My grandmother Flora Kainz, née Sobotka, who everybody called “Lola” grew up with her three sisters, Käthe, Agi and Mitzi, in Kaiser Ebersorf near Vienna in a bourgeois family. Her father, Ignaz Sobotka, was the manager of the brewery in Kaiser Ebersdorf (see article on beer brewing in Vienna). She was born in 1902 and received the standard education of a middle class girl of the time. In the course of the musical education that all girls of her class underwent at that time, it was discovered that she had some talent for the piano. Lola showed an intense interest for the opera and regularly went to see performances at the Vienna Opera in the standing room area, which was extremely popular among the young in those days. Lola was a very charming happy-go-lucky girl who loved all kinds of entertainment and went out a lot, much to the regret of her father. She even had her cut, which was a sacrilege for a young bourgeois woman in the early 1920s. When she came home after her visit to the hair dresser she hid her hair under a funny hat and with jokes made her father laugh out loud and finally went unpunished. None of her sisters would have dared to challenge their father’s rules in the way she did. She liked dressing up, going to parties and going out with groups of young men and women for sports and entertainment – and the opera’s standing room. She adored tenors such as Leo Slezak, Joseph Schmidt and Richard Tauber and waited for the adored singers after the performance in front of the stage door or watched their films in the cinema.

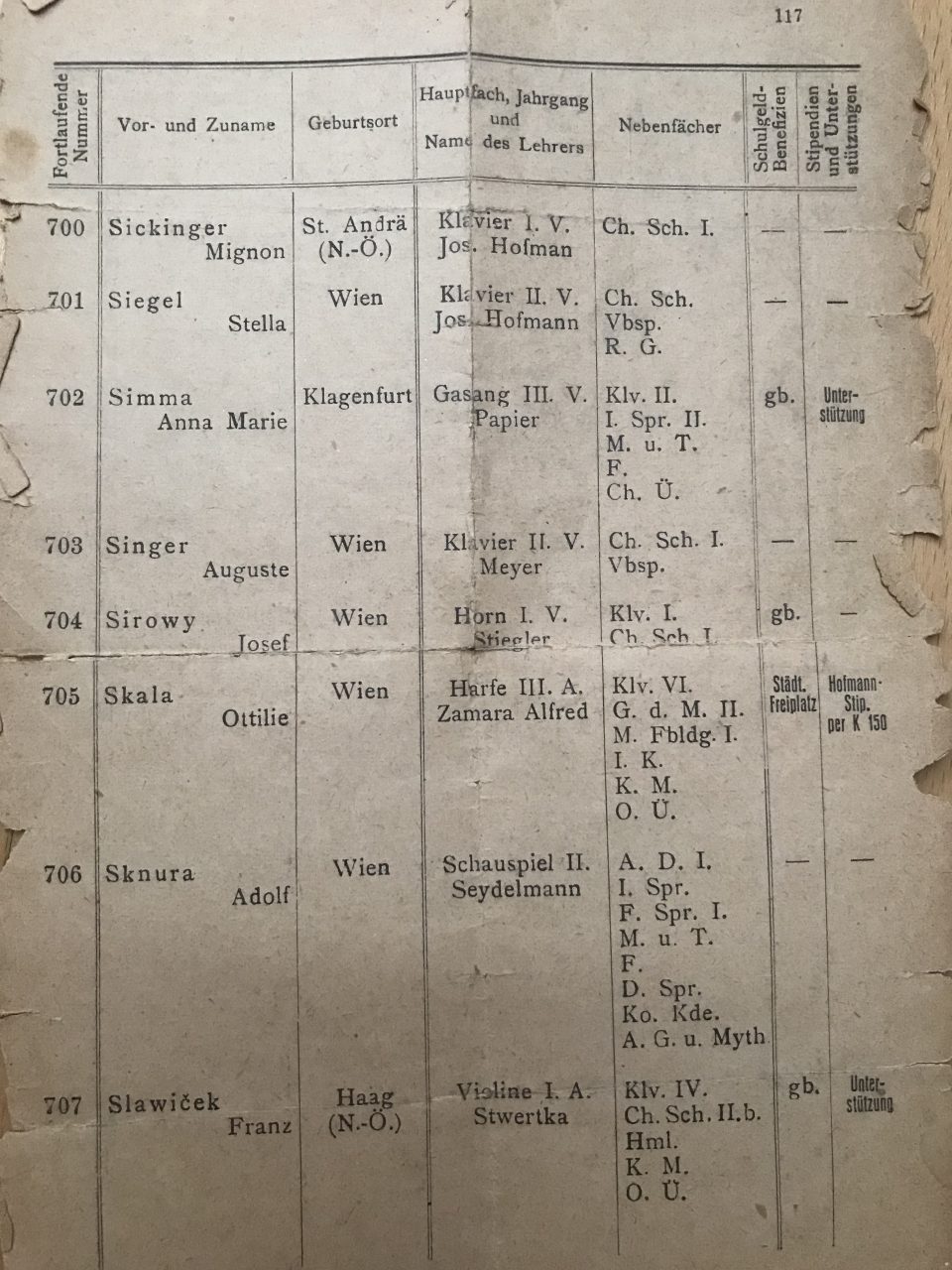

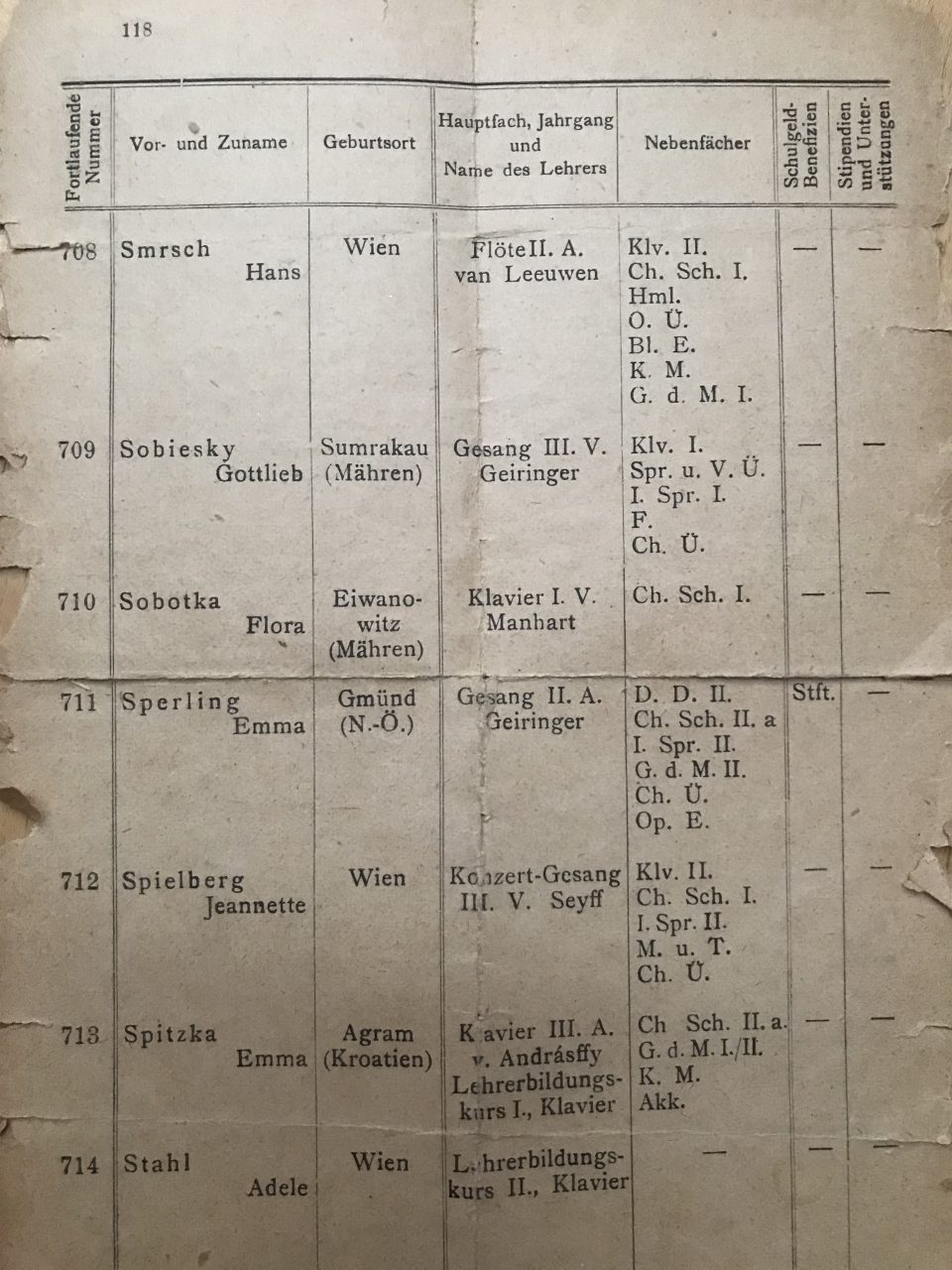

She was admitted to the Vienna Musical Academy in the piano class of Professor Manhart. Later on in her life she was still very proud of that achievement, but admitted that she had not been serious enough. She was not the hardworking studious type as she loved entertainment too much. She used the smallness of her hands and the narrow span between her fingers as an excuse and quitted the class to start work as a shop girl in a sweet shop, where she got to know her later husband, Anton Kainz, my grandfather. After Ignaz Sobotka had lost his job as the manager of the brewery in Kaiser Ebersdorf, the family moved to a small flat in Vienna, Mariahilferstrasse. Ignaz worked as a menial labourer for the construction company “Teerag-Asdag” and the family was no longer well-off. But Lola’s enthusiasm for classical music, especially the opera, never ceased and the standing tickets in the opera were very cheap. Yet despite her skills as a pianist she was always reluctant to play the piano at home. Her husband, Toni, was an amateur who loved the piano, but he always had to urge Lola and coax her into playing with him four-handed piano pieces. Nevertheless, the classical opera remained with her all her life and when I was a child we always had to listen to the one-hour radio programme after lunch the “Opera Concert”, when she told me about the greatest opera singers and her favourite arias. My parents, her daughter Herta and her husband Werner, carried on that tradition. During my whole childhood and youth we listened to records of classical music in the evening – there was no television set bought – and went to operas, classical concerts and operettas. At the reopening of the Vienna Opera house on the “Ring” in 1955, which was destroyed at the end of World War II, my parents acquired a subscription for the Vienna Opera, which they kept until just a few years before they died in 2016. My mother being a dressmaker and my father an electrician, they could only afford the cheapest category, which was the last row before the gallery standing room, but they loved it and were very proud of their subscription that dated back to the reopening of the opera. They knew the opera lovers sitting next to them and enjoyed the atmosphere of the standing room audience behind them without having to endure hours standing up while listening to Wagner, Verdi and Richard Strauss. They also saved up for tickets to see one of the first “New Year’s Concerts” in the now world-famous “Musikverein” after the war.

Lola in front playing with children in Kaiser Ebersdorf

Lola as girl

Lola with short hair

Lola with short hair as a student

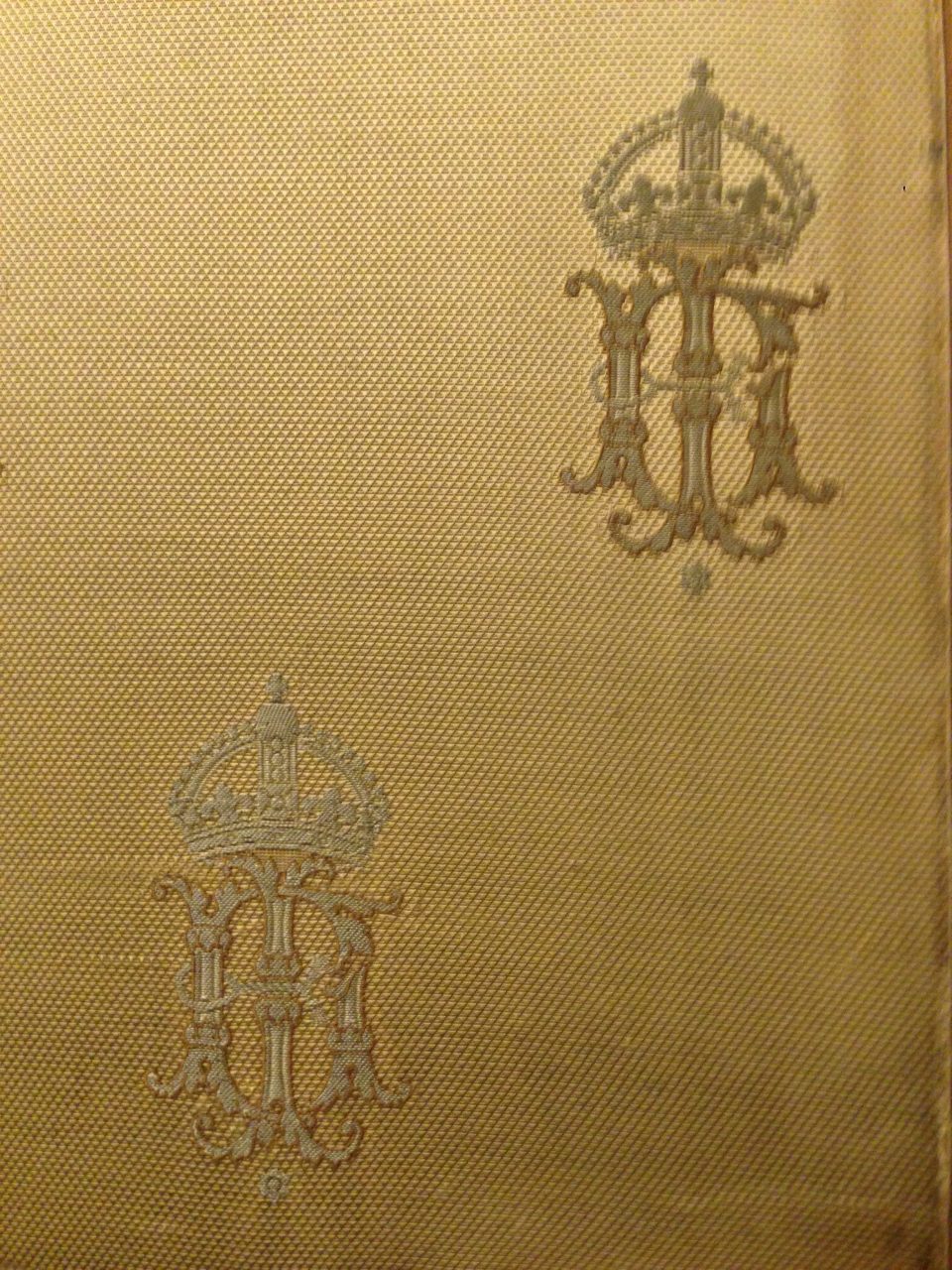

The Vienna State Opera was a court theatre at the time of the Habsburg Monarchy, financed by the state, just as the “Burgtheater”. After the end of the monarchy, the Austrian Republic took over the financing of the state operas and theatres. In 1870 the old court opera house, the “Kärntnertortheater” was demolished and a new building was erected at the Ringstrasse – today’s “Staatsoper”. The architects van der Nüll and Sicardsburg designed a building in the romantic- historical style. The new opera house was opened in 1869 with Mozart’s “Nozze di Figaro”. After an Allied bombing attack the opera was destroyed on 12 March 1945. Only the main walls, the great staircase and the Emperor’s tearoom survived. Soon after the end of the Second World War the reconstruction of the legendary monument to Vienna’s love for classical music started. The opening ceremony took place on 5 November 1955, when Karl Böhm directed Beethoven’s “Fidelio”.

The Viennese are characterised by a passion for classical music – a long-time tradition that comprises different social strata from the university professor and society lady to the secretary and the taxi-driver. Currently 10,000 tickets for classical music events are sold on average daily in Vienna – a city with a population of 1.8 million. This makes 70,000 tickets per week – a number that is enormous when compared to much bigger cities such as Paris, London or New York. One among other reasons is the phenomenon “standing room” in the opera houses, theatres and concert halls in Vienna. The Vienna Opera alone sells around 600 standing tickets every evening at a price of three or four euros each. This phenomenon goes back a long time and is unique. It allows young and less well-off people to enjoy classical music of the highest quality with world famous stars at the price of just a little more than a cup of coffee. While in other big opera houses and theatres in Europe standing room tickets have been scrapped, in Vienna the tradition is alive and booming. Queuing up for the standing room tickets in the Vienna Opera for hours before the performance and then being the first to rush to the different standing room areas – behind the parterre or up on the gallery – is a much loved leisure time activity. While in Paris or London the opera is an elitist entertainment, in Vienna it is still today open for everyone, also because the directors of opera houses and theatres are committed to the standing room tradition and to keeping the price of standing tickets low. In the State Opera half of the standing tickets are located behind the parterre with excellent acoustics and the other half up on the gallery behind the last balcony seats. Some of the opera loves believe that these are the best standing places while others regularly flock to the standing places behind the parterre. Even today long queues form at the box offices for the 100th repetition of a performance of Mozart’s “Nozze di Figaro” and every detail of the performance is analysed by the standing room audience. Their opinion influences the atmosphere in the whole auditorium and the applause for an especially successful performance can last up to 20 minutes, whereas it would be a maximum of six minutes in Paris, for example. In Vienna up to 200 people wait for the artists at the stage door after the performance and journalists regularly attend performances of classical music events in order to review the performances. Ten to fifteen articles appear daily on classical music and theatre in Vienna in all media – on-line, social media, the press and television. When the conductor Welser-Möst suffered an attack of lumbago during a performance at the opera and had to be transported to the hospital after the first act at 18.45, this fact was in the TV news at 19.00.

Lola, on the right, loved dressing up for fancy dress parties

Lola on the right in the summer of 1923 at the “Eislaufverein”

There is no place in the Vienna Opera with more mythical atmosphere, more history and more tradition than the standing room. In 1910 the newspaper “Neues Wiener Journal” wrote that the standing room was a small state in the empire of the theatre. It was called the “fourth gallery” in the Viennese theatres and in fact it was the highest authority. The newspaper reported that in the parterre and the boxes those that represented society were seated, but high up in the standing room the future generations were standing and their reaction to the performance was what counted. Artists in Vienna sang and acted “up towards the fourth gallery” – if they were able to get in contact with the standing room audience and elicit a positive reaction from there, “the battle was won”. The legendary “fourth gallery” of the Vienna Imperial State Opera is mentioned in many literary articles, novels and autobiographies. For a young, enthusiastic and interested Viennese the attendance of an opera performance from the standing room area was just like the visit of a coffee house – a necessity. The composer Alban Berg met his later wife, Helene Nahowski, in the standing room and Hugo Wolf, another composer, described his memorable experiences of Wagner there. The famous writers Joseph Roth and Stephan Zweig reported on the atmosphere of the opera’s standing area. Stephan Zweig wrote in his book “The World of Yesterday” that he as well as his father were enthusiasts of the opera and the standing room. He reported that for a first night he had to start to queue up with his school mates for standing tickets at 3pm and that was the time when a large part of the pupils fell mysteriously ill and could not attend school in the afternoon. On the “fourth gallery” new musical trends were acclaimed, which were slated by the conservative critics in the press, such as the “Second Viennese School” of Schönberg, Berg and Webern. Richard Strauss’ “Rosenkavalier” was enthusiastically celebrated in the standing room, while he just received polite short applause in the parterre. Already in 1895 Carl Lafite described the young music students who listened to the performances every evening in the standing room and survived hour-long acts without a single murmur in unbelievable positions because their feet hurt so much. The verdict of the “fourth gallery” was decisive for failure or success of a performance or star. In 1919 the “Neue Wiener Journal” protested against the noise the “fourth gallery” produced after every act of Wagner’s “Meistersinger”. The standing room audience had silently lifted the ban on shouting the names of artists and since then the supporters of singers acclaimed their favourites vociferously. My grandmother, Lola, often spoke about those young people who formed the “Claque” who were sometimes even paid to offer high-volume backing to a singer, no matter whether his or her performance that night was really excellent or not.

Lola was lucky because when she turned 17, women were finally allowed to attend performances from the standing room after the end of the Empire on 1 November 1919. During the time of the Habsburg Empire the standing room was separated into two areas, one reserved for the military, the other half for civilians, which was not appreciated by the majority of the standing room audience. This regulation ended together with the reduction in price of the standing tickets for members of the military in uniform (20 Heller – 100 Heller to 1 Krone) in 1919 as well. The First Austrian Republic had introduced the active and passive voting right for women and made equality of men and women possible in opera houses and theatres, too. It is unclear why this absurd regulation was introduced in the first place because women were allowed in every part of the opera houses and theatres, in the seating areas, the lounges, but not in the standing room during the Habsburg Empire.

Schönbrunn, March 1929, the sisters Mitzi, Agi and Lola on the right with a young gentleman

Lola on the left, Agi in the middle with two young gentlemen in Schönbrunn, March 1929

In the past as well as today the standing room audience consists of regulars, young, middle-aged or even elderly who attend performances three times a week on average or a few times a month and newcomers who want to enjoy the special atmosphere of the standing room. In the 1920s Lola was a typical regular who came to the opera’s standing room because she loved the opera, was involved in musical studies, but most of all because she enjoyed the fun, the discussions and meeting other young people, waiting for stars at the stage door after the performance and, of course, going out after the performance. With respect to standing places, the Vienna Opera was and is unique. Even today a quarter of the tickets are standing tickets (567 out of 2,284). The cheapness of the standing ticket only offers one explanation for its perpetual popularity – a very good ticket in the seating area costs around fifty times the price of a standing ticket. It is the community spirit of the very diverse standing room audience which is united by its enthusiasm for classical music. Standing for hours requires more physical effort and enhances the concentration. There is more movement and unrest in the standing room area and closer contact to the neighbours. Queuing up for hours before the performance already offers the possibility for communication and discussion about musical issues between strangers and regulars. Those people who attend performances regularly accumulate an enormous amount of experience and knowledge about classical music. There are some who use the opportunity to boast with their expertise and try to impress others. The rush to get to their favourite standing places and reserving it with a shawl, for example, might lead to squabbles with other standing ticket owners. But these vexations are compensated for by the privilege of entering the auditorium before all other spectators. Different opinions sometimes result in heated discussions and the emotional reactions of the standing room audience are often enigmatic for the rest of the spectators. The vociferous exclamations create a special atmosphere in the audience that show the power of the standing room which can make or fail an artist in Vienna, justly or unjustly. The standing room is made up of artists, music students, and supers who love the stage, but usually have a non-artistic profession, of experts who know all the conductors and singers past and present and usually work in a non-musical job as well. Furthermore there are the fans who support special singers, Richard Wagner enthusiasts and tourists who want to experience this special atmosphere.

As long as there is incessant demand for standing tickets in Vienna, classical music is not as dead as a dodo. The emotional experience of live music can reduce mental stress and the combination of music and theatre is probably the most emotionally intense form of art. The repeated listening to the same piece of music leads to a recognition effect which in its turn triggers a reaction of the brain by releasing the hormone dopamine. This results in a feeling of happiness which gets stronger the more often a person attends an opera performance. That is also the reason why the standing room audience reacts more emotionally than the rest. In this way classical music can become a sort of drug; you can live your emotions in the opera world and forget about real life. When staying with my grandmother, Lola, we had to listen to the radio “Opera Concert” after lunch every day and I remember her joy when she would recognise the composer and the opera after listening to the first notes of the musical piece – and quite often the singer’s name, too. Most of the standing room audience see themselves as pseudo-experts and express their opinions sometimes with immoderate arrogance. They think they are the true “rulers” of the opera because they have listened to and seen so many performances. They even call their favourite singers by their first names. Fanaticism seems to have been most pronounced in the 1920s and early 1930s when the “Claque” groups boosted certain stars and it was difficult to express a different opinion in the standing area. In those days disapproval was expressed by whistling, not like today by catcalling. The standing room audience was made up of lots of teenagers then who adored certain singers, male or female. At that time standing was even more bothersome than today because there were no railings to cling to.

Who was interested in classical music and the theatre ended up at some time in the standing room of the opera or a theatre in Vienna in the first half of the 20th century. Hubert Deutsch, who worked for the Vienna State Opera from 1955 until the 1990s, wrote that his father had told him about his wonderful experiences in the standing room behind the parterre of the “k.k. Hofoper” when he was a child. The director of the orchestra was not evidenced in the programme in those days and it was a big challenge for the standing room audience to guess who the director would be. If it was Gustav Mahler, there was special applause at the start of the opera. So in 1937 Hubert Deutsch was happy to be able to attend a Vienna State Opera performance for the first time at the age of 12. Sometime later he was allowed to get his own standing room ticket. He joined the queue in front of the box office two hours before the beginning of the performance and then rushed, ticket in hand, up to the “fourth gallery” to “conquer” a good place there. He was permitted to go to the opera once a month on Saturdays only if his school marks were satisfactory. As soon as he became a student of the Vienna Music Academy he went to the opera standing room daily. He loved the standing room atmosphere among youngsters of the same age, the supporters of the various singers who shouted their first names at the end of a performance. Before World War II the Vienna State Opera had the best singers and every performance was of the highest quality, so that the standing room audience was involved in lots of discussions who would be best for which part. The young fans awaited the singers at the stage door and handed over envelopes with requests for autographs and photos, which usually arrived some time later in the mail of the fans.

The composer Walter Arlen, who was born in Vienna in 1920, remembered that his culturally interested parents regularly went with him to museums and exhibitions like the “Albertina” and the “Kunsthistorische Museum” and had a box in the opera, where he was allowed to attend his first opera performance at the age of 11. In grammar school he became a regular at the standing room up on the gallery together with his school mate Paul Hamburger, later a famous pianist. Up on the “fourth gallery” he was turned into a Wagner enthusiast. There the young people admired Bruno Walter, Maria Jeritza and rejected everything “old” and welcomed everything “new” like Korngold’s “Tote Stadt” or Pfitzner’s “Palestrina”. Arlen’s sister Edith was even admitted to the Vienna Opera’s ballet school. For the Arlens everything ended in March 1938 with the Nazi takeover. His sister was kicked out of the ballet school, the family had to leave their flat; they were dispossessed and forced into emigration after his father had been imprisoned in the concentration camps of Dachau and Buchenwald. Walter had already composed his first music before 1938 and continued his studies in the United States. He was one of the many Jews in Vienna, like Lola and her friends, who were enthusiasts of classical music and talented musicians.

Lida Winiewicz describes in her autobiographic novel “Der verlorene Ton” (The Lost Note) how she wanted to become a singer, but because her grandmother was Jewish she was not allowed to perform after March 1938, which was so traumatic for her that she could no longer sing the highest note “G” of Schubert’s “Heideröslein” and all her life never recovered the highest notes of her voice. Her first teacher was Fritzi Lahr-Goldschmied, who had worked with famous opera singers before, but after 1938 she lived “underground” in Vienna, which was called as a “U-Boot”, meaning without papers, without food stamps, without money and without shelter, always afraid of being discovered and deported into a concentration camp. But she still gave lessons to the girl and was paid in kind. Ms Lahr-Goldschmied also taught a friend of Lida, Antonia, who she had encountered in the standing room of the Vienna Opera, namely in the left “Kipferl” (croissant) – this was the left corner of the standing room behind the parterre. There were regulars in the left “Kipferl” and other regulars who preferred the right “Kipferl”. Antonia studied at the Vienna Music Academy with professor Anny Konetzni. The academy was housed in the building of the famous “Akademietheater” and the students could use the stage for opera rehearsals. There Lida sneaked in and watched the rehearsals of Antonia and the other students from which she had been banned. My grandmother Lola had studied piano there, too. Had she not quitted before she would have been banned as well for being Jewish,

Flora Sobotka Nr 710 in the piano class of Prof. Manhart at the Vienna Music Academy

The forerunner of the Vienna Music Academy opened in 1817 as a singing school directed by Antonia Salieri in the “Singerstrasse” in Vienna. In the following years instruction in the various instruments was introduced. In 1848 this school was closed and reopened in 1851 as “Musikkonservatorium”. The violinist Josef Hellmesberger stood at the helm of this musical academy for 40 years. Just a year later classes in dramatic arts were offered as well and the number of students continually increased. In 1854 the school counted 190 students, whereas in 1890 already more than 1,000 young people studied there. In 1909 the “Konservatorium” was nationalised and called the “k.k. Akademie für Musik und darstellende Kunst” (Academy for Music and Drama). At that time the institution employed 70 teachers and instructed 877 students. The institution moved from the Singerstrasse to the Tuchlauben and then to the Karlsplatz ( today’s “Musikverein” building) until it ended up in a new building next to the “Konzerthaus”. The academy building was linked to the “Akademietheater” (that’s where the name comes from) in Lothringerstrasse in 1913. In 1924 the focus was laid on musical instruction and in 1928 a separate school for drama, the famous “Reinhardtseminar” was founded. The Nazis integrated both into the “Reichshochschule”, but after the end of World War II the academies for music, drama and art were turned into independent institutions again, financed by the state. In 1948 the Academy for Music and Drama was awarded university status.

When in March 1938 Hitler made Austria a part of the German “Third Reich” of the Nazis, the Nazi cultural politics immediately set in in Austria. Since 1933 bureaucratic measures of the German Nazis had led to the expulsion of artists of Jewish descent from all artistic institutions. Obligatory membership in cultural chambers was introduced and the guidelines for membership excluded Jewish artists and artists with Jewish relatives from these chambers. At the same time total censorship of all film, theatre and music productions and all media publications set in. Responsible for this drastic supervision was the propaganda ministry of Joseph Goebbels. Furthermore, the Nazis eliminated all artists who were suspected of communist, socialist, anti-fascist political opinions from the cultural scene, as well as religious activists and homosexuals who were all vilified by being called “parasites of German culture”. At the same time the cultural institutions were misused by the Nazis to stabilise their hold on power. They took over the German bourgeois love for the classics and promoted it after having eliminated all Jewish artists, dead or alive. By that they wanted to prove at home and abroad that the supposedly revolutionary regime of the Nazis was following in the cultural footsteps of the former monarchic and bourgeois rulers. Even more intensive was the Nazi interference in the entertainment industry, especially the film industry, whereby the formerly Austrian film production firm “Wien-Film” was turned into a Nazi film production machinery that inundated the market with superficial and treacly operettas. This was a clever psychological move to distract the population from on-going repression and racial persecution.

Most of the artists, with just a few exceptions, quickly adapted to the new political system, partly also because at a time of high unemployment the increased state expenses for politically correct art improved their working conditions initially. Resistance was only expressed privately and in some cases by helping persecuted colleagues clandestinely. Modern art and modern music were exposed to drastic Nazi aggression: the first exhibition of “Entartete Kunst” (Nazi synonym for degenerate, improper or disgusting art and music) took place in Munich in 1937 and of “Entartete Musik” in Düsseldorf in 1938. Any kind of avant-garde was highly suspicious, be it cubism, expressionism, surrealism or the “Second Viennese School” because it could not be instrumentalised for political ends. The exclusion of all Jewish artists from the Viennese cultural scene was executed quickly and smoothly with a lot of support from inside, initiated by the various artists’ associations and the management of the Viennese cultural institutions. It is estimated that around 1,500 artists had to leave Austria. By instrumentalising “German high culture” with the exclusion of Jewish artists, Hitler was able to do more or less without a special Nazi culture in Germany and in Austria, too. The central cultural policy element was the Nazi entertainment industry: even during the war it was important to keep theatres and cinemas open to provide distraction for the suffering population. What was provided there was a well-calculated mixture of entertainment and “high culture” to appease and seduce the masses. The consequences of the racist cultural policy of the Nazis were discussed in the media; especially the stage ban of many favourite artists and the dismissal of many employees of cultural institutions, such as stagehands, prompters and dressers was public knowledge. On the 12th of November 1938 it was decreed that Jews were not allowed to attend performances of “German culture”, but in fact the number of spectators had already drastically fallen due to the fact that many former spectators had fled the country or were interned. Despite a generous distribution of free tickets by Nazi organisations like “Kraft durch Freude” (“Power through Joy”) many classical concerts took place in nearly empty auditoriums because no new groups of spectators could be attracted. Nevertheless, Nazi politicians like Hitler, Göring or Goebbles did use the theatre stage for political propaganda, too, by appearing at well-orchestrated performances to get acceptance from the groups of theatre and opera lovers.

Just within a few weeks after 12 March 1938 1,200 people from the music business alone were expelled from cultural institutions and were banned from working. Some did not want or could not go into exile or were caught up by German troops during their escape. Most of these were murdered in concentration camps and many of them also did not survive “Theresienstadt”, the “VIP ghetto”. The artists who remained in Austria either pandered to the Nazis in an obsequious way or they took the chance to replace Jewish artists in order to further their career. Still some resorted to silent passive resistance and just very few tried to assist their persecuted colleagues. The myth that Vienna had a special position in the cultural policy of the Nazis is flat wrong; Austria, the “Ostmark”, was completely under the control of Berlin. A special NS theatre law saw to it that what was put on stage in Austria had to please Hitler and his acolytes. The Nazi takeover of the Viennese theatres and opera houses was well-orchestrated because the Nazis had already infiltrated Nazi supporters in the institutions before who then immediately took control in March 1938. This transition was often accompanied by sadistic demonstrations of power: for example the transformation of the “Theater in der Josefstadt” of Max Reinhardt into a Nazi élite stage by Robert Horky and Erik Frey, or the case of Rudolf Beer, the former director of the “Volkstheater” and the “Theater Scala” was dragged out of a pre-performance, brutally beaten up by Nazi rogues and thrown out of a car at the “Vienna Höhenstrasse” on 23 April 1938. Just a few days later Beer committed suicide. Other directors gave in to Nazi threats and handed over their position like the director of the “Volksoper”, Jean Ernst. Others were opportunists, like the director of the “Volkstheater” Rolf Jahn, who had succeeded Rudolf Beer in 1932 and had already established contacts to Berlin in February 1938 – he was at the right place at the right time in March 1938.

After the “Anschluß” of March 1938 all Viennese theatres and opera houses had to draw up lists of all Jewish artists and employees, who were then dismissed on 30 April 1938. In order to prevent a complete break-down of the operation of the theatres, “half-Jews” and “Arians” married to Jews were allowed to continue working provisionally. Three Viennese theatres, the “Volkstheater”, the “Raimundtheater” and the Komödie” in the Johannesgasse (today “Metro-Kino”), were run by the Nazi organisation “Kraft durch Freude” from 1938 on, where the Nazis tried to attract new groups of spectators to theatres at reduced prices. By humiliating Jewish theatre subscribers, the Nazis tried to drive them out of the auditoriums. In the Vienna State Opera Jewish subscribers were challenged from the stage to leave the auditorium and when they then wanted to cancel their subscriptions they were forced to continue to pay, although they were no longer allowed to attend the opera performances. During the war the theatres were kept open and had to provide light and amusing entertainment to distract the Viennese; special performances were organised for armaments workers and family members of soldiers paid only half-price. The Nazi propaganda had taken over the auditorium as well: on Hitler’s birthday all workers could attend performances free of charge and on Mother’s Day the mothers of fallen soldiers were paraded in the “Burgtheater” and the audience was advised to welcome them with standing ovations. In 1942 and 1943 the drastic effects of the war could no longer be hidden: no programmes were printed any more, in winter the theatres were often closed due to lack of fuel and in all theatres instructions in case of bomb alarms were omnipresent: The audience could take their coats with them and all combustive material was removed from the auditorium. Male actors and singers were drafted and in September 1944 Goebbels announced the “total war effort of the artists”, by which personnel of theatres was conscripted to work in the armaments industry. Finally in the theatres only readings took place on stage. At Christmas 1944 there was the last performance in the “Burgtheater”, which was hit by a bomb four months later and burnt out, just like the “Staatsoper”. The actor Fred Hennings who had opened the doors of this theatre to the Nazis and taken over the running of the “Burghteater” in 1938 continued to act there after the war and he was even showered with honours in the 1960s and 1970s (Honorary Member of the “Burgtheater” in 1963 and the Ring of Honour of the City of Vienna in 1977)

The Imperial Tea Room in the Vienna State Opera that survived the bombing of 1945 and the precious tapestry with the initials of Emperor Franz Joseph I

The opera singers that my grandmother Lola admired most were Joseph Schmidt and Richard Tauber, who both suffered the same fate as exiles.

Leo Slezak (1873-1946), the Austro-Hungarian tenor and actor, was in the last phase of his opera career, when my grandmother watched his performances in the Vienna Opera from the standing room. He was from a simple rural background in Moravia and worked in many jobs until he finally had his first appearance on the opera stage in Brno in 1896 as Wagner’s “Lohengrin”. In 1901 he started his enormously successful career at the Vienna Opera, where he sang many famous parts until his last opera performance in April 1934 in Verdi’s “Othello”. He was a fascinating “heroic tenor” with a legendary “pianissimo” and an imposing appearance on stage with 1.95 m and 150 kg. In 1932 he began his second career as a film star. In those German and Austrian films he usually sang and acted the comic parts. During the Second World War he acted in anti-Nazi films, so the Nazis imposed a ban on him and forbid his acting in films in the whole “Third Reich”. Slezak was famous for his humour and his quips. When in his role as Lohengrin a stagehand moved the swan from the stage too early in an Upper-Austrian opera house, Slezak was not distracted, but shouted, “Please, when goes the next swan?” The famous tenor also wrote several humorous books and memoirs.

The Vienna State Opera

The younger tenor Richard Tauber (1891-1948) was considered at that time the most important tenor next to Enrico Caruso. He was born in Linz, in Upper Austria, where his mother was a “soubrette” at the theatre and his father an actor and where he also started his career. He was famous for his interpretation of Mozart roles and most importantly of the music of Franz Lehár, who in the 1920s wrote many songs for him, the most famous of which is “Dein ist mein ganzes Herz” (Yours is my whole heart). Lehár and Tauber together wrote the famous operetta “Das Land des Lächelns” (Land of Smiles), which made him an international star. Tauber merged opera, operetta and popular songs, which was the foundation of his enormous international success and reputation as the first “pop star” of the 20th century. In 1933 he was driven out of Nazi Germany and returned to Austria, from where he had to flee in 1938. During a world tour he complained that he only wanted to sing. What did that have to do with the fact that his grandfather was Jewish? He emigrated to Great Britain and never returned to Austria again. His destiny stands for the fate of many who were destroyed by the inhuman and racist policy of the Nazis. During the war he gave many charity concerts to support the British in their war effort. He was a very generous man and a lover of women, which contributed to his serious financial difficulties despite his international fame. He died, heavily indebted, of lung cancer in January 1948 in London just a few months after his huge success on 27 September 1947 as Don Ottavio in Mozart’s “Don Giovanni” with the orchestra of the Vienna State Opera under director Josef Krips at the Royal Opera Covent Garden. Richard Tauber is buried in London in Brompton cemetery with the inscription: “A golden singer with a sunny heart / The heart’s delight of millions was his art / now that rich, roaring, tender voice beguiles / attentive angels in the land of smiles.”

downstairs standing room

upstairs standing room

The Vienna State Opera

The second famous young tenor of the time was Joseph Schmidt (1904-1942) who was born in the eastern province of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Bukovina, as the son of a German-speaking orthodox Jew. Already as a child he sang in the temple in Czernovitz. He was only 1,54 m tall, which made it difficult for him to take over parts on a stage – his first stage performance took place in Berlin in August 1929 in “Die drei Musketiere” by Ralph Benatzky, an Austrian composer who had to flee the Nazis, too. That’s why he started his career as a lyrical tenor on the radio and in opera recordings on gramophone records. Around 1930 he was one of the most important lyrical tenors in the German-speaking area, yet he went on tour to Western and Northern Europe as well – to concert halls in Ghent, Antwerp, Oostende, Helsinki etc. On the 20th of February 1933 he sang for the last time for a German radio station in “Der Barbier von Bagdad” by Peter Cornelius. Just a week later he was banned from entering the radio station. After the premier of his world-famous film “Ein Lied geht um die Welt” (A Song Goes around the World) in May 1933 he came to live in Vienna. During this time in Vienna many of his internationally acclaimed musical films were made – some of them also in an English version – , such as “Wenn du jung bist, gehört dir die Welt” (If You Are Young, the World Belongs to You) in 1933, “Ein Stern fällt vom Himmel” (A Star Falls from the Sky) in 1935 or “Heut ist der schönste Tag in meinem Leben” (Today is the Most Beautiful Day of My Life) in 1936. His most acclaimed opera roles were Rudolfo in Verdi’s “La Bohème” and Canio in Leoncavallo’s “Pagliacci”. Despite his small stature he was much loved by his female audience and had many admirers. He went on tour to Palestine and New York, but had to flee again from Austria in 1938, first to Belgium and then in November 1940 to France, where he was later interned by the Vichy regime. His friend Max Neumann tried to organise concerts for Joseph Schmidt in Vichy France. The concert that was to take place in March 1942 in Marseille was sold out, but the French administration forbade a concert where Arian and Jewish artists were on stage together. On the 14th of May 1942 he sang on stage for the last time in the opera of Avignon. After several unsuccessful attempts he managed to flee alone and on foot to Switzerland in October 1942. He was so weak and exhausted and suffered from serious throat problems that he broke down in the streets of Zürich. Consequently he was interned in the Swiss camp in Girenbad waiting for the bureaucratic review of his case. After a short stay in hospital he was brought back to the camp Girenbad, where he died two days later at the age of 38. He is buried in the Jewish cemetery in Zürich, where on his grave stone is written in Hebrew and German “Ein Stern fällt” (A Star Falls).

The Musikverein standing room

Marcel Prawy (1911-2003) attended performances in the standing room of the Vienna State Opera from an early age on and his memories offer an interesting insight into the atmosphere there and the mind set of these young enthusiasts. He was later known as the “opera guide of the nation”, a Viennese oddity, a quaint personality and outstanding connoisseur of classical music who was notorious in Austria for his TV broadcasts on classical music after his return from exile in the United States. His birth name was Marcell Horace Friedmann Ritter von Prawy. His family was of Jewish-Polish descent and his grandfather was knighted by the Emperor Franz Josef. After the breakdown of the Habsburg Empire all titles of nobility were abolished in Austria and so his name was Marcell Frydmann. As a young man and enthusiast of the Vienna Opera he was employed as secretary of the famous opera tenor Jan Kiepura, who told him to get rid of this ugly name and use the old Polish title, meaning “the Righteous”. That’s when he became “Marcel Prawy”. His father was a high ranking civil servant in the Supreme Administrative Court, who was said to know all operas by heart and his grandfather Dr. Marcell Frydmann (1847-1906) was a well-known jurist and journalist, who was editor-in-chief of the newspaper “Fremdenblatt” since 1886 and was knighted in 1899 for his achievements. The opera turned out to be Marcel Prawy’s “surrogate religion”. Already as a young grammar school pupil he regularly attended performances in the standing room of the Vienna State Opera. He knew many famous musicians personally from Richard Strauss to Leonard Bernstein and was head dramaturg at the Viennese “Volksoper” and the Vienna State Opera after the war. During his last ten years of life he rented a room in the Hotel Sacher, close to his beloved opera house, probably because he had turned his flat into a depot and archive of classical music and there was no more room to live in. He wrote about his years as a young frequenter of the standing room of the Vienna State Opera, where he saw the premiere of Puccini’s Turandot, that as soon as Jan Kiepura, the young Polish tenor, had made his spectacular debut in Vienna, they – the young grammar school boys – had no success with Viennese girls anymore because they were all “Kiepura girls”. Prawy admired the “sex appeal” of his voice, his charm and his media presence and later became his assistant. He remembered a special event, when the young people from the standing room supported and boosted the success of the premiere of “Wozzeck” by Alban Berg in 1930. The young opera fans were fascinated by the modern music of this young genius. What’s more, Prawy was an admirer of Rose Pauly in the leading part, whom he was proud to accompany to her home on Petersplatz after performances. At that time Richard Tauber was at the height of his career and Prawy mentioned that the composer Franz Lehár wrote many parts for Tauber’s voice to allow it to shine at its best. Together with Jarmila Nowotna he praised them as the star couple of the Viennese operetta and arias such as “Meine Lippen, die küssen so heiß” became world-famous hits and were sung by him and his friends in the streets of Vienna. In the early 1930s operettas were performed at the Vienna State Opera regularly, for instance “Die Fledermaus”, “Der Zigeuenrbaron” or “Giuditta”. Prawy was a fan of the singer Elisabeth Schubert, too, whom he followed into the “Burggarten”, where she walked her dogs and he managed to glean several autographs from her. Although Prawy was an enthusiastic supporter of Jan Kiepura, he also appreciated the marvellous voice of Alfred Piccaver, a Brit who had transformed himself into a Viennese celebrity, but as he hated travelling he unfortunately remained a local star in Vienna. The young standing room frequenters called him “our Pikki”.

Literature:

Fassbind, Alfred, Joseph Schmidt. Ein Lied geht um die Welt. Spuren einer Legende, Zürich 1992

Hartmann, Lukas, Der Sänger, Zürich 2019

Prawy, Marcel, Die Wiener Oper, Molden Verlag 1969

Steinthaler, Evelyn, Morgen muss ich fort von hier! Richard Tauber – Emigration eines Weltstars, Milena Verlag 2011

Stockinger, Heide & Garrels, Kai-Uwe, Tauber, mein Tauber. 24 Annäherungen an den weltberühmten Linzer Tenor Richard Tauber, Verlag Bibliothek der Provinz 2017

Winiewicz, Lida, Der verlorene Ton, Wien 2016

Wir vom Stehplatz, Löcker Verlag Wien 2018