PERSONAL EXPERIENCES OF A VIENNESE SOLDIER IN A SAPPERS’ DIVISION OF THE GERMAN „WEHRMACHT” DURING THE MILITARY CAMPAIGN IN FRANCE 1940 (PART1)

German World War II defensive constructions at the French Channel coast

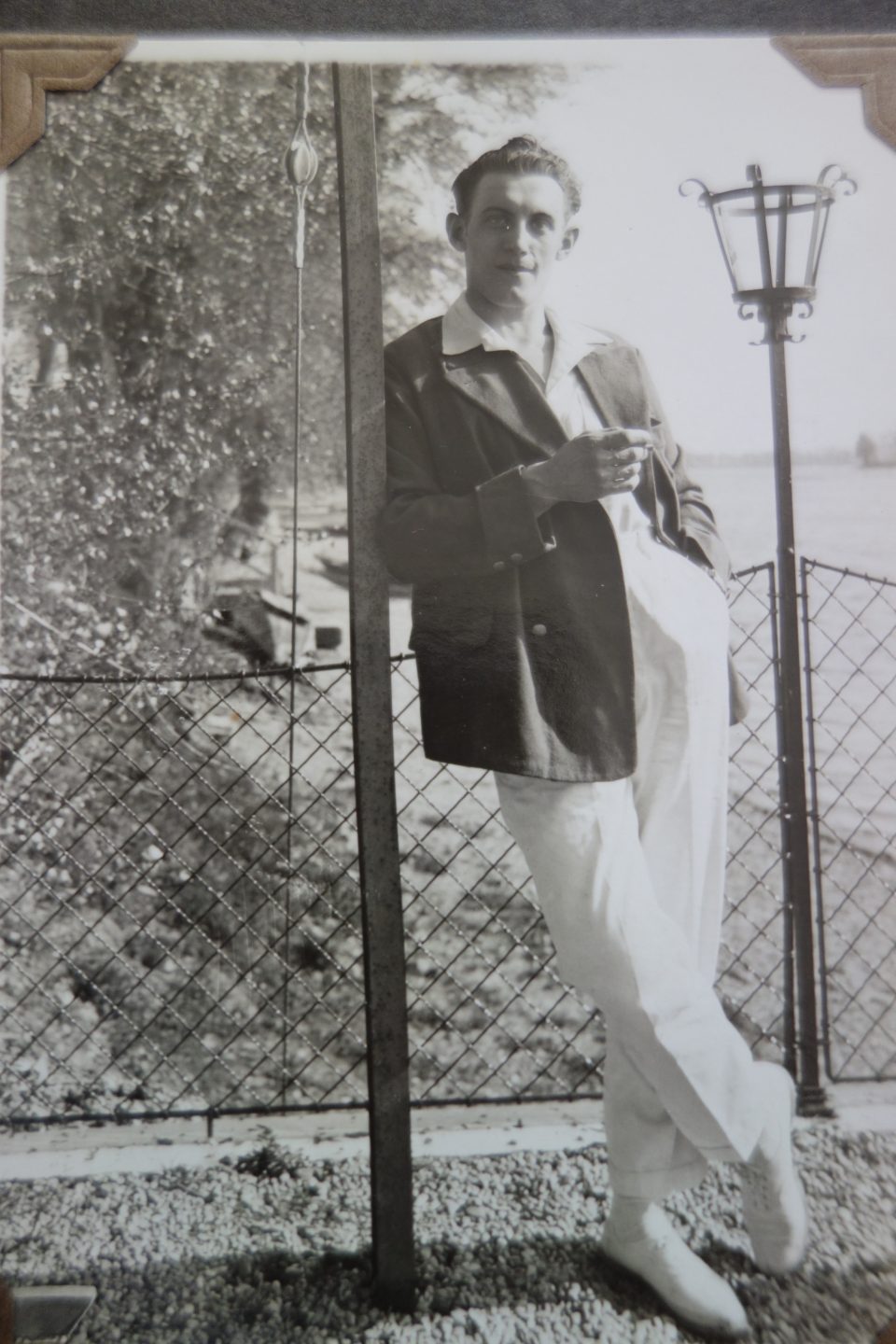

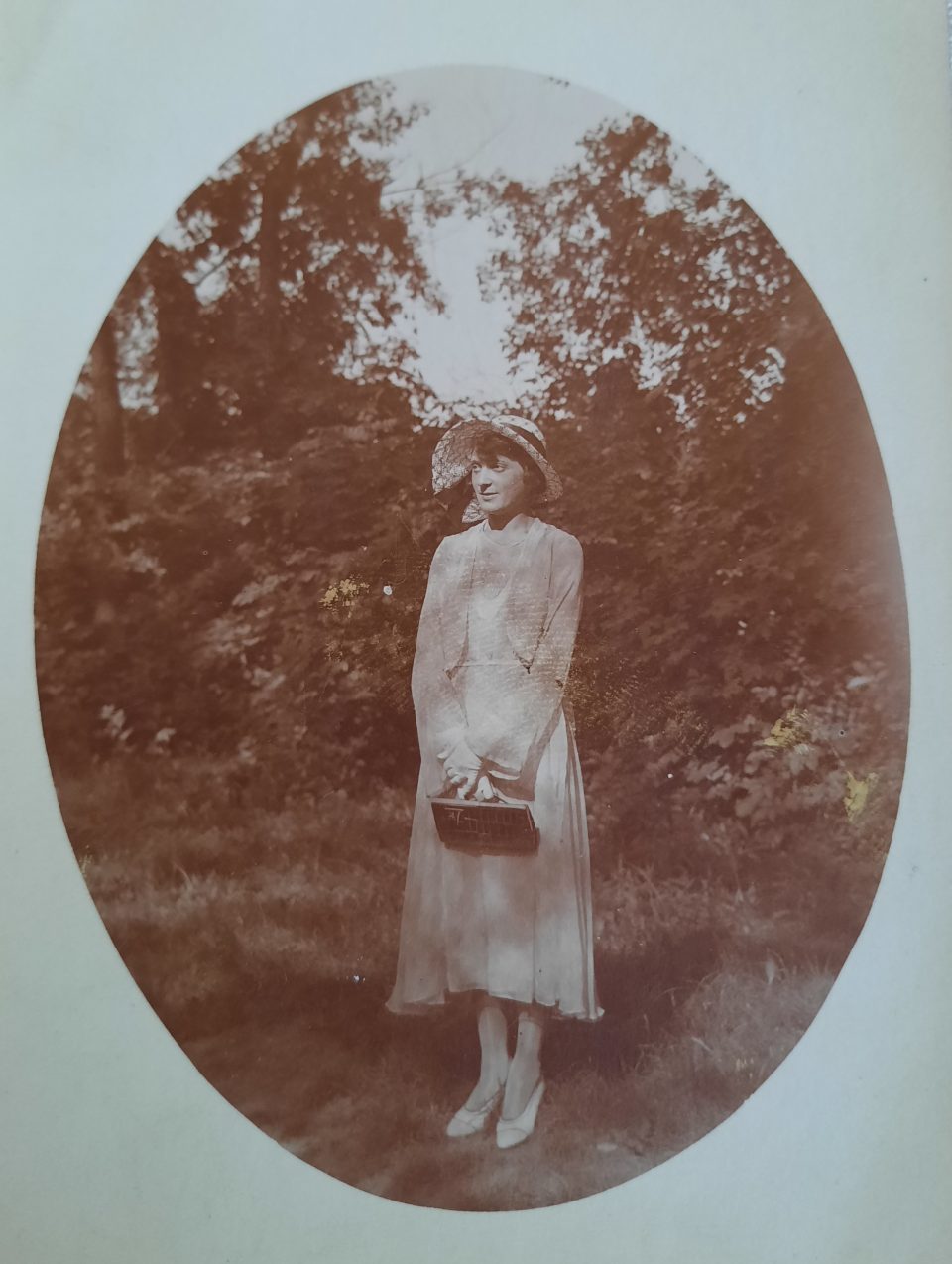

Lola, the sapper Toni’s beloved wife, before their marriage on the left and on the right Toni with Lola standing and Lola’s parents, Ritschi and Ignaz, with their little granddaughter Herta before the war

Anton Kainz (Toni), my grandfather, was drafted to the German “Wehrmacht” in March 1939 a year after Hitler had incorporated Austria into the German “Reich”. When the 2nd World War had broken out in Septmeber1939 Toni was assigned to the “3rd Sappers’ Battalion XVII 79/B” of the German “Wehrmacht” as sapper (“Bausoldat”) in February 1940 and had to complete ten weeks of training. He was sent to France in June 1940 and remained there until September 1940. From September 1940 until June 1941 he was with the “2nd Sappers’ Battalion 153 /288” in Poland (the then so-called “Generalgouvernement”) until he was dismissed from the German “Wehrmacht” and declared “not to be used” (“nicht zu verwenden: nzv”) because he refused to divorce his Jewish wife, Lola, my grandmother. In this one year as a soldier he wrote 246 long letters and a few postcards to his beloved wife and daughter with detailed descriptions of the life of a common soldier, his tasks and activities, his feelings and emotions and his attempts at handling the precarious situation of his wife and daughter in Vienna from a distance. He was 34 years old when he was drafted and had been trained as cook and waiter in his father’s inn in Vienna in the 18th district Währing. He had travelled to Switzerland and France during his years of professional formation and after quitting the “Anton Kainz Inn” he ran a coffee house in Vienna in the 8th district Josefstadt from 1935 until 1937 together with Lola (see article on “Viennese suburban coffee houses”).

Toni (on the left) in St. Moritz, Switzerland, New Year’s Eve 1925/26 with three young colleagues working there, too.

From May 1939 on he worked in the restaurant service of “Mitropa”, the “Central European Restaurant and Sleeping Car Company” with destinations in many European cities and later at a fish monger’s in the 1st district of Vienna “Hofbauer & Hammerschmidt”.

A postcard Toni wrote, picturing a “Mitropa” railway company’s dining car, on 22 July 1939 on the track Vienna- Villach

Toni spoke a little French and loved the French way of life, art and culture and the cuisine. He himself was an amateur painter, photographer and enjoyed playing the piano, especially four-handed together with his wife Lola. Toni was a keen sportsman, too; he loved tennis, football, skiing, hiking, climbing and sailing. To his great regret he came back to France as a member of a conquering army and he reported how ashamed he was of the behaviour of some of his comrades, in France as well as later in Poland. A detailed analysis of his documented experiences forms the core of this article.

Toni in the “Wehrmacht” uniform

The integration of Austrian soldiers in the German “Wehrmacht” revealed prejudices on both sides from the beginning of the war on. Some reports characterise the relationship between Austrian and German soldiers as friendly, but most contemporary witnesses stress the condescending and contemptuous attitude of the Germans towards the Austrian soldiers, which might have been rooted in the Prussian disdain for the former Austro-Hungarian army. The Austrians called all men with origins north of Bavaria “Prussians”, disparagingly “Marmeladinger” or “Piefkes”, whereas the Austrians were called “Ostmärker” (The NS name for people from former Austria), pejoratively “Kamerad Schnürschuh” (Comrade Lace-up), by the Germans, signifying the supposed lack of soldierly qualities. Consequently the Austrian soldiers had to succumb to degrading treatment by German military instructors. This derogatory attitude of German sergeants was often copied by ordinary German soldiers. The classical prejudice persisted, namely that Austrian soldiers were “inferior material”. In the melting pot of the German “Wehrmacht” the Austrians as “Ostmärker” (after the annexation of Austria by the German Nazis) were classified together with the soldiers from the German “Altreich” as “Volksgruppe 1” (“Ethnic Group 1”), the German ethnic soldiers from Silesia and Czechoslovakia “Ethnic Group 2 or 3” and those from Poland “Ethnic Group 4”. Despite being in group 1 the Austrians were treated with arrogance and condescension, just as the other German-speakers from Central, Eastern and South-Eastern Europe. Sometimes even Bavarians had to succumb to degrading treatment. Some German officers resorted to fierce threats, especially towards the end of the war, stating that Austrians were unreliable, cowardly and only to be used as cannon fodder. Austrian privates also tended to be assigned the worst accommodations. Yet some Austrian soldiers reported that a friendly and comradely relationship with German soldiers was possible, but that they were usually careful, most of all when discussing political issues, because an imprudent or rash comment could have very serious consequences.

The important connection to the home country was guaranteed by the forces’ postal service of the “Wehrmacht”, which was astonishingly efficient. The ordinary soldier was forbidden to keep a diary. Several soldiers circumvented this ban, but these diaries usually only survived if the soldiers managed to hide them at home in the form of loose sheets. Taking photos, nevertheless, was permitted as long as the soldiers did not take photos of military installations or actions. Photography had become a popular hobby since the early 1930s and the soldiers photographed more or less everything without facing any sanctions. Most soldiers sent the photos home in letters and this is the way how just a few of Toni’s photos survived. Another important channel of information was the exchange of letters. The daily mail call was one of the most important distractions from military routine and a very important moral support for the soldiers. This was the reason why the High Command put emphasis on the smooth functioning of the army’s postal service. Several thousand people were responsible for a frictionless postal connection between the home territories and the military front-line. The service was hierarchically organised, just like the army. Due to secrecy reasons neither the military unit nor the geographical position of the soldier were to be mentioned in the address, but only the name, rank and the forces’ five-digit postal service number. Parcels up to 250g could be sent free of charge and up to 1kg 0.20 RM (Reichsmark) had to be paid (the daily pay of a private was 1 RM). The soldiers “lived” from one mail call to the next – so important was the connection to their families. Usually the service was regular and took two to three weeks from home to the front-line or vice versa. Except for special cases, the letters were not censured because that would have delayed delivery endlessly considering the amount of letters dispatched every day. But if the army command had letters censured they tried to make it look as if the writer himself had crossed out some words. Yet the army made the soldiers believe that their mail was checked regularly, so that no military information or bad news was disclosed. Most soldiers did not report negative or disastrous news home anyway because they did not want to upset their families. Some sent coded messages to and fro, one of which is also mentioned in the letters below. The postal service was only interrupted during a transfer of troops and before and during an attack.

The other important distraction the soldiers were looking forward to was furlough or home leave. It was stipulated that “Wehrmacht” soldiers were entitled to two weeks’ home leave in their second year of service, three from their third year on and four from their ninth year on. Additionally special furlough could be granted in case of serious family matters, as in the case of Toni, the death of his mother, or for health reasons or university studies. Before or during a campaign all furloughs were cancelled and those on home leave had to return to the front-line. In the course of the war some soldiers could not go home for two or more years, which had disastrous effects on their psyche. Some even committed suicide, although there are no official records of these suicides, only reports of contemporary witnesses. For the journey home and back the army paid for the train tickets and the soldiers could travel on any train available, but it usually took them a long time to get home and many changes of trains, which is documented in Toni’s letters. Yet the days of the journey were not included in the duration of their furlough. If the soldier wanted to travel somewhere during his home leave he had to apply for a permit and the train tickets, otherwise he had to face serious sanctions. He had to wear his uniform and only with a special permission was he allowed to put on civilian clothes. If a soldier did not return to his division after his home leave or tried to hide or disappear, this meant certain death. It was known that the chances of survival were higher as a front-line soldier than as a deserter. The army bureaucracy at home and its “substitute army” worked as smoothly as the front-line army with an intricate web of supervision and control. The military police was everywhere, in the cities, in the country, in bars and restaurants, on trains and buses, at traffic junctions and they were manned by fanatical NSDAP party members. Without his marching orders, a soldier was lost. But with his marching orders he just had to report to the military authorities in every town he passed through. In larger cities the authorities sometimes even organised accommodation and sightseeing. Toni wrote to Lola how much he enjoyed those journeys because there was so much to see. He would have been a globetrotter, he only lacked money, time and opportunity. Some soldiers were granted extra furlough for special bravery or “to sort out unpleasant occurrences at home”, such as “unfaithfulness of the wife”, “foreigners who were accommodated in their homes” or homes which were destroyed by bombs. A furlough ban was the worst punishment for any soldier.

Receiving unbiased and objective information was a challenging task for ordinary soldiers as all media were under the NS party control in the “Third Reich”. At the front-line newspapers arrived by mail weeks later and not all barracks provided radios. The army command had set up an army radio station which briefly reported the latest news daily, but as soon as the “Wehrmacht” was no longer winning battles, but losing them, the news reports were increasingly distorted and used for propaganda purposes. Privates had nearly no knowledge of what was going on, as can be seen from Toni’s letters. When they were transferred they were not told where to, even when they were already on the trains or trucks. They had to rely on rumours. Every piece of information was checked and censured by the army and the party.

Hygiene in the army was of the highest priority, especially when with the outbreak of the war the infection rates of venereal diseases rose dramatically. Taking a bath or doing the laundry at the front-line was often a real problem for ordinary soldiers, and what’s more the ubiquitous plague of lice. So soldiers took to swimming in rivers and lakes whenever possible. Furthermore the soldiers were regularly vaccinated – Toni mentioned the inoculations against typhoid fever. When Toni was working in the kitchen urine and stool samples of all cooks were tested for hygienic reasons, as is known from his letters.

War memorial in Normandy

Hitler’s next target after attacking Poland in September 1939 was France and this was the sequence of events of the invasion of France by Nazi Germany: Since September 1939 France and Britain had been at war with Nazi Germany, but in the first months there had been nearly no fighting. The Allies wanted to strangle the Nazi war economy by imposing a blockade while at the same time building up their own military potential. Their plan was to mount an offensive in 1941 or even 1942 as soon as their armies were fully prepared. They hoped to hold the Germans off, if they attacked in the meantime. The old fortifications of the “Maginot Line” protected the French-German border, but the frontier with Belgium and Luxemburg was unprotected. To the Allies’ surprise the Germans launched an offensive on 10 May 1940 invading Holland, Belgium and France. Already three days later the Germans crossed the river Meuse and moved towards the British Channel. This military move threatened to cut off the British, French and Belgian armies in Belgium. After the capitulation of Holland and Belgium a large part of the British forces was evacuated across the Channel between 26 May and 4 June from the port of Dunkirk. At that point in time there was almost no more British military presence on Continental Europe. That was the chance for the German Nazis to turn south towards the centre of France. The French government decided to evacuate Paris on 10 June 1940 and the Germans arrived there four days later. On 22 June the French government had to sign an armistice with Germany, which meant that in only six weeks the French had been defeated by the German Nazis. A huge wave of people was moving south from Paris fleeing the German troops. The immediate consequences of the defeat were disastrous for France. Half of the country was occupied by German troops and in an unoccupied area in the south an authoritarian regime with its capital at Vichy was installed by the grace of Hitler under Marshall Pétain. As a consequence that was the end of democracy in the whole of France until the liberation by British and American armies in 1944. Yet the trauma of the defeat of 1940 and the following Nazi occupation continued to mark the French people for many years to come. The “Fall of France” was an event that resonated throughout the world as the disaster of the destruction of a most civilised and cultured nation. In fact, the defeat of France in 1940 led to a massive escalation of World War II and turned a so far European conflict into a worldwide war. The totality and speed of the French collapse surprised everyone. The Fall of France was not just a military defeat, but also signified the collapse of a political system, the break-down of the alliance with Great Britain and in the end almost a disintegration of the French society.

In the interwar years France had been a pacifist nation. The memories of the 1st World War weighed heavily with 1.3 million Frenchmen dead, 1 million war invalids, 600,000 widows and 750,000 orphans. Unlike Britain and Germany, France had suffered severely because the war had been largely fought on its territory. By the end of the 1st World War many towns in the north-east had been destroyed as well as a large part of the fertile agricultural land. The rebuilding of this devastated area took ten years. As a consequence of these experiences the French were profoundly pacifist. Some of this pacifism was rooted in exhaustion and a deep pessimism, whether the country could survive another war. The pacifist mood changed after the Munich Agreement of September 1938 with Hitler when it was proven that Hitler could not be trusted. In July 1939 a poll showed that 70% of French now were prepared to resist another aggressive German move. When eventually war was declared in September 1939 it seemed that the pacifist atmosphere had subsided. The French did not show great enthusiasm for war, but they accepted the necessity to resist Hitler. Even after the declaration of war many people still hoped for peace. In the months of waiting that followed the war declaration, morale both in the French army and among civilians deteriorated. The patriotic rhetoric of 1914 did no longer work in 1940. The question was what Britain and France were fighting for after the fall of Poland. At that point in time the war was not yet seen as a fight against Fascism in France.

It is further clear that in 1940 France was a country in economic and demographic decline and was being outstripped by Germany. The confidence of France that they could win a confrontation with Germany rested on the trust in the alliance with Britain. When de Gaulle went to London in 1940, he declared that the defeat of France was only the first round in a world war. There are many myths about Germany in 1940, especially the elusive notion of “Blitzkrieg” (“lightening war”), which was supposed to have been a specially conceived strategy. In reality the “Blitzkrieg” emerged in a haphazard way from the experience of the French campaign, whose success surprised the Germans as much as the Allies. Germany’s victory in France only led to the adoption of the “Blitzkrieg” concept afterwards with the invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941. Nonetheless, the German plan for the attack on France could just as well have gone wrong. It is well known that the Nazi administration was chaotic and inefficient, especially with respect to rearmament, although they had a head start over the British and the French. The German army in 1940 for example was more dependent on horse-drawn transport than the French. Furthermore the morale among German soldiers was rather low, too. Even the German security police reported in 1939 that the Germans were full of resignation, fear of war and longing for peace. At a governmental press conference on 1 September 1939 journalists in Germany were instructed not to use the word “war” in headlines to avoid a mass panic. Even the German High Command was worried about the “lack of fighting spirit” among the German soldiers during the Polish campaign. That’s why the German military leaders viewed the Fall of France in 1940 as a “miracle”. The greatest German weapon in the French campaign was the element of surprise.

The defeat’s immediate consequences were the collapse of the Third French Republic and the ideological crusade of the “Vichy regime” to remake France. Pétain signed the armistice with Germany on 22 June 1940 and according to its terms France was split up into an “Occupied Zone” in the North and along the Atlantic coast and an “Unoccupied Zone” in the South. The new regime in the “Unoccupied Zone” was to be authoritarian and anti-democratic, although the armistice as such did not foresee any political arrangements there. The opponents of the French Republic took over in Vichy. Yet Vichy rested on more than just political reaction and revenge. Marshal Pétain was really popular among the population, not just as war hero of the 1st World War. His speeches about authority, family and security appealed to the French and the defeat provided Vichy with its moral authority and formed the foundation of the Vichy regime. Since the defeat of France seemed to ensure a German hegemony over Europe, the Vichy regime collaborated with the German conqueror. This pro-German stance was partly driven by ideological affinity; the regime was even close to re-entering the war on the side of Germany. By the end of 1941 a European war had become a global one and the military powers of the United States and the Soviet Union dwarfed the European ones and eventually led to the bipolar world of the Cold War after 1945.

The Belgian coast

To France, which had to sign an armistice agreement on 22 June 1940, the Germans had a special relationship; they respected the French as a “cultured nation”, as opposed to their attitude towards the Russians and other Slav peoples who the German Nazis considered inferior. Not all French were hostile to “Wehrmacht” soldiers, too, as can be deducted from Toni’s reports, which came from the region of Alsace-Lorraine. They were astonished about the quick defeat and 12,000 Frenchmen joined the German “Wehrmacht” later to fight against the Soviet Union. 8,000 Frenchmen even enlisted as volunteers in the “Waffen-SS” in the SS-Division “Charlemagne”. Many of those young French volunteers wanted to fight against Communism and for a “Nouvelle Europe”. Only very few of them survived World War II. On the other hand, several Frenchmen and women fiercely fought against the German invaders in the “Résistance” and many of them lost their lives in the fight against the occupiers, too.

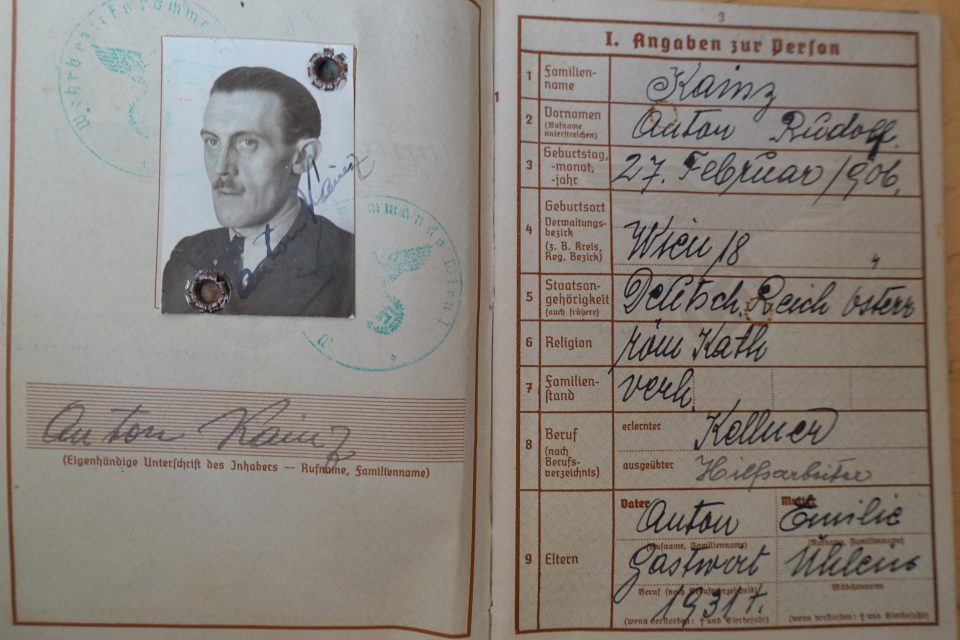

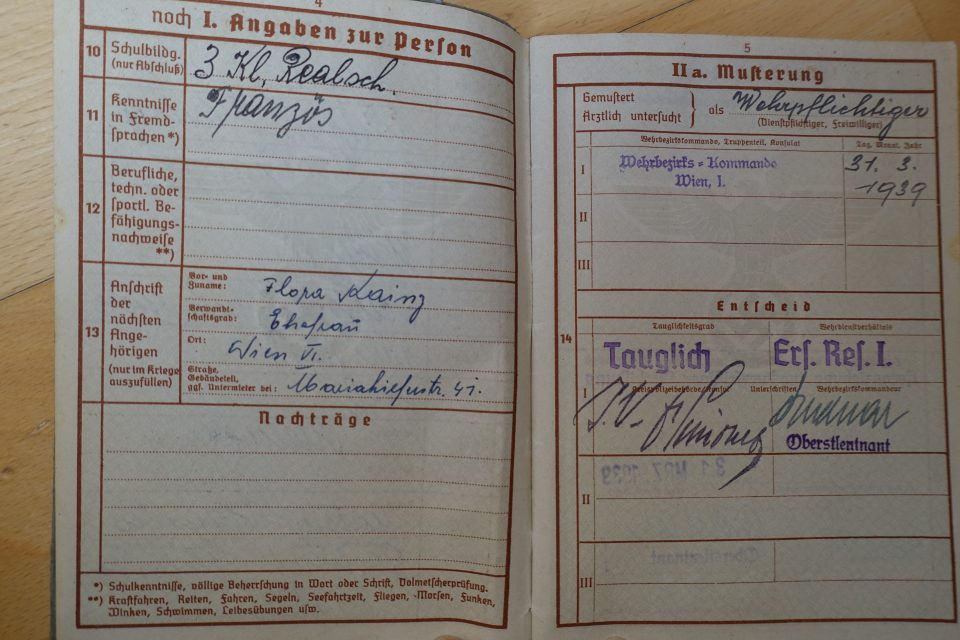

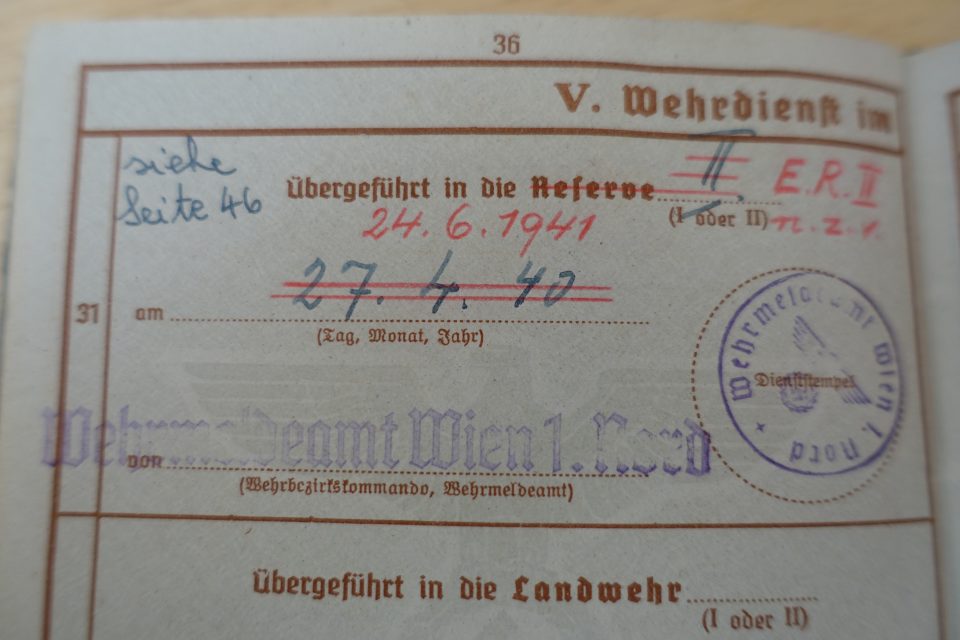

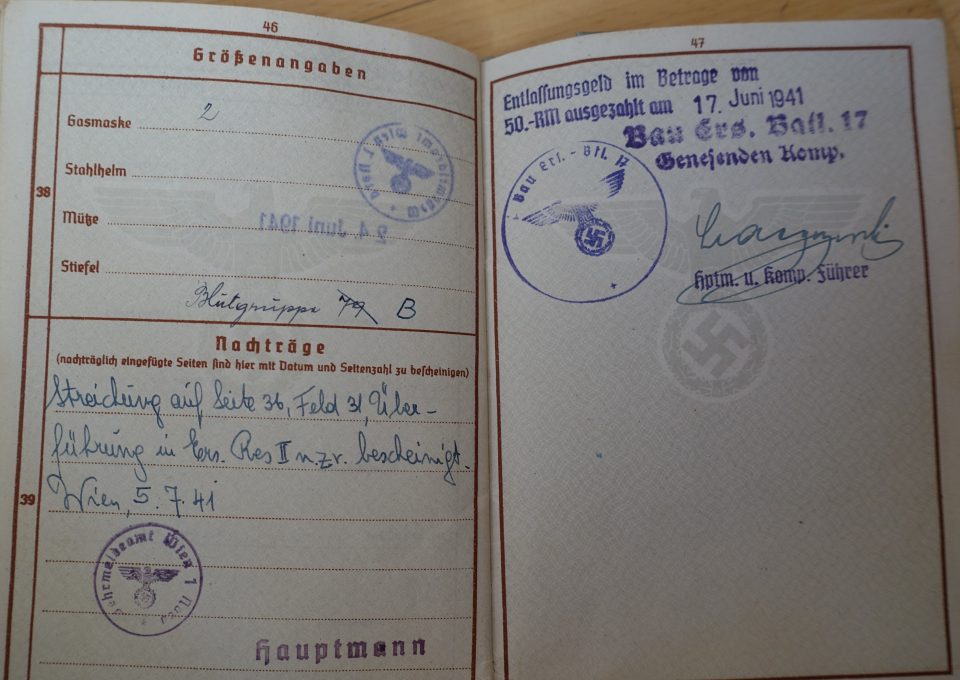

Anton Kainz was drafted to the German Wehrmacht on 1 February 1940 and went with the 2nd Sappers’ Battalion 153 to France on 21 June 1940 and later to Poland, which period will be discussed in part 2 of this article. He was dismissed from the army on 17 June 1941 and was transferred to the home front “Vienna 1 North” on the basis that he was declared “n.z.v.” (not to be used) because he strictly refused to divorce his Jewish wife Lola, as already mentioned above.

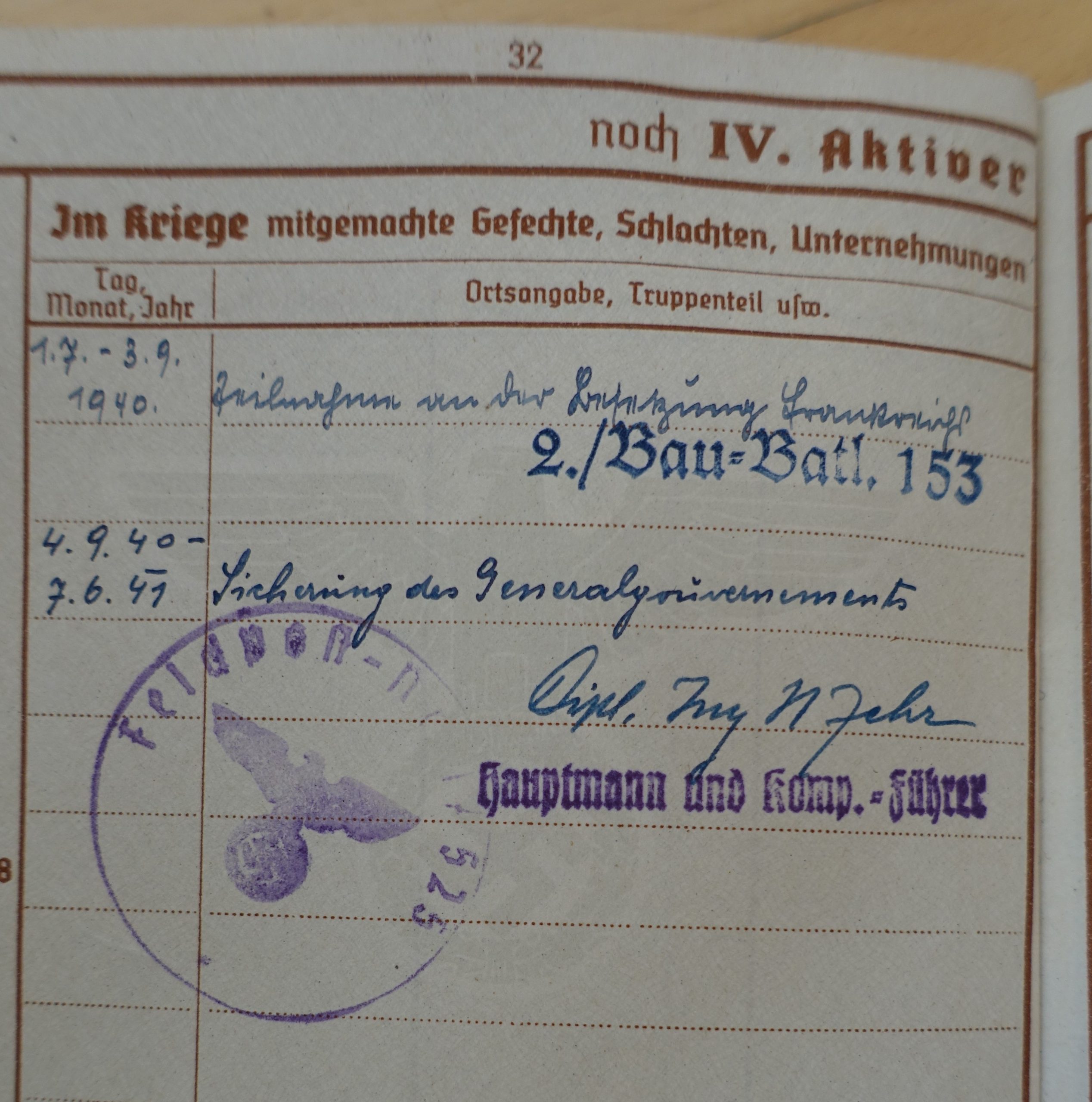

Toni’s military service book:

Toni was stationed in France from 1 July until 3 September 1940 and from 4 September 1940 until 7 June 1941 in Poland

“n.z.v.” is entered into his military service book in red and once more below:

The historical analysis of the 246 letters which Toni wrote to his wife in this period is divided into three categories: first, information about the military campaign, where he was stationed, the military tasks and operations, and the conditions of the military service; second, in which way he tried to support his family in Vienna and how he organised important tasks at home from a distance and third, his emotional conditions on the military front-line.

…