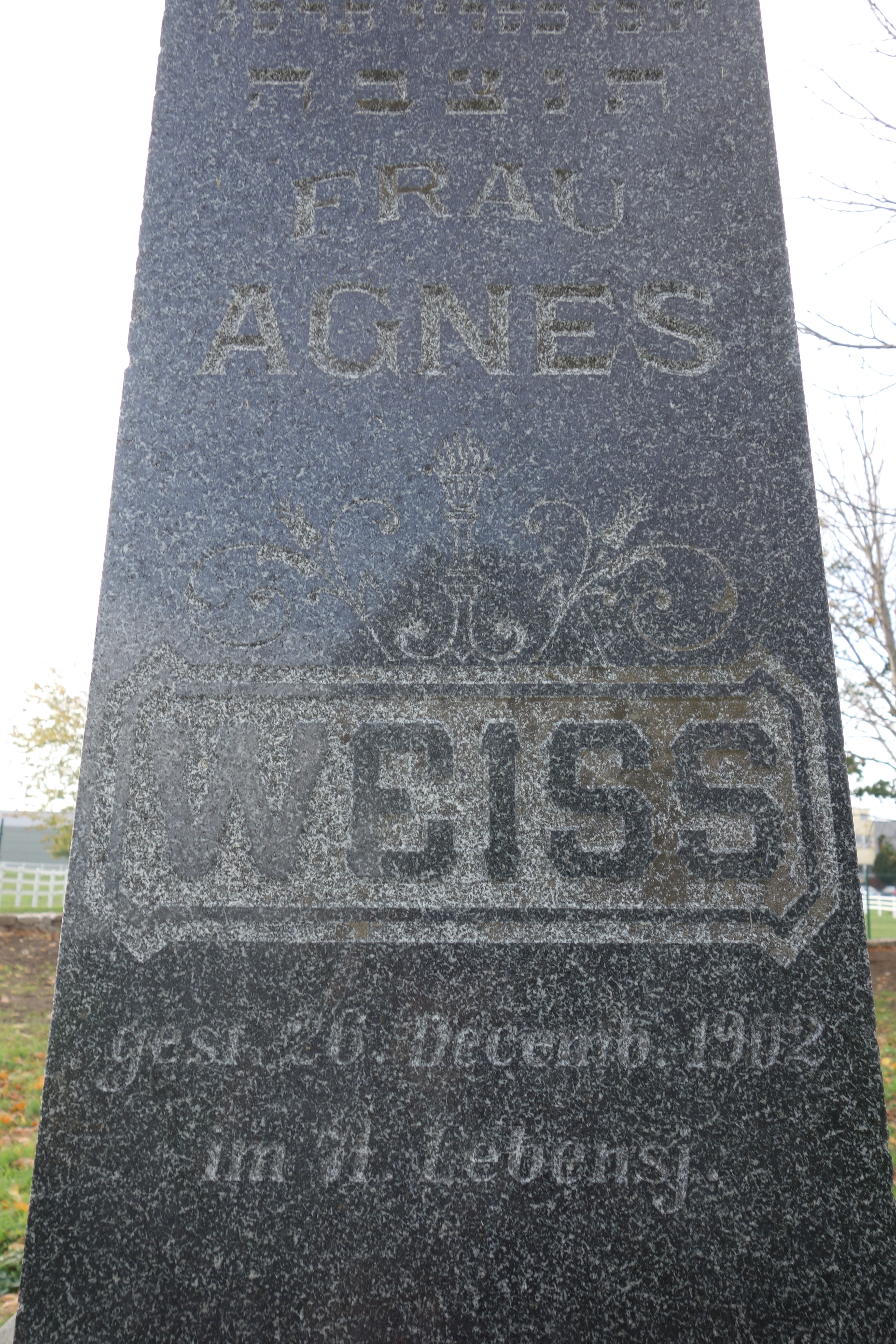

The gravestones of Josef Weiss, medical doctor, and Agnes Weiss, his wife, my great-great grandparents, Eywanowitz (Ivanovice na Hane)

„Every Viennese has a Bohemian grandmother”, this popular Viennese saying is partly true for me as well, but she was a Moravian and not a Bohemian grandmother because Lola was born in Eywanowitz (today Ivanovice na Hane) in Moravia in 1902 as the second daughter of Leopoldine, née Weiss, and Ignaz Sobotka, a beer brewer. Soon after her birth the family moved to Vienna because Ignaz started to work for the brewery in Kaiser Ebersdorf. She did not speak any Czech, but told me some lines of Czech nursery rhymes she still remembered and she spent her childhood holidays at the house of relatives in Znaim (Znojmo). In 2015 I visited for the first time the little village of Eywanowitz and saw the church, the castle and the brewery. In 2017 I discovered, to my great surprise, a Jewish cemetery that was preserved between a petrol station and a sewage treatment facility on the outskirts of the village and accessible to the public. To my even greater astonishment I spotted among the graves the well-preserved gravestones of my great great-grandparents Josef Weiss, general practitioner, who died in 1901, and Agnes Weiss, his wife, who died in 1902.

Jewish cemetery in Eywanowitz

In the 16th century larger Jewish communities existed already in Moravia, contrary to the Habsburg lands, for instance in Nikolsburg (Mikulov) Trebitsch (Trebic) and Proßnitz (Prostejov). The Jews had been expelled from the imperial cities at the end of the 15th century and mostly lived on the estates of the landed nobility in smaller villages. The Bohemian capital city of Prague hosted the biggest Jewish community, next to Frankfurt, of Ashkenazi Jews. Those were Jews who had originally settled along the Rhine River in Western Germany and Northern France and continually moved eastward out of the Holy Roman Empire in the late Middle Ages in the wake of pogroms. But the majority of Jews in Bohemia and Moravia lived in small villages dispersed across the countryside. After the pogrom of Vienna of 1670 many Viennese Jews fled to Bohemia and Moravia, but also to Hungary where they could settle on the estates of the Hungarian nobility, like the Counts Palffy. The majority of Hungarian Jews lived in the part of Hungary that was still under Osman rule which can be explained by the more tolerant religious policy of the Osman Empire which guaranteed relatively better legal security for Jews than in the Habsburg lands.

Jewish cemetery Eywanowitz

In Moravia the Jews on the countryside drew up a constitution for the community, based on older statutes, in 1651, which regulated elections of community representatives, taxation, membership in the community, jurisdiction, commercial practices and religious affairs. This internal constitution was amended in the course of several synods until 1748, when the Habsburg state started to interfere in the internal affairs of the Jews via police orders. The close link of the Jews to their noble lords in these regions led to a great vulnerability in case of a change of sovereignty. Usually the new lord as a consequence asked for higher taxes, a sort of danegeld. On the other hand the local Jews enjoyed liberties that Jews in other regions could not even imagine, namely they were granted the privilege to rent distilleries, tanneries and other factories that were owned by the nobility. They were even allowed to pursue certain crafts and trades. In Prague the Jews were permitted to form guilds similar to the Christian guilds. In the 17th and 18th century such guilds also developed in Moravian cities, such as Nikolsburg (Mikulov). The situation of the Jews on the countryside was more favourable than in the cities because the noble landlords usually interpreted the imperial laws in favour of the local Jews. Mostly the Jews were involved in trade, nevertheless conflicts with Christian craftsmen and guilds erupted now and then. In 1677 Prince Liechtenstein had to settle a dispute between Jewish traders and Christian tailors. In Moravia the Jews concentrated on the trade in clothes which included large profitable army contracts. Mass production was introduced which formed the basis of the important Moravian textile industry. In 1682 the city of Nikolsburg (Mikulov) asked to move the Saint Michael’s Market to another date because on the original one the Jews celebrated their New Year.

In the 1720s “Jews’ lanes” (“Judengassen”) were established in order to move the Jews away from the city centre. These existed until the middle of the 19th century. The emperor Charles VI decreed that the number of Jews in Moravia and Bohemia had to be limited and ordered the expulsion of Jews from these regions, but the Bohemian nobility resisted and did not execute this imperial order because of its economic interests in Jewish businesses. But the so-called “family law” stipulated that the number of Jewish families was fixed at a certain number and only the eldest son was allowed to marry at the age of 24, not earlier and not before his father had died. Wealthy Jews could pay a fine and purchase a marriage permission, but poorer Jews rather tended to convert to Catholicism in order to escape the restrictions. Empress Maria Theresia ordered a pogrom of Jews from Prague and later also from Moravia and Bohemia in 1744. Well-to-do Jews tried to intervene and contacted various European ruling houses, even the Pope and the Osman Sultan. In the end Maia Theresia insisted on the expulsion of the Jews from Prague, which led to an economic crisis in the whole of the region because the Jewish sellers and buyers were gone. Even the Christian guilds now petitioned for the return of the Jews, which took place in 1748, when the Jews returned to the devastated Jewish part of Prague.

The “Patent of Tolerance” of Emperor Joseph II allowed the Jews so far unknown emancipatory liberties in the spirit of Enlightenment and the separation of state and religion. Immediately the first Jewish schools were established in Moravia and Bohemia that taught Bohemian geography, Austrian history, commercial subjects, biology, drawing etc. The children of poorer Jews attended these “normal schools” (“Normalschulen”), but many Jewish children went to Christian schools and the richer families employed private teachers. In the wake of this humanist movement a reformed Jewish orthodoxy spread in the region and the interest in German literature and art boomed, not just among the wealthy Jews and the ones living in the cities, but also in the country and in all enlightened Jewish households. Literary societies were founded and the first Jewish writers published their work in German.

Nevertheless many restrictions persisted. In 1797 a patent was issued for Bohemia and Moravia (“Systemalpatent”) which was abolished in 1848. It confirmed the limitations of civil rights of the Jews and interfered in internal religious matters. Between 1816 and 1848 the number of Jews in the region rose from 70,000 to 108,000. They tried to escape the ghettos and settle in Christian quarters, which caused lots of complaints of Christians. The already established textile industry expanded enormously and until 1850 many small- and medium-sized enterprises were founded, many by Jewish entrepreneurs, who employed tens of thousands of workers. Tensions between employers and workers erupted in anti-Jewish protests in Prague in 1844. Another area of conflict was the German language. Since the 18th century the Jews in Bohemia and Moravia had adopted the German language, which since 1830 led to a confrontation with the Czech national movement. Some Jewish intellectuals attempted to approach the Czech nationalists; among them Moritz Hartmann, who later became editor of the “Neuen Freien Presse”, an important Viennese newspaper. The Czech nationalists rejected this offer, nevertheless. They were of the opinion that the Jews had assimilated to the German language and lifestyle and they should therefore remain “Germans”. The revolution of 1848 confirmed and intensified the bondage of the Jews with the German language and culture in Bohemia and Moravia.

After the revolution of 1848 and the introduction of equal civil rights for Jewish citizens in the Habsburg Empire a large migration movement set in. For the first time Jews had the possibility to move freely in the empire and migrate to cities that before had been closed to them. Especially the Jews in the Moravian countryside moved away to bigger cities, such as Brünn (Brno), but most of all to the capital city Vienna. In 1848 445 Jews lived in Brünn (Brno) and in 1910 the number had increased to 8,945, which constituted 7.1 % of the population of the city. The constitution of 1867 led to a further liberalisation, which boosted the migratory movement to the cities and to the western parts of the empire. This resulted in a considerable increase of the percentage of the Jewish population in the cities of Budapest and Vienna. In 1910 the Jewish population made up nearly 10% of the Viennese population. In Bohemia and Moravia the share of the Jewish population likewise shrank in these years. The reasons for this decrease were the difficult economic circumstances due to national – Czech – and religious – Christian – boycott of Jews.

Nikolsburg, Jewish quarter in the 19th century

Nikolsburg (Mikulov), located just across the border from Austria to the Czech Republic today, housed the most important and largest Jewish community in Moravia and was the religious centre of this province of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy. Historical documents prove that the first Jews were active in this place in the second half of the 14th century. A permanent settlement in the city was documented, when refugees of the pogrom of Duke Albrecht had to leave Vienna and Lower Austria and found shelter in Nikolsburg. The next wave of migrants to Nikolsburg was triggered by the expulsion of Jews from the royal cities of Bohemia and Moravia in 1454. Most of these Jews were from nearby Znaim (Znojmo) and Brünn (Brno). They settled on the west side of the castle hill outside the city walls by buying the property from the Christian population. This was unique because in most other regions Jews were forbidden to own property. But the authorities of Nikolsburg were aware of the usefulness of the Jewish settlement for their Christian community and soon provided a secure legal environment for a flourishing commercial and religious coexistence. Even the imperial sanctions against Jews were not executed in Nikolsburg because the noble families who ruled the city, first the Liechtensteins and later the Dietrichsteins, protected the Jews of Nikolsburg because they knew about their value for the commercial success of the city and appreciated it. In return the Jews accepted the conditions of the noble overlords, namely, they paid much higher taxes than the Christians, were subjected to compulsory labour service for the noble lords, paid for the castle guard from their own resources and provided meat and oil for the castle weekly. Their civil rights were much restricted in comparison to the Christian subjects, but they also enjoyed some privileges. In 1591 they were permitted to make payments in cash and kind instead of the compulsory labour services and to self-govern their community. In the following years these privileges were confirmed and extended by the ruling nobility. They were for instance no longer subject to the city’s jurisdiction, but directly to the castle’s jurisdiction. Furthermore they were granted the privilege to trade the wine of Nikolsburg and were allowed to take refuge inside the city walls in case of war, for a substantial fee, of course. These favourable conditions together with the excellent geographical position on an important trade route contributed to the growth of the Jewish community until it was the biggest in Moravia and it became a religious centre, too, when Emperor Maximilian II gave permission for installing a rabbi for the whole province in Nikolsburg in the 16th century. For 300 years from the middle of the 16th century to the middle of the 19th century this city was the spiritual, political and cultural centre of Jews in Moravia.

Jewish community in Nikolsburg

The Jews in Nikolsburg concentrated on trade and benefitted from the crossing of traditional trade routes in the city. They participated in trade fairs in Moravia, Austria and Hungary. Nikolsburg as such boasted seven trade fairs annually. They traded in wool, leather, animals, wine and also luxury goods. In 1593 the Emperor Matthias assigned them the linen trade in Austria and they specialised in the trade in feathers as well. Above all, they were involved in money business. The surge in commerce was promoted by the new imperial road that connected Vienna and Brünn via Nikolsburg. This road was built between 1727 and 1753 and soon after the opening Bernard Goldschmied established the first Jewish wholesaling business there and many more should follow. Nikolsburg was turned into the most important trading centre of southern Moravia and a trans-shipment point for wool, iron wares and wine. In the Jewish quarter trade in linen, textiles and haberdashery prospered and the breeding of geese. The liver of the geese of Nikolsburg was a famous delicacy in Vienna. The Jews of Nikolsburg did not only establish trade relations between Moravia, Bohemia, Austria and Hungary, but also to Silesian and Polish cities.

“Upper Synagogue” in Nikolsburg

Another outstanding characteristic of the position of Jews in Nikolsburg was the expansion of artisan activities. In other parts of the Habsburg Empire the Jews were forbidden to carry on a craft. Craftsmanship was reserved for Christians. In Nikolsburg the number of Jewish craftsmen increased in the 17th and 18th century. In 1647 the permission was granted to open a Jewish tailor business and this event broke with a centuries’ old prohibition that Jews were not allowed to own property or pursue a trade. Since that point in time barbers, soap makers, goldsmiths, candle makers, glass makers, button makers, tailors, butchers, shoemakers and bakers, organised in guilds, worked in the city and also had their own synagogues. Not even catastrophes such as wars, epidemics and fires eventually had a serious impact on the flourishing Jewish quarter. In 1669 146 Jewish families were registered in Nikolsburg and when the Jews of Vienna were expelled in 1670 Duke Dietrichstein allowed 80 more families to settle in Nikolsburg. But at that time the Jewish quarter was already much too small and in some cases eight families had to share one house. In 1718 a fire broke out in this overcrowded part of the city and nearly destroyed the whole ghetto. It damaged the nearby castle as well. The reconstruction of the ghetto was partly financed by family members, the Viennese Jews and trading partners. But after this event the Jewish community in Nikolsburg stopped to grow, in part also due to the new family law of 1726 that only allowed the eldest son to marry and limited the number of Jewish families allowed to live in Nikolsburg to 600. That’s why the other family members had to leave the city and most of them moved to Slovakia and Hungary. At the end of the 18th century 620 families lived in Nikolsburg and in the whole of Moravia only 5,400 Jewish families were permitted. The land register of Empress Maria Theresia recorded 107 houses in the Jewish quarter and one synagogue, one school and a city hall with approximately 2,000 inhabitants. This constituted one third of the whole city population.

In the first half of the 19th century the Jewish population of Nikolsburg grew again to 3,520 person or 42% of the population in 1836. Unfortunately for the city, the new railway line between Vienna and Brünn was built away from Nikolsburg which ended modern trade in the city. There were no more trade fairs held there and in the 1840s the slow decline of the city set in. The revolution of 1848 improved the citizen rights of the Jewish population decisively and the people started to move out of the Nikolsburg ghetto to the large cities like Brünn and Vienna where they could profit from better economic and social conditions. The only remaining enterprises in Nikolsburg were more or less exclusively run by Jews; a small chemical factory, a suitcase producer, a lime kiln, a production of mother-of-pearl buttons and the famous wine production of the family Teltscher. With the end of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy in 1918 and the establishment of Czechoslovakia the independent Jewish community was dissolved.

Jewish cemetery Nikolsburg

For the preservation of the memory of this important Jewish community the decline of importance of Nikolsburg was a benefit because the city retained its medieval character and was not modernised in the age of industrialisation. That’s why we can today see so many well-preserved structures of the Jewish quarter. The oldest and still preserved synagogue is the “Upper Synagogue” or “Altschul”, which probably dates back to the 15th century. In 1550 a Renaissance building is documented there. At least two major fires (1561 and 1719) made extensive restructurings necessary during the following centuries. After 1938 the building was used as a store room and decayed. In 1977 restoration works were started, which were finished in 1989. The second-biggest synagogue in Nikolsburg, called “Lower Synagogue” or “Neuschul” dates back to the 16th century and was also turned into a store room in 1938 and later a gym. In 1977/78 it was unfortunately torn down. At the time of its bloom the Jewish community of Nikolsburg boasted many more religious buildings, such as ritual bath houses, school rooms and prayer rooms. In the first half of the 19th century there were at least twelve synagogues or prayer rooms in the city, some of them on the first floor of family houses, named after their founders or the professions of the devoted, such as shoe makers, butchers, or religious groups, such as Ashkenazim or Chassidim. With the decline in importance of Nikolsburg as a religious centre and the emigration of the Jewish population the synagogues lost their religious community, too. At the end of the 19th century, there were just five in operation and just before World War II religious ceremonies were only celebrated in the “Upper Synagogue”.

Jewish cemetery Nikolsburg

The largest Jewish cemetery in Moravia is preserved on the western slope of the castle hill of Nikolsburg in the northwest of the Jewish quarter. Its location in the city centre proves that it was not moved from its original place since its foundation in the 15th century. The graveyard was continuously extended, which explains its irregular shape. In 1898 a big ceremonial hall was built by the Viennese Architect Max Fleischer. The religious centre of the cemetery is the so-called “Rabbis’ Hill” with Renaissance and Baroque graves of rabbis of the region; some of them world-famous. In the course of its existence probably tens of thousands of Jews were buried here. Today 4,000 gravestones are in their original positions, most of them with their inscriptions facing south. The oldest gravestone, where the inscription is still legible, dates back to 1605 and is dedicated to Samuel ben Leb Aschkenasi. The more modern gravestones of the second half of the 19th century resemble Christian grave stones with inscriptions mostly in German.

Bilingual gravestone, Jewish cemetery Nikolsburg

Synagogue, Trebitsch

Another important Jewish centre in the region was Trebitsch (Trebic), where the Jews settled in the vicinity of the Benedictine monastery. In 1338 their presence is first documented. The Jewish quarter developed in the area of the village that served the monastery. Only in 1723 a Jewish ghetto was installed at the command of the owner of the dominion, Jan Josef von Waldstetten, who ordered that Christians and Jews had to be separated and the Christians of the village had to sell their properties to the Jews. Additionally plans for a separating wall were under way. The first synagogue was built in 1669 in the Renaissance style and the increasing number of members of the Jewish community led to the construction of a second synagogue in the Jewish quarter. After several official rejections they were finally allowed to extend this new synagogue at the beginning of the 18th century and to decorate it with beautiful Baroque frescos. Before the construction of the official town hall of the Jewish quarter in 1660, private houses served as meeting places. Here the representatives of the community met and the community’s archive was installed there as well. This new building also included shops, a ritual bath house for women and a well. The town hall’s property value was higher than that of the synagogues. The rabbi’s house is the oldest in the Jewish ghetto. It was built between 1613 and 1621, yet originally it housed shops because the rabbis were not allowed to receive a salary and had to pursue a trade. Consequently the community did not have to provide a house for the rabbi. This changed towards the end of the 17th century, when the Jewish community of Trebitsch provided this house for the rabbi. In the same way, the children were first taught in private houses before a school was erected in the beginning of the 18th century.

Jewish quarter Trebitsch

Jewish cemetery Eywanowitz

The original cemetery of the Trebitsch Jewish community had to be moved from the city centre to the northern outskirts, approximately 400 meters from the ghetto. This new cemetery was first mentioned in 1636 and also the first gravestone with a legible inscription dates from the 1630s. Jewish as well as Christian stone masons cut those gravestones. From the late 19th century on one can also find bilingual inscriptions here: Hebrew and German or Hebrew and Czech. In Bohemia and Moravia the stone masons cut reliefs with symbols into the headstones, which represented Jewish symbols such as the star of David, the Torah, grapes, lions, a crown or symbols of the names of the dead persons such as stag, bear, lion, goose, cock, mouse or symbols of the trades of the deceased, such as scissors for the tailors, books for traders, medical instruments for doctors, musical instruments for musicians. Today this is one of the biggest preserved Jewish graveyards in the region.

Jewish quarter in Trebitsch

Eywanowitz

Eywanowitz

Eywanowitz

My great-grandparents left Moravia in 1902 for Vienna like many Moravian Jews, but also due to the fact that my great-grandfather, Ignaz, was born in Vienna and the capital city offered better career opportunities for him. The parents of my great-grandmother, Rudolphine (Ritschi), had lived in the village of Eywanowitz and had run a surgery there. The medical doctor Josef and his wife Agnes Weiss died in Eywanowitz in 1901 and 1902.

Gravestone of my great-great grndfather, Eywanowitz

Gravestone of my great-great grandmother, Eywanowitz

Literature:

Brugger, Eveline u.a., Geschichte der Juden in Österreich, Überreuter 2006

Veselska, Dana u.a., Die Juden in Nikolsburg, Mikulov 2008

Trebic. Geschichte und Denkmäler, Trebic 2006