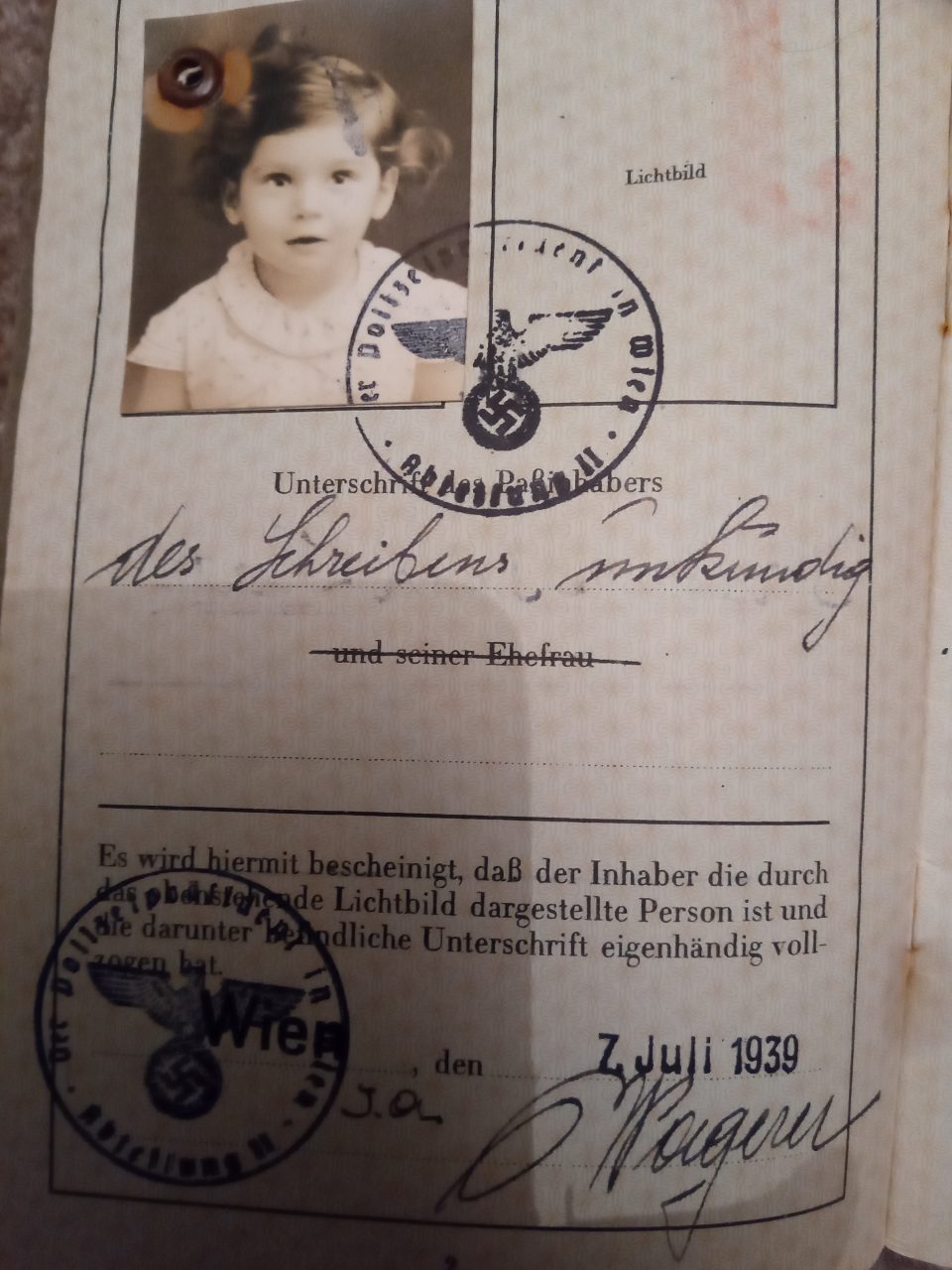

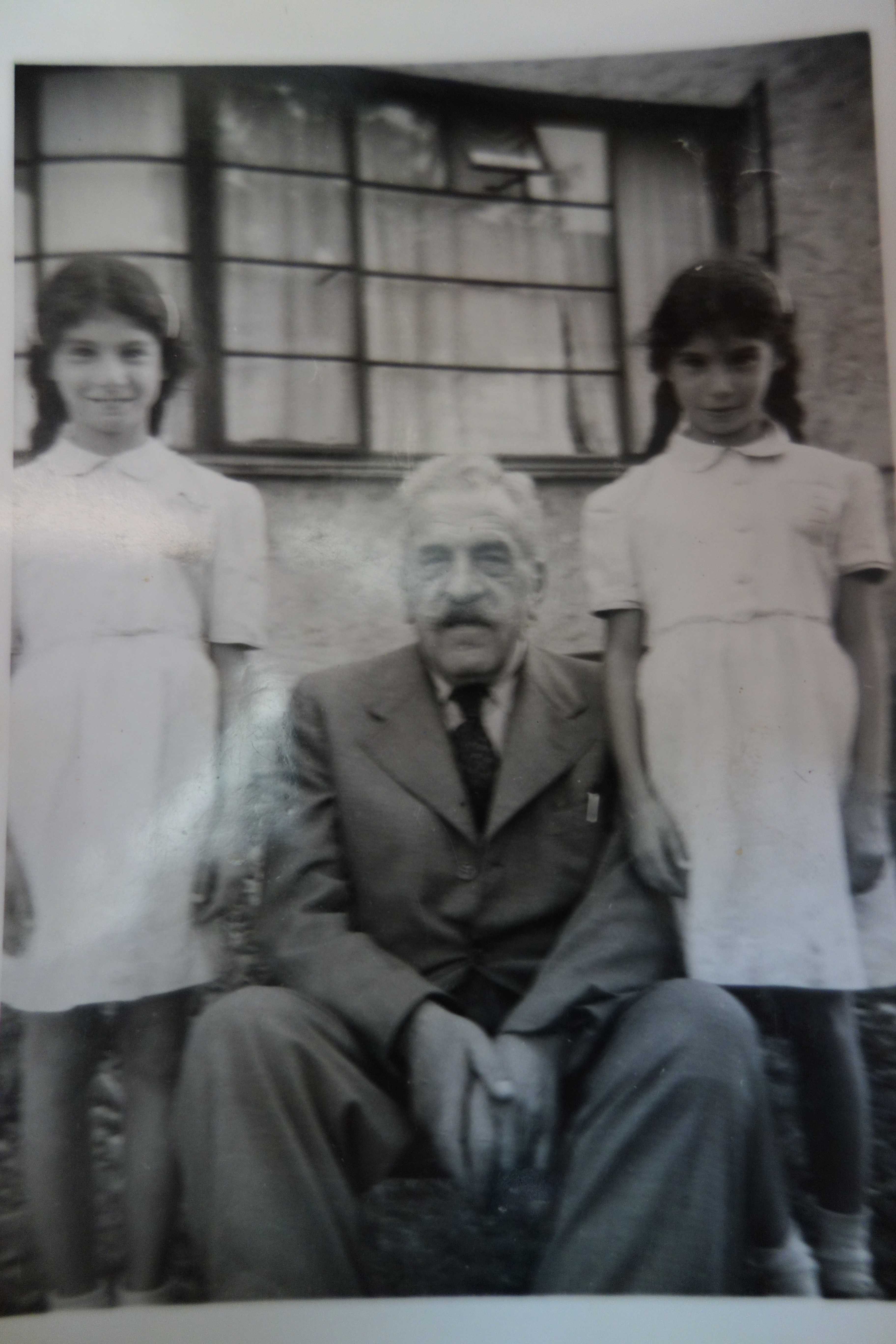

Agi with her twins, Susi and Josi

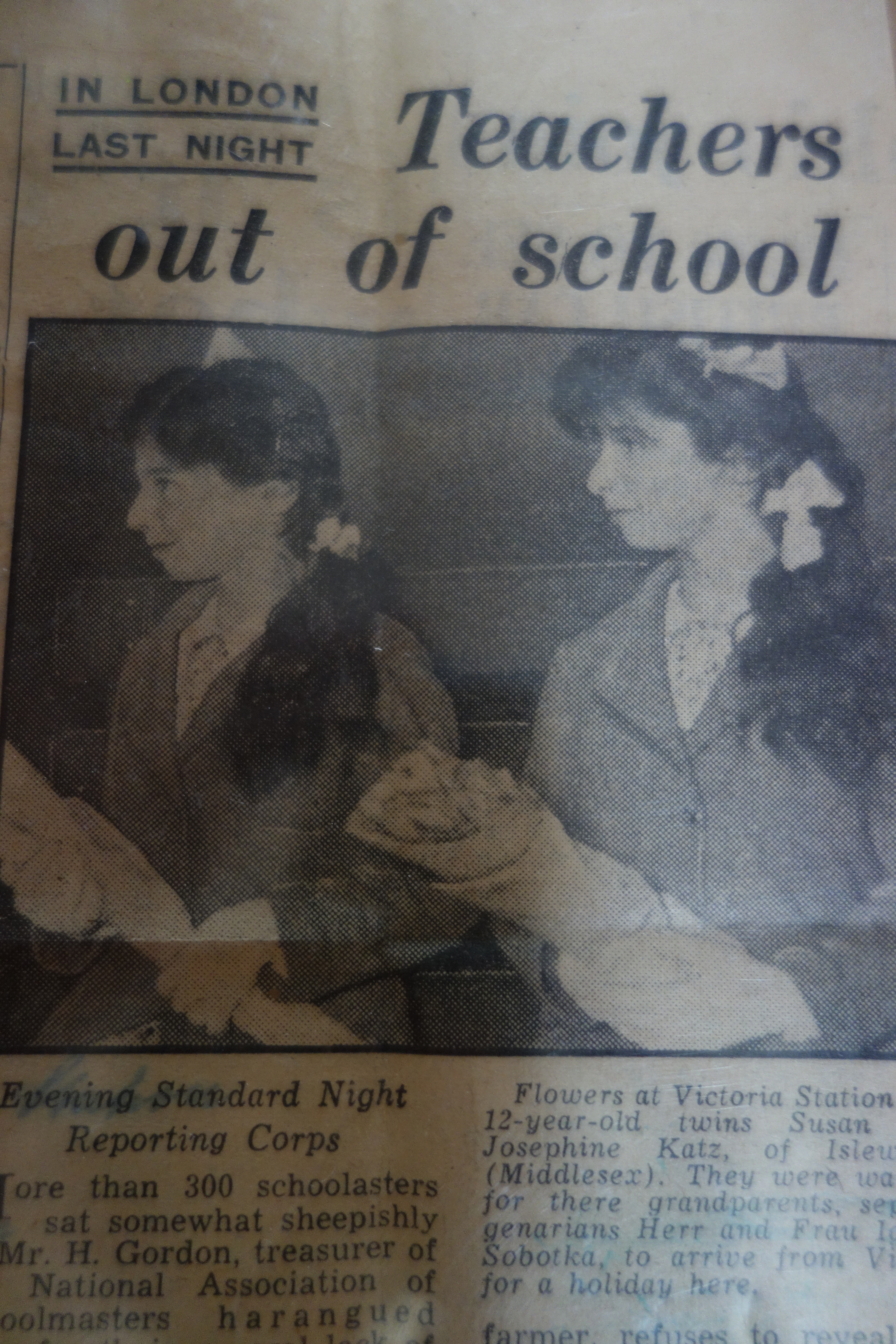

Agi Katz, the younger sister of my grandmother had found refuge in England as a maid in the household of her sister Käthe’s mistress, but she could not bring her two-year-old girl twins, Susi and Josi with her. Käthe had helped to organise from across the channel to have the girls transported via a “kindertransport” to England to Quaker foster families. Unfortunately the twins had to be separated not only from their mother, but also from each other, which caused serious and long-lasting emotional damage. They were reunited with their parents after the war. The family then decided to become British citizens and remain in the UK. In 1948 the Evening Standard printed a picture of the twins then aged 12, “Flowers at Victoria Station. 12-year-old twins Susan and Josephine Katz of Isleworth (Middlesex). They were waiting for their grandparents, septuagenarians Herr and Frau Ignaz Sobotka to arrive from Vienna for a holiday here.” (see below)

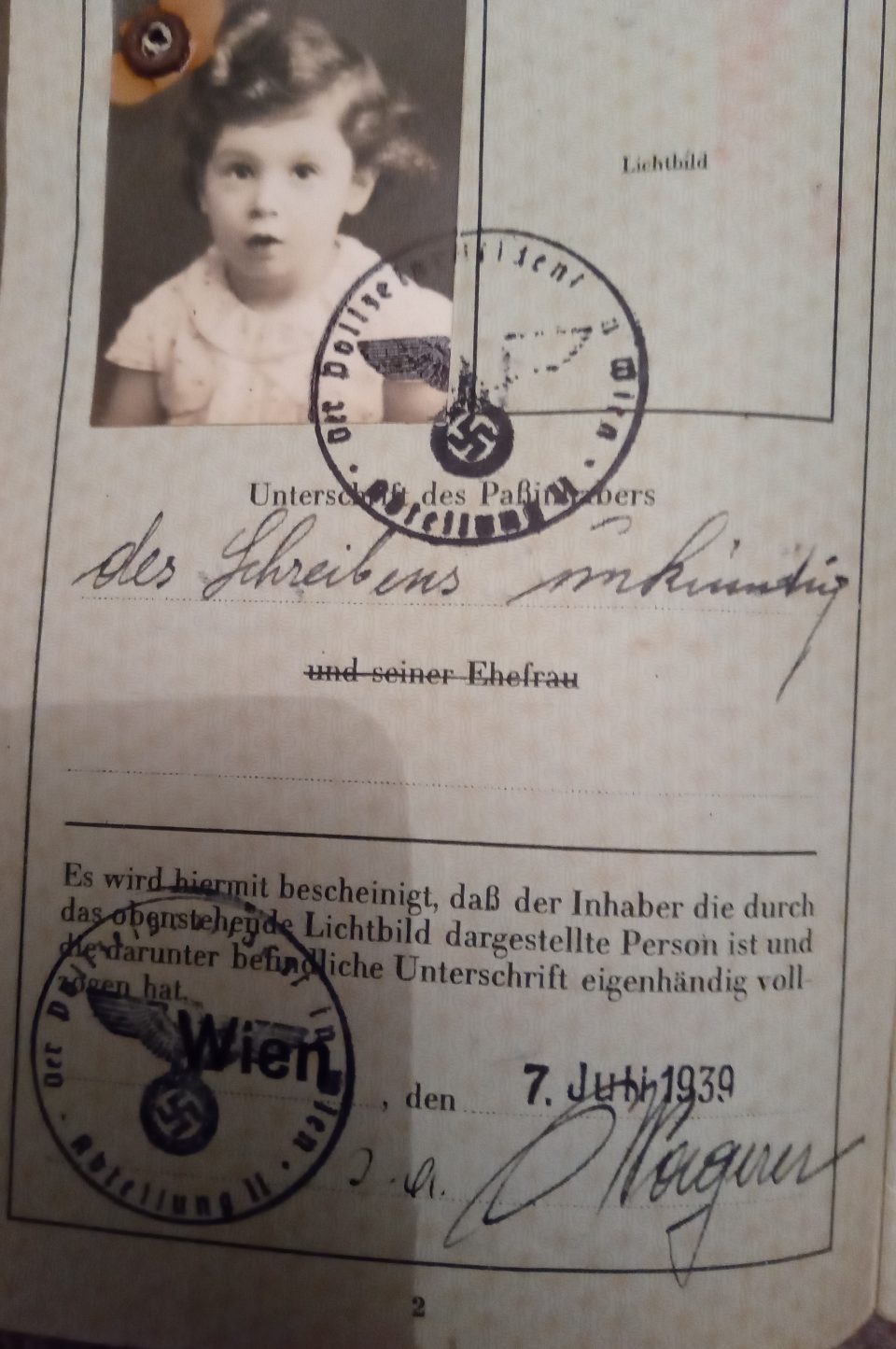

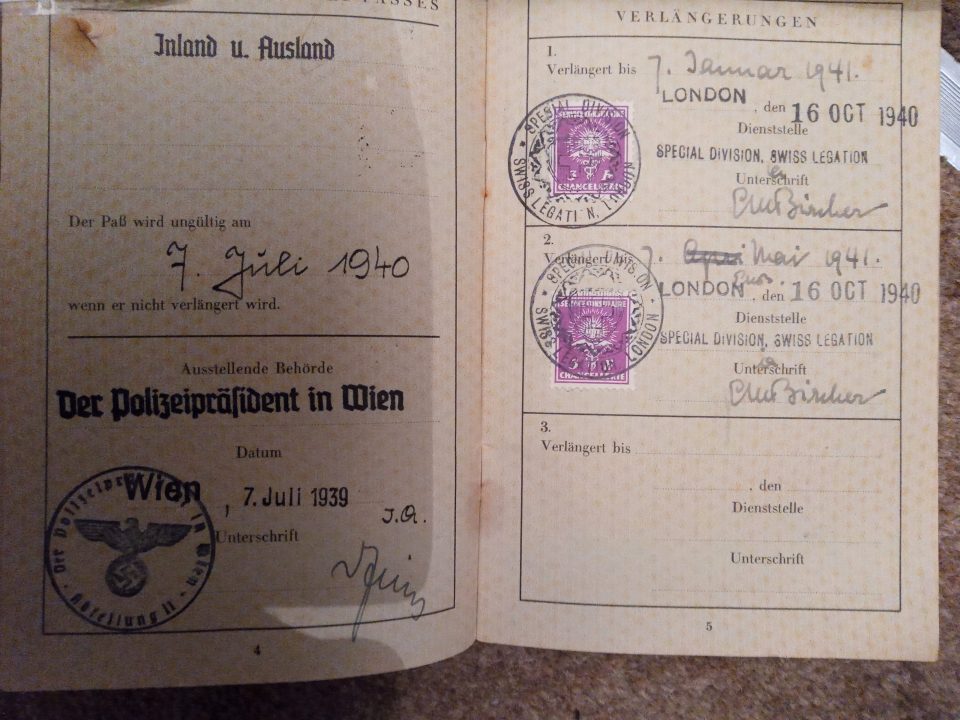

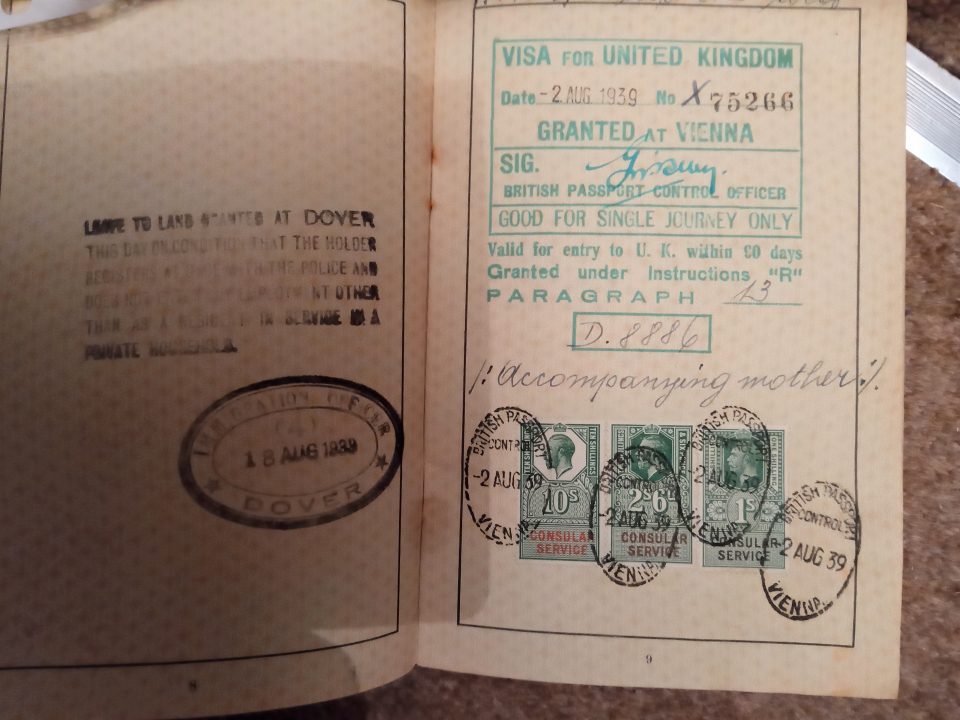

The twins, Susi and Josi, still in Vienna

With the permission of the British, Dutch and Swedish governments aid organisations in “Greater Germany” (Germany and the occupied territories) organised kindertransports in 1938 and 1939 on special trains to send endangered children west to safety. The children on board these trains left their parents and other family members at the railway stations of Prague, Vienna, Frankfurt, Berlin, Leipzig, the free city of Danzig and the Polish city of Zbonszyn. Descriptions and eye witness reports abound of chaos, tears and the pain of the parents. The kindertransports from Austria took the train route through Germany via Cologne, over the border to the Netherlands, up to the Hook of Holland, across the North Sea by boat to dock at Harwich. Some of them were sent to London from there, others were transported to Dovercourt Bay, a holiday camp taken over to accommodate arriving youngsters. Newspaper reports describing the violence of the November pogroms prompted public sympathy and government action in the UK. The Times reported on 14 November 1938, “The position of Austria’s Jews is becoming daily more precarious… Although the more violent demonstrations have ceased the Nazis have prohibited non-Jewish stores, restaurants and cafés from selling to Jews. As no Jewish shops have been allowed to reopen the effect has been to reduce many Jews to a position dangerously near starvation.” The plight of children struck an especially resonant chord. Stories circulated in the UK about attacks against Jewish orphanages and children roaming the countryside on the verge of starvation.

So the Anglo-Jewish community marshalled its resources to mount an effort to rescue children. Helen Bentwich, member of the education committee of the London County Council and Dennis Cohn, chair of the emigration department of the Jewish Refugees Committee presented a plan to the Council for German Jewry. Their aim was to recue as many children as possible. They envisioned an initial group of 5,000 children brought to England, 200-500 at a time, and housed in holiday camps that stood empty at that season. They did not stop to consider details, e.g. whether these camps were winterised. In fact, the winter 1938/39 was one of the coldest and harshest in England in the whole century and the children suffered in the draughty summer huts that were not equipped with heating facilities. The Council adopted the Bentwich-Cohn plan and appointed a delegation to take the matter to the Prime Minister. The November pogrom was a great embarrassment for Chamberlain, who had assured the House of Commons that the surrender of the Sudetenland to Germany and the “Munich Agreement” had paved the way for a peaceful relationship with Hitler’s Germany. The Bentwich-Cohn proposed the admission of children and young people under the age of seventeen who would leave Britain again after education or training had been completed. Jewish organisations guaranteed that no public funds would be required. In short, a politically advantageous plan from every point of view. Pressure continued to build when the British press reported that most of the refugees were not eligible for visas since they were stateless due to the loss of their Austrian, Czech and German citizenships. The various Jewish training camps in which the young were taught farming and other trades in preparation for a new life abroad were devastated or closed since the November pogroms. The plan was accepted and the authorities stated that homes could be found in this country for a large number of children without any harm to the population. If the action came at a price for Britain, it was far dearer for the parents involved. They had to choose between sending their children to a foreign country or continuing to live under the terrible conditions in Nazi Germany.

Susi and Josi in England

With the policy in place and a transit route established, Jewish communities under Nazi rule and the Movement for the Care of Children from Germany started to fill the trains. Around 60,000 children in Austria and Germany sought safety and refuge in Britain and the problem was how to choose from these the limited number that could make the journey and unfortunately favouritism could not be excluded. The welfare department of the “Kultusgemeinde” in Austria had already drawn up a register of children looking to emigrate after the “Anschluß” to Germany in March 1938. Within a few weeks they had recorded 10,000 names. They now composed lists and sent them to the movement offices in London, where the names were sent on to the records department, which issued the home office permit: a simple card with particulars and a photograph replaced a passport. Stamped by the passport control office, these papers were flown to Vienna, where the Kultusgemeinde submitted them to Third Reich officials for permission to emigrate. Stamped again, the cards were given to the leaders of the transports to show upon arrival in England. Children who had not found guarantors in Britain through personal channels were so-called “unguaranteed cases”, as no one had guaranteed to maintain them until the age of eighteen or to send them to school. Touched by newspaper reports and movement appeals, guarantors sprang up across Britain. Offers of hospitality poured in from all areas and classes. The warm response by individuals all over the country shaped the guarantee system. Anyone, British citizen or foreigner, who deposited the required cash sum of fifty pounds could sponsor a particular child.

On 11 December 1938 the New York Times reported in its headline, “630 Children Quit Vienna: One Jewish Mother Dies on Seeing Child Depart for Holland.” The train departed from Hütteldorf station and carried 530 children destined for England and 100 for the Netherlands. The article continued, “Mothers and relatives were not permitted to enter the station. They held what may have been their last meeting with the children in near-by hotels…. The emotional stress of parting was too much for some of them. One mother died of a heart attack after kissing her 5-year-old child good-bye. The child was not told. Seven mothers fainted as the children marched to the train.” The decision to send the children abroad was an act of courage and also an act of great faith as the parents believed they would be reunited in a matter of months. But only a few were so fortunate as Agi and Norbert and their twins. The guarantors met their charges in Liverpool Street station, if the transport came via Harwich, or Charing Cross station, if via Folkestone. Siblings were often separated. Perhaps war rationing and transport difficulties influenced the decision to also keep them apart later on. Possibly the notion that the children would adjust more easily unencumbered by family ties played a role or nobody had ever thought about the problems arising. For the first few months, while refugee aid workers focused on “unguaranteed urgent cases”, children went directly to the summer holiday camps the Bentwich-Cohn plan had identified. Conveniently located near Harwich, Dovercourt Bay opened first and housed the greatest number of youngsters. Anna Essinger, founder and director of Bunce Court School, was asked to run the camp with some of her staff and older students. She wrote some years later, “Thousands of children were saved, but these were necessarily hurried arrangements, and perhaps it was only natural that serious mistakes could not be avoided.” The system was nick-named the “cattle market” because people who wanted to take children in their homes were sent along the camp and a number of children were called into the office to be shown to those people to choose one.

The Quaker’s “Society of Friends’ German Emergency Committee” (GEC) was founded in 1933 by the “Executive Committee of the Society of Friends in Great Britain” after news about violence against Jews in Germany reached the UK. On 1 April 1933 the British representative of the “Quaker International Centre” in Berlin was arrested by the Gestapo. Yet despite some efforts the number of refugees rescued by the German Emergency Committee was rather small. Although the Quakers’ principle stated that they would assist any person in need, the work of the committee concentrated its rescue effort on so-called “non-Aryans”, i.e. baptised Jews, agnostic Jews and political refugees. Yet Agi’s husband, Norbert, was a believing Jew. That’s one reason why Käthe had to take the initiative from England to rescue the family. The British Quakers had affiliates in the countries of origin of the refugees, similar to British Jewish rescue organisations, but also these were under pressure from the Nazis. Originally the Quakers supported the families of the politically persecuted. Until 1939 the Quakers ran “holiday homes” for the persecuted in Germany. Furthermore members of the “Society of Friends” gained access to Nazi concentration camps, e.g. in 1935, after which they protested internationally against the working and living conditions there. The wave of refugees in 1938 also led to an increase in support by the Quakers to help Jews leave Germany and the occupied territories.

In Austria the first aid organisations of the Quakers were founded in 1919 and especially after the civil war in 1934 Quakers supported the families of the arrested and incarcerated socialists. The Vienna Centre, founded by British and American Friends, started to help people who were persecuted by the Nazis to flee Austria immediately after the takeover of the Nazis in March 1938. By July the Vienna Centre had the names of over 1,000 people who wanted to escape registered on its lists, and more names were added daily, especially those of Jews, all hoping for an affidavit allowing them to leave. Although also the Quakers were under observation of the Nazis like all rescue organisation, their books were not checked by the Nazis. So they could run an agricultural trainings camp in Kagran with 140 adults and 32 children – to prepare them for agricultural work in the UK – who received the permission to travel to Great Britain in September 1938. The number of people who were helped by the Quakers to leave Austria is unclear; it is estimated between 2,500 and 4,500. But the Quakers were also involved in the kindertransports and it is known that overall approximately 1,000 children, among them Susi and Josi, were rescued by them. The Quakers issued a brochure in London in 1938 and 1939 with the title “How you can help the refugees”, where they listed their activities as follows: “1. Advice about non-Aryan Christians and others, 2. Training in agriculture and trades, 3. Arrangement of personal guarantees, 4. Emigration. Until the outbreak of World War II 2,844 Jewish children were evacuated via these kindertransports from Austria.

All in all, around 10,000 children were rescued, most of them Jewish, from Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia and Poland; non were accompanied by their parents, a few were babies carried by other children. The British government had permitted an unspecified number of children under the age of 17 to enter the UK on temporary travel documents as they were supposed to re-join their parents after the crisis. A 50-pound bond had to be posted for each child to assure the ultimate resettlement. The children travelled in sealed trains. One very last transport left on the freighter Bodegraven from Ymuiden on 14 May 1940, the day Rotterdam was bombed and one day before the Netherlands surrendered to Nazi Germany. The eighty children on deck had been destined for Holland.

Kindertransport was the informal name for this rescue operation, where Jews, Quakers and Christians of many denominations worked together. Many organisations and individuals assisted in settling the children in the UK, such as youth organisations, the Society of Friends (Quakers) and many Jewish and non-Jewish organisations. Private gifts of money, bedding and clothing were received as well as offers for foster homes and houses for group homes. The children were dispersed over the whole island. About half lived with foster families, the others in hostels, group homes and on farms in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. Those who were older than fourteen were mostly absorbed in the UK’s labour force after a few weeks of training, mainly in agriculture and domestic service, unless they were sponsored by individuals and sent to boarding schools or taken in foster care. A number of children joined the British or Australian armed forces as soon as they turned eighteen. They were given new names to protect them in case of imprisonment and they then joined the fight against the Nazis. During the “Fifth Column Scare” in 1940, when the British feared infiltration by Nazi supporters, more than 1,000 children of the kindertransports, who were over the age of sixteen, both boys and girls, were interned on the Isle of Man and other sites. Sent on the same ships as Nazi prisoners-of-war, some boys were transported to Canada, some to Australia. After German U-boats sank one ship carrying 1,200 internees, the Arandora Star, with the loss of 600 lives, public pressure built against indiscriminate internment. Then a large number of the deported returned and also joined the army, which had decided to accept “enemy aliens”.

Most of the children were not so lucky as Susi and Josi; they never saw their parents again. Many of the children were well-treated and developed close bonds with their foster families; others however were mistreated and abused, as eyewitness reports document. One kindertransportee remembered for example, “I was basically a maid, hovering and polishing and washing up, and I was a young pair of legs for going shopping. Then of course we come to the time when I left school at fourteen. On the next Monday I was introduced to my first factory job, where I promptly ran a needle of the sewing machine through my thumb. I don’t think I lasted very long in that factory. But then there was always another one. And so it went on until I was eighteen, when I decided to leave my foster parents. I took lodgings with one of my workmates. Until I left my foster parents I was sort of continuously homesick, and it’s a horrible feeling.” But another of the kindertransportees told in an interview, “In Cambridge I moved to a very nice family. They had a son about the same age as I was, a beautiful house and a big dog, and I started school. I think the family would ideally have adopted me because they had a boy and I was a girl, but then the mother had to go into hospital to have an operation and so I went to another family in Cambridge. After that I was in a hostel and another family.” For most of the children England became their new home and a large number of them remained in the UK, mostly all those who were orphaned during the war.

When accepting to care for refugee children from the kindertransports the foster families themselves usually had expectations, hopes and wishes of their own at the arrival of the foster children. Some wanted to compensate for having no children of their own or wanted a sibling for their son or daughter, some wanted help in the household or the shop and some even had missionary intentions. The majority of foster families had no training and had no idea of the problems they might be facing because their good intentions were often put to the test. A great part of the kids that arrived at foster families were not small nice thankful beings, but scared and terrorised children that did not understand English, did not know anything about the English way of life, missed their parents and siblings and felt lost, helpless and deserted. That led to regressive processes in the development of the child, which meant that the children were either depressed and conformed without resistance or they were angry, defiant and unable to cope. Those that organised the kindertransports concentrated on the physical rescue of the children and their material subsistence and integration in the British society. There was no time and also no understanding for the emotional needs of the kindertransportees. But Anna Freud, the daughter of Sigmund Freud, already started in 1940 to deal with the issues of separation and loss when dealing with babies and small children in the “Hampstead Nurseries”. Today we know that the separation from a close person of reference leads to regression in small children and strange behaviour. If the foster parent then cannot cope with the situation the child feels rejected. Small children who cannot express themselves verbally react in the form of eating and sleeping disorders and behavioural disorders. Anna Freud was now and then asked to assist in such situations in care homes, but never when the children were already housed in foster homes.

Susi and Josi with their grandfather, Ignaz Sobotka, after the Second World War in England

Even the English press reported about the arrival of Ignaz and Rudolphine Sobotka, survivors of the concentration camp “Theresienstadt”, in England to meet their granddaughters, Susi and Josi

Older children experienced identity clashes. Most children were of Jewish background but at that time the special Jewish identity of the children was of no significance and not taken into account. Rebekka Göpfert wrote later about her experiences, “I am not religious, I don’t have any religious beliefs. I’m an agnostic, and I never felt any religious need to be Jewish, but I’m a hundred per cent sure of my Jewish identity. And the fact that my parents died because they were Jewish, made me very strongly want to remain Jewish.”

After the war only few children were so lucky as Susi and Josi to be reunited with their parents. Those who were, faced another trauma: neither parents nor children were the same as before the separation; they were estranged. Some children, especially the ones like Susi and Josi who were toddlers when they arrived, did not speak or understand German anymore and they had adapted to the new culture. Consequently conflicts of loyalty between foster parents and natural parents arose. Some parents could not cope with the new situation and were overwhelmed by guilt. Most of the children remained in England and made a living there. Mordechai Ron wrote in his memoir, “England was the accidental place of my rescue. I developed a love for this country and its inhabitants and their lifestyle, not just because – as I realised – this country was the cradle of democracy. I experienced friendliness, kindness, understanding and empathy and until today I admire the attitude of these people during the time of the Blitz.” All in all it can be said that only few children were happy in their foster families and the years until the end of the war were characterised by many ruptures, losses and difficulties, but nearly all children developed a close and loving relationship to Great Britain. This can be seen from the fact that many of the young Jewish men who came of age during the war joined the British army to fight the Nazis. Consequently after the war men who had fought had achieved a higher status in society than women who had worked as maids or nurses and by that felt much more content and accepted in the British environment.

Already during the Second World War some child psychiatrists dealt with the question of the effects of the war on children. Anna Freud and Dorothy Burlingham studied and treated children in their “Child Nurseries” and examined the consequences of war trauma for the child’s development and health. In 1967 the so-called “Survival Syndrome” was described that is characterised by first, severe depression, helplessness and apathy, second, a pathological guilt complex, third, psychosomatic illnesses, fourth, a state of panic, sleeplessness, nightmares and extreme tension, fifth, especially in very young children, an interruption of the child’s development and finally psychotic and paranoid disorders. In 1980 these symptoms were diagnosed as “Post Traumatic Stress Disorder”. The children were confronted with a wall of silence with respect to the Holocaust, especially in Austria until the 1980s and this persistent silence or even denial caused further emotional injuries and led in many cases to constant re-traumatising processes. This could lead to distrust towards the outside world and the loss of any trust by those confronted with this silence who in turn kept silent, too. From today’s point of view one can say that the twins, Susi and Josi, who were nine years old when the war ended, both suffered from severe depression and psychological disorders in their adult lives, although as teenagers they seemed to be carefree, happy and cheerful young girls – at least outwardly. Susi committed suicide in her seventies after having cared for her aging mother, Agi, and her sister, Josi, who lived in a care home.

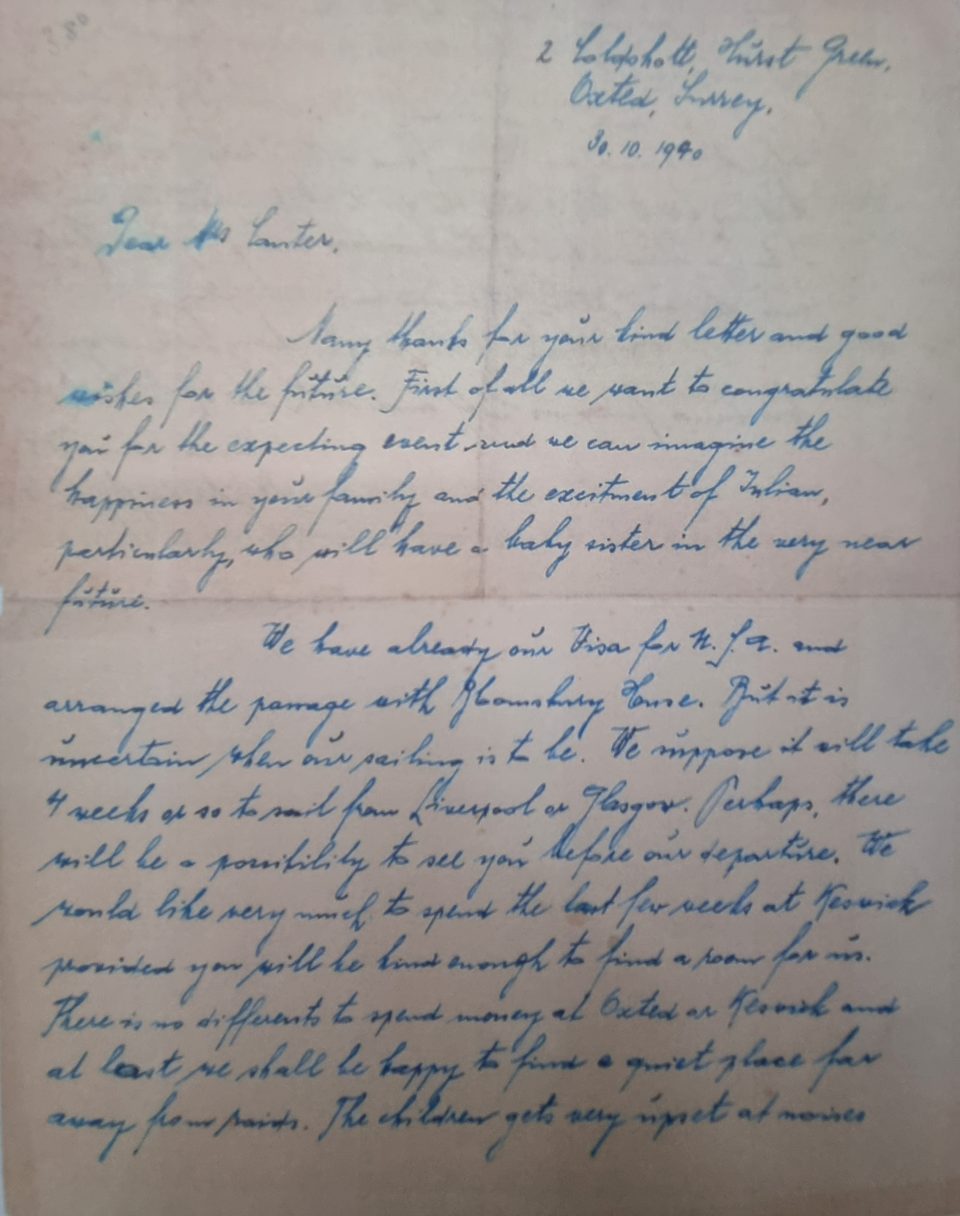

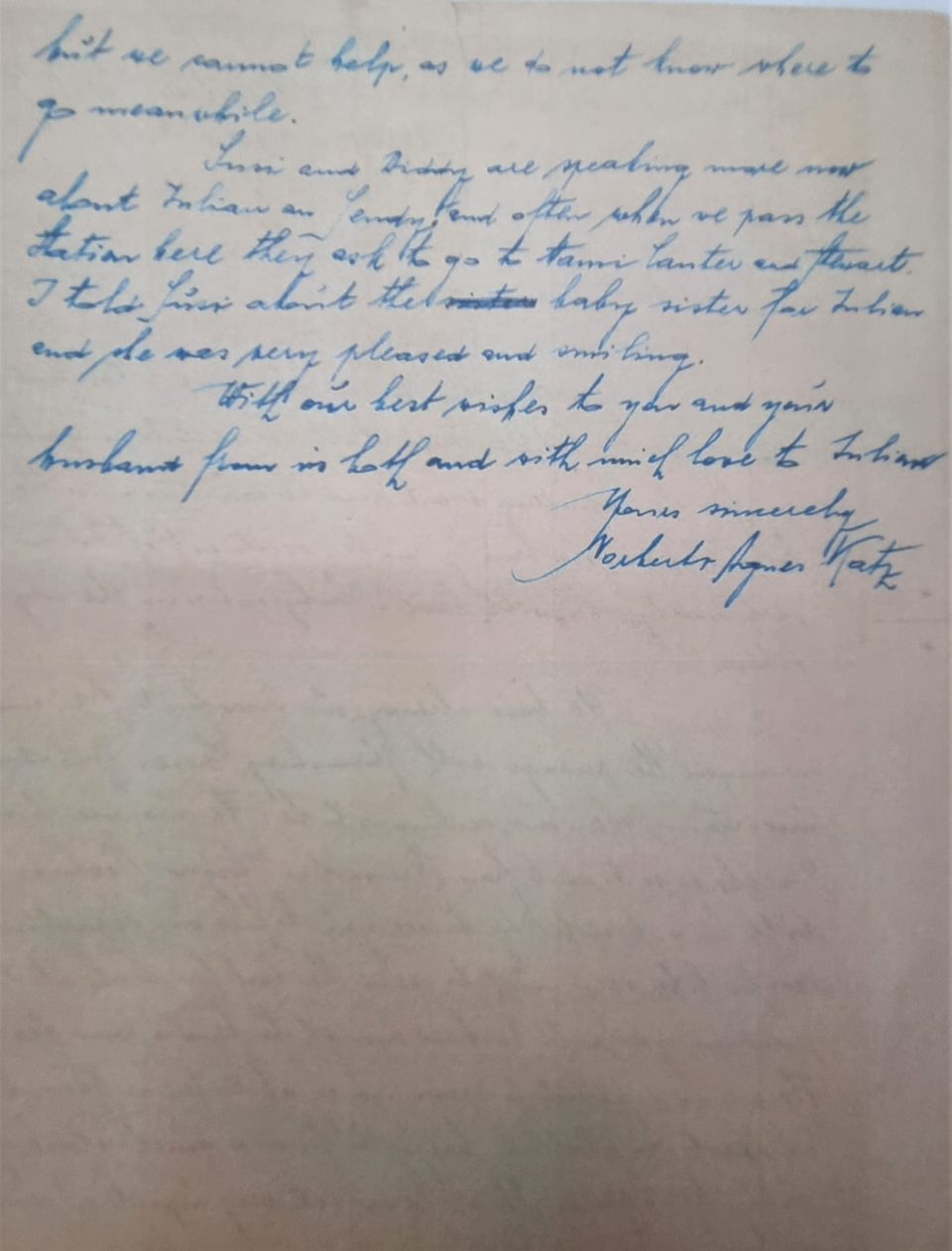

The twins of Agi and Norbert, Susi and Josi, were taken in by Quakers in England in the autumn of 1939 and cared for until they were handed over to their parents. The Quakers Doris and Bernard Canter were foster parents to Susi in Norwich in the autumn and early spring 1939 to 1940. Their son Julian was approximately the same age as Susi. Josi, called Diddy, was placed with another Norwich Quaker family, the Stuarts. Mr. Canter had the job of bringing the twins by train from London when they arrived. Their mother Agi worked as a maid in Mrs. Prest’s mansion, where her elder sister Käthe was employed as a cook. It is unknown why the small twins were separated, which had a disastrous psychological effect on them. Yet they were supposed to meet up with their mother now and then. Their father Norbert was interned in the transit camp Riseborough in Kent at that time, awaiting visas for the whole family to go to the USA, which did not work out in the end. So, they had to remain in England. He managed to visit his children in Norwich in November 1939. Finally, the twins were able to join their parents in Surrey around spring 1940. A letter of Norbert to Mrs. Canter of 30 October 1940 has been preserved, where Norbert congratulated the Canters on expecting a baby girl, a sister for Julian (Ms. Vanessa Morton). He further mentioned that they had already received their visas for the USA, but did not know when they would be able to leave from Liverpool or Glasgow by boat. He asked the Canters if they could find a quiet place in Keswick for them awaiting departure because at Oxted in Surrey, where they were staying, the children got very upset about the air raids of the “Blitz”. He would rather pay for a quiet place in Keswick than in Oxted, as they did not know where else to go in the meantime. Norbert informed them that the twins were now talking more about Julian and Sandy (the children of the two foster families) and when the family passed the train station, they asked to go to Mami Canter and Mami Stewart – it seems they had been traumatised by being shuffled between different families at such an early age.

The Katz family did not manage to emigrate to the USA due to the war, so they moved to London, where they stayed together with Käthe, Agi’s elder sister, in a flat. There Norbert got a job, did some football coaching and even played matches occasionally. In July 1943 Mr. Canter visited the Katzes and stayed overnight there. A letter of Mr. Canter to his wife has been preserved where he told her about the visit to the Katzes. He was amazed that “Their affection for us is absolutely overwhelming… They seem so hungry for friendship… The background of fear & cruelty in their lives at times makes me feel a slow horror.” Norbert met him and went with him by train from Waterloo station and insisted on paying the fare. They offered him a huge supper and had him stay overnight in what Mr. Canter assumed was Käthe’s room. They asked him to come and visit them any time he felt like it. In this letter Mr. Canter also described their nice two-bedroom flat in London, “very English”, yet they managed to give it a “foreign touch” by making the beds up in a different way. He reported that Käthe had worked as a saleswoman at Selfridge’s before and now did dressmaking in some West End firm: “She looks more plain & tired than she was at the Prests (the household where she worked as a cook), but still she is the most sound of the 3 – Agi I think next & Mr. Katz, though very lovable, never seeing quite as far as the others. He has taken up football-coaching at Ealing! And sometimes plays: he looks very fit & happy, & so does Agi.” Mr. Canter confirmed in his letter what the family in Vienna thought of Norbert, namely that football was everything to him and he was not bothered too much by the political situation and did not plan ahead, which was always Käthe’s task. Mr. Canter is amazed how much Susi remembered from her time with them and how disappointed Josi was that “her other daddy” (Mr. Stuart) did not come to visit them. She was always” the quieter and deeper” one, he observed, while Susi was more “lively and sociable”. They were both not as “tall or advanced” as Julian, “but that’s not to be wondered at, with the great interruption of their lives at 2 years old”. Mr. Canter was shocked about the petty snobbery and prejudice they had to endure, such as “of course she’s a Jew, so what can you expect?” The Katzes asked him whether they should consider changing their religion, Church of England or the Quakers, to allow their children a carefree life in England without prejudices. Mr. Canter was heart-broken to hear they should be considering anything like that after all they had been through. The Katzes’ neighbours often assumed that they were not Jewish and made racist comments. In the end they realised that even in England “the assumption that Jews are something less than human has crept in, following them wherever they go.” It has to be noted here, that Norbert never converted to Christianity, but with the years became a devout Jew, which surprised everyone in Vienna where all the family members were either agnostics or had converted like Agi and Käthe’s sister Lola. Mr. Canter went on, “What interested me more than anything was Agi and Käthe’s confession that, charming & kind as Mrs. Prest was, it hurt them in innumerable ways to be there – the unconscious assumption that she was somebody & they weren’t – I see now how they had felt. When I went with the twins (Mr. Canter took them on the train to Mrs. Prest’s mansion to see their mother), Mrs. Prest took charge of me & swept me into her dining-room… somehow without being obdurate it wasn’t possible to feel natural both with her & with the others in the kitchen… Their (The Katzes’) frank references to the unconscious little slights people give to refugees – even the most well-meaning people- makes me feel how really well-grounded one’s attitude must be, & makes me wonder how much of a snob I really am.” After the war the main communication between the families would be at Christmas, but around 1951 the Canters visited the Katz family in London and Julian remembered meeting Susi again and being shyly impressed by how pretty she had become.

How were those Kindertransports organised from Vienna to London? Just a few days after the November pogrom of 9 to 10 November 1938, the “Night of Broken Glass”, the British government loosened entry requirements for children who were considered “Jewish” in terms of the Nazi “Nuremberg race laws” and a public appeal was launched to the British to provide foster homes for those children. Jewish children under 17 years of age were allowed to immigrate to the UK as long as they had a guarantor and a foster family. This enabled more than 10,000 children to leave for the UK from Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia and Poland from November 1938 until 1 September 1939. From Vienna there were six transports in December 1938, two transports in January 1939, one in February, two in March, one in May, three in June, four in July and the last four in August 1939. Gertruida Wijsmuller-Mayer, the wife of a Dutch banker travelled to Vienna and negotiated with the Nazi minister Adolf Eichmann the first transport of 600 Jewish children from Vienna to England within a very short time. The organisation “Refugee Children Movement” (RCM) was responsible for the refugee children. They came by train, departing in Vienna from the West Station (“Westbahnhof”), then via Hoek van Holland by ship to the English port of Harwich mainly. For arriving in Great Britain the children required a guarantee of 50 pounds to cover the travelling and resettlement costs. Originally it was planned that the children would be distributed in the whole country, go to school there and later return to their families. The British Jewish community guaranteed for the necessary sums. That’s why for every child a sponsor had to be found. The RCM assessed the applications and permit numbers, organised the trip by train and boat and took care of the first admission of the children in England, the selection of the foster parents, the placement and follow-up support. After the outbreak of the war further resettlement of the children became virtually impossible. Soon the number of arriving refugee children exceeded the number of foster homes and some of the elder children were exploited as free-of-charge housemaids. Adding to the tragedy, many younger children did not understand why they had been sent away and felt that they had been rejected by their families. Older children suffered because they understood the dangers their parents, brothers and sisters were facing, but they were not able to save them. After the war a large part of the children stayed in Britain with their foster parents because the majority had lost their parents in the Nazi death camps.

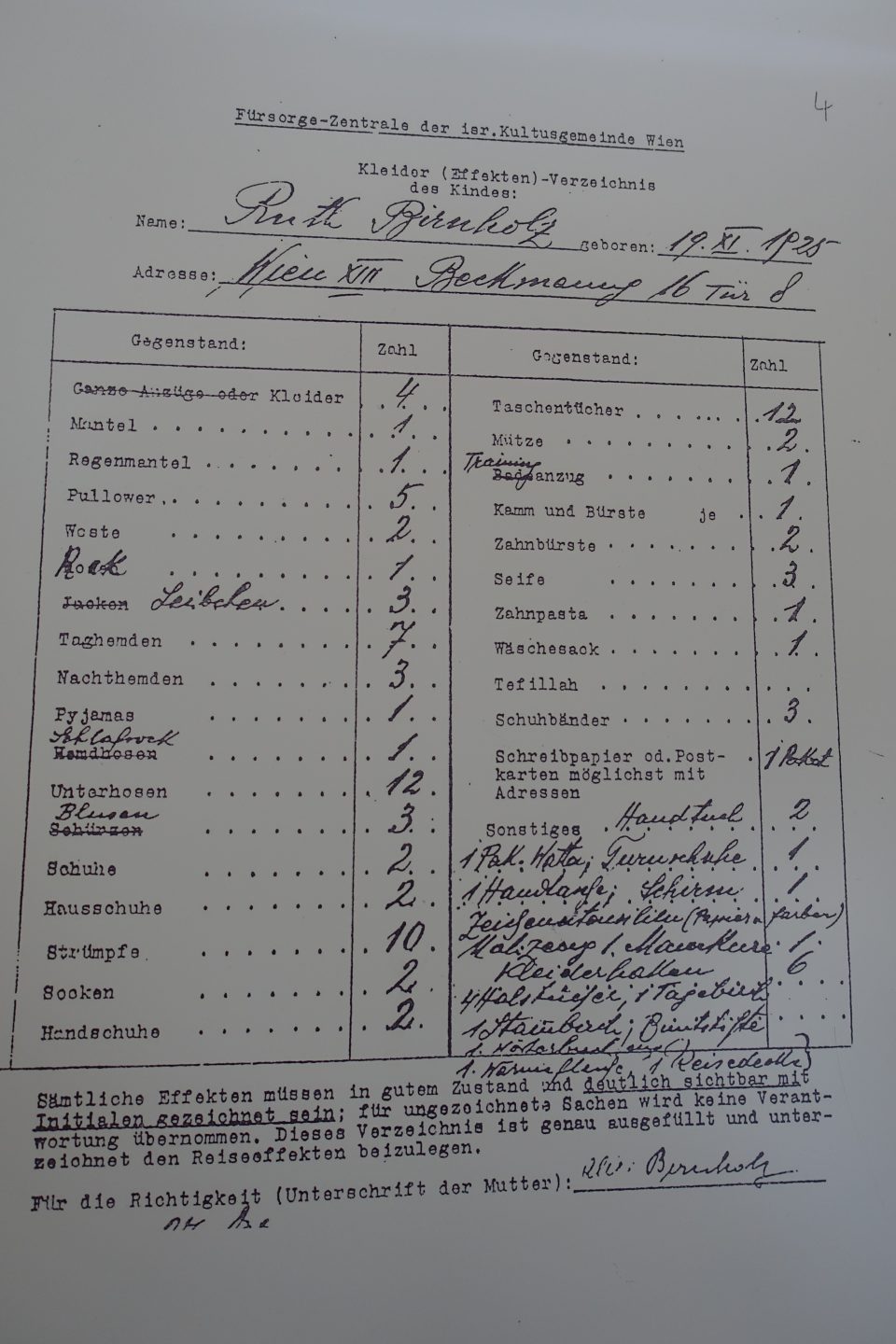

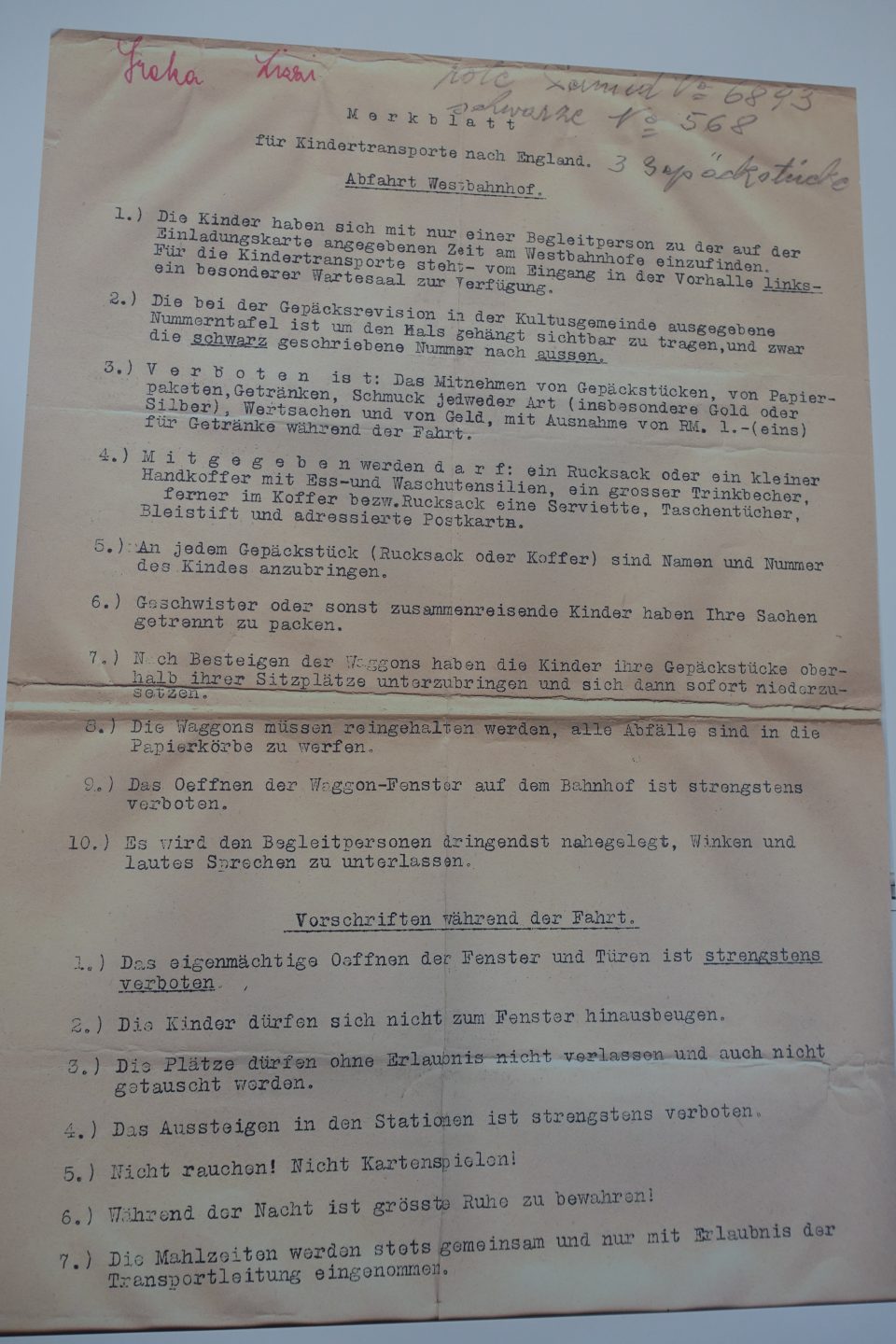

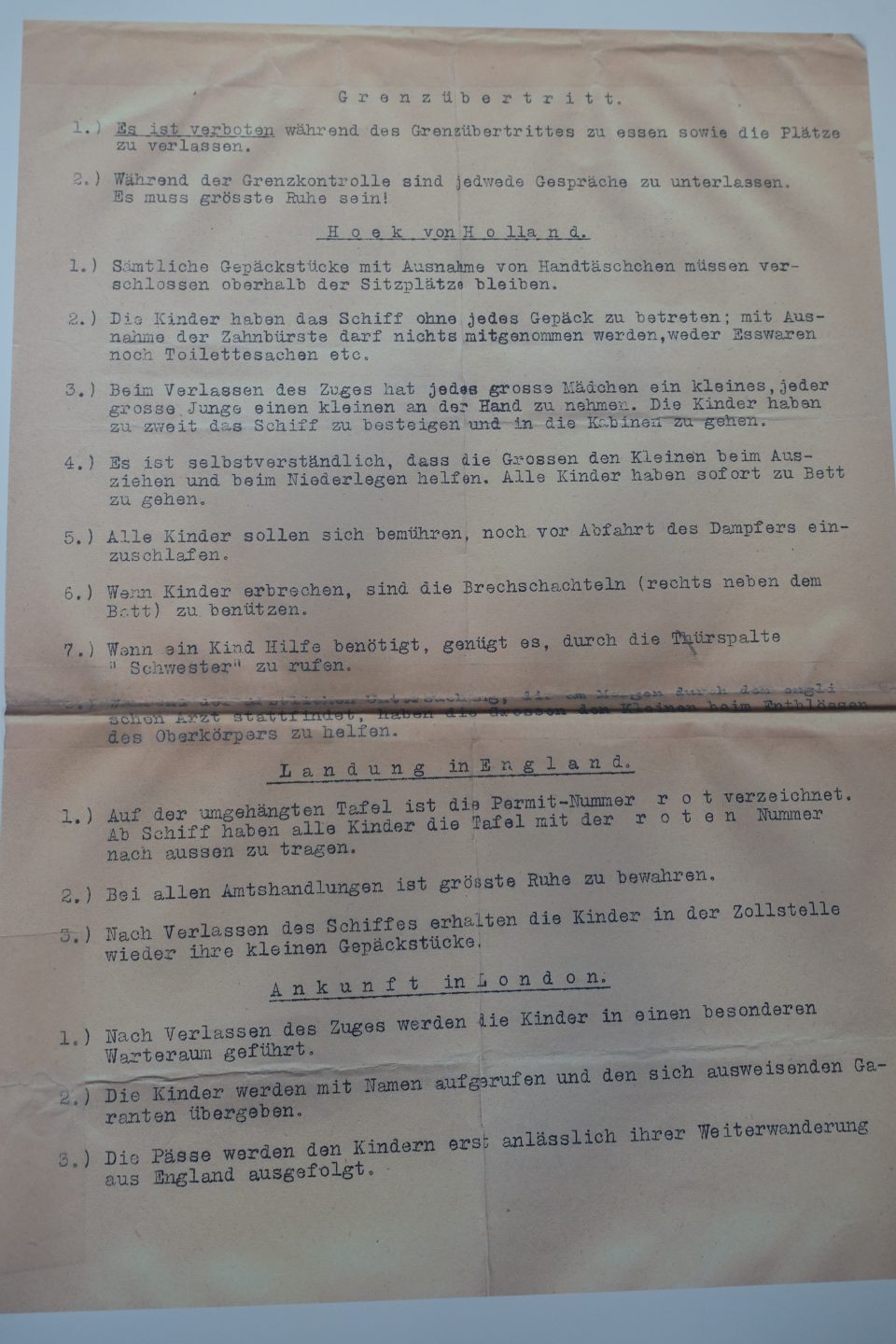

When getting a place for their children on one of the Kindertransports, parents did not learn about the exact departure date until two to fourteen days in advance. Each child was allowed to take one suitcase, a handheld bag and one German “Reichsmark” for buying drinks on the trip. Toys were prohibited and valuables were confiscated by the Nazis. It was agreed that the parents informed the children only shortly before departure. Furthermore the parents were not allowed to accompany their children onto the departure platform of the train. The enumeration of possessions of one child leaving from Vienna Westbahnhof, signed by her mother, has survived and lists meticulously the number of night shirts, blouses, underwear, shoe laces, socks, shoes, towels, one coat, one raincoat, an umbrella etc. Detailed instructions for the transport of the children from Vienna to London were handed to the parents and the accompanying persons. At the Vienna Westbahnhof there was a separate waiting room where the children had to be dropped off. After having checked the luggage the Vienna Jewish religious community, which organised the transports, assigned to the child a black number plate which had to be carried around the neck. No valuables or jewellery, no parcels or drinks were permitted on the journey. The children could take with them a small hand luggage or rucksack with some food, a sponge bag, pencils and postcards with the address already filled in. After boarding the train the instructions said that the children had to sit down immediately, never to open the windows, not to wave or speak loudly and, of course, not to leave any rubbish in the compartment. The children were not allowed to leave their seats without permission or to change seats, they were ordered to be quiet at night and only to eat when permitted. During border control no one was to talk, to eat or to leave the seat. At arrival in Hoek van Holland the children had to go on board the ship without any luggage except a tooth brush, no food, no drinks, no sponge bags. Older children had to guide younger ones onto the ship and into the cabins and they all had to go to sleep before the departure of the boat. The vomit boxes next to the bunk beds had to be used and only in cases of emergency the children were allowed to call for the nurse through the crack of the door. When landing in England all children had to wear the red number plates around their necks and after the border controls they received their hand luggage. When the train from Harwich arrived in London, the children were brought to a special waiting room, where they were handed over to their respective guarantors. They then received their passports for the onward travel in England.

Which were the organisations and individuals that rescued the children? Jews, Quakers and Christian organisations worked together in this rescue operation. During the early years of Hitler’s dictatorship the Quakers established a reputation for assisting Jews and other persecuted persons who sought refuge from Nazi oppression. The Quakers and the Jehovah Witnesses offered help to Jews in distress as a formal church policy. Soon after the November pogrom 1938 they lobbied and funded Jewish emigration out of Austria and Germany. They further responded to the growing problem of caring for thousands of unaccompanied minors by taking an active role in the Kindertransports. My relatives Susi and Josi were taken in by Quakers in England, too. Another group were the “Cristadelphians” that organised collections to fund the evacuation of the children and found homes for the refugee children within their community. Hostels for teenage refugee boys were established during the war as well. An important personality in the rescue operation was Nicholas Winton, who visited Prague in late 1938. He was then 29 years old and worked as a clerk at the London Stock exchange. After having observed the situation in Central Europe for two weeks he was so alarmed by the influx of refugees endangered by the imminent Nazi invasion that he decided to make every effort possible to get at least the children out. He consequently set up office at a dining room table in his hotel in Prague. Parents started to crowd into the hotel desperate to get their children out of Czechoslovakia. Winten managed to set up the organisation for the Czech Kindertransports in Prague in early 1939 before he went back to London to handle all the necessary bureaucratic matters from there. In nine months of campaigning Nicholas Winton managed to get out 669 Czech, Austrian and German children on eight trains. Another important rescuer was Rabbi Solomon Schonfeld who personally saved the lives of thousands of Jews in Central and Eastern Europe between 1938 and 1948. This dedicated man single-handedly brought several thousands of refugees to England and provided them with homes, education and jobs. Following the “Night of Broken Glass” (Kristallnacht”) Julius Steinfeld, a communal leader in Austria, called on Rabbi Schonfeld to organise a Kindertransport to England. Schonfeld immediately boarded a train to Vienna and helped organise a transport of nearly 300 children, providing the British government with his personal guarantee in order to secure their entry. Eventually he saved over four thousand children. After the outbreak of World War II he continued to lobby intensively to find temporary refuge and to secure visas for people to escape. After the war he rushed to liberated European countries to evacuate the survivors of concentration camps. The sculpture by Flor Kent “Für das Kind” (“For the Child” 2008) at Vienna Westbahnhof, from where most of the Kindertransports departed, commemorates these rescuers.

The classified ads below were published in the London Jewish Chronicle between 1938 and 1939 by parents and relatives of Viennese Jewish children in search for guarantors and foster families in England:

| Would a family kindly receive a Viennese boy, 10, in their home? Leiberg 57/7, Kaiserstrassse, Vienna 7 | Heartbreaking case. Could any person adopt temporarily a boy of 12 years, good Jewish family, well educated. Apply for further information: Ehrmann, Wien IX, Müllnergasse 13 | Desperate parents beg benevolent people to take care of their boy (14 ½), grammar school, well mannered, all sports, intelligent – Linder, Vienna 2, Darwingasse 37 |

| Would family take boy (10), son of Jewish lawyer, musical, well-bred? – Bretschneider, 10/13 Myrthengasse, Vienna 7 | Who will receive 13-year-old boy until his parents are able to take him again? Good manners, speaks English – Kerpen, 77 Döblingerstrasse, Vienna 19 | Jewish teacher’s family seek for their daughter, healthy, aged 13, talented music and languages, and for their son, aged 8, one or two generous families, who would take charge of them – Benedikt, 20 Pfeilgasse, Vienna 8 |

| Would generous family receive fourteen-year-old boy, well-bred, (half-orphan) to learn a trade –Write “Hearty Thanks” c/o Adv.Off. Emil Hirsch, 14 Himmelpfortgasse, Vienna 1 | Two girsl, 8 and 9 years old, beautiful, blond, healthy, well-educated, father well-knoen Viennese solicitor, in great distress, request kind-hearted people to take them in their families, Address 1,568 Jewish Chronicle | Viennese boy (13) very gifted, would like to be taken by family who could look after him – Leo Fiderer 44/13 Kandlgasse, Vienna 7 |

| Home wanted with kind-hearted family for well-bred Jewish girl (13 ½ years) for period 1-2 years to finish her schooling. Mother must regretfully part from only child owing to unhappy circumstances Write Zoltan Seibold, Köllnerhofgasse 1, Vienna 1 | Urgent: Director of Viennese Chocolate Factory, whose circumstances are sadly depleted due to political situation, is extremely anxious to place his son with refined and charitable family: boy aged 10 is of bright and happy disposition – Address 1,850 Jewish chronicle | Would kind-hearted family take good tempered Viennese boy, aged 16? Forced to leave Vienna very urgently. Parents missing. Please help and write to Dr. Frankel, Pallas-Imperial House, South Street, London EC2 |

Literature:

Bollauf, Traude, Dienstmädchen – Emigration. Die Flucht jüdischer Frauen aus Österreich und Deutschland nach England 1938/39, 2011

Dwork, Deborah & van Pelt, Robert Jan, Flight from the Reich. Refugee Jews 1933-1946, 2009

Jugend ohne Heimat. Kindertransporte aus Wien, Jüdisches Museum Wien 2021

Salewsky, Anja, “Der olle Hitler soll sterben!” Erinnerungen an den jüdischen Kindertransport nach England, 2001

Wexber-Kubesch, Anna, Vergiss nie, dass du ein jüdisches Kind bist. Der Kindertransport nach England 1938/39, 2013

Für das Kind. Museum der Erinnerung. Der Kindertransport zur Rettung jüdischer Kinder nach Großbritannien 1938/39. Katalog 2014