THE LIVES OF PEOPLE IN „MIXED MARRIAGES“ AND OF „MIXED-RACE CHILDREN“ (ACCORDING TO THE NAZI NUREMBERG RACE LAWS) IN VIENNA 1938-1945

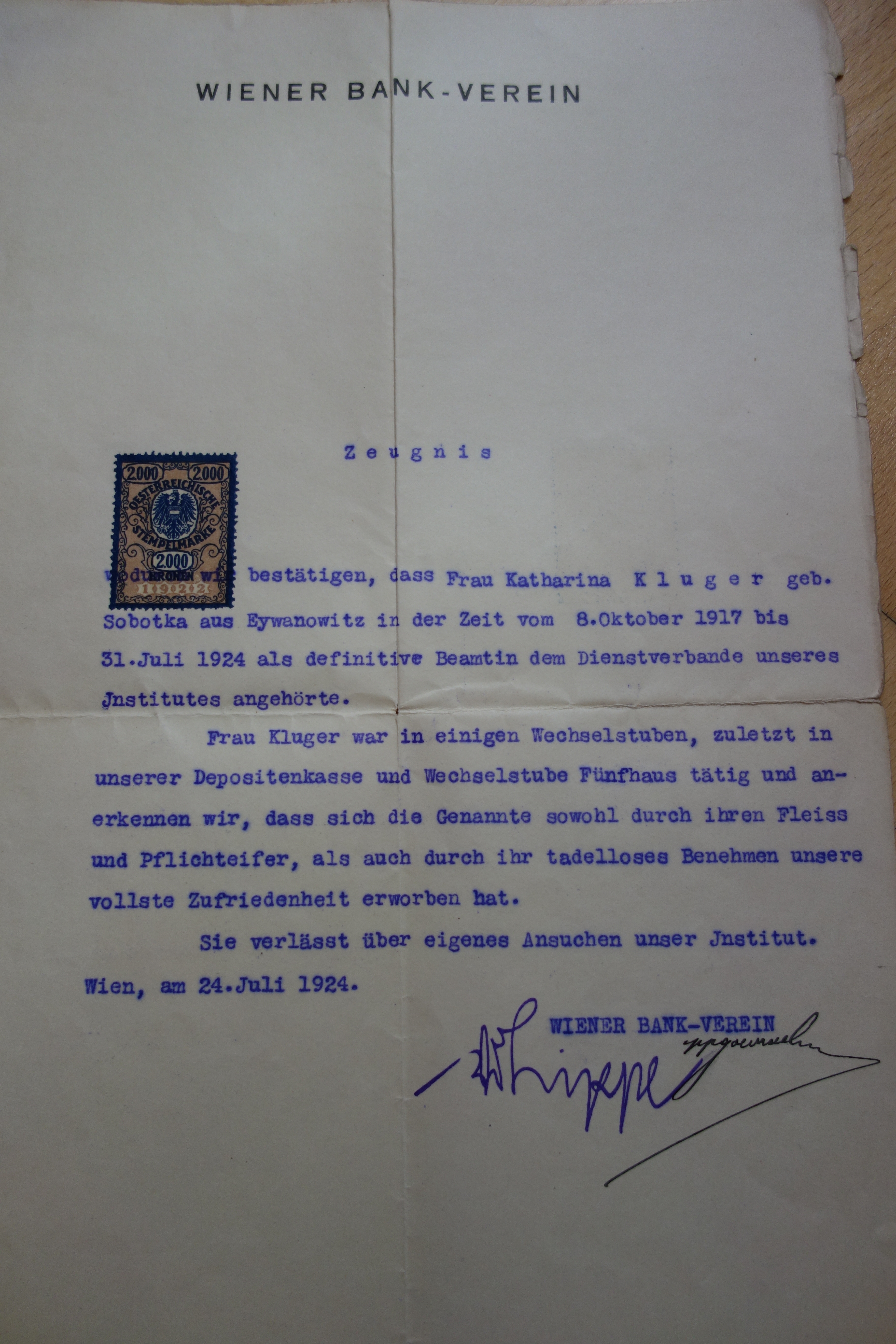

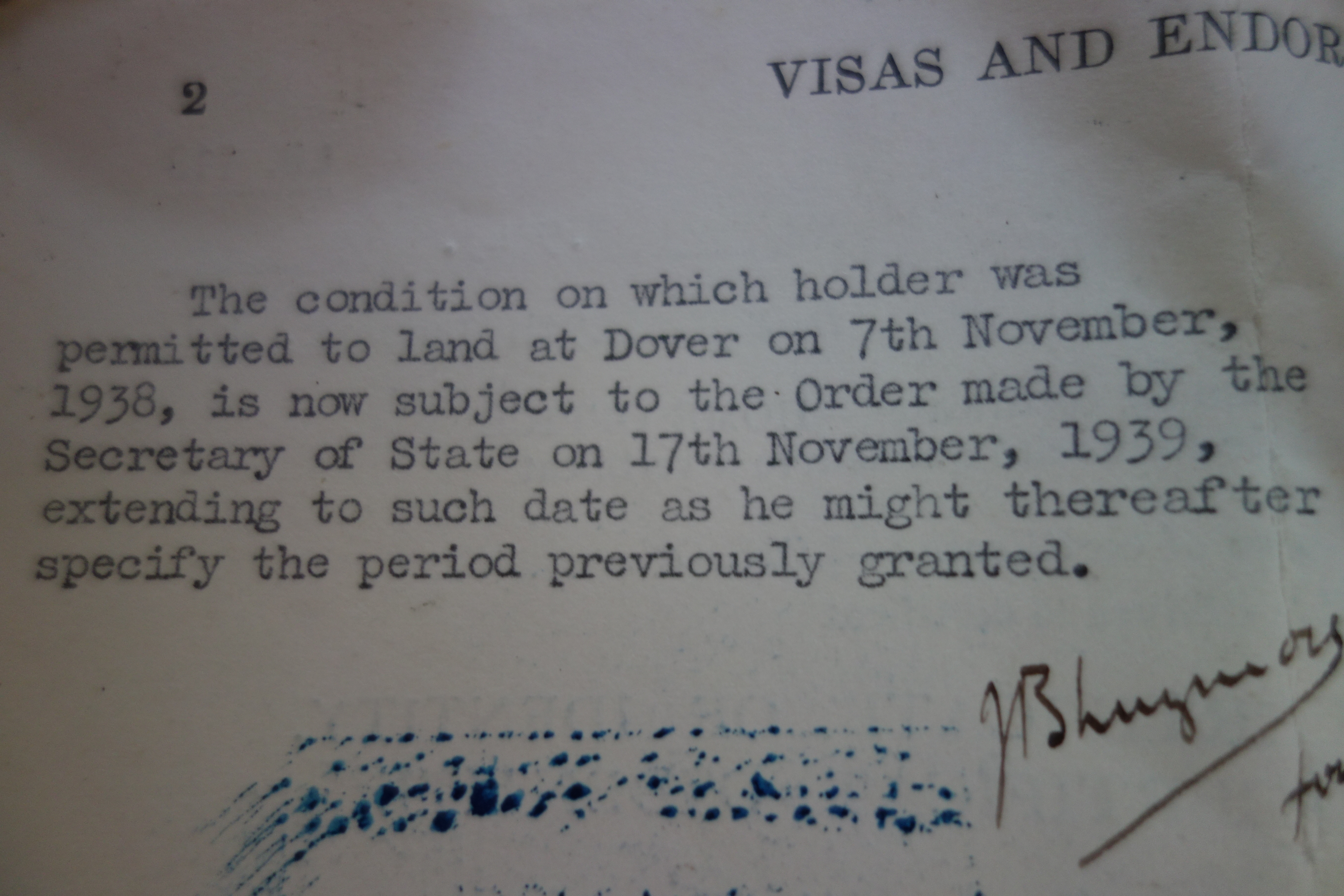

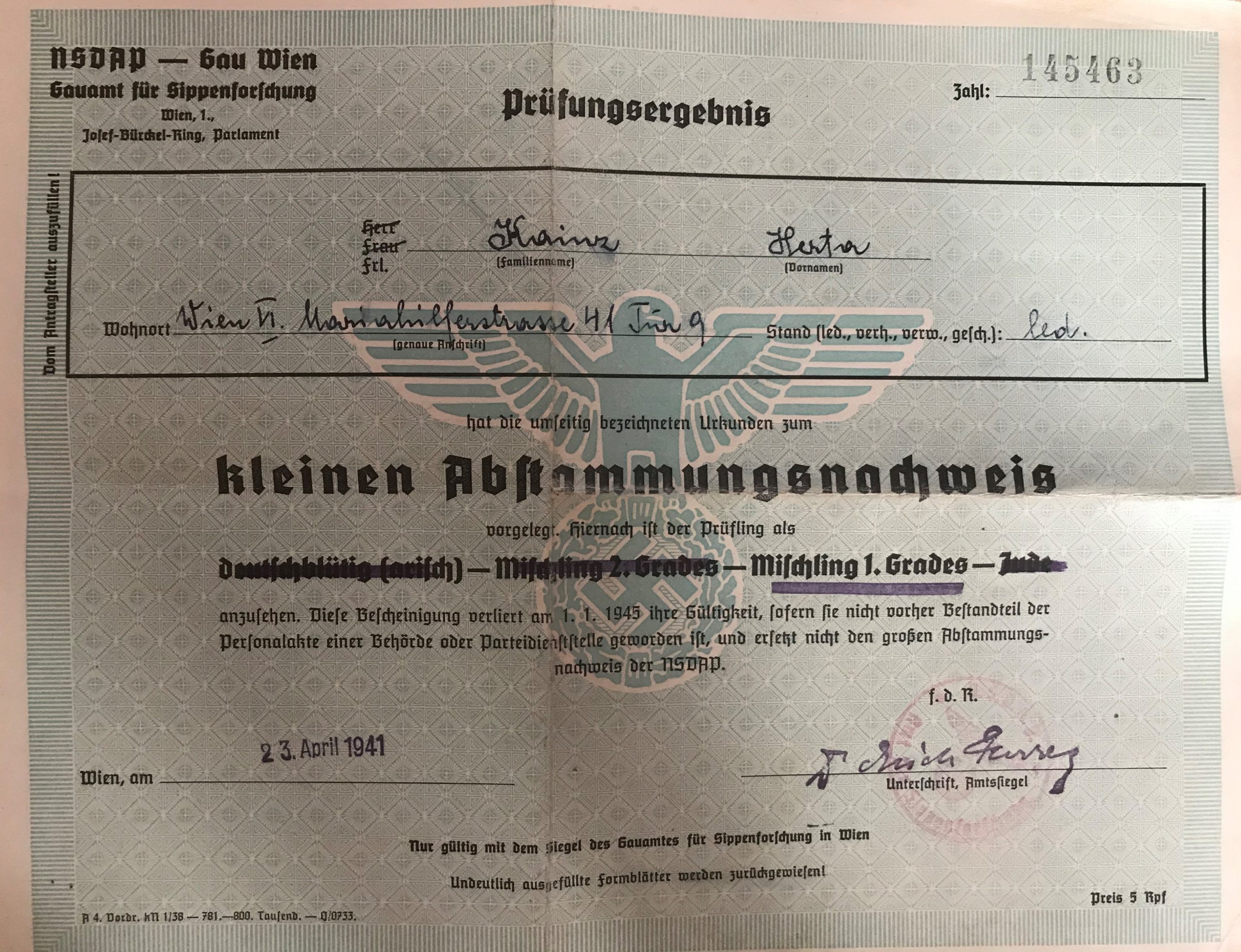

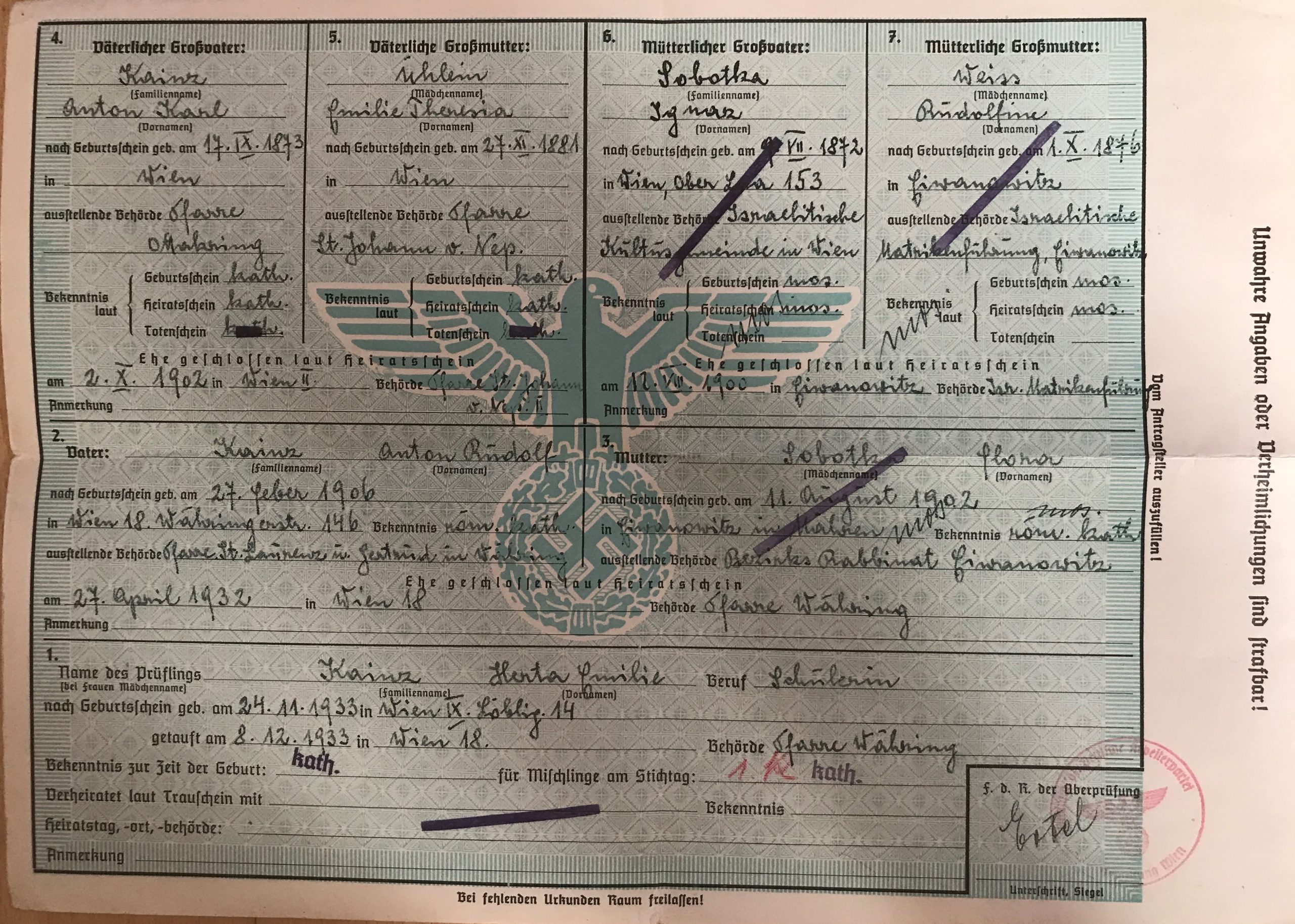

After the “Anschluß”, the takeover of the Nazis in Austria on 12 March 1938, the racial background of every citizen was documented according to the Nazi Nuremberg race laws and my mother, Herta, was classified as a “Mischling 1.Grades” (a “mixed race child of the 1st degree”) – as can be seen in the documents above. Her mother, my grandmother Lola (Flora Kainz), was a Catholic of Jewish descent with Jewish parents, my great-grand parents Ignaz and Rudolfine Sobotka, which meant that all of them had to bear the full brunt of racial discrimination of the Nazi dictatorship. But as long as my grandfather, Anton Kainz, the father of Herta, stood by his family and did not divorce my grandmother Lola, at least Lola and Herta were somehow “protected” because he was a certified “Aryan”. But this “protection” was constantly on the brink of being withdrawn, despite the fact that Toni loved his wife dearly and adored his daughter and would never have thought of giving in to Nazi pressure. This constant insecurity and permanent racial discrimination left deep scars especially in the psyche of Herta, who was four and a half years old at the time of the “Anschluß”. She first lost her aunts and uncles who had to flee Austria, then her grandparents, who were deported to the KZ Theresienstadt and then was in constant fear that her mother would be arrested and deported, too. At the end of the war she was eleven and a half and was not only terribly afraid of the Allied bomb attacks on Vienna, but even more of the knocking on the door and a surprise visit of the GESTAPO which would take away her mother. It was impressed on her by her father that she had to run to the fish shop where he was the branch manager and inform him immediately if anything happened to Lola. Herta remembered that her parents had lots of friends and kept in contact with them during the Nazi occupation. One of them was a high-ranking NSDAP party member and he proposed that Lola should hide in his flat in case of emergency, because no one would suspect him of secretly protecting a Jewess, so she would be safe at his place. But fortunately this was not necessary. Till the end of her life this fear accompanied Herta. Despite the tragic political circumstances and the discrimination she faced as a child, she stressed what a happy childhood she had had because her parents doted on her and this love carried her through those hard times – and the close friendship to a girl who lived in the same house in Mariahilferstrasse 41 and was an outcast just like her. Her name was Herta, too, and she was a very unruly foster child. This unlikely couple, the extremely timid and withdrawn Herta, my mother, and her daring wild playmate remained friends until old age despite the fact that their lives took very diverging paths: My mother became a master dressmaker and “the other” Herta a bar singer. Maybe the discrimination they faced as children created a lasting bond.

The fate of Jewish partners in “mixed marriages” and of “Mischlingskinder” (“mixed race children”) in Vienna was a doubly tragic one because after the war their sufferings were not recognised, neither by the 2nd Austrian Republic nor by the Jewish or Catholic community with the argument “nothing had happened to them – they had survived”. Yet the fast succumbing to a very severe form of dementia at a rather early age can be contributed to the trauma Herta had experienced during the Nazi occupation and that had never been diagnosed or treated. It seems that children carried these traumas with them all their lives and despite apparently functioning very well as adults, the harm that was done to their souls came up again much later in life once more.

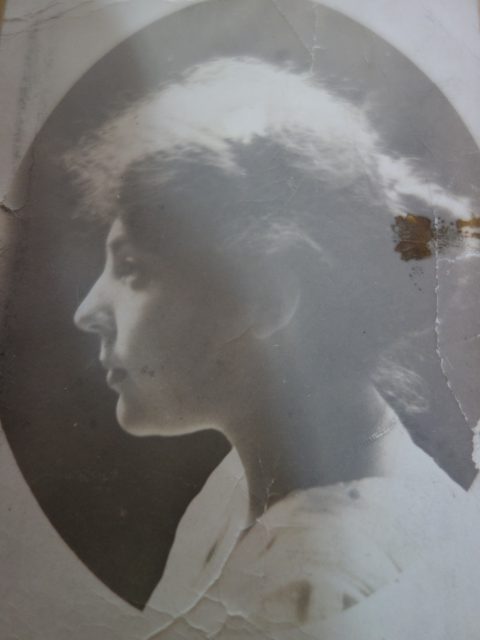

Herta with her mother, Lola, and at the age of three, a very shy little girl

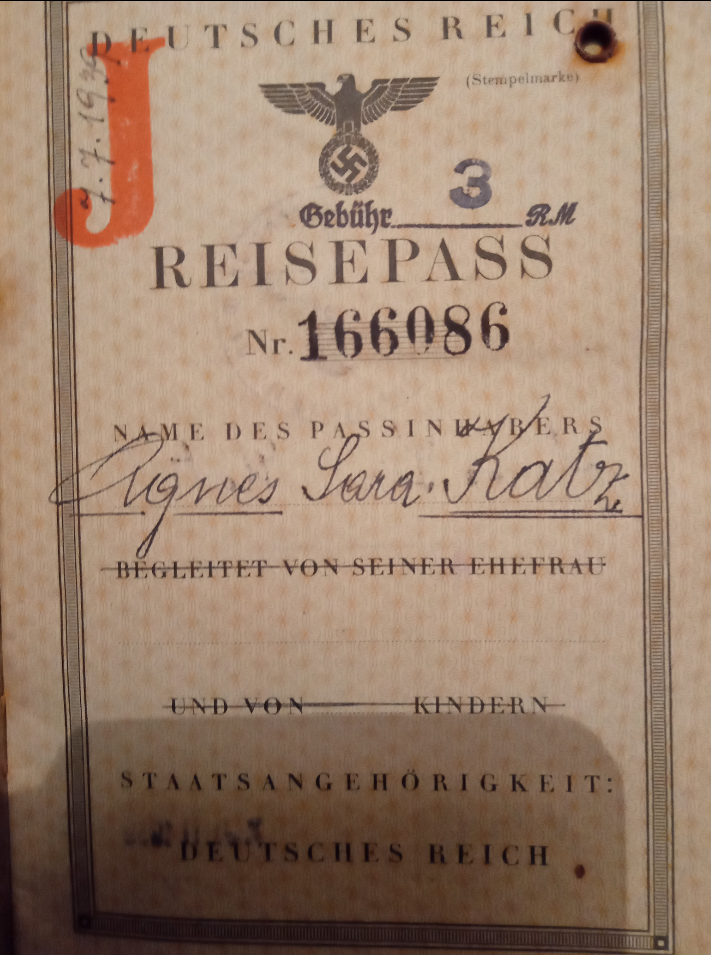

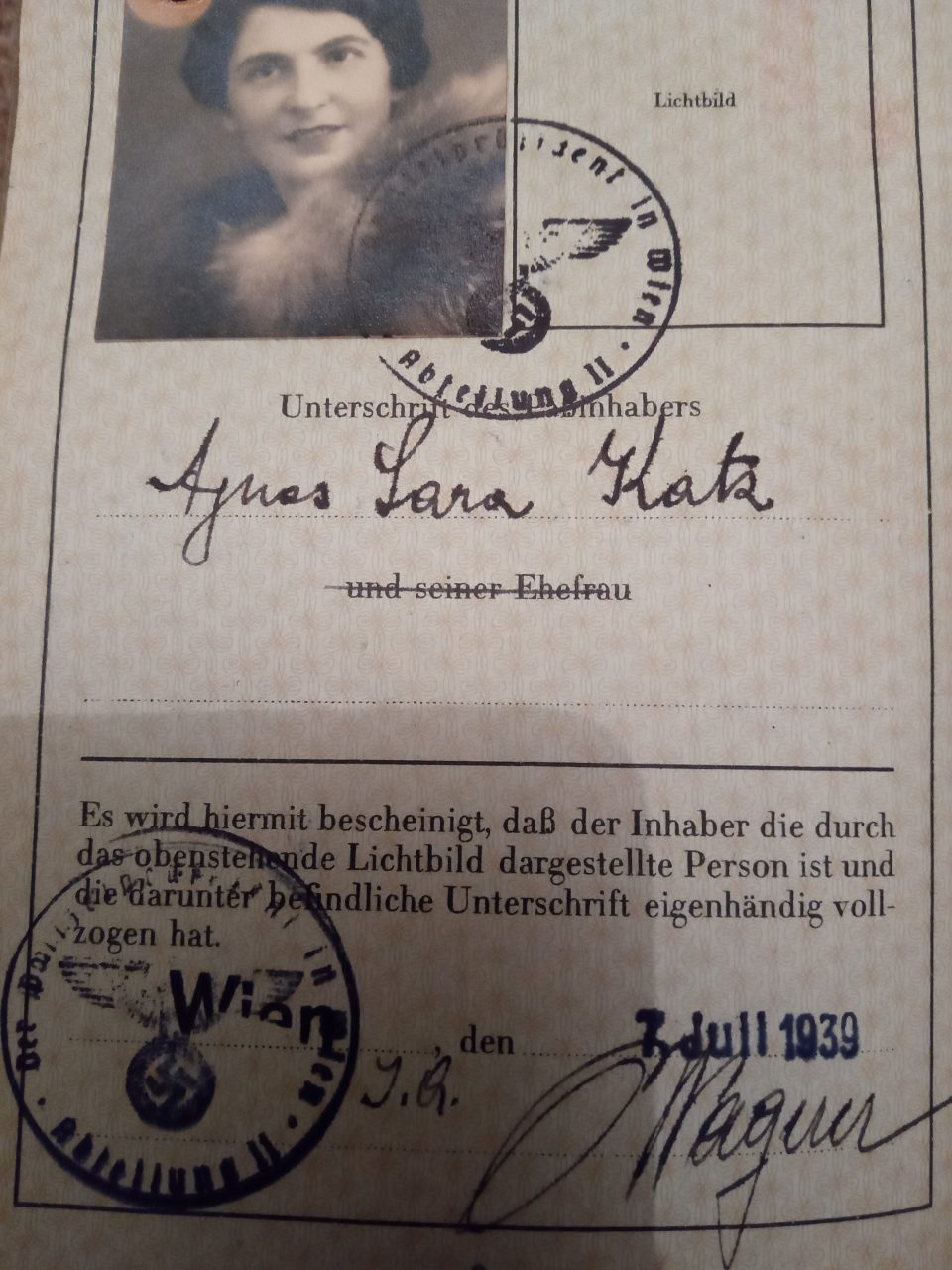

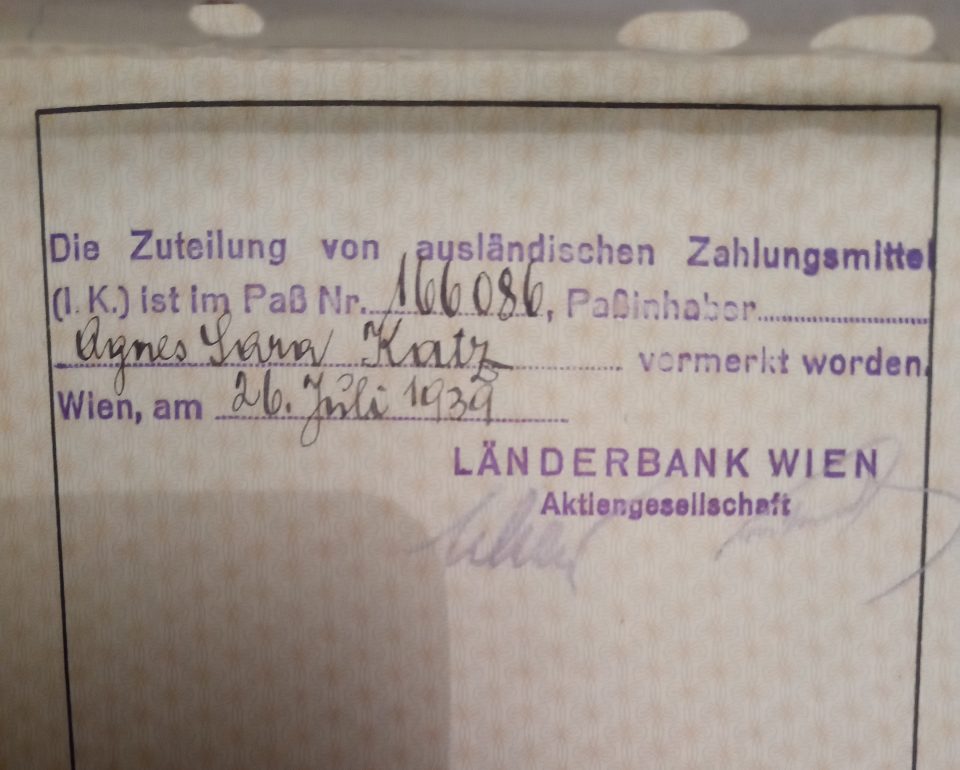

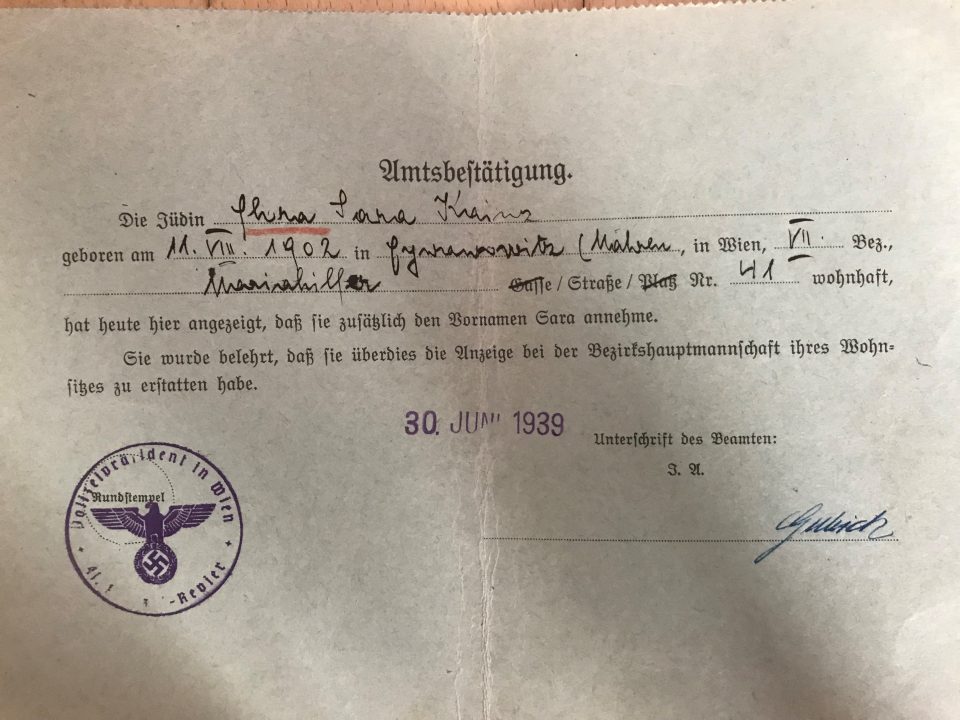

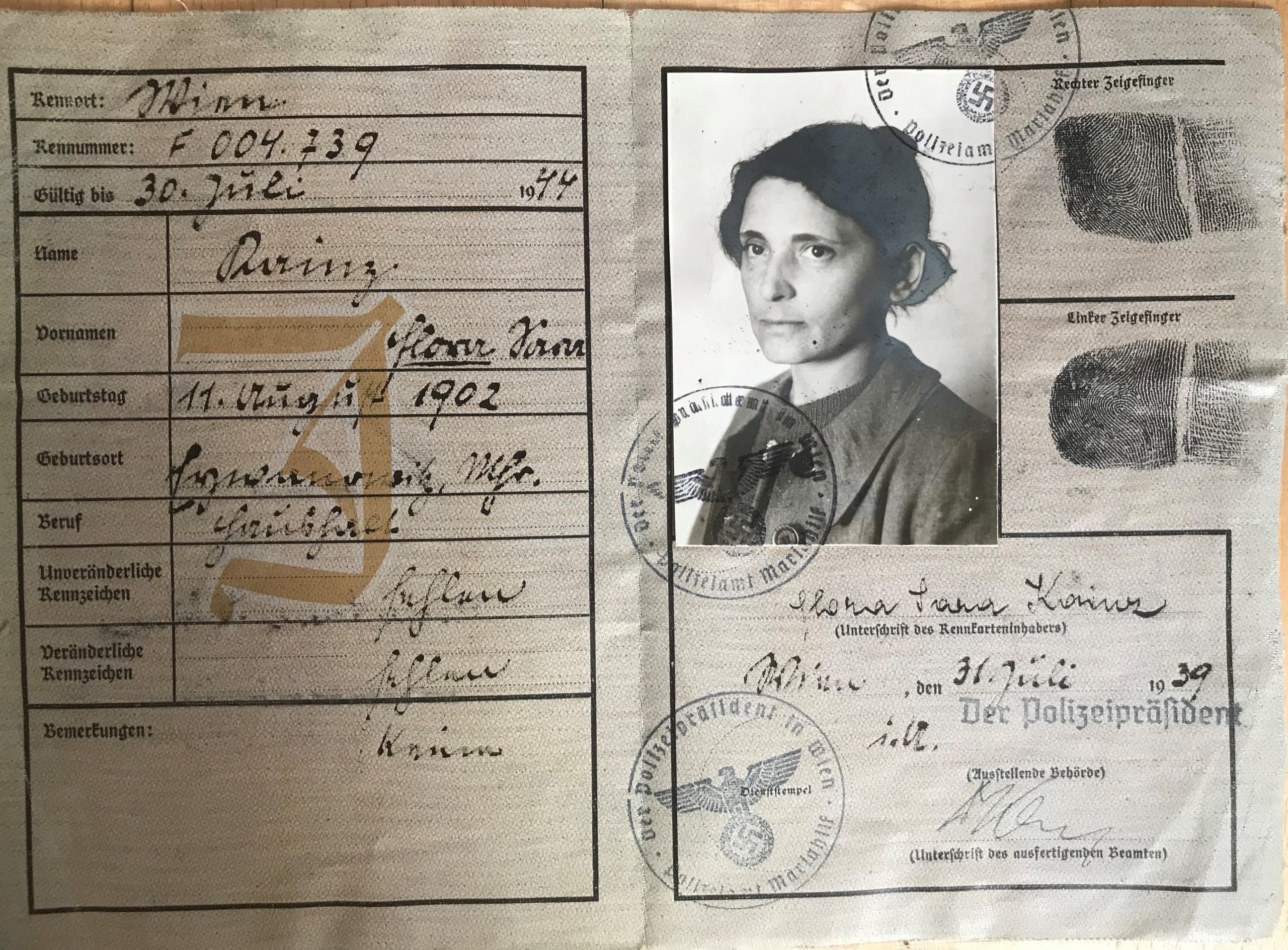

All Jewish women were forced by the Nazis to take on the name “Sara”, as can be seen in this document of the 30 June 1939 of my grandmother Flora Kainz, called Lola. Jewish men had to include “Israel” in their names.

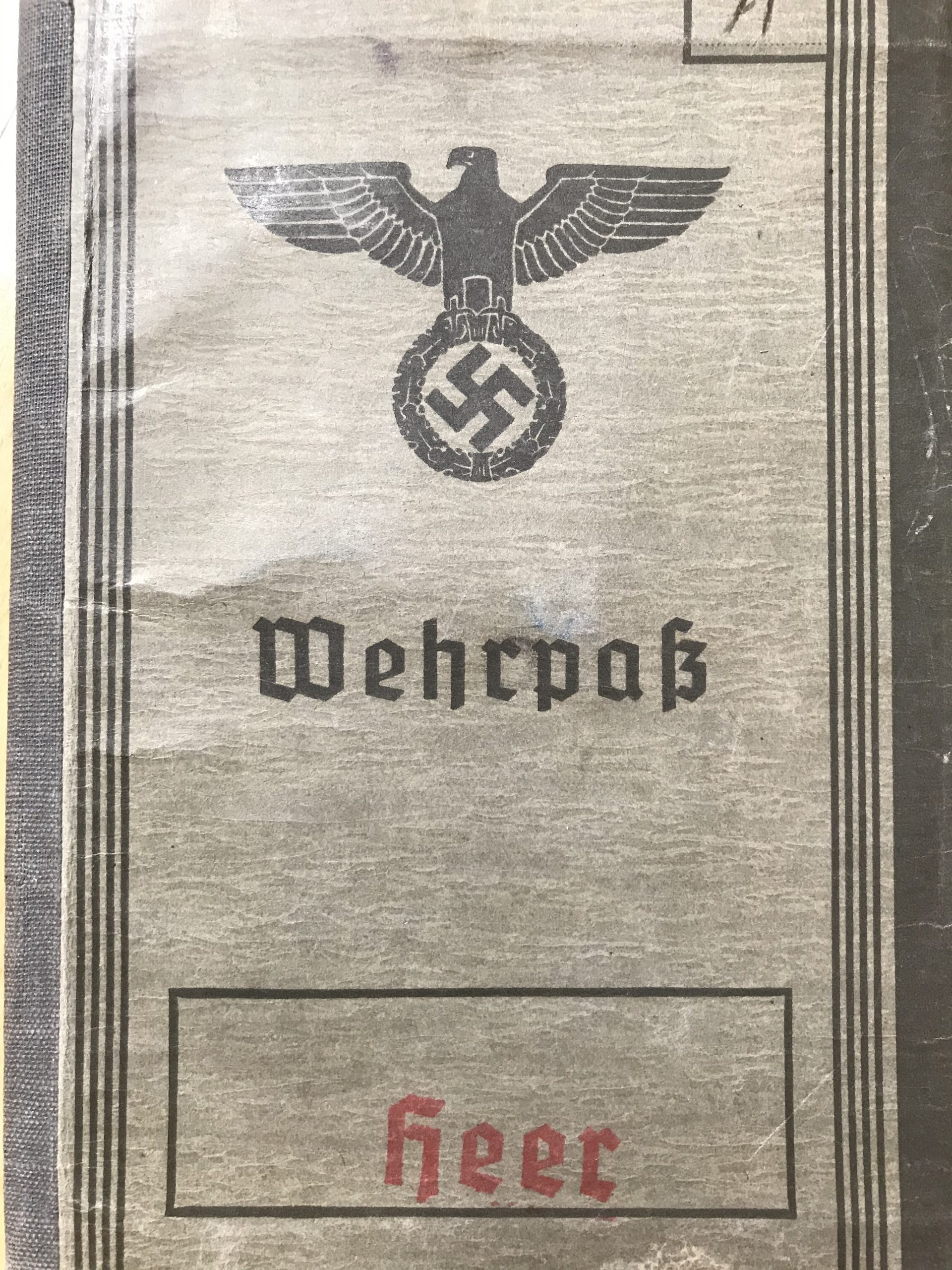

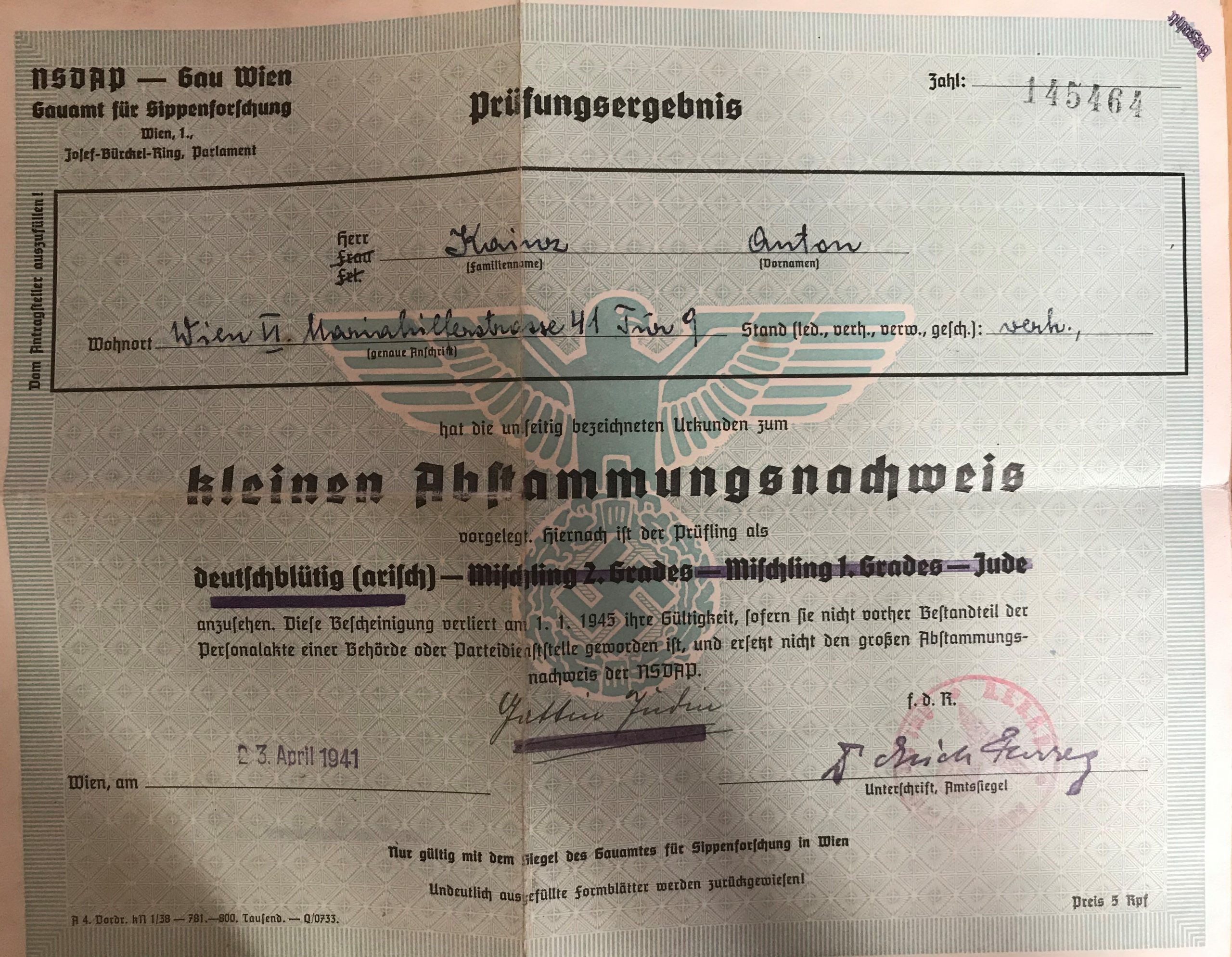

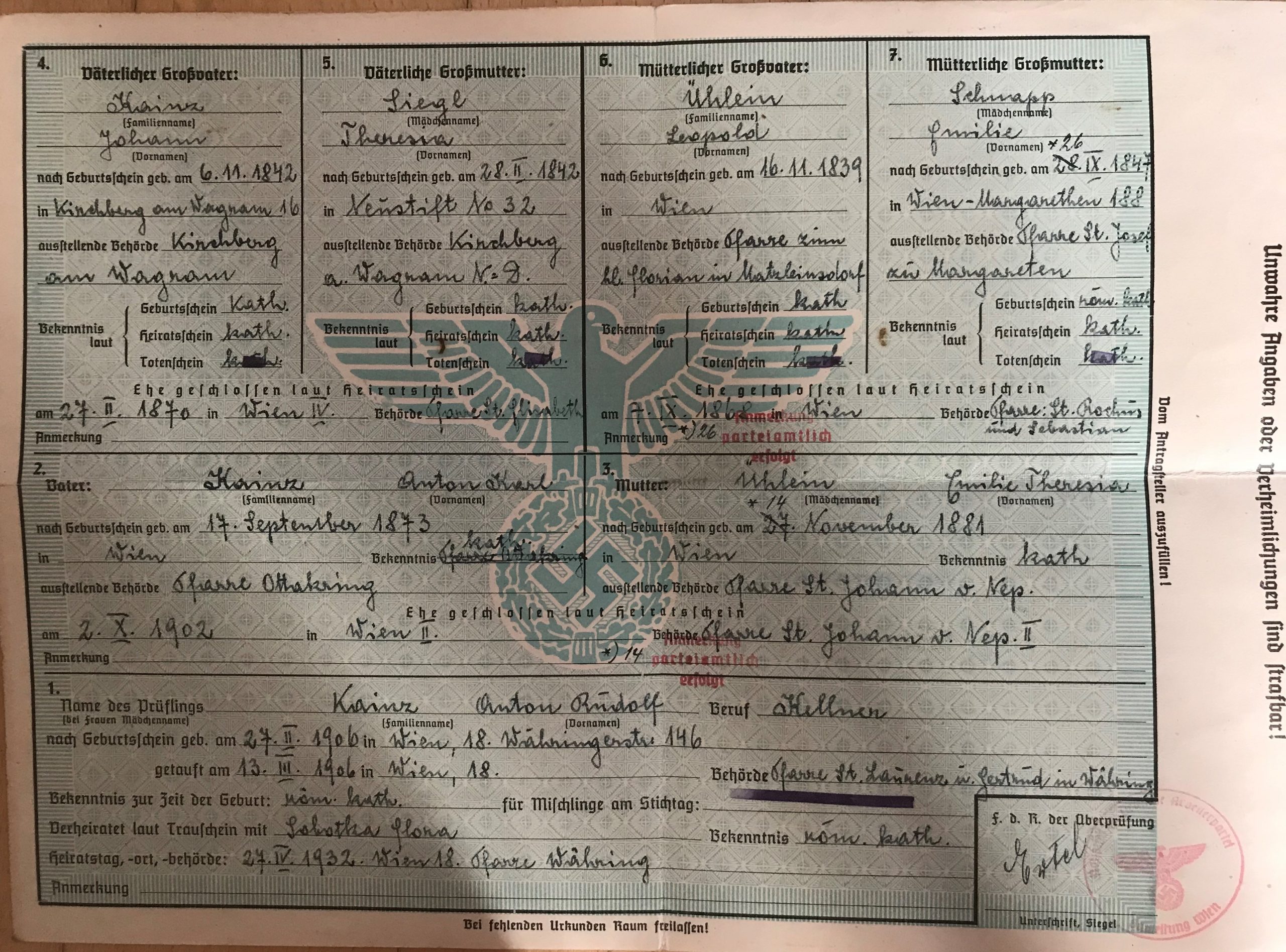

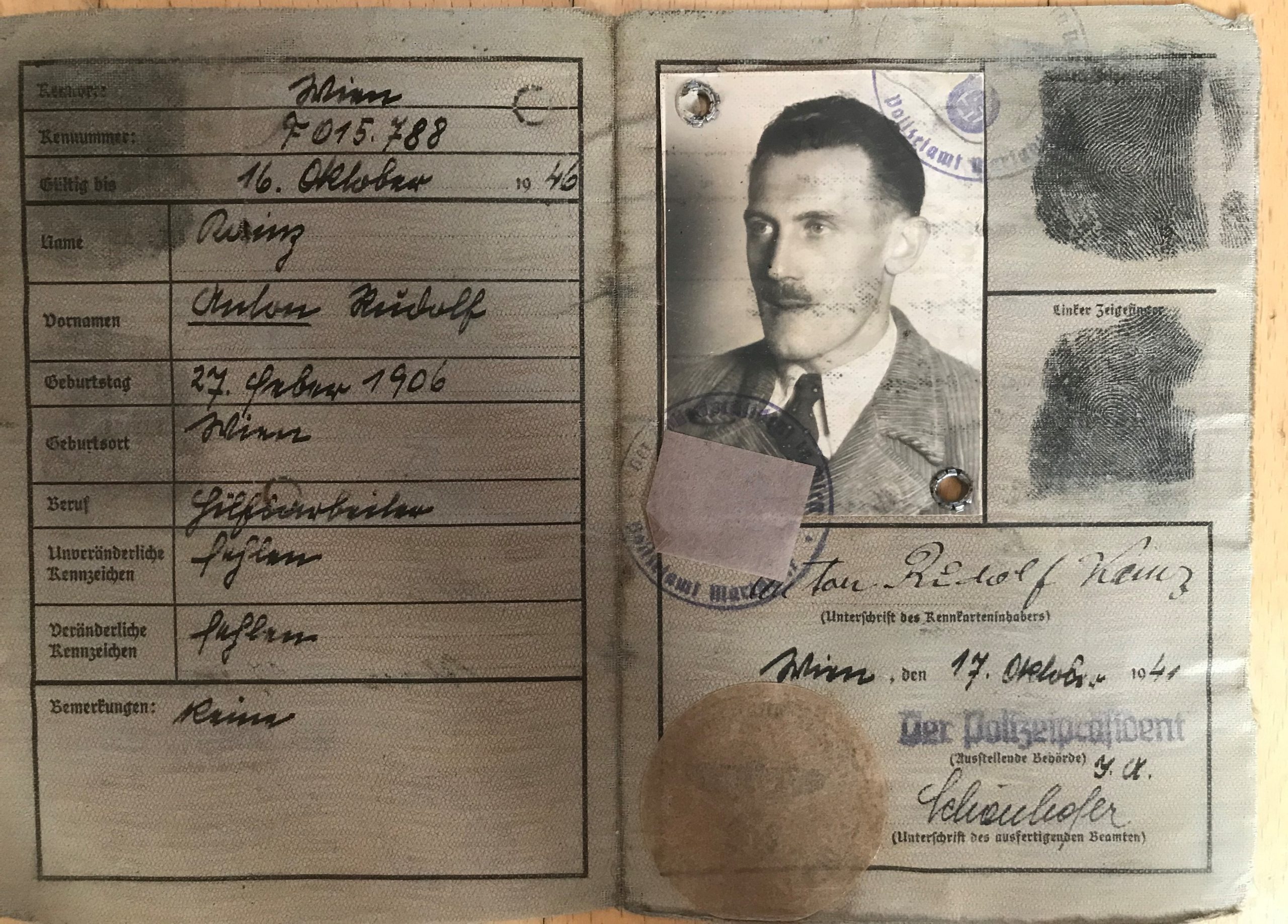

“Ariernachweis” (“Aryan Certificate) of Anton Kainz, Herta’s father. This document proved the “Aryan” status of Toni, which provided some fragile protection for Lola and Herta. The handwritten addition stated that Toni was married to a Jewess.

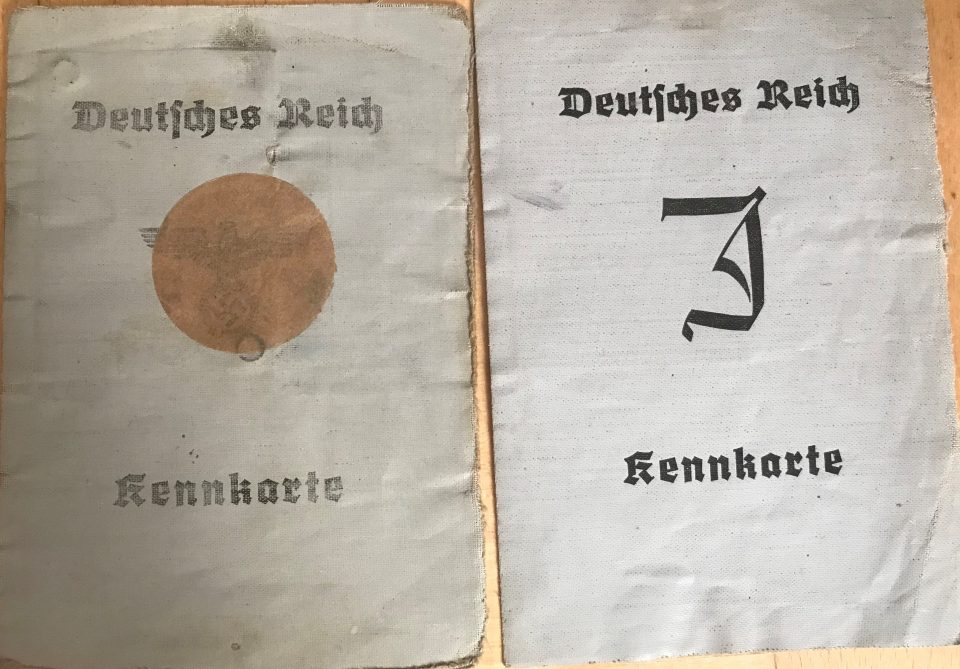

The Nazi IDs of Toni (left – the Nazi eagle was covered, probably because the ID was still in use after the liberation by the Allied Armies) and of Lola (right – marked with a “J” for Jewish)

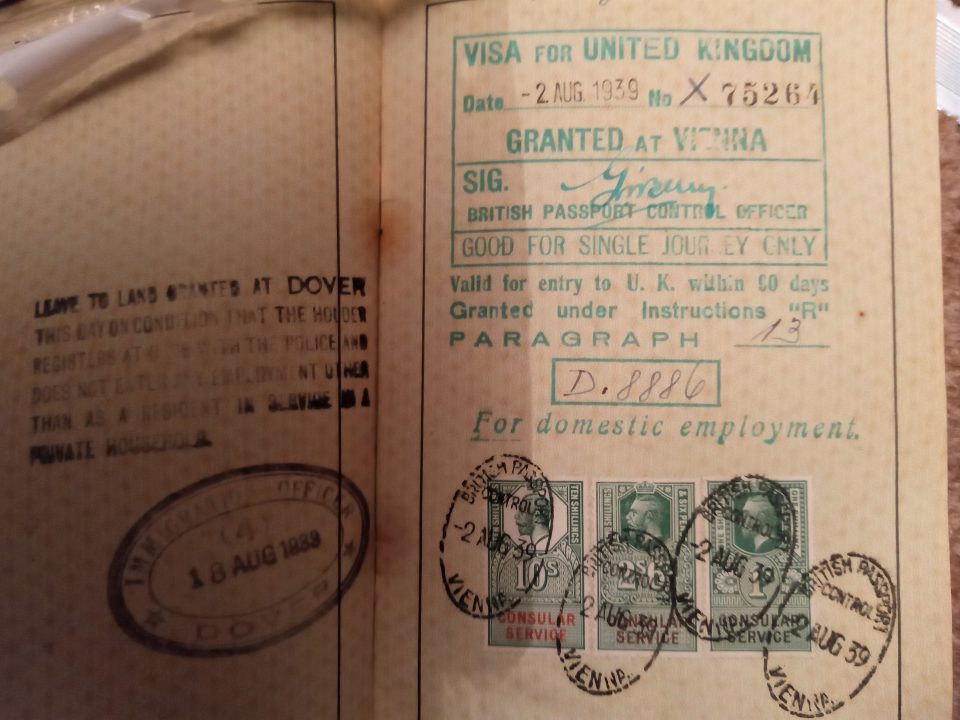

If this photo of Lola of 1939 is compared to the photos of her before 1938 in the articles on classical music, suburban inns and suburban cafés on this research website, one can see that the happy-go-lucky beautiful young woman of those days had turned into a terrified, emaciated and desperate one within a year.

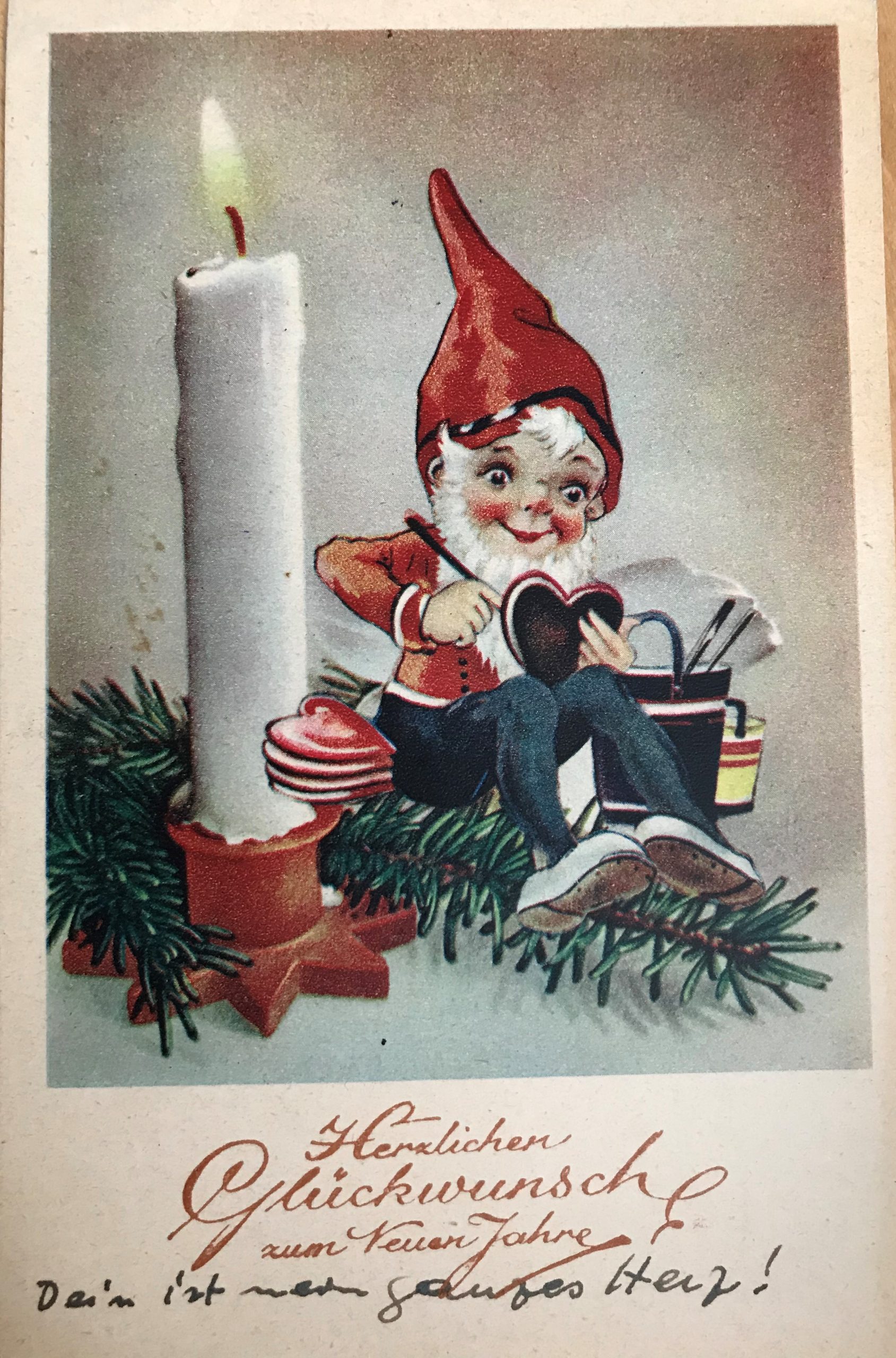

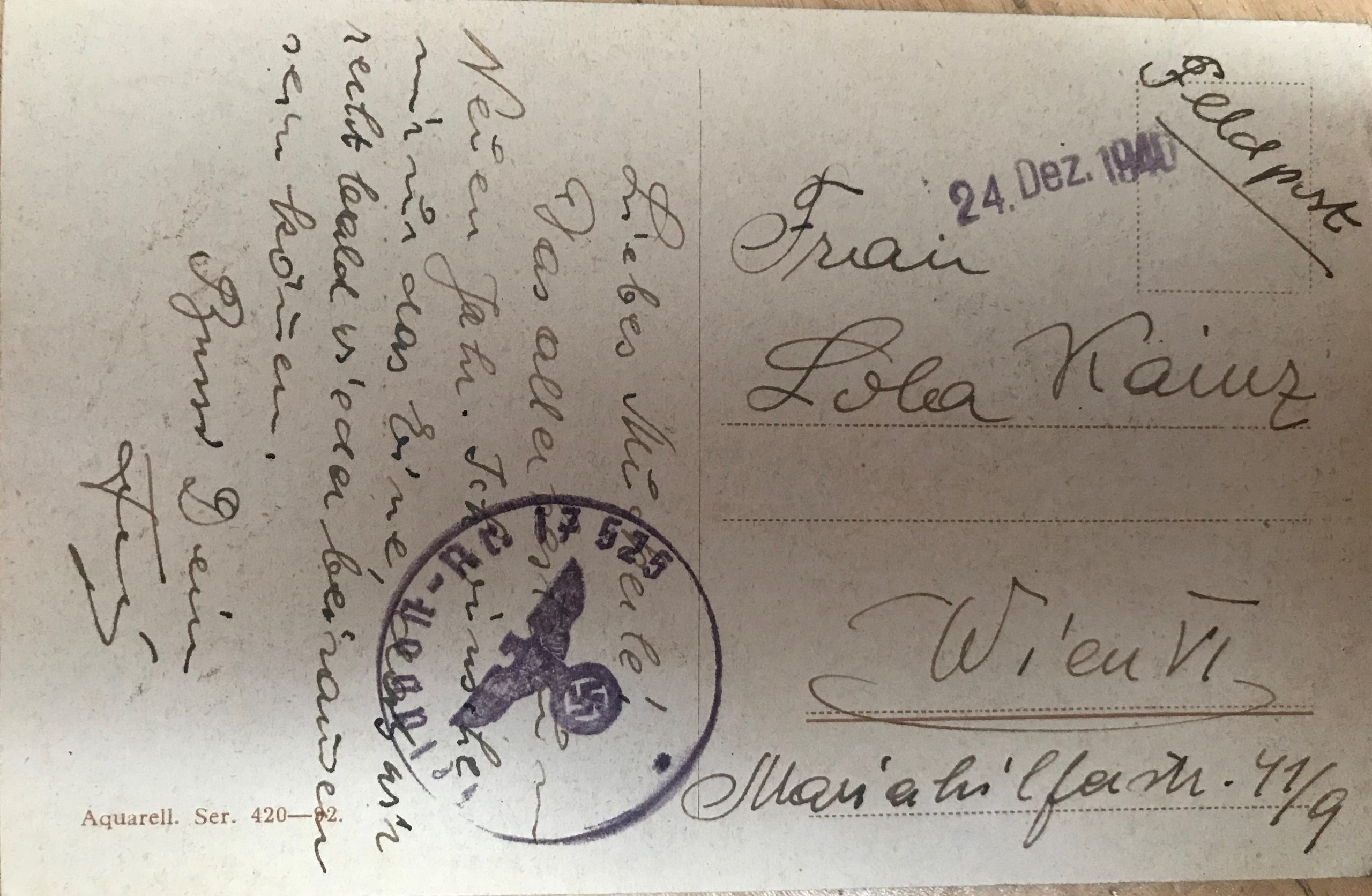

When Toni was drafted by the “Wehrmacht” for the campaign against France, he wrote this Christmas card to Lola from the front on the 24th December 1940 declaring his never ending love for her despite Nazi pressure to divorce her. He quoted the famous lines of the operetta aria “Das Land des Lächelns” by Franz Lehár: “Yours is my whole heart” on the front of the card.

The text Toni wrote, which was censured by the Army High Command, says: “Dearest Muckerle! All the best for the New Year. I only wish for one thing which is being together again very soon. Kisses, yours Toni”

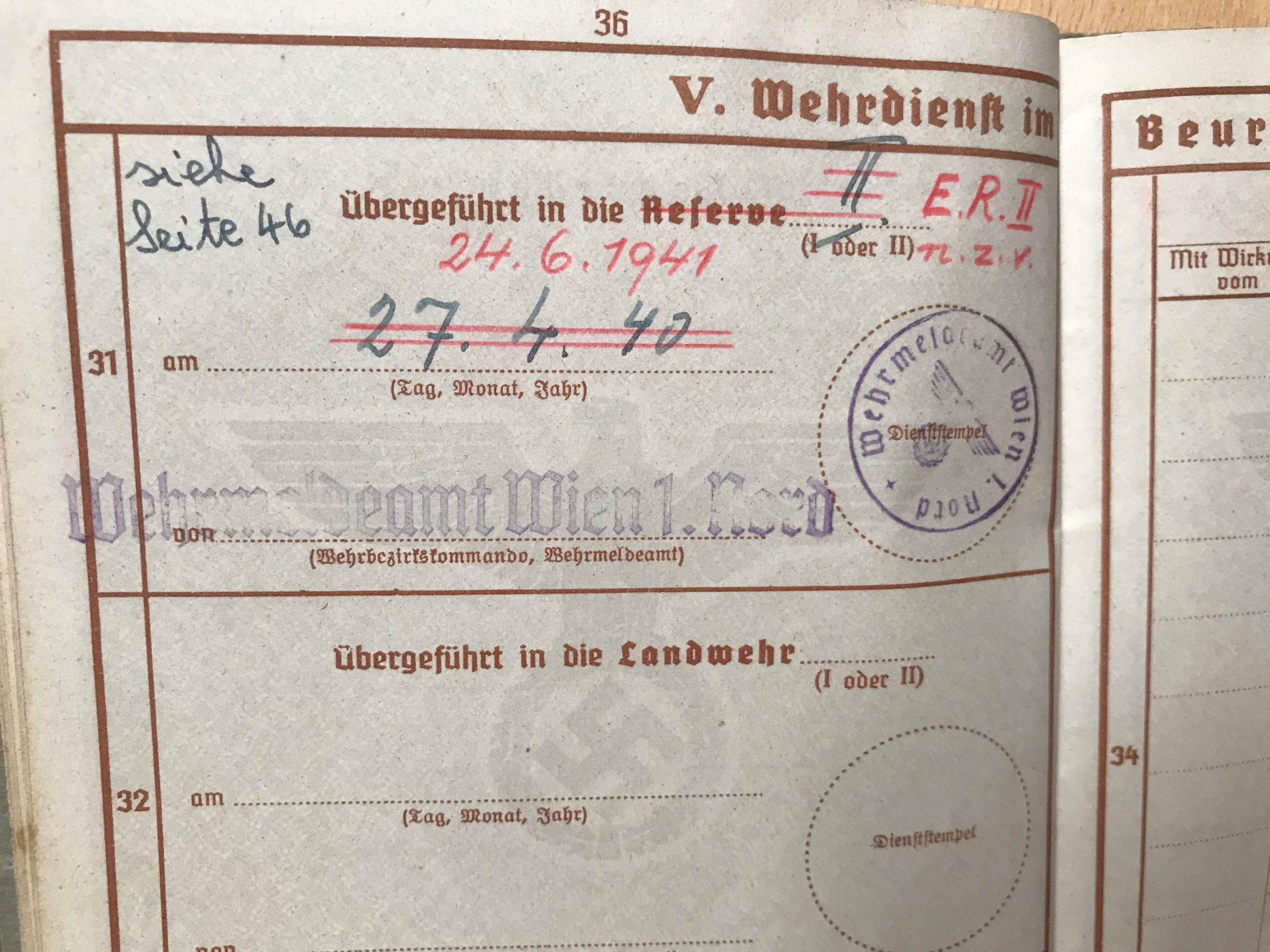

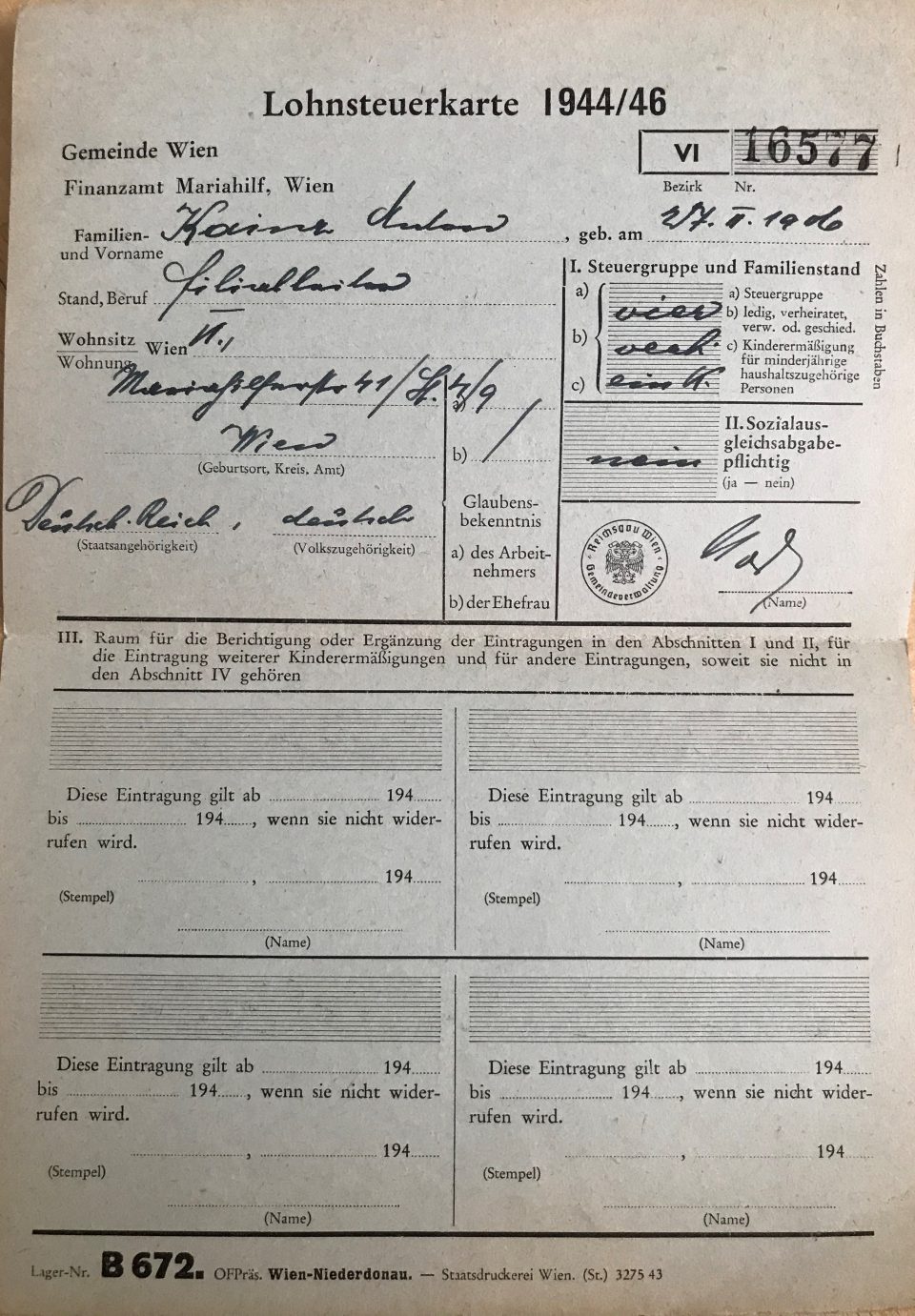

Toni,2nd on the right in front of the fish shop in Vienna, and his income tax card of 1944. He was made branch manager of a fishmonger’s after being dismissed from the army as “n.z.v.” (meaning “not to be used” ) because he had refused to divorce his Jewish-born wife, Lola. This is evidenced in his military service book in red: