Café Hummel, Josefstädterstrasse (next to Hamerlingpark) in the suburb of Josefstadt. The house was built in 1805 and in 1856 an inn opened there which was later turned into a coffee house. In 1896 a vaudevillian singer, Carola Biedermann, wife of the Viennese folk singer Julius Biedermann took over the coffee house and named it “Café Carola”. This coffee house offered separate reading and gaming rooms, a smoking room and a ladies’ room, as well as a conservatory with palm trees. The couple had to flee from its creditors to New York and the new owner staged daily concerts and kept the coffee house open the whole night. Among the many owners that followed was Joseph Carlo Popper, who had worked as a lion tamer and circus employee in South Africa in his youth and had earned his living as a gold digger. In memory of his youth he called the coffee house “Café Pretoria”. The coffee house changed its name often until 1937, when the family Hummel finally bought it.

In the vicinity, just outside the “Linienwall” (today’s Gürtel) in the suburb Neulerchenfeld, a coffee house with a conservatory, palm trees and parrots continued this tradition until the 1960s, the “Café Wintergarten”, where I went with my grandmother, Lola, as a child. Today it’s a musical event location, the “Café Concerto”.

In 1934 my grandparents, Toni and Lola Kainz, took over the running of a coffee house on Hamerlingplatz in the suburb of Josefstadt. My grandmother loved the contact to the guests and my great-grandmother Ritschi (Rudolphine Sobotka) helped with the cooking. Her specialities were “Krautfleckerl” (small pasta with cabbage), a Jewish speciality that is much praised in Friedrich Torberg’s book “Die Tante Jolesch” (Aunt Jolesch), “Sulz” (brawn) and sweet dishes, such as “Buchteln”, chocolate cake and “Apfelstrudel”. The recipes of these coffee house classics have been passed on in the family.

Here are some simple and tasty recipes of Ritschi and Lola, which are typical Viennese coffee house specialities. There are not always precise indications of quantity as the recipes were communicated orally:

Simple chocolate cake

Ingredients: 40g butter, 100g sugar, 1 egg, 40g cocoa, some milk, 1/2 package of baking powder, 150g flour

Mix everything and beat for some time, then bake in the oven in a square baking dish until no longer liquid inside. Fill with the following cream:

100g butter, 3 soup spoons of cocoa, 2 soup spoons of black coffee, 3 soup spoons of sugar and whip everything until it is creamy

“Buchteln”

Mix 500g flour with active dry yeast, 250g butter, 3 eggs, 70g sugar and ¼ l of milk and beat for at least 10 minutes. Then put the dough in a warm place to rest for an hour. As soon as it has doubled its volume, cut it in small dumplings, fill them with a special plum jam (Zwetschkenröster) or sweetened cottage cheese, then dip the dumpling in melted butter and fill a square baking tray with the dumplings. Let the dish rest in a warm place for half an hour before baking in the oven until the dumplings are golden. Serve them still warm.

“Krautfleckerl”

Cook 250g small square noodle pasta “al dente”. Meanwhile slice half a white cabbage thinly. Heat a little lard, add a little sugar and cumin. Then fry the white cabbage until it is brown, add pepper and salt and in the end mix it with the small pasta noodles.

“Sulz”

Fill a pressure cooker with: 4 pig’s feet, and a pig’s tail, 400g tender pork meat, an onion, two garlic cloves, salt, pepper, 1/8 l of vinegar, a carrot, some celery, some parsley and fill the pot with water until everything is totally covered. Cook in the pressure cooker for an hour. Then pour the liquid into a porcelain bowl through a sieve and cut up the meat in small slices together with some of the jellied skin of the pig and stir it into the liquid. Put it into the fridge overnight. When solid, cut it up in slices and serve with thinly sliced onions and a little bit of vinegar and sunflower oil.

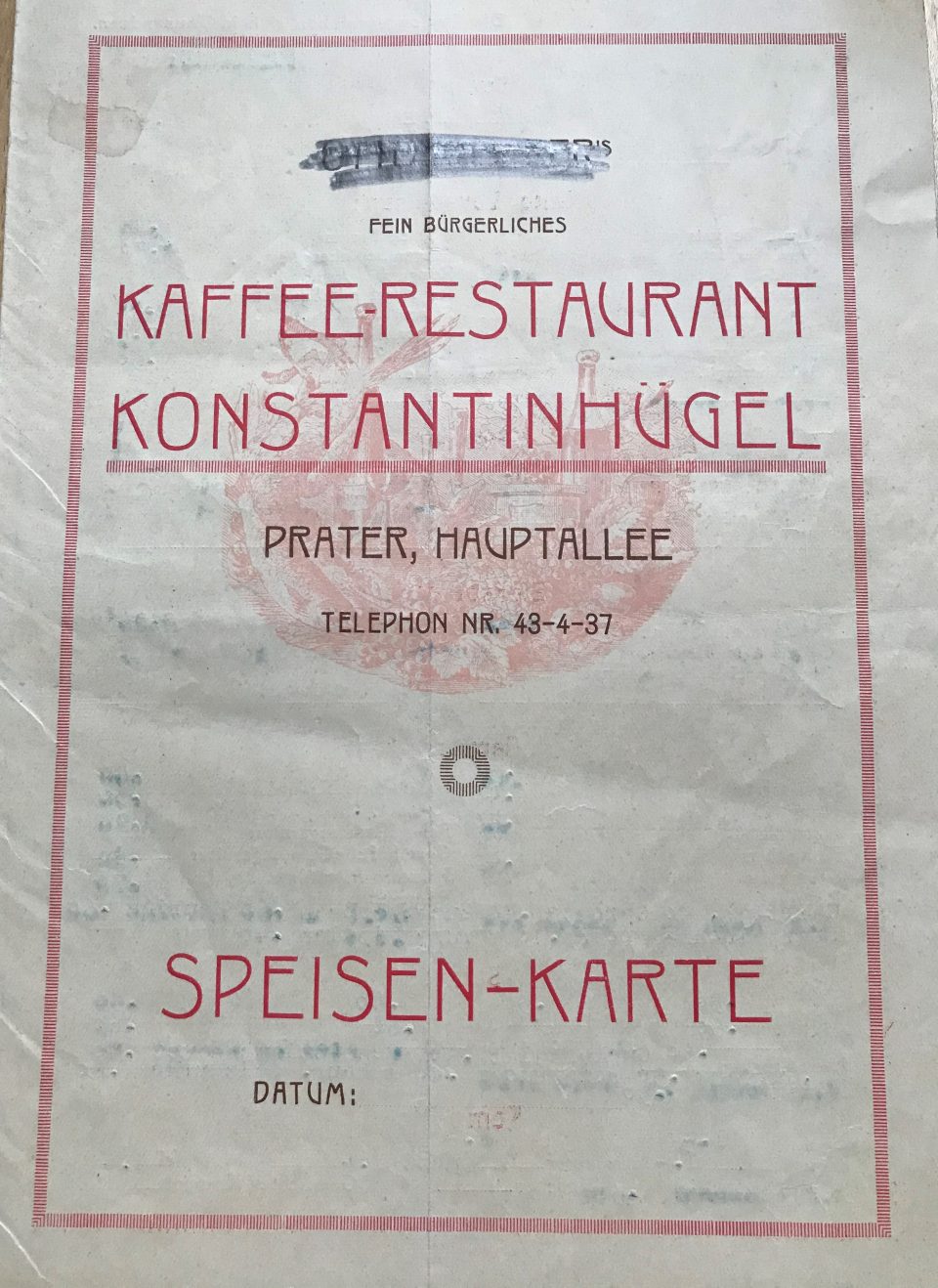

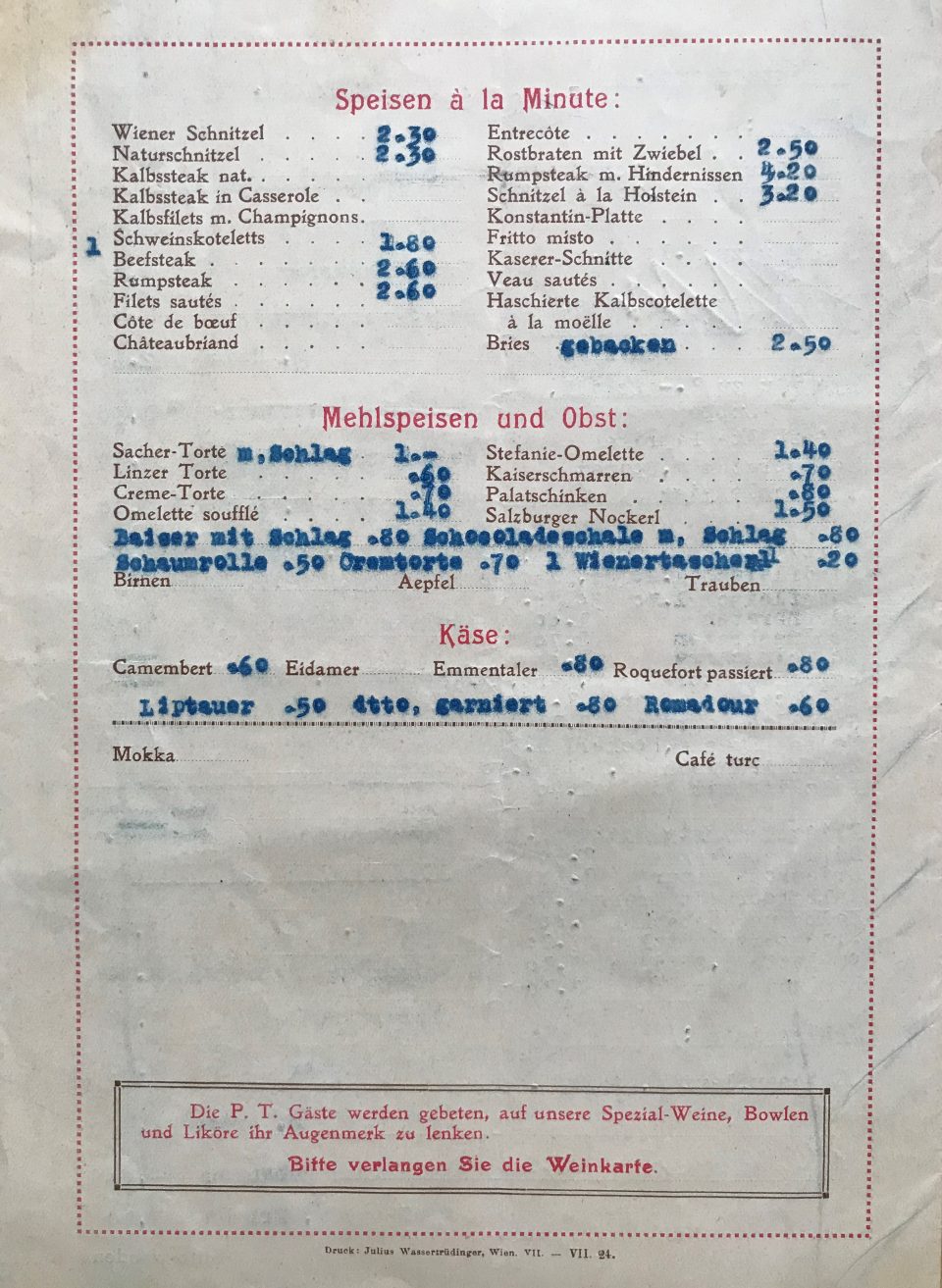

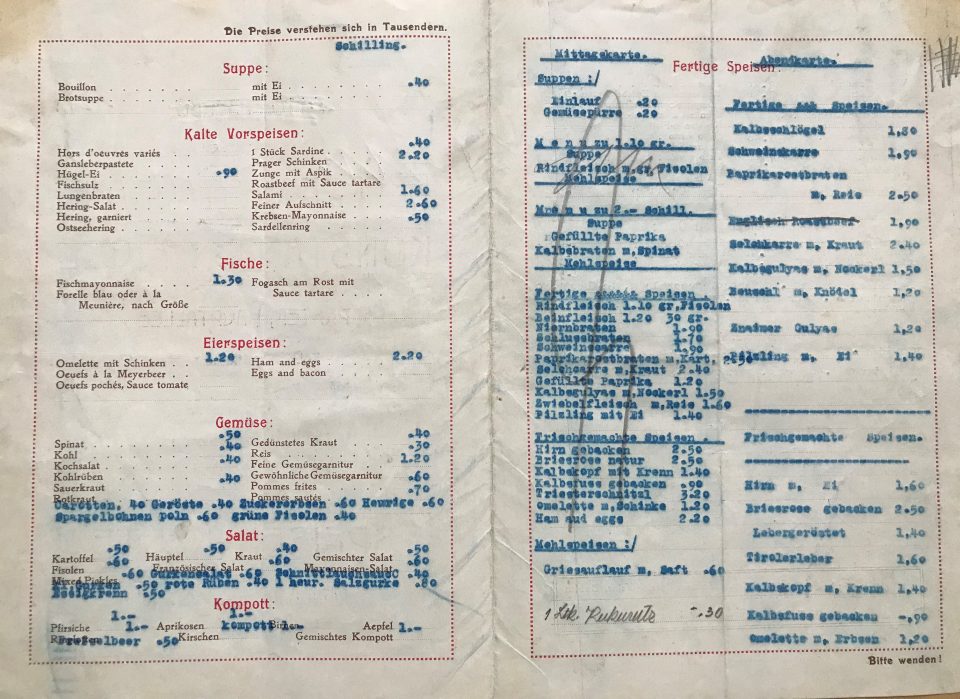

Menu card of the coffee house and restaurant in the suburb Leopoldstadt, Prater “Konstantinhügel” , 1927

In some Viennese coffee house coffee was formerly made in the traditional porcelain “Karlsbader” coffee makers – widespread in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Two of my grandmother’s “Karlsbaders” have survived. When preparing the coffee, she added a pinch of salt and a spoonful of cacao to the ground coffee beans in the porcelain sieve before slowly pouring the boiling water over it.

“Karlsbader” coffee makers

There was a lot of competition in the immediate vicinity of my grandparents’ café: The “Café Weinwurm”, the “Café Hummel” and the “Hamerlinghof” – so it was not easy to survive as a cafetier. Although Toni was a trained cafetier, cook and waiter, they went bankrupt after only a few years. This was also due to the fact that from 1930 on the financial crisis of 1929, the “Big Slump” in New York, showed its serious effects on the lives of the common people in Vienna, too: unemployment was rife, consumer spending was at an all-time low and the little people’s savings had been wiped out by inflation already earlier. This was not the perfect time for opening a coffee house and last but not least, my grandparents were not very gifted entrepreneurs, as Lola conceded.

Lola and Toni’s coffee house was located on Hamerlingplatz in the suburb of Josefstadt – it does not exist anymore.

Inside Toni and Lola’s coffee house on Hamerlingplatz: Lola with the white apron and the waiter in the traditional black suit and black bow tie of Viennese coffee house waiters

Hamerlingpark, in front of the café, where Lola went for a breath of fresh air when it got too stuffy in the coffee house. It is named after the Austrian poet Robert Hamerling (1839-1880)

On the western side of Hamerlingpark there was the restaurant “Hamerlinghof”, which no longer exists. The house was built in 1905 by the architect Carl Bittmann and in 1907 an elegant restaurant with bowling alleys, the “Hamerlinghof”, opened there.

At the address Hamerlingplatz 2 there was another coffee house, the “Café Weinwurm” which was run by Karl Weinwurm from the 1920s until the 1960s.

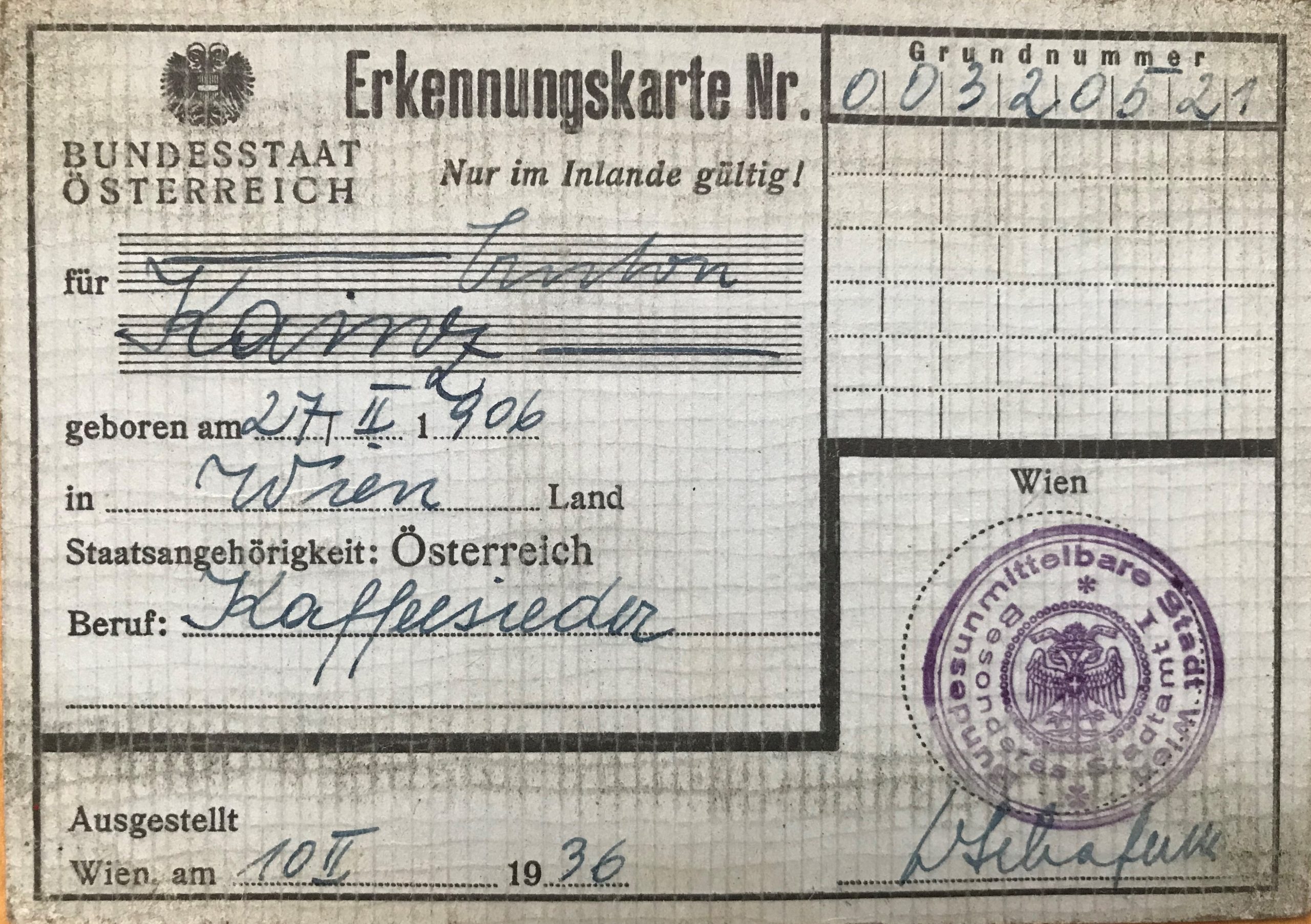

Toni’s ID of 1936 where his profession is evidenced as “Kaffeesieder (cafetier), which is an old term for coffee house owner or manager. In Vienna the sale of coffee was strictly regulated and in order to find a solution for the fight between “Kaffeesieder”, coffee house owners, and “Wasserbrenner”, the producers of spirits about who was allowed to sell what in their establishments, it was decreed that coffeehouses should only sell coffee and the inns should sell alcoholic drinks, but with many – typically Viennese – exceptions, for example: in inns coffee could be served at the end of a meal. But these restrictions were never really implemented.

Toni and Lola loved sport, entertainment, fun and fancy dress parties, some of which took place in the café:

Toni first on the left, sitting, in an amateur football team1936. Cafés were commonly the headquarters of all types of sports clubs, professional as well as amateur

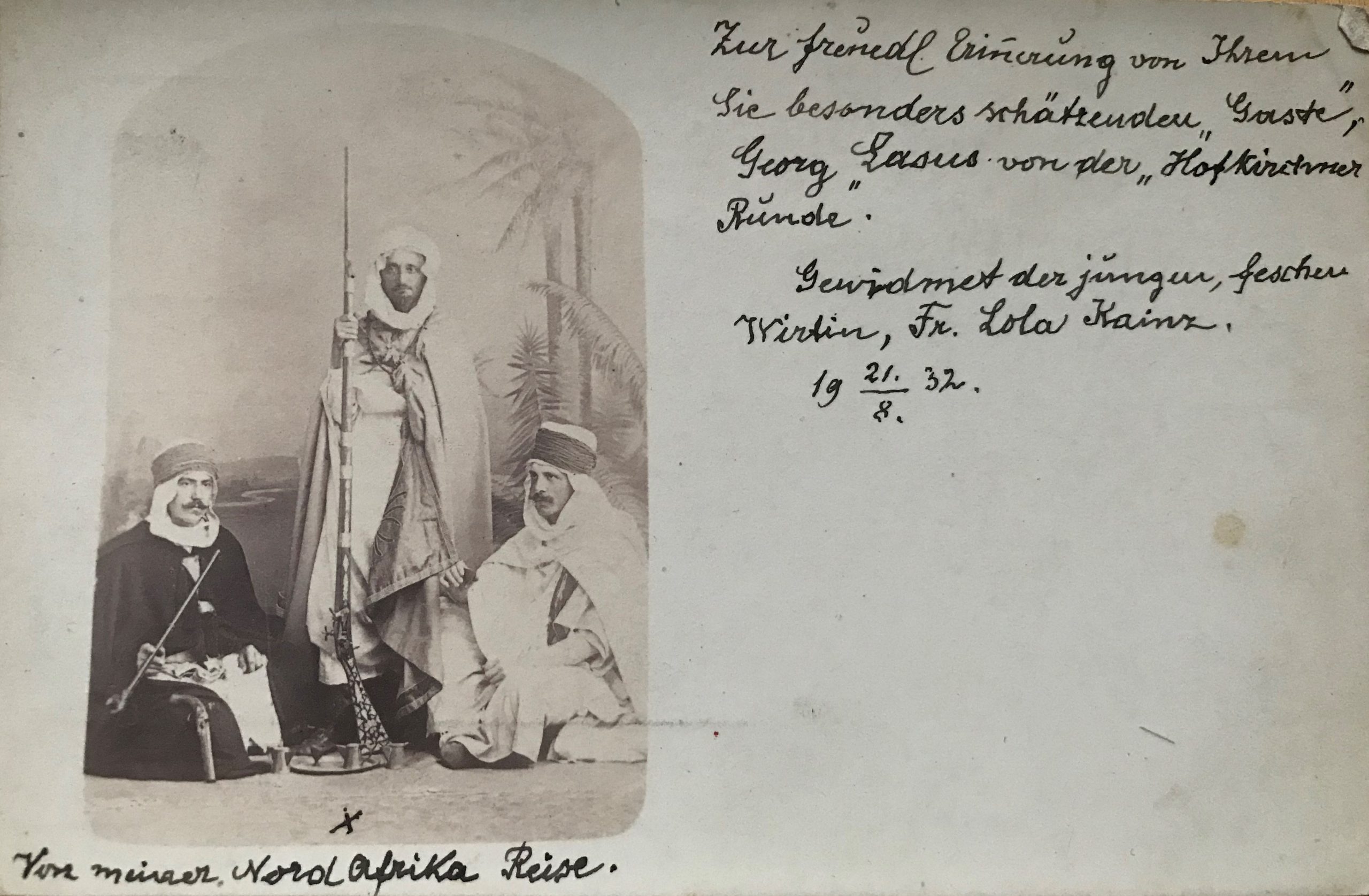

A postcard to my grandmother, Lola, “dedicated to the young and beautiful hostess, Mrs. Lola Kainz, in memory of her dedicated guest, Georg Lasus, from his journey to North Africa”

Toni and Lola had moved into a small flat in the suburb Mariahilf (Mariahilferstrasse 41/6/9) with their small daughter, Herta (my mother), after leaving the “Anton Kainz” inn in Währing in 1934 and taking on the running of the coffee house on Hamerlingplatz. Here they lived until the end of World War II and in such a passage off Mariahilferstrasse my mother spent her childhood.

Despite its unbroken and even mythical tradition in Vienna, the coffee house was not invented here. On the contrary, coffee was introduced rather late in the city. In Vienna a small cup of strong black coffee is called “Mokka” – emulating the name of the city Mokka in Yemen, from where coffee was originally exported since the early 16th century and the Ottoman Empire, which occupied this territory, watched closely over its coffee monopoly. The English, the Dutch and the French tried to circumvent the monopoly by smuggling plants out of the area and starting coffee plantations in their colonies. The Imperial court in Vienna learned about the oriental practice of coffee drinking supposedly from the Flemish diplomat and scientist Ogier Ghislain de Busbecq, who was sent by Emperor Ferdinand I as an ambassador to Constantinople. From 1554 until 1662 he stayed at the court of Suleyman I and in his correspondence he mentioned the custom of coffee drinking in Constantinople. When he returned to Vienna he brought with him exotic plants such as tulip and hyacinth bulbs and the lilac bush. Hundred years later, in 1665, the Ottoman ambassador Kara Mehmed Pascha arrived in Vienna with his entourage of 295 servants and among them two cooks whose only task was to prepare coffee the whole day. Nine months later the ambassador left Vienna, after having thoroughly inspected the Viennese fortifications, but meanwhile the Viennese had fallen in love with the new drink. Several Armenian and Turkish traders were in business in Vienna and among their oriental wares were also coffee beans. One among them, an Armenian who called himself Johannes Diodato, was sent by the Emperor as a messenger and spy to the Ottoman Empire and on his return in 1685 he was awarded the Imperial privilege and monopoly to run a coffee house in Vienna for twenty years in exchange for his valuable services to the Emperor. So two years after the siege of Vienna by the Ottoman Turks in 1683, the first coffee house opened in Vienna in Rotenturmstrasse 14, the private home of Diodatus; in the street where the warehouses of the “Orientals” were located. But already in 1686 three more persons received the Imperial privilege to serve coffee in Vienna because they had acted as spies for the Emperor during the siege of Vienna, among them Georg Franz Kolschitzky, who was born in Polish Sambor in 1640 and had learned the Turkish language in the service of the Imperial ambassador to Constantinople. During the time of the siege of Vienna Kolschitzky had a shop for “oriental wares” in Vienna and he volunteered for the dangerous mission of traversing the enemy lines to reach the relief army. Within a very short time several coffee houses had opened in Vienna despite the protests of Diodato, who saw his monopoly violated.

Professional coffee grinders

In Vienna a power struggle raged between the city of Vienna and the territorial sovereign, the Emperor, about the right to award the privilege of making and selling coffee. Those who were allowed to conduct a special trade in Vienna were first, citizens of the city and second, organised in a guild which strictly regulated the number of members and the prices. These regulations limited the entrepreneurial possibilities and the working of the free market. That’s why already in the middle of the 16th century the representatives of the Emperor in the city awarded special Imperial privileges to those artisans and traders who supplied the Imperial court. These Imperial suppliers were furthermore permitted to provide ordinary citizens with their goods and services, too. Consequently fierce competition erupted in Vienna. The only difference between the two licenses was that the bourgeois guild masters could pass on or sell their concession, while the Imperial privileges expired with the death of the Emperor or the owner of the concession. In 1714 Emperor Charles VI guaranteed the Viennese cafetiers their guild privileges and the limit of eleven cafetiers in the city. But at that time additional twenty coffee houses with Imperial privileges already existed in the city and numerous more in the suburbs. Today’s “Schwedenbrücke” was the only connection to the Jewish ghetto (later the suburb Leopoldstadt) and this bridge formed the access point to the city for all traders and travellers coming from the east. Near “Schwedenbrücke” in the Jewish ghetto the first three suburban coffee houses opened, which were popular with travellers as well as the Viennese: the Cafés Hugelmann, Steinböck and Jüngling. At the same time the so-called “Wasserbrenner” (the distillers) served coffee, too, which annoyed the cafetiers. As a consequence Empress Maria Theresia joined the two guilds and permitted both to sell coffee and spirits.

Small coffee grinder

At the beginning of the 18th century the Viennese coffee house was still a rather dark vault where a cafetier with Turkish headgear and trousers served coffee in brass cans, but over the next two centuries the Viennese coffee house developed its uniqueness. Two factors played an important role in this transformation process, namely newspapers and games in the form of card games, chess, dices, billiard and gambling. Despite various Imperial attempts at prohibiting gaming in the coffee houses in Vienna, the cafés developed into popular centres for gamblers. Even before the first coffee houses opened in Vienna, billiard was well-known here. The billiard tables originating in France that were used at royal and imperial courts were much larger; for example the Scottish Queen Mary Stewart got to know and love the game when married to the French dauphin. But even the modified version was too big for a bourgeois household, so the billiard tables were set up in the coffee houses. In contrast to all the movable games, such as cards, dices and chess, these heavy billiard tables were a source of income for the authorities because permissions had to be granted and taxes could be levied. So in Vienna the billiard tables constituted an important extra source of income for the coffee house owners and the sovereign. It was in the interest of the cafetier to have all the billiard tables booked incessantly. A special waiter, the “Marqueur” (from French: marquer) recorded the points in the games and in Vienna the term was still used in the 20th century for the waiter who accepted the guests’ payments in a coffee house. Yet the authorities were worried that the players could spread revolutionary ideas during a game of billiard and that led to curious prohibitions. Empress Maria Theresia prohibited in 1745 the installation of billiard tables on the first floor because on the ground floor the Imperial guards could check on the players through the windows and also Chancellor Metternich enforced this ruling in the beginning of the 19th century. Only after the revolution of 1848 the positioning of the billiard tables in the Viennese coffee houses was irrelevant. The modern form of billiard was introduced in Vienna by the Napoleonic soldiers in 1805, where the measurement of the tables was fixed at 1:2. But in Vienna the special measurement was 0.95 metre to 1.90 metres. The reason for this extravagance was the floor plan of Viennese coffee houses. They had the form of an “L”, whereby on the long side the game tables were positioned and on the short side the reading area was located. The common width of a room in Vienna was five metres, which meant that five tables could be set up if the breadth of the billiard table was 0.95 m. In this way the cafetier could squeeze in more tables and earn more. Furthermore the billiard game was reduced to three balls and the ball was no longer potted – the rules for carambol billiard were born; the most common form of billiard in Viennese coffee houses. The American form of pool billiard was introduced in Vienna after the Second World War only. In the 18th century the before mentioned Café Hugelmann in Praterstrasse 2, just across the “Schwedenbrücke” in the suburb of Leopoldstadt, was a centre for billiard players in Vienna and the Hungarian “Marqueurs” were famous for their expertise. One of the passionate players there was Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart who lost a lot of money in the coffee house because he composed during the games and often did not realise when he was being cheated. If a player was bankrupt, the loan sharks were already waiting to “assist” the unfortunate gambler.

Gaming rooms were common in suburban coffee houses. Guests played card games, chess and billiard, too, if tables were available

The second important characteristic of a Viennese coffee house was the large range of newspapers on offer. The first newspapers were edited in Paris and London, but the first coffee houses that subscribed to newspapers and offered them to their guests for free reading were the Viennese coffee houses. In 1621 the “Ordinari Zeittung” was printed in Vienna, which published foreign news. In 1622 the “Ordentliche Postzeittung” printed news from the Imperial court and from southern and eastern Europe. Soon numerous newspapers inundated the market of the capital city of the Habsburg Empire, such as the “Corriere ordinario”, the “Gazette de Vienne” or the “Wiener Blättchen”, which was published daily and sold in the whole Empire. In 1703 the most important printer in Vienna, Johann von Ghelen, published the “Wiennerische Diarium” with international news, but no local ones. It further included news of the Imperial court and the nobility and official announcements. It changed its name to “Wiener Zeitung” in the end; a paper which is still issued and which is the oldest existing newspaper in the German-speaking area. Very soon after the opening of the first coffee houses in Vienna, cafetiers offered their guests newspapers to read free of charge, which was a huge success. On a journey to the Habsburg lands a French Benedictine monk, Casimir Freschot, reported in 1704 that in Viennese coffee houses many “idlers met, read newspapers, talked politics and criticised the government” and he was shocked about the freedom of speech that reigned there. So there is historical evidence that only approximately twenty years after the opening of the first coffee houses in Vienna people already met there to read newspapers, discuss international political developments and to exchange opinions.

But local news was rare because censorship prevailed in the Habsburg Empire. In Vienna all publications were subject to censorship by the Jesuit University. Even after the transfer of censorship from the Jesuits to a state authority under Empress Maria Theresia, freedom of speech did not exist in the Empire. Yet criticism could not be suppressed continuously and in the coffee houses hand-written flyers went from hand to hand. The authorities’ reaction was to offer a reward to anyone who would report the writers of such unofficial newspapers. “Kramer’s” coffee house, which opened in 1719, was soon well-known for its wide selection of newspapers on offer. When Emperor Joseph II liberalised the censorship laws, more newspapers were founded, the variety of papers in the coffee houses grew and the hand-written flyers disappeared. From Vienna a practical invention spread to many other countries, the “newspaper holder”, which locked the newspaper into a wooden stick which was closed with a small padlock, so that the pages did not get muddled up or lost. The coffee house was transformed from a dark vault into a comfortable – in the city often elegant – meeting place for the intellectuals of the Enlightenment.

A newspaper holder

During the Napoleonic wars strict censorship was imposed again and the newspaper readers in the coffee houses were offered harmless and uninteresting local news only. After the Vienna Congress 1814/15 censorship was still harsh, but the economy was recovering and more and more elegant coffee houses were established in Vienna, just as in London, Paris or St. Petersburg. One of the most beautiful was “Café Wagner”, just across the before mentioned “Café Hugelmann”. The famous architect Joseph Kornhäusl equipped it with elegant columns, mirrors and silken wall coverings. Wagner’s young daughter, Toni, was seated at the cash till. The female seated cashiers were at that time the only women in a café because female guests were still not allowed into coffee houses.

Traditional cash till of a Viennese coffee house: Toni and Lola trusted their personnel too much and did not check on them properly. That’s why they were often cheated by their coffee house waiter

Another tradition of a Viennese coffee house is the serving of a glass of water together with the coffee. In the past it was assumed that coffee drained double the amount of liquid from the human body and this liquid had to be replaced by drinking a glass of water. This is only partly true, but there are several benefits of drinking water together with a cup of coffee, namely the taste of the aroma of the coffee is intensified and water neutralises the acid production in the stomach. Most of all the quality of Viennese water was and is excellent since the construction of the “Wiener Hochquellwasserleitung” in the second half of the 19th century, which brings drinking water from the Styrian Alps to the city.

“Café Eiles”, traditional coffee house in the suburb Josefstadt, former “Café Motéle”, founded in 1840

Culture and literature have always played an important role in the Viennese coffee house. In the second half of the 19th century the rise of the bourgeoisie, the emancipation of the Jews and the emergence of a working class culture produced a vibrant platform for communication, culture, education and business which found its focus point in the coffee house. In the “Café Griensteidl”, opened in 1847, journalists, writers and poets met in the 1880s, as well as a group of young intellectuals, called “Jung-Wien”, among them Hermann Bahr, Arthur Schnitzler, Felix Salten, Hugo von Hoffmannsthal, Adolf Loos, Alfred Polgar, Karl Kraus, Peter Altenberg and Hugo Wolf. Stefan Zweig wrote in “Jugend im Griensteidl” (Youth in the Café Griensteidl) how the intellectual atmosphere in the coffee houses had influenced him as a young man. When the “Café Griensteidl” was closed in 1897, the intellectuals moved to the “Café Central”. Karl Krauss made a famous statement about the Viennese coffee house: In the coffee house you are not at home and still not outdoors (“Man ist nicht zuhaus’ und doch nicht in der frischen Luft”). Peter Altenberg even used the “Café Central” as his postal address and had all his mail delivered there. In the 1920s the intellectuals moved to the “Café Herrenhof”. Here Hermann Broch, Franz Kafka, Robert Musil, Anton Kuh, Stefan Zweig, Egon Friedell, Joseph Roth, Franz Werfel and Friedrich Torberg met and discussed. The glorious days of the intellectual circles in Viennese coffee houses ended abruptly in March 1938 when the Nazis took control of the city and the Jewish intellectuals who did not flee in time were deported to Nazi concentration camps and the free intellectual and innovative spirit of the Viennese coffee house was extinguished. After 1945 the “Café Herrenhof” tried a restart but failed. From the 1960s on some of the Viennese intellectuals met in the “Café Hawelka”.

“Café Sperl”, traditional suburban coffee house in the suburb of Mariahilf. It was opened in 1880 under the name “Café Ronacher”, but was sold a year later to the family Sperl. From the start this coffee house attracted writers and billiard players alike.

Although the literary Viennese coffee house is famous world-wide, it is not representative of the Viennese coffee house culture; much more popular among the common Viennese was the suburban coffee house. There is a special term in Viennese dialect for such popular, cosy, but rather shabby suburban cafés: “Tschecherl”. The word’s origin is unknown; probably it is a transformation of the name of a very old inn which was called “Zum linken Schächer” (the left one of the thieves who was crucified together with Jesus) and the Viennese reshaped the “Schächer” (murderer) into “Tschecherl”. This is the term that somehow corresponds to the Viennese word for a cosy suburban inn, “Beisl”. The word “Beisl” has its origin in Yiddish and was used in the jargon of petty criminals. That’s how it found its way into the common language of the Viennese. One of these suburban cafés was celebrated in a famous song of the 1930s: “In einem kleinen Café in Hernals” (“In a Small Café in Hernals” – a suburb of Vienna) by Hermann Leopoldi, who was a famous composer, comedian and cabaret star in Vienna. He was deported to the Nazi concentration camps Dachau and Buchenwald by in 1938, but his wife managed to pay for his release and sent an affidavit from New York. When Leopoldi finally arrived in New York, he kissed the ground of the United States– a photo that was shown worldwide in the media.

“Café Ritter” in the suburb of Ottakring still is a “club café” for several clubs which meet there regularly, a venue for musical events and a haven for enthusiasts of all types of games, such as card games, chess and billiard, as can be seen at the façade. The coffee house was founded in 1907 by Wilhelm Ritter. At that time it was called “Café Merkur” because Ritter also ran a coffee house in the suburb of Mariahilf, called “Café Ritter”, which still exists, too. In 1936 the “First Billiard Club of Ottakring” was founded, which had its headquarter in this coffee house. From the start it has been the home of many card and chess players, too.

Another speciality of the Viennese coffee house is the traditional varieties of coffees that were and are served there still today. First of all, the pronunciation of the German word “Kaffee” (coffee) differs in Austria from Germany, namely it is stressed on the second syllable and not on the first, just like the word for coffee house “Café”. Nowadays a coffee house lists approximately sixteen different types of coffee. Yet drinking coffee is not the reason for going to the coffee house, it is the means to the end of reading newspapers for free, socialising, discussing politics or culture, doing business and meeting people. In a coffee house you can remain for hours after ordering a “kleiner Brauner” (a small cup of coffee with a little milk), for instance, and you can even ask for another free glass of tap water and another and another. In the song “In einem kleinen Café in Hernals” two lines of the lyrics mention this: “… dort genügen zwei Mokka allein, Um ein paar Stunden so glücklich zu sein…“ (…two small cups of black coffee suffice for enjoying several hours of bliss…) If you were a regular guest in a coffee house you would receive messages there and people would come to this coffee house to meet you. The cafetier would reserve a quiet table for you so that you could work there and the waiter would serve you your favourite coffee variety, a “Mokka” or a “kleiner Brauner”, etc. before you have a chance to order it. Some cafés were also open after midnight and they were the insider’s tip for night owls. These were for instance the “Café Europe” on Stephansplatz before the 2nd World War and the “Café Hawelka” afterwards. Artists, journalists, theatre and concert goers and students frequented these “night cafés” regularly.

Going to a coffee house frequently in Vienna is definitely not a sign of laziness, on the contrary, in a café you can work, you can get in contact with people much better than anywhere else and you can also “find yourself”; as Alfred Polgar said, a coffee house is the right place for people who want to be alone, but in company (“… für Leute, die allein sein wollen, aber dazu Gesellschaft brauchen”). The coffee house is a very democratic institution because you can stay there the whole day paying for one coffee only. So, even people in dire straits can afford going to a coffee house and enjoying all its amenities. Peter Altenberg wrote: if you were suicidal, go to the café; if you hate and despise all people, but you can’t do without them, go to the café.

Ground coffee beans were often mixed with surrogate coffee, such as malt coffee, not only in times of need. During the Second World War regular coffee house guests used to row over which café offered the better “substitute coffee”.

Smoking was a widespread practice in Viennese coffee houses until the end of the 20th century. The first documented use of tobacco for smoking in Vienna dates back to the middle of the 17th century, but it can be assumed that already before tobacco was planted in Austria and also consumed, mostly chewed or sniffed. Around 1800 the smoking of pipes was considered a custom of poorer classes of the society and of so-called “Orientals” and Greeks, whereas cigars were rather smoked by the well-to-do. In the early 20th century cigarettes developed into the most common form of tobacco consumption by the masses. In the 17th and 18th century tobacco consumption in public was more or less prohibited. That’s why coffee houses and inns became refuges for tobacco lovers. It is supposed that first “oriental” guests consumed tobacco in Vienna in the “Griechenbeisl” on Fleischmarkt. In 1786 it is reported as a sensation that guests smoked in the “Schanigarten” of cafés and inns (chairs and tables on the pavement in front of the establishment), but in the 19th century smoking in coffee houses and inns was commonplace. Smoking in public was forbidden until 1848 and also later was regarded as bad mannered. These strict measures triggered a form of resistance among the Viennese: they regarded smoking as a sign of protest. My grandfather Toni smoked sixty cigarettes a day, which was common for cafetiers and innkeepers at the time; probably the main reason why he died at the age of 58 of a heart attack.

Music has always been part of the coffee house culture, too. With the demolishing of the city walls and the creation of the “Ringstrasse” there was more space for bigger coffee houses, where also small concerts could be performed and the basic equipment of every respectable coffee house was a piano. The first editions with scores of music of Johann Strauss and Josef Lanner were published for concerts in coffee houses. These included the arias of operas and operettas which the Viennese loved best, but the music was not supposed to be in the foreground because people went to the coffee house to interact and socialise. After the First World War jazz, film music and the latest popular songs were played by the coffee house musicians. Hitler’s National Socialism did not only herald the end of the traditional Viennese coffee house culture, but also the end of the typical coffee house live music. All the Jewish cafetiers were expropriated and driven out of the country or interned. Their venues were either destroyed or “aryanised”, namely handed over to party members for a bargain. Only at the end of the 20th century new forms of musical events were staged in some traditional coffee houses again, among them the famous concert cafés “Schmid Hansl” in the suburb of Währing” and “Wintergarten” in the suburb of Ottakring.

For the Viennese Jewish population the coffee house was a safe refuge and meeting place. Here they could debate, consume, play chess, billiard and tarot, and most of all, they could inform themselves about new developments. This urge to acquire as much knowledge as possible as soon as possible – a characteristic of the Viennese Jewish community – brought about the creation of reading rooms in coffee houses. Around 1900 and in the interwar years the Viennese Jews were at the centre of the city’s culture, but at the margin of its society. In 1938 more than 200,000 Jews lived in Vienna, which constituted 9% of the population. It was the biggest Jewish community in the German speaking area and the third largest in Europe. The constitution of 1867 offered them equal citizen rights in the Habsburg Empire. Consequently the cultural atmosphere of Vienna attracted many Jews to the capital city, where they helped forge its special fin-de-siècle atmosphere. The “Jewish café” is not only characterised by the fact that Jews owned or ran those cafés, but also that they were guests and contributed to its special ambience. The writer Friedrich Torberg was a regular guest not in one – the “Café Herrenhof”-, but in three Viennese coffee houses. He stated that a polite guest put his chair on the table when he left the coffee house- meaning: he only leaves, when the coffee house closes for the night and the cleaners wipe the floor. The “Café Herrenhof” was the first in Vienna that was requisitioned by the Nazis on 15 March 1938.

Most of the cafés in Leopoldstadt, where a large part of the Jewish population lived, were not as elegant as the “Herrenhof”; they were small suburban cafés where new arrivals from far-flung places of the Empire could get information about jobs and accommodation in the city. Business was conducted there and news were exchanged. The “Café Post” in Blumauergasse offered large portions of “Mohnstrudel” (a sweet dish filled with crushed poppy seeds) for unemployed or poor guests at a low price without asking them to order coffee or a drink as well. Many cafés were located in Praterstrasse, where musical entertainment was part of the attraction and where artists were looking for jobs. The nearer you got to the “Prater” (a recreation area and funfair), the shabbier the cafés were and the more dubious the clientele. The “Café Rembrandt” in Untere Augartenstrasse was one of the many popular cafés where those who owned and ran the cafés were deported to concentration camps and murdered there. The owner Dora Wildner could flee, but her tenant, Bernhard Wolf Weiser, and his family were deported to Theresienstadt and Auschwitz and killed there. The Nazis considered the Viennese coffee house a “Jewish institution” and closed them or aryanised them as early as March 1938, immediately after the Nazi takeover. They pretended that the cafés had to be “liquidated” because they were bankrupt, although in reality they were booming businesses. New coffee house privileges were awarded to incompetent party members. The Nazis detested humour and irony which was an essential part of the intellectual atmosphere of the Viennese coffee house culture.

“Café Westend”, a traditional coffee house next to the West Station in the suburb of Neubau. It is located in the so-called ”Zachariashof”, built in 1899, and has always attracted commuters and travellers due to its vicinity to the train station.

At the back of the West Station (“Westbahnhof”) there was the famous “Café Palmhof” in Mariahilferstrasse 135. The Pollak family originally came from the Czech part of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy. Otto Pollak was seriously wounded in the First World War and lost one leg. After the war he successfully repositioned the café together with his brother Karl as a coffee house during the day and a concert hall, jazz club and dance café at night. The café offered room for 350 guests and was famous for its innovative programming. Like most Viennese cafés it soon turned into a meeting point, social hub, extended living room and work space for its guests. Over the years it was redesigned by fashionable architects of the time, among them Leopold Liebl, Leonhard Schöppler and Ernst Kornfeld and live concerts were even broadcast from the “Café Palmhof” on the radio. The Viennese yearning for entertainment was very pronounced during the interwar years and musical cafés like the” Palmhof” served the needs of the population. In 1919 Vienna boasted 24 concert cafés in the inner city only, not counting the numerous establishments in the suburbs offering musical entertainment. The success of the “Palmhof” lay in the excellent mixture of tradition and innovation, characteristic of the Viennese amusement scene of the 1920s and early 1930s. In 1925 the waiter Johann Schmidt celebrated his 50th anniversary of service in the coffee house and when he retired four years later, a fund was set up to enable him a carefree life as a pensioner. Honouring a waiter for his life’s work was a novelty and a sign of recognition of an underprivileged professional group. In the café the memory of the Habsburg Empire met with modern times: in 1926 a commemorative bronze bust of Johann Strauss was unveiled in the café and in the same year a modern dance floor was constructed. In the 1930s the café increasingly became an important jazz location and a spring board for young jazz musicians.

Otto Pollak was a board member of the Austrian Association of Concert Venue Owners and campaigned for the rights and obligations of the employers and employees in this business sector. In the 1920s and 1930s the café suffered anti-Semitic attacks and repeated violent assaults. In 1925 a group of National Socialists tried to storm the “Café Palmhof” and in 1934 a bomb attack by illegal Nazis hit the venue. Just five days after the takeover of the Nazis the “Café Palmhof” was aryanised and handed over to a party member, Gustav Raisinger, who had worked as a waiter there from 1928 to 1938. Otto Pollak ended up in a so-called “collective apartment” in the suburb of Leopoldstadt before his deportation to Theresienstadt. The Pollak family members were imprisoned in various concentration camps; Karl Pollak together with many others was murdered. Otto Pollak and his daughter Helga survived, but he was a broken man, disillusioned by the delaying of the restitution of his café after 1945 and the continued anti-Semitic attitude of the political parties and authorities in Austria. Although he got his café back in the end and was encouraged by many regulars to reopen it, he could not take up his previous life and leased the establishment to a leather factory – today it is a supermarket.

The “Kultur-Café Max” in the suburb of Hernals has a long tradition of offering a home to card, chess and billiard players and cultural events, too. The coffee house opened in 1914 and was bought by Max Teuber in 1957. Until today the old chess sets, the old carambol billiard tables and the library corner have been preserved.

A Viennese curiosity in the area of the coffee house culture is the chain of cafés & pastry shops called “Aida”. After the First World War the Bohemian pastry cook Josef Prousek came to Vienna and bought with his wife a pastry shop in the suburb of Alsergrund. He loved the opera and decided to call his shop “Aida” – briefly he had considered the name “Tosca” as well. Ten years later he already ran eleven branches, of which only the one in Wollzeile in the city centre also acted as a coffee house. After the Second World War he relaunched the business; this time offering cakes for Soviet soldiers and doughnuts and ice cream for US soldiers. In 1948 he reopened his shop in Wollzeile with the first professional espresso machine in Austria. The “Aida” branches were all furnished in a simple, cheap and functional 1950s design by architect Rudolf Verderegger, and equipped with modern espresso machines; the first of which opened in 1954 at Opernring, opposite the State Opera. The characteristics were small stools and high Formica tables for a stand-up espresso, linoleum floors in a black and white a chess-board pattern and the dominant colours pink and brown. The many “Aida” branches in Vienna have kept their design of the 1950s, which has achieved cult status meanwhile, and they have survived the onslaught of international chains like Starbucks. They are popular with the common Viennese for a quick espresso and one of the famous pastries or cakes, which are even exported abroad.

Literature:

Die Wiener Kaffeehauskultur im Wandel der Zeit, Echomedia 2019

Eckstein, Theresia ua (Hrg), Wir bitten zum Tanz! Der Wiener Cafetier Otto Pollak, Katalog Jüdisches Museum Wien 2020

Haslinger, Ingrid, Die Wiener Küche. Kulturgeschichte und Rezepte, Mandelbaum Verlag 2018 + exhibition in „Österreichisches Gesellschafts- und Wirtschaftsmuseum“

Heering, Kurt-Jürgen (Hrg), Das Wiener Kaffeehaus, Insel Verlag 1993

Schwarzer Bock Blauer Hecht. Die Josefstädter Gaststätten von ihren Anfängen bis in die 1960er-Jahre, Bezirksmuseum Josefstadt 2019

Sindemann, Katja, Das Wiener Cafe. Die Geschichte einer ewigen Leidenschaft, Metroverlag 2010

Torberg, Friedrich, Die Tante Jolesch oder der Untergang des Abendlandes in Anekdoten, , 1975