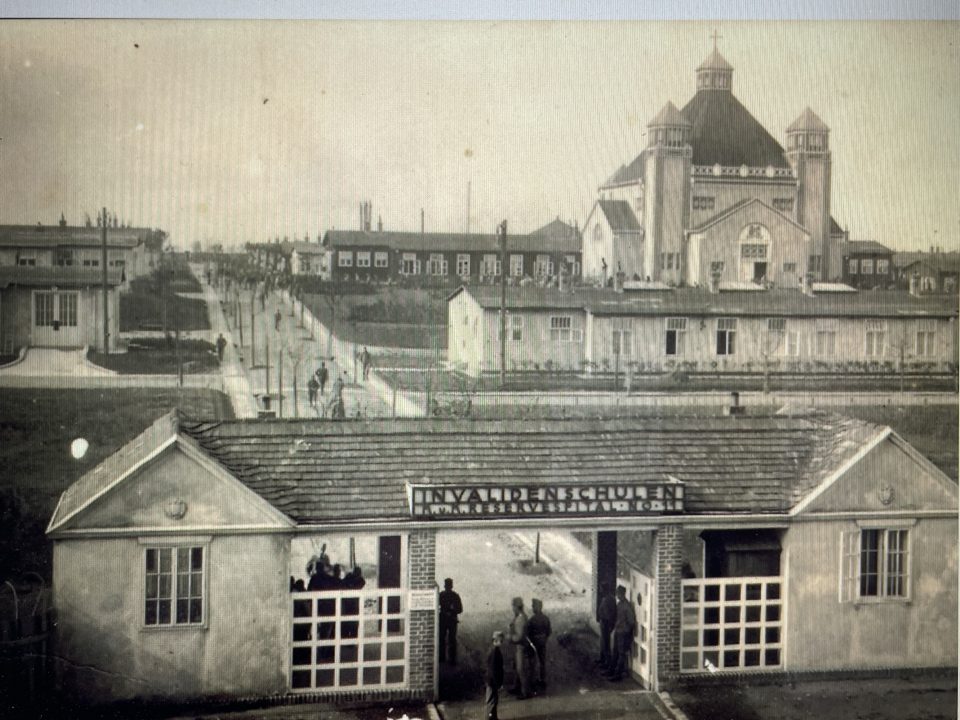

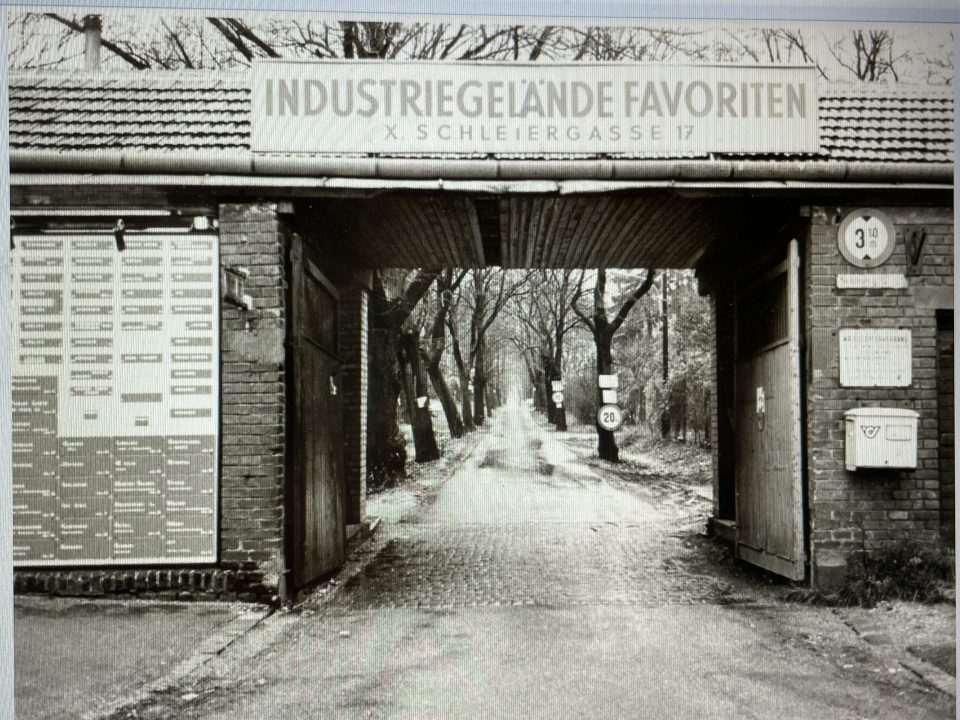

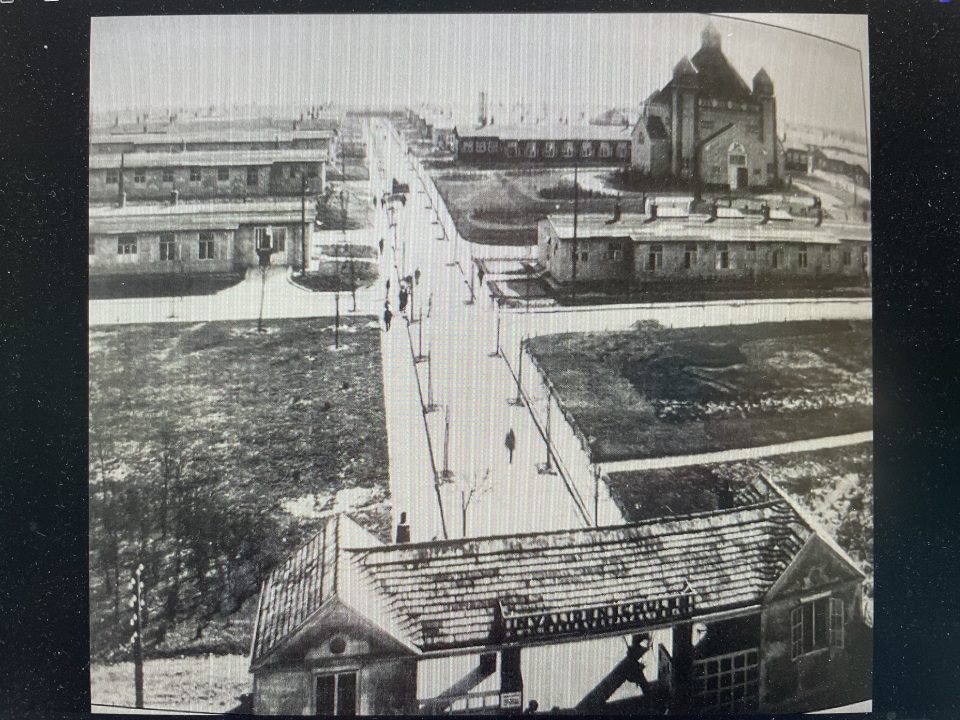

Area of the “Schleierbaracken” in the Viennese working-class district of Favoriten, Schleiergasse 17, at the beginning of the 20th century. Left: the rehabilitation and re-training centre for invalid soldiers of World War I. Right: after the end of World War I, the wooden barracks were rented to small suburban businesses as workshops and used until the 1970s

Today only few of the wooden barracks, which were used as workshops have remained; a part of the area was turned into a small park. The street signs with the address Schleiergasse 17, 10th district Favoriten, are still there:

My mother, Herta Tautz, was a master dressmaker and I remember the trips with her to the outskirts of Vienna, to the “Schleierbaracken”, to buy fabrics. There was an abundance of different fabrics on offer in the factory outlets at very low prices, which were affordable for the less well-off like us. The sales outlets for textiles were always crowded, because professional tailors as well as amateur seamstresses bought everything they needed for making clothes there. I always enjoyed the outings to the wooden barracks in the outskirts, which usually took half a day, because that meant my mother would sew some new dress for me.

Herta, the seamstress (left), me and Herta, my mother, both of us dressed in her creations in 1963

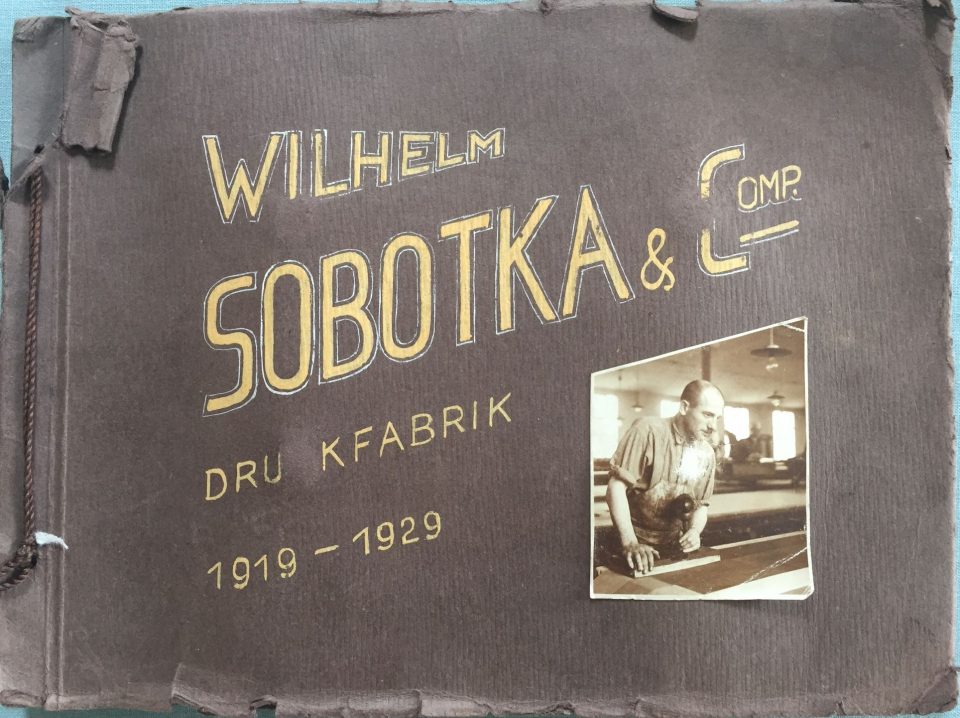

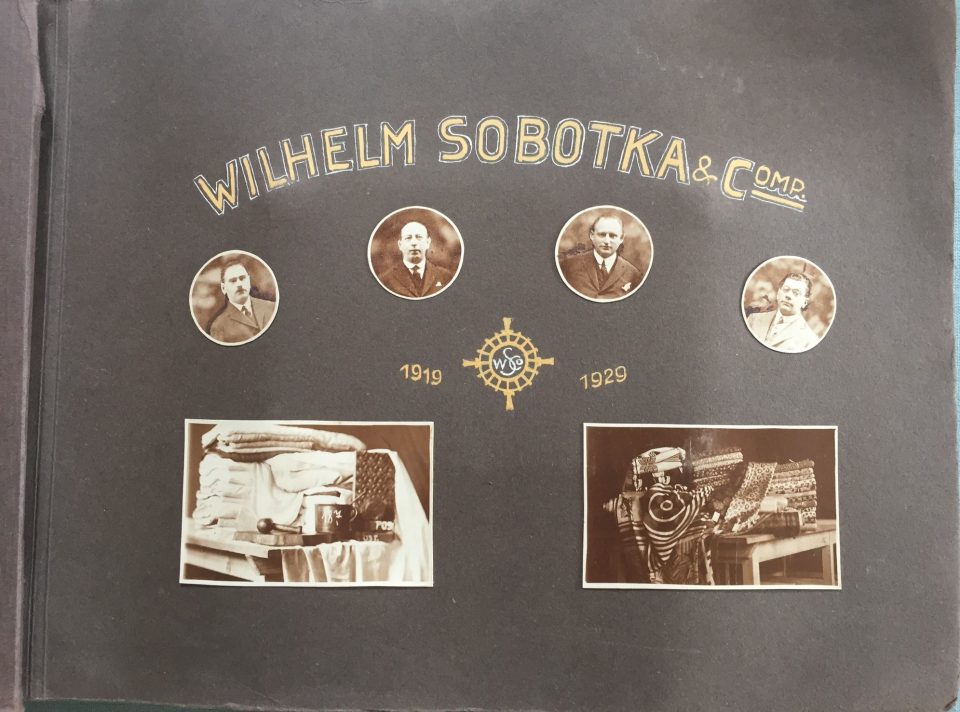

Another much more interesting personal connection to the “Schleierbaracken” were the workshops which the youngest brother of my great-grandfather, Ignaz Sobotka, Wilhelm Sobotka, had rented there in 1919 and where he printed textiles until the Nazis disowned him because of his Jewish origin and seized his business and all his possessions in 1938. He managed to flee Vienna with his wife Marta and his younger son Walter to Belgium, but was caught up by the Nazis there. They were deported to France, Camp des Milles in Drancy and from there Wilhelm and Marta were dragged to Auschwitz, where the couple was murdered on 19 August 1942 in the Nazi KZ (concentration camp). Their two sons, Hans and Walter Sobotka, survived and miraculously the photo album that celebrated the 10th anniversary of the foundation of the textile printing company was rescued, too. Hans, born in 1920 in Vienna, fled to England with the album and joined the British Army to fight the Nazis. After the end of World War II, he moved to Australia, but the landlady, where he had stayed in England had kept his photo album safe all those years and when he came to England to visit her, she handed over this album. It contains photos of the workshops in the “Schleierbaracken”, the workers, the office, and the shop in the 1st district of Vienna, Tiefer Graben. The photos of Wilhelm’s album are © Valérie Sobotka & John Stenford.

“Wilhelm Sobotka & Partners, Printing Factory 1919-1929” with a photo of a worker (left) and all four partners, Wilhelm on the right, with samples of the printed fabrics they produced in the “Schleierbaracken” (right)

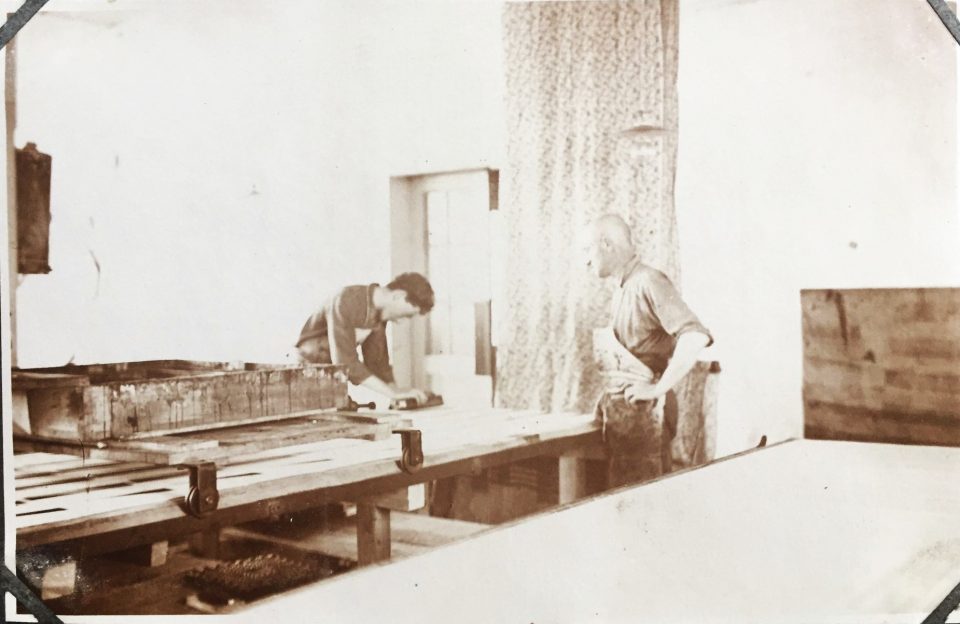

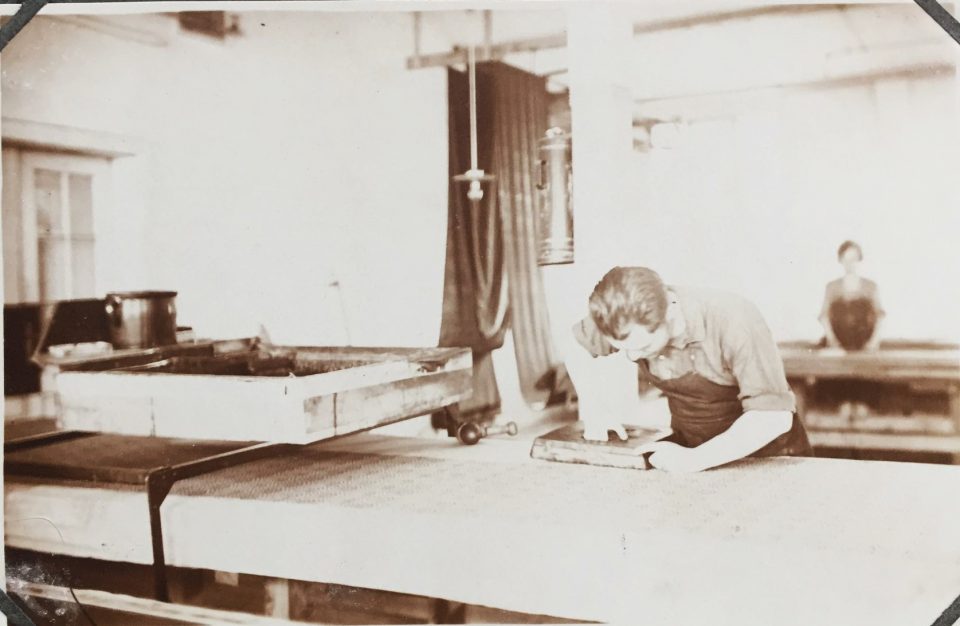

One of the company’s workshops in the “Schleierbaracken” (left) and inside a workshop a worker printing a cloth (right)

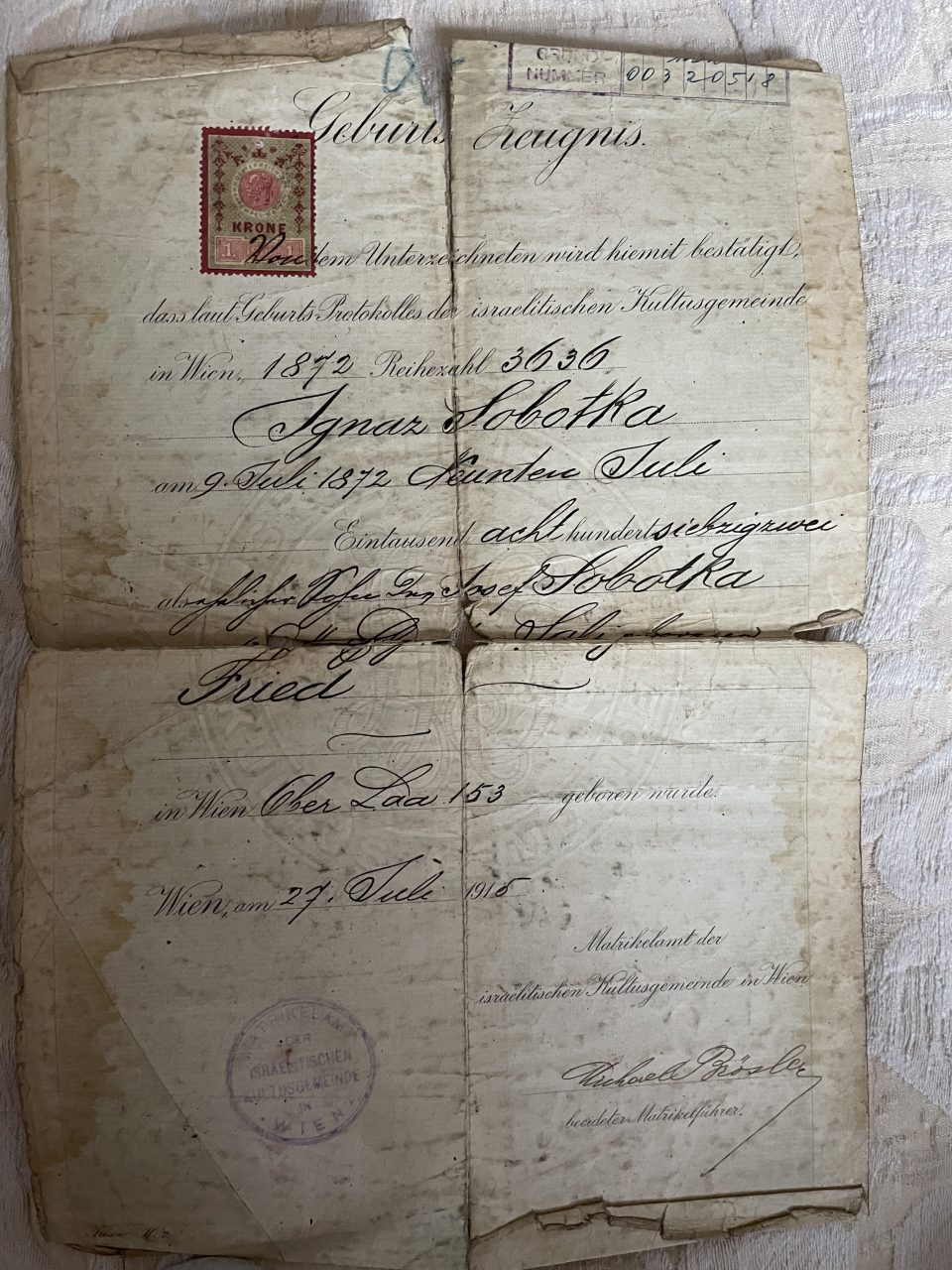

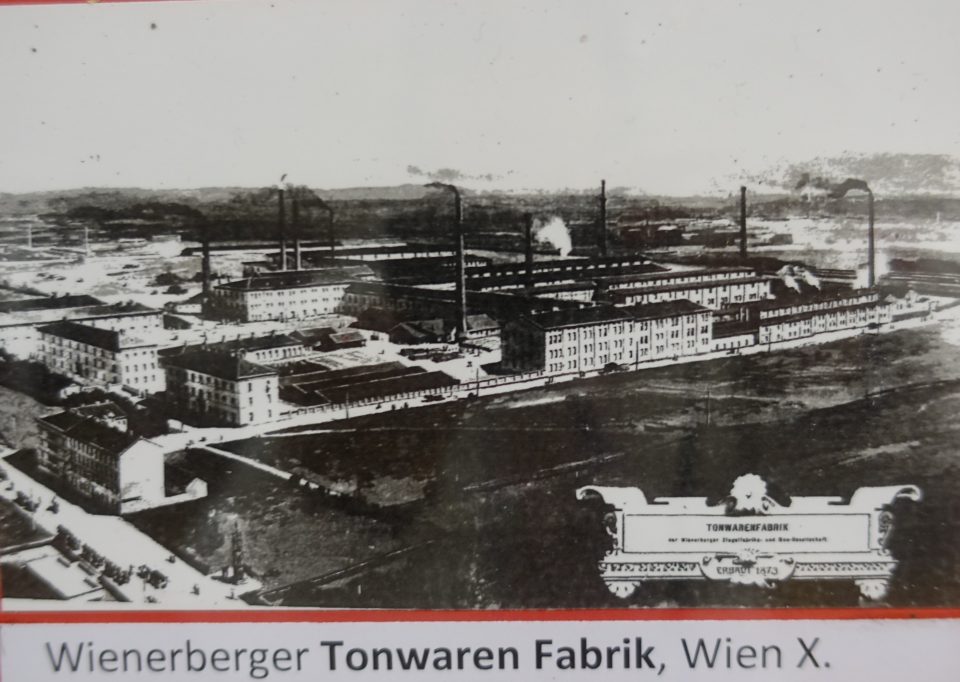

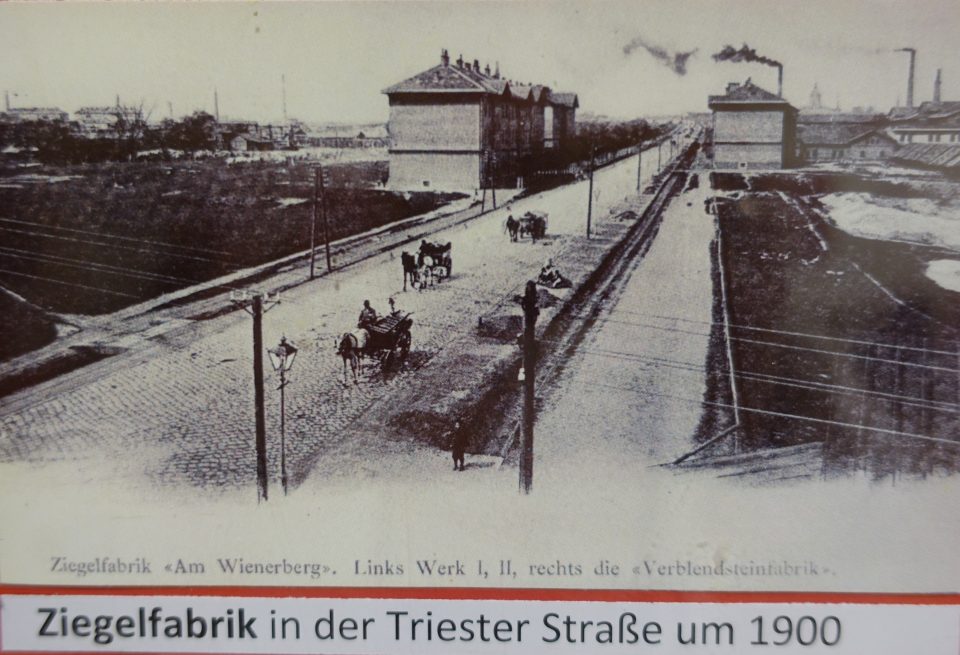

Another much more important hub of industrial history in Favoriten was the “Wienerberger” brick factory on the Wienerberg, where Josef Sobotka, the father of Ignaz and Wilhelm worked as a foreman. How did this come about? Josef Sobotka was born in Chysky in today’s Chechia, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, with a sizable Jewish minority. He married Rosalia Fried, called Sali, from Brno. The new Imperial State Treaty of 1867 allowed the Jewish minority to move freely inside the Habsburg Empire and to train for and exercise all trades, offering freedom of movement and freedom of trade to all citizens of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Josef and Sali took the chance to leave the impoverished place of Chysky with their first three children, Hermann, Julius and Amalie, called Mali, and moved to the capital city of the Empire, Vienna around 1869. Josef found work in the huge brick factory “Wienerberger”, south of Vienna in Oberlaa as a foreman. In Oberlaa their last three children Ignaz, my great-grandfather, who later ran a brewery in Kaiser Ebersdorf near Vienna, and Wilhelm, who became an entrepreneur in textile printing, and Leni, were born.

The huge brickyard was basically run by thousands of poor, often illiterate Czech menial workers who had migrated from Moravia and Bohemia to Vienna to find work. It can be assumed that Josef Sobotka, who was literate, spoke German and seemed to have had some basic education, as most male Jews living in Bohemia and Moravia, was hired in a more elevated position, namely as a foreman or crew leader at “Wienerberger’s”. This meant that he and his family enjoyed better living and working conditions than the vast majority of unskilled workers, called deprecatorily “Ziegelböhm” (Brick Bohemians) by the Viennese. They lived on site of the factory, renting one of the worker’s dwellings for families of artisans and crew leaders, “Ober Laa 153” (see birth certificate of Ignaz below), consisting of two rooms and a kitchen. It is possible that Josef had already worked for a Czech landowner in Chysky, as these landowners sometimes employed members of the Jewish minority to run small brick yards or furnaces in the countryside on the basis of their rudimentary education in reading, writing, and arithmetic.

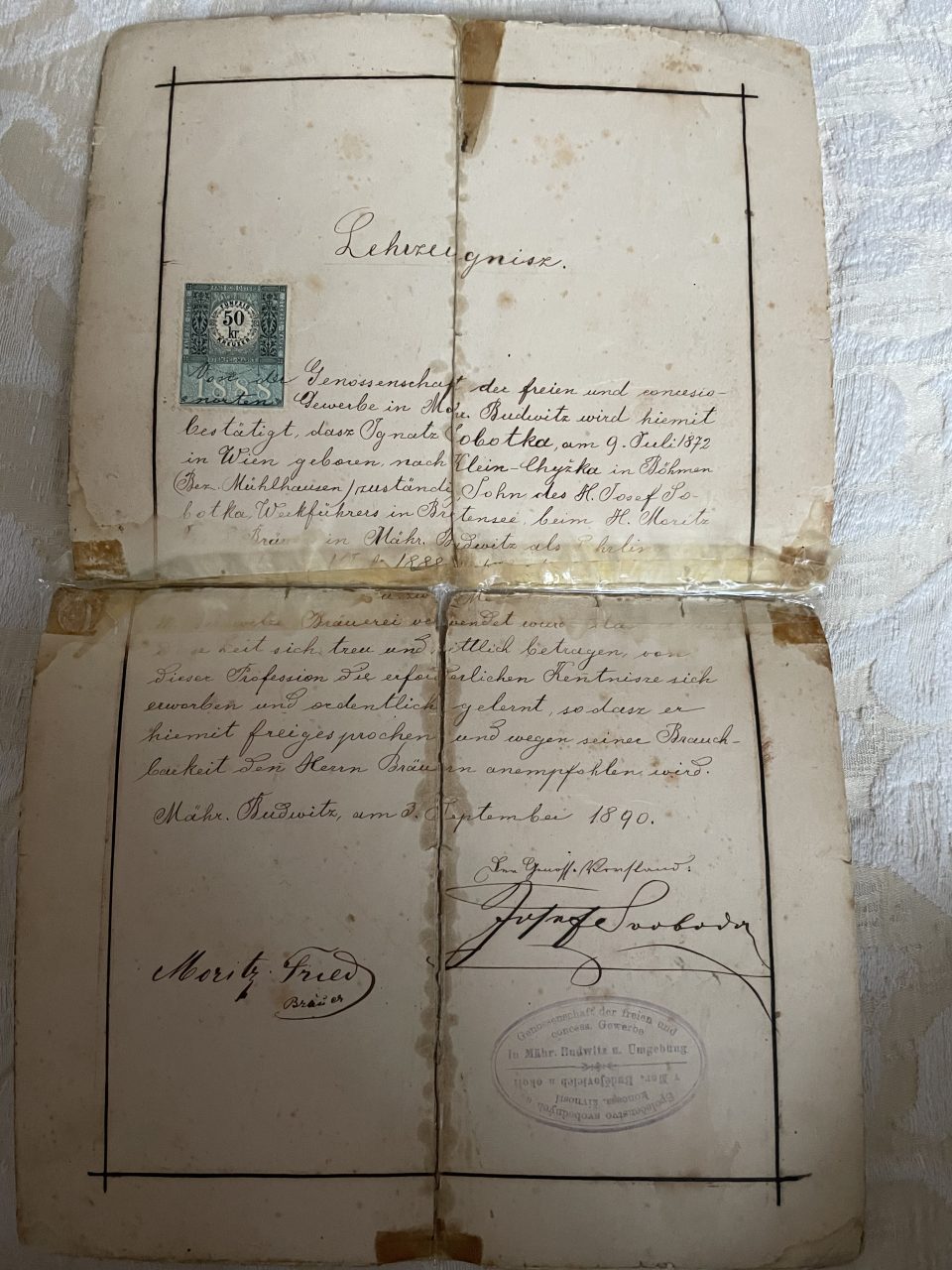

Ignaz was born in 1872 and Wilhelm, called Willi, in 1889 in Oberlaa and the family formed part of the Viennese proletariat. They renounced all connections to Jewish traditions and lived a secular life, completely merging into the indigenous Viennese milieu. Josef wanted his offsprings to fit into the Viennese society and climb the social ladder. Josef had a jolly character; he loved drinking and gambling, but he also saw to it that all his four sons learned a trade, which enabled them to become part of the Viennese middle class and escape the poverty of the proletariat. In 1890 Josef Sobotka had already been promoted to brick yard manager in the factory in Breitensee, then in the 16th district of Vienna, Ottakring, today in the 14th district (see document “Lehrzeugnis” below).

See article: http://centraleuropeaneconomicandsocialhistory.com/working-living-conditions-in-small-medium-sized-proto-industrial-iron-manufactoring-enterprises-and-their-ancillary-industries-along-the-austrian-iron-route-in-the-19th

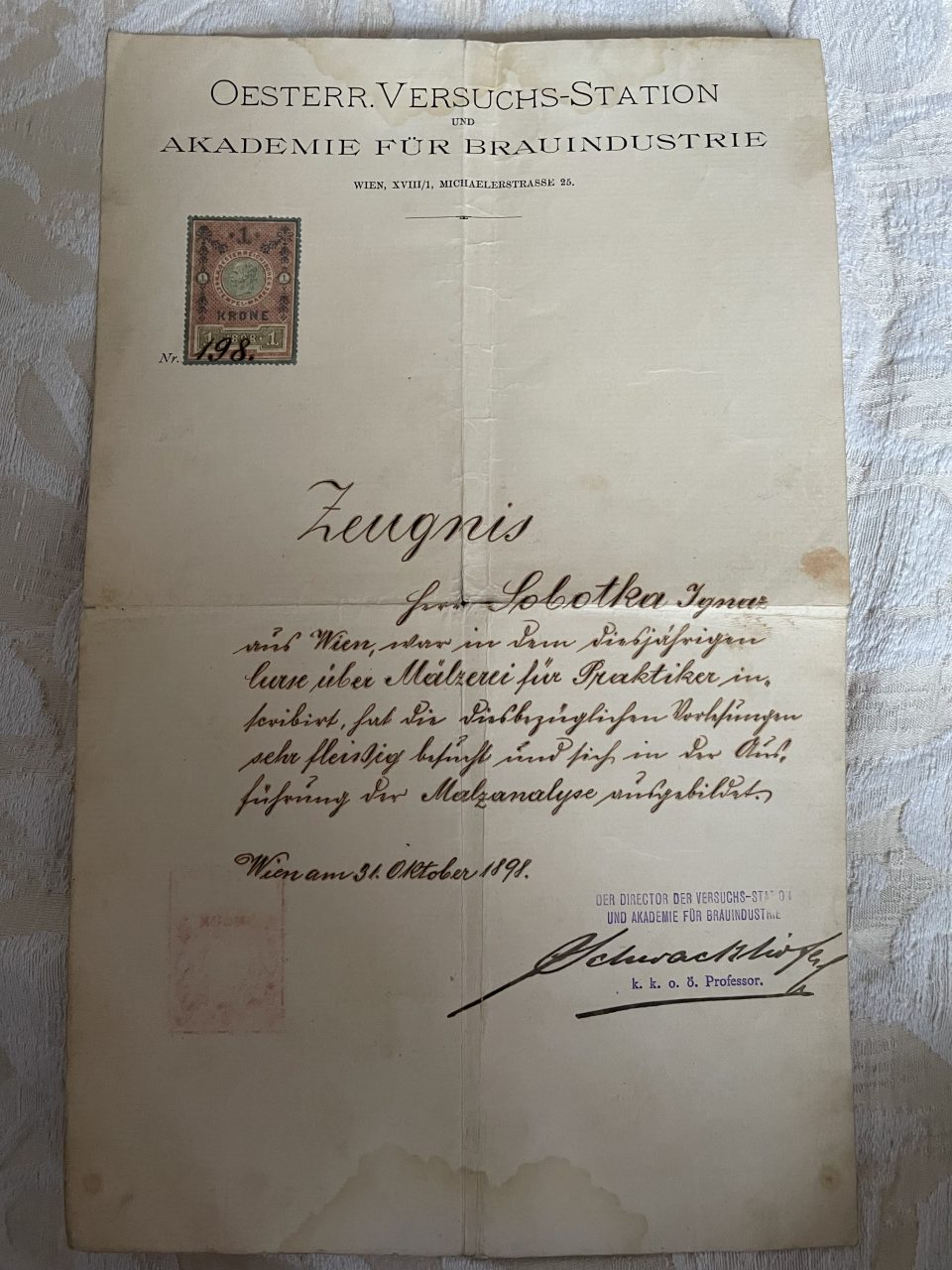

It was common for a young fellow of a guild to perfect his skills by travelling from one enterprise to the next for a few years before being permanently employed, which Ignaz did in the Czech lands, probably using family connections. There he met his future wife, Rudolfine Weiss in Eywanonwitz. The Certificate of Completion of Apprenticeship mentions that his father, Josef Sobotka, was working as a manager in the brickyard in Breitensee in the 16th district of Vienna, Ottakring.

See article: http://centraleuropeaneconomicandsocialhistory.com/the-career-as-a-beer-brewer-in-vienna-around-1900

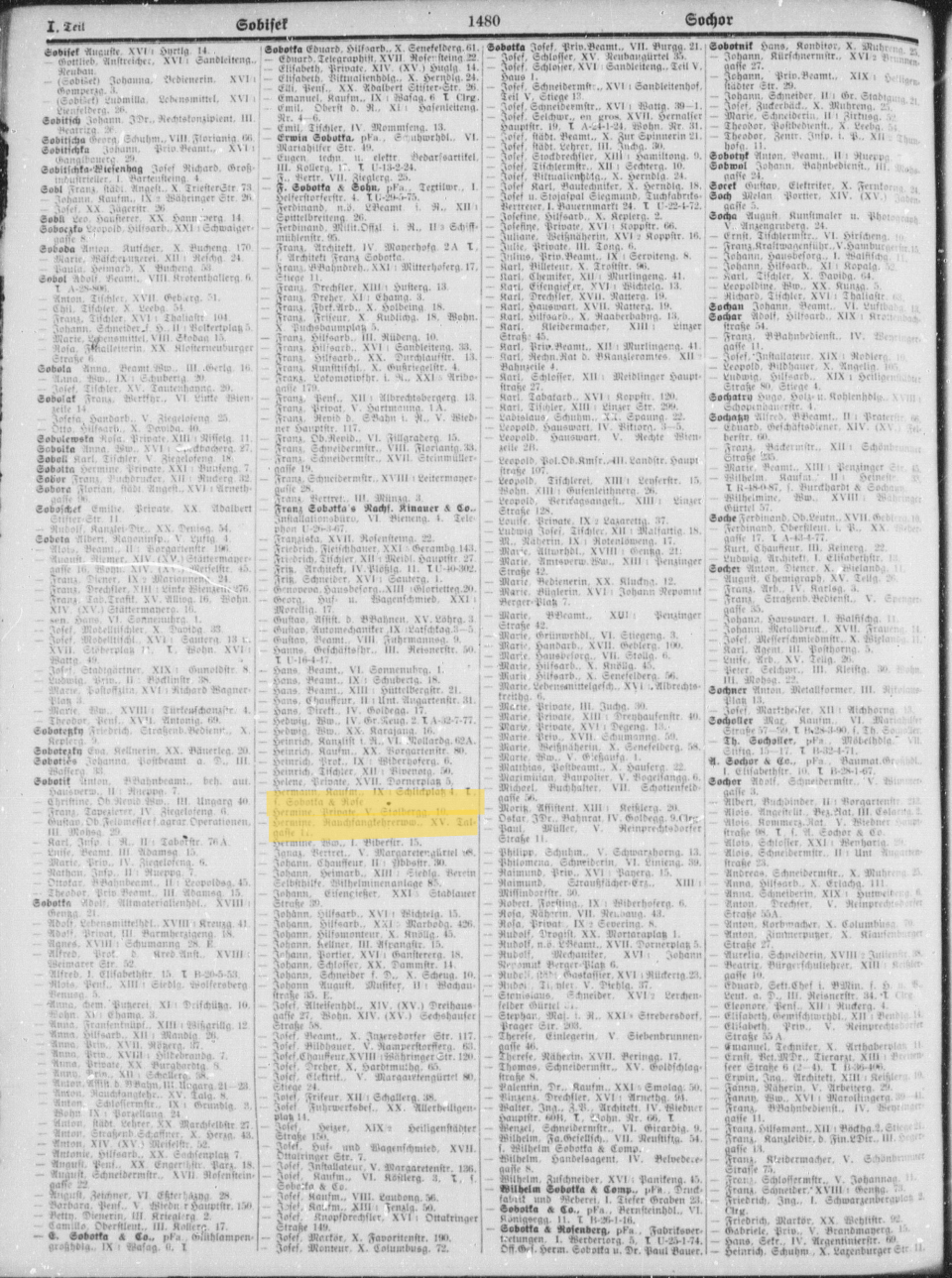

The eldest brother of the Sobotka family, Hermann, born in 1864 in Chysky, learned the trade of a textile printer and married Ida Feldmahr from Vienna. He first set up a small textile printing business in the Czech lands and before the outbreak of World War I Hermann opened a shop in Vienna’s 9th district, Alsergrund, at Schlickplatz 4 with a partner “Sobotka & Röfe”, where his younger brother Wilhelm learned the trade. This enabled him to set up the prestigious textile printing and flag making business “Wilhelm Sobotka & Comp,” with his partners in Vienna in 1919. Willi married Marta Appelfeld from Lidice and like Ignaz, completed his training on the “Walz” in Bohemia and Moravia, including a stay in Prague.

The prime location of Hermann’s textile shop “Sobotka & Röfe” on the ground floor of this building in the 9th district of Vienna, Schlickplatz 4, today

Life of the workers in the “Wienerberger“ brick factory, Favoriten

In the second half of the 19th century the city scape of Vienna was radically transformed into an urban metropolis of 2 million inhabitants, who had moved from all parts of the Habsburg Empire to the capital city, many of which from Bohemia and Moravia. They for instance found work in the brickyards of Favoriten, which expanded at an enormous speed due to the building boom in Vienna. Brick production was hardly mechanised at the time and meant dire working conditions for the thousands of unskilled brick workers. In the second half of the 19th century nearly one half of the population of Bohemia and southern Moravia emigrated because of the economic crises in their home region. Some of the male workers returned to their families during the winter time, when there was no work in the brick yards, but since the 1870s whole families migrated to the brickyards in Oberlaa, Favoriten, where men, women and children worked in the brick production.

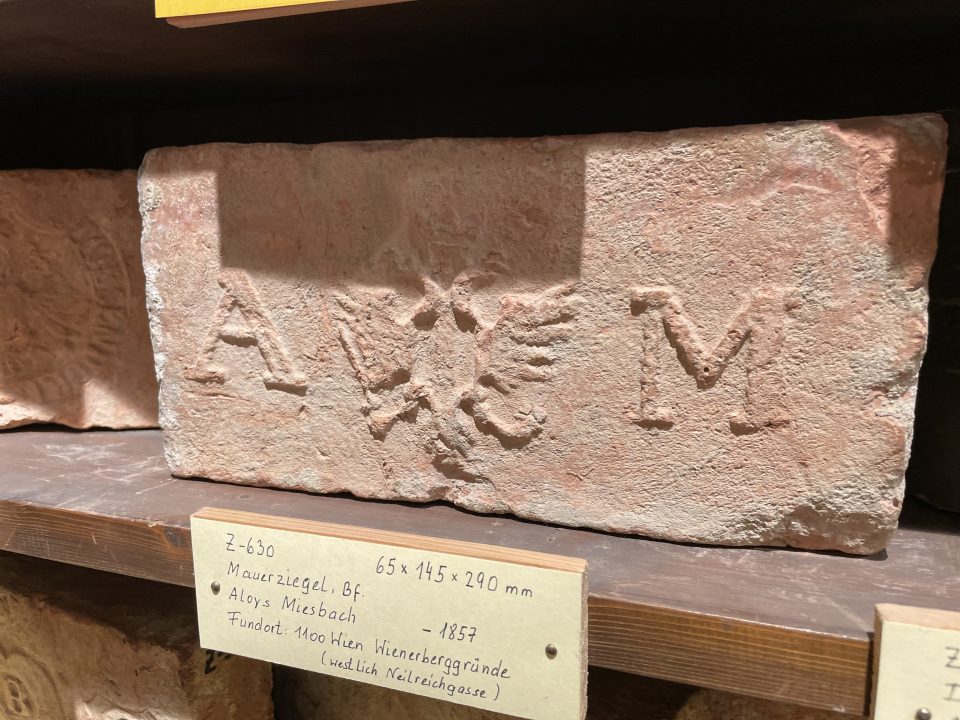

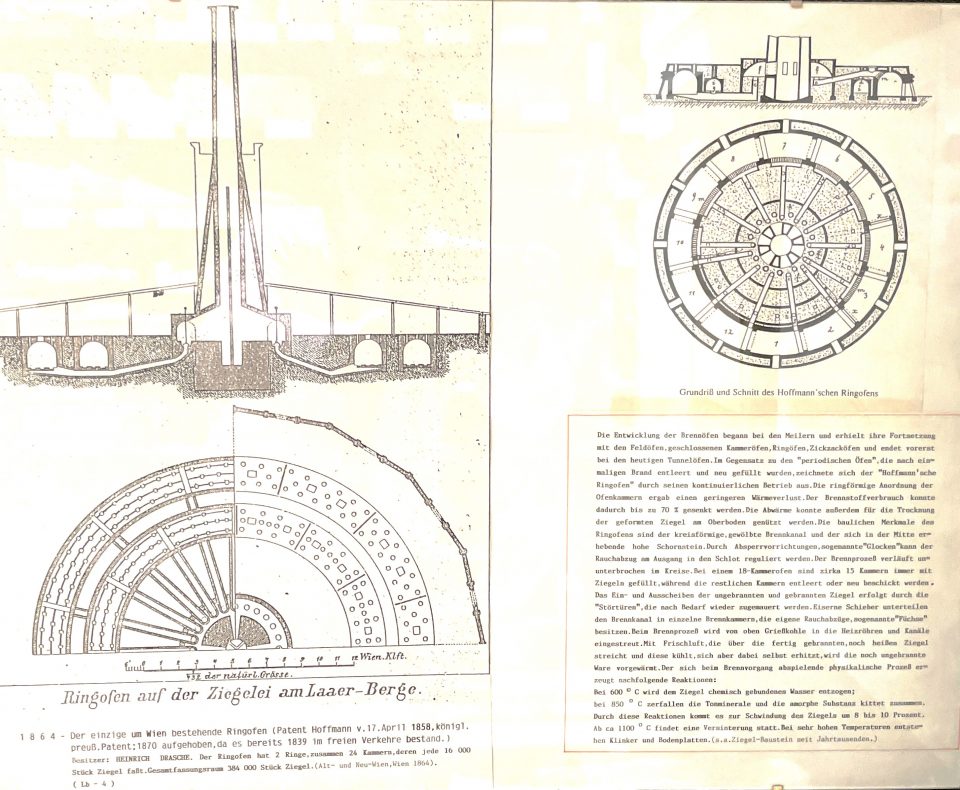

Left: A brick with the sign of AM (Aloys Miesbach)1857; right: draft of a “Ringofen” (ring kiln)

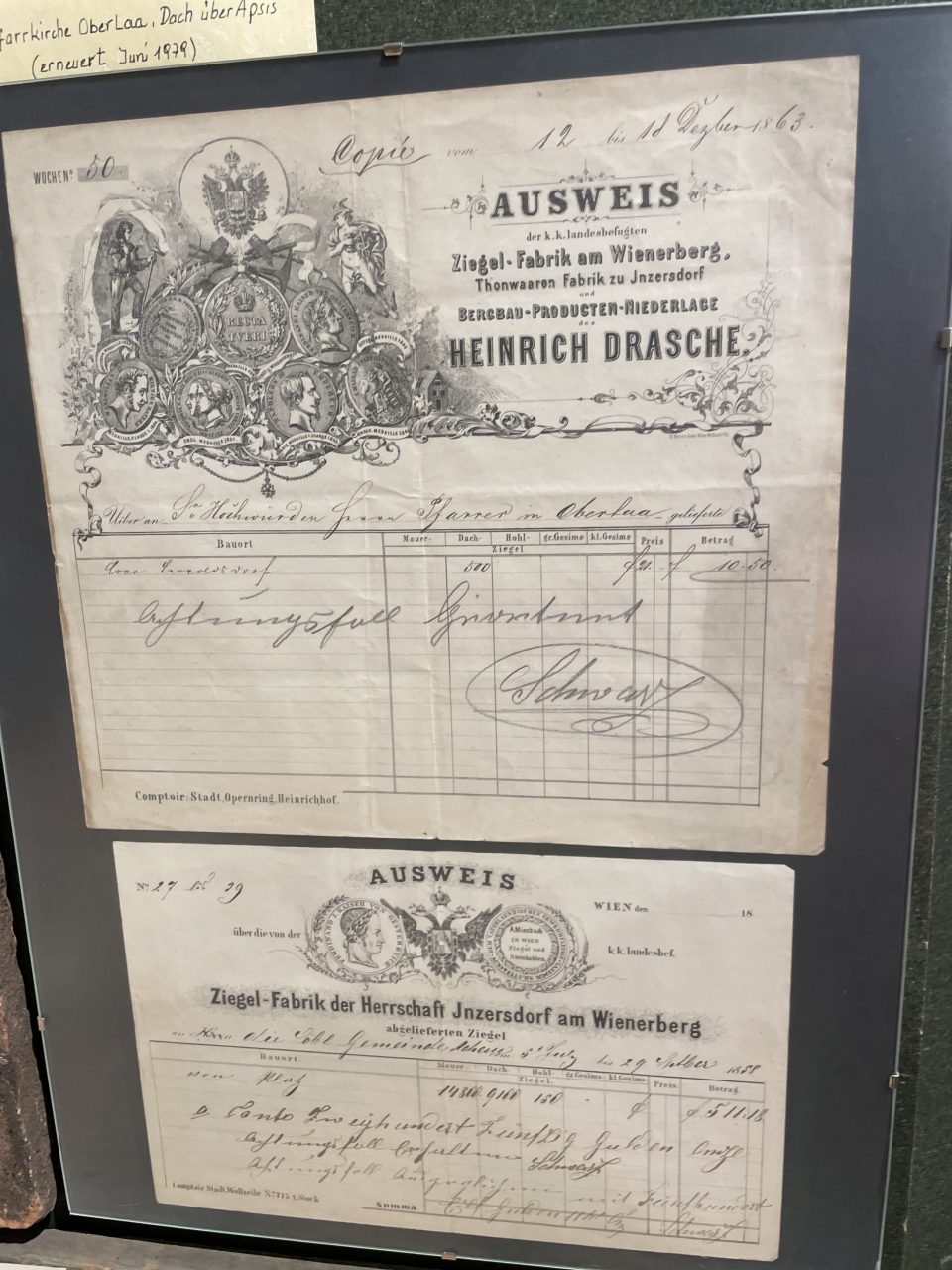

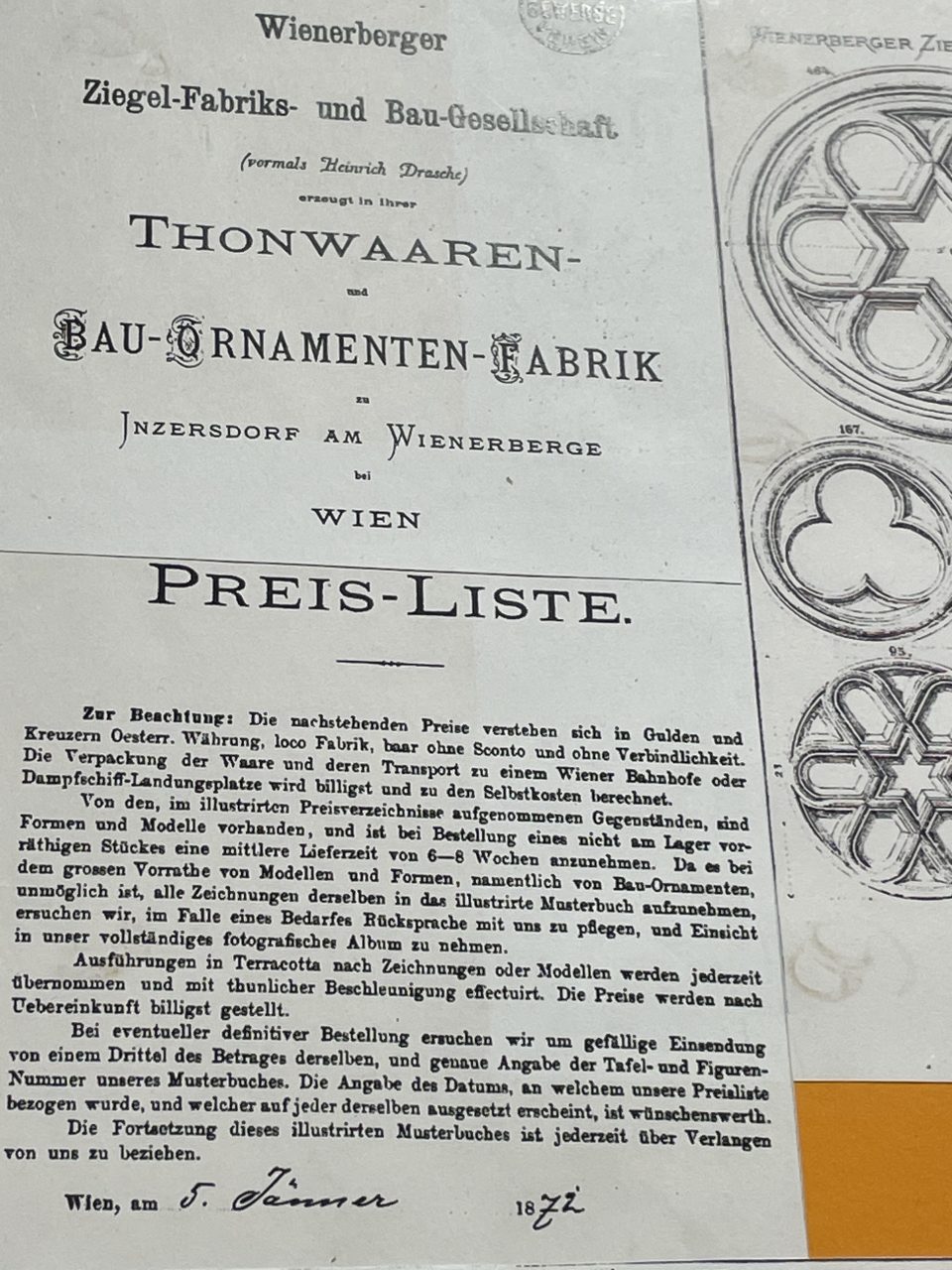

Left: Wienerberger brick delivery note of 1863; right; price list of Wienerberger pottery factory of 1872

In the 1850s the entrepreneurs of the brickyard Miesbach and Drasche had 100 workers’ dwellings built on the Wienerberg. Originally every family had a living room, a bedroom and a kitchen, the rent of which was deducted from their wages. Additionally, the company provided coal and wood for heating free of charge. But with the transformation of the company into a public limited company, enormous pressure was built up to increase shareholder value exorbitantly and quickly. The vast expansion of the production together with the influx of masses of unskilled workers, furthermore exacerbated the working and living conditions of the brick workers dramatically. The kitchen equipment in the workers’ dwellings was removed and every room was filled with 40 to 50, sometimes even 70 workers, who had to sleep on the bare floor. The noise, the dirt and the stench was unbearable, workers had to sleep in the stables as well as in abandoned ring kilns. At one end of a room a baby was born, whereas at the other end a man was dying and there was fighting and shouting everywhere.

The workers suffered from rheumatism, gout, and inflammations. Constant exposure to cold water and the inclement weather, the carrying of heavy weights and the abysmal hygienic conditions together with malnutrition and cramped living conditions contributed to outbreaks of epidemics, such as dysentery, cholera, smallpox, and typhus. The mortality rate among brick workers was extremely high and the infant mortality was far beyond average. Mostly men succumbed to alcoholism. They spent their scarce spare time on the factory canteen or a nearby pub, where they squandered their wages on beer, rum, or schnaps, and took on debt. All this led to quarrels and violence within the families.

In response, the management of the “Wienerberger” brick factory decreed strict factory regulations. Workers were forbidden to leave the factory grounds even in their spare time. As the workers were living on site, the slightest offence or misdemeanour led not only to the loss of the job, but also the home. Although the “truck system” was prohibited in the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, the “Wienerberger” workers were still paid in tokens made of plate, not money terms. These tokens were only accepted as means of payment in the canteens and pubs of the company at excessive prices. Every worker was assigned to one company shop and canteen, where they were allowed to purchase food, drinks, and the bare necessities of inferior quality at inflated prices. It was strictly forbidden to shop or consume elsewhere. Workers and their children were severely beaten by the management for the slightest offences. On Wednesdays any misbehaviour of children was reported to the factory managers and the parents had to pay for the damage caused from their scarce wages while the children were beaten up by their fathers.

“Wienerberger” brick factory and brick workers around 1900 (as presented in the District Museum of Favoriten)

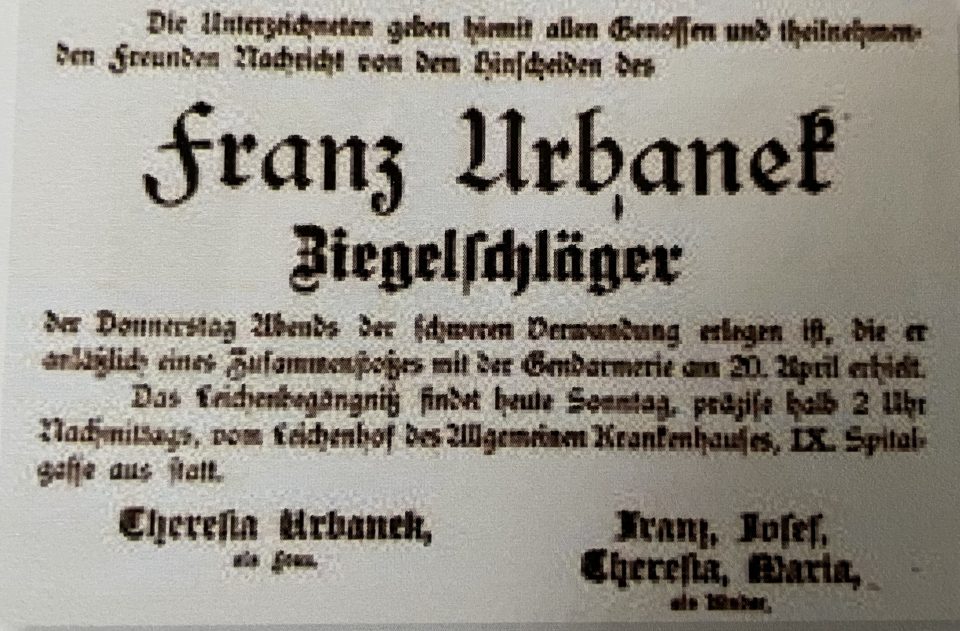

Far away from the glamour of fin-de-siècle Vienna the working and living conditions of the brick workers were unknown to the capital city’s well-to-do inhabitants. That is why two brick workers, Johann Raab and Ludwig Halder, approached the Viennese doctor for the poor, Victor Adler. Disguised as a brick layer, Victor Addler clandestinely sneaked into the factory area of “Wienerberger” and experienced hands-on the working and living conditions in the factory. In the paper “Gleichheit” (Equality) he wrote several articles on the hardship of the “brick slaves” in 1888. For the first time someone made the public aware of the exploitation und the unbelievable misery of the brick workers, which resulted in a public outcry. The authorities intervened and some improvements for the workers were carried out, such as the abolishment of the “truck system”, which had been illegal anyway. Yet the bourgeoise press vilified Adler’s articles as gross exaggerations. But in the wake of the strikes in the early 1890s, after the foundation of the Social Democratic Workers’ Party in 1888/89, the conservative media changed their coverage, too. In 1895 ten thousand brick workers went on strike in Vienna and the clashes with the police ended with several wounded and one dead brick worker, Franz Urbanek. Finally, the factory owners were prepared to make concessions and entered into negotiations with the brick workers.

Death notice of the victim of the strike of 1895, Franz Urbanek

Victor Adler wrote in his article of 1 December 1888 in the paper “Gleichheit” about the workers’ crews and their crew leaders or foremen, a position that Josef Sobotka held. A workers’ crew consisted of 70 to 100 single men, who had to report to their foremen. During summer they earned 6 to seven fl (=Gulden, guilder in English) each, in winter only 4, 20 fl. Every crew was assigned to a canteen, where they had to spend their wages in the form of tokens. Bread outside the factory premises, in Inzersdorf, cost for example 4 kr. (Kreuzer, kreutzer in English), in the canteen, where the workers had to buy, 5 kr. The same was true for everything else: beer, schnaps, sausages, cigars etc., but the quality of these products was wretched. The workers had to purchase everything with tokens, even the clothes and shoes for work and all was a third more expensive than outside the factory premises. A worker was not permitted to shop outside the “Wienerberger” grounds. He had no money anyway, but if he by chance came by some true money, he was not allowed to spend it outside. The managers of the canteens and shops counted their workers, took note of their purchases and kept order with a bull’s whip. If a worker was discovered, who had bought something outside, he was instantly dismissed. The foremen kept the accounts of every worker and the workers usually could not keep track of their earnings and spendings in tokens, which resulted in the hoax that the foremen usually told the workers that they owed the company money. They were at the mercy of usurers. But the workers were “allowed” to beg. Consequently, they went to the canning factory “Inzersdorfer” after work, where they were sometimes offered a disgusting soup, called “Goulaschsaft” and if they were able to walk one and a half hours to Neudorf, they might have received a vegetable soup with some meat, which Mr Seyfried, the local executioner, distributed; approximately 80 servings daily. It was difficult to go begging in the vicinity of the company, because a 15-hour working day and a 90-hour working week were standard and left little spare time for begging.

Because the foremen had to have full control over their workers, the workers had to sleep on site in cramped conditions, for which they had to pay a very high rent. In 1884 an imperial inspector recorded that at the Wienerberg the rent for a worker’s dwelling was 56 to 96 fl. monthly. Yet, married foremen, bricklayers and artisans were much better off than all the other unskilled workers, who had to sleep on the bare ground without blankets, cushions or even straw. There was no possibility to wash or clean their clothes. The canteen managers and foremen had to keep strict control over the workers who were assigned to them and had to count them every morning and evening. If they found someone had slept outside, he was immediately dismissed and if he then continued to sleep in an abandoned ring kiln, he was severely beaten and chased from the factory premises. It was said that the foremen received a 10 to 15 per cent share of the profit from the canteen managers. The “Wienerberger” company was responsible for these abysmal living and working conditions because they asked a very high rent from the canteen and shop managers and knew about the exploitations and abuses. A worker who read newspapers or participated in assemblies, was immediately sacked. The company reacted to protest with instant dismissals and got the police to imprison the leaders, such as the two workers who had contacted Doctor Victor Adler.

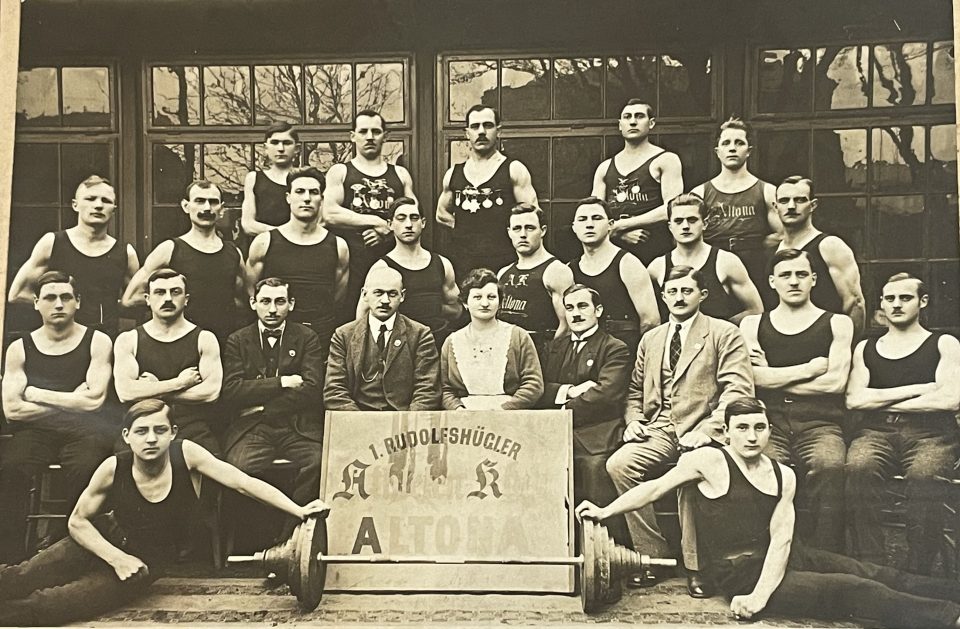

Because of the strike of 1895 the working hours were reduced to eleven per day and Sunday was time off work. In order to fight alcoholism and illiteracy, workers’ educational clubs and cultural associations were founded. Additionally, a works band and a works choir were set up. Already in the 1889s a fun fair was established in the vicinity of the brick factory, the “Böhmischer Prater” (Bohemian Funfair), which still exists. Around 1900 football became popular at the Wienerberg and in 1921 the brick workers founded their own football club, the “Arbeitersportverein Wienerberg”.

Photos of a football club in Favoriten in the 1920s, from the photo album of Wilhelm Sobotka, celebrating the 10th anniversary of the foundation of his textile printing company in the “Schleierbaracken”, probably representing some workers of “Wilhelm Sobotka & Comp.”.

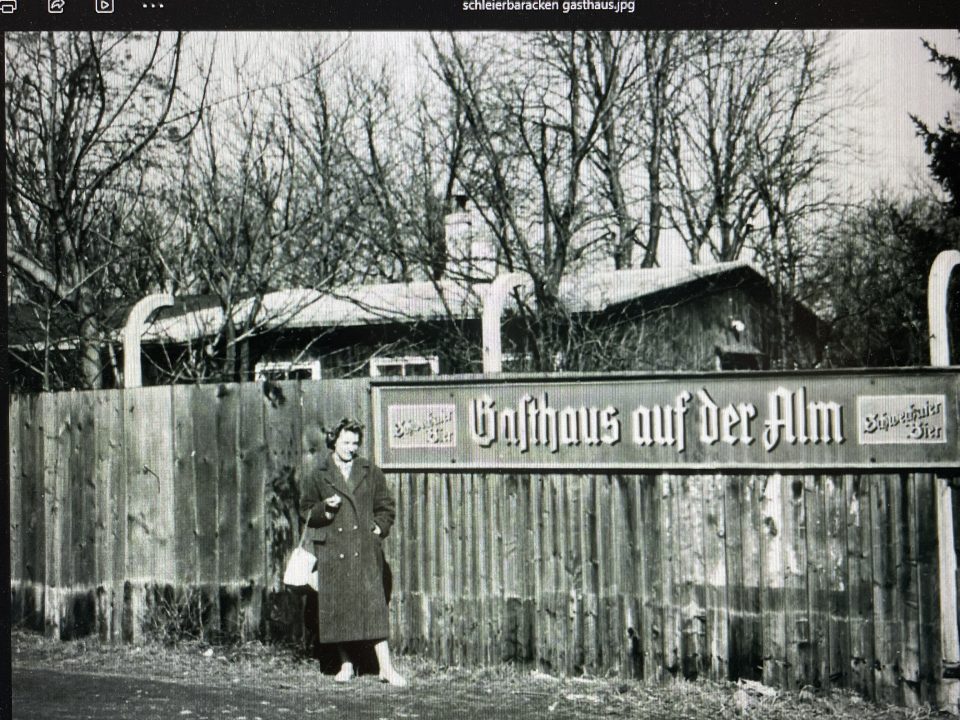

Entertainment in Favoriten; left: weight lifter club; right: popular inn at the “Schleierbaracken”, called “Gasthaus auf der Alm”.

“Böhmischer Prater” (Bohemian Fun Fair) today

Before World War I “Wienerberger” employed 8,000 workers and produced at 16 different locations. After the end of the war and the end of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy the company gave up all production sites outside the Republik of Austria and experienced very difficult economic times during the interwar years and the Great Depression in the 1930s. The economic downturn continued during World War II, but the post-war economic boom of the 1950s and 1960s with the need for rapid reconstruction of the war-damaged country contributed to the stabilisation of the company. Yet the brickyard on the Wienerberg in Favoriten, which gave the company its name, was closed in the 1960s due to unprofitability. In the 1980s the booming company expanded abroad at an enormous speed. Right now, they produce in more than 200 production sites in 30 countries and are the world’s largest producer of tiles for roofs and the number one in Europe for all types of pipe systems. Outside Europe “Wienerberger Baustoffindustrie AG” is active in Canada, the USA and India.

“Schleierbaracken” Favoriten

During World War I the Austro-Hungarian military administration erected a large barracks area at Schleiergasse 17 in Favoriten at the beginning of 1915, the “Invalidenschulen des k.& k. Reservespitals Nr.11” (a hospital and school for war invalids), consisting of 14 school barracks and 30 barracks accommodating war invalids and personnel. Heinrich Drasche, the owner of the “Wienerberger” brick factory, who supported the training of war invalids, sold the area cheaply to the k.& k. military. The first school for invalids at Schleiergasse opened in August 1915. As the school was quite far from the war hospital, a special tramline connected the hospital with the school for war invalids between Gassergasse and Schleiergasse four times a day. The 14 workshops and administrative barracks, labelled A to O, and the 27 (to 30) numbered residential barracks can be seen on the map below:

Apart from the barracks, the entrance, the church, and the operating theatre can be seen on the map. Additionally, there were a music pavilion, an experimental agricultural field, and a small prison on site, which are not accounted for in the drawing.

The schools for war invalids were dedicated to work therapy. The various workshops were headed by trained masters, who the war ministry paid for. Additional to the medical and military management, a technical expert was employed. Of the school barracks in the east of the area, one was dedicated to administrative purposes, two were used for theoretical lessons and the remaining ones were workshops. The size of every barrack was around 750m2. The workshops were the size of a medium enterprise. The invalid soldiers were provided with the most modern tools, so that they could work again in their original professions after rehabilitation. If that was not possible, they received re-training in a new profession.

Schools for invalids and a church on the premises, 1915

Even though the war had ended and Austria was turned into a republic, the invalids still needed support, so the schools still cared for the war invalids. The whole area was transferred to a commission that compensated war invalids and the schools kept on teaching until 1922. Three barracks were rented to invalids for housing and some were rented to artisans or small businesses. A document of 1938, which is preserved in the District Museum of Favoriten, lists barracks 11, 14 and 19 as housing barracks for war invalids, accommodating 220 people. Yet it can be assumed that in the years after 1922 more barracks were rented for housing purposes, but the largest part of the barracks was rented to small, mostly artisanal, enterprises between 1920 and 1938.

An aerial image of 1926 with the “Schmied” Steel Works in front and the “Schleierbaracken” in the background

Wilhelm, who founded the textile printing business “Wilhelm Sobotka & Comp.” in 1919, and Marta Sobotka, who married in 1918 in Vienna

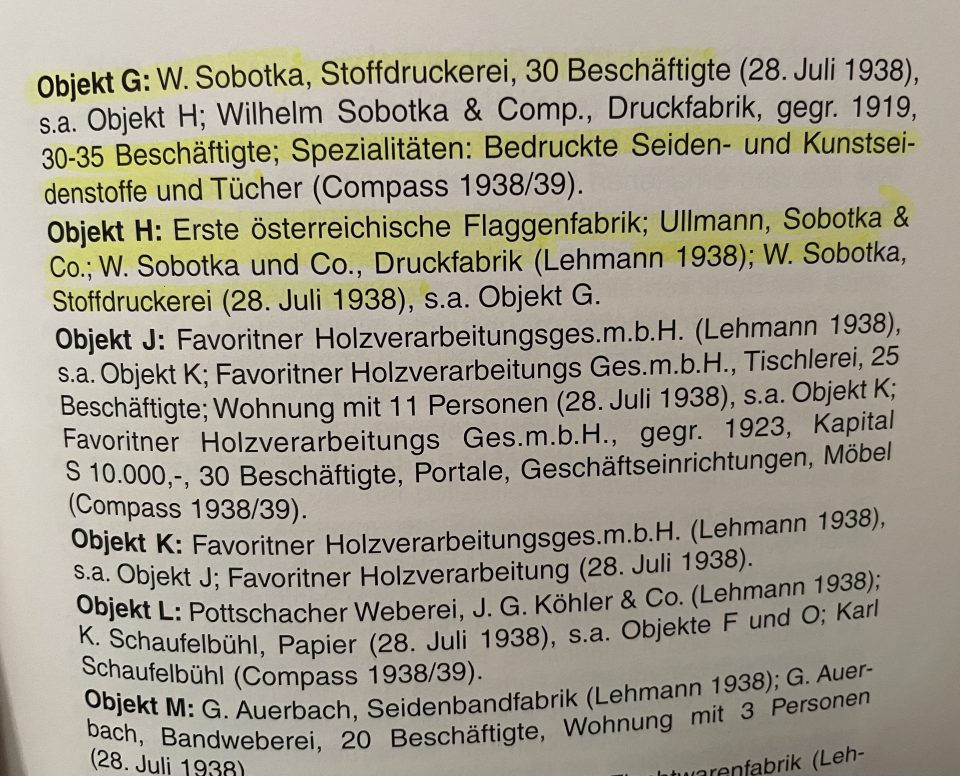

This list shows that “Wilhelm Sobotka & Comp.” had rented Objects G and H: “Wilhelm Sobotka & Comp.”, founded in 1919, employed 30-35 employees, printing silk, artificial sil,k and scarves in Object G. In Object H “Ullmann, Sobotka & Co.”, the first Austrian flag factory, produced flags.

It is not possible to identify all businesses that had rented workshops on the premises of the “Schleierbarcken” between 1920 and 1938, when this nick name seemed to have emerged in Vienna. Yet a large variety of artisanal enterprises that produced in the “Schleierbracken” during the interwar years are documented in this list of 1938. Many of these artisanal handicrafts are now extinct in Vienna, such as the production of silk ribbons, the spinning and weaving of textiles, the production of “ice boxes” – early refrigerators, which were wooden boxes, where large junks of ice, which were delivered to households and pubs, kept food and drinks fresh -, hat production, saddlery and harness manufacturing, cart building, “Quargel” (a cheese speciality) production, production of “puffed rice”, the “Monolith” company producing stone-wood flooring or wickerwork manufacturing. Other businesses concentrated on carpentry, knit ware, ceramics – the historical Viennese brand “Keramos” produced at the “Schleierbaracken” -, book printing and binding, textile printing, silk weaving and tights production, machinery, paper and carton manufacturing, production of envelopes, stoves, the chrome industry, and toys manufacturing.

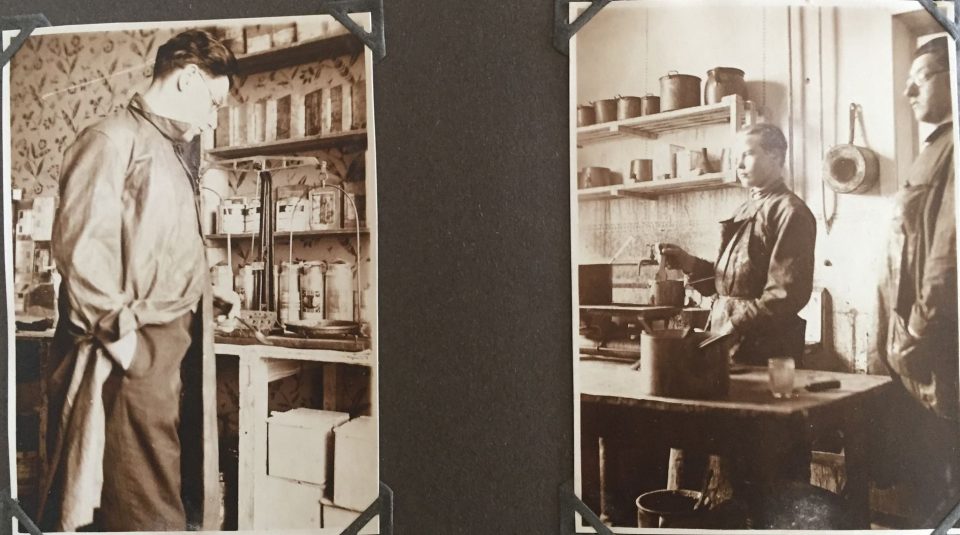

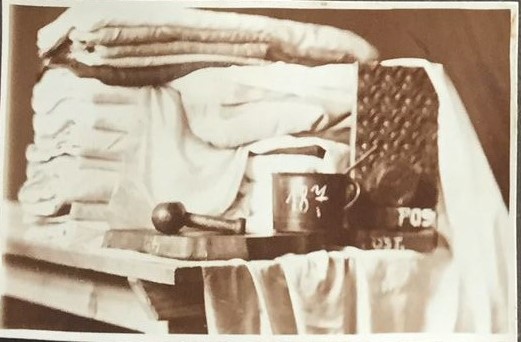

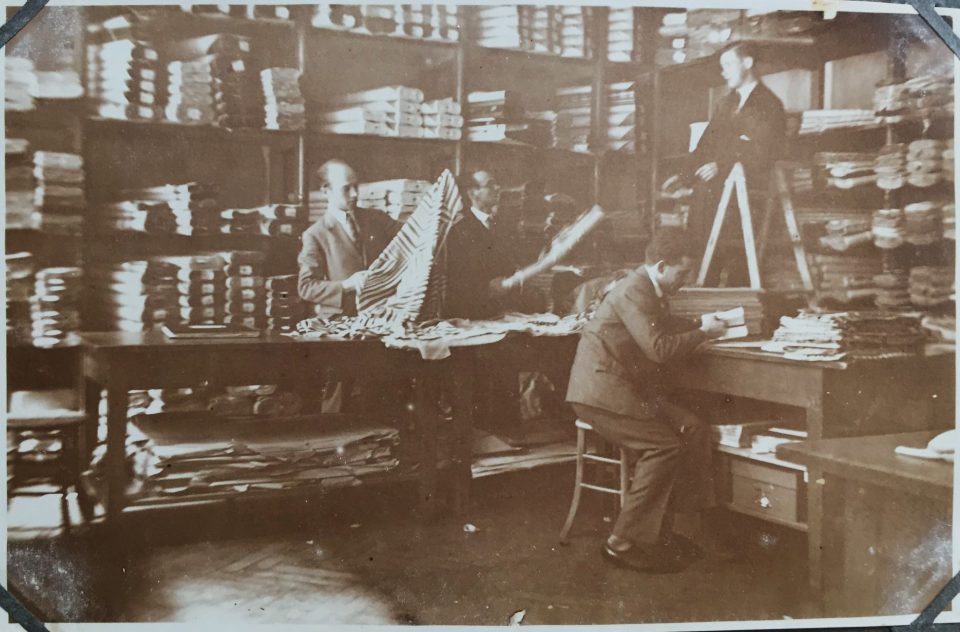

From Wilhelm’s photo album: workshops and textile printing in the “Schleierbaracken” 1919-1929

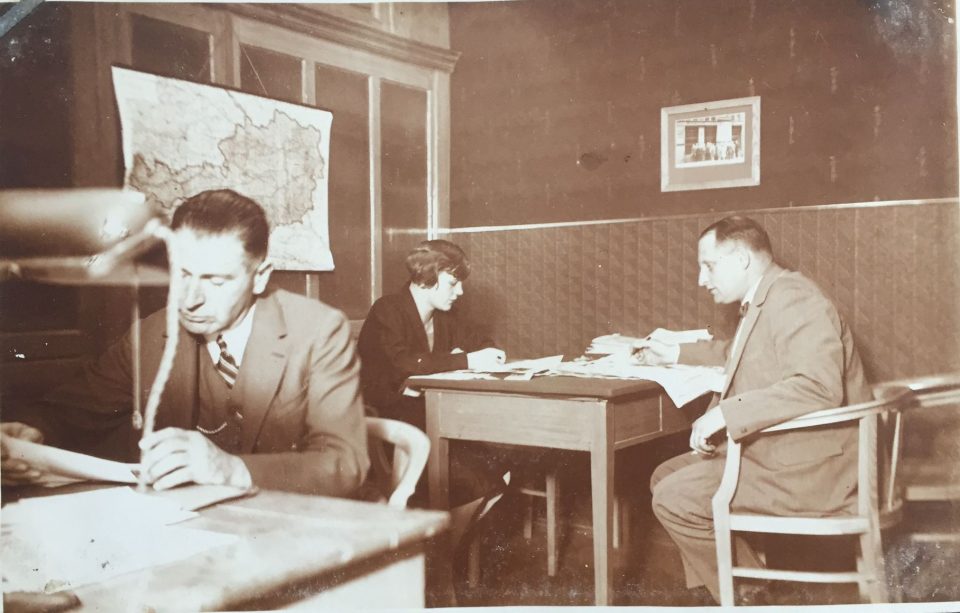

Left: workshop. Right: Map of the newly founded Republic of Austria on the wall of the office, below: textile printers

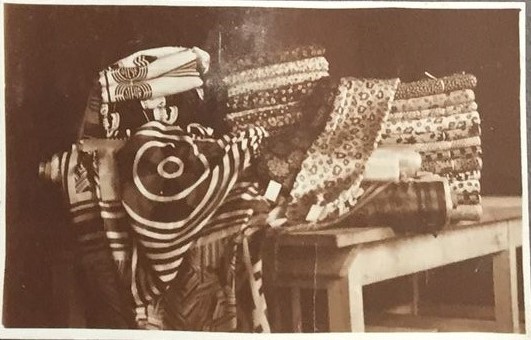

Samples of the textiles produced by “Wilhelm Sobotka & Comp.”. Some of the silk fabrics were printed with designs à la “Wiener Werkstätte”.

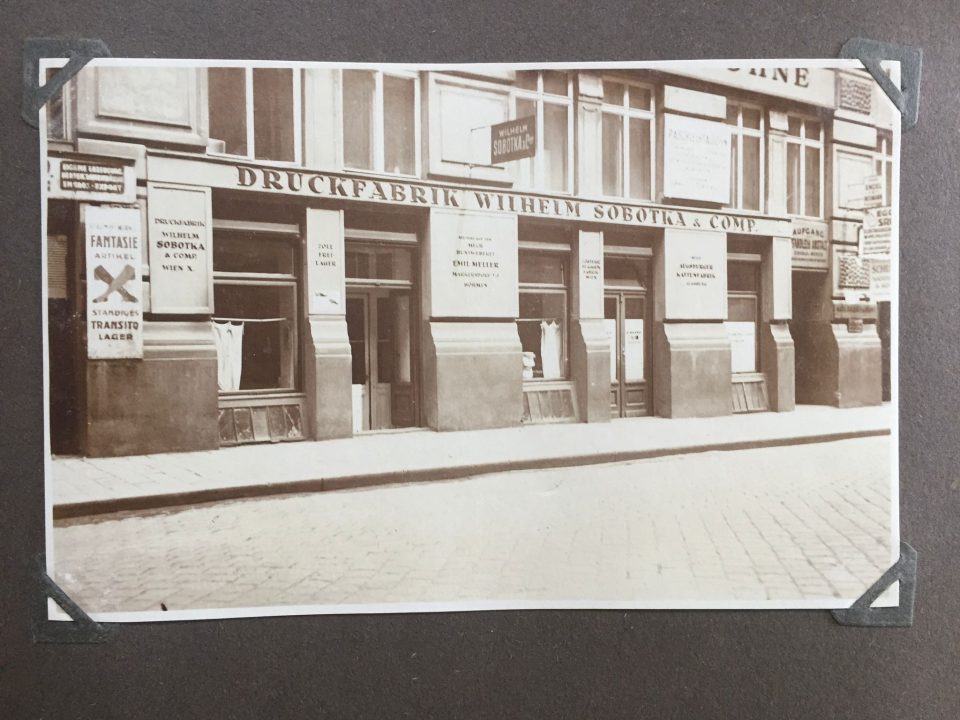

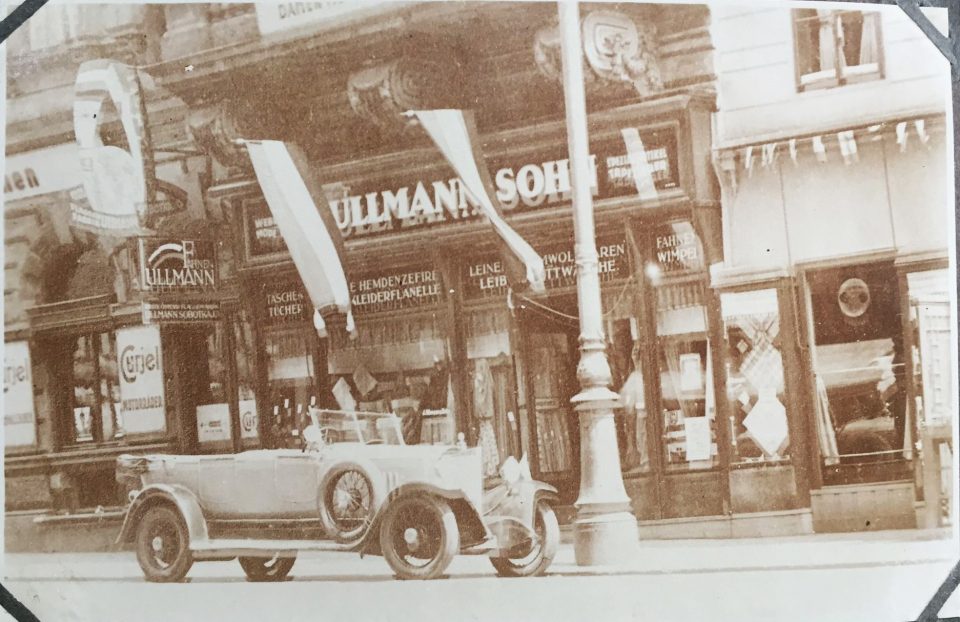

Wilhelm’s shop in Vienna’s prestigious 1st district at Tiefer Graben, showing the employees in front of the shop.

Below: The shop in the 1920s and the premises today

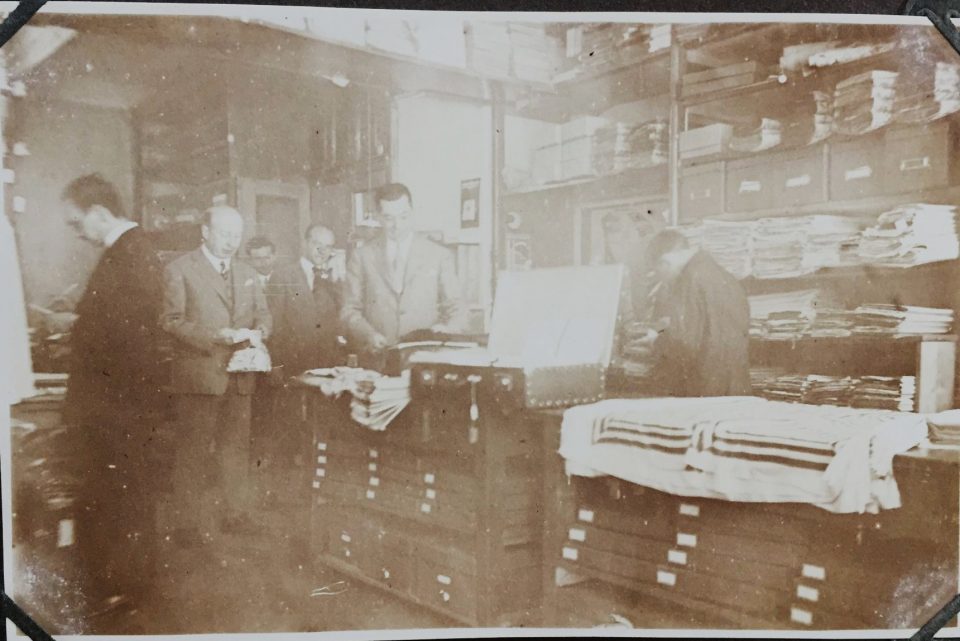

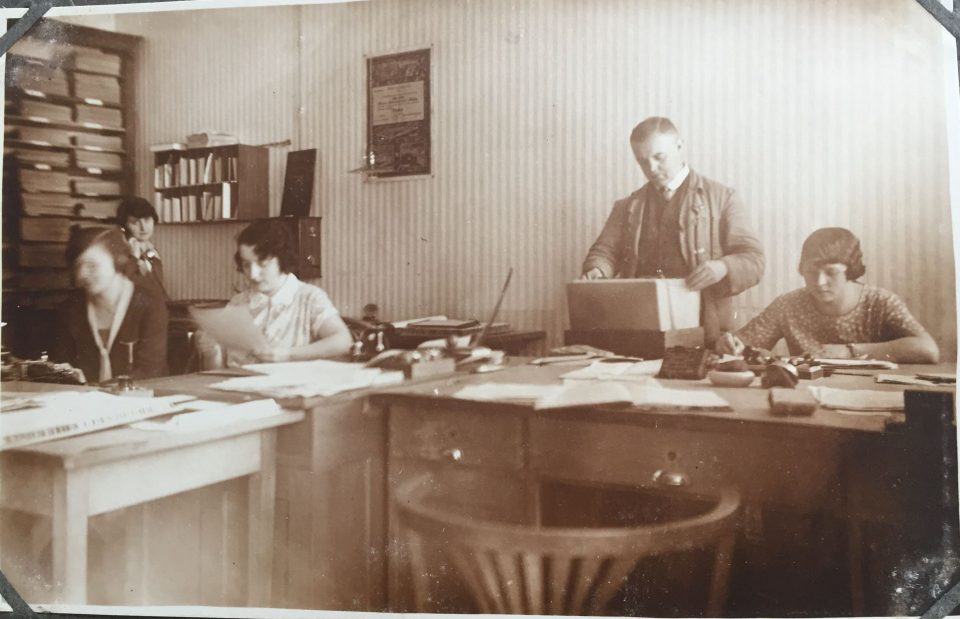

Inside Wilhelm’s shop at Tiefer Graben, the office and employees and the partners in front of the shop, below on the right side

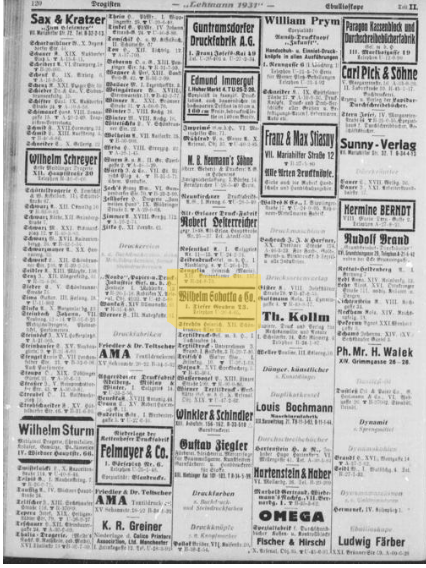

Left: Viennese directory “Lehmann” of 1931 with “Wilhelm Sobotka & Comp.’s” shop at Tiefer Graben; right: Wilhelm’s flat in Neustiftgasse 54/14 in the 7th district of Vienna

“Gewerbefestzug” (Parade of Artisans) on 9 June 1929 during the “Wiener Festwochen“ (Vienna Festival), a parade of Viennese and Lower Austrian businesses, starting at the Vienna Townhall, marching along the Ringstrasse and Praterstrasse to the Prater Hauptallee. “Wilhelm Sobotka & Comp.” participated with their own parade cart and the “First Austrian Flag Company” and the flag shop.

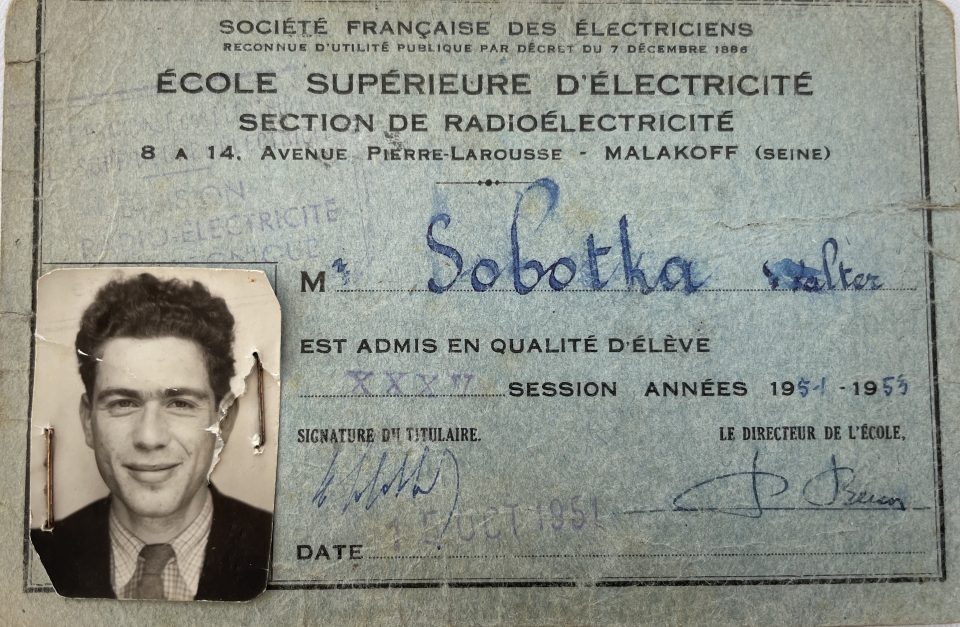

In March 1938 Austria became part of Hitler’s “Third Reich” via the so-called “Anschluss” and the “Nazionalsozialistischer Kriegsopferversorgung NSKOV”, a Nazi organisation for war invalids, took over the area of the “Schleierbaracken”. They immediately started with a wave of “aryanisations”, the dispossession of all Jewish-born tenants and business owners, robbing them of all their possessions. Wilhelm and Marta Sobotka did not see, why they should leave their home country and remained in Austria until the last minute before deportation to a NS concentration camp. A Belgian free mason and business friend of Wilhelm’s managed to get Wilhelm and Marta and their younger son Walter, born in 1928 in Vienna, to Belgium. Their elder son Hans Sobotka, born in 1820 in Vienna, had already fled to England, changed his name to John Stenford, and joined the British Army in the Second World War. The family was caught up by the advance of the Nazis in Belgium and were deported to the Camp des Milles in Drancy, southern France. Walter was hidden in a Catholic school, where he could continue his education, but his parents were deported to the KZ Auschwitz on 19 August 1942, where they were murdered. John emigrated to Australia after the end of the war and Walter remained in France after being informed about the death of his parents at the end of the war. Having experienced a lot of bureaucratic hassle, the two brothers, John and Walter, were denied compensation for the injustice and the losses their family had experienced in Austria during the Nazi period and the family business was not returned to them.

Wilhelm, Marta Sobotka, and the boy(s) in Vienna before World War II:

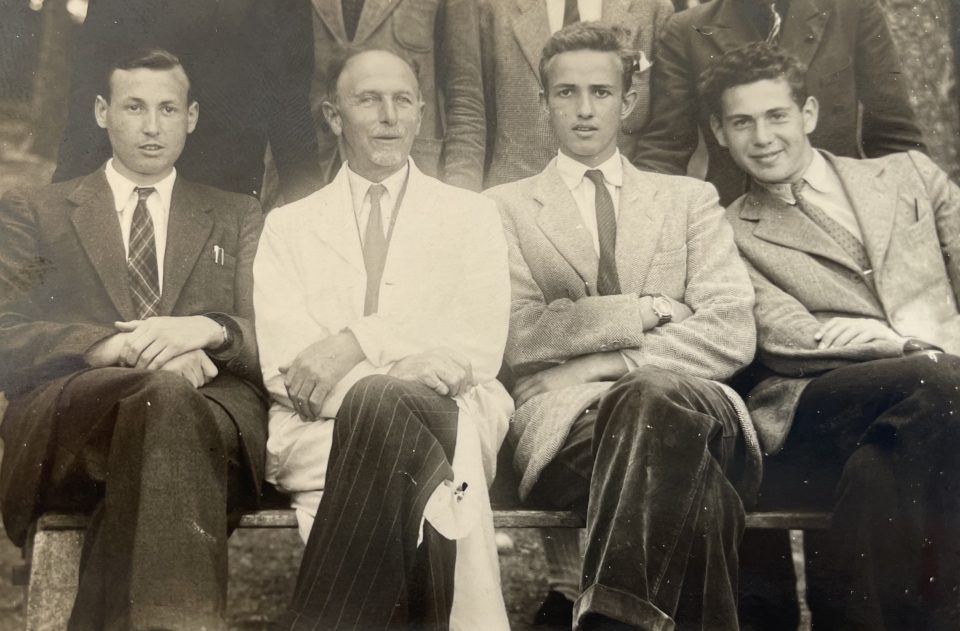

Walter in France at the school for electricians after World War II (young man on the right in the photo)

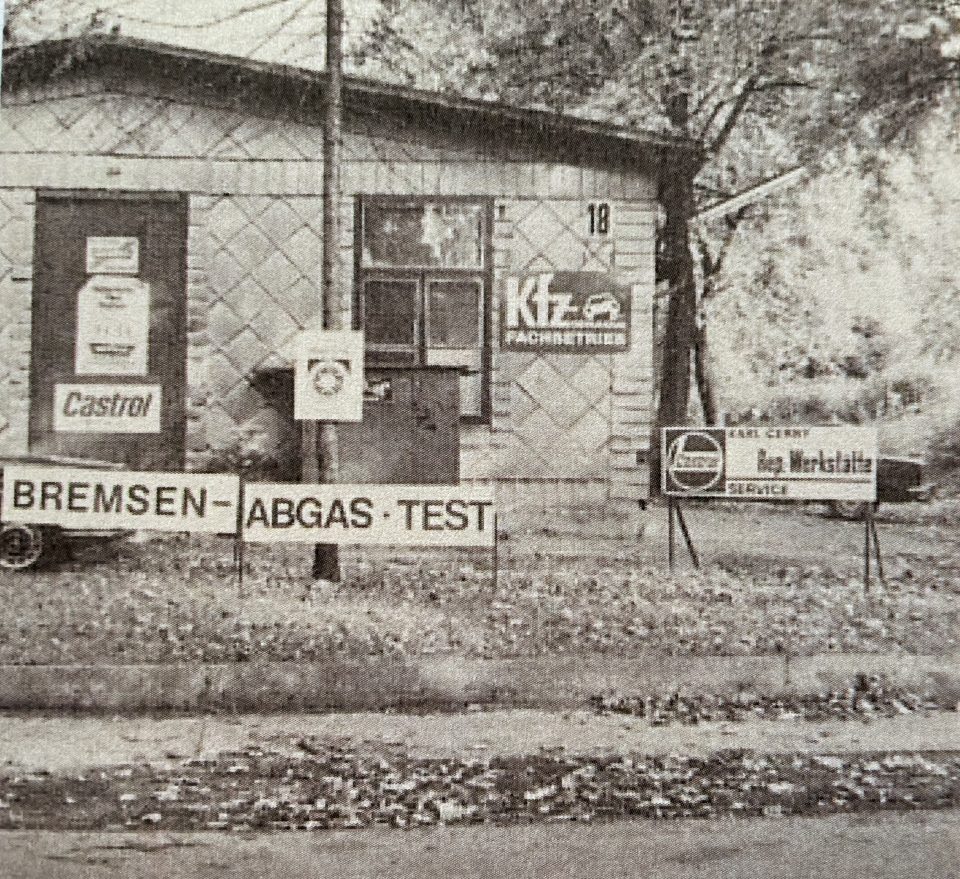

Between 1945 and 1979 the “Schleierbaracken” developed into a motley of untouched nature and wooden barracks, used as workshops or company outlets of small and medium-sized businesses. In 1982 the young photographer Johannes Faber documented for the magazine of the Viennese tramways “Wien aktuell” the derelict “Schleierbaracken” between Grenzackerstrasse and Schleiergasse in Favoriten, where in 1979 around 40 companies, mostly artisans and services, had formed an association and bought the park-like area with the wooden workshops in the hope of expanding and modernising their production, while at the same time keeping the natural surroundings intact; yet in vain.

In 1984 the project of the “Favoritner Gewerbering” was launched and most of the wooden buildings were demolished and substituted by new modern housing estates, just a small park remains in memory of the “Schleierbaracken” and a few run-down shacks:

Expropriation of Jewish businesses in the Viennese working-class districts Favoriten, Ottakring or Hernals

Jewish entrepreneurs constituted a significant part of business owners in the 10th district of Vienna, Favoriten. Like today in Austria, migrants tend to be more entrepreneurial than the indigenous population and are more inclined to starting small and medium-sized businesses. On the one hand, they were and are disadvantaged with respect to employment in the local administration and bureaucracy and on the other hand, they did not and currently do not shy away from risk. Migrants rather prefer the independence of decision making of a sole tradership or partnership as compared to the working conditions under an employment contract. This trend can be seen in Vienna today, where many start-ups and sole traderships or partnerships are established by migrants and refugees. In Favoriten several entrepreneurial new arrivals from Bohemia and Moravia, of Jewish descent, set up businesses around 1900, for example Fritz Mendl the first large industrial bakery, “Ankerbrot”. In 1938 the factory employed 1,700 people and immediately after the “Anschluss” in March 1938 the Jewish management of the “Ankerbrot AG” and all Jewish employees were dismissed and those who had politically opposed the NS regime and the Austro-fascist regime from 1934 until 1938, too. They were all replaced by party members of the NSDAP (National Socialist Party), among them 18 members of the SS and 16 of the SA (“Schutzstaffel” and “Sturmabteilung”, both radical NS party organisations). The company was sold for a third of its true value to the National-Socialist IBÄCK. Nevertheless, some workers kept up resistance against the NS regime and organised a strike at the beginning of the year 1939. The strike was brutally crushed and the striking workers were persecuted and imprisoned. Three resistance fighters of the factory were later shot: Käthe Odwody, Franz Misek and Ludwig Führer. Hungarian Jews were interned in a slave labour camp in Schrankenberggasse 32 and 97 during World War II, most of which were constringed to do forced labour at the bakery. After the war the “Ankerbrot” bakery was restored to its former owners, the family Mendl, who sold it in 1969.

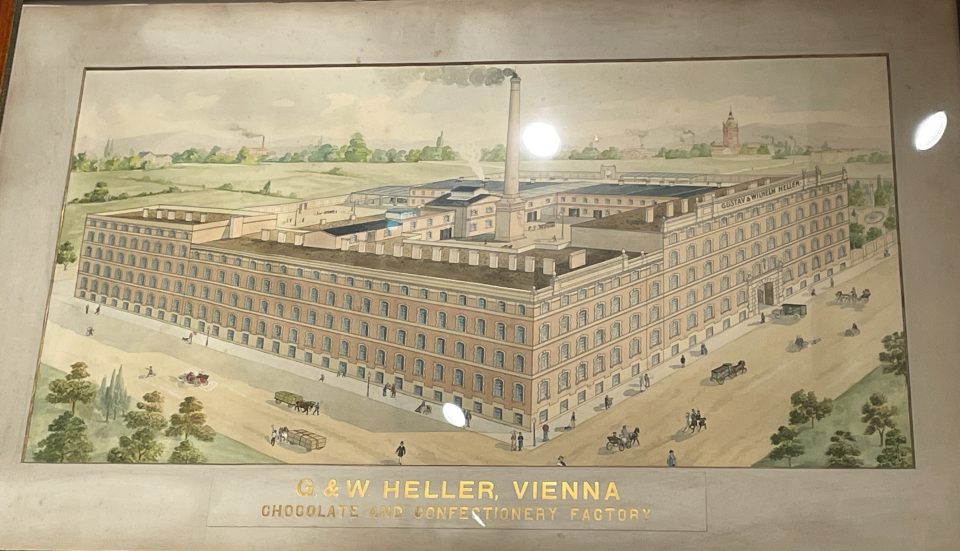

The large confectionary company “Gustav & Wilhelm Heller” in Favoriten, too, was “Aryanised” by the Nazis in 1938 and the Jewish owners dispossessed and chased out of the country:

“Ankerbrot” and “Heller” factories in Favoriten

Simon Löb, for example, was dispossessed as well, and his popular “Café Annahof” at Laxenburgerstrasse 16, was sold at a very low price to the “Aryan” professional footballer Matthias Sindelar by the Nazis. The list of Jewish market stall owners – there were three markets in Favoriten, open from Monday to Friday – who were dispossessed is very long and many of them did not only lose their livelihood as travelling market traders, but ended up in NS extermination camps. Just at the Victor-Adler-Markt 27 Jewish traders are documented, who lost their market stands, which were passed on to sympathisers or party members of the NSDAP. 368 small and medium-sized Jewish businesses are listed, which were forcefully taken from their owners by the Nazis in Favoriten alone. On this list figures: “Wilhelm Sobotka & Comp.” (“Wilhelm Sobotka, born 18.2.1889, Schleiergasse 17, textile manufacturing and textile printing”). Furthermore, all Jewish tenants of council house flats were immediately evicted in March 1938 due to the “Nuremberg race laws” of the Nazis, which ostracised Jewish-born citizens, and the private landlords followed suit.

The Jewish Kuffner family from southern Moravia had lived in Ottakring since 1848 and ran the two large beer breweries in the outer districts Ottakring and Hernals, the “Ottakringer Brauerei”, which still exists, and the “Hernalser Brauerei”, which was closed in 1936 and later demolished. Ignaz Kuffner was mayor of Ottakring from 1869 until his death in 1882 and financed various charities to support the impoverished population of Ottakring, for example a low-price canteen and free meals for the poor, a caring home for destitute children of all religions, a trust for needy pupils, a trust for the poor and war invalids. He headed the voluntary fire brigade and founded a grammar school, a library and built a second horse-drawn tramway in the district of Ottakring. The family supported contemporary artists by purchasing their works and including them in their art collection. The entrepreneur Moriz Kuffner was dedicated to scientific research as well, especially focussing on astronomy. He built the observatory ”Kuffnersche Sternwarte” in 1886, which was one of the most important observatories in the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy and is still a scientific institution. He further financed the publication of scientific research in this field.

Kuffner Observatory and “Ottakringer Brauerei”, still existing brewery in Ottakring, founded by the Kuffners

The family was expropriated by the Nazis in 1938. Wilhelm Kuffner, who died in 1923 left a widow, who fled with their children to France; two of their daughters were murdered in Auschwitz, the destiny of the third is unknown. A memorial plaque in the courtyard of the “Ottakringer Brauerei”, nowadays the most important private brewery in Vienna, shows the names of the expelled former Jewish owners and the 30 workers who were murdered by the Nazis.

The Kuffners furthermore contributed to the erection of the “Volksheim Ottakring”, the first evening adult education centre in Europe, which was opened in 1905 and offered the chance to workers to receive an affordable education after work. Only the best thinkers, authors, and scientists were lecturing there free of charge. The founders were both of Jewish descent in Moravia and Bohemia, but had converted to Christianity, Ludo Hartmann and Emil Reich. The “Ottakinger Volksheim” turned into the most innovative, modern, and open-minded adult education centre of excellence in Central Europe, which became a model for other such institutions in the Habsburg Empire and Germany. A large number of supporters, volunteers, employees, and lecturers of the “Ottakringer Volksheim” were expelled from Hitler’s “Third Reich” in the late 1930s and killed by the Nazis. Fortunatelly, the “Volkshochschule” still exists and constitutes an essential part of current adult education in Vienna.

The “Volksheim Ottakring” today; the new name “Volkshochschule Ottakring” above the entrance

The old name “Volksheim” and the year of foundation 1905 on top of the building

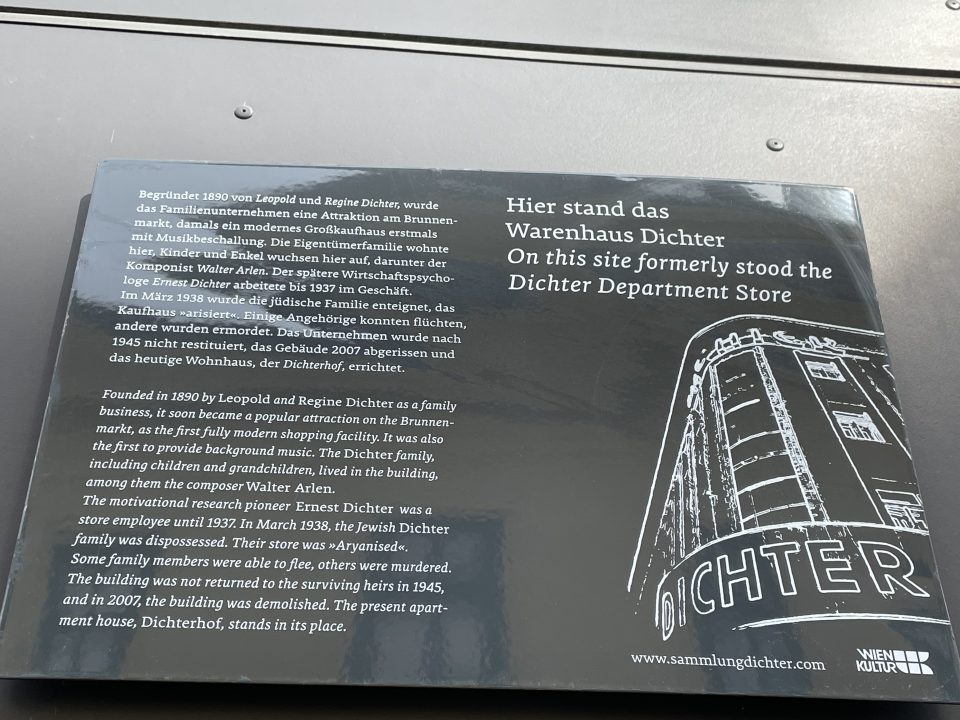

In the outer districts Ottakring and Hernals the Jewish traders Arlen, Wachtel and Dichter opened the first department store in a working-class district, the “Warenhaus Dichter”, Brunnengasse 40 next to the “Brunnenmarkt” one of the largest street markets in Europe. This family, too, was persecuted and dispossessed, just like the many small business owners, who ran libraries, shops of all kinds, such as groceries. Furthermore, Jewish pharmacies, surgeries and legal cabinets were “Aryanised” in Ottakring and Hernals, not to speak of thousands of Jewish workers and families who could not afford to flee Vienna and were killed in NS concentration camps.

The site of the former “Warenhaus Dichter” at the “Brunnenmarkt”

Living conditions of workers in the outer districts of Vienna

Until the end of the 19th century the 16th district of Vienna, Ottakring, developed into one of the most important industrial areas of the city and the district with the densest concentration of inhabitants. In the area of Neulerchenfeld tenements of four to five floors and 30 to 80 flats dominated the city scape. In the outer working-class districts poverty and destitution were hidden behind facades of impressive beauty, which were modelled on the architecture of the fin-de-siècle “Ringstrasse”. In Ottakring and Hernals the main streets, as well as the small alleys boasted tenements of stunning architectural excellence. The topography of Vienna was organised along concentric cercles, starting at the centre, the 1st district, which was surrounded by the inner suburbs, followed by the outer suburbs, the working-class districts; gradually deteriorating socially from the wealthy inner circles to the impoverished outer circles. There the inside of the tenements stood in stark contrast to the appealing outer facades. The flats were minute; in more than one third of these tiny apartments so-called “Bettgeher”, mostly single men, rented a bed for a few hours of sleep. The tenants who sub-let a bed for a few hours could not afford the rent for their tiny flat without the money from sub-letting one or two beds to those even poorer “Bettgeher”. For the working-class population of these outer suburbs such a cramped apartment was an urgently needed refuge without any privacy. In 1890 more than 25,000 people lived in Ottakring, more than 10,000 of them “Bettgeher”. More than 32 per cent of the flats consisted of one room only, which was often workshop and bedroom at the same time.

In comparison, one third of the inhabitants of the 1st district lived in a flat of seven rooms, more than 65 per cent of which could afford servants. In contrast, in Ottakring only 11 per cent of the inhabitants employed a servant. The rents in the outskirts of Vienna were extremely high compared to the income of the workers. When Ottakring became a part of the city of Vienna, the living conditions there were the worst of the whole 2-million metropolis and the environmental conditions unbearable: not the smallest green patch, apart from the hills of the Viennese Woods in the distance, thick smoke that rose from the many factory chimneys and in winter the smoke from the stoves; black soot covering everything. The workers had to endure 100-hour working weeks, Sunday work, no holidays, extremely low wages, child labour and at the same time rising rents and food prices. The speculation in the housing sector was exorbitant; the builders used the cheapest materials and exploited every tiny space for accommodating as many people as possible. Tuberculosis was so wide-spread that it was called the “Viennese disease”; children were neglected, dirty, malnourished, and ill. They suffered from tuberculosis, enuresis, rachitis, scrophulosis (a form of tuberculosis affecting the lymph nodes), and anaemia. These feral children were left to their own devices the whole day because all family members had to work long hours to make ends meet.

Examples of tenements in the outer suburbs, built around 1900 in Hernals and Ottakring, many of which are currently inhabited by today’s migrants and refugees:

The worst-paid groups of workers were those who worked in breweries – that’s where Ignaz Sobotka did his apprenticeship -, and the weavers who worked at home on looms provided by the textile factories. While in Hernals a very important sector was the food and confectionary industry. All apprentices were exploited shamelessly. Ottakring was the district with the highest birthrates, whereby the number of children born out of wedlock was extremely high, around 30 per cent, because young people could not afford to set up a family household. Although the infant mortality rate was extremely high, too – 30 per cent in the first year of a child – Ottakring could boast an ever-rising birth surplus. The population of Ottakring rose in the last decade of the 19th century from 106,000 to 148,652. The two biggest industrial enterprises were the “Ottakringer Brewery” and the “Tobacco Factory”. Many workers were employed in the metal industry, the lumber and wood-processing industry and the textile industry. Around 40 per cent of the women in Ottakring were employed workers, who were paid far lower wages than male workers. The working conditions in the factories and workshops were abysmal and contributed to the spreading of diseases. Glass cutters and glass grinders for example had to stop working at the age of 30, when they usually succumbed to tuberculosis.

Remnants of run-down tenements, erected around 1900, now mostly housing migrants and their businesses:

Else Feldmann (1884-1942), a Jewish-born socially committed journalist from very humble background, had already earned herself a reputation before World War I as someone who unsparingly unveiled the misery of Viennese children and adolescents in the outer working-class districts. In her articles she disclosed child labour in factories, the terrible conditions in hospitals for the poor, in institutions for disabled children of the proletariat, and in the public soup kitchens that provided one hot meal a day for the poorest of the poor. All her articles ended with an appeal for donations. She acted as a social worker before the job even existed in Austria. As a voluntary she campaigned for poor children and their mothers and for so called “failures in life”. In 1922 she published her partly auto-biographic novel “Löwenzahn. Eine Kindheit” (Dandelion. A Childhood), which earned surprising praise by fellow writers, such as Felix Salten, but also among literary critics. In this book Else Feldmann described childhood poverty inside the grey walls of the bleak outskirts of Vienna from the children’s perspective. The book was published in instalments in the “Arbeiterzeitung”, the Social Democratic paper. When in 1934 the Austro-Fascist regime destroyed the democratic First Republic in Austria and prohibited the Social Democratic Party, the publication of “Löwenzahn” was stalled. The social and political atmosphere of Vienna during the interwar years was not conducive to the career of a young female Jewish journalist from impoverished background. The poverty-ridden and destitute Vienna she described stood in stark contrast to the bourgeoise fin-de-siècle Vienna of Stefan Zweig’s “Die Welt von gestern” (The Word of Yesterday). After 1934 Feldmann continued to write, but she could not make a living, as her articles were not printed because they were politically inconvenient. In 1938 she was sick, destitute, and penniless, when as a Jew she was chased from her flat by the Nazis together with her old mother and her brother, who was unemployed and traumatised by his experiences as a soldier in World War I. She was moved from one Jewish “collection camp” in Vienna to the next until on 14 June 1942 she was deported to Poland on transport number 27 and most probably murdered immediately after arrival in the extermination camp Sobibor.

In 1901 the “Ottakringer Settlement” was founded. The settlement idea originated in England, where the first “Toynbee Hall” was erected in London, named after Arnold Toynbee, a British economist and historian. Highly-educated and bourgeoise people deliberately moved into poor areas of the city with the intention of helping the deprived local population and offering opportunities for education and training. Marie Lang of a well-to-do bourgeoise Viennese family, first married the imperial jeweller Theodor Köchert and after their divorce the Jewish lawyer and son of a factory owner, Edmund Lang, who converted to Protestantism when marrying her. This was quite common in the Viennese assimilated Jewish community. My grandmother, Ignaz’ daughter, Lola Sobotka, converted to Roman Catholicism, when she married my grandfather, Anton Kainz, the son of Viennese innkeeper in Währing, the bourgeoise 18th district of Vienna. Marie Lang’s partner in founding the “Ottakringer Settlement” was Else Federn from an assimilated intellectual Viennese-Jewish family. She had spent several months at the Women’s University Settlement in London in 1900, where she came into contact with this social reform project. Else Federn and her family lived in the “Ottakringer Settlement” and was the first work manager. Together with Marie Lang she organised workshops for mothers in the evening. The first Settlement House in Ottakring was donated by the Kuffner family, a well-to-do entrepreneurial Jewish family, who promoted modern scientific, artistic, and social movements – see above. It was situated in Friedrich-Kaisergasse, and the office of the charity was designed by the prestigious Viennese fin-de-siècle artists Josef Hoffmann, Kolo Moser and Alfred Roller. In 1918 the organisation moved into three bigger houses in Lienfeldergasse 60. Marie Lang already died in 1934 and Else Federn had to flee in 1938 to England. In the 1980s Ernst Federn became President of the “Ottakringer Settlement”, which was closed for good in 2003.

Apart from workers, many small sole traders in family businesses and self-employed entrepreneurs lived in Ottakring. They were hard hit by the economic hardships after the end of the Habsburg Empire and the Great Depression in the interwar years. Consequently, many children were either left to themselves in the streets or sent out to work or – mostly girls – were working at home in a form of cottage industry, helping their mothers to achieve inhuman targets of piece work. The wretchedness of the lives of workers and their families in the outer districts of Vienna after 1900 was well documented by socially committed journalists and researchers, such as Max Winter, Emil Kläger and Robert Neumann, but the intellectuals and artists of the time rather indulged in the glamour of fin-de-siècle Vienna and tended to ignore the other side of the coin. Nevertheless, in legends, myths, and the traditional Viennese song, the “Wienerlied”, the miseries of the Viennese outer suburbs were present. Themes, such as famine revolts, excessive drinking, gambling, and dancing as a means of forgetting about the miserable living conditions, were “celebrated”. The balls of washer women, rag balls and so-called “Glasscherbentänze” (broken glass dances) in infamous dens and wretched bars, the youth gangs at the “Schmelz” and on the “Hernalser Flohberg”, petty criminals and social rebels were extoled in songs and glorified.

Contrary to these working-class attitudes, as already mentioned with respect to the Sobotka family, other, mostly skilled, workers saw chances of social advancement via education and training. Their ambitions were supported by the rising Social-Democratic movement, where the representatives promoted educational and training courses for workers, access to art and science and the rejection of alcoholism and gambling, as in the “Ottakringer Volksheim” (see above). After 1918 the demands for decent living conditions, just wages and affordable healthy housing had priority for the Social Democrats in the First Austrian Republic in Vienna. With their majority they could transform the city in line with their ideals in the project of “Red Vienna”. Many inhabitants of the outer suburbs, for instance Favoriten, Ottakring or Hernals, politically supported the Social Democratic Party and among them were many Jews, such as my grandfather Ignaz Sobotka. With Austro-fascism and the abolishment of the democratic system in February 1934 this innovative Viennese social reform programme was terminated:

See articles:

http://centraleuropeaneconomicandsocialhistory.com/red-vienna-1923-1933-educational-reforms

http://centraleuropeaneconomicandsocialhistory.com/red-vienna-1923-1933-housing-reforms

http://centraleuropeaneconomicandsocialhistory.com/red-vienna-1923-1933-social-welfare

The assumption that the Viennese Jewish population was a homogenous economic group is totally absurd, but was widely propagated by racist, nationalist populist politicians. In some of the outer districts the misery of the Jewish and non-Jewish population was indistinguishable before 1938. The anti-Semitic propaganda kept denouncing the Jewish millionaires and financiers, ignoring the masses of Jewish beggars, of the Jewish homeless, and of starving and freezing Jewish families and children. No studies about the living conditions of the poor Jews were carried out in Vienna at the time and there are no historical statistics available, but it can be assumed that the social strata were the same as in the rest of the Viennese population; approximately one sixth of the Viennese Jewish population was bourgeoisie and one third were working class and lived in very cramped circumstances. The largest part was lower middle class; they were educated employees, small business owners, and artisans. Before World War I the lower middle-class rented flats with two rooms, a kitchen and maybe a small closet for a servant. After World War I the economic conditions worsened and all tenants had to sub-let a room or the closet and take in lodgers to be able to pay the rent. Meanwhile it had become virtually impossible to rent a flat as a Jew in the interwar years in Vienna, if they did not already have an unlimited lease contract, because Jews were harshly discriminated against. Historically, anti-Semitism was wide-spread in Vienna, but after the break-down of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, it seemed to have been unleashed uninhibitedly. This anti-Semitic atmosphere did not end with the break-down of the NS regime in 1945. Rudolf Gelbard, a survivor of the KZ Theresienstadt, reported an incident of 1945, when he went to the cinema in Hernals with two other adolescents. They were prevented from entering the cinema, as they were suddenly surrounded by a mob of racist adults who insulted and attacked the youngsters, regretting that they had not been “gassed in the KZ”. In the Kalvarienbergkirche in Hernals, there is a baroque “way of the cross”, where at station number 14 the figure of a Jew is represented, which until recently had been spat at by some Christian visitors, as was common before World War II. It is the so-called “Körberljud”, who was so often attacked, that the head of the statue had to be replaced by an iron copy.

Kalvarienbergkirche, Hernals: baroque façade and “way of the cross”

The metropolis Vienna: a conglomerate of socially divided, segregated urban entities

The most valuable asset of the vast migration from all parts of the Habsburg Monarchy to Vienna was the influx of so many different talents that lived side by side and taught the capital city to integrate different perspectives and a variety of experiences in its mind and concepts. The Viennese directory “Lehmann” boasted 940 pages of five columns each of Viennese businesses in trade, industry, and crafts. Nevertheless, the city was divided into the elitist centre and the suburbs, populated by migrants, workers, and the urban poor: masses of disadvantaged people who were yearning for social equality and a just sharing of the wealth the city produced. The Vienna of the poor proletariat was outside the detached perception of the “haute bourgeoisie”. The Slovenian author Ivan Cankar described the working-class district Ottakring, where he lived for some time, in vivid colours: the seamstresses who worked in their dark and sordid flats, where the sun never reached them, the black soot of the factories that covered everything and even stuck to the inhabitants’ faces. The tenements were high and boring, and the people you encountered in the streets were raggedly dressed, pale and famished – they looked destitute and there seemed to be no end to this bleak suburb.

The writer and journalist Max Winter researched in a social report of 1910 the living conditions of the migrant workers who flocked into the city; bricklayers, construction workers, carpenters, and masses of unskilled workers who came from all corners of the Empire to the capital city. They often left their wives, children and the old in their rural backward homes. Whenever a river had to be regulated, a tunnel had to be built, a railway line was constructed or a quarry was in need of menial workers, Italians, Ukrainians (then called Ruthenes), Bosniaks, Macedonians, Czechs, and Slovaks came with the little they possessed on their backs, prepared to do hard work because everything was better than the destitution and poverty in the villages at home. Vienna around 1900 was like a magnet that attracted migrants. Even without affordable means of public mass transport the people of the Habsburg Monarchy had always been mobile; for example, apprentices went on the “Walz” after completion of their apprenticeship. For artisans, flexibility and adaptation to the customs of a strange region were state of the art of an artisanal training. This mobility was important for the promotion of trade and the transfer of skills and technology. But the travelling artisans were also known for being rebellious from time to time and for being the ones who did not always play by the rules and evaded or even escaped authorities. At the time of industrialisation not only servants and artisans were a – mostly seasonal – travelling group, but before the outbreak of World War I people from all regions, from all walks of life, most of all Jews, Czechs, Croats, and Slovaks moved to Vienna because despite working-class destitution and poverty in Vienna, the wages in the city were by far higher than what these migrants could earn in their rural home regions. Vienna was an industrial boom town at the time, even more attractive than the industrial towns in Moravia and Bohemia. There was a huge demand for labour in all sectors, service, construction, artisanal manufacturing, and industry; and what is more the railways facilitated transport and further boosted mobility.

At the newly built grand terminal railway stations, in the south, north east and west of the metropolis, the migrants arrived and in the vicinity of these stations cheap high- rise buildings were erected, where the landlords exploited the newly arrived migrants. The flats there measured a maximum of 30 m2 and often six to eight people were housed under precarious conditions of sub-letting or just renting a bed. In 1910 700,000 inhabitants lived under such conditions. Felix Salten, anonymously published his novel “Josefine Mutzenbacher” in 1906, where he highlighted the social circumstances of stark poverty, crowded housing, and sexual abuse. The homeless found out about a bed to rent or a room to sub-let via word-of-mouth or small notices pinned to the entrance doors of flats. The raging inflation and the drastic price rises for food and rents led to mass riots in the city. If the rent could not be paid in full the landlords reacted with evictions, which increased the already disturbingly high rate of homeless. The detachment of the inner-city elites can be seen in the comment of the Viennese mayor Karl Lueger and the city parliament in 1908, saying that no one in the city would be homeless in winter unless it was his / her own fault. The only refuge for the homeless were a bed to rent for a few hours, sleeping outdoors or climbing down into the canal system, as Emil Kläger reported.

The city of Vienna tried to combat the housing disaster by promoting the construction of charity-funded boarding houses for men. It would have been better to limit the power of the Viennese landlords, who could raise the rents as they wished and could evict those who could not pay within a fortnight. But approximately half of the members of the Viennese city parliament were landlords and lobbied for their interests there. If the police detected someone who tried to sleep in the open air over night, they transported the person to a workhouse if he or she was able to work and the invalids to an asylum for the homeless. But these asylums were only opened when the night broke and they only welcomed Viennese citizens and families and not unaccompanied children below the age of 14. Normally persons were allowed to stay in such a shelter for seven nights only within the period of three months, but for families exceptions would be made. In a boarding house for men around 58 men slept in one big dormitory. For 550 men there were six toilets available during the day, but there was no possibility to wash your hands. The inhabitants of such boarding houses had to carry their belongings with them all the time because the renting of a wardrobe was very expensive. The food offered in the canteens was much too pricy with respect to the quality offered. The men tried to make do by queuing up in front of small stoves, where they tried to cook their own meals. As the city of Vienna meanwhile considered the renting of a bed unhygienic, they established a boarding house for men financed and run by the city in the 20th district, Meldemannstrasse. The six-storey house offered 544 cubicles in dormitories, which were separated by thin walls, a dining hall for 180 persons, two reading rooms, several bath rooms and a doctor’s surgery. Emil Kläger, a journalist renowned for his social reports, sneaked into this boarding house and reported that it had the atmosphere of a simple hotel at the entrance, that it was well-heated, the food was good and cheap and sanitary conditions were exemplary. Most inhabitants had work in the new factories, but no home. On average the men should not stay longer than 50 days in the city’s boarding house for men. The boarding house’s most “infamous” inhabitant was Adolf Hitler, who stayed from 1910 to 1913 for 1,200 days at the boarding house for men in Meldemannstrasse..

Juvenile food riots in Ottakring in 1911

The dynamic relationship between centre and periphery in the city of Vienna, between inner city and outer suburbs, resulted in a tension between the elitist culture of “fin-de-siècle Vienna” and the popular culture of proletarian pubs, fun fairs, and the gloomy taverns of petty criminals. This class-related strain created new forms of economic, cultural, and social inequality and fission in the developing modern metropolis. The societal dynamic promoted the development of early forms of mass culture. In the minds of the underclass the distance of popular ways of life to the elites in the inner city was historically perpetuated and boosted the culture of resistance and obstructiveness of popular “sub-cultures”. These suburban sub-cultures were viewed by the fin-de-siècle Viennese elite – if they were even noticed and mentioned – as crude, uncivilised, dangerous, and heinous. These representatives of the proletariat were “without history”, which characterised their impotence and absolute subjection. This situation of subjugation of the poor can be defined as a form of “domestic colonialism”, which determined the continuous attempts at dodging the elite’s dominance and control. This insubordination of the impoverished masses of the outer suburbs and the abysmal living conditions there led to suburban cultural retreats, for example, the grimy dens, dance halls, musical halls and varietés, and the “Heurigen” (simple taverns where the new wine was and still is sold and the “Wienerlied”(Viennese song) with its defiant lyrics, an expression of social revolt, was sung). A typical area of this resistant sub-culture was “Neulerchenfeld” in Ottakring, where social and cultural deviance was celebrated and found expression in petty crime, youth gangs, and prostitution:

As a consequence of this atmosphere of social tensions, on 17 September 1911 a hunger rebellion erupted in Ottakring. It was the first and most wide-spread outbreak of the marginalised and disadvantaged masses of the outer working-class districts. The revolt was not just sustained by the Viennese urban under-class, but by the many young migrants who had come to the city to improve their living conditions and were frustrated by the poverty, hopelessness, and lack of opportunities they encountered. At the end of the first decade of the 20th century an explosion of food prices affected the urban working class, which suffered the most. They lost a third of their purchasing power. The reason for the enormous price rises of food stuffs was the backwardness of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy’s agriculture, which meant that many products had to be imported from abroad at high import-tariffs. This situation was exacerbated by the serious problem on the housing market, characterised by criminal speculation on property, building materials and high taxes that resulted in a virtual stand-still of construction activities in the field of workers’ housing in the outer districts. Consequently, the rents were rising disproportionally and the poor masses who were suffering under the price-hikes had to sub-let their tiny flats to survive. Thousands were homeless because they could not even find a bed to rent. These unbearable living conditions led to an outbreak of violence in the suburbs. The Social Democratic Party did not receive any support from other parties to remedy the situation and on 17 September 1911 not just the city’s authorities, but also the Social Democratic Party lost control over the mass protests. Early in the morning around 100,000 protesters were marching from the outer districts to the city centre. Social Democratic members of the city parliament tried to calm the situation, when a confrontation with the police forces ensued, but in vain. Youngsters protested in front of the flat of the mayor in the 1st district, Lichtenfelsgasse, and devasted nearby inns, when they threw glasses, plates, chairs and sticks at the policemen and their horses. Complete chaos followed and masses of young rioters marched across the city towards their home turf, Ottakring. On their way they devastated the city; no shop window, no street lantern remained intact. The youth gangs, consisting of 14 to 15-year-old boys from the impoverished hot spots at the “Schmelz” and Ottakring, had joined the demonstrators. The events of the day brought all the inhabitants of Ottakring to the streets to observe the ongoing events. The military occupied the tobacco factory in Ottakring and the police and soldiers received the order to shoot at the demonstrators. Nevertheless, the violent riots continued and the youngsters attacked and destroyed everything possible in their home district: schools, libraries, the vaccination institute, the chocolate factory Manner in Hernals. Finally, at 10.00 pm the police forces were in control of the situation, Ottakring was in complete darkness and three demonstrators were dead. Schools, libraries, and scientific institutes were primary targets of the youthful rioters because they represented the “modern written order”, which they were not part of – most of them were illiterate – and which they therefore resisted as a symbol of the state’s exploitative power that tried to discipline them. Literacy and science, exactly what had led the Sobotka family out of working-class poverty, had become symbols of a modern economy and society that the juvenile rioters could not profit from and therefore rejected. Currently a similar trend can be observed, whereby those who feel they have been left behind by the modern digital revolution, reject science, technology, and university education.

Symbols of modernity, such as factories, schools and scientific institutes were attacked by the juvenile rioters in Ottakring and Hernals:

The confectionary factory “Josef Manner & Comp.”, Hernals (still active today;

The tobacco factory, Ottakring (a school building and housing complex today)

The grammar school at Schuhmeierplatz, where classrooms, offices and the library were devastated

The former vaccination institute in Ottakring, Possingergasse

LITERATURE

Adunka, Evelyn & Anderl, Gabriele, Jüdisches Leben in der Wiener Vorstadt. Ottakring und Hernals, Mandelbaum Verlag 2013

Adunka, Evelyn & Anderl, Gabriele, Jüdisches Ottakring und Hernals, Mandelbaum Verlag 2020

Cockett, Richard, Vienna. How the City of Ideas Created the Modern World, Yale 2023

Contreras, Ruth, Das Jüdische Favoriten. Ein Gedenkbuch, Mandelbaum Verlag 2025

Feldmann, Else, Löwenzahn. Eine Kindheit, Milena Verlag 2025

Haller, Günther, Café Untergang. Stalin, Hitler, Trotzki, Tito 1913 in Wien, Molden Verlag 2023

Judson, Pieter M., The Habsburg Empire. A New History, Harvard 2016

Lang, Anton, Die “Schleierbaracken”. Von den Invalidenschulen zum Gewerbepark. Favoritner Museumsblätter Nr. 25, Wien 2000

Maderthaner, Wolfgang & Musner, Lutz, Die Anarchie der Vorstadt. Das andere Wien um 1900, Campus Verlag 2000

Rathkolb, Oliver, Ökonomie der Angst. Die Rückkehr des nervösen Zeitalters, Molden Verlag Wien 2025