennese to their entertainment – music, dancing, wine drinking at the “Heurigen” (wine growers’ places where the new wine is sold) and beer drinking etc. in Hernals. The adoption of the “American” system, inaugurated in New York in 1832, allowed the use of tracks at street level that did not impede the transport by horse-drawn carriages on the same road. The narrow streets and the steep hills in the city created problems for the construction of the tramways. Normally one horse-drawn tramway was run by two horses and carried 36 passengers, but there are many steep lanes where additional horses had to be harnessed. A year later the tramway line was extended to Dornbach, where there was even more entertainment waiting for the Viennese. New private tramlines were opened because they were affordable for the Viennese and a commercial success for the private entrepreneurs. In 1867 the “Viennese Tramway Company”, a public limited company was founded. So in 1868 the next line opened up new cheap access to a much loved entertainment area of the Viennese, namely to the Prater, the large leisure area near the Danube, the former imperial hunting grounds, which were opened for the public in 1799 and hosted the World Trade Fair in 1873. The English word “tramway” was introduced into the Viennese dialect, in which still today the tramway is called [‘tramwai] instead of “Straßenbahn”.

The city map of Vienna with two ring roads and many radial roads that lead star-like out of the city lent itself to the construction of tramways. The double –track construction was often not possible because of the narrowness of the lanes. This obstacle was overcome either by using two parallel roads for the two different directions, which you can still sometimes see today (e.g. tramway line 9: Rosensteingasse – Taubergasse) or using a single-track tramway line with passing places. An improvement for the passengers was the introduction of fixed stops in 1869, whereas before it was possible to stop the tram anywhere, which caused long delays. The different tramway lines were marked with coloured round or square symbols, which was very confusing for the passengers. But even more opaque was the ticket price system with different fares for different sectors and different lines and different days of the week and different times of the day. In 1907 the obscure system of symbols was replaced by a system of numbers and letters: those lines running round the city were numbered 1 to 20 and those running from the centre outwards were numbered 21 to 82 and the lines which were a combination of both were marked with letters. The confusion about fares only ended when the City of Vienna took over the running of the Vienna Tramways. This happened step by step, as the city took over one private tramline after the other and in a final effort the Viennese Mayor Karl Lueger founded the “Bau-und Betriebsgesellschaft für städtische Straßenbahnen in Wien” in 1899, which was liquidated in 1902, when finally the whole tramway system was in communal hands with the name “Gemeinde Wien – Städtische Straßenbahnen”. Even today the whole transport system of Vienna, “Wiener Linien”, is in the hands of the municipal administration. In 1908 only two private tramways still existed in Vienna and they were both “train lines”, the cogwheel railway to the Kahlenberg and the railway from the Opera to Baden, a famous spa south of Vienna, which opened in 1899 and was fully electrified in 1906. This tramline was also used to transport the bricks from the huge brickworks south of Vienna , Wienerberg – this site gave the name to the world-wide operating Austrian brick company “Wienerberger”- to the Ringstrasse, where the world-famous “Ringstrassen Palaces” were built with those bricks. This “Badner Bahn” still runs and is operated in cooperation with the administration of Lower Austria.

At the time of the first tramway lines all carriages ran on the left-hand side, as in the UK today, which meant that also the trams had to run in the same direction. After World War I driving on the rights was gradually introduced in Austria starting in the west of Austria, in Vorarlberg. In 1935 the planning for the reorganisation of the Viennese tramways was completed and the works for changing the tram stops, the depots and the final stops started, but the high costs hindered a fast switch to driving on the right. Yet when in 1938 the Nazis invaded Austria, they immediately adapted the Austrian system to the German right-hand traffic system on 19 September 1938. At the final stop of the tram line 38 to Grinzing, the famous “Heurigen” village on the outskirts of Vienna, one can see that originally it was a left-hand traffic system because the tram shelter is still on the wrong side.

The first steam tramway, which was able to cope with the steep slopes in Vienna, was constructed in 1883 by the Austrian company “Krauss & Comp.” and brought its passengers from Hietzing, a well-to-do suburb next to the Imperial castle Schönbrunn, to Perchtoldsdorf, another “Heurigen” village and leisure area. A private cogwheel steam railway had already been running a profitable service up the Kahlenberg from Nußdorf on the Danube and the company wanted a direct connection to the city centre via a steam tramway line, but there was massive resistance against the noise, smoke and soot of steam engines in the narrow streets of Vienna. So a mixed service of horse-drawn trams in the city centre and steam-driven trams in the outer districts was offered as a compromise. The tramline D was constructed from the city centre to Nußdorf, another “Heurigen” village, where the passengers could change to the cogwheel steam train up the Kahlenberg. This private line was closed in 1921, but the D tram still exists and runs around the former lower terminus of the “Kahlenbergbahn” at its final stop in Nußdorf.

The electrification of the Viennese tramways took some time as well, although several companies had submitted offers. Finally the company “Siemens & Halske” was offered the contract of electrifying the Viennese tramways in 1897, but the works were not going to plan. So when in 1902 Mayor Karl Lueger managed to take over the Viennese tramways, the electrification was financed by the “Länderbank” and executed by the Austrian “Schuckertwerke” within six months. The delay in electrification was caused by the resistance of the Imperial family and the high nobility of the Austro-Hungarian Empire against the overhead tram wiring in Vienna, which would obstruct the view from their palaces. But a trial run with ground wiring was unsuccessful because the hooves of the horses drawing carriages, which were still widespread in the city, got stuck in the rails and received electric shocks, which caused panic reactions of the horses so that they could no longer be held in check. Another solution was tested, namely the use of battery-driven carriages, but their capacity was not sufficient. The northern transversal tramline 5 was opened in 1873 as a horse-drawn tramline, but it had to overcome five steep passages, which needed fifteen additional horses and as a consequence it was the first tramline to be electrified in 1897. Even today it runs partly parallel to the outer ring lines on the “Gürtel”, which is somewhat amazing, but can be explained by the fact that it was constructed just inside the customs border, the “Linienwall”.

The city was growing fast around the turn of the century – in 1900 it was the second-biggest city in Europe after London with respect to the surface area -, but several private initiatives to construct a fast link between the seven terminal train stations and from the city centre to the outer districts came to no avail. In the densely populated city with its narrow lanes and steep passages the only practical solution would have been an underground train system, which was considered as much too costly because it could only be constructed with mine drilling techniques. Two new projects presented by the German firm “Siemens & Halske” and the Englishman Joseph Fogerty restarted the discussion. The project that was finally chosen was steam-driven train lines around the city constructed mostly above ground with just a few underground passages. This new “Stadtbahn” could only be planned on clear space, which could be found only near the newly regulated Danube and “Wienfluß” and the demolished “Linienwall”, the “Gürtel” area. Between 1898 and 1901 the first “Stadtbahn” lines started operating. Finally in 1924 the city administration took over also these “Stadtbahn” lines and electrified them. The line connecting the western outer suburbs, the “Vorortelinie” remained in the hands of the nationalised railways and went out of operation in the middle of the 20th century. Consequently it was abandoned and left to decay. In 1987 after a complete renovation of the historical buildings it was reopened as the fast train line S 45 and is still in the hands of the national railways, but forms part of the Viennese transport system, just as the “Badnerbahn” on the territory of the city of Vienna. The “Stadtbahn” and the “Vorortelinie” were not just planned for passenger transport, but also for goods transport and they had a military aspect, too, as the Empire was afraid of the rebellious nature of its Viennese subjects. These fast train connections would allow a quick mobilisation of the army against a rebellious population.

The architectural planning of the whole “Stadtbahn” and “Vorortelinie” project was handed over to Otto Wagner, one of the most famous architects of the Viennese fin-de-siècle. He designed a uniform architectural concept for the “Stadtbahn” from the stations to the viaducts, bridges and galleries. It is a “Gesamtkunstwerk” (complete artwork) that can still be admired today and is an integral part of the modern Viennese public transport system. Otto Wagner designed all aspects of this infrastructure project from the banisters, to the door handles, the lighting, the signs and the black and white tiling of the stations. 33 Otto Wagner stations still exist and are now part of the Viennese underground and fast train system. Otto Wagner was an outstanding architect, but not such a prescient city planner because he outright rejected plans of an underground system in Vienna, which was introduced in the 1970s only, but is fast expanding even now. In the other great metropolis of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Budapest, a modern electric underground system was built at the same time as the “Stadtbahn” in Vienna. It was the third underground system in the world and the first on the European continent – the world-wide first steam-driven one was opened in London in 1863. The first fully electric underground line in Budapest started its operation in 1896.

The municipalisation of the Viennese infrastructure started with Karl Lueger taking office as the first Christian-Socialist mayor of Vienna, much against the wishes of the Emperor Franz Joseph. The formerly ruling Liberal Party had promoted unrestricted industrialisation and the large entrepreneurs of the haute bourgeoisie and had resisted any regulation or interference of the state in the economy. The Liberals ignored the destitution of the poor and the negative impact of this policy on the lower middle class as well, such as artisans, landlords and small traders. These disillusioned Viennese were the fervent supporters of the populist and anti-Semite Karl Lueger. The petite bourgeoisie needed affordable electricity, water, gas and reliable public transport and Lueger’s consequent municipalisation provided that. Even at the time of modern economic neo-liberalism Vienna has never renounced the principle of communalization of infrastructure of the city and that’s why today it is one of the best administered metropolis in the world, ranking first or second in all “best cities to live in” surveys. In taking over the Viennese tramways Lueger tricked the international investors when he announced in the City Council that he did not intend to communalize the tramway lines by purchasing all the shares of the private companies. This move together with some other economic trends led to a dramatic plunge of the share prices of the tramway lines, which opened up the possibility for the company “Siemens& Halske” together with the “Deutsche Bank” to buy up all the tramway lines’ shares for the newly founded “Bau-und Betriebsgesellschaft für städtische Straßenbahnen” and this paved the way for the later municipalisation. The city administration was guaranteed considerable influence in the organisation where it introduced five-minute intervals of the trams and a new and fair ticket price regime. In the course of the electrification of the tramlines and the public lighting system of the city, the municipality managed to take over the private electricity works of the city step by step, so that just before World War I the whole electricity supply was in the hands of the city of Vienna, too.

Despite improving the infrastructure of the city considerably Karl Lueger had no interest in alleviating the ever growing destitution of the lower classes because they had no voting rights and could not keep him in office as the small shopkeepers, artisans and landlords could. The capital city of the Habsburg Empire was growing fast, which meant that since the 1880s extremely low wages could be paid because there was a never ceasing inflow of new immigrants to the city. The massive industrialisation in the suburbs of Vienna resulted in unimaginable poverty and inhumane living conditions there. Life was characterised by famine, destitution and desperation; beggars, homeless, unemployed, feral children and criminals roamed the streets of the suburbs. The entrepreneurs were not in any way restricted in their operations by state regulation which resulted in extreme exploitation of the workers. The working conditions at the Viennese tramways were especially abysmal. From 1886 on the banker family Reitzes was the main shareholder of the “Vienna Tramway Company” , which resulted in a further deterioration of the working conditions. 16-hour work days and very low wages increased the dissatisfaction of the workers – in factories an 11-hour work day was common. Furthermore, the workers had to pay for repairs of damage to the carriages from their meagre salaries and they had to pay fines to the owners if their tramway was too early or too late because they had to observe the timetable meticulously, which was impossible in the jammed streets of Vienna. Already in 1885 the priest Rudolf Eichhorn from the suburb Floridsdorf made the unbearable conditions of work at the Vienna tramways public, but to no avail.

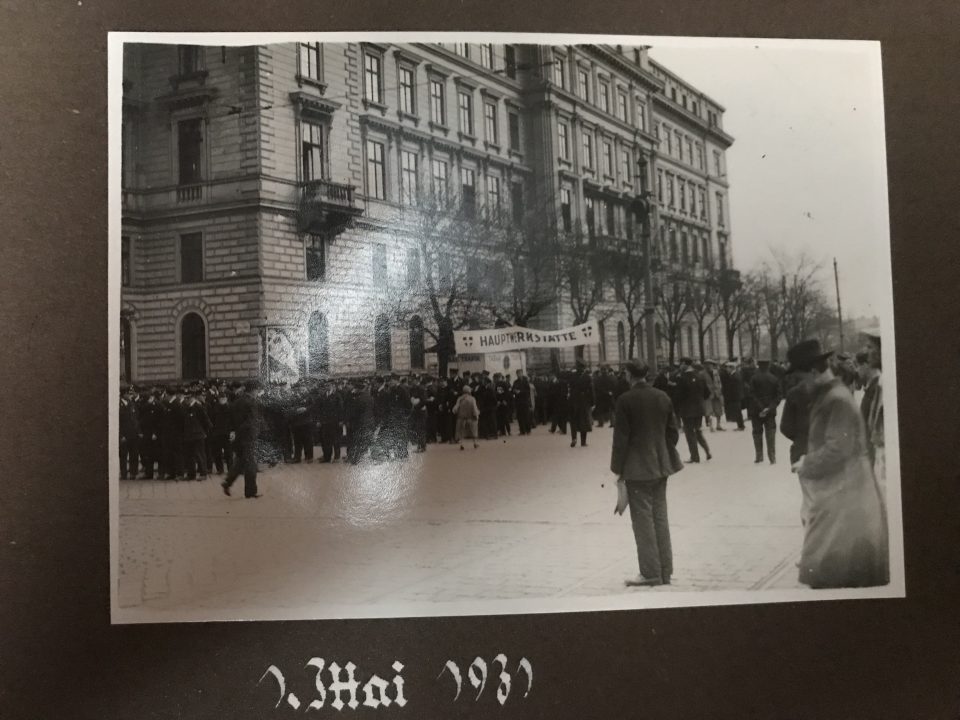

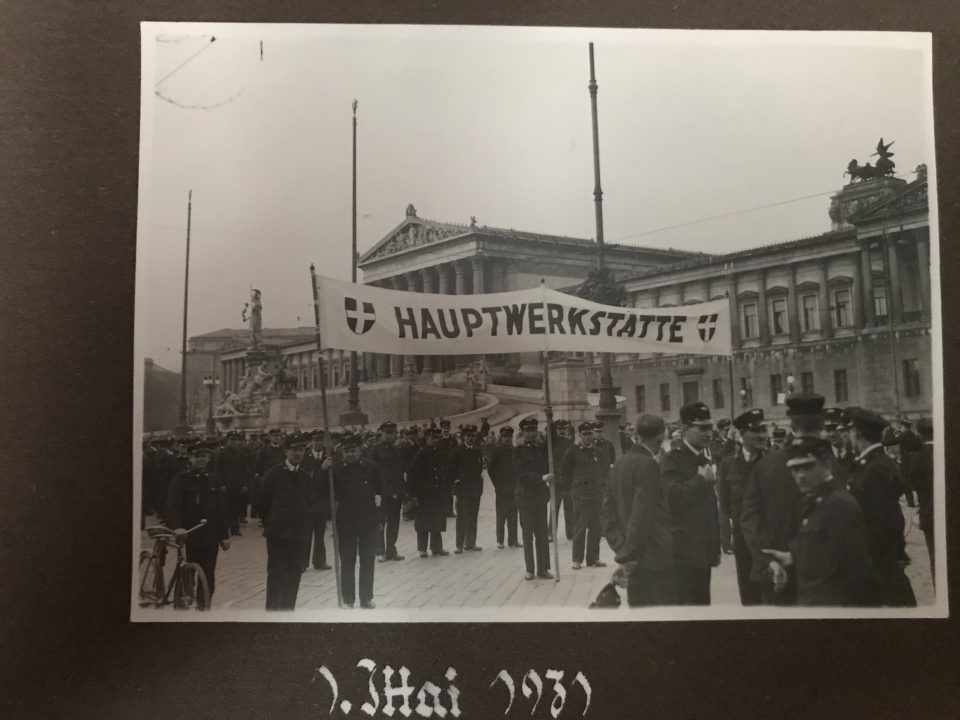

When the workers were fined for an early or late arrival at individual stops, not just at the end of the line, “the white slaves of the company Reitzes” started their protest. In April 1889 the first strike of the Vienna tramway workers shook the foundation of the Viennese social structure. The imperial authorities crushed the protest violently and without mercy, but the unrest spread to the suburbs of Favoriten, Ottakring and Hernals and the army was sent in to deal with the strikers. The management employed strike breakers, but the population was overwhelmingly in support of the strikers despite the disruption of the public transport system and attacked the strike breakers. The army then turned the Viennese suburbs into a battle field. The medical doctor Victor Adler, who had in January of the same year founded the Social Democratic Party supported the strikers and was sentenced to four months’ imprisonment. The strike of the Viennese tramway workers and the massive support of the Viennese population for the strikers was noticed abroad and commented on by the German Socialists Karl Kautsky and Friedrich Engels, who were pioneers of the workers’ movement. Victor Adler could not participate in the first 1st of May celebration in the Vienna Prater 1890 because he was in prison. But in all the following 1st of May celebrations the Viennese Tramway workers played a leading role. This can be seen in some of Karl’s photos from 1931. The protest was successful as the management of the tramways had to make concessions and had to give in to some of the demands of the strikers, most of all the abolishment of the fines.

The strike of the tramway workers 1889

Opening of a new depot and workshop in Währing 1902

In World Wars I and II the tramways were used for the transport of goods as well as people, especially for food products and coal and they also acted as postal trains. In the 1st World War the trams transported army material and wounded soldiers to hospitals and dead bodies at night to the “Zentralfriedhof” and other cemeteries. In both World Wars the Vienna tramways employed women, mostly as conductors, but also to a lesser degree as drivers. From 1915 on 8,500 women between 20 and 40 years of age were employed by the tramways. This was more than half of the overall staff of the tramways, but the women were paid lower wages than their male colleagues. The female conductors became a symbol of new times and the changes that were taking place: they could do the jobs of men even in public space and cope with their duties of housewives and mothers as well. With the end of the 1st World War and the establishment of the 1st Austrian Republic the women finally received equal active and passive voting rights, but with the end of the war they were driven back to their housewifely duties and the tramways replaced all female employees with men returning from the war. Only widows of fallen soldiers were allowed to stay on a bit longer. The same development is visible in the 2nd World War with the exception that foreign forced labour, especially women from Nazi occupied Netherlands and Belgium were recruited as conductors for the Viennese tramways as well. There was a lot of pressure on the conductors in the overcrowded trams because they had to squeeze through the trams, check the tickets, sell them, deal with the cash and see to it that no one used the service without paying.

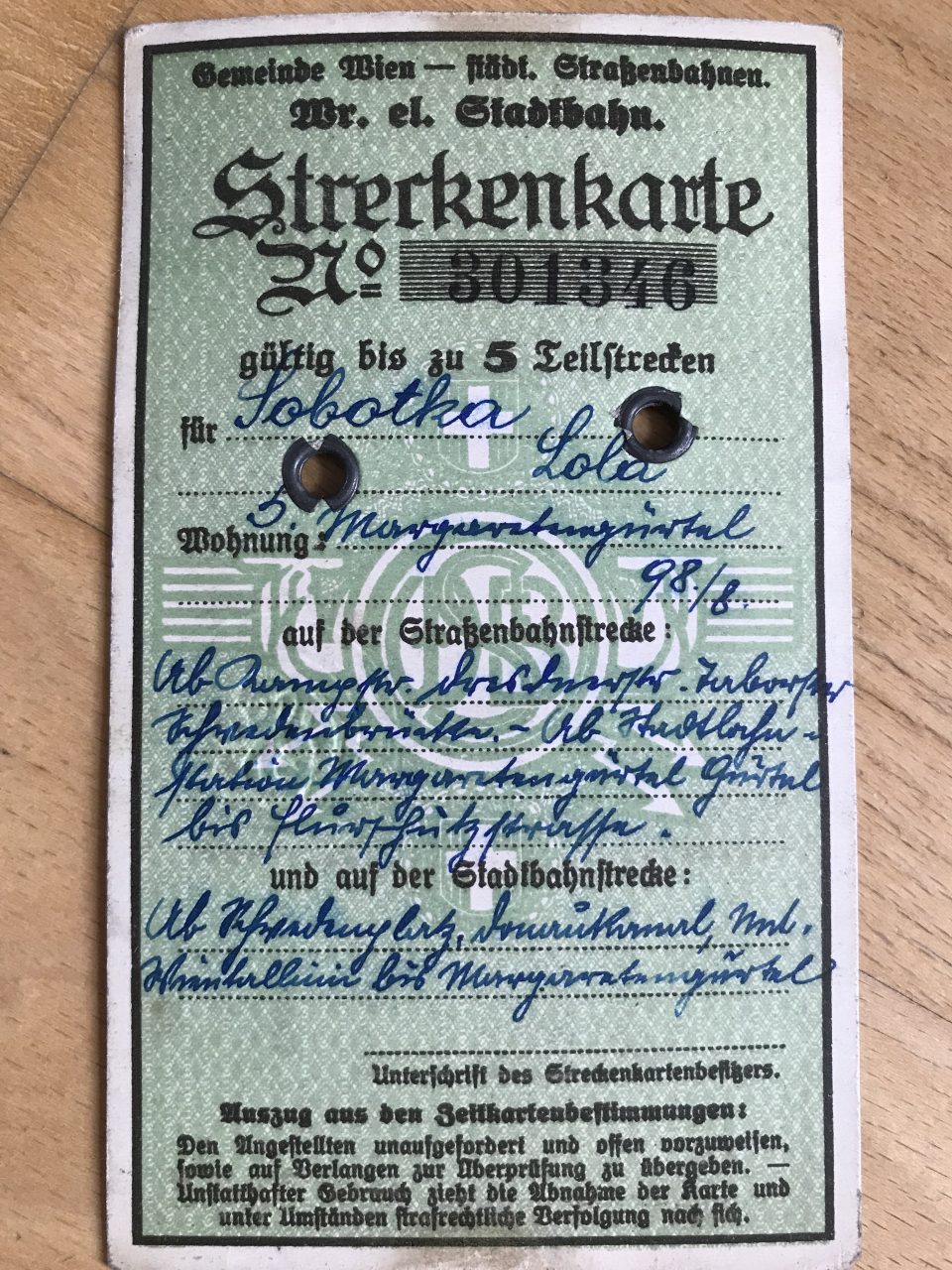

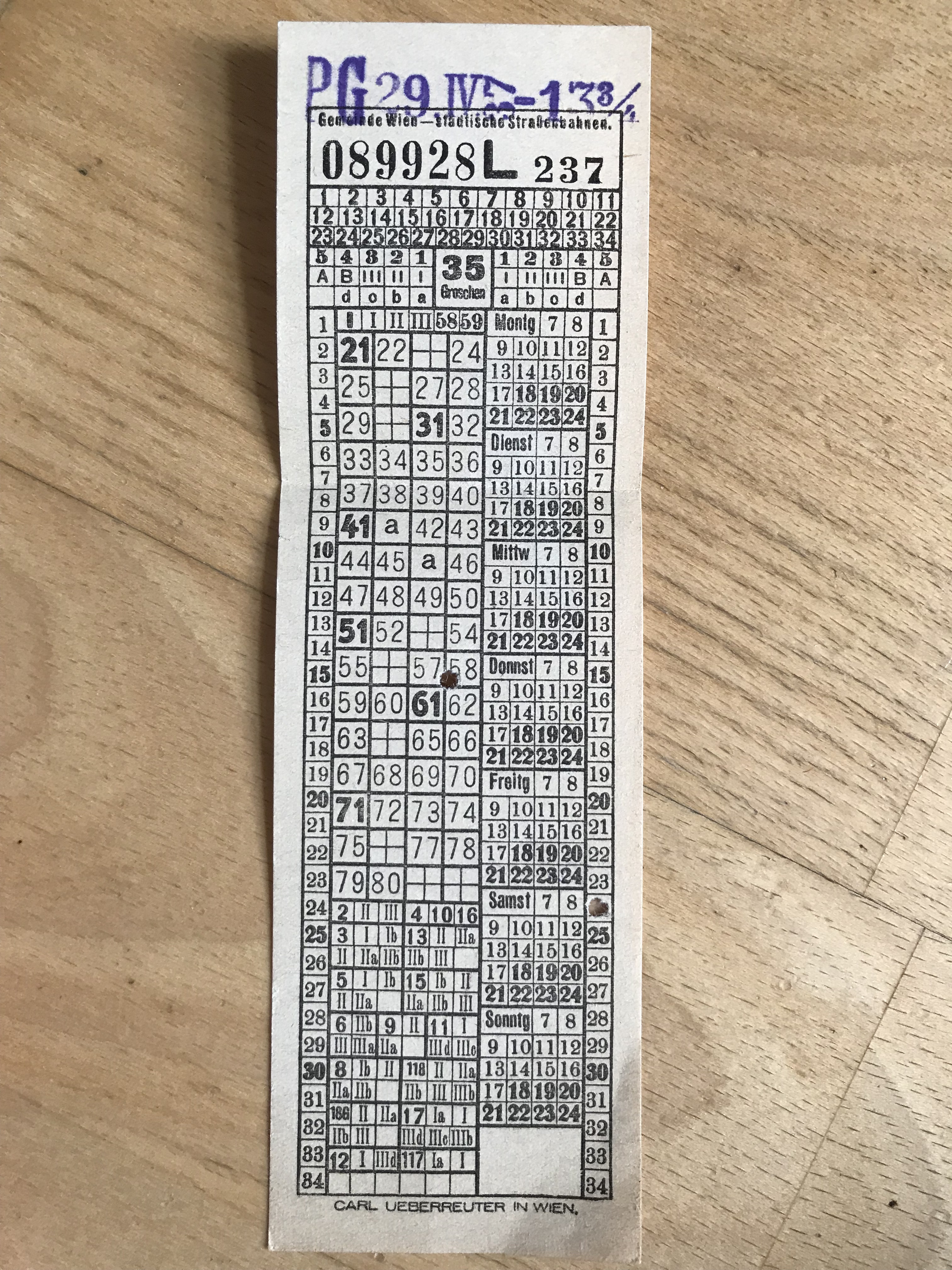

The monthly tramway ticket of my grandmother Lola, 2nd March -1st April 1927

1st of May celebrations 1931 of the main tramway depot

The banner of the main tramway depot in front of the Parliament building

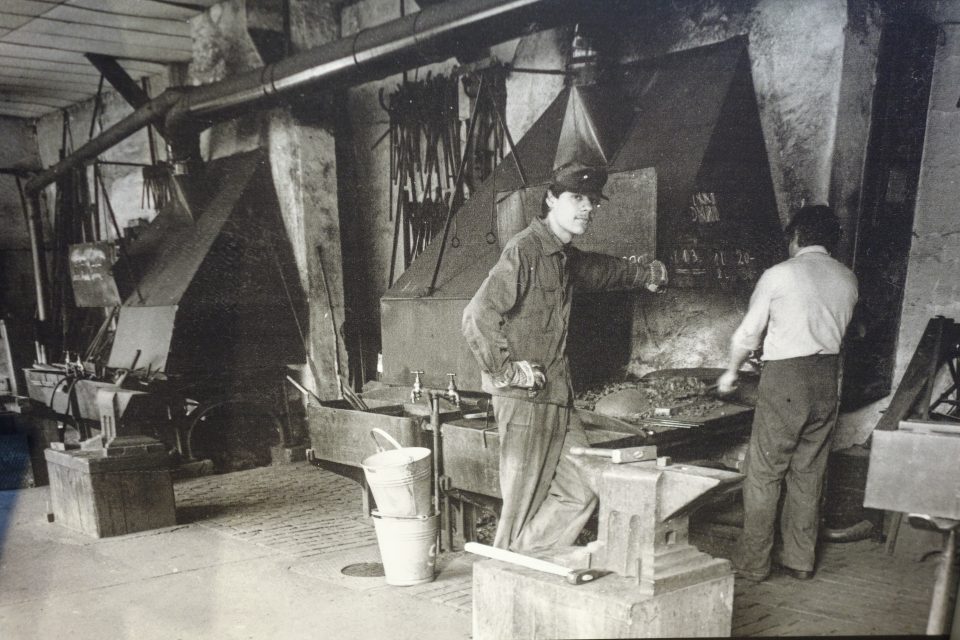

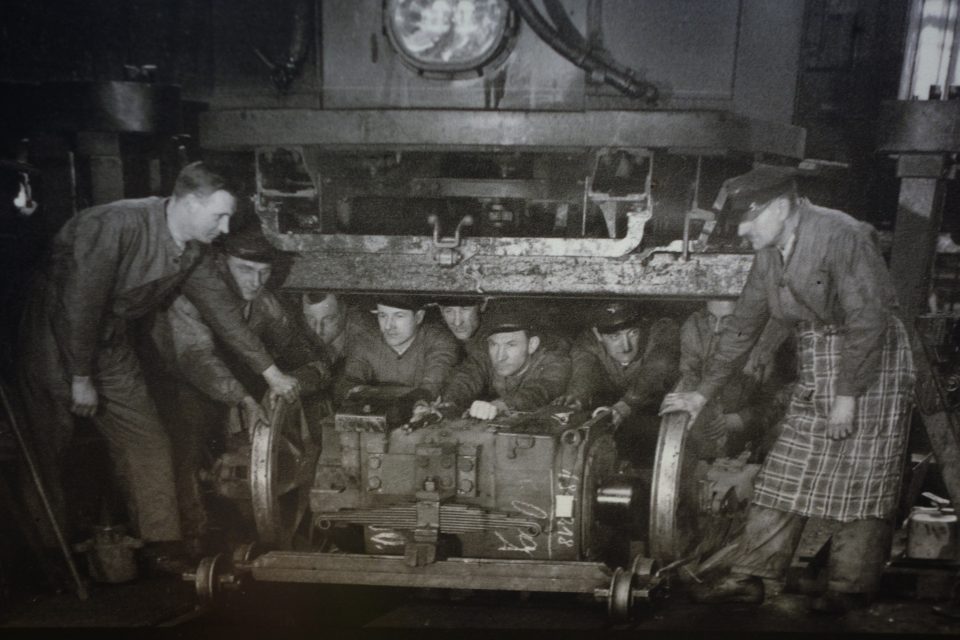

After World War I Vienna was the capital city of a very small republic, no longer of a big empire, which meant that any plans that had existed before for the construction of an underground system had to be cancelled. Nevertheless, the tramway network reached its largest extension with 330 kilometres and more than 3,500 carriages in the late 1920. From 1925 on my great-uncle Karl worked there as a metal worker and mechanic in the depot “Hütteldorf”, where he was shop steward for three years from 1930 to 1933.

Tramway depot in Rudolfsheim

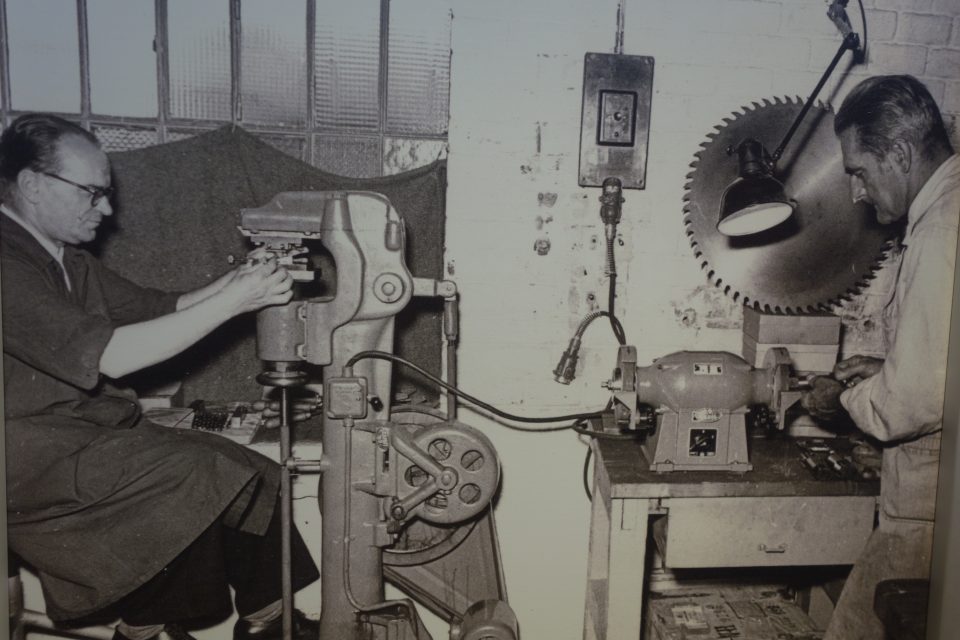

Tools and spare parts were manufactured by hand

The tramways were used to transport construction material for the huge social housing project of “Red Vienna”, the extensive social reform programme of the Socialist city administration 1920 till 1934. In the civil war of February 1934 the Austrian workers’ movement resisted the Austro-Fascist regime of Christian Socialist Engelbert Dollfuß, who had put an end to the first democratic parliamentary republic in Austria. Important resistance was not only found in Socialist and Communist party organisations in Vienna, but also among the working population. After three days of massive resistance against the Austro-Fascist regime the workers had to give up. The opposition parties were forbidden and most leaders of the resistance were imprisoned. But the underground opposition against the regime was especially strong in the workers’ districts of Simmering and Floridsdorf and the communalized companies, especially the tramways, the railway and the fire brigade. In these enterprises the community spirit and solidarity were especially prominent and despite the threat of harsh punishment, there were collections organised for the families of imprisoned workers and leaflet campaigns were initiated.

In the tramway workers’ trade union the majority were Social Democrats, like Karl. Their trade Union was called “Freier Gewerkschaftsbund”, which in the elections for trade union representation regularly won 75 per cent of the votes. They were strongest in the workshops, in the depots and among the employees of the “Stadtbahn” with more than 90 per cent. The second biggest group, which was called “Organisation der Straßenbahner”, was close to the military arm of the Austro-Fascists, the “Heimwehr”, and later the Nazis and gained 15 per cent of the votes in 1930. The Christian trade union gained 5 per cent in 1930 and deteriorated to 2 per cent in 1932. Even less important were the Communists, due to the fact that the Social democratic trade union already represented very leftist positions and therefore there was no room for Communists. The Social Democratic union of the tram workers published a half-yearly paper where in 1930 the high degree of unionisation was evidenced: of the 16.052 employees, 12.969 were members of the Social Democratic “Freie Gewerkschaftsbund”. This trade union offered a wide range of cultural and educational activities, such as political education, “Esperanto” language courses (an artificial language which was seen as a means of international communication at the time), library and radio courses. 29 libraries offered 75,000 books to the tramway workers free of charge and in 1930 7,000 theatre tickets were organised by the trade union for the workers. The Vienna tramways had its own orchestra, brass band and string orchestra and in 1928 an orchestra school for the children of tramway workers was opened, where 120-140 children were instructed.

Many of the Viennese tramway workers were not only members of the Social Democratic party, but also members of its military arm, the “Schutzbund”, which was defeated in the civil war of February 1934. The tramway depots were important collection points for the Social Democratic resistance fighters against the Austro-Fascist regime of Dollfuß. This meant that during the days of the fights on all premises of the Viennese tramways there were fighters of the Social Democrats as well as those who did not want to get involved in the confrontation and Austro-Fascists. Nevertheless no violent incidents were reported. The fiercest fights took place around the biggest council house blocks, such as “Karl Marx Hof”, “Reumannhof”, “Goethehof” (all of these council houses are now architectural jewels of the era of “Red Vienna”) and the workers’ hostel in Ottakring. There was no coherent strategy behind the activities of the tramway workers apart from the start of the general strike on 12 February 1934. The police searched several depots, tramway stations and workshops for stored weapons, but there were no violent clashes. After the defeat of the Social Democrats and the banning of the party by the Austro-Fascist regime four tramway workers were sentenced to death, a verdict which was later turned into life-long and 15 years of imprisonment. A sizable number (the exact number is not known) was accused of rebellion and sentenced to imprisonment, whereby approximately a third was acquitted later. But a fifth of all known tramway workers, who were reprimanded or convicted by the Austro-Fascist regime were not persecuted in connection with the events of February 1934 but later in connection with their political attitude, resistance activities and the solidarity they showed towards their imprisoned colleagues. Much too late did the Austro-Fascist regime realize that without the Social Democrats they had no chance of resisting the Nazi invasion of Austria. Just a few days before the occupation of Hitler they granted amnesty for all political crimes.

But it got worse, when in March 1938 Austria became part of Hitler’s “Third Reich”, the Socialist and Communist tramway workers did not only risk their freedom and livelihood, but their lives. Any show of solidarity such as donations to and support of family members of persecuted colleagues was treated as high treason and the accused were sentenced to imprisonment in a concentration camp and in the 1940s sentenced to death and executed without a trial. 42 tramway workers lost their lives in the resistance movement between 1934 and 1945. Many were imprisoned or interned in a concentration camp. Those of the tramway workers who were Jewish or had Jewish ancestors, like Karl, had to flee the country to escape persecution, but not all of them managed to find refuge abroad in time and were murdered in Nazi concentration camps.

In the days and weeks after the invasion In March 1938 violent Nazi groups roamed the streets of the city and hunted down Jews and political opponents; they even occupied tramway carriages, attacked the passengers, demanded free rides and the expulsion of the Jewish population from the carriages. In no case did the police interfere. Around 70,000 Austrians were imprisoned in the first days after the Nazi takeover, so that even the Germans were astonished about the “efficiency” of the Austrian Nazis. The Nazis immediately took control of the economically important enterprises of the city of Vienna and rewarded their loyal party members with important positions. The Nazis were continually stepping up the pressure on the tramway workers via a dense spy network of supervision and repression. All in all 550 Viennese tramway employees, whose biographies are documented, were persecuted by the Austro-Fascist and the Nazi regime, 95 of which were victims of racial persecution as my great-uncle Karl. His file in the personnel department of the Viennese tramways states the following facts:

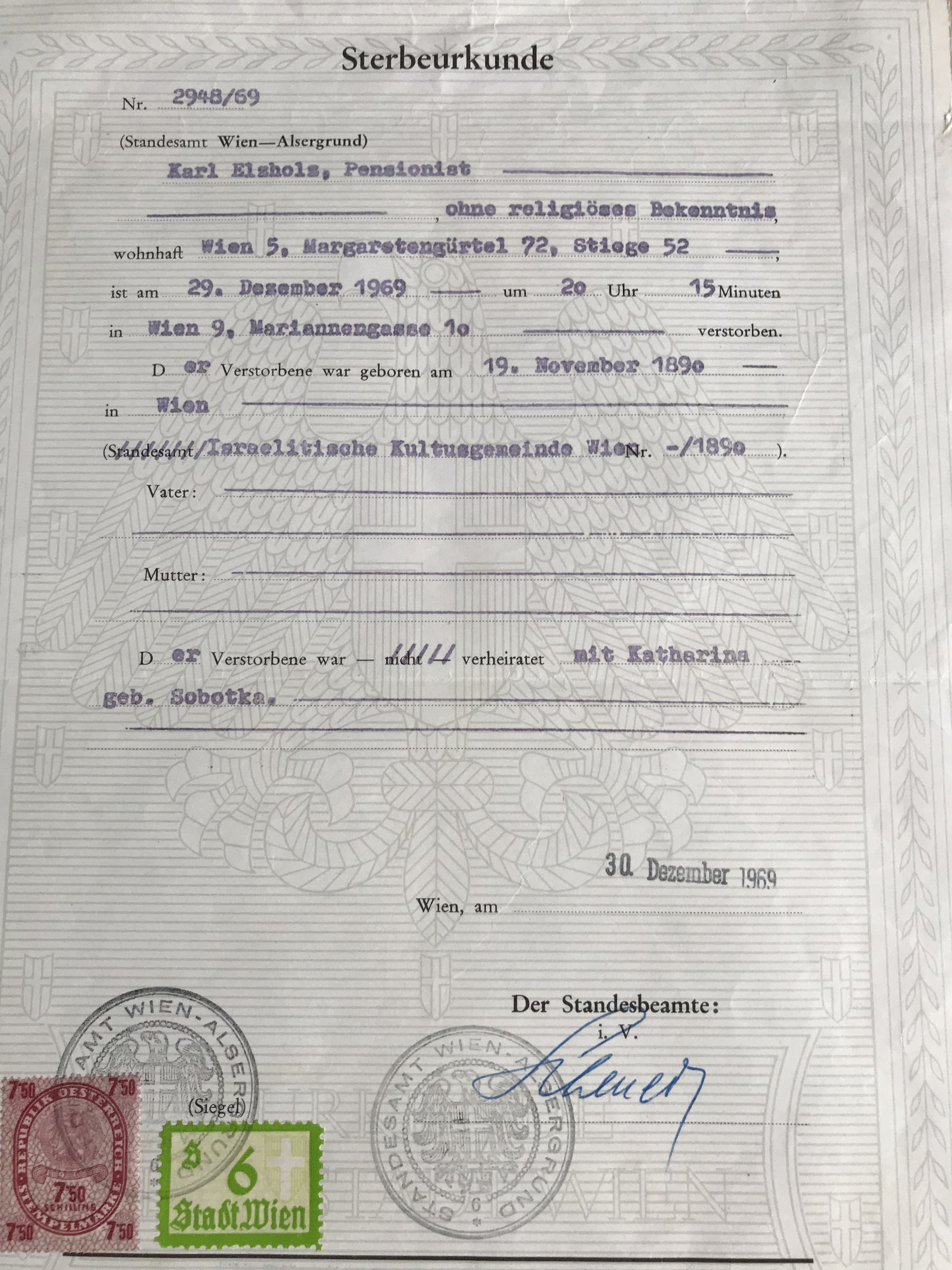

KARL ELZHOLZ

Born: 19 November 1890 in Vienna. Died: 29 December 1969 in Vienna. Locksmith & mechanic, married.

Address: 5th district of Vienna, Margaretengürtel 42.

Professional data: Start of employment: 9 November 1925. Metal worker in the tramway depot Hütteldorf. 14 November 1930-20 November 1933 Shop Steward.

Reprimand: 1 May 1938 Dismissal (Jewish).

Re-employment: 25 August 1948: Metal worker W (meaning central or main work shop).

Retirement: 1 May 1955

His forced exile in Bolivia from 1939-1948 is not mentioned. The Vienna tramways immediately re-employed all employees who had been dismissed on the basis of the “Nürnberg Racial Laws” of the Nazis in 1938, which were 68 persons in the years 1945-1948. Of the overall 95 racially persecuted tramway workers nine had died in the Holocaust. A memorial for the 42 Viennese tramway workers who were victims of the Austro-Fascist and Nazi regimes was erected in the Vienna tramway headquarter in 1953 and can now be seen near the underground depot Erdberg. Several other depots have erected memorials for their fallen resistance fighters. It is very difficult to reconstruct the resistance activities of the tramway workers today, but it can be said that the activities concentrated on the establishment of and collaboration in illegal “Communist” organisations, the printing and distributing of resistance leaflets, donations to and support of families of interned colleagues, listening to foreign “enemy” radio broadcasts and uttering of remarks critical of the regime.

Already at the start of World War II in September 1939 the lack of trained personnel for the Vienna tramways became evident, so female conductors were again employed- 1,768 in 1940 – but with no entitlement to a permanent position in the enterprise. As women were also needed in the armaments production, it became increasingly difficult to recruit female staff for the tramways despite an increase in working hours and the lowering of the age of employment. So in 1941 “foreign workers” were first recruited for the Viennese tramways. These “foreign workers” were in fact forced labour from Nazi occupied territories. They were employed in the workshops and used for the repair and construction of tracks, for example those that were built to transport material to the “Flak Towers” built in the city in order to attack Allied bombers. As conductors and drivers mostly Belgians and Dutch were employed; other forced labourers came mostly from occupied Greece, the Ukraine, the Soviet Union and Poland. Most of them remained around one year with the tramways, more than a hundred longer than three years. Approximately a third (442 persons) of the 1,351 forced labourers at the Viennese tramways were Dutch; the only group where half of them were women. 33 “foreign workers” were arrested; mostly they were accused of a refusal to work, stealing or attempts to flee. Due to the Nazi racial hierarchy Slavic workers were more harshly punished than Dutch or Belgian workers. Nearly a third of all Polish and Dutch forced labourers ended their employment by way of escape, especially in the chaos of the last months of the war.

The biography of the Viennese female conductor Emilie Uldrych illustrates the attitude of some Viennese towards the Nazis. She was one of the persons who were called “Märzveilchen” (“March violets” ) in Vienna because she tried to get a position with the Nazis immediately after the invasion in March 1938 pretending that she had already been a fervent illegal Nazi before. The Nazi management of the tramways endowed her with the responsibility of supervising the Dutch female conductors. In this SS position she tried to improve the quarters where the women were housed. After the war she used this as an argument to get struck off the list of Nazi collaborators. She further pleaded that she was given an early illegal NSDAP party number against her wish because at heart she had always been a Social Democrat and she had only collaborated with the Nazis because she was unemployed and poor. The leading Nazis functionaries of the tramways had already left Vienna before the arrival of the Soviets in spring 1945. The former director of the Vienna Tramways, Karl Schöber, fled to Schärding in Upper Austria and was arrested in February 1946 by the Allied forces. A Soviet court in Vienna sentenced him to three years imprisonment in 1948 and all his fortune was seized, yet at the beginning of 1949 he was already released on parole.

Since the summer of 1944 the Vienna tramways were severely damaged by bomb attacks and when the Red Army of the Soviet Union reached Vienna on 6 April 1945 all tramway traffic was halted. At that point of time 75 per cent of the equipment was destroyed and a large part of the tracks was damaged by bombs and covered in rubble. 50 per cent of the overhead wiring was destroyed as well and nearly all bridges across the Danube and the Danube canal were severely damaged or completely ruined. Nevertheless, on 29 April 1945 the Vienna tramways resumed operations of a few tramlines.

Destruction of the tramway lines in Vienna

Two days before the 2nd democratic Austrian Republic had been inaugurated by the Allied forces with a provisional government. The administration of the 21 districts of Vienna was distributed among the Soviets, the Americans, the British and the French. Only the 1st district, the city centre, was under the shared administration of all four Allied forces until 1955 when the signing of the “State Treaty” turned Austria again into a free and independent state. But between the different military zones there were no barricades and only random controls which did not inhibit the functioning of public transport. The Soviets renamed squares and streets in their zone of administration, for example “Schwarzenbergplatz” was renamed into “Stalinplatz” and a memorial for the Red Army that had liberated Vienna from Nazi terror was unveiled there. The new Soviet street names were abolished again in 1955 with the signing of the “State Treaty” by the four Allied forces, but the memorial to the Soviet Army on “Schwarzenbergplatz” is still cared for by the City of Vienna.

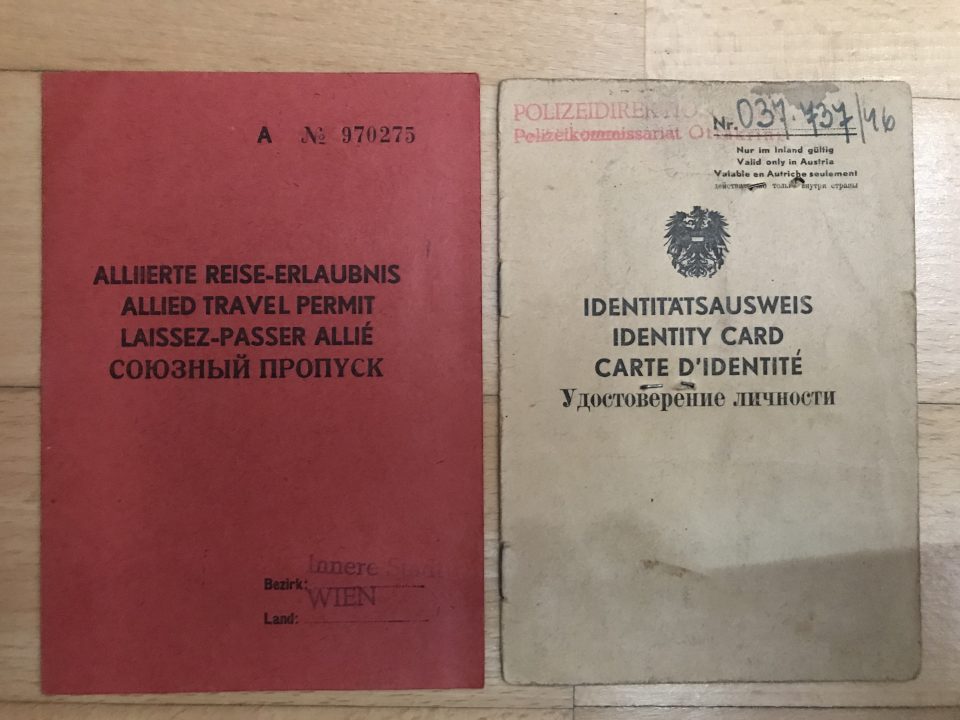

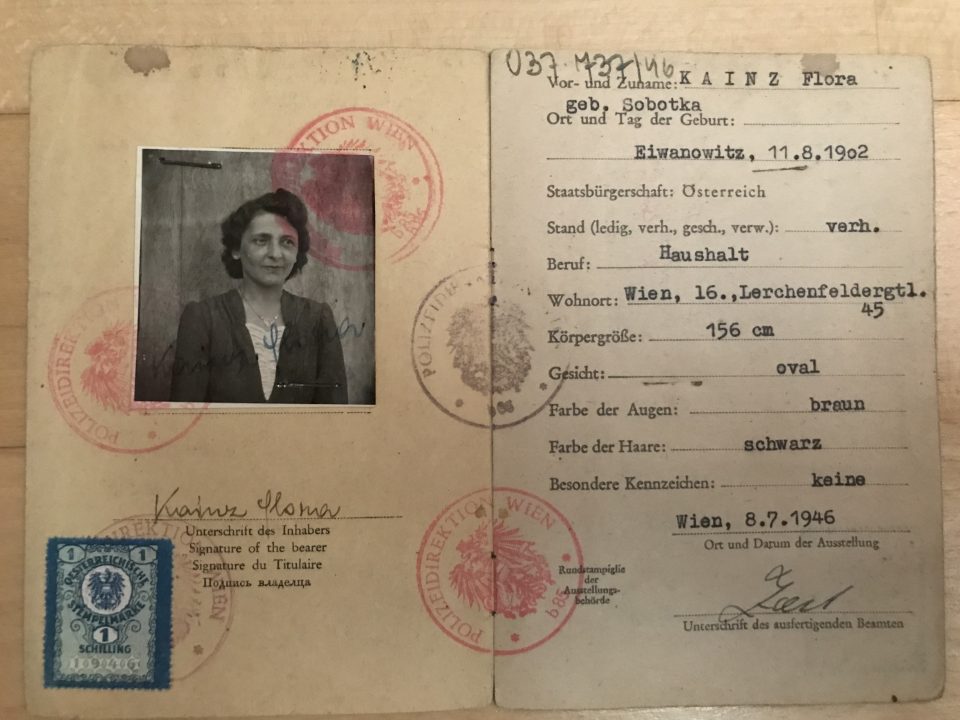

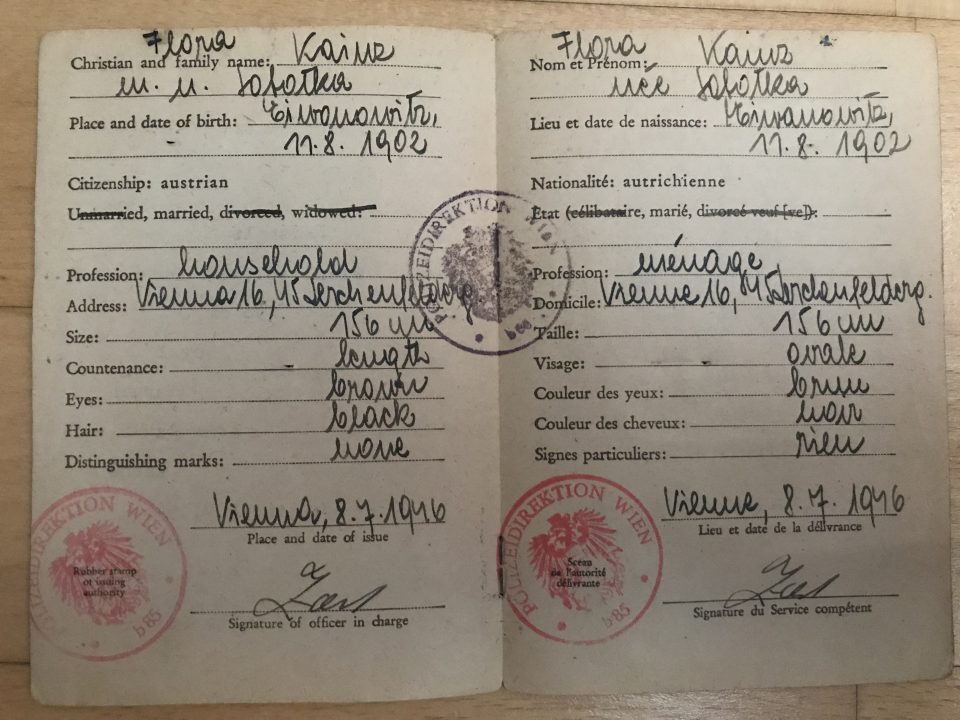

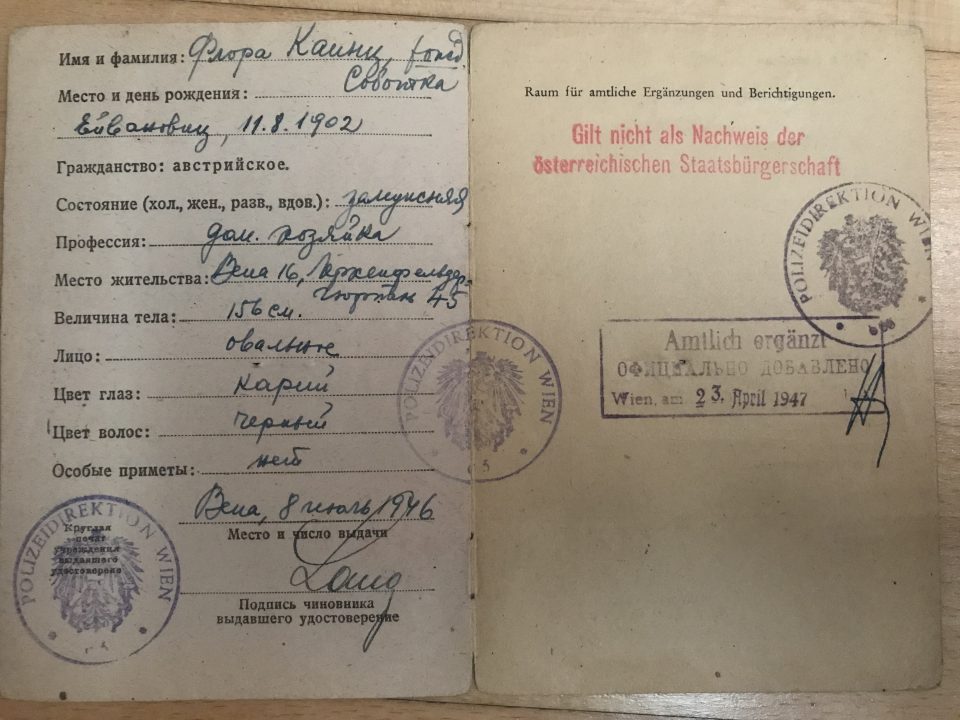

Allied Travel Permit and Allied Identity Card for my grandmother, Flora (Lola) Kainz 1946 in four languages: German, English, French and Russian

Within a very short time the Vienna tramways were functioning again in most parts of the city and in 1946 nearly 250 kilometres of tramlines were restored. The trams were again used for goods transport, just as in times of war, but now masses of bomb rubble were transported to disposal sites. Unfortunately the winter of 1946/47 was an extremely harsh one which meant a setback for the operation of the tramways and several tramlines had to stop their service. The reconstruction of the “Stadtbahn” took longer due to the severe bomb damages, but in 1954 also this traditional means of public transport was reopened. At that time many experts and politicians dreamt of a “car-friendly” city and wanted to get rid of the slow tramways and replace them by buses, but fortunately, contrary to many other European big cities, the tramways continued to flourish in Vienna because the nostalgic Viennese did not want to do without them. Nowadays several European cities revive their old tramlines or build new ones to boost the inner city public transport. In 1946 the Viennese city council decided to merge the different communal enterprises into one communal group of companies, the “Wiener Stadtwerke” (WStW). The merger of the communal electricity, gas and transport works was completed in 1949.

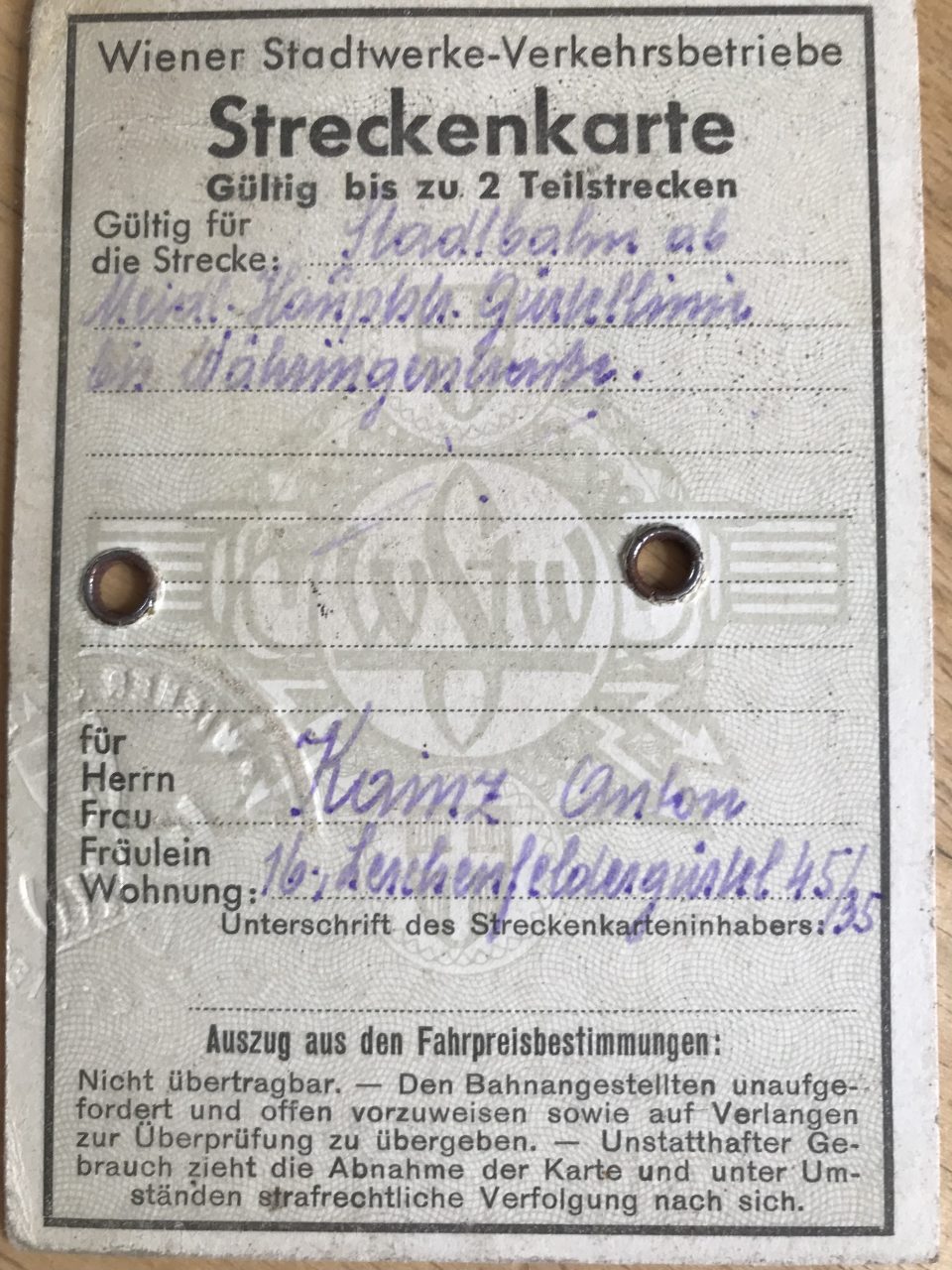

Monthly tram ticket of my grandfather Anton Kainz 2 August to 1 September 1962

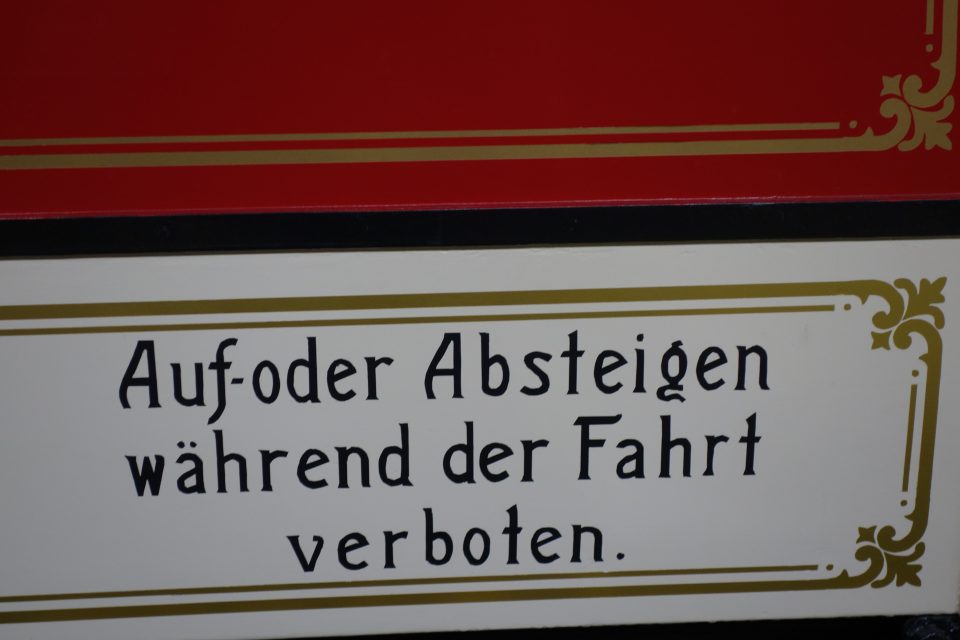

Before the invasion of Hitler in 1938 smoking was allowed in a specially marked carriage of the Vienna tramways – usually the last carriage – and the “Stadtbahn”, which was rather uncommon in the rest of Europe, but the Nazis introduced the non-smoking policy in the Vienna tramways. With the liberation from the Nazis several Viennese smokers challenged the non-smoking policy and pledged for a return to smokers’ carriages. It was the duty of the conductor to execute the non-smoking policy, which was quite difficult in the face of smoking Allied soldiers on the tram who could not be admonished by the conductor. Similar heated discussion followed the introduction of ticket inspectors, called “Schwarzkappler” (black caps) by the Viennese because of their black uniform. Especially for young Viennese fare dodging had become a sport and the Vienna tramways had to stop this “habit”. The young loved another sport connected to riding the tramways, which was jumping on and off running trams and clinging to the running board like free riders (“jumping on the bandwagon”). Especially in the 1950s this sport was commonly practised, mostly on the way to and from sports events such as football matches. Today both the non-smoking policy and the ticket inspectors form part of the public transport policy of Vienna, but free riding has lost its glamour because there are no more open carriages.

Warning sign against free riding 1950

“Vorortelinie” 1986 (before renovation)

Literature:

Farthofer, Walter, Tramway Geschichte(n). Die Wiener Straßenbahner im Kampf gegen den grünen und braunen Faschismus, Wien 2015

Farthofer, Walter, „Menschenmaterial: unbefriedigend“. Zwangsarbeit bei den Wiener Verkehrsbetrieben, Wien 2017

Hödl, Johann, Vom Sesselträger zum Silberpfeil. 200 Jahre Wiener Verkehrsgeschichte, Wien 2015

Kaiser, Wolfgang, Die Wiener Straßenbahnen. Vom „Hutscherl“ bis zum „Ulf“, München 2004

Wegenstein, Peter, Wege aus Eisen in den Straßen von Wien. Zur Geschichte der Wiener Straßenbahnen, Schleinbach 2018