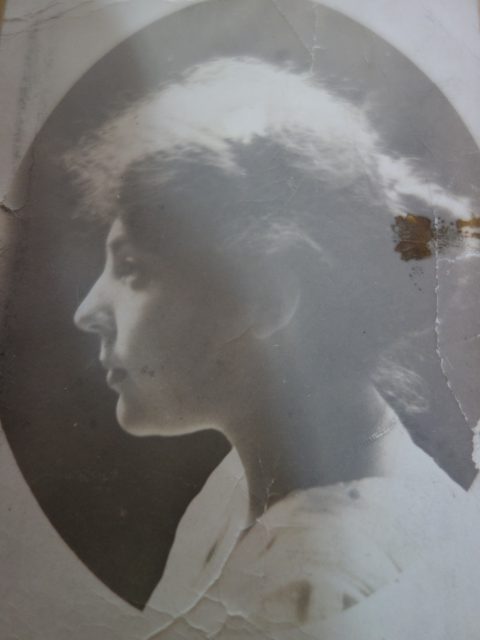

Käthe as a young woman in Vienna

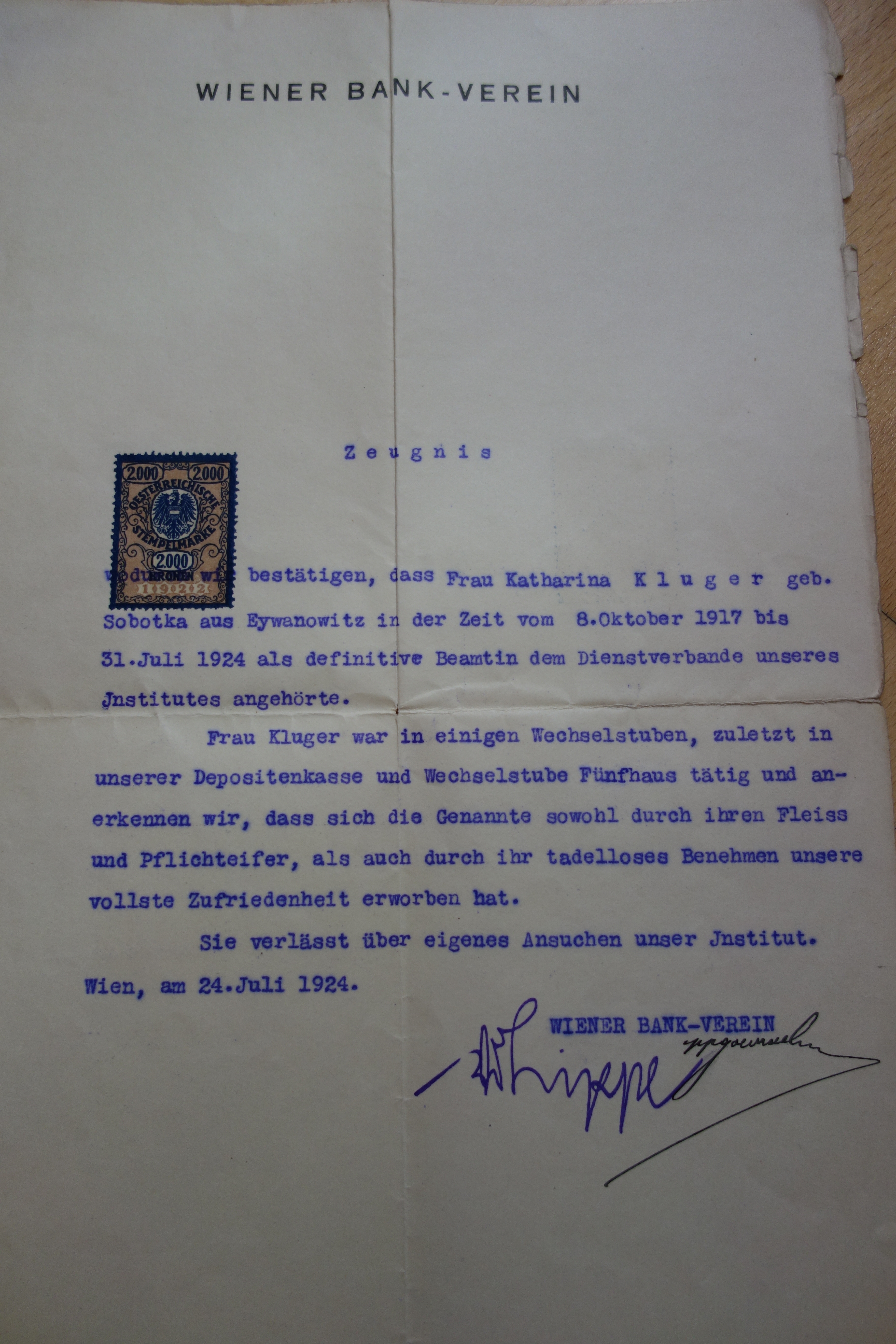

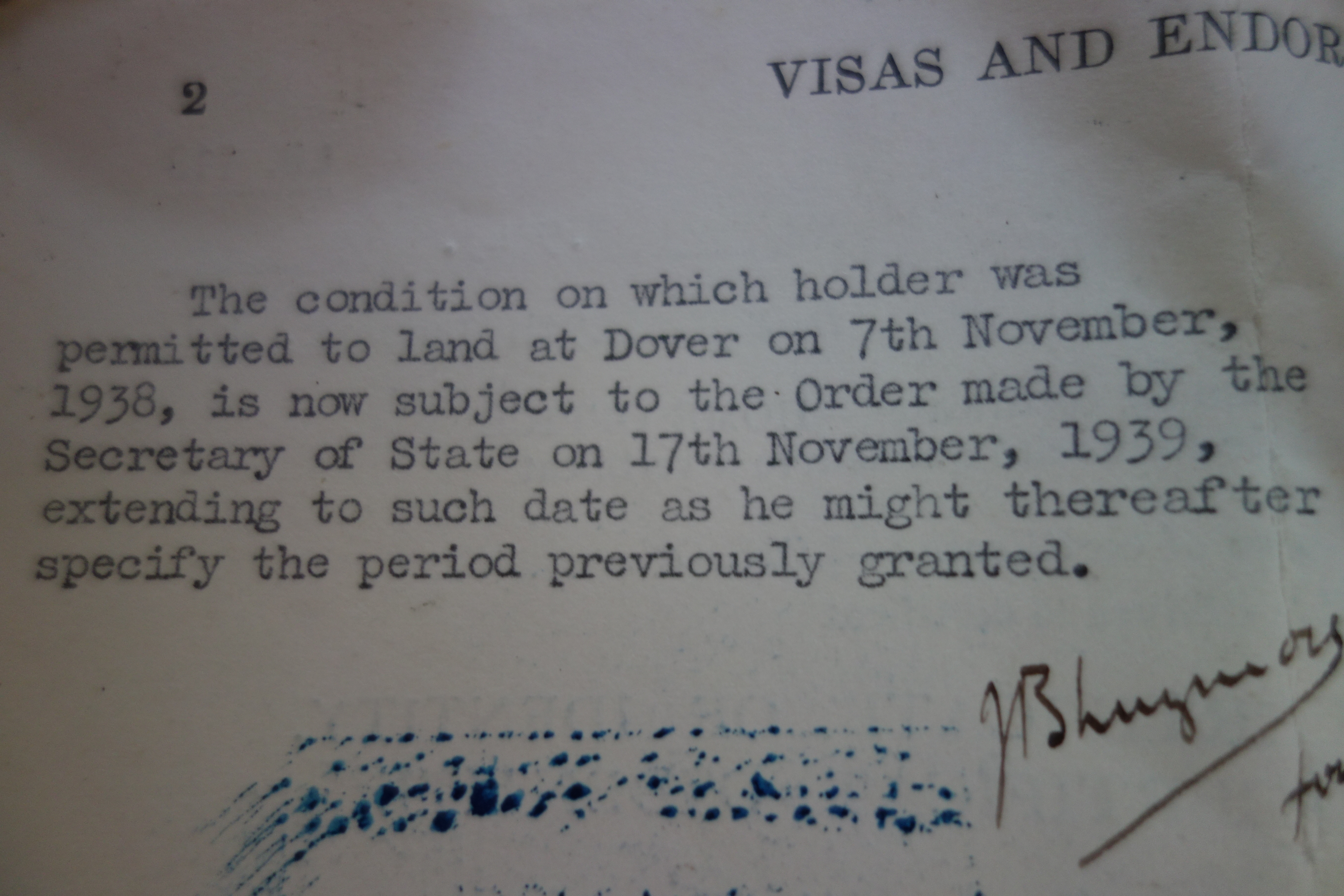

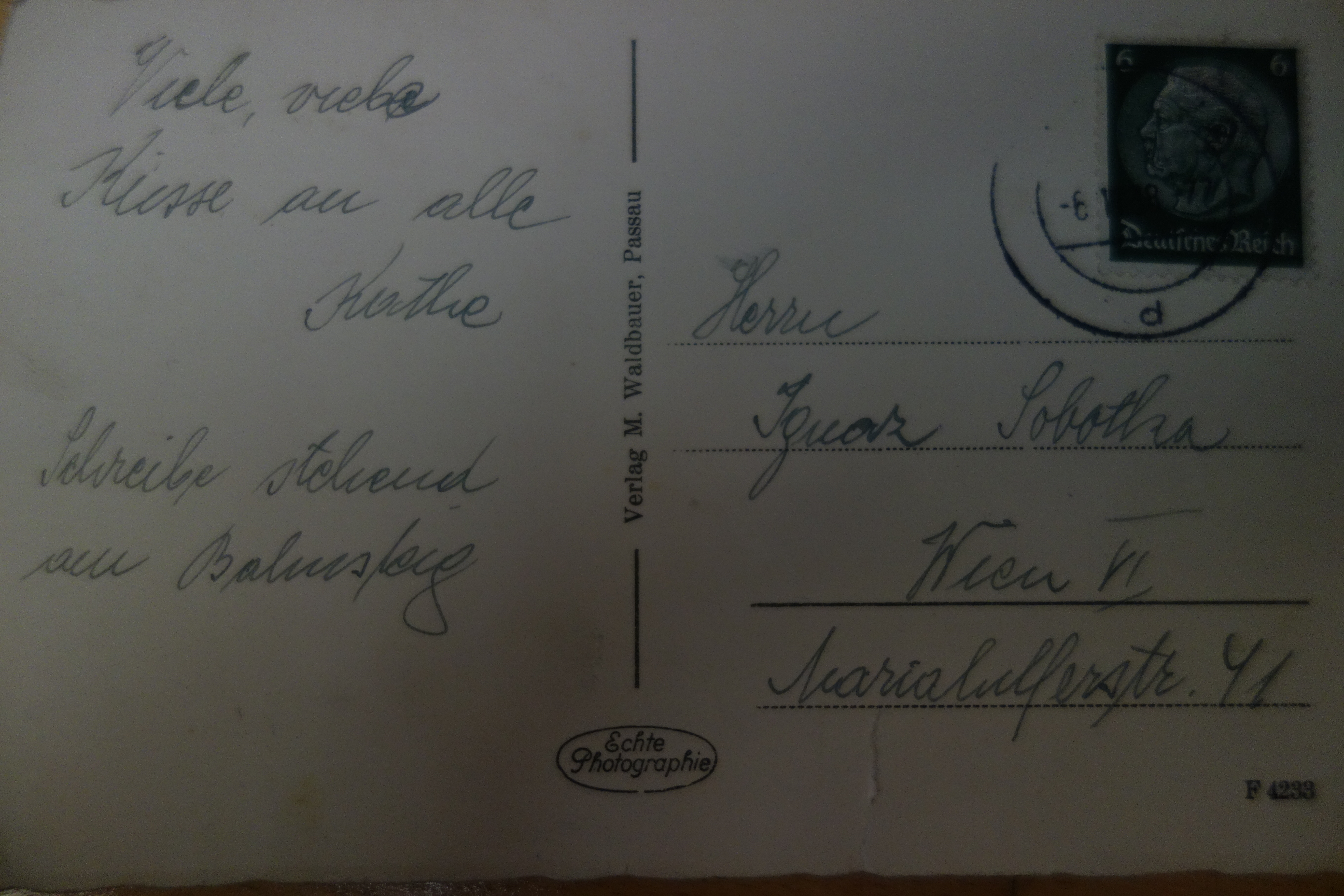

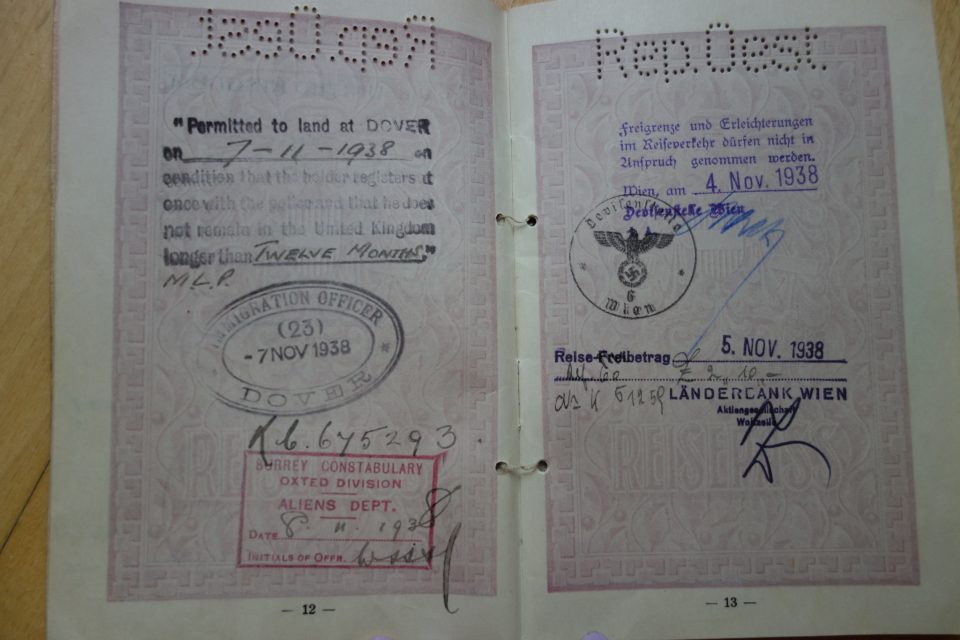

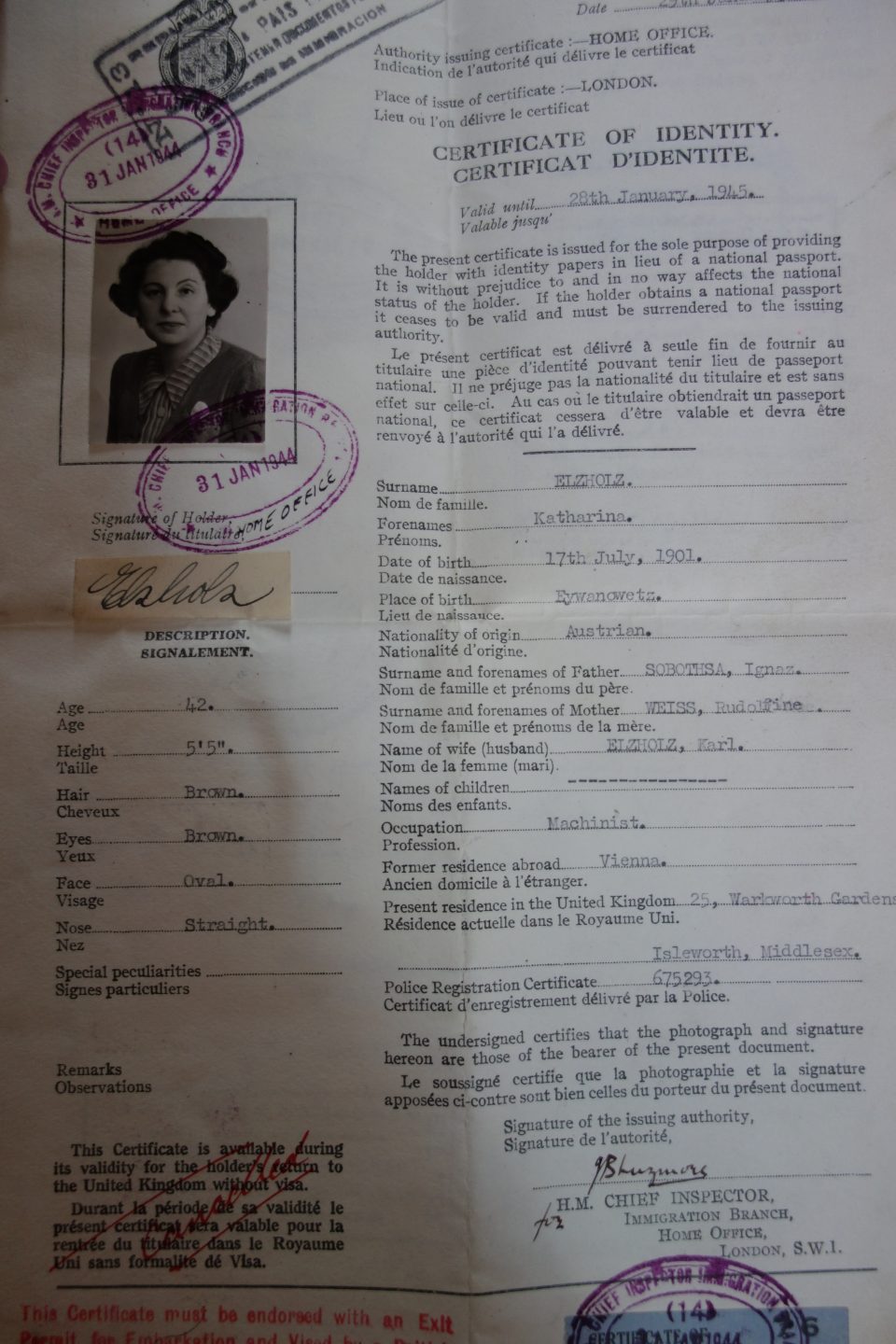

My great-aunt Käthe, born in 1901, was a bank clerk at the Wiener Bank Verein and had lost her first husband, Poldl Kluger, soon after the wedding, victim of a lung disease, in illness that was wide-spread in Vienna at that time. When she lost her job at the bank in 1924, being tall and slim, she made ends meet by accepting occasional jobs as a fashion model. After the civil war in 1934 and the coup d’état of the Austrian fascists, Käthe, an assimilated and agnostic Jewess and a socialist, realised that sooner or later she would have to flee Austria. Being single facilitated the decision-making process. She diligently prepared for her escape from the Nazis by learning English and acquiring cooking skills. She then applied for the position of cook in a wealthy English household and landed in Dover on the 7th of November 1938. Having arrived at a safe haven in England with a domestic permit, she tied to get out of Austria as many of her family as possible. She worked in 25, Warkworth Gardens in Isleworth in Middlesex and managed to convince her generous and understanding mistress to hire her younger sister, Agi, as a maid in the same household and by that offered her a last-minute escape from deportations from Viennese collection points in the 2nd district to the concentration camps of the Nazis. So let’s look at this special rescue model, a window of opportunity for young Jewish women from Austria in 1938, which was closed in 1939.

Käthe’s employment as a bank clerk at the “Wiener Bank Verein” 1924

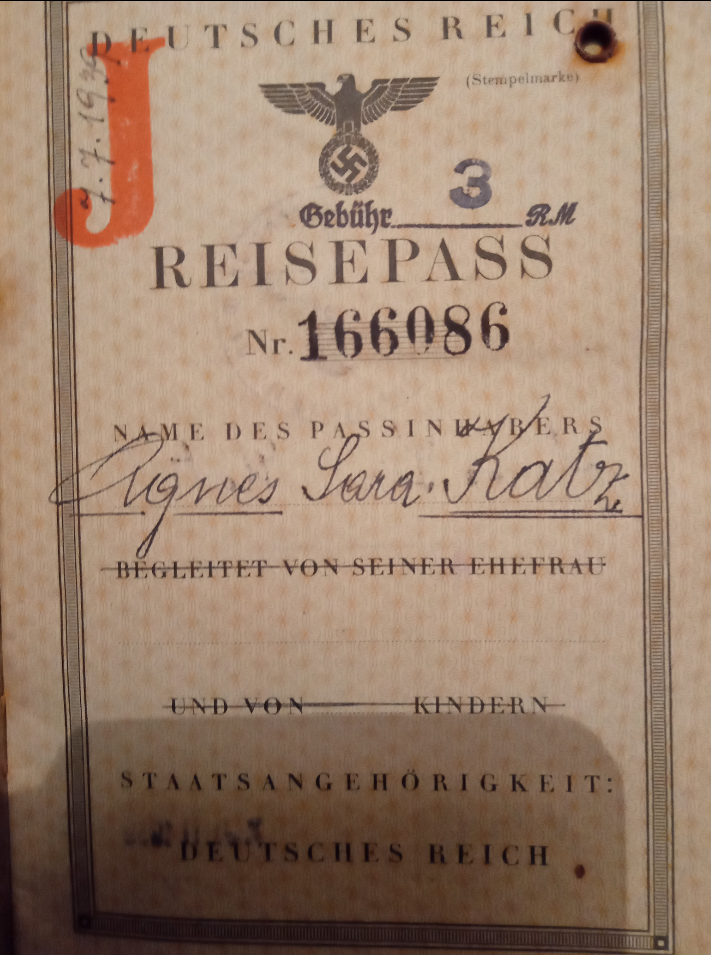

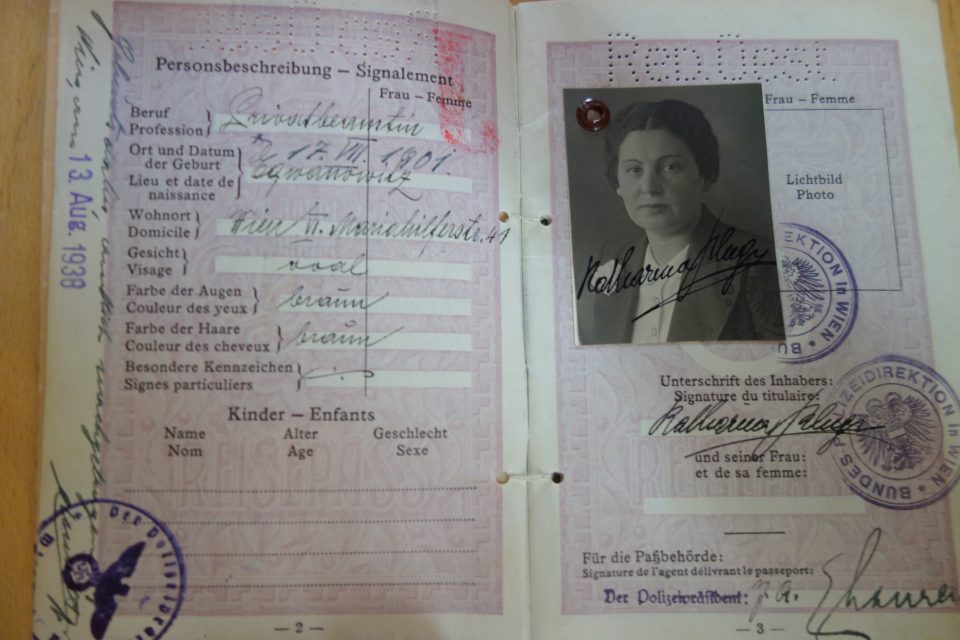

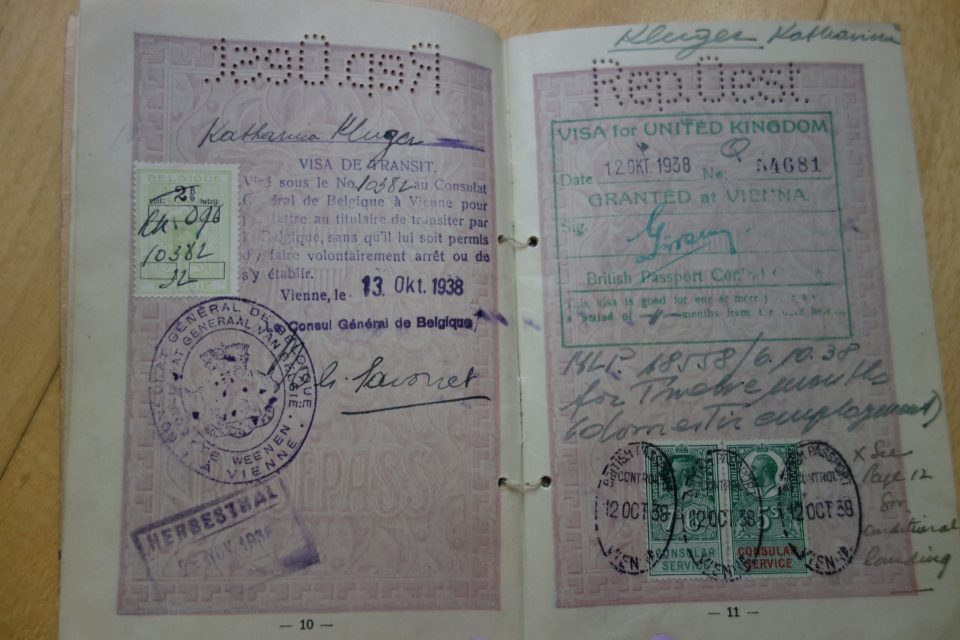

Käthe’s passport stamped with a “J” for “Jude”

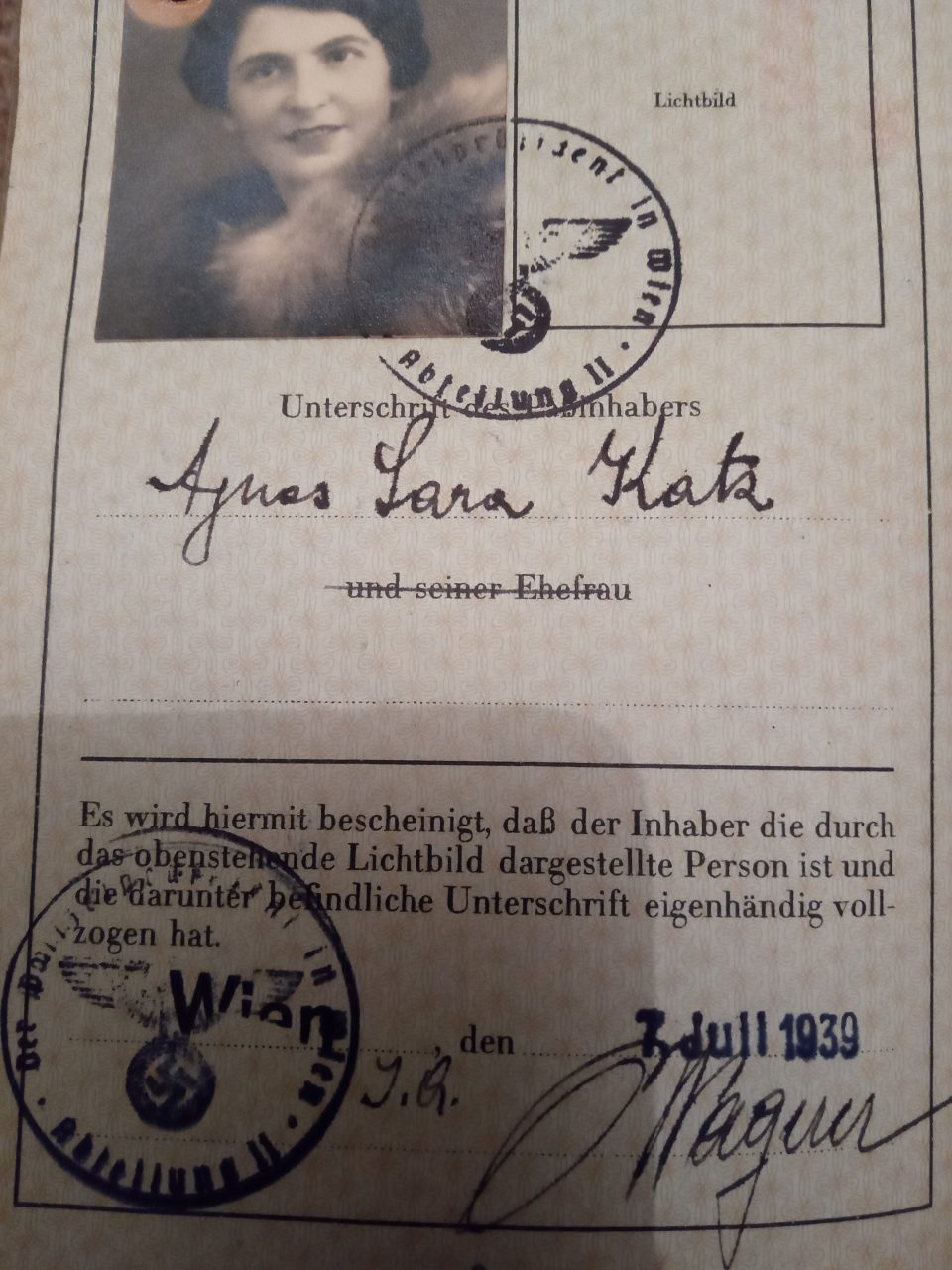

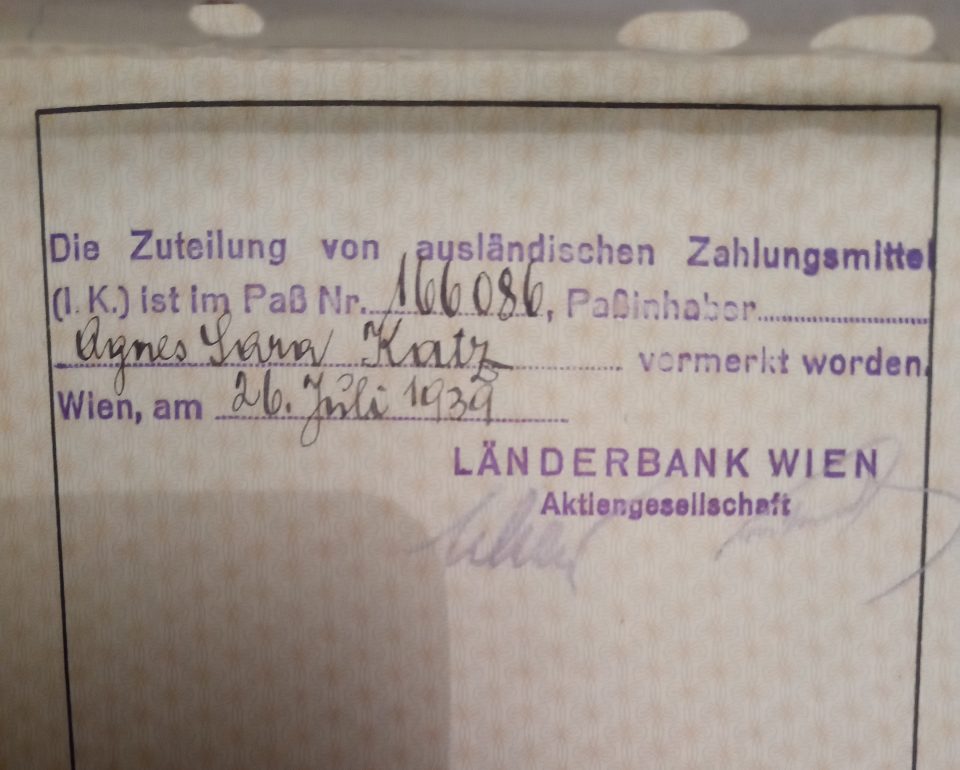

Detail of the passport

Around 20,000 Jewish women, three quarters from Austria, fled in 1938/39 to England with a so-called “domestic permit”. This was a work permit for foreign domestic staff which British employers could use since the 1920s to alleviate the chronic shortage of maid servants despite otherwise very strict immigration restrictions. A considerable percentage of these women were not actually domestics by trade, but had only been able to enter the UK on permits for domestic work. They found themselves in a relationship of dependency to their mistresses, but work as a maid guaranteed a livelihood because domestic servants were the only ones who had permission to legally work in England. Yet they were officially not allowed to leave the areas of these private households. The majority of male refugees with a permission to enter the UK needed an affidavit from an influential personality or an institution.

Postcard of Käthe written to her parents in Vienna from the border to Germany, Passau 1938

During the First World War the proportion of women employed in the metallurgical, mechanical, electric and chemical sectors of the industry had increased dramatically in the UK. The employment of women in clerical, commercial, agricultural and industrial occupations in July 1918 as compared to 1914 showed a rise of nearly 1.6 million in addition to the 3.2 million already employed in July 1914. So in 1919 after the end of World War I more than a million women had to be integrated into the peace economy or sent home. Many English households had reduced their domestic personnel during the war, rather to save costs than due to patriotic feelings. Now they wanted to return to their accustomed way of life. Yet domestic service was not a truly attractive alternative to independent work in a factory or any other business. Maids were reluctant to return to domestic service because they received higher wages, enjoyed more personal freedom and experienced the camaraderie of the colleagues at the factories. They did not want to end up in the stifling dependency to a mistress again. So a lack of domestic service personnel was prevalent in England until the 1930s. Interestingly, domestic service did not only persist in England in the interwar years, it even expanded. That’s why in 1937 the National Council of Women urged the Minister of Labour to grant permits freely to “approved young women of other nationalities, who desire to come to this country to enter domestic service; such permits to be renewed automatically upon satisfactory evidence that these foreign women continue to be engaged in domestic service.” The argumentation of the National Council of Women was that “…the difficulty of obtaining domestic help tends to restrict families to an extent dangerous to the State”.

The main reason for this shortage of maids were the abysmal conditions under which domestic servants had to work and nothing had really changed since the end of World War I. Domestic work still employed more women in 1930 than any other occupation, but it was the least organised of all trades, both as to employers and employed. It was the least regulated by law with a completely inadequate pay. A National Domestic Worker’s Union was only founded in June 1938 when the refugee movement of young Austrian and German women to England was already in full swing and the trade union representatives were vehemently opposed to the continued importation of foreign domestic workers, who were not eligible for membership in the newly founded union anyway.

Many young Austrian women applied for positions in England. Several charitable organisations in Vienna worked together with English employment agencies to send young women as maids to English private households, e.g. “Englisch-österreichische Damen- und Dienerschaftsunion” or “Klub für österreichische Hausgehilfinnen”. Some of them offered English language classes and cookery lessons against payment of a fee. The English employment agencies linked up the organisations in Austria with the future employers in the UK, then the women received the domestic permits and left Austria. The British “Aliens Order 1920” required from the UK employers a permit that was issued by the Ministry of Labour. The permit was issued on condition that no British citizen could be found for the vacancy. A minimum wage of 36 pounds p.a. or 15 shilling a week for domestic servants was introduced in 1931 to avoid wage dumping. Permits were issued for one year and could be extended two further years. Until 1937 there were no work or residence permits necessary afterwards. One reason why many more Austrian than German women were hired could have been a preference of English mistresses for Austrian maids, who had a reputation as excellent cooks. On 27 January 1939 the Manchester Guardian even published “Recipes from Vienna. By a refugee” and suggested “Erdäpfelsuppe, Faschierter Braten & Nusstorte” for Sunday dinner. The Viennese Kitty Köberle self-published a booklet “Wie koche ich in England” in August 1938 in preparation for British domestic service, which included a dictionary for kitchen vocabulary and instructions how to make tea etc. Käthe was much praised for her cookery skills by her mistress and her mastery of the British as well as the Austrian traditional dishes. The two women were bound by a life-long amicable relationship. Käthe introduced “English breakfast” in our family when she returned after the war and she left several excellent English recipes, e.g. English marmalade, on top of the many Austrian ones.

Before 1938/39 the percentage of Jewish girls who applied for a domestic permit was very low because they were reluctant to become servants when other alternatives as white collar or factory work were available. When the Nazis took over they introduced a programme to induce non-Jewish German and Austrian maids to return to their countries of origin. As a result, a very large number of non-Jewish servants from Germany and Austria were compelled by the German government to leave England. Consequently, the demand for household help increased again significantly in the UK. This opened up opportunities to place Jewish women, not older than 45, who were not allowed to do any other kind of work, as domestics in English private homes.

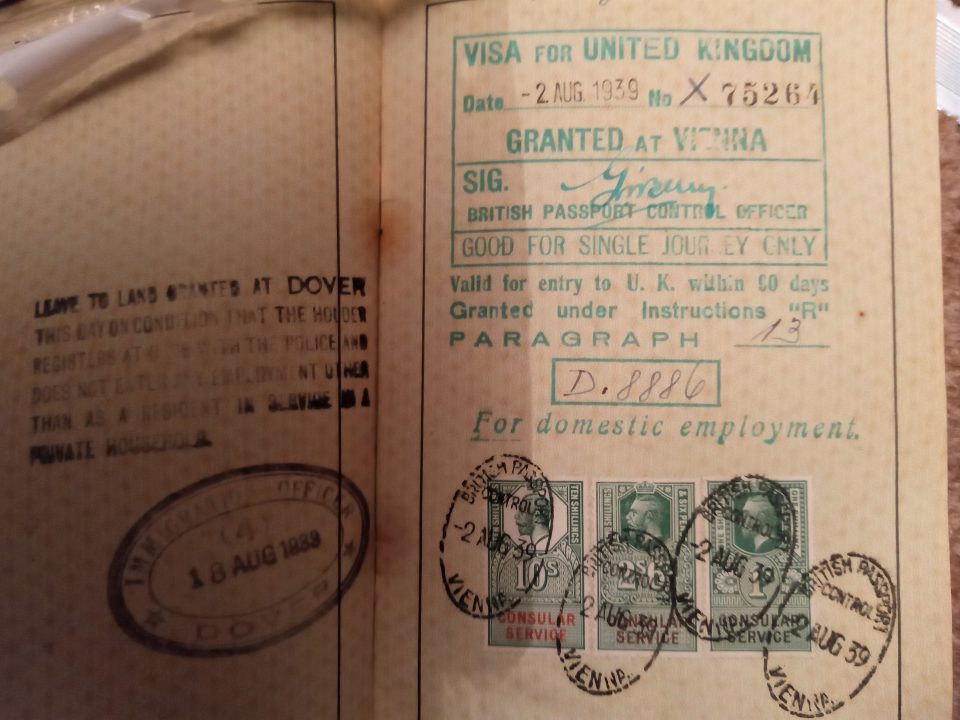

When Hitler rose to power in Germany in 1933 the UK refugee policy had already been quite restrictive despite a long tradition of offering asylum to political refugees. Already in 1905 the “Aliens Act” ordered Immigration Officers to reject penniless asylum seekers as “undesirable immigrants” as they might incur costs for the British state. In 1920 the “Aliens Order” stipulated that only people who had the necessary means to provide for themselves and their families were allowed to enter the UK. Yet throughout the whole period of 1933-1948, little of the policy for managing the refugee influx was formally articulated and the British system allowed officials wide scope for decision-making in line with their departmental objectives. From 1933 on the Jewish Community offered to take over all costs incurred by the temporary or permanent care for Jewish refugees “without time limit and without ultimate charge for the British state”. Donations and fundraising, which was originally organised by the Central British Fund for German Jewry, later Central British Fund for World Jewish Relief, provided the means. On the basis of this guarantee of provision for the Jewish refugees, the cooperation with the British Home Office and volunteer refugee organisations was started. In 1938 the Home Office demanded the setting up of an umbrella organisation for all refugee organisations to facilitate the coordination of the rescue effort. The “Aliens Order 1920” enforced the principle that no foreigner was permitted to take on a job that a British citizen would apply for. Yet maids could still enter the UK without any bureaucratic hassle with their domestic permits and many Austrian women took this opportunity. From May 1938 on visa were required for all travellers from Germany and all areas occupied by Germany, i.e. Austria, the Sudetenland etc. The test was supposed to be whether or not the applicant was likely to be an asset to the UK. If, however, the holder of a permit for domestic service appeared unsuitable, a visa could be withheld. The pre-selection of refugees was the task of the British embassies and consulates. As the Vienna embassy was turned into a consulate with fewer employees after the take-over of the Nazis in March 1938, there was a bottleneck in handling visa applications. Even after the international Evian conference on the refugee crisis Britain rejected any interference from abroad concerning its handling of the refugee problem. There was never an opening up of British borders for refugees from Nazi Germany and its occupied territories. Those who had found refuge in the UK, like Käthe, Agi and her family, knew how lucky they were. It may be estimated that perhaps only one in ten succeeded in gaining entry, depending on the profession. Only five per cent of Austrian doctors who applied for entry in the UK were granted visa, but 85 per cent of maids.

In 1939 the conditions under which a refugee would receive a domestic permit were formulated. Among them were a medical certificate, the women had to be single, divorced or widowed and between 18 and 45, married women were only accepted if the husband was already in the UK and married couples were allowed entry only if both were employed in domestic services – single men were excluded. The work undertaken had to be in a private household and the minimum wage had to be paid. Knowledge that domestic service in Britain offered one of the best methods of escape came through classic immigrant sources of information, such as friends, family and the British domestic employment agencies. One large company specialised in recruitment from Vienna and that was another reason why so high a proportion of foreign domestics were Austrians. Finally, Jewish communal organisations provided up-to-date information on the different immigration policies operating throughout the world in journals such as “Jüdische Auswanderung”. The Jewish community in Vienna, the “Isrealitische Kultusgemeinde” already informed the readers of its “Zionistische Rundschau” about the possibility of a domestic permit for England in June 1938.

Yet Jewish domestic servants were not always welcome in the UK. Unfortunately also Britain had a long tradition of anti-Semitism that did not just erupt during the Second World War and the British authorities were aware of anti-Jewish sentiment in the British public. Even Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain wrote in a private letter to his sister Hilda in 1939, “I believe that the persecution arose out of two motives, a desire to rob the Jews of their money and a jealousy of their superior cleverness. No doubt Jews aren’t a loveable people. I don’t care about them myself; but that is not sufficient to explain the pogrom.” Politeness, hospitality and a general willingness to help among the British population, as evidenced by the actions and attitude of Käthe’s employer, did not exclude a certain anti-Semitic tendency in the general public. Despite the pressure from the National Union of Domestic Workers, the government continued to issue domestic permits to Jewish women in great numbers. Probably because the government was under the influence of the wealthy middle class that was in urgent need of domestic servants rather than the unions. There were even some who opposed the payment of the minimum wage. A pastor wrote to the Domestic Bureau, which was responsible for checking the payment, in December 1938, “I am amazed to find that such a stipulation is being made by the Home Office that 15 shillings per week should be the minimum wage… I cannot contemplate paying so much to the refugees who probably know nothing about housework and cannot answer the telephone for some month.”

Although Britain stressed that it only granted “temporary refuge”, British authorities and, above all, the Jewish aid organisations were focusing on the importance of assimilation and good conduct in the UK. The German Jewish Aid Committee issued a brochure in English and in German in 1939 with the title “While you are in England. Helpful Information and Guidance for every Refugee”. In this brochure the Jewish refugees were advised to learn English as quickly as possible and not to speak German in public, never to criticise Britain, the government or its policies, not to join any political organisation, to be polite, to show good manners, not to speak loudly or wear unusual clothes, to assimilate and to behave according to the values und customs of the British, to help others and to serve the host country. The British historian Bill Williams sees this brochure as “the most explicit form of behavioural control ever attempted by British Jewry”. The refugee organisations expected the newly landed refugees to show a certain degree of humility towards the country that saved them. Even more humility was expected from those employed in domestic service. The Domestic Bureau issued a pamphlet in English and German in 1939 “Some Suggestions for Employers and Employees”, in which they stressed that the English appreciated low voices and slow movements and it was therefore recommended to move in the house as quietly as possible. It was further advised to wear woollen underwear and a warm coat in the house because British houses tended to be much colder than houses on the continent as central heating was practically unknown in the UK. For the benefit of the employers the pamphlet pointed out the differences between running a household in Britain and on the continent. Käthe remembered an episode, when her mistress came excitedly into the kitchen and told her the new maid, her sister Agi, was throwing the blankets and bedspreads out of the window. In fact, Agi was airing the blankets on the window sills in the morning as it was usually done in Austria in good weather with the duvets. What’s more the Domestic Bureau tried to raise the mistresses’ awareness to the fact of class differences, namely that many of the Jewish maids came from a wealthy middle class background and had higher education and might therefore have had deficiencies in domestic skills. This pamphlet was also designed to protect refugees from exploitation because it stressed the payment of the minimum wage and the obligation of the employer to contribute to the compulsory health insurance. Suggested working hours were 88 hours per fortnight for maids under the age of 18 and 96 hours per fortnight over 18, but this was no binding regulation. A half day off per week was common. There was exploitation of maids, but also the other extreme of close and often life-long friendships that developed despite the imposed mistress-servant relationship, as in the case of Käthe.

In 1940, during the war, the Domestic Bureau issued another brochure in which it stressed again the differences of English households, for instance that maids were supposed to handle open fires and kitchen stoves fired with wood and coal while on the continent central heating and gas stoves were common. Furthermore English food was different and although the employers might have enjoyed a new dish from the home country of the maid, shopping for it might have been difficult, stated the brochure. It reminded the employers that “for most of the maids this is a new career…. England is a foreign country for these maids, and they may be home-sick, even though their homeland has become for them intolerable.” As for the refugee domestic servants, the brochure reminded them that “they are received into English households through friendliness and good will and it behoves them to be a credit to their people and to their religion, as the public are apt to judge all from one.” Many of the women found themselves in this new situation quite unprepared, unlike Käthe, who had prepared herself diligently before departure. Many of them encountered this new way of life at a period of their life when they were experiencing tremendous emotional stress. Domestic servants in Britain were incorporated in a strict hierarchical system with little scope for personal freedom and decision-making. They were completely dependent on a single person, their mistress, and suffered under this dependency, especially in the countryside where they were much more isolated than they had ever been in their lives so far. The hierarchy among the domestic service personnel in larger households was completely unknown to these refugee women.

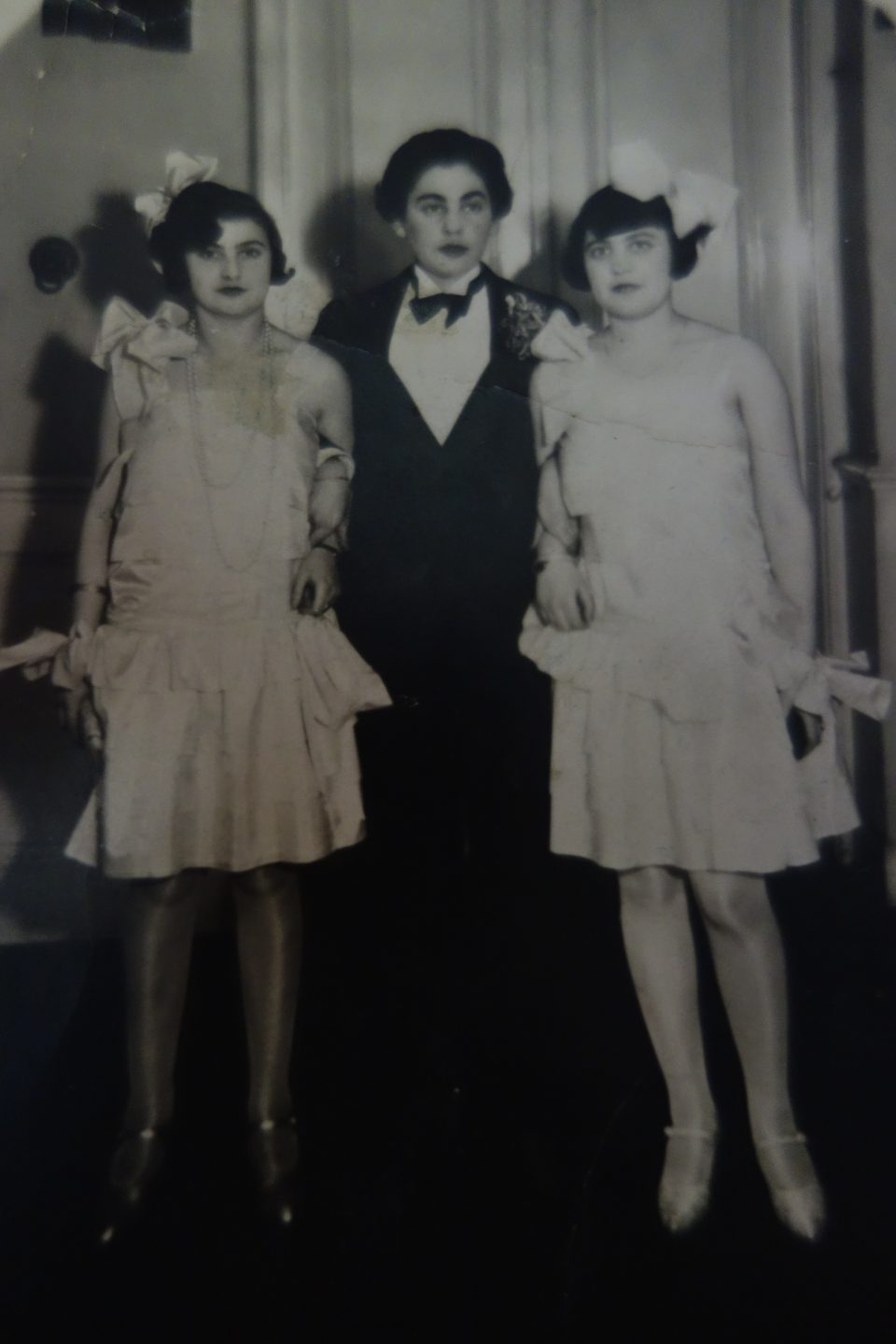

Käthe in the middle (Carneval in Vienna)

Käthe in Vienna

The classified ads below were placed in the London Jewish Chronicle between 1938 and 1939 by Viennese Jews in desperate search for employment in Great Britain:

| Please help me. I am an intelligent 19-year old girl from Vienna and would be more than thankful for the possibility of finding work in England. Please don’t pass by my appeal – Grete Landauer, 26/10 Stumpergasse, Vienna 6 | Austrian domestic servant asks noble people to help her bring her old mother to this country. Is able partly to maintain her – Rosi Grossmann c/o Mrs. Cutcliffe, Broad Stand, East Horsley, near Leatherhead | Non-Aryan of German nationality, 51 years old, single, former merchant, compelled to emigrate and in a desperate situation, implores for a post as domestic worker and for permit enabling him to come to England – Write to Paul Weiss, Vienna VII, Neubaugasse 7, Tür 61 |

Literature:

Bollauf, Traude, Dienstmädchen – Emigration. Die Flucht jüdischer Frauen aus Österreich und Deutschland nach England 1938/39, 2011

Dwork, Deborah & van Pelt, Robert Jan, Flight from the Reich. Refugee Jews 1933-1946, 2009

Kushner, Tony, An Alien Occupation – Jewish Refugees and Domestic Service in Britain 1933-1948, 1999

London, Louise, Whitehall and the Jews 1933-1948. British Immigration Policy and the Holocaust, 2000

Wasserstein, Bernard, Britain and the Jews of Europe 1939-1945, 1999

A novel based on the experiences of a refugee maidservant in England in the late 1930s: Solomons, Natasha, The House at Tyneford, 2011