This social and economic history research website looks at various aspects of the lives of ordinary people in Vienna; their different backgrounds, their lifestyles, their occupations and pastimes. It deliberately chooses “common people”, not artists, not industrialists, not high bourgeoisie or nobility. My family constitutes the template on which the blog is based and the different chapters are linked to the destiny of one of those “common people” that were members of my family and are representative of the lives of many of their contemporaries. The chapters analyse from a social and economic history point of view various aspects of life of indigenous Viennese, of immigrants and emigrants.

The German philosopher Walter Benjamin wrote in 1940, “It is more difficult to honour the memory of the nameless than that of the famous. The historical reconstruction is dedicated to the memory of the nameless.” And furthermore, “History is not just the history of those who triumph, who dominate and who survive, but most of all the history of the suffering of the world…..It’s what history is based on: those anonymous people without name and without memory.”

Their four daughters: Käthe, Lola (my grandmother), Agi, Mitzi

This history starts in the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy with Ignaz (Natzl) and Leopoldine (Ritschi) Sobotka, a beer brewer and a doctor’s daughter, both assimilated Jews. Ignaz was born in Vienna and Leopoldine in Eywanowitz in southern Morvia. They came to Vienna at the beginning of the 20th century to run the brewery in Kaiserebersdorf near Vienna. They had four daughters in quick succession: Katharina, named Käthe, Flora, named Lola – my grandmother -, Agnes, named Agi and Marianne, named Mitzi. They were well-to-do middle class. As the writer Stefan Zweig wrote in his book “The World of Yesterday” (1942), “Everything in our almost thousand-year-old Austrian monarchy seemed based on permanency, and the state itself was the chief guarantor of this stability… Everyone knew how much he possessed or what he was entitled to, what was permitted and what forbidden. Everything had its norm, its definite measure and weight. He who had a fortune could accurately compute his annual interest. An official or an officer, for example, could confidently look up in the calendar the year when he would advance in rank, or when he would be pensioned… Whoever owned a house looked upon it as a secure domicile for his children and grandchildren; estates and businesses were handed down from generation to generation… In this vast empire everything stood firmly and immovably in its appointed place, and its head was the aged emperor; and were he to die, one knew (or believed) another would come and take his place, and nothing would change in the well-regulated order. No one thought of wars, of revolution or revolts. All that was radical, all violence, seemed impossible in an age of reason.”

But the Empire ended, nevertheless, with the end of World War I and the First Austrian Republic was established. Ignaz was not drafted during the First World War because beer brewing was considered a “war-necessary industry” and most of all he was already 42 when the war broke out. Yet the four girls still enjoyed a careless youth during the 1920s in Vienna with lots of sport, parties and entertainment until the Great Depression hit. With anti-Semitism on the rise Ignaz lost his job as a manager of the brewery and had to work for Teerag-Asdag as a road construction worker. They had to move into a tiny flat in Vienna. My grandmother had to stop her piano lessons at the Music Academy of Vienna – she later mentioned that she had been too lazy anyway and had enjoyed life too much to become a pianist – and work as a shop girl in a sweet shop. This was in fact a lucky turn because there she met my grandfather, Anton Kainz, named Toni, who was infatuated with the beautiful shop girl and proposed to her: a “big disaster” for his conservative Catholic bourgeois family, the owners of a traditional restaurant in Währingerstrasse in the prestigious district of Währing. He was no longer the heir to the house and restaurant due to this marriage with a Jewish girl and the young couple rented a café on Hamerlingplatz, which they ran with very limited success and even less profit. Meanwhile my mother, Herta, was born in 1933, in a time of crisis. Yet she always stressed what a wonderful childhood she had had despite the political circumstances, cared for by two doting parents. But rising racism and political strife put a lot of pressure on this young family.

Stefan Zweig wrote in 1942, “It was reserved for us, after centuries, again to see wars without declaration of war, concentration camps, persecution, mass robbery, bombing attacks on helpless cities, all bestialities unknown to the last fifty generations, things which future generations, it is hoped, will not allow to happen.” Toni was immediately drafted in 1939 and took part in the German offensive against France. He detested this participation in the war, not just because he was a fervent anti-Nazi, but also because he loved France, which he had got to know during his years of training as a waiter and cook in preparation for taking over the family business.

With the Austrian civil war in 1934, the establishment of the Austro-Fascist regime and the Nazi takeover in 1938 the personal situation of all four sisters had changed dramatically. Käthe, who had lost her first husband, Poldl Kluger, very early, lost her job as a bank clerk and had to make a living as a fashion model. She decided to emigrate to England as the first member of the family and work there as a cook in a wealthy household. Later she managed to organise the flight of her sister Agi and her 2-year-old twins, Susi and Josi, by getting her employer in England to take on Agi as a maid. The twins were separated and looked after by English Quakers. Agi’s husband, Norbert Katz, a gifted Austrian football player, was interned on the Isle of Man, because the English feared Nazi spies that might have infiltrated the refugee groups. Mitzi together with her much older husband Karl Elzholz, a socialist and mechanic at the Viennese tramways, both excellent mountaineers escaped across Alpine paths to Italy and from there on a ship to Bolivia. Käthe, despite all her efforts, was not able to get their parents out of Vienna. They were first moved to a collection point in Vienna in the 2nd district and then deported to the concentration camp Theresienstadt. My grandmother, Lola, was deemed safe as she was married to an “Aryan” who was devoted to her and resisted any pressure to divorce her. But the situation for her and my mother, who was categorised as a “mixed-race” child under the Nazi regime, became more and more precarious; it was a life at limbo. My grandmother had to wear the yellow Jewish star on her clothing and worked for the ammunitions industry, while my mother was excluded from any social activity of the time, even in primary school the regulation was to have “mixed-race” children sit on their own in the last row. The threat of a deportation of the two was continuously present and could be prevented only due to the courageous and determined stance of my grandfather, who was fortunately deemed an “unreliable soldier” and was sent back to Vienna to work again in his old job in a fish shop of Hofbauer-Hammerschmidt, an “undertaking necessary for the war effort”. He withstood the mounting Nazi pressure to divorce his Jewish wife until the end of the war.

Meanwhile Mitzi had found a new love in Bolivia, a German refugee named Bill. Together with her husband Karl she had established a shirt-sewing enterprise in Sucre. Karl had known Käthe from before the war and so they decided to marry long-distance. Käthe left England during the war in a British ship convoy across the embattled Atlantic, under the permanent danger of Nazi U-boat attacks, to join her new husband in Bolivia, where the two newly formed couples made a living from the shirt production business in Sucre. My grandparents learned about these new relationships only after the war to the great surprise of everyone.

Miraculously all members of my closer family survived the 2nd World War and the Holocaust, even my great-grandparents returned to Vienna from Theresienstadt. Karl and Käthe, dedicated Austrian socialists, returned to Vienna immediately after the war, Mitzi and Bill emigrated to the United States and Agi and her family remained in England. They moved to London, where Norbert worked in the football business. Toni continued to work in the fish shop in Vienna after the war and Lola worked again as a shop assistant and cared for her parents, Ignaz and Ritschi, who very extremely feeble after their return from the concentration camp, until their death in 1958 and 1959. My mother, Herta, had suffered a lot under the conditions of the war, under bombardments and racial segregation, so when she met Werner Tautz, a young man originally from Silesia, my father, she was overwhelmed by his attention for her and could hardly believe it. Werner was born out of wedlock, his mother the maid of a German landowner in Görlitz. He was treated extremely badly at home, so when he was sent on an organised children’s holiday programme to Obersiebenbrunn, near Vienna, he could hardly believe that he was treated the same way as the children of the family of Anna and Franz Rupp. So at the age of thirteen he decided to leave home and was accepted as a foster child of the Austrian family. Herta and Werner married in 1953 and I was born four years later.

All these people contributed to the democratic reconstruction of Austria after 1945 and formed the heart and the conscience of the 2nd Republic of Austria, which was a long process characterised by denial of any guilt in war crimes and in the holocaust and focusing on the image of Austria as the “first victim of Hitler”. The Austrian psychiatrist Erwin Ringel described in his book “The Austrian Psyche” in 1984 the post-war atmosphere in Austria as dominated by three principles: politeness, parsimony and obedience. Excessive servility and obsequiousness characterised the post-war Austrian who was prepared to obey commands even before they were even expressed. Ringel quoted a line of a famous song of the Johann Strauss operetta “Die Fledermaus” (“The Bat”), much appreciated in Vienna, “He is happy who forgets, what cannot be changed”. Ringel called it the secret national anthem: forgetting and suppressing means resigning and that’s what took place in Austria and Vienna after 1945. As a psychiatrist he recommended to change the line into: “He is unhappy who forgets what cannot be changed”. The Austrian author of Jewish descent, Friedrich Torberg, wrote after the war, “Brother, you could have saved some, and now they are dead, brother, you should have been alert, but you dreamt, you should have taken quick steps, but you tarried.” That’s why Alfred Polgar quipped before the war, based on the line of another popular song, “Vienna remains Vienna – and that’s the worst one can say about this city.”

The four sisters making fire in the garden of the brewery: Lola on the right, Käthe with the dog and Mitzi on the left and Agi hidden by the smoke

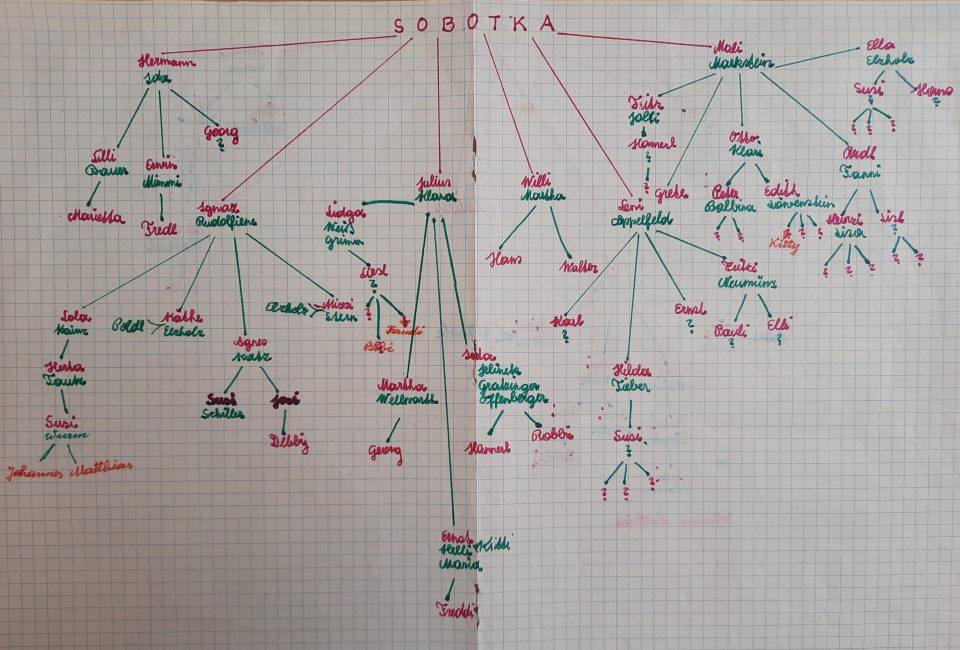

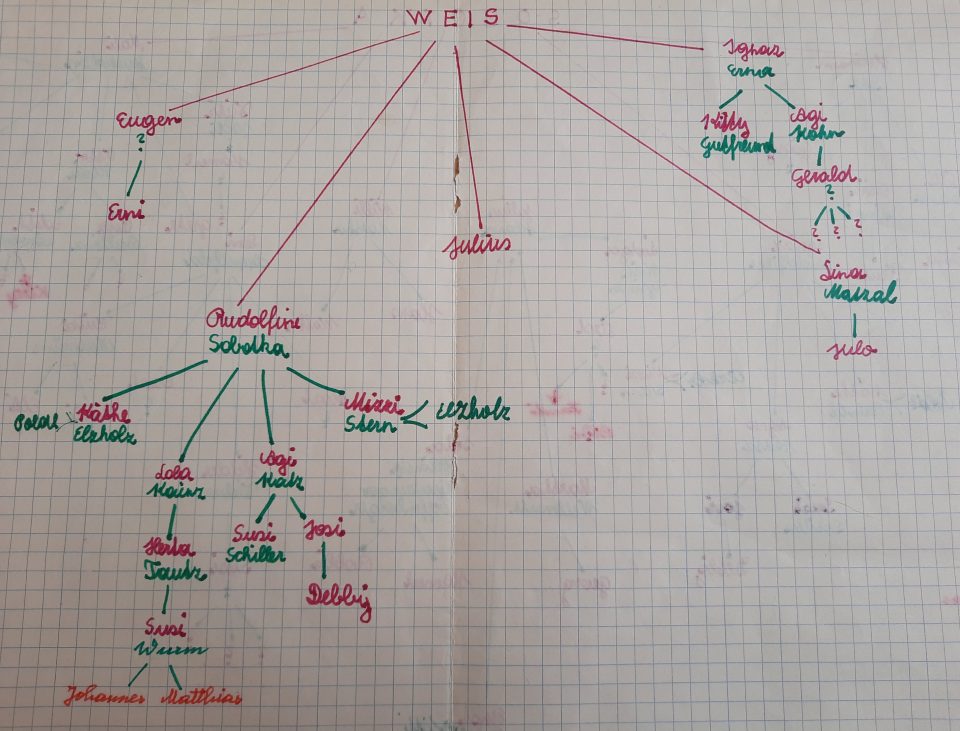

The family trees Lola drew up together with me in the 1960s and which my mother Herta tried to complete:

The family tree of Lola’s father, Ignaz Sobotka

The family tree of Lola’s mother Rudolfine Weiss (the family name is misspelled in the document)