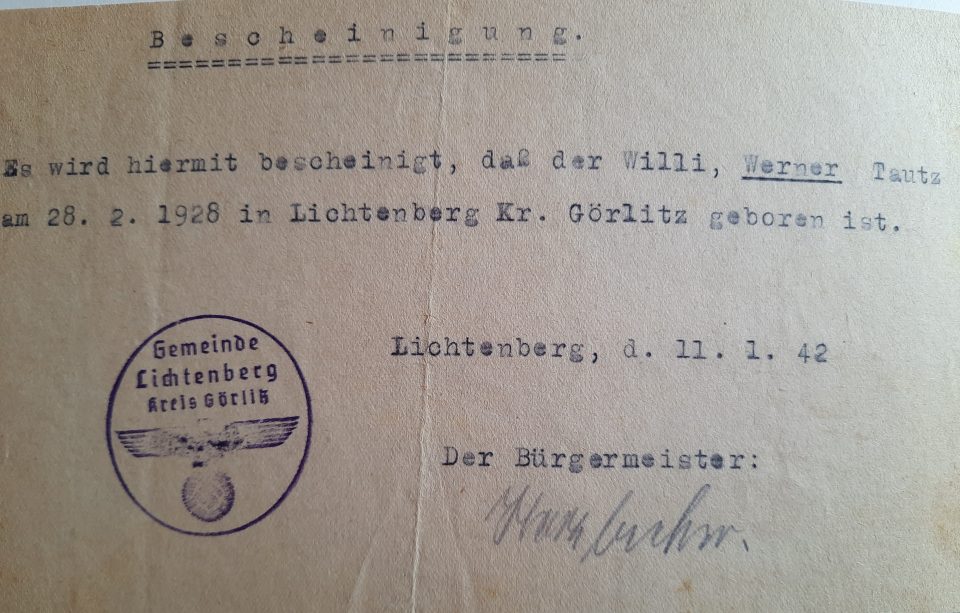

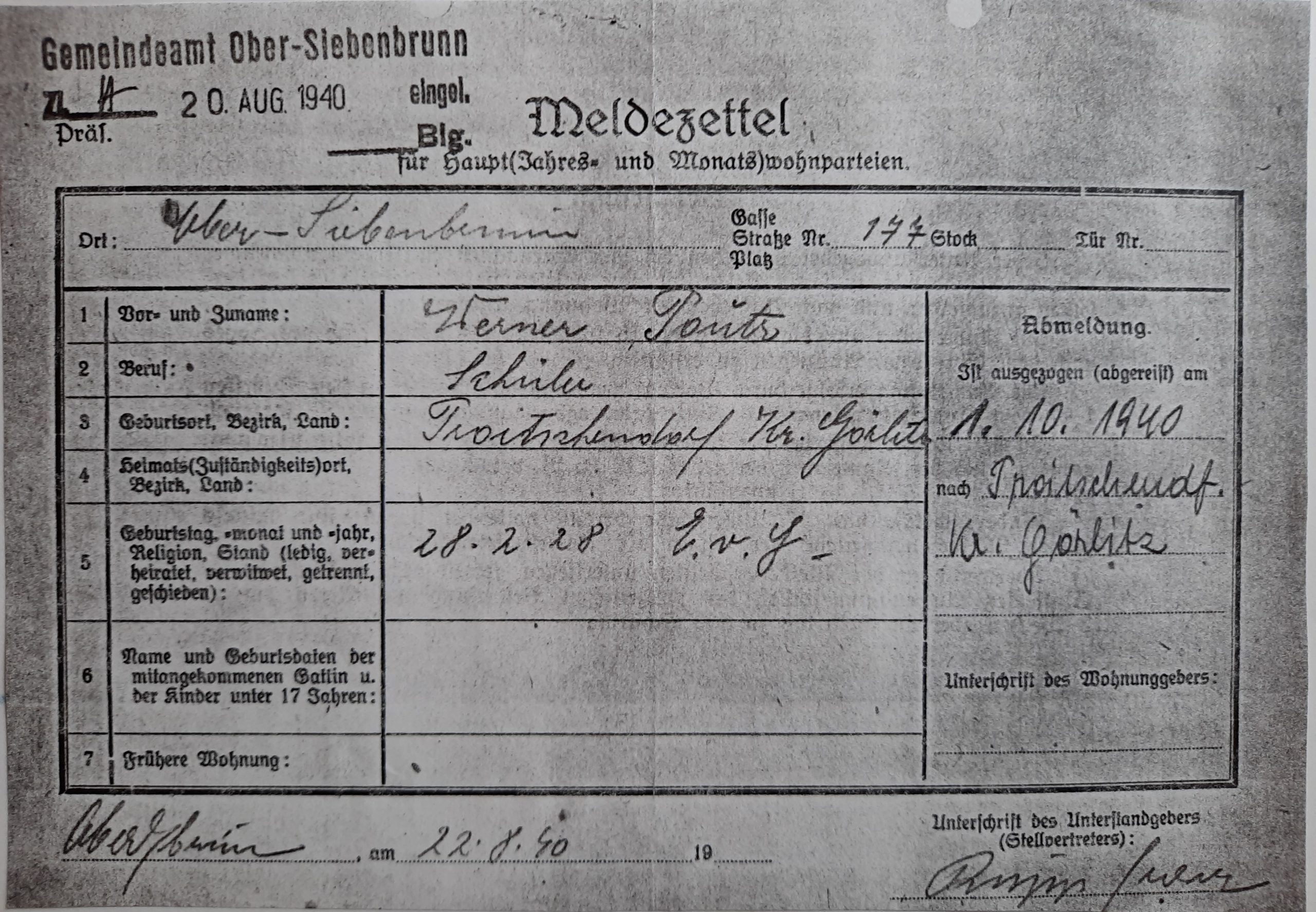

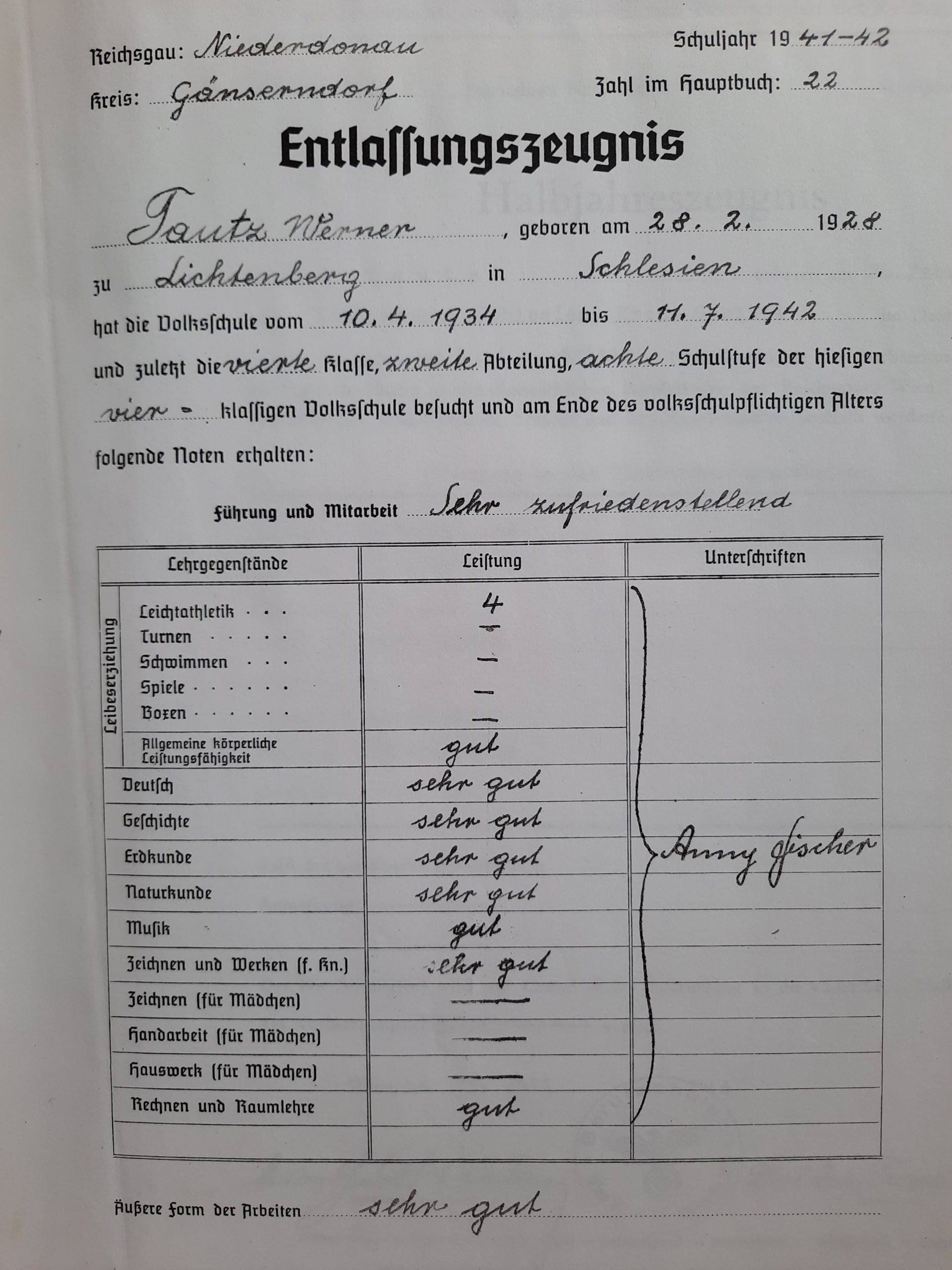

The certificate of registration of the pupil Werner Tautz, my father, who was sent from Troitschendorf near Görlitz in Silesia to host parents in Obersiebenbrunn near Vienna via the Nazi children evacuation programme “Kinderlandverschickung”. He stayed from 22 August 1940 until 1 October 1940 with the family of Franz and Anna Rupp

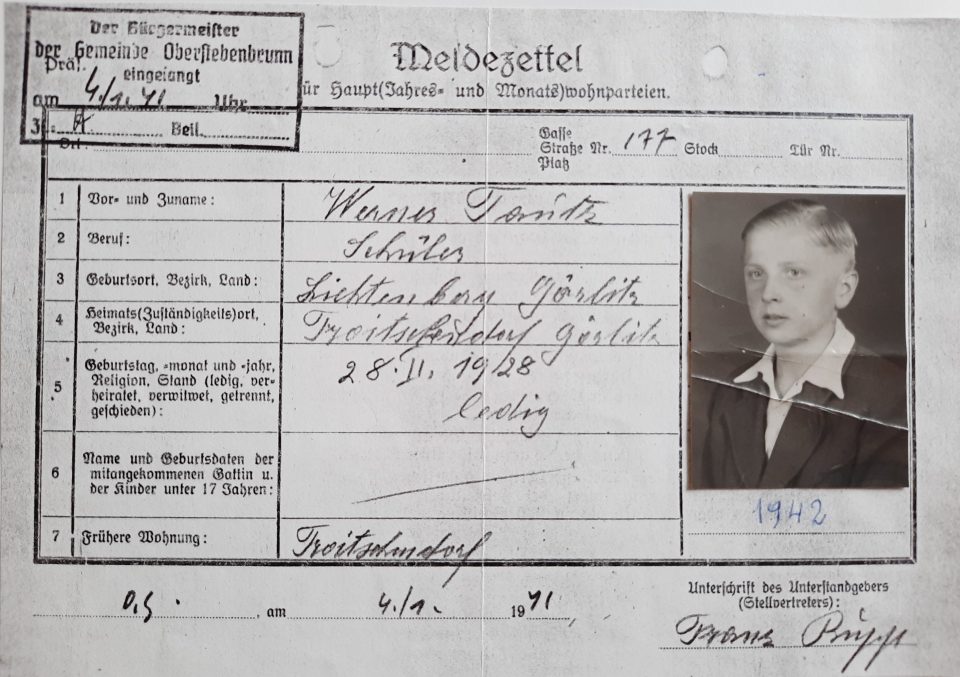

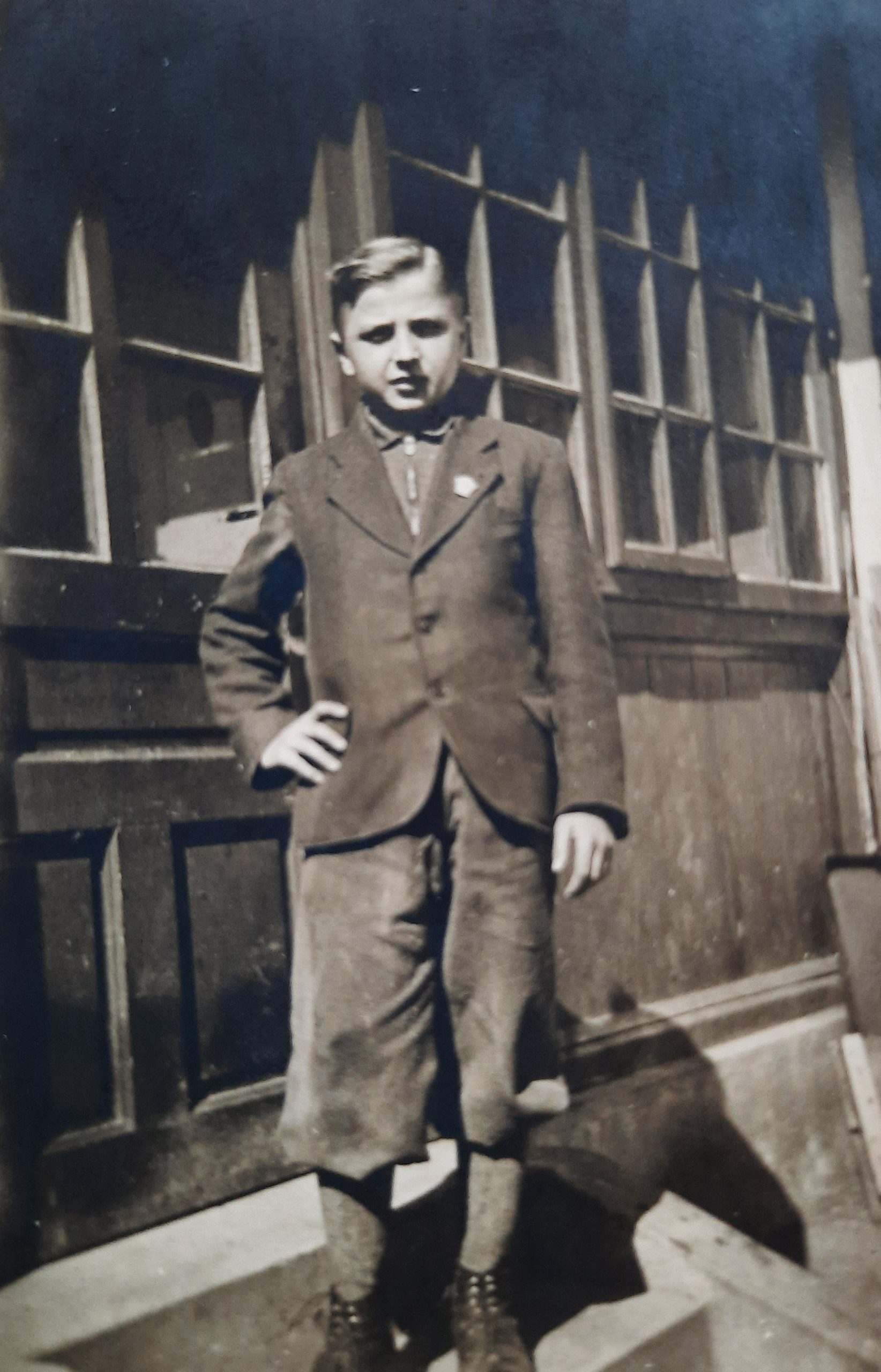

On 4 January 1941 Werner returned on his own to Franz and Anna Rupp, who had agreed to take him in as a foster child. The photo of Werner of 1942 was later added to the certificate of registration

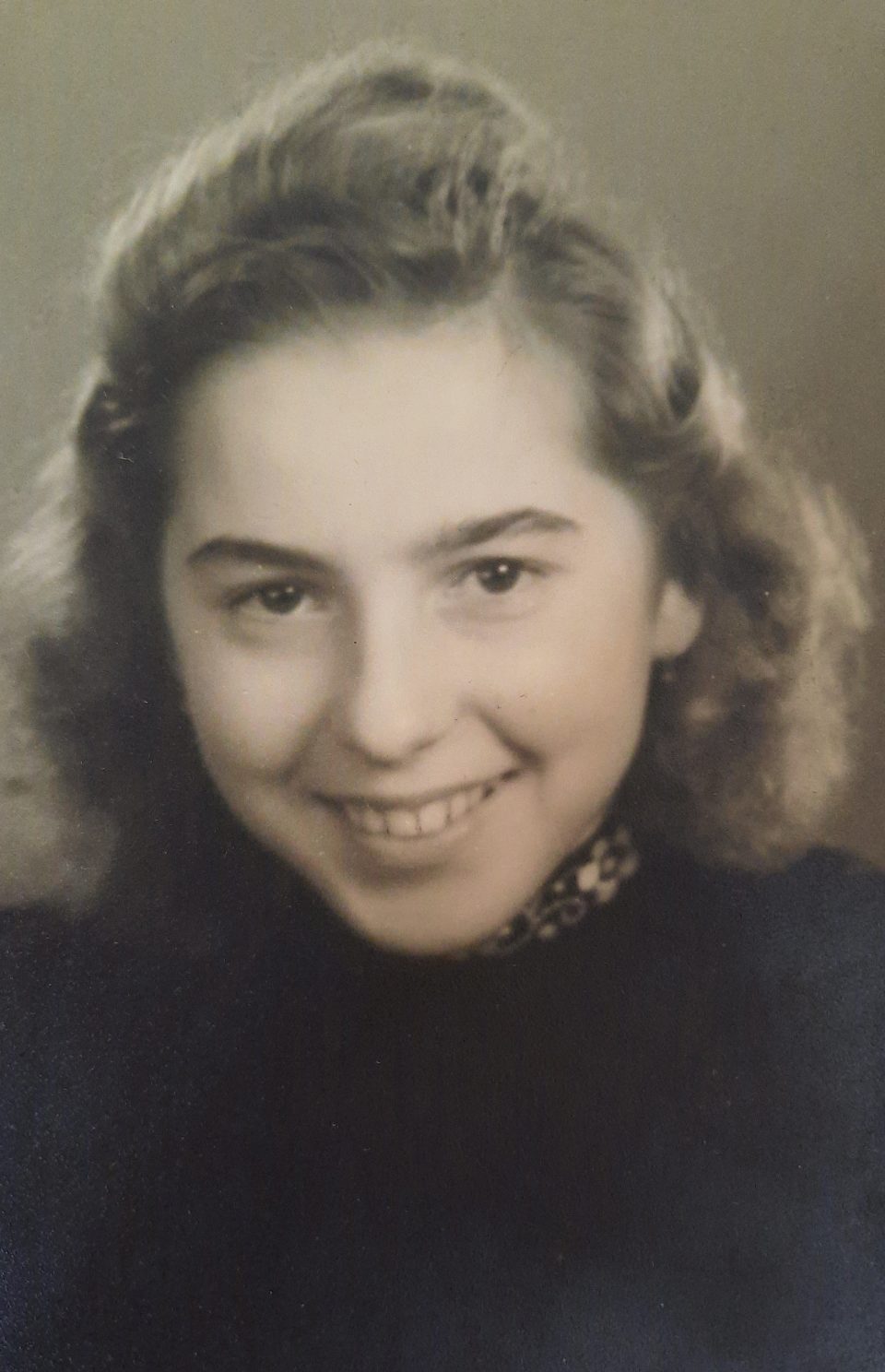

As in most Viennese families of the first half of the 20th century family members came from a variety of geographical, cultural and ideological backgrounds. My mother Herta’s family were on the one hand indigenous Viennese bourgeoisie from Währing and on the other hand urban assimilated Jews born in Vienna and southern Moravia. On the other hand, my father Werner’s background was rural from farming communities near Görlitz in Silesia, formerly German and now Polish territory. He was selected as one of two children by the headmaster of his school to be sent to Lower Austria near Vienna in August 1940 via the Nazi “Kinderlandverschickung” to a host family in Obersiebenbrunn, where the host father, Franz Rupp, had been a NSDAP member since 1931 with an interruption and was later stationed in Norway as a “Wehrmacht” soldier. In his memoirs Werner wrote, “I enjoyed my time at the Rupp family so much that I definitely wanted to return to them after my KLV stay there (which ended on 1 October 1940). Back home I urged my grandparents to help me and I told them that I would be able to learn a profession in Lower Austria (at that time “Gau Niederdonau”) and would not have to work for the farmers after school any more. My grandmother supported me and threatened my mother that she would not inherit their house if she did not allow me to move to foster parents in Obersiebenbrunn. As my mother did not want to forego the house, she agreed. But she took revenge. She saw to it that my foster family did not receive the 20 RM (Reichsmark) monthly alimony, which my (biological) father paid my mother…. I was the “illegitimate” child of the owner of a large-scale farm, where my mother had worked….. So on 4 January 1941 I moved to my new foster family Rupp and the alimony of around 600 RM over the years was deposited at the Dresdner Bank. I never received the money because after the war this region came to be situated behind the Iron Curtain and after 1989 I had no written proof that this money belonged to me. So it is still there.”

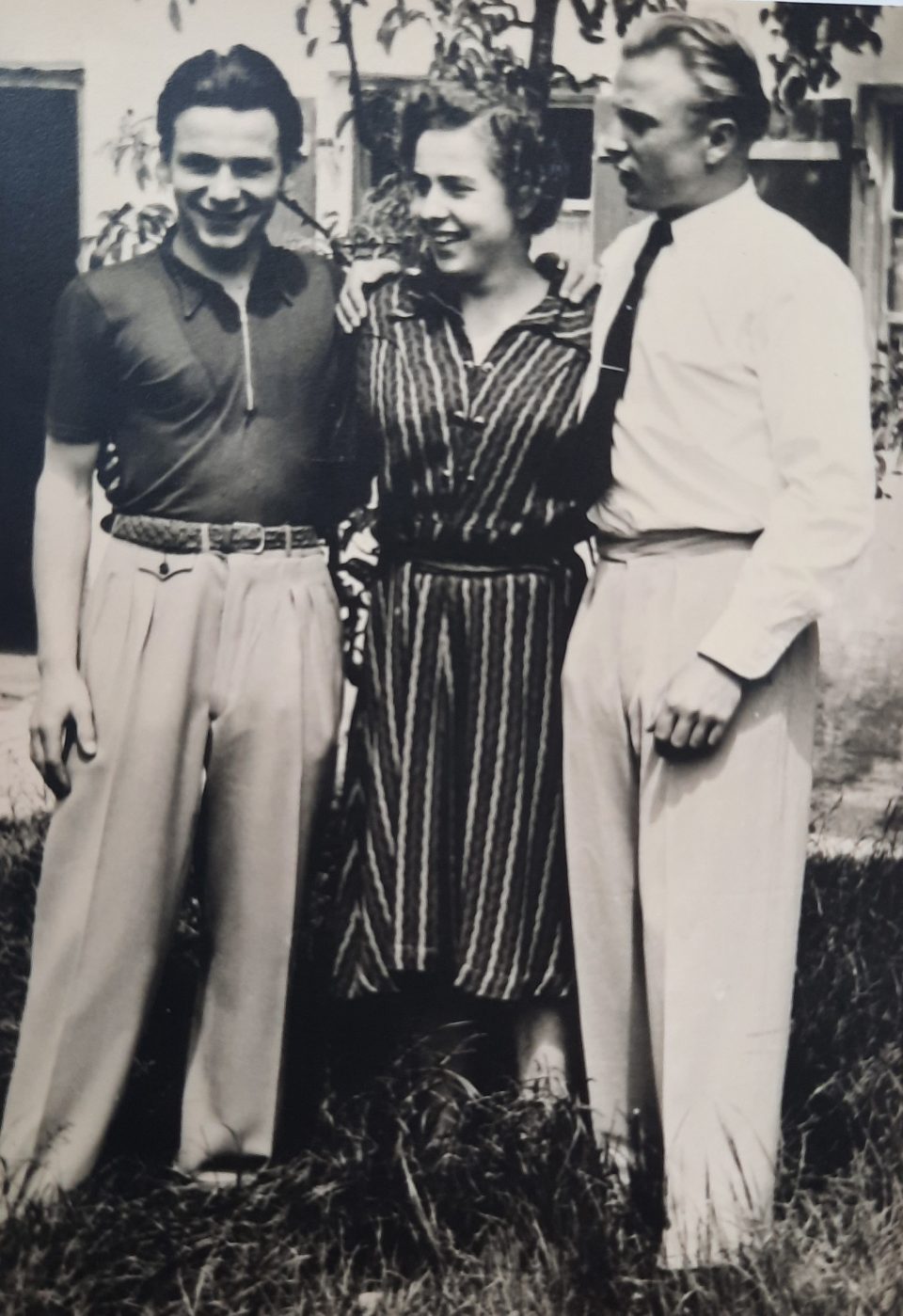

Werner’s foster family: on the left his foster mother Anna Rupp with his new-born foster sister Christine on the lap (born in December 1941), his foster brother Franzi on the left (born in 1926), his foster sister Anni (born in 1925) and Werner on the right (born in 1928). Werner’s foster father, Franz Rupp, in “Wehrmacht” uniform on the right

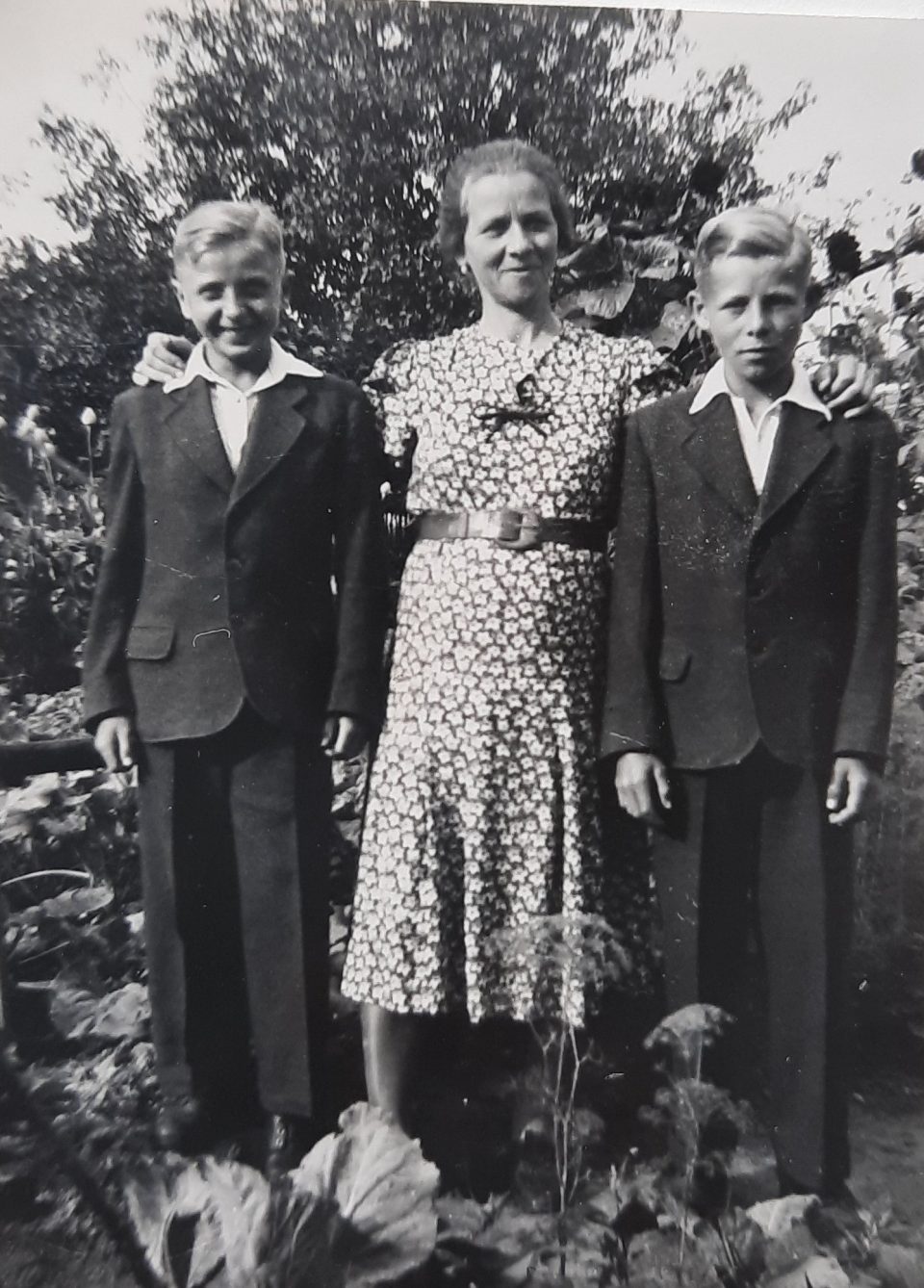

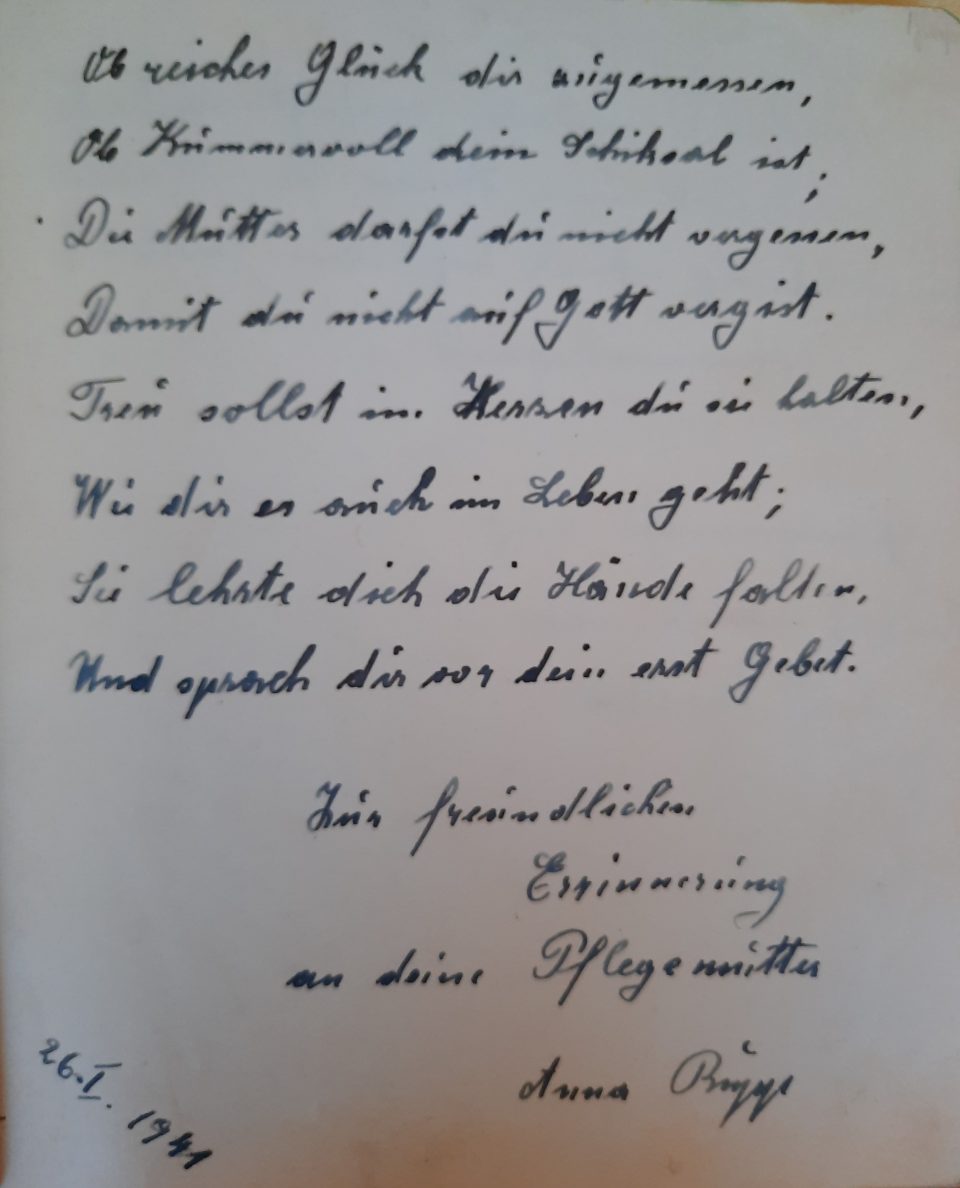

Anna Rupp, Werner’s foster mother, was a strong and warm-hearted woman and a devout Roman Catholic. She ran the family single-handedly during the war in a confident and efficient way. There was always enough food on the table, pigs, hens, geese, small fields to grow potatoes and maize, the bees for honey and a vegetable garden and orchard- and above all, all children were treated equally. She made a cosy home for Werner, who had never known anything like that before. His biological mother rejected him and especially after the birth of his half-sister Elsbeth, her marriage to Karl Perschke and the birth of his half-brother Günter, his mother discriminated against Werner to the extent that his grandparents wanted a better life for him with the foster family Rupp. Anna Rupp had no time or understanding for NSDAP party policy like her husband and ruled the family with a strong hand, which meant that after the war and the return of Franz from Norway there were many rows between the two spouses because she resisted the dominance of her rather authoritarian husband. This was the only aspect of life with the Rupps that bothered Werner. Anna was of a family with Slovak roots in the region, named Zimak, and she spoke Slovak well, which helped a lot when dealing with the Russian soldiers who were staying in her house for some months from April 1945 on. Anna’s father had left the family and had emigrated to the United States, when the three sisters, Marie, Anna and Mali and their little brother Pepi were still small children. He supposedly went bankrupt over there; he never returned and did not support his family either. So the girls had to work for the farmers in the region at an early age to earn a living. There were big farmers in the “Marchfeld” region who treated the girls fairly, paid them small wages and offered them food to take home for the family, but there were others, too, who exploited them shamelessly. This was so exhausting that Anna suffered from serious lung problems at the age of 18, but fortunately fully recovered. Her sister, Mali, never married and supported and cared for their mother. She worked in the sugar refinery in Leopoldsdorf like nearly everyone in the family. Franz Rupp was an unskilled worker there, his son Franzi learned the trade of fitter in the factory before he was drafted and Werner was apprenticed as an electrician in the same refinery. After the war Anna also worked in the sugar refinery every year during the time of the sugar beet harvest.

Werner soon felt completely at home with the Rupps and he later stressed that he was treated like their own child. No difference was made between him and the other three children of the family; he even received the same outfit as his foster brother Franzi; a kindness he had never experienced at home with his biological mother, Frieda. Werner adapted quickly to his new surroundings, spoke the local dialect and converted to Roman Catholicism, which was Anna’s wish. His whole life Werner was considered the model of a “true Viennese”, although he was born in Silesia and spent the first twelve years of his childhood there. Just like the grandfather of his later wife, Ignaz Sobotka, who was by birth right, looks and poise a “true Viennese”, but the Nazis denied him this status and persecuted him because he was born a Jew (see article on “Viennese Beer Brewers”). This example proves what a mixed people the so-called “true Viennese” were and still are and how stereotypes govern people’s perceptions.

Werner, who had received the same outfit as his older foster brother Franzi, in the garden of the Rupps’ house in Obersiebenbrunn, Bahnstrasse 177; on the left with Anna Rupp, his foster mother, and on the right with his foster sister Anni.

The house of the Rupp family in Obersiebenbrunn, near Vienna, and Werner in the yard below

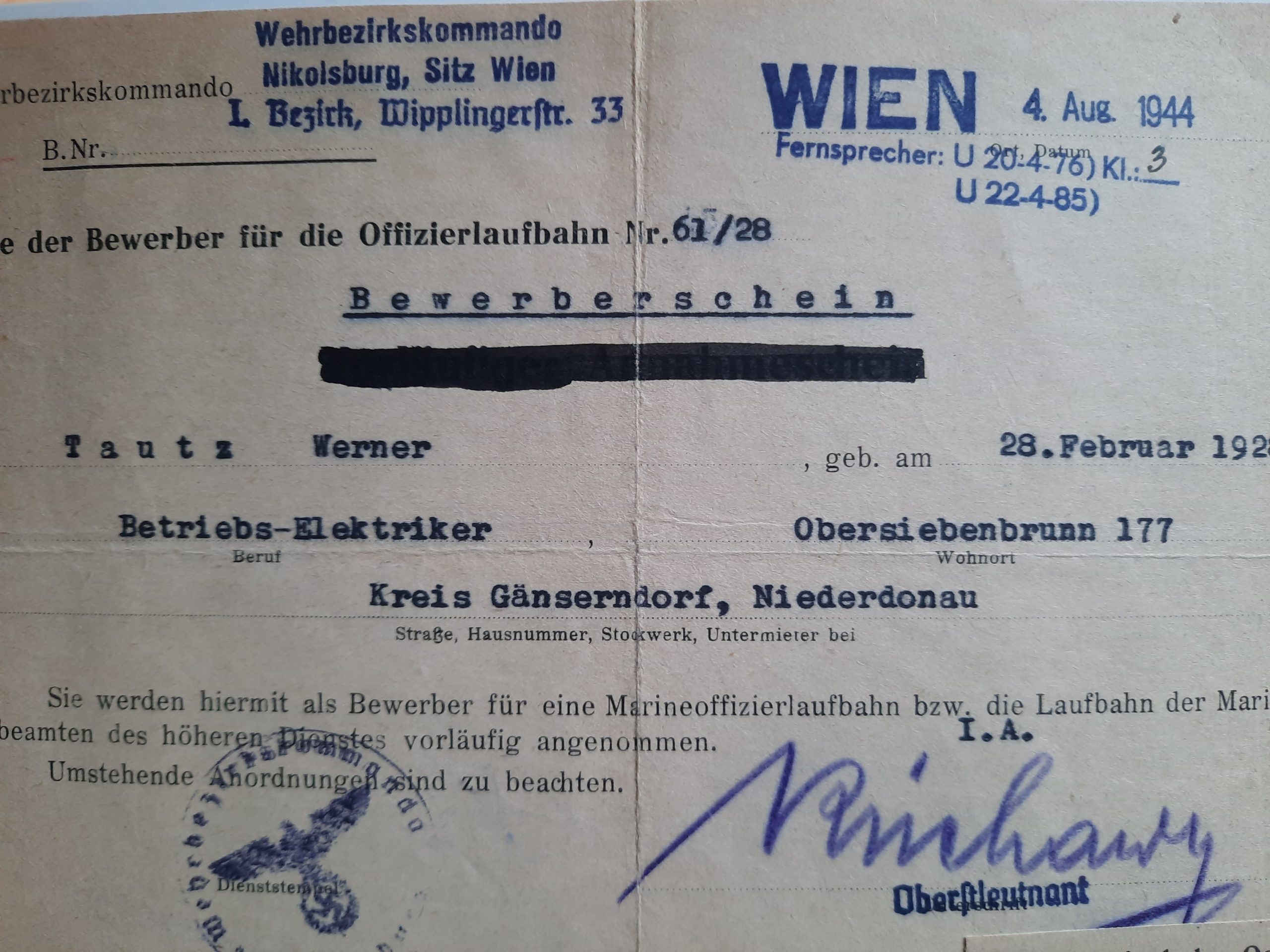

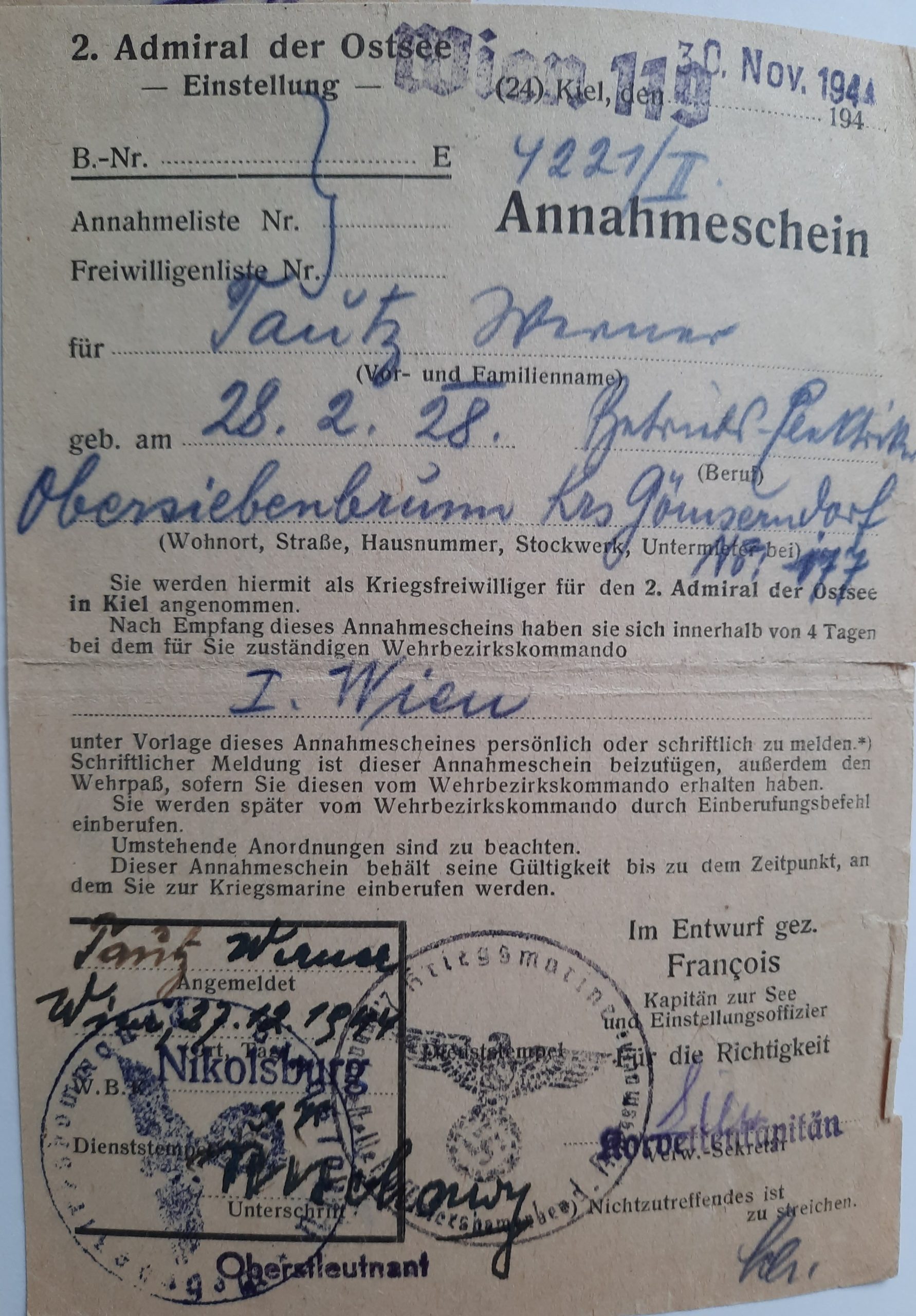

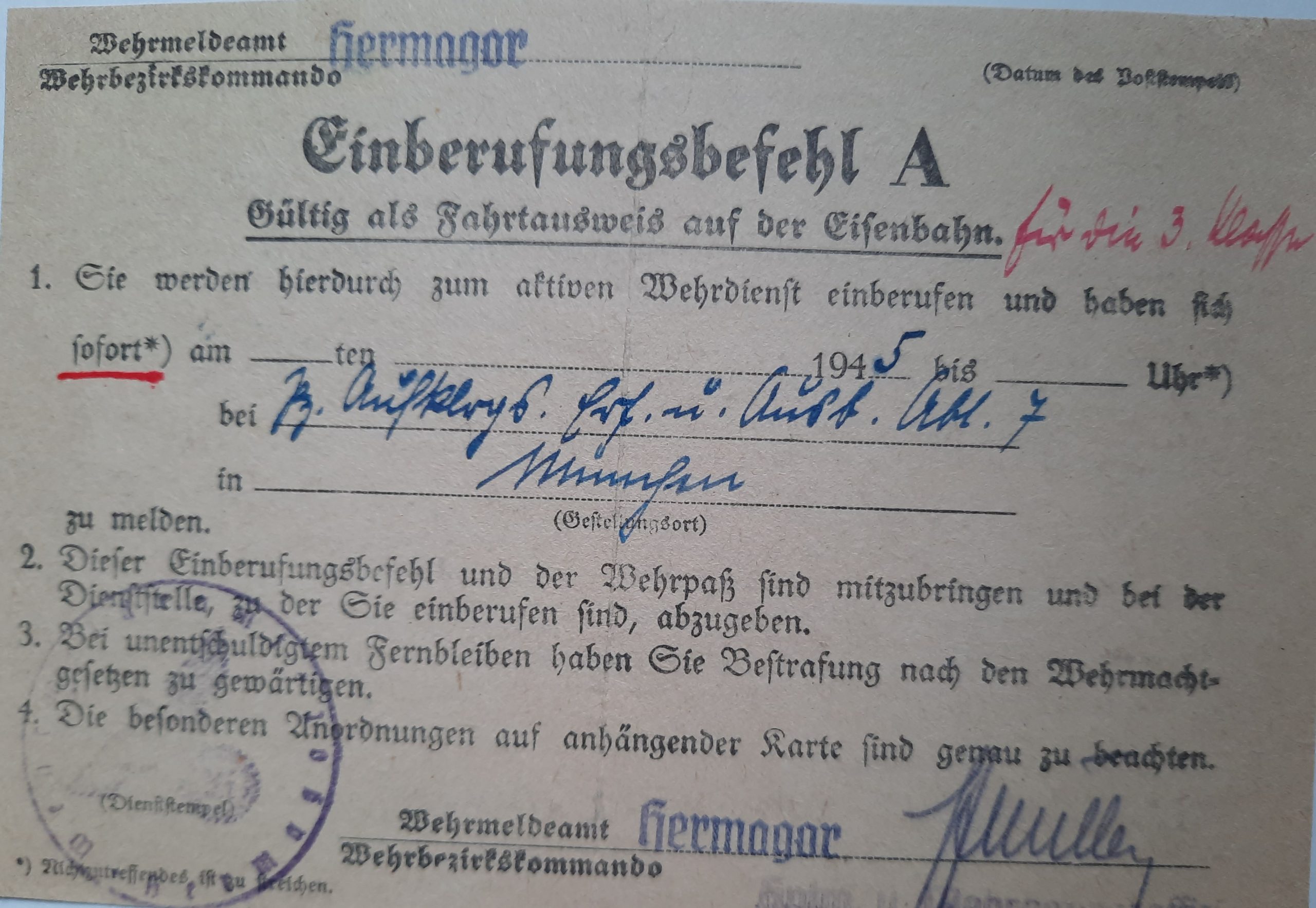

So how did this children evacuation programme “Erweiterte Kinderlandverschickung” (KLV) work in Hitler’s so-called “Third Reich” between 1940 and 1945? It was a huge transfer of children during the war to move them from cities under threat of bomb attacks to areas which were supposedly safe from Allied bombings. The Nazis insisted on not calling this programme “evacuation movement” because they feared the population would get worried when hearing this term and would no longer believe in the Nazi “Endsieg” (final victory). Most of all, this programme was a social and ideological experiment, namely to tear children from their families for months and educate them in a National Socialist surrounding and to indoctrinate them with Nazi ideology. This worked more or less well in the KLV camps which were set up, but not necessarily so with the children who lived in host families, although those were selected by the local NS party organisations and considered “reliable”. Overall, the impact of NSDAP party ideology and the pressure from NSDAP camp leaders resulted in the fact that a high percentage of boys who had gone through the KLV programme volunteered for the NS special troops SA (“Sturmabteilung”) and SS (“Schutzstaffel”) and especially towards the end of the war, the “Waffen-SS”. Contemporary witnesses who had stayed in KLV camps reported that the boys who did not volunteer for the special units SA or SS were ridiculed and discriminated against. This might not necessarily have been the case for boys in host families. Werner did not volunteer for the SS, but his foster brother Franzi did. He was drafted in 1943 at the age of 17, joined the “Waffen-SS” and was killed in the war. Werner was drafted in 1944 and opted for the marines. In fact, Franzi was a shy and melancholic boy who seemed to have enjoyed the presence of Werner in their home because until then he had suffered under the dominance of his elder sister Anni. His authoritarian father Franz forced him to join the “Waffen-SS “to make a man out of him”, because Franz Rupp himself was an SS-man and Franzi always did as he was told. Together with two other boys from the same village they were sent to France. In Marseille the other two decided to desert from the “Wehrmacht” towards the end of the war and urged Franzi to escape with them, but Franzi did not dare to join them. The other two returned home safely, whereas no trace of Franzi was ever found. He was declared missing in France. On 15 August 1944 the US troops had landed at the Cote d’Azur near St. Tropez with 60,000 men and were supported by the “Free French Army” of Charles de Gaulle. This landing is known as the “Operation Dragoon”. In the following days another 120,000 Allied soldiers landed on the southern French coast involving 880 war ships. The operation was half the size of the “Operation Overlord” on the coast of Normandy on 6 June 1944. Nevertheless it is nearly forgotten except in France. Hitler decided on 17 August 1944 to withdraw his troops from southern France except from the fortified strongholds in Toulon and Marseille. Around 250,000 to 300,000 “Wehrmacht” soldiers had to march north in the direction of Alsace. Either in Marseille or on the march north Franzi was killed. Fortunately Werner was sent to Freilassing, Bavaria, for army training in March 1945, where he decided to flee from the “Wehrmacht” returning to Obersiebenbrunn on foot at the end of the war.

Franzi, Werner’s foster brother, in uniform, aged 17, and his foster father, Franz Rupp, as a Wehrmacht soldier in Hammerfest, Norway

The KLV was decidedly a NSDAP programme, organised and financed by the party, whereby hundreds of thousands of children were taken from their families and transferred to other parts of the “Third Reich”. The exact number of transferred children cannot be defined because at the end of the war all KLV files were destroyed at Hitler’s command. Some German historians estimate that around 2.8 million children took part in the KLV programme, whereas others believe that around 850,000 children between 10 and 14 years of age were cared for in camps and approximately the same amount in host families. There are no reliable numbers for Austria, which formed part of the “Third Reich” in those years and also not for the “Gau Niederdonau” (this included not just Lower Austria, but also parts of Burgenland, southern Moravia and southern Bohemia), but in around 200 KLV camps in “Niederdonau” approximately 10,000 – 20,000 children might have been lodged annually, not counting the children in the host families. A study in the Czech Republic found out that in nearby Bohemia and Moravia around 350,000 children were accommodated in 400 KLV camps.

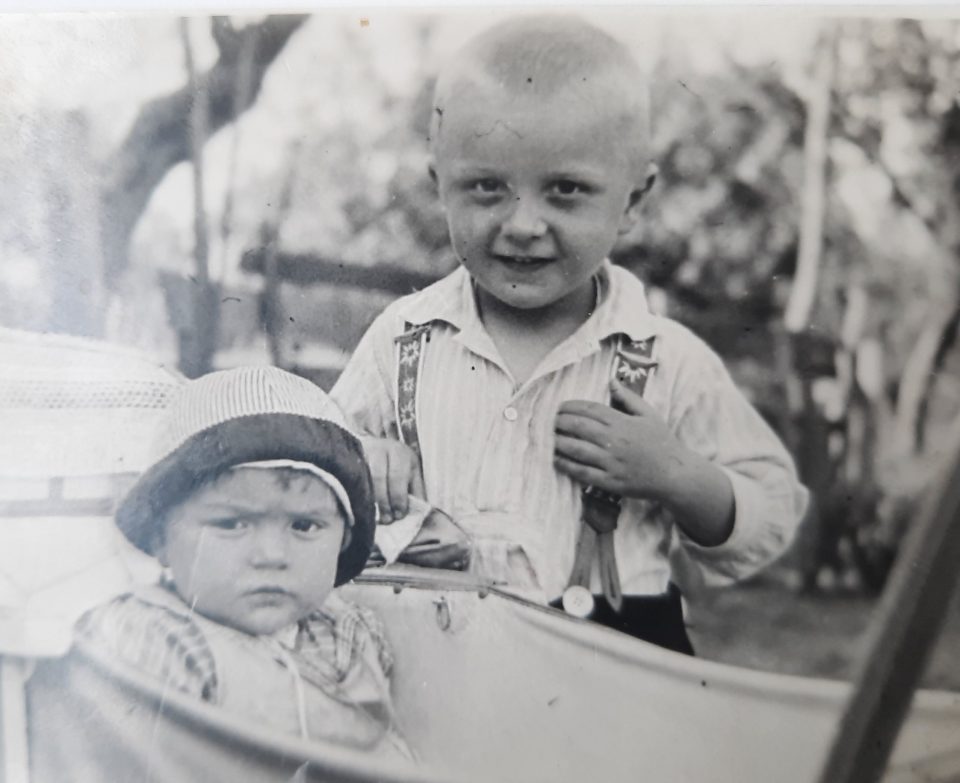

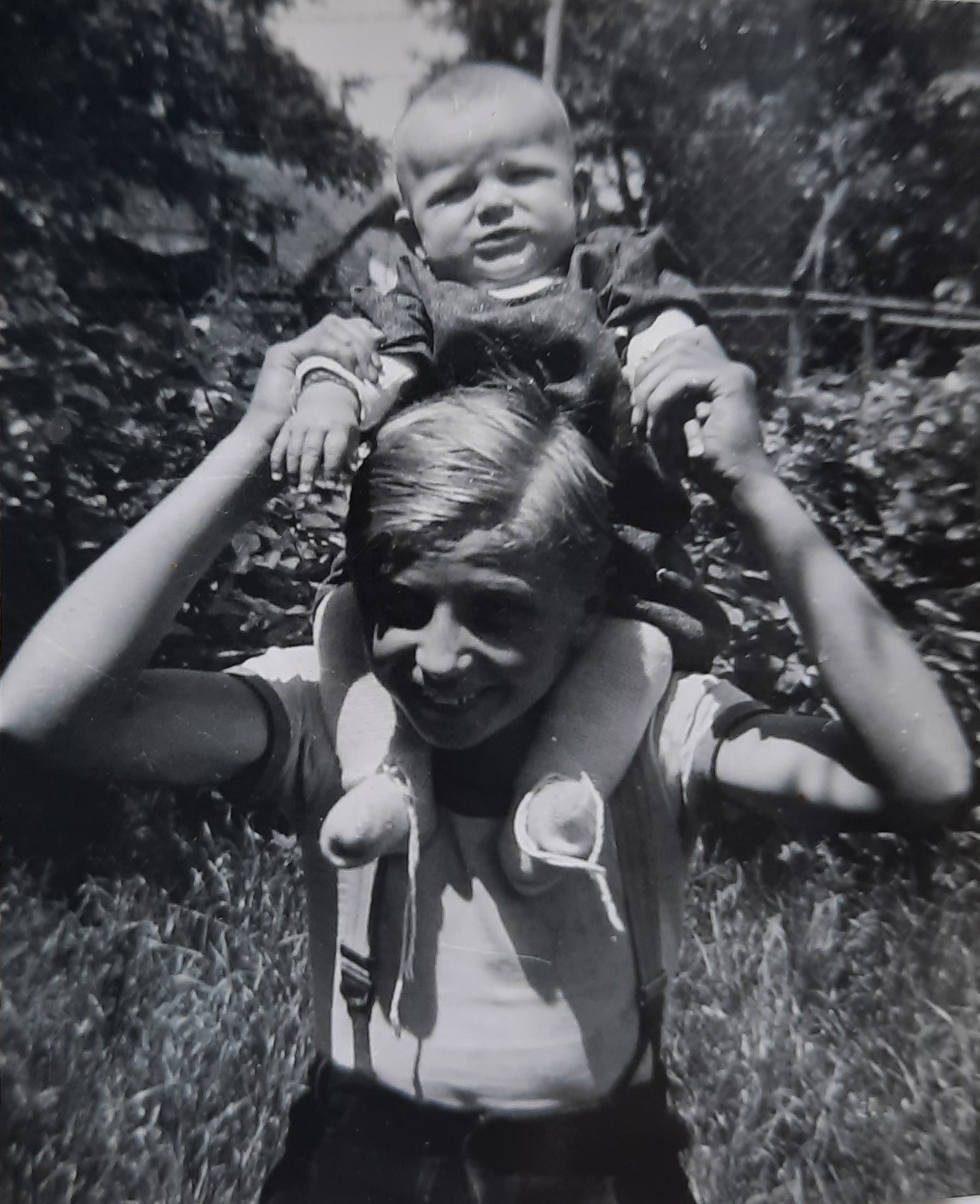

Werner on the left with his much loved foster brother Franzi on the right and below with his new born foster sister Christine, who he remained very close to all his life

Werner felt welcome and at home at his host family and wanted to live with them for good, but the majority of KLV children suffered a lot under the separation from their families. Also in England evacuation programmes for children were organised to protect them from German bombers. Anna Freud, the daughter of Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, who had fled with his family from Vienna to England, established psychoanalysis in England and together with Dorothy Burlingham ran the Hampstead War Nurseries, where they treated traumatised evacuated children during the 1940s and after 1945 orphans from the Nazi concentration camp Theresienstadt, too. Anna Freud found out that the German bomb attacks were less traumatic for the English children than the evacuation and the separation from their families, especially from their mothers. No such studies were made in Nazi Germany, but the same was most probably true for the thousands of children in the KLV programme in the “Third Reich”, except for Werner, who had never had a proper family life and experienced the warmth of a home for the first time with the Rupp family.

A recreational stay of urban children in the countryside, called KLV “Kinderlandverschickung”, had been a well-established social programme in Germany since the end of the 19th century and was now organised by the NSV (“Nationalsozialistische Volkswohlfahrt” – National Socialist Welfare). In the summer of 1940 1,500 children were registered for a stay in “Niederdonau” via the original KLV programme, among them Werner. On 27 September 1940 Hitler decided that the programme should be extended to all children who lived in regions which were affected by Allied bomb attacks and the organisation of this “Erweiterte Kinderlandverschickung” (extended children evacuation programme) was to be taken over by the NSV together with the HJ (“Hitlerjugend”- Hitler’s youth) and the NSLB (“Nationalsozialistischer Lehrerbund” – the National Socialist association of teachers). Baldur von Schirach insisted on this terminology because it reminded parents of a well-known and established programme and by that avoided any war-related panic among the parents of KLV children. The local HJ was to identify suitable hotels, inns or bed & breakfast places where the children could be accommodated. In the region around Vienna the owners of such accommodations were happy to welcome KLV children because due to the war most tourist activity had ceased. The problem was only that the majority of locations were designed for summer tourism and provided no heating facilities. All the costs which arose from this “extended” KLV programme were to be covered by the party. Due to the resistance of middle-class and well-to-do parents to hand over their children, the party first concentrated on children from poorer families and dressed the programme up as a social measure. Werner was still selected on the grounds of the original KLV programme, as he did not come from an urban area which was threatened by bombs, but from the small village Troitschendorf near Görlitz in Silesia. He formed part of the group of children who were selected for the first KLV stay in “Niederdonau” from 20 August until 1 October 1940.

Baldur von Schirach had quickly drafted a programme of transferring 200,000 school children and 50,000 mothers with their babies and calculated that around 3,600 places of accommodation and appropriate means of transport were to be provided and around 2 million RM per day were to be raised for the implementation of his project. Hitler personally approved of Schirach’s “extended” KLV plans. Then an order was issued that all local NS party organisations had to recruit “reliable” host families, camp leaders and female personnel for cooking and cleaning and that’s when Franz Rupp volunteered as host father. The matter was urgent because the first “extended” KLV trains were to leave Berlin on 7 October 1940 – Werner was still part of the original KLV holiday programme of 5-6 weeks and had already left Görlitz in August 1940. From 1943 on nearly all big cities in Germany sent children away via the “extended” KLV. The programme was explicitly an NSDAP party programme, financed by the party and free of charge for the parents. The programme involved children until the age of 14 and in some cases until the age of 18. The party organisation NSV paid for the medical examination before departure, for transport, insurance and provisioning during the journey. Host families were entitled to a benefit that covered the costs of board and lodging. The parents were responsible for providing clothing, which was checked by the NSV before departure and in case of need the NSV issued shoes, coats etc. In “Niederdonau” the local HJ and BdM (“Bund deutscher Mädchen” – the NS association for girls) groups appointed HJ and BdM leaders who were looking after the 10- to 14-year old children in KLV camps and the HJ had to finance board and lodging of the children in camps. The teachers who were recruited by the NSLB were responsible for organising the teaching in the camps and the NSLB covered all the arising teaching costs. Children in host families like Werner usually attended local schools. Yet the HJ tried to extend its influence on the educational programme of all KLV children to boost the ideological indoctrination. It is difficult to estimate the number of children who were accommodated in the area of “Niederdonau” or Vienna because the NSDAP representatives tended to exaggerate the numbers for propaganda reasons. For example it is known that from 7 October until 4 November 1940 in the first “extended” KLV to Vienna 5,700 children were evacuated from Hamburg and in 1941 the NSDAP leader of “Niederdonau” boasted that his region was on the top of the list of KLV hosts with 200 camps and 20,000 KLV children, which was probably highly exaggerated because other sources calculate that there were lodgings available for 10,000 children only in “Niederdonau”. But again in 1943 at the time when more and more children who were affected by bomb attacks were sent south a NSDAP representative of the region spoke of 20,000 KLV children annually for “Niederdonau”.

The duration of this “extended” KLV programme was not explicitly mentioned in order not to upset the parents and the children, but it was much longer than the original KLV holiday programme of around 5-6 weeks via which Werner came to Obersiebenbrunn. Many parents were sceptical about the NSDAP children evacuation programme and did not want to hand over their children to the NS party. But the aggressive Nazi propaganda for the “extended” KLV, the threat of bomb attacks and the shortage of food in urban areas left many parents no choice. The children were taken from their families initially believing that they would return home after four to six, maximum eight weeks. The parents were from time to time soothed that they were allowed to have their children back whenever they wanted and to have the permission to visit them. In no case should it be mentioned that the children might only return home when the war was ended. In 1941 a stay of six to nine months was informally fixed and a return home before the expiry of this “extended” KLV date was not permitted; on the contrary, the parents might even be asked to agree to an extension of the duration of their child’s KLV stay. In the course of the war the KLV programme was progressively prolonged and from 1943 on it was no longer limited in time, it was an indefinite measure.

The organisation of “extended” KLV was centralised in Berlin under the leadership of Baldur von Schirach, Hitler’s commissioner for youth education, and a special NS party representative was appointed for every district (“Gau”) to coordinate the three party organisations NSV, HJ and NSLB on site. The headquarter for “Niederdonau” was located in the 9th district of Vienna, Wasagasse 10 and was headed by Otto Fenninger, who was appointed by “Gauleiter” (district leader) Hugo Jury. In “Niederdonau” the KLV officially employed around 1,900 people, including camp leaders, housekeepers, cooks, cleaners etc. plus 1,300 persons who were responsible for caring for and educating the children. It was the intention of the organisation to accommodate the children in isolated places and small villages mostly. The official argument for this choice of location was the boosting of cohesion within the KLV group in closed communities. This was of course not possible when children were lodged in host families like Werner.

The buildings which were selected by the HJ as appropriate locations for KLV camps were not always handed over voluntarily by the owners to the KLV for the purpose of installing a camp, but if no agreement could be reached the buildings were requisitioned. Nevertheless many hotel and boarding house owners cooperated willingly because the KLV children compensated to some extent the breakdown of tourism in the region during the war. All KLV camps were marked with a combination of letters and numbers: for example ND for “Niederdonau” and then the number of the camp and a uniform postage stamp was created. Those children who were sent to host families were assigned to a family which had applied for a KLV child or children. The local newspapers in Lower Austria announced that it was the “express wish of the Führer” that the local population welcomed as many children as possible because it was their “honour of duty towards the Führer”. In some villages the families even competed with each other and tried to outdo one another in complying with Hitler’s wishes. It can be assumed that only politically “reliable” families were selected because there are records of families which were rejected. Some pressure might have been applied by the local party to accept KLV children if it was known that there was unused space in a family home, such as a garden house or empty rooms. The newly established KLV camps were adapted and equipped by the KLV headquarter in Vienna, where a whole school building acted as a warehouse in which kitchen equipment, heaters, bunkbeds, lockers, shoes and clothing etc. were stored. In every KLV camp an infirmary had to be installed, too. The bureaucracy for the innkeepers and hotel owners who ran such camps was enormous and dozens of check lists had to be completed daily, for example food deliveries, in order to be compensated by the KLV. For some innkeepers this was good business nevertheless: around 1.95 RM was paid per bed and additionally 1.45 RM per child. The host families received 2 RM per child and day additionally to the child’s food stamps.

In the beginning of the programme children from different schools were sent to one destination. Werner noted that two children from his school were chosen to be sent on a 6-week KLV holiday in August 1940 and the headmaster selected him, although he was not undernourished, because he knew about his difficult family situation and because Werner was always “ready to assist with little chores, such as cleaning the aquarium or acting as beater at a hunt”. Initially northern German cities sent children to KLV camps in the south and later also Viennese children were evacuated to “Niederdonau”. From 1943 on whole schools were dispatched to KLV camps. Werner wrote that he was lucky at having ended up with the Rupp family, because they had opted for a girl and he should have been sent to the builder Steinbeck, but despite the confusion the Rupp family welcomed him in their home. According to contemporary witnesses such mix-ups happened quite often. The children usually arrived at the point of destination completely exhausted after long train rides of sometimes two days and often more than 1,000 km.

Werner in his HJ uniform

The local newspapers reported extensively about the arrival of KLV children in a village. It is noted that all children had name tags and their train tickets with them; the boys in the left breast pocket of their HJ uniforms, the girls and small children hanging around their necks. Sometimes the local party organised a reception at the train station with NS party songs, NS party speeches and welcome presents for the children, such as oranges. These welcome parties were mostly organised for children who were then lodged in host families, not for whole schools which were sent to a KLV camp. Many children suffered from home sickness and developed severe psychological symptoms, especially in camps, which were run like army camps. Only in exceptional cases children were allowed to return home. Another hurdle that sometimes complicated the communication between the KLV children, especially from Germany, the “Altreich”, and their hosts was the dialect they spoke. The children did not understand their host parents and vice versa. But the children in host families learned fast and after a long stay in Austria were no longer understood at home when they returned. Werner quickly adapted to the dialect spoken in the region of Obersiebenbrunn and was soon undistinguishable from his class mates at school.

Werner’s report card at the end of his compulsory schooling in July 1942

A main aim, if not the most important purpose of the “extended” KLV programme was the immersion of the young in Nazi ideology away from their parents’ influence. This worked best in the KLV camps, where group pressure and ideological indoctrination were continuously present. Children in host families were much less exposed to political influence. Werner’s foster father was stationed in Norway and rarely at home, while his foster mother was an apolitical woman, a Roman Catholic believer and regular church goer. Yet in the KLV camps the National Socialist mind set was omnipresent. The HJ supervised military discipline in the camps and the relentless group pressure made the children more susceptible to NS ideology. That’s why many of the older boys volunteered for the “prestigious Waffen-SS” and those who did not were made fun of and bullied. The NS drill worked well in KLV camps in isolated places, far away from family influence. Everyday life for boys as well as for girls was organised in a military manner starting with the flag salute in the morning, then morning roll call, Nazi songs, proverbs of the day, room inspections; a hierarchical order pervaded the whole organisation. In regular intervals propaganda marches were organised, when the children marched across the countryside and through villages singing NS war songs. Some camps even trained special drummers’ groups for the marches. The children were treated as little soldiers and some contemporary witnesses said that the children “did not learn much except marching”. The children were inundated with NS party propaganda via party festivities, ceremonies, talks, speeches and trainings “for ideological strengthening”. Furthermore the children were used for various collection campaigns of NS charity projects, such as “War Winter Aid”, “Toys for Soldiers’ Children”. Large sports competitions were organised in the camps with a pronounced military purpose. Those children who showed most enthusiasm were promoted to leading positions and were entitled to order about their peers and those who did not fit in had to face various forms of punishment. The mildest form was the order not to leave the camp, but children were also wrapped in a blanket and tied to a tree overnight. A KLV camp was a closed community; the children were supervised day and night and the whole day was structured and planned with no spare time between lessons, roll calls, marching, sports and other common activities. So they were gradually dragged into supporting and working for the “total war” and the “Endsieg” (final victory) of Hitler. The teachers in the camps were instructed to “finalise” the ideological education. Special work duties formed part of camp life, too. The children were assigned household chores in the camp and agricultural tasks on the farms in the vicinity.

The camp leaders successfully tried to block the influence of the Roman Catholic as well as the Protestant Church on their turf. Officially the children were allowed to attend mass in their spare time, but in practice that was often prevented by compulsory marches or service duties. There was no religious instruction offered in the KLV school programme and the children knew that attending mass was not appreciated by the camp leadership. Often the KLV camp organisers assigned “special duties” at the times when Sunday mass was celebrated in the village church. So the churches concentrated their efforts on the children in host families, who were less supervised. In “Niederdonau” the predominant Roman Catholic Church could concentrate on the Catholic children; in the case of Werner, who was from a Protestant family, his foster mother Anna asked him to convert to Catholicism, which he subsequently did, but all his life he was never a believer.

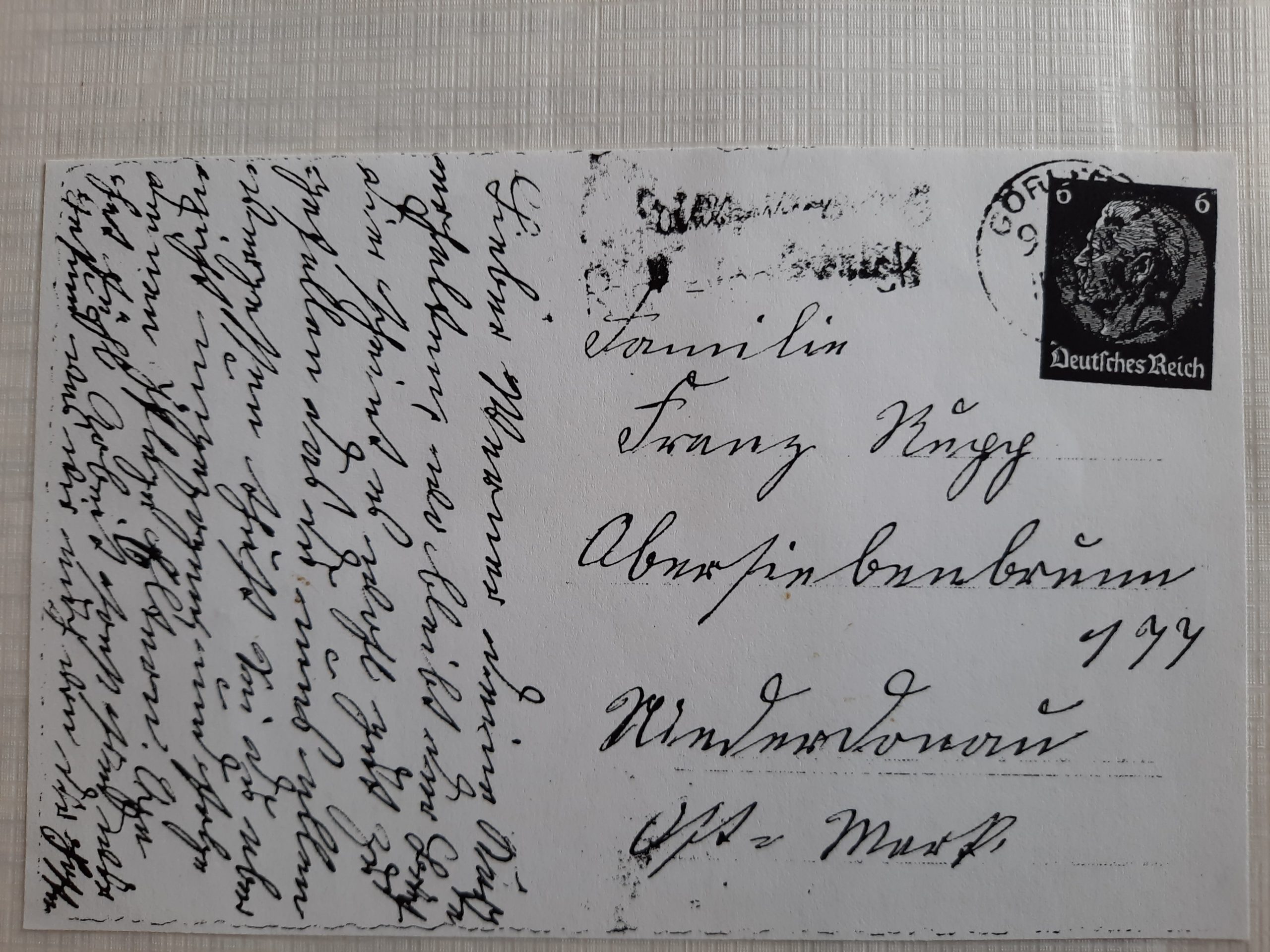

Once a month a letter to the parents was sent by the NS district organisation, which had welcomed the KLV children, to inform the parents about the “success of the KLV programme and the well-being” of their children. Furthermore the children were allowed to keep in contact with their relatives via letters and postcards. The camp censured the children’s mail and it provided the envelopes and stamps. That’s why some parents gave their children stamped envelopes to send home in order to avoid censorship by the camp organisation. Once a week the HJ organised a letter writing lesson in the camps during which the children were instructed what to write home. The children who stayed in host families had to bring along stamped envelopes to write home and tell their parents about their safe arrival in their host family.

A postcard Werner’s grandmother wrote to him in Obersiebenbrunn. His mother neither wrote to him nor visited him

As the KLV stays were extended from 1943 on, more children were missing their mothers and that’s why the possibility of parents’ visits had to be taken into consideration by the KLV organisation. For Viennese children it was common to have visits from their parents while staying in “Niederdonau”, but for those from German cities a visit from a parent was a rare event. Different camps had different regulations; some fixed special days for visits, others organised group visits of parents. In 1942 Werner had a visit from his grandfather, which he enjoyed enormously because he loved his grandfather dearly. He wrote that they had “a great time in the Wiener Prater” (a fun fair in Vienna).

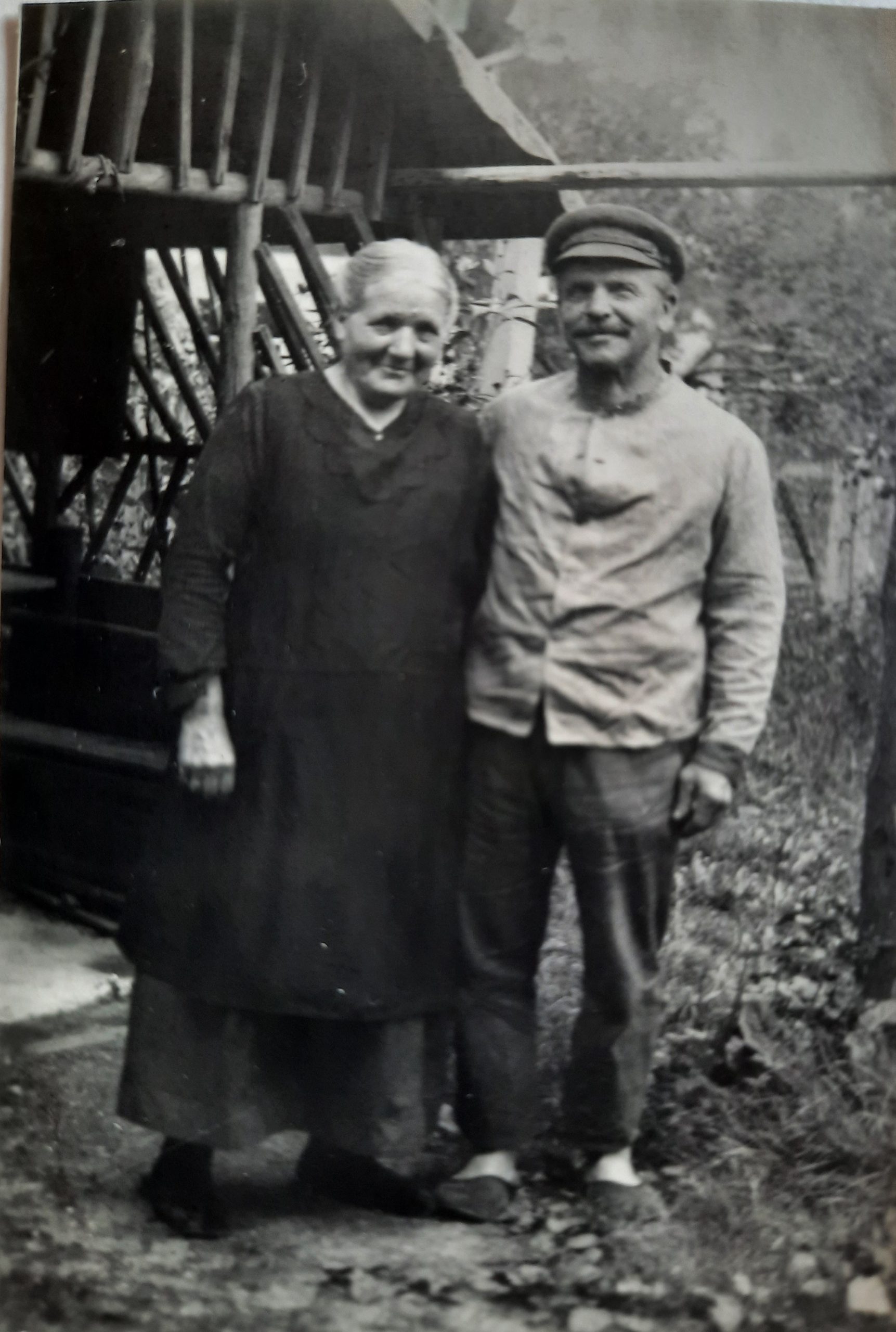

Werner’s grandmother and grandfather, who was a shoemaker and the sexton of the Protestant church in Lichtenberg, Silesia

When the children were about to return home, on some occasions the local NSDAP party organised a farewell party for the children together with the local population. For children in KLV camps this was sometimes the first time they had closer contact to the inhabitants of the villages. The last such farewell party that was recorded in “Niederdonau” took place in Prein an der Rax on 10 February 1945 and was a carnival party, where local people were invited, too. For children in host families the leave-taking from their host families was at times tearful for both, as in the case of Werner. But he was lucky to be able to come back half a year later for good. Werner was not the only child who had found a new home in “Niederdonau”. Some other children were welcomed with so much warmth and love that they remained in Austria, too. Others only returned to Germany after the war and several stayed in contact with their host families for many years to come.

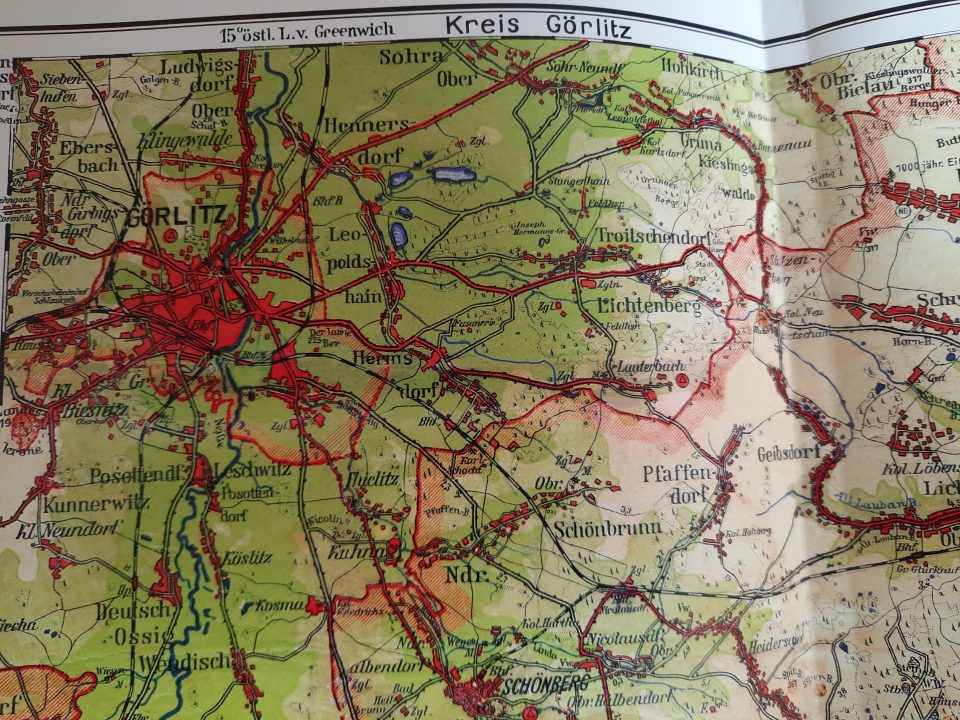

Werner’s birth place Lichtenberg near Görlitz in Silesia

Despite all its harmful and devastating effects on children, for Werner the KLV programme opened up unexpected new chances because he encountered the Rupp family in Obersiebenbrunn near Vienna. The Rupp family saved Werner’s youth and provided opportunities for him he would not have had at home in Silesia. Most of all, what had to be considered is that the family was a landless working-class family of very limited means. Nevertheless they decided to take Werner on as their foster child without receiving any alimony or other payment after the end of his KLV stay on 1 October 1940. In the scrap book of memoirs which Werner wrote towards the end of his life he recorded his sad childhood in the Görlitz region of Silesia.

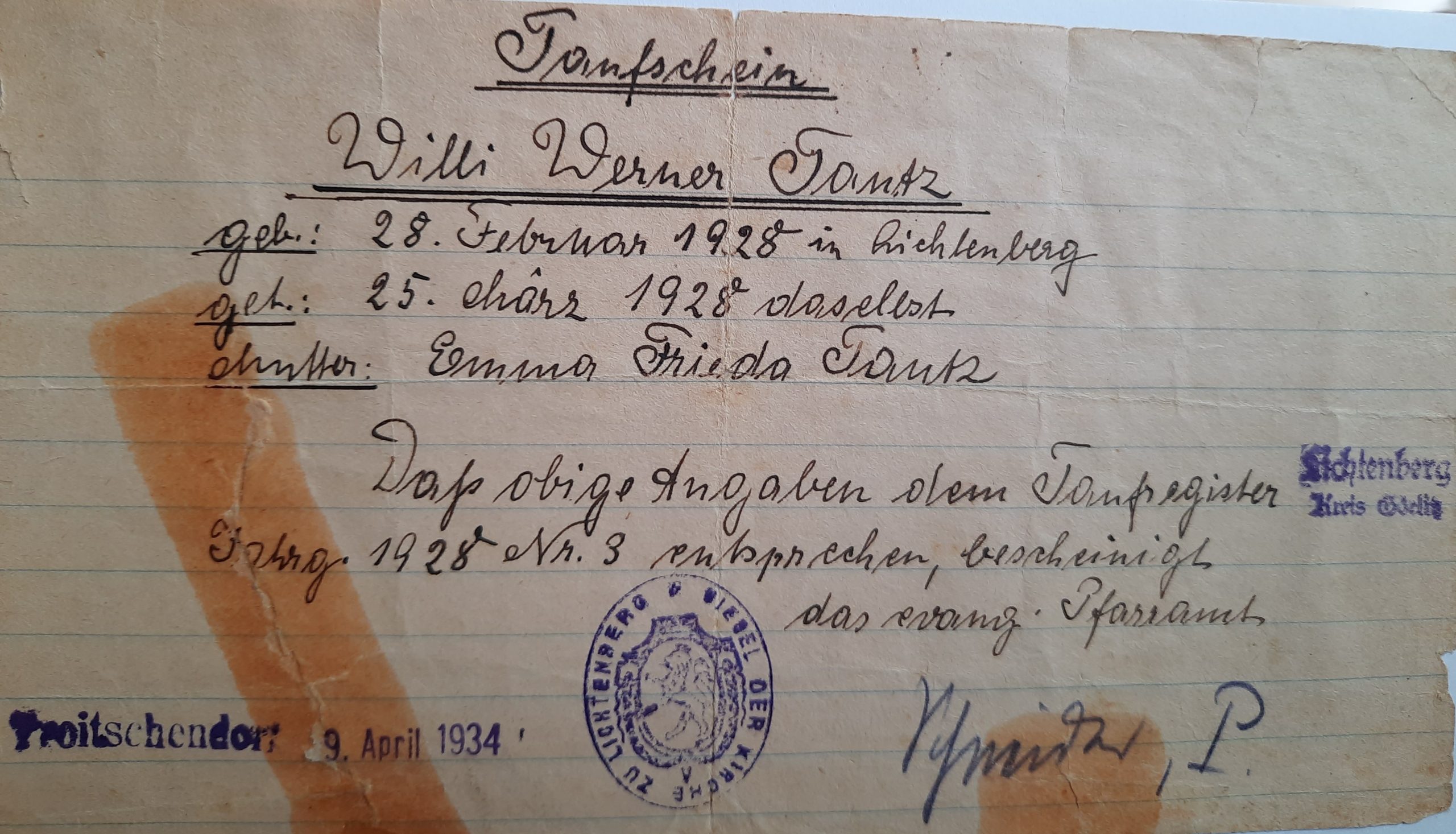

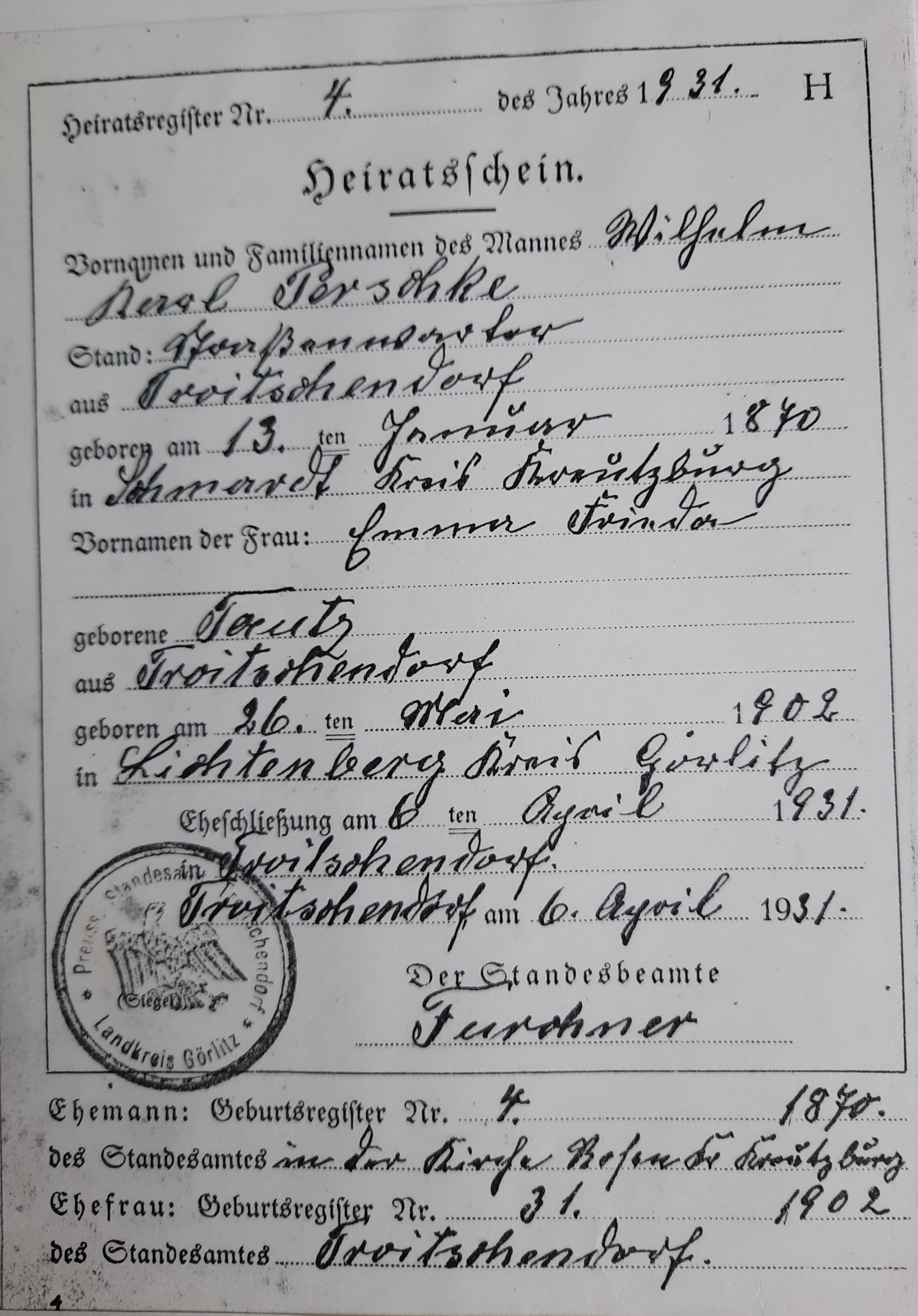

Werner was born out of wedlock in the house of his grandparents Tautz on 28 February 1928; on the right his birth certificate

A photo of Werner’s grandparents of 1914 and below his certificate of baptism in the Protestant church of Lichtenberg. In Austria the two Christian names” Willi Werner” caused confusion because in Silesia the second Christian name was the one a child was called by; that’s why he was called Werner, not Willi and his mother Frieda, not Emma.

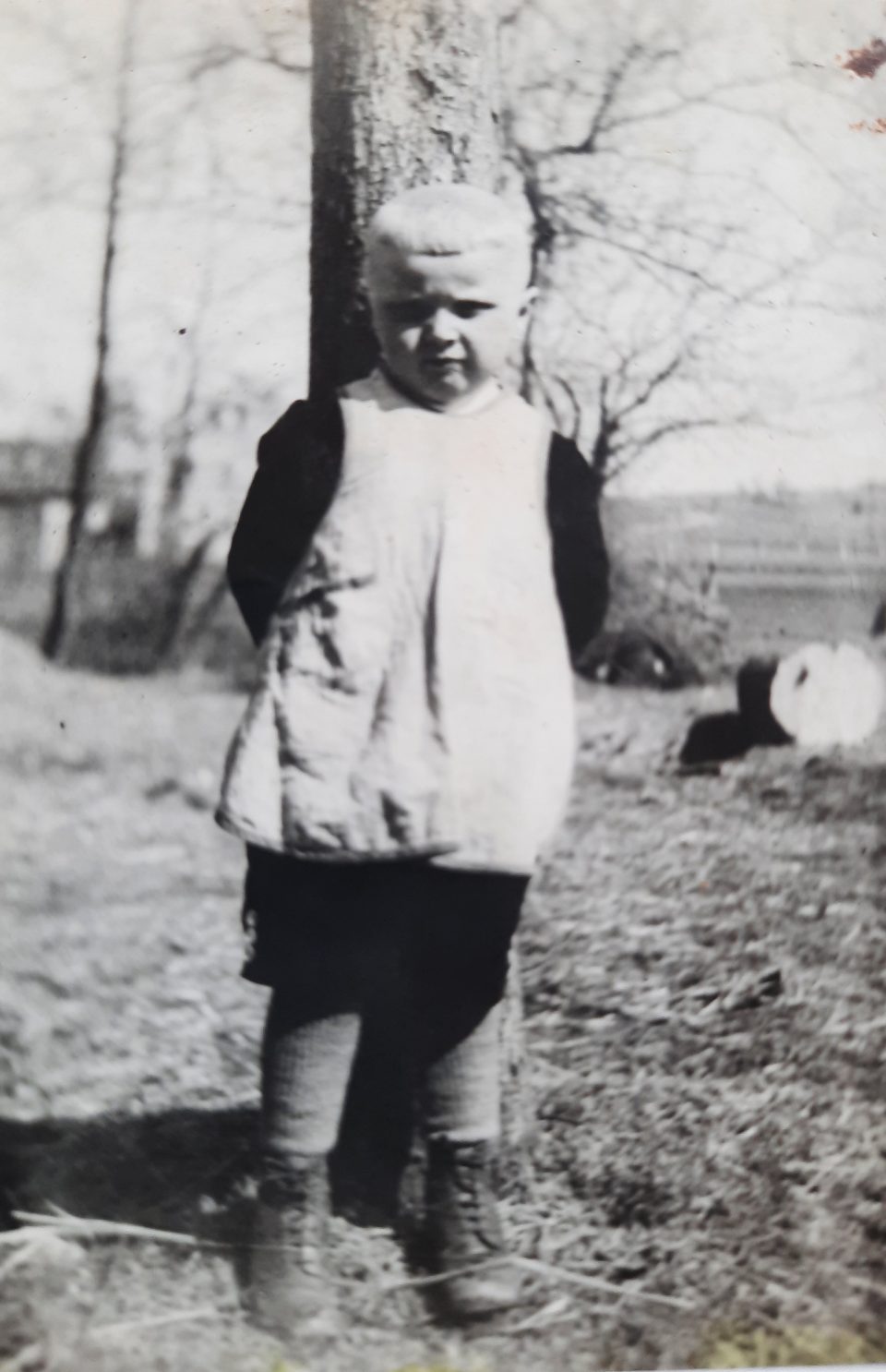

The church of Lichtenberg, where his grandfather was the sexton and his grandmother was responsible for preparing mass. On the right side Werner as a toddler: It was said that he did not like being photographed and had to be persuaded with a bar of chocolate. That’s why he rarely laughed in these early photos; only later with the Rupp family Werner can be seen laughing in every photo.

After birth, Werner was handed over to a foster family because his grandmother, who was Frieda’s stepmother, did not want to raise a child born out of wedlock, but later she seemed to have relented and Werner was allowed to live with his grandparents in Lichtenberg. In 1931 though, his mother Frieda married Karl Perschke and Werner had to move to Troitschendorf with her. It was said that he ran away several times at the age of three and marched around 800 m to his grandparents’ house on his own because he was so unhappy with the Perschkes.

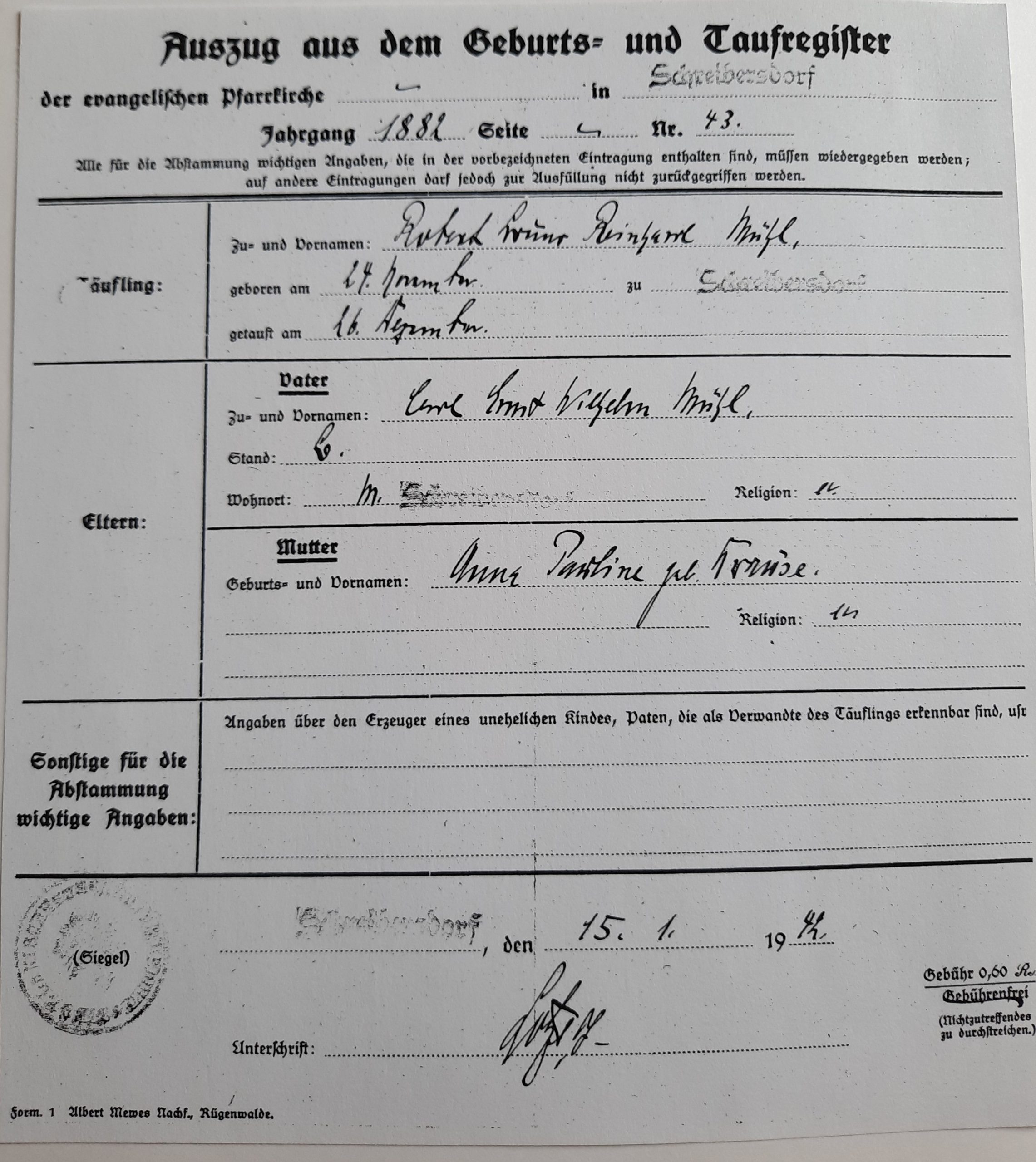

Before the wedding in 1931 his half-sister Elsbeth and in 1932 his half-brother Günter were born. At that time Karl Perschke was already 62 years old and the two children were spoilt by their parents. Werner’s biological father was Reinhard Müth, a large farmer in Schreibersdorf, where his mother Frieda had worked. Werner’s aunt Martha told him later that his father had been a womaniser who loved wine, women and songs. Finally one night he did not return from one of his pub crawls and went missing. His father regularly paid alimony to Frieda, but had no contact at all to his son.

The house of Werner’s father in Schreibersdorf in the vicinity of Lichtenberg and Troitschendorf (see map) and his father’s birth certificate below

The marriage certificate of Werner’s mother Frieda, who was 32 years younger than her husband Karl Perschke, and the wedding photo below: Frieda with the new-born Elsbeth and her husband in the middle; Werner and his grandparents to the left. Aunt Minna, Karl Perschke’s stepdaughter, was illiterate, which is not a sign of good parenthood on the side of Karl Perschke. In the photo she is the woman standing on the right side next to Uncle Gustav, the husband of Frieda’s sister Martha and their two children in front

The family lived in a three-room rented flat in the farmhouse in Troitschendorf, which can be seen below:

Werner was later told that he did not like having to take his sister Elsbeth for a walk in the pram. He supposedly said that he would like to run her into the village pond. He was probably very jealous and he furthermore had a bad memory of the village pond because he had nearly drowned there when he was little. He’d rather play with the daughter of his legal guardian Fritz Hamann, Annemarie (on the right). Hamann was the one who took most of the photos. He was friendly to Werner, but not very helpful as guardian.

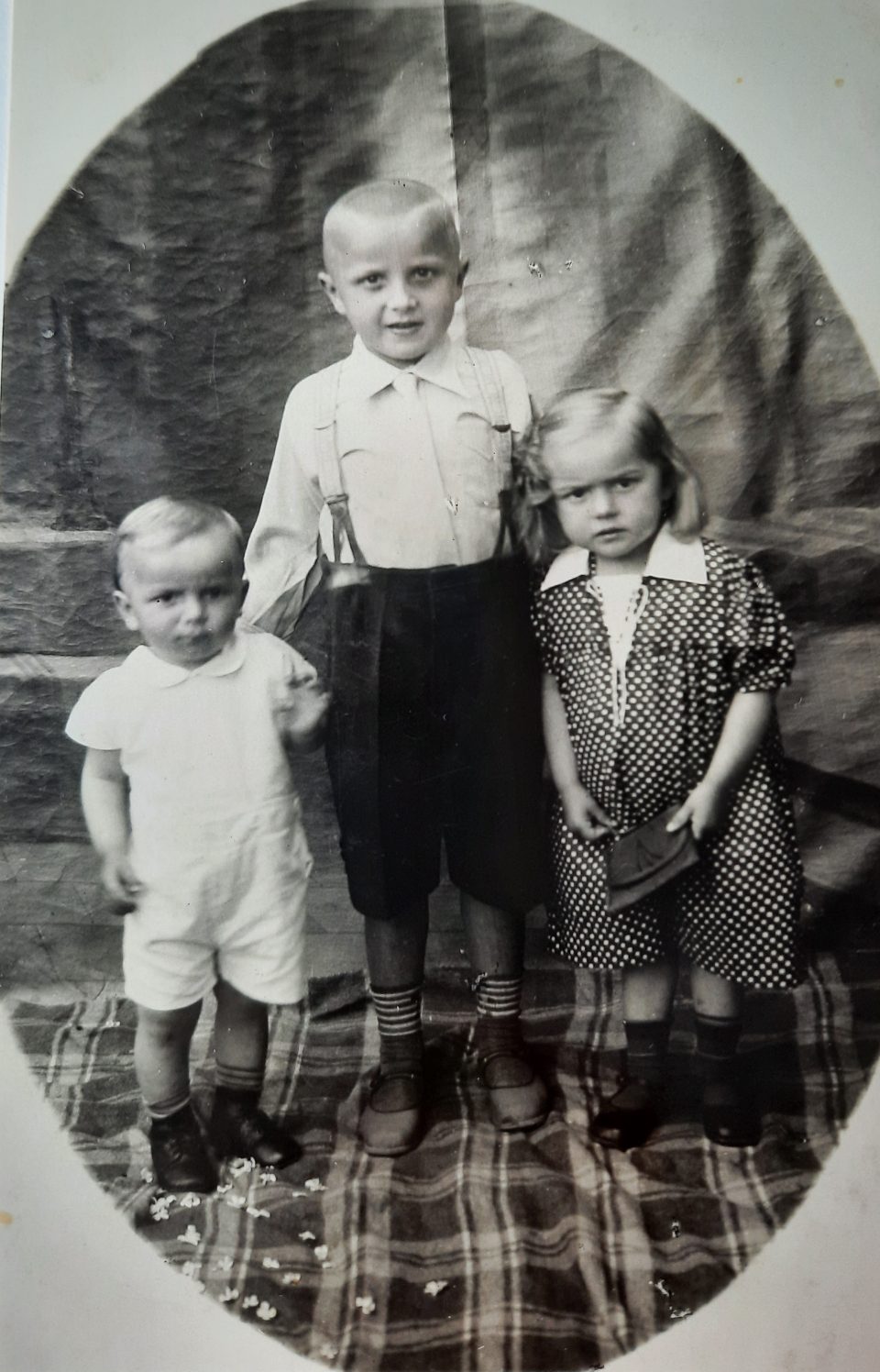

A professional photograph took photos of Frieda and Karl Perschke with the children Werner, Elsbeth and Günter

Karl Perschke died soon after the war in 1946 after the family had been driven out of the now Polish territory of Silesia and had found refuge in Mittelstetten in Bavaria. At that time Werner had already been living with his new foster family Rupp in Austria for more than 5 years.

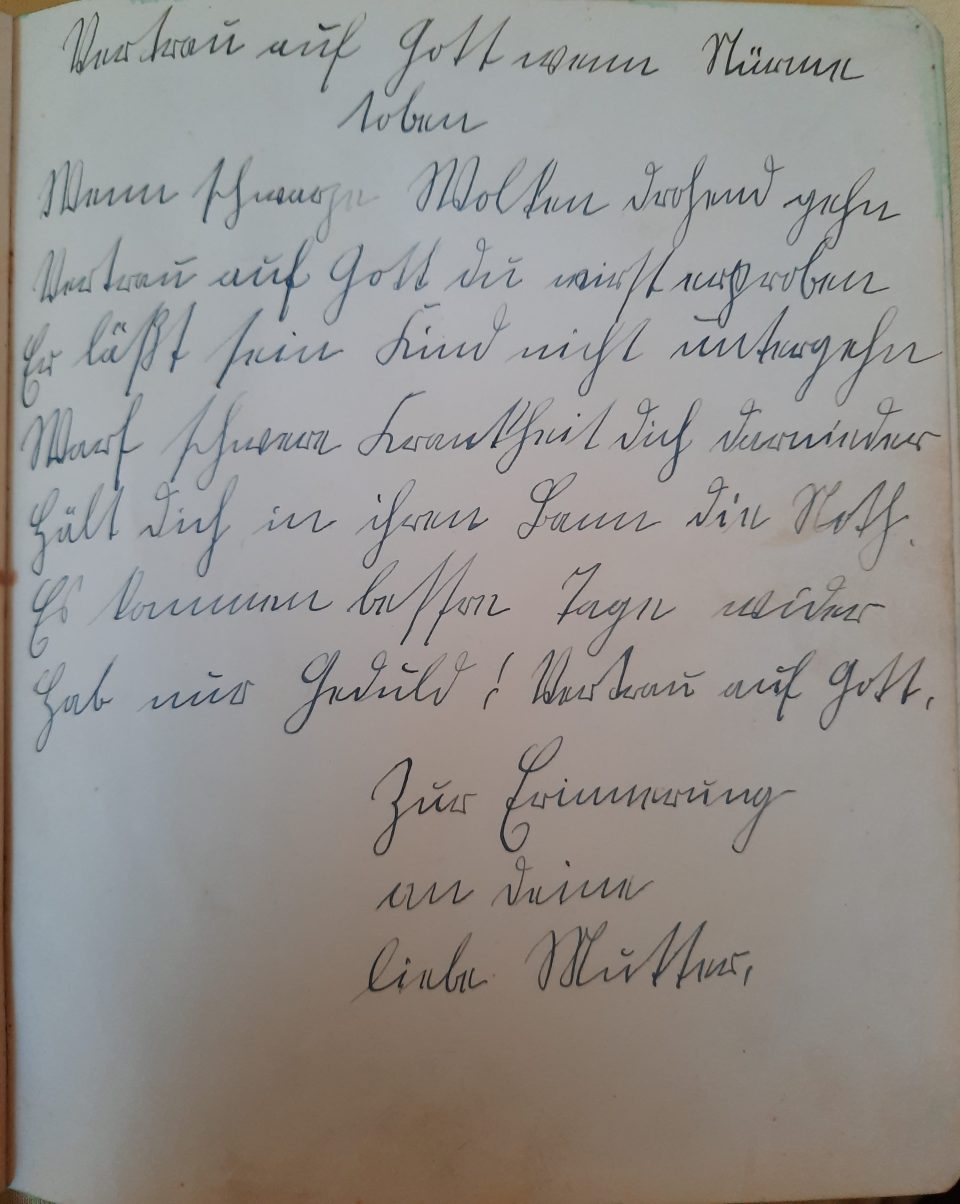

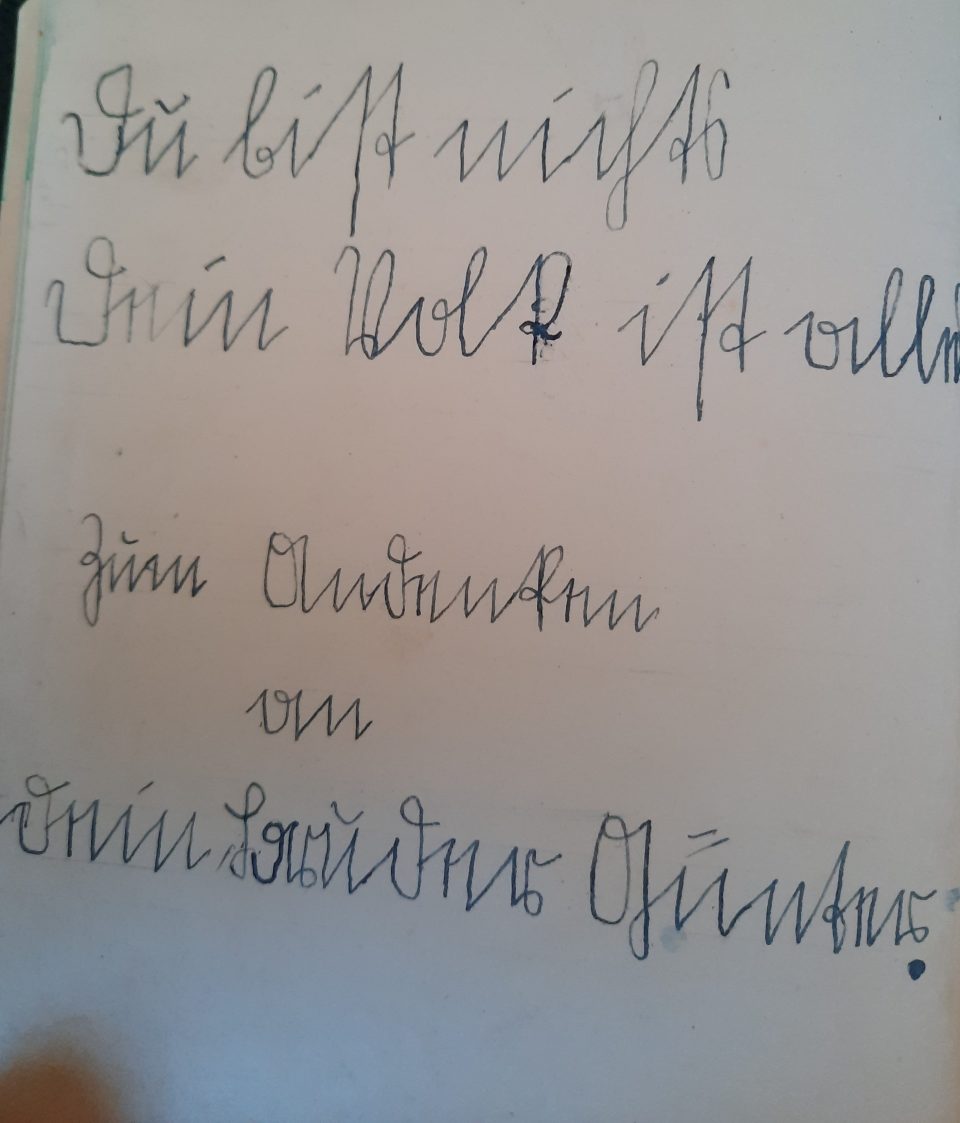

The photo of 1937 clearly documents how Werner was discriminated against in his biological family if one looks at the different quality of clothing of the three children (Werner on the right). On the right his mother’s entry into his “friendship book”, which was a common practice then.

In April 1938 Werner had to join the HJ. His grandfather was totally against it and protested. He spoke out against Hitler more and more so that the family was afraid he would be arrested. In fact, the family was ordered to meet the local NSDAP leader in the head quarter sometime later, but it was about a HJ meeting which Werner had missed. He probably had had to work at a farmer’s at the time of the meeting, as his mother forced him to work after school from an early age on.

Werner in HJ uniform with Günter and Elsbeth and with Annemarie and the bike his uncle Gustav and his stepfather had put together from old parts, so that he could ride to the farmers where he had to work after school and during the holidays. His siblings, on the contrary, received new bikes and did not have to work.

From the age of seven Werner had to go to the farmers after school to work there, for instance looking after the cows. He had no time to do his homework and so his marks at school deteriorated. He earned 25 Pf (Pfennige) per day for his mother, but that was not enough for her, so she found a famer where he had to tend 60 cows and earned 30 Pf. During the school holidays he had to work at the farmer’s the whole day and brought home 60 Pf. Yet in 1940 that still did not suffice, so his mother ordered him to work in the fields for an hourly wage of 12 Pf. There he worked the hay or harvested corn, sugar beets or potatoes, for example. Werner worked in the fields from spring until autumn and in winter he fed and cared for the cows of the farmer where they lived in rented rooms; he received dinner in exchange. His legal guardian asked his mother whether she would agree to a reduction of the monthly alimony she received from Werner’s biological father from 20 RM to 15 RM so that the money would stretch until Werner was 18 and could be used for his professional education. But Werner’s mother did not want to hear of it; she insisted on the full amount of 20 RM monthly until the end of compulsory schooling because she did not intend to allow Werner to learn a profession.

The blond boy on the left is Werner with the other farm hands and in the photo below Werner in front on a school trip to the “Riesengebirge”

Werner could earn some money for himself at the Protestant church in Lichtenberg. When he rang the bells on Sunday and on Christian holidays, his grandfather gave him 10-20 Pf. and as his grandfather was on excellent terms with Reverend Schneider, Werner could carry the cross at funerals and earn 50 Pf. each time. Whatever he earned at the church of his grandfather was his; everything that he earned at the farmers’ he had to hand over to his mother. But technically skilled Werner soon found out how to work mother’s mechanical savings box which counted the Pfennig coins and took out one now and then to buy himself some sweets or an ice cream for 10 Pf. Frieda always wondered why the mechanical counting system of the savings box did not correspond with the Pfennig coins inside.

The train station in Görlitz where Werner boarded the train on his KLV trip to the Rupp family in “Niederdonau” in August 1940 and a second and last time in January 1941 to his foster family Rupp and to a new and better life.

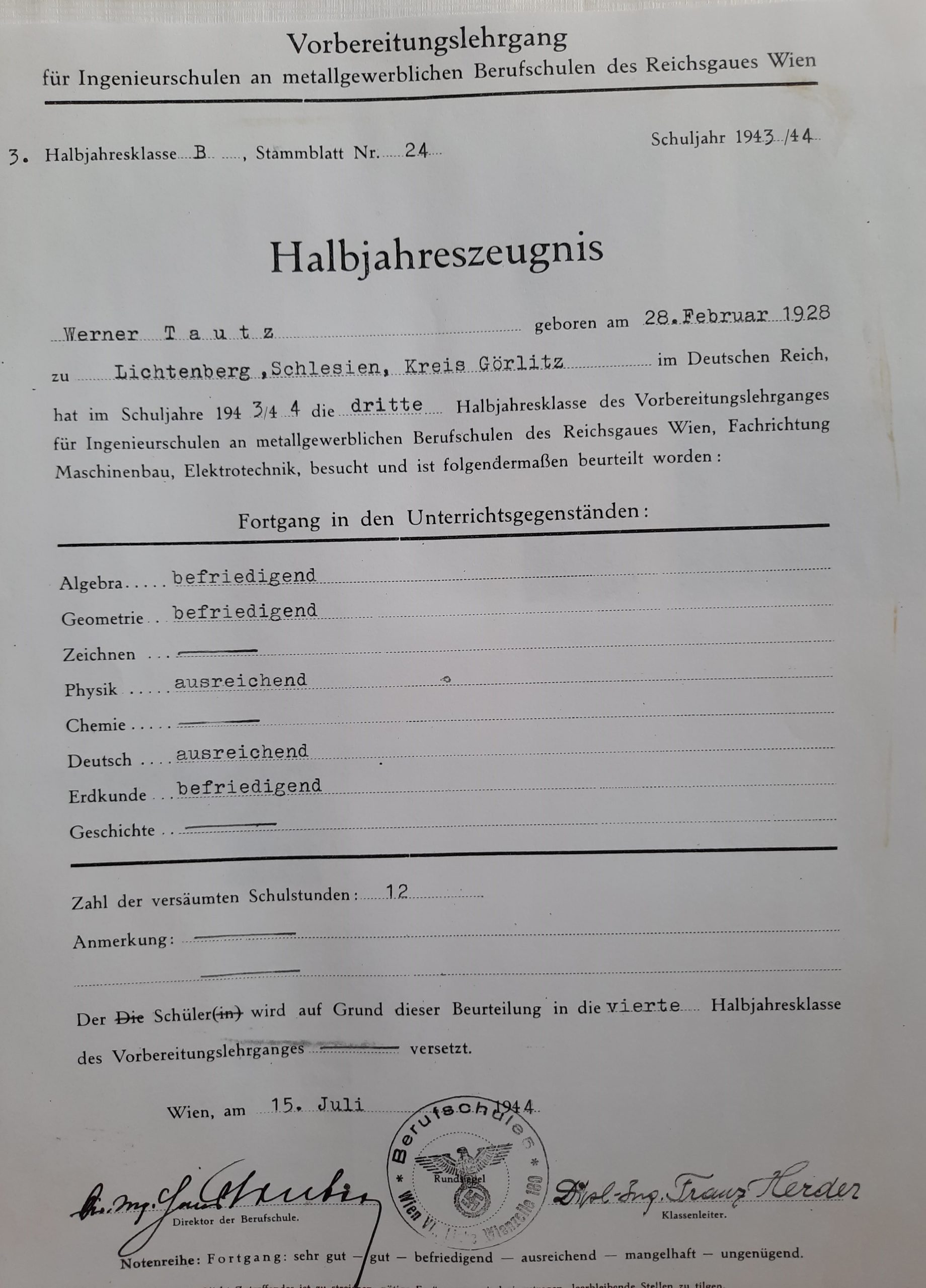

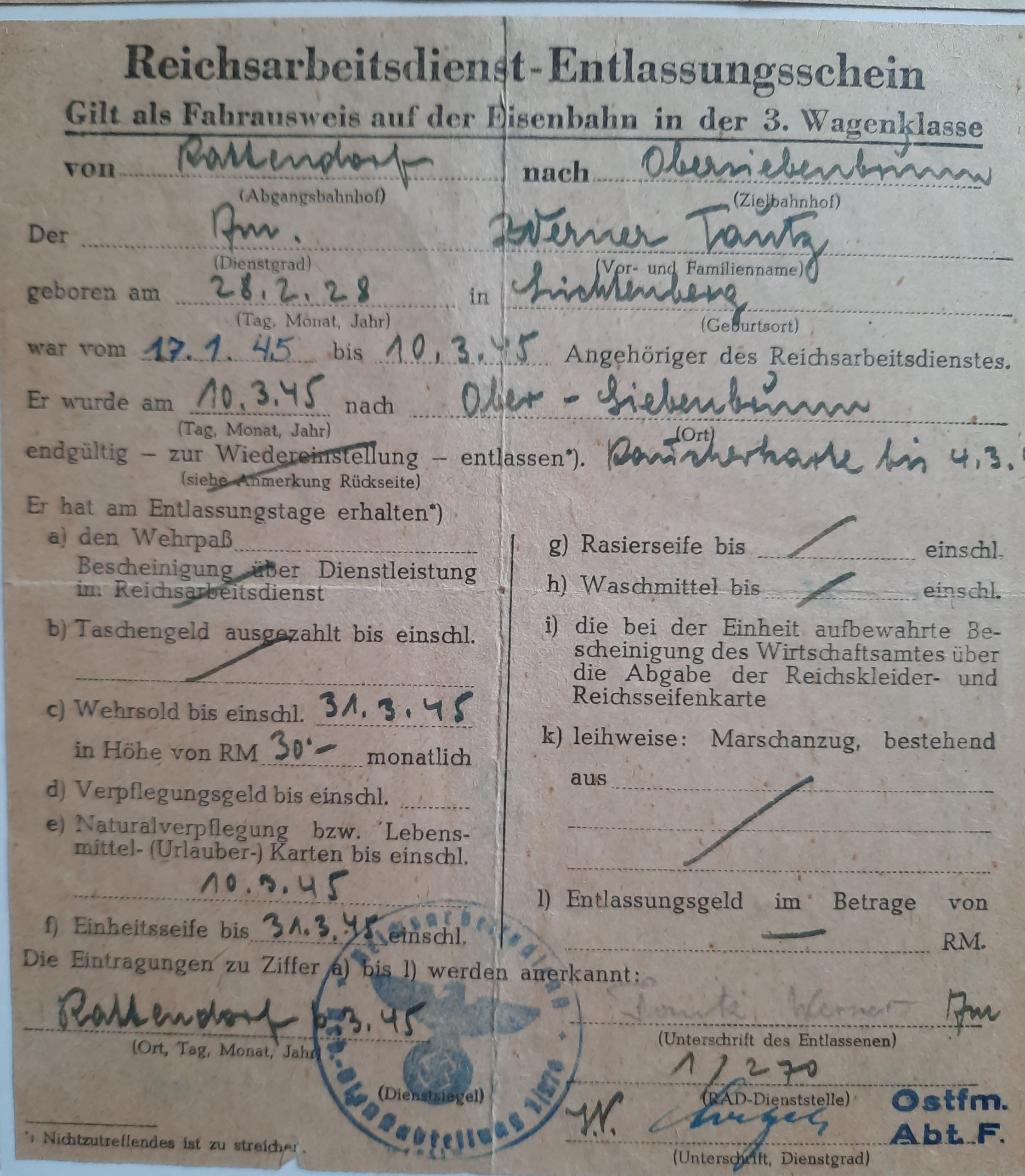

Werner left Görlitz by train all alone on 3 January 1941, but as there were enormous amounts of snow, the train remained stuck in the snow on Czech territory for 24 hours. When he finally arrived at the North Station in Vienna, he had to cross the city to reach the East Station. He said that without the help of friendly Viennese he would never have made it. He was a boy of twelve years of age then, turning thirteen at the end of February. When he finally arrived at the train station in Obersiebenbrunn, the snow was piled so high that he could not see his foster mother Anna Rupp and his foster sister Anni, who had been waiting for Werner for two days. They had been at the station for every train which arrived there. As they could not see him again they were turning to go back home, when they heard Werner’s desperate shouts. “So all is well that ends well”, Werner wrote. He was put into the third form of the local comprehensive school, but after two days it was obvious that he could not follow the lessons and was lost. He had not had any proper schooling in Silesia because he had to work for the farmers. He had never had any foreign language lessons. Therefore he was transferred back to the fourth form of primary school and that’s where he completed his compulsory schooling. His foster father, Franz Rupp, then saw to it that he was taken on as an apprentice at the sugar refinery in Leopoldsdorf, where he himself had been working. Werner was a clever boy and after the factory’s aptitude test it was decided that he would be trained to become an electrician although he had only completed primary school. Other boys who had completed comprehensive school were admitted for apprenticeships as fitters, lathe operators or forgers only. Franz Rupp paid for extra lessons for Werner with the engineer Mr. Span, so that he could catch up with what school knowledge he was missing. Additionally Werner attended the vocational school in Vienna, 6th district, Linke Wienzeile 180. Werner enjoyed his apprenticeship at the sugar refinery in Leopoldsdorf, which belonged to a group of sugar refineries with the head quarter in Vienna.

Werner’s last report card of the vocational school for engineers in the metalworking industry in Vienna before he was drafted in 1944

In the apprenticeship workshop in the sugar refinery two French forced labourers were employed- Werner remembered that they were called Daniel and Moritz, which was probably the German version of their true names. They asked Werner to bring them some French papers when he went to vocational school in Vienna and he did so. A few days later the GESTAPO (Geheime Staatspolizei” – NS secret state police) appeared in the factory and Werner was questioned for hours because another worker had reported him to the GESTAPO. He was threatened with the loss of his apprenticeship post for fetching the French papers for the two Frenchmen. In 1944 he was again denunciated because he had picked up a flyer which had been dropped by Allied airplanes in the street. The “man with a red armband” was supposed to “defend the home front”, it was said; in fact he was a Nazi informer. Werner was dragged in front of the local NSDAP party leader Mr. Ganz, but he got away with a warning because Mr. Ganz liked Werner, who had been at school with his son. After the war this informer wanted to invite Werner for a drink, but Werner told him “to fuck off”. Werner remembered that there were so many Nazis in the village and at the factory; the apprentices for instance had to greet the foremen in the factory with “Heil Hitler” every morning. After the war these dedicated National Socialists quickly turned into Social Democrats and when Werner asked them about their sudden change of political preference, they just said, “We don’t talk about the past; that’s over”. In 1947 he quitted work at the sugar refinery because he had had enough of these “Wendehälse” (turncoats); now the same people who had betrayed him in the Nazi era reported him because he had not marched with them on the 1st of May Socialist Parade. Werner told them that “he had already marched enough in his life”.

Werner’s foster father Franz Rupp was drafted in the middle of 1941. Although he was a NSDAP party member he was no longer “u.k.” (“unabkömmlich” – indispensable = deferred from military service) and stationed in Hammerfest, Norway, but it seemed that he had not always been in line with the party and would have to face a party tribunal after his military service. Fortunately after the defeat of Hitler the trial never took place. Nevertheless he was sacked from the sugar refinery in 1945 because he had been a NSDAP party member. He was reinstated in the 1950s after having joined the Social Democratic Party. In the course of the years Franz Rupp was even appointed local head of the Social Democratic Party in Obersiebenbrunn.

The Rupp family with Werner standing on the right and the women, Anna and the daughter Anni, with fox collars Franz had brought home from his army posting in Hammerfest, Norway. On the right, Anna and Franz Rupp with their son Franzi, when Werner’s foster father was drafted in 1941.

Research into the structure of the NSDAP in “Niederdonau” looked into the illegal Nazis before 1938, the NSDAP party leaders of the different districts in “Niederdonau” and the SA- and SS-members. The NSDAP district leaders showed a surprising personal continuity; they had already held these positions after 1933 during the time of illegality in the Austro-Fascist system and were able to hold on to power after the “Anschluss” in March 1938 and even to consolidate their positions of power. They were responsible for many war crimes, especially at the end of the war, when they executed arbitrary “verdicts” via drumhead trials, which were badly dressed up straight-forward murders in fact. 1,600 SA-leaders from Lower Austria sought refuge in the German “Third Reich” after Hitler had taken power there in 1933, mostly in Bavaria, where nearly all of them entered the so-called “Austrian Legion”, a paramilitary group which was trained in special SA camps. Especially in 1933/1934 they were responsible for several assaults in Austrian regions which bordered Bavaria. This contributed to the worsening relationship between Hitler’s Reich and Austro-Fascist Austria. It can be assumed that 40 percent of the illegal SA-men in Lower Austria operated in Germany before 1938. Yet the highest mobility can be attributed to the SS-men, members of the “Black Order”, but that was not a unique phenomenon in Lower Austria. The SS leadership saw to it that the SS members boasted a stable family on the “home front” by forcing them to marry and by explicitly urging them to father children. Otherwise the leadership’s aim was to sever any individual relationships of the SS-men which would impede their mobility. Himmler prevented at all costs that his SS-men formed any strong political or organisational ties at home – exactly the opposite of what was expected from NSDAP district leaders. The archives in Austria and Berlin keep a large amount of personnel files of Austrian SA and SS leaders, but also “ordinary” SS men.

The NSDAP organisational structure divided the different provinces, called “Gaue” into districts, called “Kreise”. The leader of a “Gau”, such as “Niederdonau”, appointed the leaders of the districts “Kreise”, such as “Gänserndorf” in this case, which in itself consisted of 32 “Ortsgruppen” (local groups), whereby these local group leaders reported to the “Kreisleiter”, the district leader. “Niederdonau” consisted of 26 districts (“Kreise”) with 794 local groups (“Ortsgruppen”). Nearly all of the district leaders were former illegal Nazis and 16 of them had already fulfilled the political functions they took over in 1938 earlier during the time of illegality. It can be assumed that the number is even higher, but not all biographies are documented. Their strong political dominance was cemented over years of NSDAP party activity in their districts. They came from different professional backgrounds, but as they did no longer work in their professions it is sometimes difficult to research if and if so which professional training they had had before their political career. Among those who could be identified there were several unskilled workers, three students who had quitted university, four teachers, two engineers, a civil servant and a bank clerk. 18 SS-men from Lower Austria were identified as war criminals who had committed most atrocious crimes against humanity and who had formed part of the SS-élite and acted on their own account. All of them were illegal Nazis before 1938, but this list does not comprise the many SS men who had committed unknown war crimes or decided about life and death at their office desks. Research at the “Österreichisches Staatsarchiv” and the “Dokumentationsarchiv des österreichischen Widerstands“ and the German „Bundesarchiv in Berlin“ has not disclosed any criminal activity of Franz Rupp.

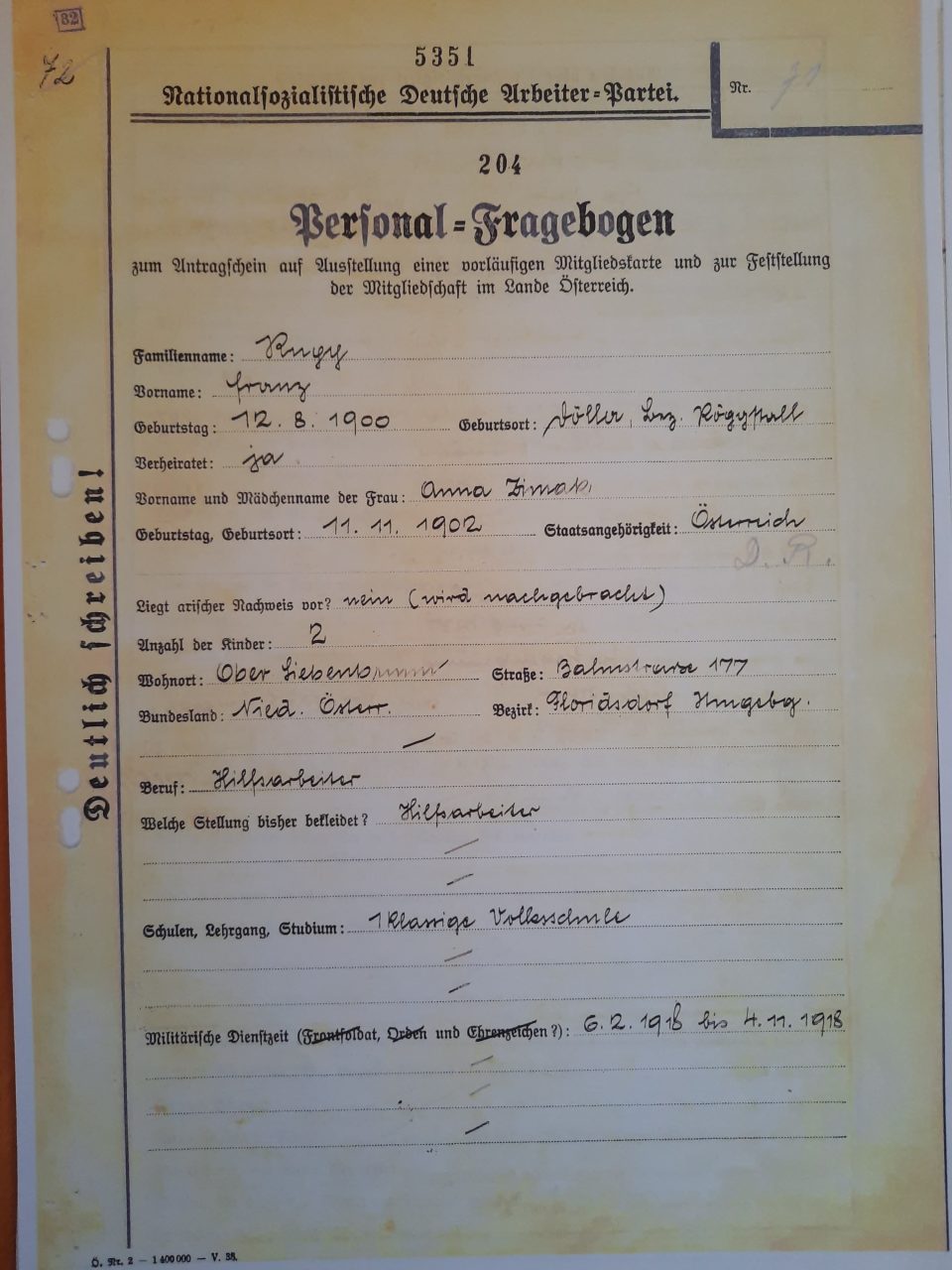

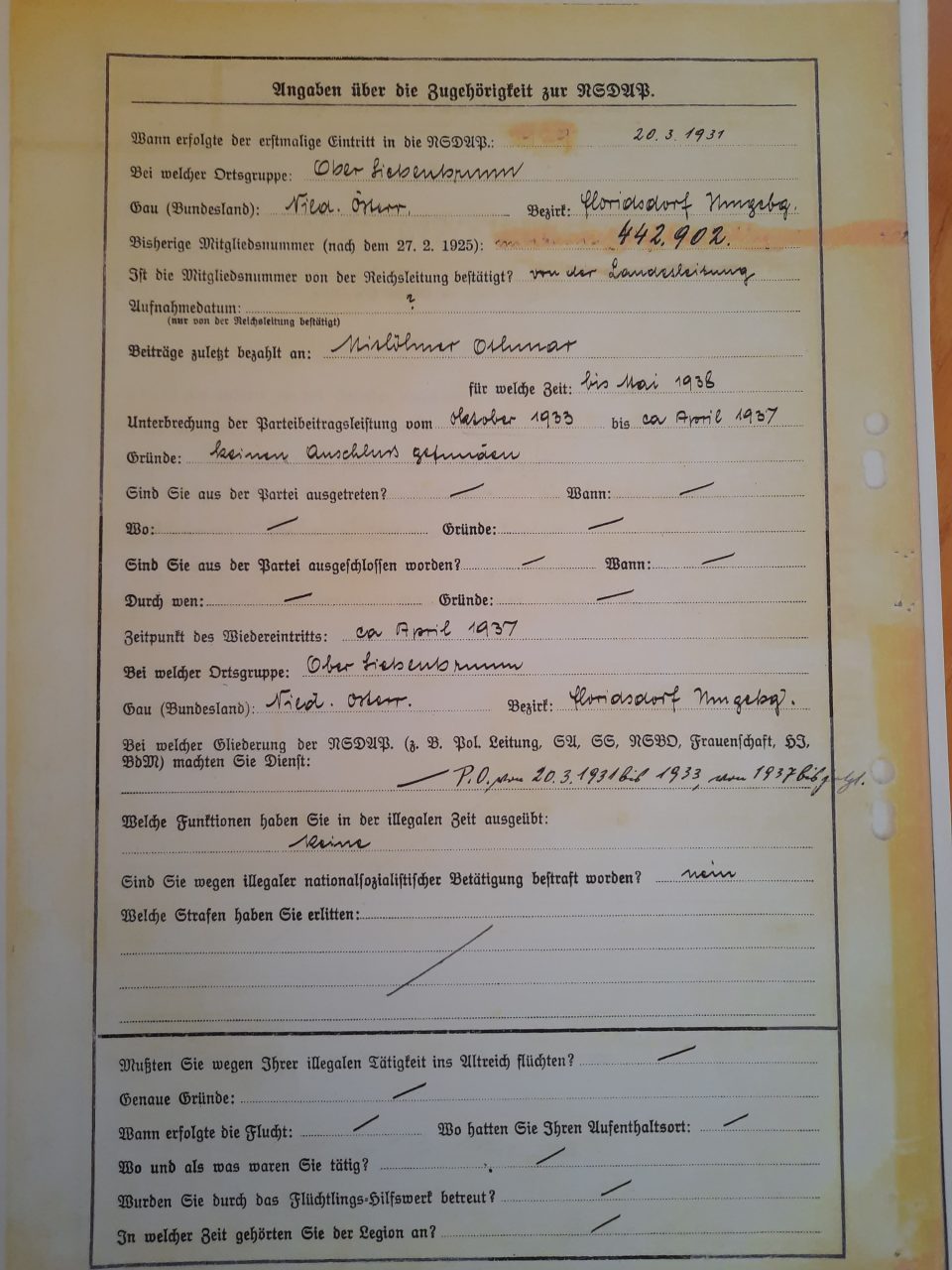

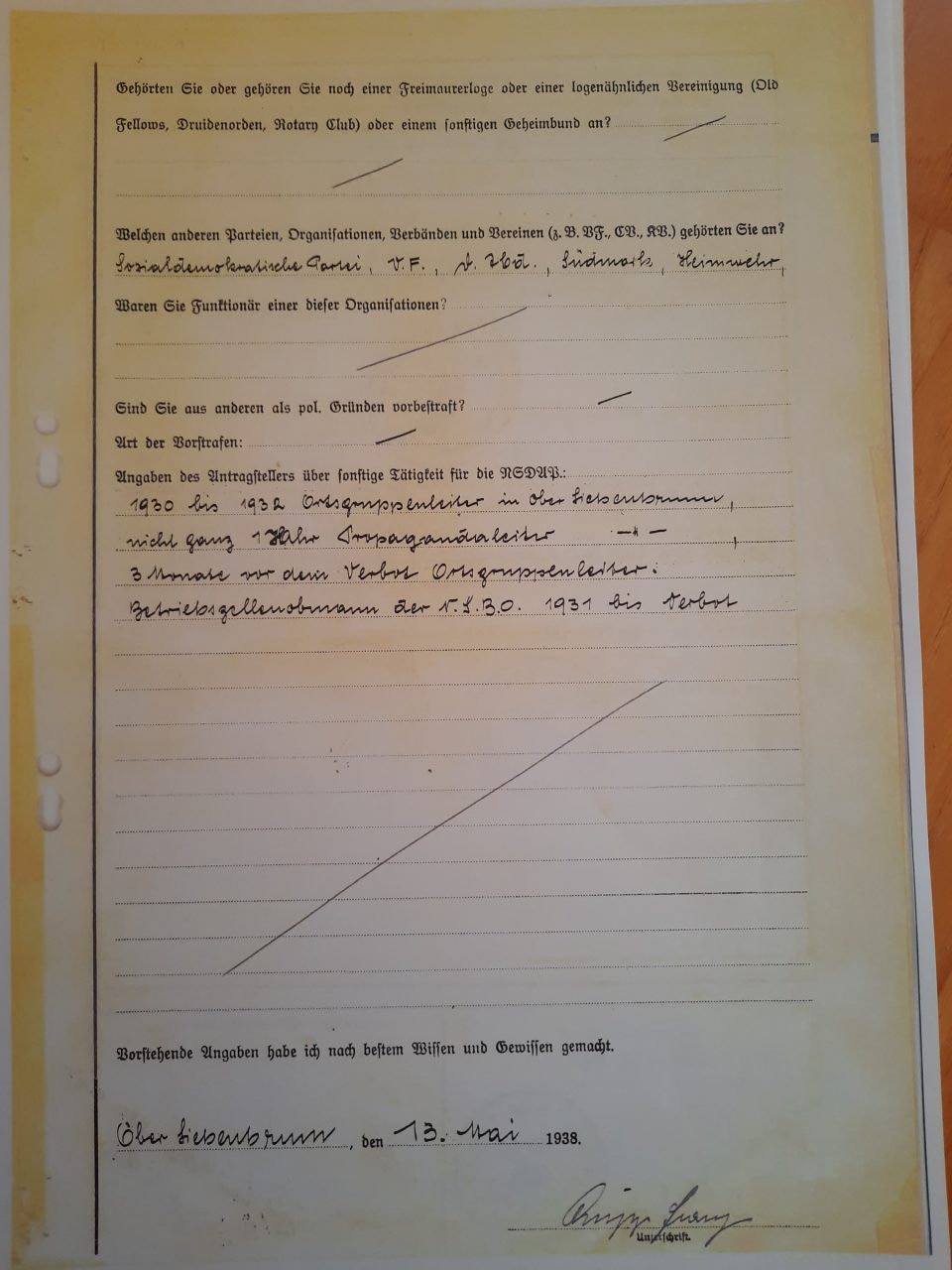

Application form for NSDAP membership of Franz Rupp, questionnaire 13 May 1938

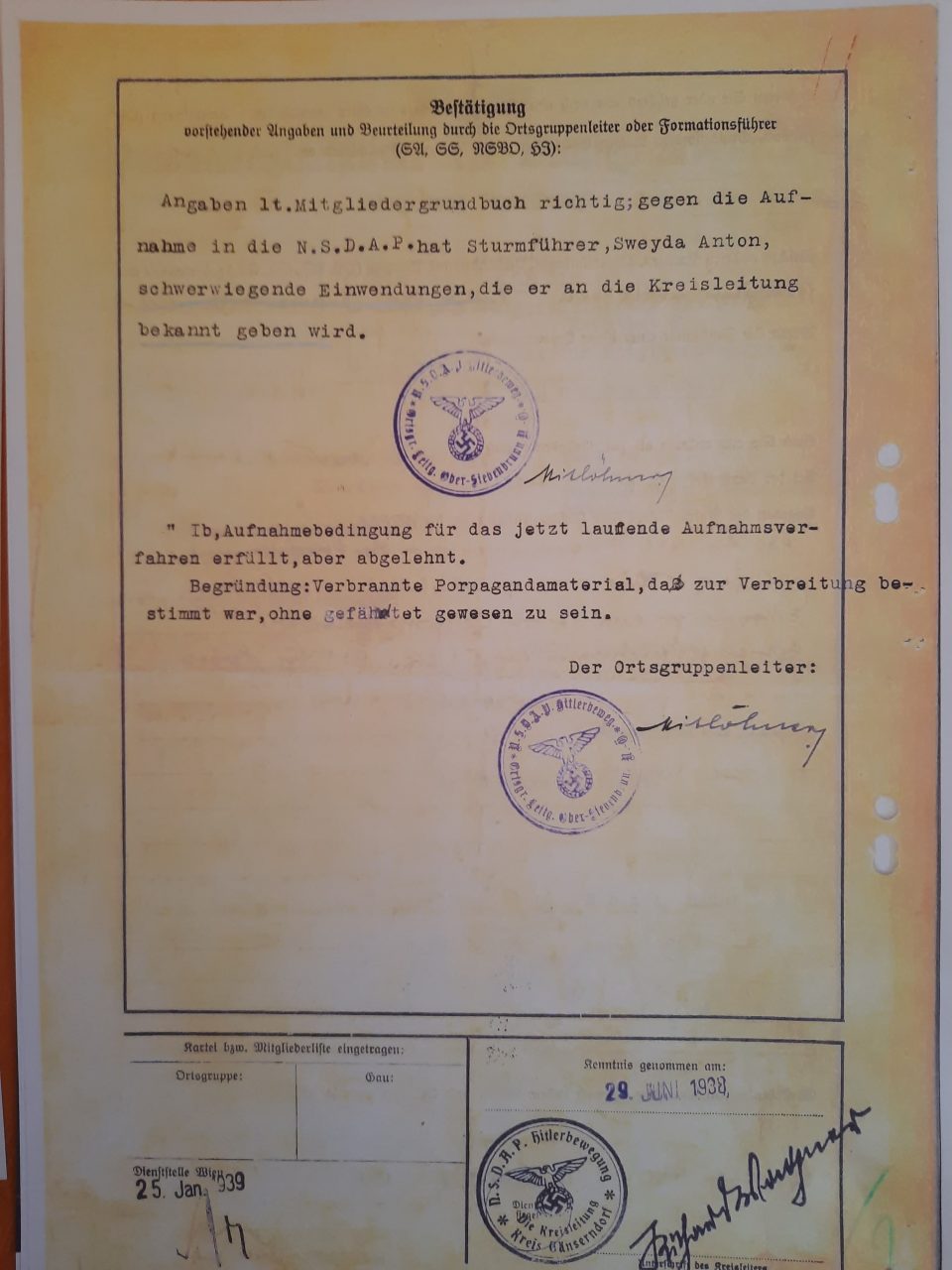

On the right the protest of Franz Rupp’s successor as “Ortsgruppenleiter” (local group leader) in Obersiebenbrunn, Ernst Mitlöhner, and Sturmführer Anton Sweyda against his readmission as a member of the NSDAP

At the end of the war the Rupps burned all documents related to the NS past of Franz Rupp, but in the German “Bundesarchiv in Berlin” the NSDAP personnel file of Franz Rupp is preserved, which exemplifies the party career of a Lower Austrian unskilled worker in the 1930s and 1940s. In the “Marchfeld”, a region characterised by large farms and some industrial sites, a young landless unskilled worker’s chances in life were very limited. Franz Rupp was born on 12 August 1900 in Dölla, district of Pöggstall, and had only completed “1klassige Volksschule” (a primary school where children of all ages are taught in one class room), had no professional training and worked as an unskilled worker at the sugar refinery in Leopoldsdorf. Yet he had ambitions, was hot-tempered and bull-headed, but deep inside self-conscious. He saw the possibility of boosting his prestige and gaining a commanding position despite his humble origins by joining powerful political organisations which promised chances of promotion and esteem. In this way many young Austrians were attracted by the NSDAP and Franz Rupp was the typical example of a person who tried to compensate his inborn insecurity by acquiring dominance over others via membership in powerful organisations and executing political functions. In the questionnaire he completed for his readmission in the NSDAP it is stated that Franz Rupp had been a member of the Social Democratic Party before joining the NSDAP for the first time on 20 March 1931 in Obersiebenbrunn (membership number 442.902), when he was already “PO”(“Politische Organisation”), meaning he was already involved in the political organisation of the party at the age of 30. He had acted as NSDAP “Ortsgruppenleiter” (local group leader) in Obersiebenbrunn since 1930 and was the head of propaganda in Obersiebenbrunn for one year. At the same time he was head of the NSDAP union representation (“Betriebszellenobmann”) in the sugar refinery. Even before February 1934, when the Austro-Fascist system under Dollfuss was established and the Social Democratic, Communist parties and the NSDAP were banned, he seemed to have changed track and joined the Austro-Fascists by becoming a member of their party organisation, “Vaterländische Front”, their trade union and of their military arm, the “Heimwehr”. He stopped paying the NSDAP membership fee in June 1933 and later justified this act by saying that he could “no longer link up with the organisation”. When he saw the demise of the Dollfuss regime coming, he took up the payment of the NSDAP membership fees again in April 1937. Franz Rupp was a member of the organisation “Südmark”, too, which was a German nationalist group founded at the end of the 19th century in Styria and Carinthia to promote the “German spirit” there at the expense of the Slovenian population. After the end of World War I, in which Franz had fought from February 1918 until the end in November 1918, Lower Austria and Burgenland joined the organisation “Südmark” with the intention of strengthening the German element against Slavic influences from Slovaks and Croatians there. During the Austrian 1st Republic this organisation’s aim was the integration of Austria in the German “Reich”. After the “Anschluss” of 1938 the organisation “Südmark” was integrated in the German NS organisation VDA (“Volksbund für das Deutschtum im Ausland”). Again the stark ideological discrepancy of Franz’ political alignments becomes visible as he was married to the Slovak speaker, Anna Zimak. His personal relationships, his quickly changing ideology and his political functions did not seem to come into conflict with each other in his opinion. In general this tends to be a character trace of many Austrians in the course of the 20th century, which might explain why they were stereotyped by foreigners as devious and obsequious. This for example can be evidenced in the comment of a French military representative in March 1938 (see below) and in the attitudes of Germans towards Austrians in the “Wehrmacht” (see the two articles on “Personal Experiences of a Viennese Soldier” part I and II). Franz Rupp was a typical Austrian “Vereinsmeier” (club fanatic) who tried to gain importance and to climb the social ladder by joining the club, organisation or party dominant at the time and quickly switching ideologies without qualms whenever necessary. From April 1937 on he seemed to have worked for the political organisation of the NSDAP again although his membership had expired. That’s why he reapplied in May 1938. But now former NSDAP “comrades” who probably bore a grudge against Franz Rupp or just wanted to spite him prevented his reintegration in the NSDAP. The NSDAP cashier in Obersiebenbrunn, Ernst Mitlöhner, who had meanwhile taken over Franz’ position as local group leader, and the Sturmführer Anton Sweyda officially protested and argued that Franz Rupp had burned NSDAP propaganda material during the time of the NSDAP ban in Austria “without being threatened”. They further stated that he showed a fickle attitude during this time, although it should have been his duty as “Ortsgruppenleiter” (local group leader) to support the illegal organisation of the party. On the contrary, he was “passive in the illegal organisation” and demonstrated an “excessive craving for recognition” by trying to gain official positions in the political organisation and the trade union organisation of the Austro-Fascists, the “Vaterländische Front” and the “Vaterländische Gewerkschaftsbewegung”. So Franz Rupp was denied NSDAP party membership until 1 January 1941, when he was once more accepted as a party member (membership number 8 534 572). In this way scores were settled in Austria at that time and the phenomenon of denunciation was rampant, as several examples in this article document. Envy, a feeling of being disadvantaged, of getting the short end of the stick characterised these members of an “informer society”. Once an informer, always an informer seemed to be the call of the day, no matter which ideology was currently predominant. Werner called such informers “turncoats” (“Wendehälse”) in his memoirs; they were proud at finally having the upper hand and being able to bully others. Once they were informers for the Austro-Fascists, later for the Nazis and after the war they checked on their workmates and neighbours for the Socialists or the Conservatives of the People’s Party. The acceptance of a KLV child might have worked to Franz Rupp’s advantage in the eyes of the NSDAP, but he was drafted to the “Wehrmacht” in the summer of 1941 nevertheless. Deep down, Franz Rupp seemed to have been as kind towards children as his wife Anna, otherwise he would not have agreed to taking in Werner as a foster child.

Werner stressed in his memoires that he had had a wonderful time with his foster parents. He said they all helped Anna when Franz had been drafted, but Anna was so skilled and efficient that they never missed anything or went hungry. They had two fields where she grew potatoes and maize and furthermore she raised hens, geese, ducks and pigs. They also had honey from bees and once Werner got stung by 50 bees because he had been feeding them in winter in shirt sleeves. He recorded that he was so proud of his swollen arm that he showed it around at school. They even had enough wheat for bread because Anna bartered honey for bread grain with the big farmers of the “Marchfeld”. Anna made an excellent job of caring for four children all on her own during the war. Werner said that since he had come to the Rupp family in Austria he had always been lucky; he even survived his fatigue duty and his army training without getting involved in any armed conflict, contrary to his foster brother Franzi. All his life he was extremely thankful for their love and support and he was grateful, too, that his grandparents had made it possible for him to leave his mother’s home.

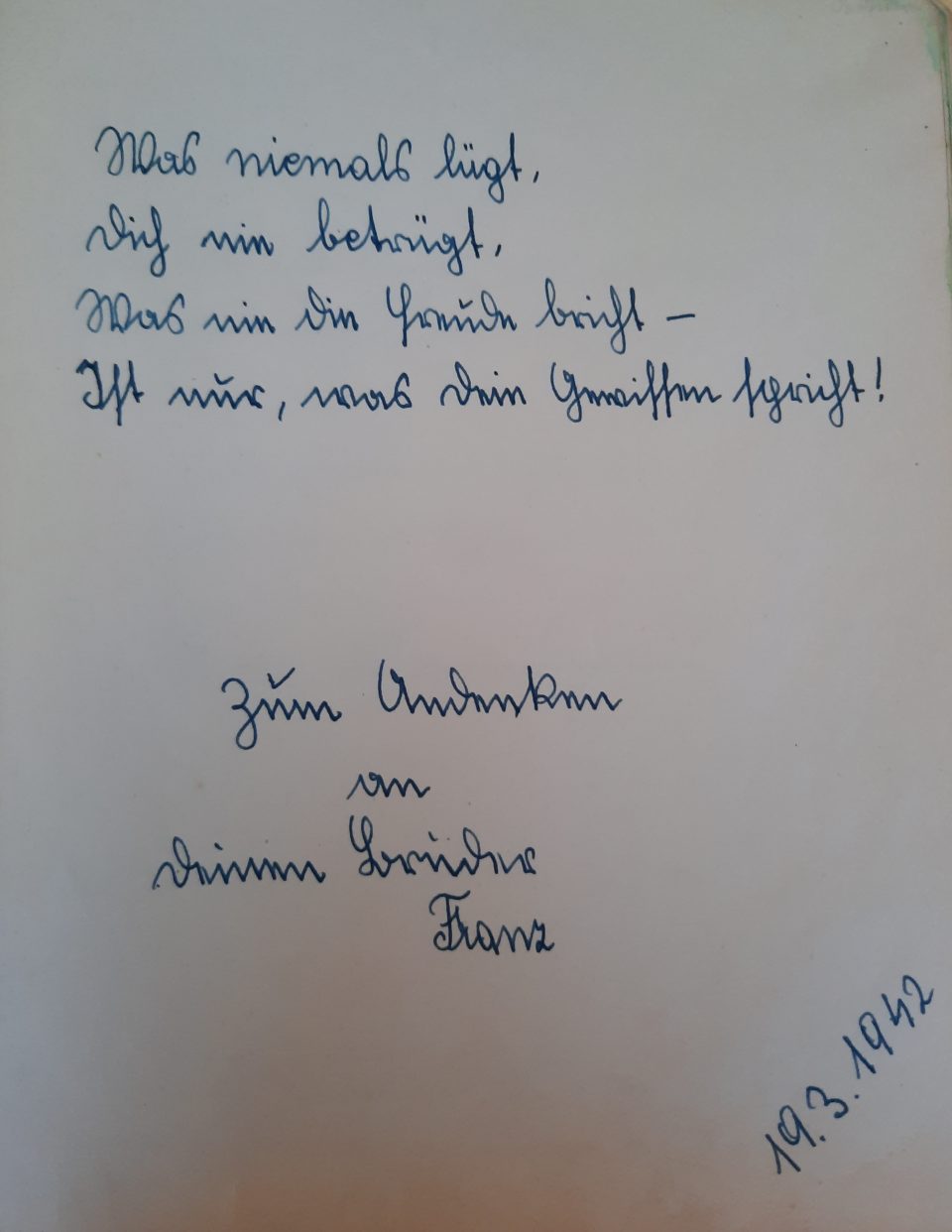

Entries into Werner’s “friendship book” by his foster brother Franzi and his foster mother Anna Rupp

His brother Günter’s entry in Werner’s “friendship book” before he left for Obersiebenbrunn for good in January 1941

Werner always stayed in contact with his biological mother Frieda although she constantly blamed him for everything until the end of her life. She died in 2002 at nearly 100 years. He continued to visit her although she wrote nasty letters to him and whenever he visited her in Bavaria she complained about the most absurd issues. Nobody understood why Werner went on to see her, but he always excused her and said that she had had a hard life. His sister Elsbeth and his brother Günter were nice and amiable people and Werner liked them very much, but they somehow seemed to be unable to cope with life: Elsbeth left her husband and joined a Turkish guest worker in a village in Anatolia as his second wife and Günter died at the age of 46 falling off his bike after one of his binge drinking sprees. None of them had any children. As absurd as it may sound, but Frieda Perschke seemed to have envied her son Werner the happy and successful life he had made for himself despite the dire beginnings. His family meant the world to Werner and that included first of all his wife Herta and myself, his son-in-law and his grandchildren, then his foster parents and foster siblings and their children and finally his biological family, too.

Werner with his siblings Günter on the left and Elsbeth in the middle and on the right

Werner’s brother Günter

Werner with his brother Günther in 1970 and with his mother Frieda Perschke and his wife Herta in Mittelstetten, Bavaria, at Christmas

To comprehend the political climate in Austria during the Nazi era and the fact that so many Austrians were supporting that atrocious regime one has to look at the social and economic background.

A photo of my great-uncle Karl Elzholz of the civil war of February 1934 which documents the military attacks of the Austro-Fascist regime of Dollfuss at the communal housing estates in Vienna, where Socialists were supposed to have hidden. A food cooperative “Konsumgenossenschaft Wien” was targeted with machine guns and shells by the Austro-Fascist paramilitary organisation and the army. With the ban of the Socialist and Communist parties and the imprisonment of their political leaders there was no longer any resistance to National Socialist agitation in Austria.

The emotions which accompanied the “Anschluss”, the takeover of the Nazis in Austria on 12 March 1938, are important for the understanding of the reactions of the population. Since the middle of February a shift in power towards the National Socialists had already been visible although they were officially still illegal. This became apparent first in Linz and Graz, where the Nazis already dominated the streets and tore up the Austrian flag. It seemed that the Austro-Fascist state capitulated daily in the face of Nazi terror. The Austrian chancellor Schuschnigg wanted to put the attitudes of the Austrians to the test in a referendum on 13 March 1938 and he expected a 65 to 75 percent vote for an independent Austrian state because he could rely on the support of the semi-legal leaders of the workers. The invasion of Hitler, which prevented the holding of the referendum, might be an indicator that Schuschnigg’s estimate could have been correct. That’s why already on 11 March the Nazis organised large demonstrations in the whole country and in a flush of victory the local NSDAP party organisations took control of all centres of power in a coup. This fact clearly contradicts the theory of “Austria as a victim”. Cities like Vienna and Graz turned into a nightmare of Nazi triumphalism in the night of the 11 to 12 March 1938. When the German “Wehrmacht” marched into Linz on 12 March deafening cheers welcomed the soldiers and the rejoicings and embraces did not end. The church bells were ringing and Hitler’s 120 km journey from Braunau, his birth place, to Linz represented without question a triumph. The frustration about the consequences of the Great Depression and the economic inefficiency of the Austro-Fascist state quickly shifted towards an irrational feeling of hope as being part of the “Third Reich”. The population did not want to see that Hitler was preparing for the next war. In frustration a French military representative commented that all Austrians, no matter of which social class, were spineless and obsequious, “a people of servants” who did not deserve any better; “they were not fit to be independent”. The writer Elias Canetti analysed that “feasting masses” then quickly turned into “inciting masses”. Their victims were defenceless; it was the hour of revenge, hate and senseless violence. The Austrians’ social frustration was especially directed towards their Jewish fellow citizens. It was not just the SA and SS; it was the care takers, the neighbours, the business competitors who seized what they could get their hands on. The many who were looking on were guilty of cruel indifference. No one would have believed that the average Viennese, the average Austrian could sink so low. Austria was internationally so isolated that except a protest from Mexico at the League of Nations and the protests of Great Britain and France in Berlin there were no significant international reactions to Hitler’s invasion in Austria. So on 13 March 1938 Austria was “reunited” with Germany and on 10 April 1938 a NS-staged referendum legitimised this move.

It is estimated that 5 percent of working Austrians were NSDAP members at that time, but 25 to 35 percent were NS supporters. A significant part of the Austrian working class shifted towards National Socialism then. The staunchest opponents were Catholics, Communists and Jews. In the spring of 1938 the Nazis targeted the apolitical section of the population and lured them with promises of jobs and an economic upturn. In the weeks before the referendum on 10 April the population was inundated with NS propaganda to a so far unknown degree. Nothing was left to accident; the NS propaganda machine aroused emotions and lulled the mind. Immediate populist measures won over the population, such as incorporating everyone into the unemployment benefit scheme, a ban of auctions of indebted farmsteads, a recreational holiday programme for workers’ children in the “Third Reich”, the KLV. The nobility, the workers, the farmers, the industrialists, the artists and even ethnic minorities soon openly expressed their support for Hitler. The very dominant Roman Catholic Church in Austria betrayed its own principles, when the Austrian bishops in a solemn declaration spoke for the NS regime on 18 March 1938. The support for Hitler in this referendum was 99.6 percent with a participation of 99.7 percent of the voting population. This result did not need any NS election manipulation because the ballots were handed over publicly and 200,000 opponents were excluded from participating.

The absurdity of the NS regime in Austria is illustrated by the fact that it combined traditionalism and modernity. The boost in technology and industrialisation was more visible in Austria because the country had suffered severe economic setbacks during the interwar years. The sizable increase in economic growth had to take into account the enormous social, economic and human costs this boost incurred. It was based on the vision of a modern totalitarian social state that excluded all “racially inferior elements”. The barbarian terror of the extermination of large parts of the society was the price for this so-called “modernisation”. The evil appeared in the disguise of welfare for the “ethnically worthy” members, the “Aryans”, of this absurd society model and Austria acted as the first testing ground for this type of “modernisation”. The so-called “Aryanisations” in Vienna were planned by highly specialised experts and were based on principles of rationalisation and urban planning. The social and human costs had to be borne by the defenceless and disenfranchised Jewish population. Initially the upgrading of the infrastructure, the boosting of the consumer goods production, the mechanisation of agriculture and the improvement of professional training had a positive effect on the economic modernisation in Austria. But with the increasing focus on production for the war economy an irrational belief in the power of the regime replaced common sense; corruption, the feudal structure of the party organisations, the overstretching of resources and the increasing lack of rational planning resulted in a decisive backward movement in the Austrian economy and a collective flight into delusion with deadly consequences for millions of people. The NS regime dissolved traditional relationships, such as family, religion or social class and pervaded the whole population with its delusional ideology. Bourgeois and working class lifestyles gradually disintegrated, and at the same time a welfare state with extensive benefits was established for the “chosen people”, the “Aryans”, such as child benefit, marriage benefit, pension system, health care and the children evacuation programme KLV. All those who did not meet the absurd criteria fixed by the Nazis were imprisoned, forced to emigrate or murdered in concentration camps. Universal human rights and the rule of law were suspended with enormous consequences for the post-war political and social attitude of Austrians. On the one hand the regime celebrated motherhood, but on the other hand it lived an aggressive and racist cult of virility and sterilised a sizable part of the female population. The increasing technological rationalisation and individualisation created a vacuum which was filled with the myth of NS “community spirit”.

Initially the expectations of many Austrians seemed to come true, but the big winner was the industry, especially the arms industry while the agricultural sector was lagging behind. The benefit of the industrial boom was unevenly distributed in Austria; while the number of industrial workers increased by 106 percent in Upper Austria, it only rose by 26 percent in Vienna. The share of women in the industrial work force remained at 25 percent. The regressive industrial development in the NS era is characterised by a return to slave labour, whose share rose to 36 per cent of the workforce in 1944 and in some industrial enterprises forced labourers constituted 80 percent of the workforce. So it can be said that the industrial modernisation in the NS state was paid for by the lives of tens of thousands of forced labourers. In Austria the unemployment rate sank from 22 percent in 1937 to 3 percent in 1939, whereby at least a third of these newly created jobs were in the war-related industry. The economic boom together with an income increase, a rise in consumer spending and an upsurge of German tourists lasted until the first war years only. At the end of the war the civilians could not acquire any consumer goods any more except basic food stuff. The excessive exploitation of the occupied territories enabled the NS regime to feed its population during the war until these regions were lost to the Allied Forces and the whole economic system of the “Third Reich” collapsed. During the last phase of the war the Nazis transferred large parts of the industrial production to Austria, 60 percent of which was armaments production, because they hoped to rescue some of their assets in the event of Hitler’s defeat as they thought Austria would be treated as a victim of the Nazis and therefore would enjoy better conditions offered by the victorious Allied Forces.

In agriculture the ambivalence of the NS dictatorship was especially stark. The NS “blood and soil” ideology flattered and pleased the farmers in Austria, but on the other hand the mechanisation of agriculture and the central planning of agricultural production with fixed prices and duty of delivery of agricultural products were clearly to the disadvantage of the farmers. Austrian agricultural production was further away from autarky than ever before. In fact the economic situation of the farming population worsened with the war, the rural exodus continued and the whole burden of agricultural work had to be borne more and more by women. To counter the trend of urbanisation, the NS authorities introduced NS fatigue duty on the land for the rural population (“Dienstpflicht”) and as well for the urban youth to assist the farmers (“Reichsarbeitsdiest”, “Pflichtjahre für die weibliche Jugend”). Anni, Franzi and finally Werner were all called to this NS fatigue duty. Additionally forced labourers were assigned to farmers. Those farmers who tried to evade the duty of delivering agricultural products were threatened with conscription to the “Wehrmacht” and in case of unofficial slaughtering with the death sentence. A huge centralised bureaucracy weighed heavily on the farmers and in the course of the duration of the war their resistance increased. In every village a NS local farmers’ leader had to execute the orders from Berlin, which became increasingly more difficult for them.

Another important aim of the NS regime in Austria was the integration of the working class. In case that did not work out, institutionalised terror would be applied by the NS authorities. Yet first they saw to it that the purchasing power of the workers did not decrease too much. The first populist measure was an appreciation of the currency in Austria by introducing the Reichsmark (RM) at an exchange rate of 3 Austrian Schillings for 2 RM. This resulted in a wage increase and a rise in purchasing power for the Austrian workers in 1938/1939. That might explain among other factors why someone as the unskilled worker in the sugar refinery in Leopoldsdorf near Vienna, Franz Rupp, was a fervent supporter of the NS regime. Nevertheless it has to be taken into account that the working hours were extended at the same time, which caused a lot of dissatisfaction among Austrian workers and that a considerable and continually rising percentage of the wages was deducted for income tax, contribution to the DAF (“Deutsche Arbeitsfront”, an obligatory NS worker organisation), the “Winterhilfswerk” (Winter Aid Programme) etc. The newly introduced pension scheme was not much different from the former one, but the job guarantee was much appreciated in the face of the high unemployment rates before 1938. Unfortunately this job guarantee was soon converted into a labour obligation and a ban on quitting jobs. Job competition and improved training was supposed to instil a better work ethic and determination for performance among Austrian workers. The NS leadership principle in fact strengthened the position of the entrepreneurs at the expense of the workers. The DAF introduced social programmes for the workers in the enterprises, such as KdF (“Kraft durch Freude” – strength via joy) sports and cultural programmes, but simultaneously supervised employees end-to-end via their NS representatives and informers. Furthermore the DAF weaved a network of small party functionaries in enterprises who were to discipline and check on the workers. They were also in charge of supervising the foreign forced labourers, which enormously increased their self-esteem; people who had had no say before could now boss around and bully others. In that way the NS state gradually gained complete control over the workers and took away any type of worker autonomy. Yet it has to be noted that the hard core of Social Democratic and Communist workers in Austria were not to be won over by this type of NS social policy. The focus on meritocracy, the intention of the NS regime to do away with the Austrian “slackness” and the clampdown on those who were “unwilling or unfit for this achievement-oriented society” led to silent protest and resistance in the form of a rising refusal to work, an increase in sick days, dawdling and even sabotage. The regime reacted with ever harsher punishments and in the end imprisonment in a labour camp or a concentration camp.

The NS mobilisation did not stop at the workers it started already with the young. The NS organisations for boys and girls, HJ and BdM, initially lured the youth to the Nazi ideology with extensive sports and cultural programmes and a possibility to break out of traditional family and social structures. HJ and BdM leadership positions offered enormous career opportunities. But when in 1939 the membership in HJ and BdM became obligatory, it lost a lot of its attraction for many young people in Austria because this compulsory service duty was linked to lots of war-related activities, among them the KLV. Never before had the young generation been politically indoctrinated to that extent. So some young people went underground in private groups and cliques, for example the “Swing Youth”. The NS image of women was ambivalent, too. Ideologically the “eternal mother” was at the centre, but the war economy forced more and more women into employed labour, so that eventually in 1944 51 percent of women were officially employed, whereas the share in Great Britain was 36 percent only. At the same time the Nazis stressed the importance of the woman as the “leader of the household”, which was her “combat sector” in the war effort. Some improvements for working women were achieved via the Maternity Protection Law of 1942 and the wives of soldiers were better provided for than during World War I. Women who were NSDAP members could dodge the NS fatigue duty or they could elude it by bearing children. Some girls enjoyed being members of the BdM or working in the NS fatigue duty because it allowed them to leave home, meet boys and enjoy more freedom, which the more conservative parts of the Austrian society did not appreciate at all. Nevertheless, the more the effects of the war were felt in Austria, the more decision making powers were handed over to women, who took responsibility in families and other areas of society, as can be seen from the example of Anna Rupp. She took the decision to care for a fourth child, namely Werner, during very difficult times as a landless working class woman with no assets and made a marvellous job of running and feeding a family of five all on her own. Another phenomenon of the last years of the war was a mixing up of society which was not intended by the Nazis, but the numbers of refugees, bombed-out people, foreign forced labourers, prisoners-of-war, KLV children etc. rose rapidly and made the “alien element” ever present even in the most remote regions of Austria. Yet it has to be mentioned that in most cases the non-German foreigner was treated with a varying degree of contempt.