THE VIENNA TRAMWAY AND ITS WORKERS – A POCKET OF RESISTANCE 1889-1945

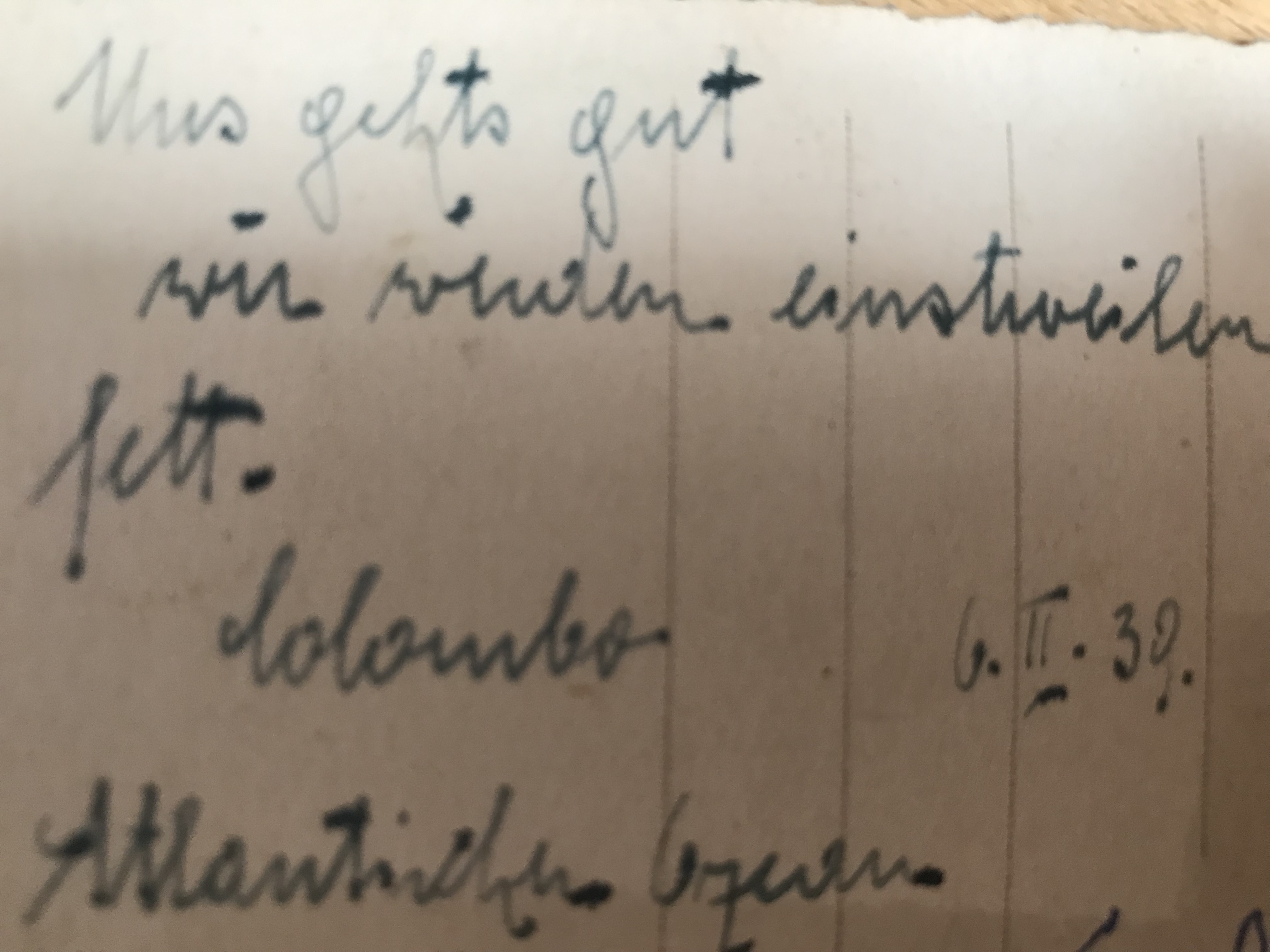

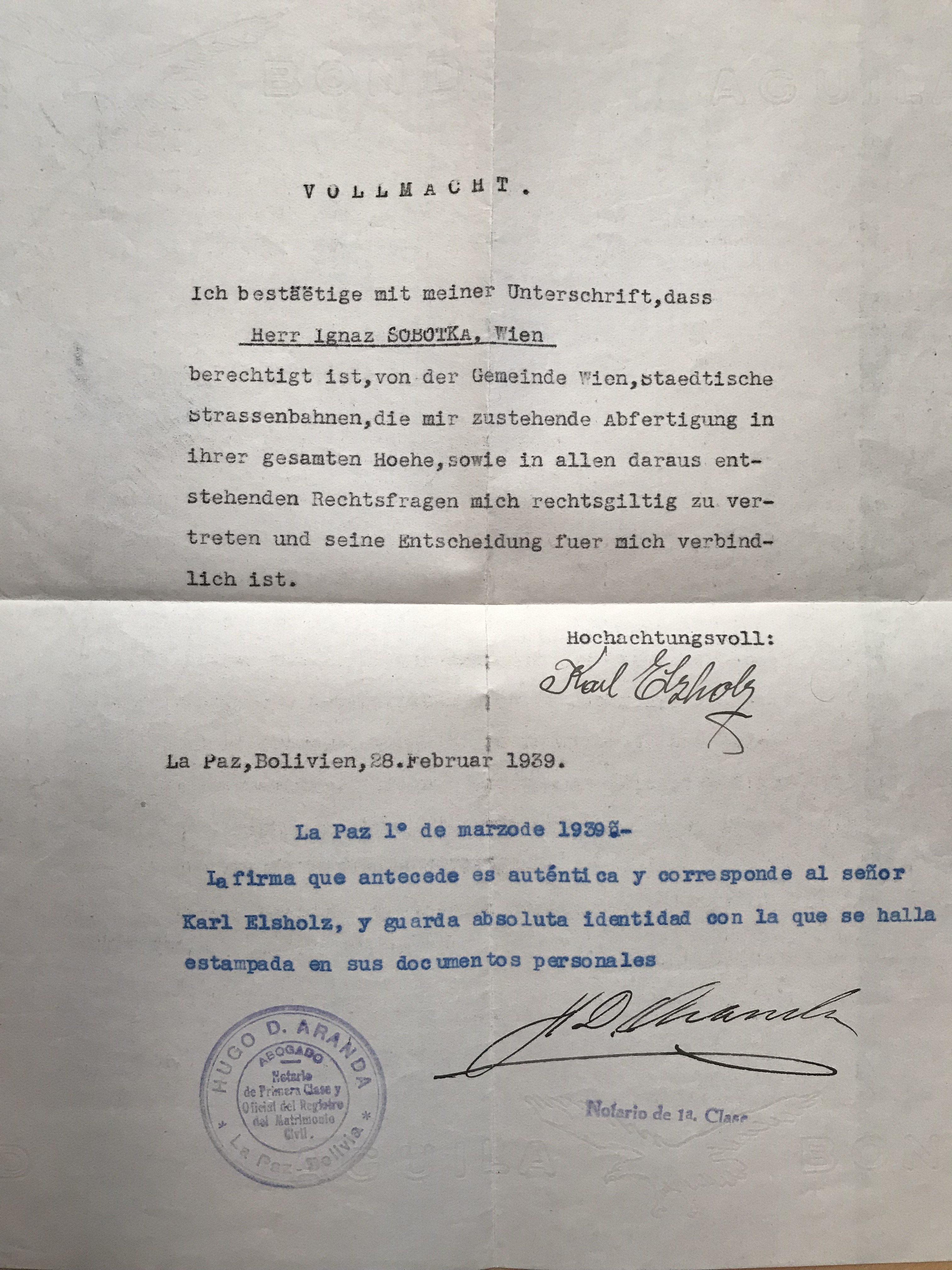

The Viennese public transport system is one of Europe’s most efficient and affordable public transport systems. It all started with the first horse-drawn tramway in 1865 that connected the former gate in the city wall “Schottentor” with the suburb of “Hernals” which was famous for its many entertainment venues where famous musicians, like the family Strauss, Josef Lanner, the “Schrammeln” and many others performed. So this tramway was built to offer the Viennese a quick and more comfortable possibility to get to their leisure activities. The fast developing network of tramways – first horse-drawn, then steam-powered, too, and finally electric – employed an increasing number of tramway workers who were an ever-present appearance in the Viennese city scape at the end of the 19th and the 20th century. Their protest against the excessive exploitation by the private tramway owners in 1889 resulted in the first wide-spread strike in Vienna and gave a boost to the newly founded socialist movement of Victor Adler. The workers of the tramways also later remained a pocket of resistance, most of all in the Austro-Fascist era 1934-1938 and then during the time of Nazi occupation 1938-1945. A monument in Vienna lists the names of 42 Fascist and Nazi victims of the Vienna transport system workers 1934-1945 (3rd district of Vienna, Kappgasse1). The tramway workers who were active Socialist party members were either dismissed in 1934 when the Austro-Fascist regime of Engelbert Dollfuß put an end to the democratic system of the 1st Austrian Republic or after March 1938 when Hitler made Austria a part of the “Third Reich”. Then all workers of the Viennese tramways who were Jews or had Jewish ancestors were not only sacked but had to flee the country, such as my great-uncle Karl Elzholz, who managed a last-minute escape to Bolivia with his wife, my great-aunt, Marianne (Mitzi), the sister of my grandmother. Those who were unable to find refuge abroad were sent to Nazi concentration camps where many of them were murdered.