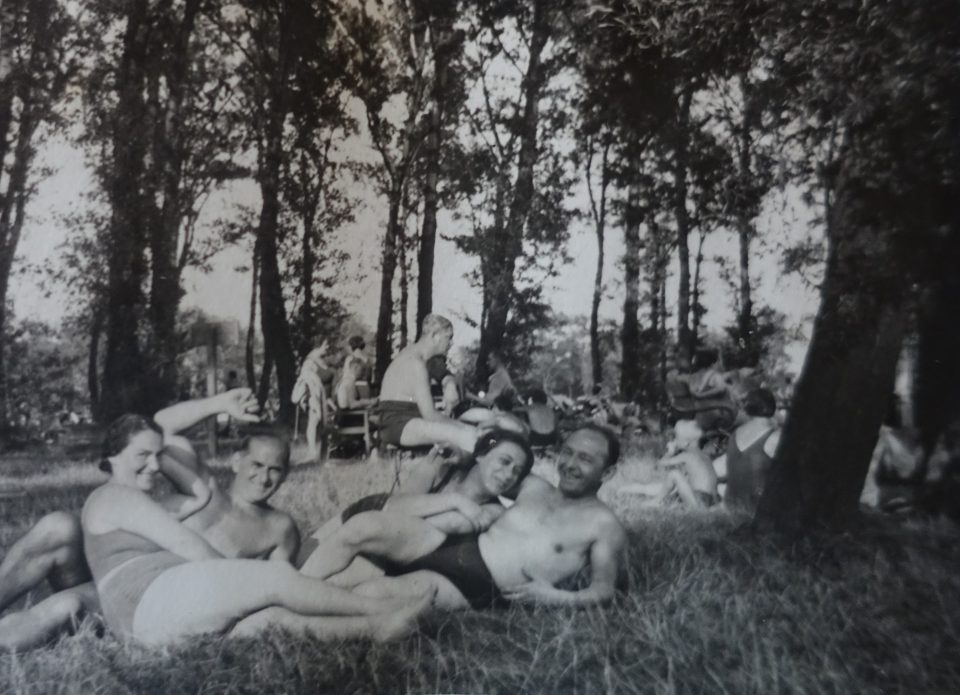

Picknick in the Vienna Wood, June 1931

A stroll in the “Prater” alluvial forest, autumn 1931

Photography was a popular and even if expensive, nevertheless an affordable hobby of the Viennese workers and the petite bourgeoisie in the first half of the 20th century. My grandfather Toni Kainz, a trained cook and waiter, innkeeper, tenant of a coffee house and fish monger, my great-uncle Karl Elzholz, a mechanic at the Viennese tramways, and my father Werner Tautz, an electrician, took many photos in and around Vienna documenting the leisure time activities of family and friends in the nature areas in the vicinity of Vienna. These photographic documents form the basis of this article which focuses on how the Viennese working class and lower middle class spent their leisure time in the extensive natural landscapes of the city in the first half of the 20th century with a special focus on the Vienna Wood and the Danube.

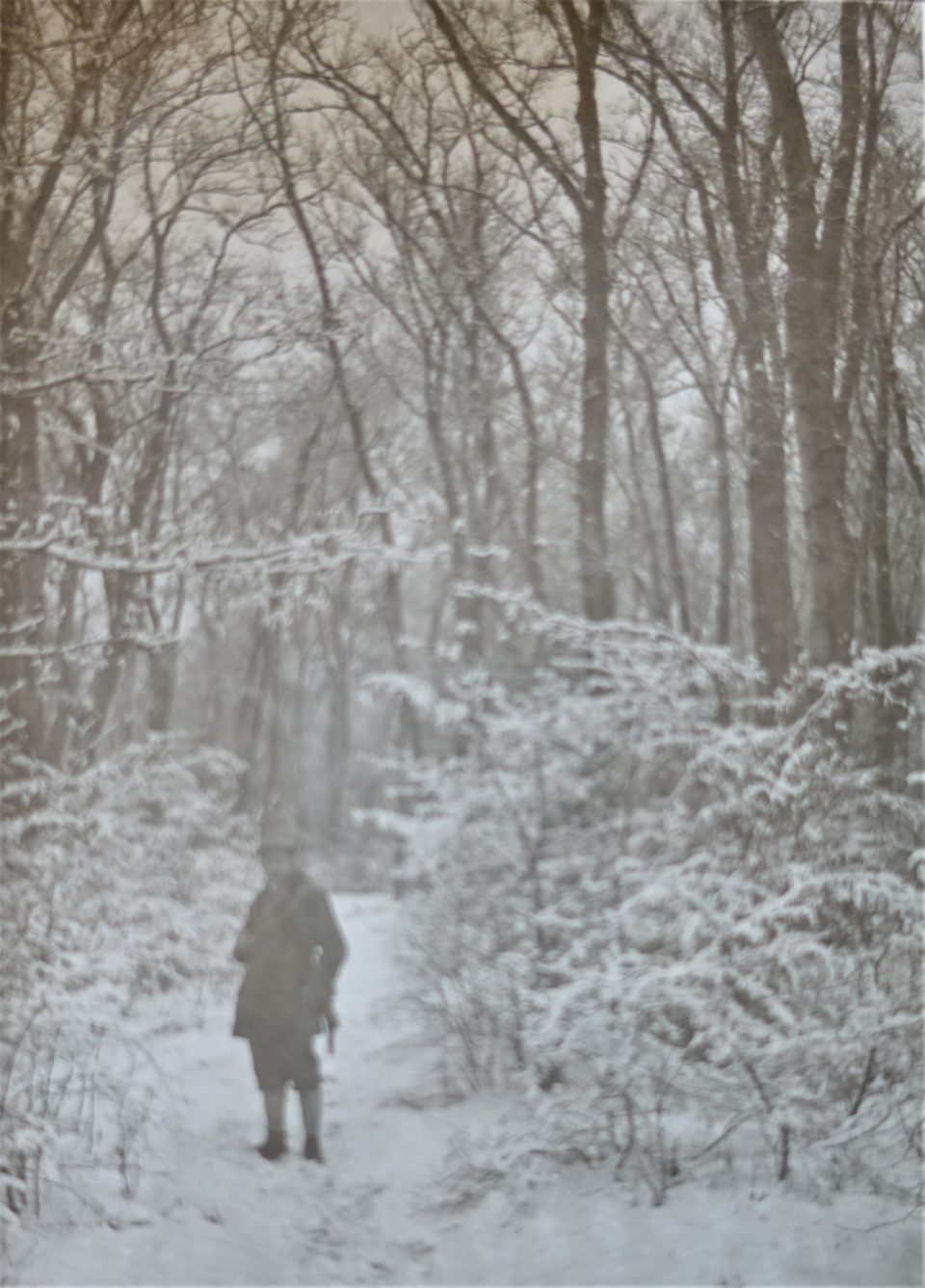

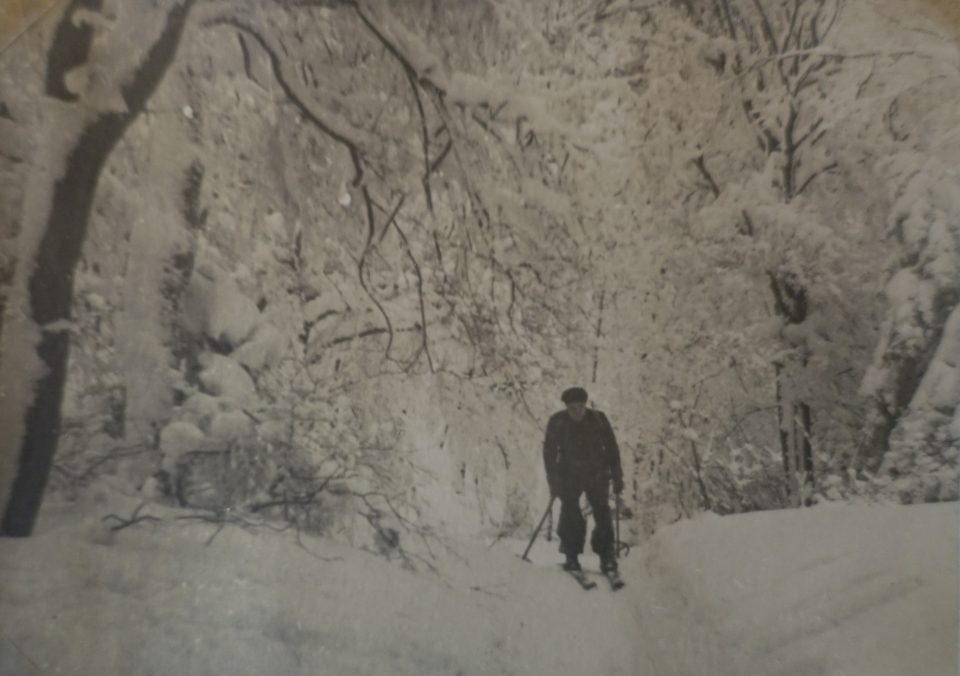

Vienna Wood in the winter of 1932

In the course of the 19th century social norms changed in Vienna whereby some social restrictions were eased, which meant that even low-income social groups could decide on their own how they would like to spend their rare free time. Some of the obligatory religious rituals were abolished due to the influence of the ideas of Enlightenment at the end of the 18th century. The large number of religious holidays which obliged people to participate in the respective Roman Catholic ceremonies were drastically reduced and some of the rigid controls of brotherhoods, guilds and professional trade associations, which had had a tight grip on the leisure time activities of their members and their whole households, were lifted. Festivities, even religious ones, were now more often celebrated with family and friends.

Until the 19th century the poorer classes often had to overcome nearly unsurmountable hurdles in setting up a family of their own. They needed a marriage permission from their master, landlord or employer, yet they usually lacked the means for supporting a family anyway. With the onset of industrialisations servants, maids, apprentices and guild members were no longer part of a household or tightly involved in professional organisations and could decide independently how to spend their leisure time. That’s why in the first half of the 19th century a large number of new places of amusement for the lower classes were established in Vienna; especially in the Viennese suburbs, where inns offered food and drinks in beer gardens and invited dance orchestras to play on Sundays (see article: “Viennese Suburban Inns”). These musical groups and small orchestras made the “Viennese Walz“ popular, so that a veritable “dance fever“ seized all social classes in Vienna in the 19th century. Traditional suburban inns erected large dance halls and some pubs on the outskirts of Vienna were turned into entertainment parks with swings, slides, carrousels, boats on artificial lakes and „chambres séparées“; for example in the „Kolosseum“ in Jägerstrasse (Brigittenau) “chambres séparées” were installed inside a wooden elephant. Indoor swimming pools were constructed, which could be covered and turned into ball rooms in winter, for example the “Sophienbad” in Marxergasse (Landstrasse) and the old “Dianabad” in Obere Donaustrasse (Leopoldstadt). The biggest dance hall of the time was the “Odeon” in Leopoldstadt, which could welcome 8,000 dancers. Especially during the Carnival season, the dance halls were crowded with people of the middle and lower classes.

Emperor Joseph II opened the Imperial hunting grounds in the “Prater” to the public at the end of the 18th century and soon on the grounds of this alluvial forest at the Danube pubs, coffee houses, “Pulcinella” (“Kasperl”) theatres opened and the family Stuwer staged elaborate fireworks. At the onset of industrialisation and its polluting consequences not just the well-to-do, but also the poorer classes discovered a yearning for natural landscapes and tried to flee the stifling city with its tightness, stench, noise and dust. An excursion into nature, the “Landpartie”, was the most favourite spare time activity of the lower classes on Sunday. In the first half of the 19th century the suburbs to the north and west, the Vienna Wood, could easily be reached via regular public coach services, the “Zeiserlwagen” and from there the people hiked up Leopoldsberg or Kahlenberg, for example. The well-to-do Viennese bought or rented small summer houses for spending the hot summer months in a natural surrounding in the vicinity of Vienna. As soon as tramways and railways were available, they transported the Viennese to their favourite natural landscapes for outings or the richer classes to their summer retreats (“Sommerfrische”).

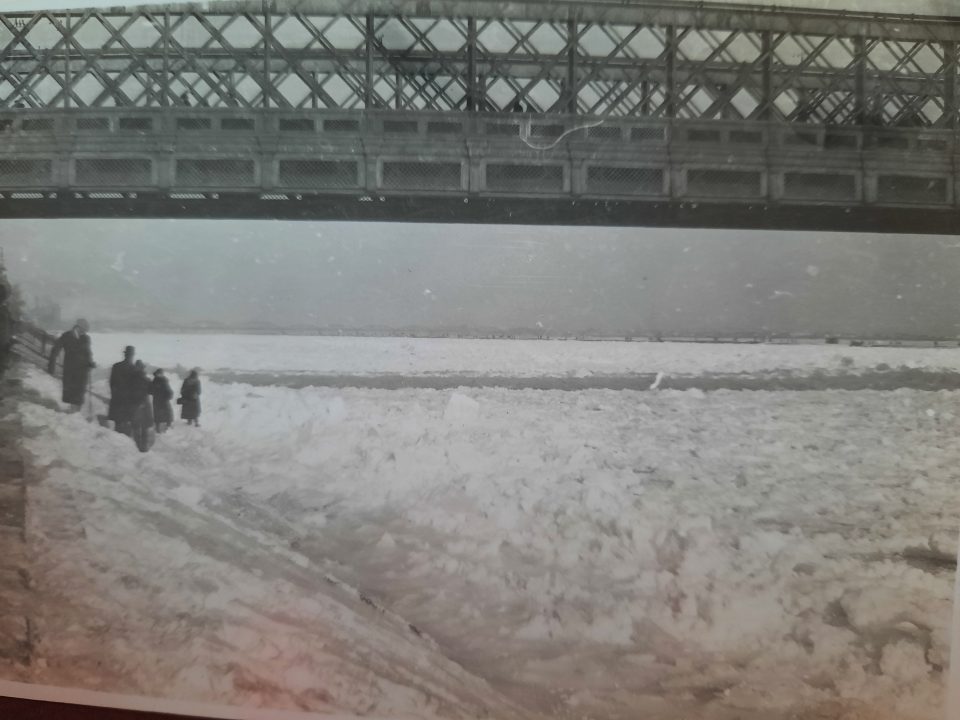

Before the regulation of the Danube, the river separated into four river branches after the narrow section between Leopoldsberg and Bisamberg, west of the city. The southernmost arm, the Danube Canal (“Donaukanal”), was used for shipping goods to the city centre and was in some way regulated since the 16th century in order to keep it close to the city. The other three arms formed the alluvial landscape, which created islands that continually changed their form after every inundation. This part of the Danube could not be used for transport. The areas of Leopoldstadt (today’s 2nd district), Roßau (today’s 9th district) or Weißgerbervorstadt (today’s 3rd district) were continually threatened by catastrophic floods and the much-feared ice jam in winter. After one of the biggest ice jams in 1862 it was decided to undertake a complete regulation of the Danube in Vienna.

Ice jam on the Danube in Vienna in 1929: photos taken by my great-uncle Karl Elzholz

The regulation of the Danube, which was begun in 1870, created a new riverbed for the Danube and a large inundation area of nearly half a kilometre. The dug-up material was used for enforcing the banks of the Danube facing the city and for filling up old stagnant arms of the river. In that way 260 ha (1 hectare = 10,000 square metres) marshland were turned into building ground for the city. The old main arm of the river was now cut off from the Danube and was turned into the recreational area “Alte Donau” (“Old Danube”), a body of still water. In 1875 the newly regulated river was opened for transport and an attempt was made to combat the recurring floods of the Danube Canal by erecting a lock at Nussdorf, which was reinforced in the 1890s. The remains of the “Kaiserbad” lock can still be seen today, namely the “Schützenhaus” designed by Otto Wagner on the Danube Canal. The so far almost impassable marshland of the Danube was now a much-needed area of settlement for the growing population. In 1900 the Danube Island, which comprised the district Leopoldstadt, was divided into two districts, the 2nd and the 20th district. In the area north of the Danube four communities formed the city of Floridsdorf in 1894, an urban area which was so big that a concept saw it as the future capital of Lower Austria, yet Floridsdorf was incorporated in the city of Vienna in 1904/05 as the 21st district.

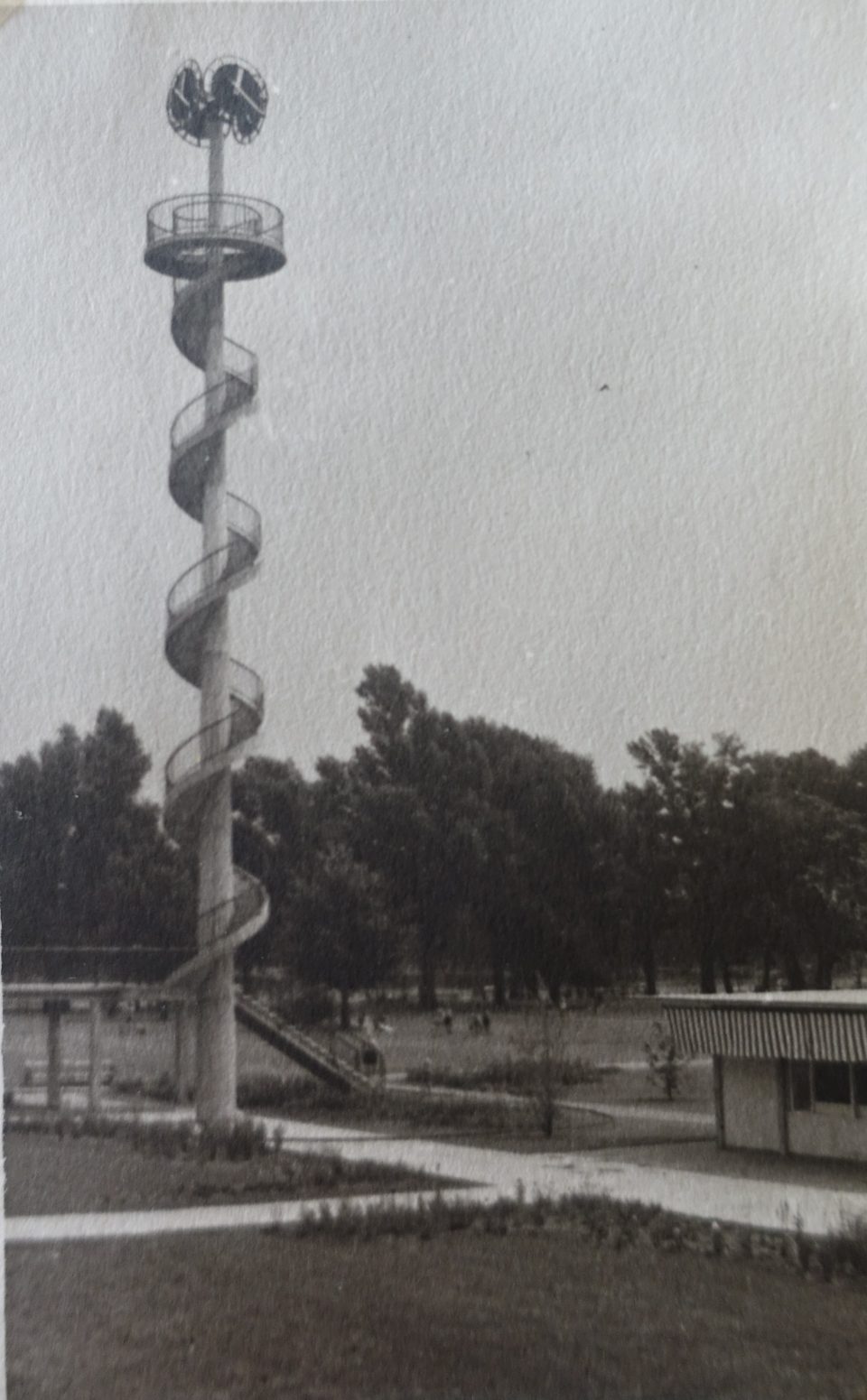

Technical innovations in the sector of leisure time activities for the lower classes in Vienna – and not just for them – were installed in the alluvial forest of the “Prater”. In 1895 the entrepreneur Gabor Steiner established the fun park “Venice in Vienna” on a large area of the “Prater “with copies of Venetian palaces, canals with gondolas, artificial lakes, theatres, water slides and toboggan runs. Steiner constantly modernised his fun park and added new attractions, looking for inspirations in London and Chicago. Following different mottos, he designed a “Flower City”, the “Electrical City” or copies of Spanish, Japanese and Egyptian cityscapes. In 1897 the “Riesenrad” (Giant Wheel) was built by the London engineer Cecil Booth of the company Maudslay, Sons and Fields. At that time 30 wagons were attached to the wheel; only after the Second World War the number was reduced to 15. The Giant Wheel survived both World Wars, while “Venice in Vienna” did not reopen after the First World War.

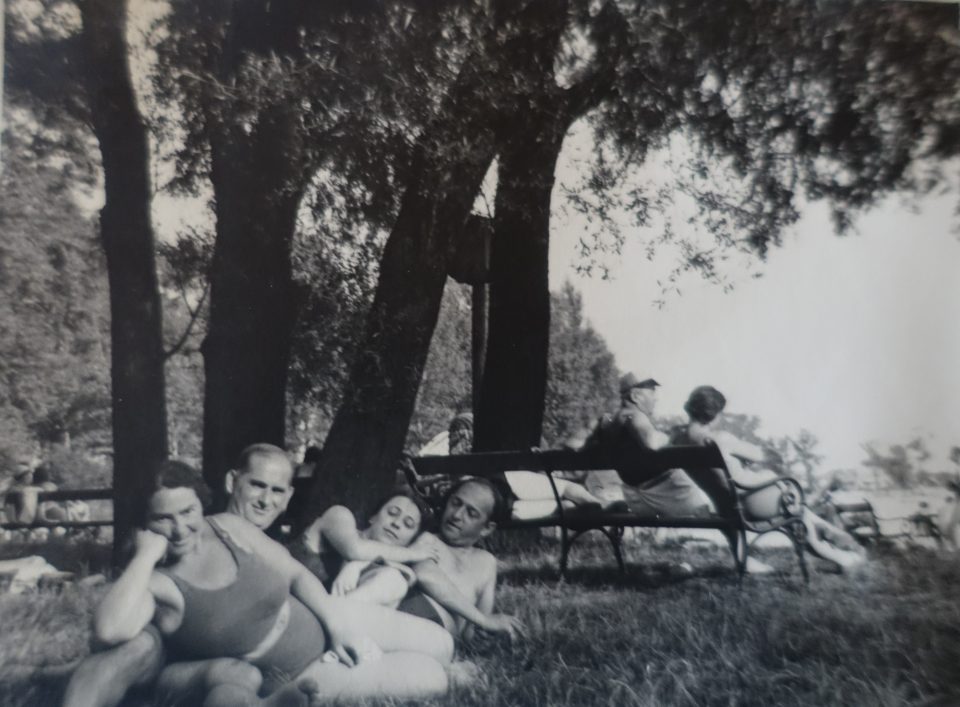

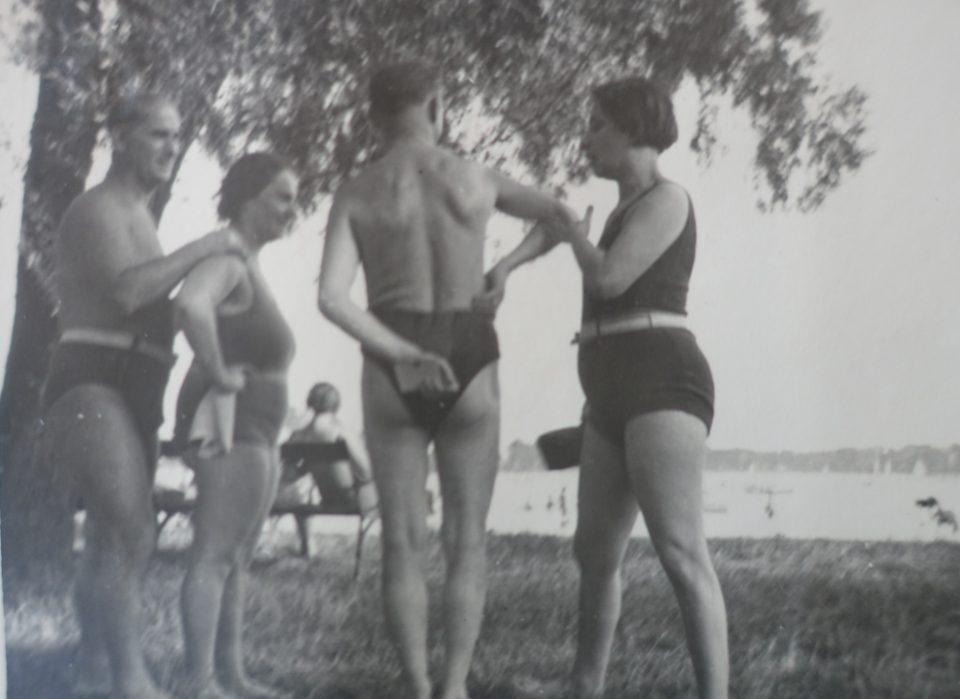

Around 1900 a new form of body-awareness became widespread among the youth of all layers of Viennese society and during the Austrian First Republic (1918-1934) this trend was leveraged. After many decades of prudishness, a renaissance of the human body was celebrated on posters, in cinemas, at sports facilities, in dance halls, public swimming pools and in the natural surrounding of Vienna. The Roman Catholic Church vehemently protested against this new openness, the “mixing of men and women” involved in sports and outdoor activities and the new “frivolous” male and female sportswear. The Church railed against this “new body culture” of the Socialdemocratic youth, but in the end the bishops had to give in, because the Catholic sports organisations indulged in the same “new body culture” in public swimming pools and mixed sports associations. The young flocked to Socialdemocratic or Conservative sports clubs, which offered common outdoor activities and soon these sports clubs, such as the ASKÖ (Austrian Workers Sports Association) or the “Sportunion” (Conservative Sports Association), counted more than a hundred thousand members. The youth of all classes went hiking in the vicinity of Vienna or swimming in the Viennese public baths or in the Danube, for instance in the “Gänsehäufl” at the “Old Danube” or the “Strombad Kritzendorf” in their spare time. The Socialdemocratic hiking club “Naturfreunde” (Nature Friends) propagated the combination of fresh air, hiking and a healthy poise. To the desperation of the Catholic Church lots of naked skin was displayed, not only in magazines and films, but also “live” in the “Lobau”, a Danube beach in Vienna, where the enthusiasts of nudism bathed. Karl Elzolz was a supporter of this “return to the natural naivety of Paradise”. Bathing and body care had highest priority in the concept of “Red Vienna” (the city was ruled by Socialdemocrats between 1919 and 1934), when public bath houses and public swimming pools were built all over the city. In 1923 2,730,000 Viennese made use of the public bath houses and the number rose to 6 million in 1931. Furthermore, the city administration made a large number of well-equipped outdoor swimming pools available to the public by the end of the 1920s, the biggest of which were the “Gansehäufl”, the “Arbeiterstrandbad” and the “Strandbad Alte Donau” on the Danube, the “Ottakringer Bad” and the “Kongress Bad” in the western suburbs. They further built several children’s swimming pools (“Kinderfreibäder”) and indoor swimming pools, such as the “Amalienbad” and the “Dianabad”.

“Gänsehäufl” in 1932, photos of Karl Elzholz

The Socialdemocratic association “Natufreunde“ was one of the largest culture and nature clubs in Austria with 74,048 members in 1932, only surpassed by the Conservative “Alpenverein”. The “Naturfreunde” organised hiking and climbing tours, they built mountain huts and shelters and organised holiday trips for workers, just like the “Alpenverein” for the Conservative middle class. The “Naturfreunde” photography club was renowned for landscape photography which was turned into an art form there. One of their slogans was, “On Sundays get out of the pubs, yet don’t go to Church, but to the mountains!”

After the creation of a new river bed for the Danube’s new shipping route in 1875 the 6-km long “Old Danube” remained as a still water fed by ground water. It soon became a popular recreational and sports area for the Viennese. In 1907 the city of Vienna opened the first public swimming area “Gänsehäufl” there on the grounds of the former Danube alluvial islands near “Kaisermühlen” (“Emperor’s Mill”: the name is derived from the many ship mills which were being operated along the unregulated river in the 18th and 19th century). These islands were called “Haufen” and were used for raising geese and that’s where the name is derived from. From the start it was a swimming facility in a beautiful natural surrounding with excellent modern conveniences which allowed free and unrestricted bathing in the Danube. Fortunately, the natural alluvial forest of the Danube was not completely destroyed by the city’s regulation efforts.

Karl’s beloved “Gänsehäufl” in the 1950s. He took these photos after his return from exile in Bolivia after the end of the Nazi dictatorship (see article “Austrians in Exile in Bolivia”):

Another popular Danube swimming and bathing area, the “Strombad Kritzendorf” near Vienna, was first created after the regulation of the Danube in 1887 in a still-water side arm of the Danube, where a “bathing ship” was anchored, which offered safe swimming even to non-swimmers and beginners. In 1903 another “bathing ship” was fixed directly in the Danube and since then the facility is called “Strombad Kritzendorf” (river swimming area). Hundreds of Viennese flocked to Kritzendorf in the summer, which made it necessary that bathing facilities, such as cabins, kiosks and wooden huts were erected. During the interwar years the area became a popular destination for Viennese of all classes. Originally the outdoor swimming area was designed for the poorer classes, but in the course of the 1920s “Kritzendorf” developed into a more fashionable resort for the bohemian Viennese. That’s why in 1927 the two architects Heinz Rollig and Julius Wohlmuth designed a modern bathing infrastructure with a beach pavilion and the famous “Rondeau” with shops, bars, coffee houses and wooden cabins which were turned into small holiday cottages and rented to the Viennese middle and upper middle class, among them many artists, writers and musicians. Even Adolf Loos was hired to design small villas in Kritzendorf. The high time of the “Strombad Kritzendorf” suddenly ended in 1938 after the “Anschluss” (takeover of the Nazis in Austria). Many of the tenants of the wooden holiday homes were of Jewish origin and on the basis of the “Nuremberg Race Laws” the Nazis terminated the tenancy agreements without notice of 80 per cent of the tenants because they were Jews, then dispossessed and persecuted them. After 1945 the “Aryanised” wooden cottages were to be handed over to their original tenants, but only few had survived the Holocaust and returned to Vienna, among them my aunt Henny Singer, whose husband, Josef Singer, rented one of the characteristic wooden cottages on stilts in Kritzendorf. With the exodus of the Viennese Jews in 1938 the era of Kritzendorf as a fashionable and exclusive summer resort had lost its glamour. After the Second World War the bathing facility had to be rescued from decay and had to find new tenants.

Danube swimming area and bath in Kritzendorf

“Bathing rules” (“For undressing the wooden cabins are to be used in order to comply with rules of decency”)

The famous “Rondeau” (left) and typical cottages built on stilts to withstand the recurring flooding of the Danube

For centuries Vienna had been threatened by inundation and ice jams. After several unsuccessful attempts the dramatic flood of 1862 finally triggered the start of a comprehensive regulation of the Danube. The huge dimensions of the project that forced the widely ramified river into a new riverbed radically changed the riverscape of the Danube in Vienna. The water surface of 23.5 square kilometres was reduced to 10 square kilometres, as several of the former arms of the river were either filled up to create building ground or dried up when they were cut off from the main river and were no longer filled with water during periods of high water. The protection against inundation was completed in 1987 with the creation of the “New Danube” and the “Danube Island”. The construction of the “Nussdorfer Spitz” in 1880 was intended to keep ice jams from the city, which was not always successful, as Karl’s photos of the ice jam in 1929 prove. But an ice jam could also be useful for the Viennese because the ice cellars of the city could be filled more easily, when horse-drawn carriages transported the ice directly to the city centre, by which long transport routes could be avoided at a time when no other form of refrigeration was known. Still in the 1950s many Viennese bought blocks of ice for refrigeration because they did not own an electric fridge.

Photos of Werner Tautz: transport of in Vienna after the Second World War

Most of the small rivers that crossed the city and flowed into the Danube are now forgotten and only remain in some topographical names, such as “Dornbach”, “Alserbachstrasse”, “Alszeile”. In the middle of the 19th century these streams still characterised the city scape, but as the sewage of neighbouring houses and industries was dumped into these rivers, every high flood flushed the stinking refuse all across the city. This consequently resulted in disastrous epidemics; for example, the catastrophic ice jam of 1830 led to a terrible outbreak of the cholera. The regulation of the Danube resulted in a regulation of all the small rivers and brooks that flowed from the Vienna Wood to the Danube as well. The geological flysch zone of the Vienna Wood led to a quick flooding of the small rivers as the material is impervious to water. Within a very short time these streams had to transport a thousand times the normal water volume in times of flooding. That’s why the Ottakringerbach, the Alserbach and the Währinger Bach were diverted underground and flowed into the canal of the Wienfluss. By 1903 the largest part of the streams originating in the Vienna Wood were vaulted underground and became part of the canal system. At the time this regulation was seen as a sign of enormous technical and sanitary progress. Nowadays the opening up of the vaulting and bringing the streams to the surface again would not only significantly improve the city scape, but would be very beneficial to the climate. Projects of bringing some streams originating in the Vienna Wood to the surface again have existed since the turn of the last century, but so far to no avail.

Where the Alserbach flows underground this mill stone of the old “Dornbacher Alserbach” mill was excavated, a remnant of one of the many mills that operated on the Vienna Wood streams

Before its regulation the floods of the Wienfluss were dramatic, too, as the river level rose within minutes after a downpour and the river bed had to transport two thousand times the amount of water compared to the period of low water. This explains the huge dimensions of the construction to regulate the Wienfluss, which were started when the city railway line “Stadbahn” was built. Since 1902 no extensive flooding of the city caused by the “Wienfluss” has occurred. This can be attributed to some extent to Joseph Schöffel, whose efforts to prevent the cutting down of the Vienna Wood in the 19th century preserved this natural area, which constitutes an enormous water storage capacity for these streams. In one of the most beautiful parks which were created on the territory of the torn-down fortifications, the “Stadtpark”, the regulated Wienfluss was integrated. Next to the many exotic species of trees which were planted there some of the elms, poplars and willow trees of the original alluvial forest of the Wienfluss are preserved in the park. In the “Kursalon”, which was erected in the park in 1867 and hosted many Viennese balls, Werner Tautz, my father, met his future wife Herta for the first time at a New Year’s Eve ball in 1952. The Stadtpark with its “Kursalon” were and still are a much-frequented natural leisure and entertainment zone in the city centre.

Another of the many popular Viennese parks for short strolls was and is the “Türkenschanzpark”, which was planned in the 19th century as an English landscape garden, just like the Stadtpark, on an area of the western suburbs, where fierce battles between the Turkish army that had been besieging the city and the Polish-led relief army had taken place in 1683. That’s where the name “Türkenschanze” (Turkish entrenchment) is derived from. This park was opened to the public in 1888 and contained water falls, a zoo, a viewing tower and a stone garden with Alpine flora.

In the Türkenschanzpark 1932: Mitzi, my great-aunt (with the while cap) photographed by her husband Karl Elzholz

Türkenschanzpark, “Paulinenwarte”, named after Pauline Metternich who had donated many exotic plants for the park

The natural banks of the regulated Danube and Danube Canal acted as a favourite recreational area for the Viennese the whole year round, but especially in the summer months as bathing was free of charge there. In the interwar years the Danube Canal hosted many open water swimming competitions. One of the participants was my great-aunt Agi (see article “Viennese Football and the Danube Maidens”).

Swimming in the Danube 1932

Kuchelau 1932, Mitzi on the right and in the middle

Leisure travel on the Danube:

Danube harbour 1932

DDSG ships on the Danube in Vienna in 1929

The first steam ship running on the Danube between Vienna and Pest (today Budapest) was the “Franz I” in 1823, but the journey took 83 hours on the way downstream to Pest and 10 days back to the “Prater” in Vienna. It is understandable that this enterprise was not successful, so in 1828 two English entrepreneurs, John Andrews and Joseph Pritchard, launched a new attempt. They were granted the Imperial monopoly of running steamships on the Danube, the “First k.k. Privileged Danube Steam Ship Company” (DDSG) in 1829. The company’s scope was to transport passengers and goods on the Danube and the rivers flowing into the Danube in both directions. From 1831 a regular service was offered, promoted by the Hungarian Count Széchenyi, who initiated the first regulation of the Danube in Pest and constructed the biggest inland wharf in Europe in Óbuda for the DDSG in 1835, which was even bigger than the wharf erected in Korneuburg near Vienna in 1852. In 1836 the DDSG published the first tourist guide and from the middle of the 19th century the first modern guide books for travels on the Danube from Linz to the Black Sea and further to Constantinople were issued. The pioneer was the “Red Murray, a Handbook for Travellers”, published in 1844 for the route Passau – Linz. The railways constituted a serious competition for the DDSG, but the regulation of the Danube in Vienna speeded up the journey, when in 1873 the ships could use the “New Danube”. At the start of the 20th century the DDSG had 11,000 employees and it owned 50 passenger steam ships and 90 freighters. The first luxury cruise ship running to the Black Sea (80 metres length and 32 cabins) was launched during the war in 1916, but it could take up its service only after the First World War in 1922. During the time of the First Republic the DDSG enterprise did not make any profit and in the economic crisis of 1929 the DDSG’s bank, the “Boden-Creditanstalt”, went bankrupt. Unfortunately, in 1935 the DDSG was taken over by the Austro-fascist Emil Fey and in 1938 by the Nazis.

During the interwar years the DDSG tried to promote its passenger voyages to the Black Sea with annually published. richly illustrated guide books, the “Handbuch für Donaureisen” (handbook for journeys on the Danube), but ordinary Viennese could hardly afford even a day trip on the Danube on a DDSG ship. The Nazis then used the DDSG ships for their leisure organisation KdF (“Kraft durch Freude”), especially the route along the very attractive “Wachau” in Lower Austria. At the same time Jewish refugees tried to flee on DDSG ships from the “Third Reich” via the Danube in order to reach Palestine as a last resort.

Desperate refugees tried to board DDSG ships in November and December 1939 in Vienna, Bratislava and Budapest on the way to Sulina at the Black Sea. From there 2,175 refugees managed to arrive in the port of Haifa in Palestine on a Turkish steam ship on 13 February 1940. Unfortunately, another attempt at escaping the Nazi persecution failed tragically: the “Kladovo Transport”. At the end of November 1939, the Jewish refugees left Vienna by train to Bratislava; each of them was allowed a backpack only for luggage. On 13 December the DDSG ship “Uranus” left the port of Bratislava, but the next day the DDSG refused to transport the refugees any further. So the passengers were transferred onto Yugoslav ships, but with no guarantee that the ships would run to the mouth of the Danube. Due to the cold winter temperatures the ships had to stop at the winter harbour of Kladovo at the “Iron Gate” of the Danube. The refugees had to remain on the ship until May 1940, when they were transferred to the village of Kladovo. From there 1,200 refugees were transported by ship back upstream to Sabac in September 1940. When in April 1941 the Nazis attacked Yugoslavia, the refugees were trapped in Nazi-occupied Yugoslavia and their situation was hopeless. In October 1941 all male refugees were shot by the German “Wehrmacht” and the women and children were dragged to nearby KZs (concentration camps) and murdered there. Only 200 adolescent refugees managed to flee. Still in 1943 DDSG ships were used by the Nazis to transport Jews from the Balkans to the KZ Treblinka via Vienna.

DDSG station on the Danube Canal “Weissgerber Lände”, designed by the Austrian artist Friedensreich Hundertwasser. This was a popular area of open water swimming in the first half of the 20th century, too

After the end of World War II between 1945 and the independence of Austria in 1955, the Danube was situated to a large degree in the Soviet zone of occupation, so practically two DDSG companies existed during those ten years, a Western and a Communist enterprise. After the State Treaty of 1955 the DDSG was finally in Austrian hands again, but the wharf in Óbuda and the mines in Pécs were not returned to the DDSG and remained in Communist hands. The Nazis had propagated the romantic idea of river journeys on the Danube in the beautiful natural scenery of the “Wachau” with folk music and traditional costumes. After the war this light-hearted sugary image of Austria of “wine, girls in dirndls and music”, deprived of its sinister Nazi past, was further promoted in numerous very popular Austrian films. The first of these films, “Hofrat Geiger”, was released in 1947 and led to a string of remakes and similar sentimental films in the idealised “Wachau” setting. The popularity of these films triggered a boom of DDSG day trips from Vienna to the “Wachau”, when the DDSG bought three new modern leisure boats and daytrips on the Danube became affordable for the average Viennese.

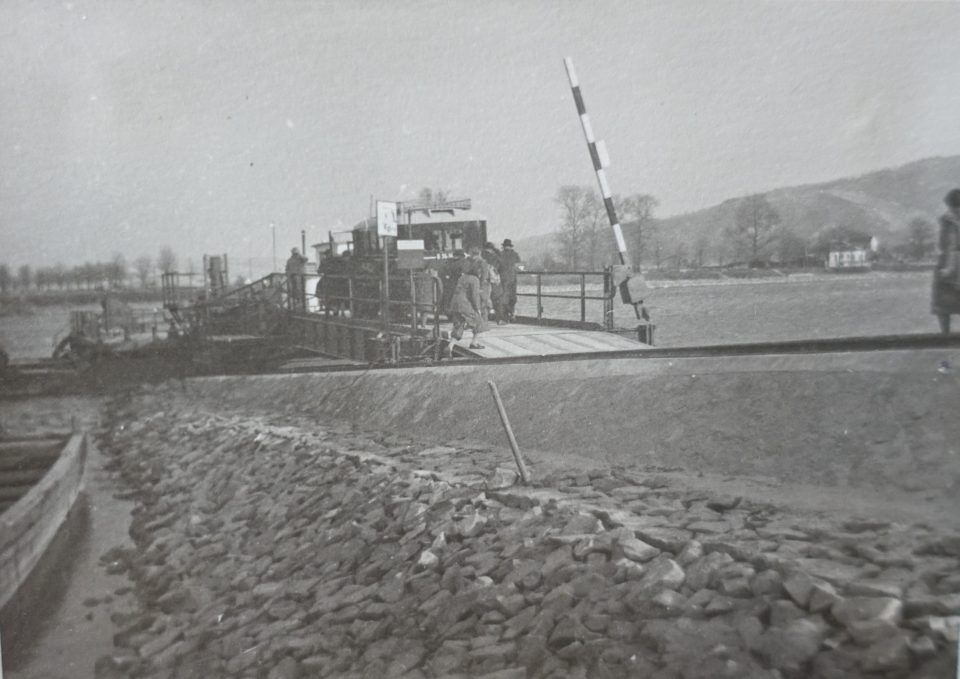

Karl (in front) titled these photos of 1932 “On the beautiful Blue Danube”:

Klosterneuburg – Korneuburg flying-bridge

The “Prater” alluvial forest and the whole inundation area, which developed in Vienna after the regulation of the Danube was completed, were one of the most popular leisure areas of the Viennese in the interwar years and the time after the Second World War and this did not only include the elegant alley “Prater Hauptallee” or the horse races in the “Krieau” or the fun park “Wurstlprater”, but the natural wilderness of the alluvial forest which in summer became notorious for the nudists and young couples enjoying their “natural sexuality”.

Working-class “Sunday leisure” in the summer of 1932

It was this contrast of town and nature which made the area so attractive as a place of leisure, but in the mentioning of the location “Prater” was already inherent a sinister, mysterious and otherworldly atmosphere and a whiff of illegality. In the 1950s the “transdanubial suburbs” near the Danube and the inundation area were working class suburbs, socially and ideologically remote from the middle-class inner districts, and as such this area was for the bourgeois Viennese society as eerie and sinister as the unruly river. Sexuality was at the centre of this bourgeois uneasiness, which literary master pieces of Austrian writers such as Arthur Schnitzler, Ödön von Horvath and Elfriede Jelinek show. The “Friedhof der Namenlosen” (Cemetery of the Nameless) on the banks of the Danube represented the climax of this creepy feeling. As a child I was fascinated by this place, when my grandmother Lola took me there to have a look at the graves. At that time the graveyard was much larger, but since then a big part had to make way for industrial production sites. Here not just those who had drowned in the Danube were buried, but also other nameless and named poor. The Austrian poetess Ingeborg Bachmann called it the “cemetery of the murdered daughters”.

“Prater” alluvial forest in winter, 1931

“Friedhof der Namenlosen”

Left a “nameless” grave and right the grave of Karl Leeb who drowned during the construction works of the harbour “Albern” in 1939

Technological innovation played an important role in the leisure pursuit of the Viennese in the second half of the 19th century. At the time of the Viennese World Exhibition of 1873 two mountain railways were built in the Vienna Wood: the cogwheel railway up the Kahlenberg and the funicular railway up the Leopoldsberg. Both private enterprises hoped for a rush of visitors triggered by the World Exhibition, but only the funicular railway to the Leopoldsberg was completed in time. Within five minutes each of the two steam-driven engines transported 100 passengers up 288 metres altitude. As soon as the curiosity of the Viennese was satisfied, the passenger numbers dropped, maybe also due to an innate fear of the new technology. At the same time the now finished “Kahlenbergbahn” (1874) offered a more attractive leisure time adventure and had the competitive advantage of being directly linked to a tramway to the city centre, namely to “Schottenring”, whereas the “Leopoldsbergbahn” could only be reached via the “Franz-Joseph’s Railway” or via a ship on the Danube. The cogwheel railway up the Kahlenberg started at today’s final stop of the tram D in Nussdorf and wound up the mountain for five kilometres, surmounting an altitude of 300 metres in half an hour. Six steam engines transported goods and persons up the mountain. In 1876 the “Kahlenberg-AG” (public limited company) bought up its competitor, the “Leopoldsbergbahn” together with all its properties. As a consequence, they could extend the cogwheel railway and connect it to the “Kahlenberg Hotel”. After not even three years of service the funicular railway up the Leopoldsberg was dismantled and the architects Fellner and Helmer, the most famous builders of theatres in the Austro-Hungarian monarchy, erected the “Stefaniewarte” at the Kahlenberg from its bricks in 1887. This viewing tower became a famous attraction for those spending their leisure time on the Kahlenberg:

Technological innovation played an important role in the leisure pursuit of the Viennese in the second half of the 19th century. At the time of the Viennese World Exhibition of 1873 two mountain railways were built in the Vienna Wood: the cogwheel railway up the Kahlenberg and the funicular railway up the Leopoldsberg. Both private enterprises hoped for a rush of visitors triggered by the World Exhibition, but only the funicular railway to the Leopoldsberg was completed in time. Within five minutes each of the two steam-driven engines transported 100 passengers up 288 metres altitude. As soon as the curiosity of the Viennese was satisfied, the passenger numbers dropped, maybe also due to an innate fear of the new technology. At the same time the now finished “Kahlenbergbahn” (1874) offered a more attractive leisure time adventure and had the competitive advantage of being directly linked to a tramway to the city centre, namely to “Schottenring”, whereas the “Leopoldsbergbahn” could only be reached via the “Franz-Joseph’s Railway” or via a ship on the Danube. The cogwheel railway up the Kahlenberg started at today’s final stop of the tram D in Nussdorf and wound up the mountain for five kilometres, surmounting an altitude of 300 metres in half an hour. Six steam engines transported goods and persons up the mountain. In 1876 the “Kahlenberg-AG” (public limited company) bought up its competitor, the “Leopoldsbergbahn” together with all its properties. As a consequence, they could extend the cogwheel railway and connect it to the “Kahlenberg Hotel”. After not even three years of service the funicular railway up the Leopoldsberg was dismantled and the architects Fellner and Helmer, the most famous builders of theatres in the Austro-Hungarian monarchy, erected the “Stefaniewarte” at the Kahlenberg from its bricks in 1887. This viewing tower became a famous attraction for those spending their leisure time on the Kahlenberg:

Viewing tower “Stefaniewarte” (named after the wife of Crown Prince Rudolf) at the Kahlenberg, 1929

Until the First World War the cogwheel railway was much frequented by the Viennese enjoying their leisure time in the Vienna Wood, but during the war years the railway was dismantled, partly in search for metals, partly by looting. After the war the city of Vienna considered taking over the “Kahlenbergbahn” and integrating it into the Viennese public transport system, but the city lacked the funds for restoring it and in 1922 it was closed down. The tracks of the railway were partly integrated in the newly built road up the mountain, the “Höhenstrasse”, in 1934/35.

Even more important for the quality of life and the availability of recreational leisure areas in Vienna was the decision of the Viennese city council under Mayor Karl Lueger to establish a “belt of forests and meadows around Vienna (“Wald-und Wiesengürtel”) in 1905. The idea was not new; already in the 1870s Joseph Schöffel had fought for the protection of the Vienna Wood and later Eugen Faßbender had suggested the creation of a “green belt” (Gürtel grüner Anger) of 750 metres width from Nußdorf to Hietzing and via Meidling to the “Zentralfriedhof” (Central Cemetery). But the decision of the city council in 1905 could finally guarantee the preservation of this natural landscape and execute a building ban. Mayor Lueger had a future 4-million Imperial capital city in mind and the city planners predicted the complete destruction of the Vienna Wood by 1950 if the city were continuously extended in a circular way as had been the case until 1905. The legal protection of the natural landscape of the Vienna Woods in 1905 shows the impressive foresight of the city planners of the time. With the end of the Habsburg Empire after World War I any planning for a 4-million city was obsolete, but the Viennese natural landscapes were protected against building speculation to some extent.

The Viennese nature enthusiasts of the late 19th and the first half of the 20th century were to a significant degree of Jewish origin, often assimilated Jews, agnostics and Socialdemocrats. They were dedicated sportsmen and -women, hikers and swimmers from the working class, such as Karl Elzholz or bourgeoise Catholic romantic naturalists like Toni Kainz, both of whom have provided the photographs of the Vienna Wood here. Viennese Jewish artists and intellectuals did not only help to create the fascinating myth of the “Sommerfrische” (summer retreat) and the adulation of the Alps, they also played an important role in the promotion of the Viennese landscapes, the Vienna Wood and the Danube, for recreation. What might have triggered this fascination with nature? It was probably the yearning for untouched natural surroundings of the city dweller combined with the hope of belonging, of becoming part of the Viennese community in doing sports and joining in the leisure activities of the Catholic Viennese majority. For some their long past migratory history from small villages in the East to the capital city of the Empire might have awakened lost memories of country life.

At all seasons the Viennese flocked to the Vienna Wood in search of such natural experiences, of picturesque and romantic impressions and carefree entertainment since the beginning of the 19th century. But a fast-progressing capitalist industrialisation in the Habsburg Empire threatened this unique nature reserve on the outskirts of the two-million capital city of the Empire. How could the Vienna Wood be protected and how could this recreational area escape the clutches of capitalist profiteers? Joseph Schöffel was the first who pointed out the importance of preserving the Vienna Wood for the Viennese as a natural landscape. He was born into a Bohemian family of civil servants in 1832 and after his military career he tried to do away with corruption and civil service mismanagement and arbitrariness in various official positions, which was not really appreciated by the Imperial administration. Consequently Schöffel stepped down from official functions and retreated into private life continuing his nature studies which he had started as a young man. After the defeat against Prussia in 1866 the Empire’s finances were depleted and the remedy was seen in an excessive privatisation of Imperial state property in the whole Habsburg Empire. Eventually the whole of the Vienna Wood of 30,000 ha, which was under the administration of the ministry of finance, was to be sold to private speculators. Initially the plan was kept secret because the administration feared violent protests of the local communities situated in the Vienna Wood and the inhabitants who lived from working and selling the timber of the forest. The promoters of the selling plan decided to inform the Viennese public only bit by bit via the press stressing the advantages of the sale. But first the true value of the property had to be artificially reduced, so that the public could be convinced of the benefit of selling the Vienna Wood to private investors. Against the advice of the civil servant responsible for the Vienna Wood, Ritter von Feistmantel, the minister of finance Becke signed a contract with the Viennese timber merchant Moritz Hirschl, which granted him the monopoly on the timber production of the Vienna Wood at an extremely low purchase price combined with very advantageous conditions with respect to the amount of timber to be extracted. The Viennese who spent their leisure time in the Vienna Wood had to watch powerlessly as the forest was cut down and destroyed ruthlessly. Stunned local woodworkers, timber merchants and carters had to stand by helplessly as they were robbed of their livelihoods. The Empire’s “k.k. Forest Administrators” were ordered not to interfere with the clearing of the forest. The Imperial “Forest Bank” even assisted in the speculative deforestation and the press kept silent, while the city administration of Vienna was powerless. Yet many of the members of Parliament, the “Reichsrat”, were profiting personally from this speculative privatisation.

In 1870 the “Reichsrat” passed a law which permitted the sale of the “Anninger Forst” of 5,409 acres, the last of the remaining state-owned part of the Vienna Wood. That triggered the start of the media campaign of Joseph Schöffel against the sale of the Vienna Wood. Moritz Szeps, the chief editor of the “Wiener Tagblatt”, supported him. From 20 April 1870 on Schöffel published a detailed documentation of the corruption, mismanagement and speculation linked to the sale of the Vienna Wood twice a week. The Viennese mayor sent inspectors to the forest to survey the damage, but their missions were continuously obstructed. The public finally demanded an immediate cancellation of all contracts connected to the sale. In return Schöffel was accused of libel five times and once of incitement to hate. In the end, Schöffel’s campaign was successful, when the government stopped the logging. Then Schöffel demanded that all civil servants involved in this corruption scandal were to be made liable. He stressed the importance of the Vienna Wood for the climate of the city and the health and the livelihood of its inhabitants in a new series of well-researched articles. His friend Ferdinand Kürnberger supported Schöffel in uncovering the names of the perpetrators and their crimes. The pressure on Schöffel grew: he was to receive 50,000 guilders if he stopped the publication of his articles and a forester was offered a fortune, if Schöffel was “incidentally killed by an off-target shot” during a hunting party. But the man warned Schöffel, who was then asked not to participate in any hunt in future by his supporters. When Schöffel continued his fight in the “Deutsche Zeitung” he was again charged and the paper confiscated. Yet, once more the jury acquitted Schöffel and finally the government realised that they had lost the fight. Several members of government disappeared from public sight or fled to the United States, some civil servants ended up in prison, the “Forest Bank” went bankrupt and the contracts with Moritz Hirschl were declared void. So, after three years of fight for saving the Vienna Wood, Schöffel had won in 1972 for the time being. He was elected member of the “Reichsrat”, where he continued his battle against corruption and mismanagement. It was amazing that a single journalist had managed to bring about the downfall of a huge Imperial project.

Left: Outing to the Vienna Wood after the end of World War II – enjoying a break: Toni (my grandfather), Käthe (my great-aunt just returned from exile in Bolivia), Herta (my mother) and Lola (my grandmother), from left to right

Right: Picknick in the Vienna Wood with Herta’s twin cousins Susi and Josi visiting from England in the middle

Among many more social and communal projects of Schöffel, his commitment to saving the “Duckhüttler” (people living in wooden huts) was of greatest importance. These were poor woodworkers of the Vienna Wood, who lived with their families in small huts in the forest and were to be driven from their dwellings in 1874 by officials of the ministry of finance who were about to dispossess them. Schöffel succeeded in convincing the Emperor Franz Joseph I himself, who repealed the act of demolishing the huts and decreed that the “Duckhütten” (wooden cottages) were to be restored into the property of the woodworkers who had come from various parts of the monarchy to work in the deserted parts of the forest. The small huts they had built there had come into their possession via consuetudinary law. Schöffel died in 1910 and is buried together with his friend, the poet Ferdinand Kürnberg, at the cemetery of Mödling. In his testament he wrote that he hoped, should the Vienna Wood be threatened again by speculators, someone would stand up in time and protect it successfully once again.

The last preserved “Duckhütten” in the Dambach valley in Purkersdorf

After the Second World War another speculative project could be prevented by a brave fighter for the preservation of the Vienna Wood, Karl Panek, the borough mayor of the district of Hernals. The City of Vienna had bought the derelict landscape garden of Count Lacy, an English Catholic who had fled England together with King James II and had fought in the armies of the Austrian Empress Maria Theresia. In 1765 he bought the estate and castle of “Neuwaldegg” and created an English landscape garden there. He later enlarged the garden by purchasing the “Marswiese” (today a large outdoor sports facility) from the “Schottenkloster” (Scottish Monastery) and in designing the garden was inspired by Rousseau. On the highest point of the estate, he built seventeen comfortable cottages for his guests and himself with a beautiful view. It was called “Holländerdörfl” (little Dutch village) because according to Dutch custom a tree was planted in front of every hut; the Viennese called it “Hameau” (the French word for little village). Lacy opened his park for the public, imitating his friend, Emperor Joseph II, who had opened the “Prater”, his hunting ground, to the public. In 1801 Lacy died childless and was buried in his park. The heirs of his castle and park were the Princes Schwarzenberg, who the park is now named for. The cottages of the “Hameau” were in such a bad state that most of them had to be demolished, but an inn provided the leisure-seeking Viennese with food and drink there and the landscape garden gradually merged in the Vienna Wood again. When in 1957 the City of Vienna bought the park for 16 million Austrian shillings from the administration of the Schwarzenberg patrimony, they planned to turn it into a private golf club, but the borough mayor Karl Panek vehemently resisted this project of privatisation and preserved a beautiful part of the Vienna Wood once more for the Viennese population.

Schwarzenbergpark:

Left: Schwarzenberg Alley with children sledging

Right: Tomb of Count Lacy

After the tearing down of the city walls of Vienna 1857-1865 and the abandonment of the fortification called “Linienwall”, which protected the Viennese inner suburbs, the inner and outer suburbs were integrated into the city of Vienna in 1893 and the excessive building boom of the “Ringstrasssen Era” permitted the growth of the city to the size of 2.5 million inhabitants around 1900; a population number the city has not even reached at the beginning of the 21st century again. Most of these new inhabitants were crammed into newly built blocks of flats. During the First Republic (1918-1934) the last of the empty spaces were used for the construction of council housing and the establishment of extensive allotments, called “Schrebergärten”, where the poorer classes could enjoy some natural surrounding and plant vegetables and grow fruit to top up their meagre daily diet. Since 1900 several such allotment garden cities were established on waste ground following the principles of the German medical doctor Schreber (1808-1861), who wanted to improve the health of the impoverished classes and provide them with fresh fruit and vegetables. These allotments were founded on the settlers’ own initiative and were organised as a cooperative association with strict regulations and a “Schutzhaus” (shelter and inn) at its centre. Many of them still exist and provide natural space for leisurely strolls, for example the “Schmelz” or “Rosental”.

After the end of the Nazi dictatorship the construction of housing and transport facilities enlarged the city towards the north and the south, while the wooded areas of the Vienna Wood and the alluvial forest along the Danube remained protected natural areas. Nevertheless, the built-up area of the city doubled from 1945 to the end of the 20th century while the number of inhabitants, which had shrunk to 1.6 million inhabitants in 1945, remained stable during this period. This resulted in a growth rate of built-up area in percent within half a century which was the same as in the whole period of 2,000 years of the city’s existence before. This definitely constituted a threat to the natural surrounding and the climate in the city.

Before it became a tourist attraction and a popular destination for Sunday outings of all Viennese classes the Vienna Wood was a densely wooded and deserted area with few settlements. Especially after the Second Turkish Siege of Vienna in 1683 and the liberation by the armies of Karl von Lothringen and the Polish King Sobieski the Vienna Wood was depopulated. Thousands of houses, churches, castles and fortresses were destroyed or severely damaged after the flight of Kara Mustafa and his soldiers. Only gradually the inhabitants of the area who had fled from the embattled region returned, but they were very few. That’s why the government tried to lure settlers from far away places of the Habsburg Empire to the Vienna Wood in the following years. Numerous benefits were offered to attract future inhabitants. In Perchtoldsdorf for example those who bought a destroyed house and then rebuilt it were granted the status of citizens. On average such a destroyed site cost 30 guilders, but on the condition that reliable witnesses vowed that the previous owner was dead and had no heirs. If this could not be proved the sale of the property was suspended for 32 years. Additionally, the Emperor granted many afflicted Vienna Wood villages ten or more tax-free years. The majority of settlers came from Styria, most of them woodworkers, farm hands and artisans. They cleared the forest to provide building timber for reconstruction. Other settlers originated from Salzburg, Upper Austria, Silesia, Moravia, Carinthia, Prussia, Poland, Swabia, Saxony and even from Switzerland, France, Italy and Holland, as the parish records show. The Imperial Forest Administration granted the newly arriving loggers financial assistance and a piece of land for rent, deep in the dense forest, where they could build their wooden cottages, the so-called “Duckhütten” and raise animals. These loggers and their families had to work hard, but they also enjoyed several benefits, such as free fire wood and building timber, tax exemptions and some assistance in case of illness or accidents. Consequently, they sometimes had a better life than the families in the farming villages. In the course of time the woodworkers were granted property rights on the ground where they had built their “Duckhütten”. Many villages in the Vienna Wood had developed from such settlements; for example, Wolfsgraben, Baunzen, Hochrotherd, Hochstraß and several more. The indigenous population was not too happy about the new wave of settlement, especially as the new arrivals had no expertise in wine-growing, the other important sector in the region, and were of no use for the wine-growers as menial workers in the vineyards.

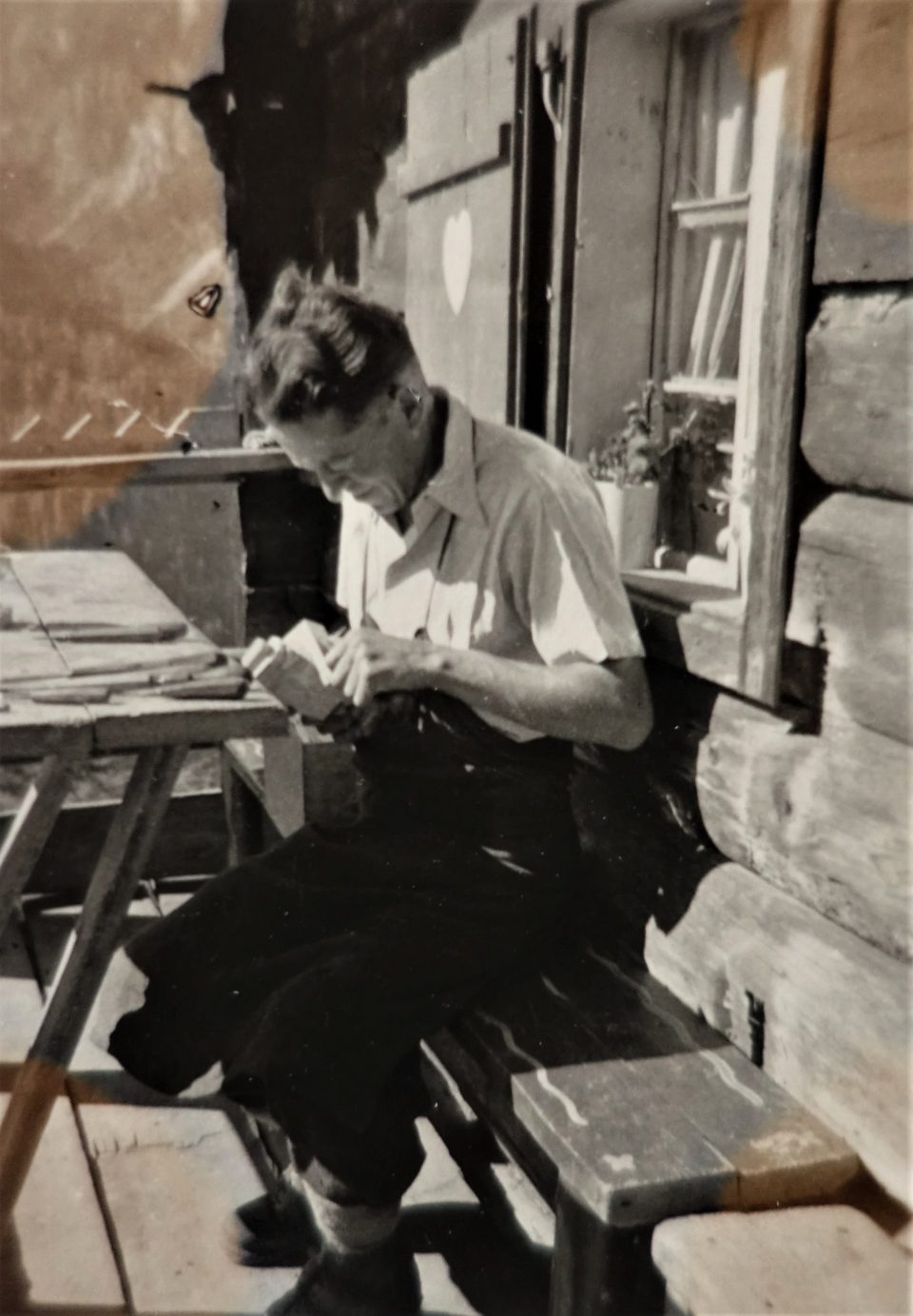

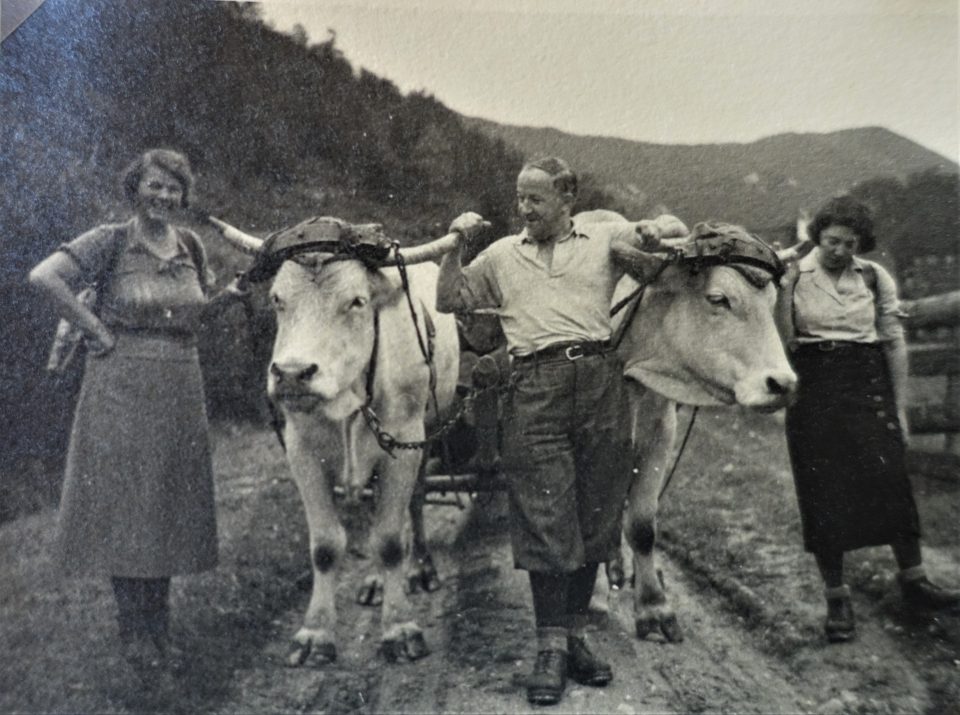

Woodworkers in the 1930s

As it was very difficult to transport the precious wood out of the forest via oxcarts or horse-carts to Vienna, the logs were sluiced whenever possible. Some sluiceways for logs are still preserved in the Vienna Wood.

Wine was one of the most important economic factors in the city and a Viennese export good since the Middle Ages. That’s why more and more arable land, meadows and forest were gradually turned into vineyards despite various attempts at forbidding this transformation because wine-making was much more profitable than the selling of timber or grain. In the course of the 19th century many places in the west of Vienna which formed part of the Vienna Wood, such as Währing, Gersthof, Pötzleinsdorf, Neustift am Walde or Salmannsdorf, which were eventually integrated in the city of Vienna, were turned into wine-growing villages, where the Viennese flocked to on Sundays and for evening entertainment. Until the 18th century wine was even grown in less favourable areas, such as Hütteldorf, Hacking or Lainz, but these wines could not compete with the excellent quality of wines produced at the “Nußberg”, for instance. The less fertile slopes of the Vienna Wood were then used for cattle raising and dairy production. Livestock farming was important in the 19th century for wine-growers, too, because they needed the manure of the animals as fertiliser before the wide-spread use of chemical fertilisers. The wine-growers’ village of Sievering in the Vienna Wood counted 700 pieces of cattle and two parish bulls around 1850. When in 1872 the vine stocks were destroyed by the vine pest, many wine-growers on the slopes of the Vienna Wood had gone bankrupt by the end of the 19th century and many estate owners sold their vineyards for urban development. The territory was parcelled and quickly villas of the well-to-do were erected on the former vineyards. This transformation took place for example in Salmannsdorf or Gersthof in the 1880s. Many of the small wine-growers did not survive or they turned to the planting of fruit trees, especially plums, which they used for distilling schnaps. Eventually the import of pest-resistant American vines rescued the Viennese wine production. From 1900 until 1930 the Viennese vineyards had shrunk from 548 ha to 310 ha. But during the interwar years the vineyards in Grinzing, Nußdorf and Heiligenstadt were again greatly extended and the wine-growing villages in the Vienna Wood became popular destinations for outings of the Viennese again. This trend has continued ever since and currently the Viennese vineyards cover around 700 ha of the city’s surface.

Even today some vineyards reach into the city, as here in Hernals, where there is also an old wine press exhibited. Going to the “Heurigen” was and still is one of the most popular leisure time activities for the Viennese

One of the many wine-growers who run a “Heurigen” (selling of the new wine together with some typical snacks) in the Vienna Wood

”Heurigen” with a view of “Kahlenberg Dörfl”

“Heurigen” with a view of the “Kahlenberg”

The loggers in the Vienna Wood often worked as pine-tappers as well because the resin of the black pine tree, “pinus nigra”, which is endemic in the southern Vienna Wood, was much in demand as a raw material for artisans, the industry and as a household remedy. The price of resin fluctuated widely and the sale of resin very often did not compensate the pine-tappers for their hard work. As they were not the owners of the forest where they worked, they had to hand over 50 per cent of their income to the forest owners. After the Second World War this amount was reduced to 40 per cent to increase their earnings. One black pine tree could yield resin for up to a hundred years. The resin they tapped was then further processed in so-called resin-huts in the forest. In the course of industrialisation all those small resin-huts were closed and the pine-tappers who had run them received a small compensation. In the end the production was concentrated in large factories.

Oxcart

The production of charcoal was another important source of income in the Vienna Wood which disappeared at the beginning of the 20th century, when charcoal was replaced by coal. There were those who produced the charcoal in the forest and those who transported the charcoal on carts along narrow wooded paths out of the forest to Vienna, their biggest market. Today the name “Kohlmarkt” in the city centre still reminds of the sale of charcoal there. Furthermore, lime kilns and a few glass foundries existed in the Vienna Wood. The glass that was produced there was low-quality simple glass, called “forest glass”, yet glass production was much less widespread in the Vienna Wood than in the Bohemian Forest (“Böhmerwald”), which was a centre of high-quality glass production in the Habsburg Monarchy. The lime kilns in the Vienna Wood were of much greater importance for the Empire and in the forest remnants of former lime kilns can still be found in the undergrowth. In the course of the 19th century also the lime production was concentrated in large factories, for example in Perchtoldsdorf and Kaltenleutgeben. In Gumpoldkirchen one lime furnace, erected in 1869 by the industrialist Heinrich Drasche, has been preserved. The last lime kiln was closed in 1979.

For centuries the huge forest area served the respective landlords as their hunting ground, which implied strict regulations for all forms of agricultural use of the property of the territorial rulers. Even bee-keeping was forbidden in order not to irritate the “princely game” and initially the construction of settlements, roads and carriage trails was prohibited, too. This privileged status of an aristocratic “Bannwald” (protected forest) in a way protected the forest for future generations of Viennese. A reminder of the times of aristocratic forestry and hunting is the “Lainzer Tiergarten” in Vienna. Even at times of greatest distress the territorial rulers did seldom allow the inhabitants to hunt for food. Any violation of the hunting ban was punished with the loss of house and farm and sometimes even with labour camp. These strict punishments were imposed until 1818. In 1849 the Imperial state property and the private property of the Emperor were separated in the region of the Vienna Wood and after the end of the Habsburg Empire the Vienna Wood was incorporated in the administration of the Austrian Federal Forest Administration (Österreichische Bundesforste) with the exception of the “Lainzer Tiergarten”, formerly the private property of the Emperor, which has been administered by the city of Vienna since 1918. Before 1918 it was the Emperor’s private hunting ground and is surrounded by a 22.6 km wall, which was erected between 1782 and 1787.

The “conquest” of the Kahlenberg and Leopoldsberg in the Vienna Wood for leisure purposes had started in the early 19th century for the wealthy Viennese who could afford a trip there and enjoy the splendid nature and panorama view. Ever since a great number of establishments serving food and drinks were opened there, such as inns, “Heurigen” or the so-called “Meierei” on the Cobenzl (a huge livestock farm selling its premium “Alpine” dairy products in a kind of coffee house), a reminder of the importance of livestock farming in the Vienna Wood. From the early 20th century on this possibility for leisurely entertainment became affordable for the Viennese working class, too. The construction of the “Höhenstrasse” in the 1930s partly on the tracks of the former cogwheel railway “Kahlenbergbahn” made the area more accessible for everybody via a public bus service. Even in winter the Vienna Wood attracted many not-so-well-off Viennese who could enjoy winter sports in the vicinity of the city, such as hiking, skiing and sledging. The road was built between 1934 and 1938 to attract tourism to Vienna and to provide jobs in economically very difficult times after the Big Slump of 1929. At that time the danger of harming the forest by drawing a lot of car traffic into the Vienna Wood was not considered, especially as very few Viennese possessed a private car at that time anyway.

“Höhenstrasse” with the historical paving

Left: “Häuserl am Berg” 1937

Right: On the way to the “Black Tower”

Left: Hoar frost in the Vienna Wood 1937

Right: Getting off the tram with skis and sledges

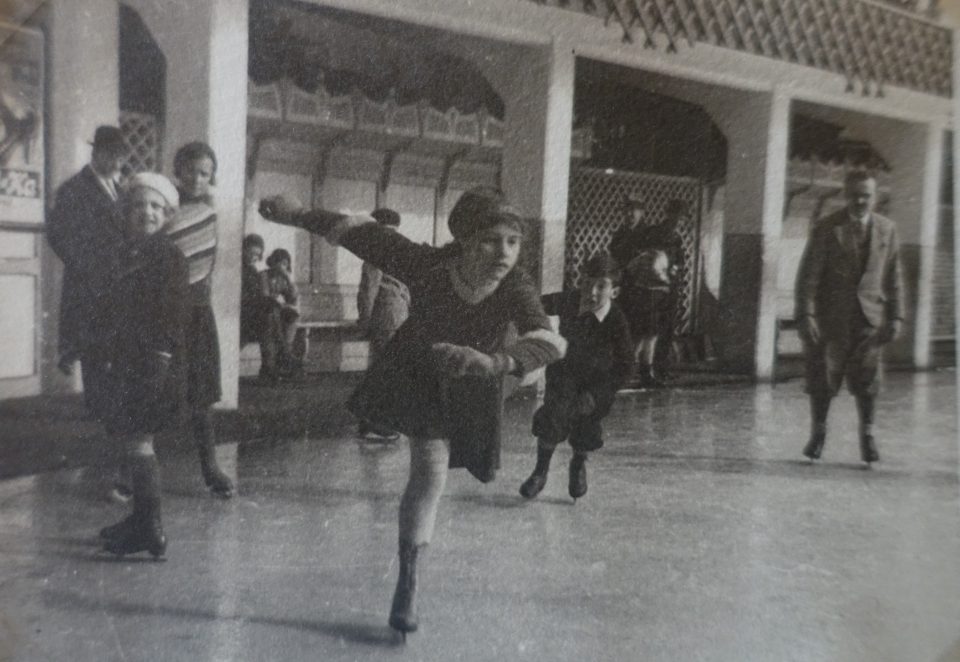

Ice-skating was a popular leisure time activity, too, especially as on the frozen “Old Danube” it was free of charge. Very popular ice rinks were the “Wiener Eislaufverein” situated on the Heumarkt and the “Engelmann” in Hernals, which was the first artificial ice rink.

Wood was until the 18th century the only source of energy and way into the 20th century still very important for Viennese households and the construction industry. The Vienna Wood and the alluvial forests of the Danube provided this precious resource for the city from the start and the production of charcoal was widespread in the Vienna Wood, which further threatened the tree population. Since the reign of Empress Maria Theresia in the 18th century the poor were allowed to collect wood in the forest, but a lot of abuse of this right, thieving and trafficking caused enormous damage in the woods around Vienna. As a consequence, special licenses were issued for those poor who were allowed to collect wood and the sanctions for stealing timber were stepped up; for instance, imprisonment or banishment of the whole family to the Timisoara Banat. During the interwar years the widespread destitution led to an excessive illegal cutting down of the forest. Especially during the harsh winters of the 1920s whole areas of the “Satzberg” or “Wolfersberg” in the Vienna Wood were logged and so-called clearing settlements were erected. Examples of such clearing settlements of the interwar years are Kolbeterberg, Eden, Wolfersberg, Friedensstadt and Waldegghof.

In 1918/19 poor Viennese had logged the Wolfersberg because of a drastic lack of fire wood and in 1920 25.3 ha of this area was made available by the city administration as an allotment area. 500 members of a settlement community were each assigned a parcel of this area, but 2,000 further applicants had to be rejected. In 1926 these 500 settlers were granted a building lease for 60 years. Another example was the settlement in the “Lobau” on the banks of the Danube, where unemployed industrial workers who no longer received any unemployment benefit occupied the area of the alluvial forest at the “Unteren Mühlenwasser” in the 1920s. They cut down the trees, planted vegetables and created shelters for themselves and their families from wooden boxes and old railway carriages. In 1927 the city of Vienna allowed a certain number of unemployed workers and their families to lease the area of 1.2-1.4 ha at a very low rent. In 1934 most lived on what they produced and from selling their vegetables and small animals, but some settlers had already acquired a cow or a horse.

Yet after 1945 the living conditions of the average Viennese had dramatically exacerbated again and fire wood was rare. Between 1945 and 1947, for instance, the forest administration of “Neuwaldegg” issued 20,000 licenses for collecting fire wood, but much of the needed fire wood was illegally collected and only in 1949 the number of applications for such licenses decreased. After the State Treaty of 1955 and the withdrawal of the Soviet army from the Vienna Wood, which had sacked many of the museums, castles and other historical building in the region and either burnt wooden artifacts for cooking and heating or declared others as “German property” and transported them to the Soviet Union, the post-war boom started. Tourism in the Vienna Wood declined, but the demand for second homes for the Viennese in the wooded area rose significantly and the communities in the Vienna Wood had to impose restrictions on building permits there, as this construction boom severely damaged the quality and attractiveness of this important recreational area.

Some sort of construction had always taken place in this large forest which had initially been an impenetrable ancient woodland, a “Bannwald”. Since the start of tourism in the 19th century small summer houses and later villas had been erected by the wealthy Viennese who flocked to the area in order to enjoy the natural surrounding and this drastically changed the landscape of the Vienna Wood, which had formerly only seen dispersed farm houses, whereby the inner part of the forest only gradually began to be populated in the 17th and 18th century. But in the first half of the 19th century, the time of the so-called “Biedermeier”, the Vienna Wood was praised as the ideal natural landscape, which in a way reflected the yearning for the light and the atmosphere of the “South”. In the 2nd half of the 19th century the wealthy Viennese were no longer satisfied with an outing to the Vienna Wood, they wanted to possess at least a cottage there. A very special type of architecture developed, from small little wooden summer houses to grand villas with carved verandas. At the same time the indigenous population of the Vienna Wood experienced the hardships of the Industrial Revolution. In several of the rural villages modern factories were established, where the workers were harshly exploited. Even their children had to work 13 hours a day, because two working adults could not feed a family as both their salaries were needed to pay for the rent of a tiny flat in the suburbs. On the other hand, the income of the farmers had dropped drastically as well. They earned approximately 2 Kreuzer per day for their families, but 1 kilogram of beef cost 60 Kreuzer. These abysmal living conditions triggered the participation of the rural population in the Revolution of 1848 in Vienna, which eventually led to a liberation of the farming population and a land reform. But the new liberty also included the payment of monetary compensation to the former landlord and the risk of bankruptcy and consequently the loss of house and farm.

In contrast, for many artists, musicians and writers the Vienna Wood was a place of inspiration and recovery, such as the musicians Ludwig van Beethoven, Johann Strauß, Josef Schramml, Franz Schubert, Arnold Schönberg, Anton Webern and the writers Franz Grillparzer, Josef Weinheber, W.H. Auden, Peter Altenberg, Heimito von Doderer and Hans Weigl, to name just a few. They all spent some time in one of the cottages or “Wienerwald” villas. Whereas the poorer classes enjoyed a Sunday outing to the Vienna Wood and stopped for a bite and a pint in one of the many inns, “Heurigen” or mountain shelters or they climbed one of the several viewing towers.

Peilstein viewing tower 1935 and “Wienerwald” cottage

Typical small “Biedermeier” houses in the Vienna Wood area

Villas around 1900 with the typical woodwork of the Vienna Wood architecture

Many tourist guides for the Vienna Wood region were published for the enthusiastic Viennese naturalists and hikers of the working and the middle class. They described half-day and full-day outings as well as longer hikes. Additionally, they detailed how to reach the destinations via public transport and which attractions awaited the ramblers. One of the most popular guidebooks was Förster’s.

In Förster’s “Tourist Guide” of 1906: Karl Ronninger praised the natural landscapes in and around Vienna as the most beautiful of all European metropoles

The short version of Förster’s guide to the Vienna Wood of 1922

J. Frank wrote a guide book to the surroundings of Vienna in 1929, divided into hiking trips from 4 hours up to 2 and a half days

The large and densely wooded area of the Vienna Woods was populated rather late by settlers from various European regions and this diversity was reflected in the customs and religious traditions there. The sparsely populated areas of the inner Vienna Wood, where the woodworkers lived in their “Duckhütten”, were characterised by popular religiosity and superstition, by fear of the devil and ghosts. Loggers, pine-tappers, charcoal burners and lime burners excessively celebrated those customs in the course of a year, in a way to compensate the dangers they faced in their daily work in the forest. The “Kraxenkirtag” (parish fair) in Gaaden for example was a festivity of the woodworkers, carters, stone workers and lime burners. The “Kraxen” (wooden bearer frame) was the symbol of the heavy burdens they had to carry on their backs. In many villages and especially in the monastery “Heiligenkreuz” festivities dedicated to the patron saints of the loggers, Saint Blasius and Saint Vinzenz, were celebrated. After the holy mass the people went to eat and drink and dance in the local inns. Their special wooden guild signs were displayed in the inns the wood workers frequented, two of which can be seen in the Vienna “Volkskundemuseum”. The pine-tappers started their working year with a celebration of Saint Vinzenz, too, and they drank a lot on this day because they were convinced that the resin would flow more freely if they started the year with binge-drinking. Similar to the wine-growers the pine-tappers ended their working year in autumn with a lot of drinks and rich food in order to “boost the fertility of the next year”. On Carnival Sunday the pine-tappers were invited by the farmers for whom they worked and were served a sequence of rich dishes, which was strictly regulated: soup, cooked beef, sausages, smoked pork, fried meat, all with side dishes, sweet donuts and schnaps. What they could not eat they were allowed to take home. The dances, balls and the parish fairs of the pine-tappers were so popular that people flocked from farther away to these festivities. The customs of the wine-growers and the pine-tappers were very similar in the Vienna Wood as in those regions where wine-growing was abandoned because of the low quality of the produced wine due to the poor soil, the wine-growers’ customs were taken on by the pine-tappers. The influence of the moon phases was important for all those who worked in the forest and this influenced their customs and festivities, too.

After the vines were well-tended and the wine-growers were waiting for the vintage, always in fear of bad weather, thunderstorms, hail and pests, many pilgrimages were undertaken, mostly on the “Via Sacra” to “Mariazell”, a famous sanctuary to the Holy Mary. The wine-growers tried to disperse thunderstorm clouds with shots and harmful ghosts with bell ringing. Many wine-growers from Ottakring and Hernals undertook a pilgrimage to “Mariabrunn” near Vienna early in the year to protect their vineyards from pests. From the end of August on the wine-growers hired so-called “Hüter” (guardians) to protect the ripening grapes from damage by birds and other animals. Until the 1920s every “Hüter” had to name a guarantor who vouched for his honesty and they had to comply with strict working rules. They had to keep their hats on (“Hut” means hat) and were not allowed to stay long in an inn during their working time. Additionally, they were urged to hold a parade at the start and end of the period of watching over the ripening grapes. In Perchtoldsdorf they had to whiten a special stone every year at the start of their seasonal work, which can still be seen today. Usually after the vintage, the whole village celebrated excessively with the guardians, the “Hüter”, the end of the working year. All these customs, fairs and parades attracted many Viennese tourists.

Vienna Wood 1929

Autumn in the Vienna Wood

Monastery Heiligenkreuz

One curious tourist attraction was the small “Kahlenberg Cemetery” on the slopes of the Kahlenberg, where early graves date back to 1783. Only 130 persons were buried there, most of them during the first half of the 19th century, whereby two of them are most interesting: the grave of the 21-year-old Karoline Traunwieser, who died on 8 March 1815 “in the prime of life” (left) and the one of the statesman of the Vienna Congress 1814/15 Carl Joseph Lamoran de Ligne (right):

Karoline Traunwieser was the beautiful daughter of the female owner of the Kahlenberg, then called Josefsdorf, who was supposed to be the most beautiful girl of the “Vienna Congress” (1814/15 ending the Napoleonic Wars), even more beautiful than her mother, and a great singer. No picture of her has been preserved, but her beauty made her a legend. The famous orientalist Josef Freiherr von Hammer-Purgstall was smitten with love and dedicated to the then 17-year-old “Lottchen” his translation of Edmund Spenser’s sonnets. Among her many admirers was de Ligne, who had rented a summer house from her mother on the Kahlenberg, died three months after Karoline and was buried in this little cemetery, too. Yet Karoline decided to give her love to the French colonel Rameuf, who died on Napoleon’s retreat from Moscow in November 1812. Karoline died two and a half years later of consumption. Legends surrounded her death and as one can see her grave is still being commemorated today.

Literature:

Bouchal, Robert & Sachslehner, Johannes, Eintauchen in den Wienerwald. Natur, Geschichte und Kultur einer einzigartigen Landschaft, Styria Verlag 2021

Frank, J., Führer durch die Umgebung Wiens, Hartleben’s Verlag Wien 1929

Katalog: Hast du meine Alpen gesehen? Eine jüdische Beziehungsgeschichte, Jüdische Museen Hohenems und Wien 2009

Katalog: Mit uns zieht die neue Zeit. Arbeiterkultur in Österreich 1918-1934, Wien 1981

Katalog: Wiener Landschaften, Historisches Museum der Stadt Wien 1994

Mattl, Siegfried, Geschichte Wiens. Wien im 20.Jahrhundert, Edition Wien 2000

Öhlinger, Walter, Geschichte Wiens. Wien in Aufbruch zur Moderne, Edition Wien 1999

Petschar, Hans (Hg), Die Donau. Eine Reise in die Vergangenheit, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek Wien 2021

Ronninger, Karl, Förster‘s Touristenführer in Wiens Umgebungen, Wien 1906

Ronninger, Karl, Wienerwald, Artaria Wien 1922

Trumler, Gerhard, Das Buch vom Wienerwald. Landschaft – Kultur – Geschichte, Verlag Brandstätter Wien 1985