“Schubertpark”, former cemetery of the Viennese district Währing”, opened 1769. Famous personalities, such as the musicians and composers Franz Schubert, Ludwig van Beethoven and the authors Franz Grillparzer and Johann Nestroy, were buried here before the transfer of their remains to the newly opened “Zentralfriedhof”. This graveyard was closed in 1873 and completely abandoned before it was turned into a park in 1924/25.

“Es lebe der Zentralfriedhof “ (Long Live the Central Cemetery)

Viennese song & lyrics by Wolfgang Ambros, published in 1975, which celebrates the 100th anniversary of the opening of Vienna’s largest graveyard in sarcastic words:

Es lebe der Zentralfriedhof und alle seine Toten!

Der Eintritt ist für Lebende heut‘ ausnahmslos verboten.

Weil der Tod a Fest heut gibt, die ganze lange Nacht.

und von die Gäst‘ ka einziger a Eintrittskarten bra[u]cht.

Wann’s Nacht wird über Simmering, kummt Leben in die Toten,

und drüben beim Krematorium tan s‘ Knochenmark anbraten.

Dort hinten bei der Marmorgruft, dort stengan zwei Skelete,

die stessen mit zwei Urnen z’samm und saufen um die Wette.

Am Zentralfriedhof is Stimmung, wia seit Lebtag no net woa,

weil alle Toten feiern heut seine ersten hundert Jahr.

Es lebe der Zentralfriedhof und seine Jubilare.

Sie liegen und verfaul’n scho da seit über hundert Jahre.

Draußt is kalt und drunt is warm, nur manchmal a bissel feucht,

wenn ma so drunt liegt, freut ma sich, wann’s Grablaternderl leucht.

Es lebe der Zentralfriedhof, die Szene wird makaber;

die Pfarrer tanzen mit die Huren, und de J u d e n mit d‘ Araber.

Heut san alle wieder lustig, heut‘ lebt alles auf.

Im Mausoleum spielt a Band, die hat an Wahnsinnshammer drauf.

Am Zentralfriedhof ist Stimmung wia seit Lebtag no net woa,

weil alle Toten feiern heute seine ersten hundert Jahr.

Es lebe der Zentralfriedhof! Auf amoi macht’s a Schnalzer,

der Moser singt’s Fiakerlied und die Schrammeln spüln an Walzer.

Auf amoi is die Musi still, und alle Aug’n glänzen

weil dort drübn steht der Knochenmann und winkt mit seiner Sensen.

Am Zentralfriedhof ist Stimmung wia seit Lebtag no net woa,

weil alle Toten feiern heute seine ersten hundert Jahr.

Translation:

Long live the Central Cemetery and all its dead!

Admission is strictly forbidden to the living today.

Because Death is throwing a party tonight, all night long.

And none of the guests need tickets.

When night falls over Simmering, the dead come to life,

and over at the crematorium, they fry bone marrow.

Back there by the marble tomb, two skeletons are standing,

they’re toasting with two urns and drinking competitively.

At the Central Cemetery, the atmosphere is like never before,

because all the dead are celebrating their first hundred years today.

Long live the Central Cemetery and its jubilarians.

They have been lying there and rotting for over a hundred years.

It’s cold outside and warm down there, only sometimes a little damp,

when you’re lying down there, you’re happy when the grave lanterns light up.

Long live the Central Cemetery, the scene is becoming macabre;

the priests are dancing with the whores, and the Jews with the Arabs.

Today everyone is happy again, today everything is coming to life.

A band is playing in the mausoleum, and they’re really rocking it.

The atmosphere at the Central Cemetery is like nothing we’ve ever seen before,

because all the dead are celebrating their first hundred years today.

Long live the Central Cemetery! Suddenly there’s a snap,

Moser sings the Fiakerlied and the Schrammeln play a waltz.

Suddenly the music stops, and everyone’s eyes shine

because the Grim Reaper is standing there, waving his scythe.

The atmosphere at the Central Cemetery is like nothing we’ve ever seen before,

because all the dead are celebrating his first one hundred years.

Viennese “Leichenwirtshäuser” (in Viennese: “corpse inns” = funeral inns) and “Leichenschmaus” (in Viennese: “corpse meals” = funeral feast)

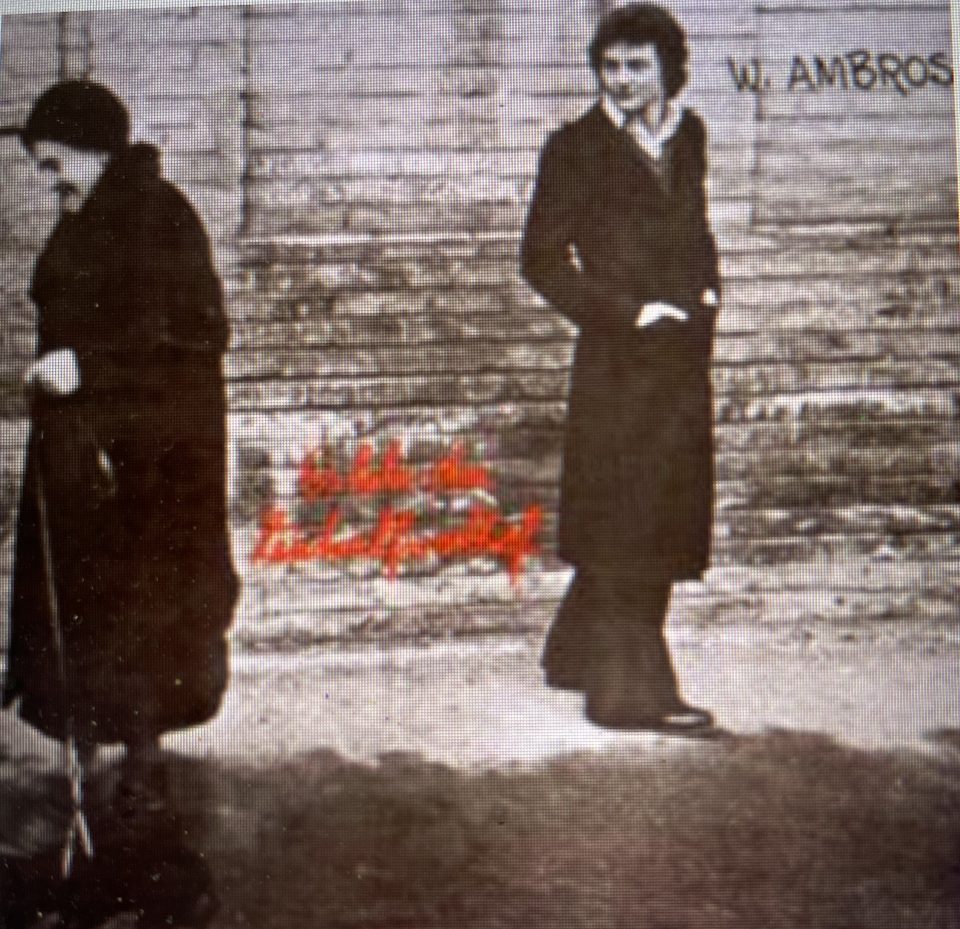

The newly opened “Schubertpark” with its cemetery in the 1920s, photographed by my grandfather, Toni Kainz, who was the son of the owner of the “Anton Kainz Gasthaus”, opposite the former graveyard, originally a typical Viennese “corpse inn”. These inns have always thrived on the celebrations after a burial, the “Leichenschmaus” (“corpse meal”). Therefore, such inns next to graveyards were called “Leichenwirtshäuser” in Viennese:

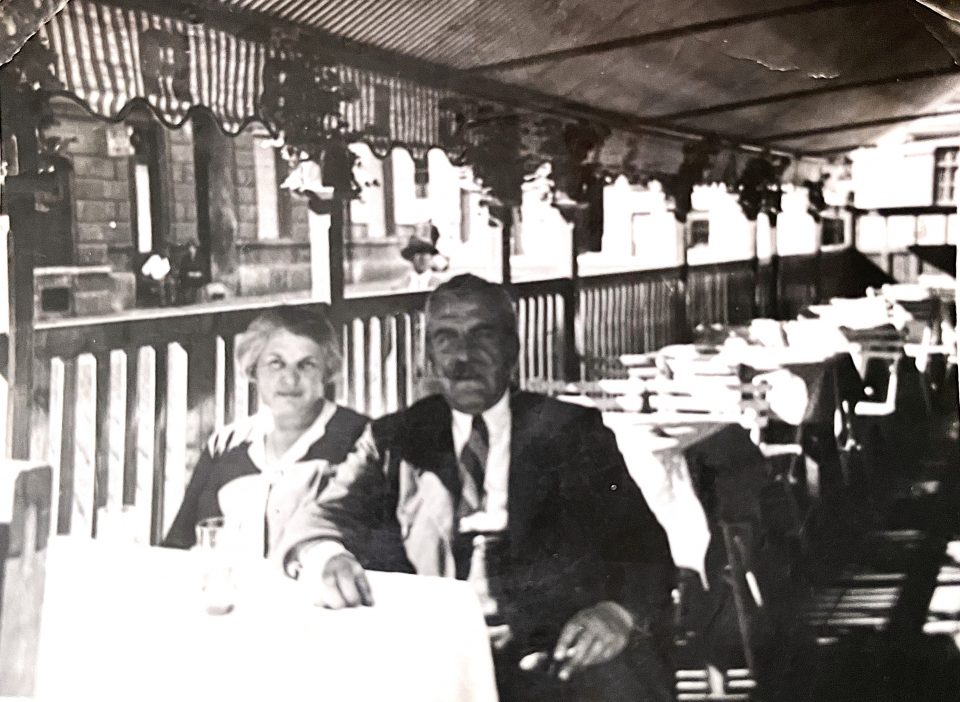

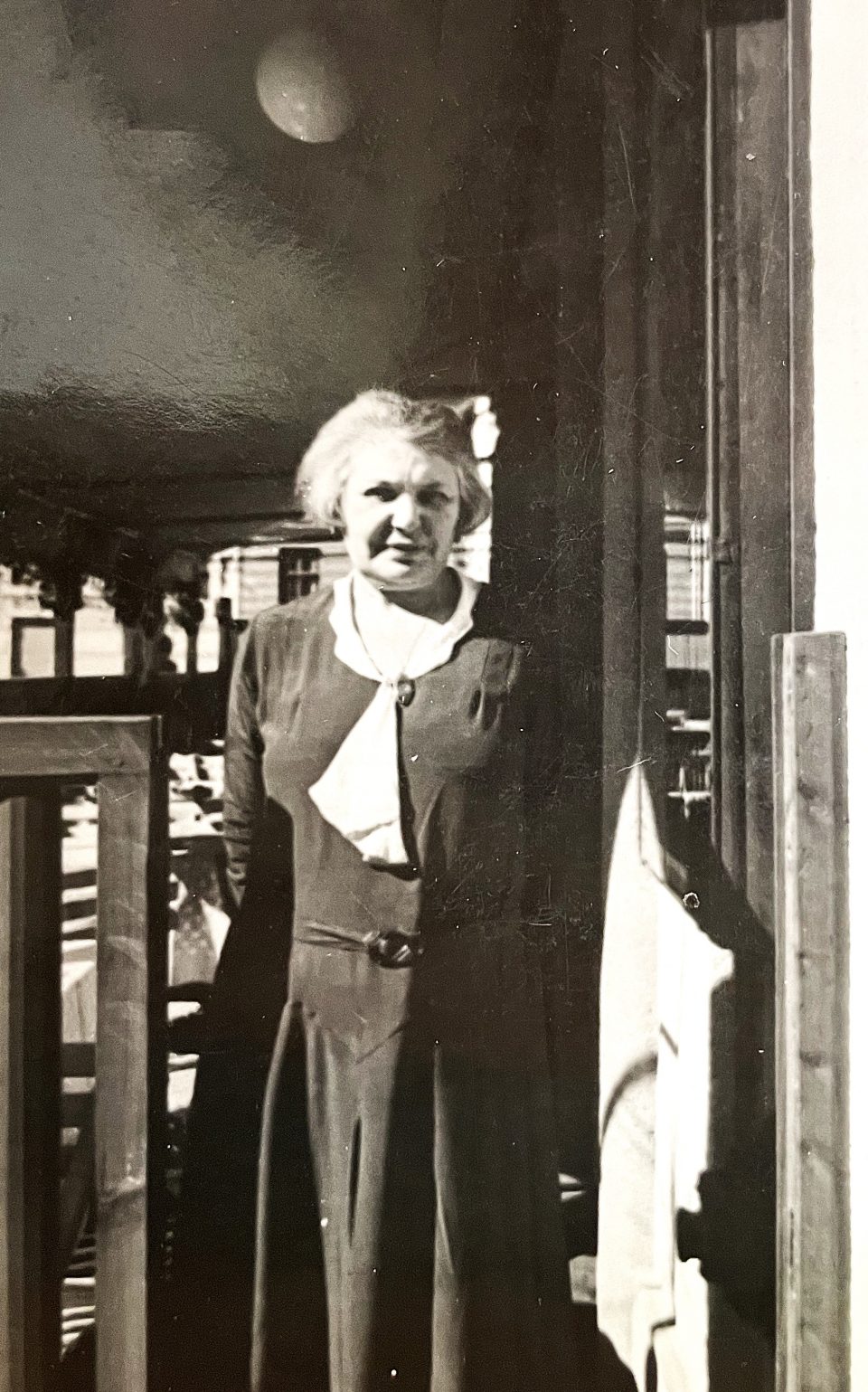

“Anton Kainz Gasthaus” opposite the “Schubertpark” in the late 1920s: left: my grandmother Lola Kainz in the entrance, right: my great-grandparents on the “terrace”, called “Schanigarten” in Vienna.

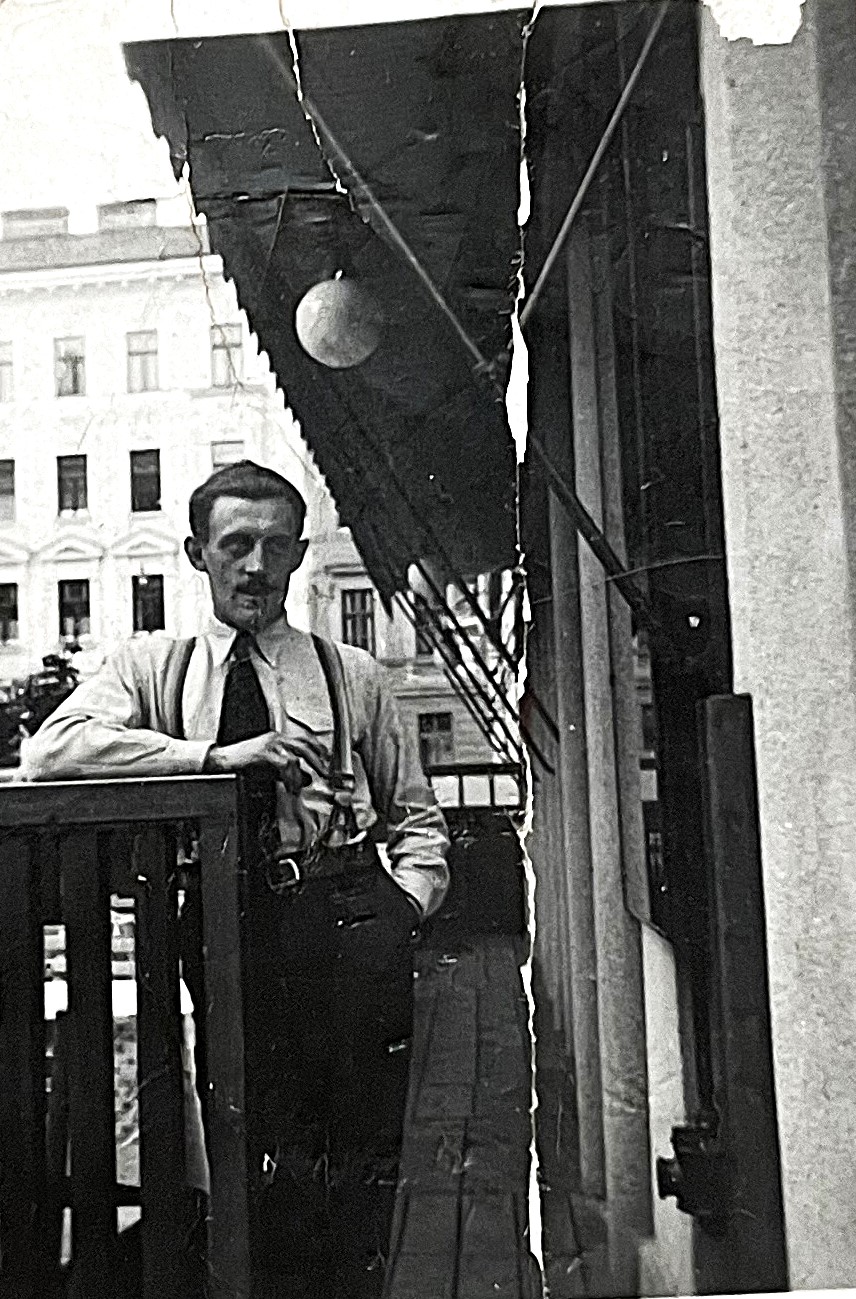

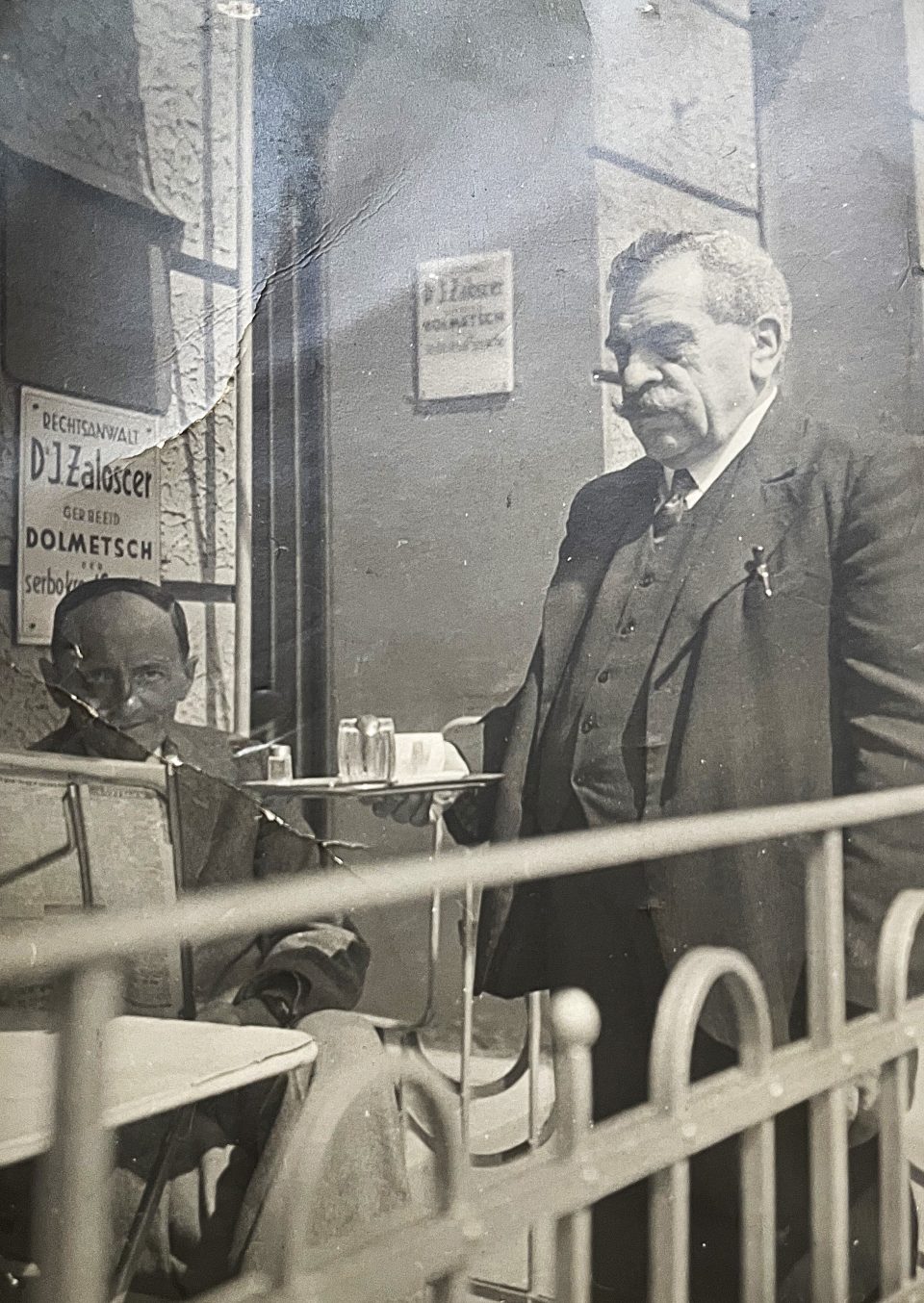

Left: my grandfather Toni Kainz on the “terrace”, in the middle: my great-grandfather, Ignaz Sobotka, serving, and right: my great-grandmother, Rudolfine Sobotka, at the entrance to the terrace of the “Anton Kainz Gasthaus”

When in the second half of the 19th century the inner-city graveyards were closed and later turned into public parks, the so-called “corpse inns”, moved to the outskirts of the city, where the Viennese were now buried and the celebrations after the burials took place in the inns nearby. The “Leichenschmaus” (“corpse meal”) could last several days and no matter the social class or income, it was the aim of every Viennese to have a dignified burial with an appropriate festive gathering of the mourners after the ceremony in an inn with food, lots of drink, mostly alcoholic, and sometimes musicians, who performed the traditional Viennese songs (“Wienerlieder”), often mentioning death in a humorous , sarcastic or ironic way. Among these were the songs that the deceased loved during his lifetime and listened to at the “Heurigen”, the places where even today the young wine is drunk, simple food is served, and musicians perform the Viennese songs the customers want to hear. These traditions are still alive in Vienna.

Opposite the “Zentralfriedhof”, main gate 2, the traditional Viennese sausage stand “eh scho wuascht” offers respite for the visitors of the by far largest cemetery in Vienna in the 11th district, Simmering. Its name illustrates the sarcastic and humorous aspect of the Viennese’ fascination with death: the direct translation of the Viennese dialect phrase is: “it is already sausage”, meaning “it doesn’t matter any longer,” and the “sausage” is a favourite Viennese snack which you can eat there. Sausages are eaten standing, with your fingers or with tooth picks, and these sausages are traditionally named after places, such as Debrecen, Frankfurt, or Krain.

Next to the monumental entrance of the “Zentralfriedhof” there is a much-frequented prestigious coffee house and pastry shop (“Oberlaa”) for the mourners, where they can indulge in Viennese cakes and cheer the deceased.

Another excellent example of “Leichenwirtshaus” (“corpse inn”) is the “Concordia Schlössel”, opposite the “Zentralfriedhof”, which is a favourite spot for visitors of the cemetery, but also a location of “corpse meals” and many other festivities.

My parents, my grandparents, my great-aunt and great-uncle and my great-grandparents were all buried at the “Zentralfriedhof” and mostly the celebrations after their burials, the “Leichenschmaus”(“corps meals”) took place in this location.

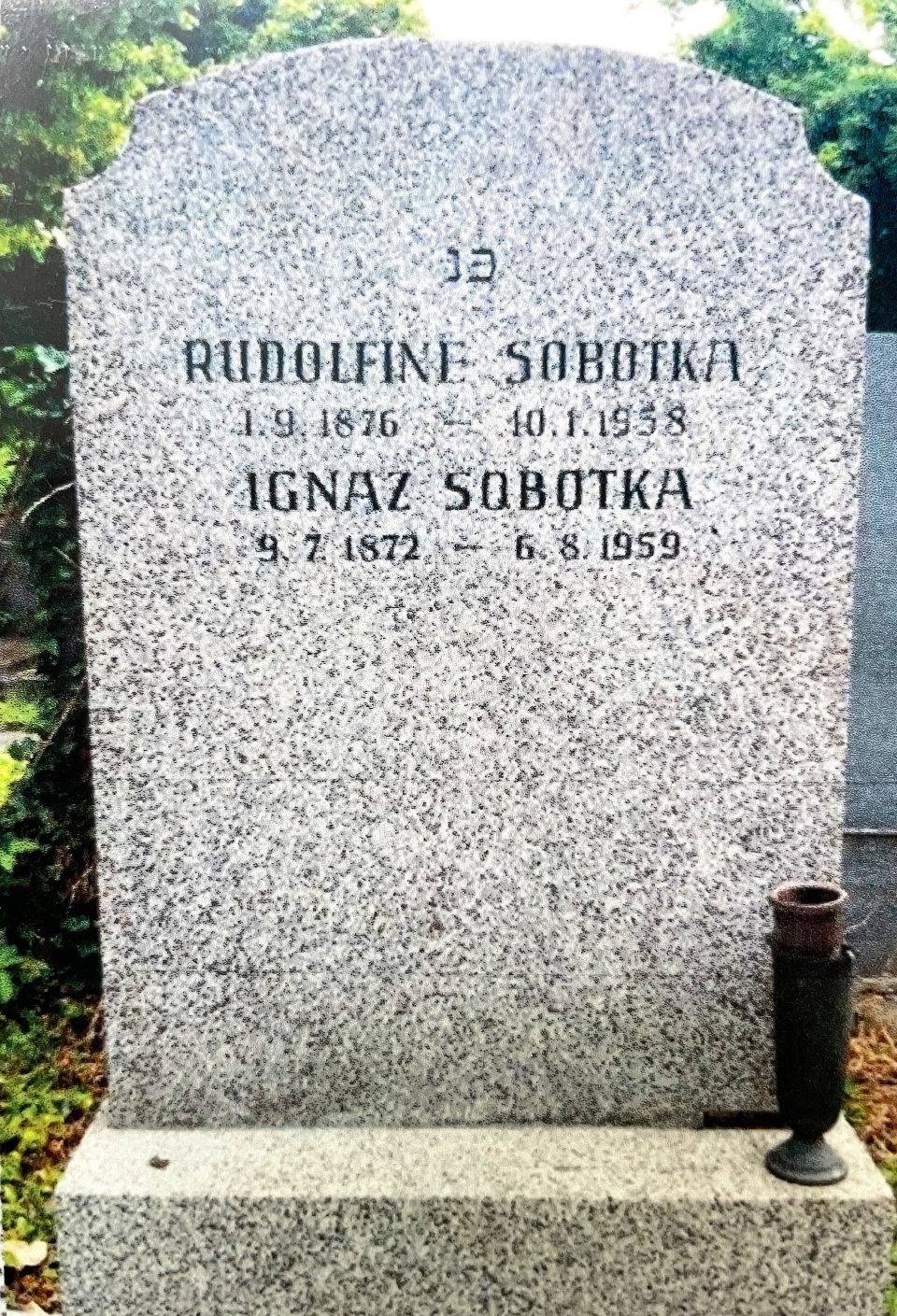

Left: The grave of my great-grandparents, Rudolfine & Ignaz Sobotka, in the new Jewish part of the “Zentralfriedhof”, right: the grave of my grandparents, Anton & Lola Kainz, in the Catholic part of the “Zentralfriedhof”

The graves of my great-uncle and great-aunt, Karl & Katharina Elzholz, and two of Karl’s ancestors, and my parents, Herta & Werner Tautz, in the crematorium part of the “Zentralfriedhof”

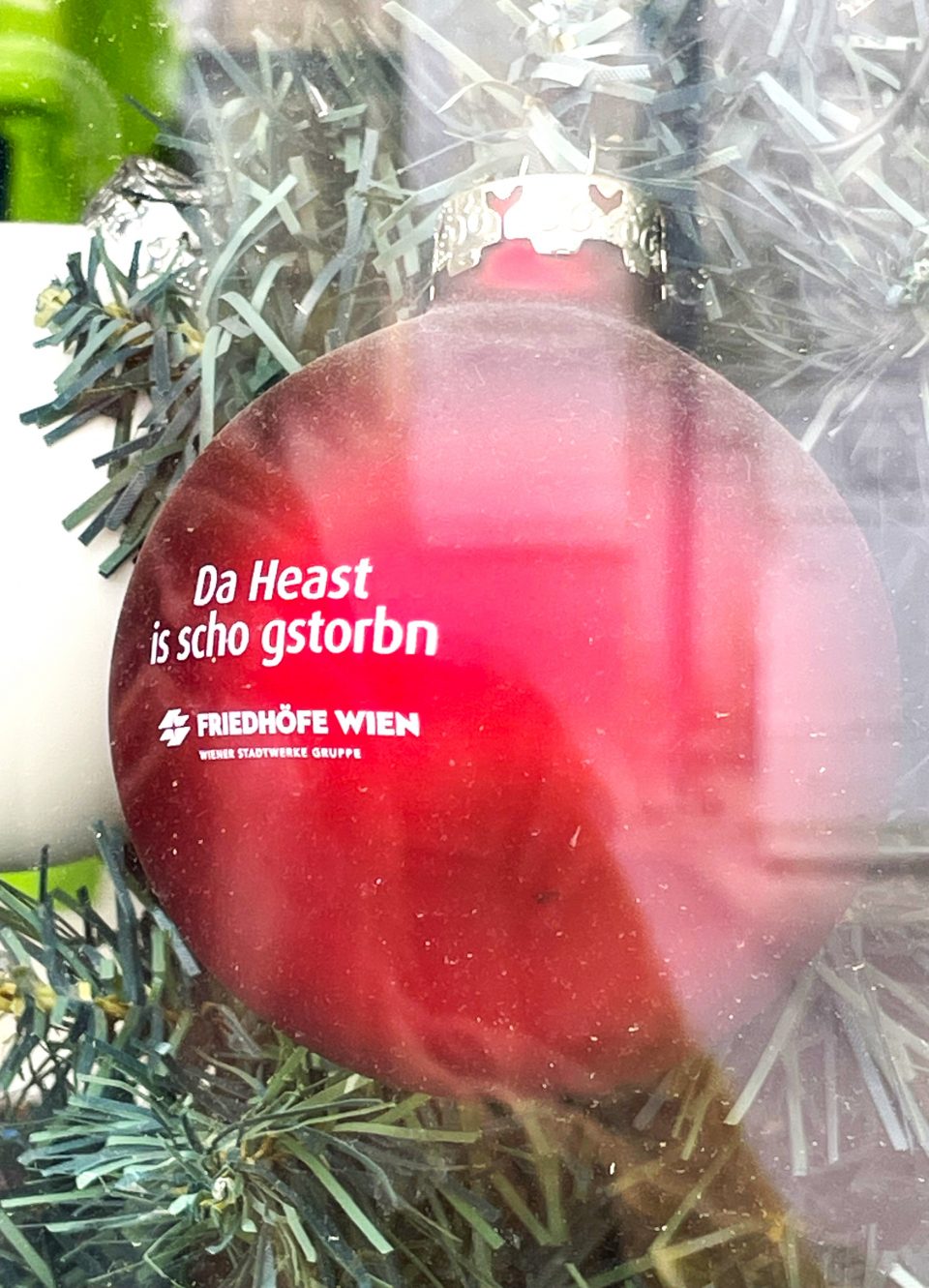

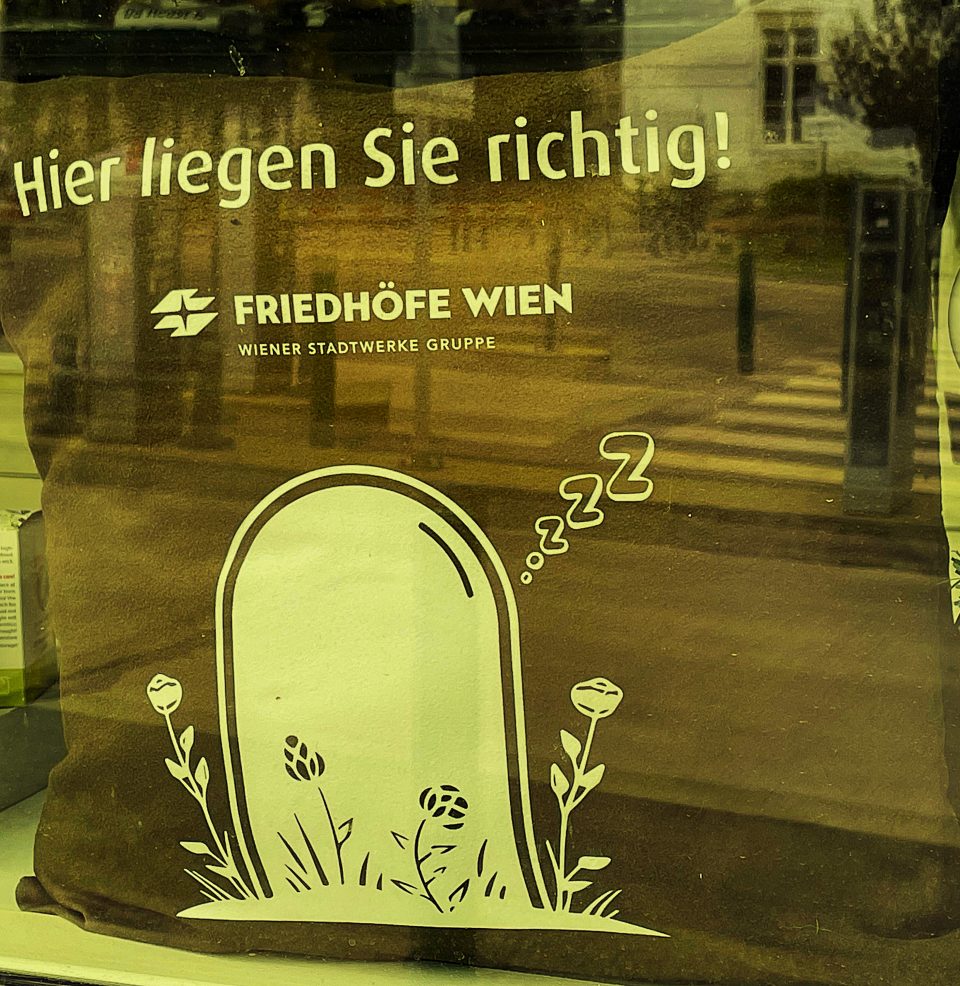

The Viennese fascination with death can further be seen in the much-visited “Bestattungsmuseum” (Burial Museum) at the “Zentralfriedhof”; located in a beautiful art nouveau building, where articles from the gift shop with macabre Viennese dialect slogans are much in demand, not just bought by tourists but also by the indigenous population:

Burial Museum

Gift shop articles: left: Christmas glass ball: “Da Hearst is scho gstorbn” (“The “hey” is already dead”), right: a black pillow “Hier liegen Sie richtig” (“Here you are lying in the right place: Graveyards Vienna”)

“Summer Collection” of the Burial Museum’s gift shop

“Zentralfriedhof” (Central Cemetery)

Due to the fast-rising population numbers in Vienna at the end of the 19th century, a new large central graveyard was opened on 1 November 1874 on the outskirts of the city in Simmering. It is not only the largest cemetery in Vienna, but the second largest in Europe after Hamburg-Ohlsdorf. Its size is 2.5 million m2 and it was planned to be the only graveyard in Vienna in future, but this plan was never realised. Yet it is the most important cemetery of the city with sections for various religions, Roman Catholic, Protestant, Orthodox, Jewish, Buddhist and best known are the graves of all those famous personalities who were granted a grave of honour.

Old Jewish Cemetery „Zentralfriedhof“

New Jewish Cemetery „Zentralfriedhof“

Graves of the Viennese Jewish writers and musicians: Gerhard Bronner, Friedrich Torberg, Arthur Schnitzler

“Heurigen” & “Wienerlieder”

Viennese songs “Wienerlieder” were and still are often sung at the “Heurigen” and often in commemoration of the deceased, friends and relatives celebrate in such locations, toasting the dead loved ones with wine and beer:

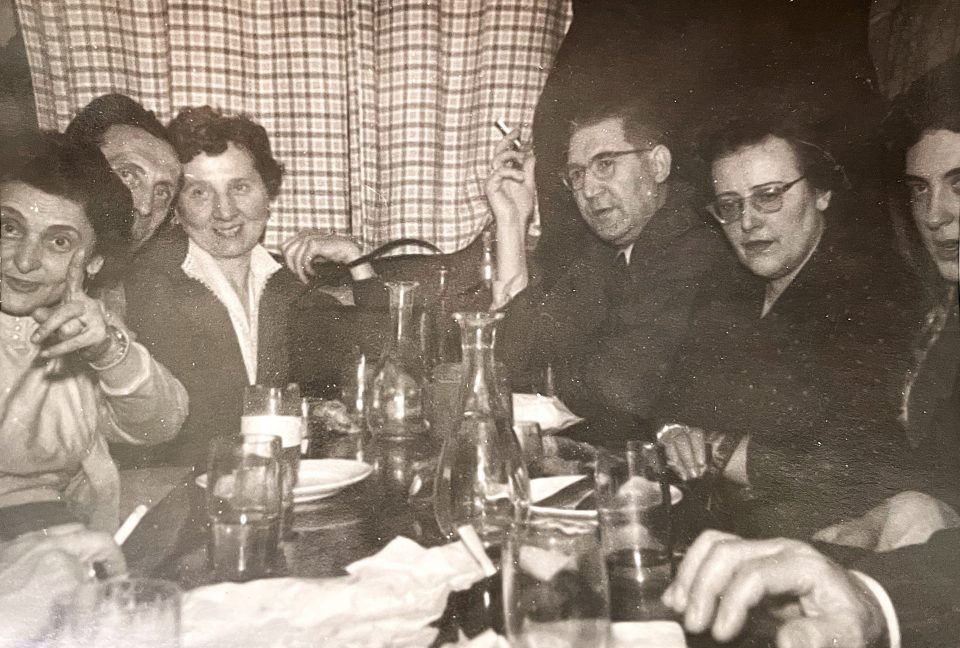

Guests asking the musician to play a special “Wienerlied” (in this photo Lola, Toni, my grandparents and Karl Elzholz, my great-uncle). My great-grandfather Ignaz always asked for a special “Wienerlied”, “Das silberne Kanderl” (The silver jug), which nearly none of the musicians knew and therefore various versions of the song were performed, which was quite common with “Wienerlieder”.

Left: my mother Herta Tautz, in the background a typical “Wienerlied” formation of musicians: violin, accordion and guitar

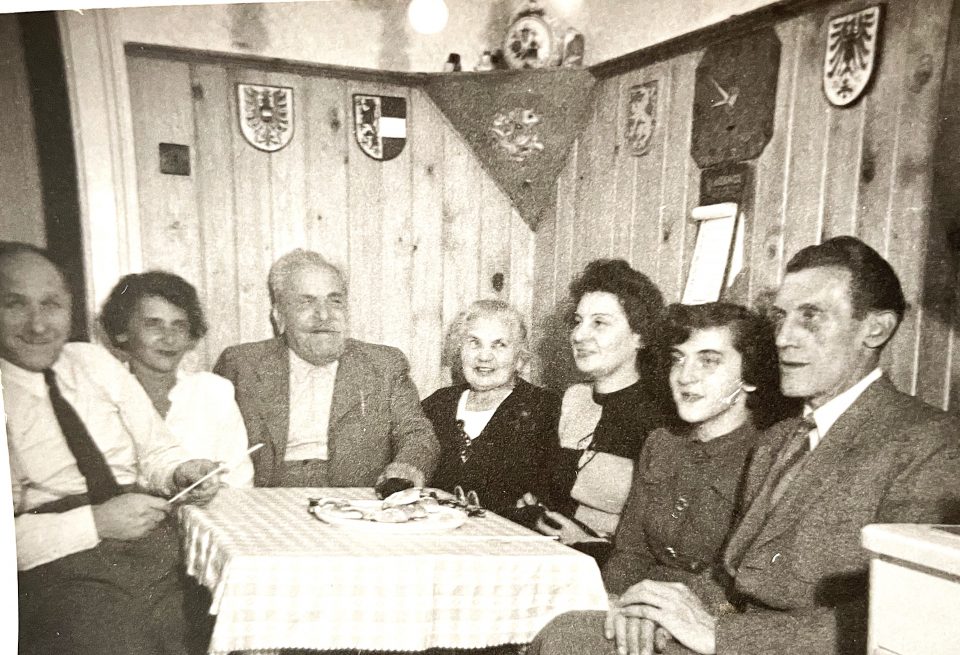

At a “Heurigen” with the offers of wine and food – different types of home-made sausages – advertised on the wooden panelling; my mother, Herta Tautz in the middle and my father, Werner Tautz, to the right

Viennese Baroque Burial Ceremonies & Death Rites

For centuries the Viennese cultivated a Baroque vision of death as the fulfilment of life. The various aspects that characterised Viennese thinking were all part of this attitude towards death, whereby death constituted a bulwark against change. Many intellectuals, artists, writers, and musicians living in Vienna were freemasons, for example Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, who preached a conviction held by many here, namely that death forms part of life. The writer Stefan Zweig saw in the Viennese custom of staging magnificent funerals, known as “a schene Leich” (“a beautiful corpse”), a symptom of Viennese aestheticism. Of course, showmanship pervaded the Viennese funerals of the nobility and the well-to-do, but it was more than just a mere love of pomp, because on a much less grand scale it affected the funerals of the poorer classes, too. Well into the 20th century Austrian Catholics believed that the dead live on in the souls of their relatives and friends, and some still do. Funerals of much-loved Viennese personalities, such as the former Socialist Mayor of Vienna Helmut Zilk, or the shady businessman, cheap showman and lover of very young women to whom he gave animal pet names, such as “Mausi” or “Katzi”, Richard Lugner, document the persistence of such opulent burial customs in the 21st century:

Left: Mayor Helmut Zilk’s funeral at the “Zentralfriedhof”, 2008; right:The funeral of Richard Lugner, fan and star guest of every Vienna Opera Ball, Saint Stephen’s Cathedral 2024

The “little people”, portrayed by writers such as Ferdinand von Saar and Marie von Ebner Eschenbach, viewed death as release from an uncomprehending world and from a dire existence. Crowning a lifetime of deprivation and humble satisfactions, death loomed as the one grand event. Still a drawback marred even the most pompous funerals, of which the Viennese were so fond: The city was tempted to wait until after a gifted personality had died before it honoured the deceased. Exaggerated reverence for the dead encouraged tragic indifference to the living. During the mid-nineteenth century Vienna’s physicians seemed to prize the results of postmortem autopsies more highly than saving a patient. Yet the results of this research practice contributed to the rise in reputation of the Viennese medical school at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century.

Worship of the dead reinforced the preference for things past, which permeated Viennese taste. Extolling the past while revering death led to an attitude, where most Viennese indulged in a self-satisfaction, which was beguiling, but incapable of self-renewal. Viennese writers who around 1900 frequented coffeehouses and wrote feuilletons shared a preoccupation with evanescence, especially with its definitive form, death. Fascination with the transitory characterises the works of Hofmannsthal, Schnitzler, Beer-Hofmann and Altenberg. Fascinated by decay, these unemployed sons of upper- and middle-class families carried Baroque reverence for death to unheard-of extremes. To them death promised release from boredom, from “ennui”. In a world gone stale, death alone remained a mighty unknown. Committing suicide was what many of them dreamed of doing. Contemplation of death, relishing the ubiquity of death formed the reverse side of Viennese gluttony and zest for living the moment excessively, the Viennese Phaeacianism.

“Biedermeier” cemetery Saint Marx

This graveyard was opened in 1784, “4,800 steps from the city”, and the last burials took place in 1874, when the “Zentralfriedhof” was inaugurated. Most of those who were buried here came to Vienna from other parts of the Habsburg Empire, usually poor, deprived and alone. They had to pay for their education and training under dire circumstances; teachers and priests selected the most promising young people and relatives or benefactors at home financed the careers of this growing “petite bourgeoisie” that developed in “Biedermeier” Vienna at the end of the 18th and the early 19th century.

The first generations of this Viennese lower middle class were buried here. At times this early suburban bourgeoisie was exposed to abysmal living conditions and poverty and suffered under the suppression of the authoritarian regime of Chancellor Metternich and other reactionary representatives of the Habsburg police state. Among those affected were many intellectuals, artists, and musicians; the probably most famous of them was Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, who died in poverty in Vienna in 1791 and received a pauper’s funeral at Saint Marx outside the city. It was therefore a mystery where exactly Mozart’s grave on the “Freydhofe ausser St. Marx” was really situated, because Mozart was buried in a so-called “Schachtgrab” (shaft or pit grave) that could hold 20 corpses and which was usually emptied of the human remains and vacated after 10 years. At Mozart’s time it was not common to put a wooden cross with the name of the deceased on such a pauper’s grave. For many years after his death attempts were made to find his burial spot at this graveyard, but in vain. In 1855 an official investigation was launched after many urgent petitions of admirers of Mozart’s music. The trade with famous skulls and death masks was booming during the “Biedermeier” period in Vienna, for example the skulls of the composer Joseph Haydn and the author Ferdinand Raimund were illegally unearthed and traded. So, in this way also “a scull of Mozart” appeared in 1842. This can be seen as another macabre example of the fascination with death in the city. In 2006 a DNA analysis was carried out of “Mozart’s skull”, but the authenticity could not be proved because there is no existing comparative sample. On the plot where formerly the paupers’ graves were located a memorial was erected for Mozart in 1859, which was transferred to the sections of the musicians at the “Zentralfriedhof”. The position of the paupers’ graves at St. Marx graveyard was nearly forgotten, until the local graveyard keeper collected some abandoned stone fragments and erected a memorial for Mozart there, which was heavily damaged in 1945 and restored thereafter.

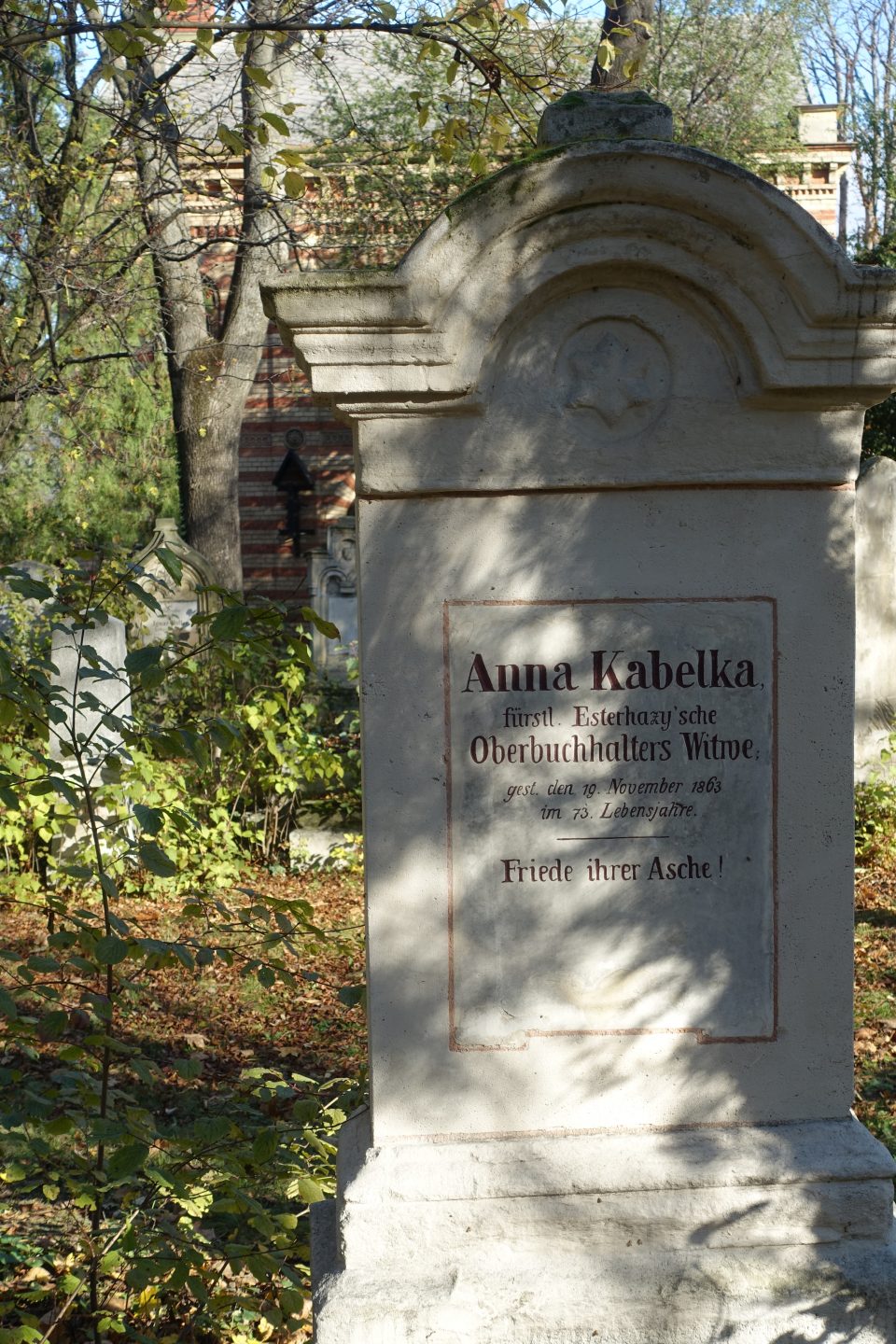

If the lower middle-class Viennese managed to climb the social ladder and rise in the Viennese social hierarchy, they and their families were proud to mention the positions they had achieved and the honours they had been granted on their grave stones.

In the late 18th and 19th century it was common among the Viennese bourgeoise population to mention the profession of the deceased or the profession of the father or husband of the deceased on the grave stone:

Left: Cavaliere (Italian title for a businessman) Carlo de Ceresa from Lodi, right: Karoline Huschel, daughter of a bourgeois shoemaker

Left: Anna Krenn, daughter of a bourgeois kitchen gardener, right: Petronilla Meyerhofer, widow of a bourgeois ship master

Left: Carl Mostler, bourgeois kitchen gardener, right: Franz Ritters von Seifried, titled civil servant of the k.k. administration

Left: Anna Kabelka, widow of the head book keeper of Fürst Esterhazy, right: Franz Heinz, bourgeois butcher

The most celebrated Viennese poet of death of the fin-de-siècle was the Jewish doctor, Arthur Schnitzler (1862-1931). Son of a Hungarian-born laryngologist, young Schnitzler grew up as a dandy in “Ringstrassen Vienna”. He revealed his vagaries as an apprentice to his father in his autobiography, written between 1915 and 1918. There he described how differently death appears in the dissecting room and at the bedside of a patient. In numerous novellas Schnitzler explored how death assuages the wounds of the living. Schnitzler’s affinity with the theories of Sigmund Freud is visible in his works: Death heals by imparting liberation to the living in the manner of psychoanalysis. Revering emotion as more contagious than language, Schnitzler sought to expose a latent world behind the manifest one. Death afforded a supreme arbiter to symbolise at once the latent content of life, the unconscious, and emotions which words cannot transmit. In his novellas only the death of a friend, for example in “Der Tod des Junggesellen” (Death of a bachelor) 1907, exerts impact enough to shatter the pretences of everyday life. For Schnitzler every moment meant a little dying followed by a rebirth. In his famous drama “Professor Bernhardi” 1912, a Jewish physician is trying to sooth a young dying woman by not allowing a Catholic priest to approach her on her death bed in order not to shock her by being exposed to the “last rites”, as she is not aware of her imminent death and dreaming of a wonderful future. For this act of mercy, the Professor is harshly criticised and sanctioned by his anti-Semitic colleagues.

Between 1860 and 1938 an astonishing number of Austrian intellectuals committed suicide; Crown Prince Rudolf, the writers Adalbert Stifter, Ferdinand von Saar, the physicist Ludwig Boltzmann, the social theorist Ludwig Gumplowicz were among those who chose to terminate their unbearable anguish by ending their lives. Symptomatic of the conditions in Austria were suicides prompted by conflict between inner conviction and outer circumstances, such as the one of the architect of the Vienna State Opera House, Eduard van der Nüll, who could not cope with the negative reception of his work. After 1900 several Austrian intellectuals in their twenties took their own lives, for example Otto Weidinger, Maximilian Gumplowicz, the painter Richard Gerstl, the chemist Max Steiner, the poet Georg Trakl. Three young men who later achieved fame tried unsuccessfully to kill themselves during this period: the artist Alfred Kubin, the musicians Alban Berg and Hugo Wolf. Suicide occurred so frequently among persons under thirty that members of the Vienna Psychoanalytical Society, led by Alfred Adler, devoted a symposium to the topic in 1910; in particular, they probed suicides by gymnasium students. Adler saw in adolescent suicide an escape from uncompensated feelings of inferiority. But Freud expressed disappointment at the result of the symposium, observing that the participants had offered no explanation as to what process destroys the innate instinct of self-preservation.

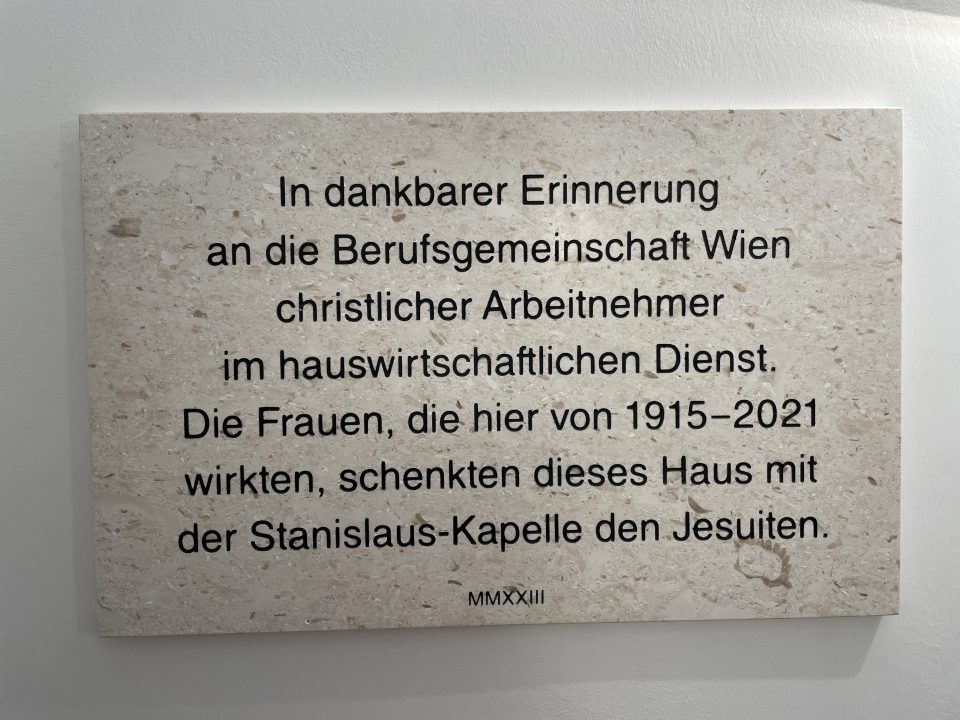

An important aspect of young suicide victims in Vienna was the extremely high rate of suicides among young unmarried pregnant women, most drowned themselves in the Danube. They were members of the large female servant population, who as girls had come to Vienna from the country to work in one of the many aristocratic, upper-and lower- middle class households and were easy prey for the male members of these households. The situation was so dramatic that charity organisations were set up to assist these young women. One example is the house Steindlgasse 6 in the 1st district of Vienna, where the “Christlicher Verband der weiblichen Hausbediensteten in Wien” was located from 1915 until 1938, when the Nazis took over the house and sold it for a profit. The house was returned to the charity after World War II in 1948 and in 2021 the charity donated the house to the Jesuites.

Stanislaus Koska Kapelle in the house Steindlgasse 6, where the charity for the female servants in Vienna was housed.

This leads to another very unique type of suicide in Vienna, namely when the Nazis took over Austria in the so-called “Anschluss” in March 1938 and started the excessive dispossession and persecution and expulsion of the Austrian Jews. Many desperate Viennese Jews saw no other way of escape from this tragic situation than to take their own lives, among them famous intellectuals, such as Egon Friedell and Stefan Zweig.

Could it have been the Baroque ceremonial cult of death combined with the fin-de-siècle intellectuals’ view of evanescence that made suicide seem so attractive? Even devout Roman Catholics like Adalbert Stifter were not deterred by religious scruples and might even have been attracted to suicide in a culture that esteemed death as an undisclosed side of life. As shown by Otto Weininger, proclivity to suicide could spring from therapeutic nihilism. The character of Shakespeare’s Hamlet attracted these young men. Hamlet epitomised an attitude that afflicted many of the intellectuals around 1900; like Hamlet they could not decide to live. The Viennese circle of intellectuals of the time, called “Young Vienna”, opted out of politics, and had a strong influence on their successors to acquiesce in the demise of their world. The Viennese were once called “a people who could not say no”. By refusing to say no to violence and to death, the Viennese intellectuals and artists of 1900 cultivated an openness that made them pioneers of modernity. Yet flaccidity excluded them from reaping any fruits during their lifetime. Having compromised with death, they and their successors might unwittingly have abetted the Nazi perpetrators of the Holocaust.

“Wienerlieder” (Viennese Songs) & Death

Commemorative plaque of famous Viennese coachmen, called “Fiaker”, who were often celebrated interpreters of Viennese songs, too. In the middle Josef Bratfisch, who was the favourite coachman and “Wienerlied” singer of Crown Prince Rudolf. He drove the prince and his lover Mary Vetsera to the imperial hunting lodge in Mayerling and sang for them before the Crown Prince shot Mary and committed suicide in 1889.

A Viennese saying “Sicher ist nur der Tod“ (Only death is certain) illustrates the fact that the world of dying and death have always been present in Viennese every day life, especially in popular Viennese songs, mostly with an ironic or sarcastic touch, as the song of Wolfgang Ambros of 1975 at the beginning of this article shows, which celebrates the 100th anniversary of a cemetery.

The commemorative plaque of the “Wienerlied” composer Hans von Frankowski in the 16th district, Neulerchenfelderstrasse 39

Frankowski composed among many other songs the following morbid one: “Erst wann’s aus wird sein” (Only when it is over)

Erst wann’s aus wird sein, mit aner Musi’ und ‘n Wein,

Dann pack’ ma die sieb’n Zwetschk’n ein, eh’nder net.

Wann der Wein verdirbt und amol die Musi’ stirbt,

In die mir Weana so verliabt, is’s a G’frett!

Solaung im Glaserl no’ a Tröpferl drin is,

Solaung a Geig’n no’ voll Melodien is

Und solang als no’ a dulli g’stelltes Maderl da,

Da sag’n ma immer no: ‘Halt ja!’ und fahr’n net a’!

Translation:

Only when it’s over, with music and wine,

Then we’ll pack up the seven plums (=die), but not before.

When the wine spoils and the music dies,

In which we Viennese are so in love, it’s a shame!

As long as there’s still a drop left in the glass,

As long as the violin is still full of melodies,

And as long as there’s a nice plump girl there,

We’ll always say, “Hold on!” and don’t leave (=die)!

This is the “Heurigen” in Ottakring (16, Speckbachergasse 14), where the musician and composer Karl Hodina got the inspiration for his “Wienerlied” “Hergott aus Sta” in 1956:

The topic of many a Viennese song is the relationship of the Viennese with God and Death, a bit sentimental, but never tragic, rather with a pinch of irony:

In Ottakring drausst in an uralten Haus

in dem Hof in da Speckbacher Gassn

da is gloant ganz verstaubt seiner Zierde beraubt

A Herrgott aus Sta so verlassn.

I hab eam entdeckt und als Kind dort versteckt

a s’Kittroehrl hädens ma g’stohln.

Herrgott aus Sta du nur allan

hast mi als Biabal verstandn

Hast mein Besitz immer beschuetzt

bist wie a Freund davor g’standn.

Oft hab i g’want mi an di g’lant

denn Kindersorgen san gross

Herrgot aus Sta du nur alla

du warst mei anziga Trost.

…….

Hergott aus Sta i glaub mir zwa

habn uns no rechtzeitig g’fundn

Hast mein Besitz immer beschuetzt

bin dir als Freund no verbundn

I trag di ham und pick di z’samm

san deine Schmerzen a gross

Herrgott aus Sta du nur alla

Du woarst mein anziger Trost.

Translation:

In Ottakring, outside, in an ancient house,

in the courtyard on Speckbacher Lane,

there stands, covered in dust, robbed of its adornments,

a Lord God made of stone, so abandoned.

I discovered him and hid there as a child,

When they had also stolen my blowpipe.

God made from stone, you alone,

understood me as a child.

You always protected my possessions,

stood before them like a friend.

I often longed for you,

for children’s worries are great.

Lord God, you alone,

were my only comfort.

……

God made from stone, believe me,

we found each other just in time.

You always protected my possessions,

I am still bound to you as a friend.

I carry you home and glued your pieces together,

Even if your pain is so great,

God from stone, you alone,

you were my only comfort.

When the Viennese talk about death, write about death in literary works or sing about death in Viennese songs, they often reduce it in importance and by trivialising it make death their “friend”. The musician Roland Neuwirth mused that the down-to-earth Viennese accept the ubiquitous presence of death, so that they can savour life the more. Another explanation of this special Viennese attitude to life and death might be the naïve Roman Catholic belief in a much more beautiful life after death; in Victor Frankl’s interpretation, only death makes life meaningful in some way. As Vienna has been a melting pot of nations, beliefs, languages, and religions for centuries, many different influences formed this ambiguous approach to life; savouring life on the one hand and celebrating death on the other. That’s why the Viennese have so many different dialect expressions, when talking about death without ever quoting the word “death” itself.

Karl Hodina was not just a musician, but also a painter of the Viennese group of Phantastic Realists, together with Ernst Fuchs and Arik Brauer. Karl Hodina’s interpretation of the legendary Viennese character “Lieber Augustin” (Dear Augustin), a musician who survived unscathed a night in the plague pit in Vienna, thanks to his abundant consumption of wine while singing and playing in a Viennese pub during the bubonic plague epidemic.

Historians assume that the “Dear Augustin “never existed, although a bagpiper Marx Augustin, who lived from 1643 until 1705, is registered in Vienna. The figure of the “Dear Augustin” is more the symbol of a lively vagabond who ignores law and order and survives because of his humour, wine, and songs. The Viennese song of the “Dear Augustin” exists in many versions, but the chorus lines are always the same and characterise the black humour of the Viennese with respect to death:

Ei, du Lieber Augustin,

S’Geld is hin, s’Mensch is hin,

Ei, du lieber Augustin,

Alles is hin!

Translation:

Oh dear Augustin,

The money’s gone, the girl’s gone,

Oh dear Augustin,

Everything’s gone!

“Everything is busted, everything is gone” is a characteristic of the Viennese gallows humour and figures in many Viennese songs in lines such as “Verkauft’s mei Gwand, I fahr’ in Himml…” (Sell my clothes, I’ll rise to heaven) or “Es wird a Wein sein und wir wer’n nimmer sein….” (There will be wine and we will no longer be…)

The character of Augustin appears in different literary forms over centuries. Harald Leupold-Löwenthal, the psychoanalyst, believed that the legend of the “Dear Augustin” proves the power of denying reality and makes Vienna one of the most resilient cities. Since 1995 “Augustin” is the patron and name-giver of the Viennese homeless newspaper.

The Viennese song tradition dates back to the Middle Ages, where the first drinking songs are documented in the 14th and 15th century. The street musicians must have been so popular that Ferdinand I issued a police order against street musicians, singers, and performing poets in Vienna in 1552. In the 17th century the first female harp player is documented in a Viennese inn and by the end of the 18th century this phenomenon had spread: in 1784 58 houses on the Spittelberg, the contemporary amusement area of Vienna, had the license not only to sell alcohol, but to have blind harp players entertain the guests. Around 1820 the classic “Wienerlied” developed and was performed in many Viennese inns by popular female singers, such as Emilie Turecek, called “Fiaker-Milli”, Anna Fiori or Antonie Mansfeld. Ferdinand Raimund wrote for his drama “Der Verschwender” (The spendthrift) a song, “Das Hobellied“ (Song of a plane), where the character Valentin says good-bye to the world in the face of death. This became one of the most popular Viennese songs, which was sung by star actors, such as Alexander Girardi, Paul Hörbiger and Josef Meinrad. The song tells of fading resistance against death and the acceptance of his / her final destiny:

Da streiten sich die Leut‘ herum

Oft um den Wert des Glücks, Der eine heißt den anderen dumm,

Am End weiß keiner nix.

Da ist der allerärmste Mann

Dem andern viel zu reich,

Das Schicksal setzt den Hobel an

Und hobelt’s beide gleich.

…..

Zeigt sich der Tod einst mit Verlaub

Und zupft mich: Brüderl kumm!

Da stell ich mich im Anfang taub

Und schau mich gar nicht um.

Doch sagt er: Lieber Valentin!

Mach‘ keine Umständ‘! Geh!

Da leg‘ ich meinen Hobel hin

Und sag‘ der Welt Adje.

Translation:

People argue

Often about the value of happiness, One calls the other stupid,

In the end, no one knows anything.

There is the poorest man

Far too rich for the other,

Fate takes up the plane

And planes them both the same.

……

When death comes calling, with all due respect,

And tugs at me: ‘Brother, come!’

At first I pretend not to hear

And don’t even look back.

But when he says: “Dear Valentine!

Don’t make a fuss! Go!”

Then I put down my plane

And bid the world farewell.

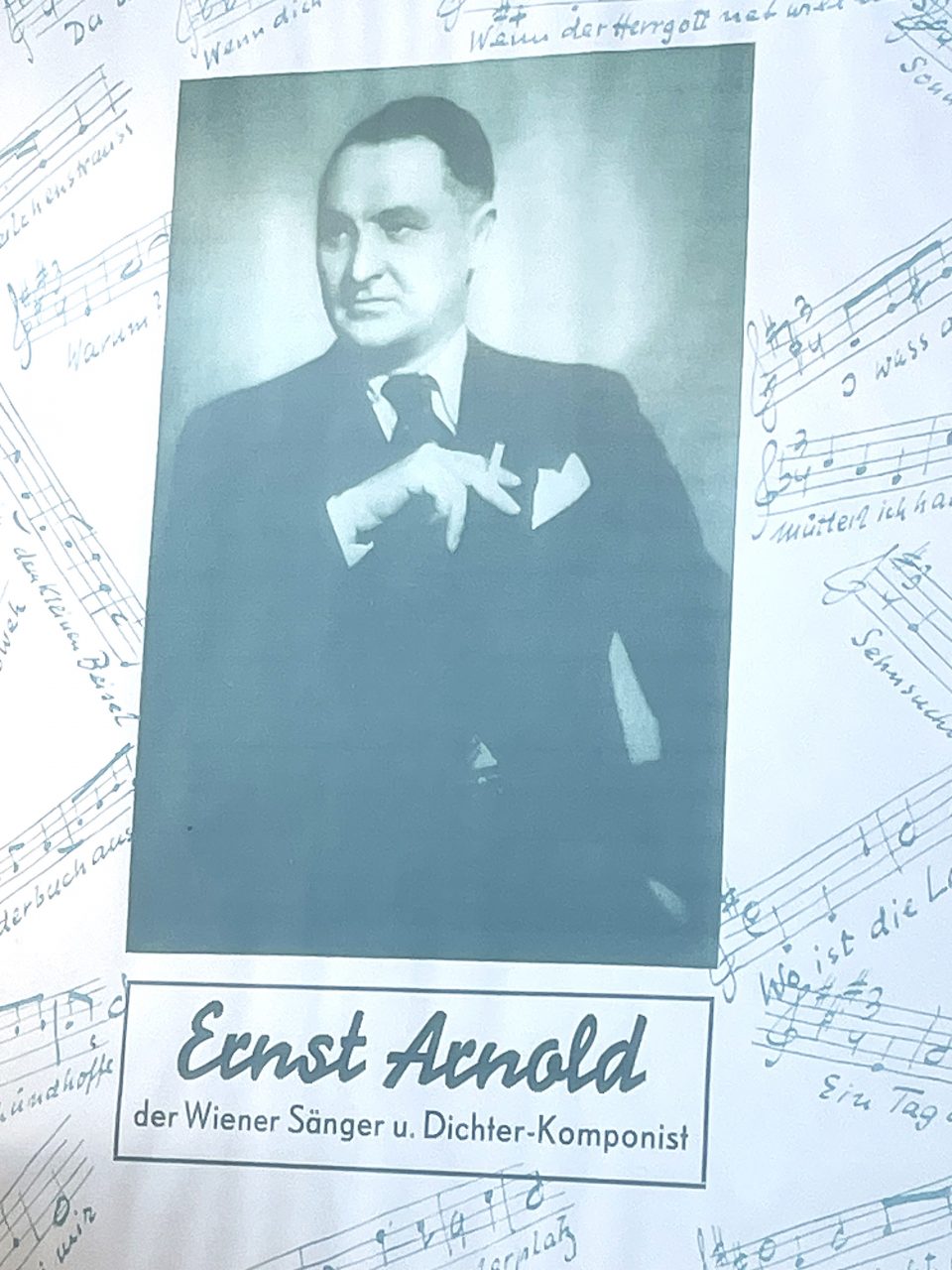

Ernst Arnold (1892-1962) was a composer and singer of Viennese songs and a regular at the Café Rüdigerhof. He wrote around 800 Viennese songs and when in 1938 the Nazis took over in Austria, he was forbidden to perform in Vienna, yet he continued to write songs unofficially. After the end of World War II, he became one of the most popular “Wienerlied” singers on the Austrian radio.

The writer and composer Hans Weigl (1908-1991), who had to flee Austria after the “Anschluss”, wrote the sarcastic song “Wien bleibt Wien” (Vienna remains Vienna) in 1935, where some lines are characteristic of the Viennese attitude to death and their city:

….

Ich will mein Grab nur am Donaustrand haben,

Es stirbt sich am besten in Wien.

…..

Wien bleibt Wien – und das geschieht ihm ganz recht.

Translation:

I want to have my grave only at the banks of the Danube

The best way to die is in Vienna

….

Vienna remains Vienna – and that serves her right.

“Friedhof der Namenlosen” (Cemetery of the nameless): Old cemetery for the drowned on the banks of the river Danube

This cemetery was set up for those who drowned in the Danube and whose corpses were washed ashore on the banks of the river, many of which were young single female servants who were pregnant and saw no way how to survive with a child born out of wedlock because they were destitute and had no one to support them. There are no more burials here, but volunteers tend to the graves of the many tragically drowned victims.

Graves of an unknown drowned person (left), of a female servant (middle) and of a worker who died at the construction of the harbour on the Danube next to the cemetery (right)

The composer Franz Ferry Wunsch (1901-1963) had his first success as a composer of Viennese songs with “Heut’ kommen d’Engerln auf Urlaub noch Wean” (Today the angels arrive in Vienna on holiday) and this song was slightly transformed during the Nazi rule into “Heut kommen d’Piefke auf Urlaub nach Wean” (Piefke = a pejorative term for Germans in Austria). After World War II his greatest success was another song with a hint to heaven and death: “Stellt’s meine Roß’ in Stall” (Put my horses into the stable). In this song he talks about the death of a cabman, a “Fiaker”, who ends his career and undertakes his last journey – to heaven.

Viennese song writers of Jewish origin

The most important composers of Viennese songs after 1900 were of Jewish descent: Alexander Krakauer, Robert Ehrenzweig und Adolf Hirsch, while Hermann Leopoldi was the most glamorous representative of the Viennese “Schlager”. Many of the amusing and ironic texts and the scores of such Viennese “Schlager” of the first half of the 20th century were created by Jewish artists. Next to Hermann Leopoldi, it was Fritz Grünbaum (1880-1940) and Karl Farkas (1893-1971), who were the best-known composers and writers of lyrics, as well as performers. Gustav Pick (1832-1921) wrote one of the most popular Viennese songs, the “Fiakerlied” (A cabman’s song), again a song about the life and death of a cabman:

I hab zwa harbe Rappen,

Mei Zeugl steht am Grabn‘

….

Sei Stolz war, er war halt a echt’s Weanakind

Translation:

I have two lively horses

my cab is stationed at the Graben

…

His pride was that he was a true Viennese child

In 1940 the famous “Wienerlied” singer Schmid-Hansl was asked to perform in front of Josef Goebbels, the NS propaganda minister, and his guests from Berlin at a “Heurigen” in Vienna, Grinzing. Yet he refused, so Schmid-Hansl had to be coaxed into coming to the location, where he finally sang the “Fiakerlied”. Goebbels was enthusiastic and asked who had composed this wonderful song, when Schmid-Hansl answered, “a Jew”. An embarrassed silence followed, but Goebbels preferred to ignore the answer. Ernst Arnold performed this song again in 1942 in Berlin and as soon as the Nazis discovered that the song had been written by a Jew, Arnold was immediately deported to Vienna and the performance of the song of the “untalented Jew Gustav Pick” was prohibited.

Hermann Leopoldi (birth name: Hersch Kohn) was born in 1888 in Gaudenzdorf, a part of the 12th district of Vienna, Meidling. He received his musical training from his father, just as his brother, and they performed together in cabarets and music halls across the Habsburg Empire. Leopoldi incorporated the musical traditions of the Danube Monarchy. He was a German-speaking Viennese musician and singer, but for someone who was socialised around 1900 in the Habsburg Empire and became famous during the inter-war years, the musically, artistically, and ethnically inter-cultural area of Central Europe with its many influences was ever-present. Even if Leopoldi did not sing the Serbian or Hungarian songs in the original language, they accompanied his career and their rhythms and melodies influenced his compositions. The “Viennese element” remained a constant in Leopold’s artistic work, which his Hungarian-born Jewish father, Nathan Kohn, had already instilled in him. He was raised in the musical atmosphere of folk singers and his first compositions were influenced by traditional Viennese songs. After World War I he wrote amusing and ironic lyrics to accompany new American songs. Yet sometimes the songs could not be more Viennese, such as “Weidlingau” or “Dornbacherlied” – both titles citing place names in Vienna. In 1922 he wrote the morbid Viennese song “Wien, sterbende Märchenstadt” (Vienna, dying fairytale city), lyrics by Fritz Löhner-Beda and in 1930 “Beim Heurigen in Wien”, lyrics Arthur Rebner, again a song that made fun of and at the same time bemused a dying tradition, the “Heurigen”, that was being turned into a tourist attraction. He returned from exile to Vienna in 1947 full of self-doubts, but he continued to write songs, whereby his unperturbable optimism and carefree ease were the call of the day in a society that was still stuck in a leaden rigour. In 1948 he sang “I bin a waschechter Meidlinger Bua” (I’m a dyed-in-the-wool Meidlinger boy), which must have been a mixture of hard-won optimism and a traumatic negation of the past in the post-Nazi Viennese environment. The irony, Jewish self-mockery, the erotic vitality, and boisterous recklessness of his songs appealed to the post-war Viennese. Yet Leopoldi had never overcome the ordeal of two concentration camps, Dachau and Buchenwald, and the death of his relatives in the Holocaust. He was seriously ill with diabetes, smoked a lot and drank too much coffee, while working intensively without breaks, which led to his death in 1958.

Roland Neuwirth commented that the Viennese wanted to have a “schene Leich’” (“beautiful corpse”), no matter whether they were rich or poor. The poor paid into a burial insurance, “Wiener Verein”, their whole lives and wanted to boast a “beautiful corpse” in the end, so that they did need not to be ashamed. These “Leichenvereine” (“Corpse associactions”) in Vienna date back to Baroque Catholic fraternities and were wide-spread. The members paid monthly into such funeral funds and in 1930 the relatives of the deceased received 300 Austrian shillings for a dignified burial ceremony, “a schene Leich’”.

It was a common notion in Vienna that the dead would be received at the pearly gates of heaven by angels who filled their wine glasses and by the famous Viennese musicians, Ziehrer, Lanner and Strauss, who played for them in heaven. They would be sitting in the first row of clouds because the Viennese were the Father in heaven’s preferred children. My grandmother, Lola, confirmed this Viennese notion, when she told me with a wink that she would be sitting on a cloud in heaven and would be having a lot of fun singing, seeing her beloved husband Toni again, looking down on us and sending us her love, once she was dead.

This Viennese sentimental illusion inspired Georg Kreisler (1922-2011) to write the humorous song “Der Tod, das muß ein Wiener sein” (Death must be a Viennese). He had to flee Vienna, too, and ended up in the United States, where he performed in front of US troops. As a US citizen he returned to Vienna in 1955 and became director of a theatre together with the exile Gerhard Bronner, where both continued to write and perform sarcastic Viennese songs:

Da droben auf der goldenen Himmelsbastei,

Da sitzt unser Herrgott ganz munter

Und trinkt ein Glas Wein oder zwei oder drei

Und schaut auf die Wienerstadt runter

….

Der Tod, das muß ein Wiener sein,

Genau wie die Lieb a Französin.

Denn wer bringt dich pünktlich zur Himmelstür?

Ja, da hat nur ein Wiener das G’spür dafür.

Der Tod, das muß ein Wiener sein.

Nur er trifft den richtigen Ton:

Geh Schatzerl, geh Katzerl, was sperrst dich denn ein?

Der Tod muß ein Wiener sein.

Translation:

Up there on the golden bastion of heaven,

Our Lord sits, full of cheer,

Drinking a glass of wine or two or three,

And looking down on the city of Vienna.

…..

Death must be a Viennese,

just like love is French woman.

For who will take you to heaven’s door on time?

Yes, only a Viennese has the knack for it.

Death must be a Viennese.

Only he strikes the right note:

Come, sweetheart, come, darling, why are you locking yourself in?

Death must be a Viennese.

Old Jewish Cemetery Währing

Here one can find the graves of Jewish men and women of different social status, wealthy and titled members of the Viennese society, who had access to the Habsburg Empire’s rich and powerful aristocratic circles, as well as members of the bourgeoisie, such as lawyers, doctors, merchants, teachers and employees of all kinds. Representatives of different trades were buried here as well, such as the much-despised “Branntweiner”, who produced and sold cheap spirits to the poor in grimy little pubs, furthermore artisans, such as hat makers, umbrella makers, glove makers, smiths, upholsterers, and dyers; furthermore musicians, from street musicians to members of the orchestra of the Vienna Court Opera House, peddlers, beggars and 31 persons, who had committed suicide, mostly in 1973, when the stock market in Vienna crashed and triggered a Europe-wide economic crisis. Suicide victims were not denied a burial place within the walls of this Jewish graveyard, as was the rule in Catholic cemeteries of the time. Especially women and children died very young; many babies and toddlers did not survive the first years. The buried originated from all corners of the Habsburg Empire and from many German cities. In 1880, when the last burial took place in this graveyard, more than 73,000 Jews lived in Vienna.

The graveyard is out of use as it was closed in 1874, when the “Zentralfriedhof” was opened, yet many important Jewish personalities of the 19th century were buried here, such as members of the families Oppenheim and Arnstein, of whom the salon lady Fanny Arnstein was the most famous.

Anton Strauss is also likely to have been buried here. His widow Adele married the world-famous “Waltz King” Johann Strauss Jr., who took in Anton and Adele’s daughter Alice. To make the marriage possible, both converted to Protestantism. However, many years later, in 1939, Alice’s Jewish heritage led to persecution by the Nazis and to the later expropriation of the heiress, who possessed a large amount of Strauss memorabilia.

Anton Strauss is no longer buried in the Währing Jewish Cemetery; neither are his mother Wilhelmine and his sister Hermine, who died at the age of four. All three bodies were exhumed in August 1941 and reburied at the “Zentralfriedhof”.

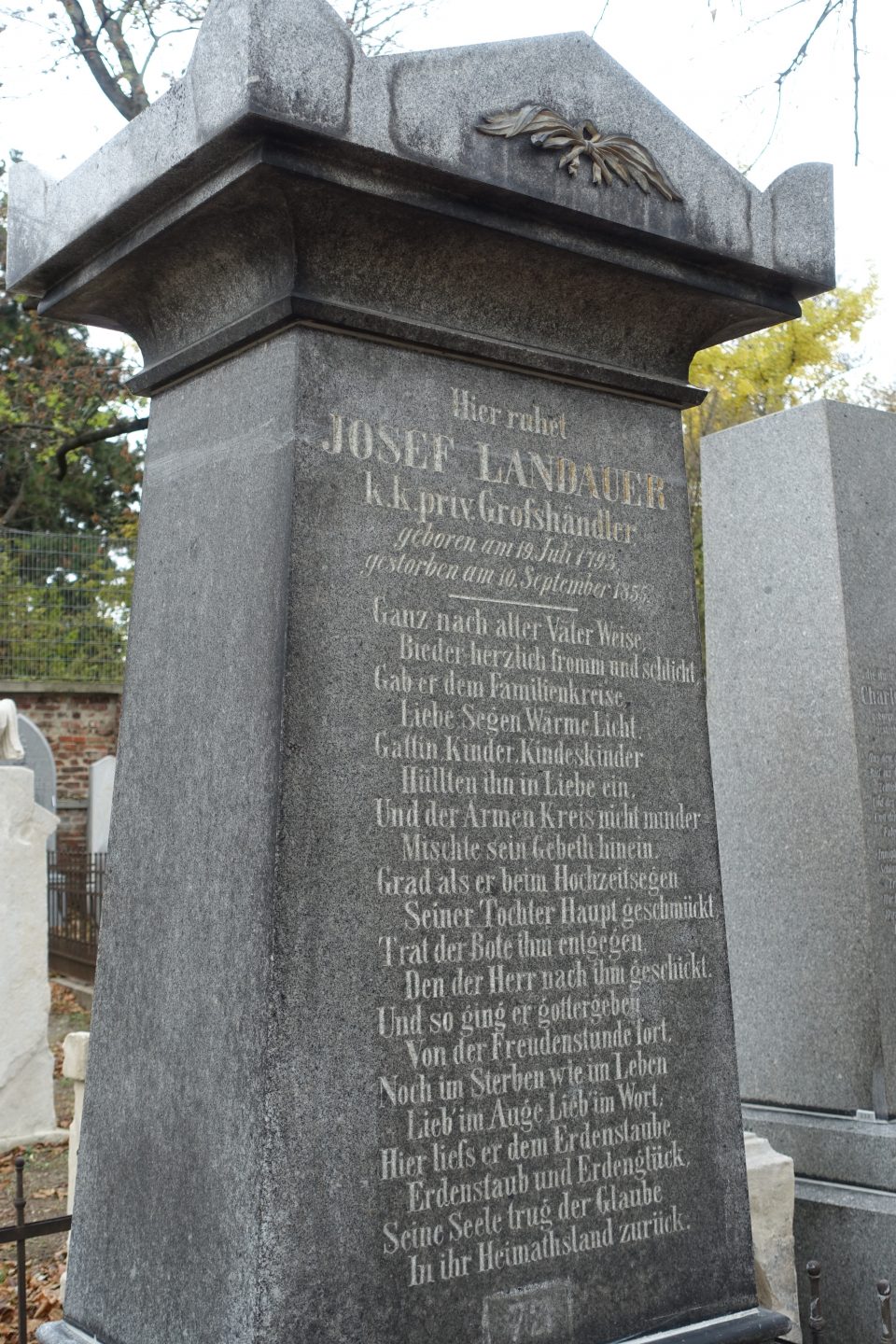

The Jewish families, who were important pillars of the Habsburg Empire, such as the Epstein (left) and Landauer (right) were buried here

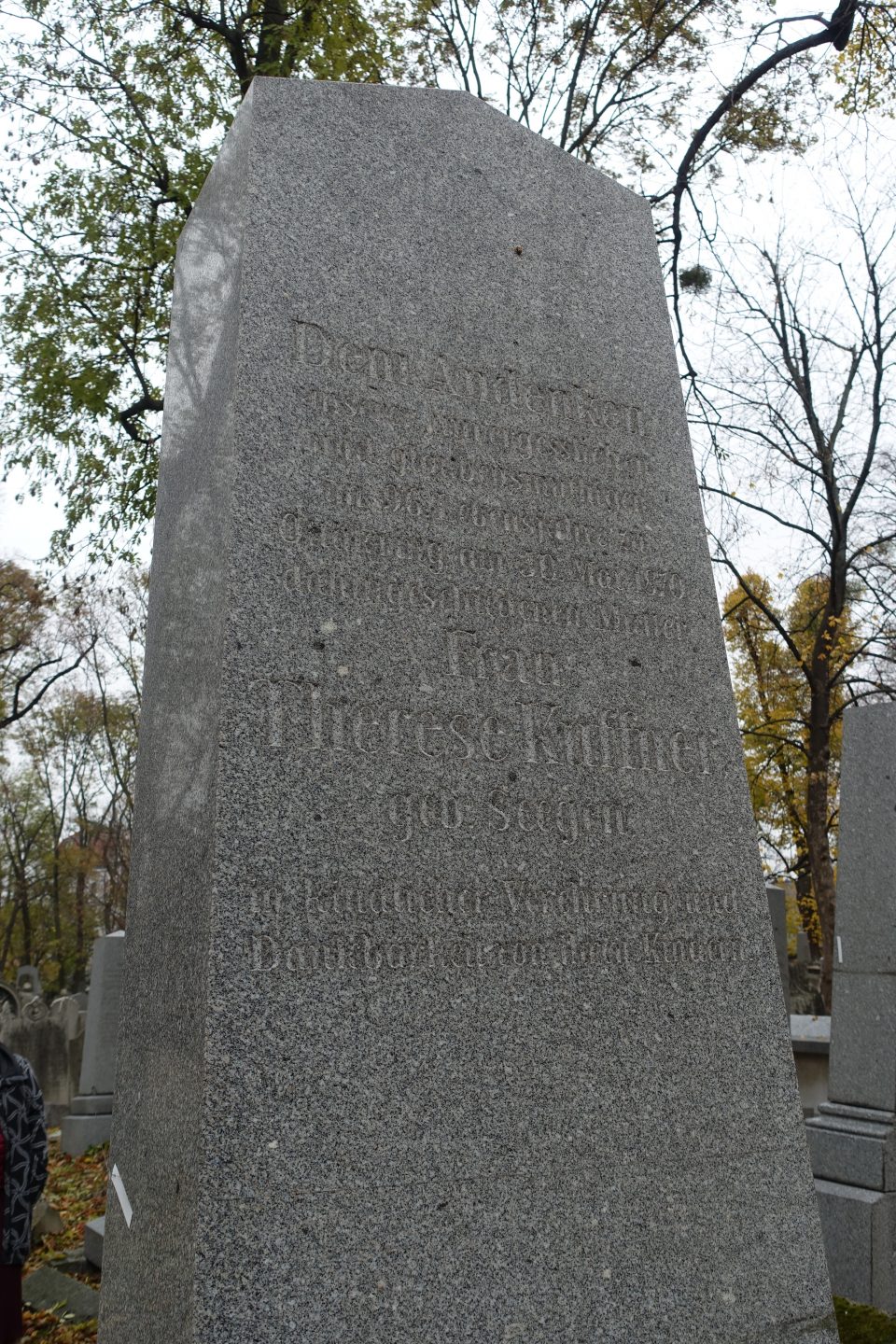

… as well as the families Schey (left) and Kuffner (right)

… and families Wertheimer (left) and Pollak (right)

…and the families Ephrussi, Sichrovsky and Grünebaum

Vienna until 1938 was not just a city, it was a way of life: one did not take oneself too seriously, but music and the theatre so much the more. One met with friends at the “Heurigen”, drank wine, and sang of death and the Father in heaven or went to the coffee house, where one met all those intellectuals and dandies with nothing to do, who did not believe in prowess or the significance of achievements; cosmopolitan, sometimes even provincial, but never pathetic or humourless. In 1938 all that changed: the formerly much-loved and praised darlings of Viennese society, the writers, musicians, artists, and intellectuals were suddenly spat at, degraded, insulted, and physically attacked. Dispossession, persecution, and murder in the Holocaust followed. The Jews were a segment of Viennese society that the city’s culture could not do without. These artists and intellectuals had loved Vienna from the bottom of their hearts and they had contributed to a large degree to the Viennese culture and identity as we now know it. Milan Dubrovic wrote that Vienna had become a different town from one day to the next in March 1938; it was an absurdly strange city, which resembled an empty stage setting that just represented a memory of the past. The absurdity of the situation of 1938 was illustrated by the fact that many Viennese assisted in the process of extermination of their indigenous culture and identity. It is the greatest joke in history that those Viennese who cheered the “Anschluss” of the Nazis, never really loved their hometown’s culture and identity. When Goering said that Vienna had to become a “German city again”, it was a complete absurdity. The German writer Thomas Mann wrote in exile that the Austrian people were of no significance to the German Nazis, they did not care for them at all and if they did not hate the Austrians, they were at least alien to them. Those who could flee the Nazi oppression, never felt at home abroad. The singer Hans Jaray noted that as soon as they had arrived in exile, they were dreaming of their return. Homesickness (“Heimweh”) now had a double meaning – it hurt now to think of home. After 1945 those who had survived the Holocaust, hoped to receive an invitation from home to return to Austria, but that call never came. They were not welcomed home, on the contrary, there was silence and no expressions of regret.

Of some of the much-loved darlings of the Viennese musical scene before 1938 it is not known where and when they were murdered or what was their destiny. These musicians and composers just disappeared, were silenced and in post-war Austria ignored and eliminated from memory. Two famous Viennese songs depict this tragic and silent farewell of the Viennese musical artists: “Sag beim Abschied leise Servus” by Peter Kreuder, 1936 (At parting say a silent “servus”) and “Nicht Lebewohl, nicht Adieu” (Not goodbye, not adieu) by Richard Czapek,1913-1997). Gustav Pick’s songs for example are almost all lost except his famous “Fiakerlied”, which was forbidden by the Nazis. Hermann Leopoldi was forced by the SS to sing this song on the transport to Buchenwald in a cattle carriage. Gustav Pick was an uncle of Arthur Schnitzler and the author Friedrich Torberg called the “Fiakerlied” a “jewel of Viennese – Jewish symbiose”. The famous actor Paul Hörbiger continued to sing it during the NS period despite Nazi warnings, which contributed to the death sentence the Nazis pronounced in 1945 over Paul Hörbiger for collaboration with resistance groups. He was saved in time by the Allied liberation.

At the “Heurigen”, where the Viennese songs were often performed, there was no class differentiation. The poor and the well-to-do sat on the same wooden benches and drank the same new wine and listened to the same “Wienerlied” music. Especially here the Viennese indulged in “Weltschmerz” (melancholy) and death nostalgia. The Viennese dialect, in which the lyrics of Viennese songs are usually written, has developed in a multi-cultural city and is therefore influenced by many French, Italian, Czech, Hungarian and Yiddish words. Hitler did not only hate Vienna, but also the Viennese idiom, and that is why he wanted to eradicate the “Heurigen” tradition and the traditional “Wienerlieder”, which were composed and written by “non-Aryans”, such as Eysler, Kalman, Leopoldi, Benatzky, Adolfi, Ascher, Katscher, Löhner-Beda, or Krakauer. The Nazis destroyed all scores of Jewish musicians they could get their hands on. In 1939 playing music in the streets and in courtyards, which was common in Vienna, was forbidden by the Nazis. Even the stars made of straw, which signified that a “Heurigen” was open and selling new wine, were prohibited because they – in the eyes of the Nazis – resembled the star of David; hence only branches of pine trees were allowed. Johann Strauss, the famous Viennese composer and one of Hitler’s favourite musicians, was of Jewish origin, which had to be “remedied” by the Nazis. They sent the marriage register of Saint Stephen’s Cathedral, where next to the name Johann Strauss was written: “grandfather, Jewish, single, born in Ofen” to Berlin. There the page was cut out of the register and replaced by a faked copy without mention of Strauss’ Jewish origin.

The Viennese are known to bluff their way through life, to prefer avoiding conflicts, and to flee reality if necessary. Wine and songs can be helpful hereby and coping with death in this way can be useful, too. Suicide is another topic that can be handled ironically in Vienna. The writer Johann Nestroy said that many think suicide is an expression of cowardice, but they should try it first before they talk about it. And the former Jewish-born Social-Democratic Austrian Chancellor Bruno Kreisky is said to have commented in the 1970s, when he was told that his minister of defence, Lütgendorf, had committed suicide, “No, wenn er sich’s verbessern kann!? (If he can better himself!?) The news was wrong, but tragically Lütgendorf really committed suicide a few years later. With respect to death another Kreisky quip is documented: When he was asked in 1975 after five years as chancellor, when he would retire, he reportedly said, “Sterben muß jeder, aber drängen laß’ I mi net” (Everyone has to die, but I won’t be rushed).

Oldest Viennese Jewish graveyard Rossau (9th district, Seegasse)

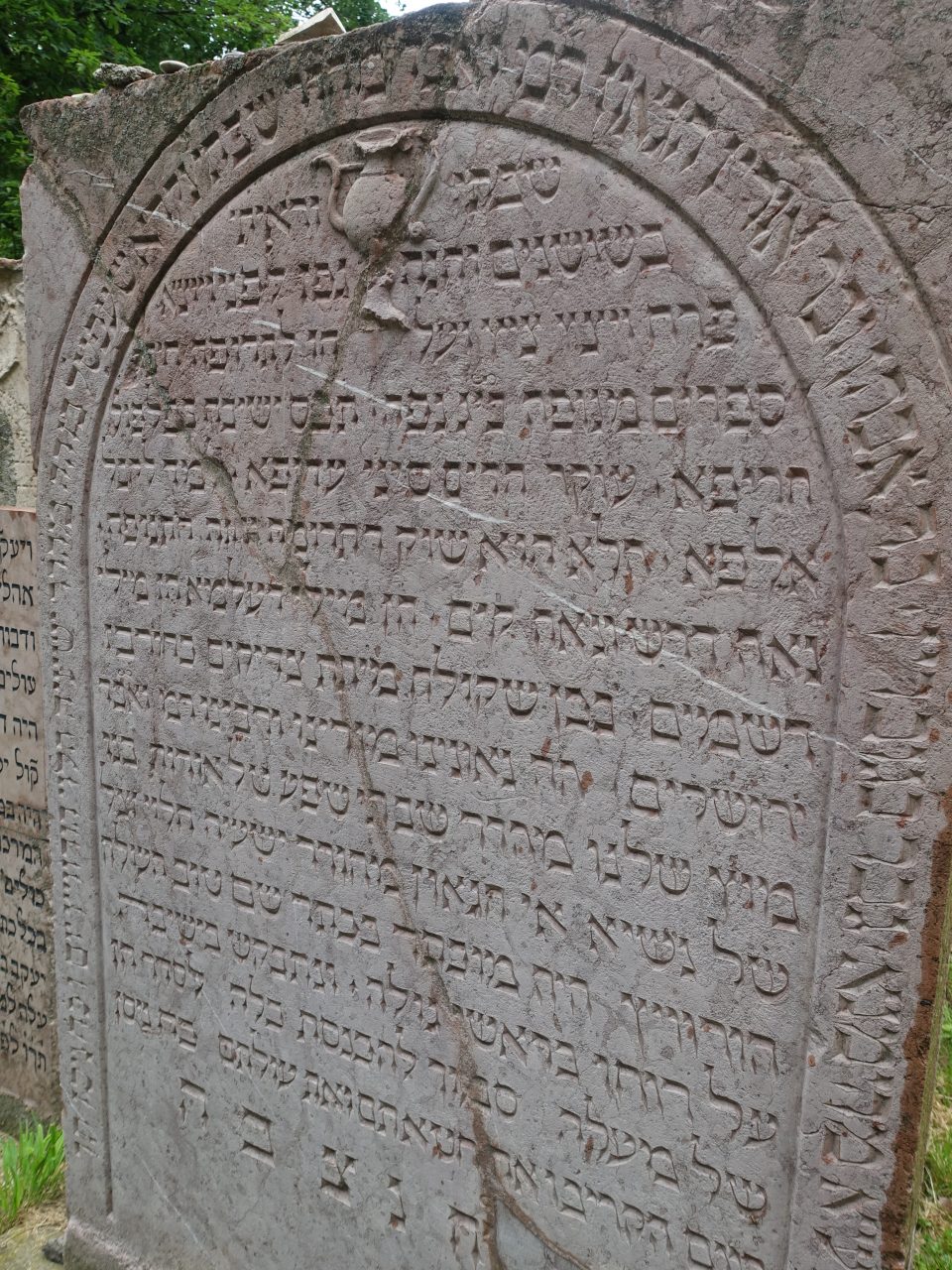

The graveyard is now situated in the courtyard of a retirement home. It was completely devastated by the Nazis and researchers are in the process of piecing together fragments of gravestones which can be found as far away as the “Zentralfriedhof”. They are reconstructing this oldest orthodox Jewish cemetery that dates back to 1570 and only contains grave stones inscribed in Hebrew. In 1784 no more burials were allowed in this area, when the Jewish part of the cemetery in Währing was opened. Experts are now trying to find the original positions of the gravestones they uncover, but the largest part of the graveyard is situated under existing buildings. In 1941, when it was decreed that all Viennese Jewish cemeteries were to be dissolved, part of the Jewish graveyard in Währing was declared a bird sanctuary and thereby preserved. The graveyard in the Rossau was to be levelled as well. What was rescued of the human remains and grave stones was secretly hidden under heaps of earth on site or at the “Zentralfriedhof” and other hidden places. It is said that a NS party member convinced the Nazis, who planned the complete destruction of the Rossau cemetery, to keep some mementos of the Jewish past in Vienna for a planned museum after the extinction of the Jewish race and the final victory of the NS regime, the “Endsieg”. That is the reason why a small part of this graveyard could be preserved.

It is one of the oldest Jewish cemeteries in Europe and its approximately 900 grave stones can be dated between 1450 and 1783. One of the most interesting graves is the one of Samuel Oppenheimer (1630-1703), the banker who was financing the Habsburg Empire’s military campaigns against the Osman Empire and the French King. The Habsburgs never paid back their debts and consequently the Oppenheimer bank went bankrupt. There are several graves of influential bankers, industrialists, and railway engineers, of the families Hoenig, Epstein, Pollak, situated here, as well as so many unknown “little people” of humble professions.

The gravestone of Rabbi Sabbatai Scheftel, who was a much-admired Jewish scholar from a family of rabbis who were of extraordinary importance in the Prague Jewish community. He was probably born in 1590 in Volhynia and arrived in Vienna in 1658, where he died in 1660. His most important work “Sawwa’ah” was printed in Amsterdam in 1649 and orthodox Jewish pilgrims still pray at his grave here.

The gravestone of Rabbi Sabbatai Scheftel, who was a much-admired Jewish scholar from a family of rabbis who were of extraordinary importance in the Prague Jewish community. He was probably born in 1590 in Volhynia and arrived in Vienna in 1658, where he died in 1660. His most important work “Sawwa’ah” was printed in Amsterdam in 1649 and orthodox Jewish pilgrims still pray at his grave here.

LITERATURE:

Dachs, Robert, Sag’ beim Abschied…, Verlag der Apfel, Wien 1994

Der jüdische Friedhof in der Seegasse, wiederhergestellt, Bundesdenkmalamt 2012

Heimlich, Jürgen, Wiener Zentralfriedhofs-Führer, tredition 2019

Johnston, William M., The Austrian Mind. An Intellectual and Social History 1848-1938, University of California Press 1972

Keil, Martha ed., Von Baronen und Branntweinern. Ein jüdischer Friedhof erzählt, Mandelbaum Verlag Wien 2007

Kunz, Johannes, “Der Tod muss ein Wiener sein…“. Morbide Geschichten und Anekdoten, Amalthea Wien 2009

Smith, Duncan J.D., Nur in Wien. Ein Reiseführer zu sonderbaren Orten, geheimen Plätzen und versteckten Sehenswürdigkeiten, Verlag Christian Brandstätter 2005

Traska, Georg & Lind, Christoph, Hermann Leopoldi – Hersch Kohn. Eine Biographie, Mandelbaum Verlag Wien 2012

Veigl, Hans, Der Friedhof zu St. Marx. Eine letzte biedermeierliche Begräbnisstätte in wien, Böhlau 2006

Veran, Traude, Das steinerne Archiv. Der alte Judenfriedhof in der Rossau, Mandelbaum Verlag Wien 2002