AUSTRIAN FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS IN CEE DURING THE INTERWAR YEARS

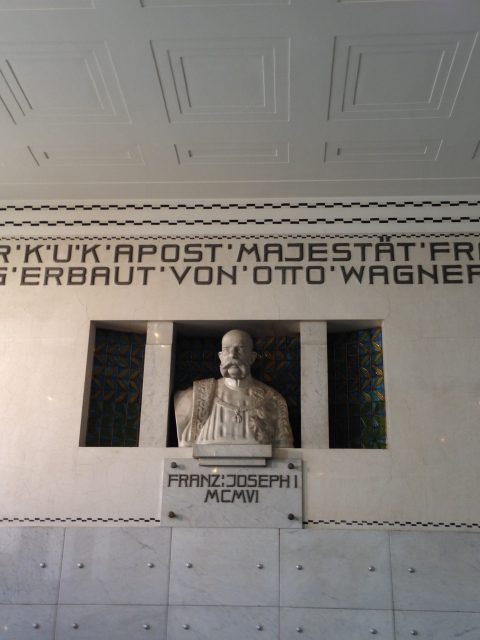

Österreichische Postsparkasse, Vienna, founded 1883 “k.k. Österreichisches Postsparkassenamt”, architect: Otto Wagner (built 1904-1912)

As a result of the First World War the persistent shortage of domestic and foreign capital for investment in the economies of Central and Eastern Europe, as mentioned above, worsened. At the same time, due to the devastation of the war the demand for capital rose dramatically. After the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1918 new stock exchanges were established in the successor states of the former empire. The scene had been dominated by the Vienna Stock Exchange and to a much lesser degree the Prague Stock Exchange, founded in 1871. In the 1920s new stock exchanges opened up in Belgrade, Bratislava, Brno, Ljubljana, Warsaw and Zagreb, which competed with Vienna. Their main business was in dealing in securities, bills and foreign currencies and not shares. The same was true for the Vienna Stock Exchange during the interwar years. Only in the years 1926/27 did the currency situation stabilise after the hyper-inflation in the successor states of the Habsburg Empire after the First World War and central banks had been established in all new states. The finances of Austria, Hungary, Poland and Bulgaria were under international supervision and the new central banks had to be independent from the state, but they had to act as lenders of last resort together with the respective governments. Especially in Austria the “Franc Speculation” further destabilised the financial scene.…