Left: scythe, right: sickle, both produced along the “Iron Route”

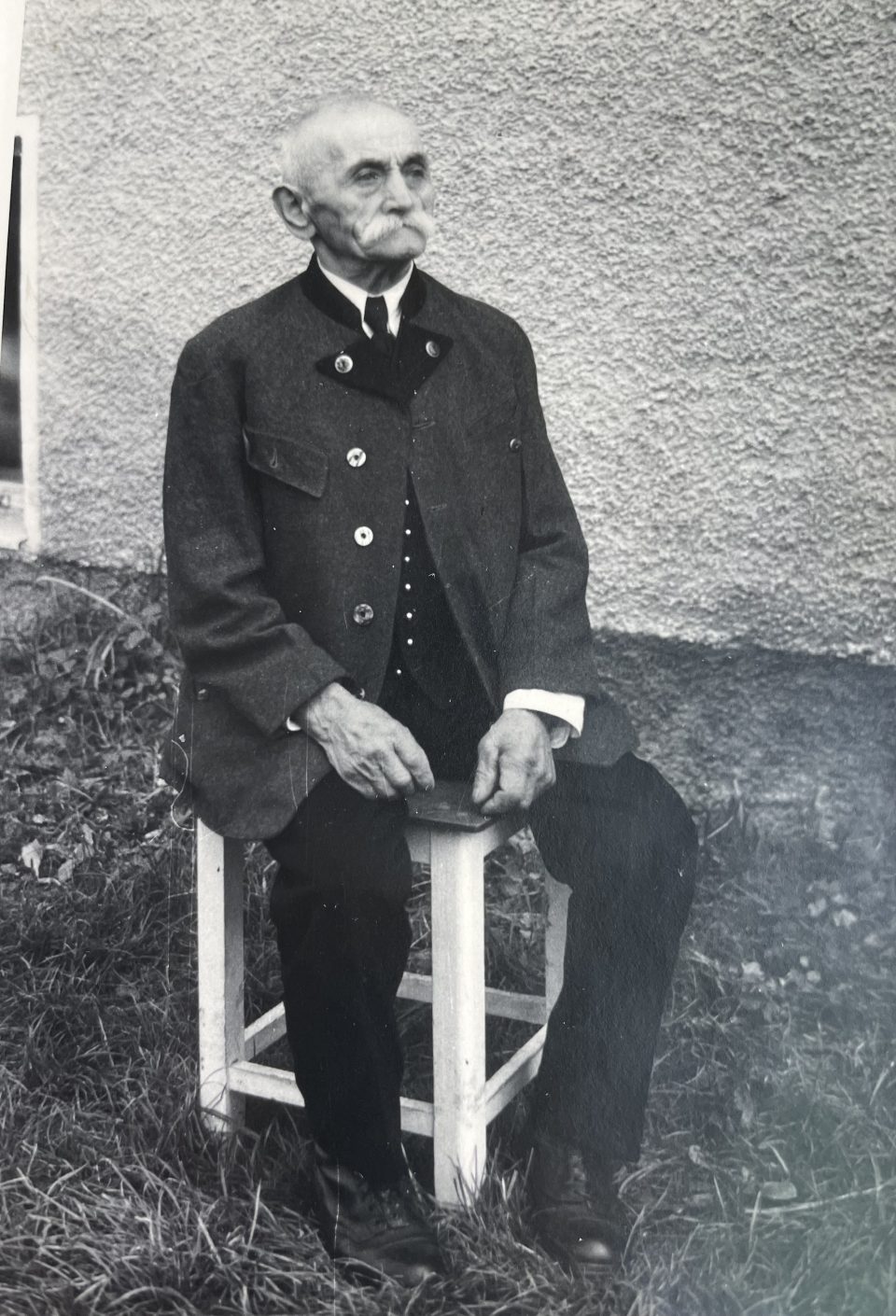

Johann Wurm, my husband Karl Wurm’s grandfather, a scythe smith like his father:

Left: Johann as a boy (left) with his elder brother (in the middle) and his mother

Right: Johann (right) with a colleague in the festive dress of scythe smiths

Left: Johann as an Austro-Hungarian soldier in the First World War on the Italian front line; right: Johann at his wedding

Left: Johann with his two sons Johann (left) and Karl (in the middle), my husband’s father; right: Johann’s two sons, Johann & Karl, as young men

Johann Wurm, born in Randegg in the “Iron Roots” (Eisenwurzen) region in 1874 and Karl’s grandfather, was a trained scythe smith, just like his father, Karl’s great-grandfather. At the time it was common to pass on the knowledge about special techniques of making scythes in the family and keep it from other apprentices, who might turn into future competitors on the labour market. Like his father, Johann was a travelling craftsman, who worked at several hammer mills or trip hammers along the Styrian and Upper Austrian “Iron Route”. For a longer period, he worked at the hammer mill in Roßleithen, one of the last still existing scythe production sites world-wide.

The hammer mill was run by the family Schröckenfux and comprised several buildings, which formed a small village including accommodation for the travelling scythe smiths and the apprentices and menial workers, a shop, an inn, the living quarters of the management and the manor house of the owner of the mill. Right: Karl in front of the office building of the current iron manufacturing company.

The old hammer mill village and on the right the hammer mill shop

“Iron Route” & “Iron Roots”

Iron was mined at the “Erzberg” (Iron Mountain) in Styria probably since the 6th century by Slaws, who had settled there and had adopted Roman techniques of smelting iron ore. The region north of this important iron ore mining site, where the iron of the “Erzberg” was processed was later called “Innerberger” iron manufacturing area and covered the banks of the rivers Enns, Ybbs and Erlauf. Here the “Iron Route” leads from the “Erzberg” to the two main competing market towns Steyr in Upper Austria and Waidhofen in Lower Austria. This is the region we are concentrating on in this research, whereas the area south of the “Erzberg”, where iron was manufactured and traded was called “Vordernberger” iron manufacturing area and covered Leoben and parts of Styria. The “Innerberger” region is also called “Eisenwurzen” (Iron Roots), which literally means “iron + roots”. This geographical term refers to the fact that where iron was mined, which was a key cultural technique, the workers were not autarkic. The land was not conducive to agricultural activity, so the miners could only survive, if the arable farmland of the Alpine foothills provided them with nourishment and all the ancillary crafts they needed for mining, for example lumbering and charcoal production. The “roots” were the peasants and farmers who provided food and bought the iron produce they needed for their work, such as sickles, scythes, hammers, nails, and horse shoes. Around the “Erzberg”, the miners and the smelters settled; in the higher regions of the Alpine foothills with their steep and narrow river valleys the hammer mills were situated, which processed rough iron, whereas further down the rivers the hammer smithies and trip hammers produced specialised iron products such as nails, scythes, and sickles, just as in Roßleithen. On the fertile agrarian soil, the farmers grew the necessary provisions for the miners and smiths and in the large market towns the iron traders gleaned huge profits from the hard labour and exploitation of the workers in the mines and in the hammers and of the peasants.

The “Innerberger Iron Route”

At the “Erzberg” the territorial landowners made sizable profits over the centuries, while the miners led harsh lives, characterised by deprivation. They lived in small huts, worked in the dark under-ground, and mined iron ore with the help of blind animals and primitive tools that had not changed since the Middle Ages. The working and living conditions of those who worked in the hammer mills in the narrow and humid valleys of the rivers Salza, Jessnitz, Erlauf, Ybbs, Enns, and Schwarzbach, were not much better off. They had to settle far away from their families in solitude, at sites which were very difficult to reach, even on foot. Few were lucky and could set up their own enterprises eventually. By that they gained some wealth as owners of small-or medium-sized hammer mills. In the region they were called “Schwarze Grafen” (Black Counts). Those workers who were the best off were the ones who produced specialised iron wares, which were much in demand, such as scythes. They were also the first ones to rid themselves of the strict dependence on the feudal territorial lord.

On the other hand, there were the powerful merchants in the towns Steyr, Ybbs, and Waidhofen, who traded the rough iron as well as the finished iron products in the market towns and who acquired special privileges from the territorial rulers. The trade routes for iron and iron wares crossed the trade routes for bread grain, lard, oat etc. Along these roads, the “Three Markets Road” (Dreimärktestrasse), three market towns, Scheibbs, Gresten and Purgstall, developed into important trading centres, where bourgeois merchants grew rich as well. Any trade down-river was much more profitable at the time before the introduction of steam ships, and especially long-distance trade was the most profitable. This meant that also the territorial rulers craved the profit from these riches, imposed taxes and distributed privileges to merchants and market towns. Military conflicts now and then halted the economic expansion of the iron production in the region and that is why the iron industry experienced cyclical up- and downswings. Eventually, the industrialisation of the 19th century led to a boom of this sector along the “Iron Route”. The prices for food and lumber rose, and the wages, too. The working time during the week was expanded from early in the morning, around 3.00 or 4.00; until 18.00 in the evening. But from the middle of the 19th century on the cheap competition from England hit the local producers and many had to shut down. For a comparison: In 1572 there were 72 iron masters in Ybbsits – the 16th century was a boom time for iron production in the region – , in 1808 there were only 63, in 1860 53, in 1885 40 and in 1908 the number was reduced to 28 iron masters.

Johann Wurm in front of an iron ore mine

Johann on top of a wagon transporting iron ore out of the mine

The noble family Jörger were the perfect example of aristocratic capitalist entrepreneurs of early industrialisation in the Habsburg Empire. During this period, making profit and raising funds had become the main goal of industrial production; not as in earlier times, when raising capital was always a means to a specific end, such as building castles or waging wars. In the era of early capitalism profits, interest or rent added to the capital of the noble entrepreneur. That could be reinvested and lead to more profit – an economic concept that is still valid today. As a noble landowner Helmhard Jörger (1572-1631) was entitled to set up manufacturing businesses on his territory and he did so by erecting a factory in Pernstein in Upper Austria, which produced scythes with the help of machines. He introduced a newly invented hammer to form the rough scythes into finished products, the “Breithammer” (wide flat hammer). The guilds in the cities, which felt they had the monopoly on the production of scythes, protested, but in vain. Helmhardt Jörger used his privileges as a member of the aristocracy and exploited his far-reaching network to penetrate new markets with his new machine. He produced large amounts of scythes until the home market was saturated and too limited for the quantities his factories manufactured. So, he linked up with a Dutchman who had settled in the Habsburg Empire, Jobst Croy. He was a Calvinist and had supposedly left the Low Lands in the 1560s. He was one of the most colourful and dubious personalities of early capitalism in Austria. With the money of his wife, he started to do business here by approaching the imperial court and the Austrian nobility. The Netherlands, just as Italy, were financial pioneers. In Amsterdam the first joint stock bank and the forerunner of the first stock exchange were established in 1609, at the time when the Habsburgs were ruling the Low Lands. Jobst Croy agreed with Helmhard Jörger on a contractual pre-emption right, by which Croy would buy a certain amount of Jörger’s scythes at a fixed price and would use his international trade network to find new markets for Jörger. Early capitalists typically used this form of division of responsibilities between producer and seller. Croy was one of the early merchant bankers who traded in “loan notes”, an early form of bonds. The problem was, when merchants and traders lent money to royal or imperial rulers, they often had to wait a long time until the rulers were willing to repay at least part of the debt, if at all. In this way the Habsburgs, for example, ruined many of their financiers, often of Jewish origin. To those who had to sell their loan notes, because they were threatened by bankruptcy, Croy and other merchant bankers offered relief; Croy bought those bonds before expiry date at a much-reduced value and in the end, when the debt was paid, he made a profit from the difference. This banker’s practice developed into the discounting bills of exchange later. Many of these early merchant bankers were also involved in capitalist mining, because only few early industrialists had the funds to exploit mines industrially, as it took a long time and lots of money from starting a mine project until the first profits could be reaped. This was true for the Styrian “Erzberg”, too. The iron merchants in Steyr, for example, lent money for the mining of iron ore and in exchange they took control of all the “Innerberger” iron, which was transported to the north of the “Erzberg”. But eventually they were short of funds, too, and got indebted. They owed large sums to the “big players” of early capitalism, for instance the Welser family of Nuremberg. When the iron merchants could not repay the debt, the Welser got access to the high-quality steel production of the “Erzberg”, which was in especially high demand in times of war. In this way Styrian steel blades were even used in North American acts of war.

It is interesting to see that early capitalists in the Catholic Habsburg territory of Austria were often representatives of the nobility who had converted to Protestantism. One fascinating and long forgotten personality was Anna Neumann, who had converted to Protestantism at the age of 20. She lived at the times of religious warfare in Central Europe, the fights against the Huguenots and the 30-Years War. She was widowed five times and at the age of 82 she was without an heir, so she married the 31-year-old aristocrat Georg Ludwig Schwarzenberg, to whom she passed on the considerable wealth she had accumulated during her lifetime. Her last two marriages with much younger men were considered adoptions because they were designed to provide her with an heir. At her death in 1623 these riches formed the pecuniary basis for the rise of the Catholic aristocratic family of Schwarzenberg in the Habsburg Empire. Her father, Wilhem Neumann, had been a successful merchant in Villach, Carinthia, who owned mines in Idria, north of Trieste and in Bleiberg, near Villach. She inherited her parents’ assets, as she was the only heir and managed to purchase the seignory of Murau in Styria near the “Erzberg” for 76,000 fl. (Gulden = today around 28 million euros), because she was the main creditor of the family of her second husband, the noble family Liechtenstein, Anna Neumann was a very tough business woman and a successful money lender. At her death at the age of 88 the Habsburg Emperor Ferdinand II owed her 340,000 fl. (€ 84 million), the archbishop of Salzburg 23,000 fl. (€ 5.7 million) and several aristocratic families were indebted to her, too. These facts prove, what a successful early merchant banker Anna Neumann had been in the region of the “Iron Route”. Anna, who was extremely parsimonious, invested a large part of her fortune in the acquisition of property and huge forest areas, which were very profitable, because mining on the “Erzberg” required large amounts of lumber and charcoal. Her husband Georg Ludwig Schwarzenberg inherited 18,000 hectares of forest, which the noble Schwarzenberg family still possesses. Anna had to face a lot of hostility during her lifetime, as a Protestant, as a money lender, as a successful business woman and due to her six marriages. Twice she was accused of witchcraft. She was supposed to have triggered devastating thunderstorms, so that she could buy harvests at exorbitant prices. She was not sentenced for sorcery, on the contrary, her denouncers were put to death for false testimony. Yet at her death the archbishop of Salzburg denied her husband, Georg Ludwig Schwarzenberg, the right to bury his deceased Protestant wife in the main church of Murau, where she had been the “town lady” for decades, had donated large sums to the city and had cared for the poor in her seignory.

Iron manufacturing in the Mill Quarter

The important medieval trading city Freistadt and the Mill Quarter were a Central European region, where along age-old bridal paths, trade routes, and postal carriage ways rough iron ore, semi-finished iron products, and finished steel wares were transported by traders from small smithies to the north and east of Europe. The raw iron came from the “Erzberg” and found its way along the “Iron Route” to the Mill Quarter. Due to the huge amount of wood, which was required to process the iron, the hammers and smithies had to be moved ever further away from the mines, along the trade routes and near merchant towns. The many skilled nail smiths, scythe and sickle smiths along the way made the traditional practice of “house smithies” obsolete, where the peasants themselves had produced the iron utensils they needed from rough pig iron blocks. The expert smiths were much more skilled, were specialised in certain iron products and used more efficient combustible materials and bellows. As a result, the tools were of supreme quality and facilitated the tough chores on a farm. As the use of charcoal required an even higher amount of wood, more hammers and smithies were established along small and medium-sized rivers in the vast wooded areas north of the Danube, where the territorial lords boosted the production of iron wares. Until that point in time, settlements were not erected along these rivers, because the danger of flooding was too big. The rivers of the densely wooded area of the Mill Quarter were ideal for this purpose. They were not too far away from the “Erzberg” and situated along the trade routes to the important market towns further north, for example Breslau, Krakau, Thorn, Königsberg, and Tilsit. New technologies, such as the overshoot water wheel, lent themselves to the fast-moving smaller rivers of the Mill Quarter rather than to larger slow-moving rivers like the Danube.

Freistadt, the main market town of the Mill Quarter

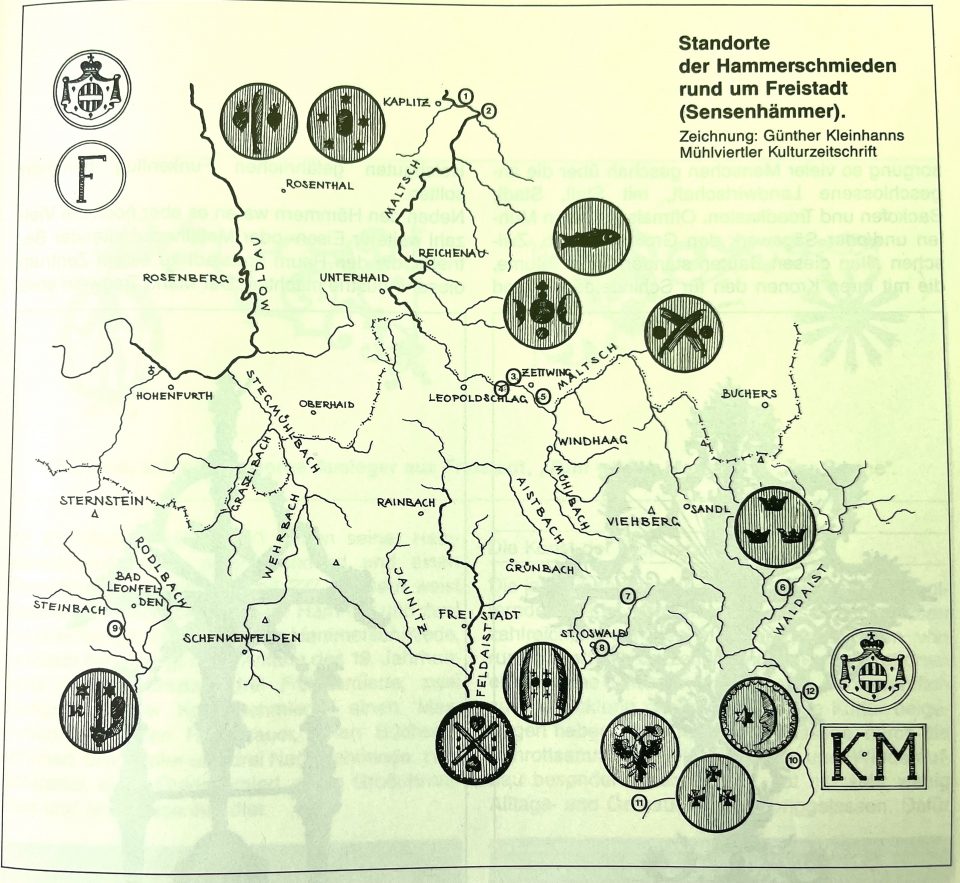

The smooth functioning of a rural iron proto-industry relied on the well-balanced coordination of mining iron ore, smelting, lumbering and charcoal production, transport, processing of the raw iron, training and provisioning of the skilled and unskilled workers, a well-organised guild structure and the prevention of technical espionage, well-regulated markets and tariffs, wholesalers and retailers and the servicing of profitable foreign markets. In this region the many small hammer mills could only exist, if they formed cooperatives, so-called “Gewerkschaften” and specialised in different fields of iron and steel production. There were around 70 highly specialised skilled crafts related to iron and steel, such as nail smiths, knife smiths, sheet smiths, saw smiths, sickle smiths, scythe smiths and so on. In the 15th century the different skilled crafts formed guilds, for example in 1449 the guild of the scythe smiths in Waidhofen / Ybbs and around 1500 in Freistadt. In the 16th century a significant economic upturn resulted in a doubling of the exports of iron wares from the region around Freistadt and the owners of the hammers mills in the Mill Quarter were called “Black Counts”, too, due to the wealth they had accumulated, which was enormous compared to the extreme poverty of the average peasant population. The value of a small hammer mill was ten times the value of a stately bourgeois house in Freistadt. Such a hammer mill with two forges and around seven workers could process 80 tons of iron a year. For the supply of the raw iron 150 horses and carts were needed, which could cover 20 kilometres a day. If we assume that a dozen to two dozen hammer mills were in operation around Freistadt, that meant a considerable traffic of carts loaded with pig iron on the road from Mauthausen on the Danube up north to the Mill Quarter. Since 1519 the iron production in Styria, Lower and Upper Austria until the border to Bohemia was under the regulatory supervision of the territorial rulers. Nine of the dozen hammer mills and scythe smithies around Freistadt were entitled to brand their products with an “F” (Freistadt) and with the Austrian coat of arms (the Austrian shield and the ducal hat), next to the special maker’s mark of every hammer mill or smithy. Those three scythe hammers which were members of the guild of Kirchdorf-Micheldorf were entitled to brand their wares “KM”- see below:

12 scythe hammer mills around Freistadt with their locations and maker’s marks. Only few tools with maker’s marks have been preserved because over time, especially in the 20th century, old iron was collected and melted down for war purposes and reconstruction during and after World War I and II

A proper hammer mill consisted of several buildings and facilities: a small river or brook, a weir, a pond and the actual hammer mill with the forges, barns for charcoal, huts for crude iron and barns, where the finished products were stored and packed for transport. Scythes and sickles were packed in barrels for transport. Additionally, there was the stately home of the owner of the hammer mill and the management; often a garden and garden house were attached to it. Furthermore, there was a house where the travelling smiths stayed, the masters together with the unmarried fellows of the guild, and a stable for the horses and carts. Apprentices and unskilled workers were housed in sheds. Often a farm was attached to the hammer mill, which provided the workers with the bare necessities and sometimes corn mills and saw mills were added to a large hammer mill site. Between all those buildings large trees with their huge crowns were planted to prevent the wooden buildings or shingled roofs from catching fire by flying sparks.

Hammer mill site with wooden sheds, Roßleiten

All across the Mill Quarter ancillary businesses were located, such as needle smithies, copper smithies, file smithies, locksmiths, horseshoers or farriers, rifle makers and iron traders.

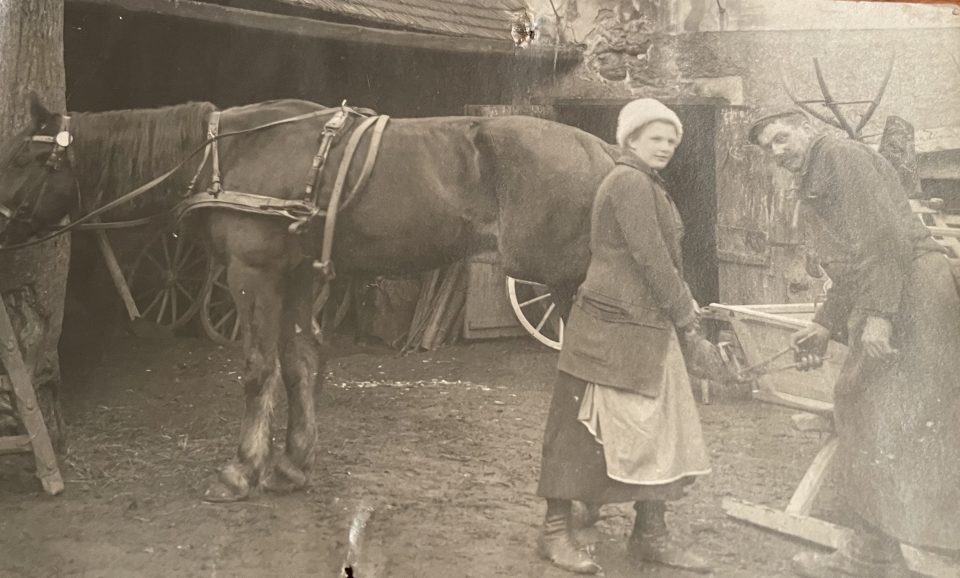

Farriers in the Mill Quarter in the 1970s

In the Middle Ages the specialisation in the iron manufacturing business started and many different types of iron tools and products were manufactured in small and medium-sized hammer mills and smithies. The industry provided employment for the local population in the region of the “Iron Route” and the Mill Quarter, such as Karl’s great-grandfather and his grandfather Johann. In the 16th century when the princely monopoly at the “Erzberg” was lifted, several small private mining sites were set up. In the Mill Quarter small mines were run in Windgföll, Weitersfelden and Gramastetten. There are reports that at the “Hungerbauerhof” sizable quantities of “iron earth” were mined until the 19th century. Freistadt was not just an important merchant city, but also an “iron storage location”, just as Vienna and Krems along the Danube. Traders who transported iron goods from the Danube north across the Mill Quarter had to stop at Freistadt and offer their wares to the local traders. Semi-finished products were therefore often finalised in one of the local hammers and smithies, as there was enough wood and waterpower available. The trade and crafts code of the guild of scythe smiths in Freistadt of 1502 is one of the oldest trade and crafts codes in Upper Austria. In 1755 six hammer mills with 39 scythe smiths and several apprentices were guild members and the inn “To the Black Bear” (Zum schwarzen Bären), Hauptplatz 12 in Freistadt, was the guild lodging house of the travelling scythe smiths.

In the 19th century the scythe production experienced a severe downturn due to foreign tariffs, the competition from Germany, old-fashioned local practices, and the higher price of Austrian quality steel. Most of all, Austrian traditional superior brands were copied and foreign competitors illegally used Austrian maker’s marks. Inside the Habsburg Empire such brand faking could be sued on the basis of the Trade Regulation Act of 1859, but foreign abuse of Austrian well-established scythe brands could not be stopped. Especially Western German and French companies copied maker’s marks of Austrian scythe producers. The aim was to penetrate traditional Austrian foreign markets, such as Russia, with illegally selling cheap Austrian copycats. When at the end of the 19th century the protection of brands was internationally negotiated and secured, the Upper Austrian scythe industry had already lost considerable market share in their most important foreign markets.

Apart from scythe smiths, there were many hammer smiths, cart smiths and farriers in the region of the Mill Quarter. Despite regulations which clearly stated which products were to be manufactured by which specialised iron smiths, there were many complaints about trespassing and abuse of rights; for instance, a hammer smith complained that a farrier was repairing cart wheels and cart axes, although this was the task of a cart smith. Such practice was usually countered by a cross action. Apart from these tensions within the iron manufacturing craft and trade guilds, serious conflicts erupted continuously between territorial rulers and hammer mill owners, mostly about the cutting of timber, which was urgently needed for the forges. The territorial lords passed rules and regulations which prohibited the felling of trees or hindered the floating of lumber downriver. In 1848 the later Mayor of Freistadt, Caspar Schwarz, tried to prove to the territorial lords how important the hammer mills were for the region in a motion in the state parliament of Upper Austria. He stated that every worker in the hammer mills contributed a profit of 5,000 fl annually, an amount that the territorial lord could not equal. Additionally, bakers, millers, brewers, farmers, butchers in the region benefited from the profit made by iron mills. Unfortunately, such attempts could not prevent the decline of the iron industry in the Mill Quarter. In 1890 the guild of scythe smiths in Freistadt was dissolved. That was probably the reason why Karl’s great-grandfather and grandfather had to look for work as scythe smiths farther away from home, along the “Iron Route”. Even the booming business of producing saw blades, which were exported to Bavaria, Romania, Poland and Russia, had to stop the production in the Mill Quarter. Only two hammer mills, J. Freyenschlag in Königswiesen and Hofwies in Windhaag survived until the end of the Habsburg Empire in 1918. During the World Economic Crisis of 1929, the export of iron products from the Mill Quarter ended completely.

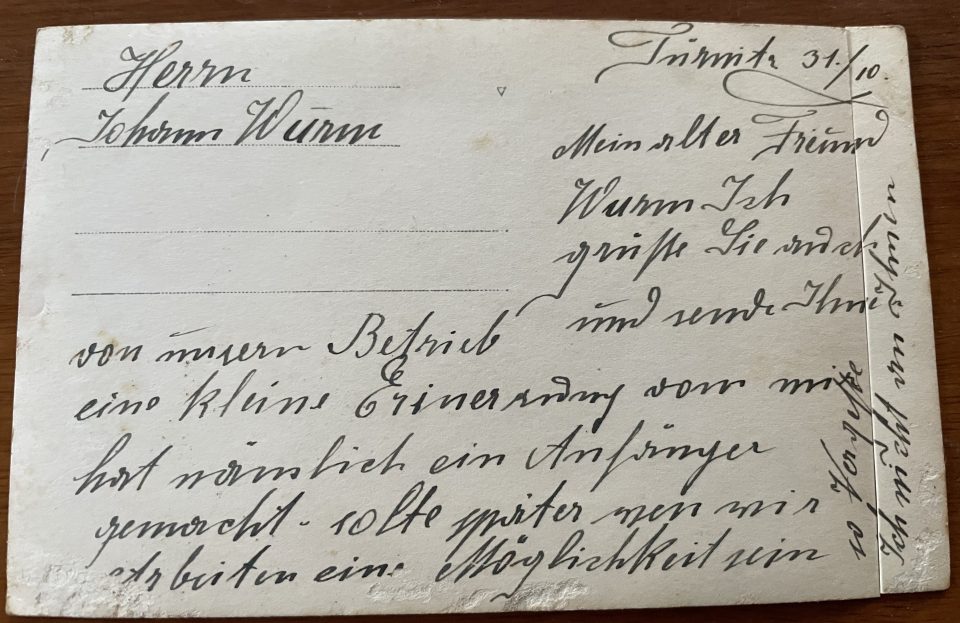

Johann Wurm, Karl’s grandfather, received these photso from a former colleague, Glaninger Gottfiried, who was then working in a hammer mill in Türnitz, Lower Austria, as a memento of the time when both had worked together

Training of scythe smiths

The training of a scythe smith was strictly regulated. Prerequisites for being accepted as an apprentice were: ”legitimate birth and honest parents”, two guarantors, who had to meet the costs of the apprenticeship and compensate the master for any damage the apprentice might cause and finally, fees had to be paid to the master, the “Aufdinggeld”, which was designed to keep the boys of poor families from learning the trade. On average, the apprenticeship for learning the trade of a scythe smith lasted three years, during which time the apprentice lived in the household of the master, who provided board and lodging and in the second and third year clothing, too. The apprentice owed the master obedience, not just at the workplace, but also in the house and on the whole site of the hammer mill. If the apprentice completed the three-year apprenticeship to the satisfaction of the master, he was “free” and became a fellow of the guild. He then either had to work one more year for the master or had to take to the road, namely to go on the “Walz”, which meant he perfected his skills by working in other enterprises, wandering from one hammer mill to the next. The most prestigious position among the guild fellows was the job of the “Eßmeister”, who had to do the most difficult part of manufacturing a scythe, the production of the scythe blade. He had to train two more years and had to provide guarantors again and pay fees. The “Eßmeister” was the most appreciated and best-paid worker in the hammer mill because the prestige of the hammer mill depended on the skills of this specialist scythe maker. After at least two years as a journeyman or with a master, a fellow could apply for becoming a master scythe smith. A fellow had to pay high fees, pass an exam and produce a masterpiece (“Meisterstück”), for instance a special scythe to prove his skills. These restrictions were eased for sons of masters and for those fellows who married the widow of a master or the daughter of a master. These obstacles were designed to prevent outsiders from becoming members of the guild. Consequently, there were only few families in Styria and Upper Austria who were running hammer mills. In documents of the 17th and 18th century only the family names of Moser, Schröckenfux, Hillebrand, Hierzenberger and later Weinmeister appear as owners of hammer mills, all of them originated in Upper Austria and had later settled along the “Iron Route”. They mostly married women from the guild of scythe smiths, so it was very difficult for outsiders to become a member of this “nobility of iron masters”. Any violation of the strict guild rules was harshly punished, for example with the ban of working for any of the guild’s masters. Strict regulations affected the specialisation of the iron production, too; a hoe smith or a scythe smith was forbidden to make horseshoes and a farrier was not allowed to make scythes or hoes for example. But on the other hand, masters had to help each other in emergencies. For instance, they had to lend each other menials in case of a labour shortage or charcoal if they lacked fuel through no fault of their own. Guild charities assisted masters and their families in times of distress, such as the death of the master and the continuation of the business or payments of funerals and church masses. In the 18th century guild regulations were tightened by stricter supervision of the state authorities. Yet since the middle of the 19th century guilds gradually lost their exclusivity and importance and eventually ended up as social clubs.

Scythe smiths, Scharnstein, Upper Austria, 1971

While in the 18th century the hammer mills producing scythes were more or less of equal size, the sizes varied considerably in the 19th century with the introduction of new industrial machines. Around 1890 a scythe factory in Judenburg employed 140 workers, while a hammer mill in St. Gallen produced scythes with 22 workers. In the same way, the production size varied considerably between 60,000 scythes and 472,000 scythes a year. Yet the living and working conditions of the workers did not change. They worked 12 hours a day or more, whereby a break of one and a half hours was deducted from the wages. Around 1870 the wages of an unskilled worker were 0.80 fl, (fl = Gulden), of a skilled worker 1.50-1.80 fl, and for the supervisor 2.50 fl a day. Additionally, the workers were provided with food and lodging and medical care. The wages of scythe smiths were very high compared to other trades, which reflected the special social standing and prestige of these craftsmen.

Festivities at a hammer mill

The Styrian writer Peter Rosegger (1843-1918) documented in a collection of short stories how he experienced the New Year celebrations at a hammer mill owner’s house in the “Iron Roots” region in the second half of the 19th century, when he was still a boy.

All the workers of the hammer mill were invited to a New Year’s meal into the big dining room of the owner’s, the “Black Count’s”, house. They were seated according to rank from the first hammer master to the youngest “coal boy”. First, they were served brown soup with minced meat and beer and as a second course, meat with horse radish sauce and two huge bowls filled with smoked pork, bratwurst sausages, and sauerkraut. The maids next served roast veal with warm cabbage and bacon. This course was accompanied by wine, which was a cheap sort of wine, while the noble guests in the “Black Count’s” private dining room drank the better wine. Often hammer mill owners had their own vineyards in the vicinity, for the purpose of producing cheap wine for the workers’ feasts, the “Leutwein”. This was followed by a stew of meat and a stew of lungs as an in-between meal before the serving of pork roast with roasted white bread soaked in wine and cinnamon – a treat which was only served on high festive days. The gluttony had lasted three hours, when the manservant lit the candles and lamps because it was getting dark. During this ceremony bowls with rice soup were served before the long yearned-for main attraction arrived, the large plates of sweet “Krapfen”, a kind of beignets, and more wine. Next followed hot steaming sweet yeast noodles soaked in sugary brown brandy sauce. That seemed to have been too much, because meanwhile all the employees of the hammer mill on the long table were tipsy or drunk. The senior hammer master got up, he staggered a bit, and announced that they would now ask the “Black Count”, whether they were allowed to thank him for the meal. He entered the “Black Count’s” private dining room, where apart from his wife, the priest, the judge, the school teacher, and a Russian agent were seated at a richly laid table, which showed the remains of an even more abundant feast. They were smoking pipes and cigars and drinking black coffee in small cups. The wife of the “Black Count” invited the employees in and one after the other, strictly according to rank, entered the room and kissed the ringed hand of the mistress, followed by all the servants, the farmhands, the hunters, the grooms, the cook, and the dairy maids. She knew the first name of all the members of the household and exchanged a few words of praise or reprimand with everyone. The mistress then announced that everyone should return to their seats at the table, if they wanted coffee. So, all the workers of the hammer mill staggered back to the big dining room table and the servants of the household to the big kitchen table. Meanwhile the tables had been laid with coffee cups and sweets and next to every coffee cup a red napkin was folded up containing a small golden coin, which a nosey young coal boy first discovered under his red napkin. Then suddenly the “Black Count” appeared in the employees’ dining room and made a short speech. He informed his workers that the company had received big orders from Russia and Turkey. Therefore, they would have to make 30,000 scythes until Easter, so he would have to take on new scythe smiths, whom they should welcome at the mill. He ended with the words, “Now you can go home!”.

House of a hammer mill owner, a “Black Count”, in the “Iron Roots”region

Villa Schröckenfux, the hammer mill owner’s house, Roßleiten

This description illustrates the patriarchal structure of a hammer mill, the important role of the wife of the owner and the close relationship of the “Black Count” and his family with the workers of the mill, who were usually well-treated and appreciated and among the best-paid craftsmen.

Daily life of iron smiths along the “Iron Route”

Rural festivities in the Mill Quarter early 20th century

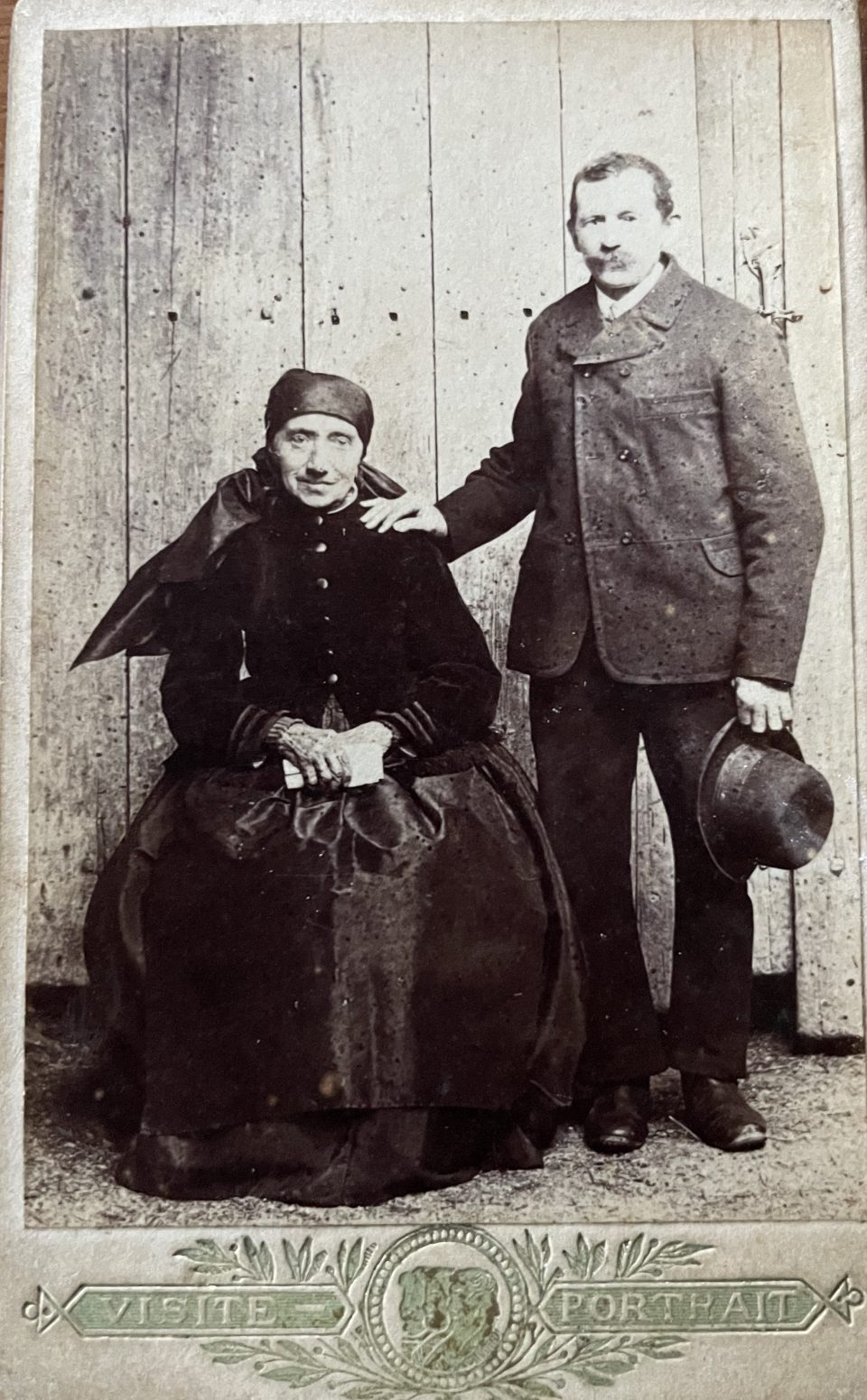

The black traditional dress and scarf of the region – Johann Wurm and his wife

It was a tough life, where a typical working day lasted from 3.00 or 4.00 in the morning until 18.00 in the evening. Most of the men were single and lived on site of the hammer mill. The owner of the mill and his wife had to be addressed as “Herr Vater” and “Frau Mutter” (Lord Father and Lady Mother), which stressed the respect they owed the master and his family, just as a family member, and the position within a feudal order. Usually, they slept in the smiths’ house and ate in the master’s house. Only later, when workers’ accommodations were built, they could marry. The noise in the hammer mills was so loud that they were soon hard of hearing; in the local dialect someone who was very hard of hearing was called “hammerterrisch” (as deaf as a hammer). Johann Wurm lived a long life, but as long as Karl knew his grandfather, he was a cheerful, humorous, happy-go-lucky man, who was very hard of hearing, namely “hammerterrisch”. Once a year a smith could visit his family, when the mill was shut down for eight days, mostly on 25 July, the feast day of St. Joachim & Anna. This day was celebrated with a exuberant festivity and an abundance of food and wine were served. Then the hammer mill was cleaned inside and outside with a large fire hose. The smiths were in a boisterous mood, put on their festive clothing, which had a more urban than rural character. Originally the hammer mill owners were dressed in black – that is where the name “Black Counts” originated from. They wore long coats and black hats with a wide brim and their wives, black dresses, and black head scarves. Later the mill owners wore more colourful coats and the women the famous golden bonnets (“Goldhauben”), while ordinary women continued to put on black head scarves on festive days. After cleaning the hammer mill, the mill workers started a night of drinking and partying to celebrate the onset of their eight-day-holiday.

The inn of the scythe smiths in Roßleiten, which forms part of the hammer mill complex

Johann Wurm was known for being a jolly character and enjoying life, drink, and women, when he was a young journeyman. Although scythe smiths earned well and his father Johann Wurm senior, Karl’s great-grandfather had been able to buy a cottage with a small farm in Anitzberg 16, near Freistadt, his son Johann, a scythe smith, too, was said to have spent most of his wages on drink. During the Second World War, he was already an elderly man, who lived alone in the cottage with the small farm. His wife had already died and his two sons were soldiers in the German “Wehrmacht”. When the war ended, he was told that his elder son, Johann, had been killed in action on the Soviet front and the younger one, Karl, was in a POW (prisoner-of-war) camp in the Soviet Union. In Johann’s small house the Soviet troops billeted several Soviet soldiers. Johann was reported to have had excellent relations with the soldiers in his house, contrary to the negative experiences some locals had with the Red Army. Johann’s grandson, Karl, was born in 1952 and Johann loved looking after him and had a lot of fun playing with the boy, often to the disapproval of Karl’s parents, Karl and Rosa Wurm, who condemned the grandfather’s pleasure-loving and easy-going lifestyle.

The cottage Anitzberg 16 in the Mill quarter near Freistadt, which Johann senior, the great-grandfather of Karl bought – together with the village bread oven (on the right)

Left: the renovated cottage, right: Karl in 1954 with his parents, Rosa & Karl, and his grandfather Johann

Johann Wurm as an old man in front of his cottage

Johann with his grandson Karl, 1954

Usually, the guild of the iron smiths celebrated their festive days of the year on the day of St.Jacob or on the day of St. John. Master and workers met in the inn of the guild, then went in a procession to church and participated at a festive mass. At the head of the parade the mill owners marched, then the “Eßmeister”, the most prestigious smiths, followed by the different types of workers down to the unskilled workers and finally the “coal boys”. After mass they all went back to the guild’s inn, where guild business was discussed and benefits to the needy were distributed from the guild’s chest and new fellows were declared “free”. After an abundant meal the dancing commenced and quite often ended in a brawl, which young smiths were famous for. Religious feast days were celebrated in the mill owner’s house, as described by Peter Rosegger above. Generally, smiths were a quite rebellious group, which did not like obeying the local rulers’ orders and regulations. In 1788 a complaint is documented in Ybbsitz, which mentions that smiths stopped their work on the evenings before Sundays and religious holidays already at 14.00 and then roamed the villages and town the whole night, drinking and rioting from one inn to the next. They were further accused of “terrible lewdness” with women. Yet the territorial government did not interfere, probably due to the prestige of the trade.

Farriers & cart smiths

A horseshoe and cart smithy in Bad Aussee, Styria, which is documented as a functioning smithy since 1147 and is therefore one of the oldest in Austria. It was closed in 1971

The farrier and cart smith Mitterlehner (in a suit) in front of his house and smithy with his assistant, a fellow of the guild (in a shirt) in the village of Ottendorf / Strengberg at around 1932 © private archive Margareta Schmidinger

Smiths in rural areas were usually more prestigious and wealthier than the local peasants and small farmers, because horses constituted an important part of the village’s economy. A village smith was often a large farmer with more farmland and more animals in the stable. A village master smith was a hard-working expert who put iron shoes on horses every day with the help of a few fellow smiths. His main tasks were manufacturing iron horse shoes and fitting them on the horses of the village. On top of that they were the classical village artisans, who with lots of power and skill produced iron funeral crosses, iron banisters and iron cross windows, all by hand. Until the 1950s and 60s there was enough demand, so that smiths could afford to employ fellows and apprentices. Compared to a farm hand, an apprentice in a smithy had many more liberties and a lot more prestige, because village artisans formed part of the village élite.

“Stör”

A horseshoer on a farm in the Mill Quarter (early 20th century)

Apart from smiths, there were often more than one shoemaker per village, where the master came to the farmhouses to measure shoes for the farmer, his family, and his servants. He stayed for several days in the farmhouse, while he was making the shoes for the farm household, which was called “Stör”. During this time, he lived and ate with the farmer and his family and farm hands at the farmer’s costs. The practice of “Stör” was common with several village artisans, such as tailors, barrel makers, blacksmiths or farriers, and everyone else who was called to a remote farmhouse to repair tools or carry out necessary tasks, which could not be done by the farmer and his household themselves. The writer Peter Rosegger wrote several stories about a village tailor who took on an apprentice and went with him on “Stör” to farm houses, where they measured and made the clothes for the farmer, his family, and servants. This practice created a very personal relationship between the rural population and its artisans. Yet in the second half of the 20th century traditional craftsmanship lost its importance in rural areas and only few, such as for example carpenters or ornamental blacksmiths, could survive and consequently only very few apprentices were trained in these crafts.

Scythe smiths

Among the rural artisans the scythe smiths held a prominent position because a scythe was a sophisticated and essential tool for the farm folk. Scythe smiths stood out due to their special culture and tradition and the fascination that surrounded the production of scythes in hammer mills. Therefore, the “Black Counts” treated their much-appreciated workers with lots of respect. The era of these proud artisans and their pre-industrial enterprises, which reached back to the Middle Ages, ended in the second half of the 20th century. Around 1900 it is recorded that the hammer mill owner, the “Black Count” Weinmeister, packed his scythes in barrels, mounted a horse and cart and drove to Russia to establish new business relations there and sell his scythes. He was away from his mill for half a year and returned with one barrel full of money. The last scythe smiths in the Mill and Wood Quarter packed their scythes into trucks and offered them to village grocers in the 1950s; with the pride of an artisan, not submissively, although they knew that they would soon have to shut down their production. Scythe smiths had been of greatest importance for the rural landscapes of the region. They offered attractive training and jobs for boys and young men, and the farmers as well as the whole village profited from them because the scythe smiths bought food and goods there, drank and ate at the village inns and in general spent their higher than usual wages in the vicinity of the hammer mills. There was not just business for the innkeepers and shopkeepers. The farmers did not only provide milk, cheese, and meat, they were also hired to transport the finished scythes in barrels with their horse carts to river boats or train stations for onward transport. Furthermore, the scythe smiths were secretly admired by the village population because they had travelled a lot and had worked in many different parts of the region, moving from one hammer mill to the next. A popular saying went, “a scythe smith, who had not worked in the whole of Austria, was no true scythe smith”.

In a hammer mill the hammer smith was the best paid and most important artisan, followed by other specialists. They were given the food the owner of the mill was served, the “Herrenkost” (the lord’s dishes), while all other workers ate, what the farm hands were offered. Food (and lodging) were considered part of the wages until World War II. When you started to work for a scythe mill you did not receive any wages for the first two weeks because you had to be trained on the job. Yet it was not easy to find someone in the mill who showed you the tricks of the trade, because towards the end for the scythe mill era, everyone was afraid of losing his job and being replaced by an unskilled worker. Whole valleys lived off the hammer mills. Many of the workers lived on site and the hammer mill compound often boasted a works canteen, a shop, and an inn, as can still be seen in Roßleiten. In the canteen and the inn, the hierarchy of the hammer mill had to be respected; a newcomer had to ask politely, if he could take a seat next to a hammer smith, for instance. The busiest time of the year at the hammer mill was autumn and winter because in spring the scythes had to be ready for delivery. During the summer repairs on the mill had to be carried out and during this time some of the scythe smiths and menial workers in the hammer mill found employment elsewhere as woodworkers, as shepherds or on Alpine pastures in transhumance. Scythe smiths were much less bound by religious norms and restrictions than the peasant population and consequently acted in a much freer way, which was on the one hand admired by some villagers and on the other hand, morally despised by others, who envied their loose ways, such as binge drinking and brawls in inns and pubs.

For four centuries the most important centres for the manufacturing of scythes in the region were Micheldorf-Kirchdorf and Scharnstein in Upper Austria, Waidhofen in Lower Austria and Judenburg, Rottenmann and Kindberg in Styria. 20 separate work steps were necessary for finishing a scythe and the quality of the end-product relied on a specialised division of labour. Only few scythe smiths were experts at all 20 work steps; every one of them was a specialist in his field and acquired the knowledge and skills during years of practice. Finally, the scythes were “dappled” with the “dot hammer”. This resulted in the characteristic dots on the scythe blades, which give the scythe the perfect tension. As a last step the scythes received the maker’s mark, were labelled and painted before being packed in barrels. A scythe hammer employed around 60-70 workers, including those employed on the affiliated farm. In the 18th century around 150 scythe manufacturing businesses produced approximately six million scythes a year along the “Iron Route”.

Among the many specialised iron craft productions in the “Iron Roots” there were three curious ones worth mentioning: nail, knife and jaw harp smiths.

Nail smiths

Those were the smallest iron manufacturing businesses, which usually consisted of one master and one to two fellows. The centre of the nail production in the region was Losenstein, where at the hight of the business activity 300 such nail smithies existed. One nail smith worked from 4.00 in the morning until 19.00 in the evening and produced 1,500 nails a day. They manufactured a vast variety of nails from shoe nails to huge nails, which were used in the construction of weirs. They were known as being especially rebellious and many historical documents report about the “Störer Buben” (young men who made trouble). They were regularly involved in strikes and riots, especially when masters wanted to replace the guild fellows by cheaper unskilled workers. Soon the industrial production of nails, starting with the industrialist Andreas Töpper, put an end to the nail smithies.

Knife smiths

Waxenberg in the Mill Quarter in 1971, pen knife production

Knife smiths produced a large variety of knives, too, but famous were the pen knives of the Trattenbachtal near Ternitz. Originally pen knives were invented in France, but in the 15th century Bartholomäus Löschenkohl adopted this idea and started to produce pen knives in Steinbach at the river Steyr and his successors laid the foundation for the booming pen knife production in the Trattenbachtal in the 16th century. They were called “Trattenbacher Zauckerl” and are still known in Austria as “Taschenfeitel”. At the end of the 19th century 17 family businesses were situated there, which did not only produce for the Habsburg Empire, but exported their pen knives to Russia and Dutch India, too. The knowledge and skills of producing the blade and the wooden handle were kept as family secrets and only passed on to the successors in the smithy.

Jaw harp smiths

Jaw harp production Molln 1974

This musical instrument was much appreciated in poor mountainous regions, because it was small, light, and cheap. The centre of production was Molln. Until way into the 20th century 30 family businesses produced around three million jaw harps there and still today 400-year-old jaw harps can be admired in the oldest and biggest manufacturing businesses in Molln, the companies Schwarz and Wimmer.

Export markets for Styrian and Upper Austrian scythes

An abandoned hammer mill in Grubegg, Styria, before 1875

Scythes were produced in different sizes, lengths, and weights, all in all 17 different varieties, adapted to the working practices of farmers in different regions. There were for example “Hungarian” scythes, which weighed 1.12kg, while “German” scythes weighed between 0.9 and 1 kg. A “8-handed Russian” scythe had a length of 75 cm and weighed 0.6 kg. Sickles were much smaller, whereas straw knives had approximately the same weight as scythes, but the main product manufactured in all the hammer mills along the “Iron Route” were scythes. The individual maker’s mark of every hammer mill guaranteed the quality and origin of the product, which was much appreciated abroad. The maker’s mark was linked to the hammer mill and could be inherited or bought together with the hammer mill. Since the 16th century finished scythes were exported from this region. In earlier times unfinished scythe blades were traded as well. The finished scythes were either sold directly at the hammer mill or in nearby towns and at markets or fairs. On the other hand, there was a booming peddler trade run by the menials at the hammer mill. They left the hammer mill at the end of April, usually at St. George’s Day (23 April) before the first haymaking and journeyed across the countryside from church fair to church fair until 10 August (St. Laurence’ Day), when the harvest and the last hay of the year had been cut. Peddling was a cheap and easy income for the peddlers and the hammer mills, although limited in size. The trade of scythes to more distant markets required the proper packing of the finished products, which was done in barrels. In a properly stacked barrel 400-500 scythes could be transported, in a large one 800 scythes. Hungary was one of the most important markets for scythes from the “Iron Route” and after the end of the wars of the Habsburg Empire against the Osman Empire, which severely damaged the scythe trade, Turkey became an important customer. In Vienna they were traded by Osman traders, mostly Greeks and Jews, and in the year 1767 scythes were their main export good in Vienna. They were further shipped via Trieste to the Osman Empire. Whenever a new conflict erupted, the export of scythes, sickles and straw knives was prohibited by the Habsburg rulers, as they feared the blades would be transformed into weapons. The large foreign markets of Poland and Russia were serviced via Krems and Vienna on the Danube. Since the middle of the 18th century Russian traders came to Austria, too, and bought directly from the hammer mills. Polish scythe traders, such as Lancowitz from Krakow, bought directly from the hammer mills or at the trade fairs in Linz. In 1764 the Russian Empire ordered 300,000 scythes in Austria, a third of which were produced in the “Iron Roots”. The Russian customers were so satisfied with the superb quality of the Austrian products that they ordered another consignment of the same size, but the hammer mill owners could not meet the large demand. This document illustrates the attitude of the Austrian scythe makers. They would rather sell superior quality at a high price in small quantities than inferior quality at a low price in large quantities. This was one of the reasons why the Austrian scythe production drastically declined in the course of the 19th century with the onset of industrialisation. The Austrians furthermore preferred face-to-face contact with their customers.

Model of a large “Redtenbacher” scythe, 1971

Apart from the export to Eastern territories, another destination for scythe exports was Southern Germany and France. The products were shipped via Murau, where Anna Neumann had contributed to the wealth of this market town, Tamsweg, Schladming, Aussee und Ischl to Salzburg. Yet the export to Western destinations was frequently hindered by military conflicts between Austria and France. In the 19th century the patriarchal structure of the small- and medium-sized hammer mills along the “Iron Route” could no longer compete with the fast industrialisation process in Western Europe and Germany. They ignored the trend towards rationalisation, mechanisation, and concentration and in the end lost out to large-scale factory production of scythes. The Austrian producers furthermore did not risk any investments into the much cheaper and more efficient sea trade via Trieste and Odessa, but still exported their scythes mostly by land via Brody to Southern Russia and via Radziwilow to Poland and northern Russia. Eventually, due to the liberalisation of European trade towards the end of the 19th century, small hammer mills were at a disadvantage compared to large industrialised producers, who could purchase pig iron and coal in large quantities at much reduced prices. Furthermore, brown coal, which was predominant in the region of the “Iron Roots”, was not as efficient as black coal. Furthermore, wood prices, which factory owners could pay, were much too high for hammer mill owners. On top of that, the high-quality iron from the “Erzberg” was exported abroad because higher prices could be achieved there. Foreign competitors lured skilled scythe smiths away from the “Iron Roots”, which raised the wages of the remaining specialised workers. Count Strachwith for instance paid scythe smiths, who emigrated to his county Komancza in Galizia, much higher wages and offered them a pension after 20 years of service or paid for their journey home after 5 years of work in his mills. Cheaper low-quality scythes were mass produced in Western Germany, France, and Switzerland, which even copied Austrian maker’s marks illegally and damaged by that the image of the Austrian scythe production due to the low quality of their scythes. In this difficult economic environment at the end of the 19th century Russia, the Balkans and Italy remained as the last important export markets for Styrian and Upper Austrian scythes. But the downturn could not be stopped, so that in the course of the 20th century ever more hammer mills had to shut down.

Large model of a “Schröckenfux” scythe, 2024

Literature:

Anna Neumann und das 16.Jahrhundert. Begleitband zur Ausstellung im Murauer Rathaus, Murau 2023

Eppel, Franz, Die Eisenwurzen. Land zwischen Enns, Erlauf und Eisenerz, Salzburg 1968

Fahrengruber, Reinhard, Entlang der Eisenstrasse. Kultur, Natur und Industrie, Ennsthaler Verlag Steyr 2007

Girtler, Roland, Sommergetreide. Vom Untergang der bäuerlichen Kultur, Böhlau Wien 1996

Gittler, Mariella, Pfeifer, Andreas & Schöber, Peter (ed.), Österreich die ganze Geschichte Band 1, Molden Wien 2024

Heitzmann, Wolfgang, Die Eisenstrasse. Landschaft und Geschichte, Alltag und Freizeit, Landesverlag Linz 1987

Kleinhanns, Günther & Fellner, Fritz, Eisenverarbeitung im Raum Freistadt, in: Mühlviertler Kulturzeitschrift: Arbeitswelt im Bezirk Freistadt, JG 27, 4/1987

Tremel, Ferdinand, Steirische Sensen, in: Blätter für Heimatkunde 27, 1953