„DEATH MUST BE A VIENNESE“ , A QUOTE FROM A FAMOUS VIENNESE SONG & THE VIENNESE FASCINATION WITH DEATH

“Schubertpark”, former cemetery of the Viennese district Währing”, opened 1769. Famous personalities, such as the musicians and composers Franz Schubert, Ludwig van Beethoven and the authors Franz Grillparzer and Johann Nestroy, were buried here before the transfer of their remains to the newly opened “Zentralfriedhof”. This graveyard was closed in 1873 and completely abandoned before it was turned into a park in 1924/25.

“Es lebe der Zentralfriedhof “ (Long Live the Central Cemetery)

Viennese song & lyrics by Wolfgang Ambros, published in 1975, which celebrates the 100th anniversary of the opening of Vienna’s largest graveyard in sarcastic words:

Es lebe der Zentralfriedhof und alle seine Toten!

Der Eintritt ist für Lebende heut‘ ausnahmslos verboten.

Weil der Tod a Fest heut gibt, die ganze lange Nacht.

und von die Gäst‘ ka einziger a Eintrittskarten bra[u]cht.

Wann’s Nacht wird über Simmering, kummt Leben in die Toten,

und drüben beim Krematorium tan s‘ Knochenmark anbraten.

Dort hinten bei der Marmorgruft, dort stengan zwei Skelete,

die stessen mit zwei Urnen z’samm und saufen um die Wette.

Am Zentralfriedhof is Stimmung, wia seit Lebtag no net woa,

weil alle Toten feiern heut seine ersten hundert Jahr.

Es lebe der Zentralfriedhof und seine Jubilare.

Sie liegen und verfaul’n scho da seit über hundert Jahre.

Draußt is kalt und drunt is warm, nur manchmal a bissel feucht,

wenn ma so drunt liegt, freut ma sich, wann’s Grablaternderl leucht.

Es lebe der Zentralfriedhof, die Szene wird makaber;

die Pfarrer tanzen mit die Huren, und de J u d e n mit d‘ Araber.

Heut san alle wieder lustig, heut‘ lebt alles auf.

Im Mausoleum spielt a Band, die hat an Wahnsinnshammer drauf.

Am Zentralfriedhof ist Stimmung wia seit Lebtag no net woa,

weil alle Toten feiern heute seine ersten hundert Jahr.

Es lebe der Zentralfriedhof! Auf amoi macht’s a Schnalzer,

der Moser singt’s Fiakerlied und die Schrammeln spüln an Walzer.

Auf amoi is die Musi still, und alle Aug’n glänzen

weil dort drübn steht der Knochenmann und winkt mit seiner Sensen.

Am Zentralfriedhof ist Stimmung wia seit Lebtag no net woa,

weil alle Toten feiern heute seine ersten hundert Jahr.

Translation:

Long live the Central Cemetery and all its dead!

Admission is strictly forbidden to the living today.

Because Death is throwing a party tonight, all night long.

And none of the guests need tickets.

When night falls over Simmering, the dead come to life,

and over at the crematorium, they fry bone marrow.

Back there by the marble tomb, two skeletons are standing,

they’re toasting with two urns and drinking competitively.

At the Central Cemetery, the atmosphere is like never before,

because all the dead are celebrating their first hundred years today.

Long live the Central Cemetery and its jubilarians.

They have been lying there and rotting for over a hundred years.

It’s cold outside and warm down there, only sometimes a little damp,

when you’re lying down there, you’re happy when the grave lanterns light up.

Long live the Central Cemetery, the scene is becoming macabre;

the priests are dancing with the whores, and the Jews with the Arabs.

Today everyone is happy again, today everything is coming to life.

A band is playing in the mausoleum, and they’re really rocking it.

The atmosphere at the Central Cemetery is like nothing we’ve ever seen before,

because all the dead are celebrating their first hundred years today.

Long live the Central Cemetery! Suddenly there’s a snap,

Moser sings the Fiakerlied and the Schrammeln play a waltz.

Suddenly the music stops, and everyone’s eyes shine

because the Grim Reaper is standing there, waving his scythe.

The atmosphere at the Central Cemetery is like nothing we’ve ever seen before,

because all the dead are celebrating his first one hundred years.

Viennese “Leichenwirtshäuser” (in Viennese: “corpse inns” = funeral inns) and “Leichenschmaus” (in Viennese: “corpse meals” = funeral feast)

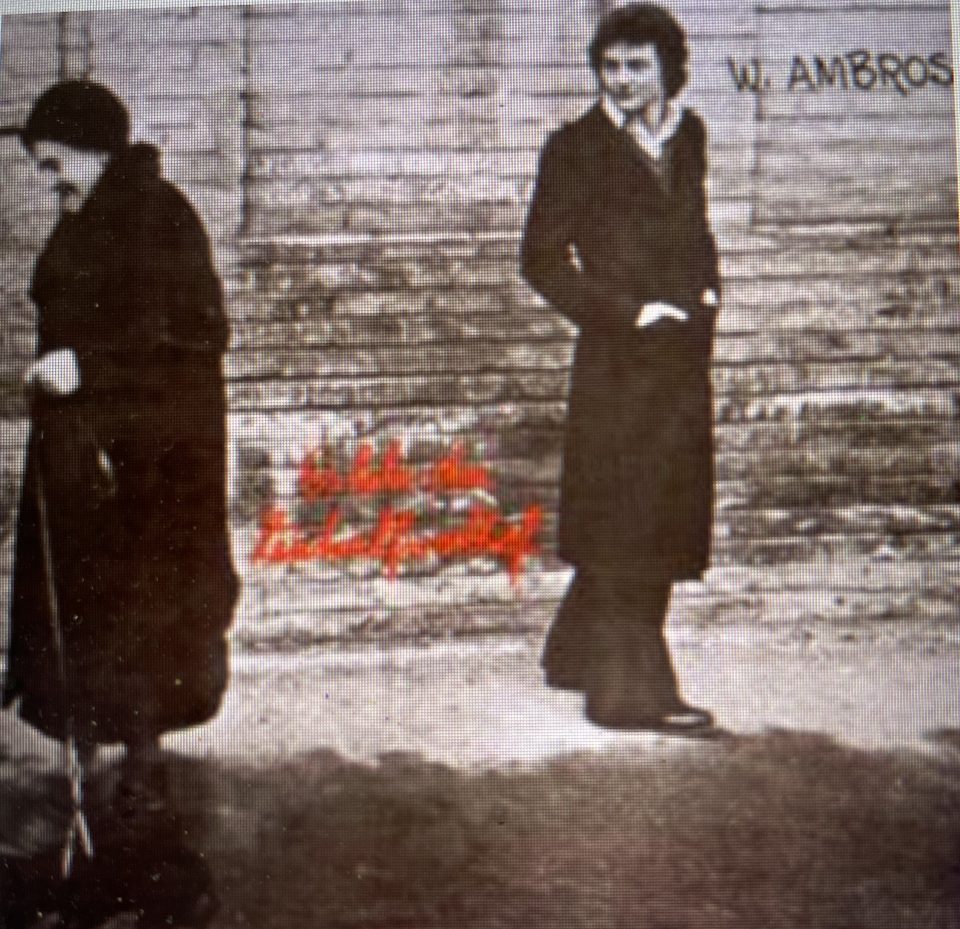

The newly opened “Schubertpark” with its cemetery in the 1920s, photographed by my grandfather, Toni Kainz, who was the son of the owner of the “Anton Kainz Gasthaus”, opposite the former graveyard, originally a typical Viennese “corpse inn”. These inns have always thrived on the celebrations after a burial, the “Leichenschmaus” (“corpse meal”). Therefore, such inns next to graveyards were called “Leichenwirtshäuser” in Viennese:

“Anton Kainz Gasthaus” opposite the “Schubertpark” in the late 1920s: left: my grandmother Lola Kainz in the entrance, right: my great-grandparents on the “terrace”, called “Schanigarten” in Vienna.

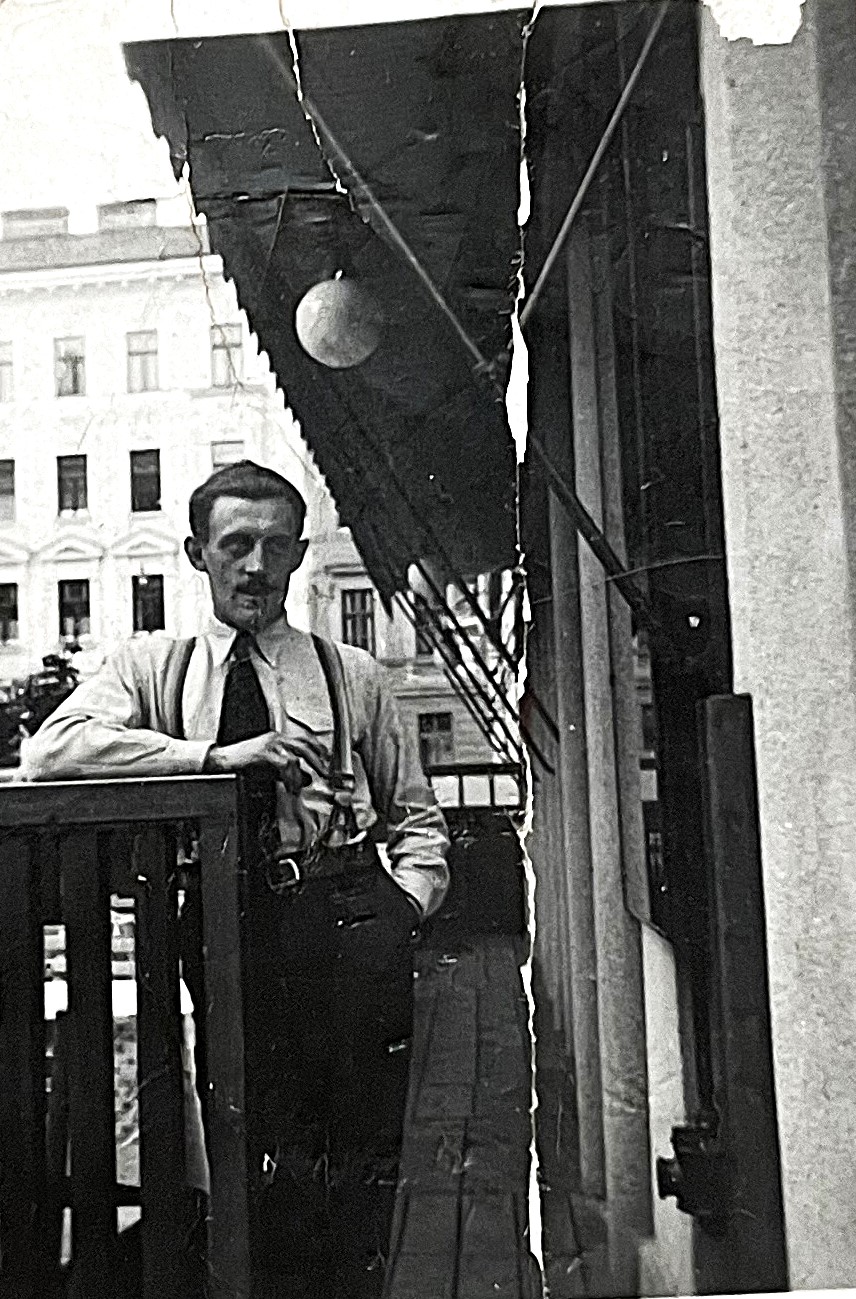

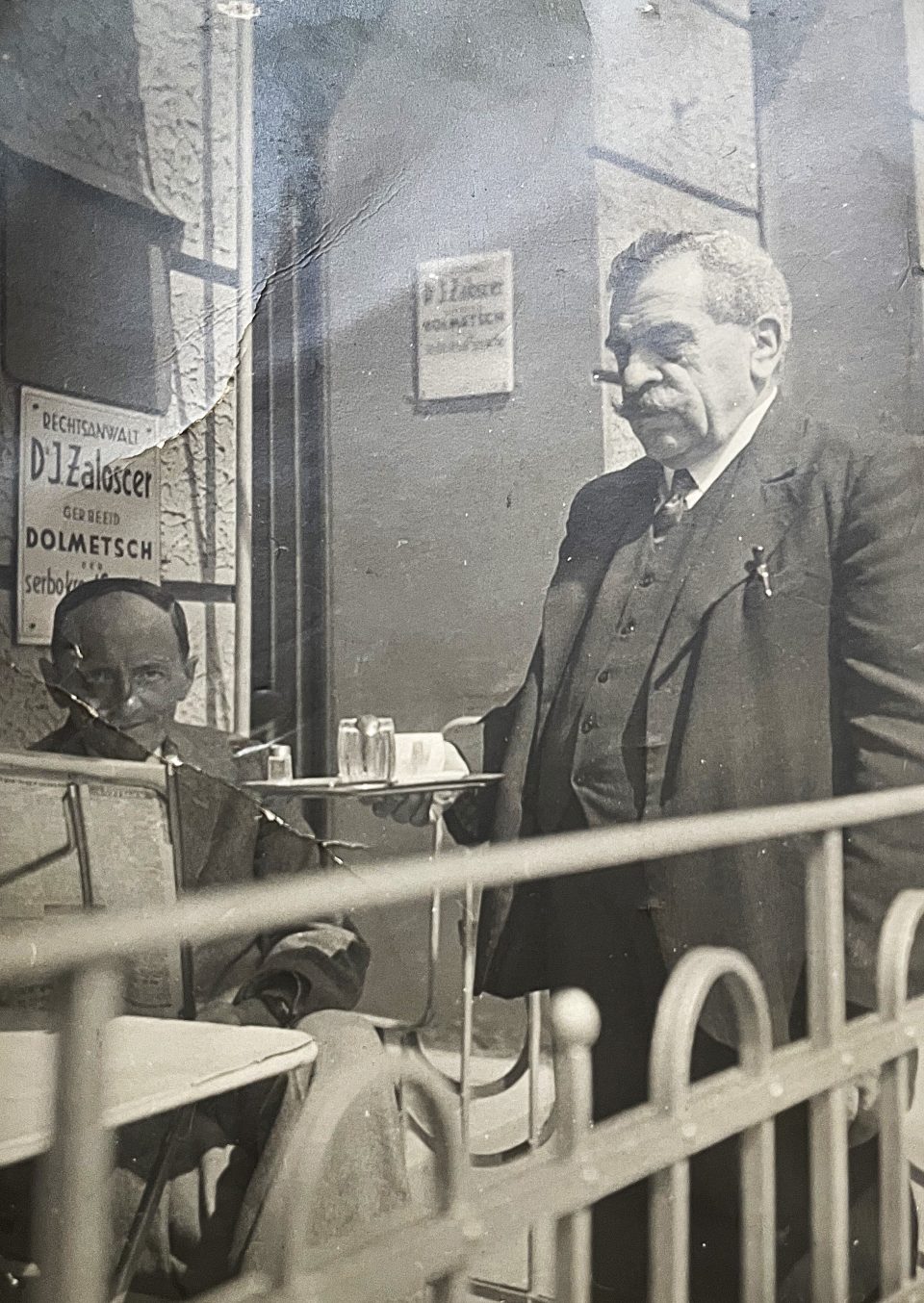

Left: my grandfather Toni Kainz on the “terrace”, in the middle: my great-grandfather, Ignaz Sobotka, serving, and right: my great-grandmother, Rudolfine Sobotka, at the entrance to the terrace of the “Anton Kainz Gasthaus”

When in the second half of the 19th century the inner-city graveyards were closed and later turned into public parks, the so-called “corpse inns”, moved to the outskirts of the city, where the Viennese were now buried and the celebrations after the burials took place in the inns nearby. The “Leichenschmaus” (“corpse meal”) could last several days and no matter the social class or income, it was the aim of every Viennese to have a dignified burial with an appropriate festive gathering of the mourners after the ceremony in an inn with food, lots of drink, mostly alcoholic, and sometimes musicians, who performed the traditional Viennese songs (“Wienerlieder”), often mentioning death in a humorous , sarcastic or ironic way. Among these were the songs that the deceased loved during his lifetime and listened to at the “Heurigen”, the places where even today the young wine is drunk, simple food is served, and musicians perform the Viennese songs the customers want to hear. These traditions are still alive in Vienna.

Opposite the “Zentralfriedhof”, main gate 2, the traditional Viennese sausage stand “eh scho wuascht” offers respite for the visitors of the by far largest cemetery in Vienna in the 11th district, Simmering. Its name illustrates the sarcastic and humorous aspect of the Viennese’ fascination with death: the direct translation of the Viennese dialect phrase is: “it is already sausage”, meaning “it doesn’t matter any longer,” and the “sausage” is a favourite Viennese snack which you can eat there. Sausages are eaten standing, with your fingers or with tooth picks, and these sausages are traditionally named after places, such as Debrecen, Frankfurt, or Krain.

Next to the monumental entrance of the “Zentralfriedhof” there is a much-frequented prestigious coffee house and pastry shop (“Oberlaa”) for the mourners, where they can indulge in Viennese cakes and cheer the deceased.

Another excellent example of “Leichenwirtshaus” (“corpse inn”) is the “Concordia Schlössel”, opposite the “Zentralfriedhof”, which is a favourite spot for visitors of the cemetery, but also a location of “corpse meals” and many other festivities.

My parents, my grandparents, my great-aunt and great-uncle and my great-grandparents were all buried at the “Zentralfriedhof” and mostly the celebrations after their burials, the “Leichenschmaus”(“corps meals”) took place in this location.

…