NAZI COLLECTIVE CAMPS (“SAMMELLAGER” ) AND LIFE IN HIDING AS A SO-CALLED „U-BOOT“ (“SUBMARINE”) IN VIENNA 1938-1945 AND THE SURVIVAL STRATEGIES OF THE PERSECUTED

Memorial for the victims of deportation 1941/1942 at the location of the former train station “Aspangbahnhof” in the 3rd district of Vienna

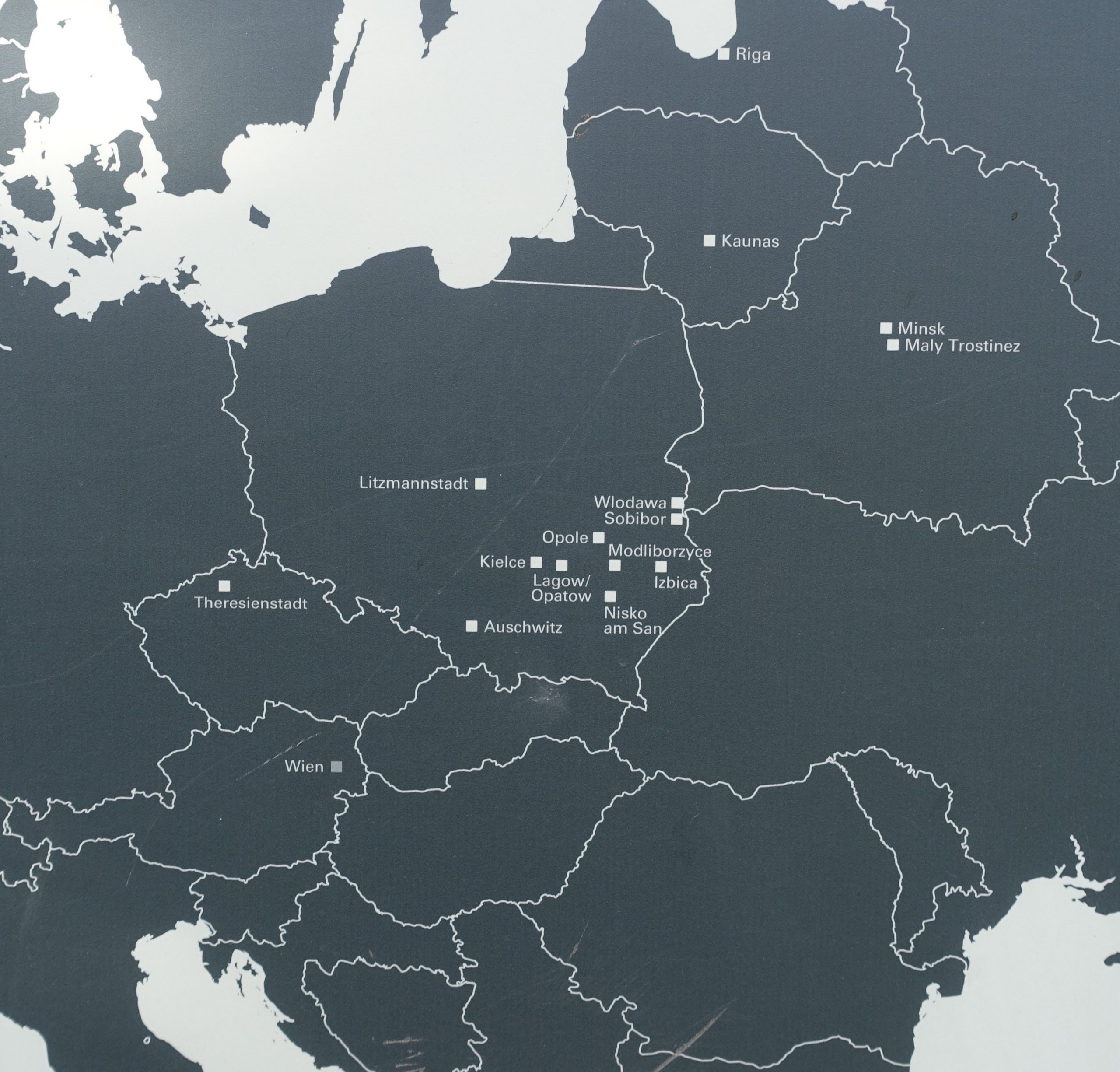

This map shows the ghettos and concentration camps the Nazis deported the Jewish population to from the collection camps in Vienna via the “Aspang” train station

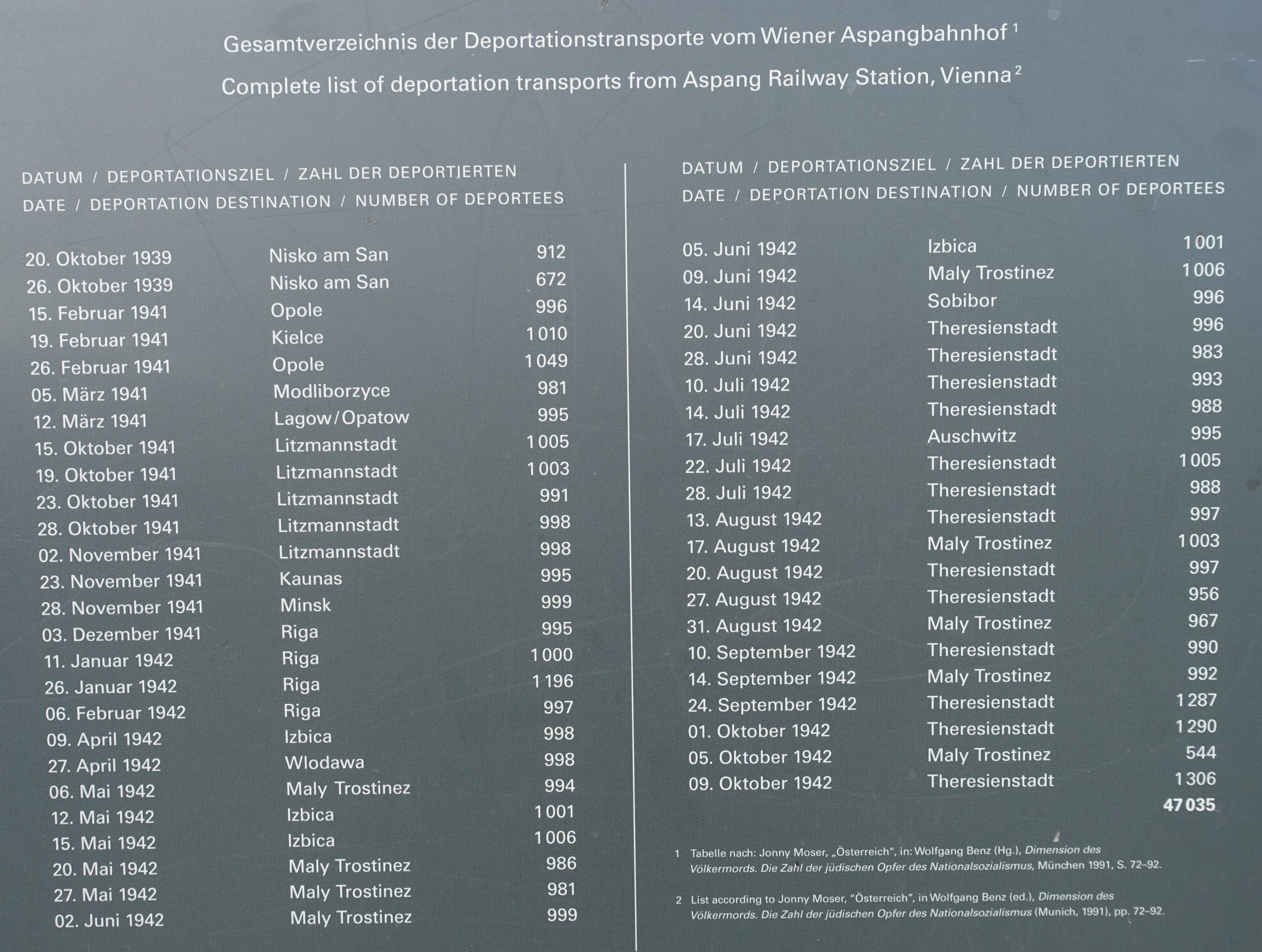

The list with the dates and destinations of the 47 transports from the Aspang train station to ghettos and concentration camps 1939, 1941/1942. My great-grandparents Ignaz and Rudolfine Sobotka were to be deported on the 28 July 1942 to Theresienstadt, but then their transport was postponed to 13 August1942

The famous Viennese artist, the painter Arik Brauer, reported in an interview that a school mate and friend of his had come running to his flat in the 16th district of Vienna, Ottakring, when they were both around 13 years old, telling Arik that the next day he and his family had to report to the Nazi authorities in a collection camp in the 2nd district. He wanted his friend to have his collection of books by Karl May, a very popular adventure book writer of the time, because he was not allowed to take the books with him and he wanted to say good bye to Arik, too. Arik asked him why he did not run away and his friend answered, “Where shall I run to?” At that time no one believed that this transfer to the collective camps (“Sammellager”) in Vienna, also euphemistically called “collective flats” (“Sammelwohnungen”), led straight to the extermination camps of the Nazis. The former chief rabbi of Vienna, Chaim Eisenberg, told the story of his father who had survived in hiding as a “U-Boot”: he had never laughed so much in his life as during these terribly trying times. Jewish humour kept them alive and helped them not to give up hope. But many could not bear the humiliation and terror and committed suicide. More than 130,000 people could flee before the complete ban of emigration of Jews in October 1941. Yet around 17,000 of those were caught up by the Nazi terror machine in their countries of refuge, such as France, the Netherlands and Belgium. In the years 1941/1942 45,527 persons were hauled from the Viennese collective camps via the “Aspang” train station in 47 transports to ghettos and concentration camps in the “East” (as the Nazis called the occupied territories in Central and Eastern Europe), among them my great-grandparents, Ignaz and Rudolfine Sobotka. They were interned in a collective camp in Krumbaumgasse 6/14 in the 2nd district of Vienna on 9 July 1942 before they were deported to the ghetto Theresienstadt (today Terezin) on 13 August 1942. They were liberated after three years of imprisonment by the Allied Forces on 7 July 1945. Of the 1,634 people who are recorded as “U-Boote” in Vienna 1,000 survived more than one year in hiding, more than 400 attempted to survive in hiding, but were discovered before disappearing successfully and were deported. All in all 66,000 Austrian Jews were murdered in the Shoah and Vienna became a model for the organisation of Nazi terror and the extermination of the Jewish population, which was later copied in the rest of the German “Third Reich”.

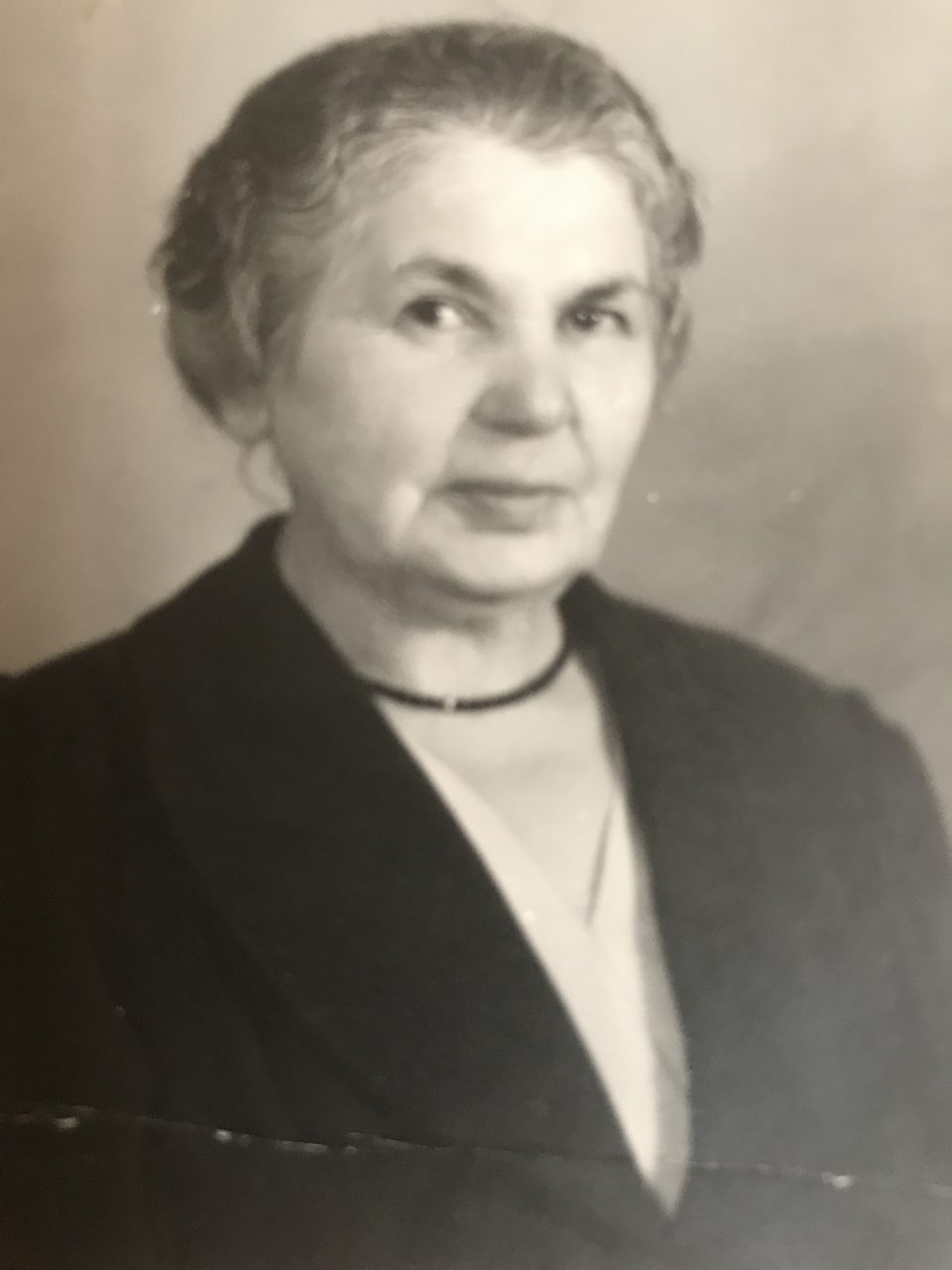

Rudolfine (born on 1 October 1876) and Ignaz Sobotka (born on 9 July 1872). They were forced into a collective camp and then deported at the ages of 66 and 70

The collective camp in Krumbaumgasse 6/14 in the 2nd district of Vienna, where Rudolfine (Ritschi) and Ignaz Sobotka were held prisoners until their deportation to Theresienstadt

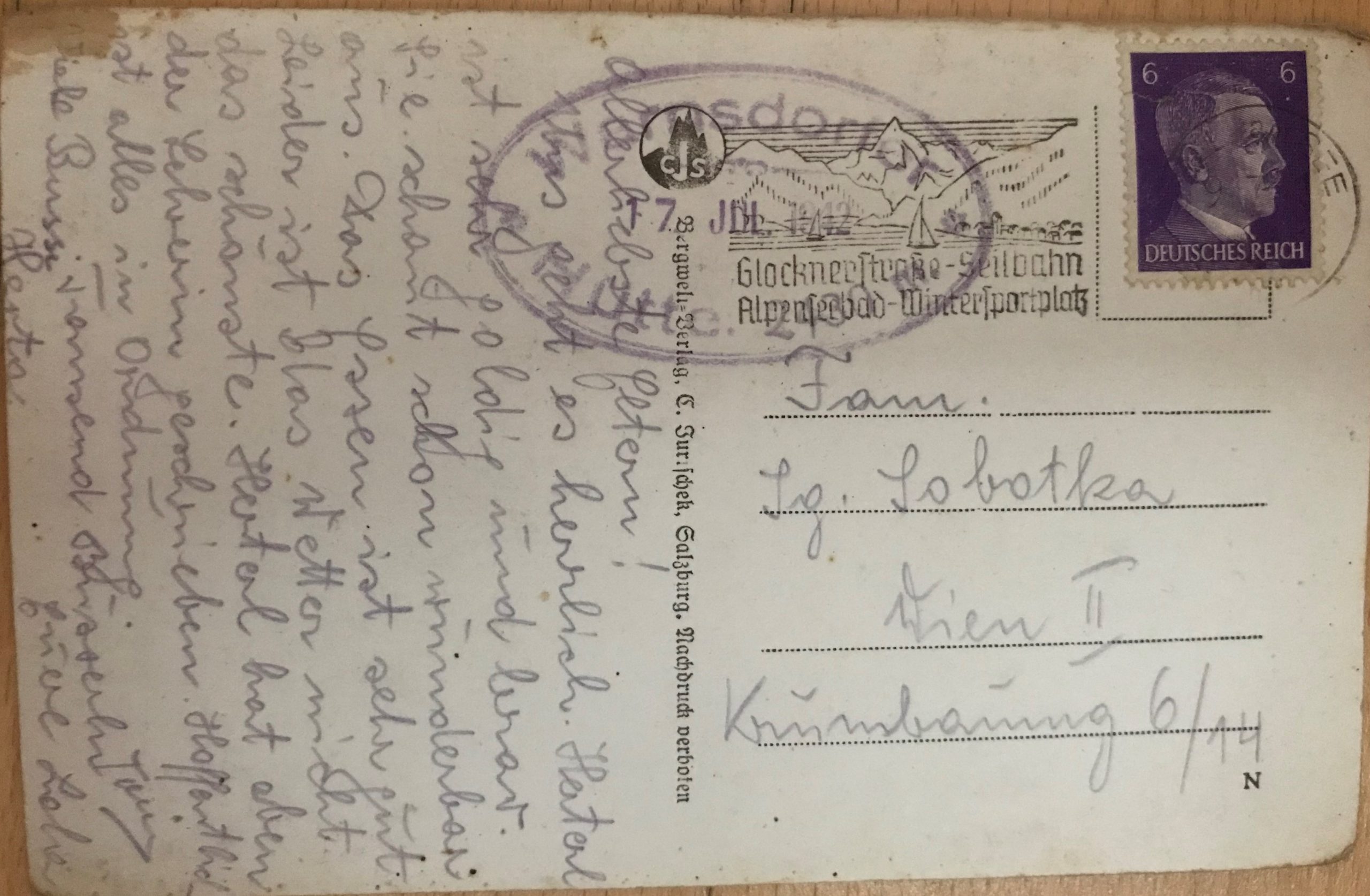

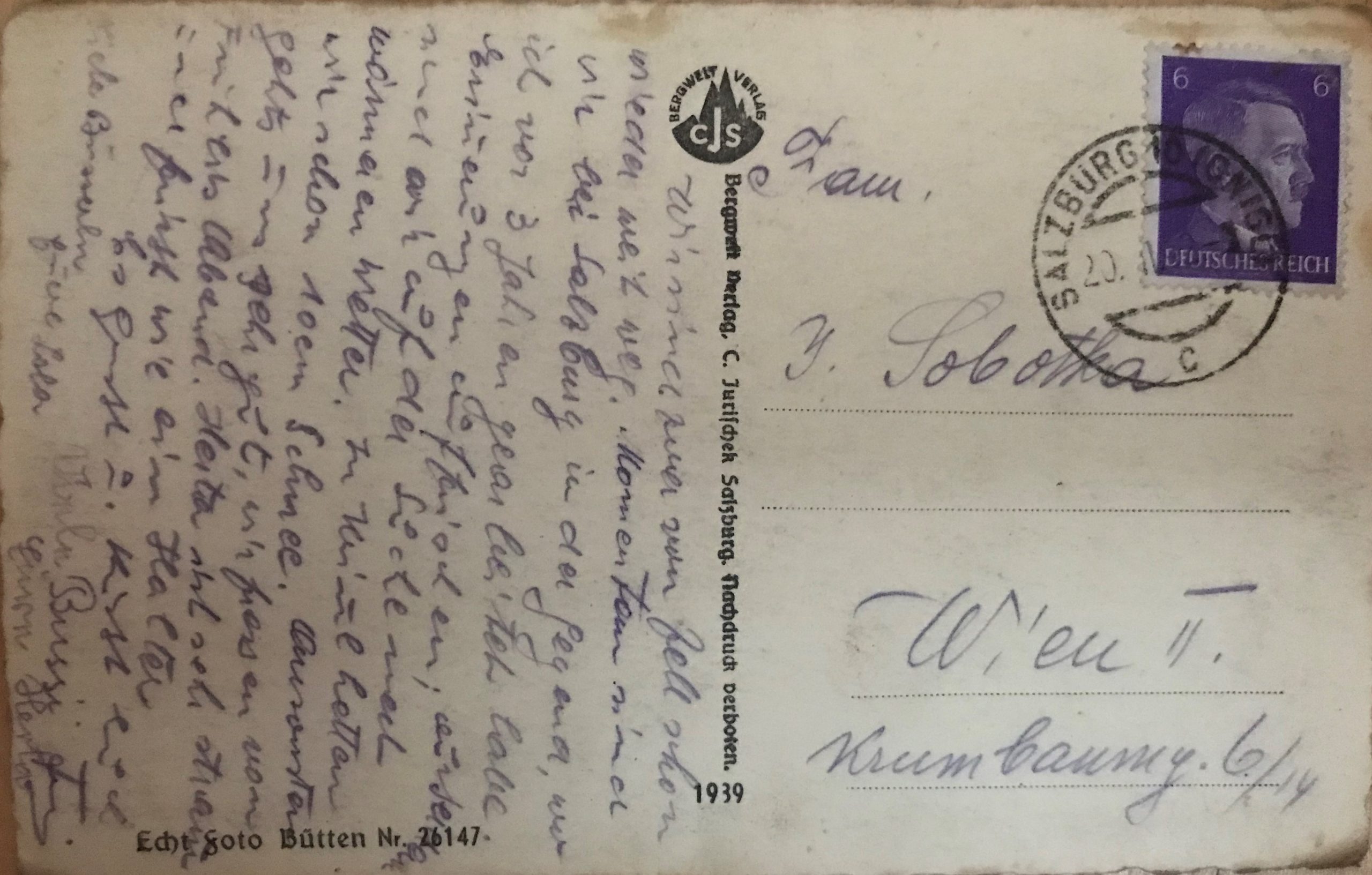

The postcard my grandmother Lola Kainz sent to her parents in the collective camp from their mountaineering holidays in the Großglockner region in Salzburg

“Dearest parents, We are great. Herterl (my mother) is a sweet and good girl and looks great. The food is wonderful here. Unfortunately the weather is not too good. Herterl has just written to her teacher. Hopefully everything is ok. Many kisses Herta. Thousand kisses Lola and Toni”

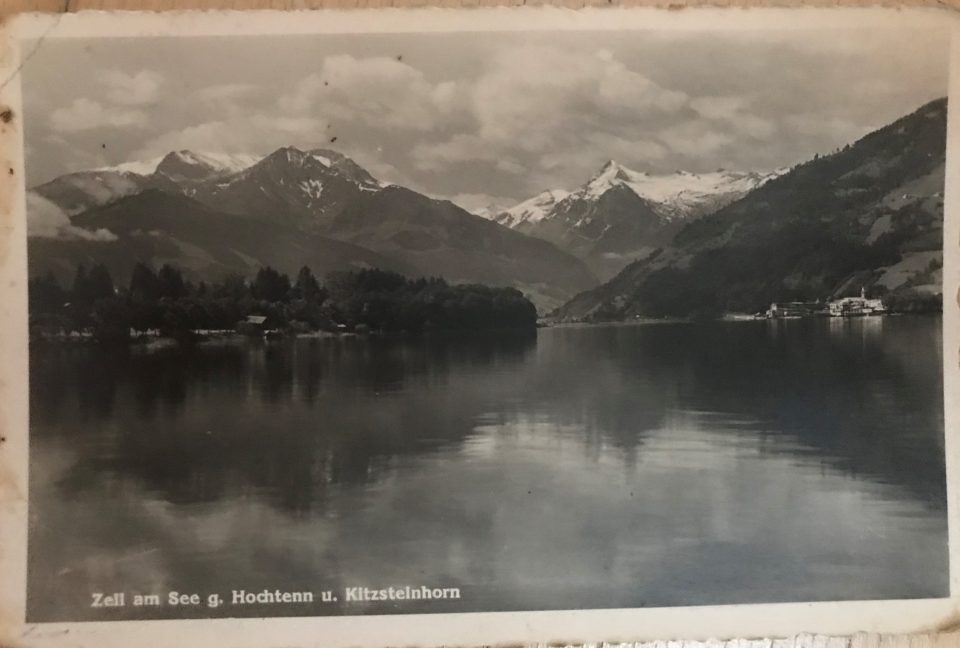

The postcard my grandfather Toni sent them from the same holiday from Zell am See

“We are already far away from Zell am See. At the moment we are in Salzburg in the region where I worked three years ago; refreshing memories; most of all we are looking for warmer weather. In Krimml we already had 10 cm of snow. Otherwise we are doing fine; we are shovelling food from morning till evening. Herta has put on weight and eats a lot. Greetings and kisses Toni. Many kisses, yours Lola. Many kisses, yours, Herta.”

The content of the two postcards, which were sent to Ignaz and Ritschi in the collective camp by their daughter Lola and their son-in-law Toni, support the statement of Arik Brauer that the families were not aware of the deadly seriousness of the GESTAPO orders to report at the collective camps and that the stay there was just a transition to the deportation to ghettos and concentration camps. But the banality of the reports about holiday experiences, food and weather in Salzburg might also have been intended to boost the morale of the parents and to sound positive, optimistic and hopeful. Ignaz and Ritschi never talked about their experiences during the time of imprisonment from 9 July 19242 until 7 July 1945. That’s why it is so important to research this dark period of Viennese history now in times of rising anti-Semitism in an attempt to prevent similar disasters in future, because as the writer William Faulkner once said, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”…