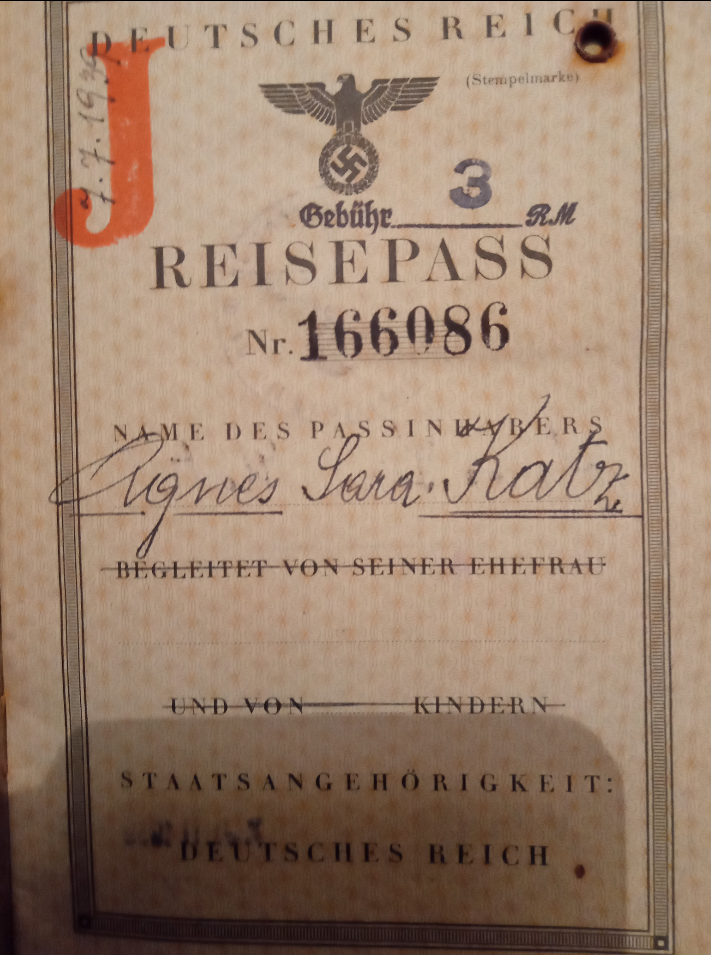

MAID SERVANTS IN ENGLAND: AUSTRIAN JEWISH WOMEN IN EMIGRATION 1938/39

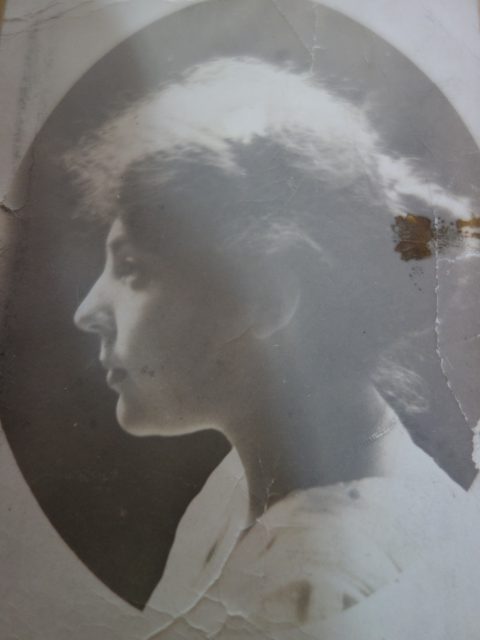

Käthe as a young woman in Vienna

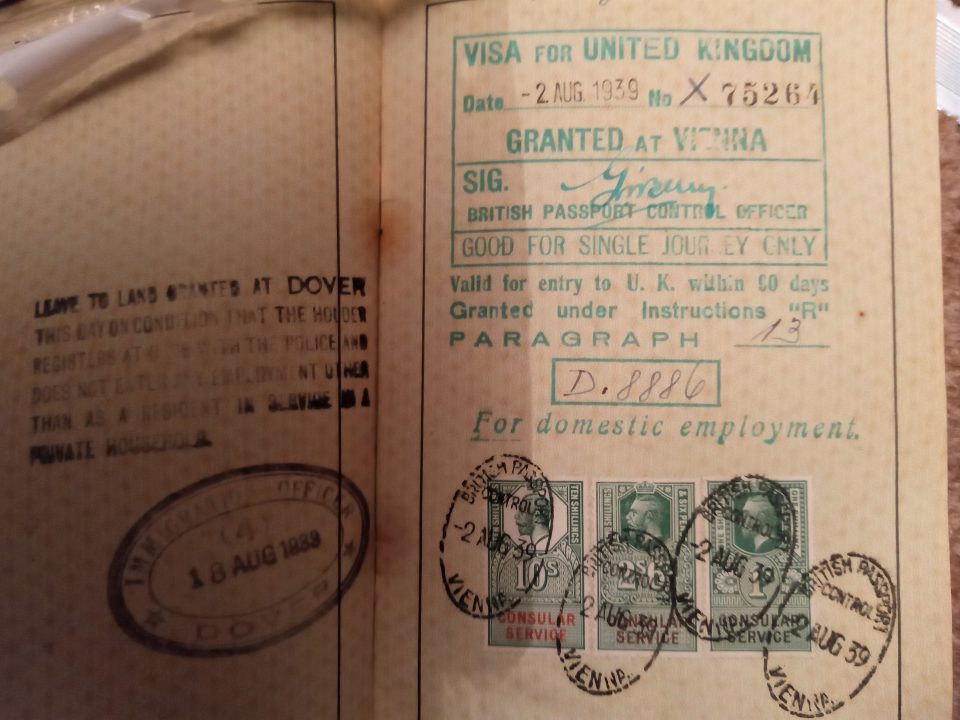

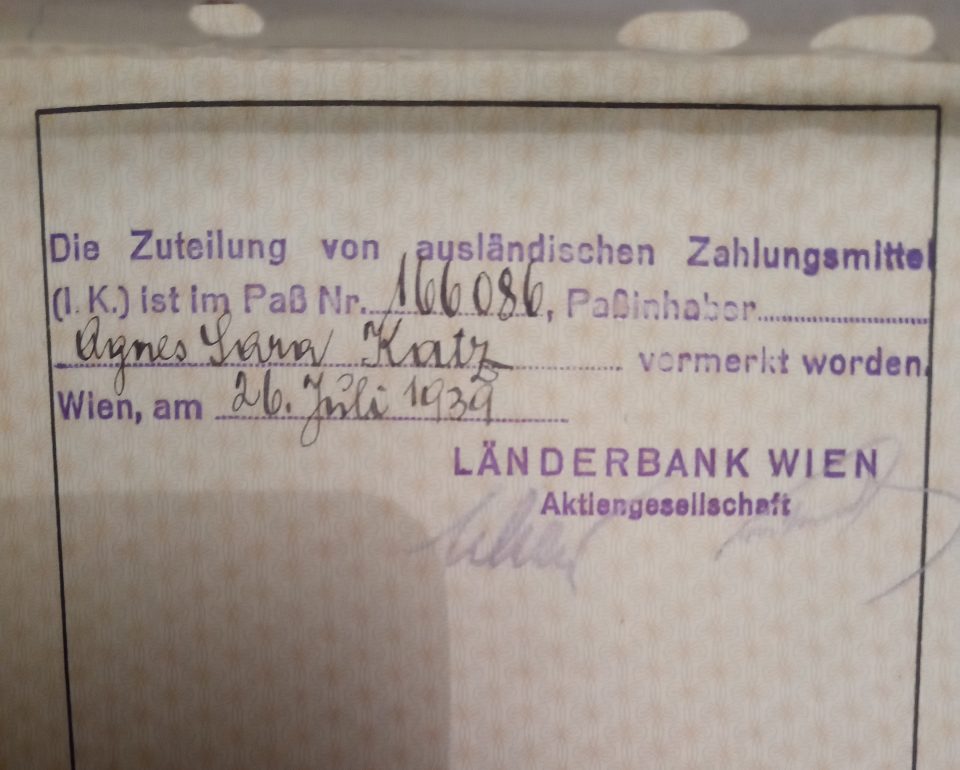

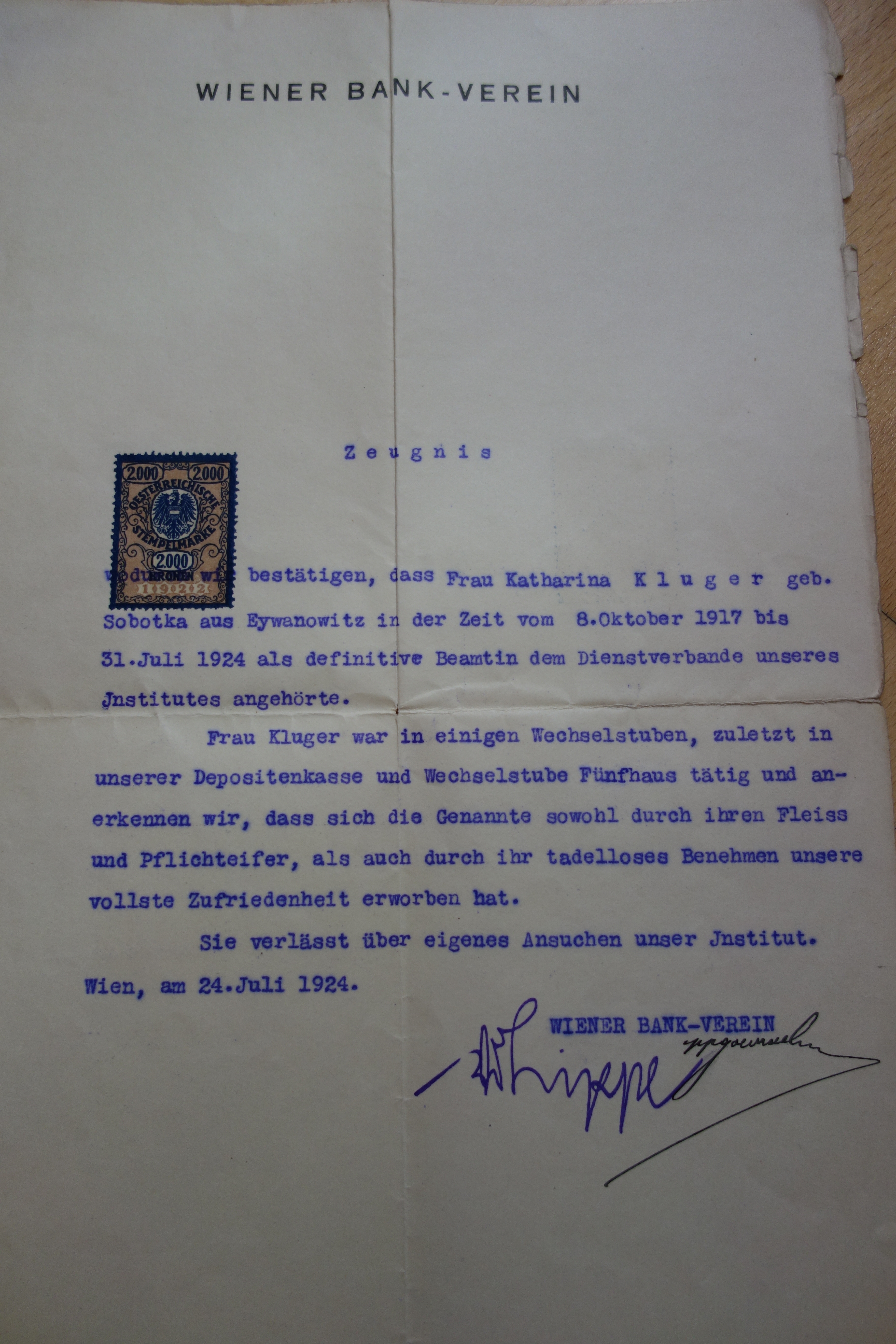

My great-aunt Käthe, born in 1901, was a bank clerk at the Wiener Bank Verein and had lost her first husband, Poldl Kluger, soon after the wedding, victim of a lung disease, in illness that was wide-spread in Vienna at that time. When she lost her job at the bank in 1924, being tall and slim, she made ends meet by accepting occasional jobs as a fashion model. After the civil war in 1934 and the coup d’état of the Austrian fascists, Käthe, an assimilated and agnostic Jewess and a socialist, realised that sooner or later she would have to flee Austria. Being single facilitated the decision-making process. She diligently prepared for her escape from the Nazis by learning English and acquiring cooking skills. She then applied for the position of cook in a wealthy English household and landed in Dover on the 7th of November 1938. Having arrived at a safe haven in England with a domestic permit, she tied to get out of Austria as many of her family as possible. She worked in 25, Warkworth Gardens in Isleworth in Middlesex and managed to convince her generous and understanding mistress to hire her younger sister, Agi, as a maid in the same household and by that offered her a last-minute escape from deportations from Viennese collection points in the 2nd district to the concentration camps of the Nazis. So let’s look at this special rescue model, a window of opportunity for young Jewish women from Austria in 1938, which was closed in 1939.

Käthe’s employment as a bank clerk at the “Wiener Bank Verein” 1924

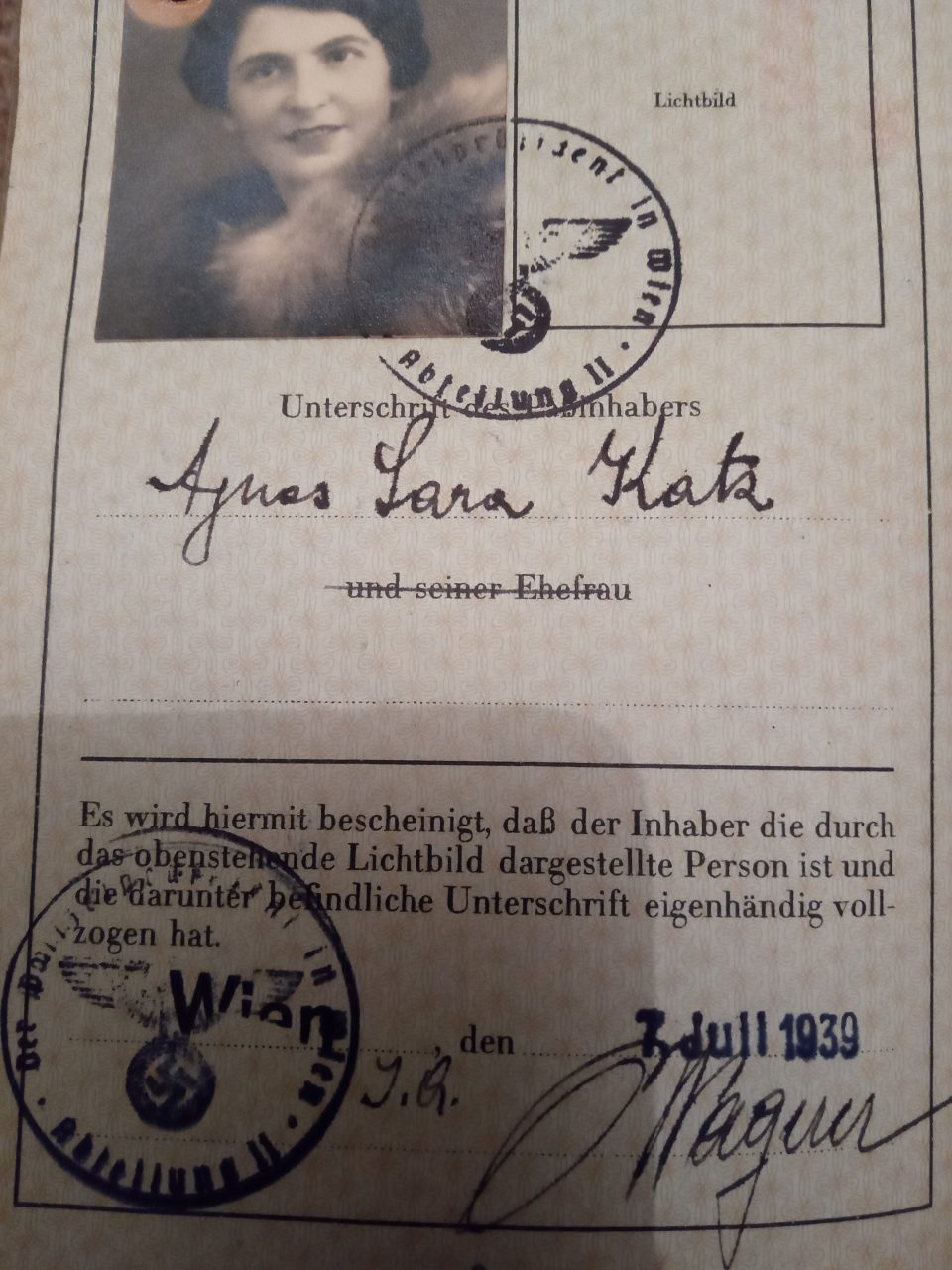

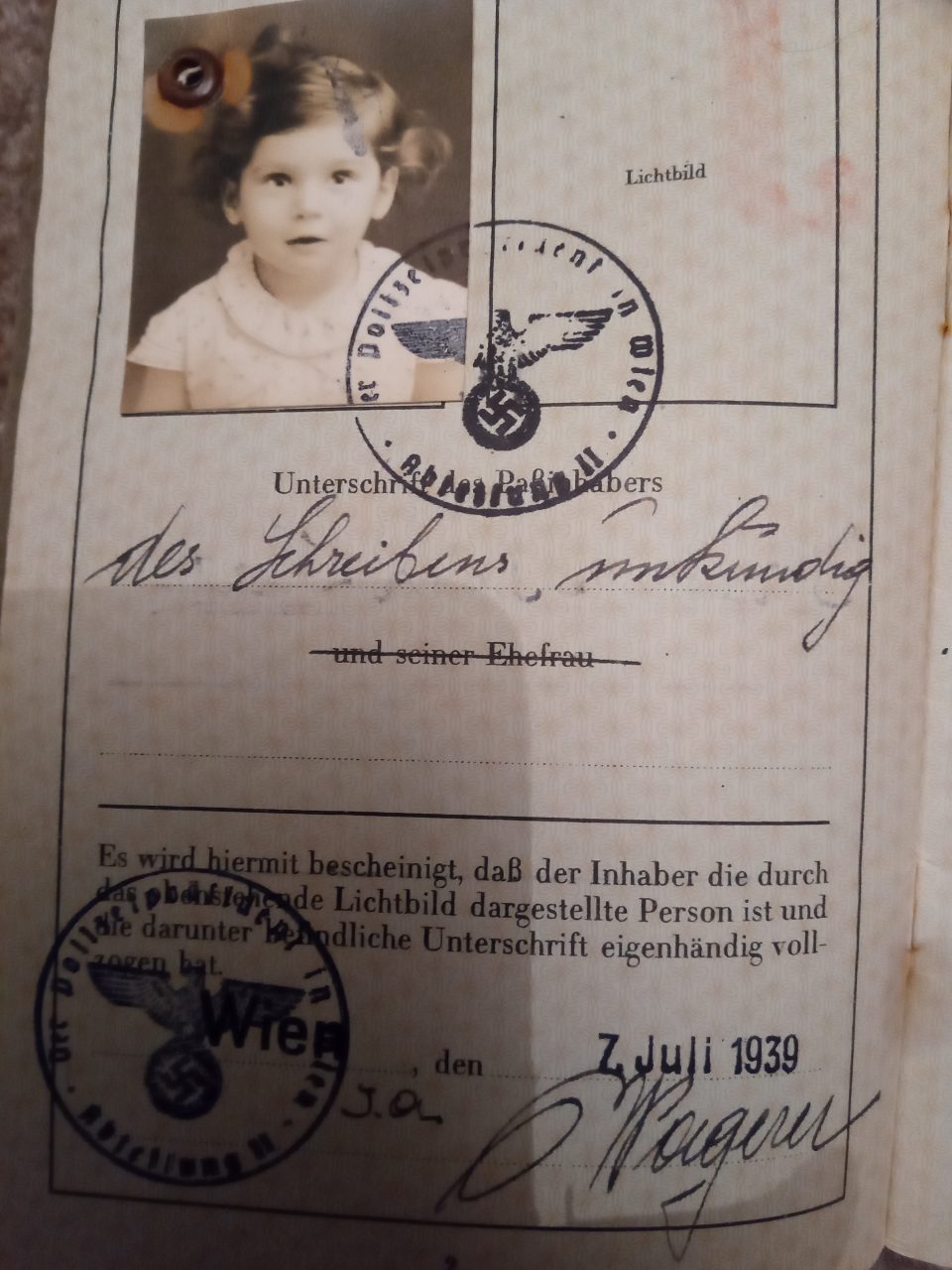

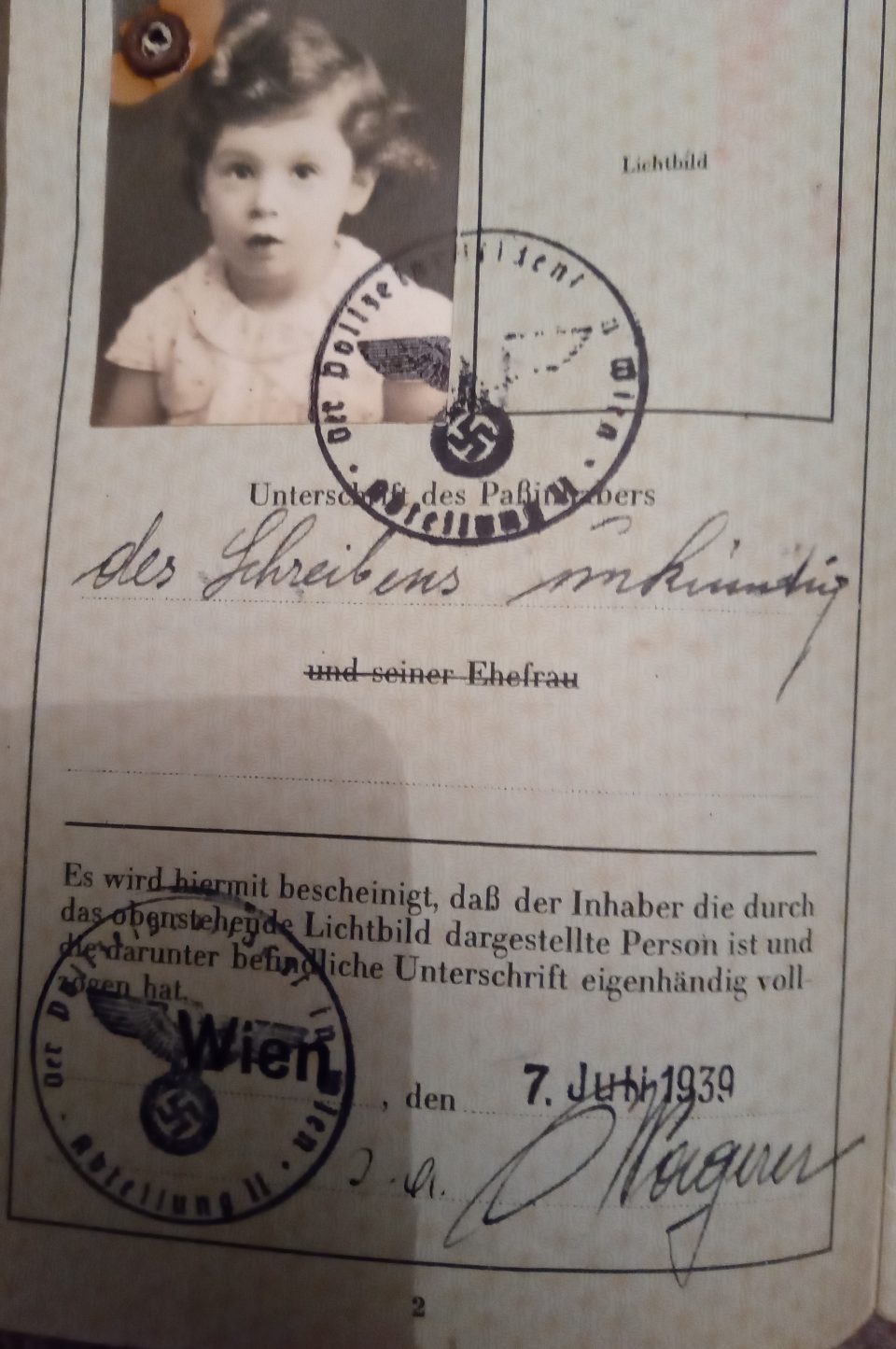

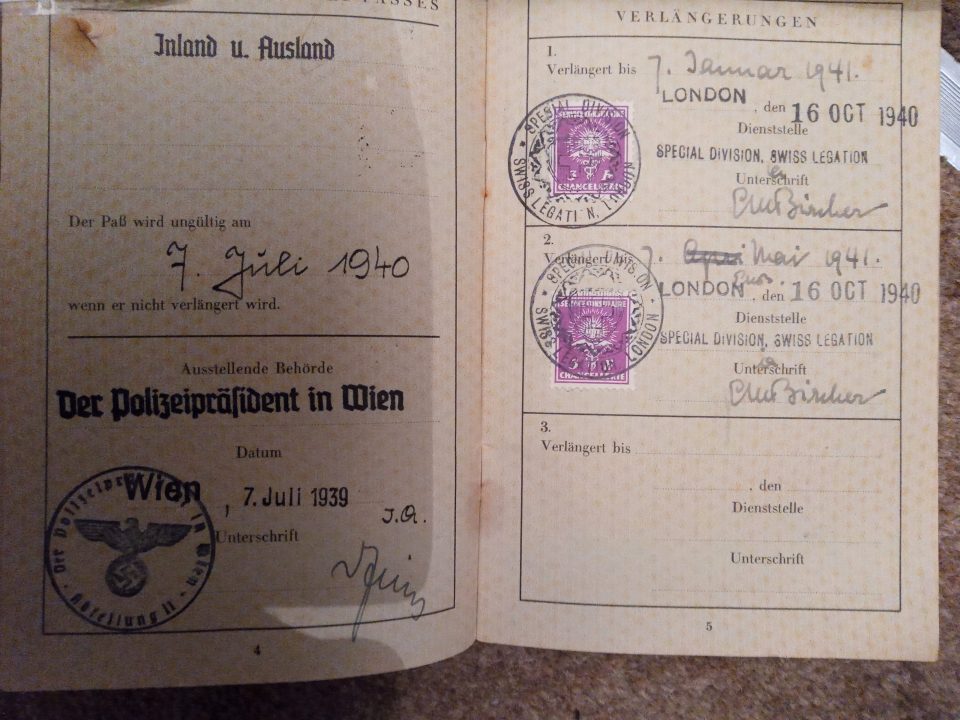

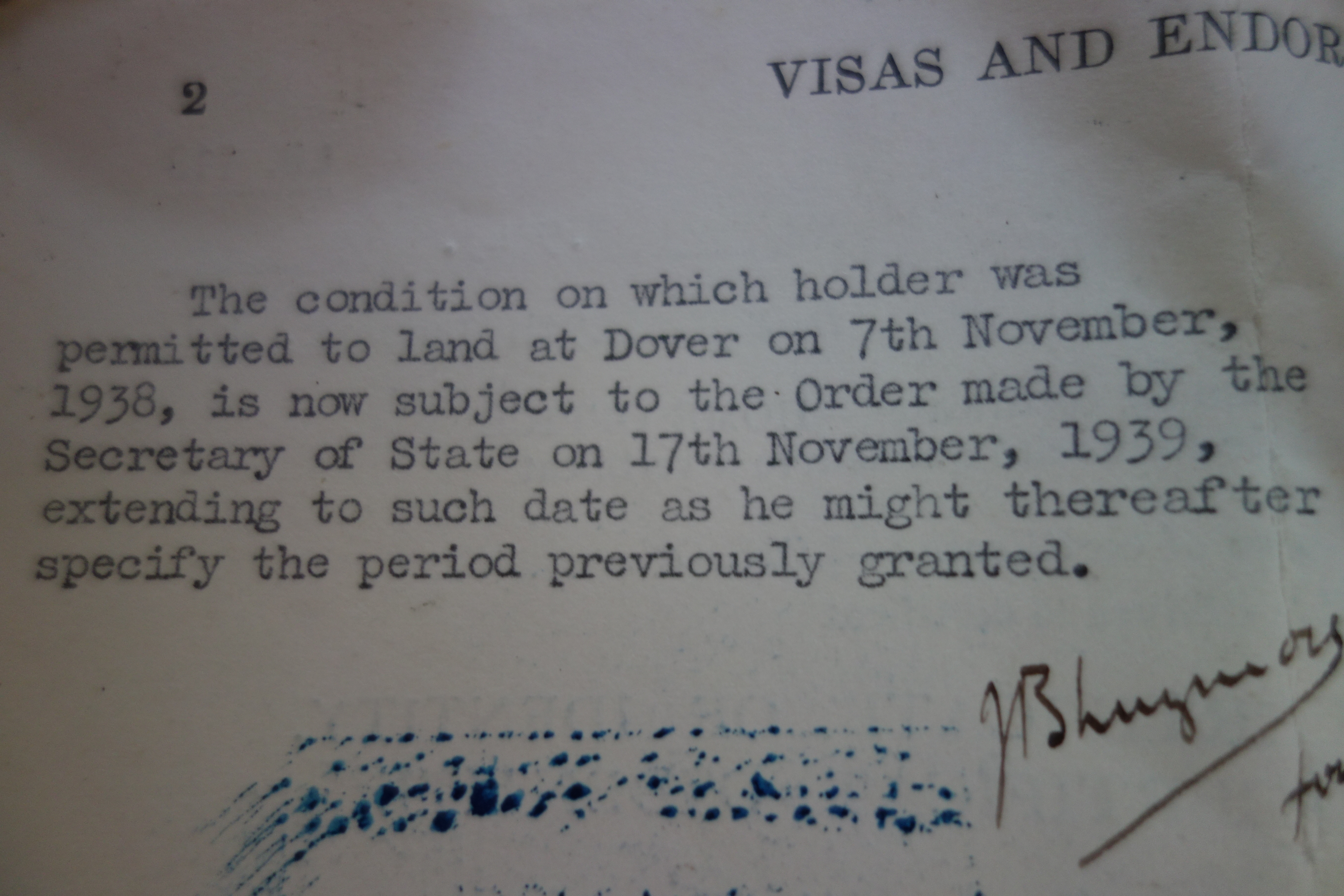

Käthe’s passport stamped with a “J” for “Jude”

Detail of the passport

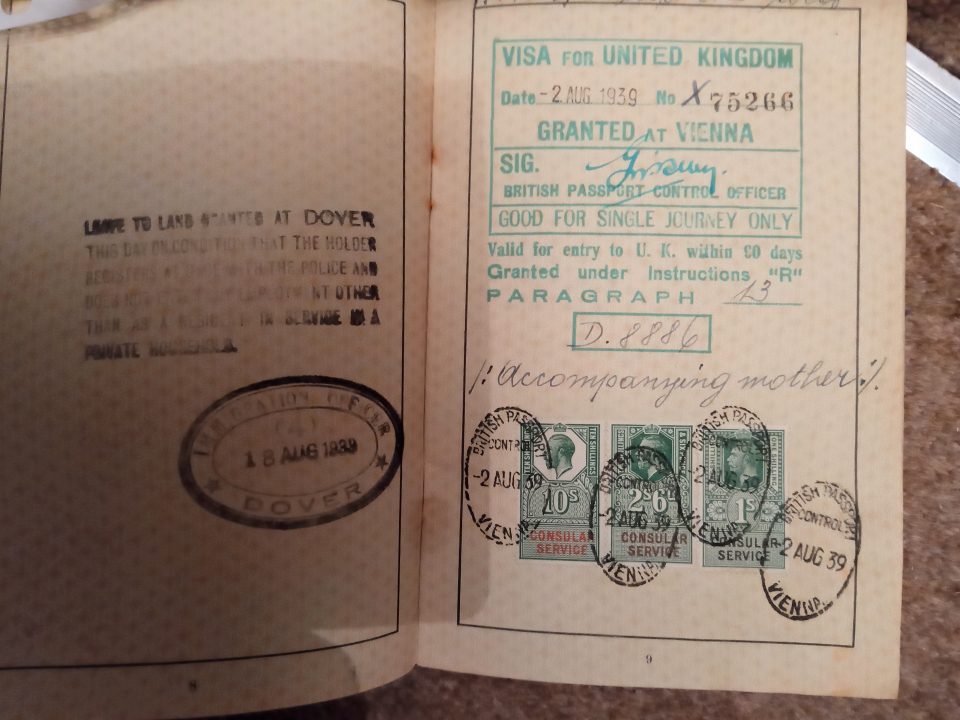

Around 20,000 Jewish women, three quarters from Austria, fled in 1938/39 to England with a so-called “domestic permit”. This was a work permit for foreign domestic staff which British employers could use since the 1920s to alleviate the chronic shortage of maid servants despite otherwise very strict immigration restrictions. A considerable percentage of these women were not actually domestics by trade, but had only been able to enter the UK on permits for domestic work. They found themselves in a relationship of dependency to their mistresses, but work as a maid guaranteed a livelihood because domestic servants were the only ones who had permission to legally work in England. Yet they were officially not allowed to leave the areas of these private households. The majority of male refugees with a permission to enter the UK needed an affidavit from an influential personality or an institution.

…