VIENNESE JOURNEYS INTO THE COLD WAR. LITERARY AND PERSONAL IMPRESSIONS

Travel diary entry of my mother, Herta Tautz, on 20 September 1977 in Krakov, Poland. On their 25th wedding anniversary my parents, Herta and Werner Tautz, the creators of travel slide shows to the East Bloc countries, clinked glasses with Russian champagne at the Holiday Inn hotel

“Austria island of the blessed”?

The writer Jörg Mauthe ironically called Austria the “island of the blessed”, because many Austrians considered the country as a kind of “special case” since the early Cold War, which could be kept out of any political and military crisis or conflict and some still believe this today. Unfortunately, this concept has always been imaginary and never realistic and it is just as illusionary today. Since 1945 Austria has always been an “object” in the international arena rather than a “subject”, an actor. Local knowledge about the early incidents of infringement of Austrian territory by foreign conflicts is rare. There were Ukrainian partisans crossing Austria in the spring of 1945, terrorist attacks in the late 1940s, military emergency plans of the Western Allies in case of a Soviet aggression during the early Cold War years and intensified secret service and spy activities of all four Allied occupation armies, the Soviets, the Americans, the British and the French. Furthermore, the Soviets secretly supported the October strikes in Austria in 1950, they militarily suppressed the Hungarian anti-Communist revolution in 1956, when a wave of refugees swept across Austria and there was the Lebanon crisis in 1958 with Western military jets violating the Austrian airspace – to name just a few incidents. In all these and the following foreign conflicts, which affected Austria, the country never played an active part on the international stage that could influence its destiny; except during the 13-year chancellorship of Bruno Kreisky from 1970 until 1983. The State Treaty of 1955 marked the resurgence of Austria as an independent state and the withdrawal of all occupying armies on the condition of Austria’s neutrality. The first test of this neutrality was the crisis in Hungary on the eastern Austrian border in 1956 and the threat of a Soviet invasion, imagined or real. Austria had to be aware that in this East – West confrontation it was well-advised to establish a fair balance between and a safe distance from the Soviets as well as the Americans. While Austria started out with a pronounced pro-American policy, yet in the face of multiple international crises Austria approached the Soviet Union as well and tried to style itself as a hub in the Cold War and a crossroads between East and West. Bruno Kreisky, first as foreign minister and then as chancellor, developed a form of “active neutrality”, different from the Swiss one, and put it into practice as a “policy of the possible”. With the end of the Cold War in 1989 Austria had to re-define its neutral position in Europe, which led to Austria joining the European Union in 1995. The concept of the “island of the blessed”, which had always been just fiction, was consequently obsolete.

Until the coming down of the Iron Curtain, Austria bordered Communist dictatorships along more than 1,000 km. The frontier to Hungary and Czechoslovakia was hermetically sealed off with electric fences, trenches, and guard posts, a true “Iron Curtain”, as the British prime minister Winston Churchill had called it in a speech in 1946 already before the start of the Cold War. Due to the many Cold War crises, such as the building of the Berlin wall in 1961, the Cuban crisis in 1962, the uprising in Prague 1968, the Polish upheavals in 1980/81, Austria had to re-define its neutrality progressively. In 1955 the British predicted that Austria would act “neutralistically” – this negative term was used because Moscow had insisted on Austria’s neutrality, although the Western Allies had been against it – and that Austria would be a “double agent between East and West”.

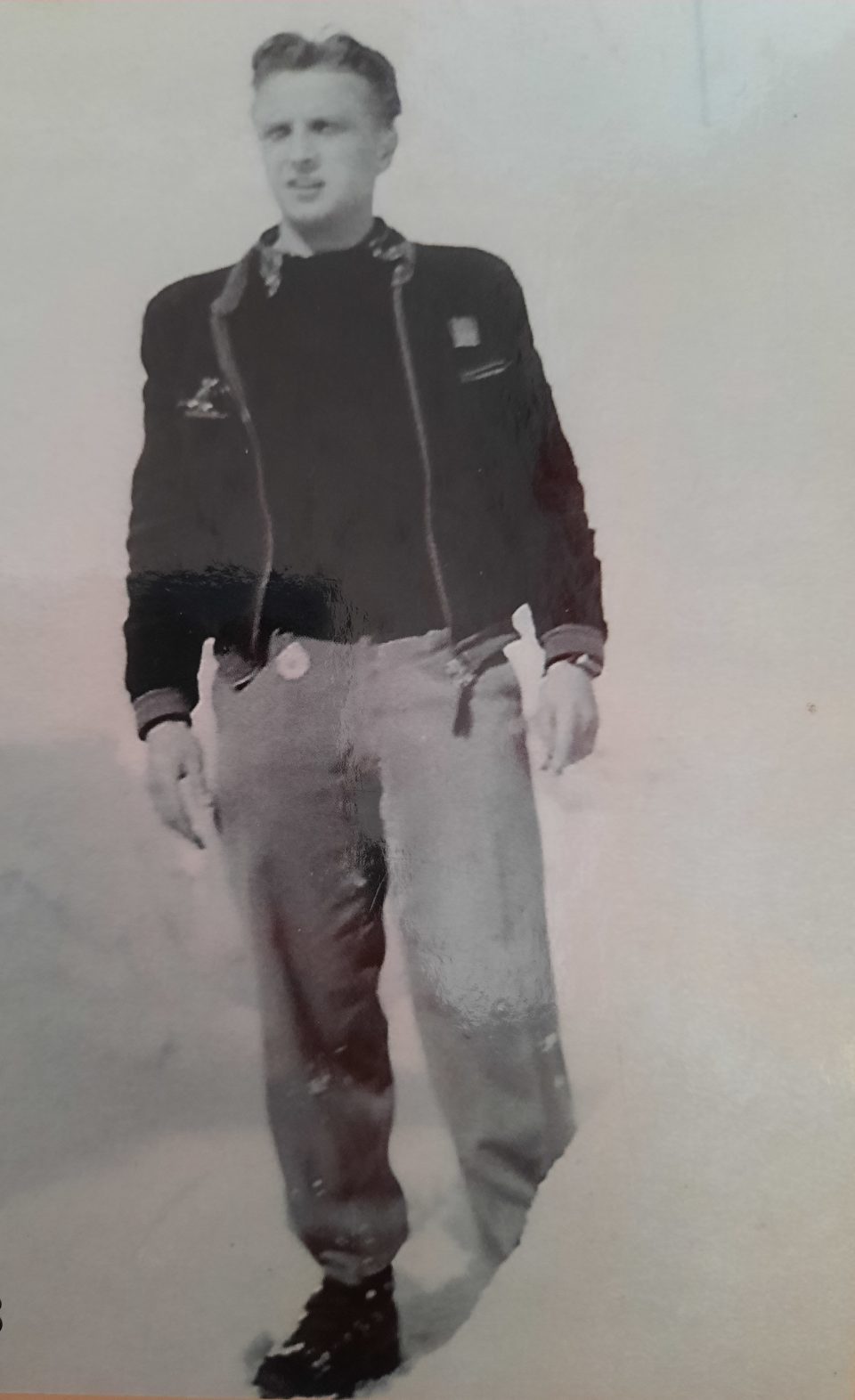

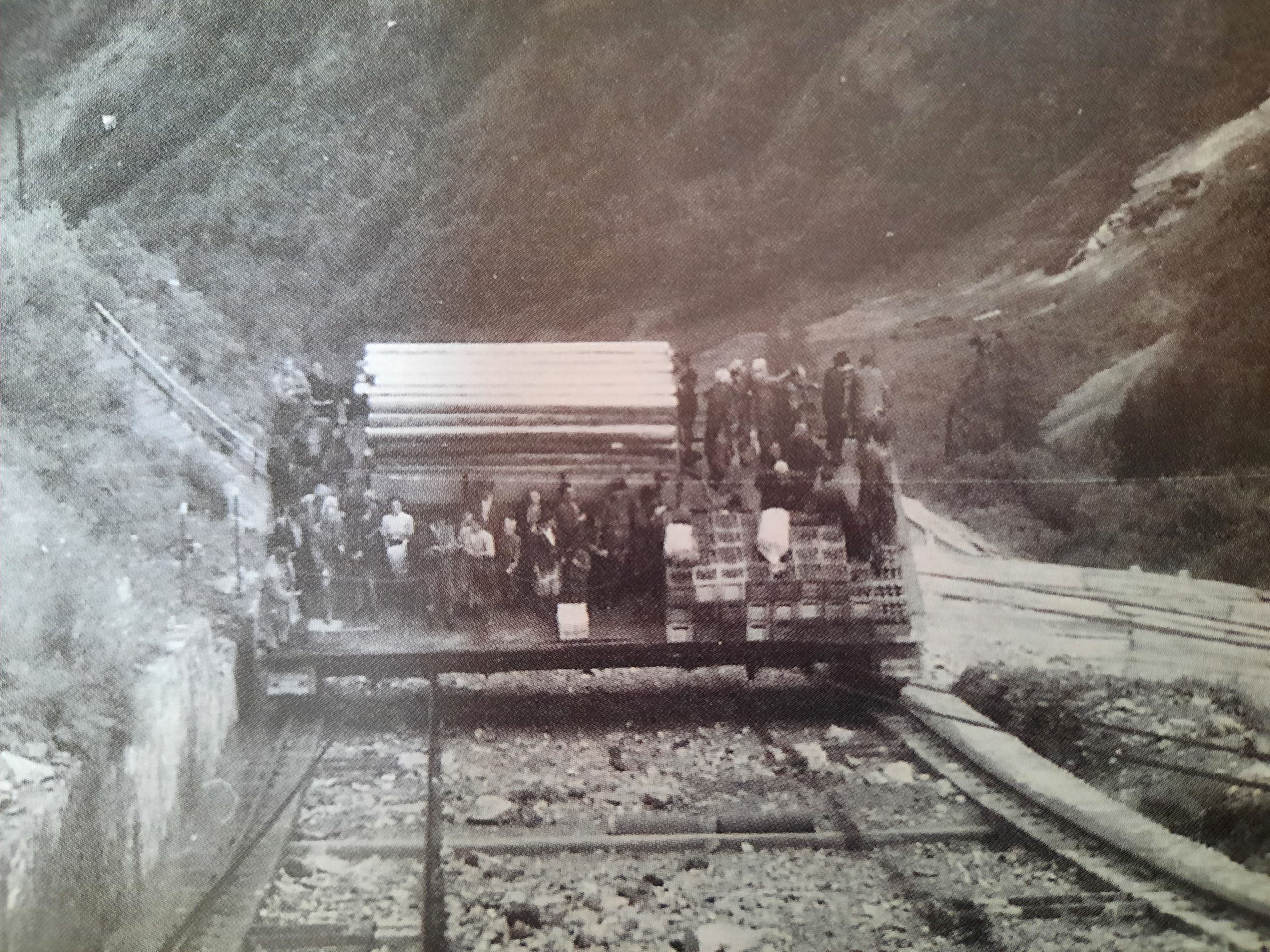

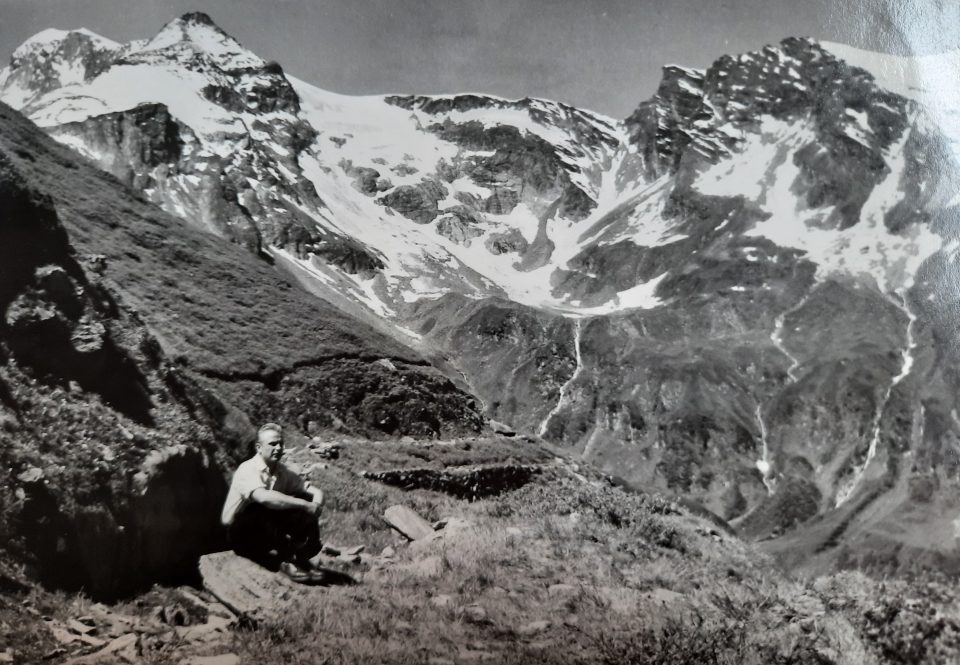

Werner’s contemporary photo impressions of everyday life in Vienna during the early Cold War

The start of the Cold War

After the end of World War II, the process of a formation of two fiercely competitive blocks – East and West – started the Cold War in 1947 in Austria. This was the beginning of the establishment of a bi-polar world and a new international order after the break-down of a European system of states which had been created by the National-Socialist expansion of the “Third Reich”. This culminated in a military power struggle and an ideological confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union. The two contrasting poles developed their own unique social, political, and economic orders, which they tried to impose on the rest of the world in a competitive manner. The atmosphere between the two power centres was characterised by a constant fear that the opposing side could infringe on the influence sphere they claimed for themselves and by that threaten their security interests. This led to the political division of Germany and Europe and a mentality of permanent siege and fierce competition for spheres of interest and military presence world-wide. In this so-called “Cold War” there was no clearly defined aggressor and no clearly defined defender. The ideological confrontation was characterised by a constantly changing situation that was dictated by the actions and reactions of the other side. Objectively it cannot be stated without doubt who started the Cold War. While immediately after the end of the war, the USA acted in a rather circumspect way towards its former ally, the Soviet Union, Stalin already exercised an aggressive expansionary policy in Eastern Europe. After a phase of permanent mutual mistrust, the United States reacted much more aggressively to the new post-war Soviet “security policy” at the beginning of 1946. Both world powers progressively stepped up their willingness to go into a geopolitical confrontation between 1945 and 1947. Despite its own military and economic capacities, the USA progressively perceived the Soviet Union as a threat to Europe and the rest of the world.

Towards the end of World War II, the British Foreign Office had expressed ideas for a post-war resurrection of the state of Austria as independent from Germany and the British found that this independence could best be guaranteed by an “ultimate association of Austria with some form of Central or South-East European Confederation”. Yet the Soviets were strictly against any confederation of Austria with Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and Poland, which would in their eyes create a Catholic conservative alliance that could threaten the Soviet Union. When Winston Churchill launched his idea of an independent Central European block of states, Stalin rejected this concept categorically, because he feared a resurrection of the Austro-Hungarian Empire as a “Danube Confederation” of Austria, Bavaria and other neighbouring Catholic states under Otto Habsburg, the successor to the throne of the abolished Habsburg Empire, which could as a result form a block with other Catholic European states, such as Spain, Italy, France, and Poland.

The Soviets wanted to exploit the Austrian economic capacities as a compensation for the massive war damage, which had been caused by the German “Wehrmacht” in the Soviet Union. Tens of thousands of Austrians had served in the German “Wehrmacht”. At the conference of the ministers for foreign affairs in Moscow in April 1947, US General Mark W. Clark blocked an agreement for a State Treaty for Austria, because he feared that the huge Soviet reparations demand would politically destabilise Austria. Earlier in spring 1945 the US had shown very little interest in the future political development in Austria and had concentrated on their projects for post-war Germany, but when in October 1945 the Soviets tried to take over the two biggest financial institutions in Austria, the “Creditanstalt-Bankverein” and the “Länderbank”, the US started to be alarmed. The US had already promoted an “Austrification” of the media and had launched the radio broadcasting station “Rot-Weiß-Rot” (RWR) and the newspaper “Wiener Kurier”, both with a rather pronounced anti-Communist tendency. When the first post-war elections in Austria in November 1945 resulted in a devastating defeat of the KPÖ (Austrian Communist Party) with only 5.41 per cent, the Soviet political officers were not amazed because they had never believed in the predicted 20 per cent for the KPÖ, as the Communist party had not achieved more than 10 per cent in the works council elections despite excessive Soviet election campaigning. From now on the Soviet policy in Austria became much more rigid. The Soviets demanded from the newly elected Austrian government a strict persecution of Nazis and the dismissal of all NSDAP members and former Austro-Fascists from official positions. Before the start of the Cold War in Austria the Soviets were prepared to forego the seizure of “German property”, if it had been Jewish business property that had been robbed by the Nazis and if it was economically not too important for Soviet Union. They either tried to return it to the original owners or put it under provisional administration. After the election in November 1945 the Soviets confirmed the importance of the continued stationing of Soviet troops in Austria and blamed the Western Allies for the failure to come to an agreement on the Austrian State Treaty. They hoped that the KPÖ would profit from the negotiations concerning Austrian sovereignty and independence, but to the contrary. The Austrians put the sole blame on the Soviets for the continuing presence of Allied occupational troops in Austria in the end. Access to Russian archives after the coming down of the Iron Curtain in 1989 proved the strong dependence of the KPÖ on the Soviets, but these researches also showed that the Soviets recognised the special geographical position of Austria as a “country between the two blocks”, Surprisingly, the data showed that they did neither favour a Communist coup d’état in Austria nor a separation of the country into an eastern and a western part like Germany.

…