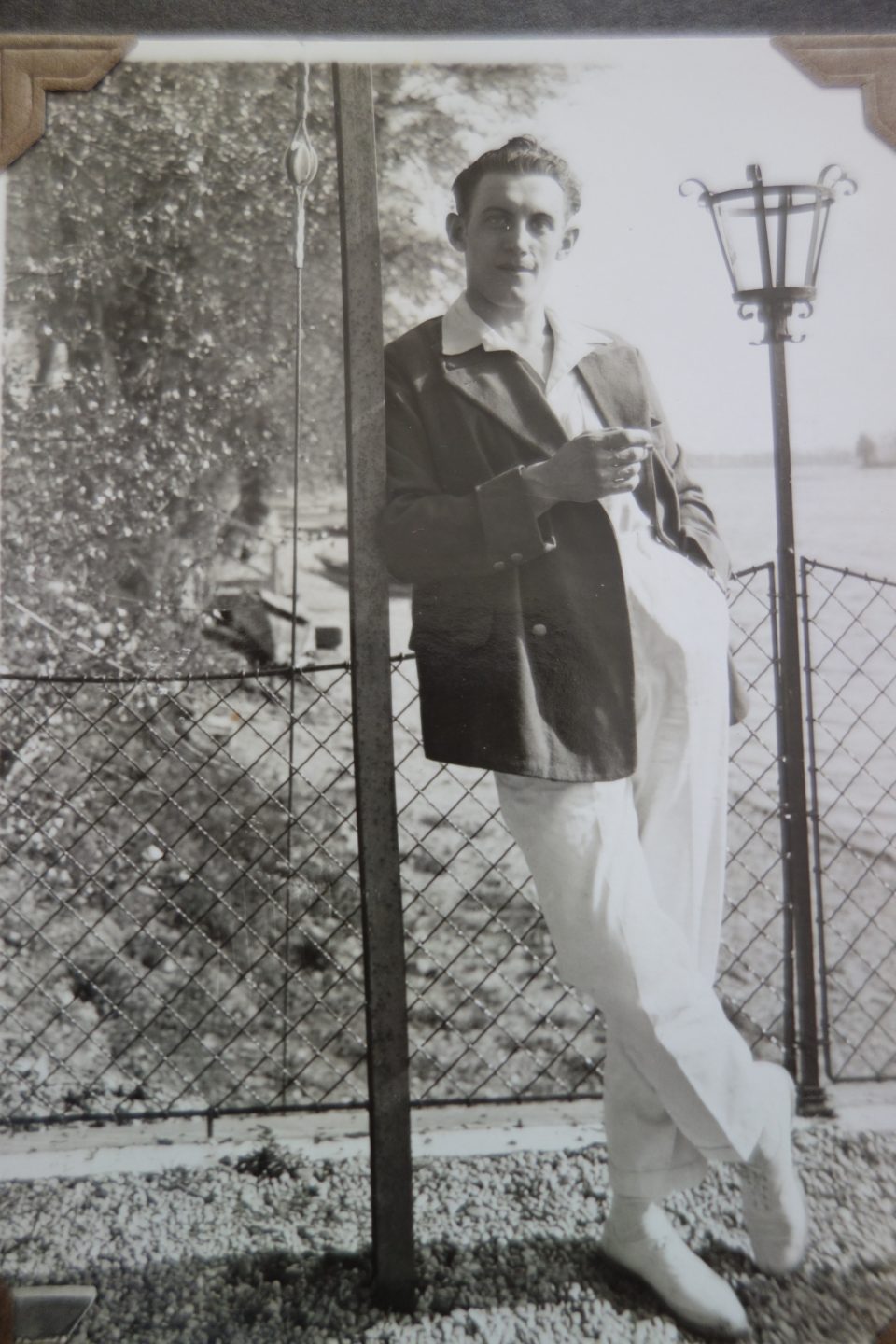

My grandmother Lola Kainz, née Sobotka, as a sweet shop girl around 1930 in Vienna /left)

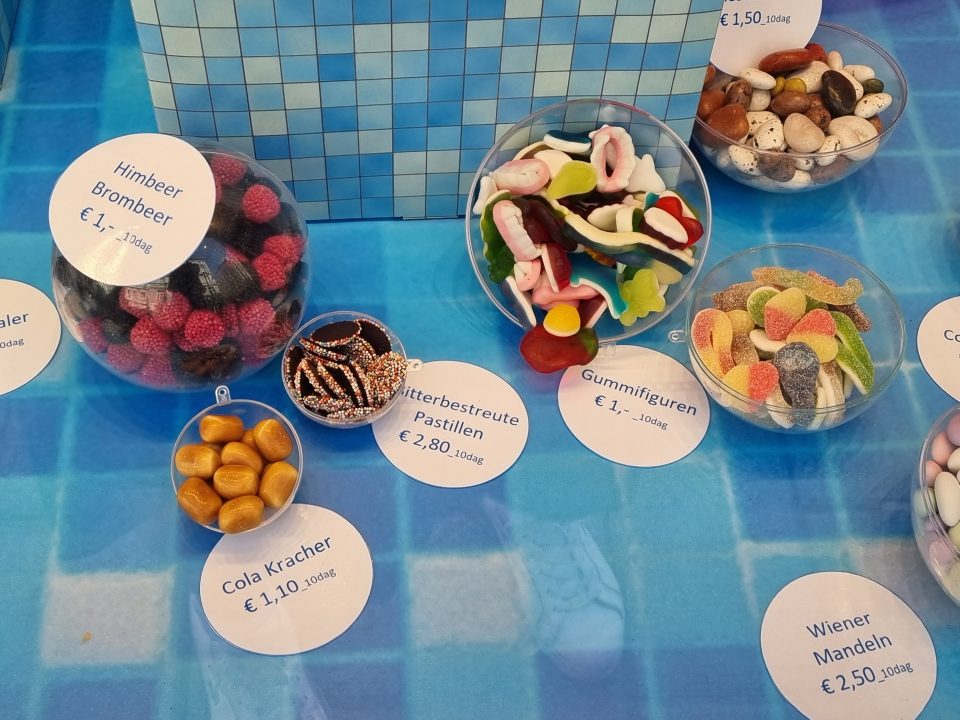

A typical Viennese sweet shop window display with glass containers for candy (right)

My grandmother, Lola, born in 1902, worked as a shop girl in a Viennese sweet shop around 1930 after having given up her education as a pianist at the Viennese Musical Conservatory. At that time Vienna abounded with sweet shops and the job as a sales girl in a sweet shop was quite prestigious, but badly paid, as virtually only female personnel were employed there. Sales girls in sweet shops were supposed to be pretty, well-mannered, and polite. So, qualification criteria for the job were prettiness, good manners, and politeness and the selection process was tough because the number of applicants was usually abundant. It is known that for instance the company Altmann & Kühne put a special focus on the appearance and behaviour of its female sales personnel. When Lola worked at a sweet shop in Währingerstrasse, she was spotted by the young son of the innkeeper of the nearby “Gasthaus Anton Kainz” in Währingerstrasse 146, Toni Kainz. It was love at first sight on Toni’s side and every day Toni bought sweets in the shop – candy which he did not even like very much – just to see Lola. Lola was a pretty, young woman, a bit superficial, who loved life – socialising, fashion, entertainment and a good laugh (That’s what she later told about herself). She even ignored her father’s strict order stipulating that his four daughters were not allowed to have their hair cut short, as it was the fashion of the 1920s and early 1930s in Vienna. Her father, Ignaz Sobotka, had been the manager of the brewery in Kaiserebersdorf near Vienna. After secretly having had her hair cut short – see photo above -, she came home with a funny hat sitting at an awkward angle on her head and she did not even take it off in the family dining room. When her father told her harshly to take off her hat, her funny face and clown demeanour made him laugh and she escaped punishment, much to the astonishment of her three sisters. She was the sunshine of her otherwise severe father.

“Anton Kainz Gasthaus”,18th district of Vienna, Währingerstrasse 146, the inn of Toni’s father in the early 1930s with Lola in the entrance (left) and now (right)

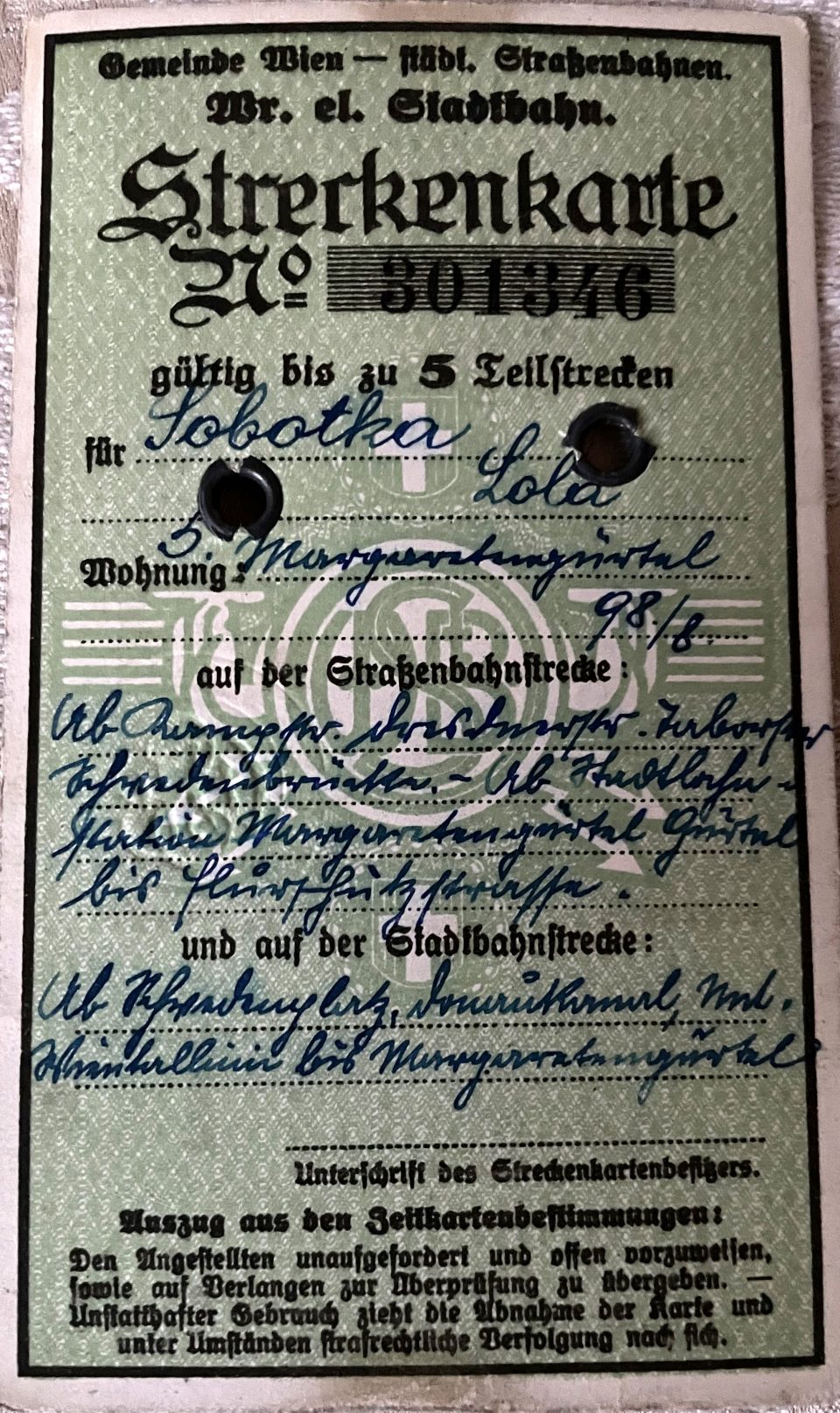

In order to reach her workplace in the 18th district of Vienna, Lola had to take public transport from her parent’s flat on Margaretengürtel 98/8 in the 5the district of Vienna. Here is her monthly tram and “Stadtbahn” (city train) ticket of March 1927:

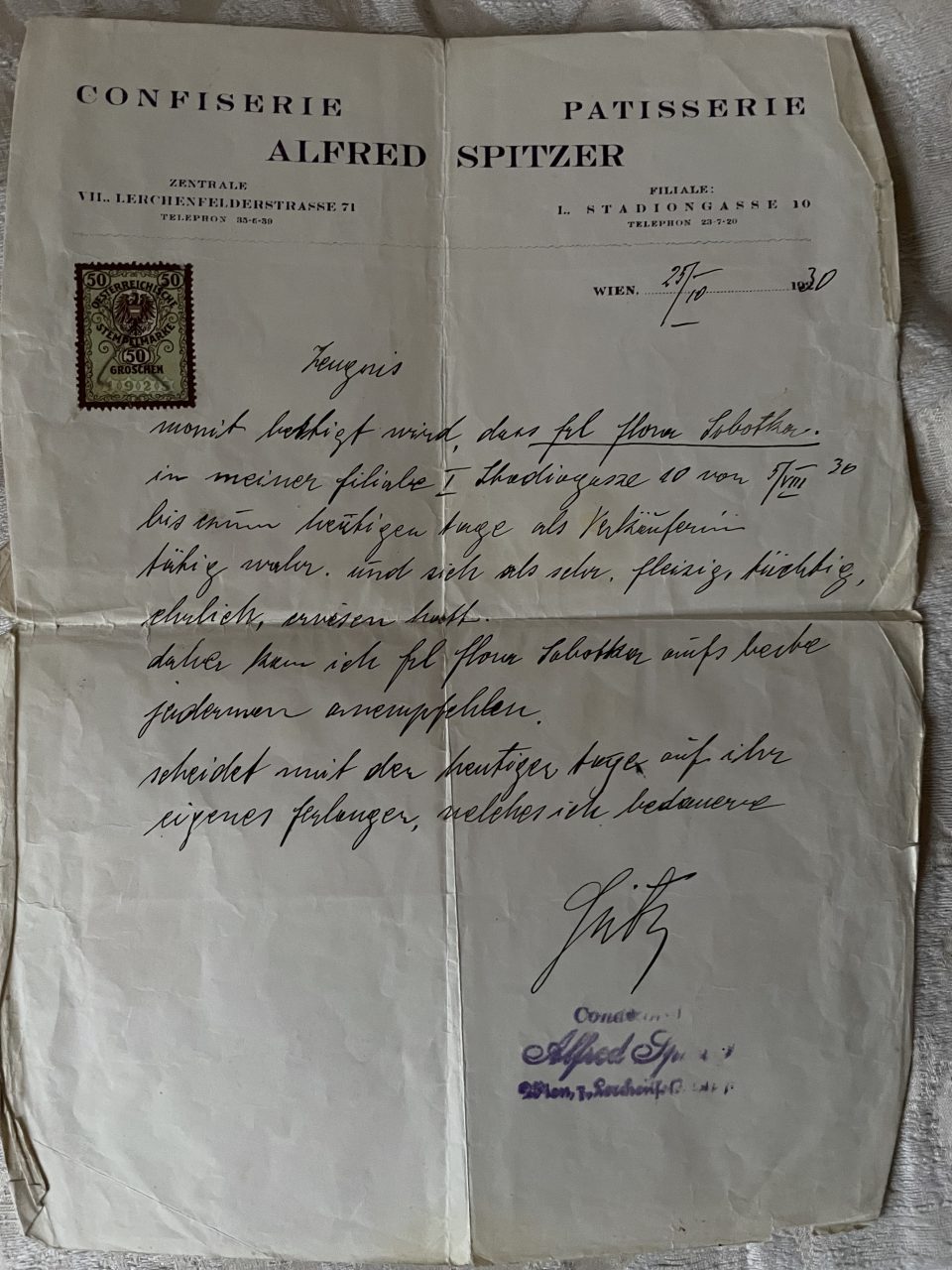

Lola had worked in another sweet shop before, “Confiserie & Patisserie Alfred Spitzer” in the first and 7th district of Vienna (below left)

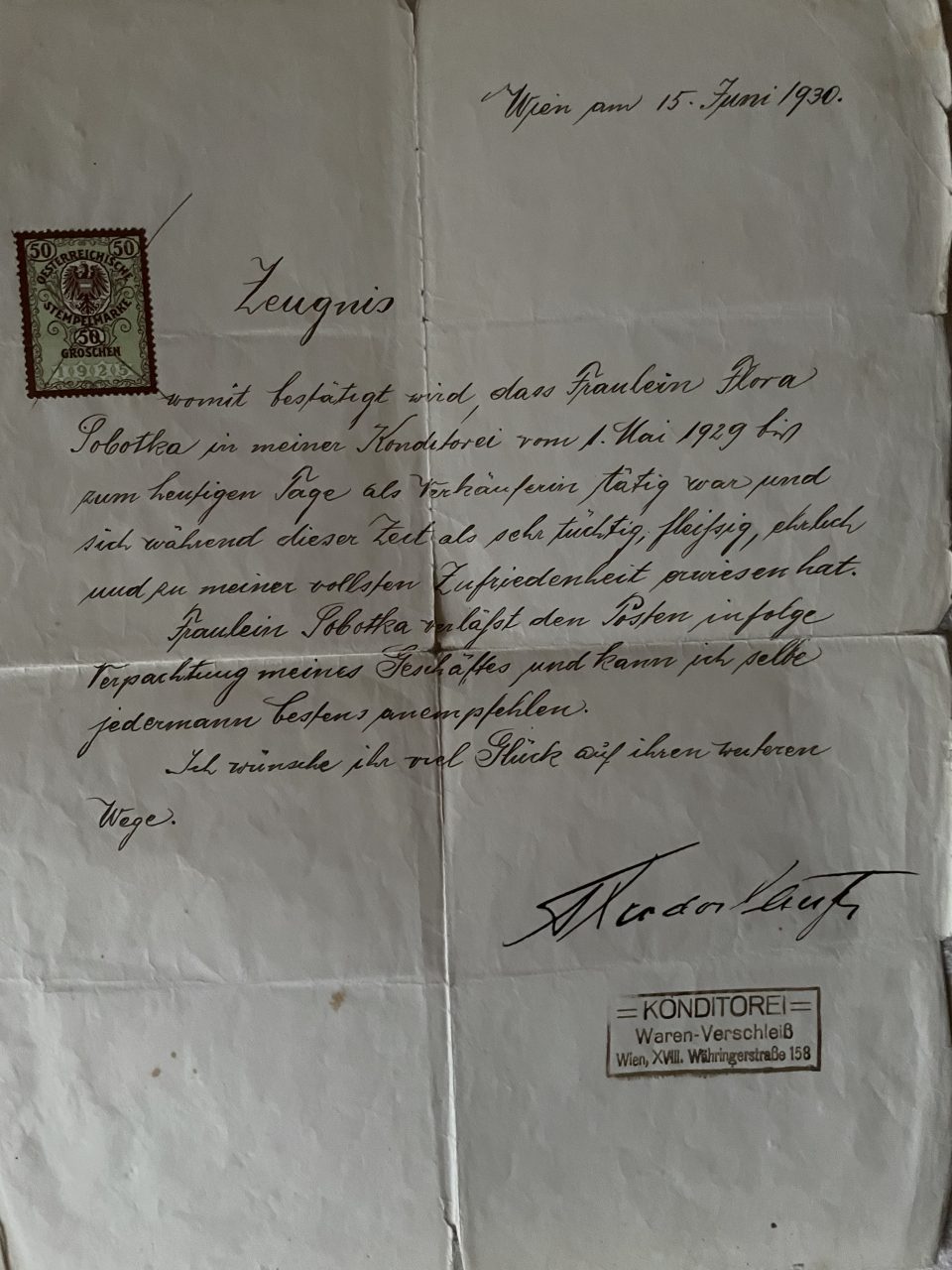

In June 1930 the sweet shop owner of Währingerstrasse 158 rented out his shop and had to make her redundant. He wrote the following appraisal, an excellent assessment of Lola’s job performance (right)

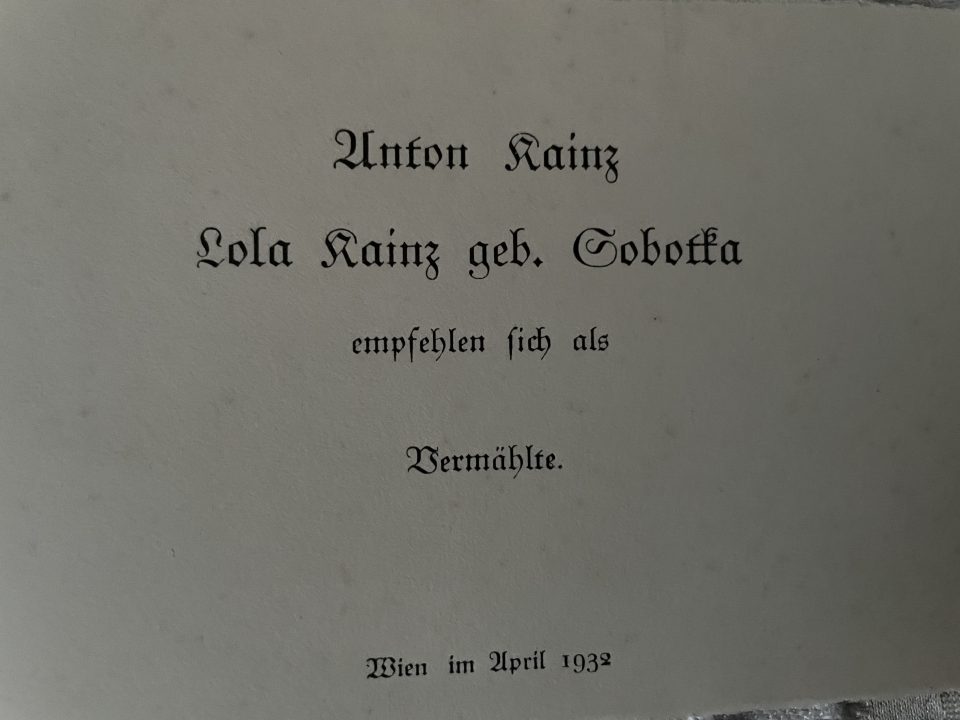

In 1932 Lola and Toni were married and from then on Lola worked in the inn of her parents-in-law:

Viennese chocolate & sweets production

At the Emperor Charles VI’ court in Vienna the exotic product “chocolate” was introduced in 1711, but chocolate drinks were already popular before among the high clergy. Pietro Buonaventura Metastasio even composed a “Cantata alla Cioccolata” at the court of Charles VI in Vienna and the ascetic preacher there, Abraham a Santa Clara, scolded the aristocratic ladies in his sermons for their habits of drinking chocolate at eleven in the morning. Empress Maria Theresia issued an order for Viennese balls in 1752, which stipulated that tea, coffee and chocolate were to be offered at Viennese balls “of good quality, high quantity and at a cheap price”. She herself did not even like chocolate, but her husband, the Emperor Franz Stephan, did. The haute bourgeoisie of Vienna followed in the footsteps of the aristocracy, which is documented in the dialogues of Viennese comedies of the 18th century and even in the libretti of operas, such as Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s “Cosi fan tutti” and “Don Giovanni”, where chocolate is much in demand. Mozart himself wrote that he loved walking in the “Augarten” (a park in the 2nd district of Vienna) in the morning, where he had his breakfast with coffee, chocolate, and tea. He even sent large amounts of chocolate from Vienna to his much-revered master in Italy, padre Martini. As chocolate was extremely expensive at the time, the amounts consumed were very small, from 1812 until 1816 400 tons of cocoa beans were processed in Vienna. Yet before 1800 the majority of the population had never tasted chocolate, as it was a status symbol and a stimulating luxury drink.

For candy the most important ingredient was sugar, which until the middle of the 18th century was cane sugar, whose trade and production was extremely costly and cumbersome. Apart from apothecaries, who were allowed to use cane sugar for the concoction of medicine, only the rich classes of the society could afford cane sugar. But in 1747 the fodder beet, indigenous in Europe, was discovered as an excellent natural resource of sugar. From the fodder beet the sugar beet was cultivated and changed the manufacturing of sweets in Europe dramatically. The sugar beet cultivation and the production of beet sugar turned into a flourishing business sector at the end of the 18th century and the Habsburg Empire turned into one of the biggest producers of beet sugar. Within a few decades sugar had become a commodity that was affordable for a much larger part of the population. Consequently, the manufacturing of candy and other sweets experienced a boom in Vienna and the Habsburg Empire. Yet the fabrication of confectionary products was still a very complex procedure done by hand. A cook of Prince Joseph von Schwarzenberg, Franz G. Zenker, left several recipes for manufacturing “Zuckerl” (candy) in 1834, for example “vanilla bonbons” or “venus bonbons”. Every bonbon was wrapped in colourful paper together with an appropriate motto and on the outside jokes or funny words were printed, which expressed taste, spirit, and wit. The recipe book was aimed at middle-class housewives and their cooks. The commercial production of candy and sweets was to a diminishing degree still in the hands of pharmacists and increasingly in the hands of confectioners. In 1861 the Viennese “Lehmann” directory counted 240 confectioners in the city and with the enlargement of the territory of Vienna in 1895 there were 400. They soon faced fierce competition from the rise of large industrial producers, such as Victor Schmidt. While important Viennese companies, for example Pischinger, Cabos and Manner (see table of Viennese producers below), focussed on the production of wafers, cocoa, chocolate, cakes, and biscuits, Ullmann, Heller, and Schmidt concentrated on the manufacturing of candy and sweets; whereby different types of cough lozenges were always part of their product range. All these companies had their specialities, often with glamorous foreign names, for example “Rock Drops”, “Military Rocks”, “Candy Caramels”, “Brioni”, or “Grado Bonbons”.

In 1887 Anton Hausner warned against the use of toxic materials in the industrial production of candy and in wrapping papers, namely various colourants, and essential oils, such as white lead, chrome yellow or Prussian blue, and he recommended natural plant and animal substitutes, for example saffron, curcuma or indigo.

Despite such warnings the demand for sweets increased dramatically in the first half of the 19th century. At all the famous Viennese balls sweet stands offered bakeries, sweet almonds, candy, and other types of sweets and in the second half of the 19th century the emerging industrial production of chocolate and candy turned an exclusive aristocratic product into a mass-produced consumer good, which was affordable for a larger part of the Viennese population. Already in 1790 cocoa beans were crushed mechanically and now all steps of the production process were industrialised with the help of wind or water mills and later steam engines. Consequently, chocolate was no longer consumed in liquid form only. In 1828 van Houten first separated cocoa butter from the cocoa mass and so opened up the market for a variety of chocolate products. The innovators in the field of chocolate production were to be found abroad, while the Austro-Hungarian Empire was lagging behind: van Houten founded the first factory in Zoon in 1815, followed by Cailler in Vevey in 1819, Suchard in Neuenberg, Switzerland, in 1826, Cadbury in Birmingham in 1831 and Stollwerck in Cologne in 1839. But towards the end of the 19th century the Viennese chocolate and sweets production was fast catching up and attaining international reputation.

The first important chocolate producer in the Habsburg Empire was Victor Schmidt, who failed with his initial enterprise, which he had founded in 1858, but his restart in the early 1870s was hugely successful. In his footsteps several entrepreneurs followed; innovators, often with a minority background: Josef Küfferle, Julius Meinl, the brothers Kunz, Josef Manner and the brothers Heller for example. But foreign groups tried to get a foothold in the Empire’s market, too, such as Suchard in Bludenz, Vorarlberg. Stollwerck in 1896 and Bensdorp in 1907 set up subsidiaries in Vienna. These foreign companies expanded in Austria, especially after World War I, when Austria had shrunk to a tiny state with a very restricted domestic market and huge financial and economic problems. Bensdorp became one of the most favoured brands for the poorer classes with its “10-Groschen” small chocolate bar during the interwar years and after the Second World War with the “1-Schilling” and “2-Schilling” cheap chocolate bars.

The rise of the Viennese chocolate and candy production and the international reputation it gained showed similar characteristics in all the newly founded enterprises in the Habsburg Empire. Victor Anton Schmidt came from a family in Burgenland, which was situated at the interior customs border between the Hungarian and Austrian part of the Empire. His father was a customs officer and he trained as a confectioner and pastry cook in Bratislava. There Victor Schmidt founded his first pastry shop, then moved to Budapest and finally at the end of the 1850s to Vienna. In 1858 Victor Schmidt started a chocolate production in Vienna. His company suffered severely when an economic crisis shook the Habsburg Empire in 1864/65 and Schmidt had to file for bankruptcy. This misfortune was followed by a steep uprise of the recovered company, so that by the end of the 19th century Victor Schmidt & Söhne was the leading chocolate and sweets manufacturer in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Victor Ladislaus Schmidt became the first president of the Empire’s Association of Chocolate Manufacturers, which was founded in the 1890s. Between 1880 and 1905 the factory employed between 800 and 1,000 workers, mostly women. Financially the enterprise had recovered and could pay out all the former creditors of its own free will. In 1905 a new factory building was erected in the 11th district of Vienna, in Simmering, and even in the inter-war years, when business was extremely slack in Austria, which suffered economically after the break-down of the Empire and during the Great Depression, Victor Schmidt & Söhne employed 1,200 to 1,400 mostly female workers, especially from August until Christmas, the high season of the chocolate production in Vienna. In 1934 a new brand of cheap chocolate bars was launched, the “Famos” series, which remained highly popular for 40 years, only interrupted by the Nazi dictatorship 1938-1945. “Treat yourself to a Schmidt Famos” remained a well-known advertising slogan for many years.

In 1891 Gustav Heller, the founder of the company G. & W. Heller, together with his brother Wilhelm set up a factory for the production of special candies, called “Seidenzuckerl” in Vienna in a rented location below the “Beatrixbad”, an indoor swimming pool, where they were using the vapour from the bath for the steam engines. This type of specialised candy was formerly only produced in Switzerland. They profited from the steep fall in the price of sugar on the world market, so that within six years the number of employees rose to 280. They sold their “Seidenzuckerl” in special glass containers, which beautifully presented their wares in the shop windows of sweet and pastry shops. Initially the goods were delivered by carrying frame or wheelbarrow. In 1899 the company launched their most famous product, the “Wiener Zuckerl”, a candy with natural fruit flavour filling, wrapped in colourful paper and a little later the “Likörbonbon” with liquid liquor filling, wrapped in tinfoil.

Left: Heller’s assortment of fruit candy. The Heller tradition is carried on by the “Zuckerlwerkstatt” whose owners were given some of the old Heller recipe books; right: “Seidenzuckerl”(a crispy sugar coating filled with jam or nougat)

In 1899 a new factory was opened in the 10th district of Vienna, Favoriten, and Heller quickly expanded their business employing 600 to 800 workers. Nearly every second year the factory had to be enlarged due to the high demand inside the Empire and abroad.

Josef Manner was the son of a butcher who had opened a small inn in Vienna. Joseph did an apprenticeship as a merchant in Perg in Upper Austria and then opened a shop selling chocolate and a coffee substitute made from figs with a partner, the chocolate manufacturer Friedrich Günther, at Stephansplatz in the 1st district of Vienna. But Josef Manner was dissatisfied with the quality of the chocolate that Günther produced; he declared this chocolate “uneatable”. So, he decided to start his own chocolate production and bought a chocolate shop plus machinery for 500 fl (kroners) in the 5th district of Vienna in 1890. Soon he moved the production to his parents’ house in Hernals, where the main Manner factory is still situated:

From 1890 until 1896 Manner ran his chocolate manufacturing business with only few employees and hand-driven machines, but in 1896 he bought a powerful steam engine (20 horsepower) and employed 100 workers a year later. In 1898 he managed to produce 500 kg chocolate per day and in 1899 700 kg. The Manner business developed from a small artisan enterprise to a large factory business, so that the factory in Hernals had to be enlarged step by step until 1913, when the Manner company went public. The factory now consisted of two huge blocks with more than 2,000 windows. The turnover rose from 49,000 fl in 1892 to 377,000 fl in 1898 and was still increasing. Just before the outbreak of World War I the chocolate production reached 16 million kg in 1913, which was 16 times the output of 1901 and the factory employed 3,000 workers. In 1913 the company reached the peak of its expansion policy: Josef Manner owned a third of the shares in his company, the Anglo-Bank, a third and the other third was held by Johann Riedl, who had taken over the shares from Alfred Teller, the former accountant of the company. Gradually the two families Manner and Riedl were able to buy up the largest part of the shares held by the Anglo-Bank, so that in the end the two families held 92 per cent of the shares, whereby a contract stipulated the shared management of Manner & Company of the families Manner and Riedl.

Carl Hofbauer was the son of a Lower Austrian barrel-maker, who trained as a pastry cook and opened his own manufacturing business after his journeys as a fellow of the guild and the completion of his training in the 5th district of Vienna, in Margaretenstrasse 73 in 1882. His enterprise grew rapidly and his son Ludwig Hofbauer expanded the business by producing all types of quality chocolate and sweets products for wholesalers and by boosting sales via elaborate marketing and advertising of special brands. His “Chocolate Maroni” (dark chocolate with a chestnut cream filling) and “Toffees” ware famous in Austria and its neighbouring countries.

From the end of the 19th century until the middle of the 20th century so-called “Bonbonnieren” (boxes of chocolate) became very popular in Vienna as a precious and elaborate present, where the boxes and the wrapping were at least as important as the chocolate inside, if even not more important. Defining characteristics were an noble appearance, a French touch – even their names, such as “Elegance”, “Connaisseur”, “Praliné”, “Exquisit”, were French, and the presentation was to be exclusive. Pastel colours, rose, gold and white were dominant, and gave the boxes an appearance of excellence and noblesse. The chocolate bonbons inside were made up of several layers and the smaller they were the more high-class and expensive they were. This was only surpassed by the premium packaging, whereby the big size of the boxes of such “Bonbonnieren” with respect to the small size of the content was typical. The wrapping was part of the aesthetic enjoyment and often consisted of several layers. No other product of the time was sold in such outsized packaging.

Altmann & Kühne were and still are exclusive producers of such “Bonbonnieren”, filled with tiny chocolate bonbons, called “Liliputkonfekt”. The various boxes are still much coveted and all the originally 80 varieties were designed by Emil Altmann himself, who was a trained goldsmith and a gifted draftsman.

The distribution and sales of candy and chocolates were organised in several ways in Vienna. The large companies, such as Heller, employed travelling salesmen who were looking for retailers, where they could place their products, for instance sweet shops, pastry shops, delicatessen shops and inns. Originally handcarts and carrying frames were used, later horse-drawn carriages. Some of the producers, like Victor Schmidt or Manner started early to open their own retail shops. Since the end of the 19th century the number of Viennese sweet shops increased rapidly until the 1930s. Another means of distribution were itinerant sellers, for example sweets peddlers or “Zuckerlzwerge” (candy dwarfs), or market stalls, so-called “Süßigkeitenbuden” (candy booths). Around 1900 the promotion of the consumption of sweets reached a peak in Vienna. In 1901 a two-day charity event, the “Zuckerlfest” (candy feast) took place in the garden of the Belvedere Castle and in 1911 a “Bonbontag” (day of the bonbon) was organised, when in the Austrian half of the Empire in 200 places 400,000 “Emperor’s bonbons” were sold for charities with a picture of the Emperor Franz Josef I on the wrapping.

In Vienna even balls were and are still organised during the Carnival Season, which celebrate sweets and the confectionary business, the “Zuckerbäckerball” (Confectioners’ Ball) and the “Bonbonball” (Bonbon Ball)

Towards the end of the 19th century a progressive concentration of the industries became visible in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. This trend towards concentration, modernisation and economies of scale affected the sugar industry, too. The political power and influence of the Empire’s “Sugar Barons” was even bigger than that of the iron, steel, and beer industry. In 1897 the “Great Sugar Cartell” was set up, which was closely linked to the tax and premiums policy of the state. Via this construction the interests of the sugar producers and the state were intertwined, as the cartel was based on a sugar tax, protective tariffs, and export premiums. In this way the Empire’s sugar industry was protected from foreign competition and inside the customs union of the Empire their cartel made it possible to fix prices, limit output and carve up markets. Due to the fast-rising consumption of sugar in the Habsburg Empire the sugar tax became one of the most important food taxes, more important than the high taxes on beer and spirits. Between 1888 and 1904 the share of the state revenue deriving from the sugar tax rose from 2.3 per cent to 6.7 per cent in the Austrian half of the Empire. The political power of the sugar industry could be seen, when in Germany Saccharin was discovered by chance by the chemist Fahlberg. This artificial sweetener was called the “sugar for the poor” and since 1896 the Austrian sugar industry continually warned against the dangers of Saccharin to people’s health in order to protect their “Great Sugar Cartel”. Saccharin was imported from abroad and could only be sold in pharmacies from 1898 on. This resulted in a brisk smuggler activity between Switzerland, where Saccharin was freely available and which became the hub of the production of artificial sweeteners, and Austria. Eventually, during World War I Saccharin would shed its negative image and the restrictions were lifted and that exactly at a time, when the people were in urgent need of the nutritional qualities of beet sugar due to famine and malnutrition. Around Vienna the beet sugar industry had grown rapidly and employed hundreds of workers, especially at the time of the harvest of sugar beets, the so-called “Zuckerkampagne”. All the members of the foster family of my father, Werner Tautz, were workers in the sugar factory “Leipnik-Lundenburger Zuckerfabriken AG” in Leopoldsdorf in the Marchfeld, one of the biggest agricultural areas of Austria near Vienna: Franz Rupp and his wife Anna Rupp, my (foster)grandparents worked there, my father’s foster brother Franzi, who was killed in World War II, and Werner himself were apprentices in the same sugar factory. Werner trained as an electrician there. Such sugar factories created employment for whole regions in Austria, for farmers as well as for workers.

Left: Werner’s apprenticeship contract with the “Leipnik-Lundenburger Zuckerfabriken” AG in March 1943; right: the company’s excellent appraisal, when Werner quitted in August 1947

In a similar way, the chocolate industry experienced enormous growth rates in the Austrian half of the Habsburg Empire around 1900. Primary products, such as sugar and cocoa beans had become cheaper despite the heavy governmental tax burden. Industrialisation reduced the price for chocolate further and at the same time improved the quality. Within a very short time several businesses were established in Vienna, which quickly increased in size and in importance for the Austrian economy. In 1910 the group of Viennese industrialists, who had successfully accumulated a considerable wealth with the production of foodstuffs, namely beer, spirits, sugar, and substitute coffee, counted 60 millionaires. It must be noted that just before the outbreak of World War I the sugar industry in Vienna had reached its peak. The consumption of sugar in the Habsburg Empire had increased from 2 kg to 20 kg per person in the second half of the 19th century and at the same time the Empire had turned from an importer of sugar to an important exporter thanks to the cultivation of sugar beets. The “Sugar Barons” in Vienna were well-known personalities, who figured in the thriving cultural scene of the fin-de-siècle: Benies, Bloch-Bauer, Hatvany-Deutsch, Redlich, Schoeller, Skene, Strakosch, Stummer. The Blochs were one of the biggest sugar producers in Bohemia and are famous for the portraits Gustav Klimt painted of Adele Bloch-Bauer. The Hatvany-Deutsch had a large modern art collection, too. Both families, as well as the Benies, were persecuted by the Nazis and their art collections are dispersed in the whole world. Chocolate and candy were the attractions of a newly industrialised society and the producers of these products could become rich quickly because everyone wanted to offer “sweet presents” to children, family, and friends. The history of the Viennese confectionary producers, such as Victor Schmidt, the biggest enterprise in Vienna before World War I, Josef Manner, Gustav und Wilhem Heller, illustrate this economic trend.

The Jewish part in the industrialisation and in the cultural innovation of the Habsburg Empire was significant, especially in Vienna. Around 500 important Viennese Jewish families were registered, but the definition of a “Jewish family” is difficult in Vienna of the time. Normally, religion, culture and origin are criteria for defining who is a Jew. “Religion” would refer to who was a member of the “Israelitische Kultusgemeinde” (Jewish religious community) in Vienna, but several families who had come to Vienna had converted to Protestantism, Roman Catholicism or were agnostics. “Culture” would mean social and familial Jewish connections, yet many Jews in Vienna had assimilated and were part of the mainstream society. Finally, “origin” is a very problematic subject matter in Vienna because it would be immediately connected to the NS racist ideology and the holocaust. The famous Viennese painter of “Phantastic Realism”, singer and composer Aric Brauer, who came from a humble working-class background in Vienna, once said that it had been Hitler who had made him a Jew. Most Viennese Jews of the fin-de-siècle were no longer “religious Jews”. The religious ones were those who had fled to Vienna from pogroms in the East at the end of the 19th century.

The success stories of the Jews in the Habsburg Empire had several reasons. Sometimes the disadvantages of the past can turn into advantages of the present. Centuries-long persecution and migration increased the mobility of the Jewish population and the high special taxes which were imposed on the Jewish population by the rulers forced them to focus on profit-oriented management of their businesses. Furthermore, Jews were prohibited by successive monarchs from working in agriculture, from acquiring land or property and from working in any craft or artisan businesses which were regulated by guilds, which in fact meant all of them. This led the Jews to attempt earning a living in the only remaining sectors, namely trade and finance, and in the 19th century industrial production, which was not restricted by guilds. Above all, in the course of the second half of the 19th century the Jewish population of the Habsburg Empire gradually gained all civil rights, just like the rest of the population. Yet the experiences of the past were conducive to Jewish success in the new age of capitalism and industrialisation: the well-to-do Jews usually had familial connections in different parts of Europe and the world; they had the concept of a multi-national market in mind and often had expertise in financial markets. What’s more, the status of a persecuted minority had taught them that mutual support in the community could be vital and essential for economic success. Another important aspect was the historical focus on learning and the high value, which was traditionally attached to studying. As soon as the Empire’s universities opened their doors to the Jewish population, a large number of Jewish students flocked to all universities of the Empire and especially to the University of Vienna. Soon the presence of Jews in research and development, law, medicine, technology, and commerce was significant and surpassed their percentage in the overall population. They formed the core of the Viennese liberal “Bildungsbürgertum” (educated middle-class). They were fervent Austro-Hungarian patriots, admired German culture from Goethe to Wagner and played an important part in the Viennese cultural boom of the fin-de-siècle as actors as well as sponsors. Many of them were assimilated, had got rid of their traditional Jewish roots, and had even converted to Protestantism or Catholicism. Nevertheless, they were faced with aggressive anti-Semitism in Vienna. Anti-Semitism was convenient because if you were dissatisfied with the fast changing social and economic system you had a well-known scapegoat. The nobility and the non-Jewish bourgeoisie did not have to express their discontent of capitalism or industrialisation, they could blame the Jews instead, and that went down well with the working class and all the poor who were exploited by the capitalist system of the late 19th century. The Viennese Mayor Karl Lueger masterfully exploited the scapegoat image of the Jews and was much admired by Adolf Hitler for his savage anti-Semitism and his reckless populist policies. What is often forgotten: the by far largest part of the Jewish population of the Empire and of Vienna was not wealthy, but lower-middle class or working class, or even utterly poor, especially when they had just arrived from the rural enclaves of the East. They were workers in the foodstuff industries and not “Sugar Barons”.

The First World War devastated the Viennese confectionary businesses. First, they nearly had to stop the production during the war; second, they lost the huge market of 55 million consumers when the Habsburg Empire collapsed and third, the economic crises in Austria and the rest of Central Europe at the end of the war and since1929 weakened the purchasing power of the consumers drastically. The fin-de-siècle had been the heyday of Viennese chocolate production, facilitated by low prices of sugar, especially beet sugar, and cocoa beans and the economies of scale created by the application of ever more efficient machinery. These trends improved the quality of the chocolate produced and made it affordable even for low-income families. Home-made chocolate tasted bitter and grainy, while factory-produced chocolate was of much better quality. The income of the lower classes rose and so they could spare a few “Groschen” (pennies or cents) for the purchase of a small quantity of candy and chocolate in sweet shops or pastry shops. Giving small “sweet presents” to family and friends at festive days became more and more popular, also among the working class, especially around Christmas. All the big Viennese confectionary factories made most of their turnover around Christmas. Consequently, they started to increasingly produce so-called “sculptured chocolate” for Christmas, for Saint Nicolas, for Easter, and furthermore presents for visitors, godfathers and godmothers, sweets to take on journeys and country walks, such as the famous “Manner Schnitten” with the registered logo of St. Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna:

The original “Manner Neapolitaner Schnitten” were first officially mentioned in 1898 as “Neapolitaner Schnitte Nr. 239”. The filling of the thin wafers consists of sugar, coconut fat, cocoa powder, and hazelnuts from the region of Napoli in Italy: 5 layers of wafers and 4 layers of filling. The bite-size measure is still 49 – 17 – 17 mm. Originally the wafers were sold singly, later in cardboard boxes and since 1960 in the present aluminium wrapping with the red opening thread.

Here is a list of the cocoa and chocolate producers in Vienna in 1920:

| Company | Year of foundation |

| Bensdorp & Co | 1907 |

| J.Brünauer & Co | 1875 |

| Charles Cabos | 1863 |

| Ch. Demels Söhne | 1813 |

| Paul Deutsch | 1828 |

| Gustav & Wilhelm Heller | 1891 |

| P.Korff & Co | 1911 |

| Jos.Küfferle & Co | 1865 |

| Brüder Kunz | 1877 |

| Jos. Manner & Co | 1890 |

| Julius Meinl | 1862 |

| L. Pischinger & Sohn Nachf. | 1849 |

| Adolf Schicht’s Nachf. | 1910 |

| Victor Schmidt & Söhne | 1854 |

| Gebrüder Stollwerck | 1896 |

| D.Ullmann’s Söhne | 1842 |

Later:

| Altmann & Kühne | 1928 |

Chocolate was one of the first products, where specially targeted marketing contributed to the successful launching of a product and to the creation of customer loyalty, the building of a faithful customer base from childhood until old age. Confectionary products were massively advertised via billboards, attractive packaging, in-packs, for example little pictures, collectible cards or figurines, and vending machine, which were used for sweets early on. Scientists and advertising experts worked together insofar as nutritionists and adventurers, such as Nansen and Amundsen, stressed the high nutritional qualities and the excellent results they had with the consumption of chocolate on their expeditions. Renown graphic designers, for example of the “Wiener Werkstätte” created marvellous packaging and sometimes even designed the sweet shops, for example Altmann & Kühne:

Three graphic designers worked for Emil Altmann between 1930 and 1935: Emmy Zweybrück, who had studied at the Vienna School of Arts and Crafts with KoloMoser, Katò Lukàts, who had studied at the Budapest Academy of Applied Arts and Fritzi Löw, who had studied at the Vienna School of Applied Arts with Josef Hoffmann. Some of their paper designs are still in use.

Franz Singer and Leopoldine Schrom designed the shop “Confiserie Garrido & Jahne”, Operngasse 10 in the 1st district of Vienna in 1932. The design of the small sweet shop next to the Vienna Opera was so innovative and luxurious with a front completely made of glass so that the whole shop became the window display and the wares were presented in front of a lighted wall of alabaster glass and sold to the customers on a quarter-circle glass sales counter with designer tubular steel chairs. This shop design must have been so expensive that the newspapers attributed the double suicide of the owners, the sisters Emma and Anna Jahne, in 1933 to their desperate financial situation:

The architect and designer Franz Singer was trained at the “Kunstgewerbeschule” in Vienna and the “Bauhaus” in Weimar and together with Friedl Dicker ran an architectural firm in Vienna’s 9th district, Alsergrund, “Singer & Dicker”. Franz Singer escaped the Holocaust in England, while Friedl Dicker was deported to the KZ Theresienstadt and murdered in the KZ Auschwitz – See article: http://centraleuropeaneconomicandsocialhistory.com/the-kz-theresienstadt-the-deceit-of-the-nazis-of-a-jewish-ghetto-for-the-privileged-and-the-old-the-true-living-conditions-especially-of-the-elderly

Two famous architects designed the portal and the interior of the three Altmann and Kühne shops in the Viennese city centre – on Graben (photo), Kärntnerstrasse and Kärntnerring: Josef Hoffmann of the Vienna Secession and Oswald Haerdtl. a student of Josef Hoffmann and member of the “Wiener Werkstätte”; Mathilde Flögl contributed a hand-painted ceiling.

After 1900 more and more Viennese workers bought and consumed chocolate and candies and they gradually became one of the most important customer groups for the producers. Most Viennese had memories of their childhood Christmas and Saint Nicolas chocolates in different shapes wrapped in silver foil hanging on the Christmas tree or stuffed into their polished boots on Saint Nicolas’ Day. Lola and Toni’s daughter Herta, my mother, who was born in 1933 remembered that during the harsh war years of the Second World War her piano teacher gave her an old piece of chocolate decoration for Christmas, wrapped in tinfoil, which was already totally grey. She brought it home and her father, who was a trained cook, made a “wonderful chocolate mousse” from it. Chocolate and sweets production was extremely crisis-prone, so the Great Depression and World War II hit the Viennese confectionary production very hard. The sociologists Lazarsfeld, Jahoda and Zeisel carried out a study on the effects of unemployment in the town of Marienthal near Vienna in the 1930s and found out that chocolate expressed the last thread of hope and a yearning for joy, so that shortly after receiving their meagre unemployment benefits the dismissed workers spent their scarce money on purchasing sweets for their children and themselves; mainly the discarded pieces of chocolate from the factories, which the companies could not sell, or banana lollies. Nevertheless, the sale of sweets dropped by 57 per cent in the region at the time of the Great Depression. During the Second World War chocolate and sweets were more or less unobtainable for the Viennese population because the confectionary factories had to revert to the production of nourishment which was essential to the war effort. From 1945 on the black market became rampant and such luxury products as chocolate from the Western Allies, for example British Cadbury chocolate, were the currency of the day. Yet soon in the 1950s chocolate and candy lost their touch of exclusivity again and they became mass products. The share of sugar and chocolate consumed per capita rose from 9 per cent before the war to around 15 per cent at the end of the 1950s.

Left: Traditional Viennese Christmas tree decorations made of chocolate, right: sculptured chocolate for Christmas

“Arabesken”, small “Tautropfen” bags and “Tauperlen“ bags for the Christmas tree

The Nazi takeover in Austria in March 1938 had a significant impact on the confectionary production and sales in Vienna, as well as the outbreak of World War II in September 1939. The fierce persecution of the Jewish population in Austria and Vienna led to the expropriation of Viennese industrialists of Jewish origin and the brutal persecution of Austrian citizens with Jewish roots, well-to-do and poor alike. The family business Gustav & Wilhelm Heller was one of those which were first targeted by the Nazis. Heller products were sold in 64 countries world-wide and had an excellent reputation not only in all countries of the former Austro-Hungarian Empire, but also in Serbia, Romania, Bulgaria, Turkey, Egypt and oversees, too. The company owned Heller subsidiaries in London, Paris, and New York. Heller could compensate the loss of the large domestic market of the Habsburg Empire by adding the production of fruit preserves to its product mix. Hans Heller, the son of Gustav Heller wrote in his memoirs “Between Two Worlds” about this time of persecution and exile. As a young man he was not very interested in taking on a position in the family firm. He wanted to make a living as a writer and was a member of the Viennese literary circle, “Weltbühne Zirkel”. In 1936 he published his first novel about persecution, “Ein Mann sucht seine Heimat” (A man is looking for his homeland); further novels and theatre plays could not be published because Hans Heller had to flee Austria. He described his parents, father Gustav and mother Mathilde, the “Queen of Viennese Society”, as a typical bourgeoise Viennese family with high ambitions. His father earned a lot of money and mother spent it. The children did not see their mother a lot, who was either socialising or suffering from migraine. In this class of the Viennese haute bourgeoisie earning much was nothing you talked about, it was a necessity and nothing to be proud of. Hans suffered the sneer and ridicule of his class mates who called him a “koof-mich” (a buy-me). When he was asked what his father did for a living, he answered “Zuckerl” (candy), while his noble schoolmates, for example Handofsky, came from families who were living on their income and did not work for a living. But he had Jewish peers, too, highly-educated and motivated migrants from Bohemia, Moravia, Hungary, Slovakia, or Poland.

The Hellers were assimilated Jews; they celebrated Christmas and other Christian holidays and never any Jewish holidays and had no knowledge of the Old Testament. Some Jewish traditions had been passed on by his grandfather Moritz Heller, but Hans was aware of the aggressive animosities and prejudices which prevailed in Vienna against Jews from his childhood days on. He attended the elitist “Akademisches Gymnasium” in the first district of Vienna, which offered an ultra-conservative humanist education with a focus on Latin and ancient Greek and the world of Roman and Greek antiquity. At the same time radical youth movements of the left and the right, which wanted to destroy the traditional system, roamed the streets of Vienna outside the protective walls of the elitist grammar school. Hans was attracted by the Socialist youth movement; he even participated in Socialist demonstrations, while his parents clung to the old world of the Empire, even when it had already disappeared. Hans fought in the First World War at the Isonzo Front and towards the end of the war he was arrested for participating at a Communist demonstration in the uniform of a lieutenant-colonel during his furlough. His mother’s connections to the Minister of the Interior got him free and the minister warned him to desist from such actions in future. In 1919 he married his lover, the young and flirty beauty Gretl, who had accompanied him on the leftist demonstrations. During the inter-war years Hans enjoyed the thriving art and literary scene of Vienna. The two even had a “project of building a small villa” designed by Josef Hoffman in 1923, which was never realised. He became junior partner in the confectionary firm of his father and uncle, which was an easy task for him, but very boring.

His father Gustav had an enormous commercial talent, which he never boasted about, on the contrary, he stressed his interest in classical literature and his love of nature, both of which he passed on to Hans. His extended travels and participation in cultural circles helped Hans later, when he had to make a living in emigration. Hans described the comfortable life he enjoyed in the cafés, cabarets, bars and at balls in Vienna of the 1920s and 30s; sexually free, lots of love affairs, two marriages, dabbling in art, literature, music, and politics. Hans Heller reported that they called him a “dabbler and parasite, in fact a Renaissance man”. He and his friends enjoyed the parodies of Hitler and the Nazis in the many Jewish cabarets in Vienna, but he realised in 1933 that the time was over, when they thought they could fight against the Nazi spirit with novels, musicals, and comedies.

When his father died in 1936 the family found out that he had had a lover for many years: Sophie Schwarz, the secretary of the “Verband der Schokolade-und Zuckerwaren-Fabrikanten” (Association of the chocolate and confectionary producers). He had handled this love affair very discreetly, visiting Sophie daily on his evening walks to the “Gösser” beer hall and the apartment he had bought for her nearby. He had purchased for her an elegant sweet shop as well and had taken her on trips to the French Riviera and Switzerland. With the death of his father Hans had to take on more responsibility for the firm, especially for the international business. He arranged the establishment of Heller subsidiaries in Portugal and Italy. He sympathised with the Socialists, did not want to see the danger the Nazis posed for Austria and tried to ignore the rising radicalisation. He spent the weekends in the hunting lodge in Klausen and the summer holidays on Grundlsee in the Austrian “Salzkammergut”.

Then suddenly in March 1938 the “Anschluss” took place (takeover of the Nazis in Austria). Hungarian Nazis stormed into the offices of G. & W. Heller, robbed everything in the company’s safe and the SA (NS Sturmabteilung) arrested Hans and his cousin Stephan. There were many who wanted to get their hands on the profitable firm, Hans Heller reported, while he was trying to find a well-meaning buyer for their business. The “game of cat and mouse with the Nazis” lasted from March until August 1938. His brother -in-law Opalski, a Nazi, set up a pro-forma sales contract with a very small sum for the purchase, promising to help the family with their emigration from Austria, but that was all a hoax. Hans Heller had to battle with the new NS manager of the business daily and had to pay enormous sums of money to a NS lawyer. He wrote that for the first time in his life he was poor in cash and friends and always carried a potassium cyanide capsule with him. His English friend, Jack Jones, the director of the London Rowntree Candy Manufacturers, saved his life. Jack Jones flew to Vienna with his wife, met Hans in Vienna and smuggled a mandate signed by Hans Heller out of the Third Reich. Back in London he managed to withdraw the 30,000 pounds, Gustav Heller had deposited for his children in Switzerland, and have it transferred to England. Hans and his wife Inge were able to buy very expensive 4-week-visa for England and settled in a rented flat in Liverpool, where Jack Jones handed him over the money. His share of the money would last him half a year only, so he tried to set up a Heller company in England. His friend Jack Jones helped him once again, this time with Hans’ elder son Peter, who had been interned on the Isle of Man and Jack got him free and took him in.

Running the business in England turned out to be very difficult because of the lack of primary material during the war and the rationing of sugar and cocoa beans. So, Hans tried to contact former business partners and friends in the USA. He managed to arrange a cooperation with the US firm “Barker & Dobson” and with a 3-month-visa he risked crossing the Atlantic during the war from Liverpool to New York. His wife Inge promised to join him later, but as their marriage had already been shattered, she never came. As soon as he had arrived, he started looking for a partner for the US company Heller. Meanwhile he found employment with a former customer in Vienna, the company “Altmann & Kühne”, whose owners had been robbed of their company by the Nazis in Vienna, too. They had opened an exclusive confectionary shop on Madison Avenue in New York. Hans wanted to raise funding for a chain of confectionary shops and his connections and reputation helped him to find five partners who were prepared to invest $ 10,000 each in a Heller factory on 145th Street. He bought used machinery from a Swiss chocolatier and the business was flourishing thanks to all those who had helped him in the US, his uncle Ignaz Kreidl, the brother of his mother, and Anna Freud and Dorothy Burlingham, who he had known in Vienna because his son Peter had attended the Burlingham School in Vienna. Hans was in close contact with Alfred Polgar, the Viennese feature writer, who he met in coffee houses and drugstores in New York, and together with Berthold Brecht and Hermann Broch they issued the democratic journal “The New Austria”. Hans enlarged his business in New York, but the rationing of sugar and syrup in war times hindered his expansion plans. He tried to attract the New Yorkers to his shop by focusing on elegant European taste. He had another emigree, Emmy Zweybrück from the “Wiener Werkstätte”, design his packaging and the shop decoration and the architect Simon Schmiederer plan the furnishing of the shop. He was very successful with fresh strawberries dipped in chocolate and the famous Heller “Wiener Zuckerl” with natural fruit fillings. He even had a huge “Wiener Zuckerl” fixed to the factory front. When it was clear that the Western Allies and the Soviet Union would soon win the war, Opalski tried to contact Heller in New York hoping to secure a future for himself after the break down of the “Third Reich”, but Hans Heller refused any negotiations. Nearly all his family, who had not managed to leave Austria in 1938/39, had been deported to the KZs (concentration camps) Theresienstadt or Dachau and none of them had survived. Before 1938 the whole Heller family, who had lived in Vienna, had enjoyed very good and friendly relations, so Hans wanted to return to Vienna as soon as possible and get his company restituted.

“Altmann & Kühne” were well-known for the quality of their sweets and chocolates and the elegance of their presentation in Vienna. In 1935 they had a stall in the Art & Industry Exhibition in Budapest, the “Viennese Candy Store”. And in 1937 they even received a request from the secretary of the English royal Edward, Duke of Windsor, for the delivery “white peppermints without chocolate” and “green peppermints”. The radicalisation in Vienna and mounting anti-Semitic aggression led Emil Altmann in the autumn of 1933, after Hitler taking power in Germany, to hand over all the precious paper designs of his company to the MAK (Museum of Applied Arts) in Vienna, where they are still preserved today. After the Nazi take-over in Austria, in April 1938 the two owners, Emil Altmann and Ernst Kühne, were accused of delaying bankruptcy and the Nazis falsely claimed a company debt of 250,000 Austrian Shillings. They were then both arrested. In May Altmann and Kühne were forced to agree to selling their three stores in Vienna to Schenk-Weber for 190,000 Reichsmark, which were never paid out in the end, and to dismiss the four Jewish employees, because the new owner would only employ “Aryans”. But the National Socialist Party (NSDAP) had other greedy contenders for the grabbing of the Altmann & Kühne business, among them the NS administrator Mühr. Furthermore, the accusation of bankruptcy delay would offer the chance for the Nazis to liquidate the business without even paying a small sum to the owners. More accusations were filed against Altmann and Kühne and they had to report to the GESTAPO daily. By June the Altmanns had acquired the necessary emigration papers and visa and secretly left Vienna with hand luggage only via Switzerland to Brussels, where they received a permit of visit for England. In London they could finally procure the affidavit for the USA in November 1938, but unfortunately several members of their family had to be left behind and had already been arrested by the GESTAPO. The NS sympathiser Madler received the trade licence for the “Altmann & Kühne” shop on Graben, but was not allowed to use the “Jewish brand name” Altmann & Kühne. Schenk-Weber, who took over the shop in Kärntnerstrasse, was asked in February 1939 to pay 10,000 Reichsmark to an account of the NS “Vermögensverkehrsstelle” (the NS office which expropriated the Jewish citizens) in the name of Emil Altmann, to which Altmann had no access without the consent of this agency. Such was the perfidious process of robbing the Jewish citizens of all their assets and their citizen’s rights. At the same time the files of Altmann and Kühne were closed with the remark “Jews moved abroad”. In May 1939 the “Ariseur” (expropriator) Hans Schenk-Weber was accused of still using the “Jewish name Altmann & Kühne” by the German Association of Confectionary Producers and was ordered to erase it completely. From New York Altmann and Kühne tried to fight against their expropriation, but to no avail.

After his arrival in New York Emil Altmann attempted to get a foothold in the city by opening a confectionary store in the Gotham Hotel, taking on debt and with the help of investors the business took off. The company’s name was changed to “Altman”. Altmann took in another refugee from Vienna and a childhood friend, the architect Victor David Grün, who designed the furnishing of the new shop in New York’s 5th Avenue. The shop’s elegant window displays attracted the attention of the New Yorkers. Altmann was an advertising expert, which helped to promote his business in the US. The posters and wrapping paper showed the original name of the company in Vienna, adapted to English-speaking customers “Altman & Kühne” and he again used the services of Emmy Zweybrück in designing paper with Austrian motives. When the US entered the war, the economic conditions worsened and Emil Altmann and his wife ran the business on their own, which was not viable for a longer period. Consequently, they had to sell the shop on 5th Avenue to Mr. Duval, who then employed them and paid them apprentices’ salaries. The employment conditions were unbearable; consequently, they had to quit. Based on his excellent reputation Emil Altmann was hired by the US company “Barton’s Candy Corporation” as artistic director. Ernst Kühne died in 1944 in exile, but Emil Altmann and Ernst’s widow Wilma Kühne tried to get their business in Vienna restituted after the end of World War II.

When Austria was incorporated into Hitler’s “Third Reich”, the foodstuff industry profited from the larger market at first, but when in September 1939 Hitler started the 2nd World War all food production, including the confectionary businesses, was declared “essential to the war effort” and had to adapt the production to the needs of the NS war machinery; for example, the well-known coffee roaster Julius Meinl. The founder, Julius Meinl I, was born in 1824 in Kraslice and opened his first shop on Fleischmarkt in the 1st district of Vienna in 1862. In 1913 he handed over the business to his son Julius Meinl II with sales outlets all over Central Europe. With 115 sales outlets and 1,100 employees it was one of the leading foodstuff enterprises in the Habsburg Monarchy. Even after the break-down of the Austro-Hungarian Empire the business model of Julius Meinl worked. Between 1919 and 1933 he set up eleven to twelve new shops every year in Austria, whereby he focussed on a vertical integration of his business adding preserves, margarine, liqueur, oil, and mustard production to his product mix. By 1937 Julius Meinl II was active in eight countries, many of them successor states of the Habsburg Empire, with 493 sales outlets and 3,000 employees, most of them women and half of them in Austria. In 1938 the founder’s grandson, Julius Meinl III, emigrated to London with his family, while his company was run by NSDAP managers. Julius Meinl III stated that he no longer had any influence on the running of his company, while staying in Great Britain. He returned in 1947 to Vienna. His father, Julius Meinl II had remained in Austria during the war, but had withdrawn to his country residence in Alt-Pernau and died in May 1944. The incorporation of Austria into Hitler’s “Third Reich” gave an enormous economic boost to the enterprise. In 1943 the Julius Meinl group had grown to 687 branches. Due to its involvement in the NS regime, the Julius Meinl enterprise lost all its business outlets and production sites abroad after the end of the Second World War and had to concentrate its business activity on Austria.

First “Julius Meinl” shop at the Fleischmarkt in the 1st district of Vienna

Julius Meinl headquarters and the “Meinl Villa” in Vienna’s 16th district Ottakring, Julius Meinlstrasse, conveniently located next to the rails of the “Vorortelinie”, a city trainline (top left). Formerly “Julius Meinl” shop at the Graben in the city centre of Vienna (top right) Below left: the traditional logo: the little boy with a fez hat; right: the new logo – just a “fez” hat

Ottaking and Hernals were important Viennese working-class districts, known for the production of chocolate, sweets and foodstuffs; left: a former chocolate factory, right: Eibensteiner production, which is now producing some of Heller’s specialities, such as “Wiener Zuckerl”.

Josef Manner factory in Hernals, Wilhelminenstrasse, and the registered logo of Saint Stephen’s Cathedral, which Manner has been using since 1889. Manner still pays the salary of a stone mason at Saint Stephen’s “Dombauhütte” (cathedral builders’ hut), who works dressed in “Manner pink” overalls.

Contrary to Julius Meinl, the Josef Manner enterprise experienced a severe downturn in its business activity during the Great Depression. The number of employees had to be reduced from 1,500 to 800. Most of the female workers were seasonal workers and were only employed between August and December, when the business was running at full capacity. In 1935 the company had to reduce the share capital from 6 million Austrian Schillings to 4.5 million and the founder of the business withdrew from managing functions in the same year. Business did not immediately recover after the Nazi take-over in Austria in March 1938. Only in the 1960s the turnover of 1914 was surpassed. But Manner, just as Meinl, profited from the fact that the foodstuff industry was declared “essential to the war effort” by the Nazis in 1939. Despite restrictions with respect to availability of necessary primary materials and rationing, Manner experienced considerable growth. Already the year 1939 was declared a satisfactory business year for Manner due to a large number orders from the German army, the “Wehrmacht”. Manner profited from the expropriation of Jewish competitors by acquiring their assets cheaply and by getting rid of their competition. Furthermore, all foodstuff companies in Vienna participated in the exploitation of foreign forced labour on a large scale, organised by the Nazis. Manner reported a profit of 3.3 million German Reichsmarks in 1941 and issued a dividend of 6 per cent. Carl Manner later stated that the company was “forced” to produce for the ”Wehrmacht” as an army supplier. Among other foodstuff they produced “Fliegerschokolade” (fighter pilot’s chocolate) for the “Wehrmacht”. Being an enterprise “essential to the war effort” Manner was assigned certain quantities or rationed cocoa beans until 1945. The Nazis installed an NSDAP party member as manager of the Manner factory, while the founder’s son was employed as technical director of the company. The factory in Hernals was only slightly damaged by Allied bombardments and when the Soviets liberated Vienna in April 1945, the Soviet army requisitioned all stocks of sugar and cocoa stored in the factory. That’s why the factory had to reduce production drastically in the following two years due to a lack of basic commodities.

Since 1892 August & Josef Küfferle produced “Katzenzungen”, which are still popular: the form was derived from “sponge fingers”, called “langue de chat” in French.

August Küfferle set up business together with his brother Josef, both born in Vienna, in 1866. He started with the production of malt and malt coffee and then chocolate. After the death of their father in 1911, his sons Walter and Josef took over the managing of the company. The First World War was a difficult time for them as well, and after the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire they lost all their branches abroad. They went public in 1925, which gave a boost to the company, employing around 400 workers. In 1931 they opened an elegant store in the” Equitable Palais” in Vienna’s 1st district, Kärnterstrasse 2, which was designed by the eminent architect Hubert Gessner. For decades their production site was situated near the train station “Meidling” on Eichenstrasse 60. During World War II the company was run by a Nazi manager, but after the end of the war and a period of recovery in 1950 Küfferle launched one of its most successful products ever, which is still on the market today, especially at Christmas, the “Schokoschirmchen” (chocolate umbrellas), originally called “Schokoknirpse” after the Viennese term for a small version of an umbrella. They can still be found on Christmas trees in Vienna and Austria and are now produced by Lindt:

Above: Küfferle “Chocolate umbrellas”; below: the former Küfferle malt factory in Deinleinstrasse in the 22nd district of Vienna, now a place for art students

The Küfferle family were close friends of my aunt Henny and her husband Pepi Singer, – see article: http://centraleuropeaneconomicandsocialhistory.com/illegal-rescue-transports-of-jewish-children-and-adolescents-from-vienna-to-palestine-1939-1945

who traded in textiles. Both families spent their summers on the Danube in Greifenstein in two neighbouring wooden houses on which were typical of this summer resort on the banks of the Danube near Vienna.

Geifenstein, Sackgasse, left: the summer house of the Küfferles, right: the summer house of my aunt and uncle Henny and Pepi Singer

The former Küfferle prime sales outlet in the 1st district of Vienna, Kärntnerstrasse 2: “Palais Equitable”

Forced labour in Vienna during the NS period

In Vienna the racist ideology of the Nazis fell on fertile ground among the population. NS empirical social research carried out a survey among Viennese enterprises and then drew up a “scale of utility” of forced labour according to racial criteria. The Viennese NS bureaucracy adopted this racist categorisation and applied it, when assigning forced labourers to Viennese businesses. Viennese Jewish citizens, who were not able to emigrate until the start of the war – like my great-grandparents Rudolfine and Ignaz Sobotka – or thought they did not need to flee because they were married to an “Aryan” partner, for example – like my grandmother Lola, were constringed to do forced labour. Ignaz Sobotka, who was in his late 60ies, had to do forced labour at the road construction firm TEERAG until his and his wife’s deportation to the KZ Theresienstadt – see article: : http://centraleuropeaneconomicandsocialhistory.com/the-kz-theresienstadt-the-deceit-of-the-nazis-of-a-jewish-ghetto-for-the-privileged-and-the-old-the-true-living-conditions-especially-of-the-elderly .

Lola was forced to do hard manual labour in a lumber factory, “Wiener Holzwerke”, until late at night. The Jewish forced labourers who lived in Vienna usually slept in a “collective flat” – see article: http://centraleuropeaneconomicandsocialhistory.com/the-lives-of-people-in-mixed-marriages-and-of-mixed-race-children-according-to-the-nazi-nuremberg-race-laws-in-vienna-1938-1945

and had to appear at their place of work daily on time, otherwise they faced severe punishments and if at all, they were only paid a minimal fee.

My grandmother Lola in 1939, when she was forced to adopt the additional name Sara by the NS terror regime (bottom left) and was issued a “Juden Kennkarte” (Jewish ID)- (top left). It is striking how the beautiful young carefree face of the sweet shop sales girl of 1930 had changed in 1939. Lola was compelled to do forced labour in Vienna at a lumber company – (top right)- confirmation that she had to work until 22.30 (March 1943) and her tax card of 1944 identifying her as a Jew and her name as Flora Sara Kainz (bottom right)

Lola’s “Arbeitsbuch” (work book), which every forced labourer had to carry with her all the time, otherwise she would immediately be arrested by the GESTAPO.

The NS forced labour categorisation stipulated that

- forced labourers from Germany received a basic salary minus 10 per cent,

- “Western” forced labourers between minus 30-50 per cent and

- “Eastern” forced labourers minus 60 per cent.

Additionally, employers could cut salaries with respect to performance on the job and general behaviour; overtime and Sunday work was not paid. Hunger was used to discipline especially Jewish and Eastern slave labourers. There was a lack of accommodation, clothing, and food for all of them. By 1942 they were so famished that they ate their day’s ration immediately after distribution. If the workers did not arrive at their place of work, they had to forgo the only warm meal of the day in the forced labourers’ camp. Sometimes local workers left their personal lunch packets behind for the forced labourers to alleviate their hunger. After the start of the war most of the adult men in Germany and Austria were drafted, like my grandfather Toni, Lola’s husband, – see article: http://centraleuropeaneconomicandsocialhistory.com/personal-experiences-of-a-viennese-soldier-in-a-sappers-division-of-the-german-wehrmacht-during-the-military-campaign-in-france-1940-part1

and towards the end of the war even teenagers were drafted, like my 16-year-old father Werner and his foster brother Franzi. – See article: http://centraleuropeaneconomicandsocialhistory.com/the-nazi-children-evacuation-programme-erweiterte-kinderlandverschickung-in-the-vicinity-of-vienna-1940-1945-and-the-ideological-indoctrination-of-the-young

This resulted in a drastic lack of male labour, so that many formerly male jobs were taken on by women. But that was by far not enough, so civilian labourers were hired or abducted abroad and forced to work for the NS war industry, originally from NS-occupied France, Poland, and Yugoslavia, additionally to the prisoners-of-war, who were transferred to hard labour camps. In 1944 a third of all jobs in the “Third Reich” was done by civilian foreign forced labourers, especially in construction, transport, industry, and agriculture. Since 1942 KZ prisoners had to work for the Nazi “war machine”. All of them worked under conditions that no German or Austrian worker would have accepted and even if the productivity of the slave workers was lower due to the conditions under which they were dragged to Vienna and had to live and work there, the businesses would have had to close down without them.

The forced labourers in Vienna came from all parts of Europe, which had been occupied by the German “Wehrmacht”. Civil foreign labourers were issued ration cards with a reduced amount of food until 1945, yet Jews did not receive any ration cards. Nearly 100,000 ration cards were issued in Vienna, which allows an estimate of how many slave labourers were exploited in Vienna, not counting all those who did not receive ration cards, such as Jews, KZ prisoners and prisoners-of-war. The whole Viennese economy profited from forced labour during the war; nearly all sectors, but especially those which were considered “essential to the war effort” by the Nazis, namely all industrial and arms production, the construction industry, the transport and the foodstuff sectors. All those huge FLAK-towers (air-defence towers) in Vienna, which can still be seen in the city, were constructed by foreign slave labour. The forced labourers cleared the rubble after Allied bombardments and they kept the Viennese trams, trains and buses running. But many small and medium-sized private enterprises exploited slave labourers, too. They paid them tiny salaries, if at all. This massive exploitation of slave labour in Vienna allowed an upkeep of the city ‘s infrastructure during the war and by that benefited all Viennese citizens.

Of course, the majority of the foreign labourers were hostile towards the NS authorities and the indigenous population and therefore the Viennese NS administration passed several “special laws” in order to strictly supervise the forced labourers, to severely punish any sabotage or lack of morale at work. Among foreign slave labour from the East a communist resistance movement, the “Anti-Hitler Movement of the Eastern Workers”, resorted to sabotage in Vienna and the NS authorities answered with brutal retaliation, especially against those they had abducted from the Soviet Union. The slave labourers managed to establish resistance cells in individual factories and businesses. On 27 January 1944 in the “Vereinigten Wäschereien” (laundries), in the „Elektron-Siebenhirten“ (an electric firm) and several other enterprises the GESTAPO arrested all the Eastern labourers and deported them without a trial to concentration camps, where most of them died under atrocious circumstances. In Vienna the surviving slave workers were liberated by the Soviet Red Army, but the Soviet Union was undecided how to deal with these “Eastern workers”. Initially they were all put into camps and collectively sent to their countries of origin. There they were often accused of collaboration with the Nazis and put into labour camps or prisons. In Vienna the memory of these slave workers was quickly deleted in an attempt to cover up all collaboration with Nazi Germany.

From the start of the war the foreign forced labourers were housed in haphazard camps in Vienna. Research has identified more than 610 such camps in the area of Vienna (during the NS period the administrative unit was called “Groß-Wien”, which comprised Vienna and some parts of Lower Austria), which can be spotted on an on-line interactive map. At the end of 1942 the NS Viennese Health Service registered 637 camps for foreign forced labourers, but there were definitely many more, because some businesses and factories did not want their slave labour to commute and quartered them on site in cellars, yards or barracks. The Viennese forced labour camps housed more than 100,000 slave workers. In May 1944 12.779 foreign slave labourers were officially registered in Vienna. Additionally, there were several thousand Hungarian Jews and KZ prisoners from KZ sub-camps in “Groß-Wien”. In Vienna they not only worked in large armaments industries, such as “Ernst Henkel Flugzeugwerke”, the “Flugmotorenwerke Ostmark”, both aviation industries, “Akkumulatoren-Fabrik”, batteries production – today VARTA – or “Gräf & Stift”, engines, but these slave workers were also employed by the City of Vienna via the INHA, “Industrie-und Handwerksförderungsgesellschaft” – see below. This company was especially set up for the distribution of foreign forced labour by the City of Vienna, the GESTAPO and many smaller enterprises, for example a tent-producing business in the 2nd district of Vienna, which housed the slave workers in its cellar. Sometimes the foreign forced labourers were forced to sleep in camps in public places, parks, sports grounds, or abandoned schools in Vienna. All these accommodations were overcrowded and lacked proper sanitary and heating facilities. The workers had to walk to their places of work or if they were too far away, they were transported by public transport. These foreign civilians were constringed to clear the rubble after bombardments of the city and even to defuse explosive devices, for example unexploded bombs.

Most of the foreign forced workers in Vienna came from Albania, Denmark, France, Greece, Italy, Yugoslavia, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Russia and the Ukraine, Czechoslovakia, Turkey, and Hungary. In the summer of 1944 the Viennese Mayor Hanns Blaschke, asked the leading NS official in Germany, Ernst Kaltenbrunner, to send him more foreign labourers to Vienna to compensate the drastic shortage of workers. So, in July 1944 Eichmann established a SEK (“Sondereinsatzkommando”) office in Vienna’s 2nd district, Castellezgasse 35, especially for the administration of forced labour. In the middle of 1944 55,000 Hungarian Jews were deported to Vienna and eastern Austria and used as slave labourers together with thousands of KZ prisoners, who were chased in death marches westwards, when the Soviet Red Army progressed. Several of the forced labourers were killed, when they tried to flee, for example across the Danube, or shot by NS guards.

Although slave labour was used in all areas of the “Third Reich”, the subject matter of forced labour in Vienna shows very special characteristics. Vienna experienced an economic upturn after the take-over of the Nazis in 1938 and soon the lack of personnel threatened to slow down the economic growth. Already in August 1940, 11 months after the outbreak of World War II, more than 17,000 prisoners-of-war were doing forced labour in Vienna and the surrounding area of Lower Austria. When the first groups of Polish prisoners-of-war were transferred from POW status to forced labourer status, they were employed in Vienna. It is important to note that initially the POW status allowed some sort of protection based on International Law, which the forced labourer status did not offer and this was very convenient for the Nazis. In April 1941 officially more than 50,000 foreign forced labourers from 13 states were working in Vienna and Lower Austria and just a few months later these numbers had doubled. The early phase of exploitation of slave labour in Vienna was characterised by individual initiatives of companies and the city administration. There was a lack of coordination in the fight for scarce and cheap forced labour. When the labour shortage in Vienna got worse after the disastrous military attack against the Soviet Union, the city administration made plans to centralise the distribution and administration of slave workers. City officials were of the opinion that it was cheaper to use prisoners-of-war than civilian forced labour because they were easier to supervise and anyway “the productivity of three foreign workers was the equivalent of one German worker”, they stated, referring to the not surprisingly low work morale of deported foreign forced labourers. The trigger for an attempt to centralise the distribution of forced labourers was the urgent need for seasonal workers in agriculture east of Vienna, especially the sugar beet and potato harvest, the storing and processing of foodstuff. Eastern slave workers were to fill this gap, so they were assigned to agricultural enterprises from the end of 1942 on. Outside the harvest season there was the possibility to “lend” them to private food producing companies, such as Manner. But there was a lot of resistance against this central authority, especially from the Viennese city gas and electricity works, so that only at the end of 1943 one department, G 45, was administering all forced labour in the enterprises of the city of Vienna and it was responsible for supervising all forced labour camps in Vienna, too.

The exploitation of the slave workers worsened as the war progressed and the scarcity of all commodities in the “Third Reich” became visible in all spheres of life. The forced labourers were increasingly demotivated, because those who had been hired abroad and not deported like the Soviet citizens, had been promised proper jobs with salaries and now they were faced with harsh living conditions and exploitation, barely any food and squalid cold accommodation without proper sanitary facilities. The disappointment of the workers hired abroad resulted in frustration and aggression. There were reports that they jumped from the lorries that should have brought them to their places of work or they did not appear in the morning for work and disappeared the whole day. That’s why the city authorities preferred prisoners-of-war because they were heavily guarded and could be disciplined more harshly. All in all, the whole effort of compensating the drastic labour shortage in Vienna with the use of foreign forced labour was a failure. Most of all in the years 1941 and 1942 the whole “Reichseinsatz” (the project of forcing foreign workers to keep the NS war industry running) was chaotic, disorganised, and inefficient, because the NS bureaucracy was characterised by “over-organisation”, micro-management, chaos of competences and the acting on several bureaucratic levels at the same time. The companies, for example. had to send back workers to the camps because they had no proper shoes or warm clothing to do the jobs they were required to do and often only two thirds of the assigned workers arrived at the respective companies. As they were only allowed to leave their home countries with a small backpack or hand luggage, they lacked everything, when they arrived in Vienna and it soon became clear that the false promise of a voluntary transfer to the “Third Reich” to take on a job was one of the many perfidious lies of the NS regime.

In the end the Viennese businesses managed to acquire public funding and set up the INHA (Industrie-und Handwerksförderungsgesellschaft) in 1942 to sort out this chaos and establish proper forced labour camps and prisoner-of-war camps on the territory of “Groß-Wien” and guard them. The INHA used as headquarters a building the NS had robbed from its former Jewish owners in Vienna’s 1st district, Biberstrasse 14. The INHA extended its fields of operation and in the year 1943 they already made a considerable profit from the procurement of board and lodging for the slave workers. They had put up, administered, and rented camps for 8,000 forced labourers and this turned out a very profitable business model for the INHA. The businesses passed on the costs for board and lodging and “security” (the guards) to the slave workers themselves. These costs were automatically deducted from their wages. Furthermore the INHA demanded an additional fee from the businesses for worker hired from the INHA. The Vienna transport corporation had their foreign forced labour quartered in INHA camps, just as Siemens – Halske which hired their workers from the INHA camp in “Siebenhirten”, and the “Wiener Flugzeugwerke” from the INHA camp in “Fischamend”. Another of the big INHA camps was situated in “Inzersdorf”. The living conditions of the forced workers in the INHA camps was in no way better than in the other haphazard forced labour camps. In the INHA camps the enterprises had the support of the “Wehrmacht” and therefore tighter control and disciplinary measures, which resulted in higher productivity and that pleased the companies, which hired their forced labour from INHA camps. In 1945 the INHA still demanded 852,882 Austrian Schillings from the businesses, which had hired workers from them during the war. The INHA kept collecting claims from these companies or their successors until 1959, when the INHA was finally dissolved. The work of the Viennese INHA, which as a private profit-making business disciplined and exploited forced labour on a grand scale, subsidised by public loans, was a unique phenomenon in the “Third Reich”.

The wages that were to be paid to the foreign forced workers were centrally regulated by the NS authorities. In this NS “fictitious state of law” the world was again appeased with lies and made believe that these wages were equal to those of German workers, but in fact their wages were far lower due to large percentage deductions according to which category they were ranked in (see above). In this way the workers from the Soviet Union and the workers of Jewish origin were the most exploited (see above). Furthermore, they were exposed to the arbitrary despotism of the factory managers and foremen who were permitted by law (Reichsverordnung vom 30.6.1942) to reduce the wages of Eastern forced workers by 50 per cent if they felt their work was lacking in quality. In this NS “fictitious state of law” they were even entitled to health insurance, maternity leave, and other social benefits, which in reality they never received. The archives of the wages and salaries administration of the building department of the City of Vienna, G 45, have been preserved, where the wages of a small part of the 11,000 official foreign forced workers, who worked for the City of Vienna were registered. It is important to mention that even the wages of a” German” worker in Vienna in 1940/41 did not suffice to meet the basic needs. In the few preserved documents of the wage accounting department of the City of Vienna’s construction department a worker from Germany had a basic wage of 1.10 RM (Reichsmark) and received 90 per cent of his wages for November 1944, while a Soviet male worker had a basic wage of 0.75 RM and received 32 per cent of his wages for March 1943 and a Soviet female worker had a basic wage of 0.60 RM and received 50 per cent of her wages for March 1943 and a last example: a worker from Italy had a basic wage of 0.75 RM and received 73 per cent of his wages for December 1943. These examples show clearly how racist and misogynist the NS wage system for foreign forced labour was. Due to an array of possible deductions, it could happen that a foreign forced worker would receive no salary at all, but had to pay an amount to the employer, which would be deducted in the following months from his wages. In January 1945 a Polish worker with a basic wage of 0.75 RM received no wages, but had to pay 6.21 RM to the City of Vienna’s construction department.