THE NAZI CHILDREN EVACUATION PROGRAMME „ERWEITERTE KINDERLANDVERSCHICKUNG“ IN THE VICINITY OF VIENNA 1940-1945 AND THE IDEOLOGICAL INDOCTRINATION OF THE YOUNG

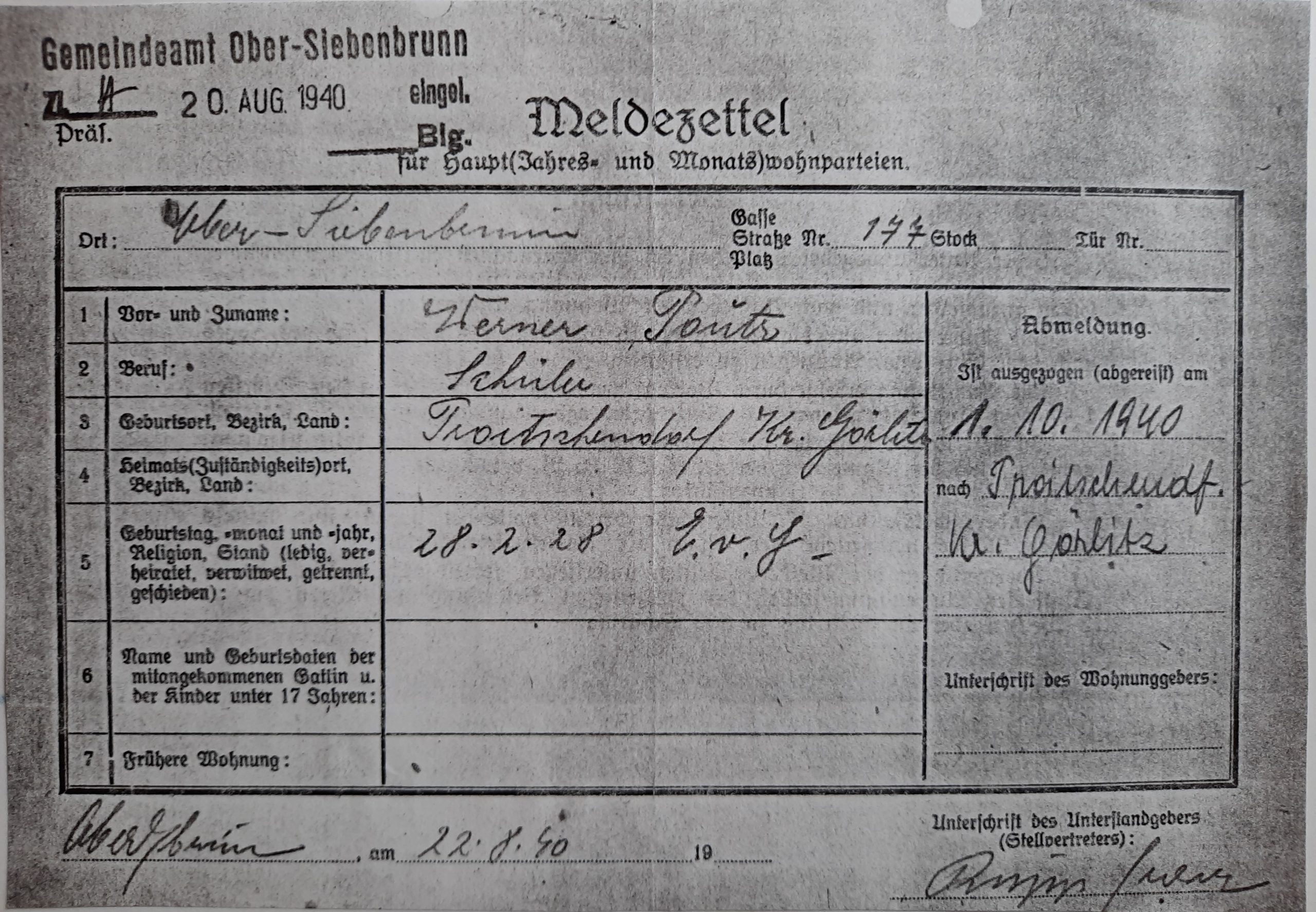

The certificate of registration of the pupil Werner Tautz, my father, who was sent from Troitschendorf near Görlitz in Silesia to host parents in Obersiebenbrunn near Vienna via the Nazi children evacuation programme “Kinderlandverschickung”. He stayed from 22 August 1940 until 1 October 1940 with the family of Franz and Anna Rupp

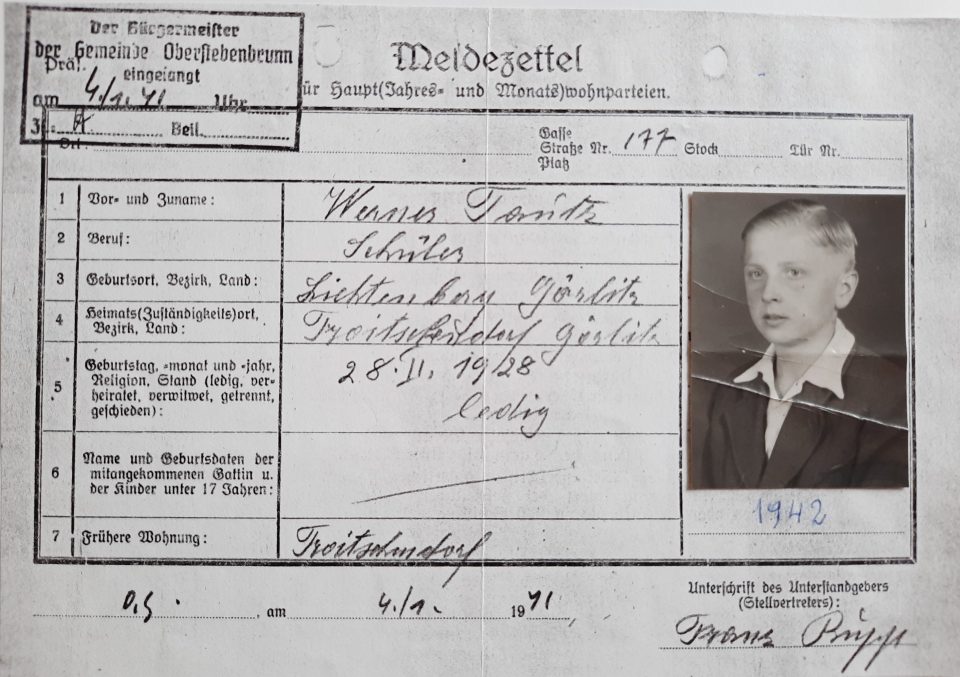

On 4 January 1941 Werner returned on his own to Franz and Anna Rupp, who had agreed to take him in as a foster child. The photo of Werner of 1942 was later added to the certificate of registration

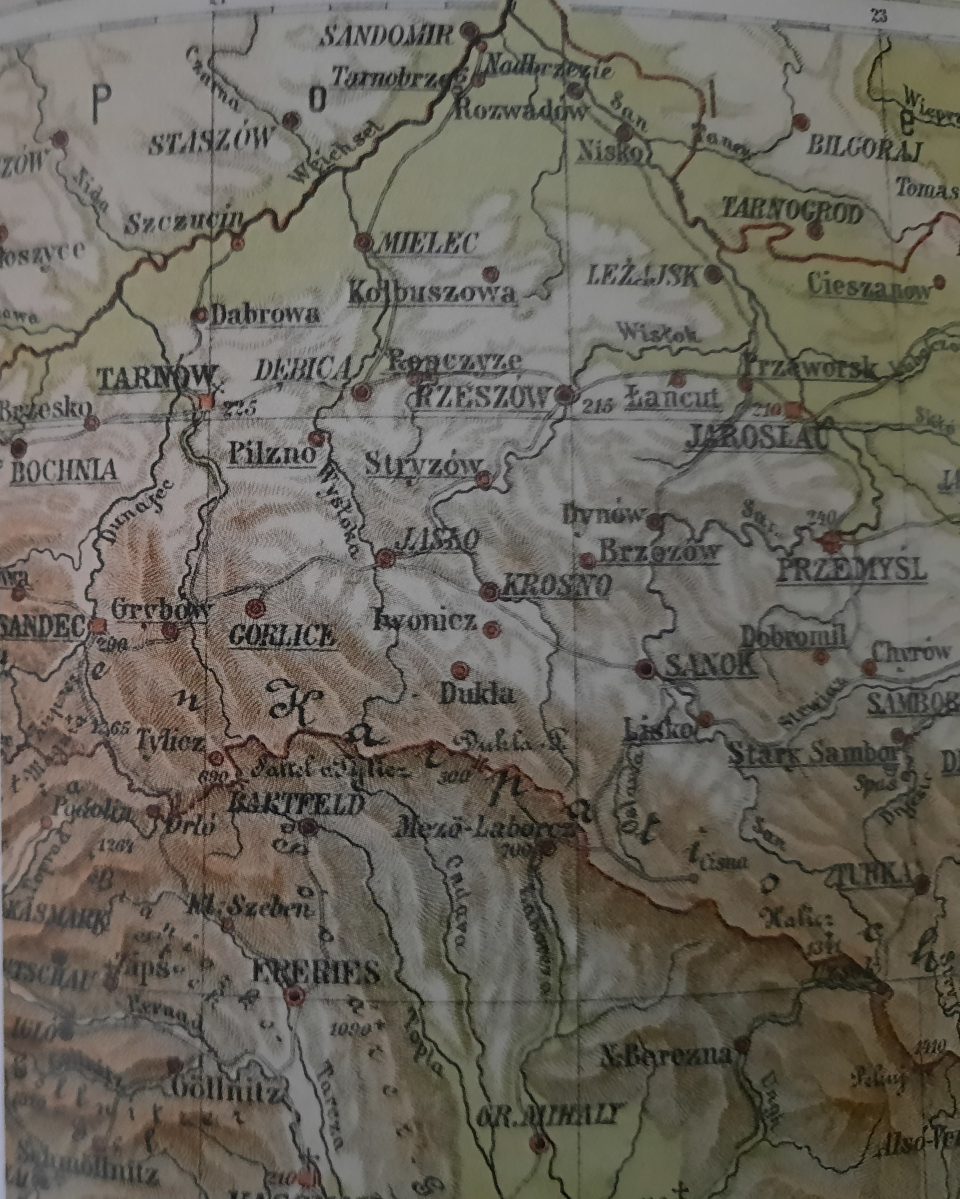

As in most Viennese families of the first half of the 20th century family members came from a variety of geographical, cultural and ideological backgrounds. My mother Herta’s family were on the one hand indigenous Viennese bourgeoisie from Währing and on the other hand urban assimilated Jews born in Vienna and southern Moravia. On the other hand, my father Werner’s background was rural from farming communities near Görlitz in Silesia, formerly German and now Polish territory. He was selected as one of two children by the headmaster of his school to be sent to Lower Austria near Vienna in August 1940 via the Nazi “Kinderlandverschickung” to a host family in Obersiebenbrunn, where the host father, Franz Rupp, had been a NSDAP member since 1931 with an interruption and was later stationed in Norway as a “Wehrmacht” soldier. In his memoirs Werner wrote, “I enjoyed my time at the Rupp family so much that I definitely wanted to return to them after my KLV stay there (which ended on 1 October 1940). Back home I urged my grandparents to help me and I told them that I would be able to learn a profession in Lower Austria (at that time “Gau Niederdonau”) and would not have to work for the farmers after school any more. My grandmother supported me and threatened my mother that she would not inherit their house if she did not allow me to move to foster parents in Obersiebenbrunn. As my mother did not want to forego the house, she agreed. But she took revenge. She saw to it that my foster family did not receive the 20 RM (Reichsmark) monthly alimony, which my (biological) father paid my mother…. I was the “illegitimate” child of the owner of a large-scale farm, where my mother had worked….. So on 4 January 1941 I moved to my new foster family Rupp and the alimony of around 600 RM over the years was deposited at the Dresdner Bank. I never received the money because after the war this region came to be situated behind the Iron Curtain and after 1989 I had no written proof that this money belonged to me. So it is still there.”

Werner’s foster family: on the left his foster mother Anna Rupp with his new-born foster sister Christine on the lap (born in December 1941), his foster brother Franzi on the left (born in 1926), his foster sister Anni (born in 1925) and Werner on the right (born in 1928). Werner’s foster father, Franz Rupp, in “Wehrmacht” uniform on the right

Anna Rupp, Werner’s foster mother, was a strong and warm-hearted woman and a devout Roman Catholic. She ran the family single-handedly during the war in a confident and efficient way. There was always enough food on the table, pigs, hens, geese, small fields to grow potatoes and maize, the bees for honey and a vegetable garden and orchard- and above all, all children were treated equally. She made a cosy home for Werner, who had never known anything like that before. His biological mother rejected him and especially after the birth of his half-sister Elsbeth, her marriage to Karl Perschke and the birth of his half-brother Günter, his mother discriminated against Werner to the extent that his grandparents wanted a better life for him with the foster family Rupp. Anna Rupp had no time or understanding for NSDAP party policy like her husband and ruled the family with a strong hand, which meant that after the war and the return of Franz from Norway there were many rows between the two spouses because she resisted the dominance of her rather authoritarian husband. This was the only aspect of life with the Rupps that bothered Werner. Anna was of a family with Slovak roots in the region, named Zimak, and she spoke Slovak well, which helped a lot when dealing with the Russian soldiers who were staying in her house for some months from April 1945 on. Anna’s father had left the family and had emigrated to the United States, when the three sisters, Marie, Anna and Mali and their little brother Pepi were still small children. He supposedly went bankrupt over there; he never returned and did not support his family either. So the girls had to work for the farmers in the region at an early age to earn a living. There were big farmers in the “Marchfeld” region who treated the girls fairly, paid them small wages and offered them food to take home for the family, but there were others, too, who exploited them shamelessly. This was so exhausting that Anna suffered from serious lung problems at the age of 18, but fortunately fully recovered. Her sister, Mali, never married and supported and cared for their mother. She worked in the sugar refinery in Leopoldsdorf like nearly everyone in the family. Franz Rupp was an unskilled worker there, his son Franzi learned the trade of fitter in the factory before he was drafted and Werner was apprenticed as an electrician in the same refinery. After the war Anna also worked in the sugar refinery every year during the time of the sugar beet harvest.

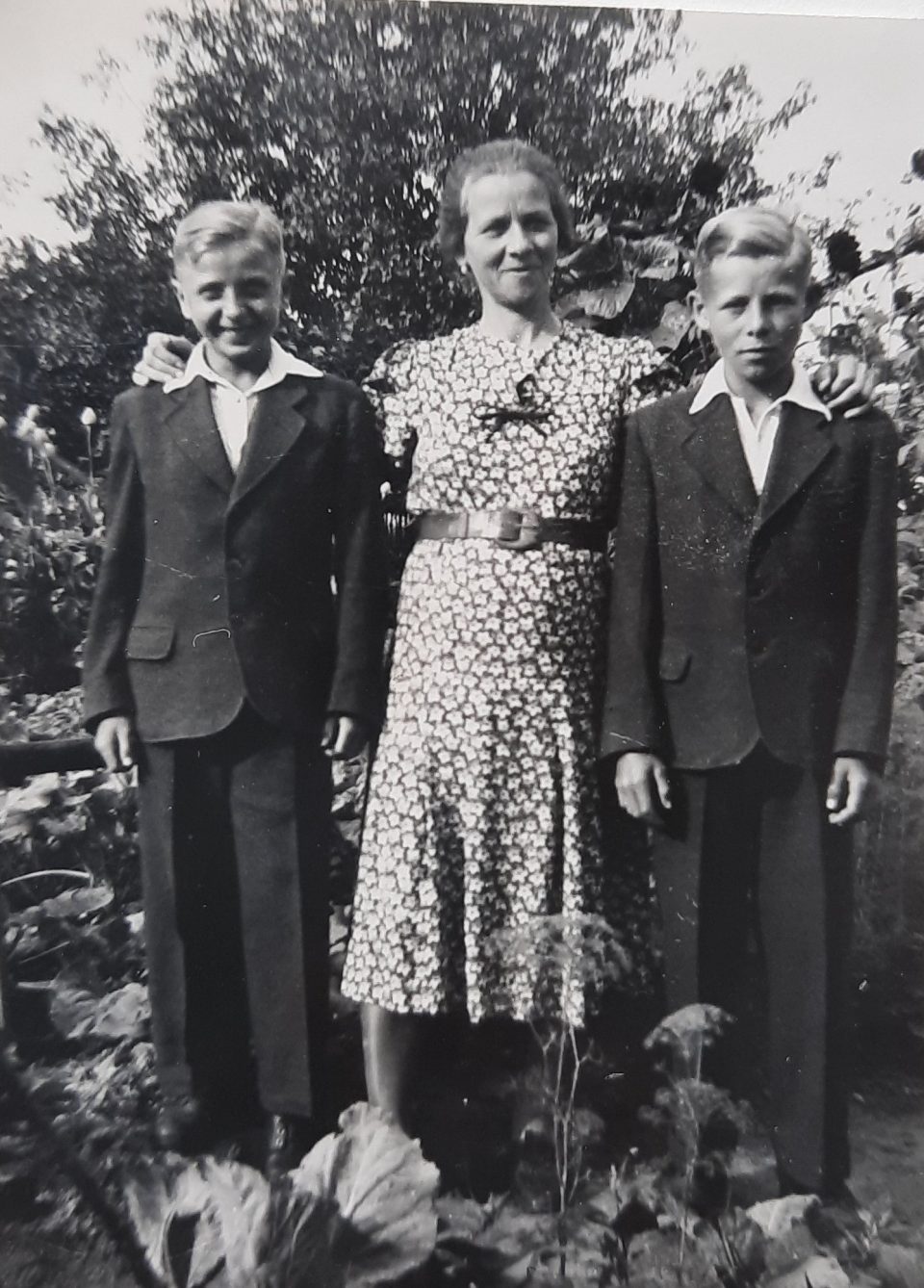

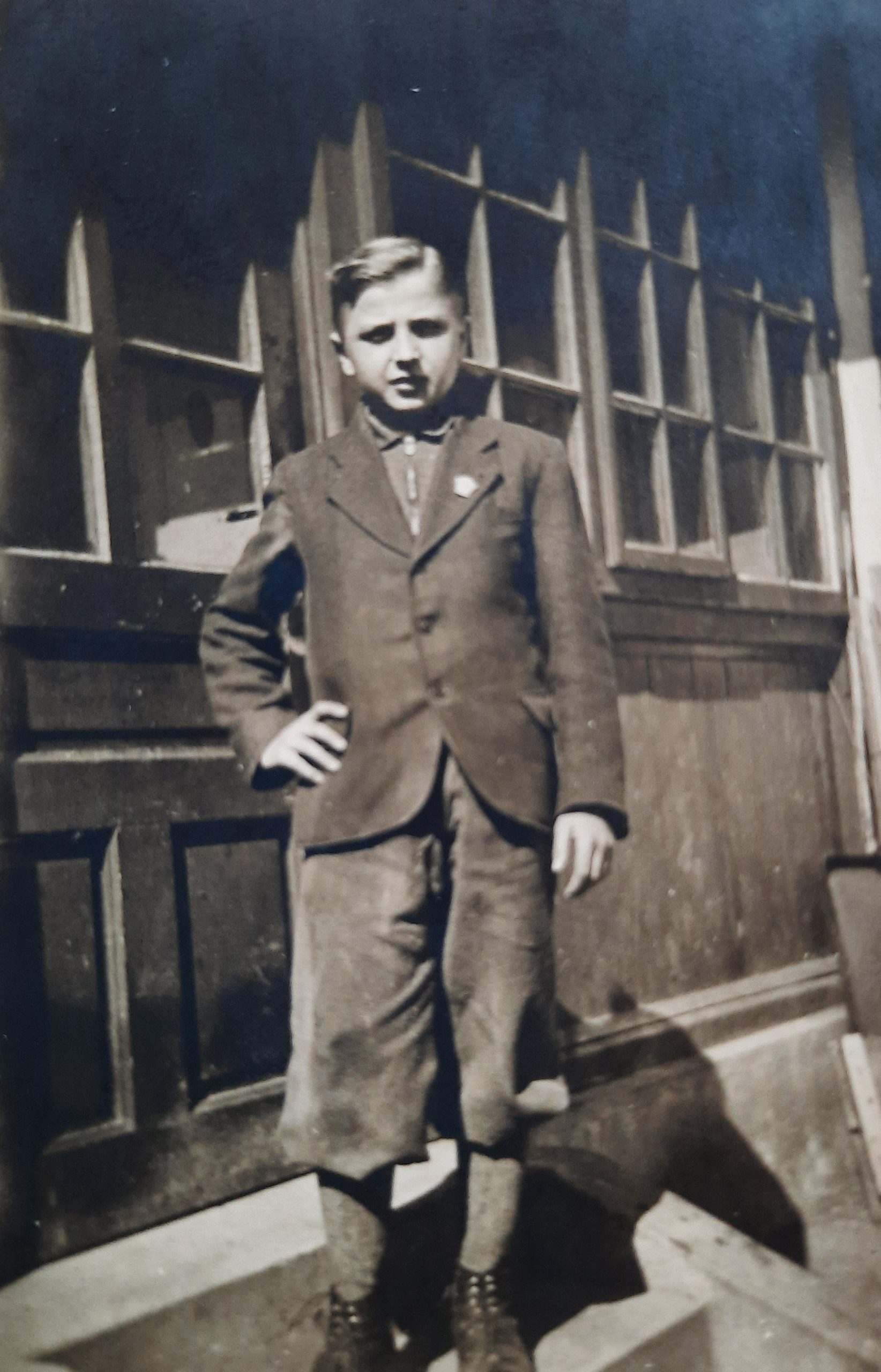

Werner soon felt completely at home with the Rupps and he later stressed that he was treated like their own child. No difference was made between him and the other three children of the family; he even received the same outfit as his foster brother Franzi; a kindness he had never experienced at home with his biological mother, Frieda. Werner adapted quickly to his new surroundings, spoke the local dialect and converted to Roman Catholicism, which was Anna’s wish. His whole life Werner was considered the model of a “true Viennese”, although he was born in Silesia and spent the first twelve years of his childhood there. Just like the grandfather of his later wife, Ignaz Sobotka, who was by birth right, looks and poise a “true Viennese”, but the Nazis denied him this status and persecuted him because he was born a Jew (see article on “Viennese Beer Brewers”). This example proves what a mixed people the so-called “true Viennese” were and still are and how stereotypes govern people’s perceptions.

Werner, who had received the same outfit as his older foster brother Franzi, in the garden of the Rupps’ house in Obersiebenbrunn, Bahnstrasse 177; on the left with Anna Rupp, his foster mother, and on the right with his foster sister Anni.

The house of the Rupp family in Obersiebenbrunn, near Vienna, and Werner in the yard below

So how did this children evacuation programme “Erweiterte Kinderlandverschickung” (KLV) work in Hitler’s so-called “Third Reich” between 1940 and 1945? It was a huge transfer of children during the war to move them from cities under threat of bomb attacks to areas which were supposedly safe from Allied bombings. The Nazis insisted on not calling this programme “evacuation movement” because they feared the population would get worried when hearing this term and would no longer believe in the Nazi “Endsieg” (final victory). Most of all, this programme was a social and ideological experiment, namely to tear children from their families for months and educate them in a National Socialist surrounding and to indoctrinate them with Nazi ideology. This worked more or less well in the KLV camps which were set up, but not necessarily so with the children who lived in host families, although those were selected by the local NS party organisations and considered “reliable”. Overall, the impact of NSDAP party ideology and the pressure from NSDAP camp leaders resulted in the fact that a high percentage of boys who had gone through the KLV programme volunteered for the NS special troops SA (“Sturmabteilung”) and SS (“Schutzstaffel”) and especially towards the end of the war, the “Waffen-SS”. Contemporary witnesses who had stayed in KLV camps reported that the boys who did not volunteer for the special units SA or SS were ridiculed and discriminated against. This might not necessarily have been the case for boys in host families. Werner did not volunteer for the SS, but his foster brother Franzi did. He was drafted in 1943 at the age of 17, joined the “Waffen-SS” and was killed in the war. Werner was drafted in 1944 and opted for the marines. In fact, Franzi was a shy and melancholic boy who seemed to have enjoyed the presence of Werner in their home because until then he had suffered under the dominance of his elder sister Anni. His authoritarian father Franz forced him to join the “Waffen-SS “to make a man out of him”, because Franz Rupp himself was an SS-man and Franzi always did as he was told. Together with two other boys from the same village they were sent to France. In Marseille the other two decided to desert from the “Wehrmacht” towards the end of the war and urged Franzi to escape with them, but Franzi did not dare to join them. The other two returned home safely, whereas no trace of Franzi was ever found. He was declared missing in France. On 15 August 1944 the US troops had landed at the Cote d’Azur near St. Tropez with 60,000 men and were supported by the “Free French Army” of Charles de Gaulle. This landing is known as the “Operation Dragoon”. In the following days another 120,000 Allied soldiers landed on the southern French coast involving 880 war ships. The operation was half the size of the “Operation Overlord” on the coast of Normandy on 6 June 1944. Nevertheless it is nearly forgotten except in France. Hitler decided on 17 August 1944 to withdraw his troops from southern France except from the fortified strongholds in Toulon and Marseille. Around 250,000 to 300,000 “Wehrmacht” soldiers had to march north in the direction of Alsace. Either in Marseille or on the march north Franzi was killed. Fortunately Werner was sent to Freilassing, Bavaria, for army training in March 1945, where he decided to flee from the “Wehrmacht” returning to Obersiebenbrunn on foot at the end of the war.

Franzi, Werner’s foster brother, in uniform, aged 17, and his foster father, Franz Rupp, as a Wehrmacht soldier in Hammerfest, Norway

The KLV was decidedly a NSDAP programme, organised and financed by the party, whereby hundreds of thousands of children were taken from their families and transferred to other parts of the “Third Reich”. The exact number of transferred children cannot be defined because at the end of the war all KLV files were destroyed at Hitler’s command. Some German historians estimate that around 2.8 million children took part in the KLV programme, whereas others believe that around 850,000 children between 10 and 14 years of age were cared for in camps and approximately the same amount in host families. There are no reliable numbers for Austria, which formed part of the “Third Reich” in those years and also not for the “Gau Niederdonau” (this included not just Lower Austria, but also parts of Burgenland, southern Moravia and southern Bohemia), but in around 200 KLV camps in “Niederdonau” approximately 10,000 – 20,000 children might have been lodged annually, not counting the children in the host families. A study in the Czech Republic found out that in nearby Bohemia and Moravia around 350,000 children were accommodated in 400 KLV camps.

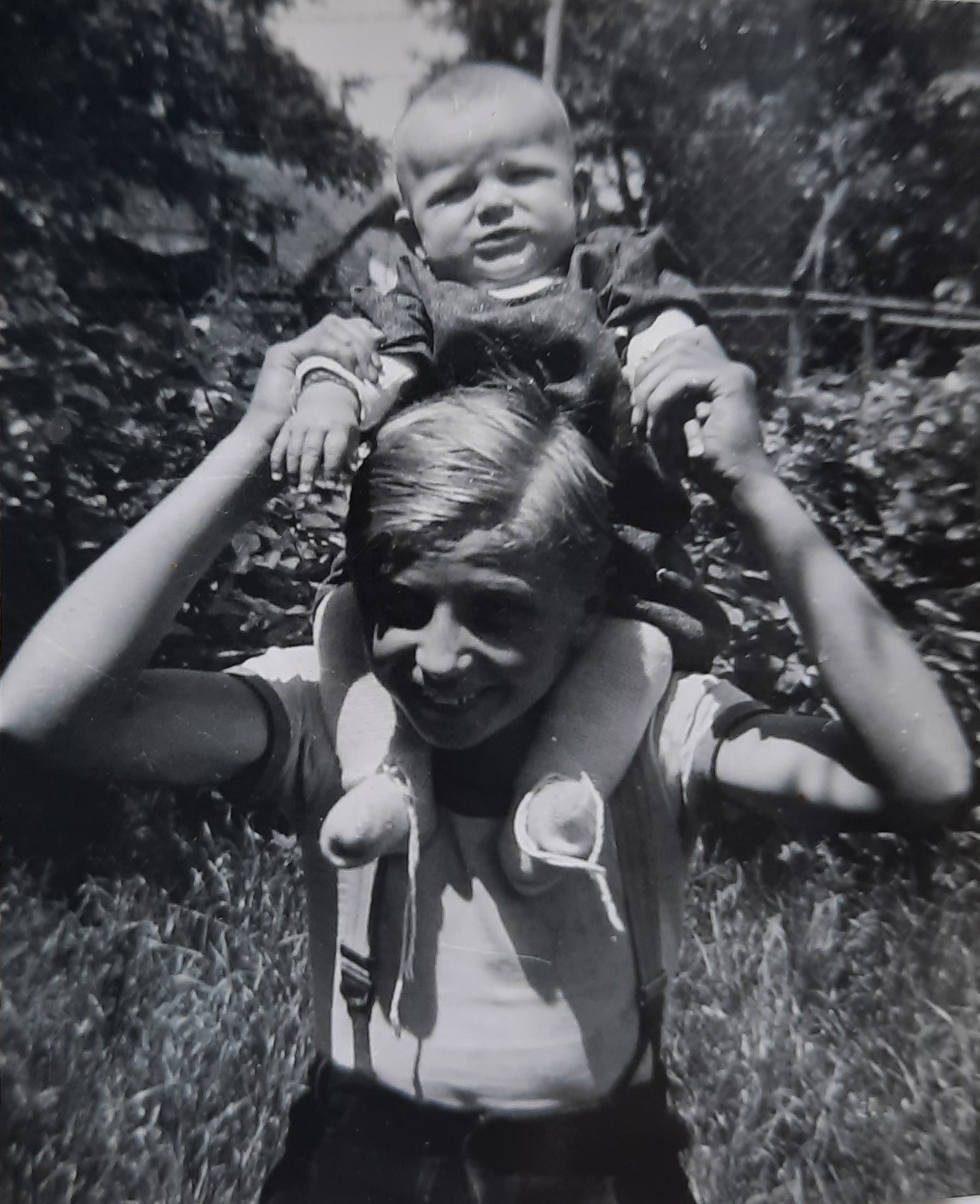

Werner on the left with his much loved foster brother Franzi on the right and below with his new born foster sister Christine, who he remained very close to all his life

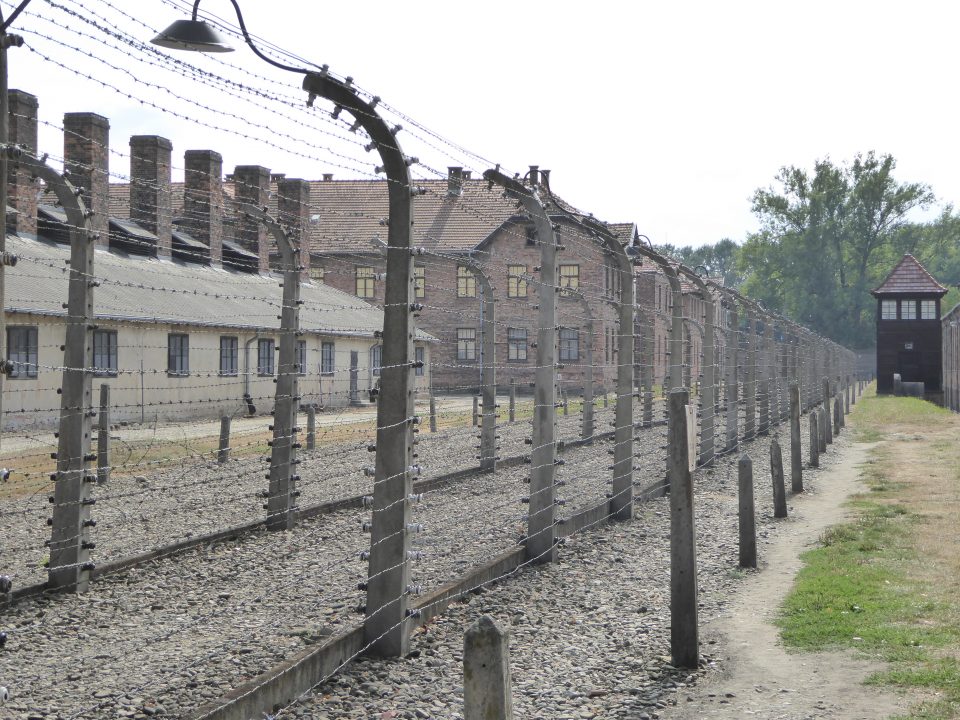

Werner felt welcome and at home at his host family and wanted to live with them for good, but the majority of KLV children suffered a lot under the separation from their families. Also in England evacuation programmes for children were organised to protect them from German bombers. Anna Freud, the daughter of Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, who had fled with his family from Vienna to England, established psychoanalysis in England and together with Dorothy Burlingham ran the Hampstead War Nurseries, where they treated traumatised evacuated children during the 1940s and after 1945 orphans from the Nazi concentration camp Theresienstadt, too. Anna Freud found out that the German bomb attacks were less traumatic for the English children than the evacuation and the separation from their families, especially from their mothers. No such studies were made in Nazi Germany, but the same was most probably true for the thousands of children in the KLV programme in the “Third Reich”, except for Werner, who had never had a proper family life and experienced the warmth of a home for the first time with the Rupp family.

A recreational stay of urban children in the countryside, called KLV “Kinderlandverschickung”, had been a well-established social programme in Germany since the end of the 19th century and was now organised by the NSV (“Nationalsozialistische Volkswohlfahrt” – National Socialist Welfare). In the summer of 1940 1,500 children were registered for a stay in “Niederdonau” via the original KLV programme, among them Werner. On 27 September 1940 Hitler decided that the programme should be extended to all children who lived in regions which were affected by Allied bomb attacks and the organisation of this “Erweiterte Kinderlandverschickung” (extended children evacuation programme) was to be taken over by the NSV together with the HJ (“Hitlerjugend”- Hitler’s youth) and the NSLB (“Nationalsozialistischer Lehrerbund” – the National Socialist association of teachers). Baldur von Schirach insisted on this terminology because it reminded parents of a well-known and established programme and by that avoided any war-related panic among the parents of KLV children. The local HJ was to identify suitable hotels, inns or bed & breakfast places where the children could be accommodated. In the region around Vienna the owners of such accommodations were happy to welcome KLV children because due to the war most tourist activity had ceased. The problem was only that the majority of locations were designed for summer tourism and provided no heating facilities. All the costs which arose from this “extended” KLV programme were to be covered by the party. Due to the resistance of middle-class and well-to-do parents to hand over their children, the party first concentrated on children from poorer families and dressed the programme up as a social measure. Werner was still selected on the grounds of the original KLV programme, as he did not come from an urban area which was threatened by bombs, but from the small village Troitschendorf near Görlitz in Silesia. He formed part of the group of children who were selected for the first KLV stay in “Niederdonau” from 20 August until 1 October 1940.

Baldur von Schirach had quickly drafted a programme of transferring 200,000 school children and 50,000 mothers with their babies and calculated that around 3,600 places of accommodation and appropriate means of transport were to be provided and around 2 million RM per day were to be raised for the implementation of his project. Hitler personally approved of Schirach’s “extended” KLV plans. Then an order was issued that all local NS party organisations had to recruit “reliable” host families, camp leaders and female personnel for cooking and cleaning and that’s when Franz Rupp volunteered as host father. The matter was urgent because the first “extended” KLV trains were to leave Berlin on 7 October 1940 – Werner was still part of the original KLV holiday programme of 5-6 weeks and had already left Görlitz in August 1940. From 1943 on nearly all big cities in Germany sent children away via the “extended” KLV. The programme was explicitly an NSDAP party programme, financed by the party and free of charge for the parents. The programme involved children until the age of 14 and in some cases until the age of 18. The party organisation NSV paid for the medical examination before departure, for transport, insurance and provisioning during the journey. Host families were entitled to a benefit that covered the costs of board and lodging. The parents were responsible for providing clothing, which was checked by the NSV before departure and in case of need the NSV issued shoes, coats etc. In “Niederdonau” the local HJ and BdM (“Bund deutscher Mädchen” – the NS association for girls) groups appointed HJ and BdM leaders who were looking after the 10- to 14-year old children in KLV camps and the HJ had to finance board and lodging of the children in camps. The teachers who were recruited by the NSLB were responsible for organising the teaching in the camps and the NSLB covered all the arising teaching costs. Children in host families like Werner usually attended local schools. Yet the HJ tried to extend its influence on the educational programme of all KLV children to boost the ideological indoctrination. It is difficult to estimate the number of children who were accommodated in the area of “Niederdonau” or Vienna because the NSDAP representatives tended to exaggerate the numbers for propaganda reasons. For example it is known that from 7 October until 4 November 1940 in the first “extended” KLV to Vienna 5,700 children were evacuated from Hamburg and in 1941 the NSDAP leader of “Niederdonau” boasted that his region was on the top of the list of KLV hosts with 200 camps and 20,000 KLV children, which was probably highly exaggerated because other sources calculate that there were lodgings available for 10,000 children only in “Niederdonau”. But again in 1943 at the time when more and more children who were affected by bomb attacks were sent south a NSDAP representative of the region spoke of 20,000 KLV children annually for “Niederdonau”.

The duration of this “extended” KLV programme was not explicitly mentioned in order not to upset the parents and the children, but it was much longer than the original KLV holiday programme of around 5-6 weeks via which Werner came to Obersiebenbrunn. Many parents were sceptical about the NSDAP children evacuation programme and did not want to hand over their children to the NS party. But the aggressive Nazi propaganda for the “extended” KLV, the threat of bomb attacks and the shortage of food in urban areas left many parents no choice. The children were taken from their families initially believing that they would return home after four to six, maximum eight weeks. The parents were from time to time soothed that they were allowed to have their children back whenever they wanted and to have the permission to visit them. In no case should it be mentioned that the children might only return home when the war was ended. In 1941 a stay of six to nine months was informally fixed and a return home before the expiry of this “extended” KLV date was not permitted; on the contrary, the parents might even be asked to agree to an extension of the duration of their child’s KLV stay. In the course of the war the KLV programme was progressively prolonged and from 1943 on it was no longer limited in time, it was an indefinite measure.

The organisation of “extended” KLV was centralised in Berlin under the leadership of Baldur von Schirach, Hitler’s commissioner for youth education, and a special NS party representative was appointed for every district (“Gau”) to coordinate the three party organisations NSV, HJ and NSLB on site. The headquarter for “Niederdonau” was located in the 9th district of Vienna, Wasagasse 10 and was headed by Otto Fenninger, who was appointed by “Gauleiter” (district leader) Hugo Jury. In “Niederdonau” the KLV officially employed around 1,900 people, including camp leaders, housekeepers, cooks, cleaners etc. plus 1,300 persons who were responsible for caring for and educating the children. It was the intention of the organisation to accommodate the children in isolated places and small villages mostly. The official argument for this choice of location was the boosting of cohesion within the KLV group in closed communities. This was of course not possible when children were lodged in host families like Werner.

The buildings which were selected by the HJ as appropriate locations for KLV camps were not always handed over voluntarily by the owners to the KLV for the purpose of installing a camp, but if no agreement could be reached the buildings were requisitioned. Nevertheless many hotel and boarding house owners cooperated willingly because the KLV children compensated to some extent the breakdown of tourism in the region during the war. All KLV camps were marked with a combination of letters and numbers: for example ND for “Niederdonau” and then the number of the camp and a uniform postage stamp was created. Those children who were sent to host families were assigned to a family which had applied for a KLV child or children. The local newspapers in Lower Austria announced that it was the “express wish of the Führer” that the local population welcomed as many children as possible because it was their “honour of duty towards the Führer”. In some villages the families even competed with each other and tried to outdo one another in complying with Hitler’s wishes. It can be assumed that only politically “reliable” families were selected because there are records of families which were rejected. Some pressure might have been applied by the local party to accept KLV children if it was known that there was unused space in a family home, such as a garden house or empty rooms. The newly established KLV camps were adapted and equipped by the KLV headquarter in Vienna, where a whole school building acted as a warehouse in which kitchen equipment, heaters, bunkbeds, lockers, shoes and clothing etc. were stored. In every KLV camp an infirmary had to be installed, too. The bureaucracy for the innkeepers and hotel owners who ran such camps was enormous and dozens of check lists had to be completed daily, for example food deliveries, in order to be compensated by the KLV. For some innkeepers this was good business nevertheless: around 1.95 RM was paid per bed and additionally 1.45 RM per child. The host families received 2 RM per child and day additionally to the child’s food stamps.

In the beginning of the programme children from different schools were sent to one destination. Werner noted that two children from his school were chosen to be sent on a 6-week KLV holiday in August 1940 and the headmaster selected him, although he was not undernourished, because he knew about his difficult family situation and because Werner was always “ready to assist with little chores, such as cleaning the aquarium or acting as beater at a hunt”. Initially northern German cities sent children to KLV camps in the south and later also Viennese children were evacuated to “Niederdonau”. From 1943 on whole schools were dispatched to KLV camps. Werner wrote that he was lucky at having ended up with the Rupp family, because they had opted for a girl and he should have been sent to the builder Steinbeck, but despite the confusion the Rupp family welcomed him in their home. According to contemporary witnesses such mix-ups happened quite often. The children usually arrived at the point of destination completely exhausted after long train rides of sometimes two days and often more than 1,000 km.

…