Introduction

During and after the First and Second World War the food supply was severely hampered in Vienna, which resulted in famine, undernourishment and malnutrition-related diseases, especially among the Viennese young. Children and young people of impoverished and not so well-off families were most affected and consequently suffered from rachitis, tuberculosis and osseous tuberculosis. After the First World War measurements of Viennese apprentices of every age group showed that they weighed 10 kg less than the same age group before the war and their hight was 10 cm less as well. Already during the war poor undernourished Viennese children were sent on recreational holidays to the country and in 1917 the Viennese municipal councillor Heinrich Löwenstein organised a recreational stay in Switzerland for a few children. In May and July 1918 72,000 Viennese children were sent to farmers in western Hungary – then part of the Habsburg Empire – via the “Kaiser Karl Wohlfahrtswerk”, an imperial charity. 90 per cent of the children were more or less malnourished. Unfortunately, the positive effect of this summer holiday dwindled away within a few weeks. After the end of World War I and the break-down of the Habsburg Empire, its capital city Vienna was cut off from its traditional food supply chains and the newly established small Republic of Austria was destitute. During the disastrous winter of 1918/1919 the population of Vienna and other big cities in Austria was starving, most of all the young. The international press reported about the atrocious conditions under which the poor Viennese children had to live. Men like Max Winter with “Expeditions into the Darkest Vienna” and Emil Kläger with “Across the Viennese Quarters of Destitution and Crime” had already earlier in the new century pointed to the excruciating conditions under which the Viennese poor were scraping by. The international community was so shocked that in 1919 the first children relief programmes were launched, which not only provided the Viennese children with urgently needed food, clothing and medication, but organised recreational stays abroad as well. In 1919 13,366 Viennese children were invited to Switzerland, Italy and Southern Germany for a few weeks. From 1920 on more countries joined in the effort and financed longer recreational stays abroad from several months up to a year or more. These recreational holidays at foster families’ or in children’s homes abroad were organised by non-governmental charities, such as the Red Cross or the Caritas. Between 1918 and 1924 312,255 Viennese children were sent to the Netherlands, Hungary, Switzerland, Czechoslovakia, Germany, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Italy, Yugoslavia, Romania and other European countries. The children were registered for such a stay abroad at school, at the local parish or the youth welfare office and then medically examined. They were assembled at the train stations in Vienna, where they were equipped with a little cardboard sign around their neck, which stated their names and the names and addresses of their future foster parents. Already during the long train rides, they received provisions because they only had a small backpack with a change of underwear and a second pair of trousers or a second dress or coat with them. Sometimes the foster parents invited the children a second or more times to come back and stay with them, which resulted in life-long friendships. When the children arrived in their country of destination, they did not understand a word of the language spoken there (except when they came to a German-speaking canton in Switzerland or to Southern Tyrol or Southern Germany), but when they returned, they had mostly forgotten their mother tongue. It is amazing that rather poor countries such as Italy and Sweden offered generous humanitarian help to the destitute Viennese children and that is the reason why one focus of this article is on the post-World War I children emergency programmes “I bambini di Vienna” of Italy and “Rädda Barnen” of Sweden.

The so-called “children’s trains” initiatives were terminated in 1924 and only 20 years later the Viennese children were suffering under the same devastating conditions again, aggravated by the trauma of bomb attacks and Nazi persecution, until finally in April 1945 the Second World War was ended, the Nazi regime defeated and the city of Vienna liberated by the Allied Forces. Yet in 1945 the food supply of Vienna collapsed completely once more and the especially harsh winter of 1946/47 further aggravated the situation for the children in the city. The Viennese writer who had to emigrate to England when the Nazis took over, Robert Neumann, published his novel “The Children of Vienna” in his English exile in 1946. The book was translated into 25 languages and Neumann himself later published it in German. This novel portrays the destiny of poor children in Vienna in the days and weeks after the end of the war. In a humorous, bitter-sarcastic style he tells the story of six children living in the cellar of a bombed-out house in Vienna, trying to scrape by a living. He describes their special art of survival from the children’s point of view and tells of adults who try to interfere with them, such as a black US army pastor, who wants to send them to Switzerland, but whose plans fail, when the Russians take over the administration of their quarter. This novel raised international awareness for the plight of the Viennese impoverished children after World War II.

Post-World War I

During the First World War Viennese children whose health was affected by the consequences of the war were sent on recreational holidays, as already mentioned in the introduction. The priests in the country were asked to appeal to rural parishes to accept poor and sick urban children and care for them, cosset them and nurse them back to health for some weeks. The organisations who tried to set up a structure for recreational holidays for Viennese children in need who came from poor families or lived in slums were underfunded and inefficient. Only very few children profited from such recreational stays. In 1917 it was decided to set up a youth welfare office in Vienna, which initially included Lower Austria. 14 branch offices were opened in Vienna and its surroundings; the organisation of recreational holidays was one of their tasks, but little was done because of a drastic lack of funds after the war had ended in 1918. That’s when foreign countries stepped in. Tens of thousands of Viennese children were saved from hunger, sickness and death by these recreational stays abroad. In 1919 the youth welfare office sent 13,366 Viennese children to Switzerland, Southern Tyrol, Italy and Southern Germany for several weeks. Until 1924 the Netherlands welcomed 28,523 Austrian children, for example. The aim was, of course, to nurse the Viennese children in Austria, but the extremely poor new republic lacked the resources. So, in 1920 the American food aid programme was used to send 25,000 children to holiday homes and farmers in Austria. When in 1922 Vienna was separated from Lower Austria and was turned into an independent federal state, the city of Vienna launched its own youth welfare office. Due to the desperate financial situation of the city, municipal funds for recreational holidays for Viennese children only made up one eight of the arising costs per year. The City of Vienna reacted with donations campaigns, “Child Rescue Week” (Kinderrettungswoche), and a lottery. What’s more, parents who could afford it, were asked to make a contribution. In this way annually 30,000 to 35,000 Viennese children spent the summer holidays in the country. On top of that, 20 recreational day-care centres were opened on the outskirts of Vienna, where the children arrived in the morning, spent the day there in the natural surroundings of the Vienna Wood, were fed, participated in games and sports and in the evening, they returned to their homes. Furthermore, the city of Vienna acquired a few recreational children’s homes, which were operational the whole year round. Already in April 1916 the Vienna City Council had passed a law on “recreational care” due to the food shortage in the city, which stipulated that famished children should be cared for during the day in four leafy areas in the green belt around Vienna, which were bought by the city: Laaerberg, Girzenberg, Schafberg, and Kobenzl, between 1916 and 1919. In August 1916 the first recreational day-care centre for children was opened on Laaerberg, where some wooden military shacks were set up for the children. In 1918 1,200 children were cared for there on a daily basis. In the summer of 1918, the children’s day-care centres on Kobenzl and Girzenberg were opened and welcomed, respectively 400 and 100 children. In 1918 the Bellevue castle was acquired by the city on Kobenzl and was restructured as a day-care centre and in 1919 the centre on Schafberg followed. Undernourished Viennese children in need of recreation were fed and cared for in these day-care centres for four weeks. The 6- to 12-year-old children were examined by schools’ doctors before and at the end of their stay. All in all, in 1928 the city of Vienna owned five such day-care centres and it had set up another one on the banks of the Danube, the “Gänsehäufl”. They were run either by the WIJUG (“Wiener Jugendhilfswerk” since 1922) or the “Kinderfreunde” and “Volkshilfe”, private charities linked to the Social Democratic party, which was ruling the city from the end of World War I until the Austro-Fascist take-over of Austria in 1934. Immediately after the war around 1,200-1,500 children were sent to homes in the vicinity of Vienna, to Ober-Hollabrunn and Pottendorf, as well. Overall, 5,474 Viennese children benefitted from these domestic recreational stays in 1919. In 1923 2,575 Viennese children, who were threatened by tuberculosis and other diseases linked to malnourishment, were sent to ten children’s homes in other parts of Austria. It is obvious that this was completely insufficient in the face of starvation. An extensive famine relief programme was needed.

Let’s return to the situation in Vienna after the end of World War I in 1918. Hermine Weinreb, an eminent pedagogue and co-founder of the Social-Democratic children’s organisation “Kinderfreunde” started in 1918 an initiative for recreational stays of Viennese children in a home in Gmünd, Lower Austria, with the help of the American children relief programme, where 1,400 children were cared for during a six-week summer holiday. She was involved in the cooperation with Italy, too, “I bambini di Vienna”. The famine crisis in the city was somehow alleviated by emergency food transports from abroad. The French and the British sent “food trains” with urgently needed basic food rations to prevent starvation in the city in 1919. Denmark and Sweden set up public kitchens which tried to feed the famished masses. But what really remained in the memory of the Viennese was another international emergency programme: the recreational holidays for Viennese and other urban Austrian children abroad. Tens of thousands of poor and famished Viennese children were invited in 1919 and 1920 to stay with foster families or in children’s homes for several months in Denmark, Norway, Sweden, England, the Netherlands, Germany, Switzerland, Spain and Italy. These were private initiatives and one of the first transports left Vienna on 3 February 1919 with the destination Switzerland. The primary school teacher Oskar Kahn from Ottakring, a working-class district of Vienna, accompanied a group of Viennese children and he remembered that the children had to sleep in the train carriages and ate only cheese and bread because of the straitened circumstances. Yet as soon as they had crossed the border to Switzerland, the experience of hunger was a past memory. In the border town Buchs the children received for the first time a warm meal, chocolate and cake – and “the food was abundant and excellent”. At the same time, they were given little presents by the locals, mostly chocolate. Unfortunately, as the small stomachs were used to fasting only, they could not digest the large amounts of sweets. The group finally reached Bern, the capital city of Switzerland, and the reception there was marvellous, too. The population awaited the children and had to be kept back by policemen, when they wanted to storm the train carriages to welcome the children who were given presents once more.

These children emergency programmes met with a wide response in the Austrian public. The press reported about the departures of “children’s trains” carrying children to their recreational holidays abroad. Apart from rare memoirs this is now the most important historical source for the aid programmes of 1919/1920. The famous Austrian writer and journalist Joseph Roth wrote for the Viennese paper “Der Neue Tag” and described the parents who were taking their children to the train station. They were poor working-class parents who stood tightly packed on the platform, thin and emaciated, “resembling squeezed-out lemons”. “Wiener Bilder”, a Viennese weekly magazine, reported about the cheery warmth with which Viennese children were welcomed in England in October 1920. In March 1920 “Das interessante Blatt” published an article about the departure of Viennese children to the Netherlands from the North Station. Furthermore, the Viennese journalist Max Winter who for years had been publishing very well-researched articles on the plight of the Viennese poor in the “Arbeiterzeitung”, the Social-Democratic paper, launched an international media appeal for the rescue of the famished Viennese children of the underprivileged. He is today seen as the innovator of social reporting, the inventor of which is considered Egon Erwin Kisch. Max Winter went much further, though, and painted devastating pictures of the underground of the glamorous capital city of the Habsburg Empire. He raised awareness for the destitution of the homeless who lived in the canal system of Vienna. He dressed up as a homeless person and spent time in the canal system, in shelters and the slums of the city. By that he reduced the distance between the journalist and the subjects of his research. He was trying to be close to the poor, to understand their living conditions, their language and he sympathised with them. His meticulous research and analysis under which the children of the poor lived in Vienna after World War I provoked a public outcry and triggered widespread international concern, which contributed to the start of various private aid initiatives.

Neglect and abuse of children had spread before and during the First World War in Vienna among the poor, which the first Children’s Congress of 1907 confirmed. At that time neglect of children was linked to criminal activity, juvenile delinquency and anormal behaviour of the young. When the war broke out, fathers were drafted and working-class mothers were called to fatigue duty, so the situation worsened as the children were left to themselves. When the food supply was drastically cut in Vienna, working-class mothers were preoccupied with the daily fight for scraps of food to feed their children and no time was left for caring for these children. Teachers documented the bad health of the pupils und described under which disastrous conditions the children lived at home; in one dirty, mouldy room where several people had to eat, sleep and live. In September 1917 the “Arbeiterinnenzeitung” wrote that a teacher reported that she did not know where to store the pupils’ hats and coats because they were full of lice. A doctor who had examined these pupils found that 90 per cent were ridden with lice. Everywhere on the walls and benches of the school rooms vermin crawled; they were even stuck to the teaching aids and bugs were swimming in the ink pots. Scabies was so widespread that even the teacher was affected by it. Due to the war the school hours were reduced and these children then spent most of their time in the streets of Vienna. Several were orphaned due to the war or had lost contact to their families. The Viennese police tried to find their parents via appeals to the public, mostly in vain. This phenomenon is documented in contemporary police statistics which categorise the roaming children as young criminals. Complaints of juvenile delinquency up to 14 years of age rose from 1,848 cases in 1913 to 5,926 in 1917 and 4,972 in 1919 and those between 14 and 18 years of age increased from 4,314 to 8,995 in 1918 and 8,059 in 1919. Stealing in order to procure some food was rampant and the children sold everything possible on the black market to be bartered for food, even the family’s own scarce furniture. Max Winter appealed to the government in 1915 that it was unsupportable that children in Viennese working class districts started to queue in front of shops at 10 pm to receive some flour when the shop opened at 7 am. Many women and children had seriously fallen ill due to the night-long queuing in the freezing cold. The Viennese paediatrician Clemens von Piquet documented the effect of the social and moral neglect and the widespread famine on the health of Viennese children at the “Wiener Kinderklinik” in 1918. Of the 498 children treated there 90 per cent were severely undernourished. Boys had 20 per cent less weight than normal and girls 18 per cent, which meant on average 6 kg less for boys and 5 kg less for girls in the age groups of 6 to 14. Yet during adolescence the weight loss was even more drastic: 14-year-old girls weighed 8 kg less and 14-year-old boys 10.7 kg less than normal. Due to these deficiency symptoms their bodies were drastically underdeveloped and the process of growth was retarded. Unfortunately, this affected their brains and their psyche, too. The children showed apathy, were exhausted and feeble, which sometimes resulted in an inability to walk and those children were then bed-ridden. Their fecklessness made them susceptible to infectious diseases; famine oedema, rachitis and tuberculosis were rampant among them. The increase in tuberculosis cases was most drastic in the age group of 5 to 20, Piquet found. His hospital recorded a doubling of related deaths during the war years. The Viennese statistic of death rates of children of school age showed 1068 in the year 1914 and 1995 in 1918. Max Winter documented in 1916 in “Der Kinderfreund” that the destitution of Viennese children was now incomparable to the destitution before the war; so many lost, neglected and famished children in Viennese streets as never before, so many soldiers’ children whose mothers could not procure enough food and so many working-class children whose parents had to work in ammunitions factories and still could not feed their families due to the catastrophic inflation. Heinrich Löwenstein stressed that it was necessary to reduce the mortality rate among children, which was 43 per cent in the age group of 5 to 10 and 26 per cent in the age group of 10 to 15 and he pleaded for recreational holidays of Viennese children in the Vienna city council. Löwenstein had already organised recreational holidays in Switzerland in 1917 and then coordinated the Danish relief effort in 1920. The Spanish flue in 1918 further exacerbated the situation in Vienna and pushed up the mortality rate in all age groups because due to their weakened health conditions the children quickly succumbed to the Spanish flu and had no defences.

The Italian post-World War I children relief programme

At the end of the year 1918 the Americans and their Allies diagnosed Austria as one of the countries that was most severely hit by the aftershocks of the war. One focus of this article is laid on the generous help of countries welcoming Viennese children for recreational stays, which were themselves rather poor countries struggling with economic difficulties after the war, namely Italy and Sweden. While Sweden had not been in involved in World War I, Italy suffered under the atrocities of the so far bloodiest war in history and had been fighting together with France, Great Britain and the United States against the Habsburg Empire and its Allies. That’s why it is a show of exceptional humane spirit that northern Italian regions lent a helping hand to starving Viennese children as one of the first countries in the world by inviting them to stay with host families in Italy, “I bambini di Vienna”. The appeal of the Viennese journalist Max Winter was heard in Italy, where immediately committees were founded and communities, religious institutions and even sports clubs offered to help. The first Italian regions to react were Bologna, Reggio Emilia and Milano, followed by Ravenna. A first appeal to welcome starving children from Vienna in Italy was issued in the Italian press at the end of 1919. On 24 November 1919 Pope Benedict XV asked the Italian public for help, too. Apart from Catholic aid organisations, Socialist-governed Italian regions and cities wanted to show their solidarity with the poorest of the poor. It was important to take the Viennese children to Italy before the harsh winter months set in because that was the toughest time for the children. “Red Cities”, such as Milano, Bologna and towns in Reggio Emilia were prepared to host poor children from Social-Democratically governed “Red Vienna”. Consequently, several smaller cities and communities joined in the aid effort. Already in December 1919 the first trains left Vienna heading towards northern Italy with famished Viennese children on board. On the way back the trains carried food, medication and clothing to the hard-hit city. On 29 December 1919 the Social-Democratic newspaper “Arbeiterzeitung” reported the departure of the first “children’s train” to Italy, which took 428 undernourished Viennese children to the Italian Riviera with the support of the Socialist communities in northern Italy and on the initiative of the Viennese “Kinderfreunde” representative Hermine Weinreb. The “Wienerzeitung” wrote, “THE FIRST CHILDREN’S TRAIN TO ITALY. Sunday at 9.30 pm the first train with Viennese children left from the South Station to Italy, to the country of the enemy of yesterday, where today, thanks to the aid organisation of the Social-Democratic communities of Northern Italy, most noble love of mankind is awaiting them, in order to give them back in body and mind, what the war robbed them of. The train is solely equipped and financed by the city of Milano and runs via Milano, Genova and San Remo to the children’s colonies of the city of Milano in Porto Maurizio, Pietra Ligura, Leano, Borgio and Scalorno on the wonderful Riviera, where already blooming violets are awaiting them and the lucky children will remain in this paradise until the end of April, when also here the violets will be blooming and the spring sun will be warming up our homes on their return… The train is accompanied by the comrade mayor of Milano Caldaro,…… and what’s more ten children’s nurses and the necessary personnel for the train and the kitchen. The train consists of ten carriages. The children are accommodated in well-heated 2nd-class carriages and each of them has a warm blanket. The kitchen carriage and the hospital carriage, which form part of the train, are well-equipped and the larder attractively stocked. All in all, 438 boys and girls at the age of seven to twelve are travelling, who have been sorted into groups of 25 by the workers’ club Kinderfreunde. In the afternoon they were examined by the Italian doctors at the headquarter at the Heumarkt. Already at 5 pm they arrived at the station together with the pedagogical head Kanitz, the club’s representatives Stuppäck,…. Hermine Weinreb, Karola Eckel and three ladies from the youth welfare office will accompany the children on the journey. Many were waving Italian flags to greet their Italian friends, who in the most heart-warming way immediately took care of them, carried them into the carriages and showed them their seats. The children realised immediately that these were loving friends in whose care they were given.” Then the children’s choir of the “Schönbrunner Hort” (a Viennese Social-Democratic pedagogical reform project) paraded on the platform and sang the “Kinderfreunde song” for the departing children. ”The parents could not be present on the platform, when the children were loaded onto the train, so some asked anxiously: Will my mother still come? Then the parents had enough time to take leave of their children, because when the children were fed – there was soup, bread rolls and oranges – the platform had to be cleared again.” The Vienna Vice Mayor Winter then took leave of the children, gave them a songbook each and thanked all the Italian representatives present. “When the train finally started rolling, there were lots of tears, but also joy and waving of flags of the happy children. All those left behind were convinced that the children were travelling towards happy days as they had been observing the warm-heartedness of the Italian comrades, even the most worried parents. On the way back a tramway worker said to his crying wife: Stop crying, the children will have a good time; we have seen that!”

In the last December days of 1919 another train arrived in Ravenna, which carried 120 children at the age of seven to thirteen. In the following days these children were distributed among the surrounding towns and villages. For instance, 25 boys arrived in Faenza on 1 January 1920. Initially the boys were accommodated in the rooms of the Palazzo Mazzolani, which housed a local charity that was run by the medical doctor Antonio Bucci. The local paper “Il Socialista” had already announced the arrival of the children and appealed to the solidarity of the population with the stricken children. They wrote, “The children of Vienna are hungry….The proletariat is supporting them in the name of humanity that unites all peoples.” This appeal was successful and the necessary funds to feed and house the children were raised. Already in the first week after the appeal the donations amounted to 1,383 Italian lira which finally rose to 8,843 Italian lira, which would be 10,200 euros today; a large amount of money for the small region of Faenza after the war. The organisers saw to it that all children received an equally good board and lodging. On 11 April 1920 a festivity was organised in Faenza to celebrate the end of the children’s stay and apart from the local dignitaries, one of the Viennese boys spoke words of gratitude in correct Italian for the whole group of boys. Within a few months the boys had regained their strength and energy; they were lively boys again. They had received good warm meals, they had learned Italian, had participated in games and sports activities, had visited other cities and undertaken excursions. Their days had been fully planned. The success of the programme was reflected in the Viennese press at the end of the winter, too, where the papers reported about the warm welcome the Viennese children had experienced in the region of Ravenna. Yet unfortunately, one of the boys the 10-year-old Carl Binder, who had been suffering from tuberculosis when he arrived in Italy, died in the local hospital of Faenza on 2 April 1920 despite intensive medical care by doctor Italo Civalleri. The population of Faenza formed a long funeral procession along the streets from the hospital’s chapel to the graveyard. On the cemetery of Faenza the grave of “Carlo Binder Vienna 1910 – Faenza 1920” can still be seen. “Al di sopra delle frontiere” (across frontiers) is written at the bottom of the tombstone. Because Carl’s mother could not come to his funeral in Faenza in time, hundreds of local women dressed in black and followed the cortège of the little Viennese boy as a sign of respect and solidarity with the Viennese family and the stone mason created the tomb stone for Carlo at the cemetery of Faenza free of charge. During these recreational stays in Italy apart from Carl Binder one more child died of malnutrition-related diseases. On 19 April 1920 the remaining 24 boys boarded the train in Ravenna and arrived at the Vienna South Station few days later. A commemorative plaque at the Palazzo Mazzolani commemorates “I bambini di Vienna”: “In memory of the Viennese children who were welcomed by the community of Faenza in a brotherly way 1920-1990”. The “Neue Zeitung” reported in December 1919 that the first transports to Italy were supposed to bring 1,500 children to northern Italy.

Angelo Emiliani, who researched this aid initiative, called this Italian famine relief programme offered to starving Viennese children by the “Italian workers less than a year after the end of the Great War one of the most beautiful aspects of the early 20th century”. After the disaster of World War I the Italian communities, governed by Socialists, led by Milano, Ravenna and Reggio Emilia decided to come to the rescue of the Austrian children “who were condemned to death by the cynicism of the victors no less than the inevitable consequences of the war”. This gesture was intended “to promote the peace-making between peoples who until a few months before had been killing each other in the trenches of an atrocious war”, namely the Austrians and the Italians. Another motivation of the Italian initiators of the programme was, according to Emiliani, the boosting of “the solidarity of the working class across borders, as it had paid the highest price in this military conflict and was still paying the price after the war”. In the province of Ravenna the appeal fell on most fertile ground. The Chamber of Labour of Ravenna, as the only one in Italy, agreed to welcome around a hundred children of Viennese trade union members and they asked their own members to donate 5 lira per man and 2 lira per woman to meet the costs of this recreational holiday programme. Furthermore, funds were raised in other trade union centres in the region. Goivanni Giovannnetti and other functionaries and representatives of several cities in the region went to Vienna to arrange the transport and accompany the children on their journey to Italy. The medical doctor from Faenza, Antonio Dalprato, “the doctor of the poor”, cared for the Viennese children on this ”children’s train”. The train arrived in Ravenna on the 1st of January 1920 with 120 children on board, accompanied by two teachers. 26 of them were hosted at the local Chamber of Labour which provided a dormitory, a dining hall, a kitchen and a school room with cloakroom for the Viennese children. The other 8- to 12-year-old children were welcomed in the communities of Faenza, Lugo, Massa Lombards, Bagnacavallo, Fusignano, Mezzano and Cervia. The local communities tried to raise further funds for board and lodging of the children via lotteries and appeals to members of the Socialist party. The children were invited to opulent dinners by local families and participated in local festivities. At Faenza the children were lodged in five rooms of the Palazzo Mazzolani. Citizens of Faenza remembered that the children were pale, emaciated and some even sick. On 19 April 1920 the children returned to Vienna, as was noted in the newspaper “Il Socialista”, which used the children’s recreational holiday for propaganda purposes and spoke of the “international brotherhood of the workers”.

The presence of hundreds of poor children from Vienna in Italy for four months triggered an ideological dispute, which somehow superimposed this message of hope and solidarity. The local press either ignored the stay of the Viennese children or used it for its political polemics. The Catholic paper “L’Idea Popolare” sarcastically described the relief programme as “the red committee of Faenza”, which separated the “poor famished and unhappy children” from their families and “forced them to work in order to lock them up in a colony in Cervia”. Although in Bagnacavallo some of the children were handed over to nuns of a religious institution, the paper claimed that the children had been brought to Italy not to cocker them up, but “to lead them away from Christendom and to poison these innocent children with the ideas of pseudo-freedom”. The republican papers did not mention the programme at all, but wrote about an initiative of Gabriele D’Annunzio, which was directed by Benito Mussolini, and which was launched in opposition to the project “I bambini di Vienna”, namely the “rescue of children from Fiume “(Rijeka), which the Fascists called the “crusade of the little legionaries”, whereby several hundred children from Fiume in Istria were transferred to Milano and other cities in northern Italy by the central committee of the Italian Fascists in April 1920. D’Annunzio abused the children of Fiume to support his claim of the city for Italy, as the city was contested by the newly founded Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. While the Fascists exploited once more the nationalistic antagonisms which had caused World War I, the project of “I bambini di Vienna” tried to overcome just these antagonisms and set an example of peace, not to consider borders as walls and promote humanism and solidarity among people of different nationalities. The Viennese children, children of soldiers who just a few months ago had been forced to shoot at Italian soldiers, were invited by Italian families for dinner, families who were definitely not wealthy themselves. The children were cared for, cured of diseases caused by deficiency symptoms, they were taken on outings, visited sights and later told their families at home about their happy experiences. The project “I bambini di Vienna” seemed to have petered out due to Italian political polemics and unfortunately did not survive the onslaught of Fascism of Mussolini and D’Annunzio. Max Winter wrote in 1927 that the “children’s trains” to Italy, organised with the help of the Italian Socialists Pittoni from Trieste and Caldaro, Mayor of Milano, enabled 7,000 Viennese children to spend a four-month holiday in Italy.

The Dutch post-World War I children relief programme

In a similar way the Dutch relief programme was characterised by political and religious strife in the host country itself. Yet it has to be stressed that the Dutch and the Danish children emergency programmes were offered by two countries which were economically better off than Italy. Both countries managed to stay neutral during the First World War, but the Netherlands were in a precarious situation as soon as its neighbour Belgium was occupied by the German Empire. Dutch initiatives to fetch Austrian children to the Netherlands for recreational stays after the war were carried out by private religious and political groups, which were only reluctantly supported by the state, as the government aimed for a coordinated national relief action, but that was never achieved. This situation reflected a society which was torn along ideological, religious and class front lines, similar to Italy. The strong competition among these groups culminated in a race for moral superiority; orthodox Protestant groups against liberal Protestant groups, Catholic groups and orthodox Protestant groups against each other and both against a liberal state and finally Social Democrats against the capitalist bourgeoise state. Yet this competitive spirit had the positive effect for the Austrian children that every group tried to get a state permission to welcome as many children as possible in the Netherlands for their individual committees. The battle for moral superiority was fought in the Dutch media as well.

The Protestant committee selected only Protestant children to be hosted by Protestant families in the Netherlands. Originally, they were not allowed to accept Viennese children because the Dutch state had given this permission to Catholic, Jewish and Social Democratic committees, but in the autumn of 1920 also Viennese Protestant children were transported to the Netherlands. Before the children were handed over to the foster families, they were all billeted in a hotel which was turned into a hospital and quarantine station. There also the children who travelled on to Great Britain were examined and it was checked whether they suffered from any diseases of the skin or respirational apparatus, had lice or – surprisingly – the girls were examined whether they had venereal diseases. All of the children who arrived were feeble, small, pale and skinny, were undernourished and anaemic. If they caught an infection, it always turned into a serious sickness with high fever and grave after-effects. During the first month the children put on two to three kilogrammes, but they were still anaemic and the foster parents were advised not to offer too much food at the start because their small stomachs could not digest it and they would suffer from gastroenteritis. The vast majority of children were from a well-to-do middle-class background and only very few working-class children were selected; for instance, the first train from Graz transported 485 children, 50 of which were working-class children. In October of 1922 the Protestant children emergency programme was terminated and it is not documented how many Austrian children were hosted by this organisation.

The Jewish committee started to bring children to the Netherlands in July 1919 in a train that carried 480 children, most of them from Vienna. In the year 1919 3,000 children found Jewish host parents, mostly in large Dutch cities, as very few Jews lived in the Dutch countryside. The Jewish committee welcomed more than 4,000 children from Vienna until the end of the relief programme in 1921. In the year 1919 the Jewish relief organisation cared for a quarter of all Austrian children in the Netherlands, namely 3,000 out of 11,400, but their numbers then dropped continuously, probably due to the complaints of opposing groups that funds for domestic recreational stays of Dutch children were “wasted”. Yet the committee countered that the Viennese Jewish children were not staying in the country anyway, but in large Dutch towns and above all, the initiative contributed to an excellent international image of the Netherlands. As half of the Jewish population of the Netherlands, which constituted less than 2 per cent in 1920, lived in Amsterdam, this city had a crucial role in raising funds for the recreational holidays of Viennese Jewish children. Contrary to other committees, the Jewish committee’s cooperation with its counterparts in Vienna was frictionless, most of all due to the commitment of Anitta Müller-Cohen, who organised the recreational holidays and the food transports to Vienna. Several complaints of the other committees were voiced with respect to the unwillingness or inability of the offices on site in Austria to select children who were matching the wishes of foster parents related to religion, class, age or gender of the foster children.

The Catholic Dutch committee represented the 40 per cent Catholics in the Netherlands and worked together with priests and religious organisations in Austria and the Catholic Farmers’ Union. They hosted the Austrian children in the south of the country, which was predominantly Catholic. The Catholics in the Netherlands felt threatened by a state which stressed the Protestant and liberal nature of the nation. All in all, the Catholic committee offered recreational holidays to 28,523 children from Austria, which constituted 44 per cent of all Austrian children in the Netherlands. The Dutch Catholics felt discriminated against and projected this feeling onto the Viennese children, stressing the moral duty of “Christian Caritas” and the message of “Christian love and peace”, which could be sent to the world via this initiative. The Catholic committee worked together with the Catholic Women’s Club in Austria and from autumn 1919 on with the Maltese chivalric order, headed by Graf Wolff-Metternich. The number of Catholic children sent to the Netherlands increased drastically until 1920 and then gradually declined until 1924.The appeal of the committee to welcome Austrian children was exclusively directed towards Catholic families. The Catholic propaganda focused on the “special need of Catholic children in Vienna who suffered most”. Willem Galesloot published a number of articles about the conditions in Vienna, which he had written when travelling with a “children’s train” and staying in Vienna for a month in the autumn of 1919. These articles were published in the Netherlands and represented the state of an ideologically divided society. Galesloot stressed that the Catholics were discriminated against by the Social Democratic city administration in Vienna and compared this to the supposed disadvantage the Dutch Catholics experienced at home. He claimed that “the Socialist city administration with respect to the distribution of food only left tiny scraps for Catholics”. Apart form attacking Socialists and Liberals, he also dwelled on anti-Semitic stereotypes and accused all of the other committees of indoctrinating Catholic children in non-Catholic families. Galesloot further made the totally false claim – for propaganda reasons – that bourgeoise children had to be preferred because in Vienna “the middle class suffered the most, while workers were earning high salaries and cooperating with war profiteers”. He mobilised all possible religious, ideological and class resentments against “Red Vienna” in order to stress that the Dutch had to prevent a similar development in their country. He stated that “the workers earned unbelievably much and had to spend much less on clothing and rent than civil servants… In Vienna the world was turned upside-down; there was political chaos and the police did not interfere. The power was in the hand of workers’ councils and soldiers’ councils and the Catholics were at the mercy of despotism and terror.” He then contrasted this distorted picture of Vienna of 1919 with the glorious past of Vienna as the city of culture and music and threatened that all that was lost in Vienna might also soon be lost in the Netherlands. As a result, the Catholic committee abused the children rescue programme excessively for its own propaganda purposes in order to stress the supposed moral and religious superiority of Catholicism.

Finally, the Dutch Social-Democratic aid for Austrian children was founded as the last committee in August 1920 by the Dutch trade unions and the Dutch Social Democratic party. They focused on inviting only children of Austrian trade union members. Until February 1922 they sent around 3,000 children on five “children’s trains” to the Netherlands. Host parents were mostly found in Social-Democratically dominated regions, such as large cities and the provinces of Groningen and Friesland. Contrary to the Protestant, Catholic or Jewish committees they could not rely on donations of rich citizens; they had to resort to aid campaigns, selling postcards and flowers in the streets and tapping the funds of the trade union and the party. They used propaganda, too, stressing the duty of every worker to help the famished workers’ children in Vienna. They blamed “the Viennese bourgeoisie which did not attend to the misery of the workers; religion and bourgeoisie did not do their duty and bring help to those who needed it most.” The Social-Democratic committee mentioned the nostalgic image of Vienna as the city of culture, too, in the sense that they wanted the Dutch workers to be able to profit from these cultural ideals and values as well. The liberal committee tried to integrate all different Dutch groups and tried to help across barriers of religion, ideology or class, but also the liberals focused on assisting the Austrian middle-class via their personal connections to Austria. Overall, the Dutch children relief programmes strictly divided the Austrian population along religious, ideological and class lines and the majority of Austrian children who profited from Dutch aid were from the well-to-do bourgeoisie. The city of Vienna named the “Hollandstrasse” in the 2nd district after the Dutch to thank them for the children recreational holiday programmes after World War I.

The Danish post-World War I children relief programme

In a similar way the Danish initiative to bring Austrian children to Denmark for recreational holidays was mainly directed towards Viennese middle-class children and the city of Vienna named a social housing complex “Kopenhagenhof” in the 19th district, Billrothstrasse 8-10, and a street, “Dänenstrasse”, to thank the Danes for their effort to rescue Viennese children after World War I. The Danish committee for Austrian children originated in a private Danish-Austrian network of relatives and friends of the liberal Copenhagen bourgeoisie. It turned into a national institution within a short time and represented the ideal type of humanitarian assistance that characterised Danish charities over the following decades. The “Viennese children” held a special place in the hearts of the Danes and in Danish social history for a long time. The wife of the Danish ambassador in Vienna, Emmy von Medinger, started the project with the help of friends who invited 104 Viennese children to Copenhagen. When the “children’s train” arrived, other interested Danish citizens contacted the organisers, whereby usually private contacts to Vienna were the trigger. The Austrians tried to organise the children’s project along the lines of the Swiss project, which Heinrich Löwenstein had launched. Löwenstein then headed the Danish project on the Viennese side as well. The aid for Vienna was justified in the Danish press, in public appeals and talks as a philanthropic project and a moral duty to alleviate the misery the Viennese bourgeoisie was undergoing. It was aid for equals and the Danish bourgeoisie could project their fears and insecurities on the suffering Viennese bourgeoisie. Although geographically Vienna was far away from Copenhagen, the Danish middle-class identified with the destiny of Vienna, the “occidental capital city of culture and music”, which in the eyes of the Danish bourgeoisie was threatened by Bolshevism that could spread to other parts of Europe, namely Denmark, as well. The lines of argumentation were the following: if the distress in Vienna was not combatted, it would open the door for a Bolshevik takeover there. Vienna’s past as a metaphor for bourgeoise culture and art from Mozart, Beethoven and Schubert to the Viennese waltz was glorified and it was stressed that in “this topsy-turvy world, provoked by the war, this high culture was threatened”. This explains to some degree why the aid for Viennese children was supported to such a high degree by the Danish middle class. Another aspect was that Vienna was not “German” and although German cities like Hamburg, Kiel and Berlin were geographically closer, the children emergency programme for Germany did not meet with the same enthusiasm among the Danish population. The advantage of Vienna seemed to have been that it offered the in the Danish bourgeoisie much loved German culture without the threat of German hegemony. For a long time, a close link had existed between Copenhagen and Vienna with respect to culture and lifestyle, while Sweden and Germany were rather seen as old rivals and enemies.

This class-conscious attitude of the Danish committee was not undisputed, especially the close cooperation of the committee with the Austrian nationalist and Catholic “Jugendbund”, which was in opposition to the Social-Democratic Viennese city administration. The committee was accused of not accepting any working-class children, but finally a compromise was found with the Danish Social-Democrats. The Danish committee claimed that 60 per cent of the Viennese children who had been hosted in Denmark had been working-class children and they agreed that in every “children’s train” 75 children of trade union members would be transported. Controversies about the children relief programme did not erupt along religious lines in Denmark, but along party and class lines. Another problem cropped up, when only very few German children were invited by Danish foster families, because the “Viennese children” were much preferred, which might have hampered the transit of the “children’s trains” across Germany.

In Vienna the “Jugendbund” organised the selection of the children and the necessary medical examination. The children had to be undernourished, but strong enough to endure the long journey and they were not to suffer from any infectious diseases. In the Protestant school at Karlsplatz this selection procedure took place twice within two weeks and the children were rid of lice and other vermin. The “Jugendbund” organised and paid for the transport to the Danish border and the Viennese parents had to pay a contribution of 100 Danish crowns. This of course excluded any poor children from this recreational holiday. On 4 November 1919 the first “children’s train” left the “Franz Joseph’s Station” in Vienna with 416 children on board. The journey normally took 30 hours, but this train was delayed at Warnemünde, where they had to wait for the ferry for some hours. On the ferry the children received their first warm meal consisting of milk, “smörrebröd” (bread, butter and cooked fish) and cake. Then a train took the children from Gedser to Copenhagen. On 6 November 1919 at 11 pm the first children were handed over to their foster parents, while the remaining 150 children were transported to the warehouse of a bookseller, where camp beds had been set up amid the book shelves and the children were fed cocoa and cake. Afterwards these children were taken to Funen, Jutland and North Seeland. It can be seen that the first transports were rather improvised. Later the children were properly fed during the train journeys by the Red Cross and American food aid and a school in Copenhagen was equipped with beds for the children in transit to other parts of Denmark.

The Swedish post-World War I children relief programme

Sweden was one of the countries, which was most generous in extending help to Viennese children, although it was not well-off and went through difficult times after 1918, economically and politically. Sweden was small in population size and rather poor, compared to Switzerland for example. Yet despite this lack of resources the Swedish private initiatives organised help on site and offered long-term recreational stays of several months up to a year or more, while other countries offered usually two-month-holidays to the needy Austrian children. The Swedes felt they had to lend a helping hand to the Austrians because they had had the luck of escaping Austria’s fate of being involved in the war as a neutral country. The Swedes were shocked by the reports they read describing under which conditions the Viennese children had to live. They felt they had to rescue the young for a peaceful future of Europe, because only the young generation would be able to lead their home country out of destitution and poverty. The memoirs of Elsa Björkman-Goldschmidt, who was working in Vienna for the Swedish children emergency programme ”Rädda Barnen” (Save the children), constitute a valuable source of information for understanding how the programme worked. She worked as a foreign correspondent for the “Dagens Nyheter” and came to Vienna in September 1919, where she married a Jewish Viennese doctor. Another source of information is a book of commemoration published in 1926 to thank the Swedes for their generous help. Most of the Swedish aid initiatives targeted Viennese children. Other countries had already started their aid programmes, when in the spring of 1919 the Swedish Red Cross set up its headquarter in the imperial castle “Hofburg” in Vienna and in November of the same year “Rädda Barnen” was launched. The Swedish Red Cross (SRC) headquarter was situated in the former imperial audience chamber, where the Swedish and the Austrian personnel took their meals in Habsburg opulence. Never before had ordinary people eaten simple thick soups made of potatoes, cabbage and few small meat chunks in this environment.

The motto of “Rädda Barnen” was “The only international language is the crying of a child”, meaning that all children should be helped, no matter which ethnicity, language, religion or colour of skin. Most of the money for the aid programme of the Swedish Red Cross came from Swedish citizens, only 15 per cent was contributed by the state and two thirds of the funds were used to help Austria, most of all Vienna. The Swedish ambassador in Vienna, Oskar Ewerlöf, coordinated the aid programme in Vienna, where the Swedes first had to learn something about the Viennese mentality. The Swedes thought that the Viennese would feel ashamed of having to accept help and so they tried to organise the food and clothes distribution as impersonal as possible with vouchers which entitled the needy to receive aid parcels. Yet the Swedes found out that the Viennese loved talking about their plight and pouring out their hearts when receiving help. Furthermore, it was difficult for the Swedish aid workers to find the right persons in Vienna to assist them on site because the Viennese thronged the Swedish outposts in the hope of receiving a warm meal. The Swedes at home could purchase a food parcel cheque for 10 Swedish crowns, which would then be distributed in Austria to the needy, the so-called “Kronenpakete” (crown parcels). There were five categories of food parcels, yet most of the categories contained flour, oatmeal, cocoa, fat, condensed milk, corned beef and potatoes. The Swedes could either purchase the parcel cheques anonymously or make them out to specific persons in Austria. There were also monthly cheques available which entitled the recipient to receive a smaller food parcel every month for a specific period of time. In the harsh winter of 1919/1920, the Swedes organised a special money and seed grain collection for Austria and they launched the so-called “colleagues’ aid” (Kollegenhilfe), whereby Austrian workers, teachers, soldiers, doctors, students, etc. were assisted by their Swedish colleagues. Apart from distributing food and clothes parcels and inviting children to Sweden, the Swedish charities also supported existing institutions in Austria, such as for example children’s and apprentices’ homes, pulmonary sanatoriums and the sanatorium for osseous tuberculosis in Grimmenstein. In the tuberculosis hospital “Spinnerin am Kreuz” in Vienna “Rädda Barnen” cared for around 300 children with tuberculosis and a special initiative in Sweden linked up Swedish schools with patients in the hospital. The hospital sent reports about the health of the little patients to the school children in Sweden and the school children supported their sick partner children, often after their release from hospital, too. In Grimmenstein, where the Viennese social reformer, doctor and city councillor, Julius Tandler, had laid the foundation for a sanatorium, Swedish funds paid for the erection of a special pavilion for children suffering from osseous tuberculosis. There the children were treated and received board and lodging financed by a Swedish charity for two years. Tuberculosis, osseous tuberculosis and rachitis were considered “Viennese diseases” in those years.

The Swedish children emergency programme focused on holidays in Sweden for undernourished adolescents threatened by tuberculosis, while poor or sick younger children were to be assisted in Austria. The logistic effort of transporting the children to Sweden in the post-war years was enormous, because the small exhausted and newly-established Austrian Republic lacked everything. There were not enough rail carriages, not enough train engines, not enough coal for the engines and not enough food for provisioning the children during transit. For every train that carried children to their recreational holiday destination abroad a doctor and a nurse, and personnel accompanying the children – one per thirty children – had to be provided. There had to be a possibility to cook for the children on the long journey to Sweden. As soon as the train had left Austria, the host country took over the costs for the transport, which was considerable in the case of Sweden.

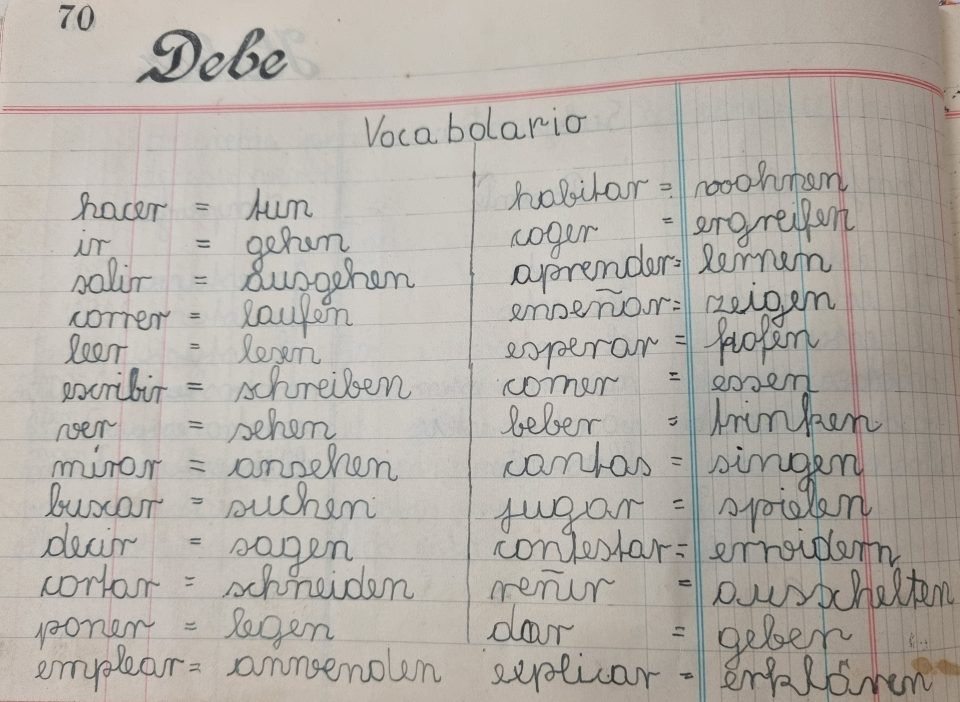

For the children leaving home and arriving in a very different environment, where they did not understand the language, and staying there for several weeks or even months was not always easy. A 15-year-old girl who was sent to Sweden in the spring of 1920 remembered that she was put on the train “in her best clothes and with a lot of warnings in her little backpack”. There was chaos at the train station; excited parents and children everywhere. The children were given a little card board sign with the name and address of their host parents to hang around their necks and her mother wrote down this information. When she finally arrived in Stockholm, she was lost and feelings of anxiousness and joy mixed. At the Swedish train station, the foster parents were waiting and the children’s names were announced. Several women were checking the names on the cardboard signs around their necks. There were fewer and fewer children and the girl was still there, already so tired she could not stand upright any longer. She was desperate when she was left with two dozen boys and girls standing in the station concourse, because they had not been chosen by prospective foster parents. Finally, they had to get on a bus and were driven to a children’s home.

A 12-year-old boy who came to Sweden in 1920 remembered that he had a small backpack with a few sets of underwear, one pair of trousers and one jacket with him and a small blanket. There was straw on the floor of the train carriage and they slept with the blanket and the backpack as pillow either on the floor or on a wooden bench. There were usually no toilets on those “children’s trains”, so they had to use buckets. Everything was marked with cardboard signs with names and addresses. In Sassnitz they boarded the ferry to Sweden, which took several days. Already on the ship they were served wonderful sandwiches “and they were offered to them; they did not have to beg for food and they could eat as much as they wanted – what unusual joy!” They were even offered bananas, which most of them did not know and tried to eat together with the peel, which was disgusting.

There was criticism in Sweden because of the high costs of this holiday programme and the question arose whether the money could not be used more efficiently in Austria, but the positive aspects of holidays abroad seemed to have outweighed the negative ones. Despite the fact that some Viennese parents feared an estrangement of their children abroad and the fact that the youngsters were missing out on school education, the places for the Swedish holiday programme were much in demand. The Swedes were astonished that even better-off parents tried to snatch a place for their children by using their “connections in high places”. Originally the Swedish government wanted to invite children from Germany, Poland and the Baltic States and host them in children’s homes in Sweden over the summer months, but they then realised that they lacked the appropriate capacities. When an appeal for foster parents in the paper “Dagens Nyheter” was so successful, they decided for the foster family option. The future foster parents not only had to pay for the board and lodging of the foster child, but often for the transport, too. The Swedish foster families decided to accept a foreign foster child, first due to humanitarian reasons, but also because they wanted a playmate for their own children and they saw the possibility to boost the German language skills of their own children, who were taught German as the first foreign language at school. Usually, the pastor helped when language problems arose in a family. If a Swedish family asked for a strong adolescent boy, the Swedish Red Cross refused to send a child because they feared the boy would be exploited as cheap labour. Some childless couples offered to take in a foster child in the hope of adopting it later. The Swedish Red Cross visited the families before assigning a child and it was stressed that the children were in Sweden to recover and they were not supposed to work in either household or farm. The foster parents were further advised that the children had to sleep one or two hours during the day and go to bed early because they were so exhausted due to undernourishment. They were not to participate in long walks or exhausting games. In case the children were nervous, the foster families should not ask them about their traumatic experiences and should divert them by offering calm and not stressful occupations. What’s more, the children were not to be given fat or heavy food at the start because their famished stomachs were not used to this kind of food. Especially this rule caused a lot of disappointment among the host children because they did not understand why they were not allowed to eat the wonderful bacon in the larder, for example. The idea of the organisers was that the Austrian children should get to know the “Swedish Model” of peaceful social stability and then put it into practice in Austria later. The children who stayed longer than just the summer months were supposed to go to school in Sweden, too. The foster parents rather opted for girls than for boys, who had basically no chance to find a foster family if they were older than fourteen. Girls were seen as easier to care for than boys and they could help in the household, too, although “Rädda Barnen” objected to this practice.

Why Austrian, and most of all Viennese children, were preferred by Swedish foster families had several reasons. Vienna was the capital city of the former great Habsburg Empire and it was cut off from its former food supply; that’s why the destitution there was the most blatant. What’s more, Vienna was famous in Sweden as the world city of culture and music and the articles in the Swedish press about the plight of the Viennese children created excellent propaganda for them. The first train to Sweden left Vienna in September 1919 and in the year 1920 the focus shifted from German to Austrian children completely, which then constituted 62 per cent of foster children in Sweden, the vast majority of them from Vienna. The Swedish Red Cross even had to ask the public to accept German children, too, because nearly all foster families opted for Viennese children and the “War Children Office” in Stockholm was worried that Germany would refuse the passage of trains from Vienna across Germany to Sweden, if Sweden did not take on a few German children as well. One of the Swedish journalists who promoted the Viennese children was Gerda Marcus from the “Svenska Dagbladet”, whose articles about the destitution of the Viennese children regularly resulted in a new peak of donation activity. She even slightly distorted the facts to enhance the pity for the Viennese kids among the Swedish readers. One “Viennese war widow with eight children” Marcus sold to her readers as a “the widow of a general” and as a result many donations went to this “general’s widow” from Sweden. Consequently, the local aid organisations in Vienna did not know how to deal with these personalised donations, because this “general’s widow” did not exist. Finally, they distributed the donations among other needy families in Vienna and Elsa Björkman-Goldschmidt sent personal letters to the donators. So, Swedish public relations for Vienna were excellent.

On the initiative of the Viennese social pedagogue Eugenie Schwarzwald, Sweden further subsidised public communal kitchens, which distributed hot meals to the poor in Vienna. In the summer of 1920 63 communal kitchens fed children and youth up to 18 years of age and even middle-class Viennese got hot meals there for a small fee. The Swedes saw to it that no political or social distinction was made in the distribution of aid to the needy. Elsa Björkman-Goldschmidt noted that the Viennese, in contrast, approached the Swedish aid organisations with glamorous titles in the tradition of the Habsburg Empire. To the surprise of the Swedes, the bigger the wishes they had the higher the title they awarded to the Swedish personnel: Elsa was addressed as “Baroness”, “Her Excellence”, “Duchess” or even “Baroness Rädda von Barnen” (because the Viennese did not know that “Rädda Barnen” meant “Save the children”). Yet Elsa confirmed that the Viennese were not ashamed to accept help or acted in a servile way. On the contrary, they showed “a poise of unconscious self-confidence in the way that they were Viennese and by that something special… The Viennese had a simple and natural way of accepting presents with grace and to enjoy them without bitterness; a kind of faded pride that arose from an ancient culture”. In selecting foster children for the holidays in Sweden the SRC later cooperated directly with the day-care centres for children and war orphans, led by Louise von Leithner, a socially committed aristocrat. Basically, no differentiation was to be made with respect to religion and class when assigning foster children, but there were foster parents in Sweden who preferred Protestant children, which was supported by pastor Nathan Söderblom. Leithner and Björkholm-Goldschmidt accepted these wishes and tried to assign children to foster families of the same religious belief. Only very few Jewish children travelled to Sweden, although the rabbi of Stockholm received several requests from Vienna, but pastor Söderblom mentioned that he had heard that Jewish children and students in Vienna had already received enough support for the time being, so that no further helping hand had to be extended to them.

In 1921 the SRC terminated its programme for war children and any costs arising from recreational stays with Swedish foster parents now had to be borne by the foster parents themselves or the children’s parents. All in all, 11,004 children were hosted in Sweden between 1919 and 1924, when the programme “Rädda Barnen” was stopped. This number includes the journeys of children who went to Sweden more than once, too. The Austrian state tried to express its gratitude to Sweden officially, but as the Austrian Republic was a terribly deprived state, the honours and tributes had to be cheap. After the end of the Habsburg Empire the names of lots of streets, squares and bridges were changed anyway, so that was a brilliant chance to rename in 1919 the “Ferdinand Bridge” into “Sweden Bridge” (Schwedenbrücke) and the “Ferdinand Square” into “Sweden Square” (Schwedenplatz). A strange curiosity was the decision of the government of the Austrian Republic in 1920 to present Sweden with a special object from the Habsburg “Schatzkammer” (treasure chamber) to show its gratitude to Sweden: the tunic of King Gustav II Adolf of Sweden, which he had worn in the battle of Lützen, and which had been handed over to Emperor Ferdinand II as a war trophy in 1632. It was to be seen as a present to the Nordic countries, Sweden, Denmark and Norway; probably because Austria did not find an equivalent in the Habsburg treasure chamber for the other two countries. The absurdity of the present is underlined by the fact that those three countries were not allies in the 30-Years-War, on the contrary Norway was a part of Denmark and Denmark was not always on the side of Sweden then. Now this important Swedish memorabilia is exhibited in the Nordic Museum in Stockholm and unofficially the Swedes commented that “this present was not necessary”; Sweden had done its human duty and the tunic was much too precious an object for a present. It can be assumed that the Austrian Republic parted easily with this war trophy of the Habsburgs.

Post-World War II

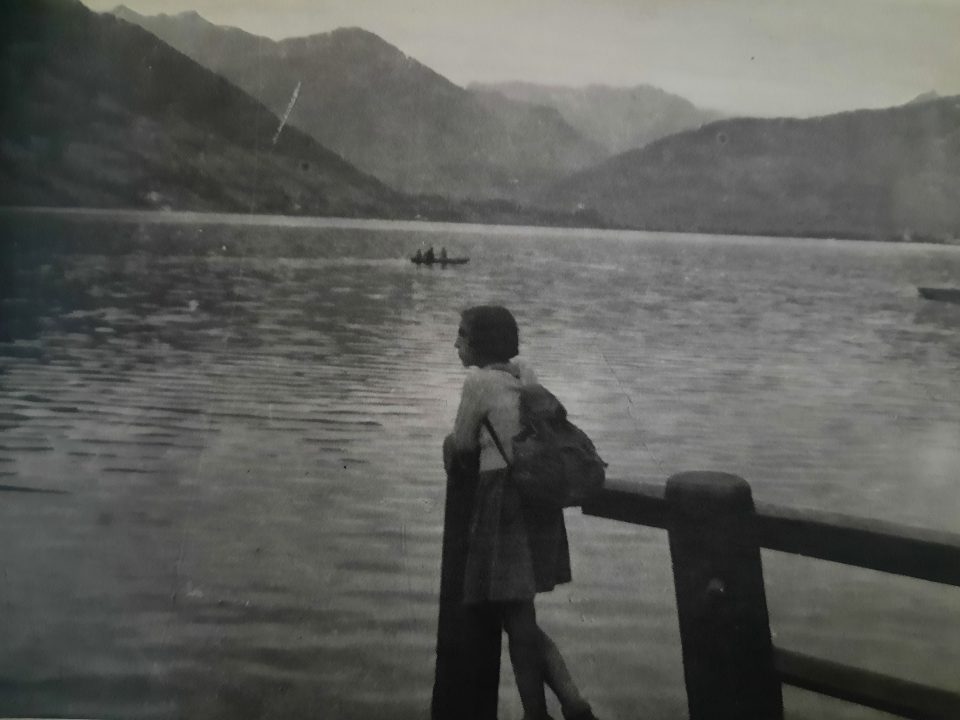

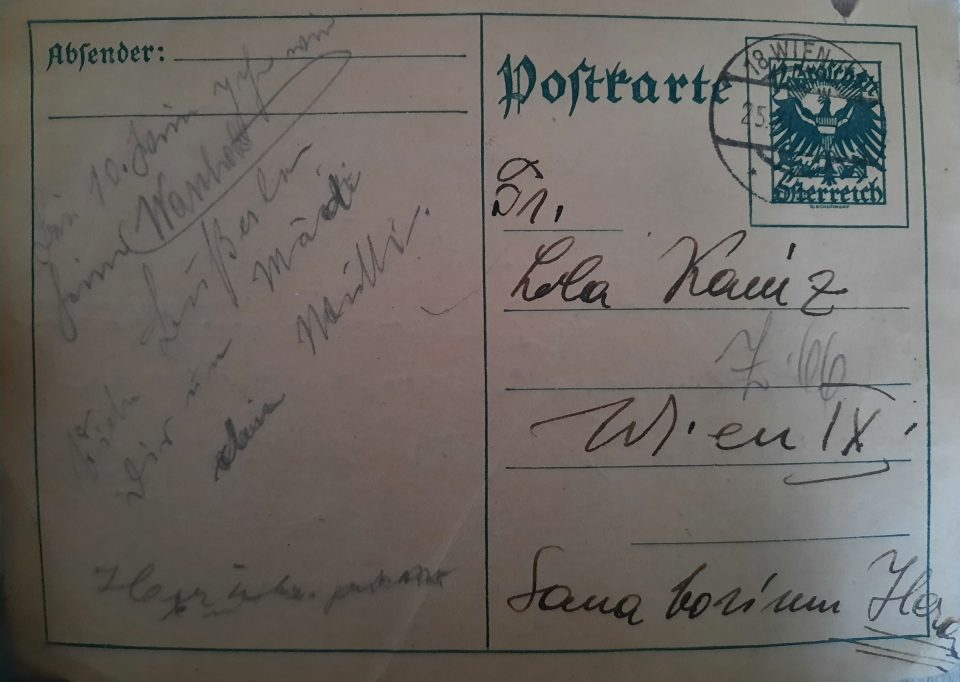

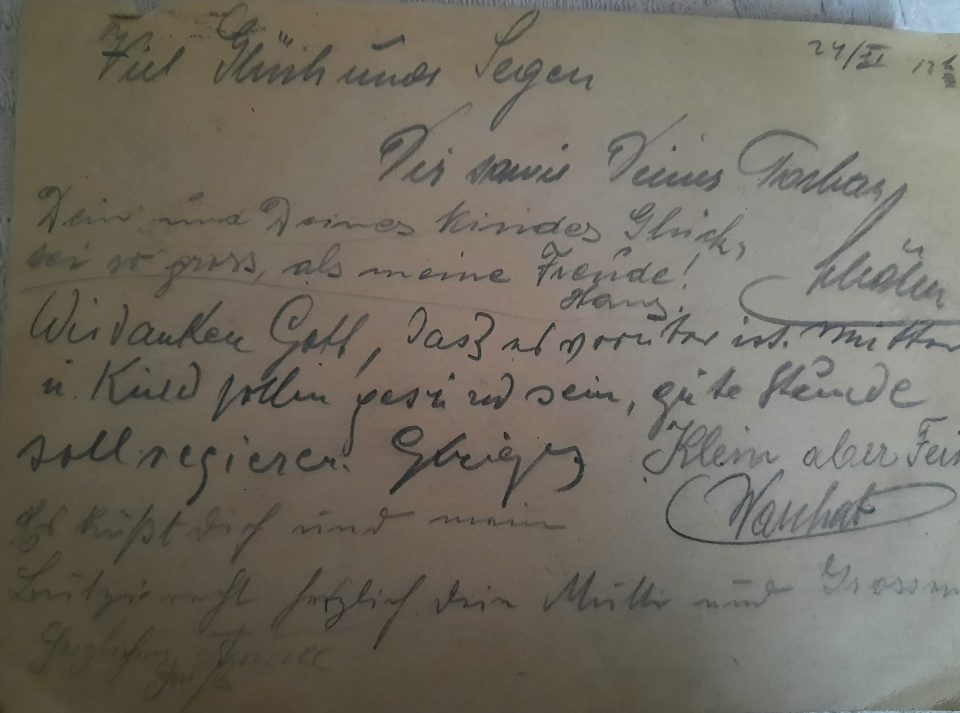

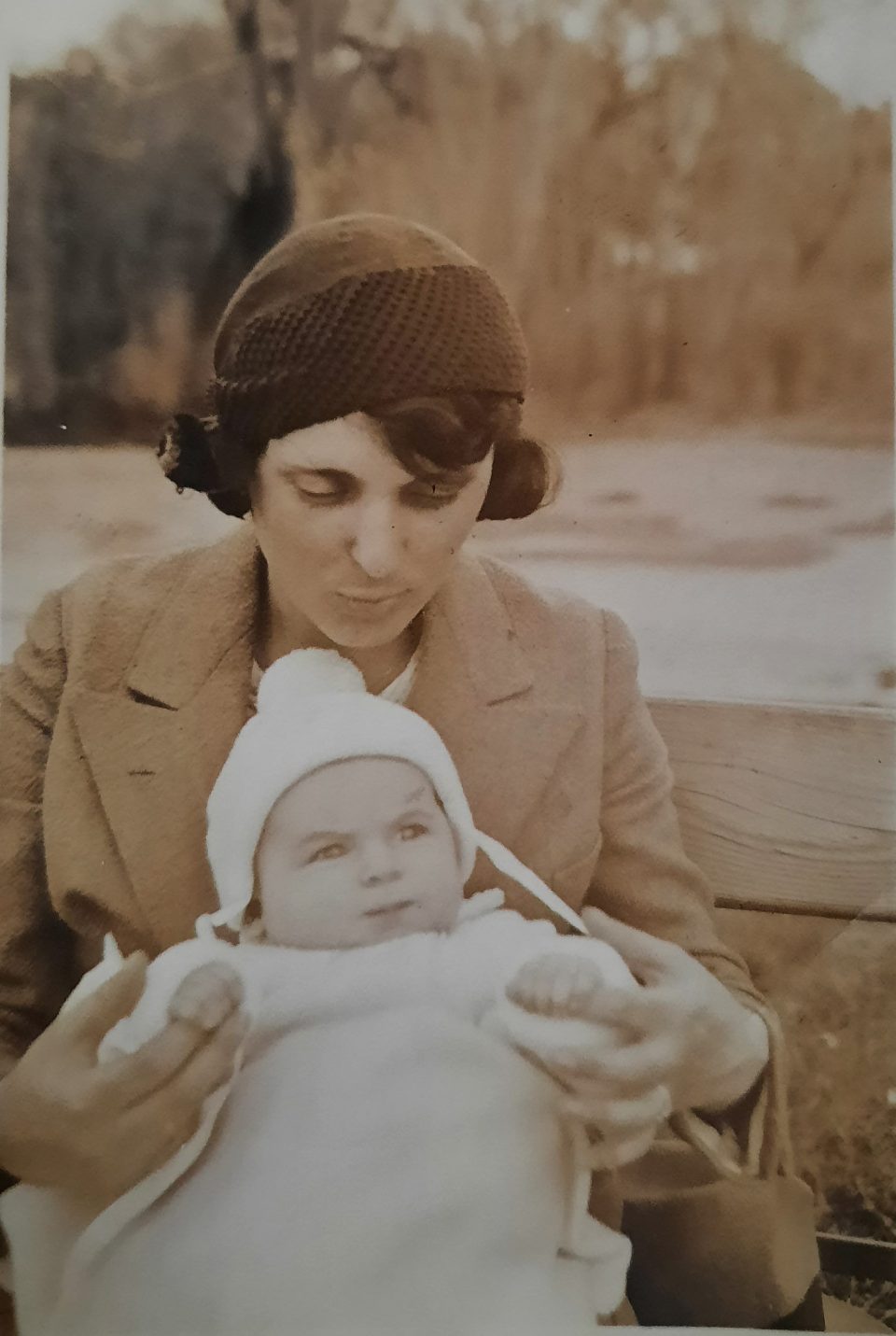

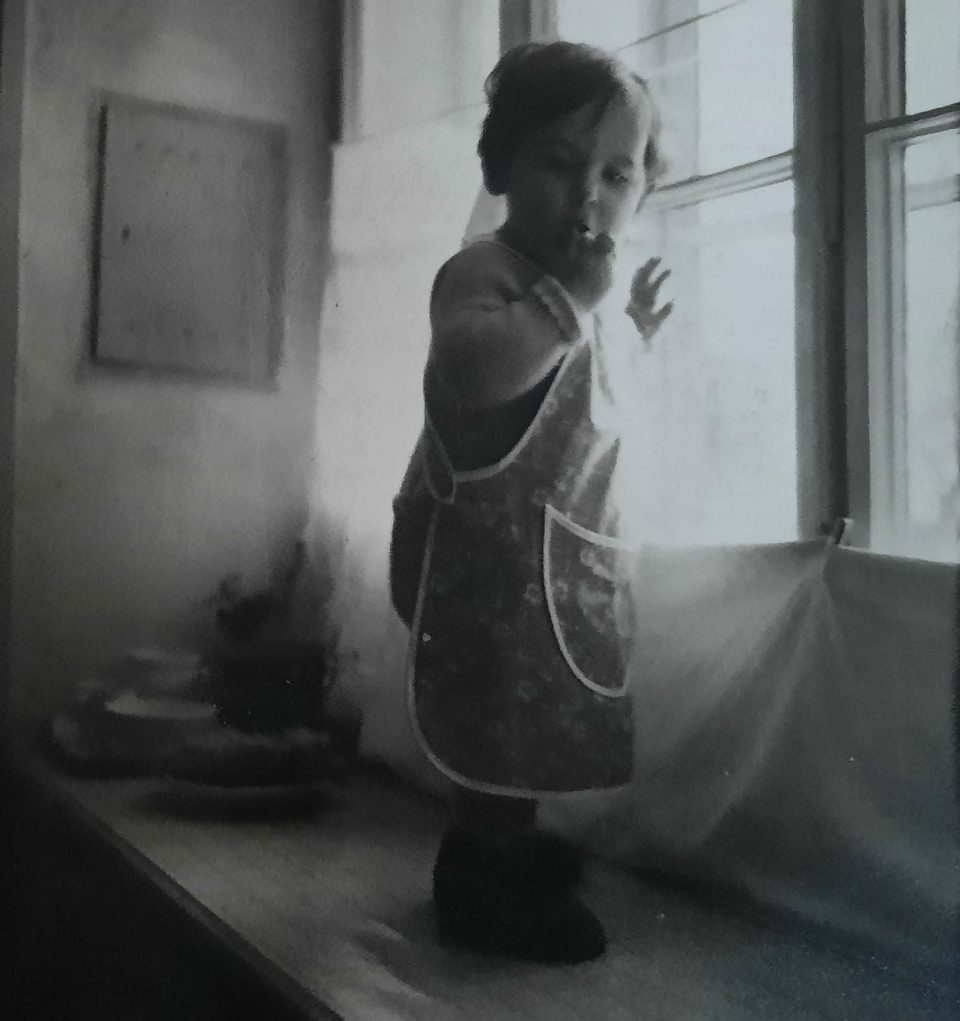

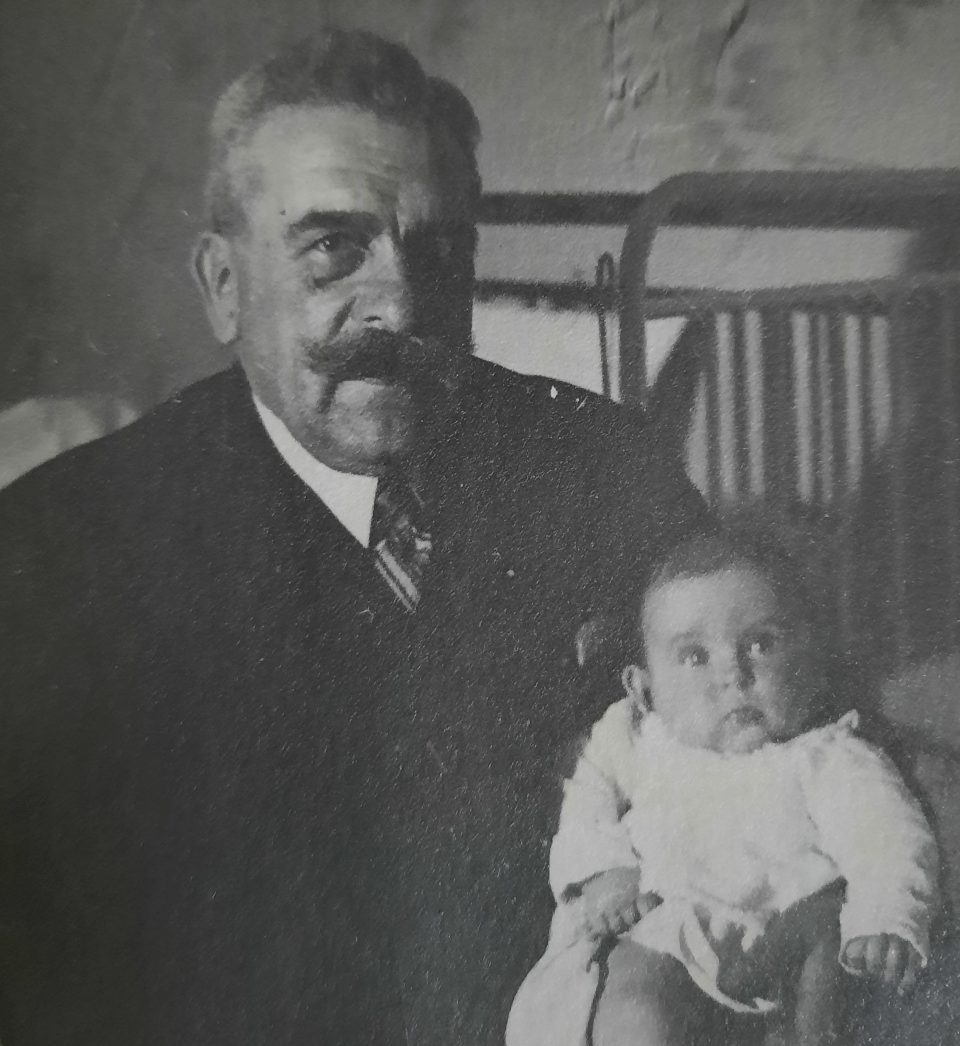

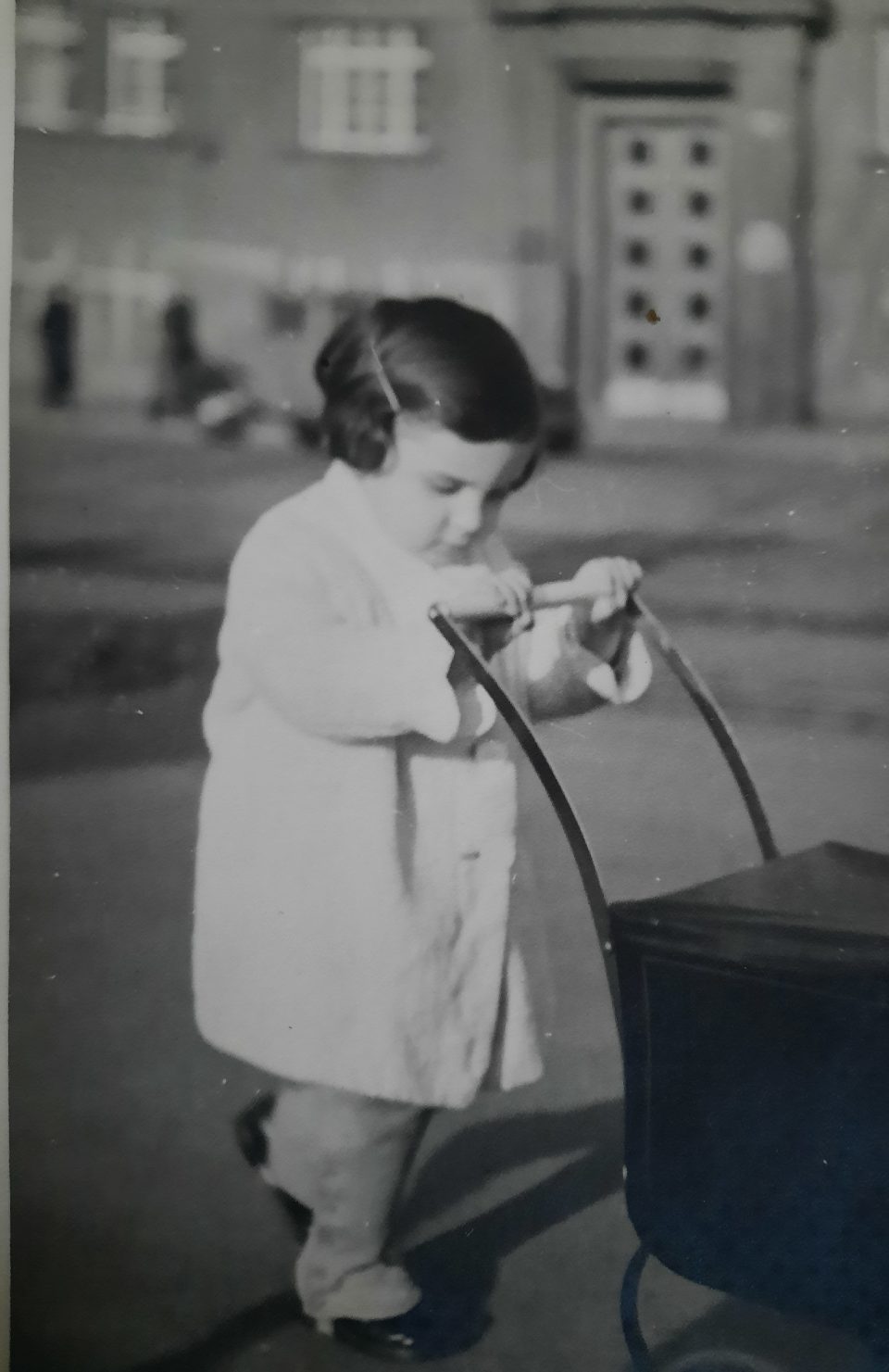

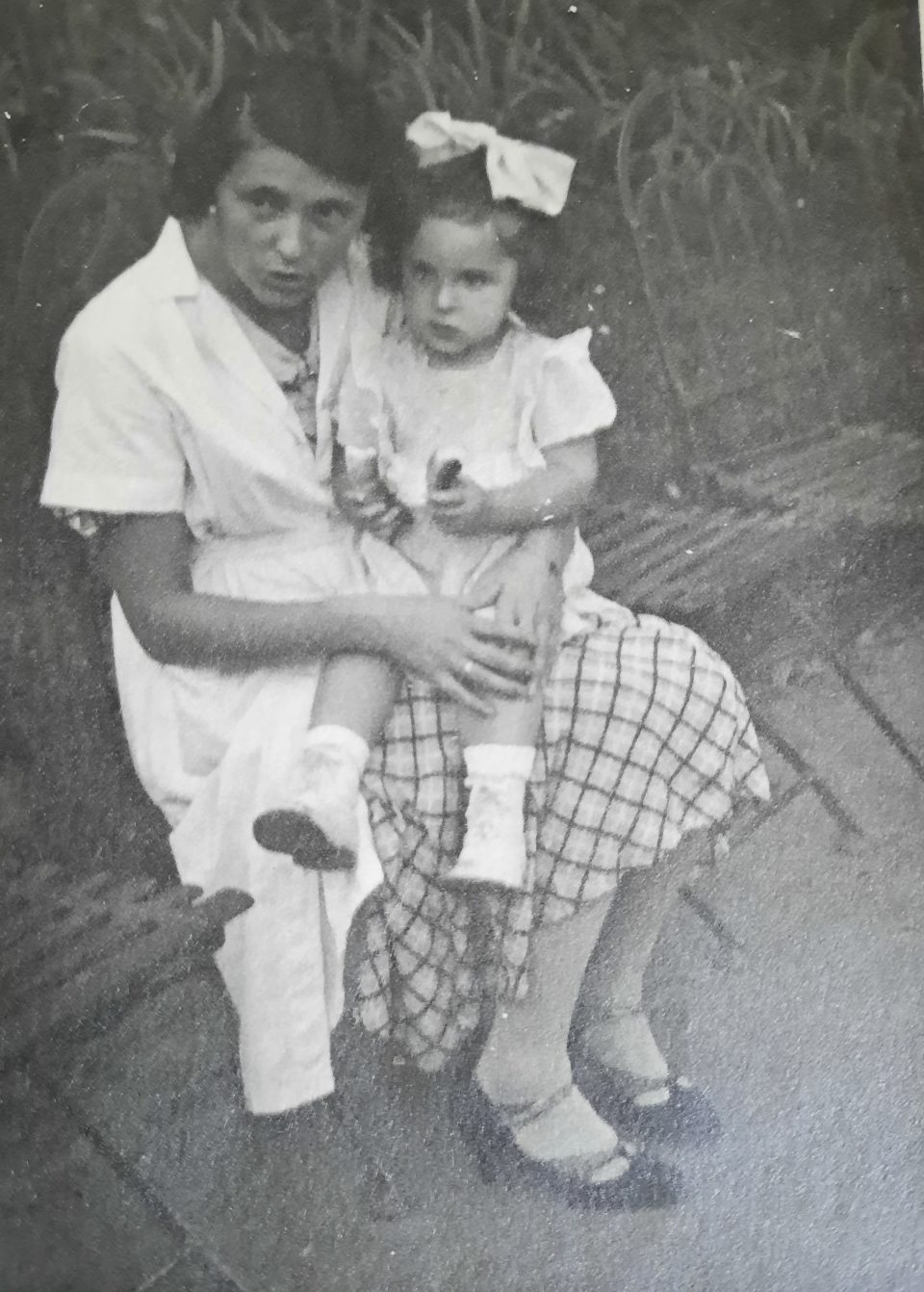

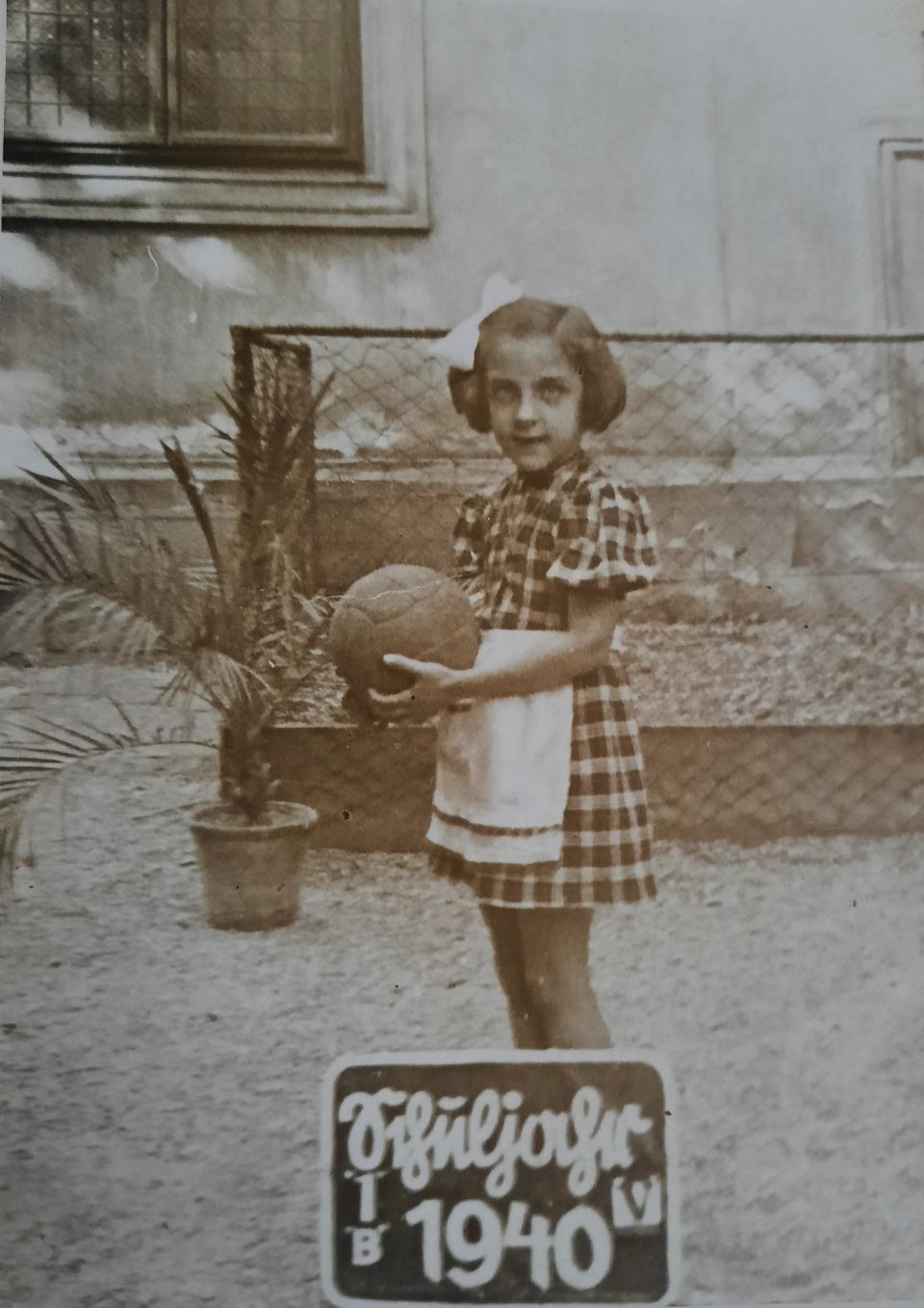

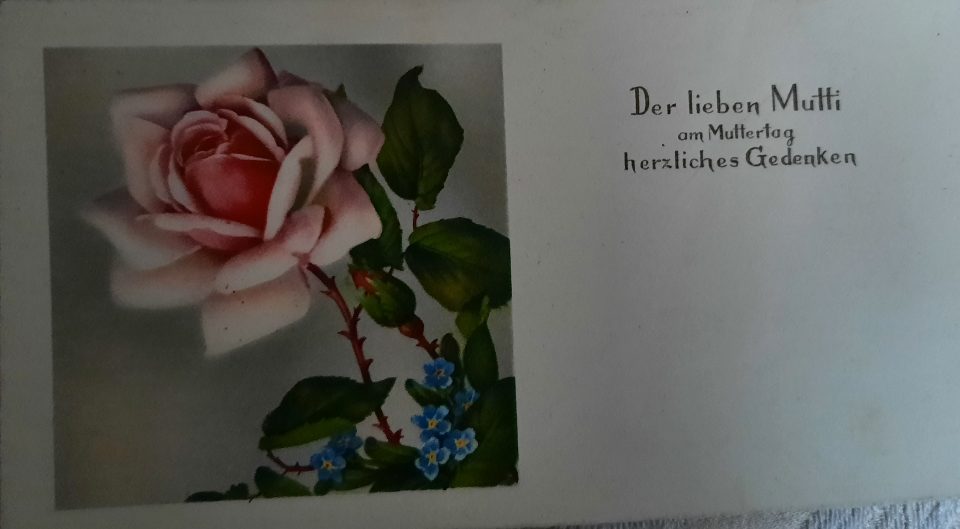

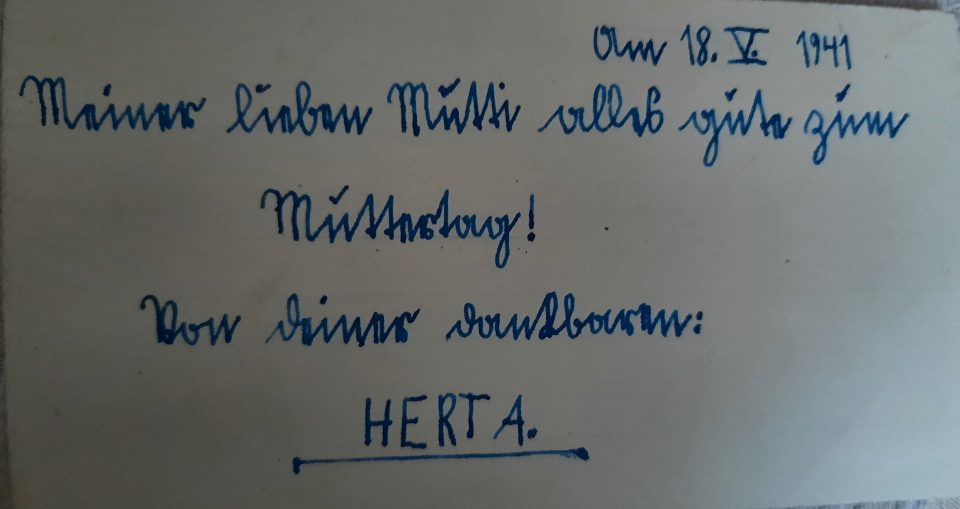

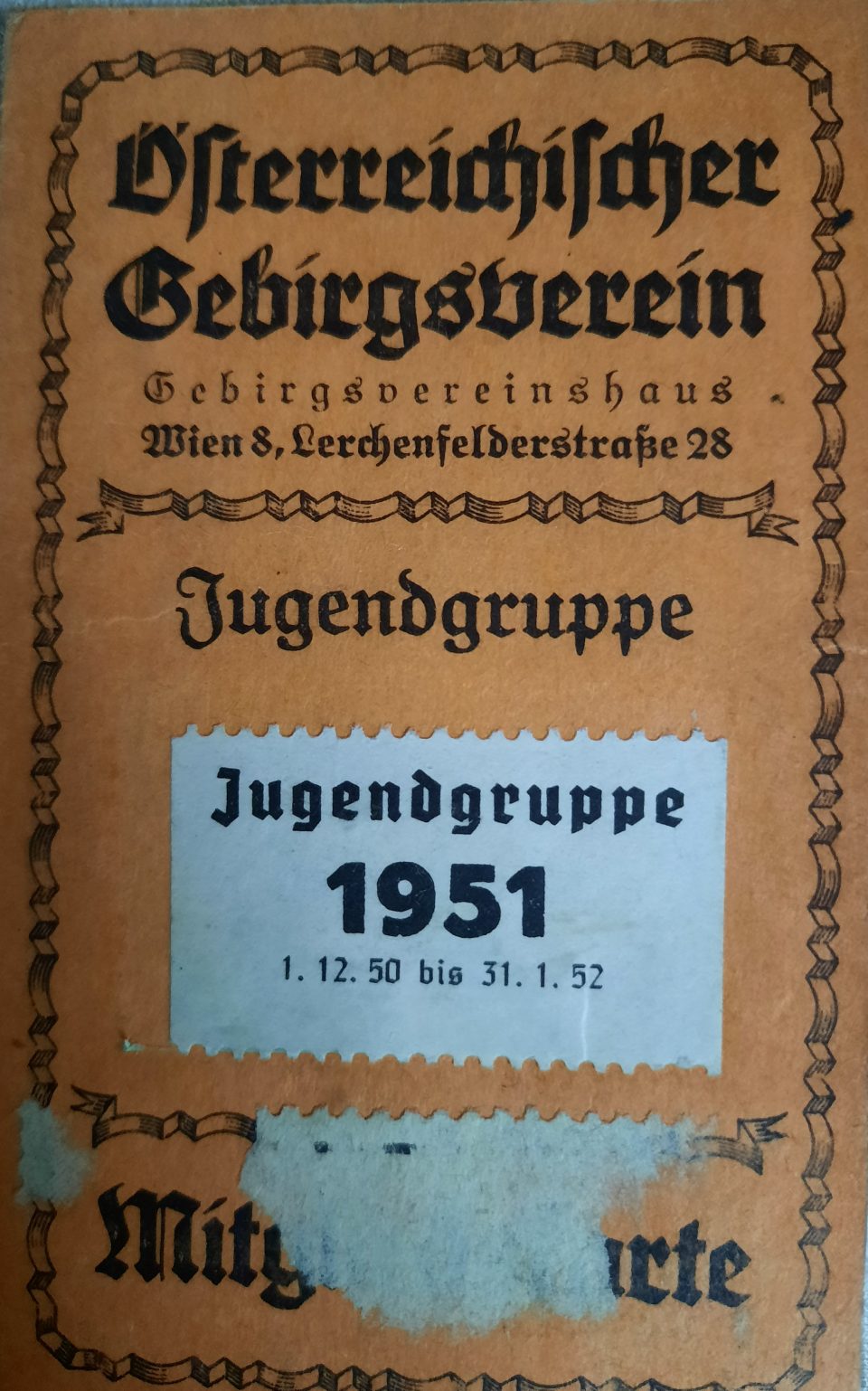

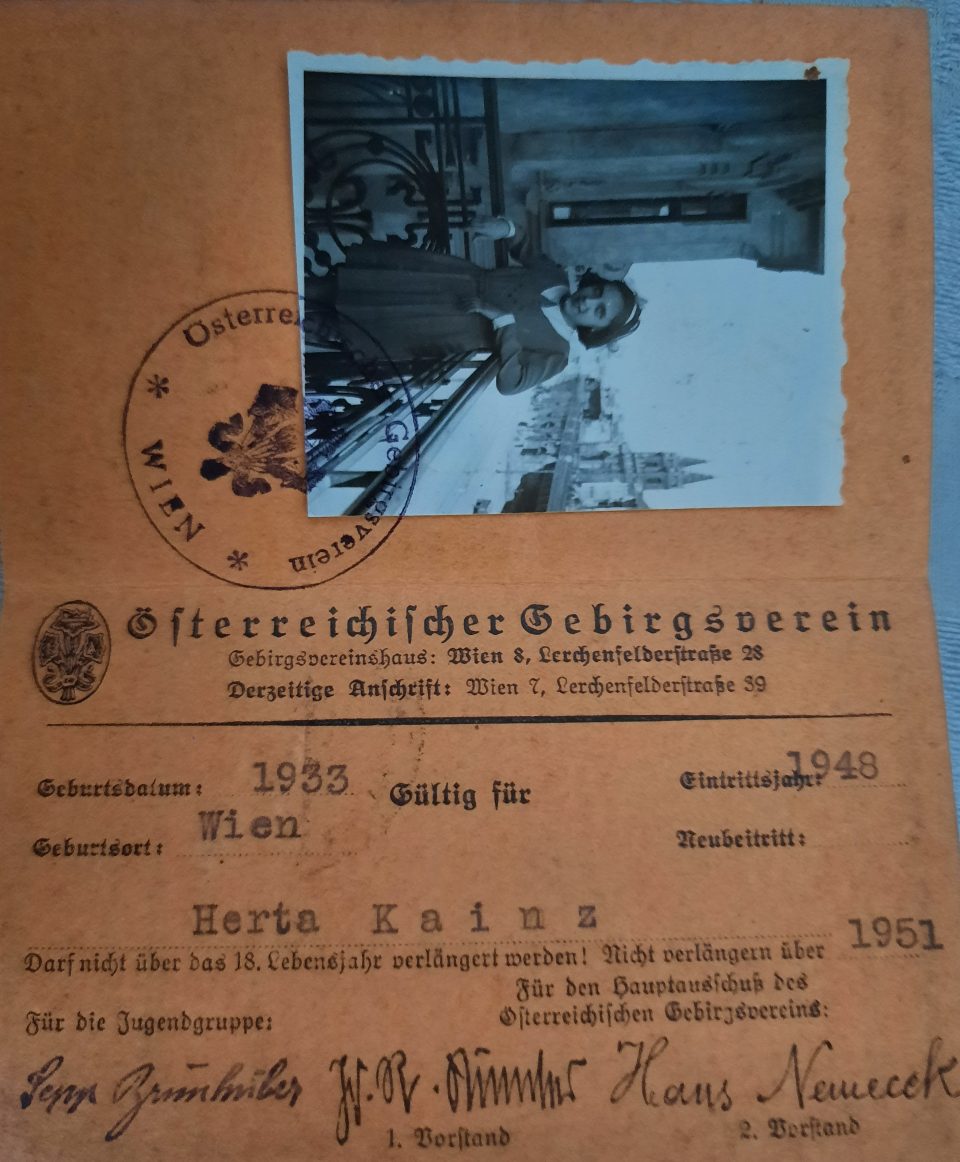

My mother, Herta Kainz, was 11 years old in the spring of 1945 and despite the never ceasing efforts of her doting parents, Lola and Toni, to feed their only child properly, she was undernourished and sickly. Herta lost most of her teeth in her early twenties due to malnourishment and she suffered from constipation and migraines from an early age on and was severely traumatised (see article: “Mixed Marriages and Mixed-Race Children during the Nazi Period”). She was not only affected by the fear of bomb attacks, but of losing her Jewish-born mother and her beloved grandparents, too (see article: “Nazi Collective Camps in Vienna”). Nevertheless, Herta always stressed that despite the war, the Nazi discrimination and the threat to her family she had had a wonderful childhood, because she had received so much love and warmth from her parents, her grandparents and the rest of her family that this compensated for all the hardships she had experienced.

Many children had to be sent on recreational holidays after World War II to pick up strength and gain weight, which was the case of Herta, too. But on no accounts could Herta be separated from her parents and from her grandparents, who had just returned from the concentration camp “KZ Theresienstadt” for a longer period of time. That’s why a stay abroad was inconceivable for her. So, she was assigned to a youth hostel in the country for some weeks. She did gain some weight there, but she suffered severely from homesickness and was desperate to be reunited with her family. She did not enjoy the recreational stay at all, although she liked the girls who she shared the room with.

After the Nazi period and the end of World War II the need had arisen again that the city of Vienna offered recreational holidays for the undernourished Viennese children, just as after World War I. So, in 1946 several day-care centres were re-opened, among them, “Sonnenland” in the district of Ottakring on the Gallitzinberg. In 1945 some of the recreational homes were restored with the help of international aid organisations, the first of which the “Sanatorium Wienerwald” in Feichtenbach/Pernitz, where Herta stayed. In the same year 959 Viennese children were cared for in domestic homes, 250 in foreign homes and 1,010 in Swiss foster families. The number of children spending recreational holidays in domestic homes rose to 25,203 Viennese children and 10,620 in day-care centres in 1951. Current studies have uncovered that these recreational stays of several weeks in children’s homes or youth hostels in the mountains or at lakes in Austria, which were prescribed by doctors to help the children recover and gain weight, were not always pleasurable experiences for those children. Not only Herta detested the hospital atmosphere and crowded conditions there. As she was a very timid, shy and obedient girl, she was not involved in any conflicts either with the other girls or with the care personnel. In contrast to her, other children did experience humiliation, abuse and physical violence. This can be attributed to the fact that the “ideal of the National-Socialist education model” persisted in Austria for a long time after 1945 and most of the personnel was trained during the Nazi period and had already worked with children during that time. A very restrictive, violent and militarist educational system can be traced back even further to the origin of the so-called “black pedagogy”, whose aim was to “break” children by using humiliation, intimidation and violence. Fortunately, in Vienna the “reform pedagogy” of “Red Vienna” was back on the agenda after the end of the Nazi dictatorship, too. That’s why some institutions run by the city or the “Kinderfreunde” tried to implement modern educational methods along the lines of Montessori, Aichhorn or Bernfeld. In the summer kindergarten “Sonnenland”, for example, small children played and bathed naked during the summer months up to the 1960s in order to combat a wide-spread disease among Viennese children in the post-war years, rachitis, but probably also to counteract a restrictive Catholic moral concept. I spent a few days in the summer of 1963 in this ”summer kindergarten”, which I detested. As an only child, spending the whole day naked in group activities was not my preferred leisure time activity, but it was considered necessary to prepare me for school. Yet it turned out that there had been no need for this experience for me. Although I had strictly refused to return to the “Sonnenland”, I did very well at school. In the same way my mother had to endure such a recreational stay after the end of World War II, but for four weeks and not just for a few days and she suffered tremendously.

Many other Viennese children were sent to foster parents abroad for several months or even a year and more after World War II. Partly those children emergency programmes were linked to programmes which had been established after World War I, for example in Switzerland, Denmark, Norway, Sweden and Belgium. Sometimes even the same foster family now took in the children of their former foster children. Once more, after the Second World War two rather poor countries offered humanitarian help to Austria, namely Portugal and Spain. Around 5,000 Austrian children were sent to foster parents in Portugal between 1948 and 1952, organised by the Caritas and 3,500 to Spain. Both countries were Fascist dictatorships at the time – Salazar in Portugal and Franco in Spain – and wanted to polish up their international image in this way. But the warmth and generosity with which the Portuguese welcomed the children from Vienna and other big cities in Austria, such as Linz, Graz and Salzburg, was amazing and some of the foster parents invited the children again and again, not only paying for their board and lodging, but also for their journey and showering them with presents. 56 former “Portugal children” wrote down their impressions of their stays in Portugal and these documents form a valuable source for this research, which wants to draw attention to humanitarian efforts made by not so well-off communities in southern and northern Europe to help children in need in a far-away foreign country who were famished and traumatised by war.

The Swiss post-World War II children relief programme

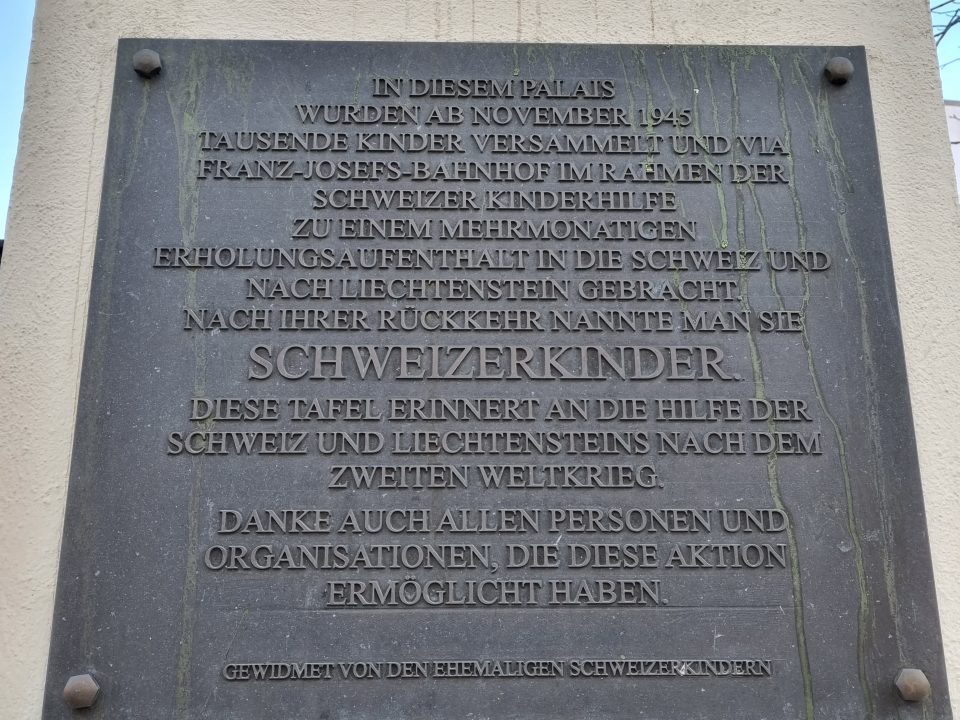

After the Second World War the first country which offered to take in famine-threatened Austrian children, was Switzerland, which had been a neutral country during both wars and had even profited economically from the war demand and its good relationship with the Western Allies as well as with Nazi Germany. In 1944 Switzerland had already established an umbrella organisation for all relief efforts, the “Schweizer Spende”, where all aid agencies, such as the Catholic Caritas, Protestant aid organisations and workers’ aid agencies were represented. The aid was funded partly by these organisations, by the Swiss state and donations. The headquarter of the organisation was located in Bern and it continued a long-standing Swiss tradition of charity, which had already helped Austrian children after the First World War. The “Schweizergarten” in Vienna, near the Belvedere castle, was named after Switzerland to thank the Swiss for their humanitarian aid after World War I. Now several Austrian families who had already had contacts to Swiss families asked them whether their children could stay in Switzerland after the war. That’s why some Austrians profited from Swiss hospitality even in the second generation. Already in the summer of 1945 the first Swiss relief transports arrived in Austria carrying food, clothing, medication and emergency shelters. On 22 October 1945 the first “children’s train” from Innsbruck passed the Swiss border in Buchs. A little later the first trains from Vienna left on 22 November 1945, when chaos still reigned in the destroyed city. In Vienna the Swiss Red Cross took over the organisation of the transports. Already in 1945 Switzerland welcomed 3,801 Austrian children. Until the end of 1946 every month three “children’s trains” with 350 to 450 children each left for Switzerland, in 1947 two and in 1948 one train per month. The aid project “Schweizer Spende” was terminated in 1948, when the UNICEF took over the financing of communal kitchens and recreational stays. The children normally remained three months with their host families. Yet how many children were cared for in Switzerland is not known, but it can be assumed that all in all 100,000 children profited from a holiday stay in Switzerland.

In Vienna the desperation of the people reached its peak when in March and April 1945 the war front approached the city and the bombing was intensified. They were afraid of the Soviet soldiers when they arrived in the city at the end of April, but the Soviet front-line fighting troops were friendly to children, those that followed were responsible for looting and violence against women. Many fathers had been killed in the war or were stuck in prisoner-of-war camps and the mothers had to procure the basic necessities for survival. That’s why also the children were asked to contribute to the families’ upkeep. They had to fetch water from far away water tanks or queue in front of shops that distributed rationed basic food stuff. The Soviets distributed bread from trucks, but the amount of bread never sufficed. Who was not there in time or did not send children to queue in front of the few places that gave out food, had to do without it. As public transport had completely broken down in the city and most bridges were destroyed, the Viennese had to take long walks to reach their destinations. What was more, there was no milk available, which affected babies most, which resulted in a catastrophic increase in infant mortality. With Swiss aid all Viennese children up to three years of age received half a litre of dried milk twice a week. Nevertheless, still in 1946 the number of totally exhausted and famished children in Vienna was shocking. For several Viennese children the recreational stay in Switzerland represented their rescue at the last minute. Some children were sent on recreational holidays during the summer months, but more often it was important to get the Viennese children out of the city before the freezing cold winter months started, without any material for heating and without adequate food.