The title “Cooking for Peace” is wishful thinking on my side, but the following investigation into food supply measures, cooking techniques and recipes during war times will illustrate the similarities of methods in dealing with these challenging situations of want on both sides of the front, the later victors as well as the defeated. Furthermore, despite nationalistic rhetoric on both sides, such as naming recipes, for example “Hötzendorf Gemüse” (a vegetable stew named after the Austrian military commander) in the Austro-Hungarian Empire during World War I or “Victory in the Kitchen. Wartime Recipes” in England during World War II or the patriotic “Eintopf Sonntag” (“one-pot stew Sunday”) of the Nazis in World War II, “enemy dishes” were still around. English “puddings” (“Wurstpudding”, a pudding made of sausage), “orange marmalade”, “Marillenjam” (a jam made of apricots) and “mixed pickles” recipes were popular in Vienna during World War I and on the other hand, there was an influx of Viennese cooking traditions in England via Viennese refugees who worked as maids and cooks in wealthy English households and even booklets with continental recipes were distributed in England. Women on both sides of the trenches had to deal with the same problems trying to make ends meet and still put tasty meals on family tables in Vienna and in England. The highest priority was to avoid any waste of food and to provide the people on the “home front” with healthy and nutritious dishes, which might be of greatest interest also today because many of the techniques of preserving food, using vegetable scraps, replacing meat and an economical use of fuel, such as the use of a “cooking crate” (“Kochkiste”), are advertised nowadays, too, in order to improve our diet to reduce health-damaging consequences of too much fat, meat and sugar in our present-day meals. You can for instance find guidelines for building your own cooking crate, which was introduced in World War I, online now, which helps to reduce the costs of energy and preserves the vitamins in the steamed vegetables.

You will ask now, what’s the connection to my family? Well, first of all my great-grandfather, Ignaz Sobotka, who was 42 years old, when World War I broke out, was involved in the war effort on the home front by brewing beer in Kaiser Ebersdorf near Vienna and growing animal fodder and vegetables on the grounds of the brewery. An interesting document of 15 April 1917 signed by Anton Iritzer, the owner of the brewery, asks for “… the dispensation from military service of Ignaz Sobotka, manager of the malt factory and living on the premises of the factory (11th district of Vienna, Mailergasse 5) as he is indispensable for the war industry…. My company is busy producing fodder for animals and transforming worthless rubbish into animal fodder and I therefore need my manager. Further I have to dry coffee surrogate and I use 15,000 square metres of my garden to plant vegetables, cabbage and beans, etc. I furthermore collect the otherwise worthless vegetable cuttings in Kaiser Ebersdorf in large quantities and turn them into urgently needed animal fodder which I deliver to the fodder centre…. The k & k Uniform Depot has stored large quantities at my premises and these need an overseer who lives on site… All these tasks are carried out by my manager alone and he is therefore indispensable and there is no replacement. In case of his conscription operations would have to be terminated and the uniform depot would have to be vacated.” My grandfather, Anton (Toni) Kainz, whose father owned an inn in Vienna’s 18th district in the Währingerstrasse, was a trained cook and waiter, who had acquired experience in Switzerland and France after the successful completion of his apprenticeship in 1924 (see the certificate below).

After being drafted by the Nazis for the campaign against France at the age of 33 – much to his regret because he loved the French and their way of life – immediately after the outbreak of World War II, he was later sent back to Vienna to work as a fishmonger – a war-necessary trade at the home front – because he had stubbornly refused to divorce his Jewish wife, my grandmother Lola, and was therefore considered “unreliable” by the Nazis. Contrary to the Nazi’s intention, this offered Toni the possibility to protect his wife and his daughter, my mother Herta, from deportation to concentration camps. My mother often recounted the wonderful dishes he cooked from the meagre provisions that were available during the war. Once she received from her piano teacher a single small piece of old and grey chocolate in tinfoil, a former Christmas tree decoration, which she brought home. Toni cooked the most marvellous chocolate cream from this one grey piece of old chocolate at a time when chocolate was unavailable in Vienna. My grandmother, Lola, on the other hand did not like cooking very much and happily handed over the pots to Toni, whenever there was a family festivity. In the interwar years Lola and Toni ran a café in Vienna’s 8th district at Hamerlingplatz, where my great-grandmother, Ritschi Sobotka, Lola’s mother, did the cooking. Ritschi’s famous “Buchteln” (yeast dough dumplings filled with curd cheese and / or a special type of plum jam) is a simple recipe for a rich, fluffy and tasty Viennese sweet that can be eaten as a main course. But Lola herself was extremely skilled at bargaining for food during the 2nd World War. This was called “hamstern” in Vienna and signified the attempt at bartering any possessions city dwellers still had for food from the farmers in the vicinity of the city. In that way she put to good use her beauty and her charm in helping feed her family because Toni always sent her to the farmers and remained discretely behind. Two of Lola’s Viennese recipes are still treasured in our family, namely a delicious cocoa cake made of only two eggs and little butter or margarine and her famous brawn made of pigs’ feet is always served at our New Year’s Eve celebrations.

My great-aunt Käthe, a bank clerk and Lola’s sister, diligently prepared for her escape from the Nazis in 1938 – Austria had become part of Nazi Germany in March 1938 – by learning English and acquiring cooking skills. She then applied for the position of a cook in a wealthy English household and landed in Dover on the 7th of November 1938. She worked in 25, Warkworth Gardens in Isleworth in Middlesex as a cook until she joined her newly-wed second husband, Karl Elzholz, in Bolivia in 1944. She passed on her collection of English wartime recipes and her handwritten Viennese recipes to me. In the same way as she had introduced Viennese cooking in the English household in Isleworth, she brought back to Vienna English recipes after the 2nd World War, such as the traditional full English breakfast and her recipe for making traditional English marmalade of oranges.

Two more members of my family brought Viennese cookery to the Anglo-Saxon world: First, my grandmother’s youngest sister, Mitzi, who had fled with her first husband, Karl Elzholz to Bolivia. There she married the German Bill Stern and migrated with him to the United States after the 2nd World War where she worked as a housekeeping skills teacher, teaching cookery, sewing, knitting, etc. until her retirement, when she moved back to Vienna with Bill to live in Baden near Vienna. Her concept of cooking was meanwhile strongly influenced by the American way of life, which caused some amusement among her Viennese relatives in the 1960s and 70s: She for example advised against the consumption of milk which was supposed to be health damaging, or she excessively washed a chicken inside out with soap before roasting it to eliminate any bacteria, and she complained about the quality of apples in Austria which at that time still housed worms – something unimaginable in the US of the time where pesticides were widely and abundantly used. Second, a cousin of my mother, Edith Loewenstein, the granddaughter of Mali Markstein, Ignaz Sobotka’s sister, lived in London and worked as a cookery and German teacher there after the 2nd World War. I remember her wonderful Viennese speciality, “Brandteigkrapferl” (choux pastry puffs) with chocolate sauce. She was, above all, the one to introduce me to my best English friend since adolescence, Lynette, one of her pupils, who loves Viennese sweet dishes and desserts.

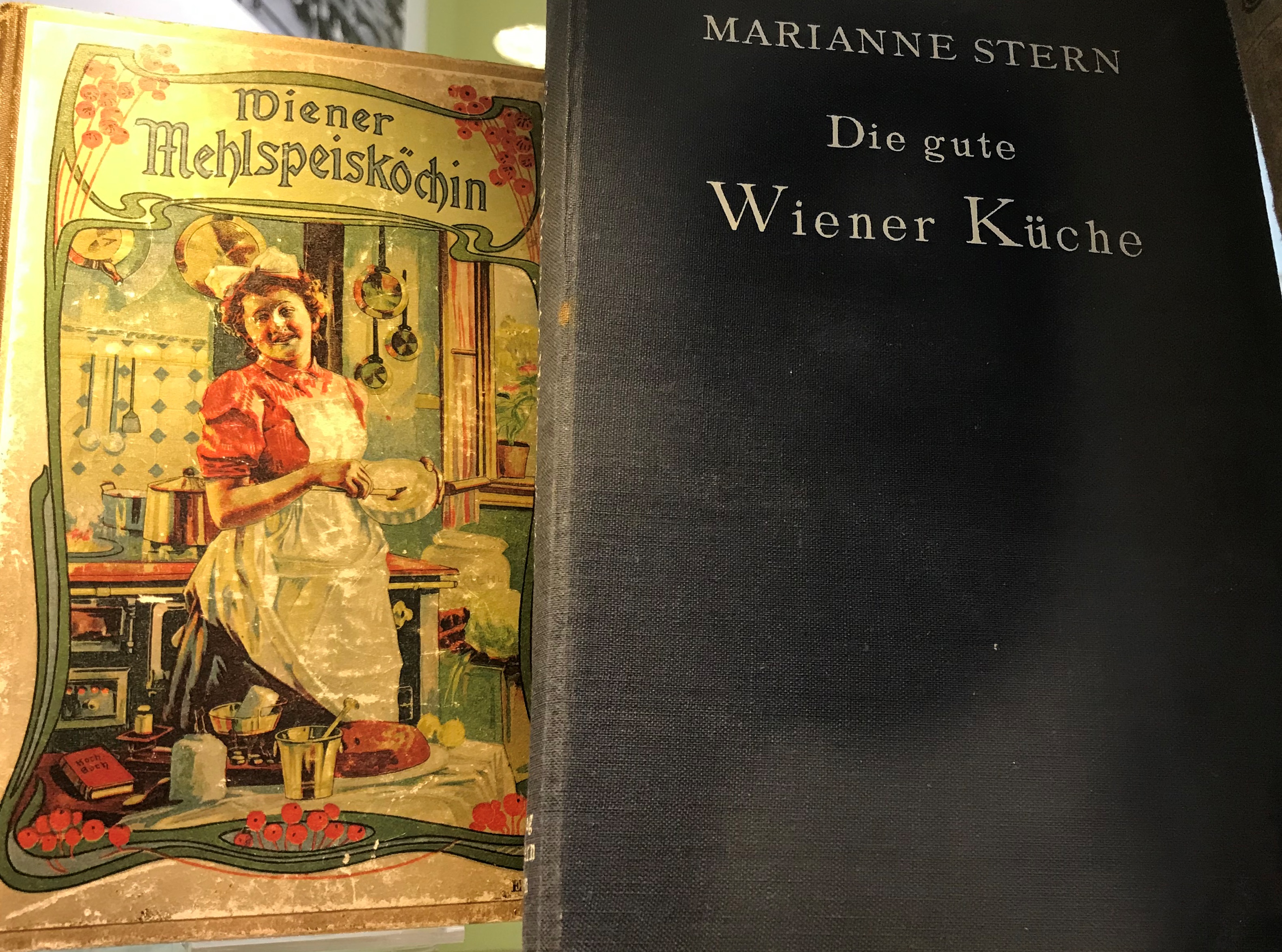

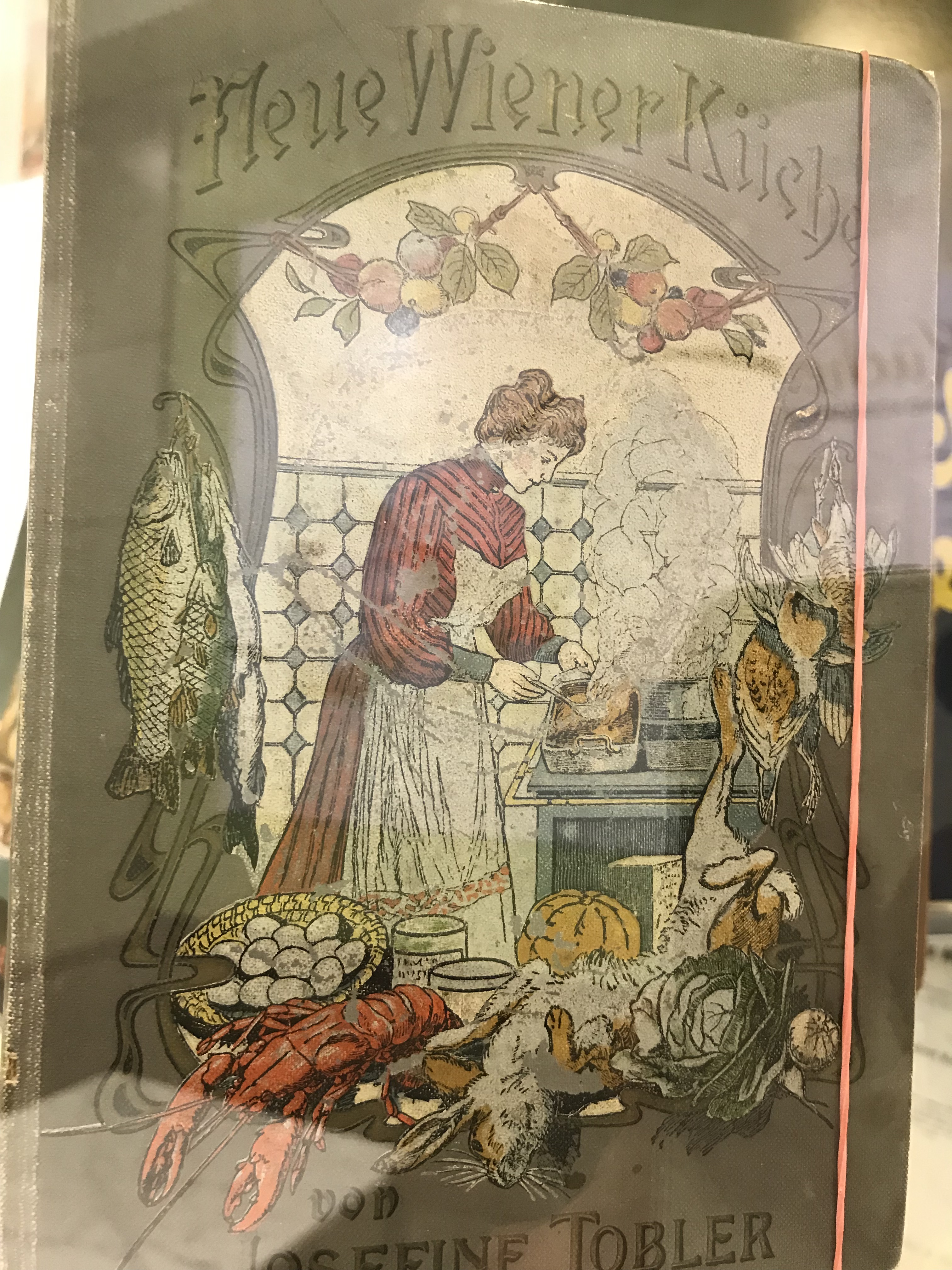

The time of the two World Wars was a trying time for Viennese cookery, which was and still is characterised by a lot of meat and sweet dishes and therefore suffered from the lack of wheat flour and dairy products and the near absence of meat and fat. Already in the spring of 1915 the Austro-Hungarian authorities realised that they were totally unprepared for adequate food provisions under wartime conditions. As early as autumn 1914 – 2 months after the start of the war – “war kitchens” were opened for deprived women and children, which distributed free meals. The excessive price rises for food made it impossible for less well-off people to purchase what was available in ever shrinking quantities. Food could no longer be imported from enemy countries, like France, Great Britain and later Italy and the “Entente” (Great Britain and France) further prevented any purchases of food on world markets by the Habsburg Empire. From 1916 on it was even impossible for middle-class Austrians to buy meat products. Wartime recipe books were published which included no meat recipes and concentrated on soups, vegetable, fish and sweet dishes made of polenta, maize, chestnut, barley and rice flour because wheat and rye were exclusively used for bread production. Another focus was laid on the simple conservation of fruit and vegetable products and the use of potatoes in all forms for sweet and salty dishes. The traditional Viennese three-course meal of soup, main course and sweet dish or dessert could only be taken up again after the end of World War I. In the 1930s Franz Ruhm wrote the most important Viennese cookery book of the interwar years, the “Kochbuch für alle” (a cookery book for all), which Käthe took with her to England in 1938 and which is now in my library. Ruhm clung to the traditional Viennese cooking concept despite of the disintegration of the Habsburg Empire, which had contributed the ingredients and the recipes from all parts of the empire to the typical Viennese cookery and he tried to further develop this tradition. He for instance included some starters in his recipe book, although they did not form part of authentic Viennese cooking.

The incorporation of Austria into Nazi Germany in March 1938 nearly wiped out the Viennese cooking tradition because German cookery was advertised by the Nazis instead. Between 1938 and 1945 the Viennese were inundated with information propagating German wartime recipes based on the northern German “Eintopf” dish, a now meatless one-pot stew. Already on the 1st of October 1933, after taking power in Germany, Hitler declared the first “Eintopf Sonntag” (one-pot stew Sunday) as a national duty, which was supposed to be the patriotic answer to deprivation and shortages. Kunigunde Knorr of the German company Knorr producing soup cubes and ready-made soups and sauces, was shown in the San Bernardino County Sun on the 26th of February 1934 cooking a “one-pot stew” for the crew of a German ship and the US newspaper commented that “ …members of the crew on Nazi vessels eat only food which may be cooked in one pot to save money. The savings are sent back to Chancellor Hitler to feed unemployed Nazi workers”. Despite the fact that “Eintopf” stood in the Nazi era for the “unity of the German nation” and the racial exclusion of others, the dish was no invention of the Nazis. In northern Germany various forms of one-pot stews were regional specialities even before the industrial revolution. They were combinations of meat, vegetables and legumes and they were common in schools, hospitals, barracks and public soup kitchens in northern Germany. During the First World War they became the staple dish in all German war kitchens, but they were detested in Bavaria because in southern Germany and also in Austria these one-pot stews were not to the taste of the local people. Here the people were used to at least a two-course meal with soup and main course and for them “Eintopf” was the synonym of a “bad, unimaginative and tasteless dish”. In his cookery book written during the 2nd World War Franz Ruhm included some one-pot stew recipes and gave them Austrian place names to remind the Viennese of former better times, such as “Dornbacher Eintopf” or “Kahlenberger Eintopf”, but without success. In Austria the term “Eintopf” still has a negative connotation and stands for a tasteless and uncreative dish.

Even after the war the provisions were scarce and the Viennese cookery had to resort to conserves and sausages instead of meat. Mostly vegetable dishes made more nourishing with the addition of oat flakes, constituted the daily diet of the Viennese together with sweet dishes made of polenta and maize flour and Maizena, made of American maize. Most important was the use of all scraps, so that nothing was wasted. These were used for soups and sauces. In the years after the end of World War II it depended on which occupation zone a Viennese lived in, the Soviet, the American, the British or the French zone whether the food supply was satisfactory or not. Those in the American zone were best off. Lotte Katscher issued a small cookery book for Americans stationed in Vienna: “Favorite Recipes – Yours and Mine”, which was bilingual and included many traditional Viennese recipes and just a few American ones. A true revival of the Viennese cooking tradition started in the 1970s with the publication of the first “Great Sacher Cookery Book” by Franz Maier-Bruck.

Now back to the 1st World War: in 1916 Gisela Urban published guidelines for a complete change in the dietary habits of the Viennese, compelled by the shortages of provisions during the First World War, and the cooking of tasty and filling dishes with the essential nutrients, but without or nearly without wheat, fat or meat. Housewives were to cook economically without wasting anything and creatively by replacing ingredients which were unavailable by other healthy surrogates. She stressed that the wealthy Viennese had eaten too much meat and fat anyway, which was not conducive to a healthy diet. That’s why the medical doctors welcomed the fact that due to war-related shortages fat and meat had to be drastically reduced. She was of the opinion that fat could be replaced by the consumption of sugar, a source of carbohydrates, together with bread, potatoes, maize, barley, rice and polenta flour. She further stressed that carbohydrates were also present in vegetables, fruit and “Maggi” products, the new readymade soup cubes, sauces and puddings. Sugar should be consumed in sweet dishes (as main courses) and with fruit in the form of marmalades, jams, jellies and stewed fruit as compotes. Urban pointed out that despite the hardships and shortages, meals should be prepared with love and care because food was supposed “to generate a feeling of pleasure” at all times.

What were the hints for a healthy diet in times of war in Vienna during World War I? First of all, soups were considered a healthy fat- and meatless dish which was filling and could be served at dinner and lunch times together with bread and fruit. Soups could be enriched with some yeast, soup cubes and even gelatine. Gelatine was used for fruit jellies and all types of cheap brawns made of vegetables and scraps of meat, fish or innards. Secondly, a focus was laid on the consumption of salt-water fish, which had been eschewed by the Viennese so far. They detested the smell and were afraid of fish poisoning. Experts of the time tried to convince the Viennese of the beneficial qualities of fish meals and offered advice how to get rid of the smell – washing with water and vinegar and adding a glowing piece of charcoal to the boiling water and most of all, burning all the paper the fish was packed in and all the cuttings. They further pointed out that meat and sausage poisonings were much more frequent than fish poisonings – no wonder as very few people ate fish in Vienna at that time! In order to avoid fish poisonings the experts advised cooking a sample of the fish and if it still stank, it was rotten. The entire fish could be put in cold water and if it was fresh, it would sink immediately, if not it would gradually float to the bottom of the pot. Most of all, it was recommended to cook stockfish, dried and salted cod, which was easily available and more to the taste of the Viennese. It had to be watered for at least 36 hours and then cooked with a pinch of baking soda (natron) to soften the meat and render the fish tender. Fish should be cooked with lots of spices, with vinegar and root vegetables and the cooking water and vegetables should be kept for sauces and soups. As fish is easily digestible it was recommended to serve it with lots of side dishes like vegetables and potatoes, rice or noodles to render the meal more filling.

Another important change in the diet of the Viennese was the replacement of wheat and rye flour, where the included gluten facilitate the baking and cooking of dishes of high quality, by surrogate products; first of all potato flour which was recommended for baking cakes, cookies, “gugelhupf”, even for yeast dough (mixed with some mashed potato puree) and casseroles. Rice flour was not so easily available, but should be mixed with a little jam, rum, liquor or raspberry juice to improve the result when making porridge, cakes, or other sweets with rice flour. Maize flour was usually in the shops after the harvest and was supposed to be used for all sweet dishes with an addition of orange or lemon juice or peel, rum, Arrak (a spirit made of sugar and rice) or other spirits to improve the flavour of the dishes. The use of home-made caramel sugar (roast coarse sugar in a pan, add a little hot water in the end and then leave it to cool) further improved the quality of the end product. In order to prevent maize flour from becoming rancid, knitting needs should be stuck into the flour sacks because the metal prevents the fat in the maize from turning rancid. Maizena was made from American maize and was said to be especially nutritious and digestible, especially when mixed with some cold liquid such as milk. When the USA joined in the war together with the “Entente”, Maizena was no longer available in Vienna. Tapioc and manioc flour was a totally new product in the Viennese kitchen. Both were made from the dried roots of the manioc plant and produced a very fine and starchy flour, similar to arrowroot and sago. Those types of flour were used for soups, porridges, baking and jellies. Finally bean flour was recommended to be mixed with other types of flour when baking sweet dishes, but it was supposed to be used only in small quantities, yet it helped the dough to rise quickly and made it fluffy.

Housewives were advised not to serve fresh bread, because at least a quarter could be saved if only two-or three-day-old bread was eaten. This bread had to be chewed more carefully and by that it was more filling and better digestible for the stomach. Stale bread should be roasted to make it better digestible and then turned into bread crumbs which could be used in various ways to make soups and stews more substantial and bread cubes could be used to make bread dumplings. My mother remembered those from the 2nd World War, but she much preferred those made of white roles (“Semmeln”) as in traditional Viennese recipes to the dark bread dumplings of the war. Unfortunately, nutritious dried legumes such as lentils or beans were rare during the war because they were reserved for the soldiers at the front, but there were some tips to make the most of them if you were able to get hold of some: The cold water which was used to soak the dried legumes should be used for cooking the legumes slowly in a high pot and to add hot water from time to time to keep the valuable nutrients. In order to make the dish better digestible it could be worked into a puree and most of all, it should only be salted when served. All recipe books further stressed that all types of dried milk powder products and condensed milk was “natural” milk and just as valuable as fresh milk, but deprived of all pathogenic substances. There were recipes for surrogates of sour cream and double-cream which are much used in Viennese cookery. For sour cream you had to mix milk powder or condensed milk with water, vinegar, flour and a little sugar. You could also add a little grated cheese or paprika powder. Instead of whipped double-cream, you had to beat 2 whites of the egg with a little sugar and apple juice in a hot bain-marie. Housewives were also asked to preserve potatoes, when they were available and they did not have the possibility to store them appropriately in a potato box in a cool place because potatoes were the staple nourishment of the Viennese, especially in times of distress. They were to be peeled very thinly and then grated into small flakes and dried on paper in the sun or in the oven and then stored in tightly closed sacks or glass jars for later use.

The focus of war recipes was on vegetables, which the Viennese formerly had only eaten as a side dish. Green vegetables were not supposed to be soaked in water, but only washed under running water to preserve the precious vitamins and minerals and they should always be cooked without a lid to keep the nice green colour. Cabbage, red cabbage and kraut had to be cooked with cumin to reduce their flatulent effects and the white turnips, imported from the neutral Netherlands, were to be cooked like swedes (or rutabagas), which are well-known in Viennese cookery. Vegetable scraps and the green leaves of radishes, swedes or cauliflower should never be thrown away, but kept for soups and vegetable stews. The same was true for the root vegetables necessary for cooking broths and consommés, the “soup greens”. They were to be cooked whole and then added to the broth or turned into vegetable aspics or fish brawn or used in a salad mixed with cooked potatoes and sliced apples. In traditional Viennese recipes soup greens are roasted in fat before added to the water to achieve a nice brown colour of the consommé. This would be a waste of fat in times of need and therefore should be avoided, but a little tomato paste could be added instead for colour.

The wartime recipe booklets furthermore include lots of hints of how to preserve vegetables and fruit for later use. Onions were very expensive, so whenever they could be bought at reasonable prices they were supposed to be cooked and mixed with pork fat and preserved in earthenware pots or glass jars covered with grease-proof parchment paper. Good apple harvests offered a rich source of vitamins for the Viennese and they were advised to always eat them with the skin because just under the peel the most important nutrients are concentrated. Lots of Viennese sweet dishes make use of apples and any left-over scraps such as apple cores and peels were turned into jellies and jams by cooking them for hours together with some sugar (400 grams for 1 litre of juice). Chestnuts were highly recommended as well; roasted, baked or cooked they were mixed into sweet dishes, porridges and vegetable stews and used as a surrogate for cocoa. Oranges were imported from neutral countries and the experts circulated recipes for conserving the orange peels by cooking the finely sliced orange peels without the white inner parts in water until they were soft, then put them in cold water, strain them and then pour sugar water over the orange peels and let them rest overnight. The next day the orange peels were cooked in the sugar water until the peels were transparent and the sugar liquid was viscous. The orange peels were then dried on paper and the syrup kept for further use. A jam made of orange juice, orange peel and apples was recommended for breakfast.

Marianne Stern published in 1918 a war cookery book that concentrated on the preservation of vegetables and fruit with no or very little sugar – sugar had meanwhile become scarce, too. She further included some vegetable, mushroom and meat-surrogate dishes. She stressed the importance of “drying” as a means of preserving fruit and vegetables without sugar, which was nearly unknown in Vienna until then. Furthermore she recommended the use of a cooking crate to save fuel and to work very diligently in the kitchen because any contamination might ruin a conserve, which would be an unnecessary waste in times of food shortages. The summer harvest should be best exploited by preserving as much as possible for later use. Fortunately the war was over before the end of 1918, but the provision of food did not improve quickly and especially the poorer Viennese were suffering from starvation and malnutrition way into 1919/1920. Vegetables were preserved in vinegar or vapour or they were dried. There are interesting recipes for dill in vinegar, salted endives in earthenware pots, carrot and pumpkin compotes, pumpkin jam, mixed pickles made of cauliflower, radish, cucumber, cabbage, carrots and onions, further peas in vinegar, green tomato jam, yellow turnip jam, and asparagus conserved in salty water. Stringy swedes could be dried and used in soups instead of liver and soup greens. Fruit was preserved with no or very little sugar – a procedure that could be very appealing today! Ms Stern offered recipes like apple jelly or apple jam made of frozen apples: if in a cold winter the apples in the cellar got frozen you should not throw them away, but cook them into an apple jam by putting them into cold water first and then cut them before they thaw because only then do they rot. Jam and fruit juice was made of wild berries, such as barberries (Berberitze), sorbs (Eberesche), rosehips (Hagebutte), sloes (Schlehen) and even elderberries (Holunder) were dried. Because the beloved meaty bread spreads were unavailable in Vienna, recipes for alternative spreads such as blueberry and mountain cranberry spread were published. Melons were preserved in vinegar and in vapour, turned into jams and sour pickles. Quinces (Quitten) were very tasty when conserved as quince bread (Quittenkäse): You have to cook them first, then peel them and cut them up before straining them and cooking the quinces with sugar until the mass is really thick, season it with cinnamon, cloves and lemon peel and let it rest in a warm place for a day or more and then keep it between grease-proof paper. Rhubarb and gooseberries (Stachelbeere) were made into wine in the same way as many other fruits. The father of my childhood friend in England, Lynette, still produced wine from fruits in his shed in a London suburb in the 1970s, for instance “banana wine”.

Cheese was rare in the 1st World War in Vienna and the much loved curd was nearly unavailable. Since the Italians had joined the war on the side of the “Entente”, Parmesan cheese was not to be had as well, so cheese was imported from Switzerland and Holland. There was a huge lack of fat, too, during the war. Fat was to be replaced by soup made of soup cubes. Cooking oil and vegetable fat, such as margarine was rare and very expensive as well. Ox kidney fat was used as a surrogate. Baking powder was another innovation that helped housewives to produce good quality dishes and save on eggs, which were expensive and rare. Remains of meals should be turned into new, cheap and tasty dishes, such as soups, salads or sauces by adding some fresh products.

There was not only a lack of food to cope with at that time, but also a lack of heating fuel. The invention of the so-called “cooking crate” was seen as the solution to the problem. There were also so-called “cooking bags” and “self-cookers”, but the cooking crate was the most popular version. The main principle behind the invention was to keep the heat and steam in a cooking pot by enclosing it in a box stuffed with not thermally conductive material, such as hay, wood shavings or wood wool. The box was then tightly closed and the food was cooked slowly for hours in the box without the use of fuel. If necessary, the pot or pots could be taken out again and reheated for a few minutes and then put back again into the box. It was important to keep the lid tightly on the pot to prevent the escape of vapour with it essential nutrients. This procedure was considered as not only fuel efficient, but very healthy and also time efficient because the cook could leave the pots in the cooking crate for hours without the danger of burning the meals. Gisela Urban offered the cooks a table for cooking times of different dishes: usually she suggested a 5-15-minute pre-cooking time on the stove and then 1-3 hours cooking time in the cooking crate depending on the dish: sweet dishes and vegetables around 1-2 hours, legumes and meat 3-4 hours. She additionally included the do-it-yourself manual for a cooking crate of Ms Hedwig Jaitner from Vienna who suggested lining the wooden box with six 3-4 millimetre thick asbestos plates to insulate the box and improve the result. This suggestion is better not put into practice today! During the 2nd World War the Nazis revived this idea and circulated construction manuals for those who no longer had their cooking crates from the 1st World War. Nowadays they are becoming popular again and you can purchase these products online or build them yourself with the help of online manuals. My mother still used to cook rice in a slightly modified way in the 1960s and 1970s by leaving the pot on the stove for about 10 minutes and then wrapping it in a towel and letting it rest in the bed under the duvet. The result was extremely fluffy and well-cooked rice.

All those thrifty recipes came in handy only two decades later, when unfortunately in 1939 the next world war broke out. When Käthe started to work as a cook in England in November 1938, she was not yet restricted by war-induced shortages. She had brought Franz Ruhm’s Viennese cookery book, but she quickly acquired the skills to prepare favourite English dishes, too. She possessed the “Continental Cookery” booklet of Regulo, the producer of “New World Gas Cookers”. Here the names of the recipes are printed in English and German and in the introduction the differences between English and continental cooking are pointed out: More care is taken when cooking vegetables on the continent. It is explained that vegetables and fruit are essential for both adults and children because they contain valuable mineral salts and vitamins, without which the body cannot develop or function properly. The salts being entirely and the vitamins partially soluble in water, it is evident that much value is lost, when vegetables are boiled and the water subsequently thrown away. Some vitamins are soluble in fat, but should a small quantity of fat be used in cooking vegetables, the vitamins are not lost as the fat is absorbed and served with the vegetables. Other vitamins are gradually destroyed by heat. So the English housewife should avoid soaking broken vegetables in water, she should use only little or no water in the cooking and avoid unnecessary long times for cooking. Another advice stresses that if vegetables are served more frequently in England, they need to be made especially attractive by varying the methods of preparation, the texture and appearance of the cooked food. Included in the booklet are recipes for cauliflower with crust, red cabbage, Bavarian cabbage, pancakes with asparagus, baked beetroots and also typical Viennese dishes such as “brain rissoles” (Hirnschnitten).

The outbreak of the 2nd World War then had a huge impact on the kitchens and meals of the English. In Germany as well as in England the language used with relation to food and cooking became patriotic and even nationalistic, e.g. food was “ammunition for war” because without it soldiers could not fight and civilians could not contribute to their nation’s “war machine”. Even ordinary people on the home front had to be sustained, so for Britain food imports were essential, but again in the 2nd World War, the sea became a battleground as the German submarines targeted ships carrying vital consignments of food. Therefore the English were compelled not to waste any imported food once it had arrived safely. Already in the 1st World War it had become obvious how vulnerable Britain was to attacks on merchant shipping, although the English were not as deprived of food as the Austrians. But with supplies from abroad again threatened, the English had to exploit more fully what could be grown and produced in the country. The “Dig for Victory” campaign of the government encouraged the conversion of parks, playing grounds, railway embankments and flower beds into vegetable patches. Women replaced male farm workers and were mobilised in the “Women’s Land Army” and “Land Girls” were conscripted from towns and villages. These agricultural efforts tried to increase the British food production to make Britain more resilient. Another aspect of the British strategy was to fairly share what was produced to avoid a civil crisis that would pit the wealthy against the poor in purchasing ever more expensive food items. In January 1940 food rationing was introduced and the Ministry of Food, which had been established in World War I, was resurrected to administer rationing and distribute food evenly across the population. Ration books were sent out to every household, which allowed the buying of strictly limited quantities of rationed foodstuffs. The personal weekly allowances of items like meat, butter, cheese, sugar and tea varied during the war. People had to register at local shops, from where they were required to buy rationed food and as a consequence exhausting queues became a characteristic of daily life during the war again. The black market for rationed goods thrived despite harsh penalties for buyers and sellers. Even sharing rationed goods beyond the household was forbidden. The third main aim of the Ministry of Food, apart from self-sufficiency and rationing, was stretching food supplies to the limit in households.

Public information leaflets and radio shows advertised combinations of rationed and non-rationed foodstuff. Popular cooks like Marguerite Patten tried to inspire and convince English housewives of new forms of preparing family meals. Recipe booklets advocated substitutes for missing ingredients, such as eggless cakes, or honey as a sweetener, rabbit as a substitute for strictly rationed other meat. New vegetarian creations were promoted like “Lord Woolton Pie” (named after the Minister of Food), filled with swedes, cauliflower, onions and carrots and blended with oats and topped with a potato crust. The wholemeal “National Loaf” of bread, which was not rationed, was not much loved because the people missed their white bread. The administration further tried to convince the English of the public health benefits of the wartime diet with less fat and more fibre. In a patronising way the message was imposed on the population in the form of “Dr. Carrot” and “Potato Pete”. The population was also advised to run their households economically and by no means to waste any food scraps. Official advice was to clean dishes just once or twice a day in big batches to save fuel. The wartime recipes published by the Ministry of Food tried to keep the British from hunger during the war and even beyond the war’s end, when the population had to live through further years of rationing and austerity. The poor were used to struggles for food and they therefore did not need to be told how to make the most of their supplies. Unfortunately only the wealthiest were still able to purchase non-rationed foodstuffs to a large extent.

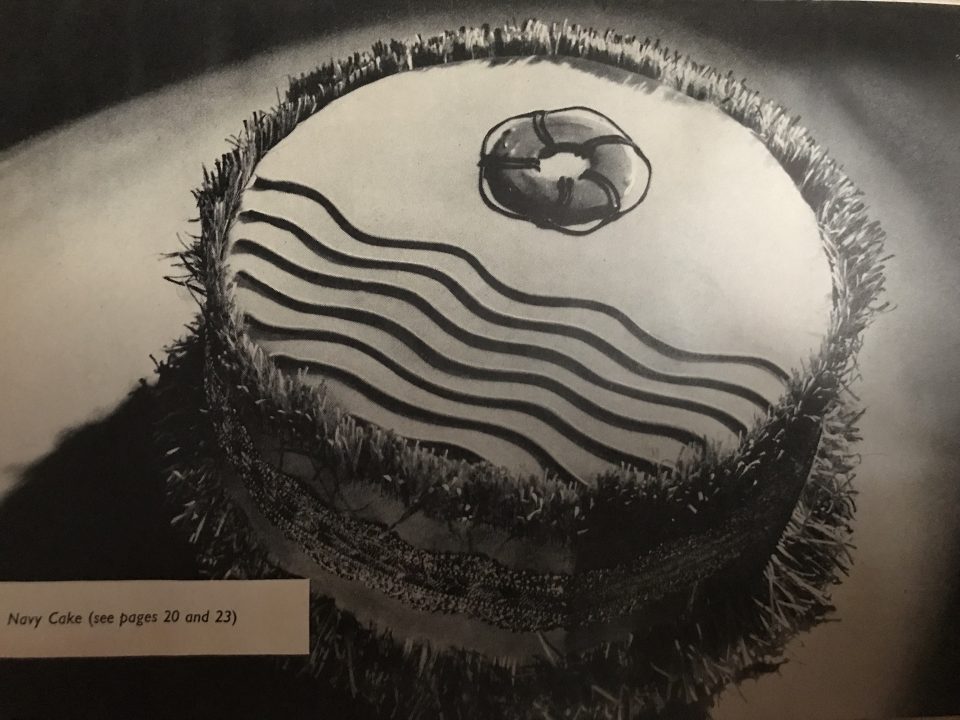

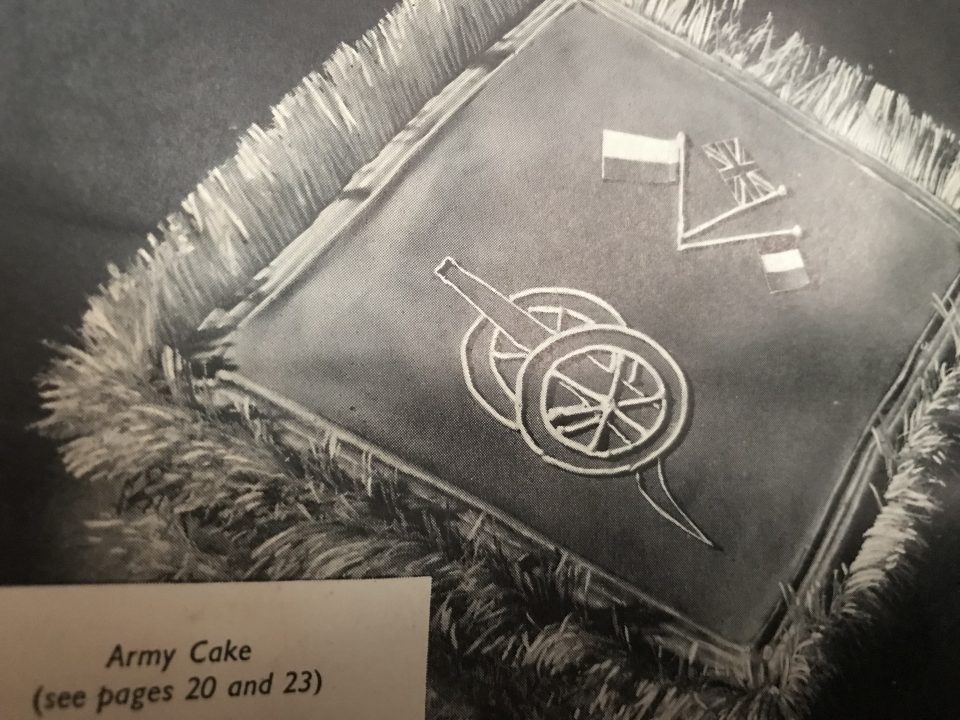

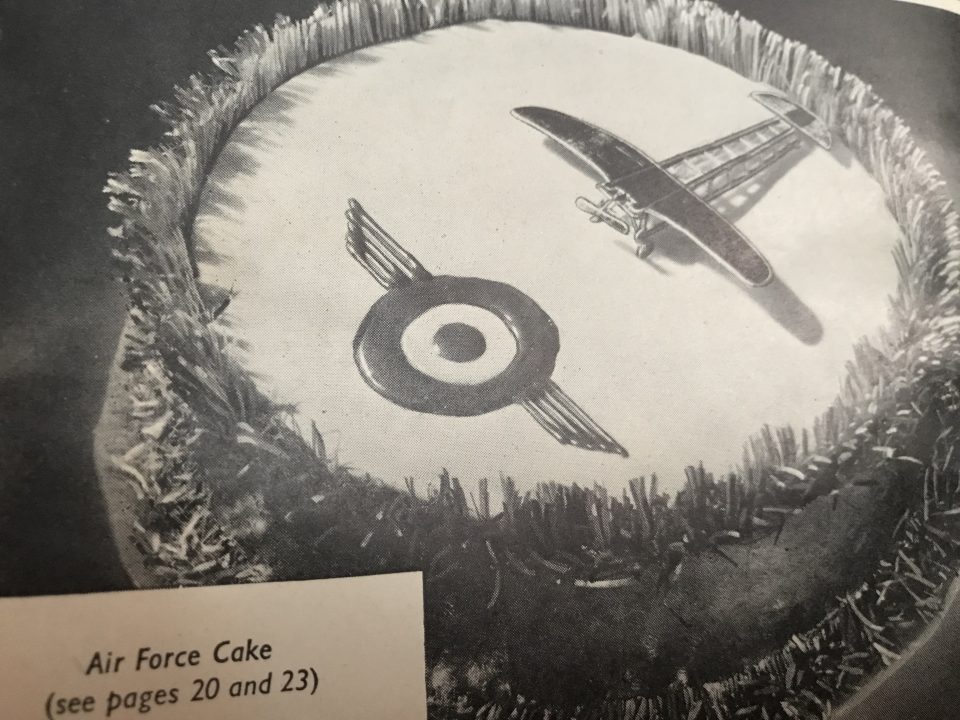

The wartime recipe booklets advised how to plan meals to suit wartime supplies and how to economize. Some households had grown by taking in children from other families, whereas other households had shrunk. The booklets catered for all those people, even the “forlorn grass-widower” who had to do the cooking and the washing up. There was advice how to save your dinner if air raids come and how to make “Emergency Bread” at home. Another chapter concentrated on the baking of cakes with less fruit and with alternatives to sugar; even wartime Christmas and party cakes to be sent to the soldiers in the field were illustrated with icing and decoration.

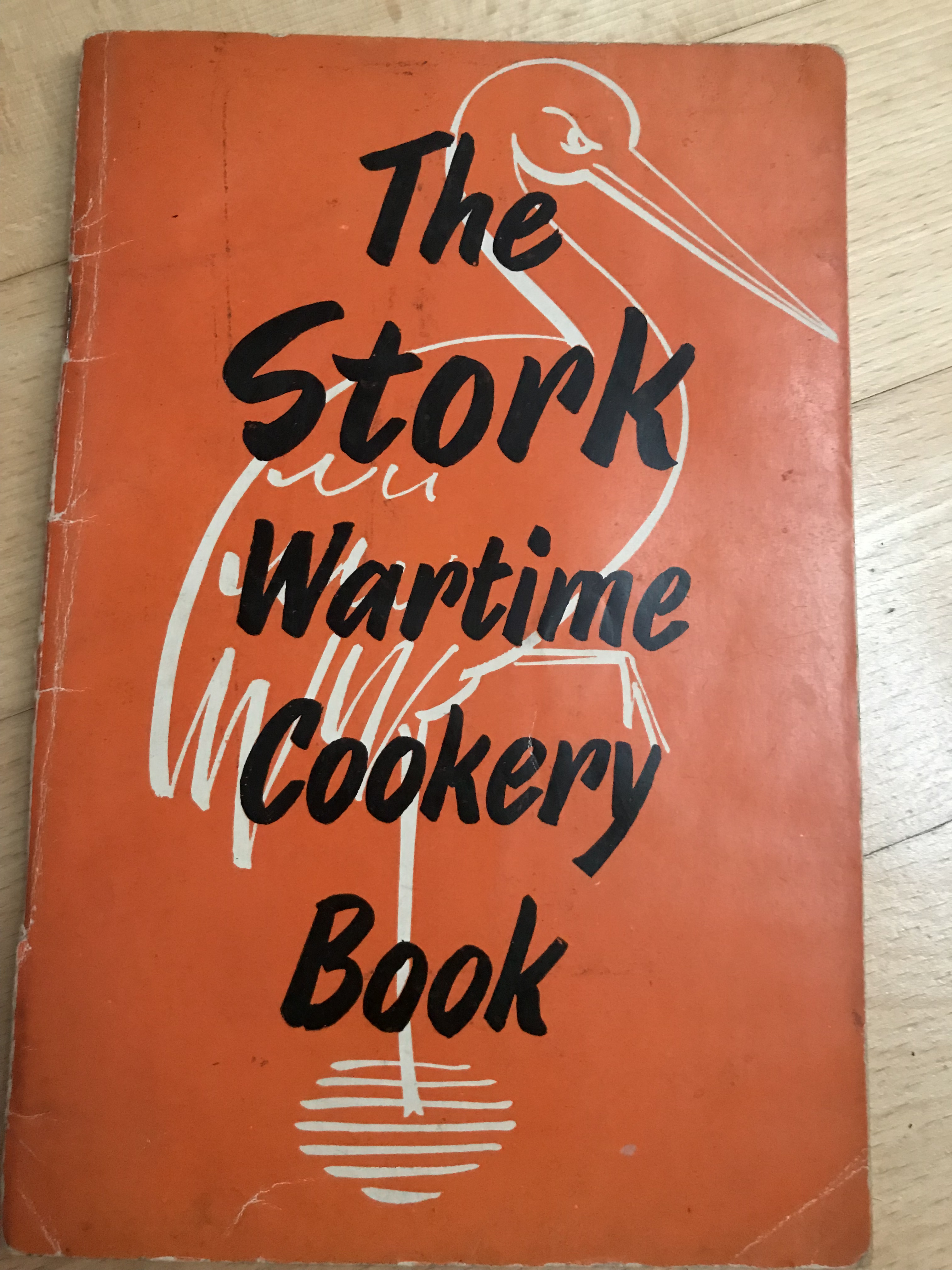

Stork margarine published recipes of puddings, creams and pastry made with margarine, which “cost very little and provided valuable vitamins in an easily digested and delicious form”. In “The Stork Wartime Cookery Book” Susan Croft reported interesting episodes that illustrated the state of affairs in wartime England: “I have heard many stories about evacuated children (some of them sad, most of them funny), and many of the women who write to me for advice about their cookery difficulties have asked how they are to feed town children: They don’t like vegetables and they won’t eat soup, these women say. In fact, they don’t seem to like anything but fish and chips and bread and jam.” They are advised to offer them a good hot dish with plenty of gravy in it and a slice of bread with Stork margarine. As meat was becoming scarce even in Britain, recipes with liver, sweetbreads (Bries), tripe (Kutteln) and kidneys were published, as well as cooking “a neck of mutton or knuckle of veal slowly with vegetables, herbs and condiments, so that the result is a richly flavoured stew with savoury gravy”. The chapter “A few elementary directions for grass widowers” include amusing instructions like “How to cook eggs and bacon; How to make tea; How to boil potatoes; How to cook sausages”. Another chapter focusses on scrap-saving and how to make up scraps into nice dishes and how to economize fuel in cooking by planning meals so that they can be cooked either on top of the stove or in the oven. Here we find more or less the same instruction for how to use stale bread for bread crumbs in meals that we already found in the Viennese war recipes of the 1st World War. Advice for cooking vegetables resembles a little the benefits of the cooking crate: “Cook the vegetables with Stork margarine and a few tablespoonful of water….Serve the vegetables with the liquid they have been cooked in. The lid of the saucepan must fit tightly, so that none of the steam escapes. Put a sheet of greaseproof paper under the lid, if necessary, to make it fit closely”. The booklet closes with how to make the most of tinned food and how to cook savoury sauces “to make wartime food more interesting”.

The Good Housekeeping Institute pointed out that “It is only recently that we as a nation have become really conscious of the full value of vegetables, and even now do not always serve them as freely as we should. Now that there are fewer imported fruits on the market the value of vegetables can hardly be overrated. For the main meal of the day, try serving two or even three vegetables instead of one, or make them into a vegetable hotpot or pie covered with mashed potatoes….. Remember also to avoid overcooking vegetables…. Remember also only to use a small amount of liquid for boiling vegetables in order to minimise losses of mineral salts. Any liquid left over should be used for soups, sauces, or gravy….. Cereals such as bread, flour, rice, oatmeal, etc. are among the least expensive foods. They provide the body with heat and energy at minimum cost… Potatoes are one of the most useful of energy foods, since they need not only be served plain boiled, mashed, roasted, but blend so well with many other ingredients to make a substantial dish. To save losses due to wasteful peeling, it is important to boil or steam potatoes in their skins. Mineral losses will be reduced.”

The measures regarding food provisions, rationing and guidelines for housewives taken by the governments in times of war were more or less the same in both world wars and on both sides of the military front. But one can say that the food supply on the home front was deteriorating fast in Vienna and Austria in the course of both world wars so that towards the end in 1918 and 1945 especially the urban populations were on the brink of starvation, whereas in England and Great Britain the status of nourishment of civilians was far better and despite deprivations they did not suffer from famine because England was not so completely cut off from imports as Nazi Germany was, although Germany had already started to prepare for war in 1933 when Hitler took power. The German Nazis had taken into account the consequences of declaring war for the food supply in the German territory and future occupied areas and had started planning rationing, the distribution of ration books and the boosting of local production to avoid an excessive dependence on imports from overseas producers long before the start of World War II. Most of all, foreign currency was not to be spent on nourishment, but on weapons. So, when Hitler declared war on France and Great Britain in September 1939, the German regime for food supply and rationing in wartime was already in place. Even the thrifty wartime recipe booklets must have been written and printed long before the declaration of war because they were distributed immediately at the beginning of September 1939. The efficient and ever-present Nazi propaganda machine set in at once, advertising the consumption of German “patriotic” food like one-pot stews of potatoes, cabbage and turnips and the abandonment of meat and fat products in favour of vegetable products. In autumn and winter 1939 foodstuffs were still abundant on the home front and households could purchase what was in their ration books, but that changed quickly. Nationalistic films, radio shows, women’s magazines and newspapers propagated from the start thriftiness, the avoidance of waste and a radical change of diet from meat- and sausage-based meals to vegetarian dishes. The farmers were ordered to produce for wartime needs and make as much as possible available for military and civilian nourishment. German actresses like Brigitte Mira, Gisela Schlüter and Ursula Herking did not hesitate to work for the Nazis in propaganda films promoting meatless recipes and the consumption of foodstuffs that could be produced in Germany, distributed by organisations like the “Deutsche Frauenwerk” (German Women’s Welfare) or the “Reichsausschuss für volkswirtschaftliche Aufklärung” (The Reich’s Committee for Economic Enlightenment) and the “Reichsnährstand Blut und Boden” (The Reich’s Foodsupply Blood and Soil). The propaganda campaign was well prepared and skilfully planned: it warned for instance against the consumption of coffee, trying to convince the population that malt coffee produced in Germany was much healthier and better; it even stated that “bean coffee has never been a people’s drink”. Yet important party members always had sufficient quantities of excellent bean coffee at their disposal until the end of the war! The surrogate coffee made of malt, barley, rye and chicory with the brand name “Linde” was popular in Austria even after the war because the “Linde” offered little plastic animals as an in-pack in their packages in the 1950s and 1960s which many children wanted to collect. My mother used to mix a spoonful of “Linde” with bean coffee whether she prepared coffee in a percolator or in a filter coffeemaker. A similar surrogate coffee brand was “Caro Kaffee”, an instant grain coffee, mostly drunk by children in the after-war years for breakfast or tea.

1940 was the first year of a flourishing black market in foodstuffs in the “Third Reich” as a consequence of the Nazi war economy. Vital products of daily use were price-fixed, so there was more money in circulation than supply of foodstuffs, which resulted in strict rationing. This consequently led to a diversion of money to the black market, where prices now rose excessively. Lots of newspaper articles were published as a deterrent about the harsh punishments black market traders faced – buyers and sellers alike, but to no avail. The Nazis could no longer hide the fact that there was a lack of basic foodstuffs because the rations were the same as at the beginning of the war, but the products were unavailable. The harvest was bad and more appeals to thriftiness advised people to rinse every cooking pot and use the water for soups etc. before washing it and to collect potato skins and nutshells for heating ovens and to collect eggshells for fertilising the vegetable patches. 1940 was declared the “Year of the potato, the most German of all foodstuffs” by the Nazis. Potatoes was used as a substitute for all types of missing victuals and turned into dishes, such as sour potatoes, potato stew, potato casserole, potato noodles and dumplings, potato cake, potato wafers and fake fried eggs made of potatoes (a mashed potato- buttermilk pulp is baked in the oven in the form of fried eggs and then topped with a mixture of tomato paste and cooked vegetable scraps representing the yoke of the egg).

The food situation deteriorated drastically in 1941. Nevertheless, the Nazis celebrated two years’ of rationing by comparing the current “satisfactory situation” to the supposedly much worse conditions during the First World War and, of course, in the enemy countries. The Nazi propaganda stressed that the German blockade had the most dramatic effects on the food supply in England and the Nazis told their soldiers at the front, that their families at home were only deprived of coffee, tobacco and some rare delicacies, and everybody was happy to renounce those for the sake of the well-being of the soldiers at the front. There were probably still lots of people who believed that lie, but they became fewer and fewer. The grocers had to introduce lists of customers for fruit, vegetables and potatoes, but this had no effect on the long queues. For the first time large amounts of frozen fruit and vegetables came on the market together with dried vegetables, which many knew already from the First World War. But the Nazis tried to convince the population that their dried vegetables were of much superior quality, yet they were called “barbed wire” by the people. Low-quality clarified butter was brought on the market with instructions for housewives how to use it. Moreover housewives were asked only to put wholemeal bread made of oat and rye on the family table because who ate white bread – which was unavailable anyway – would lose their teeth quickly, the ads said.

The rations of flour, fat and meat were cut drastically again, e.g. in 1939 there were still 700 grams of meat for a “regular consumer” and in June 1941 there were only 400 grams. The Nazis explained the reduction with the need of feeding prisoners of war and “foreign workers” – meaning slave labour. In 1942 the Nazis could not hide their military defeats from the population anymore and women were recruited at home for the war industry – also my grandmother Lola had to work in the armaments industry. So women had no longer time to prepare family meals when working ten hours a day in a factory. The new cookery books published under titles like “”Trotz wenig Zeit-gut gekocht” (Despite little time – well cooked) were adapted to these new conditions and offered mostly recipes for bread spreads, cold meals and salads. There was bread, although not enough, but no spreads: there was no butter and very little cheese, cold cuts or sausage, so spreads had to be made at home. The new recipes included spreads made of potatoes, innards, root vegetables and oat flakes. A honey surrogate was made of grated apples and buttermilk. Now vegetables and fruit were declared “scarce foodstuffs”, too, and were distributed only after a special announcement in the newspapers. Per week the ration of a “regular consumer” was reduced to 2,000 grams of bread, 206 grams of fat and 300 grams of meat – if the foodstuffs could be found in the shops! Like in England parks, playgrounds and lawns were converted into vegetable patches and the housewives were required to unearth their cooking crates from the 1st World War or build new ones themselves to save fuel. Meat was virtually unavailable and that’s why now meat surrogate recipes abounded. They were called “Bratlinge” (“fried stuff”) and were made of lentils, oat flakes, barley groats (Gerstengrütze) or pearl barley (Graupen) and shaped like a burger and then fried. Other recipes suggested making varieties of “Bratlinge” from mixtures of sauerkraut and potatoes or from swedes, celery, pumpkin, cabbage or sorrel (Sauerrampfer) and some grain, flour or breadcrumbs. These recipes could be an inspiration for modern-day vegan meals and barbecues.

Yet it has to be mentioned that the deprivation the population living on the territory of the so-called “Third Reich” had to face in those years was nothing compared to the hardships the millions of prisoners of war, slave workers and concentration camp workers had to endure with respect to their nourishment. Of the nearly six million slave workers from the Soviet Union more than three million died of malnourishment, diseases and exploitation, not to speak of the millions of concentration camp prisoners. The authorities fixed the necessary amount of calories per day for Germans at 2,100 calories (this amount was never achieved from 1943 on!), for “foreigners” at 1,200 calories, but for Poles and Russians at 600 and for Jews at 150 calories – this referred to Jews that were exploited as slave labour in the armaments industry and were rented out to enterprises at six marks per day. The rations in the concentration camps, like for instance “Theresienstadt”, where my great-grandparents, Ignaz and Leopoldine Sobotka, were interned, were even further reduced drastically: approximately one litre of soup (warm water without vegetables, legumes or potatoes) and 300 grams of bread per day.

Children were involved in the war effort from the start of the war, too. They were absorbed by the Nazi propaganda machine, squeezed into uniforms and allowed to “play war” for real in the German “Hitler Youth”. They were sent to the streets to collect money for “Winter Aid” and the schools organised the collection of all types of war-relevant material. Nothing was to be thrown away: the children were even ordered to collect bones, which were turned into soap. In a newspaper article the authorities complained that some children soaked the bones in water before they handed them over to be weighed and by that achieved more weight, which was considered “unpatriotic cheating”. Also in the “Third Reich” children were evacuated and sent to the countryside, just as in England, but there was a political motive behind those “Kinderlandverschickungen” (KLV for “children evacuation programme”) because many of the children were taken away from their parents and collectively indoctrinated in children’s homes, castles, monasteries and hotels that were requisitioned by the Nazis for such “KLV camps”. By that the children were withdrawn from the influence of their parents and were turned into willing soldiers for the Nazis. In the end they were even prepared to denounce their own parents. Between 1941 and 1944 more than 800,000 children were “evacuated” in this way. My father, Werner Tautz, came via the KLV programme from Silesia to a small village in Lower Austria, but he was extremely lucky because he was taken in by a caring family that later became his foster family. There he never suffered any food shortages during the war because his foster mother, Anna Rupp, ran a small farm and grew everything that the family needed herself, raised pigs, held bees and a cow.

In 1943 the situation on the home front had deteriorated to the extent that everything which was made of copper had to be handed over to the authorities, including cooking pots. The stealing of cabbage from vegetable patches was persecuted and poultry thieves were even sentenced to death. The queues in front of the grocery shops diminished because there was nothing to purchase, so queuing was a waste of time. New instructions in 1944 of how to simplify and reduce the household chores were futile, because there was nothing left to cook. The “Vitamin C Campaign” for miners was a joke – it consisted of a weekly role of vitamin lozenges. Vegetables were to be cooked without fat and the production of anything made of sugar was prohibited. More death sentences were passed for crimes against the war economy, such as black market trading of food or stealing foodstuff. Many of the judges who pronounced those absurd verdicts were still allowed to dispense justice after the end of the war. When the allied airplanes dropped ration books on the cities of the “Third Reich”, the people grabbed them and tried to use them because the food situation was really dramatic. The Nazis threatened that those who made use of those “allied” ration books would be sentenced to death, but even this deterrent did no longer work becaue the people were suffering from famine. In December 1944 an ironic announcement was published in the newspapers that those who had no more ration stamps in their ration books would not receive the extra double ration for Christmas, but no one had any ration stamps left. Foodstuffs had meanwhile disappeared in party offices and on the black market. Children were asked to collect acorns, which were roasted, then peeled and the core cooked in salty water to take away the bitter taste. Then the acorns were dried and minced and used as acorn flour, which could be half mixed with any other flour. The experts advised housewives to make surrogate coffee from acorns or crisp bread and even a vegan form of black pudding (made out of acorn flour, potatoes, onions and bread) was recommended. Furthermore, women and children were now ordered to collect wild herbs, mushrooms and berries because the “war will be won in the cooking pot” and new recipes were delivered together with this appeal. Some of them sound really interesting and might have already become a staple of today’s organic or vegan cookery, such as sorrel soup, dandelion (Löwenzahn) salad, daisy (Gänseblümchen) salad, stinging nettle (Brennessel) casserole, stew of chickweed (Vogelmiere), hop sprout (Hopfensprossen) salad, rosehip soup and elderberry soup. Some of these thrifty dishes of the difficult times of food shortages during World War I & II might offer unexpected inspirations for today’s Viennese cookery and might produce surprising, healthy and tasty results. Bon appétit!

Literature:

Wiener Kochrezepte für die Kriegszeit, Wien 1916

Gisela Urban, Unsere Kriegskost, Wien 1916

Marianne Stern, Zeitgemäße Kriegsküche. Obst-und Gemüserezepte, Wien 1918

Susan Croft, The Stork Wartime Cookery Book

Good Housekeeping’s Book of Thrifty War-time Recipes

Good Housekeeping’s New War-time Recipes

Continental Cookery with the Regulo. Vegetables and Savouries

Ingrid Haslinger, Die Wiener Küche. Kulturgeschichte und Rezepte, Wien Mandelbaum Verlag 2018

Victory in the Kitchen, IWM 2017

Rainer Horbelt ua, Tante Linas Kriegskochbuch, Bechtermünz Verlag 2004