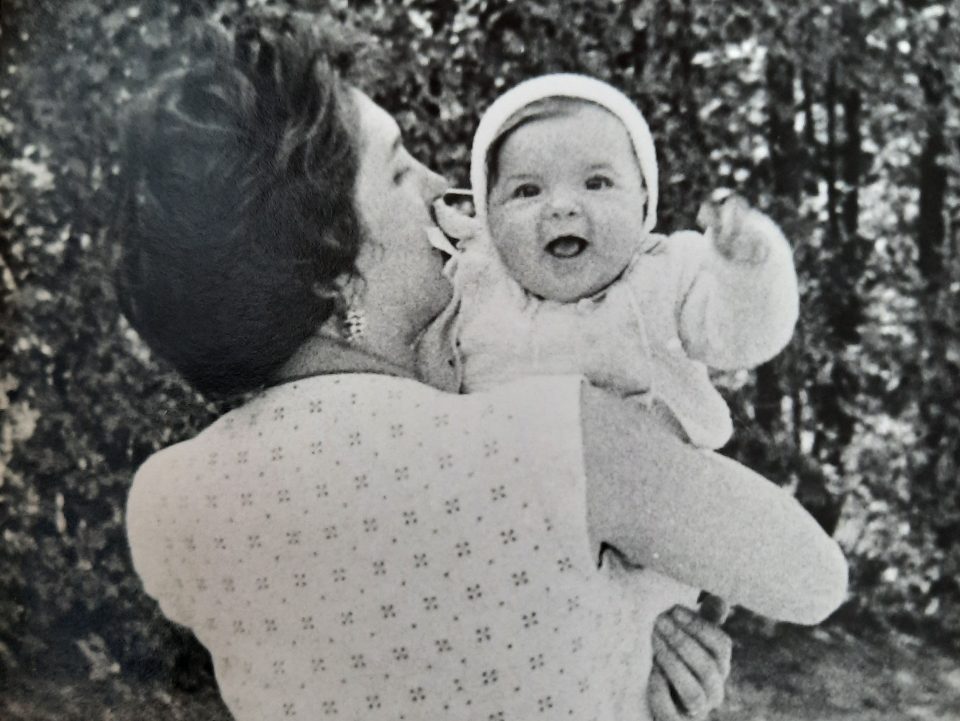

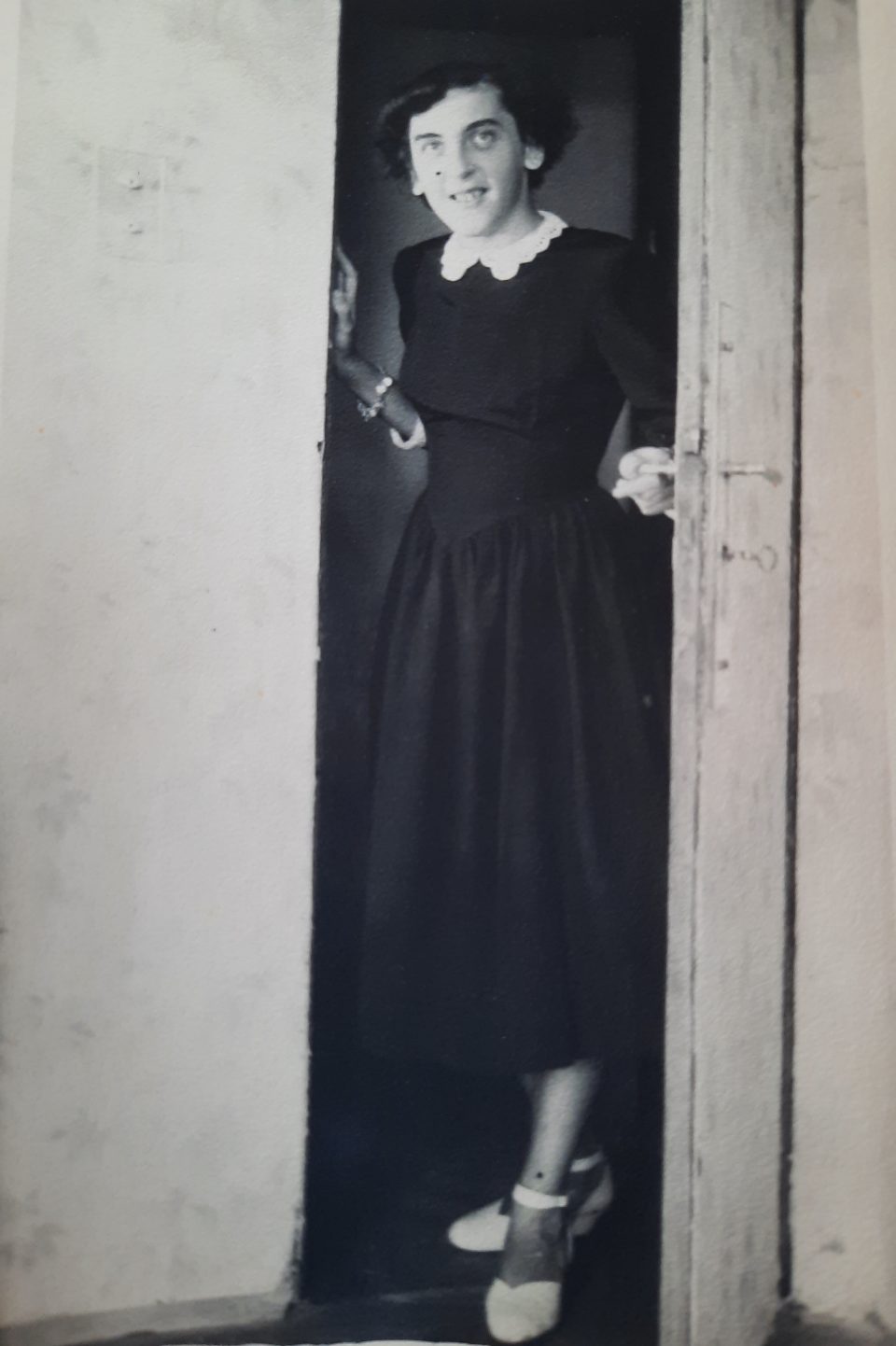

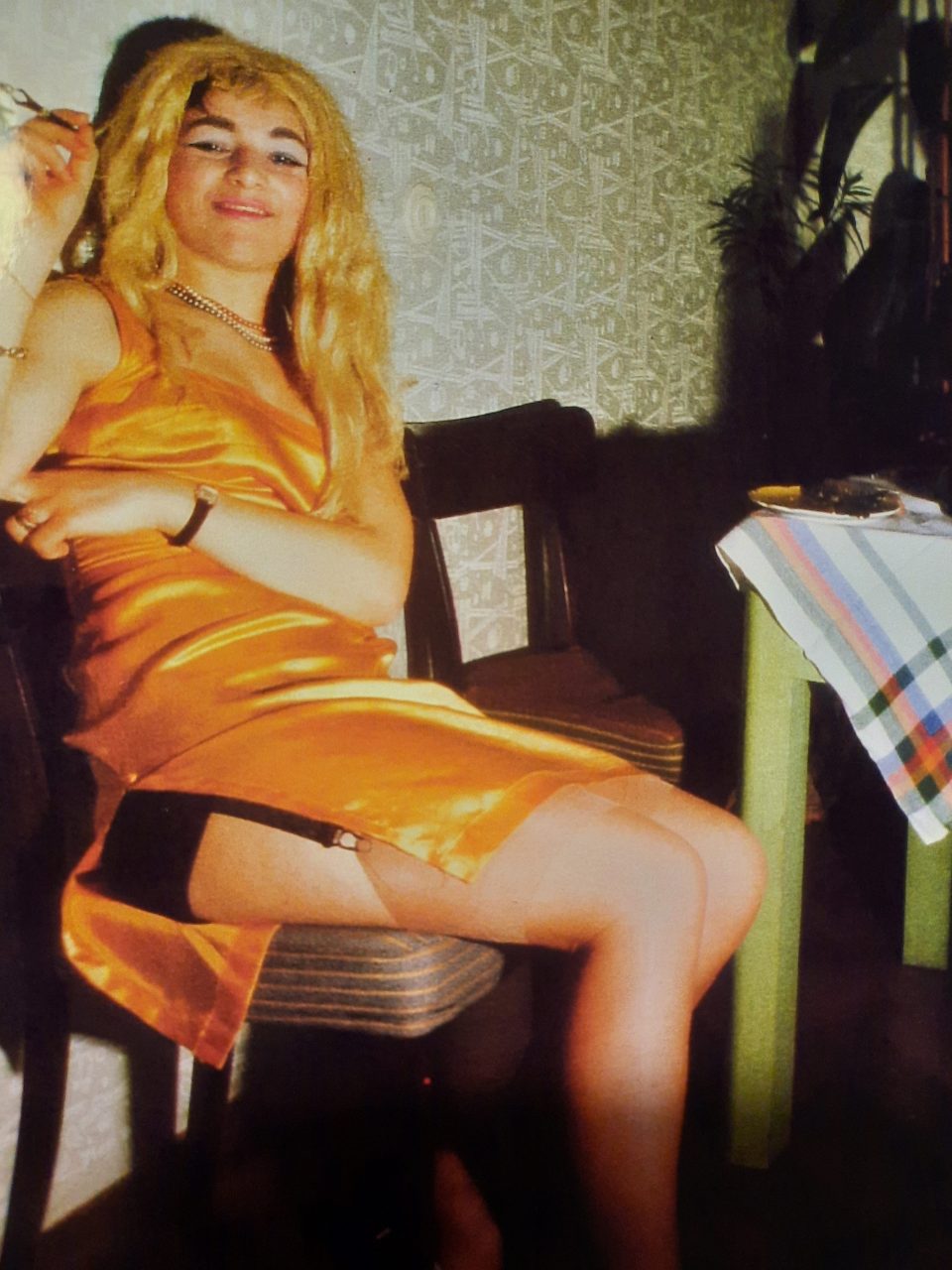

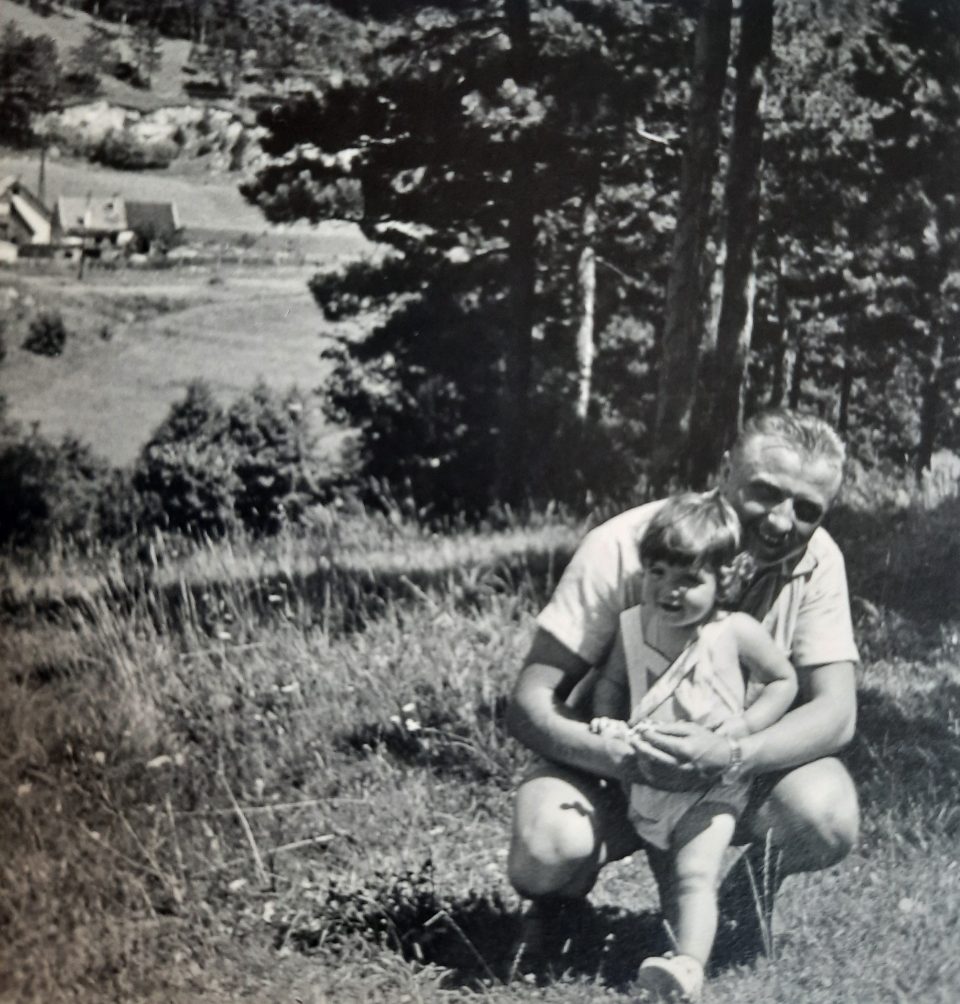

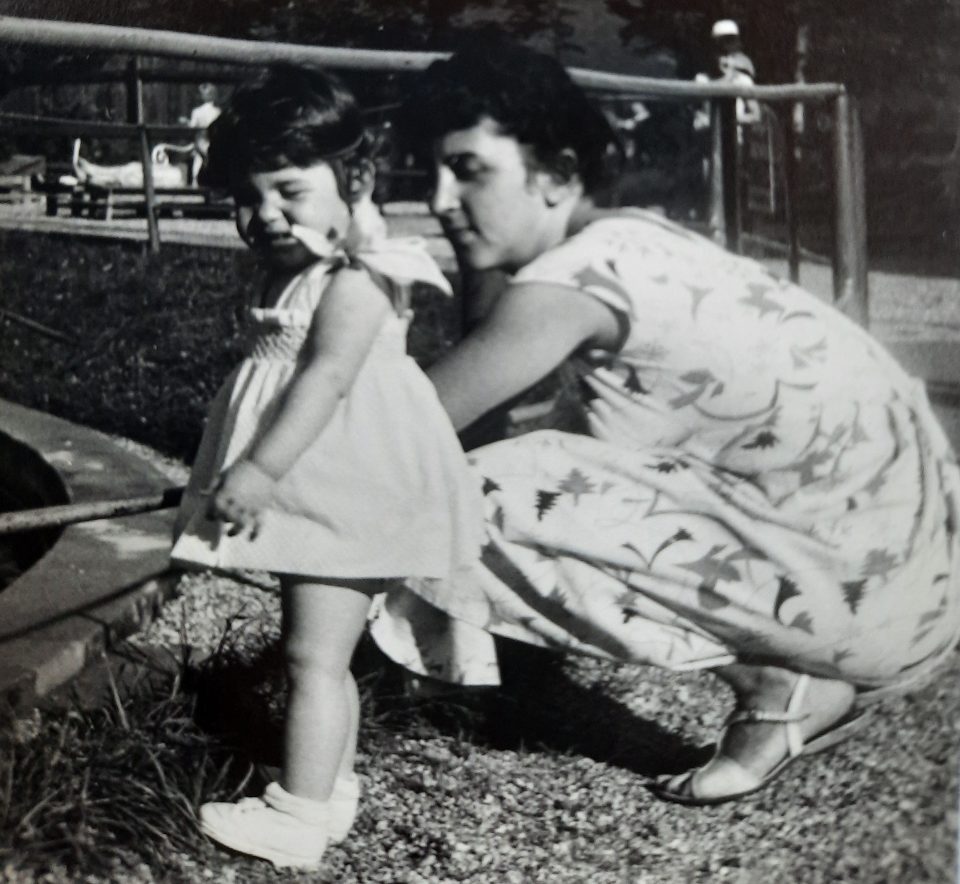

Fashion and interior design of the 1950s in Vienna (my mother Herta with Susi – myself- on her lap -right)

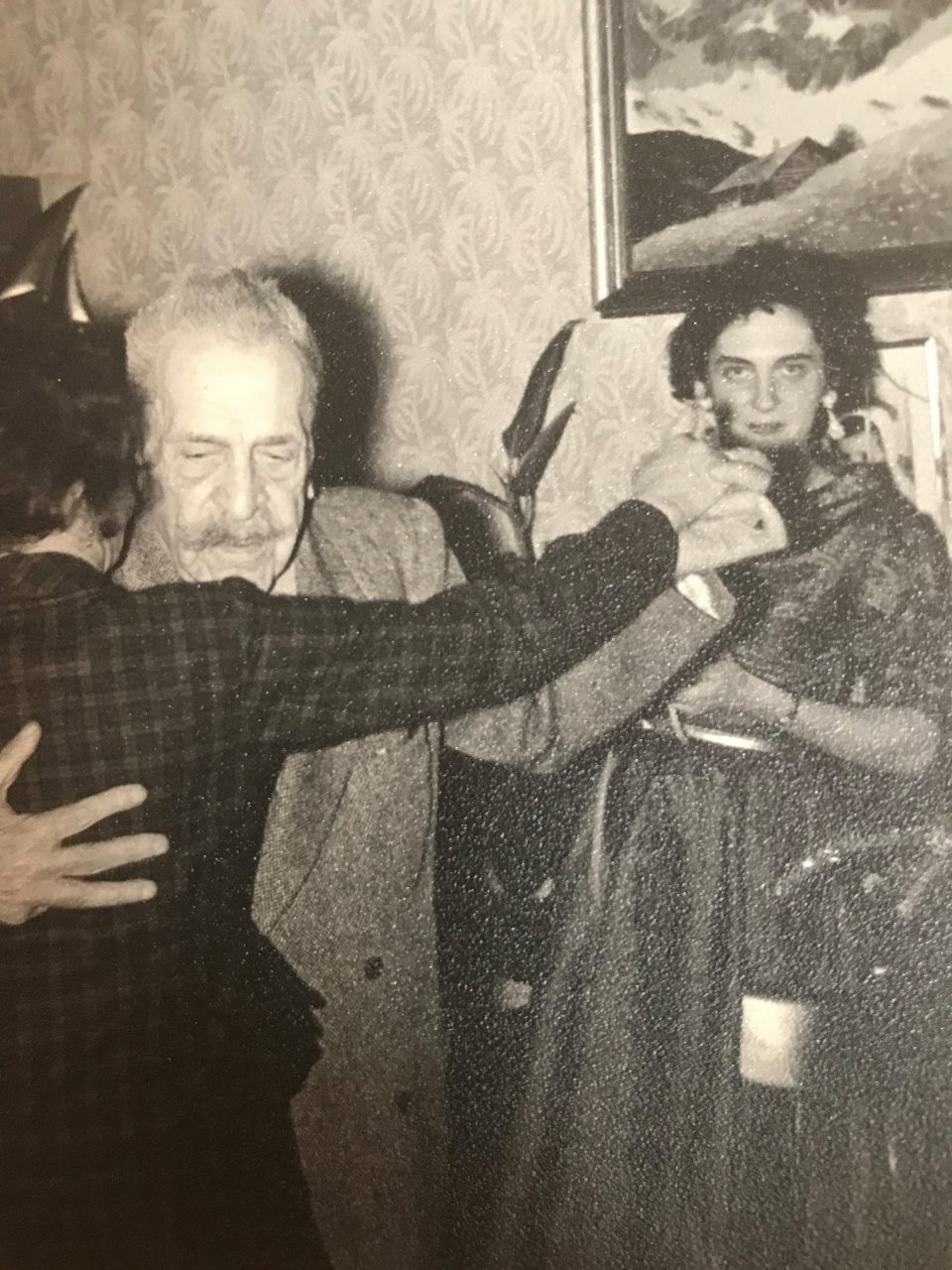

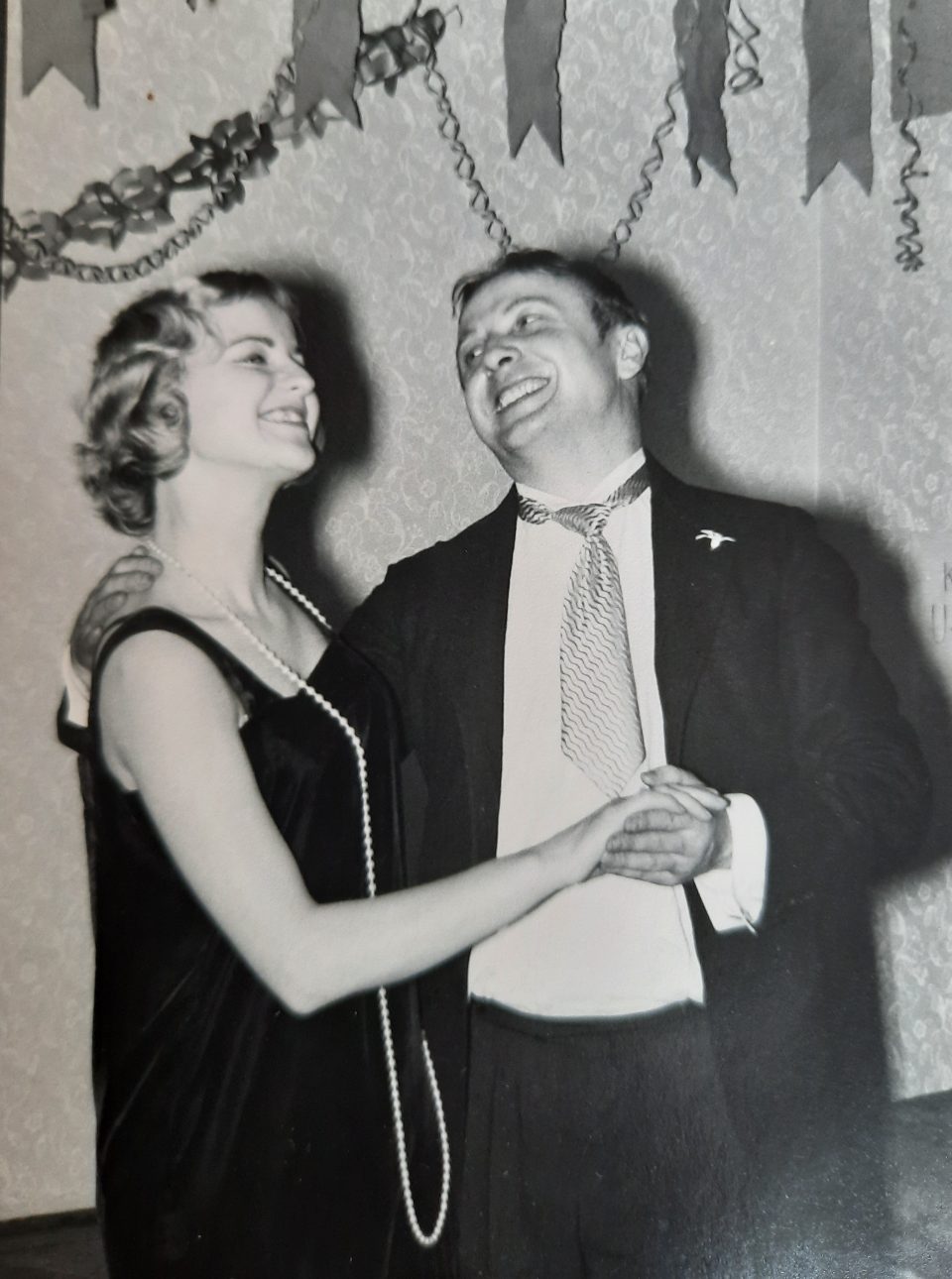

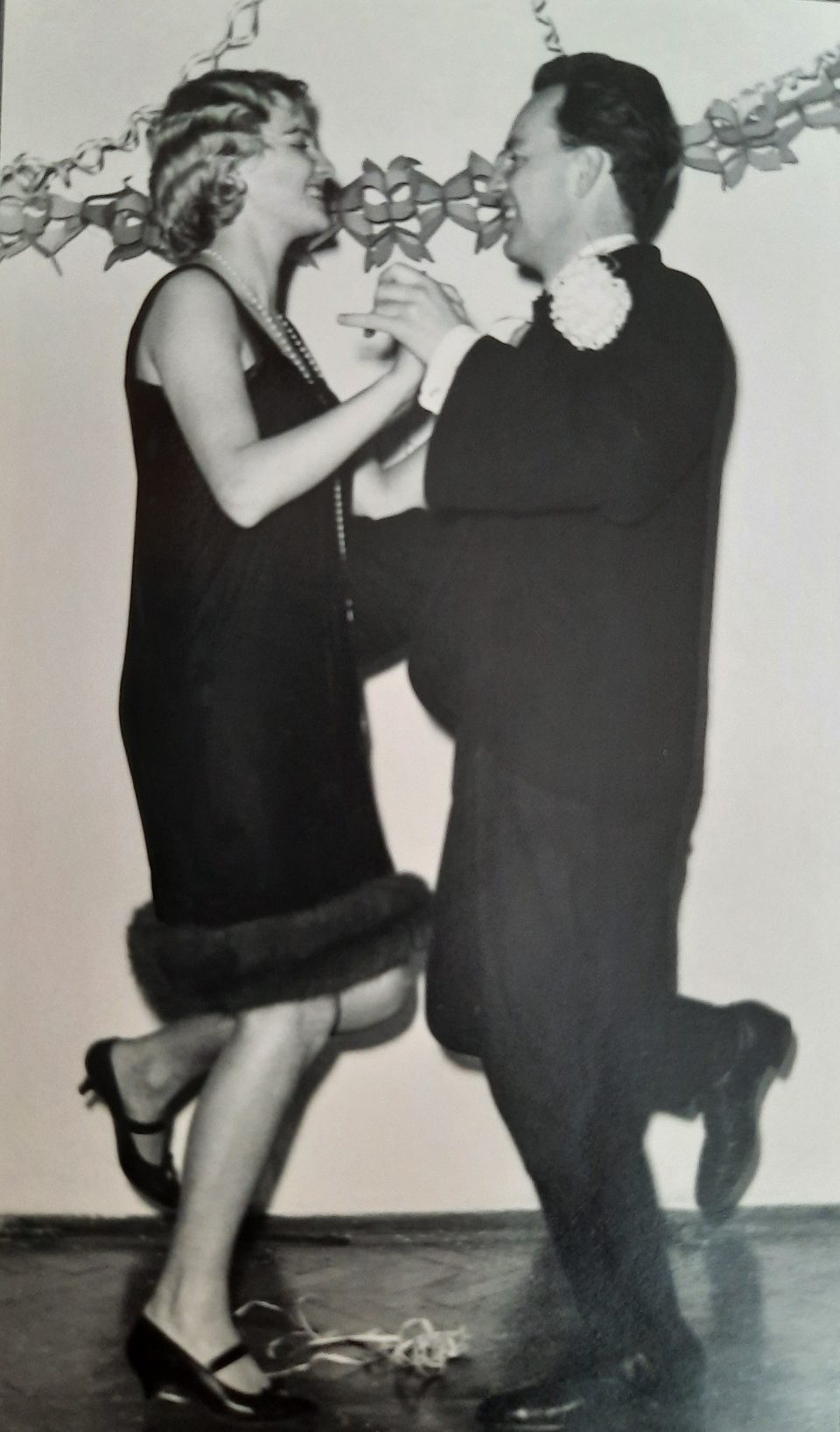

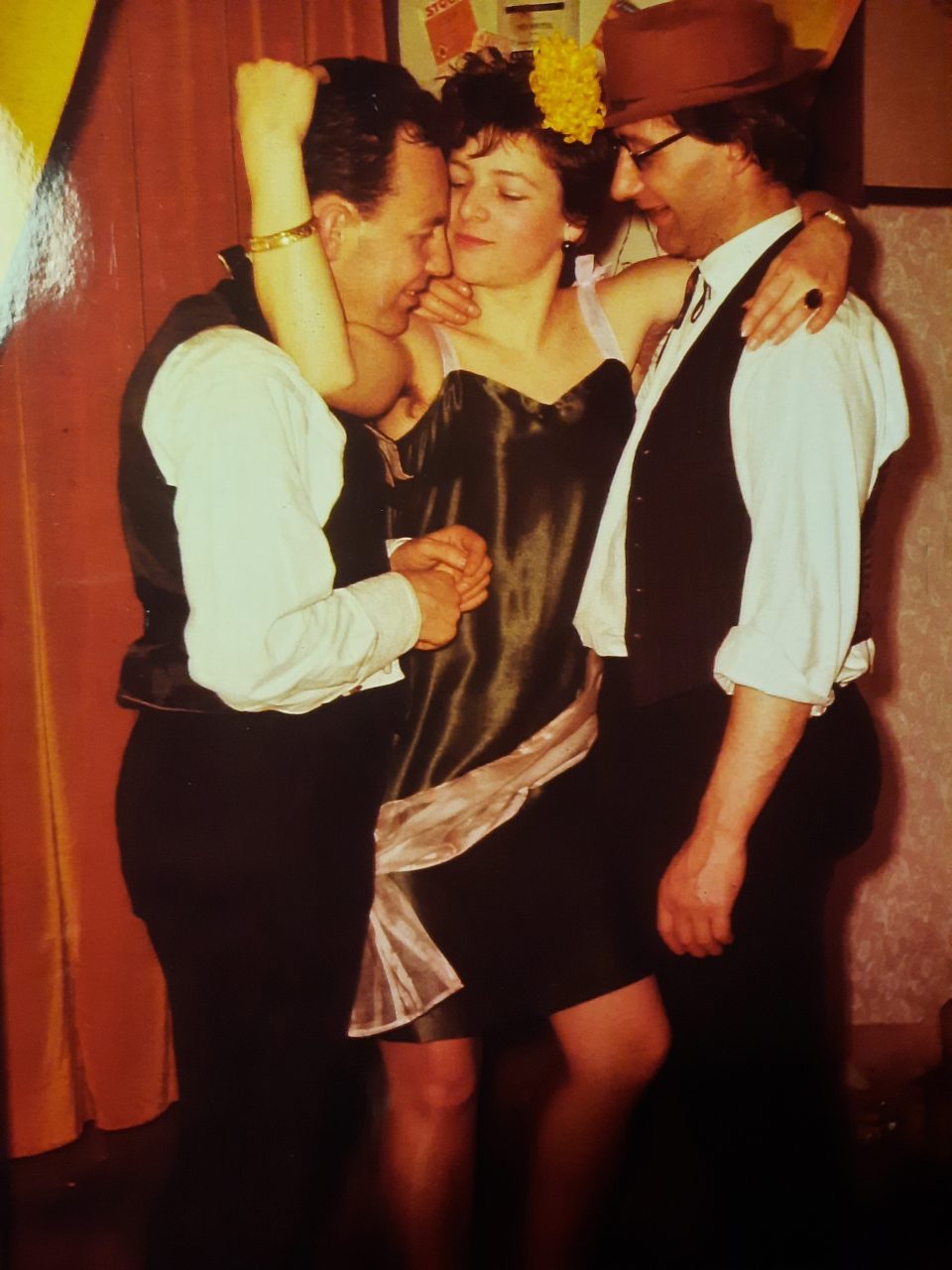

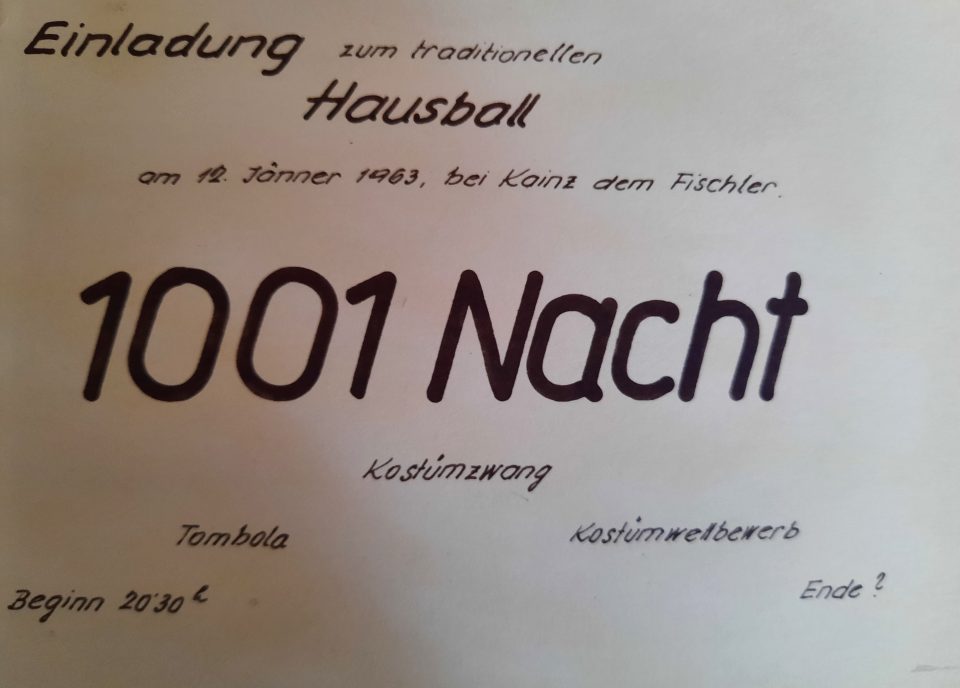

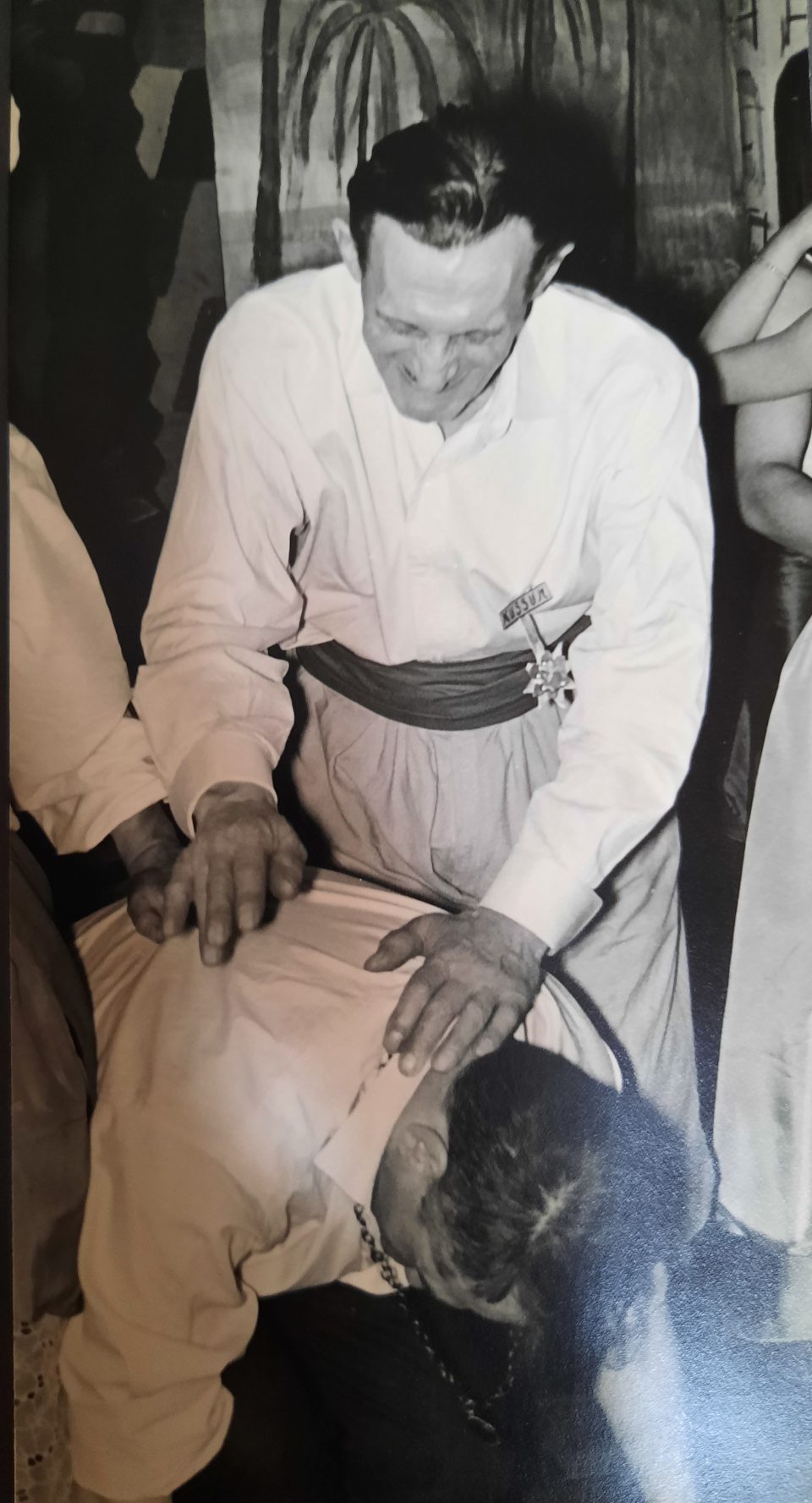

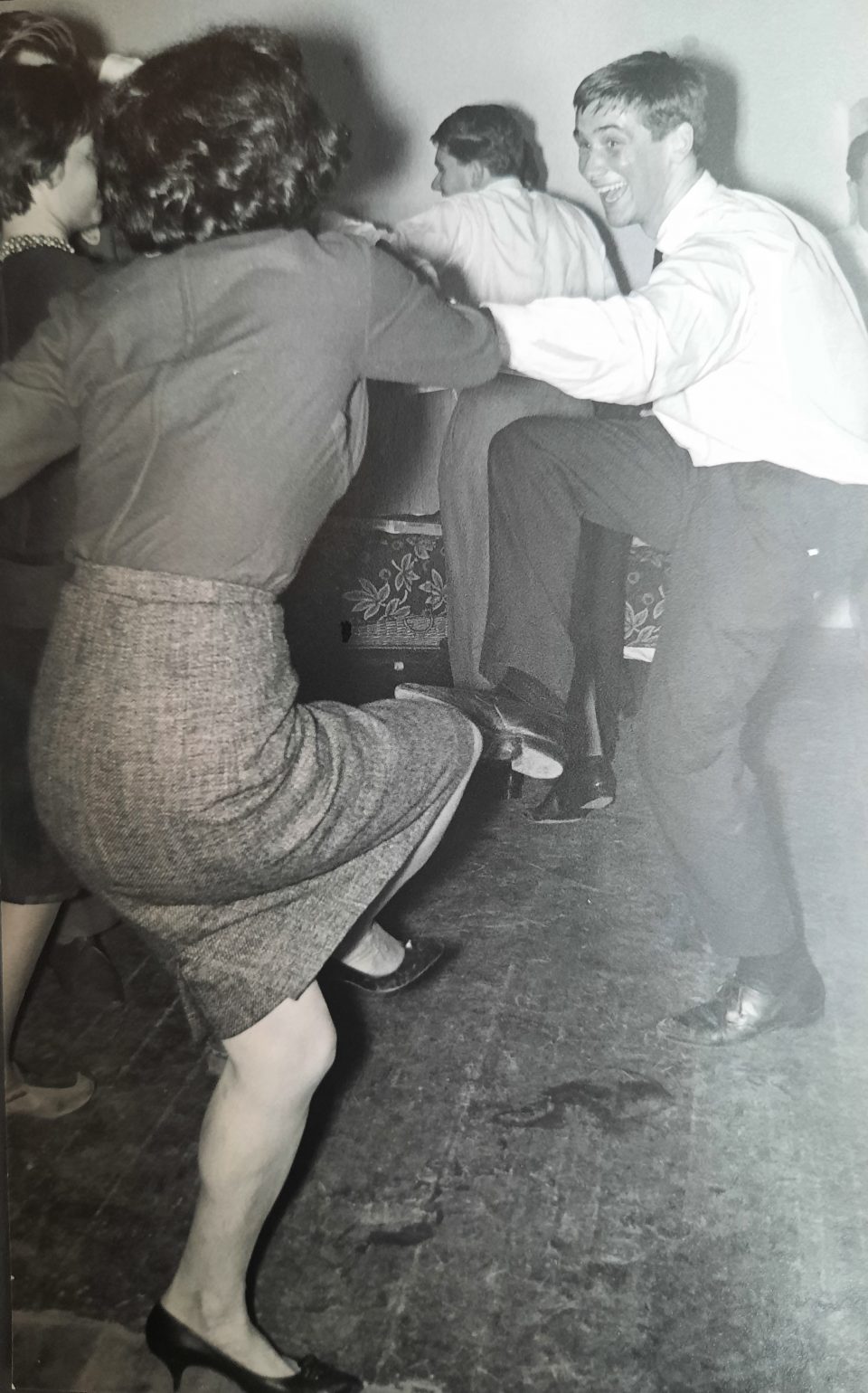

Entertainment: private balls organised in the flat of Toni and Lola Kainz, my grandparents, in Vienna, Neulerchenfeld

The social and economic period of the “long 1950s” started around 1947 and finished in the middle of the 1960s. The historian Eric Hobsbawn called it one of the most revolutionary periods in European history despite its general image of boring conservatism. He explained his surprising analysis with the unprecedented economic growth rates, the unrestrained adulation of technology and productivity and the breakthrough of Americanised industrialised mass culture. In Austria this period started with the currency reform of 1947 and the establishment of the post-war “Social Partnership” between employers and employees with the first wage and price control agreement. American aid via the Marshall plan (1948-1952) triggered the Austrian economic “miracle years” and in 1948/49 the former Nazis were again integrated into Austrian society with the virtual end of the denazification process. The Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union characterised the whole period with Austria positioned in the middle; geographically the most eastern point of the Western World, situated directly at the Iron Curtain. Culturally the aftershocks of the Nazi era and the Second World War were felt during the whole period, but gradually abated. The consequences of the lost war, the Allied liberation and occupation and the excessive veneration of virility by the Nazis gave way to a revival of the traditional conservative roles of men and women. The early 1960s were the years of marriage and childbearing, the “baby-boomer years” in Austria. After a very short period of cultural awakening right after the war, in the 1950s Austrian art and culture experienced a kind of “counter-enlightenment”, a return to very conservative art concepts. The student movement of 1968 ended this period and hailed a new era of sexual and artistic revolution which ended the post-war conservative Austrian concept of “the unity of the good, the true and the beautiful”.

If the Austrian standard of living was measured against the Western European standard at the beginning of this period, Austria was 40% below that, but the gap shrank to 20% in 1961. The gross national product of Austria grew from 49.6 billion AS (Austrian shillings) in 1950 to 134.6 billion AS in 1959. The economic structure developed towards the “American model” via increasing productivity, growing real incomes, an expansion of the labour force, a rising supply of goods and linked to that a dynamic consumerism. The introduction of the “American ideal of beauty” led to a dramatic increase in spending on cosmetics products in the same way as the craving for a motorised vehicle, a modern technical “American-style” kitchen and modern easy-clean furniture resulted in a dramatic increase in purchases in these sectors. Yet an average Austrian family could not afford a car or a fridge; the solution was presented in the form of hire purchase agreements. The new needs and wants of consumerism could be satisfied in this way. The higher living standard in Austria was paid for dearly with the health of the workers via piece work and overtime work. Despite the fact that the workers experienced pay rises to compensate the high inflation rates, the wealth gap between working class and middle class incomes was still widening and the new wealth was distributed unevenly. Even if a Viennese worker’s family had acquired a fridge via hire-purchase, they probably did not have a bathroom in their flat. This fact was covered up by the ruling “Social Partnership” of ÖVP (People’s Party) and SPÖ (Social Democrats), of trade associations and trade unions. The battle for a share of the new wealth was fought on the negotiating table between the government and representatives of employers and employees. Yet Austrian young workers tended to acquire the tastes of the middle class during this period. They bought the same clothes, saw the same films, bought the same technical gadgets, enjoyed the same leisure time activities and went on holiday to the same destinations, which in the long run diminished the differences in class consciousness in Austria.

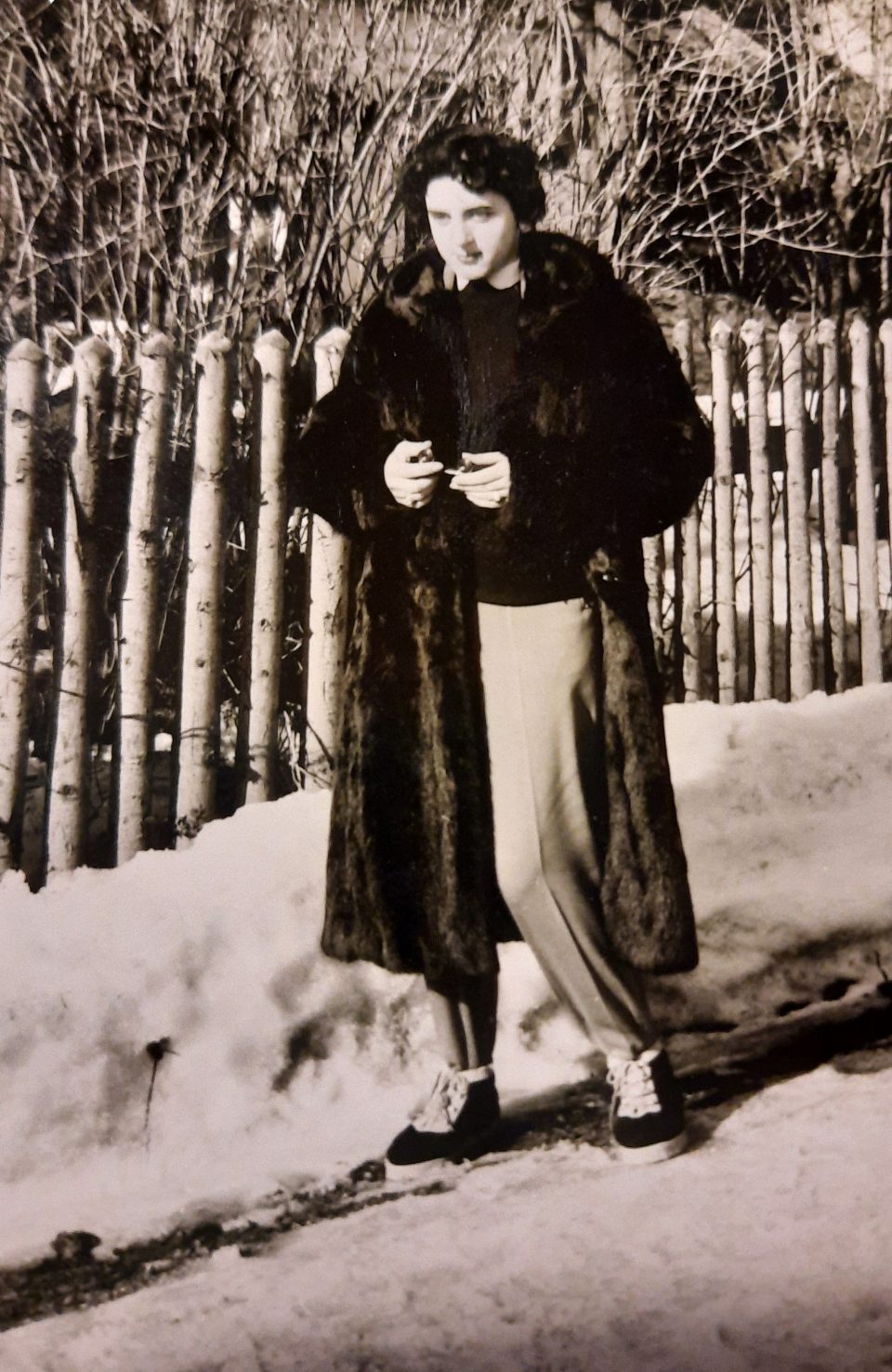

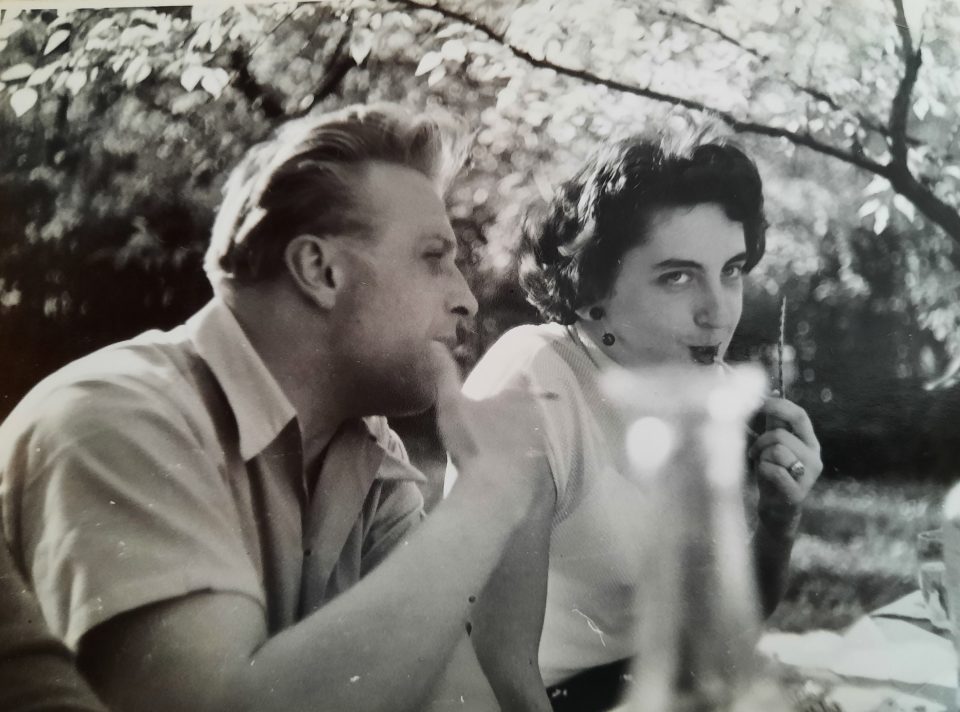

All in all, every politically relevant group profited in the 1950s from the economic boom and the household expenses for food and clothing decreased, while the expenses for furniture, transport and leisure increased. Between 1950 and 1960 net private consumption rose by 71%. Expenses for education, training and entertainment increased by 81% during this period, for transport by 169% and expenses for furniture and household wares even by amazing 228%. Immediately after the war the prices for non-rationed goods skyrocketed and that’s why their share of expenses was extremely high, but 1950/51 was the first post-war year with free choice of consumer goods and no more rationing and by 1953 the ration coupons had completely vanished in Austria. Gradually the population bought more expensive, low-calorie and qualitatively higher food products and more ready-made products and that is partly the reason why the consumers spent 52% more on food stuffs in 1960/61 than in 1950/51. Many enterprises now offered canteen lunches, which phased out the Austrian habit of taking lunch boxes to work. Smoking and drinking was socially acceptable and much appreciated in those years, which can be seen in the photos of the time below. Alcohol consumption rose 88% per capita from 1950 to 1963, which meant an increase of 5.4% per annum. Cigarettes were a means of payment after the war and a status symbol. US cigarettes represented the new American way of life. In the 1920s and 1930s the light oriental tobacco dominated the Austrian market; it constituted 70% in 1937, but sank to below 10% after World War II. US Virginia tobacco was introduced in Austria during the years of the black market with US cigarette brands such as Camel, Lucky Strike and Chesterfield. Immediately after the war the cigarettes produced in Austria were the notorious “extra mixtures” (“Mischung A & B” and “Austria 1, 2 & 3”), but from 1948 on also more expensive brands with Virginia tobacco were produced such as “Jonny” and “Austria D”. Apart from the black market the Soviet USIA (Soviet property in Austria) cigarettes undercut the Austrian tobacco monopoly until 1955, when the Soviet army withdrew from Austria. In 1950 the Russian army administration established around 80 so-called USIA shops in the Soviet zones which offered a wide range of Soviet products from cigarettes and alcohol to food, textiles, sweets and even typewriters. The quality of these products did not necessarily meet the consumers’ standards, but the products were offered at dumping prices. The Communists advertised these shops as the Soviet form of aid for Austria, the Soviet “Marshall Plan”. But for some Viennese purchasing in USIA shops was considered a “betrayal of public morals”, others saved around 200 AS per month when shopping there. The demand for new clothing also underwent big changes as the Austrians moved towards ready-made clothing, which had a huge impact on the dressmaking sector, in which Herta worked; more and more dressmakers and tailors were dismissed facing long periods of unemployment and the small and medium-sized workshops had to close down.

A burning problem was the lack of housing. Vienna was short of at least 200,000 flats in 1951 and of those that existed only 14% had their own bathroom, 56% had no running water in the flat and 60% no toilet inside. Toni and Lola’s flat at Lerchenfeldergürtel 45/35 in Ottakring (16th district) was a “luxury” flat by those standards because it was large (four large and one small room) and had running water and a toilet inside, but no bathroom. Before they had a shower installed in the kitchen, the whole family had to go to a public bath house. In 1950 the Viennese public bath houses still counted 5 million visitors annually and the city of Vienna ran around 20 such bath houses. Herta’s family frequented the one in Ottakring, Friedrich-Kaisergasse 11.

The public bath house in Ottakring, Friedrich-Kaisergasse 11, is probably the last remaining “Tröpferlbad” (Viennese term meaning a trickle of water because the water flow was sometimes less than abundant)

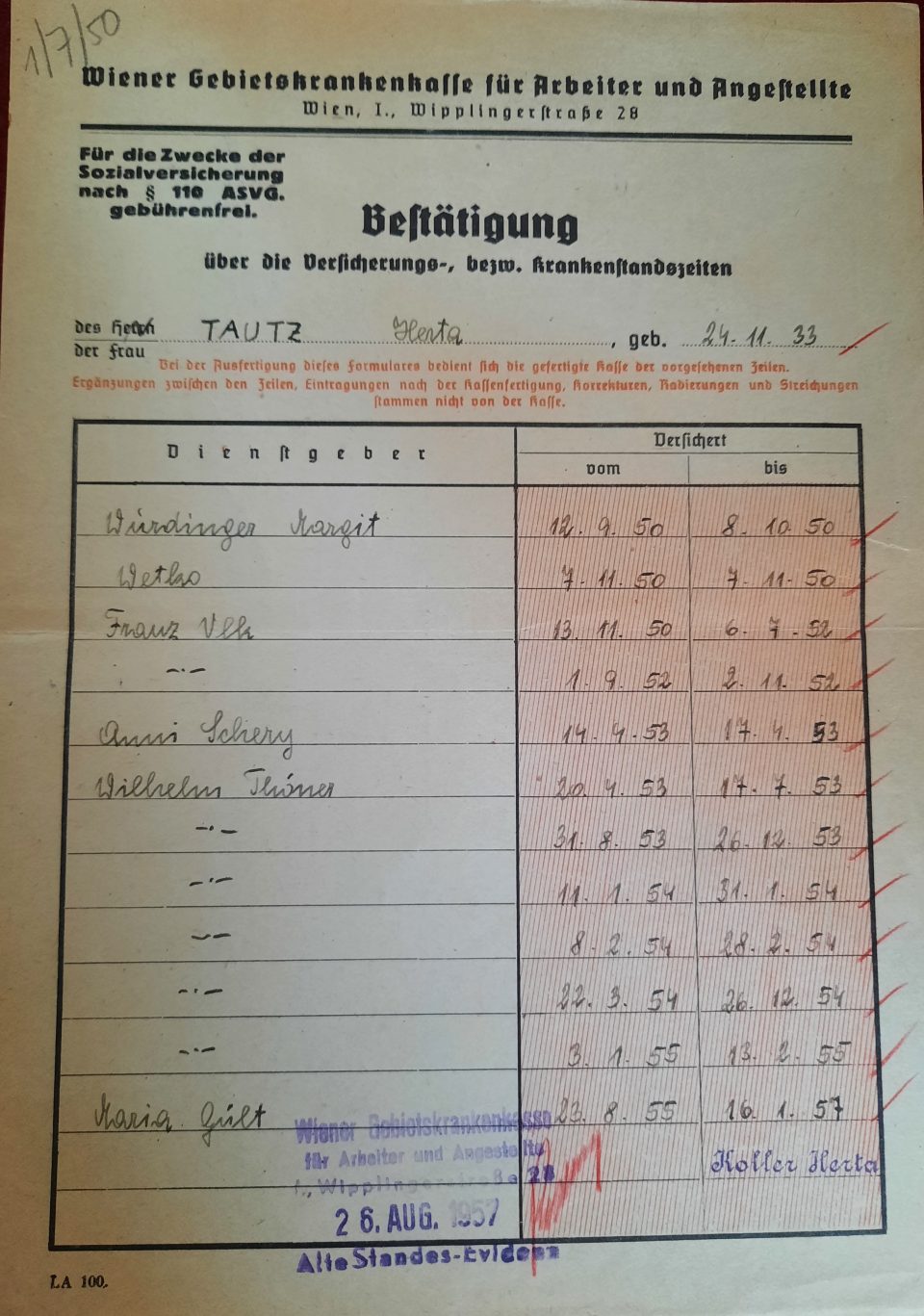

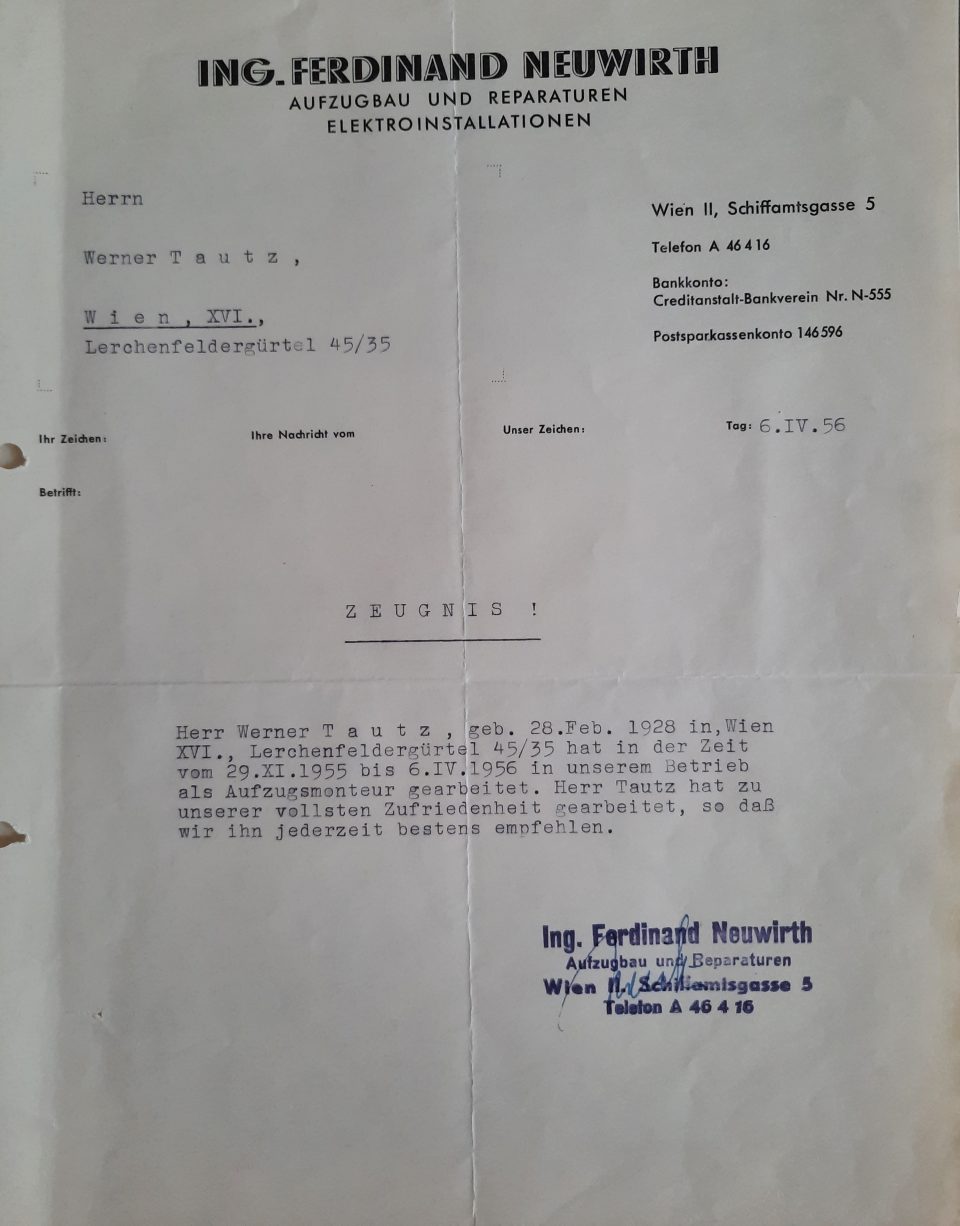

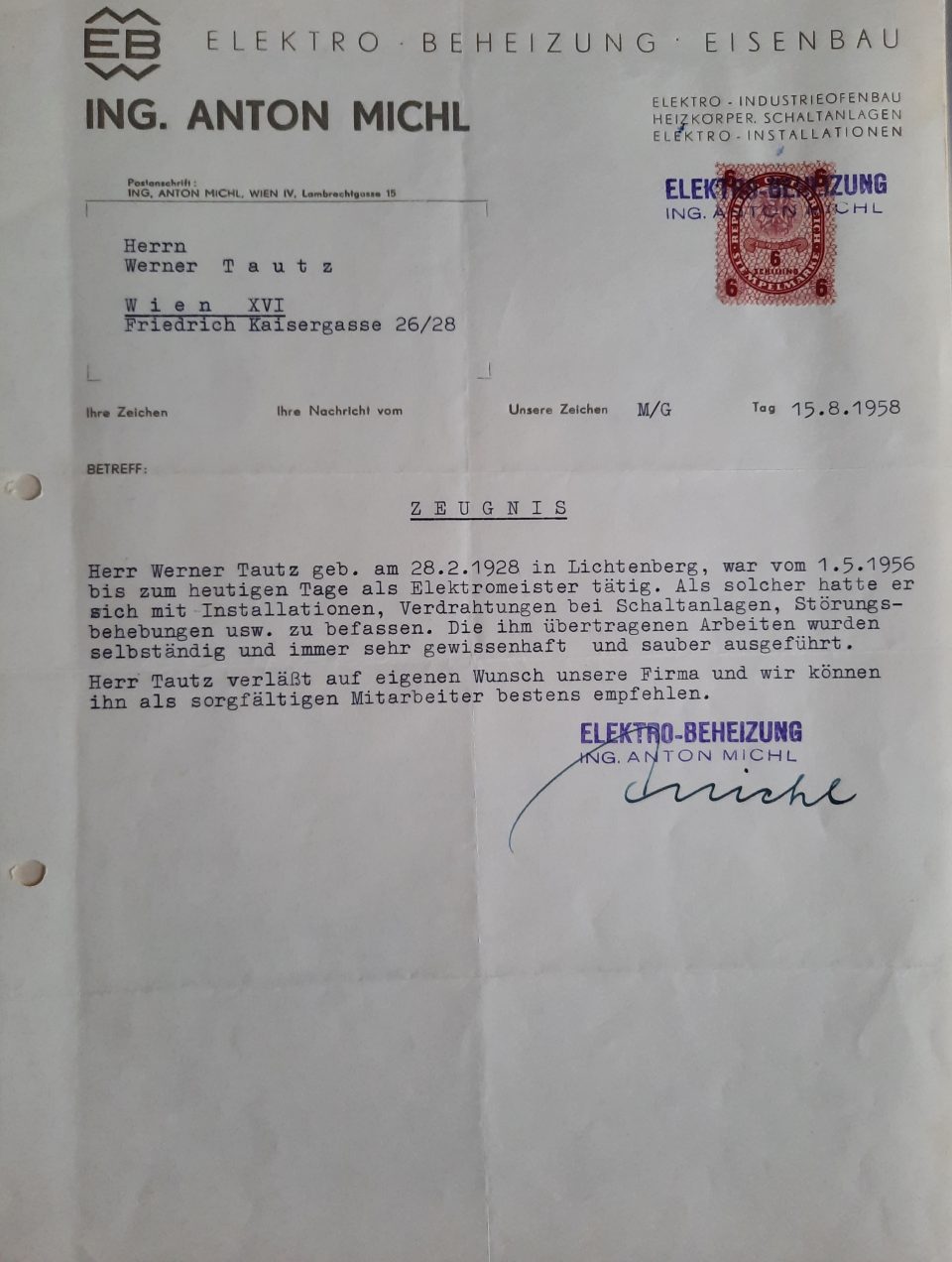

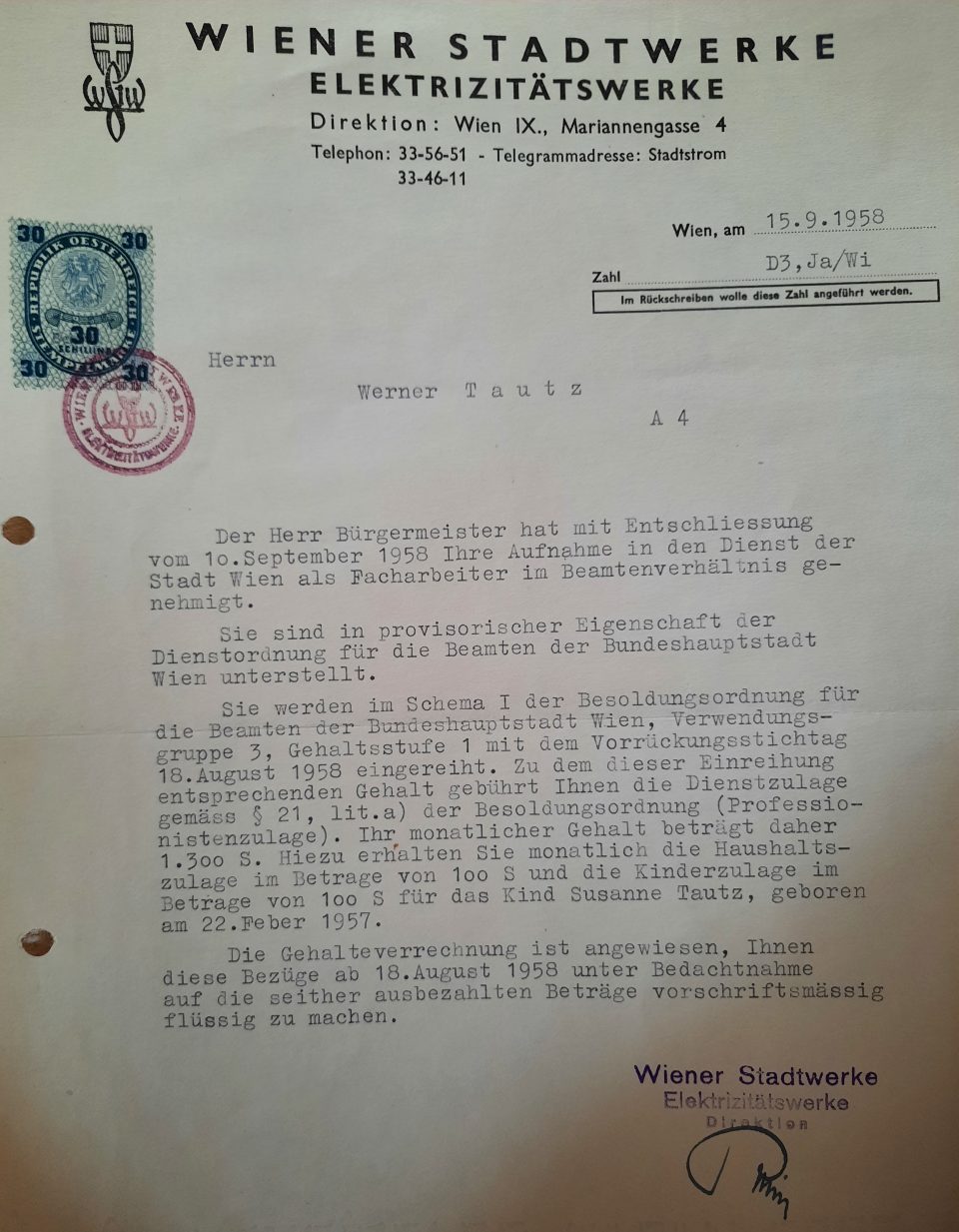

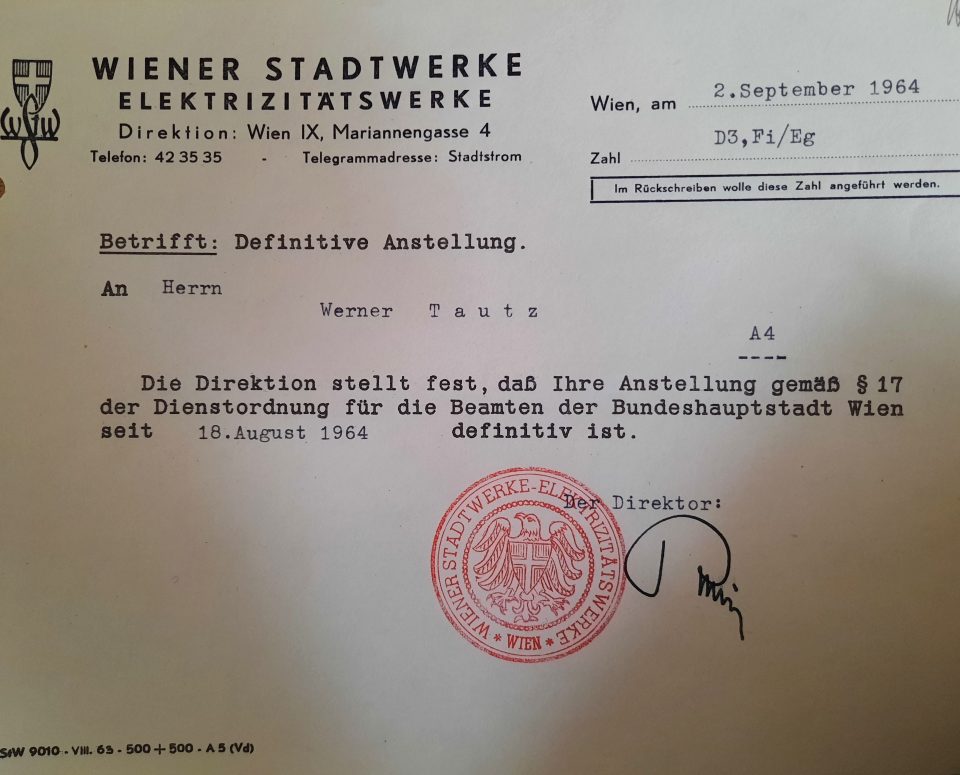

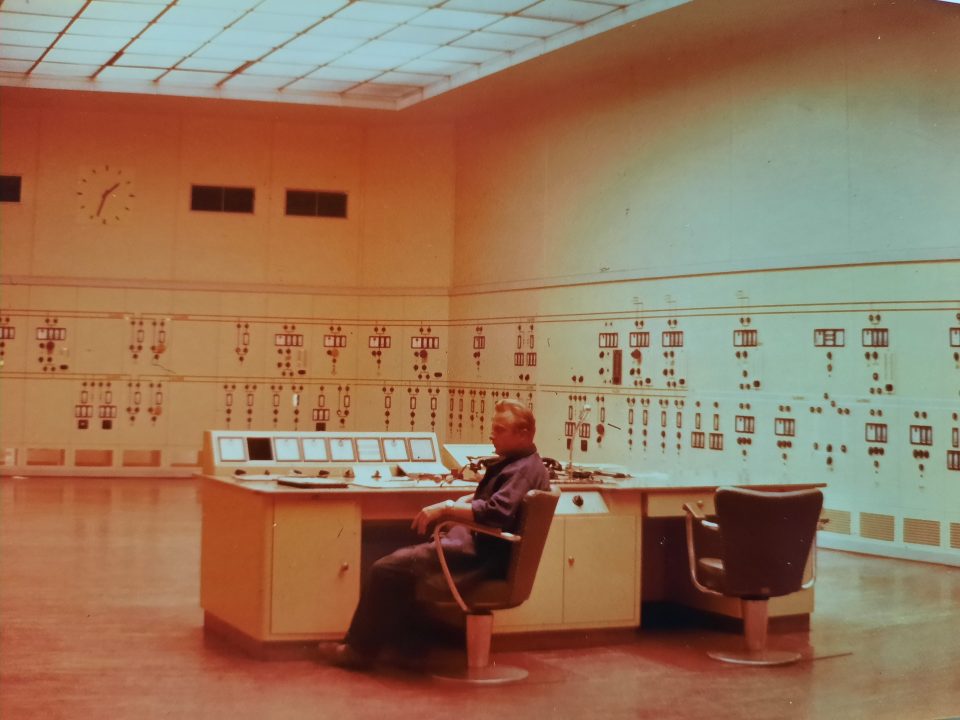

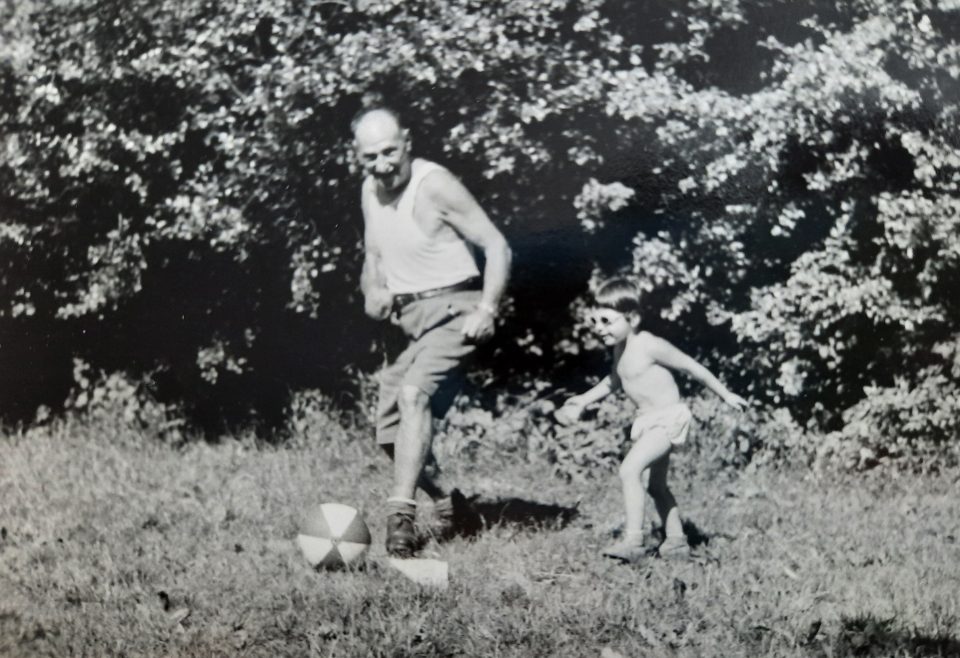

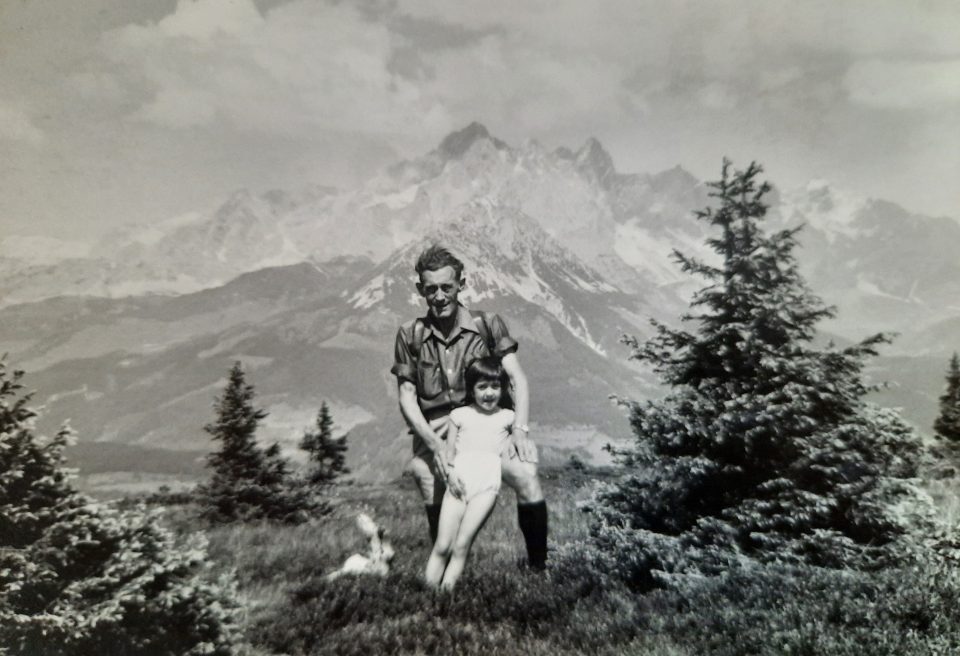

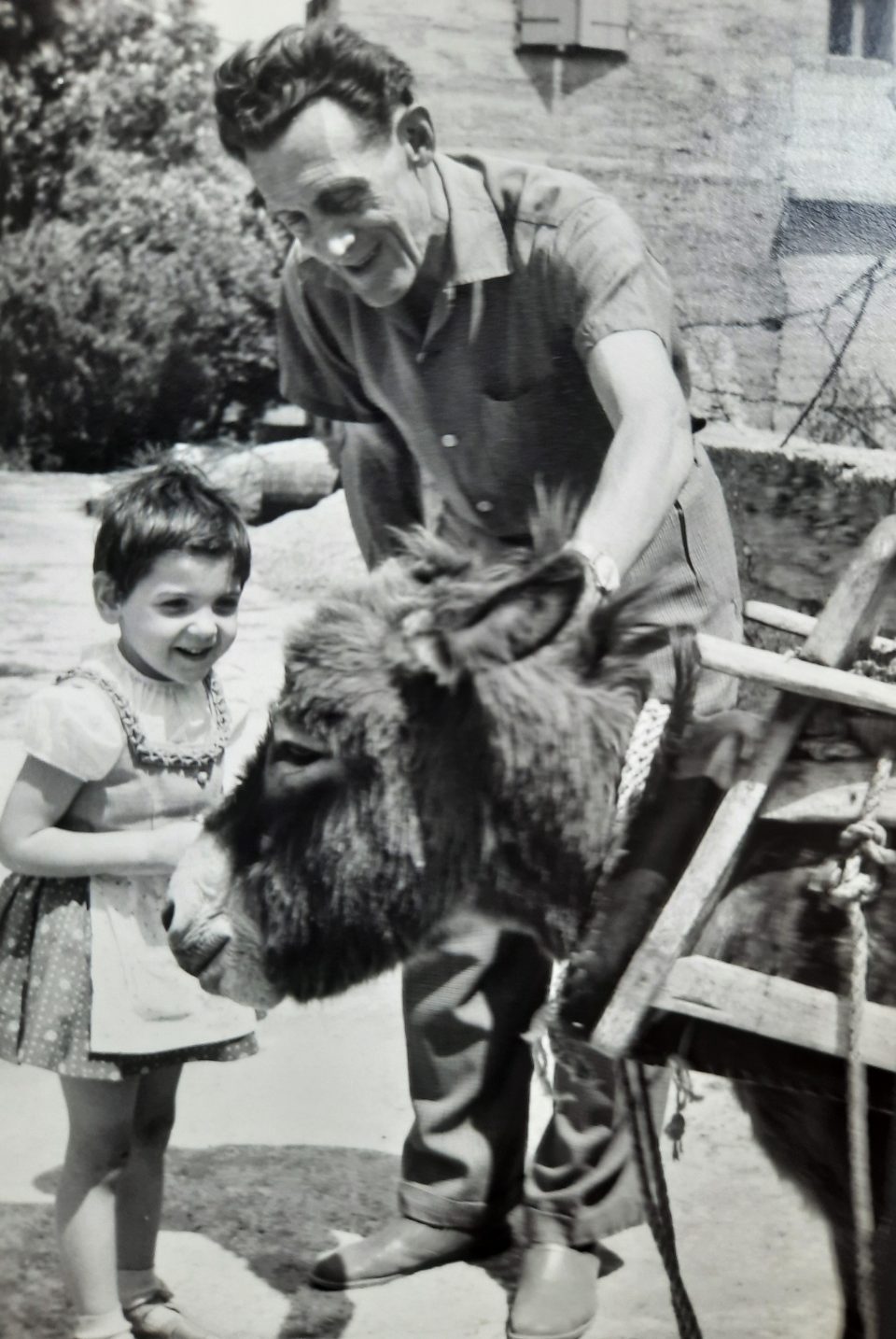

This explains how proud the young couple Herta and Werner were, when they could pay the deposit for their newly built cooperative flat in Ottakring, Friedrich-Kaisergasse 26/28 on the fourth floor: 48 square metres with bathroom, toilet, kitchen, hall, two rooms and a balcony, in 1954. The deposit was 20,000 AS and the rent was 450 AS per month. Werner had earned well when working at the hydroelectric power plant Kaprun until 1955 (see article “Workers at the construction of the hydro-electric storage power plant Kaprun”) and they had both saved further 45,000 AS, which they used to furnish the new flat, when they moved in in 1956. When I was born in 1957, Herta stayed at home and Werner started to work at the Vienna Electricity Works, where he earned 1,300 AS per month, which meant that after paying the rent of 450 AS, gas, electricity and heating, not much was left for food, clothing or leisure activities. At that time Werner stopped smoking and Toni and Lola, my grandparents, paid for holidays together or outings.

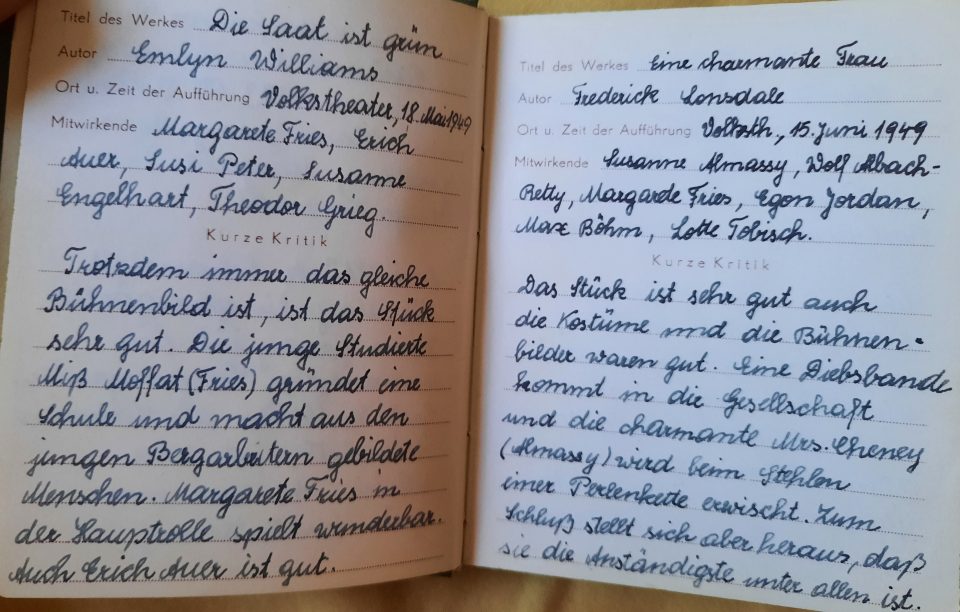

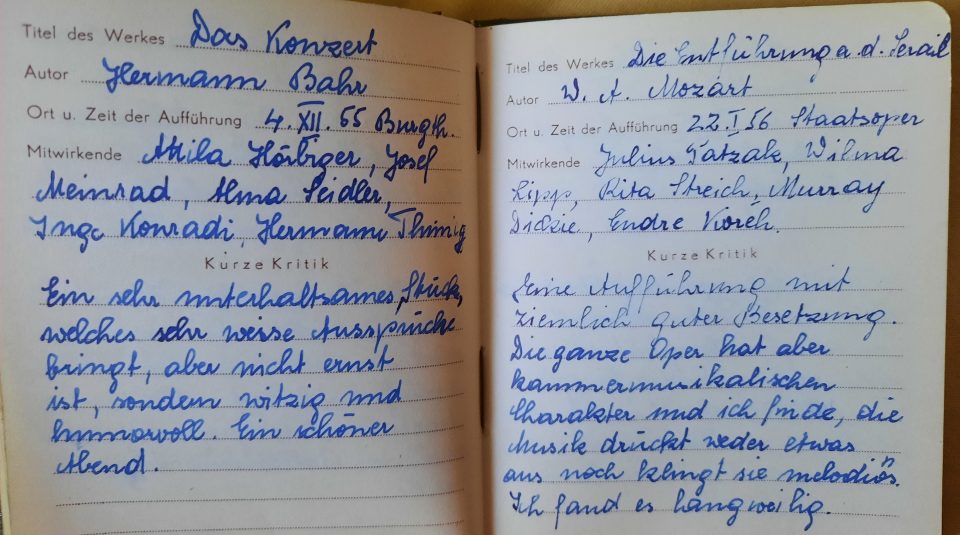

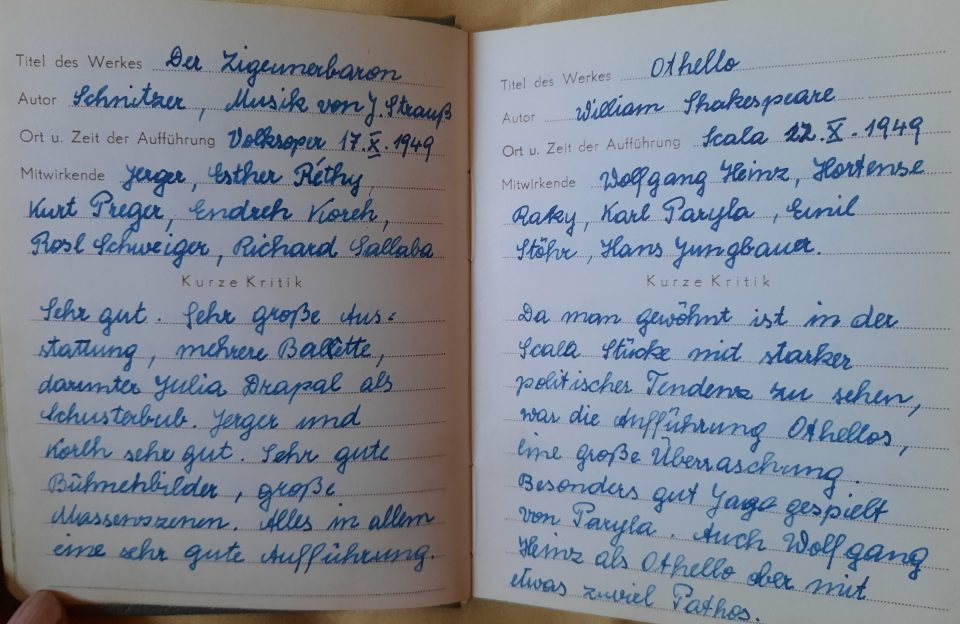

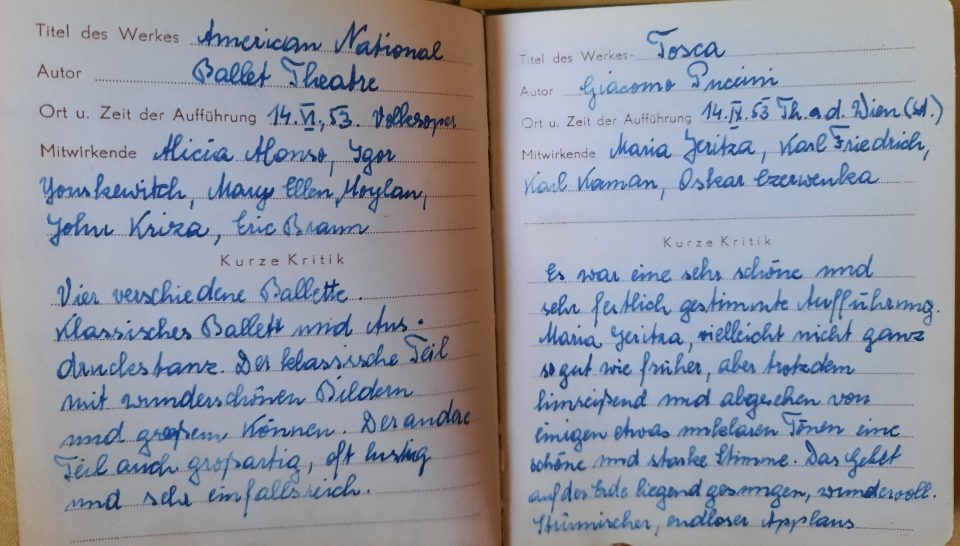

After the war the pent-up demand for consumer goods resulted in a spending spree in three surges in the 1950s: first the “food surge” 1947/48, then the “clothing and furniture surge” 1949-51 and since 1953/54 the “fridge and car surge”. In 1964 the amount spent on furniture and household wares had doubled as compared to 1954. Social housing and tenant protection in Vienna prepared the ground for higher standards of home décor: American-style kitchens, fitted wardrobes, fridges, hoovers, washing machines turned out to be status symbols of middle-class lifestyle, most of it bought via hire-purchase. In 1956/57 the last surge started, the “travel and TV surge”. Only since then TV sets could be bought in Austria: in 1957 12,500 sets were registered and in 1958 33,000. In Vienna most inns and coffee houses had a TV set for public viewing. Werner and Herta did not buy a TV set, they preferred listening to classical music records, but when ice-skating competitions were broadcast I sometimes went with my grandmother Lola to the “Café Hummel” in Josefstädterstrasse to watch TV or when the children’s programme “Kasperl” was on all the children of the house met in front of the TV-set of my friend Sissy’s parents. During the whole period of the “long 1950s” cinemas, theatres and concerts experienced a boom in Vienna, but from 1960 on the cinemas started to feel the impact of television and the number of cinema goers slumped.

Religion

During the last years of the war a return to Roman Catholicism could be felt in Austria and this trend persisted way into the 1950s, but it was not a return to the politicised Catholicism of the Austro-fascist regime of the 1930s. The Church deliberately tried to distance itself from party politics and had finally accepted the Austrian Democratic Republic. As a consequence the relationship between the Church and the Socialists returned to normal. After the Nazi period the school prayer and religious instruction was reintroduced in Austria and in the country the Roman Catholic calendar dominated the lives of the people again much more than in Vienna, whereby religious feasts took on a folkloristic touch, which was useful for boosting tourism. At the same time many former Nazis used the Catholic Church to hide under its “protective cloak”. The yearning for stability intensified the attachment to age-old Catholic rituals, such as the “Corpus Christi processions”. In the course of the “long 1950s” the Americanised consumer and leisure society pushed its way through the Austrian traditional culture resulting in a drastic decline of mass attendance and a secularisation even on the countryside from the middle of the 1960s onwards. Many Viennese reverted to a “selective Catholicism” which was characterised by the celebration of “the great moments of life” only, such as baptisms, first communions, confirmations, weddings and funerals. Nevertheless throughout the “long 1950s” the Church’s hold on the control of sexuality was unbroken. That was probably the last young generation which had to cope with the rigidity of Catholic morals.

Above: Herta after the war and the return of her grandparents Ritschi and Ignaz Sobotka from the KZ Theresienstadt (in the photo dressed up for the “Corpus Christi procession” with her grandmother). Below left: Herta’s Confirmation group (Herta sitting first on the right)

Right: Herta’s Aunt Marianne (second from the right) had come to Vienna from the United States to act as godmother at Herta’s Confirmation. She is sitting between Ignaz and Ritschi, Herta’s grandparents, and next to Herta her Uncle Karl and her Aunt Käthe, who had returned from exile in Bolivia.

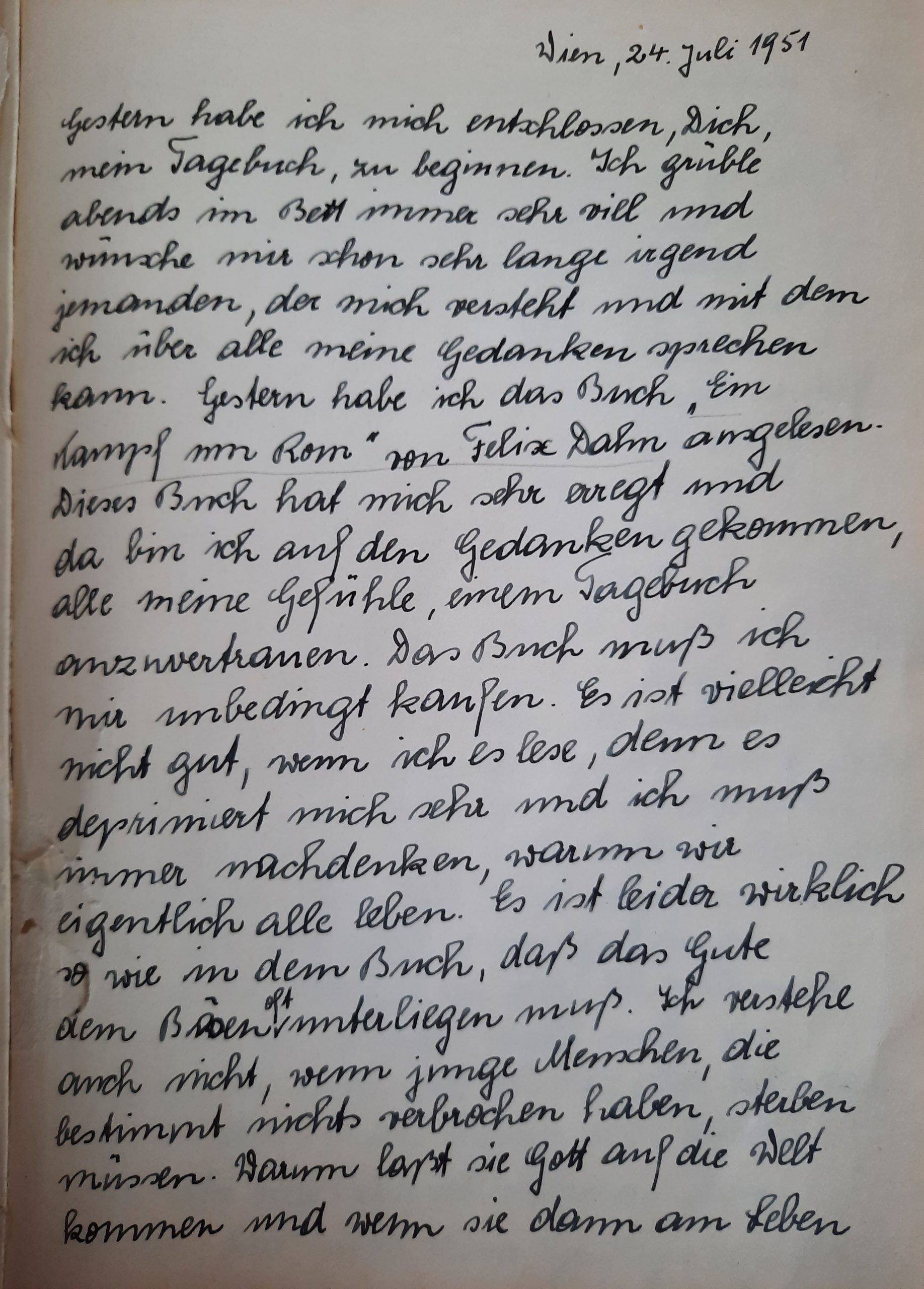

Herta wrote a diary from July 1951 (she was 17 then) until August 1955, which has been preserved:

On 8 June 1952 Herta wrote in her diary (she was 18 then) that her Aunt Marianne (Mizzi) had arrived from New York and they had had her Confirmation ceremony in church. ”I’m very, very happy because I had been longing for that for such a long time. I’m sure it was right that I have been waiting so long… I wanted a godmother who really liked being my godmother. I didn’t want one with money, but someone with whom I could share all my thoughts and sorrows and someone who I was convinced would understand me and could advise me; someone who I could turn to and who would always stand by me and such a person I have found now in Aunt Mizzi.” On 23 June 1952 Marianne left again for the USA and Herta was deeply sad and cried a lot because she had found a close friend in her aunt and she continued to write to her regularly and hoped she could visit her sometime in the USA, which never came about. But Marianne returned to Austria as soon as she and her husband Bill retired. Two and a half weeks after Mizzi’s departure Herta was still very melancholic, but she wrote, “I wish she were with us. But I must not think like that as she is so happy there and enjoys a much more beautiful life than she would have here.”

„Corpus Christi procession“ in Vienna, Ottakring, 1960

Nativity plays were performed by primary school classes (me as Holy Mary) in a “Wärmestube” (“Warm Room”) in Ottakring before Christmas every year. Such “Warm Rooms” were provided by the city of Vienna and run by a charity for people who were too poor to buy heating material and proper food, mostly the elderly. The charity was founded in 1922 and in 1945 the city of Vienna installed such “Warm Rooms” in every district, where the people who had no money to heat their flats could warm up in winter. They acted as a point of communication and entertainment for the elderly, too. Furthermore the visitors were provided with a hot drink and hot soups.

Herta read a lot and pondered much about God. In her diary she mentioned the books she had borrowed from the local library and which impressed her. Many of her lines are very profound and philosophical, characterised by a serious search for goodness and justice in the world and although a true Catholic believer she sometimes doubted the existence of God, who allowed such terrible things to happen. She started her diary because she had read the novel ”A Fight for Rome” by Felix Dahn, which had impressed her tremendously. “Maybe it’s not good, if I read it again, because it depresses me so much and I always have to think, why we are all really living. Unfortunately, it is just like in the book, the good is always defeated by the evil. I don’t understand why young people who have committed no crime, have to die. Why does God let them be born and as soon as they enjoy life, they have to die… I don’t know, but I cannot believe so firmly any more. Maybe because I don’t understand. But it is said that those who do not understand, but nevertheless believe, they are blessed. I don’t want to say that I don’t believe in God any more, but I cannot understand why he permits all this suffering and wars, where so many people die who have committed no crime….. I should not brood because everybody is so good to me and I must not think of God like that because he is very good to me, too. I will try hard not to think like that anymore”, she wrote on 24 July 1951 (Herta and her family had experienced unimaginable terror during the NS period in Vienna).

Middle-class lifestyle

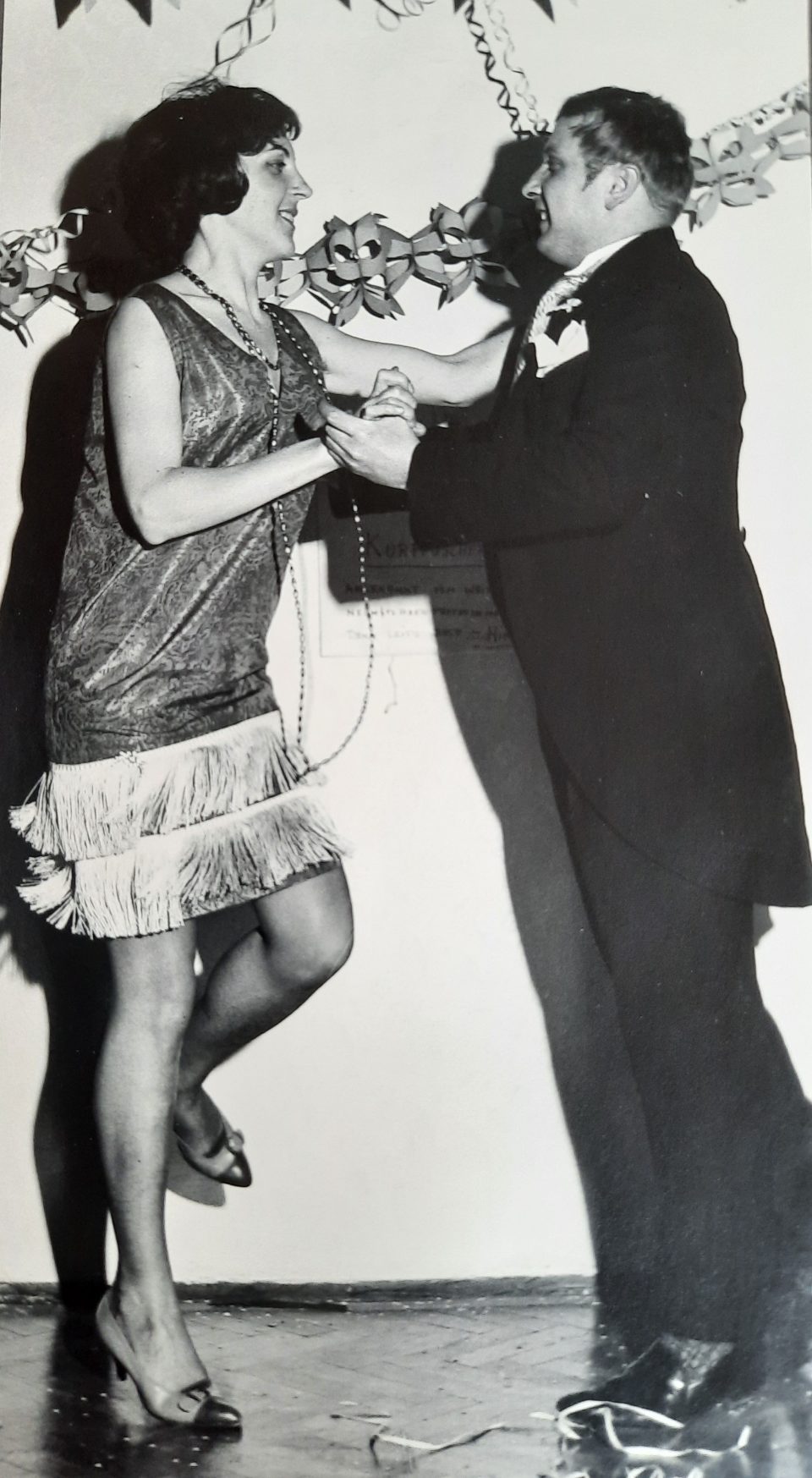

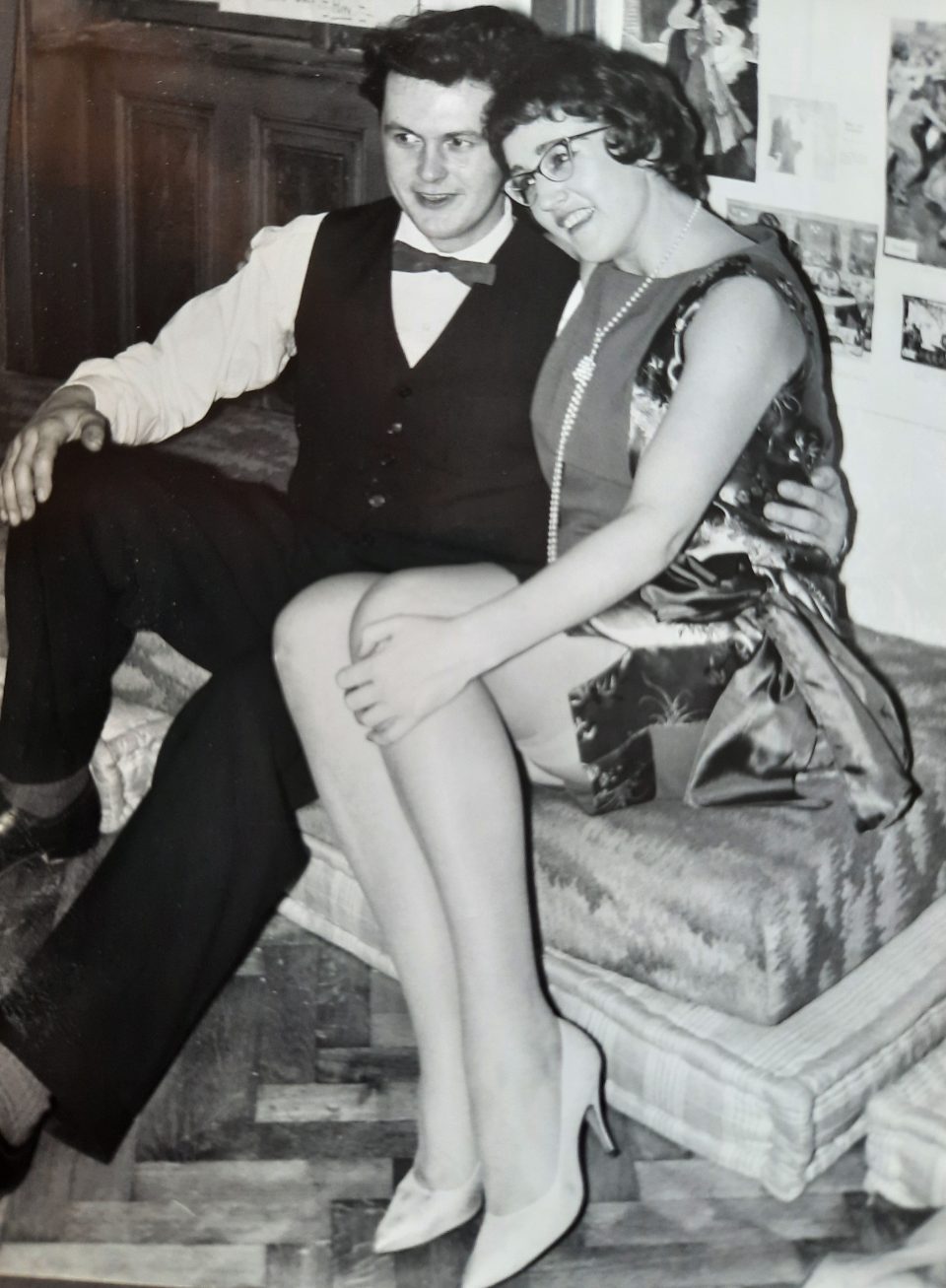

The ordinary people in Vienna soon started to enjoy the cosy normality of bourgeois life. Proper behaviour and nice clothing were again in demand and above all, the dancing schools were again more popular than ever, as well as the Viennese balls during the Carnival season. The bourgeois lifestyle was not a thing that was to be taken for granted. It was now open to the working class as well, but had to be acquired. One of the most decisive trends of the time was this absolute and unswerving will to rise in society, to get an education and to perform on the job. The memoirs of Werner, my father (born in 1928), and the 1950s-diary of Herta, my mother (born in 1933), are testimonies of these social and cultural ambitions.

The dressmaker Herta and the electrician Werner ready for a Viennese ball and dancing there on the right

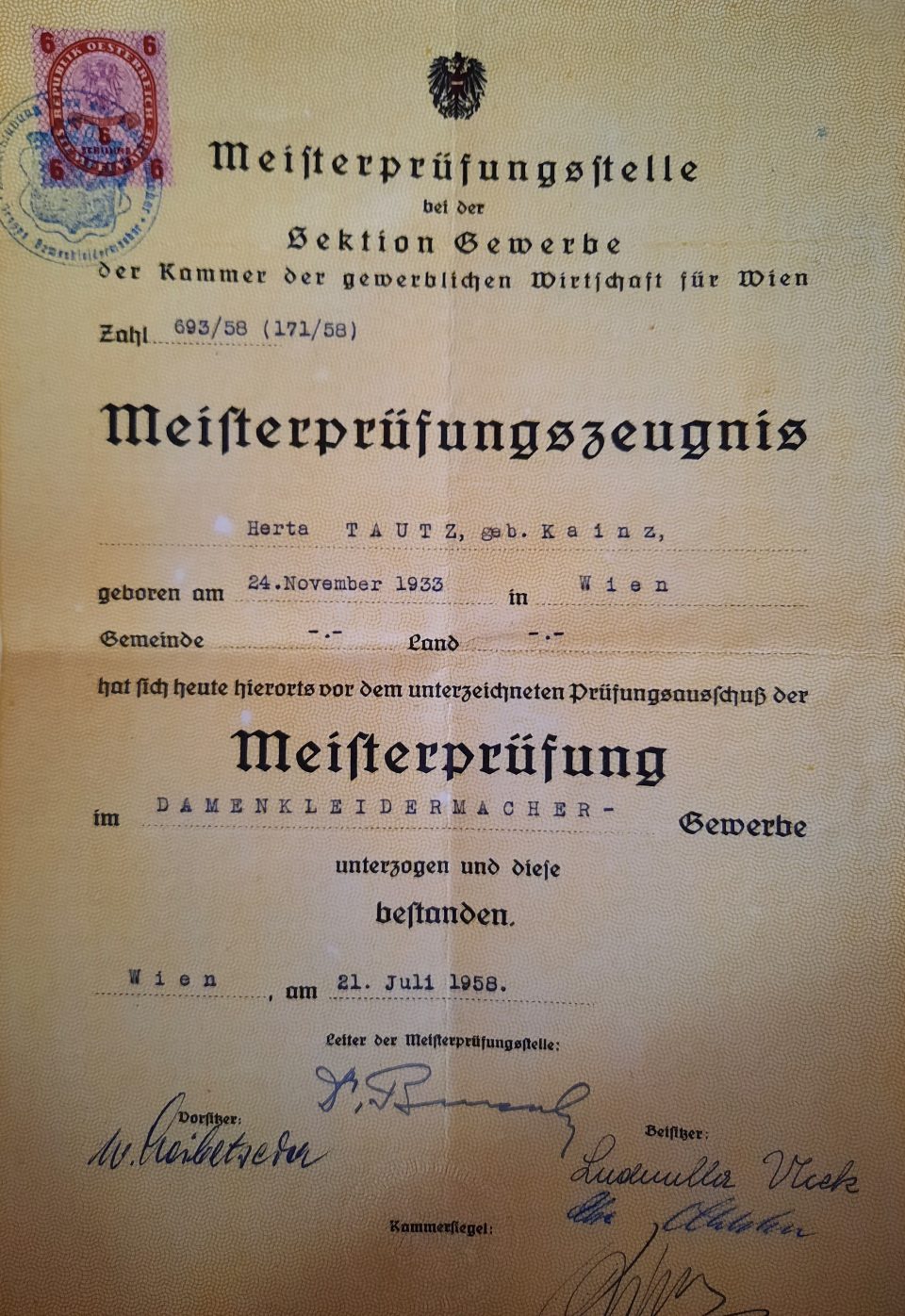

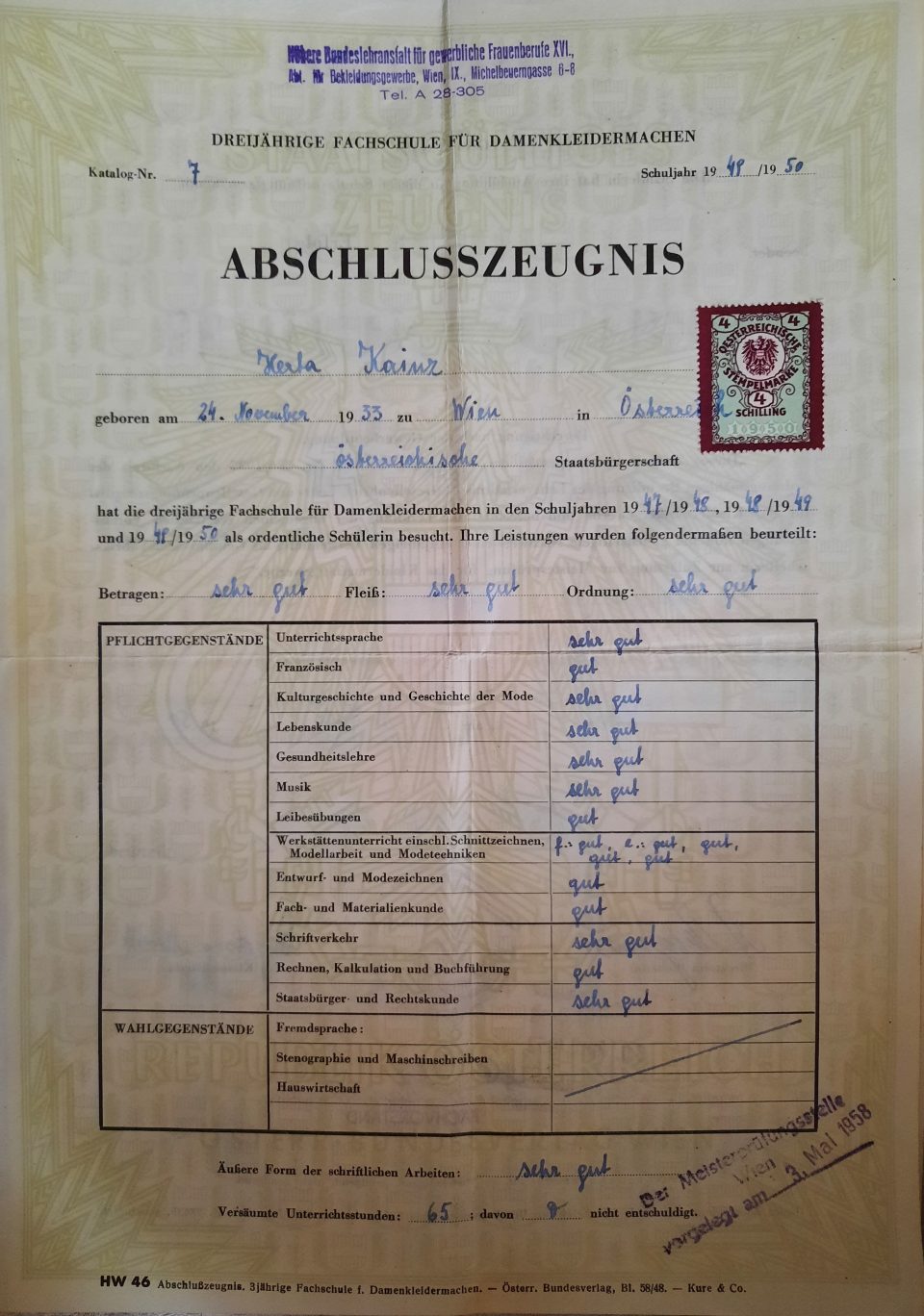

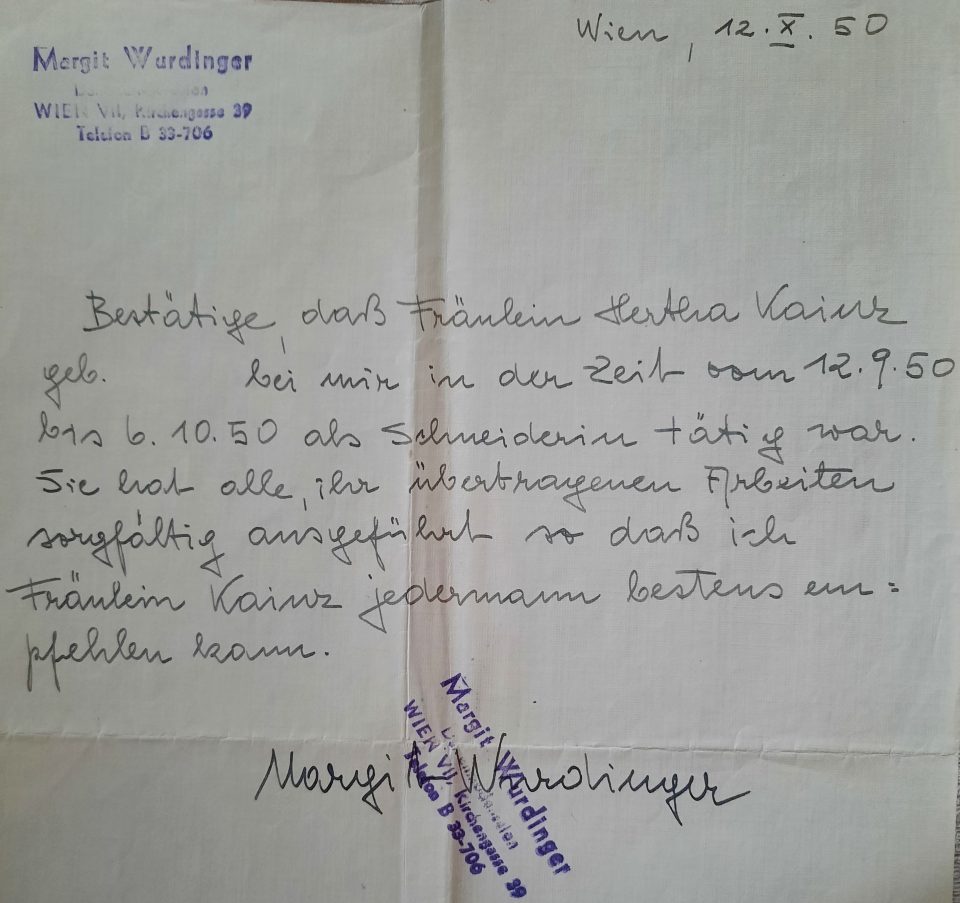

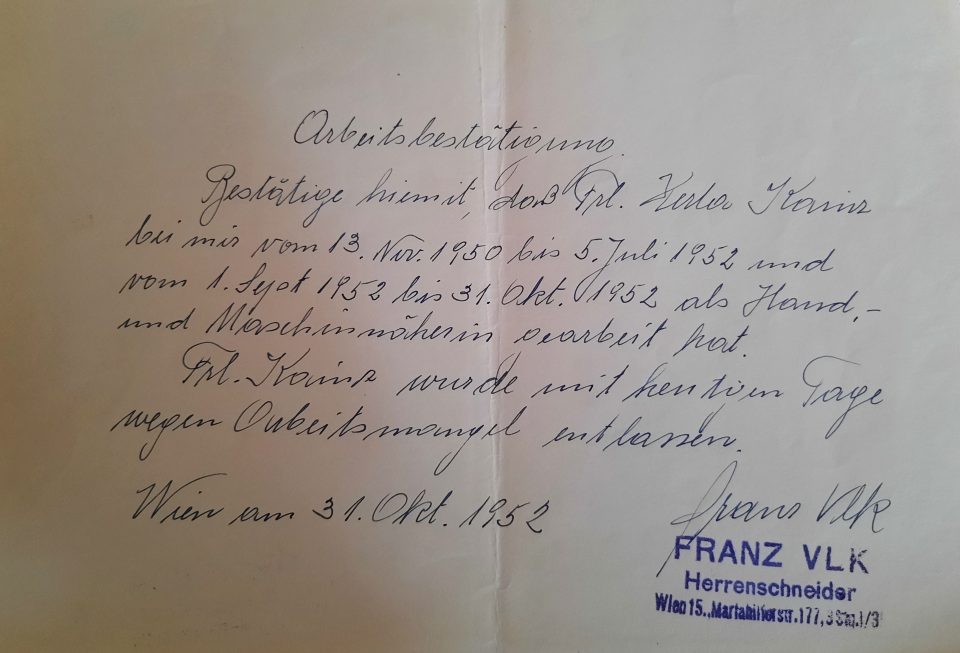

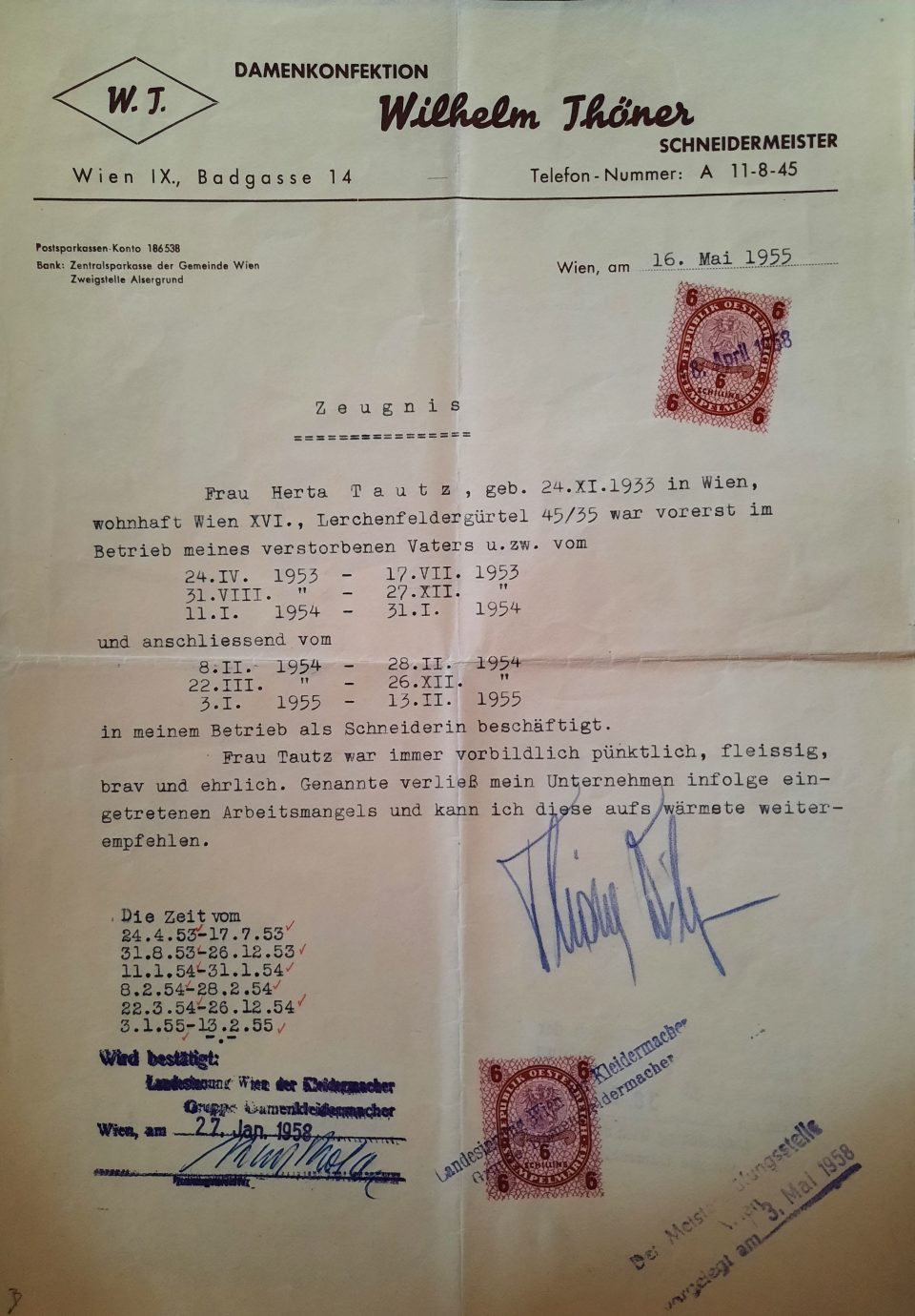

While working full time Werner and Herta both took evening classes and successfully passed their respective master classes in 1958, Werner as a master of electrical engineering and Herta as a master dressmaker

Part of the conservative paradigm in Austria was a resurfacing of nostalgia for the Habsburg era and a glorification of Vienna as the Imperial city and Austria as a folkloristic Alpine idyll for tourists. The revived folk traditions served the surging tourist industry well. Ideologically the society seemed to converge politically on an anti-authoritarian course with a focus on a strict anti-Communist stance, which became the standard repertoire of Austrian political culture. Here age-old fears and nightmares of the “threat from the east” surfaced and historical invasions from the “East”, such as by the Huns, the Avars and most of all the Turks were invoked. The “East”, embodied by Soviet-dominated Eastern Europe, portrayed an alternative social model which threatened Austrian core values. The fierce anti-Communism of the Nazis merged with the negative experiences some Austrians had had with Soviet soldiers during the time of the Allied administration of Austria. Although this persistent hunt for Communists might have threatened key democratic rights, it also contributed to a consolidation of a free Western democracy in a country which had had no long-lasting democratic experience before.

The female role & family

On 26 July 1951 Herta wrote in her diary, “This evening Lotte and me went to a meeting of the “Gebirgsverein” (an Austrian Alpine hiking association), but I did not feel comfortable there. They only talked about mountains and that’s too one-sided for me. There is unfortunately no other topic there. It probably is me; maybe I’m too boring, but a leopard can’t change its spots and that’s probably why I don’t have a boyfriend yet.” Herta often talked in her diary about her family and how much she loved them and especially her Aunt Käthe, who had returned with Karl from exile in Bolivia. Herta was such a shy and timid young woman that she did not even dare to ask her aunt and uncle if she could stay with them for a night, which she usually enjoyed so much. She always waited to be invited and Käthe probably did not even know how much Herta yearned to be with her. She mentioned that Uncle Karl could be quite grumpy sometimes and that Käthe always felt rushed, when she visited Herta’s grandparents and she even secretly gave them the sweets she had brought for them so that Karl would not see (Karl had much regretted his return to Austria after having been driven out of his home by the Nazis – see article “Austrians in exile in Bolivia”). Herta felt that her dear grandparents deserved better. She also admired tremendously her two teachers, Ms. Pfleger and Ms. Michelmann, who had assisted her at school during the terrible years of the NS dictatorship as a “mixed-race” child (see article “Mixed-race children in Vienna during the Nazi period). Aunt Henny had disappointed her because she felt that she turned out to be a rather proud and domineering woman.

Christmas was the happiest time of the year for Herta. On 27 December 1951 she wrote that Christmas had again been so wonderful at home. She had taken three days off before Christmas to help her father Toni in the fish shop, which was the busiest time of the year there. Herta did that every year until Toni died suddenly in 1964 of a heart attack. As usual they all came home from the fish shop very late at Christmas Eve. “The handing out of presents was very late. It was again very beautiful, as Christmas is always in our family. When Vati plays the song “Silent Night, Holy Night” and we all enter the room and wish each other luck, the Christmas tree shines with lights and smells so nicely and everyone is so loving and caring, I could cry my eyes out. Käthe and Karl were with us and Karl was not grumpy at all.”

Herta at Christmas with the whole family (left), with her beloved grandparents and Werner (right)

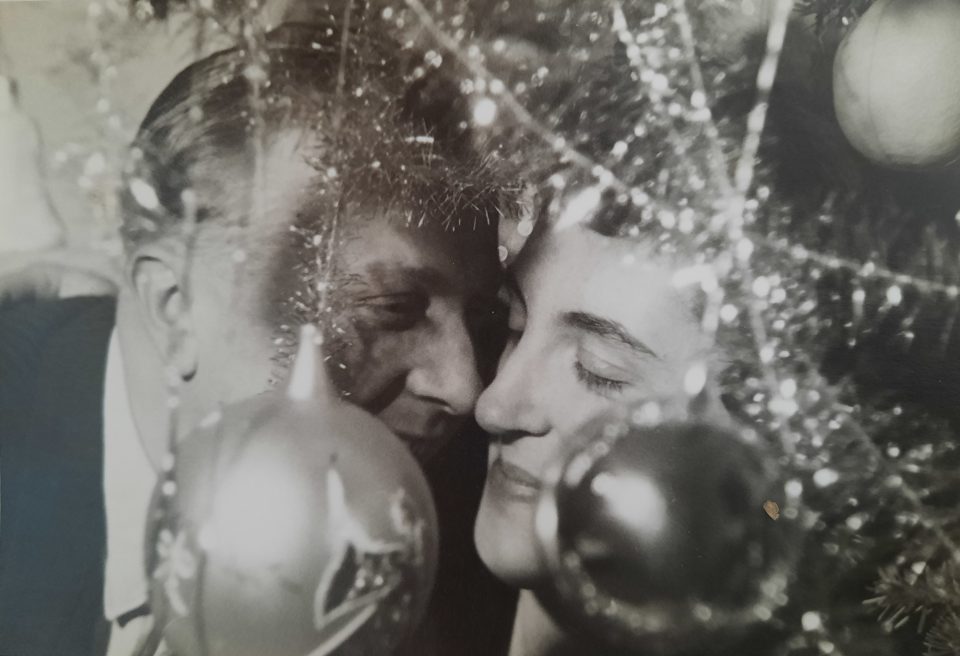

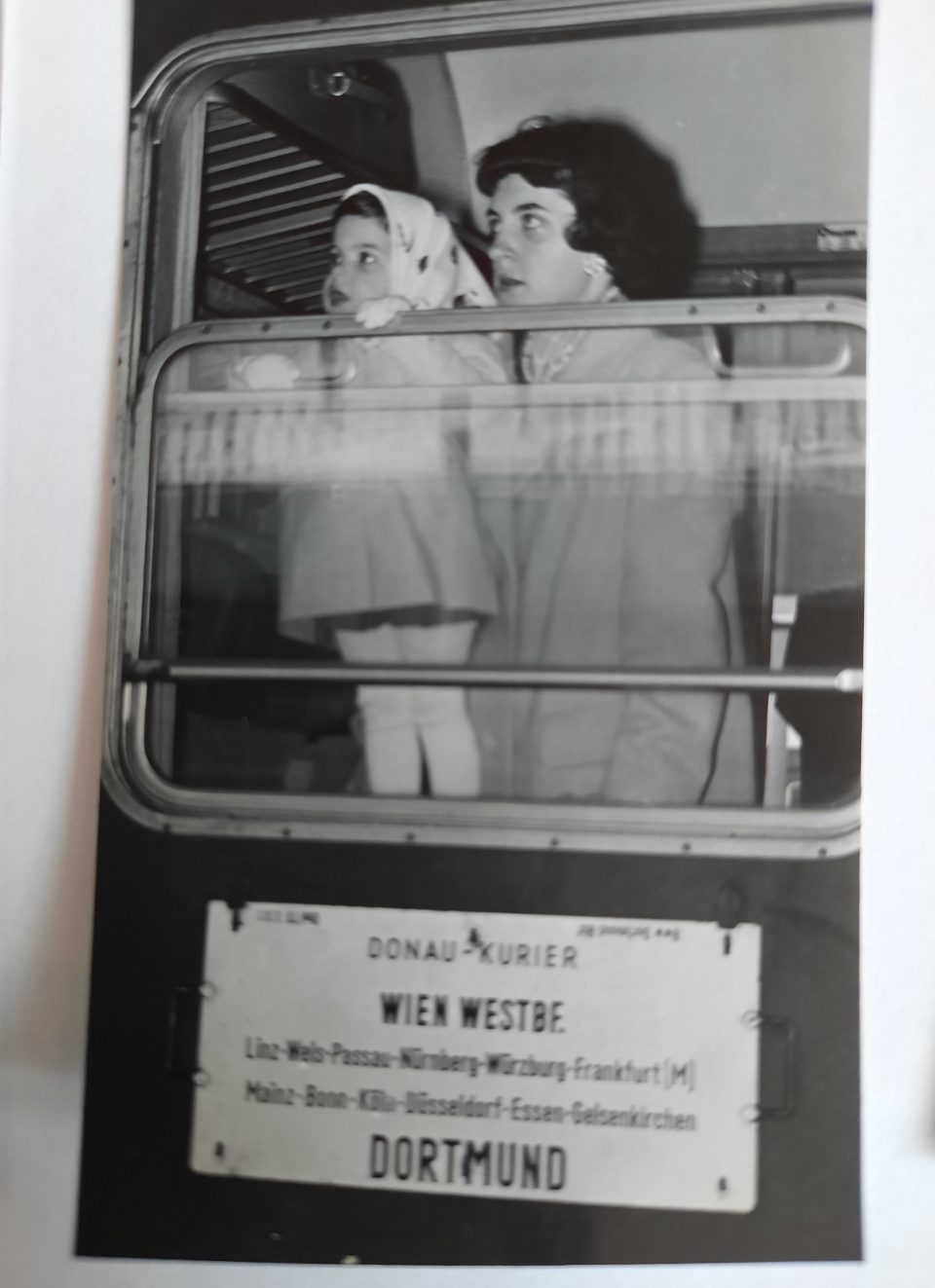

On 22 January 1953 Herta described in her diary how she had met Werner. “At New Year’s Eve we three (Toni, Lola and herself) wanted to go to the “Moulin Rouge”, but it was too expensive. So we went to “Hübner’s Kursalon” and had a lot of fun. At midnight we drank some sparkling wine and the whole time a very nice young man who also spoke nicely danced with me. He is very intelligent and we decided to meet again in the “Casa Piccola” and then we went to the “Raimundtheater”. We went out four times, twice to the cinema and on the last evening before he had to return to his job at Kaprun we went to the “5o’clock Tea” at the “Hochhaus” and afterwards to the very nice “Espresso Kolibri” in Mariahilferstrasse. Today I received his third letter. I like him very much.” On 26 January Herta was enthusiastic because she was going out so often now, to attend the “Ball of the Upper Austrians” in Konzerthaus, to the “Sandleiten” cinema to see “Matura” with her grandparents and with Lotte to the “Ehrbarsäle” to listen to the concert “Lustiges Wien”. Herta was getting more secure and was glad to be more self-confident, as she was getting invited by more young men. She was attending an English language course in the evening, which she enjoyed a lot. She was just a bit angry with herself because she did not dare to practise conversation with Aunt Käthe who had lived and worked in London during the war (see article “Maid servants in England”). “If I could just bring myself to do it once, it would be easier then and if I spoke English more often, I would learn a lot.” On 31 January Herta reported about a mishap with Werner’s appointment. They had arranged that she would meet him at the West Station, but she had waited in vain because he was late. At home she received his phone call and they met the next day for the cinema and some drinks afterwards. “We talked for two hours and have the same opinions; it was most interesting. I came home at 12.15 and Mutti was alarmed again. She is an angel, but worries too much about all of us.” On 2 February 1953 Herta continued her report of the Carnival season. She had gone to a ball with Lotte, who had found a young man to dance with, but Herta hadn’t. As she did not want to stand around like a “wall-flower” she went home at 11.30. On the way she discovered that she had forgotten her latchkey for the entrance door in Lotte’s bag. She got off the tram and tried to phone her parents from a telephone booth, but they were not at home and her grandparents did not hear the phone ring. When she came to the house, she tried to wake the care taker, but he did not answer the door. So she went to the next police station and waited there. In her desperation Herta finally phoned her Aunt Käthe, who told her to come to their flat in Margareten, “I slept there and was so happy. She and Uncle Karl were so nice to me and I was glad that my adventure had ended happily. Vati, Mutti and I will go to the “Flower Ball” in “Konzerthaus” tomorrow and I hope I won’t fall ill.” She was glad when Werner had a few days off and they went again to dance at a ball in Vienna, yet “I’m not sure about Werner, but we will see how everything will develop.” It is interesting to see that according to Werner’s memoirs at that point in time he was already sure that he had found the right woman to marry.

Herta noted that she had put on three kilos, which annoyed her, although no one could see it yet and in March 1953 her mother Lola had seriously fallen ill with throat troubles, but fortunately recovered and Herta mused in her diary how terrible it would be to lose her mother, “Another person like Mutti doesn’t exist. She understands me completely and helps me wherever she can. In short, I cannot imagine a life without her. That’s why I’m always so desperate when Mutti and Vati quarrel or are angry. I’m sure there is nothing worse than a child without a mother… Werner is writing regularly and for his birthday I sent him a cake I’d baked myself and he seemed delighted with it. I wish all people would like me and I would like to love all people. If all human beings loved each other, there would be no war in the world and war is terrible. I pray to God every day that my beloved ones should live a long life and stay healthy and that there is no more war. These are my biggest wishes. This is something I don’t understand about religion. You should not forget the morning and evening prayer. I tell God everything I have experienced and all my thoughts and I believe this is more important than a rattled out prayer. I think God prefers if I talk to him, but the Church requires the prayer.” On 5 March Herta wrote in her diary that Werner had written to her that he wanted to make a home with her. She thought she would like to get an offer for marriage from him, but she could not imagine being married. “It’s not the great love, but I think this is not necessary, this might develop as we get to know each other better.” And she thought of her friend Herta (Schörg), who was so different from her and had had many relationships with men and had even had an abortion half a year ago. Still she is a good friend of hers, because she is always honest and true.

On 7 April Herta told in her diary that Werner had been in Vienna for five days. On one day they went to Styria to “Roseggers Waldheimat” and there he asked her what her plans for the future were. He would like to take the electrician’s master course in the evening in Vienna and he would like to get a flat there, but he thought that in the beginning both of them would have to work to earn enough – and he said that he wished she would become “his sweet little wife”. Yet during the course of that stay they had also had some serious discussions because Werner complained that she did not really show her love and that she did not support his plans actively. Herta confessed in her diary that he had been right; she was not really sure whether she loved him enough, but she also did not know what true love was. “Now and then we really don’t know what to say and that’s not right… Then I think the ideal man who I wish for does not exist and we all have our faults, to which one has to get accustomed…. I know that I’m sometimes prickly, but I don’t like his boisterous caresses.” On top of her love worries Herta was afraid that Lola would fall ill again because last time she had had an abscess on her tonsils and now she had a fever and swollen tonsils again.

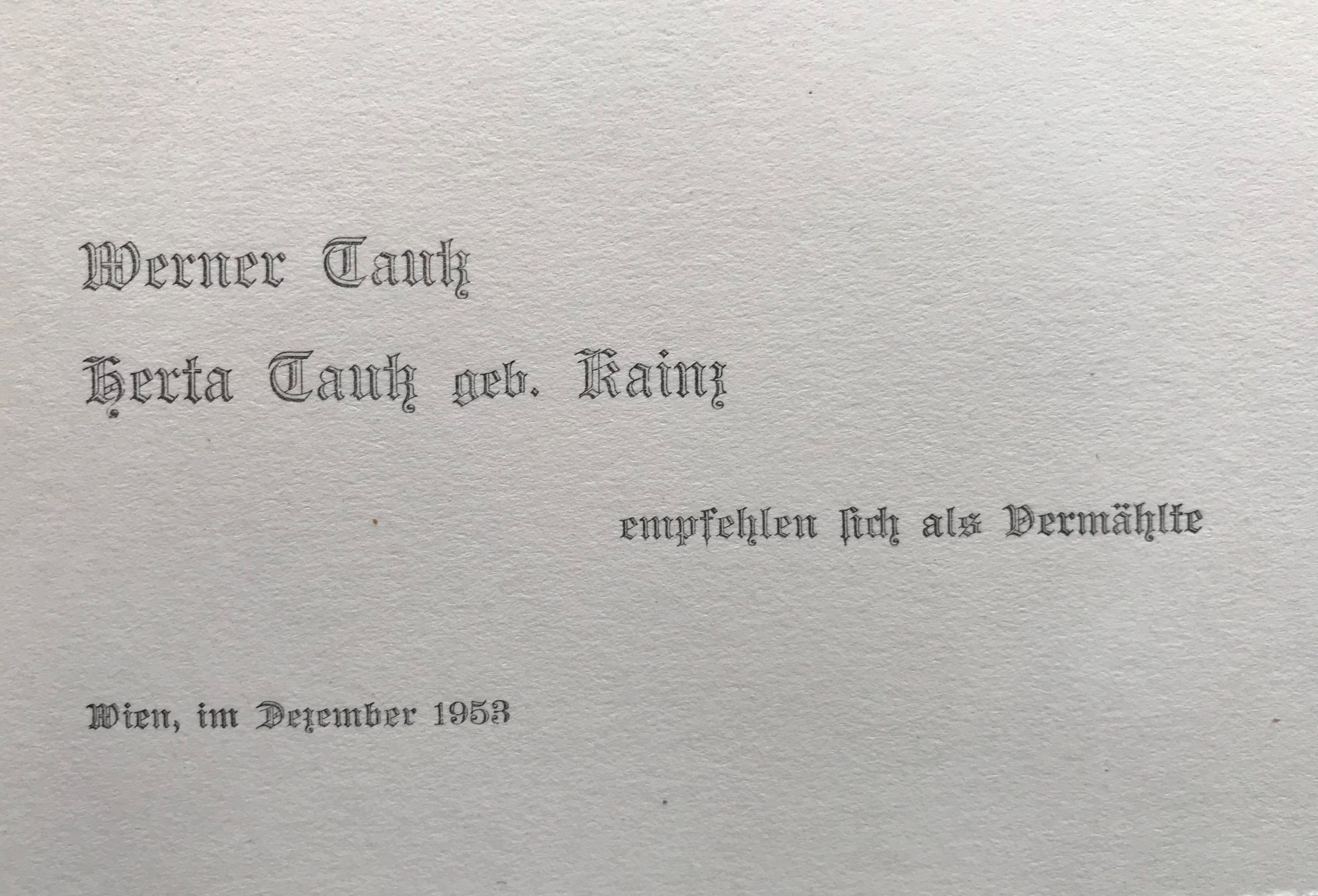

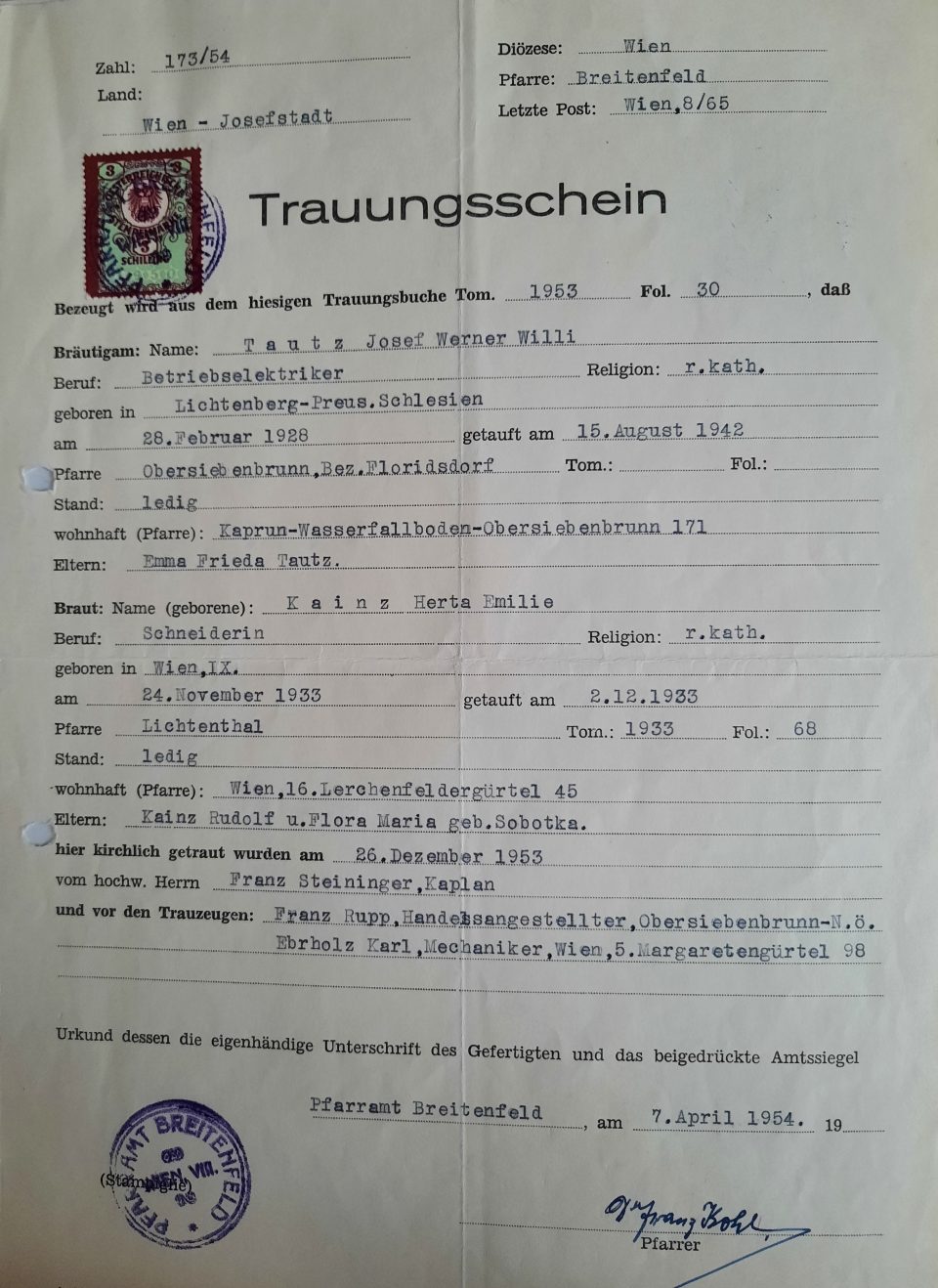

Werner and Herta got married on 26 December 1953 in the still damaged church of “Breitenfeld” near Herta’s home. Herta remembered that it had been freezing cold and she had shivered in her wedding dress, which was made by her friend Anni (dressmakers should never make their own wedding gowns, Herta said. That’s why she sewed Anni’s, when Anni married Willi Gaube)

Their witnesses to the Catholic marriage were in the “artificial post-war atmosphere of political unity” Franz Rupp, Werner’s foster father, a fanatic Nazi and now Socialist and Karl Elzholz, Herta’s uncle, a born Jew and fervent Socialist, just returned from exile in Bolivia.

Below: The church “Breitenfeld” did not look so nice in December 1953 because it had been hit by bombs

The wedding party took place in Herta’s home. Apart from the table ware, which Herta never liked because it seemed so old-fashioned to her, the broom should be noted on the right

Herta’s happy grandfather, Ignaz, and her parents, Toni and Lola

… and a boisterous wedding party despite the dire circumstances: Herta with Werner and their best man in the civil ceremony, Robert Walter

On 13 May 1954 Herta visited Werner in Kaprun and she wrote in her diary, “Werner is so loving and caring. I love him so as I could not have imagined earlier. Sometimes I’m a bit annoyed with him, but that passes quickly.” Then she continued that they had several people visiting and she liked watching people and thinking about them, “I love all people on earth; there is no one whom I hate. I only want that all people are friendly to me. There are different kinds of people. Some are uninteresting; you get to know them and forget them immediately. They don’t have anything special, not even a tiny aspect that might fascinate you. They are all very similar, but there are others who somehow impress you and you feel that person is unique in his or her special way. There are lots of such people; you just have to look out for them because many of them are shy or due to any other reason you don’t notice them immediately.” Herta was a very gifted writer and she would have made an excellent authoress. Later in her life she could use her talent when she wrote all the scripts for Werner and Herta’s slide shows and she also recorded the texts. In this diary entry she describes an elderly stout man in such charming detail and with so much love for the whole mankind that it is really amazing for a young woman of 20 years of age. “The nature here is wonderful. Sometimes I think it must be great to be able to write poems. There is something new at every hour of the day and every day there is something special to discover. In the morning when the sky is so blue as I have never seen it before with a few small white clouds and the snow is brilliant white and shines and glitters; or when from all sides dark black clouds move in or when the sun is high up in the sky at midday and everything around seems strangely clear and near, or when it snows and everything looks so melancholic and sad, and when the sun sets in the evening, what a spectacle!…. I thank God that I can live this wonderful dream. Therefore I would like to help others if I can, so they can also lead such a happy life.”

More than a year later Herta wrote again from Ebmatten on 9 August 1955, “I’m having a holiday from myself. I cannot remember ever being so happy, so contented, so quiet and without desires…. At home I’m not quiet if I don’t work, but now I’m living a different life for 14 days and this is very nice. I would not like every day to be like this, but now I have time for myself and I’ve always loved to ponder. It often made me depressed, but now I’m happy and nothing makes me sad because I find beauty everywhere.” On 11 August Herta was worried about Werner because he was unhappy working in Kaprun and he wanted to quit. His greatest wish was to learn and to progress in life and Herta admired his ambition. The day before the termination of the construction of the power plant Kaprun had been celebrated with the “last bucket of concrete” and everybody was there, also their best man Robert, who explained everything to Herta. Herta was so proud of Werner because everyone seemed to know him and greet him, even some celebrities, but Werner was not conceited or pompous in any way, just like usual. “I know that he has a very important job with a lot of responsibility and supervises several men, but he never talks about this or gives himself airs; he acts as if that wasn’t anything special. And I like that about him. Most men who I know from here brag and continually talk about their achievements. It’s nice to be the wife of someone who everybody respects. All who know me greet me politely and those who don’t know me whistle and call out after me. On the one hand this is embarrassing, but on the other hand I like it, too. Which woman doesn’t want to be admired and desired? It diminishes my inferiority complex. I’m not very clever, but I think Werner is proud of me because he presents me to all those academics here and he is not afraid that I would behave in an embarrassing way. Meanwhile I’ve got rid of some of my shyness and I can get involved in conversations and express my opinion.” These are a young woman’s impressions about “womanhood” in the 1950s.

By 1945 many men had died in the war or had not returned from prisoner-of-war camps, but the women at home had meanwhile experienced and managed enormous changes in the social, political and economic life. While in the course of the 1950s the situation gradually normalised, a dramatic backlash took place with respect to which role women had to fulfil in society. The men who had returned from war wanted their uncontested positions as heads of the household back. Economic productivity and success should compensate their “virility lost in defeat”. That’s why the already overcome traditional female roles of wife and mother had to be cemented once more. During the Austro-Fascist and National Socialist period the “obedient wife who was destined to bear children” was the female concept which the Austrians were indoctrinated with. Yet during the war the women had run not only the household, but the economy and now they were again asked to make room for the returning men, to give up their paid employment and get back to the domestic hearth. Motherhood continued to be glorified and women were not expected to have “selfish desires of personal fulfilment”. On the contrary, women were asked to make allowances for what the men had experienced and to concentrate on their duties of bearing and raising children and making a home for them and their husbands. Any professional education of girls was just considered a transitional period before their marriage. Many women had serious difficulties with this dramatic return to conservative role models and the divorce rates rose drastically after the war. Politicians and the media made sure that single women who “did not fulfil their duty to society” could not count on any sympathy. They were advised to stop making their own decisions and acting independently, because that’s what the men expected from them. But the times were changing and many young women did not want to follow in the footsteps of their mothers. Between 1950 and 1965 the number of working women doubled in Austria, most of all due to the fact that the desired standard of living of a family could not be reached with one income only. So, increasingly more girls received a professional training.

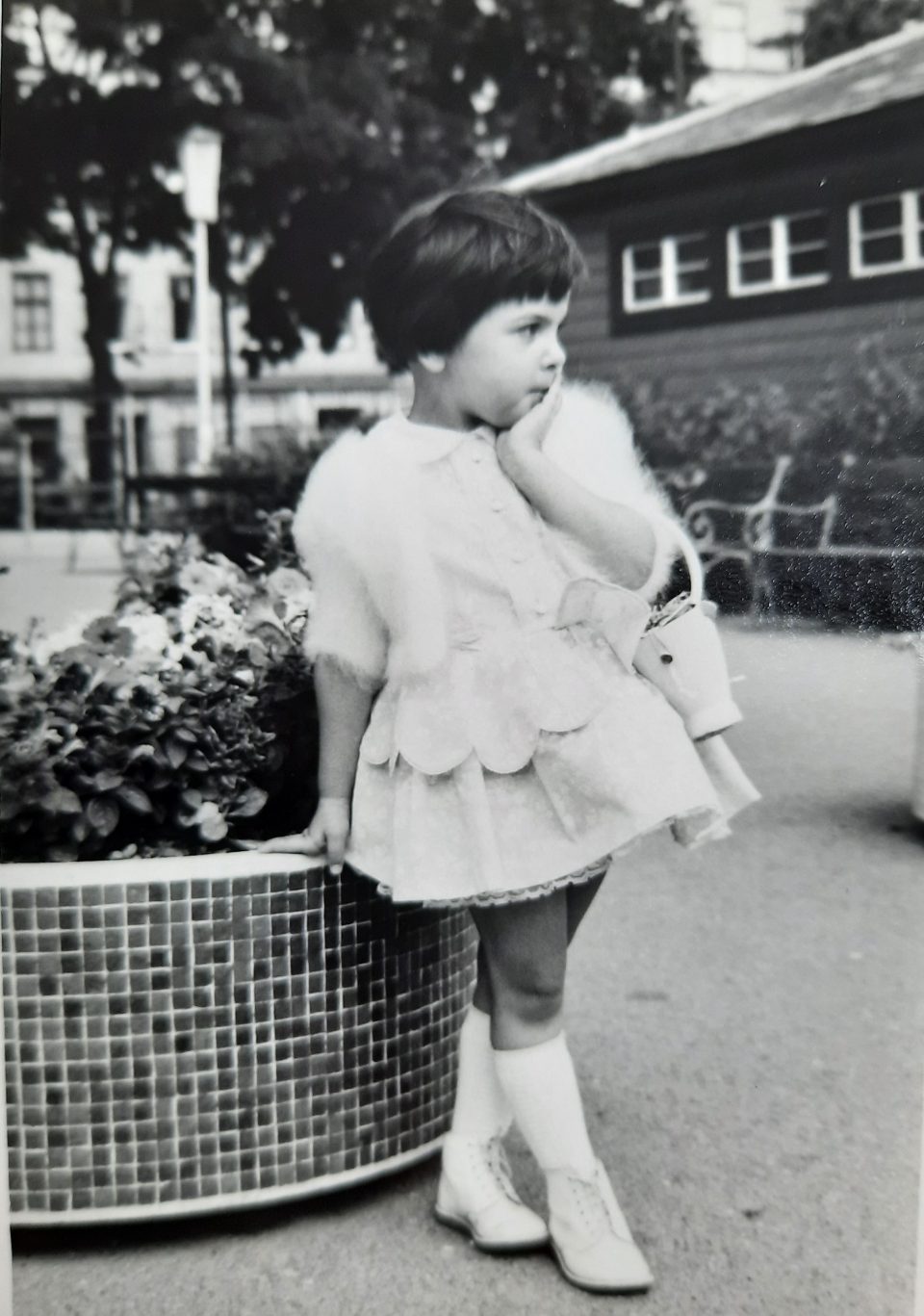

Herta was a trained dressmaker and as a master could have opened her own studio, but unfortunately the 1950s were the time when people started to buy cheaper ready-made clothes rather than tailor-made ones. Herta worked until I was born and then Werner wanted her to stay at home. He was proud to provide the income for the small family on his own, although it was very tough. Herta was shy and obedient and would never have protested; on the one hand because she liked to make a home for Werner and me and on the other hand because there were no child care facilities for babies. Furthermore she knew that she was no unrelenting business woman and would probably not succeed financially, if she set up a dressmaker’s studio. Her mother Lola started to work again as a shop assistant at “Quelle” in Mariahilferstrasse as soon as her parents, Ritschi and Ignaz, who she had to care for after their return from the KZ Theresienstadt, had died in 1958 and 1959. She had to add to the income of Toni, who was the manager of a small fish shop of “Hofbauer& Hammerschmidt”, so she could not take care of baby Susi. Some of Herta’s married female friends worked, but usually part-time or they did piecework at home; as a consequence they earned very little because they were either seamstresses, too, or untrained. But Herta often stated that she did not want me to go the same way and she did everything to support her daughter to get university training and to be a working mother. Her experiences during the NS period as a “half-Jewish mixed-race child” had made her extremely timid and self-conscious, so she took on her role as housewife willingly and uncomplainingly in contrast to her mother Lola and also her mother-in-law Anna Rupp, who both were much more confident and self-reliant women. This example illustrates the retrogression which happened in Austria in the 1950s with respect to the role of women in society (see articles on “Mixed marriages and mixed-race children in Vienna during the Nazi period” and “Nazi children evacuation programme”)

Herta as a mother and housewife (right: in the popular “Kleiderschürze”, the house dress of the time)

The conservative politicians and the media tried once more in the “long 1950s” to reduce the woman’s role to the “three K” (in German: “Kinder, Küche, Kirche” =children, kitchen, church) in Austria. To their minds the “proper spheres of interest” of women were: caring for and raising children, household and cooking, home and garden, handicraft and sewing, health and beauty, and proper Catholic morals. At a conference in 1955 the minister of education Heinrich Drimmel and the head of the federal state of Styria Josef Krainer, both ÖVP politicians, stressed that it was “God’s will that the woman’s position was in the home” and the “guarding of love, the noble, the good and the beautiful” were her most important tasks. “Female gainful employment of mothers was the biggest mistake and a social aberration”. Women were pushed back into the home after 1945 as a consequence of the military, political and economic breakdown. The Catholic Church immediately voiced complaints about the unwillingness of women to “sacrifice themselves for matrimony and motherhood” and the Church stated that gainful employment “spoilt their character” and women would “lose all female characteristics” which were “essential for wedlock and desirability for men”. This attitude towards women was cemented in the Austrian law system and women’s rights activists had been fighting it for decades. The legal position of a woman in marriage and family was completely dependent on the husband. If a married woman wanted to take on a job she needed the permission of her husband and in cases of difference of opinion between spouses the husband had the right to the final decision. Single mothers were discriminated against and the youth welfare office took over the position of legal guardian of the missing father. Especially difficult was the situation of young single mothers who had children with foreign soldiers, which was considered a terrible shame by their families and communities. Around 400 children of black American GIs were born in Austria during this period and the youth welfare offices, especially in the west of Austria, tried to take these children from their mothers and offer them for adoption abroad, so no memory of this “era of occupation” might “spoil the clean post-war image of the miracle years”. The tragedy for the women and children was that even those GIs who wanted to marry the girls, were usually transferred from Austria as soon as the US army learned of their relationship with a local girl and if they asked for permission to marry, black GIs were never allowed to marry a white girl. These single mothers and their children had to bear the whole brunt of every-day racism in Austria all their lives.

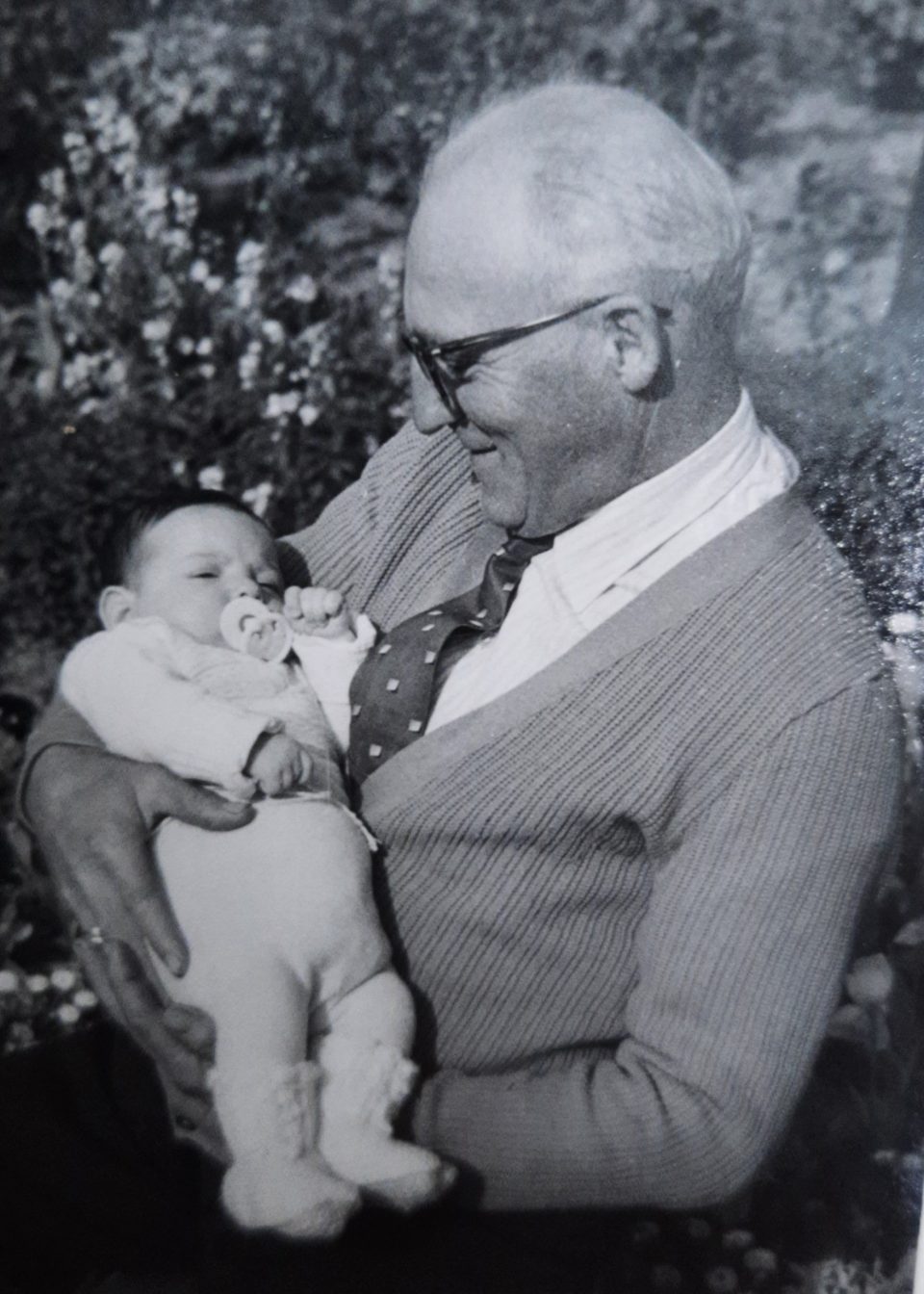

“Motherhood”: Herta with baby Susi and Werner, Toni, Lola, Ignaz and Ritschi (left)

… and Werner’s happy foster parents, Anna and Franz Rupp, with baby Susi

During and after the war women had moved from household-related jobs to industrial and service jobs, which resulted in a higher unemployment rate of women, when men who had returned from war were taking their jobs. A social study of 1954 of the “Sozialwissenschaftliche Arbeitsgemeinschaft” suggested that it would be best not to grant any unemployment benefits to married women, so they would return to their homely duties and not search for gainful employment. Every attempt was made to restrict the access to the job market to married women. Even the educational system, which until 1962 rested mainly on the principles established during the Austro-Fascist and National Socialist period, focussed on a separate education of boys and girls with different curricula after primary school. Despite all these conservative efforts of excluding married women from the job market, the gainful employment of women rose steadily after the Second World War. In fact, the expanding tertiary sector relied on the female workforce and the higher life expectancy of women allowed them to return to their jobs after their children had left school. During the 1950s the number of single women, unmarried or widowed, was very high and Austria registered a surplus of women of half a million in a country of not quite 7 million inhabitants in 1951. Nevertheless, the share of employed women only again reached the level of 1911 of 40% in 1961. The amount of married women on the job market was 39% in 1951, but reached already 47% in 1961 because the Austrian economy needed the female labour power. The apotheosis of the “perfect woman employee who combined representation and productivity” was the female secretary in the 1950s; her image was strongly influenced by motherhood. Meanwhile on the labour market as well as in the educational system the reality had overtaken the political discussion. In the school year 1959/60 85% of all compulsory schools were co-educational and the curricula for boys and girls only varied with respect to physical education and handicraft. Contrary to the American model the working woman in Austria had no technological household to assist her in tackling job, home and family. In 1959 the Austrian trade union carried out a survey among working women, most of them married with at least one child, and this showed that only 23% had a hoover and a fridge, 7% a blender and 4% a washing machine.

Internationally the ideal of female beauty was represented by film stars such as Marilyn Monroe, Jane Mansfield, Brigitte Bardot and Sophia Loren. But the films produced in Austria and Germany were devoid of such sex symbols; they would have marred the “idyllic atmosphere” of the “Heimatfilm” (sentimental film in an idealised regional setting). The ideal conservative female role model was represented by the young Romy Schneider in her “Sissi films”. Here the Austrian film making industry indulged in the glorification of banal Imperial myths and the ideal of the naïve, meek and obedient young woman. Because of the uncertainty after the war and the lack of trust in the new democracy people sought assurance in the old patriarchal order of the Habsburg monarchy, at least in the dream world of films. Many could not cope with the quickly changing social structure and the new distribution of the roles of men and women. The vast majority of Austrian films avoided any confrontation with the recent past of Austro-Fascism, National Socialism and the Second World War and also with the present political and social situation of the 1950s. The film represented a withdrawal into the glorified Imperial past or into the idyllic and exotic world of dream and holiday scenery. The Austrian film – many of them musical films – had no connection to the reality of the 1950s and the problems people had to deal with; it was an escape from the real world, which the Austrians yearned for after the terrible experiences of the last decades. Women had to take on jobs because their wages had to top up the family budget, but in all those films the working married woman was portrayed as a temporal aberration and it was clear that the place to be for a woman was the home. Working mothers usually did not appear at all in those films, although in this period already a quarter of all women in gainful employment had children. 58.8% of all working women were under 40 years of age, only in the age group 45 plus the majority of women were still housewives. Nevertheless, no one discussed the problem of the multitude of tasks married mothers had to juggle and they themselves seemed to take it for granted that they had to handle the multi-fold burden alone. The lives the women in the films led were far removed from the Austrian everyday reality. There was little leisure time and this was spent now and then in the cinema, listening to the radio, hiking, reading or engaging in a hobby. The holiday destinations illustrated in the films were not for the average Viennese or Austrian; only few could afford to go on holiday and if so they spent it in a bed-and-breakfast in Austria. So the Austrian film of the 1950s represented the last gasp of the old patriarchal order and an escape from the nasty recent past.

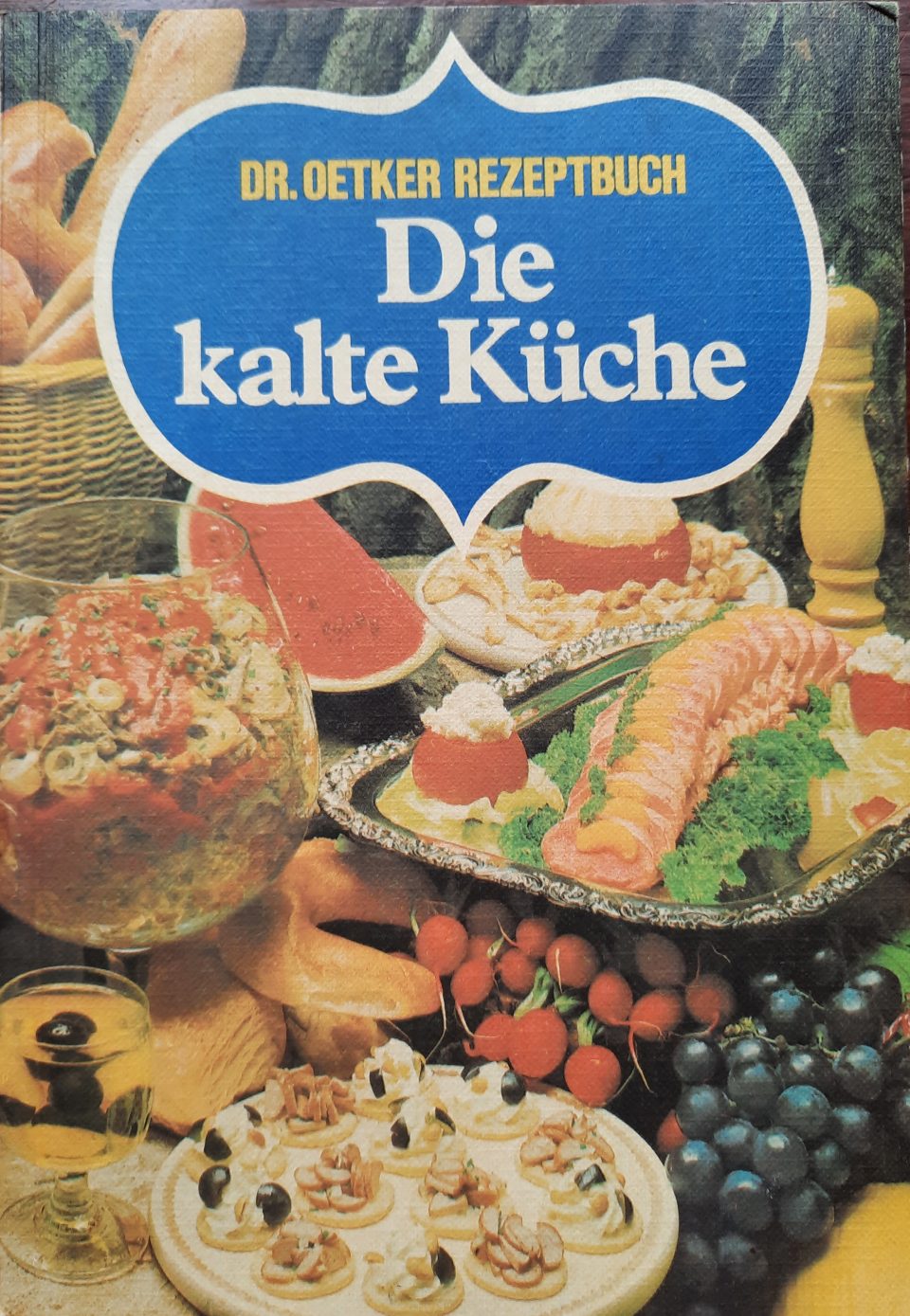

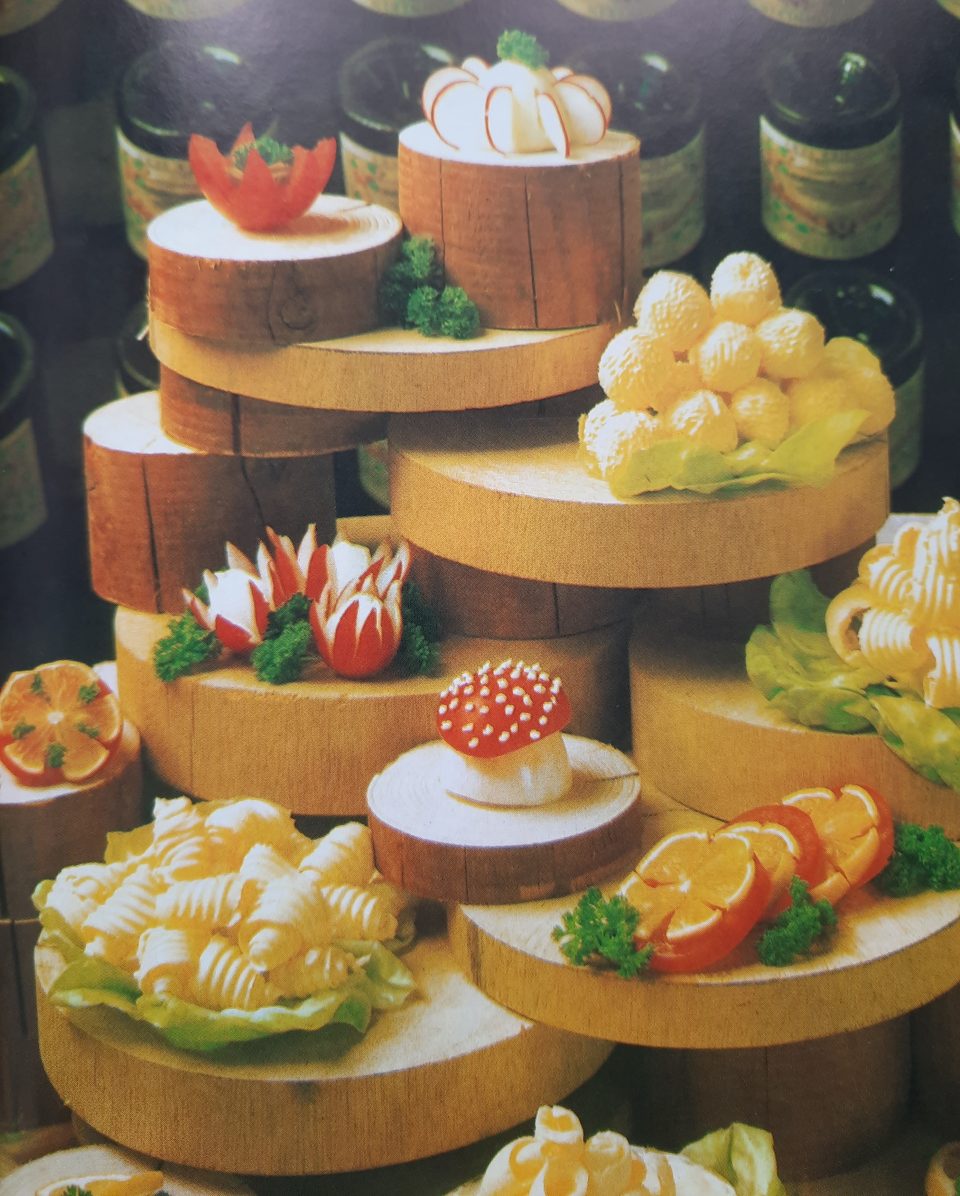

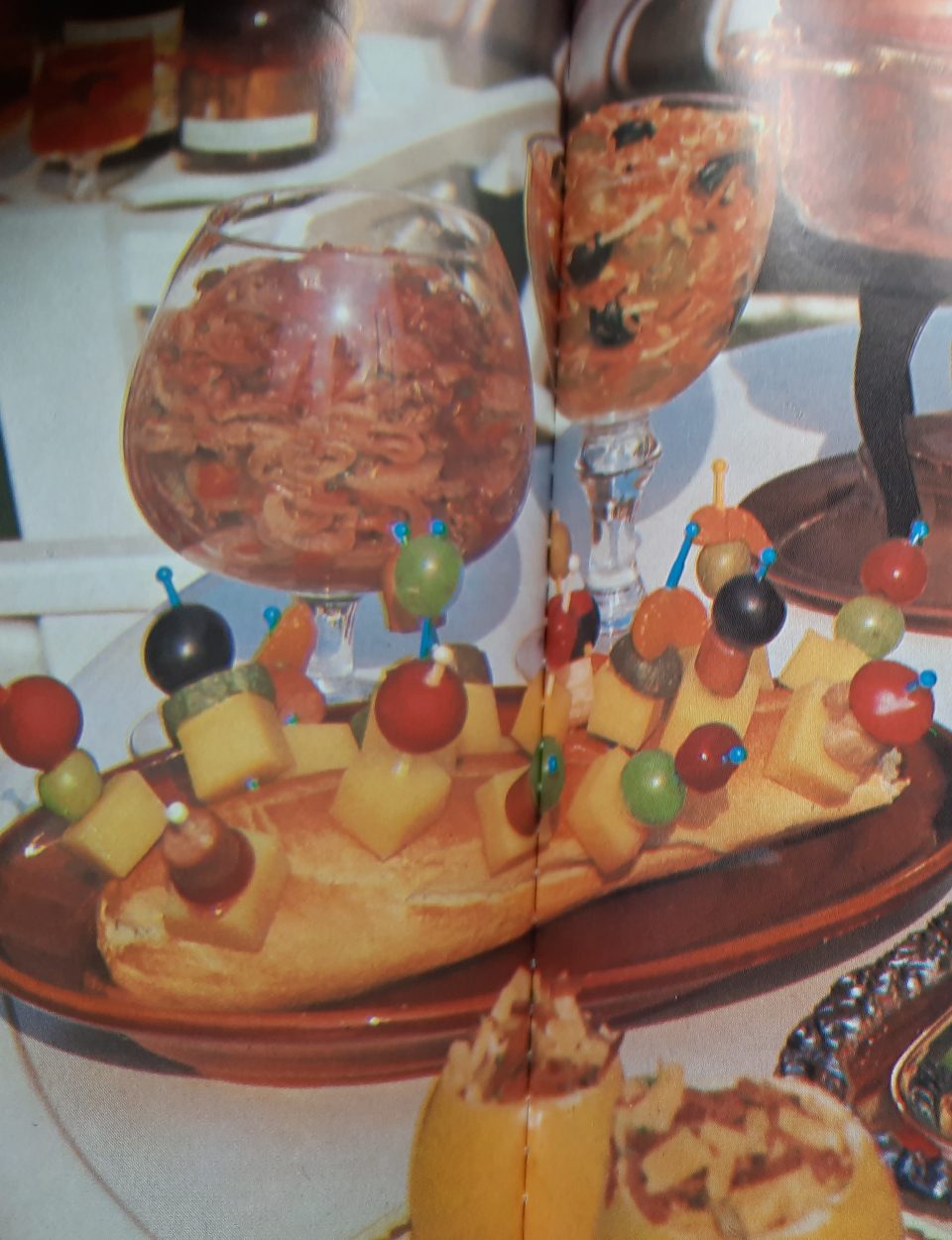

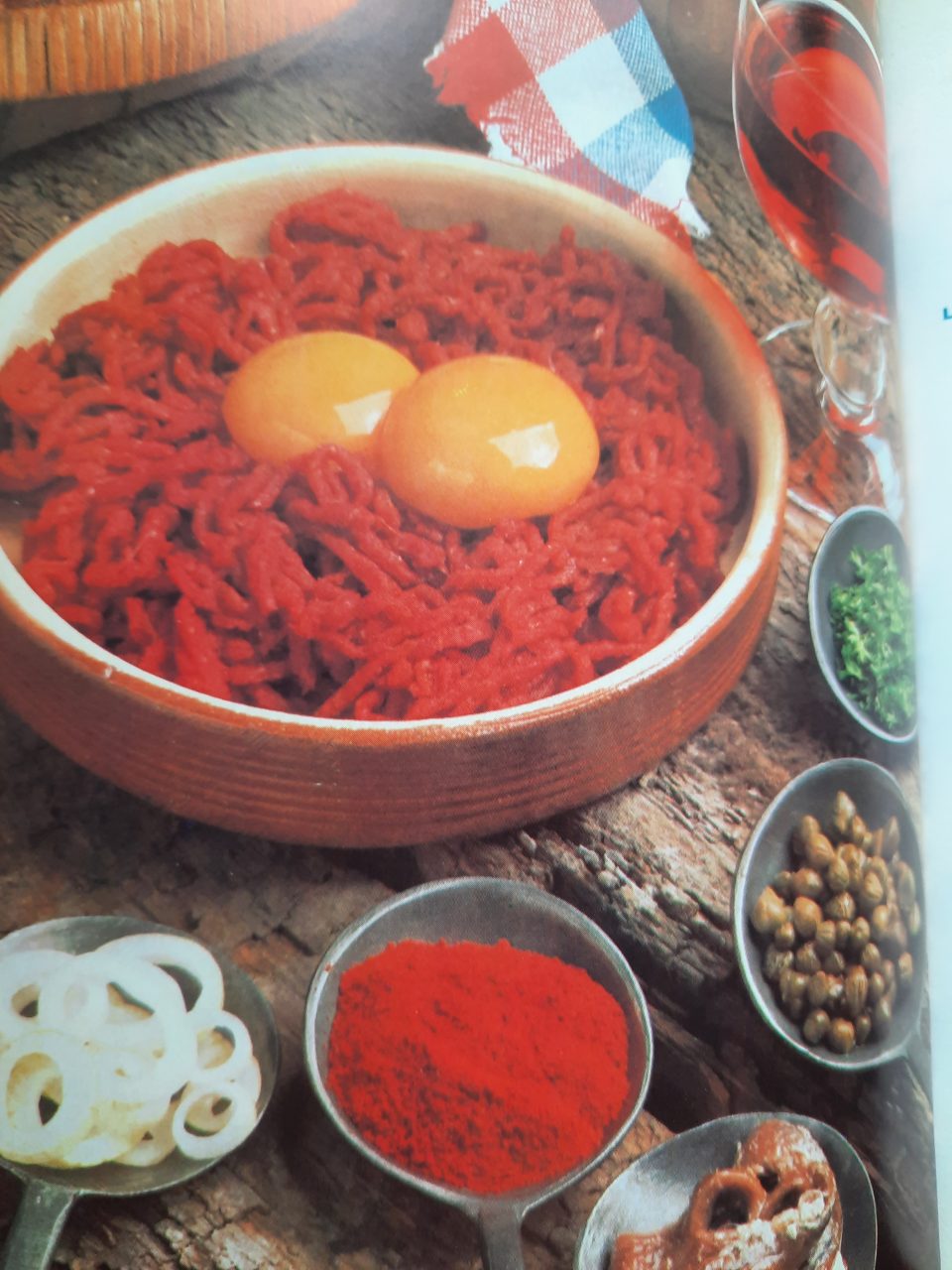

The “realm of the woman” was to be her home and women’s magazines and cookery books advised her on thrifty and tasty recipes for the family and parties at home

From Herta’s 1964 “Dr. Oetker” cookery book

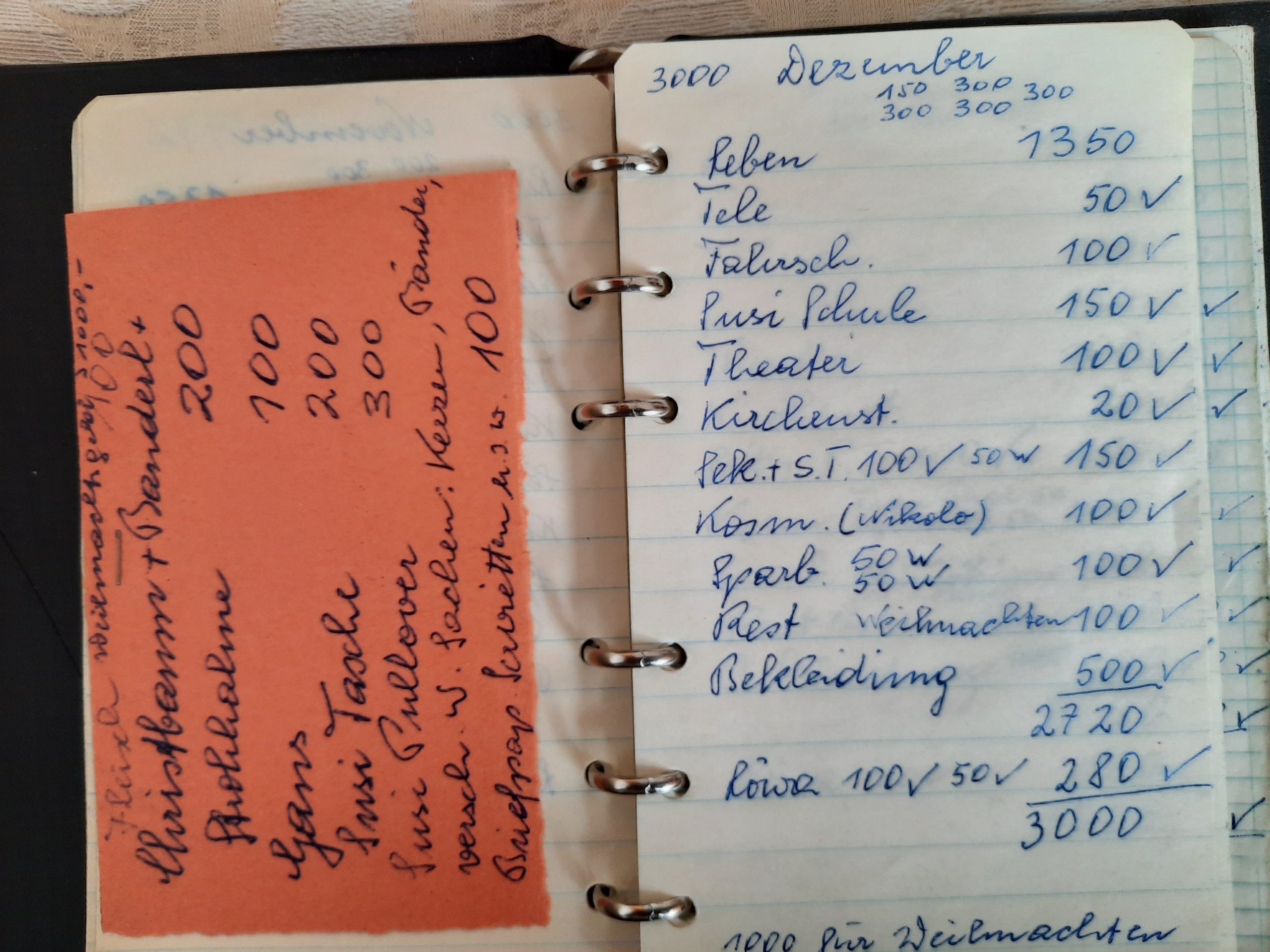

In the eyes of the 1950s a woman had to have several unpaid jobs in the household: cook, cleaner, washerwomen and nursery teacher, and above all she had to be economical and make ends meet on a very small household budget which was granted to her by the husband. Lots of different women’s magazines and advice booklets counselled her how to manage the household financially and where to buy to save money. In a housekeeping book the housewives had to register their expenses weekly or monthly for the inspection by the husband. Women had to make enormous efforts to save some money for the acquisition of modern technical gadgets, such as a hoover or a blender.

A page of Herta’s housekeeping book (December 1970)

Fashion & interior design

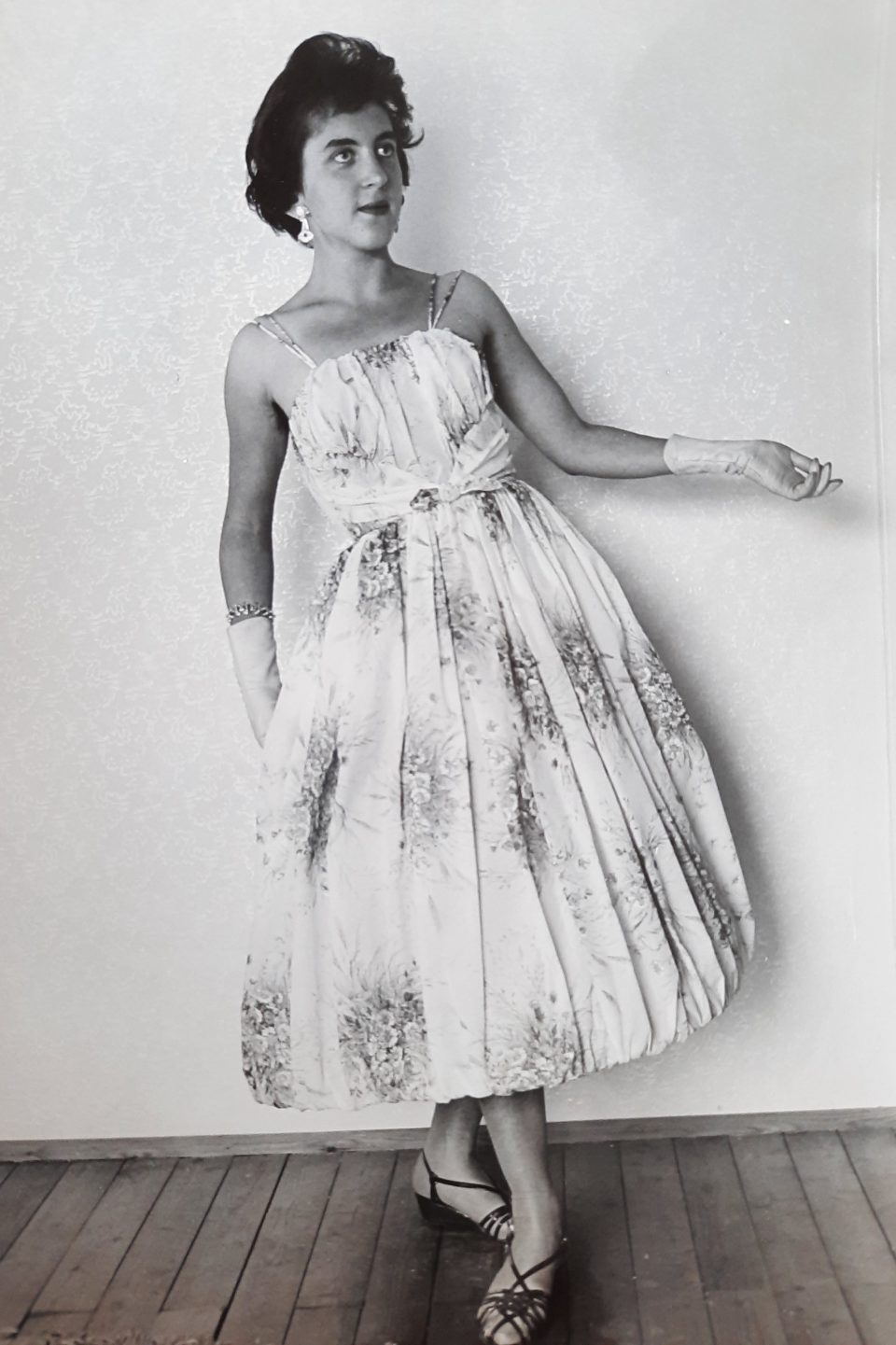

The 1950s were an era of innovation with respect to dressing. For the average woman underwear was of greater importance not just in forming the body, but also in offering more comfort. The petticoat was designed as a colourful non-transparent piece of underwear that was worn during leisure time especially by working class women, when enjoying the sun after a walk or picnicking in a park or on a meadow. It was probably the first undergarment that was used as leisure wear, too. In Vienna it was called “Kombinäsch”, probably derived from the English word “combination” and the French word “combinaison”. Another staple of the housewife of the 1950s was the flower-patterned house dress, called “Kleiderschürze”, which was worn at home. After the dresses had been lengthened immediately after the war, from 1948 on dresses got shorter again, offering better opportunities to show off the newly imported nylon stockings. They arrived in Austria in 1945 with the US soldiers. Originally a pair cost six times the price of ordinary stockings and was easily ruined by runs. That’s why special workshops were established in Vienna, where you could have your runs repaired (“Repassiergeschäft”). In the course of the 1950s underskirts made of nylon or “Perlon” became fashionable and transparent nylon blouses, which were worn with wide black skirts made of taffeta and broad rubber belts. Seamed stockings were replaced by seamless stockings in Austria in 1958 and the Austrian company “Palmers” provided many of these luxury products as soon as the GIs had left Austria and this source of supply had trickled off. Another invention of the 1950s fashion industry was the “Baby Doll”, a sexy nightwear consisting of a short nylon top and a nylon slip in pastel colours. As the model of ideal beauty of the 1950s was Marilyn Monroe, bras had to be designed that created and supported a voluptuous bust and offered insight into a spectacular décolleté.

Herta at Christmas with a petticoat, Taffeta skirt and white blouse and with her friend Lotte in a simple, but elegant outfit

Herta in dresses of the late 1940s she had received from her American Aunt Ida

Left: Herta with her mother Lola

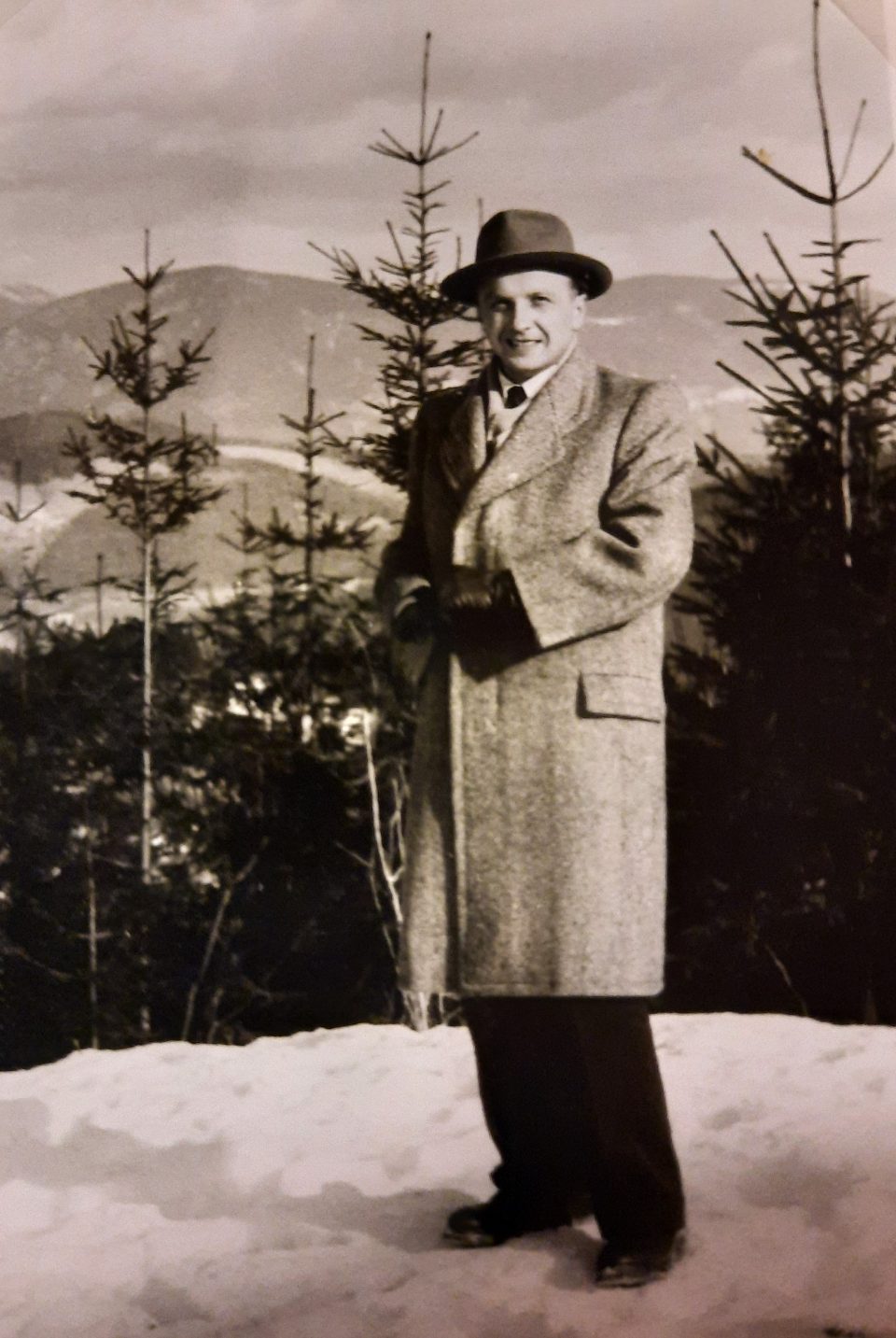

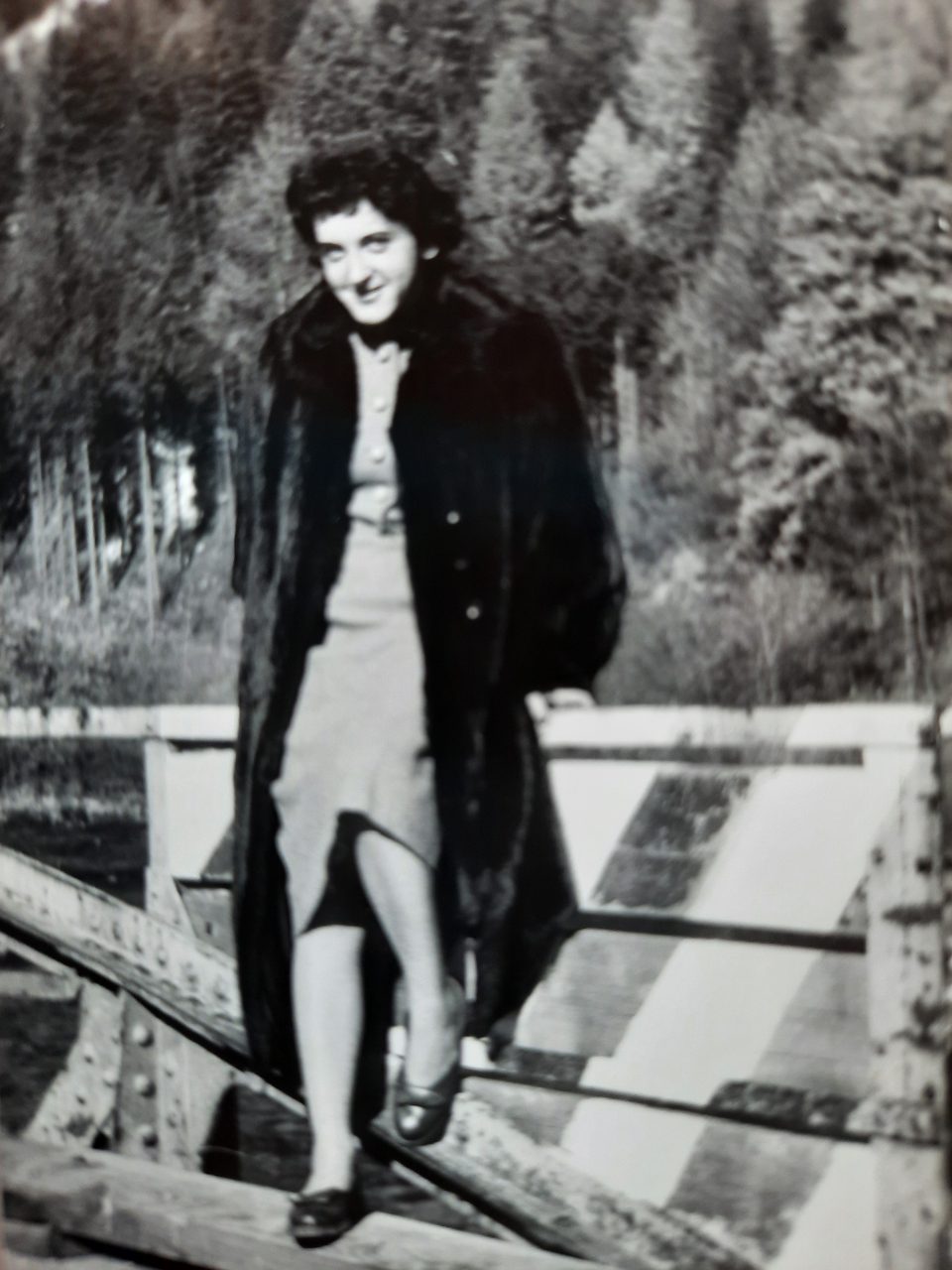

Herta and Werner in elegant winter outfits

Herta wore dresses and suits she had sewn herself as soon as she had started fashion school

Herta in Schönbrunn and with Werner in the Volksgarten

In the “long 1950s” Herta sewed all the dresses for Susi and herself

…and the coats and ladies’ suits as well

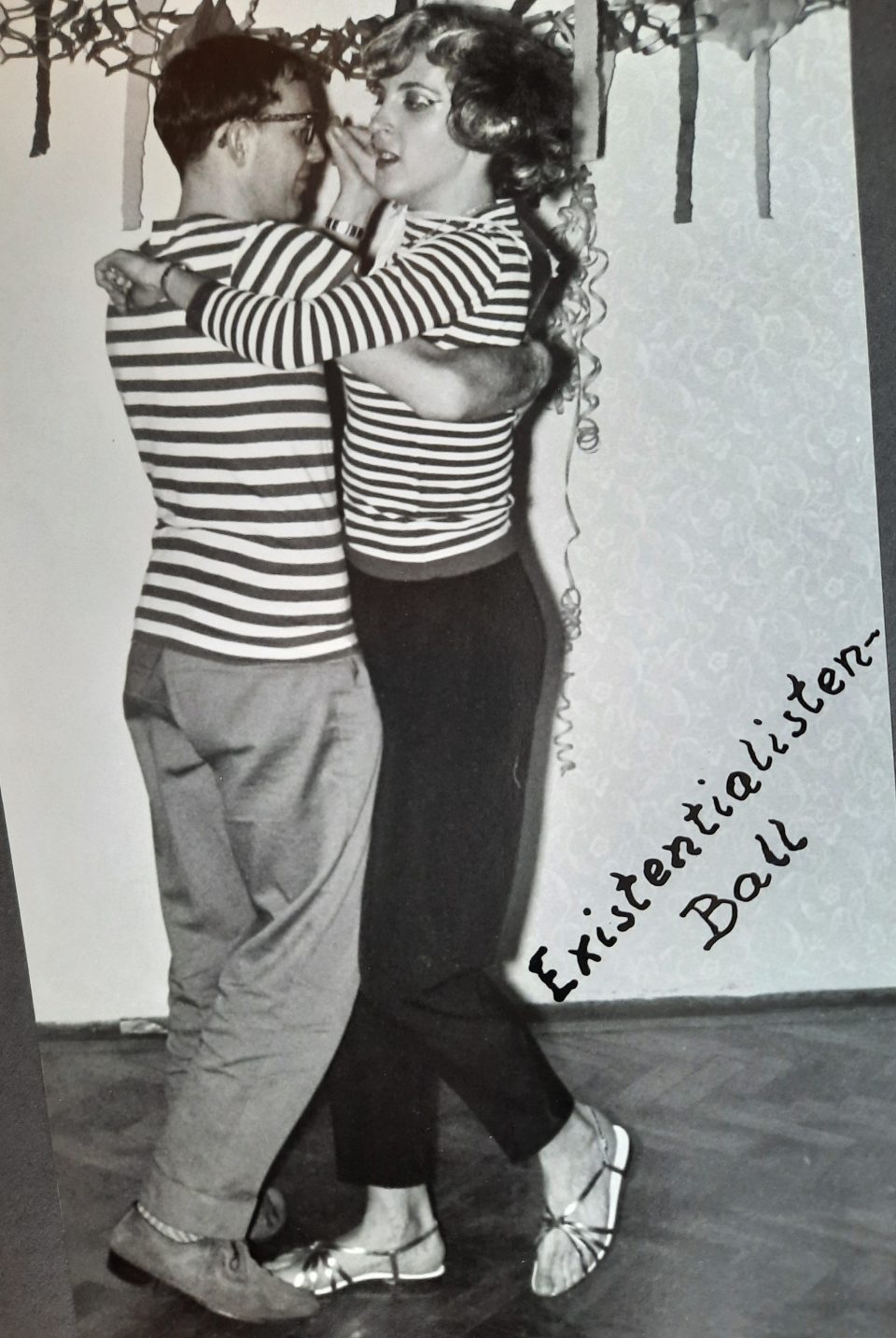

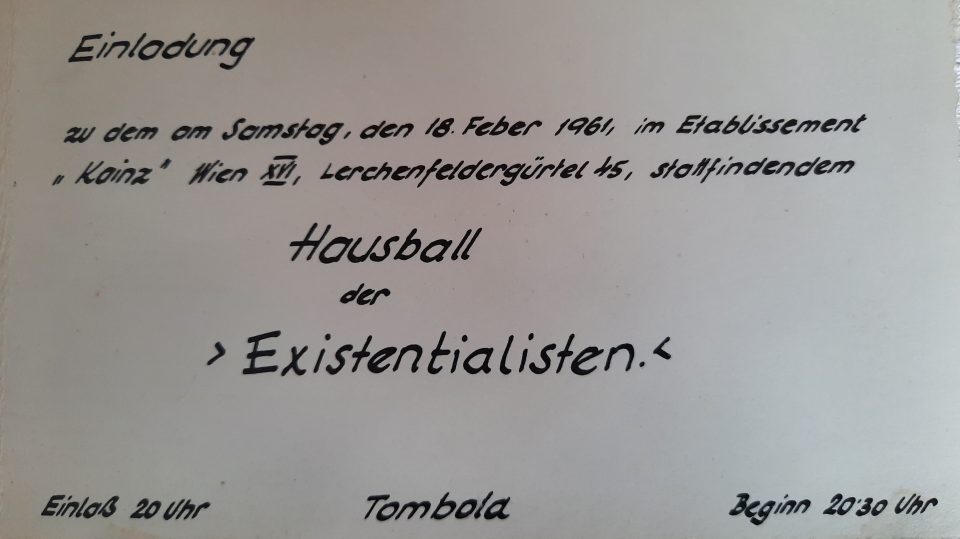

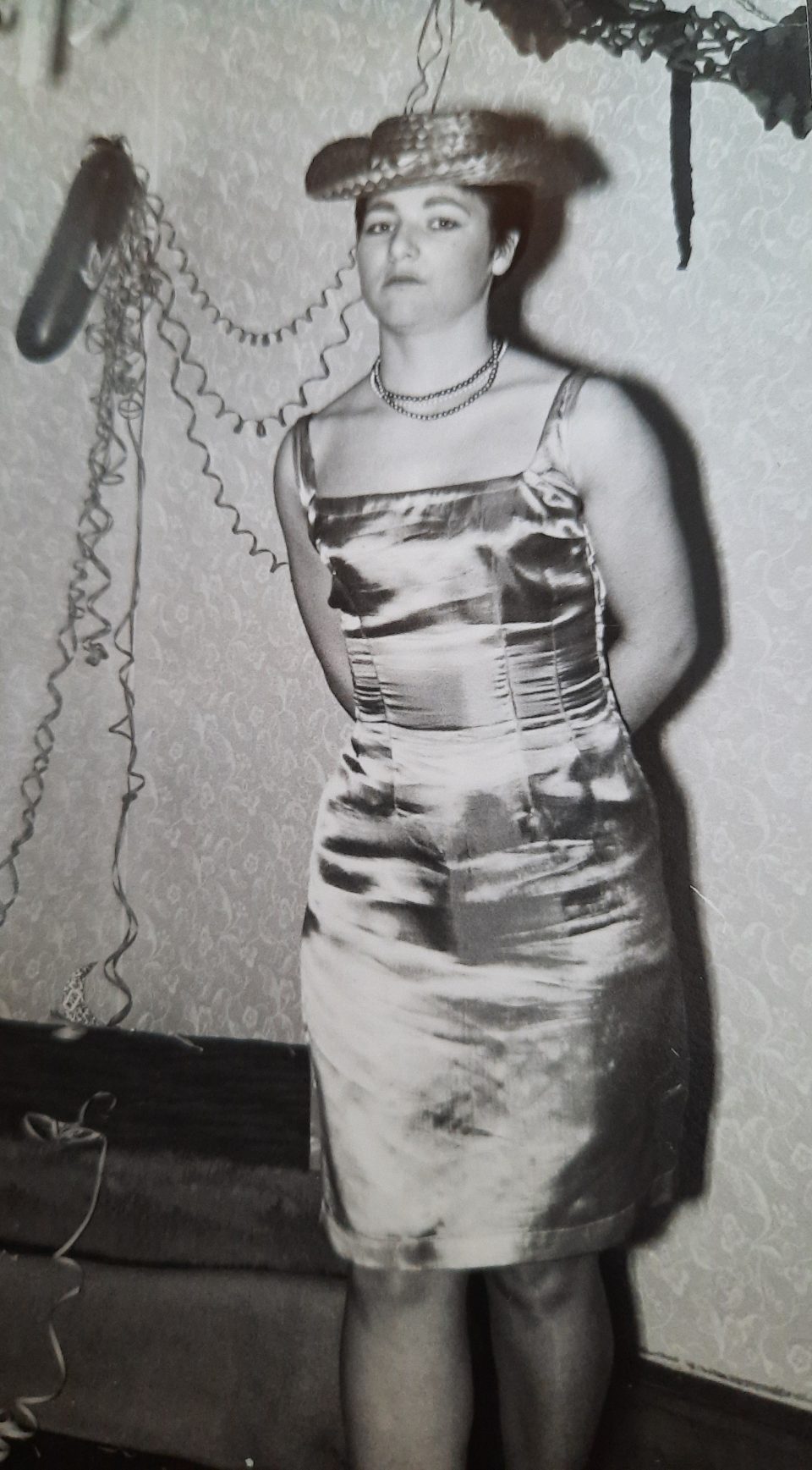

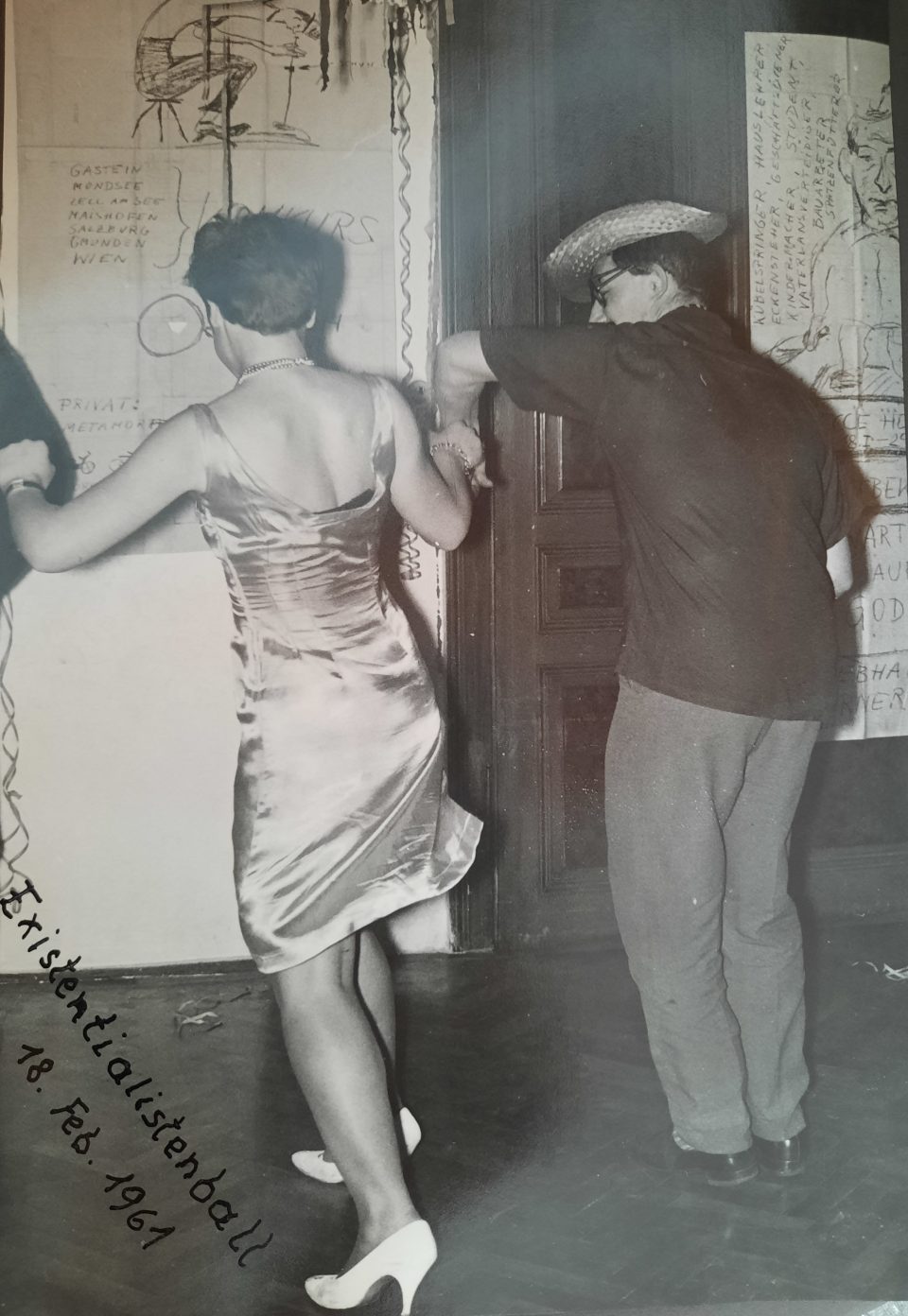

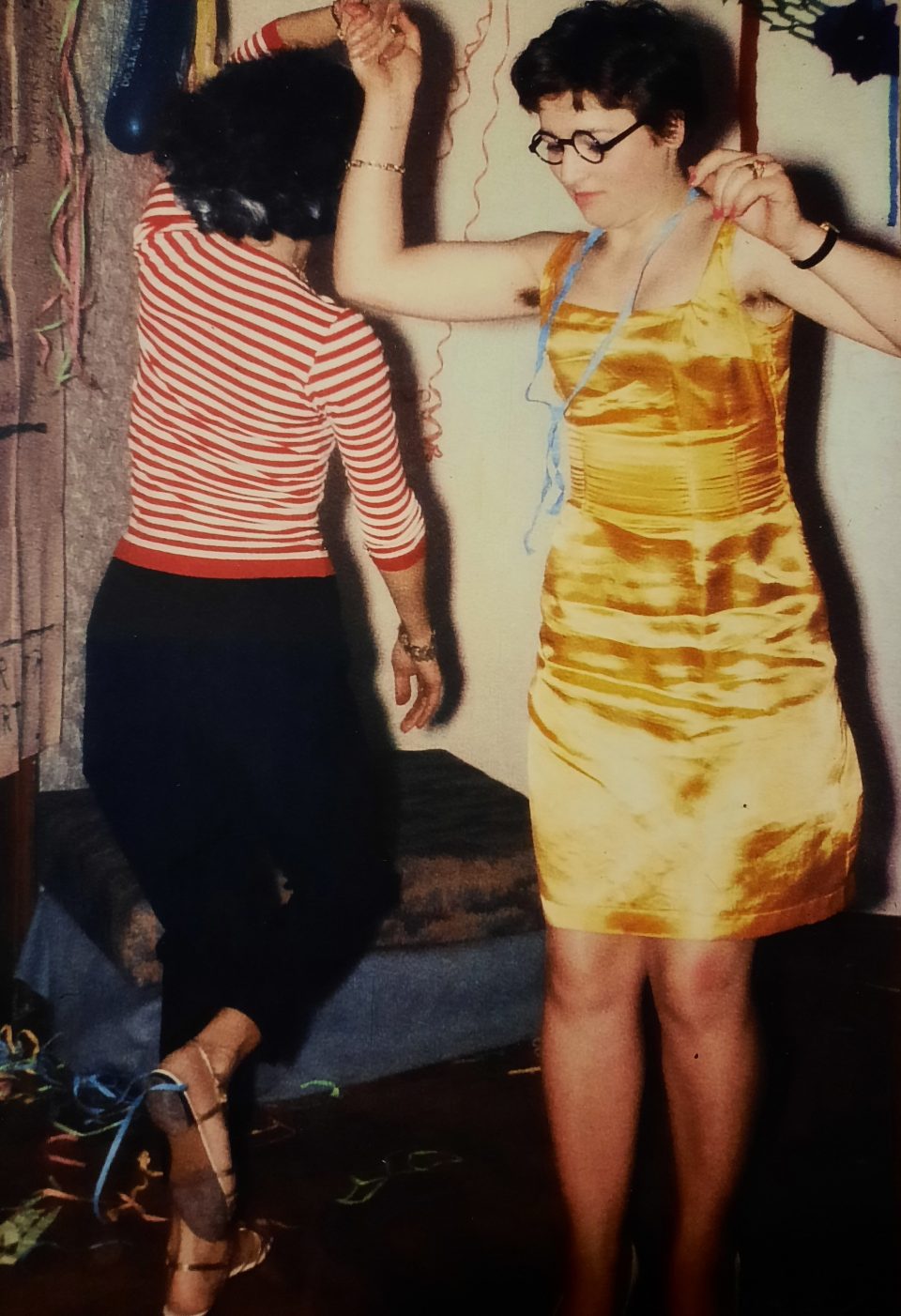

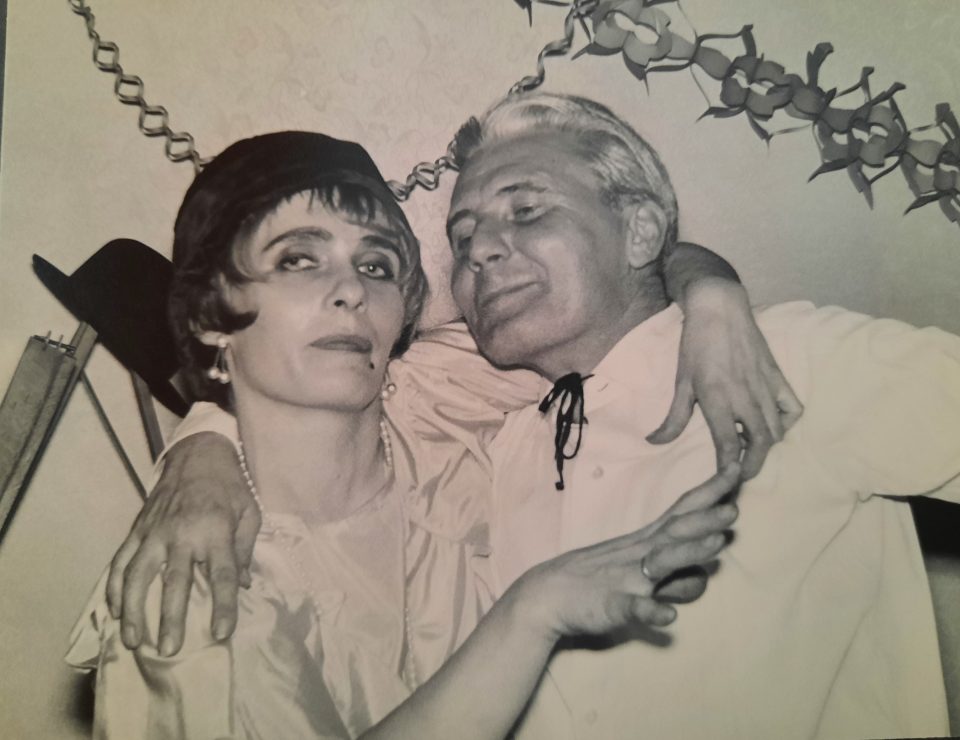

The cult objects of the 1950s female fashion were petticoats, ballerinas, pencil skirts, stilettoes, ponytails, teased pinned-up hair, English female suits, jeans, Capri trousers and cocktail dresses. Fashion and accessories were popular in gold and cream colours or with oriental patterns. The US “college-style” reacted to the needs of young people and offered combinable sets of skirts, jumpers, jackets and trousers – comfortable and cheap and ideal for sports and dancing. Unusual jewellery made of glass, wood or plastic was worn with these outfits. The new fashion trends were influenced by the USA, which meant “small, smart and understated”. While the elegant lady was more influenced by the rather reactionary Paris fashion trends of Dior – with shoes, handbag, hat and gloves bought in a set. After years of war, repression and deprivations, the Viennese women wanted to be beautiful again. At the same time the new “Pop culture” had an impact on fashion, whereby different philosophical trends were expressed in terms of fashion, too: for example the Paris scene of the “Existentialists” of the cafés of St.Germain-de-Prés. These melancholic youngsters indulged in art and philosophy, roamed the streets between cafés, university and jazz clubs and led their lives as if they could be terminated at any moment. Herta and Werner represented them at the theme ball they organised, ”The Existentialists” of 1961. The “film noir” series, Jean-Luc Godard’s “À bout de souffle”, the music of Edith Piaf, Juliette Greco and Gilbert Bécaud influenced this movement, which rejected traditional norms and heteronomy. In the second half of the 1950s the yearning for exotic places also reached the fashion world and dresses, patterns, sun hats, sandals, earrings, bracelets and necklaces sported exotic motives and patterns. Even home decoration, African masks as wall decoration and cocktail glasses decorated with exotic motives, followed this trend which was kicked off by musicians like Elvis Presley. Colourful bikinis and swimming suits, cocktail dresses, clutch bags, Bolero jackets, and stoles tried to create a holiday feeling in fashion.

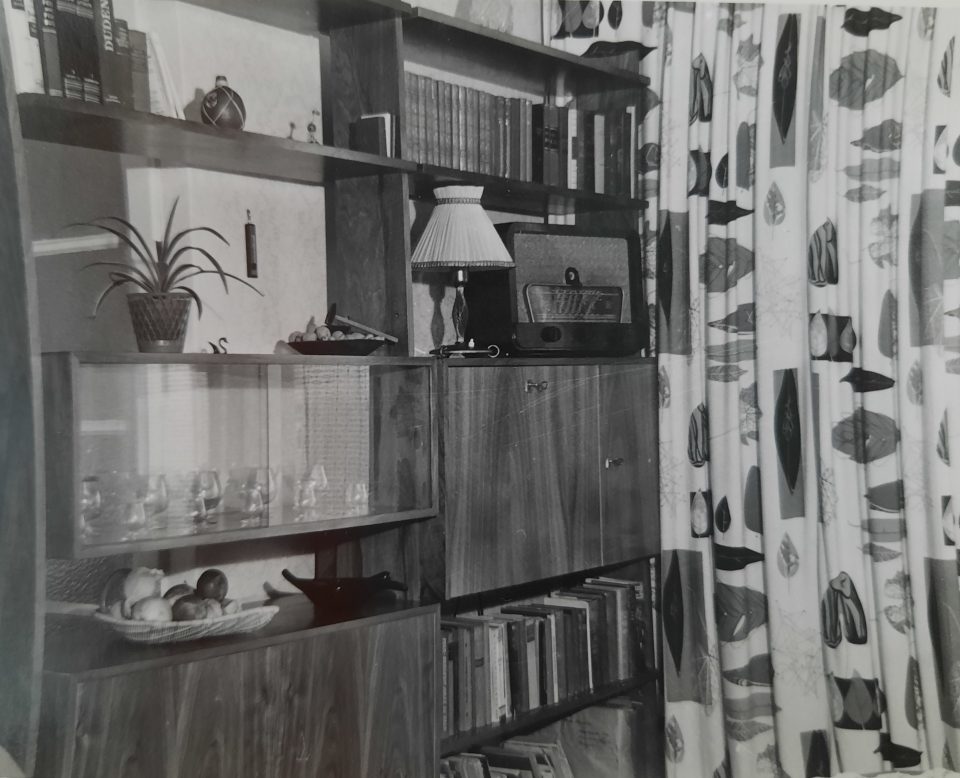

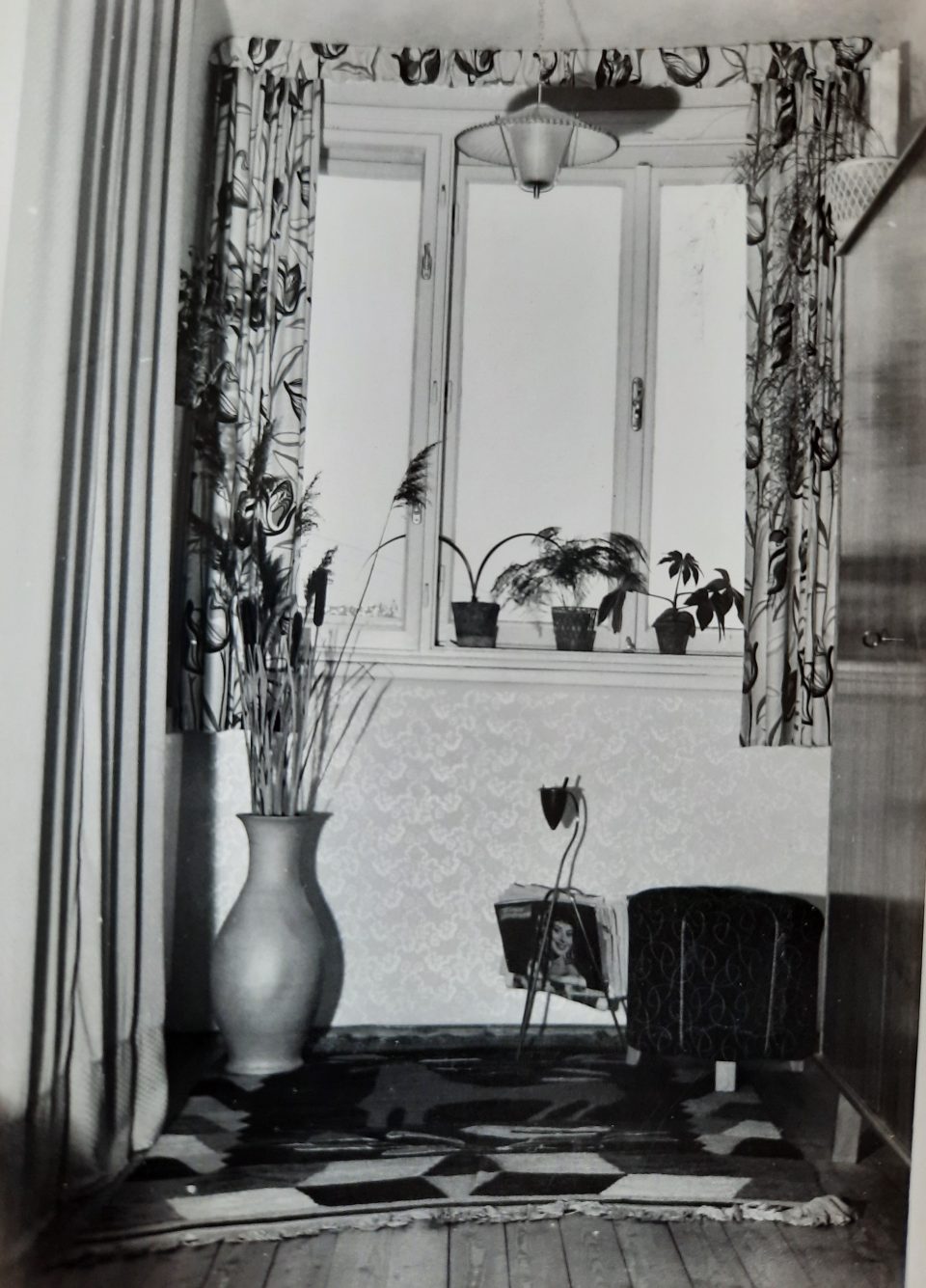

Herta and Werner’s new flat in Ottakring, Friedrich-Kaisergasse 26/28 in 1956 (pregnant Herta, Werner and Lola)

In the period after the war many small flats with bathroom and toilet inside were built in Vienna, which were around 28-48 square metres in size. The “Marshall Plan” helped with the financing, although most of this aid went to the west of Austria and the zones of administration of the Western Allies and not to Vienna. The blocks of flats were mostly built by the city’s council house programme or by housing cooperatives. The low- and medium-income people who moved into those flats could not afford the type of classical big solid wood furniture and this type of furniture would not fit into these small rooms anyway. The organisation of Socialist women soon realised that furnishing these new small flats economically was a problem that had to be dealt with quickly. Together with the architect Franz Schuster, who had worked in Frankfurt together with Grete Schütte-Lihotzky and Ferdinand Kramer and had experience with the concept of the “Frankfurt kitchen”, was searching for a “basic concept of the elementary” of modern floor plans and furnishing. The workers had to get rid of the concepts of “seigneurial” furnishing ideas and develop their own culture of living. The workers were supposed to see their new flats as a room for relaxation and a place for meeting friends in a cosy environment. The unique position of the woman in this concept of housing and living was stressed. The first programme was presented at the Vienna Trade Fair in 1950 and was named “The Woman and her Flat”. The idea of simplicity dominated this furnishing concept; clear forms, pastel colours, simple designs and most of all, the incorporation of technological gadgets to facilitate the household chores and offer more leisure time to the housewife.

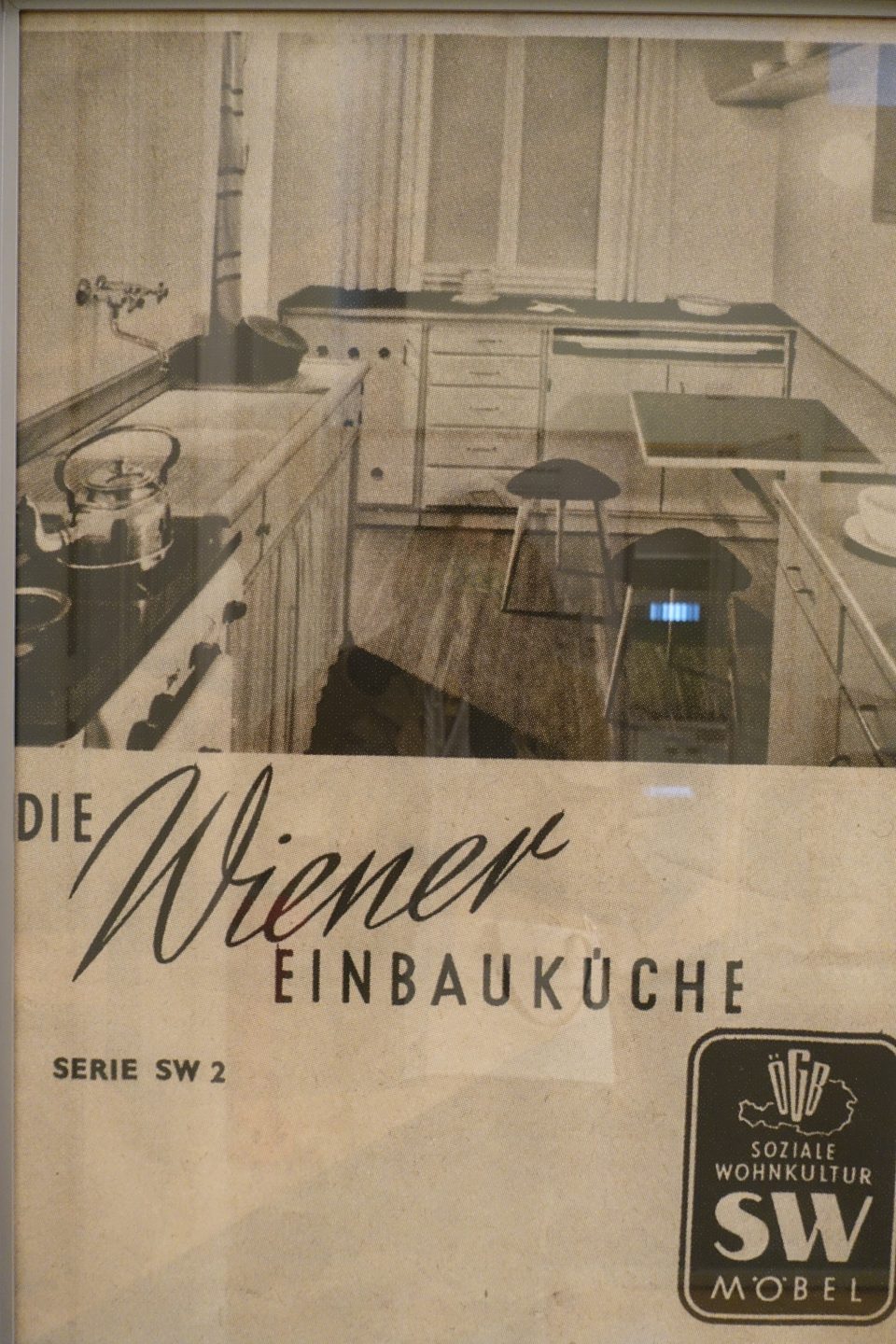

The SW “Wiener Einbauküche” with “Lilienporzellan Daisy” on the table

Originally the workers were not much impressed with these designs because they were simple and practical and therefore lacked any grandeur and were no objects of prestige. Yet the Viennese middle class was fascinated by the new interior design and so the workers followed suit. But still capital was missing on the side of the workers as well as on the side of the producers. So the project “Soziale Wohnkultur” (SW= “Social interior design”) was launched. First the experts created the designs of the furniture and submitted them to a committee of trade union representatives. A selection was then exhibited at the “Soziale Wohnkultur” show. A special credit system was devised to finance the production and distribution of the “SW furniture” with the head quarter in Vienna. The association “Soziale Wohnkultur” checked all the contracts of designers, producers and distributers, the price and the quality and then awarded the SW plaque to the piece of furniture. From 1954 on the first furniture shops sold “SW furniture”. Already in 1954 13 million AS turnover was reached, which increased to 100 million AS in 1959. Representatives of the SW association advised the customers in the 280 furniture shops Austria-wide. All in all, the first Austrian furniture association was a big success. The prices were kept low also thanks to the new methods of mass production, so that finally workers could afford new modern furniture on a specially provided hire-purchase basis. Furthermore they could purchase this furniture step by step because the different elements could be combined and matched in colour and design. So more and more council flats and cooperative flats were furnished with folding tables, folding beds, collapsible chairs and combinable cupboards and wardrobes in various sizes made of local veneer. The slender conical legs of chairs and tables made of wood or metal underlined the effect of lightness and flexibility and facilitated the cleaning of the flat. In 1956 the SW series consisted of two lounge and bedroom sets and a kitchen set, called “Wiener Einbauküche”, but in 1958 the selection was already much more diverse; it comprised 77 pieces of furniture which were produced by ten firms that employed around 450 people. Soon the chipboard, melamine-faced or veneered, was introduced, which further cheapened the SW furniture. Pastel-coloured furniture was offered with a variety of trimming and sold under the brand “Wiener Wohnkultur” and towards the end of the 1950s more and more plastic material was used for surfaces and golden plastic trimmings. Ten years later the SW association had accomplished its goals; it had changed the taste of the workers and had led them away from a false sense of “representation”. SW was the trend setter with respect to home design in Austria and other producers set in. SW had offered financing possibilities to producers, retailers and the workers in the dire post-war years. As soon as full employment had set in and the workers earned more, they could pay back their loans to the SW association – the city of Vienna and the trade union congress with its bank had provided the funds – and ended their membership in the SW association. In the 1960s the city of Vienna withdrew its financial support of the SW association and the rising living standard made the provision of cheap furniture obsolete. So in 1976 the SW association was dissolved.

Small modern “hall furniture”, mirror, umbrella stand and telephone in the hall, which was a “quarter telephone”, which meant that four households shared one telephone connection. So as long as one of them was on the phone, the other three could not use the line. Herta and Werner‘s new bedroom with a “Keramos” figure as a lamp base on the left Right: Porcelain coffee set, design of the 1950s (Hutschenreuther “Diadem”)

Left: “Gloriette Keramik” elephant; right: “punch bowl set”, both very popular household accessories in the 1950s. The popular recipe of the time for making cold punch was: a tin of pineapples or a tin of peaches, cut the tinned fruit up and mix it with a bottle of white wine, keep it in the fridge for some time and top it up with a bottle of sparkling wine before serving cold

Rationalisation and technological innovation in the household and in the kitchen along the lines of Taylorism was the call of the day in the 1950s. Unfortunately the majority of Viennese households could not afford such technical gadgets. There was furthermore no tradition in rationalising work in private households because of the concepts of building small flats to house as many people as possible in the interwar years. The construction of blocks of council house flats of “Red Vienna” 1920-1933 offered technically equipped communal facilities, such as communal laundries and sometimes even communal kitchens, so there was no need for technical kitchen aids and washing machines. After 1945 all council house buildings and cooperative housing complexes had communal laundries and often the bathrooms and kitchens were much too small to offer room for modern washing machines for example. Therefore there was also no domestic production of household machinery in Austria; everything had to be imported and was extremely expensive. Nevertheless it was now important to have smooth and easy-to-clean surfaces to help speed up housework for housewives and working women. The “heart” of every flat in Vienna was now the living room, where the family got together in a cosy atmosphere, guests were received and small private parties were held; it was no longer a room for representation at special occasions. The furniture had to be bright and light, so that it could be easily moved around to be adapted to the different occasions. The chairs and tables were low because this was considered comfortable. Organic and dynamic forms were fashionable, for example the “kidney table”. The furniture had to be “flexible”, which meant one piece could be used for more than one purpose. A collapsible sewing machine, which could be turned into a desk, was to be found in many households. The patterns popular with curtains, carpets, lamp shades or tableware were abstract, derived from Mirò, Klee or Picasso paintings and the flats were cluttered with specially designed modern small pieces of home décor, such as umbrella stands, radio tables, newspaper stands, floor vases or serving trolleys. Exotic plants, such as Indian rubber trees, paintings and ceramic figurines added to the Viennese home a touch of faraway places. “Gloriette” or “Keramos” figurines were extremely popular home décor accessories in the 1950s. “Keramos” was founded in Vienna after the First World War and produced hand-made ceramic objects designed by famous sculptors, such as Rudolf Podany and Anton Klieber. Josef Hoffmann, the founder of the “Wiener Werkstätte”, was for many years a partner of “Keramos”. After the Second World War the public interest in exotic places and female sexuality boosted the production of African motives. Animals and female nude sculptures for home décor were produced. In the area of tableware the Austrian company “Lilienporzellan” dominated most Viennese households and its porcelain series “Daisy” with its clear geometrical shapes and pastel colours, where plates, cups, saucers etc. were easily combinable. The logo showed three lilies, the crest of its production site, Wilhelmsburg, and the lilies in the name of the nearby monastery “Stift Lilienfeld”.

Entertainment & leisure

Private parties at Toni and Lola’s flat in Neulerchenfeld: Ignaz with Anni and Willi Gaube (left photo), Toni in the middle and Willi on the right (right photo)

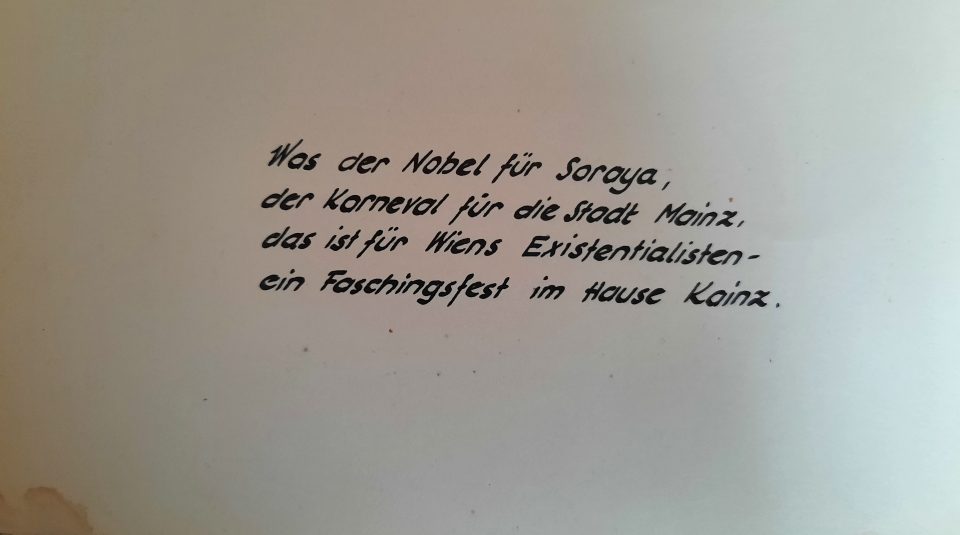

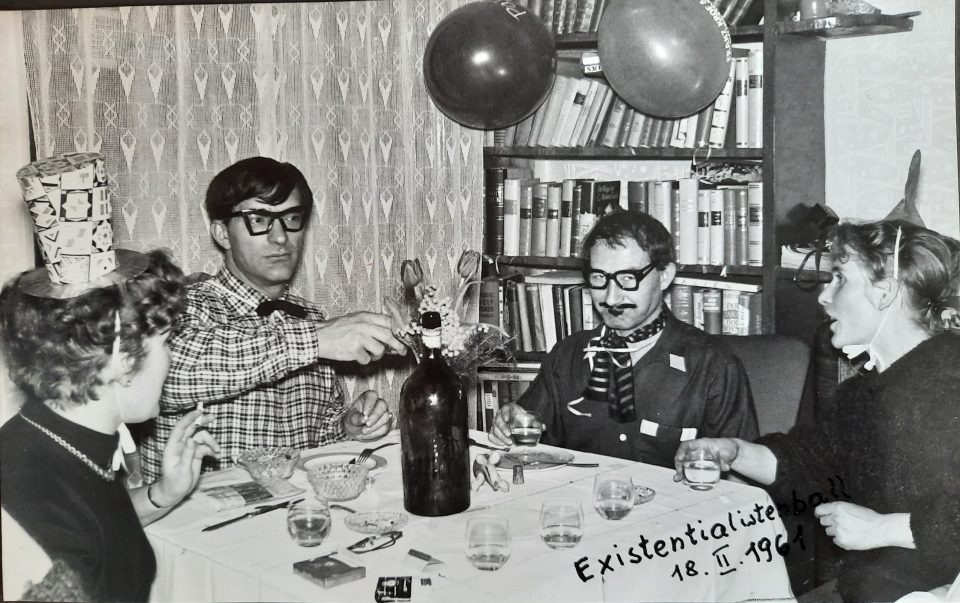

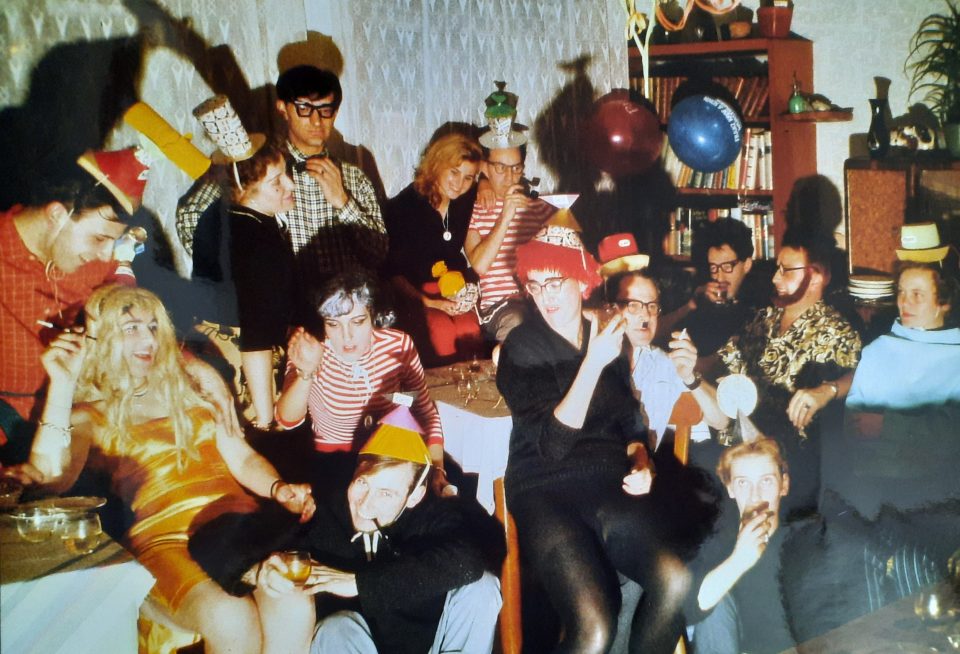

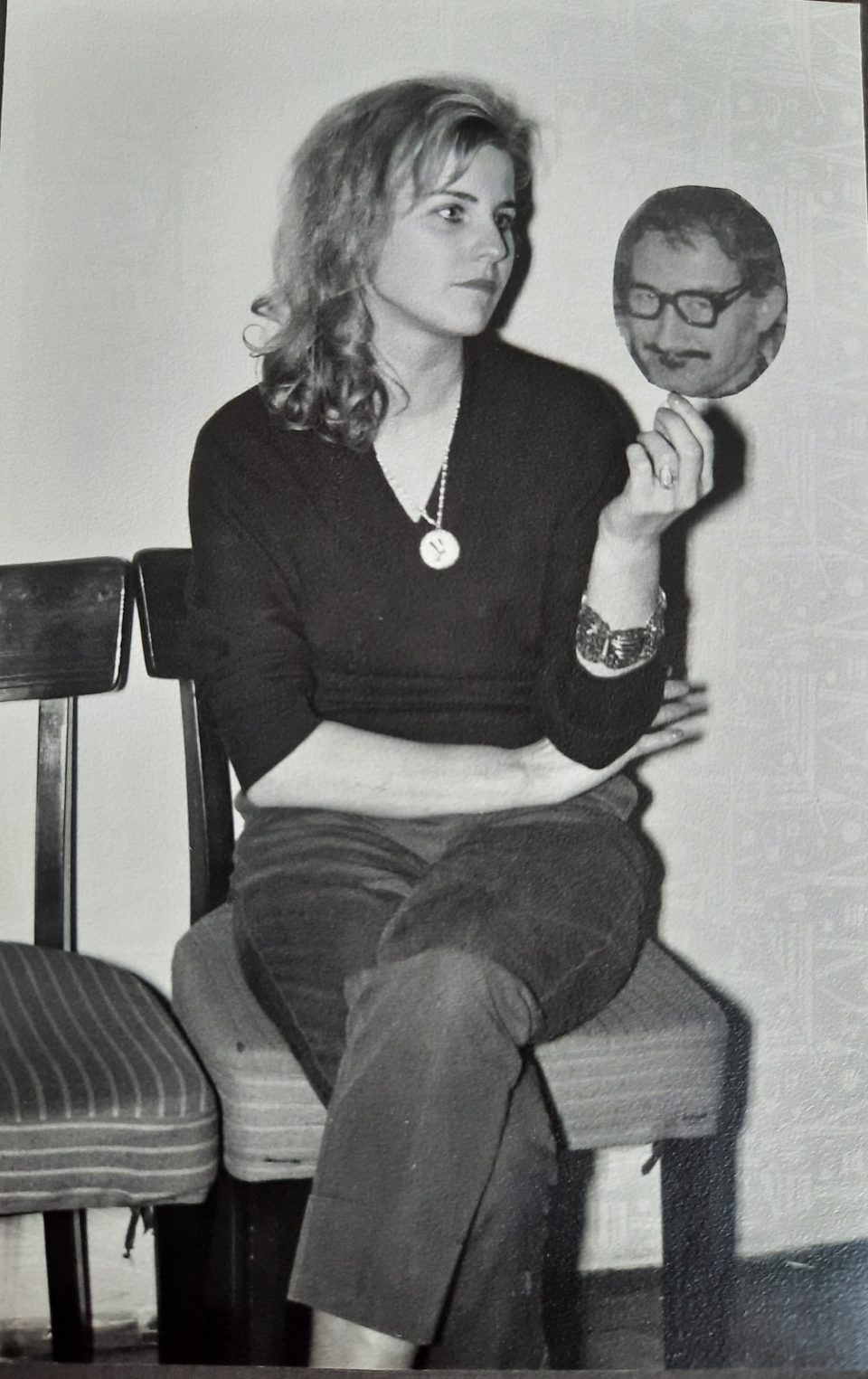

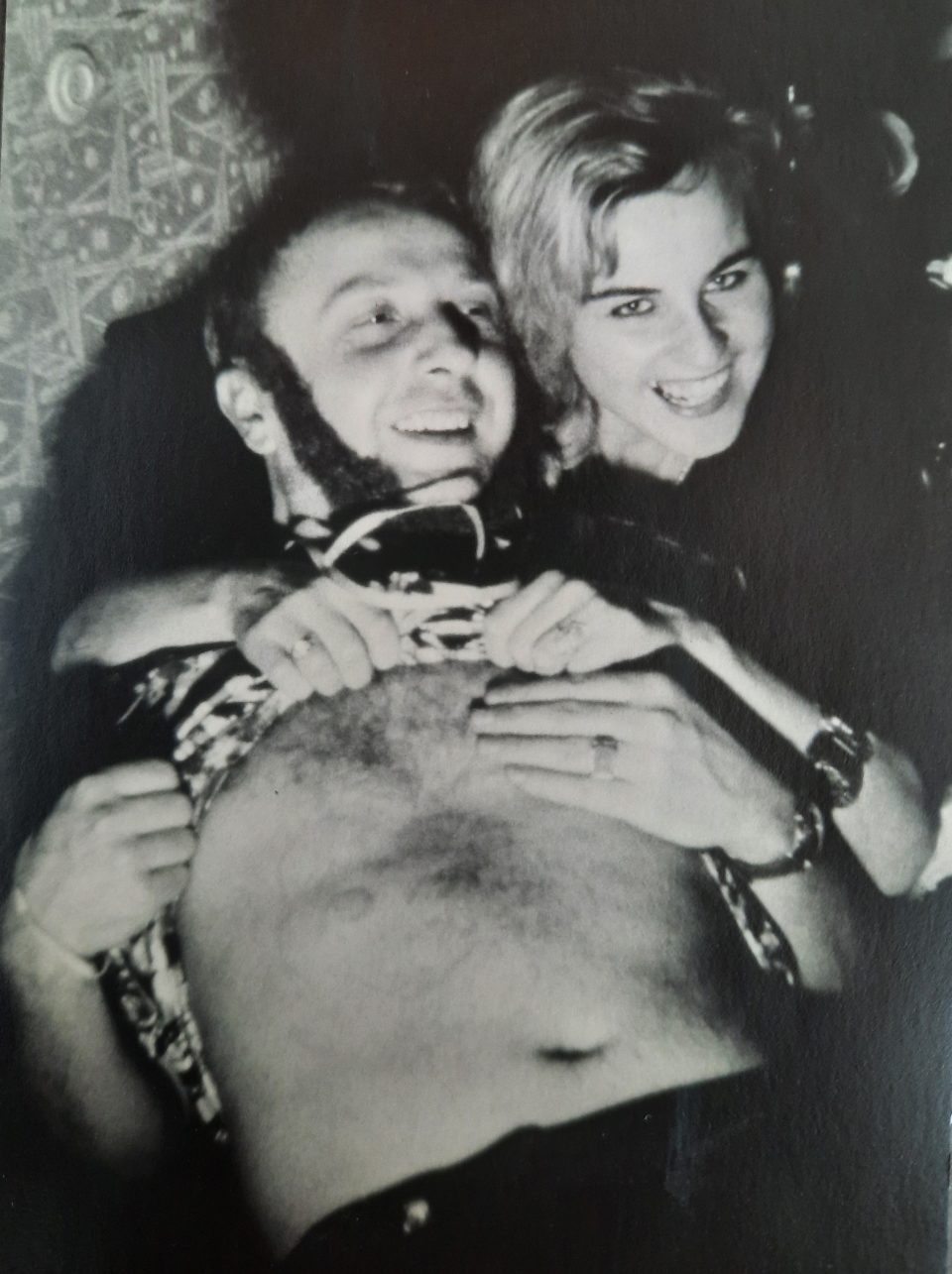

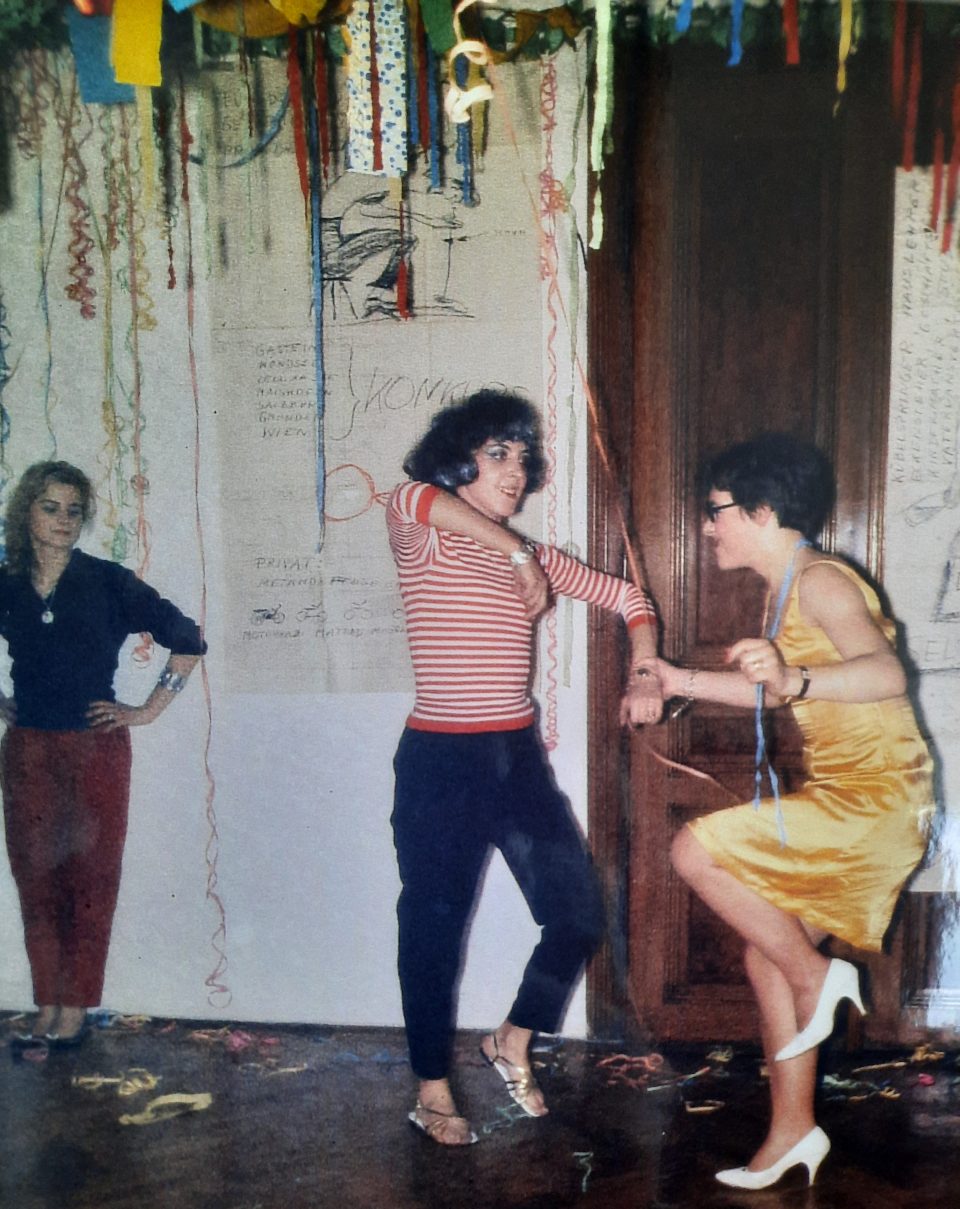

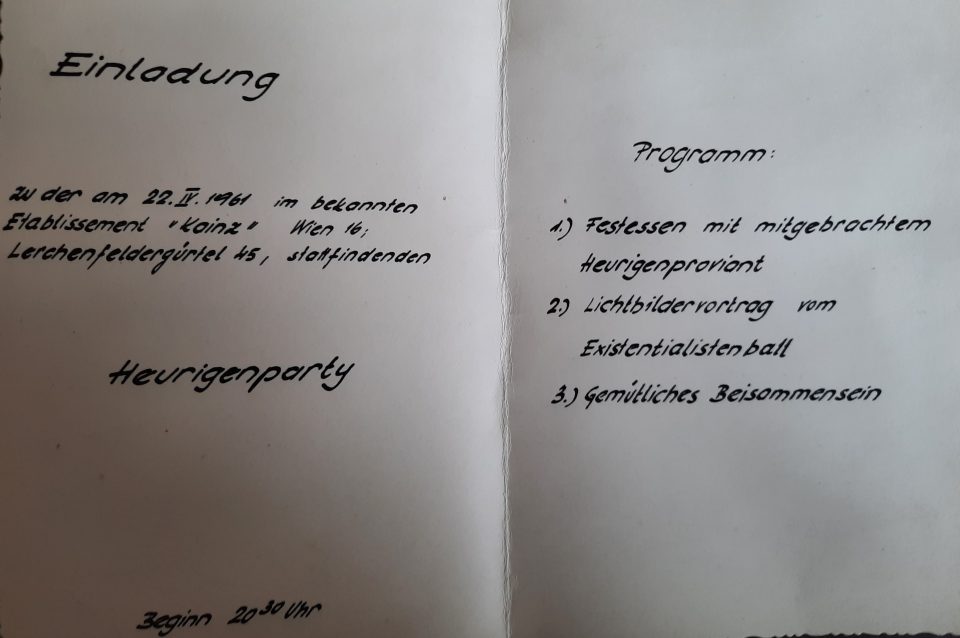

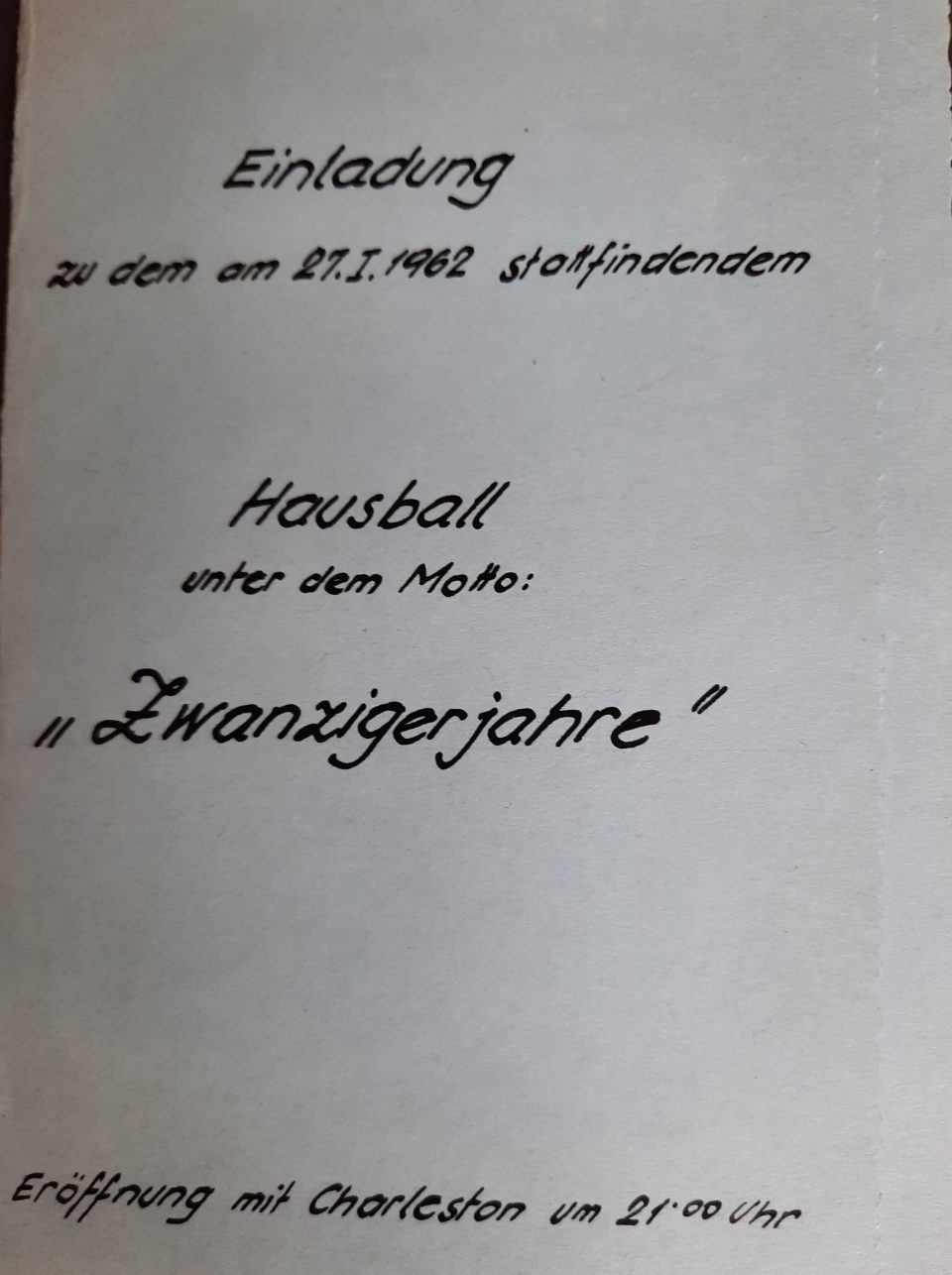

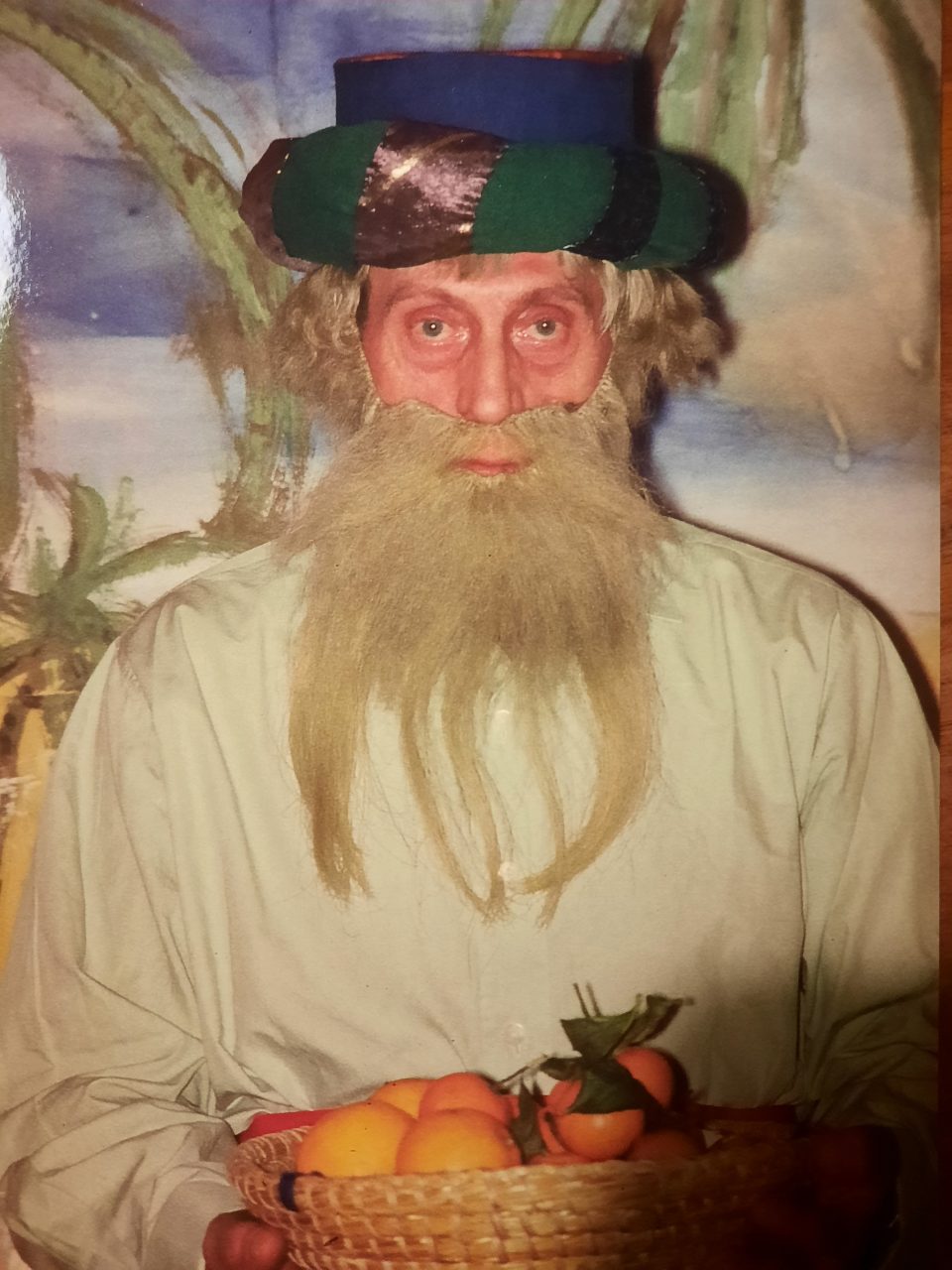

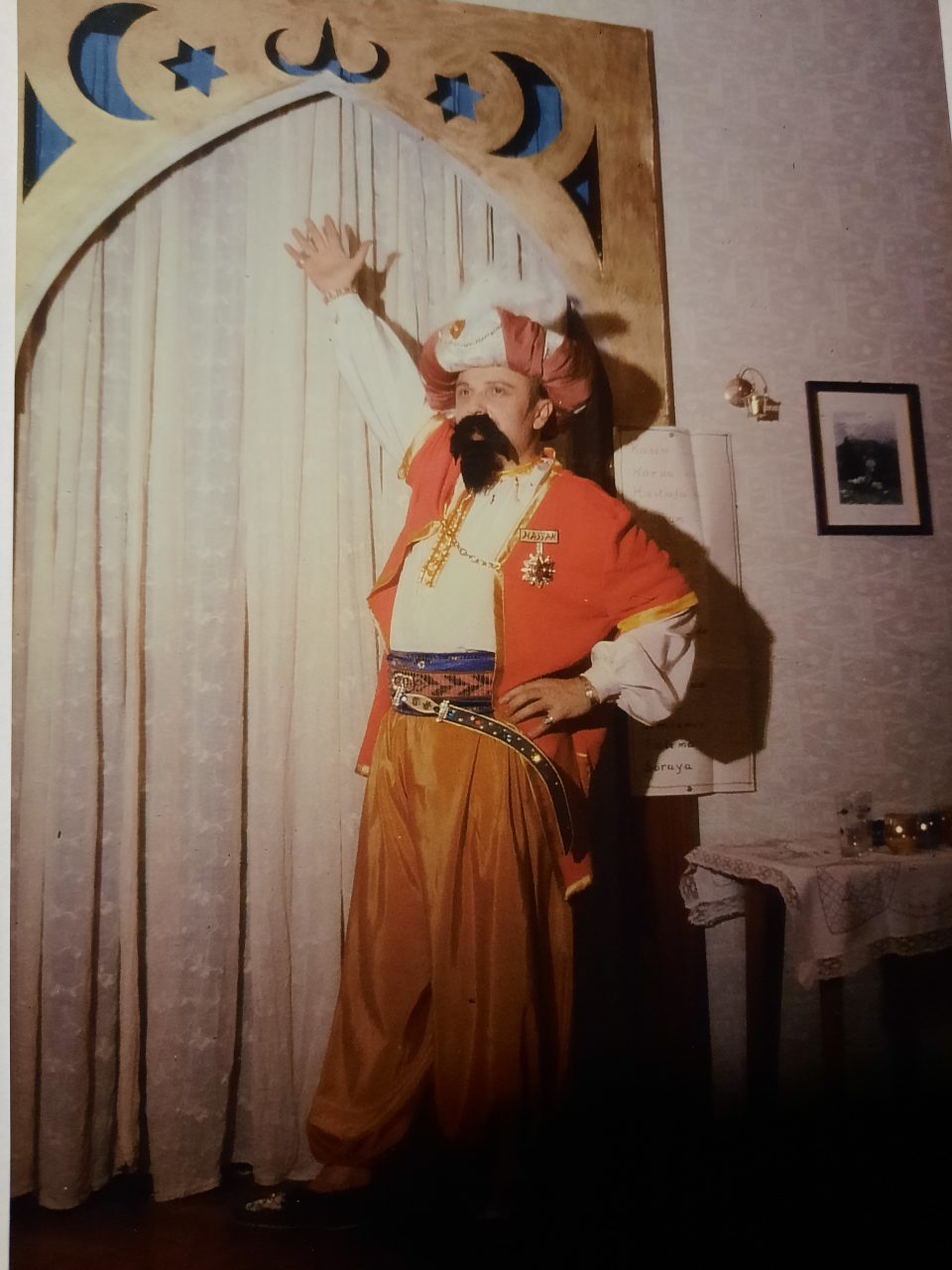

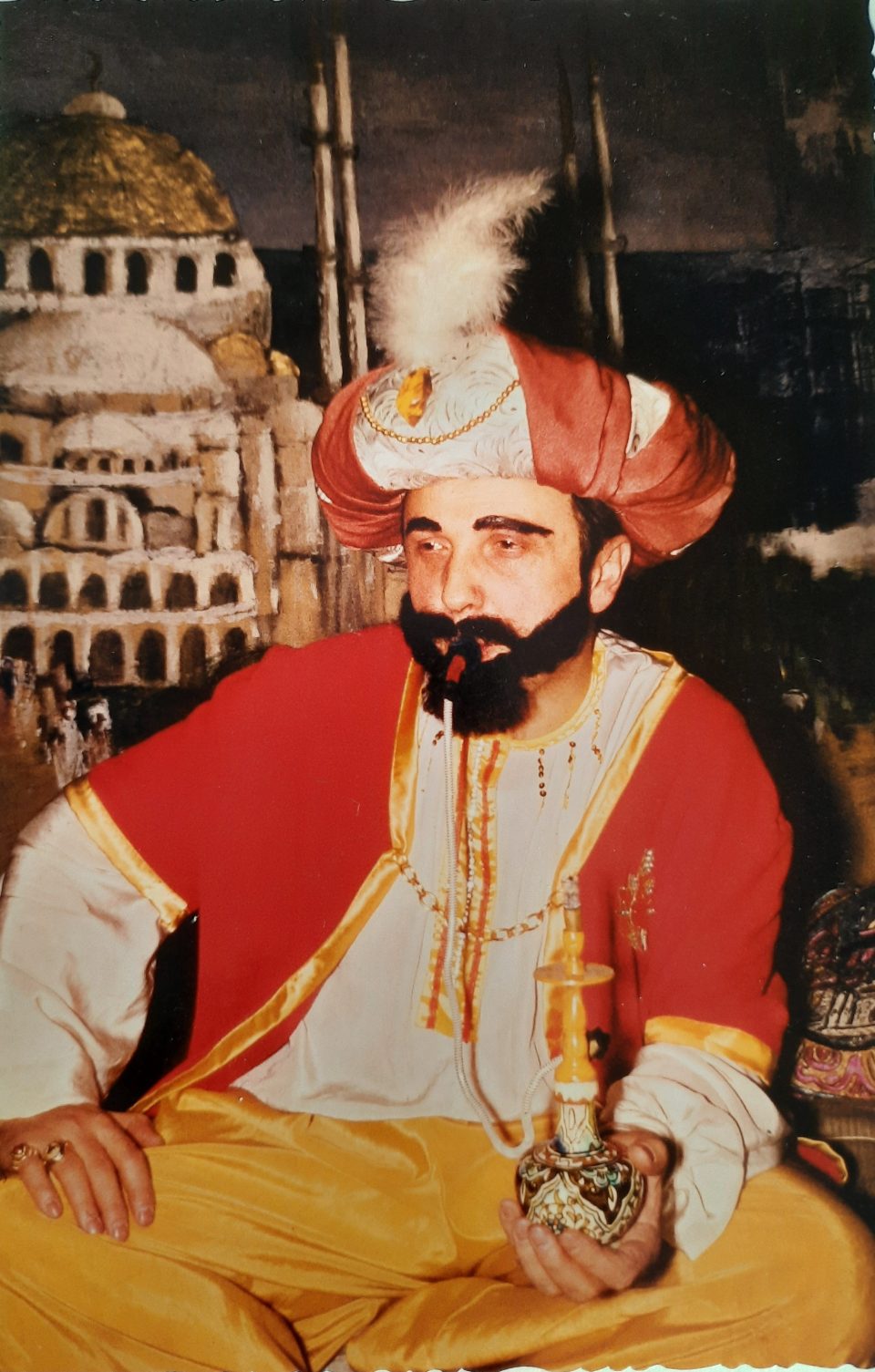

Herta and Werner together with Toni and Lola organised elaborate theme balls during the Carnival season in Toni and Lola’s flat together with their friends. They created the decoration, planned the programme, Herta, Anni and Maria sewed the costumes. The preparation took weeks, during which time the flat was in chaos, and it involved lots of get-togethers in Neulerchenfeld, which lasted whole nights and lots of alcohol and cigarettes were consumed. The young people even took dancing lessons to prepare for the appropriate dances. Werner did not only take the photos, but also made 8mm films of these theme balls with a well-prepared plot and script. Here are some glimpses of the glamorous spectacles they were able to put in place with little money and lots of enthusiasm:

Theme ball “Existentialisten” in 1961

Maria on the left and Christine, Werner’s sister, on the right

“Heurigenparty” (traditional Viennese informal get-together where the new wine is drunk) in 1961, again with Toni and Lola as hosts:

Lola on the dance floor with Willi

Theme ball “The 1920s” in 1962:

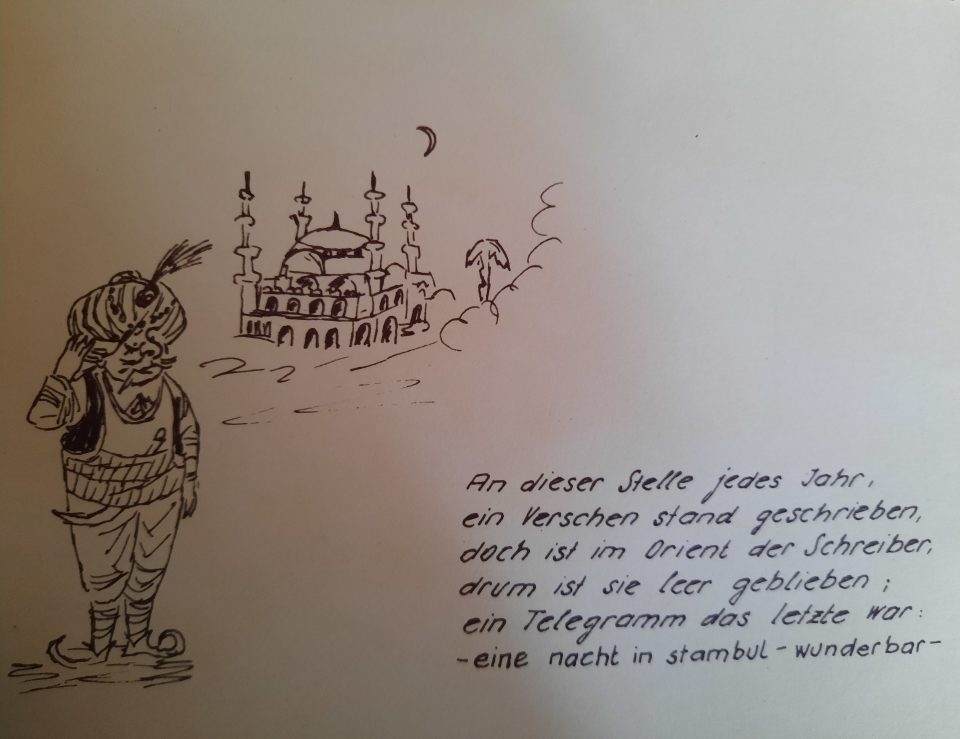

Theme ball “1001 Nights” in 1963:

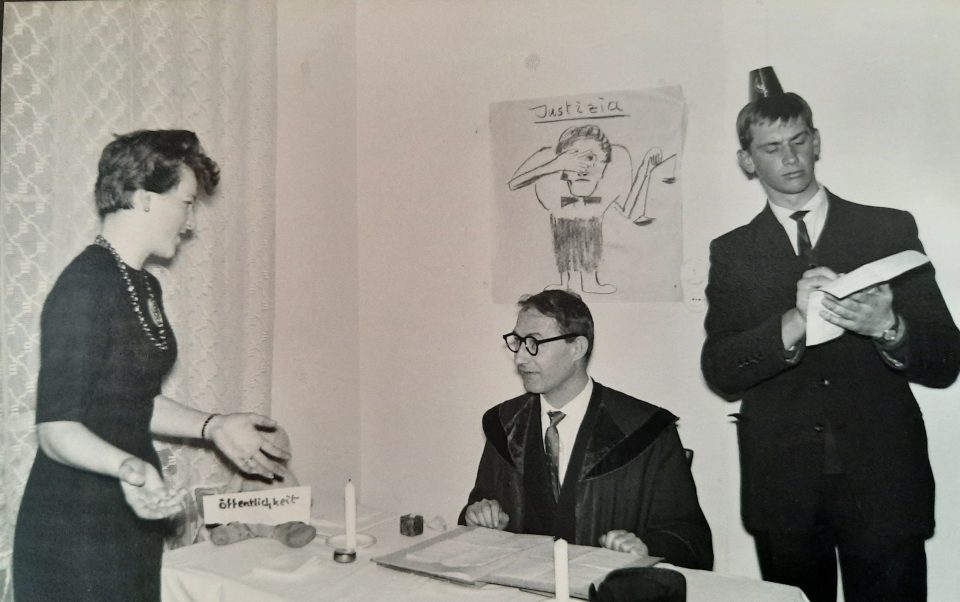

“Mock Trial Party” at Toni and Lola’s in 1963:

Willi as “judge”

In sports apart from the all dominating football in Vienna, ice-skating was extremely popular in the 1950s as a leisure activity. This sport had a long tradition in Vienna with many internationally well-known stars, such as Eduard Engelmann, Karl Schäfer and Herma Plank-Szabo. New ice skating rinks had been built in Hernals, the “Engelmann ice rink”, an ice-rink next to the Konzerthaus ”Wiener Eislaufverein am Heumarkt” and several natural ice-skating areas in Margareten or at the “Old Danube”. In 1955 the “Golden Era” of the post-war Viennese ice-skating sport started, when the World Championships took place at the “Wiener Eislaufverein”. The Austrian stars of the 1950s were Hannerl Eigel, Ingrid Wendl, Eva Pawlik, Regine Heitzer, Sissy Schwarz and Kurt Oppelt. For many of the young Viennese ice skaters becoming a member of the world-famous “Wiener Eisrevue” opened up an excellent professional career perspective. The “Wiener Eisrevue” was founded in 1945 – Karl Schäfer had initiated such an ice-skating performance during the war – and already toured in seven countries in its first year of existence, among them Norway, Switzerland and the Soviet Union. From 1960 on two ensembles toured the world simultaneously and in the season 1963/64 they had 689 performances, 593 of them abroad. At the height of the Cold War the “Wiener Eisballet” performed in Leningrad and Moscow and was revered there. The different scenes were connected by a narrative thread and a live orchestra played original music by Robert Stolz in a kind of “Ice Operetta” while Austrian European and World Champions performed in the ice rink. For the average Viennese ice skating was an affordable leisure time activity because you could rent the equipment and the natural ice skating arenas were even for free. Every year at Christmas I received tickets for the “Wiener Eisrevue” in the “Wiener Stadthalle” in January.

“Wiener Eislaufverein” am Heumarkt

Photography and filming were another popular hobby in the 1950s. Lots of beautiful photos of Karl, Toni and Werner have been preserved. The Austrian company “Eumig” provided amateur enthusiasts with pricey, but solid equipment for 8mm filming. Toni gave such an “Eumig” 8mm film camera and projector to Werner for Christmas, although he had to pay for it on hire-purchase terms.

Toni with his photo camera and Werner’s “Eumig” film projector

The Vienna “Prater” offered popular entertainment to the Viennese, as did public swimming pools, the Danube and lakes in the vicinity:

Herta and Werner in the “Prater” (left) – Karl, Herta, Lola and Käthe there (right)

Herta’s cousins from London, Susi and Josi visiting the “Prater” (left, next to Lola) and Herta with Susi (right)

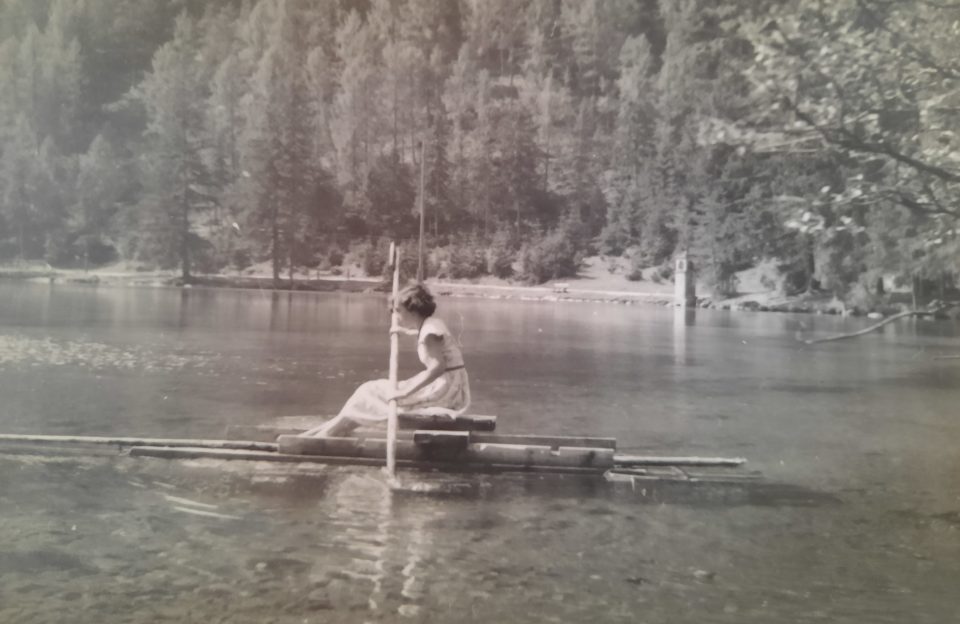

Herta at “watersports” on the right with Werner

Betting on horse races in the Krieau and Freudenau was another popular pastime in Vienna as well as visits to the many “Heurigen” at the outskirts of Vienna:

Lola in front of the betting offices (left) and the family at the “Heurigen” (right)

Handicraft was a leisure time activity of the 1950s which was not only cheap, but also offered the possibility of making beautiful presents for family and friends. Most of my toys were made by Werner and Herta:

…like the electric toy train, the doll’s kitchen, all the doll’s dresses and a “Hollywood swing” (below)

Presents hand-made by Werner

US American influence & youth culture

Unfaltering belief in technological progress and unrestrained American-style consumerism were further characteristics of the 1950s’ young and not-so-young generations. A city like Vienna had to become “car-friendly” when the car became the cult object of the time. In 1948 there were 34,000 cars in Austria, compared to 880,000 in 1966. Yet by far not every Viennese could afford a car in the 1950s; Werner and Herta for example did not own a car before the 1970s. Yet what was more easily affordable was a moped, of which existed 40,000 in Austria in 1953 and 440,000 in 1962. It was the vehicle for the young and the poor. What’s more, the motorcycle was turned into a symbol of protest of a specific youth culture of the 1950s, the “Halbstarken” (yobs), whose role model was Marlon Brando in his film “The Wild One” (1953). The moped or motorcycle, jazz, boogie-woogie, rock ‘n roll, jeans and leather jackets became the signature of this anti-conformist youth culture, which was especially prominent in the overcrowded working class districts of Vienna, like Neulerchenfeld, where Toni and Lola lived with their family. The advance of American mass culture was about to threaten the traditional classical Austrian cultural tradition. Although Austria produced lots of films during this period, the American movies inundated the cinemas and the number of American films shown in Austrian cinemas rose from 52 in 1949 to 229 in 1955. The US “cultural invasion” was extremely successful, while the Soviet attempt of a “cultural offensive” failed spectacularly. From the start the Soviets had lost the Cold War on the culture front. “Jeans, Jazz and Coca-Cola” stood for modernity, innovation and a global Western civilisation and fortunately it did not suppress local traditions, but complemented them. For the more conservative part of Austrian society these American innovations came as a shock as they undermined in the long run the “hard-earned conservative stability” of the 1950s. Another aspect of American modernity, US-style consumerism was more to the taste of Austrian conservatives. They craved for nylons, American kitchens, easy-clean furniture and technological gadgets, too. The new “model woman” cared for husband and children, ran the household, was always well-groomed and sometimes held a job as well.

During the “long 1950s” the influence of American culture was strikingly obvious in Vienna. All four liberating armies, the Soviets, the Americans, the British and the French, which were administering Austria for ten years from 1945 until 1955, had the same opportunities to influence the lifestyle, culture and politics of Austria. But only the USA made use of this chance to the full. They could build on the old European dream of the American democracy as the foundation of mass welfare and they were the only one of the Allied forces which had the financial means to organise a cultural programme that covered all spheres of life. During these ten years the course was set by the US military and diplomatic administration in Austria for trends which often came to fruition years later. The Austrians could study the American way of life when watching the thousands of American GIs; some of the girls even fell in love with them and were called “Chocolate girls” or more contemptuously “Amihuren” (American prostitutes) in Vienna.

Immediately in the first days of the occupation the American authorities established a special cultural agency which had been planned way ahead and which portrayed the USA in the most positive light possible, the ISB (Information Services Branch). This agency founded for example modern popular newspapers such as the “Salzburger Nachrichten” and the “Wiener Kurier” and soon other Austrian papers copied this style. Austrian journalists were trained by American counterparts in Austria or in the US and there they learned how to do quality journalism which was also popular. One of them, Hugo Portisch, later described that he had learned in the USA the professional way to deal with news before publishing them: “check, re-check and then double-check” the facts. Many Austrian newspapers published articles and photos which were provided by the “US-Feature and Pictures Services” and furthermore, the US news agencies managed to break the pre-war monopoly of French and German news agencies and to establish a prominent position in Austria. The ISB published special issues for workers, farmers, doctors, teachers, intellectuals and the youth. The US broadcasting station “Rot-Weiß-Rot” became the most popular radio station in Austria and greatly influenced the making of radio broadcasts here. Of course, all news reports were pro-American, but “Rot-Weiß-Rot” was so popular because it copied the innovative style of American radio broadcasts. What the Austrians had been used to before was the Nazi propaganda radio and now they could listen to entertaining shows, quizzes, participation of the listeners and hourly news broadcasts; American radio shows, but in an Austrian form, were produced, as soon as the management hired talented young Austrians for the creation of the programmes. In 1948 well-made commercials were introduced, a thrilling new feature for the Austrian population, and in 1949 the first Austrian disc-jockeys, Fred Ziller and Günther Schifter, broadcast their selection of modern music. But that was not the only American-style radio station, there were others, too, such as the “American Forces Network”, “Voice of America”, “Blue Danube Network” and “Radio Free Europe”, where especially the young could listen to the latest US hits.

Twelve “America Houses” were established in Austria, where hundreds of thousands of Austrian visitors were offered American books, magazines, newspapers, films and records. They were brought in contact with American art, music, science and technology in lectures and events organised by these “America Houses”. Thousands of books were donated to schools and Austrian publishers who edited American titles were subsidised. “America Buses” carried books, films and records to the remotest places in Austria. The “America Houses” prepared, organised and often subsidised the performances of American plays, musicals and shows and they even made possible the guest appearance of US productions, for example George Gershwin’s brilliant “Porgy and Bess” in 1952 at the Vienna “Volksoper”. Marcel Prawy, who had to flee from the Nazi terror in Austria, returned after the war as a US cultural officer and established the American musical in Vienna. For the first time Austrian school books dealt with American topics, advised by US experts and English finally became the first foreign language in most Austrian schools. At the universities Austrian students explored enormous amounts of American topics for the first time and many US guest professors were invited to teach here. At the same time Austrian students were granted scholarships for US exchange programmes, the most famous of which was the Fulbright programme. I remember well the “America House” behind the Vienna town hall, which is closed now, as an interesting hoard and stronghold of knowledge and American lifestyle.

The ISB furthermore organised a variety of programmes for children and youth, such as sports events, parties, youth clubs, school meals and outdoor swimming pools. They introduced the US organisation “4-H clubs” (4-H stands for head, hands, heart and health) for the country youth and made them familiar with the latest agricultural innovations from the US. The already mentioned important US contribution to the Austrian economic recovery, the Marshall Plan (ERP= European Recovery Programme) always used a small percentage of its budget for propaganda purposes as well as for the support of the Austrian democratic system and the underpinning of Austria’s anti-Communist stance. They introduced not only American products, but also American technology, production methods and management styles. So the 1 billion-US dollar- aid was an enormously fruitful investment. The Austrians on average knew very little about the US in 1945, but their “dreaming the American dream” had an important impact on the political development in the 1950s. America stood for modernity, wealth, freedom, consumerism and peace, which was what Austrians craved for most. The official US policy soon after the war swerved from an anti-Fascist stance to an anti-Communist one. Nevertheless the US cultural policy propaganda had been extremely successful in Austria and even persisted after 1955, when the US troops left. The world of the mass media had become an American one and it dominated the film, music and in the late 1950s the TV productions in Austria. Between 1950 and 1960 40% to 50% of films shown were American ones and all these demonstrated to the much poorer Austrian viewers and listeners the rich and glamorous American way of life. But the Austrians had not shed all the prejudices of the past and those girls who had relationships or even a child with an black American GI had to face harsh discriminations. Even when the black US singer Theresa Greene was invited to perform in the “Wiener Konzerthaus” in 1956 the boarding house she had been booked in suddenly had no vacancies when she appeared.

In the course of the 20th century Europe did not only lose its dominant political and economic position in the world to the US, but also its pre-eminence in the media and music business. Television was a predominantly American medium and the first productions in Austria were largely influenced by US shows. With the invention of the vinyl record also the centre of the music business moved across the Atlantic. After World War II the US producers RCA-Victor, Columbia, Capitol and Decca dominated the market. There were just four European companies that could compete with them in some way, EMI, Philips, AEG-Teldec and Siemens-Deutsche Gramophon. But in the 1950s popular music started to inundate the vinyl market; approximately 90% of all productions were popular songs (“Schlager”) here. So Herta and Werner were an exception to the rule because they only bought classical vinyl records, which they listened to at home alone or with friends.

Soon after its appearance in the USA in 1954 the rock n’ roll reached Austria, too. It was the type of music which was exclusively for the very young and it was extremely successful. When in December 1956 the film “Rock Around the Clock” with Bill Haley and the Comets was shown in Vienna the cinema asked the viewers to keep their skirts and blouses on, even if it was getting hot and to make sure that the cinema chairs survived the performance. But nothing untoward happened; the riots the police had to deal with were rather linked to football matches. The fast penetration of the music market in Austria with US popular music was helped by the introduction of the US jukebox. In 1957 there were already 2,790 installed in Austria, although they cost between 40,000 and 80,000 AS – by comparison a tiny car, a “Steyr-Puch 500”, cost 30,000 AS at the time. The jukeboxes were much loved by the youth and every of the new “Espresso” bars (modern-style small café-bars) had to have one and that was the place where the young met. The “Halbstarken” (yobs) met there, too, in their tight corduroy jeans and large-checked jackets. Once they demolished the Café Kittner in Vienna because one group, called “Platten”(gang), had lost a rock n’ roll competition. Other notorious meeting places of the “Halbstarken” in Vienna were the “Café Colosseum” in Meidling, the “Espresso Putz” in Märzstrasse and “Zum Sonnenaufgang” in Hernals. The media reported excessively about the “crimes” these youth gangs committed. So the Viennese police president, Joschi Holaubek, promoted the founding of youth clubs, such as the “Black Panther” in Ottakring, Wurlitzergasse (named after the Viennese word for juke-box), to get the youth off the streets of the city and in 1958 he announced that the teenagers were now all enjoying themselves in clubs and at private parties, which was wishful thinking.

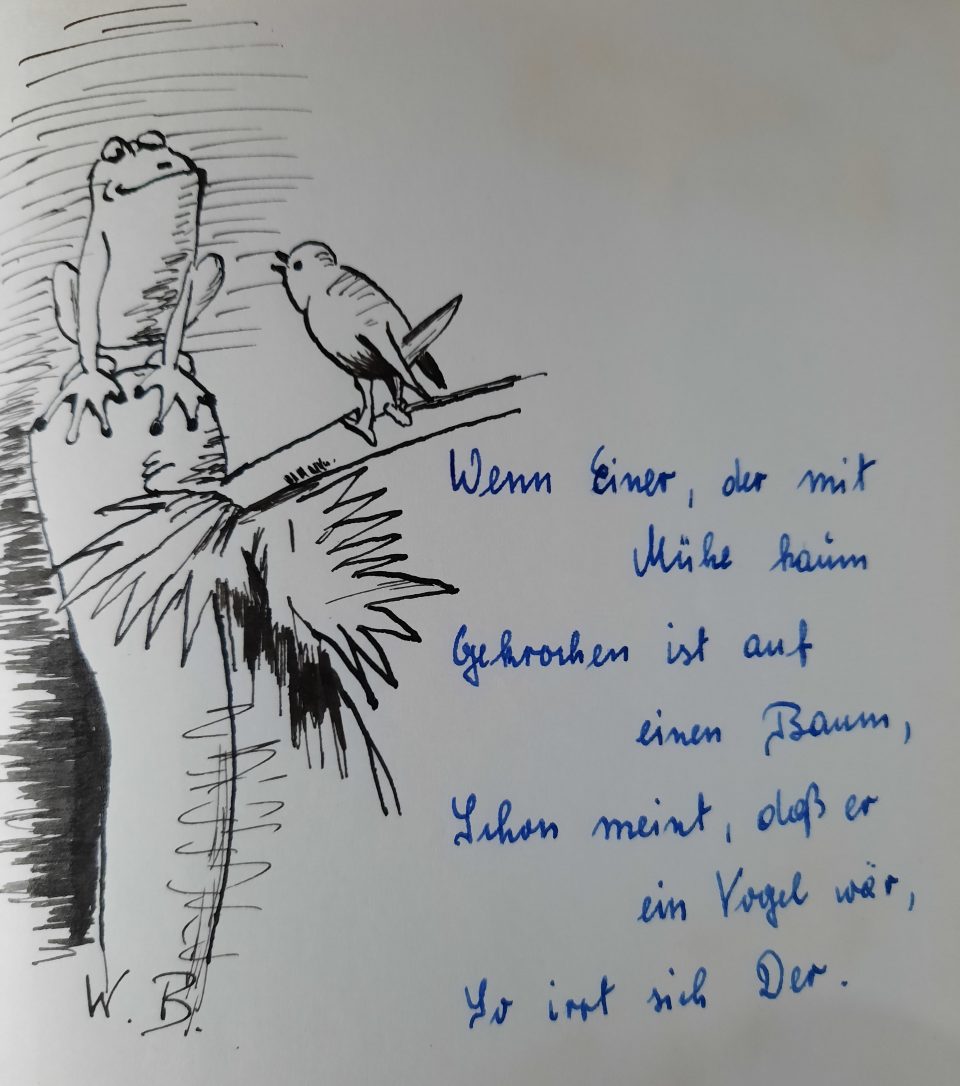

Another aspect of American culture that outraged the conservative educated bourgeoisie in Austria was the comic. They even went so far as to pass a law in 1956 which was to “fight immoral publications to protect the young against moral hazard”. This law forbid any publication where the illustrations outweighed the text, which was clearly aimed at comics. This would have affected such popular German publications as “Struwelpeter” (Shockheaded Peter) and “Wilhelm Busch”, too. So Walt Disney productions asked for the expert opinion of the constitutional lawyer Christian Broda, who later was minister of justice under Bruno Kreisky and responsible for ground-breaking judicial reforms. Consequently the law was considered unconstitutional because “it had to be proved first that Donald Duck misled the youth to violence and lechery; otherwise a ban of the distribution of comics was not justifiable”.

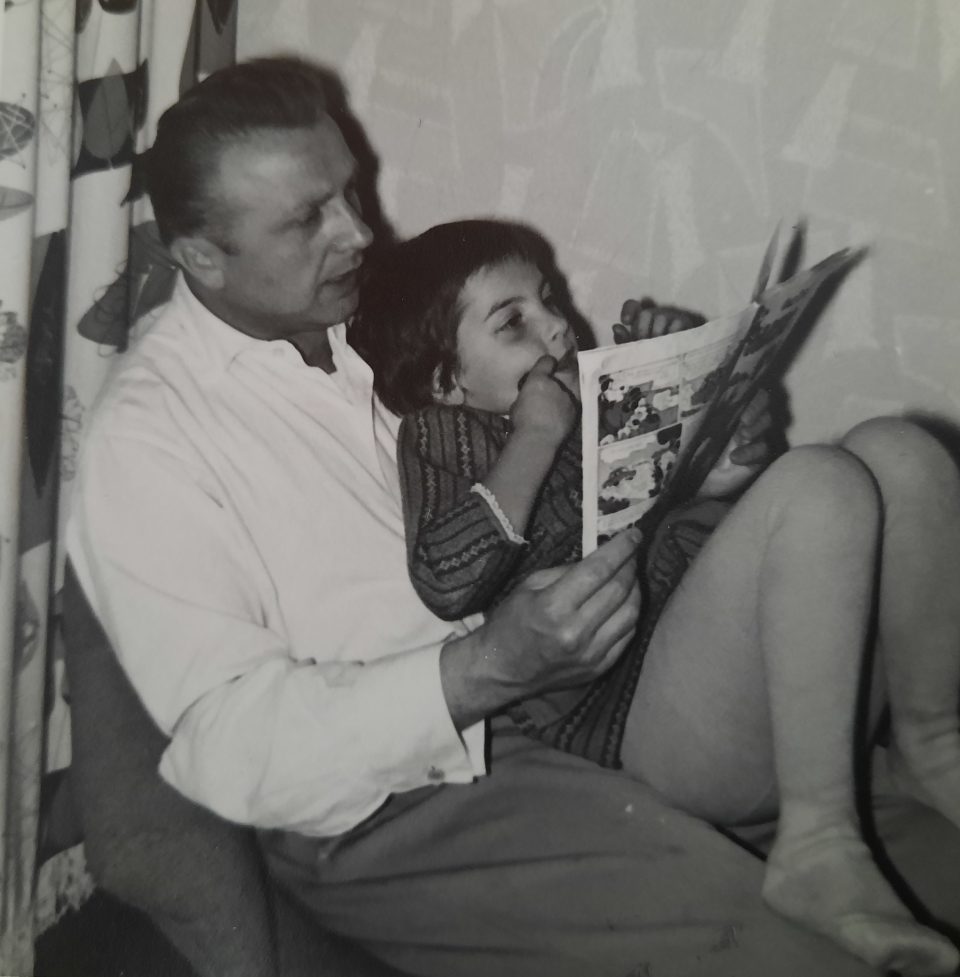

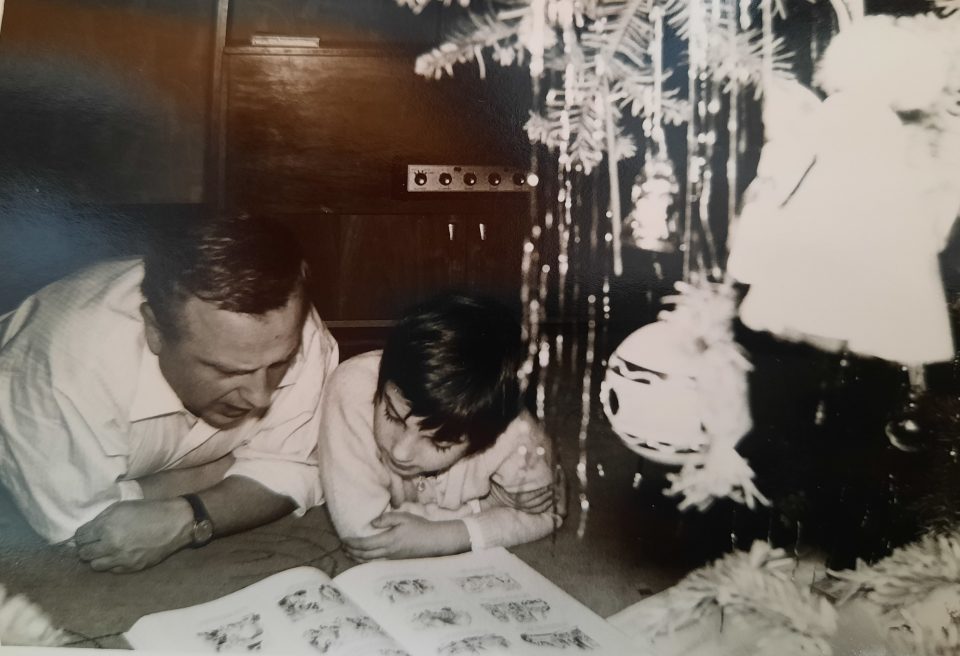

Werner’s drawing of a “Wilhelm Busch” scene for my friendship book (left) and Werner reading a Walt Disney comic to me

Werner reading “Wilhelm Busch” to me