LIFESTYLE OF THE „LONG 1950s“(1947-1965) IN VIENNA

Fashion and interior design of the 1950s in Vienna (my mother Herta with Susi – myself- on her lap -right)

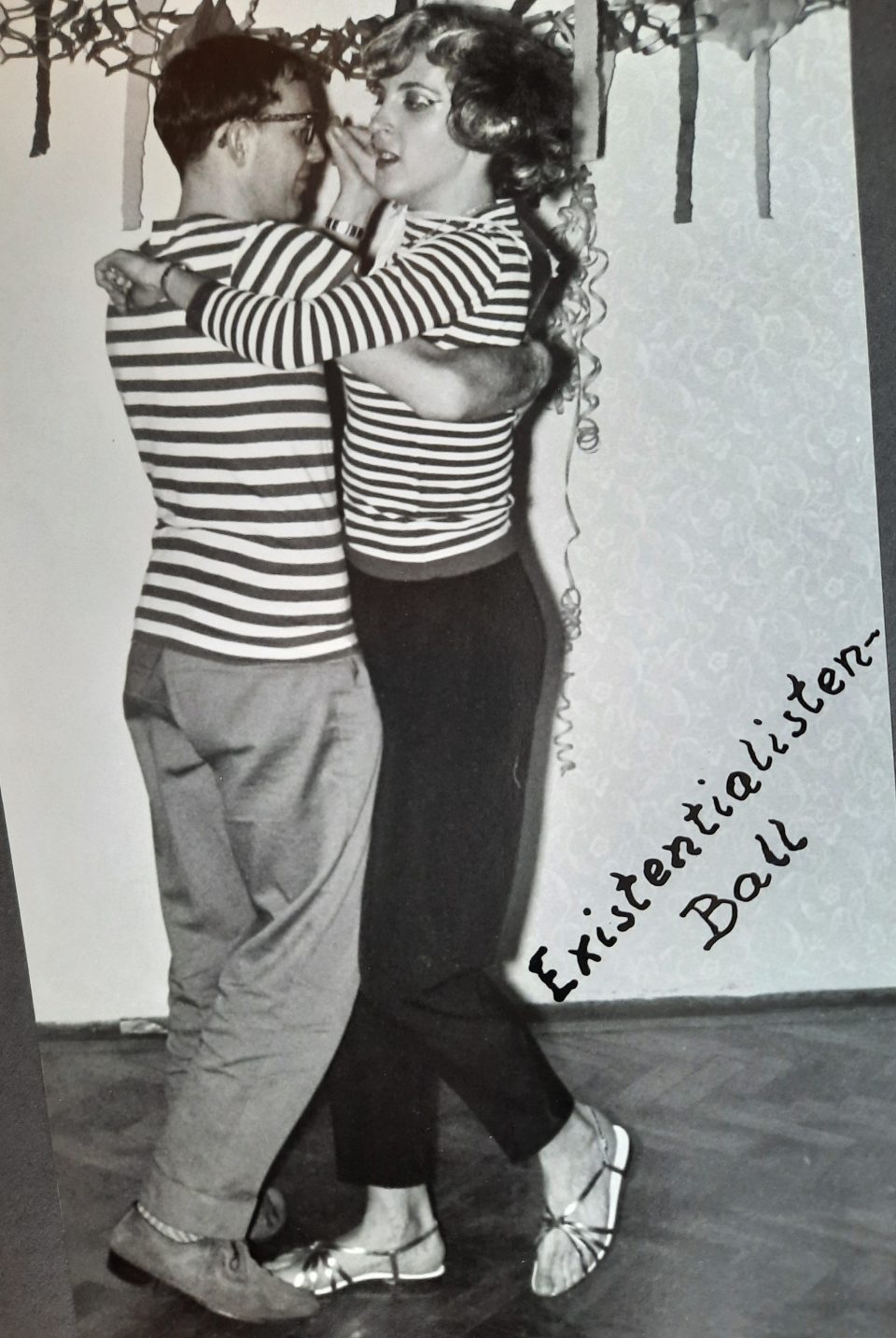

Entertainment: private balls organised in the flat of Toni and Lola Kainz, my grandparents, in Vienna, Neulerchenfeld

The social and economic period of the “long 1950s” started around 1947 and finished in the middle of the 1960s. The historian Eric Hobsbawn called it one of the most revolutionary periods in European history despite its general image of boring conservatism. He explained his surprising analysis with the unprecedented economic growth rates, the unrestrained adulation of technology and productivity and the breakthrough of Americanised industrialised mass culture. In Austria this period started with the currency reform of 1947 and the establishment of the post-war “Social Partnership” between employers and employees with the first wage and price control agreement. American aid via the Marshall plan (1948-1952) triggered the Austrian economic “miracle years” and in 1948/49 the former Nazis were again integrated into Austrian society with the virtual end of the denazification process. The Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union characterised the whole period with Austria positioned in the middle; geographically the most eastern point of the Western World, situated directly at the Iron Curtain. Culturally the aftershocks of the Nazi era and the Second World War were felt during the whole period, but gradually abated. The consequences of the lost war, the Allied liberation and occupation and the excessive veneration of virility by the Nazis gave way to a revival of the traditional conservative roles of men and women. The early 1960s were the years of marriage and childbearing, the “baby-boomer years” in Austria. After a very short period of cultural awakening right after the war, in the 1950s Austrian art and culture experienced a kind of “counter-enlightenment”, a return to very conservative art concepts. The student movement of 1968 ended this period and hailed a new era of sexual and artistic revolution which ended the post-war conservative Austrian concept of “the unity of the good, the true and the beautiful”.

If the Austrian standard of living was measured against the Western European standard at the beginning of this period, Austria was 40% below that, but the gap shrank to 20% in 1961. The gross national product of Austria grew from 49.6 billion AS (Austrian shillings) in 1950 to 134.6 billion AS in 1959. The economic structure developed towards the “American model” via increasing productivity, growing real incomes, an expansion of the labour force, a rising supply of goods and linked to that a dynamic consumerism. The introduction of the “American ideal of beauty” led to a dramatic increase in spending on cosmetics products in the same way as the craving for a motorised vehicle, a modern technical “American-style” kitchen and modern easy-clean furniture resulted in a dramatic increase in purchases in these sectors. Yet an average Austrian family could not afford a car or a fridge; the solution was presented in the form of hire purchase agreements. The new needs and wants of consumerism could be satisfied in this way. The higher living standard in Austria was paid for dearly with the health of the workers via piece work and overtime work. Despite the fact that the workers experienced pay rises to compensate the high inflation rates, the wealth gap between working class and middle class incomes was still widening and the new wealth was distributed unevenly. Even if a Viennese worker’s family had acquired a fridge via hire-purchase, they probably did not have a bathroom in their flat. This fact was covered up by the ruling “Social Partnership” of ÖVP (People’s Party) and SPÖ (Social Democrats), of trade associations and trade unions. The battle for a share of the new wealth was fought on the negotiating table between the government and representatives of employers and employees. Yet Austrian young workers tended to acquire the tastes of the middle class during this period. They bought the same clothes, saw the same films, bought the same technical gadgets, enjoyed the same leisure time activities and went on holiday to the same destinations, which in the long run diminished the differences in class consciousness in Austria.

All in all, every politically relevant group profited in the 1950s from the economic boom and the household expenses for food and clothing decreased, while the expenses for furniture, transport and leisure increased. Between 1950 and 1960 net private consumption rose by 71%. Expenses for education, training and entertainment increased by 81% during this period, for transport by 169% and expenses for furniture and household wares even by amazing 228%. Immediately after the war the prices for non-rationed goods skyrocketed and that’s why their share of expenses was extremely high, but 1950/51 was the first post-war year with free choice of consumer goods and no more rationing and by 1953 the ration coupons had completely vanished in Austria. Gradually the population bought more expensive, low-calorie and qualitatively higher food products and more ready-made products and that is partly the reason why the consumers spent 52% more on food stuffs in 1960/61 than in 1950/51. Many enterprises now offered canteen lunches, which phased out the Austrian habit of taking lunch boxes to work. Smoking and drinking was socially acceptable and much appreciated in those years, which can be seen in the photos of the time below. Alcohol consumption rose 88% per capita from 1950 to 1963, which meant an increase of 5.4% per annum. Cigarettes were a means of payment after the war and a status symbol. US cigarettes represented the new American way of life. In the 1920s and 1930s the light oriental tobacco dominated the Austrian market; it constituted 70% in 1937, but sank to below 10% after World War II. US Virginia tobacco was introduced in Austria during the years of the black market with US cigarette brands such as Camel, Lucky Strike and Chesterfield. Immediately after the war the cigarettes produced in Austria were the notorious “extra mixtures” (“Mischung A & B” and “Austria 1, 2 & 3”), but from 1948 on also more expensive brands with Virginia tobacco were produced such as “Jonny” and “Austria D”. Apart from the black market the Soviet USIA (Soviet property in Austria) cigarettes undercut the Austrian tobacco monopoly until 1955, when the Soviet army withdrew from Austria. In 1950 the Russian army administration established around 80 so-called USIA shops in the Soviet zones which offered a wide range of Soviet products from cigarettes and alcohol to food, textiles, sweets and even typewriters. The quality of these products did not necessarily meet the consumers’ standards, but the products were offered at dumping prices. The Communists advertised these shops as the Soviet form of aid for Austria, the Soviet “Marshall Plan”. But for some Viennese purchasing in USIA shops was considered a “betrayal of public morals”, others saved around 200 AS per month when shopping there. The demand for new clothing also underwent big changes as the Austrians moved towards ready-made clothing, which had a huge impact on the dressmaking sector, in which Herta worked; more and more dressmakers and tailors were dismissed facing long periods of unemployment and the small and medium-sized workshops had to close down.

A burning problem was the lack of housing. Vienna was short of at least 200,000 flats in 1951 and of those that existed only 14% had their own bathroom, 56% had no running water in the flat and 60% no toilet inside. Toni and Lola’s flat at Lerchenfeldergürtel 45/35 in Ottakring (16th district) was a “luxury” flat by those standards because it was large (four large and one small room) and had running water and a toilet inside, but no bathroom. Before they had a shower installed in the kitchen, the whole family had to go to a public bath house. In 1950 the Viennese public bath houses still counted 5 million visitors annually and the city of Vienna ran around 20 such bath houses. Herta’s family frequented the one in Ottakring, Friedrich-Kaisergasse 11.

The public bath house in Ottakring, Friedrich-Kaisergasse 11, is probably the last remaining “Tröpferlbad” (Viennese term meaning a trickle of water because the water flow was sometimes less than abundant)

This explains how proud the young couple Herta and Werner were, when they could pay the deposit for their newly built cooperative flat in Ottakring, Friedrich-Kaisergasse 26/28 on the fourth floor: 48 square metres with bathroom, toilet, kitchen, hall, two rooms and a balcony, in 1954. The deposit was 20,000 AS and the rent was 450 AS per month. Werner had earned well when working at the hydroelectric power plant Kaprun until 1955 (see article “Workers at the construction of the hydro-electric storage power plant Kaprun”) and they had both saved further 45,000 AS, which they used to furnish the new flat, when they moved in in 1956. When I was born in 1957, Herta stayed at home and Werner started to work at the Vienna Electricity Works, where he earned 1,300 AS per month, which meant that after paying the rent of 450 AS, gas, electricity and heating, not much was left for food, clothing or leisure activities. At that time Werner stopped smoking and Toni and Lola, my grandparents, paid for holidays together or outings.

After the war the pent-up demand for consumer goods resulted in a spending spree in three surges in the 1950s: first the “food surge” 1947/48, then the “clothing and furniture surge” 1949-51 and since 1953/54 the “fridge and car surge”. In 1964 the amount spent on furniture and household wares had doubled as compared to 1954. Social housing and tenant protection in Vienna prepared the ground for higher standards of home décor: American-style kitchens, fitted wardrobes, fridges, hoovers, washing machines turned out to be status symbols of middle-class lifestyle, most of it bought via hire-purchase. In 1956/57 the last surge started, the “travel and TV surge”. Only since then TV sets could be bought in Austria: in 1957 12,500 sets were registered and in 1958 33,000. In Vienna most inns and coffee houses had a TV set for public viewing. Werner and Herta did not buy a TV set, they preferred listening to classical music records, but when ice-skating competitions were broadcast I sometimes went with my grandmother Lola to the “Café Hummel” in Josefstädterstrasse to watch TV or when the children’s programme “Kasperl” was on all the children of the house met in front of the TV-set of my friend Sissy’s parents. During the whole period of the “long 1950s” cinemas, theatres and concerts experienced a boom in Vienna, but from 1960 on the cinemas started to feel the impact of television and the number of cinema goers slumped.

…