My great-great-grandmother Magdalena Ühlein, innkeeper in Nußdorf (1885) Anton Kainz, my great-grandfather, innkeeper in the Viennese suburb Währing

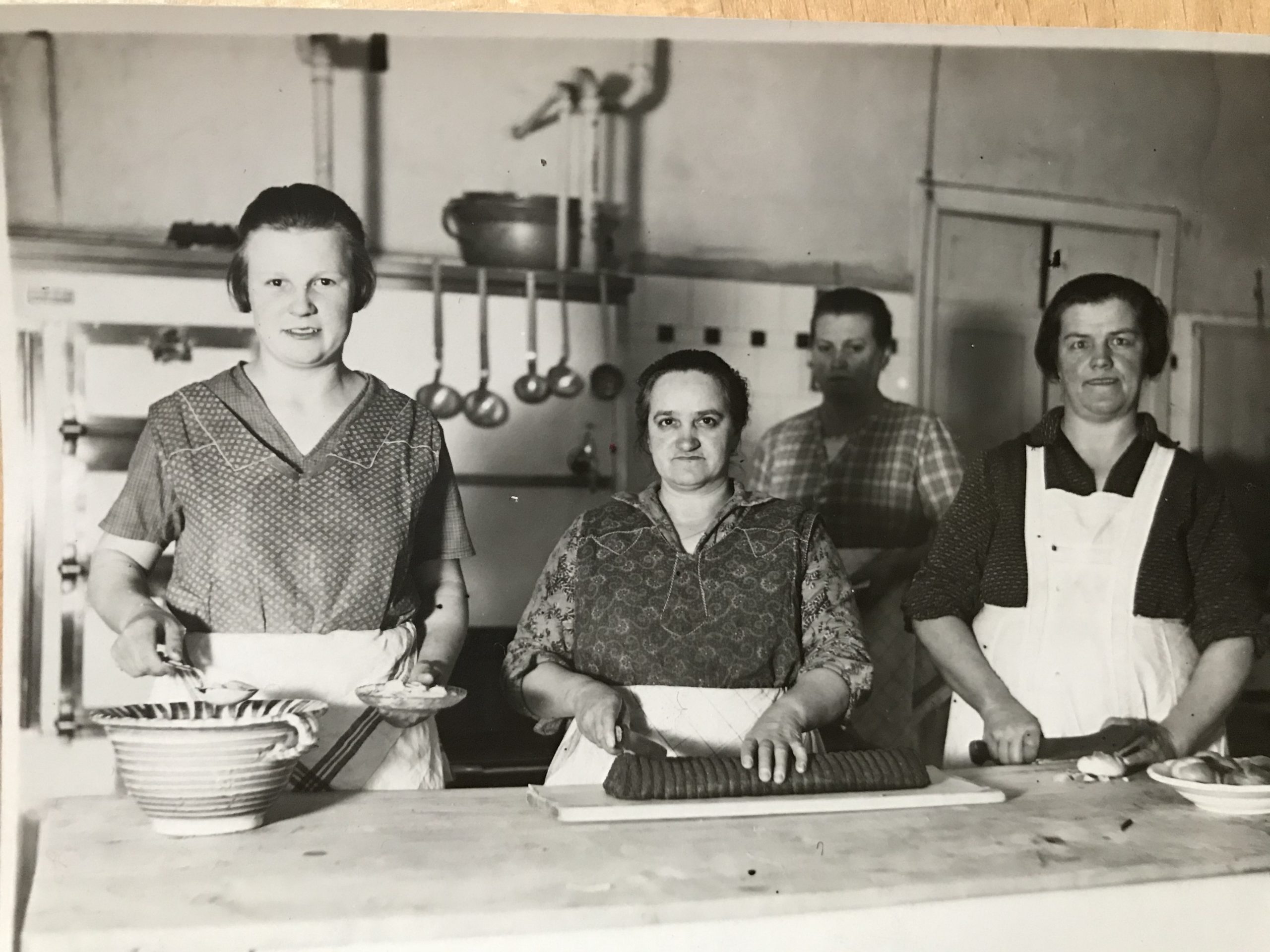

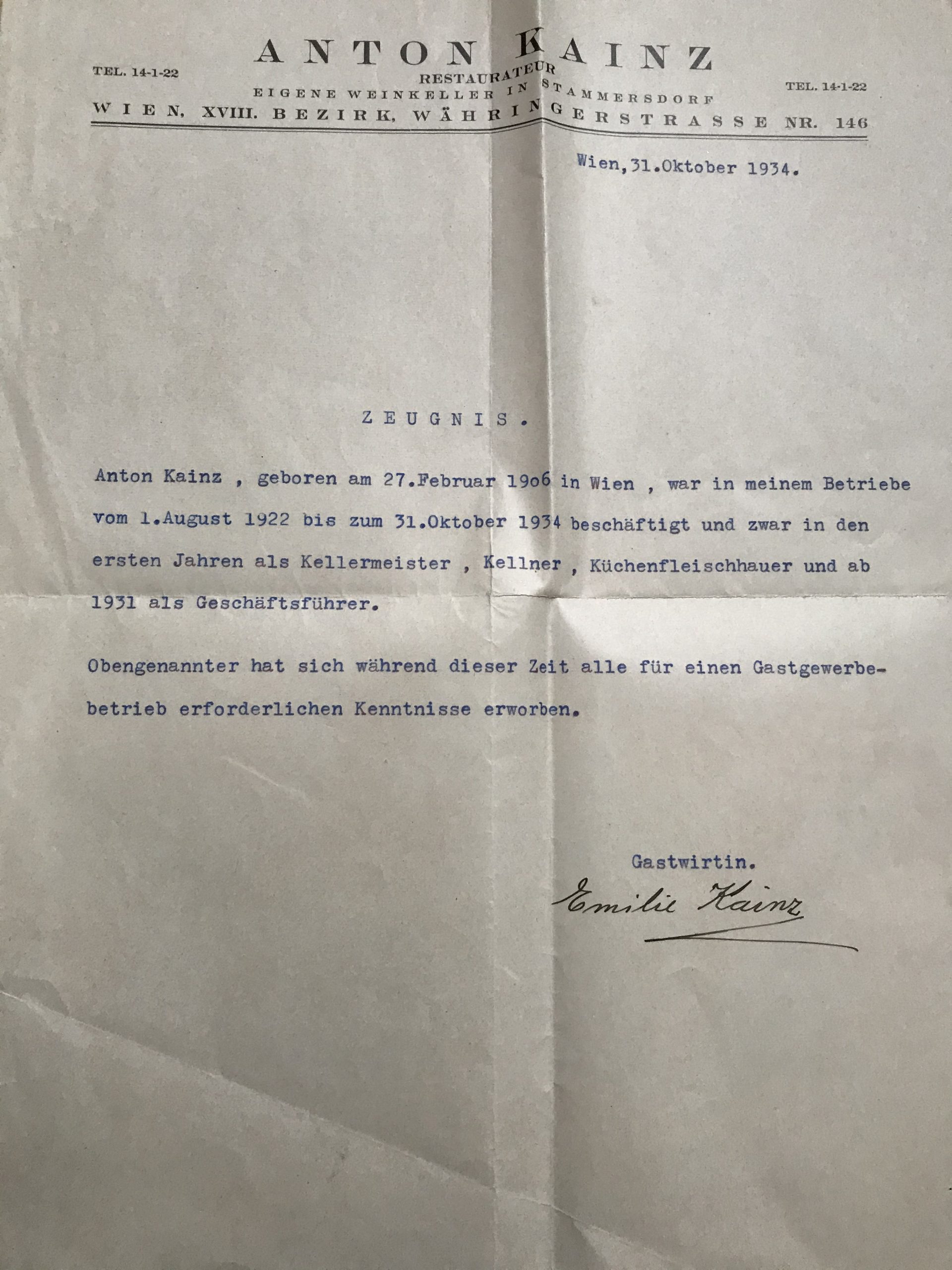

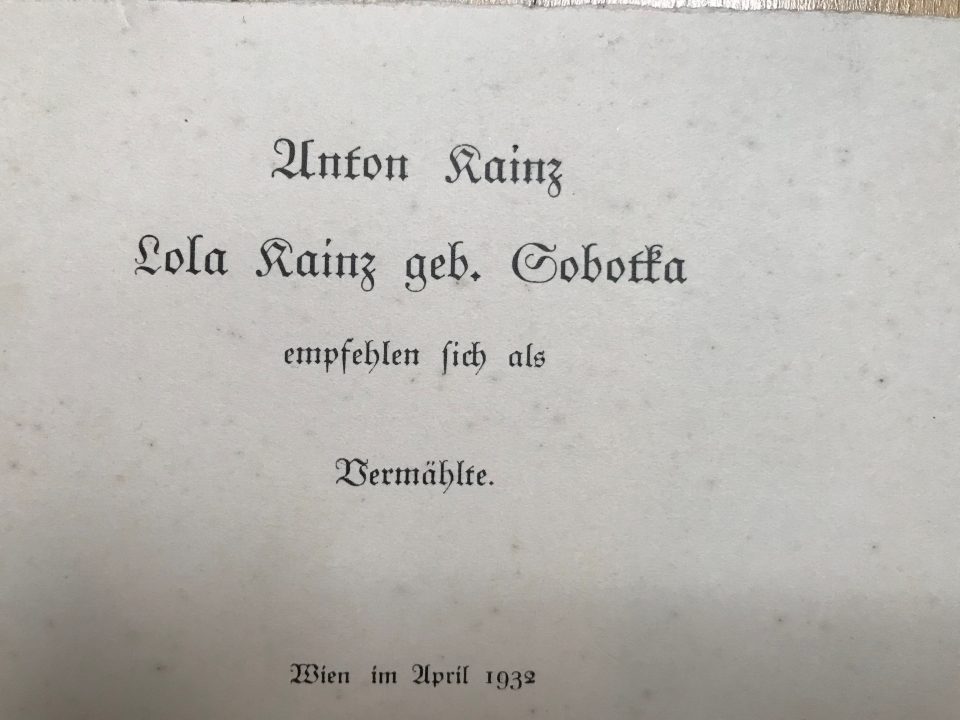

Anton Kainz senior, my great-grandfather, was the innkeeper in the outer suburb of Vienna: Währingerstrasse 146 in the 18th district. My grandfather, Toni was raised there and as he was destined to take over the running of the inn, he was trained as a waiter and cook and went abroad to perfect his catering skills working as a waiter and cook in hotels and restaurants in Switzerland and other fashionable destinations of the bourgeoisie of the 1920s. After the early death of his father his mother took over as innkeeper and when Toni fell desperately in love with my grandmother, he married her against the will of his mother. His mother resisted the marriage because she considered Lola, a beautiful Jewish shop girl in a confectionary shop, an inappropriate match for her middle-class son and heir to an inn. Nevertheless the young couple moved into a tiny room above the inn and worked in the inn alongside the grumpy and tyrannical Mrs. Emilie Kainz, the widowed innkeeper. Toni was the manager of the inn since 1931, but his mother remained the innkeeper; a constellation that could never have succeeded. She continuously harassed both of them until they decided to leave and rent a coffeehouse in the 8th district, Josefstadt. Emilie Kainz was born Emilie Ühlein, daughter of the innkeeper Rudolf Ühlein in Nußdorferstrasse 50 in the 9th district. She must have been the prototype of the strict, rough and uncompromising Viennese innkeeper’s wife, as on can see in the photo:

The innkeeper Emilie Kainz in the background in the kitchen of the inn “Anton Kainz”

My grandmother Lola at the entrance of “Anton Kainz” inn, Währingerstrasse 146, Vienna 18

The house today: the inn was replaced by a drycleaner, shoe repair shop and a barber

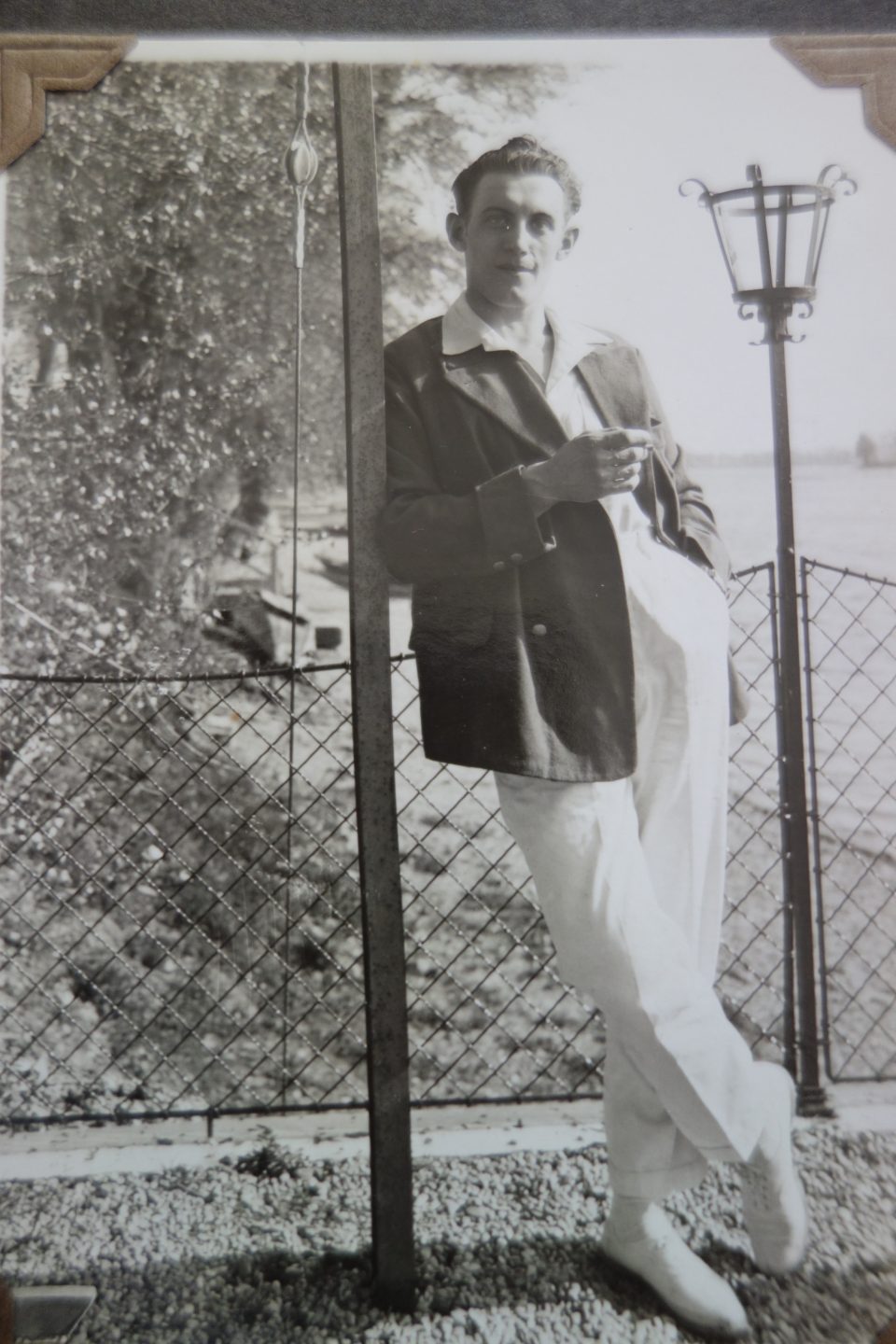

Toni and Lola, the “young bohemians”: They both enjoyed the carefree life of middle class Viennese youngsters in the “Roaring 1920s”.

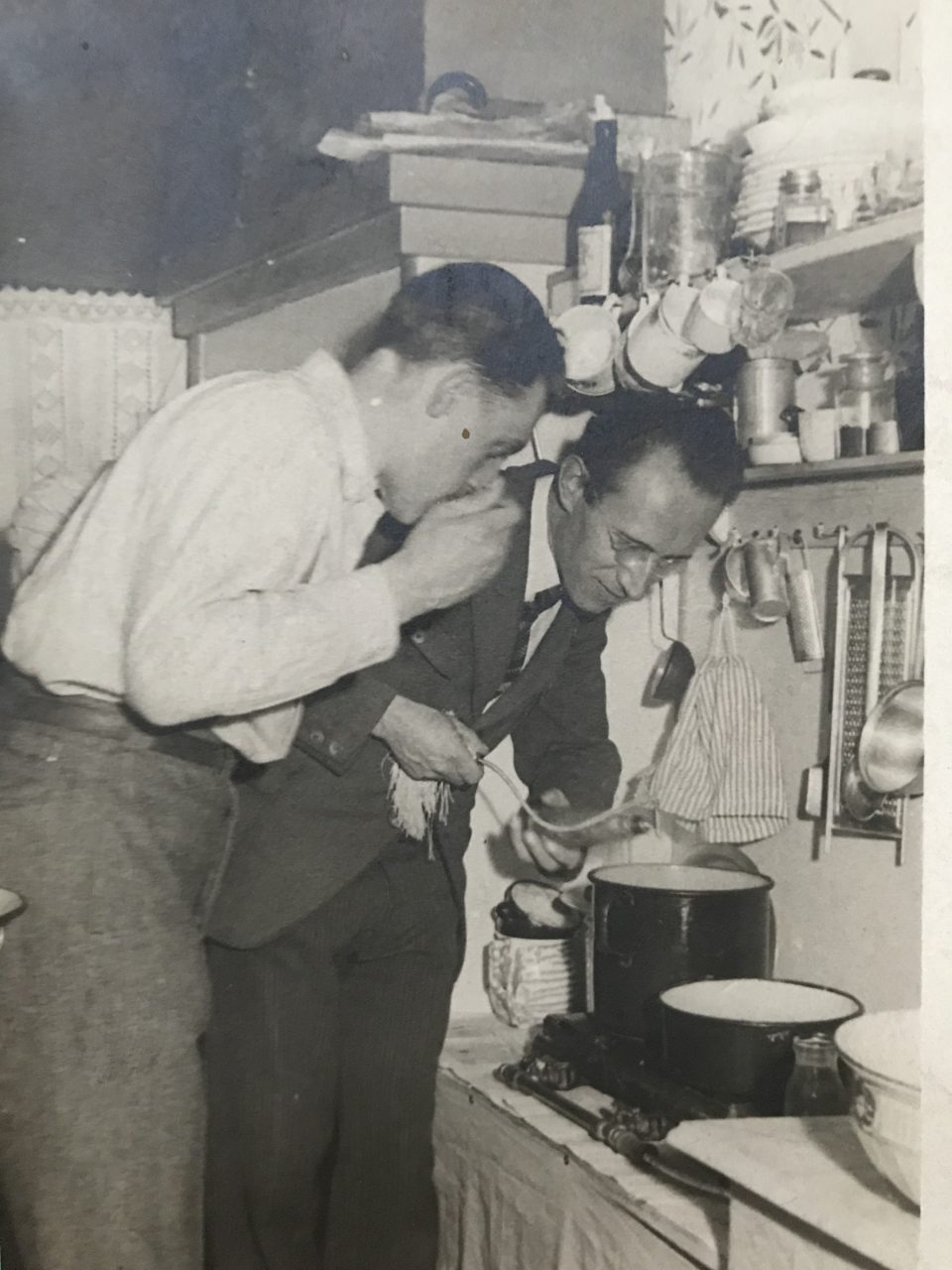

My grandmother remembered that they both, Lola and Toni, were not cut out for an innkeeper’s career and that they were definitely not gifted entrepreneurs, in fact they were lousy managers. They never seemed to regret not running the “Anton Kainz” inn. Lola immensely enjoyed the company of the guests, but she was no good in the kitchen, where she was supposed to work as long as her mother-in-law was the innkeeper, and Toni loved cooking, but rather for family and friends. He was a rather withdrawn person with lots of aesthetic and philanthropic interests such as philately, music, photography, painting, woodcraft and he loved sport, but not necessarily managing an inn.

When quitting work at the inn in October 1934 Toni’s mother, Emilie Kainz, wrote a reference for him certifying his employment as cellar master, waiter, kitchen butcher and since 1931 as manager of the “Anton Kainz” inn in Währingerstrasse 146 from 1st August 1922 until 31st October 1934

The simple announcement of the marriage of my grandparents in April 1932

Lola as a young wife at Christmas with the Christmas presents of Toni in the inn – in the background on the left the photo of the deceased Anton Kainz senior

My grandmother, Lola, in her apron in their tiny room above the inn and Toni with new-born Herta, my mother, in November 1933 in the same room

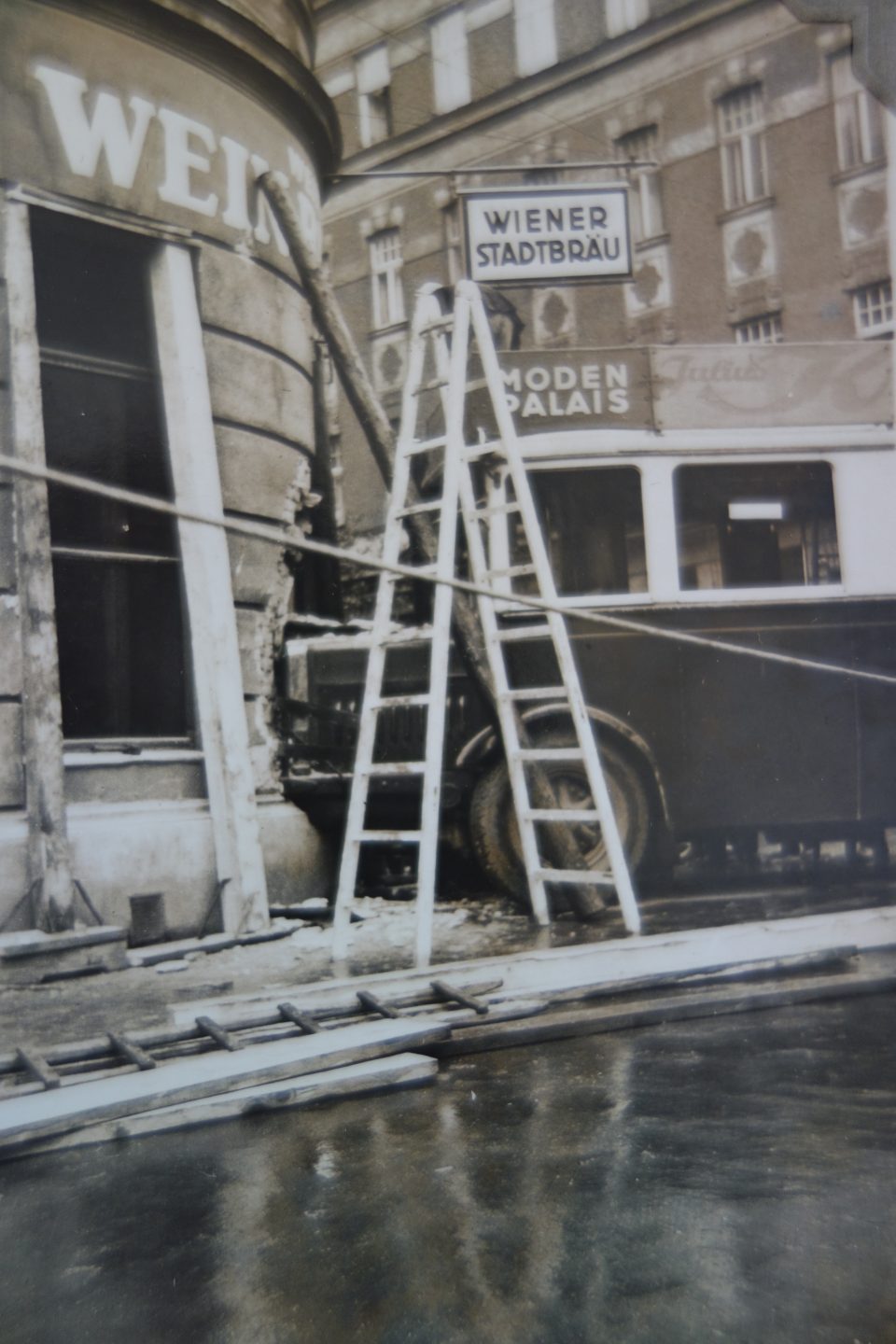

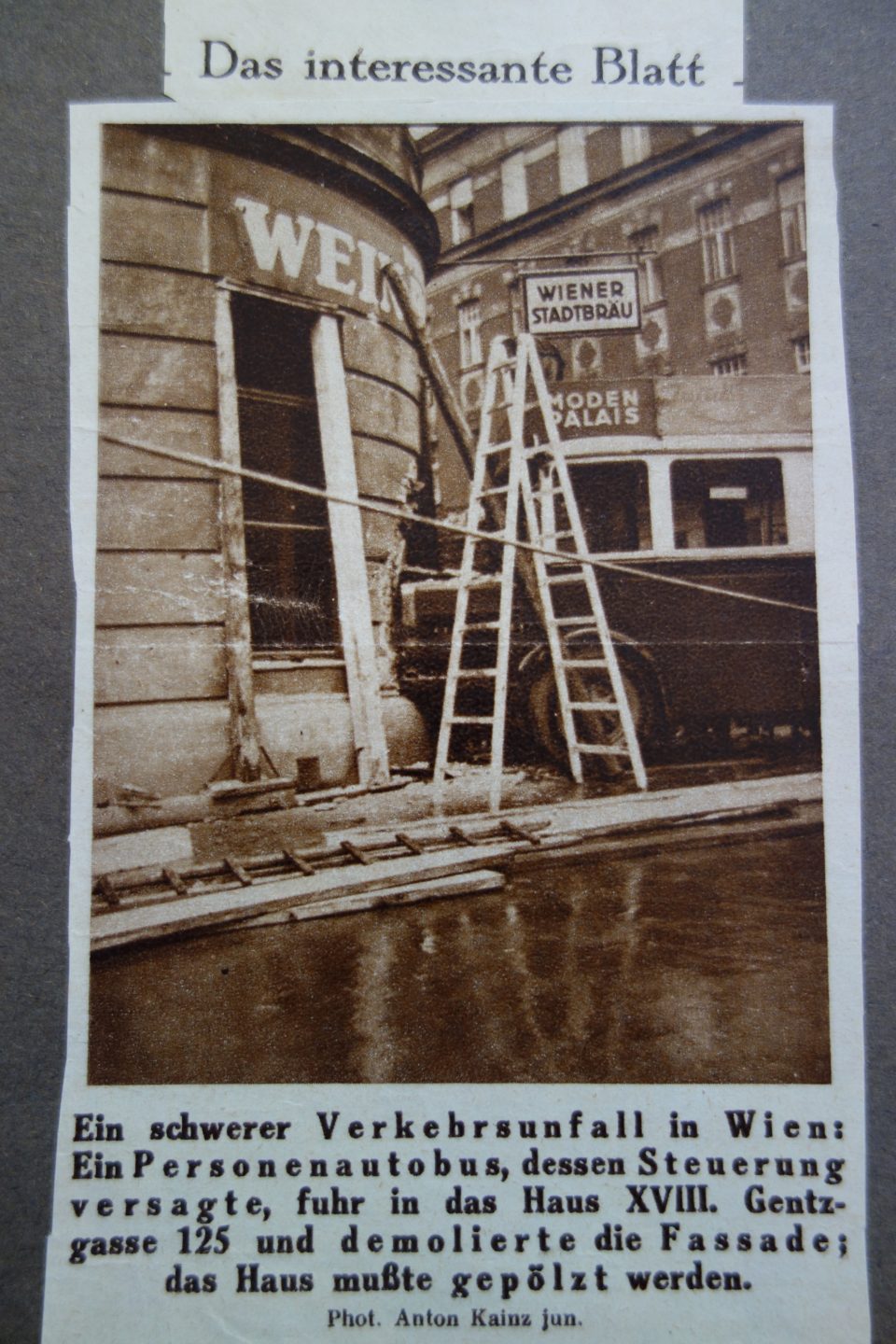

Already as a young man Toni was a keen photographer and when near the inn a car accident happened, his photo was printed in the newspaper

Toni (on the left) in the kitchen and my grandmother, Lola, in a white apron reading in the public room of the inn

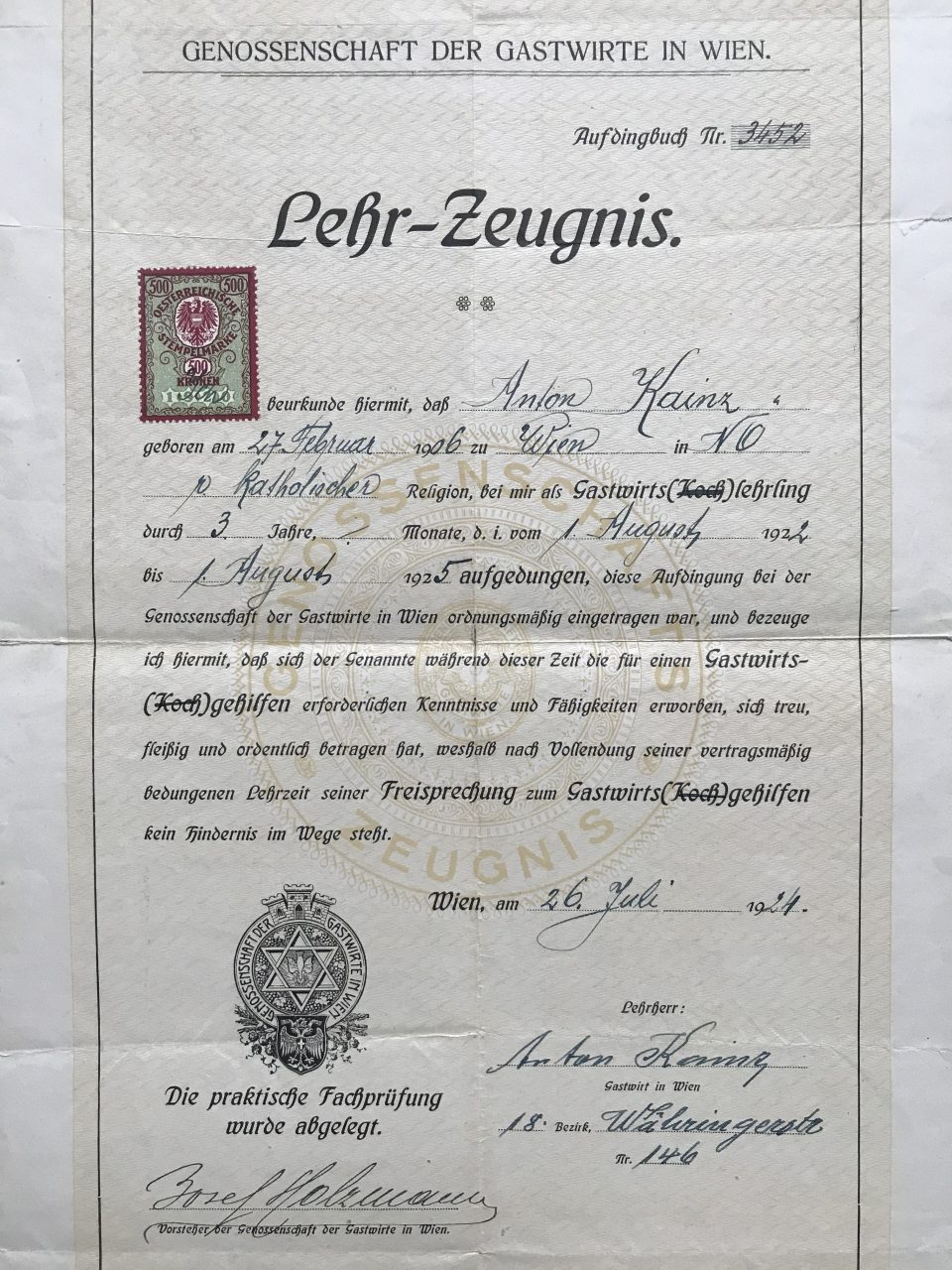

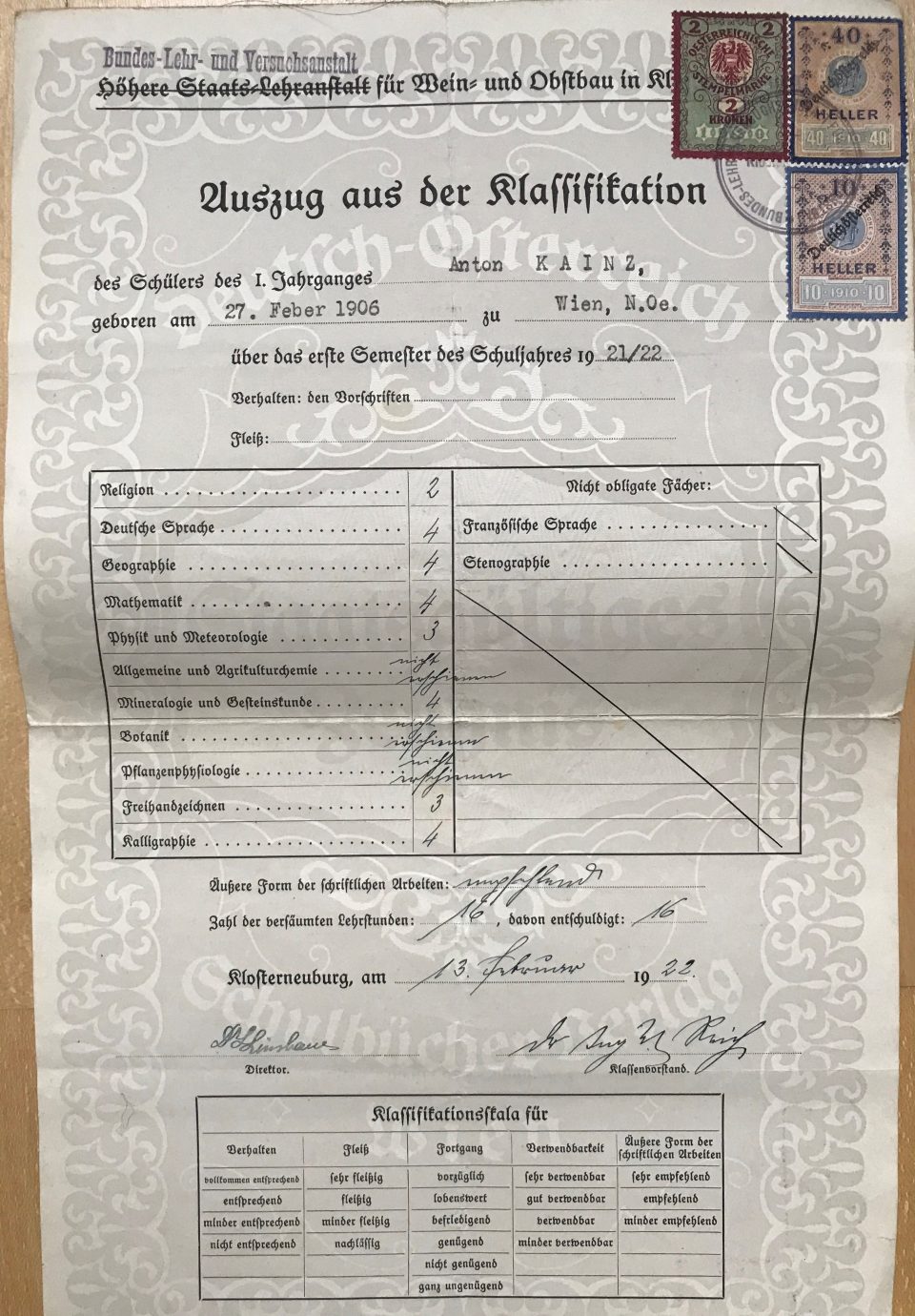

Toni completed his apprenticeship as cook and waiter in the inn of his father after a not very successful school career, as can be seen in the report card of the first semester of 1921/22 of the vocational college for wine and fruit production in Klosterneuburg near Vienna:

Two years later Toni successfully completed the vocational college for “Inns, Hotels and Coffeehouses” in Vienna and the apprenticeship at his father’s inn in 1924 and was thereby qualified to work as an assistant in the catering business:

Toni’s professional certificate issued by the Cooperative of Viennese innkeepers 1924

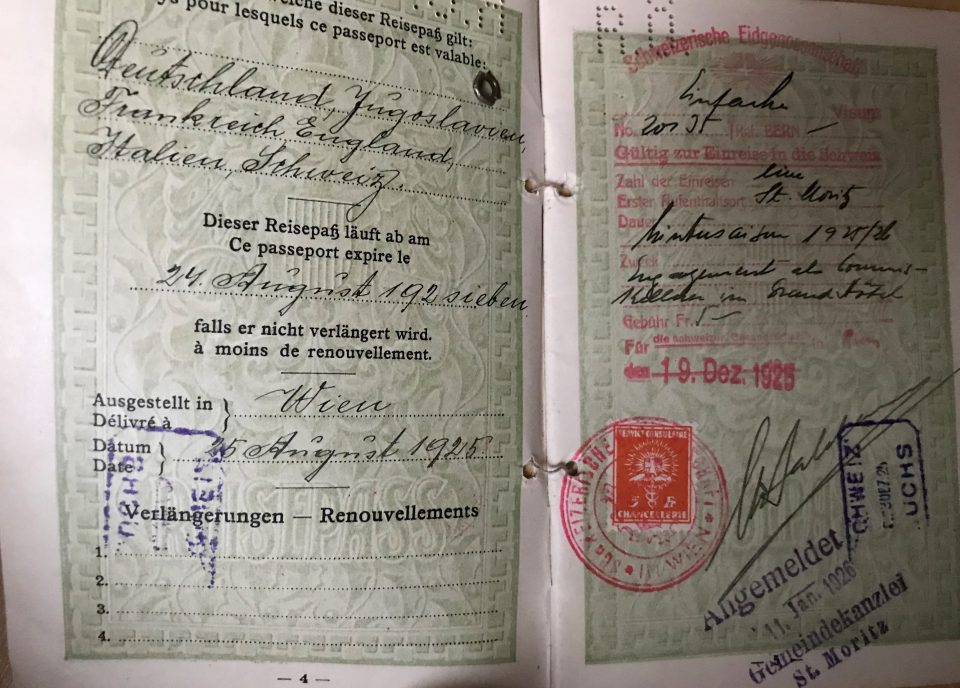

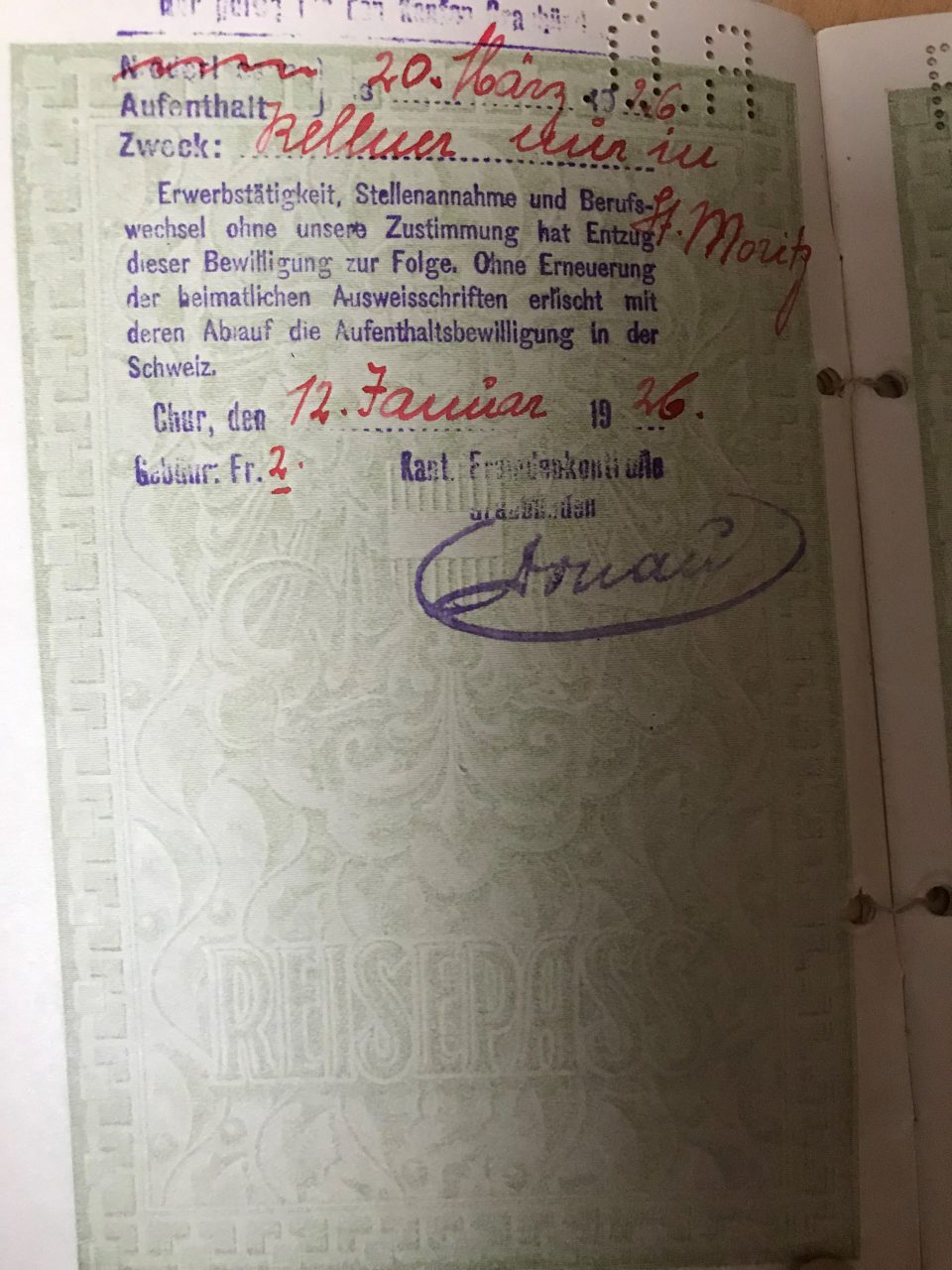

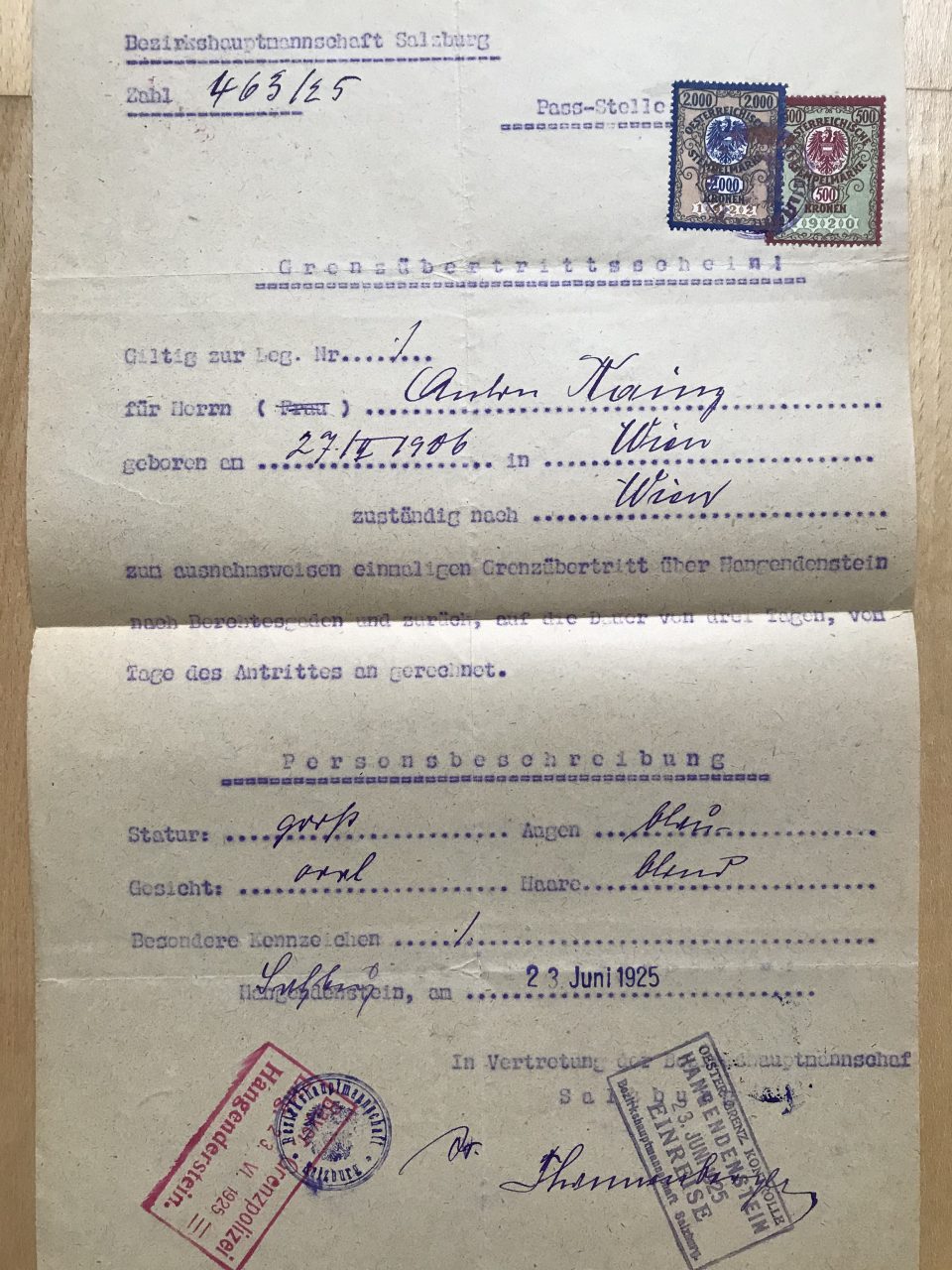

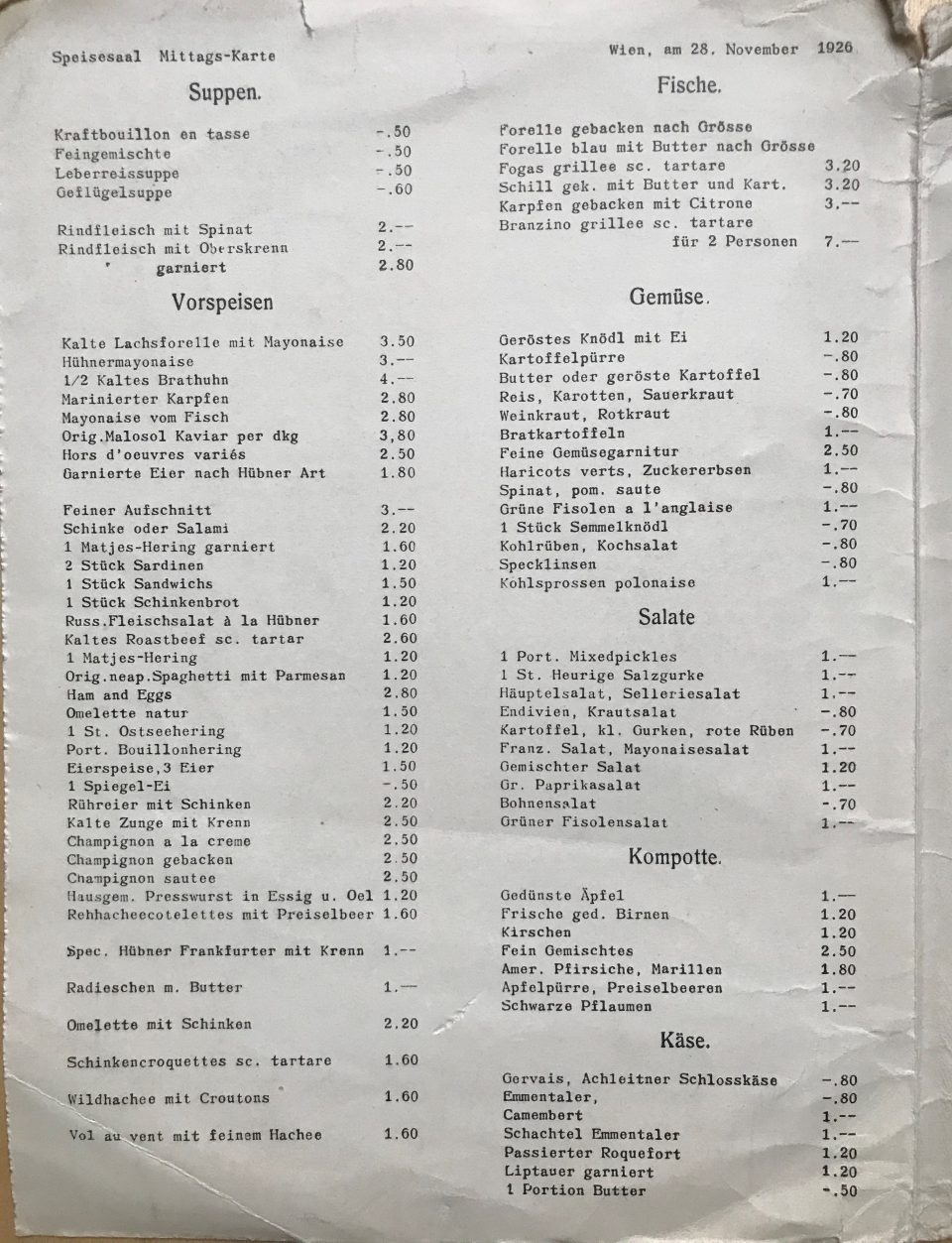

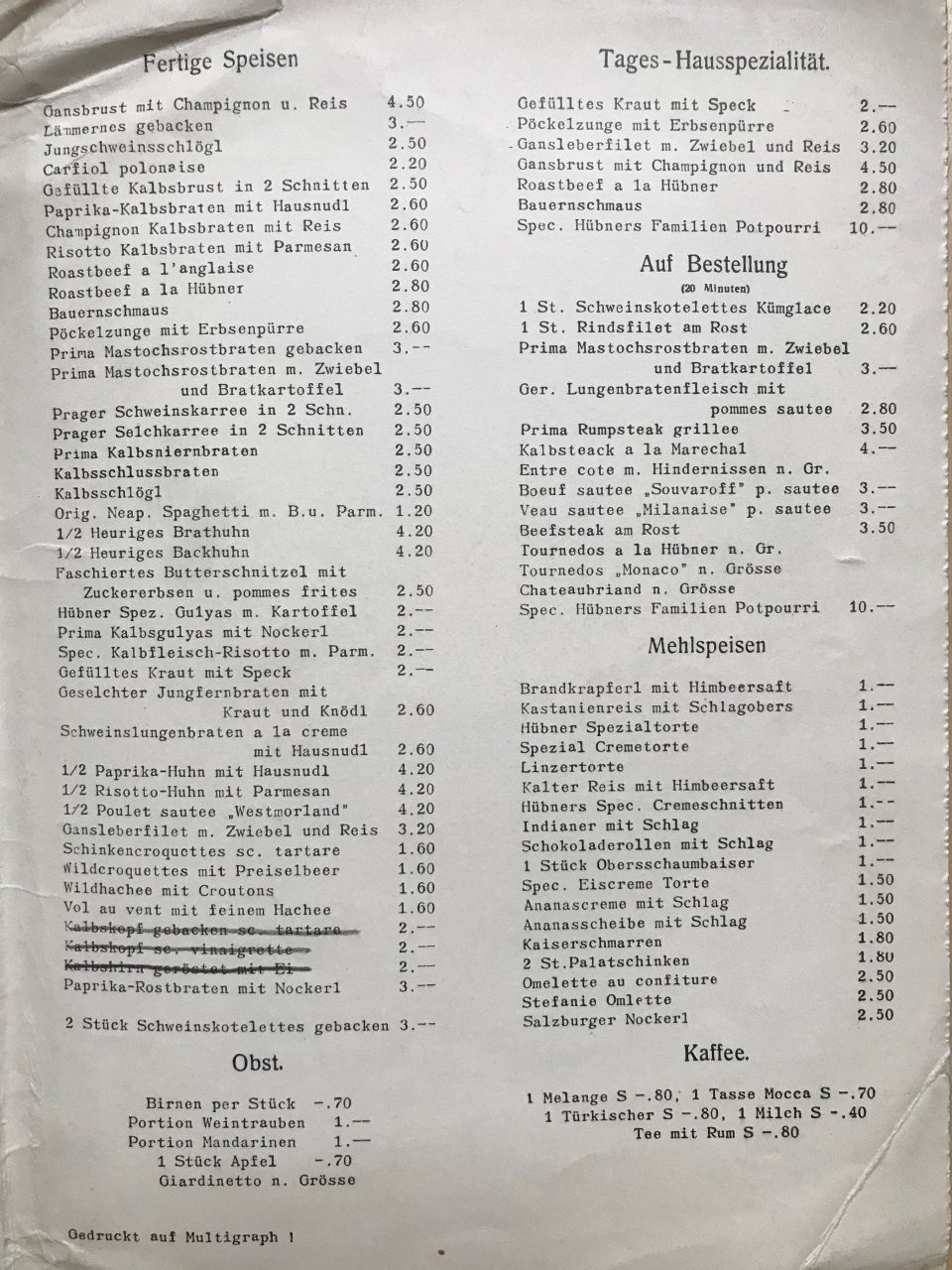

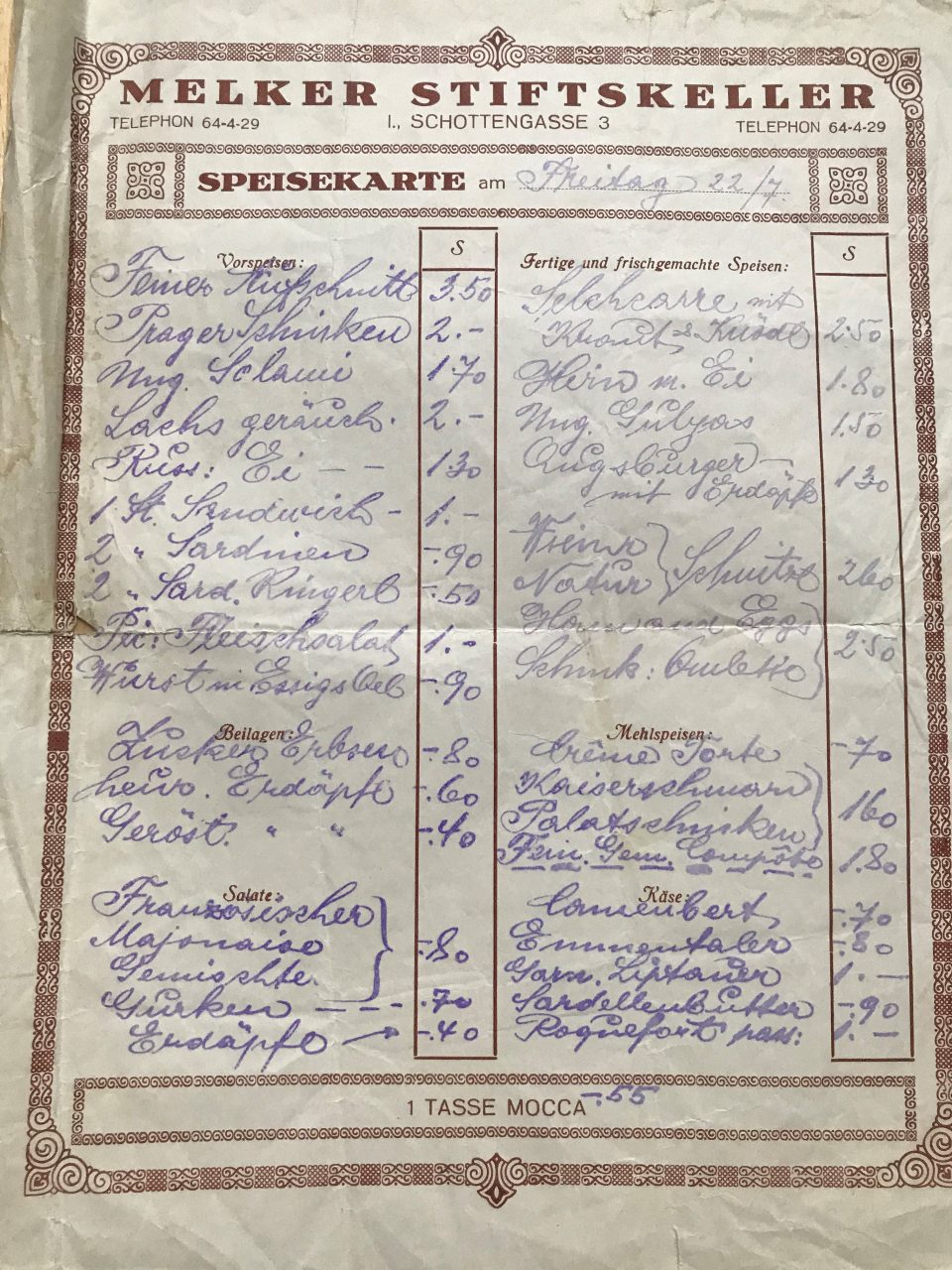

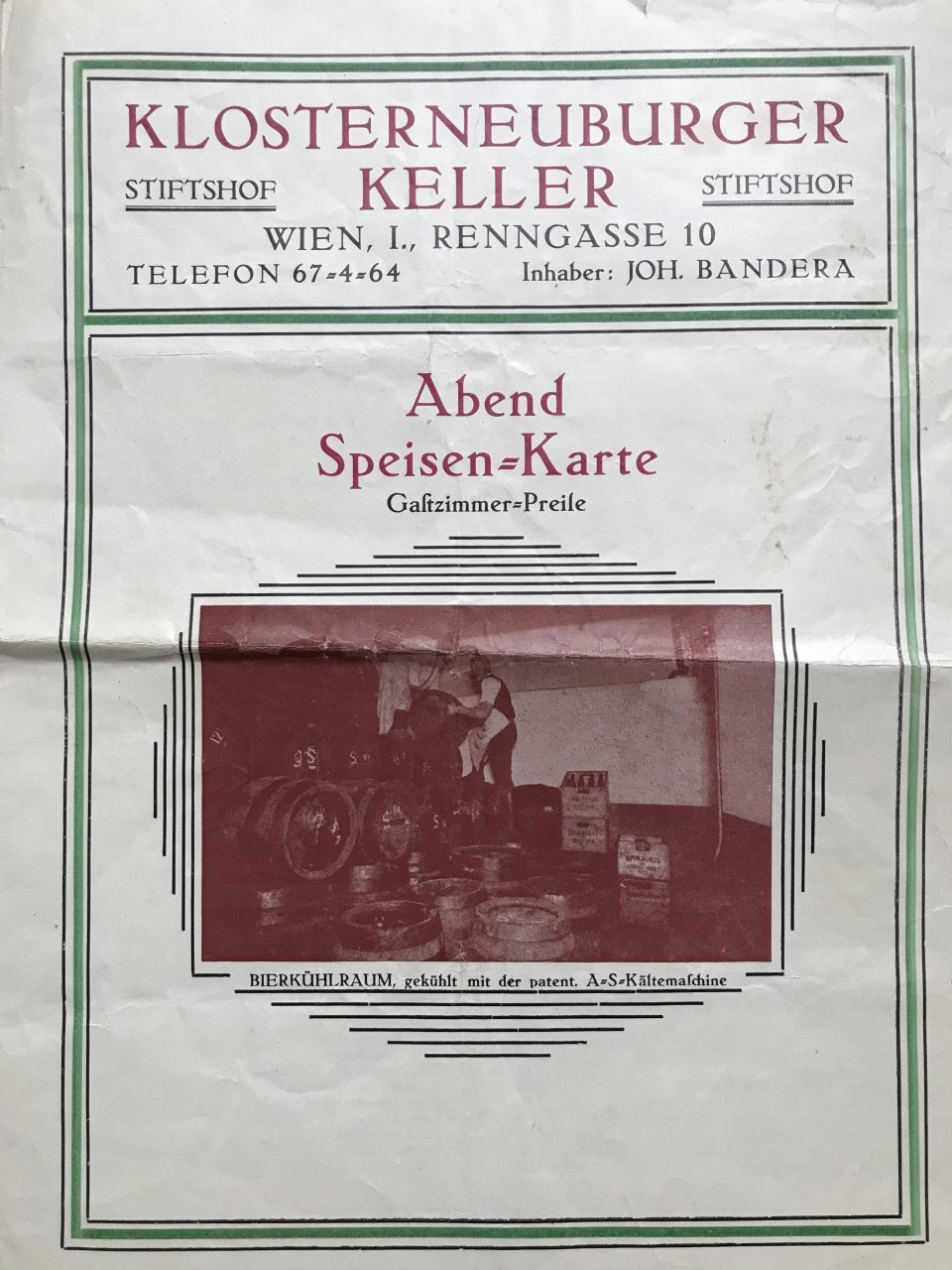

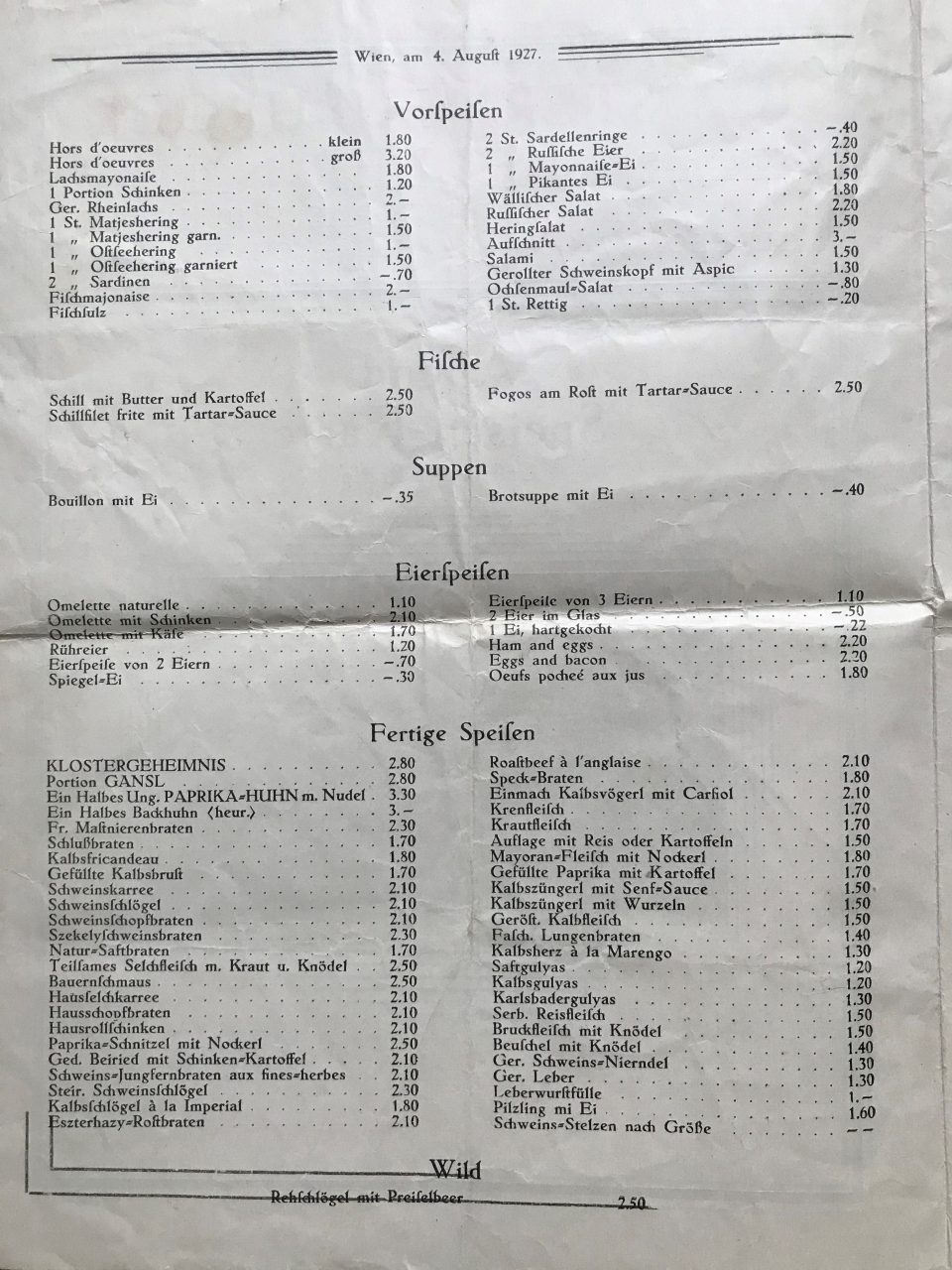

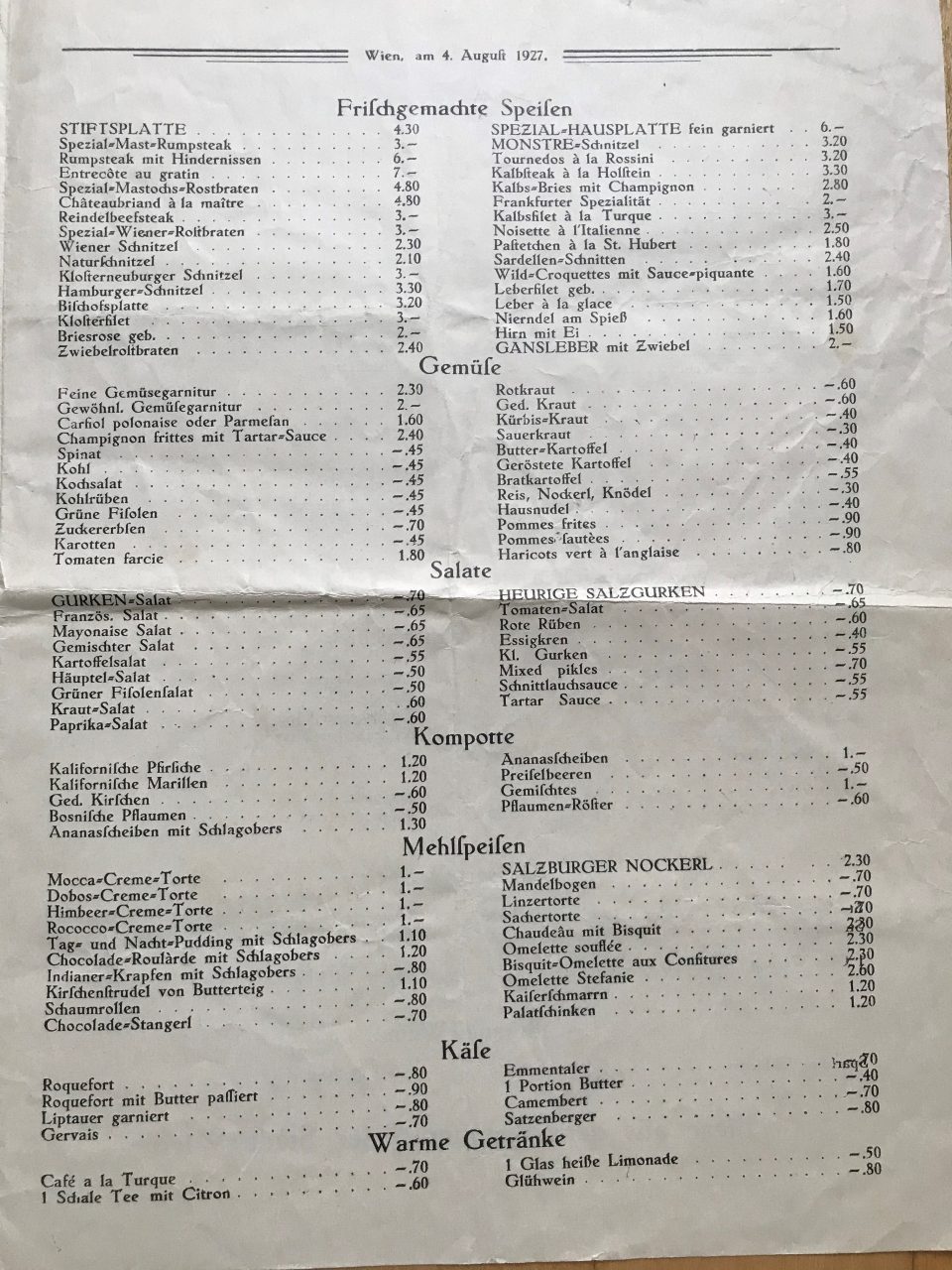

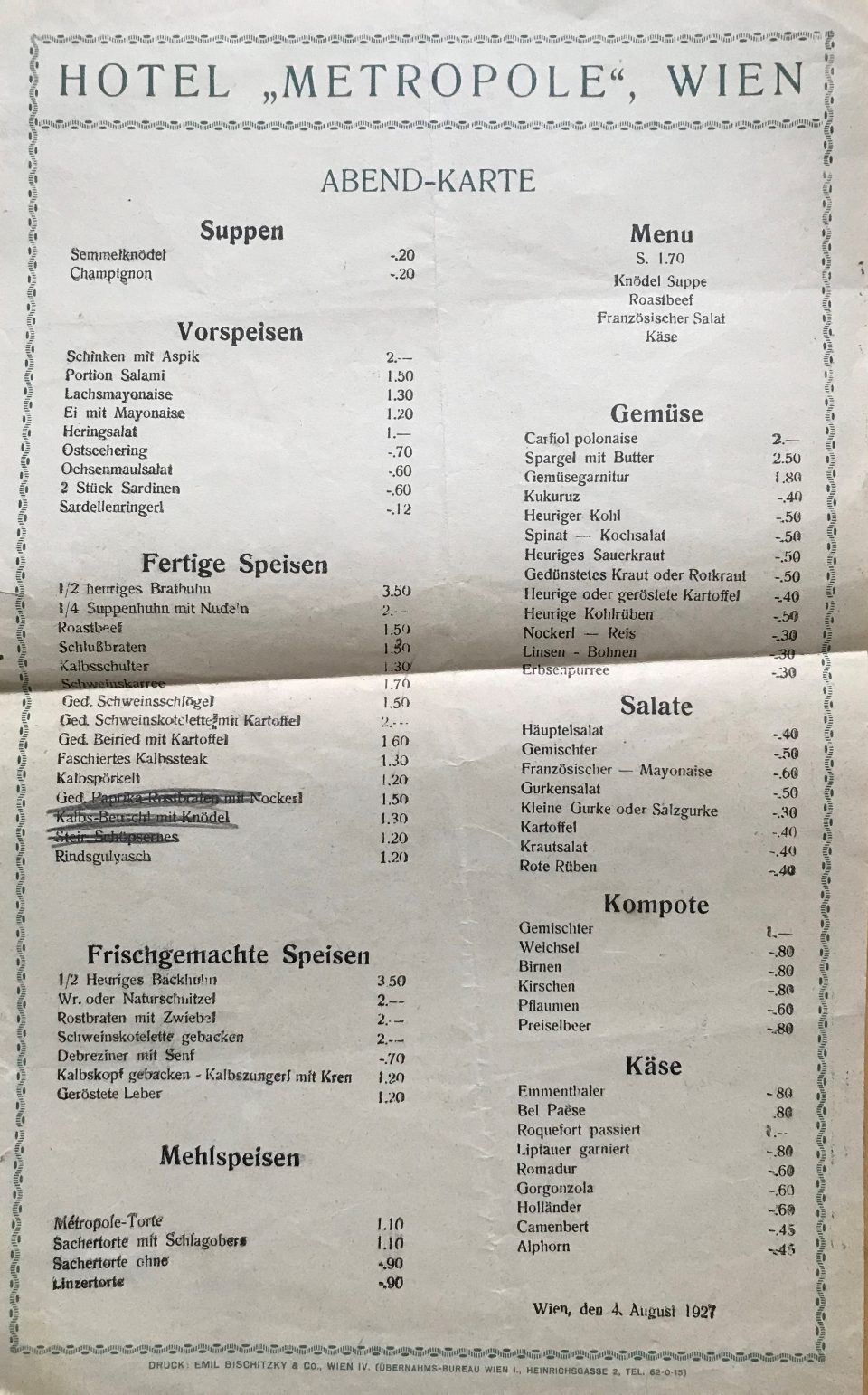

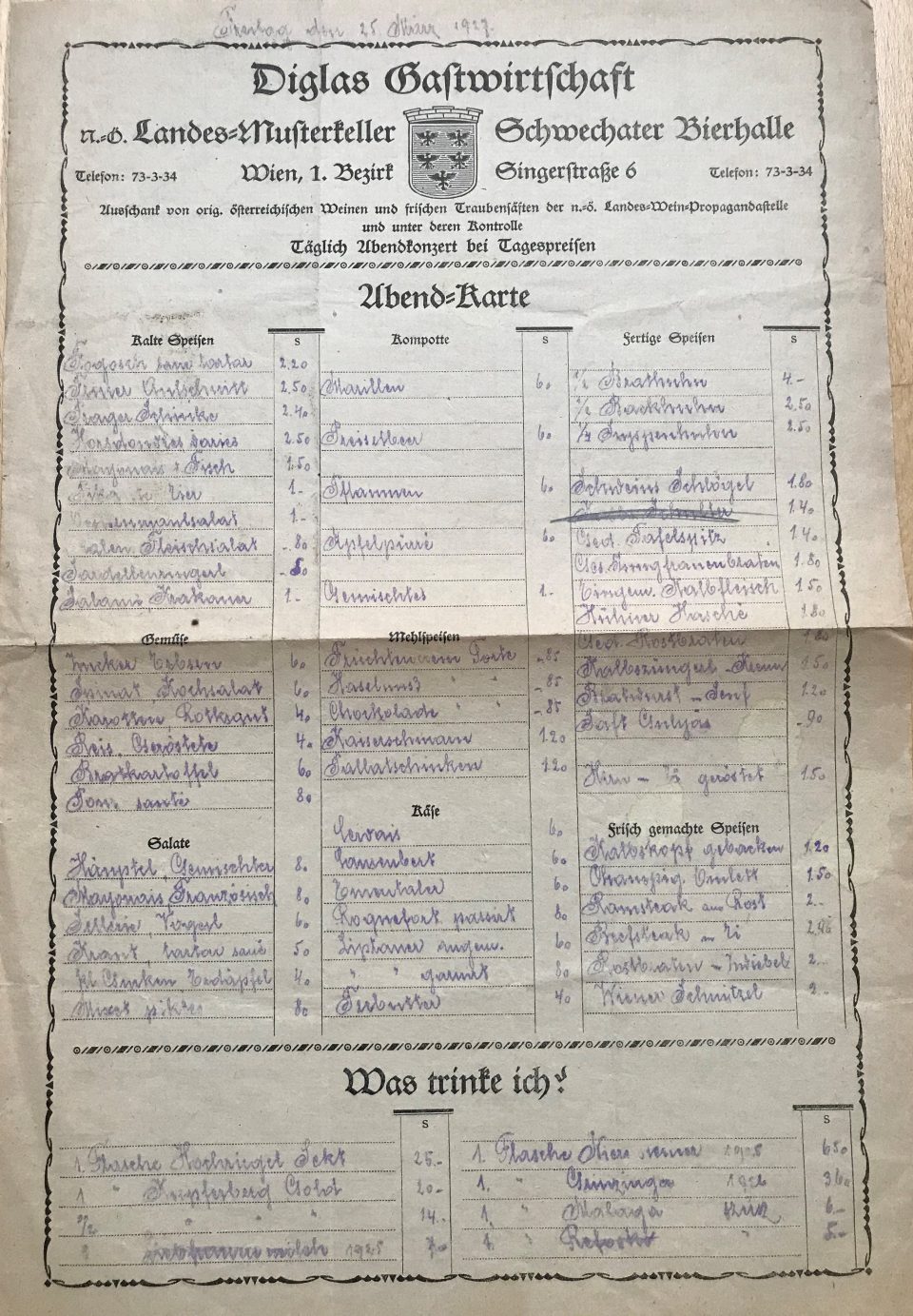

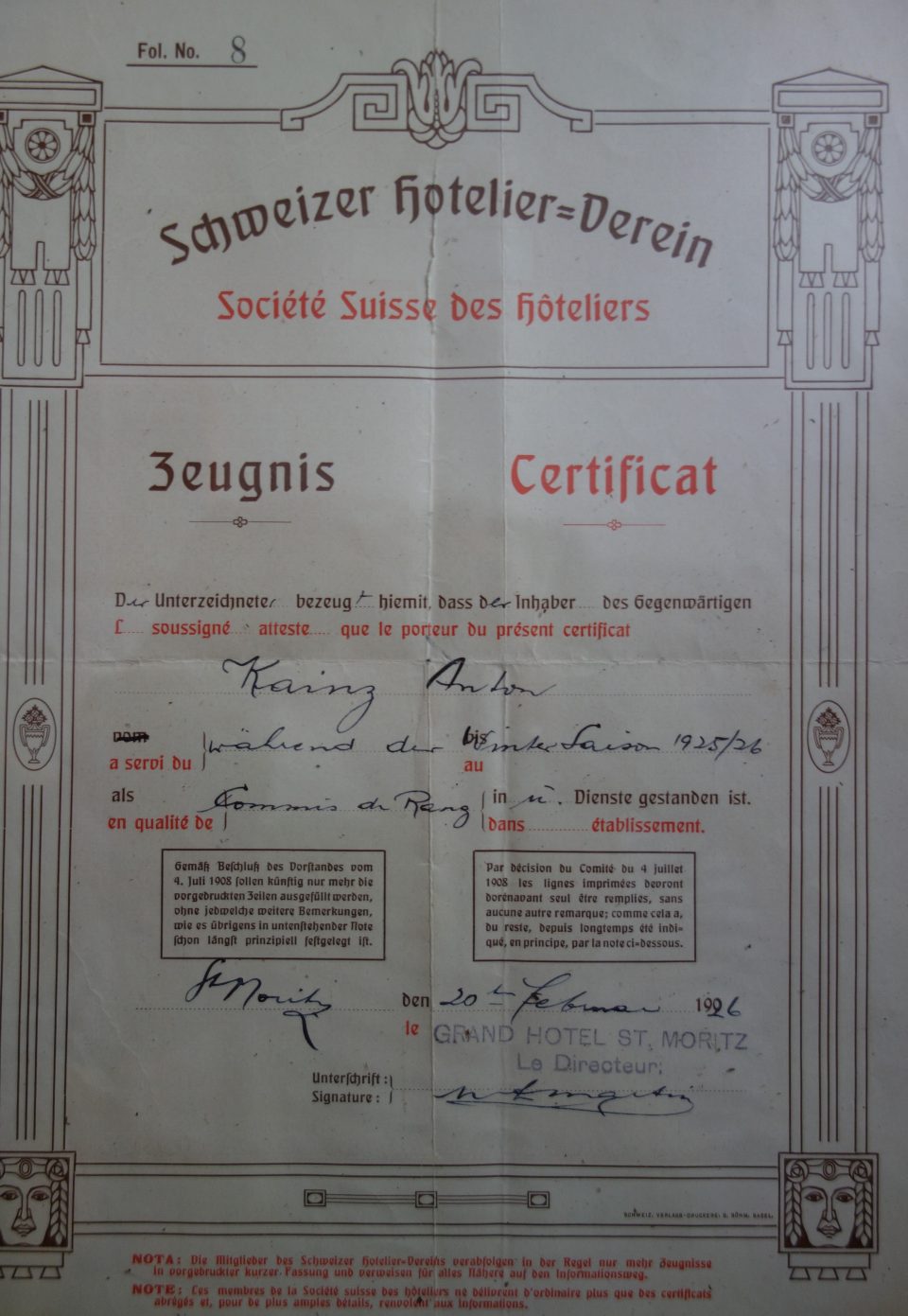

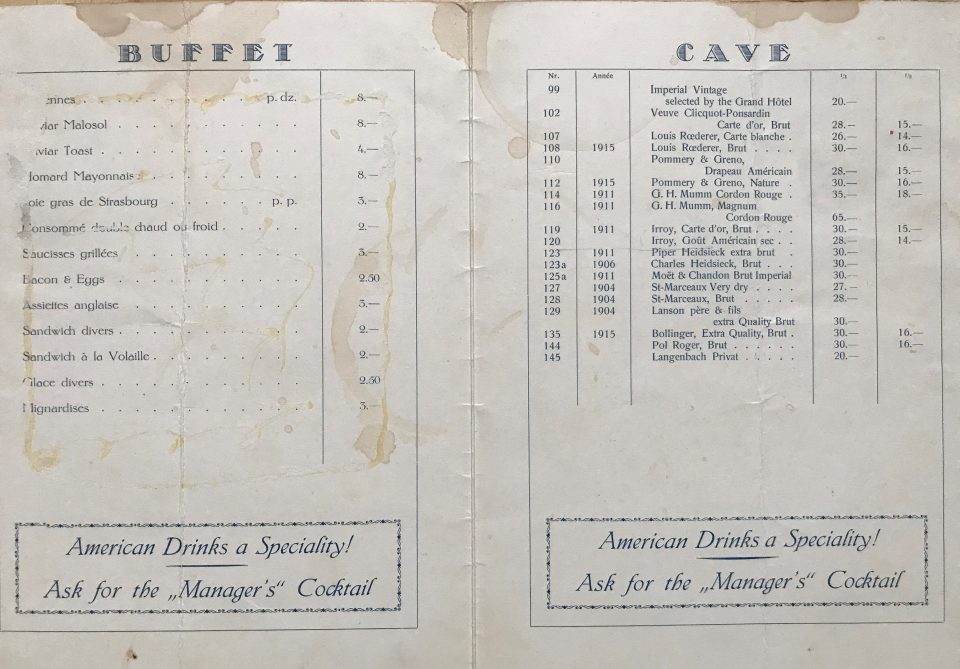

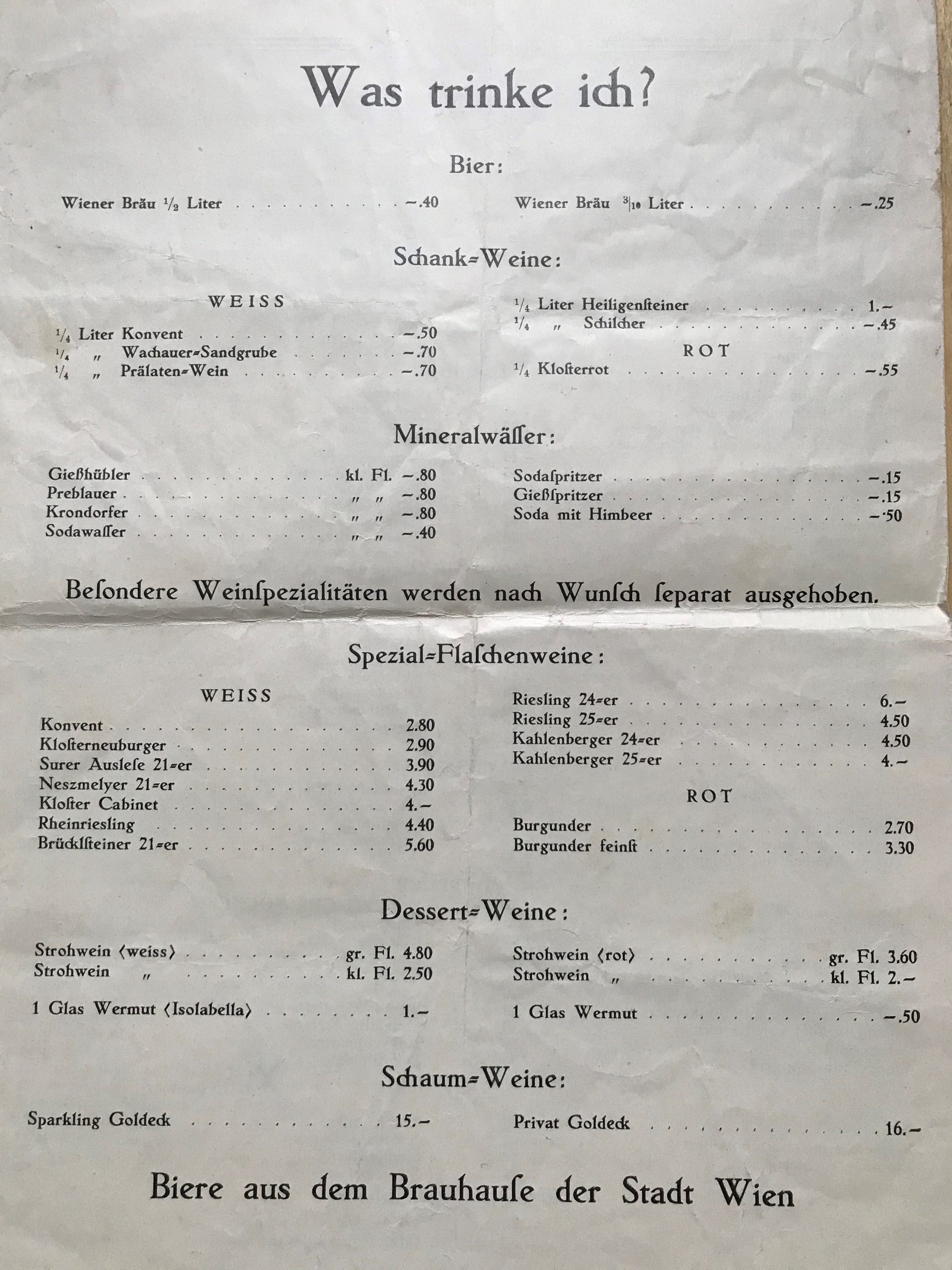

Immediately afterwards Toni left Vienna in order to gain experience as a waiter and cook on the “Walz” (the tradition of travelling artisans who had completed their apprenticeship, widespread in the Austro-Hungarian Empire since the Middle Ages and still practised in the first half of the 20th century). His enthusiasm for the hotel and catering business in the chic resorts of the well-to-do of Central Europe is visible in his collection of menu cards of the places where he worked in the 1920s.

Toni’s passport of 1925 with the permission to enter Switzerland in order to work in St. Moritz as a waiter in the Grand Hotel

Toni’s permission to pass the border from Salzburg to Berchtesgaden to work there in June 1925

Toni’s certificate of work in St. Moritz in 1925/26

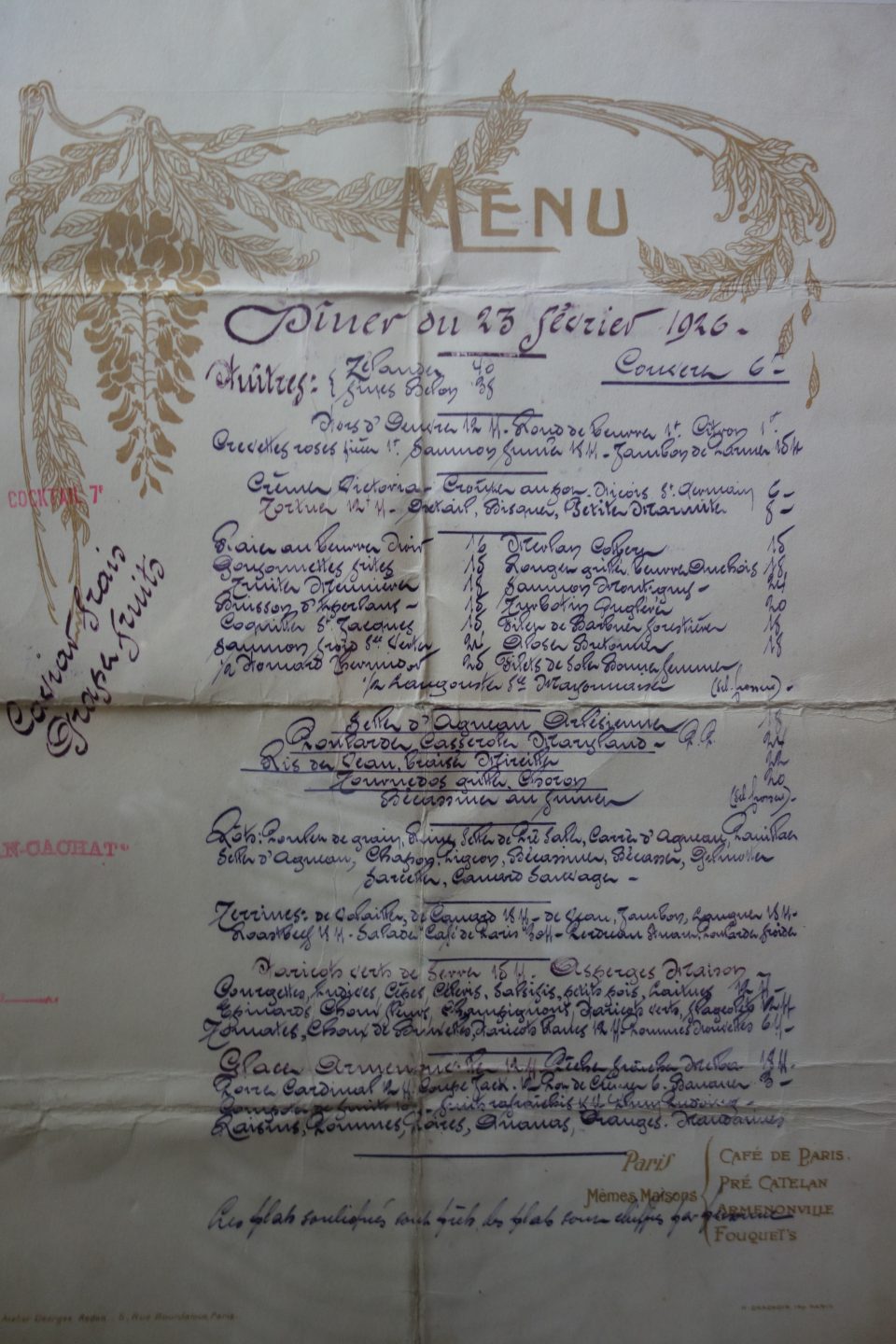

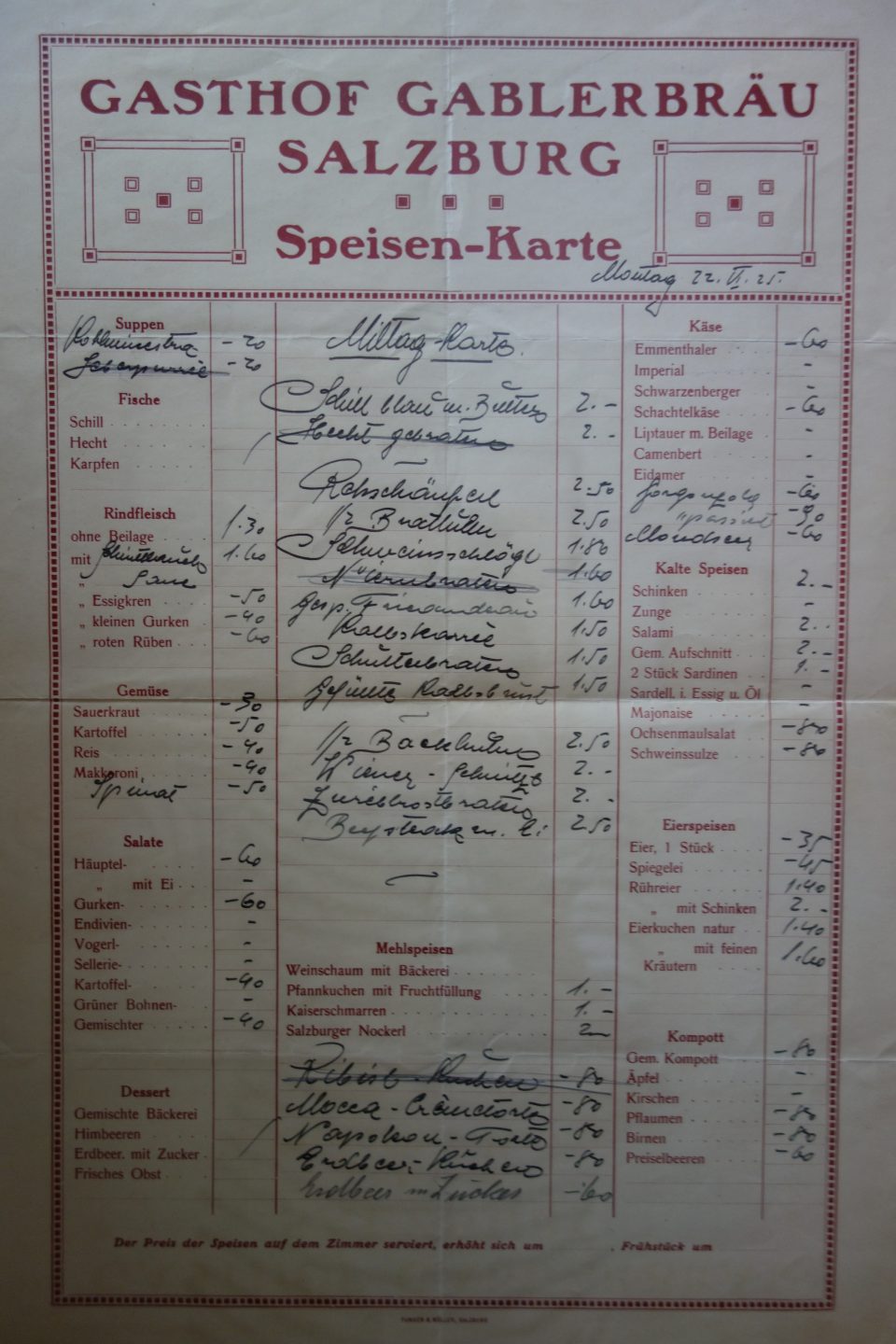

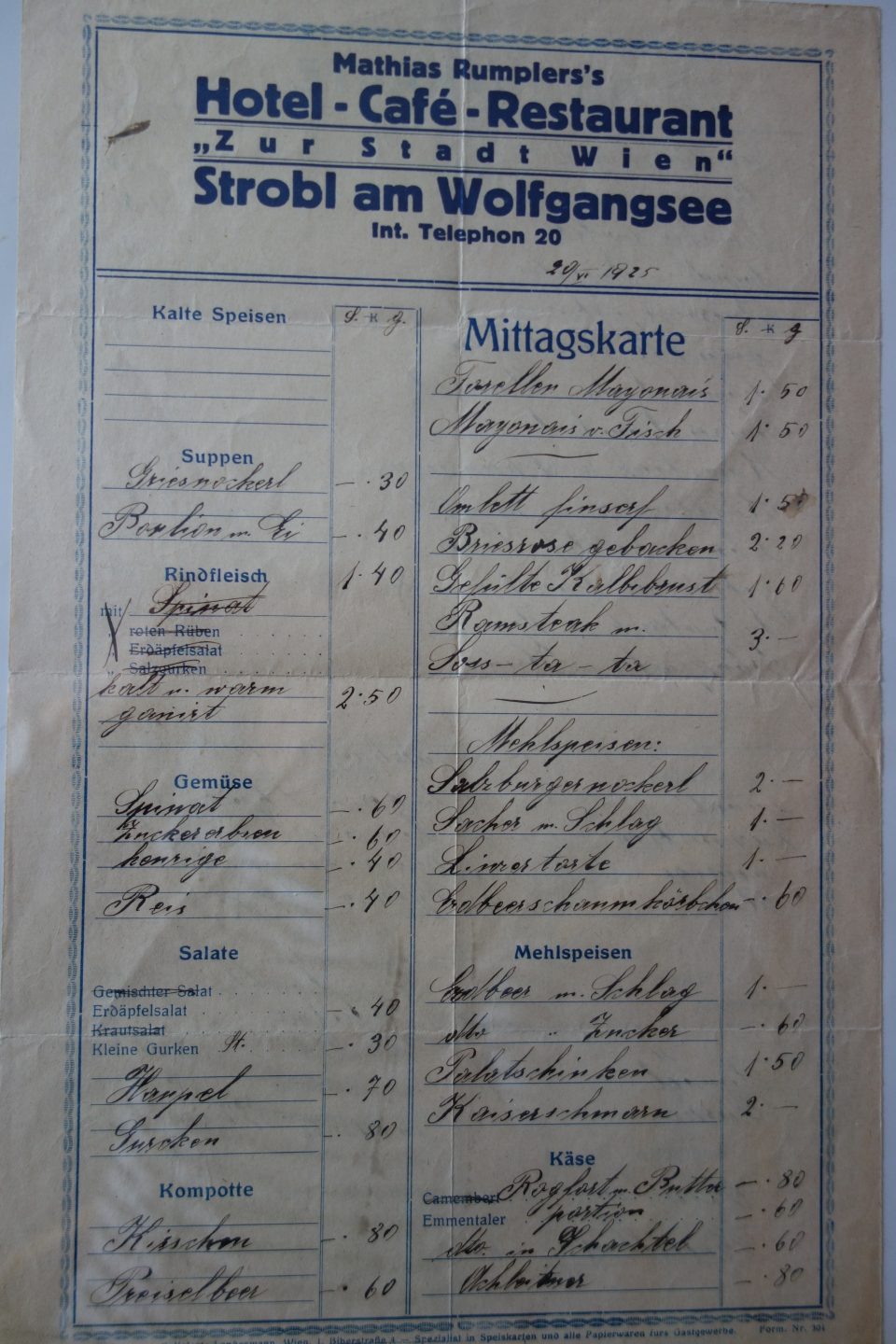

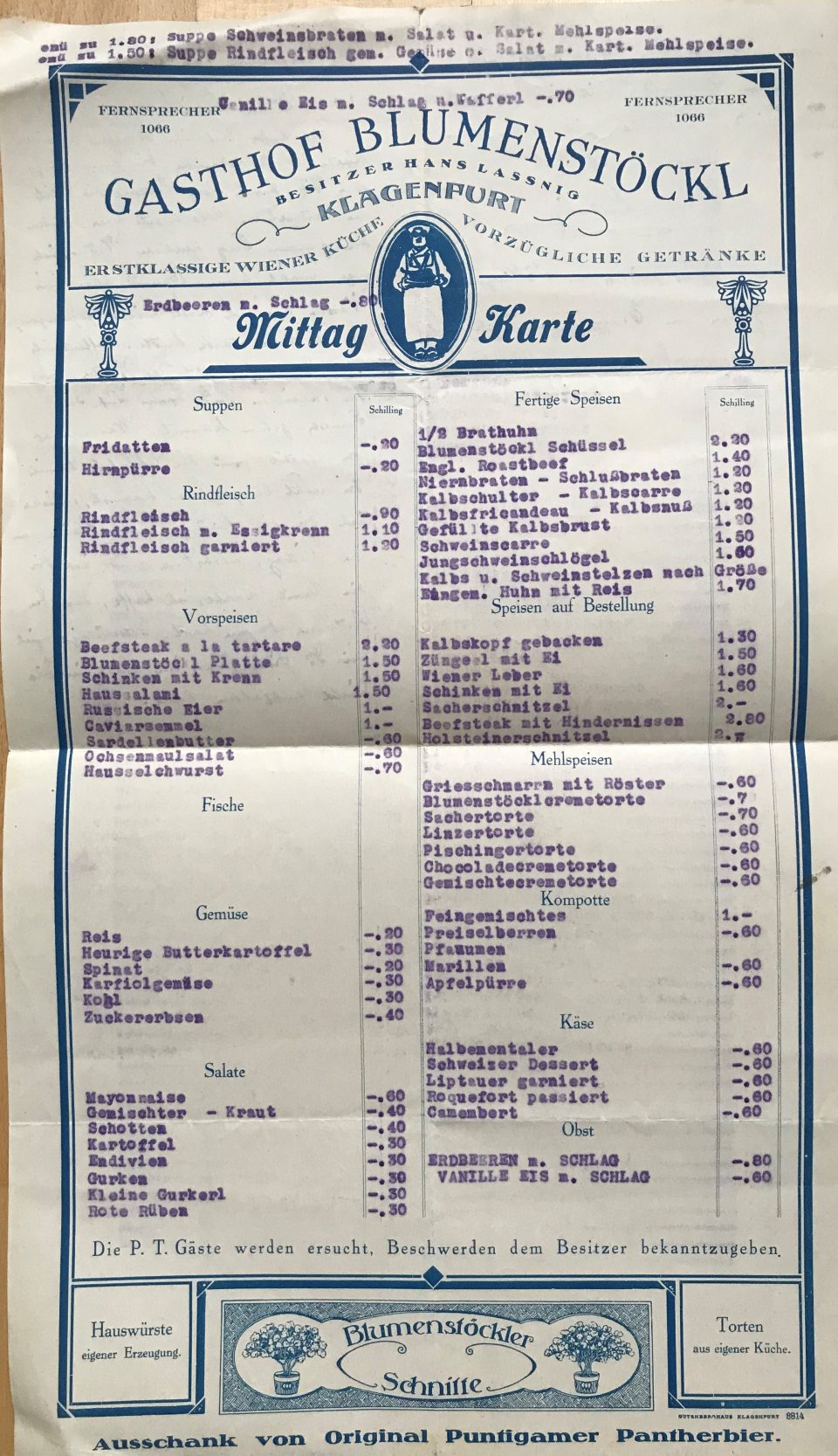

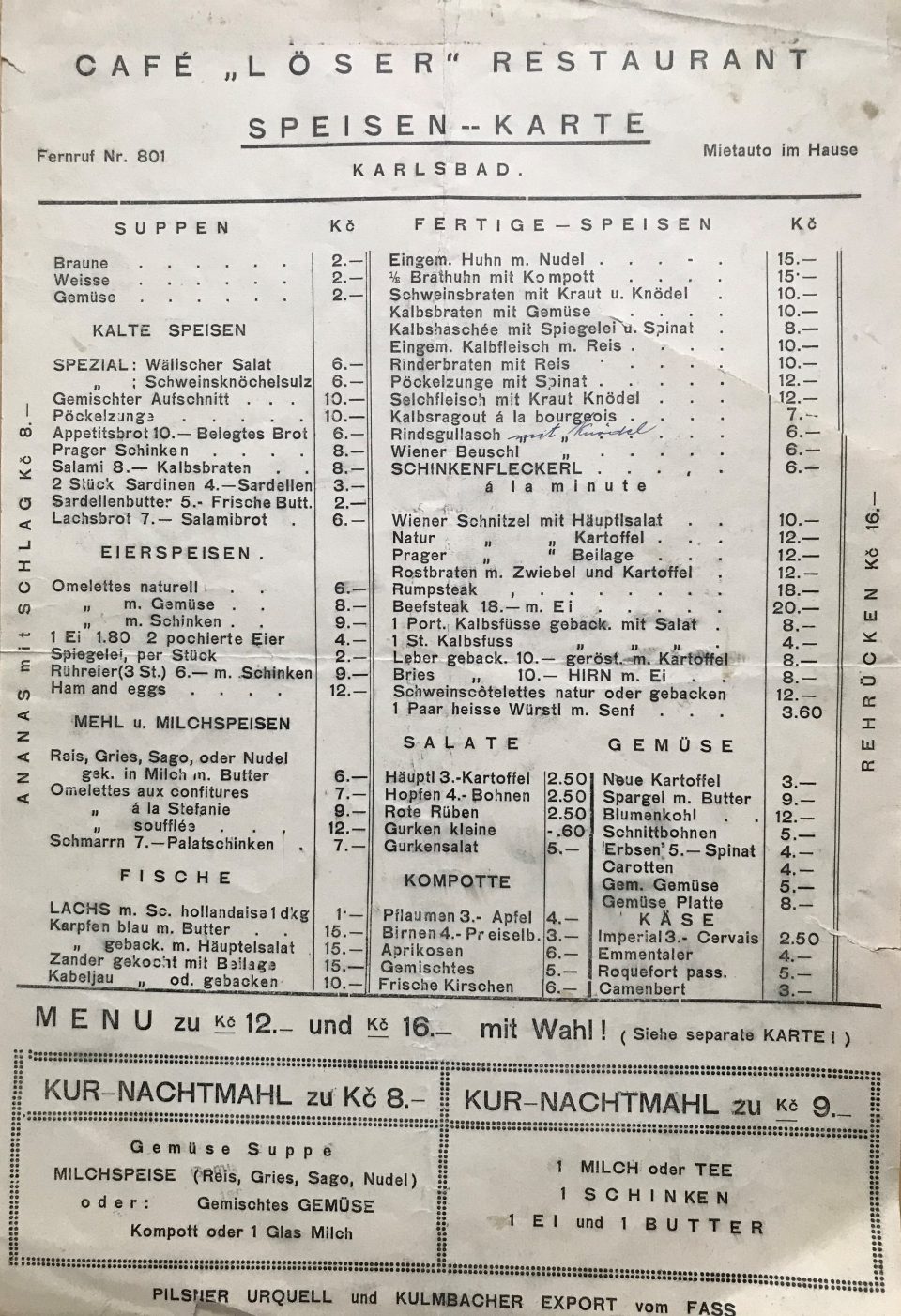

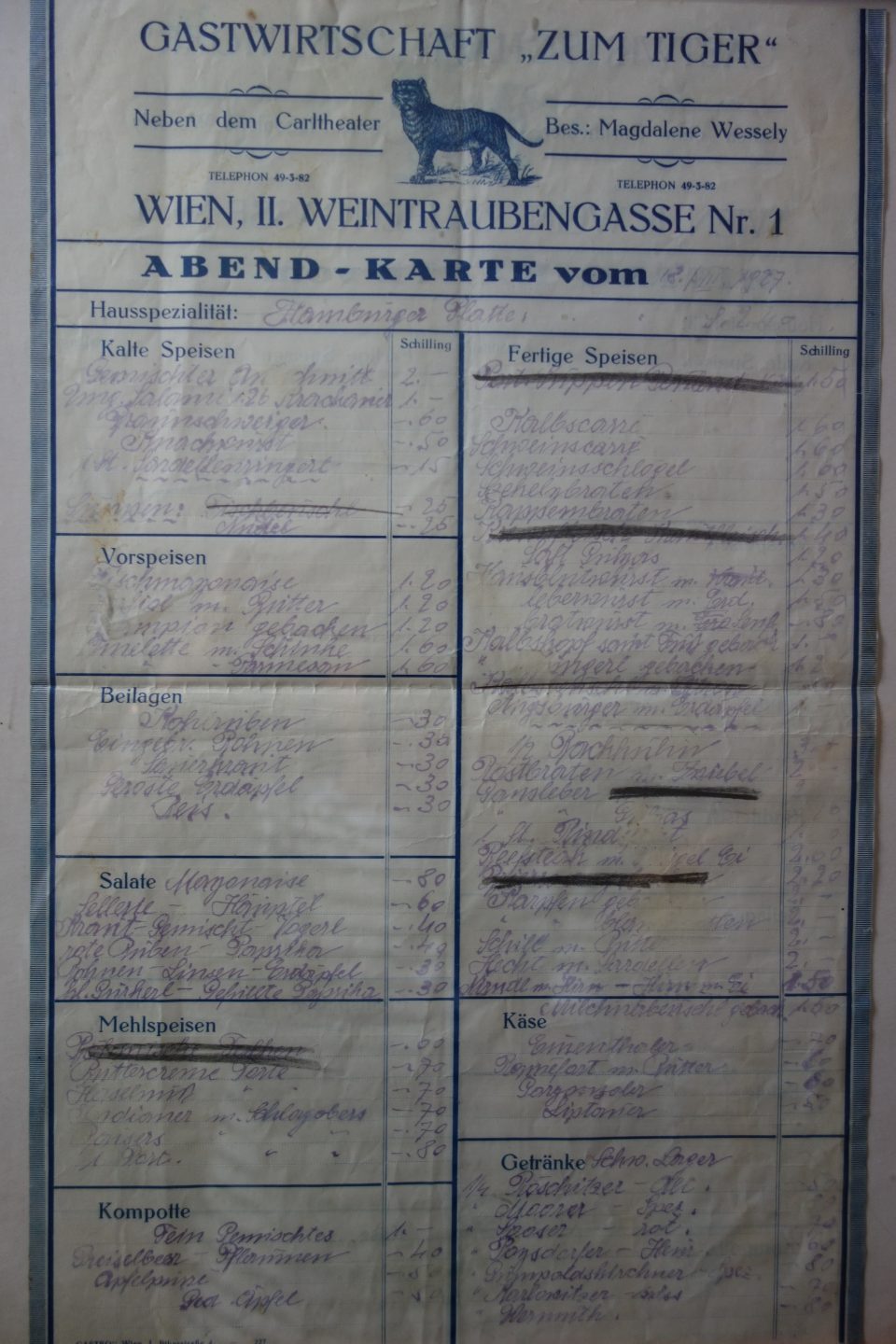

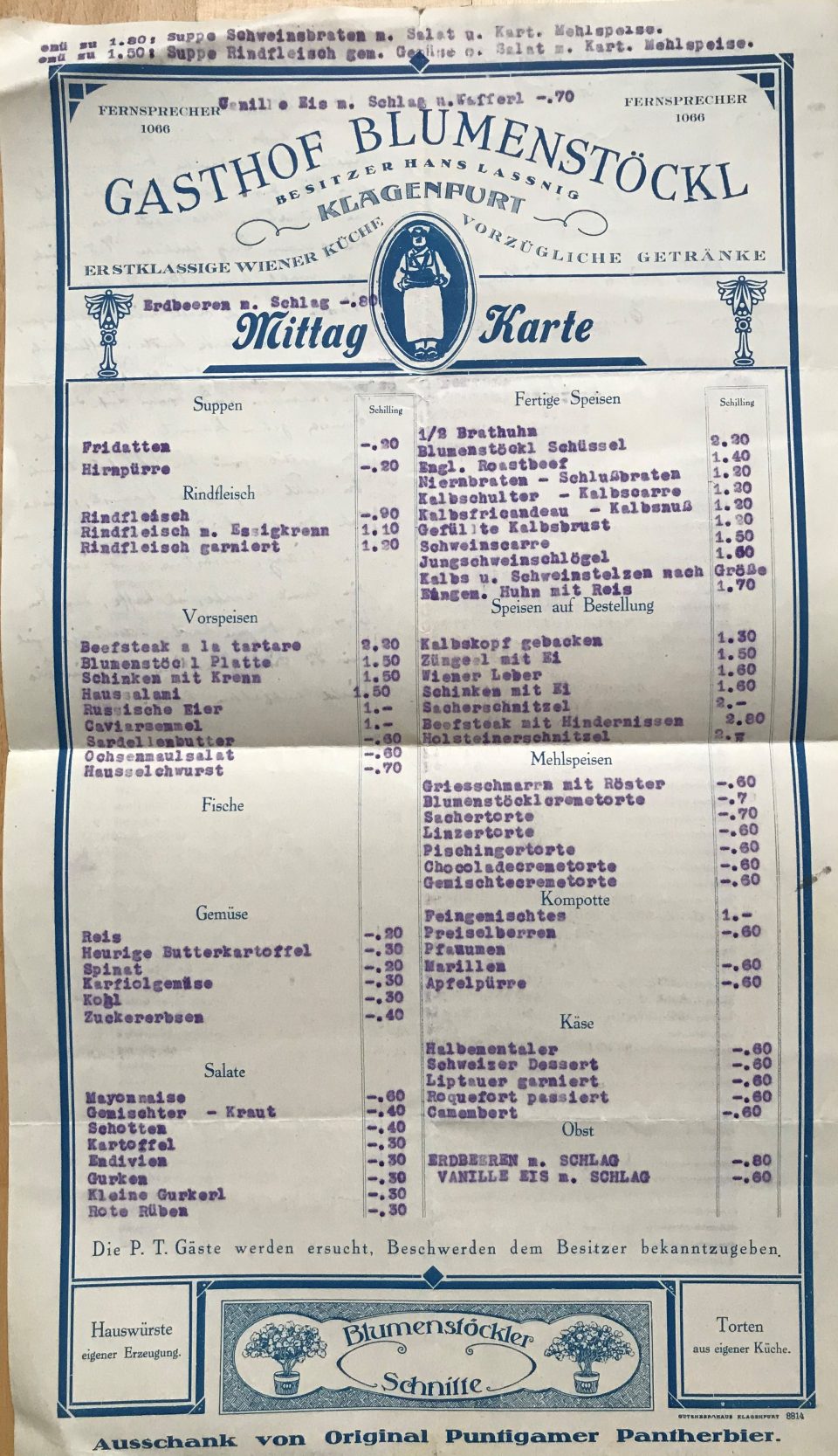

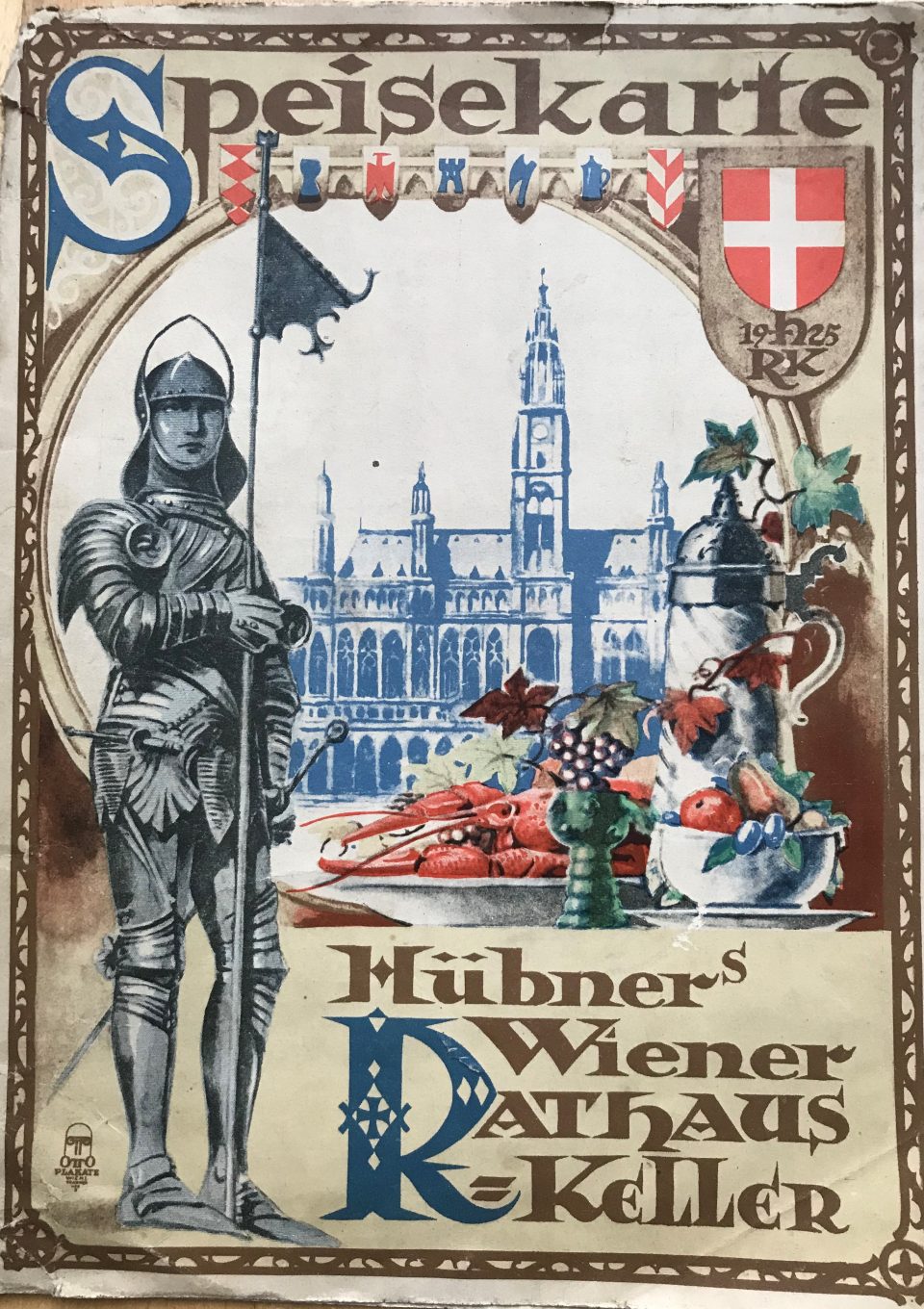

Toni’s collection of menu cards acquired during his “Walz”:

Hotel & Café “Zur Stadt Wien”, Strobl am Wolfgangsee, Austria 1925 & Inn “Blumenstöckl”, Klagenfurt, Austria 1927

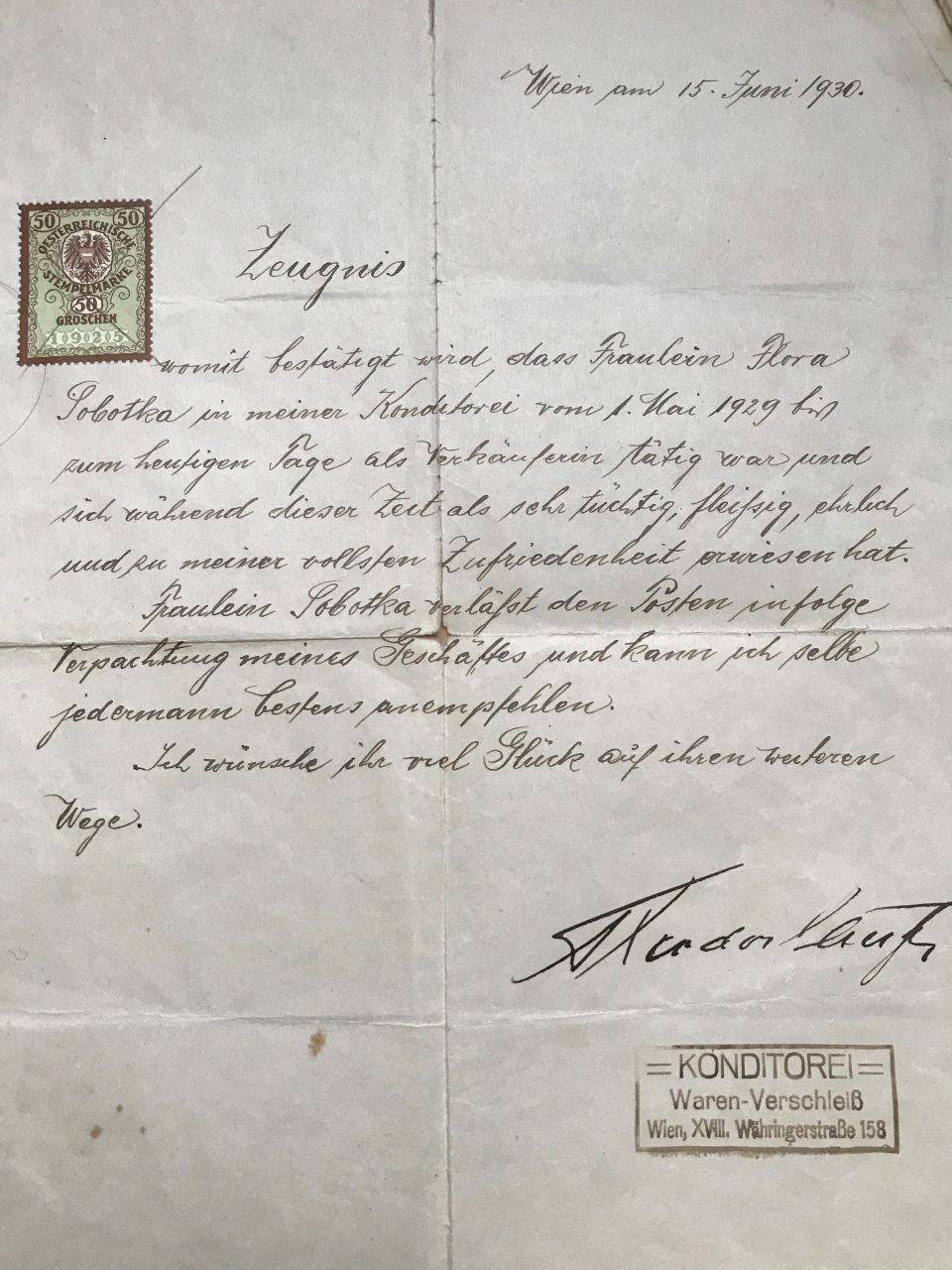

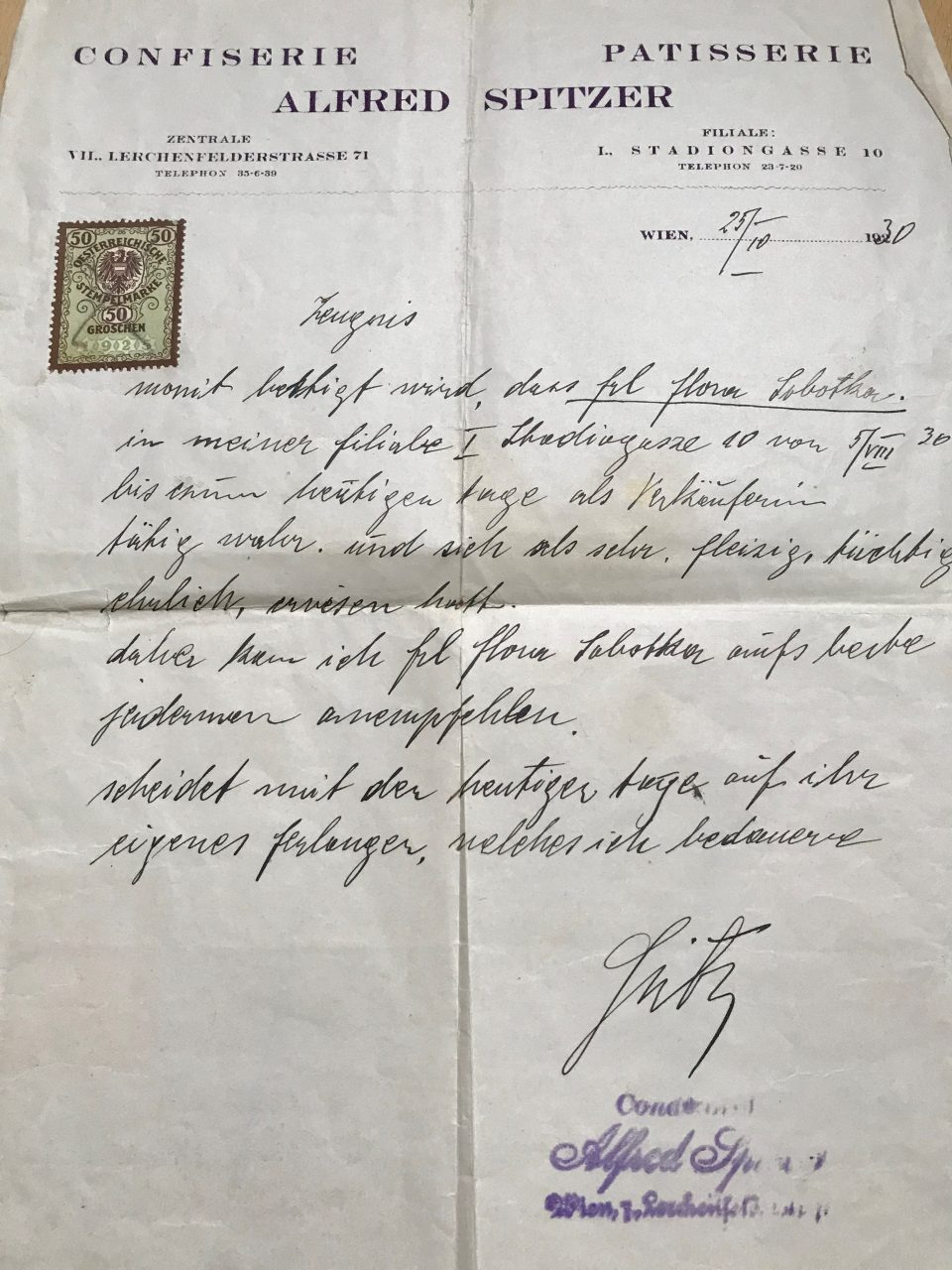

The training of my grandmother, Flora Sobotka, called Lola, for the catering business was much less professional. She worked as a shop girl in a confectionary shop before her marriage, where Toni got to know her and regularly bought sweets he didn’t even like, just to see her. From 1 May 1929 until 15 June 1930 she worked in a confectionary shop in Währingerstrasse 158, close to the inn and afterwards in Alfred Spitzer’s confectionary and patisserie in the 1st district in Stadiongasse 10.

The Viennese suburban inns have been an important point of encounter in the city for centuries and form part of a special myth as well. To tourists they are much less well-known than the Viennese coffeehouses and the “Heurigen”, where the new wine is sold, but the Viennese suburban inns have been an unglamorous social microcosm of everyday life in the city for hundreds of years and are the embodiment of everyday culture of the “little people” between stand-up bar and separate guest room. The personality of the innkeeper and/or his wife is of prime importance; their presence in the inn is required and taken for granted. The regulars order the same drink and the same meal at every visit and this tenacity and resistance against international trends is a characteristic of the Viennese suburban inn. The term “Beisl” was the derogatory term for a suburban inn for the poor, where they could drink wine, beer or spirits standing at the bar and talk politics and, most of all, grumble – a Viennese tradition. The word is derived from the Yiddish term “Baiz” and was originally used contemptuously to describe the suburban inns of the underclass. The number of such inns skyrocketed in the course of the 19th century together with the fast increase of the working class in the city, which lived under abysmal conditions. They usually had the means to rent a bed for a few hours only and had no access to kitchen facilities or heating in winter. That’s why in their scarce spare time they went to the inn to drink alcohol, eat a cheap meal and get warm in winter. In the outer suburbs of Vienna (the outer suburbs were the villages outside the “Linienwall” – the outer line of defence of the city -, today’s “Gürtel” and the inner suburbs were located outside the city walls , today’s “Ringstrasse”) one could find on street crossings up to three inns of that type. In this way these inns became the “living room” of the poorer Viennese, where they found a home and an outlet for their daily hardship, exhaustion and pent-up anger. Here they could plan strikes, organise workers’ clubs and ethnic clubs of the many immigrant nations of the Habsburg Empire, as for example Czech workers’ clubs. Furthermore there were wine, beer and liquor houses in the Viennese suburbs, but also large more sophisticated inns for the bourgeoisie that offered traditional Viennese food and stop-over inns which were located at the many roads leading into the city centre, mostly at toll booths and customs checkpoints. They offered food, drinks and a bed for the coachmen and a stable for the horses, as for instance the still existing inn at the customs barrier at the “Linienwall” in Lerchenfeld.

“Gasthaus Sittl” at the crossing Neulerchenfelderstrasse /Lerchenfeldergürtel (the garden was the former yard, the sign “The Golden Pelican”).

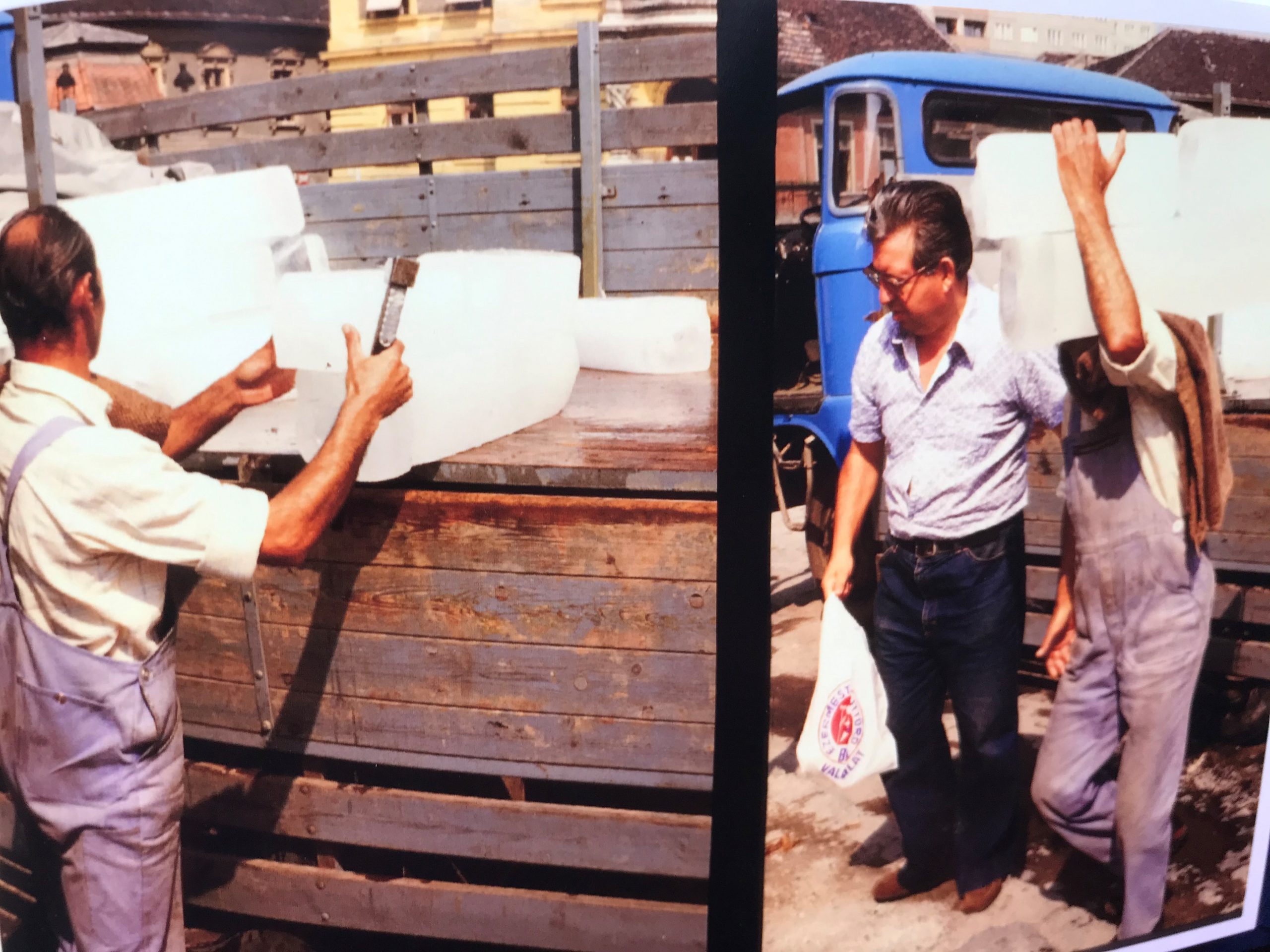

The furnishing and typical equipment of a Viennese suburban inn consisted of a wooden stand-up bar with a metal surface and sink for cooling the two-litre wine bottles in running water and the wooden refrigerating boxes built into the wall behind. The refrigerating boxes were equipped with heavy wooden doors and filled with blocks of ice which were cut from frozen lakes and the mountain glaciers in winter, stored in deep cellars and delivered the whole year round to the inns and private households from the late 19th century onwards. Only in the second half of the 20th century electric refrigerators replaced the blocks of ice.

A second characteristic element was the wooden panelling. This was supposed to create an aura of cosiness and to cover up the shabbiness of the suburban inns. The advantage of this type of furnishing was that it lasted more or less eternally; the coats of the guests which were hung up on hooks fixed to the panelling were not dirtied by whitewash and the panelling symbolically offered “protection from the dangers of the harsh outside world” like a fence.

Lola in the white apron on the right in the “Anton Kainz” inn with regulars – the typical wood panelling with the hooks can be seen in the background

Toni carved the traditional wood panelling himself for my grandparent’s kitchen at Lerchenfeldergürtel 45

Every inn also had a partition element, usually made of wood and glass, which divided the separate guest room from the bar room, where the guests were drinking beer, wine or spirits standing at the bar or sitting on benches opposite. In the separate guest room, the guests were served meals and drinks. Simple wooden tables were in the early 20th century covered with chequered table cloths in red and white; later a characteristic of a suburban inn. The blackboard with the daily menu, usually just a variation of the Viennese dishes served every day, was placed outside, while the blackboard listing the offered wines was usually fixed on a wall inside the inn. The typical glasses were bulbous half-litre glasses with a handle for beer and small wine glasses with a decoration of grapes and wine leaves. These were introduced as soon as industrialisation reduced the cost of glass production; in earlier times wooden, ceramic or tin mugs were used.

A symbol of the slightly increasing wealth of the population of the suburbs was expressed by the free offer of salt, pepper and sauces on every table, especially the well-known and much loved brand “Maggi” used for seasoning soups and practically everything else – “the guest joins in the cooking”!

What made an inn a typical suburban Viennese inn was the innkeeper. The characteristic atmosphere was created by the presence of the innkeeper, no matter how decrepit the inn itself looked. That might be the reason why all attempts at replacing these inns by restaurant chains failed in Vienna. In Vienna the female innkeepers, of which Emilie Kainz, my great-grandmother, was a prominent example were seen as a local curiosity. They were famous for being very strict and grumpy and for showing guests they did not like the door. In a famous anecdote the former Austrian chancellor, Franz Vranitzky, was refused entrance to the “Gmoakeller”, where the Austrian actress Erika Pluhar celebrated her birthday, and only after some coaxing one of the “Novak sisters” allowed him to join the party in their inn.

Kitchens and stoves were rather primitive in Vienna and fired with wood, but when wood prices rose dramatically in the course of the 18th century, the introduction of the English Rumford stove, which saved a lot of wood, revolutionised cooking in Vienna, so more complicated dishes could be prepared in inns at low prices. Yet small innkeepers were only able to afford such modern stoves in the middle of the 19th century. Basically, the kitchen in a Viennese suburban inn looked much like the kitchen in a well-to-do Viennese household, as can be seen in the photo of the kitchen of the “Anton Kainz” inn:

Another characteristic of the Viennese inn was the “garden” on the pavement outside the inn, where the guests were and are served in warm weather, the so-called “Schanigarten”. The name is probably derived from the call of the innkeepers to their waiters to prepare the “garden outside” at the start of spring. The name “Schani” was widespread in Vienna and was a nickname for Johann – in this case “Schanigarten” would have its roots in the love of the Viennese for the music of Johann Strauss father and son- or for Giovanni – in that case the term would refer to the name of the Italian coffeehouse owner Giovanni Taroni, who supposedly received the first official permission for such a “Schanigarten” in Vienna in 1750.

My grandfather, Anton Kainz, in the so called “Schanigarten” of the inn in Währingerstrasse 146 & a „Schanigarten“ in the exhibition of the „Österreichisches Gesellschafts- und Wirtschaftsmuseum“ Vienna

The suburb „Neulerchenfeld“ was the centre of the culture of entertainment in Viennese suburban inns from the 19th century until the 1950s. Neulerchenfeld was incorporated in the city of Vienna together with the suburb Ottakring in 1892 and it is the area where my grandparents moved to after the 2nd World War. This suburb was notorious for its violence, squalor, roughness – and entertainment since the end of the 18th century. In 1803 Franz de Paula Gaheis counted 83 wine and beer houses in a village of only 155 houses, 103 of which had the right to serve alcoholic drinks. Neulerchenfeld was founded around 1700 as a settlement of small artisans and traders in a farming area: three straight roads from east to west and two straight roads from north to south with small gardens attached to the houses. In 1704 the newly constructed “Linienwall” (today’s Gürtel), formed the border towards the city. This line of defence, mainly against Hungarian rebels, formed a customs border, where from 1829 on a special tax on food and drinks imported into the city was levied, the “Verzehrsteuer”. This meant that outside this line board and lodging was much cheaper and this made Neulerchenfeld an attractive location for housing and entertainment for the poorer strata of the Viennese society, which was driven out of the city centre due to exorbitant living costs. Furthermore the textile industries in the inner suburbs of Schottenfeld and Neubau attracted textile workers who settled in cheaper Neulerchenfeld. The rapid industrialisation in Vienna led to a fast increase in the population and agglomeration in places like Neulerchenfeld. Between 1850 and 1890 the number of inhabitants grew sevenfold to more than 45,000 without any significant spatial extension. As a result, Neulerchenfeld boasted many negative records in the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy: the highest number of inhabitants per house, two thirds of the flats consisted of one room only which was shared by more than four persons. Tuberculosis, destitution, housing speculation, illiteracy, child mortality and unemployment were rampant – it was one of the worst slums on the outskirts of the city.

Nevertheless the entertainment business boomed in Neulerchenfeld. Several suburban inns, such as “Zur blauen Falsche” (To the Blue Bottle) or “Zum goldenen Luchsen” (To the Golden Lynx) and dance halls, such as the “Thaliasäle”, which opened in 1883, attracted many more wealthy guests, too. In 1873 the first Viennese “Lumpenball” (“beggar’s ball”) was hosted in the inn “Zur roten Bretze” (To the Red Pretzel) – a masquerade, where all guests had to appear in beggar’s rags. Yet most of the inns, dance halls, beer and wine houses were frequented by the poor. Many of these establishments were in the hands of professional or immigrant groups and acted as an informal information centre for job opportunities and accommodation. Here the revolutionary potential of the Viennese working class was visible and the inns became hot spots for political debates and spontaneous revolt. Ferdinand Sauter, a supporter of the revolution of 1848, was a regular in the inn “Zur blauen Flasche”. That’s why the police supervised these places from the early 19th century on and in the 1870s the authorities decreed a ban on the formation of workers’ clubs and on public assembly there. The workers in Neulerchenfeld reacted with spontaneous violent revolts and they evaded the ban on organising workers’ clubs by founding camouflage clubs in Neulerchenfeld inns. The popular workers’ leader Franz Schuhmeier organised the “Smokers’ Club Apollo” and in 1889 he founded the “Workers Educational Club” in the inn “Zum schwarzen Adler” (To the Black Eagle); in 1898 the “Nature Friends” were founded in the inn “Zum goldenen Luchsen” and in 1899 the “Workers’ Biking Club” (later ARBÖ) in the inn “Zur roten Bretze”. Around 1900 with the rise of the social democratic movement the importance of the inns in Neulerchenfeld as headquarters of workers’ clubs decreased. On the contrary, the inns were now seen by the Socialist Party as synonyms of poverty, destitution and alcoholism, which should be eradicated. But in 1910 a new era started for Neulerchenfeld as it became one of the most important locations for the first cinemas in Vienna. Several of the famous suburban inns, such as “Zur blauen Falsche”, “Zum goldenen Luchsen”, “Zur roten Bretze“, were turned into cinemas.

The meals served in a suburban Viennese inn were cheap traditional Viennese dishes. This was the food that was cooked in the private households and its virtue was its simplicity. Most of the recipes originated in the 19th century with older roots in all parts of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Despite this multicultural background the dishes in a Viennese inn had to have a homely flair; the regulars expected to see typical Viennese dishes such as goulash, beef broth, “Wiener Schnitzel”, “Krenfleisch”(boiled pork served with horseradish) on the menu. Soup was served with every meal in a special metal cup, from which the boiling soup was poured into the guest’s soup plate, in order to keep it hot. The characteristic of a meal in a Viennese inn was meat and alcohol, for example “goulash and a Seidl beer” (1/3 litre of beer). The extraordinarily high consumption of meat in Vienna was already noticed by foreign travellers in the 19th century. Between 1850 and 1910 meat consumption doubled and the spending on meat per person rose from 10% to 30% of the overall expenditure. Most of all, the inn was always THE place for alcohol consumption, especially for the male population of Vienna. Any attempts at changing this habit failed. In the 19th century the consumption of meat in urban areas became a status symbol of increasing wealth. The vegetarian movement tried to counter this trend and spoke out against the consumption not only of meat, but also alcohol, coffee and tea. The workers in Vienna could not be won over to Vegetarianism because for them meatless dishes represented a sad remembrance of their times of poverty. Yet the ideologies of Socialism and Vegetarianism corresponded from the start as they both tried to solve one of the most urgent social problems of the time: alcoholism. In times of economic crisis meatless dishes were wide-spread because they were cheaper and therefore also offered in the Viennese inns. Meat might have been of highest importance in Viennese cooking, but just as characteristic was the making use of leftovers and filling dishes with no or little meat, such as the famous “Schinkenfleckerl, Krautfleckerl or Knödel mit Ei” (pasta with bacon, pasta with cabbage, dumpling with egg). These could be found on nearly every menu as well as all types of Lenten fare in a predominantly Catholic country, such as fish, crabs and – even otters and beavers were served during Lent – a very creative interpretation of “meatless dishes” including everything that swims in water. Until today traditional Viennese inns offer a special meatless dish on Fridays. In the course of the 20th century the varieties of animal meat that was cooked in Viennese inns was much reduced, but even in 1950 the meat of the deceased elephant Bubi of the zoo in Schönbrunn was served by a female innkeeper in the 9th district of Vienna as a speciality and the circus elephant Piccolo was turned into a tasty goulash.

There were inns serving Hungarian and Bohemian specialities, too, and since the middle of the 19th century Jewish inns opened in Vienna, where kosher food was offered. Before the reign of Emperor Joseph II (1780-1790) Jews were not allowed to enter inns, but the majority of them was too poor to be able to afford food and drinks in an inn, anyway. Some of the kosher inns that were established in the second district, Leopoldstadt, from the end of the 19th century on became well-known for the quality of their food, as for example “Neugöschl” in the Lilienbrunngasse and “Tonello” in Obere Donaustraße, which was famous for its “Sholet” (a bean stew). So-called “Sausage Inns” (Würstelgaststätten), for example Biel, Piowaty, Löwy and Deutsch, were frequented by both, the poor and the well-to-do Viennese.

In the 1920s the first inns opened in the many allotments in the Viennese suburbs, which were important for the provision of fruit and vegetables for the poorer population of Vienna. Originally the tenants of these allotments used the whole space for growing food for the family and did not waste space for a hut. That’s why the inns within the allotment area were called “Schutzhäuser” (shelters) because they provided shelter, food and drinks for the tenants of the vegetable patches. They were built and run by allotment societies. A well-known one is and was the “Schutzhaus Zukunft” (Shelter Future) on the Schmelz in the 15th district.

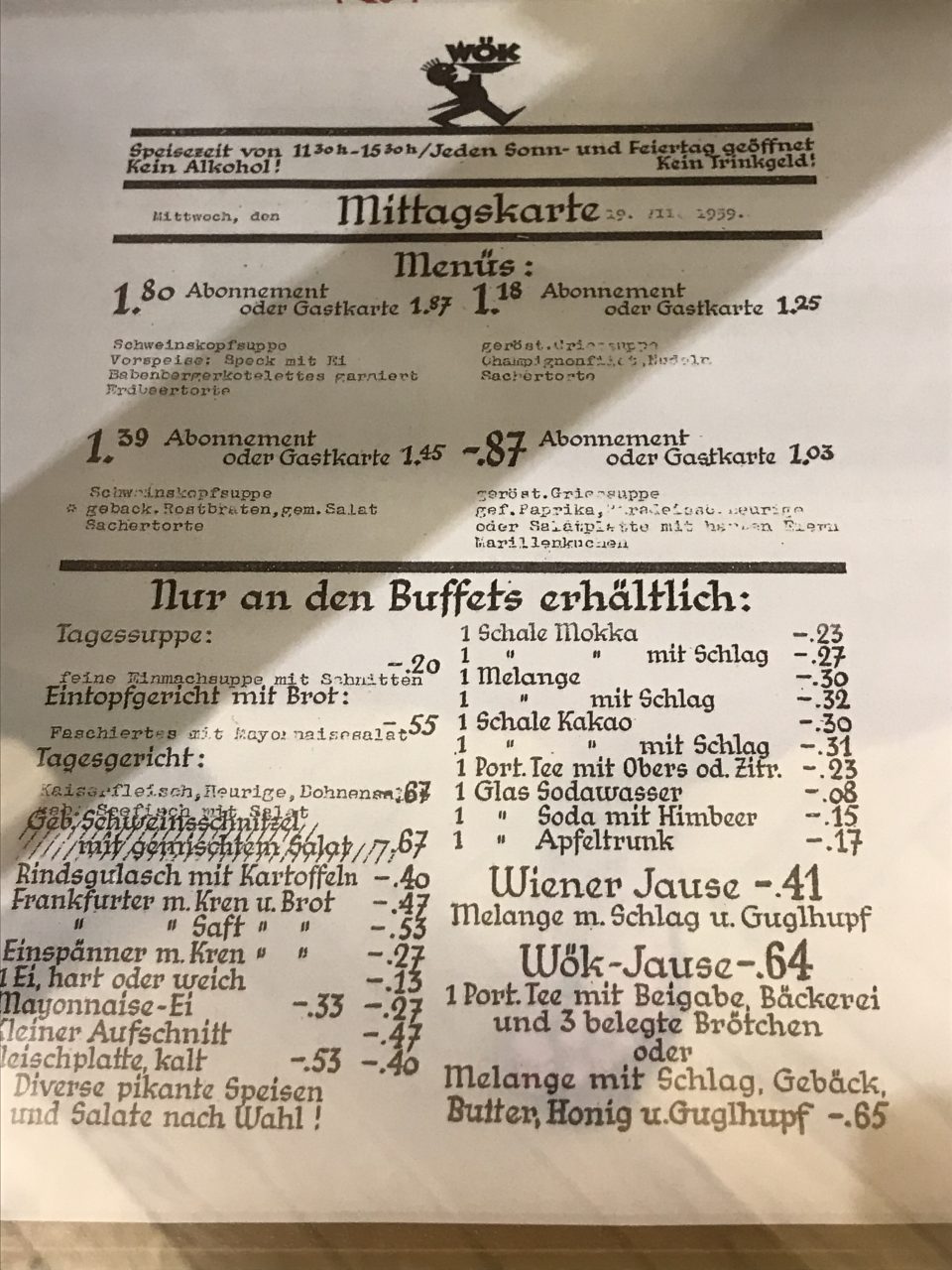

What type of food was offered in Viennese inns? Here are some menu cards from Toni’s collection of the 1920s:

Inn “Zum Tiger”, Vienna 2, 1927 & “Gösser Bräu” Vienna 1, 1927

“Melker Stiftskeller” Vienna 1, one of the many monasteries that ran inns, wine and beer cellars in Vienna – this one owned by the monastery of Melk in Lower Austria and the one below owned by the monks of Klosterneuburg, Lower Austria

From the Middle Ages on wine was the main alcoholic drink in Vienna because the wine growing areas around the city were much larger than today, but population numbers were far lower. In the 16th century the vineyards around Vienna reached their largest extension, yet the wine growers were facing an increasing competition, mostly from beer, spirits and fruit cider producers. In the course of the 18th and 19th century the consumption of wine shrank in Vienna because wine became too expensive for the poorer part of the Viennese population. That’s why the famous Viennese wine cellars in the city, such as the “Melker” and “Klosterneuburger” wine cellars were frequented by the better-off Viennese then. Already in the 18th century the selling of “fake wine” is documented in Vienna. Wine traders and innkeepers offered wine that was mixed with various “unhealthy substances” to improve its colour and taste and to market the wine under the brand names of more popular Hungarian and Italian varieties because of the preference for sweet wines in the 19th century. In 1727 a large number of confiscated barrels of such “fake wine” were spilled on the “Graben” (a main road in the city centre). But the wine forgers were not deterred by these measures, on the contrary, in the “Wiener Diarium” a classified advertisement was published searching for a person who would turn sour or spoilt wine into drinkable wine within 48 hours. Many recipes that offered instructions how to make wines stronger and better tasting by adding various dubious substances were circulated in Vienna. Some of the famous wine houses went bankrupt as a consequence of the illegal faking of wine. In 1832 it was uncovered that a wine house in Liliengasse in the city served red wine to which lead sugar was added and the authorities consequently dumped the barrels of tampered wine between Singerstraße, Rotenturmstraße and Stephansplatz colouring the streets red, much to the amusement of the Viennese. The production of artificial wines was not forbidden in the 19th century, but they had to be declared as such, which was difficult to check. So in 1907 all production of fake or artificial wines was prohibited by law. Yet still in the 1920s the practice of adding sugar and mixing wine with fruit cider was rampant in Vienna.

At the end of the 18th century the beer consumption had already surpassed the wine consumption and in the first decades of the 19th century beer was the fashionable drink of the civil servants, intellectuals, students and revolutionaries. The trend towards mass consumption of beer in Vienna can be explained by the fact that the poorer classes could not afford wine any more. As a child my mother often fetched a ½ litre of beer in a beer glass with handle for her father from the wine and beer house next to their flat, the beer and wine house “Wunsch”, today’s “Weberknecht” at Lerchenfeldergürtel.

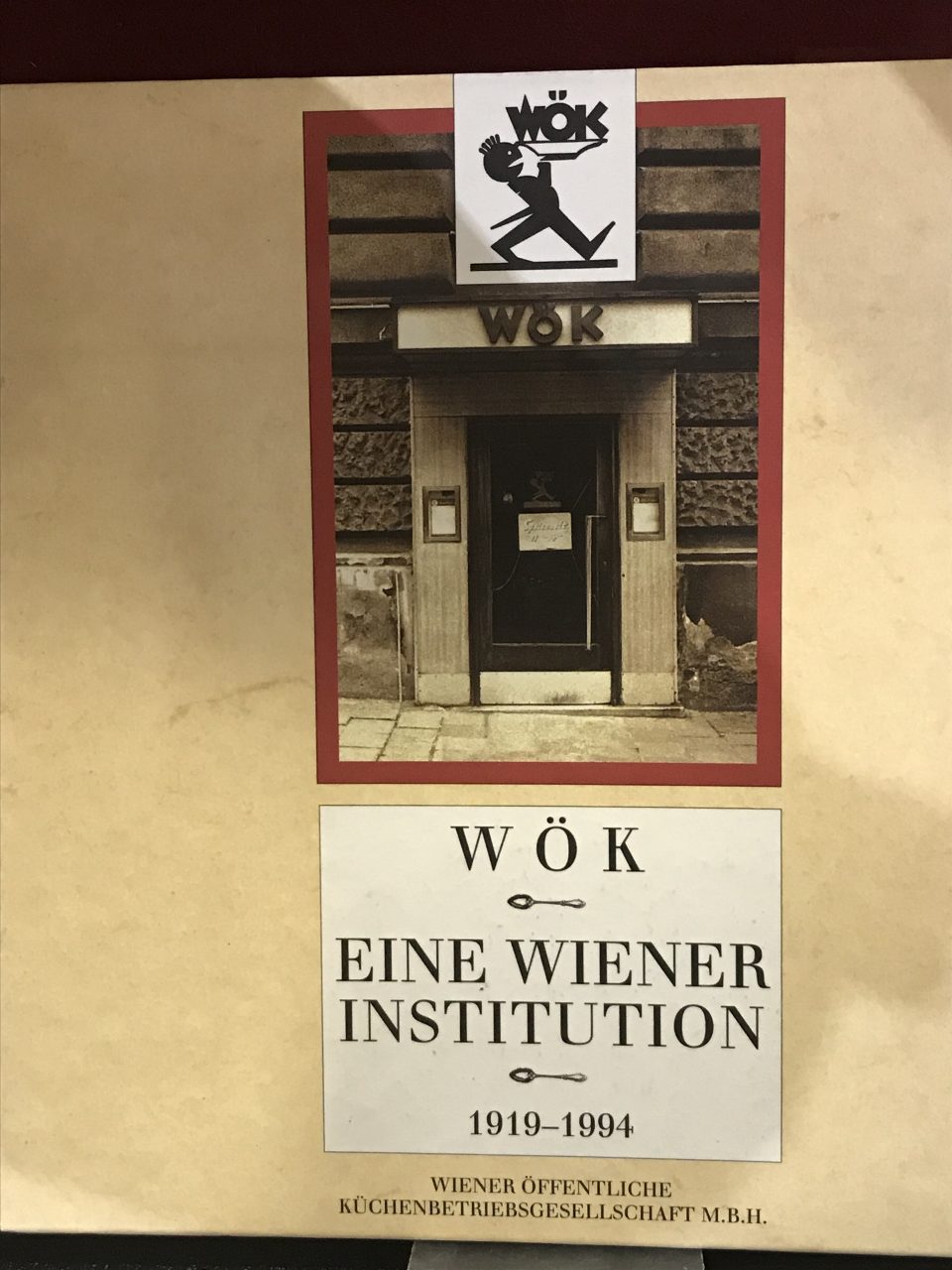

Inn “Diglas”, Vienna 1, attracting guests with daily evening concerts free of charge

After the 1st World War “The Vienna Public Feeding Company” was founded by the US President Hoover to organise a fair distribution of the food donated by the Americans to the Viennese public. In 1920 this organisation was turned into the WÖK (Wiener Öffentliche Küchenbetriebesgesellschaft) and became a popular gastronomic institution in Vienna in the after-war decades. It was a cooperative run by the City of Vienna and the Austrian State and opened many branches in Vienna. Its objective was to offer high quality healthy dishes at affordable prices and this was made possible by an efficient kitchen management, economies of scale and the integration of associated businesses, such as butchers, vegetable producers, and bakeries. Its characteristic was free drinking water in a jug on every table; alcohol and tips were forbidden. The WÖK posed a real threat to the traditional suburban inns with their cheap menus for workers and the association of innkeepers tried to fight this new competition, but in vain.

The WÖK offered Viennese dishes, just as the inns, but at very low prices for the poorer part of the population. As a reaction, the inns no longer expected their guests to order alcoholic beverages. The serious problem of alcoholism among the male working class population did not seem to pose a problem any more in 1970, when the WÖK abolished the ban on alcohol in its restaurants. From the start experts advised the cooks of the WÖK on calories and vitamins and lobbied for a healthy diet; the slogan of the WÖK was “gut und billig” (good and cheap). They offered an array of meatless dishes and put a focus on a reduction of fat because many of the customers were young or middle-aged women working in offices who took their lunches there and watched their weight. That’s why they also offered small helpings (“half portions”) at WÖK, a custom which the inns took over as well, especially for the female and retired clientele.

Finally, music played an important role in the Viennese suburban inns, too. Originally, street musicians, harpists, singers and barrel organists entertained the common people in Viennese inns, asking for a small contribution from the audience. Inns had a guitar or zither available in the guest room and anyone who wanted could make use of them. Sunday was the only day off for the workers and they liked to spend it in the suburban inns, where food and drink was much cheaper and where musical entertainment was provided free of charge.

A Viennese female folk singer, famous for the Viennese form of yodelling: “dudeln”

A ladies’ orchestra, a traditional Viennese attraction

That’s why Neulerchenfeld” was called “the biggest inn of the Holy Roman Empire”. In the gardens and guest rooms of suburban inns Viennese, Styrian or Tyrolian musicians performed. Dance halls were established in the suburbs and small and large orchestras played on improvised stages there. But in many of the small and shabby inns along the ”Linienwall” musical entertainment was provided on a daily basis, not just on Sundays. Folk singers, violinists from Linz and Tyrolian yodellers performed there and influenced the development of the Viennese musical tradition. In the suburbs the night life was rougher and, most of all, less supervised by the police and this attracted also many wealthy guests. These suburban inns organised balls for the neighbourhoods, too. I went to such a “Children’s Carnival Ball” in an inn in Friedrich-Kaisergasse, Ottakring, myself in 1960.

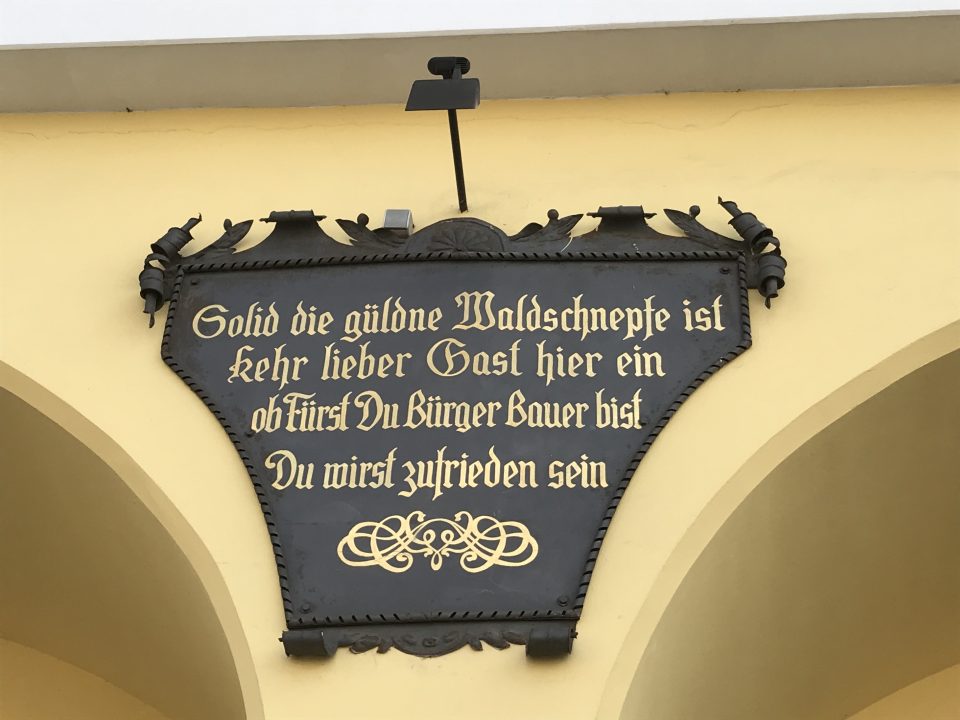

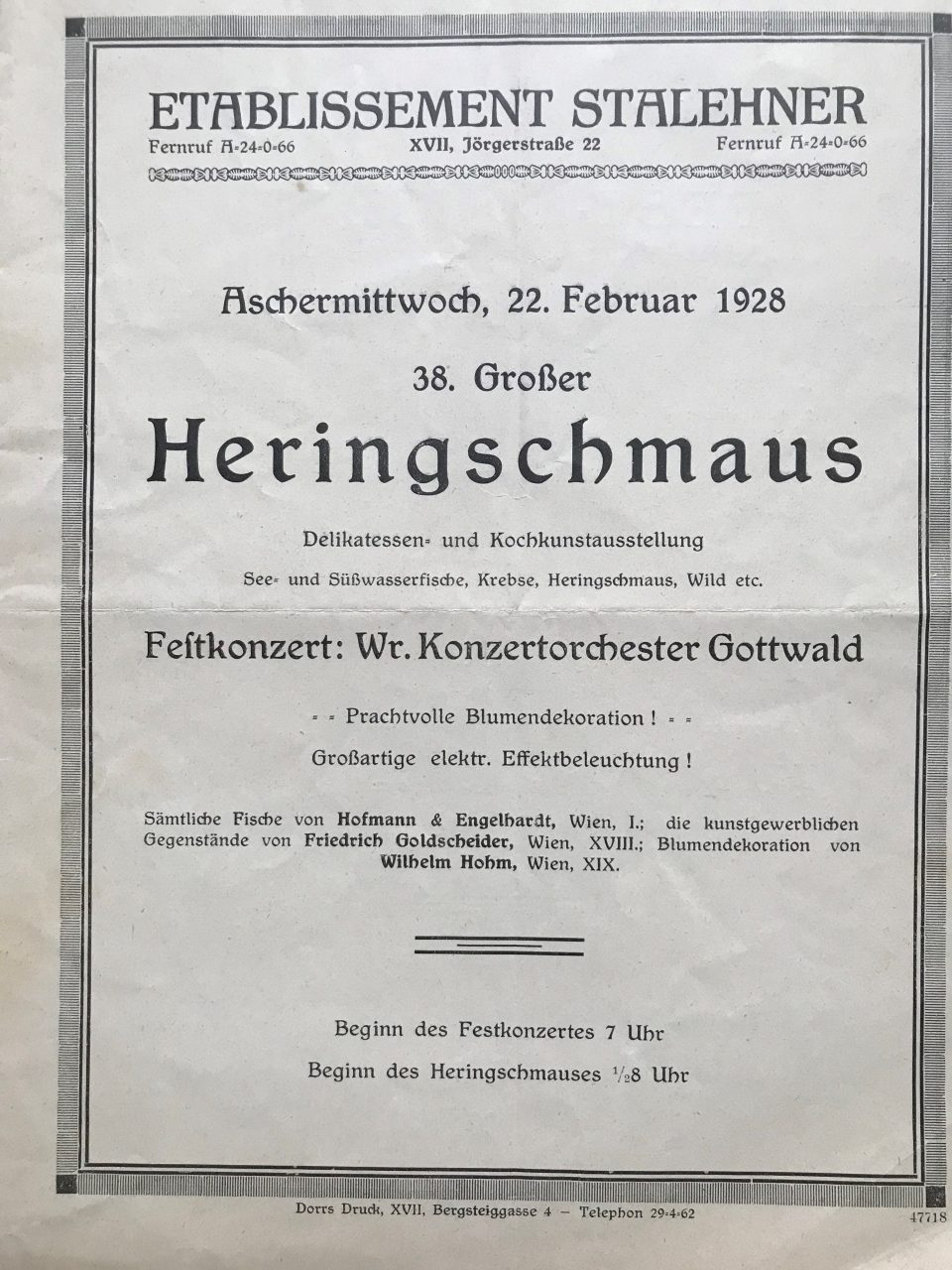

Lerchenfeld, Hernals and Ottakring were the hot spots of relaxed musical entertainment and revelling in Vienna until the 1950s. The “Gschwandner” and “Stahlehner” were inns with huge dance halls (the “Gschwandner” opened in 1873), where Johann Strausss or the Schramml brothers performed. In the inn “Zur güldenen Waldschnepfe” (To the Golden Woodcock) in Dornbach the best singers, often cabmen, such as Josef Bratfisch, entertained the guests from all over the city, so that at times 300 coaches were reportedly parked in front of the inn in the 1880s. Some of these “musical” suburban inns survived the rapid decline in business in the second half of the 20th century, as for example “Grünspan” (the former “Bisinger”) in Ottakringerstrasse or the “Liebhartstaler Bockkeller”, where the brothers Gammer built a separate dance hall in 1906.

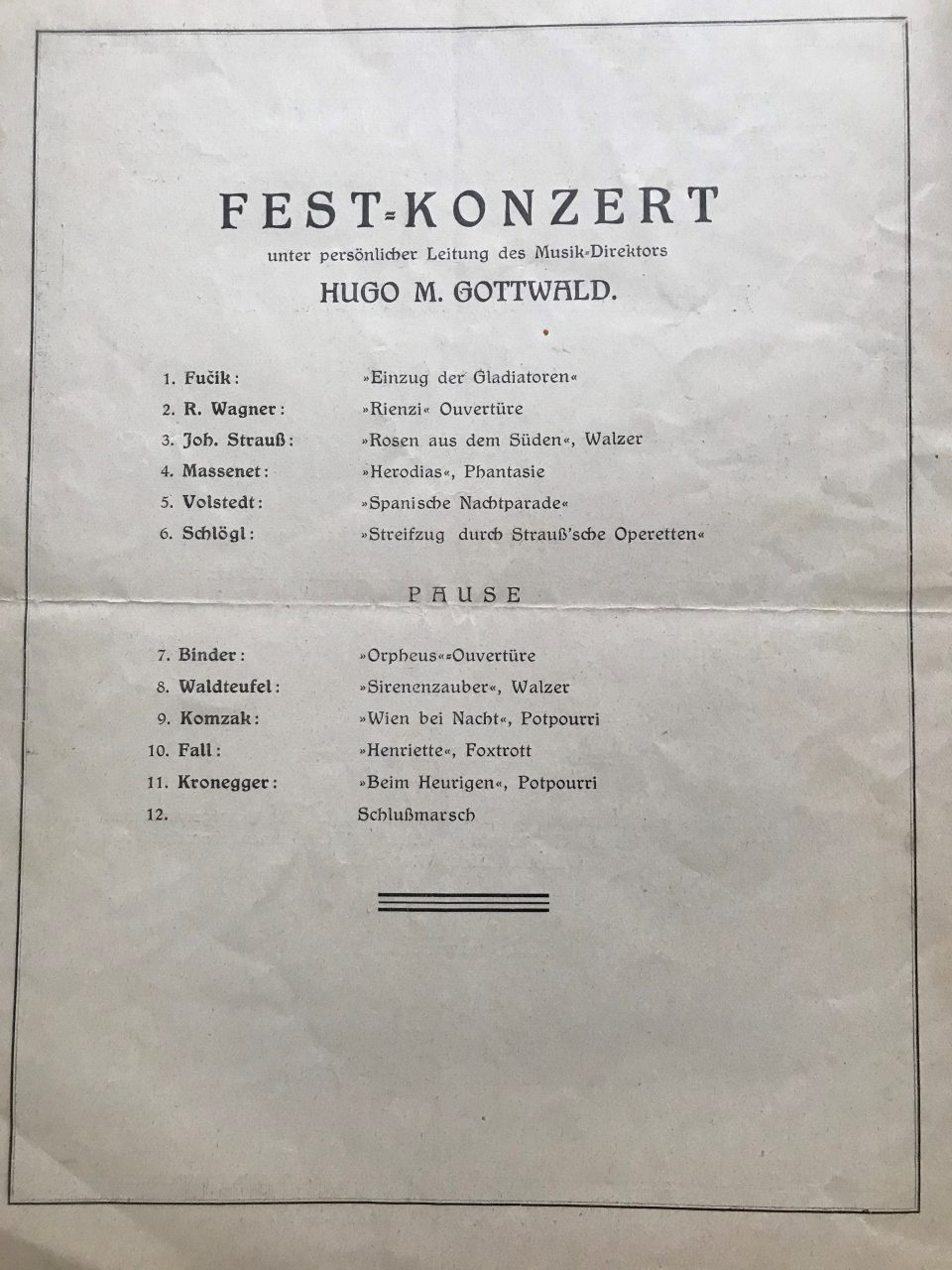

The suburb of Hernals was a centre of musical entertainment in Vienna until World War II. The largest and most famous establishments were “Stalehner” and “Gschwandner”.Below the concert programme and menu card of the end of carnival celebration of 1928 in the “Etablissement Stalehner” can be seen. The house was destroyed in World War II -today it’s a supermarket with an ice rink on the roof.

The dance hall of the “Gschwandner”, Vienna 17 (1873), rescued from complete decay

Literature:

Bousska, Hans Werner, Zu Gast in Wien. Beisl, Restaurants und Kaffeehäuser in historischen Bildern, Sutton Verlag 2019

Haslinger, Ingrid, Die Wiener Küche. Kulturgeschichte und Rezepte, Mandelbaum Verlag 2018 + exhibition in „Österreichisches Gesellschafts- und Wirtschaftsmuseum“

Kos, Wolfgang ua (ed.), Im Wirtshaus. Eine Geschichte der Wiener Geselligkeit, Wien Museum, Czernin Verlag 2007

Schwarzer Bock Blauer Hecht. Die Josefstädter Gaststätten von ihren Anfängen bis in die 1960er-Jahre, Bezirksmuseum Josefstadt 2019