Agi and Norbert at their wedding in Vienna

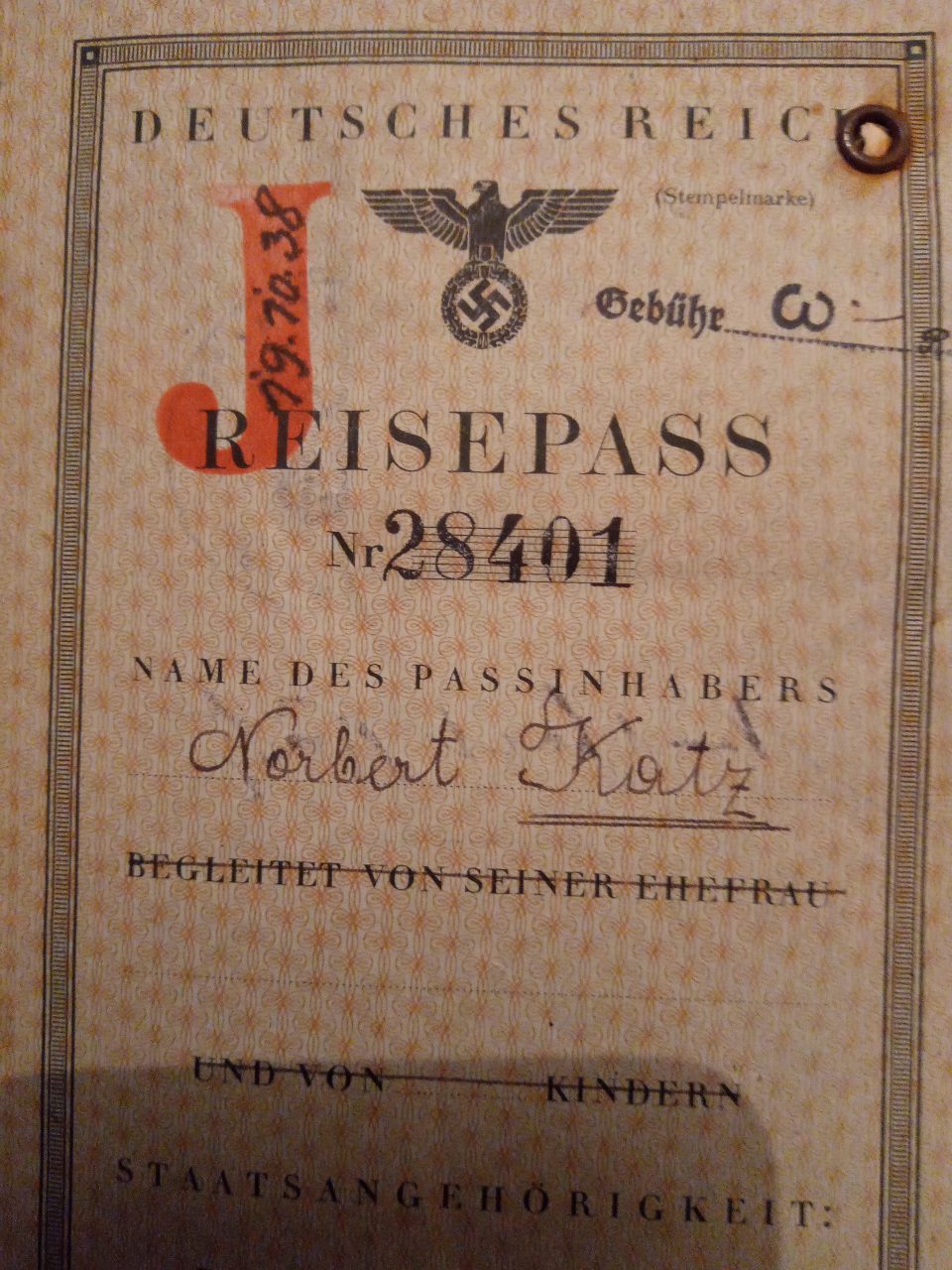

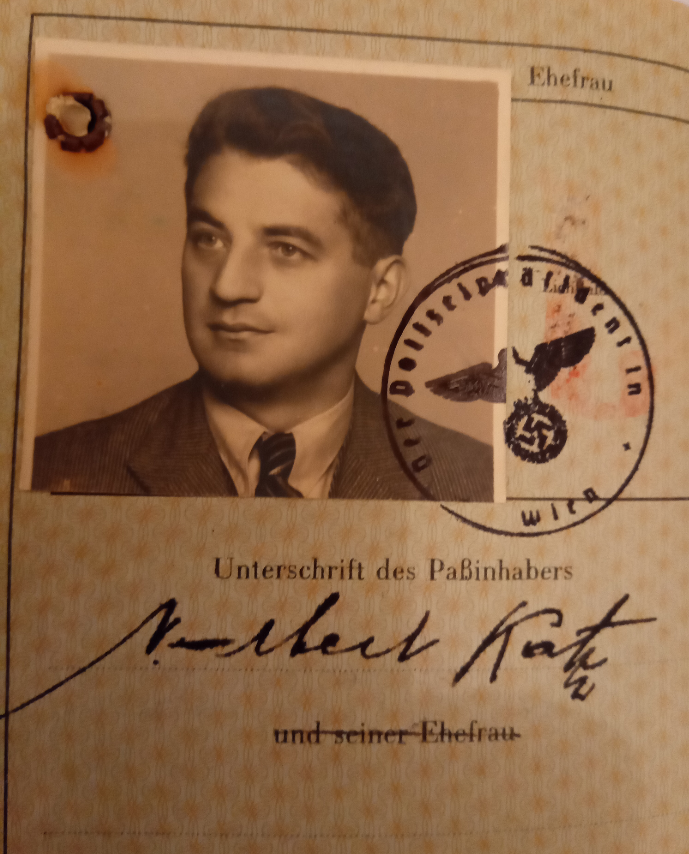

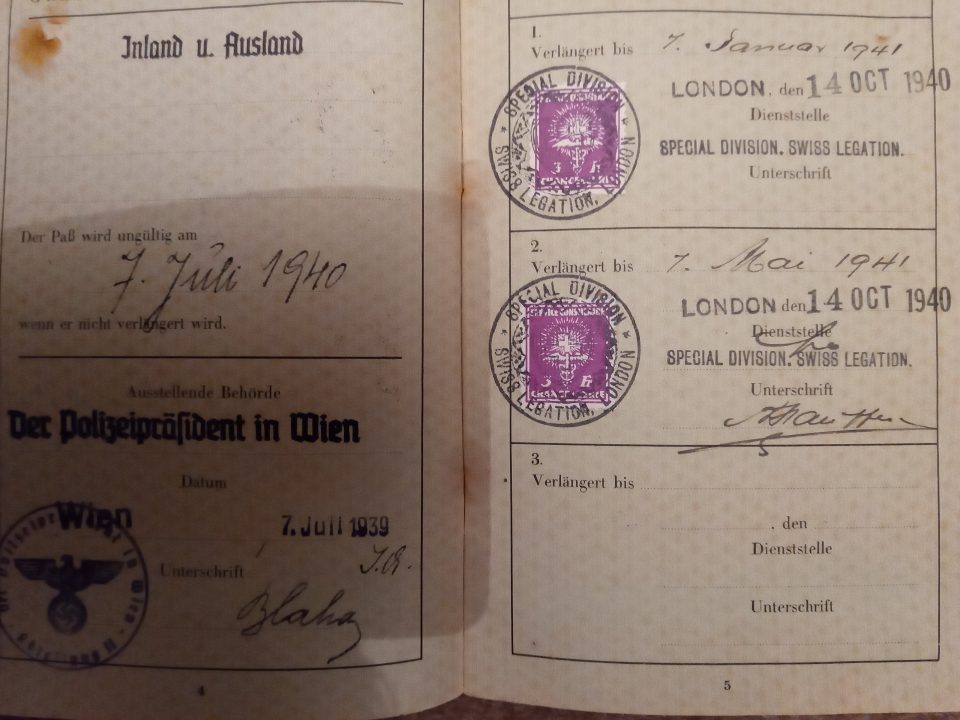

The husband of Agi, Norbert, an excellent Austrian football player, managed a last-minute escape to England with the help of his sister-in-law, Käthe in a domestic household. Unfortunately as a fit young “enemy alien” he was considered a threat to British military security and interned on the Isle of Man after the outbreak of World War II.

Norbert Katz as a young man

What were possible escape routes out of Austria? As a reaction to the threats against Jews in Germany and Austria and the resulting refugee crisis the US President Roosevelt initiated an international conference on the refugee problem out of Germany. From 6 to 14 July 1938 the Conference of Evian took place in Evian-les-Bains in France. Representatives of 23 countries took part. To allay fears that the United States would demand great concessions, the invited nations were told that no country would be expected to receive a greater number of emigrants than was permitted by its existing legislation and all new programmes would be financed by private agencies and not public monies. The purpose of the meeting was to facilitate the emigration of political refugees from Germany and Austria, not Jews. Despite extensive media coverage the conference ended without achieving significant results. On the contrary, the participating countries stated that they would on no accounts change their existing refugee policies. Representatives of the threatened Jewish communities were deeply disappointed by the results. The governments that participated were still unwilling to solve the problem and fell back on palliatives. The more difficult the tasks became, the smaller their will to deal with them efficiently. An Intergovernmental Committee, headquartered in London, was established to improve coordination, but it was still in a preliminary stage of development when the war broke out.

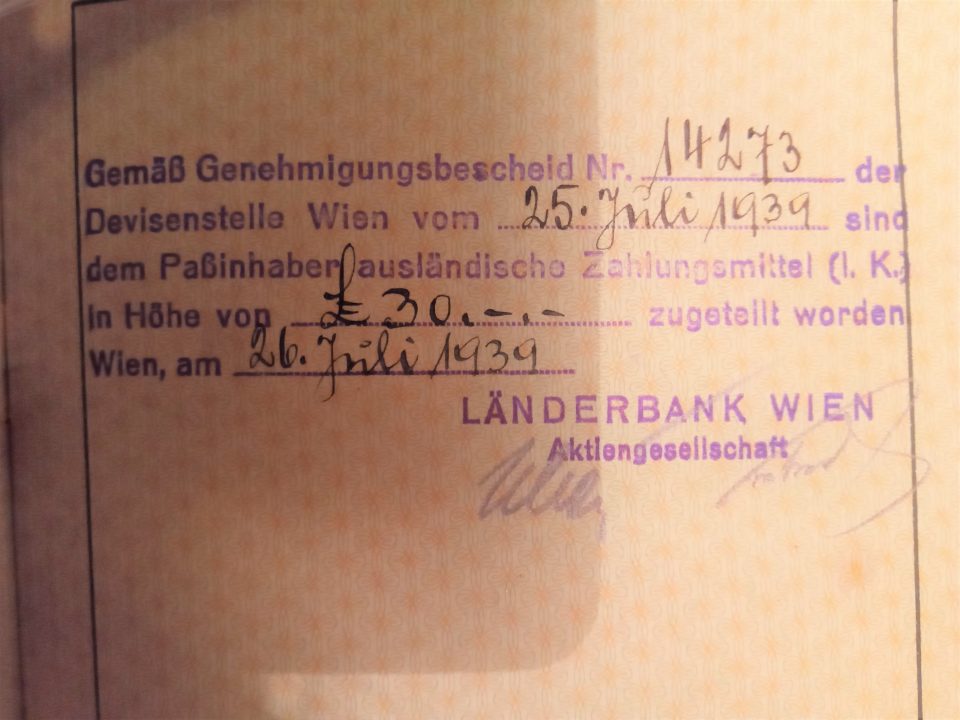

Information about possible safe havens was circulated since 1936 in the “Jüdische Auswanderung” and since 1938 in the “Philo-Atlas. Handbuch für jüdische Auswanderung”. Both publications were advertised in the “Zionistische Rundschau”. What followed for those who had to leave Germany and Austria were queues, continually postponed dates at embassies and consulates of possible destinations, humiliating interviews and crushed hopes. The “Zentralstelle für jüdische Auswanderung” could only help those that had already received visas for a country willing to welcome them. Although the Jewish community in Austria, the “Isrealitische Kultusgemeinde”, promoted the flight to Palestine, the preferred destination of Austrian Jews were the United States. Yet only if a US citizen guaranteed for the new immigrant in the form of an affidavit, could someone emigrate to the USA. On top of that the affidavits were not to surpass the annual quota for the individual country. The Austrian quota for 1938 was 1,413 and was only valid for those born in Austria proper, not for those born in any other part of the former Austro-Hungarian Empire, as Käthe, who was born in Eywanowitz. Those were subject to the quota of the respective successor state. Yet the quotas for those Central and Eastern European countries were very low. In April 1938 France introduced a very restrictive immigrant policy and any illegals were threatened with expulsion to Germany. Switzerland re-introduced visas for Austrians in March 1938 and finally closed its borders in August 1938. The stamping of all passports for Austrian and German Jews with a “J” was introduced by the Nazis in response to a Swiss initiative. Spain was experiencing a disastrous civil war from 1936 to 1939 which ended with the victory of the fascist General Franco. Portugal stated categorically in 1938 that it did not offer asylum and sent back Jewish immigrants to Vienna in September 1938. Also the Netherlands wanted to introduce visas after the Nazi takeover in Austria, but then offered special permits to 800 refugees. All in all, the Netherlands accepted approximately 10,000 refugees from Germany and Austria. Astonishingly, Fascist Italy was a relatively easily accessible refuge country in the beginning. But after the “Anschluß” of Austria by Nazi Germany in March 1938 Italy closed the borders to Austria and in the autumn of 1938 also Italy introduced the anti-Semitic race laws of the Nazis and the Jewish population had to flee Italy. Initially Yugoslavia also accepted refugees, especially those evicted from Italy, but then resorted to an anti-Semitic race policy as well.

What options were left for those desperate to leave Austria? Great Britain and Latin America, especially Cuba. Both areas were originally seen as transit countries to the final destination, the USA. Australia offered to accept 15,000 refugees from Austria, but only 5,000 annually. That’s why only 7,000 managed to get to Australia before the outbreak of the war. The emigration to South Africa that had started promisingly in 1935, mostly for German Jews, nearly ground to a hold when restrictive legislation was introduced in 1937 and was stopped completely in 1939. For approximately 18,000 to 20,000 Jews Shanghai became a safe haven after November 1938 because no visas were needed for Shanghai. Before Italy’s entry in the war on the side of Hitler, the refugees left from Trieste by ship through the Suez Canal, but in June 1940 the Mediterranean was closed for civil shipping. From then on the only possible route of escape to Shanghai was the 6,000 miles land route by Trans-Siberian Railway across Russia and Siberia on a Russian transit visa. When Germany attacked the Soviet Union in June 1941 the last escape route was barred. The Austrian flight to Palestine “Alijah” only started on a greater scale in 1938, but the Alijah was regulated by a complicated selection process. The certificates were issued by the British mandate authorities in the form of quotas on the basis of wealth or useful job qualifications. An important preparation for the Alijah was a training course for agriculture or for special trades. The Youth Alijah, organised by London as well, rescued many children and young people, but not all of them reached Palestine, some of them got stuck in England. At the height of the refugee crisis the British stopped any migration to Palestine. That was when the “Alijah-Beth”, the illegal migration to Palestine started. It can only be estimated how many people deemed “Jewish“ according to the Nazi race laws (“Nürnberger Gesetze”) managed to escape. For Austria the estimates state 130,000, for Germany 280,000. A secret NS decree of 23 October 1941 ended the Jewish emigration und opened up the way for the “Final Solution”, the extermination of the Jews, the Holocaust. A large number of refugees were caught up by the Nazis in their refuge country, e.g. Czechoslovakia, France, the Netherlands and did not survive the war.

Britain, unlike the United States, never envisioned itself as a country of immigration; not in 1933 and not in 1938/39. As London, Berlin and Vienna had abolished their mutual visa requirements in 1927, London saw the need to control the influx of refugees and Britain re-introduced the visa obligation. Consular authorities were advised to deny visas to many groups of people, such as small shop-keepers, artisans, retail traders etc. But they could grant visas to “those of international repute”. In short, the British refugee policy was a means of enriching Britain’s intellectual, cultural and business capital. Those ordinary Jews that had found refuge in Britain, nevertheless, like Norbert, saw themselves confronted with a new situation in 1940. Already in March 1940 the Labour MP Parkinson suggested that the “enemy aliens” employed as domestic servants near military bases constituted a threat to the security of the UK and should be interned in camps. At that time the minister responded, “I do not think that this suggestion is a practical proposition or that it would commend itself to public opinion.” Two months later after the Nazi occupation of Norway and Denmark Churchill became Prime Minister. In May the Netherlands were run over by the Germans and the Dutch government and royal family sought refuge in London. These events radically changed the attitude of the British public. Already in April 1940 the British press passed on rumours that Nazi sympathisers had assisted in the fall of Oslo and that the local population had helped the Germans. The press used the term “The Fifth Column” to describe this support for the German Nazis among the local population and they saw the refugees among these sympathisers. The British ambassador in the Netherlands, Neville Bland, who had fled Den Haag, submitted a report titled “The Fifth Column” in May 1940 where he stated that the German and Austrian domestic servants constituted an enormous danger to the security of the country, “I venture to submit, with all the emphasis in my power, as a result of our recent experiences in Holland, that immediate steps should be taken to intern all persons in this country with German or Austrian connections……. It is clear, either by inference or by direct evidence, that the paltriest kitchen maid with such connections, not only can be, but generally is, a menace to the safety of the country….. Every German or Austrian servant, however superficially charming and devoted, is a real and grave menace, and we cannot conclude from the experiences of the last war that “the enemy in our midst” is no more dangerous than it was then. …. We cannot afford to take this risk. ALL Germans and Austrians, at least, ought to be interned at once.”

It is amazing that at that time no one dared to mention that these people had fled the Nazi terror in Germany and Austria and were Hitler’s victims. This is probably due to the fact that even people who sympathised with the refugees believed that Hitler had infiltrated the groups of refugees with his own spies. Now many of the domestic servants had to face hostility and suspicions by their employers or were dismissed. In May 1940 the Churchill administration established so-called “protected areas” along the east and south coast of England and decreed that all refugee women and children had to leave the area within 48 hours and all refugee men between 16 and 60 were to be interned. As a consequence hundreds of domestics had to be evacuated from these protected areas by Order of the Government. The majority came to Bloomsbury House for help and advice. The Assistance Board maintained 2,710 Jewish cases in October 1940. In the early summer of 1940 the German air raids started and the British coined the term “The Blitz” for the disastrous, continuous bombardments of London and other English cities from 7 September 1940 on. The Domestic Bureau took stock of the situation of these domestic servants, “Deprived of the opportunity to work, driven out of their posts where they had been happy and were making good, seeing their husbands and friends being interned, suffering under a long period of day and night air raids, all this proved a strain and overwhelming demands were made upon the depots in their task of encouraging the women to hold on and wait with patience and courage.”

Contrary to France, where immediately after the beginning of the war all “enemy aliens” between 17 and 65 years of age were interned, Britain initially refrained from indiscriminate mass internments of all “enemy aliens”. The British authorities nevertheless started to investigate and check all Germans and Austrians on British soil from the summer of 1939 on. It is recorded in the parliamentary debates of the House of Commons that “examiners will sit not only in London but in the provinces, and each of them will examine all cases in the district assigned to him with a view to considering which of these can properly be left at large and which should be interned or subjected to other restrictions.” These “tribunals” were installed to check the reliability of all enemy aliens in Britain. 120 tribunals were dispersed over the whole territory and were chaired by jurists. The hearings were not public and no legal counsel was permitted, but the enemy aliens could be assisted by a friend. The members of the tribunals were advised: “Germans and Austrians in this country, being nationals of a state with which His Majesty is at war, are liable to be interned as enemy aliens, but most of the Germans and Austrians now here are refugees from the regime against which this country is fighting, and many of them are anxious to help the country which has given them asylum … It would therefore be wrong to treat all Germans and Austrians as though they were enemies.” The refugee organisations could send so-called liaison officers to the tribunals.

The tribunals categorised the enemy aliens into three categories: category A were to be interned, category B were not interned but subject to certain restrictions of movement and category C were left at liberty. Irrespective of this categorisation, all aliens over 16 years of age had to be registered at the police stations of their place of residence since the beginning of the war and had to have the police identification card with them at all times. The tribunals further differentiated between “refugees from Nazi oppression” and “non-refugees”. The tribunals started their work in the first week of October 1939 and at the end of October already 13,000 aliens had been checked and only 186 were interned. The assignment of category B seemed rather arbitrary. In some areas nearly all aliens were categorised B, in others C. Peter and Leni Gillman wrote in the book “Collar the Lot!” that investigated the British internment policy critically that a tribunal in Sutton, Surrey categorised all car owners in category C and all the others in B. In March 1940 569 aliens were interned, 6,782 were category B and 64,244 were category C. This means that the large majority of refugees were seen as such and were not subject to any restrictions.

Unfortunately this period of tolerance ended in the spring of 1940. The press demanded tougher measures and especially among the middle and upper classes a xenophobic attitude was prevalent. So on 12 May 1940 mass internments started, first in the protected areas along the south and east coast. All male Germans and Austrians between the ages of 16 and 60 were interned because a German invasion was expected. Already on 15 /16 May all male enemy aliens category B were interned. As the German troops progressed also category C males were interned and the age limit was raised to 70. When Italy joined Hitler in the war, also all male Italians were interned. The British authorities stressed that the spirit of British fair play should reign in the internment camps and the commander of one internment camp on the Isle of Man issued an appeal on 1 June 1940 that rules and regulations in the camp were to be obeyed as they guaranteed the security of the interned and prevented any frictions between different refugee groups. But the indiscriminate internment of Jews, Nazi sympathisers and Mussolini sympathisers caused problems and was deemed “tactless, stupid and unimaginative” by Francois Lafitte who opposed the internments in Parliament. He published the results of his research in 1940 “The Internment of Aliens” and harshly criticised the methods, “We have shown how the British Government has declared war to the wrong people, how its policy of internment and deportation is needlessly discouraging vital progressive forces all over Europe and, maybe, turning friends into enemies.”

In June 1940 the deportations of the interned to Canada and later to Australia started. Churchill had insisted on this drastic measure. By the end of the war 8,000 enemy aliens had been transported to British Dominions. The catastrophe of the sinking of the “Arandora Star” on the way to Canada off the Scottish coast on 2 July 1940 by a German torpedo raised awareness in the British public for these deportations and the public opinion was influenced by the disaster. The Evening Standard wrote, “We are locking up our friends, some who are skilled, all who are ready to work…. It is worse than folly. It is sabotage against the war effort. It is a damnable crime against the good name of England.” A new survey in August 1940 showed that now only one third of the British population supported the internments, compared to 55 per cent a month earlier. A White Paper of the government consequently fixed which categories of people could be released from internment camps, among them people under 16 and over 70 (who should not have been interned in the first place), invalids, key industrial personnel, skilled workers, scientists, doctors, dentists, aid workers, religious personnel, employers of at least twelve British employees – unfortunately, for Norbert, professional footballers were not in these categories. More complicated was the release from camps in Canada and Australia. Both countries were reluctant to release the refugees and only towards the end of the war offered them the countries’ citizenship.

The Hutchinson Camp one of several camps on the Isle of Man, where Norbert was interned, was established in July 1940. By the end of the month it counted 1,205 internees, most of them Germans and Austrians with a large proportion of Jews and anti-Nazi activists. The internment camp was closed in 1944 to make room for a prisoner-of-war camp. The camps were organised on a principle of self-government. The internees were not prisoners, but enjoyed freedom of movement and association within the limits of the camp. The persons detained were themselves to a large degree responsible for the maintenance of good order and discipline. A military Commandant was in charge of each camp and the internees were organised into companies, each under the supervision of an officer. Camp discipline was enforced by withdrawing some or all privileges, such as exercise, recreation, visits etc. This usually meant confinement to cells or quarters for a maximum of 28 days. Most of the camps had a small sick bay located in one of the houses. Hutchinson Camp used Arrandale. Each camp had one or more interned doctors who were responsible for the treatment of sick internees. A British civilian doctor visited each camp once per day to supervise certain cases and to counter-sign prescriptions. More serious cases were dealt with by civilian hospitals.

In all of the camps on the island workshops were established. There were tailors, barbers and in Hutchinson Camp a Viennese baker offered cakes at the “Artists’ Café” in the washroom. Artists could sell their works of art as well. Labour was also required in the island’s quarries and this paid quite well. Demand for labour on the island’s farms remained very strong throughout the war. Internees working on farms were better fed and the farmers contributed to the internee’s official pay. The cinema remained the most popular form of entertainment in all camps on the island. Once or twice a week an entire camp would proceed to a cinema in town. In Hutchinson Camp the newspaper “The Camp” was published. It was written in English by and for the internees and included stories and news from within the camp and outside it. The first issue was published in September 1940. The “Onchan Pioneer” was published in Onchan Camp. Kurt Schwitters’ short story “The Flat and the Round Painter” was translated into English by another internee and published and distributed in Hutchinson Camp.

The internees did a lot of sports, too. They established a football league, in which most camps on the island participated. Most of the games took place on Onchan Camp’s football ground, where Norbert was probably a star. Another sport that was open to internees was supervised swimming in the Bay of Douglas or games of boules. As there were many talented and well-educated people among the internees, they founded a “Camp University” a few weeks after their arrival on the Isle of Man. Lectures and classes were held in a building called “Lecture Hall” or in good weather on the lawn in front. Artists and musicians offered private instruction in their rooms. An internee, Fred Uhlman, wrote, “Every evening one could see the same procession of hundreds of internees, each carrying his chair to one of the lectures, and the memory of all these men in pursuit of knowledge is one of the most moving and encouraging that I brought back from the strange microcosm in which I lived for so many months.”

Hutchinson Camp was characterised by a vibrant cultural and artistic life. One month after the opening of the camp an art exhibition was organised, where internees could exhibit their works of art created on site. As there was a lack of material the artists used unusual produce for their art. “The room stank. A musty sour indescribable stink which came from three Dada sculptures which had been created from porridge, no plaster of Paris being available. The porridge had developed mildew and the statues were covered with greenish hair and bluish excrements of an unknown type of bacteria.”, Kurt Schwitters noted. Hutchinson Camp’s Commandant, Captain Daniels, was enthusiastic about art and saw to it that Kurt Schwitters and Paul Harmann had rooms they could use as an atelier and he also provided material for them. He furthermore promoted musical activities and organised musical instruments for the internees. Soon there was a “Camp Orchestra” that played Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms etc. Probably the most famous musician in the camp was the pianist Marjan Rawicz who staged concerts in the camp. There were also theatrical performances in Hutchinson Camp. It is known that a production of John Steinbeck’s “Of Mice and Men” and a parody of Shakespeare’s “Romeo and Juliet” were staged there. Early forms of “Performance Art” took place in the camp when Kurt Schwitters performed his 40-minute poem “Ursonate”. Freddy Godshaw remembered Hutchinson Camp, “The camp was full of interesting characters, not only world famous people, Noble prize winners, musicians, authors etc., but also a lion tamer who was unlucky to be born in Germany while the circus was over in that country. He was one of the first to be released, as his wife could not handle the lions by herself. He was a special friend of mine and I shall never forget him… His talks were always well attended as he had been out to Africa to capture the animals before actually training them. Kurt Schwitters though was our main star. Not only was he a world famous artist, but he was also a most fascinating raconteur and could keep a full house entertained for hours. He wrote and recited a symphony in words. It lasted for 15 to 20 minutes and the musicians at the camp were most impressed… There was hardly an evening that we did not have lectures, talks or concerts. Three of the Amadeus String Quartet met in Hutchinson Camp.”

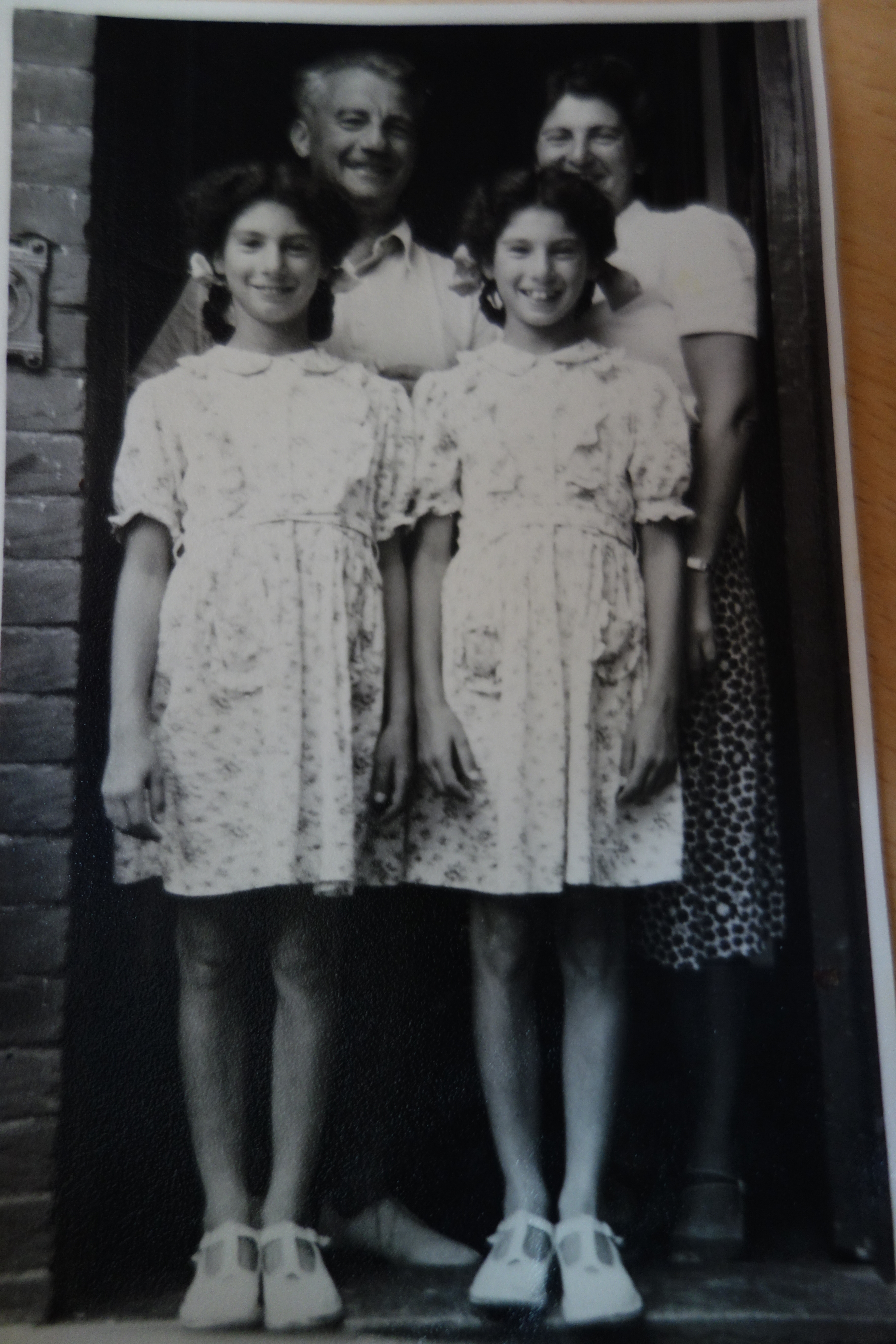

Norbert Katz, reunited with his family: his wife, Agi, the twins, Susi and Josi, in England after the Second World War

Literature:

Bollauf, Traude, Dienstmädchen – Emigration. Die Flucht jüdischer Frauen aus Österreich und Deutschland nach England 1938/39, 2011

Dwork, Deborah & van Pelt, Robert Jan, Flight from the Reich. Refugee Jews 1933-1946, 2009

Gillman, Peter & Leni, “Collar the Lot!” How Britain Interned and Expelled its Wartime Refugees, 1980

Lafitte, Francois, The Internment of Aliens, 1940