THE KZ THERESIENSTADT: THE DECEIT OF THE NAZIS OF A “JEWISH GHETTO FOR THE PRIVILEGED AND THE OLD” & THE TRUE LIVING CONDITIONS, ESPECIALLY OF THE ELDERLY

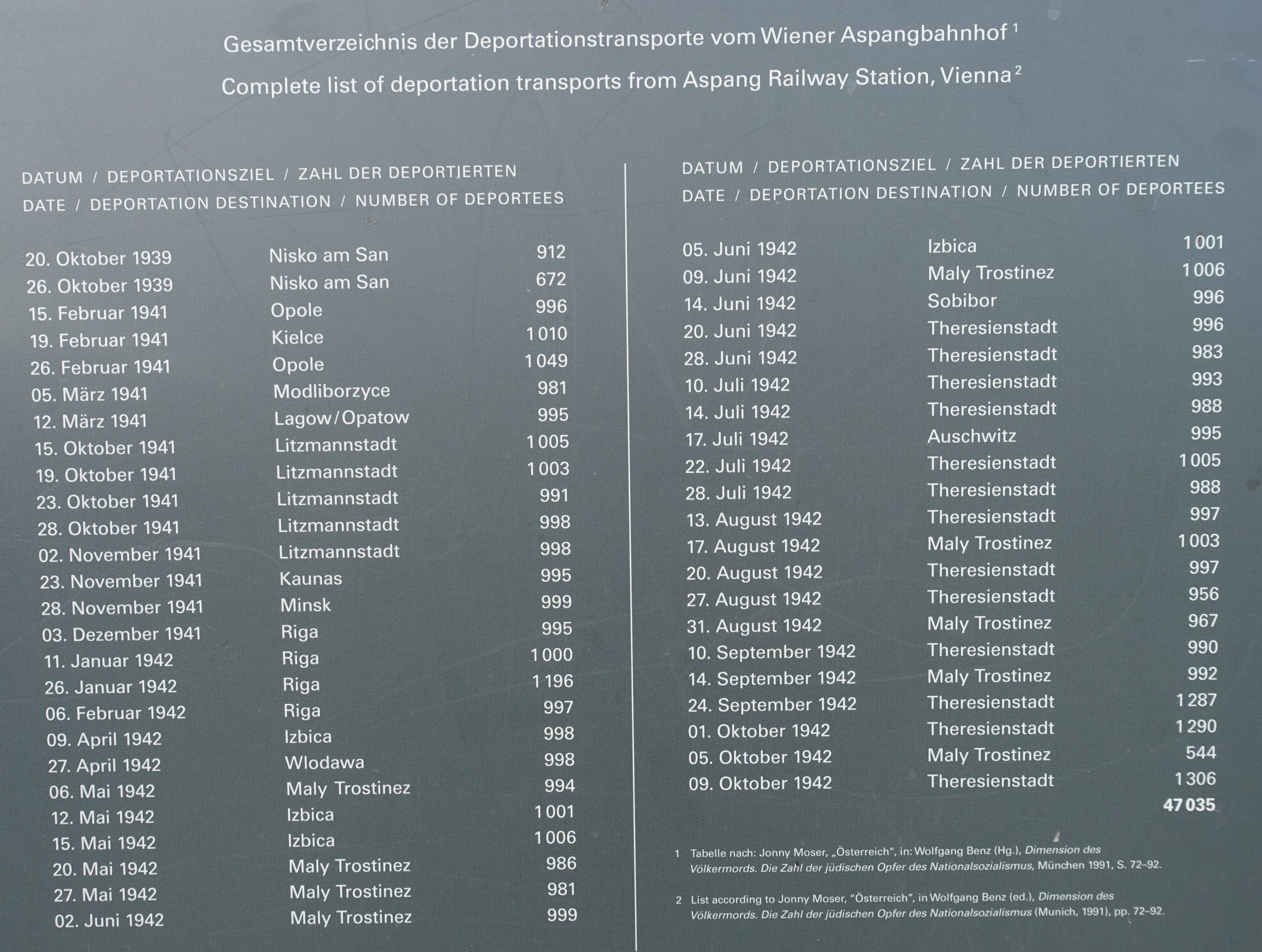

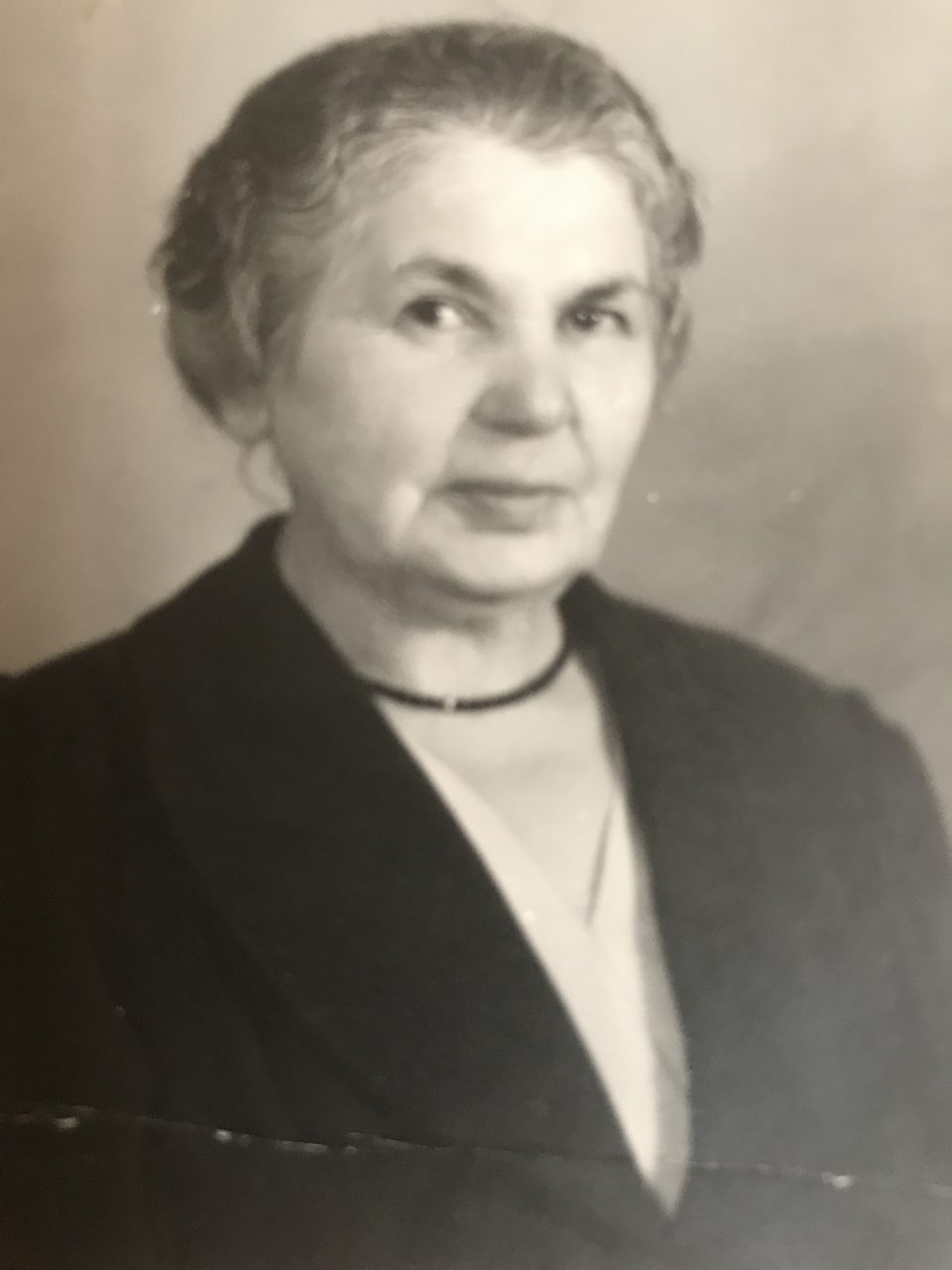

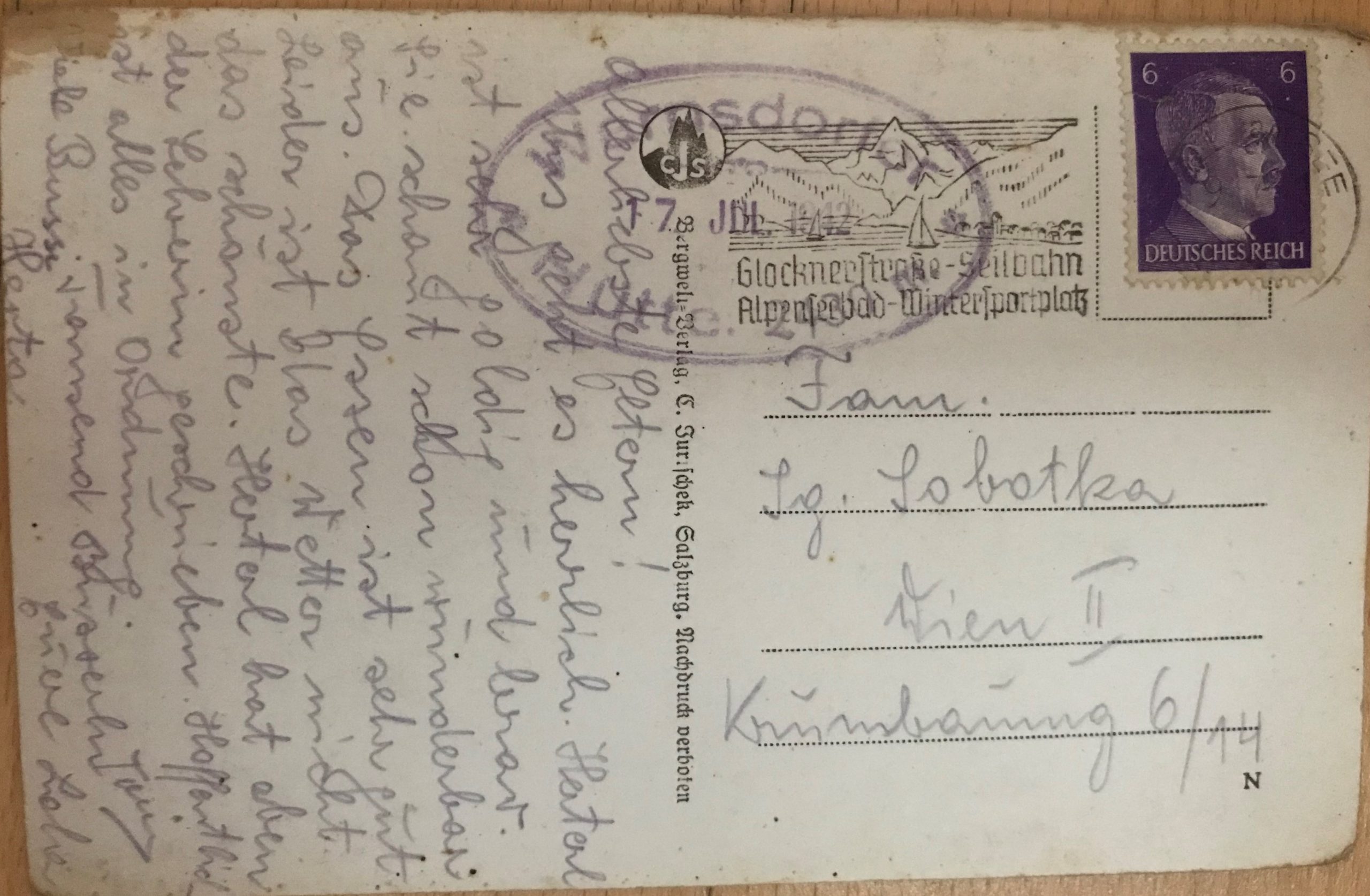

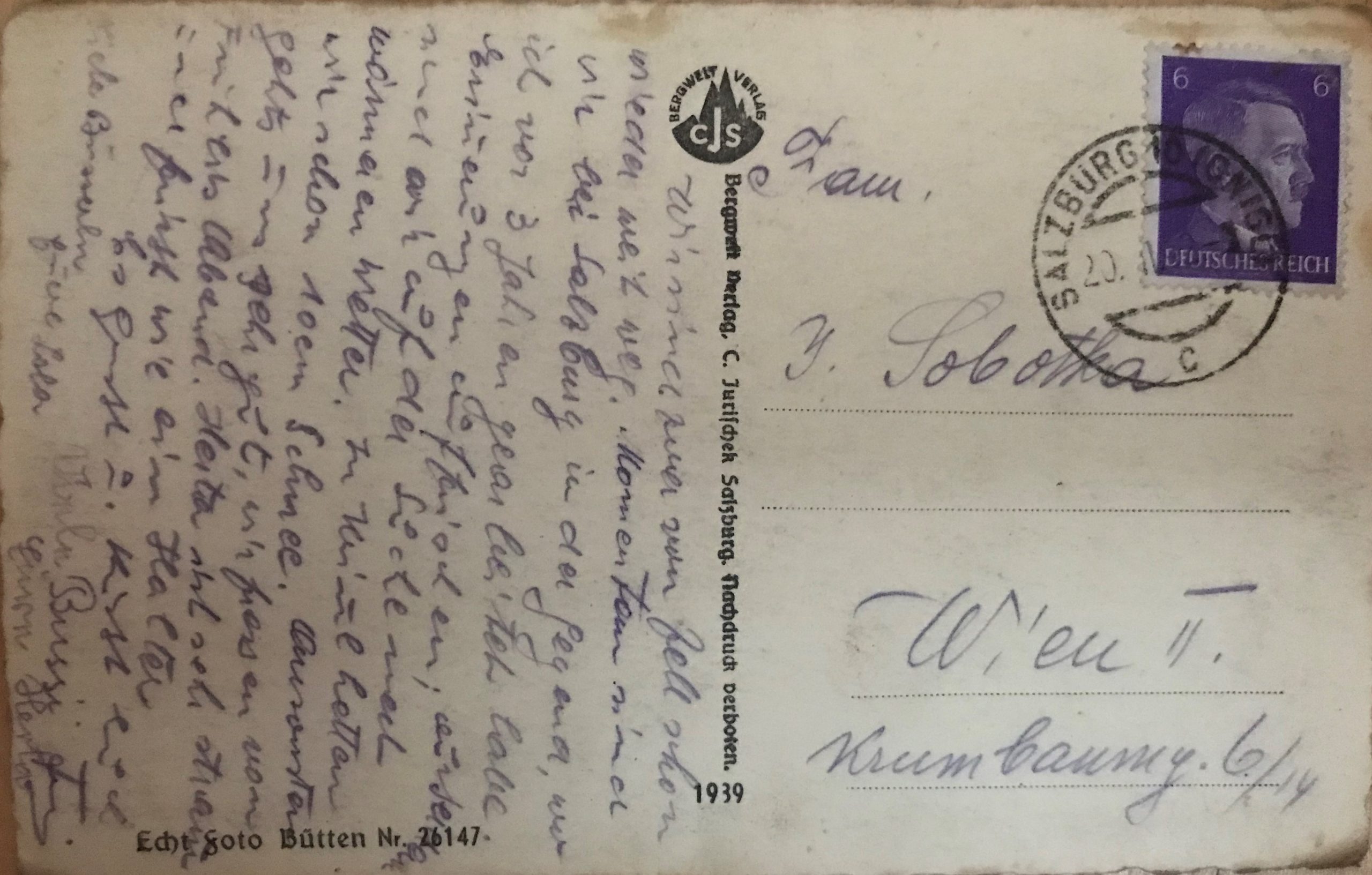

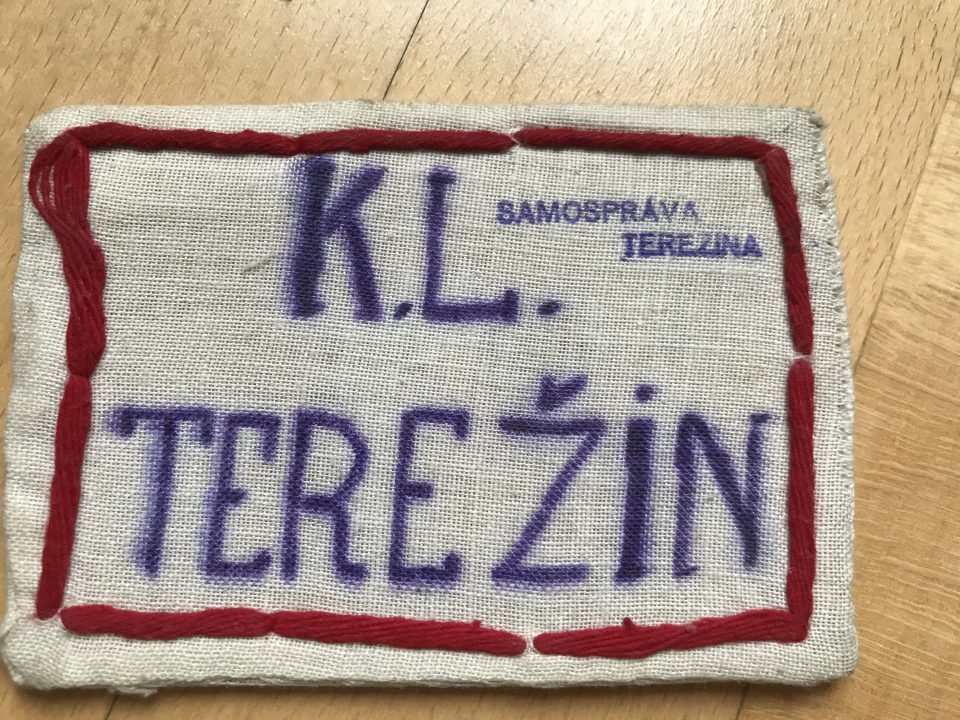

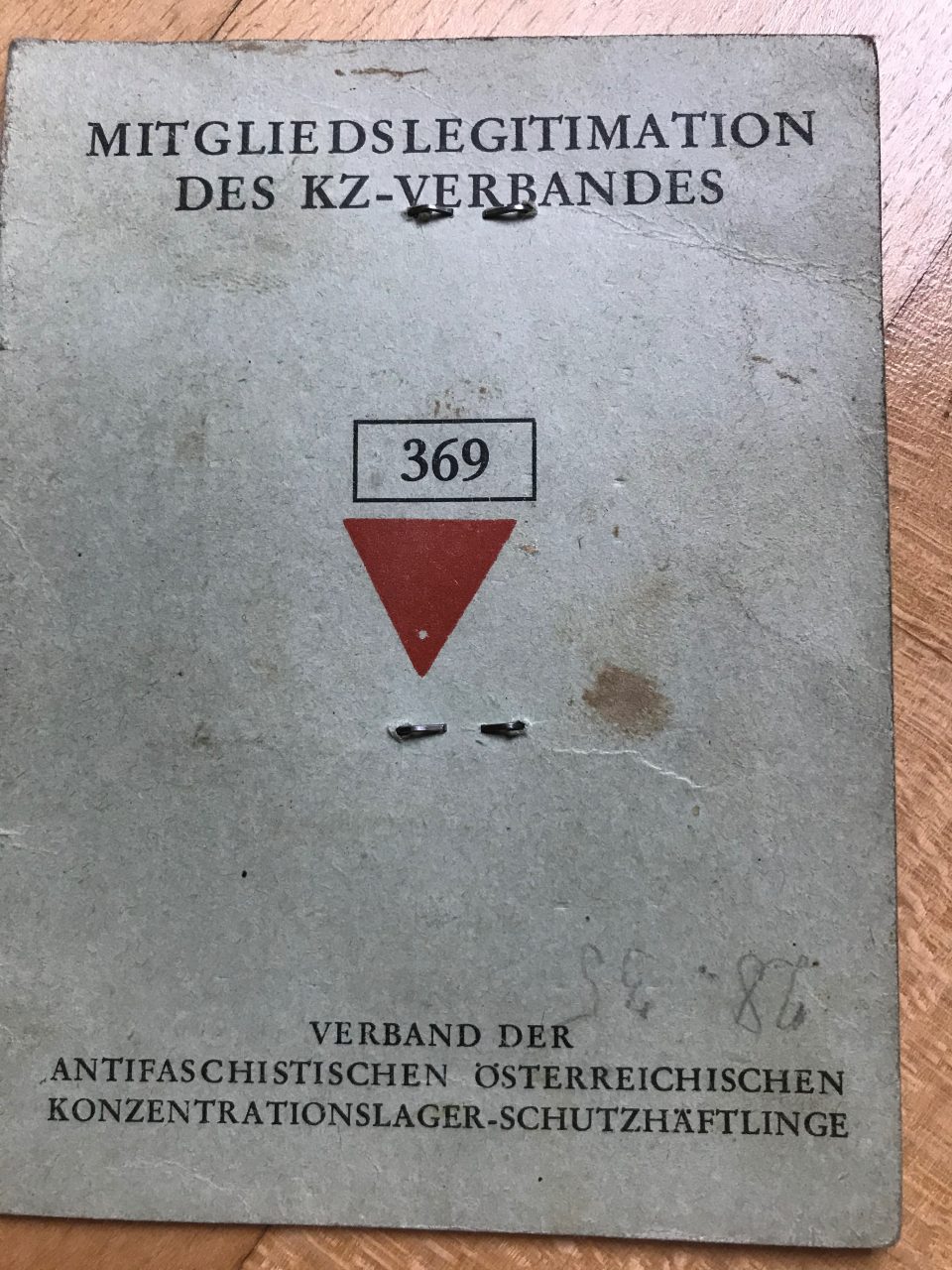

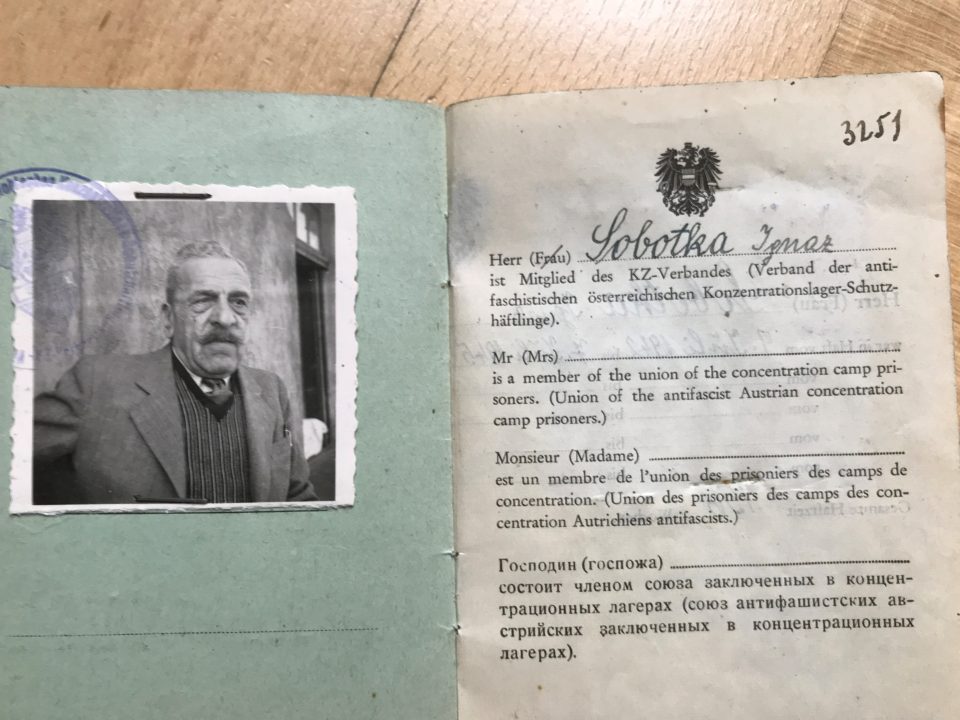

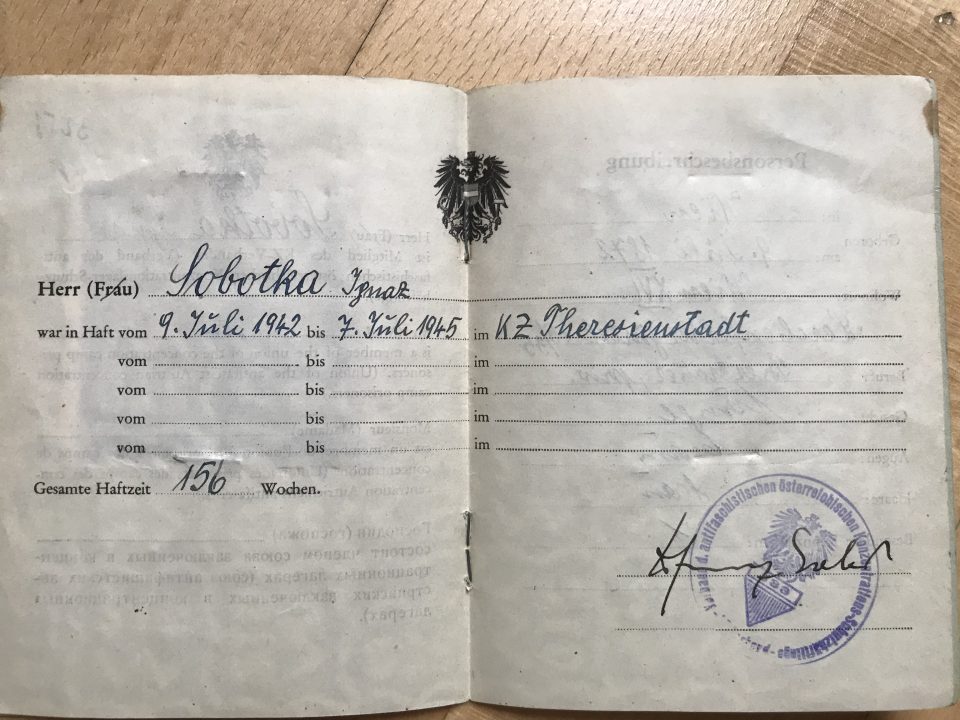

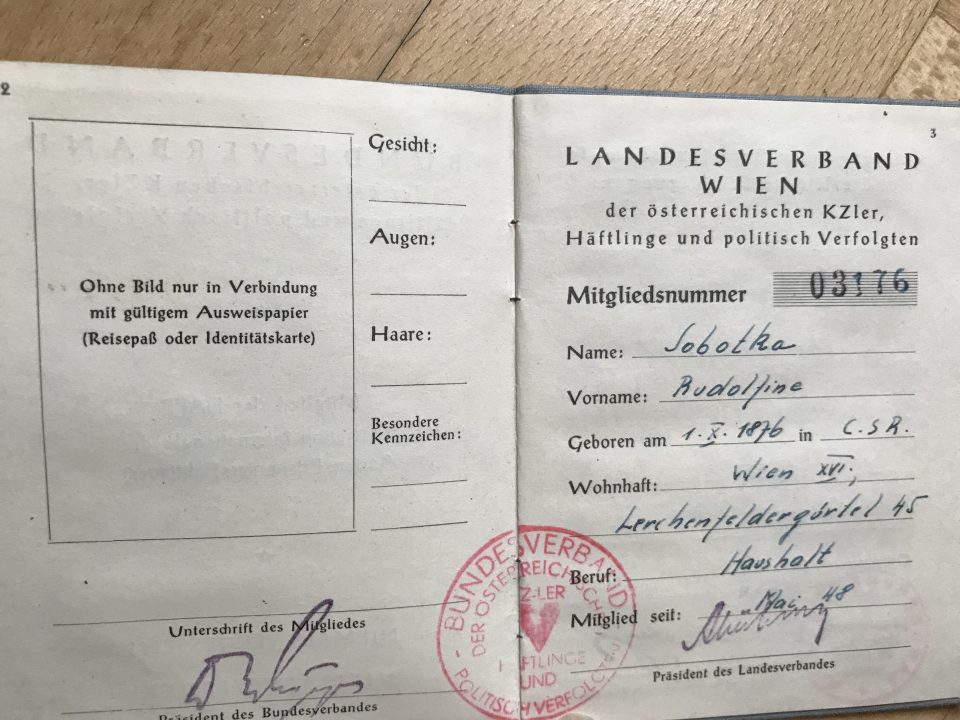

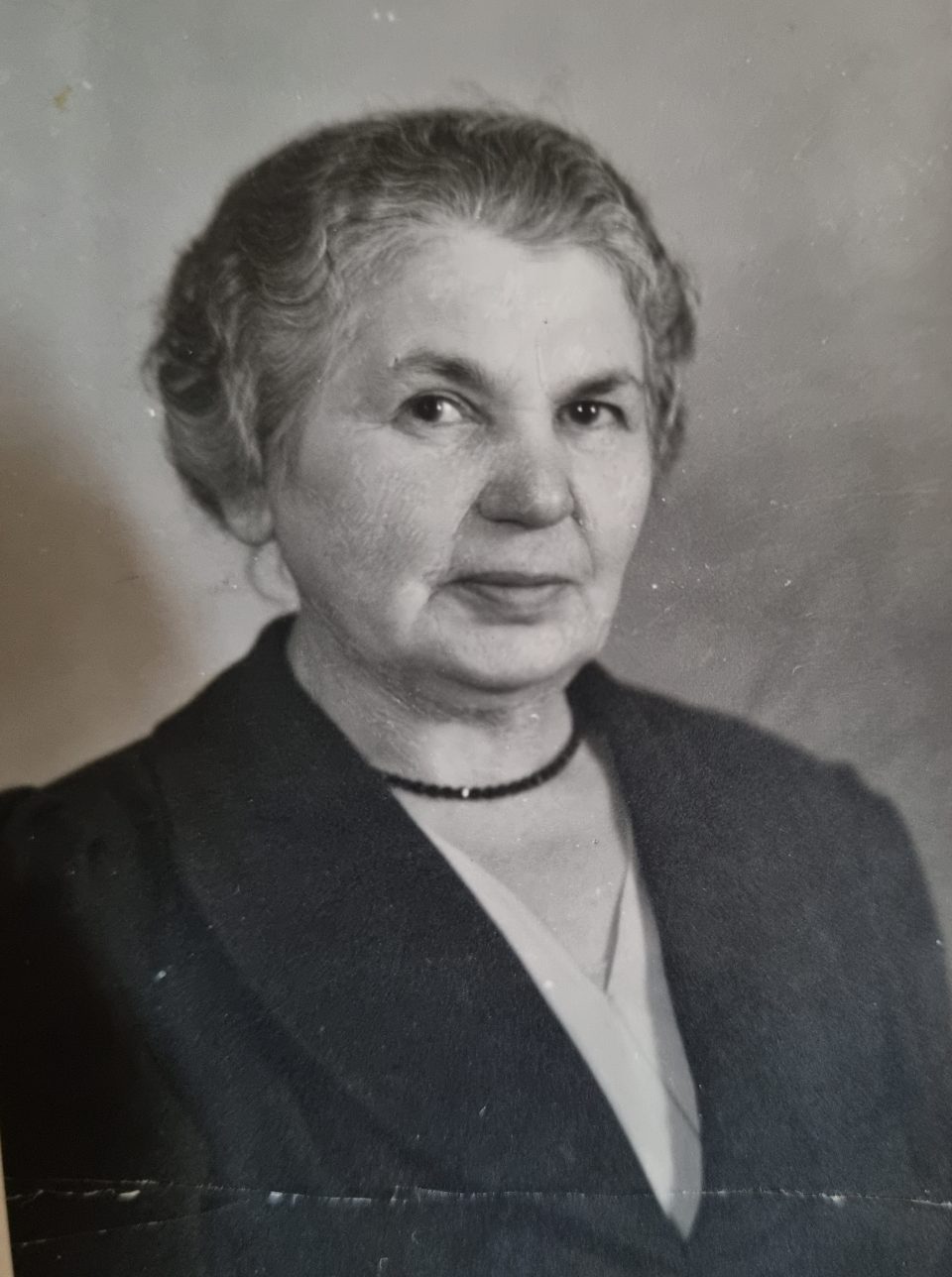

This article deals with the desperate attempts of the prisoners of the KZ (concentration camp) Theresienstadt at keeping up appearances of a fragile normality and at maintaining scraps of human dignity under the inhuman conditions of the NS (National Socialist) concentration camp. Furthermore, this research would like to destroy once and for all the myth the Nazi propaganda had created for the international public of the KZ Theresienstadt as a “Jewish ghetto for the privileged and the old”, where music, art and theatre thrived. This vicious piece of NS propaganda has been so long-lived and tenacious that it sometimes pervades documentaries about the KZ Theresienstadt even today and often involuntarily creates a romanticised picture of life in this atrocious collection and transit camp. My great-grandparents Ignaz and Rudolfine Sobotka were imprisoned there from 9 July 1942 until liberation by the Allied armies on 9 May 1945. They miraculously survived the hardships and the terror and returned to Vienna and the family of their daughter Lola, my grandmother. They formed part of the group of elderly prisoners who were crowded into this former Austro-Hungarian fortress city. Ignaz was born on 9 July 1872 and Rudolfine, called Ritschi, on 1 October 1876. So, Ignaz was imprisoned on his 70th birthday and Ritschi was turning 66 in October when she arrived at the concentration camp in July 1942. At the end of the Habsburg Empire they were quite well-to-do middle class Viennese citizens. Ignaz was born in Vienna and after training as a beer brewer he ran the brewery in Kaiser-Ebersdorf near Vienna as a manager. He got to know Ritschi in Eywanowitz in Moravia, when he was working at the brewery there. She was the daughter of the local family doctor and moved with Ignaz to Vienna after the birth of the second of their four daughters. (see article: “The Career as a Beer Brewer in Vienna”). Here are some documents that have been preserved from their stay in the KZ Theresienstadt (KL Terezin in Czech):

In Vienna Ignaz and Ritschi’s situation worsened when the Austro-Fascists took power in February 1934 and Ignaz lost his job as the brewery’s manager.

Left: Ignaz and Ritschi with their daughter Lola and her husband Toni and Herta, my mother, on Ritschi’s lap in 1934

Right: They lived on Margaretengürtel in Vienna, where heavy civil-war fighting took place in February 1934, when the Austro-Fascists put an end to democracy in Austria. One of their sons-in-law, Karl Elzholz, lived there, too, and took a photo of the damaged public housing building and “Konsum market” (co-operative market), where army and police had shot at the Socialists in the building

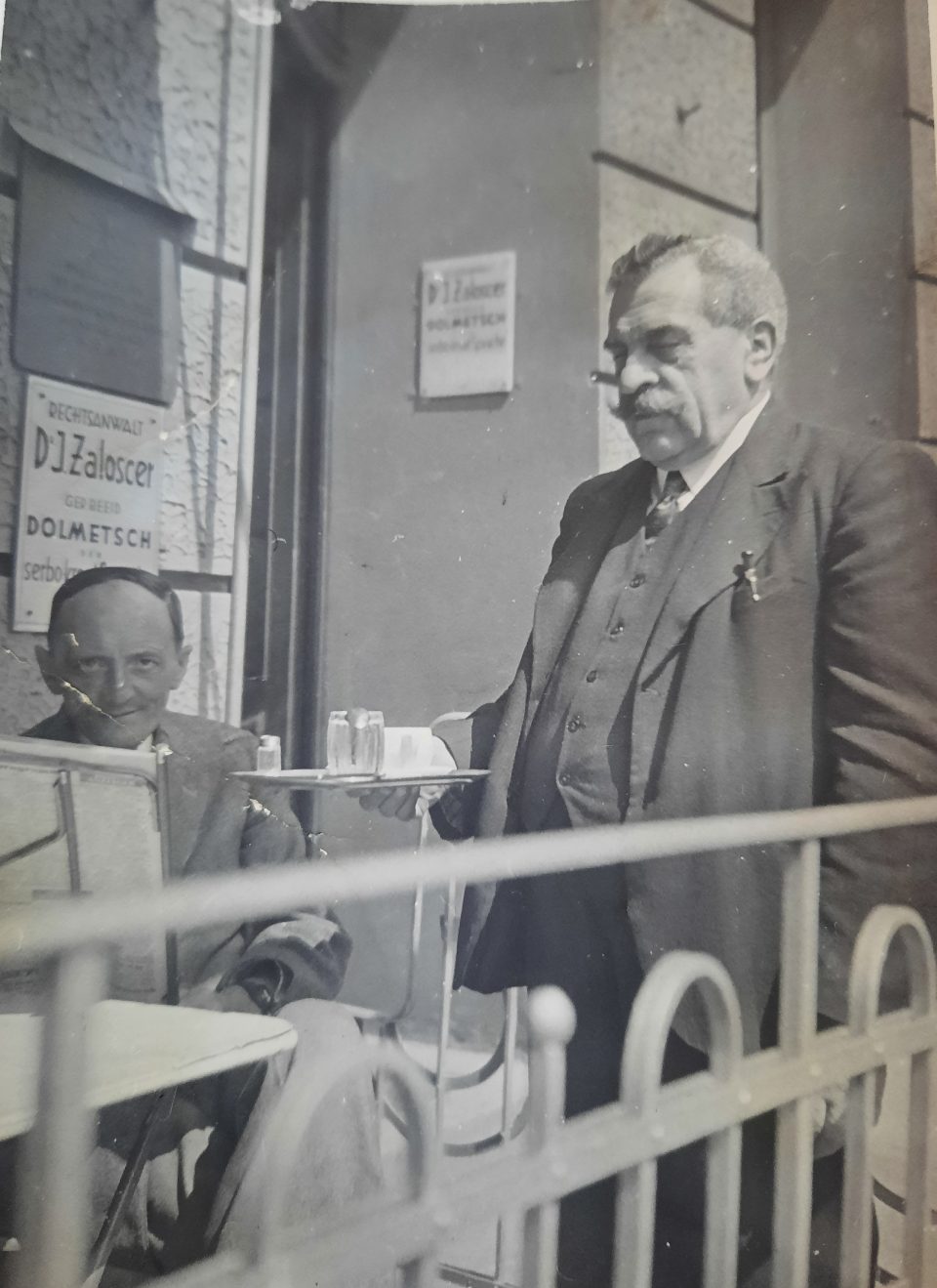

Ignaz and Ritschi both helped Lola and Toni run a coffee house at Hamerlingplatz (see article: “Viennese Suburban Coffee Houses”) in the 8th district of Vienna

When they lost their flat due to the NS race laws, directed against the Jewish population in Vienna, they moved in with Lola, Toni and Herta. Ignaz had to do forced labour for the road construction firm Teerag until they were ordered to move into a “Sammelwohnung” (collective flat) in the 2nd district of Vienna (see article “Nazi Collective Camps in Vienna…”) before their deportation to the KZ Theresienstadt. Their three daughters and their husbands who had managed to flee from Vienna in 1938 / 1939 had tried to get their parents out of Nazi-ruled Vienna, but for the elderly without money it had become impossible to leave because no country wanted to grant them a work or residence permit. Unfortunately, their daughters Käthe and Agi failed to get them visas to join them in England, and Mitzi and Karl were unsuccessful in obtaining permits for entry in Bolivia, where they had fled to. So, they had to remain in Vienna with their daughter Lola and her non-Jewish “Aryan” husband Toni, who in the end was unable to protect them.

From March 1938 on the mass emigration of Jews from Austria was speeded up and any country that was prepared to grant them a work permit and a visa became a potential destination. Despite all difficulties and despite having been robbed of their savings and their movable possessions many Austrian Jews managed to leave the country in time. At the beginning of 1938 185,246 Jews lived in Austria and before the deportation to concentration camps started in 1941 128,500 had succeeded in fleeing the area. Yet it should not be forgotten that many of them were soon afterwards caught up in the Nazi terror and persecution because they had sought refuge in countries which were later occupied by the German “Third Reich” during the 2nd World War. Those who had been left behind, became victims of the Nazi “Endlösung der Judenfrage Europas” (Final solution to Europe’s Jewish question). After the outbreak of World War II in September 1939 58,000 elderly and sick Jewish citizens had remained in Austria, most of them in Vienna, with practically no chance to flee; of these only 2,000 managed to leave until 23 October 1941. After this date any emigration of Jews was categorically prohibited. In Vienna Jews were harassed, abused, used as forced labour and then hoarded into so-called “Sammelwohnungen” (collective flats) in the 2nd district before their deportation to concentration camps.

The term “KZ Theresienstadt” is applied here because it was the term used by the survivors, which is documented in the book of commemoration “Theresienstadt” (see: literature list), where former prisoners of Theresienstadt used the term “KZ Theresienstadt” exclusively, and Ignaz and Ritschi called it a KZ, too. That is why the term is being used here; in deference to the victims, whose memories should not to be questioned. There are discussions among historians about the technicalities of the organisation of Theresienstadt in the NS bureaucracy, which can be considered irrelevant in an analysis of the living conditions there. According to these historians’ findings Theresienstadt was neither a ghetto nor a concentration camp, but in fact a kind of collection and transit camp. No matter which term is used for the terror regime there, the truth remains that thousands of prisoners died of famine, disease and maltreatment and were transported to the death camps from there. In the small fortress of Theresienstadt many prisoners were murdered on site and the death rates in the KZ Theresienstadt were so high that a crematorium had to built to deal with the large amount of dead bodies.

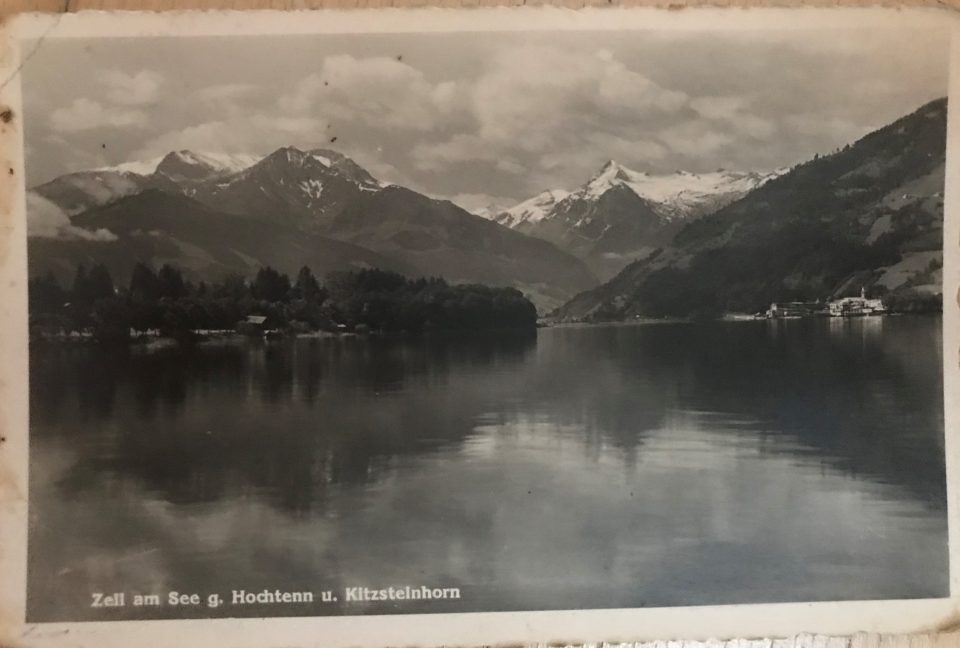

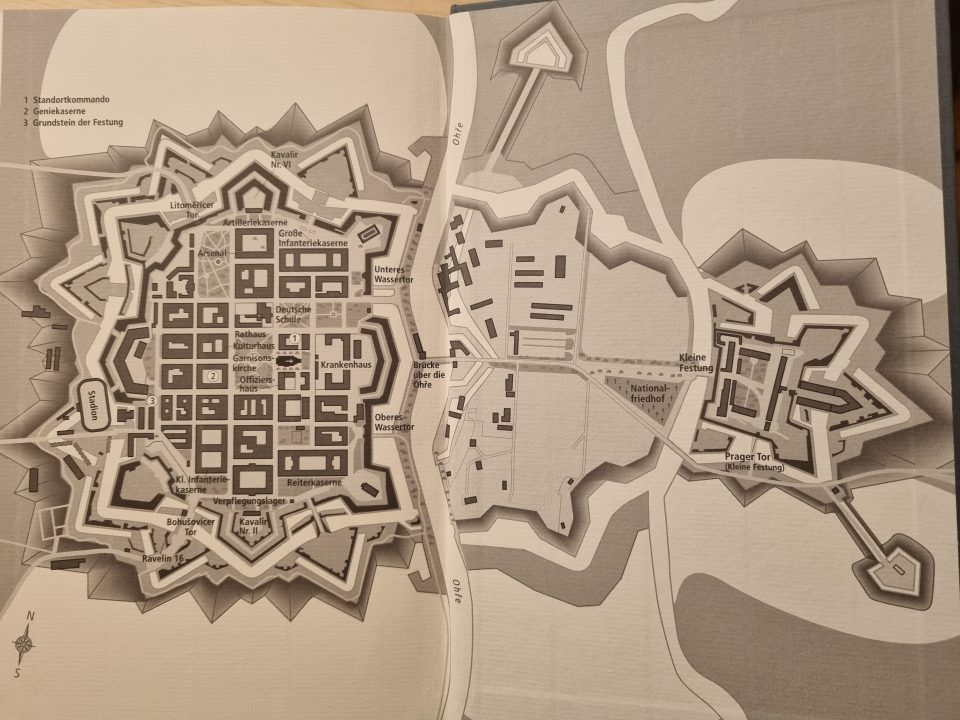

The Austro-Hungarian emperor Joseph II had this fortified city, Theresienstadt, built in the Czech lands at the end of the 18th century and named it after his just deceased mother, Empress Maria Theresia. It was strategically important in the confrontation with Prussia, but was never involved in any acts of warfare and remained a garrison town. The small fortress was used as a prison for military and political prisoners in the 19th century. Already in 1940, the Nazis established a GESTAPO prison there, while at the end of 1941 the grand fortress, the fortified city, was used as a collection and transit camp, called “Ghetto Theresienstadt”, for Jews from Bohemia and Moravia initially, then from Austria and Germany and finally from other Nazi-occupied parts of Europe, too. Before the Nazi occupation the city housed 7,000 people including soldiers, while the Nazis planned to cram 50,000 to 60,000 Jews into the city. The original inhabitants of Theresienstadt were forced to leave. On 18 September 1942 the highest number of people imprisoned there was registered as 58,497, but due to the mass transports from KZ Theresienstadt to extermination camps, such as Auschwitz, the fluctuation of numbers was huge. All in all, from the so-called “Protektorat” (the Nazi-occupied parts of Bohemia and Moravia) 74,000 Jews were deported to the KZ Theresienstadt, 43,000 from Germany, more than 15,000 from Austria, 5,000 from the Netherlands, 466 from Denmark, 1,500 from Slovakia and around 1,000 from Hungary. Towards the end of the war 15,000 prisoners from liquidated concentration camps in the east were transported to Theresienstadt, as well. Overall, 150,000 were imprisoned in the KZ Theresienstadt.

The KZ Theresienstadt is characterised by shameless cynicism, diabolic deception, and hypocrisy of the Nazi perpetrators even more than any other Nazi centres of internment and extermination. The world public was systematically and cunningly deceived about the true purpose of this “Ghetto Theresienstadt” and consequently did not see through the genocidal intentions of the NS race policies. On top of that, the victims of NS terror were forced to participate in the charade, as for example the “beautification programme” which was staged in preparation for the visit of an international Red Cross delegation and the production of a propaganda film. The prisoners were furthermore coerced to serve the Nazis by organising the administration of the KZ themselves on orders from the SS commanders. The NS cheat and deceptive manoeuvre has unfortunately been successful until today. Even in serious research literature it is still mentioned that the living conditions in Theresienstadt were supposedly much better than in other concentration camps, that children and young people were offered formal education and nowhere hints to the “rich cultural life in the ghetto” are missing. The fascination with the artistic, literary, and intellectual productivity there must be uncoupled from the abysmal conditions under which the activities took place. Otherwise, such analyses present a distorted and unrealistic image of life in the KZ Theresienstadt. It is a shame that more than 70 years after its liberation the NS propaganda still nourishes this illusion of Theresienstadt as “the better KZ”. Nowadays it is very difficult to say how much the world knew about the conditions there and in how far the global public closed their eyes and did not want to see the genocide. It is still impossible to imagine what life was like in the KZ Theresienstadt; a life between hope and terror, between deception and extinction.

KZ Theresienstadt “Little Fortress”

Prison cells in the “Little Fortress” and “water boarding” torture of prisoners

…