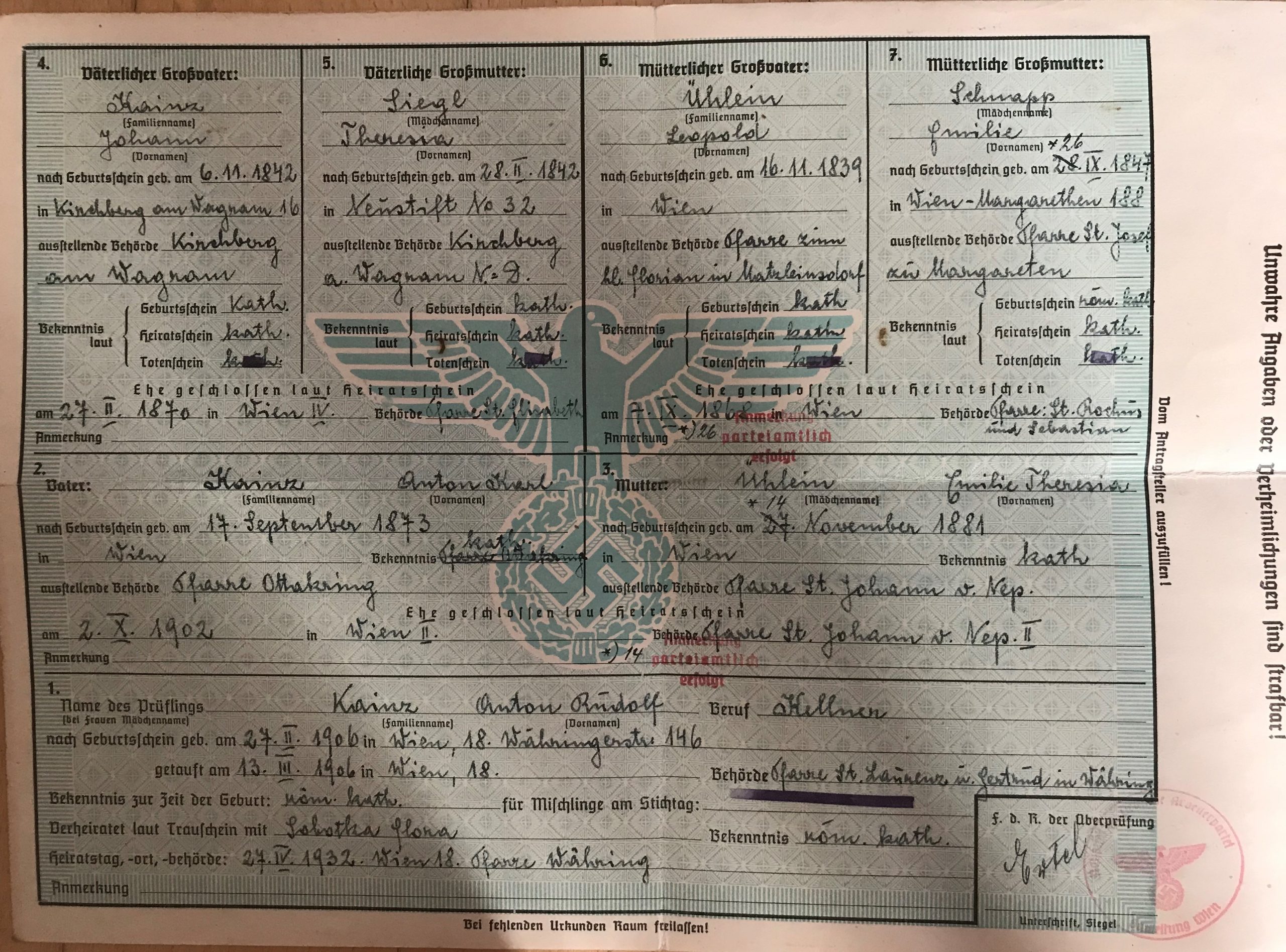

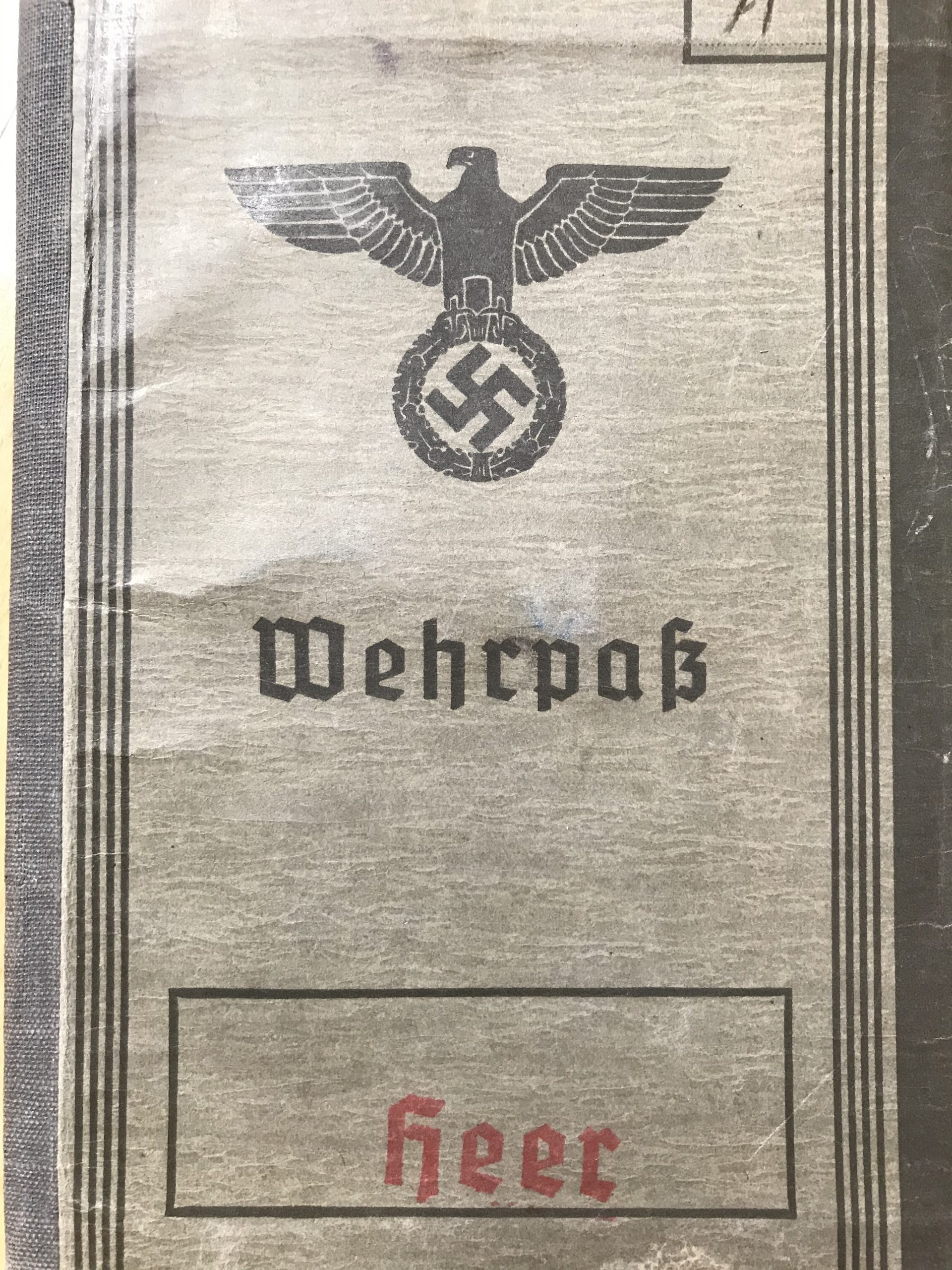

VIENNESE CONFECTIONARY PRODUCTION & SWEET SHOPS SINCE THE SECOND HALF OF THE 19th CENTURY & THE IMPACT OF THE NATIONAL SOCIALIST REGIME 1938-1945

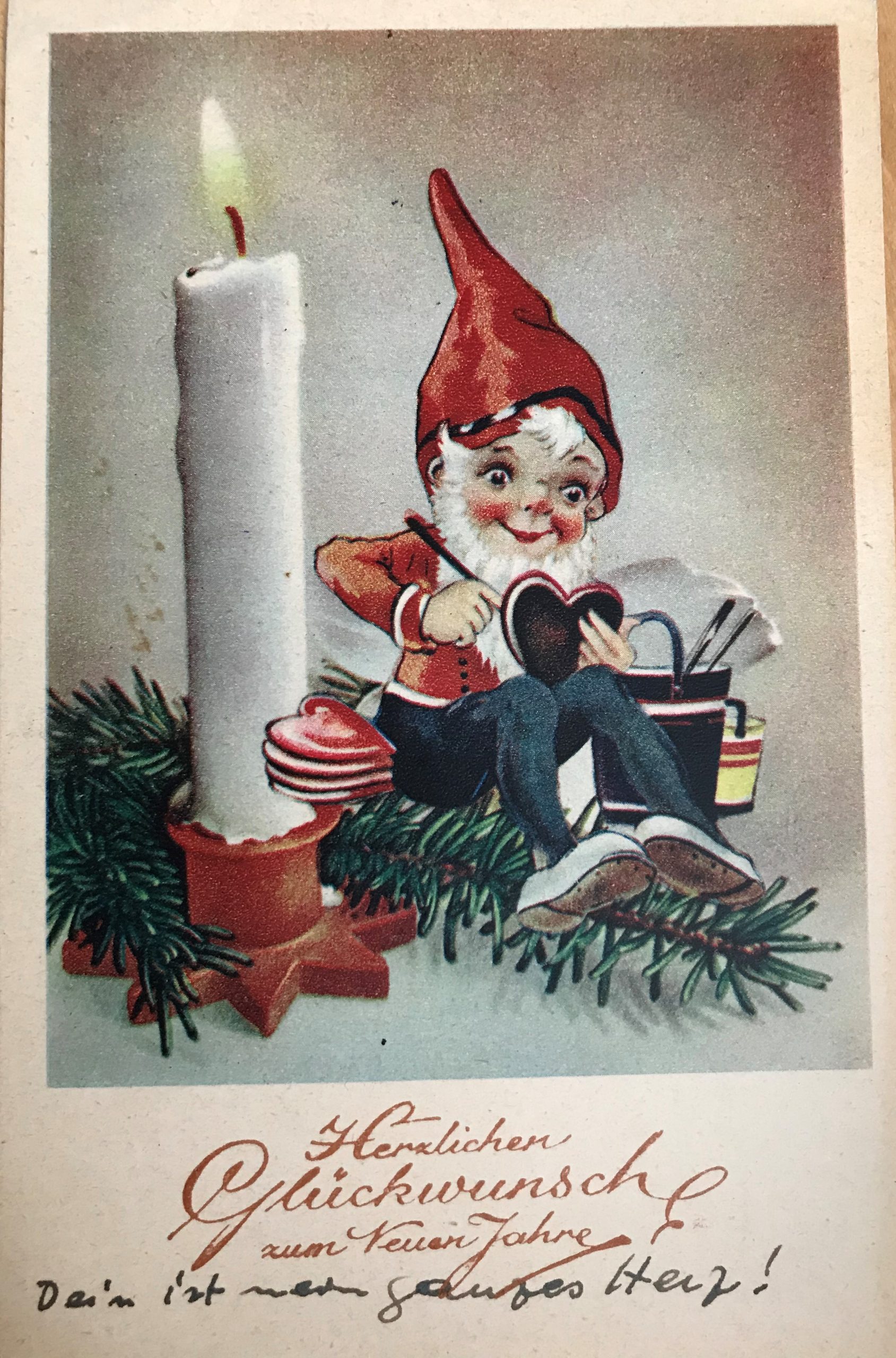

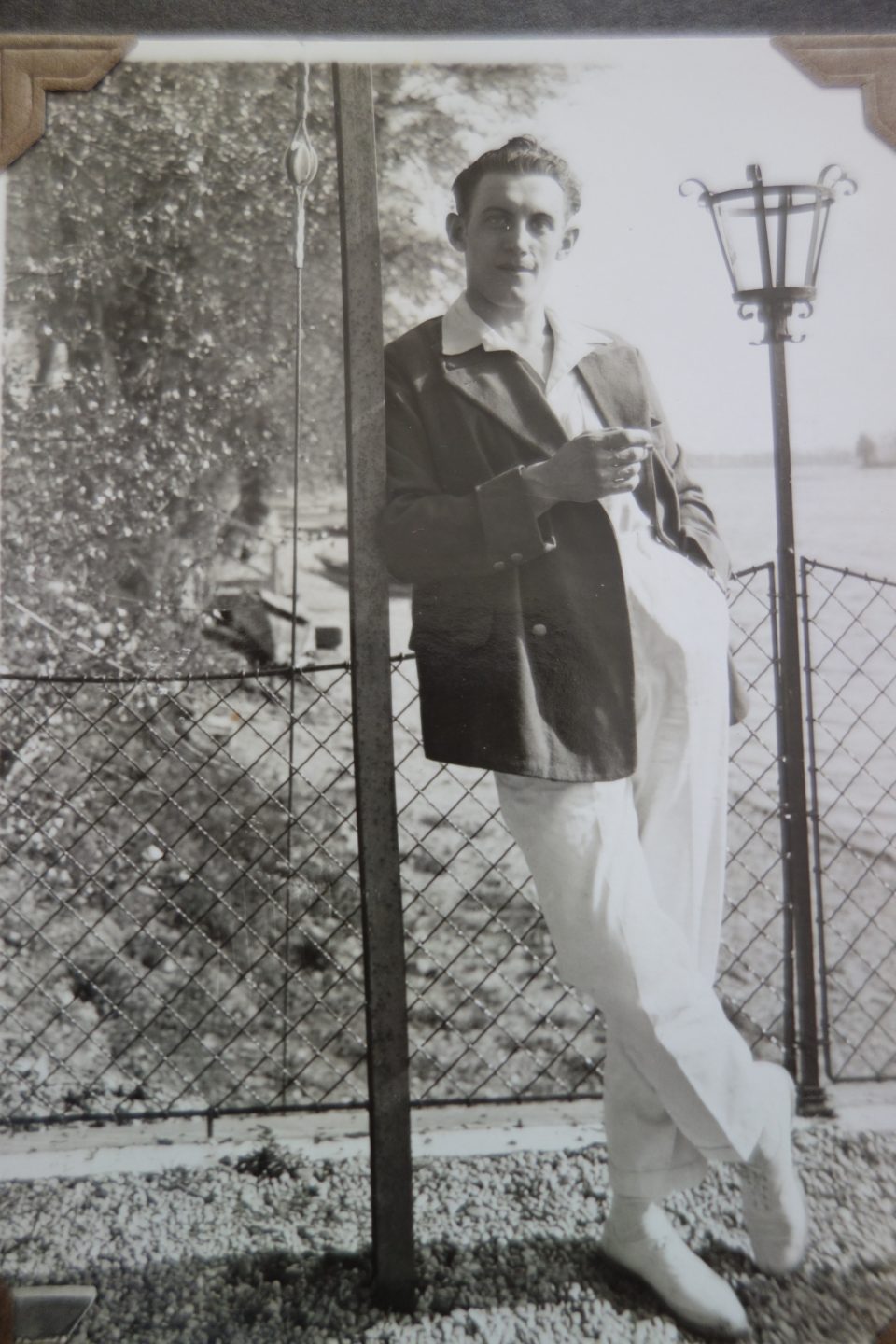

My grandmother Lola Kainz, née Sobotka, as a sweet shop girl around 1930 in Vienna /left)

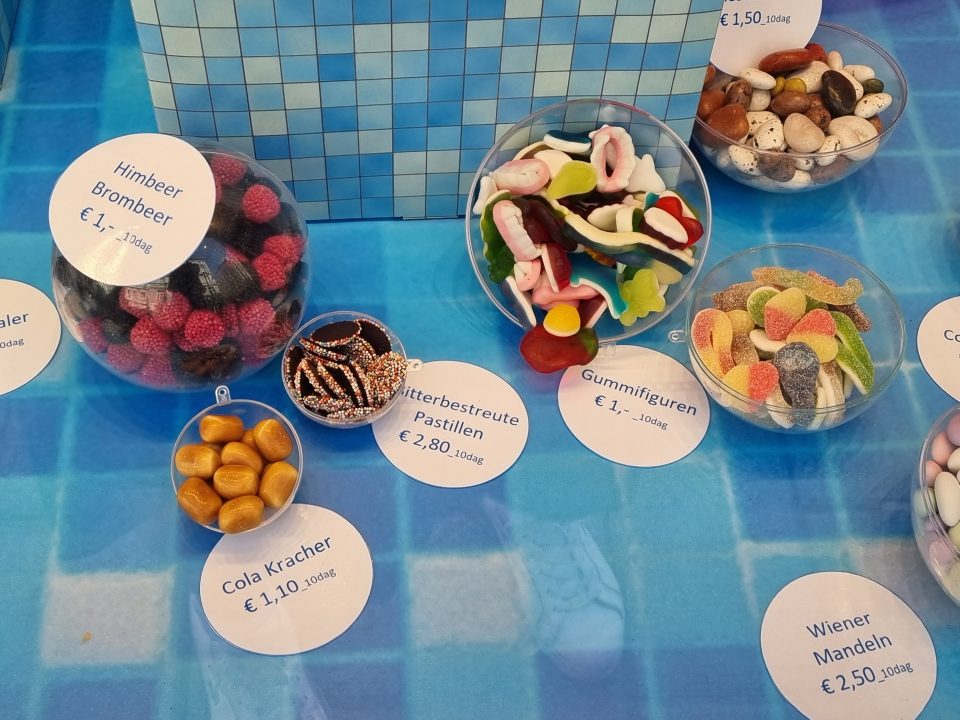

A typical Viennese sweet shop window display with glass containers for candy (right)

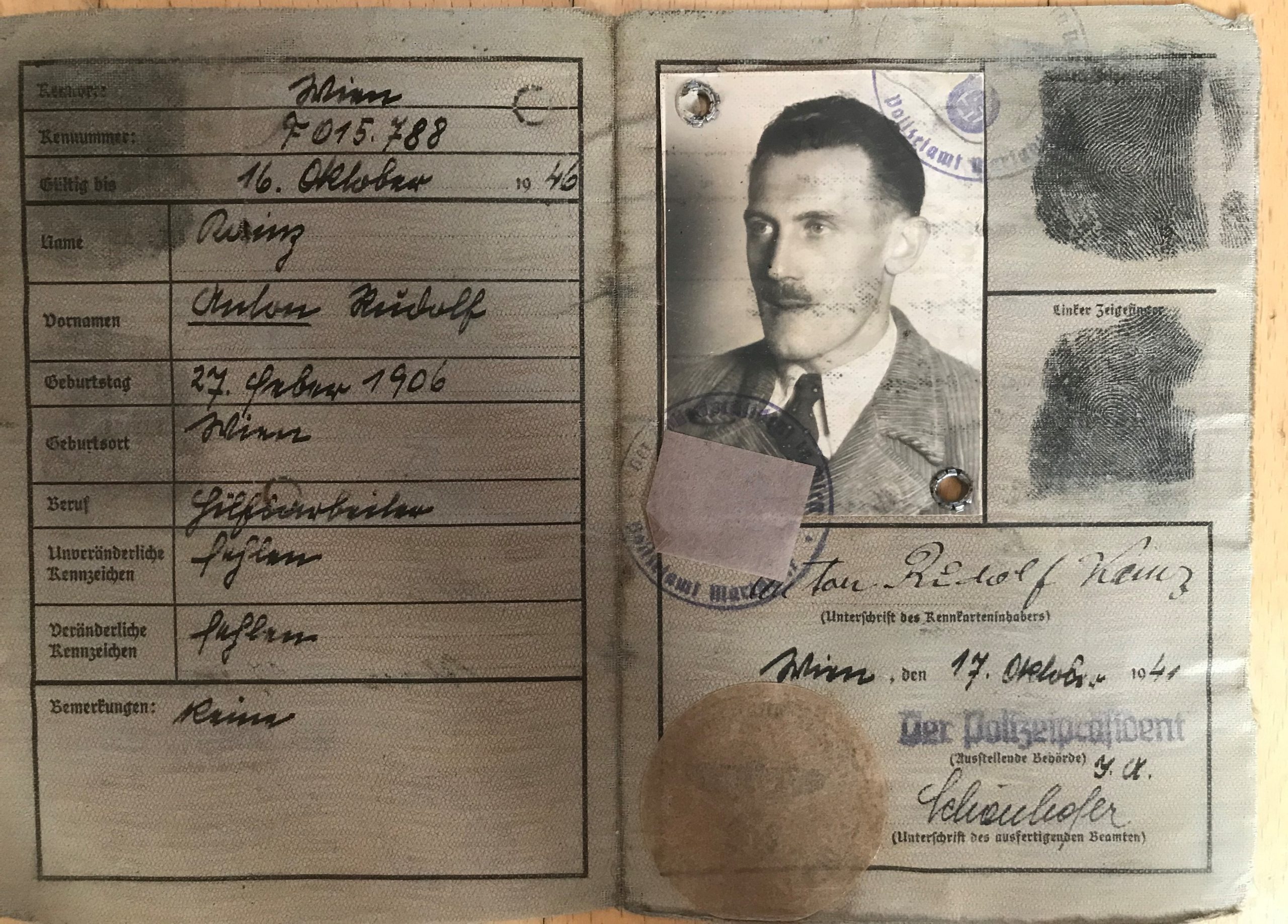

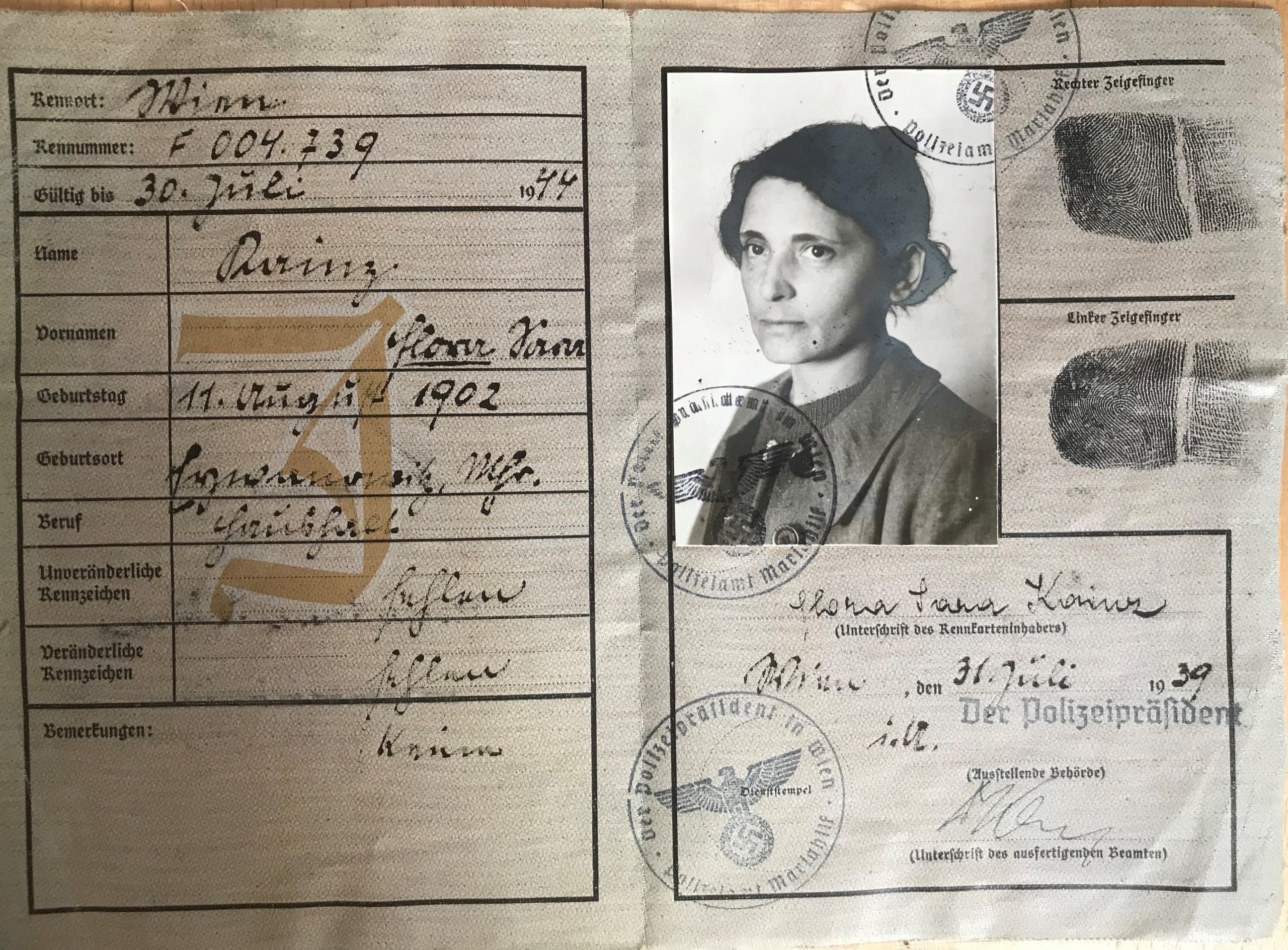

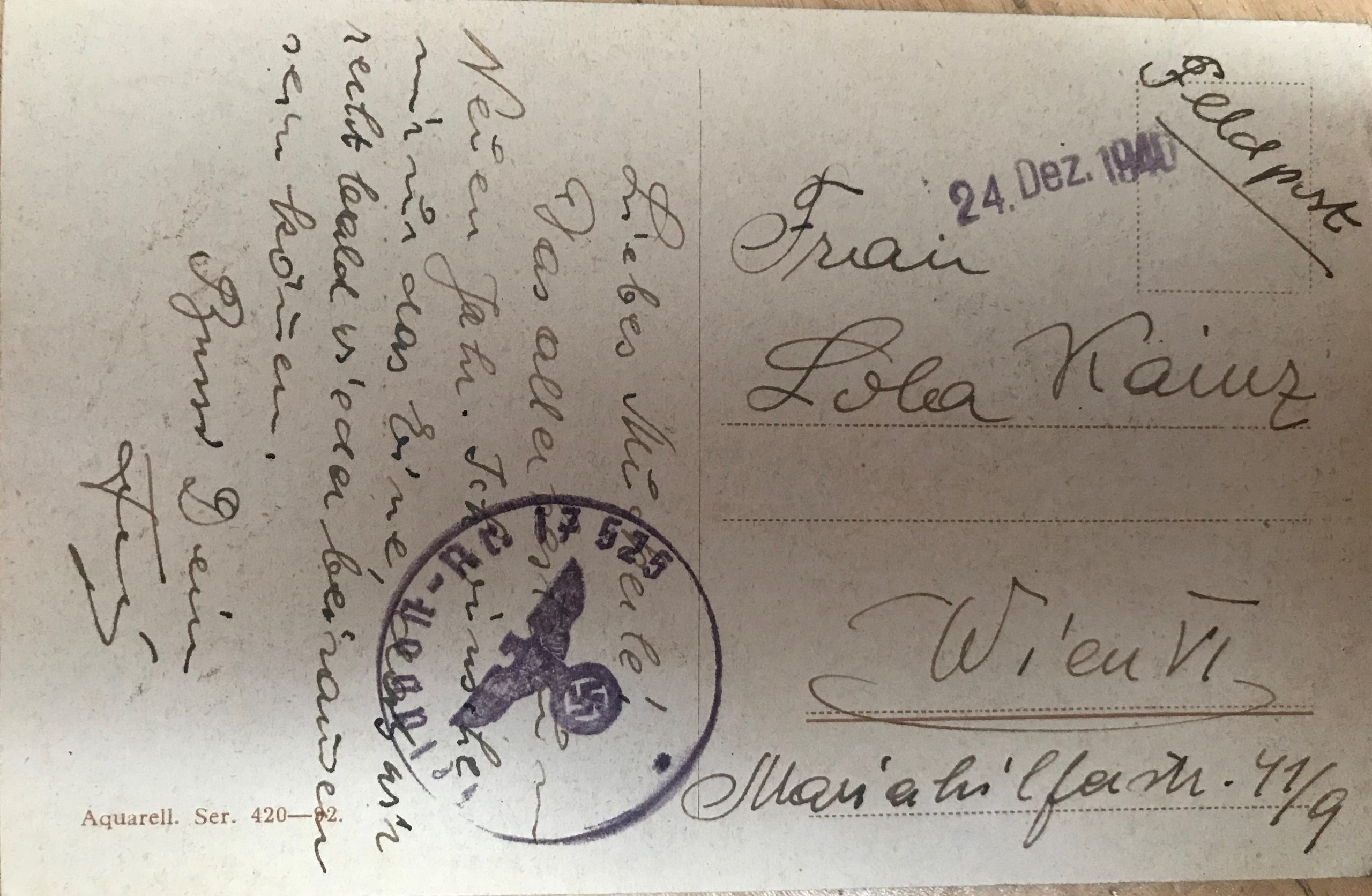

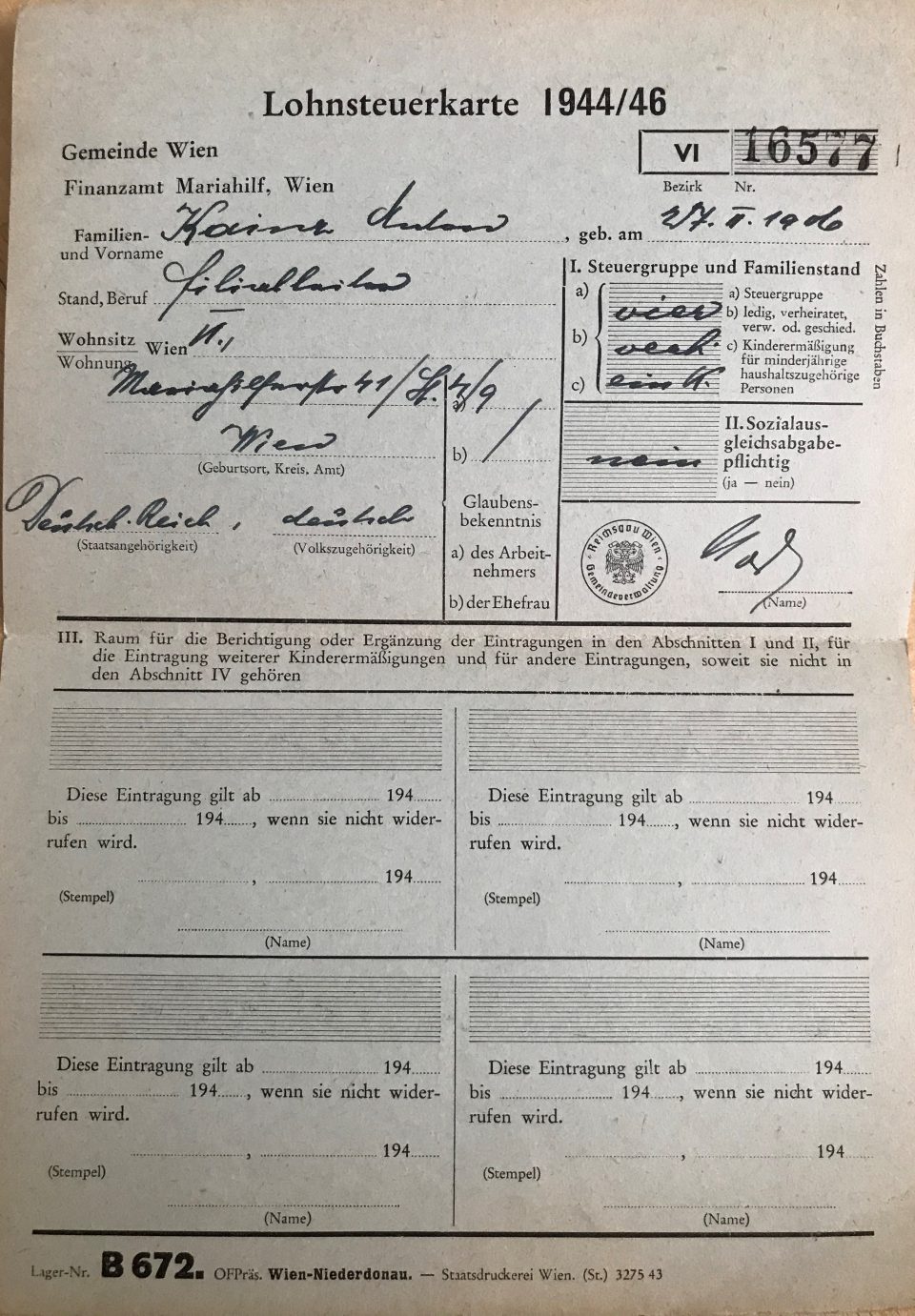

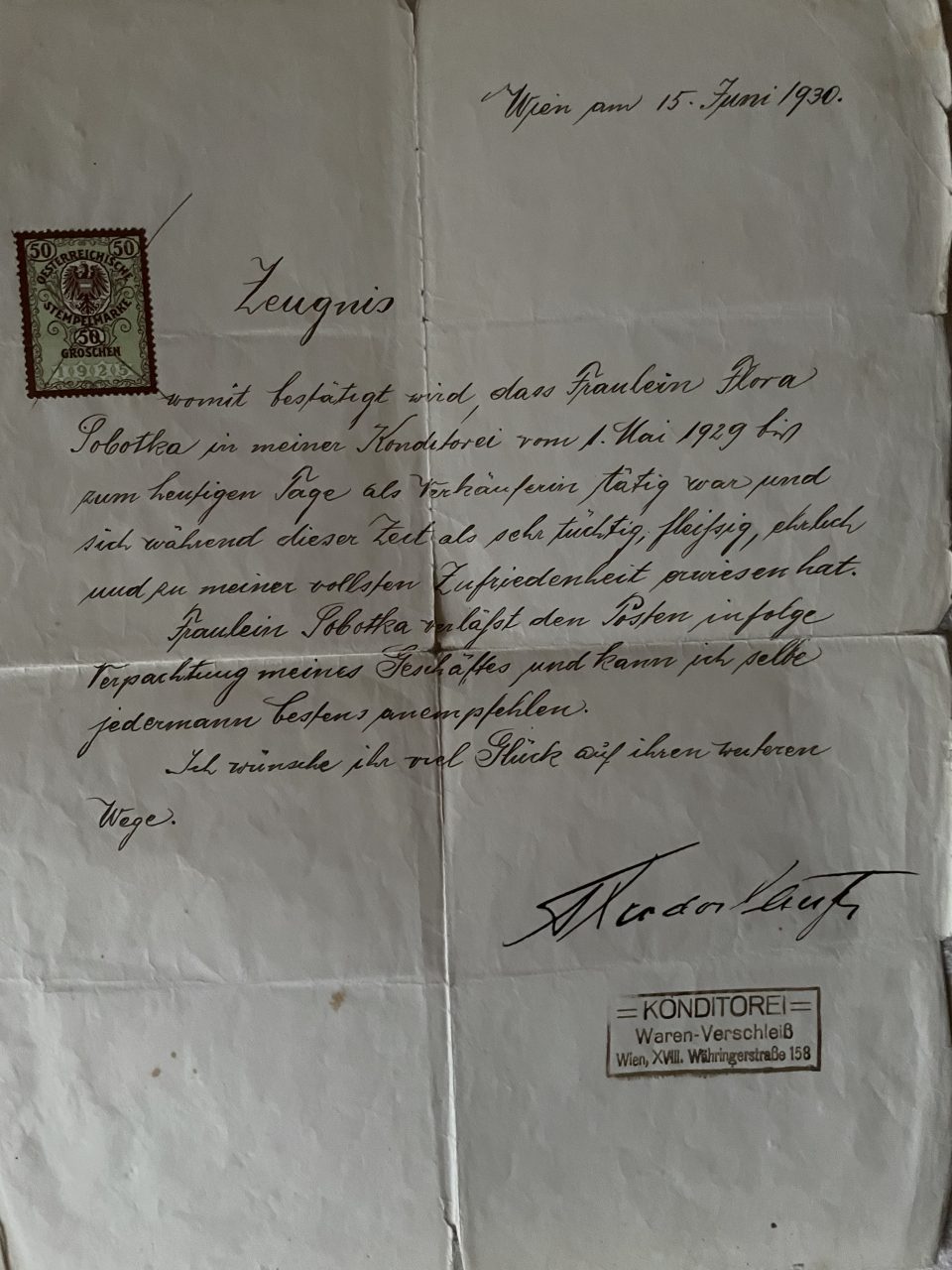

My grandmother, Lola, born in 1902, worked as a shop girl in a Viennese sweet shop around 1930 after having given up her education as a pianist at the Viennese Musical Conservatory. At that time Vienna abounded with sweet shops and the job as a sales girl in a sweet shop was quite prestigious, but badly paid, as virtually only female personnel were employed there. Sales girls in sweet shops were supposed to be pretty, well-mannered, and polite. So, qualification criteria for the job were prettiness, good manners, and politeness and the selection process was tough because the number of applicants was usually abundant. It is known that for instance the company Altmann & Kühne put a special focus on the appearance and behaviour of its female sales personnel. When Lola worked at a sweet shop in Währingerstrasse, she was spotted by the young son of the innkeeper of the nearby “Gasthaus Anton Kainz” in Währingerstrasse 146, Toni Kainz. It was love at first sight on Toni’s side and every day Toni bought sweets in the shop – candy which he did not even like very much – just to see Lola. Lola was a pretty, young woman, a bit superficial, who loved life – socialising, fashion, entertainment and a good laugh (That’s what she later told about herself). She even ignored her father’s strict order stipulating that his four daughters were not allowed to have their hair cut short, as it was the fashion of the 1920s and early 1930s in Vienna. Her father, Ignaz Sobotka, had been the manager of the brewery in Kaiserebersdorf near Vienna. After secretly having had her hair cut short – see photo above -, she came home with a funny hat sitting at an awkward angle on her head and she did not even take it off in the family dining room. When her father told her harshly to take off her hat, her funny face and clown demeanour made him laugh and she escaped punishment, much to the astonishment of her three sisters. She was the sunshine of her otherwise severe father.

“Anton Kainz Gasthaus”,18th district of Vienna, Währingerstrasse 146, the inn of Toni’s father in the early 1930s with Lola in the entrance (left) and now (right)

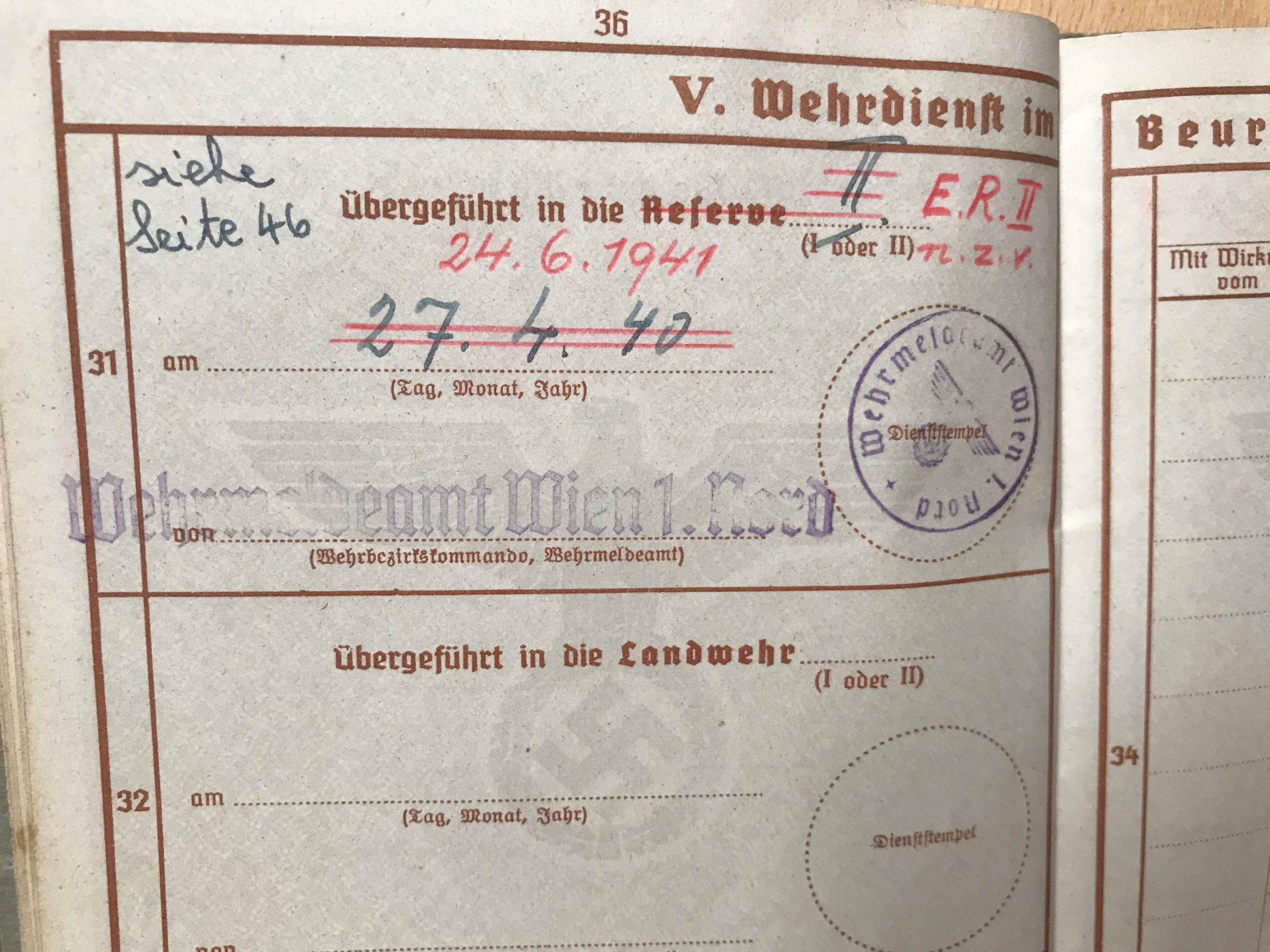

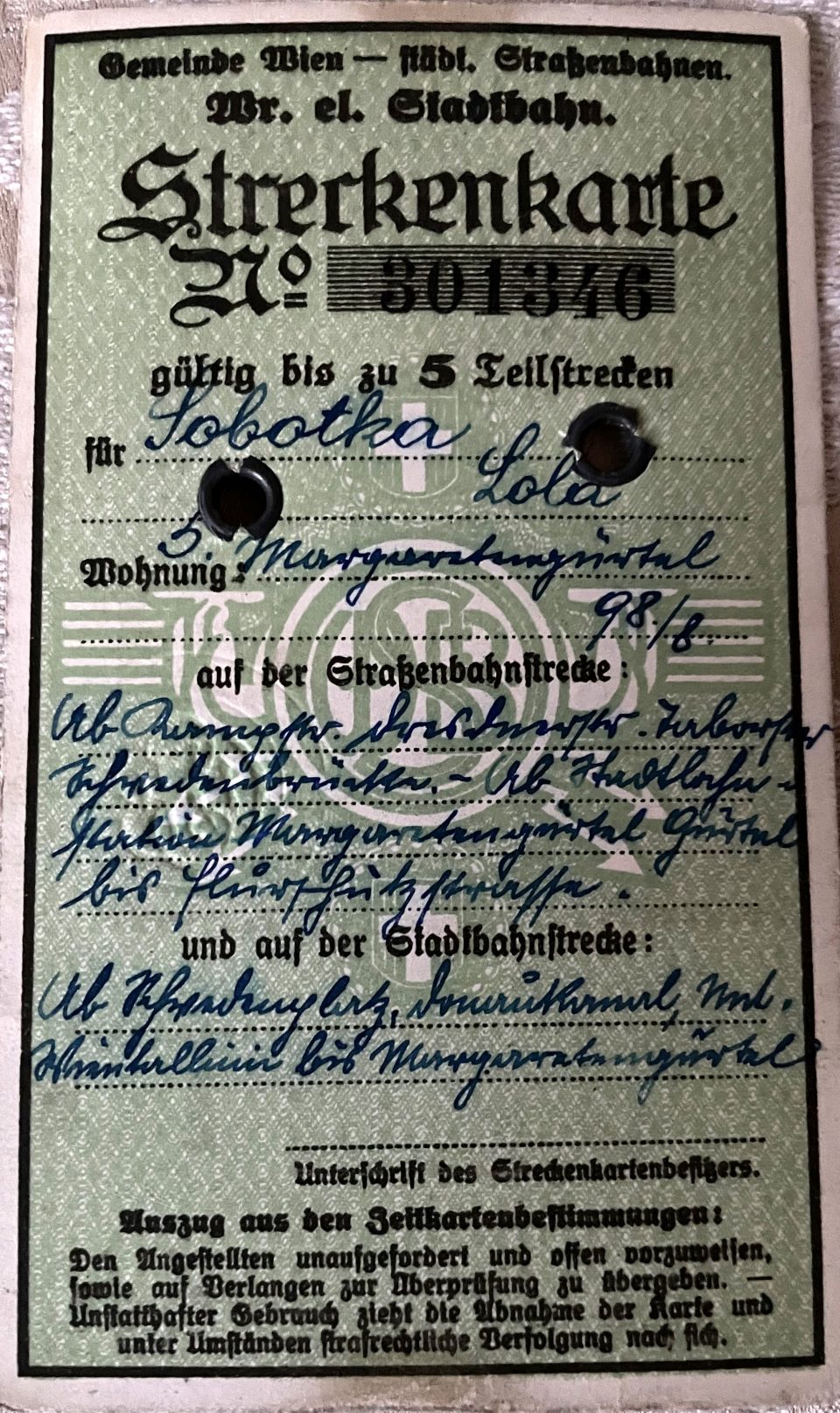

In order to reach her workplace in the 18th district of Vienna, Lola had to take public transport from her parent’s flat on Margaretengürtel 98/8 in the 5the district of Vienna. Here is her monthly tram and “Stadtbahn” (city train) ticket of March 1927:

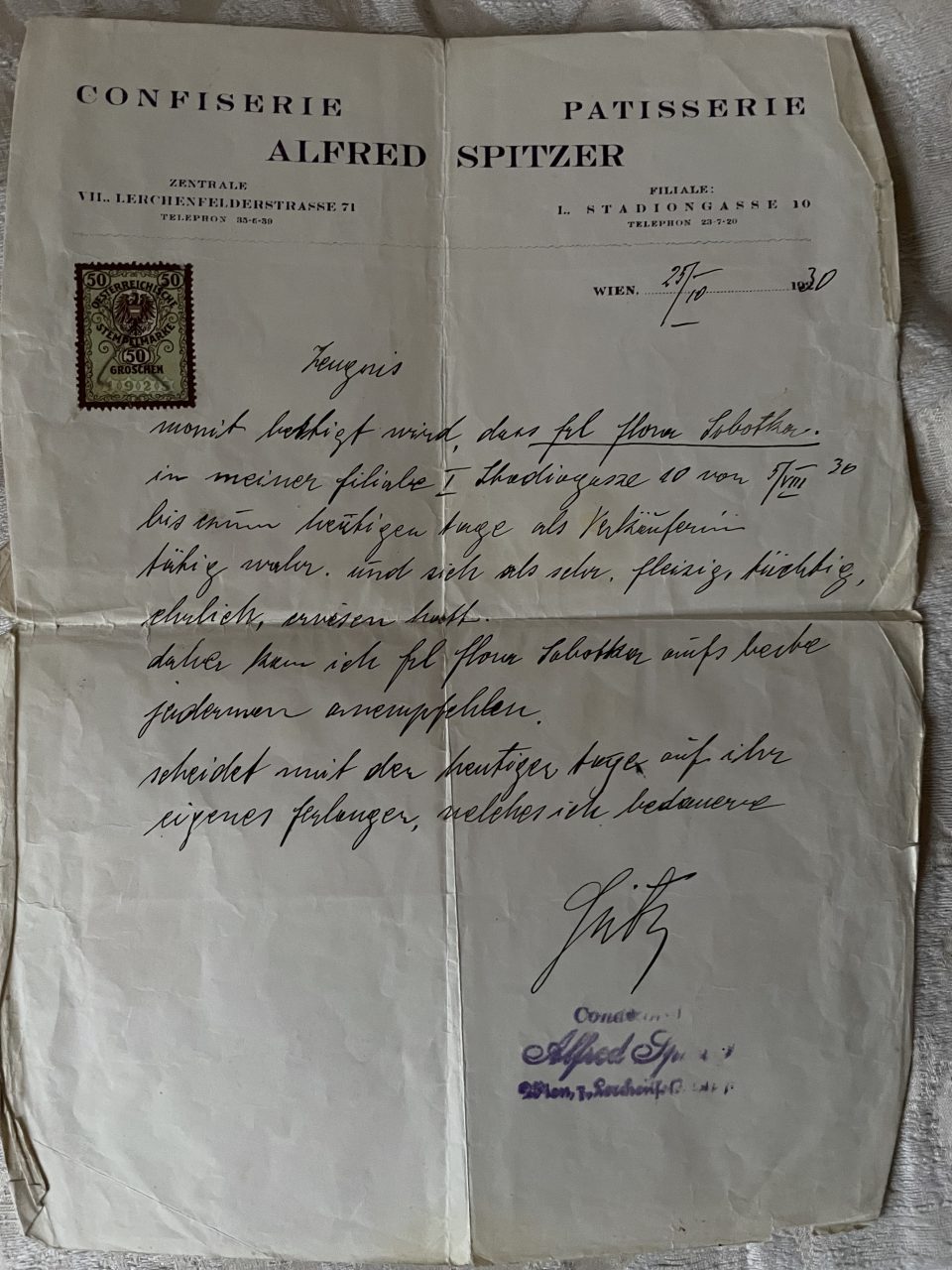

Lola had worked in another sweet shop before, “Confiserie & Patisserie Alfred Spitzer” in the first and 7th district of Vienna (below left)

In June 1930 the sweet shop owner of Währingerstrasse 158 rented out his shop and had to make her redundant. He wrote the following appraisal, an excellent assessment of Lola’s job performance (right)

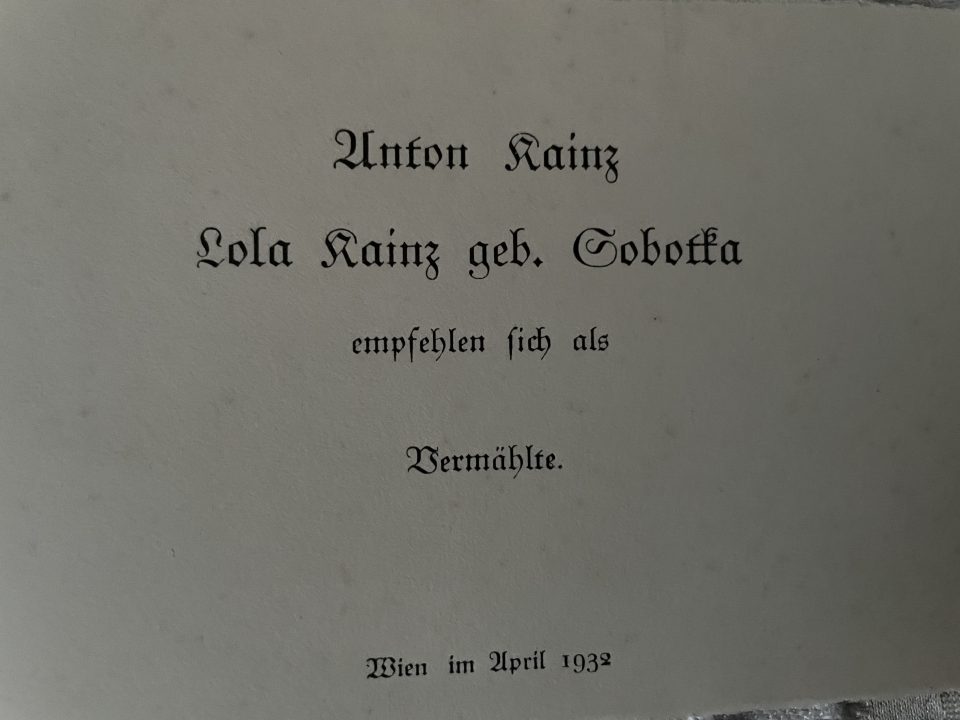

In 1932 Lola and Toni were married and from then on Lola worked in the inn of her parents-in-law:

Viennese chocolate & sweets production

At the Emperor Charles VI’ court in Vienna the exotic product “chocolate” was introduced in 1711, but chocolate drinks were already popular before among the high clergy. Pietro Buonaventura Metastasio even composed a “Cantata alla Cioccolata” at the court of Charles VI in Vienna and the ascetic preacher there, Abraham a Santa Clara, scolded the aristocratic ladies in his sermons for their habits of drinking chocolate at eleven in the morning. Empress Maria Theresia issued an order for Viennese balls in 1752, which stipulated that tea, coffee and chocolate were to be offered at Viennese balls “of good quality, high quantity and at a cheap price”. She herself did not even like chocolate, but her husband, the Emperor Franz Stephan, did. The haute bourgeoisie of Vienna followed in the footsteps of the aristocracy, which is documented in the dialogues of Viennese comedies of the 18th century and even in the libretti of operas, such as Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s “Cosi fan tutti” and “Don Giovanni”, where chocolate is much in demand. Mozart himself wrote that he loved walking in the “Augarten” (a park in the 2nd district of Vienna) in the morning, where he had his breakfast with coffee, chocolate, and tea. He even sent large amounts of chocolate from Vienna to his much-revered master in Italy, padre Martini. As chocolate was extremely expensive at the time, the amounts consumed were very small, from 1812 until 1816 400 tons of cocoa beans were processed in Vienna. Yet before 1800 the majority of the population had never tasted chocolate, as it was a status symbol and a stimulating luxury drink.

For candy the most important ingredient was sugar, which until the middle of the 18th century was cane sugar, whose trade and production was extremely costly and cumbersome. Apart from apothecaries, who were allowed to use cane sugar for the concoction of medicine, only the rich classes of the society could afford cane sugar. But in 1747 the fodder beet, indigenous in Europe, was discovered as an excellent natural resource of sugar. From the fodder beet the sugar beet was cultivated and changed the manufacturing of sweets in Europe dramatically. The sugar beet cultivation and the production of beet sugar turned into a flourishing business sector at the end of the 18th century and the Habsburg Empire turned into one of the biggest producers of beet sugar. Within a few decades sugar had become a commodity that was affordable for a much larger part of the population. Consequently, the manufacturing of candy and other sweets experienced a boom in Vienna and the Habsburg Empire. Yet the fabrication of confectionary products was still a very complex procedure done by hand. A cook of Prince Joseph von Schwarzenberg, Franz G. Zenker, left several recipes for manufacturing “Zuckerl” (candy) in 1834, for example “vanilla bonbons” or “venus bonbons”. Every bonbon was wrapped in colourful paper together with an appropriate motto and on the outside jokes or funny words were printed, which expressed taste, spirit, and wit. The recipe book was aimed at middle-class housewives and their cooks. The commercial production of candy and sweets was to a diminishing degree still in the hands of pharmacists and increasingly in the hands of confectioners. In 1861 the Viennese “Lehmann” directory counted 240 confectioners in the city and with the enlargement of the territory of Vienna in 1895 there were 400. They soon faced fierce competition from the rise of large industrial producers, such as Victor Schmidt. While important Viennese companies, for example Pischinger, Cabos and Manner (see table of Viennese producers below), focussed on the production of wafers, cocoa, chocolate, cakes, and biscuits, Ullmann, Heller, and Schmidt concentrated on the manufacturing of candy and sweets; whereby different types of cough lozenges were always part of their product range. All these companies had their specialities, often with glamorous foreign names, for example “Rock Drops”, “Military Rocks”, “Candy Caramels”, “Brioni”, or “Grado Bonbons”.

In 1887 Anton Hausner warned against the use of toxic materials in the industrial production of candy and in wrapping papers, namely various colourants, and essential oils, such as white lead, chrome yellow or Prussian blue, and he recommended natural plant and animal substitutes, for example saffron, curcuma or indigo.

…