A VIENNESE FEMALE REFUGEE CROSSING THE ATLANTIC OCEAN FROM BRITAIN TO AMERICA ON AN ALLIED CONVOY DURING WORLD WAR II

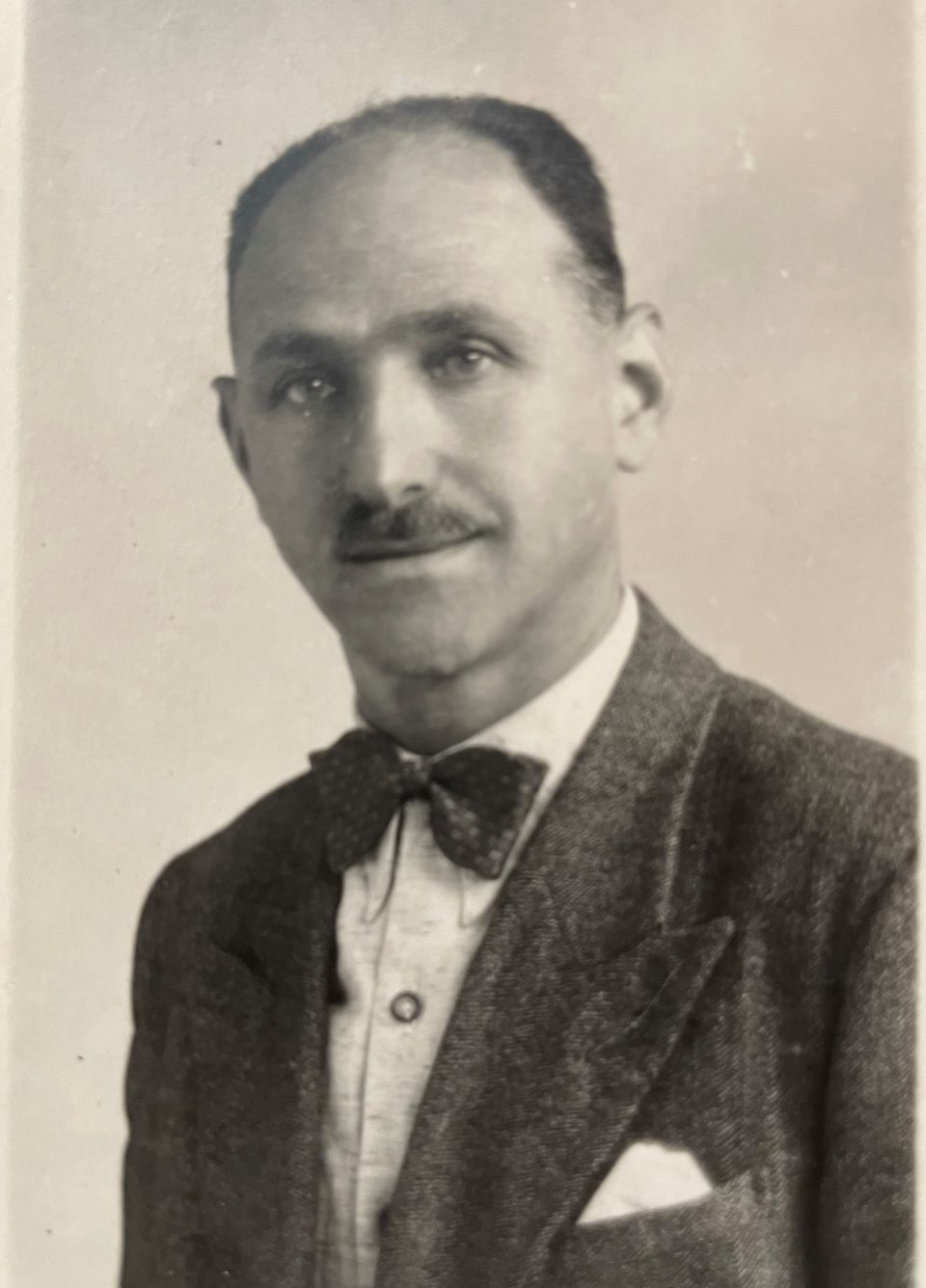

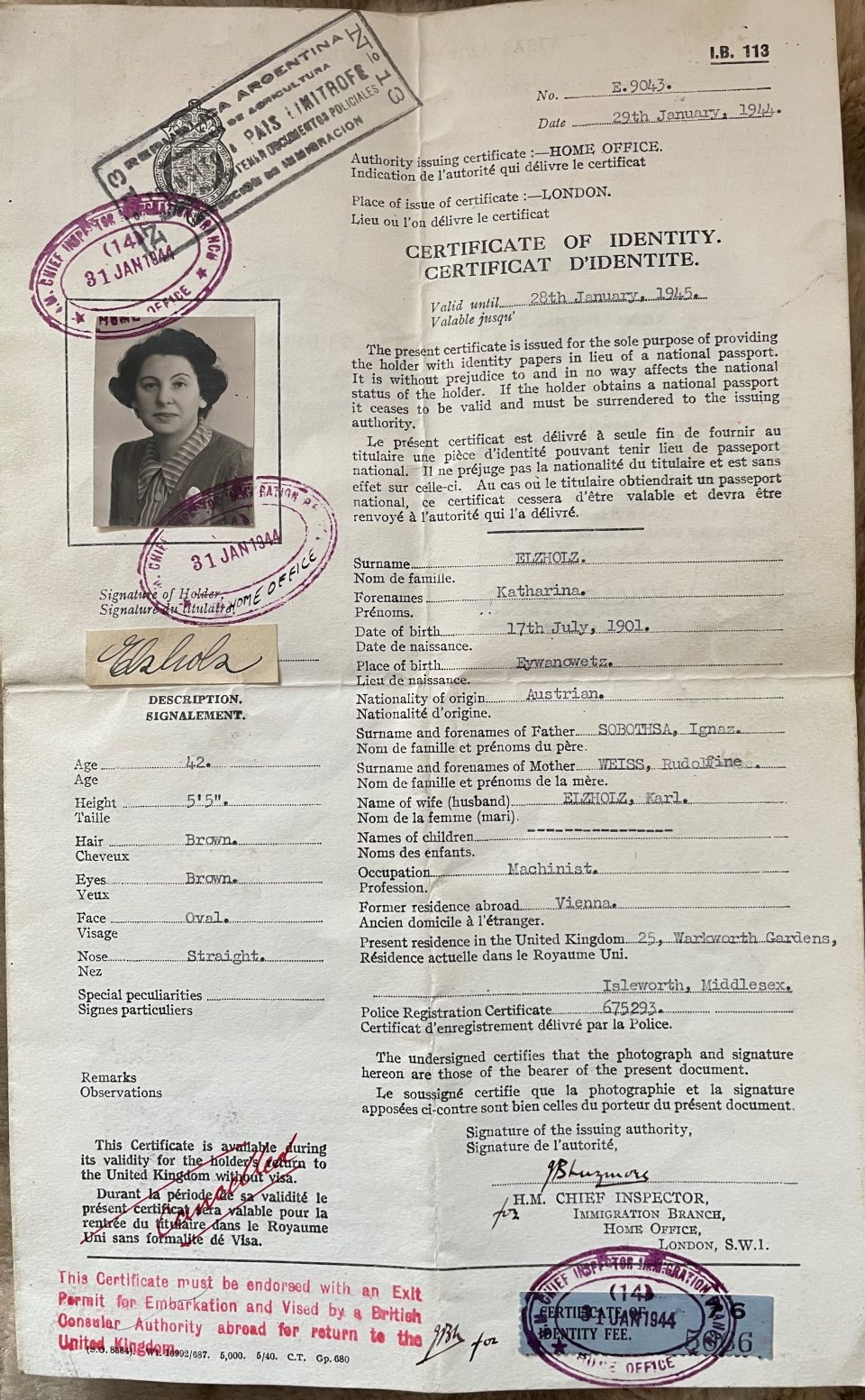

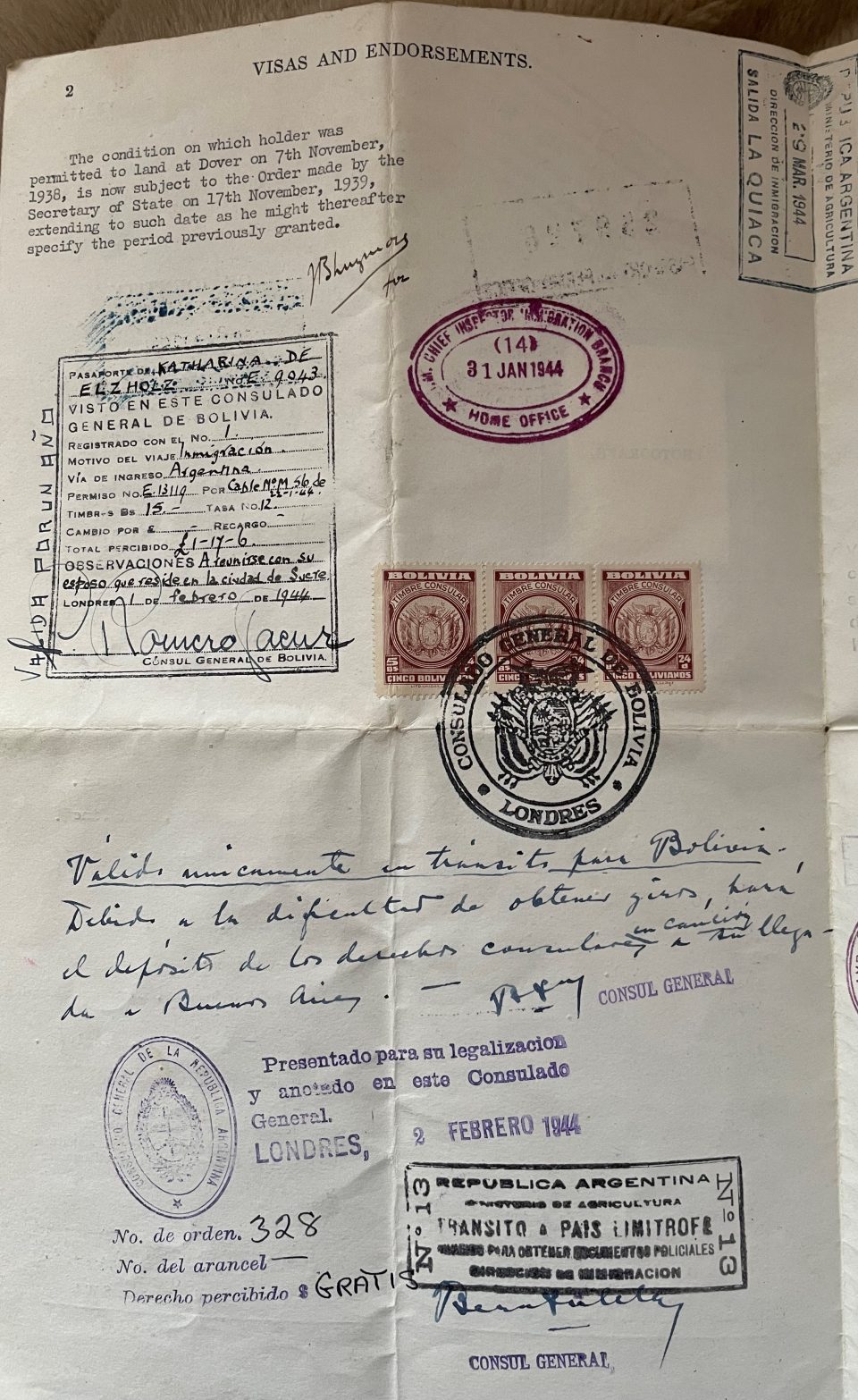

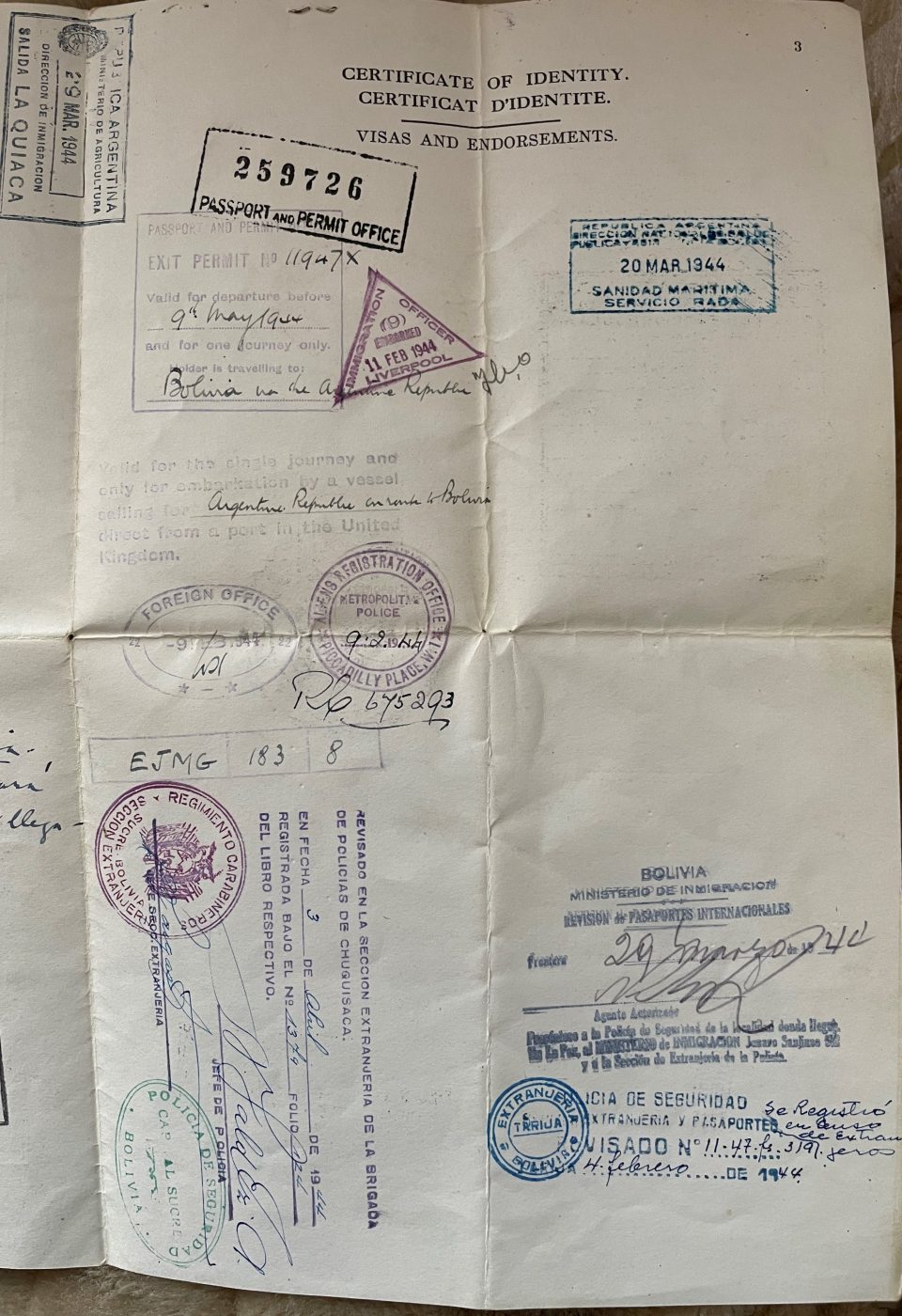

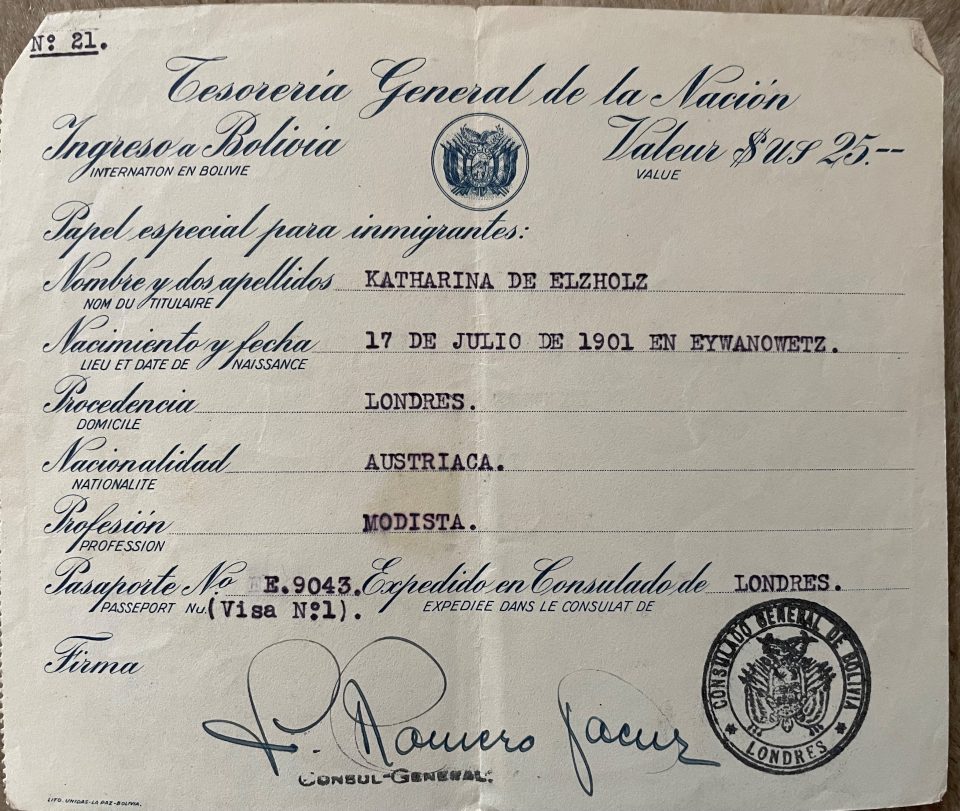

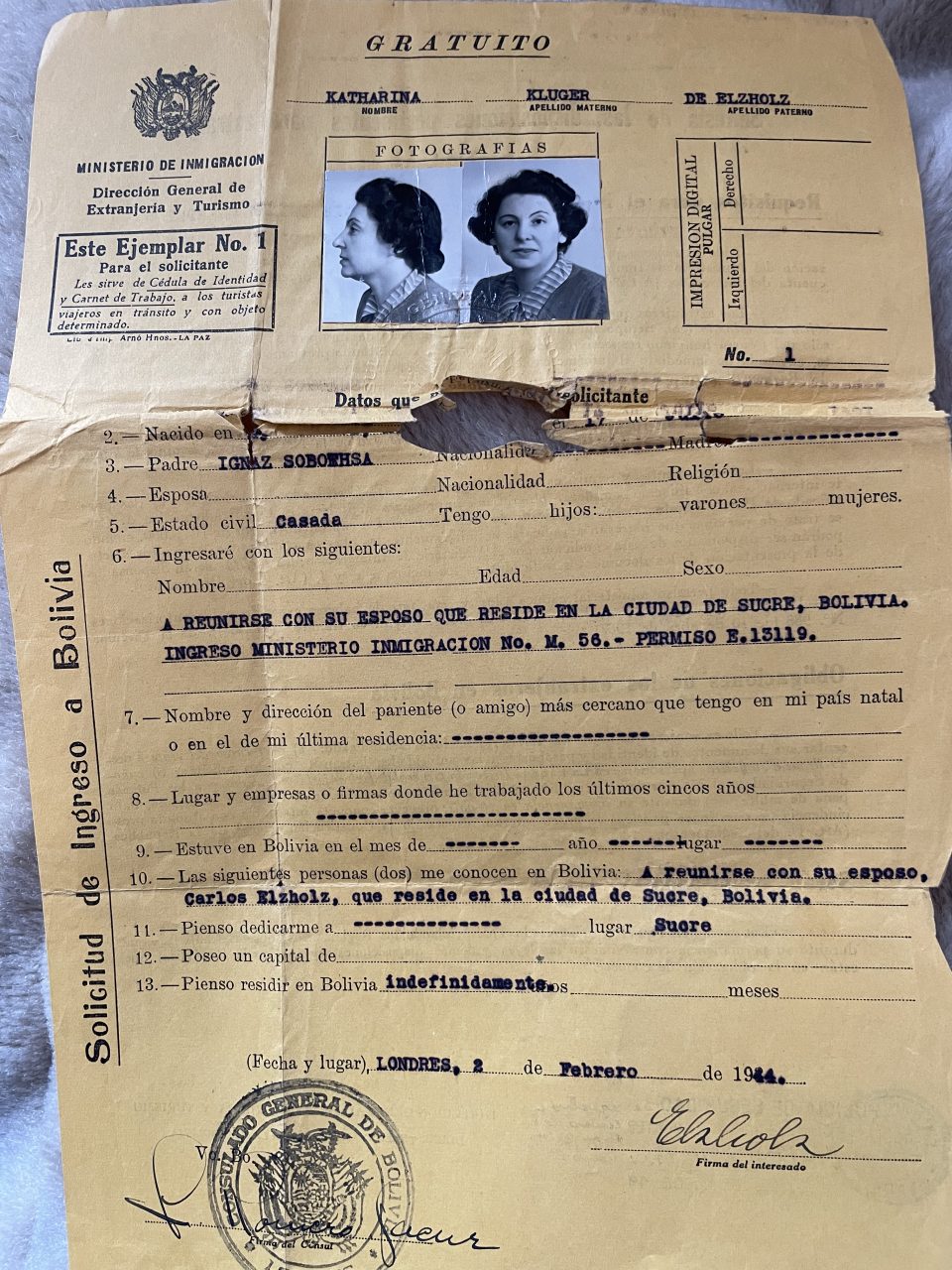

My great-aunt, Katharina (Käthe) Elzholz, a very tough and courageous woman, crossed the Atlantic alone on an Allied convoy during World War II in the winter of 1944 to join her husband, Karl Elzholz, in Bolivia. Käthe, a bank clerk, had fled the Nazi persecution of Jewish citizens in Vienna in November 1938 taking on a job as a cook in an English household. She married Karl Elzholz, who had fled to Bolivia and whom she knew in Vienna, on 11 August 1943 in London in a long-distance civil wedding ceremony. Due to intense fighting on the Atlantic, the “Battle of the Atlantic”, she could not risk the dangerous voyage to Bolivia until 14 February 1944. At her arrival on 2 April 1944, she was given this commemorative brooch by her husband (see above).

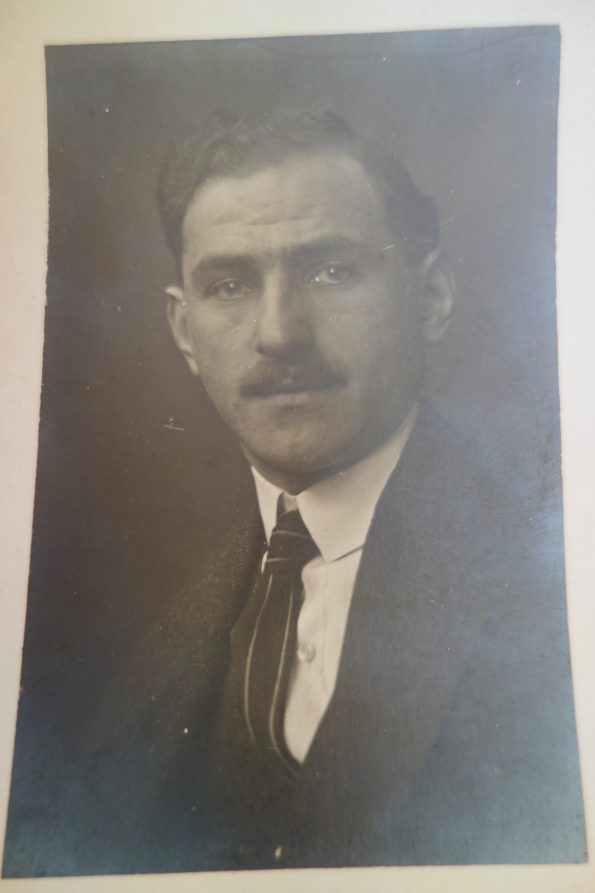

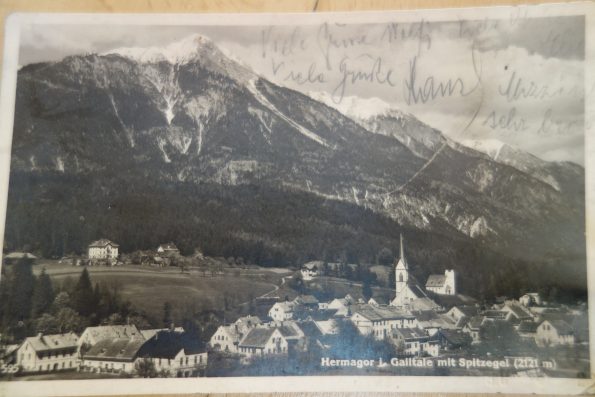

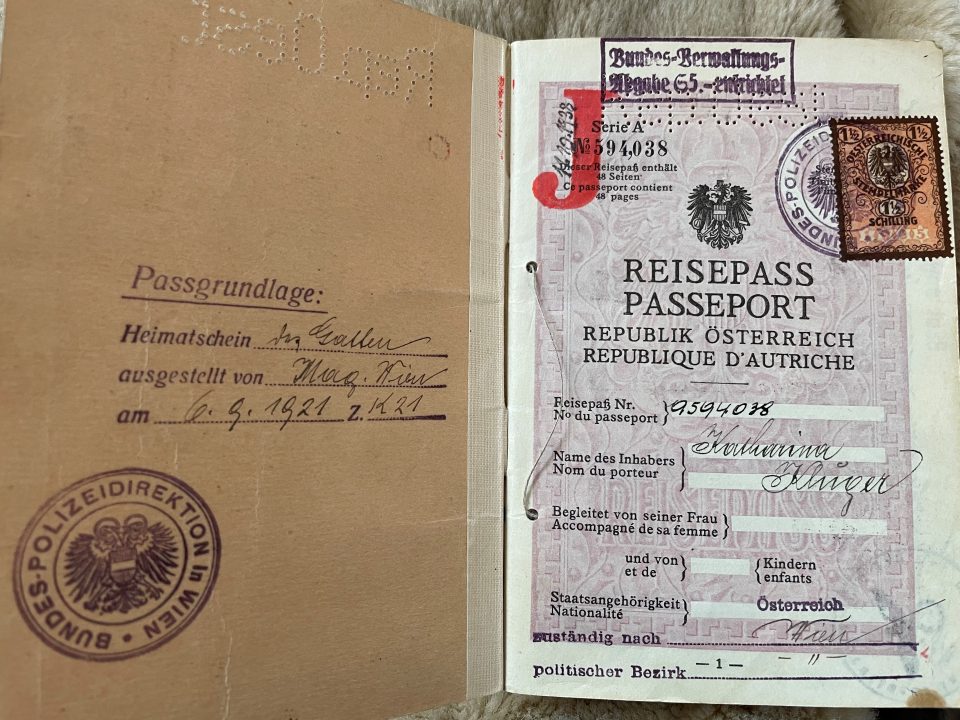

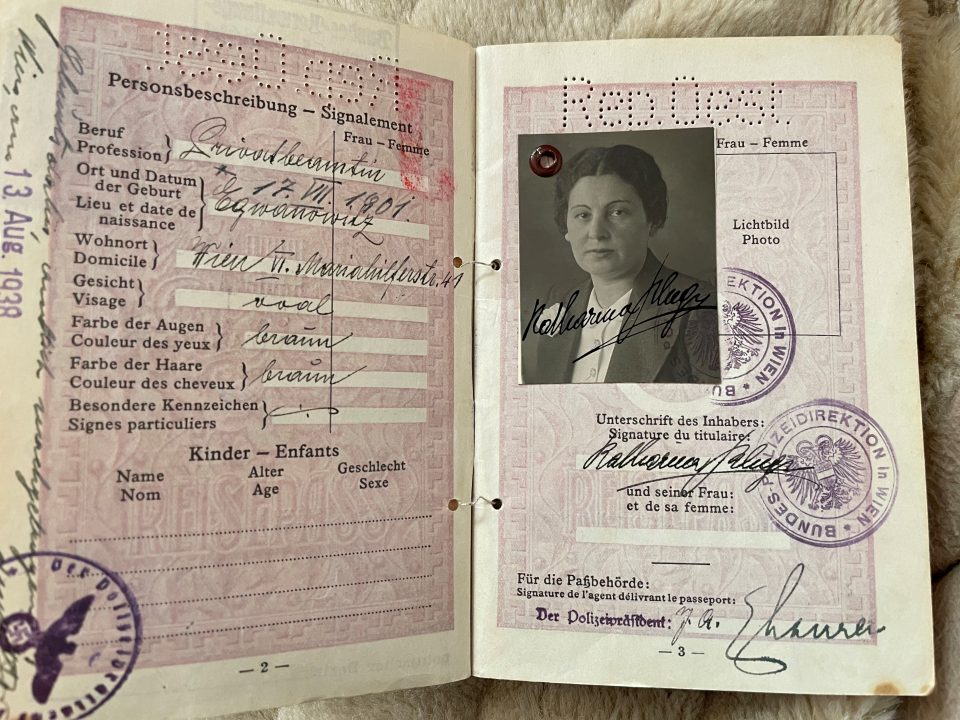

Käthe, born on 17 July 1901, was a widow after the early death of her husband Poldl Kluger. She had been forced to quit her job as a bank clerk due to the Nazi race laws introduced in Austria in March 1938 and had to work as a fashion model to earn her livelihood. She clearly saw the threat the racist NS ideology posed for those in Austria who were born Jews – she herself was not devout – and tried to flee the country as soon as possible and help her family members to do the same. She was the eldest of the four “Sobotka sisters”: Lola (my grandmother), Agi and Marianne (Mitzi). As the eldest sister Käthe felt responsible for their well-being as well as for that of their parents, Ignaz and Rudolfine (Ritschi) Sobotka. She took cooking lessons, learned English and eventually managed to get a work permit and a visa as a domestic servant in England (see article “Maid Servants in England”). Unfortunately, Käthe was not able to get her elderly parents out of Vienna and regrettably also her sister Mitzi together with her husband Karl could not procure visa for Ignaz and Ritschi to join them in Bolivia. They ended up in the concentration camp “KZ Theresienstadt”, but miraculously survived (see article: “The KZ Theresienstadt”).

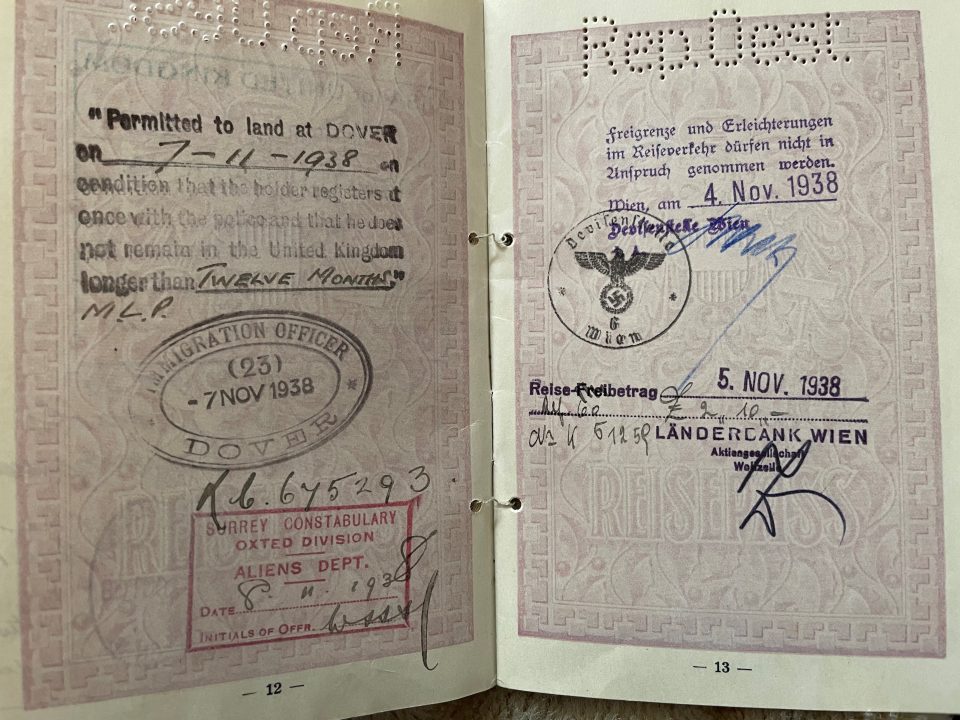

All Käthe’s small savings were taken by the Nazis because Austrian Jews had to pay the “Reichsfluchtsteuer” (a tax levied on Jews who managed to leave the country) and they were not allowed to take any valuables abroad. Käthe was allowed to bring 2.10 pounds as “travel allowance” to England and she was denied any exemption limit and travel relief, as visible in her passport.

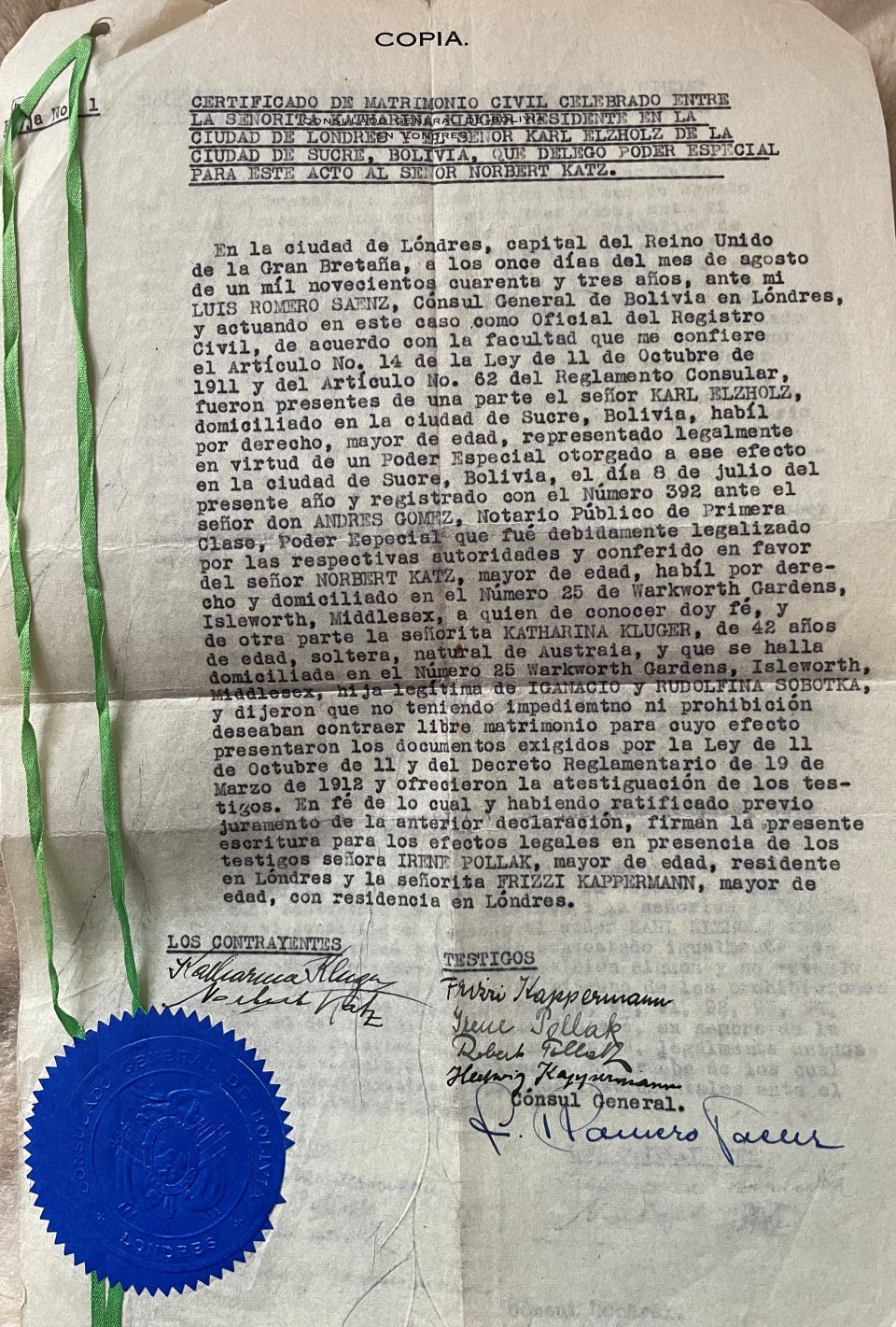

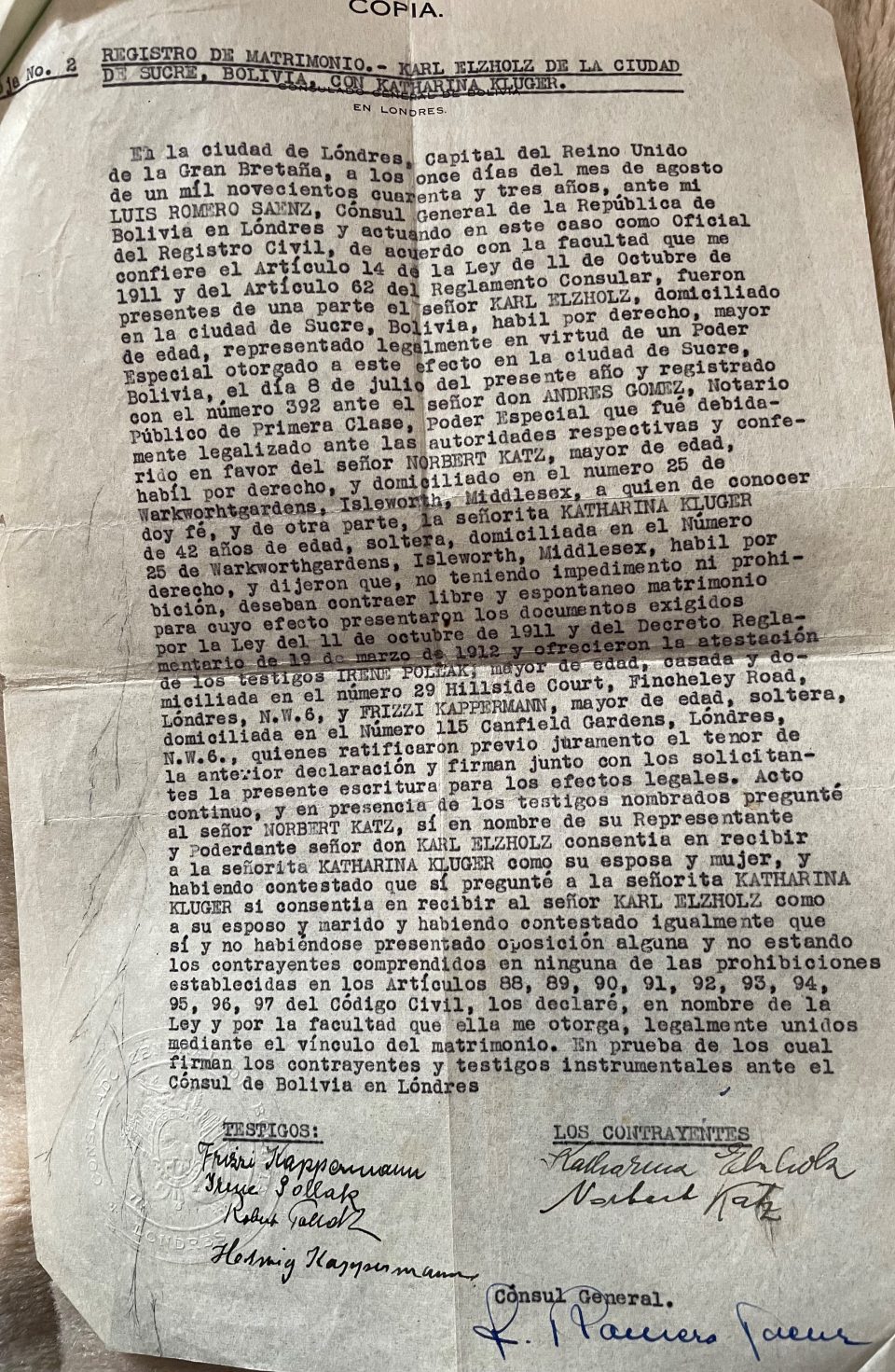

From England Käthe managed to get a work permit and a visa for her younger sister Agi Katz to work as a maid in the same household and to have Agi’s two-year-old twins, Susi and Josi, brought to England on a “Kindertransport” (see article “Kindertransports from Vienna to England”) to join their parents. My grandmother Lola was at that time considered “safe” in Vienna as she was married to non-Jewish Toni Kainz, my grandfather. Käthe’s youngest sister Mitzi fled with her husband, Karl Elzholz, to Bolivia in January 1939 (see article: “Viennese in Exile in Bolivia”.) Karl was nearly 20 years older than Mitzi. After their arrival in Bolivia Mitzi fell in love with a young German refugee, Bill (Wilhelm) Stern, and wanted to marry him. The couple decided to divorce and while Mitzi married Bill, Karl asked Käthe, his former wife’s elder sister, to marry him. They had known each other in Vienna as in-laws and were closer in age to each other. Karl was 11 years older than Käthe, so when they finally married on 11 August 1943, Käthe was 42 and living in England, 25 Warkworth Gardens, Isleworth, Middlesex, and Karl was 53 and living in Sucre, Bolivia, running a small shirt manufacturing business together with Mitzi and Bill.

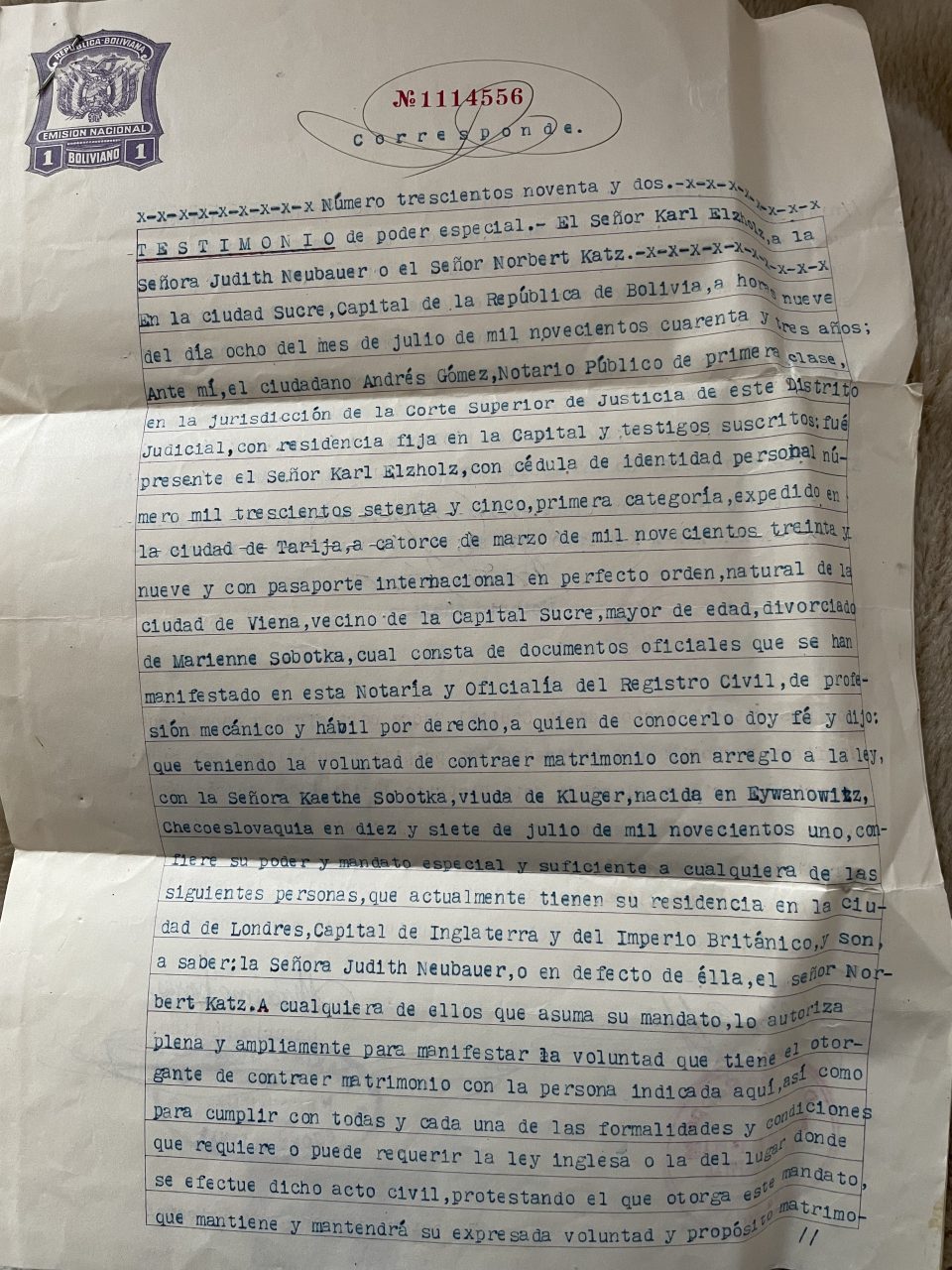

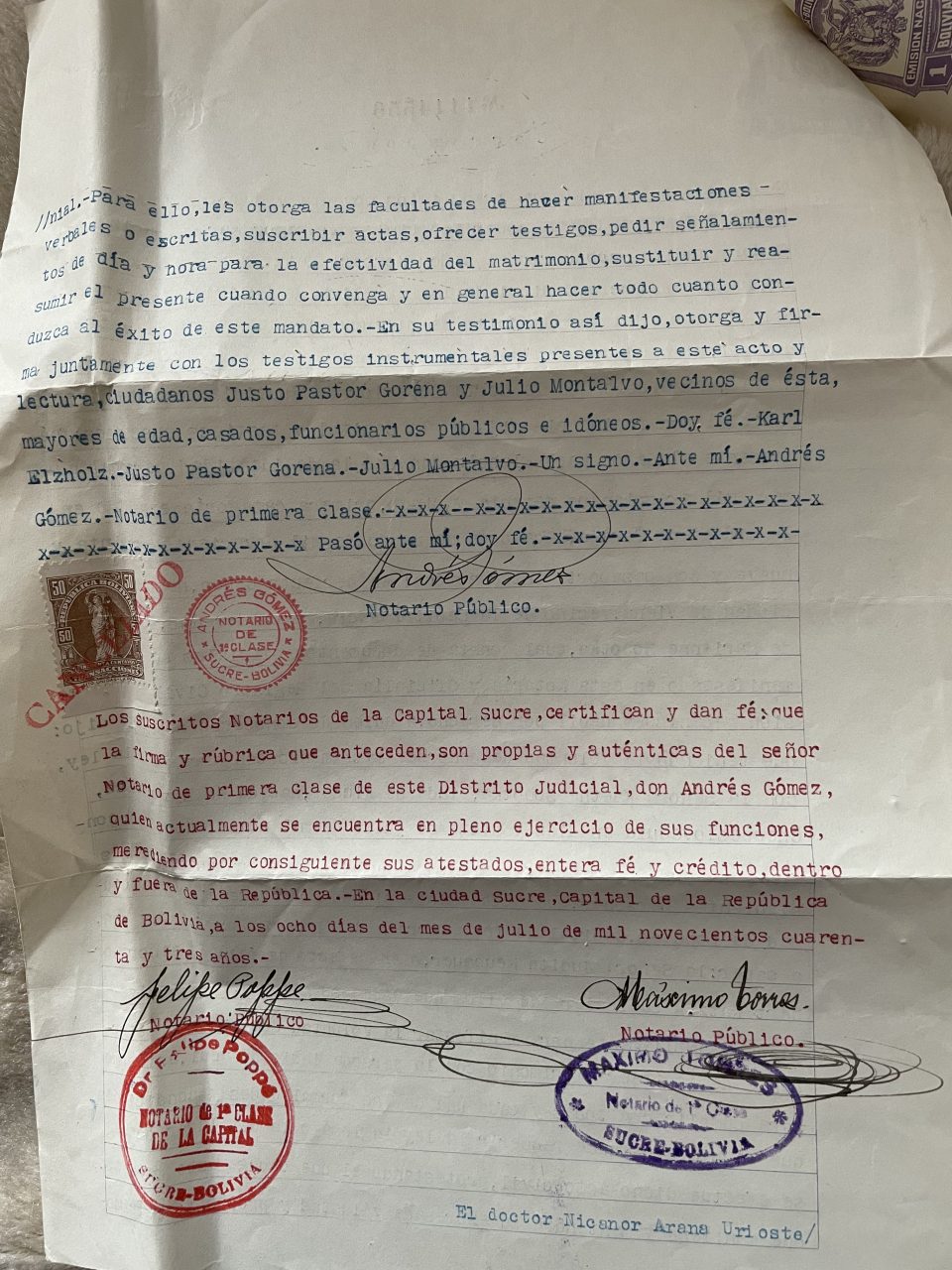

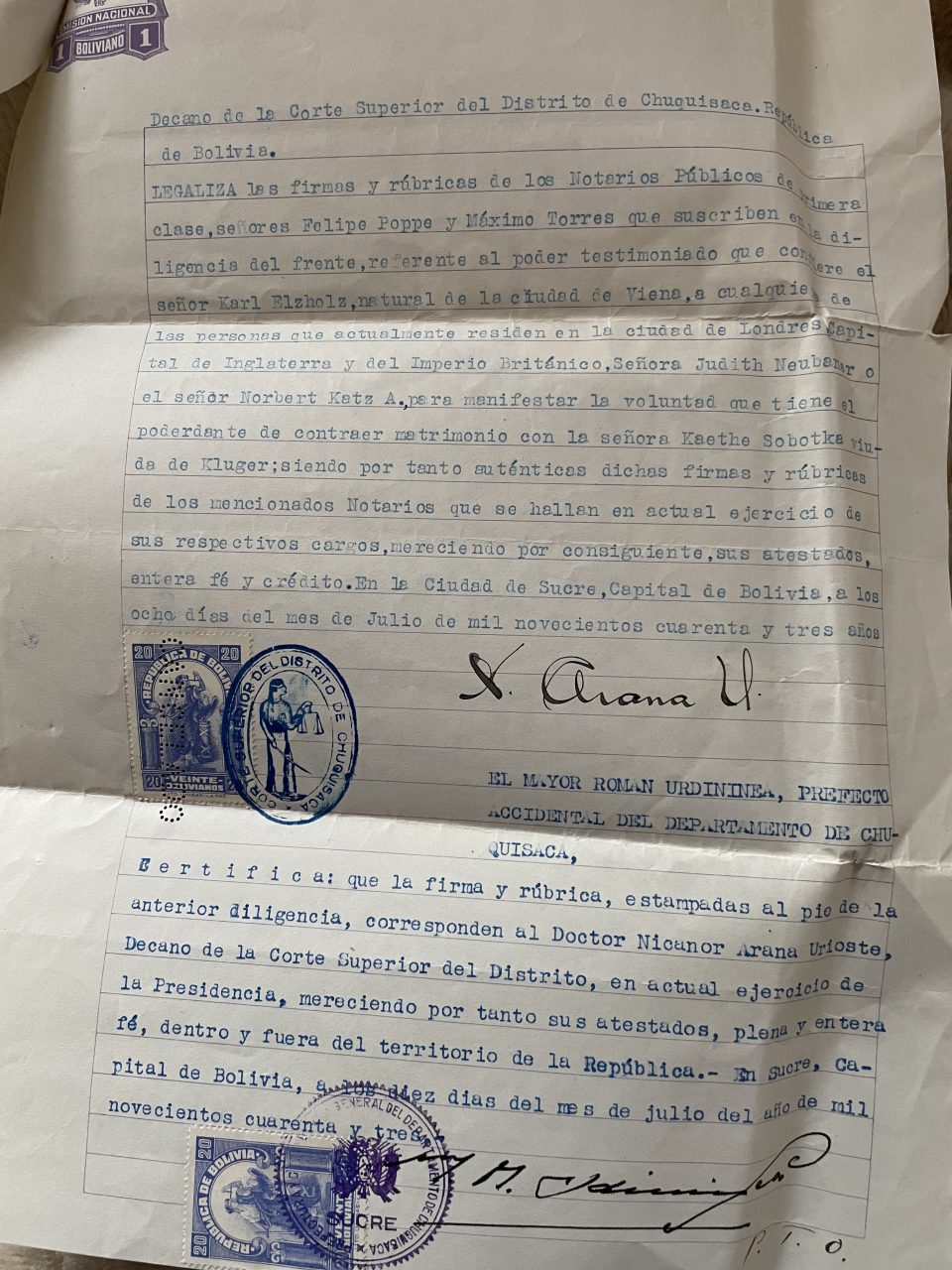

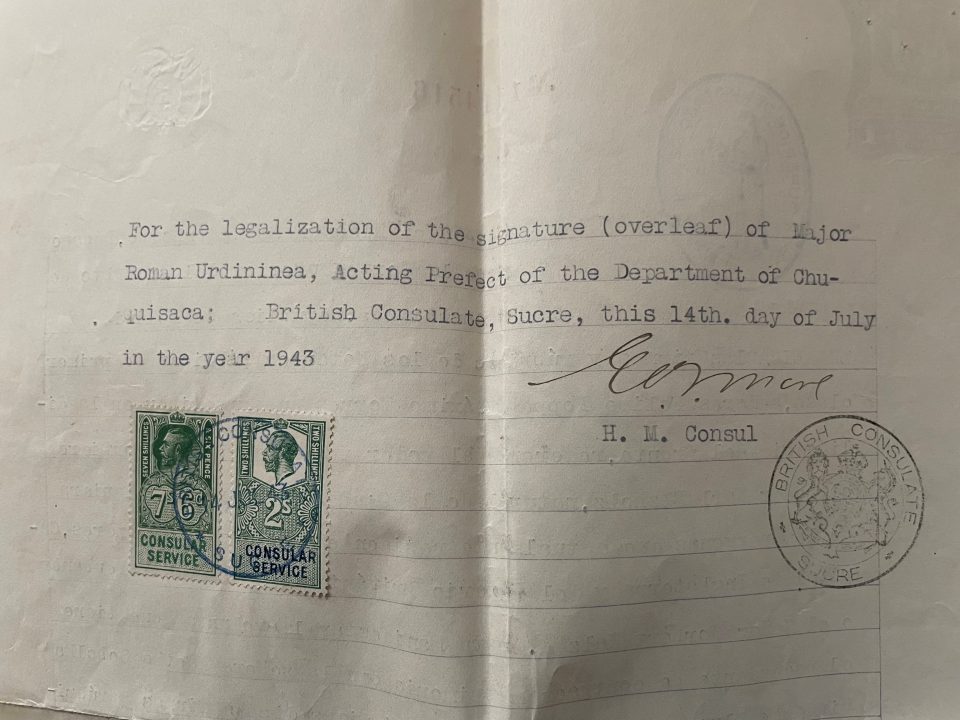

Below a copy of their marriage certificate can be seen: It was issued by the Bolivian ambassador in London. Karl Elzholz was represented in London by Norbert Katz, the husband of Agi and brother-in-law of Käthe and formerly also brother-in-law of Karl, when he was still married to Mitzi. So, they were all family and at that time Kathe, Agi, Norbert and the twins lived together in the flat in Isleworth. Two other refugees from Vienna, Irene Pollak and Fritzi Kappermann and their husbands, Austrian refugees in London, acted as witnesses to Käthe’s marriage in London.

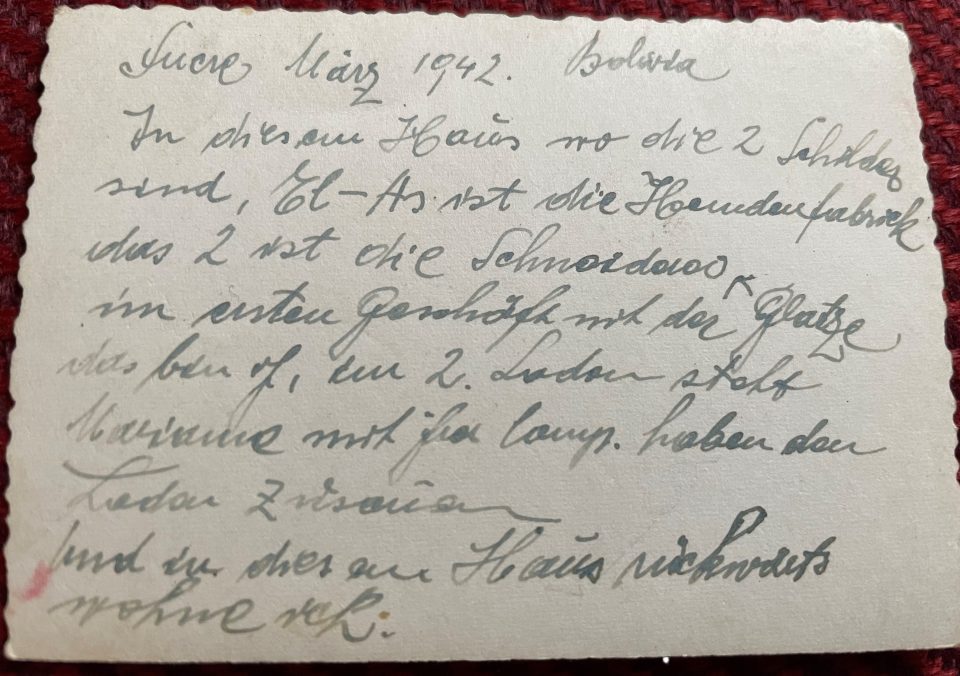

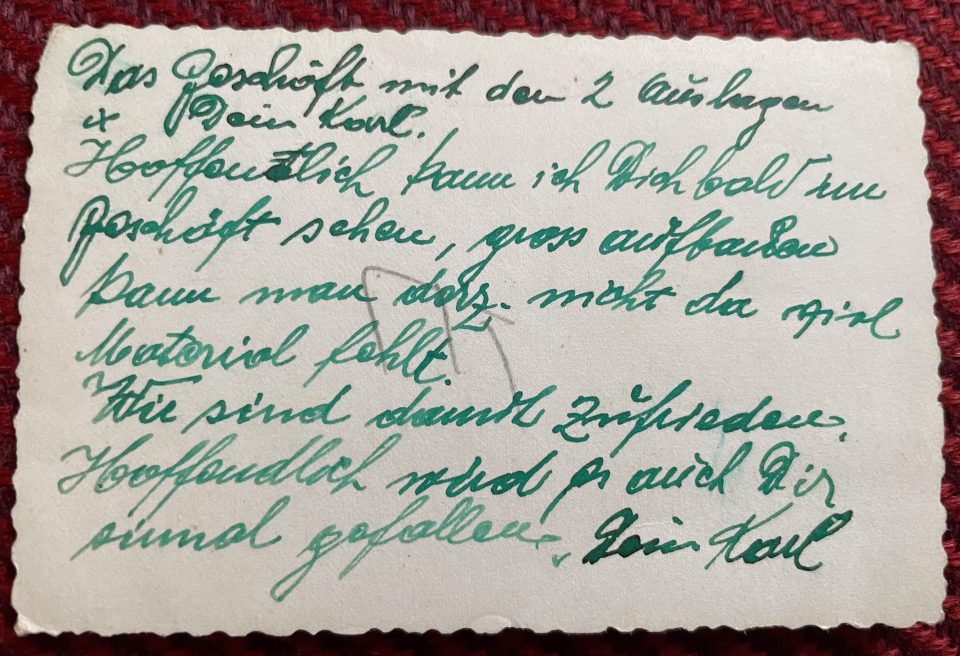

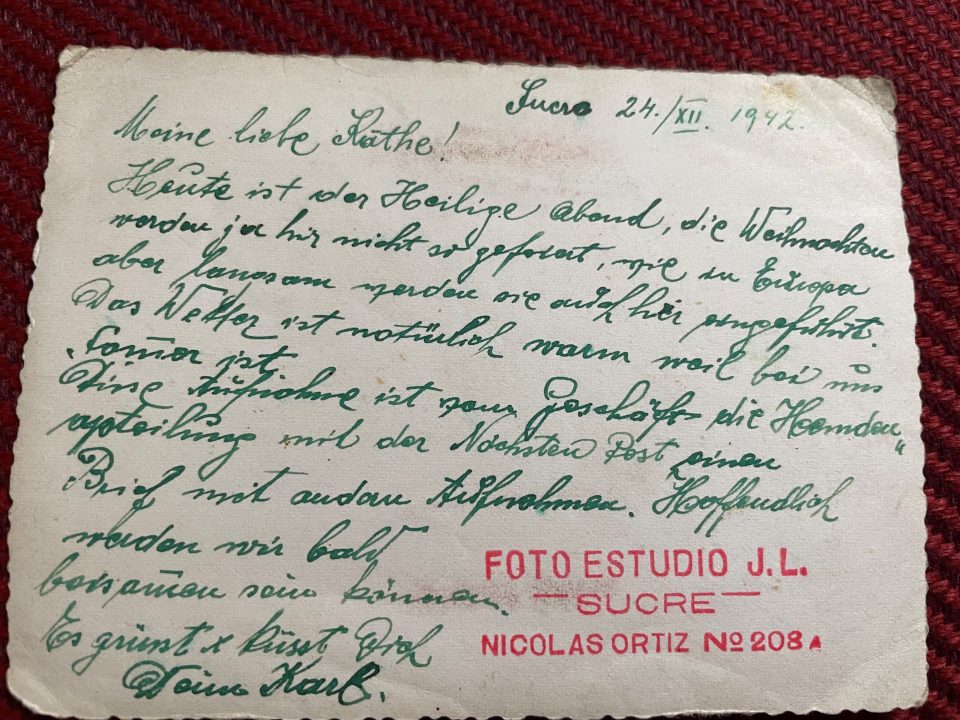

As soon as Karl had proposed to Käthe and they had decided that she would join him in Bolivia, she started to learn Spanish. For Käthe moving to Bolivia meant fleeing the war in Europe. During the war Käthe’s sister Lola, my grandmother, and her family, who had remained in Vienna, had no idea what was happening to their relatives in England and Bolivia and they were immensely surprised to hear about the divorce of Karl and Mitzi and the marriage of Karl and Käthe and Mitzi and Bill after the war. It can be assumed that Karl and Käthe both suffered from the loneliness and isolation typical of refugees in a foreign country, especially as they both lived in the same household with relatives who had their own families: Käthe with her sister Agi’s family and Karl with his former wife Mitzi and her new partner Bill. Although they were no longer young, they seemed to have yearned for a partner with whom they got on well. Käthe and Karl had been planning their marriage since 1942, which is documented by some photos Karl sent her to England from Bolivia. At the back of the photos Karl described where he lived, what Sucre and the shop they ran there looked like:

Käthe had endured the “Blitz”, the heavy German bombardment of London and its surroundings from September 1940 until May 1941, and the imminent threat of a Nazi invasion, which if successful, would have meant deportation to NS concentration camps and near certain death for her and her sister Agi Katz, her husband Norbert Katz, a famous Viennese footballer (see article: “Viennese Football”), and their young twins. In 1943 Käthe was waiting for an opportunity to get a place on one of the ships crossing the Atlantic Ocean in an Allied convoy to join her husband Karl in Bolivia. Yet for the time being the “Battle of the Atlantic”, which reached its peak in March 1943 with the highest losses of ships in Allied convoys due to German submarine – “U-boat”- attacks, made a crossing for her impossible and much too dangerous.

Käthe and Karl were finally reunited on 2 April 1944 after Käthe had undergone a long journey of 48 days from England by boat to Argentina and then on to Sucre in Bolivia.

The problem for Käthe was to get permission to purchase a place on an Allied convoy crossing the Atlantic Ocean amid World War II. Convoys, groups of merchant ships and liners sailing under the protection of an armed escort, had been organised by the British since the Napoleonic wars, but became crucial in the First World War, when the Germans waged “unrestricted” submarine warfare against Allied shipping routes. If the US had not come to Britain’s rescue in 1917 the German attacks would have turned out calamitous for the British. At the beginning of World War I the British Admiralty had not given due weight to the threat of the then new German maritime weapon, the submarine or “U-boat”. They regarded the convoy system as outmoded because coal-fired ships travelling together in large numbers would form a prominent target for the enemy. Furthermore, the military authorities were reluctant to use warships defensively as convoy escorts, but rather use them in open battle confronting the enemy. What’s more, the British shipowners and speculative investors opposed the concept of leading their ships through the war zone under the protection of the Royal Navy. They preferred that their ships would be sailing independently because they were faster as no stragglers in a convoy slowed down their passage. Furthermore, no logjams were created in the respective harbours of arrival, which was unavoidable if thirty or more ships arrived simultaneously at a destination. Above all, the shipowners and speculators profited as handsomely when their ships were sunk by the enemy as when their cargoes reached their destinations safely. They not only benefitted from huge insurance pay-outs in case of the loss of a vessel, but at the same time from the growing demand for ships to replace the losses. It is no exaggeration to say that the more ships were sunk by the Germans, the richer the British investors became. For all these reasons, the British were slow to react to the growing threat of an ever-larger German U-boat fleet. Yet the Germans no longer abided by the international “Prize Rules”, which stated that no merchant vessel could be sunk by a submarine until it had been searched and its crew provided with a place of safety. Following the unilateral repudiation of the “Prize Rules” by the Germans, the number of Allied sinkings rose sharply. The deployment of US warships on escort duty in 1917 transformed the course of World War I at sea. The US saved Britain from being starved into surrender and proved the importance of the convoy system in protecting the Allied lifeline across the Atlantic from U-boat attacks, which the British Admiralty had resisted for so long.

During the interwar years, Britain lobbied unsuccessfully for an outlawing of submarines; they only managed to get international support for a reform of the “Prize Rules”; a quite ambiguously formulated treaty, the “London Naval Treaty” of 1930. In 1936 more than 30 nations added their signatures to the “Second Naval Treaty”, including Germany. Again, the British Admiralty was convinced that the Germans’ unrestricted submarine warfare during World War I had proved so disastrous for them that they would not make the same mistake again. Royal Naval officers neglected to analyse data that showed that escorted convoys supported by aircraft had saved the nation in 1917 from collapse. The Royal Navy was proud of its warships and cruisers and did not want to “waste” them in a mundane task of escorting merchant ships – it was a far too defensive concept for them. The sinking of the “Athenia”, a passenger liner, within hours of Britain’s declaration of war in September 1939 shattered the British Admiralty’s concept. The British Prime Minister Churchill as First Sea Lord was informed on 4 September that the Germans had sixty U-boats and that a hundred more would be in operation by early 1940. On 6 September the Admiralty made the formal decision to re-introduce the convoy system, but the Royal Navy was alarmingly short of escort vessels and those available were mostly unsuitable in size and type and their crews were untrained. Air support for the convoys by the RAF (Royal Air Force) was virtually inexistant. The limited supply of fighters and bombers was not to be used for such defensive tasks as safeguarding British maritime supply lines. But Hitler’s “Third Reich” was far from ready to confront the US on the Atlantic Ocean, too, which is documented by Hitler’s anger about the sinking of the “Athenia” and the Germans’ breach of the “London Naval Treaty” of 1936. Hitler had a continental war in mind; he wanted to subjugate Europe and then to invade Russia, which would require a close cooperation of the German army and the air force. The German navy would have to take third place. So, both Germany and Britain were ill-prepared and ill-equipped for the “Battle of the Atlantic”. Yet in November 1939 unrestricted U-boat warfare was the German commander Dönitz’ official, though still unstated, policy. Although individual merchant ships sailing alone were now attacked by German submarines, the targets that really mattered for Dönitz in terms of tonnage of freight were the convoys. Locating and destroying convoys by means of concentrated attacks of U-boats, so-called “wolf packs” of eight up to twenty U-boats, presented the opportunity for the “Third Reich” to strangle Britain’s Atlantic lifeline.

…